Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/196/02. The contractual start date was in January 2016. The final report began editorial review in November 2017 and was accepted for publication in June 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Rob Anderson is a current member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research Researcher-led Prioritisation Committee. However, in this role he would not be involved in any discussions or decisions about grant proposals in which he has any personal, institutional or financial connections to any of the applicants. Alex Aylward declares personal fees outside the submitted work from the Northern, Eastern and Western Devon Clinical Commissioning Group, the Devon Local Medical Committee, the British Medical Association, the Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (South West Peninsula) and the NHS England Medical Directorate (South).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Campbell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Understanding the general practitioner workforce crisis

Ninety per cent of NHS patient contact takes place within the context of primary care; this equates to 1.3 million consultations every working day and 340 million consultations per year, with a projected primary care workload of 430 million consultations per year by 2018. 1,2 Some patient groups disproportionately contribute to this demand for NHS services; for example, patients aged > 75 years – a population that is increasing – currently have an average of 15 contacts per year in primary care. 2 Such groups, who often have complex comorbidities, may therefore be particularly vulnerable to changes in the availability and accessibility of primary care services caused by workforce problems. In particular, around 66% of primary care contacts take place with a general practitioner (GP). GPs are trained in handling complex disease presentations and have unique abilities in respect of the diagnosis and management of this complex multimorbidity.

General practice has been described as ‘the jewel in the crown’ of the NHS. 3 International evidence has identified that, without strong primary-care-based health care, adverse consequences are likely to be reflected in increased costs of care, reduced satisfaction with care, increased health inequalities and adverse health outcomes for the population. 4 Authoritative reports have identified the need for both local and national approaches to workforce planning and for an acknowledgement of the inherent uncertainties of the process. 5

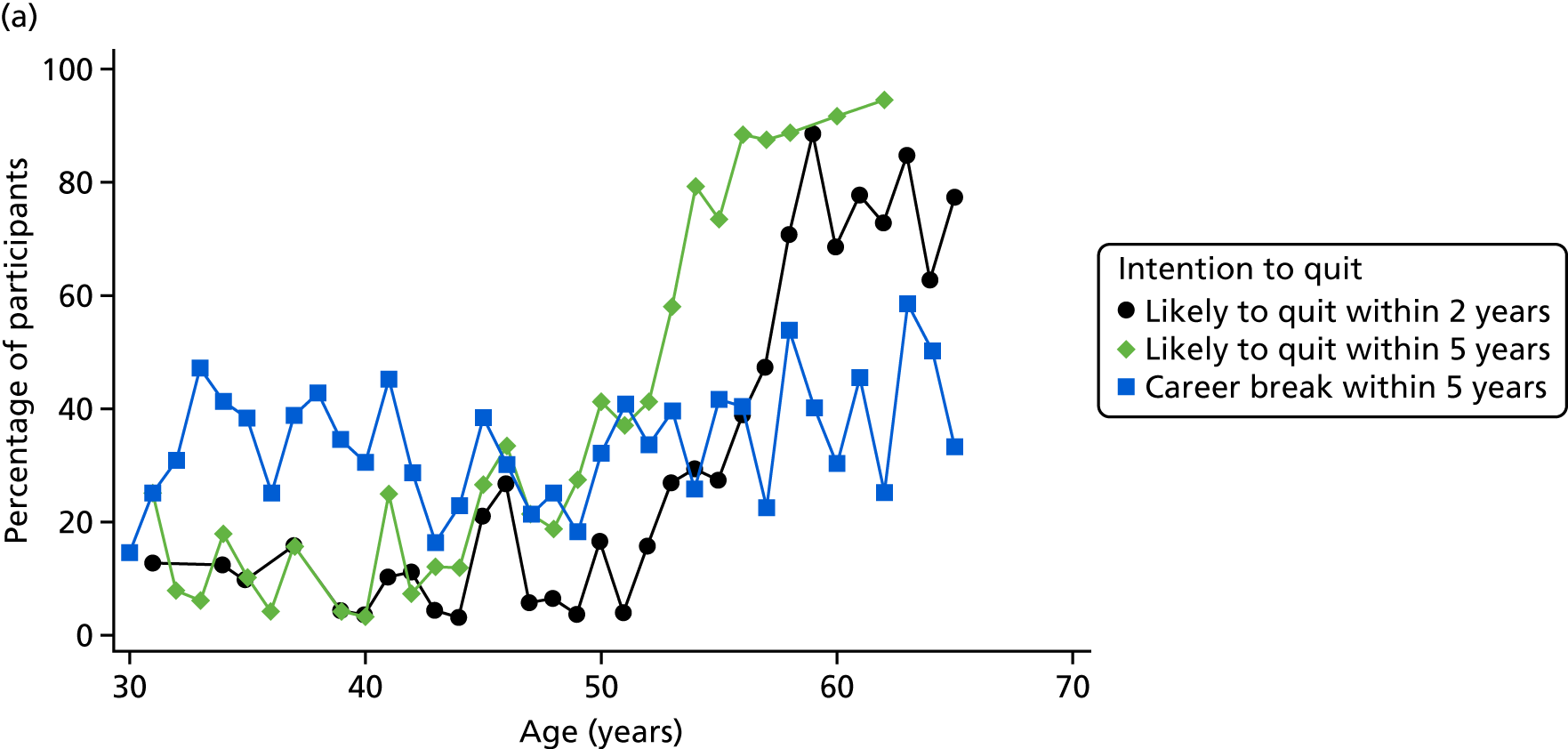

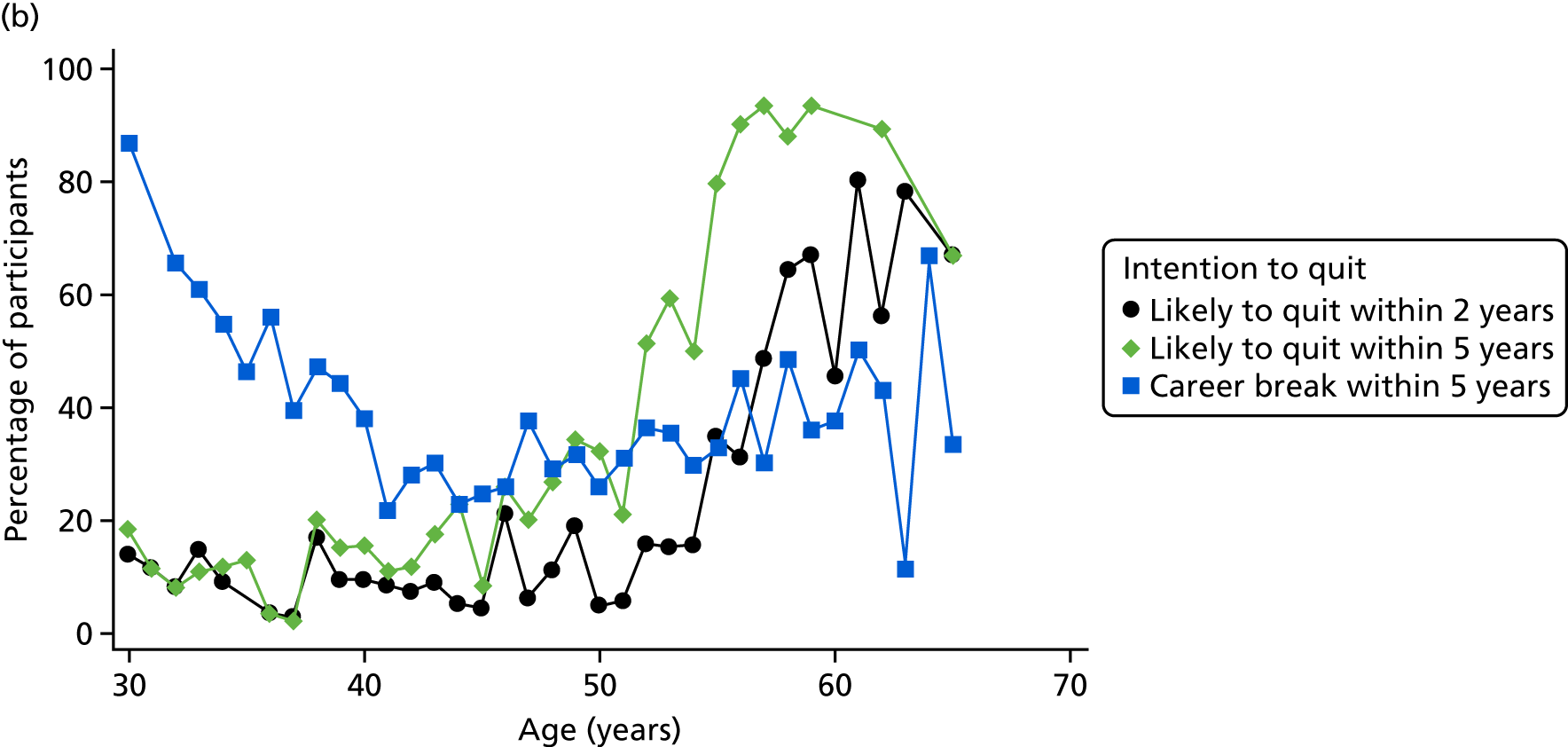

UK general practice is facing a workforce crisis, with imminent GP shortages and a clear resulting risk to patient health and well-being. More than 50% of GPs aged > 50 years (who account for 32% of all practitioners6) anticipate quitting direct patient care within 5 years. Research from the British Medical Association (BMA) has highlighted the continuing problem. In the study of 431 doctors from the 2006 cohort of medical graduates, those in general practice reported the lowest morale of all cohort doctors, with higher than expected workload being identified as a key problem. 7 In addition, the shifting demographic profile of GPs is likely to contribute to full-time equivalent (FTE) shortages. Ninety per cent of male doctors plan to work full time, compared with just 40% of female doctors. Among doctors who graduated 7 years previously, 35.1% were working in general practice; the figure for male doctors was just 25.6%, whereas for female doctors it was 42.5%. These figures thus set the scene for a potential problem in workforce capacity. A near quadrupling of unfilled GP posts was observed between 2010 and 2013 (from 2.1% to 7.9%). 8

Our research aimed to develop policies and strategies to support GPs returning to work after a career break or retaining the experienced GP workforce. We anticipated that the policies and strategies may have components relating to the clinical support of GPs and, thus, may build on the work of Drennan et al. 9,10 on the potential for physician assistants in supporting GPs, Sibbald et al. 11 in relation to the potential of diversifying the primary care workforce through the increased use of nurses in primary care and Avery and Pringle12 regarding the potential for the increased use of pharmacists in roles extending beyond medication management to include structured care for individuals with long-term conditions and in the provision of health-care advice for a range of individuals. 13 The role of the pharmacist has been identified as an area of particular interest and scrutiny in the context of GP workforce issues. 14

What policies and strategies might avert the crisis in the general practitioner workforce?

The future of NHS care15 is likely to involve new models of care, with innovations in respect of both horizontal and vertical integration, involving professional skill mix and health/social care, and in respect of new approaches to managing the service15,16 and in federations of previously independent practices. 15 As these models develop and emerge, it is vital that the GP workforce is sustained now; without strong general practice input, the ability to develop and implement these new models of care will be threatened. Our research therefore targets the critically important area of developing policy and strategy interventions that target the retention of experienced GPs in direct patient care, especially those GPs considering or likely to take early retirement and those GPs who have taken a career break (most often on account of family circumstances).

A preliminary scoping search suggested that there was a pre-existing body of literature involving a range of methods and settings that needed to be formally reviewed and that appeared, on initial inspection, potentially to offer useful background information. Furthermore, a limited pilot survey of GPs, and beta-testing of a novel mathematical model for assessing the 5-year risk at the individual practice level of supply–demand imbalance, appeared successful17 but also identified missingness in data sets and limitations on data availability as issues to consider in future research, such as we describe here.

Our earlier preliminary research also involved qualitative work with a small sample of experienced GPs in which we explored decision-making around quitting direct patient care. 18 In that preliminary work, we identified some factors that appeared to be of potential importance in influencing retirement/quitting decisions, including ‘push’ factors (e.g. health concerns, impact of personal ageing, workload concerns, changing work environment) and ‘pull’ factors (e.g. career opportunities, pension issues). However, although we succeeded in identifying potential retirees, we previously encountered difficulty identifying and accessing doctors on career breaks and implemented relevant strategies to take into our present research.

