Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/01/17. The contractual start date was in October 2014. The final report began editorial review in November 2017 and was accepted for publication in September 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Disclaimers

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Beresford et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Increased life expectancy, brought about mainly by improvements in health care, presents a number of health and care policy challenges. Increased rates of hospital admissions due to long-term health problems or frailty, subsequent delays in discharge from hospital, and growing demands for social care caused by heightened rates and levels of dependency have placed significant demands on services.

The 1990s saw the development of models of care to address these challenges, which, collectively, came to be designated as ‘intermediate care’. 1,2 This concept became formally recognised and defined in the National Service Framework for Older People,3 published in 2001:

. . . a new layer of care, between primary and specialist services . . . to help prevent unnecessary hospital admission, support early discharge and reduce or delay the need for long-term residential care.

p. 13. 3

In response to the National Service Framework, and supported by £900M investment from the UK government, new models of care, or practices, emerged.

The health-care sector saw the development of admission avoidance and supported early discharge schemes, typically described, or defined, as intermediate care. Importantly, some – but not all – supported early discharge schemes specifically sought to restore an individual’s ability to look after themselves, perhaps independently, in their own homes.

Similarly, local authorities (LAs) began to develop interventions for individuals who presented concerns in terms of their ability to continue to stay well and live independently, or at least remain in their homes with low levels of support. 4 Importantly, these latter developments were informed by a challenge, issued by the Department of Health and Social Care and directed at LAs, to develop approaches to care that reduced dependency on services and supported individuals to ‘make most use of their own capacity and potential’. 5 These twin levers saw the emergence of services across the country that shared similar features: short-term and intensive support delivered in the home with a focus on regaining, or preventing the decline of, daily living skills and social participation. By the early 2000s this approach had gained considerable traction and government support. 5,6 The term ‘reablement’ was used to describe the approach and significant levels of investment made in the development of such provision. In some countries, a similar shift in, approach to providing social care support was also taking place; some also referred to this new approach as ‘reablement’. Others, for example the USA, Australia and New Zealand, used the term ‘restorative care’. 7

The challenge of defining reablement

The past 15 or so years have seen changing and inconsistent use of the terms ‘intermediate care’ and ‘reablement’, both within policy8 and as applied to specific health and social care provision. In terms of the latter, the criteria, or ‘labels’, applied to different government funding initiatives (typically directed via health to encourage integrated planning) go some way to accounting for this.

In the context of this study, it is not useful or necessary to recount these changes in great detail. However, this lack of a shared definition was something that had to be explicitly addressed when developing the bid for funding and the study protocol. Indeed, the lack of an agreed description of reablement using a standard intervention framework9 continues to present significant challenges to those seeking to review existing evidence and those conducting primary research. 10

Defining reablement for the purposes of the study

This study was commissioned in mid-2014, and arose from a commissioning call issued by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) in early 2013. From the outset, it was essential that a clear definition of reablement was established that was relevant and meaningful in terms of current policy and practice, and made reference to the concepts of intermediate care and rehabilitation. Therefore, an analysis of recent evaluative literature11,12 and current policy and practice guidance documents7,13 was carried out. It was clear from this exercise that two key characteristics distinguish intermediate care and reablement from other health and care services:

-

The objectives of intermediate care/reablement. These are – acute admission avoidance at the point of clinical need for acute care; early supported discharge after acute admission; longer-term avoidance of unplanned hospital admission; reduction in the use of home-care services; and avoidance of admission to long-term care.

-

The time-limited nature of the service offered (usually up to a maximum of 6 weeks). This is the key defining characteristic that distinguishes intermediate care or reablement from, for example, generic rehabilitation services.

A further characteristic emerged as distinguishing reablement from intermediate care, namely its restorative, self-care approach. In other words, a reablement service is about enabling people to regain or retain self-care function for themselves, rather than providing input that replaces that function (e.g. reablement teaches people how to cook for themselves again, rather than providing meals on wheels). Table 1 sets out these distinctions, and overlaps, between reablement and intermediate care.

| Intervention characteristics/objective | Type of intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-limited? | Restoring self-care abilities? | Intermediate care or reablement? | |

| Acute admission avoidance at the point of clinical need for acute care | Yes | Not usually | Intermediate care |

| Early supported discharge after acute admission | Yes | Sometimes | Reablement if it includes a restorative element, otherwise intermediate care |

| Longer-term avoidance of unplanned hospital admission | Yes | Yes | Reablement |

| Reduction in the use of home-care services | Yes | Yes | Reablement |

| Avoidance of admission to long-term care | Yes | Yes | Reablement |

The study’s definition of reablement

Drawing on the work referred to above, the following definition of reablement was used.

-

Intervention objective:

-

to support people to regain or maintain independence in their daily lives.

-

-

Intervention approach:

-

to restore previous self-care skills and abilities (or relearn them in new ways) that enable people to be as independent as possible in the everyday activities that make up their daily lives (e.g. cleaning the house, shopping, or bathing and dressing themselves) rather than having someone (e.g. an informal or formal carer) do things ‘to’ them or ‘for’ them. 7,8 The provision of equipment may be used to support this

-

individualised and goals-focused.

-

-

Population:

-

individuals returning home from hospital or other inpatient care setting following an acute episode

-

individuals in whom there is evidence of declining independence or ability to cope with everyday living.

-

-

Nature of intervention delivery:

-

intensive

-

time-limited (up to 6 weeks)

-

goals-focused

-

delivered in the usual place of residence.

-

This definition aligns with current policy and practice guidance. 14,15

Subsequent developments in policy and definitions of reablement

While the study was under way, the Care Act 201415 – heralded as the most significant reform to social care in over 60 years – became law. Full implementation of the Act is ongoing, but phase 1 implementation had significant implications in terms of the perceived role of reablement within the wider portfolio of social care provision.

First, reablement was presented as one of the core interventions that can delay, or reduce, demands for care services and keep individuals living independently in their own homes. To this end, LAs are now required to consider providing reablement before, or alongside, carrying out a needs assessment. Furthermore, this approach should now be considered both for individuals not previously known to adult social care and for existing users. Second, reablement was presented as an intervention falling under the umbrella term of ‘intermediate care’, and was specifically identified as having the function of helping individuals leave hospital in a timely way and regain their independence. The need for integrated working with health services to deliver this was made explicit.

Together, these elements of the Care Act 2014 – and the continued growing and significant concerns within the NHS about the delayed discharge of older patients16 – have seen the emergence and adoption of ‘discharge to assess’ pathways, with these pathways including discharge to social care for assessment and reablement. 17

The 2017 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance, Intermediate Care Including Reablement14 makes clear that, as an intervention, reablement is regarded as one of the four core elements of ‘intermediate care’, the other three being (health) crisis response and bed- and home-based intermediate (health) care. It is important to note that the guidance continues to represent reablement as being distinctive in its restorative approach and focus on supporting independence in self-care and everyday life skills, with social care leading on its delivery. The guidance also stresses the need for integrated working within the context of providing intermediate care.

These significant changes in health and social care policy and guidance had two important implications for this study. First, it meant that changes to services and service developments were happening during the study period (2014–17), and are ongoing. Second, it signals that, as an intervention, reablement is highly topical and likely to remain a core aspect of meeting the health and social care needs of older people. As a result, the findings from this study are highly relevant and timely.

Existing evidence on reablement

The 2017 NICE guideline14 offers a useful review of existing evidence. It concludes that the quality of existing evidence on the effectiveness of reablement is not as high as for other forms of intermediate care (e.g. home- or bed-based intermediate care). To date, there have been just three comparative evaluations, of variable quality, that have used randomisation,18 none of which is UK-based. Among another four non-randomised comparative evaluations,19–22 two were carried out in England, both of which reported in 2010. 19,20 On the basis of this set of evidence, the following conclusion was drawn:

There is a moderate amount of moderate quality evidence that reablement is more effective when compared with conventional home care.

It was noted that the evidence was most consistent and positive with respect to care needs or impact on service use. Similarly, overall, findings related to quality of life and ability to carry out activities of daily living (ADL) suggest that reablement is an effective intervention, although this was not found in a low-quality trial. 11,12 NICE also reports that it did not find any evidence on cost-effectiveness that was relevant to the UK.

A separate set of evidence concerns issues of the design of reablement services. Here, low- to moderate-quality evidence indicates that access to particular specialisms (e.g. physiotherapy, occupational therapy) may influence the effectiveness of reablement. 19,23,24 In addition, there is reasonable evidence to suggest that the skills of reablement workers may have an impact on outcomes,24,25 for example being able to judge the timing and degree of support to offer a service user when carrying out a task and increasing service users’ confidence and motivation. Two studies conclude that reablement services should include the ability to respond to users’ goals that concern their social or leisure lives, which, for some users, will be a high priority or have the greatest impact on their lives. 25,26 Finally, there is some indication that service models should incorporate the ability to be flexible and responsive to user needs and progress. 24 However, this may have implications for service users’ views and experiences of the service. 23,24

Some existing studies have investigated issues related to the characteristics of the service user. There is reasonable evidence that individual motivation may have an impact on the effectiveness of reablement. 24,25 More specifically, there is weak- to moderate-quality evidence, primarily based on practitioner views, that individuals with end-of-life care needs or complex needs should not be referred to reablement services. 19,20,27 No studies have investigated the effectiveness of reablement in people living with dementia.

Finally, in terms of service users’ and family members’ views and experiences, the key issue identified by existing research is the potential lack of understanding of the objectives of reablement, and the fundamental difference of approach compared with home care. 23,24,26,27

A number of other systematic reviews of reablement were published in 2016/17. 10,28–30 Their inclusion criteria (in terms of study design and quality) vary and, as a result, the conclusions drawn differ somewhat. However, all note the pressing need for further research as a result of the core place given to reablement within health and social care policy, particularly with respect to older people and the investment in services delivering this intervention.

Evidence gaps

Studies into the effectiveness of reablement per se are beginning to be reported, although, as noted above, more are required. A further gap in evidence concerns the way in which to deliver reablement. Since the early days of ‘reablement’ in the late 1990s, different localities and sectors have developed different service models by which to deliver this intervention. 7,14,31 Thus, in addition to evaluating the impact of reablement with a no-intervention comparator group, a complementary stream of research is required that looks at different approaches, or service models, to providing reablement. In addition, although there is some evidence on factors that may have an impact on intervention outcomes (e.g. service user characteristics such as motivation/engagement, reason for referral to reablement, comorbidities and living circumstances), clearly, further work in this area is required and particularly with respect to factors that are amenable to intervention. Finally, and also highlighted in the 2016 NICE guidance,32 increasing the evidence base on the costs and cost-effectiveness of reablement and providing reablement to people with dementia are both important priorities.

Study aims and objectives

This study was funded by NIHR in response to a commissioned call33 that sought research proposals addressing the following overarching questions: how effective are reablement services in enhancing self-care and independence in the population they are designed to cover; and how are they best delivered?

