Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/5003/01. The contractual start date was in June 2014. The final report began editorial review in November 2017 and was accepted for publication in April 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

David J Stott reports grants from National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) during the conduct of the study. Peter Langhorne reports grants from NIHR, grants from the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme during the conduct of the study and HTA Clinical Trials Board Membership (2014–18). Sasha Shepperd reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study and membership of the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research commissioning panel. Mary Godfrey, Graham Ellis and Pradeep Khanna report grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Gardner et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

The health-care context of the research

Concern about the organisation and quality of health-care services for frail older people has been voiced for a number of years. In the 1930s, the high rate of institutionalisation for frail older people was brought to attention by the pioneering work undertaken by Marjory Warren, Lionel Cosin and Sir Ferguson Anderson,1,2 who noted that medical, psychological and social dimensions were seldom assessed and active rehabilitation was rarely provided to older people who required hospital-level health care. Organising health systems to optimise the health outcomes of older people, and at the same time contain costs, continues to be a priority as populations around the world age and the demand for health care continues to rise. People over the age of 65 years are the largest users of hospital care in the UK,3 and when there is a breakdown in the quality of care the consequences for older people can be devastating. 4,5 A growing older population is accompanied by an increase in the rates of chronic illness and hip fractures and in the number of people with cognitive decline and dementia that, when combined with a physical decline in health, will have a large impact on health and social care services. 6 Evidence is required on how to provide high-quality cost-effective health care to the growing number of older people who are living with multiple long-term conditions. 7

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

Efforts to improve the assessment and care planning for older people in hospital have often centred on the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA), a multidisciplinary diagnostic process that is focused on determining a frail older person’s medical, functional, psychological and social capability to ensure that problems are quantified and managed appropriately. 8 The multidisciplinary team (MDT) that delivers the CGA includes, at a minimum, specialist medical, nursing and therapy staff and social services representatives. Members of the MDT are responsible for goal-setting, delivering the recommended treatment or rehabilitation plan (such as physiotherapy input or occupational therapy, diagnostics or medical treatment) and complex discharge planning. The benefits of the CGA (e.g. a reduction in mortality and the need for long-term care) have been confirmed in several systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials (RCTs). 9–14

Over the past 30 years, the CGA has developed and it is now being delivered at different levels of intensity in different settings. 8,13,15 Examples include a designated inpatient unit for the CGA and rehabilitation, an inpatient consultation service in non-designated units, the CGA in a hospital-at-home setting and as an outpatient assessment service, and the CGA in nursing homes. There is an expectation, both within the UK NHS and elsewhere, that moving care out of hospital will improve population health, the quality of patient care and patient outcomes, and will reduce costs. 16 However, although there is little disagreement that the CGA is a worthwhile process, there are questions about the implementation of the CGA at the interface of hospital and community care, the cost-effectiveness of hospital CGA and the goals, structure, processes and elements of geriatric assessment for clinical decision-making. Despite a global policy emphasis on care closer to home,16 efforts to innovate and provide health-care services that provide an alternative to hospital admission for older people have been piecemeal, and they often lack a health-system perspective.

Summary of the programme of research and overview of methods

This programme was developed by a collaboration of researchers and clinicians in response to a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research call for proposals on how to deliver the CGA in a cost-effective way. The aim of the research was to improve our understanding of the effectiveness, implementation and cost-effectiveness of the CGA across secondary care and acute hospital-at-home settings. The objectives of the research were to:

-

improve our understanding of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the CGA across hospital and hospital-at-home settings

-

describe the content and process of implementing the CGA and the barriers to implementing the CGA from a patient, carer and health service perspective across acute hospital and hospital-at-home settings

-

improve understanding and develop consensus of the key components of the CGA through an incremental synthesis of the data collected across the programme of research.

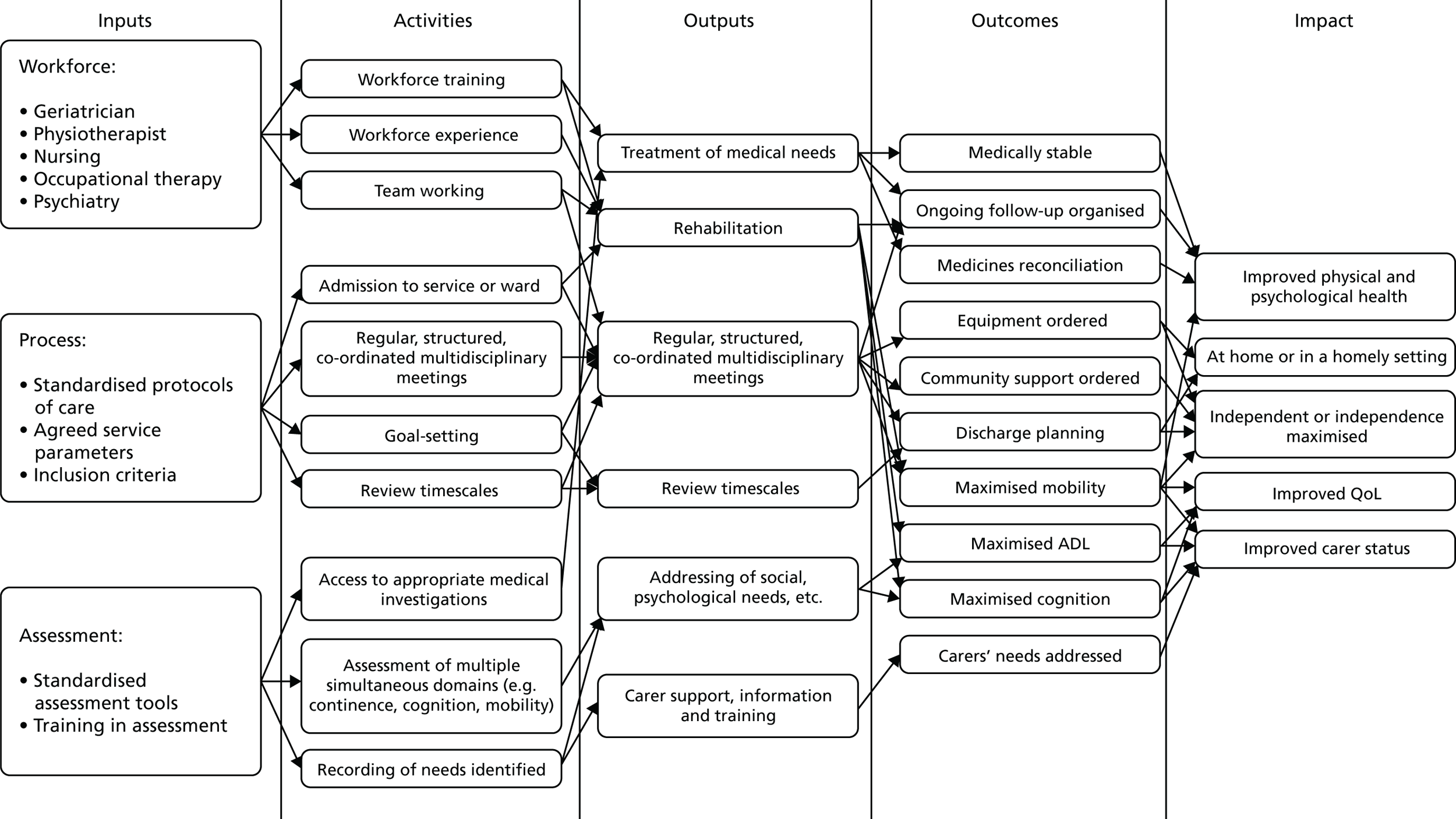

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment is a complex intervention that provides a structured way of organising health care for older people, to reduce dependence and maintain independence by targeting health-related events that bring about a functional decline and are not uncommon in older people requiring hospital-level health care. Possible pathways that might constitute the mechanism of action of the CGA include a multidimensional structured assessment that informs care planning, clinical leadership, MDT working, implementing the care plan and goal-planning. A co-ordinated approach, and avoiding fragmented care, is a key feature of the CGA in much the same way as it is a defining characteristic of stroke units. 1

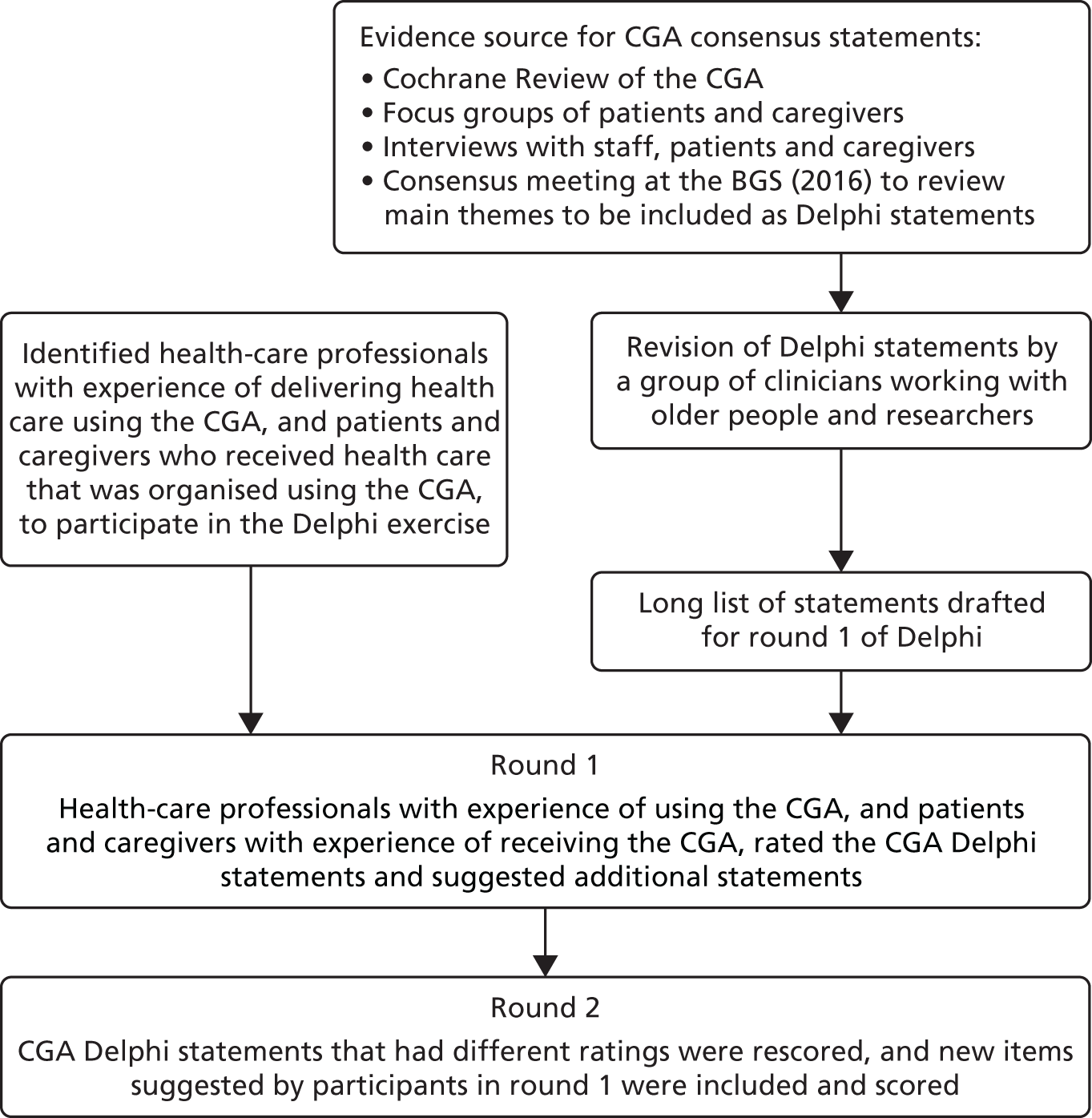

We used different research methods to generate different types of data to assess cost-effectiveness, to identify the substantive aspects of the CGA from the perspective of health-care staff, patients and caregivers and to draw out policy-relevant research findings (Table 1). We integrated the different sources of data through the use of a Delphi exercise, and we built on a protocol logic model to guide the integration of the key findings from each project. We used the theory of change17 to guide the development of the logic model and to identify the mediating factors that might affect the outcomes of the CGA. We refined and challenged the logic model during the course of the research with the findings from the interviews with staff, patients and carers.

| The cost-effectiveness of the CGA | Implementation of the CGA in different contexts | Develop consensus of the key components of the CGA |

|---|---|---|

| Update of the Cochrane review of the CGA with IPD, modelling of cost-effectiveness, a survey of international triallists and refinement of a logic model | Survey and follow-up interviews, in-depth case study and interview study of the implementation of the CGA in inpatient and community settings and analysis of Scottish administrative data | Consensus meeting and Delphi exercise with clinicians, patients and carers |

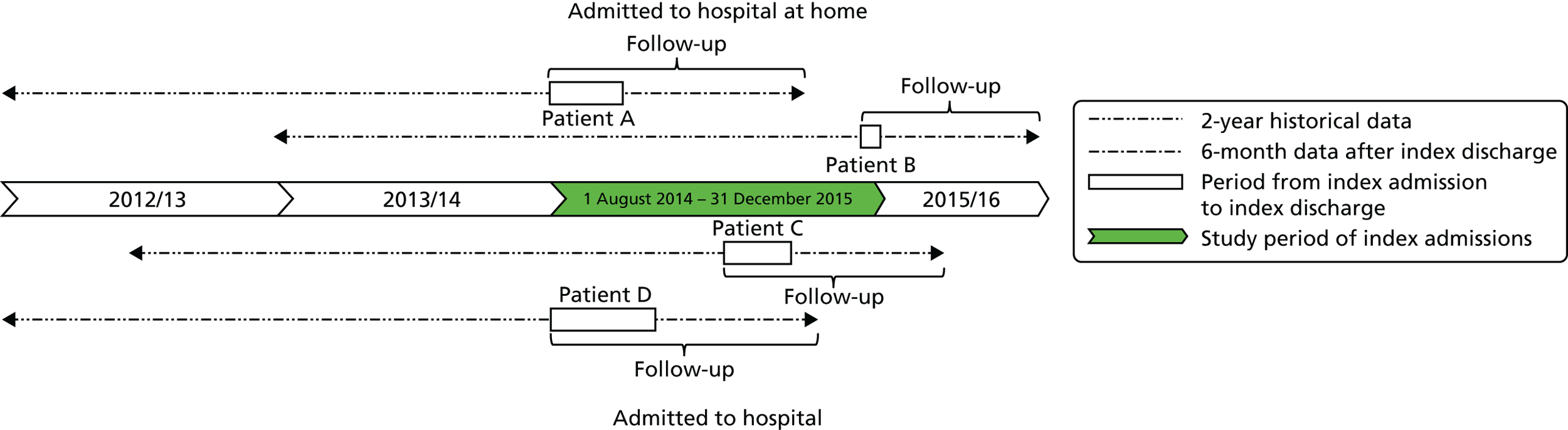

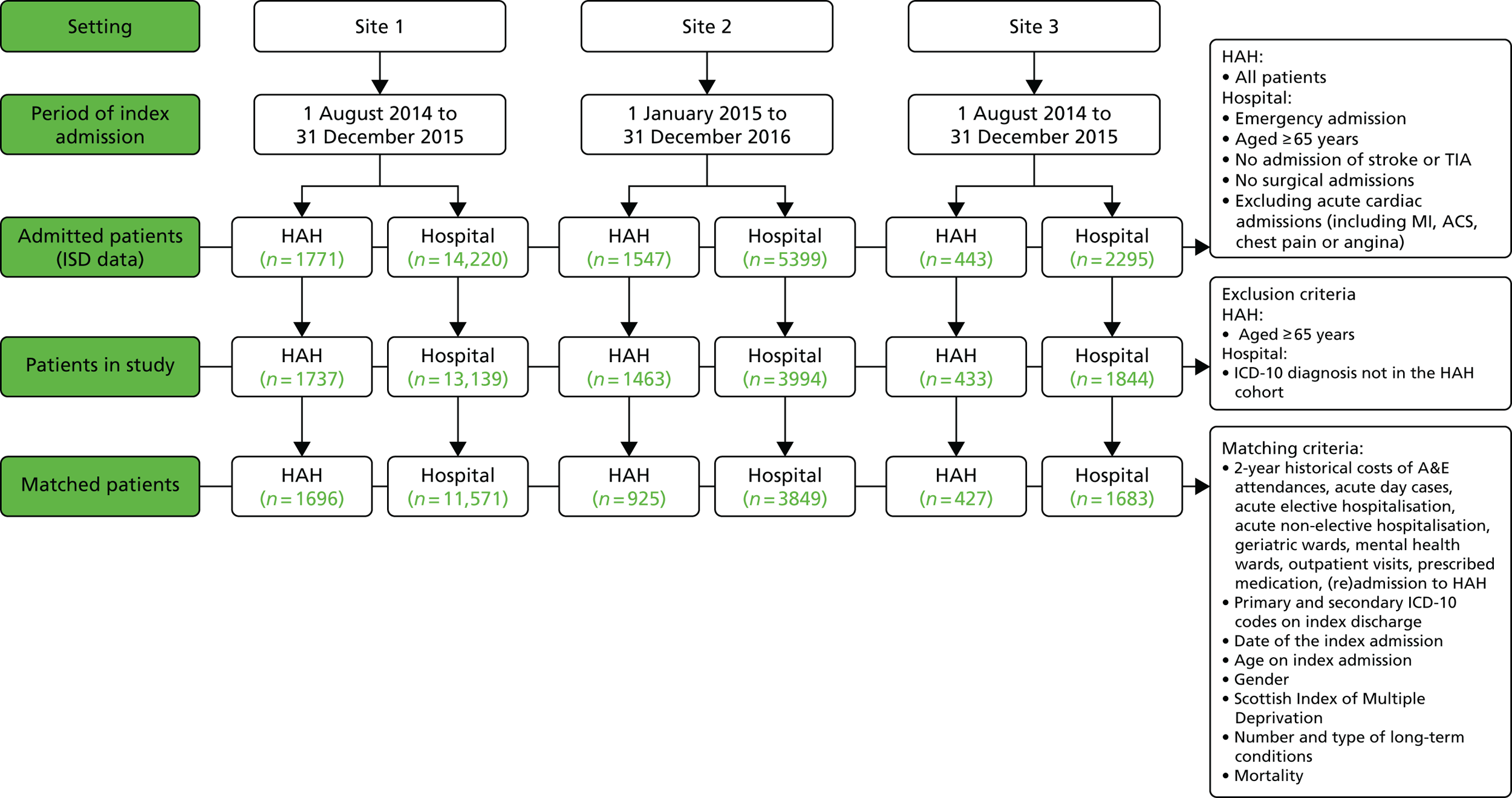

Development of the research programme

We developed a protocol and statistical analysis plan to compare populations receiving hospital at home with those who received hospital-based health care, using data from the Information Service Division (ISD) in Scotland (see Chapter 4). This project replaced the planned analysis of data from a survey of the CGA implemented in hospitals, part of a parallel programme of research led by Professor Stuart Parker at the University of Newcastle that had a low response rate. Following advice from the Study Steering Committee (SSC), we increased the size of the panel that was invited to participate in the Delphi exercise and included patients and carers to identify the critical components of the CGA.

