Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/136/93. The contractual start date was in January 2014. The final report began editorial review in July 2017 and was accepted for publication in December 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Macfarlane et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

When this project was first designed, in 2012, a succession of analyses showing raised mortality among patients admitted to hospital at weekends was being published, and so-called ‘weekend effects’ were prominent on the policy agenda in England. Five years later, the number of published studies on these topics has grown and arguments about their interpretation and policy relevance continue. Maternity and neonatal services have always had to operate 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Analyses of births and their outcome by time of day, day of the week and season have a longer history and are vital for informing the adequacy of arrangements for staffing and safety.

In designing this research project, we aimed to explore the implications of patterns of birth timing for NHS maternity and neonatal services, using administrative data for births in England and Wales in the early years of the 21st century. The research questions arose from previous research undertaken by two of the co-investigators, from the 1970s onwards,1–4 combined with the current policy focus on improving safety, extending midwifery-led care and choice of place of birth, and ensuring quality 24-hour care.

The funding for this research was both timely and relevant to proposed changes in maternity service provision. To carry out this study, we planned to draw on and extend data linkage developed in two previous projects. The first project linked data recorded at birth registration with data recorded at birth notification, at which point babies’ NHS numbers are allocated. 5,6 The second project linked these linked data to records of hospital care at birth in England7 and in Wales8 to create a new linked dataset bringing together the relevant data from several sources.

Unfortunately, this project has been seriously undermined by a series of obstacles. In our second project, we experienced delays in getting permission to access data from what was then the Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC). We attempted to learn from this and use our experience to prevent similar problems from occurring again, but prior knowledge was insufficient to keep this project to schedule. We have experienced substantial delays and barriers as a consequence of the impact on data access of the implementation of the Health and Social Care Act 20129 and the wider implications of the unsuccessful attempt to establish the care.data system. 10,11 These barriers, followed by information technology (IT) infrastructure problems, slowed us down and meant that, despite an extension to the original time frame, our funding ended while we were still in the relatively early stages of the analysis. Regrettably, having created a unique and reliable 10-year database, we have not had time to complete many of the planned analyses, particularly analyses of outcomes. We are applying for further funding to complete these.

After setting the scene in Chapter 1, by describing the health policy context of our project and the previous work on the timing of birth and on data linkage, we go on in Chapter 2 to describe the methods and results of our data linkage and quality assurance work. In Chapter 3, we describe the methods of our planned analyses, before presenting and discussing the results of those analyses that have been completed. Chapter 4 explains how patient and public involvement (PPI) was integral to our project. In Chapter 5, we discuss the results of our linkage work and analyses and the gaps left by the work we were unable to do. The implications of our experiences for health care and for further research using administrative data are set out in Chapter 6. Appendix 1 describes the barriers that impeded our research and our attempts to overcome them.

Health policy context

To set policies about the 24-hour health service and its relevance to maternity care in context, we start with a broad overview of the ways in which policies for maternity care in England and Wales have developed in the longer term and then review the new policies set in train in recent years while our project has been under way.

Confidential enquiries

Quality health care has been defined as care that is safe and effective and results in a positive experience. 12

There has been a longstanding concern about the safety of maternity care, in terms of maternal mortality and of stillbirths and neonatal mortality. The UK has the longest-running programmes of confidential enquiries into pregnancy-related deaths in the world. After earlier developments in Scotland, Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths have been run in England and Wales since 1928. 13 Following confidential enquiries into perinatal deaths at regional and local levels, the Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirth and Deaths in Infancy was set up nationally in 1993. 14,15 Learning from the enquiries regarding ways to reduce preventable factors associated with deaths has led to considerable improvements in service quality. Following a retendering exercise, the MBRRACE-UK (Mothers and Babies: Reducing Risk through Audits and Confidential Enquiries across the UK) consortium is now responsible for these enquiries and has a key role in monitoring current policies. 15

Choice of settings for birth

At the beginning of the 20th century, nearly all women gave birth at home; by the end of the century, hospital birth was almost universal. Many factors contributed to this major change, but from 1970 onwards there was an explicit policy that all births in England should take place in hospital. In response to this, the proportion of births occurring at a mother’s home in England and Wales fell from 13% in 1970 to < 1% of all births in 1987, before starting to rise again. The rise was already occurring when the House of Commons Health Committee reviewed available evidence in its Inquiry into Maternity Services. 16 The Inquiry’s conclusions were wide-ranging, but it is perhaps best remembered for its conclusion that:

The policy of encouraging all women to give birth in hospital cannot be justified on grounds of safety.

Although limited, the evidence, coupled with demand from women and support from maternity charities and the Royal College of Midwives (RCM), led to changes in government policy in both England and Wales during the 1990s. 16,17 The Welsh Office issued the Protocol for Investment in Health Gain, which emphasised the need for women to have more control and an informed choice about the care given in pregnancy and childbirth. 18 In England, the Department of Health and Social Care responded to the report by setting up the Expert Maternity Group. Its report, Changing Childbirth,19 published in 1993, endorsed many of the policy changes set out in the Health Committee’s report, moving towards woman-centred care and a greater role for midwives, with at least 30% of women having a midwife as the lead professional.

These policies continued after the change of government in 1997. They were set out in detail in 2007 in Maternity Matters,20 after the aims had been outlined earlier in the National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services. 21

The policy called explicitly for ‘an evidence-based culture’, which learned from adverse events and highlighted the value of routine data collection and analysis. 20

There was a strong emphasis on choice and this included a ‘choice guarantee’ on place of birth and other aspects of maternity care. 20 The Maternity Matters document stated that a ‘guiding principle’ for the modern maternity services was that:

All women will need a midwife and some need doctors too.

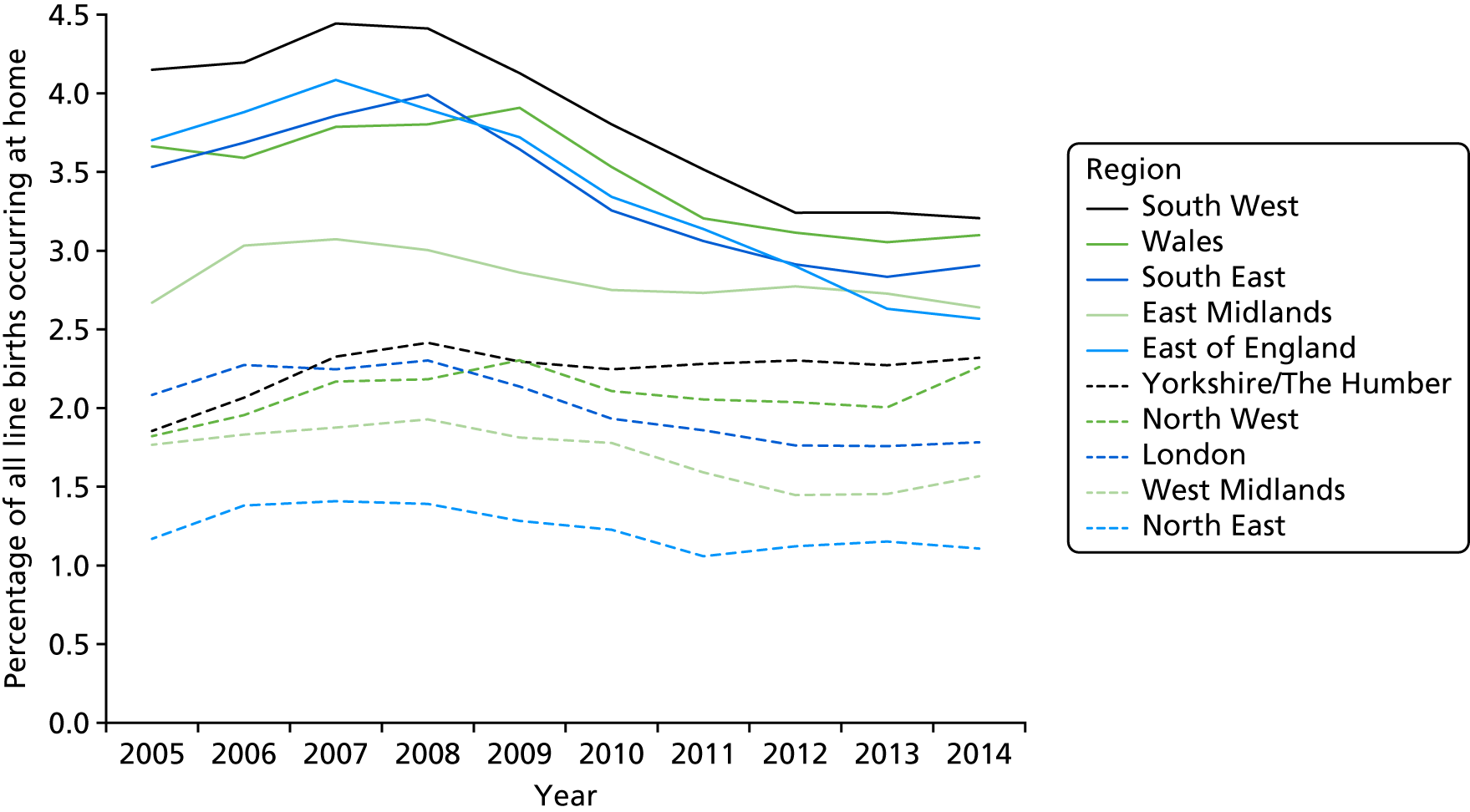

Although the proportion of births taking place at the mother’s home rose to well over 2% in the decade after the Changing Childbirth report was published, this was followed by a small decrease from 2008 to 2012. The number of alongside midwifery units (AMUs) rose from 26 in 2007 to over 100 in 2016, whereas the number of freestanding midwifery units (FMUs) rose slightly from 56 to 62 over the same time period (Miranda Dodwell, BirthChoiceUK, 2016, personal communication). In 2012, an estimated 9% of women gave birth in an AMU and 2% of women gave birth in a FMU. 22 This represented some change but fell well short of the 30% proposed in Changing Childbirth. 19

In 2002, the Welsh Assembly Government set a target of 10% for home births by 2007 as part of its strategy to develop midwifery-led care and access to services that were unfamiliar to many communities. 23 The National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services in Wales24 had similar ambitions to those for England. This was followed by Strategic Vision for Maternity Services in Wales, the cornerstone of which continued to be tackling health inequalities. 25 Choice of place of birth and access to midwifery care pathways were part of the plan.

In response to the limited nature of the previous evidence and a recommendation by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for further research, the Birthplace Programme of Research, a large-scale prospective cohort study, was funded. It aimed to evaluate and compare the risks and benefits for healthy women with straightforward pregnancies, who are at ‘low risk’ of complications, of giving birth at home or in FMUs, AMUs or obstetric units (OUs), focusing in particular on birth outcomes. 26 The Birthplace research found that outcomes for babies were similar for women planning birth in all settings but compared with women planning a hospital birth, women planning a home birth or birth in a midwifery unit had a lower risk of having a caesarean section, an assisted delivery or a haemorrhage.

The research also found that women planning a home birth or midwifery unit birth were more likely than women planning for birth in an OU to have a ‘normal’ birth. 26

This research was used as a basis for the 2014 revision to the NICE Intrapartum Care Guideline. 27 Birthplace26 also confirmed that the policy of choice of place of birth was safe, and that planning care in midwife-led care settings at home and in FMUs or AMUs for women at low risk of developing complications during labour and birth resulted in fewer invasive and costly medical procedures. 27

Health inequalities

One of the themes in the House of Commons Health Committee’s report that received less attention was health inequalities and maternity care for disadvantaged women. This reflects the extent to which the degree of emphasis placed on preventing health inequalities, investing in public health and improving access to maternity care has varied over time and between governments.

From 1997 to 2010, during the 13 years of Labour government, there was a clear emphasis on inequalities in health outcomes and the need to know where specific health ‘gains’ could be achieved. The National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services, published in 2004,21 followed frameworks for other key areas of health care, including cancer, heart disease and diabetes. It looked at perinatal mortality and morbidity, and other aspects of child health, in relation to structural inequalities, as well as at the impact of poverty and disadvantage succeeding from one generation to the next. 28 There was an emphasis on cross-departmental policies to reduce the number of children living in poverty. 29 A key strategy for improving maternity experiences included improving maternity rights and pay.

The strategic review of health inequalities in England, chaired by Michael Marmot, emphasised the social determinants of health and health inequality. 30 The review team concluded that, in addition to the social justice argument for addressing health inequalities, there was also a pressing economic imperative for change as annual costs to the exchequer attributable to inequality in illness were estimated to be £31–33 billion in productivity losses, £20–32 billion in lost taxes and higher welfare payments and over £5.5 billion in additional NHS costs. 30 It was therefore also necessary to engage members of the public in protecting and promoting their own health.

Reducing the costs of litigation

Broader sociopolitical changes were also influential, including the regulation of hours by the European Working Time Directive,31 reductions in the numbers of junior doctors and the increasing cost of maternity litigation. A report by the NHS Litigation Authority showed that between 2000 and 2009, 5087 claims for injury were made against the NHS, for which it paid out £3.1B in damages. 32 The three most frequent categories of claim were those relating to the management of labour, caesarean section and cerebral palsy. 32 Improving the overall quality of maternity care and reducing deaths and injury are important, as is the need to make the best use of limited resources.

Recent policy developments

After the change in government in 2010, it was several years before new maternity policies were developed. The NHS Five Year Forward View,33 published in October 2014, set out a vision for how the NHS in England would have to adapt to meet the needs of a changing population and committed further funding for the NHS. It stated that a ‘one size fits all’ approach to health care was no longer applicable to a diverse population and proposed new models of care, including in relation to maternity care. Speaking of the need to move away from a factory-like model of ‘care and repair’, the NHS Five Year Forward View set out a greater focus on community engagement and prevention of disease through improved public health, although its view of this was based more on individual than on structural measures.

It also spelled out the considerable growing demands on the service as a result of people living longer, opportunities and pressures to provide ever more complex science- and technology-led interventions and the continuing impact of smoking, alcohol use, lack of exercise and rising levels of obesity on levels of diabetes, stroke, heart disease and cancer. A national maternity review was subsequently commissioned to investigate the changes to maternity services needed to meet the needs of the population. 33

It was also asked to ensure that the recommendations of the Morecambe Bay investigation34 of ‘serious failures of clinical care’, which led to avoidable deaths of mothers and babies in one maternity unit, could be embedded throughout the NHS in England. 35

The review’s findings were incorporated in a Five Year Forward View for maternity, Better Births,35 a strategic framework with many broad-ranging aims. It aimed to make a significant culture change, based on two fundamental principles, described as being:

The importance of women being able to make choices about their care, and the safety of the mother and baby being paramount.

This safer, more personalised care, in which maternity services are responsive to the needs and circumstances of individual mothers and babies, would be focused on reducing avoidable deaths and damage through a focus on acute services delivered by multidisciplinary teams. In addition to the distress caused to families by negligence during maternity care, compensation costs the NHS an average of £560M per year. 35 This care would also encompass more community-based and midwife-led services for women with a straightforward pregnancy who are at low risk of complications. Better Births35 also preserved the commitment to the choice of place of birth given in Maternity Matters. 20

Meanwhile, the Welsh Government set out its strategic vision for maternity services in 201125 and set up the Maternity Network Wales in 2015. 36 This has three main priority areas: (1) to lead on a number of interventions to reduce stillbirth rates in Wales, (2) to improve the quality of maternity services by implementing the recommendations made by the Quality and Safety subgroup of the All Wales Maternity Service Implementation Group in its report published in June 201337 and (3) to work in partnership with women and families. 38 This is to be achieved through a number of subgroups set up by the Network.

NHS care at weekends

From 2001 onwards, a considerable number of analyses have shown higher mortality rates among patients admitted to hospital at weekends than on weekdays and there has been considerable debate about how to interpret these rates. 39,40

We have not attempted to summarise them here, as we are aware that a systematic review is under way. 41 Instead, we have given examples that highlight some of the arguments. For example, a study using routinely collected data for over 4 million emergency admissions found that the overall adjusted odds of death was 10% higher for weekend admissions than for weekday admissions. 42 Another study using patient records for 14 million hospital admissions found a higher risk of in-hospital death within 30 days of admission for weekend admissions than for weekday admissions, but the chance of actually dying at the weekend was lower than the chance of dying mid-week. 43 In contrast, a prospective cohort study with 74,000 stroke patients showed no difference between 30-day survival at weekends and on weekdays. 44

Even if there are weekend effects, it is unclear if they reflect differences in quality of care or differences in case mix. For example, one study found that patients admitted at the weekend were more seriously ill than those admitted during the week. 45 Another suggested that the weekend effect arises from patient-level differences at admission rather than reduced hospital staffing or services. 46 Even where it is suspected that staffing makes a difference, there are questions about whether this reflects numbers or type of staff or their seniority. One study examining nearly 4 million elective procedures concluded that consultant seniority has no impact on predicting 30-day mortality. 47

These uncertainties have not impeded calls from politicians and others for a 7-day health service. NHS England established a Seven Days a Week Forum and its report, published in November 2013,48 was cited prominently in the report of the Review Body on Doctors’ and Dentists’ Remuneration published in 2015. 49

Despite the conflicting evidence, in the NHS Mandate published in 2015, the Secretary of State for Health for England, called for ‘a truly seven-day health service’:

The NHS should be there for people when they need it; this means providing equally good care seven days of the week, not just Monday to Friday.

Although these policies have been labelled ‘24/7’, the analyses have been largely restricted to differences between days. As we show in the following section, this is not the case for analyses of births, and times of day have been taken into account when discussing the staffing of maternity services. Although it is self-evident that maternity services need to operate 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, there are still many questions about the type and seniority of staff needed.

Staffing of maternity hospitals

Although adequate staffing is central to delivering high-quality, efficient health care, most of the debates have been about medical staffing and have mainly related to consultants, although they featured in negotiations about revisions to junior doctors’ contracts49 and their decision to take industrial action in response. Although the RCM repeatedly expresses concern about shortfalls in midwifery staffing, it has not been in this context. This is a matter of concern to the College and it has supported our project at each stage, stating that the information we aimed to produce would have been useful to it.

The National Patient Safety Agency ‘Hospital at Night’ Programme,50,51 set up in 2005, proposed that the way to achieve safe clinical care was to have out-of-hours care delivered by a multiprofessional team with the full range of skills and competencies across a whole range of disciplines in a hospital to meet the immediate needs of patients. This did not apply to obstetrics as, according to the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG),51 women in labour needing medical care would be managed by obstetricians within the department and not by the Hospital at Night team. Thus, the emergency obstetric rota would be staffed for 168 hours a week (‘24/7’) from within the discipline of obstetrics and gynaecology.

For a number of years, the RCOG advocated increasing the hours of consultant presence in maternity units. 52,53 Initial recommendations were for units to have a minimum of 40 hours of consultant obstetrician cover a week, with exceptions for units with fewer than 1000 births a year and those with low complication rates. In addition, units with > 5000 births were to have 60 hours of consultant cover a week. The Healthcare Commission’s maternity services report, Towards Better Births, reported that only 68% of trusts reported meeting this standard in 2007, with some trusts reporting a very minimal presence, as low as 10 hours per week. 54

In 2007, new recommendations were made for a minimum of 60 hours of consultant presence in all OUs, with a specific recommendation of 98 hours for units with 4000–5000 births. For units with over 5000 births per annum, the RCOG recommended consultant presence on the labour ward both day and night, for 168 hours per week, referred to as ‘24/7’ cover, by 2010. For the largest units with over 6000 births, the suggested time frame for implementation was earlier, by 2008. 55

This drive for increased consultant presence came at a time when there were also increasing pressures on the workforce. The RCOG report High Quality Women’s Health Care56 identified the impact of the European Working Time Directive on women’s health care, and specifically the introduction of the 48-hour week, which led to a need to increase the numbers of consultants to provide cover. The RCOG report, The Future Workforce in Obstetrics and Gynaecology,57 calculated that 168 hours’ cover for a delivery suite, along with other clinical activity, would require the employment of 18–21 consultants per OU. This led to proposals for obstetric services to be centralised, with the closure of small OUs, as these might be uneconomic to run with the recommended level of consultant presence.

In terms of obstetric staffing, the Strategic Vision for Maternity Services in Wales policy referred to compliance with the European Working Time Directive, the need for services to comply with the RCOG guidance for 40 hours of consultant labour ward presence per week, depending on the number of deliveries per year, and for a middle-grade doctor at level Specialty Trainee 3 or higher or at Staff Grade, Associate Specialist and Specialty Doctor grades to cover the labour ward at all times at which a consultant is not present. 25

By 2014, only two units in the UK had achieved 168 hours per week of consultant presence58 even though numbers of consultant obstetricians and gynaecologists in England had risen substantially. Over the years between 2002 and 2017, numbers of full-time equivalent staff had almost doubled, with an increase of 20% in the last 5 years of this period. 59,60

Despite the decisive strategic direction taken by the RCOG, the evidence that these levels of consultant presence would increase safety for mothers and babies was not clear, particularly in relation to the increase in size of OUs resulting from this policy. 61,62 A systematic review and related case studies from England, France and Sweden concluded that ‘A model considered equitable by consultants and which includes prospective cover for holidays, thus truly providing continuous consultant labour ward presence, requires 26 consultants’. 63 This would be possible only within current budgets for England only in very large, tertiary level units providing care for a disproportionately large number of women with complex care, and so attracting the higher tariffs available for paying for their care.

Based on several factors, including limited available evidence on the impact of 24-hour consultant presence, with little to show that this improves the quality of care, together with competing arguments for deploying any additional staffing, such as employment of more midwives or having greater consultant obstetrician presence at weekends, the authors concluded that the case for 24-hour consultant obstetrician presence on the labour ward had so far not been demonstrated. 63

Given the lack of evidence that 24-hour resident consultant presence on the labour ward has any impact on women’s outcomes, the RCOG subsequently produced a report to update its guidance on obstetric staffing. 64 It stated that:

It is recognised that there is huge variability of service provision around the country in terms of workload complexity, geography and current middle grade staffing. For this reason, there is no single staffing model which is suitable for all UK units . . . Within obstetrics it is no longer possible to make recommendations about hours of consultant presence on the labour ward based on number of deliveries because of the diversity of consultant contracts and working practices.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Providing Quality Care for Women: Obstetrics and Gynaecology Workforce. London: RCOG; 2016. 64 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists © 2018

It did, however, strongly recommend that all OUs should have a minimum labour ward consultant presence during working hours between Monday and Friday, with the aim of extending this to every day of the week. 64

Reducing stillbirths and neonatal deaths

As well as the focus on keeping care for healthy women straightforward and on avoiding iatrogenic effects and rising costs, there has been a concurrent focus on a traditional cornerstone of quality maternity care, that is, improving safety by reducing avoidable maternity and perinatal injuries and deaths. This comes at a time of rising birth rates, rising ages at childbirth and increasing rates of obesity and other clinical and social complexity. These factors have led to greater demands on the service, and an increased proportion of women needing medical care and more intensive midwifery support. The Morecambe Bay Inquiry34 highlighted the importance of careful needs assessment and close interdisciplinary working to ensure consistent and improving levels of safety in maternity care. These are all drivers affecting commissioning priorities and strategic decision-making in service delivery.

As part of the Five Year Forward View, the government’s ambition is to halve the rates of stillbirth and neonatal death in England by 2030;65 the Saving Babies’ Lives Care Bundle is designed to guide commissioners and clinicians on how to develop services to make this happen. 66 It brings together four elements of care: (1) reducing smoking in pregnancy, (2) risk assessment and surveillance for fetal growth restriction, (3) raising awareness of reduced fetal movement and (4) effective fetal monitoring during labour.

In 1928, the stillbirth rate for England and Wales was 40.1 per 1000 total births and this fell steadily from the 1950s to the turn of the century, but then levelled off and thus became a cause for concern. In 2012, the stillbirth rate started to fall again, reaching 4.5 per 1000 total births in 2015. Even before the implementation of the government’s strategy, over the period 2013–15, the stillbirth rate in the UK as a whole, published by MBRRACE-UK, fell by almost 8%, largely because of a reduction in antepartum stillbirths at gestational ages of 32 weeks and over. 67

The neonatal mortality rate for England and Wales (i.e. deaths in the first month of life) fell more steadily from 30.9 per 1000 live births in 1928 to 2.7 per 1000 live births in 2013 and 2.5 per 1000 live births in 2014, although the decline had become less marked and the rate increased slightly to 2.6 in 2015. Data for the UK as a whole, published by MBRRACE-UK, showed that neonatal death rates fell marginally from 1.84 per 1000 live births in 2013 to 1.74 per 1000 live births in 2015. 67 In 2015, nearly two-thirds of these neonatal deaths were of babies who were born preterm and two-thirds of the stillbirths occurred before the pregnancy reached full term. 67 Rates published by MBRRACE-UK differ from those from civil registration as MBRRACE-UK systematically excludes events following the termination of pregnancy at ≥ 24 weeks of gestation and the deaths of babies born before 24 weeks of gestation. 67

Preterm birth and congenital anomalies account for a significant proportion of neonatal deaths and stillbirths, but the causes of preterm birth are poorly understood. Some countries, notably the Nordic countries, whose stillbirth and neonatal mortality rates our politicians aspire to emulate, have much lower rates of preterm birth and also lower rates of obstetric intervention than the countries of the UK. 68 A better understanding of the causes of preterm birth and the development of interventions to prevent them are urgently needed. This requires research programmes to evaluate the efficacy of both preventative and ‘rescue’ interventions.

The MBRRACE-UK consortium has led a coalition of stakeholders in developing a national, standardised Perinatal Mortality Review Tool to support local review processes. This is expected to improve assessments of the quality of care and postmortem investigations. The quality and incompleteness of data are also issues, preventing a full picture from being known, and also preventing accurate monitoring of changes.

In 2014, the RCOG launched a long-term quality improvement programme, Each Baby Counts, with the aim of halving the number of babies who die or are left severely disabled as a result of preventable incidents occurring during term labour, by 2020. Each Baby Counts is a measure that brings together the number of babies who are stillborn at term, who die within the first week of life or who are diagnosed with severe brain injuries. 69

In Wales, the National Assembly’s Health and Social Care Committee held an inquiry into stillbirths in 2012, which was reported in February 2013. It made a number of recommendations to reduce stillbirth rates,70 including the setting up of the Maternity Network Wales to take this work forward. 38

Variations in the patterns of the time when babies are born may affect stillbirth and neonatal mortality rates and can have implications for the staffing needs of maternity services. This can affect the care that women receive and their experience of that care. Investigations into patterns of birth timing and subsequent outcomes may inform changes in service provision that can improve care to make it safer and more personalised.

