Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HS&DR Evidence Synthesis Centre, contracted to provide rapid evidence syntheses on issues of relevance to the health service, and to inform future HS&DR calls for new research around identified gaps in evidence. Other reviews by the Evidence Synthesis Centres are also available in the HS&DR journal.

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/47/11. The contractual start date was in June 2018. The final report began editorial review in December 2018 and was accepted for publication in May 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Rodgers et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

NHS England uses the term ‘digital-first primary care’ to refer to delivery models through which a patient can receive the advice and treatment they need from their home or place of work via online symptom checking and remote consultation. 1 In these models, the patient’s first point of contact with a general practitioner (GP) is through a digital channel, rather than a face-to-face consultation, although the latter may remain an option if required.

Since 2015, NHS England has invited a number of organisations to become new care model vanguard sites, each:

. . . taking a lead on the development of New Care Models, which will act as the blueprints for the NHS moving forward and the inspiration to the rest of the health and care system.

NHS England’s Harnessing Digital Technology workstream seeks to provide support to these organisations focusing on implementing digital solutions:

. . . to rethink how care is delivered, given the potential of digital technology to deliver care in radically different ways, [and] help organisations to more easily share patient information.

The Health Innovation Network was commissioned by the Harnessing Digital Technology workstream to undertake a review of the evidence base for technology-enabled care services. The review, which was published in 2017, looked for evidence on short messaging service (SMS), video consultation, digital health applications (apps), web-based interventions and telemonitoring. 3

However, this review did not look exclusively at digital innovations in primary care, such as ‘digital-first primary care’, as conceptualised by NHS England. As digital-first services have increased in number and reach, so have questions about the implementation and effects of such services. For example, the implications of digital-first primary care for general practice payments was the subject of a national consultation undertaken in July–August 2018. 1

In October 2018, a the UK government published a policy document on the use of technology, digital and data within health and care to meet the needs of all users. 4 The stated objective is the provision of care and improved health outcomes for people in England. To achieve this, a clear focus is needed on improving the technology used by NHS staff, social care workforce and the different groups who deliver and plan health and care services for the public. The document sets out a vision to develop a new approach collaboratively and setting clear standards for the use of technology in health care. 4

NHS England initially approached the Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) Evidence Synthesis Centre to help identify published evidence of potential relevance to digital-first primary care. An iterative process of scoping the literature was agreed. The first stage, to scope and summarise existing evidence, was undertaken and the findings discussed with NHS England, resulting in further refinement of the research questions of interest to be undertaken in the second stage.

Chapter 2 Methods

Stage 1: scoping and summary of the evidence

Initially, NHS England requested a map of the available published literature relevant to digital health in primary care. Given the limited resources and likely large volume of literature, this primarily focused on secondary research.

Identification of evidence

Scoping searches were carried out during July 2018 to identify systematic reviews relating to digital health in primary care. The search strategy consisted of terms for digital health combined with terms for primary care. No date or geographical limitations were applied. In MEDLINE a further set of terms were added to the strategy to limit retrieval to systematic reviews. The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and the Health Technology Assessment database. Searches were conducted in July 2018, without any date restrictions. The PROSPERO database was also searched to identify protocols of ongoing systematic reviews.

In addition, a range of research, policy and government websites were searched to identify relevant reports. Authors of ongoing work were contacted. Search strategies can be found in Appendix 1.

Selection criteria

Two reviewers screened the title and abstracts of retrieved records against the following inclusion criteria.

Study design

-

Systematic reviews, meta-analyses and other forms of evidence syntheses. Reviews could include primary studies of any design. Though the searches focused on evidence syntheses, any related primary studies incidentally encountered were also included when relevant. However, this study did not systematically search for relevant primary research evidence.

Population

-

Primary care medical staff and (1) patients (or their caregivers) of any age and/or (2) other medical professionals.

Interventions

-

As the known literature rarely conceptualised interventions as ‘digital primary care’, any form of non-face-to-face interaction, including e-mail, online/video, messaging and artificial intelligence-led systems or triage, were included. Reviews that included telephone consultation alongside digital forms of interaction were included at this stage. Reviews focusing predominantly or solely on the following were excluded:

-

improving adherence to treatment or rates of attendance through the use of reminders

-

remote monitoring or self-management of conditions without some form of two-way interaction being a key component

-

remote treatment, coaching or rehabilitation-focused interventions (e.g. remote therapy for mental health conditions).