When responding to this call, we chose to focus on some of the specific evidence gaps discussed in the previous section. Table 2 presents the study aims and associated objectives as set out in the study protocol. 34

| Aim | Objective |

|---|---|

| To establish the characteristics of generic and specialist reablement services in England | Undertake a national (England) survey to map different models of reablement services that currently exist (WP1) |

| To establish the impact of different models of reablement on service-level and service user outcomes | Using an observational cohort study design, to carry out outcomes and economic evaluations of different generic reablement models. Follow-up time points are to be at discharge from reablement and 6 months later. In addition, to carry out a nested process evaluation to understand the views and experiences of all relevant stakeholder groups (WP2) |

| To establish the impact of different models of reablement on different groups of service users | |

| To establish the indicative costs to the health and social care system of different models of reablement | |

| To establish how local context influences the ability of reablement services to achieve their goals | |

| To establish how specialist practice/services have developed for individuals with complex needs or ‘atypical’ populations who would benefit from reablement | To carry out a qualitative study of specialist reablement practice and service models (WP3) |

Thus, the focus of the study was not the effectiveness per se of reablement. Rather, its aim was to evaluate and compare existing reablement service models and to also conduct a smaller, parallel piece of work focused on reablement for groups for whom adjustments to a generic model of provision may be required (e.g. young adults, people with dementia).

Structure of the report

The report comprises 10 chapters. Chapter 2 provides a high-level overview of the study and reports deviations from the original protocol. Chapter 3 reports on work package (WP) 1, the national survey of reablement services and the reablement service models derived from that work. Chapter 4 describes the selection and recruitment of research sites for WP2 and provides a description of the characteristics of each site. In Chapter 5 we report the outcomes evaluation (WP2a). Chapter 6 describes one element of the process evaluation (WP2b), namely the interviews with reablement staff. In Chapter 7 we report the second element of WP2b: the user perspective. The economic evaluation (WP2c) is reported in Chapter 8. Chapter 9 turns to WP3, the qualitative study of practitioner views and experiences regarding reabling people with dementia. Chapter 10 discusses the implications of the study findings for health and social care, and recommendations for future research.

Chapter 2 Overview of study design and methods

Introduction

This chapter provides a broad overview of the design of the study and any deviations from the protocol. A detailed description of objectives, design and methods are described in the chapters reporting the various aspects of the study. The original protocol for the study has been published. 35 However, deviations from this protocol were required, all of which were discussed with the project’s Study Steering Committee (SSC) and approved by NIHR.

Study design and structure

The study comprised three WPs:

-

WP1 – mapping reablement services and developing a typology of reablement service models.

-

WP2 – a mixed-methods comparative evaluation of up to four reablement service models, as identified in WP1, investigating outcomes, costs, cost-effectiveness, and service user and practitioner experiences.

-

WP3 – an investigation into specialist reablement services/practice approaches, and the rationale for adjustment made to generic provision.

A survey was used to map reablement services (WP1). An observational study design was used to generate quantitative and qualitative evidence regarding the outcomes, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different reablement service models and the factors affecting individual outcomes (WP2). Qualitative methods elucidated descriptions of practice and practitioners’ views regarding the provision of reablement to people with dementia. WP1 preceded WP2 and WP3. WP2 and WP3 ran concurrently. The study was conducted between October 2014 and November 2017.

Ethics considerations

Work package 1 was defined as a service audit by the Health Research Authority and did not require ethics approval. For WPs 2 and 3 ethics approval was obtained from the North East York Research Ethics Committee (REC), UK (REC reference 15/NE/0299). Substantial amendments arising from deviations from the original protocol were approved by this committee.

Public and service user involvement

We worked with public and service user representatives throughout the project. During the project design phase, we consulted our research unit’s longstanding Adults, Older People and Carers Consultation Group about the proposal we were developing. We also sought advice from professionals who represent voluntary sector organisations supporting people who use reablement services. These discussions highlighted several issues that informed our decision-making:

-

the need to track the use of health/community/social services and not just hospital services

-

the belief that in-house and outsourced services may be different, with in-house teams regarded as ‘care driven’ and contracted-out services perceived as ‘profit driven’

-

to compare, if possible, NHS and LA provision

-

the importance of exploring the ethos/philosophy used by service managers

-

the importance of examining the impact multiple impairments have on outcomes and how these are addressed by reablement services.

Throughout the project we updated, and sought feedback from, this group. This helped us to be certain that the aims of the project remained important to the public, as well as to service commissioners and providers, and that the outcome measures were relevant to service users.

The SSC included service users who had experience of reablement services and representatives of voluntary sector organisations supporting people who use reablement services. Throughout the project, the SSC provided advice on methods, research materials and project management. The service user and public representatives were contacted between meetings for feedback on recruitment and data collection materials. The SSC also provided a forum for the research team to discuss their initial research findings and consider their implications. Members were kept up to date between meetings with a quarterly newsletter.

Work package 1: mapping reablement services and developing a typology of reablement service models

The aims of WP1 were to generate ‘stand-alone’ evidence on reablement services in England and to develop a typology of reablement service models. This typology was then used to identify and select (up to) four service models for evaluation in WP2. It was also used to provide preliminary evidence and inform sampling decisions for WP3. Survey methodology, comprising a three-stage process, was used:

-

identification of all reablement services in England

-

identification of a key informant(s) in each reablement service

-

data collection from these key informants.

Deviations from the protocol

There were no deviations from the original protocol.

Work package 2: an evaluation of different models of providing a generic reablement service

The purpose of WP2 was to evaluate different reablement service models in terms of service user outcomes, the experiences of delivering and receiving reablement, and the relative costs and cost-effectiveness of the models. It comprised three elements:

-

WP2a – outcomes evaluation

-

WP2b – process evaluation

-

WP2c – economic evaluation.

Samples for WP2b were drawn from the WP2a sample (service users) and WP2a research sites (staff). Service user-reported data for WP2c were collected within WP2a data collection processes.

We encountered significant issues with WP2 with respect to:

-

recruitment of research sites

-

study set-up in research sites

-

in some research sites throughput was much lower than expected, which significantly affected recruitment.

The first two issues caused considerable slippage in the project timetable. Given this, and coupled with the very slow rates of recruitment in two research sites, the decision was made not to extend the study until sample size requirements had been achieved across all research sites. As a result, the study closed early in three sites and recruitment was not started in the final site. Deviations from the protocol are detailed later in this section.

Work package 2a: the outcomes evaluation

The original objectives of the outcomes evaluation were as follows:

-

to conduct a quantitative, comparative evaluation of the effectiveness of the four reablement service models identified by WP1 in terms of service user outcomes at discharge and 6 months post discharge

-

to explore and test the impact of service (e.g. in-house vs. contracted-out provider; skill mix on the team) and user characteristics (e.g. reason for referral, comorbidities, engagement with the intervention) on outcomes.

