Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/156/08. The contractual start date was in February 2016. The final report began editorial review in June 2018 and was accepted for publication in February 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Donetto et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and context

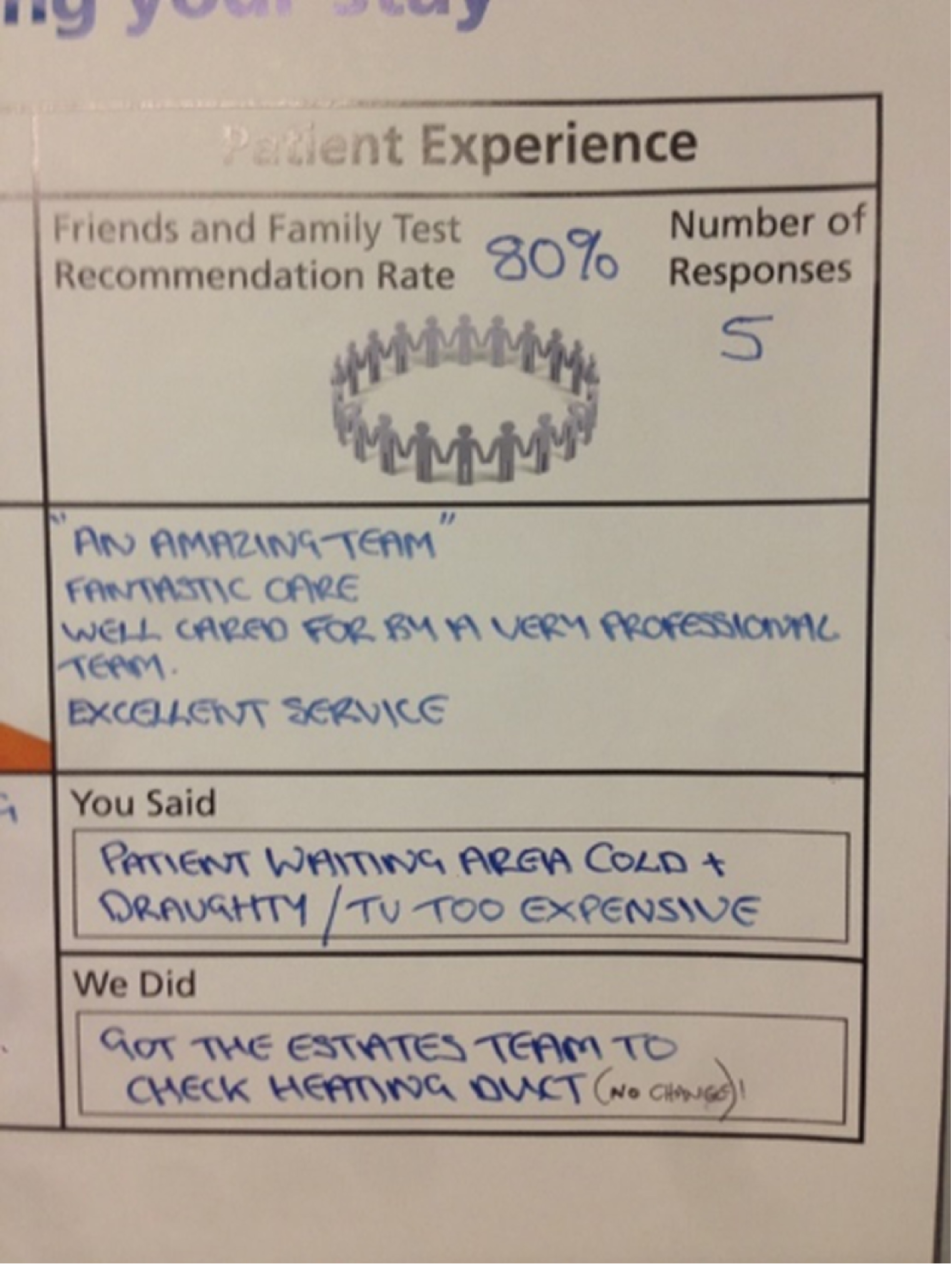

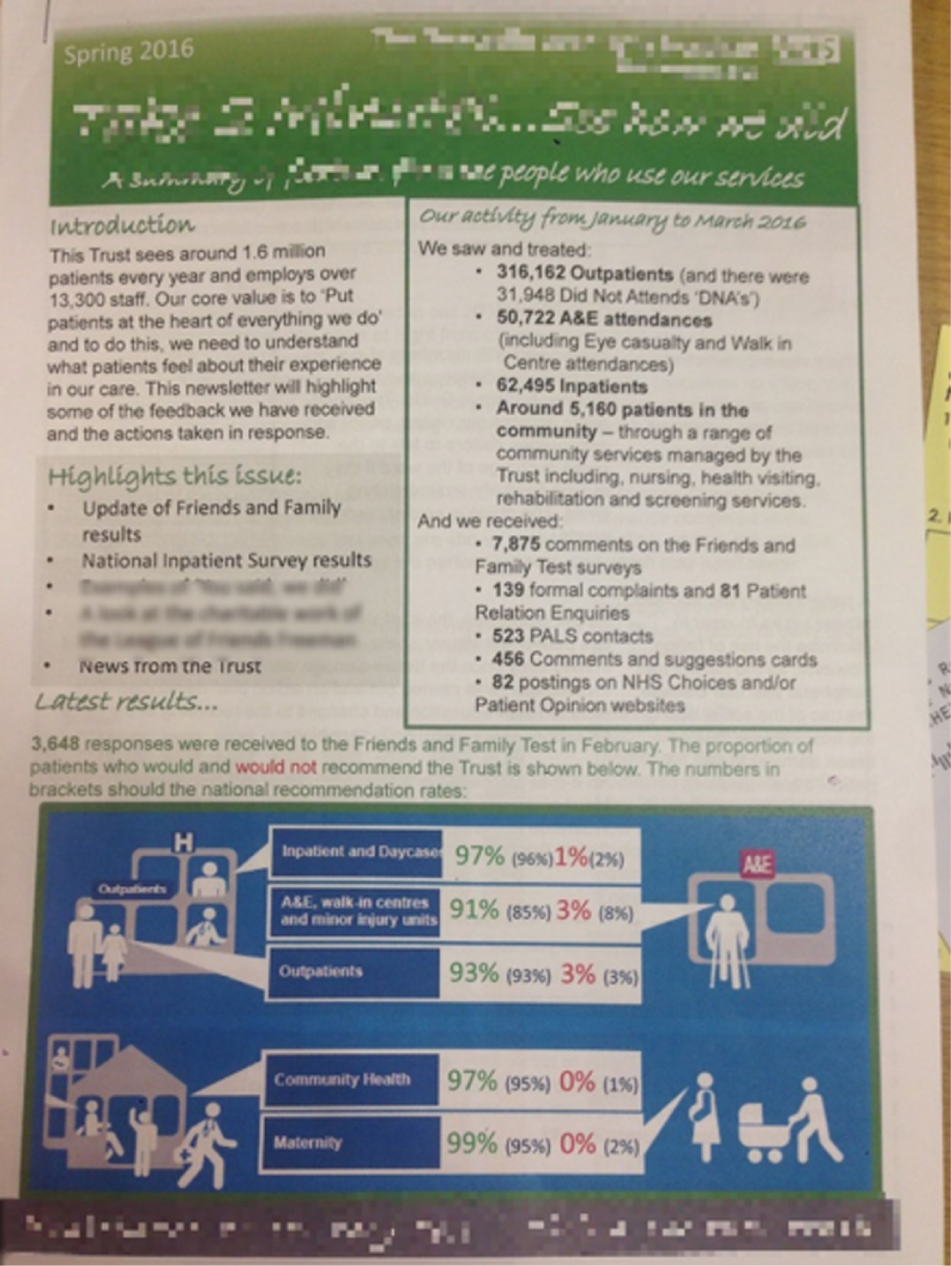

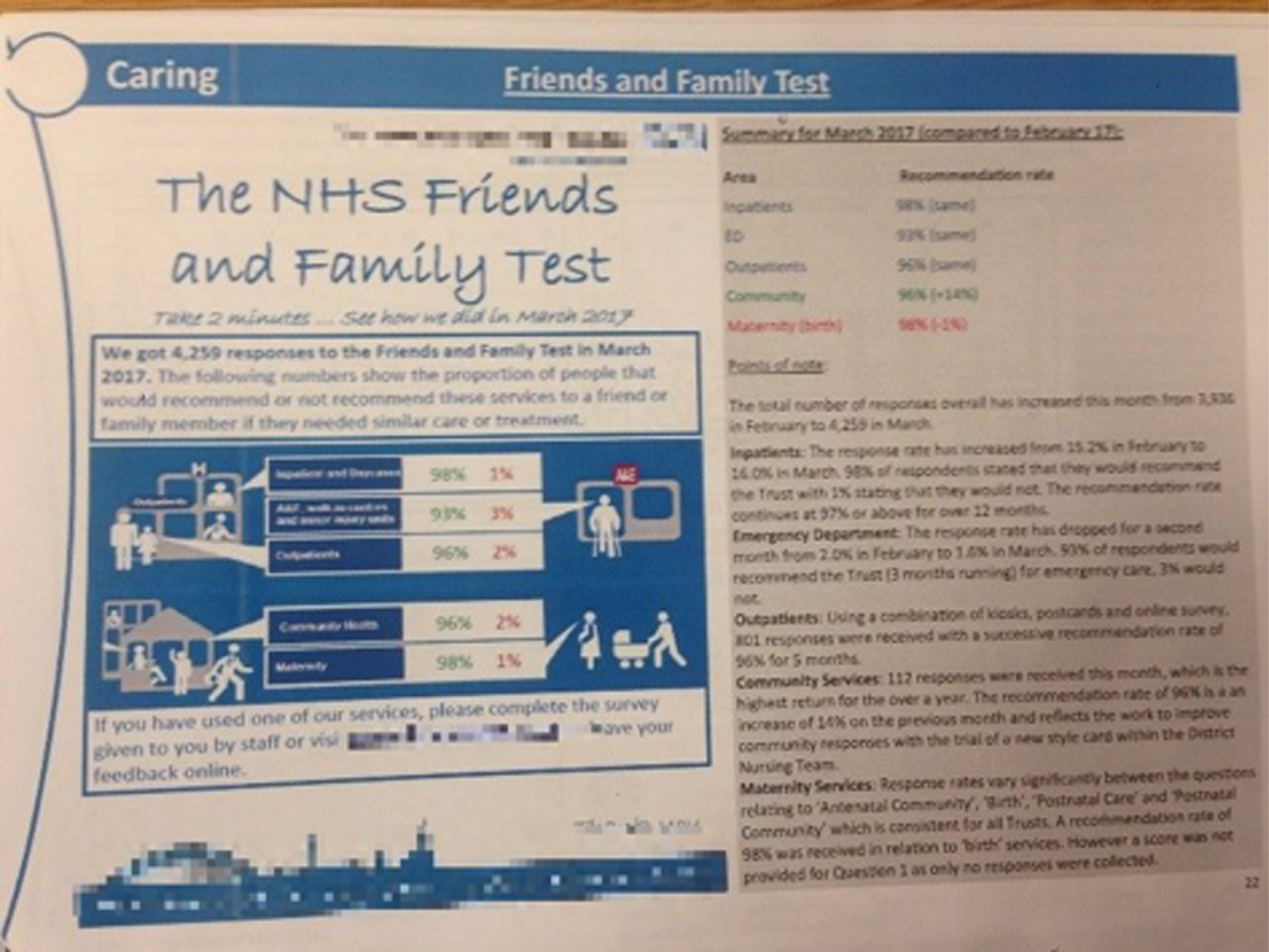

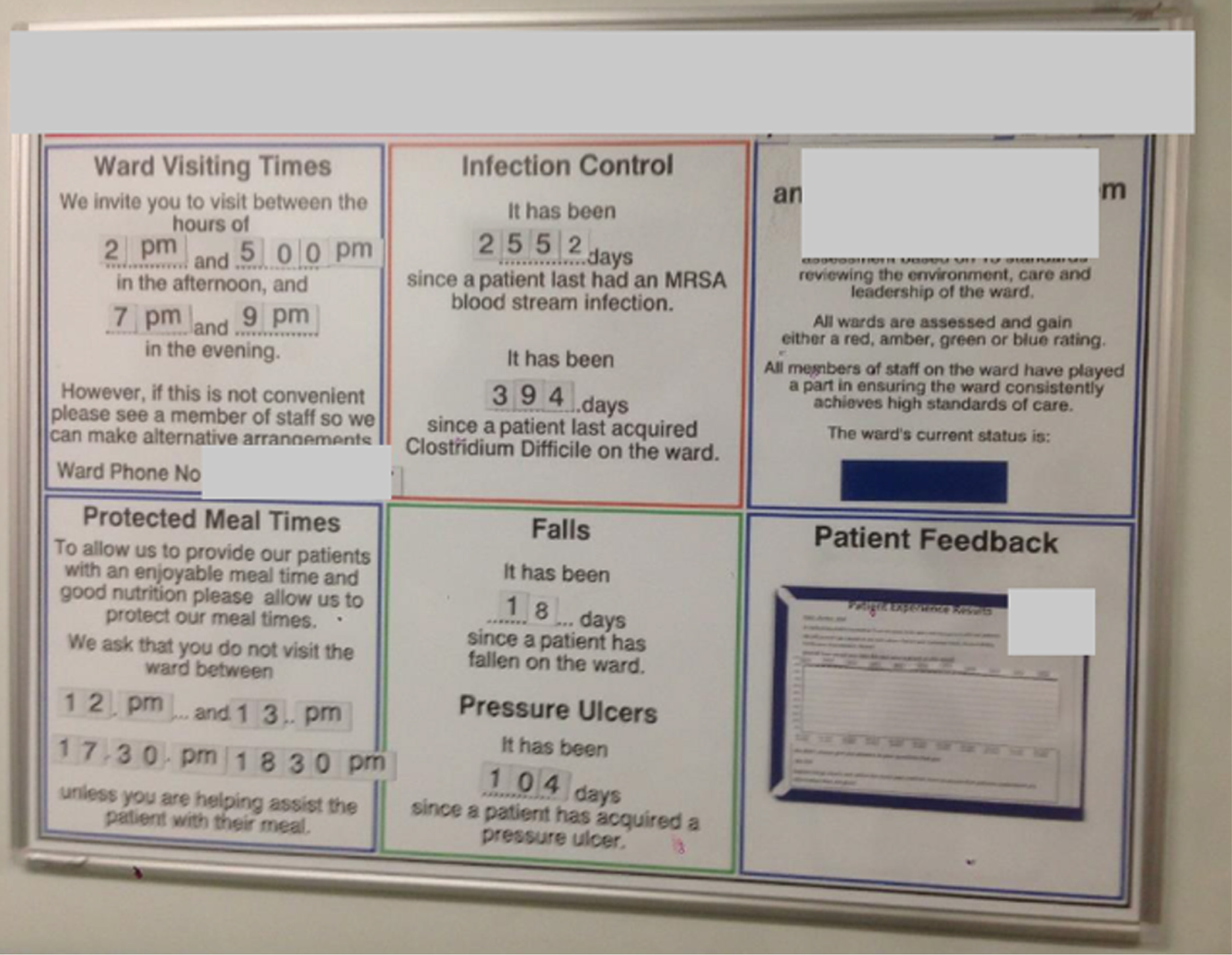

Patients’ and carers’ experiences of hospital care are an important aspect of health-care quality. Together with patient safety and clinical outcomes, they are considered one of the three fundamental elements contributing to quality of care, so much so that in 2013 NHS England appointed a director of patient experience (now director for experience, participation and equalities) and in 2018 NHS Improvement published a Patient Experience Improvement Framework1 to support NHS trusts to optimise their performance in relation to Care Quality Commission (CQC) standards. NHS trusts develop their formal strategies to monitor and improve experiences of care and collect data about patients’ experiences using a wide range of methods. These methods include detailed postal questionnaires (e.g. the national Adult Inpatient Survey2), much smaller sets of satisfaction-type questions [including the nationally required ‘Friends and Family Test’ (FFT)], patients giving formal and informal complaints and compliments, hand-held devices given to patients on wards to provide ‘real-time’ data, patient stories recorded through face-to-face interviews and feedback posted on patient/public websites (such as NHS Choices and Care Opinion). Such data are collected so that they can be used to fulfil a wide range of functions. These include identifying local quality improvement (QI) priorities, allowing organisations to benchmark their performance against that of their peers, communicating the results to the general public as part of wider engagement and transparency efforts and informing internal and external quality inspections and regulatory processes.

Previously published studies have examined the types of patient experience data currently in use in the NHS, the systems (or lack thereof) through which these data inform QI specifically, and the initiatives that are implemented as a result. 3–7 In 2012, a survey highlighted the main methods used to collect patient experience data, the frequency with which these data were collected, and the mechanisms through which they were reported and made available to the public. 8 Furthermore, an evidence scan in 2013 reviewed existing approaches to measuring patient experience and their relevance to person-centred care,9 and essential aspects of care experiences indicative of good care can be found in national clinical guidelines. 10

Developing and testing interventions

Research has highlighted that, despite the vast number of data that are collected about patients’ experiences, it is not clear if, and how, NHS organisations use these data to identify and implement improvements in health-care quality. In response to the widespread acknowledgement of the relative lack of improvement deriving from eliciting patient feedback on a large scale, recent years have seen the emergence of several initiatives to develop and test various ward- and service-level interventions in the NHS in terms of their impact on quality (encompassing patient experience as well as patient safety). 11,12 For example, feasibility testing, including a process evaluation, of the Patient Reporting and Action for a Safe Environment (PRASE)11 intervention found that ‘ward staff were positive about the use of patient feedback for service improvement and were able to use the feedback as a basis for action planning, although engagement with the process was variable’. 11 The researchers suggested that the ‘value of collecting evermore data is questionable without a change to the conditions under which staff find it difficult to respond’ to these data. 12 In the USA, Grob et al. 13 have developed and piloted a prototype method for rigorously eliciting narratives about patients’ experiences of clinical care that may be useful for both public reporting and QI. 13 A further applied research example is the ongoing Patient Experience and Reflective Learning (PEARL) study,14 which is seeking to promote reflective learning that links patient experience as directly and immediately as possible to both group and individual performance; the researchers are seeking to develop a theory-based framework of workplace-based reflective learning tools and processes, with the potential to be incorporated into national training programmes.

Despite the growing interest in studying and improving ways of gathering and using patient experience data, the existing evidence base has not often addressed questions around issues of responsibility and accountability for their collection and use. For example, to date, only anecdotal evidence exists as to the allocation of responsibilities for the patient experience strategy at the hospital level. 3,4 Furthermore, differences in strategic approaches to the use of patient experience data have not been examined, nor have the specific mechanisms through which such data translate (or not) into successful quality improvements. This is particularly problematic in view of the growing policy emphasis on the importance of improving patient experience as a core dimension of overall care quality.