Evidence explaining why this research is needed now

Immediate challenges face the NHS in respect of GP workforce capacity. Recent years have seen falling recruitment to a GP career. In addition, 54.1% of GPs aged > 50 years anticipate quitting direct patient care within 5 years. 19 Thirty-two per cent of the UK GP workforce is aged > 50 years. 19 England has an ageing GP workforce, particularly in inner-city settings, where the problems of recruitment and retention are compounded by issues relating to the sociodemographic mix of the population and the increased demands for care. Retaining the GP workforce is, therefore, urgent. If unaddressed, some authorities have previously suggested that ‘meltdown’ in NHS care may follow within the foreseeable future. 1 The situation has been described as a ‘crisis’20 and there has been a call for policies and strategies to help retain GPs. 8,21

In England, at around the time this present research was commissioned (in August 2015), some major initiatives had been announced to support primary care and GPs. 22 NHS England announced (in January 2015) a £10M joint initiative administered via Health Education England (HEE), the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) and the BMA, targeting enhanced training in difficult-to-recruit areas, offering part-time working arrangements for GPs considering retirement, actively promoting GP careers, examining the potential for non-medics to support GPs and providing enhanced induction and support for GPs considering returning to patient care after a career break. 23,24 Although the RCGP’s key policy statement on ‘The 2022 GP’ anticipated important changes in the organisation and delivery of care and the training and support of GPs, and suggested that by 2022 ‘the general practice workforce will have grown to reflect need, with more doctors and nurses working in practices and community-based settings, more GPs entering and remaining in the profession, and better support for GPs wishing to return to practice’, the challenges of attaining that vision were also recognised with a developing body of evidence and concern in respect of difficulties encountered in recruitment and increasing loss of GPs from direct patient care. 25 The Care Quality Commission (CQC) had also recently developed relevant policy and practice taking account of workforce considerations. 26 Despite these initiatives, little firm evidence existed at the time at which this research was commissioned to inform the development of policies and strategies targeting the recruitment and retention of the GP workforce. 27–34

Against this changing policy and practice background, there was also an evident need for detailed information at a practice level to facilitate and support the planning of services; use of GP workforce information has historically been at regional and national levels to understand current and future capacity. It appeared clear that greater granularity was urgently required to identify practices at imminent and foreseeable risk – the research specifically addresses this area of need for the NHS.

Elsewhere, the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and the US Institute of Medicine have recognised increasing pressures on, and opportunities for, the primary care workforce on account of changing demographics, and in fiscal and domestic health policy, and have suggested that there is a need for new models of integration in primary care. 35,36 In its study, the AAFP suggested that a predicted deficit of 44,000 US family doctors by 2025 may be an underestimate of the anticipated reality, with concerns being expressed regarding the recruitment and retention of family doctors. 35 Similar pressures, with an associated need for GP workforce planning, have also been recognised in Canada, Australia and New Zealand. 37–39

Targeting the recruitment and retention of the GP workforce is thus timely and urgent. Although provision of a primary care workforce benefits from skill mix (e.g. the use of nurses, pharmacists and physician assistants), unless the GP workforce issue is addressed urgently, an imminent crisis looms in respect of both leadership in primary care and inequalities in provision of care, especially for patients with complex multimorbidity. Failure to address these challenges runs the risk of failure in NHS care provision. Given the 10-year (minimum) trajectory for training a new medical student to become a qualified GP, and the falling recruitment to general practice, the research we report here will remain relevant and important to the needs of the NHS for at least the next 20 years.

Aims and objectives

Our research addressed two research questions. First, what are the key policies and strategies that might (1) facilitate the retention of experienced GPs in direct patient care and (2) support the return of GPs to direct patient care following a career break? Second, how feasible is the implementation of these policies and strategies? To address these questions, we outlined four aims, each of which is described below, along with its associated objectives.

Aim 1

To develop a conceptual framework and comprehensive assessment of factors associated with GPs’ decisions to (1) quit direct patient care, (2) take career breaks from general practice and (3) return to general practice after a career break. There are two objectives:

-

to conduct a systematic review of existing literature to describe factors affecting these decisions in the UK and other high-income countries

-

to conduct a census survey of GPs in south-west England to provide a sampling frame to provide qualitative evidence from GPs intending to quit direct patient care and those who are currently taking or who are considering taking a career break with a view to identifying factors affecting quitting intentions, and to identify potentially modifiable factors relevant to these groups of GPs.

Aim 2

To identify the potential content and assess the evidence supporting key potential components of policies and strategies aimed at retaining experienced GPs and/or supporting the return of GPs to direct patient care following a career break. There are two objectives:

-

to outline the content of policies and strategies that will support the retention of these groups of GPs in direct patient care

-

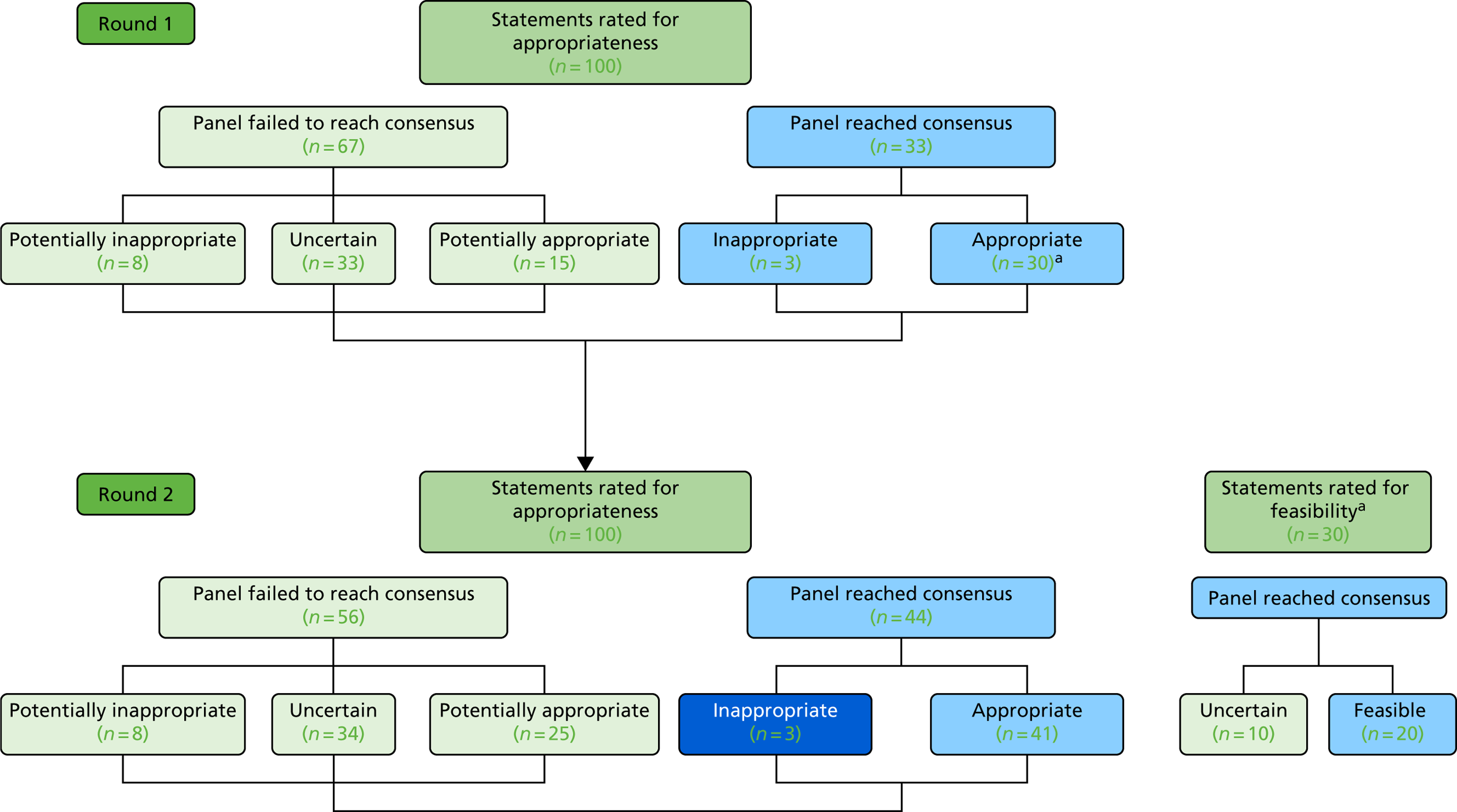

to prioritise, using an expert panel and validated methodology [RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method (RAM)], the proposed policies and strategies in respect of their feasibility and effectiveness.

Aim 3

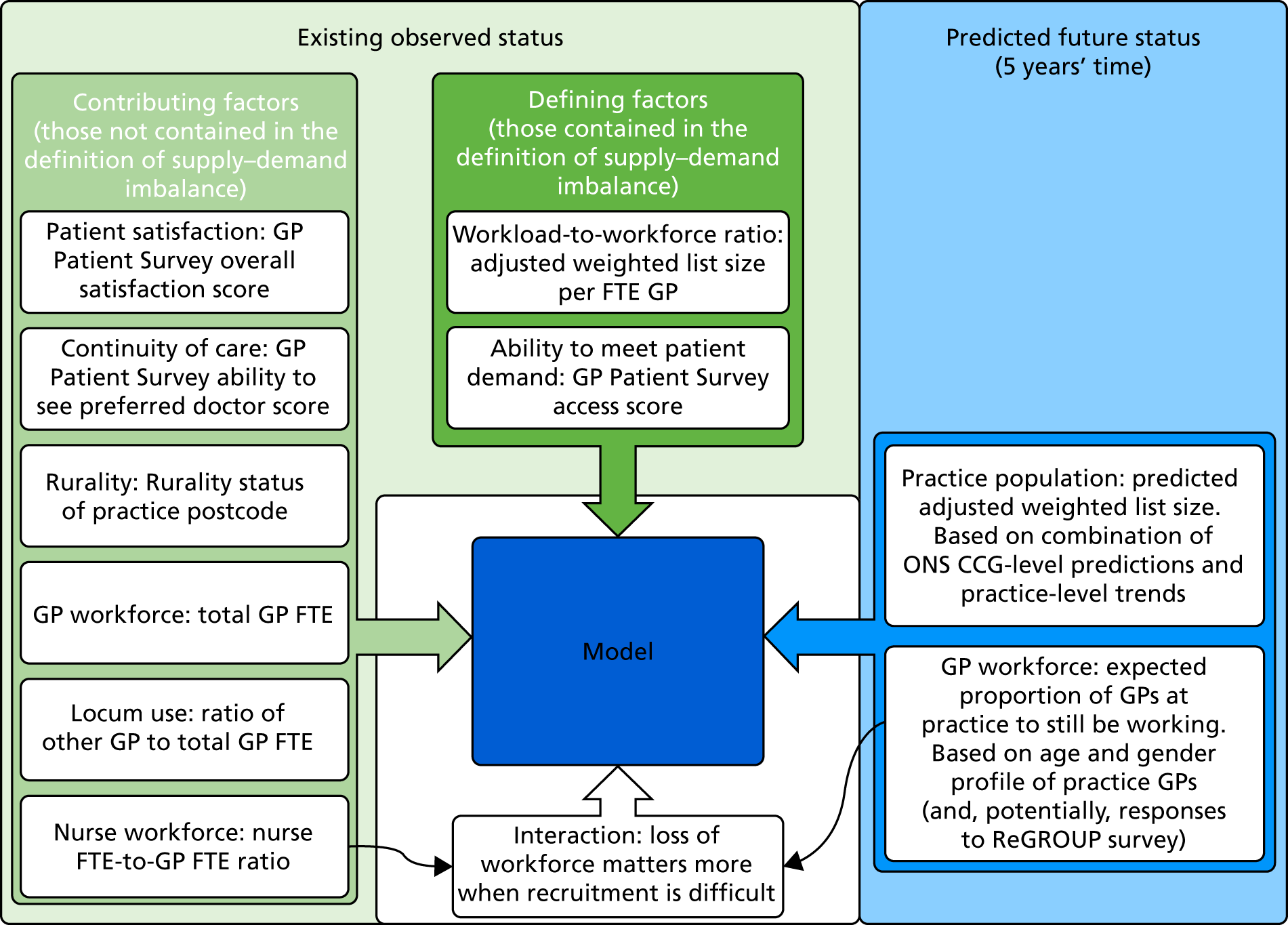

To identify practices that may face supply–demand workforce imbalances at the macro (regional) and micro (general practice/GP) level within the next 5 years, with a view to strategically targeting relevant policies and strategies. There are two objectives:

-

drawing on a range of data, including the previously mentioned survey, to specify, develop and test the approach necessary to identify supply–demand imbalance at the level of individual practices

-

to use the approach developed in aim 3, objective 1, to identify general practices in south-west England (an area with broad representation of practice settings) at risk of workforce shortages owing to early retirement from direct patient care among experienced GPs and owing to GPs planning, or currently taking, a career break.