Structure of this report

We report the methods and findings of each of the research projects that was designed to assess the effectiveness and implementation of the CGA. In Chapter 2, we report the findings from an updated Cochrane review of the CGA for older adults admitted to hospital, a cost-effectiveness analysis using individual patient data (IPD) and published data, together with the findings from a survey of researchers whose trials were included in the review. We drafted a logic model, which was derived from the descriptions provided by the triallists whose studies were included in the Cochrane review, to describe the inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes and impact of the CGA. In Chapter 3, we report the methods and findings from a UK-wide survey of community trusts that deliver the CGA in community settings. The survey was designed to establish the range of different models of health care that are being provided in community settings and that might provide an alternative to admission to hospital. In Chapter 4, we report the methods and findings of an analysis of data provided by the ISD in NHS Scotland that compared the populations that had received acute-level health care in their home with those that had received health care in hospital and the cost to the health service of each of these types of health care. We report the findings from focus groups with patients and caregivers, and interviews with health-care professionals, patients and caregivers in Chapter 5; we also describe how the CGA works from the perspective of those delivering it and how it is experienced by service users and caregivers in the same chapter. In Chapter 6, we bring together the findings from the updated Cochrane review of the CGA, the focus groups and interview study by developing a series of statements to establish consensus of the necessary components of the CGA that lead to effective outcomes; we describe the methods we used to test consensus and the findings of the Delphi exercise. In Chapter 7, we provide an integrated summary of the findings of this programme of research and place these in the context of current health policy and demands on the health service, and we conclude with a set of recommendations for future research.

Patient and public involvement in the research

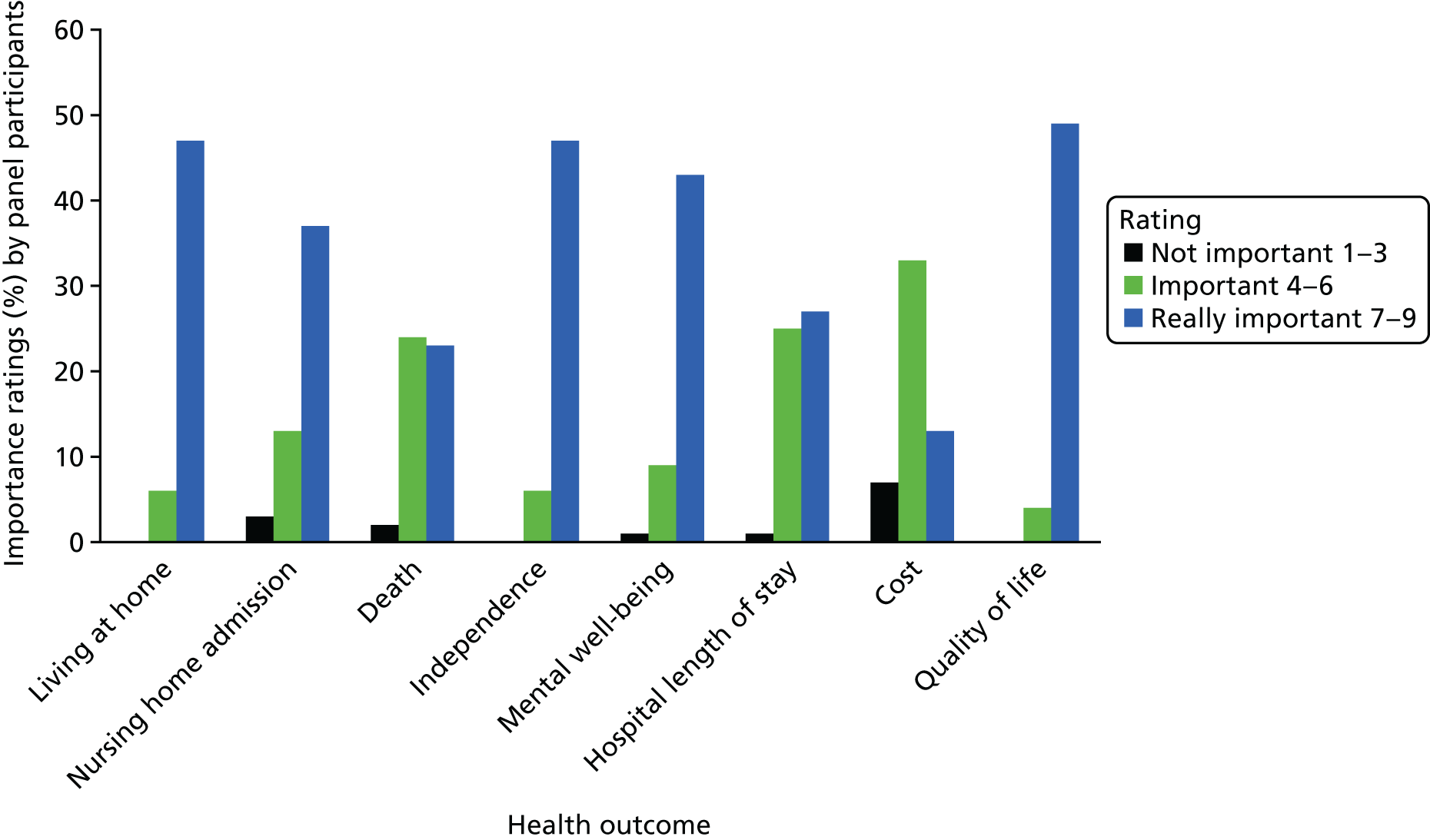

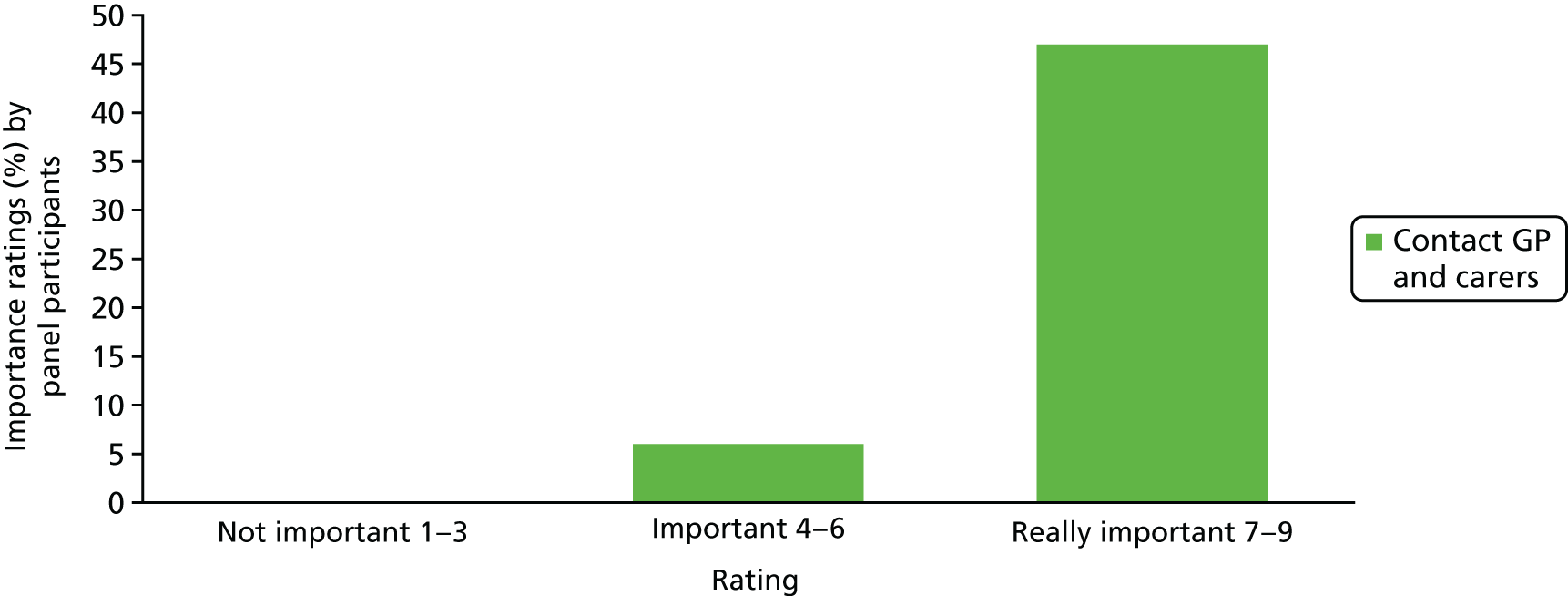

At the outset of the programme of research, we met with a patient/public panel that included older people who lived with long-term conditions; we sought advice from the panel on the areas that we might include in the semistructured interviews. We organised additional focus groups with older people who had recent experience of receiving health care in hospital or hospital at home, and their caregivers, to discuss the priority they attached to the different aspects of the health care they had received. A member of the CGA SSC was a caregiver to his wife who had dementia and was a member of the Friends of DeNDRoN (Dementias and Neurodegenerative Diseases Research Network). He contributed to the Delphi exercise and also invited members from a NIHR public contacts database in Oxford to participate in the Delphi exercise. We also invited patients and caregivers to participate in the Delphi through the CGA patient and public involvement (PPI) lead at the University of Sheffield and the PPI lead for the NIHR Ageing Speciality Group. We were in contact with Age UK, which provided feedback on the drafting of the statements for the Delphi exercise and advertised the Delphi exercise through their networks.

Chapter 2 Update of a Cochrane review: Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment with individual patient data and a survey of triallists

Introduction

We updated a Cochrane review of the CGA that was 7 years out of date18 to include eligible new trials, obtain IPD to model cost-effectiveness, conduct a survey of triallists and refine a logic model. In a meta-analysis of different service-based interventions for older people, Stuck et al. 13 provided a framework for the definition of inpatient models of the CGA. The first was delivered by a team in a geriatric ward; one of the characteristics of this model was that the team had control over the delivery of the MDT recommendations. These units are also known as Geriatric Evaluation and Management (GEM) units or Acute Care for Elders (ACE) units. The second model was delivered by a mobile MDT that assessed patients and also delivered recommendations to the physician caring for the older patients. We included both models of the CGA in the updated Cochrane Review.

Common components of the CGA13 include specialty expertise (e.g. a consultant geriatrician), a multidimensional assessment that uses a structured format to quantify possible medical, functional, mental, social and environmental problems of the frail older person, and multidisciplinary meetings. Other key features include the formulation and delivery of a plan of care that includes rehabilitation. Rubenstein et al. 8 have highlighted that, prior to the development of the CGA, few older patients with frailty received rehabilitation services.

A Cochrane Review of the CGA was published in 2011 (Search 2010) (22 RCTs recruiting 10,315 patients across six countries)18 and reported that older people who received the CGA were more likely to be alive and in their homes at follow-up than those who received routine inpatient medical care. There were additional benefits, for example in reductions in the likelihood of being admitted to residential care and a reduced likelihood of death or deterioration. Seven trials reported a reduction in cost associated with CGA care and two trials reported an increase.

Objectives

To improve our understanding of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of specialist-led CGA across secondary care.

Research question

Does specialist-led CGA improve patient health outcomes and reduce costs to the health service compared with admission to hospital without the CGA?

Methods

We included individual participant randomised trials that recruited participants aged ≥ 65 years who were admitted to hospital for acute care or inpatient rehabilitation after an acute admission with medical, psychological, functional or social problems. Trials typically recruited patients on the basis of age alone (i.e. all admissions aged > 75 years) or on the basis of criteria such as changing functional status, prior disability, cognitive impairment or classic geriatric syndromes (such as falls, immobility, delirium and non-specific presentation).

Types of intervention and comparison

We used the definition of the CGA that was developed by Rubenstein et al. 8 to identify studies that were eligible for inclusion in the review ‘CGA is a multidisciplinary diagnostic process intended to determine a frail elderly person’s medical, psychosocial, and functional capabilities and limitations in order to develop an overall plan for treatment and long-term follow-up’. We included RCTs that compared the CGA delivered on a specialist ward or across several wards by a mobile team with usual care on a general medical ward without the CGA. We excluded studies that did not evaluate the CGA in an inpatient setting and studies of condition-specific interventions (e.g. stroke units, geriatric orthopaedic rehabilitation),19,20 as these condition-specific interventions require specialist skills for assessment, acute management and rehabilitation.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was living at home (the inverse of death or admission to a nursing home combined) at follow-up. Secondary outcomes were death, admission to a nursing home, dependence, activities of daily living (ADL), cognitive function, length of stay, re-admission, cost and cost-effectiveness.

Inclusion criteria are detailed in Table 2.

| Study characteristics | Inclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Study types | Randomised trials |

| Participants | Aged ≥ 65 years and admitted to hospital for acute care or inpatient rehabilitation after an acute admission with medical, psychological, functional or social problems |

| Interventions | CGA delivered on a specialist ward or across several wards by a mobile team. Case management by a geriatrician at the point of discharge into the community from an acute medical unit |

| Comparators | Usual care on a general medical ward without the CGA |

| Outcomes | Living at home, death, admission to a nursing home, dependence, ADL, cognitive function, length of stay, re-admission, cost and cost-effectiveness |

Identification of studies

We searched the following databases with no restrictions (language or date) on 5 October 2016:

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016, Issue 9) in The Cochrane Library

-

MEDLINE (Including Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations) via OvidSP (from 1946)

-

EMBASE via OvidSP (from 1974)

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL EBSCOhost; from 1982)

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE; 2015, Issue 2) in The Cochrane Library

-

Health Technology Assessment (HTA database; 2016, Issue 3) in The Cochrane Library.

We also searched the following clinical trials registers on 5 October 2016:

-

ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov)

-

World Health Organization’s International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (http://apps.who.int/trials/search/Default.aspx).

In Appendix 1 we detail the search strategies for MEDLINE, EMBASE, The Cochrane Library and CINAHL. We also checked the reference lists of studies included in the review, along with the reference lists of related systematic reviews and meta-analyses. 9,10,14,21–23 When we contacted triallists to request IPD, we also asked whether or not they had identified any published or unpublished data.

The titles and abstracts of all the studies identified by electronic searches were screened for inclusion by one review author (MG), full-text papers were assessed by two authors working independently (MG and GE) and disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (SS).

Data extraction

We designed a data extraction form based on a modified version of the Cochrane good practice extraction form. 24 Sections of the data extraction form included:

-

population and setting – inclusion/exclusion criteria

-

methods – aim, characteristics and conduct of the randomised trials (e.g. unit and method of allocation), year and method of recruitment

-

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) risk of bias criteria (classified as low/high/unclear) and justification of each judgement

-

participants – number of participants, mean age, male-to-female ratio, clinical details

-

interventions – team members and team organisation for intervention and control groups, location, team/ward

-

outcomes – outcome definition, time points measured

-

results – number of events, mean, standard deviation (or other variance) and number of participants for the intervention and comparison.

Two review authors (MG and GE) independently extracted the data on all the studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria and disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (SS).

Survey of triallists

We sent a survey to the triallists of the 29 trials included in the review to obtain a detailed description of the CGA models evaluated in the RCTs (see Appendix 2). We contacted the investigators by e-mail or telephone and each triallist was sent a minimum of three reminders. The survey included questions on (1) the population using the service (including mean age of the population, location and inclusion/exclusion criteria), (2) the intervention characteristics (including details of the core team members, the processes of care and clinical leadership) and (3) the control group characteristics (e.g. whether or not standard assessment tools were used).