In view of the evidence mentioned above, we have not, as stated in our study protocol, undertaken a systematic or scoping review of the literature. Related studies simultaneously commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme are conducting scoping or systematic reviews to examine what methods are potentially available to elicit patient experience data in the UK,15 to find out what is known regarding online feedback from patients,16 and to identify, describe and classify approaches to collecting and using patient experience data to improve inpatient mental health services in England. 17 However, to help contextualise the policy and practice implications arising from our study findings (see Conclusions and implications for policy, practice and research), and with regard to situating our study of the relationship between patient experience data and QI in relation to the contemporary literature, we highlight below three particular recent contributions: a viewpoint piece by Flott et al. ,18 a 5-year programme of research by Burt et al. 19 and an empirical study by Graham et al. 20 Each of these acknowledges that patient surveys, in multiple forms, continue to dominate the patient experience data landscape. We also discuss the different perspectives found in the work, for example of Ziewitz21 and Pflueger,22 to provide a fuller picture of the scholarly work relevant to the analysis of the impact of patient experience data. Finally, we offer a brief overview of the theoretical lenses and tools that inform our work, which we discuss further in Chapter 4.

Contemporary studies of the collection and use of patient experience data

Flott et al. 18 suggest eight ‘key challenges’ contributing to a disconnect between the collection and the use of patient survey feedback. As is common in the contemporary literature, these authors’ work focuses largely on the structural and technical features of the collection systems. 18 We summarise the eight ‘key challenges’ in Box 1.

-

Staff may show scepticism towards data, especially if they do not understand the conditions under which they were generated.

-

Clinical and managerial staff may not be trained in social research methods and so lack the skills to understand data.

-

Data garnered from large surveys can be complex to understand.

-

Patient feedback in national surveys are presented as aggregate data, which hinders local ownership.

-

Patient experience data are not often linked to other relevant data or other indicators of quality.

-

Different feedback mechanisms can lead to different messages about the quality of care; these disparate data are not often reconciled.

-

Guidance documents for national surveys are complex and require a high level of technical expertise within providers.

-

Providers may receive some or no external support to make sense of survey data and how to translate these into improvement; there is no consistency of support across providers.

In the light of these challenges, the authors propose how to enhance the use of patient-reported feedback. They advocate for methodological expertise and training (similar recommendations have been made in the specific contexts of both patient-reported experience measures23 and patient-reported outcome measures),24 the trialling of more dynamic collection methods (which the authors suggest does not necessarily mean new vehicles for collection, but rather enhancements to existing collections) and innovations applied to sampling. The authors note that ‘the underuse of patient-reported feedback is well documented’,18 but they argue that the complexity underlying this underuse had previously not been adequately illustrated.

Although our research focuses on acute NHS trusts only, many of the issues highlighted by Burt et al. 19 in their study of the measurement and improvement of patient experience in the primary care sector in England remain relevant. Among their conclusions was that large-scale postal surveys are likely to remain the dominant approach for gathering patient feedback in primary care for the time being, although a range of other methods are being developed [including real-time feedback, focus groups, online feedback, analyses of complaints, patient participation groups and social media]. In terms of using patient experience data for QI, the authors found that ‘broadly, staff in different primary care settings neither believed nor trusted patient surveys’19 for a range of reasons (doubts centred on the validity and reliability of surveys and about the probable representativeness of those who responded, as well as the fact that some practices had negative experiences, with pay linked to survey scores). In short, staff viewed surveys as necessary but not sufficient, and there were clear preferences for more qualitative feedback to supplement survey scores as this provided more actionable data on which to mount QI initiatives.

Following on from Burt et al. ’s19 research programme (which also included an exploratory trial of real-time feedback in a primary care setting), Graham et al. 20 conducted a study to develop and validate a survey of compassionate care for use in near real-time on elderly-care wards and accident and emergency (A&E) departments, as well as evaluating the effectiveness of the real-time feedback approach to improving relational aspects of care. 20 The study found a small but statistically significant improvement in relational aspects of care and that staff implemented a variety of improvements to enhance communication with patients. The authors made a series of recommendations for future research (summarised in Box 2) that relate not only to several of the other studies cited in this section but also to the findings and some of the implications of our own study detailed in Chapter 9.

