Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/5005/10. The contractual start date was in December 2013. The final report began editorial review in August 2018 and was accepted for publication in May 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Carol J Peden has performed consultancy work for Merck & Co./Merck Sharp & Dohme (Kenilworth, NJ, USA) and for the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (Boston, MA, USA). Graham Martin reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and personal fees from the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd (London, UK) and is a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) National Stakeholder Advisory Group. Dave Murray reports personal fees from the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit (NELA). David Cromwell reports grants from NELA and is a member of the NELA project team, which provided data and assistance to the project. Mike PW Grocott is a NIHR Clinical Research Network Specialty Lead for Anaesthesia Perioperative Medicine and Pain; the chairperson of the National Institute of Academic Anaesthesia Board; the president of the Critical Care Medicine Section, Royal Society of Medicine; a board member of Evidence Based Perioperative Medicine (EBPOM) UK (London, UK), EBPOM USA (Bannockburn, IL, USA) and EBPOM International; and a board member of Medinspire Ltd (Bridgnorth, UK). Rupert M Pearse holds research grants, has given lectures and/or has performed consultancy work for B.Braun Medical Ltd (Sheffield, UK), GlaxoSmithKline plc (London, UK), Intersurgical Ltd (Wokingham, UK) and Edwards Lifesciences (Irvine, CA, USA). Rupert M Pearse also holds a grant for the submitted work and a NIHR Research Professorship and is a NIHR HTA General Board member.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Peden et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

More than 1.53 million adults undergo inpatient surgery in the UK NHS each year, with a 30-day mortality of 1.5%. 1 However, patients undergoing emergency abdominal surgery have a much greater risk of death. 2,3 Around 30,000 patients undergo these procedures in NHS hospitals each year, with 30-day mortality rates in excess of 10%. 2 There are widespread variations in standards of care between hospitals,2,3 including the involvement of senior surgeons and anaesthetists and postoperative admission to critical care. These variations have been associated with differences in mortality rates. 2,3

In small studies, quality improvement (QI) initiatives to implement either individual interventions or ‘bundles’ including several treatments have been associated with improved survival after emergency abdominal surgery. 4–7 In a report commissioned by the UK Department of Health and Social Care, the Royal College of Surgeons proposed more extensive improvements to quality of care for this patient group. 8 Recommendations included consultant-led decision-making, cardiac output-guided fluid therapy and early admission to critical care. However, the feasibility of implementing such an extensive acute care pathway on a national scale, and the benefits of doing so, remain uncertain. There are good examples in which discrete QI interventions have been associated with improved patient outcomes,9,10 but other studies yielded disappointing results. 11–13 This is especially true for complex interventions requiring co-ordinated change across a health-care system. 14–17 The benefits of QI initiatives are self-evident to some,18 but others question the value of these projects, citing high costs, failure to engage clinicians and a lack of scientific rigour. 19,20 Despite this, the direction in health-care policy is towards ever more widespread use of QI to drive large-scale change. 21

The launch of the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit (NELA) in December 20132 provided a unique opportunity to study a QI programme to implement a complex care pathway at a national level. We conducted a stepped-wedge cluster randomised trial, with an embedded ethnographic evaluation process and health economic analysis, to evaluate the effect of implementing this pathway on survival following emergency abdominal surgery in NHS hospitals.

Chapter 2 The EPOCH trial intervention

Parts of this report have been reproduced from Stephens et al. 22 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

The use of QI approaches to reduce variations in health-care processes and improve the standards of health-care delivery has been increasingly encouraged over the previous two decades. QI interventions can be considered complex interventions, often with numerous active ingredients intended to influence the behaviour or clinical practice of a range of different professionals and/or patient groups. 23 There is published guidance on accurately describing complex interventions such as those used in QI [e.g. the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist24 and the Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) guidelines25], but such detailed reporting has not always been the norm in the QI literature. In this chapter we describe the design, rationale and delivery plan for the Enhanced Peri-Operative Care for High-risk patients (EPOCH) trial intervention in line with this guidance. Chapters 4 and 5 describe how the intervention was delivered in reality, how it worked in practice and how this differed from the intended design.

Trial intervention

The trial intervention was a QI programme designed to improve care processes and outcomes for patients undergoing emergency laparotomy. Recruited hospitals were grouped into 15 clusters of six to eight geographically co-located hospitals. Each recruited hospital was asked to nominate three senior clinicians (consultants) to act as QI leads from key clinical areas (surgery, anaesthesia and critical care), and to confirm executive board support from each hospital. The aim of the EPOCH trial QI programme was to enable the nominated QI leads and their teams to effectively improve the care pathway for patients undergoing emergency laparotomy.

The EPOCH trial intervention operated at two main levels. At the cluster level, we developed a QI programme to train and support QI leads and their colleagues in the delivery of the hospital-level intervention. The hospital-level intervention was what was to be delivered by QI leads and their colleagues in each of the 93 trial sites. QI interventions can be seen as having a ‘hard core’, the clinical processes or practices that are the focus of improvement, and a ‘soft periphery’, the improvement methods that will enable change to occur. 26 In the EPOCH trial, the ‘hard core’ of the hospital-level intervention was a set of recommended clinical processes, organised within a care pathway for patients undergoing emergency laparotomy. The QI intervention (the ‘soft periphery’ of the hospital-level intervention) was designed to enable the QI leads and their teams to effectively implement the care pathway for patients undergoing emergency laparotomy. In this chapter we detail the development and content of these interventions.

The cluster-level intervention: the EPOCH trial quality improvement programme

We developed a QI programme to change the practice and culture of care for patients undergoing emergency abdominal surgery. QI leads from each stakeholder discipline (surgery, anaesthesia and critical care) were tasked with leading hospital-wide improvement to implement the care pathway with the support and guidance of the national EPOCH trial QI team. The key aims of the programme were to (1) reframe the high mortality rates for these patients as a ‘social problem’, requiring reorganisation of existing care processes rather than technical innovation; (2) support QI leads to engage their front-line colleagues and executive leaders in the change process; (3) train local QI leads and their colleagues in basic improvement skills based around the model for improvement;27 and (4) support teams to analyse and feed back key process measure data to their colleagues to drive change. The EPOCH trial QI team provided a 1-day activation and training meeting for each geographical cluster shortly before or during the first week of activation. The purpose of this meeting was to develop the knowledge, skills and attitudes that the QI leads required to achieve change. Nominated QI leads were informed 14 weeks before the date of activation to the QI intervention. Five weeks before activation, QI leads were sent a ‘pre-activation’ checklist, which included the requirement to review five sets of notes from recent patients to establish current performance and identify gaps in care delivery. A notes review tool was provided and each hospital presented their findings at the initial cluster meeting. A training package was designed for hospital QI leads and their colleagues, the main content of which was delivered at the initial cluster activation and training meeting, and employed a mixture of didactic, workshop and discussion sessions. Publicity resources, such as pens, posters, lanyards and mugs, were distributed to each team on the day to be shared with colleagues to raise awareness about participation in the EPOCH trial.

A virtual learning environment (VLE) housed all training resources and acted as a repository for all the tools and documents required to enact the EPOCH trial QI strategies. This was created to support QI leads who had attended the training and desired further QI resources, as well as ensuring that QI leads and other team members who could not attend the training meeting could view all the necessary presentations and resources. In particular, the site housed a tool developed to allow the creation of time series charts, using local NELA data, to allow QI leads to monitor key care processes during the improvement period. It also incorporated an interactive ‘route map’, providing evidence sheets for each of the clinical recommendations within the EPOCH trial pathway (Box 1). All hospital QI leads were automatically registered for the VLE 5 weeks prior to activation, and could request that additional colleagues and team members be registered.

-

Consultant-led decision-making.

-

CT imaging within 2 hours of decision to perform test.

-

Early goal-directed therapy for patients with severe sepsis/septic shock.

-

Analgesia within 1 hour of first medical assessment.

-

Antibiotic therapy within 1 hour of first medical assessment.

-

Correction of coagulopathy.

-

Maintain normothermia.

-

Active glucose management.

-

Documented mortality risk estimate.

-

Provided patient and relatives with oral and written information about treatment.

-

Surgery within 6 hours of decision to operate.

-

Consultant-delivered surgery and anaesthesia.

-

WHO safe surgery checklist.

-

Early antibiotic therapy (unless inappropriate).

-

Fluid therapy guided by cardiac output monitoring.

-

Low tidal volume protective ventilation.

-

Maintain normothermia.

-

Active glucose management.

-

Prescribe postoperative analgesia.

-

Prescribe postoperative nausea and vomiting prophylaxis.

-

Prescribe postoperative venous thromboembolism prophylaxis.

-

End-of-surgery risk evaluation.

-

Measure arterial blood gases and serum lactate.

-

Confirm full reversal of neuromuscular blockade.

-

Document core temperature.

-

Re-evaluate mortality risk estimate.

-

Admission to critical care within 6 hours of surgery.

-

Analgesia: early review by acute pain team.

-

Continued antibiotic therapy when indicated with microbiology review.

-

Prophylaxis for post-operative nausea and vomiting.

-

Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis.

-

Maintain normothermia.

-

Active glucose management.

-

Daily haematology and biochemistry until mortality risk is low (senior opinion).

-

Nutrition: early dietitian review with consideration of benefits of enteral feeding.

-

Chest physiotherapy review on day 1 after surgery.

-

Critical care outreach review on standard ward with use of early warning scores.

CT, computerised tomography; WHO, World Health Organization.

Once a cluster was activated, telephone and e-mail support for the intervention was available. Separate e-mail contact, including a regular newsletter, was maintained with all hospitals (both activated and those in waiting) by the trial manager. Each hospital was offered a small amount of funding (£3700) for QI leads to spend on relevant activities. Half-day follow-up meetings were added soon after commencement of the trial to offer teams formal opportunities to share successes and challenges as they progressed, supported by advice from the programme leads. All clusters were offered a follow-up meeting. There were also two national meetings to facilitate shared learning during the trial period. QI leads were eligible to attend these only if their hospital had been activated to the trial intervention.

The hospital-level interventions

Evidence-based care pathway (37 recommended processes of care)

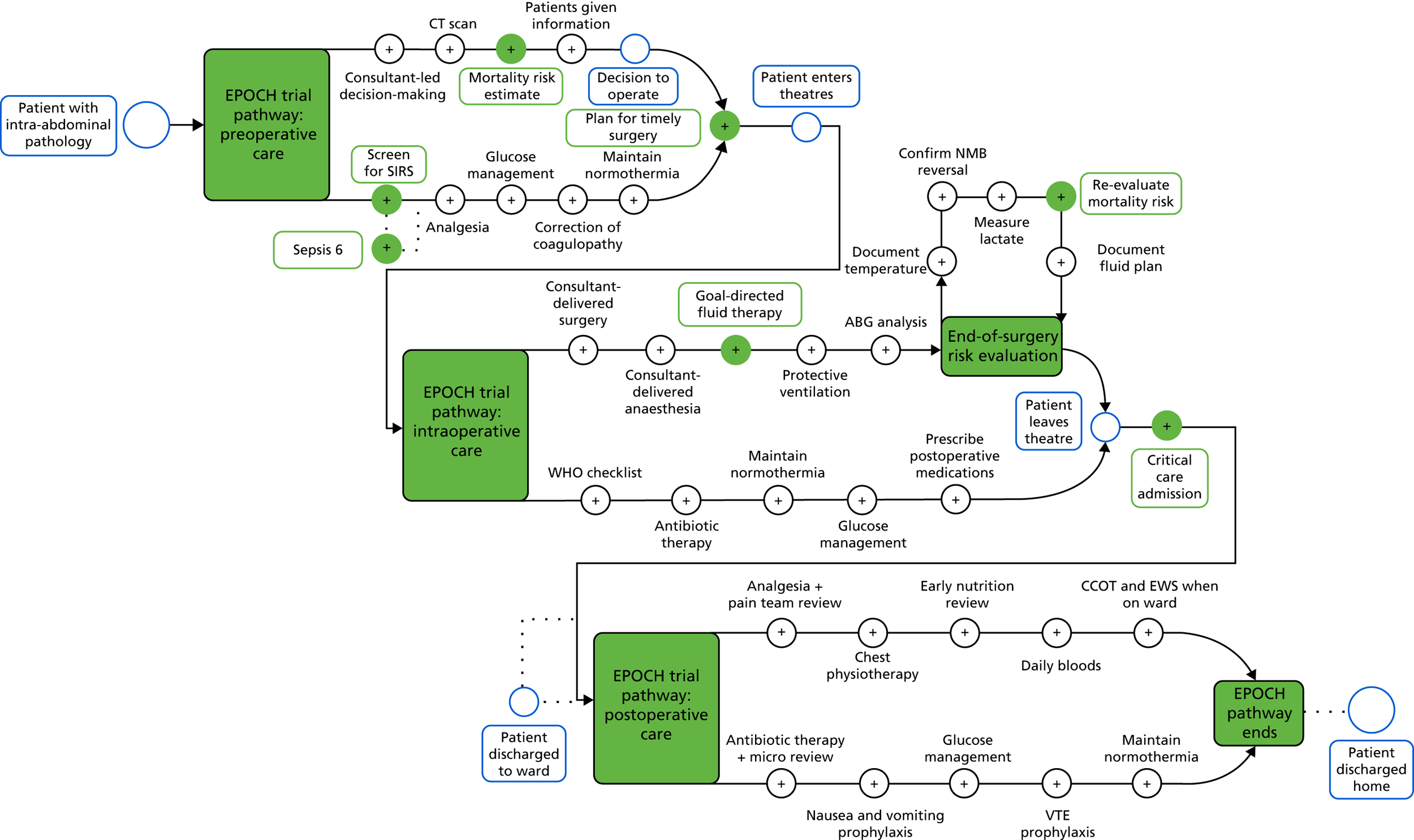

The EPOCH trial care pathway was developed through an evidence-based Delphi consensus process to update existing guidelines published by the Royal College of Surgeons. 8 The purpose of the pathway was to define the gold standard of care for this patient group. Evidence for the component interventions was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) criteria. 28 The 37 component interventions are detailed in Box 1 and a graphical display, designed for the QI programme to show how the patient may move along the care pathway, is in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The EPOCH trial care pathway. ABG, arterial blood gas; CCOT, critical care outreach team; CT, computerised tomography; EWS, early warning score; NMB, neuromuscular blockade; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; VTE, venous thromboembolism; WHO, World Health Organization. Reproduced from Stephens et al. 22 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