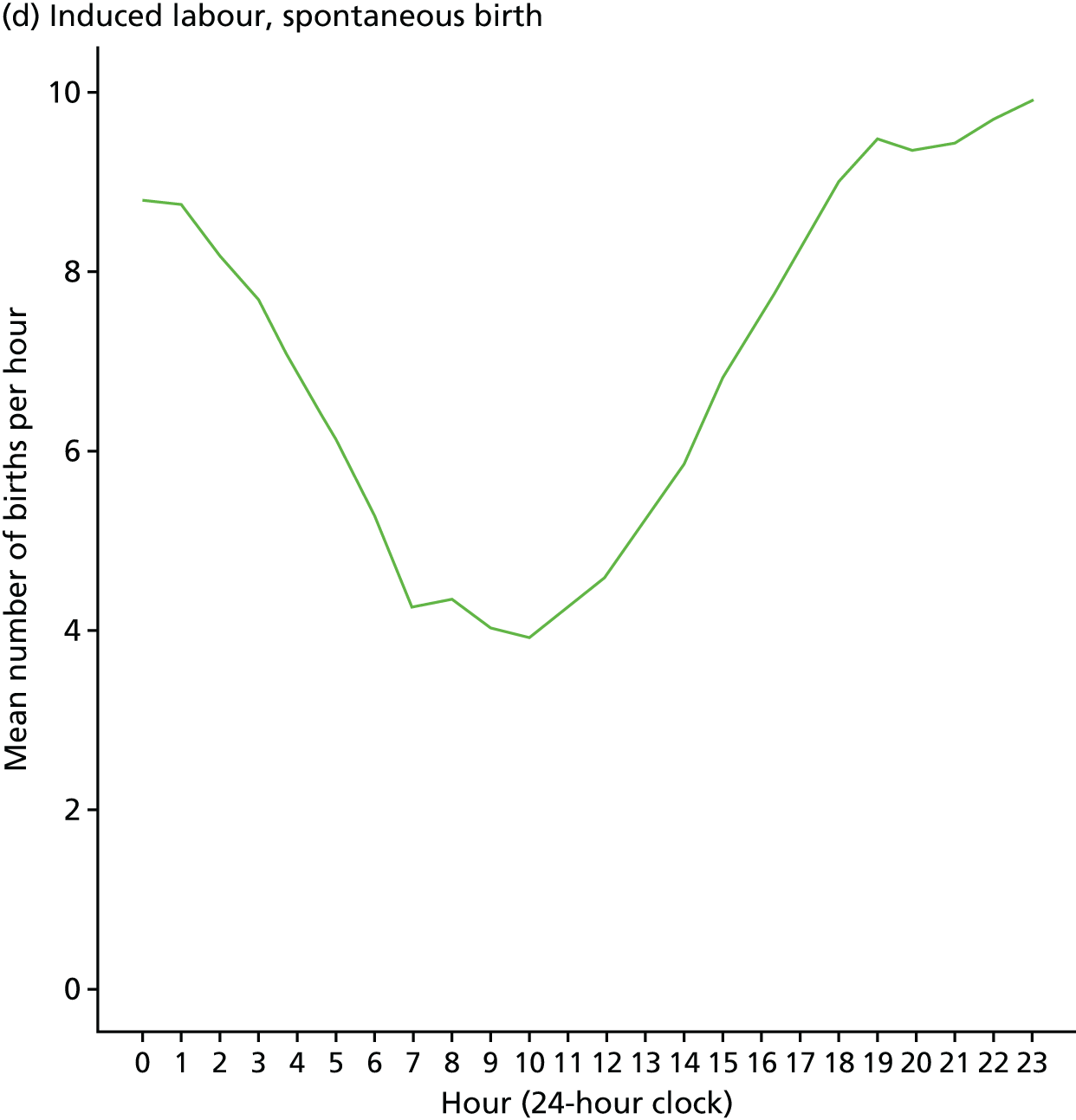

In particular, the strategy to reduce stillbirths may increase rates of induction of labour, which would have implications for the proportion of women eligible for midwifery-led care and for the pattern and timing of births in different settings. 66,69

Previous research on the timing of birth

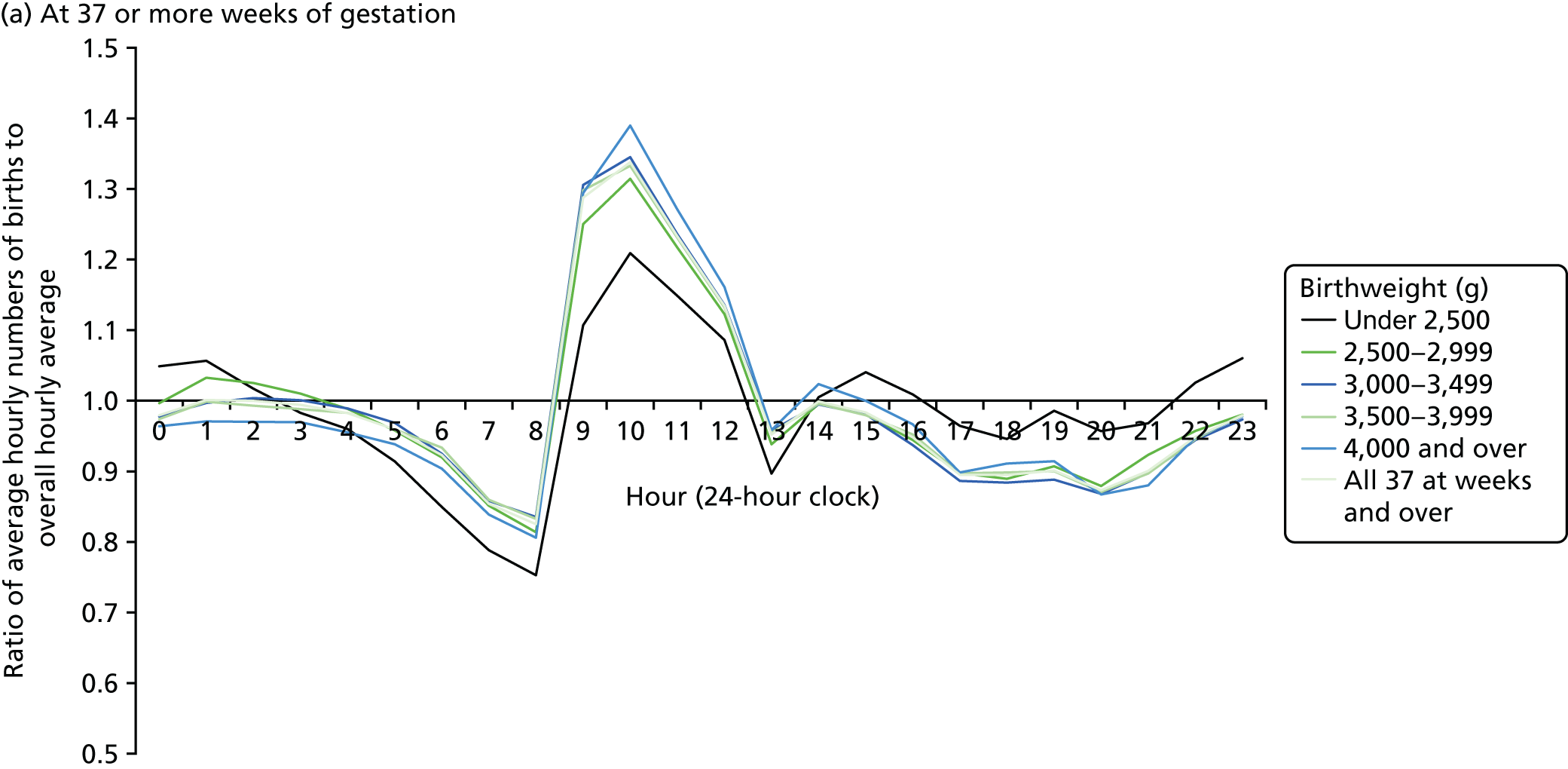

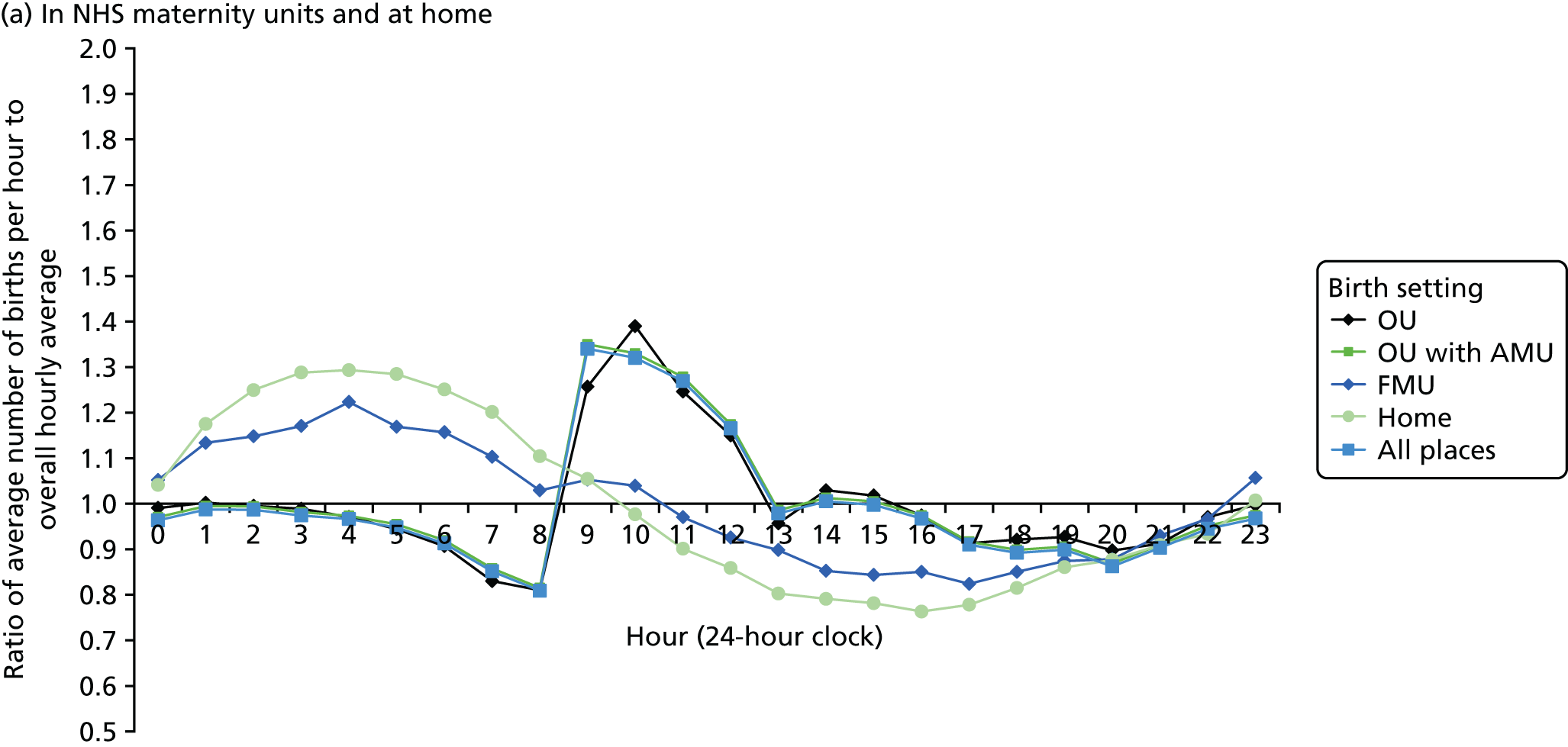

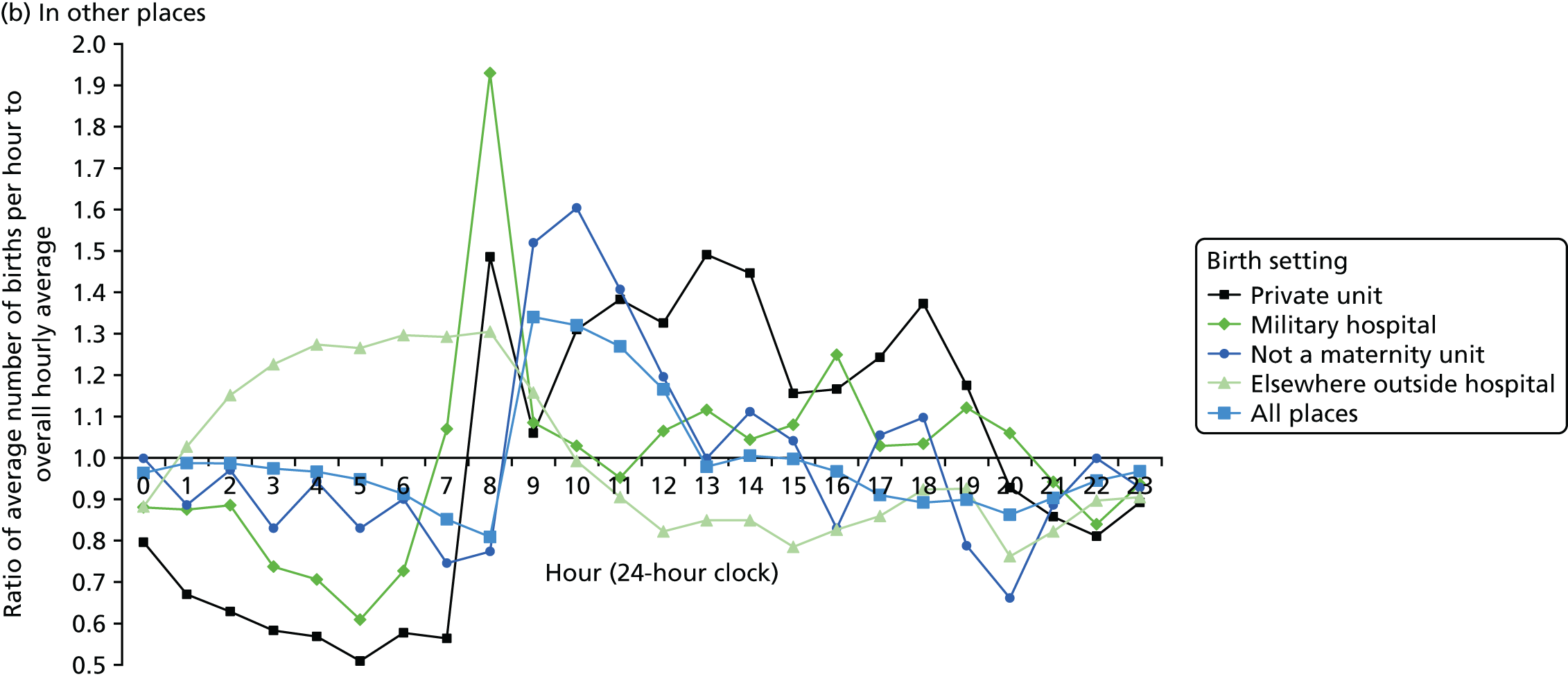

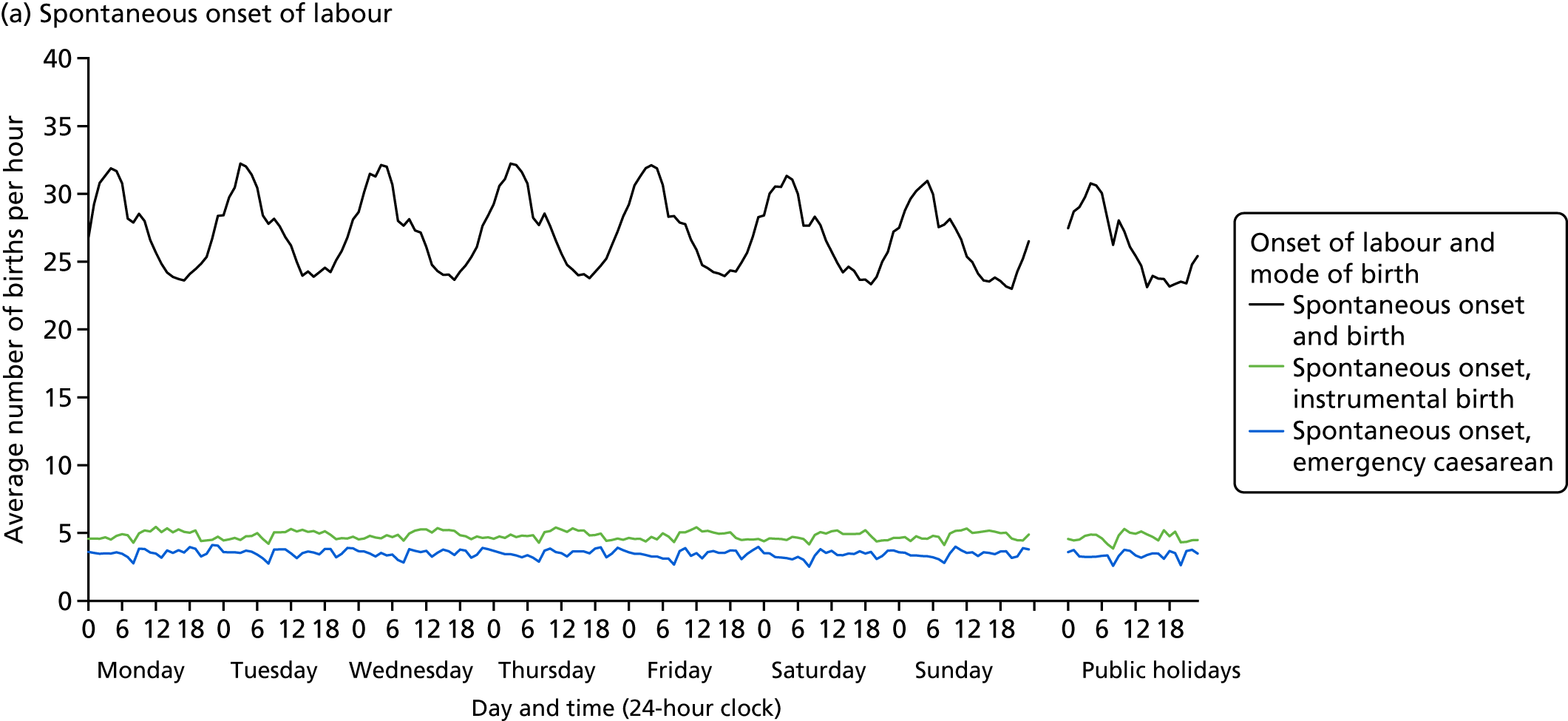

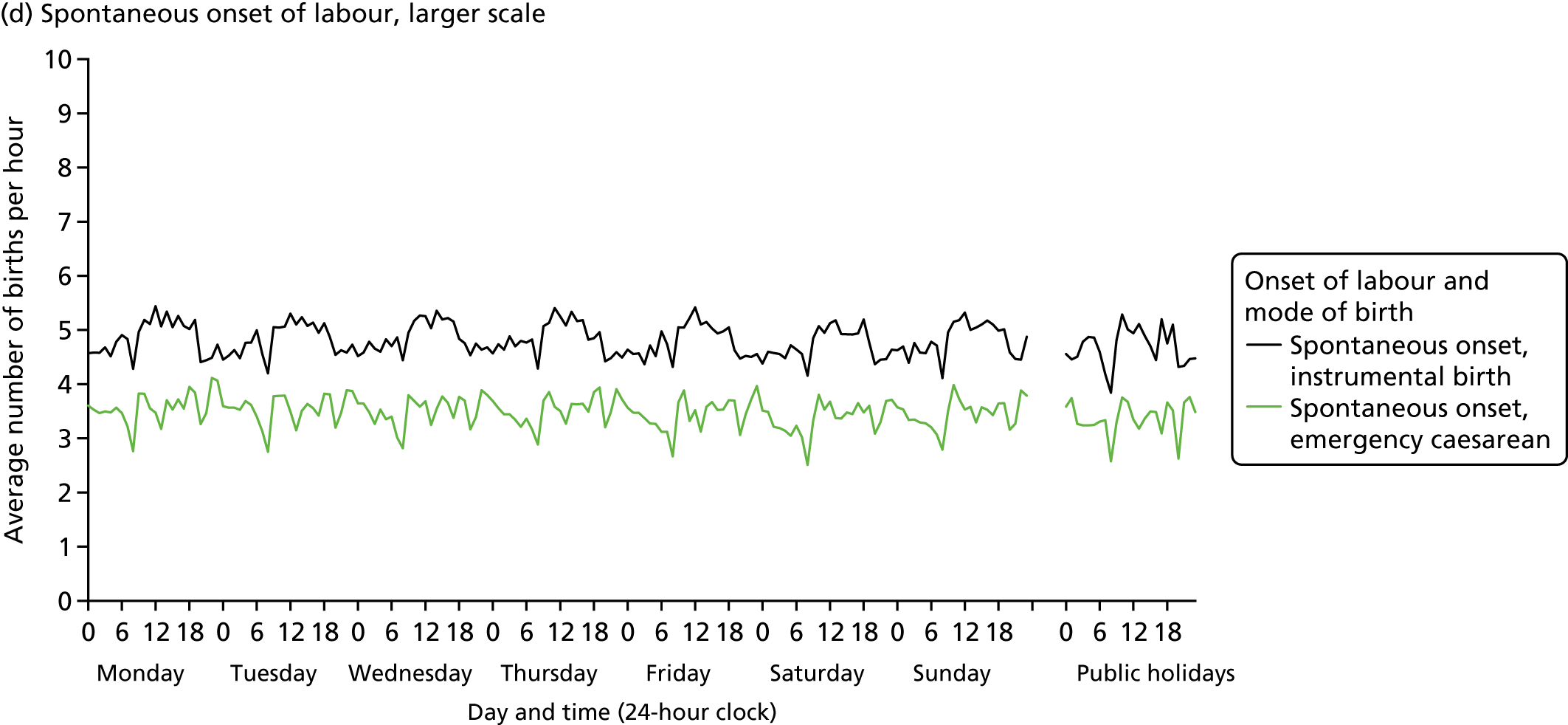

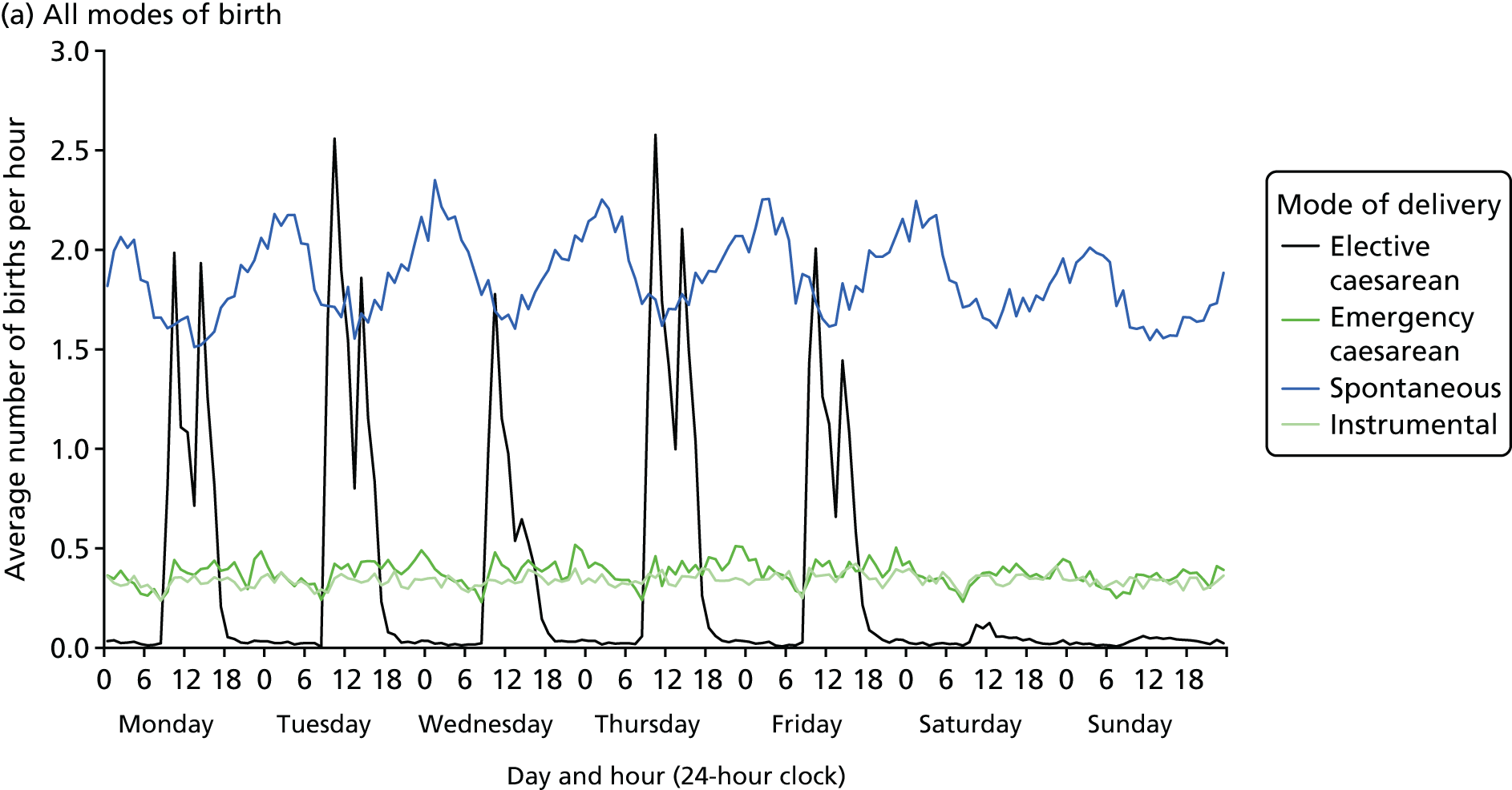

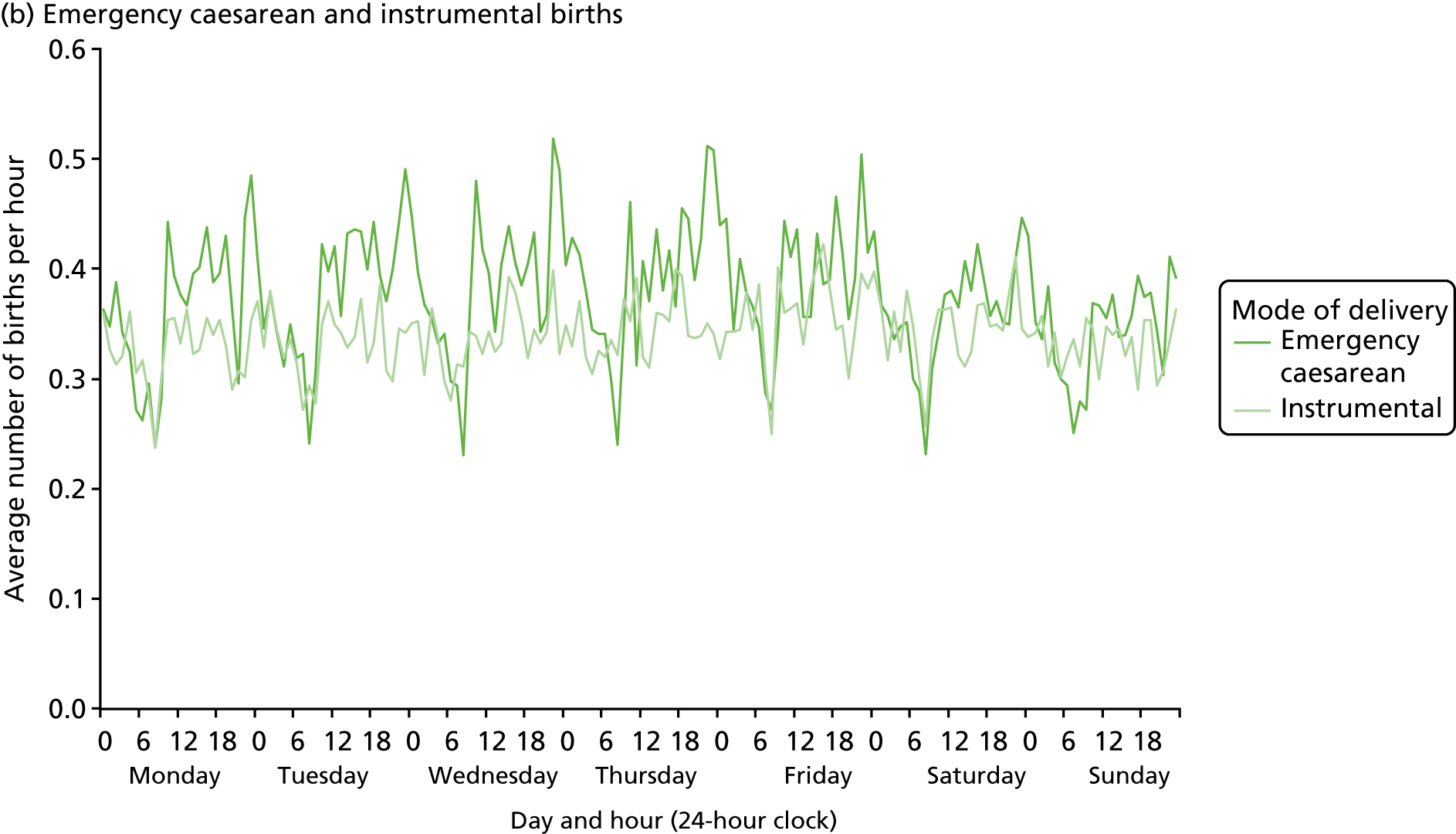

Time of day of birth

Up to the middle of the 20th century, there was a popular assumption that times of birth and death were by and large predetermined, although it was recognised that unexpected, possibly untoward, events could change them. The second half of the century saw increasing use of medical intervention to influence the time of birth and to prolong the lives of babies born very preterm or with conditions previously thought to be incompatible with life.

