Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/156/32. The contractual start date was in November 2015. The final report began editorial review in July 2018 and was accepted for publication in February 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Sheard et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Patient experience

Patient experience (PE) is a highly contested concept. On the one hand, it can be conceived as ‘what patients think of the care we deliver as a health-care organisation’. This is commonly divided into the functional aspects of care (e.g. timely management of symptoms, effective treatment, a clean environment and good transfers between teams/units) and the relational aspects of care (dignity, respect, involvement, honesty and clear communication). On the other hand, PE is about what it is like to be a patient who is ill in hospital: the lived experience. This distinction is important because data that are routinely collected by health-care organisations (referred to as ‘measured’ below) almost exclusively generate information about the functional and relational aspects of care, whereas social media [e.g. Care Opinion1 (Care Opinion CIC, Sheffield, UK; www.careopinion.org.uk)] and patient narratives (e.g. in experience based co-design) provide information about the lived experience.

Historically, there has been some debate about whether (measured) PE tells us anything new or useful about the quality of care in hospital;2 the argument is typically around whether or not patients really know enough to comment on the technical aspects of care, whether or not it is possible to robustly measure anything useful with the noise from patient expectations and the effect of outcomes on patients’ reflections on their experiences. In other words, if the treatment was not effective, they may judge their experience as poor irrespective of the quality of care. However, there is emerging evidence,3 an increasing policy focus and now near universal agreement that PE feedback is necessary in order to deliver high-quality care. 4–6 In 2013, Doyle et al. 7 concluded from their systematic review of the literature that ‘patient experience is positively associated with clinical effectiveness and patient safety . . . and is one of the central pillars of quality in healthcare’. Clinicians should resist side-lining patient experience as too subjective or ‘mood-oriented’. Similarly, a more recent review in the USA8 found that higher ‘star-ratings’ for hospitals based on PE feedback were associated with fewer complications and fewer readmissions.

In the UK, significant resource is now allocated to the collection of PE feedback and the Friends and Family Test (FFT) has become mandatory for all hospital trusts to collect. Other measures include local surveys or audits, annual patient surveys designed by the Picker Institute, complaints, patient-reported safety incidents and comments through social media outlets such as Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; www.twitter.com), Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com), Care Opinion1 and NHS Choices9 (www.nhs.uk). However, the overt emphasis and huge resource allocated to collecting PE data has not been matched by efforts to utilise and evaluate the impact of feedback on service improvement. 10 There is ongoing debate about the comparative value of quantitative or qualitative feedback,10 and the capacity for staff to make sense of different feedback types has not been given sufficient attention. 10 A recent systematic review of 11 studies of the use of PE data to make improvements in health care11 concluded that ‘a lack of expertise in QI [quality improvement] and confidence in interpreting patient experience data effectively’ was a significant barrier and that the use of data to inform changes in behaviour, and to measure the impact of these changes, needed greater attention. In fact, the authors note that it was very difficult to identify what changes had been made or to understand what impact these changes had.

We know that NHS staff are currently exposed to many different data sources but we do not know to what extent PE data synthesis/triangulation is undertaken, whether or not wards have capacity for combining multiple data sets, or if every measurement tool is considered in isolation or in a patchwork fashion. There is some evidence that failure to concentrate on staff capacity while continuing to collect ever more feedback could do more harm than good. A large multimethods study found that, in the main, health-care professionals (HCPs) do want to provide the best-quality care for their patients but challenges such as poor organisational and information systems can prevent them from doing so, in turn lowering staff morale in the process.

Conceptually, we approached this project using the notions developed by Wolf et al. 12 in order to provide us with our overall epistemological framework; these are that PE is deemed by HCPs at all levels to be the ‘sum of all patients’ interactions’. These are shaped by an organisational culture that influences patient perceptions across a continuum of care. Improving PE requires an approach that is ‘integrated’ (i.e. not simply a collection of disparate efforts), ‘person centred’ (recognising that the recipient is a human being) and a ‘partnership’ (with the patient and family). Our starting position for this study was a belief that it is critical that PE is embraced and respected by health-care providers.

Through this research, our research team seeks to unpack the requirements for an effective PE feedback process. We will contribute to shifting the debate around data types from one that focuses on whether quantitative or qualitative data are more useful, to one that seeks to understand how HCPs can be supported to make the right decisions themselves about what data types are most appropriate for their different needs. There is increasing recognition that the complexity of PE is such that multiple sources of feedback (mixed, qualitative and quantitative) are required to get a ‘full picture’. 13 The challenge in this project is to understand the purpose served by different sources of patient feedback, and when they are required. A thorough investigation of what PE data types exist, which are currently viewed and used, and how they could be used more effectively in service improvement, enabled us to articulate the different roles for different sources of data and provide a categorisation not currently available. Our aim was to develop a set of criteria that allowed us to more usefully conceptualise the forms of patient safety feedback and to develop this conceptualisation throughout the programme of work.

To do this, we drew on systems understandings of a safe and quality health-care system14 and extended the notion that what is required by staff to make improvements is ‘intelligence’,15 timely access to appropriate insights about how the system is currently working and what could be improved.

We will place significant attention on the processes necessary for staff to interpret and action data effectively. There is increasing recognition that using data sources to change practice demands creativity and skills from staff, and that these have been poorly defined to date; hence the tendency to present staff with data and expect change to happen as a result. 16 Knowledge mobilisation (KMb) frameworks3 help us to understand the dynamic and contextual factors that affect the way HCPs will make sense of any data they are provided with. Such frameworks recommend the move away from linear notions of data presentation for problem-solving, recognising that the aim of improving health-care organisation and delivery is characterised by uncertainty. HCPs will be required to use multiple data sources, as solutions will be distributed throughout the organisation and will be multifaceted. The burgeoning investment in improvement science in health-care settings reflects this shift in conceptualising knowledge for change. 17 Quality improvement methods support change as an iterative process with continual access to feedback (intelligence), yet these have not been combined with PE data systems to date, which, as Coulter et al. 10 state, is an opportunity that needs exploring. Thus, in the current project our aim is to bring together, via a toolkit, our understanding of PE feedback sources with improvement science, to bridge the gap between data and action.

The body of knowledge developed by our research team on issues of patient safety, experience and quality in previous studies informed our approach throughout. The Yorkshire Contributory Factors Framework (YCFF)18 provides an evidence-based model of the factors (e.g. teamwork, communication, access to resources) that affect the quality and safety of a health-care system. The effectiveness of a tool designed to capture patient feedback about these factors called PRASE (Patient Reporting for a Safe Environment) was the subject of a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grants for Applied Research-funded randomised controlled trial (RCT) led by this research team. 19 We have learnt many lessons from these studies about ways in which ward-based staff use the patient feedback on safety, and the organisational capacity that is required, but not always available, to learn from and support service or organisational-level change. 15 In addition, the framework for ‘The measurement and monitoring of safety’14 helped us to understand the range of different forms of intelligence required (e.g. access to information on past harm, reliability of behaviour, processes and systems, and sensitivity to what is going on). Although we recognise that this framework pertains to safety measurement and so is not entirely relevant here, what this framework did was to help us think about categorising the different forms of PE information available in health care in terms of their function. This, we propose, helps to provide a way of thinking about the disparate sources of information that could guide others in considering what types of data, collected at what level in the system, are most appropriate.

In this programme of work, we also draw on design principles as a basis for developing the Patient Experience Toolkit (PET). Following a process of creative co-design20 involving NHS staff members, managers, patients and researchers, our central tenet was to develop a toolkit to improve PE, rather than a toolkit to use PE data, recognising that achieving the second aim might not necessarily lead to achievement of the first aim.

