Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HS&DR Evidence Synthesis Centre, contracted to provide rapid evidence syntheses on issues of relevance to the health service, and to inform future HS&DR calls for new research around identified gaps in evidence. Other reviews by the Evidence Synthesis Centres are also available in the HS&DR journal.

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/182/14. The contractual start date was in September 2017. The final report began editorial review in June 2018 and was accepted for publication in September 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Rodgers et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background and research questions

The volume of crisis calls related to people with serious mental ill health is an increasing challenge for police services. The limited training that these services have in mental health care can affect the appropriateness of their response in some circumstances. Often police officers have to decide on the management of mental ill health on the spot with limited options available to them other than temporary detention for assessment.

In February 2014, 22 national bodies involved in health, policing, social care, housing, local government and the third sector came together and signed the Mental Health Crisis Care Concordat: Improving Outcomes for People Experiencing Mental Health Crisis that set out how public services should work together to respond to people who are in a mental health crisis. 1

Although people experiencing a mental health crisis can be identified through primary care or hospital emergency contacts, in many cases, the affected people themselves or members of the public may call 111 or 999. Consequently, police officers often become the first responders to mental health-related incidents and thus a common gateway to care. This has raised concerns about the use of police resources and police officers’ relative lack of knowledge, skills and support when handling the mental health needs of individuals in crisis.

If a police officer believes that someone is experiencing a mental health crisis in a public place and is deemed to be in immediate need of care or control, section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983 (S136)2 provides the officer authority to take that person to a ‘place of safety’ so that their mental health needs can be properly assessed. In the past, this has meant that people often ended up in a police cell, which could be frightening and could potentially precipitate a worse outcome. The Mental Health Act 1983: Code of Practice 20153 required the specific use of health-based places of safety (HBPOS) where mental health services can be provided. In practice, psychiatric units and hospital accident and emergency (A&E) departments are commonly used as HBPOS. In January 2017, the Policing and Crime Act4 resulted in a number of changes to S136. These were (1) police must consult mental health professionals (MHPs), if practicable, before using S136, (2) police stations cannot be used as a place of safety for people under the age of 18, (3) police stations can only be used as a place of safety in specific ‘exceptional’ circumstances for adults and (4) the period of detention is reduced from 72 hours to 24 hours with the possibility of a 12-hour extension under certain defined circumstances. 2,4–6

In May 2015, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) made available £15M in capital funding to improve the provision, capacity and quality of HBPOS to better support people detained under S136. 7 A further £15M of funding was announced in October 2017 through the Beyond Places of Safety grant scheme. 8

Previously, S136 applied only to people who were encountered in a public place; section 135 of the Mental Health Act 1983 (S135) required a magistrate-issued warrant when police officers intended to enter private premises to remove a person to a place of safety for assessment. The Policing and Crime Act 20174 changes to S135 and S136 now allow an assessment to take place in the premises/home under certain circumstances (S135), removing the need to be in a place to which the public has access (S136).

In part, the Mental Health Crisis Care Concordat: Improving Outcomes for People Experiencing Mental Health Crisis1 was established to promote local multiagency arrangements to improve the quality of care for people experiencing a mental health crisis and to ensure that they are diverted to health rather than police settings. Mental health ‘street triage’ schemes were established in a DHSC pilot in 2013 and an evaluation was published in 2016. 9 Street triage, as piloted in England, typically takes the form of MHPs supporting police officers when they respond to emergency calls for cases that involve a person who may be suffering from a mental illness. These individuals often come into contact with the police despite not necessarily having committed an offence, and street triage interventions aim to direct these people to appropriate services, thereby avoiding inappropriate further interaction with the criminal justice system (CJS). 10 In such interventions, MHPs may be deployed to an incident with police officers and/or be situated in police force control rooms, where they can help monitor emergency calls and provide advice and support to call handlers and officers who may be interacting with a person in mental distress or crisis.

Another approach closely related to street triage is the Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) model. This involves specially trained police officers responding to calls involving suspected mental ill health either alone or alongside mental health and addiction professionals. As with street triage, the aim is to divert persons with mental ill health from the CJS to mental health treatment, when appropriate. 11,12 This approach was pioneered in the USA and there is an increasing interest in the UK in mental health training for front-line police officers. 11–13

In contrast to street triage, liaison and diversion (L&D) services are typically concerned with helping people when they are suspected of having committed an offence. Teams of specialist mental health-trained staff are located at police custody suites or courts to give an assessment and refer the person on to more appropriate mental health services outside the justice system. Alternatively, these specialist teams may support an individual while they remain in the justice system if their index offence or risk means that they cannot be diverted immediately. 11,12 However, it is conceivable that in the future L&D service providers, in agreement with local police forces and health commissioners, could extend their role to cover street triage objectives. 10

There is no universally accepted taxonomy of interventions in this area. A recent scoping review of interagency collaboration models between the police and other agencies for people with apparent mental ill health identified a range of possible models. 14 These included:

-

Pre-arrest diversion – providing police officers with specialist mental health training to better manage situations involving people with mental ill health and to offer treatment as an alternative to arrest, such as CIT.

-

Co-response – a shared protocol pairing specially trained police officers with MHPs to attend police call-outs involving people with mental ill health (often how UK street triage pilot schemes have been conceptualised).

-

Information-sharing agreements – information about people with mental ill health being shared between police and other agencies or between the individual with mental ill health and the police and other agencies.

-

Co-location – MHPs being employed by police departments to provide on-site and telephone consultations to officers in the field.

-

Consultation – police agencies accessing advice from MHPs when working with people with mental ill health, often via telephone.

Schemes that have described themselves as street triage can incorporate aspects of some or all of the above approaches; it can be seen that street triage is often used to describe one form of intervention that belongs to a larger cluster of interventions with similar aims. This rapid evidence synthesis will, therefore, use the term police-related mental health triage (PRMHT) interventions rather than street triage. This study is interested in all intervention models that aim to improve outcomes when police officers are called to incidents primarily relating to mental health rather than criminal concerns.

Initial scoping work

Scoping searches

To inform the protocol development, we undertook initial scoping work to gauge the focus and extent of the current evidence base. Scoping searches were carried out in August 2017 to identify existing reviews, primary studies and ongoing research relating to PRMHT interventions. The following databases were searched: Epistemonikos (a source of systematic reviews relevant to health decision-making; The Epistemonikos Foundation, Santiago, Chile), MEDLINE, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) and PROSPERO. In total, 498 records were identified and scanned for relevance. In addition, a variety of approaches for identifying further relevant material were utilised, such as contact with experts, reference checking of relevant studies and web searching.

Results of scoping work

Initial scoping work identified five systematic reviews that described and evaluated PRMHTs. 11,15–18 In addition, a number of non-systematic literature reviews also described relevant intervention models. 19–22

The existing reviews incorporated overlapping literature searches, the most recent of which was completed in June 2016. Although these reviews provided a useful overview of the existing evidence, the reviews also highlighted the methodological inadequacy of many existing evaluations for drawing firm conclusions about the effects of PRMHT interventions. Consequently, a new systematic review of the literature on effectiveness is unlikely to add much additional knowledge.

In addition to these evaluations, several qualitative and mixed-methods primary studies focused on PRMHT interventions that have been published, although scoping searches did not identify any published syntheses of these data. A rapid evidence synthesis of the existing primary research data in this area was considered to be of value.

Further details of the initial scoping work are provided in the protocol. 23

Research questions

What is the evidence base for models of PRMHT interventions?

-

Which models have been described in the literature?

-

What evidence is there on the effects of these models?

-

What evidence is there on the acceptability and feasibility of these models?

-

What evidence is there on the barriers to, and facilitators of, the implementation of these models?