-

Outcomes

-

Outcomes were not restricted but could include impact on care in terms of effectiveness and safety; patient access/convenience; and system-level efficiencies and related issues, such as workforce retention, training and satisfaction. In terms of patient access, this includes a better understanding of which patients are able to use digital consultations and what conditions are/are not appropriate for non-face-to-face engagement.

Stage 2: narrowing the evidence base – rapid evidence synthesis

NHS England requested a very rapid, brief and high-level overview of the evidence retrieved in stage 1. Although a full systematic review was not possible, given the time and resources available, the HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre attempted to introduce a level of transparency and reproducibility not typically associated with these kinds of briefings. Therefore, aspects of systematic review methodology, such as a priori inclusion criteria, critical appraisal of included evidence, and process measures to avoid bias and errors, were introduced.

Revised research questions

After examining the retrieved scoping materials, NHS England refined their initial list of questions to the following:

-

What are the benefits of digital modes and models of engagement between patients and primary care? To patients, GPs, the system?

-

As GP workload and workforce is the main threat to primary care, how do we use these innovations to alleviate this, rather than only increase patient convenience and experience?

-

Which patients can benefit from digital (online) modes and models of engagement between patients and primary care?

-

What channels work best for different patient needs and/or conditions?

-

Are there differences in synchronous and asynchronous models?

-

-

How to integrate ‘digital-first’ models of accessing primary care within wider existing face-to-face models?

-

How to contract such models and how to deliver: what geography size, population size?

We conducted a rapid synthesis of the most relevant evidence identified during the scoping exercise (stage 1) to establish if and to what extent these questions can be answered by the identified research. Given the limited time and resources, a comprehensive systematic review was not attempted.

Revised selection criteria

To understand what evidence might be available to address each of these questions, we further refined the list of documents to the following:

-

systematic reviews/evidence syntheses, including evidence on the use of digital (online) modes and models of engagement between patients and primary care (telephone/audio alone was excluded unless it was alongside digital modes)

-

ongoing research and any incidentally identified primary studies focused on the use of digital (online) modes and models of engagement in any health-care setting.

When evidence was available to address one of the above questions, the relevant results/conclusions were extracted. When no evidence was available from the included documents, this was made clear.

Selection procedure

All records were screened by two reviewers, with disagreements resolved by consensus or consulting a third reviewer.

Data extraction

For each included record, data were extracted on study/review methods, type of digital intervention, patient population(s), outcomes and authors’ conclusions. Data were extracted by one reviewer and checked by a second.

Critical appraisal

Critical appraisal of included evidence was facilitated by relevant assessment tools and reporting standards. These included the DARE database selection criteria for systematic reviews,5 the Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) for the reporting of realist syntheses6 and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist for qualitative research. 7 The quantitative studies were assessed by reviewers for adequacy of reporting of methods used. Assessments were conducted by one reviewer and checked by a second.

No evidence was rejected on the basis of critical appraisal. Findings of the critical appraisal were tabulated and used to inform judgements about the internal and external validity of included research results presented in the thematic synthesis. A brief narrative summary of the main concerns raised by the critical appraisal process is presented in Chapter 3, Critical appraisal and limitations of the secondary data and Critical appraisal and limitations of the primary study data.

Synthesis

The seven research questions identified by NHS England formed the basis of a thematic framework. When empirical evidence and/or related conclusions were identified in the evidence, they were coded, grouped and synthesised according to the following themes.

-

Benefits of digital modes and models of engagement between patients and primary care:

-

issues relating to GP workload and workforce

-

patients subgroups that can(not) benefit

-

the effects of different channels for different groups/settings

-

differences between synchronous and asynchronous models.

-

-

Integration of digital-first models within wider existing face-to-face models.

-

Issues relevant to contracting delivering digital-first models (e.g. geography size, population size).

When included publications looked at health care in general, only evidence applicable to primary care was coded and synthesised. Similarly, when publications included evidence relating to traditional telephone consultations, this was coded only when the data could also be applicable to digital modes of engagement.

External engagement

As described in Stage 2: narrowing the evidence base – rapid evidence synthesis, this work was conducted for NHS England, which was contacted at the start and end of each major iteration of the project.

