Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/07/87. The contractual start date was in September 2014. The final report began editorial review in April 2018 and was accepted for publication in January 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Robert Grant reports grants from King’s College London during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Harris et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

This mixed-methods realist evaluation of intentional rounding (IR) in acute hospital wards in England, conducted in four phases, was designed to address the research question: what is it about IR in hospital wards that works, for whom and in what circumstances? This chapter describes the background to IR in England and the structure of the report.

Background

State-funded systems of health care in advanced economies are facing unprecedented challenges arising from ageing populations and increasing demands for care in the context of stretched resources. The revelations of the systemic and appalling failures of compassion and care at the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust that took place between 2005 and 2009 were a profound shock to the public, government, health-care system and professions, and led to Sir Robert Francis’ landmark inquiry, report1 and recommendations to improve accountability and governance for the paramount purpose of protecting the interests of patients. The Francis report1 raised fundamental questions about the nature of compassionate organisational cultures and nursing care in the NHS and called for more research.

In response, the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research programme commissioned a stream of new research intended to generate evidence to meet the gaps in knowledge of service delivery, and to discover what worked well for whom and at what cost. The call, After Francis: Research to Strengthen Organisational Capacity to Deliver Compassionate Care in the NHS [see the commissioning brief on the project web page; URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/130787/#/ (accessed 4 July 2019)], invited robust evaluations of interventions to improve the leadership, organisational culture and quality of front-line care across a broad range of staff. One of the concerns of the Francis report1 was the neglect of some patients by dysfunctional nursing that failed to respond to fundamental needs, such as pain, hydration, hygiene and comfort, and failed to ensure patient safety. One of the 290 wide-sweeping recommendations made by Francis in his final report (Volume 3, p. 1610) was that:

Regular interaction and engagement between nurses and patients and those close to them should be systematised through regular ward rounds.

Francis. 1

Regular patient rounds, often called back rounds or comfort rounds, have always been a plank of nursing care and have recently received renewed interest in the USA and the UK with what has become known as ‘intentional rounding’ (IR), a structured intervention that systematises regular nursing ward rounds. It was this model of regular rounding that attracted attention from policy-makers, triggered by public-interest concerns following the publication of the Francis report. 1

The origins and meanings of intentional rounding

The specific intervention recognised as IR was developed in 2007 in the USA by the Studer Group,2 a private, for-profit health-care consultancy company (Pensacola, FL, USA), and the Alliance for Health Care Research. The term ‘intentional rounding’, originally coined by the Owensboro Medical Health System Inc. (Owensboro, KY, USA), is not universally used and IR has also been called ‘hourly rounding’,2 ‘proactive patient rounds’,3 ‘comfort rounds’4 or ‘rounds with intent to care’. 5 IR is a timed, planned intervention that sets out to address fundamental elements of nursing care, typically by means of a regular bedside ward round. The aim is to proactively identify and meet patients’ fundamental care needs and psychological safety. The typical format of IR, as developed by the Studer Group, is based on the 4Ps (Box 1), although there are lesser-used variants based on 3Ps (pain, position and personal needs),9,10 5Ps (potty, position, pain, possessions and patient focus)11 and 6Ps (pain, positioning, proximity, personal care, pumps and promise). 12

During each round, the following standardised protocol is used by a nurse for each patient.

-

An opening phrase is used by the nurse to introduce his or herself and to put the patient at ease.

-

Scheduled tasks are then performed.

-

A discussion follows of the four key elements of the round, often called the ‘4Ps’:

-

positioning – making sure the patient is comfortable and assessing the risk of pressure sores

-

personal needs – assessing a patient’s personal needs, including whether or not they need assistance with getting to the toilet

-

pain – asking patients to rate their level of pain on a scale of 0–10

-

placement – ensuring that any items a patient needs are within easy reach.

-

-

An assessment of the care environment, such as checking the temperature of the room or any fall hazards.

-

Ending the interaction with a closing phrase such as ‘Is there anything else I can do for you before I go?’.

-

The patient is informed of when the nurse will return.

-

The nurse documents the round.

If patients are unable to respond during the round, the nurse may follow this process with family members. 7

Reproduced from Harris et al. 8 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The policy context for the introduction of intentional rounding in England

Even before Sir Robert Francis’ recommendations, and in anticipation of his report,1 emerging concerns about what had happened at the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust increased the level of concern about patient care and patient safety among the public, health-care professionals and politicians. Interest in IR began when it was identified by The King’s Fund Point of Care programme as a possible way of improving the patient experience of care. Around this time, some senior nurse managers in the UK had visited the USA and had been exposed to IR, as expounded by the Studer Group. 13

Prime minister announcement

In January 2012, while visiting Salford Royal Hospital, in the Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, the then prime minister David Cameron announced a raft of changes, including measures designed to bolster leadership, improve care and allow patients to rate their care. 14 He stated that nurses should make hourly rounds to ensure that each patient was comfortable. In the same speech in 2012, he set up a new national body called the Nursing and Care Quality Forum (NCQF) to promote ‘best practice’ among staff.

As the study was nearing its end, we were able to talk to an official who was close to implementation of the policy about the circumstances of the introduction of IR. The policy development was rapid and took place over the Christmas/new year break to be included, together with the formation of the NCQF, in an announcement by the then prime minister David Cameron on 6 January 2012 as part of the plans to manage the expected messages in the Francis report. 1 The ideas were generated at speed and were not given the usual time for the measured, consultative and thoughtful processes expected of policy development. Although not a statutory requirement (and, therefore, not mandatory), it was supported by the chief nursing officer (CNO) at the time and, therefore expected to happen. Not surprisingly, there were no guidelines to support its implementation and IR was not defined other than as an intervention to be delivered by registered nurses (RNs) in order to see their patients hourly using the 4Ps as discussed in the US evidence (see Box 1). It was expected that RNs would use their professional judgement about how to deliver IR, what to ask the patients and how to interpret and act on the subsequent interaction. Interestingly, it was envisaged that IR would not be explicitly documented on a specific IR form, although documentation about care delivered and patient condition was expected to be written in a patient’s notes, which could be done retrospectively at the end of a shift as long as the evidence was recorded. Furthermore, there were no resources to support the development and implementation of IR, as it was thought that RNs would be regularly checking their patients anyway. There was no expectation that progress with implementation of IR would be reported back to the Department of Health and Social Care. The NCQF was tasked with supporting IR implementation as part of its ‘having time to care’ workstream.

Role of the Nursing and Care Quality Forum

When the NCQF was convened, it inherited supporting the implementation of IR as part of its role. Some NHS trusts were early adopters, piloting and implementing aspects of IR in 2011 before the majority of other trusts,15 so some of the key aspects of structured rounds were already under way in a few places. The NCQF was well informed by the experience of IR in early-adopter trusts and endorsed the implementation of IR as part of their workstream on making time to care,5 in which they planned to:

. . . accelerate the implementation of person centred approaches such as ‘rounding with intention to care’ – where every individual receiving care knows they will have at least hourly contact with staff . . .

NCQF. 5

The forum of nursing experts were concerned that IR could easily become a tick-box exercise; however, it was thought that it would support nurses in prioritising talking to their patients. Therefore, the content of IR was considered less important than the interaction that it would enable and so the 4Ps structure was not expected to be used rigidly. The NCQF assumed that there would be a form to document IR. However, there were no guidelines for trusts about how to implement IR or recommended documentation. Furthermore, there was no evidence of a strategy for introducing IR across the country or for overseeing its development and impact. To address this, the NCQF supported the development of seven ‘demonstrator sites’ for IR, chosen to reflect a variety of health-care and social care providers in a range of geographical locations to support implementation of IR.

The NCQF commissioned a small study4 to learn from these sites, the findings of which noted the potential benefits and limitations of IR, variations in practice and included recommendations of how to conduct IR. This was released in August 20134 as widespread national implementation of IR was already under way and a new CNO was appointed at NHS England, who launched a new vision for nurses called Compassion in Practice. 16 At this point, the role of the NCQF became unclear and it is not known how widely this report was circulated. It was available on an NHS website (www.6cs.england.nhs.uk) until 2016, but is no longer publicly available. A freedom of information request was submitted to the Department of Health and Social Care in January 2018 for the report and minutes of NCQF meetings, but no documents were available.

Structure of the report

This report is structured as follows:

-

Chapter 2 reports the study aims and objectives, and the methodological approach used to address these.

-

Chapter 3 describes the first phase of the study, the realist synthesis of the evidence for IR. The aim of this phase was to generate hypotheses on what the mechanisms of IR may be, what particular groups may benefit most or least and the contextual factors that might be important to its success or failure.

-

Chapter 4 describes the second phase of the study, the national survey of non-specialist NHS acute trusts in England. This survey explored how IR was being implemented and supported across England and the way in which organisational context (or features of services and health-care organisations) influenced its implementation.

-

Chapter 5 gives an overview of the three case study sites and their staff data, describing how IR has been implemented, developed and supported at each site. This chapter also investigates trends in patient outcomes and provides an analysis of the costs and benefits of IR.

-

Chapter 6 explores nursing staff and other clinical, management and administrative staff experiences of IR, how they believed it affected the way they delivered care and the barriers and facilitators they experienced. Through observations of nursing staff undertaking IR and of the care that patients received, Chapter 6 also highlights how IR has been implemented on the ground.

-

Chapter 7 explores patients’ and carers’ experiences and perceptions of how IR influences their experiences of care.

-

Chapter 8 synthesises the data from each phase of the study to identify what aspects of IR work, for whom, in what circumstances and why.

-

Chapter 9 sets out the key messages from the study, reviews the approach and methods used and discusses the implications of the findings for policy, practice and research.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter reports the study aims and objectives and the methodological approach used to address these.

Aims and objectives

The overall aim of the study was to investigate the impact and effectiveness of IR in hospital wards in England on the organisation, delivery and experience of care from the perspective of patients, their carers and staff. The research question was ‘what is it about IR in hospital wards that works, for whom and in what circumstances?’ We investigated this at four levels of the organisation and delivery of health services – (1) national, (2) service provider organisation, (3) individual ward/unit and (4) individual person – to identify the ways in which the context (i.e. the environment and organisation) at each of these levels influenced the mechanisms (i.e. the assumptions and theories about the ways in which IR achieved its objectives) and the outcomes or impact. The study objectives were to:

-

determine the number of NHS trusts in England that had implemented IR and analyse how this had been developed and supported

-

identify how IR had been implemented on the ground and evaluate its contribution to the delivery of patient care as a whole and how it fits in alongside other approaches to improving quality and safety

-

explore nursing staff, health-care assistants’ (HCAs’) and other clinical and management staff experiences of IR and how it affects the way they deliver care

-

explore patients’ and their carers’ experiences and perceptions of how IR influences their experiences of care

-

investigate trends in patient outcomes (retrieved from routinely collected NHS ward data) in the context of the introduction of IR and other care improvement initiatives that have been introduced by using statistical process control methods such as cumulative sum charts

-

examine the barriers to and facilitators of the successful implementation of IR

-

conduct a bottom-up analysis of the costs of IR by identifying the resources used by case study wards to develop and implement it

-

synthesise the data from each of the study phases to identify which aspects work, for whom and in what circumstances.

Project methodology

Study design and conceptual basis

A multimethod study design was undertaken using realist evaluation methodology17 to evaluate the implementation of IR in England. Realist evaluation is a theory-driven approach designed for evaluating complex social interventions, such as IR. 18,19 It does not seek to answer the question ‘does this intervention work?’ but instead acknowledges that complex social interventions only ever work for certain people in particular circumstances. The key task of a realist evaluation is to therefore understand and explain the patterns of success and failure by asking the exploratory question: ‘what is it about this intervention that works, for whom and in what circumstances?’17,19 It achieves this through the identification of causal explanations of how an intervention or programme is anticipated to work, known as context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations.