Chapter 2 Methods

Synthesis approach

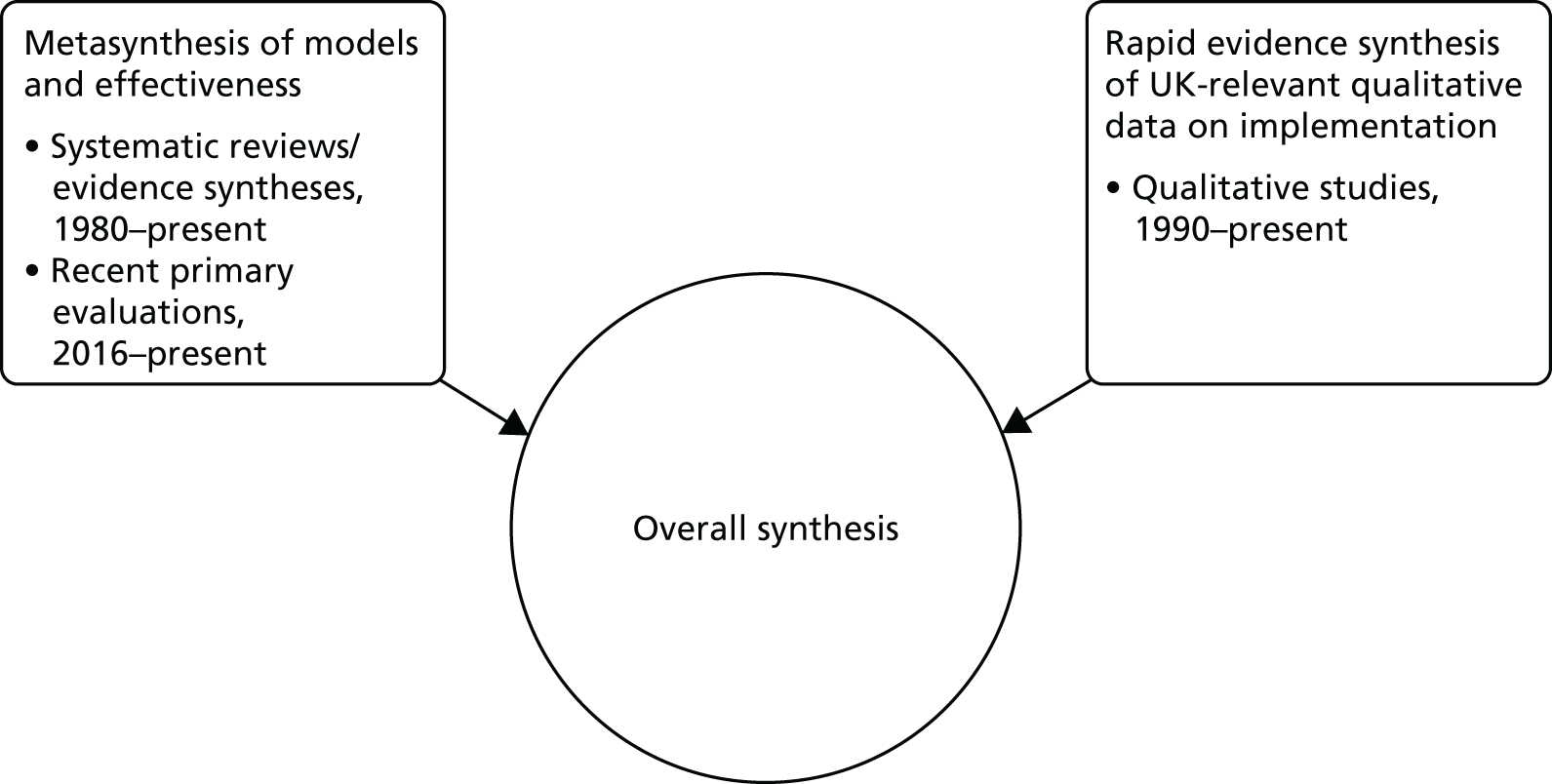

Based on the findings of the scoping work, we undertook a three-part evidence synthesis of evidence on PRMHT interventions:

-

Metasynthesis of evidence on the effects of PRMHT intervention models –

-

undertook a taxonomy of evaluated PRMHT interventions and described the different underlying intervention models

-

summarised quantitative evidence on the effects of PRMHT interventions.

-

-

Rapid evidence synthesis of UK-relevant qualitative data on implementation.

-

Overall synthesis –

-

combined the findings from the quantitative and qualitative components in a narrative synthesis

-

outlined the evidence for what works in what circumstances and for whom, potentially setting the scene for further research (outside the scope of this project) to develop programme theories of the more successful models.

-

Literature searching

Evidence on the effects of police-related mental health triage intervention models

Search strategies from an ongoing systematic review by Park et al. 16 were used as a basis for the literature search to identify recent reviews or primary evaluations of PRMHT interventions.

The following databases were searched in November 2017: ASSIA, Criminal Justice Abstracts, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PAIS Index, PsycINFO, Scopus, Social Care Online, Social Policy & Practice, Social Sciences Citation Index and Social Services Abstracts. Searches were limited to English-language studies published from 2016 onwards.

Additional web searching was undertaken. Relevant UK reports were identified through searches of the following websites:

-

College of Policing (see www.college.police.uk/)24

-

Mental Health Foundation (see www.mentalhealth.org.uk/)25

-

Crisis Care Concordat (see www.crisiscareconcordat.org.uk/)26

-

Centre for Mental Health (see www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/)27

-

Connect Evidence Based Policing (see http://connectebp.org)28

-

the East Midlands Police Academic Collaboration (see www.empac.org.uk/). 29

A focused search of Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), using the advanced search interface, was also undertaken to identify any further UK-relevant reports.

UK-relevant qualitative data on implementation

The literature search aimed to identify qualitative primary studies of PRHMT interventions. The search strategy from the ongoing review by Park et al. 16 was used with the addition of a previously tested search strategy designed to limit retrieval to qualitative studies. 30 Limits were applied to restrict retrieval to English-language studies published from 1990 onwards. Preliminary searches indicated an absence of relevant evidence prior to this date; even if evidence were to exist, the difference in service delivery context from the present day would limit its value. The search was not limited by geographical location or setting.

The following databases were searched on 9 November 2017: ASSIA, Criminal Justice Abstracts, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and the Social Sciences Citation Index.

As for quantitative data, additional web searching and a focused search of Google, using the advanced search interface, were also undertaken to identify any further UK-relevant reports.

Full search strategies can be found in Appendix 1.

Selection criteria

Evidence on the effects of police-related mental health triage intervention models

A metasynthesis of existing reviews, identified through initial scoping searches, was undertaken, supplemented with an updated search of the literature to consolidate the most recent evidence on the effects of known models of PRMHT.

Population

Reviews and studies were included if they evaluated interventions relating to individuals who are perceived (by themselves, by others or by police officers) to be experiencing mental ill health or a mental health crisis and who come into contact with the police.

Interventions

Reviews and studies were included if they described interventions that met the following definition of PRMHT:

-

Police officers responding to calls involving individuals perceived to be suffering from mental ill health or a mental health crisis.

-

A judgement about the most appropriate route of care for the person concerned is made in the absence of suspected criminality or a criminal charge (e.g. the use of L&D services to assess and refer individuals to an appropriate non-CJS treatment or support service, would be relevant; L&D services related to out of court disposals, case management and sentencing would not be relevant).

Study design and comparators

Reviews/evidence syntheses and recent relevant primary studies (those that were published after the search dates of included evidence syntheses) were included. Emphasis was placed on reviews that use transparent or reproducible methods [as determined by the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) criteria]. 31 It is mandatory that reviews demonstrated adequate inclusion and exclusion criteria, a literature search and a synthesis. In addition, a formal quality assessment of primary studies and/or sufficient study details must have been reported. Further details of the assessment are available from the review authors. Reviews that failed to meet these standards were tabulated and referenced. For recent primary studies, inclusion was restricted to quantitative evaluative methods, either as a stand-alone methodology or as a discrete part of a larger mixed-method study. Non-evaluative descriptive publications were excluded but recorded for information; details can be found in Appendix 2. Ongoing studies are listed in Appendix 3.