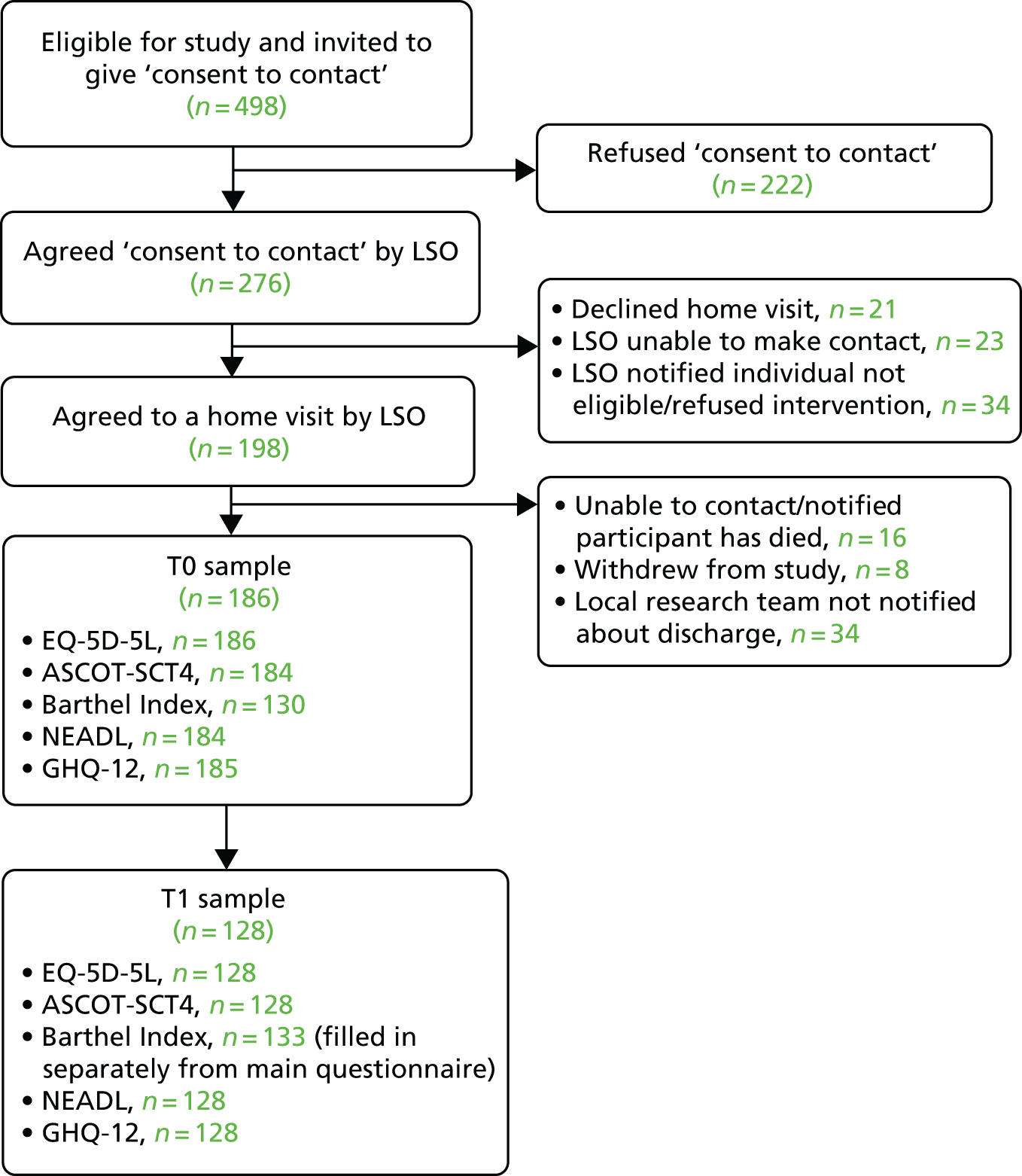

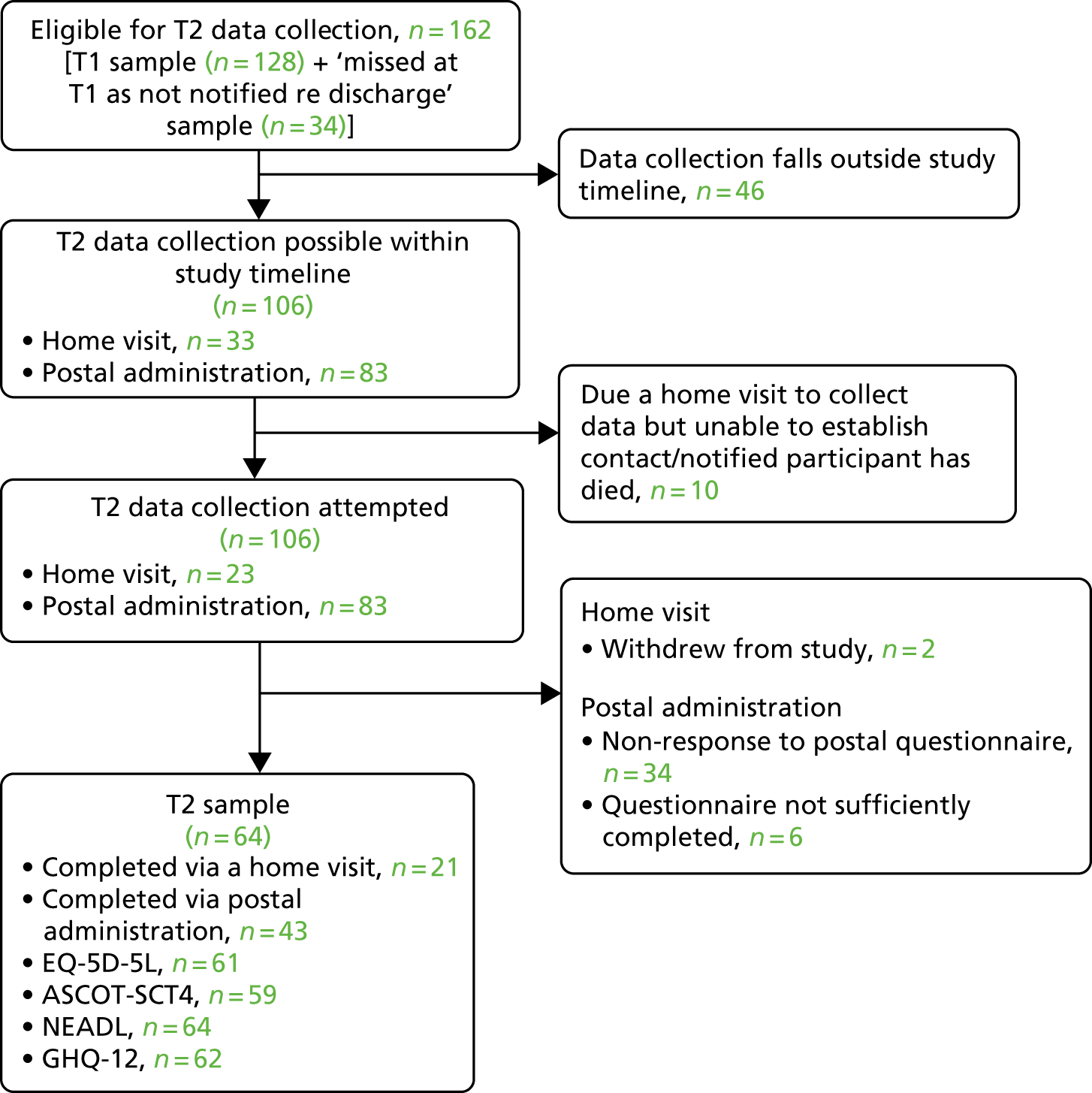

The evaluation design was an observational study of a cohort of service users receiving reablement from one of four reablement services across England, each identified as typical of one of the service models identified in WP1, in which outcomes were tracked from entry to the service (T0), at discharge (T1) and at 6 months post discharge (T2). Self- and practitioner-reported outcome measures were used. Data collection from service users was carried out via home visits.

Difficulties with under-recruitment within the study timeline required the following changes to the objectives and design of WP2:

-

significant under-recruitment in two sites meant that comparisons between service models were not possible

-

delays in the study and the decision not to extend the timeline to accommodate these delays meant that it was necessary to move the primary outcome time point from T2 (6 months post discharge) to T1 (discharge from intervention)

-

the small sample size meant that the exploration of the impact of user and service characteristics on intervention outcomes at T1 was only exploratory

-

only an initial and exploratory analysis of T2 data was possible.

The revised objectives, agreed with the SSC and NIHR, were as follows:

-

to provide a descriptive, exploratory description of changes in outcomes between entry into (T0) and discharge from (T1) a reablement intervention

-

to provide a descriptive, exploratory analysis of outcomes at 6 months post discharge (T2), compared with outcomes at entry into (T0) and discharge from the intervention (T1)

-

to explore whether or not outcomes at discharge from reablement are associated with –

-

individual characteristics

-

intervention delivery characteristics

-

service characteristics

-

-

to contribute to study design and methodological knowledge related to the evaluation of reablement interventions.

Deviations from the original protocol

Revised design and study objectives are reported above (see Work package 2a: the outcomes evaluation). Other deviations are reported here.

Number of service models represented in work package 2

Owing to significant delays in study set-up, one of the service models identified in WP1 was not represented in WP2.

Mode of data collection at 6-month follow-up in work package 2

Owing to the early closure of the study and the consequent loss of local study teams, some T2 data were collected via postal administration rather than home visits. Although this was a necessary deviation from the original protocol, it did allow us to collect some useful data on the impact of mode of administration on study retention.

The use of routinely collected service audit data

The original protocol included collecting 12 months’ service audit data from research sites (e.g. ‘destination’ after discharge). However, it became apparent in WP1, and confirmed when approaching services to act as research sites for WP2, that this information was not routinely recorded by services. Therefore, we did not attempt to collect these data.

Work package 2b: the process evaluation

The overall aim of the process evaluation was to generate rich data from the key stakeholders on the delivery of reablement, the impacts of reablement, and how and why these effects may vary between individuals and different service contexts. The objectives of this element of the evaluation were, therefore, to develop an understanding of:

-

the immediate and wider context in which reablement service models exist

-

the experiences of providing and delivering reablement, and what has an impact on the process of service delivery

-

the different effects reablement can have on service users

-

how and why these effects vary between recipients and different service models.

A qualitative, descriptive case study approach was used, with the unit of analysis being the delivery and receipt of reablement. We sought the perspectives of service users and family members, service leads, reablement assessors, reablement workers and commissioners. Individual interviews and focus groups were used to collect data.

Deviations from the protocol

There are two deviations to report. First, we had planned to identify and recruit reablement workers via service users participating in the process evaluation. The reason for this was to allow us to explore different perspectives with respect to the same delivery of reablement. However, the use of multiple reablement workers with a single case in some research sites meant that this was not appropriate. Second, we had planned to use individual interviews with reablement workers. We revised this to using focus groups, believing that this would generate a richer set of data as we were no longer seeking different perspectives with respect to specific instances of delivering/receiving reablement.

Work package 2c: the economic evaluation

The original objective of the economic evaluation was to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of four reablement service models. This objective was revised in response to under-recruitment and early closure of sites. The revised objectives were:

-

(as per the original protocol) to review the economic evaluation methods used to evaluate reablement and use this to inform data collection for WP2c; this has been published in Faria et al. 36