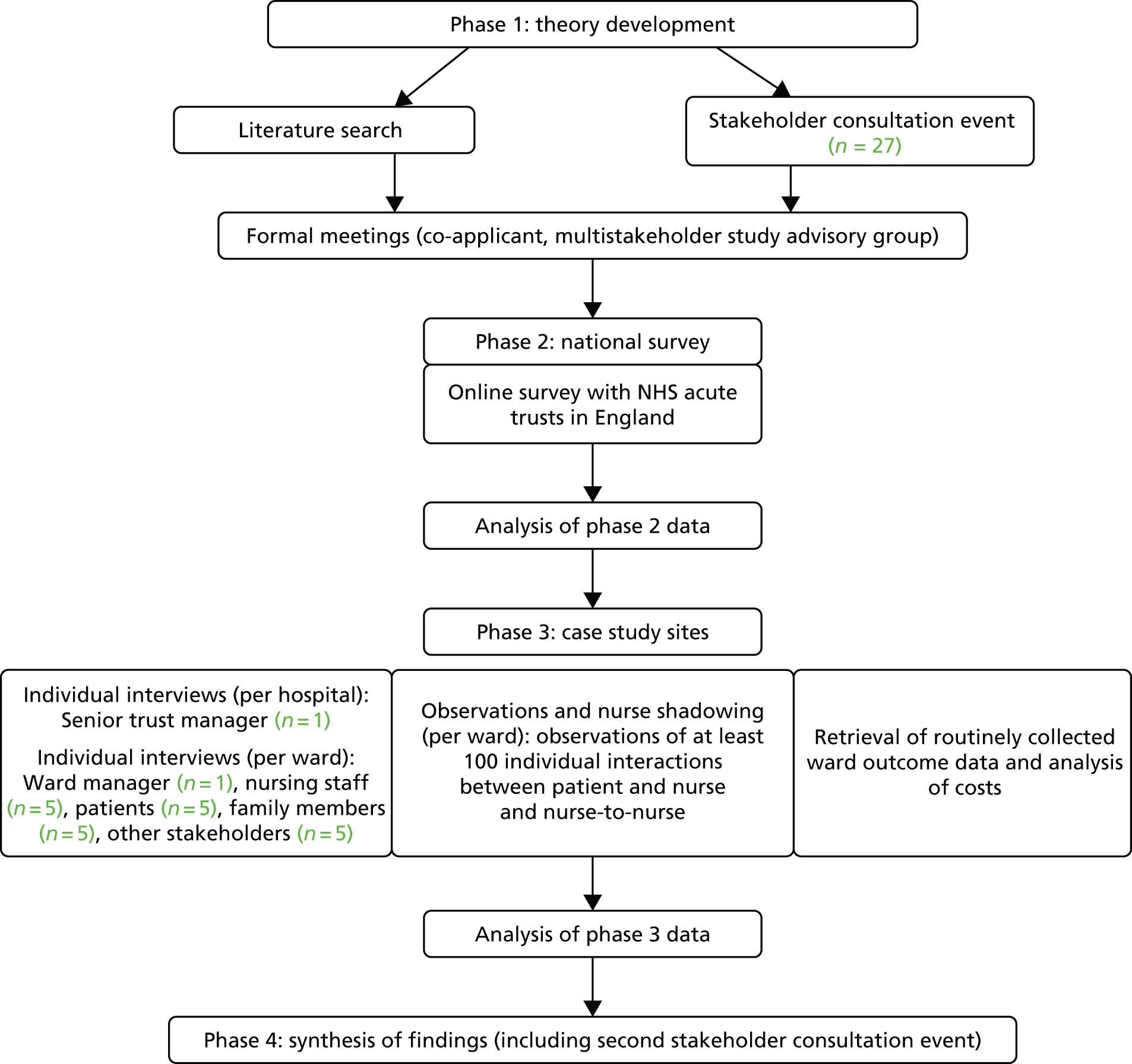

The study was conducted in four phases: (1) theory development; (2) a national survey of all NHS acute trusts in England; (3) in-depth case studies of six wards in three NHS acute trusts involving individual interviews with health-care staff, patients and their carers, observations of IR and nurse shadowing, retrieval of routinely collected ward outcome data and analysis of costs; and (4) synthesis of study findings. Figure 1 shows the study flow diagram. More detailed descriptions of the methodology for each phase is provided in individual phase chapters.

FIGURE 1.

Study flow diagram. Reproduced from Harris et al. 8 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the NHS Health Research Authority South East Coast – Surrey Research Ethics Committee (reference number 14/LO/1977). All participants were informed that they were free to refuse to participate or withdraw from the study at any time.

Patient and public involvement in the research

Patient and public involvement was an integral part of this study; it was guided throughout the study duration by a multistakeholder advisory group consisting of NHS senior managers and health-care professionals and patient and carer representatives. Nine patient and carer representatives were recruited from local voluntary sector organisations and other networks, where role descriptions were circulated. The advisory group met three times over the course of the study and meetings were chaired by Sally Brearley, who has worked with patients and carers on a variety of research and service improvement projects. Other members of the research team assisted by facilitating small group discussions and taking notes. Service user representatives in the group were paid an honorarium of £100 per meeting for their time and contribution. All travel expenses for attending the meetings were paid from the research budget and a newsletter was distributed in between meetings to keep members updated with study progress. The input of the advisory group was of great value to the study. The group came together at key points in the process and contributed to all aspects of the research, including commenting on the study mechanisms, national survey questions, interview schedules, data analysis and dissemination strategy, and ensuring that the study was grounded in the issues and perspectives of key stakeholders.

Chapter 3 Phase 1: theory development – a realist synthesis of the evidence

This chapter describes the first phase of the study: the realist synthesis of the evidence for IR. The aim of this phase was to generate hypotheses on what the mechanisms of IR may be, what particular groups may benefit most or least, the contextual factors that might be important to its success or failure and the associated outcomes. This theory development drew on principles of realist synthesis18 and the subsequent framework was to be tested in phases 2 and 3 of the study.

Method

In stage 1, a search of academic, policy and grey literature was undertaken to develop initial programme theories of IR. Expert advice was sought from library and information science specialists around generating relevant search terms, and between June and July 2014 four electronic databases were searched [Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), MEDLINE and the Royal College of Nursing Archive] alongside searches of Google and Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), InterNurse, Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE) and NHS Evidence using the strategies highlighted in Table 1. Relevant documents were independently examined by two researchers to identify any purported mechanisms of IR (i.e. theories or assumptions about why/how IR worked/was expected to work).

| Strategy for searches in AMED, CINAHL, MEDLINE, RCN Archive, PsycINFO, HMIC, EMBASE, Scopus, BMJ Journals and The Cochrane Library |

|---|

| Free-text terms and operators |

|

“Intentional round*” OR “hourly round*” OR “patient round*” OR “purposeful round*” OR “nursing round*” OR “comfort round*” AND “nurs*” [Limiters: Abstract only (where applicable), English language only] |

| Strategy for searches in Google, Google Scholar, InterNurse, SCIE, NHS Evidence (each search undertaken separately) |

|

“Intentional round” “Hourly round” “Patient round” “Purposeful round” “Nursing round” “Comfort round” |

Between October and November 2014, stage 2 of the synthesis was undertaken, with the aim of identifying empirical research that either supported or refuted the mechanisms identified in stage 1, or identified any new mechanisms. A comprehensive search for empirical research was undertaken using the search strategy highlighted in Table 1. Snowball searches and citation searches in CINAHL and Scopus were also conducted. A structured data extraction form was completed for every paper, recording either salient details on the study design, objectives and participants, or the reason for its exclusion. Broad inclusion criteria were used, meaning that a paper was included if it described nursing rounds occurring every 2 hours or less and highlighted empirical evidence of any associated context, outcome or mechanism. In line with realist synthesis methodology, conventional approaches to quality appraisal were not used;21 instead, each study’s ‘fitness for purpose’ was assessed by considering its relevance and rigour. The evidence collected from these papers was synthesised by drawing together all information on contexts, mechanisms and outcomes. Similarities and differences in findings were sought in order to build a comprehensive description of each mechanism and its role in IR. Focused literature searches were also conducted for mechanisms for which little evidence was found.

A third and final search of the literature was undertaken in February 2016 to ensure that the synthesis was up to date and that no research published in the interim period had been missed. Searches were repeated as in stage 2, but focused only on research published between December 2014 and February 2016. Snowball searches and hand-searches were also undertaken. In addition to the review of the relevant literature, a stakeholder consultation event was held in February 2015, at which key figures associated with IR (e.g. Directors of Nursing of NHS hospitals, health-care staff) plus members of the study’s advisory group were asked to discuss their understanding of IR and their reasoning for its implementation, to further elicit realist theories on the mechanisms.

Findings

This section presents the findings of the realist synthesis. A total of 44 papers were included in the realist synthesis, drawn from a variety of sources [i.e. the professional press (n = 21),3,7–9,22–38 peer-reviewed journals (n = 18),39–56 study reports (n = 4)4,57–59 and one doctoral thesis]. 60 The research was primarily undertaken in the USA (n = 25)3,7–9,22,25–27,32,33,35–42,44,47,48,52–54,60 but also included research from the UK (n = 12),4,23,24,28,30,31,34,46,51,57–59 Australia (n = 5),43,45,49,50,55 Canada (n = 1)29 and Iran (n = 1). 56 Studies were conducted in a variety of settings, including accident and emergency, intensive care, mental health, maternity, orthopaedics and medical-surgical units and used both qualitative and quantitative research methods. The papers were published between 2006 and 2017, with a peak in publication in 2012. The two earliest published papers (2006 and 2007) were authored by Meade (and colleagues),22,39 who was directly connected to the Studer Group; these papers were heavily cited by authors publishing at later dates. The 44 papers were written by a total of 168 authors, with only three authors (Meade,22,39,40 Braide23,24 and Neville25,41) authoring or co-authoring more than one paper. This suggested that there had not been a major programme of research by one group of researchers in IR.

Eight potential mechanisms of IR were identified in the first stage of the literature search; these are highlighted in Table 2, along with their provisional descriptions. In Table 3, the programme theories for each of the eight mechanisms are presented in descending order according to the number of papers addressing them and the CMOs are summarised. A number of individual CMO configurations were identified and examples of these have been provided for selected mechanisms in Boxes 2 and 3. It must be noted that these programme theories were not mutually exclusive, with one context and/or mechanism feeding into another or becoming an outcome of a third. However, they have been separated here for clarity.

| Mechanism title | Mechanism (resources) | Mechanism (reasoning/responses) |

|---|---|---|

| Consistency and comprehensiveness* |

|

This provides reassurance and confidence in the quality of care to patients, their carers and staff |

| Allocated time* | IR gives nurses allocated ‘time to care’ (i.e. gives time to check that patients are comfortable and their needs are being met, thereby treating patients with dignity, and replaces ‘presumed care’) | This helps nurses to organise their work and feel able to prioritise this aspect of nursing care |

| Accountability* | Staff are required to complete and sign the IR document to say that they have carried out hourly checks |

|

| Nurse–patient relationships and communication* |

|

This enables staff to get to know patients better and become more aware of their needs, notice unusual behaviours/appearances and detect subtle/significant changes that can affect comfort and safety |

| Visibility* | IR increases the visibility/presence of nurses within a unit by increasing the time that nurses spend in the direct vicinity of their patients (i.e. it gets nurses to the patient’s bedside) |

|

| Anticipation* | IR enables nurses to anticipate/pre-empt and proactively address patient needs instead of being reactive and waiting for patient call bells and alarms | This ensures that all patients receive regular care instead of unequally distributed care among patients focused towards those who have frequent call bell use |

| Staff communication and/or teamworking | IR provides health-care professionals with documented evidence | This is used to enhance staff communication, teamwork and prioritise care in future rounds |

| Patient empowerment | IR provides an opportunity for nursing staff, patients and carers to get to know each other better | This empowers patients to ask for what they need in order to maintain their comfort and well-being |

| Mechanism title | Context | Mechanism (resources) | Mechanism (reasoning/responses) | Outcomes (from literature) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMO 1: consistency and comprehensiveness |

|

|

|

|

| CMO 2: allocated time |

|

IR gives nurses allocated ‘time to care’ (i.e. time to check that patients are comfortable and their needs are being met, thereby treating patients with dignity and replaces ‘presumed care’) | This helps nurses to organise their work and to feel able to prioritise this aspect of nursing care |

|

| CMO 3: accountability |

|

Staff are required to complete and sign the IR document to say they have carried out hourly checks |

|

|

| CMO 4: nurse–patient relationships and communication |

|

|

This enables staff to get to know patients better and become more aware of their needs and, through this knowledge, nurses can gather a keen sense of unusual behaviours and appearances and detect subtle/significant changes that can affect comfort and safety |

|

| CMO 5: visibility | Ward setting/layout | IR increases the visibility/presence of nurses in a unit by increasing the time that nurses spend in the direct vicinity of their patients (i.e. it gets nurses to a patient’s bedside) |

|

|

| CMO 6: anticipation |

|

IR enables nurses to anticipate/pre-empt and proactively address patient needs instead of being reactive and waiting for patient call bells and alarms |

|

|

| CMO 7: staff teamwork and communication |

|

IR provides health-care professionals with documented evidence | . . . that can be used to prioritise care in future rounds | . . . and this leads to improved staff communication and teamwork |

| CMO 8: patient empowerment |

|

IR provides an opportunity for nursing staff, patients and carers to get to know each other better | This empowers patients to ask for what they need in order to maintain their comfort and well-being | . . . and this leads to higher levels of patient and carer satisfaction with care |

Using a repeated-measures design, fall rates and risk assessment data were collected at three time points (before, during and 1 year post implementation of IR) in two postoperative orthopaedic units in a large academic medical centre in the USA. Four focus groups were also held with 14 nurses several weeks post intervention. 42

-

Context: postoperative orthopaedics setting, where a number of procedures are elective in otherwise healthy patients.