After receiving a very brief outline of the topic area via the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), the research team arranged a teleconference with several NHS England representatives to establish the goals and methods of the original scoping work. On the basis of this call, the research team wrote a brief research protocol, undertook the scoping exercise, and produced an interactive spreadsheet and brief summary document for NHS England.

After reviewing the scoping materials, the research team and NHS England held another teleconference, after which NHS England provided a revised set of research questions (see Revised research questions). The research team updated the research protocol to outline methods to be used in stage 2.

After submitting a written report on the results of stage 2, the research team made a presentation on the findings of both stages 1 and 2 to NHS England representatives. Following this presentation and subsequent discussions, the research team drew together the materials from each stage of the process to produce the current report.

Although this report summarises some evidence relating to patient and public views, patient and public representatives were not directly involved in the development of this work.

Chapter 3 Results

Stage 1: results of the initial scoping work

In total, 2846 records were retrieved and screened, and 92 included. All the included documents were summarised in a brief narrative overview, alongside an annotated spreadsheet that could be ordered or filtered according to the following characteristics:

-

reference number

-

author

-

funder/document source

-

country

-

year

-

title

-

nature of document (e.g. primary study, systematic review, review of reviews, realist review, call for proposals)

-

publication status (published, ongoing)

-

technology(ies) of interest

-

primary focus of document (e.g. primary care, emergency care, health care in general)

-

health condition(s) or population of interest

-

nature of evidence: effects (e.g. efficacy/effectiveness/risks/harms), implementation (e.g. enablers/barriers), cost-effectiveness, qualitative data

-

link to full text (when available)

-

notes.

The spreadsheet was sent to NHS England together with abstracts for all retrieved publications and an overview of the evidence. A copy of the spreadsheet is available from the authors and the overview is presented in Chapter 3, Stage 1: summary of key evidence from scoping work.

Stage 1: summary of key evidence from scoping work

A brief textual summary of key evidence was submitted alongside the annotated spreadsheet. The spreadsheet was intended to allow NHS England to interrogate the literature at a high level. The summary was intended to draw attention to the documents likely to be of greatest interest to them:

-

There are many reviews of digital alternatives to face-to-face consultations; however, many are primarily concerned with ‘mainstream’ technologies, such as telephone consultation/triage. Only a minority specifically focus on primary care.

-

Most very narrowly evaluate the introduction or use of a class of technology (e.g. internet video consultation), rather than the integration of such technologies as part of a broader reorganisation or reimagining of services.

-

The Technology Enabled Care Services review commissioned by NHS England and published in April 2017 provides a good overview of these broader reviews, and discusses the available evidence in the context of the new care models vanguard sites. 3

-

A report by the Nuffield Trust, published in November 2016, although not a formal evidence synthesis, cited a small amount of ‘evidence of impact’ relating to wearables/monitoring technology, online triage tools, online information/advice/targeted interventions/peer support, online booking/transactional services, remote consultations, online access to records/care plans and apps. 8

-

Much of the most recent work relevant to digital-first consultations in primary care has been undertaken by Helen Atherton from Warwick Medical School. Among other publications, she has co-authored two recent (February 2018 and June 2018) NIHR HSDR-funded projects on the potential of alternatives to face-to-face consultation in general practice9–11 and the role of digital clinical communication for NHS providers of specialist clinical services for young people. 12–14 The first of these included a realist review to identify explanations of why and how various alternatives to face-to-face consultations might work (or not) in primary care. 9–11 The second aimed to provide an overview of how video is actually being used in health-care settings, by reviewing the existing published reviews. 12–14 An ongoing NIHR-funded systematic review to explore patient and clinical experiences with two-way synchronous video consultations in health care was due to be completed by this group in July 2019. 15

-

In addition to the Warwick projects, the NIHR HSDR programme has funded a systematic review of digital and online symptom checkers and health assessment/triage services. This work was being completed by the NIHR HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre in Sheffield. 16 We corresponded with the authors who said that, although the remit was limited to systems that attempt to direct people to appropriate services based on information about their symptoms, some of the studies looked at these as part of broader digital primary care systems (Duncan Chambers, University of Sheffield, 2018, personal communication). This systematic review searched for evidence on both generic and named systems (e.g. askmyGP, webGP, WebMD, GP at hand, Push Doctor, Engage Consult), and was undergoing peer review, though the authors were happy to share the final draft report (which has subsequently been published).