Aim 4

To assess the acceptability and feasibility of implementing the policies and strategies. The objective is:

-

to gather feedback from key stakeholders on the acceptability and likelihood of implementing the policies and strategies at a local level.

Research plan and methods

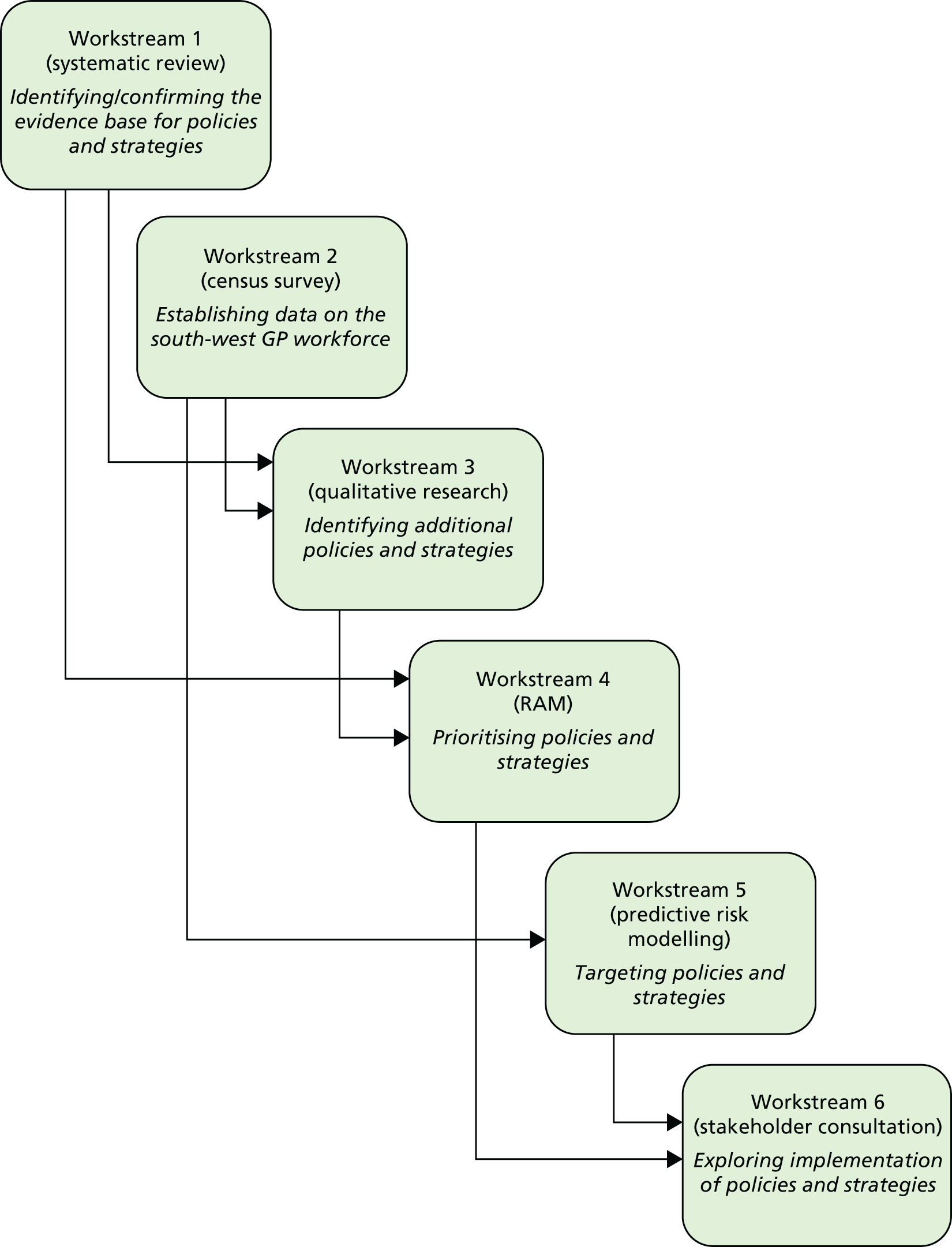

We conducted a mixed-methods project, consisting of six inter-related workstreams (Figure 1) to address our study aims and objectives. Patient and public involvement (PPI) was woven throughout the programme of work, including input to the development of the funding application, obtaining ethics approval, project management and contributions to individual workstreams (reported in full in Appendix 1). Each workstream is described in detail within the chapters following this section, with a list of abstracts for each piece of work available in Appendix 2.

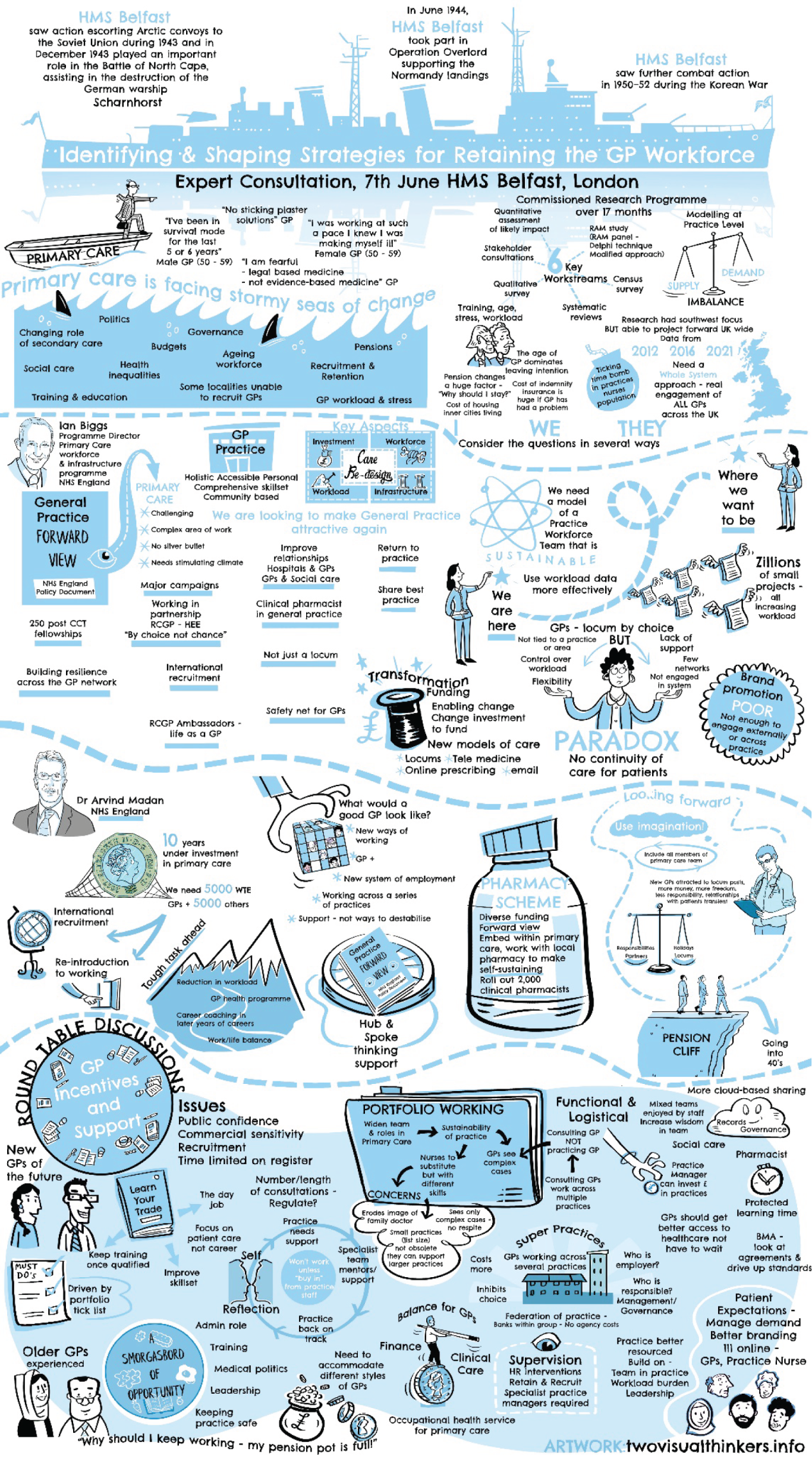

FIGURE 1.

The ReGROUP project workstreams. ReGROUP, retaining experienced GPs and those taking a career break in direct patient care.

Chapter 2 Workstream 1: systematic review

Introduction

Current problems in the general practitioner workforce

There is said to be a ‘crisis’ in general practice in the UK on account of GPs leaving direct patient care or reducing their hours, and many others intending to do so. 40 A survey of UK GPs by the Commonwealth Fund in 2015 found that, at that time, nearly 30% of GPs planned to leave general practice within 5 years. 41 As well as those planning to retire, this included a substantial minority intending to switch medical specialty and others aiming to completely change career. Table 1 summarises the proportion of UK GPs who were aiming to leave general practice or direct patient care within the next 5 years from various studies.

| Study (year of publication) | Year surveyed | Percentage aiming to quit | Specific quitting question asked | Country (region) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sibbald et al. (2004)11 | 1998 | 14.0 | Likelihood of leaving direct patient care within 5 years, on a 5-point scale (1 = none, 5 = high); score of 4 or 5 classified as intending to quit | England |

| Sibbald et al. (2004)11 | 2001 | 22.0 | England | |

| Simoens et al. (2002)42 | 2001 | 19.9 | Leave general practice within 5 years | England and Scotland |

| Gibson et al. (2015)43 | 2015 | 35.3 | A ‘considerable likelihood’ that GPs would quit patient care in next 5 years | UK |

| Davis et al. (Health Foundation/Commonwealth Fund; 2016)41 | 2015 | 29.0 | Wish to leave general practice within the next 5 years (an additional 17% were not sure) | UK |

| Campbell et al. (2015)17 | 2014/15 | 35.0 | At high risk of quitting direct patient care within 5 years | England (south-west) |

| Dale et al. (2015)44 | 2014/15 | 41.9 | Saying ‘no’ to intention to remain in general practice beyond the next 5 years | England (West Midlands) |

In the three earlier surveys, conducted in England and Scotland between 1998 and 2001, between 14% and 22% of GPs said that they were likely to leave direct patient care within 5 years. By 2014 and 2015, the proportion of GPs in the UK saying that they would leave general practice in the next 5 years varied from 29% to 42% in different regions of England, with proportions of 29% and 35.3% in two surveys that randomly sampled from all UK GPs.

General practitioners appear to be more stressed and more dissatisfied than ever before, and more so than GPs and primary care physicians (PCPs) in all other countries surveyed. 41,43 This is happening at a time of increasing demand for primary care services, owing to demographic changes, such as the ageing population, and to more health care shifting away from hospital settings and disease specialists. There is, therefore, an urgent need to understand what factors are driving GPs to leave patient care, and which GPs may be targeted by interventions that aim to improve the retention of GPs in patient care.

Justification and review question

Although there have been recent systematic reviews of the effectiveness of strategies to retain primary care doctors in the workforce, or of strategies to reduce specific determinants of quitting (such as ‘burnout’), this is the first comprehensive systematic review to identify and describe the factors that underlie GPs’ decisions and intentions about quitting, taking career breaks or reducing their work hours. Our review question was ‘what are the factors which affect GPs’ decisions to quit direct patient care (including reducing their time commitment to it), take career breaks from general practice or return to general practice after a career break?’.

The review protocol was registered on the PROSPERO prospective register as PROSPERO CRD42016033876.

Review methods

Searches

We sought published articles and ‘grey’ literature published in English from 1990 onwards. The first search identified published, unpublished and grey literature studies and was run in a variety of relevant databases. The second search drew on supplementary search methods (e.g. forward and backward citation chasing, web searches of relevant organisations) to locate unpublished studies and grey literature. The grey literature searches are fully described in Appendix 3.