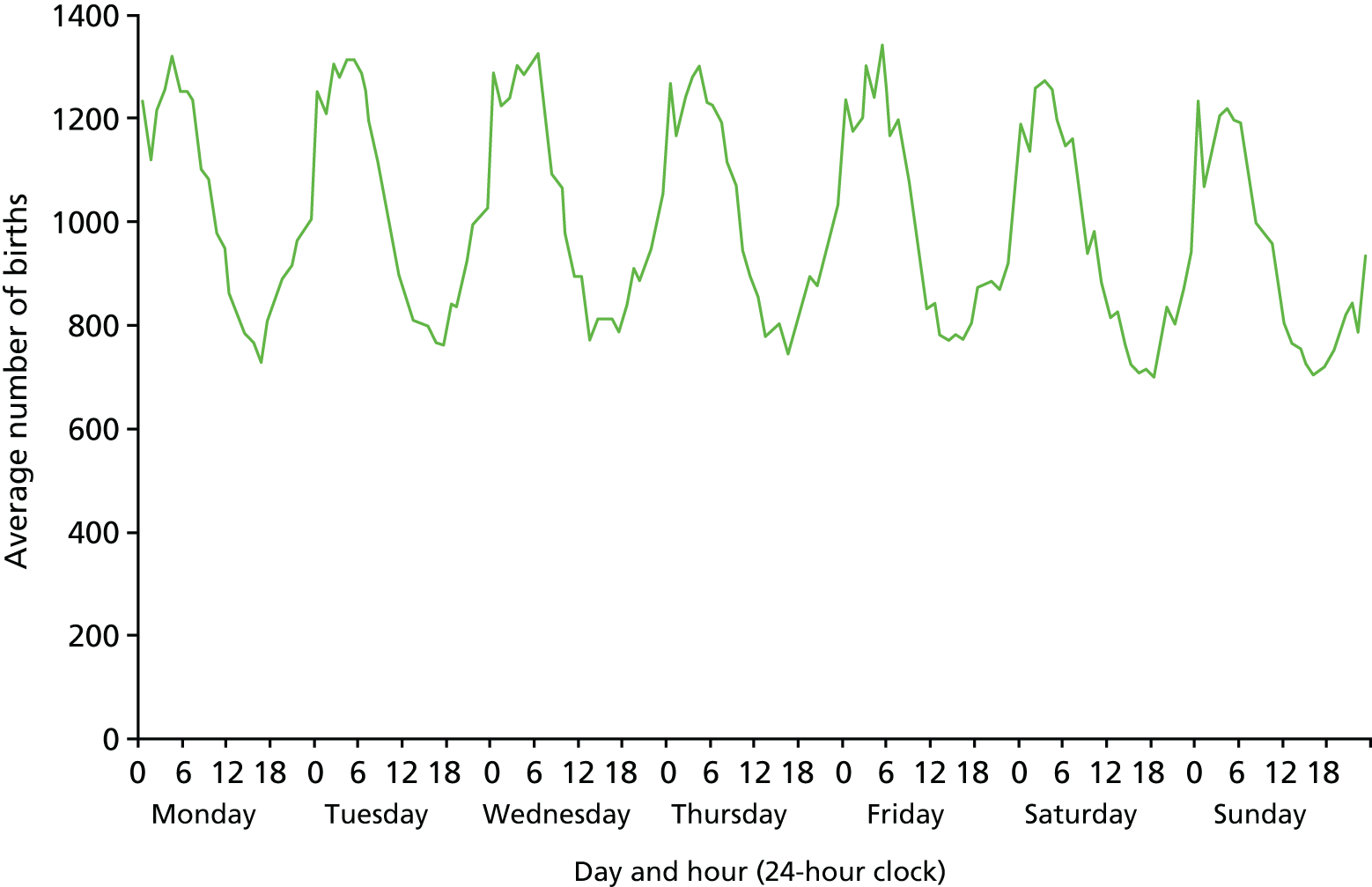

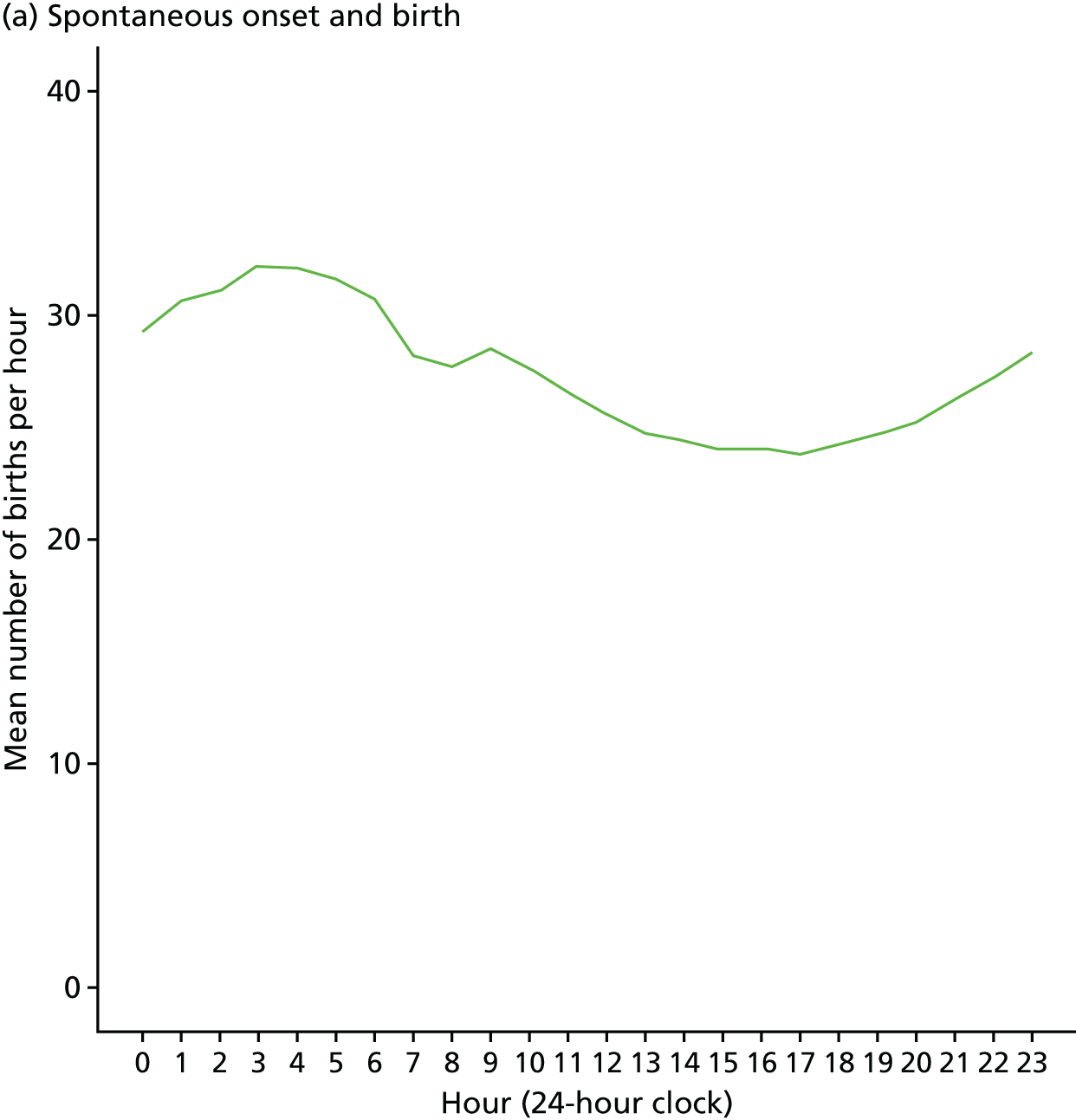

It was established in the 19th century that numbers of spontaneous births varied by time of day and were higher at night than during the day. 71–73 For example, in his Essai de physique sociale,74 published in 1835, Adolf Quetelet cited data from Brussels and Hamburg, which showed that the numbers of live births in the 6-hour periods before and after midnight were higher than those in the corresponding periods before and after noon. An exception was found in the Hamburg data, which were subdivided by season and which showed that numbers of live births were high on winter mornings.

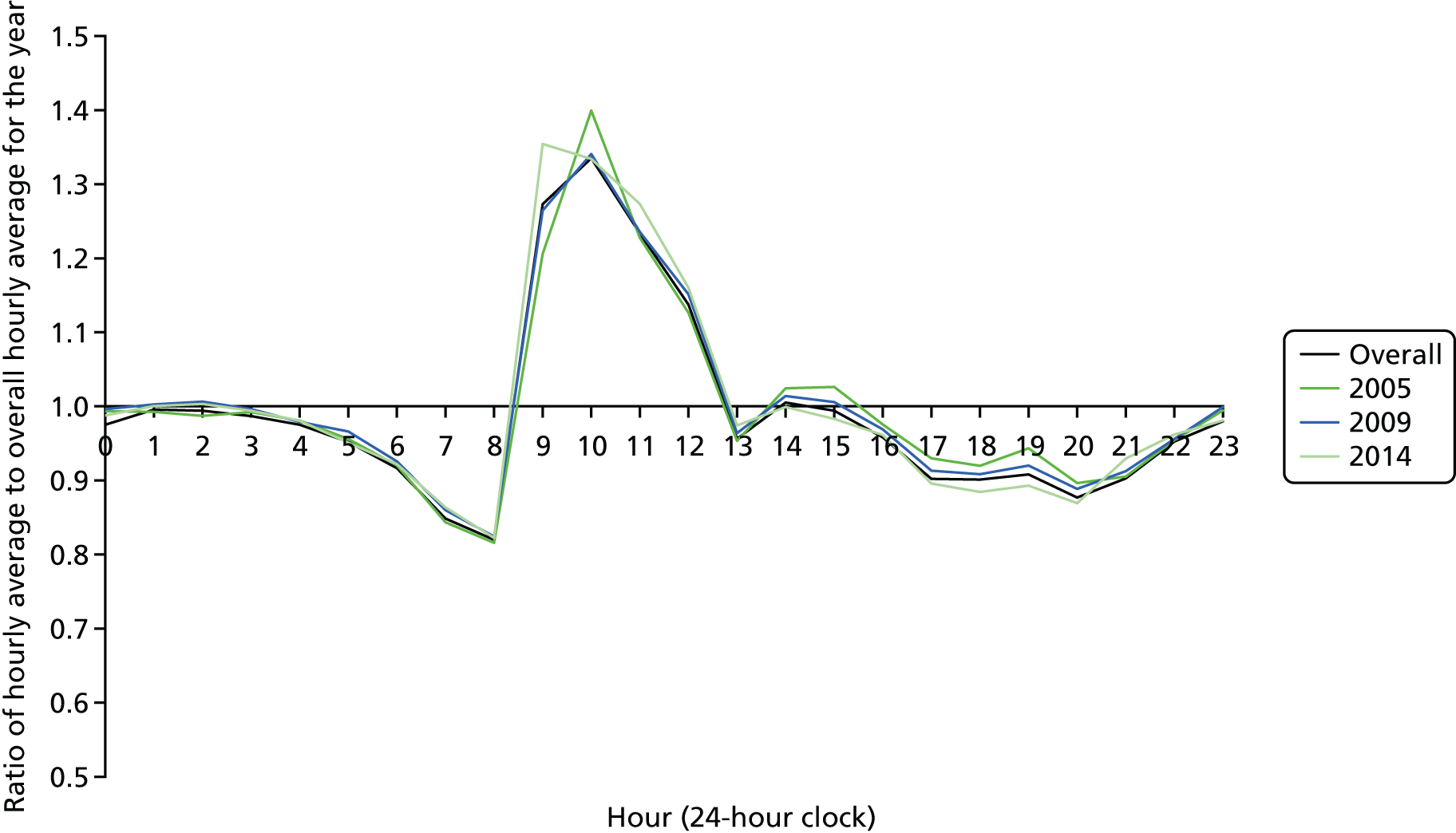

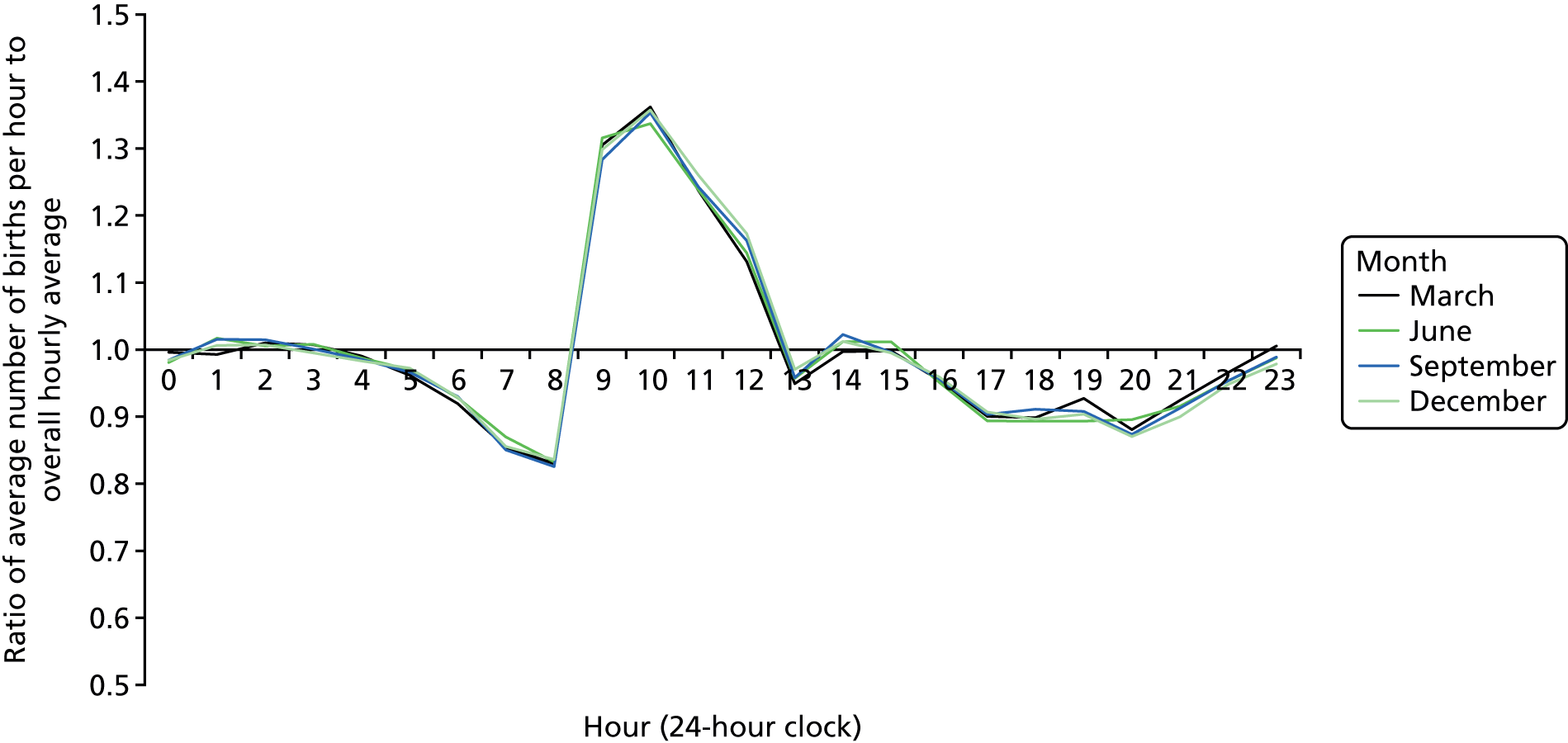

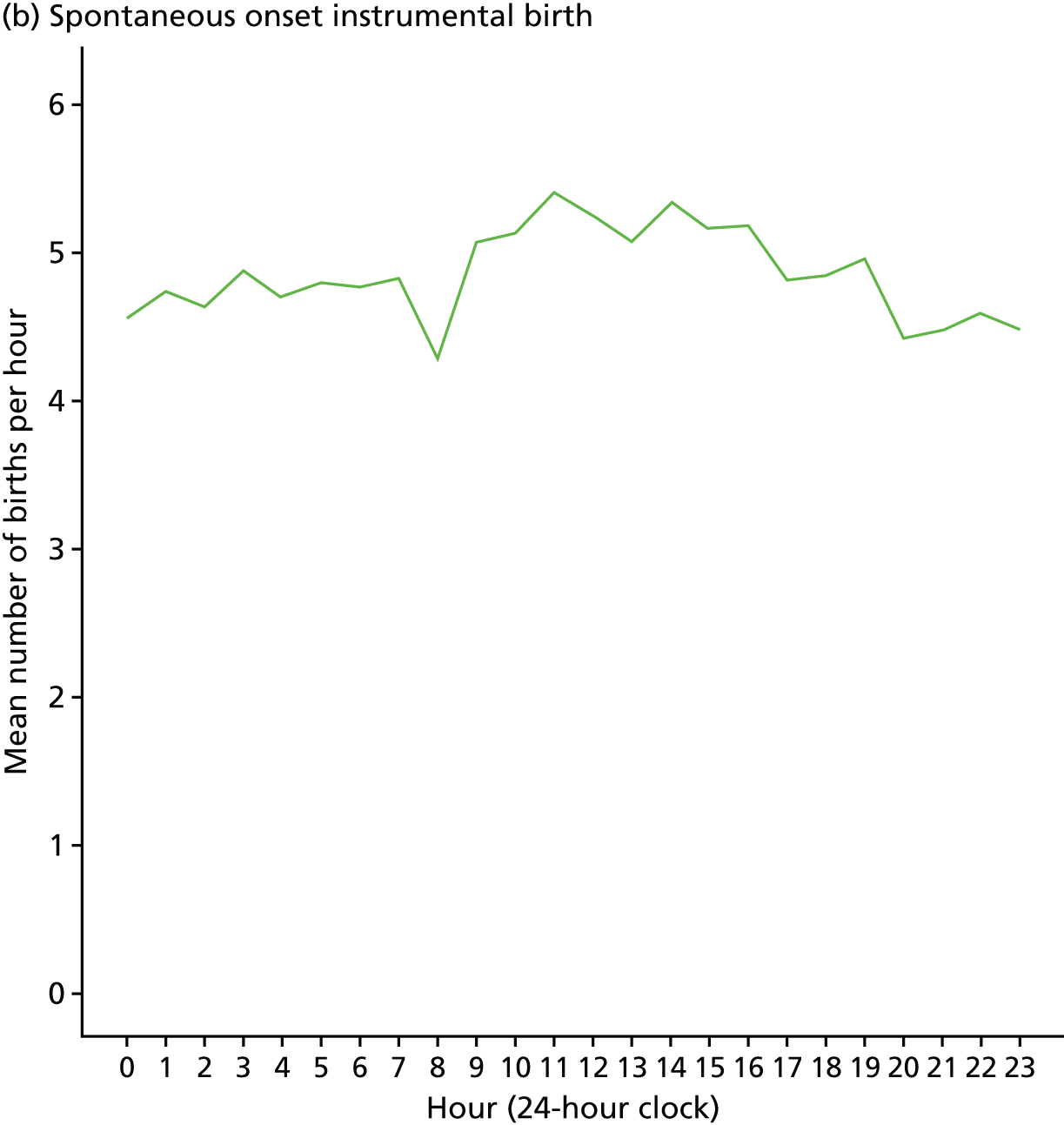

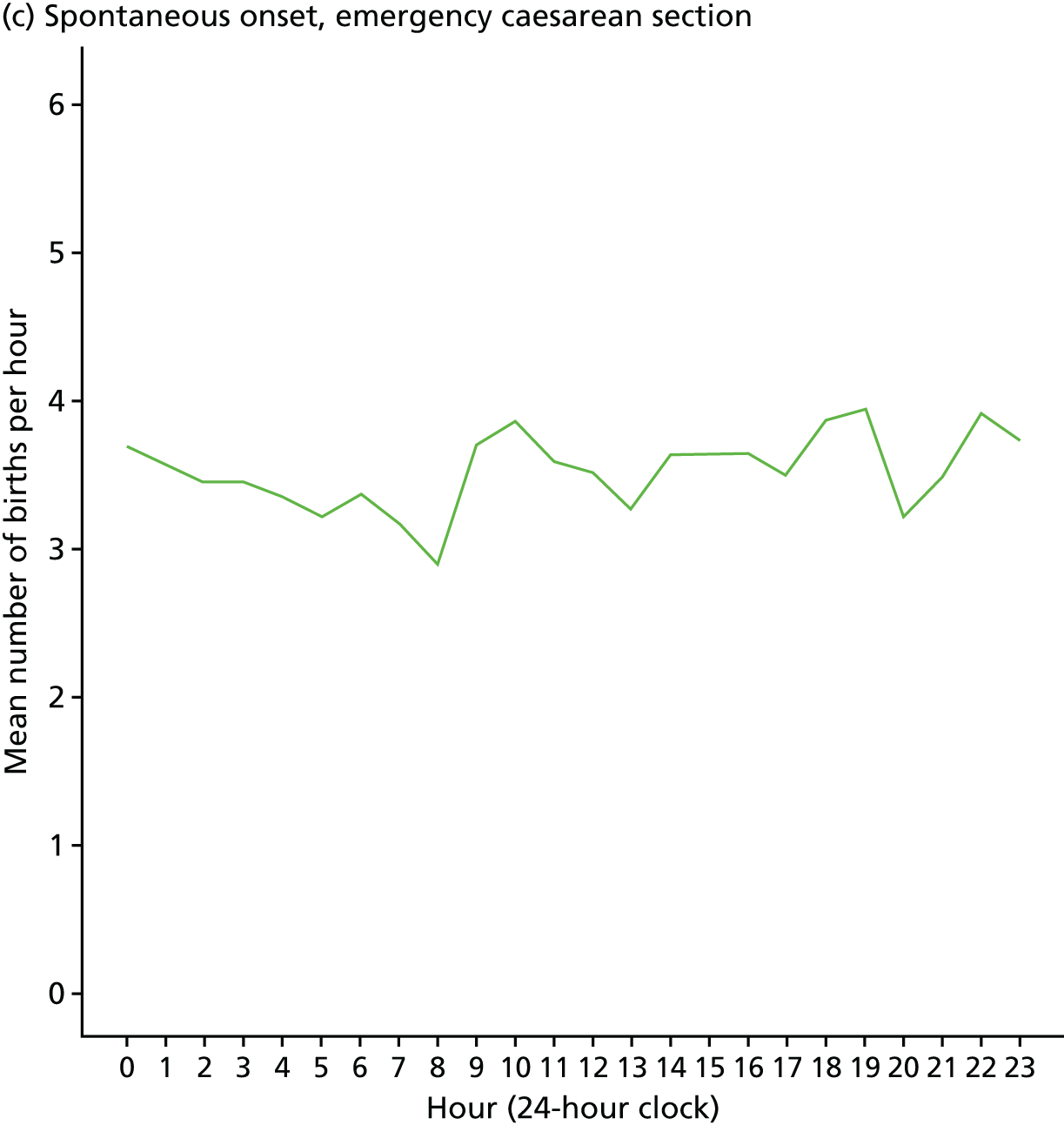

In the 20th century, data from a special birth certificate in use in Buffalo City, New York, showed that numbers of spontaneous births in 1937 were highest in the early hours of the morning from 03.00 to 05.00, whereas the much smaller numbers of births involving obstetric intervention peaked from 09.00 to 11.00. 75 A study of over 16,000 births in Birmingham, England, in the early 1950s focused on the time of onset of spontaneous labour and found that it peaked in the middle of the night, around 02.00, especially for primiparous women, with numbers of births peaking from 03.00 to 05.00. 76 Intervention rates were low in this period but caesarean sections were more likely to occur during the day.

