Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/59/40. The contractual start date was in September 2014. The final report began editorial review in July 2017 and was accepted for publication in February 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

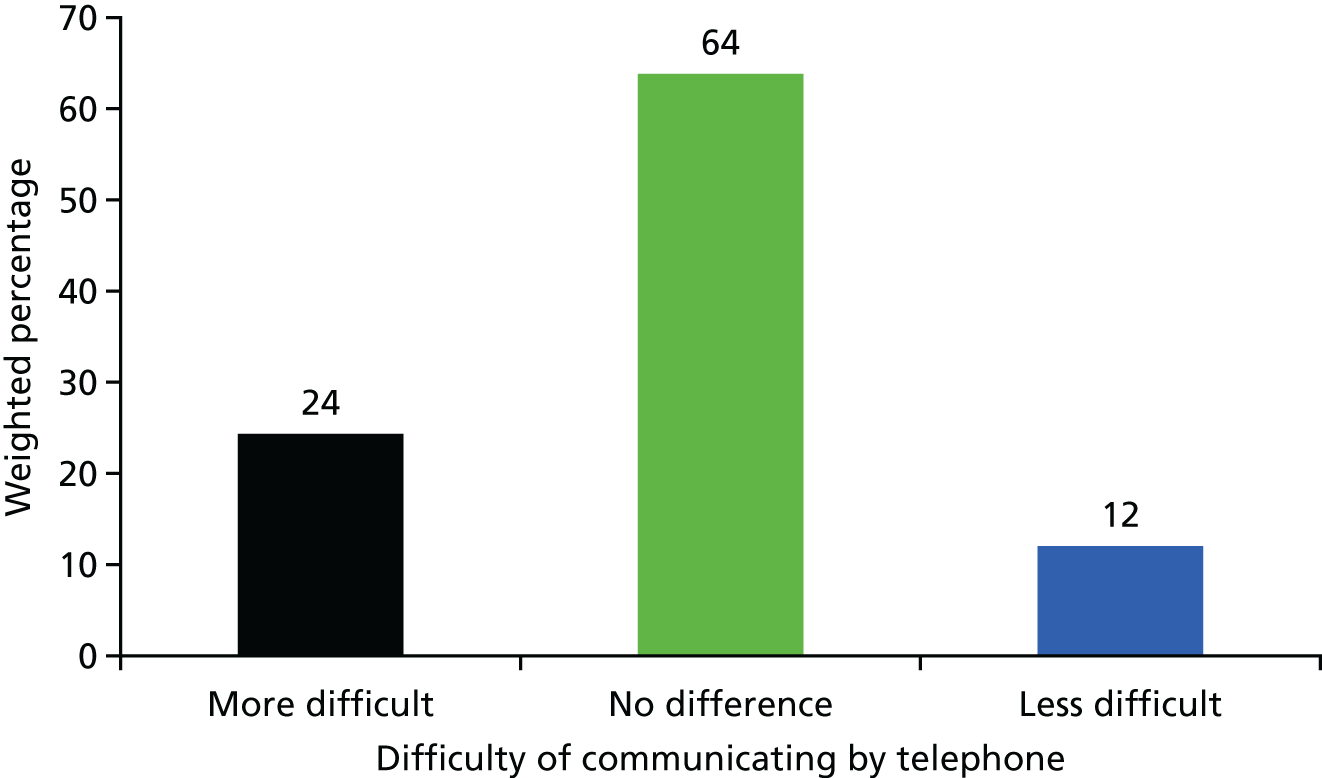

Eleanor Winpenny reports grants from UK Clinical Research Collaboration [Medical Research Council (MRC)] and grants from MRC, outside the submitted work.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Newbould et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Context

Some sections of this report have been reproduced from Newbould et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/; from Ball et al. 2 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2018. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/; and from Newbould et al. 3 © British Journal of General Practice 2019 This article is Open Access: CC BY-NC 4.0 licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

A commission on the future of the primary care workforce in England,4 published in 2015, highlighted a number of challenges for primary care, including an increasing population size, an increasing number of patients with complex needs and an increasing overall demand with growing numbers of primary care visits each year. A number of changes have taken place in primary care to respond to these changes in demand. These changes include greater use of telephone or e-mail systems for triage or telephone consultation as an alternative to face-to-face appointments.

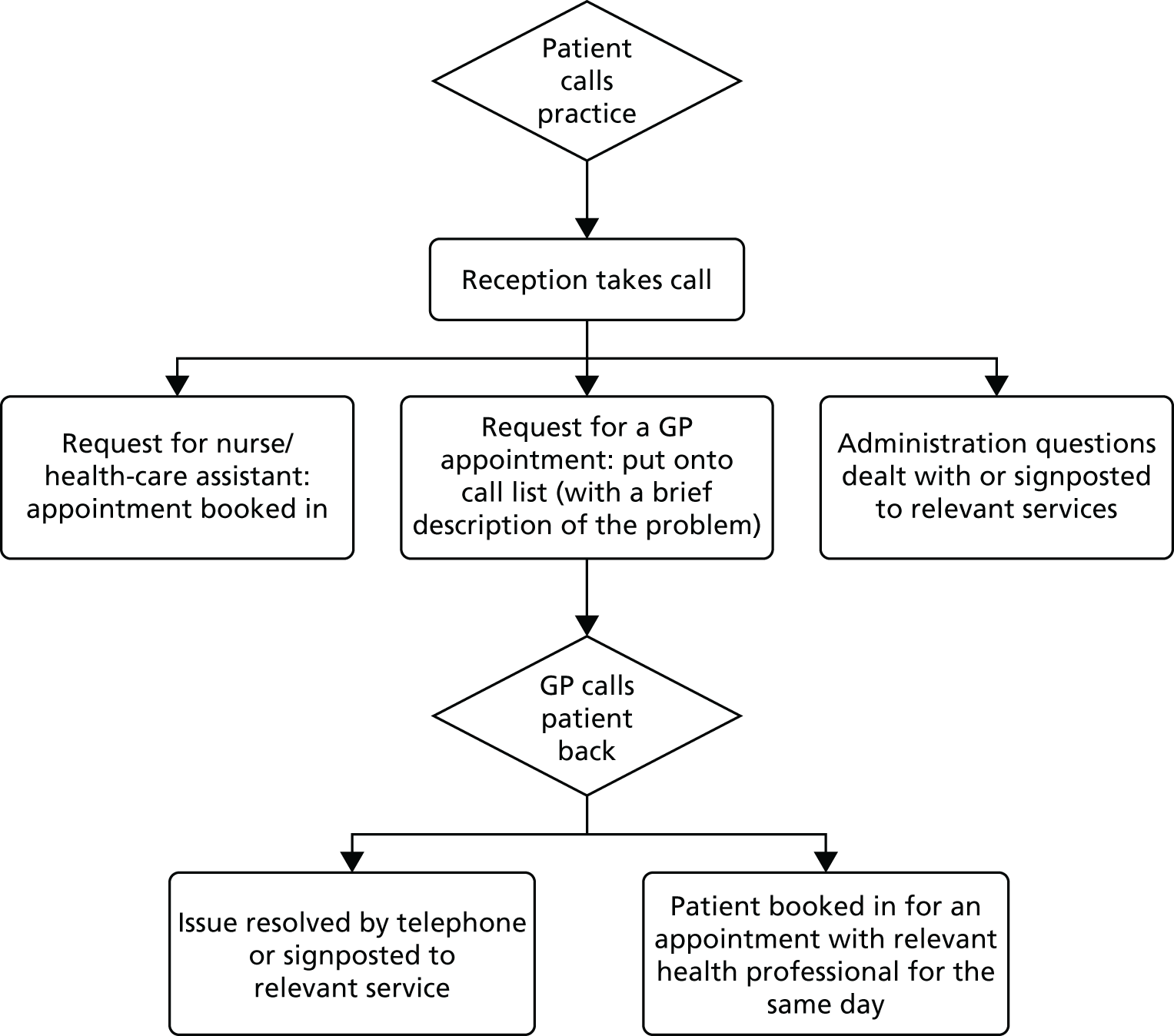

Despite the growth in the use of telephone consultations in general practice in England, there is limited evidence as regards their effectiveness in reducing overall workload in primary care, with studies suggesting that increasing the use of telephone consultations has a neutral impact on workload or may actually increase it (see Chapter 2). Currently, two commercial companies in England, GP Access Ltd (Cossington, Leicestershire) and Productive Primary Care Ltd (Woodhouse Eaves, Leicestershire; commonly known as ‘Doctor First®’), offer a new and significantly different pathway for patients seeking a face-to-face general practitioner (GP) appointment. The approach was first rolled out in 2011 and has been taken up by a small but growing number of practices (147 practices had been using the approach for ≥ 6 months at the time of this study). Starting with a detailed analysis of demand and workforce capacity, the ‘telephone first’ approach (described in detail in the following sections) promoted by these companies requires all patients requesting an appointment to first speak to a GP on the telephone rather than arranging a face-to-face consultation directly. After contacting the surgery, patients are called back on the same day by a GP and, at the end of this call, a decision is made regarding whether the patient needs to come in to see a GP face to face (usually on the same day), whether they need to be directed to an alternative health-care provider or whether their concern can be satisfactorily and appropriately dealt with on the telephone. At the start of the day, the majority of GP appointment slots are free, giving GPs the control to determine when, and for how long, to book face-to-face appointments. Patients are required to contact the surgery on the same day that they wish to be seen. It also means that all patients requesting an appointment with a GP will at least speak to a GP on the same day. Figure 1 shows how a ‘telephone first’ system typically works. We suggest the term ‘telephone first’ for this approach to differentiate it from ‘telephone triage’ or ‘telephone consultation’, which are terms used widely in the literature. ‘Telephone triage’ implies assigning priority to seeing patients, which, although this is an element of the ‘telephone first’ approach, is too limited to describe the wider system change. ‘Telephone consulting’ involves a discussion between a health professional and patient focused on the management of an existing condition or the diagnosis and treatment of a newly presented condition.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of a typical ‘telephone first’ system.

Significant claims have been made as to the effectiveness of these ‘telephone first’ systems; for example, in 2013, a NHS England guide to the evidence base for urgent and emergency care5 stated that:

Proven and tested systems exist in England, where telephone consultations are used routinely in general practice, whilst other developed systems include telephone assessment of all patients prior to attending the practice [. . .]. The ‘Doctor First®’ model [one of the operating models available] has demonstrated a cost saving of approximately £100k per practice through prevention of avoidable attendance and admissions to hospital.

Reproduced with permission from NHS England. 5 Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0

These claims are based on data from companies that have a commercial interest in promoting their product. Despite this overall positive assessment of the Doctor First model, the NHS England report also highlights that there is insufficient evidence to know to what extent these systems may generate new demand through help-seeking for minor conditions, the acceptability of the non-face-to-face consultations for certain patient groups including older people and any consequences for patient safety, for example through the loss of visual clues. 5

Evaluations and academic literature have not focused on ‘telephone first’ systems to date; for example, a recent cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) (the ESTEEM trial)6 provided robust evidence comparing nurse-led and GP-led triage systems in primary care. In contrast to the ‘telephone first’ approach, in which all requests for face-to-face GP appointments are triaged, the ESTEEM trial practices were running a traditional booking system in which the majority of appointments are booked in advance by reception staff and triage was used only for patients requesting same-day consultations within general practice. 7

As ‘telephone first’ systems are being rolled out across England, there is a need for rigorous evaluations to understand the impact of these telephone-based systems. These evaluations may include understanding patient experience, including appropriateness for hard-to-reach groups; impact on consultations from the perspective of patients and staff; and impact on subsequent use of primary and secondary care services.

It is also important to understand the cost consequences of these systems for general practice.

Study design

This evaluation of the ‘telephone first’ approach was a multimethod study. A number of methods were used to enable detailed exploration of the impacts of the ‘telephone first’ approach in general practice. The study comprised three key elements: (1) quantitative, (2) economic and (3) qualitative. The study design used a controlled before-and-after (time-series) approach using national reference data sets; this approach enabled exploration of the impacts of the ‘telephone first’ approach on primary and secondary care services; the latter was a particular focus of this study, given the claims made about ‘telephone first’ approaches in NHS England literature. 5 Such documents also advocate the cost savings of such an approach; as a result, we incorporated an economic element in the study to explore the cost consequences of the approach in general practice.

Given the radical change that a ‘telephone first’ approach has on the way a practice operates, we also wanted to identify the impacts on patients, staff and hard-to-reach groups. We used a qualitative approach for this element of the work, to enable us to explore in detail the views and experiences of staff and patients using a ‘telephone first’ approach.

Aims and objectives

Our research sought to address three main research questions:

-

How does a ‘telephone first’ approach affect patient experience and use of primary and secondary care services?

-

What is the impact of ‘telephone first’ approaches on the nature of consultations for patients and staff, and how appropriate is this approach for hard-to-reach groups?

-

What are the cost consequences of a ‘telephone first’ approach in general practice?

To address these questions, we used a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches and a cost–consequences analysis for the economic evaluation. The research focuses on practices using a ‘telephone first’ approach provided by one of two known commercial providers in England: Doctor First (provided by Productive Primary Care Ltd) and GP Access (provided by GP Access Ltd).

Selected ‘telephone first’ approaches

Figure 1 summarises how both approaches (Doctor First and GP Access) work for patients seeking an appointment. Box 1 provides further details for patients seeking an appointment with a GP, based on the GP Access standard approach. For all contacts, patients are encouraged to telephone the practice, although exceptions are expected for patients for whom this is not feasible (e.g. deaf patients). It is important to note that systems can be adapted by practices. We found more information on a specified standard approach for GP Access than on a specified standard approach for Doctor First, and this is reflected in the detail provided in Box 1.

-

Practice receptionist will take the patient’s details (name, date of birth and contact telephone number) and may ask for a brief description of the problem and any special requests (e.g. for callback not to be at a certain time). A specific subset of calls may be directly booked in with the GP (e.g. antenatal checks).

-

The call can be directly transferred from reception to a GP or added to the GP’s callback list. GP Access specifies two approaches that a practice could use to organise callback lists: (1) a list from which all GPs pick patients (may have GP initials by patient to indicate preference) or (2) a separate list for each GP on duty for callbacks in that session.

-

The GP prioritises calling patients back based on the information provided, rather than in chronological order. GP Access specifies that a GP may decide to bring the patient in without a call, if the problem note and history mean a call would be redundant. The doctor phones the patient and together they decide if and when the patient needs to be seen face to face in the surgery (either by a GP or by another health professional) or if the issue can be dealt with via telephone or needs to be directed to another service.

-

If at the end of the telephone consultation the patient still wants to be seen, the GP will book them in for a face-to-face appointment. When a face-to-face appointment is arranged, the majority (both GP Access and Doctor First report around 80%) will be arranged to take place on the same day as the call.

Support offered by the companies

It is important to note that the two providers do not just provide a ‘telephone first’ appointment system but seek to work with practices to understand and manage demand and provide support in the implementation of and transition to their specific ‘telephone first’ approach. Doctor First has a three-stage approach for transitioning to a ‘telephone first’ approach over an 18-week period: (1) data gathering, to help practices to gain a clear understanding of activity, backlog, capacity and demand in order to identify how many clinical sessions are required per day to meet the demands of patients (takes 4–8 weeks); (2) an implementation phase, to reduce backlog of appointments and provide training to all staff to help with the smooth transition to Doctor First, inform patients of upcoming changes and clinical system configuration (takes 10 weeks); and (3) following ‘going live’, 4 weeks of patient feedback and monitoring to help gather views on the system and communicate with patients. 9

The other provider, GP Access, has a five-stage approach over 12 weeks; this is described as (1) coming to a consensus among partners and appointing a change leader (week 1), (2) preparing the whole staff team, patients and the system [includes an e-learning session for GPs on telephone consulting (weeks 1–3)], (3) support on the launch day (weeks 3–4), (4) access to rapid support by telephone following changeover (weeks 5–11) and (5) confirming decision to continue with approach 12 weeks after implementation. GP Access also offers practices a 3-month subscription to an analytical support service, which provides measurement, feedback and advice to address problems as they arise. 10

Reported benefits of the approach

Both providers report substantial benefits of the system to practices, in terms of both reduced stress for practice staff and cost savings as a result of time saved and more efficient use of time. The providers also report that practices that have switched to the new system have increased patient satisfaction. The nature of the claims made by Doctor First and GP Access on their websites are summarised in the following sections. As noted, there is no independent evaluation to date to support or refute these suggested benefits; our study seeks to address this gap in the evidence base.

Claims made by Doctor First

On its website,11 Productive Primary Care has made a range of claims relating to benefits of Doctor First for both patients and GPs/practice staff. For patients, the stated benefits include being able to see the doctor of their choice at the time they choose, greater patient satisfaction (as indicated by a reduction in complaints) and the fact that the approach ensures that the sickest patients are seen first. With respect to clinician satisfaction, claims are made regarding the system enabling a more productive and satisfying way of working, with increased knowledge of and control over workload and working life. With respect to benefits for practice staff, it is claimed that there are improvements in the work environment and satisfaction of reception staff as a result of the availability of sufficient appointments to meet the needs of all patients (so that they are no longer acting as a barrier to, but rather as a facilitator of, the patients’ journey through practice systems) and the fact that they are not required to make decisions outside their area of expertise, which would be better made by clinicians. In addition, claims are also made regarding benefits to the practice overall, including the near-complete disappearance of ‘did not attends’ (DNAs), financial savings (for reinvestment) of > £30,000 per annum per full-time GP, and a happier work environment as a result of a reduction in stress for patients, GPs and practice staff alike. 9 Finally, there are reported benefits with respect to savings for the NHS more broadly, with reference to a 20% reduction in accident and emergency (A&E) attendance for practices using Doctor First. 11

Claims made by GP Access

Similarly, GP Access has made a range of similar claims on its website. Patient satisfaction is identified as a key benefit,12 linked to reported improvements in continuity of care (e.g. an increase in continuity of care in one Norfolk practice from 53% to 60% over 6 months following the introduction of the approach, and 80% continuity being achieved in a Dorset practice that had been using this model for 11 years)13 and the claim that the approach provides the capacity for the GP to see the patients who need to be seen as soon as possible and usually on the same day. 12 With respect to benefits for GPs and practice staff, claims are made regarding the potential to raise GP productivity by 20%, leading to reduced stress, saving time and resulting in a happier practice. 10 Again, claims are made regarding benefits to the practice overall, including reductions in the numbers of DNAs14 and financial savings (with reports of a saving of £90,000 per annum in one Leicestershire practice). 15 Finally, there are reported benefits for the wider NHS, with a reported 20% reduction in emergency admissions from practices using the GP Access model. 16,17

Structure of the report

This report begins by presenting a literature review of existing evidence around telephone consultation approaches in general practice, designed to establish what is already known about our main research questions (see Chapter 2). The following chapters present the method and results from each of the main parts of the study, namely analysis of data from practices (see Chapter 3), our patient experience survey (see Chapter 4), our practice manager survey (see Chapter 5), analysis of data from the national GP Patient Survey (see Chapter 6), analysis of hospital utilisation data (see Chapter 7), economic analysis (see Chapter 8), interviews with patients (see Chapter 9) and interviews with staff (see Chapter 10). The discussion and conclusions are presented in Chapters 11 and 12.

Impact of patient and public involvement

The study team benefited from input from a number of patient and public involvement (PPI) members during the study; for example, the PPI members recommended the inclusion of out-of-pocket patient expenses in the economic analysis. We also had patient input on written documents, such as patient information leaflets and consent forms, ensuring that information disseminated to participants was suitable and understandable to a lay audience. Rather than repeating this information in each chapter, we have summarised the contribution of PPI in Chapter 11, Impact of patient and public involvement.

Ethics approval and consent

This study was reviewed and given a favourable opinion by the West of Scotland Research Ethics Committee 5 (reference number 15/WS/0088). Written informed consent was sought from all participants for participation in and audio-recording of interviews and for the publication of anonymised quotes.

All required research governance approvals were obtained.

Changes to the protocol

During the course of the study, under the guidance of our study steering committee (SSC), a number of minor changes to the original protocol18 were made regarding the design and methodology of the study. The changes relating to each element of the study, along with the rationale underlying the amendments, are set out in the following sections.

Analysis of administrative data from general practices (see Chapter 3)

Changes to the outcomes considered

In addition to the outcomes presented in Chapter 3, our original protocol stated that we would also analyse DNA rates, waiting times in surgery, recall rates and time for GPs to return calls. However, when we got into detailed discussion with the commercial provider who was making data available, it was clear that these data could not be reliably extracted and, therefore, they were not in the list of data items supplied by the company.

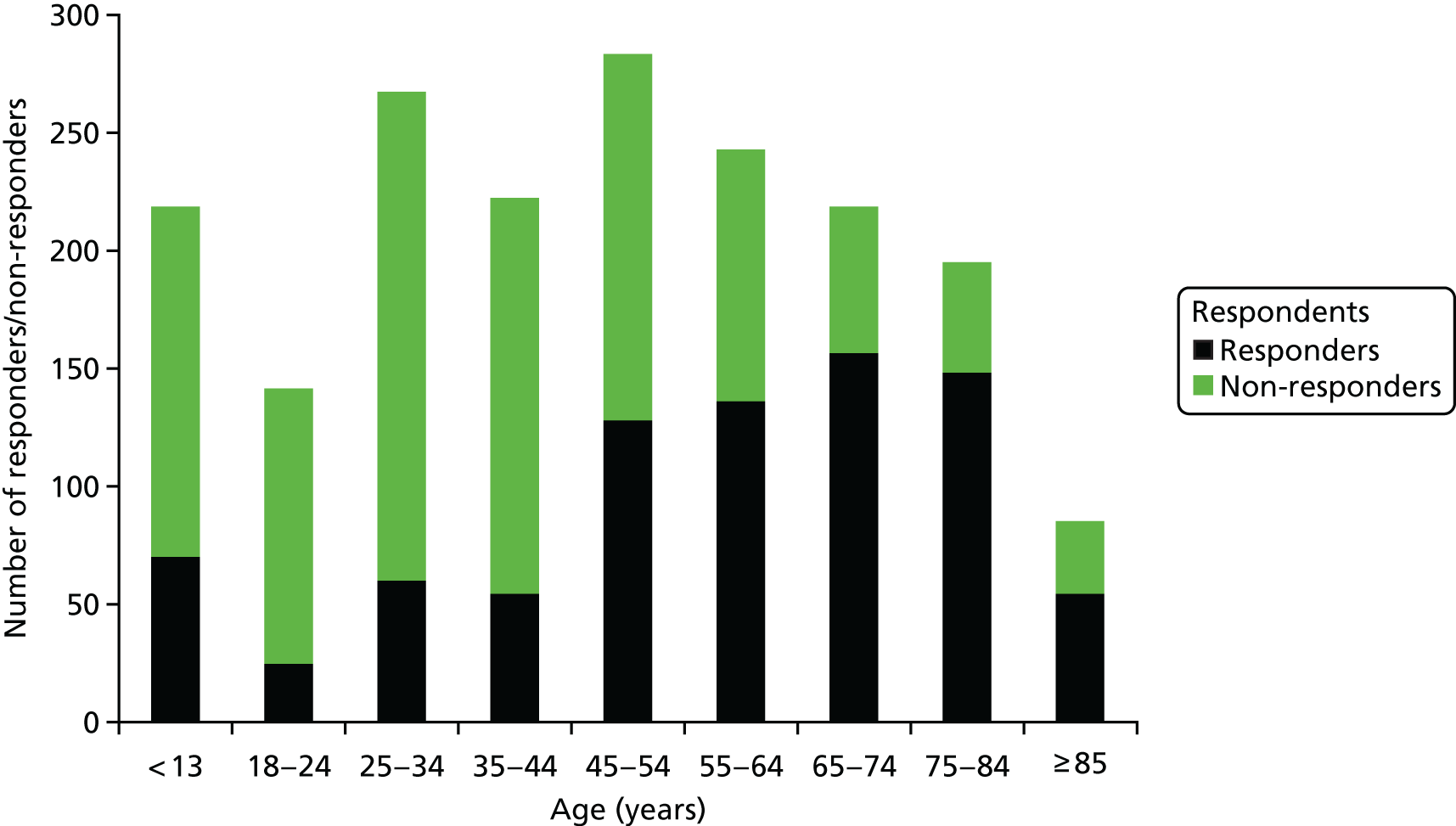

Patient experience survey (see Chapter 4)

Change to the number of practices surveyed

The number of practices taking part in the patient and carer survey element of the study was reduced from 28 (as specified in the original protocol) to 20, and the number of surveys sent out by each practice was increased. The rationale for this change was to ensure a more efficient use of resources without significantly affecting the power of the study to detect differences between groups. Under the original plan, we anticipated 450 responses from 28 practices; 837 responses were ultimately received from 20 practices.

Change to inclusion criteria for patients and carers

On the recommendation of the SSC, changes were made to the inclusion criteria for patients and carers to be sent a survey in order to address potential risks regarding confidentiality for particular groups of patients (e.g. teenagers, patients at risk of domestic violence and patients dealing with sensitive issues, for whom receiving a postal survey indicating that they have had a recent appointment may be a risk to confidentiality). A step was introduced into the protocol: GPs screened the list of patients selected to receive a survey and removed those patients for whom inclusion was considered to be a risk. In addition, whereas parents of patients aged ≤ 12 years were sent a survey to complete on behalf of the child, parents of teenage patients were excluded because of potential risks to patient confidentiality for this age group.

Patient experience: analysis of data from the national GP Patient Survey (see Chapter 6)

Change to included covariates in regression models

In the original protocol, practice-level covariates (practice size, rurality, deprivation and ethnicity/age/sex profile) were planned to be included in regression models along with patient-level covariates. However, on attempting to run these models they were found to be very slow to converge, making analysis impractical. As a random intercept for practice was included, the practice-level effects should already have been controlled for, and so these variables were dropped from the analysis to simplify the models. It was not expected that this would make any material difference to the results obtained.

Secondary care utilisation: analysis of Hospital Episode Statistics data (see Chapter 7)

Change to included covariates in regression models

As with the analysis of GP Patient Survey data, it was found that the models using Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data were very slow to run and simplifications had to be made. Again, practice-level covariates were not included in line with the GP Patient Survey analysis. It was not expected that this would make any material difference to the results obtained.

Economic analysis (see Chapter 8)

Change from postal to telephone survey for collection of cost data

In developing the survey on costs (which was to be completed by practice managers at all intervention practices), it became apparent that, given the complexity of some of the answers required, and following discussion with external colleagues with experience of gathering similar data, it would be more appropriate to complete the questionnaire over the telephone than by sending it out by post. This enabled the provision of guidance and support in completing the required information that would not have been possible if it had been completed independently in paper form. Sending out a complicated questionnaire by post would have been likely to result in a low response rate.

Reduction in the number of practice managers invited to participate in the cost survey

Because it was anticipated that a better response would be achieved by using a telephone survey than by using a postal questionnaire, we revised the protocol so that we planned to approach up to 30 practice managers, selected at random from the 102 intervention practices, rather than sending a postal questionnaire to all practice managers. In total, 18 practice managers participated, and this sample was considered sufficient to gain an understanding of the costs involved.

Change to method for obtaining pricing of systems

Fees paid to the commercial providers were provided by the practice managers in the cost survey. Therefore, it was unnecessary to contact the providers for this information.

Change to analysis approach for cost survey data

Because of the anticipated difficulty in obtaining reliable quantitative data, we altered the approach to the analysis of the cost survey data to comprise a description of the cost items involved, supplemented by limited quantitative analysis (including identification of upper and lower cost bounds for sensitivity analysis) when meaningful and appropriate.

Change in the time horizon

In the original protocol,18 we proposed using data extracted for up to 3 years prior to and up to 2 years post the adoption of a ‘telephone first’ approach. Instead, we simply used Prescription Cost Analysis data (NHS Business Services Authority)19 and HES data from 2009 to 2016 in control practices and ± 12 months from the launch of ‘telephone first’ in intervention practices, mirroring the outcomes analysis.

Change to summary of results

Because we were unable to estimate a mean cost of installing and running the systems in a reliable quantitative manner, we do not present an overall cost per month but instead present a text summary of all of the cost components.

Interviews with patients and staff (see Chapters 9 and 10)

Change to the number of practices involved in the qualitative element of the study

In the original protocol, we planned to interview patients and staff at eight practices about their experiences relating to the ‘telephone first’ approach; however, in order to allow greater variation in the characteristics of the practices selected for study, because of the observed wide variation in practice setting, practice characteristics and how the approach had been implemented, we proposed to increase this number to 14 practices.

Analysis of disenrolment data (not conducted)

The original protocol included examining disenrollment data. However, because of the delays in obtaining HES data, we decided not to request additional data on disenrolment as it would have caused further delays in the delivery of the project.

Chapter 2 Literature review

The literature review aimed to review and synthesise existing evidence around telephone triage and telephone consulting in primary care settings in the UK and other high-income countries.