-

Consistency and comprehensiveness mechanism present: otherwise healthy patients are asked about toileting every hour.

-

Outcome: nurse feels ‘silly’ and uncomfortable asking these questions, which results in her not asking patients toileting questions during IR.

Interviews with 15 RNs from one public hospital in Australia were reported, with data arising from a larger research project examining missed nursing care. Relevant IR policy documents, charts and notes were also gathered and reviewed. 43

-

Context: IR is considered as ‘fundamental nursing care’ by management.

-

Allocated time mechanism absent: the time required to undertake rounding is not factored into the nursing workload and attempts to factor rounding into staffing numbers are unsuccessful.

-

Outcomes: increased nursing workload, which means either that IR is omitted or the documentation is completed at the end of the shift.

Programme theories

Context–mechanism–outcome 1: intentional rounding ensures that consistent and comprehensive care is delivered to all patients by all nurses

A total of 21 papers4,9,11,24,26–32,41–47,57,58,60 highlighted the link between IR and consistent and comprehensive care. The structured, systematic approach to IR prompted and guided the delivery of care to a required standard, helped staff to remember to conduct all aspects of care on each round4,58 and identified tasks that might otherwise be missed. 9 The format helped ensure continuity of care across staff members, which was thought to be particularly important for guiding junior/unqualified staff and those less familiar with patients. 4 IR enabled staff to speak regularly to all patients, which helped prevent quieter patients from being overlooked. 4

However, in most studies there was recognition that a dependence on standardisation did not always ensure successful IR and that a flexible approach may be more appropriate. 28,41,43–45,47 Nurses were reported to use their clinical judgement and professional autonomy to modify the rounding process, assessing patients on an individual basis and making informed choices about how frequently to conduct rounds and what questions to ask. 4,24,27,32,41,42,44,45,60 Others highlighted how the breadth of care elements covered in IR could be modified in order to comprehensively address all potential patient needs and make it relevant to individual settings. 4,26 The setting of care was an important influencing context for this mechanism. For example, in mental health wards, there were reports of IR being disproportionate for ‘low-risk’ patients4 or too intrusive for those experiencing psychotic symptoms. 32 Other influencing contexts were time limitations, low staffing levels and conflicting priorities; all of these made IR more difficult. 31,41,57,60 Understanding of the principle and practice of IR was also reported to vary according to individual staff characteristics. 4

Context–mechanism–outcome 2: intentional rounding gives nurses allocated ‘time to care’

A total of 19 papers4,9,22,24,28,29,31,33,39–41,43,45,48–50,57,58,60 discussed the ‘allocated time’ mechanism. There was no indication that nurses were given specifically allocated time in which to conduct IR (i.e. no discussion of other aspects of nursing workload being reduced or extra resources being provided). There was, however, some evidence that IR could have time-saving benefits for nurses, enabling them to better organise their workload and free up more ‘time to care’. 4,9,57 No other descriptions of the mechanism were highlighted and reported outcomes were limited, although some reported improved staff satisfaction22,39 reflective staff practice4 and positive patient feedback. 57

There was more empirical evidence regarding the absence of the mechanism, with some staff stating that IR was ‘nothing new’, that it was akin to what they were already doing or that made no difference to their practice. 4,28,31,40,45,50 There was also evidence that staff believed that IR resulted in less ‘time to care’ and added to, rather than reduced, their workload. 24,28,43,45,50 It was felt by some that the documentation associated with IR took nurses away from delivering patient care28 and others talked about having to fit in rounds around the rest of their workloads. 29,43,60 In these situations, higher-priority duties could take precedence33 and more complex patients could be prioritised. 24,41,49,60 The need for cultural change in an organisation was an important influencing context for this mechanism,4,24,28,48,49 as was successful teamworking. 41

Context–mechanism–outcome 3: intentional rounding increases nurses’ accountability for the standard of care provided

A total of 19 papers4,9,24,30–33,41–45,47,48,50,51,57,58,60 discussed this mechanism. Accountability was perceived by some to underpin IR;4,9,33,43,48,60 however, there was no evidence that increased personal accountability led to the delivery of higher standards of care, as the accountability of staff generally related only to responsibility for ensuring that they completed the IR documentation, rather than responsibility for carrying out high-quality rounds. Similarly, although the documentation associated with IR did enable care delivery to be audited, there were concerns that such audits provided information only about staff compliance with documentation procedures and not evidence of rounding quality or confirmation that any action(s) required had taken place. 4,24,31,58 There were also concerns that such audits may provide an incentive for staff to simply ‘tick boxes’ on the documentation, rather than completing the task in full,30 and incidents were reported of nurses completing all documentation at the beginning/end of their shift4,43–45,48 or falsifying information on IR documentation when they had forgotten to complete it. 43

The suitability of rounding documentation was an important context for this mechanism, with evidence that, where documentation was not ‘fit for purpose’ or duplicated nursing effort, non-compliance with IR protocols was more likely to occur. 4,31,41,42,57 The visibility and placement of rounding documentation was also an important context,9,44 with evidence that keeping documentation physically close to patients helped to ensure that it was completed as required. 9,45 Finally, leadership and management support was also an influencing factor. 4,9,42,45,47,60 Few studies discussed the outcomes of the mechanism, but some reported that nurses felt patronised, insulted or untrusted,31,43,50,60 and one study43 reported that it was believed that IR devalued nursing work by focusing on processes rather than professional judgement. 43

Context–mechanism–outcome 4: intentional rounding enhances nurse–patient communication and/or relationships

A total of 17 papers highlighted the positive impact that IR could have on nurse–patient communication. 4,22,24,28,30,34,35,40,41,43,45–47,57–60 It was widely reported that IR increased the frequency of nurse–patient communications;4,28,34,40,47,57,58 staff believed that this was welcomed by patients and their carers,24,28,40,46 making them feel more involved in their care,28 more likely to voice concerns40 and less likely to feel ignored/neglected. 57 There was less evidence that IR improved the quality of nurse–patient communication, although some staff felt that it was the final question (‘Is there anything else I can do for you?’) that was crucial, perceiving this to demonstrate respect and compassion. 45 There was little discussion of the impact of IR on nurse–patient relationships. Some staff felt that IR helped them to get to know patients better57 and made them more aware of patients’ conditions and needs,28,40,45 which could potentially affect patient outcomes28 and lead to better teamworking,57 fewer patient complaints and increased nurse satisfaction. 24,28,45,57 However, not all outcomes were positive and there were reports of patients being irritated or annoyed by IR. 28 Some staff felt that using predetermined scripts stripped communications of authenticity and made nurse–patient contacts a matter of routine,43 whereas some patients highlighted the importance of quality interactions with staff, noting the value of meaningful contacts and feeling connected. 30,57,59

Context–mechanism–outcome 5: intentional rounding increases nurse visibility and/or presence

A total of 11 papers9,23,24,28,40,45,47,49,57,58,60 discussed this mechanism. Some staff believed that IR increased the visibility of nurses on a unit;40,45 this was generally viewed positively, with perceived benefits such as enhanced nurse–patient communication,28 helping patients to feel well cared for and increasing staff satisfaction. 47 However, some negative outcomes of increased visibility were also reported by staff, including an increase in non-urgent requests from patients. 49 It was noted that rounding could be particularly challenging in rehabilitation settings, with reports that increased visibility of staff led to patients doing less for themselves and instead waiting for staff to assist them during their rounds. 28 Some staff questioned any association between IR and increased visibility, believing that they were visible to patients even when they were not undertaking rounds. They could not, however, confirm whether this was also the patients’ perception. 57 In the few studies that did explore patient and carer perceptions, it was generally agreed that increased visibility of nursing staff was valued by both patients and their carers. 9,23,24

Context–mechanism–outcome 6: intentional rounding enhances a nurse’s ability to anticipate and proactively address patient needs

A total of 11 papers4,9,25–27,43,46,48,57,58,60 addressed this mechanism. A number of staff identified IR as an intervention that enabled them to be proactive in anticipating patient needs, as opposed to being reactive to patient call bells or requests for help. 9,27,43,46,48,60 There were a number of staff-reported outcomes associated with this mechanism, including increased patient satisfaction,27 reduced anxiety,46 increased reassurance,4,46 reduced call bell usage4,57 and an overall sense of calm on the ward. 4 IR was also reported to enable nurses to intervene earlier when a patient’s medical condition was deteriorating46 and to prevent quieter patients from being overlooked. 4,43,57 Few studies reported patient experiences of the mechanism, although patient questionnaires demonstrated an improvement in patient satisfaction25 and patient perceptions of nursing proactivity following the implementation of IR. 57 One influencing context was the type of patient on the ward where IR was being carried out and their particular needs. For example, changing position and getting in and out of bed were identified as activities that could be anticipated and addressed by hourly rounding, whereas pain management and toileting could not be anticipated by hourly rounding. The layout of the ward was also an influencing context, with IR helping to ensure that patients in side rooms were not forgotten. 58

Context–mechanism–outcome 7: intentional rounding enhances staff communication and/or teamworking

A total of nine studies9,27,29,32,40,41,47,57,60 discussed this mechanism. Several studies9,29,32,47,57 discussed staff communication and its interconnecting relationship with IR (i.e. strong staff communication was perceived to be crucial for effective rounding, and rounding was perceived to improve staff communication). In addition to communication, some studies also noted the relationship between IR and staff teamworking (both unidisciplinary and mulitidisciplinary);9,40,41,60 once again, an interconnecting relationship was noted between the two (i.e. teamworking was perceived to be crucial to successful IR60, and effective rounding was perceived to improve staff teamworking). 9 Some staff believed that rounding improved ‘camaraderie’ on a unit; led to a calmer, less ‘chaotic’ atmosphere; and helped prevent tasks being missed. 9 When staff communication and teamworking were deemed to be ineffective, this caused frustration and concern among staff and reduced the effectiveness of IR. Some highlighted nurses’ reluctance to ask other team members for help as a barrier to effective IR;60 other influencing contexts were staff involvement, ownership of practice29,47 and the busyness of the ward. 27

Context–mechanism–outcome 8: intentional rounding fosters patient empowerment

Overall, the evidence related to this mechanism was weak, with only four studies4,25,28,57 identified and no detailed descriptions provided. The brief definition of the mechanism was supported only by limited empirical evidence, primarily drawn from one UK study. 4 This reported that individuals in care homes became more ‘forthcoming’ when they knew that staff were coming to see them regularly, empowering them to ask for what they needed. 4 As in the original definition, this study4 also found patient empowerment to be closely entwined with nurse–patient communication and relationships. Tentative evidence related to patient empowerment as an outcome of IR was identified by three other studies. 25,28,57

Influencing contexts and outcomes of intentional rounding

Although the aim of realist syntheses is to better understand the interplay of how a particular context affects a specific mechanism to produce outcomes,61 this review has found that such detailed theoretical explanations of IR are rarely provided in the literature. A list of potential ‘backdrops’ believed by authors to influence IR and a list of potential outcomes reported to arise from it were, however, identified and are highlighted in Appendices 1 and 2. The findings of this synthesis echo those of a systematic review of the barriers to effective implementation and sustainment of IR on medical and surgical wards,62 as well as identifying additional barriers. In Table 3, the theories by which IR may work are made explicit, and CMO configurations that are to be tested and refined in later phases of the study are summarised.