We therefore undertook a four-stage research project. In stage 1, we conducted a scoping review along with qualitative inquiry to arrive at an extended conceptualisation of what PE is and the role of different types of measures for improvement. In stage 2, we used action research (AR) to co-design and implement a PET that drew on our conceptual work in stage 1, along with the expertise of an improvement scientist to ensure that it contained methods consistent with the principles outlined in dynamic KMb frameworks. The aim of this toolkit was to address the complex needs of HCPs in interpreting, making sense of and using cyclical action and feedback in their working context. Therefore, we brought participatory design expertise to ensure that HCPs directed the design of the toolkit based on their lived (personal) and professional experience. In stage 3, we independently evaluated the AR to make findings transferable to a wider audience and used these in stage 4 to inform a refinement of the toolkit for the wider NHS.

Our research addresses two of the four gaps outlined in the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research commissioning brief: ‘How should patient experience data be presented and combined with other information on quality, effectiveness and safety to produce reliable quality indicators?’ and ‘What kind of organizational capacity is needed in different settings to interpret and act on patient experience data?’. We view these as related issues that our overarching research question seeks to address: what processes are necessary to ensure that hospital staff can receive and act on PE data so that they can effectively improve PE in their settings?

Evidence explaining why this research is needed now

-

The need to address systemic problems of quality and safety is paramount and the role of the patient voice in achieving this is considered vital. 4–6

-

Questions around PE feedback type and organisational capacity for interpretation and action are gaining momentum. 10,21,22

-

Recognition of the process skills required to generate and utilise knowledge for service improvement is increasing, which provides important insights for debates around the collection of and acting on PE feedback. 16

-

There is burgeoning interest in using improvement methodology to support front-line staff to make changes. 17 This approach has been applied to related fields such as patient safety improvement,23 but rarely in the field of PE.

-

Given the volume of PE feedback currently collected by the NHS, research is now urgently needed that seeks to understand how staff consider different forms of data, how multiple forms of data could be better presented and/or synthesised and then work with staff to engender real and lasting changes to services. Our proposed research will meet these objectives.

Aims and objectives

The overall aim of this project is to understand and enhance how hospital staff learn from and act on PE data. The following objectives will allow us to achieve this aim:

-

Understanding what PE measures are currently collected, collated and used to inform service improvement and care delivery.

-

Co-designing and implementing a PET using an AR methodology.

-

Conducting a process evaluation to identify transferable learning about how wards use the PET and the factors that influence this.

-

Refining and disseminating the PE improvement toolkit.

Selection of trusts and nomination of six wards

Three hospital trusts and six ward-based teams were involved for the duration of the whole study. This involvement spanned the qualitative study in Chapter 3, the co-design process in Chapter 4, the AR study in Chapter 5 and the mixed-methods evaluation in Chapter 6. The three trusts were selected to provide diversity in size and patient population. The smallest trust is a small district general hospital that serves an affluent town and a wider rural population. The middle trust is a medium-sized teaching hospital based in a large city with some of the highest levels of deprivation and ethnic diversity in the UK. The largest trust has a very large teaching hospital (one of the largest hospitals in Europe) in a major city that has pockets of affluence and deprivation.

The specialties of wards involved in the study was heterogeneous. We sampled the six wards based on a divergence of specialty, size and patient throughput. The specialities of the wards were: accident and emergency (A&E), male surgery (this represents two wards at different trusts), maternity department (including ante- and post-natal services), female general medicine and an intermediate care ward for older patients. Wards became involved based on consensus between the ward personnel and senior management at the trust, by a voluntary approach. This voluntary approach was necessary to ensure an initial high level of commitment from ward teams. We did not want any ward teams to feel under pressure to take part.

Chapter 2 Scoping review

This chapter discusses understanding different types of patient experience feedback in UK hospitals. 24

Introduction

The use of PE feedback as a data tool within quality improvement (QI) is receiving much interest as evidenced by a systematic review11 into how different types of feedback have been used in QI, and a more discursive piece on PE feedback as measurement data. 13 Both provide more questions than answers, relating to what feedback to collect, and how and when, and then how to use feedback to inform and measure QI. We also know that much feedback is collected but is not used10 and that when staff are presented with feedback and encouraged to use it for QI, they are faced with a complexity of social and logistical barriers. 15 In order to inform our later study where we develop an intervention to assist hospital staff in the effective use of PE feedback, we conducted the following review and categorisation exercise:

-

A scoping review of all types of PE feedback currently available to hospital staff in the UK that builds on previous reviews of surveys to include other feedback available.

-

Development of a list of characteristics that we believe to be important in understanding potential use within QI that consolidates what is already known, combined with our own research experience of improving quality of care.

-

Use of these characteristics to define types of feedback identified in our scoping review into distinct categories that can begin to inform policy-makers, researchers and those responsible for collecting and using PE feedback of their potential comparative uses.

Although we use NHS hospitals in the UK as a case study, we anticipate that our characteristics list and categories will be relevant to types of PE feedback in hospitals elsewhere.

Background

In the systematic review of uses of PE types,11 quantitative surveys were revealed to be the most frequently collected type of PE data (often mandated) but the least acceptable to health-care teams with respect to use within QI. Conversely, other more qualitative types of feedback, particularly those with high levels of patient participation, were less widely collected, suffering from a dearth of evidence around impact and prohibitive resource requirement, but were most acceptable to teams for use in QI. In England, there is currently a specific debate about the usefulness of the mandated FFT survey, which some proponents argue offers timely, continuous and local-level data ripe for use in QI at many levels,25 although others26 suggest that it is problematic for all uses (with respect to validity, representation and adequacy of detail). There is interest in utilising complaints as data,27,28 as well as online reviews,29 but as yet supportive evidence is lacking. Furthermore, in the mix are methods such as experience-based co-design (EBCD): frameworks that hospital staff can choose to adopt to collect very in-depth feedback specifically for use in QI but which, by their authors’ own admissions, require further evidence to justify directing significant resources at wide-scale use. 30 In addition to understanding comparative uses for different types of feedback, it is also suggested that health-care staff should mix different (and multiple) types of PE data to triangulate and obtain the most comprehensive information for improvement. 13 PE feedback is becoming a complex and potentially resource-intensive agenda for health-care organisations.

We therefore need to understand what data are needed within QI, and what PE feedback can offer in relation to this. It is helpful to return to fundamental concepts of QI and ‘data-as-measurement’ to unpack what it is that different types of information can offer. In 1997, distinctions between ‘The 3 Faces of Performance Measurement’ were made that we propose are useful to revisit now. 31 This referred to data used for accountability (outcome measurements used for benchmarking), data for the improvement process (used in problem identification and monitoring of change) and data for research (generating universal knowledge). 31 The first two uses are specifically relevant to the interests of this study. Indeed, the distinction between data that can be used for benchmarking and data that can be used to drive improvement has been made again more recently. 32 We can apply this distinction to PE feedback to help begin to understand potential roles.

In 2013, an evidence scan33 outlined a wide range of PE feedback types available, from quantitative surveys to qualitative patient stories, and characterised them by their ability to generalise (quantitative types) or describe (qualitative types). Subsequently, there have been two reviews of quantitative PE surveys available worldwide, one34 of which assesses them for utility arguing that their primary use is for ‘high-stake purposes’, such as benchmarking, hospital rankings and securing funding (an accountability function). The other35 reaches a similar conclusion and also summarises why they are not suitable for informing local (e.g. ward-based) improvement initiatives: they do not provide locally attributable data and they lack nuance and detail. It is also suggested that some surveys, if designed and supported to allow local interpretation and timely processing, could be used to monitor local improvement process as well. 36,37 With reference to the ‘3 Faces of Performance Measurement’,31 we can also see why other types of feedback may offer what is necessary to manage improvement processes: many of the more qualitative forms identified within33 (e.g. patient stories, complaints and interviews) are much more locally attributable and enable sufficient detail to suggest a use in the first step of the QI process: problem identification. Some sources such as the FFT in England do provide continuous information, so they could potentially be used for the monitoring of the improvement process. Finally, in addition to its locally attributable and detailed nature, it is argued that qualitative feedback can provide additional insights that are necessary to understand aspects of PE that are not possible to elicit through quantitative surveys;38,39 these are the ‘relational’ aspects that are so important to concepts of PE (e.g. how were you treated?), as opposed to the more transactional components (e.g. was a service provided on time?) that are targeted by surveys.