Methods

Our review drew on scoping review methodology20 to establish what is known about telephone triage and telephone consulting broadly, and in relation to our three main research questions. We sought to capture but did not explicitly search for or restrict our search to ‘telephone first’ approaches. Full details of the search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria and data extraction and synthesis are given in Appendix 1. An electronic search of the PubMed research literature database was conducted up to 9 November 2016. In addition, The King’s Fund Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) data were searched (from 1995 to 16 January 2017). The main search terms were ‘primary care’ or ‘general practice*’ AND ‘phone’ or ‘telephon*’ AND ‘triag*’ or ‘consult*’. Studies were excluded if they had a sole focus on nurse-led, emergency or out-of-hours triage, if they were published in a language other than English and if they did not focus on high-income countries. No exclusions were made on the basis of publication type or on date of publication for PubMed. Guided by our research questions, data were extracted on study type and methods, type of telephone system (triage or consultation or both), details of telephone system, setting (geographical and health care), reported outcomes [health outcomes, patient safety, staff experience, patient experience (hard-to-reach groups), impact on service use, impact on consultation, and cost] and other notable findings. We sought to undertake a narrative synthesis rather than pool numerical results, based on our research questions and knowledge of the literature. We did not seek to exclude studies based on quality, although we noted methodological concerns in our synthesis.

Results

A total of 911 articles were identified via the database searches outlined in Methods and detailed in Appendix 1. Of these, 836 were excluded based on screening of titles/abstracts, in line with our inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 75 were selected for full-text review and data extraction. Of these, two were unavailable and 18 were excluded following full-text review, because they did not contain empirical research or only touched tangentially on telephone consulting.

Fifty-five papers were included in the review: 23 relating explicitly to telephone triage systems, 31 to telephone consultations and one to a range of primary care patient interfaces, such as e-mail. Papers came from the UK (53), the Netherlands (1) and the USA (1). These included 22 non-peer reviewed pieces (e.g. news articles, editorials, letters and opinion pieces) and 33 peer-reviewed articles. Study types included:

-

studies related to two RCTs (8 papers)

-

systematic reviews (2)

-

a literature review with undefined methods (1)

-

an audit (1)

-

qualitative interview/focus group studies (4; across 5 papers)

-

patient–doctor dialogue analyses (3)

-

studies using primary survey data (of patients, practice staff and/or GPs) (12)

-

a national retrospective analysis of the amount and nature of primary care activity (1)

-

quantitative analyses of prescribing behaviour (1) and patient recall of the content of consultations (1).

Key studies and bodies of work

The majority of studies reviewed were based in the UK (53), and among these it is worth noting two dominant bodies of work, that is, papers relating to the same study or involving the same authors.

The first is the ESTEEM trial, to which nine papers relate. 6,7,21–27 The ESTEEM trial was a cluster RCT comparing nurse-led and GP-led telephone triage systems with usual care for patients requesting same-day consultations in general practice in England. 28 The core intervention in the ESTEEM trial consisted of a number of steps. Following an initial telephone conversation with a receptionist, patients requesting a same-day face-to-face appointment with a GP were called back by either a nurse or a GP. The phoning clinician discussed the patient’s condition and chose from a range of management options, such as dispensing self-care advice, booking a same-day or future face-to-face appointment or referral to other appropriate services. 6 In addition to presenting evidence around clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of GP- and nurse-led triage, papers resulting from the trial also explore patient and staff experience, patient satisfaction and impact of telephone triage on GP workload.

The second dominant body of work is a series of five papers by McKinstry and colleagues. 29–33 These include qualitative research around GPs’, other staff members’ and patients’ views on the safety and appropriateness of telephone consultations compared with face-to-face consultations, as well as a two-site RCT investigating the use of doctor time and subsequent service use for telephone consultations compared with face-to-face consultations (as a way to manage requests for same-day appointments). 31 The RCT excluded urgent cases and patients asking to speak to the GP specifically for advice. In addition to the original journal articles, the RCT also accounts for seven letters to journal editors,34–39 written in response, and one editorial40 included in our review.

Terminology

The literature refers to both ‘telephone triage’ and ‘telephone consultation’, but it can be challenging to differentiate what is meant by each. In many cases, the terms appear to be used interchangeably or are ill-defined or poorly described. 41 The term ‘telephone triage’ is generally applied to an approach in which patients requesting a face-to-face appointment are asked to first speak to a doctor by telephone before a decision is made regarding whether or not the patient needs to attend and how quickly that should happen. ‘Telephone consultation’ can be understood as a more general term, which encapsulates consultations undertaken as part of triage or consultations that are undertaken by telephone for other purposes, such as scheduled check-ups or follow-up for the management of chronic conditions. In this chapter, we use the term ‘telephone consultation’ to encompass both triage and more generic consultation systems. It was not clear if any of the systems covered in the literature related directly to ‘telephone first’ approaches as presented in this study.

Prevalence of telephone consultations

There are few empirical studies that give an indication of the level of use of telephone consultations in general practice. A survey of general practices in Devon,42 published in 2001, showed that 19% of practices (n = 15) surveyed were offering telephone consultations for patients seeking same-day appointments that were not deemed urgent. A survey of practice managers in Wales,43 published in 2008, reported that 42% of those who responded (n = 167) had introduced GP telephone consultations more systematically since 2003, when a new General Medical Services contract was introduced. More recently, a survey of the use of different forms of alternatives to face-to-face appointments30 showed that two-thirds of practices (211/318, 66%) surveyed, across south-west England and Scotland, reported that they were using telephone consultations ‘frequently’, although this was not further defined.

Before the publication of a retrospective analysis of 100 million consultations in England (2007–14)44 in 2016, information on the proportion of consultations that take place by telephone within a general practice was mainly restricted to information provided by individual GPs in letters to journals. In these,34,37,45 GPs make the claim that telephone consultations form an important part of appointment provision, accounting in one case for 43% of all appointments. 45 The much larger retrospective analysis by Hobbs et al. 44 included analysis of GP and nurse consultations for registered patients at 398 English general practices from April 2007 to March 2014. The largest change observed in patterns of consultation over this period was a doubling of GP telephone consultation rates. This increase compared with a 5.2% increase in GP face-to-face consultations over the same period, although face-to-face consultations still accounted for 90% of all consultations despite the increase in use of telephone consultations.

Impact on access to primary care

One potential advantage of telephone consultations is that they improve access, either by negating the need to travel or by increasing convenience for patients; however, there is limited research addressing this directly. A qualitative study in Scotland33 reported that GP telephone consultations were generally seen to improve patient access. For patients who worked full time, had reduced mobility, valued not needing to travel to the surgery or lived in rural and remote areas, telephone consultations were seen as a helpful way to overcome physical distance and the need to travel. In urban practices, greater emphasis was placed on using telephone consultations for acute presentations as a way of managing demand.

The ESTEEM trial of telephone consultations for patients requesting same-day appointments23 reported that, although the introduction of the telephone consulting system was associated with improved access in terms of getting through on the telephone, there was no overall difference in ease of access to prompt care, comparing patients receiving the GP-led telephone system and those receiving usual care. The study also found that the introduction of telephone consultations did not seem to alleviate the challenges faced by working patients in accessing flexible and convenient care. 23 Patients unable to take time away from work or who could do so only with difficulty reported lower satisfaction than those who did not have these challenges, and this did not vary depending on whether patients were receiving GP-led telephone consultations or usual care. 27

Perceived appropriateness of telephone consultations

Patient and doctor perceptions of the appropriateness of using telephone consultations to deliver care in general practice appear to be given most focus among earlier published studies. Two studies46,47 found little agreement between doctors and patients in perceived appropriateness of GP telephone consultations for a given complaint. Stevenson et al. 46 found that, after face-to-face consultations, doctors and patients were in agreement about only 5.5% of 1067 face-to-face consultations in terms of whether or not the issue discussed could have been dealt with by telephone. Doctors showed a greater inclination towards telephone use than patients, with consultations considered in hindsight to be appropriate for management by telephone in 13.9% of cases for GPs, as opposed to 11.4% of cases for patients. 46 The single-practice study by Kernick et al. 47 also found little agreement between patients and doctors, who were separately interviewed before booked face-to-face consultations regarding whether they felt that the patient could have been appropriately managed by a telephone consultation with the GP or a consultation with a specially trained nurse. The study reported that both patients and doctors considered that only a small number of cases were suitable for management by telephone (5.8% and 5.1%, respectively). Among GPs interviewed by Hallam,48 there was broad agreement on the types of complaint that could be appropriately handled by telephone, including minor, self-limiting conditions and certain recurring conditions, whereas those thought to be inappropriate for telephone consultation included chest pain, abdominal pain, breathing difficulties, illness in a young child or new patient, non-traumatic bleeding and high fever.

More recently, the ESTEEM trial process evaluation6 suggests that patients are more open to telephone consultations and have greater confidence in the GP assessing their problem on the telephone. Patients appreciated the convenience offered by GP telephone consultations and felt that it made sense for the doctor, rather than the patient, to decide whether or not an appointment was needed and to weed out ‘time wasters’.

Experience of patients

Patient satisfaction

A range of studies published from 1992 to 2015 report on patient satisfaction with GP telephone consultations. These studies tend to report high levels of satisfaction, although many do so without a comparator. 49–52 Jiwa et al. 49 reported that 98% of patients responding to a survey in one general practice were satisfied with the outcome of a GP telephone consultation and 84% [95% confidence interval (CI) 76% to 90%] would happily receive the service again in similar circumstances. Two RCTs21,31 reported no significant difference overall in patient satisfaction between those who received telephone consultations and those who received face-to-face consultations with their GP. Analysis from the ESTEEM trial also allowed comparison between patients managed by telephone consultation by a GP or by a nurse. Calitri et al. 21 found that, compared with GP face-to-face consultations, patients who received a nurse telephone consultation alone, or who received a nurse telephone consultation with a subsequent GP face-to-face consultation, were less satisfied than those whose telephone call was with a GP initially.

Confidentiality

One discussion paper,53 one qualitative study29 and the ESTEEM trial process evaluation6 raise specific concerns around confidentiality and telephone consultations. The qualitative study,29 involving patients, clinicians and administrative staff, reported a broad range of concerns. These related to conversations that could potentially be overheard (whether at home, in the surgery, at work or in public spaces) and the disclosure of personal information to the receptionist. In addition, difficulty of maintaining privacy in small communities, errors in identification and identity fraud, the use of answering machines, third-party conversations (e.g. between the doctor and a relative if the patient’s consent is unclear) and teenagers’ confidentiality, especially in relation to sexual health, were raised as concerns. 29

Experience of hard-to-reach and vulnerable groups

Although the introduction of telephone consulting may help to overcome some barriers to access for primary care, such as physical distance, a number of studies reflected concerns that telephone consultation systems may exacerbate access inequalities or differential experiences for hard-to-reach or potentially vulnerable groups of patients. Groups of concern in the literature include those without access to a telephone or with language or other communication difficulties,54 as well as older people, ethnic minorities and the economically deprived.

Older people

Two studies51,55 showed that older patients were one of the largest and most frequent users of telephone consultation services. Although a recent survey of general practices in England and Scotland30 highlighted concerns among some GPs that elderly patients could be disadvantaged as a result of telephone consultations, there is very little research from which to judge whether or not this concern is realised in practice. One study across five general practices56 found that older patients were not disadvantaged by telephone consultations in primary care, and that Patient Enablement Instrument (PEI) scores (a self-reported measure of a patient’s ability to cope with illness) following telephone consultations did not differ between older (aged > 70 years) and younger respondents.

Ethnicity

Two studies27,57 considered the experiences of patients from ethnic minority groups with telephone consultations and suggest that the pattern of experience is varied and sensitive to the type of health-care professional involved. In the ESTEEM trial, differences in satisfaction with different telephone consultation approaches reported between ethnic groups were generally small (with those from ethnic minority groups being less satisfied than British white patients), and substantially less than differences in overall satisfaction reported by ethnic minorities compared with white British patients. 27

However, an earlier qualitative study by Rashid and Jagger57 compared views and experiences of telephone consultations among Asian and non-Asian patients, and reported that more Asian patients disliked management of illness by telephone and consultations that did not involve GPs (e.g. with a nurse) than non-Asian patients. The authors reported that only 6% of Asian patients reported difficulty explaining their symptoms in English and concluded that cultural differences were more likely to explain the differences in experiences and views of telephone consultations and other aspects of using health care.

Deprivation

The ESTEEM trial found a non-significant difference in reported convenience for GP-led telephone consultations and nurse-led triage compared with usual care by patients in more deprived groups. 27

Experience of staff

Clinicians

Clinicians’ experiences were explored in the ESTEEM trial process evaluation,6,26 although the authors note that findings may have been affected by the implementation of telephone consultations under trial conditions.

The authors found that attitudes towards telephone consultations varied between practices and doctors. Telephone consultations were seen to benefit practices in a number of ways. They were viewed as an optimal use of resources, allowing them to allocate appointments more equitably, efficiently and rationally, and facilitating more appropriate appointments6 than before. Perceived benefits were accentuated by overwhelming demand that staff reported having experienced previously, and telephone consultations were often seen to have helped in this regard. Indeed, clinicians’ experiences of reduced pressure and stress as a result of the introduction of telephone consultations were also noted across some of the grey literature. 58

However, factors such as the effective allocation of resources and support, division of workload and roles and communication also affected successful implementation and staff acceptability. Workload disparity between clinicians was a key challenge, with some GPs taking on more calls than others, whether because of patient preference (e.g. female GPs taking on more female patients) or because of the use of a ‘duty doctor’ system, in which specific GPs were charged with taking calls at any given time. Although the latter could have the potential to even out workload, some of the staff who were interviewed felt that this placed additional burden on non-duty doctors, who had to cope with the demand for face-to-face appointments by doing additional sessions or taking paperwork home,26 thus highlighting the importance of careful planning in staff allocation in the use of telephone consultation systems. Although some GPs were entirely comfortable with using the telephone, others found the experience stressful, dissatisfying and inefficient. 6 The manner in which system change is communicated and discussed among staff was also important to how the telephone consultation approach was received,26 and a supportive staff team and culture of adaptability to change improved acceptability.

Reception staff

Two studies reported on reception staff’s experiences and showed that these were mixed, possibly dependent on the model of telephone consultation and variable roles for receptionists within these. Receptionists interviewed as part of the ESTEEM trial felt that the telephone consultation system made their job less stressful by relieving the burden of finding appointments, dealing with patient frustration or having to make judgements about the urgency of patients’ complaints;6 however, the authors also noted the importance of resource allocation to support and empower reception staff in their new roles within the telephone-based system,26 and indeed a qualitative study in Scotland29 emphasised the discomfort felt by some receptionists because of the responsibility placed on them to request information about a patient’s condition(s) for the purposes of triage.

Education and training

The importance of education regarding the proper use of telephone consultations for clinicians and staff, as well as for patients, was highlighted by some authors, although it was not the main focus of any study reviewed.

Three papers55,59,60 from the grey literature highlighted concerns regarding a lack of specialised training for clinicians delivering telephone consultations, with GPs having to learn by trial and error. 55 The lack of training for receptionists and their key role in distinguishing urgent from non-urgent cases was also seen as a potential risk to patient safety. 60

Patient education and understanding of telephone consultation systems was also a factor explored in the literature, although to a small degree. A published survey of four practices in England52 linked significant differences in levels of patient awareness of telephone consultation systems between practices to the practices’ approaches to publicity. These included receptionists telling patients, use of leaflets or posters or reliance on word of mouth. 52 The study found that only half of the total number of patient respondents (n = 1025) knew that they could speak to a doctor by telephone. More recently, the ESTEEM trial process evaluation6 found that some patients were confused about how their new consultation system worked.

Impact on the nature of consultations

Two studies in the UK that compared the nature and content of patient–doctor interactions in telephone and face-to-face consultations61,62 found that telephone interactions were shorter and largely focused on single-issue or biomedical concerns. Telephone consultations emphasised biomedical information exchange over psychosocial or affective communication, and doctors used closed questions much more commonly than they used open ones;62 however, Hewitt et al. 61 point out that brief telephone consultations are appropriate when telephone consultations for new problems would lead to a face-to-face meeting. The ESTEEM trial25 also compared nurse and doctor telephone interactions with patients in a sample of video- and audio-recorded consultations. They reported that, although the length of calls was similar, nurses asked patients more questions [mean 14.72 questions, standard deviation (SD) 6.42 questions] than GPs (mean 5.51 questions, SD 4.66 questions), on average, whereas GPs asked more questions eliciting patient concerns or expectations and to obtain medical history than nurses (43% of GPs’ questions were of this nature, compared with only 11% of nurses’ questions). In interpreting these apparently large differences, it is important to note that the nurses, but not GPs, were using computer-aided software when they took a patient history.

Patient safety and health outcomes

A number of papers raise concerns about patient safety in relation to use of the telephone as an alternative to face-to-face contact with GPs, and indeed conclusions with regard to safety have been the subject of disagreement and debate among researchers;63 however, few studies have provided empirical evidence to support these concerns. 64

Studies that reported that telephone consultations appear safe did so only on the basis that patient–doctor communication can be adequate and patient recall of safety-netting instructions is improved. Most recently, although the authors could not rule out differences between groups for measures of safety, the ESTEEM trial found that GP- and nurse-led telephone consultations appeared safe, and were not associated with excess deaths, hospital admissions or attendance at emergency departments. 23

Impact on service utilisation and delivery

Impact on primary care contacts

The impact of GP telephone consultations on primary care workload and on the number of face-to-face appointments was a key issue in a range of studies, which suggests that, although telephone consultations can result in initial reductions in primary care demand, over time this may represent a redistribution of workload rather than an overall saving. There is some evidence in small-scale studies49,65 and claims in letters34,55,66 that GP telephone consultation systems reduced patient demand for face-to-face appointments, out-of-hours services49 and home visits. 34,65 Earlier studies of patient perspectives also suggested that telephone consultations resulted in resource savings, as approximately three-quarters of patients surveyed who had received telephone consultations would have made a face-to-face appointment had they not spoken to the GP on the telephone. 51,67

However, the ESTEEM23 and McKinstry et al. 29 RCTs suggest that an initial drop in face-to-face contacts is associated with a redistribution rather than reduction of GP workload. The authors found that GP telephone consultations led to an increase in consultations (of all types) in the subsequent 2 weeks (from 0.4 to 0.6 consultations, 95% CI of difference 0.0 to 0.3 consultations)6,31,35,41 or an overall increase in combined telephone and face-to-face contacts compared with usual care. 6,23

The ESTEEM trial found that GP telephone consultations were associated with a 33% increase in the mean number of contacts over the next 28 days compared with usual care (face to face and telephone combined) [2.65 (SD 1.74) contacts (telephone consultation system) vs. 1.91 (SD 1.43) contacts (usual care), rate ratio (RR) 1.33, 95% CI 1.30 to 1.36]. Although GP telephone consultations reduced face-to-face contacts by 39% (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.69), the mean number of telephone consultations per patient increased 10-fold. Thus, the authors identified an overall redistribution of GP workload with GP telephone consultations, with any time savings from reduced face-to-face contacts more than balanced by increases in the number of telephone contacts undertaken. 6

Impact on the duration of clinician contact

The ESTEEM23 and McKinstry et al. 29 RCTs also examined the impact of telephone consultations on the duration of clinician contacts, and found no significant difference and some time savings, respectively, when compared with usual care. The ESTEEM trial found no overall clinician time savings from GP telephone consultations: the composite duration of clinician–patient contact on the day of the request was 10.3 minutes for GP telephone consultations and 9.6 minutes for usual care, with no clinically significant difference in the overall GP time required between the two. 24

The two-site RCT by McKinstry et al. 31 found that the use of telephone consultations for same-day appointments was time-saving overall, in terms of patient–doctor contact, compared with those appointments that were made directly face to face, but the longest clinician contact was for those who consulted by telephone and were subsequently asked to come to the practice (mean 10.9 minutes, SD 4.4 minutes);35 however, shorter-term savings may have been offset by the higher subsequent reconsultation noted above. Two trials24,31 found that the duration of a GP face-to-face consultation combined with a preceding telephone consultation was longer than that of a face-to-face consultation in usual care.

Impact on use of out-of-hours and emergency services

Although the grey literature reviewed includes claims of lower numbers of A&E attendances as a result of the introduction of telephone consultation systems,68–70 the evidence to bear out these claims is limited, as only one study23 reported on the impact of telephone consultation systems on the use of health services outside primary care. The ESTEEM trial23 found no significant difference between the use of NHS Direct or emergency care services for patients assigned to GP- or nurse-led consultations and usual care. The authors found no significant increase in the proportion of patients with at least one emergency admission within 7 or 28 days of the consultation request, in either the GP- or nurse-led telephone groups, when compared with usual care. Additionally, similar proportions of patients reported contact with NHS Direct in the 28-day follow-up across the three groups (roughly 2%), with similar mean numbers of contacts, at 0.05 and 0.04 per person for GP telephone consultations and usual care, respectively. 23

Impact on costs

Although significantly increased telephone costs45,49,58,68,71 and concerns around the initial financial outlay30 associated with the implementation of telephone consultation systems were raised in the literature, robust evidence on costs is sparse. An economic evaluation conducted as part of ESTEEM23 found that, although GP telephone consultations were associated with increased contacts, there was no significant difference in average costs of health care over 28 days from a same-day consultation request between patients who received GP telephone consultations and usual care, possibly attributable to the reduction in GP face-to-face contacts.

The impact of telephone consultation on prescribing behaviour was raised as another concern in relation to cost. Some authors argued that a tendency for telephone consultation to foster ‘automatic’ repeats of medication would result in overprescribing and higher costs for patients and the health system. 72 Yet, studies that investigated prescribing patterns31,48 found limited use in telephone consultations or no difference in GP antibiotic prescribing behaviour compared with face-to-face consultations.

The potential for telephone consultations to offer patient cost savings, especially on travel in remote rural areas, has also been noted,73 but remains unexplored in the literature.

Summary

We have given an overview of the existing evidence base around telephone consultations in primary care as it relates to patient access, patient experience (including that of hard-to-reach and vulnerable groups), clinician and staff experience, the nature of consultations, patient safety, service utilisation (both within and outside general practice) and costs. Although the limited nature of the evidence has been noted here and elsewhere,36,54 in the last decade key studies and bodies of work, such as the ESTEEM trial23 and the work of McKinstry and colleagues,29–33 have clearly contributed towards a more robust evidence base in the UK. We did not seek to exclude studies on the basis of quality, which runs the risk of overinferring from poor-quality studies. This said, we have noted study type and any major limitations to interpreting findings throughout our synthesis.

In relation to our three research questions, the existing evidence around telephone consultation remains patchy and somewhat inconclusive. There is evidence to suggest that the content and focus of consultations is altered in telephone consultations compared with face-to-face consultations, but there is limited evidence from which to assess whether or not this has an impact on patient safety. Overall, patients seem no less satisfied with telephone consultations than with face-to-face consultations, although telephone-based systems do not appear to necessarily overcome challenges of access for those in work, or improve satisfaction for those living remotely. Nor is there evidence to suggest that particular patient groups, such as older patients, are specifically disadvantaged through the use of telephone consultation systems. Patients from ethnic minority groups may have different experiences of telephone consultations compared with white British patients, but the reasons for this need further exploration. The experience of clinicians and wider practice staff is varied and contingent on the system and practice context into which telephone consulting is introduced. In terms of resource use, although telephone consultation may reduce primary care contact (e.g. through consultation length) initially, it seems likely from the evidence that this is not sustained when subsequent contacts are taken into account. Similarly, it is not clear that telephone consultations result in changes in patients’ use of wider health services, such as emergency care, changed patterns of GP prescribing or potential cost savings. The evidence base needs to be strengthened in this regard.

Chapter 3 Analysis of administrative data from general practices

Data were provided by one commercial provider (GP Access) using data from administrative information within the clinical records of practices using the ‘telephone first’ approach. The analysis aimed to explore if, and how, appointments changed following the introduction of the approach.