The quality improvement intervention, comprising six core improvement strategies

Two clinicians with QI and training expertise (TS and CJP) developed the programme theory for the QI intervention, defining ‘the how’ and ‘the why’ of the QI intervention (Box 2 and Table 1). The EPOCH trial programme theory was based on current evidence and learning from a range of other QI programmes. 29–32 Six QI strategies were developed to facilitate the translation of the programme theory into practice by local QI leads at their hospitals. These were intended as a minimum set of activities for QI leads and colleagues to undertake. The strategies were:

-

QI leads hold a stakeholder meeting after activation.

-

Each hospital forms an interprofessional improvement team.

-

QI leads analyse their own data (NELA data ± case note reviews and local audit data) and feed back to colleagues regularly.

-

QI leads and team members use time series charts (‘run charts’) to inform progress.

-

QI leads and team members segment the patient pathway to assist implementation planning.

-

QI leads and team members use plan–do–study–act (PDSA) cycles to support process change.

relevant data are reviewed and fed back to teams regularly, and

key professionals come together to form an improvement team, and

QI leads and colleagues learn basic QI approaches, and

relevant stakeholders are made aware of the project and improvement goals . . .

then . . .a shared view of performance and improvement gaps can be created, and

professionals can work as a team to define and achieve local improvement goals, and

basic QI approaches can be employed to achieve the improvement goals, and

stakeholders will be more engaged in the need for change and aware of how improvement will occur . . .

so that . . .improvements in care delivery in line with the recommended care pathway can be achieved . . .

so that . . .mortality after emergency laparotomy can be reduced.

Reproduced from Stephens et al. 22 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The box includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original table.

Table 1 details the relationship between the EPOCH trial programme theory, the QI resources available and the QI strategies proposed.

| Desired outcome | QI strategy | QI programme activity and resources | Evidence for inclusion in programme theory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation for change created among stakeholders and improvement goals clearly understood | QI leads hold a stakeholder meeting after activation (QI strategy 1) |

|

|

| Interprofessional collaboration fostered | Each hospital to form an interprofessional improvement team (QI strategy 2) |

|

|

| Shared view of current performance created (‘situational awareness’) | QI leads analyse their own data (NELA data ± case note reviews and local audit data) and feed this back to colleagues regularly (QI strategy 3) |

|

|

| Front-line teams develop and use basic QI skills to effect change | QI leads and other team members:

|

|

|

Discussion

We designed a complex, evidence-based intervention that we hypothesised would improve the care pathway, and ultimately reduce mortality, for this patient group. Like many complex interventions, it was designed to operate on multiple levels, was to be adapted to fit local contexts, required behaviour change by a range of different actors and needed varying levels of skill to achieve this, in both the recipient and the delivery teams. 23 The intervention drew on current evidence about ‘what works’ in QI and was also designed to fit within the prevailing UK NHS paradigm of clinician-led improvement. To that end, the cluster-level intervention was relatively parsimonious, requiring minimal contact time and providing all resources online and by remote e-mail/telephone support. The hard core of the hospital-level intervention, the care pathway of recommendations, was more extensive and was based largely on current Department of Health and Social Care and Royal College of Surgeons guidance. 8 The soft periphery of the hospital-level intervention, the QI intervention, was conceived with the non-QI expert clinician in mind and designed to be as easy as possible to use. As such, we viewed the EPOCH trial programme and interventions, overall, as enabling clinicians to implement guidance that was in line with what already existed, but that had not been put into practice nationally. Several observers have argued that this pathway is not ‘evidence based’. We believe this relates to a misunderstanding of what evidence-based medicine is. The EPOCH trial pathway was developed through a Delphi consensus process following a systematic literature review, with evidence ranging from expert opinion to high-quality randomised trials. Expert opinion has always played a role in evidence-based guidelines. Some interventions (e.g. consultant-delivered care) are based on weak evidence but are, nevertheless, evidence based and strongly recommended. 44 Strengths included the clinician-led programme and relevance of the project with regards to patient care, both of which have been shown to enhance buy-in among clinical teams. 31 The multimodal training resources (face to face, online and by telephone and e-mail) also meant that the training to support use of the intervention was highly accessible. Both the clinical and QI interventions were also based on best-available evidence and the rationale underpinning the QI intervention, the programme theory, focused and guided the intervention design. However, although the trial interventions drew on learning and evidence from similar, smaller-scale work, the primary limitation was the lack of pilot trials of this particular set of interventions, in this particular context, to test both the efficacy of the pathway, under stricter trial conditions, and the feasibility of using the recommended QI intervention to implement the pathway in a more pragmatic pilot trial setting.

Chapter 3 Stepped-wedge cluster randomised trial

Introduction

Emergency abdominal surgery is associated with poor postoperative outcomes. Around 30,000 patients undergo this type of surgery each year in the UK NHS, with 30-day mortality rates in excess of 10% and wide variation in standards of care between hospitals. Several groups have studied the effect of QI initiatives to implement individual interventions or ‘care bundles’ of several treatments, and so improve care for these patients. Overall, the findings of these small studies suggest survival benefit, but most utilised uncontrolled cohort designs, which are associated with a high risk of bias. The feasibility and benefit of a national QI programme to implement a more extensive acute care pathway for this patient group remain uncertain. We conducted a stepped-wedge cluster randomised trial, with an embedded ethnographic evaluation, to evaluate the effect of implementing this pathway on survival following emergency abdominal surgery in NHS hospitals.

Methods

Trial design and participants

The EPOCH trial was a multicentre, stepped-wedge cluster randomised trial of a QI intervention to promote the implementation of a perioperative care pathway for patients undergoing emergency abdominal surgery. The trial protocol was published prospectively by The Lancet (protocol 13PRT/7655) and on the trial website (URL: www.epochtrial.org/protocol; accessed 18 July 2019). The trial was prospectively registered at isrctn.com on 27 February 2014, but a registration number was not issued until 7 March 2014 (ISRCTN80682973).

NHS hospitals delivering an emergency general surgical service were eligible for inclusion, provided they undertook a significant volume of emergency abdominal surgery cases and contributed data to the NELA. Hospitals were required to nominate specialty leads from surgery, anaesthesia and critical care, and to secure support from their NHS trust board or equivalent. Hospitals that were already implementing a care pathway to improve treatment for this patient group were excluded. Patients were eligible for inclusion in the data analysis if they were aged ≥ 40 years and undergoing emergency open abdominal surgery in a participating hospital during the 85-week trial period (from 3 March 2014 to 19 October 2015). Patients were excluded from the analysis if they were undergoing a simple appendicectomy, surgery related to organ transplant, gynaecological surgery, laparotomy for traumatic injury, treatment of complications of recent elective surgery or if they had previously been included in the EPOCH trial.

Data collection

Trial data were collected through the NELA database (URL: www.nela.org.uk; accessed 6 September 2019) and then linked using unique patient identifiers to Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) and Office for National Statistics (ONS) in England and Wales, and the Information Services Division of NHS Scotland, to provide data describing mortality and hospital readmissions. The trial was approved by the East Midlands (Nottingham 1) Research Ethics Committee (reference number 13/EM/0415). Data were analysed without individual patient consent in accordance with section 251 of the National Health Services Act 2006. 45

Randomisation and masking

We planned to include 15 geographical clusters of five to seven hospitals. The QI intervention lasted 85 weeks, with one geographical cluster commencing the intervention each 5-week step from the 2nd to the 16th time period. Clusters were randomly assigned to 1 of 15 start dates for the QI intervention by an independent statistician, using a computer-generated random allocation sequence. As each geographical area started in the usual care group and ended in the QI group, there were 17 time periods in total. Local investigators in each geographical area were notified 12 weeks in advance of activation of the QI programme at their hospital. As they were engaged in delivery of the intervention, it was not possible to mask hospital staff. Patients were masked to trial group allocation. The organisation of hospitals into geographical clusters minimised any contamination between sites due to natural workforce movements between hospitals.

Trial intervention

The EPOCH trial care pathway and QI methodology are described in Chapter 2.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was all-cause mortality within 90 days following surgery. Secondary outcomes were all-cause mortality within 180 days following surgery, duration of hospital stay after surgery and hospital readmission within 180 days of surgery. We selected 10 predefined process measures (key components of the care pathway) for inclusion in the main report: (1) consultant-led decision to operate; (2) consultant review of patient before surgery; (3) preoperative documentation of risk; (4) time from decision to operate to entry into operating theatre; (5) patient entered operating theatre within time frame specified by their urgency (< 2 hours, 2–6 hours, 6–18 hours, or > 18 hours); (6) consultant surgeon present in operating theatre; (7) consultant anaesthetist present in operating theatre; (8) cardiac output-guided fluid therapy used during surgery; (9) serum lactate measured at end of surgery; and (10) critical care admission immediately after surgery.

Statistical analysis

A stepped-wedge design was chosen to improve statistical power by facilitating within-cluster comparison. Sample size calculations were based on the Hussey and Hughes approach,46 for an analysis with fixed time effects and random cluster effects, modified to exclude data collected during the 5-week period in which the intervention commenced in individual clusters. Using HES data, we estimated that 27,540 eligible patients would be registered across 90 NHS hospitals over 85 weeks, with a 90-day mortality rate of 25% in the usual care group and a between-hospital coefficient of variation of 0.15. Assuming a constant case load (18 patients/5 weeks/hospital), independent hospital effects and a 5% significance level, the trial would have 92% power to detect a reduction in 90-day mortality from 25% to 22%. If the assumption of independent hospital effects was not met, and the 15 geographical clusters functioned effectively as 15 large hospitals, power would be reduced to 83%.

All analyses were conducted according to intention-to-treat principles. All eligible patients with available outcome data were included in the analysis and analysed according to the randomisation schedule. 47 Patients who presented during the 5-week time period immediately after QI activation were excluded from the analysis. Hospitals that initially agreed to participate but subsequently withdrew prior to the trial start date were excluded; however, hospitals that withdrew after the trial start date, or did not implement the intervention, were included in the analysis. Hospitals that merged with other hospitals during the trial period were included in the analysis up to the point of the merger.

We were unable to procure data describing survival status after hospital discharge for patients in Wales. We therefore changed our primary analysis from binary to a time-to-event approach allowing inclusion of mortality events censored at hospital discharge. This affected 909 patients in Wales, 179 (20%) of whom died in hospital and 730 (80%) of whom were censored at hospital discharge. All analyses included time period as a fixed effect using indicator variables, and were adjusted for age, sex and indication for surgery using fixed factors. 48 Age was included as a continuous covariate, assuming a linear association with outcome. 49 Missing baseline data for indication for surgery were handled using a missing indicator approach. 50 All-cause mortality within 90 days of surgery was analysed using a mixed-effects parametric survival model with a Weibull survival distribution. The model included random intercepts for geographical area, hospital and hospital period (i.e. the time period in hospital). This allowed additional correlation between patients in the same hospital and the same period, compared with patients in other periods, as is recommended. 51,52 All-cause mortality within 180 days was analysed using the same approach. Duration of hospital stay was analysed using competing risk time-to-event models, with mortality before the outcome event acting as the competing risk and robust standard errors to account for clustering by geographical area. The hazard ratio (HR) from this analysis measures the relative probability of hospital discharge between treatment arms, with a HR of < 1 indicating a lower probability of discharge in the QI group (and therefore longer hospital stay). Hospital readmission within 180 days was analysed using the same approach (with a HR of < 1 indicating a lower probability of readmission).