Outcomes

Inclusion was not restricted by outcome. Outcomes of interest were the:

-

rate of utilisation of police cells in relation to S135 and S136

-

quality and timeliness of assessment, referral and treatment

-

mental health outcomes

-

demand on police resources and police officer time

-

demand for community mental health services

-

rates of hospitalisation via A&E or acute mental health services

-

level of service engagement

-

rates of reoffending or arrest

-

changes in case-finding and access to health services (e.g. mental health, substance misuse, sexual health and contraception)

-

experience of services for service users

-

experiences of police and mental health staff (including future staff training needs) and other relevant stakeholders

-

costs to health and police services.

Settings

Inclusion was not restricted by country or setting.

UK-relevant qualitative data on implementation

A rapid evidence synthesis of qualitative and mixed-methods primary studies was undertaken to identify factors affecting implementation. Given the differences in service organisation and wider cultural differences between countries, this part of the work was restricted to UK evidence.

Population

Studies were included if they reported data on interventions relating to individuals who are perceived (by themselves, by others or by police officers) to be suffering from mental ill health or a mental health crisis and who come into contact with the police.

Interventions

Studies were included if they described interventions that met the following definition of PRMHT:

-

Police officers responding to calls involving individuals perceived to be suffering from mental ill health or a mental health crisis.

-

A judgement about the most appropriate route of care for the person concerned is made in the absence of suspected criminality or a criminal charge (e.g. the use of L&D services to assess and refer individuals to an appropriate non-CJS treatment or support service would be relevant; L&D services related to out of court disposals, case management and sentencing would not be relevant).

Study design

Inclusion was restricted to well-reported qualitative studies that collected data using specific qualitative techniques (such as unstructured interviews, semistructured interviews or focus groups, either as a stand-alone methodology or as a discrete part of a larger mixed-method study) and from which the data were analysed qualitatively (e.g. using thematic analysis, content analysis or other recognised qualitative method). Studies that collected data using qualitative methods but then analysed these data using quantitative methods were excluded.

Outcomes

Inclusion was not restricted by outcome. Outcomes of interest included stakeholder (including service users’ and providers’) perspectives on the acceptability and feasibility of PRMHT, with specific reference to:

-

attitudes, beliefs and experiences about the use of the intervention

-

perceived facilitators of and barriers to implementation (e.g. willingness, capability and capacity of both police and mental health workforces, organisational and procedural factors)

-

health equity issues [e.g for black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities, people without English as their first language, people with neurodevelopmental disabilities]

Settings

Given the unique governance arrangements for delivering a mental health triage service in the UK, as well as important differences in social context and the delivery of health and criminal justice services between countries, inclusion was restricted to qualitative data on interventions that were undertaken in the UK.

Selection procedure

Three reviewers screened the results of the literature searches in EndNote X7 [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA]. Each record was screened by one reviewer, with clearly irrelevant records rejected. The remaining records were classified as clearly relevant or of borderline relevance and were independently assessed by a second reviewer. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus with a third reviewer.

All studies included on the basis of title and abstract were screened again based on the full publication and following the same procedure.

Records that were initially classified as ‘borderline’ but ultimately excluded can be found in Appendix 4.

Data extraction and risk-of-bias assessment

Key review and primary evaluation characteristics were extracted and tabulated.

Risk of bias in reviews was assessed using the Egan et al. -adapted criteria32 previously used in a Health Services and Delivery Research metasynthesis on support for informal carers and the provision of services in the UK for armed forces veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. 33,34 As part of a methodological piece of work, we had also intended to use the ROBIS assessment tool35 which is a more detailed and nuanced assessment, but because of a lack of time and resources it was not used.

The risk of bias of primary evaluations of effects was to be assessed using study design-specific tools. The quality of the more robust primary study designs was critically appraised, conventionally considered to be randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled trials, using the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care risk-of-bias tool for controlled studies. 36 However, many of the remaining studies were predominantly single-group designs based on retrospective data collection from routine sources. When comparisons were reported, these often used historical data prior to the intervention. These designs are typically considered less methodologically robust. Although these single-group studies were not formally assessed for methodological quality, the adequacy and clarity of reporting on context, methods and impact was considered.

The methodological quality of qualitative studies was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for qualitative research. 37

Data coding and synthesis

Evidence on the effects of police-related mental health triage intervention models

The aims, characteristics, results and risks of bias of included reviews and recent primary evaluations of effects were tabulated and combined in a narrative synthesis. This describes the most prominent models of intervention alongside evidence on the nature, strength and direction of observed effects for these interventions.

UK-relevant qualitative data on implementation

Characteristics of included studies were extracted and tabulated and their full text entered into NVivo version 11 (QSR International, Warrrington, UK) for coding and thematic analysis. 38 Texts were coded by one reviewer and checked by another. Descriptive and analytical themes were developed using the themes reported by Reveruzzi and Pilling9 as a framework. This framework was selected because it allowed us to rapidly integrate additional primary research evidence with that derived from the DHSC pilot studies.

Overall synthesis

An overall narrative synthesis (Figure 1) drew together evidence from the effects of PRMHT interventions in the UK using UK-relevant qualitative data on implementation, to address the stated research questions:

-

Which models have been described in the literature?

-

What evidence is there on the effects of these models?

-

What evidence is there on the acceptability and feasibility of these models?

-

What evidence is there on the barriers to, and facilitators of, the implementation of these models?

FIGURE 1.

Structure of the rapid evidence synthesis.

In the absence of adequate evidence, detailed recommendations were made for the design and conduct of any future evaluations in this area.

Advisory group

A project advisory group was convened to help to provide expert advice and input. This involved researchers from primary evaluations of PRMHT interventions and police staff, including a control room sergeant and a street triage supervisor. The advisory group were free to comment on any aspect of the rapid evidence synthesis, including, but not limited to:

-

refining the definition of PRMHT if necessary

-

identifying the highest-priority outcomes

-

identifying UK-relevant data from the international literature

-

discussing findings

-

developing practical recommendations for the various stakeholder audiences

-

identifying highest-priority areas for further research.

Comments and suggestions from the advisory group were incorporated into the final report.