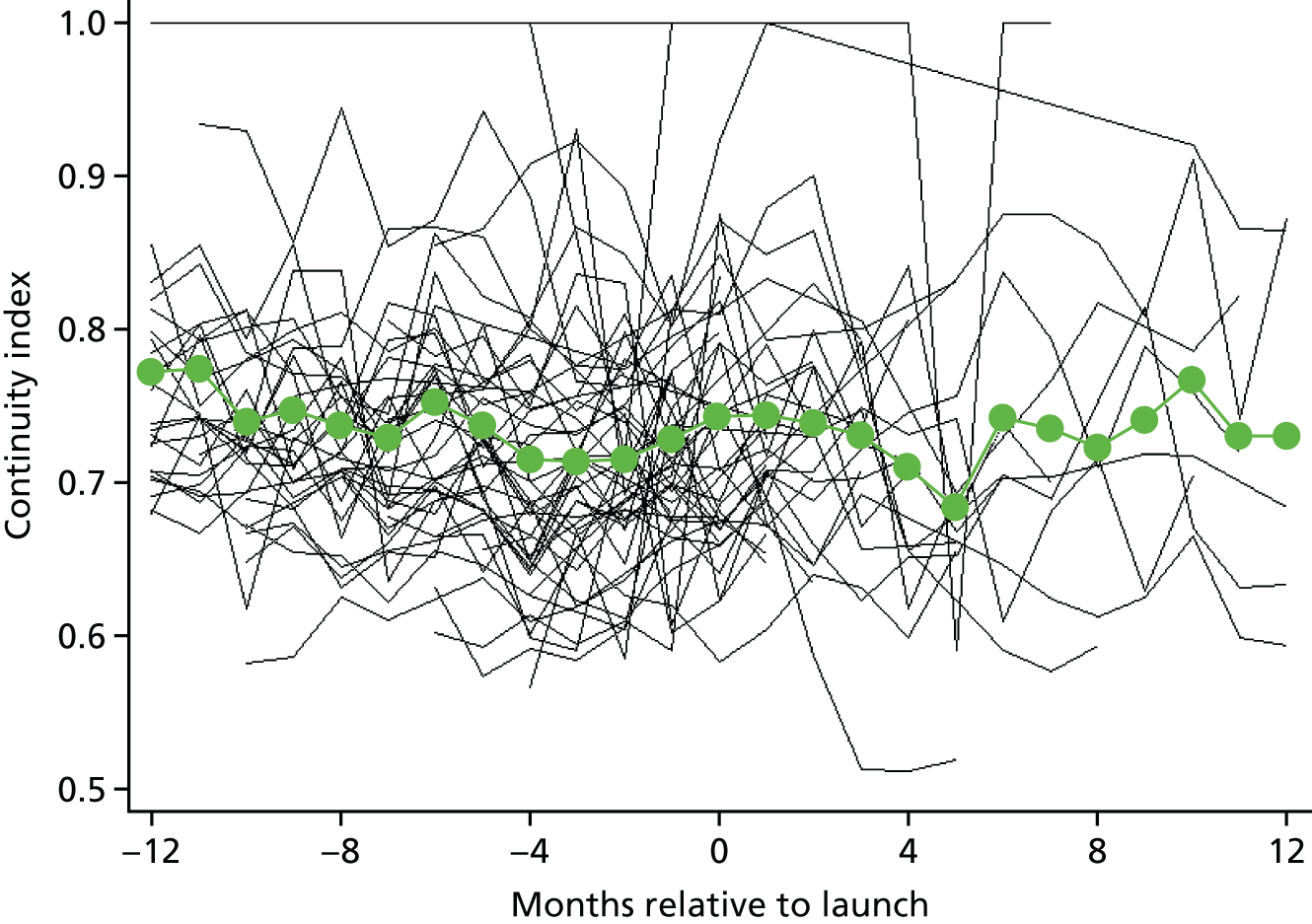

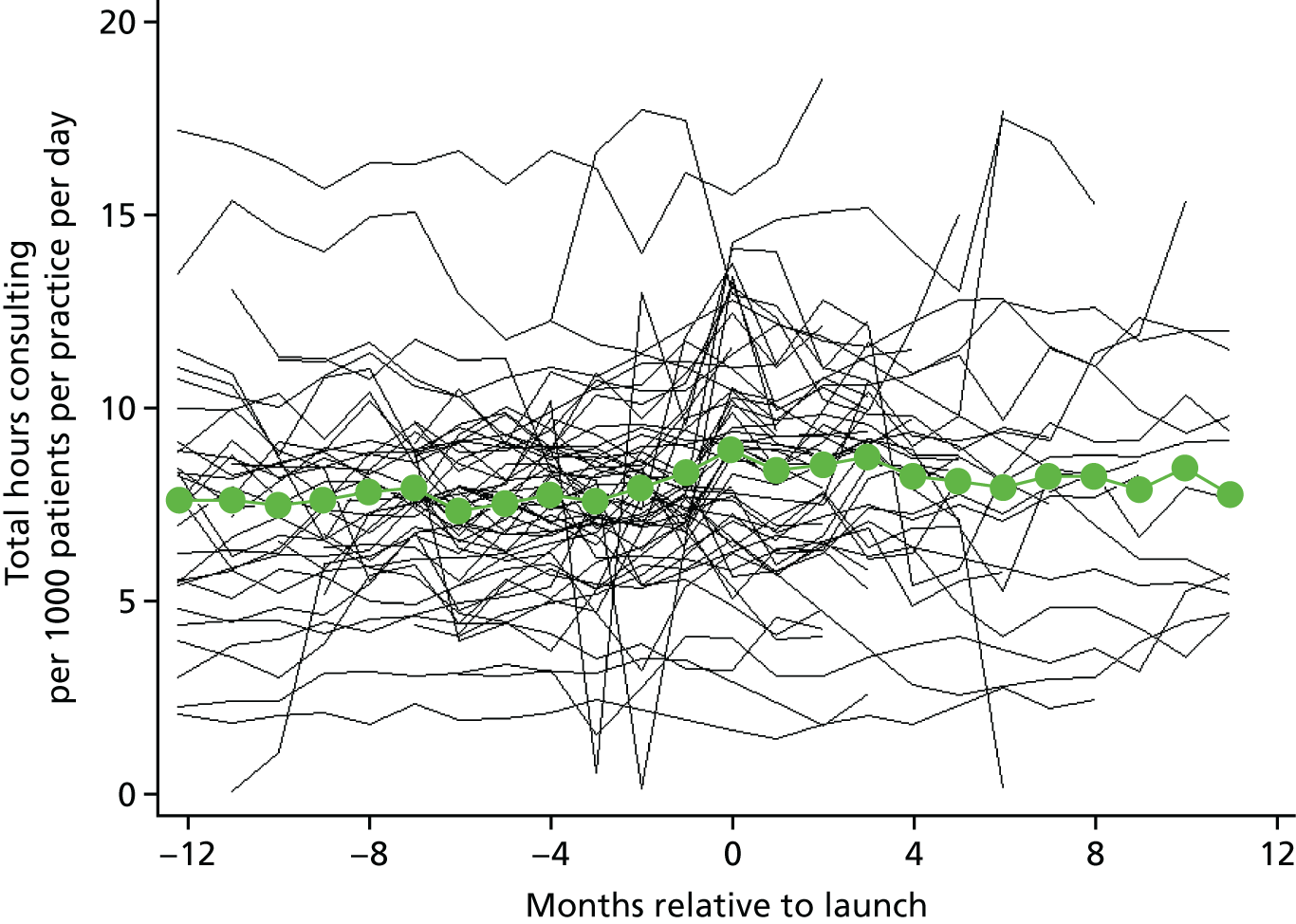

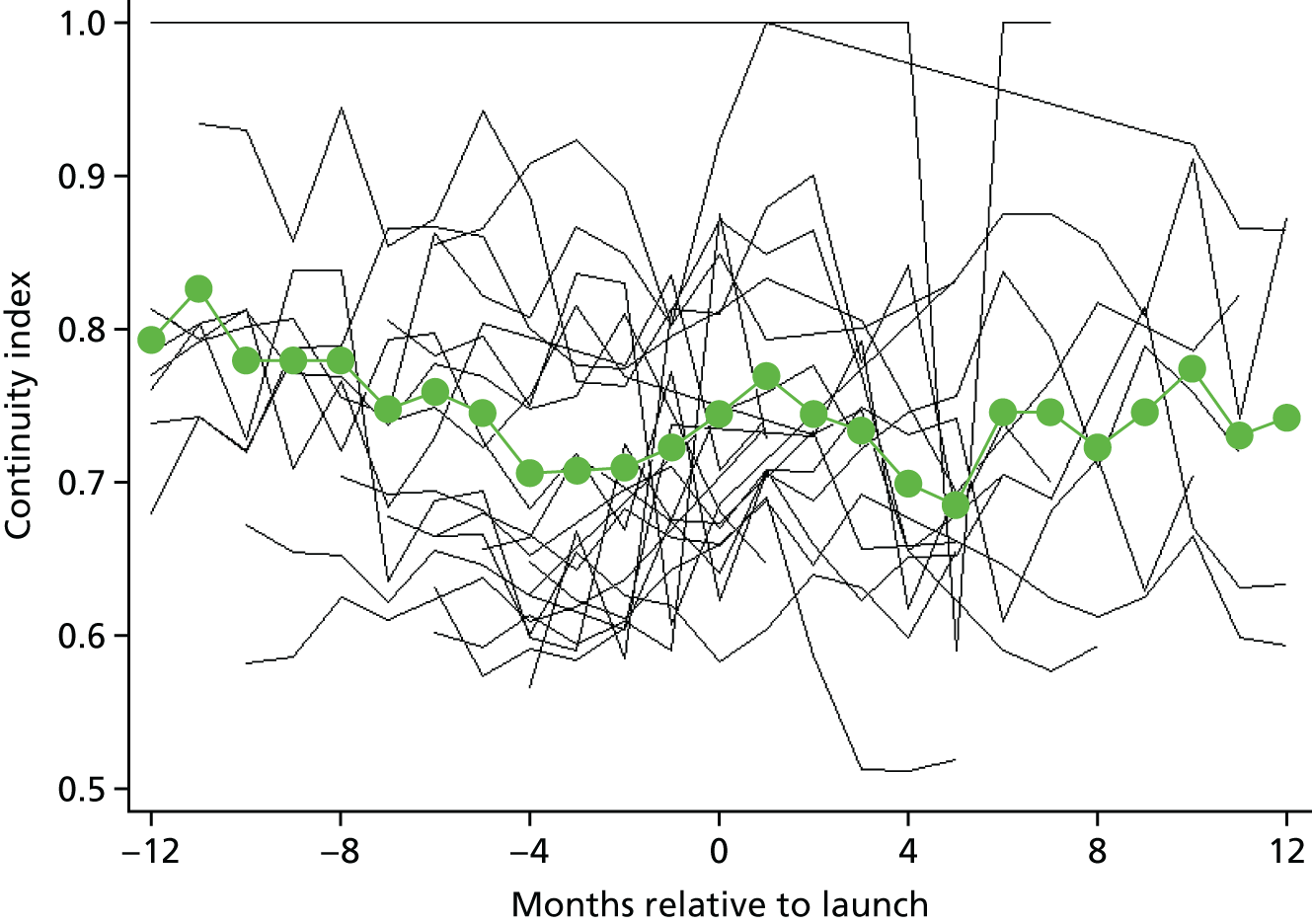

Methods

Data on telephone and face-to-face appointments and on continuity of care were extracted from the practices’ computer systems by the commercial company up to 28 October 2016 and transferred to the research team as anonymised data sets for analysis. For individual appointment-level data, information was available regarding the date and time when an appointment was booked, the date and time when the appointment took place, the type of appointment (face-to-face, telephone, home visits or administrative) and who the appointment was with (GP, nurse or other). Continuity of care was measured over short time periods in the months following the introduction of the ‘telephone first’ approach. The continuity of care data included the usual provider continuity (UPC) score (the proportion of visits that are with the most frequently seen GP) and patient age. To preserve anonymity, the commercial company created the UPC score;74 this was calculated for each patient who had two or more appointments in any 1 calendar month as the number of appointments with the GP most frequently seen divided by the total number of appointments in that time period. Patients could not be linked across different months. The company also provided details on the date when the ‘telephone first’ approach was introduced and the current status of the system [i.e. whether, in their view, the practices were still running the ‘telephone first’ system per protocol, running a hybrid system (e.g. permitting some degree of advance booking) or had ceased using the approach]. Only practices that launched the ‘telephone first’ approach before 31 December 2015 were included in the final data set to allow sufficient time for the system to have bedded in (potentially allowing ≥ 10 months of post-intervention data for each practice, although in reality this was often less).

As data were available for intervention practices from only one commercial company, there are no control practices. Care must therefore be taken in attributing changes to the intervention, as outside factors (e.g. other contemporaneous changes in the NHS) could have had an influence on the results. We examined changes in the following outcomes (see Table 1 for full definitions):

-

number of appointments

-

time waited for an appointment

-

length of appointment

-

total time spent consulting (by GPs) per day

-

continuity of care.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined in Table 1. The reason for excluding appointments that took place on Saturdays or Sundays (and appointments booked on these days when considering the time waited for an appointment) was that the very small numbers compromised statistical modelling. Given their rarity, excluding these appointments was unlikely to have had an important overall effect on our conclusions. Consultation lengths were determined by how long patient records were open for each consultation, rather than the actual time spent consulting. Although consultations lasting > 30 minutes do take place, we considered that recorded durations of > 30 minutes were more likely to reflect a record being left open beyond the end of a consultation and so, when considering the length of appointments or the total time spent consulting per day by practice GPs, appointments lasting > 30 minutes were excluded from the analysis.

| Outcome | Definition | Inclusion criteria | Model | Unit of analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of appointments | The total number of appointments (face to face, telephone or home visits) with a GP per practice per day |

|

Mixed-effects Poisson regression | Each day in each practice |

| Time waited for an appointment | The number of days between booking the appointment (face to face or by telephone) and the time the patient had the appointment with the GPa |

|

Linear mixed model | Individual appointments |

| Length of appointment | The time in minutes between the start and the end of an appointment (either face to face or by telephone) with a GP |

|

Linear mixed model | Individual appointments |

| Total time spent consulting (by GPs) per day | The total time in minutes that GPs spent in appointments (face to face and by telephone) with patients per practice per day |

|

Log-transformed for analysis Linear mixed-effects regression model |

Each day in each practice |

| Continuity of care | For patients with two or more appointments in 1 month, the proportion of appointments that are with the GP most frequently seen in that month (score from 0 to 1) |

