Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/5003/02. The contractual start date was in November 2014. The final report began editorial review in January 2018 and was accepted for publication in June 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Simon Paul Conroy reports working for the Acute Frailty Network, an improvement collaborative focusing on acute hospital care for frail older people. Graham Martin was a member of the Health Services and Delivery Research Priority Research Advisory Methods Group during the course of this study. Stuart Parker reports grants from the Alzheimer’s Society, grants from the British Heart Foundation and grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research, during the conduct of the study. Helen Roberts is a member of the NIHR Journals Library Editorial Group.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Conroy et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction to the Hospital-Wide Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment study

About language

The internationally recognised name of a medical specialty (Geriatric | Medicine) and the title of its key technology [Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA)] are now well established and contain the term ‘geriatric’, the origins of which were described in a treatise by Ignatz Leo Nascher, published in 1913 and entitled ‘Longevity and Rejuvenescence’, as follows:1

Geriatrics, from geras, old age, and iatrikos, relating to the physician, is a term I would suggest as an addition to our vocabulary to cover the same field, in old age, that is covered by the term ‘paediatrics’ in childhood.

Nascher IL. ‘Longevity and Rejuvenescence’ (1913), quoted in Freeman JT. Nascher: Excerpts from His Life, Letters, and Works. Gerontologist 1961;1:17–261

Unfortunately, in the intervening century, and in contrast to the adjective ‘paediatric’, the term ‘geriatric’ has acquired a pejorative meaning when applied to older people (or indeed to objects), implying uselessness and decrepitude, as the following quotations illustrate:

Geriatric judges with 19th century social and political prejudices only bring the rule of law into disrepute. 2

I hear and read such phrases as ‘geriatric old twit’: an expression which would hardly have sprung to the lips of the pious Aeneas. 2

In the preparation of the report for this project, challenges were presented by older people attending a dissemination event, and by the project’s external steering group, to consider alternative language to replace the term ‘geriatric’ throughout the report. This was a challenge, not least because the word appears in the name of the health and care technology that is the subject of the report.

Accordingly, we held a discussion with members of the Voice North group and circulated the content of the discussion for comment by members. All agreed that the term ‘geriatric’ had acquired a pejorative meaning, particularly when applied to older people. Alternative descriptors for older people were suggested by group members, who advised that we should avoid the terms ‘geriatric’ and ‘the elderly’ and should instead refer throughout to ‘older people’, which we have tried to do.

In addition, instead of using ‘CGA’, ‘multidisciplinary assessment and management’ is used, which is consistent with the most commonly used definition of CGA, namely that of a multidimensional, multidisciplinary process that identifies medical, social and functional needs, and the development of an integrated/co-ordinated care plan to meet those needs. 3

For consistency with the existing literature, the abbreviation ‘CGA’ is used to refer to this assessment and management process.

The origins of a multidisciplinary approach being used and applied to vulnerable and older people in the UK can be traced to what has become the foundational literature of the medical specialty of older people’s medicine (OPM) in the 1940s. 4 Subsequent development and, importantly, evaluation in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) was reported in the 1980s. By the 1990s, meta-analyses of multiple RCTs were being reported and are being maintained up to the present day. 3,5,6

The term ‘CGA’ has become established as shorthand for the ‘technology of older people’s medicine’. It is no longer new7 and it has acquired status as a proven, effective and essential component of the assessment and management of older patients in hospital and community settings.

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment is usually delivered by a multidisciplinary team (MDT), sometimes working in a specific ward environment but more often as part of a mobile or peripatetic consultation service. 3 CGA teams may use specific assessment tools and protocols to aid the assessment process and usually meet regularly to discuss and co-ordinate the assessment and, crucially, the associated treatment goals and management plans of older people. 3

Compared with ‘usual care’ in RCTs in hospital settings, CGA has been shown to have positive effects on key personal and operational outcomes. The CGA process increases the likelihood of being alive and living at home and avoiding institutionalisation, death and deterioration3 in relation to an episode of inpatient hospital care.

The participants in the trials that established the effectiveness of CGA were mostly older people, defined by the norms of the era and location in which the trials were performed. Some may find it surprising that participants in these trials could be as young as 50 years, with the majority of participants being described as in the ‘60+’ and ‘65+’ age ranges. 8

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment in hospital settings

Structural population change and improved health over the past 100 years has led to older people becoming the predominant users of inpatient hospital services. Older people admitted to hospital often have complex needs, have multiple comorbidities and are at high risk of complications and adverse outcomes. They often present with the clinical syndromes associated with frailty, which include falls, loss of mobility, confusion and incontinence9–13 – the so-called ‘Geriatric Giants’. 14

There is considerable evidence for using CGA in the care of patients with these clinical problems, including in a variety of specialised inpatient settings, and for conditions that are common in old age. 15,16 For example, many hospitals have ‘Evaluation and Management Units’ in which a MDT provides a multidimensional assessment and develops a management plan in collaboration with the patient and carers. These plans include rehabilitation, discharge-planning, co-ordination and follow-up and are personalised for each patient. This model is also seen in single-condition care units, such as orthopaedics (fracture) and stroke units, which were developed using the principles of comprehensive assessment and multidisciplinary care that underpin the CGA process. 17,18

Elsewhere in hospitals, CGA has been less available and understood, perhaps on account of uncertainty about how to direct care to suitable recipients. The clinical trials that showed the effectiveness of CGA did not always stratify participants by characteristics that we consider important today, such as the presence or absence of specific clinical syndromes, or the presence or severity of frailty. Neither were they focused on identifying solutions for the whole hospital,19 for example by providing CGA at the front door,20,21 or the cost-effectiveness of different services and settings.

There is emerging evidence of the development of new forms and settings to deliver CGA. A recent benchmarking survey conducted in 49 acute services in the UK22 showed that 34% of trusts had developed enhanced teams in the emergency department (ED) and 42% of trusts had developed frailty units. About half of short- and intermediate-term hospital-based assessment units were using CGA, with 25–44% having a dedicated team. This survey identified that in 59% of the health and social care economies surveyed, recognised assessment tools and pathways for frailty were used.

Hospital-wide Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

As population ageing progresses, older people are becoming the majority users of inpatient hospital services. In this context there is a clear need for the hospital of the future to provide services structured around the needs of patients. 23 Any coherent vision of a hospital fit for the future must, of course, include making hospitals ‘good places for old people’. 24

Although a compelling argument can be made for the effectiveness of CGA,3 and we can see that it is beginning to be delivered outside the traditional boundaries of the specialised ‘Evaluation and Management Unit’, the question of its potential beyond specialised inpatient services remains open.

It is possible that optimisation of inpatient care could include the provision of CGA by hospital inpatient services so that all hospital inpatients with the potential to benefit from the process would receive timely and effective CGA to shape the clinical decision-making process to meet their complex needs. For example, for those undergoing elective surgery, CGA might be incorporated into the pre-operative care pathway25 to ensure that decision-making around the procedure itself, as well as post-operative rehabilitation, might be optimised in a way that might improve outcomes, minimise length of stay and facilitate recovery.

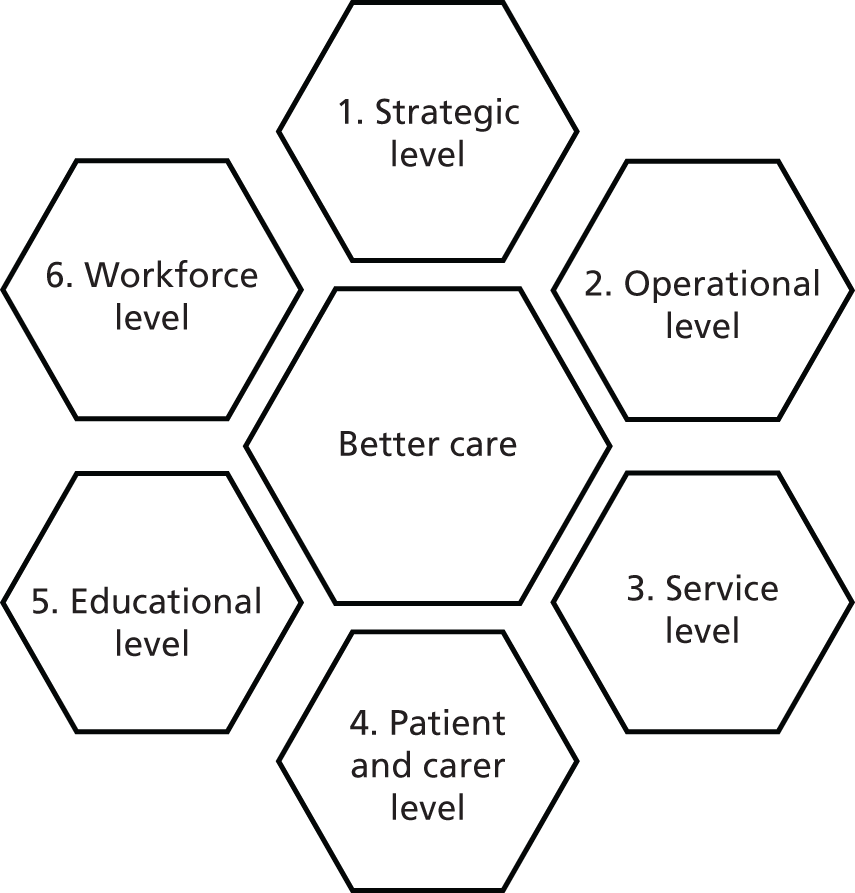

To achieve a vision of timely and effective use of CGA on a hospital-wide basis, the development of new and innovative service models and the tools to support its implementation are required.

Overview of the Hospital-Wide Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment study

Consideration of these issues prompted a call for research proposals by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), one result of which is the collection of research projects described in this report. In this series of interdependent studies, existing models of care and the development and validation of tools to deliver CGA on a hospital-wide basis are described.

Research questions

The main questions addressed by this programme of research were:

-

How is CGA defined and recognised?

-

How, and in what forms is CGA currently organised and delivered in the UK?

-

Who receives CGA, and can we identify who benefits most?

-

How can we develop tools to assist the delivery of CGA on a hospital-wide basis?

Aims and objectives

Aim

The overarching aim of this ambitious programme of work was to provide high-quality evidence to support the delivery of CGA on a hospital-wide basis.

Objectives

The objectives of this proposed integrated research programme were to systematically:

-

define CGA, its processes, outcomes and costs in the published literature

-

identify the processes, outcomes and costs of CGA in existing hospital settings in the UK

-

identify the characteristics of the recipients and beneficiaries of CGA in existing hospital settings in the UK

-

use this new knowledge to develop tools that will assist in the implementation of CGA on a hospital-wide basis.

To achieve these aims and objectives we used a series of interdependent work streams, with an overarching management structure and embedded patient and public involvement (PPI), which aimed to ensure relevance to key stakeholders and timely delivery within budget.

Presentation of this report

Multiple components of this project are presented in the following chapters. Chapter 2 presents an umbrella review of the literature and an overview of new and emerging service models. Chapter 3 presents the results of a national survey of services providing CGA in acute hospitals. Chapters 4–7 deal with the creation of tools to understand the need for CGA, characterising beneficiaries and testing Hospital Episode Statistics (HES)-based proxies for frailty using a range of approaches, including:

-

population segmentation

-

diagnoses linked to frailty

-

clustering diagnoses linked to frailty

-

deriving an ordinal ‘frailty score’ from clusters

-

costs of CGA

-

combined information tools.

Chapters 8 and 9 present the development of implementation strategies and tools and the evaluation of the toolkits and their implementation. Chapter 10 provides a summary and discussion of the Hospital-Wide Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (HoW-CGA) project and its findings.

Patient and public involvement has been critical to the project, indeed forming one of the five main workstreams (WSs). In addition to being cited where relevant in the individual chapters, a summary of the PPI activity is included in Appendix 1.

Chapter 2 Defining hospital-wide multidisciplinary assessment and management

In this chapter, two forms of literature review are presented, the aim of which is to summarise current research evidence for CGA in hospitals and to describe new and emerging aspects of service delivery. The review protocol and both reviews have now been published. 8,26,27

Umbrella review

An umbrella review provides an overview of existing systematic reviews. 28,29 The principal objectives of this review were to:

-

define characteristics of the main beneficiaries of CGA

-

define key elements of CGA

-

define principal outcome measures

-

summarise evidence on the cost-effectiveness of models of delivery of CGA

-

highlight gaps and weaknesses in the evidence base across relevant inpatient clinical areas.

Methods

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) umbrella review method was used. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses that described the provision of CGA to hospital inpatients aged > 65 years were reviewed. Comparisons of inpatient CGA to usual inpatient care were included.

Five reviewers (PM, SPC, SP, HR and KP) worked in pairs to review titles and abstracts, before the full texts of potentially eligible papers were obtained. Final selection for inclusion in the review was by agreement between both members of the selecting pair. Disagreements were arbitrated by another member of the team.

The following databases were searched: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews and Effects (DARE), MEDLINE and EMBASE (for search strategy examples, see Appendix 2).

Searches were limited by year (2005 to February 2017) and restricted by the level of evidence to systematic review and meta-analysis, or other evidence syntheses. English-language papers only were selected.

Methodological quality/bias risk was recorded using the JBI critical appraisal checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses (see Appendix 3).

The JBI data extraction tool was used to extract data from the included reviews after discussion and piloting its use. Several additions and modifications were demanded by the nature of the review question. A database of evidence tables was created for definitions and key elements of CGA, setting and staff, key participants, outcome measures and costs. The database was then used to create the summary tables that were used to develop a narrative overview of the evidence.