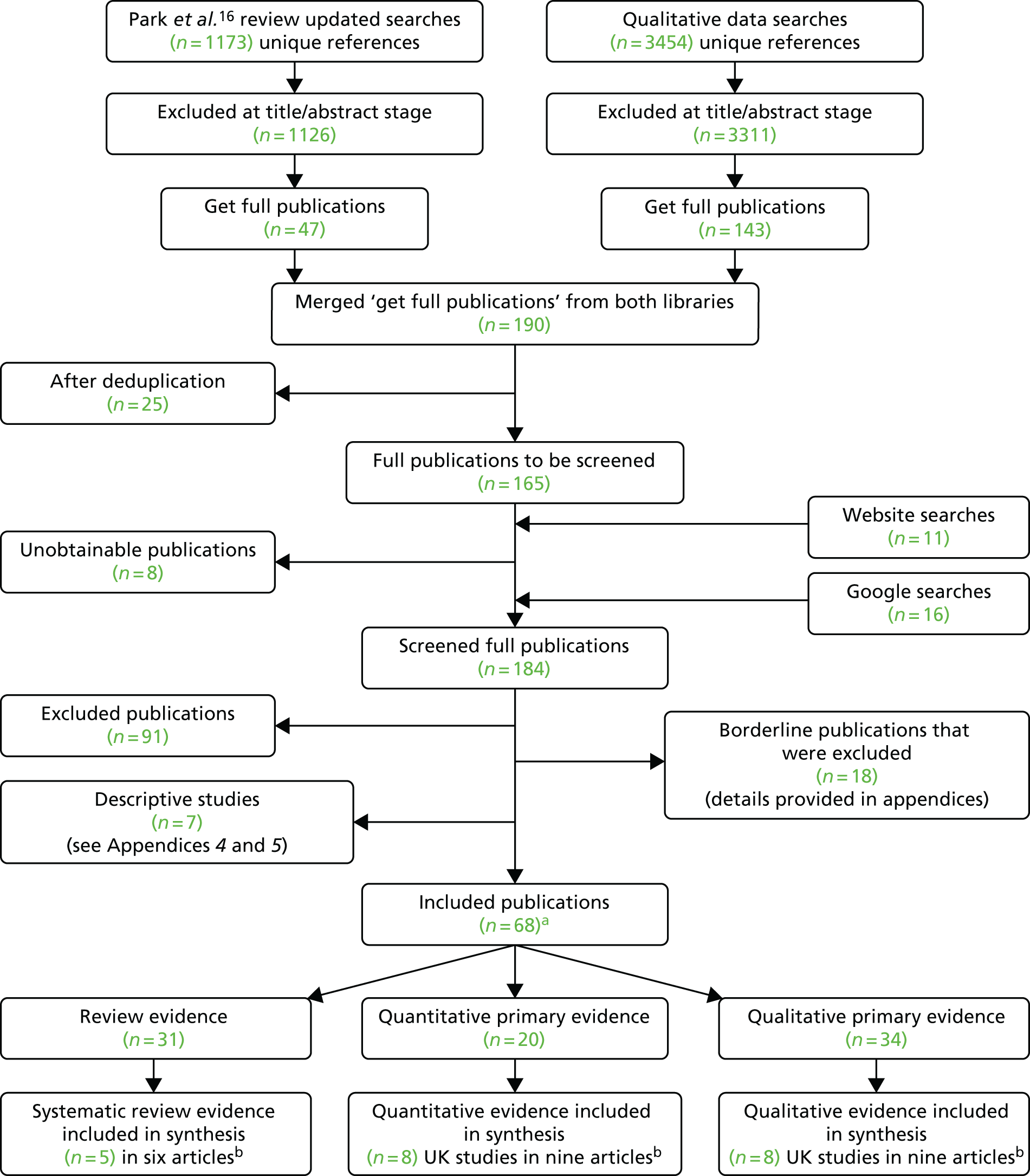

Chapter 3 Search results

Sixty-eight publications were included. Any one paper may have contributed to more than one section of evidence (e.g. provided systematic review, quantitative or qualitative evidence). Thirty-one publications provided review evidence, 20 publications provided quantitative evidence and 34 publications provided qualitative evidence (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart. a, Any one paper may have contributed to more than one section of evidence [hence, the total number (n) increases from 68 to 85]; b, studies not included in the synthesis are detailed in the appendices.

Chapter 4 Metasynthesis of evidence on the effectiveness of models

Systematic reviews

Overall, 31 review articles evaluating PRMHT interventions were identified. This study focused on those reviews that used systematic, transparent or reproducible methods, as determined by the DARE criteria. 31 This resulted in five reviews being included in the synthesis. 11,12,14,15,39,40 There were six articles published for the five reviews as Kane et al. 11 also published their review protocol. The remaining 25 review articles were excluded from the synthesis as their methods were deemed less robust (according to DARE criteria) or were not reported. These reviews are listed in Appendix 5 and DARE assessments for all identified reviews are presented in Appendix 6.

Below is a summary of the five included systematic reviews. Three reviews were evaluations of PRMHT interventions,11,12,15,40 one review evaluated mental health training programmes for PRMHT39 and one was a scoping review of interagency collaboration models for PRMHT. 14 Details of the study characteristics are also provided in Table 1. The level of detail of participants, interventions, comparators, outcomes and findings varied between reviews. Terminology also differed and was often undefined. We have endeavoured to report the findings in as much detail as was available from the original reviews.

| Reference details of included studies: countries, study designs, number of studies, date range of studies | Review objective/aim and inclusion/exclusion criteria | Full description of intervention(s) and comparator(s) (when reported) | Summary of authors’ conclusions and summary of implications for research and health care, as reported by the authors | Commentary: (1) brief interpretation of internal validity and (2) issues relevant to external validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic reviews of interventions | ||||

| aKane et al.11,12 | ||||

|

Countries: unclear, although appears to include Australia, Canada, the USA and the UK (England) Street triage: (when reported) Australia, Canada, the USA and the UK (England) CIT: Australia and USA Multiple intervention comparison: USA Study designs: L&D – controlled studies (n = 5), pre–post studies (n = 2) Street triage – controlled studies (n = 3), pre–post comparison studies (n = 2) CIT – meta-analysis (n = 1), controlled studies (n = 6), pre–post studies (n = 2) Comparison across intervention types – unclear Number of studies: 23 L&D (n = 7) Street triage (n = 5) CIT (n = 9) Comparison across intervention types (n = 1) (two papers) Date range of studies: L&D: 2005–15 Street triage: 2000–16 CIT: 2004–16 Comparison across intervention types: 1999–2000 |

To evaluate the effectiveness of police–mental health service interventions for responding to ‘people with mental disorder and suspected offending or public safety problems’ Included studies had to relate to an intervention for those with mental ill health or a ’problem’; report objective outcome measures regarding offending or mental health; involve participants aged > 18 years; the design had to be experimental/quasi-experimental and had to include an intervention and comparison group(s) or a pre/post comparison; comparison group members had to be individually matched to intervention participants, or baseline comparability was demonstrated, or allocation of participants was random PhD theses and articles not in English were excluded, as were papers published before 1980 |

Street triage: various, including a mobile crisis unit that provides two police officers and one nurse from 15.00 to 22.30 for 7 days a week, with a psychiatrist available for telephone consultation and an initial response to 911 calls identified as psychiatric emergency situations is also provided; mental health mobile crisis unit partnership between mental health services, police and emergency health services offering short-term crisis management, using a mobile team that consists of a plain-clothes police officer and a MHP; and PACER; street triage pilot schemes in England (no further detail reported) Comparisons (when reported) included areas with no service or retrospective data collected from a time when teams were not on duty CIT: in some studies officers had 40 hours of training Comparators (when reported) appeared to be no training Studies on L&D services were also reported |

Authors’ conclusions: the studies reviewed offer some positive evidence for the interventions. However, the research base remains underdeveloped, needing more large-scale, well-designed trials. Only two studies looked at the differences between approaches, and neither one is conclusive. CIT is the intervention with the most robust evidence underpinning it but is not widely used outside the USA. In England and Wales, although not operating with any design fidelity to the CIT model, there is some local integration of approaches that are elsewhere delivered as discrete interventions Implications for research and health care: future services should take note of the current research and seek to capitalise on what works, and further build the evidence to refine and develop integrated interventions |

|

| bPaton et al.15 | ||||

|

Countries: the UK, Canada, the USA and Australia Study designs: mainly descriptive studies (n = 2) and quasi-experimental (n = 4) Number of studies: six (relevant to our rapid evidence synthesis) Date range of studies: 2000–14 |

To conduct a rapid synthesis of evidence on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of models of care (at each of the four stages of the care pathway identified by the Crisis Concordat) for treatment and support of people experiencing a mental health crisis For urgent and emergency access to crisis care: eligible for inclusion were quantitative (controlled) and qualitative studies of people with mental health problems accessing emergency services and emergency department care. Eligible interventions were those designed at service level (including training) to improve service and service user outcomes (e.g. waiting times, hospital admissions, reduced use of force/restraint, self-harm, violence, mental health outcomes and service user experience) |

Street triage or telephone triage by health or social care professionals in collaboration with police officers (some in receipt of CIT training) Various, including a telephone triage service (RAID); a street triage crisis partnership involving mental health services, municipal policy and emergency health services; and a comparison of interventions including police officers with mental health training and assistance provided to police by community service officers; and a mobile crisis team Comparators included nothing (or pre-intervention data only), areas with no access to services, or interventions compared with each other Police officers receiving training in mental health Training interventions were based on CITs or MHIT Comparators included none (or pre-intervention data only); or police officers not in receipt of training |

Authors’ conclusions: there is very limited evidence for support (via training, street or telephone triage) to police officers from MHPs. Street triage and training of police offers were both associated with reduced police time at the scene of mental health-related incidents; street triage may also improve user engagement with outpatient treatment services. People with mental health problems were more likely to be taken to a health-care setting (as opposed to being arrested) as a result of mental health training undertaken by police officers. There was no evidence of intervention effect on levels of force used by police officers in mental health-related calls Implications for research and health care: rigorous, high-quality evaluation is needed. The authors did not report any implications for practice |