We need to build on the original distinction between accountability and improvement process31 to understand how various characteristics of data influence use in QI. As described36,37 quantitative surveys vary considerably (e.g. in their ability to capture local granularity). As evidenced,33 qualitative feedback also varies ranging from that provided within a complaint (because a patient seeks a response) to that provided within a patient story (because staff want to improve a service).

Methods

A scoping review of sources of patient experience feedback in the UK

We conducted a scoping review comprising academic databases, grey literature databases and websites, and supported this with our own knowledge from the field and that of our study steering group. We also hand-searched citations contained within returned documents. We identified surveys from the existing reviews34,35 and then conducted our own search of academic databases to update and focus on the UK only. We used grey literature and websites to identify other types of PE feedback that we knew, because of their non-validated status, were not likely to be found in academic journals, but more likely to be discussed in ‘guidance’ documents and commentaries. We adopted a scoping review method, and not a systematic review, because flexibility of search terms within grey literature was paramount to enable as wide a range of PE feedback to be returned. Comprehensibility of sources available in the UK, although important, was secondary to our aim of developing a characterisation system and categories that we anticipate could be applicable to other types as they emerge. We were informed by a five-step framework for conducting scoping reviews40 as shown in Table 1.

| Step | Our approach |

|---|---|

| Identifying the research question | ‘What sources of PE feedback are currently available to hospital staff in the UK?’ |

| Identifying relevant studies |

Search of academic databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL Plus, AMED, Scopus, Web of Science, PsycINFO, ProQuest Hospital collection) using terms: ‘patient experience’*’patient’ outcome assessment (healthcare)’, measures*. Timeframe: 2000–2016 Search of grey literature [Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), Google Scholar, Grey Literature Database, Royal College of Nursing database, Care Quality Commission (CQC), Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC), The Health Foundation, HealthTalk.org, iWantGreatCare, HealthWatch, The King’s Fund, NHS England, NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, NHS Surveys, Mumsnet (Mumsnet Ltd, London UK),41 Patients Like Me, Patient Experience Portal, Patient Experience Network, Care Opinion, Picker Institute, Scottish Government, World Health Organization] using terms ‘patient experience feedback within the NHS’, ‘patient experience feedback of hospital care’, ‘NHS use of patient experience feedback of hospital healthcare’, ‘improving patient experience’, ‘patient experience toolkit’. These were subsequently adapted to suit different ways organisations use terms. Time frame: 2005–2016 – narrower than for academic databases owing to high number of returns. Note that different terms were used for academic databases than those for grey literature because of the different content likely to be returned through each route |

| Study selection |

Inclusion criteria: any sources of feedback relating to PE of hospital care; patient or carer perspective; for use in UK acute hospital setting Exclusion criteria: sources of feedback relating to PE of specific aspects of quality such as safety, clinical outcomes, person-centred care, performance of individual clinicians or health-care staff, treatment/condition-specific experiences; not patient or carer perspective; not secondary care; those aged < 18 years; for use outside UK |

| Charting the data |

The search returned 38 different types of PE feedback for which we immediately created three broad categories that were informed by our general understanding of the way feedback varied. This enabled the results to be displayed in four separate tables to aid comparison: Appendices 1 (17 × surveys), 2 (12 × patient-initiated feedback processes) and 3 (7 × feedback and improvement frameworks). We found that two types of feedback did not fit well in any, and placed these in a fourth table as Appendix 4 (other) This was deemed a reasonably objective task and was therefore performed by one researcher (RP) with two additional researchers confirming these categories |

| Collating, summarising and reporting the results | Our categorisation exercise, detailed in Developing a list of ‘defining characteristics’, fulfils this stage |

Developing a list of ‘defining characteristics’

We established a consensus team to develop a list of 12 key descriptive characteristics to help understand the role of different feedback types in QI. This list is provided in Table 2. The team comprised the principal investigator (PI; Professor in Psychology of Healthcare), four health services researchers (one psychologist, two social scientists and one sociologist), two design researchers (concerned with the presentation and usability of patient feedback), one health-care improvement specialist and one patient involvement facilitator. The list developed iteratively through the following stages:

-

The PI first used the evidence referred to above, combined with own knowledge of QI and PE, to produce an initial list of nine characteristics and presented this to the consensus team.

-

The consensus team then added a further four characteristics to make 13 characteristics.

-

One researcher (RP) attempted to use this list to characterise six of the types returned through the review, finding that twelve of the characteristics worked effectively and only one did not so it was removed. This was ‘whether or not the feedback related only to specific patient groups’, which was not possible to ascertain from descriptions of the types.

| Characteristics of PE feedback | Character options |

|---|---|

| Nature of data obtained from feedback | |

| Type |

|

| Level of applicability |

|

| Evidence for validity (applies to surveys only) |

|

| Timing of feedback |

|

| Mode of feedback collection | |

| Internal or external sources | Formal hospital system for collecting feedback and externally supported websites |

| Quantitative | Survey (paper, telephone, internet or a combination) |

| Qualitative | Interviews, observation, focus groups |

| Availability of feedback | |

| Requirement for feedback |

|

| Supporting hospital systems |

|

| Timeliness of feedback availability to service |

|

| Regularity of feedback |

|

| Perspective captured | |

| Who initiatives feedback? |

|

| Who provides feedback? |

|

| Defined role in QI | |

| Extent of the defined role |

|

This list of 12 characteristics was then presented to the study steering group to ensure that it made sense beyond the consensus team. This process led to clarification of the definitions and potential variability (character options) of each characteristic as listed in Table 2.

Five broad headings (i.e. nature of data obtained, mode of feedback collection used, availability of feedback, perspective captured and defined role in QI) were used to group the 12 characteristics.

Assigning ‘characters’

These characteristics were then applied by the researcher RP to all returned types of PE, which generated ‘raw’ descriptive categories (see Appendices 1–4). These were checked by two other members of the team before finalising.

Findings

Four categories of types of patient experience feedback

We then used our characteristics list to further analyse, understand and subdivide the descriptions contained in these ‘raw’ tables. As well as enabling us to provide a more nuanced presentation of the distinctions between PE types, this process led us to more indicative titles for the categories than those we used as appendices titles. The refined categories and their subcategories are shown in Box 1. The distinctions that we make between them are now described, highlighting potential implications for roles within improving PE.

The NHS Adult Inpatient Survey (England). 22,42,43

Scottish Inpatient Patient Experience Survey. 44

Inpatient Patient Experience Survey (Northern Ireland). 45

Any levelYour NHS Patient Experience Survey (Wales). 46

Service or specialty:

NHS A&E Survey (England). 43,47

NHS Maternity Services Survey (England). 43

Scottish Maternity Care Survey. 48

1b. Voluntary Hospital levelHospital Care & Discharge. 49

Any levelPPE Questionnaire 15. 50

OxPIE. 51

Newcastle Satisfaction with Nursing Scale. 52

VOICE survey. 53

Service or specialty:

PEECH. 54

ICE Questionnaire. 55

New Models Study. 56

Urgent Care System. 57

Patient carer diary. 58

2. Patient-initiated qualitative feedback 2a. Formal hospital systemLiaison Service concerns. 9,62–64

Hospital-supported feedback cards.