Results

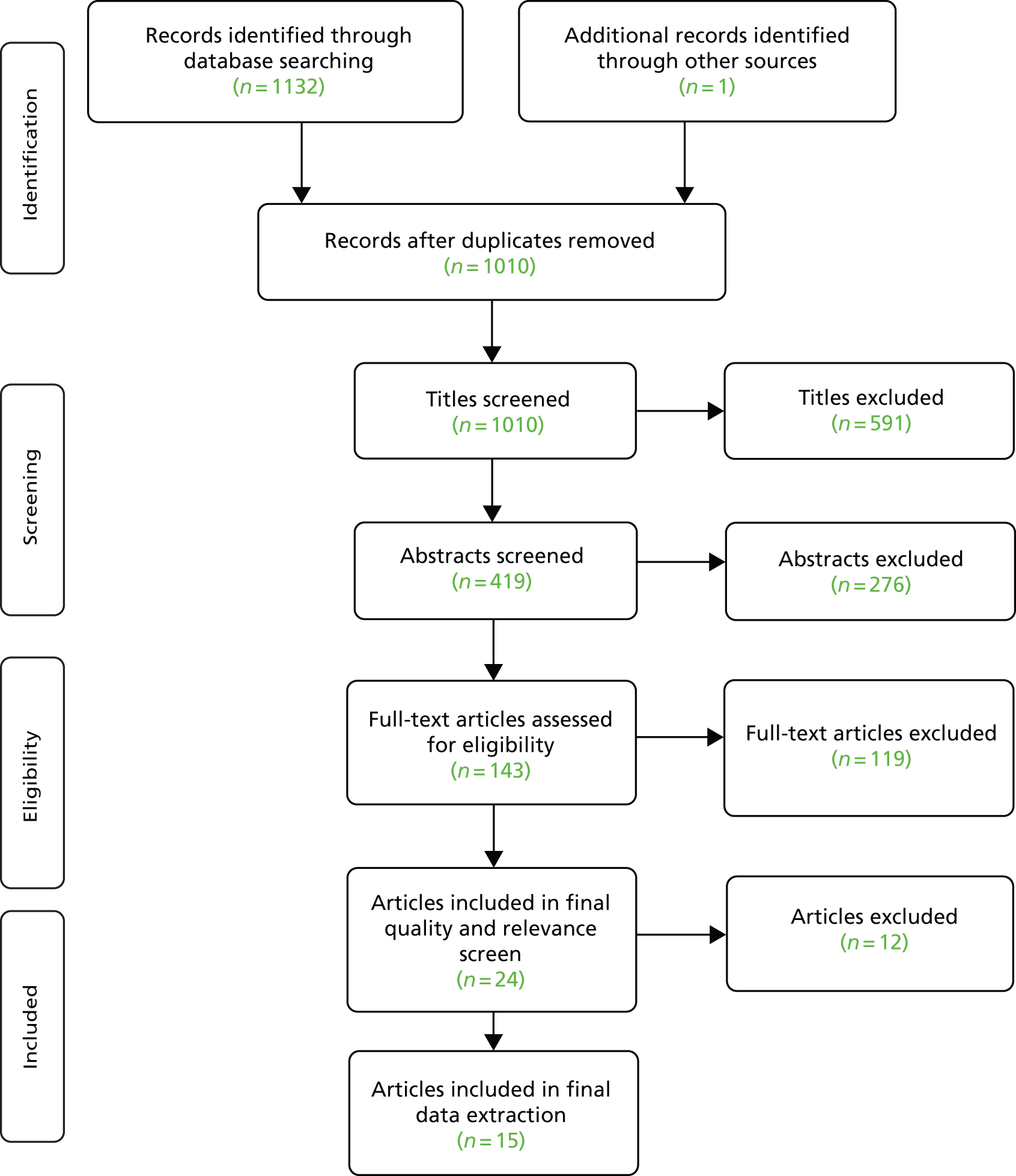

A total of 1010 titles and 419 abstracts were screened for eligibility, 143 full articles were reviewed for relevance and 24 were included in a final quality and relevance check (Figure 1). Thirteen reviews, reported in 15 papers,3,15,16,30–41 were selected for review. The most recently conducted trial included in the reviews was reported in 2014; all other trials were reported between 1983 and 2012.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart detailing the identification and selection of research syntheses for inclusion in the umbrella review and also used for the new and emerging models of care review. Reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press from Parker SG, McCue P, Phelps K, McCleod A, Arora S, Nockels K, Kennedy S, et al. What is Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA)? An umbrella review. Age Ageing 2018;47:149–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afx166. 8

Ninety-five original articles were cited 166 times. Twenty-six original articles were cited more than once. The most commonly cited articles were Landefeld et al. ,42 Asplund et al. 43 (seven citations each) and Counsell et al. 44 (six citations). Removing all except one of the reviews,3,31 which cited these three most highly cited papers, did not significantly affect our conclusions with regard to the population characteristics, intervention definition, settings and comparisons and clinical outcomes. Some health economics detail was lost in this sensitivity analysis.

The main beneficiaries were older (≥ 55 years) hospital inpatients in acute care settings. In most studies, frailty was not explicitly identified as a characteristic of CGA recipients; however, one review (which included most of the most highly cited trials) attempted to stratify trials by frailty.

The most widely used definition of CGA was that of a multidimensional, multidisciplinary process that identifies medical, social and functional needs, and the development of an integrated/co-ordinated care plan to meet those needs. 3

Dimensions of CGA reported consistently included medical/physical, psychological/psychiatric, socio-economic, function, and nutritional assessment.

Most of the reviews used the same body of literature (from 1983 onwards) to examine some aspect of in-hospital CGA. Reviews citing literature mainly outside this highly cited core included a review of interface care,30 gerontologically informed nursing assessment and referral32 and MDT interventions39 (Table 1).

| Descriptor | Author and publication year | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baztán et al. (2009)15 | Conroy et al. (2011)30 | Deschodt et al. (2013)16 | Ellis et al. (2011),45 Ellis et al. (2011)31 | Fealy et al. (2009)32 | Fox et al. (2012),33 Fox et al. (2013)34 | Kammerlander et al. (2010)35 | Linertova et al. (2011)36 | Tremblay et al. (2012)37 | Van Craen et al. (2010)38 | Hickman et al. (2015)39 | Ekdahl et al. (2015)40 | Pilotto et al. (2017)41 | |

| CGA definition | |||||||||||||

| Multidimensional, multidisciplinary process – identifies medical, social and functional needs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Acute inpatient setting in which multidimensional assessment and management takes place | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Consistent with a multidisciplinary approach | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| No clear explicit definition | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| CGA literature descriptions | |||||||||||||

| Provision of CGA in dedicated acute patient environment | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| A specialised team working on a specialised ward, such as inpatient ‘Geriatric Evaluation and Management Unit’ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Descriptions of complex care collaborations involving multidimensional assessment and management | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Including both inpatient and outpatient components | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| At the interface between hospital and community care | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| A hospital inpatient consultant team | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Components of CGA | |||||||||||||

| Medical/physical assessment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Psychological/psychiatry assessment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Socioeconomic assessment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Function assessment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Nutritional assessment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Mobility and falls assessment | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Care planning | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Goal-setting | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Treatment/rehabilitation | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Discharge-planning | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Follow-up | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Participants | |||||||||||||

| Older person | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Frail older person | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Frail elderly person | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Age specified (years) | |||||||||||||

| ≥ 55 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| ≥ 60 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| ≥ 65 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| ≥ 70 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| ≥ 75 | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Type of admission | |||||||||||||

| Emergency | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Excluded condition-specific interventions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Inclusion of specific conditions | |||||||||||||

| Acute illness or injury | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Cancer | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Hip fracture | ✓ | ||||||||||||

Key clinical outcomes (Table 2) were mortality (12/13 reviews), activities of daily living (13/13 reviews), cognitive functioning (9/13 reviews) and dependency (6/13 reviews). Principal operational outcomes were length of stay (11/13 reviews) and re-admissions (12/13 reviews). Destinational outcomes included living at home (7/13 reviews) and institutionalisation (11/13 reviews). Four reviews mentioned resource use and costs. Patient-related outcomes (health-related quality of life, well-being and participation) were not usually reported.

| Outcomes | Study (author and publication year) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baztán et al. (2009)15 | Conroy et al. (2011)30 | Deschodt et al. (2013)16 | Ellis et al. (2011),45 Ellis et al. (2011)31 | Fealy et al. (2009)32 | Fox et al. (2012),33 Fox et al. (2013)34 | Kammerlander et al. (2010)35 | Linertova et al. (2011)36 | Tremblay et al. (2012)37 | Van Craen et al. (2010)38 | Hickman et al. (2015)39 | Ekdahl et al. (2015)40 | Pilotto et al. (2017)41 | |

| Clinical | |||||||||||||

| Mortality (includes composite outcome ‘death or dependence’) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Activities of daily living | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Cognitive functioning (including delirium) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Dependency | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Other psychosocial | |||||||||||||

| Health status | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Quality of life | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Satisfaction | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Carer strain/burden | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Falls | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Delirium | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Iatrogenic/other complications of hospitalisation | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Operational | |||||||||||||

| Length of stay | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Re-admission | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| ED visits | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Destinational | |||||||||||||

| Living at home | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Institutionalisation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Poor discharge destination | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Discharge destination | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Economic | |||||||||||||

| Resource use | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Costs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

Few studies considered costs; none took a broader view and included direct costs (staff and resources), subsequent costs (such as community health and social care costs), costs to the patients and wider societal costs. Furthermore, although the reviews and trials describe multiple intervention configurations, these were mostly not standardised. An exception to this33 removed one outlier study, and the result of meta-analysis showed that the costs of specialised acute unit care were less than those of usual care [weighted mean difference US$245.80, 95% confidence interval (CI) US$446.23 to US$45.38; p = 0.02]. 33 Two studies3,15 concluded that many hospital-based services showed reduced costs associated with CGA. In a review of trials of Acute Care for Elders (ACE) model components, little cost evidence was available to differentiate and compare relative effectiveness between components of the ACE model.

New and emerging models of care review

Methods

To provide information about the development of new and emerging service models of relevance to clinical practice, the search strategies used in the umbrella review were used to retrieve recent trials and other study types, published in journal articles or presented as abstracts at international meetings. These searches were performed in MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials), the Cochrane Trials Register, and included reports published from the most recent review included in the umbrella review (described above) up to the end of 2015. Papers and abstracts that described hospital CGA services were selected and used to classify and tabulate emerging service models.

Results

The studies that were found were mostly observational, with many available only as abstracts. They included descriptive evaluations of new types of service and emerging evidence of new service models, some of which are, as yet, barely evaluated. The examples of new and emerging models for the delivery of CGA that were uncovered by this process are categorised and shown in Table 3.

| Practice examples and setting | Journal articles [author (year)] | Conference abstracts [author (year)] |

|---|---|---|

| Ward-based acute care | ||

| ACE unit (and components) |

Barnes et al. (2012)46 Allen et al. (2011)47 Flood et al. (2013)48 Ahmed et al. (2012)49 |

Allison et al. (2011)50 Gausvik et al. (2015)51 Dang et al. (2012)52 Flood et al. (2011)53 |

| Acute geriatric ward | Gharacholou et al. (2012)54 | |

| Acute medical unit for older people | Gregersen et al. (2012)55 | Butler and Biram (2012)56 |

| Ward-based care programme | Gharacholou et al. (2012)54 | Hoogerduijn et al. (2012)57 |

| CGA in acute medical units | Conroy et al. (2011)58 | |

| Daily board round | Isom et al. (2013)59 | |

| High-dependency care | Greco et al. (2013)60 | |

| Delirium assessment | Alonso Bouzon et al. (2011)61 | |

| CGA plus dental health assessment | Burkhardt and Baudermann (2014)62 | |

| Interventions based in the ED | ||

| ANP in ED |

Aldeen et al. (2014)63 Argento et al. (2014)64 Grudzen et al. (2015)65 |

Argento et al. (2011)66 Argento et al. (2013)67 |

| Enhanced ED team (risk screening + focused CGA) | Foo et al. (2014)68 | Adams et al. (2013)69 |

| Frailty (or ACE) unit in proximity to ED |

Conroy et al. (2014)70 Ellis et al. (2012)71 |

Ellis et al. (2011)72 |

| CGA in ED/assessment/decision units |

Conroy et al. (2014)70 Clift (2012)73 |

Beirne et al. (2012)74 Carey et al. (2011)75 and Carey et al. (2011)76 Clift et al. (2013)77 Hughes et al. (2014)78 Fernandez et al. 201479 |

| Medicine for older people team review (ED admissions) | Byrne et al. (2013)80 and Byrne et al. (2014)81 | |

| Geriatrician-led admission avoidance service | Jones et al. (2012)82 | |

| Services across ward boundaries | ||

| Mobile ACE unit |

Farber et al. (2011)83 Hung et al. (2013)84 Yoo et al. (2014)85 |

Hung et al. (2011)86 |

| Medical floor-based interdisciplinary team | Yoo et al. (2013)87 | |

| Geriatric consultation teams |

Deschodt et al. (2014)88 Dewhurst (2013)89 |

|

| Surgical/perioperative care | ||

| Pre-operative surgical care protocols. Risk report/order set | Cronin et al. (2011)90 | |

| Hospital-wide complex intervention with surgical focus | Bakker et al. (2014)91 | |

| ACE unit for acute medical/surgical ward | Krall et al. (2015)92 | |

| Audit against NCEPOD standards | Garbharran et al. (2012)93 | |

| Geriatric consultation team in hip fracture patients | Deschodt et al. (2011)94 | |

| CGA in oncology | ||

| Use of screening tools (risk profiling) |

Kenis et al. (2013)95 Extermann (2011)96 |

|

Here, each of the emerging service types outlined in Table 3 is expanded on and discussed.

Ward-based acute care

Features of the ACE unit, the specialised acute (‘geriatric’) ward and the acute frailty unit appear to be very similar. The ACE unit concept has been evaluated in RCTs and subsequent meta-analysis. 33 Recent ACE unit studies have examined discrete dimensions of the model, such as the delirium protocol or the health economics (see Table 3).

The broad idea of delivery of CGA to hospital inpatients on wards is being refined and developed to deliver CGA very close to the point of presentation of acute care need, for example in acute medical units and in relation to ward-based high-dependency care.

These studies have reported positive outcomes such as reduced length of stay, reduced costs, reduced incidence of delirium, reduced mortality and reduced re-admissions. Some studies showed improved functional status at discharge, but not at longer-term follow-up.

Emergency department-based acute care

Enhancements to ED-based services include advanced nurse practitioners in the ED; bringing the OPM team into the assessment process (during or after an ED attendance); and embedding a CGA service and the associated MDT in the ED, with or without the creation of a dedicated physical environment for patients requiring CGA in the ED setting.

Studies have indicated that ED-based CGA may reduce admission to acute wards and to intensive care units, increase referrals to palliative and hospice care, increase patient satisfaction and slow the decrease in functional status.

Services that function across ward boundaries

These are mobile services that take the principles of multidisciplinary assessment and management to patients who are not on wards specialising in care for older inpatients and are developments of already well-established concepts, namely the ACE unit and the Specialised Inpatient Consultation Team. A key issue for these teams is to overcome the tendency not to implement the recommendations arising from the comprehensive assessment process, by delivering care directly on wards where it is not normally provided.