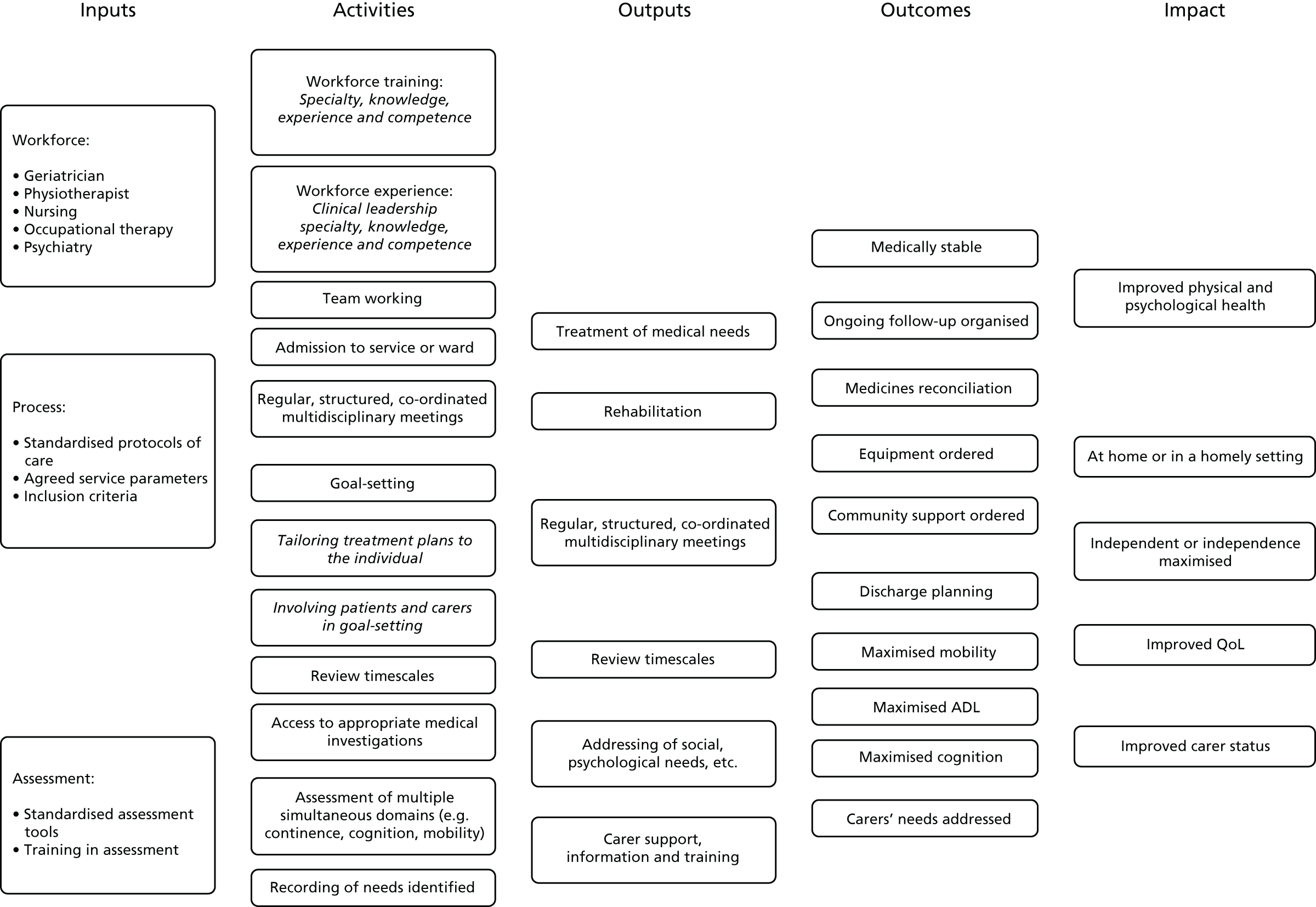

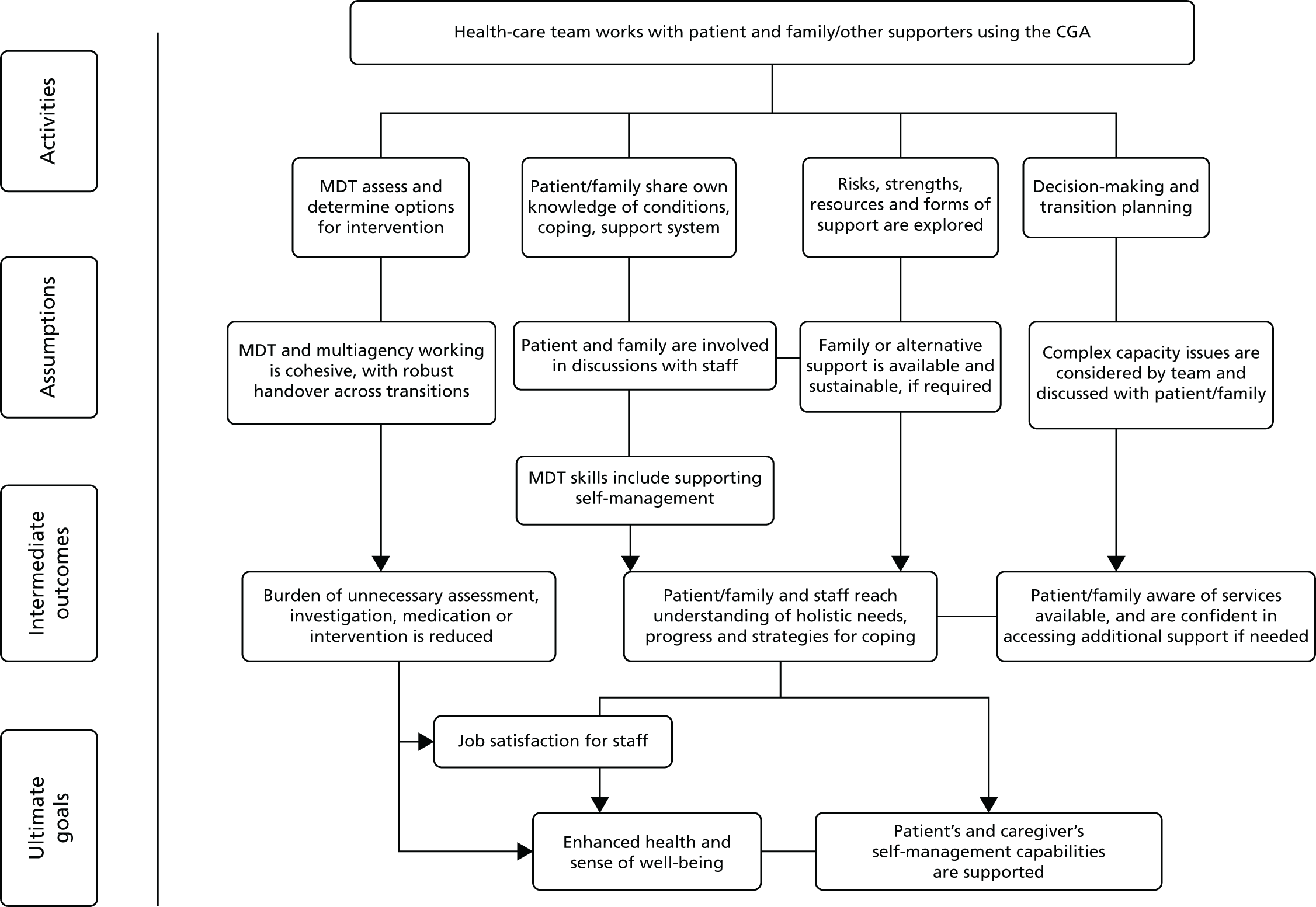

Prior to this update of the Cochrane review, we developed a logic model (Figure 1) to help explain the relationship between the key components of the CGA intervention that were intended to achieve the desired outcomes. We refined the logic model with the findings from the survey and revisited the pathways that constitute the possible mechanism of action of CGA as researched.

FIGURE 1.

Logic model. QoL, quality of life.

Risk of bias of included studies

The risk of bias of the included studies was independently assessed by three review authors (MG, GE and SS) using the Cochrane EPOC risk of bias criteria. 25 We resolved areas of uncertainty or disagreement by discussion.

Statistical analysis plan

The aims of the statistical analysis were to:

-

update the meta-analyses with published data and IPD

-

estimate the impact of the CGA on health-care utilisation costs and determine the cost-effectiveness of the CGA

-

examine whether or not the treatment effects and costs differed for patients with different levels of frailty, and to investigate any differences in care home costs between the compared services (the analysis of care home costs was not possible because of a lack of data on care home length of stay)

-

conduct a metaregression analysis to assess the effects of trial covariates on the primary outcome (living at home).

Missing data

We contacted authors of the included studies for missing data and for missing information from the trial survey.

Data synthesis

We combined published data using fixed-effect meta-analysis for living at home, death, admission to a nursing home, dependence, ADLs, cognitive function, re-admission to hospital and length of stay. We grouped trials by ward or by team for all outcomes. We calculated relative risks (RRs) for binary outcomes, standardised mean differences (SMDs) for continuous measures that used different scales to measure ADLs and cognitive function, and mean difference for continuous outcomes, such as length of stay. We analysed dependence by combining a binary definition of dependence (as defined by trials) with deterioration in ADLs. Tests of heterogeneity were undertaken using Cochran’s Q26 and the I2 statistic27 and we did not retain a pooled analysis if the values of I2 were > 70%.

We conducted a metaregression analysis by using a fixed-effect model to assess the effects of trial covariates on living at home at the end of follow-up period (3–12 months). 28 Trial covariates consisted of team or ward intervention, age or frailty as a criterion for targeting the delivery of the CGA (frailty typically included criteria such as geriatric syndromes, risk of nursing home admission and functional or cognitive impairment), timing of admission from emergency department directly or after 72 hours (stepdown) and outpatient follow-up. We used post-estimation Wald tests to derive F-ratios and p-values. We used metaregression to test for an interaction between the covariates (e.g. team and ward) for the outcomes of living at home at the end of follow-up (3–12 months), mortality at the end of follow-up (3–12 months), admission to a nursing home at the end of follow-up (3–12 months) and dependence.

We used Stata® version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and RevMan version 5 (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) when performing all analyses.

Cost-effectiveness

We conducted a cost-effectiveness analysis to examine whether or not costs and health outcomes differed between those receiving inpatient CGA and those not receiving the CGA.

We used the cost of length of stay in days from 17 trials as the main driver of resource use. We derived the costs of providing the CGA from IPD provided by one trial29,30 that evaluated a version of the CGA that included an attending geriatrician and outpatient follow-up. We valued relative costs using English unit cost prices for 2013/14,31 and a NHS health service perspective was taken. 32 We compared incremental health outcomes of the CGA versus usual care. For trials that reported the cost of the CGA we used the following measure of cost-effectiveness:

-

We calculated quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) using IPD from three trials29,33,34 that assessed patient ADL with the Barthel Index. We converted the Barthel Index to EQ-5D-3L (EuroQoL-5 Dimensions, three-level version) UK scores, based on methods described by Kaambwa et al. 35 to calculate QALYs. We selected studies with mean Barthel scores at baseline that were similar to the population in the Kaambwa et al. 35 study (Barthel score ranged from 14.8 to 16.5, on a scale of 0 to 20). We used the IPD provided by Edmans et al. 29 to validate the mapping exercise by comparing the QALYs calculated using the Barthel Index with QALYs based on EQ-5D-3L using IPD from Edmans et al. ,29 as this study provided data for the EQ-5D (EuroQol-5 Dimensions) and the Barthel Index. A meta-analysis using a fixed-effect model was performed to estimate incremental QALYs.

-

We estimated life-years (LYs) using the IPD from four trials29,33,34,36 by calculating the time to death from recruitment expressed as a fraction of a year.

-

Using the IPD, we created a variable ‘life-years living at home’ (LYLAHs) after discharge from hospital, as a measure of independence and well-being in an older population, based on IPD from two trials. 29,36,37

We constructed a decision model to estimate an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of inpatient CGA compared with inpatient care without the CGA. The ICER was expressed as a cost per QALY gained, cost per LY gained and cost per LYLAH gained from a health service perspective. We used the RR of living at home at the end of follow-up in the decision model and multiplied this by the incremental LYLAH to adjust LYLAH with the probability of living at home. The input parameters used in these models are presented in Table 3. Uncertainty in the input parameters of the model was addressed by performing 10,000 draws of all incremental cost and incremental health outcome parameters using prespecified distributions and recording incremental costs, incremental QALYs, incremental LYs and incremental LYLAHs from each draw. These results were plotted on cost-effectiveness planes and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves to display the uncertainty in the estimated ICERs.

| Outcome data | Source | Estimate |

|---|---|---|

| RR: living at home (end of follow-up on ward) | Meta-analysis of 12 RCTs (n = 5705 participants)12 | RR 1.07, SE 0.92 |

| RR: living at home (end of follow-up on ward and by team) | Meta-analysis of 16 RCTs (n = 6799 participants)12 | RR 1.06, SE 1.20 |

| RR: admitted to a nursing home (end of follow-up on ward) | Meta-analysis of 11 RCTs (n = 5512)12 | RR 0.77, SE 0.06 |

| RR: admitted to a nursing home (end of follow-up on ward and by team) | Meta-analysis of 14 RCTs (n = 6285)12 | RR 0.80, SE 0.06 |

| Mean difference in length of stay in hospital, days | Meta-analysis of 17 RCTs (n = 5303 participants)12 | MD 0.03, SE 0.22 |

| Mean length of stay (days) in a nursing home after discharge – CGA | Saltvedt et al.34 | Mean 49.91, SE 8.12 |

| Mean length of stay (days) in a nursing home after discharge – UC | Saltvedt et al.34 | Mean 40.87, SE 8.44 |

| Mean difference in LYLAH | Meta-analysis based on IPD (Edmans et al.,29 Saltvedt et al.34) | MD 0.009, SE 0.022 |

| Mean difference in QALY | Meta-analysis based on IPD (Edmans et al.,29 Kircher et al.,33 Saltvedt et al.34) | MD 0.012, SE 0.019 |

| Mean difference in QALY (severe patients) | Meta-analysis based on IPD (Goldberg et al.,36 Somme et al.38) | MD 0.018, SE 0.024 |

| Mean difference in time to death | Meta-analysis based on IPD (Edmans et al.,29 Goldberg et al.,36 Kircher et al.,33 Saltvedt et al.34) | MD 13.06, SE 6.66 |

| Cost (£) of bed-day in hospital | Weighted average of elective and non-elective hospitalisation based on NHS Reference Costs 2013 to 201439 | 874 |

| Cost (£) of nursing home day | Personal social services: expenditure and unit costs, England 2013–14, final release: unit costs by CASSR39 | 77 |

| Cost (£) of CGA per patient | Tanajewski et al.30 (the AMIGOS trial) | 208, SE 8.93 |

Analysis using individual patient data

We requested IPD from the investigators of the trials included in the update of the Cochrane review of the CGA (including the original review). We contacted the investigators by e-mail or telephone and each triallist was sent a minimum of three reminders. We performed a two-stage meta-analysis of IPD with each model initially run within each trial. 40

We used fixed-effects logistic meta-analyses for two outcomes: living at home and death. 40 For a third outcome (time to death), we used fixed-effect time-to-event meta-analysis and used Cox regression models to calculate the log hazard ratio and its standard error; the pooled effect was expressed as the hazard ratio for inpatient CGA compared with general medical care. All three meta-analyses were adjusted for the participant’s age, sex and baseline index by applying a threshold score of ≤ 15, out of a maximum score of 20. 41

Sensitivity analysis

We ran random-effects meta-analyses using the DerSimonian and Laird method42 in a sensitivity analysis and compared the results with those of the fixed-effects meta-analyses used in the analyses. 40 We assessed the impact of excluding three trials43–45 that included participants who were admitted to hospital from a nursing home for the outcomes of living at home and admitted to a nursing home. We also assessed the impact of using data at 6 months’ follow-up, rather than 12 months’ follow-up, for three trials. 34,46,47

Reporting bias

We assessed reporting bias by creating a funnel plot for the main outcome (living at home) at 3–12 months’ follow-up, recognising that, if there are a small number of trials, these plots are not necessarily indicative of publication bias.

Certainty of evidence

We used the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) framework to assess the certainty of the evidence by creating a summary-of-findings table, and followed the approach of the GRADE working group48 and guidance developed by EPOC. 49 We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and risk of bias) to assess the certainty of evidence as it relates to the main outcomes,48 and graded the evidence as being of very low, low, moderate or high certainty. We included the most important outcomes of living at home, mortality, admission to a nursing home, dependence, cognitive function, hospital length of stay and cost-effectiveness. Three review authors (MG, GE and SS) independently assessed the certainty of evidence.

Patient and public involvement

We established a SSC to ensure delivery, governance and advice, which met five times over the course of the project. A lay member of the public was on the committee and gave valuable feedback on various aspects of the project, including the review. We were also in contact with, and received feedback from, the Oxford-based DeNDRoN and Age UK.

Results of the review

Study selection

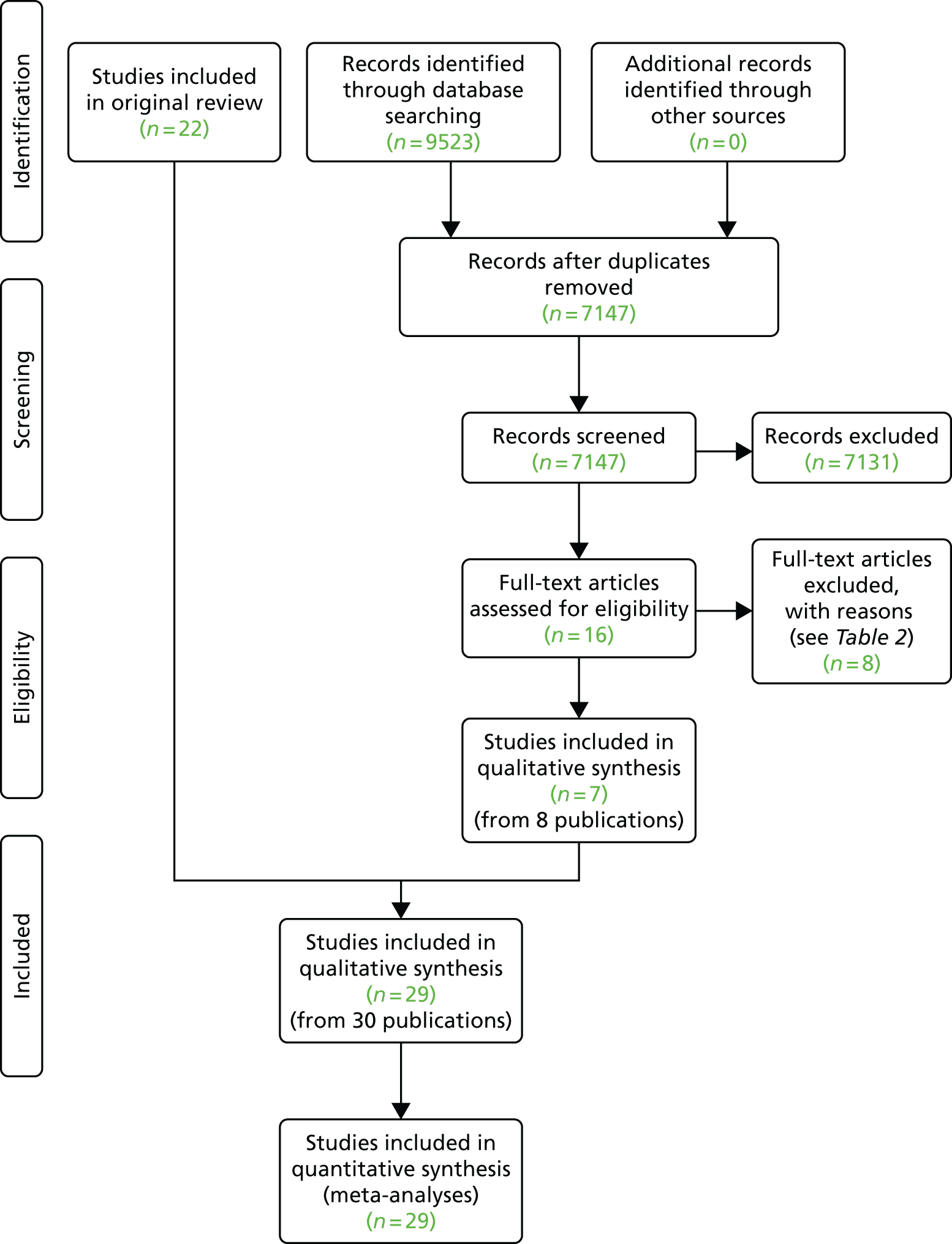

For this update, we screened 7147 titles and abstracts for eligibility in the update of the review and we excluded 7131 records. The flow of studies through the search process is outlined in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

The PRISMA flow diagram for identification of published studies included in review.