-

Our searches also encountered several recent or ongoing primary studies that have been conducted alongside evidence syntheses. Although not focused on primary care, a recently published NIHR HSDR study (June 2018)17 used multilevel mixed methods to examine remote video consultations in three contrasting clinical settings (diabetes, antenatal diabetes and cancer surgery) in an NHS acute trust. 17

-

We also identified two currently open NIHR calls for proposals (Digital Technologies to Improve Health and Care;18 and Evaluating the Digital 111 Offer: NHS 111 Online). 19

Stage 2: narrowing the evidence base – rapid evidence synthesis

Included studies

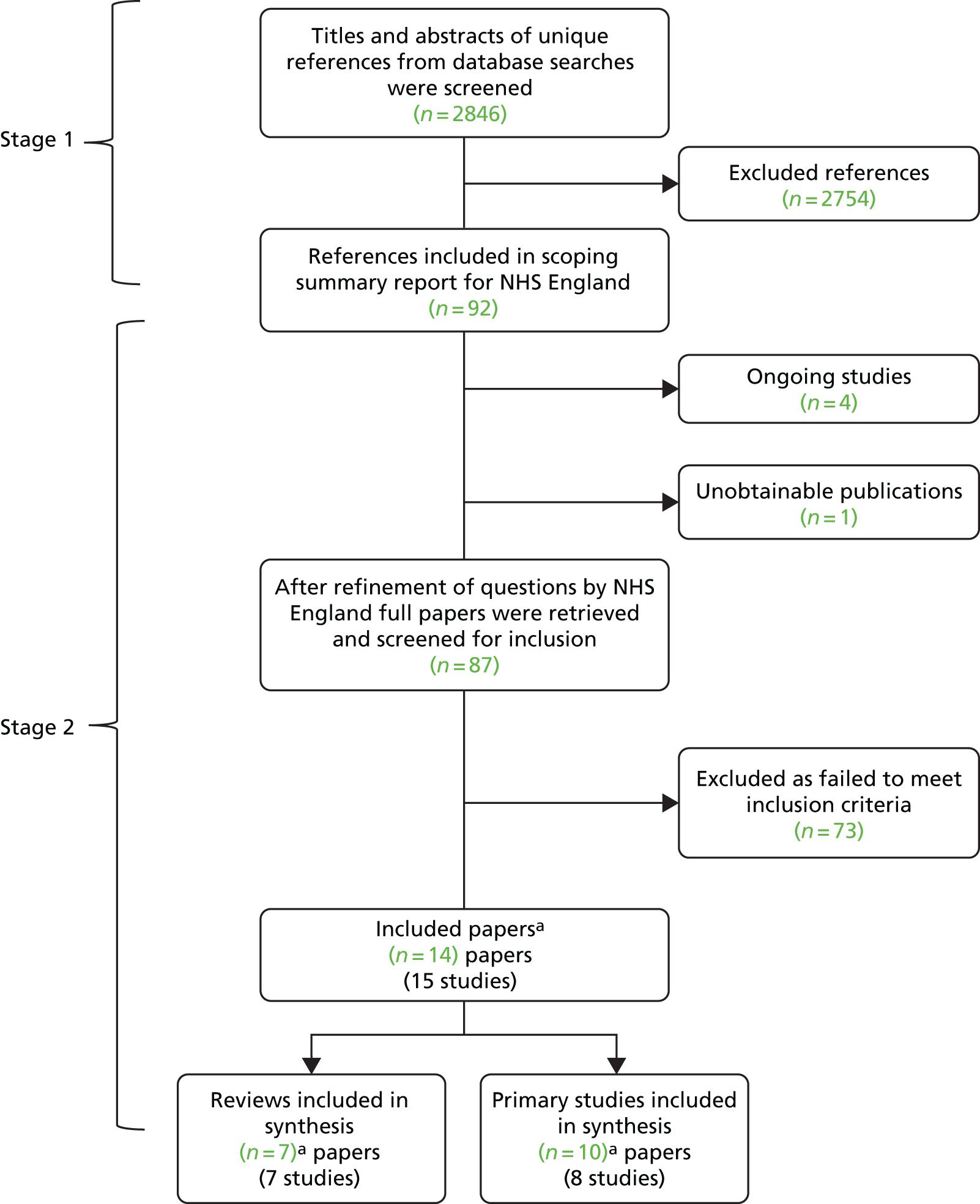

Ninety-two papers were included in stage 1 (scoping and summary of evidence). After further assessment of full papers, a total of 15 reviews and studies (in 14 publications8–11,20–29) were included in stage 2. One project (Atherton et al. 9) contributed to more than one form of evidence (i.e. a conceptual review, survey, case study and analysis of routine data) in multiple publications. Seven studies provided review evidence8,9,20–24 and eight studies9–11,25–29 provided primary quantitative and qualitative evidence (Figure 1). A number of ongoing studies were also identified and are listed in Appendix 2 together with details of one paper we were unable to obtain, despite e-mailing the author.

Stage 2: overview of included evidence

Characteristics of included reviews

The seven8,9,20–24 included reviews were published between 2012 and 2018. Out of the seven reviews, two were systematic reviews,21,24 two were realist reviews9,23 and three were produced in a ‘literature review’ style format. 8,20,22 When reported, the publication dates of studies included in the reviews ranged from 1995 to 2018.

The authors of five reviews were UK based. 8,9,21,23,24 Two of the UK-based reviews were funded by the NIHR HSDR programme,9,24 one by the Cochrane Collaboration21 and one by the Arden Cluster Research Capability Fund. 23 The review by Castle-Clarke and Imison8 was published by the Nuffield Trust and based, in part, on research commissioned by NHS England.

Type(s) of technology

In terms of technology, two reviews20,21 focused on e-mail communication only between patients and physicians20 and any health-care professionals. 21 The review by Hickson et al. 22 examined the use of e-visits, which were defined as any online consultation between patient and clinician. However, the review excluded any study related to care delivered via video, teleconferencing or telephone. It therefore may have been predominantly focused on communication via e-mail, although this is not stated in the review. Atherton et al. 9 examined alternatives to face-to-face consultations, which included telephone consultations (but not triage), e-mail, e-consultations, video, SMS text messaging, telehealth and any other form