We performed two secondary analyses for the primary outcome. The first evaluated the effect of the intervention over time. This analysis included patients who presented to hospital during the 5-week period immediately after implementation of the intervention. We analysed patients according to the following four groups: (1) no QI implemented (usual care group); (2) QI implemented for < 5 weeks; (3) QI implemented for between 5 and 10 weeks; and (4) QI implemented for > 10 weeks. Our second analysis evaluated the intervention in other patient populations that may have been affected by the intervention. This included patients who either underwent laparoscopic surgery or were aged 18–40 years, and who met all other eligibility criteria. Owing to the small number of patients in this group, we summarised results descriptively rather than undertaking a formal statistical analysis.

Patient and public involvement

We actively involved patient and public representatives throughout this project. Our co-applicants on the original funding application included two patient representatives, one of whom has lived experience of emergency abdominal surgery. They have supported us in the oversight and conduct of the trial, advising on numerous issues from the preparation of patient-facing materials to advising on the patient perspective of registry data use without individual patient consent. Both are named authors of this report and have specifically helped in drafting the Plain English summary.

Results

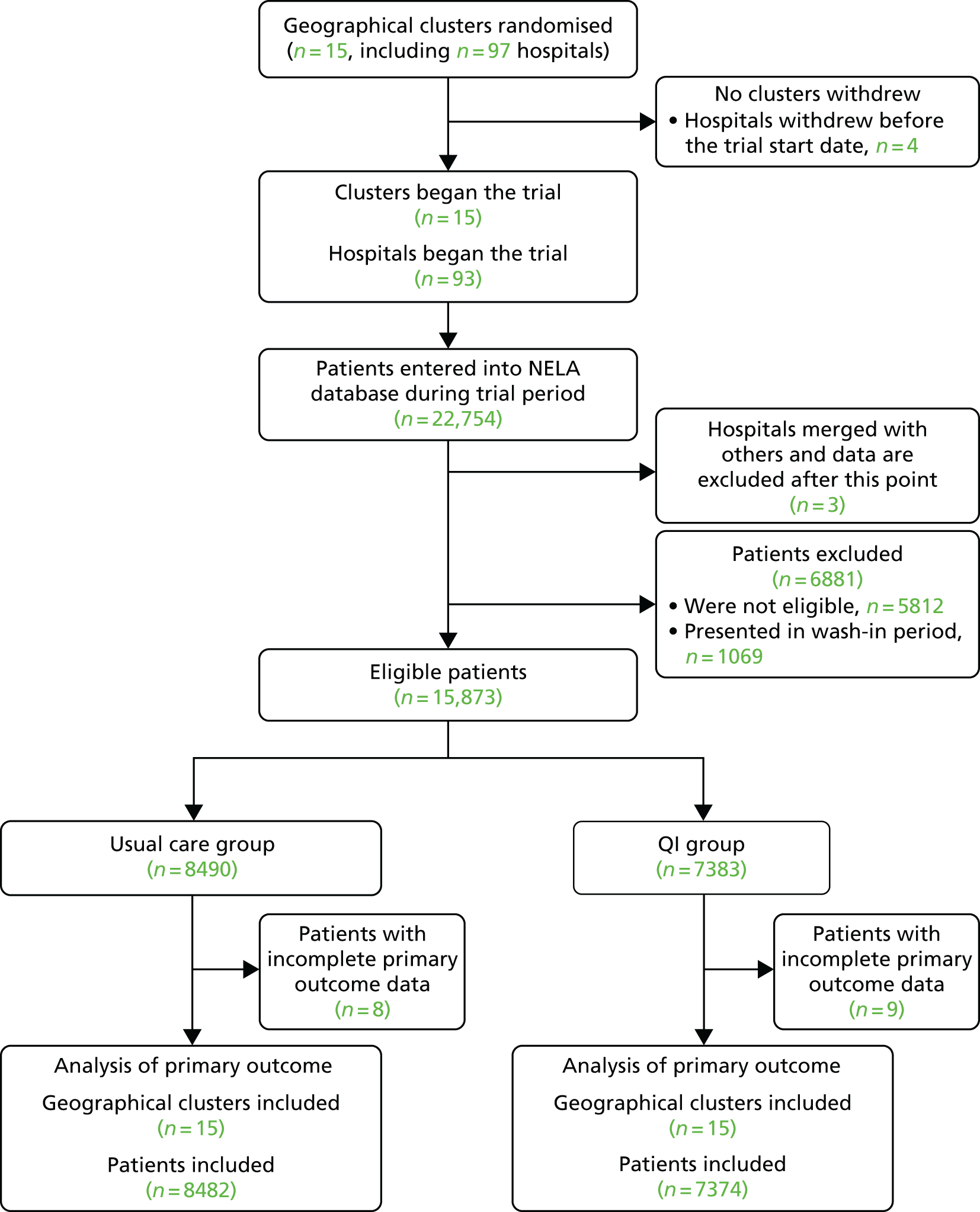

Fifteen geographic areas underwent randomisation, including 97 NHS hospitals. Four hospitals withdrew before the start of the trial, leaving 93 hospitals participating. Between 3 March 2014 and 19 October 2015, 15,873 eligible patients underwent surgery in participating hospitals, with data recorded in the NELA database (usual care, 8490 patients; QI, 7383 patients) (Figure 2 and Table 2). Baseline characteristics were similar between groups (Table 3).

FIGURE 2.

Inclusion of hospitals and patients in the trial.

| Geographical area (cluster) | Period | Total | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | ||

| 1 | 53 | – | 39 | 54 | 41 | 46 | 39 | 36 | 44 | 35 | 41 | 28 | 37 | 43 | 39 | 31 | 37 | 643 |

| 2 | 62 | 52 | – | 57 | 32 | 45 | 52 | 54 | 34 | 58 | 43 | 37 | 59 | 58 | 50 | 56 | 39 | 788 |

| 3 | 89 | 92 | 100 | – | 93 | 98 | 95 | 88 | 91 | 105 | 84 | 83 | 107 | 79 | 69 | 62 | 60 | 1395 |

| 4 | 60 | 49 | 52 | 67 | – | 55 | 68 | 55 | 75 | 67 | 78 | 64 | 82 | 72 | 74 | 71 | 55 | 1044 |

| 5 | 23 | 26 | 31 | 30 | 34 | – | 24 | 27 | 20 | 46 | 30 | 33 | 34 | 48 | 25 | 36 | 34 | 501 |

| 6 | 59 | 59 | 64 | 52 | 61 | 69 | – | 53 | 57 | 52 | 65 | 52 | 33 | 59 | 58 | 54 | 62 | 909 |

| 7 | 74 | 62 | 76 | 79 | 55 | 64 | 79 | – | 68 | 79 | 63 | 84 | 73 | 71 | 78 | 68 | 83 | 1156 |

| 8 | 64 | 56 | 66 | 70 | 50 | 63 | 59 | 60 | – | 73 | 44 | 58 | 55 | 65 | 55 | 55 | 54 | 947 |

| 9 | 104 | 91 | 95 | 88 | 69 | 72 | 98 | 77 | 86 | – | 86 | 76 | 83 | 72 | 70 | 58 | 69 | 1294 |

| 10 | 65 | 64 | 71 | 90 | 68 | 69 | 94 | 83 | 79 | 80 | – | 68 | 85 | 76 | 75 | 61 | 80 | 1208 |

| 11 | 82 | 79 | 91 | 111 | 90 | 117 | 77 | 94 | 91 | 102 | 117 | – | 96 | 117 | 103 | 91 | 85 | 1543 |

| 12 | 85 | 79 | 82 | 80 | 64 | 69 | 58 | 75 | 66 | 60 | 70 | 73 | – | 82 | 90 | 89 | 89 | 1211 |

| 13 | 55 | 60 | 59 | 61 | 57 | 61 | 76 | 54 | 70 | 56 | 56 | 69 | 52 | – | 60 | 67 | 55 | 968 |

| 14 | 55 | 60 | 54 | 57 | 56 | 65 | 50 | 43 | 45 | 69 | 62 | 68 | 66 | 55 | – | 43 | 46 | 894 |

| 15 | 95 | 95 | 74 | 98 | 79 | 69 | 72 | 68 | 65 | 87 | 91 | 85 | 86 | 118 | 101 | – | 89 | 1372 |

| Total | 1025 | 924 | 954 | 994 | 849 | 962 | 941 | 867 | 891 | 969 | 930 | 878 | 948 | 1015 | 947 | 842 | 937 | 15,873 |

| Characteristic | Number of patients with missing data | Summary measure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 8490) | QI (N = 7383) | Usual care | QI | |

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Female, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4550 (54) | 3938 (53) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 68 (13) | 68 (13) |

| Indication for surgery, n (%) | 13 (< 1) | 5 (< 1) | ||

| Peritonitis | 352 (4) | 251 (3) | ||

| Perforation | 765 (9) | 693 (9) | ||

| Intestinal obstruction | 3840 (45) | 3379 (46) | ||

| Haemorrhage | 213 (3) | 149 (2) | ||

| Ischaemia | 366 (4) | 332 (5) | ||

| Abdominal infection | 296 (3) | 239 (3) | ||

| Other | 523 (6) | 472 (6) | ||

| Multiple indications | 2122 (25) | 1863 (25) | ||

| Preoperative characteristics | ||||

| Estimated risk of death, n (%) | 158 (2) | 22 (< 1) | ||

| Not documented | 3762 (45) | 2468 (34) | ||

| Low (< 5%) | 1354 (16) | 1646 (22) | ||

| Medium (5–10%) | 1019 (12) | 1102 (15) | ||

| High (> 10%) | 2197 (26) | 2145 (29) | ||

| ASA grade, n (%) | 156 (2) | 23 (< 1) | ||

| I (no systemic disease) | 615 (7) | 533 (7) | ||

| II (mild systemic disease) | 2815 (34) | 2461 (33) | ||

| III (severe systemic disease) | 3112 (37) | 2745 (37) | ||

| IV (life-threatening systemic disease) | 1605 (19) | 1465 (20) | ||

| V (moribund patient) | 187 (2) | 156 (2) | ||

| P-POSSUM score, median (IQR) | 152 (2) | 13 (< 1) | 7.6 (2.9–22.7) | 7.4 (2.8–22.9) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | 255 (3) | 147 (2) | 128 (24) | 128 (25) |

| Glasgow Coma Score, mean (SD) | 221 (3) | 72 (1) | 14.8 (1.4) | 14.7 (1.5) |

| Blood lactate (mmol/l), median (IQR) | 4103 (48) | 2870 (39) | 1.6 (1.1–2.8) | 1.5 (1.0–2.6) |

Process measures

Ninety-one out of 93 (98%) hospitals were represented at the initial QI meeting for the relevant geographical cluster and 53 out of 93 (57%) hospitals were represented at the follow-up QI meeting. This representation included a named hospital QI lead for 89 out of 93 (96%) hospitals at the first meeting and 47 out of 93 (51%) hospitals at the second meeting. Most meetings (13/15) occurred within 2 weeks of the activation date. Patient-level process measures are described in Table 4. In accordance with our analysis plan, we did not test these for statistical significance.

| Process measure | Number of patients with missing data | Summary measure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 8490), n (%) | QI (N = 7383), n (%) | Usual care, n (%) or median (IQR) | QI, n (%) or median (IQR) | |

| Consultant decision to operate | 184 (2) | 72 (1) | 7472 (90) | 6589 (90) |

| Consultant reviewed patient at time of decision | 448 (6) | 334 (5) | 5961 (85) | 5271 (84) |

| Preoperative documentation of risk | 158 (2) | 22 (< 1) | 4570 (55) | 4893 (66) |

| Patient entered operating theatre within specified urgency time frame | 1012 (12) | 430 (6) | 5636 (75) | 5515 (79) |

| Consultant surgeon present in operating theatre | 155 (2) | 17 (< 1) | 7117 (85) | 6472 (88) |

| Consultant anaesthetist present in operating theatre | 160 (2) | 14 (< 1) | 6313 (76) | 5832 (79) |

| Goal-directed fluid therapy used during surgery | 180 (2) | 24 (< 1) | 3942 (47) | 4329 (59) |

| Serum lactate measured at end of surgery | 171 (2) | 24 (< 1) | 4474 (54) | 4431 (60) |

| Time (hours) from decision to operate to entry into operating theatre | 630 (7) | 417 (6) | 5.0 (2.1–16.8) | 4.3 (2.0–15.3) |

| Critical care admission immediately after surgerya | 163 (2) | 22 (< 1) | 5395 (65) | 5050 (69) |