Characteristics of included studies

Full details of the included studies (population, intervention, comparison, outcomes and risk of bias) are described in Appendix 3. We retrieved the full text of 16 articles and identified seven eligible trials (from eight publications) to include in this update. 29,36,38,50–53 Twenty-nine RCTs (n = 13,766 participants) were included in this review (seven studies of these were from the update) from nine countries (Australia, Canada, China, France, Germany, Norway, Sweden, the UK and the USA). We received IPD from five trials;29,33,34,36,38 this limited this aspect of the analysis to a subgroup of trials (n = 1692).

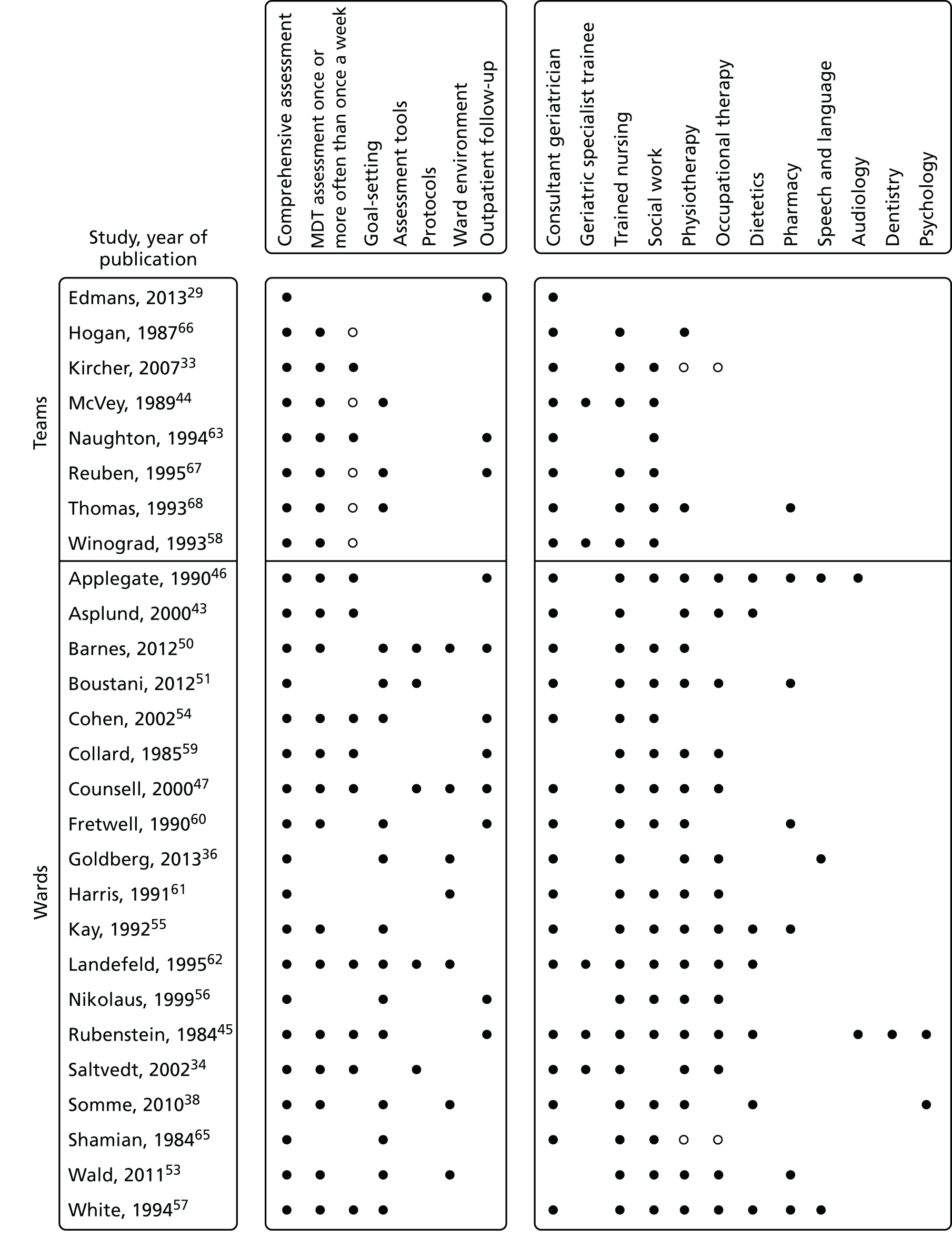

Eleven trials targeted the CGA to the frailest or most at-risk participants,29,33,34,36,45,46,54–58 and 11 targeted CGA on the basis of age. 38,43,44,47,50,53,59–63 The CGA was delivered in a dedicated geriatric ward in the majority (n = 20) of trials34,36,38,43,45–47,50,51,53–57,59–62,64,65 and by using a team approach that covered more than one ward/unit in eight trials. 29,33,44,58,63,66–68 The process of the CGA in the two models is described in more detail in Figure 3.

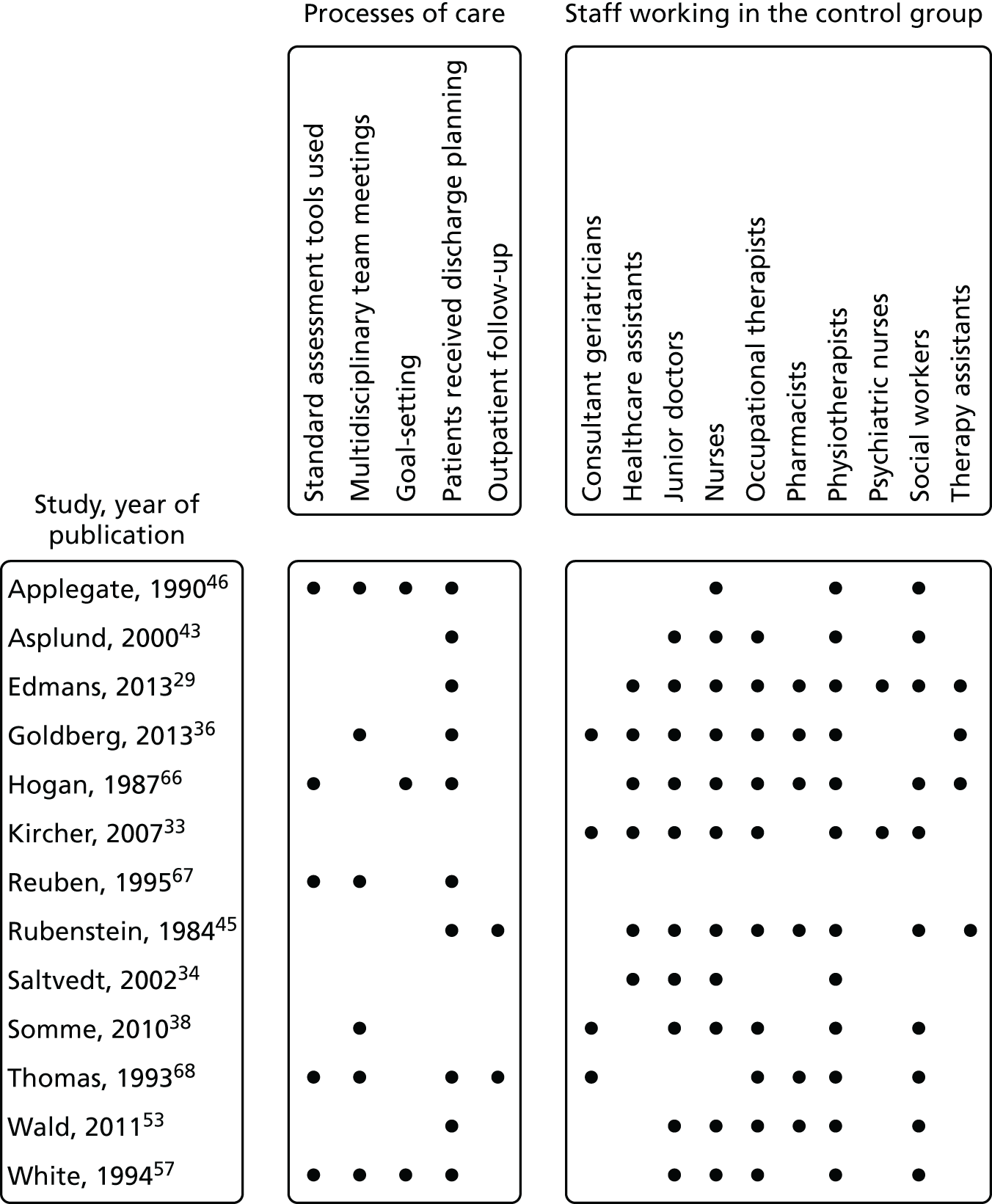

FIGURE 3.

Components of in-hospital CGA. ●, present or carried out; ○, recommendation made or staff accessed from general pool.

The intervention was case management by a geriatrician at the point of discharge from an acute medical unit in the AMIGOS (acute medical unit comprehensive geriatric assessment intervention study) trial,29 and, in another study, the CGA intervention was care in a specialist medical and mental health unit. 36 Most trials described the control group as usual care, but in three trials the control group received enhanced care. 29,36,51 For one trial,36 the control group was a mixture of care on geriatric medical wards (70%) and general medical wards (30%). Outpatient follow-up was provided in nine trials and duration of follow-up ranged from 3 to 12 months.

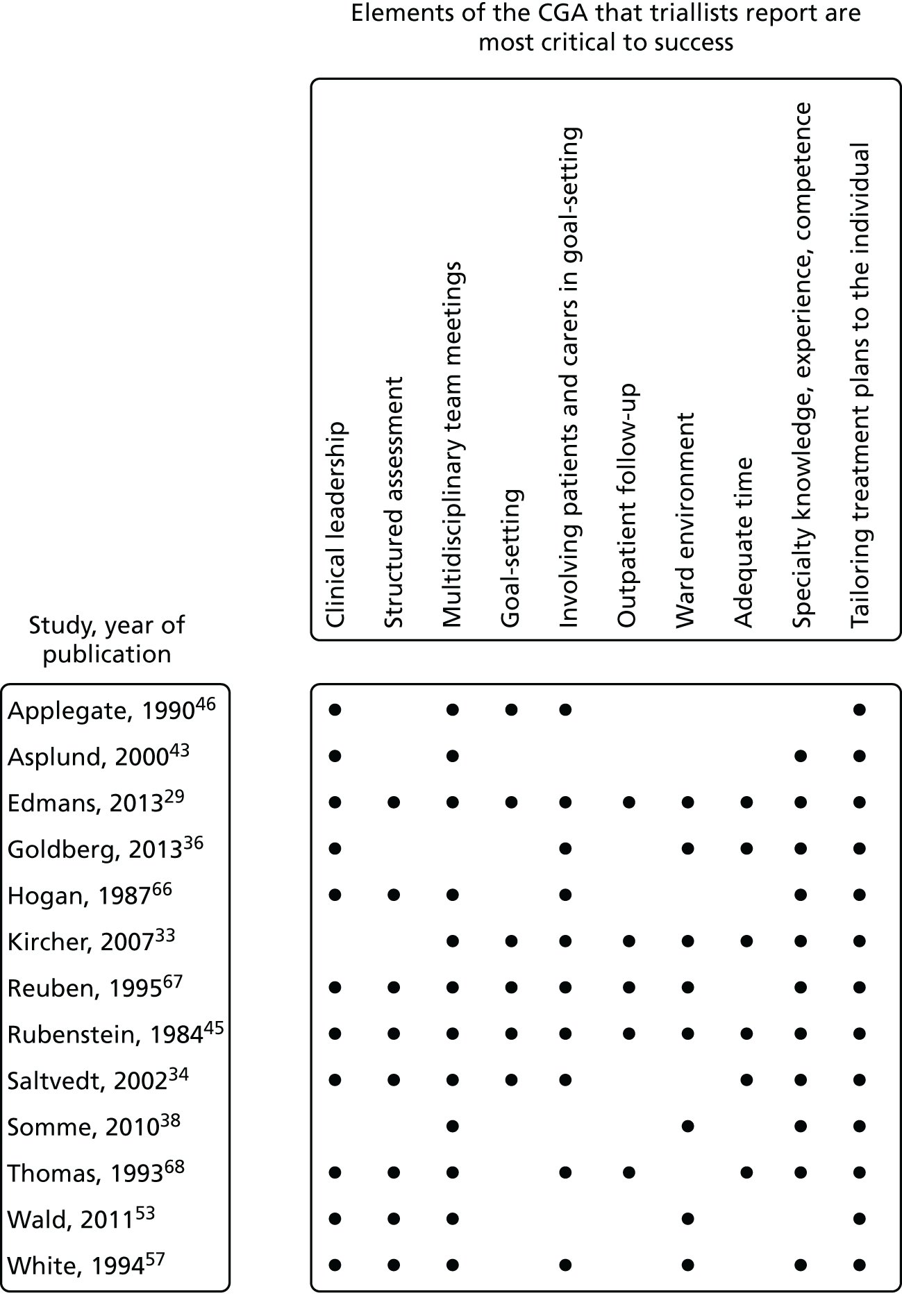

Survey of triallists

Thirteen of the 29 triallists completed the survey29,33,34,36,38,43,45,46,53,57,66–68 and reported that the elements of the CGA that they considered to be critical to success were tailoring treatment plans to the individual (13 out of 13 trials), MDT meetings (12 out of 13 trials), clinical leadership (10 out of 13 trials), specialty knowledge, experience and competence (11 out of 13 trials) and involving patients and carers in goal-setting (10 out of 13 trials) (Figure 4). Interestingly, triallists reported similar staff profiles in the control group and the CGA intervention group (see Figures 3 and 5). The main exception was that only four trials reported that a specialist trained geriatrician was part of the control group (Figure 5). 33,36,38,68 MDT meetings took place in the majority of trials in the CGA intervention group (12 out of 13 trials), but in only 6 out of 13 trials in the control group. 36,38,46,57,67,68

FIGURE 4.

Key components of the CGA reported by triallists.

FIGURE 5.

Components of in-hospital control group: processes of care and staff profiles.

Risk of bias within included studies

Risk-of-bias assessments of the included studies are reported in Table 4. Two trials were available only as abstracts52,67 and these were assessed as having unclear risk of bias for each of the domains. The majority of the trials were assessed as being at low risk of selection bias (judged by sequence generation and allocation concealment), and two trials that used an open allocation schedule were assessed as having a high risk of bias. 53,61 We classified all trials as having a high risk of performance bias, as it was not possible to blind participants or personnel to the allocated intervention, and we assessed detection bias as low risk for objective measures of outcome. We assessed subjective measures of outcome as having low or unclear risk of bias in 26 trials and a high risk of bias in one trial,53 as the outcome assessors were not blinded to functional status. We assessed attrition bias as being low or unclear in 24 trials and as high in three trials,43,59,63 with one of these trials59 reporting attrition for functional outcomes of > 25%. Twenty-five trials did not publish a protocol and, therefore, we assessed them as having unclear risk of selective reporting bias; four trials did publish protocols29,33,36,67 and we assessed these as having low risk of selective reporting bias. In 21 trials, there was low or unclear risk of contamination of the control group as there was little evidence that the control group received the CGA intervention. However, in six trials it is likely that the control group received the intervention33,36,51,53,56,67 and, therefore, these trials were classified as having a high risk of bias.

| Study, year of publication | Domain | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random sequence generationa | Allocation concealmenta | Blinding of participants and personnelb | Blinding of outcome assessment (objective outcome measures)c | Blinding of outcome assessment (subjective outcome measures)d | Incomplete outcome datad | Selective reportinge | Risk of contamination to the control group | |

| Applegate et al., 199046 | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Asplund et al., 200043 | Unclear | Low | High | Low | Unclear | High | Unclear | Low |

| Barnes et al., 201250 | Low | Low | High | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Boustani et al., 201251 | Unclear | Unclear | High | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear | High |

| Cohen et al., 200254 | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Collard et al., 198559 | Unclear | Unclear | High | Low | Unclear | High | Unclear | Low |

| Counsell et al., 200047 | Low | Low | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Edmans et al., 201329 | Low | Low | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Fretwell et al., 199060 | Unclear | Unclear | High | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Goldberg et al., 201336 | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Harris et al., 199161 | Unclear | High | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Hogan et al., 198766 | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Kay et al., 199255 | Unclear | Unclear | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Kircher et al., 200733 | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Landefeld et al., 199562 | Low | Low | High | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Li et al., 201552 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| McVey et al., 198944 | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Naughton et al., 199463 | Unclear | Low | High | Low | Low | High | Unclear | Low |

| Nikolaus et al., 199956 | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Powell and Montgomery 199064 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Reuben et al., 199567 | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High |

| Rubenstein et al. 198445 | Unclear | Unclear | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Saltvedt et al., 200234 | Low | Low | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Shamian et al., 198465 | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Somme et al., 201038 | Unclear | Low | High | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Thomas et al., 199368 | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Wald et al., 201153 | High | High | High | Low | High | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| White et al., 199457 | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Winograd et al., 199358 | Low | Low | High | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