|

Linear mixed-effects regression | Individual patients in each month |

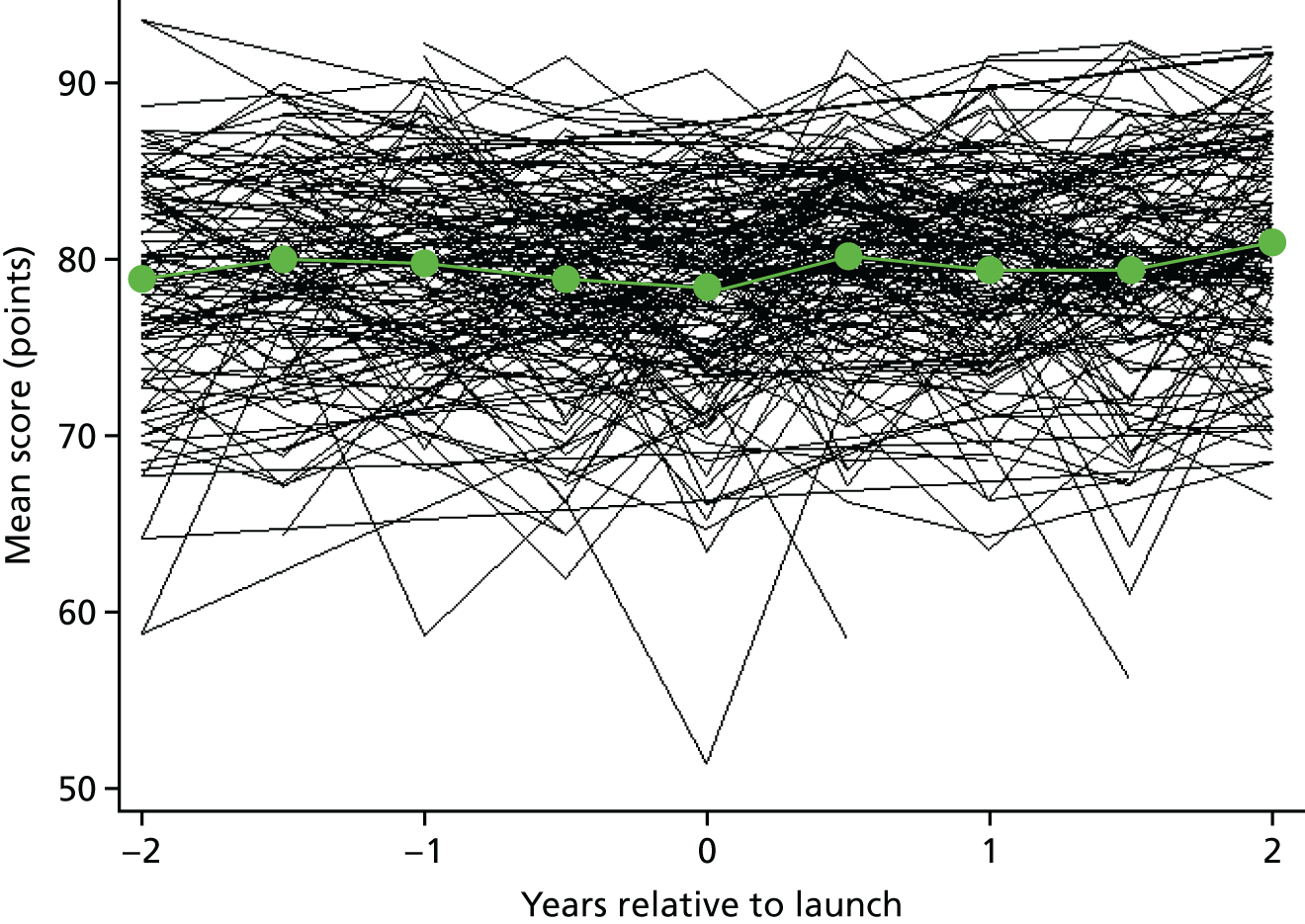

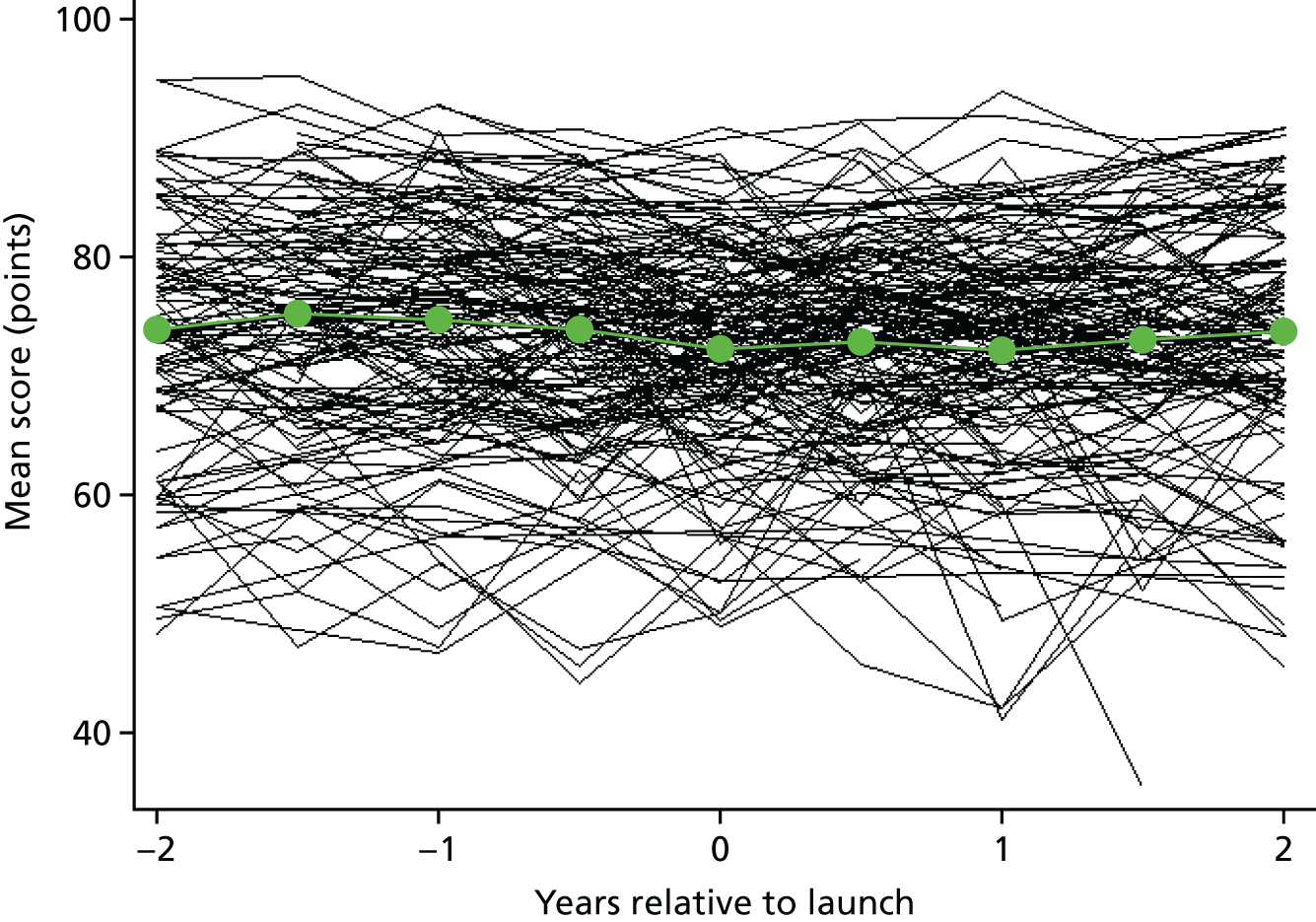

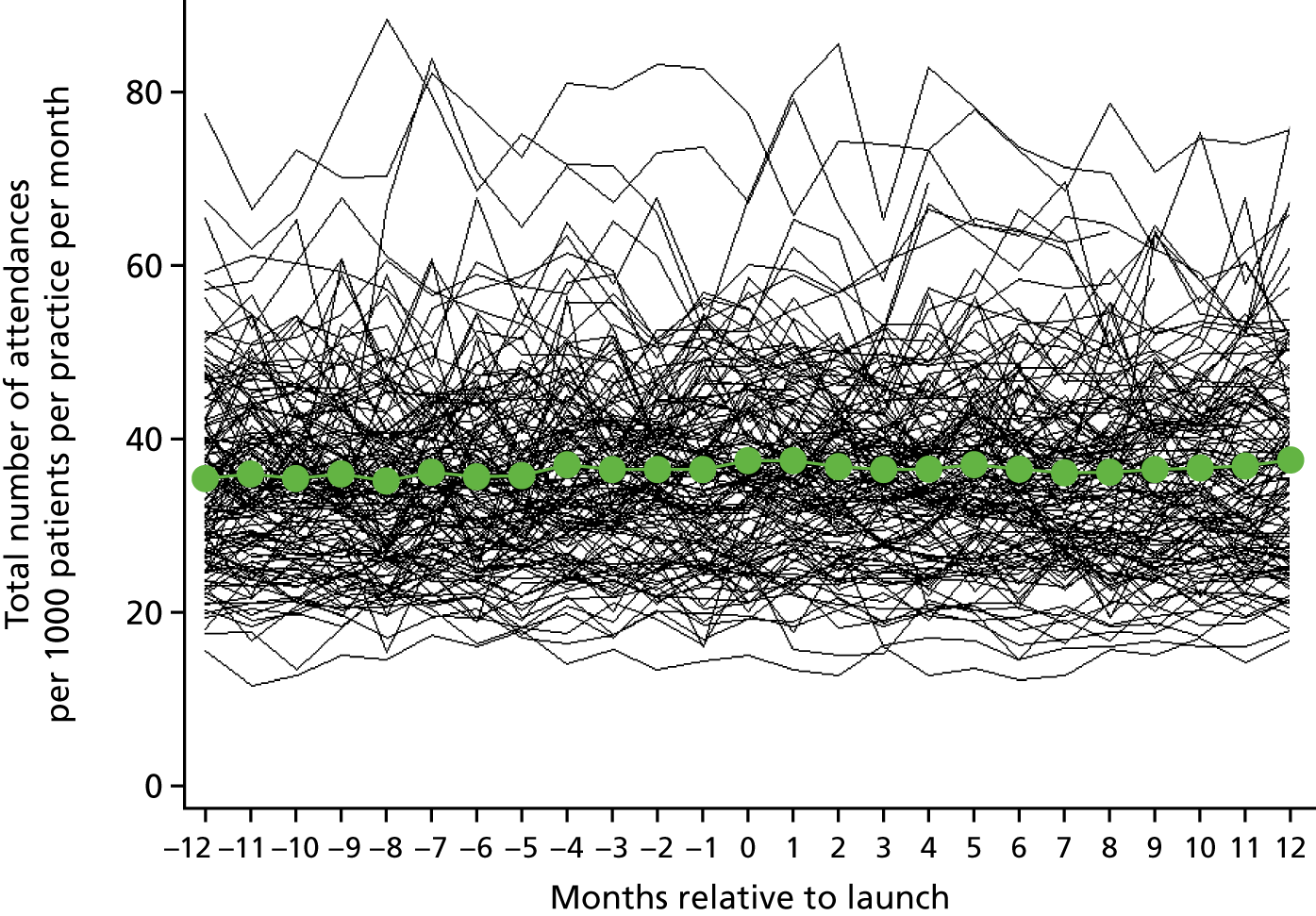

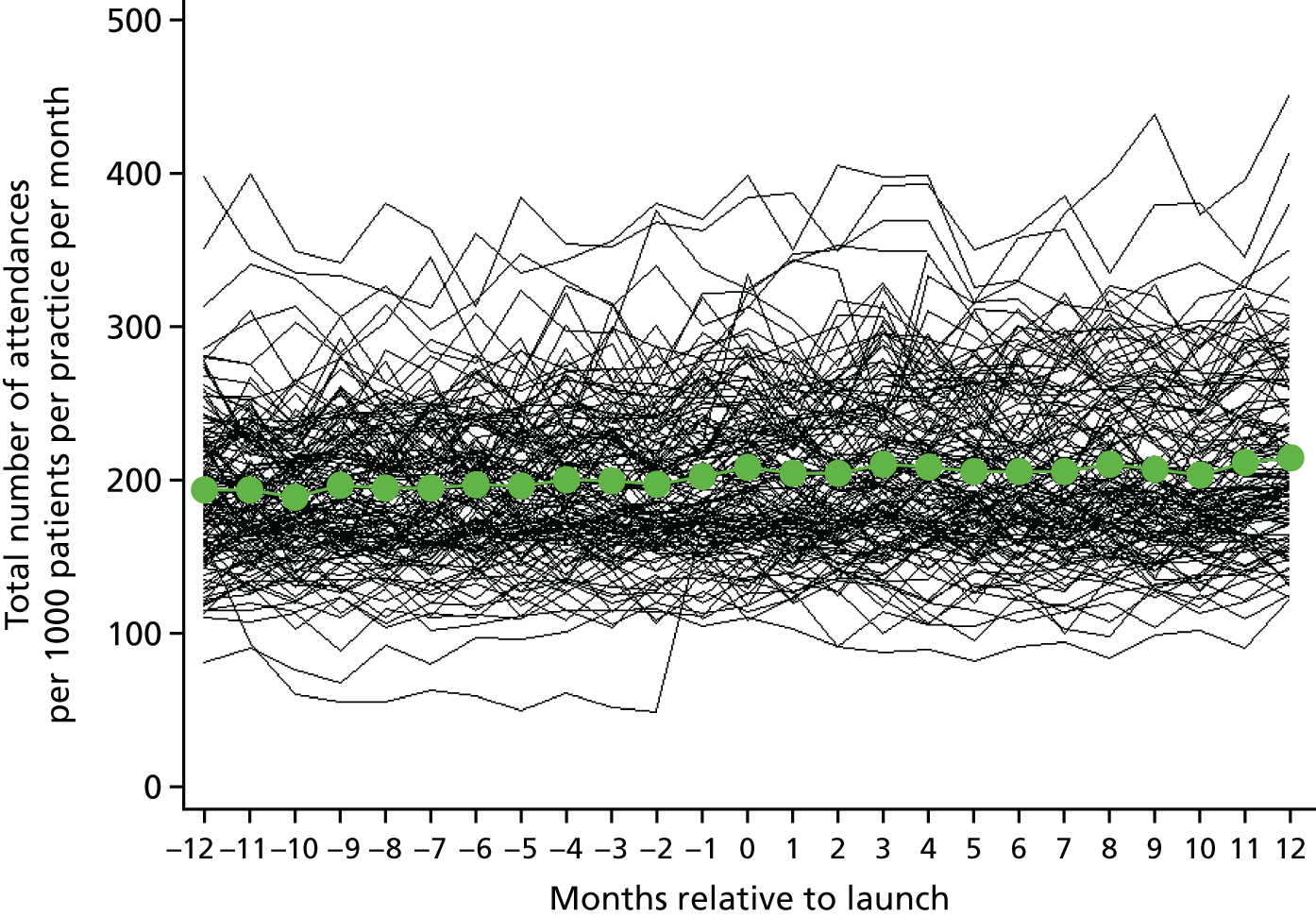

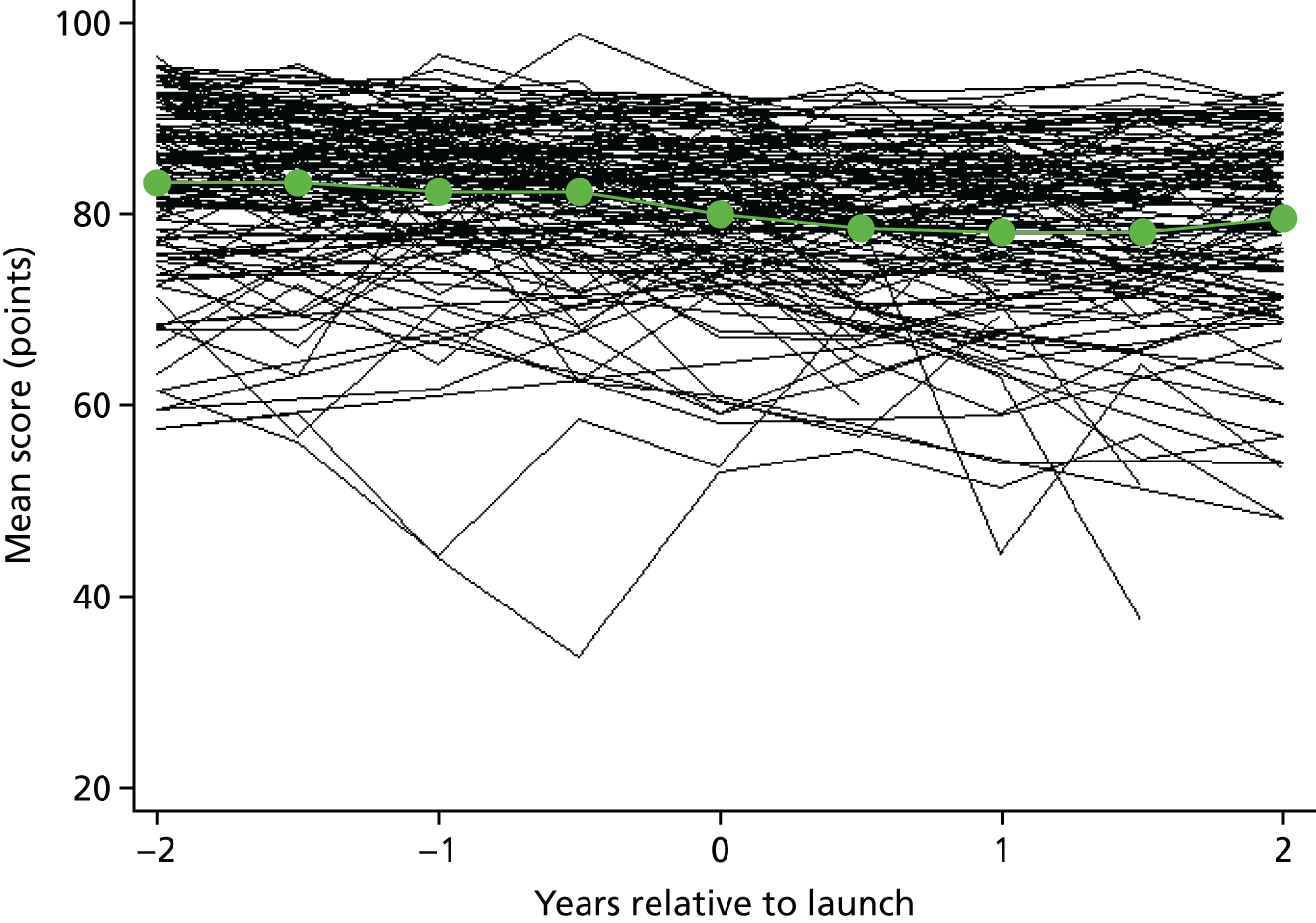

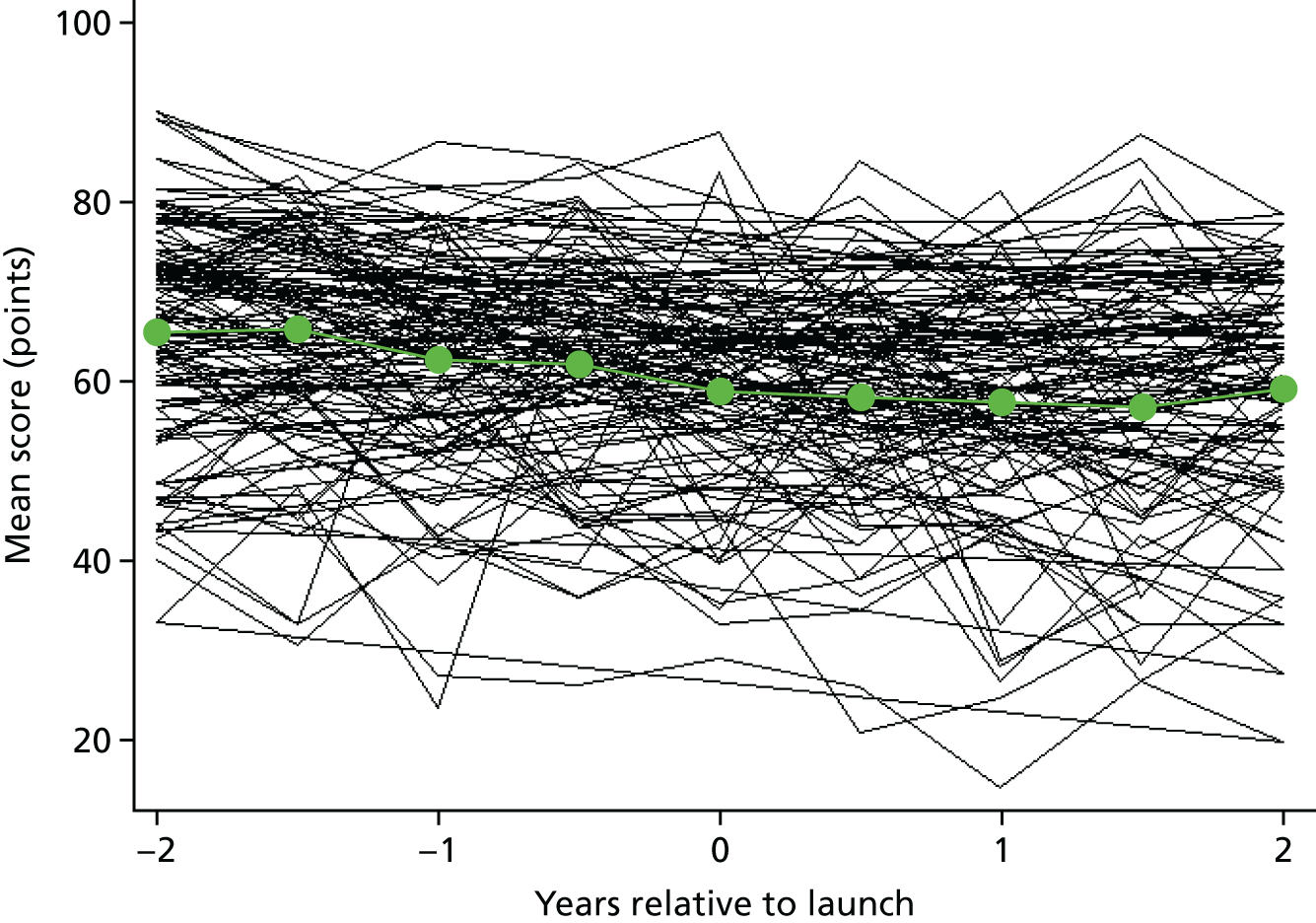

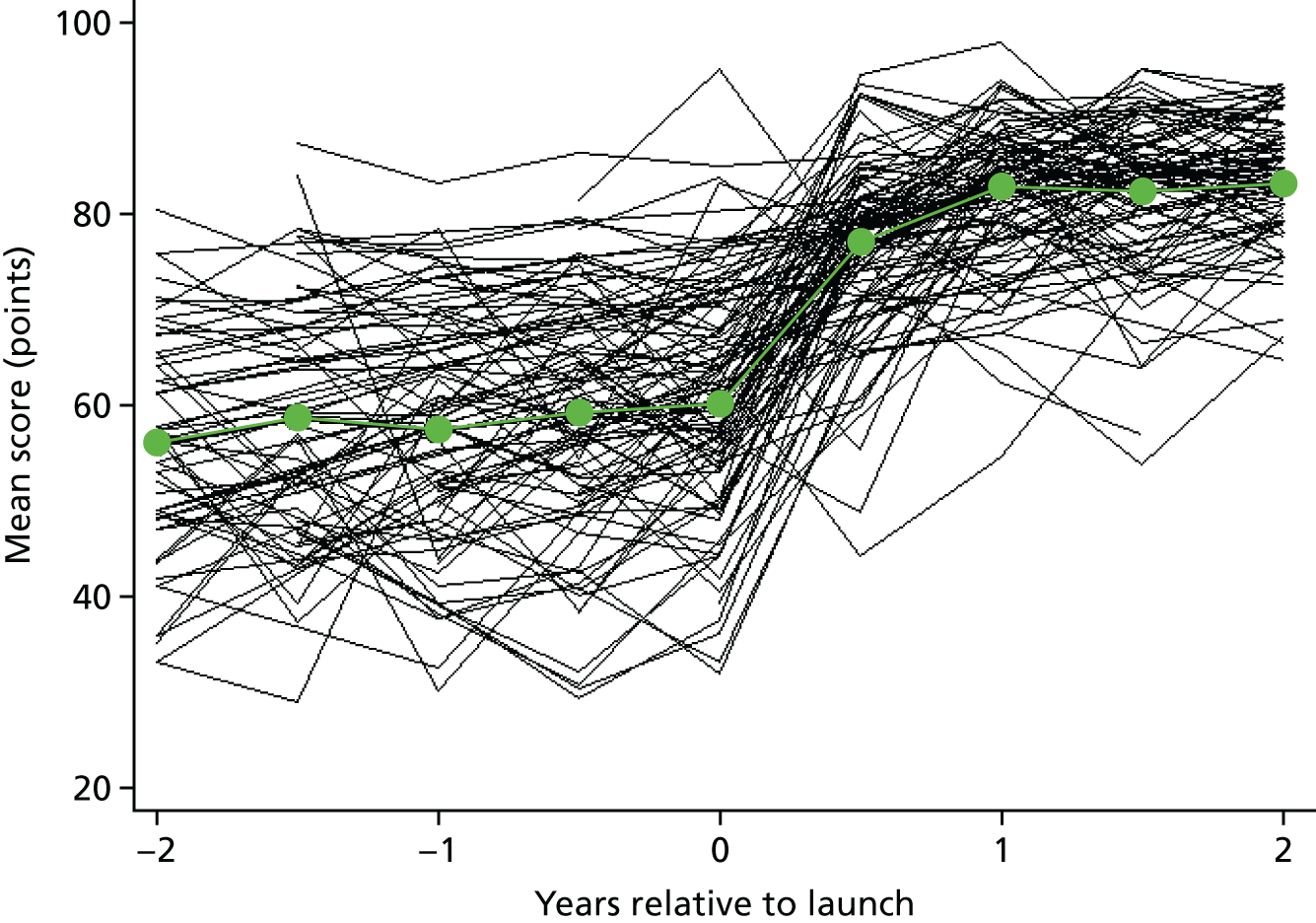

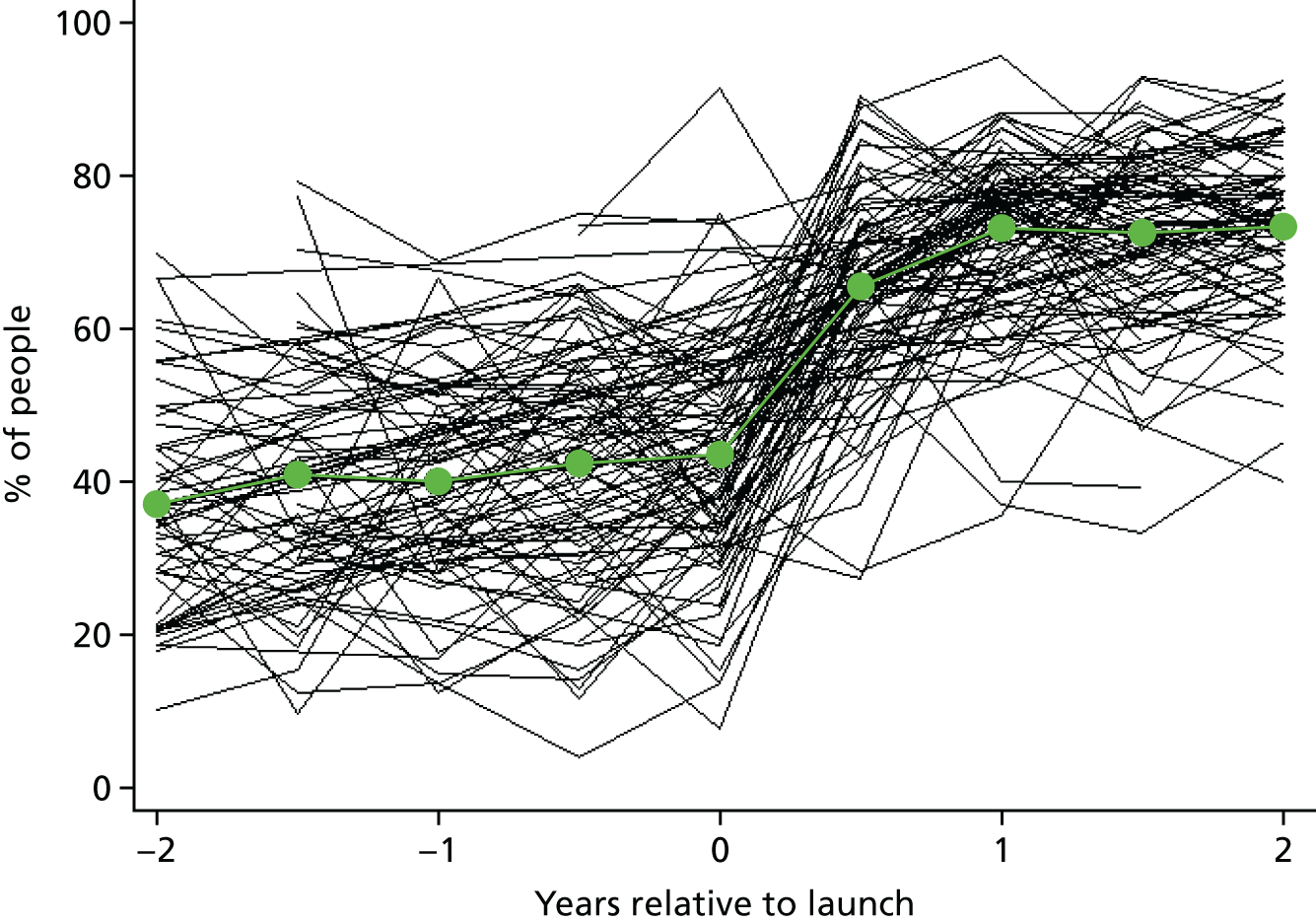

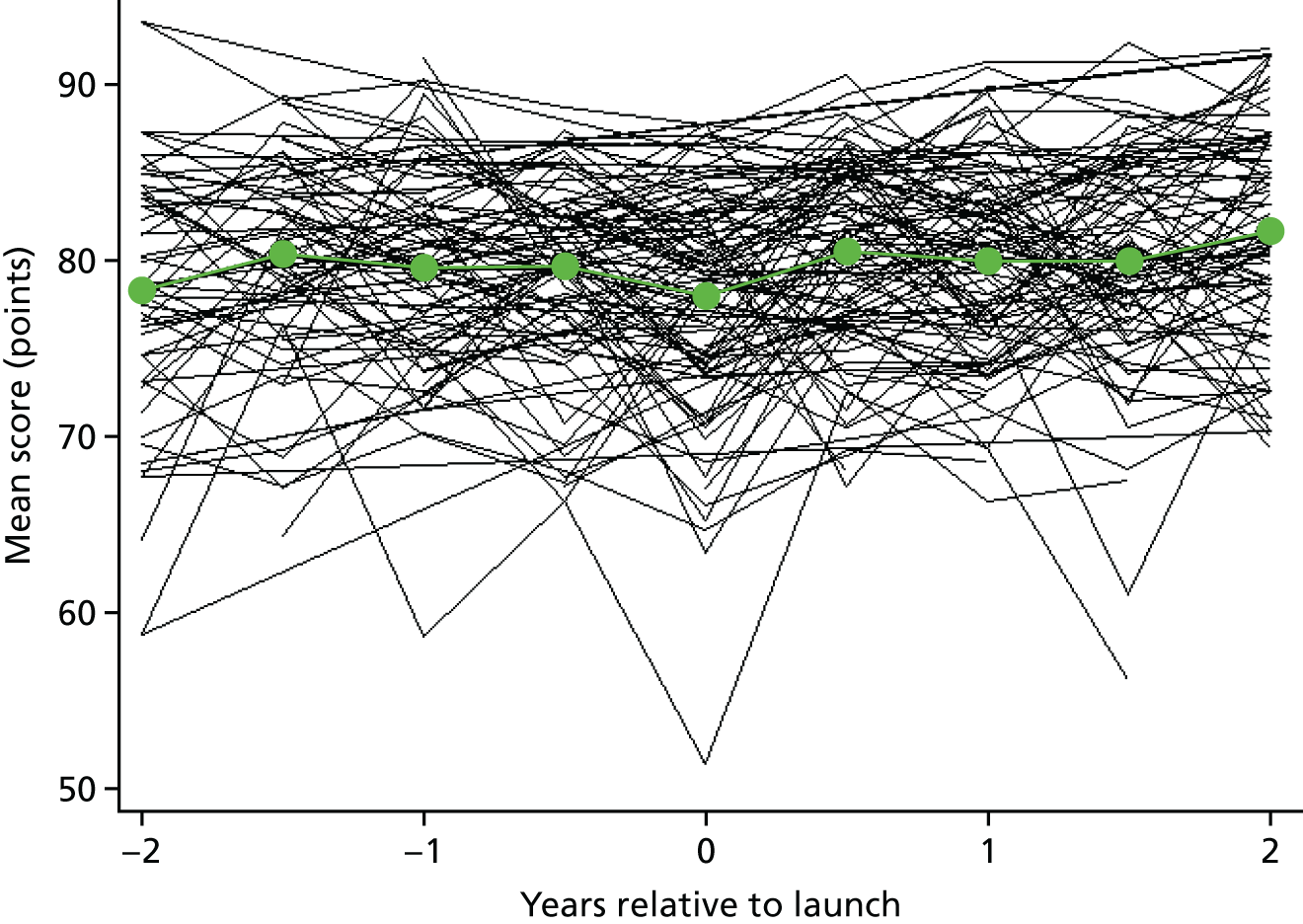

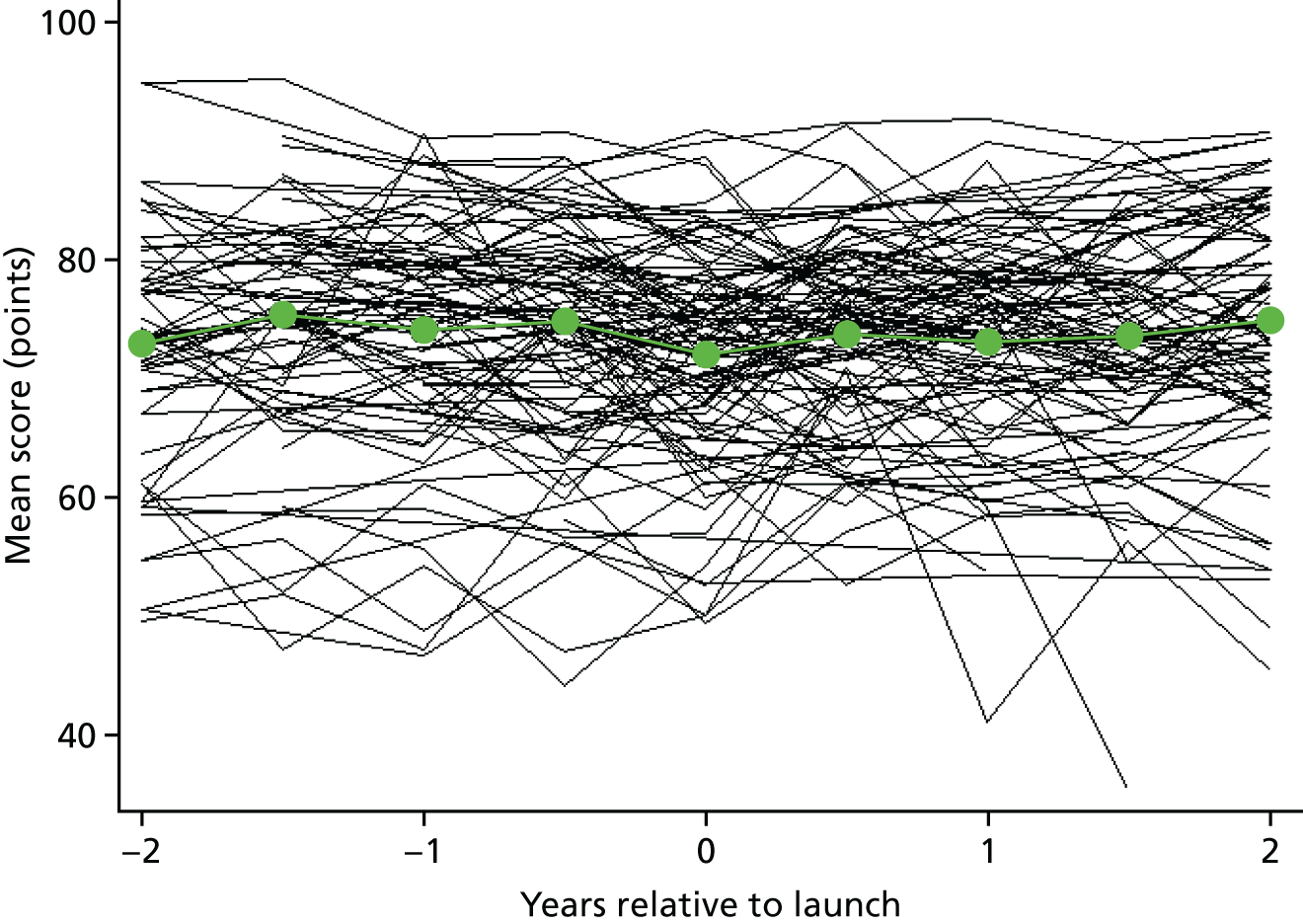

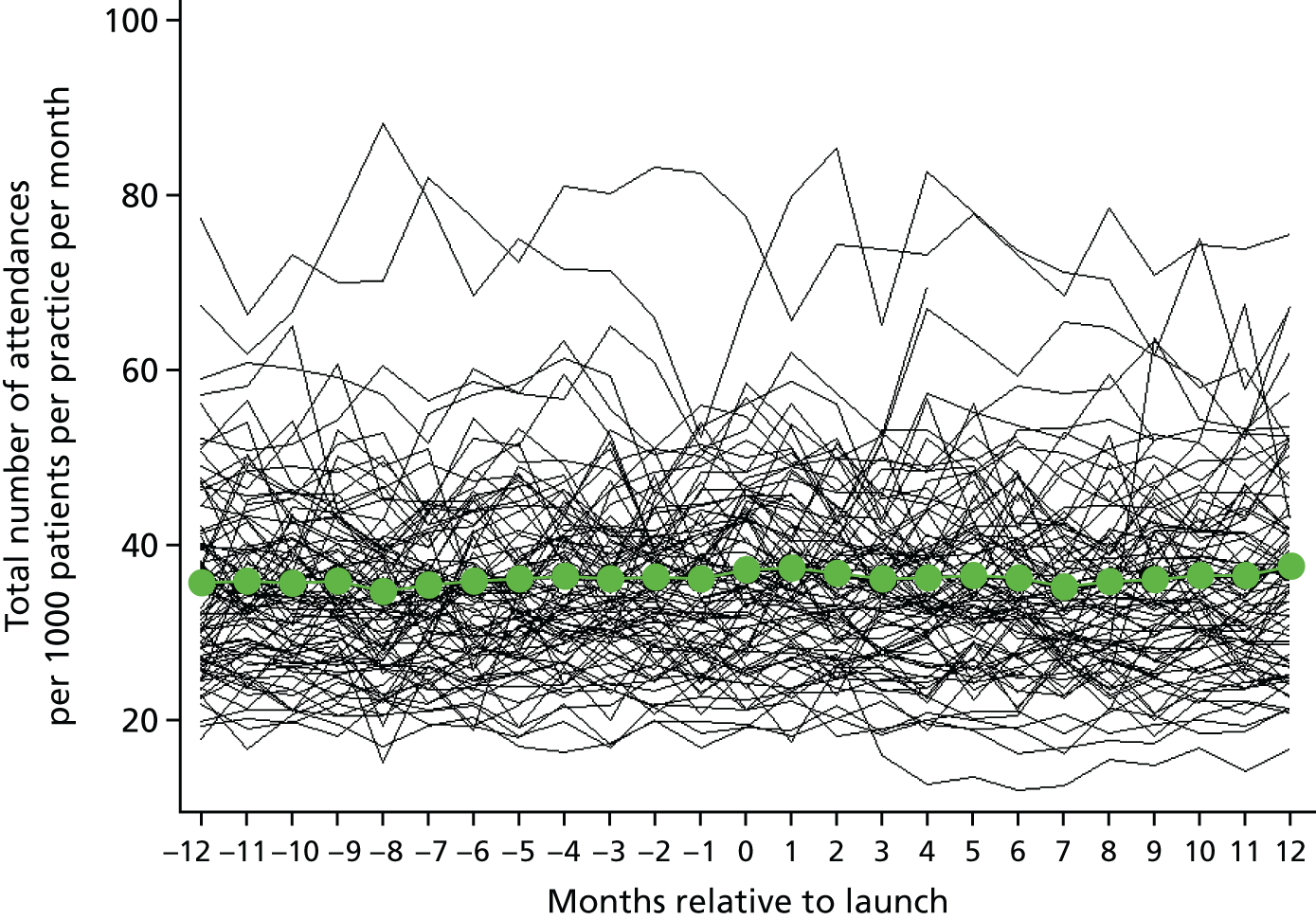

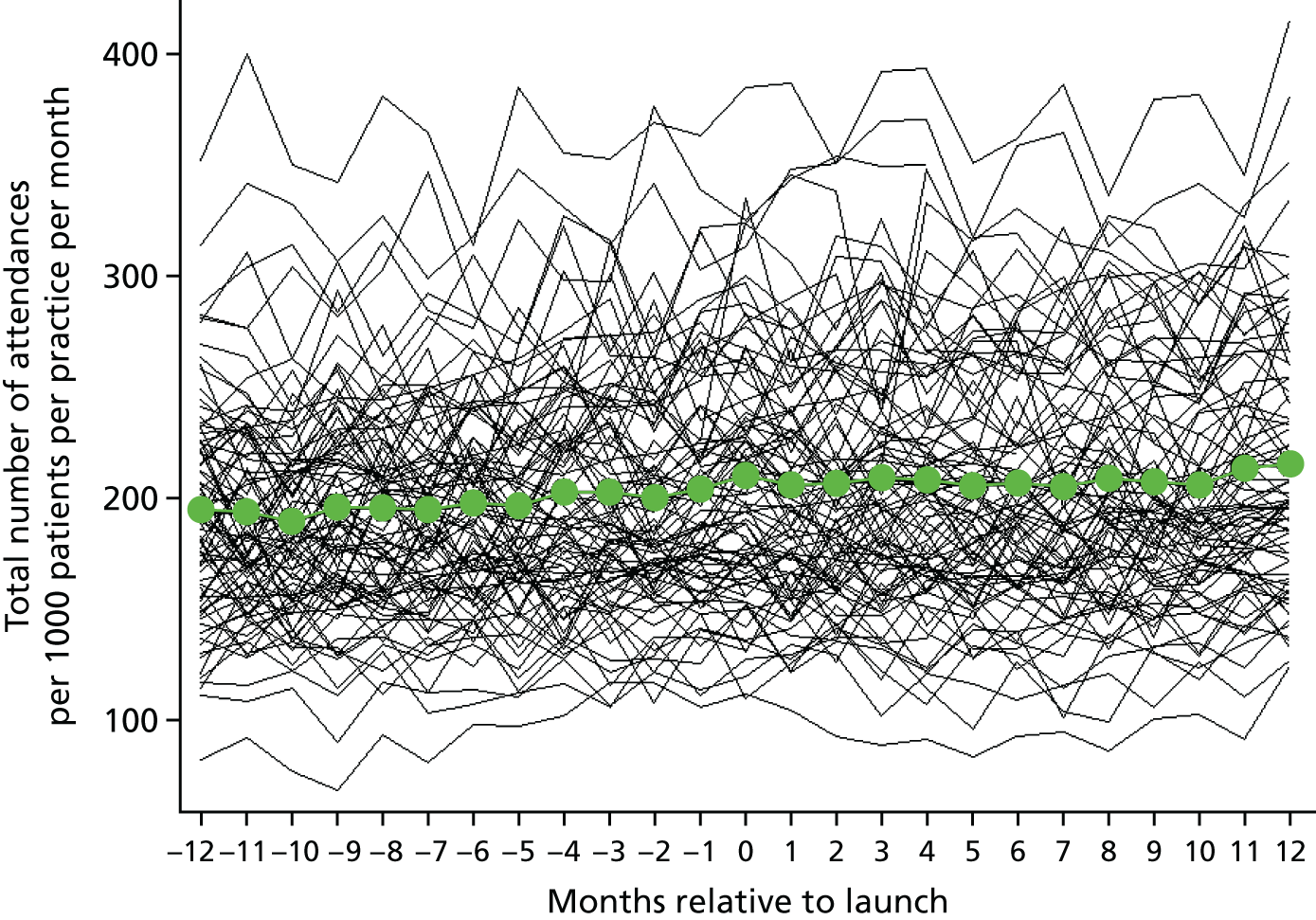

Statistical analysis

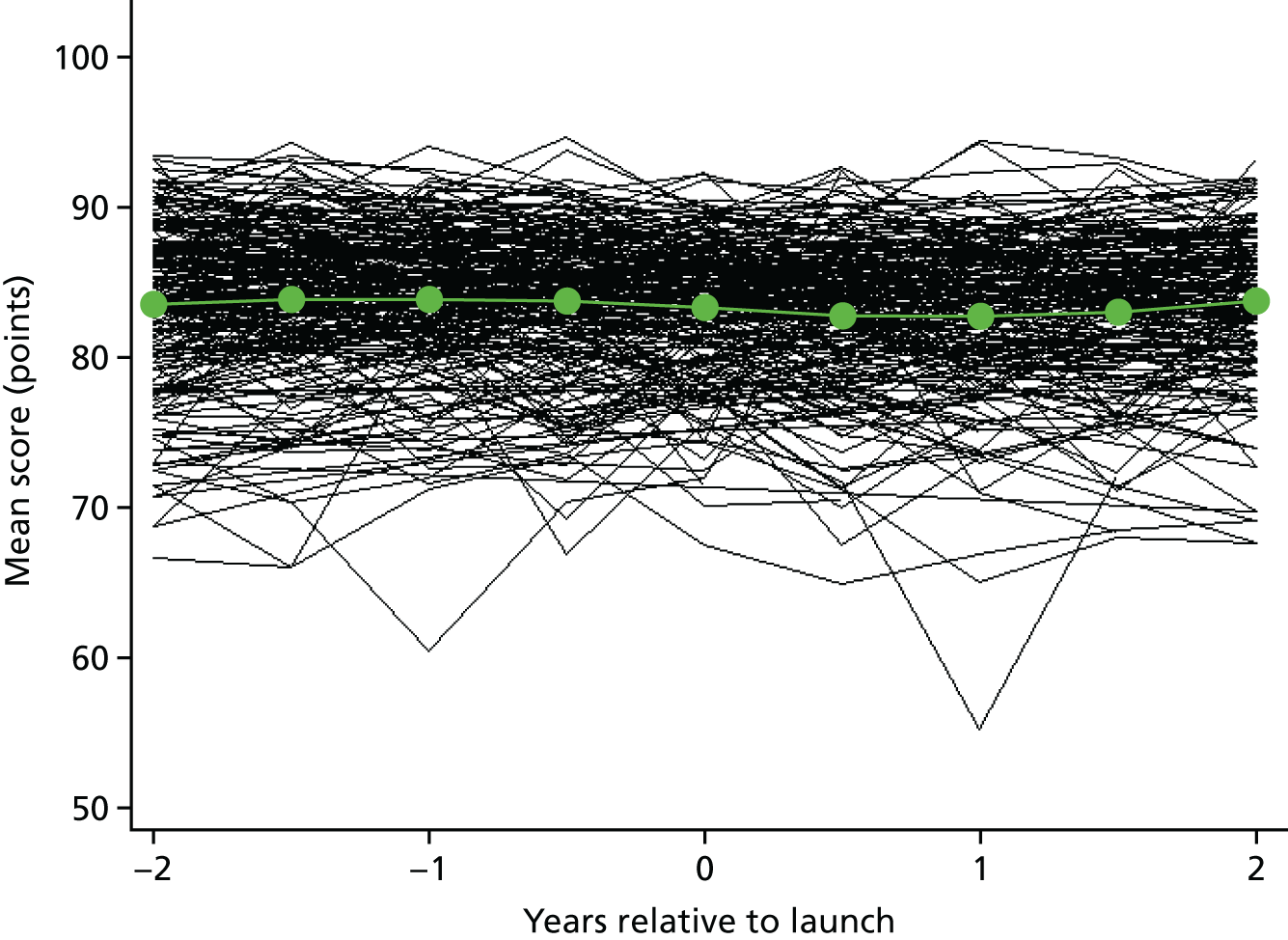

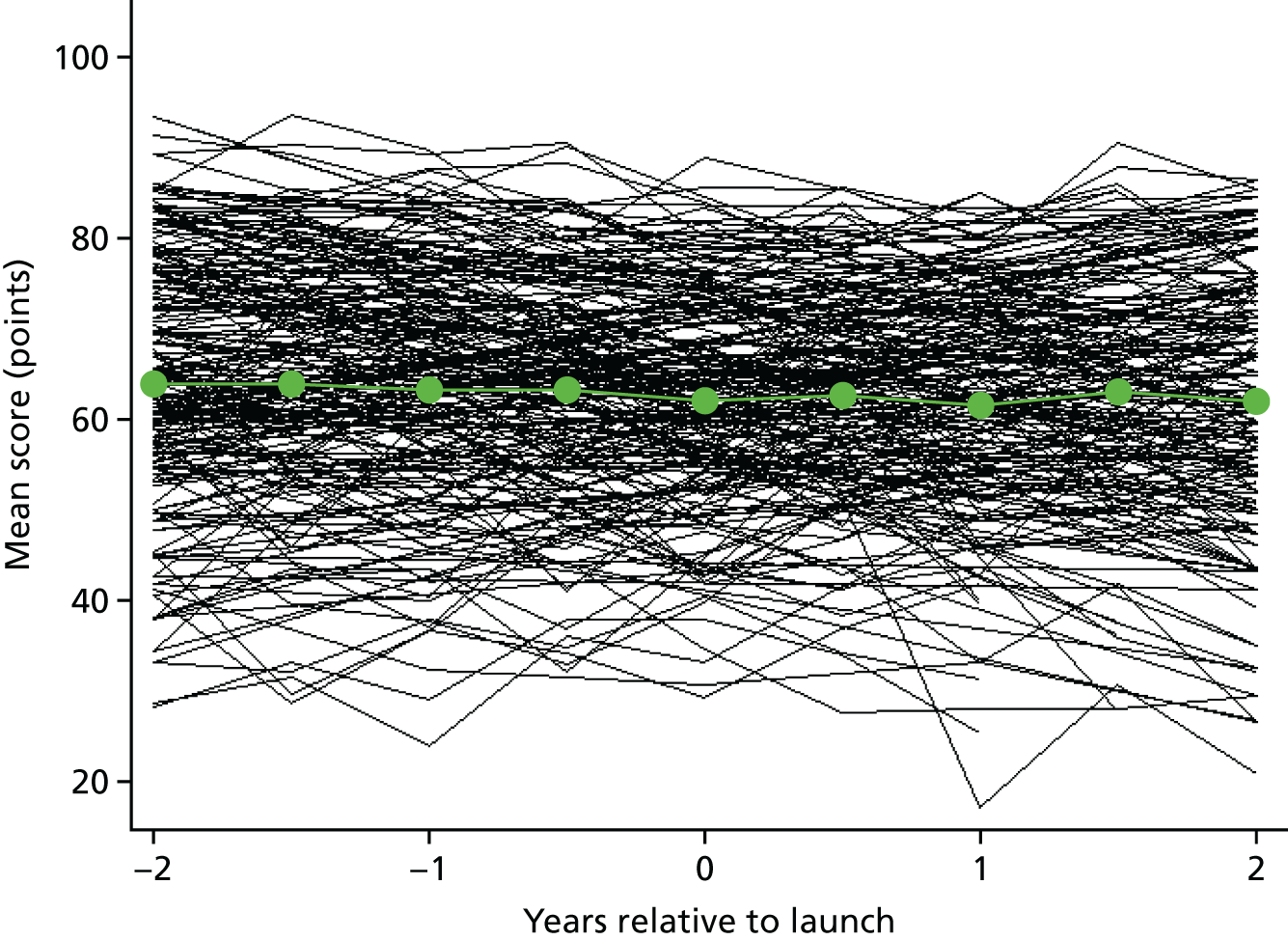

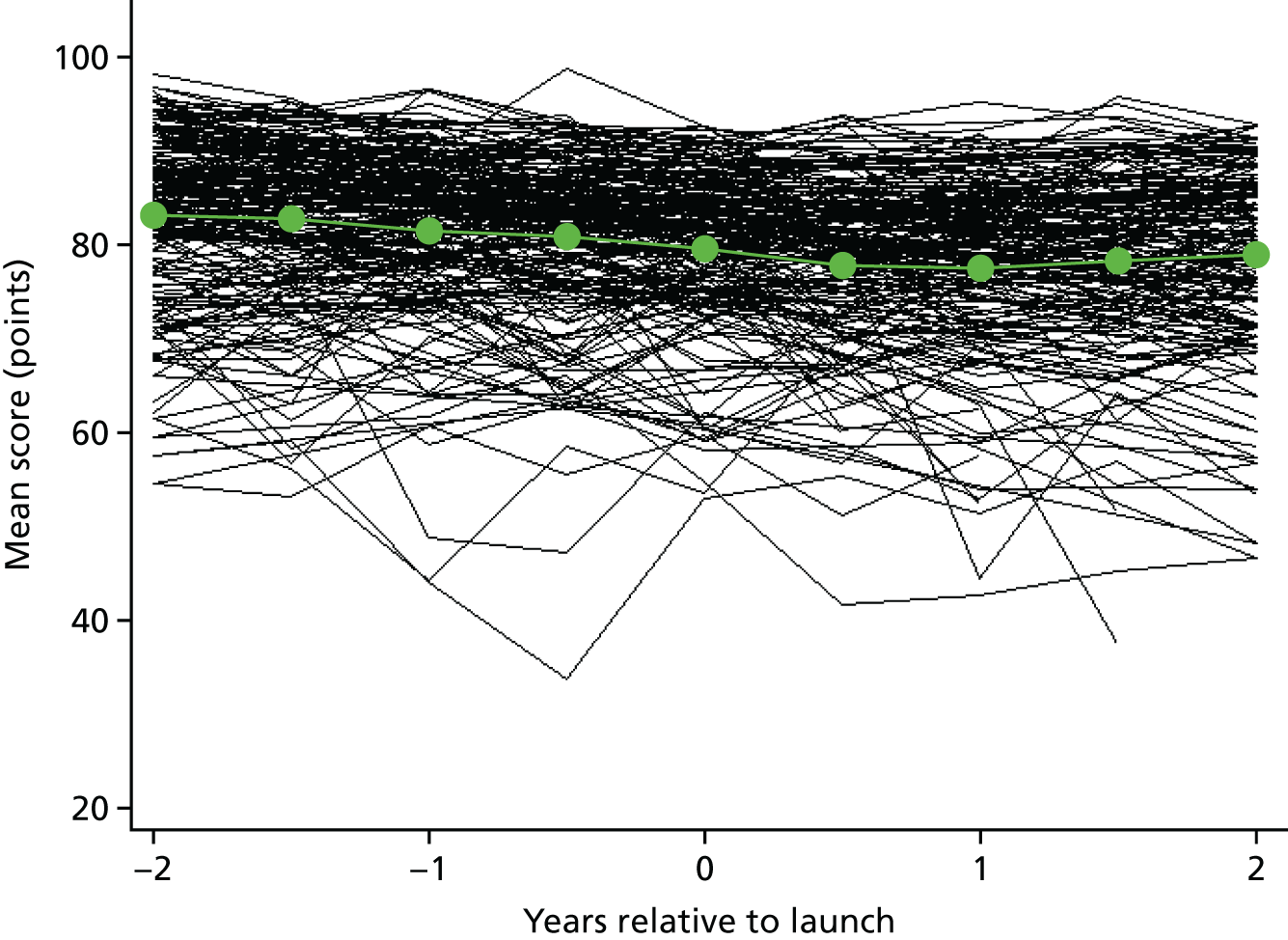

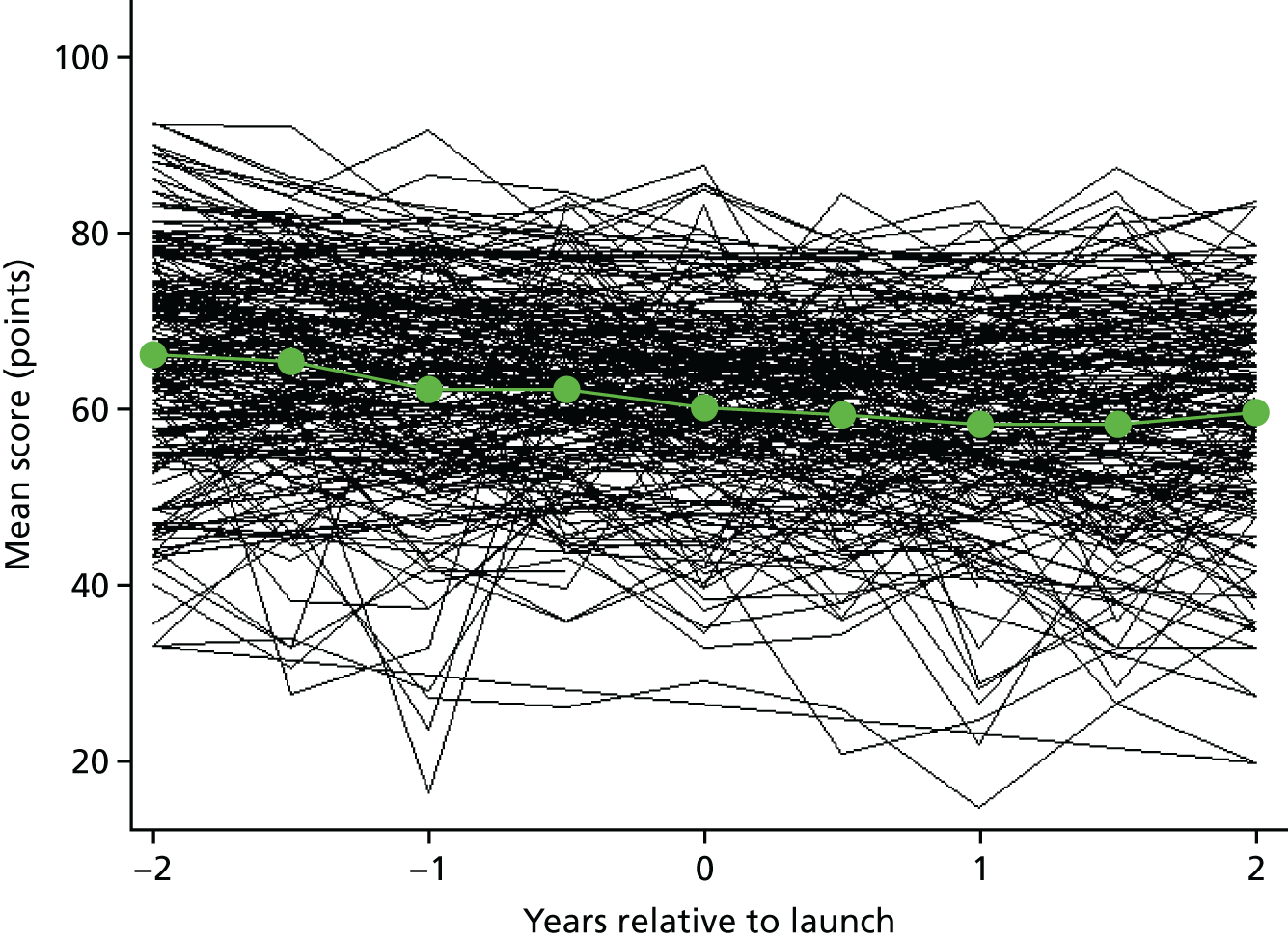

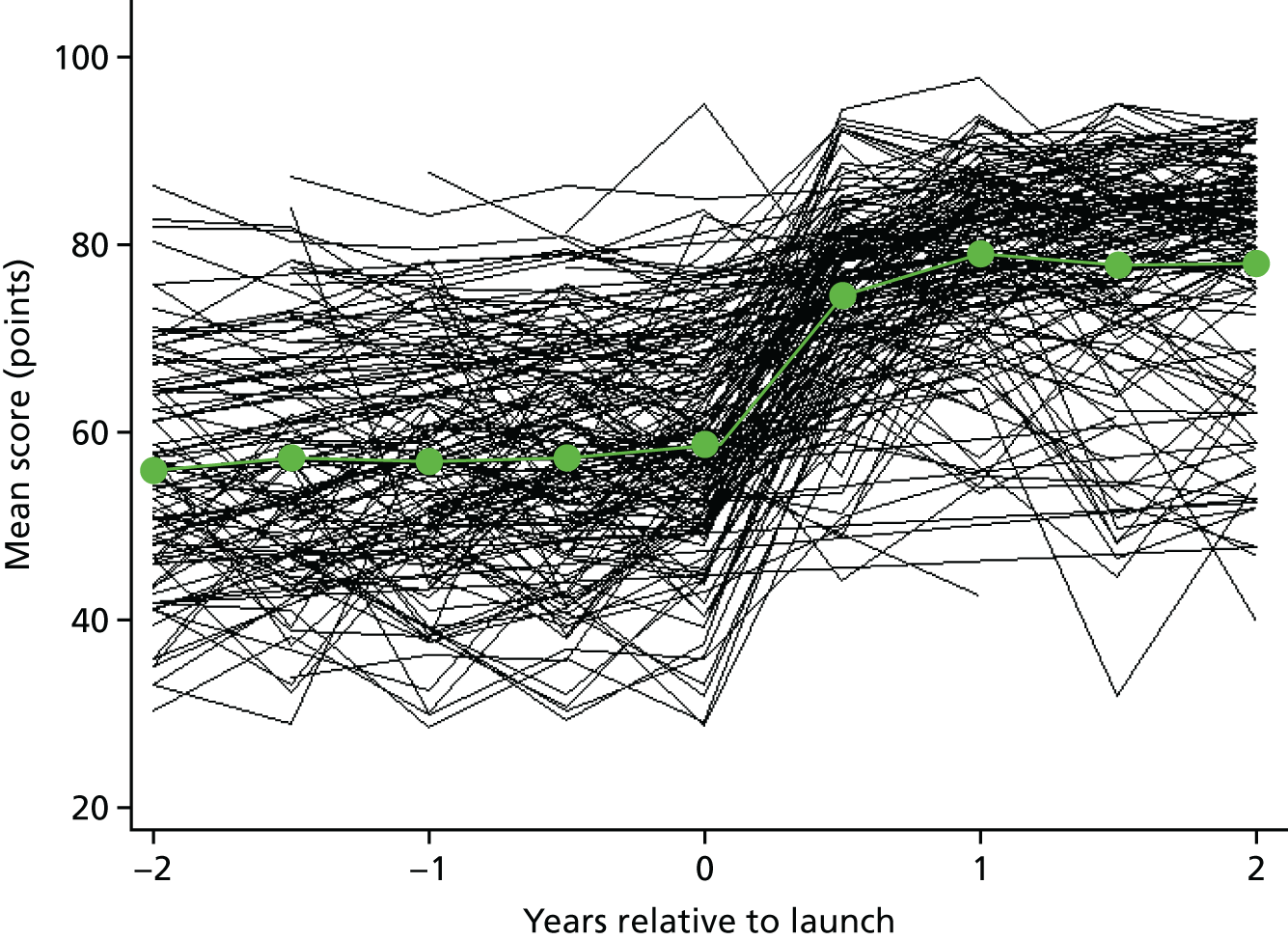

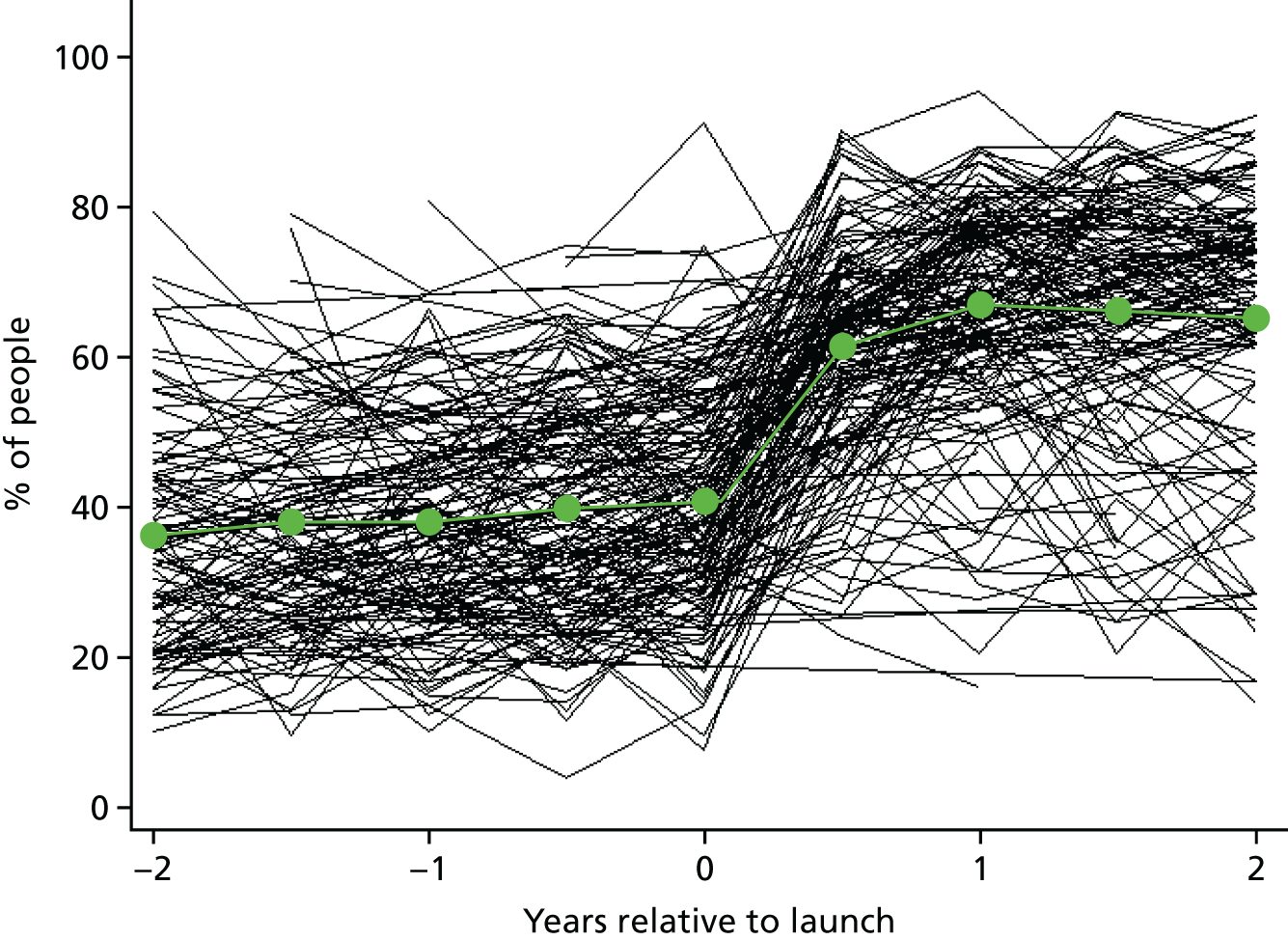

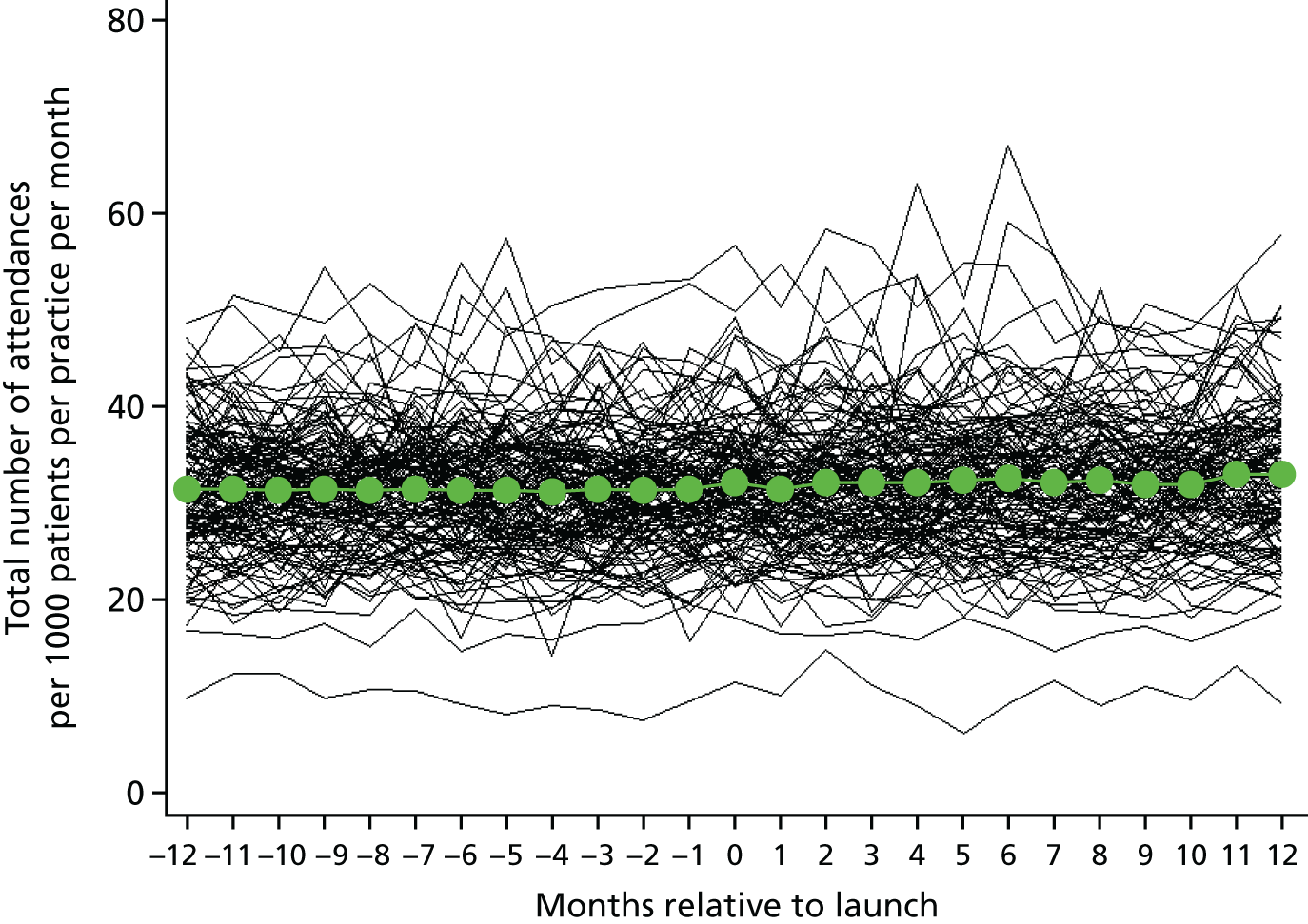

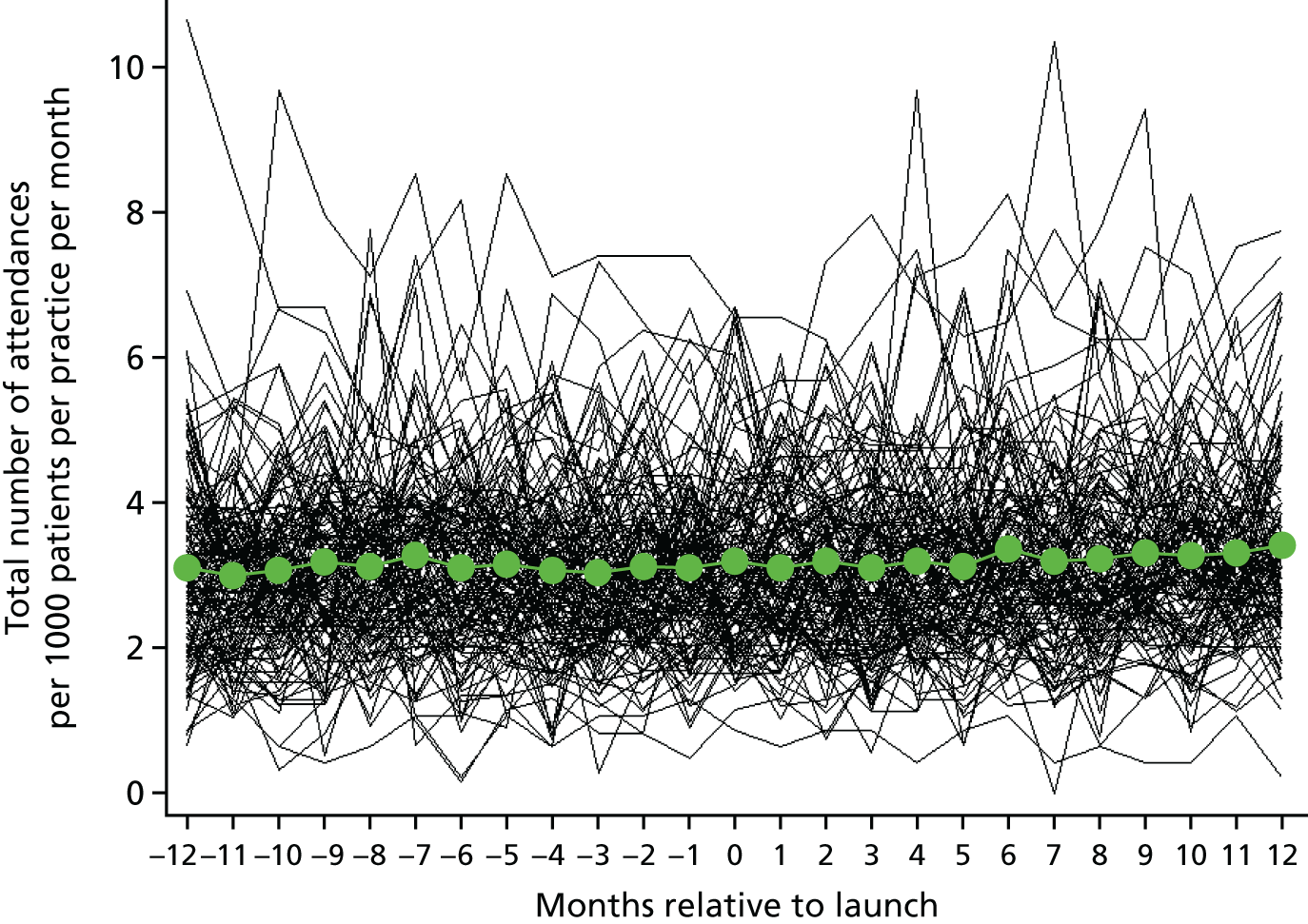

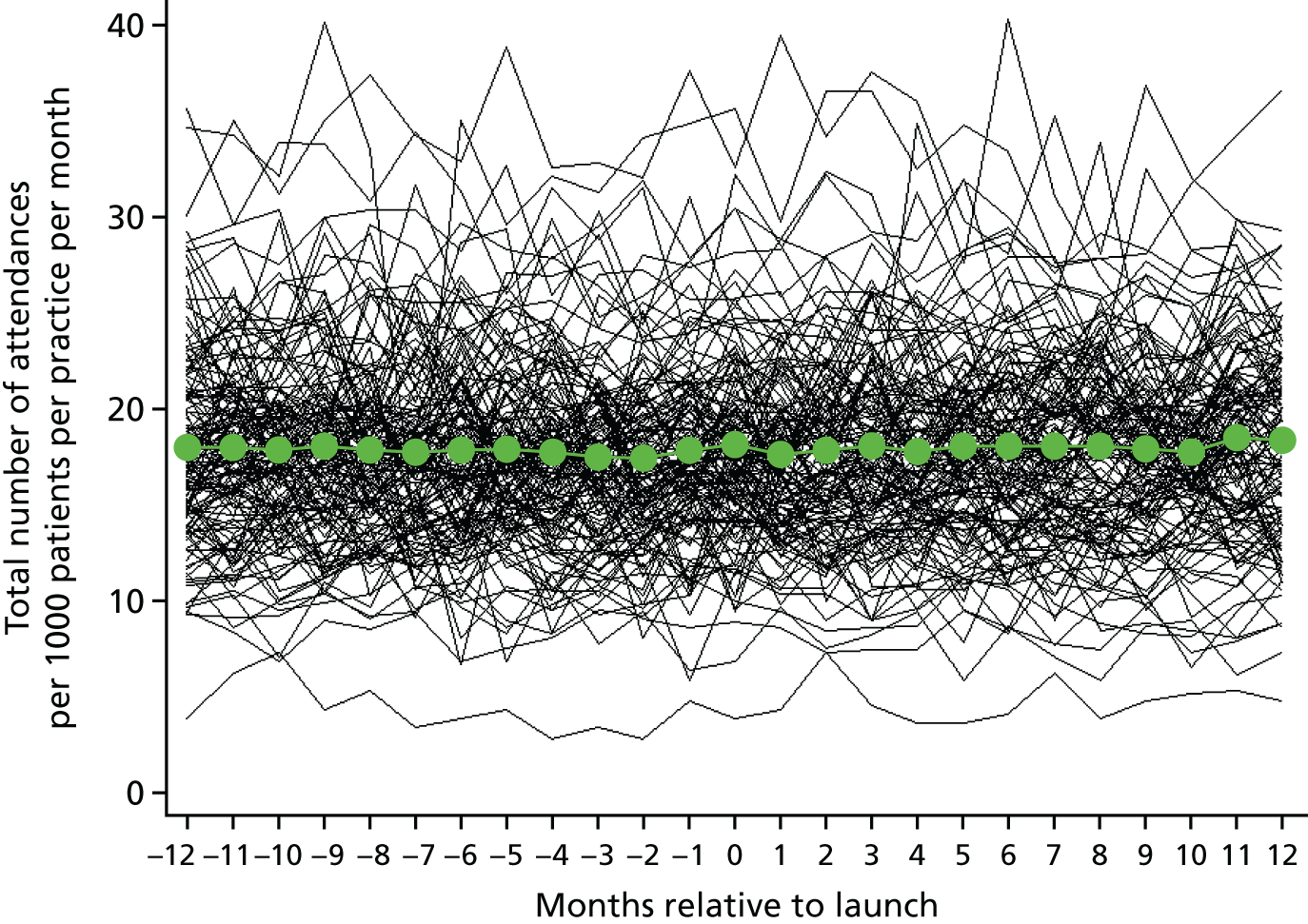

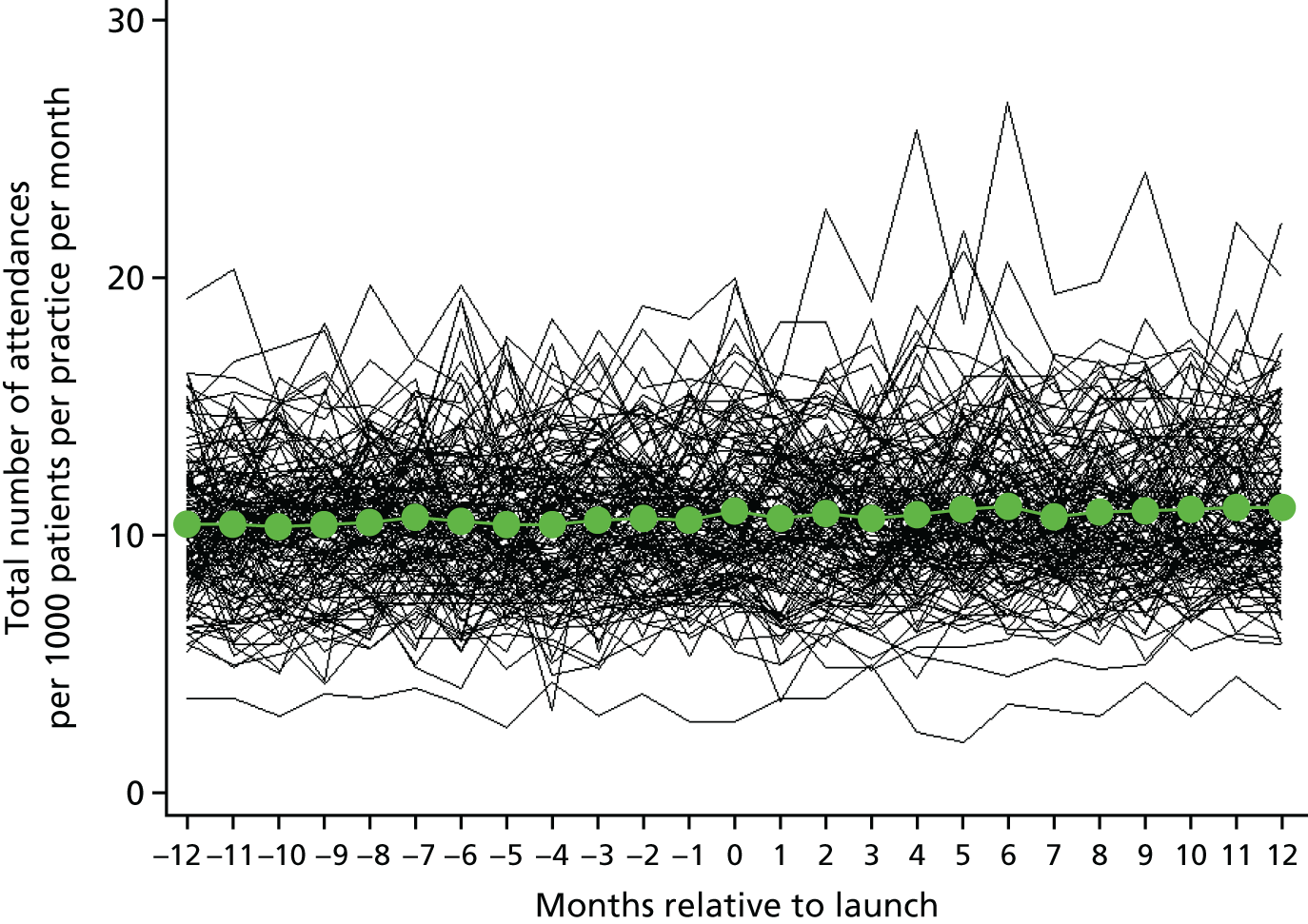

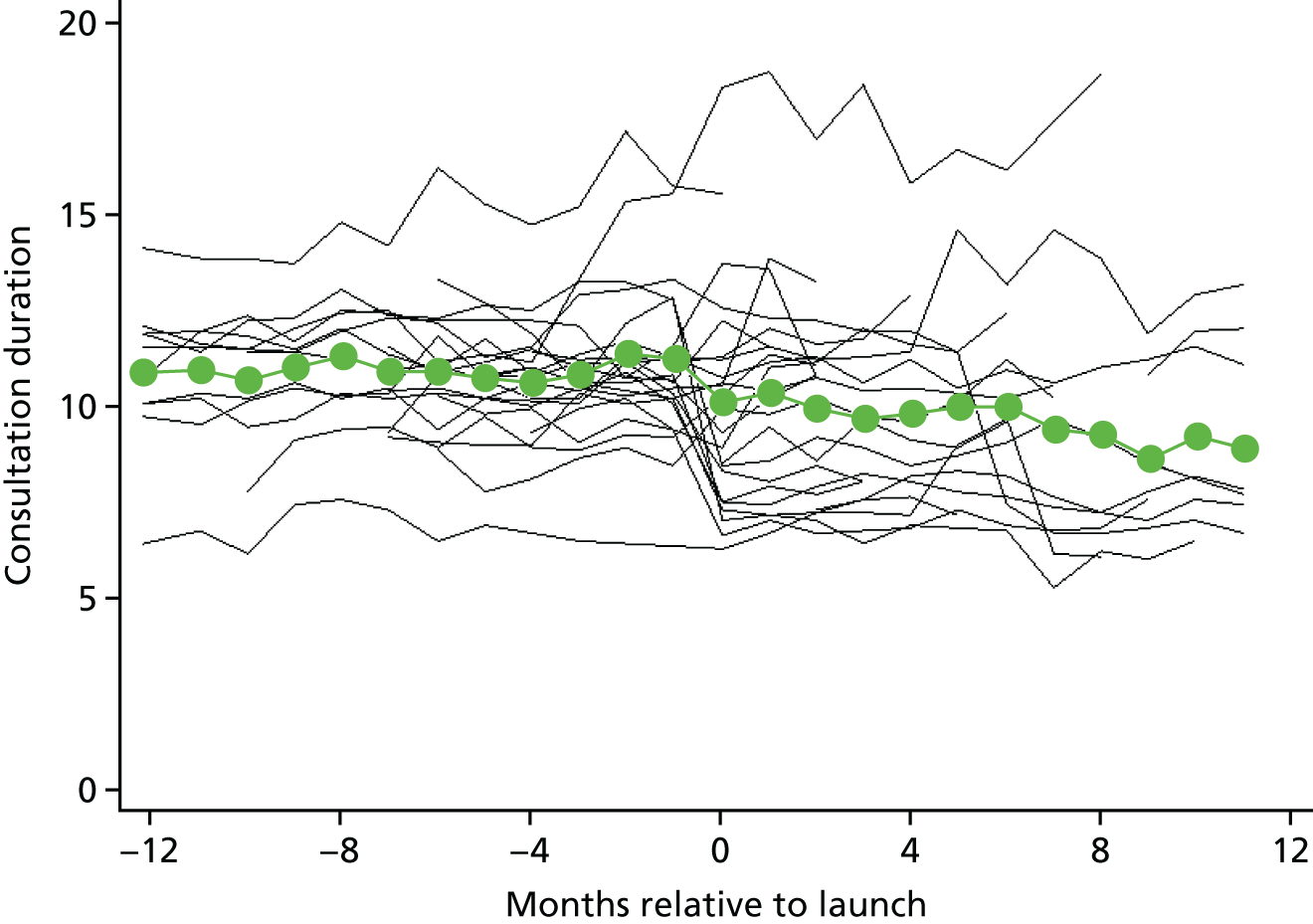

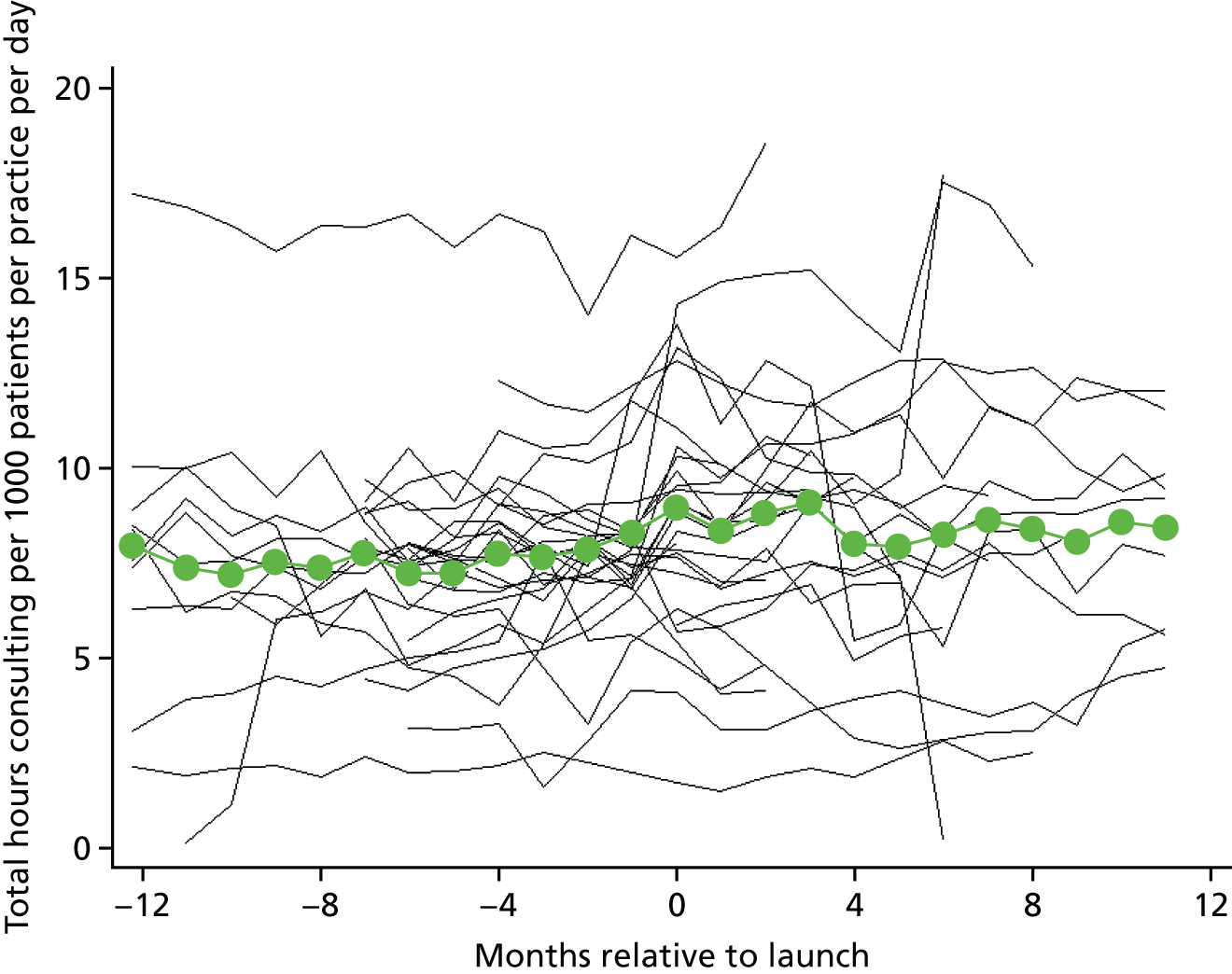

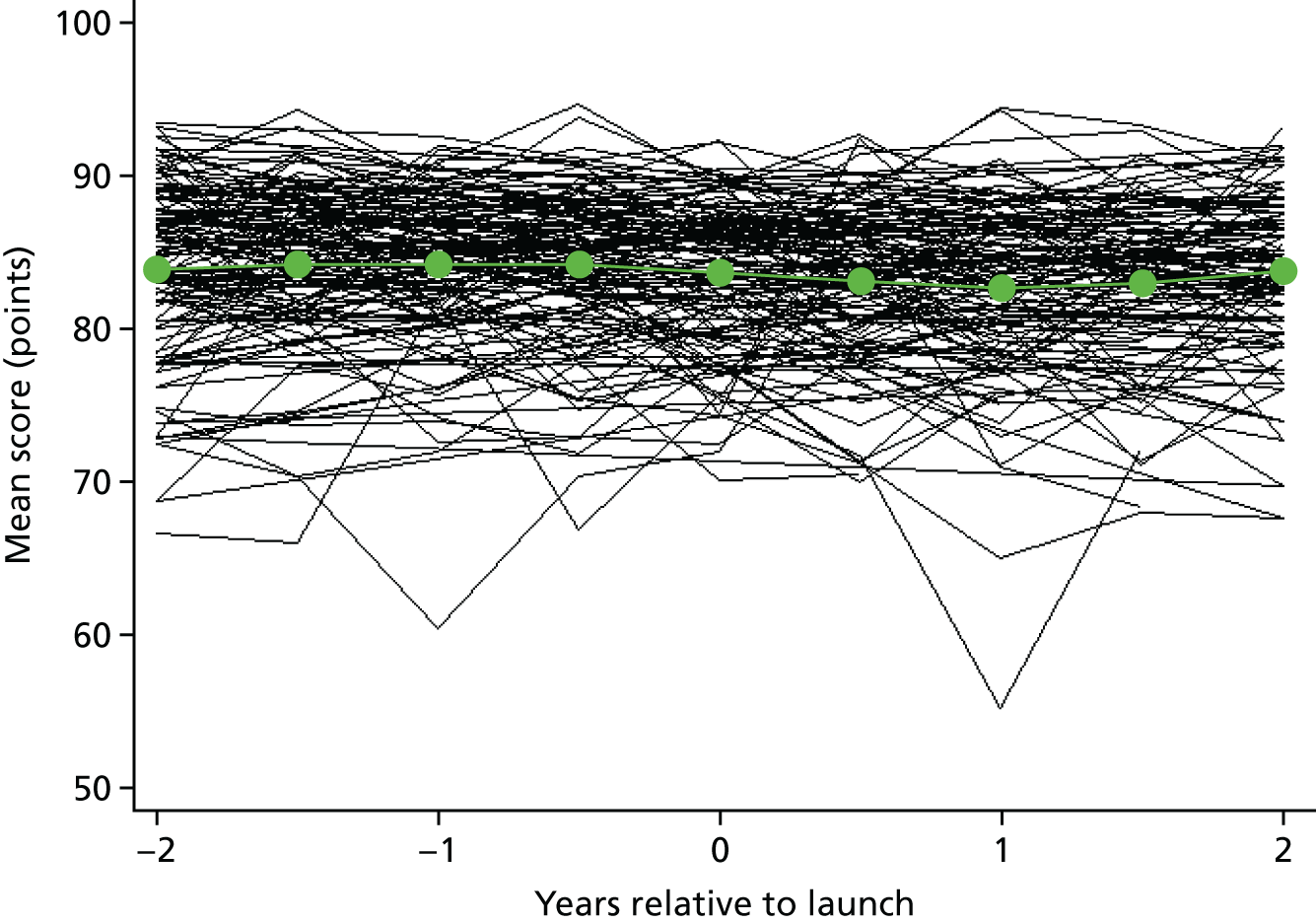

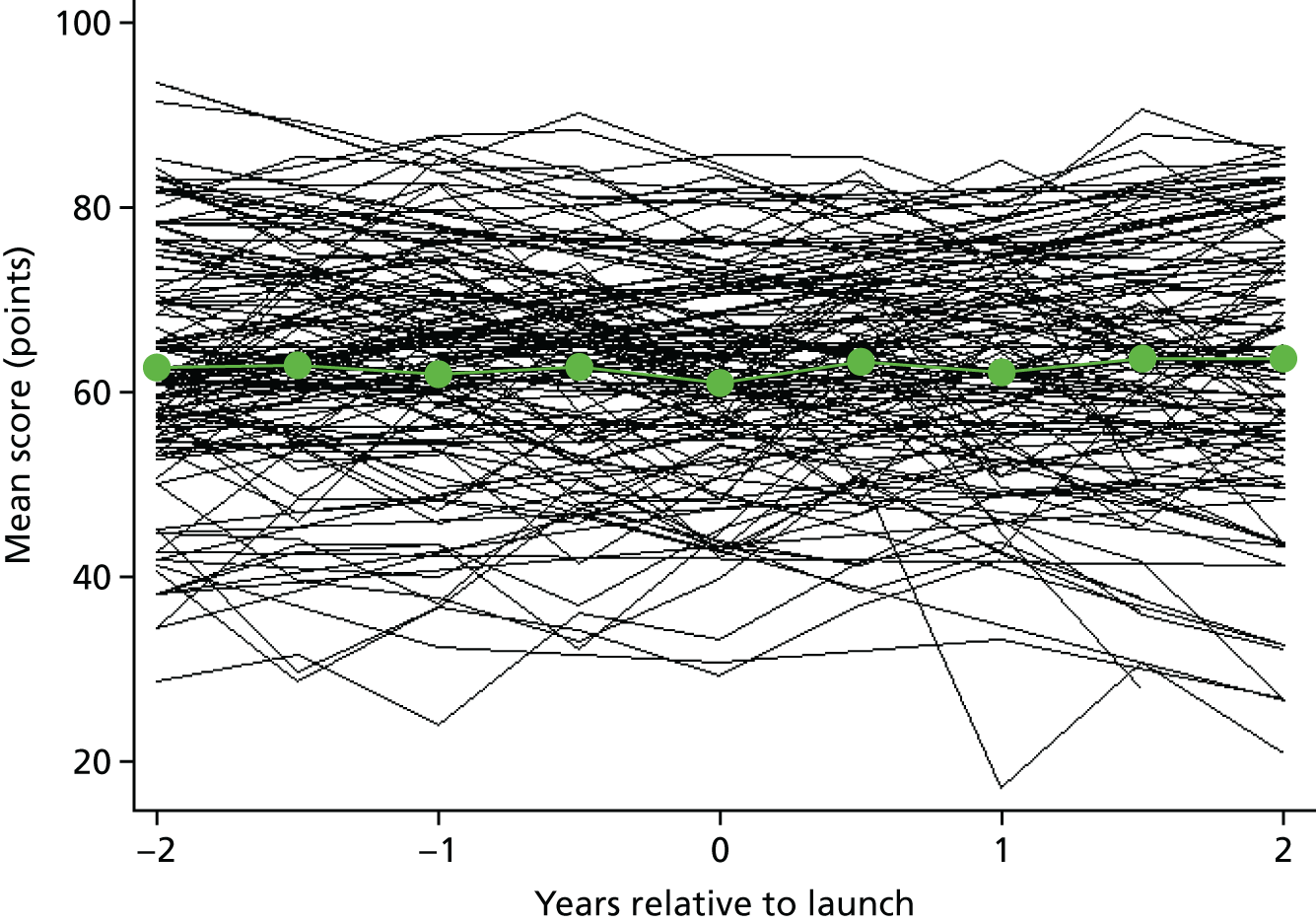

Two types of analysis were carried out for each of the outcomes. The first was a before-and-after analysis, illustrated by the ‘superposed epoch graphs’ which (see Figures 2–4) in the chapter where the introduction of the system in each practice is set at time zero. A superposed epoch graph is a way of visually representing changes that take place over time in a number of practices when an intervention took place in all of the practices but at