Clinical outcomes

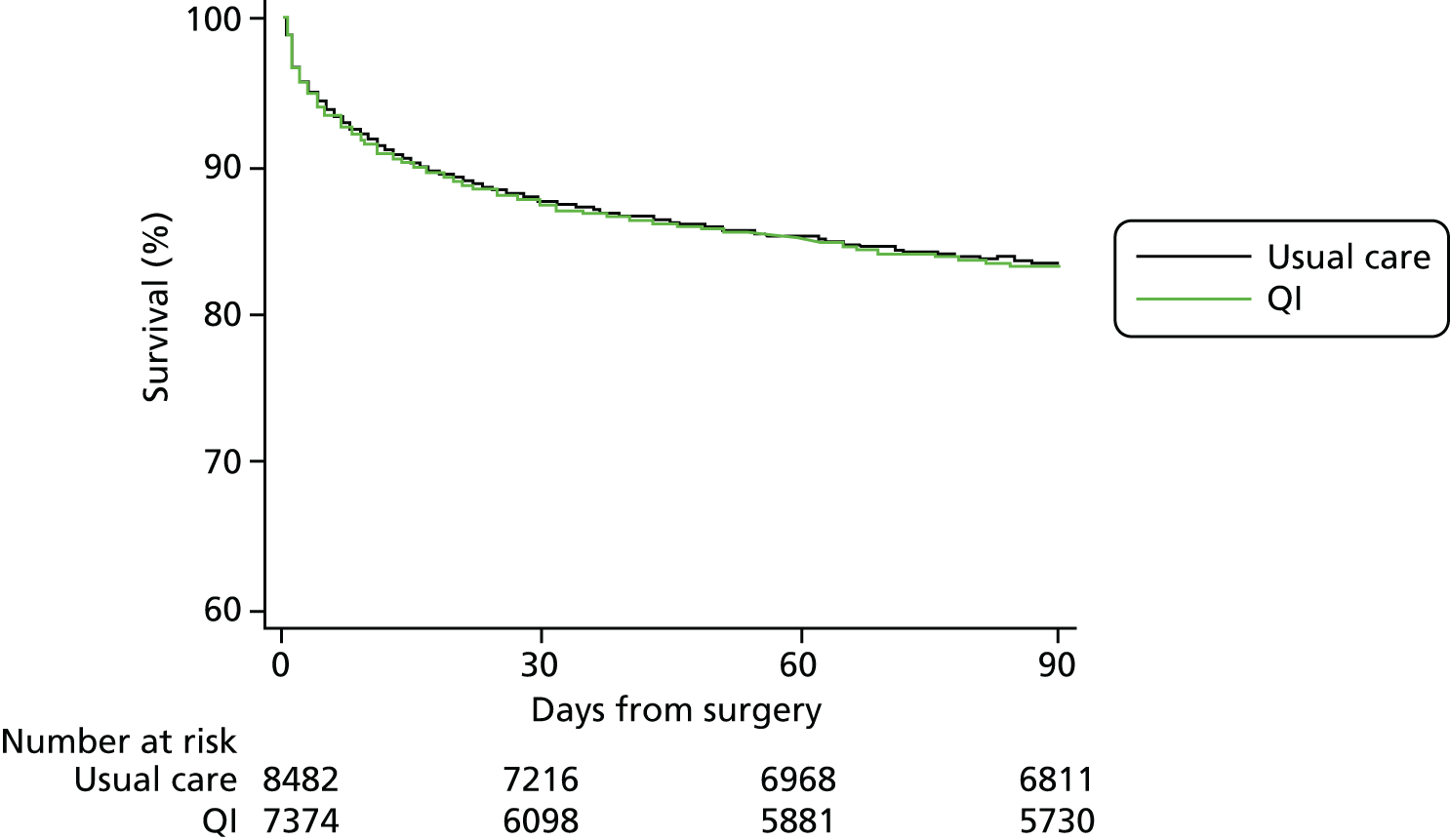

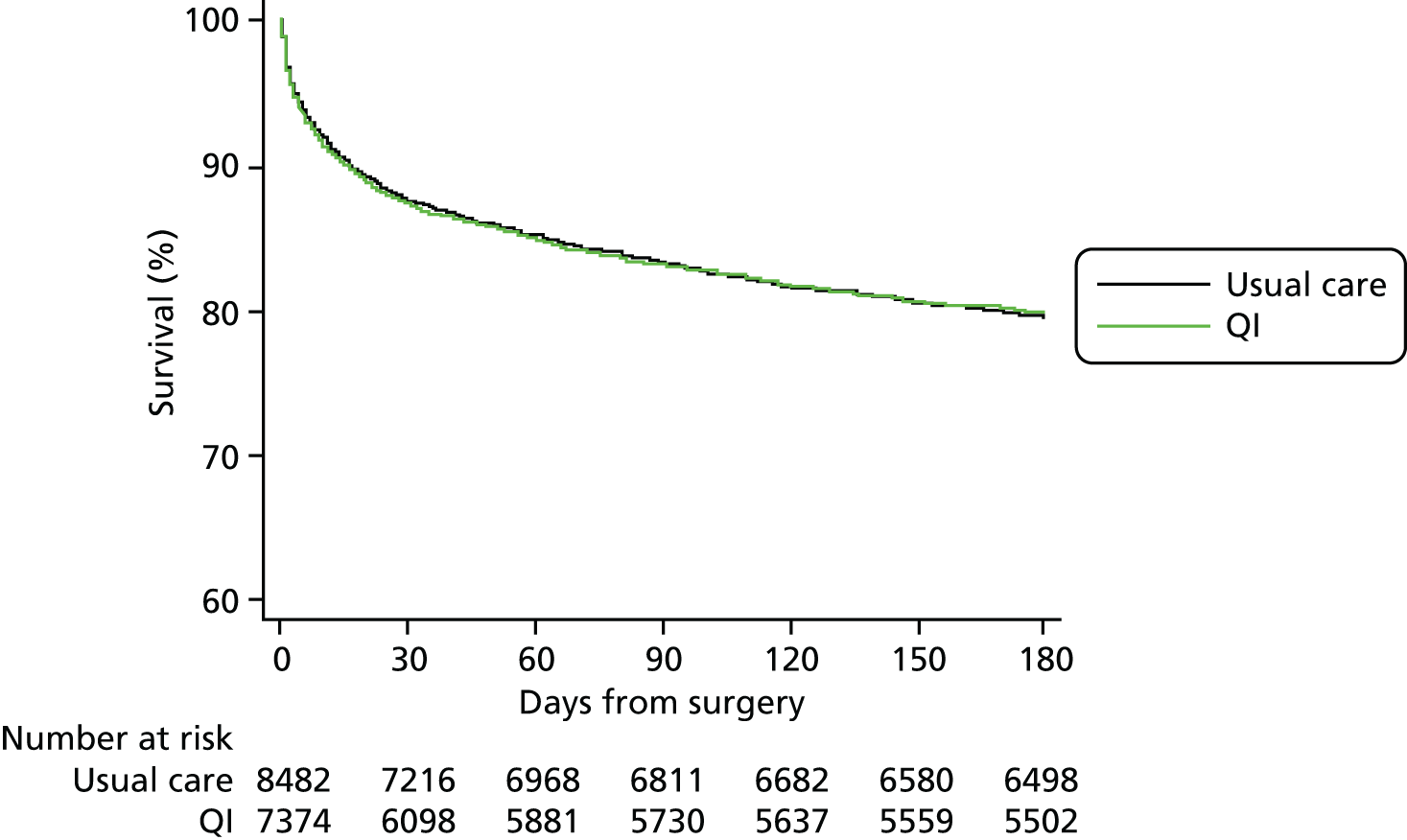

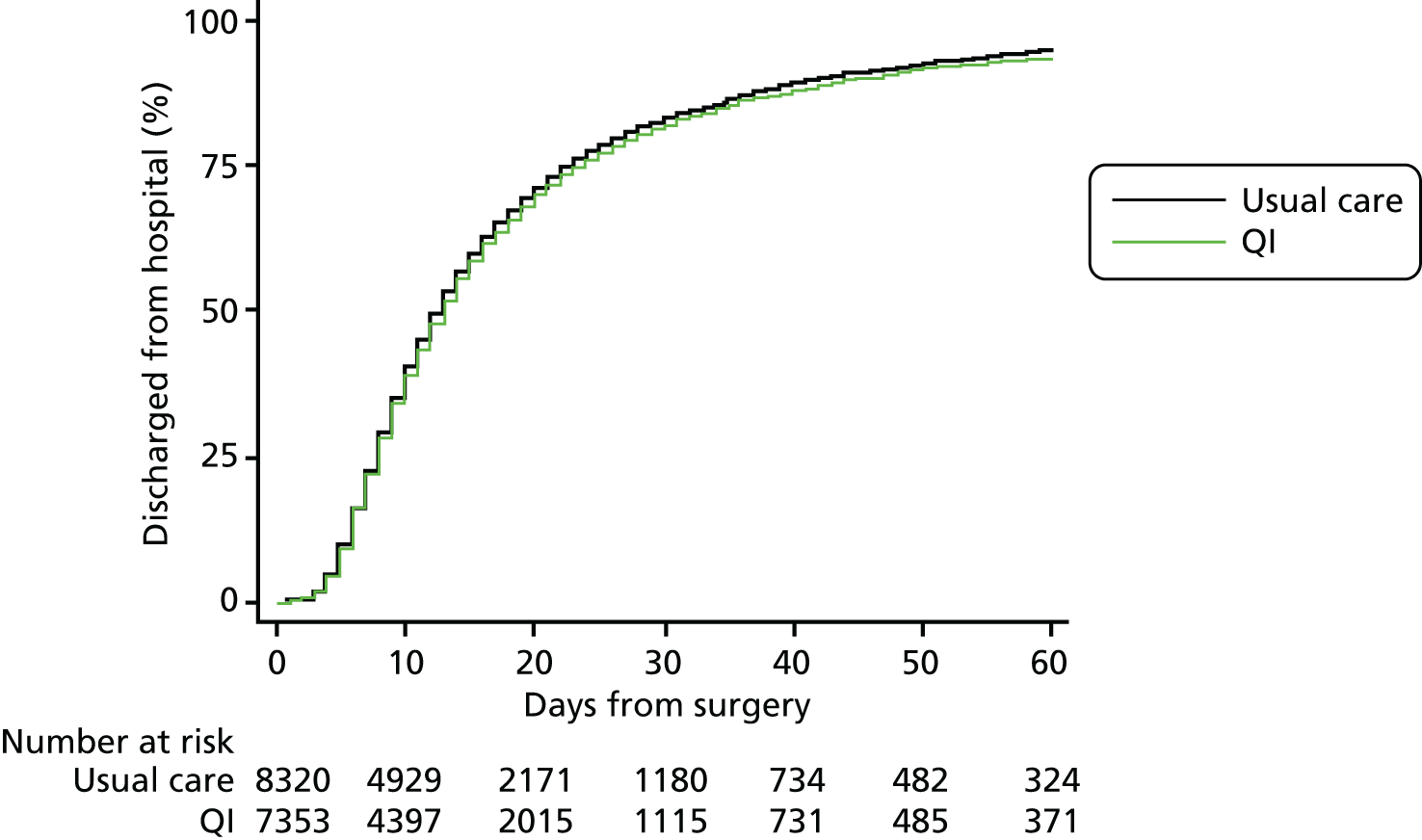

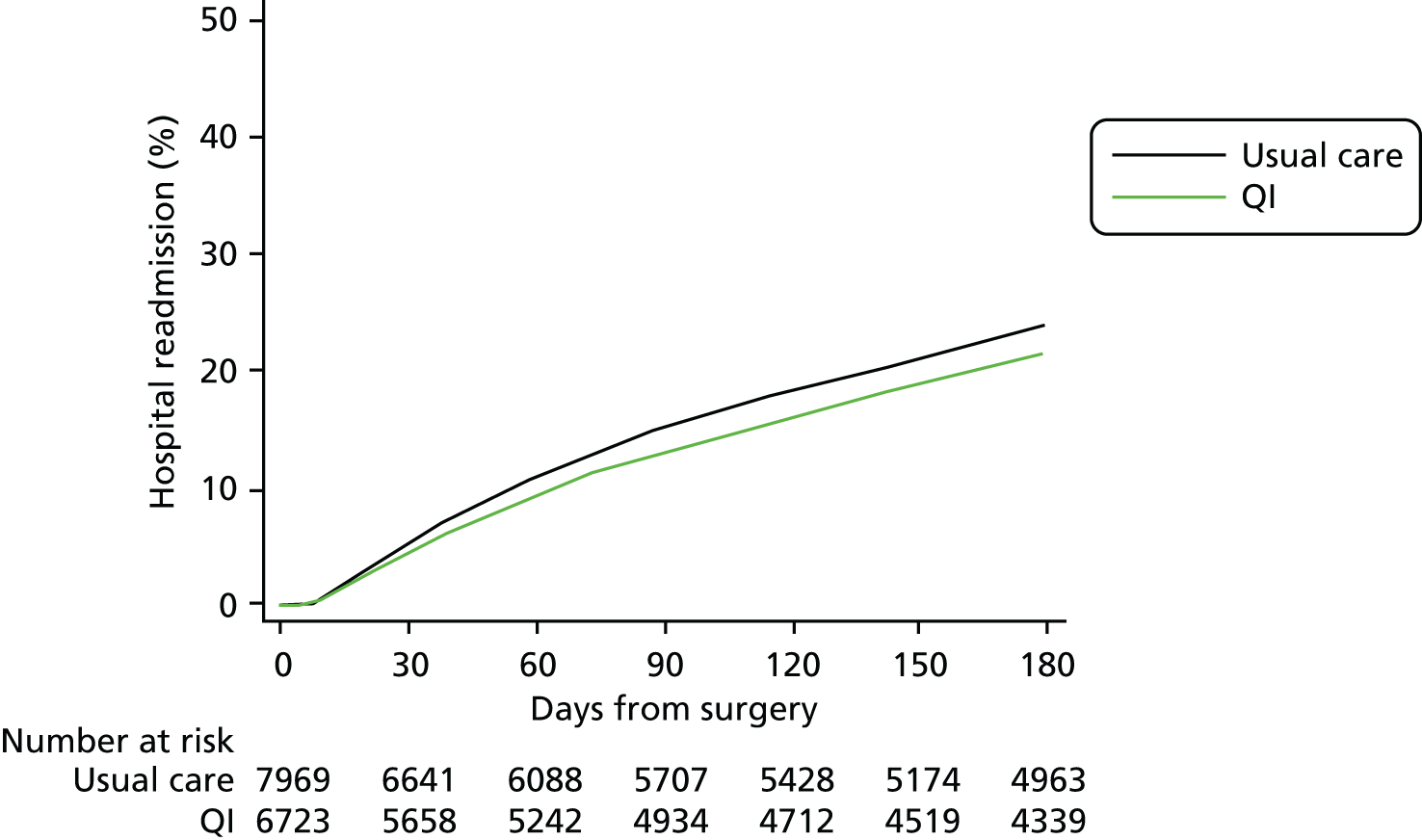

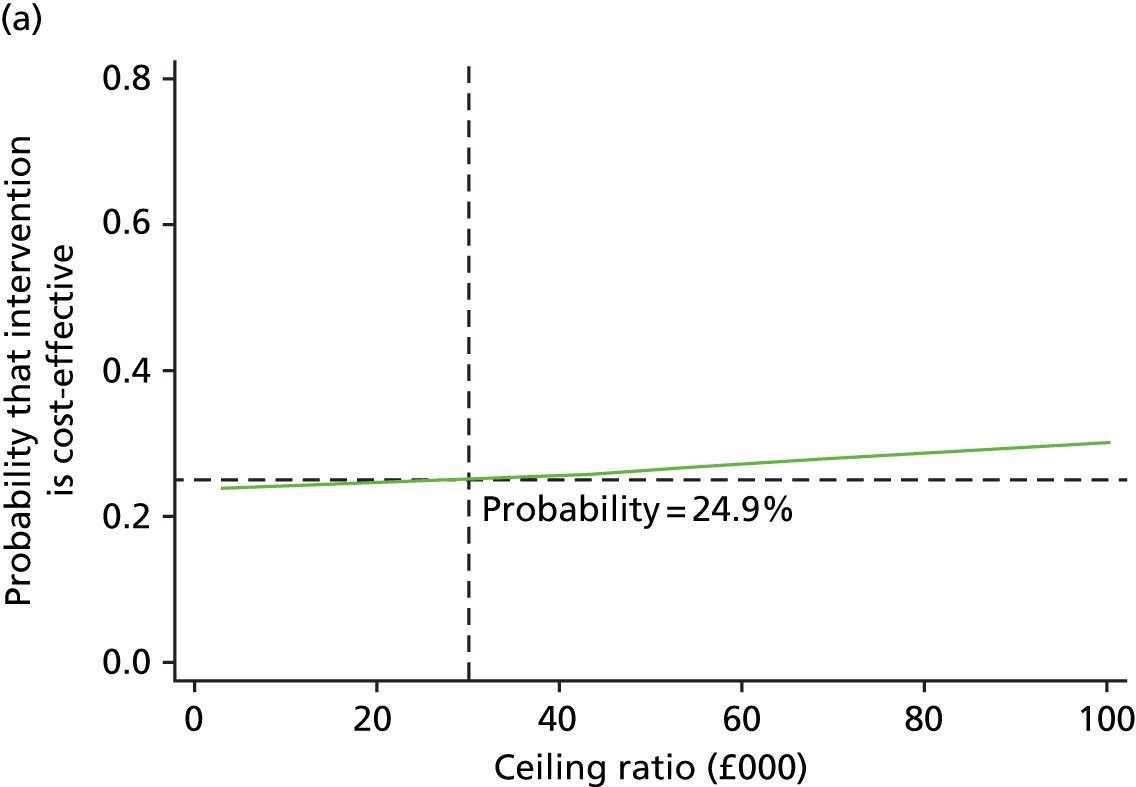

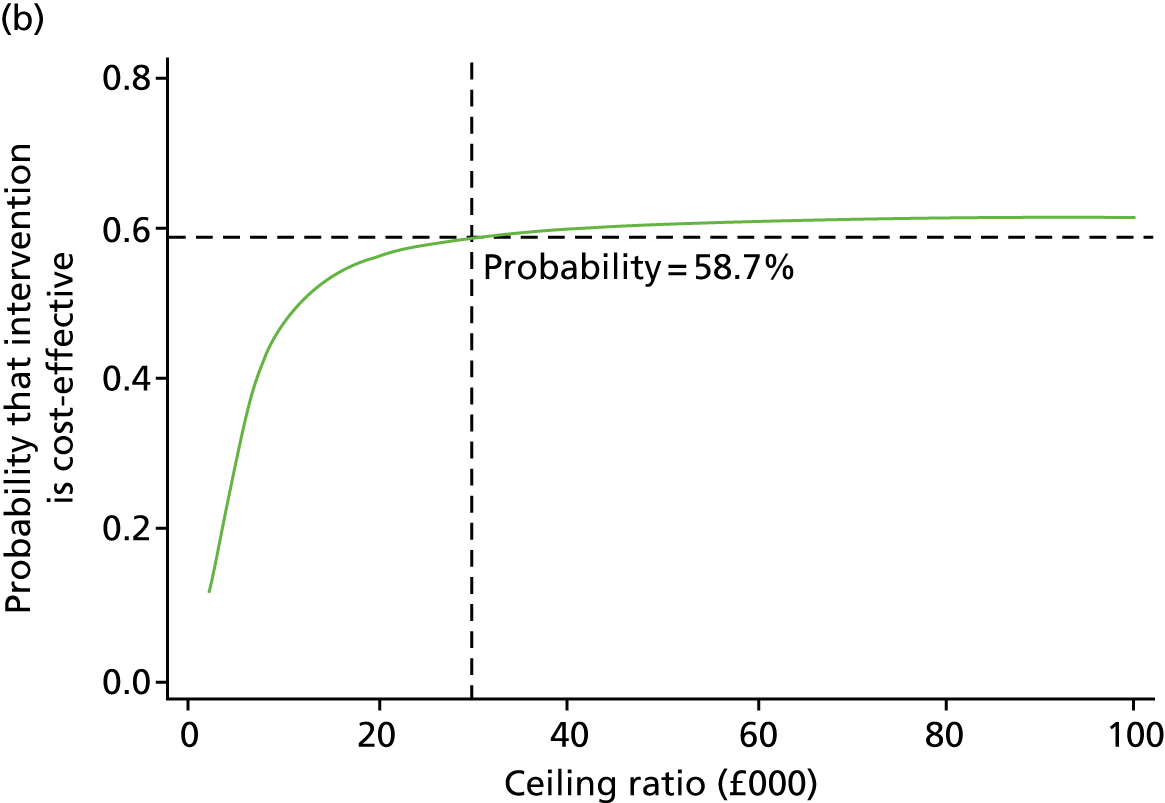

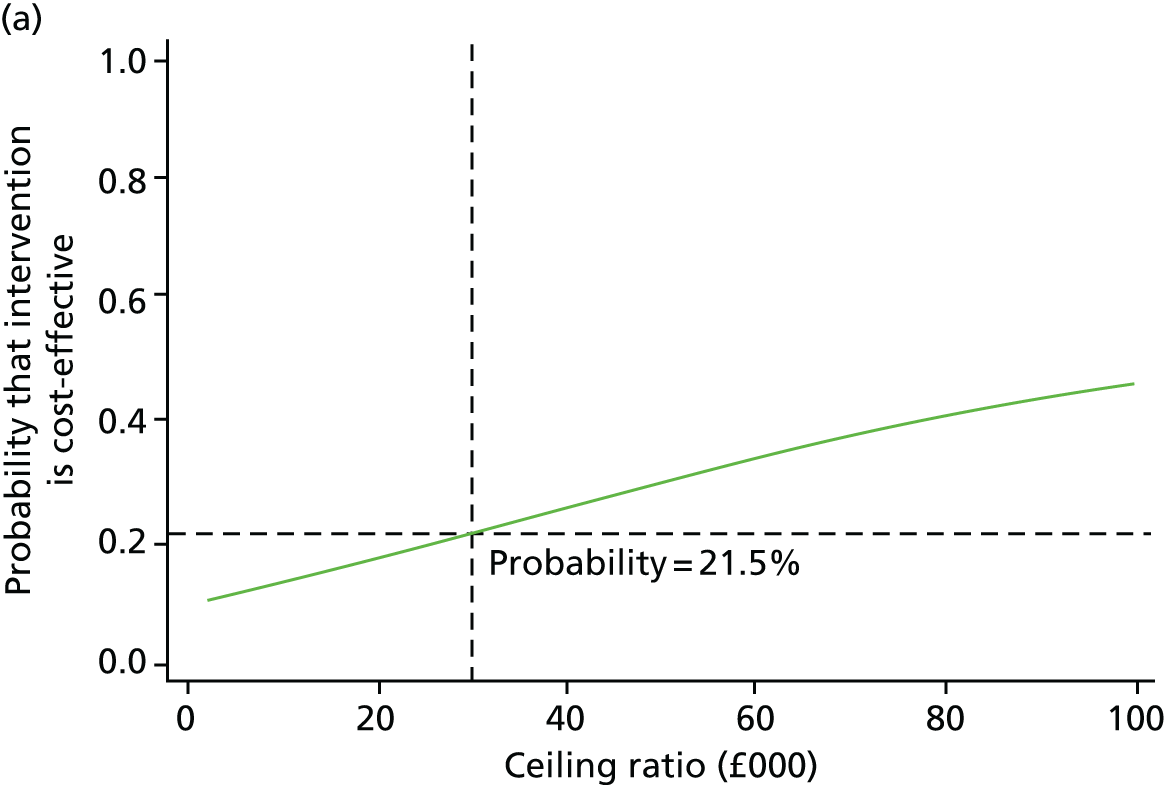

Complete primary outcome data were available for > 99% patients (see Figure 2). The primary outcome of 90-day mortality occurred in 1393 usual care group patients (16%) compared with 1210 QI group patients (16%) [QI vs. usual care HR 1.11, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.96 to 1.28] (Figure 3 and Table 5). Results were similar for 180-day mortality (HR 1.12, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.28) (Figure 4). Patients in the QI group had a lower probability of hospital discharge (HR for hospital discharge 0.90, 95% CI 0.83 to 0.97), leading to a marginally longer hospital stay {days in hospital: usual care 13 [interquartile range (IQR) 8–23] days vs. QI 13 (IQR 8–24) days}, although this difference was not clinically meaningful (Figure 5 and Table 6). There was no difference between groups in hospital readmission within 180 days [usual care, n = 1618 (20%) vs. QI, n = 1242 (18%), HR for readmission 0.87, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.04] (Figure 6 and Table 7). In a secondary analysis, we found no evidence that the QI strategy became more effective the longer it had been adopted (Table 8). To assess the impact of missing mortality data following hospital discharge from patients in Wales, we assessed the number of mortality events that occurred after hospital discharge but before 90 days in English and Scottish hospitals. Only 5% (631/13,034) of patients died between hospital discharge and 90 days, suggesting that few outcome events in Wales were missed. Analysis of the effect of the intervention over time is presented in Table 8 and of the inclusion of younger patients and those undergoing laparoscopic surgery in Table 9.

FIGURE 3.