Synthesis of results

Living at home

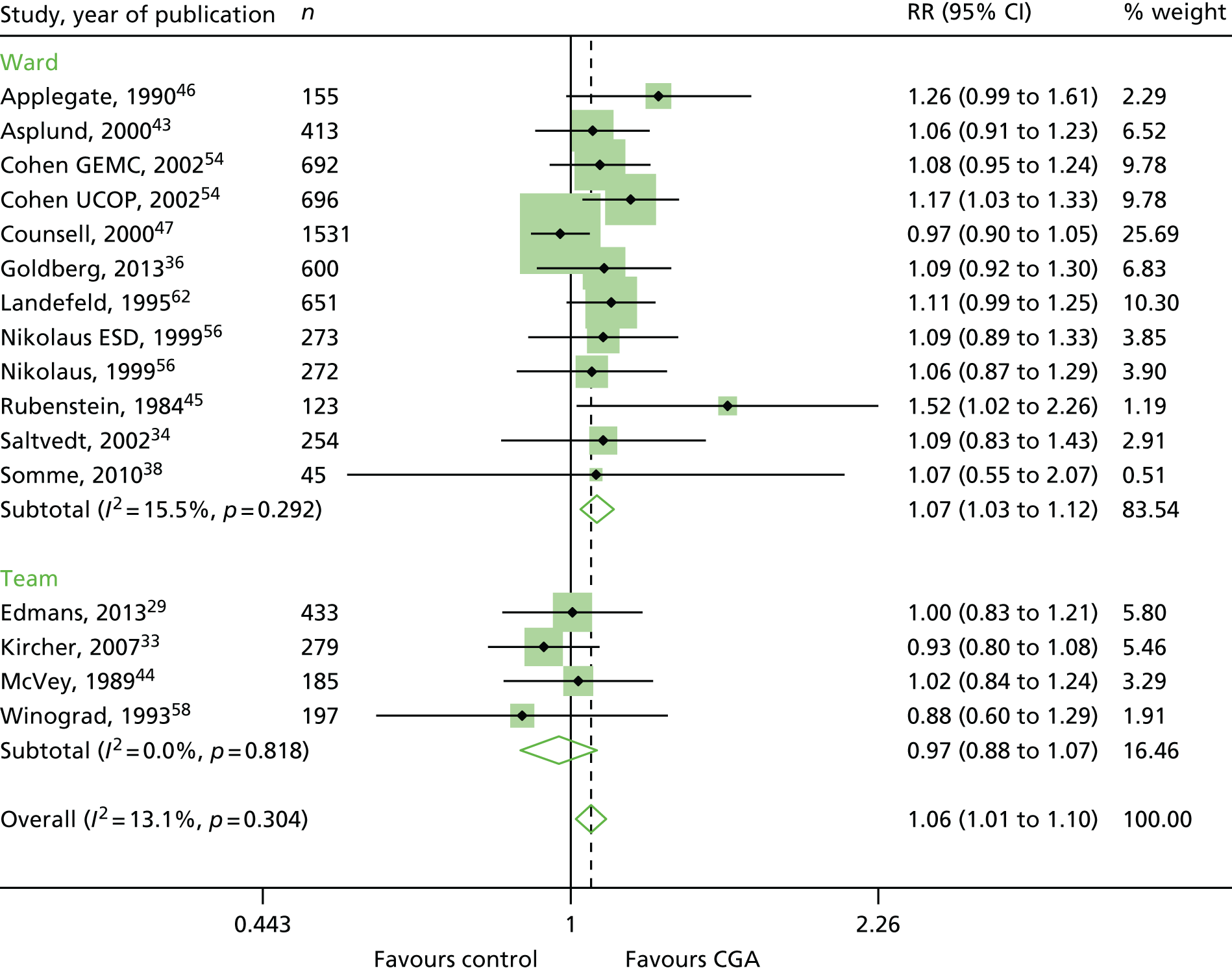

The CGA increases the likelihood of patients being alive and in their own homes at hospital discharge [RR 1.05, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.01 to 1.10; 11 trials, n = 4346 participants, high-certainty evidence; I2 = 43%],44,45,50,53,55,57–60,62,63 and at 3–12 months’ follow-up (RR 1.06, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.10; 16 trials, n = 6799 participants, high-certainty evidence; I2 = 13%). 29,33,34,36,38,43–47,54,56,58,62 (Figure 6). There was little evidence of an interaction between ward and team (F = 3.54, p = 0.08; meta-regression).

FIGURE 6.

Living at home, RR (end of 3–12 months’ follow-up). ESD, early supported discharge; GEMC, Geriatric Evaluation and Management Centre; UCOP, usual care outpatients.

Mortality

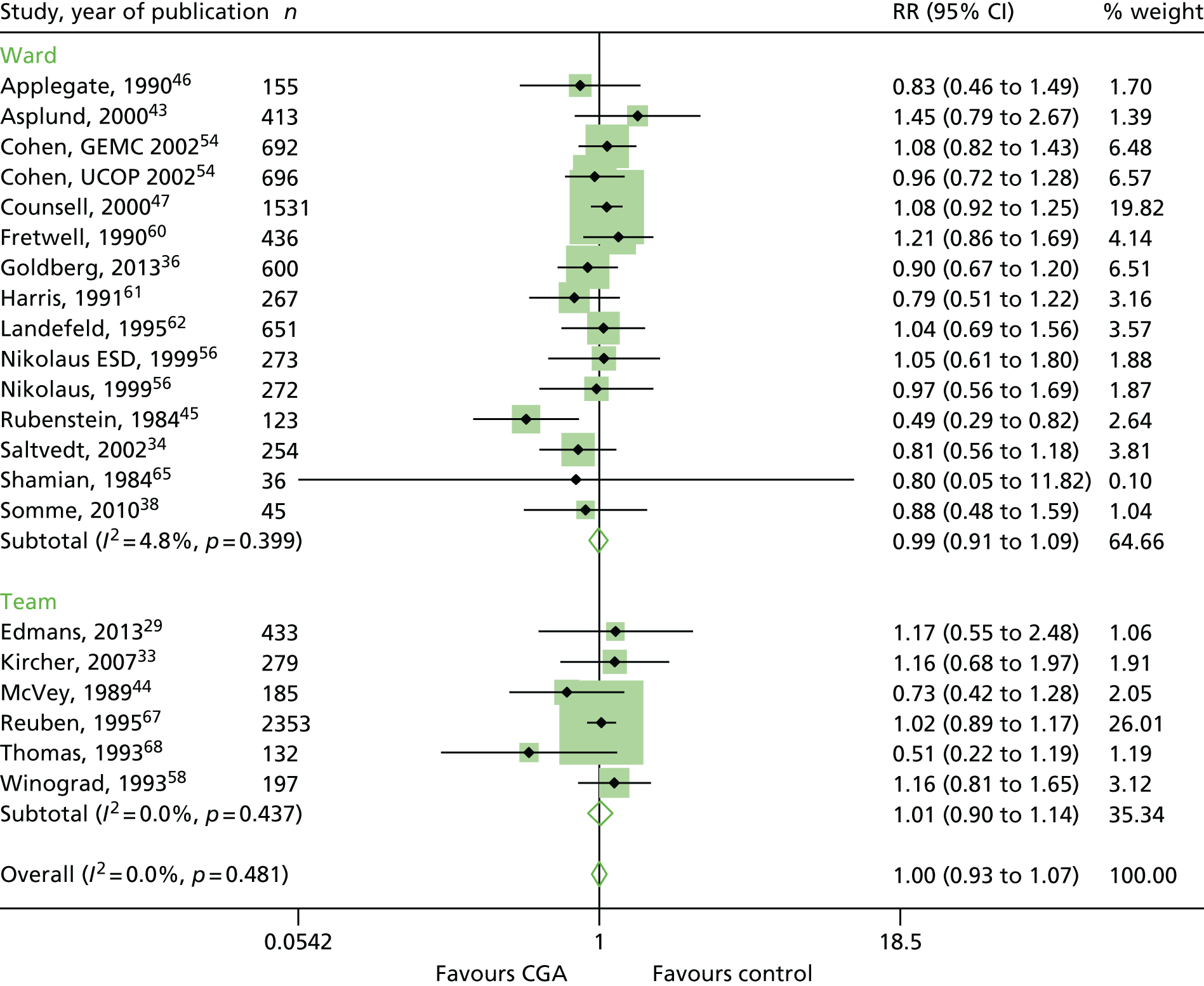

The CGA results in little or no difference in mortality at hospital discharge (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.32; 11 trials, n = 4346 participants, high-certainty evidence; I2 = 16%),44,45,50,53,55,57–60,62,63 or at 3–12 months’ follow-up (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.07; 21 trials, n = 10,023 participants, high-certainty evidence; I2 = 0%). 29,33,34,36,38,43–47,54,56,58,60–62,65,67,68 (Figure 7). There was no evidence of an interaction between ward and team (F = 0.07, p = 0.80; meta-regression).

FIGURE 7.

Mortality, RR (end of 3–12 months’ follow-up).

Admitted to a nursing home during follow-up

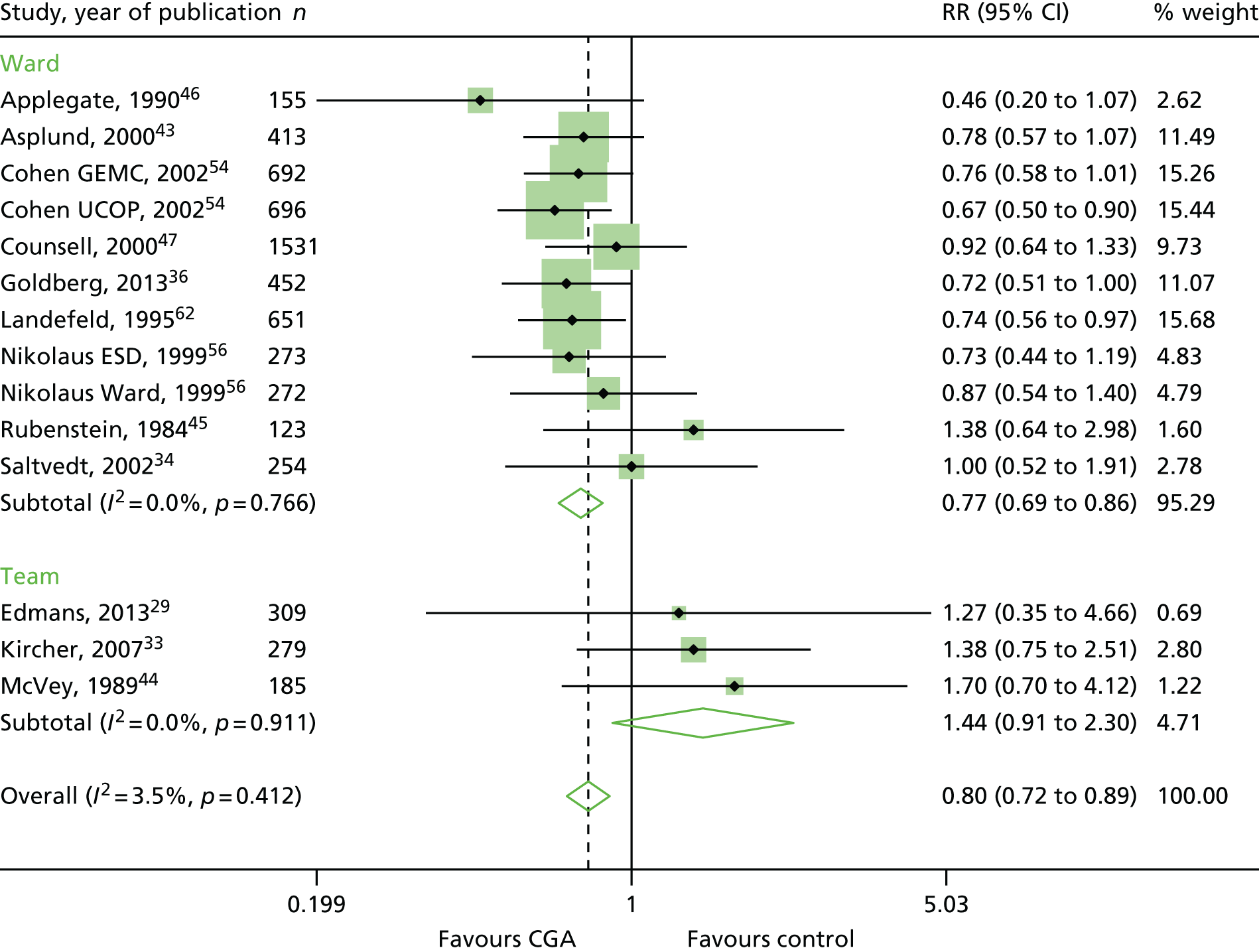

The CGA decreases the likelihood of patients being admitted to a nursing home at discharge (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.98; 12 trials, n = 4459 participants, high-certainty evidence; I2 = 31%)44,45,50,53,55,57–60,62,63,66 and at 3–12 months’ follow-up (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.89; 14 trials, n = 6285 participants, high-certainty evidence; I2 = 3%). 29,33,34,36,43–47,54,56,58,62 (Figure 8). There was evidence of an interaction between ward and team (F = 7.64, p = 0.02; meta-regression).

FIGURE 8.

Admission to a nursing home, RR (end of 3–12 months’ follow-up).

Dependence

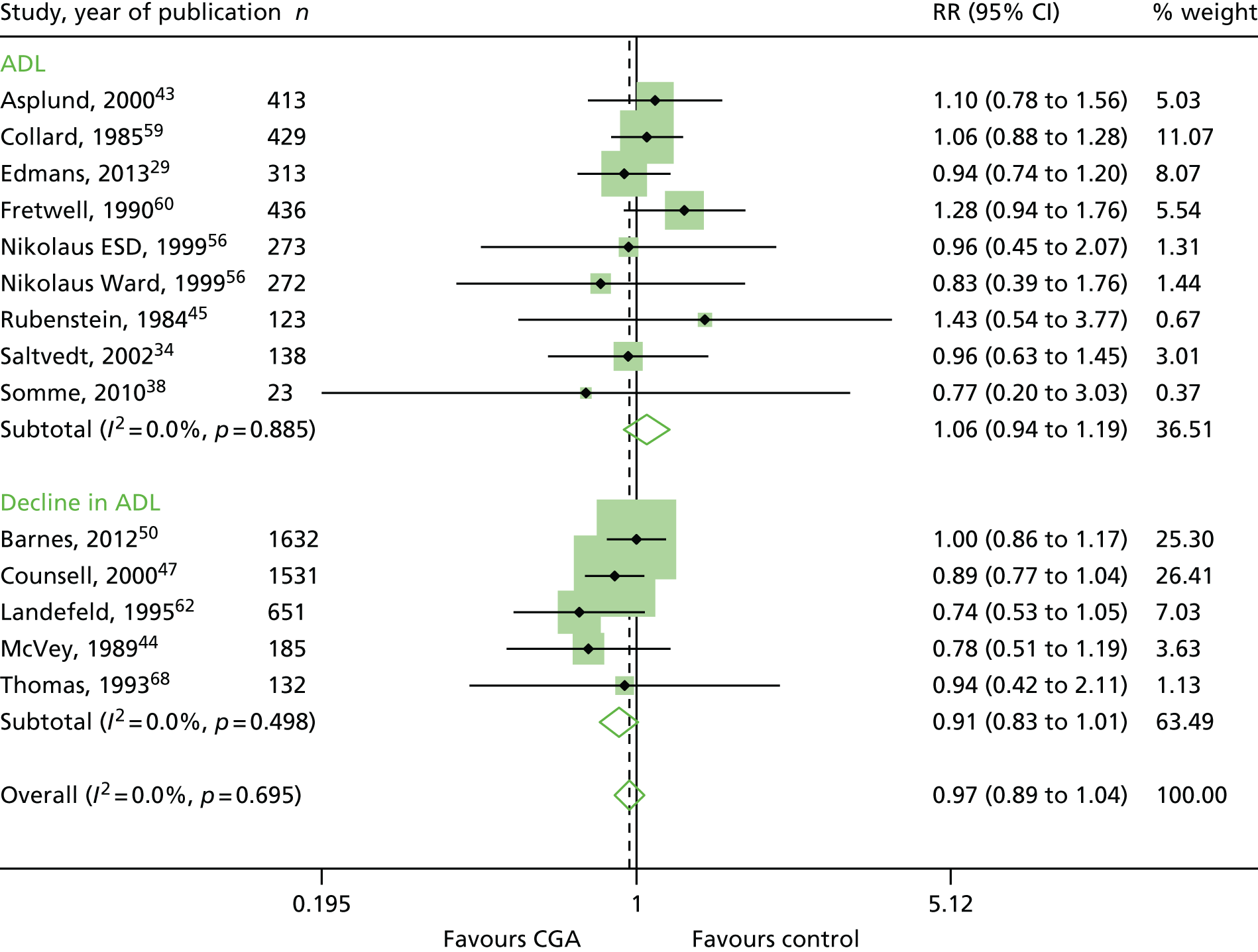

The CGA results in little or no difference in dependence (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.04; 14 trials, n = 6551 participants, high-certainty evidence; I2 = 0%). 29,34,38,43–45,47,50,56,59,60,62,68 (Figure 9). There was no evidence of an interaction between ward and team (F = 0.61, p = 0.45; meta-regression).

FIGURE 9.

Dependence, RR.