The following databases were searched in January 2016 with update searches in April 2016: MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, PsycINFO, Healthcare Management Information Consortium (HMIC), The Cochrane Library, Applied Social Sciences Index of Abstracts (ASSIA) and Web of Science.

Inclusion criteria and processes

Condition or domain being studied

This was leaving or returning to direct patient primary care for any reason (e.g. through early retirement or taking a career break). Early retirement is defined as retirement before the statutory age of retirement for medical professionals in a given country.

Participants/population

The participants were GPs and other primary-care-based generalist doctors practising in high-income Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries (see Appendix 4), regardless of age or number of years since qualification.

Types of study included

Any empirical research studies (qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods) that either aimed to assess factors that are associated with GP retention/return to patient care decision-making or are likely to have generated research data about such factors were included. We therefore excluded opinion or discussion papers and highly summarised sources (such as conference abstracts).

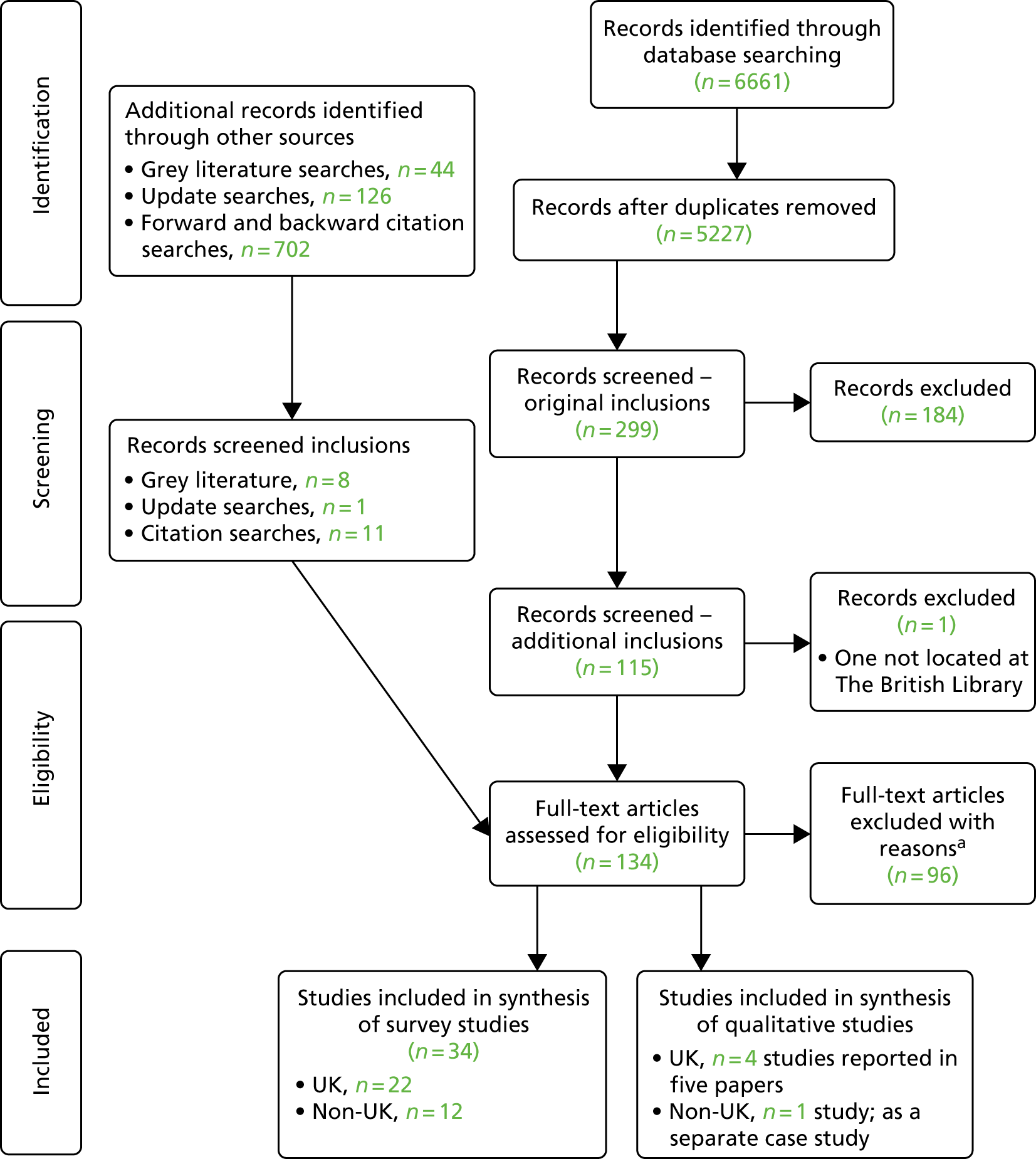

Process of identification and selection of studies

The titles and abstracts of search results were screened against these criteria (an initial sample was independently screened by two reviewers to establish consistency in exclusion decisions). Titles and abstracts that could not be excluded were sought as full-text articles, and the inclusion criteria were applied to these. The process and resulting search hits are shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram showing the process of study selection. a, See Appendix 5 for a list of full-text exclusions with reasons.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction

Data to capture study aims, setting, methods and findings data were entered in a Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) (see Protocol47). If included studies involved evaluation of or information about a specific strategy or policy affecting early retirement or career break flexibility, any available information about the components and implementation of the strategy was captured (including, if necessary, through contacting study authors).

Main variables or issues of interest in studies

These were factors, either positive (enablers) or negative (barriers), that affect the retention of GPs in primary care or their return to work following a career break. The review aimed to gather evidence on GPs’ actual quitting (behaviour) or intention to quit (attitudes) direct patient care, and any factors associated with these behaviours and attitudes. We also focused on how these factors relate to the individual characteristics of GPs, or to practice and country- or system-level characteristics (e.g. pension options, service changes).

Study quality assessment

For studies reporting surveys of GP attitudes and experiences, we adapted the Center for Evidence-Based Management (CEBM)’s quality-assessment tool for critically appraising survey studies. 48 The tool includes questions covering both the conduct and the reporting of studies. Our adaptations to the tool comprised the inclusion of a supplementary question (to the original selection bias question item) on the adequacy of the sample size, reframing three questions about representativeness of the sample and applicability of the findings to all GPs or PCPs in the source region or country of the study, and an additional generalisability question to assess whether or not the survey’s findings can be confidently applied to all GPs in the current UK NHS (see Appendix 7). For assessing the quality of qualitative research studies, we used an adapted version of the Wallace checklist (see Appendix 8). 49

Strategy for data synthesis

Methods for synthesis of quantitative survey studies

A narrative description, grouped by included studies assessing similar types of quitting and similar study design, was undertaken, supported by summary tables. Fuller and separate consideration was given to studies from the UK, both because they comprised the majority of included studies and because of the wide diversity and lower generalisability of the studies in non-UK countries (see Report Supplementary Material 1). The classification of the different types of quitting behaviour, plus whether it was intended or actual quitting, was developed from the types of such outcomes that were reported in included papers/reports. Similarly, the different broad types of factors (determinants or correlates) of quitting were based on an initial appraisal and grouping of the detailed factors that were analysed and reported in included studies.

Methods for synthesis of qualitative studies and evidence

Synthesis of qualitative study data broadly followed the principles of thematic synthesis of textual data and was conducted in three stages, which overlapped to some degree: the coding of text ‘line by line’, the organisation of these ‘free codes’ into related areas to construct data-driven ‘descriptive themes’ and the development of theory-driven ‘analytical’ themes through the application of a higher-level theoretical framework. 50 The textual data were both study authors’ descriptions and primary quotations from GPs.

Two key data-rich UK papers were coded by one reviewer (LL), and the descriptive themes were used to create an overall analytical framework consisting of five main themes. 17,51 The same two key papers were independently coded by a second reviewer (Dr Darren Moore) and the analytical framework was agreed through discussion. This framework was used to code the remaining four semistructured interview papers/reports (three of UK GPs and one of Australian GPs) by one reviewer, with modification or additional themes when necessary. Data, in the form of quotations from the GPs themselves, key concepts or succinct summaries of findings, were entered into QSR’s NVivo software (version 11) (QSR International, Warrington, UK) for qualitative data analysis.

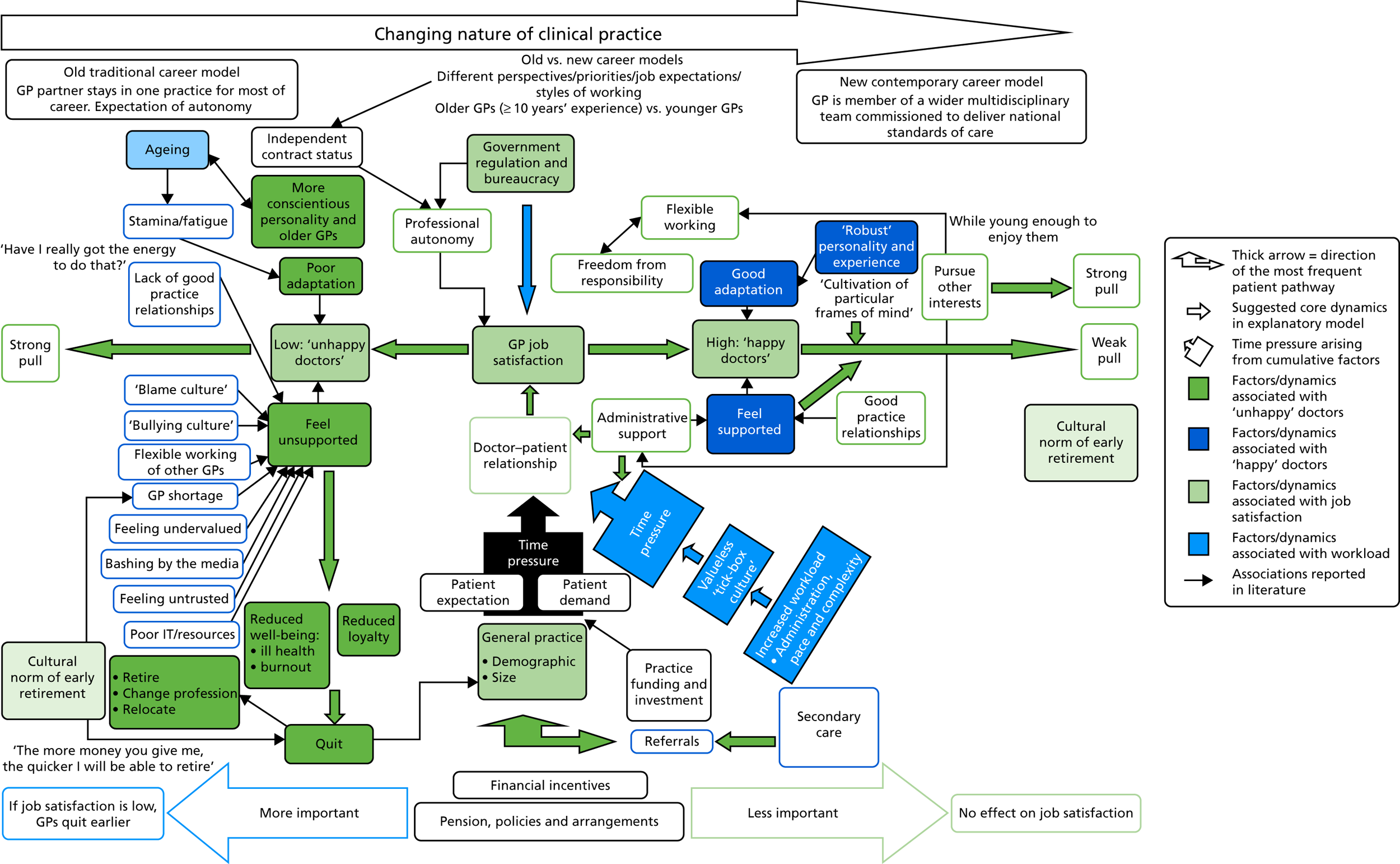

The identified themes, specific factors and the links between them were also represented in a pictorial ‘explanatory model’, presented in the form of a flow diagram (see Figure 5). This model was also independently checked by a second qualitative reviewer (DM) and any suggested modifications were incorporated.