Discussion

The absence of any theoretical development of IR was notable in the synthesis, as many studies reported only the outcomes of implementing IR without providing any explanation of how or why these outcomes occurred. Similarly, many studies discussed the contexts that influenced IR but failed to explain how these conditions interacted with mechanisms to produce specific outcomes. This poor understanding of how IR works poses a major challenge to learning, replication and sustainability of the intervention.

The synthesis identified a number of discrepancies between how IR is purported to work and how it operates in practice, as well as international differences in how the intervention has been implemented. For example, guidance from the US states that the intervention should be utilised in a standardised manner so that all patients receive the same input. 2 Yet other countries, including the UK, appear to have adopted a more flexible approach, based on nurses’ clinical judgements of patient needs and preferences. The intervention has, therefore, not been consistently implemented across settings, but has been adapted and extended to suit local circumstances. This leads to an important question of how flexible the approach to the delivery of IR can be before it can no longer be considered IR.

Managing risk has also been acknowledged as an important driver for the introduction of IR. Assumptions have been made that IR will increase the personal accountability of nurses and raise the overall standard of nursing care. However, this synthesis has identified that this is not necessarily the case. IR may assist organisations to monitor and audit the care provided by their nursing staff, but evidence suggests that these audits focus on compliance with documentation procedures rather than on the quality of the rounds. This illustrates another ambiguity in the purpose of IR: is it to support nurses to improve the care they deliver, or to provide nursing managers with detailed evidence of nursing activity? Or is it an assurance tool for nurse directors seeking to report the quality of care to their boards and the public?

Summary

-

Despite the widespread use of IR, there is ambiguity surrounding its purpose and limited evidence of how it works in practice.

-

Differences in the implementation of IR demonstrate the importance of care delivery context and highlight that IR has been adapted in different contexts and as time has progressed.

-

This synthesis generated eight CMO configurations (see Table 3), which were tested and refined in subsequent phases of the study.

Chapter 4 Phase 2: a national survey of NHS acute trusts in England

This chapter describes the second phase of the study: the national survey of NHS acute trusts in England. This chapter addresses objective 1 of the study, exploring how IR was being implemented and supported across England and the way in which organisational context (or features of services and health-care organisations) influenced its implementation.

Method

In phase 2, a national survey of NHS acute trusts in England was conducted to explore how IR was being implemented and supported. A structured questionnaire to be administered online via SurveyMonkey® (Palo Alto, CA, USA) was developed and piloted in a local hospital trust. Following feedback from this pilot and the study advisory group, the survey was amended and shortened to maximise the response rate (see Report Supplementary Material 1). It included questions about:

-

when IR was implemented

-

provision of staff training/education opportunities to prepare staff to conduct IR

-

specific details about how the intervention was being implemented, which members of staff conducted rounds, how often they were conducted and how the rounds were documented and audited.

Details of NHS trusts in England were accessed online from the NHS website (www.nhs.uk; accessed 1 September 2015) and e-mail addresses for each chief nurse (often called ‘executive director of nursing’) were obtained from a list supplied by the CNO at NHS England to enable each director of nursing to be contacted directly. The list of trusts and contact details were compiled based on trust configuration, giving a total of 155 acute trusts. Trust acquisitions and mergers, and organisational and leadership changes occurring at this time were not insubstantial, meaning a dynamic approach during the data collection phase had to be adopted to maximise the response rate. An invitation to participate in the study with the link to the online survey was sent directly to each chief nurse in April 2015, with the request that they completed it themselves or forwarded the link to an alternative senior nurse with responsibility for implementing nursing services. Up to three reminders were sent by e-mail or telephone. Information about the survey was circulated and promoted by regional directors of nursing in England at their regular meetings with trust chief nurses, by the chief nurse at Health Education England and by the NHS Trust Development Agency in their newsletter to directors of nursing. Responses to the survey were collected in a SurveyMonkey web form, stored by SurveyMonkey in a secure, EU-based server and downloaded by the researchers when the collection was complete. The findings were then analysed in Stata® version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The questions were a mix of multiple choice and free-text entry. Categorical questions were counted and percentages were calculated after allocating free text. Numerical questions were summarised with histograms, medians and quartiles. Free-text answers were examined and used to inform the qualitative research that followed.

Findings

Sample and respondent characteristics

Responses were received from 108 (70%) of the 155 English NHS hospital trusts that were sent the survey, of which 76 (70%) were acute trusts, 23 (21%) were integrated acute and community trusts and nine (8%) were specialist trusts. The mean number of beds in the responding trusts was 709 (range 39–2000) and 98 (91%) trusts had wards that were structured as predominantly smaller bays (typically 4–6 beds in a bay); 44 (41%) had wards that were made up of predominantly single rooms and 26 (24%) had wards that were predominantly Nightingale wards (i.e. the majority of beds in one large ward area). A total of 102 respondents provided their job title, which showed that the majority of the surveys [N = 89 (87%)] were completed by corporate-level nursing leaders in the trust, that is chief nurses (n = 31), deputy chief nurses (n = 43) or another corporate-level senior nurse (n = 15). The remaining 13 questionnaires were completed by divisional or directorate level heads of nursing. At the beginning of the survey, a brief definition of IR was given:

. . . a structured process whereby nurses in hospitals carry out regular checks, usually hourly, with individual patients using a standardised protocol to address issues of positioning, pain, personal needs and placement of items.

A total of 103 respondents (95%) indicated that this was their understanding of IR; there were four missing responses, and one respondent thought that the definition made the interaction sound mechanistic and failed to capture the essence of IR (i.e. showing patients, at regular intervals, that staff are concerned about meeting their needs).

Descriptive statistical analysis

Implementation of intentional rounding

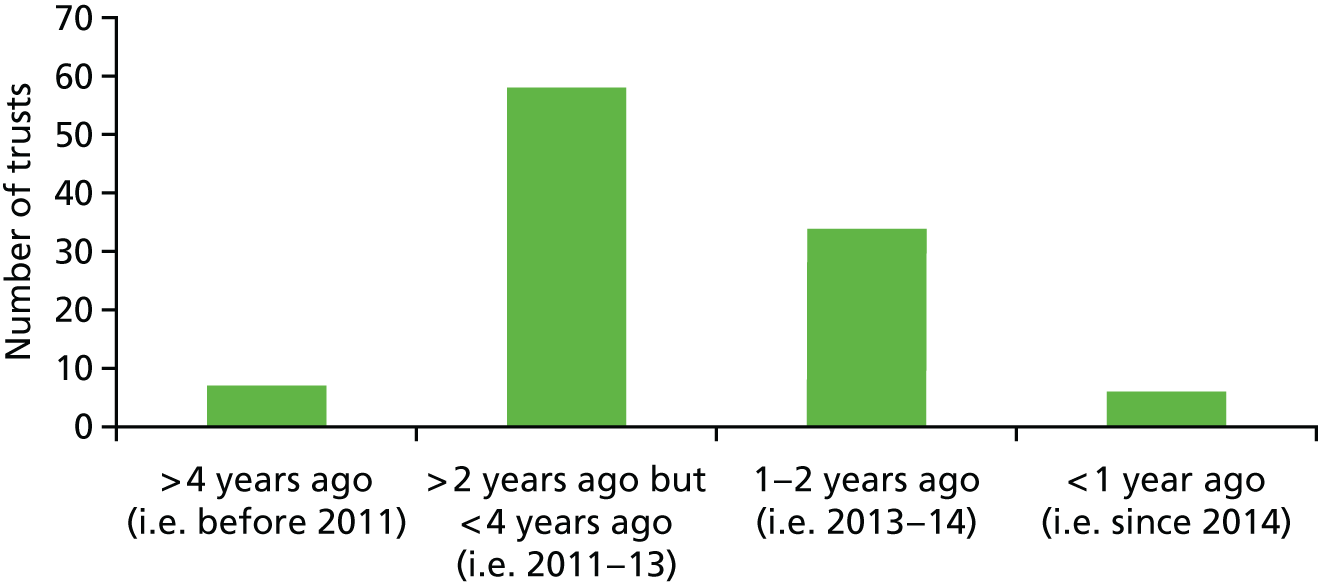

A total of 105 (97%) trusts stated that they had implemented IR in some way, although details around how and when it was implemented varied widely. For example, the vast majority of trusts implemented IR between 2011 and 2014. Seven trusts could be considered ‘pioneers’ or ‘innovators’, having implemented IR before 2011, and six could be considered late adopters, stating that IR had been adopted after 2014. Further breakdown is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

When was IR implemented?

Once IR had been implemented, few trusts [n = 18 (17%)] reported that it had been interrupted for any length of time. Those that did gave the following reasons for the interruption: difficulty in implementing/sustaining IR, with several changes to documentation and pilots (n = 9); to review that IR was meeting its objectives (n = 3); staff shortages (n = 2); winter bed pressures (n = 1); ward managers deciding to stop IR and then re-introduce it (n = 1); poor understanding of the structured approach (n = 1); and to transfer documentation to an electronic record (n = 1).

Most trusts used the term ‘intentional rounding’ [n = 54 (53%)], although a large number of other different terms were also used, with ‘comfort rounds’ being the most common alternative [n = 14 (14%)] (Table 4).

| Alternative name | Trusts, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Comfort rounds | 14 (14) |

| Care round or Care rounding | 11 (11) |

| Hourly rounding or Hourly rounds or Hourly care rounds | 4 (4) |

| Essential care rounds | 2 (2) |

| Care and comfort rounding | 2 (2) |

| Patient contact round | 1 (1) |

| Rounding | 1 (1) |

| Intentional safety care bundle | 1 (1) |

| Better-care rounding tool | 1 (1) |

| Patient-focused rounding | 1 (1) |

| Time to care | 1 (1) |

| I-Care | 1 (1) |

| Safety and comfort checks | 1 (1) |

| Care and comfort checks | 1 (1) |

| Around-the-clock care | 1 (1) |

| Patient-focus rounding | 1 (1) |

| Well-being standards | 1 (1) |

| Caring around the clock | 1 (1) |

| Rounding with a reason | 1 (1) |

| Quality rounds | 1 (1) |

The majority [n = 67 (64%)] had implemented IR on all wards in the trust, although 18 trusts (17%) had implemented it on specific wards only and 20 (19%) had other more specific arrangements (Table 5).

| Clinical area | Trusts, n (%) |

|---|---|

| All adult inpatient areas | 101 (96) |

| Acute admissions | 91 (87) |

| Emergency department | 80 (76) |

| Maternity areas | 74 (70) |

| Day-care areas | 74 (70) |

| Paediatric wards | 72 (69) |

A few trusts had implemented IR in only a small number of clinical areas (e.g. in surgical wards only). Other trusts had implemented IR in specific areas, such as intensive therapy units (n = 1), operating theatres (n = 1), surgical assessment units (n = 1) and outpatient waiting areas (n = 1). Some trusts indicated that there was variation in where and how IR was implemented in their organisation. For example, one trust chose not to mandate IR but to leave it up to ward managers to decide. Another trust had initially implemented IR on all wards for all patients, but revised this to select patients ‘at risk’ (e.g. those with confusion or dementia, those post surgery or those at a high risk of falling).

A total of 84 (80%) trusts reported that, on the wards where IR had been implemented, it occurred for all patients. Where IR did not occur for all patients [n = 21 (20%)], this was mainly based on patient need, with nine responses indicating that patients who were assessed as being at higher risk/vulnerable received IR and seven responses stating that patients who were self-caring or mobile did not receive IR. One respondent said that some patients opted out of IR.

In 93 trusts (89%), a mix of RNs and unregistered nursing support staff conducted IR. In one trust (1%), only RNs conducted IR, and in two trusts only unregistered staff (2%) conducted IR. Nine (9%) trusts responded that allied health professionals (AHPs) were also involved in IR, with two trusts adding that doctors had occasionally been involved.