-

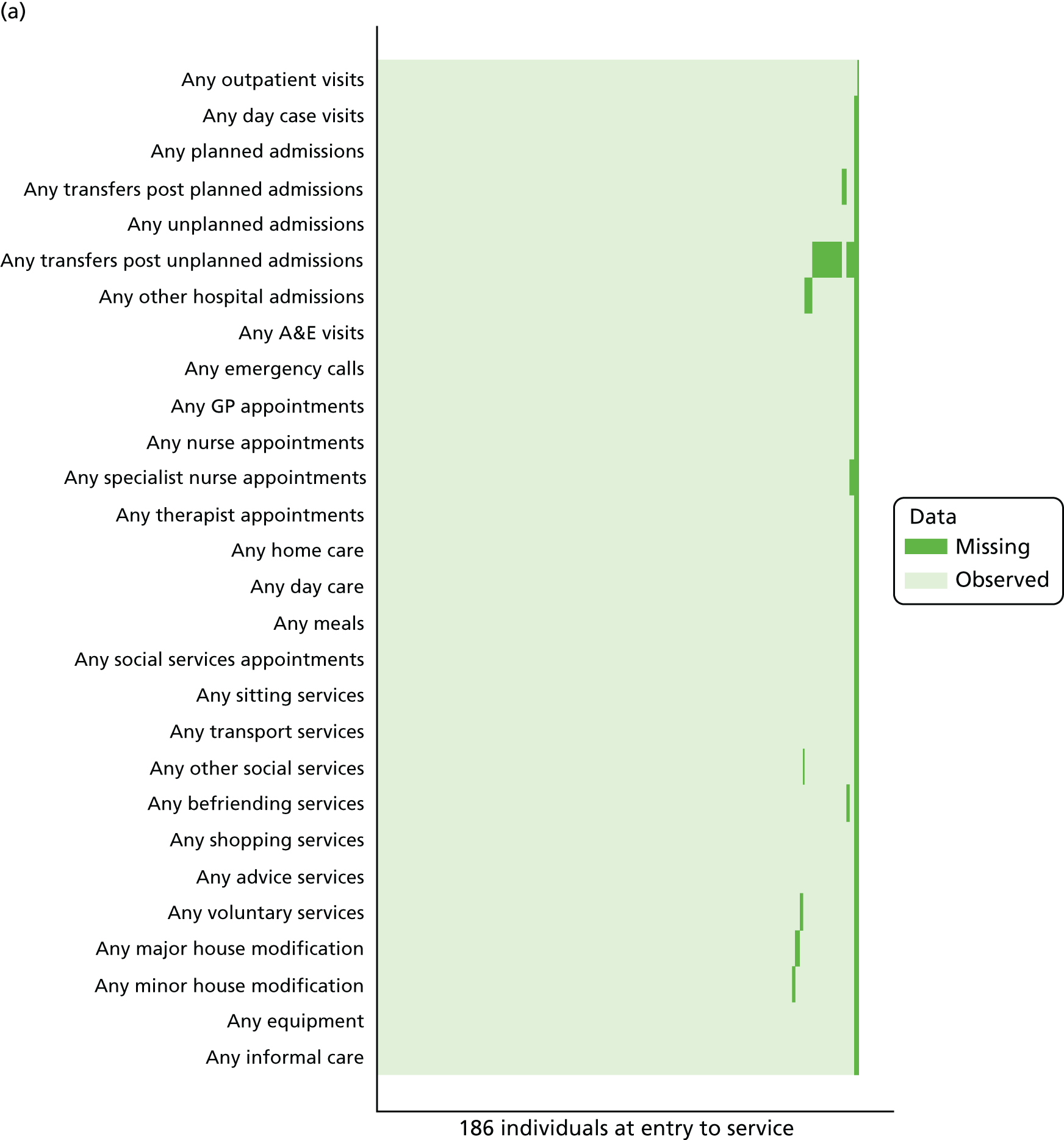

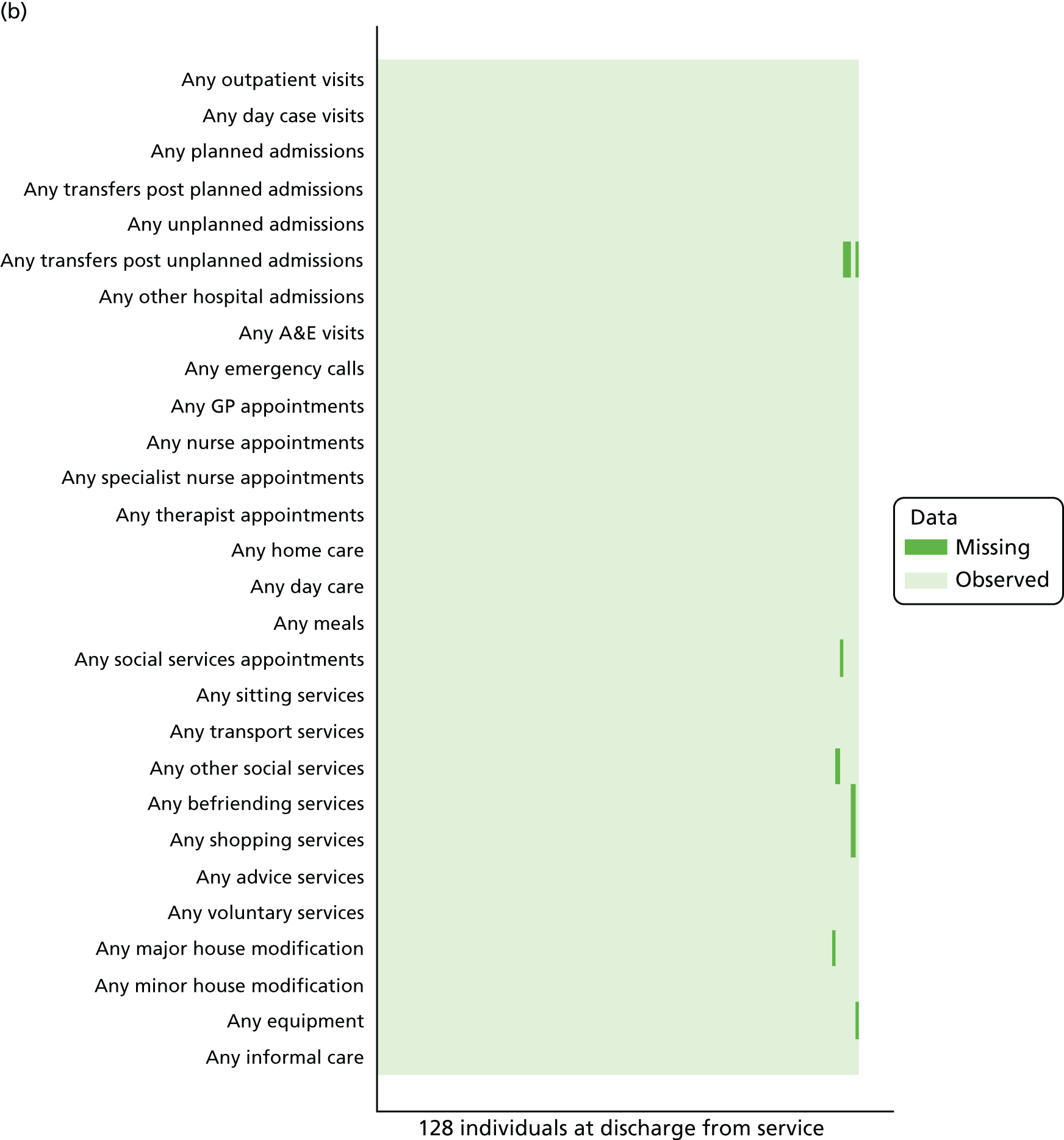

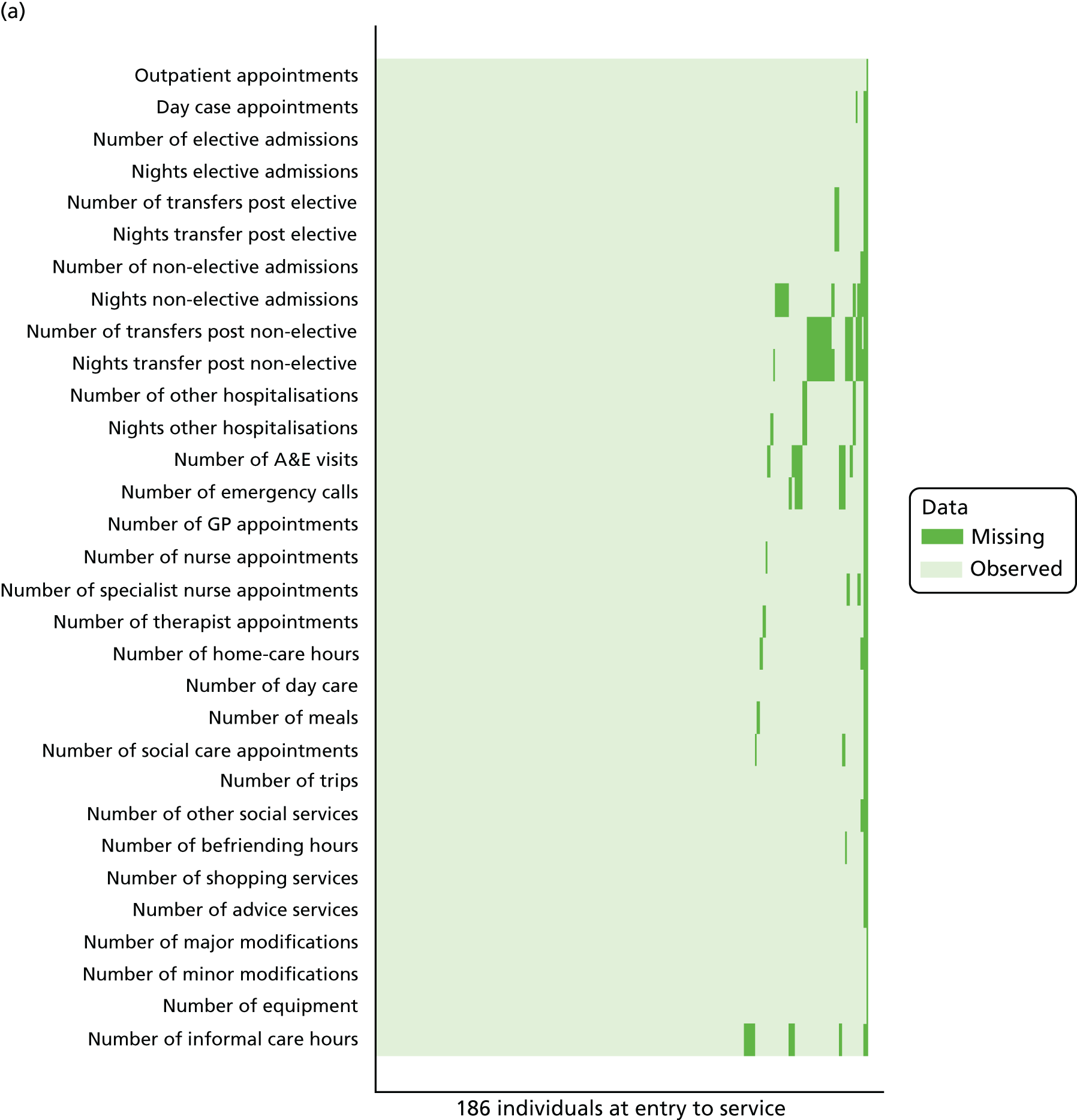

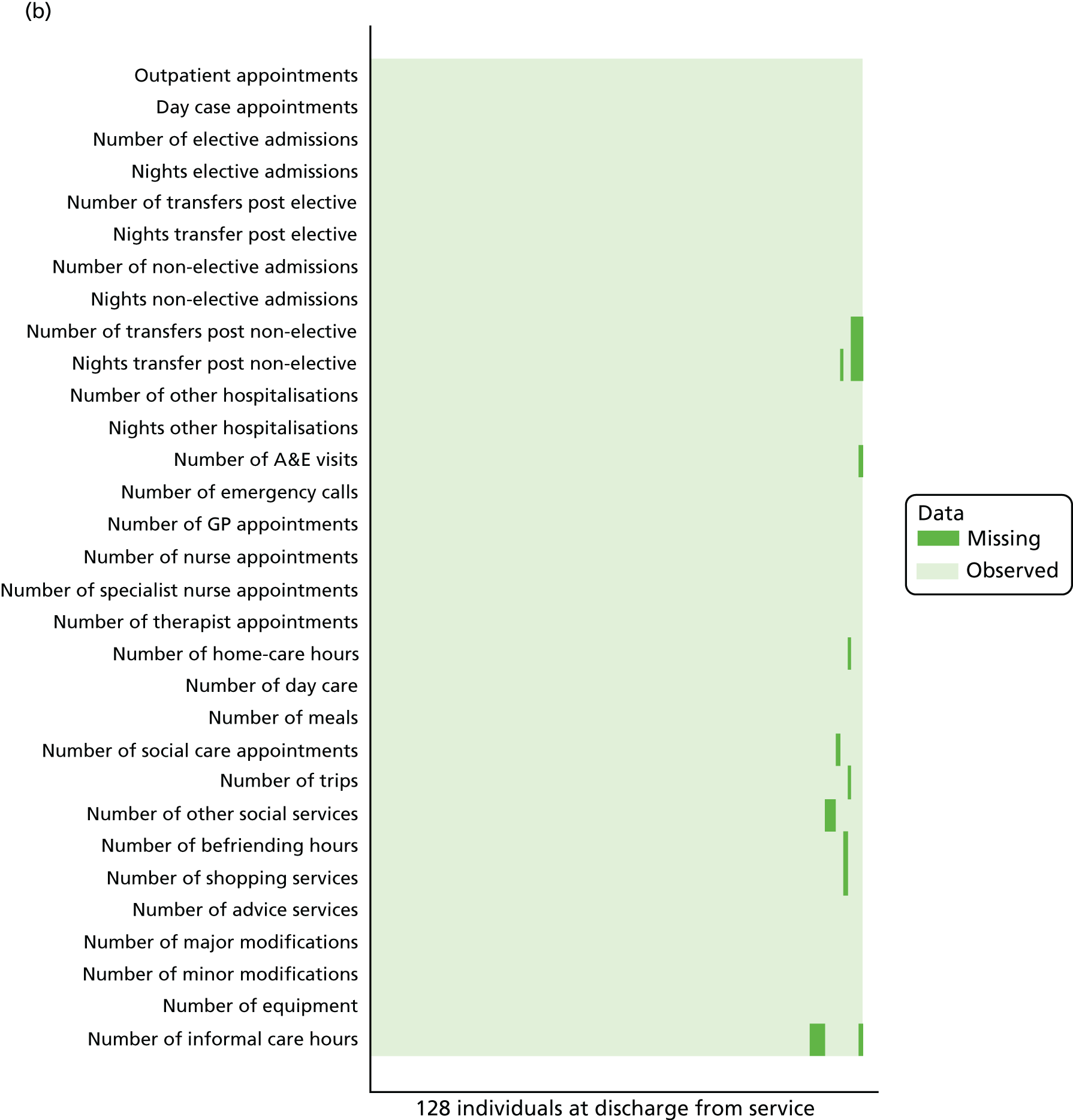

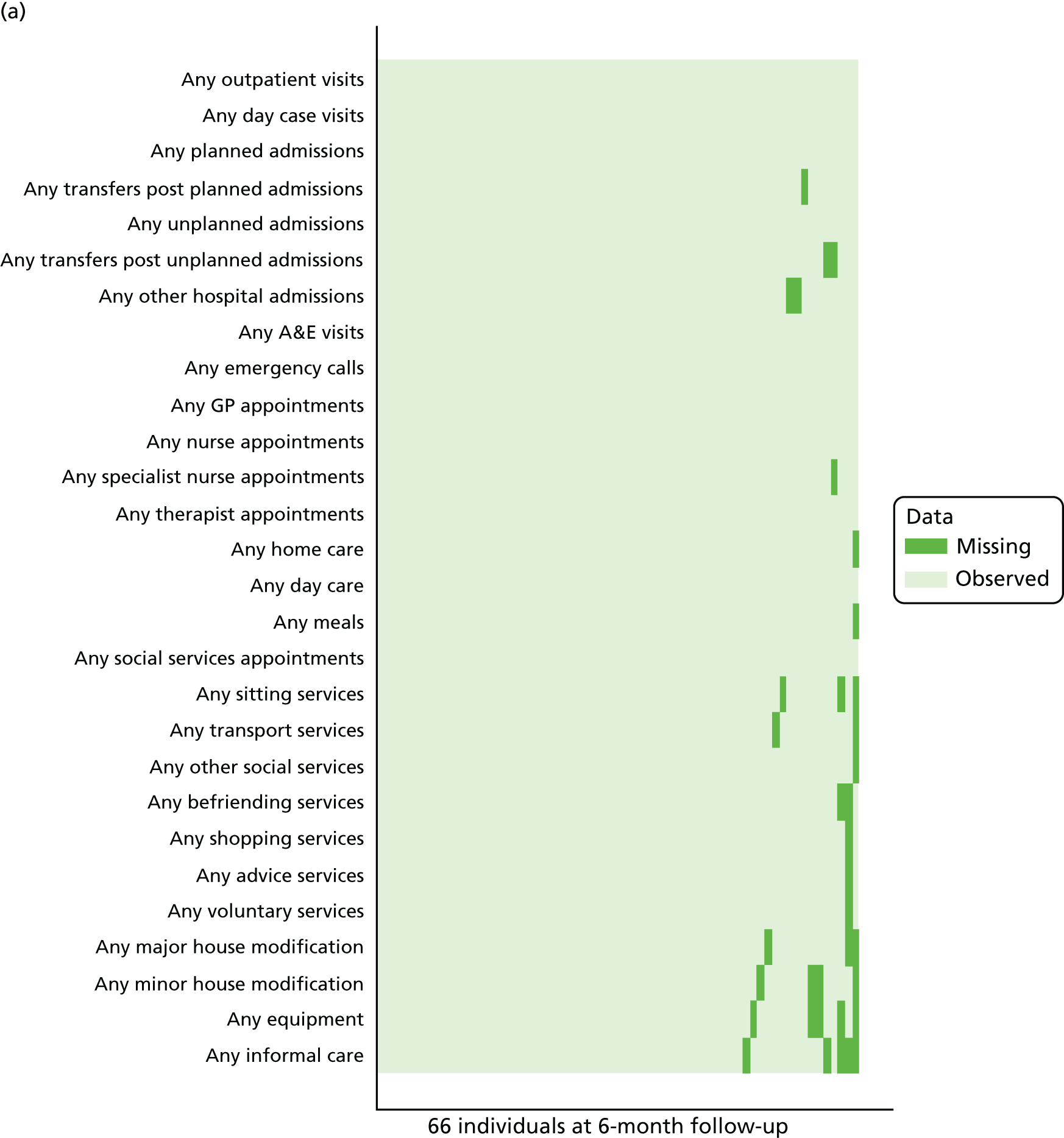

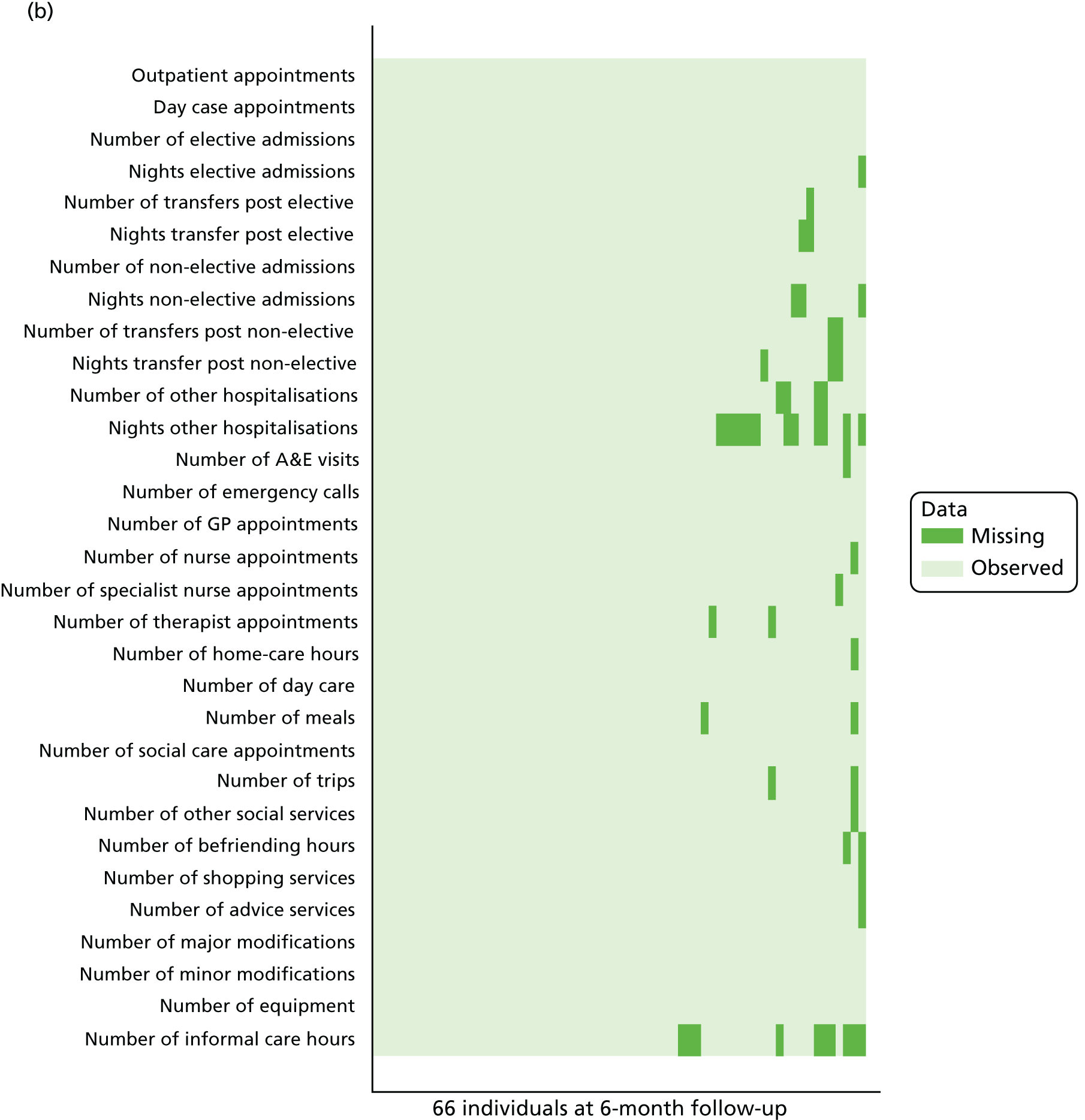

(as per the original protocol) to develop a new instrument to collect data on resource use and costs from service users [the Services and Care Pathway Questionnaire (SCPQ)] and to explore the feasibility of using the SCPQ in terms of data quality (e.g. number of missing data)

-

to describe the costs of providing reablement using data collected during WP1 and WP2

-

to describe and compare resource use and costs of reablement at T0, T1 and T2

-

to explore whether or not the costs during receipt of reablement and in the 6-month period following reablement can be predicted in terms of service user and service characteristics.

Deviations from the protocol

For WP2c, a site-specific questionnaire was developed collecting detailed information on caseload and costs of providing reablement. Unfortunately, research sites did not answer the questionnaire. As a result, we were only able to calculate an estimate of the cost of providing reablement based on the information collected in WP1.

Work package 3: an investigation into specialist reablement services/practice approaches

The aim of WP3 was to investigate the organisation and delivery of reablement services to people with specialist needs.

The findings from WP1 indicated that the majority of specialist provision or practice concerned people with dementia. Therefore, with support from the SSC, and with agreement from NIHR, WP3 focused exclusively on this population.

This WP comprised:

-

a case study of ‘adapted or extended practice’ within generic reablement services and of specialist provision across 10 case sites

-

an investigation into the costs of such provision in each site.

Qualitative interviews with service leads and reablement workers were used to investigate the approaches, service structures, practices and experiences of providing reablement to people with dementia. Data on service costs were collected via a structured questionnaire administered during the interview with service leads. Data were collected from January to July 2016.

Deviations from the protocol

There were no deviations from the original protocol.

Chapter 3 Work package 1: a national survey of reablement providers

Introduction

The main purpose of WP1 was to provide a current picture of reablement provision in England. This included describing the organisational, structural and skill mix features of reablement services and the scope of reablement being delivered, and then looking at how these features affect intervention objectives, operating practices, referral routes, assessment tools and processes, outcome measurement and destination following discharge. It also sought to establish the costs of reablement.