different times. The plots show trends over time relative to the time at which the intervention started, which is defined as time zero, enabling visual inspection of changes before and after the intervention. Second, an interrupted time-series regression analysis was performed for each outcome, looking (1) for within-practice step changes at the time when the intervention was introduced and (2) for a within-practice change in the preceding trend (e.g. slowing down of a previous increase). We also model heterogeneity in these changes to examine whether or not the intervention has a different effect in different practices. Full details of the statistical analysis are given in Appendix 2.

A large proportion (30%) of data on length of appointment were missing from the practice data provided by the commercial company, especially for telephone consultations (52% compared with 18% for face-to-face consultations). Ignoring appointments with missing durations would have led to a systematic underestimation of the total time spent consulting. To overcome this, appointment length was imputed for those appointments with missing length and then added to the observed lengths to obtain a better estimate of the total time spent consulting for each day in each practice. Because we were imputing individual consultation lengths rather than total time spent consulting per day in a practice, a single imputation was made using a linear regression model similar to that used in the analysis of individual consultation lengths, but with fixed effects for practice rather than random effects, and stratified by before and after the intervention launch. Single, rather than multiple, imputation was used because of the computational burden. The use of single imputation will not lead to a biasing of estimates but may lead to an underestimate of standard errors (SEs). To combat this, the imputed SEs were multiplied by the square root of the ratio of the proportion of cases requiring no imputation.

Our main analyses were all done on an intention-to-treat basis. This included all practices identified by the commercial company as having used the ‘telephone first’ approach, even when the practices were using a hybrid form of the approach (e.g. by allowing some prebooked appointments) or had since ceased using it altogether. In this and other analyses, a sensitivity analysis (see Appendix 3) was performed, restricting the analysis to practices in which we believed, on the basis of information provided by the commercial company, that the system was being run consistently with the company’s protocols. The companies were asked to classify all practices that had used their ‘telephone first’ approach as ‘running’, ‘hybrid’ (i.e. allowing some additional degree of advance booking of appointments) or ‘reverted’ (i.e. had stopped using the ‘telephone first’ approach). In the per-protocol sensitivity analyses, we included only practices classified by the companies as ‘running’.

Results

The main intention-to-treat analysis included data from 59 practices with 1,926,979 appointments spread over 16,795 practice-days. The sensitivity ‘per-protocol’ analysis (see Appendix 3) included data from 27 practices covering 997,772 appointments over 8158 practice-days.