-

Explore the impact of different styles of reporting formats, including graphics, as there is a need to find an optimal reporting format.

-

Understand the best channels for dissemination of results within trusts.

-

Understand the roles volunteers play in various activities at NHS trusts.

-

Understand the full costs and benefits of the approach to hospitals and the NHS.

-

Explore the acceptability of the survey instrument designed to measure relational aspects of care in different hospital settings and with other patient populations.

-

Consider whether or not existing instruments already used within the NHS could be adapted to include a greater focus on relational aspects of care and for use with a near real-time feedback approach.

We highlight the three contributions above at this early stage in our report as they provide an important counterpoint to the approach we have taken in our study. Although increasing attention to the most effective ways of collecting and using patient experience data to improve local services is to be welcomed, there is a tendency in the literature to reinforce points already acknowledged (e.g. regarding the limitations of surveys) or to make fairly unspecific calls for ‘more and better data’. The starting point for our study is, therefore, that a theoretically grounded and more nuanced perspective on what patient experience data are, what they do and what they might do may be of potentially greater benefit.

Different perspectives

We agree with Flott et al. ’s18 call for a better understanding of ‘how patients can facilitate the uptake of these methods (to make feedback more useful) and inform other, more innovative solutions to using their feedback’18. However, we are struck by the primarily technical nature of both the challenges and the proposals that are often suggested for addressing them. As we have written elsewhere, reflecting on the existing literature:3,18,22

. . . social science research has shown a striking lack of interest in critically reflecting on broader issues related to the nature of data, i.e. on the very value of collecting patient experience feedback in the first place. Indeed, there has been little investigation of the ontological reality of data . . .

Desai et al. 25

In parallel with more interventionist research studies (see Developing and testing interventions), there has also been a recent interest in making greater theoretical contributions to ‘patient experience’ as an important aspect of health-care QI work. For example, Ziewitz21 undertook an ethnographic study that is particularly relevant to our own research, as it asked ‘what does it take to mobilise experiences of care and make them useful for improving services?’21 His fieldwork focused on a UK-based patient feedback website (Care Opinion: www.care.opinion.org.uk; accessed 19 September 2019) and sought to ‘develop a critical perspective on patient experience as a contingent accomplishment and a focal point for eliciting, provoking, and respecifying relations of accountability’. He21 found that:

. . . capturing the patient experience is not so much a matter of accurate reporting . . . but rather an exercise in testing versions of reality through the ongoing respecification of objects, audiences, and identities.

Ziewitz21

Renedo et al. 26 have also used ethnographic fieldwork applied to patient-involvement initiatives in England to explore how health-care professionals articulate the relationship between patient experience and ‘evidence’, arguing that they create hybrid forms of knowledge that ‘help professionals to respond to workplace pressures by abstracting experiences from patients’ biographies, instrumentalising experiences and privileging “disembodied” forms of involvement’. 26

Pflueger,22 drawing on an empirical study in the NHS, highlighted how accounting (‘standardized measurement, public reporting, performance evaluation and managerial control’22) has become increasingly central to efforts to improve the quality of health care. However, he highlights the flaws in the common conceptualisation of the ‘problem of accounting as a matter primarily of uncovering or capturing information’22 and explains how this mistaken assumption can:

. . . produce systems of measurement and management that generate less rather than more information about quality, that provide representations of quality which are oriented away from the reality of practice on the front line, and that create an illusion of control while producing areas of unknowability.

Pflueger22

Pflueger’s22 central argument is that, although existing practices of accounting for quality have a variety of dysfunctional and even counter-productive effects, accounting is often ineffective, not because it is inherently incomparable with quality and the complexities of health care, but because its underlying characteristics have not been fully acknowledged or understood. He argues that there are three ways in which the ‘role of accounting for QI might be reimagined on more theoretically and empirically sound terms which is likely to provide the greatest potential for producing improvements’:22 (1) by being cautious towards the ‘ever more centralized, standardized and unified measures of quality’ by advocating the cultivation of ‘new, messy, overlapping, and always incomplete representations of quality’; (2) by carefully examining and evaluating ‘the sorts of activities, actions, behaviours, and consequences that result from knowing about quality through a particular style or set of concerns’ (i.e. the evaluation of accounting regimes in terms of what they do to practice); and (3) by thinking of quality management less in terms of ‘operating on the basis of numbers’ and more in terms of ‘operating around numbers, and using them to show not what is known but the boundaries of the unknown’. 22 Pflueger acknowledges that the new sorts of accounting systems he envisages will not create ‘illusions of certainty, accountability and control’, rather, they will highlight the limitations of all of these things. 22

Related to Pflueger’s work, two very recent studies27,28 start from the premise that ‘formal metrics for monitoring the quality and safety of healthcare have a valuable role, but may not, by themselves, yield full insight into the range of fallibilities in organizations’. These studies refer to ‘soft intelligence’, defined as the:

. . . processes and behaviours associated with seeking and interpreting soft data – of the kind that evade easy capture, straightforward classification and simple quantification – to produce forms of knowledge that can provide the basis for intervention.

Martin et al. 27

One of the two studies is based on interviews with senior leaders, including managers and clinicians, involved in health-care quality and safety in the NHS and illustrates how participants valued a softer form of data but struggled to access these and turn them into a useful form of ‘knowing’. 27 More specifically, the approaches participants used in the act of systematising the collection and interpretation of soft data (e.g. aggregation, triangulation) risked replicating the limitations of ‘hard’, quantitative data. As an alternative, the authors27 highlight the potential benefits, as do Renedo et al. 26 and Pflueger22, of seeking out and hearing multiple voices and how this is consistent with conceptual frameworks of organisational sense-making and dialogical understandings of knowledge. The second recent study28 was also based on interviews but involved personnel from three academic hospitals in two countries, and participants from a wide range of occupational and professional backgrounds, including senior leaders and those from the sharp end of care. 28 The authors found that the ‘legal and bureaucratic considerations that govern formal channels for the voicing of concerns may, perversely, inhibit staff from speaking up’28 and argued that those responsible for quality and safety should consider ‘complementing formal mechanisms with alternative, informal opportunities for listening to concerns’. 28

Actor–network theory

To bring similarly critical but different sensibilities to our own study, we adopted a methodological approach grounded in actor–network theory (ANT). 29–33 In doing so, we drew on the broader landscape of sociomaterial approaches to the study of organisational processes and health-care practices. 34–42 Although not a unitary theory, ANT provides a framework and tools that allowed us to pay attention to the ‘materiality’ of organisational activity and the inseparability of the technical and the social aspects in organisational practices. 43–45 In a recent paper,25 we have argued that research approaches to the study of patient experience data informed by ANT have the potential to make at least two contributions to current debates on health-care improvement. First, ANT perspectives and sensibilities emphasise the enacted nature of patient experience data and quality improvement:

. . . bringing to the fore the ways in which quality improvement emerges, or fails to emerge, as a result of a contingent series of interactions between various human (individual, institutional) and non-human actors (bureaucratic documents, policies, technologies, targets, etc.).

Desai et al. 25

Second, ANT sheds light on useful dimensions of organisational structure and functioning that might otherwise be overshadowed by more traditional perspectives that see data ‘as inert, open to infinite technical refinement in the service of quality improvement’25 (see Contemporary studies of the collection and use of patient experience data). When data travel in an organisation, transforming and translating as they travel (into reports, narratives, interventions, etc.), ‘it makes and reveals alternative organizational relations to those which are officially recognized’. 25 In the case of hospitals, which are formally hierarchical institutions with specific configurations of roles and responsibilities, paying attention to the interactions in which data become embedded:25,46,47

. . . may reveal alternative decision-making processes and may bring to the fore the role of certain actors (such as health care assistants or receptionists) who are conventionally marginal, but who nevertheless often come to play an unexpectedly central role in ensuring the quality of care.

Desai et al. 25

The flattened perspective afforded by ANT approaches, ‘which treats actors as equally important regardless of their assumed place in an institution,’ at the same time requires and ensures ‘that better attention is paid to alternative organizational arrangements as well as to forms of agency which would otherwise go undetected, including non-human agency’. 25

A widely recognised discrepancy exists between the proliferation of forms of patient experience data collection and the limited ways in which such data are used to inform QI. Our study is predicated on the basis that ANT allows us to shine a light on the interactions and negotiations between actors, keeping ‘the messy, everyday mechanics of improvement centre stage’. 25 Recent research has highlighted the value of paying attention to the role of artefacts, such as dashboards and real-time feedback devices (see sections Developing and testing interventions and Contemporary studies of the collection and use of patient experience data), in supporting the organisation of health-care work, with particular reference to QI. 48,49 Drawing on ANT and sociomaterial approaches to health-care practices, our study contributes to emerging understandings of the infrastructural context of QI work. 34 We describe in more detail how we drew on ANT and applied it to our questions relating to the collection and use of patient experience data for QI in Chapters 3 and 4.

Our study seeks to add to the existing scholarship and ongoing studies summarised above by examining in detail selected examples of current strategies and practices in English acute NHS trusts relating to the collection and use of patient experience data through the lens of ANT. By adding the further dimensions we described to the existing evidence on current strategies, our study moves beyond well-known ‘challenges’ (e.g. see Flott et al. 18 above) and generates a strong evidence base with clear implications for how to optimise organisational strategies and practices, including the roles and responsibilities of nurses, in the collection, validation and use of patient experience data.

Structure of the report

Having set the background and context for our study, including the theoretical lenses we chose to adopt, in Chapters 2 and 3 we describe the aims and objectives of the study and detail the study design (explaining any changes to the original research protocol) and the analytical processes that we used to make sense of our data. We then present three findings chapters.

In Chapter 5 we describe what counts as patient experience data in the participating NHS trusts and begin to explore the similarities and differences between practices at different trusts, the multiple nature of any given type of data, the extent to which some data practices appear to be more regular than others, and the variation we observed in the organisation of labour around patient experience work at different study sites.

In Chapter 6, we illustrate three essential points around what patient experience data do and how they do it: (1) how data can ‘act’ in different ways owing to their multiple forms, and how social actors develop strategies to compensate for flaws in data; (2) the key qualities that characterise interactions between social actors (be they people or organisational processes/external entities) and data when these data can clearly be seen to lead to care improvements; and (3) how the interaction between various human and non-human actors with standardised forms of data [e.g. the National Cancer Patient Experience Survey (NCPES)] produce unexpected outcomes that make the data more or less able to lead to quality improvement.

In Chapter 7, we take a step back from our direct observations of data practices in NHS trusts and illustrate the ways in which patient experience data work was re-examined and discussed in the light of our preliminary findings by representatives of participating trusts and policy-makers during our Joint Interpretive Forums (JIFs).

In Chapter 8, we summarise the relevance of our findings in the context of patient experience and quality improvement practices in the NHS and of the academic literature on health-care quality improvement.

Finally, in Chapter 9, we distil the implications of our findings for health-care policy, practice and research.

As recommended by our study’s Advisory Group, this report presents findings in a way that highlights the themes that cut across individual trusts’ cultures and contexts. As a result, it does not include detailed descriptions of the five individual organisational realities and challenges. Our aim was to suspend our reflections on (the more familiar aspects of) hierarchical structures, power relations and organisational cultures and instead to focus on the interactions and associations of human and non-human actors around patient experience work. This is one of the key innovative aspects of our study.