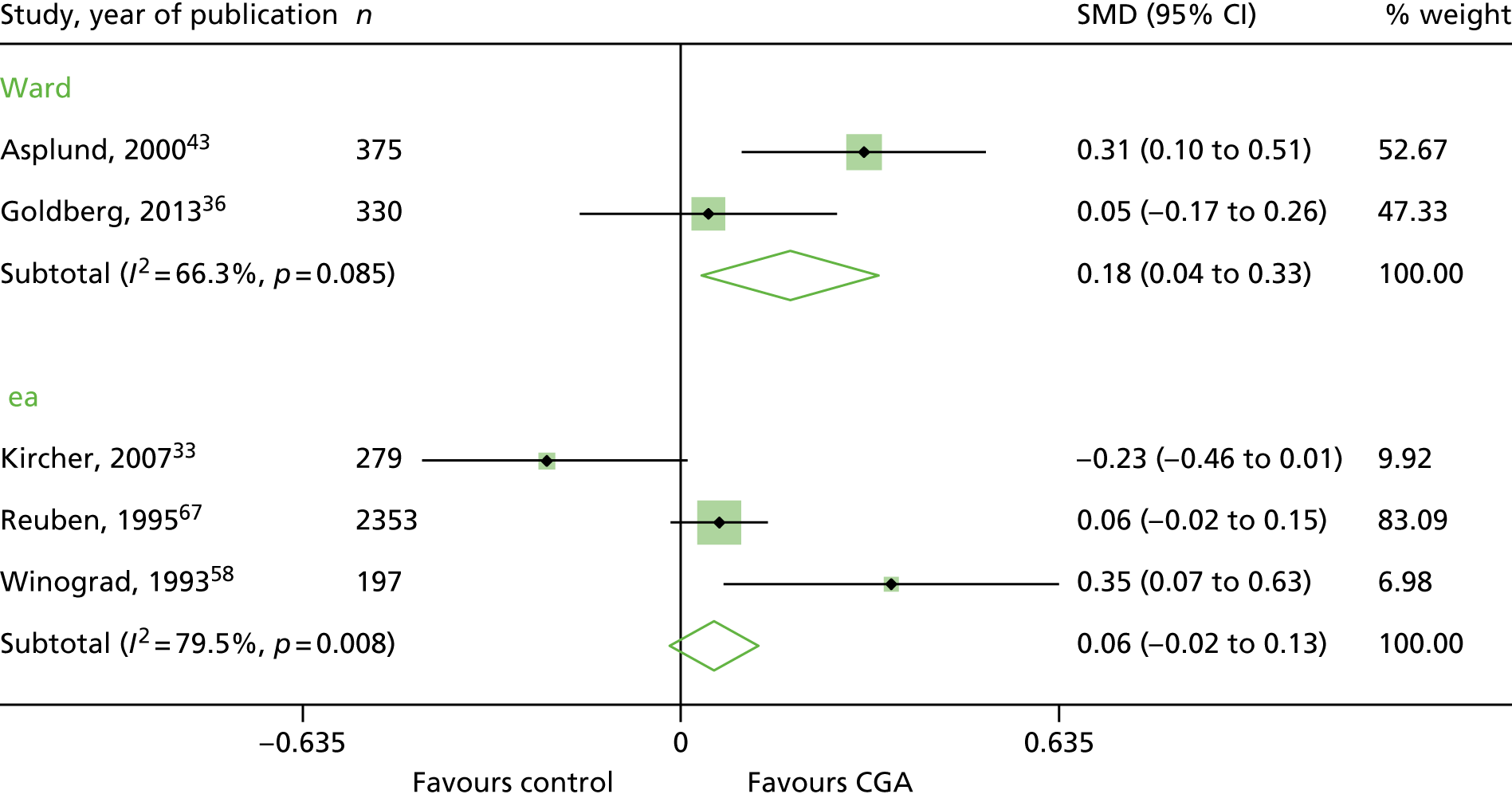

Cognitive function

Five trials reported cognitive function at follow-up, but because of the high level of statistical heterogeneity we did not retain the meta-analysis (n = 3534 participants; low-certainty evidence; I2 = 73%). 33,36,43,58,67 The SMD ranged from –0.23 to 0.35 (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10.

Cognitive function, SMDs.

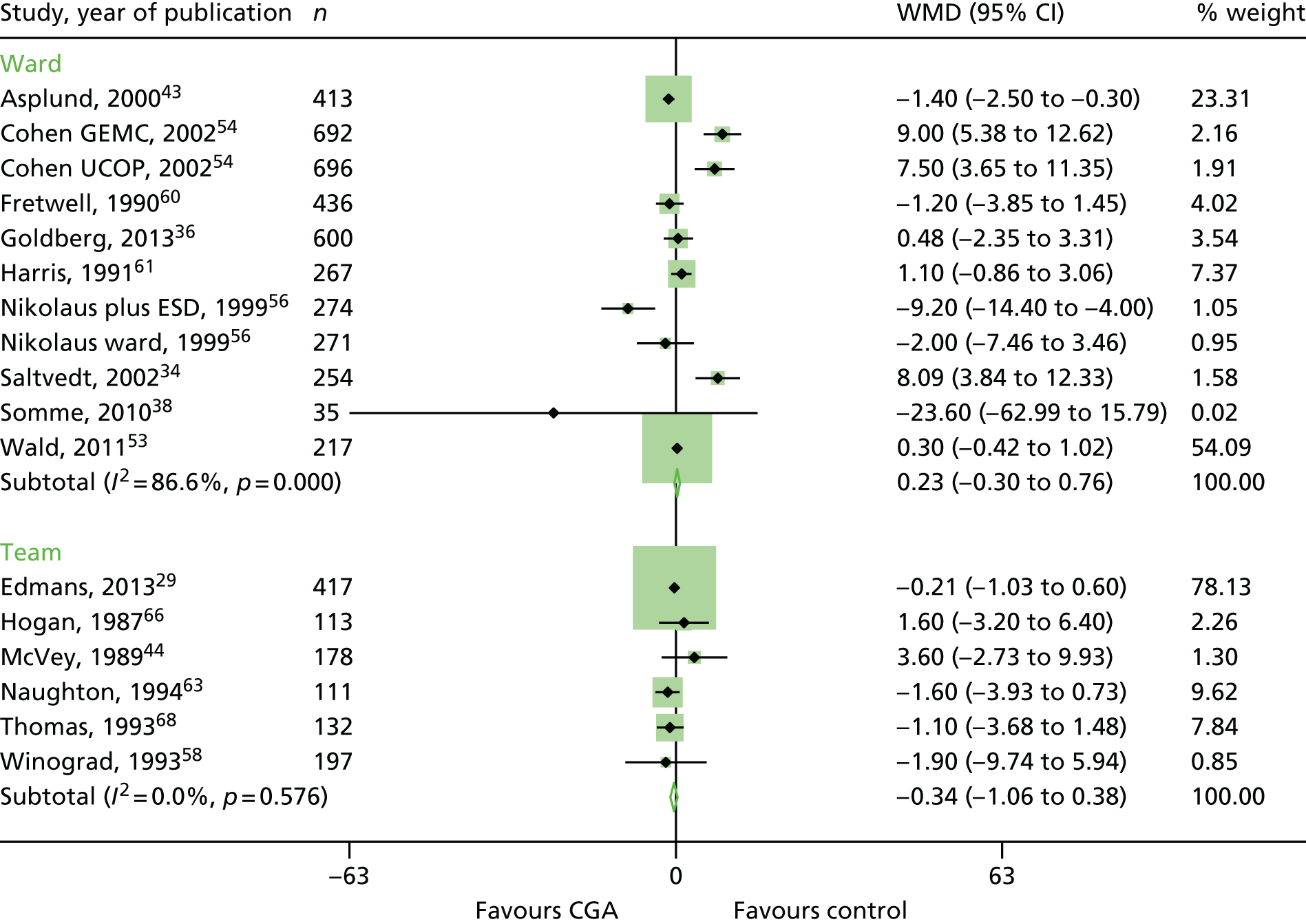

Length of stay

There was a high level of statistical heterogeneity in the 17 trials that reported length of stay; therefore, we did not retain the meta-analysis (n = 5309 participants; low-certainty evidence; I2 = 80%). 29,34,36,38,43,44,53,54,56,58,60,61,63,66,68 Mean hospital length of stay ranged from 3.4 days to 40.7 days in the CGA group and from 3.1 days to 42.8 days in the control group (Figure 11).

FIGURE 11.

Length of stay, mean differences. WMD, weighted mean difference.

Cost-effectiveness

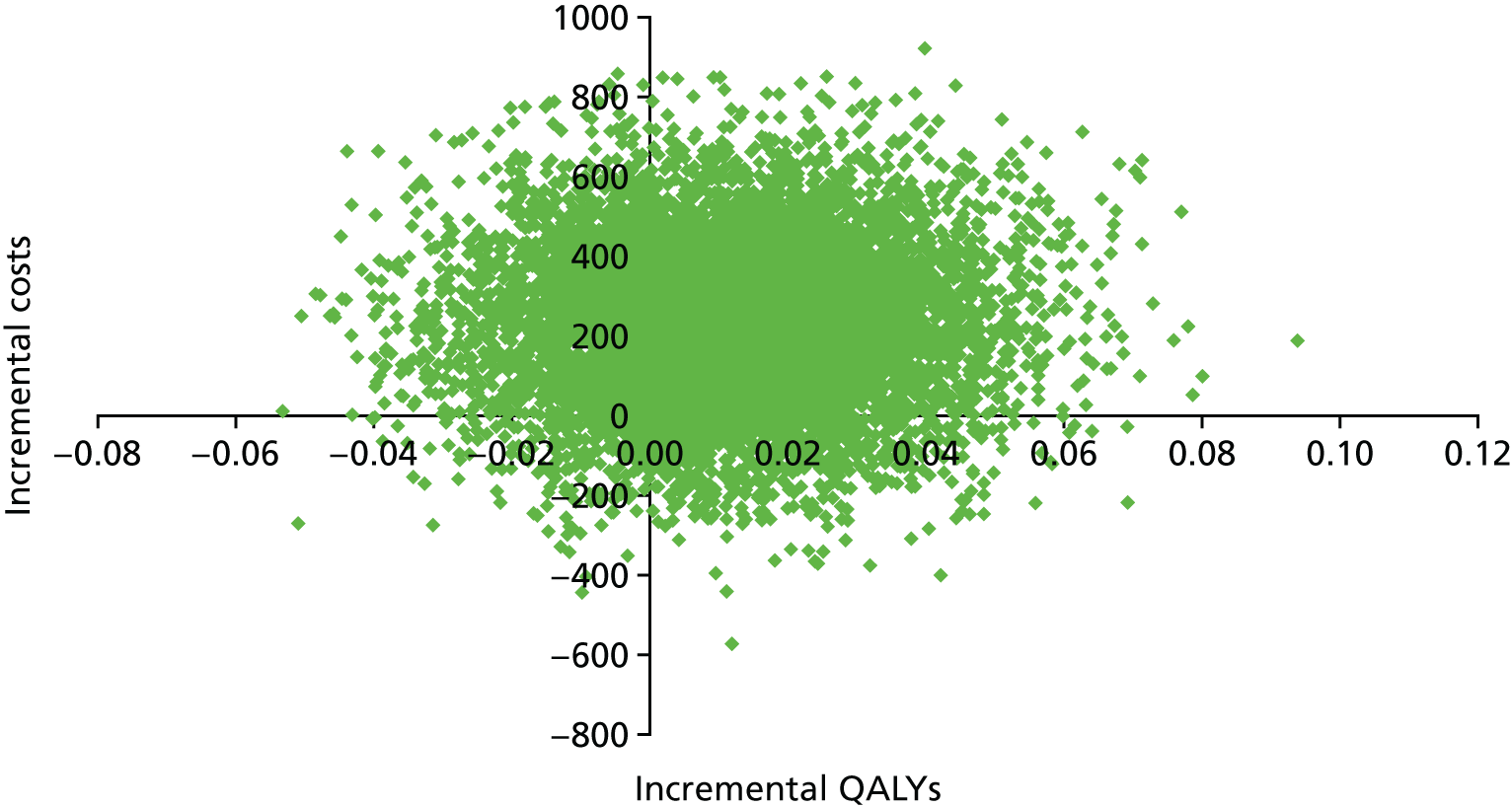

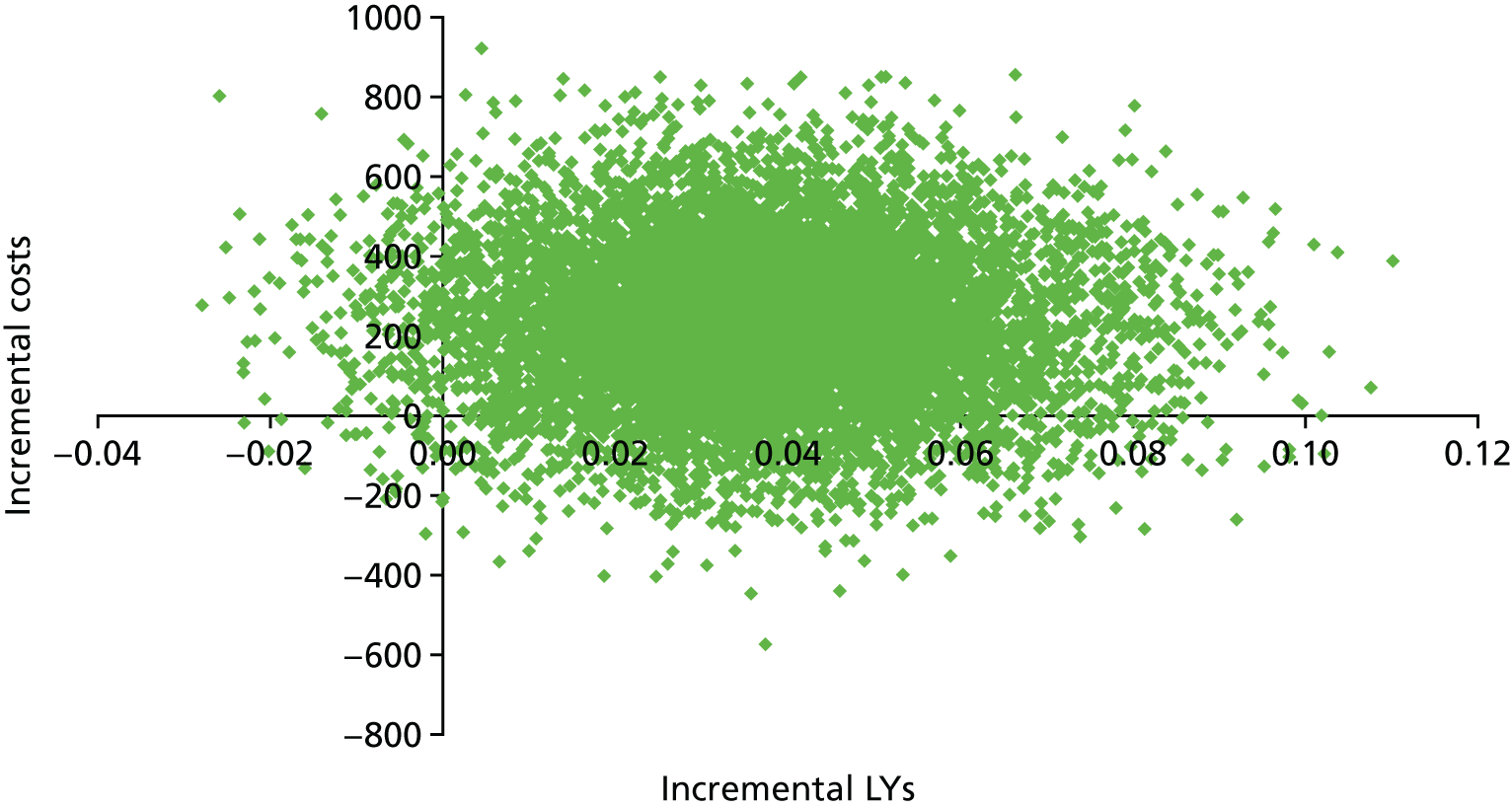

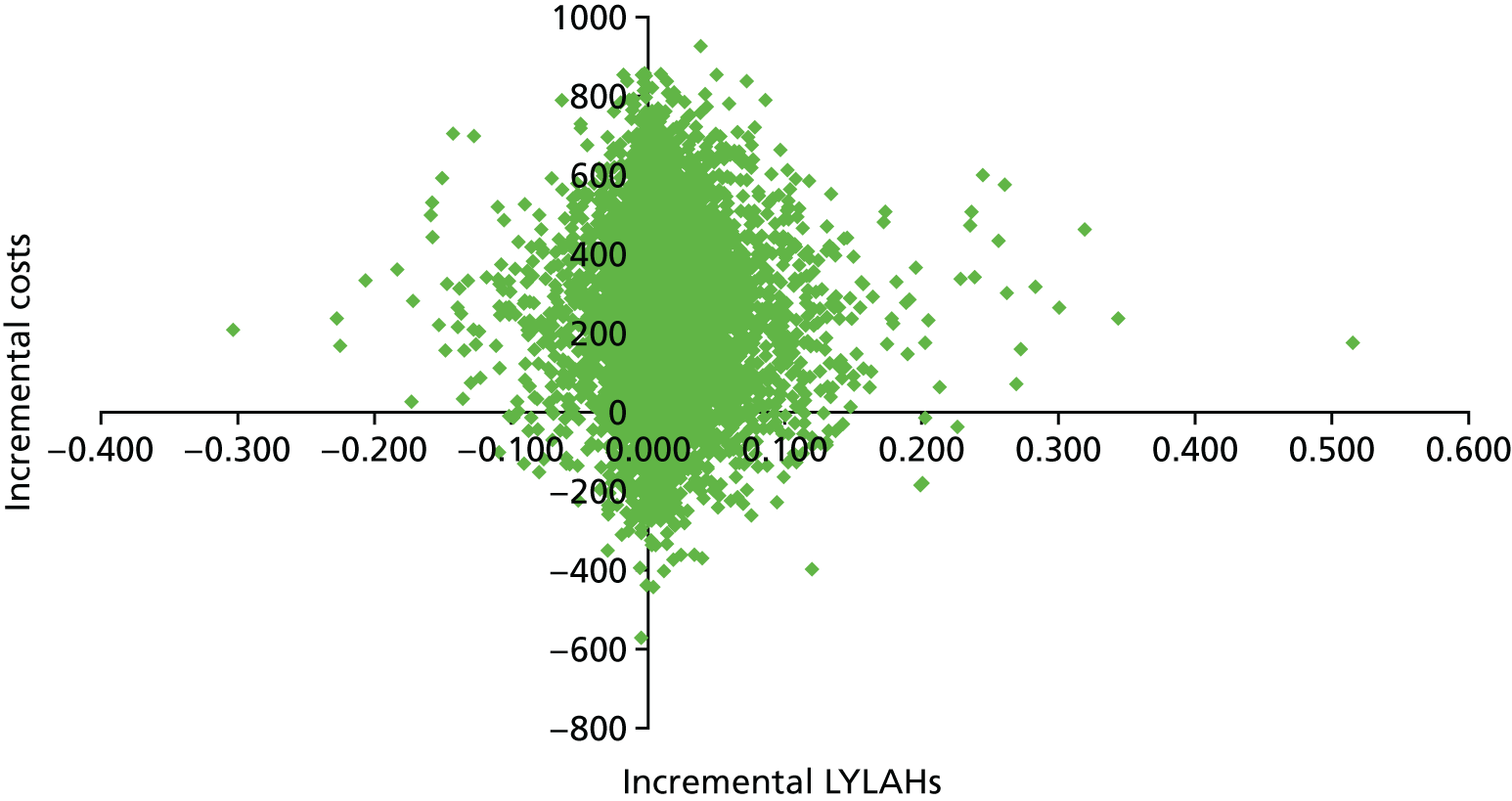

We used the meta-analysis of published data from 17 trials, and IPD from five trials,29,33,34,36,38 to estimate the incremental cost and incremental health outcomes of the CGA versus usual care. Results from the main cost-effectiveness analysis are detailed in Table 5. Health-care costs per participant in the CGA group were estimated to be £234 (95% CI –£144 to £605; 17 trials, low-certainty evidence) higher than in the usual-care group. Furthermore, the CGA may lead to a slight increase in QALYs of 0.012 (95% CI –0.024 to 0.048), a slight increase in LYs of 0.037 (95% CI 0.001 to 0.073) and a slight increase in LYLAHs of 0.019 (95% CI –0.019 to 0.155) (see Table 5). The ICER in terms of QALYs was £19,802, which is close to the threshold suggested by NICE as a ceiling value for a QALY;32 the cost for a LY gained was £6305, and, for a LYLAH gained, the cost was £12,568. The probability that the CGA will be cost-effective at a £20,000 ceiling ratio for QALYs, LYs and LYLAHs was 0.50, 0.89 and 0.47, respectively (see Table 5). We have plotted the cost-effectiveness planes with ICERs expressed as cost per QALY gained (Figure 12), per LY gained (Figure 13) and per LYLAH gained (Figure 14); these give the distribution of each draw of all incremental cost and incremental health outcome parameters.

| Incremental outcomes | ICER (£) | Probability of the CGA being cost-effective at a £20,000 ceiling ratio | Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| QALY (cost–utility analysis) | 19,802 | 0.50 | 0.012 (–0.024 to 0.048) |

| LY (cost-effectiveness analysis) | 6305 | 0.89 | 0.037 (0.001 to 0.073) |

| LYLAH (cost-effectiveness analysis) | 12,568 | 0.47 | 0.019 (–0.019 to 0.155) |

FIGURE 12.