Some recent descriptions of mobile CGA services have suggested reductions in length of stay, adverse events and costs.

Surgical/perioperative care

Surgical CGA services have included pre-operative protocols,90 a hospital-wide complex intervention to deliver CGA,91 having surgical patients in an ACE unit,92 delivering CGA for older patients requiring abdominal surgery and the use of a multidisciplinary consultation team for older hip fracture patients. Reported effects included improved function and a reduction in delirium, falls and pressure sores.

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment in oncology units

A CGA framework can identify additional problems not picked up in routine oncology consultation. 97 Observational studies have reported the use of risk screening in oncology and the provision of CGA by liaison and have suggested that a package deal of screening and liaison may be used as a way of modifying tolerance to chemotherapy with promising results. 98

The umbrella review showed welcome consistency about the definition of CGA, which includes both assessment of needs in multiple domains and the development of a plan to meet those needs (i.e. CGA is not just an assessment but an integrated process of assessment and care). Settings included ward-based and hospital-wide services that functioned at the interface between acute and community care and were delivered by nurse-led teams and MDTs. The key outcomes were death, disability and institutionalisation. Operational goals included reducing length of stay, re-admission rates and institutionalisation rates. Furthermore, despite CGA being a patient-centred process, few studies have examined the role of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). There has been only limited economic evaluation, which suggests that CGA may save on hospital costs.

Critically, for the current research project, we observed that the impact of frailty as a determinant of CGA outcome has not been explicitly or widely examined. The one review that attempted this40 concluded that, for frail patients, ward-based CGA may increase function and reduce institutionalisation but that the degree of evidence was limited.

Hospital-wide CGA for frail older people is the topic of this report, so the other element of key importance is the development and evolution of services to provide hospital-wide CGA. The established evidence base tends to favour ward-based over consultation services, and there is a widespread belief99 that older people with frailty are the key target population.

Emerging evidence from NHS Benchmarking shows that some services are developing to deliver CGA across the hospital. 22 Emerging evidence from recent observational studies and service descriptions reported here support the notion that hospital-wide approaches to the delivery of CGA for those who may benefit are beginning not only to be developed but also evaluated in multiple locations and settings.

These literature reviews marshal evidence that clearly suggests that more work needs to be done on identifying potential beneficiaries of CGA and ensuring that they receive an effective intervention that meets their needs and is provided on a hospital-wide basis. A case for the development of tools to assist in the delivery of CGA on a hospital-wide basis can be made. Additional trials would be justified and should be stratified by frailty, use PROMs and collect sufficient economic data to determine cost-effectiveness. RCTs of hospital-wide CGA must almost inevitably use the hospital as the unit of randomisation (or else it is not hospital-wide) and this pushes the limits of the feasibility of the methodology. Such trials will need to have careful process evaluations embedded within them, in line with current research frameworks for the evaluation of complex interventions. 100,101

Chapter 3 A national survey of acute trusts

Having defined key characteristics of CGA from the literature, we now move on to attempt to identify services in which CGA, or elements of CGA, are currently being delivered in inpatient hospital settings.

This survey aimed to identify the type of services that deliver multidisciplinary assessment and management of the older patient (‘CGA’) and attempts to provide a description of current provision across the UK.

The aims of the survey were to:

-

develop a simple semistructured questionnaire to survey current practice of CGA

-

pilot the questionnaire with clinicians and managers with relevant health-care responsibilities locally

-

survey relevant senior clinicians using the post-pilot questionnaire

-

analyse the questionnaire responses to provide a map of the different forms of CGA in current practice and provision in England and the devolved nations.

Methods

Survey development and piloting

The survey was developed by a team of professionals with diverse (health) backgrounds. The survey was developed to reflect the multifaceted nature of the services provided, with the team selecting the final survey questions through a consensus process. The development work included the:

-

identification and selection of existing survey questions from an earlier community-based survey

-

development of questions via information from our umbrella review (see Chapter 2)

-

development of new questions

-

pilot testing and validation of the survey instrument.

Questions were listed, phrasing and selection were refined and the respondent format was developed. The questions were refined further using the cognitive interviewing technique,102 a six-step decision process for questionnaire design.

The final step of development was the grouping together of questions into distinct subject modules to ensure that they were clear and presented in a logical order.

An initial pre-test of the survey was undertaken by 19 people (four of whom were PPI volunteers). Key issues emerging from the pilot survey were collated and actioned.

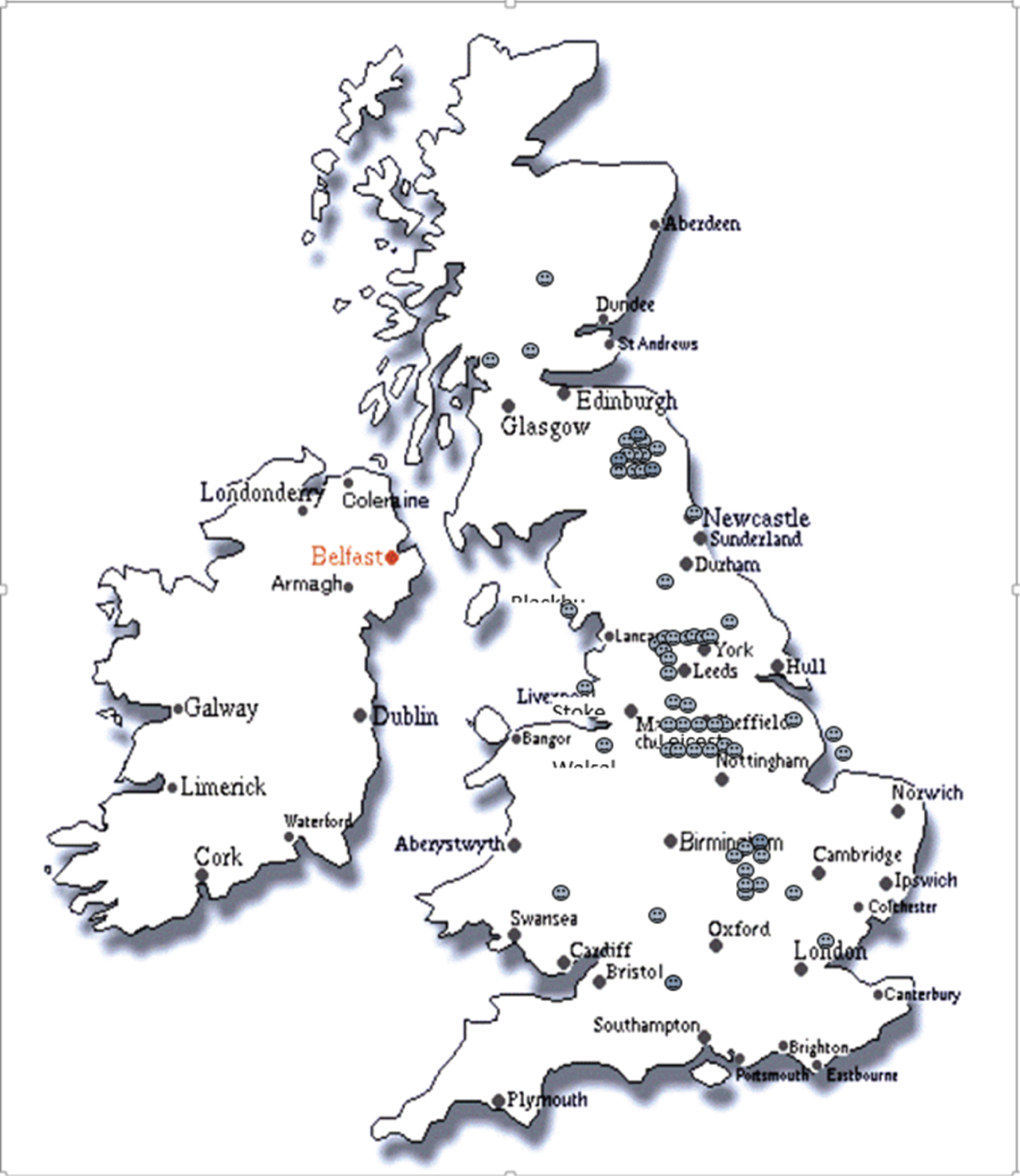

Acute hospital trusts were identified from the health-care databases NHS Choices (England), NHS UK (Wales), NHS.gov.scot (Scotland) and online.nscni.net (Northern Ireland).

The survey process

The online survey was sent in two parts. First, a letter was sent to each Chief Executive Officer (CEO) inviting them to take part and to identify respondents via a short online form. The respondent was then contacted by e-mail with login details for the trust survey. This part of the survey confirmed that the trust provided inpatient care for older people with medical/surgical conditions, identified services that the trust provided and gave contact details for the responsible health-care professionals who were nominated to complete the service-level survey.

The completion of trust- and service-level responses was encouraged through e-mails and telephone calls and by utilising the NIHR Ageing Research Network’s regional specialty lead. It was also facilitated by the Royal College of Physicians of London patient safety and quality improvement department.

The service-level survey included questions about the characteristics and assessment of people using the service, the organisational features, the staff providing the service, the care processes and implementation. It was administered via a web-based interface.

Results

The trust-level questionnaire

After excluding community and mental health trusts, and accounting for recent trust mergers and duplications, 175 trusts were asked to consider participating in the survey. Ninety-nine (57% of those approached) agreed to participate. Sixty of these 99 (61% of potential respondents) returned a trust questionnaire (Table 4). A total of 58 of the 60 (97%) respondents reported providing acute inpatient care for older people with medical/surgical conditions.

| Country | Number (%) of trusts | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Contacted | Agreed to participate | Returned trust questionnaire | |

| Scotland | 14 | 9 (64.3) | 6 (42.9) |

| Northern Ireland | 5 | 4 (80.0) | 4 (80.0) |

| Wales | 7 | 2 (28.6) | 2 (28.6) |

| England | 149 | 84 (55.7) | 48 (32.2) |

| Total | 175 | 99 (56.6) | 60 (34.3) |

Non-response bias

Comparable data were available from online data sources for trusts in England and were used to test factors that could plausibly affect the likelihood of responses being received. In brief, no systematic differences between responding and non-responding trusts were seen. Some influence of the NIHR network was possibly observed; there was a trend towards increased participation by trusts in a NIHR region with an active regional ageing speciality lead in place, which bordered on statistical significance (see Report Supplementary Material 3).

Types of services provided

The trusts were asked if they provide a multidisciplinary assessment in acute care for older people who are frail in a number of clinical areas. Responses described 323 services in 10 predefined clinical areas (Table 5). The predefined framework captured the majority of service types. Services recorded in the ‘Other’ category (n = 7) included ‘Enhanced Care’, a dementia and delirium team and a rehabilitation unit.

| Trusts providing a multidisciplinary assessment in acute care for older people who are frail in the following clinical areas | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Orthopaedic department | 53 (88) |

| Wards specialising in OPM | 55 (92) |

| Admission ward | 44 (73) |

| Stroke team | 47 (78) |

| Inpatient medical wards | 32 (53) |

| ED | 26 (43) |

| Emergency assessment unit/decision unit | 21 (35) |

| Inpatient surgical wards | 20 (33) |

| Hospital consultation service | 22 (37) |

| Oncology department | 7 (12) |

| Other | 3 (5) |

An assessment of non-response bias for service-level responses using the same criteria used to analyse trust-level responses did not identify systematic differences between responding and non-responding trusts.

Admission avoidance

A key issue in the provision of effective acute inpatient services is a close relationship between acute and community-based services. Accordingly, we asked questions about the provision of a community admission avoidance service. Most (79%) of the 58 responding trusts indicated that they offered such provision. Approximately half (48%) of these services were provided by a consultant specialist in OPM, who was part of the team in 25 services, available to the team in 3 services and had no involvement in 32 services.

Post-acute care

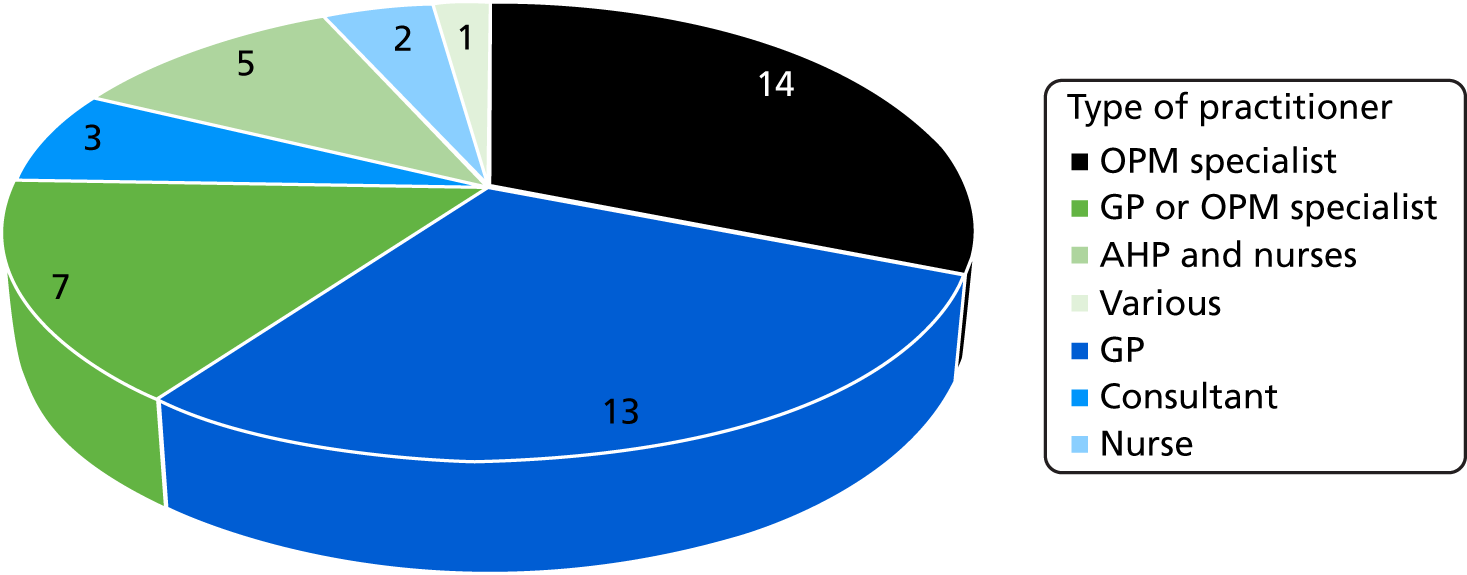

Forty-five trusts (78%) reported that they work with or provide a post-acute service. Most (n = 34) of these services were based entirely in the patients’ home and nine also had access to community beds in which to provide post-acute services. Thirty-four trusts (59%) reported that their post-acute service was provided by a consultant specialist in OPM. The types of practitioner with overall responsibility for the service are shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Types of practitioners with overall responsibility for the service.