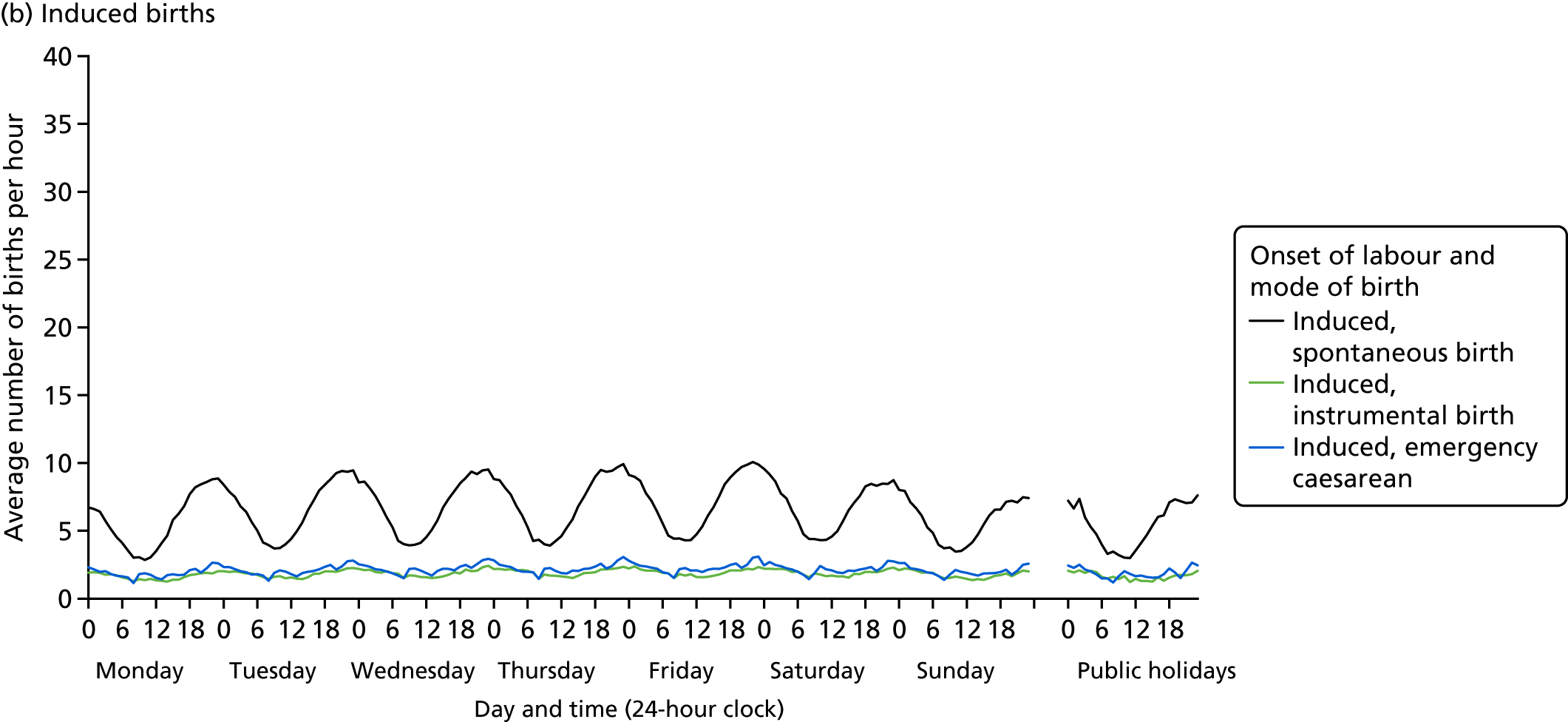

Reviews published in the 1960s and 1970s found that, in previous studies, births were most likely to occur between 01.00 and 06.00. 71,73 Further studies in the 1960s pointed out that this peak was apparent only in predominantly normal births, which did not involve invasive clinical procedures. Some of the rationale for the rising rates of induction, acceleration and caesarean section from the 1970s onwards was an intention to concentrate births into conventional working hours in order to optimise access to clinical care. 77–79

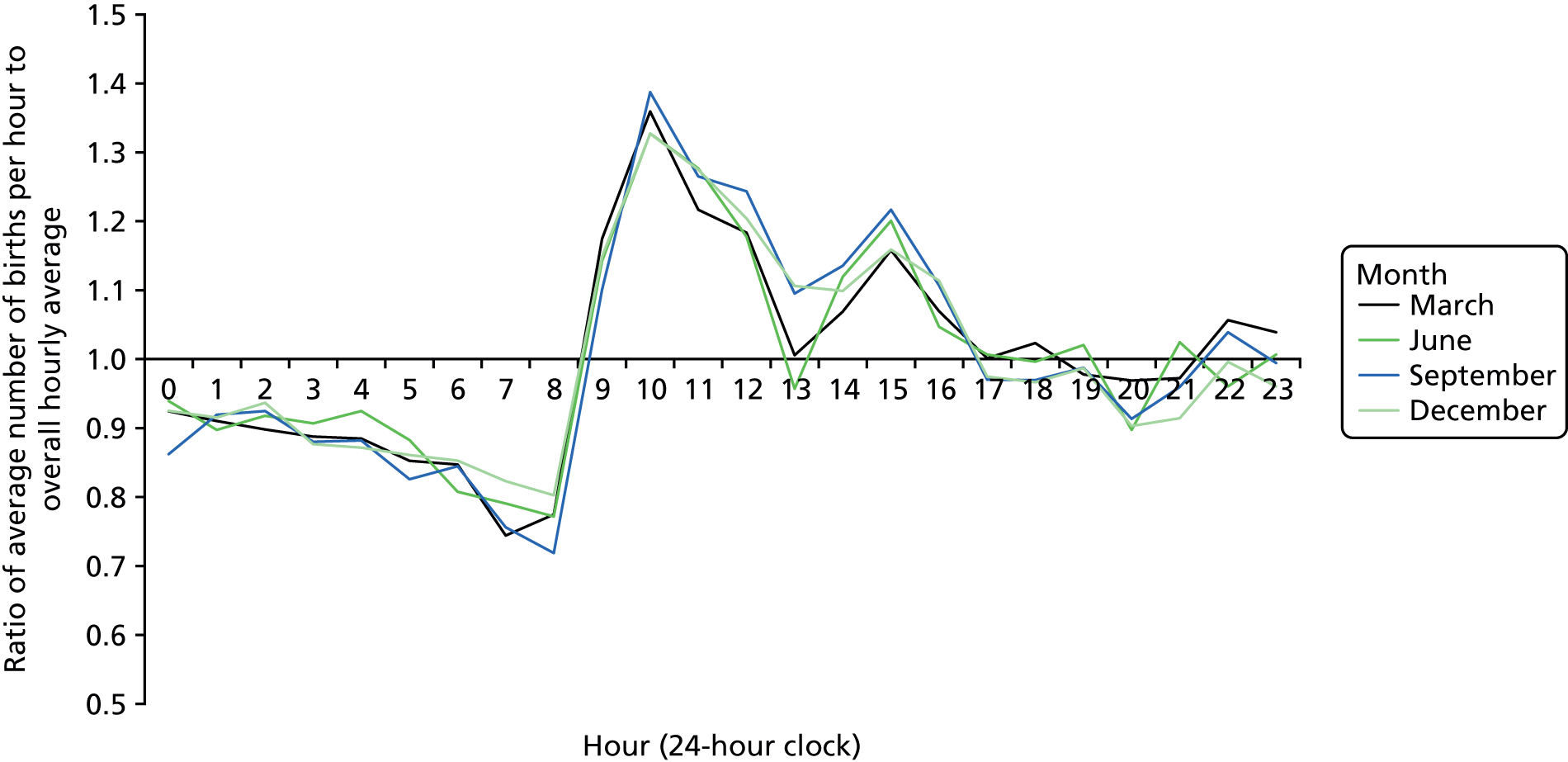

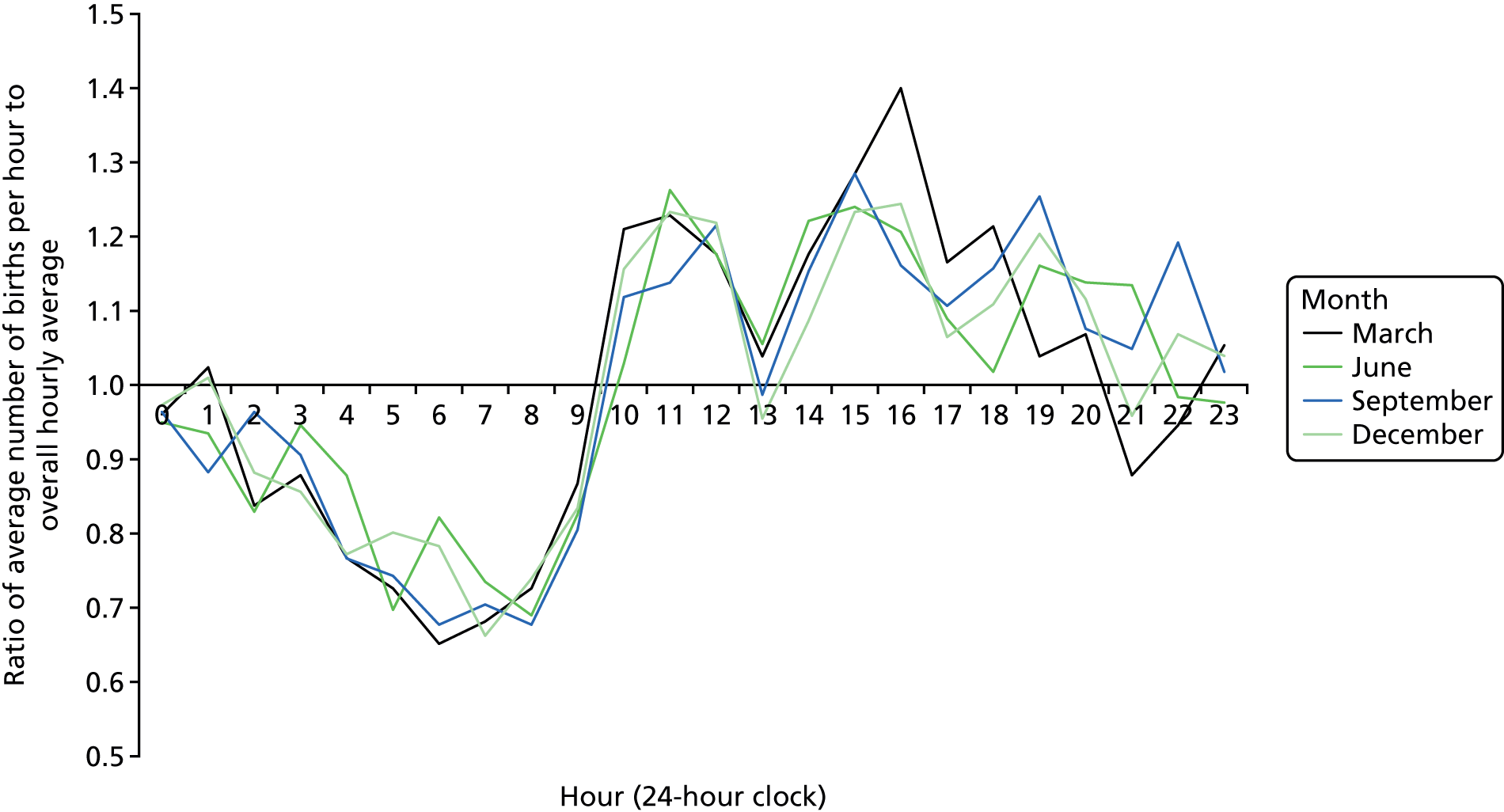

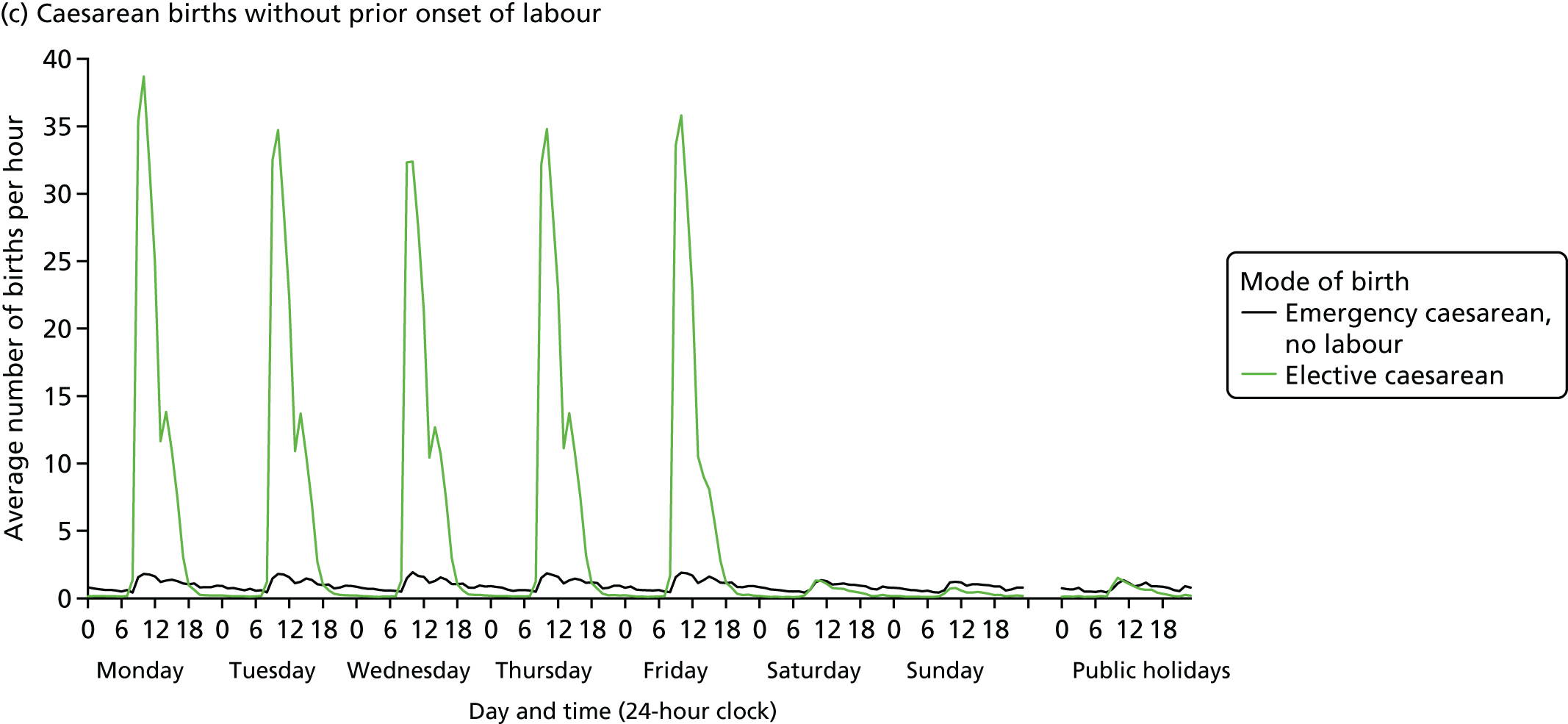

The impact of these rising rates was to move the peak in overall numbers of births into daytime hours. For example, studies in Switzerland of births from 1979 to 1981 showed that the highest numbers of births occurred on weekdays between 08.00 and 16.00,80 but this analysis did not subdivide births by mode of onset and birth. An analysis of all births in the state of Massachusetts, USA from 1989 to 1995 showed a peak between 07.00 and 09.00, the times associated with planned caesarean section. 81 When the analysis was restricted to singleton vaginal births of spontaneous onset without stimulation, the variations were less marked but numbers of births were slightly higher in the daytime between 09.00 and 15.00, with a peak from 11.00 to 13.00.