Cost-effectiveness plane with ICERs expressed as cost per QALY gained.

FIGURE 13.

Cost-effectiveness plane with ICERs expressed as cost per LY gained.

FIGURE 14.

Cost-effectiveness plane with ICERs expressed as cost per LYLAH gained.

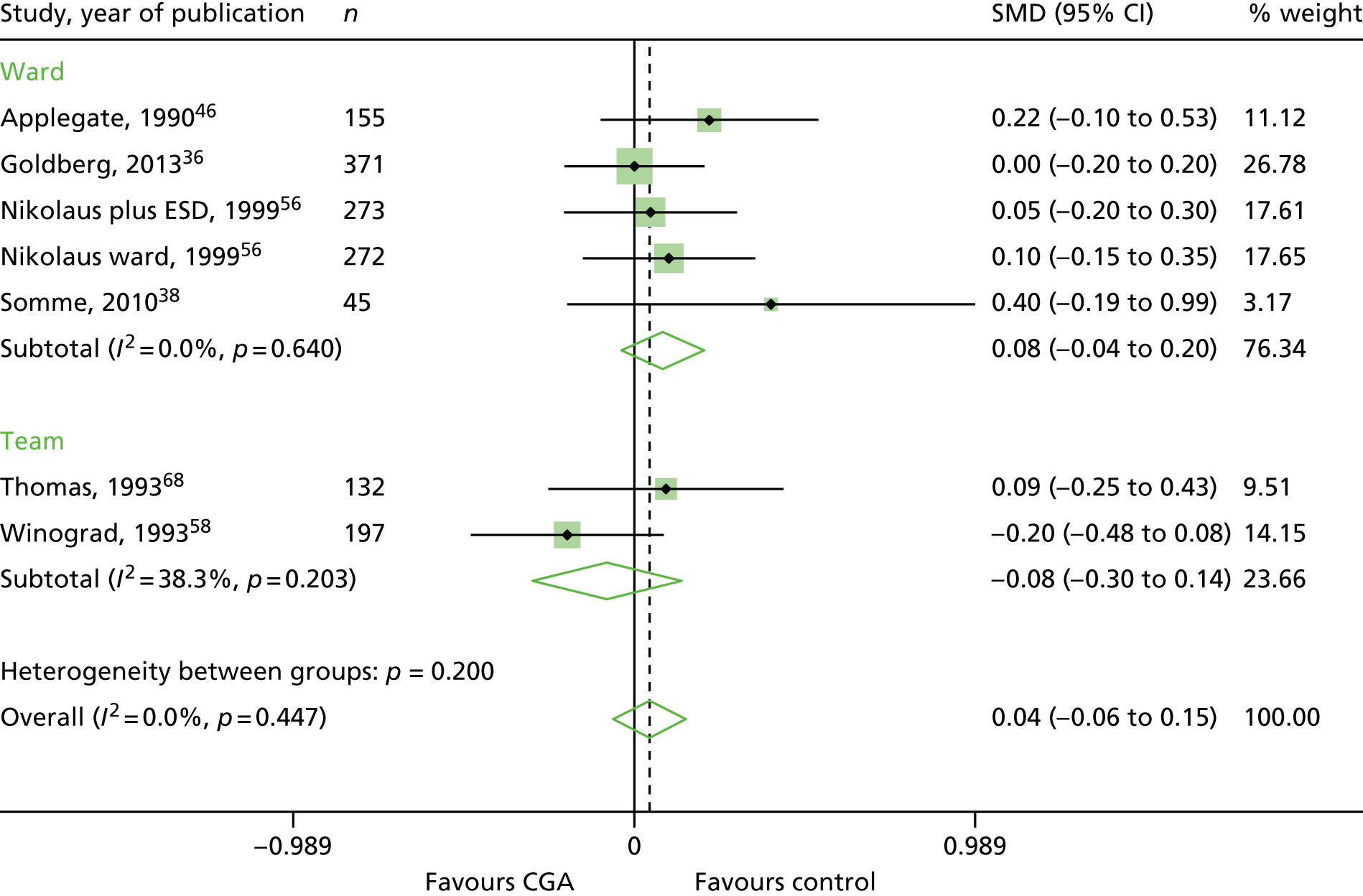

Activities of daily living

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment probably leads to little or no difference in ADL (standardised mean difference 0.04, 95% CI –0.06 to 0.15; seven trials, n = 1445, moderate-certainty evidence; I2 = 0%)36,38,46,56,58,68 (see Appendix 4).

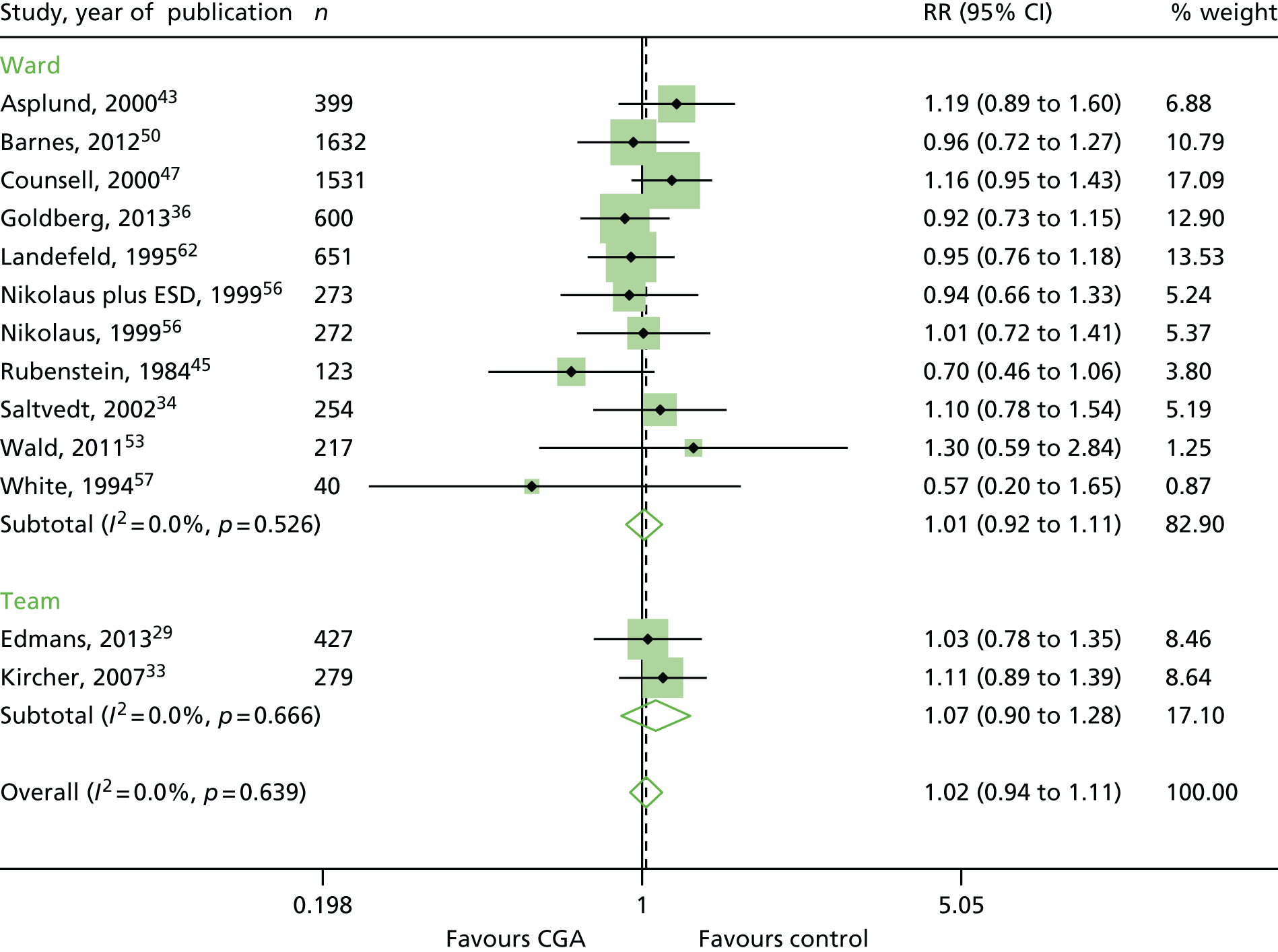

Re-admissions

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment results in little or no difference in re-admission to hospital (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.11; 13 trials, n = 6698, high-certainty evidence; I2 = 0%) (see Appendix 4).

Results from metaregression

Differences in effectiveness of the CGA delivery between wards and teams for each outcome were uncertain, and these analyses were underpowered (discharged home: F = 1.91, p = 0.20, n = 8 trials ward, n = 3 trials team; living at home at the 3–12 months’ follow-up: F = 3.54, p = 0.08, n = 12 trials ward, n = 4 trials team). There was also uncertainty about using age versus frailty as a criterion for targeting the delivery of the CGA on the main outcome of living at home [at discharge: F = 0.18, p = 0.68, n = 7 trials for age, n = 4 trials for frailty; end of follow-up (3–12 months): F = 0.98, p = 0.34, n = 5 trials for age, n = 11 trials for frailty], delivering the CGA on admission to hospital versus 72 hours after admission [at discharge: F = 0.51, p = 0.49, n = 6 trials for the CGA on admission to hospital, n = 4 trials for the CGA delivered 72 hours after admission; end of follow-up (3–12 months): F = 0.45, p = 0.51, n = 4 trials for the CGA on admission, n = 7 trials for the CGA delivered 72 hours after admission] and between outpatient follow-up versus no outpatient follow-up (at end of follow-up: F = 0.17, p = 0.69, n = 5 trials outpatient follow-up, n = 7 trials no outpatient follow-up).

Subgroup analysis using individual patient data

Results of subgroup analysis using IPD indicate that, in the five trials providing IPD (n = 1692, 12% of the total number of participants, adjusted for age, sex and frailty), there was little or no difference in the odds of living at home at the end of follow-up for participants in the intervention group versus the control group [odds ratio (OR) 0.95, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.24; I2 = 0%] (see Appendix 5). 29,33,34,36,38 Similarly, results on mortality indicate little or no difference in the odds of mortality at the end of follow-up (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.21; I2 = 0%) (see Appendix 5). Time-to-event analysis showed little or no difference in the time to death [hazard ratio (HR) 0.88, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.08] (see Appendix 5).

Sensitivity analysis

Rerunning the analyses using random-effects rather than fixed-effect models, or removing trials that did not exclude participants who were admitted to hospital from a nursing home, had little effect on the associations (data not shown).

Publication bias

The Harbord test (bias = 0.87, p = 0.18) and Egger’s test (bias = 0.87, p = 0.17) show little evidence of small trial bias for the main outcome of living at home at the end of follow-up (3–12 months).

Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation

The summary of findings is given in Table 6.

| CGA vs. admission to hospital without CGA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Patient or population: older adults admitted to hospital Setting: unplanned hospital admissions in nine largely high-income countries Intervention: CGA Comparison: usual care |

|||||

| Outcomes | Study population | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Anticipated absolute effectsa (95% CI) | |||||

| Risk with usual care | Risk with CGA | ||||

| Living at home (end of 3–12 months’ follow-up) | 561 per 1000 | 595 per 1000 (567 to 617) | RR 1.06 (1.01 to 1.10) | 6799 (16 RTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH |

| Mortality (end of 3–12 months’ follow-up) | 230 per 1000 | 230 per 1000 (214 to 247) | RR 1.00 (0.93 to 1.07) | 10,023 (21 RTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH |

| Admission to a nursing home (end of 3–12 months’ follow-up) | 186 per 1000 | 151 per 1000 (136 to 169) | RR 0.80 (0.72 to 0.89) | 6285 (14 RTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH |

| Dependence | 291 per 1000 | 282 per 1000 (259 to 302) | RR 0.97 (0.89 to 1.04) | 6551 (14RTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH |

| Cognitive function | NR | SMD ranged from –0.22 to 0.35 | – | 3534 (5 RTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb |

| Length of stay |

Not estimable Mean length of stay in the control group ranged from 1.8 days to 42.8 days |

Mean length of stay in the intervention group ranged from 1.63 days to 40.7 days | – | 5303 (17 RTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb |

| Cost and cost-effectiveness | Health-care costs per participant in the CGA group were, on average, £234 (95% CI –£144 to £605) higher than in the usual-care group (17 trials) | – | 5303 (17 RTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb | |

| CGA led to 0.012 (95% CI –0.024 to 0.048) more QALYs (three trials), 0.037 (95% CI 0.001 to 0.073) more LYs (four trials), and 0.019 (95% CI –0.019 to 0.155) more LYLAH (two trials) per participant | |||||

| Cost per QALY gained was £19,802, per LY gained was £6305 and per LYLAH gained was £12,568 | |||||

| CGA was more costly in 89% of 10,000 generated ICERs and led to QALY gains in 66% of cases, LY gains in 87% of cases and LYLAH gains in 74% of cases | |||||

| The probability that CGA would be cost-effective at a £20,000 ceiling ratio for QALYs, LYs and LYLAHs was 0.50, 0.89 and 0.47, respectively | |||||

Logic model

We refined the protocol logic model to map out the chain of events, or pathways, that constitute a mechanism of action of the CGA as researched, using the information we received from the survey of triallists (Figure 15). We have highlighted these additions (specialty knowledge, experience and competence, tailoring treatment plans to the individual and involving patients and carers in goal-setting) in italics (see Figure 15).

FIGURE 15.

Logic model: the CGA in hospital from Cochrane review and survey of triallists. Italicised text indicates additions to the protocol logic map, as a result of information received from the survey of triallists.

Discussion

We included 29 randomised trials that evaluated the effectiveness of the CGA versus inpatient care without CGA. Older people admitted to hospital who receive the CGA may be more likely to return and remain at home (16 trials, n = 6799 participants) and less likely to be admitted to a nursing home during 3–12 months’ follow-up (14 trials, n = 6285 participants) than those people who do not receive the CGA. We are uncertain as to whether or not the results for living at home show a difference in effect between wards and teams, as this analysis was underpowered. There was some evidence of a difference in effect between wards and teams for the results for admission to a nursing home. However, meta-regressions are observational and, hence, might be susceptible to bias through confounding.

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment may be slightly more costly, although the evidence for the cost-effectiveness analysis is of low certainty because of imprecision and inconsistency among studies, and our analysis did not include the cost of home or social care. Furthermore, implementing the CGA across health services may require investment in training and the development of specialist staff. Further research that evaluates the cost-effectiveness of the CGA would increase the certainty of our estimates. The issue of adjusting a LY for health-related quality of life in this population has been debated, and well-being based outcomes have been suggested as alternatives. 69 In response to this debate, we used the outcome measurement LYLAH as an indicator of independence and well-being; this outcome aligns to the primary outcome used in this review. Further research that tests the robustness of the LYLAH, and alternative methods to value outcomes used in cost-effectiveness analyses of interventions in older people, would be of benefit.

Chapter 3 Survey and interviews of community health-care providers

Introduction

The effectiveness of delivering the CGA in a hospital setting is well established,12 but little is known about the provision of the CGA in community settings. We therefore conducted a national survey of community trusts and health boards in the UK to gather information about the content and process of delivering out-of-hospital services that provided the CGA for frail older people, and conducted follow-up interviews with a sample of providers. We sought information on the content and process of delivering the CGA and the barriers to delivering the CGA in NHS out-of-hospital community settings. We used the following definitions of out-of-hospital services that were covered by the survey:

-

Admission Avoidance Hospital at Home – an episode of specialist care delivered at home as an alternative to being treated in an acute hospital environment, in which the care is overseen by a consultant or equivalent specialist [e.g. general practitioners (GPs) with an interest in hospital at home] and is time limited – from a few days to a few weeks. Hospital at Home involves more intensive medical support than intermediate care at home.

-

Early Discharge Hospital at Home (also known as early supported discharge) – rapid access to community rehabilitation and support with a mix of health and social care services delivered at home to support faster recovery and early discharge from hospital, and to optimise independent living.

-

Intermediate Care Beds – a time-limited episode of intermediate care provided in a dedicated capacity within a care home or community hospital setting. May be step-up (from home as an alternative to hospital admission) or step-down (following hospital admission).

-

Care Home in Reach Services – experienced nurses (e.g. registered general nurses and registered mental health nurses) will work alongside care home staff to improve the quality of nursing care received in the care home and help to avoid admissions to hospitals. The service is time limited and may include medical reviews by hospital specialists. The service may include reviewing and assessing the patients’ mental and physical needs and their care plan and help staff deal with difficult situations (crisis prevention/early intervention). This differs from primary care services to care homes though it may complement these.

-

Case Management – proactive and co-ordinated care management and support for people with complex chronic disease or frailty at high risk of future exacerbations and emergency admissions to hospital or to a care home. The episode is not time limited, often continuing over many weeks or months, and the care is generally led by a GP and/or community MDT.

-

Community Matrons – senior nurses with advanced health assessment/prescribing skills who care for patients at home during an acute episode of their long-term condition. The aim is to improve the quality of care and prevent unnecessary hospital admissions.