Findings informed a number of elements of the evaluation WP (WP2), including selection of sites, decisions regarding the selection of explanatory variables within the outcomes analyses and the topics covered in the process evaluation. WP1 data were also used to identify the focus of, and thereby potential services to approach for, WP3.

Methods

Identification of reablement services

All LAs (n = 152) in England were contacted for the details of individuals commissioning reablement in that locality. Thirteen LAs either declined to provide this information (n = 8) or did not respond (n = 5); therefore, Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) in these localities were contacted, but this did not help identify any reablement services.

Introductory e-mails, followed up with telephone reminders, were used to contact the commissioners identified, inviting them to complete a brief screening survey, which was administered via a structured telephone interview (see Report Supplementary Material 1). This established whether or not the individual was commissioning any services that potentially fulfilled our definition of reablement (Box 1). When a service was identified, the commissioner was asked for the name of the service and its contact details.

-

Intervention objective: to support people to regain or maintain independence in their daily lives.

-

Intervention approach: to restore previous self-care skills and abilities (or relearn them in new ways) using a goals-focused approach.

-

Population: individuals returning home from hospital or other inpatient care setting following an acute episode; individuals in whom there is evidence of declining independence or ability to cope with everyday living.

-

Nature of intervention delivery: intensive, time-limited (up to 6 weeks) and delivered in the usual place of residence.

Confirmation that the service fulfils inclusion criteria and identification of ‘key informant’

Service managers/service leads of services identified by commissioners were contacted by the research team by telephone or e-mail to check that the service fulfilled the study inclusion criteria. In localities where commissioners had reported more than one service, we also clarified whether these were separate as opposed to being a locality team, or outsourced provider, within a wider service. The algorithm used to screen services into the survey sample was as follows:

Service helps people to leave hospital more quickly than they would otherwise

AND/OR

Service helps to prevent admission to long-term care when people are at risk of it

AND/OR

Service helps to reduce people’s need for home care (social care)

AND/OR

Service helps prevent longer-term avoidance of unplanned hospital admission

AND

Service helps people to regain everyday living skills

AND

Service is provided in person’s usual place of care

AND

Service is time limited (usually 6 weeks but may be some flexibility round this)

AND

Service users are not charged for the service

Service managers/service leads were then asked to confirm that they were the most appropriate individual to act as ‘key informant’ with respect to the service (i.e. the person most able to provide detailed information about the service).