There was some variation among trusts regarding the frequency with which IR was carried out during the day on wards where IR was implemented. Twenty-three (22%) trusts implemented IR hourly, 21 (20%) implemented IR every 2 hours on all wards and 29 (28%) implemented IR hourly for some wards and every 2 hours on other wards. Thirty-two (30%) trusts had some variation in frequency, usually dependent on individual patient risk/needs. One trust specified that frequency was prescribed by a RN and another that need was assessed daily. Six trusts did not specify a frequency but said that it was dependent on patient need. Other variations were indicated, for example that IR should be conducted five or six times per day (n = 1), that it should be conducted hourly for high-risk patients and three times in 7 hours for other patients (n = 1), or that it was ward specific (n = 1).

A similar varied pattern was found for the frequency with which IR was conducted during night-time on wards where IR was implemented. Ten trusts (10%) implemented IR hourly, 26 (25%) implemented IR every 2 hours on all wards and 26 (5%) conducted IR hourly for some wards and every 2 hours for other wards. A total of 43 (41%) trusts had some variation in frequency, usually dependent on individual patient risk/needs, as during the day. Several respondents indicated that staff made hourly checks but that patients would not be disturbed or woken up to do IR.

A total of 85 (81%) trusts said that they had a structured protocol, script or procedure in place during IR. Table 6 shows the aspects of care included as part of IR. The most frequently included items were personal needs, positioning and pain assessment, which are in keeping with the accepted definition of IR. The majority of trusts also included placement of patient items, environmental safety checks and checking pressure areas. However, there were a significant number of items not usually considered part of IR that were also included [e.g. interactions with carers and checking fluid balance and intravenous (i.v.) lines and infusions], suggesting that the IR protocol was adapted by many trusts to address additional patient needs. Additional items that other trusts included were continence, nutrition, falls risk assessment, cognitive status and mouth care.

| Aspect of care | On all wards, n (%) | On some wards, n (%) | On no wards, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Items in Studer version of IR | |||

| Placement of patient items | 62 (83) | 9 (12) | 4 (5) |

| Positioning | 77 (92) | 8 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Checking of pressure areas | 61 (81) | 12 (16) | 2 (3) |

| Pain assessment | 75 (90) | 6 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Personal needs (e.g. toileting) | 78 (93) | 6 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Environmental safety checks | 61 (82) | 8 (11) | 6 (7) |

| Items in trust adaptations of IR | |||

| Checking vital signs | 13 (25) | 12 (23) | 28 (53) |

| Checking i.v. lines and infusions | 19 (33) | 15 (26) | 24 (41) |

| Checking fluid balance | 36 (55) | 12 (18) | 17 (26) |

| Interactions with carers | 37 (58) | 10 (16) | 17 (26) |

A total of 50 (48%) trusts reported that individual wards had flexibility about what they included in the IR. This flexibility included wards adding to the standard content of IR for their specific patient group or specialty (n = 9), staff using ‘common sense’ to ask only relevant questions (n = 7), adaptation of IR questions for specific patient groups (n = 8) and having a free-text option to record additional information.

Most trusts documented IR [n = 101 (96%)]. The majority used paper documentation kept by the patient’s bedside [n = 90 (86%)] or at the nurses’ station (n = 6). Some used electronic documentation at the bedside using a mobile device (n = 4) or at the nurses’ station (n = 1). One trust documented IR on a whiteboard and 10 trusts used a combination of paper and electronic documentation. Documentation was supposed to occur after every round in most trusts [n = 91 (87%)] or at the end of the shift at five trusts (5%). Timely documentation after every round was seen as better, but five trusts acknowledged that, in reality, staff documented IR at the end the shift some or most of the time.

Intentional rounding was audited by the majority of trusts [n = 68 (65%)], although five respondents did not know if IR was audited or not. Audits tended to be part of monthly general nursing compliance and metrics audits (n = 13), weekly or fortnightly senior nurse/ward manager quality rounds or documentation audits (n = 8) or spot-checked on daily ward manager/matron rounds (n = 9). Other, less frequent, responses included that IR was not audited formally, but was used in the management of incidents and complaints (n = 3); that IR was looked at as part of 6-monthly or annual reviews (n = 7); that IR was assessed as part of patient experience surveys (n = 2); and that it was reviewed in ‘Back to the Floor’ senior nurse reviews (n = 1).

The majority of respondents perceived that IR had a positive impact on patient experience (82%) and safety (79%) or had made no difference (Table 7). They thought that IR had less of an impact on carers’ experiences, but that the impact it did have was positive (55%). IR was thought to have some positive impact on staff experience (44%), although 10 respondents thought that IR had a negative impact on staff experience. The majority thought that IR had a positive impact on accountability (66%), although 34% thought that it made no difference to staff accountability. Some trusts perceived improvements in the number of falls and pressure ulcers; however, 19 trusts thought it was very difficult to say whether or not any improvements were due to IR, as other initiatives undertaken may also have had an impact.

| Area of change | Change, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive impact | Negative impact | No difference | |

| Patient experience | 77 (82) | 0 (0) | 17 (18) |

| Patient safety | 75 (79) | 0 (0) | 20 (21) |

| Carer experience | 48 (55) | 0 (0) | 39 (45) |

| Organisation of care | 61 (66) | 1 (1) | 30 (33) |

| Staff experience | 39 (44) | 10 (11) | 39 (44) |

| Accountability | 61 (66) | 0 (0) | 31 (34) |

Sixty-three (60%) trusts provided education for staff when IR was introduced and 52 (50%) trusts made IR education mandatory as part of the induction of new staff. Only 18 (17%) trusts provided education about IR as an ongoing requirement for all staff, although 27 trusts (26%) said that education was locally arranged in ward areas/specialties. Some trusts provided more than one approach to education and 15 trusts (14%) had no planned programme to educate and prepare staff for using IR. Two (2%) respondents did not know whether or not IR education was provided for staff.

The survey included opportunities to provide additional information about how IR was implemented. A total of 108 trusts responded to the survey; of these, 94 provided a free-text response to at least one question. These responses were analysed to search for examples of contexts, mechanisms or outcomes associated with IR; this is reported in Appendix 3.

Summary

-

A total of 70% of all NHS acute trusts in England responded to the national survey.

-

Of these

-

97% said that they had implemented IR in some way

-

89% had a mix of registered and unregistered nursing staff conducting IR

-

81% had a structured protocol, script or procedure in place for IR

-

96% documented IR.

-

-

Large variations were noted across trusts as to when, on which wards and for which patients IR was implemented; how regularly IR was conducted; what aspects of care were included in IR; and what educational opportunities staff received about IR.

Chapter 5 Phase 3: in-depth case studies – ward profile data, patient outcomes, and costs and benefits

This chapter addresses objectives 2, 5 and 7 and gives an overview of the three case study sites and their staff data, describing how IR has been implemented, developed and supported at each site. This chapter also investigates trends in patient outcomes (retrieved from routinely collected NHS ward data) in the context of the introduction of IR and other care improvement initiatives that have been introduced. An analysis of the costs and benefits of IR is also provided.