Number of appointments

Superposed epoch analysis

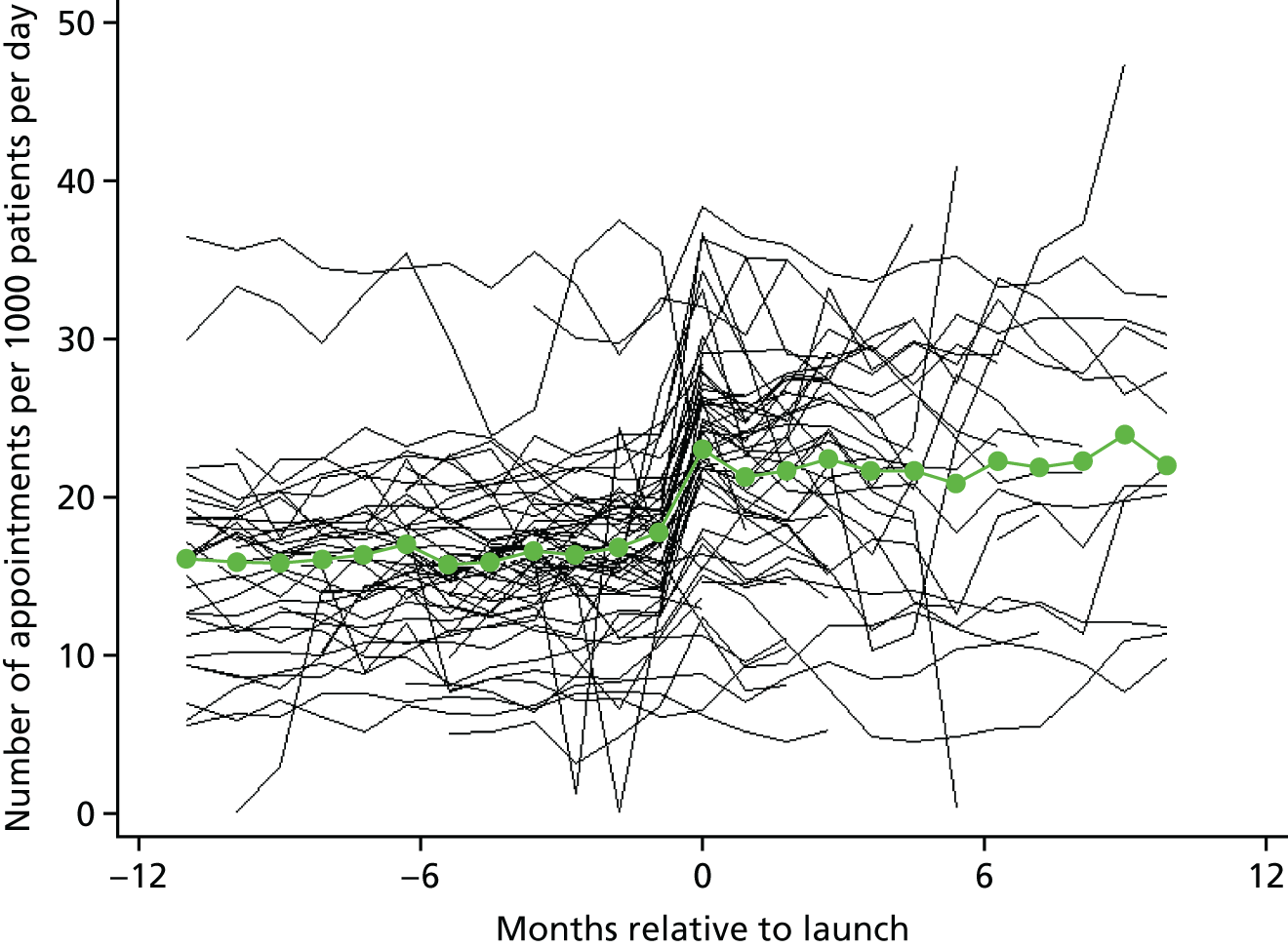

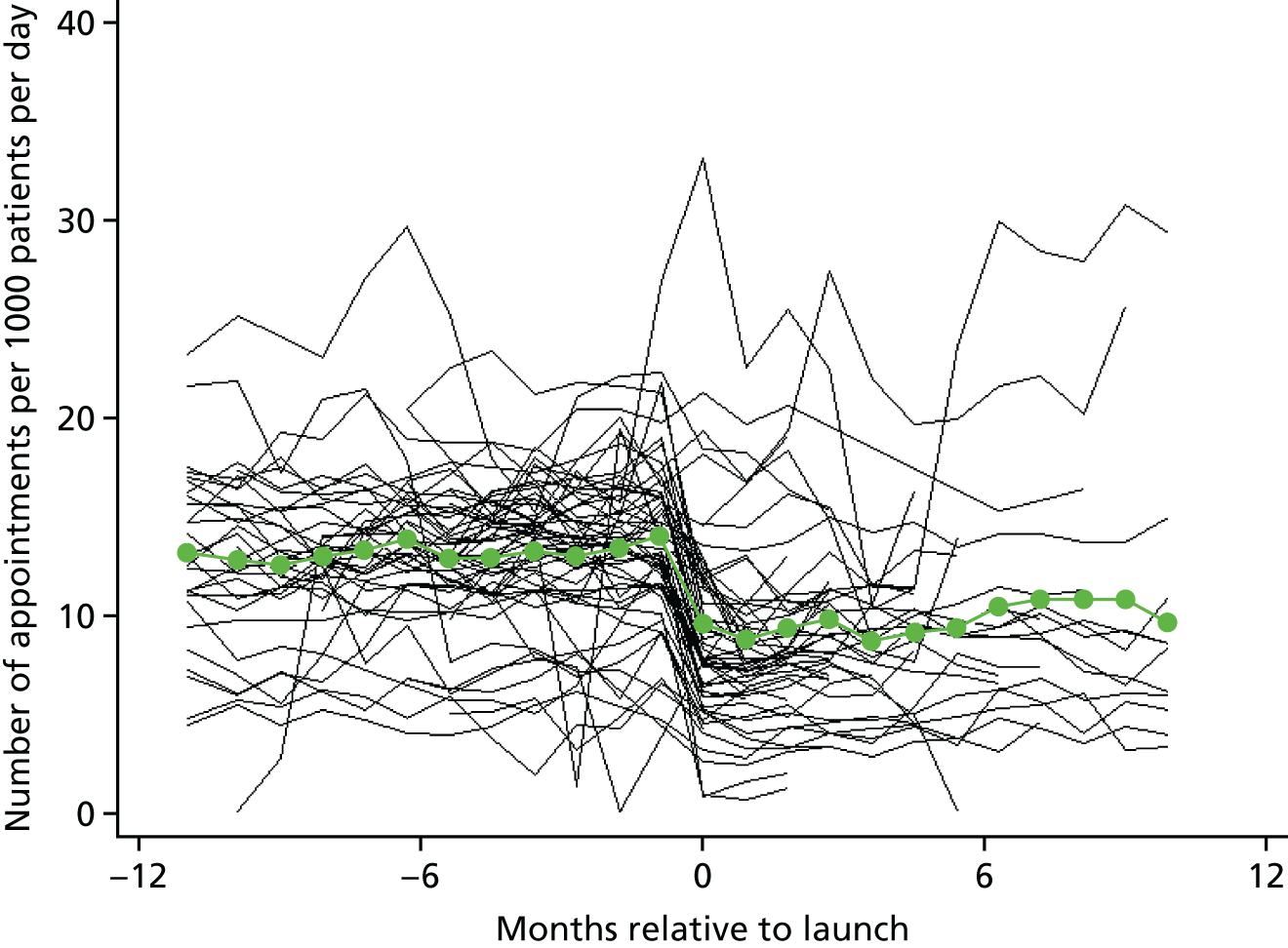

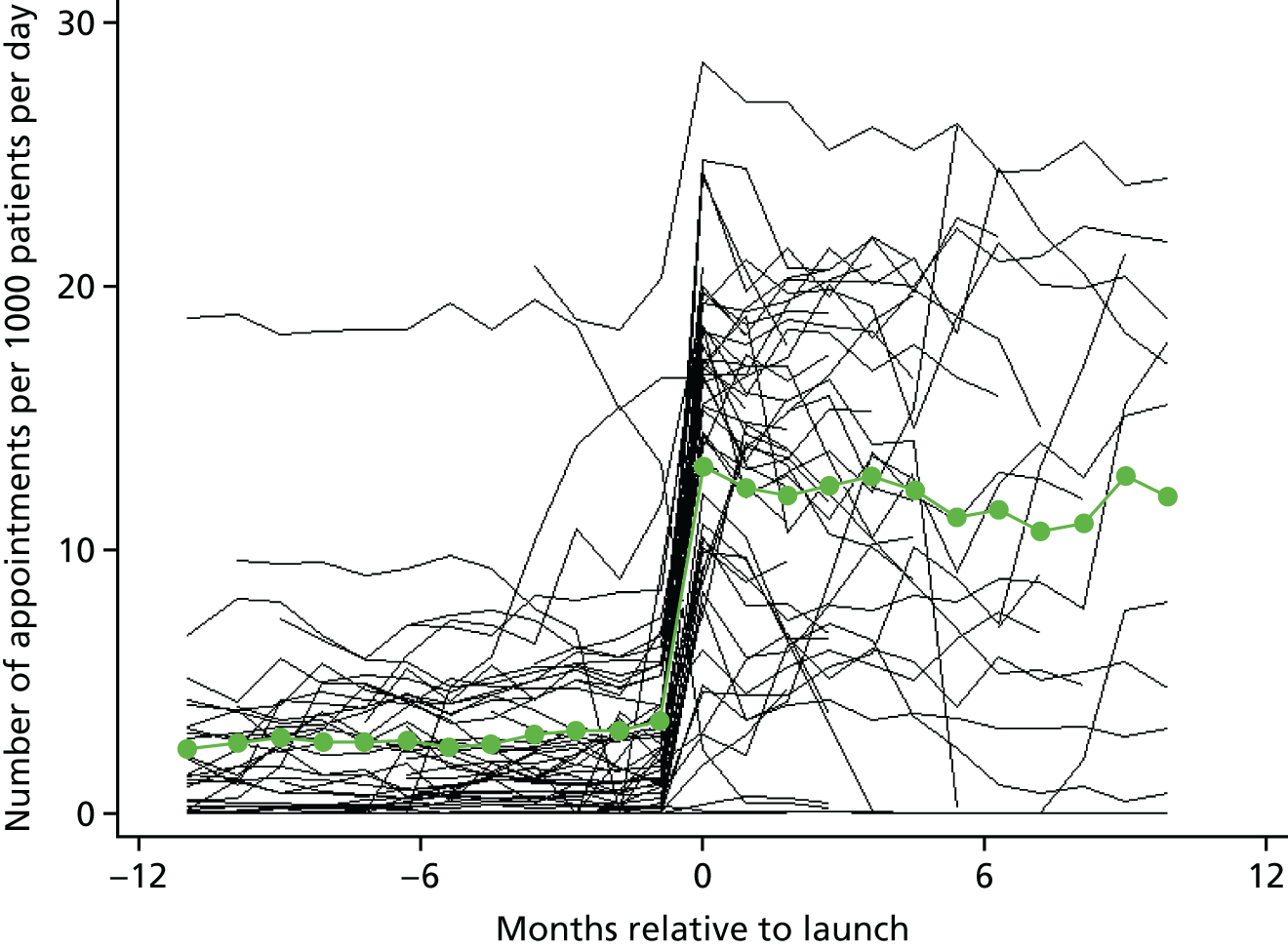

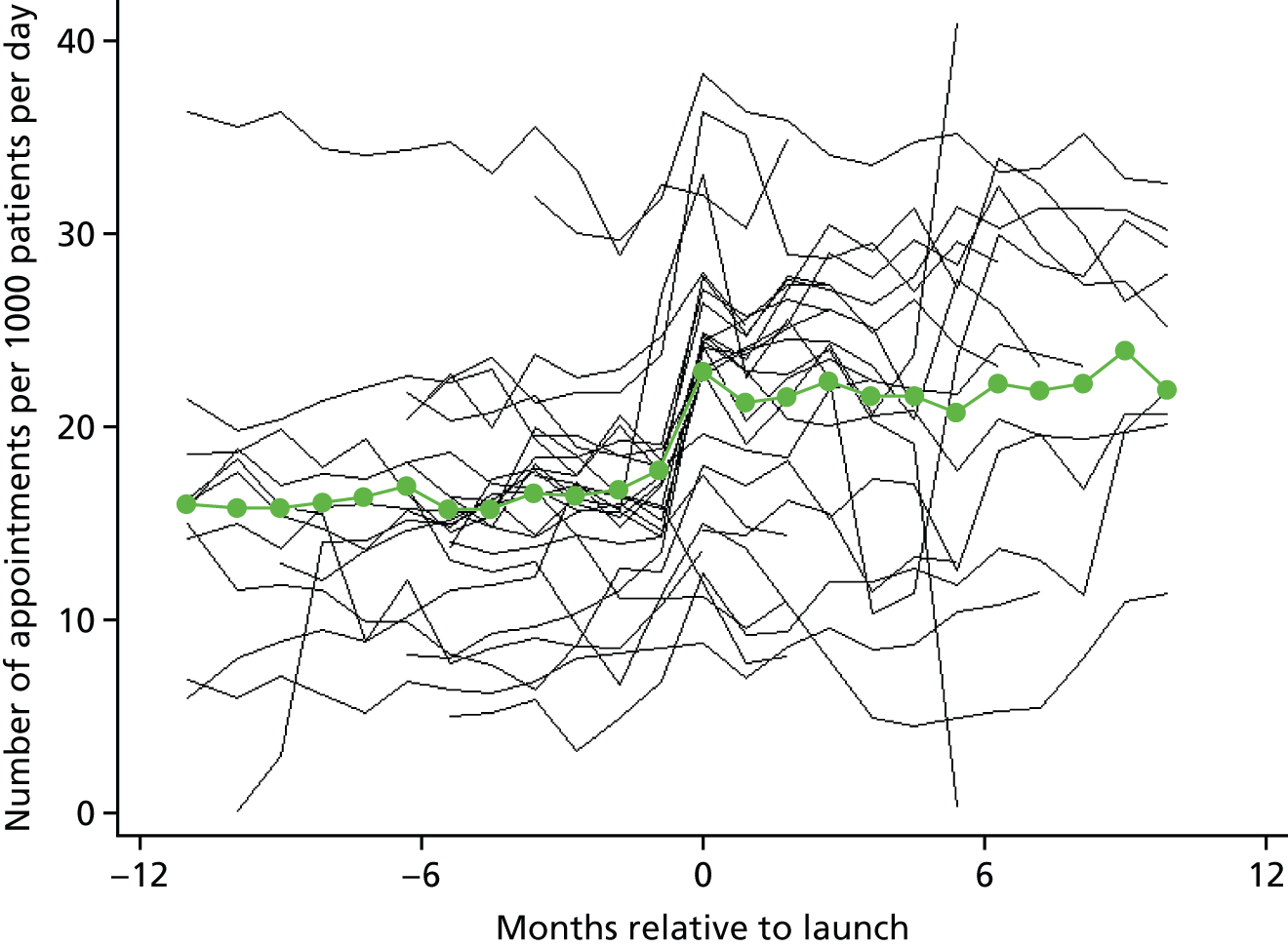

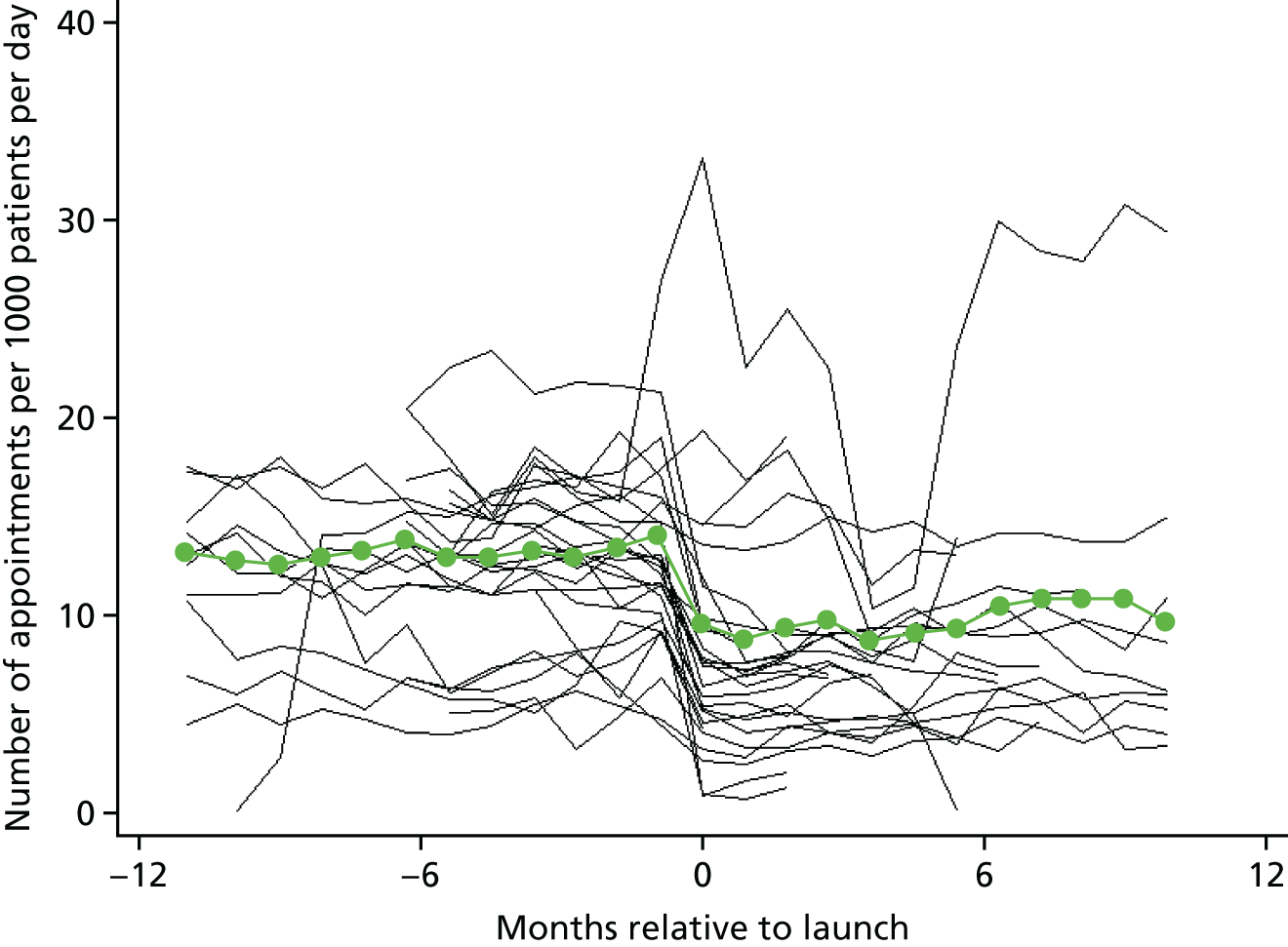

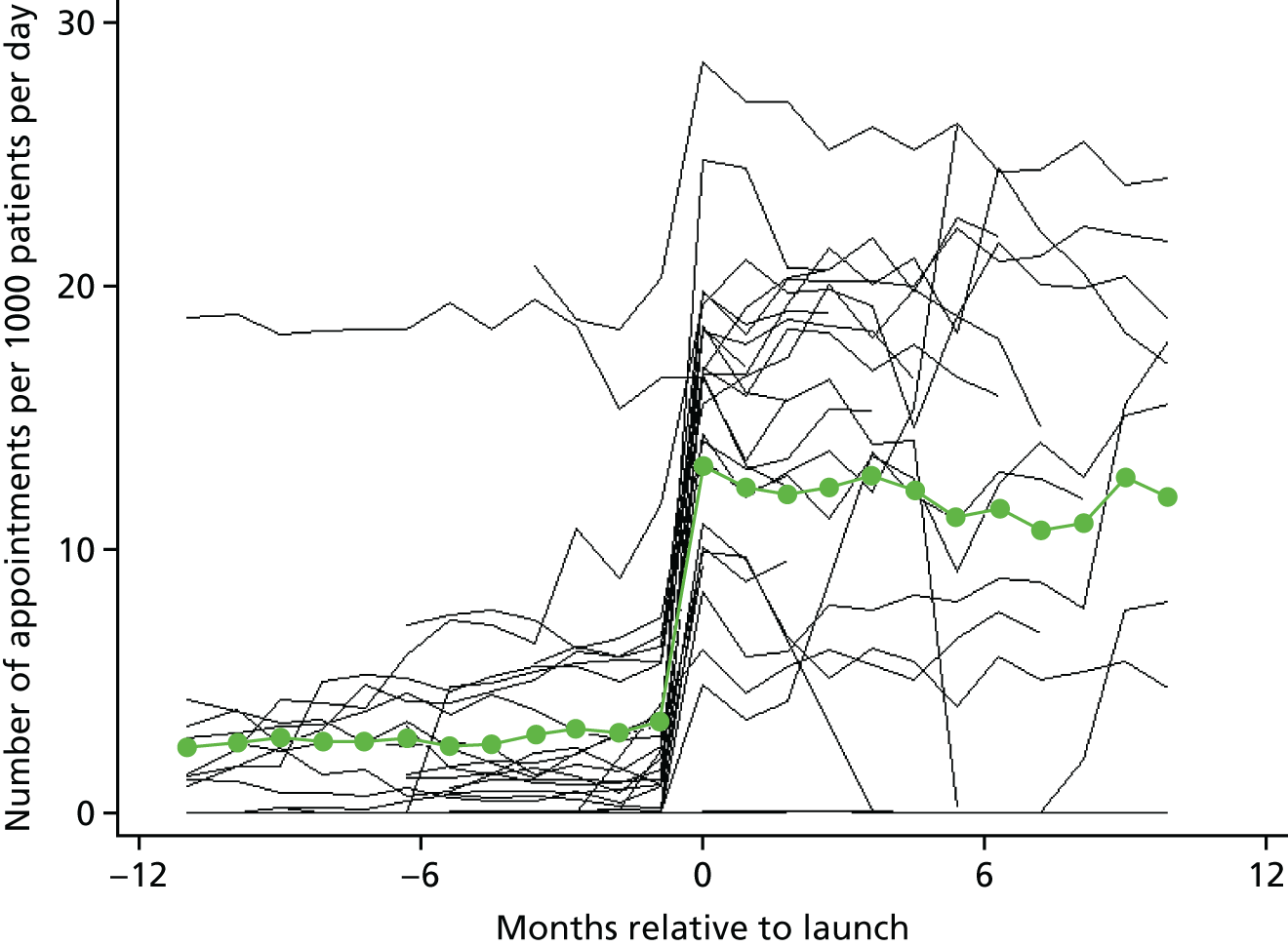

The mean number of appointments per 1000 patients per day was 16.5 (SD 6.3) before the intervention started; this increased to 21.8 appointments (SD 8.1 appointments) post intervention (Figure 2). This increase differed by appointment type, with decreases seen in the number of face-to-face appointments, from a mean of 13.0 appointments (SD 4.5 appointments) to a mean of 9.3 appointments (SD 5.5 appointments) (Figure 3), and increases seen in the number of telephone appointments, from a mean of 3.0 appointments (SD 4.0 appointments) to a mean of 12.2 appointments (SD 7.5 appointments) (Figure 4).

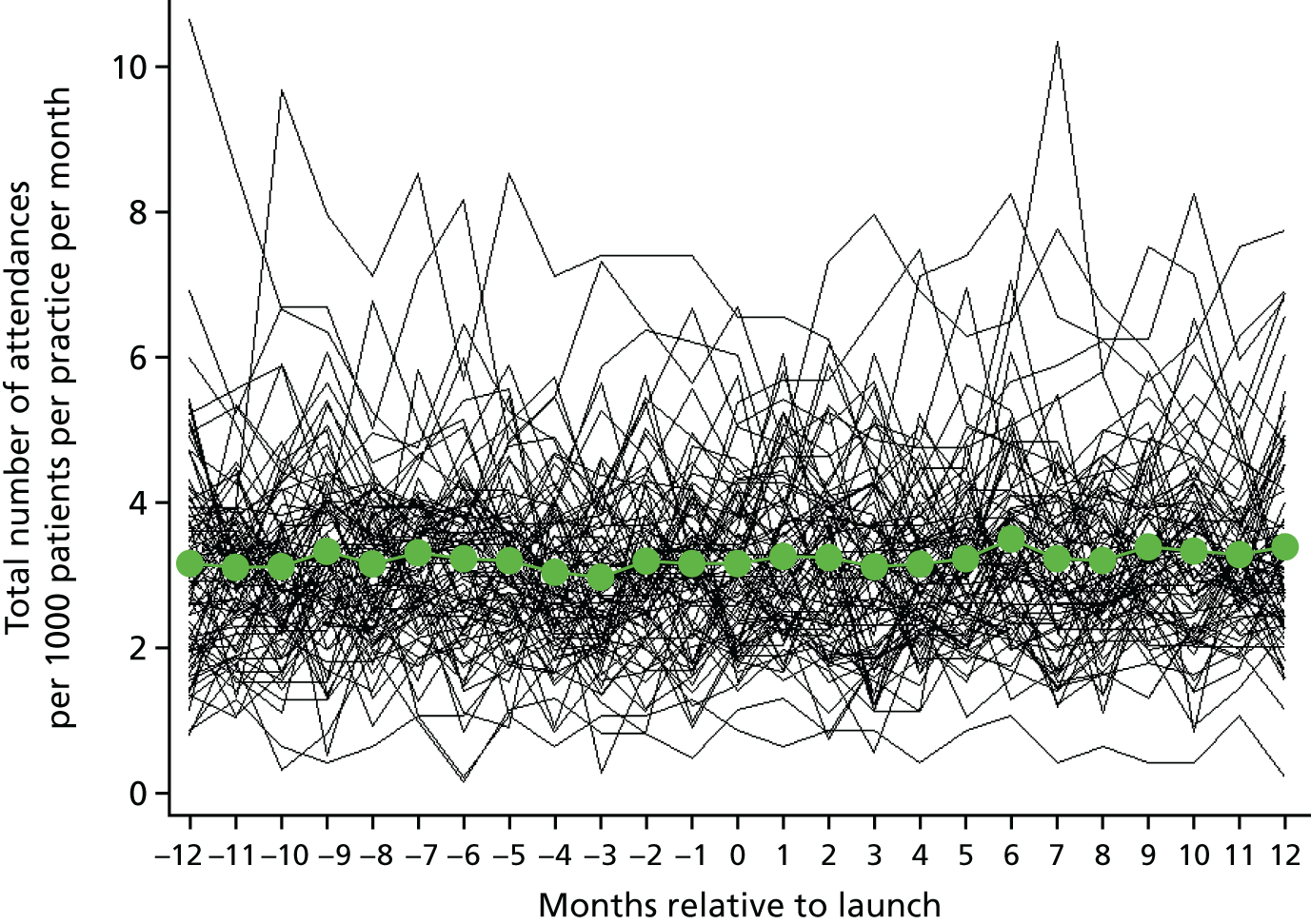

FIGURE 2.

Superposed epoch analysis showing the change in the total number of appointments per 1000 patients per day relative to the intervention launch. The black lines represent the mean within a single practice relative to the launch time, with each black line representing a single intervention practice. The green dots represent the mean of individual practice means.

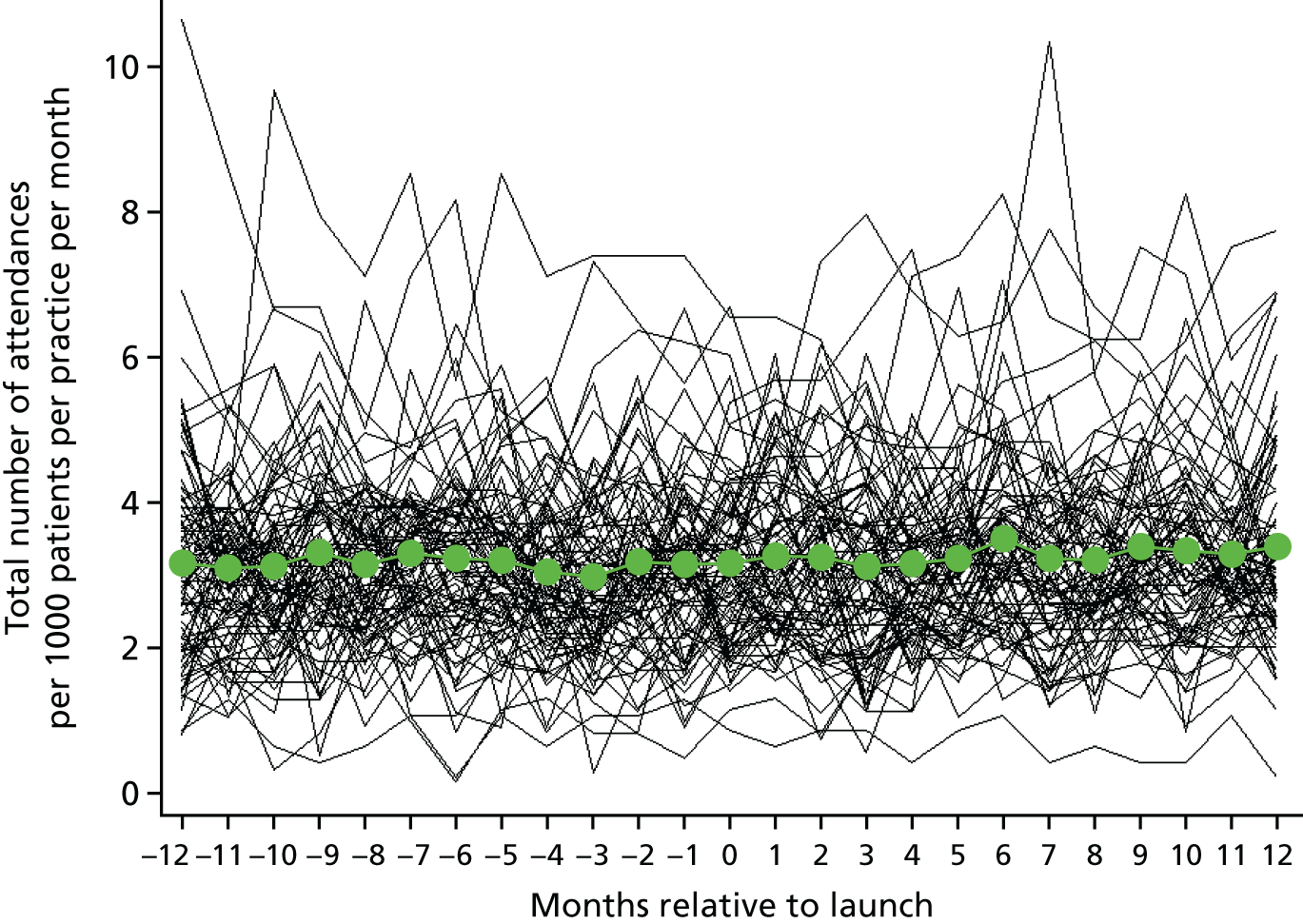

FIGURE 3.

Superposed epoch analysis showing the change in the number of face-to-face appointments per 1000 patients per day relative to the intervention launch. The black lines represent the mean within a single practice relative to the launch time, with each black line representing a single intervention practice. The green dots represent the mean of individual practice means. Reproduced from Newbould et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

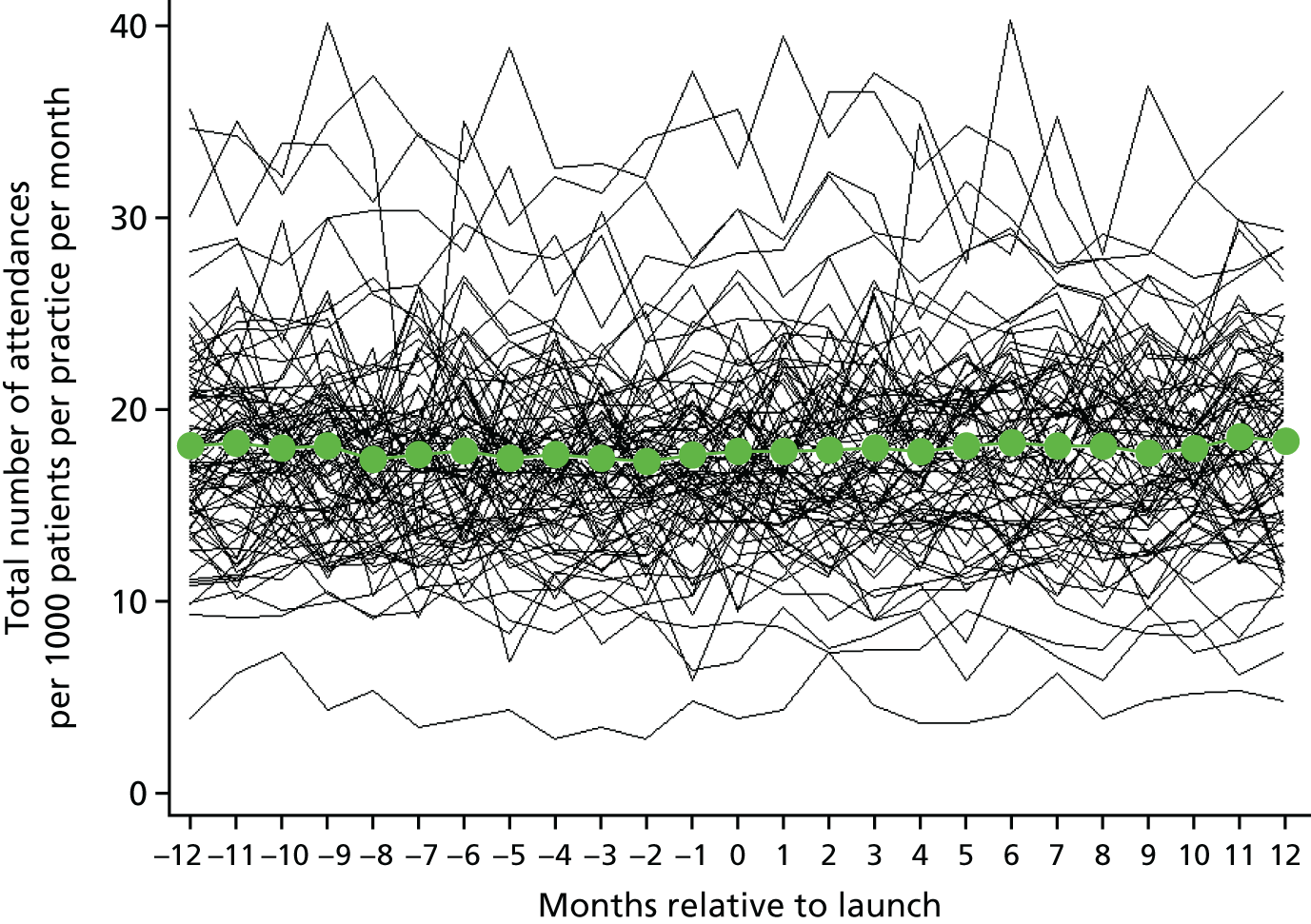

FIGURE 4.