Chapter 2 Research objectives

The main aim of the study was to explore and enhance the organisational strategies and practices through which patient experience data are collected, interpreted and translated into quality improvements in acute NHS hospital trusts. The secondary aim was to understand and optimise the involvement and responsibilities of nurses in senior managerial and front-line roles with respect to such data.

Our objectives were to:

-

Identify suitable case-study organisations for our in-depth qualitative fieldwork. This was based on a sampling frame that drew on the CQC’s reporting of the national adult inpatient survey results and took into account the findings from the HSDR study by Locock et al. 50

-

Carry out an ANT-informed study of the journeys of patient experience data situated within two clinical services (cancer and dementia care) in each of our case-study sites. This aimed to explore the origins of these data, what these data do and how they interact with human actors to ultimately influence, and/or translate into, quality improvements.

-

Distil generalisable principles that may facilitate the journeys of patient experience data to quality improvements in acute NHS hospitals.

-

Develop practical recommendations and actionable guidance for acute NHS hospital trusts that will optimise their use of patient experience data for quality improvement. This was carried out together with stakeholders from the case-study sites (including patients and carers), national policy-makers and representatives from patient organisations.

Chapter 3 Methodologies and changes to the protocol

The study was organised in two overlapping phases. Phase 1 (February 2016–January 2018) comprised the majority of the ethnographic fieldwork within the five participating NHS trusts. Phase 2 (January–May 2018) included the sense-making workshops modelled on JIFs51 that were held first in London in January 2018 (with representatives from all five trusts and policy-makers) and then at each of the individual trusts (February–May 2018).

Phase 1

The ethnographic fieldwork drew on ANT-inspired approaches for the study of organisational processes. We carried out interviews, observations and documentary analyses at five acute NHS hospital trusts in England over a 13-month period. To identify potential participating trusts, we constructed a sampling frame based on the following:

-

acute trusts’ scores on section 10 of the national inpatient experience 2014 survey as reported online by the CQC (see the CQC website2 for the latest survey results available)

-

preliminary findings from a national survey undertaken as part of another NIHR study led by Professor Louise Locock under the same funding call50

-

trusts’ characteristics, including geographical location, size and willingness to participate.

We reviewed questions 67–70 of section 10 of the survey (‘overall views and experiences’ section). These questions asked patients to indicate whether or not they felt that they were treated with respect and dignity; to rate their experience of care on a numeric scale; to report whether or not they had been asked about their experience of care; and to report whether or not they had been given information about how to complain.

We then grouped trusts according to whether they were performing ‘better than others’ on one or more dimensions of ‘overall views and experiences’, performing ‘about the same as others’ on all four dimensions of ‘overall views and experiences’ or performing ‘worse than others’ on one or more dimensions of ‘overall views and experiences’ (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Classification of acute NHS hospital trusts for sampling purposes.

We then excluded trusts that had already been approached by Professor Locock’s team to be recruited to the main part of her study, because participating in additional research would have constituted an excessive burden. When approaching trusts, we considered information from Professor Locock’s study about whether trusts were collecting patient experience data from patients with cancer and/or patients with dementia.

We originally aimed to recruit a total of four sites: two from the ‘performing about the same as others’ group and one from each of the ‘performing better than others’ and ‘performing worse than others’ groups. However, none of the five eligible trusts from the ‘performing worse than others’ group could be included in the final sample because two trusts declined to take part and three failed to respond. For the other two groups, we held preliminary meetings with five trusts that had expressed interest in our study in response to e-mail invitations. Following these meetings, at which all trusts showed considerable commitment, we decided to carry out fieldwork at all five sites to increase the theoretical generalisability of our findings for relatively little additional cost (NIHR approval to this change was obtained in August 2016). Our final sample included two trusts from the ‘performing better than others’ group and three trusts from the ‘performing about the same as others’ group for section 10 of the national inpatient experience survey. These trusts are located in different areas of England and represent a range of sizes (see Table 3).

Our observations and interviews in each of the five trusts focused on patient experience work in three broad areas: at the trust level, in cancer care and in dementia care. Three researchers carried out fieldwork at the five trusts, visiting them for meetings, informal conversations, observations and formal individual interviews (Table 1).

| Trust | Visits (n) | Days of fieldwork | Number of interviews | Participants for each |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 24 | 25 | 12 | 9 staff, 3 patients/carers and/or governors |

| B | 9 | 20 | 12 | 10 staff, 2 patients/carers and/or governors |

| C | 7 | 27.5 | 15 | 13 staff, 2 patients/carers and/or governors |

| D | 11 | 24 | 11 | 10 staff, 1 patient/carer and/or governor |

| E | 6 | 20 | 15 | 11 staff, 4 patients/carers and/or governors |

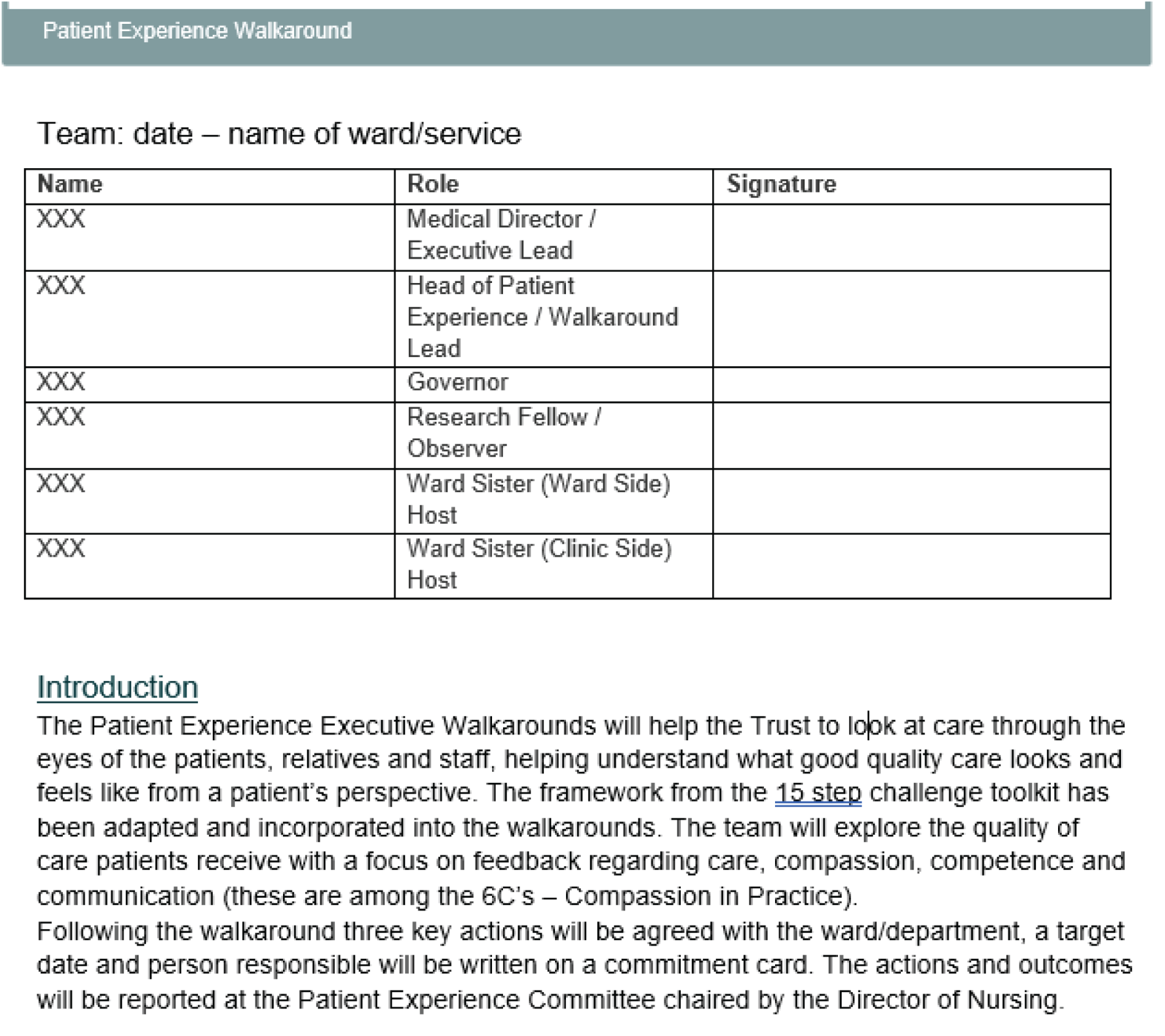

At the trust level, some of our fieldwork was focused on observing and talking to those with responsibility for patient experience data, such as members of patient experience teams (where these teams existed),as well as senior trust staff (e.g. heads of patient experience, directors of nursing) with responsibility for patient experience. We spent time in patient experience offices, observing the collection, processing, analysis and communication of feedback. We also observed patient experience committee meetings, quality committee meetings, trust board meetings, governors’ meetings on patient experience, meetings relating to complaints and trust-wide nursing meetings such as Matrons’ Forums. We also accompanied governors and/or trust directors and other senior staff on ‘walkarounds’ and observed ward accreditation or assessment processes.

As outlined in our protocol, we selected dementia care and cancer care services because their similarities (a high number of patients; inpatients admitted to different wards in the hospital; the crucial role of carers) as well as their differences (long-standing use of well-established formats for patient experience data in the area of cancer care, in contrast to the challenges of documenting patient experience in the context of care in the area of dementia) would allow us to draw useful comparisons.

Both cancer services and dementia services at the participating trusts did not constitute whole, discrete environments but rather a set of care and administrative practices distributed across wards, clinics, departments and divisions. However, at all trusts, cancer services existed as an administrative unit responsible for conducting audits and surveys and managing compliance with nationally mandated targets and quality standards, whereas dementia services did not. We grew to know cancer and dementia lead nurses and clinical nurse specialists (CNSs), as well as ward managers of wards to which cancer patients or patients with dementia were often admitted (e.g. surgical wards for the former; care of the elderly wards for the latter). We also observed cancer CNS team meetings, ward manager/senior sister meetings and dementia committee/steering group meetings. We also interviewed and talked to cancer managers and administrative staff from ‘cancer services’ and observed their meetings at which patient experience data were discussed.

Although our study was largely focused on trust staff and organisational practices, we also interviewed patients, carers and former patients and observed trust-sponsored meetings of patients, carers or former patients at which patient experience data were presented and discussed. Our observations and conversations with key informants at the trusts aimed to clarify what types of patient experience data were being generated and used within the organisations. We considered a variety of artefacts conveying patient experience information, paying attention to the interactive contexts (e.g. meetings, conversations, reports) in which they were deployed. At all trusts, we paid significant attention to the modes of generation, processing, interpretation and use of the FFT, CQC national Adult Inpatient Survey2 and the NCPES data as these were the formats that offered opportunities for comparison across all trusts in our study. We also paid particular attention to data formats that were specific to an individual trust or had different prominence in different organisations, prioritising the links they provided to QI work within a particular organisation. The researchers took detailed handwritten notes during observations and interviews, which were then typed or written up into detailed field notes very soon after. We also viewed and/or collected documentary evidence, including steering group/committee meeting minutes and agendas, patient experience/quality strategies, patient experience executive ‘walkaround’ forms, patient-story booklets and board meeting minutes and agendas. For phase 1 we also carried out individual semistructured interviews with 65 participants. These formal interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis. A breakdown of the interviewees’ characteristics is presented in Table 1. We selected potential participants for one-to-one semistructured interviews on the basis of our observations and their involvement with patient experience data. Transcripts were anonymised at the point of transcription and assigned a composite numeric identifier.