Mortality within 90 days of emergency abdominal surgery.

| Outcome | Number of patients included in analysis | Summary outcome measure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 8490), n (%) | QI (N = 7383), n (%) | Usual care, n (%) or median IQR | QI, n (%) or median IQR | HR (95% CI) (QI vs. usual care) | |

| All-cause mortality within 90 days of surgery | 8482 (> 99) | 7374 (> 99) | 1393 (16) | 1210 (16) | 1.11 (0.96 to 1.28) |

| All-cause mortality within 180 days of surgery | 8482 (> 99) | 7374 (> 99) | 1698 (20) | 1440 (20) | 1.12 (0.98 to 1.28) |

| Duration of hospital stay (days) | 8320 (98) | 7353 (> 99) | 8 (13–23) | 8 (13–24) | 0.90 (0.83 to 0.97) |

| Hospital readmission within 180 days of surgery | 7969 (94) | 6723 (91) | 1618 (20) | 1242 (18) | 0.87 (0.73 to 1.04) |

FIGURE 4.

Mortality within 180 days.

FIGURE 5.

Duration of hospital stay after emergency abdominal surgery.

| Outcome | Hospitals (N = 93), n (%) |

|---|---|

| All-cause mortality within 90 days of surgery (primary) | 93 (100) |

| All-cause mortality within 180 days of surgery | 93 (100) |

| Duration of hospital stay (days) | 91 (98) |

| Hospital readmission within 180 days of surgery | 87 (94) |

FIGURE 6.

Time to hospital readmission.

| Outcome | Usual care, n (%) | QI, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Duration of hospital stay | ||

| Censored while in hospital | 29 (< 1) | 102 (1) |

| Discharged | 7195 (86) | 6250 (85) |

| Died in hospital | 1096 (13) | 1001 (14) |

| Hospital readmission within 180 days of surgery | ||

| No | 4954 (62) | 4331 (64) |

| Yes | 1618 (20) | 1242 (18) |

| Died without admission before 180 days | 1397 (18) | 1150 (17) |

| Duration | 90-day mortality, n/N (%) | HR (95% CI) | p-value (overall) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No QI | 1393/8482 (16) | Reference | 0.15 |

| QI for < 5 weeks | 198/1069 (19) | 1.11 (0.94 to 1.32) | |

| QI for 5–10 weeks | 185/983 (19) | 1.21 (1.01 to 1.44) | |

| QI for > 10 weeks | 1025/6391 (16) | 1.05 (0.90 to 1.23) |

| Outcome | No QI (N = 1503), n (%) | QI (N = 1459), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 90-day mortality | 101 (7) | 66 (5) |

Discussion

The principal finding of this trial was that there was no survival benefit associated with a national QI programme to implement an evidence-based care pathway for patients undergoing emergency abdominal surgery. Furthermore, there was no beneficial effect on 180-day mortality, hospital stay or hospital readmission. At a national level, there were only modest improvements among the 10 measures selected to reflect key processes of care within the pathway. In some cases, the baseline rate of adherence to process measures was higher than anticipated.

The strengths of this trial include wide generalisability (a large number of consecutive patients were enrolled by many hospitals), robust trial design and the devolved leadership to local clinical QI teams. The evidence-based EPOCH trial care pathway was developed through a Delphi consensus process to update national professional guidelines. 8 Partnership with the NELA allowed an efficient trial design with no additional data collection for participating staff. However, our final data set required linkage to four national registries in the devolved nations of the UK, and despite completing the trial on time, some organisations involved imposed substantial delays in access to these data sets. On several occasions, organisations changed their position on information governance regulations, requiring revision of previous agreements between each of the parties involved. In hindsight, we would have encountered fewer problems had we confined the trial to the jurisdictions of fewer organisations with information governance oversight. Despite the large sample, fewer patients than expected underwent emergency abdominal surgery and the 90-day mortality rate was lower than anticipated. The sample size calculation was based on HES data, which do not provide a specific diagnostic code for emergency abdominal surgery. Instead, we identified a series of codes for relevant procedures. We chose to power the trial to detect a very modest treatment effect, partly to accommodate the possibility that these data were poorly representative of the EPOCH trial population. However, the 95% CI for our primary effect estimate was narrow, with a lower limit that indicates a maximum potential relative mortality reduction of 4%. Our findings are unlikely to change with a larger sample size. Because of the difficulty in obtaining post-discharge survival data in Wales, we changed our primary analysis from a binary to a time-to-event approach, allowing the inclusion of mortality events censored at hospital discharge. However, post-discharge data from England and Scotland suggest that few events were missed as a result of this approach.

Chapter 4 Process evaluation

Introduction

Quality improvement interventions, such as that delivered in the EPOCH trial, are complex due to their interacting components, and the multiple organisational and social levels at which they operate. 53 Delivering a complex intervention, into a complex system such as the perioperative care pathway in a hospital, is challenging, with many possible barriers to achieving the intended outcomes. Even in a trial setting, such complexity may mean that the target group is not actually exposed to the intervention as planned. 24 Therefore, in addition to the main trial, we conducted a concurrent ethnographic evaluation in six trial sites and a post hoc process evaluation of the trial overall. There is published guidance on complex intervention reporting (the TIDieR checklist24 and the SQUIRE guidelines25), but such detailed reporting is not common in the QI literature. 54

In this chapter we focus on the process evaluation data to describe how one of the largest trials of a QI intervention to date was delivered and received across 93 hospitals that offer emergency abdominal surgery in the NHS, and provide detailed analysis to facilitate a greater understanding of the main trial results. The ethnographic evaluation is described in Chapter 5.

Methods

We undertook a mixed-methods process evaluation based on recommended guidance for the evaluation of cluster trials,55 which was structured using the following framework: how clusters and sites were recruited, delivery of the intervention at the cluster level, response to the intervention at the cluster level, delivery of the intervention at the site level and the response to the intervention by individuals targeted (in this case, the EPOCH trial QI leads).

Data sources and data collection

Table 10 details the evaluation foci and the data sources used to investigate each. Following commencement of the trial, the variability of engagement with the QI programme prompted a wider-scale, post hoc process evaluation, with the aim of capturing data across the trial cohort. For the post hoc component of the process evaluation, we collected a range of QI programme activity data (see Table 10) and sent an exit questionnaire to all QI leads. The 37-item, online questionnaire, administered at the end of the trial, was designed to allow description of activities undertaken, as well as their overall experience of leading the improvement projects. The questionnaire comprised categorical, yes/no and free-text questions, with opportunities to elaborate on any answers as free text. The questionnaire was piloted multiple times in line with best practice. Only one response was required per hospital, but QI leads were asked to complete the questionnaire with colleagues. QI programme data were collected by the programme co-ordinator (TS) and included data on participation in programme activities, such as meetings and use of the trial VLE.

| Aspect of process evaluation | Data collection method | Data collected and data type |

|---|---|---|

| Recruitment of sites | Review of trial administrative records |

Recruitment strategy, including inclusion and exclusion criteria Reasons given for non-participation (text in trial administrative documents) |

| Delivery to the clusters |

Collation of registers from QI programme meetings (30 meetings) Collation of VLE usage logs |

Names, roles and hospital of each of the attendees at the QI programme meetings (two meetings/cluster) The level of usage of the VLE per hospital, determined by the number of visits/views logged by any staff member from each hospital |

| Response of the clusters | Online exit questionnaire | Free-text responses regarding the positive and negative aspects of the programme |

| Delivery at the site level: QI intervention | Online exit questionnaire |

Whether or not a stakeholder meeting was held (QI strategy 1) Whether or not a QI team was formed and professional composition of any such team (QI strategy 2) If and how data feedback occurred (QI strategy 3) Whether or not run charts were used (QI strategy 4) Whether or not the patient pathway was segmented (QI strategy 5) Whether or not the PDSA approach was used (QI strategy 6) |

| Response of sites/individuals | Online exit questionnaire | Free-text responses to two reflective questions: if you were to be involved in EPOCH trial again, (1) ‘what would you continue doing’ and (2) ‘what would you do differently’? |

Data analysis

The programme activity and questionnaire data were analysed and reported using descriptive statistics [frequency (%) for categorical data or median (range) for continuous data]. Free-text data in the exit questionnaire were coded by two investigators, using both inductive and deductive content analysis techniques. Findings were discussed until themes were agreed and draft results were discussed with the ethnographic researchers to enhance external validity. 56

Results

Programme activity data, as defined in Table 10, were available for all 93 hospitals. Eighty-three per cent (77/93) of QI leads completed the exit questionnaire. All but four responses (73/77) included input from clinicians from the disciplines of anaesthesia or critical care. In comparison, 17 out of 77 (22%) responses included surgical input and 6 out of 77 (8%) included nurse input. The evaluation results are structured using the following framework: delivery of the intervention at the cluster level, response to the intervention at the cluster level, delivery of the intervention at the site level and the response to the intervention by individuals targeted (the EPOCH trial QI leads).

Recruitment of clusters

Hospitals were recruited following an open call and promotion through existing critical care and perioperative medicine research networks. All NHS hospitals in the UK (except Northern Ireland) were eligible to take part if emergency general surgery was performed on site and if there was no previous or ongoing improvement work focused on emergency laparotomy.

We have documented records of 14 hospitals expressing interest, but subsequently not participating due to existing improvement work in that site. For other hospitals that expressed an interest but subsequently did not join the trial, the most common reason given was that there was insufficient support from colleagues for the trial interventions.