This data extraction focuses on only data presented for urgent and emergency access to crisis care (including street triage) as part of a wider review, which also addressed access to support before crisis point, quality treatment and care in crisis, promoting recovery/preventing future crisis

|

| cTaheri40 | ||||

|

Countries: the USA and Australia Study designs: quasi-experimental (including two studies with matched control) Number of studies: eight Date range of studies: 2006–14 |

To evaluate the evidence on the effects of CITs, with a specific focus on its effects on the core elements set forth by the Memphis model Included studies had to use a quasi-experimental or experimental design (at the very least involving a post-intervention measure of outcomes and a comparable control group), with a focus on CIT in individuals with mental ill health (all definitions included) Outcomes of interest were official or officer-reported arrests of a person with mental ill health, police officer use of force or of police officer injury |

CIT: although the characteristics of included CIT models were not reported, an operational definition of CIT was provided for the review (i.e. any specialised, police-based, jail diversion response to persons with mental ill health following the Memphis model) All included studies evaluated a CIT programme implemented by law enforcement Comparators: included matched controls (two studies: one matching police districts, one matching individual officers); six studies compared CIT-trained officers with non-matched samples of non-CIT trained officers |

There is insufficient evidence to conclude if CIT models reduce officer injury when police officers encounter people with mental ill health. There appears to be some evidence of no effect in relation to CIT and arrest outcomes or officer use of force; overall, findings are mixed. This result does not indicate that CIT programmes should be discontinued Higher-quality evaluative research should attempt to use matched control designs, record both pre- and post-intervention data and use both official and self-reported measures |

|

| Scoping review of interagency collaboration models | ||||

| dParker et al.14 | ||||

|

Countries: Australia, Canada, the USA, the UK and the Netherlands Study designs: (overall review) various, mostly – descriptive, mixed-methods, service evaluations, controlled before and after studies. Other designs – survey, qualitative, case study, audit, scoping review, prospective observational study Number of studies: 125 Date range of studies: not reported |

To identify and map the evidence on interagency collaboration models/mechanisms, the broad areas/issues covered and views/experiences connected to the models Eligible for inclusion were English-language studies of empirical evaluations or descriptions of interagency collaboration models Evidence had to be UK based or from any Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development country Models had to include police engagement with members of the public with apparent mental ill health, mental vulnerabilities or learning disabilities Any outcome was considered. Studies published before 1995 were excluded |

Pre-arrest diversion (43 articles): first-line response police officers with special mental health training who liaise with mental health services. Most widely reported was the CIT model (17 articles) Comparators: not reported Co-response (36 articles): a shared protocol between specially trained police officers and MHPs. Three articles focused on UK-based ‘street triage’ involving initial police call handlers referring to the street triage team (a dedicated police officer and a psychiatric nurse working together) or (when the team was busy) telephone support to police attending an incident Comparators: not reported Co-location (five articles): MHPs employed by police departments to provide assistance (on-site and over the telephone) to police officers attending an incident Comparators: not reported Consultation model (three articles): typically, telephone advice (e.g. a dedicated 24-hour contact number) providing police access to advice from MHPs Comparators: not reported Service integration models (three articles): multiagency integrated service (e.g. community-care networks) involving a network co-ordinator (often a community psychiatric nurse), a personalised action plan for the individual in mental distress and active follow-up with signposting to the relevant agency Comparators: not reported |

Authors’ conclusions (overall): 13 different interagency collaboration models to deal with various mental health-related interactions were identified (12 models involved the police and mental health services/MHPs) Implications for research and health care (overall): a systematic review of effectiveness would be possible for some service models, others warrant more robust evaluation (such as a RCT). Future evaluation should target health-related outcomes and have an impact on key stakeholders |

This data extraction focuses on models of interest to our rapid evidence synthesis, as follows: pre-arrest diversion, co-response, co-location, consultation model; service integration models (Other models included in the scoping review: information sharing agreement models; court diversion models; comprehensive systems model; special protective measures; joint investigation training; re-entry programmes; integrated model) 1. The scoping review contained an appropriately broad question and a corresponding search strategy covering published and unpublished literature. Selection criteria were clearly stated. The review process demonstrated attempts to minimise error and bias. An established framework was used to map the literature and the results of this were clearly presented The authors acknowledge absence of study quality assessment and synthesis of the findings as a limitation of the review, thus precluding conclusions about the effectiveness of individual service models 2. The map of literature was sufficiently detailed to allow an assessment of generalisability to other countries and settings |

| Systematic review of training interventions | ||||

| eBooth et al.39 | ||||

|

Countries: the USA, Canada, the UK, Sweden and Australia Study designs: Police training – systematic review (n = 1), RCT (n = 12), prospective non-RCTs (n = 3) mental health-related training specifically for police in England: non-comparative evaluations (n = 3) Number of studies: 19 Date range of studies: 2001–15 |

To evaluate the effectiveness of training programmes and/or training resources aimed at increasing knowledge and/or behaviour or attitudes of the trainees about ill health, mental vulnerability and learning disabilities and of satisfaction with training and barriers to, and facilitators of, effective training Eligible for inclusion were studies of police officers; other police staff engaging with the public; members of the CJS; health professionals (non-mental health trained) in acute care; education workers; and other relevant professions/organisations/mental health charities Interventions of interest were any specific mental health training or learning resources aimed at improving attitudes, knowledge and skills of professionals dealing with members of the public (any age) with mental health issues or learning disabilities Comparators of interest were no training, usual practice or different modalities of training Primary outcomes of interest included changes in practice (behaviour) and outcomes for members of the public Secondary outcomes included satisfaction with training, shifts in attitude towards mental health, and changes in confidence, knowledge and skills Systematic reviews, RCTs and qualitative studies of views and experiences were eligible for inclusion Additionally (for police-related interventions only), non-RCTs, observational studies and published/unpublished audits and evaluations in England and Wales were eligible |

Interventions with a broad mental health focus For police officers CIT programmes (course content not reported) Education (including mental ill health, substance abuse, medication, treatment, civil commitment law, intervention techniques) mental health awareness training (including S136 procedures, meetings with MHPs, interactive teaching and role play) Various anti-stigma courses (including education, practical training and psychiatry lectures, workshops about mental health problems and how police can support people); online training (delivered by a combination of personal experience and information giving) MHIT (course content not reported) Comparators: when reported/when applicable, no training or alternative training For other non-mental health trained professionals Caseworker training and consultation model ‘Project Focus’ (including awareness of mental health needs, effective mental health treatment and developing action plans for youths in the community) MHFA with emphasis on self-help, including a five-step action plan (‘ALGEE’) aimed at University Resident Advisors MHFA (translated to Swedish) aimed at public sector staff Modified version of the Youth MHFA course (with ‘ALGEE’ action plan) aimed at teachers and students Peer Hero Training aimed at University Resident Assistants (including dramatisations, counselling sessions, interviews with parents of students/senior residence life professionals) Comparators: waiting list, usual practice Interventions with a specific mental health focus For police officers Awareness training on intellectual disabilities (including community-based role-play) Web-based/online video education on autism spectrum disorder – ‘Law Enforcement: Your Piece to the Autism Puzzle’ Comparators: no training, waiting list For other non-mental health trained professionals Classroom-based information on the autism spectrum disorder aimed at trainee teachers Alternatives for Families: Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (AF-CBT) aimed at community clinicians ‘The student body; promoting health at any size an online programme’ aimed at teachers and public health professionals (comprising six modules covering media and peer pressure, healthy eating, active living, teasing, adult role models and school climate) Education on adolescent depression aimed at teachers (delivered in three parts: introduction, case vignettes, discussion of specific issues) Modified Barkley’s parent-training programme adapted for teachers (and aimed at teachers and parents) to help children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder Comparators: alternative training, usual practice |

Authors’ conclusions: various training programmes exist for non-MHPs engaging with people with MH issues. Evidence indicates some short-term behaviour change for trainees Implications for research and health care: longer-term follow-up of training programmes is needed, as is better quality research evaluating training for UK police officers Note: authors report that included studies were poorly reported, with various omissions making it difficult to extract or calculate an intervention effect. The systematic review and primary studies also had poor reporting of methods |

|

Characteristics of systematic reviews

The reviews of PRMHT effects included studies conducted in Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, Sweden, the USA and the UK, published between 1999 and 2016 (when reported).