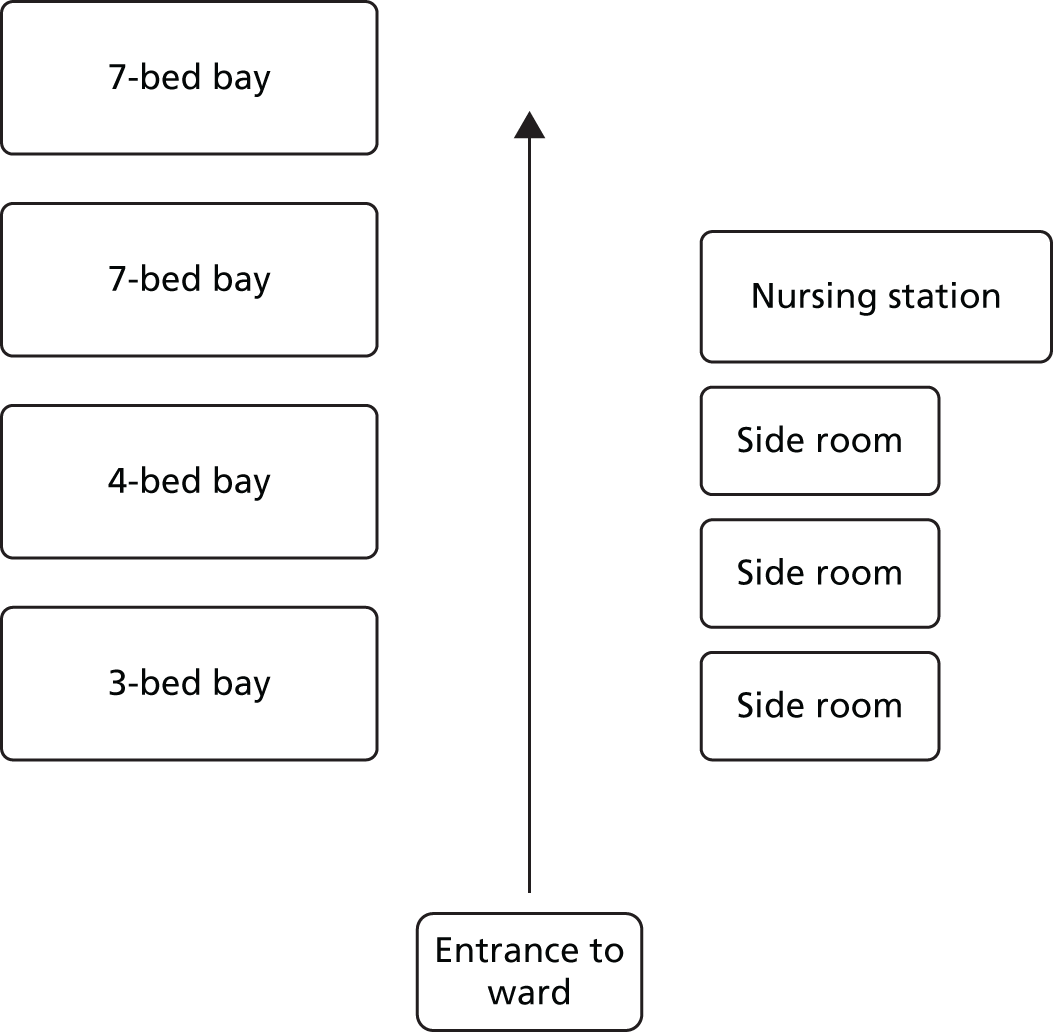

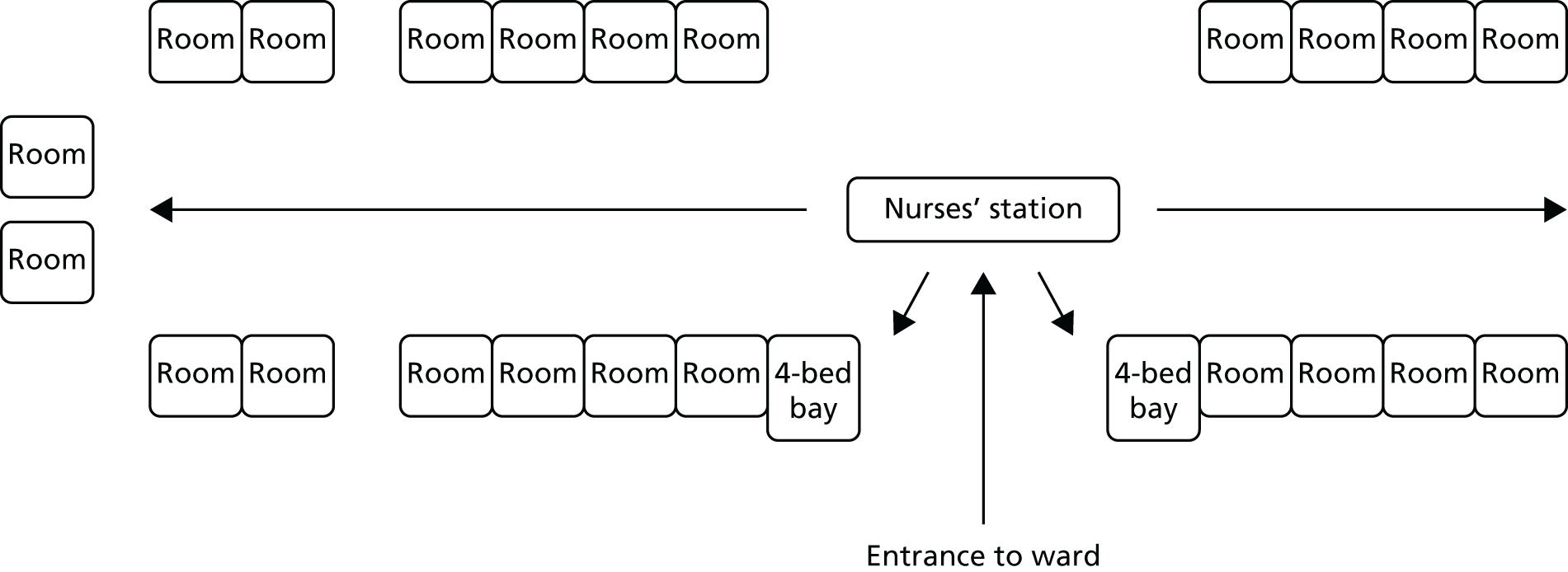

Ward profile data method

In phase 3, in-depth case studies were conducted to explore the extent to which the CMO configurations of IR identified in the literature and from the stakeholder consultation event were compatible with or relevant to modern health service delivery and the experiences of health-care staff and those of patients and their carers. The results from the survey, alongside NHS trust characteristics such as location and number of beds, were used to select the case study sites to be as broadly representative as possible, while maintaining the diversity necessary for qualitative data. The co-investigators discussed and agreed the selection of trusts together to identify sites where IR had been implemented differently (e.g. hourly versus every 2 or 4 hours), sites with different ward layouts (e.g. predominantly single rooms vs. Nightingale layouts) and sites of different sizes. Two trusts were approached and declined to participate in the study before the three case study sites were finalised.

Two wards were identified by senior trust staff in each hospital (one acute and one care of older people, to reflect the areas of concern in the Francis inquiry1). Trusts were able to choose their own wards and were not given any other criteria for how to do so by the study researchers. The research team spent 2–3 weeks based on each ward to undertake data collection.

To map the organisational and service delivery context in which IR was implemented, individual interviews were undertaken with directors of nursing/senior nurse managers and ward managers at each of the case study sites and a matron at site 3. A topic guide (see Appendix 4) was designed for this purpose, to collect information about the implementation and development of IR in each trust, details about how IR was undertaken, monitored and evaluated and any future development plans for the intervention. A total of 17 individual interviews were undertaken with trust and ward managers and a matron (Table 8). Audio files were transcribed and examined to produce a detailed description of the organisational context in which IR was introduced at each site.

| Case study site | Staff interviewed (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Senior nurse manager (Director of Nursing) | Ward manager | Matron | |

| 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

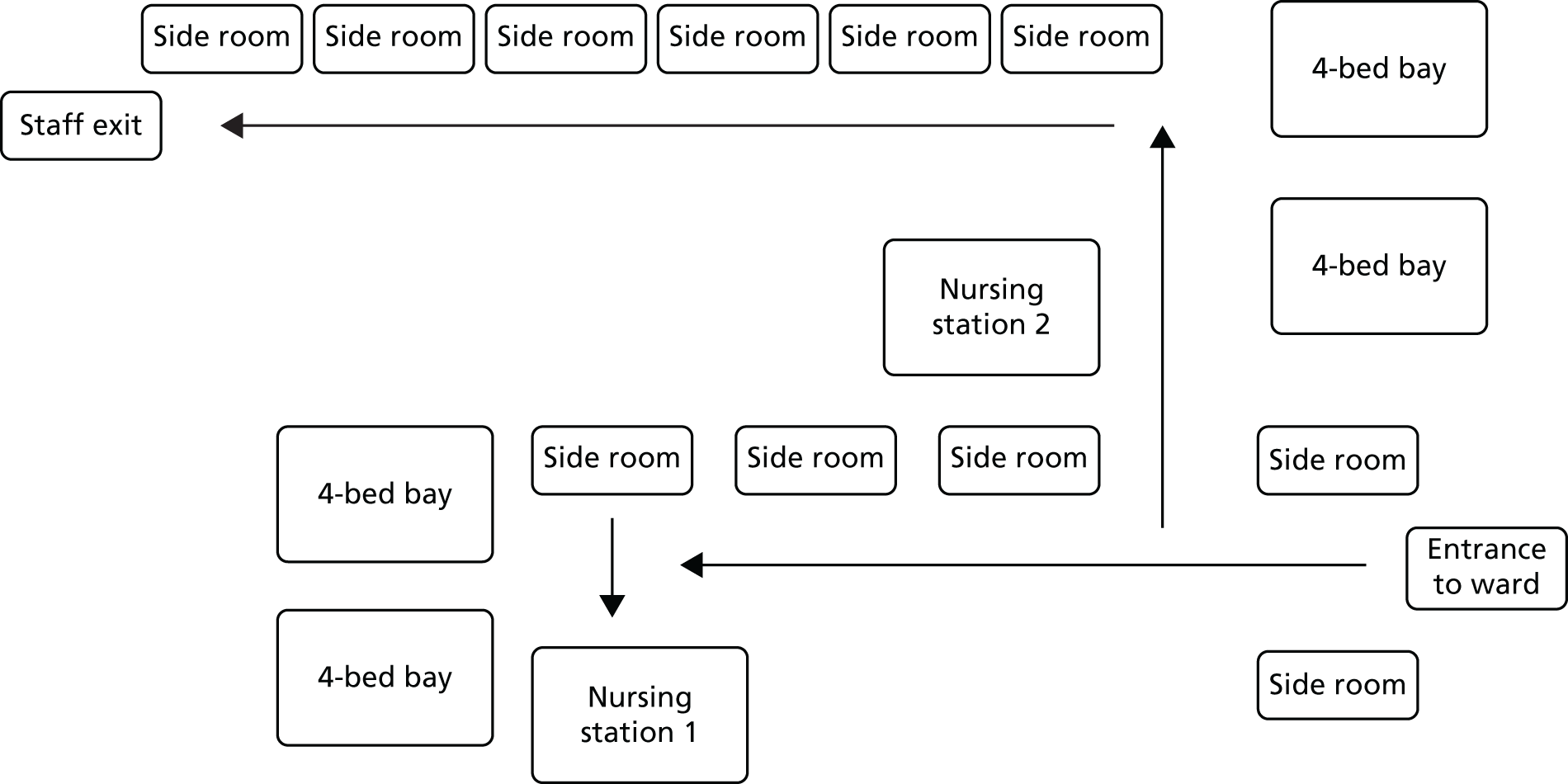

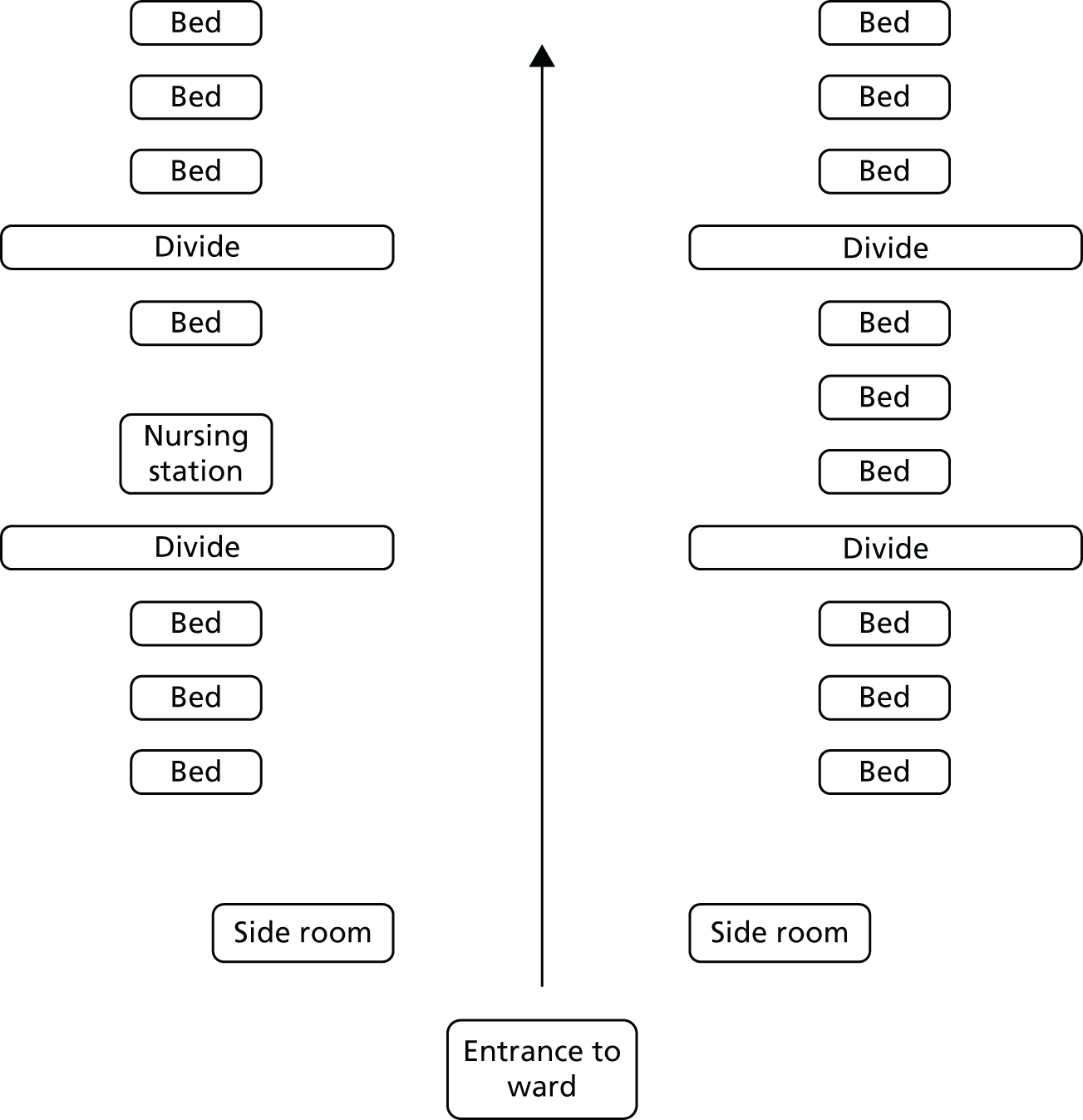

Ward and trust managers at each case study site were also asked to provide any documents that they could that contained information on their team or service, including nursing shift patterns, staffing information, sickness levels and vacancy rates. Researchers prepared ward layout maps to highlight the ecology of each case study ward, including the layout of patient beds. Detailed ward profiles including the ward layouts can be seen in Appendix 5 and a summary is provided in Tables 9–12. Reproduced examples of the IR documents for each site are provided in Appendices 6–9.