Results

Overview

Table 2 shows the key characteristics of the 22 survey studies of UK GPs published since 1990. Most of the studies were cross-sectional surveys and surveyed the actual quitting or quitting intentions of GPs in a particular year or month. The earliest survey gathered data from UK GPs in 1991–4,64 whereas five of the most recent surveys were conducted in 2014–15. 17,41,43,44,55 The sample sizes of the surveys of UK GPs ranged from 40 to 4421.

| Study (year of publication) | Year of survey(s) | Country or region | Types of GPs surveyed | Number of respondents (response rate, %) | Age of GPs (years), mean (SD if reported) | Percentage female |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baker et al. (1995)52 | NR | England (Trent) | Vocationally trained GPs not currently practising as GP principals | 166 (47.3) | Men: 37 | 60 |

| Women: 34.5 | ||||||

| Baker (2000)53 | 1998 | UK | GP principals and non-principals | 3969 (66.5) |

|

49.20 |

| Campbell et al. (2015)17 | 2014–15 | England (south-west) | All GPs | 529 (56.0) | NR | 66.5 |

| Chambers et al. (2004)54 | NR | Scotland | Unrestricted principals, aged > 55 years | 348 (72) | NR (all > 55 years) | NR |

| Dale et al. (2015)44 | 2014–15 | England (West Midlands) | All GPs | 1192 (NR) | NR | 44.30 |

| Doran et al. (2015)55 | 2014 | England | Early leavers aged < 50 years | 143 (35.0) | Median 40–44 | 50.3 |

| Evans et al. (2002)56 | 1994, 1995, 1998 and 1999 | UK | All GPs: 24, 11, 7 and 6 years since qualification | NR | NR | 38.5 (1974 graduates) |

| 51.2 (1983 graduates) | ||||||

| 55.5 (1988 graduates) | ||||||

| 67.6 (1993 graduates) | ||||||

| Total: 53 | ||||||

| French et al. (2005)57 | 2002 | Scotland | GP principals | 390 (55.0) | 39 (9) | 75 |

| French et al. (2006)58 | 2002 | Scotland | All GPs | 924 (50.0) | Male: 45 | 39 |

| Female: 42 | ||||||

| Gibson et al. (2015)43 | 2015 | UK | All GPs |

1172 (cross-sectional, 34.27) 1576 (longitudinal, 63.75) |

|

Cross-sectional sample: 50.35 |

| Hann et al. (2011)59 | 2001–6 | England | GPs aged < 50 years | 1174 (67) | NR | NR |

| Hutchins (2005)60 | 2002 | England (London) | All GPs in sampled general practices | 62 (84) | 53% between 40 and 49 years | 35 |

| Luce et al. (2002)61 | 2000 | England (northern) | GPs aged > 45 years | 518 (72.5) | 51.8 | 21 |

| Davis et al. (2016)41 | 2015 | UK | All GPs | 1001 (39.4) | NR | NR |

| McKinstry et al. (2006)46 | 2004 | Scotland | GP principals and non-principals | 2541 (67.2) and 749 (65.2) | NR | NR |

| Scott et al. (2006)45 | 2001 | England and Scotland | GP principals, salaried GPs and GP locums (GP principals, non-principals and PMS: GPs in Scotland) | 1968 (44.0) |

|

32 |

| Sibbald et al. (2003)62 | 1998 and 2001 | England | GP principals | 790 from 1998 and 1159 from 2001 (67) | In 1998: 43.75 | 31.3 in 1998 |

| In 2001: 44.35 | 29.4 in 2001 | |||||

| Simoens et al. (2002)42 | 2001 | Scotland | GP principals and non-principals | 802 (56.0) | GP principals: 45 | GP principals: 38 |

| Non-principals: 30 | Non-principals: 57 | |||||

| PMS GPs: 43 | PMS GPs: 60 | |||||

| Simoens et al. (2002)63 | 2001 | England and Scotland | GP principals and non-principals | 4421 (45.0) | English: 44 | 32 in England |

| Scottish: 43 | 37 in Scotland | |||||

| Taylor et al. (1999)64 | 1991–4 | UK | New-entrant GPs ≤ 35 years old (including the 252 who left within 2 years) | 1933 including 252 leavers (NA) | 30.4 (2.04) | 42.6 |

| Taylor et al. (2008)65 | 2004 | UK | All doctors who qualified in 1977 (GP results reported separately) | 864 (72.0) | 51 | 36.50 |

| Young et al. (2001)66 | 1998 | UK | GPs who were on GP census in 1996 but not 1997 | 613 (57.3) |

|

35.40 |

| Survey studies of non-UK GPs | ||||||

| Brett et al. (2009)27 | 2007–8 | Australia (Western Australia) | Aged 45–65 years | 178 | 52.4 (SD 5.2); median 51 (range 48–56) | 27 |

| Dewa et al. (2014)67 | 2007–8 | Canada | All | 32,026 | Mean: approximately 48.4

|

NR |

| McComb (2008)68 | 2006 | New Zealand | All | 566 |

|

38.3 |

| Norman and Hall (2014)69 | 2010/11 | Australia | All | 3377/2720 | 49.54 (11.31) | 49 |

| Nugent et al. (2003)70 | 1999 | Ireland | GP trainees who have left GP work | 209/36 | Women: 34 | 61 |

| Men: 35 | ||||||

| O’Kelly et al. (2008)71 | 2007 | Ireland | GP graduates 1997–2003 | 245 | NR | 70 |

| Pit and Hansen (2014)72 | 2011 | Australia (NSW) | All | 92 | 51 | 40 |

| RNZCGP (2014)39 | 2015 | New Zealand | All | 2486 | Mean: 50 (men, 53; women, 47) | 53 |

| Shrestha and (2011)73 | 2008 | Australia | All | 3906 | 49.5 | 45.6 |

| Sumanen et al. (2012)74 | 2008 | Finland | GPs and GP trainees | 559 | NR | 68 |

| Van Greuningen et al. (2012)34 | 2002 and 2007 | The Netherlands | Already retired | 405 | Mean retirement age: women, 54; men, 58 | 40 |

| Woodward et al. (2001)75 | 1993 and 1999 | Canada | All | 293 | NR | 57.3 |

The bottom third of Table 2 shows the key characteristics of the 12 survey studies of non-UK GPs, all but two of which report surveys conducted since 2006. The results and synthesis of these 12 non-UK studies are not reported further in this chapter (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

Geographical coverage of the surveys

Of the 22 surveys of UK GPs, seven surveyed GPs from the whole of the UK,41,43,53,56,64–66 two surveyed GPs from England and Scotland combined,45,63 two surveyed GPs from the whole of England,59,62 five surveyed GPs in a particular region or city of England17,44,52,61,76 and five surveyed GPs in Scotland. 42,46,54,57,58

Characteristics of general practitioners surveyed

Most of the surveys of UK GPs were of all practising GPs in the country or a region, regardless of age, year of qualification or contract type/mode of employment (Table 2). However, some surveyed only GP principals (i.e. practice partners)54,58,62 or recruited only GP principals and non-principals (not locums). 42,46,63 Only four studies surveyed GPs who had already quit patient care. 52,59,64,66

Most UK studies reported a mean age (or median age band) of between 40 and 55 years. However, one study had much younger respondents, because it set out to survey recently qualified GPs. 64 Two surveys specifically targeted older GPs: Chambers et al. 54 surveyed only unrestricted principals aged > 55 years (mean age not reported), whereas Luce et al. 61 surveyed GPs aged ≥ 45 years (mean age 52 years). Across the UK studies, female GPs accounted for between 29% and 75% of the GPs surveyed and tended to account for a higher proportion of GPs in the later surveys.

Overview of the UK questionnaire surveys

Coverage of different types of quitting direct patient care

Table 3 summarises the broad quitting construct investigated, together with the personal, job and other GP or practice characteristics assessed as potential factors associated with quitting. Appendix 9 shows the specific quitting constructs (and verbatim questions) in each study and the potential determinants of quitting for which data were collected.

| Study (year of publication) | Quitting construct investigated | Personal | Job characteristics | Household | Area | Policy/organisational changes | Other | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual quitting/retention | Intention to quit within 5 years | Planned age of retirement | PT/flexible working | Taking career break | Other | Age | Gender | Ethnicity | Contract type/partner/locum, etc. | Practice/list size | Working hours PT/FT | Job satisfaction | Job stressors | On call/out of hours | Income | Marital/family status | Social deprivation | Region/country | Urban/rural | |||

| Hann et al. (2011)59 | ✓ | ✓a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Taylor et al. (1999)64 | ✓ | b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Young et al. (2001)66 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||

| Doran et al. (2015)55 | ✓ | ✓c | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ✓d | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Martin et al. (2015)41 (Health Foundation) | ✓e | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Dale et al. (2015)44 | ✓f | ✓f | ✓f | ✓g | ||||||||||||||||||

| Gibson et al. (2015)43 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||

| Scott et al. (2006)45 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓h | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Simoens et al. (2002)63 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Sibbald et al. (2003)62 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Simoens et al. (2002)42 | ✓i | ✓i | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓j | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Campbell et al. (2015)17 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓k | ||||||||||||

| Baker et al. (2000)77 | ✓l | ✓l | ✓m | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Evans et al. (2002)56 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Free-text reasons for reduced time commitment to being a GP | ||||||||||||||||||

| Chambers et al. (2004)54 | ✓ | ✓n | ||||||||||||||||||||

| French et al. (2005)57 | ✓ | ✓o | ✓p | |||||||||||||||||||

| McKinstry et al. (2006)46 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓q | ||||||||||||||||||

| French et al. (2006)58 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||||

| Luce et al. (2002)61 | ✓r | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓s | ||||||||||||||||

| Taylor et al. (2008)65 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hutchins 200560 | ✓t | ✓u | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Baker et al. (1995)52 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓v | ||||||||||||||||||

Among these studies, 13 explicitly focused on retirement/quitting intentions (either within a certain number of years or at the intended retirement age) and four included GPs who had already retired or quit general practice. A longitudinal cohort study by Hann et al. 59 was the only study that included both actual quitting status and previous intention-to-quit data for the same group of GPs. Nine surveys investigated factors associated with intentions to reduce hours or take up part-time working, and four surveys included a focus on taking career breaks.

The quality of included survey studies of UK general practitioners

Table 30, in Appendix 7, shows how each of the studies was assessed against each of the items in our adapted CEBM critical appraisal tool. Most of the studies were of good quality in relation to key question items, such as the appropriateness of the research survey methods for answering the stated question. However, many had limitations in relation to the pre-study determination of the sample size and the assessment of the statistical significance of relevant associations [and presentation of confidence intervals (CIs) when relevant]. Most analyses were restricted to presenting the associations between two or three variables, typically in a contingency table, and were, therefore, deemed not to have accounted for all possible confounding variables.

In terms of reporting quality, a substantial minority of studies did not clearly report how the sample was obtained (and, therefore, are at risk of potential selection bias) or whether or not the sample obtained was representative of all GPs in that region or country. In relation to this, response rates were generally poor, with only five studies having a satisfactory response rate (of > 70%), five having unsatisfactory response rates (< 50%) and two studies not reporting the response rate.

Study generalisability was assessed in two stages (items): first, in terms of whether or not the results could be confidently applied to the GPs in the source region or country, in the year the survey was conducted; and, second, whether or not the results could be confidently applied to all GPs in the UK NHS in 2016 (which is the policy context of this systematic review).

Synthesis of findings: questionnaire survey studies

The 22 UK survey studies that focused on GPs’ intentions to quit fully from general practice (e.g. early retirement), their reasons for actually quitting general practice/patient care or intending to reduce hours/working part-time all revealed a recurrent and linked set of key job-related factors that are associated with leaving, intending to leave or reducing their hours devoted to patient care. They are workload, job (dis)satisfaction, work-related stress and work–life balance. These high-level factors associated with quitting are all inherently related to the nature of being a GP and working in NHS general practice, although they may also be related to lifestyle/personal expectations and family circumstances.