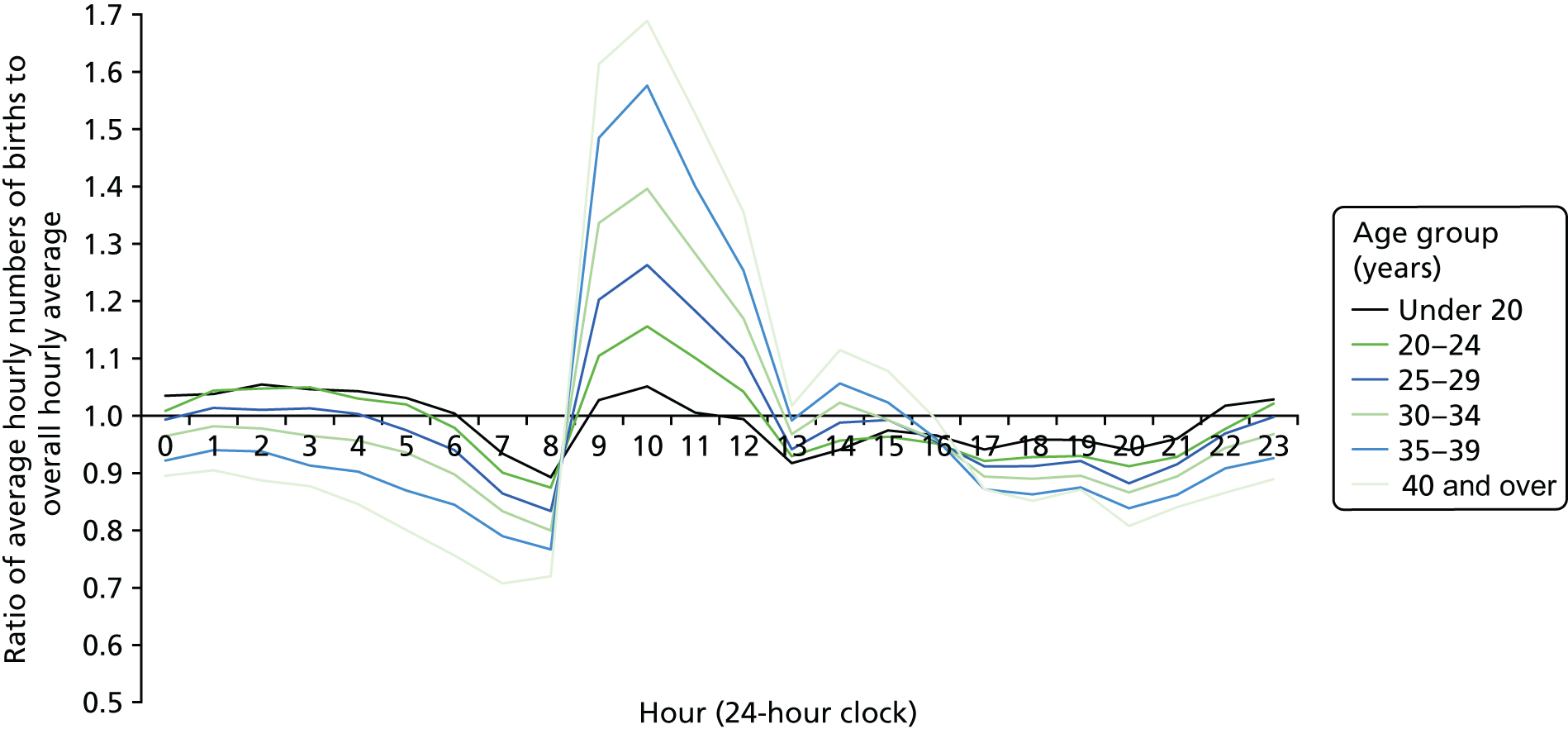

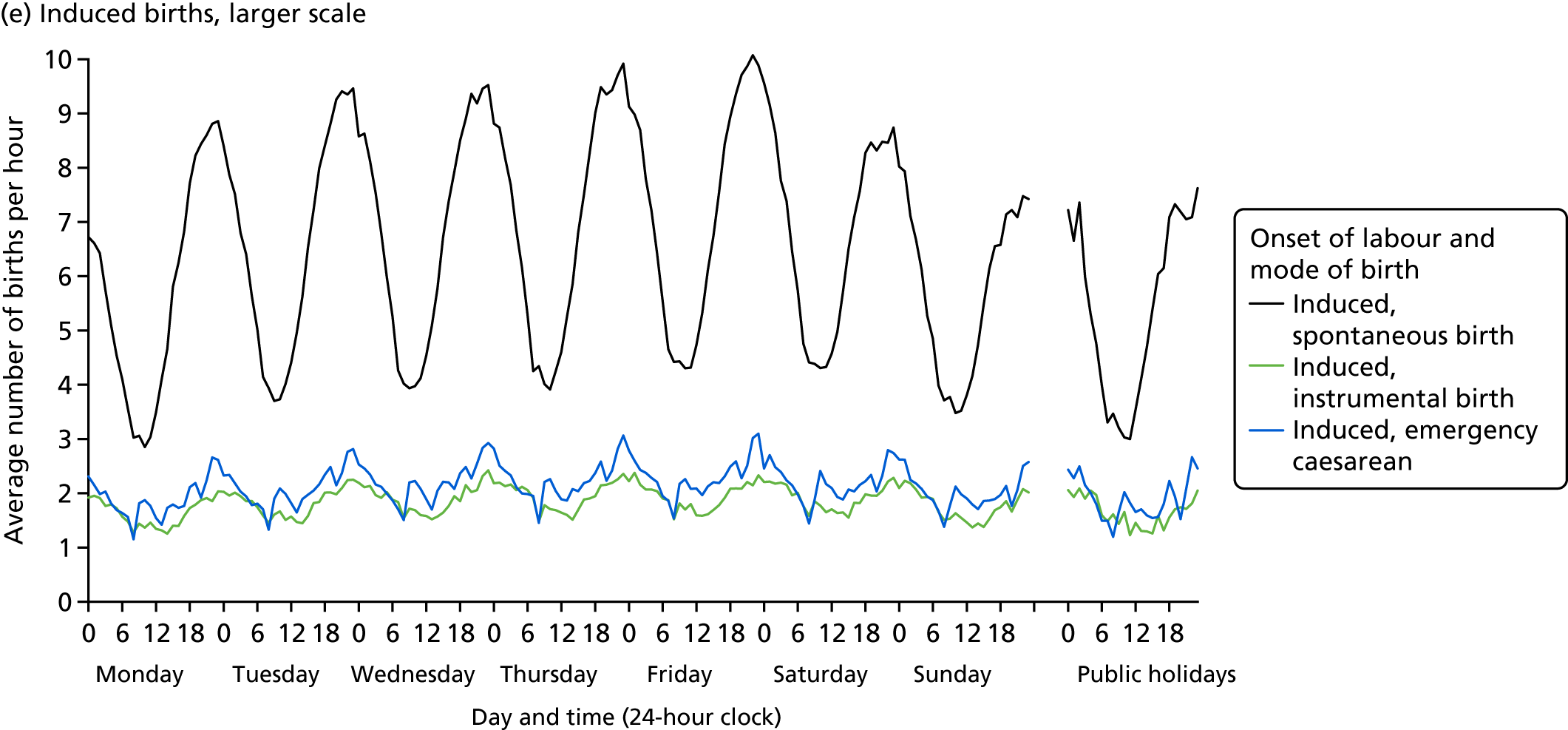

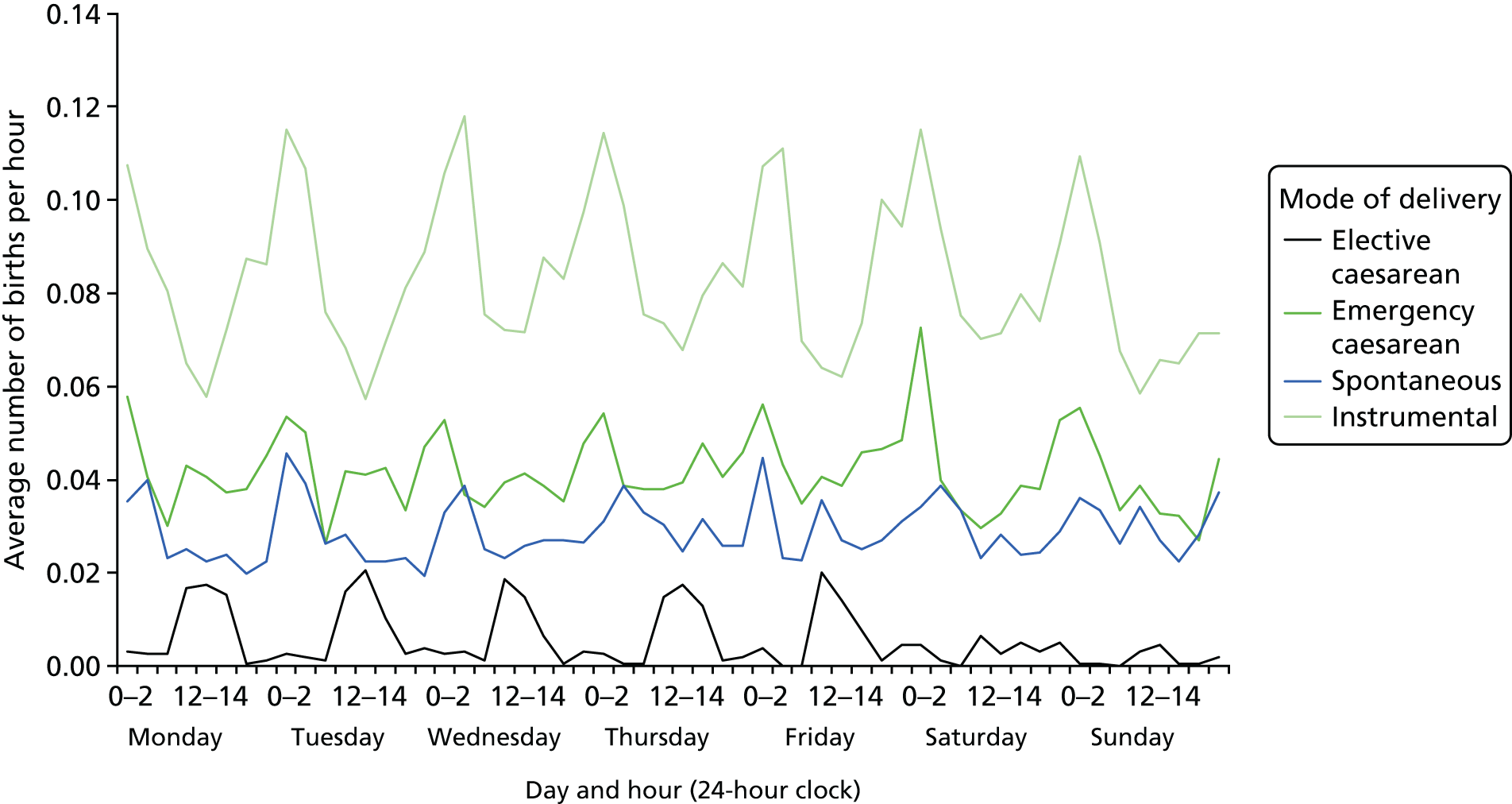

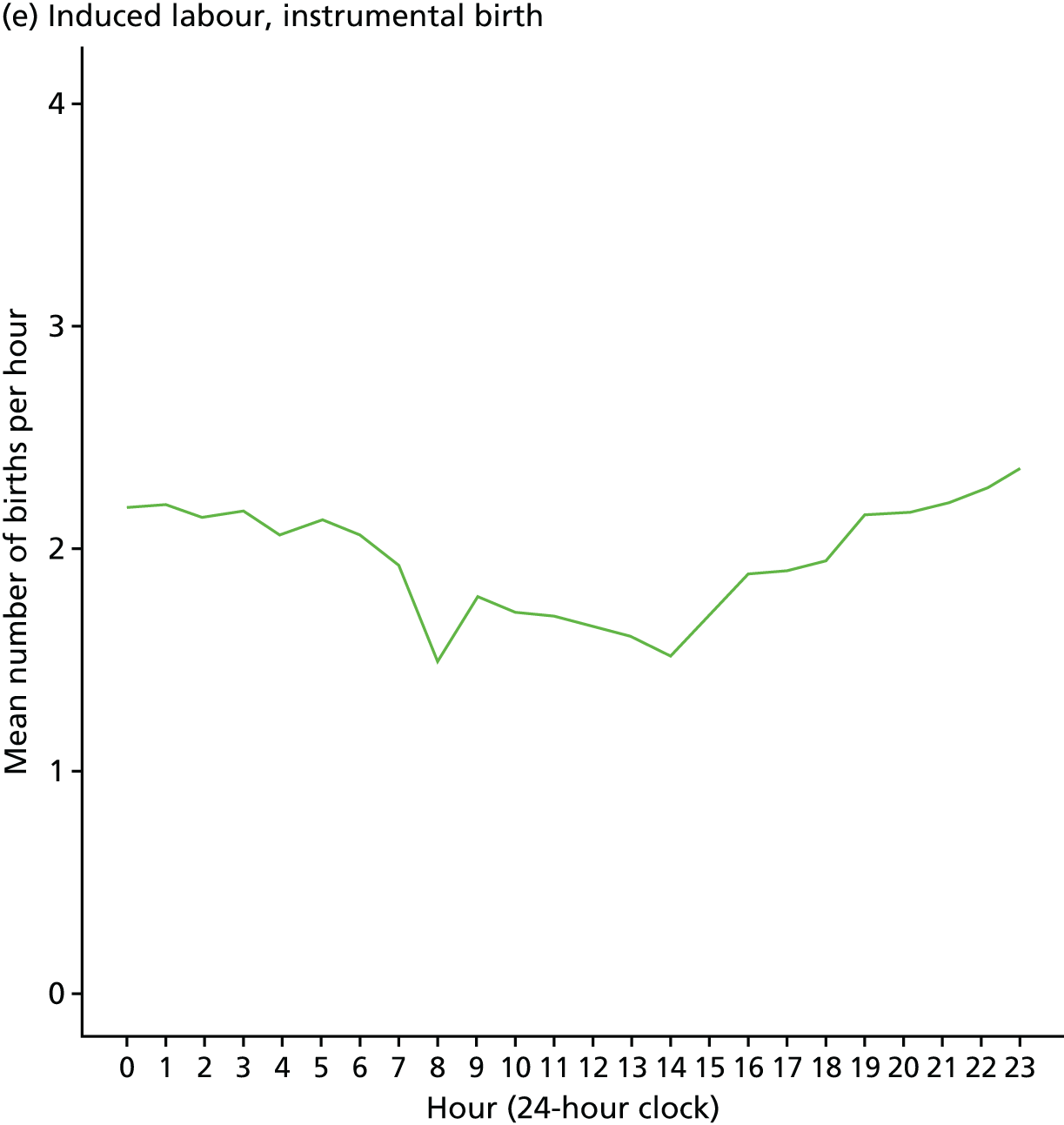

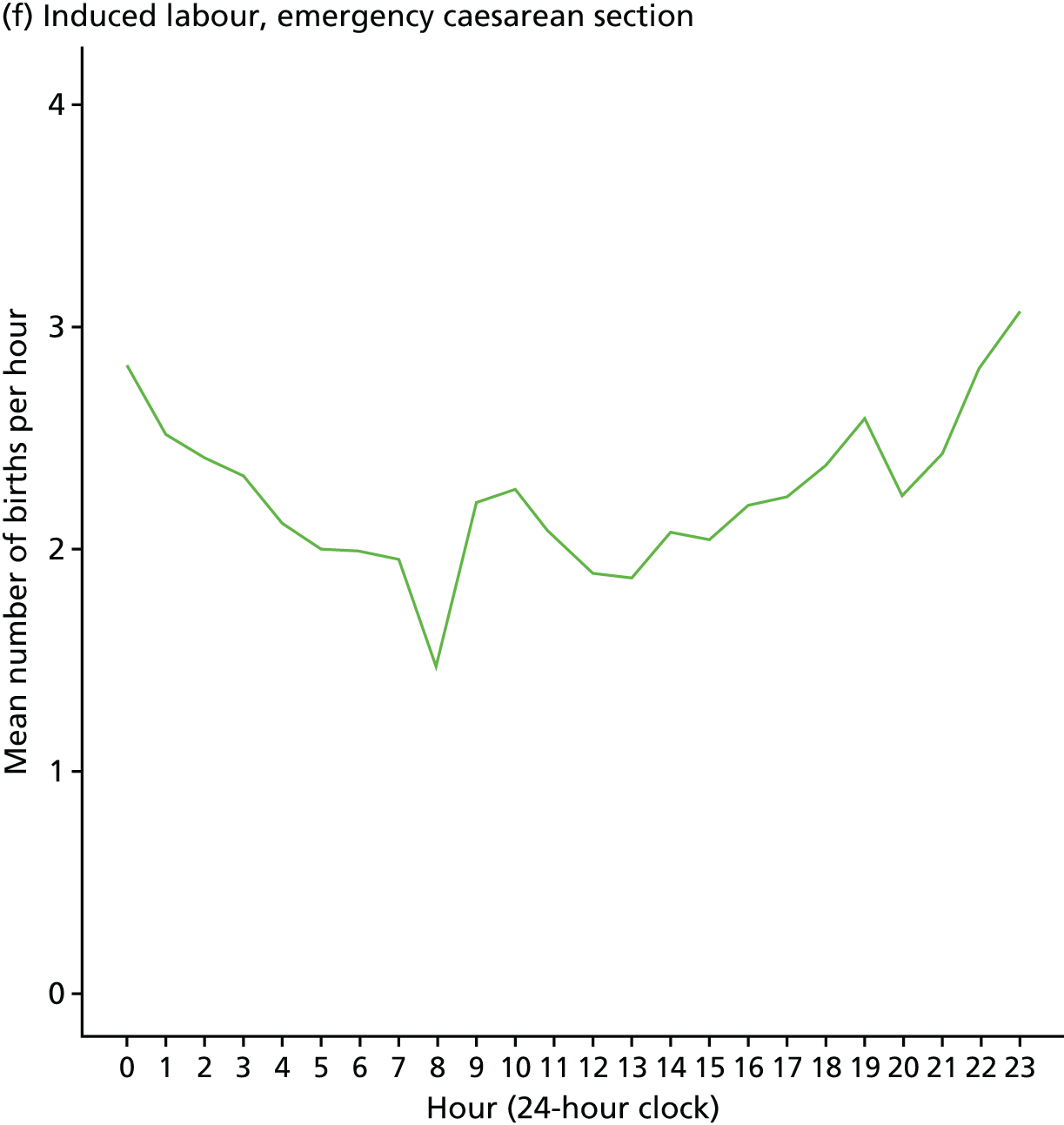

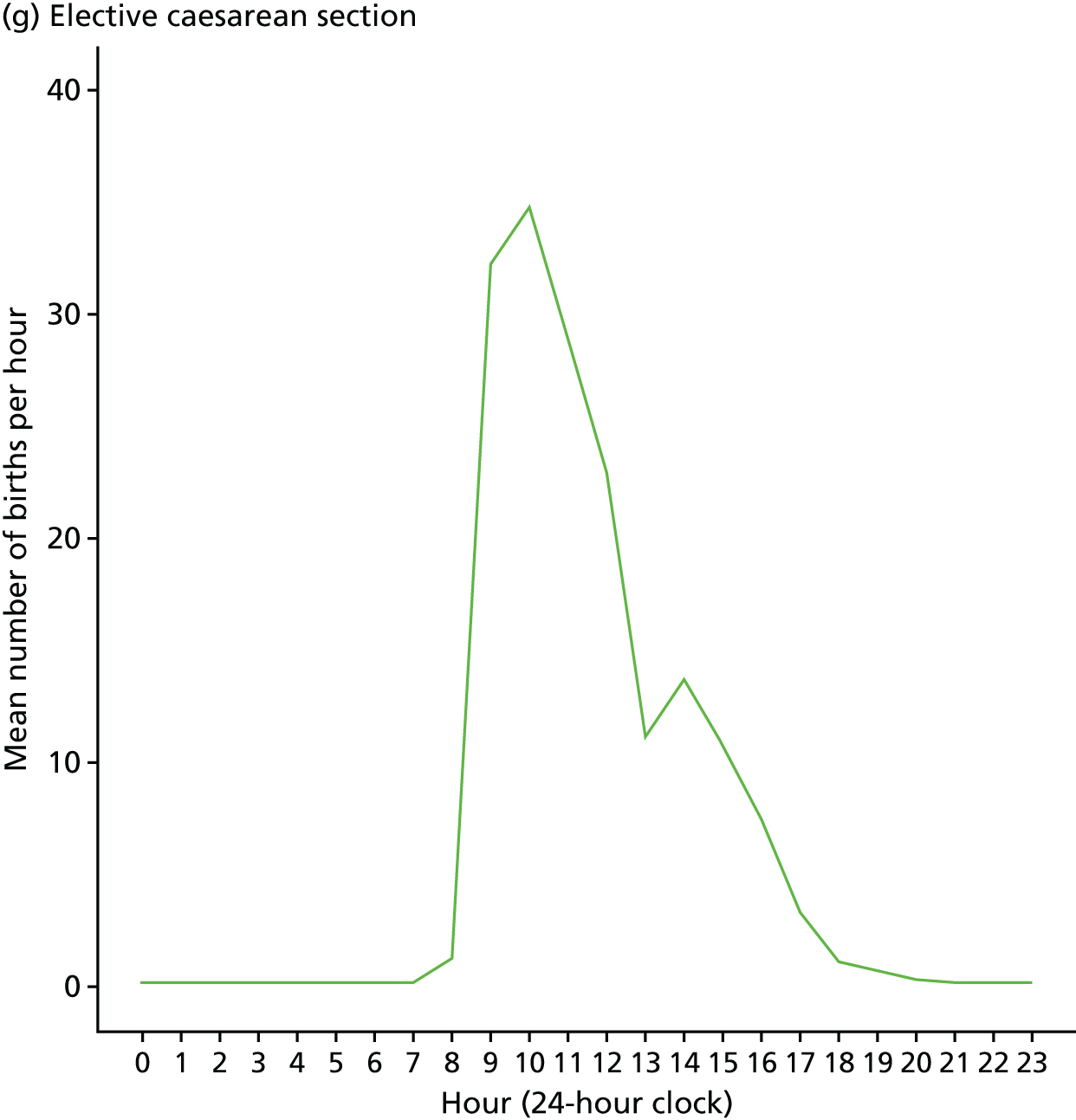

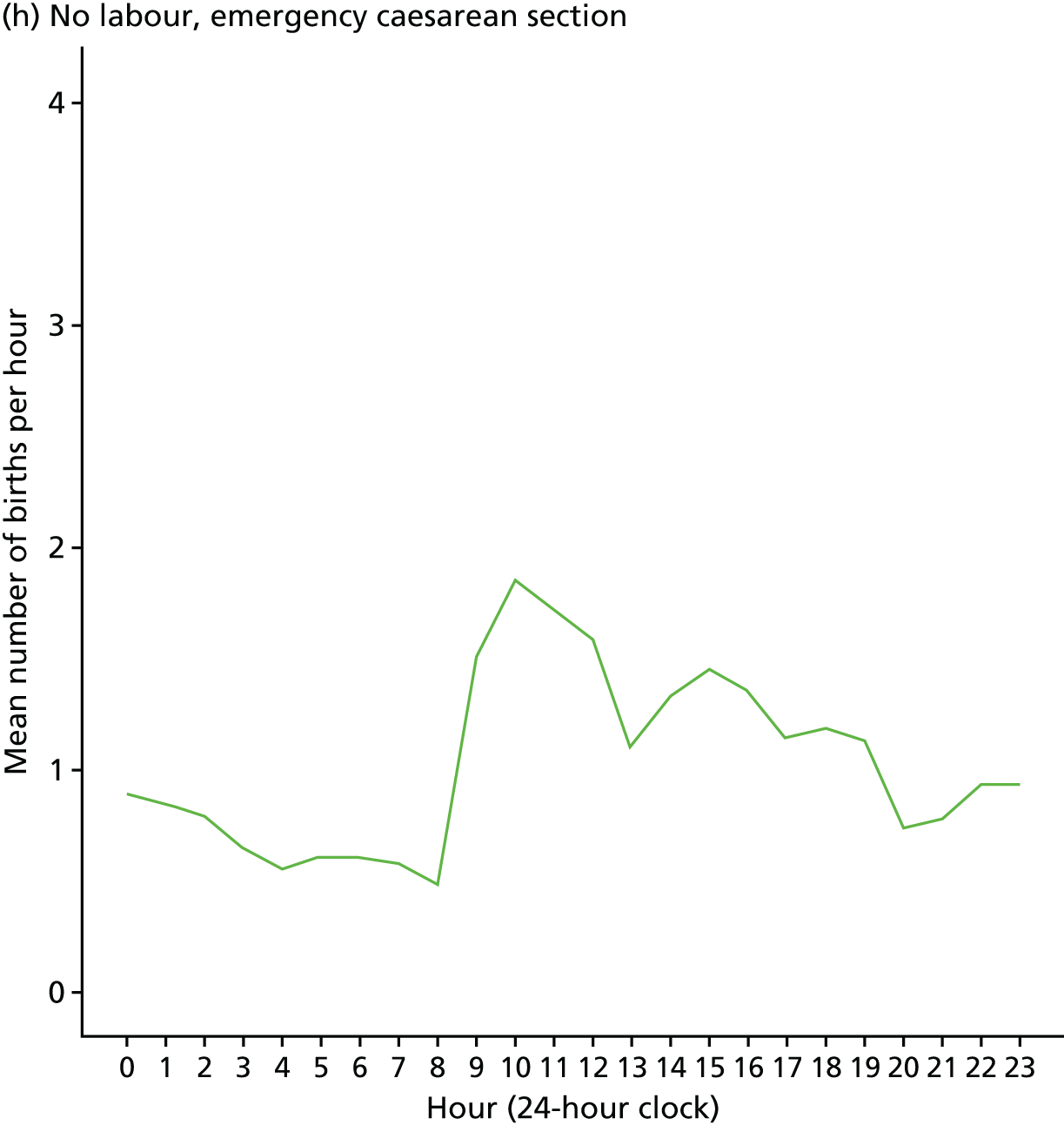

Other US states now record times of birth79 and an analysis of births in 2013 in 41 states plus the District of Columbia showed that overall numbers of hospital births were concentrated into daytime and early evening hours. 82 Elective caesarean sections were concentrated into mornings with two peaks at 08.00 and 12.00, whereas numbers of emergency caesarean sections were highest during late afternoons and early evenings. Numbers of both induced and non-induced vaginal births were highest between 12.00 and 18.00, although the numbers of non-induced births varied considerably less.

In the USA, only out-of-hospital births showed a pattern similar to that in earlier analyses, with numbers of births being highest between 03.00 and 05.00. 82 In contrast, a study in a hospital in Spain with a high caesarean section rate showed that overall numbers peaked during morning hours, but unlike in the USA, numbers of spontaneous births were still highest in the early hours of the morning. 83 Similarly to this, an earlier study in Norway found that numbers of spontaneous births peaked in the early hours of the morning, especially for births to multiparous women, whereas numbers of births to primiparous women peaked later in the day. 84

A similar effect was seen in the Netherlands in a study that compared vertex singleton term births without oxytocic drugs to women having care from midwives with those births to women having care from obstetricians. 85 Among women cared for by midwives, numbers of births to primiparous women peaked between 08.00 and 09.00 and births to multiparous women peaked at 05.00. For women cared for by obstetricians, the corresponding peaks were several hours later, between 14.00 and 15.00 for primiparous women and between 08.00 and 09.00 for multiparous women.

An unpublished study of births in seven hospitals in northern Portugal after spontaneous onset of labour showed that neither spontaneous nor operative births peaked in the early hours of the morning (Cristina Teixeira, Polytechnic Institute of Bragança, 2015, personal communication).

These comparisons raise questions about styles of practice and settings for care. A particular question is why the timing of spontaneous births has retained its traditional early morning peak in some settings, but not in others. Another question is about the extent to which births following induction are concentrated into daytime hours.