| Trust characteristic | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Large (> 800 beds) | Large (> 800 beds) | Very Large (> 1000 beds) |

| Location | Urban | Urban with rural catchment area | Urban |

| Bed occupancy (%) | > 90 | > 90 | > 90 |

| Ward characteristic | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ward a | Ward b | Ward a | Ward b | Ward a | Ward b | |

| Specialty | Health care for older people | Acute medicine, endocrinology | Acute trauma orthopaedic | Health care for older people | Acute medicine, cardiac and respiratory | Health care for older people |

| Number of beds | 24 | 24 | 32 | 32 | 26 | 18 |

| Predominant ward layout | 3–7 bed bays | 3–7 bed bays | Single, en suite rooms | Single, en-suite rooms | 4 bed bays | Nightingale |

| Nursing organisation | NS | Three teams | NS | Four teams | NS | NS |

| Shift pattern | 12-hour shifts | 12-hour shifts | Combination of 12-hour shifts and early (07.00–13.30) and late (13.00–19.30) shifts | Combination of 12-hour shifts and early (07.00–13.30) and late (13.00–19.30) shifts | 12-hour shifts | 12-hour shifts |

| Nursing team | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| February 2017 | January 2017 | April 2017 | May 2017 | July 2017 | July 2017 | |

| Nursing staff establishment at the time of data collection | ||||||

| Band 7 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Band 6 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 4.9 | 2.1 |

| Band 5 | 15.19 | 17.29 | 17.2 | 20.9 | 21.5 | 12.7 |

| Band 4 | 9 | 0 | 2.6 | 6.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Band 3 | 0 | 0 | 6.5 | 5.8 | 0 | 0 |

| Band 2 | 15.09 | 11.09 | 19.6 | 7.1 | 9.5 | 12.4 |

| Total | 33.28 | 31.38 | 50.5 | 45.0 | 36.9 | 28.2 |

| Vacancy rate | 4 (FTE) | 4 (FTE) | 4.4 (FTE) | 8.1 (FTE) | 19.78% | 9.69% |

| Agency/bank use | 127 shifts covered by temporary staff | 82 shifts covered by temporary staff | 6.7 (FTE)

|

11.4 (FTE)

|

8.06 (FTE) | 4.57 (FTE) |

| Sickness |

RN: 19.74% HCA: 0% |

RN: 11.56% HCA: 45.08% |

1.1 (FTE); 3.0% | 2.2 (FTE); 5.4% | 2.54 (FTE) | 0.38 (FTE) |

| Implementation of IR | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| When introduced | Some discrepancy; some time between 2009 and 2012, most likely 2011 | Some discrepancy, some time between 2014 and 2016, most likely 2014 | Because of staff changes, the exact date is unclear; it was around 2012/13 |

| Circumstances | Part of a strategy to reduce patient harm and increase care quality | Part of the strategy to reduce increased falls risk due to a predominantly single-room environment and develop compassionate care | Ward managers able to decide whether to implement IR or not. The majority of wards were thought to be implementing it at the time of the study |

| Staff involvement | Not initially, but recognised that this was ill-judged and staff were involved to redesign the IR process and documentation, which was piloted on some wards before roll-out to all wards | Managers reported a period of testing and piloting, although they think that IR was probably implemented too quickly across the trust | Owing to staff changes, it is unclear the degree to which staff were involved in implementation |

| Documentation | Four-page A4 booklet. Has been frequently revised according to perceived need. Includes 4Ps questions and the ‘Is there anything else I can do for you?’ question | Two-sided form. Includes 4Ps questions and the ‘Is there anything else I can do for you?’ question |

|

| Trust IR policy | Detailed trust policy | Detailed trust standard operating procedure | No formal IR policy |

| Frequency of IR | Hourly between 8.00 and 22.00, every 2 hours between 22.00 and 8.00 hours. Time intervals pre-written onto form | Frequency could vary according to risk assessment as long as rationale was recorded. Minimum frequency of every 4 hours. Time of IR was not specified, so specific time was entered by staff |

|

| Who does IR | Both HCAs and RNs. RN required to complete IR at 2.00, 8.00, 12.00, 16.00, 20.00 hours | Any member of clinical staff who had read the IR standard operating procedure and had received training in SKIN and Falls bundles | Both RN and HCA staff |

| Adaptation of IR beyond Studer format | IR documentation included questions about mobility, bed rail position, special mattress, body map to record skin integrity and presence of medical devices | IR documentation included questions offering drinks/snacks, falls prevention, body map to record skin integrity and presence of medical devices. Space available to document any actions resulting from IR | IR form for patients with a Waterlow score of ≥ 10 included assessing skin inspection, nutrition and special mattress needs |

The method of retrieval of routinely collected outcome data

Routinely collected outcome data from the NHS Safety Thermometer were retrieved for each of the case study wards. The NHS Safety Thermometer (www.safetythermometer.nhs.uk; accessed 13 September 2017) is a measurement tool to monitor commonly occurring patient harms in the NHS. It is used locally to support improvement in the delivery of harm-free care. Safety thermometer data were requested from case study trusts. The data received were analysed separately for each trust because of inconsistencies in the way in which they were recorded and aggregated. The main goal of this part of the analysis was to triangulate with the observational data. There were limitations because of the design of the study itself. Many things had changed at the same time in the health service and it would be hard to say that any pattern over time was due to IR, unless one could compare hospitals doing IR with others not doing IR. However, there were no controls (i.e. hospitals that did not undertake IR at all). It was hoped that some hospitals might have adopted early and others might have suspended IR for various reasons, giving us enough of a mixture to do a ‘synthetic controls’ analysis, which is increasingly used in economics, but this was limited as there were only six case study wards. Furthermore, safety thermometer data were collected on only 24 patients per month; analysis was, therefore, exploratory. Each of the various harms were summarised as line charts showing the percentage over time, with 95% binomial confidence intervals superimposed. Autocorrelation charts were generated to check for any persisting patterns over time, when one month seemed to influence the next. All data handling and analysis was done in Stata version 14.

The goal of quantitative analysis in this project was to fit within the realist evaluation framework. IR has not been implemented as a universal intervention that could be expected to show a homogeneous effect in all settings and times, like the introduction of a vaccine. Therefore, these quantitative analyses attempted neither causal inference nor estimation of the effect of IR. The purpose was to explore and understand patterns in the survey, Care Quality Commission (CQC) ratings and safety thermometer data, and to provide stimulus for qualitative data collection and interpretation. 63

Safety thermometer data

Safety thermometer data were obtained from the three case study sites. Each hospital aggregated, labelled and shared the data in a different way, which limited analysis. Ideally, the data would have been combined into one table and then trends over time that might relate to IR would have been explored, for example a decrease in harms such as pressure sores at the time of IR being initiated in each hospital. However, the site differences meant that each hospital had to be analysed separately. There were also the following additional limitations:

-

The data from different sites covered different time periods.

-

IR was implemented before the safety thermometer data that could be accessed (there may be older, similar audit indicators, but not in a consistent format that could be compared across sites and months).

-

Two sites gave aggregate data only, not at patient level.

-

Case mix could not be considered with the safety thermometer data as there were no variables to give context for each patient, such as demographics, prescriptions and diagnoses.

-

Sample size was small, at about 24 per month.

-

An assumption that there were no inclusion biases was required.