Study designs of the included primary studies varied across the reviews. The reviews of PRMHT interventions included a meta-analysis, controlled studies, quasi-experimental controlled studies, pre–post comparisons and descriptive studies. The review of training programmes for PRMHT included a systematic review, RCTs and prospective non-RCTs. Most studies in the scoping review of interagency collaboration models were descriptive but this review also included mixed-methods studies, service evaluations, scoping reviews and observational studies.

Police-related mental health triage interventions

Details of the interventions of PRMHT were generally only briefly reported in the reviews and included the following.

Pre-arrest diversion

Control room call-handlers identify incidents when people are in a mental health crisis and to which they can despatch unaccompanied police officers with special mental health training who can then refer to mental health services [e.g. CIT or a Mental Health Intervention Team (MHIT)]. 11,12,14,15,39,40

Co-response

Co-response includes front-line police officers being supported by a MHP as a joint, on-scene response (hours may be restricted, i.e. co-response with MHPs may be operated only during night shifts) and/or a MHP in a control room [e.g. street triage teams in the UK11,12,14,15 or a police, ambulance and clinical early response (PACER) in Australia]. 12 The Parker et al. 14 scoping review described interventions in which the MHP exclusively provided advice from a separate location (e.g. via telephone) as befitting a ‘consultation’ model.

Service integration models

This intervention was described in the scoping review of models of interagency collaborations. 14 The model describes multiagency integrated services to create a network to bridge gaps between services, decrease arrest, decrease violence, improve educational attendance and completion, and reduce symptoms of mental ill health and psychological distress. These may typically involve a network co-ordinator (often a MHP), a personalised action plan for individuals in mental distress and active follow-up with signposting to the relevant agency. This is somewhat broader than the focus of the current review as it encompasses far more than triage and/or crisis work.

Training programmes and resources

Training and resources were described for the various PRMHT interventions, which had either a specific or a broad mental health focus. 39

Mental health triage providers and users

Whenever reported, the providers of the PRMHT interventions (service providers) were police officers,11,12,14,15,40 community service officers15 and MHPs. 15 The scoping review by Parker et al. 14 reported a wide range of relevant agency collaborators from health, welfare and social care services. The review by Booth et al. 39 evaluated training programmes and described a range of trainers, such as police officers, MHPs, educators and service users. Trainees included police officers as well as others from areas such as education, welfare and social care. 39

People coming into contact with PRMHT interventions (service users) were described in only two of the reviews. Taheri40 evaluated CIT interventions and broadly described service users as those diagnosed with mental ill health. The scoping review by Parker et al. 14 described service users as adults, children, young people and mixed populations. No further details on participants were reported in any of the reviews.

Outcomes

Organisational- and service-level outcomes were the most frequently reported across the reviews. These included rates of detention,11,12,15 use of HBPOS,11,12 arrest rates,40 mental health referrals, police officer time dealing with events and police officer safety. 11,12,15

The review of training by Booth et al. 39 reported on effects on police officer awareness, attitudes, beliefs and knowledge as a result of mental health training. A range of outcomes was also reported for the training of those in education, welfare and social care including awareness, knowledge, self-efficacy and changes to the environment. 39

Approach to synthesis

Only the review by Taheri40 conducted a meta-analysis. The remaining review authors conducted narrative syntheses because of the diversity of the primary studies and PRMHT interventions.

Overlap of primary studies within the review

There was some overlap of primary studies among the reviews themselves, and also in the additional primary studies included. The overlapping studies identified are listed in Table 1.

A summary assessment of the overlap indicates that a number of studies appeared in one or more of the effectiveness reviews. 11,12,15,40 The review by Taheri40 was also included in the Kane et al. 11,12 review. Studies in the review of training by Booth et al. 39 appeared in some of the effectiveness reviews. Some of the studies in the scoping review by Parker et al. 14 were also included in the effectiveness reviews, but findings were not reported. 39

Although there was some evidence of overlap of primary studies between the reviews, it is interesting that there was not a greater overlap given that all the reviews met our inclusion criteria. This perhaps illustrates the variety in forms of PRMHT interventions that have been evaluated and the lack of consistent nomenclature in this area in general.

Quality of the systematic reviews

The reviews were assessed for risk of bias using the Egan et al. criteria. 32 Most had some potential for error and bias in the review process. Table 2 provides details for each review.

| Egan et al.’s32 quality assessment tool questions | Systematic review | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Booth et al.39 | Kane et al.11,12 | Parker et al.14 | Paton et al.15 | Taheri40 | |

| Is there a well-defined question? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Is there a defined search strategy? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Are the inclusion/exclusion criteria stated? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Are study design and number of studies clearly stated? | Yes | Partial | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Have the primary studies been assessed for risk of bias/quality? | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| Have the studies been appropriately synthesised? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Has more than one person been involved at each stage of the review process? | Yes | Partial | Yes | Partial | No |

Booth et al. 39 fulfilled all the criteria. Paton et al. 15 met all the criteria but did not report if more than one person was involved at each stage of the review process, which means that there is potential for reviewer error and bias in the selection of studies. Kane et al. 11,12 met some of the criteria but despite reporting the intention to assess the risk of bias of included studies, the results of this assessment were not reported and did not appear to inform the findings. The authors also did not clearly report the study designs or number of included studies. These omissions mean that it is difficult to judge the reliability of the individual studies. The involvement of more than one reviewer was reported for only some parts of the review process, meaning that there is the potential for reviewer error and bias. Taheri40 was the sole author, so there is the potential for error and bias in the selection of studies, data extraction and synthesis. Risk of bias of the primary studies was not assessed, meaning that it is not possible to judge the reliability of the results from the meta-analysis.

The scoping review by Parker et al. 14 met all the criteria apart from assessment of primary studies, which is acceptable for a scoping review that does not report effectiveness findings. 14

Findings from the reviews

We have focused on the outcomes relevant to our review questions. Two of the included reviews had broader objectives and we have only used the sections relevant to PRMHT interventions. 14,15 A summary of the relevant findings are reported in Table 3.

| First author | Description (when reported) of service users, service providers, region | Summary of interventions and comparators (e.g. street triage, CIT) | Outcomes and measures (if reported) | Summary of results (if reported) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic reviews of interventions | ||||

| Kane et al.11,12 |

Street triage: Service users: unclear. Most studies appear to use retrospective data collection from data on service users and clients Service providers: not reported Regions: not reported |

Street triage: Comparators: very limited reporting. Reported comparators included areas with no service or retrospective data collected from a time when teams were not on duty Number of studies – five (three controlled, two pre–post comparison) |

Street triage: rates of detention under S136 (UK), psychiatric hospitalisations, outpatient contacts, length of hospital stay, referral to place of safety other than a police station, arrests. Police officer length of time on-scene, length of time to assist |

Street triage: overall, the studies reported that street triage teams provided a quicker and more appropriate response (one study of a mobile crisis unit in the USA, one study of a mental health mobile crisis team in Canada, one study of a PACER team in Australia) Street triage can improve outcomes, including reducing the use of formal detention (one study of a pilot street triage service in Cleveland, England) or increasing use of health-based places of safety (one study evaluating nine street triage schemes in England) and reducing contact time with treatment services (one study of a mental health mobile crisis team in Canada) |

|

CIT: Service users: not reported Service providers: unclear but appears to be largely police officers and correctional officers |

CIT: Comparators: non-trained officers Number of studies: nine (one meta-analysis, six controlled studies, two pre–post studies) |