Although most of the included studies examined the bivariate associations of intention to quit or planned retirement age with some other factors (notably age, gender or contract status), four studies evaluated intention-to-quit decisions using multivariable analyses and incorporating a larger range of potential explanatory variables. These studies showed that the consistent determinants of GPs wishing to retire earlier were older age, having low job satisfaction (or job dissatisfaction) and high or intense workload. When measures of work–life balance or flexibility/choice in relation to job demands were included in the analysis, these were also often statistically significant. There seems to be a complex interplay between these three key broad factors – satisfaction, workload and work–life balance/flexibility – with the third factor possibly mediating the effects of workload on job satisfaction. Although gender was not found to be an important determinant after adjusting for age and other factors, this does not preclude that the balance of these other main determinants might be different for men and women. Social deprivation of area or practice population was not associated with intention to quit in any of the three multivariable analyses that included it as a potential factor. The finding (in one study) that either small practices or larger than average practices are associated with a more common intention to quit is intriguing and worth exploring with GP stakeholders to understand why this might be.

The UK studies that reported the stated reasons of GPs for intending to quit patient care or retire early also underlined the importance of the main factors already revealed to be associated with assessed variations in intention to quit, namely job satisfaction, workload, work-related stress and work–life balance. However, the studies of the self-reported reasons for quitting general practice reveal much more detail within and beyond these reasons; for example, underlying problems of high workload appear to be issues relating to high clinical work hours, more demanding patients and perceptions of excessive paperwork/administration. In addition, job dissatisfaction (and perhaps also work-related stress) is now reported alongside undesirable changes in the NHS, excessive managerial duties and fear of making mistakes.

These observations highlight the danger of interpreting survey findings in terms of just the most frequently cited reasons or the statistically significant associations. These studies clearly show that there are many other, more specific, reasons operating at levels other than the top-level work-related factors. These more specific and diverse reasons may be important to a substantial minority of GPs in their decisions to quit patient care or to go part-time. The survey evidence considered here suggests that there will be many GPs who have good job satisfaction and low levels of work-related stress but who nevertheless still want to quit direct patient care or retire early for one or several of the many other reasons reported. These are ultimately individual (or at least family/couple) decisions, and focusing exclusively on ‘averages’ or overemphasising the most frequently cited reasons may overlook other reasons (e.g. mental health problems or fear of litigation) that may be amenable to intervention.

As expected, age was an important determinant of intending to quit or reduce direct patient care, with the most dominant association being that older GPs of both genders were more likely to quit fully or retire early. However, gender was more likely to be a factor determining preferences related to working reduced hours and taking a career break. Although surprisingly few studies examined associations of quitting with both age and gender together, there are clues in many of the studies that there are substantial differences in the main determinants of quitting or part-time working for, for example, younger female GPs and older male GPs. Although age is clearly an important direct determinant of intentions to quit, it is also a proxy for various other potentially important factors, such as position/contract type within a practice, and there may also be cohort effects associated with differences in expectations and administrative burdens when becoming a GP, and altered patient and other demands over time. In relation to preferences for part-time working, studies showed relatively high proportions of UK GPs of all ages, both male and female, and with most contract or employment types, saying that they wish to reduce their work hours or weekly number of clinical sessions. There was some evidence that female GPs, ‘non-principals’ and ‘assistants’ were more likely to want to increase their work hours in coming years, but this may merely reflect the current lower number of working hours of these subgroups. Finally, one study highlighted the potential trade-off between part-time working and intended later retirement. Overall, although no clear picture emerges of what the main determinants of preferences to work part-time are, there are clear indicators that the motivations may be based on the age, gender and the contractual status/practice role of GPs.

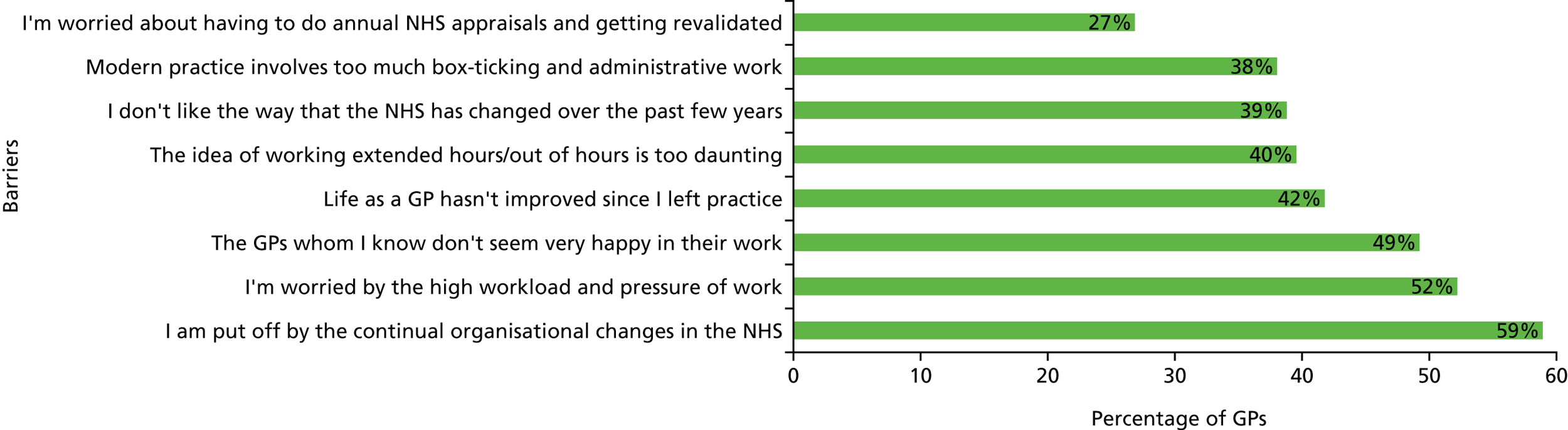

Unlike the other ways in which GPs may quit practice, intentions to take a (temporary) ‘career break’ appear to be influenced more by a specific range of ‘pull’ factors than by negative ‘push’ factors to do with the job or workload. The main reasons GPs say they will be taking a career break are to work abroad, to have or look after children, or to engage in research or further study. Although the stated reasons for intending to take a career break seem fairly different from those relating to intending to permanently quit patient care (e.g. reasons for early retirement) or intentions to reduce working hours, many of the barriers that they say would prevent them from returning to work as a GP relate to negative perceptions about the changing job of being a GP, high workload, low job satisfaction, unsociable hours, excessive administrative work, and recurrent and unwanted changes in the way the NHS and primary care is organised, which now includes revalidation (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Common barriers to returning to work as a GP percentage citing each barrier in England (2014). Data from Doran et al. 55 (From the 134 GP leavers who gave reasons relating to changes in GP work, loss of skills and concerns about life as a GP.)

Finally, the UK studies of the more detailed self-reported reasons for intending to quit or actual quitting also showed that intentions to quit general practice are not exclusively about the main job-related ‘push’ factors (workload, work-related stress, job satisfaction and work–life balance). For example, in a 2002 study, among the factors cited more than one-third of older GP principals as having a ‘great influence’ on the early retirement intentions of these GPs were the ‘pursuit of other interests’ and the ‘financial ability to retire’. 61

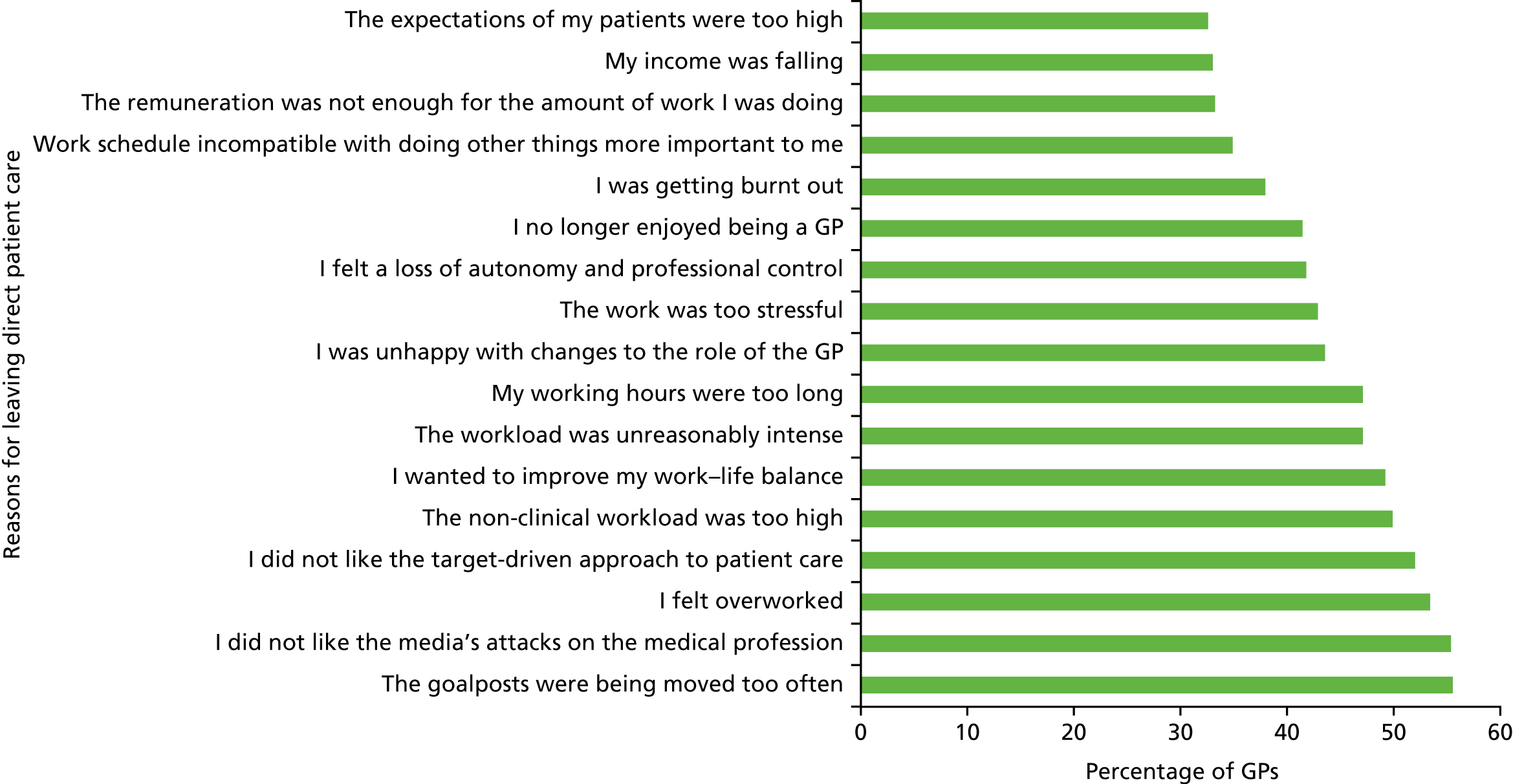

General practitioners’ stated reasons for having actually left general practice show a larger range and mix of both job-related ‘push’ factors and some family- and leisure-related ‘pull’ factors than shown by the survey studies examining associations between variables. The most common specific reasons given by GP leavers in a 2014 study by Doran et al. 55 are shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

General practitioner leavers’ most common specific reasons for leaving direct patient care (those cited by over one-third of GP leavers) (2014). Data from Doran et al. 55

Synthesis of qualitative studies

Overview of the qualitative research studies and data

Five papers based on qualitative semistructured interviews with practising or retired British GPs were retrieved; all studies had been conducted in England. A further qualitative semistructured interview study, with practising GPs who were working part-time in clinical practice in Australia, was found but is not reported in this chapter (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/1419602/#/). The main characteristics of these studies, and the GPs interviewed within them, are shown in Table 4.

| Study (year of publication) | Characteristic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of survey(s) | Country or region | Types of GPs surveyed | Aim of study | Number of GPs (interview type) | Age of GPs (years) | Percentage female | |

| Doran et al. (2016)51 | NS | England | Early leavers aged < 50 years | To explore the reasons why GPs leave general practice early | 21 (by telephone) | Median age band: 40–44 | 50.3 |

| Hutchins (2005)76 | NS | England (London) | GP principals near retirement age | Considers the reasons many GPs are wishing to take early retirement, and measures to help retain them | 20 (at surgery) | NS | 55 |

| Newton et al. (2004)78 | 2001 (implied) | England (northern) | Aged > 45 years, subgroup from Luce et al. (2002)61 | To describe ‘Plans, reasons for, and feelings about retirement’ | 21 (at surgery or GP home, except 2 by telephone) | All aged > 45 | 38 |

| aSansom et al. (2016)18 | 2015 | England (south-west) | Experienced GPs aged 50–60 years (20 still working and three retired) | To investigate the reasons behind intentions to quit direct patient care among experienced GPs aged 50–60 years | 23 (by telephone) | Age range: 51–60 | 39 |

| aCampbell et al. (2015)17 | 2014–15 | England (south-west) | Experienced GPs aged 50–60 years intending to retire in the next 5 years (n = 14) | To explore reasons behind GPs’ intentions to quit direct patient care | 17 (by telephone) | Aged 51–60 | 23.5 |

| GPs who took early retirement in the previous 5 years (n = 3) | |||||||

| 15 partners and two locums | |||||||

| Dwan et al. (2014)79 | 2008–9 | Australia | GPs working six or fewer clinical sessions per week | To explore the nature and extent of GPs’ paid and unpaid work, why some choose to work less than full-time, and whether or not sessional work reflects a lack of commitment to patients and the profession | 26 (at a location determined by GP participant) | Average age: 47 (females); 58 (males) | 66 |

Two of the papers reporting studies from England were based on almost the same set of interviews. 17,18 The 2016 study by Doran et al. 51 focused on why GPs had left medical practice, whereas the other four studies were wholly or dominantly with practising GPs. All of the semistructured interviews were quality appraised using an adapted Wallace checklist and found to be of reasonable76,80 to good17,18,51,79 quality.