Hospital-supported websitesNHS Choices. 9

Care Opinion (if adopted). 1

iWantGreatCare. 65

Facebook set up by ward/hospital.

2b. No hospital systemCompliments and thank-you cards. 33

WebsitesMumsnet. 41

Twitter.

Google reviews of hospitals.

Facebook (generally).

Care Opinion (if not adopted). 1

Other websites.

3. Feedback and improvement frameworks 3a. Focus on ‘collection’Emotional Touchpoints. 66

Discovery interview. 67

3b. Focus on ‘collection’ and ‘action’Patient Journey. 68

Kinda Magic. 69

Experience based co-design (EBCD)/accelerated experience based co-design (aEBCD). 70

Fifteen Steps Challenge. 71

Always Events. 72

4. Other Mandatory (England)FFT73

VoluntaryHowRWe74

ICE, Intensive Care Experience; OxPie, Oxford Patient Involvement & Experience Scale; PEECH, Patient Evaluation of Emotional Care during Hospitalisation; PPE, Picker Patient Experience; VOICE, Views on Inpatient Care.

There were 17 types of feedback that fitted into the first category of ‘Hospital-initiated quantitative surveys’. 22,38–40,42–58 Common to almost all of these types of feedback is that the data are predominantly quantitative, initiated by hospitals, targeting patients and not carers, and involve a significant delay (caused by processing) in providing information back to the organisation. However, closer inspection reveals a distinction between those that are mandated for high-level organisational use (for whole organisation or whole A&E or whole maternity departments) at regular but infrequent intervals, and those that are offered as voluntary tools for use as and when an organisation decides. The former most clearly exhibit accountability features: providing organisational-level data (within parameters defined and initiated by the organisation) and validated to make generalisations and comparisons (between organisations or over time) when conducted for large samples. On the other hand, with the exception of one survey, Hospital Care & Discharge,49 the voluntary surveys can be applied at any level at a timing to suit, or are especially designed for use within a local service or specialty, such as the Intensive Care Experience (ICE) Questionnaire,55 without prescribing regularity. Unlike the mandatory surveys, only some are clearly validated. Potentially, these more flexible surveys that elicit local-level information offer more scope for informing or monitoring local improvement of PE. Only one survey, Your NHS Patient Survey Wales,46 does not conform neatly to this subdivision. This survey is strongly recommended for use, not mandated, and is designed for use at any level. This implies more flexibility, and that perhaps it has been designed to inform or monitor local improvements as well as to provide accountability.

We call the second category ‘Patient-initiated qualitative feedback’ and include 12 feedback types here1,9,41,46,59–65,75 that exhibit common traits: they provide qualitative data (applicable to any level of the organisation), are initiated by patients on an ad hoc basis (whenever they choose to) and the feedback is available to the organisation quickly (referred to as in real time). The concept of validity is not applicable because all data are provided on a case-by-case basis. Within this category, the significant distinction is between those types that are formally supported, which could be because they are mandated to do so (e.g. by complaints,46,60,61,75 concerns9,62–64 and NHS choices),9 or because they choose to adopt a system (e.g. to set up a ward-based Facebook page or buy into iWantGreatCare65 to organise their feedback). Other types have no supporting system in place and include informal feedback (e.g. compliments, thank-you cards) that is received but not perceived as data requiring attention or processing. We include a caveat here because some hospitals could have more formal systems for handling these (we know anecdotally that this happens) but this is not widely acknowledged or articulated as a process. This subcategory also includes websites external to the organisation [e.g. Facebook, Twitter, Mumsnet,41 Google reviews] where patients/carers may upload feedback, but there is no guarantee that this will be viewed by hospital staff. Other less well-known sites could also exist on the internet. Care Opinion1 currently spans both subcategories: it is offered as a formal system of data management for a fee, if hospitals choose to adopt this. If not formally adopted, the platform could still be used by patients to upload feedback that may or may not be viewed by the hospital.

In summary, this category offers a different kind of ‘data’ than that offered in category one and, therefore has a potentially different role within QI. In category one, feedback offers evidence-based scope for use in benchmarking and monitoring of organisational trends. Category two feedback provides more local-level information that would not be valid for use in that way. It exhibits some characteristics (e.g. nuance, specificity) that suggest potential use within local QI processes, especially problem identification. Currently, feedback within this category is, however, presented largely on a case-by-case basis and not as collated data ready to use. This makes its proposed role as a data source more tentative than the surveys of category one, and we return to this issue in Discussion.

We name the third category ‘Feedback & improvement frameworks’, and this includes seven types of feedback66–72 with some common, defining features: feedback is exclusively qualitative, can be collected for any level of service by a variety of qualitative research methods with a varying degree of prescription in this regard. Interviews are common but focus groups, observation and shadowing all feature here. All types elicit rich data that take time to process. All have a defined role within QI, albeit to a varied extent. Feedback collection is initiated by staff, but, in striking contrast to surveys (which cover issues deemed important to organisations about their service delivery), qualitative methods are used in ways designed to tap into patients’/carers’ authentic voices. Like category two, the data elicited are qualitative but they differ significantly owing to embedding within qualitative methodology, which elicit rich (collated) data sets ready to use.

The nature of the third category can be explored further using two subcategories. In the first subcategory are two types of feedback that focus primarily on eliciting authentic voice (Emotional Touchpoints66 and Discovery Interviews). 67 Their associated guidance makes reference to the use of feedback to make changes, but this aspect is not covered in detail. The second subcategory includes frameworks for linking the collection of feedback (still attempting to tap into patients’/carers’ authentic voices) to QI techniques. With reference to QI, these frameworks do not offer data suitable for accountability (nothing generalisable for large samples). They do offer information appropriate for the QI process (problem definition and monitoring) but the specific ways in which they do this varies considerably. Some advocate linking feedback directly into the continuous learning process [Patient Journey = AR,68 Kinda Magic = links to metrics collected separately,69 Fifteen Steps and Always Events = mainstream QI approaches such as plan–do–study–act (PDSA)]. 71,72 Both EBCD and accelerated experience-based co-design (aEBCD) recommend collecting qualitative feedback of impact to assess perceptions of how the service has changed and also suggest collecting other measures about the change, for example, cost-savings to a service. Three also stand out for the way they use feedback as data for problem definition. Within EBCD/aEBCD and Always Events, feedback is interpreted together with staff and patients/carers in a process of co-design so that contextual meaning informed by those who work in the service can be added. This is an interesting category that appears to push the boundaries of how we consider feedback as data within QI. We return to this observation in the Conclusion section.

Finally, we identify a fourth category of miscellaneous, ‘Other’, with two types of feedback:73,74 FFT73 and HowRWe,74 which do not fit into any of the above three categories. They are both surveys that hospitals can initiate, asking standardised questions, but unlike those surveys in category one, they are not designed to capture large numbers of data (lots of questions) infrequently, but instead they are very short and designed to be used more frequently, potentially providing a more continuous flow of PE feedback. The FFT has only one question and HowRWe has four. They both allow qualitative comments to be added and they can both be applied to any type of health-care setting; however, this is where their similarities end. Most significantly, FFT is mandatory in England, whereas HowRWe is a voluntary tool and is therefore much less widespread. The data arising from the HowRWe standardised questions are validated to provide comparable data over time and between areas, whereas the data arising from the FFT standardised questions are not. Potentially, the HowRWe tool has more obvious potential for the measurement and monitoring of trends within QI over time and between areas than FFT. The comments provided by both tools could be used within this process. These comments can be likened to the data arising from the feedback types included in category two: qualitative and context specific. However, just like these data types, comments are not provided as collated data ready to be used and the steps to enable them to be used as data are not specified.