Delivery of the intervention at the cluster level

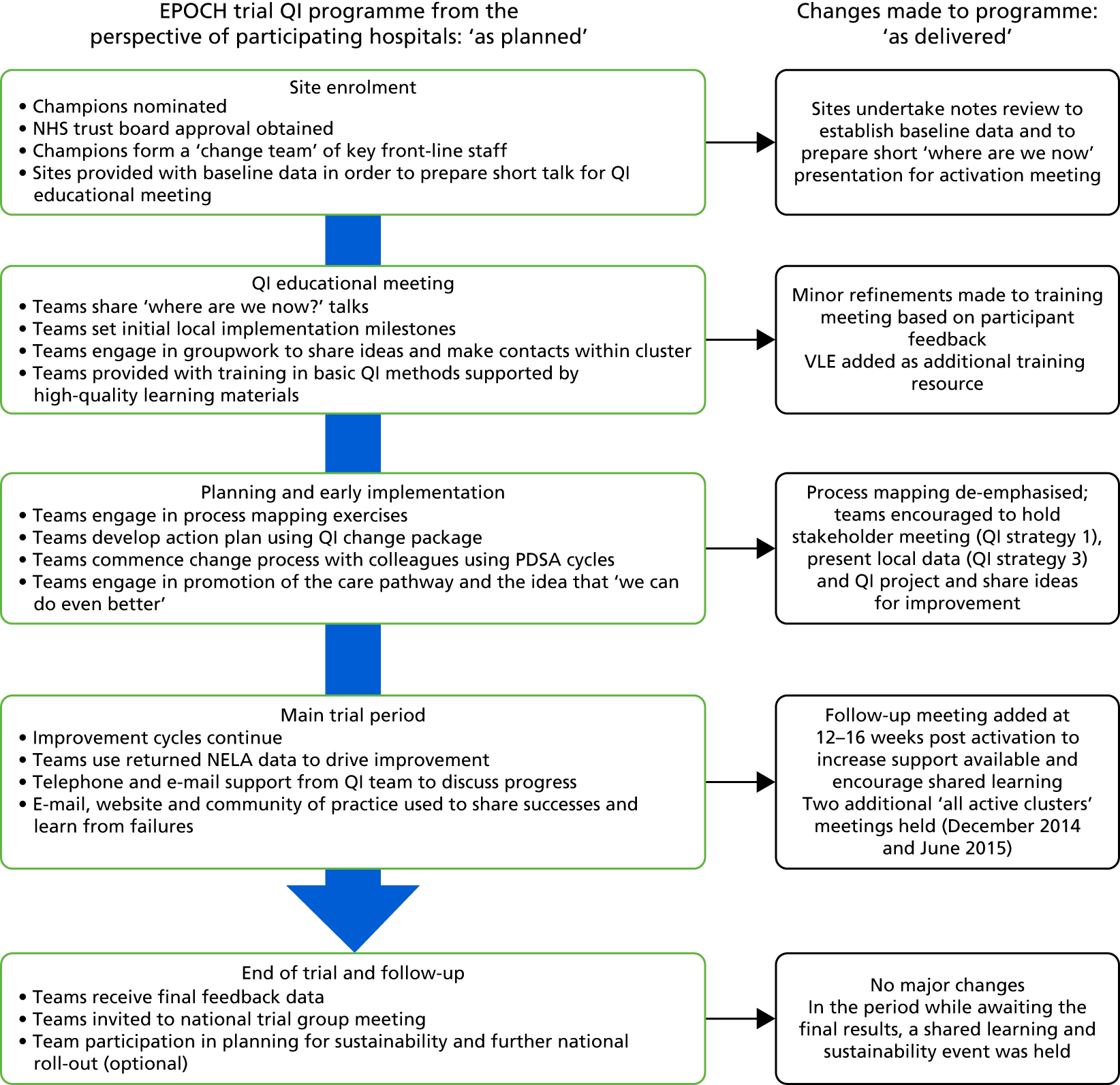

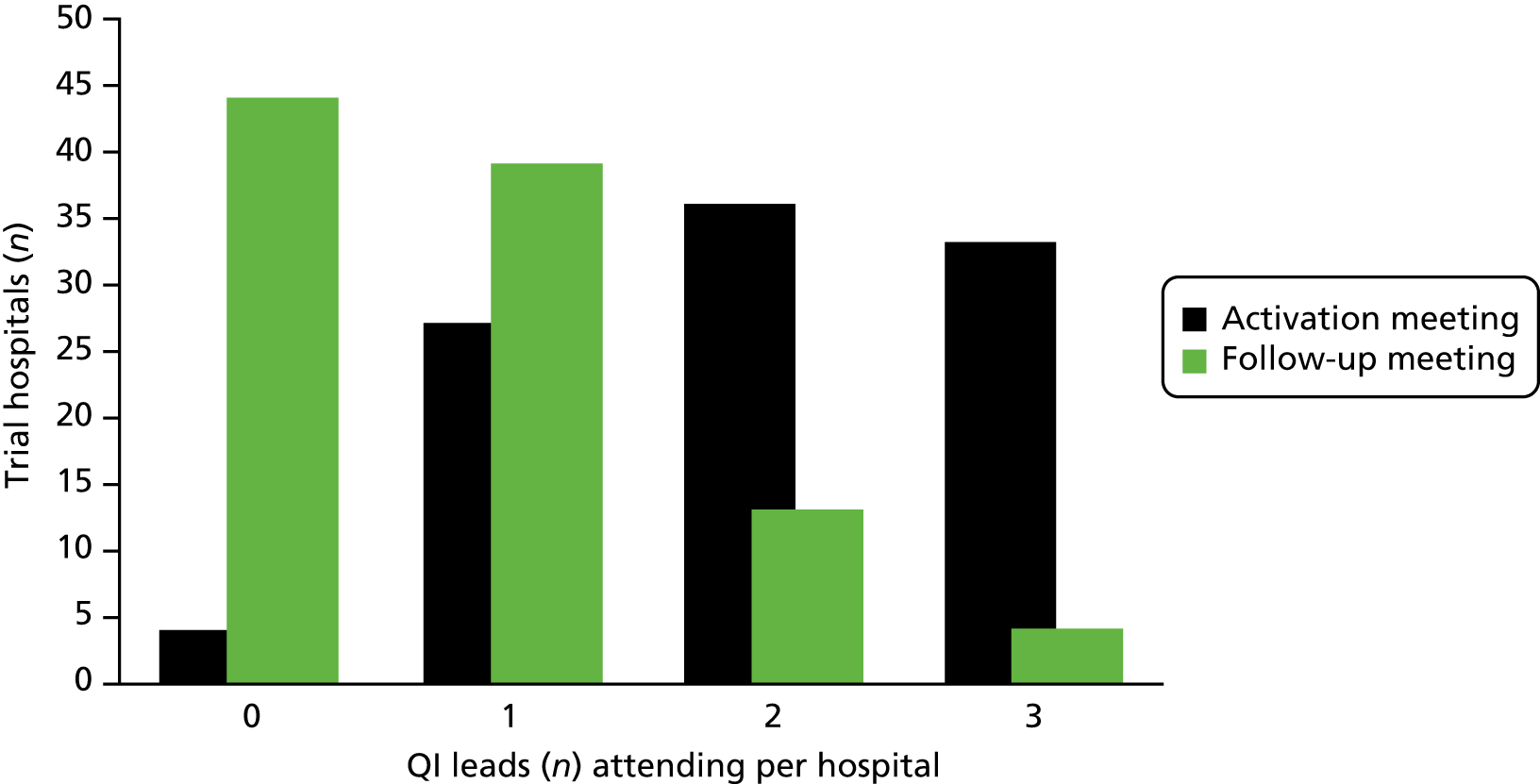

A total of 15 face-to-face QI educational meetings, planned to coincide with cluster activation and 15 follow-up meetings (one for each geographical cluster) were held as part of the QI programme. Figure 7 summarises the EPOCH trial QI programme ‘as planned’ and ‘as delivered’; the major change to the plan was the addition of follow-up cluster meetings at 12–16 weeks post activation to the intervention. Aside from local QI leads (surgeons, anaesthetists and critical care physicians), research nurses, theatre nurses and trainees in surgery and anaesthesia were the most common groups to participate in the educational meetings. The number of participants from each hospital at the follow-up cluster meeting was substantially fewer than at the first meeting. Figure 8 displays the numbers of QI leads attending the meetings from each hospital. The median number of participants (both QI leads and other invited colleagues) at the educational meetings and follow-up meetings were three per hospital (range 0–19) and one per hospital (range 0–8), respectively. The web-based resources were housed in a VLE, which contained a total of 66 pages or resources, to be viewed online or downloaded, at the commencement of the programme, increasing to 84 pages or resources by the end of the trial. The site could be accessed only by registered EPOCH trial local QI team members. In total, 16,120 ‘hits’ (visits to the site, page view and resource views or downloads) were logged over the course of the trial period. The median number of VLE hits per hospital was 136 (minimum 11, maximum 519, interquartile range 70–194). The number of users per hospital ranged from one to seven, with a median of three users, but as some site teams were small, and as online resources could be downloaded and/or printed by one user for colleagues to view, we feel the total hits per hospital is a more useful metric of VLE usage. Given the number of pages/resources available (84 by the trial end), these data suggest probable appropriate usage by much of the cohort, but with some variability and a significant minority of low users.

FIGURE 7.

The QI programme as planned and as delivered. Reproduced from Stephens et al. 22 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

FIGURE 8.

Quality improvement lead attendance at QI meetings.

Response to the intervention at cluster level

Themes derived from responses to a free-text question in the exit questionnaire about the improvement programme are described in Table 11. Themes emerged pointing to the utility of the meetings, both for learning and for networking, the overall support offered and energy for change generated by the programme team, and the helpfulness of the run chart tool. Conversely, themes emerged from comments regarding the need for greater clarity about, and fewer components in, the intervention, and more meetings and input together with more time in the intervention period.

| ‘What was most helpful about the QI programme’ (from 56 free-text responses) | ‘What could have been better about the QI programme’ (from 36 free-text responses) |

|---|---|

| QI training (at the meetings) and online resources (n = 14) | More clarity about the intervention and how to implement it (n = 10) |

| Networking with colleagues from other hospitals (facilitated by meetings) (n = 11) | More meetings and more input from the central team (n = 8) |

| Good communication and support (n = 12) | Better support/better run chart tool (n = 7) |

| The Excel tool to generate run charts from NELA data (n = 11) | A longer intervention period for those activated late (due to the stepped-wedge trial design) (n = 7) |

| Enthusiasm and motivation generated by the EPOCH trial team and project overall (n = 8) | Fewer components in the clinical pathway (n = 4) |

Quality improvement leads were also asked to rate the support they received from the QI programme team on a 5-point scale (very good to very poor). Of the 75 who responded to this question, 36 out of 75 (48%) QI leads rated support as very good, 30 out of 75 (40%) QI leads rated support as good and 9 out of 75 (12%) QI leads rated support as average.

Delivery to individuals at local site (quality improvement intervention fidelity)

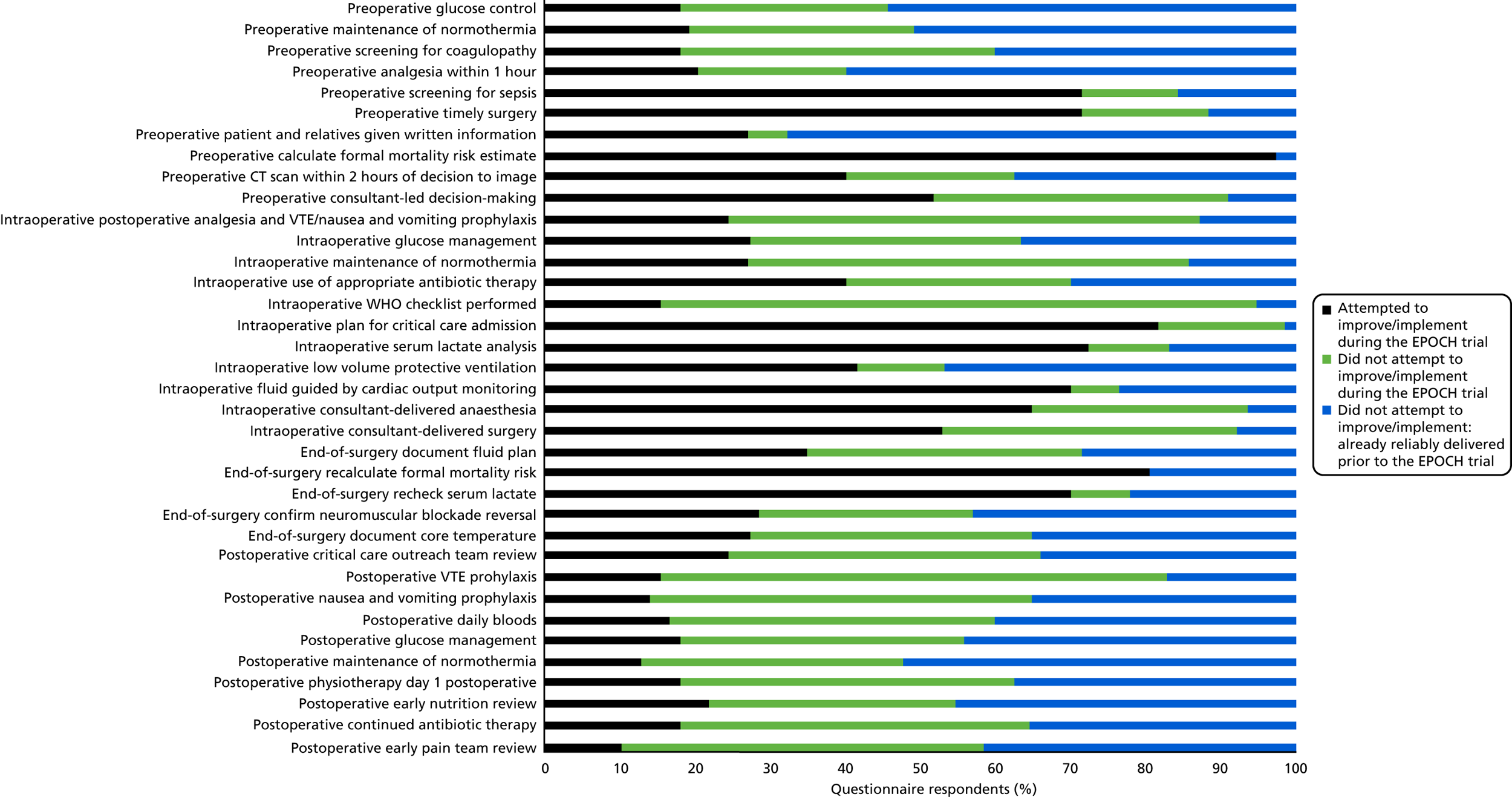

The clinical intervention was a 37-component care pathway (see Box 1). Questionnaire data showed that, regarding the care pathway, only 11 care processes were the focus of improvement efforts in > 50% of responding hospitals; the remaining pathway components had more variable uptake (see Segmenting the pathway and Figure 9). The QI intervention comprised six strategies (see Figure 1 and Table 1). Questionnaire data showed that 10 out of 77 (13%) QI leads responding said that all six strategies had been used, 23 out of 77 (30%) QI leads indicated five had been used, 21 out of 77 (27%) QI leads indicated four had been used, 8 out of 77 (10%) QI leads had used three strategies, 10 out of 77 (13%) QI leads had used two and 5 out of 77 (6%) QI leads had used just one. No QI lead reported zero QI strategy usage. Table 12 shows the reported usage of each QI strategy and each is discussed briefly below.

| Question related to QI strategy usage | Response (n = variable) |

|---|---|

| PDSA approach | |

| Did you or your colleagues use the PDSA cycle approach during your QI activities? |

|

| QI team formation | |

| At your site, was a formal team created to work on QI activities related to the EPOCH trial? Definition of QI team: a group of individuals that work together on the QI project. The team is defined by their shared goals and mutual accountability for the QI |

|

| Data collection and analysis | |

| After starting the EPOCH trial, did you or your colleagues download and analyse your local NELA data? |

|

| If yes, how frequently did you do this? |

|

| If yes, did you use run charts? |

|

| Were systems set up to collect NELA data prospectively? |

|

| Stakeholder meeting | |

| Did you hold a stakeholder meeting as one of your QI activities? For example, a meeting for all professionals involved in patient care |

|

| Pathway segmentation | |

| Please indicate the statement that most closely fits your hospital’s improvement or implementation activity during the EPOCH trial |

|

Use of plan–do–study–act

At activation meetings, the use of PDSA cycles was presented to participating teams explicitly as a model for experimentation and the planning of change, with a clear set of instructions and supporting tools for putting it into practice. The data in Table 12 indicate that this approach was used, but perhaps not in the regular, methodical manner recommended.