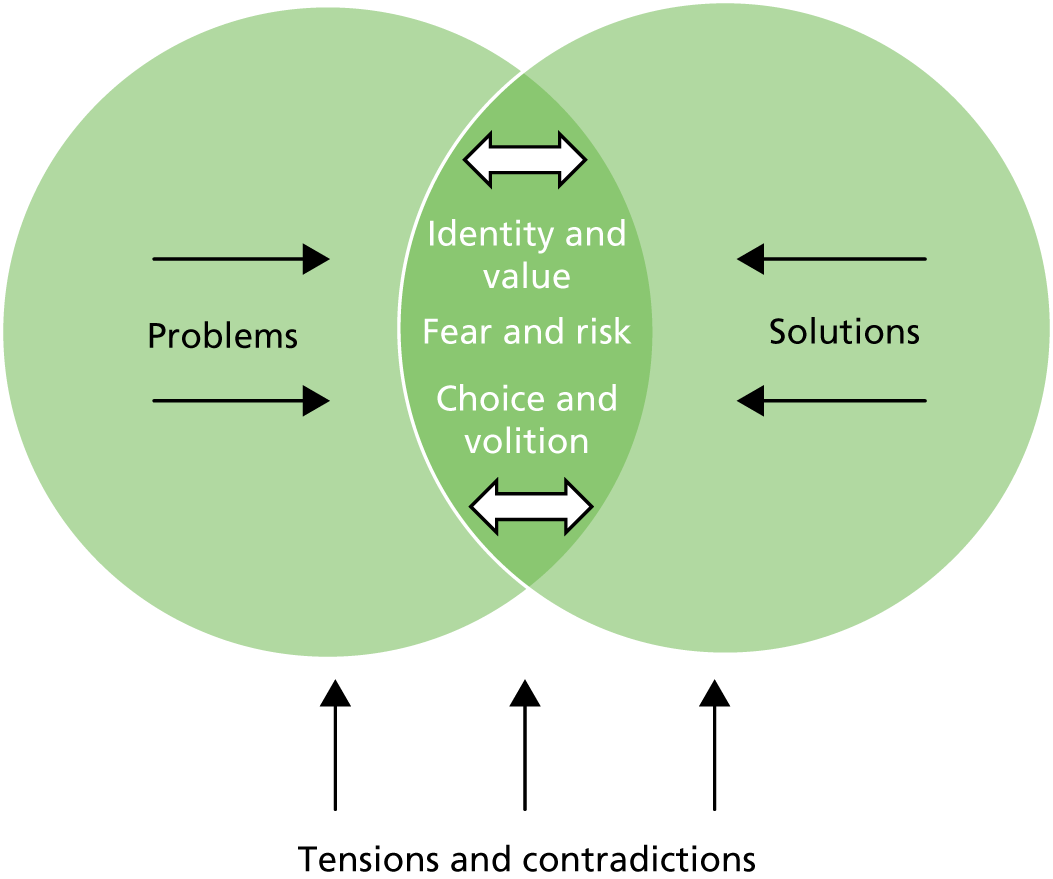

The synthesis is presented as a series of linked themes, each of which belongs to one of five categories. The five main categories of explanatory theme were undoable/unmanageable (including workload and related pressures), morale, impact of organisational changes, projected future and multiple options and strategies. This analytical framework is summarised in Table 5.

| Undoable/unmanageable | Morale | Impact of organisational changes | Projected future | Multiple options and strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

What then follows is a heavily abridged version of the qualitative synthesis; some subthemes are mentioned very briefly and there are no illustrative quotations. The full write-up of the synthesis of qualitative studies, with direct GP quotations, is available in our separate full report of the systematic review (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

Undoable and unmanageable

Many GPs are experiencing working as a GP as undoable and unmanageable owing to, among other things, high/increasing administrative workloads, high/increasing patient demand (both number of patients and their complexity and higher expectations), and a perceived lack of training and resources to cope with these pressures.

Low levels of morale

Low levels of morale were attributed by GPs to reductions in the perceived value of GP work (with loss of identity), and changes in professional culture in relation to a range of aspects of work such as a more target- and standards-driven reward system, multidisciplinary team (MDT)-based working (yet, for some, paradoxically, also lone working/isolating culture), a more aggressive top-down managerial culture within the NHS, and more widespread norms and expectations for early retirement. Low levels of morale were also seen to be associated with a perceived lack of support from both government and political parties, and negative portrayals of GPs by news media. Morale was also closely linked with job satisfaction (or dissatisfaction), neglect of personal well-being/health and feelings about work–life balance.

Impact of organisational changes

The perceived key changes or factors under this theme were changes in referrals (both restricted opportunities to refer to secondary care and higher numbers of, and more complex, referrals from secondary care), a greater focus on targets and assessments, and fears about reaccreditation (including evidence that some GPs might retire early in order to avoid reaccreditation). Some of the organisational changes had imposed increased clinical and non-clinical responsibilities and work on GPs. Together, such changes were believed to have undermined some of the basic tenets and traditional expectations of being a GP, such as the doctor–patient relationship and having autonomy and control over one’s clinical work.

Projected future

The fourth theme was how GPs projected or envisaged their future, which related to ageing, the financial viability of reducing hours or retiring early, and the extent to which GPs were personally committed and financially invested in their practices. This included problems linked to whether or not younger GPs wanted to take on the responsibility of becoming practice partners, as well as possible tensions between older and younger GP partners (in the way practices are run, in major investment/refurbishment decisions or in relation to planning for partners retiring and needing new partners to buy out their share of a practice).

Multiple options and strategies

Finally, the fifth theme and group of factors referred to the various ways in which GPs of different personalities either continue and cope or – perhaps if less committed or less resilient, or if they can simply afford to financially – decide to leave or go part-time. This theme also highlighted the major importance of flexible working or working reduced hours (e.g. by becoming a locum) as a method of coping and regaining work–life balance and job satisfaction. For others, the adoption of alternative work roles outside general practice, often part-time, allowed use of and learning of other skills – either as relief and variety from working as a GP or, for some, as a potential alternative career option. The kinds of alternative roles and options GP interviewees mentioned included becoming complementary therapists, Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) leads or advisory committee members, working for pharmaceutical consultancies or teaching in medical schools. Like part-time working, for some these might be clear routes for quitting general practice, but, for others, such variety of roles and opportunities for job satisfaction may keep them in general practice.

Explanatory model and narrative

The themes and detailed factors emerging from the qualitative synthesis of semistructured interview studies conducted in the UK were also used to construct a pictorial explanatory model (Figure 5). It provides an overview of the key contexts and factors that were found to relate to GPs quitting or intending to quit patient care. The applicability of the explanatory model was confirmed following feedback on the model during meetings with PPI representatives and co-investigators.

FIGURE 5.

Flow diagram of factors contributing to GPs leaving general practice. Admin, administrative; IT, information technology.

There are three main ‘domains’ in the flow diagram: (1) factors associated with low levels of job satisfaction, (2) factors associated with high levels of job satisfaction and (3) factors associated with linked to the doctor–patient relationship. In addition, the overarching historical context to these factors is that the career path, pressures and expectations of GPs in the UK have changed considerably since the 1990s. Today’s GP is expected to be a member of a wider MDT commissioned to deliver national standards of care and has a role barely recognisable to the one many older GPs remember (e.g. GP partners typically staying in one practice for most of their career, with less regulation and an expectation of autonomy).

Discussion

For many UK GPs, four closely related job-related factors seemed to play a major part in decision-making about both early retirement and part-time working: workload, job (dis)satisfaction, work-related stress and work–life balance. These factors were prominent in studies of both intention to quit or to reduce hours and actual decisions to quit or to go part-time. However, there were clearly many other detailed factors involved for some GPs that either underlie these higher-level factors (e.g. health service reform fatigue or unsupportive practice partner relationships) or may combine to influence an individual GP’s decision to quit general practice or reduce their hours devoted to it. Although many of the drivers of GP dissatisfaction, high workload and work-related stress seem to be at the level of the health system, medical profession or within a GP’s own general practice and the population it serves, how GPs cope with these problems may be amenable to interventions at the individual GP level.

Moreover, both the questionnaire survey and qualitative interview evidence indicate that it is not just ‘unhappy GPs’ (e.g. those with poor job satisfaction and high workload) who wish to reduce their hours or retire early. Early retirement is now a cultural norm and lifestyle choice for many in the medical profession, for example to spend more time pursuing their own interests or caring for loved ones. The five main themes and the subthemes that emerged from the synthesis of qualitative evidence include all four of the main recurrent factors that were evident in questionnaire surveys of GPs. For example, the broad factors of workload and work-related stress from the survey studies seem to map closely to the subthemes from qualitative research under the ‘undoable/unmanageable’ theme. However, the broad factors of work–life balance and job dissatisfaction (from the survey studies) appear alongside a wider range of other subthemes – identity/perceived value, lack of support, well-being and negative ‘bashing’ by the media – within the qualitative synthesis, under the major theme of ‘morale’. Understandably, the more open-ended data collection approach of interviews seems to capture a more diverse range of potential determinants of GP satisfaction and quitting, and how they appear to be conceptually or causally related. But the main factors emerging from the synthesis of quantitative studies reflect a narrower range of the more recurrent factors.

Although there were differences between male and female GPs in their intentions or preferences for part-time working, such differences were inconsistent between studies and did not adjust for current hours worked, so it is difficult to draw clear conclusions. However, overall, younger female GPs and older male GPs were generally more likely to want to work part-time. Only groups already working reduced hours wished to increase their hours. One of the survey studies and the qualitative evidence synthesis suggested an association between opportunities for part-time working and delaying retirement. That is, for some GPs, being able to work part-time (and more flexibly) may incentivise them to retire later. In contrast, there is no evidence that financial incentives would discourage early retirement; this would possibly have the opposite effect.

General practitioners’ intentions to take a ‘career break’ appear to be more influenced by a specific range of ‘pull’ factors than by negative ‘push’ factors to do with the job or workload. The main reasons GPs say they will be taking a career break are to work abroad, to have or look after children or to engage in research or further study. Although the stated reasons for intending to take a career break seem fairly different from those related to intending to permanently quit patient care, many of the barriers that GPs say would prevent them from returning to work as a GP relate to negative perceptions about the current job of being a GP (e.g. high workload, low job satisfaction, unsociable hours, excessive administrative work).

There were 12 survey studies of GPs outside the UK, from six countries (including four surveys from Australia) and covering areas such as early retirement, quitting general practice soon after qualification and working part-time. Despite the substantial differences in the way general practice is organised in these countries, among the leading reasons for intending to retire early in Australia, New Zealand and Canada were low job satisfaction and the pressure of work. One of the Australian studies assessed the factors that GPs said might encourage them to retire later than currently planned; more than one-third stated better remuneration, higher staffing levels, more general support, more flexible working hours, part-time work and reduced workload – similar to the reasons emerging from UK studies that asked an equivalent question. The main stated determinants of part-time working in Australia and New Zealand were age, poor work–life balance and having family or child-care responsibilities.