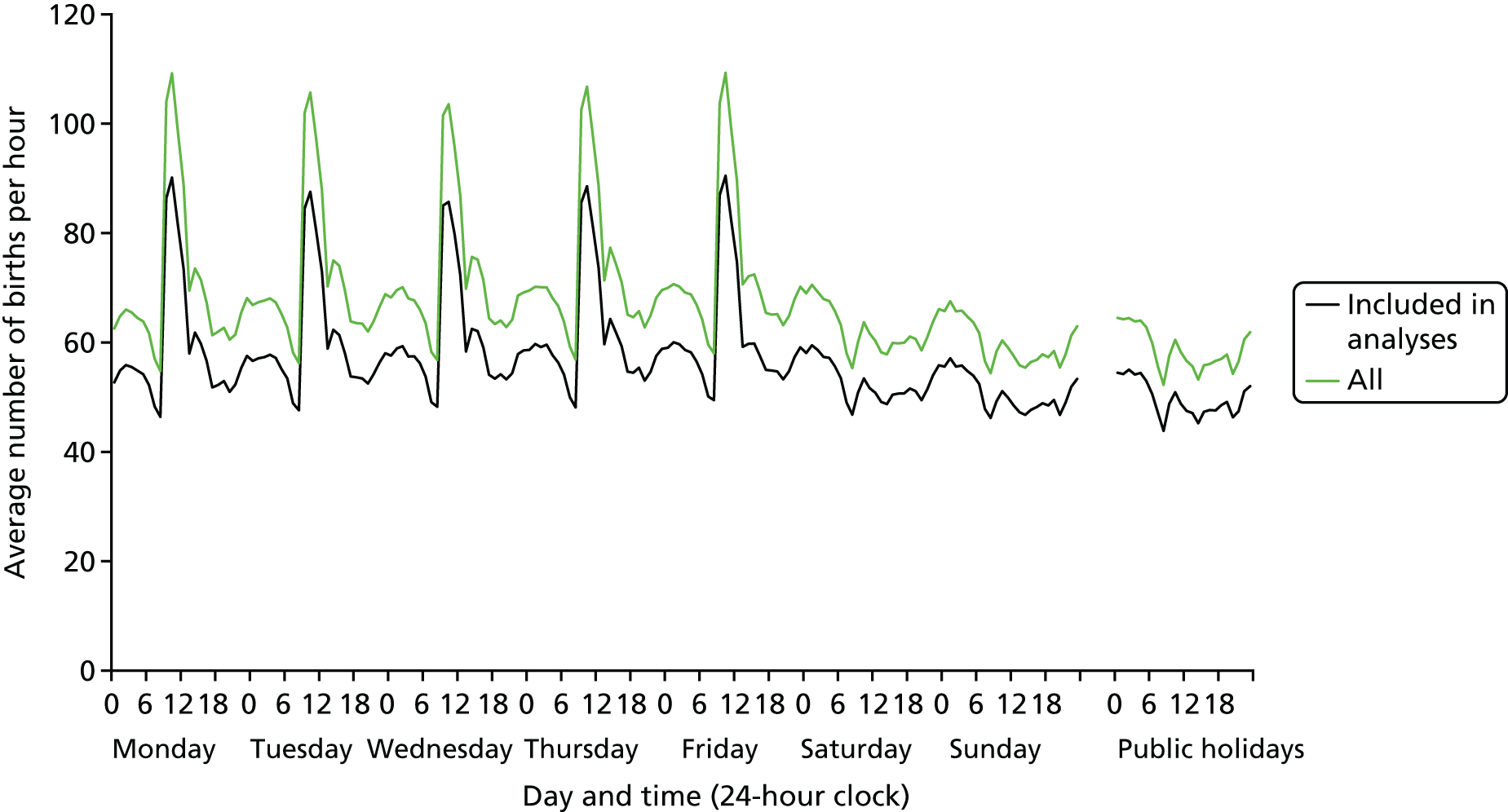

Day of birth

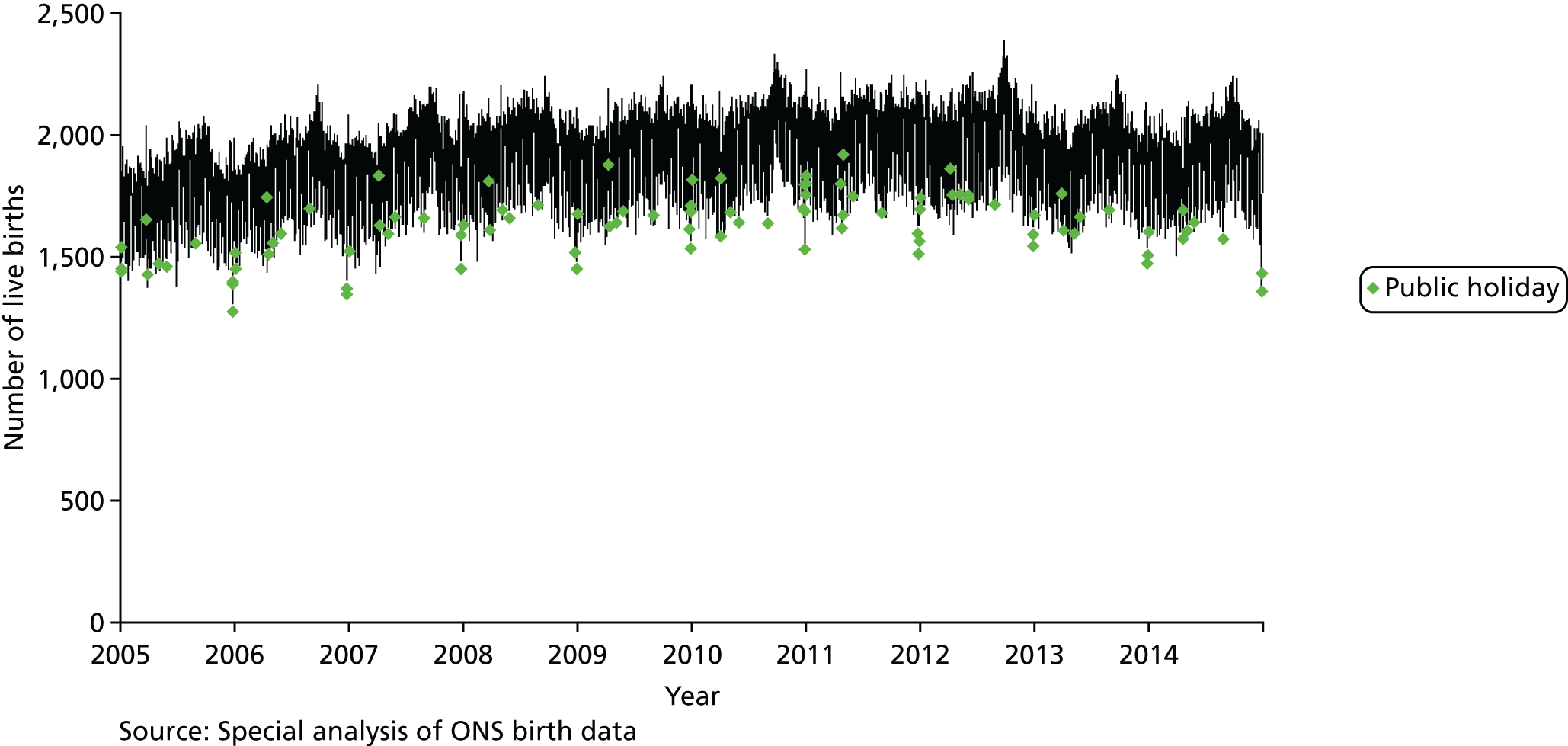

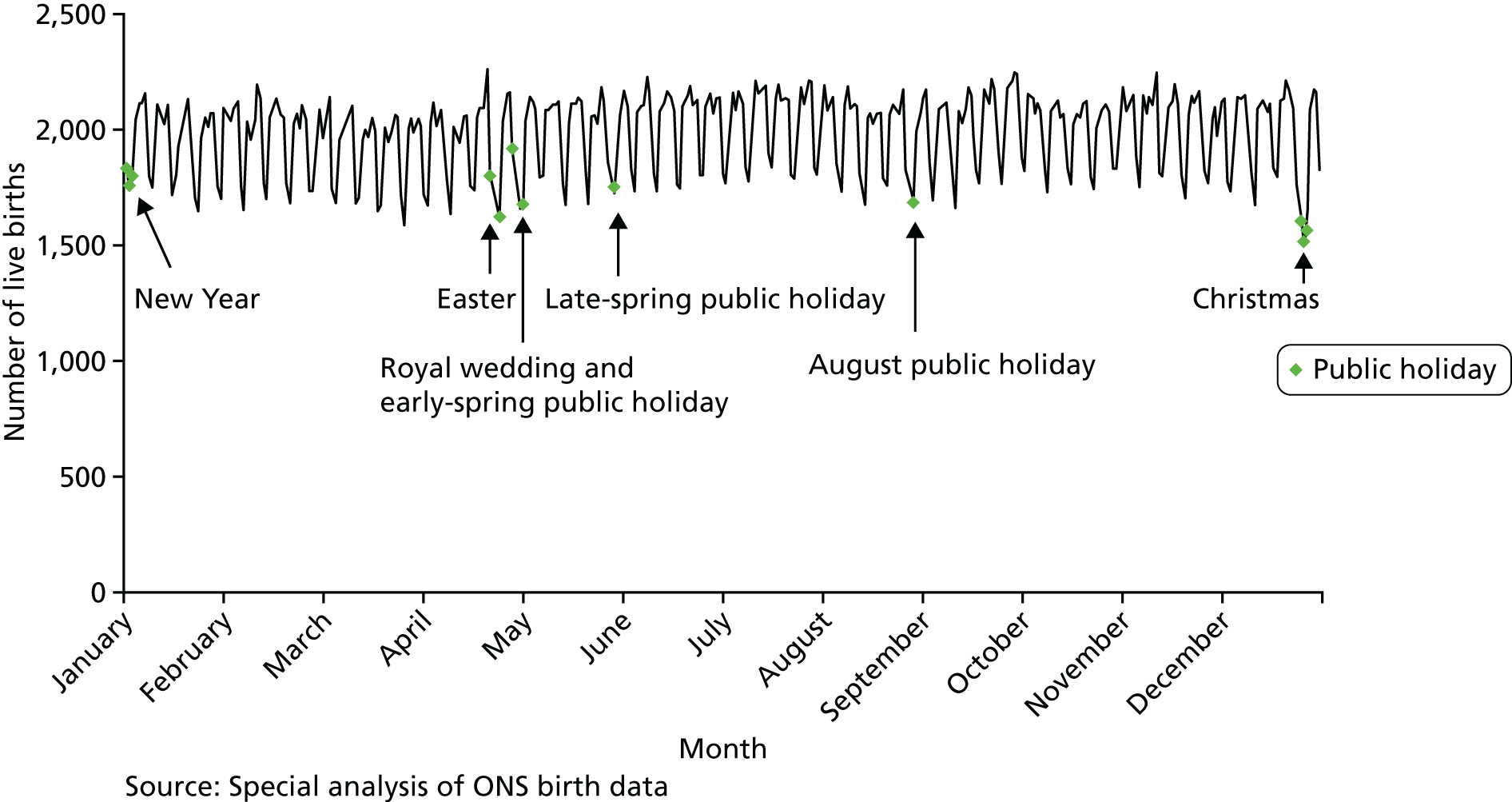

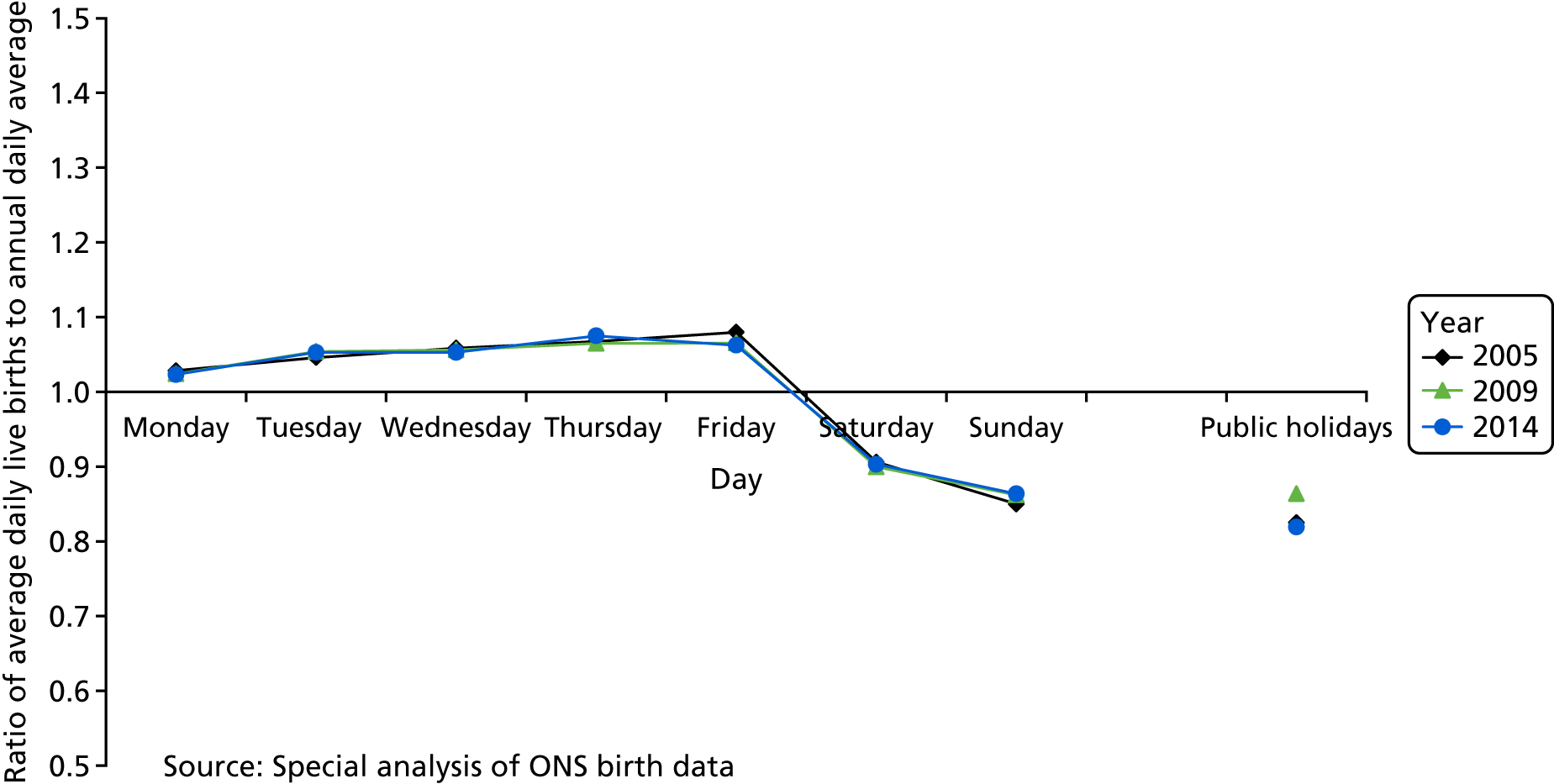

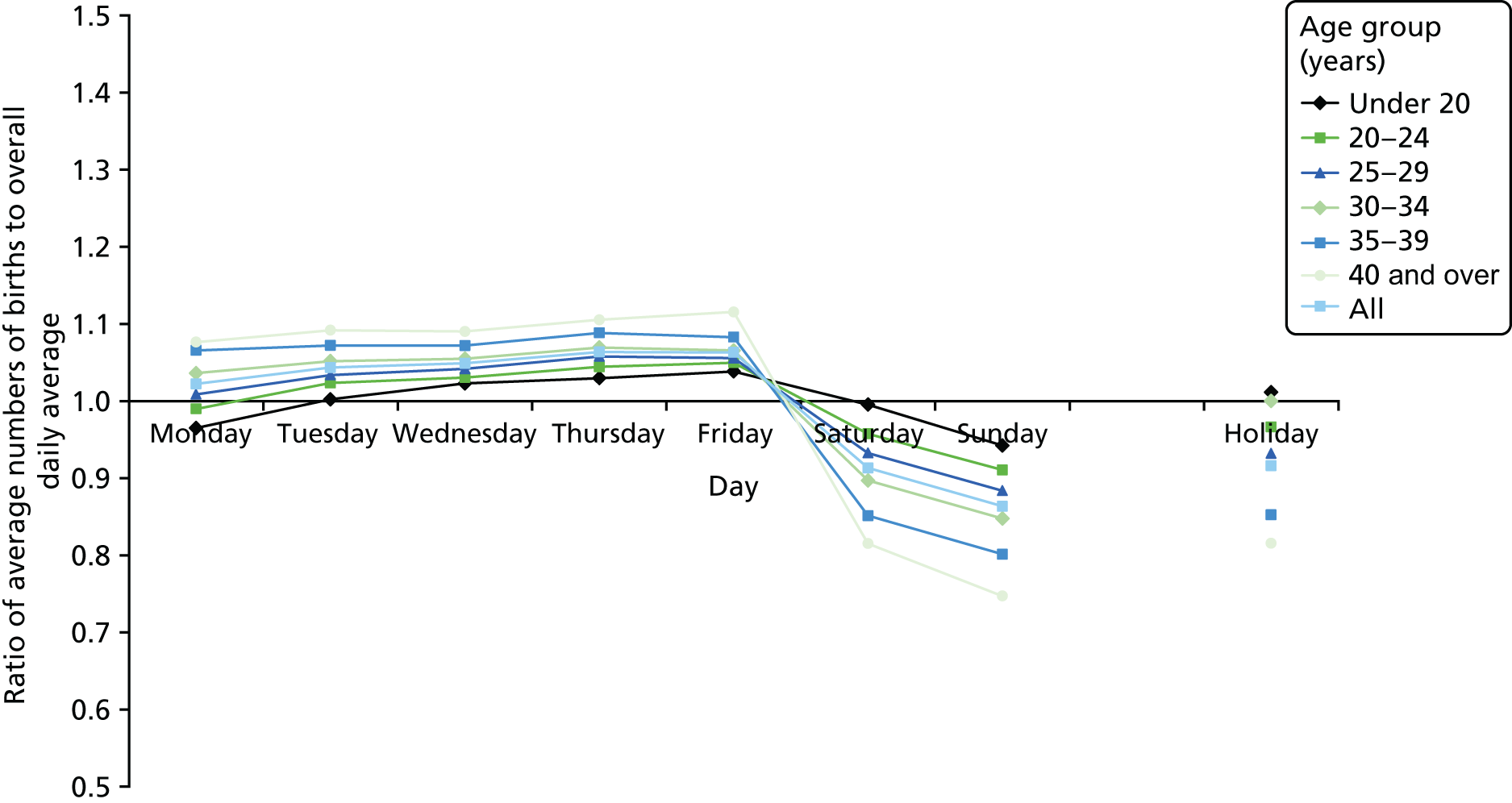

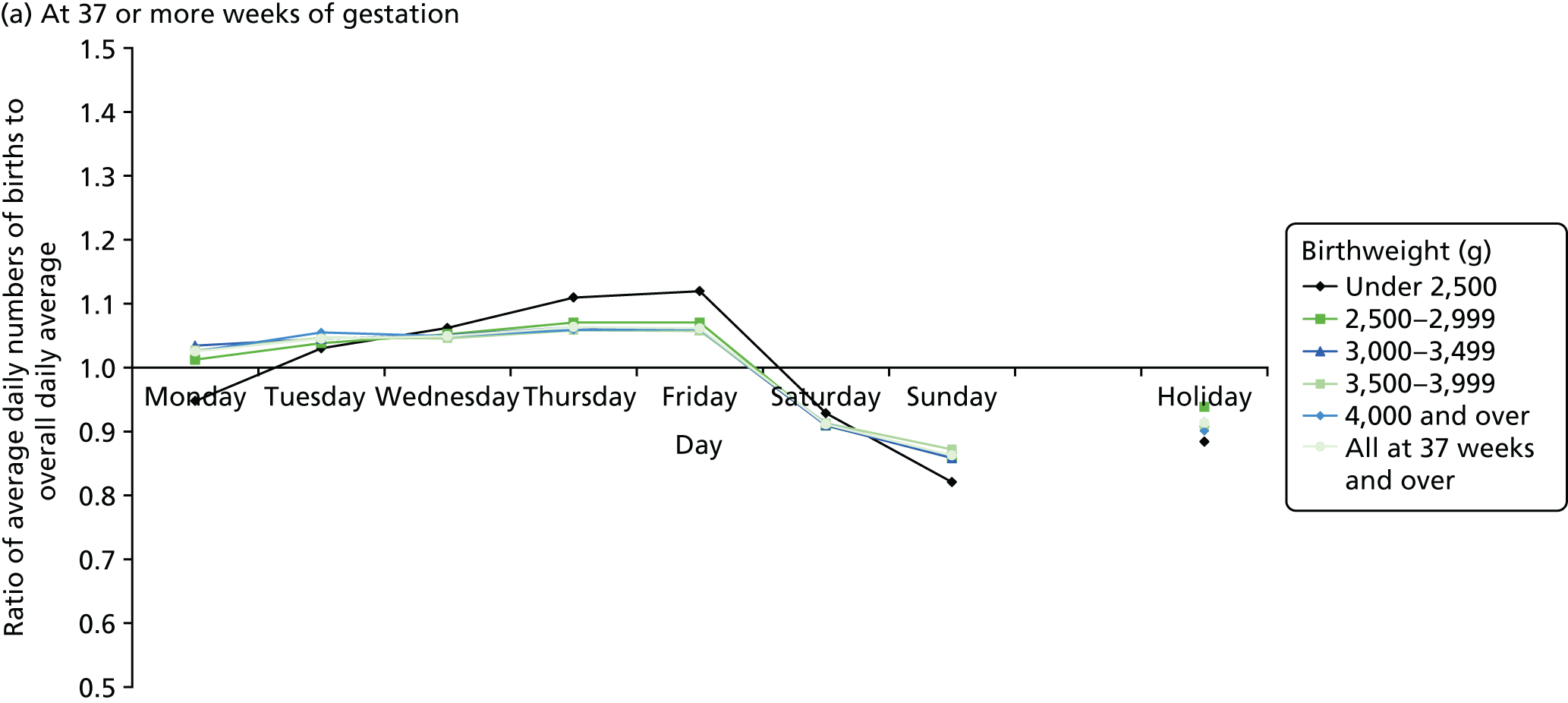

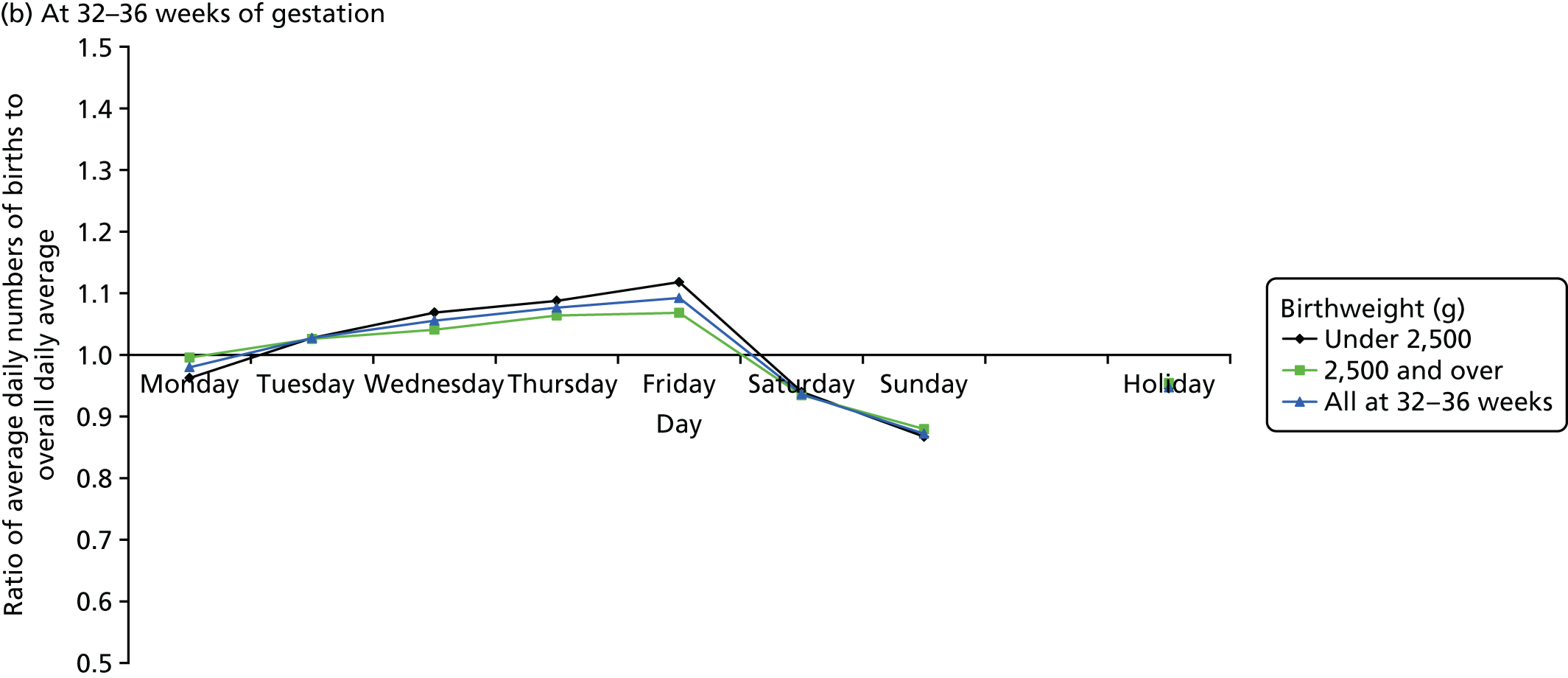

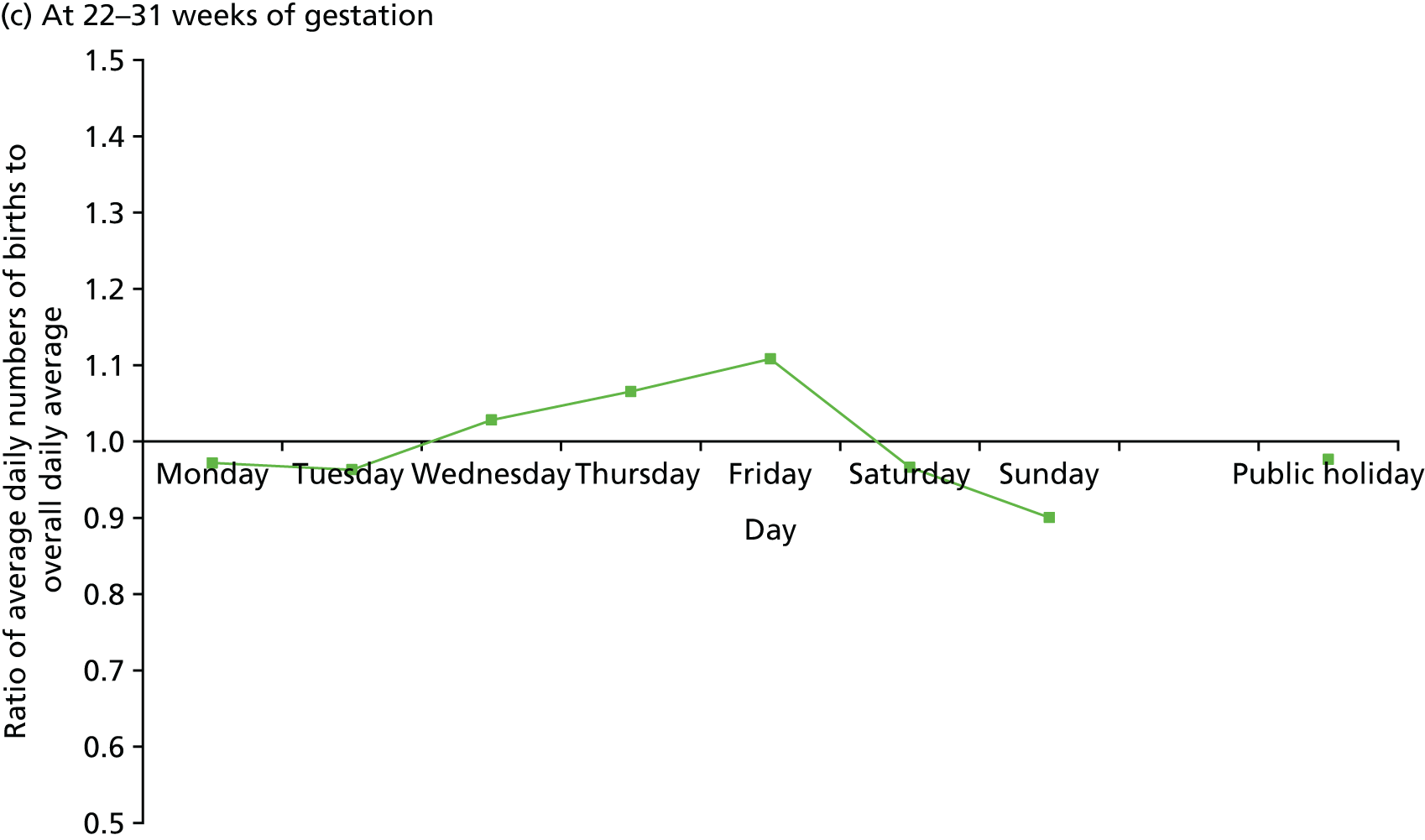

In England and Wales, a study of daily variations in numbers of births in the 1970s found a pronounced weekly cycle, with numbers of births being lowest on Sundays, followed by Saturdays, and the highest numbers of births occurring from Tuesday to Friday. Numbers of births were low on public holidays, with Christmas Day and Boxing Day having the lowest numbers of births in each year. 1,86 Similar patterns were observed in a number of other countries87–95 and an analysis of births in Israel showed a deficit on Saturdays. 96

The patterns of birth in England and Wales changed over the 7-year period of 1970–6. The ratio of the average numbers of births on Saturdays to the overall daily average for the year decreased from 1.00 in 1970 to 0.93 in 1976, while the corresponding ratio for births on Sundays fell from 0.88 in 1970 to 0.77 in 1976. The ratio for births on Mondays rose from 0.92 in 1970 to 0.97 in 1976. It was not possible to tabulate these births by method of onset of labour or delivery, but data from a different source, the Hospital In-Patient Enquiry (HIPE), showed that induction rates rose steeply in the early 1970s, from 23% in 1970 to 39% in 1974, and then fell slightly, reaching 35% in 1976. 97

Data from other countries,87,90,93 and a subsequent special analysis of HIPE data for England and Wales,98 suggested that day of the week variations in both elective caesarean section and induction made a major contribution to the daily variations observed in births. In particular, a study in France compared data for 1946–50, when there was little day of the week variation, with data for 1968–75, by which time a deficit of births on Sunday had become well established. 95

Further analyses of patterns of birth in England and Wales showed that over the period 1979–96, weekly patterns of birth in England and Wales were more stable than they had been in the 1970s. The ratio of the average numbers of births on Saturdays to the overall daily average for the year ranged between 0.92 and 0.94 over the period, and the corresponding ratio for births on Sundays rose from 0.79 in 1979 to 0.83 in 1996. The ratio for births on Mondays rose slightly from 0.97 to 0.99 over the period. 2 A second, more detailed, analysis was undertaken of births over this period but the birth registration data again took the form of counts and were not linked to data about methods of delivery. 2 Separately from this, tabulations of data from the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) for England from the mid-2000s showed the extent to which elective caesarean sections and, to a lesser extent, births following induction are more likely to occur on weekdays than at weekends. 99

Births in midwife-led settings

There has been very limited recent work on births in out-of-hospital settings. Births in midwife-led settings, including home births, are now low in number compared with births in OUs and, therefore, are more difficult to analyse.

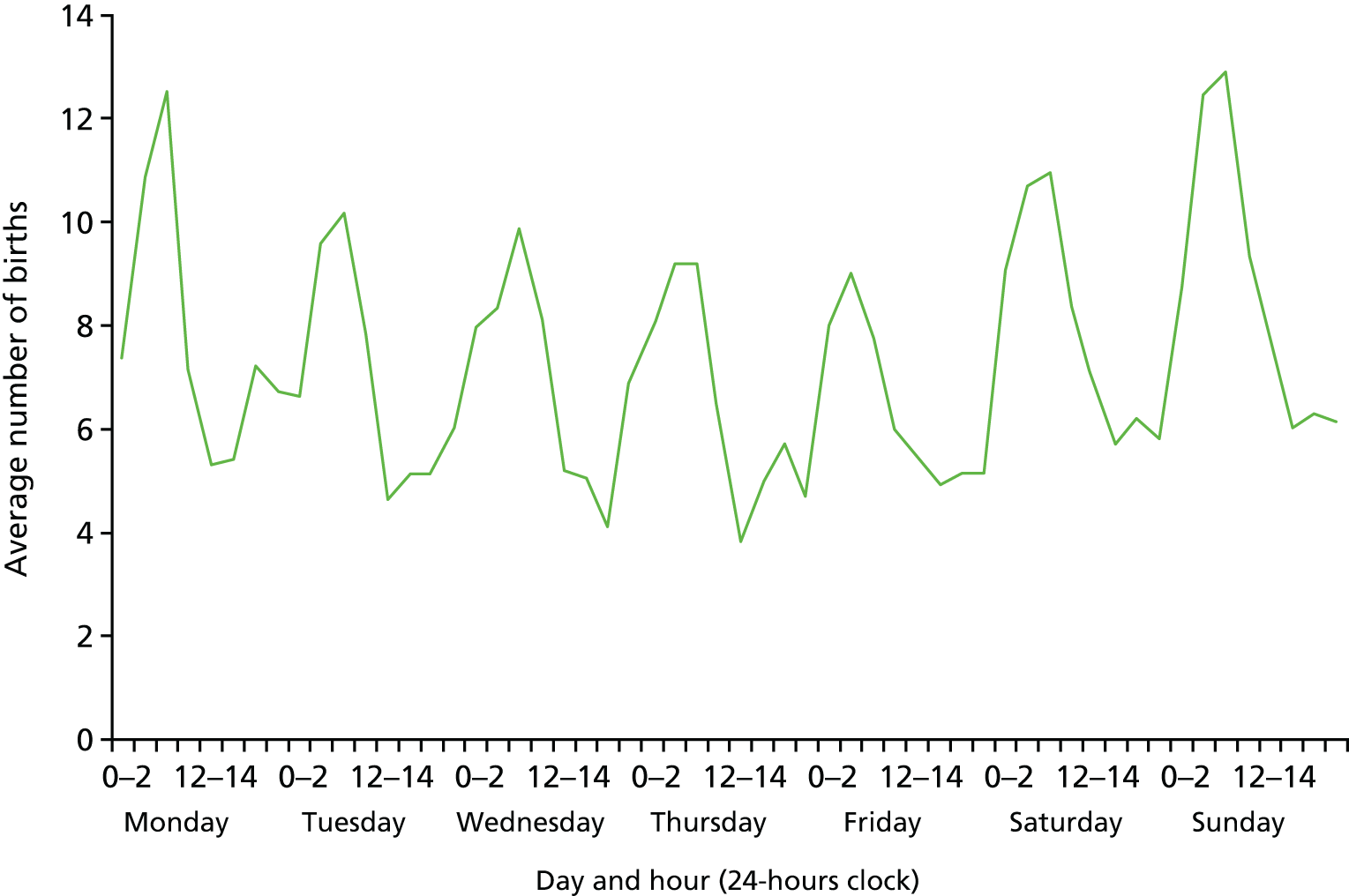

The local study of births in Birmingham, England, in 1950 and 1951 referred to previously (see Time of day of birth) showed that numbers of domiciliary births, which accounted for a much larger proportion of all births than they do now, peaked from 02.00 to 07.00 and spontaneous births, which formed a majority of births in this analysis, followed the same pattern. 76

The analysis of day of the week variation in births in the 1970s found some day of the week variation in births occurring at home, but it was very much less marked than in hospital births. 100