Discussion

In this study we have reported a three-stage process to help make sense of different types of PE feedback on offer to hospital staff in the UK. Using concepts of measurement as defined for QI,31 prior commentary on measurement for PE10,11,13 and our previous experience of researching this field, we sought to develop an understanding of the potential roles of these different types of data within QI. Our scoping review identified 38 different types of PE feedback ‘on offer’ to staff within UK hospitals. Using a consensus exercise, we drafted a list of characteristics that we believed to be important indicators of potential roles for each type. Using these characteristics to assess each type, we arrived at four distinct categories that we named: ‘Hospital-initiated quantitative surveys, ‘Patient-initiated qualitative feedback, ‘Feedback & improvement frameworks’, and ‘Other’. We have described above the nature of each of these categories with reference to roles within QI. In addition, we make the following observations.

Hospitals currently have limited access to data that can potentially help to inform and monitor local patient experience improvement

Of the mandated PE feedback types available, none of these would appear immediately suitable for informing and monitoring a local improvement process (e.g. ward level). Mandated feedback currently comprises quantitative survey data [the national inpatient surveys for whole organisations,22,42–46 A&E,43,47 maternity departments,43,44 complaints and liaison service data,9,59–64,75 one form of online feedback (NHS Choices)9 and the FFT results]. 73 As explained above, mandated surveys are most suitable for accountability purposes but do not provide locally relevant data that are accessible to those who need it, in a timely manner35,76 that would be required for informing and monitoring the QI process. The qualitative, locally applicable information collected via the FFT test, mandated for England, offers potential within the QI process;25 but this proposal is also fiercely questioned,26 described as a laudable ambition thwarted by the quantitative rating system that currently forces hospitals into achieving acceptable response rates at the expense of considering and utilising the qualitative comments effectively. There is interest in the increased use of other mandated feedback (from complaints and liaison services) by coding and theming into data sets. 27 However, there are challenges to these proposals,28 relating to system practicalities (collation of case-by-case complaints), the nature of the story told (complex and difficult to code) and availability (often infrequent and inconsistent in style). In short, seen from a QI perspective, mandatory PE data (national surveys, FFT, complaints/concerns and NHS Choices) currently appear to offer little ready-to-use data, with respect to informing and monitoring local PE improvement.

The potential for other types of feedback to help inform and monitor local improvement process is not yet clear

Other types of feedback are available should hospitals wish to use them. Hospitals could use voluntary surveys of category one, these offer more granular data and can be used more flexibly if analytical capability exists. 38 Similarly, there are proposals that online comments could be used more: they are context-specific, qualitative, and provide almost instantaneous information. Some online platforms such as Care Opinion1 and iWantGreatCare65 are being developed and offered to hospitals for this purpose, and some hospitals/wards are establishing Facebook pages as a dedicated place to collect feedback. As well as supporting use of these formal platforms, there is an emerging interest in harnessing ‘the cloud of patient experience’ from social media that exists in informal ways (e.g. Twitter, Facebook, Google). 77 All of these proposals warrant further exploration. We suggest that the process of using PE data within the improvement process needs further conceptualisation in itself before we can judge the comparative value of these different feedback types and we use some observations on category three feedback to develop this proposal.

Beyond metrics: what we can learn from ‘feedback and improvement frameworks’

Category three feedback significantly differs from category two feedback despite them both being qualitative. Each category three framework is concerned with eliciting the authentic patient voice using in-depth qualitative methods. Two (EBCD/aEBCD and Always Events), overtly attempt to develop shared meanings (staff and patients/carers) from the feedback. This indicates a shift away from the notion of patient/carer feedback as a static metric (objective data) that can be used to directly state what should be improved, and then be assessed again to measure impact. Within EBCD/aEBCD this is described as a co-design and co-creation process involving techniques that aid critical, collective reflection. 25,78

We propose that the way in which EBCD/aEBCD and perhaps other such frameworks use the patient voice to inform and to monitor progress is variable and tentative, and that the commonalities between these ways are ripe for further exploration. Of relevance to understanding this further is the arrival of the term ‘soft intelligence’ within QI more broadly, in which value is placed on understandings gained through everyday interactions and caution is urged with respect to reducing such insights to metrics. 79 When it comes to making decisions about how the seemingly ever-growing stream of PE feedback should be used, these broader conceptual developments about how the patient/carer voice can inform change appear extremely relevant and could add much to traditional concepts of QI as articulated by the ‘Three faces of Measurement’31 over 20 years ago.

Owing to the flexible approach taken to search terms, our scoping review may not have revealed all potential feedback types available in UK hospitals. In addition, because of the occasionally subjective nature of these search terms, a repeat exercise by others may not yield exactly the same results. This is also true of the characterisation and categorisation exercises in which some subjective decisions were made. In some cases there was ambiguity and we used our characteristics list as a sensitising framework rather than an absolute.

Conclusion

Our scoping review has confirmed that there are many different types of PE feedback available, or potentially available, within UK hospitals. However, our characterisation and categorisation study has revealed that, within these, there are currently no ‘ready-to-use’ data sets for informing and monitoring improvements to PE, apart from mandated data relating to high-level organisational trends. Hospitals are currently being presented with many options for engaging with the other types of feedback, some not previously regarded as data, which either already exist in their systems or that could be collected in addition to existing feedback. Some types being offered are integrated frameworks for collection and improvement. We know that hospital teams are already struggling to handle feedback that they are mandated to collect,80 therefore informed decisions about these options are crucial. To support this, we propose further analysis and conceptual development of the role of PE feedback within QI, and that the categories we present in this study are a contribution to this effort.

Chapter 3 Qualitative study

This chapter discusses the problem with patient experience feedback: a macro and micro understanding. 81

Introduction

The PE agenda is reaching a zeitgeist moment in many health-care systems globally. Patients are increasingly giving feedback on their experiences of health care via a myriad of different methods and technologies. Most commonly, these take the form of national surveys, formal complaints and compliments and social media outlets. Various publications outline a range and diversity of qualitative methods for gaining rich feedback from patients. 17 Several systematic reviews have identified a range of quantitative survey tools that are used across the world to capture PE in an inpatient setting. 34,35 These include large-scale surveys, such as the NHS National Inpatient Survey in the UK and the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems in the USA. 35 Currently in the UK, major resource is being given to the collection of the FFT,82 which has been mandatory since 2014 for all acute hospital trusts to collect.

A significant driving force for the current impetus and focus on gathering PE feedback in the UK arose from national-level recommendations such as the Francis4 and Keogh reports. 6 In addition, ‘Better Together’ in the USA and ‘Partnering with Consumers’ in Australia demonstrate that this focus has been mirrored internationally. 19 It is now widely acknowledged that patients want to give feedback about health care19 and that staff should be listening to what their patients say about the experience of being in hospital. 83 Yet, whether staff can use this feedback to make changes to improve the experiences that patients have is now a central concern. 10,11,15,22,37,84 This pertains to differing areas of the health-care system from senior management at the level of the hospital board (formalised group of directors) down to individual clinicians working on the front line. Hospital boards have received recent pressure to understand the ways in which they use patient feedback to improve care at a strategic level85 and about how they govern for QI. 86 There is a concern that the ever growing collection of feedback is not being used for improvement but, rather, represents a ‘tick box mentality’ of organisations thinking that they are listening to their patients’ views but actually not doing so. 87 Recent work in the UK has looked at how HCPs make sense of why patients and families make complaints about elements of their care88 and found that it was rare for complaints to be used as grounds for making improvements.