Strengths of the review methods

This systematic review was conducted by an experienced and collaborative review team, addressing clear review questions and using a prespecified and published systematic review protocol (CRD42016033876) and search strategy. 47 We worked closely with experienced information specialists to design the most effective possible searches for obtaining bibliographic and web sources. We found substantially more includable studies than a recent literature review that had a similar review question. 17

In terms of involving relevant stakeholders in the review, several GPs were involved in the development of the review protocol, and two GPs were closely involved in the conduct of the review (a GP trainee, and an experienced GP and Professor of Primary Care). Patients were also involved, both as co-investigators in the wider mixed-methods project and through contributing to a PPI workshop, which presented and discussed emerging findings from the qualitative and quantitative evidence syntheses. Reassuringly, the PPI workshop both endorsed and expanded our understanding of our emerging interpretations (see Appendix 10 for a fuller description of that discussion).

In terms of quality assurance, we used either two reviewers making independent inclusion/exclusion decisions or checking by a second reviewer with an independent assessment of a sample of included studies (for data extraction and quality assessment) and used established study quality assessment tools.

Limitations of the review methods

Although this review captured information about specific retention strategies, where they provided the background to a particular survey, or if the strategy was suggested on the basis of an included survey’s findings, it should be noted that identifying and evaluating GP retention strategies was not the primary aim of this systematic review and, therefore, we did not explicitly search for studies that either evaluated or described different approaches to GP retention. Although we used the most appropriate and established quality assessment tools available, the tool we adapted and used for the quantitative survey studies had a few limitations. First, there was no separate score/assessment of study design and reporting quality. Second, our judgements about the applicability of findings to GPs in the UK NHS in 2016 were based on subjectively weighing up information such as the age of the study data, the geographical scope of the study, whether or not it was limited to certain types of GP (e.g. older/younger, practice principals/non-principals) and whether or not there were differences between respondent characteristics and target GP population characteristics.

The study pragmatically focused on either survey-based (mainly quantitative) studies or qualitative interview studies. However, some of the survey studies also collected and reported some qualitative data, in the form of free-text answers to open questions (one survey study was purely a collation of such data56). We did not incorporate or separately content analyse these disparate data.

In December 2016, another qualitative research study that should have been included – unfortunately missed by our grey literature searches – came to our attention. 81 The detailed findings and four groups of ‘deeper frustrations’ identified in this study largely corroborated the insights from our synthesis of qualitative studies, including the finding that workload was the overarching factor causing GPs to leave.

Limitations of the current evidence base

Most studies examined only the association of a single quitting construct (e.g. intention to reduce work hours) with a few variables, one variable at a time. There were only four comprehensive survey studies that used multivariable analyses. The most commonly used quitting construct/question was GP intention to retire/quit direct patient care within 5 years, which was used in eight studies. But even this apparently standard question was asked in a number of slightly different ways, and questions relating to actual or preferred part-time working varied even more. Only three UK studies and no non-UK studies had any focus on why GPs take career breaks, and no studies explicitly examined the benefits and determinants of flexible working arrangements. Few studies explicitly assessed the role of GP health or ageing, or potential mediating factors, such as ‘commitment’ or ‘emotional exhaustion’ (a key component of instruments for assessing ‘burnout’), which may attenuate or accelerate the effects of job satisfaction on intentions to quit.

Most questionnaire surveys of GPs provide a snapshot of factors in a particular year and region. They therefore capture the absolute levels of perceived factors, but do not capture prior levels or prior expectations. What is clear from both the quantitative and qualitative studies is that many of the causes of quitting or deciding to work part-time have a temporal element (i.e. they relate to widening gaps between initial expectations of being a GP and current reality, or the cumulative effect of recurrent organisational changes over many years).

There were only five qualitative studies of GPs (four based on interviews with UK GPs). 17,18,51,76,77 Two of them, by Hutchins76 and Newton,80 pre-date a number of substantial changes in the organisation of general practice and the remuneration of GPs and general practices, which may limit their generalisability to UK general practice in 2016.

Conclusions

General practitioners in the UK leave general practice for a very wide range of factors, both negative, job-related, ‘push’ factors and positive, leisure-, retirement- and home-life-related, ‘pull’ factors. Although some factors clearly operate at an individual, personal level, such as the financial ability to retire, health, family/marital circumstances, or good/poor relationships with practice partners, other factors operate at the level of the general practice, local area, the whole profession or the national health system (e.g. the media portrayal of GPs, service reform and performance targets, CQC inspections and professional revalidation).

We found that four overlapping job-related factors seemed to play a major part in decision-making about both early retirement and part-time working: workload, job (dis)satisfaction, work-related stress and work–life balance. However, many other detailed factors either underlie these higher-level factors or may combine to influence a particular GP’s decision to quit general practice or reduce the hours they devote to it. In contrast, GPs’ intentions to take a ‘career break’ appear to be more often influenced by a specific range of ‘pull’ factors (e.g. working abroad, looking after children, further study) than by negative ‘push’ factors to do with the job or workload. However, many of the barriers that deter them from returning to work as a GP relate to negative perceptions about being a GP (e.g. high workload, low job satisfaction, unsociable hours and excessive administrative work). This review therefore provides a comprehensive and rich description of the wide range of possible factors on which GP retention and return initiatives could focus.

Chapter 3 Workstream 2: census survey

Introduction

This chapter presents the methods and results of the census survey undertaken with all GPs in south-west England registered on the National Performers List. 82 The principal aim of the survey was to canvass the perspectives of GPs in the region to establish the proportion of GPs planning to leave direct patient care through early retirement or career breaks, and also to provide a sampling frame to support recruitment of GPs to participate in qualitative interviews (workstream 3).

Methods

Under a data-sharing agreement between NHS England and the University of Exeter Medical School (UEMS), the National Performers List of 3523 GPs registered to practise in south-west England was provided to us by two NHS organisations responsible for maintaining the list over the region: Capita/Primary Care Services (the ‘north patch’, covering Bristol, North Somerset, Somerset, South Gloucestershire and Bath and North East Somerset CCGs) and NHS Shared Business Services (the ‘south patch’, covering Devon and Cornwall and Isles of Scilly CCGs). All GPs on the list were assigned a unique study identification (ID) number, reflecting the CCG and general practice in which the GP was located.

The survey was piloted in February 2016, using a random sample of 60 GPs from the list, stratified to ensure a 50/50 split by gender (30 male, 30 female) and, within each gender, there was a selection of 15 GPs aged < 50 years and 15 GPs aged > 50 years. Following piloting, the main survey was administered to 3453 GPs in April 2016 and closed at the end of June 2016.

The ‘Removals Log’

The list of GPs provided by the National Performers List was also supplemented by a small additional list maintained by NHS England local area teams, containing the names of all GPs who are due to be removed from the List, through notification of their intention to resign, retire, relinquish their licence to practise or cease to practise in their current region (the ‘Removals Log’).

NHS England permitted the research team access to this list of 152 GPs who had been removed (or were shortly to be removed) from the National Performers List between April 2015 and March 2016. Of these 152 GPs, 77 were still on the List (i.e. they had not yet been removed and we already had their contact details), six were not to be contacted [one was deceased, four were mandatory removals from the List, one had been suspended by the General Medical Council (GMC)] and two had moved onto the Welsh Performers List. We requested postal and/or e-mail addresses from NHS England for the remaining 97 GPs, eight of which were not supplied (one was a mandatory removal from the List, two had no contact details available, four had retired owing to ill health and one had retired owing to personal circumstances).

We therefore received additional contact details for a total of 89 of the 152 Removals Log GPs. Sixty-five of the 89 had a postal address, all of which were home addresses, and 51 of these 65 also had an e-mail address. The remaining 24 had an e-mail address only.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was based on that used within earlier work, modified to increase the number of questions from 11 to 24, including rewording of four questions to reflect alignment of wording with other questionnaires of broadly similar intent, and by providing clear definitions for key concepts in the questionnaire, including a career break, taking steps towards changing work–life balance and defining a clinical session. 17 The questionnaire (see Appendix 11) comprised items that asked GPs about their career intentions, reporting on the likelihood that they would permanently leave direct patient care within the next 2 years or within the next 5 years. 82 GPs were also asked to report the likelihood that they would take a career break within the next 5 years, or that they would reduce their weekly average hours spent in direct patient care during this time period. GPs rated the likelihood of these events from ‘very likely’ to ‘very unlikely’ using a four-point scale. The questionnaire also included a question about current level of morale and captured general demographic data: gender, age, ethnicity, region and year of graduation, current GP employment status (e.g. partner, salaried), number and pattern of sessions worked in a typical week and involvement in delivering out-of-hours care.

Data collection

General practitioners were sent study materials through the post to either their practice or their home address, and also by e-mail, if available. 82 The questionnaire was available for completion by post or online. The survey was supported by a comprehensive strategy of publicising the research through routine newsletters and circulars of relevant organisations and networks, including Local Medical Committees (LMCs), Clinical Research Networks (CRNs), HEE South West, the RCGP, UEMS and the South-West Academic Health Sciences Network (AHSN).

If a GP returned multiple online or postal surveys, only the first response received by the research team was analysed. Postal response data were double entered and discrepancy checking was undertaken. Response data were stored securely and without participant names or addresses.

Patient involvement

Although the study participants were GPs rather than patients, patient representatives contributed to the design of the survey. 82 The planned work was presented to the wider project’s PPI group, by way of sharing the process and to check the integrity of the work, and the group provided supportive feedback. 83 The survey results were presented at a project management group meeting, which included PPI representatives who directly contributed to interpreting and contextualising the results.

Statistical analysis

Differential response rates between different groups of GPs would potentially introduce bias into crude survey findings. To counter this, we employed non-response weights. 82 Inverse probability weights were calculated based on three factors: age (< 40, 40–49, 50–54, 55–59 and ≥ 60 years), gender (male and female) and role (partner, salaried and locum/other). These factors were used as they were the only ones consistently recorded for both responders and non-responders. By employing these weights, it was estimated what responses would have been received with a 100% response rate under the assumption that non-responders would have responded similarly to GPs of the same age, gender and role. Logistic regression was used to investigate the association between responses to questions regarding future career intentions (permanently leaving direct patient care within the next 2 and 5 years, taking a career break within the next 5 years and reducing average hours spent in direct patient care within the next 5 years). Each of the four sets of responses was dichotomised into ‘very likely’ and ‘likely’ versus other responses. Initially, unadjusted associations were examined for effects attributable to the explanatory factors of gender, age, country of qualification, ethnicity, role/position and rating of current morale. Subsequently, regression models adjusting simultaneously for all explanatory factors were used to examine adjusted associations. Similar models were used with reported morale as the outcome (but not including morale as an explanatory factor). Regression analyses were restricted to those respondents with complete data on gender, age, country of qualification, ethnicity, role/position and rating of current morale.

Supplementary analysis

Interactions were explored between various factors in the models. 82 Although some of these were found to be statistically significant, the magnitude of the interaction terms was generally small and did not alter the interpretation of the data, with one exception commented on in the results. For this reason, the more complex interaction models have not been reported here.

In addition, the possibility was considered that some groups of GPs, for example female GPs, may not report the intention to reduce hours spent in direct patient care because they already work fewer hours, on average, than other groups. Therefore, two supplementary analyses were conducted, including either a binary variable indicating part-time working (defined as working fewer than eight sessions per week) or a continuous variable detailing the reported number of sessions worked per week.

All analyses were conducted in Stata® version 14.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Questionnaires were distributed by post to 3370 GPs, with 1841 GPs (55%) also sent the questionnaire by e-mail (see Appendix 12, Table 36). Completed questionnaires were received from 2248 of the GPs who were surveyed (response rate 67%). 82 Of the 2248 GP respondents, 673 (30%) used the online survey. Response rates were as high for both men and women (67% and 66%, respectively). Participation was lower among GPs aged < 40 years (54%) than among GPs aged ≥ 50 years (in excess of 68% in each age group), and was lower for salaried GPs (57%) than for GP partners (71%) and non-principal/locum GPs (64%).

The median age of respondents was 48 years [interquartile range (IQR) 40–55 years, range 28–84 years] (Table 6). Eighty-five per cent of respondents reported having a practice with which they were primarily affiliated; 25% of respondents reported that they were involved in the delivery of out-of-hours primary medical care. The majority (62%) of respondents were partners in their practices.

| Characteristic | Proportion, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 1053 (46.8) |

| Female | 1190 (52.9) |

| Prefer not to say | 3 (0.1) |

| Missing | 2 (0.1) |

| Age (years) | |

| < 40 | 497 (22.1) |