Phase 2

In phase 2, we carried out a series of multistakeholder workshops in the format of a JIF: a type of group discussion aimed at encouraging ‘perspective taking’ and joint decision-making. 51 We organised six JIFs in total: one cross-site JIF in London (January 2018), which brought together key participants from each of the five study sites and policy-makers from NHS England and other organisations, and five local JIFs at each study site (February–May 2018), which a range of trust staff attended. Although in our original proposal we had envisaged the local workshops taking place prior to the cross-site JIF in London, in the course of the study we determined that it would be more fruitful to reverse the sequence and enable cross-site exchange and comparison prior to holding in-depth discussions of what learning could be extracted from our data analysis for each specific site. Our fieldwork at participating trusts highlighted that members of staff at all trusts were eager to learn about other participants and the detail of their patient experience data work. This led us to consider whether or not early sharing of thoughts and experiences across trusts would make for richer discussions during the local trust-based workshops, allowing for reflection on how different practices may or may not be implemented within local contexts and constraints.

Cross-site Joint Interpretive Forum in London

Our first workshop was held in London in January 2018 and was attended by representatives from all five trusts and five policy-makers as well as five members of the research team and a researcher colleague who took detailed notes of the workshop’s proceedings. This 4-hour workshop aimed to allow participants to share information about the patient experience practices at their trust, to enable discussion of the key issues in patient experience work (elicited with the aid of four deliberately provocative statements prepared by the research team on the basis of our emerging findings), and to provide a space for the presentation and discussion of preliminary findings from the study and their potential implications for policy and practice.

The cross-site JIF comprised four inter-related activities, organised around a structure carefully planned to maximise participation and dialogue. These activities were:

-

poster walk

-

provocations activity

-

presentation of emerging themes from our fieldwork

-

discussion of implications for the trust(s).

We detail each of these in turn.

Poster walk

An objective of the cross-site JIF was to provide an opportunity for study sites to learn about each other’s patient experience data practices and organisation. Until then, study sites had been kept anonymous from each other and trust staff were keen to learn the identities of participating trusts. We determined that asking each trust to present this information themselves at the workshop would be passive, time-consuming and subject to variation in quality and format. Rather, we wanted participants to be actively engaged for most of the workshop. Therefore, we decided to present key information about patient experience data at each of the trusts by way of five posters, one for each study site, which participants were asked to read and comment on using sticky notes. The notes allowed the research team and JIF participants to gauge what participants found interesting about each study site trust’s activities. The research team designed the posters, which were printed on A0-size paper. Each poster consisted of the same following four elements:

-

basic information about the trust – the trust name, a brief 50-word description of the trust, the number of staff and beds, the trust location on a map of England and CQC ratings (‘Overall’ and ‘Caring’ categories)

-

a description of the composition and reporting lines of the ‘patient experience team’

-

‘Talking Points’, which mentioned a noteworthy aspect of patient experience data work in each of three different areas: trust-wide, cancer and dementia (Table 2)

-

photographs of aspects of patient experience data work (e.g. FFT cards and visualisations).

| Talking points | ||

|---|---|---|

| Trust-wide | Cancer care | Dementia care |

| The trust is committed to using experience narratives in both written and filmed form to improve the quality of care via staff education programmes | CNSs have a fundamental role in implementing the action plans that stem from the results of the NCPES | The views and experiences of carers of patients living with dementia are documented by the carers’ survey administered on the wards or via telephone by volunteers |

| New requirements from the CCG have enabled trust staff to transform how patient experience data are reported on and used | The lead cancer nurse is mobilising the NCPES results to expand the forums and types of people (e.g. medical staff, patients) involved in producing action plans | The trust relies on a committed key volunteer to collect feedback from carers of patients with dementia |

| The trust has implemented initiatives to actively solicit feedback from patients and their families through PALS clinics. One effect has been to reduce the number open PALS enquiries and formal complaints | Tumour-specific CNS teams have partnered with patients in order to produce more tailored action in response to the results of the NCPES | Dementia-specific patient experience data collated by the trust is limited; a multiprofessional Dementia Steering Group relies on input from carer representatives, staff carers and the Alzheimer’s Society in developing quality initiatives to improve the experiences of people with dementia |

| The main vehicle to ensure that patient feedback is acted on by front-line staff is a long-running ward assessment and accreditation system that is run by a dedicated senior nurse and actively involves executive and non-executive directors of the trust | CNSs embed understanding patient experience and acting on feedback in their working practices and professional development and often know how to use governance structures to promote discussion of the patient experience work that they do | Acting on patient and carer experience data happens locally at wards or services and best practice is showcased through the division-specific learning sessions and the ward accreditation scheme |

| The trust has a sophisticated system for monitoring and learning from complaints that involves executive and non-executive directors through a standing committee of the board | The lead cancer nurse and her colleagues have used the NCPES to substantially improve the Macmillan Cancer Support and Information Centre | A dedicated ‘dementia team’ of nurses hold clinics and activities that enable them to know individual patients and carers. They rely less on formal feedback mechanisms |

The elements of the poster were produced from data collected from fieldwork. Posters are not included in the report to maintain participating trusts’ anonymity (see Appendix 5 for a ‘mock’ poster).

Provocations activity

The second activity consisted of small group discussions of four ‘provocations’. These were statements designed to spark debate among JIF participants. They were formulated on the basis of reflections on fieldwork by the research team during a meeting dedicated to the planning of JIFs, and the wording was subsequently refined by the researchers on the team to ensure maximum impact. The four provocations were as follows:

-

National surveys are used to benchmark rather than improve the quality of care.

-

The NHS would lose little if the FFT were abolished tomorrow.

-

It is easier to improve the experience of patients with cancer than that of patients with dementia.

-

Patient experience data do not need to be everybody’s business.

Participants were purposefully divided into four mixed groups, each of which contained members from different trusts and at least one policy-maker. These mixed groups were designed to encourage the sharing of knowledge and perspectives. Groups discussed each provocation for 10 minutes, with a short plenary session after each round in order to hear feedback from each group. Members of the research team assigned themselves to groups in order to pose questions and guide discussion if the group seemed to be straying from the statement under consideration. One purpose of the poster walk and provocations activities was to help participants engage with the study context and each other’s perspectives on patient experience before hearing from the research team directly about emerging themes from the fieldwork. This aimed to encourage active participation.

Presentation of emerging themes from fieldwork

The research team presented emerging themes from the fieldwork. The emerging themes were produced through discussions among the research team over several meetings in December 2017 and January 2018. We were committed to checking that our emerging research findings were relevant to trusts before drafting our report. The purpose of the presentation (and of the JIF as a whole) was to test whether or not the kinds of analysis and ideas we were producing, and which we considered valuable, would be of interest to study site trusts, and whether or not they would be able to act to refashion practice and policy on the basis of our project report. We provide more detail on the content of the presentation and the discussion around it in Chapter 7.

Discussion of implications for the trusts

Following our presentation, we asked participants to re-group with their own trust colleagues; policy-makers from NHS England, NHS Improvement and the Point of Care Foundation formed a group of their own. We asked participants to consider the implications of the presentation and workshop as a whole for their own trust or area of policy work. This was a 30-minute activity and each group was joined by a member of the research team. At the end of the activity, we called on groups to share their thoughts on implications in a plenary session. At the end of the event, the research team asked for oral feedback from participants on the JIF (e.g. what worked well, what could be improved) and for preliminary thoughts on whether or not similar activities would be suitable at each of the JIFs to be held at the study sites.

Local trust-based Joint Interpretive Forums

Following the London JIF, we discussed with each of our key contacts at the study sites the structure and content of JIFs to be held at each trust. Our contacts, who themselves had attended the London JIF, reported that they wanted to replicate the same structure and content for staff at their trust with certain local modifications: some of these were requested by trusts, others were the result of time constraints. All contacts were involved in planning the JIFs. Some trusts contributed additional statements for the provocation activity. The JIFs at trusts followed the same basic structure of four linked activities as outlined in the previous section.

Our key collaborators at each trust were central to organising the JIFs. At all trusts, they booked rooms, issued invitations to participants and organised catering. These collaborators, in varying degrees, also co-chaired the workshop, asked questions of participants, took notes and summarised proposals for change in trust practice. Participants for the JIF workshops were purposively selected, in collaboration with trust staff, on the basis of their role in the organisation, participation in earlier phases of the study and their willingness and availability to participate (see Table 6). The group discussions at the JIFs were captured in field notes taken immediately after the event and included in the study data set.

Patient and public involvement

Independent consultant and patient and public involvement (PPI) advisor Christine Chapman contributed to the development of the study design and the PPI strategy for the project. She offered detailed feedback on draft versions of both the outline and full application, in particular with regard to the language and style of the Plain English summary; the importance of online platforms and social media in the sharing of patient experiences of care; due attention to the role of patients’ carers; and the inclusion of patients and patient organisations in the dissemination strategy. A few months into the study, Christine Chapman became unable to continue in her role and was replaced by PPI advisor Sally Brearley. Throughout the study, Sally Brearley took part in team and Advisory Group meetings, reviewed and commented on early drafts of the final report, and provided particular input into the production of the Plain English summary and of the video animation summarising some of our key findings for non-academic audiences.

In designing the study, we had one-to-one conversations with two carers of people with dementia and an advisory meeting with two users of cancer services. Following these, we refined our fieldwork strategy to ensure that issues of mental capacity were duly taken into account and increased the time for patient advisor input (the PPI budget). Two patient and PPI advisors were members of the Study Advisory Group. They took part in Advisory Group meetings and contributed to steering the research process via these meetings. They also provided detailed feedback on draft versions of the video animation.

In phase 2 of the study, for the cross-site and trust-based JIFs, we aimed to involve patient and/or carer representatives. We consider participation in these meetings a PPI activity, in that preliminary study findings were discussed and recommendations for policy and practice were outlined. Dissemination activities have taken place at all participating trusts following study completion. Whenever possible, we have involved patient representatives in these events, especially those with a specific interest in patient experience work.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained in August 2016 from the London Bridge Research Ethics Committee (Integrated Research Application System identification number 18882). Health Research Authority approval was granted in October 2016 and individual trust research and development (R&D) approvals were secured between November 2016 and January 2017.

Changes to protocol

Versions 2 (July 2016) and 3 (December 2016) of the protocol reflected changes in the number and composition of study sites: the increase from four to five study sites, two of which were performing ‘better than’ others and three the ‘same as’ others according to section 10 of the CQC report (details of why we could not recruit a trust performing ‘worse than’ others were provided and approved by NIHR before updating the protocol). In version 4 (March 2017), the total number of planned interviews was amended to reflect the number indicated in our ethics application, which allowed for up to 16 interviews per trust rather than the 12 originally planned. Version 5 (March 2018) reflected the change in the sequence of JIFs, with the cross-site JIF in London taking place before the individual JIFs at the five participating sites.