Superposed epoch analysis showing the change in the number of telephone appointments per 1000 patients per day relative to the intervention launch. The black lines represent the mean within a single practice relative to the launch time, with each black line representing a single intervention practice. The green dots represent the mean of individual practice means. Reproduced from Newbould et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Regression analysis

The changes observed in the superposed epoch analysis are reflected in the regression analyses (Table 2). There was a 28% increase in all appointments following the introduction of the intervention (RR at step change 1.28, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.39; p < 0.0001), which comprised a 38% drop in face-to-face appointments and a 12-fold increase in the number of telephone consultations (RRs for step change are presented in Table 2; p < 0.0001 for all appointment types). It should be noted that the large relative change in telephone appointments in part reflects small numbers pre launch and that this relative increase is larger than the change in average figures as it represents the average within-practice change (the mean rate of telephone consultations pre launch will be more strongly influenced by those practices already doing many telephone consultations). Although there was a slight slowing in the initial rate of increase, the total number of appointments continued to increase post intervention by 4% per year (RR 1.04, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.05; p < 0.0001). There was considerable heterogeneity between practices in the changes in total number of appointments with the 95% reference ranges suggesting that some practices reduced overall appointment numbers by up to 32%, whereas for others the total number of appointments increased by a factor of 2.4. The per-protocol sensitivity analysis produced broadly consistent findings (see Appendix 3).

| Appointment type | Step change at transition | Trend | Interaction p-valueb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre transition | Post transition | |||||||

| RR (95% CI) | p-value | Heterogeneitya | RR (95% CI) | p-value | RR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| All | 1.28 (1.17 to 1.39) | < 0.0001 | 0.68 to 2.39 | 1.07 (1.06 to 1.08) | < 0.0001 | 1.04 (1.04 to 1.05) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Face to face | 0.62 (0.55 to 0.71) | < 0.0001 | 0.24 to 1.62 | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.04) | < 0.0001 | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.99) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Telephone | 12.04 (6.33 to 22.90) | < 0.0001 | 0.10 to 1467.39 | 1.11 (1.09 to 1.12) | < 0.0001 | 1.46 (1.43 to 1.49) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

Time waited for an appointment

Superposed epoch analysis

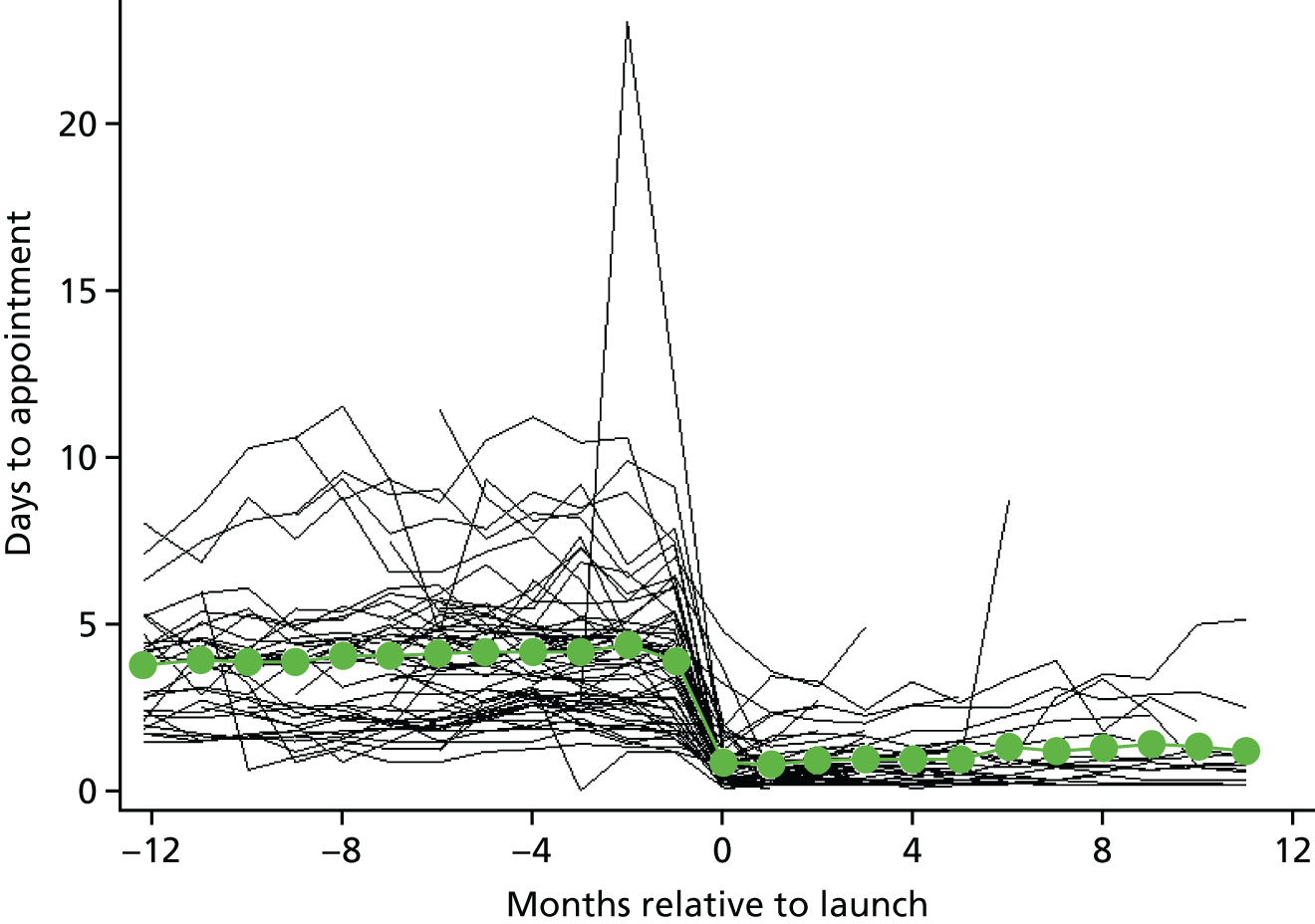

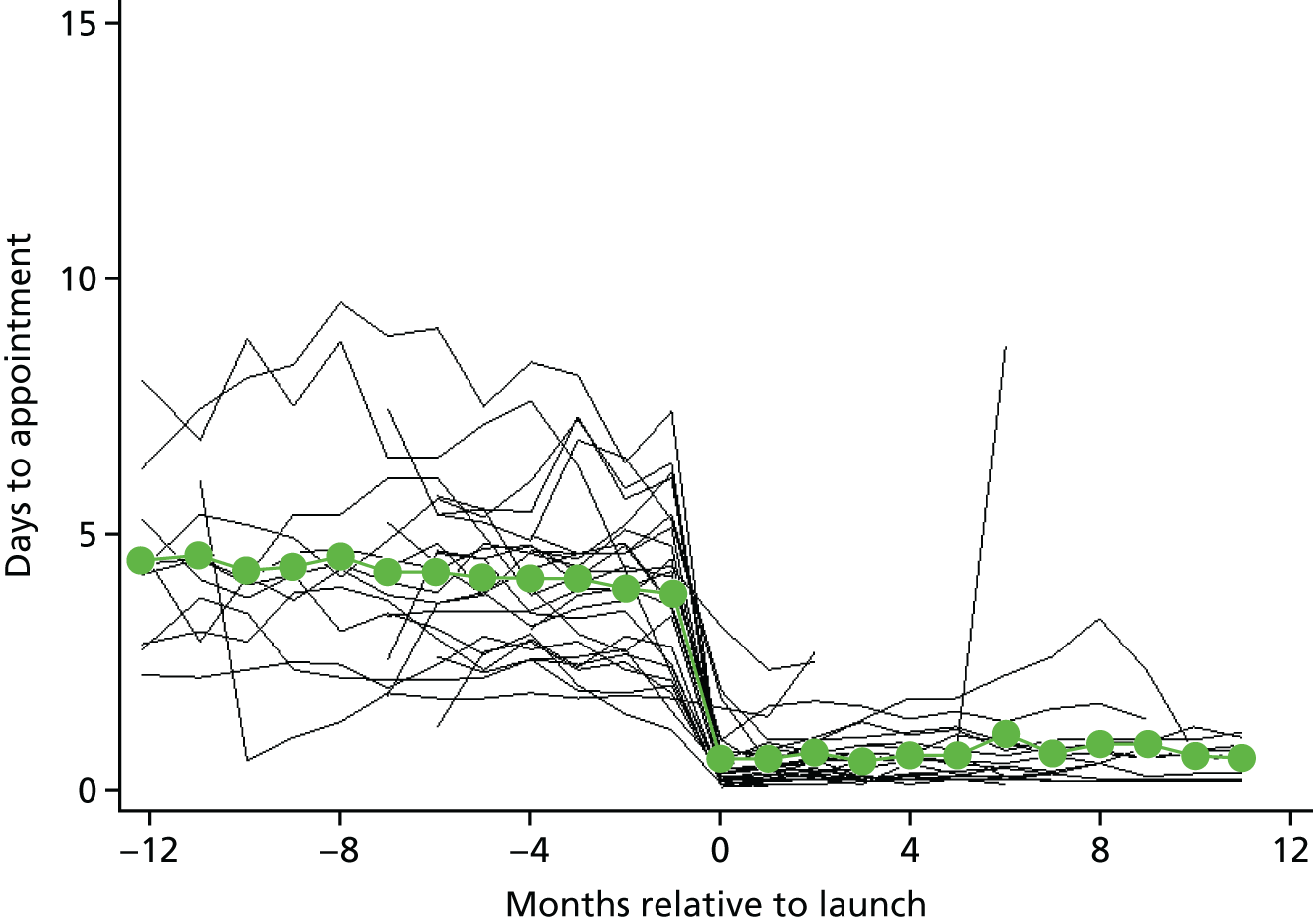

The mean number of days between booking an appointment and having an appointment across all intervention practices was 4.0 (SD 7.0) prior to the intervention and 0.9 (SD 3.9) after the intervention (Figure 5). Similar drops in time between booking and having an appointment are seen when restricting to face-to-face appointments [from a mean of 4.5 days (SD 7.4 days) to a mean of 1.8 days (SD 5.6 days)] and telephone appointments [from a mean of 1.8 days (SD 4.2 days) to a mean of 0.3 days (SD 1.7 days)].

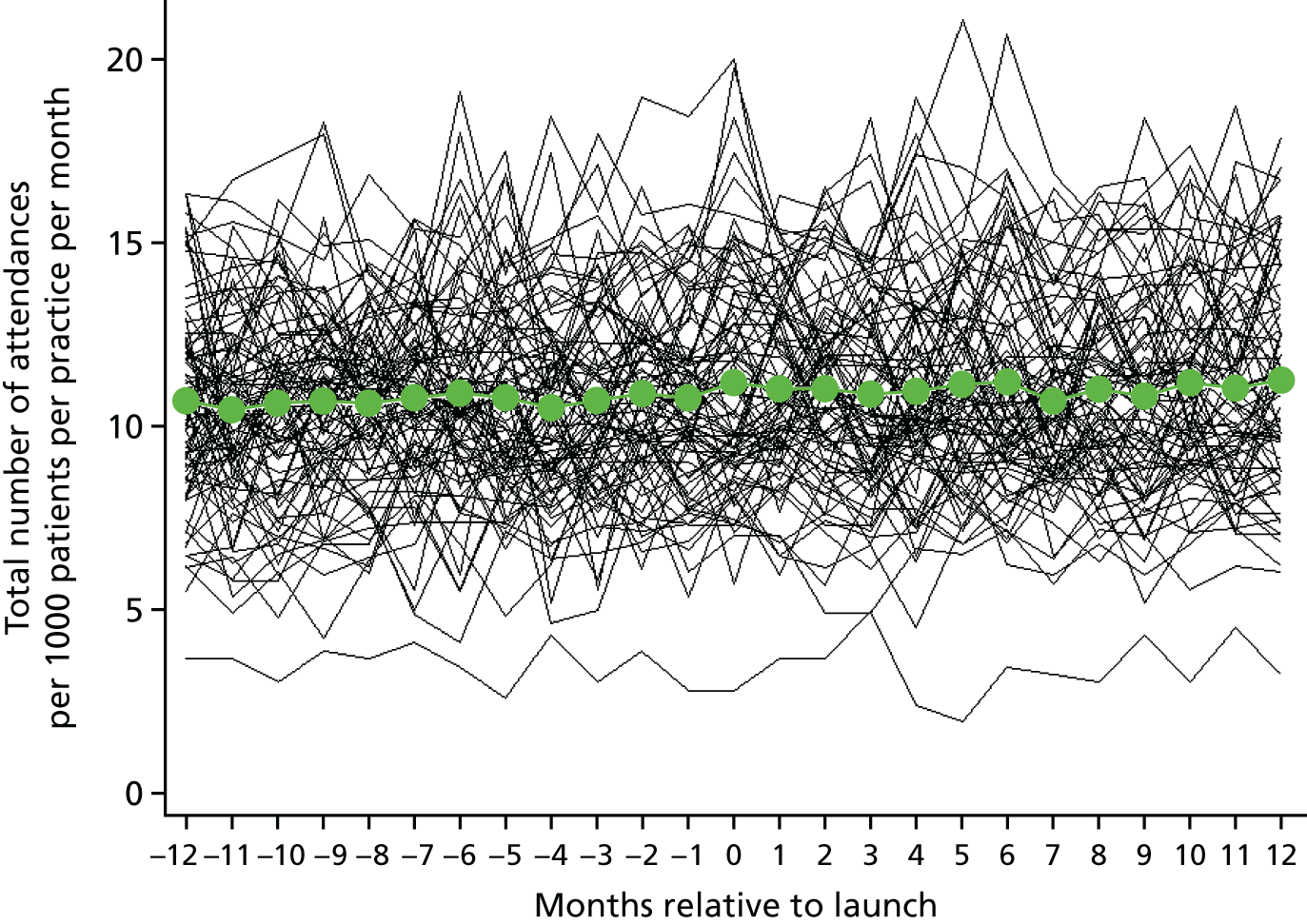

FIGURE 5.

Superposed epoch analysis showing the change in the mean time between booking and having an appointment of any type relative to the intervention launch. The black lines represent the mean within a single practice relative to the launch time, with each black line representing a single intervention practice. The green dots represent the mean of individual practice means.

Regression analysis

Decreases in the number of days to an appointment, seen in the superposed epoch graphs, are reflected in the regression analysis (Table 3). The time between booking and having an appointment dropped, on average, by 3.3 days (95% CI –3.8 to –2.8 days; p < 0.0001) after initially switching to the intervention (step change). The same decrease is seen for face-to-face appointments and a smaller reduction is seen for telephone consultations. The time between booking and having an appointment continued to increase over time following the introduction of the intervention; however, given that the annual increase in time waited is much smaller than the initial step decrease in time waited following the introduction of the intervention, it would take many years for the waiting time in the average practice to return to pre-intervention levels. Again, the 95% reference ranges show that there was substantial heterogeneity between practices in the reduction in length of time waited between booking and having an appointment; however, all practices show a decrease in the time between booking and having an appointment.

| Appointment type | Step change at transition | Trend | Interaction p-valueb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre transition | Post transition | |||||||

| Mean time to appointment (days) (95% CI) | p-value | Heterogeneitya | Mean change in time to appointment (days/year) (95% CI) | p-value | Mean change in time to appointment (days/year) (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| All | –3.30 (–3.80 to –2.80) | < 0.0001 | –5.91 to –0.71 | 0.20 (0.16 to 0.25) | < 0.0001 | 0.22 (0.16 to 0.27) | < 0.0001 | 0.6928 |

| Face to face | –3.31 (–3.89 to –2.72) | < 0.0001 | –6.31 to –0.31 | 0.53 (0.47 to 0.59) | < 0.0001 | 0.49 (0.40 to 0.58) | < 0.0001 | 0.4982 |

| Telephone | –0.78 (–1.07 to –0.48) | < 0.0001 | –2.21 to 0.71 | –0.21 (–0.26 to –0.16) | < 0.0001 | 0.15 (0.12 to 0.18) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

The per-protocol sensitivity analysis produced broadly consistent findings for the step change in time waited immediately following the introduction of the intervention, but there was evidence that the time waited between booking and getting an appointment of any type continued to decrease slightly post intervention in these practices (see Appendix 3).

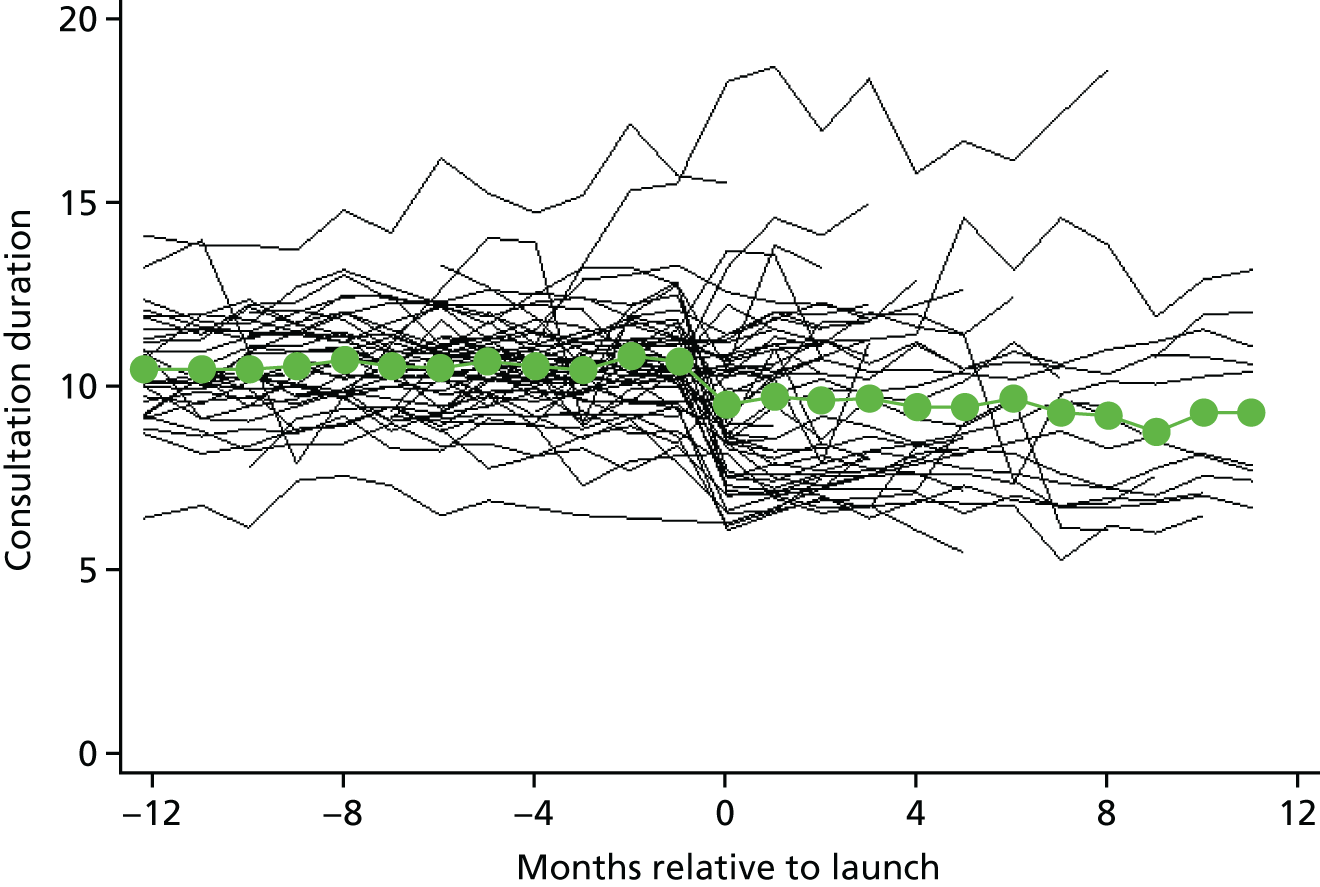

Length of appointment

Superposed epoch analysis

On average, the duration of appointments decreased from 10.5 minutes (SD 6.0 minutes) pre intervention to 8.5 minutes (SD 6.2 minutes) post intervention (Figure 6). The change in duration was less when restricting to face-to-face appointments [from a mean of 10.9 minutes (SD 5.9 minutes) to a mean of 10.2 minutes (SD 6.4 minutes)] or telephone appointments [from a mean of 7.7 minutes (SD 6.0 minutes) to a mean of 6.2 minutes (SD 5.1 minutes)], suggesting that much of the overall reduction in average appointment duration is due to a change in the proportion of appointments that are telephone appointments. It is worth bearing in mind that patients who had a face-to-face appointment may also have had a telephone appointment. For this reason, it is likely that the total consultation duration for each patient increases for patients who had both telephone and face-to-face appointments; however, as we cannot link telephone and face-to-face appointments, we cannot demonstrate that this is actually the case.

FIGURE 6.

Superposed epoch analysis showing the change in appointment duration relative to the intervention launch: face-to-face and telephone. The black lines represent the mean within a single practice relative to the launch time, with each black line representing a single intervention practice. The green dots represent the mean of individual practice means.

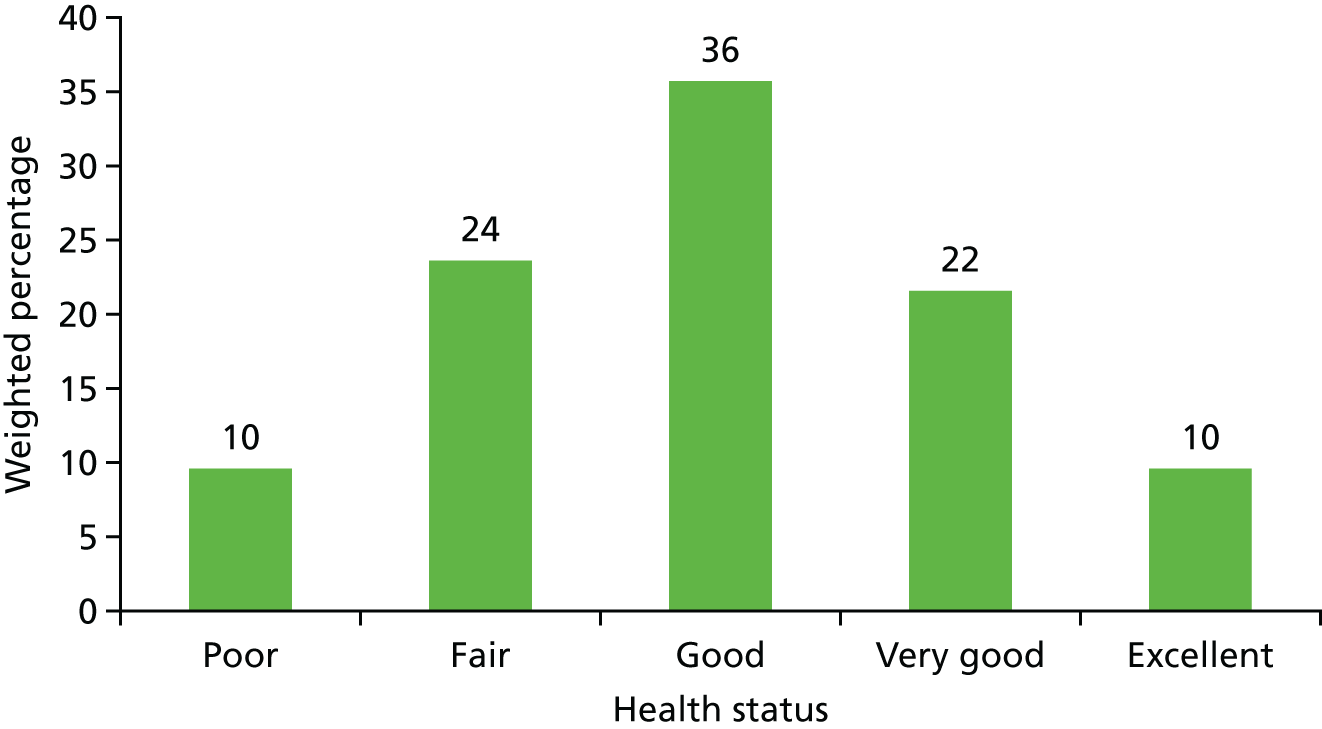

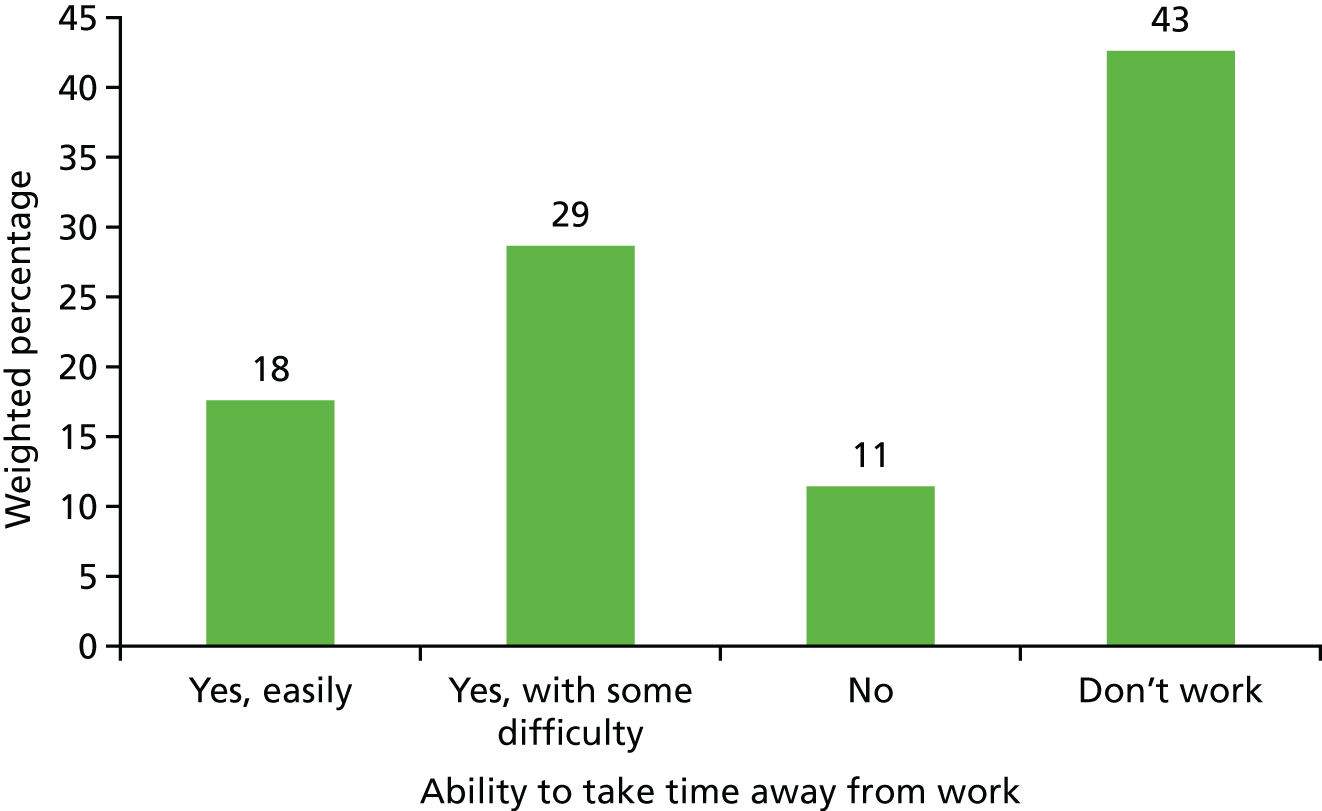

Regression analysis