Several studies have looked at teams of front-line clinicians to understand how ward staff can engage with patient feedback to make meaningful improvements. 15,22,84,89 Most of the literature in this area finds that, despite enthusiasm to make improvements and despite the vast rhetoric around this, proactive changes are often minimal and largely concentrated on ‘quick fixes’. 11 It could be said that we are currently at a key pivotal moment in terms of this debate, in relation to both national and local policy and what is occurring ‘on the ground’. This is because there is an ever clearer and acknowledged push for improvement to arise from patient feedback, but individuals and systems are constrained from doing so.

In this study, we report the findings from a qualitative study undertaken at three hospital trusts in the north of England that explored the PE landscape. We were most interested in which types of PE data were being collected, how staff were or were not using these data and whether or not there was a relationship with improvement on the wards. Here, we base our reporting on the question ‘what is impeding the use of patient experience feedback?’, which is examined through both a macro and a micro lens. We concentrate on this finding, as it was considered by the participants to be of central importance.

Method

We conducted a mixed method qualitative study using focus groups and interviews across three NHS hospital trusts in the north of England. This qualitative study was the first work package in a programme of research whereby the overall purpose was to develop a PET to assist ward staff to make better use of PE feedback. The three trusts were selected to provide diversity in size and patient population. Then, two wards per trust were approached to take part in the study, leading to six wards working with us. We sampled the six wards based on a divergence of specialty, size and patient throughput. The specialties of the wards were A&E, male surgery (this represents two wards at different trusts), maternity department (including ante- and post-natal services), female general medicine and an intermediate care ward for older patients.

Data collection

The fieldwork took place between February and August 2016. The University of Leeds ethics approval was secured in October 2015. All participants gave written, informed consent. Ward staff took part in focus groups and management staff took part in individual in-depth interviews. Ward staff mostly represented opportunistic sampling and management participants were sampled for maximum variation. Ward staff predominantly encompassed senior and junior nursing staff, support workers and the inclusion of allied health professionals in some of the focus groups. Management participants were drawn from a range of roles occupying middle- and senior-level hospital management, such as PE managers or heads of PE, matrons, heads of nursing (and their deputies), research leads, medical, quality, risk, governance and performance directors. The bulk of interview participants worked directly in or managed PE teams.

Seven focus groups and 23 individual interviews were conducted. Focus groups ranged from three to seven participants and two management participants were interviewed as a dyad. The average length of an interview was 55 minutes and 45 minutes for a focus group. In total, 50 participants took part in this qualitative study. Two topic guides were devised; one for the data collection from ward staff and another for management participants. Headline topic guide questioning was derived from the literature. Focus group questioning centred on what types of PE feedback the participants received, how they engaged with it and responded to it, and where/how it fitted in with their everyday clinical work. Interview questioning explored the different kinds of PE feedback available to the trust and how these were generated, prioritised and managed at the level of the ward, directorate and whole organisation. The formats of the topic guides and that of interview questioning were flexible to allow participants to voice what they considered to be important. All focus groups and interviews were conducted face to face in staff offices, digitally recorded and then transcribed by a professional transcriber. All participants gave written, informed consent to take part in the study. Author B collected all interview data. Authors A, B and C all collected focus group data. All are experienced qualitative health researchers with doctorates in their respective fields.

Analysis

Authors A and B took the same five interview transcripts and each independently developed a provisional descriptive coding framework. These five transcripts were chosen as those that were representative of the whole interview data set in terms of spread across the trusts and general content. The same exercise was repeated for the focus groups, albeit with three transcripts. Authors A and B held an intense analysis session where they met (along with author D) to discuss the differences and similarities in their coding frameworks, although there was general parity among them. Author A then returned to the selected transcripts and immersed herself in the data in order to devise an overall meta coding framework that would allow for data from both the interviews and focus groups to be coded together. This meta coding framework sought out themes on a conceptual level rather than a descriptive level; that is, rather than simply describing what the participants discussed, author A looked for the differing ways in which PE feedback was approached conceptually across the participants involved in both methods. Differences and similarities were identified, with Author A noticing that participants discussed the topic at different levels, with the management interviewees tending to view PE feedback in a macro manner (both explicitly and implicitly) and the ward staff focus group participants viewing it in a micro manner. The meta-level coding framework was checked with author B for representativeness and accuracy. After slight modification, author A then coded all transcripts and some subthemes were modified as coding progressed. Author A conducted further interpretative work in order to write up the findings. Initially, we began by conducting a classic thematic analysis90 but realised that this was not sufficient for our needs, as thematic analysis often relies on portraying a descriptive account of participants’ narratives. Instead, we conducted a high-level conceptual analysis. The analysis was wholly inductive and, as such, we did not structure it on any existing theoretical frameworks.

Findings

Here, we briefly set the scene by describing the main sources of PE feedback in the UK before moving on to focus entirely on ‘what is impeding the effective use of patient experience feedback?’ All participants have been ascribed a number and a generalised descriptor of their role, rather than their precise role, in order to protect their identity. We will discuss two distinct groups of participants, which we will call ‘ward staff’ and ‘managers’.

Setting the scene: what are the sources of patient experience feedback?

All participants were able to name a wide variety of the types of PE feedback that they had encountered and interacted with in their professional roles. This took the form of formalised written sources such as the FFT, complaints and compliments, thank-you cards, Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS) communication, patient stories, NHS Inpatient Survey, local surveys and other initiatives such as ‘You Said, We Did’. Senior leaders within the organisations spoke about Care Quality Commission (CQC) inspections and the use of social media as outlets for feedback, although ward staff paid less attention to these sources of data. When first asked to discuss PE feedback, ward staff spoke about the more immediate, direct, ‘in the moment’ verbal feedback from patients on their ward that they received in an impromptu manner during the course of a shift. This often took the form of patients complaining verbally (in an informal manner) about their care or the environment to the clinician caring for them or to a more senior staff member. Conversely, it also included spontaneous thanks or praise given in an interpersonal exchange. In this study, we focus on formalised sources of PE feedback and we discuss factors surrounding their effective use, as per our key areas of interest and research brief. However, it should be acknowledged that informal feedback was often used by ward staff in a timely way to improve the experience for the needs of a particular patient.

What is impeding the effective use of patient experience feedback?

We chose to focus on the factors that are impeding the use of feedback rather than an account that paid equal attention to the factors that were assisting it. Although there were certainly instances where individual personnel and small teams had instigated processes and ways of working that were beneficial, these accounts were localised and not of sufficient importance to most participants about the topic at hand. Furthermore, attempts to improve issues identified in feedback sometimes led to unintended consequences, which further problematised an already complex and fraught task. When participants talked in positive terms about PE feedback, they often spoke of idealised situations or what they would like to see happen in the future rather than what was currently happening in practice. Overwhelmingly, the participants interviewed across the data set pinpointed significantly more negative factors within their current working practices when trying to use patient feedback than positive factors and this is, therefore, where we place our analytical attention.

There is a clear division between a macro and a micro understanding of how participants discussed PE feedback within their health-care organisation. Management participants commented on feedback and the use (or not) it serves at the level of the organisation, whereas both ward staff and management pinpointed the problems at a micro level with the function and usefulness of the individual data collection sources.

At the macro level of the health-care organisation

Considering the data set as a whole, possibly the most striking element is the overwhelming nature of the industry of PE feedback. Ward staff at one hospital department at Trust C stated that they were collecting around a thousand FFT cards a month, in addition to all the other patient feedback received. Both management and some ward staff participants across the whole sample felt overwhelmed and fatigued by the volume and the variety of data that the trust collected:

So we have got the Friends and Family Test, which produces, as I am sure that you are aware, reams and reams of information but nobody is really quite sure what to do with that information. Because there’s just loads of it. I mean our goal is about 50% of people that leave fill in a card.