Chapter 4 Modes of analysis

Text data included documents collected at the participating trusts (such as agendas and minutes from steering groups, committees, and board meetings; patient-story booklets; walkaround forms; and trust-specific questionnaires), transcripts of audio-recorded interviews and of dictated notes from interviews that were not recorded, field notes from informal conversations and observations. We also took photographs that we felt captured important aspects of patient experience data collection and processing and used these to support our analysis of text data. Our analysis was based on a combination of re-examination of our textual data (re-reading notes and transcripts, producing memos and reflective notes, and open coding, mostly manual) and discussion, in groups of different sizes, of observations and reflections on field visits. By this, we mean that the analysis proceeded through individual work as much as through discussion of emerging themes and ideas. Two of the researchers on the team (AD and GZ) carried out fieldwork at four of the five sites. They shared an office and, therefore, had the opportunity to share views and nascent analytical threads as these emerged. They had regular meetings (every 2–3 weeks depending on fieldwork commitments) with the researcher (Dr Mary Adams first and SD after her return from maternity leave) who carried out fieldwork at the fifth trust. These regular meetings allowed for discussion of the practices observed and the conversations had at the NHS trusts. In our analysis, we relied on a mix of trust documents, interview transcripts and field notes; our guiding principle was our commitment to grounding our analytical themes in the evidence available and the active search for disproving examples that weakened a particular line of argument. Larger meetings (1–1.5 days’ duration) with the whole research team were also held (five meetings between January 2017 and March 2018) to discuss emerging themes and potentially useful analytical and reporting approaches.

Our principal mode of analysis was informed by ANT, developed by Bruno Latour, Michel Callon and John Law as part of Science and Technology Studies during the 1980s, which has taken in several directions since it has been included in the study of health care and health organisations. 29–33 Although it carries ‘theory’ in its name, ANT is better understood as a range of methods for conducting research, which aims to describe the connections that link together humans and non-humans (e.g. objects, technologies, policies and ideas). In particular, ANT seeks to describe how these connections come to be formed, what holds them together and what they produce.

In ANT the systems of interaction and mutual influence between people and ‘things’, humans and non-humans, are called actor–networks. In an ANT framework, actors (e.g. nurses in charge of collecting patient experience data) are able to act and to generate effects in the world only through interacting with other entities (e.g. the questionnaires used to collect data, the organisational reporting lines they are required to follow, the targets that they need to meet). In addition, in an ANT framework, and following Latour’s terminology,52 we can see different types of data as ‘actants’, which is to say ‘entities that are endowed with the potential to produce change in, and in turn to be transformed by, the course of action of other actors’. 25

As a family of approaches rather than a unitary theory, ANT provides a framework and tools that allow us to pay attention to the ‘materiality’ of organisational activity and the inseparability of the technical and the social in organisational practices. 43–45 Working with ANT tools means subscribing to the ‘notion that everything that exists in the world is the outcome of an interaction between two or more entities (be they human and/or non-human)’ and, therefore, being interested in examining very closely the connections between humans and non-humans. 25 It is with this sensibility that we approached the analysis (as well as collection) of our data. In practice, ‘doing’ ANT-informed research means that analysis is not, and cannot, be separated from fieldwork; ANT does not recognise essentialisms. This is one of the challenges of thinking with ANT. However, from our experience, using a sensibility commensurate with ANT is fruitful for thinking about patient experience data in innovative ways that can still produce actionable guidance for health-care organisations.

Three interlinked ideas follow from this basic statement about the primacy of relations between actors (or actants) in ANT. These ideas ask us not to make certain assumptions in the collection and analysis of our data. The first is that, because everything is the outcome of a relation, including the form and characteristics that an entity takes, the distinction between humans and non-humans is less important than the qualities of entities that are produced through a particular interaction. Thus, in looking at research data, we have foregrounded the qualities of entities (whether or not they can act, whether or not they have effects, whether or not they structure organisational practices) that emerge through relations rather than assume that those qualities are inherent in people or things themselves.

The second idea is that if relations and interactions are key to how entities achieve their qualities, then an ANT analysis would need to recognise, describe and account for these interactions. In doing so, it should also pay equal attention to human and non-human actors as the latter can, and do, have similar qualities (as a product of interactions) to the former. As we mentioned earlier, in the case of patient experience, exploring the enactment of data means moving beyond analyses that see patient experience data as inert, stable entities, open to technical manipulation and refinement. It means approaching the research data by asking the following question: in what circumstances do patient experience data in relation to other actors make quality improvement possible? By noting, describing and analysing these interactions, we can understand how relations around patient experience data are continuously produced and to what effect. Paying attention to the enactment of patient experience data (and looking at qualities emerging in interactions rather than specific identities) also has the corollary of providing possible alternative visions of hospital organisation, for instance the role of actors who may be usually considered marginal but can be central in ensuring improvements in care.

Finally, the third idea that guided our mode of analysis is that we do not make assumptions about the presumed power, size and influence of actors. For example, we do not assume that patient experience data presented at a trust board meeting are ‘more important’ or ‘more authoritative’ than data presented at a ward sisters’ meeting; their qualities emerge through particular interactions. We conducted our analysis by adopting this ‘flattened’ perspective, which treats actors as equally important regardless of their assumed place in an institution. This is not to say that our analysis neglects issues of power in hospital organisation; rather, it examines how particular interactions produce power as a quality of entities, whether human or non-human.

In practice, these three ideas meant that we aimed to focus on identifying what people operating within the participating trusts identified as patient experience data, observing the forms these data took, if/how they moved, whether or not and how they changed form, and the interactions of which they were part (i.e. in which ways data recruited and were recruited into more or less stable relationships by human and non-human actors). By observing practices and having several conversations with key informants at the trusts, we built rich descriptions of the ways in which different elements of patient experience data work came together, showed identifiable patterns and/or moved across the organisation. In the ways discussed above (individual analysis and group discussions), we examined our descriptions for each trust and compared practices and patterns for the three main areas of focus (trust-wide patient experience data work, work within cancer care and the care for people living with dementia) both within each trust and across trusts. The findings emerging from these comparisons were used to structure and feed into the JIFs of phase 2 (sense-making phase) of the study. These took the forms of workshops and they constituted further data but they were also part of the analytical process as well as contributing to the local impact at participating organisations. Given their significance in the analytical thinking for this study, we describe them in detail in Chapter 7.

The analysis of the research data deriving from the JIFs was somewhat different. As several members attended the cross-site JIF, we took notes of the discussions taking place in the table groups as well as in the larger group. Local trust-based JIFs were facilitated by one researcher, which meant that notes were written down immediately after the event. Our plan was to analyse notes from all JIFs thematically, with the aim of distilling practical and generalisable principles for enhancing the use of patient experience data for quality improvement. However, as a result of the delays in R&D approvals at the beginning of the study and the reduction in team capacity owing to maternity leave, the local trust-based JIFs had to be held towards the very end of the study (February–May 2018). In view of this, we found it more useful and practically relevant to discuss our notes and impressions from the trust-based JIFs in face-to-face meetings (involving AD, SD and GR). Therefore, notes from the JIFs were analysed for themes, but no systematic coding was carried out.

Chapter 5 Findings 1: what counts as patient experience data and who deals with them?

In this section, we begin to present the findings from our data analysis. After a very brief description of the five participating trusts, we explore what counts as patient experience data and who works with them. We do so by looking at (1) the variety of entities that constitute patient experience data as well as the multiple ‘versions’ into which each type of data transform as it is collected, analysed, interpreted and used to guide practice; (2) the varying degrees of regularity that characterise the processes of collection, analysis, interpretation and use of data; and (3) the nature and composition of patient experience teams at the study sites and the different ways in which these teams (or the lack thereof) affected the practicalities of data work at the sites. The characterisation of data and data practices provided in this section will constitute the basis for exploring how data are interacted with in Chapter 6.

As detailed in Chapter 3, we carried out our fieldwork at five acute NHS hospital trusts with a specific focus on cancer and dementia care. We assigned each trust a letter (A, B, C, D and E) and gathered detailed information regarding how each organisation operated, what their internal structure looked like, what areas they served, their capacity, their staffing and their main organisational strengths and pressures. In this report, we deliberately refrain from providing too detailed a picture of each trust. This is because (1) we wish to maintain confidentiality wherever possible; (2) we want to keep our focus on the observation of practices and interactions; and (3) we follow our Advisory Group’s recommendation that we organise our report findings by theme rather than by site. In keeping with our ANT-informed approach, we draw attention to the actors and interactions at hand as we describe in detail the characteristics of these interactions, the actors’ transformations and the effects of both. In Table 3, we summarise some of the key features of the five trusts in our study. These provide a sense of the variation in the organisational arrangements encountered; therefore we do not discuss them in the text. Rather than building individual trust profiles, we draw attention to the similarities and differences of these trusts and the reasons why any of these similarities or differences might appear significant to us.

| Feature | Trust | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | |

| Approximate number of beds and staff |

Beds: 750 Staff: 5000 |

Beds: 450 Staff: 4500 |

Beds: 1000 Staff: 7100 |

Beds: 950 Staff: 7000 |

Beds: 2300 Staff: 14,500 |

| Foundation trust | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Is there a formally designated ‘patient experience’ team? |

Yes 2 patient experience facilitators 1 data entry analyst |

No PALS staff carry out some patient experience functions |

Yes 1 patient experience manager 1 complaints and PALS manager 6 patient experience staff members 4 PALS officers 2 formal complaints officers |

No A team of professionals at corporate level (i.e. lead nurse for corporate services, corporate matron, quality improvement team, assistant director of service user experience) overviews the integration of patient experience work in the trust |

Yes 1 head of patient experience 1 patient experience and involvement officer 1 information analyst 1 equality and diversity lead 1 patient relations service manager Several complaints resolution and investigation officers (plus complaints administrator and secretaries) Administrative and clerical support |

| Board-level responsibility for patient experience | Director of nursing | Director of nursing | Director of nursing | Director of nursing | Nursing and patient services director |

| Report to trust board | YesBoard meeting opens with a patient story and a patient experience standing item on (1) formal complaints (2) local patient survey and (3) FFT results | YesAs part of quality report (patient experience section written by head of PALS); chief nurse presents FFT results (without open comments) and a patient story/film/NHS Choices extract or audio clip is presented | YesBoard meeting opens with patient story Patient experience part of ‘Integrated Performance Report’ (which is informed by ‘Safety and Quality Committee’ and report – see below) | YesMonthly integrated performance dashboard has three dashboards dedicated to patient experience. In addition, 6-monthly patient experience report goes directly to the board | YesHead of patient experience presents a quarterly patient experience report to the board |

| Links between patient experience and QI | Patient and staff experience committee reports to the quality assurance and learning committee (consider FFT, local survey, complaints) | Head of PALS reports to improvement programme manager, presents FFT data, comments data and complaints data to the patient quality committee, and writes the patient experience section of quality report | Patient experience and QI come together at quality governance and learning group (where the reports that each team produce are discussed to avoid misinterpretations before being collated into a single ‘Safety and Quality Committee’ report) | Through the quality and patient experience committee, ward accreditation process, and patient, family and carer experience steering group, also at divisional and clinical governance | Patient experience steering group (reports to clinical governance and quality committee) includes head of patient experience and director of quality and effectiveness. Patient are safety and quality review panels are chaired by the medical director |

As expected, in line with the existing literature on patient experience data discussed earlier, each of the trusts taking part in our study collected a vast number of patient experience data in various formats. Table 4 summaries the data formats we became aware of during our fieldwork (this is not intended to be an exhaustive list).