CIT: direction of individuals with mental ill health to mental health services, hospital attendance time, officer self-efficacy and perceptions of verbal de-escalation |

CIT: there were mixed findings suggesting that CIT-trained officers differed from untrained officers for a number of outcomes; for example, a greater proportion of people with mental ill health were directed to mental health services by CIT-trained officers than by non-trained officers (three studies). This was influenced by the nature of the incident and the local services available CIT-trained officers demonstrated different approaches towards individuals encountered with mental ill health (three studies). This was suggested to be an existing difference between trained and non-trained officers, influencing their decision to take up such training (one study and one meta-analysis). There is also some suggestion in these studies of diffusion of benefit from CIT- to non-CIT-trained officers regarding knowledge of mental health and approaches to incidents (one study) |

|

|

Service users: not reported Service providers: not reported Regions: not reported |

Comparison of three different interventions: (1) involving civilian police employees with additional training to assist police officers in mental health emergencies and difficult to resolve calls (2) a CIT unit (3) a Mobile Crisis Unit Comparators were data from usual police response Number of studies: unclear (two articles) |

Mental disturbances requiring a response, dispositions, arrest rates |

Review authors report that the structure, approach and resources of each programme suggested that although the approaches can be effective, not all were equally effective. Statistically significant differences across the three sites examined were reported for the proportion of mental disturbance calls eliciting a specialised response (Birmingham 28%, Knoxville 40%, Memphis 95%) (one study) The dispositions (final determination) of cases handled by the specialised response personnel were found to be related to the programme type. All three programmes reported average rates of arrests (featuring mental ill health) as 7%. Key factors of success included the existence of a psychiatric triage or drop-off centre where police can transport individuals in crisis, and community partnerships so that the police response is part of a wider response involving relevant agencies |

|

| Paton et al.15 |

Service users: not clearly reported Service providers: police officers and MHPs, community service officers Regions: Canada, the USA and the UK (Greater Manchester) |

Street triage or telephone triage by health or social care professionals in collaboration with police officers (some in receipt of CIT training) Various collaborative partnerships Comparator: none (or pre-intervention data), comparisons within multicomponent model, no street triage Number of studies: three (one descriptive and two described as quasi-experimental) |

Use of Mental Health Act 19832 detention, police time on-scene, engagement with outpatient treatment, taken to treatment location, situation resolved on-scene, referred to treatment, arrested | Street triage [officers receiving telephone triage (RAID)] was associated with reduced S136 detentions and a number of calls were successfully converted to hospital admissions. Police officers felt the intervention also improved communication, co-ordination and timeliness of work, although some officers cited operational difficulties with the intervention. There were positive intervention effects on police time at the scene of a suicide call (at 24 months), and improved engagement with outpatient treatment. Areas focusing on police with mental health training were more likely (than community service officers or mobile crisis teams) to transfer people to mental health services. Community service officers were more effective at resolving a crisis at the scene; arrests were highest in this context |

|

Service users: not clearly reported Service providers: police/special weapons and tactics officers, members of MHIT Other agencies reported to be involved – health participants, non-government organisations Regions: Australia (NSW) and the USA |

Police officers receiving training in mental health CIT MHIT Comparator: none (or pre-intervention data), police officers not in receipt of training Number of studies: six (two descriptive and four described as experimental) |

Level of force (including during Mental Health Act 19832 events), referral/transport to mental health services, arrests, inpatient referrals, time (including ‘dead time’ at Mental Health Act 19832 events) | No differences were found in the level of force used by police officers, or in cases resolved at the scene, following mental health training. However, compared with no training, training seemed to result in higher levels of verbal engagement and negotiation, and in more referrals/transport for treatment. Lower arrest rates and reduced referrals to intensive psychiatric services were reported. MHIT did not show significant differences in the use of force or in the quality of the relationships between police officers receiving training and health-care staff. Trained police officers spent less time dealing with Mental Health Act 19832 events and had less dead time before handing over to health professionals | |

| Taheri40 |

Service users: broadly defined, including ‘mentally ill people’, ‘diagnosis of major mental illness’; people suffering from acute mental breakdown Service providers: police officers (when reported, were male and white) Regions: US studies (three in the mid-west, four in the south-east) and Australia (one study in NSW) |

CIT (with a specific focus on the Memphis model) compared with matched-control groups, or comparisons of CIT-trained officers with non-matched samples of non-CIT-trained officers Number of studies: eight (quasi-experimental) |

Arrest outcome (official report, arrest rate, officer self-report) Use of force outcome (use of force unspecified, official report, use of force rate, officer self-report) Officer injury outcome (police injuries not specified, official incident report) |

Findings of the review and meta-analysis (of seven studies) show null effects of CITs on arrests of people with mental ill health (d = 0.180, p = 0.495) and on police officer safety (d = –0.301, p = 0.191) Note: findings on officer injuries were reported in only two studies, but there were not enough data to conduct a meta-analysis. Therefore, findings for this outcome are not reported |

| Scoping review of models of interagency collaboration | ||||

| Parker et al.14 |

Service users: adults, children and young people, mixed (adults and children) Service providers: the scoping review included the following agency collaborators relevant to PRMHT interventions – addiction services, ambulance, community organisations, emergency services, mental health clinicians, mental health services, police, schools/colleges, nurses, social workers/social services, children and family services, hospitals (acute general), housing services, welfare services Regions: not reported |

Pre-arrest diversion: police officers with mental health training liaising with mental health services (e.g. CIT) Comparators: not reported Number of studies: 43 |

Organisational/service-level outcomes Views and experiences of agency staff (e.g. police officers) Views and experiences of people in the community (e.g. service users, families and carers) Service user mental health outcomes (e.g. improvement in mood) Cost-effectiveness or wider economic costs |

Results and synthesis of the included studies were not reported (scoping review) |

|

Co-response: shared protocol between police and MHPs (e.g. street triage) Comparators: not reported Number of studies: 36 |

Organisational/service-level outcomes Views and experiences of agency staff (e.g. police officers) Views and experiences of people in the community (e.g. service users, families and carers) Service user mental health outcomes (e.g. improvement in mood) Cost-effectiveness or wider economic costs |

Results and synthesis of the included studies were not reported (scoping review) | ||

|

Co-location: MHPs employed by police departments Comparators: not reported Number of studies: five |

Organisational/service-level outcomes Views and experiences of agency staff (e.g. police officers) Views and experiences of people in the community (e.g. service users, families and carers) |

Results and synthesis of the included studies were not reported (scoping review) | ||

|

Consultation model: police access to advice (e.g. by telephone) from MHPs Comparators: not reported Number of studies: three |

Organisational/service-level outcomes | Results and synthesis of the included studies were not reported (scoping review) | ||

|

Service integration models: co-ordinated, multiagency integrated service networks Comparators: not reported Number of studies: three |

Organisational/service-level outcomes | Results and synthesis of the included studies were not reported (scoping review) | ||

| Systematic review of training interventions | ||||

| Booth et al.39 |

Training providers: not reported Training recipients: police officers Region: USA |

CITs Comparator: none specified Number of studies: one systematic review of 12 studies |

Not reported (review of systematic review) |

CIT may be effective in connecting (via police officers) people with mental ill health with appropriate psychiatric services in the USA, but this was based on limited and poor-quality primary research CIT may also have a positive effect on officers’ attitudes, beliefs and knowledge relating to interacting with people with mental ill health, although again this was based on limited and poor-quality primary studies On a systems level, CIT – in comparison with other pre- and post-diversion programmes – may be associated with a lower arrest rate and lower associated criminal justice costs |

|

Training providers: video only, online or by trainers Training recipients: police officers, student teachers, teachers and public health professionals Region: the USA, Canada and the UK (Scotland) |

Education (including web-based/online/video) and classroom-based delivery Comparators: waiting list, alternative training Number of studies: four RCTs |

Questionnaires to measure confidence and knowledge to recognise and identify attitudes towards people with autism spectrum disorder Various survey instruments to measure satisfaction with training, changes in attitudes, knowledge, skills, behaviour and confidence in teachers and health professionals Change in practice measured by the percentage of pupils reported by teachers as being depressed (lists of class cohort). Unpiloted attitudes questionnaire |