The service-level questionnaire

Response rate

Thirty-six (62%) of the 58 trusts that provided a completed trust questionnaire also provided completed service questionnaire(s). We received one response from Wales (14.3% of Welsh trusts), four responses from Scotland (28.5% of trusts), three responses from Northern Ireland (60% of trusts) and 28 (18.8% of trusts) responses from England. Between them, these 36 trusts returned service questionnaires describing 121 separate services – an average of 3.4 services per trust (Table 6).

| Country | Number (%) of trusts | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Contacted | Returned service questionnaire(s) | Number of service questionnaires received | |

| Scotland | 14 | 4 (28.5) | 16 |

| Northern Ireland | 5 | 3 (60.0) | 12 |

| Wales | 7 | 1 (14.3) | 2 |

| England | 149 | 28 (18.8.) | 91 |

| Total | 175 | 36 (20.5) | 121 |

Working with, or providing, community-based services

About half of the services provided community admission avoidance, mostly with input from a specialist in OPM. Most respondents worked with, or provided, post-acute care services, again mostly provided with or by a consultant specialist in OPM (Table 7).

| Do you work with or provide | Response, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Community services | ||

| A community admission avoidance service? | 48 (40) | 56 (51) |

| With input from consultant specialist in OPM? | 45 (37) | 11 (9) |

| Post-acute services | ||

| Post-acute care services | 85 (70) | 36 (30) |

| Provided by a consultant specialist in OPM? | 45 (55) | 18 (23) |

| Bed based or home based? | ||

| Bed only | 10 (8) | |

| Home only | 7 (6) | |

| Both bed and home based | 68 (56) | |

The survey identified a range of provision of multidisciplinary assessment and management across inpatient care settings with some areas (such as orthopaedics, OPM and stroke) being more completely provided with appropriately skill-mixed MDTs than others (such as surgical and oncology departments).

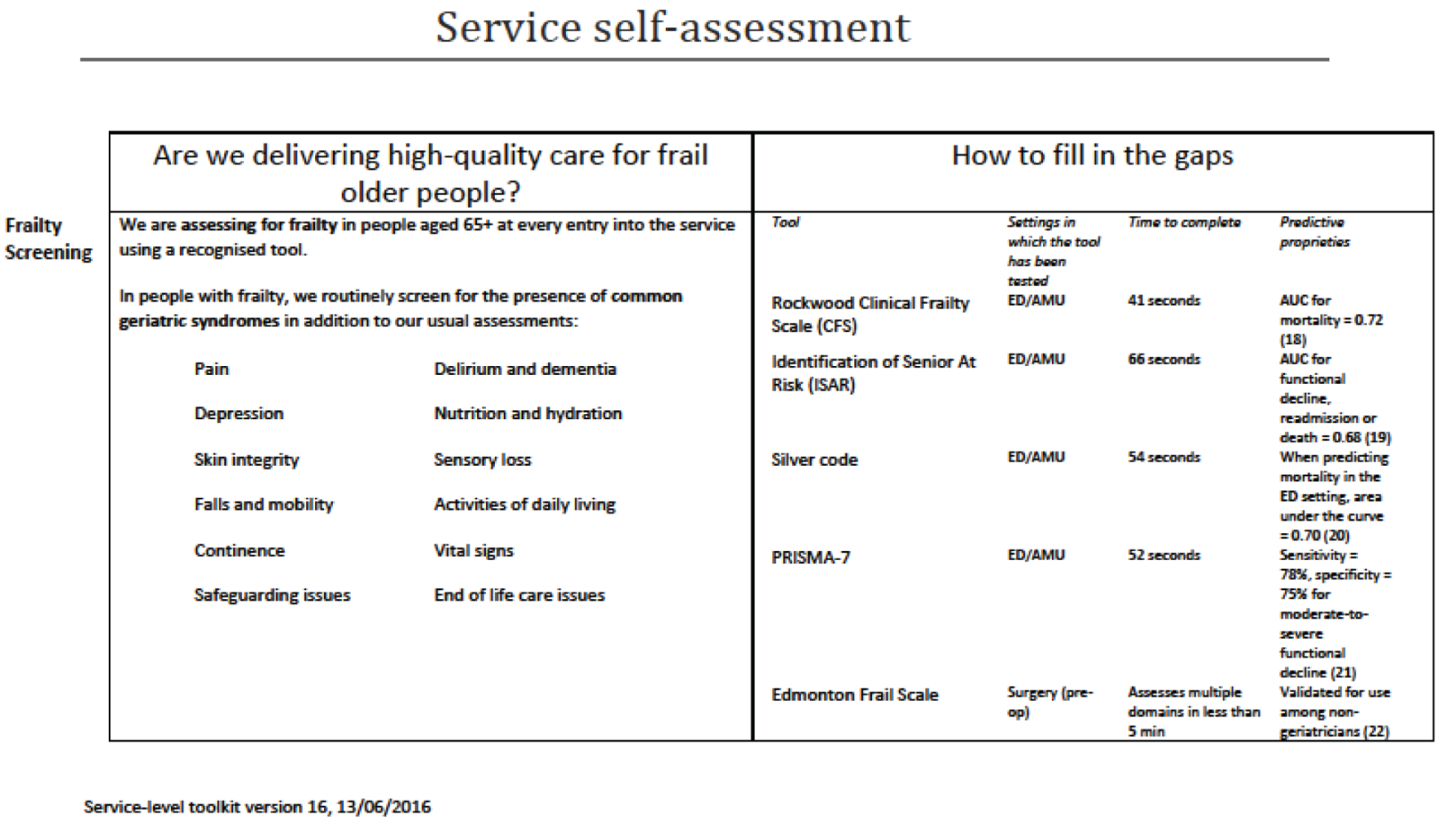

Identifying patients for multidisciplinary assessment and care

In general, clinicians appear to prefer their clinical assessment processes to standardised clinical instruments and measuring tools to identify patients for multidisciplinary care. Most services [108/121 (89%)] relied on clinical assessment processes to identify patients for multidisciplinary assessment. Of these, about half (n = 61) identified processes amounting to clinical screening by an experienced health-care professional and some (n = 20) services described MDT discussion as the main clinical assessment processes used to select patients. The use of a clinical screening tool or triage method was reported by 50 services (41%). In free-text entries these services generally identified their admission processes, locally developed screening procedures and triage processes (some specifying frailty specific triage) to identify patients who will receive multidisciplinary treatment. Admission criteria were applied by 55 services (45%). Fifty-three services (44%) had a minimum age requirement and 28 services (23%) had explicit exclusion criteria.

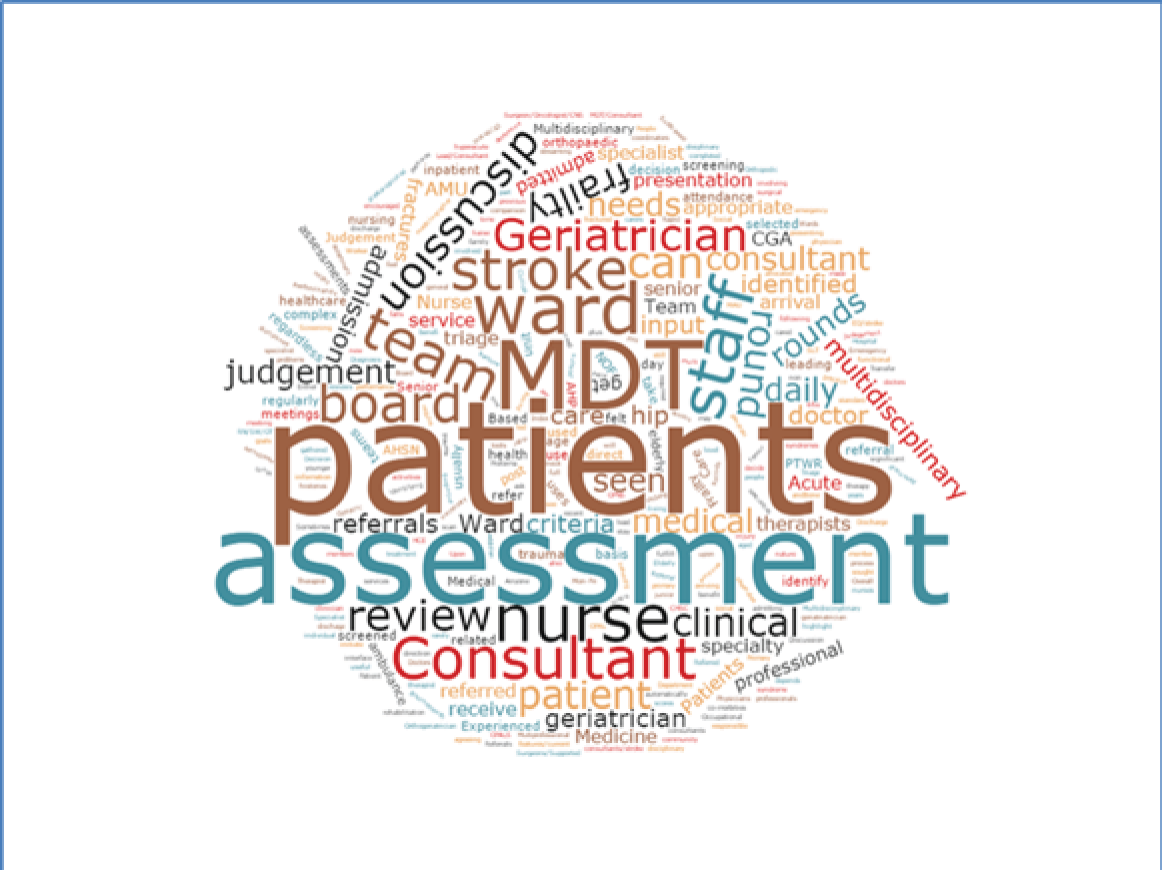

However, those services that reported the use of screening tools to identify patients for multidisciplinary assessment generally identified their admission and referral processes and locally developed screening procedures as the tools in the free-text descriptions [rather than specific, recognised or validated clinical instruments, represented graphically by the word cloud below (Figure 3)].

FIGURE 3.

Word cloud created from free-text entries describing the clinical assessment processes used to identify patients for multidisciplinary assessment.

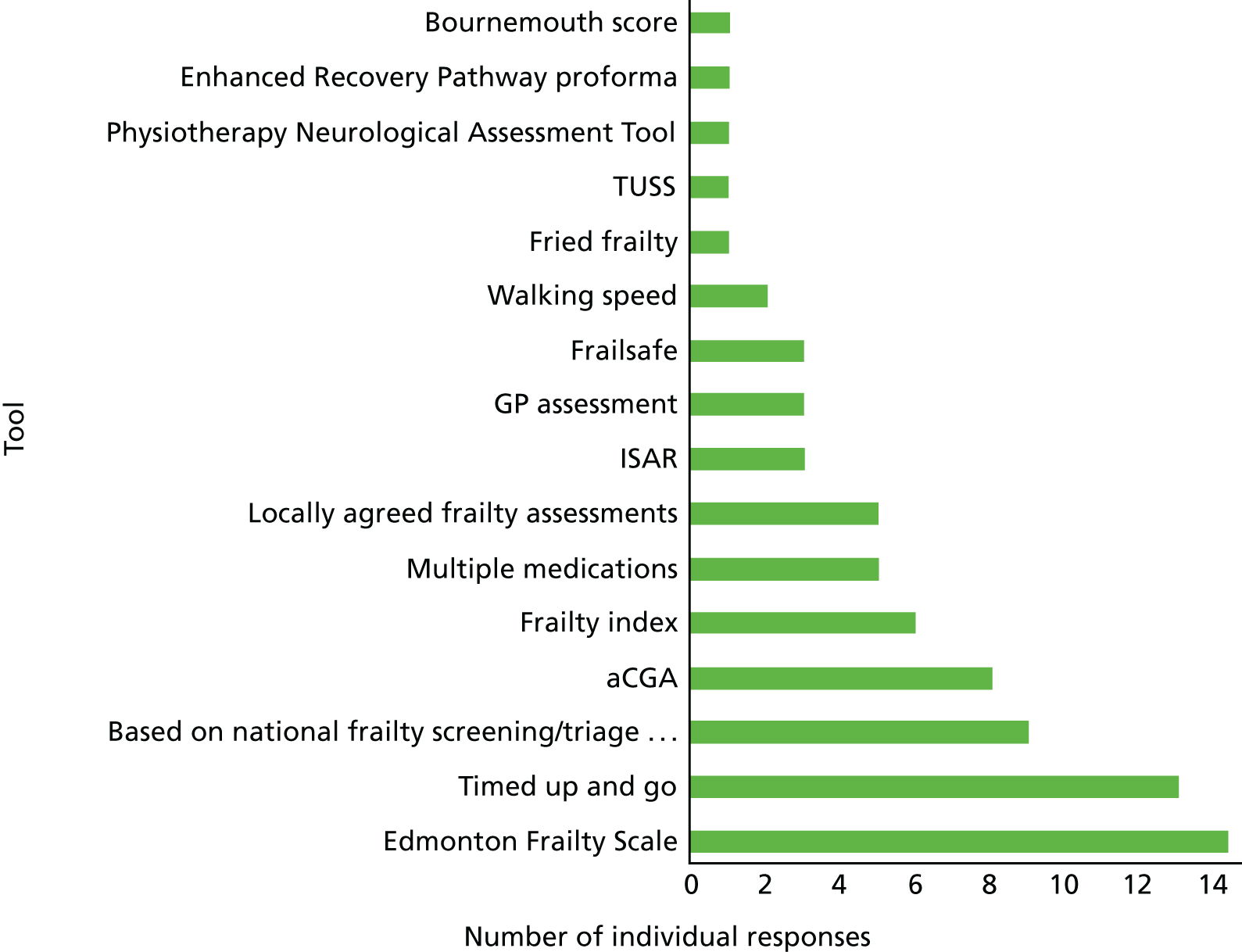

Identifying frailty

A total of 32 (26%) services used a standardised clinical method, instrument or measuring scale to identify patients who are frail. However, there was little consistency between services, among which a wide range of recognised assessment scales was used for this purpose (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Tools used to identify frailty (n = 32). aCGA, abbreviated Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment; ISAR, Identification of Seniors at Risk; TUSS, timed unsupported stand.