| Trusts | Type of patient experience data collected |

|---|---|

| All trusts (mandatory) | FFT53 |

| NCPES54 | |

| Formal complaints | |

| National Patient Experience Survey Programme2 (not strictly mandatory but relevant to CQC inspection) | |

| All trusts | Informal complaints (e.g. ‘concerns’) |

| Compliments (e.g. letters, thank-you cards, e-mails) | |

| Data feeding into Cancer Services Peer Review | |

| Patient stories (written and/or filmed and/or presented in person) | |

| Local tumour-specific cancer patient experience surveys | |

| National Dementia Audit Carers’ survey55 | |

| Online feedback | |

| Executive, non-executive or governor ‘walkarounds’ | |

| Bereavement support feedback | |

| Patient-Led Assessments of the Care Environment | |

| Some trusts | Local carers’ survey (dementia) |

| Trust bespoke inpatient survey |

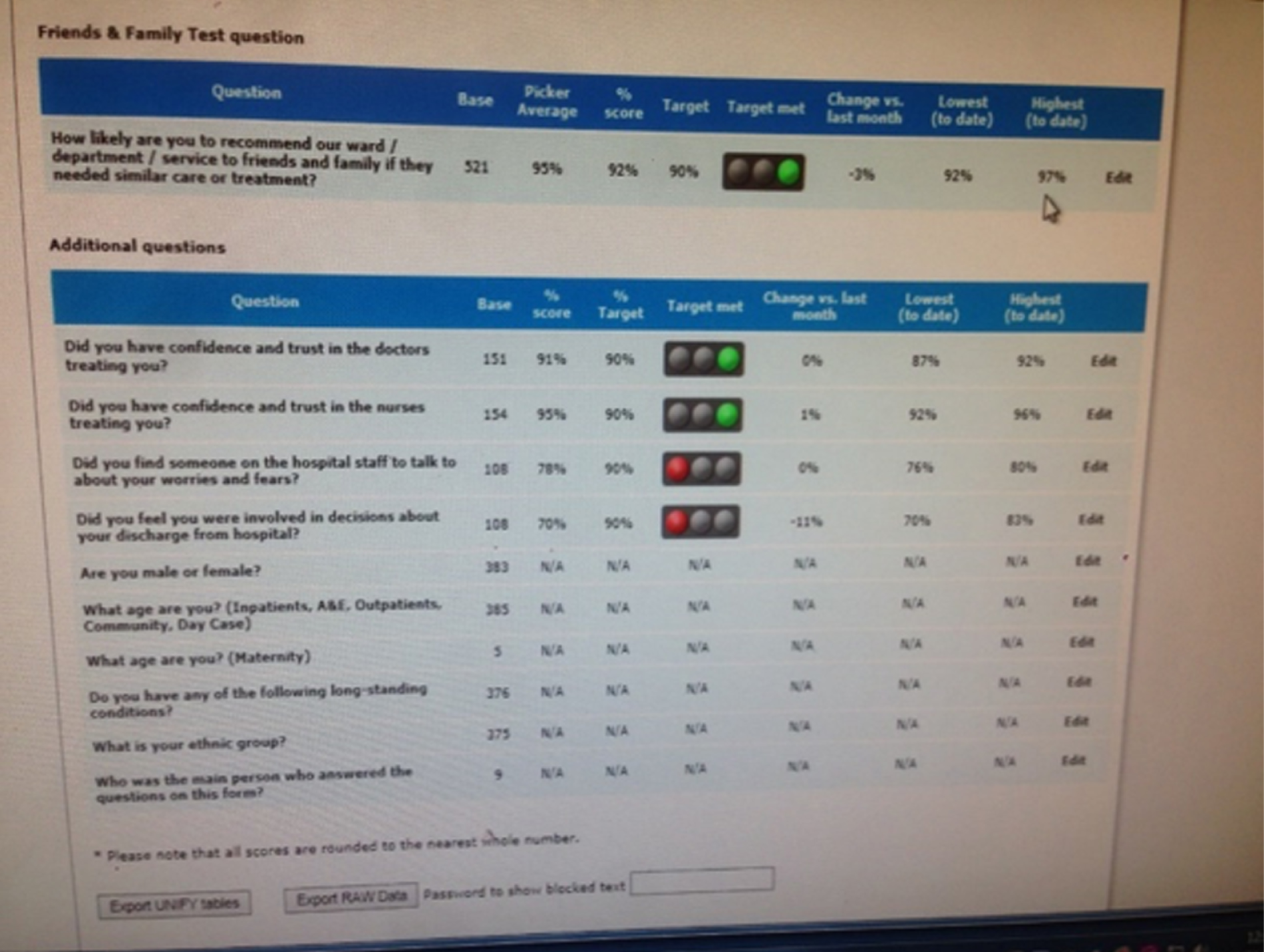

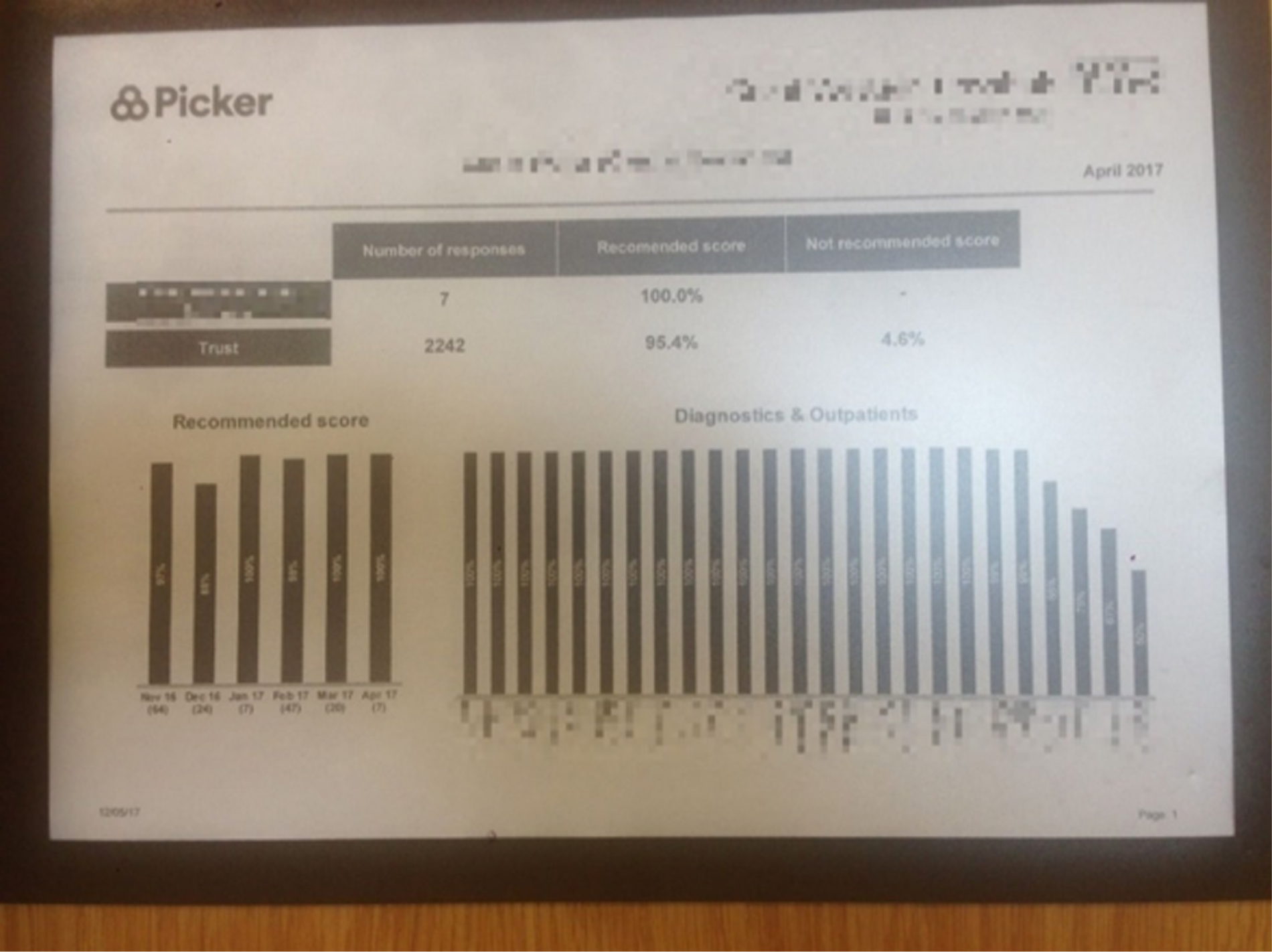

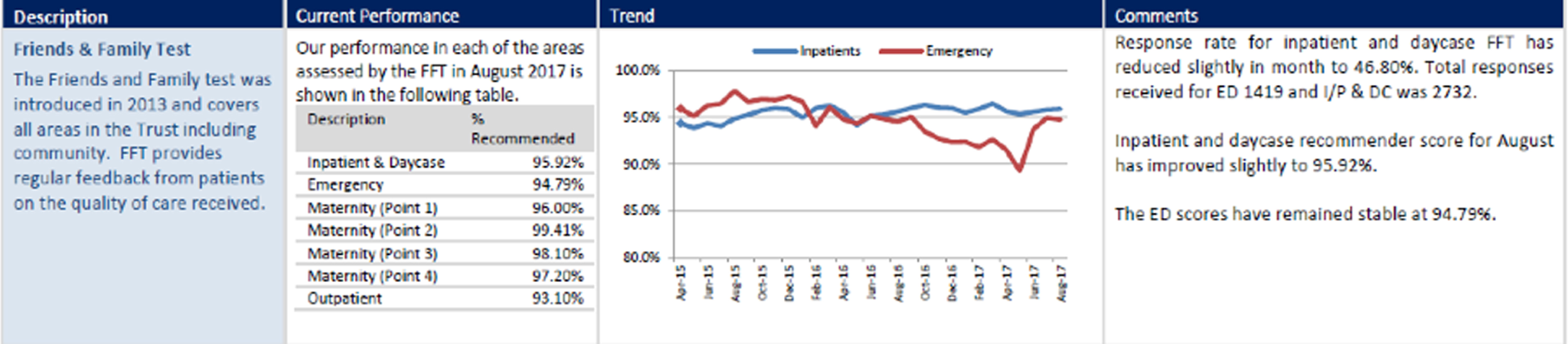

In exploring the range of ‘feedback’ (as it is often referred to) that trusts collected and analysed, we began with data formats that were well established before focusing on specificities of the two clinical areas (cancer and dementia) we had selected. We looked at how non-area-specific data were collected, collated, processed and organised; in particular, we looked at the FFT for inpatients and at the National Inpatient Survey. As our examples in this chapter will illustrate, all five trusts invested a lot of time and resources to generate data aimed at providing a picture of patients’ experience of care; they also collected information on the staff experiences of providing care, but this was not a focus of our work. However, we found a great deal of variation in how data were generated and processed at different trusts, which applied to mandatory as well as non-mandatory data formats. In particular, how the FFT was enacted in practice in the five trusts proved an accessible example that we use to highlight this variation.