Trust B, interviewee 2, patient experience management

At each of the three hospital sites, a significant, system-wide level of resource, effort and time was being expended that primarily focused on maintaining the collection rates of feedback. This was coupled with layers of hierarchies and bureaucratic processes surrounding data collection, which were felt to be confusing to staff and patients alike. Mirroring the current NHS staffing situation among the clinical workforce, some management participants felt that they did not have enough staff or appropriate expertise (often stated as qualitative expertise) in their immediate teams to be able to work effectively to produce meaningful conclusions from the data they received. This was despite an abundance of resource given to collecting feedback on the ground, leading to a bizarre situation whereby masses of data were being collected from patients but a lack of skill and personpower prohibited its interpretation and, therefore, its use:

So with all the ways and means of collecting the feedback, it’s how to actually pull out a theme to actually make an improvement. It feels as if we are overwhelmed with everything and the next step for me is, we need to actually take it to the next level and start learning from it.

Trust B, interviewee 3, patient experience management

At the centre of this situation was the idea that data collection in and of itself was considered to be the most important achievement, rather than a focus on how the feedback could be used to drive improvement. In relation to FFT, there was a narrow focus on each ward’s response rate (what percentage of their patients had completed a FFT form) and enlarging this response rate at a detriment to other activities. Regarding complaints, there was an overt focus on both the timeliness of response to complaints and on trying to reduce the volume of them rather than on achieving an understanding of what an effective response looked like and how this could be emulated:

Number of complaints is one thing, great, are they getting more or less? Less, great. Are they responding to them within our forty-day timescale? Yeah, great. For me that’s all nice and boxes we can count and tick, but actually what are the main complaints? What are the main themes? What are they doing about them? What’s on their action plan? So that we’re, we want to shift to a more action-based approach rather than counting.

Trust C, interviewee 4, performance manager

Management participants often talked in corporate terms about where the responsibility for PE feedback sat within the hospital hierarchy, which often demonstrated that PE was a fractured domain, spread across several different disciplines. However, some senior leaders explicitly articulated the artificial nature of this division and how this splintering of the response to patient feedback was hindering the ability for change to occur as a result of it. For instance, in one trust the responsibility for complaints, PALS and FFT were split across three different teams who had little crossover and, therefore, minimal capacity to consider this wealth of feedback from patients as a whole. In a different trust, a senior manager had noticed that this division was holding learning back and brought representatives from these teams together once a month in a formal event. A few participants noted how the electronic systems for collating the different sorts of feedback were completely distinct, which further compounded the lack of cross-team working. The division between complaints and PALS (both as a concept and practically) was remarked on by some management participants as being arbitrary and unnecessarily confusing to patients and the public. Some participants spoke about how several different initiatives on PE were simultaneously ongoing within the same trust, with little ability for the linkage between these to be made explicit as their remit was under different teams.

The participants interviewed for this study nearly all saw an immense value in PE feedback and most believed that it should receive a high organisational priority at a strategic and at a trust board level. Yet, this was not often the situation ‘on the ground’ in their organisations and the culture around this was said to be hard to change. Patient experience was sometimes felt to be the poor relation of patient safety and finance, with a lesser emphasis and priority placed on it:

They [directorate representatives] have to give an explanation as to why performance is bad in terms of finance, access, targets, the waiting lists and quality is one of the agenda items, but it seems it will always be the item that is skimmed over. Patients’ experience and stuff, it is on there but no one ever really pays attention.

Trust C, interviewee 3, patient experience management

Related to the above, management participants discussed where the responsibility for PE ‘sat’ within their trust. Usually, PE was housed under the nursing remit and patient safety under the medical remit. This division was said to be unhelpful by several participants who felt that PE was therefore automatically seen as an issue for corporate and shop-floor nursing staff to solve:

My only nervousness is it’s done almost entirely through nursing . . . and there’s rafts of things [feedback] that are about doctors . . . I think there is a perception, you know, the doctors do the doctoring thing and nurses do the patient care thing and it’s nurses and it’s about wards when actually when you look at it, actually quite a large volume [of feedback] is nothing to do with nurses whatsoever.

Trust C, interviewee 4, performance manager

In a drawing together of the points raised so far, it is clear that current patient feedback systems do not generally allow for learning across the organisation. The collection of PE feedback seems to be the focal point, with an intensive resource given over to this, while fractured and disparate teams struggled to make sense of the data or to be able to assist ward staff to do so.

At the micro level of the feedback itself

Both management and ward staff participants spoke about the usefulness of the PE feedback that they received. Usefulness was often aligned to whether or not it was felt that improvements could be made based on the feedback. Overall, it was felt that most wards were awash with generic and bland positive feedback that rarely guided them in identifying specific elements of positive practice. This contrasted with a smaller amount of negative feedback where patients often pinpointed precise instances of poor PE:

Usually the positives are very general, when they’re negative it’s something very specific; ‘the bins are noisy, the buzzers don’t get answered on time, I didn’t get X, Y and Z at teatime . . .’

My lunch was cold.

Yeah, usually they’re quite specific, whereas the good and the positives tend to be more general: ‘the whole ward was clean and tidy, the staff are all lovely’, do you know what I mean? So I feel sometimes we don’t always necessarily get that much information about the positives, it’s always a very general positive.

Trust A, Focus group 2

A different problem with the feedback sources currently received related to what extent ward staff were or were not able to interact with and interrogate the raw data that were passed onto them by PE team members. Senior ward staff participants were sent spreadsheets of unfiltered and unanalysed feedback. In some instances, this ran into hundreds of rows of text for a month’s worth of data. The complexity and volume of the data that ward staff had to contend with was often seen as overwhelming to the extent that some ward staff deliberately chose not to engage with the data. The two main issues that prevented ward staff from using, or in some cases even looking, at PE feedback were a lack of time and a lack of training. Taking time away from clinical duties to ‘sift through’ a large number of unsorted data was not felt to be a high priority. Likewise, it was evident that ward staff did not have the required skills to be able to perform sophisticated analytical tasks on the data they received:

The stark reality is most front-line staff, and even most managers, really struggle to find the time to look at the kind of in-depth reporting we get back. We get reports back that are, you know, extremely bulky documents and people struggle to have the time to really read them, understand them and use them.

Trust B, interviewee 4, patient experience management

In general, the raw data from patients were said to be difficult for ward staff to interact with and some participants questioned whether or not the current process was fit for purpose. A few management participants spoke about how a lack of decent analysis before the data were passed onto ward staff simply worked to compound the problem even further. Even more difficult to achieve was the idealised notion that differing data sets should be brought together to provide an overall picture of what patients thought about an individual ward. Despite all of the above difficulties, there was an expectation by senior leaders that ward staff should be using the feedback to make improvements to the ward.

Compounding the above problems of data interrogation were underlying problems that ward staff perceived to be inherent in the data already collected, even before they reached the data on the frontline. Most significantly, timeliness was seen as one of the main concerns, with it being difficult to engage ward staff with data that is not real time. A specific example of this is the NHS Inpatient Survey where patient feedback is viewed months after it has been collected. Frustrations were attached to receiving feedback that was considered historical if ward staff had already started to make improvements to address known problems. The FFT data were said to be too late if they reached ward staff a few months after they were collected. Ward staff participants struggled to remember the circumstances of a complaint if the complaint was made several months after the patient had stayed on the ward.