More recently, additional analyses of the Birthplace data looked at timing of births planned in midwife-led settings in alongside and freestanding midwifery units and at home and compared them with hospital births in terms of likelihood of having a caesarean section, an instrumental delivery, a ‘straightforward’ birth or a ‘normal birth’. Times of births were subdivided into weekdays during ‘office hours’ from 09.00 to 16.59, weekday nights and weekends. 101

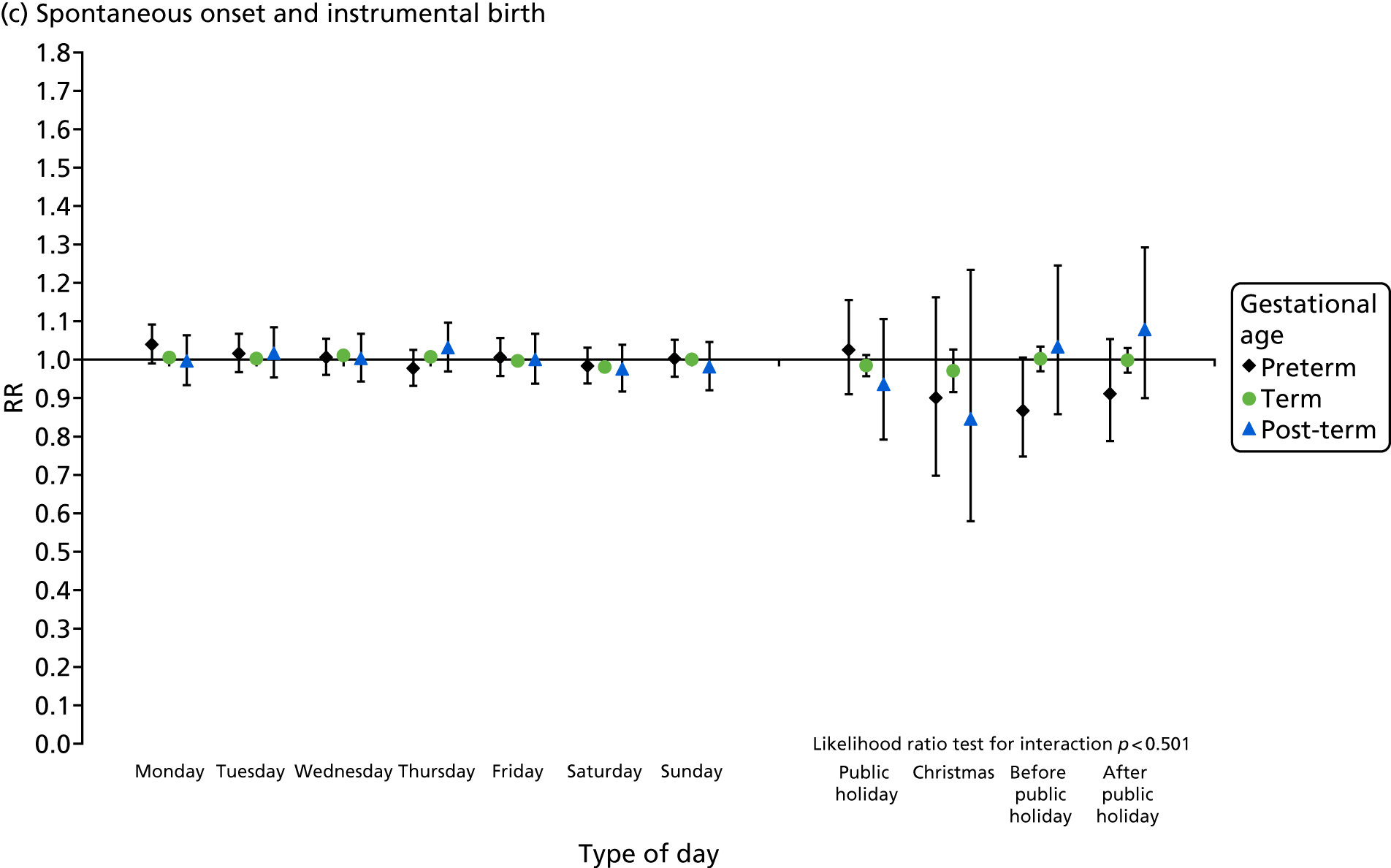

Women planning OU birth were less likely to have a birth without obstetric intervention if their birth occurred on a weekday during ‘office hours’ than if they gave birth at night. In births planned in AMUs and at home, there was no difference between time of day or day of the week and any of the main outcome measures.

Nulliparous women who planned to give birth in FMUs and who gave birth during weekday ‘office hours’ were less likely to give birth by caesarean section than nulliparous women who gave birth at night. Multiparous women who gave birth on weekdays during ‘office hours’ or at weekends were less likely to have a normal birth than those who gave birth on a weekday at night.

Overall, the authors suggested that their findings could be interpreted as consistent with a possible effect of non-clinical factors on intervention, but that there were other possible explanations and that further research was warranted. 101

Birth outcomes in relation to time and day of birth

Analyses of stillbirth and neonatal mortality by time of day and day of birth has a long history. Some early studies analysed outcomes by time of day of birth. The 19th century Brussels data included numbers of stillbirths, which were higher in the afternoons. 74 Stillbirth and neonatal mortality rates were the focus of an analysis in the early 20th century of births in New York State in 1929102 and 1936,75,103 and of an analysis of data from an unspecified location in the UK,104 which also found higher rates in the afternoon.

Subsequent analyses of mortality by time of day later in the 20th century found different patterns. Studies in Switzerland found that perinatal mortality rates were higher at night and that rates rose in births occurring through the late afternoon and the early evening and then began to fall in births occurring after midnight. 80,105,106 An analysis of births in Sweden from 1973 to 1995 found higher mortality rates among babies born at night, from 17.00 to 01.00, followed by a minimum around 04.00 and a second peak around 09.00, especially for preterm births. 107 In contrast, an analysis of neonatal deaths in California found that neonatal mortality rates were slightly higher in babies born at night, but were higher among babies born in the early hours of the morning than among those born before midnight. 106 A further study subdivided births in Sweden from 1991 to 1997 by risk of death and suggested that babies born at night were at higher risk of early neonatal death but not of intrapartum death. 108

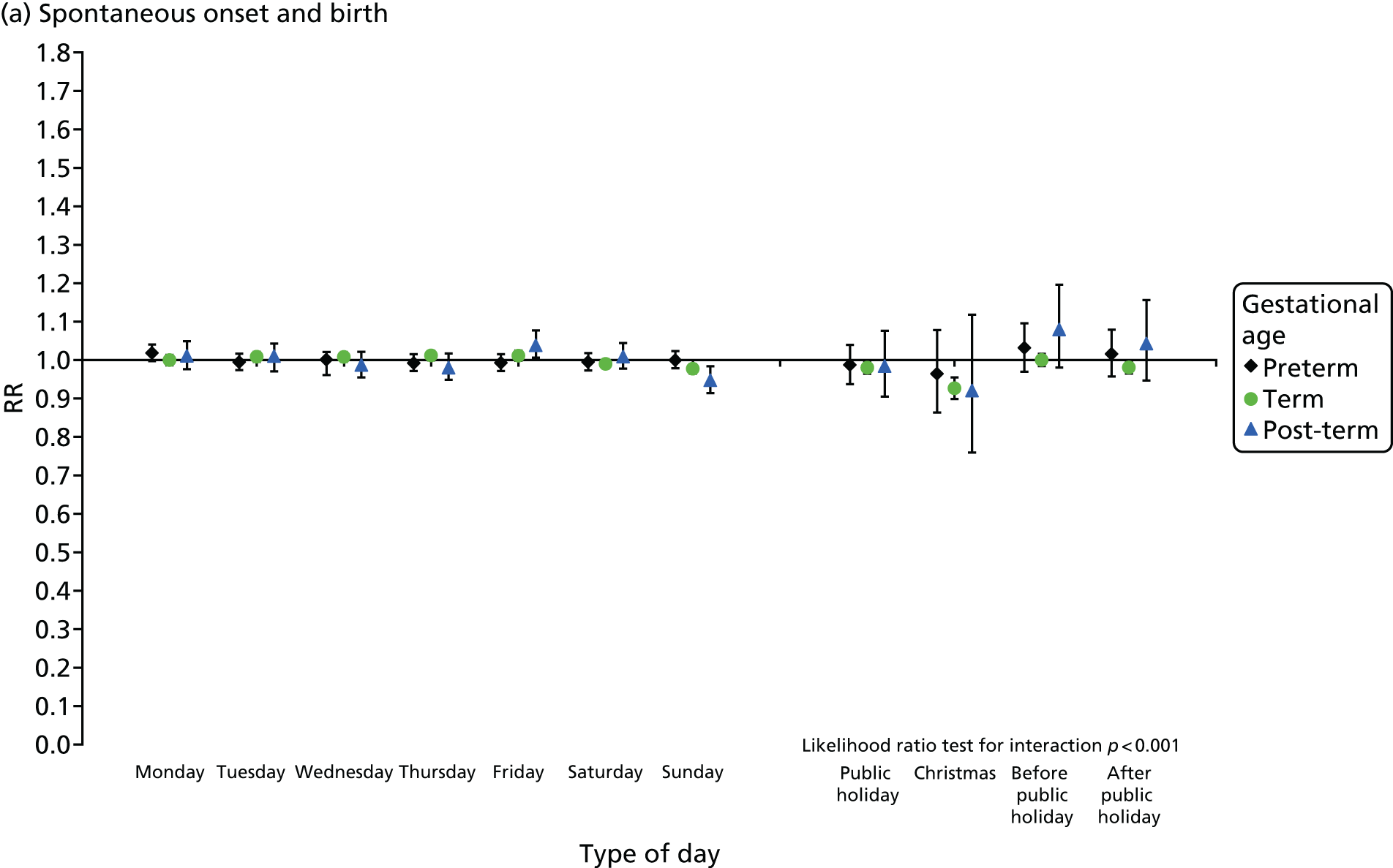

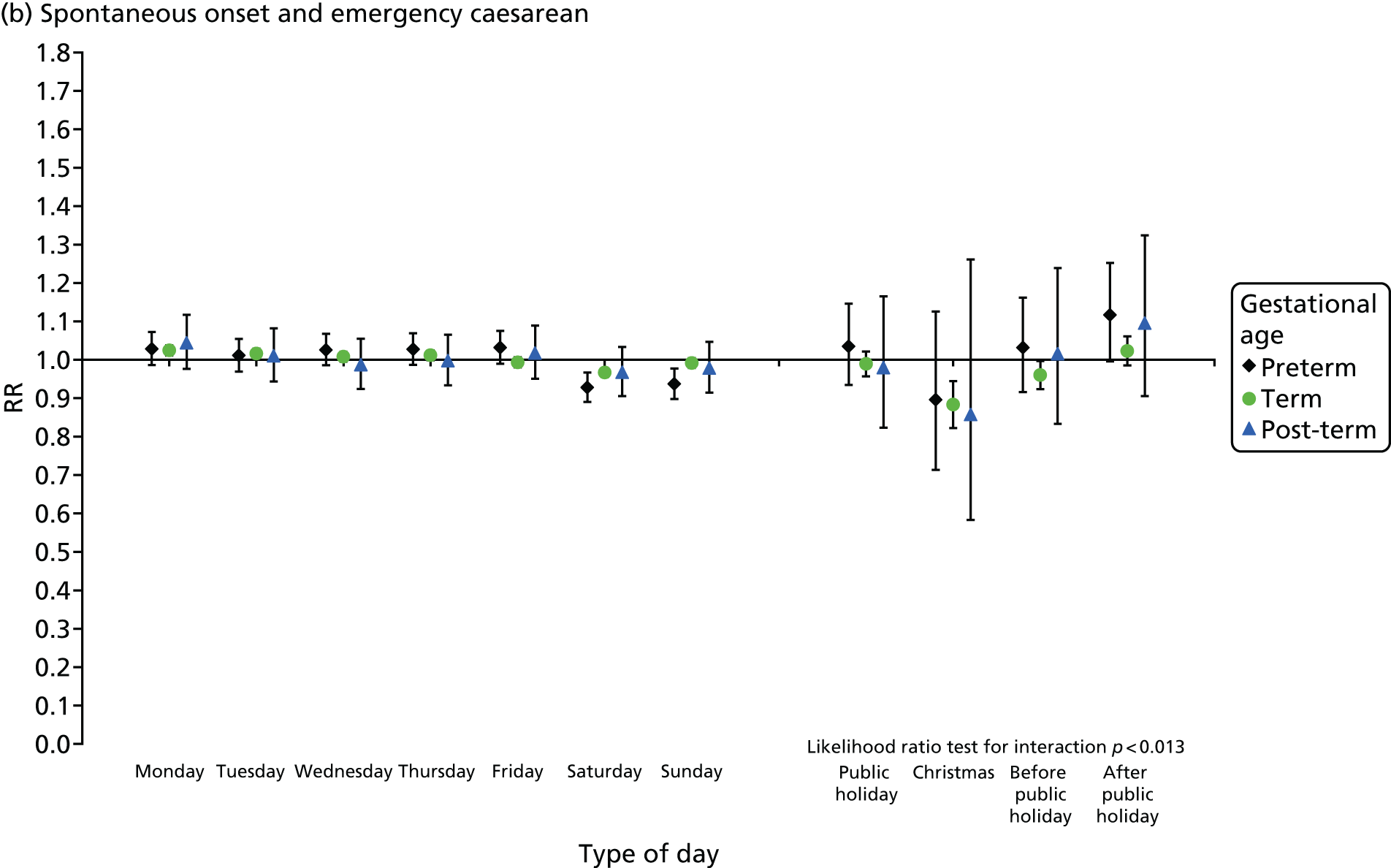

A number of studies from the 1970s onwards analysed the outcome of pregnancy by day of the week of birth. An analysis of perinatal mortality in England and Wales among births in the years 1970–61,86,100 showed a weekly cycle, with higher rates among babies born at weekends, but warned that these were crude rates, so no conclusions could be drawn. A subsequent analysis of data for England and Wales for the years 1979–962 used more advanced statistical modelling techniques and found that stillbirth and early neonatal mortality rates tended to be higher among births on Saturdays and Sundays, respectively, than among births on other days, but this was also restricted to crude rates.

The findings of other studies were inconsistent. A study in Canada found slightly higher crude rates of stillbirths and neonatal deaths among births at weekends, but the difference disappeared after adjustment for gestational age,109 and a study in Australia found no difference after adjustment for birthweight. 2,91

An analysis by day of the week published while this project was under way used unlinked HES data for England and concluded that perinatal mortality was highest at the weekend,62 although the authors’ analysis and interpretation of their results was highly criticised in subsequent rapid responses. 110–112 Like past analyses of rates of stillbirth and perinatal mortality in England and Wales, this analysis made no distinction between intrapartum and antepartum stillbirths.

Data about the exact timing of death, subdivided into before labour, during labour or not known, are recorded on the medical certificate of stillbirth. The completeness of these data has improved in recent years but the quality has not been reassessed. Better quality data are available, however, from confidential enquiries. 113–115

An analysis of data for 1993–5 from the All Wales Perinatal Survey had pointed to higher rates of mortality related to intrapartum asphyxia in the holiday months of July and August and suggested a possible association with the rotation of junior doctors to new posts in August, but this was based on relatively small numbers of deaths. 116 Similar effects were reported in intrapartum-related deaths in Scotland. 117 The analysis of data for England and Wales for 1979–96 showed that all perinatal mortality rates varied depending on the time of year. 2

Like previous analyses for England and Wales, this did not take account of the time of day of birth as it was not included in routine data systems at the time. Analyses by day of birth and time of day by method of onset of labour and gestational age were not possible, as all the relevant data items were not recorded at a national level for England and Wales, even though they have long been recorded locally.

More recent analyses of the outcome of births by day of week and time of day from Scotland118 and the Netherlands119 that have dichotomised time of day and day of the week as ‘in hours’ and ‘out of hours’ have attracted considerable media attention and raised questions about the safety of ‘out-of-hours’ care. Both studies reported raised mortality rates among babies born outside usual weekday working hours. The analysis of Scottish singleton birth and neonatal mortality data for the years 1985–2004 showed raised neonatal mortality attributed to asphyxia at weekends and on weekdays outside the hours of 09.00 to 17.00. 118 The authors found no changes over time and suggested that the findings were also true in other countries of the UK.

A ‘rapid response’ based on data from the West Midlands from 1995 to 2009 showed, however, that similar patterns were found in the region in the late 1990s but had subsequently disappeared, and there was no evidence of a raised mortality rate ‘out of hours’ in the years 2005–9. 120

The inconsistent nature of previous findings could reflect the underlying complexity of contributory factors and the challenges inherent in examining cause of death questions. The provision of care, in particular the provision of facilities to allow rapid delivery and prompt resuscitation, would be expected to affect different types of death in different ways. These provisions might be crucial in the response to an acute event, such as uterine rupture. They would not, however, alter the course of a baby affected by, for example, renal agenesis, which is invariably fatal. Furthermore, there is considerable potential for bias within any such analysis. For example, both planned caesarean delivery at term, which carries a low risk of stillbirth,91,100,109 and high-risk births, such as elective preterm births, tend to take place during the normal working week and could contribute to either an overestimate or an underestimate of the relative risk of giving birth out of hours. Finally, stillbirths and neonatal deaths are rare events, especially intrapartum stillbirth, which accounted for only around 9% of stillbirths reported to MBRRACE-UK. Therefore, a large dataset is needed to analyse births and their outcome by day of the week and hour of the day. Recent developments in data recording and linkage in England and Wales mean that these analyses are now possible for large numbers of births from 2005 onwards, as are analyses of data about any subsequent hospital care for mothers and babies. As a result of the novel data linkage work described here, the analysis planned for the project and completed in part is the first to be undertaken.

Data linkage

This project built on two preceding data linkage projects in England and in Wales5–8 and on earlier developments in routine linkage of infant, childhood and maternal mortality.

Previous analyses of data for England and Wales for the years 1970–61 and 1979–962 were based on aggregated counts. Although there was limited use of mortality data linked to births in the second of these analyses,2 mortality was not disaggregated by cause. Analyses by time of day, method of onset of labour and gestational age were not possible in these analyses, as the relevant data items were not available at a national level for England and Wales.

Recent developments in data recording and linkage have changed this. As a by-product of the change to birth notification to enable the allocation of babies’ NHS numbers at birth in 2002, a small set of variables not recorded at birth registration, including the time of day of birth and gestational age, are now recorded in the national birth notification dataset. 121 A series of collaborative projects led by City, University of London, was undertaken to build a database of linked datasets. The first two piloted the linkages and explored their potential for use in research and the production of national statistics.

In the first project, the NHS number, a unique identifier, and other common data items, such as the mothers’ and their babies’ dates of birth, were used to match the birth notification records to birth registration records for individual mothers and their babies. The methods and linkage rates are described in published articles. 5,6 This linkage, piloted using data about births in 2005, made it possible for the first time to analyse birth registration data on the basis of the gestational age at birth. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has mainstreamed this linkage and uses the linked data to publish annual statistics, which have also been used for international comparisons by Euro-Peristat. 68 The linked data were also used for analyses of preterm birth rates in babies of black Caribbean and black African ethnicity who were born in England and Wales from 2005 to 2007 by their mothers’ countries of birth. These showed considerable differences between babies with mothers born in different parts of Africa. 122

In the second project, funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC) and also led by City, University of London, the previously linked data were further linked with the Maternity HES for England, and corresponding data for Wales. This meant that the birth data were linked to data about the onset of labour and mode of birth for most, although not all, women giving birth in the years from 2005 to 2007. 7,8,123 More generally, this linkage made it possible to analyse data about the care given at birth in relation to the parents’ sociodemographic background and also to variables such as birthweight and gestational age, which are poorly reported in Maternity HES.

These two projects laid a useful foundation for the work described in this report in which the techniques used previously were enhanced and used to link these data for births in the years 2005 to 2014. As morbidity in mothers and babies is also a matter of concern, the current project has extended the database by linking births to data about subsequent hospital admissions and readmissions of mothers and babies recorded in HES and the Patient Episode Database for Wales (PEDW).

While this project was under way, another project, Tracking the Impact of Gestational Age on health, educational and economic outcomes: a longitudinal Record linkage (TIGAR),124 was funded by the MRC and is being led by Maria Quigley of the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit (NPEU). It is making use of birth and hospital data linked for this project about preterm births and subsequent hospital admissions of children. These data will be linked further to education data from the National Pupil Database for England, to look at the educational performance of children born preterm. Alison Macfarlane and Nirupa Dattani are among the co-investigators for the TIGAR project.

Our own project provided a unique opportunity to use previously unavailable data to identify any differences in outcome associated with ‘out-of-hours’ care for specific groups of women and babies, and to consider the impact of staffing levels. It was considered that this would provide a useful resource to inform the process of future reconfiguration and staffing of maternity services, including increases in consultant numbers, as well as providing some evidence of the impact of these processes on women’s experiences of care. The focus on reducing stillbirth by referring more women for induction of labour also makes it timely to have detailed data on this particular aspect of care.

Aims and objectives

Aims

To build on work done in a previous project to link data from civil registration, notification of birth to allocate NHS numbers to babies and data about care during delivery in order to analyse linked maternity and neonatal data for England and Wales about births in the years 2005–14 to compare daily, weekly and yearly variations in numbers of spontaneous and other births by time, day and season of birth and to compare variations in rates of adverse outcome.

Objectives

To achieve these aims, the objectives were to answer the following questions:

-

How do numbers of births vary depending on time of day, day of the week and time of year of birth and how does this relate to methods of onset of labour and delivery and multiplicity?

-

Subject to the availability of data, how do patterns of birth vary between maternity services in relation to variations in medical and midwifery staffing, patterns of intervention and size of unit?

-

How does the outcome of pregnancy in terms of rates of cause-specific intrapartum stillbirth and neonatal and infant mortality rates and rates of morbidity recorded at birth and at hospital admission in the first year of life vary depending on the time of day, day of the week and time of year of delivery in relation to gestational age and intervention in the onset of labour and delivery?

-

Have the patterns observed changed over the years 2005–14?

The project aimed to inform decision-making by providing information about how the numbers of births in England and Wales vary by time of day, day of week and day of the year. It separately analysed births before term and post-term births occurring after 42 weeks. In addition, it took account of whether labour and birth occurred spontaneously or whether their timing was affected by inducing labour or by undertaking either a planned caesarean section or an unplanned or ‘emergency’ caesarean section during labour, or before the onset of labour.

It was intended that the rates of death and severe problems in babies or their mothers would be analysed in relation to these factors and that the results would be related to information about midwifery and obstetric staffing in maternity units and NHS trusts and to their overall rates of induction and caesarean section. This information could have been used by the NHS in planning both levels of staffing in terms of midwives and obstetricians and in detailed rostering, with the aim of trying to match the numbers of women in labour and giving birth with the numbers of midwives available and the availability of specialist obstetric care should complications arise.

Challenges and barriers

There is a common misconception in some circles that administrative data are in the public domain and are readily available for analysis. In reality, especially in cases in which analyses draw on individual records, there are many protections in place, as well as administrative barriers, limiting access to such data to ensure the confidentiality of personally identifiable data. Although these protections are necessary, this can delay projects for many months and can make it impossible to complete scheduled research on time, as happened with this project.

In order to access the data, researchers are required to work in a controlled environment in which the security and confidentiality of the data are safeguarded. Researchers in this project used the ONS Virtual Microdata Laboratory (VML), which is run by an experienced and helpful team of staff, but which at the time of our project had an IT infrastructure inadequate to cope with a project of this scale. Many months of IT problems led to further delays. Further details and the impact of these barriers on the project, which made it impossible to complete it within the fixed-term funding period, are described in Appendix 1. Since 1 November 2017, after our funded project finished, the VML has been known as the Secure Research Service (SRS), but in this report we have retained the original name.

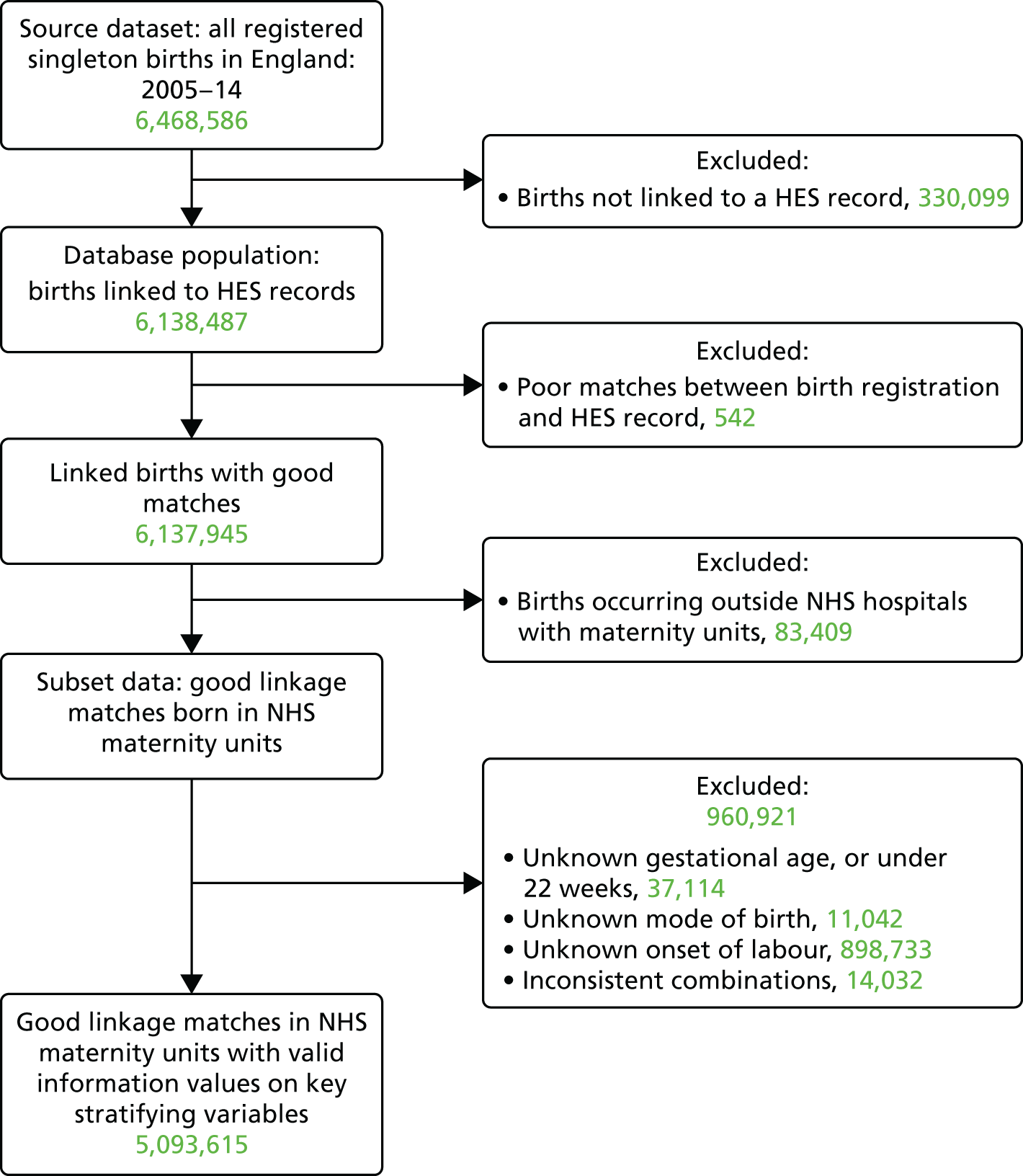

Chapter 2 Data acquisition and linkage, quality assurance and organisation

This chapter describes the data acquired for the project, the methods used to link the data and to assure the quality of the linkages when possible, together with the results of the linkages and the quality assurance. The many problems and setbacks that delayed this process are described in Appendix 1. The methods for analysing the data and the results of the analyses can be found in Chapter 3.