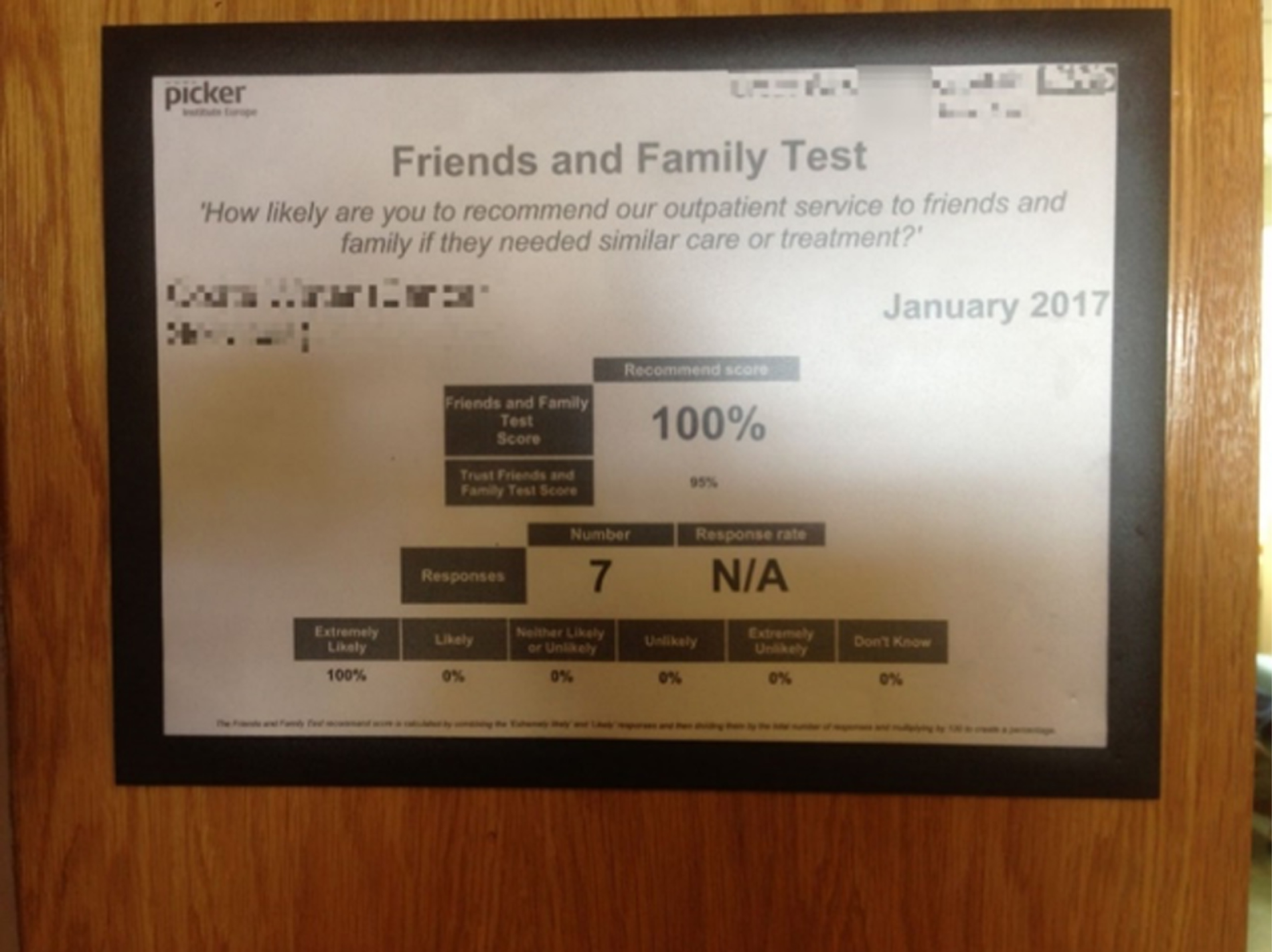

The Friends and Family Test

The FFT is mandatory for all NHS acute hospital trusts in England. Its adoption was announced in 2012 by the prime minister David Cameron; first implemented in 2013, it was then rolled out to all trusts in England in 2014. For most clinical services, the test is based on one essential question: ‘How likely are you to recommend our ward to friends and family if they needed similar care or treatment?’. The question can be answered on a five-point scale from ‘extremely likely’ to ‘extremely unlikely’ or by selecting ‘I don’t know’. There is also a free-text box for open comments. The questionnaire is intended to be anonymous; however, there is space for patients to write their name and contact details if they wish to be contacted about their feedback.

The FFT applied to all clinical areas in each trust (with varying degrees of relevance depending on the clinical area) and it was a particularly useful focus for our observations in at least two respects: (1) in four of the five trusts, significant resources and work went into ensuring that the data were generated, collated and analysed, and that the product of the analysis was reported in a variety of ways; (2) it exemplified clearly how some of the data we expected to identify as discrete entities, were, in fact, made up of a multiplicity of different entities interacting with a range of actors (both human and non-human). The first aspect of the FFT made it a productive starting point for our observations, and the second made it clearer to us how the ANT lenses would be analytically useful. Therefore, we spend a little time illustrating this particular example below. The point we make about how the FFT transforms into different entities and connects with multiple social actors can be extended to virtually all types of patient experience data we observed.

Collecting the Friends and Family Test

Although the FFT is a nationally mandated instrument, those behind its introduction anticipated that trusts would have a certain degree of autonomy as to how they deployed it. 53 We found a great deal of variation across, and within, the five trusts as to the form and method of collection, analysis and communication of the FFT. Trusts use a variety of methods to administer the FFT (paper, card, text message, online, kiosk) and to collect and analyse the information (trust staff, external contractors, data management software), and show variation in how and where such data are reported (Table 5).

| Feature | Trust | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | |

| Average number of FFT responses per month (November 2016–January 2017) | 1980 | 450 | 2389 | 551 | 2361 |

| Form | Paper (produced by the trust) | Mainly card (provided by external contractor); text message in the emergency department | Paper and online | Mainly text message | Card (provided by external contractor), kiosks, online and text messages |

| Contractor | None | Picker Institute Europe, Oxford, UK | None | Healthcare Communications (Healthcare Communications Ltd, Macclesfield, UK; www.healthcare-communications.com/) | Quality Health (Quality Health Limited, Chesterfield, UK; www.quality-health.co.uk/ |

| Management software | Meridian | Not known | Meridian | ENVOY (Healthcare Communications Ltd, Macclesfield, UK; www.healthcare-communications.com/solutions/envoy-messenger/) | Business Objects Launchpad (SAP Ltd. Feltham, UK; www.sap.com/uk/products/bi-platform.html) |

| Discussed at board? | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Used for benchmarking? | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

In addition to the main FFT question and the free-text box, each trust that used a paper-based questionnaire asked several supplementary questions. These explored aspects of care that are considered locally relevant to patient experience (e.g. trust in staff, worries and fears, involvement in the discharge process). Most also asked for a variety of demographic information about the patient (e.g. age, gender, ethnicity). This made the total number of questions about care (ward and demographic information aside) across the trusts range from two to nine.

Four of our five study trusts (all but trust D) principally used paper-based FFT questionnaires for data collection. Who distributed the forms varied across and within these four trusts, with different wards or service areas relying on a variety of staff (e.g. nurses, health-care assistants, ward clerks, volunteers) to encourage patients to leave feedback; the allocation of the FFT tasks in this regard are at the discretion of ward or clinic managers. Ideally, staff would give cards to inpatients on discharge and ask them to complete them before leaving hospital or to return them as soon as possible afterwards. However, discharge is a complex process and we heard repeated criticism from ward managers and matrons that this was an inappropriate point at which to ask patients for feedback. One deputy chief nurse recalled matrons telling her at a meeting that:

. . . there doesn’t seem to be a natural point in the patient pathway to hand out the cards. [. . .] Handing them out on discharge doesn’t work for [wards] – there are too many other things going on.

Field notes, 3 May 2017, trust B

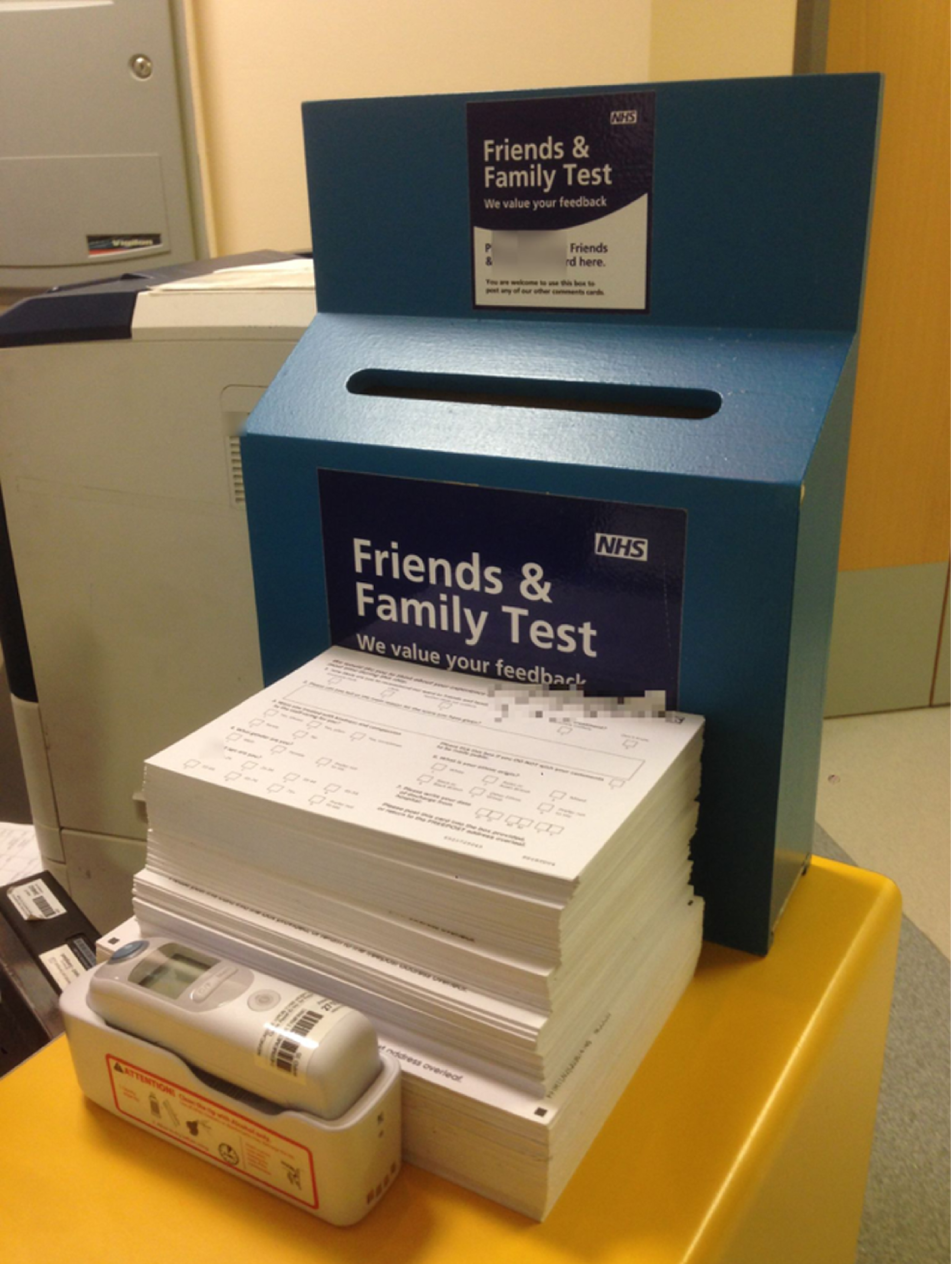

In addition, staff often expressed the view that, because inpatients were asked for feedback on discharge, they used the FFT to rate and comment on the whole of their hospital experience, which may have included contact with several wards or services throughout their inpatient stay. Thus, the fact that the card was distributed at this point caused some people to doubt the validity of the data. Completed paper and card FFTs are collected from patients and are usually placed in FFT boxes found in ward areas; patients (or their carers) also post their cards into such boxes (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Friends and Family Test cards and box on a ward reception desk, trust E. Reproduced with permission.