Staffing and assessment at the ‘front door’

Clearly, we must be cautious about generalisation, particularly when it comes to considering detailed survey responses from relatively small numbers of specialised types of service. However, with that caveat in mind, we can identify some important dimensions of the way in which services are being staffed and delivered.

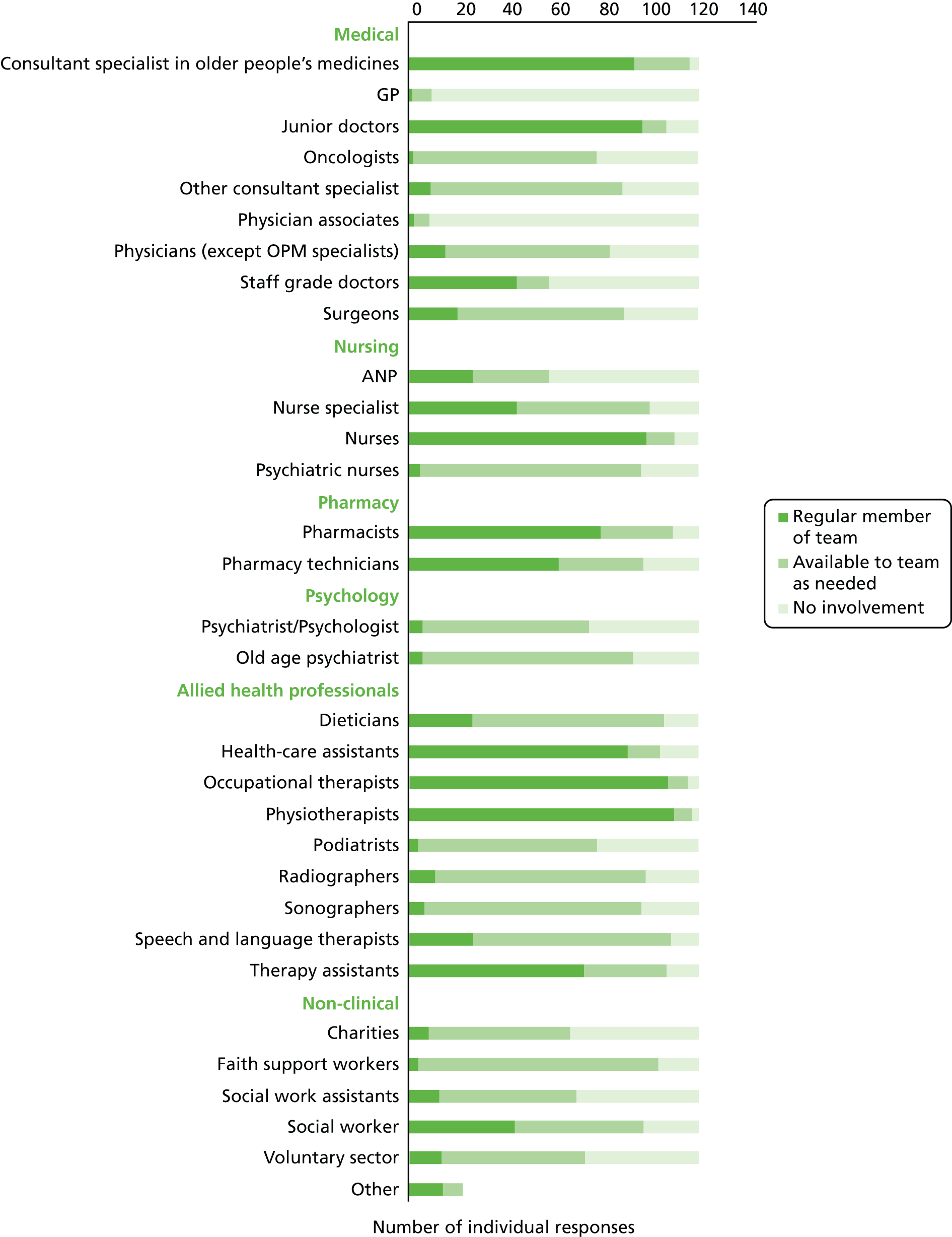

For example, it seems reasonable to say that the services generally reported being staffed by a consultant specialist, who attended regularly and was supported by junior and staff grade doctors (Figure 5). However, when asked if older people who are frail are assessed by a specialist in OPM in the ED (at the front door), only nine of the responding trusts described 16 services in which such ‘front door’ assessment is available. When available, these assessments were typically performed during the first 4–12 hours of admission.

FIGURE 5.

Staffing available in multidisciplinary treatment services.

Components of assessment

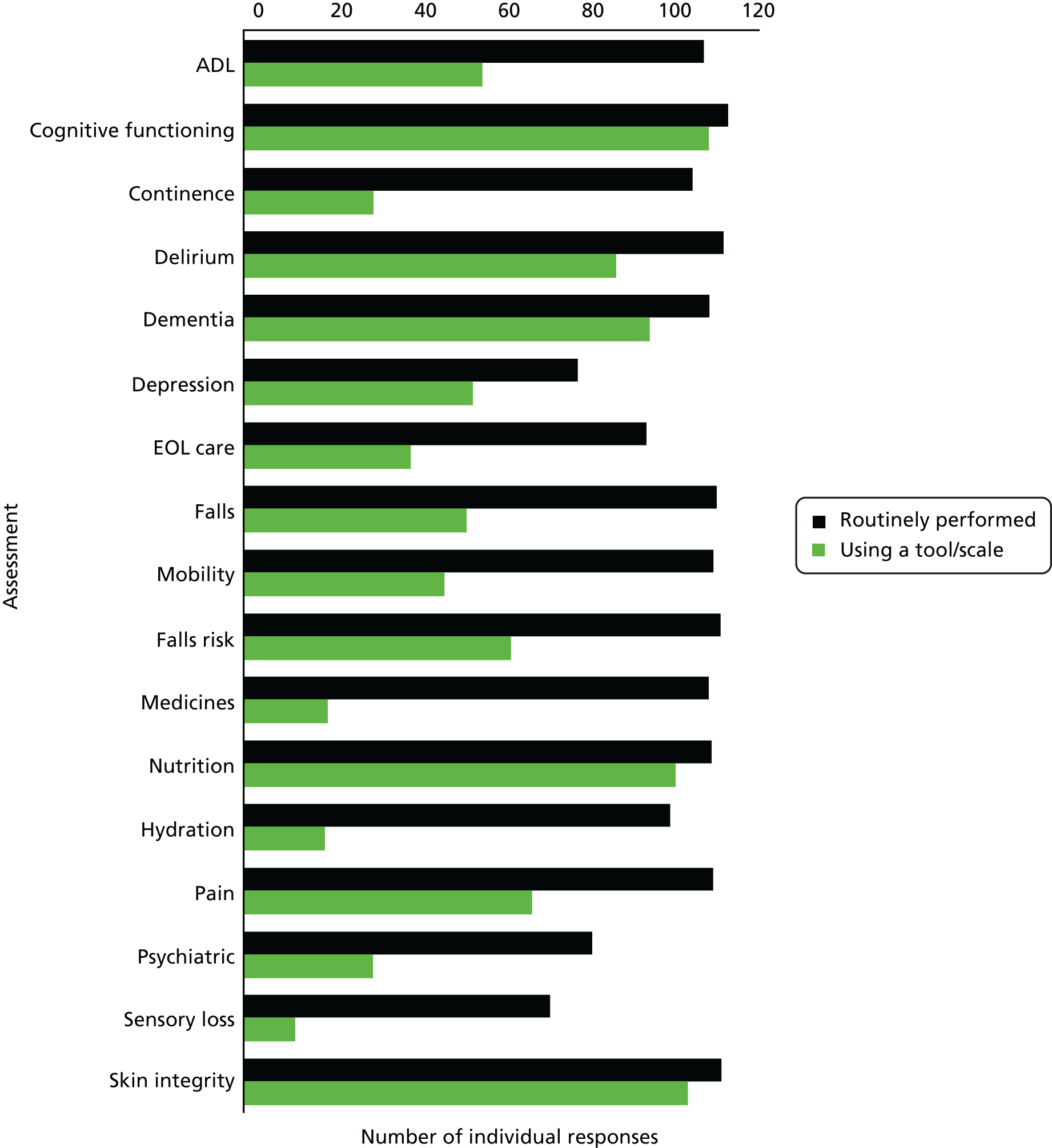

The components of the multidimensional assessments performed were similar across a range of services. More than 90% of services reported that the assessment of cognitive functioning, delirium and dementia were routinely performed, along with assessment of activities of daily living, mobility, falls and falls risk, medications, nutrition, continence and skin integrity (Figure 6). Assessment of hydration as a routine was reported in 102 services (84%) and end-of-life-care needs in 96 services (79%). Psychiatric assessment was reported in 83 (69%) of returns and 80 services (66%) reported assessing for depression. Sensory loss was the least frequently reported assessment, being reported by 73 services (60%). These data are tabulated in Table 8.

FIGURE 6.

Assessments that are routinely performed using a tool or scale (n = 121). ADL, activities of daily living; EOL, end of life.

| Assessment | Performance, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Routinely performed | Performed using a tool/scale | |

| ADL | 110 (91) | 57 (47) |

| Cognitive functioning | 116 (96) | 111 (92) |

| Continence | 107 (88) | 31 (26) |

| Delirium | 115 (95) | 89 (74) |

| Dementia | 111 (92) | 97 (80) |

| Depression | 80 (66) | 55 (45) |

| EOL care | 96 (79) | 40 (33) |

| Falls | 113 (93) | 53 (44) |

| Mobility | 112 (93) | 48 (40) |

| Falls risk | 114 (94) | 64 (53) |

| Medicines | 111 (92) | 20 (17) |

| Nutrition | 112 (93) | 103 (85) |

| Hydration | 102 (84) | 19 (16) |

| Pain | 112 (93) | 69 (57) |

| Psychiatric | 83 (69) | 31 (26) |

| Sensory loss | 73 (60) | 12 (10) |

| Skin integrity | 114 (94) | 106 (88) |

Monitoring change

The majority of services [n = 100 (83%)] had processes in place to identify the development of delirium and 89 (74%) had processes in place to identify falls. Other risk factors for adverse outcomes, such as incontinence [n = 81 (67%)], depression [n = 62 (51%)] and functional decline [n = 53 (44%)], were less consistently reported.

Prevention of in-hospital deterioration

The prevention of deterioration, and of complications of hospitalisation, is particularly important for older people who are frail. Falls, urinary complications (such as incontinence), deconditioning, demotivation and depression all increase the risk of adverse outcomes from an inpatient hospital stay (Table 9).

| Processes in place to actively prevent deterioration | Response, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Physical functioning | 80 (66) | 41 (34) |

| Continence | 46 (38) | 75 (62) |

| Delirium | 62 (51) | 59 (49) |

| Depression | 30 (25) | 91 (75) |

| Falls | 93 (77) | 28 (23) |

| Other | 7 (6) | 114 (94) |

Trusts are expected to have a falls prevention policy, so it is not surprising that 88% of services reported having services in place to actively prevent falls. However, only 31% of services reported processes to prevent deterioration in depression and only 40% reported processes to prevent deterioration in continence, illustrating the continued ‘Cinderella’ status of continence and mental health services in this context.

Results broken down by service type

A total of 121 services returned a survey questionnaire and responses are now summarised by service type. Some of the tables containing these data are relatively large (e.g. 10 rows by 6 or 9 columns) and contain large numbers of empty cells, so, for clarity, data are not presented. Narrative summaries (with quantitative data where appropriate) are presented here.

Identifying patients for multidisciplinary treatment

Most services (68–100%) reported that clinical assessment processes were used to identify patients for multidisciplinary treatment. The use of screening tools or standard triage methods was less frequent, generally being reported by around half or fewer services. About half [12/22 (52%)] of OPM wards reported the use of screening tools or standard triage methods.

Admission and exclusion criteria

No service reported the use of a maximum age criterion. The use of a minimum age criterion to identify patients for multidisciplinary treatment was seen most frequently among admission wards [11/17 (65%)].

Consultant reviews and assessments

The majority of services reported that patients were usually reviewed by a consultant. The rates for consultant review were > 90% in 7 out of 10 services (data not presented).

In contrast, a review of patients identified as frail ‘at the front door’ of the hospital was reported by 16 services, across nine different trusts. This included about one-quarter of admission wards and EDs. Three services reported that these assessments were usually carried out within 4 hours, eight reported that they take place within 12 hours and five reported that they take place within 24 hours.

Most services reported that they did not use a standardised clinical method, instrument or scale to identify frail patients. The use of these methods was distributed fairly evenly between the service types.

Staff who regularly work in the multidisciplinary teams

Most admissions wards (14/17), orthopaedics wards (20/22), OPM wards (22/23) and stroke teams (16/18) regularly worked with a specialist in OPM. All admissions wards and OPM wards regularly worked with junior doctors. Orthopaedics (12/22) and OPM wards (11/22) reported working regularly with staff grade doctors. General practitioners (GPs) were not reported as regular members of the team and neither were oncologists (except in the oncology teams).

Similar patterns were seen for nurses, nurse specialists or both, and pharmacy staff. Very few of the services had psychologists or old age psychiatrists as regular members of the team.

Allied health-care staff who were almost universally included in the regular MDT were physiotherapists, occupational therapists, therapy and health-care assistants.

Approximately one-third of teams reported social work staff as regular members, and very few charity, faith support or voluntary sector workers performed a regular function in the MDTs.

Staff who are available to the multidisciplinary teams

Most services reported having access to consultant specialists, including in oncology (62%), surgery (58%) and other medical specialties (67%). GPs were generally not reported as being available to the team, except in oncology where both services reported GP availability (see Report Supplementary Material 3).

Generally, teams reported availability of psychiatric nurses, old age psychiatrists and psychologists, rather than regular team membership (see Report Supplementary Material 3).

Similarly, availability (rather than regular team membership) was generally reported for podiatry and radiology staff (see Report Supplementary Material 3). The same can be said for speech and language therapists (SALTs) and dietitians, but not for stroke teams, all of which are usually part of the core team.