Various successes were reported following training for police offers about autism, including improved knowledge, confidence in identifying people with autism spectrum disorder and engaging with them. Training in autism delivered by podcast was significantly more effective in changing knowledge than written communication. Following an intervention to help prevent eating disorders, statistically significant improvements were reported in the knowledge of teachers in relation to restrictive dieting and peer influence. Self-efficacy to combat weight bias was improved for public health professionals. Most participants also said the intervention would encourage improvement in school environment and curriculum delivery. In another study, an education intervention to target adolescent depression resulted in increased confidence, but did not improve ability to recognise pupils suffering from depression | |

|

Training providers: mental health liaison police officers, police trainers responsible for teaching S136 procedures, MHPs or police trainers Training recipients: police officers Region: UK (England) |

Awareness training in mental health Comparator: no comparator Number of studies: two non-comparative |

Feedback form to measure the quality of presentation/content Survey measuring understanding, skills and awareness |

High satisfaction with training, better understanding of mental health services and increased awareness of the role and pressures faced by police were reported, together with an increased ability to deal with people with mental ill health | |

|

Training providers: unclear Training recipients: police officer trainees Region: UK (Northern Ireland) |

Awareness training on intellectual disabilities Comparators: no training Number of studies: one non-RCT |

‘Attitudes towards Mental Retardation and Eugenics’ validated questionnaire | A statistically significant improvement in attitudes was reported compared with control | |

|

Training providers: mental health lecturers, service users, carers, social workers, voluntary sector staff Training recipients: police officers Region: Sweden, the UK (England) and the USA |

Anti-stigma courses Comparator: alternative training or no training, or no comparator Number of studies: three (two non-RCTs, one non-comparative study) |

CAMI and WPA (2000) questionnaires, Modified Attribution Questionnaire and other validated scales measuring attitudes and behaviour towards mental ill health | Team-based approaches using mixed teaching methods showed variable success. Improved attitudes, mental health literacy and knowledge, and an increased willingness to interact with people with mental ill health after the intervention were seen in one study. In another study, a positive impact on police work was reported because of improved understanding and communication, but no effect was noted for changes in practice. In another study there were no reported differences in changed attitudes between anti-stigma videos of personal experience and information giving | |

|

Training providers: training designers were providers Training recipients: front-line police officers including constables, senior constables and sergeants Region: Australia |

MHIT Comparator: no training Number of studies: one prospective non-RCT |

Surveys (number of items and validation not reported) to measure change in practice, outcomes for people the trainees come into contact with, satisfaction with training and change in skills/behaviour | No substantial changes were observed in practice or relationship quality between police and other stakeholders. No significant differences were reported between MHIT-trained and non-MHIT-trained officers in relation to skills (except that trained officers reported less time spent at Mental Health Act 19832 events) | |

|

Training providers: PhD-level psychologists and a social worker with experience in mental health Training recipients: child welfare caseworkers Region: USA |

Caseworker training and consultation model Comparators: waiting list Number of studies: one RCT |

Questionnaire to measure change in practice | Increased awareness of evidence-based practice was reported, but no significant changes in practice or skills were noted following a child welfare caseworker training and consultation model | |

|

Training providers: trainers from the Department of Education & Children’s Services and Child & Adolescent Mental Health Service, behavioural health clinicians, experience in mental health work (health-care staff or volunteers) Training recipients: teachers, university resident advisors, public sector staff (social workers, human resource managers and employment managers) Region: Australia, the USA and Sweden |

MHFA or modified MHFA Comparators: usual practice Number of studies: three RCTs |

Strengths and Difficulties questionnaire to measure change in outcomes for people the trainees came into contact with, vignette-based knowledge test to measure changes in attitude towards mental health, questionnaires to measure change in confidence, knowledge and skills/behaviour, various other validated/non-validated questions and scales to measure change in practice, outcomes, satisfaction, attitudes, knowledge and behaviour | Team-based MHFA was associated with increased confidence and knowledge compared with control. Other benefits included readiness of public sector staff to provide help to people in a mental health crisis; students of trained teachers more frequently reported receiving information on mental health difficulties than control recipients. Effects on change in attitude were mixed. Training for resident advisors resulted in no change in practice or in the take-up of mental health services by students under their care | |

|

Training providers: online Training recipients: university resident advisors Region: USA |

Peer Hero Training Comparators: usual practice Number of studies: one RCT |

Survey to measure change in practice, referral efficacy (five-point Likert scale) to measure change in confidence | Resident advisors involved in Peer Hero Training were more likely to attend first-aid encounters with students than those receiving training as usual, they also reported improved confidence and skills | |

|

Training providers: unclear Training recipients: community practitioners (clinicians) Region: USA |

AF-CBT Comparators: usual practice Number of studies: one RCT |

35-item AF-CBT implementation measure to measure changes in practice and in skills/behaviour; 13-item training evaluation developed by the National Child Trauma Stress Network to measure satisfaction with training; 25-item CBT Knowledge questionnaire | Short-term (6 months) significant differences were noted between the intervention and control group for greater increases in teaching process, knowledge about CBT, skills (general psychological, specific skills to deal with abuse history). A high level of satisfaction with training was reported. However, these differences were no longer significant at 18 months post training | |

|

Training providers: ‘well-trained’ group leaders Training recipients: teachers and parents Region: Sweden |

Parental training programme adapted for teachers Comparators: waiting list Number of studies: one RCT |

Change in outcomes for people the trainees came into contact with was measured by attention deficit hyperactivity disorder DSM-IV scales, and the Strengths and Difficulties questionnaire | Team-based training for teachers and parents resulted in a significant reduction in parent-rated attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms and problematic behaviours at 3 months | |

The authors of the reviews reported on variations of PRMHT interventions in primary studies of various designs. It is, therefore, not possible to group the studies by model of PRMHT or outcome; the findings for each review are reported separately below.

Kane et al. (2017)

The most recently published systematic review, by Kane et al. ,11,12 included studies that reported on-street triage and CIT, plus one study that compared three different approaches with police involvement.

As a result of street triage co-response interventions, a quicker and more appropriate response by the teams was reported overall. Reductions were reported in single studies for formal detentions, an increased use of HBPOS and a reduction in time spent on-scene by the team.

Kane et al. 11,12 also reported findings for comparisons between CIT-trained officers and non-trained officers. Trained officers were more likely than non-trained officers to direct people with mental ill health to mental health services, but this depended on local services available. Trained officers also demonstrated different approaches to people with mental ill health. Although it should be noted that police officers self-selected for training, that might indicate an existing difference between trained and non-trained officers, which could have an impact on approaches and attitudes.

One study in Kane et al. 11,12 reported on a comparison of three different models operating in the USA, including civilian police employees with additional training to assist police officers in mental health emergencies, a CIT unit and a mobile crisis unit. Authors reported that ‘the dispositions of cases handled by the specialised response personnel were found to be related to the programme type’12 (no further details reported), although all three models reported an average rate of arrests of 7%. Factors reported to be related to success were the existence of a psychiatric triage or drop-off centre to which the police could transport individuals in crisis, and community partnerships in which police response is part of a wider response involving relevant agencies.

Taheri (2016)

Taheri40 reported that there were no statistically significant effects of CIT interventions, between CIT-trained and non-trained officers, on official or officer-reported accounts of arrests of people with mental ill health. However, the studies were heterogeneous and reported conflicting results. 40

Paton et al. (2016)

The review by Paton et al. 15 evaluated on-scene co-response or telephone triage by health or social care professionals in collaboration with police officers (some of whom were in receipt of CIT training). 15 These included various collaborative partnerships. One UK study of a street triage intervention, in which officers received telephone triage, was associated with a reduction in S136 detentions and a number of calls were successfully converted to hospital admissions. 42 There were also improvements in police time on the scene of a suicide call, and improvements in engagement with outpatient treatment by service users, although these findings were reported only in one or two studies.