Survey of key informants

Across the 139 LAs for which commissioners had provided information to the research team, 181 reablement services were identified. In the majority of LAs (n = 106; 76%) one reablement service was identified. In 28 LAs (20%) two separate services were identified, and a further five LAs (4%) reported three or more separate reablement services. Outside this process, the research team was notified about, or became aware of, additional services that potentially fulfilled the study inclusion criteria. The same process was used to screen these services: two were out of scope and one LA declined to provide the information required. In total, key informants of 201 reablement services were invited to take part in the survey.

The survey was administered by e-mail and completed electronically using Qualtrics© (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA) survey software. The survey questionnaire (see Appendix 1) collected information about service delivery and organisational characteristics previously identified as important in terms of process and intervention outcomes in these types of services. 20,37,38 It also collected information on service costs and funding.

E-mail reminders and telephone calls were used in cases of non-response. E-mails and telephone calls were also used as follow-up when responses were unclear. After excluding surveys that were minimally completed, a response rate of 71% was achieved (n = 143/201).

Plan of analysis

We used five variables to describe the core characteristics of the reablement services represented in the survey. Three were derived directly from survey questions: organisational base, organisational structure and contractual arrangements. Two were derived from cluster analysis of survey data with respect to staffing and reablement input provided. These core characteristics provided the framework for subsequent analyses that explored the way reablement was being implemented and delivered.

Findings

The survey findings are reported in three sections:

-

the core characteristics of reablement services

-

service provision and delivery

-

the costs of reablement.

Data not presented in the text are provided in Appendix 2.

The core characteristics of reablement services

Organisational base

Survey respondents were the individuals identified as the person able to provide the most information about individual services. The organisational base of over half (53%) of respondents was a local authority social services department (LASSD). Fifteen per cent were based in an integrated NHS and LA organisation and 4% were based in the NHS. Of the remainder, 14% were based in a private (for-profit) organisation or the voluntary (not-for-profit) sector (7%). A very small proportion were based in a social enterprise (n = 4) or LA trading company (n = 3).

Organisational structure

Just over half of the services (52%) were a separate, or stand-alone, service. The remainder were located within a wider organisation: 18% were reported to be part of intermediate care provision, 13% part of home care provision and 4% part of an early intervention/rapid response service. One service was described as part of ‘other intermediate community’ provision and two were described as part of an independent living service. Finally, three were described as part of a mental health service provision.

NHS-based services were more likely, and those based in LASSDs less likely, to be part of intermediate care provision within a locality. In addition, LASSDs were more likely, and NHS organisations less likely, to be providing a reablement service that was separate from other intermediate care provision in the locality [χ2 = 29.94, degrees of freedom (df) = 16; p = 0.018].

Contractual arrangements

Two-thirds of services (66%) were described as being wholly ‘in-house’ to their organisational base. A fifth had both ‘in-house’ and ‘contracted-out’ elements and 7% were wholly contracted out to another organisation. A small minority described other arrangements. Contractual arrangements were not related to a service’s organisational base or structure.

When some aspect of a service was ‘contracted out’ (38/143 services), this was most often the delivery of reablement support (n = 20/38), as opposed to the assessment of eligibility for the service (3/38) or the reablement assessment itself (4/38).

Staffing and skill mix

Cluster analysis was used to understand the different patterns of staffing and skill mix in the teams. There were sufficient data on 129 out of 143 services (90%) for them to be assigned to a cluster. Four distinct patterns of staffing were identified (see Appendix 2, Tables 20–22).

-

Cluster 1: reablement with occupational therapy (n = 24).

These services were very likely to have occupational therapy and social work involvement but, unlike the multidisciplinary teams in cluster 3, it was unusual for them to have a registered nurse or a health support worker.

-

Cluster 2: home-care reablement (n = 42).

All services in this cluster reported having home-care workers and were also likely to report having home-care organisers and reablement workers. They did not typically have an occupational therapist (OT).

-

Cluster 3: multidisciplinary reablement (n = 20).

All services in this cluster had OTs and physiotherapists. They were also highly likely to have registered nurses and more likely than any other type of team to include health support workers, although this was not typical.

-

Cluster 4: reablement workers (n = 43).

None of these services had home-care workers but they were highly likely to have reablement support workers and unlikely to have any of the other staff listed.

Bivariate analyses explored patterns of association between staffing and organisational characteristics. The key findings are reported below and further data are available in Appendix 2, Tables 22–27.

Staffing and organisational base

‘Reablement with OT’ teams were most likely to be found in LASSDs (28%, compared with 19% of all teams), while services based in the NHS or integrated health-social-care services were most likely to have ‘multidisciplinary’ teams (39% and 67% respectively, compared with 16% of all teams). Third-sector services were more likely to be ‘home care reablement’ teams (54%, compared with 32% of all services). These differences were statistically significant (χ2 = 44.97, df = 12; p < 0.001).

Staffing and organisational structure

Over two-thirds (68%) of reablement services being provided within wider home care provision had ‘home care reablement’ teams (68%, compared with 30% of all teams). By contrast, half of services that were part of wider intermediate care provision had ‘multidisciplinary reablement’ teams (50%, compared with 16% of all teams). These differences were statistically significant (χ2 = 51.40, df = 12; p < 0.001).

Type of reablement input

Respondents were asked about the scope of the reablement provided, that is, the domains of an individual’s life that they sought to ‘re-enable’ and which domain was the focus of the majority of the service’s input. (It was stressed that respondents should report only what they enabled service users, as opposed to what they did for them.) The domains were:

-

personal care

-

domestic tasks

-

safety (including preventing falls and providing aids and equipment)

-

information and signposting to other services or support

-

getting around in the home

-

getting out and about outside the home

-

re-engaging with social activities and friends

-

managing health-related needs

-

specific activities to help rebuild confidence and improve well-being.

Personal care re-enabling was the predominant activity, and the one that made up the majority of services’ work. Helping people to get out and about again outside the home and to re-engage with social activities were least commonly reported. Bivariate analysis suggested that patterns of reablement input varied systematically in terms of the organisational characteristics (e.g. organisational base, organisational structure, contractual arrangements) of the services (see Appendix 2, Tables 23–26).

Data reduction, again using cluster analysis, produced three stable and fairly distinct clusters of type of reablement input for 136 out of 143 of the services.

-

Cluster 1: ‘functional’ reablement (n = 40).

These services reported that they re-enabled personal care, domestic skills, safety, information, helping people to move about inside, health-related needs and confidence-building.

-

Cluster 2: comprehensive reablement (n = 87).

These services said that they re-enabled in all of the domains. Thus, they were similar to services delivering ‘functional’ reablement, but also helped people with getting out and about and with social activities.

-

Cluster 3: social reablement (n = 9).

These services reported that they re-enabled in the areas of safety, information, getting out and about, social activities and confidence-building.

Type of reablement input and staffing

Multidisciplinary teams were more likely than expected, and ‘reablement worker’ teams less likely, to be providing comprehensive reablement (see Appendix 2, Table 27). Indeed, ‘reablement worker’ teams were the only ones associated with providing social reablement.

Service provision and delivery

The final stage of analysis examined the way reablement was being provided and delivered in terms of the following:

-

service objectives

-

operating practices (e.g. referral pathways, eligibility criteria, reabling individuals with specialist needs, duration of reablement and charging policy, assessment and monitoring of outcomes)

-

destinations following discharge from reablement.

We also explored whether or not the core service characteristics described in the previous section (see The core characteristics of reablement services) were associated with the provision and delivery of reablement. Please note that the detail reported here is limited.

Service objectives

Respondents were presented with a list of service objectives and asked to select all that were part of the purpose of their service, and to identify the main objective. The objectives, drawn from policy and existing literature on reablement and/or intermediate care, were:

-

help people regain everyday living skills

-

reduce the need for ongoing (social) home care

-

prevent longer than necessary stays in hospital

-

prevent admission to long-term care when at risk

-

prevent hospital admission during acute illness.

The majority of respondents selected most of these objectives, but one (‘prevent hospital admission during acute illness’) divided the services almost equally (see Appendix 2, Table 28). NHS-based services were significantly more likely to report this as an objective than were other services (χ2 = 12.49, df = 4; p = 0.014). The most often reported main service objective was to ‘help people regain everyday living skills’ (58% of services), with LASSD-based services more likely to report this than others (χ2 = 56.38, df = 24; p < 0.001). Only two services reported ‘preventing hospital admission during acute illness’ as their main objective and, as might be expected, both of these were based in the NHS.

Services staffed by a multidisciplinary team were more likely to report ‘preventing hospital admission during acute illness’ as a service objective (40%, compared with 16% of all services). This was the only difference in objectives found across the different staffing models.

Operating practices

Referral pathways

Existing literature and our own preliminary work indicated that referrals to reablement services occurred in one of two main ways. Either everyone referred for home care or domiciliary support was first referred to the reablement service, or referral was selective (e.g. for those being discharged from hospital, those felt to be at risk of admission to long-term care, or those whom another professional felt might benefit from reablement). Survey respondents were asked to choose which of these two models best represented their service.

Just over half of respondents (52%) reported that access to their service was selective, 24% reported that it was non-selective, and 15% described other models, often incorporating some element of triaging. Over one-third of LASSD services (38%) reported that reablement was provided to all referrals for home care. Few services (27%) reported accepting self-referrals.

Not unexpectedly, a greater proportion of referrals to NHS-based services and/or those operating within wider intermediate care provision were from primary care than those to services with different organisational bases or relationships with wider intermediate care within their locality (see Appendix 2, Table 29).

Eligibility criteria

The majority of services (88%) represented in the survey accepted adults aged ≥ 18 years, imposing no upper age limit. However, social reablement was strongly associated with providing services to adults aged 18–65 years only (χ2 = 39.41, df = 6; p < 0.001).

The majority of services (86%) reported meeting the needs of a wide range of people; we defined these as ‘generic services’. We asked such services whether or not individuals who might have specialist needs [e.g. people with dementia, younger disabled adults (aged ≤ 65 years), people with learning disabilities, people with brain injury and people with sensory impairments] were eligible for their service. A great majority reported that they accepted referrals of individuals with these needs (Table 3).

| Specialist group | Type of service (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Accepts individuals with specialist needs | Accepts and has specialist pathway or protocols | |

| People with dementia | 87 | 24 |

| Younger disabled adults (aged < 65 years) | 89 | 8 |

| People with learning disabilities | 81 | 20 |

| People with brain injury | 80 | 12 |

| People with sensory impairments | 89 | 20 |

| Total (n) | 123 | 123 |

| Missing (n) | 20 | 20 |

Half of the respondents stated that their service applied other exclusion criteria, assessed either at referral or following assessment, and some provided information about these. The most frequently reported criterion was whether the person was at the end of life and/or needed palliative care. This was followed by the person not having reablement ‘potential’ (29%), the presence of cognitive impairment or dementia (28%), identified risks to care staff (19%), the client having longer-term care needs (17%), and evidence of a lack of engagement with the reablement process (13%). Over one-third reported other exclusion criteria.

Reabling individuals with specialist needs by generic reablement services

Services reporting that they provided reablement to individuals who, potentially, might have specialist needs were asked whether the service had specialist pathways and/or protocols for such individuals. Few reported having specific pathways or protocols in place (see Table 3).