Trusts reported that teams also had the following staff made available to them: Faith Support Workers (Admissions Ward, Orthopaedics, OPM Ward and Stroke Team), Social Work Assistants (Admissions Ward, OPM Ward and Stroke Team) and Social Workers (Orthopaedics, OPM Ward). Orthopaedics most commonly had more Voluntary Sector staff available to teams.

Including social workers and assistants as regular or available team members, social work availability was generally high (71–100%) in inpatient services, but less so at the ‘front door services’ such as ED and Decision Units (see Report Supplementary Material 3).

Similarly, Faith Support services were almost universally available in inpatient care settings, but less so in the receiving services (see Report Supplementary Material 3).

Discussion

In this survey we sought to understand how CGA is delivered across a range of acute hospital wards and settings in the UK.

A series of questions were asked about the provision of multidisciplinary assessment and care for older people admitted to hospital, across a range of inpatient settings. This allowed identification of the components of CGA, the types of patients and clinical problems, and, importantly, the extent to which frailty is assessed and older people with frailty targeted for receipt of multidisciplinary assessment and care. Information was also sought about the provision of/relationship with the community-based assessment and post-acute services, which are essential components of integrated systems of care.

The trust-level responses are used to describe a range of available services. The service descriptions are then used to illustrate the make-up, assessment processes and resources available among the responding services. This exercise has provided an overview of service types, which is complemented by a rich source of service descriptions (from > 120 services) and which contains important details about the services that commonly provide CGA in hospital settings.

One of the key messages emerging from this survey is that although some services appear to provide multidisciplinary assessment and management routinely (wards specialising in OPM and orthopaedic wards) or commonly (stroke and admissions wards), the practice is less firmly embedded in other parts of the hospital system (e.g. medical and emergency units) and not usually found in surgical and oncology services.

With regard to selecting patients to receive multidisciplinary assessment and management, it would appear that the professionals performing this task tend to prefer their usual clinical assessment processes, using clinical and professional judgement and discussion with members of the MDT as a way to select patients who may benefit. Relatively few teams relied on standardised scales or clinical assessment tools.

Furthermore, and despite much current interest and activity related to the topic of frailty, at the time of our survey (2016), we did not find a clear consensus about the assessment/measurement of frailty and the tools required to carry it out.

More than half (56%) of the trusts that we approached trusts agreed to participate and, following multiple rounds of contact and encouragement of trust staff, with network, college and specialist society support, 60 trusts provided trust-level information and 36 trusts provided detailed descriptions of > 120 services.

Although this is a large repository of service descriptions, it cannot be said to be comprehensive, or representative, on account of the limited proportion of UK trusts that participated in the survey. This concern is mitigated somewhat by the existence of the NHS Benchmarking survey, which was carried out at the same time, which found similar results where it asked similar questions. Over a similar time period to this survey, NHS Benchmarking was conducting its regular survey of older people’s care in acute settings. 103 NHS Benchmarking worked with 45 NHS trusts and UHBs, 15 of which also responded to our survey. Between NHS Benchmarking and our survey, we therefore covered 88 NHS trusts across the UK during a similar period of data collection. This is over half of trusts so it is worth spending some time exploring the similarities and differences between the two surveys. In summary, it would appear that when we asked about the same thing, we obtained similar results.

For example, NHS Benchmarking found that 77% of trusts/UHBs delivered CGA on care of older people wards. This decreased to 42% on other specialty wards. Our survey adds a layer of detail around the same statistic, finding high levels of CGA delivery on OPM wards (92%), orthopaedic wards (88%) and stroke wards (77%), whereas the lower levels of CGA delivery were found on 53% of inpatient medical wards and 33% of inpatient surgical wards.

Similarly, NHS Benchmarking found that 40% trusts said that they had a dedicated geriatric team in the accident and emergency (A&E) department. Forty-three per cent of our respondents stated that frail older people in the A&E were assessed by a geriatrician.

When it came to the delivery of frailty-specific care there were some clear similarities in our findings. NHS Benchmarking found that about 30% of responding trusts used a standardised clinical method, instrument or measuring scale. This is close to the 29% figure that we found when we asked, ‘Does your trust use a standardised clinical method, instrument or measuring scale to identify patients who are frail?’ and we are able to add the important qualifying detail that there is not (as yet) a clear preference or consensus about which of the many available tools and scales to use for this purpose.

In conclusion, we believe that this is the biggest, and most detailed, survey of hospital CGA services ever completed in the UK. This survey has identified a range of provisions of multidisciplinary assessment and care across inpatient care settings, with some areas (e.g. OPM, orthopaedics, stroke) being more completely provided with appropriately skill-mixed MDTs than others (such as inpatient medicine and surgery).

Generally, clinicians appear to prefer their clinical assessment processes to standardised clinical instruments and measuring tools to identify patients to be beneficiaries of multidisciplinary assessment and care.

Furthermore, it would appear that, as yet, the formal use of frailty as an identifying or stratifying characteristic of patients is patchy and non-standardised.

In an emerging landscape of hospital-wide CGA service, we cannot say that patients with frailty are being identified, assessed and managed systematically in relation to their frailty, or targeted with CGA services. There are areas of inpatient hospital care in which these features are well developed, or beginning to develop, and others in which they are not often found.

Chapter 4 Characterising beneficiaries

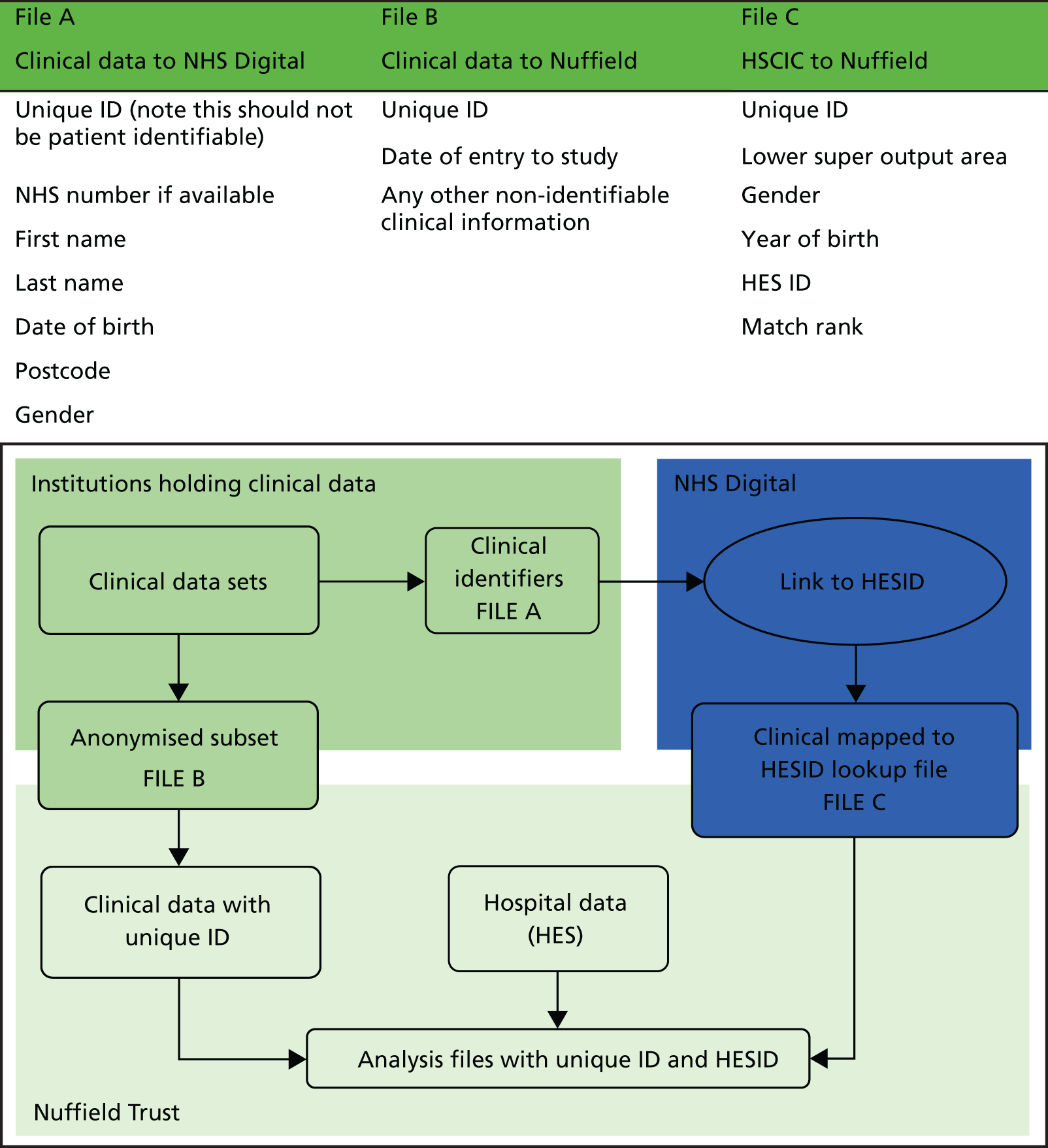

Data in this chapter are drawn from NHS Digital. Copyright © 2018, re-used with the permission of NHS Digital. All rights reserved.

Developing Hospital Episode Statistics-based proxies for frailty and creating tools to help understand the need for Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment: introduction

In this strand of work, we wanted to develop proxy measures and tools that would provide a better understanding of the needs of frail older people within a given a population. In the UK there has been a long tradition of population-based measures and the concept of needs assessment104,105 as the basis for informing decisions about where to invest/disinvest in care services. Unfortunately, comprehensive data sets that identify frailty in an individual do not exist,106 so the approach has had to be a little more tangential than previous methods employed.

There are reasonably good descriptors of the underlying population and information about health service activities contained in the fairly comprehensive Hospital Episodes Statistics (HES) data sets that record information on patients’ attendances at hospital. 107 Although these patient-level data sets have limited clinical detail, they have been fairly consistently recorded in all acute NHS hospitals in England for many years. For this analysis, we wanted to exploit this history of good data collection to look in detail at the population of older people, and, where possible, to look for frailty. The following strands of work are pragmatic and exploratory. We have sought to combine the outputs into tools that can be used for planning CGA.

Our aims were to:

-

stratify local populations to identify the number of people who may benefit from CGA

-

apply a series of health system performance measures at area and provider level that relate to the care of frail older people

-

develop simple interactive tools to compare patients’ assessed potential benefits and costs.

We used linked population-level data sets to see if we could assess the number of frail older people who may benefit from CGA. This approach built on the idea of there being a resident population of older people in a local authority (LA) area, who could then then be split into mutually exclusive groups or segments, so that we could identify a set of individuals with high needs and form a potential target population for CGA. For the sake of consistency, and acknowledging multiple caveats about the definition and measurement of the frailty syndrome, we called this group ‘frail older people who may benefit from CGA’. For this group, we identified a set of performance metrics, which we might reasonably expect to be influenced by the nature and quality of the inpatient care experienced (particularly the use of CGA), for example annualised numbers of emergency admissions.

We tried three approaches to describing the extent of frailty within a population:

-

population segmentation based on historic patterns of hospital use

-

clinical diagnoses linked with frailty – using a predefined list of diagnoses

-

clustering of clinical diagnoses to create a new approximation to frailty.

We also looked at the direct costs of CGA, which are described in Chapter 7. Information from these various analyses was combined into Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) tools.

Population segmentation approach

Population segmentation has been proposed for some time108 and in recent years has been a more practical application owing to the availability of large person-level data sets. 109,110 There are, however, no standard segmentation approaches that have been applied to look at care use by older people.

In this approach, we looked at patterns of past hospital activity to see if we could categorise groups of older people according to their previous use of hospital care. By implication we assume that this will help to indicate something about their future needs. At one end of the spectrum we have older people who are fit and healthy and have never used hospital services, and at the other end there are those with multiple chronic conditions who require multiple acute interventions. It is among this latter group that we believe ‘frail’ older people are more likely to be identified.

Testing the population segmentation approach in three local authorities

Our initial work used hospital admissions data linked over time for all residents in three LAs – Leicester, Nottingham and Southampton – as these would be used for more detailed clinical linkage work described in Chapter 6. Data were extracted from the HES by NHS Digital and held at the Nuffield Trust under permissions granted by NHS Digital based on the Nuffield Trust fulfilling the information governance requirements needed to analyse pseudonymised person-level hospital data, and linked Office for National Statistics (ONS) mortality data.