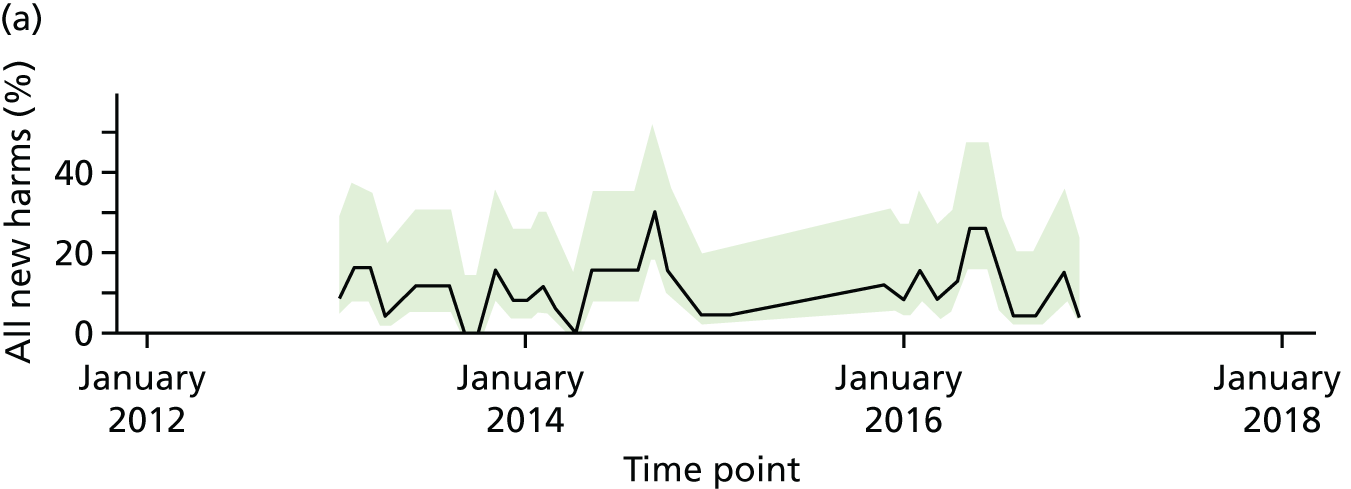

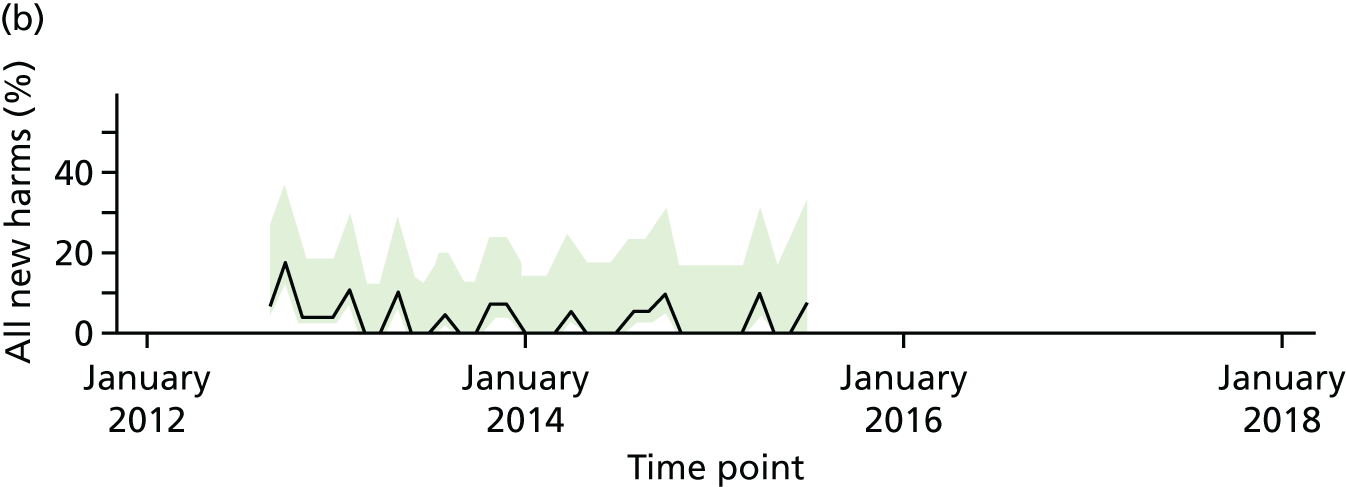

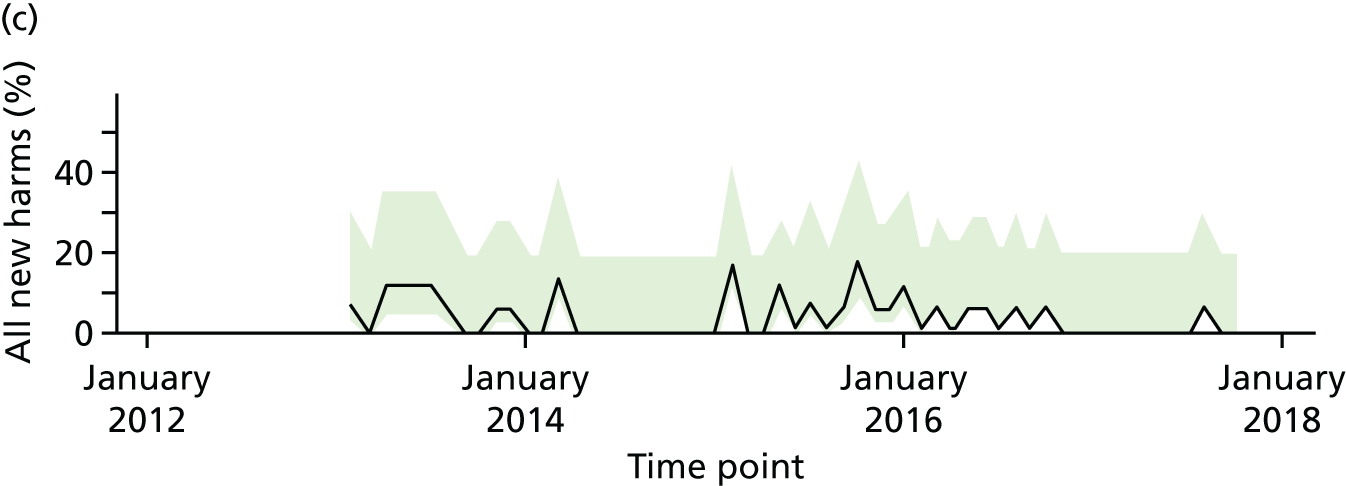

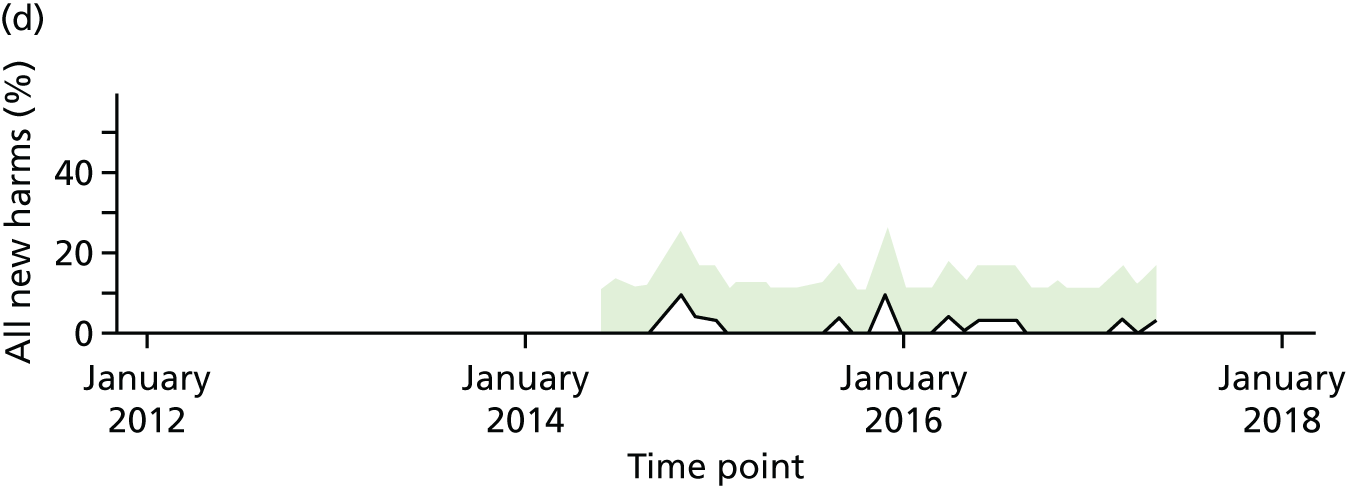

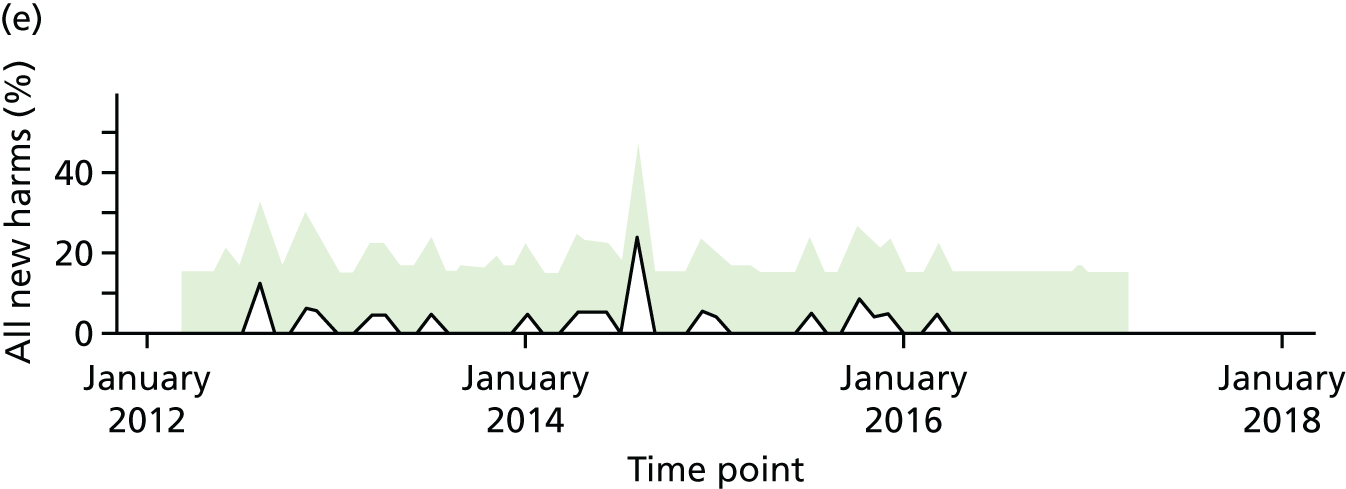

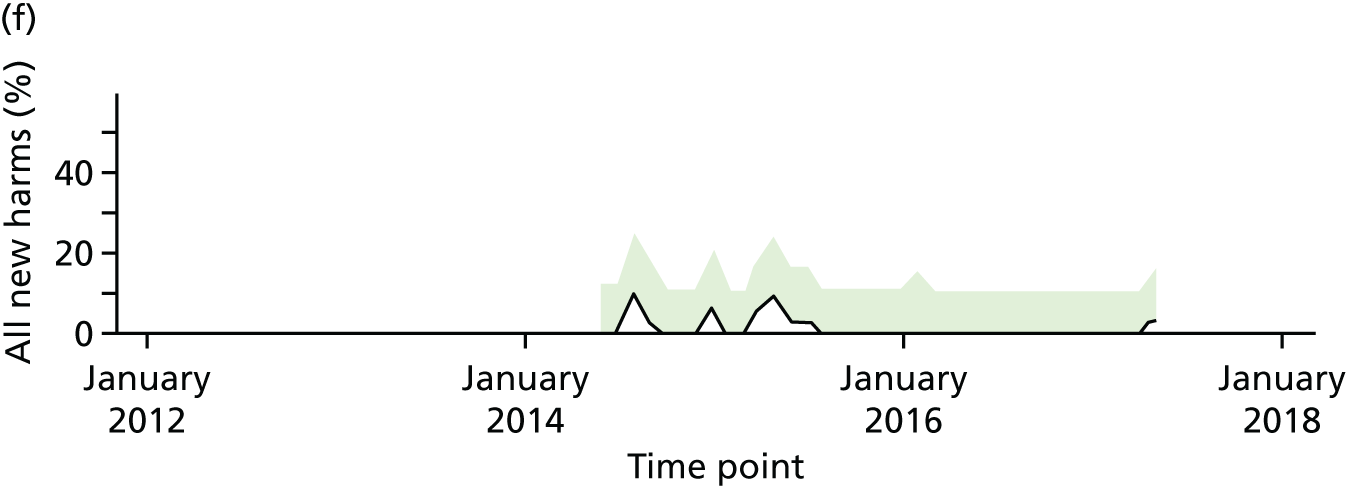

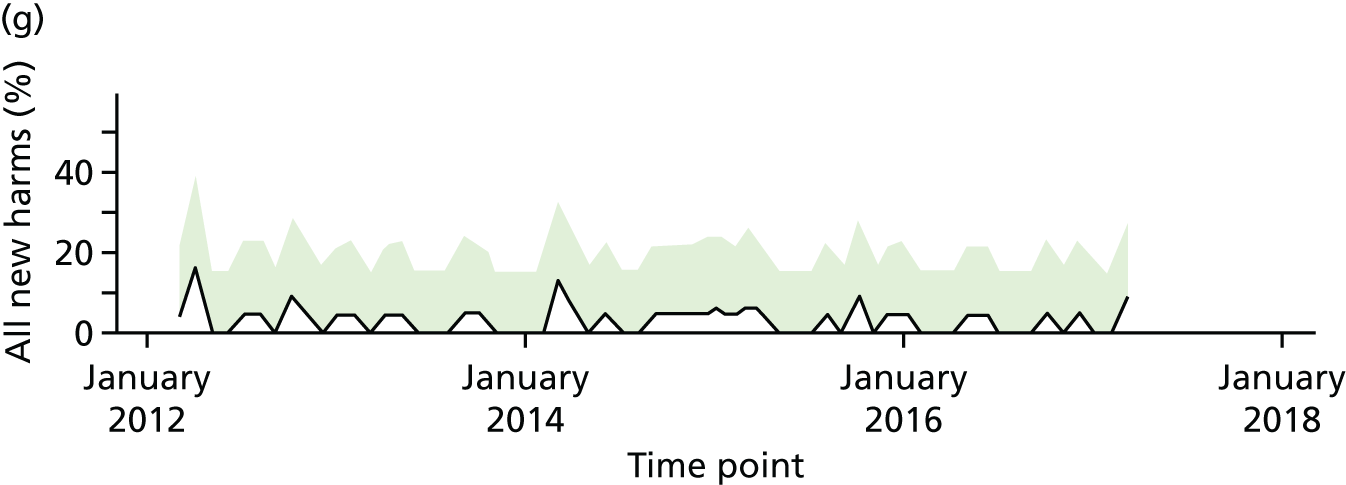

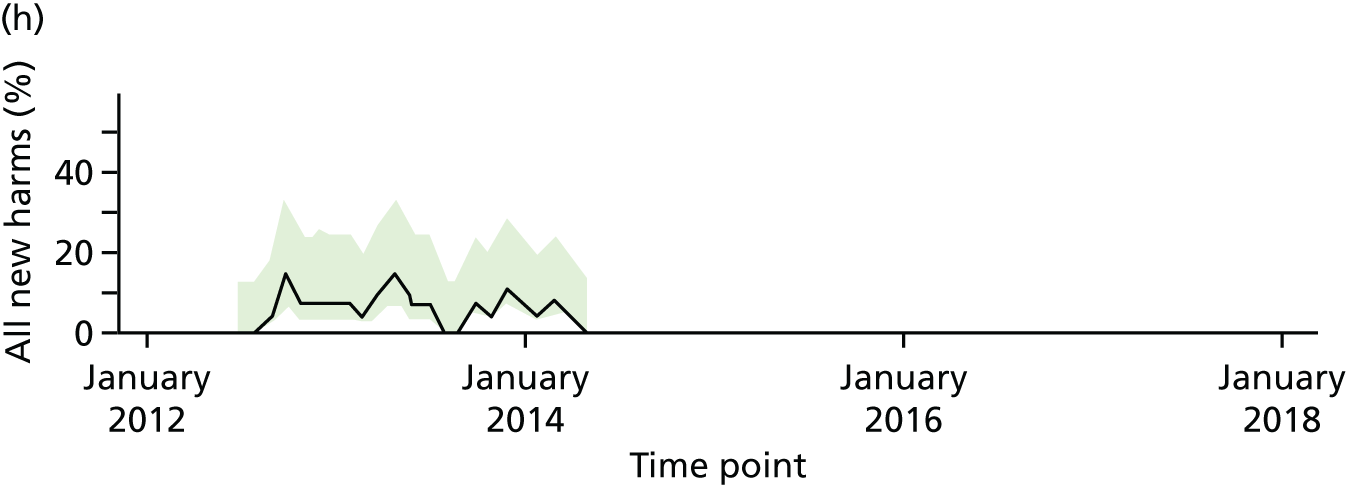

Charts of the various harms were drawn as percentages, changing over time, for each ward. On these, the 95% CI is shown: this is the range of percentages that could contain a true rate of harms, given that sometimes the safety thermometer data will, by chance, pick up too many harms and sometimes too few. If a horizontal line can be drawn across the chart that does not leave that green area, then that means that the data obtained were not inconsistent with there having been no trend over time at all. However, even this basic form of statistical inference needs a further caveat: examining several wards over many months on several indicators is likely to produce an apparently interesting pattern just by chance. For this reason, these charts were used simply to feed into discussions in interviews and to contextualize observational data. Figure 3 shows the percentages of any new harms for each ward (anonymised) that provided data. In each case, IR had been initiated before the safety thermometer data began.

FIGURE 3.

Percentages of any new harms for each case study ward.

One case study site (site 2) identified wards as having different identities before and after a change of building location; the data were analysed on this basis. There are, therefore, eight wards highlighted in Figure 3 instead of six.

Method of cost analysis