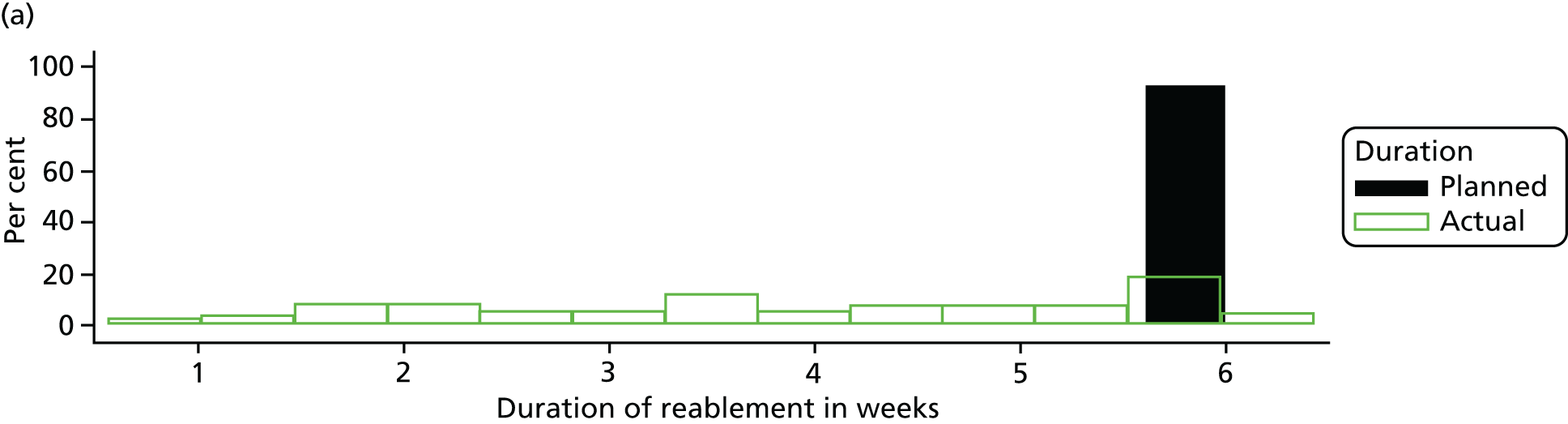

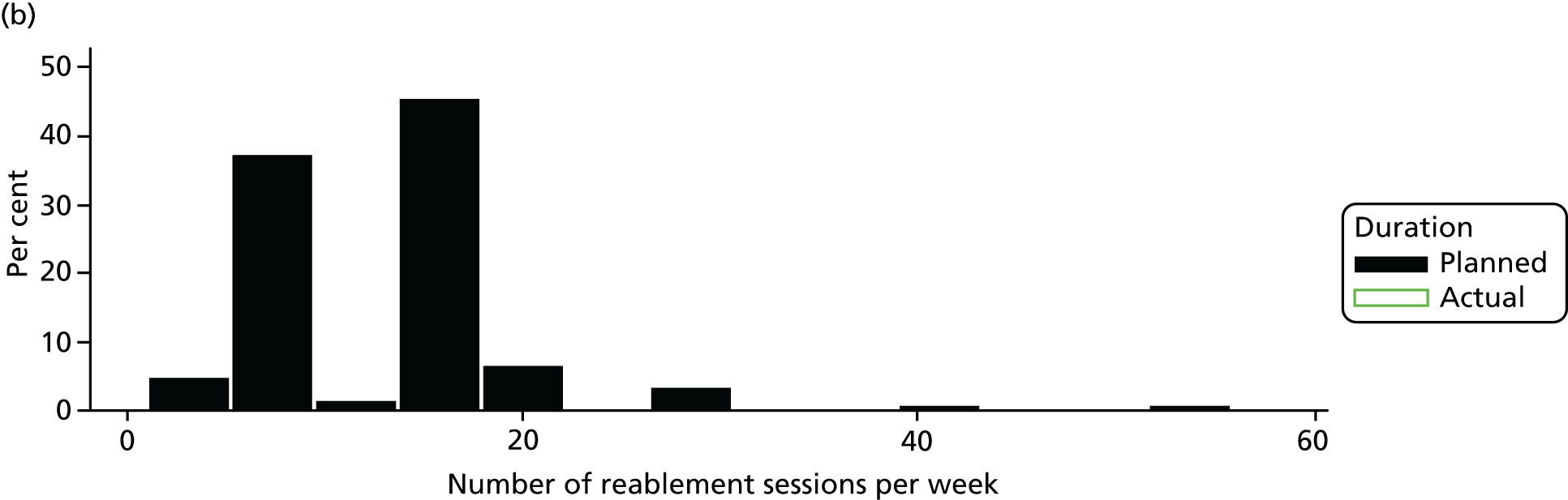

Duration of reablement and charging policy after 6 weeks

An intervention period of a maximum of 6 weeks has been a key feature of reablement in the UK since its inception in the early 1990s. In England it remains as the period of time during which service users cannot be charged. After this, LA and integrated NHS/LA providers have the option to charge for the service, in the same means-tested way that home care services are charged for.

Respondents were asked about the typical duration of reablement. Four out of five respondents reported that it was between 4 and 6 weeks, and 13% reported it as < 4 weeks (see Appendix 2, Table 30). An intervention period of < 4 weeks was significantly associated with services defined as providing ‘functional reablement’, as opposed to ‘comprehensive reablement’ (χ2 = 27.21, df = 6; p < 0.001).

The majority of services (85%) reported that the intervention period could be extended beyond 6 weeks in certain circumstances. The reason for extension was typically difficulties with onward referrals or finalising care packages (83%), rather than there being an expectation that extending the intervention would result in further improvement (22%). Of the services reporting that the duration of intervention could extend for more than 6 weeks, almost two-thirds (61%) said that there was no limit on this time period. In the remaining services, the duration of extension ranged from 7 to 21 days.

Fewer than one-third of respondents (28%) reported that service users were charged after the first 6 weeks. However, charging policies varied in terms of the organisational characteristics of services. LASSD-based services were much more likely than those based in the NHS or in integrated NHS and LA organisations to report charging after 6 weeks (χ2 = 19.47, df = 8, p = 0.013). Similarly, services that were part of wider home care provision were also more likely to report charging after 6 weeks (χ2 = 16.75, df = 8; p = 0.033) than those with other organisational structures. Wholly contracted-out services were more likely (75%), and those comprising both in-house and contracted-out elements less likely (14%), to report charging after 6 weeks (χ2 = 12.84, df = 6; p = 0.046).

Approaches to assessing and monitoring outcomes

Respondents were asked about the types of assessment carried out once an individual had been accepted by their service. Assessment, and tracking progress, may be informed by setting and reviewing personalised goals, using standardised measures, or other methods.

Most (73%) reported that assessment processes were multifaceted, covering planning how reablement could meet the person’s needs (85%), setting specific goals for reablement (79%), conducting a wider, full needs assessment (70%), and assessing any other needs (64%). Four respondents reported that their service followed a reablement programme set by another service. Only one respondent referred to carrying out ‘baseline’ assessments for outcome measurement purposes.

Goal-setting

Of the services using personalised goals (n = 118), 92% said that they always set the goals in partnership with the user, and this was done before reablement started (49%) or soon after (42%). Most services (83%) said that they used staff’s professional judgement regarding the achievement of personalised goals to monitor service users’ progress.

Occupational therapists were the professionals most often involved in goal-setting (56% of services), followed by reablement care workers (42%), physiotherapists (36%), social workers (35%) and nurses (12%). Almost half (45%) referred to a wide range of other people involved in goal-setting, including ‘assessors’ (not otherwise described) care managers, reablement managers or co-ordinators, and care co-ordinators.

Staff involved in goal-setting varied according to some service characteristics (see Appendix 2, Table 31). OTs and nurses were more likely to be involved when the services were ‘multidisciplinary’ and/or when the service ran as part of or alongside an intermediate care service. They were less likely to be involved when the reablement service was ‘standalone’ as opposed to being situated within a wider service/provision. This was also the case for physiotherapists, but they were also more likely to be involved with NHS-run services. Nurses were also more likely to be involved when the service was based in the NHS, and less likely to be involved in LA-based services. In terms of the impact of type of reablement input on the staff involved with goal-setting, OTs were less likely to be involved in goal-setting in social reablement.

Use of standard approaches for assessment and review

Of the 33 services that said they used ‘standard measures’ to assess progress towards reablement goals, almost all assessed mobility, quality of life, physical health and ADL. Fewer, but still the majority, assessed mental health and social and personal outcomes.

However, very few services reported using standardised measures. Only five reported using a standardised measure to assess mobility and quality of life, three used them for physical health outcomes, four for mental health outcomes, three for ADL, and two for social and personal outcomes.

Multidisciplinary teams were more likely to use standardised measures of ADL (50%, compared with 10% of all services, χ2 = 16.98, df = 9; p = 0.049), and/or NHS teams (20%, compared with 10% of all services, χ2 = 16.91, df = 9; p = 0.05). Small sample and subsample sizes mean that interpretation must be cautious, but these patterns do suggest different approaches that echo other differences between services reported.

Use of assessment tools other than personalised goals to review progress

Just one-quarter of services recorded outcomes (using an assessment tool other than personalised goals) at entry to the service and at some point later on. Thus, 30% of respondents reported that assessment tools were used at only one point during reablement. Of those who reported that they assessed before the service started (33% of all services; n = 47), six then also assessed during the service, six towards the end of the service and 36 after the service episode was over. Some services indicated that follow-up extended well beyond discharge, with five mentioning reviews at 6 weeks and 3 months.

Multidisciplinary services were more likely than other services to record outcomes (using an assessment tool other than personalised goals) at entry into the service and later (55%, compared with 36%); this difference was not statistically significant. Services situated within wider home care provision were very unlikely to assess outcomes before and at some later stage (5%, compared with 33% of all services). No other service characteristics were related to whether services recorded outcomes (using an assessment tool other than personalised goals) on entry to the service or at some later time point.

Destination following discharge

Respondents were asked to indicate the most common ‘destination’ for service users at the end of reablement. Almost two-thirds (62%) reported that service users were most often discharged without an ongoing care package. Eight per cent said that people were usually referred on for assessment of their eligibility for other social care, and 5% said that service users most often moved into long-term care.

One in ten gave other answers, most suggesting that outcomes were split relatively evenly between independent living (albeit with the possibility of involving informal carers) and ongoing requirements for care. Some said that although service users required further care, this was at a lower level than had previously been the case. Fourteen per cent either said that they did not know the answer to this question or did not answer it.

Services run by LASSDs were more likely than others to say that the most common outcome for service users was discharge without any ongoing involvement of care services (71%, compared with 63% of all services). Services run jointly between health and social services were most likely not to know or not to provide an answer to this question (50%, compared with 12% of all services). Services in the ‘other’ organisational category were more likely to say that the most common outcome was transfer into long-term care (29%, compared with 5% of all services). These differences were statistically significant (χ2 = 26.39, df = 12; p = 0.009), although many cell sizes were small.

Services providing ‘functional’ reablement were least likely to report that users were discharged without ongoing support (53%, compared with 66% of all services), and were most likely to report transfer into long-term care (15%, compared with 5% of all services). By contrast, ‘comprehensive’ reablement services were more likely to report discharge without other services being in place (74%, compared with 66%), and least likely to report transfers into long-term care (1%, compared with 5%). These differences were statistically significant (χ2 = 14.79, df = 6; p = 0.022).