Team approach

At the activation meetings, QI leads were strongly advised to recruit a formal team of ‘willing’ interprofessional colleagues to work with them on the local improvement activities. The data in Table 12 indicates that just under two-thirds of sites had a formal team to work on this major project.

Use of data feedback and run charts

At the activation meetings, using NELA data as a driver for engaging colleagues and monitoring improvement was promoted and tools provided to do so. The data in Table 12 shows that most, but not all, teams were analysing NELA data; far fewer were doing this on a regular (monthly/bi-monthly) basis. Many sites reported challenges in simply collecting the data, with only half of all questionnaire respondents indicating that systems had been set up to collect the audit data prospectively.

Engagement

At 5 weeks before activation to the intervention, sites were contacted and recommended to start planning a stakeholder meeting, to coincide with activation. Just over half of the respondents indicated that they had held such a meeting (see Table 12); when a meeting was held, most reported that it was successful (questionnaire data, not shown). The exit questionnaire also asked about senior support during the trial. Of the 71 who responded to this question, 15 (21%) described active executive board support for the QI work related to the EPOCH trial (e.g. funding staff time to support the project or making the project a board-level quality and safety priority).

Segmenting the pathway

At the activation meeting, QI leads were advised to consider segmenting the proposed pathway to make the workload of implementation more manageable. Advice was offered regarding selecting which elements of the pathway to work on first and how to plan a step-wise implementation of the pathway that would be workable in QI leads’ local context. The data in Table 12 suggests that the majority of sites appear to have followed this approach. However, the data in Figure 9 also suggests that most sites did not progress beyond this to attempt to introduce most or all of the pathway components.

FIGURE 9.

Clinical process change attempted during intervention period. CT, computerised tomograghy; VTE, venous thromboembolism; WHO, World Health Organization. Reproduced from Stephens et al. 22 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Response of quality improvement leads: reflections on the change process

Quality improvement leads reflected on ‘what would you continue doing?’ and ‘what would you do differently if you were to do the EPOCH trial again?’. Ninety-six per cent (74/77) of respondents left a total of 299 comments. Eighteen themes were generated for each question (36 in total) and these were further grouped into nine high-level themes (Table 13). Two clear themes, from responses to both questions, were related to the importance of effective engagement and involvement of colleagues (themes 2 and 6), and to data collection and feedback systems (themes 1 and 7). Other reflections on what QI leads ‘would continue doing’, related to QI methodology (themes 3 and 5) and the utility of specific, recommended clinical interventions, particularly mortality risk estimate scoring (theme 4). When considering ‘what they would do differently’, QI leads also highlighted some of the ‘real-life’ challenges of delivering QI at the frontline, developing leadership and project management skills (theme 9) and the need to obtain strong senior support (theme 8).

| High-level themes | Subthemes (number of supporting comments) |

|---|---|

| What QI leads would continue doing | |

| 1. Keep working on data collection and feedback | Providing feedback on performance, including data feedback (30) |

| Use run charts (19) | |

| Good data collection process/data collection support (14) | |

| Using data to create situational awareness (4) | |

| 2. Keep working on engagement, involvement and collaboration | Engage/involve all relevant stakeholders (22) |

| Interprofessional involvement (9) | |

| Form a QI team (8) | |

| Engage/involve trainees (4) | |

| Identify enthusiastic colleagues (4) | |

| Collaborate with other hospitals (2) | |

| Obtain senior support for the project (2) | |

| 3. Using a ‘systems thinking’ approach to involvement | Hardwire change into the system (9) |

| Building risk scoring into care pathway (8) | |

| Use a checklist/care bundle approach (2) | |

| 4. Specific clinical interventions | Clinical interventions (9) |

| Risk stratification (6) | |

| 5. Use an iterative approach to change | Take an incremental/stepped approach to improvement (6) |

| Persist with implementation (2) | |

| What QI leads would do differently | |

| 6. Engage and involve people more effectively | Wider engagement of stakeholders (17) |

| More surgical engagement/involvement in projects (15) | |

| More interprofessional involvement (10) | |

| Better engagement/involvement of trainees (6) | |

| Form a larger QI team (5) | |

| Involve more people (3) | |

| 7. Get data collection and feedback right | Improve data collection/more data support (17) |

| More data feedback (8) | |

| More data analysis (4) | |

| 8. Obtain stronger senior support for the project | Stronger senior leadership/board-level support (16) |

| More protected time for the project (7) | |

| 9. Work on own leadership/project management skills | Manage the QI team more effectively (10) |

| Get started sooner (6) | |

| Be more forceful (3) | |

| Focus on motivation/behaviour change (2) | |

| Use an interactive approach (2) | |

| More collaboration with other hospitals (2) | |

| Better planning of improvements/system changes (2) | |

Discussion

The principal finding of this process evaluation was that the QI programme delivered the QI skills training and resources as intended and the programme was generally well received by QI leads. Local adaptation to both the QI and clinical interventions was actively encouraged, but the extent of variability and adaptation in the implementation process was greater than anticipated, particularly in relation to the clinical processes. There were only 11 clinical processes that more than half of teams attempted to improve from the clinical pathway (the ‘hard core’ of the intervention) and only half of the trial cohort reported using five or all six of the QI strategies (the ‘soft periphery’ of the intervention) designed to enable pathway implementation. The main trial results showed no effect of the intervention on patient outcomes or care processes (see Chapter 3). Our experience during the QI programme (meeting teams, reviewing their data) suggests that some hospitals were able to make modest, and sometimes substantial, improvements in care processes, but the main trial analysis was not designed to provide this level of granularity. However, no clear signal towards substantial improvement of care processes was seen across the whole cohort as a result of the EPOCH trial QI programme.

When testing clinical interventions in a clinical trial, it is important to make the distinction between the design of the intervention and the operational elements required for effective delivery. 57 Our process evaluation adds to the main trial findings by providing insight into the challenges at both the design (or programme) level and the hospital (operational) level. At the design level, adaptability is often essential in ensuring that QI interventions can fit in different contexts, and this was built into the EPOCH trial intervention. However, fidelity to key parts of an intervention are also important to maximise the likelihood of success. 58 In this case, it may have been that an intervention design that focused on a smaller number of strategies achieved greater fidelity and, therefore, greater impact on patient outcomes. This may be especially relevant given that data from both the ethnography (see Chapter 5) and the exit questionnaire suggest that, at the operational level, QI leads faced many local challenges, including lack of engagement of colleagues and hospital executives. Data were also an operational challenge for many. NELA had commenced only 4 months before the start of the trial and, 20 months after the launch of NELA, at the end of this trial, only half of hospitals reported having prospective data collection systems in place. It is probable, therefore, that many QI leads were focused on collecting and inputting data to the detriment of other improvement activity. A key theme from the reflections of QI leads was that they would have liked to have had better mechanisms, not only for data collection but also for data feedback. Although data are central to any QI project, it is the use of this data through feedback, combined with other improvement strategies, that is likely to achieve more robust results. 30,31,38 If future QI programmes are to capitalise on concurrent national audits or other ongoing data collection, the timings need to be considered to allow embedding of data collection processes before the start of the improvement work, which may take considerably longer than anticipated. Organisational challenges may have meant that many teams simply ran out of time to implement the pathway in the intervention period. Earlier, smaller studies have shown that marked improvement may take time and can continue after the intervention period. 59

There are other plausible explanations for our failure to change the primary outcome metrics. It is possible that our programme theory was incorrect, and there was only a weak causal link between the interventions and ultimate outcomes. This seems improbable, given the evidence base for the clinical and QI interventions. Another conclusion that might reasonably be drawn from our evaluation is that the EPOCH trial intervention was too ambitious. Even where QI leads developed the capabilities to enable change (e.g. through use of the QI strategies), they were asked to lead that change in addition to their regular clinical commitments and may not have had the capacity, in terms of time, resources and other personnel, to do so. The social aspects of improvement are as likely to be as important as more technical aspects, such as data analysis and feedback, but QI leads used the socially orientated QI strategies less than those related to data. Building and maintaining effective social relationships is time-consuming and challenging, and the uptake of ‘non-technical’ and ‘socioadaptive’ interventions can be low among health professionals. 32 However, a key reflection of QI leads was that they would have liked to have spent more time engaging and involving colleagues. We would suggest, therefore, that more emphasis and training in socioadaptive interventions should be built into future programmes, together with a recognition that dedicated time is required to support front-line staff in prioritising such interventions. 39 Some leads reflected on their difficulties in engaging with senior or executive-level colleagues and only one-fifth of respondents indicated that they received active support from their board. Effective QI requires a reciprocal relationship between the employee and the organisation, and lack of organisational support is likely to have been an important barrier to improvement. 60 This is an important lesson; if the goodwill and motivation of front-line staff is to be mobilised for improvement work, then adequate time and support in the workplace plus training is required to give these professionals the best chance of success. This has ramifications for those designing future programmes: senior management and national-level policy makers.

In relation to the delivery of the programme, the time available to coach teams was limited in comparison with other reported QI interventions, such as the Institute for Healthcare Improvement breakthrough series collaborative model. 13 Our training programme was designed as a parsimonious intervention, with face-to-face meetings limited, so that it might be adapted and replicated widely if proven successful. A higher-intensity programme might have led to greater intervention fidelity, although recent evidence suggests that this may not always be the case. 13,61 The EPOCH trial may have suffered from the lack of a pilot trial and perhaps future similar interventions should be piloted first,23 or use a cluster trial design that allows for iterative intervention development within the trial period to enable ongoing intervention optimisation. 62

A major strength of this evaluation is that it provides a full, detailed description of how a large-scale trial of a complex intervention was designed, delivered and received at over half the hospitals in the UK NHS. Following calls for better intervention reporting, we hope that we have provided insights into possible reasons why, ultimately, the trial was unsuccessful and learning for future studies of this nature. 24,25 The evaluation was conducted by researchers both inside and outside the main trial team, offering both detailed, nuanced knowledge of the trial, with an external perspective; all data collection and analysis was completed before the trial results were known. This study also has several limitations. The process evaluation relied, in part, on self-reported data, often collected from a single representative of each hospital. A response rate of 83% suggests that our data were largely representative of the entire EPOCH trial cohort. However, because non-responders may have had different experiences with the EPOCH trial programme, it is possible that some relevant factors are missing. Self-reported data may be subject to both recall and/or social desirability bias. To minimise recall bias, we started collecting data within 1 month of the completion of the trial. Although we cannot quantify the magnitude of potential social desirability bias, many respondents reported both positive and negative experiences and many reported not using several of the QI strategies.

Conclusions

Programmes designed to support clinician-led improvement may need to focus on developing the necessary QI capabilities, while also advocating (or even mandating) clear organisational support for these professionals to lead change. Additional capacity, including job-planned time to engage stakeholders plus data support and/or adequate date collection mechanisms, are probable prerequisites for the successful delivery of complex interventions, such as implementing a care pathway for emergency surgery.

Chapter 5 Ethnographic evaluation

Introduction

A notable lesson from the last 15 years of efforts to improve the quality of health care in the UK and elsewhere is that the process is rarely a straightforward one. 63,64 Studies worldwide have often found that even the most well-founded improvement interventions result in mixed or negative results, and that interventions that seem to work in one setting flounder when introduced in another. 14,15,32 It is increasingly recognised that improvement is a complex endeavour, in which multiple variables interact in difficult-to-predict ways, such that improving health care is rarely a matter of implementing a single, simple intervention with a direct, causal impact on outcomes. Rather, successful improvement requires a complement of technical and social components, as it involves not only introducing proven clinical processes, but also ensuring that these are engaged in and adhered to reliably by the range of practitioners involved. 30 This also implies that context may be important, as although technical clinical interventions may be universally effective, social interventions may work better in some social, professional and organisational contexts than others, and therefore require adaptation in implementation.

The design of the EPOCH trial programmes explicitly acknowledged these challenges. The care pathway itself, comprising multiple technical interventions with an established association with improved outcomes, was accompanied by a set of social interventions designed to help secure and sustain change in the participating sites. Moreover, this set of social interventions was informed by a well-established approach to structuring health-care improvement, the QI collaborative,65 and articulated in an explicit ‘programme theory’ that explained the key interventions to be undertaken, the theory underlying them and the logic by which they were expected to result in changed practice. The existence and articulation of such a programme theory is crucial to its evaluability: it shows the components of a programme and how they are expected to give rise to the intended outcomes, and therefore provides evaluators with an object of inquiry, for which the implementation and impact can be studied. 66,67