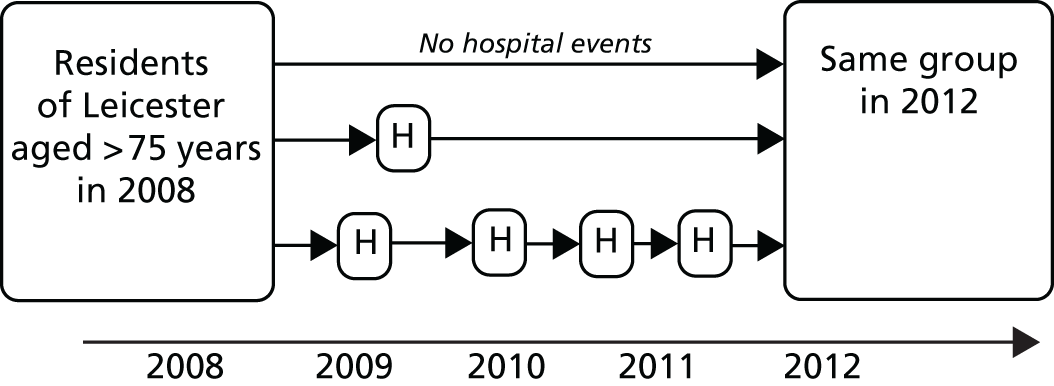

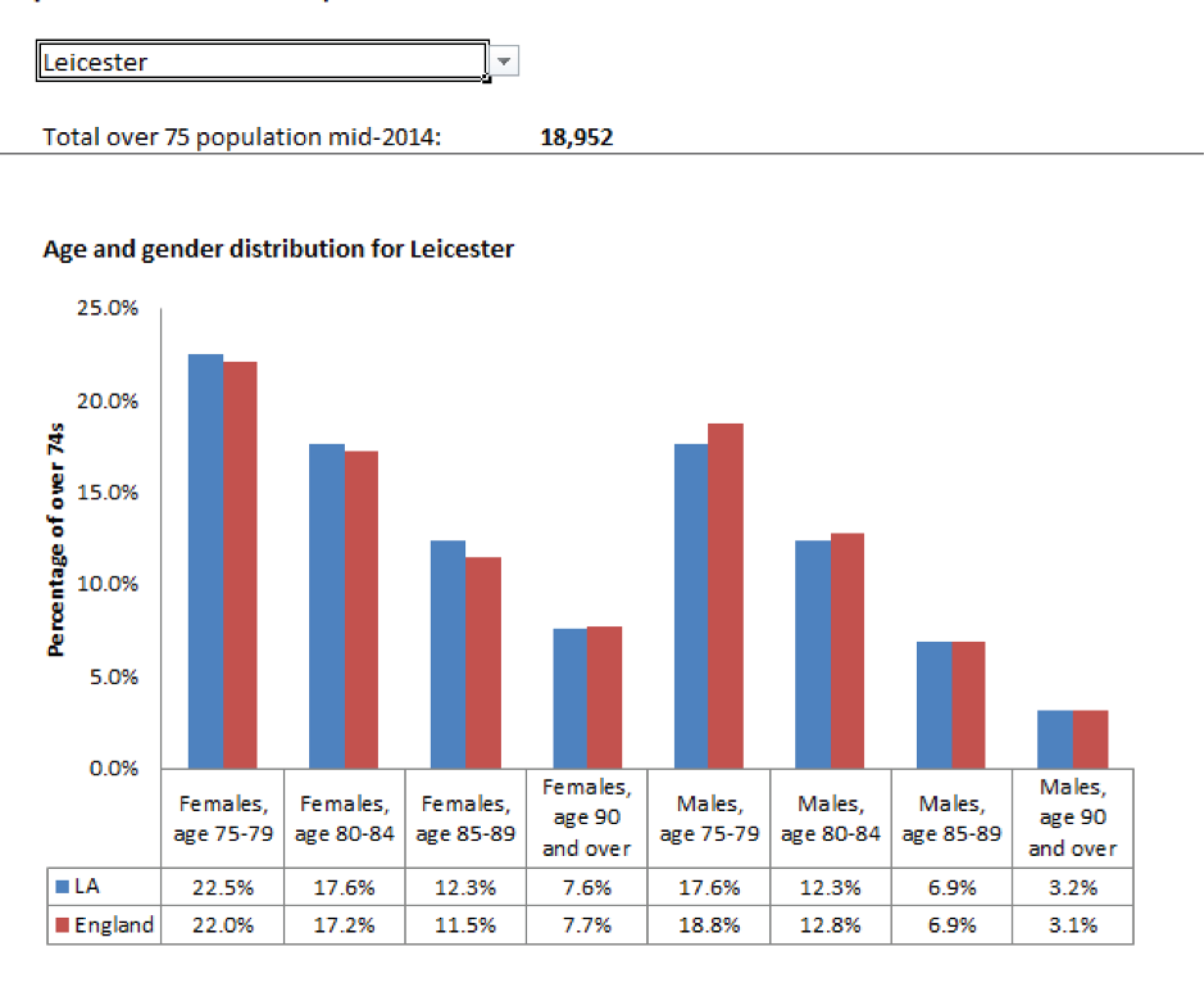

Hospital Episode Statistics provides information on individual episodes of hospital care for patients. Each record contains a pseudonymised Hospital Episode Statistics Identifier (HESID) that allows episodes of care for the same person to be tracked over time. We are also able to identify the LA area in which the person normally resides. This information contained within HES enables us to identify all the people aged ≥ 75 years in 2008 living in the LAs of the cities of Leicester, Nottingham or Southampton and then track their hospital use anywhere in the country between 2008 and 2012. Using the census population estimates for each LA, we could then estimate the proportion of the older people in these areas that had used the hospital services and also by implication estimate how many older people had not (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Outline of how individual histories were constructed from linked patient records. H, history.

We recognise that there are limitations to understanding frailty just from past hospital records. There may be people within a population who are perfectly well and not engaging with health services but who experience an event that alters their health status and health service use. These newly emergent cases are of interest as they may be less well identified through studies of past hospital records.

Table 10 summarises the number of people in our study cohort who had any hospital contact (outpatient attendance, inpatient admission or ED visit) during the 4-year study period. It shows that after 1 year, the proportion of the estimated population in each area that were aged ≥ 75 years with at least one hospital encounter was between 62% and 76%, whereas after 4 years between 91% and 100% of people aged ≥ 75 years had had a hospital encounter.

| Area | Population aged ≥ 75 years (n) | Numbers (%) with hospital event | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After 1 year | After 2 years | After 3 years | After 4 years | ||

| Leicester Unitary Authority | 17,559 | 12,122 (69.0) | 14,867 (84.7) | 16,327 (93.0) | 17,171 (97.8) |

| Nottingham Unitary Authority | 17,850 | 13,628 (76.3) | 16,312 (91.4) | 17,587 (98.5) | 18,266 (102.3) |

| Southampton Unitary Authority | 16,160 | 9953 (61.6) | 12,494 (77.3) | 13,775 (85.2) | 14,621 (90.5) |

In Nottingham the number of individuals who had had at least one hospital encounter (as measured by the number of unique HESIDs) exceeded the estimates of the resident population. This could arise for a number of reasons:

-

flaws in the HESID (e.g. people had been assigned more than one HESID, basic patient details had been recorded incorrectly at the hospital or people had moved to a new house and the HESID had not been updated)

-

underestimates of the census population,111 perhaps as a result of people living in care homes.

It is also worth noting that there appear to be quite large differences between the three LAs, with Southampton having consistently a smaller proportion of older people identified as hospital users.

Our first attempt was, therefore, to group the population into categories that roughly correspond with an increasing scale of hospital utilisation over a period of time. We were also interested in trying to separate out isolated acute hospital encounters and other manageable chronic diseases from indicators of longer-term deterioration and instability similar to the Bridges to Health Mode. 111

For this analysis, the key elements of health-care use that we could identify at patient level were derived from HES and therefore limited to emergency hospital admissions, elective hospital admissions, ED attendance and outpatient appointments.

The groups are mutually exclusive so a person can fall into only one group at any one time. The groups are also ‘hierarchical’, with an order of precedence loosely based on intensity of hospital use. For example, if someone has an outpatient appointment and an elective admission, they are grouped into the latter category. Death has not been accounted for when assigning individuals to these categories.

Table 11 shows the number (across all the three LAs) and proportion of cases (compared with the population of all those aged ≥ 75 years in those areas) in each category according to whether data over 1 year or 4 years are considered. For example, after 1 year, 28.5% of people aged ≥ 75 years had had only outpatient contacts, but after 4 years this had fallen to 12.9% as other forms of hospital contact became more likely. After 4 years the number of people aged ≥ 75 years who have multiple ED attendances but without an admission is very small (1.3%), whereas the largest group is for those with multiple emergency admissions. After 4 years, almost 37% of the older population have had more than one emergency admission. This reinforces the importance of emergency hospital use among older people as a factor in shaping needs for acute hospital care.

| Population group | Time point, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| After 1 year | After 4 years | |

| No hospital contact (implied) | 15,866 (30.8) | 1511 (2.9) |

| Outpatient only | 14,701 (28.5) | 6661 (12.9) |

| Single ED attendance (no admissions) | 1449 (2.8) | 2495 (4.8) |

| Multiple ED attendances (no admissions) | 143 (0.3) | 660 (1.3) |

| Single elective admission | 4279 (8.3) | 4486 (8.7) |

| Single emergency admission | 6499 (12.6) | 7928 (15.4) |

| Single elective and single emergency admission | 1130 (2.2) | 2198 (4.3) |

| Multiple elective admissions | 1921 (3.7) | 4314 (8.4) |

| Multiple elective and single emergency admission | 578 (1.1) | 2384 (4.6) |

| Two emergency admissions | 2968 (5.8) | 7413 (14.4) |

| Three emergency admissions | 1117 (2.2) | 4322 (8.4) |

| Four or more emergency admissions | 918 (1.8) | 7197 (14.0) |

Table 12 shows over 4 years the 12 hospital use categories grouped to create eight segments that are broadly consistent across LAs. For example, the proportion of the population aged ≥ 75 years who had only outpatient contact with hospitals over a 4-year period was between 12.1% and 13.6% across the different areas. In addition, the proportion of older people who had multiple emergency admissions ranged from 32.3% to 39.1%. Southampton had a larger implied proportion of older people with no hospital contact and a smaller proportion of older people who had multiple emergency admissions. Interestingly, in Southampton the proportion of older people with elective admissions was in line with the other areas. The implication is that the demand on urgent hospital care in Southampton by this age group is slightly less, but we cannot definitively say whether this was due to differences in the needs of the older people in this area or differences in the supply and organisation of care.

| Population group | Area (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Leicester | Nottingham | Southampton | |

| No hospital contact (implied) | 2.2 | –2.3 | 9.5 |

| Outpatient only | 13.0 | 13.6 | 12.1 |

| ED attendances (no admissions) | 6.3 | 7.2 | 4.7 |

| Single elective admission | 7.9 | 8.7 | 9.7 |

| Single emergency admission | 16.9 | 15.1 | 14.0 |

| Elective admissions and single emergency admissions | 8.3 | 9.3 | 9.0 |

| Multiple elective admissions | 7.0 | 9.4 | 8.7 |

| Multiple emergency admissions | 38.3 | 39.1 | 32.3 |

Applying the population segmentation approach across England

A hospital use classification, similar to those above, was applied to all lower-level LA areas in England (n = 326). In order to reduce the computation burden, 2 consecutive years of data were used instead of 4. Table 13 summarises the proportions of the population aged ≥ 75 years in each segment, providing information to show the distribution across all the LAs. It shows that, on average, the highest level of utilisation (people with three or more emergency admissions) made up 3.3% of the population aged ≥ 75 years, whereas 27% of the population aged ≥ 75 years had no hospital contacts.

| Measure | Number of emergency admissions (%) | Other forms of hospital contacts (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 3 | 2 | 1 | Elective admissions | ED attendances, no admissions | Outpatient | None (implied) | |

| Average | 3.3 | 4.8 | 14.4 | 13.7 | 6.4 | 29.9 | 27.5 |

| Standard deviation | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 5.8 | 7.4 |

| Minimum | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.0 | 8.1 | 0.0 | 20.2 | –0 |

| Median | 3.3 | 4.8 | 14.3 | 13.6 | 6.3 | 28.9 | 28.6 |

| Maximum | 5.6 | 6.5 | 18.2 | 21.0 | 13.7 | 61.7 | 48.2 |

The estimated numbers of people with no hospital events came from a number of areas in which the number of people identified in the hospital activity seemed to exceed the resident population. This is because, similar to what was previously observed in Nottingham, for some LA areas the number of individuals having had at least one hospital encounter (as measured by the number of unique HESIDs) exceeded the estimates of the resident population. Most of these areas were in the north-west of England; we assume from our analysis that this geographic concentration is a local artefact of how the outpatient data are collected and HESIDs assigned.

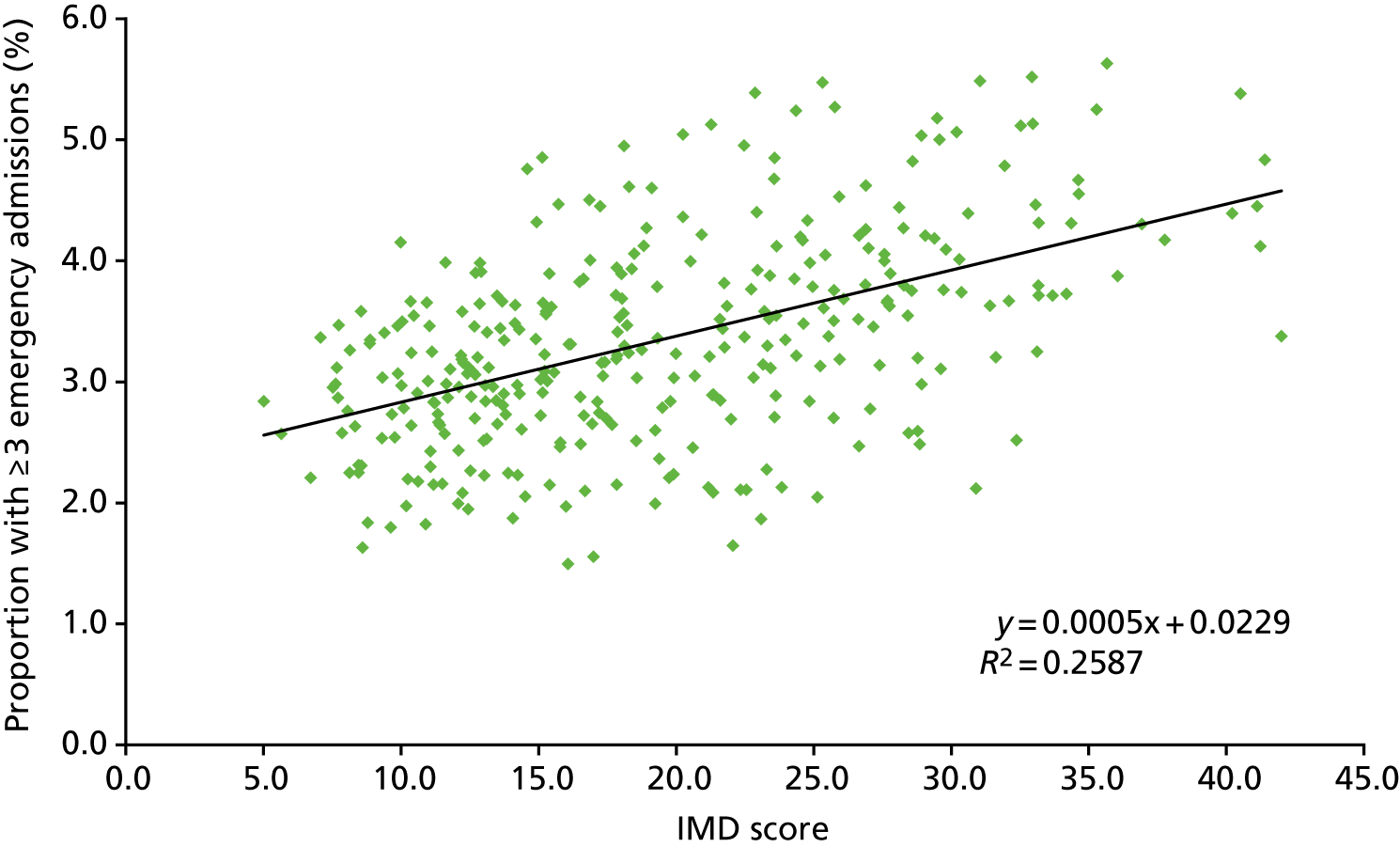

Association with deprivation

Socioeconomic factors are a key driver of differences in observed morbidity and health service utilisation. 112 For this analysis, using the national data described above, we wanted to see if underlying socioeconomic differences between LAs were affecting the profiles across our population segments. Table 14 summarises the correlation between LA levels of deprivation using the individual elements of the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD)113 and our population segments based on prior activity.