The costs of reablement

Questions on service budgets and caseload were used to gather data on the costs of providing reablement. It was outside the scope of the survey to collect information on regional variances in workforce costs, size of the population, their demographics and the local organisation of services. Therefore, the results presented here are descriptive. No inferences about reasons for differences in service costs, or the association between costs and effectiveness, can be drawn from these data.

Data collection and analysis took the perspective of the NHS and Personal Social Services. Therefore, the relevant costs were those falling on the budgets of the CCG (representing the NHS) and/or LA (representing Personal Social Services). Ideally, the costs reported by survey respondents represent the full economic cost to the commissioner of providing the service, including direct and indirect costs, and overheads. However, given that it was not possible to corroborate the data provided by respondents, we cannot be certain of this. Furthermore, the information provided may not necessarily reflect the full economic cost of providing the service. For example, if the provider is a private contractor, the cost of providing the service to the commissioner may be lower than the cost charged to the commissioner to allow for profit; conversely, it may be higher if the service is provided at a loss.

The data collected

Respondents were asked to report for the 2014–15 financial year. Different commissioning and contracting arrangements meant that data had to be collected in different forms. Thus, expenditure (or ‘spend’) on the reablement service was collected as:

-

total expenditure for wholly ‘in-house’ services

-

total expenditure for in-house and contracted-out services where the service included both elements

-

value of the reablement contract if the service was fully contracted out

-

where respondents did not know the answer to the question but the service was run from a LASSD, the NHS, or an integrated service, we asked for the cost of the service as a proportion of the budget for all older people’s services.

The survey also asked about the number of reablement ‘cases’. ‘Cases’ refers to the number of individuals who received the service, recognising that some individuals may use a service more than once.

The analytical approach

Data were summarised in terms of mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum. Analyses were conducted only if the minimum cell count was > 10. Additional data are presented in Appendix 2 (see Table 32).

Where respondents reported the total budget for older people’s services and the percentage dedicated to reablement, expenditure on reablement was calculated by multiplying the two values. The typical number of cases to whom the service was provided was converted to cases per year. The average cost per case was calculated by dividing the total expenditure for reablement in 2014–15 by the number of cases per year. The average cost per type of reablement service was explored using the core service characteristics described earlier (see Service provision and delivery) and by commissioner.

Findings

Expenditure on reablement

Around one-third of respondents (42/143; 29%) provided information on expenditure. Most answers referred to direct expenditure on the reablement service (n = 31; 22%). On average, expenditure was £2.6M. Some respondents reported expenditure in terms of the expenditure on in-house (n = 8; 6%) and on contracted-out elements (n = 7; 5%). In these cases, expenditure, on average, was £1.5M and £0.9M, respectively. Seven services reported expenditure as the proportion of the budget for older people’s services devoted to reablement; their average expenditure was £1.7M. Two services reported the total value of the reablement contract (£1.2M and £0.2M). Overall, the average expenditure on reablement was £2.4M. However, there was wide variation (range £5000 to £8.5M).

Caseload

One hundred respondents (70%) provided information on their annual caseload (n = 81; 57%) or on the typical number of cases per month (n = 19; 13%). On average, the caseload was 1383 per year (range 10 to 9500).

Cost per case

It was possible to calculate the cost per case for 37 (26%) services. The average cost per case was £1445 (range £20 to £2235). Clearly, the value of £20 per case is implausible. [This value was derived from the respondent stating that their budget for older people’s services was £1.5M, the percentage spent on reablement was 1.33% (hence £19,950) and the reablement service saw 1015 cases per year.] Data provided by a further five respondents yielded costs per case of below £500. Again, these are highly atypical. Excluding these six respondents increased the average cost per case to £1728.

Cost per case per type of reablement input

Among the services providing ‘functional reablement’ that reported costs (n = 10), the average cost per case was £1577 (range £533 to £2235). Among the services providing ‘comprehensive reablement’ that reported costs (n = 24), the average cost was £1512 (range £20 to £3333). Only six services providing ‘social reablement’ reported costs; therefore, we did not carry out a calculation with respect to this type of reablement input.

Summary

Reablement services varied in terms of their organisational base (LA vs. NHS vs. integrated service); over half were LA services. Just over half were ‘standalone’ services, as opposed to integrated within wider intermediate care provision in the locality. The latter was more likely to be observed if the service was based in the NHS. Most services were delivered by in-house teams. Where aspects of the service were outsourced, this was most likely to be the hands-on delivery of the intervention, as opposed to the assessment processes.

Services could be grouped according to the types of staff working in the service. Not all services had OTs, and LA-based services were most likely to have them. NHS or integrated services presented the most multidisciplinary profile. It appeared that workers in some services had both home care and reablement clients. The scope of reablement input varied between services. Some did not work on aspects of functioning external to the home environment: we labelled this ‘functional reablement’. ‘Comprehensive reablement’, which included reabling with respect to getting out and about outside the home and re-engaging with social activities and friends, was, however, the more common approach. The primary objective of services, and particularly among LA services, was to restore everyday living skills. Multidisciplinary teams, which tend to be based in the NHS, were most likely to report ‘preventing hospital admission’ as an objective.

Services varied in terms of the clients they worked with. Over one-third offered reablement to all referrals for home care received by their LA. Just over one-quarter accepted self-referrals. The majority of services reported that they accepted a wide range of people. The most commonly reported exclusion criteria were individuals requiring end-of-life care and for whom there was no evidence of reablement potential. Over one-quarter of services reported that cognitive impairment and/or dementia could be a reason to refuse a referral.

The typical duration of reablement reported was 4–6 weeks. Services delivering comprehensive reablement were more likely to report a longer duration than those delivering functional reablement. Most services reported that they were able to extend the period an individual remained in the service, but this was predominantly attributed to delays in arrangements for longer-term care. Charging policies for extended involvement varied. LA-based services were most likely to charge.

A small minority of services used standardised outcome measures. Professional judgement with respect to achievement of reablement goals appeared to be the predominant approach to assessing progress. Almost two-thirds of services reported that, on discharge from reablement, only a minority were transferred to home-care services. Services providing functional reablement were least likely to report this as the typical outcome at discharge.

The section of the survey on costs was poorly completed. When sufficient data were available, the average cost of reablement per case was calculated at £1728 (excluding six highly atypical cases). There was relatively little difference in cost between services providing functional reablement and those providing comprehensive reablement.

Chapter 4 Work package 2: identification and description of research sites

Introduction

This chapter reports the selection and recruitment of services to WP2, each representing one of the service models identified by WP1. Each service is then described in comparison with the others. These descriptions are based on data collected during WP1, information gathered at meetings with services during site recruitment and study set-up, documentary material, and interviews with staff and commissioners within the process evaluation (WP2c).

Identification and recruitment of the case sites

Work package 2 was a mixed-methods evaluation of up to four reablement services, each representing a different model of delivering reablement, using an observational study design. Identification of these service models was a key output of the national survey of reablement services (WP1) as reported in the previous chapter. Two concepts emerged from our analysis of the survey data that best served to distinguish reablement services: the type of reablement input, and staffing (see Chapter 3, The core characteristics of reablement services).

In terms of the type of reablement input, the survey identified three types: ‘functional’, ‘comprehensive’ and ‘social’. (The last was very unusual and not relevant to WP2 as it is restricted to mental health settings.) The majority of services (60.8%) represented in our survey reported that they delivered ‘comprehensive reablement’. ‘Comprehensive reablement’ fully adhered to what, at the time of the study, was understood to properly constitute a reablement intervention,15,39 and this remains the case. 7 Thus, for the evaluation phase, we sought only to recruit services delivering ‘comprehensive reablement’.

The second concept that best differentiated services was staffing. Four ‘types’ emerged:

-

reablement with occupational therapy

-

home-care reablement

-

multidisciplinary reablement

-

reablement workers.

For the evaluation, therefore, we sought to represent services that were delivering comprehensive reablement but differed in terms of staffing.

Outputs of the WP1 cluster analysis of staffing typologies were used to identify services to approach regarding participation in WP2. Services closest to the centre of each cluster (in other words, best representing each staffing typology) were approached first regarding their participation in the evaluation. If the invitation was declined we moved on to the next ‘closest’ service. This continued until the involvement of a service was secured. Hereafter, we refer to these services as our research sites.

Unfortunately, significant delays experienced by the project led to the decision to close, rather than extend, the study. This meant that recruitment did not open in the research site that would have represented the ‘reablement worker’ typology.

Alignment of research sites with the designated service model

By the time recruitment of service users to WP2a commenced, the three research sites had undergone significant changes. Two key factors contributed to this. First, the continued implementation of the ‘Transforming Care’ agenda and the Care Act 201415 resulted in changes in relation to wider intermediate care provision, integrated working with the NHS, and LA social care intake and assessment processes. Second, resource constraints had an impact on commissioning decisions. Examples of observed changes include changes in private providers; the introduction of joint working arrangements with other services, the reorganisation of intermediate care provision within the locality, and the reversal of joint working arrangements between the LA and NHS.

However, as this chapter reports, the research sites did represent differences according to a wide range of service characteristics that are highly relevant to policy-makers, commissioners and service providers. It is also the case that different models of provision were operating within each research site. It is the impact of these factors and characteristics that our evaluation was able to explore and test in terms of service users’ outcomes and experiences, and the experiences of providing and delivering reablement.

The work package 2 research sites

The checklist of features for describing complex interventions developed by Dorling et al. 40 was used to determine the range of information reported on research sites. This information is presented in the following sections. We note that the level of detail is constrained by the need to ensure the anonymity of the research sites. The information presented is correct for the time when recruitment to WP2 was open and the intervention was being delivered to study participants.

Overview of research sites

Information about the overall setting and location, and a high-level description of the service and the wider service context, are set out in Table 4. Sites differed in terms of their organisational context and sociogeographical characteristics. The core function of all sites was the delivery of social care assessment and reablement. All delivered reablement to individuals returning home from hospital and those living in the community who were at risk of significant increased demands on social care. Sites varied in the extent to which they were colocated within the wider intermediate care offer in the locality. In two sites there was some degree of joint working/integration of NHS and LA-funded intermediate care provision. In the two sites that used private providers for at least part of their reablement provision, private provider involvement in the study was limited in some way.

| Characteristic | Site | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | |

| Service setting | LA | A social enterprise commissioned to provide a range of community health and social care services | LA |

| Commissioner | LA | LA | LA |

| Location |

A small metropolitan borough in the northern half of England Comprises rural, urban and industrial areas. Two main conurbations, occupying around one-third of the land and where around two-thirds of the population lives. The remainder is predominantly rural Population: > 300,000; higher than national average proportion of the population is aged ≥ 65 years Relatively deprived, with many areas of significant deprivation Over 95% of the population are white British |

A small London borough Population: < 200,000; lower than national average proportion of the population aged ≥ 65 years Overall deprivation rate is low, but a few areas of high levels of deprivation Almost two-thirds of the population are white British; no large representations of specific minority groups |

A large county in the southern half of England Predominantly rural, it also has several large towns with sizeable populations Population: > 1 million; higher than national average proportion of the population is aged ≥ 65 years Overall deprivation rate is low, but there are pockets of high levels of deprivation The majority of the population (> 90%) are white British |

| Service function |

Assessment and reablement of individuals being discharged from hospital and those living in the community Delivery achieved through an in-house assessment team and two private providers |