Study design

The study design was a retrospective birth cohort analysis of linked routinely collected data about births, maternity care in labour and at birth, and any subsequent hospital admissions of mothers or babies after birth. We used the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement, the checklist of items extended from the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement, which should be reported in observational studies using routinely collected health data. 125 This can be found on the project’s page on the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Journals Library website. 126

Setting and population

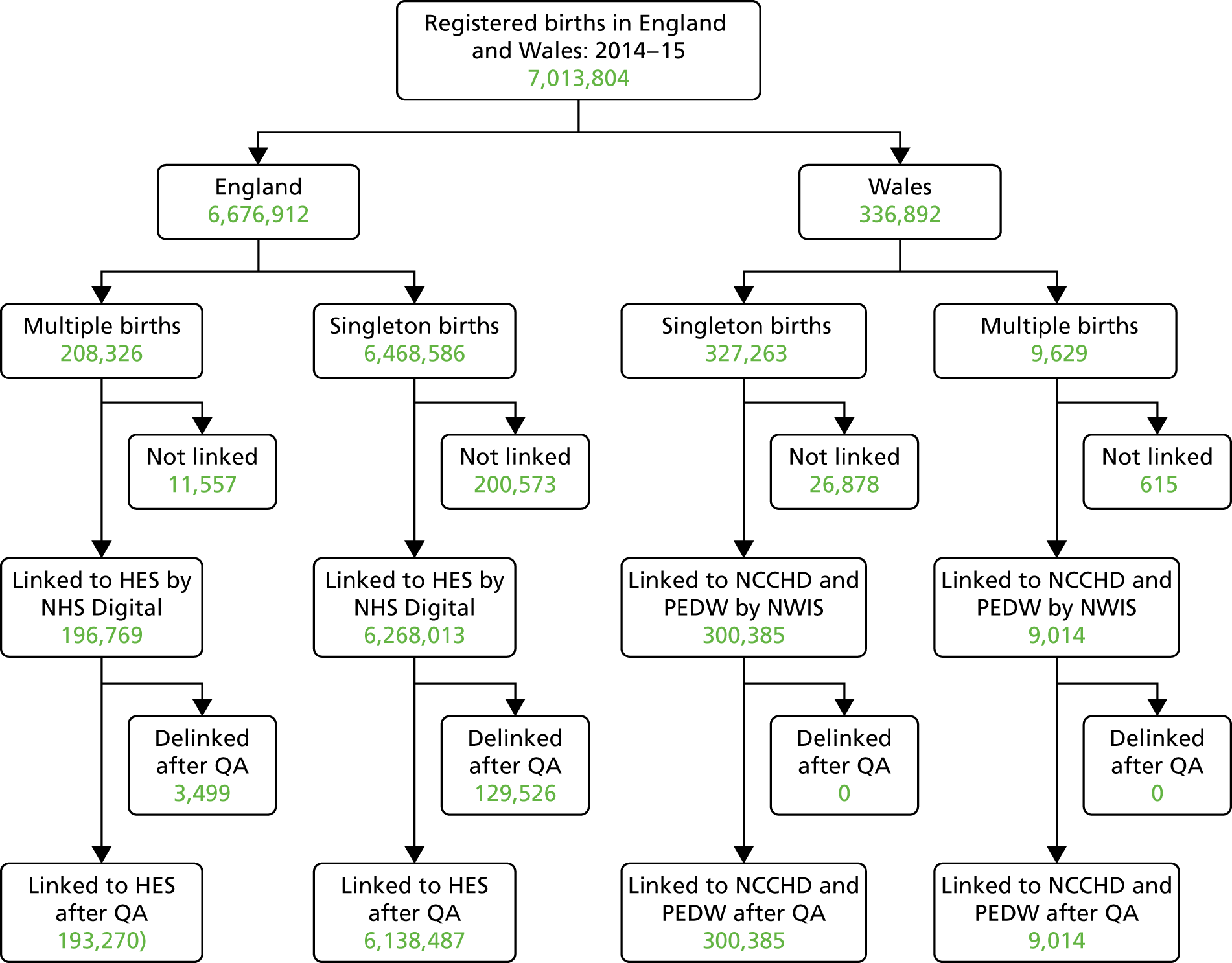

The target population was the 7,013,804 registered births that occurred in England and Wales in the years 2005–14 (Table 1).

| Year | Number of births |

|---|---|

| 2005 | 649,371 |

| 2006 | 673,069 |

| 2007 | 692,653 |

| 2008 | 711,820 |

| 2009 | 709,434 |

| 2010 | 722,081 |

| 2011 | 723,339 |

| 2012 | 732,826 |

| 2013 | 701,376 |

| 2014 | 697,835 |

Data used in the project

When a baby is born in England and Wales, data are recorded in several separate information systems. When babies’ parents register the birth, mainly socio-demographic data are collected. A smaller set of data are recorded when the birth is notified to the NHS by the midwife or other birth attendant and the NHS number, a unique identifier, is issued. The ONS links the deaths of babies and children who die up to the age of 18 years with their corresponding birth registration records. It also links deaths of women occurring within a year of giving birth to the corresponding baby’s birth record. In addition, information on causes of maternal death, stillbirth and neonatal death is collected through the relevant confidential enquiries.

Data about care at delivery are recorded in the Maternity HES if the birth occurs in England. For births in Wales, data about care at delivery are recorded in PEDW, which is linked to the National Community Child Health Database (NCCHD). HES and PEDW collect data about all hospital admissions including maternity admissions.

The maternity datasets relevant to this project are described in more detail in the following sections, starting with the main data available for England and Wales as a whole, followed by the data available for England only or for Wales only, and finishing with additional datasets identified as being useful to add to our analyses.

Data for England and Wales

Birth registration

It is a legal requirement to register all live births within 42 days of birth. The definition of a live birth, the legal basis for registration, the process and a complete list of data items collected, are described in detail elsewhere. 127 The information is obtained, usually from one or both parents, by the local registrar of births, marriages and deaths. The local child health department passes some information from the birth notification it receives from the midwives to the registrar to verify the birth. This has included the baby’s birthweight since 1975 and the NHS number, since 2002, as described below.

The process for registration of stillbirths is similar to that for live births, except that registrars do not retain the NHS number for a stillbirth and the informant will also give the registrar a medical certificate of stillbirth completed by the attending midwife or doctor. This certifies the cause of death and includes an assessment of gestational age at birth and birthweight.

The information recorded at birth registration is collected centrally by the General Register Office and made available to the ONS for the production of statistics.

Birth notification

Since 1915, midwives or other birth attendants have been required to notify births to local health services. In the early 2000s, the route of notification changed so that NHS numbers could be issued to babies at birth instead of at registration, which could be up to 6 weeks later. To enable this, an interim system, the NHS Numbers for Babies (NN4B) service, was instituted in 2002 with a small dataset, which was of limited use on its own but contained important data items not available elsewhere. This provided the opportunity to obtain information such as time of birth, gestational age, a baby’s ethnicity and birth order within multiple births. Information on gestational age at birth is of key importance, as babies born preterm, that is before 37 completed weeks of gestation, are at particularly high risk of morbidity and mortality in early years of life. 128–130

Death registration

Baby and child deaths

All deaths should be registered within 5 days of occurrence and the person registering a death must produce a medical certificate of death completed by the medical practitioner who was present at, or examined the body after, death. Since 1975, deaths of babies before they reach the age of 1 year have been routinely linked to their corresponding birth registration records. The linkage was extended in the 1990s and the ONS now links deaths of all children aged under 16 years born from 1993 onwards to their birth records.

Maternal deaths

Since 1994, deaths of women within a year of giving birth are linked to the corresponding births by the ONS for use in confidential enquiries into maternal deaths.

Data for England only

Maternity Hospital Episode Statistics

Maternity HES contain data for births occurring in NHS hospitals in England. It is not designed to collect data about births in private or other hospitals, at home or elsewhere, even though it was originally envisaged that information about all births should be compiled. 131 HES includes a range of information on care at birth such as the mode of onset of labour and birth clinical complications, gestational age and the mother’s ethnicity as well as information about the baby, such as date of birth, sex, birthweight and geographical information on where the baby was born.

There are two types of maternity records in HES: the delivery record and the birth record. Both types of records consist of a core Admitted Patient Care (APC) record with an additional 19 fields, in an appended baby ‘tail’, also known as a ‘maternity tail’.

The HES delivery record is a mother-based record containing the mother’s details with a baby tail, which can accommodate up to nine babies born in one delivery episode. In contrast, the birth registration and notification linked data consist of one record per baby.

A HES birth record is generated for the baby. It contains the baby’s details and it also has a baby tail containing the same type of information that is recorded in the corresponding baby tail of the mother’s delivery record. It is also sometimes referred to as a HES baby record.

The baby tail data coverage is not as complete as the rest of the HES data. There are a number of reasons for the incompleteness and data quality issues, such as:

-

Trusts submitting a significantly higher number of delivery episodes than birth episodes.

-

Trusts failing to submit data on the number of birth episodes where they record a high number of delivery episodes.

-

Trusts failing to submit any delivery records. This can happen when trusts have standalone maternity systems that are not linked to their hospital systems.

The HES Patient Identifier (HESID) is a pseudonymised number used to uniquely identify a patient without the necessity of viewing or using patient-identifiable information such as the NHS number. This identifier can be used to track patients through the HES database or for linkage to other datasets such as mortality. HESID is derived using a matching algorithm that looks at various combinations of the following patient-identifiable fields:

-

NHS number

-

date of birth

-

sex

-

postcode

-

local patient identifier.

The HESIDs are stored nationally in the HES index. This is updated monthly and older versions are not kept.

For each episode of care with a particular consultant or midwife, a HES record is created, but each time this record is updated with new information, a new version of the record can be created. As a result, several versions of the HES record for the same episode of care are created.

Data for Wales only

Patient Episode Database for Wales

The Patient Episode Database for Wales (PEDW) is a database of individual hospital patient records. It includes all records of inpatient and day case activity in the NHS in Wales and data on Welsh residents treated in English NHS trusts. In 1997, the mandated inpatient and day case dataset was changed to the APC record used in Maternity HES. The decision to adopt the APC was to align the Welsh inpatient and day case dataset with that of England to allow benchmarking. The APC contains demographic, clinical and administrative data items, such as the age and sex of the patient and the diagnostic and operative procedures undertaken during the episode of care in hospital.

The APC extracts received from the Welsh NHS organisations and from English NHS organisations that treat Welsh residents are used to update the PEDW.

Individual records are submitted to the PEDW on the basis of a patient’s consultant episode, which is a record of the care an admitted patient receives in the continuous care of one consultant within one Local Health Board. If the patient is transferred to the care of another consultant, either in the same or another specialty or if they are transferred to another Local Health Board for continuing inpatient care, another consultant episode will start and another PEDW record will be generated. 132

Patients whose episodes are captured by the PEDW are classified as inpatients, day cases, maternity patients and regular attendees. A maternity patient is defined as a pregnant or recently pregnant woman admitted to a maternity ward including delivery facilities. Every hospital birth in Wales should have a PEDW record. The record consists of general information, diagnosis and procedure information for the mother. A maternity tail is attached to each general record for each baby born and contains fields with data relating to the relevant mother and babies. The completeness and quality of data in the maternity tail of the record are known to be poor. 133

National Community Child Health Database

The NCCHD is Wales’ first national community child health system and contains anonymised records for all children born after 1987 who were resident, or treated, in Wales. It has been created by bringing together selected information from locally managed community child health databases. Since 2002, community child health database records have been initiated from the birth notification records but may subsequently be amended locally. The database has been used to produce maternal and child health statistics for Wales, as well as to support the administration of child immunisation and health surveillance programmes. From 2017, however, annual published maternity statistics for Wales were produced using a new Maternity Indicators DataSet. 134

Additional data

Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries, England and Wales

Prior to 2012, the Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries (CMACE) collected epidemiological and clinical data on all stillbirths and neonatal deaths in England, Wales, Northern Ireland, the Crown Dependencies of the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man. These data were collected by a network of local health professionals co-ordinated by the CMACE local offices. Data were compiled centrally and cross-matched with statutory registration data on stillbirths and neonatal deaths from the ONS. A key part of CMACE’s work was the perinatal mortality surveillance system. The aim of this was to ensure that all data collected on stillbirths and neonatal deaths were validated, analysed and published in reports. Since 2012, this work has been done by MBRRACE-UK. 15

Workforce data

Data compiled by the NHS for England and Wales separately

There are no routinely collected data about numbers of staff on duty by time of day and day of the year.

Other staffing data that are available come from the annual medical and non-medical workforce censuses of numbers and full-time equivalent staff in post in England and in Wales on 30 September each year. In England, these data are available only for trusts as a whole rather than for each maternity unit within a trust.

In England, annual workforce censuses were superseded by monthly workforce data for management purposes, which have been compiled since 2009. These were incomplete at the outset and changes were made over the time period. The primary area of work, that is ‘obstetrics and gynaecology’, may be subdivided into secondary and tertiary areas such as obstetrics, gynaecology, maternity and neonatal intensive care. ‘Fetal medicine’ was categorised separately. Thus, although midwives can be identified by their occupation codes, it is unclear to what extent doctors, nurses and other staff working in obstetrics and gynaecology are involved in maternity care.

Data from professional organisations

The RCOG compiles two-yearly reports based on asking each maternity unit to report on numbers of consultants in post and numbers of Specialty Trainees. The RCOG census for 2011 reported that data for earlier years were incomplete, but this report and the report for 2013 indicate those units that satisfy the RCOG’s recommendations for consultant staffing. 135,136

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) has been undertaking two-yearly censuses of the paediatric workforce since 1999, which include information about UK neonatal staffing. 137

Data acquired for the project

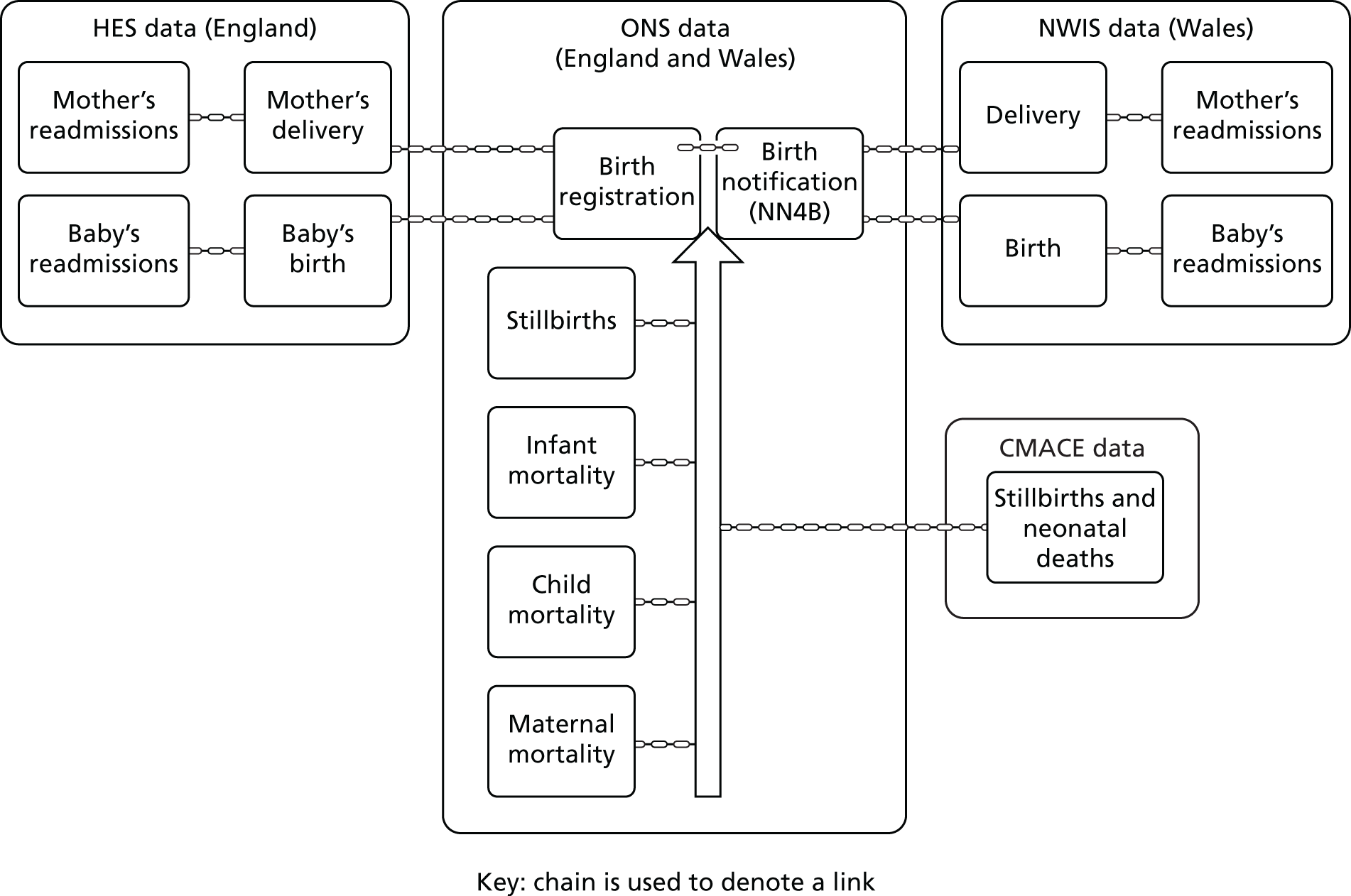

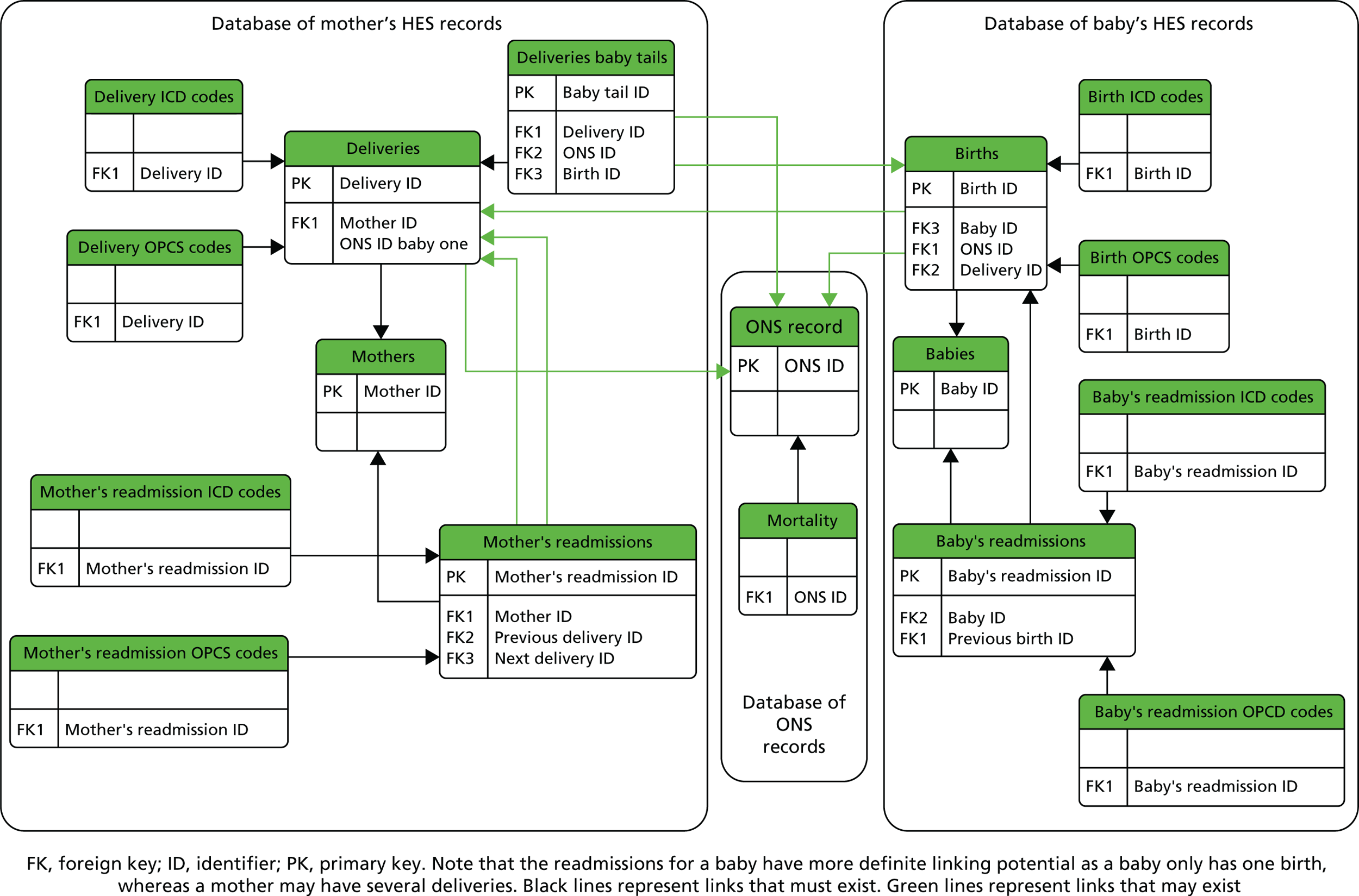

An overview of the datasets used in the project is shown in Figure 1 and the data acquired are summarised in Table 2.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of datasets used in the project. NWIS, NHS Wales Informatics Service.

| Name of dataset | Source | Years of birth | Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data from civil registration | |||

| Birth registration linked to birth notification | ONS | 2005–14 | All births in England and Wales |

| Maternal deaths linked to births | ONS | 2008–14 | Deaths of women of childbearing age within a year of giving birth in England and Wales linked to births |

| Infant deaths linked to births | ONS | 2005–14 | Deaths in the first year of life of babies born in England and Wales linked to birth records |

| Childhood deaths linked to births | ONS | 2005–14 | Deaths of children aged 1 year or over born in England and Wales linked to birth records |

| Stillbirths reported to confidential enquiries | CMACE | 2005–9 | England and Wales |

| Neonatal deaths in England and Wales reported to confidential enquiries | CMACE | 2005–9 | Neonatal deaths in England and Wales reported to confidential enquiries |

| Hospital data | |||

| Maternity HES | HSCIC | 2005–14 | England: linked and unlinked delivery and birth records |

| HES | HSCIC | 2005–14 | England: subsequent admissions of babies |

| HES | HSCIC | 2005–14 | England: subsequent admission of mothers |

| NCCHD/PEDW | NWIS | 2005–14 | Wales: linked and unlinked records |

| PEDW | NWIS | 2005–14 | Wales: subsequent admissions of babies |

| PEDW | NWIS | 2005–14 | Wales: subsequent admission of mothers |

| Workforce data | |||

| Annual workforce census | HSCIC | 2005–14 | England: aggregated annual census of numbers of staff by staff group and trust |

| Annual workforce statistics | NWIS | 2005–14 | Wales: aggregated annual census of numbers of staff by staff group and trust |

Birth registration and birth notification (‘ONS birth records’)

As a result of a project led by City, University of London, to link birth registration data with the birth notification dataset,5 the ONS now routinely links these two datasets and uses the linked data in its annual publications. 138 Linked data from this source for the years 2005–14 were provided to the project (see Figure 1). Linked birth registration/birth notification records are referred to in this report as ‘ONS birth records’.

Linked-in mortality data

Data from death registration had already been linked to ONS birth records (see Figure 1).

Data about deaths of babies under 1 year of age, linked to the corresponding ONS birth record, were provided to the project by the ONS for births in 2005 to 2014. The ONS also provided data for deaths at 1 year or over of age of children born from 2005 to 2014 occurring up to the age of 9 years.

The ONS provided records of deaths of mothers within a year of giving birth linked to the corresponding ONS birth records for births from 2008 onwards.

Data for linkage

Maternity Hospital Episode Statistics

We made an application to the HSCIC, now known as NHS Digital, for HES data for the financial years from 1 April 2004 to 31 March 2015 to cover the ONS calendar year data for 2005–14. We applied for delivery ([EPITYPE] = 2 or 5) and birth ([EPITYPE] = 3 or 6) records. The lists of fields requested are shown in Appendix 2 (see Tables 39, 41, 45, 52 and 57). We also requested mothers’ and babies’ non-delivery records. For mothers, this consisted of antenatal admissions, postnatal admissions and admissions unrelated to maternity. For babies, this included postnatal admissions and subsequent admissions unrelated to the child’s birth, for example as a result of accidents.

Patient Episode Database for Wales/National Community Child Health Database

Information from NCCHD and PEDW was provided by the NHS Wales Informatics Service (NWIS). As for HES, data were received from PEDW for financial years from 1 April 2004 to 31 March 2015. Data items included demographic and administrative fields as well as clinical fields, such as diagnoses and operative procedures during the delivery episode. NCCHD data included information about gestational age, onset of labour, the number of babies born and each baby’s birthweight, sex, live birth or stillbirth status, mode of delivery, ethnicity, birth location, breastfeeding at birth and breastfeeding at 6/8 weeks.

Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries

Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries data without patient identifiers, such as the NHS number, date of birth and postcode, were available for the years 2005–9 from the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP). These records were acquired for linkage to ONS stillbirth records to distinguish between antepartum and intrapartum stillbirths and also to ONS neonatal death records.

Data to be used in future analyses

Workforce data

As there are no routinely collected data about numbers of staff on duty by time of day and day of the year, the only way such data could be obtained would be by doing an extensive and expensive prospective data collection exercise. In the absence of such data, we identified the available data with the aim of using them to assess overall levels of staffing.