| Characteristic | Number of emergency admissions | Other forms of hospital contacts | n | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 3 | 2 | 1 | Elective admissions | ED attendances, no admissions | Outpatient | None (implied) | ||

| Income | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.61 | –0.02 | 0.42 | 0.04 | –0.37 | 0.28 |

| Employment | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.58 | 0.05 | 0.34 | 0.05 | –0.34 | 0.29 |

| Education, skills and training | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 0 | 0.19 | –0.09 | –0.12 | 0.16 |

| Health deprivation and disability | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.64 | 0.03 | 0.34 | 0.08 | –0.39 | 0.24 |

| Crime | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.57 | –0.16 | 0.48 | 0.03 | –0.34 | 0.16 |

| Barriers to housing and services | 0.04 | –0.13 | –0.26 | –0.04 | –0.03 | –0.13 | 0.17 | –0.03 |

| Living environment | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.01 | –0.15 | 0.12 | 0.05 | –0.05 | 0.09 |

| Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index (IDACI) | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.6 | –0.06 | 0.44 | 0.01 | –0.34 | 0.25 |

| Income Deprivation Affecting Older People (IDAOPI) | 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.58 | –0.1 | 0.44 | 0.06 | –0.38 | 0.21 |

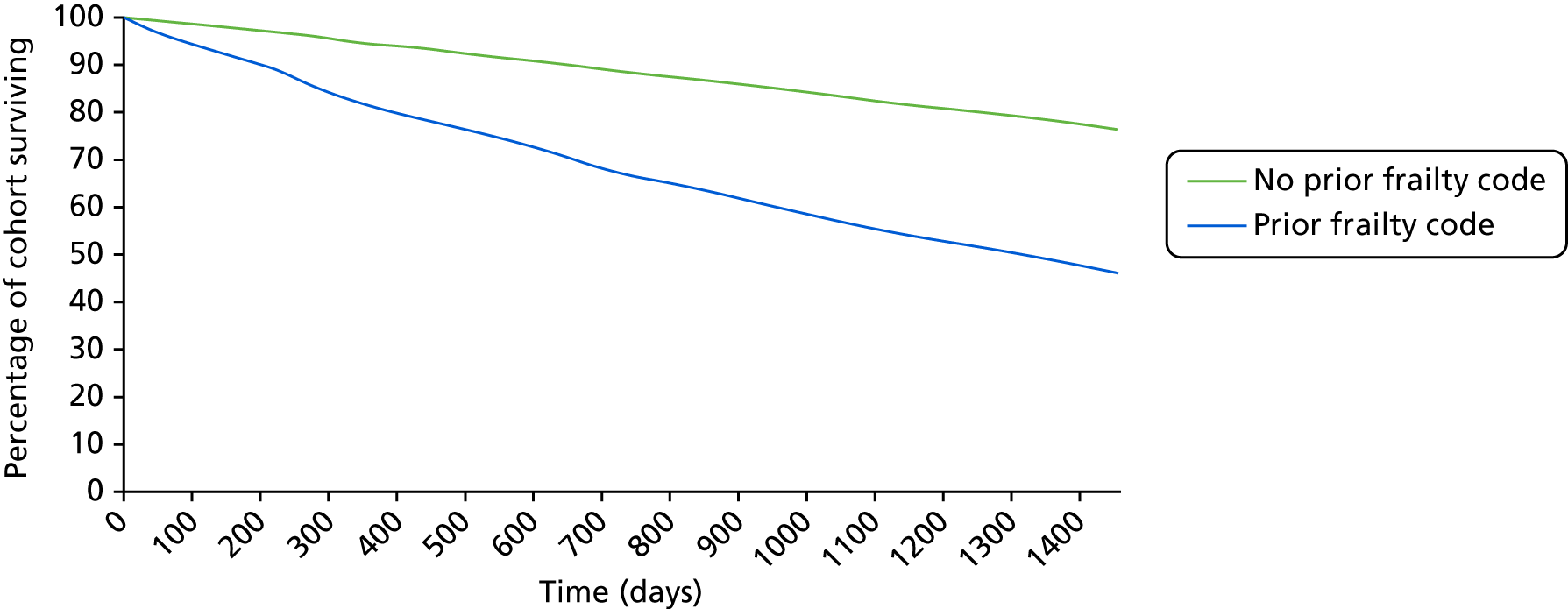

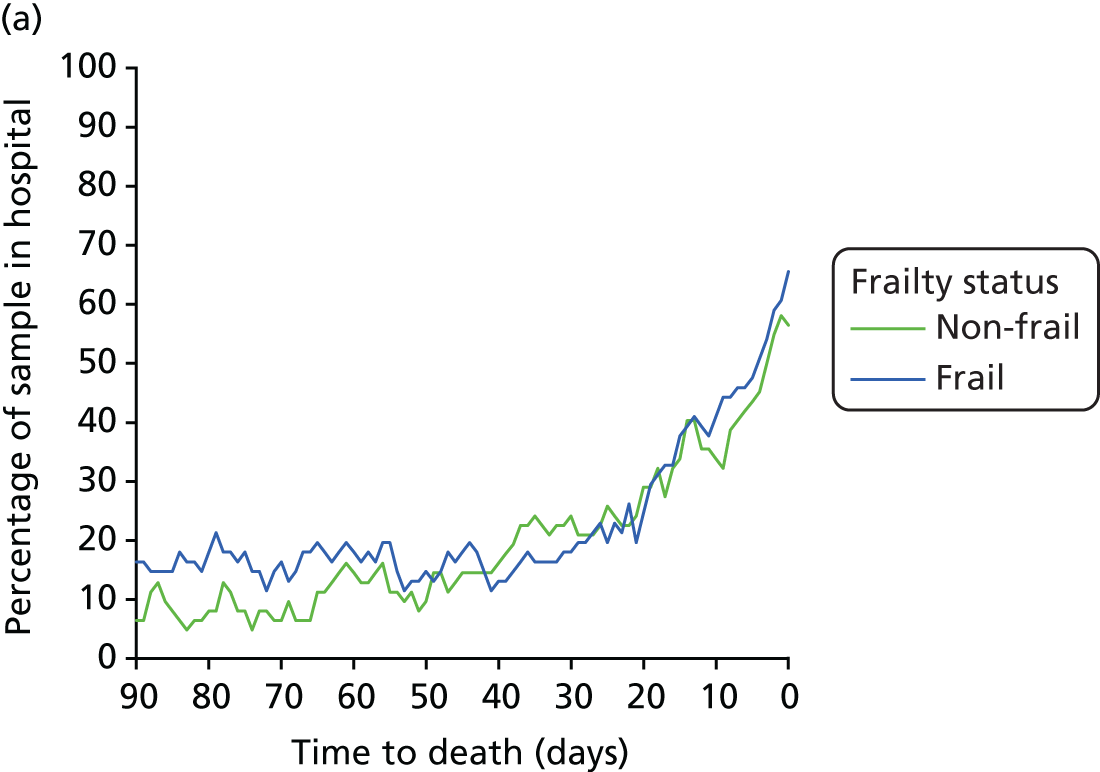

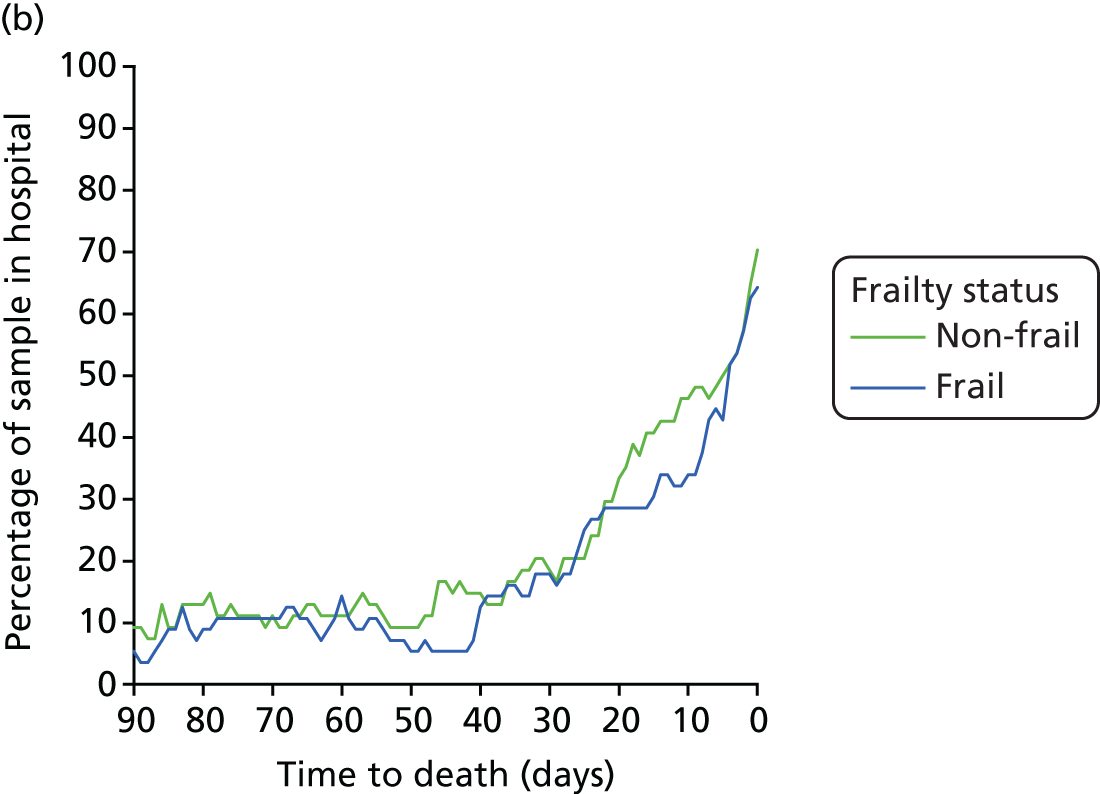

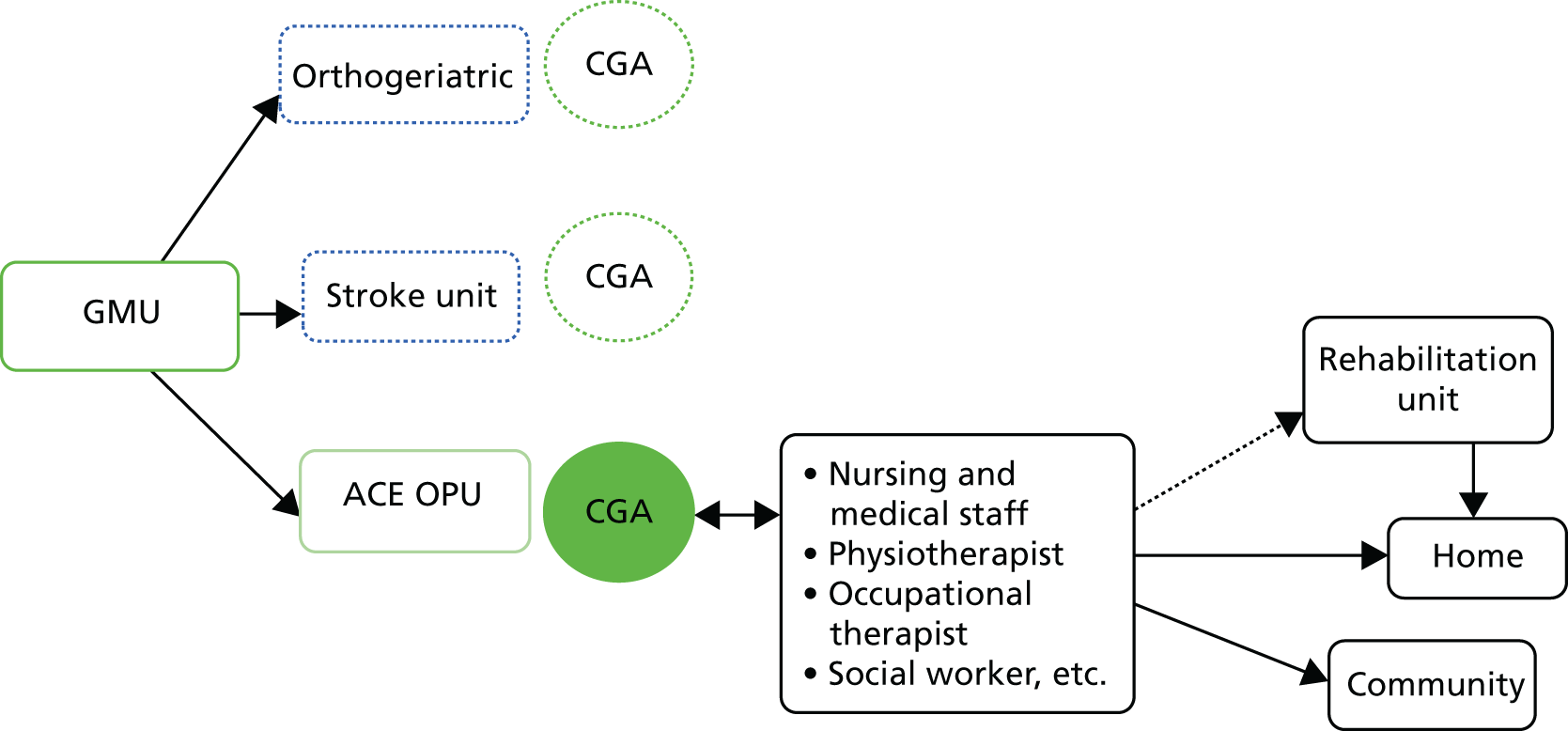

The results indicate a positive correlation between levels of deprivation and the proportion of people in the higher utilisation population segments. The correlation is particularly marked for the subset of deprivation scores in relation to ‘Income Deprivation Affecting Older People’. The exception is for the elective admissions segment for which there is no relationship. If it is assumed that deprivation is associated with greater health needs, this exception may reflect the inverse care law proposed by Tudor Hart. 114