A specific idea raised by ward staff participants concerned the limitations of current PE feedback sources, particularly those that are nationally mandated such as the FFT. Throughout the data set, there were numerous accounts of how the FFT was considered ‘more bother than it was worth’, superficial, unhelpful and distracting. It was unfortunate to learn that in two trusts the FFT had replaced several local patient feedback initiatives, which ward staff had previously placed a large emphasis on as being of use to their everyday practice and learning:

I know the feedback we get from it [FFT] is not as good as what the You Said We Did information that we used to get back.

‘Cause that was very, very specific wasn’t it?

Yeah, it was, you could relate to it and you could look at it and you could help to action things.

Trust B, Focus group 1

Considering the above micro view of the participants’ narratives, it can be seen that a large amount of feedback is positive but simultaneously generic in nature. Ward staff struggle to interact with the feedback as it is presented to them in its current format and there are questions raised over the inherent value of the sources, specifically in relation to factors such as timeliness.

Discussion

From the findings given above, we can see how the ability for effective use to be made of PE feedback is hindered at both the micro level (of how individual clinicians and teams of staff have difficulty engaging with the data sources) and the macro level (how organisational structures are unwittingly preventing progress). This is played out through various means in a macro sense such as a lack of pan-organisational learning, the intense focus on the collection of data at the expense of understanding how they could be used and fractured PE teams who want to assist ward staff but find this difficult. In a micro sense, a large amount of generic positive feedback is seen as unhelpful, with ward staff struggling to interpret various formats of feedback while they question the value of it because of factors such as the timeliness and validity of the data. The macro and micro prohibiting factors come together in a perfect storm that provides a substantial impediment to improvements being made.

Several authors11,15,37 have recently pinpointed the essential problem at the heart of the momentum to collect ever more patient feedback; that is, almost everyone interested in health-care improvement and certainly those providing front-line care now have a vested interest in listening to patients,15 yet a myriad of challenges are still preventing the wide-scale effective use of the data for QI. This problem is set against a backdrop of a simultaneous ‘movement for improvement’,91 where grassroots, bottom-up approaches to health-care improvement are being championed. It is interesting to note that despite this recent cultural turn in the literature, which acknowledges the ‘patient feedback chasm’,92 most commentators have so far paid attention to the problems only at the micro level. Flott et al. 37 discuss problems related to data quality, interpretation and the analytical complexity of feedback and then put forward ideas about how the data themselves could be improved to allow staff to engage with them better. Likewise, Gleeson et al. 11 found a lack of expertise among staff to interpret feedback and issues surrounding the timeliness of it, coupled with a lack of time to act on the data received. Sheard et al. 15 have explored why ward staff find it difficult to make changes based on patient feedback. They found that effective change largely relates to an individual or small teams’ structural legitimacy within the health-care system and that high-level systems often unintentionally hindered meso- and macro-level improvements that staff wished to make. The current study is the first to identify which concrete macro issues at the level of the organisation are obstructing PE feedback being acted on.

A meta principle that can be drawn from the findings of this study is that the way in which participant experience data are being used in health care is not changing as fast as actors on the ground strive for it to change. For instance, there is already a recognition that too much data are being collected from patients in relation to the small amount of action that is taken as a result of it. 10,87 Our participants (particularly the management participants) were very mindful of this but largely seemed powerless to prevent the tsunami of ongoing data collection within their organisation. Equally, it has been known for some time that many members of ward staff find the interpretation of data sets difficult or impossible, as they have minimal or no training in analytics or QI. 87 This issue was raised by both management and ward staff participants in our study but there was no strategy in place or forthcoming at any of the three organisations we studied to address this issue. The slow movement of culture change discussed above is likely to be related to what has recently been dubbed the ‘uber-complexity’ of health care,93 with key actors working within a system that favours centralised power structures over localised individualistic solutions.

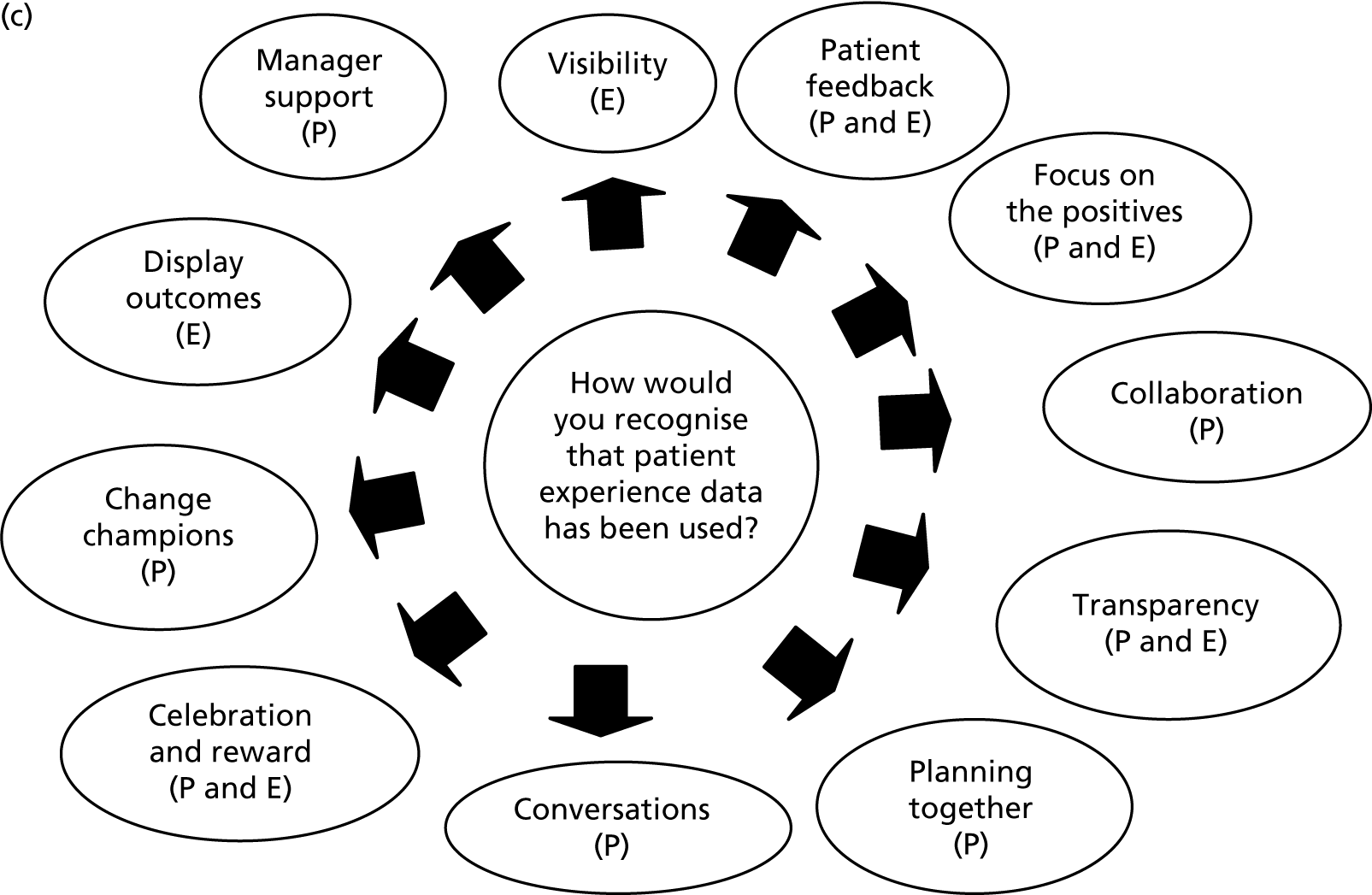

Recommendations for change