Methods

Survey development and piloting

Sample

We identified community health trusts from the Binley’s Healthcare Database70 and confirmed the contact details with the research facilitator in each trust or health board. We established contacts in 22 out of 23 community trusts in England, all 11 health boards in Scotland and all seven health boards in Wales, with the majority of contacts being a clinical lead. We obtained research and development approval from all the community trusts and health boards, and did not require Research Ethics Committee approval for this service evaluation.

We developed the survey questions by reviewing similar survey questionnaires71 and consulting with health professionals working with older people. We included questions about the population eligible for this type of service, the staff profile, organisational features and how the services were implemented. We piloted the survey with the Picker Institute Europe (Oxford, UK) and a group of clinicians working with older people. This included consultant geriatricians in NHS Lanarkshire (n = 2), NHS Lothian (n = 1) and Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust (n = 1). In addition, the survey was piloted by a team of health-care professionals at the British Geriatrics Society (BGS). Areas covered by the survey are described in Box 1.

Patient-specific questions: age, admission criteria, exclusion criteria, number of patients using the service, case-mix details and any accompanying comorbidity.

Staff providing the service: the whole-time equivalent of each staff category dedicated to CGA hospital at home, profession, seniority and specialist experience or training; type of staff working with CGA service.

Organisational features: what days are the CGA hospital-at-home services available? During what hours is care provided?

Care processes: type of assessment (e.g. confused assessment method for delirium); systems in place for reviewing progress, details on multidisciplinary meetings, engagement of patients and caregivers in goal-planning, process for identifying and implementing follow-on services.

Implementation: co-ordination with voluntary services, post-discharge planning, whether or not CGA hospital-at-home service has been audited.

We invited a named health-care professional from each NHS community trust or health board to complete the online survey hosted by the Picker Institute Europe via an e-mail link. The survey was designed to take 20–30 minutes to complete. At least two follow-up e-mails were sent prior to the closing date, and we also telephoned those who did not reply or complete the survey. We conducted interviews with a sample of those who had completed the survey to obtain a better understanding of the implementation of the CGA in community settings, the barriers encountered and examples of successful implementation. The telephone interviews were conducted by the Picker Institute Europe and ranged from 30 to 60 minutes. Details of the interview guide are detailed in Table 7. We also requested copies of service evaluations, such as formal audits or cost evaluations, from each trust or health board.

| Interview guide | Question |

|---|---|

| Background | What is the name of your Community NHS Trust? |

| Are you going to talk about the CGA hospital-at-home service for the whole trust, or a particular region of the trust? | |

| If for a particular region, what is the name of it? | |

| What is the name of the CGA hospital-at-home service you will be describing in this interview? | |

| Organisational features | Can you tell me about the CGA hospital-at-home service you provide? |

| How long has the CGA hospital-at-home service been established? | |

| Have you changed the way CGA is delivered and, if so, can you explain why you have done so? (This might include ceasing to deliver CGA) | |

| Do you plan to change the way CGA is delivered and if so, can you explain why and how you are doing this? (This might include starting to deliver CGA for the first time) | |

| Perceived successes | In your opinion, what are the successes of the CGA hospital-at-home service you provide for patients? |

| Barriers to implementation | How could patient care be improved by the CGA hospital-at-home service you provide? |

| What are the barriers to implementing the CGA service you provide? | |

| What are the threats to sustainability of the CGA service you provide? | |

| Population using your service | Does your service have the capacity to receive more patients? |

| Care processes | Can you describe how assessments (e.g. cognitive functioning) are individualised? |

| How do you follow up the implementation of care? (From the multidisciplinary team plans) | |

| Can you describe how patients and caregivers are involved in goal-setting and action plans? | |

| Implementation | How does your service co-ordinate with voluntary services to support patients? (If not, can you say why not and whether you have plans to do so?) |

| If there are any service evaluations available, such as formal audits or cost evaluations, would you be able to share this information? | |

| Other issues/ending | Thinking about the people you see, what type of patient does your service best serve? |

| How do you measure success of your CGA hospital-at-home service? | |

| Please tell us anything else about the CGA hospital-at-home service you provide |

Statistics

We calculated simple descriptive statistics using Stata (version 13); these included (1) the numbers and percentages of out-of-hospital services described in the survey, (2) the number using the services each year and the common conditions of those admitted to the services, (3) the referral route, (4) the type of health-care professional employed by the services and the whole-time equivalent (WTE) of each staff category, (5) staff expertise in the care of frail older people and (6) details of common tools to measure geriatric assessment and the length of stay.

Results

Response rate

Of the 41 community trusts or health boards contacted, 14 were excluded as they did not provide an out-of-hospital community-based service, leaving a sample of 27. We did not identify a Health and Social Care Trust in Northern Ireland that provided the CGA in the community at the time we ran the survey (2014–15). Of the 27 community trusts or health boards, 19 completed the survey. Three community trusts or health boards completed the survey but did not describe the type of service they provided. Eight respondents were interviewed, including five consultant geriatricians, two consultant nurses and a community psychiatric nurse team leader.

Survey findings

Of the 24 services described, 11 were based in Scotland, six were based in England and six were based in Wales; one respondent did not name the trust/health board (Table 8). We received two responses for Ayrshire and Arran, Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Lothian, Tayside, and Solent, and each described two services.

| Out-of-hospital services | Number of services (size of population in each area) |

|---|---|

| Scottish health board | |

| NHS Ayrshire and Arran | 2 (400,000) |

| NHS Fife | 1 (358,900) |

| NHS Grampian | 1 (525,936) |

| NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde | 2 (1,196,335) |

| Lanarkshire (Government) | 1 (652,230) |

| NHS Lothian (Edinburgh and West Lothian) | 2 (800,000) |

| NHS Tayside (Dundee and Angus) | 2 (388,780)a |

| Total | 11 |

| English community trusts | |

| Dorset Healthcare University NHS Foundation Trust | 1 (700,000) |

| Hertfordshire Community NHS Trust | 1 (1,000,000) |

| Liverpool Community Health NHS Trust | 1 (750,000) |

| Solent NHS Trust | 2 (1,000,000) |

| Torbay and Southern Devon Health and Care NHS Trust | 1 (375,000) |

| Total | 6 |

| Welsh health board | |

| ABMU University Health Board | 1 (600,000) |

| Aneurin Bevan University Health Board | 1 (639,000) |

| Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board | 1 (676,000) |

| Cardiff and Vale University Health Board | 1 (445,000) |

| Cwm Taf Health Board | 1 (289,400) |

| Hywel Dda Health Board | 1 (372,320) |

| Total | 6 |

| Other community trusts/health boards | 1 |

Of the 19 community trusts/health boards detailed in Table 8, 11 (57.9%) reported that the acute trusts provided a similar admission avoidance hospital-at-home service.

Prevalence of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment in a hospital-at-home setting

Admission avoidance hospital at home with the CGA (n = 8) was the most frequently described service. Several trusts provided more than one type of out-of-hospital service, and these were managed and operated within one organisational structure (Table 9).

| Out-of-hospital service | n (% of total surveyed) |

|---|---|

| Admission avoidance hospital at home | 8 (33.3) |

| Intermediate care beds | 2 (8.3) |

| GP-linked community geriatrician (one being a pilot of Compass in Lanarkshire, a Comprehensive Assessment for Older People) | 2 (8.3) |

| Enhanced Community Support | 2 (8.3) |

| Early discharge hospital at home | 1 (4.2) |

| Community resource team encompassing elements of admission avoidance hospital at home, early discharge hospital at home, care home in reach services and case management | 1 (4.2) |

| Early discharge hospital at home, intermediate care beds, case management and community matrons | 1 (4.2) |

| Community matrons/case management | 1 (4.2) |

| The community frailty team liaise with the frailty unit in the acute to provide timely discharges | 1 (4.2) |

| Frail Older Person’s Pathway in the ED | 1 (4.2) |

| Community frailty team | 1 (4.2) |

| Community mental health team for older people | 1 (4.2) |

| Admission avoidance hospital at home and early discharge hospital at home operating as one service | 1 (4.2) |

| Home Enhanced Care Services | 1 (4.2) |

| Total | 24 |

Population using the service

The number of people receiving out-of-hospital community-based health care per year ranged from 50 to 7500. For each of the out-of-hospital services described in Table 9, we asked the health-care professional what percentage of the patients received the CGA. In fact, each of the services described in Table 9 used the CGA; this ranged from 30% in the ‘Frail Older Person’s Pathway in the ED’ and ‘GP-linked community geriatrician, up to 100% in ‘Early discharge hospital at home’ and ‘admission avoidance hospital at home’ (the latter ranged from 75–100%). For instance, for the eight ‘admission avoidance hospital-at-home services’ described in Table 9, one service reported that 75% of patients received the CGA, another reported that 90% of patients received the CGA, a further service reported that 95% of patients received the CGA and the remaining services reported that 100% of patients received the CGA.

Of the services that had a minimum age for admission (43.5%; 10 out of 23), these minimum ages were 60, 65 and 75 years. Seventy-five per cent (18 out of 24) of the services had admissions criteria, and in some cases these were quite detailed; for example, in one ‘admission avoidance hospital-at-home’ service, these criteria were patients who (1) required intravenous antibiotics and fluids that can be managed at home or in care homes, had a diagnosis of pneumonia, a lower respiratory tract infection and exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), (2) had a diagnosis of delirium provided that there is adequate support at home or (3) were assessed for frailty syndromes and managed. In another ‘admission avoidance hospital-at-home’ service, admission criteria were (1) patients being > 75 years old, (2) patients having conditions that would otherwise lead to hospital admission and (3) patients being willing to remain at home with hospital at home. In the ‘early discharge hospital-at-home’ service, admission criteria were older adults presenting at the front door who were screened for the frailty syndrome. Of those ‘intermediate care beds’ services that included admission criteria, the criterion was that adults needed to be able to be safely managed at home during their acute illness; 95% of the patients being referred in these instances were older people. The ‘community frailty team’ service used the Bournemouth frailty criteria as admission criteria.

People who had a diagnosis of infection or sepsis, dementia, coronary heart disease or COPD constituted the majority of patients admitted to the out-of-hospital service (Table 10), and there was little variation among sites (see Appendix 6).

| Condition | n (% of total surveyed)a |

|---|---|

| Infection/sepsis | 15 (62.5) |

| Dementia | 14 (58.3) |

| COPD | 13 (54.2) |

| Chronic heart disease | 12 (50) |

| Osteoarthritis | 11 (45.8) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 9 (37.5) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 7 (29.2) |

| Diabetes | 4 (16.7) |

| Mental health condition | 4 (16.7) |

| Osteoporosis | 3 (11.1) |

The conditions of people who used these service by region are detailed in Appendix 6.

The majority of those patients who are referred to out-of-hospital services are referred by GP services (Table 11).

| Referred by | n (% of total surveyed)a |

|---|---|

| GP services | 22 (91.7) |

| Accident and emergency services | 13 (54.2) |

| Ambulance services | 7 (29.2) |

| Self-referrals from patients | 5 (20.8) |

| Care homes | 4 (16.7) |

Variation in the implementation of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

Organisational features

Fifty-nine per cent (13 out of 22) of the out-of-hospital services were set up to allow admission from Monday to Friday, and 36.4% (8 out of 22) operated 7 days a week.

Staff providing the service

The multidisciplinary teams that provided health care in the out-of-hospital services mainly comprised nurses, consultant geriatricians and occupational therapists. In many trusts, several staff categories had received training in the care of frail older people in addition to consultant geriatricians; this included nurses, occupational therapists and physiotherapists. Nurses, health-care assistants and therapy assistants made up the majority of staff employed by these services (Table 12). The WTE of each staff category for admission avoidance hospital at home (the most frequently described service) are detailed in Table 13 along with the number of patients seen per year.

| Staff | Expertise, n (%)a | WTE mean (SD) [n] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Do not know | ||

| Consultant geriatriciansb | 22 (91.7) | – | – | 1.05 (0.87) [17] |

| Dietitians | 8 (33.3) | 4 (16.7) | 6 (25) | 1.30 (0.42) [2] |

| Health-care assistant | 14 (58.3) | 2 (8.3) | 1 (4.2) | 6.54 (8.21) [7] |

| Junior doctors | 7 (29.2) | 5 (20.8) | 1 (4.2) | 0.89 (0.58) [7] |

| Nurses | 21 (87.5) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (4.2) | 5.70 (4.85) [16] |

| Occupational therapists | 19 (79.2) | 2 (8.3) | 1 (4.2) | 3.09 (2.69) [11] |

| Pharmacists | 12 (50) | 5 (20.8) | 1 (4.2) | 0.89 (0.41) [8] |

| Physiotherapists | 18 (75) | 3 (12.5) | 1 (4.2) | 3.50 (3.70) [11] |

| Podiatrists | 7 (29.2) | 4 (16.7) | 3 (12.5) | 0.5 (1) [1] |

| Psychiatric nurses | 18 (75) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (4.2) | 0.88 (0.25) [4] |

| Psychogeriatricians | 17 (70.8) | – | – | c |

| Religious/faith support | 0 | – | 6 (25) | c |

| Social worker | 11 (45.8) | 2 (8.3) | 3 (12.5) | 1.50 (1.32) [3] |

| Social work assistants | 7 (29.2) | 3 (12.5) | – | 4.25 (5.30) [2] |

| Speech therapists | 10 (41.7) | 4 (16.7) | 4 (16.7) | 0.63 (0.35) [3] |

| Staff grade doctors | 7 (29.2) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (4.2) | 2.37 (2.28) [3] |

| Therapy assistants | 15 (62.5) | 2 (8.3) | 2 (8.3) | 8.87 (8.71) [7] |

| Staff | WTE | Mean (SD, range) [n] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| West Lothian | Fife | ABMU | Lanarkshire | Aneurin Bevan | Solent | Dorset | ||

| Consultant geriatricians | 1.1 | 3 | 0.6 | 1 | 2 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 1.31 (0.91, 0.3–3.0) [7] |

| Health-care assistants | – | 3 | 4 | – | – | 12 | 22.8 | 10.45 (9.17, 3.0–22.8) [4] |

| Junior doctors | 0.25 | 2 | – | – | 1 | 0.4 | – | 0.91 (0.79, 0.25–2.0) [4] |

| Nurses | 3.8 | 1 | 11.8 | 3 | 16.8 | 13 | 8.2 | 8.23 (5.89, 1.0–16.8) [7] |

| Occupational therapists | 1 | – | – | 1 | 4.41 | 1 | 5.2 | 2.52 (2.10, 1.0–5.2) [5] |

| Pharmacists | 0.5 | 0.9 | – | – | 1 | – | – | 0.80 (0.26, 0.5–1) [3] |

| Physiotherapists | 1 | – | – | 1 | 5.34 | 1 | 3 | 2.27 (1.92, 1.0–5.3) [5] |

| Psychiatric nurses | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | 1 [1] |

| Social worker | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | 1 [1] |

| Speech therapists | 0.3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.3 [1] |

| Staff-grade doctors | 1.1 | 5 | – | – | 2 | – | – | 2.70 (2.04, 1.0–5.0) [3] |

| Therapy assistants | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 22.8 | 11.90 (15.41, 1.0–22.8) [2] |

| Number of patients per year | 600 | 1500 | 900 | 882 | 1200 | 1800 | 1500 | – |

Care processes

Most of the out-of-hospital services used a standard geriatric assessment, with ADL and cognitive functioning being the assessments most commonly used (see Appendix 7). The majority (82.6%; 19 out of 23) of the respondents reported that multidisciplinary team meetings were routine, with 33.3% (7 out of 21) meeting daily, 47.6% (10 out of 21) meeting once a week and 28.6% (6 out of 21) meeting more than once a week.

The majority (73.9%; 17 out of 23) reported that patients were reassessed based on their changing needs. In addition, the services (69.6%; 16 out of 23) had a system to follow up the implementation of the multidisciplinary team plans. All services reported that those receiving the services were involved in goal-setting and action plans (100%; 23 out of 23) and that caregivers were also involved in goal-setting and action plans (95.7%; 22 out of 23). More than half (65.2%; 15 out of 23) used a structured process for planning discharge and 47.8% (11 out of 23) of those who received care could access their care records.

Implementation

Just over one-third of the out-of-hospital services either always (39.1%; 9 out of 23) or sometimes (52.2%; 12 out of 23) co-ordinated with voluntary services to provide support to patients. The majority (87.0%; 20 out of 23) reported that they provided information about voluntary services to support patients. A minority of services (26.1%; 6 out of 23) reported that they always provided post-discharge rehabilitation. The out-of-hospital service had been formally audited or evaluated in the past 3 years in 69.6% (16 out of 23) of the trusts surveyed; this included an evaluation of the costs of running the CGA hospital-at-home service in 34.8% (8 out of 23) of the trusts, reported as a total or per-patient cost.

Interview findings

We interviewed lead clinicians from eight of the trusts to obtain more details about the services that they provided. Two of the leads described admission avoidance hospital-at-home services (Fife and West Lothian) and two described intermediate care services (Ayrshire and Arran, and Dorset). Ayrshire and Arran intermediate care service was led by a senior specialist nurse in geriatric medicine and provided step-up and step-down beds. A summary of the information provided by these four trusts is reported in Table 14. The service in Dorset was described as intermediate care and provided admission avoidance hospital at home and early supported discharge with the same staff working in both services (including a consultant geriatrician).

| Question | Trust | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHS Fife admission avoidance hospital at home | NHS West Lothian admission avoidance hospital at home | NHS Ayrshire and Arran intermediate care | NHS Dorset intermediate care(Bournemouth) | |

| Can you describe the CGA hospital-at-home service? | Function: consultant-led hospital-at-home service that avoids admissions and also provides a step down from hospital (80% of admissions are admission avoidance hospital at home) | Function: REACT; modelled on ASSET (Lanarkshire). Consultant-led hospital-at-home service as alternative to hospital admissions | Function: IC&ES facilitates early discharge from hospital and provides an alternative to hospital admissions | Function: Bournemouth intermediate care commissioned to avoid admission to acute trust for patients with acute medical conditions and early supported discharge for complex cases needing multiple professionals (60% admission avoidance, 40% early supported discharge) |

| Referral route: nurse practitioners assess and admit patient to the virtual ward; patients referred from GP or from acute setting step down | Referral route: referrals accepted from medical assessment unit, GP and accident and emergency services | Referral route: referrals accepted from GP and accident and emergency services | Referral route: referrals mostly from GPs, but also from accident and emergency services and ambulance services | |