of ‘care at a distance’ apps. Similarly, Huxley et al. 23 included a range of digital technologies potentially used for patient–clinician communication: video, e-mail, internet forums and SMS text messaging. Chambers et al. 24 reviewed the evidence in relation to digital and online symptom checkers and health advice/triage services for urgent care. The review by Castle-Clarke and Imison8 focused on seven different digital services offered by the NHS, but only two (online triage and remote consultations) are relevant to the current review.

Relevance to primary care

Of the reviews which examined clinical communication between patient and health-care professionals, only two were exclusively limited to research related to primary care and general practice. 22,23 Other reviews included some evidence from other settings, such as secondary and tertiary care. The Cochrane review by Atherton et al. ,21 on clinical communication via e-mail, included nine studies of which only three were primary care based. In addition, Antoun20 also included studies that focused on the use of e-mail for broader communication purposes, such as co-ordinating health-care appointments, reminding individuals to attend appointments, providing health promotion information and communicating the results of diagnostic tests. All of the issues above potentially limit the relevance of reported findings to the current review questions.

Populations included in reviews

Huxley et al. 23 included studies conducted with various marginalised populations, whereas the other reviews appeared to focus more generally on any adults (patients, parents or adult caregivers). Only two reviews21,24 provided specific details about the countries in which included studies were conducted. The review by Chambers et al. 24 was the only one to clearly identify UK evidence. Nine out of 27 studies included in this review were conducted in the UK. Of the three primary care-based studies included in the review by Atherton et al. ,21 two were from the USA and one from Norway. Huxley et al. 23 was the only other review to report any geographical detail, with the review authors stating that the reported evidence came from high-income countries.

Outcomes

In terms of the main outcomes of interest examined, reviews commonly reported on patient access and equity, specifically the characteristics of individuals using alternative communication methods and/or which patients could potentially benefit the most from digital consultations. 8,9,20,22,24 In addition, Huxley et al. 23 reported evidence on the potential of digital patient–clinician communication to remove key barriers to accessing general practice for marginalised groups.

Most reviews reported findings in relation to implementation, including barriers to use, or outcomes related to service delivery, safety, harms or quality of care. 8,9,20–22,24 Six reviews8,9,20–22,24 examined patient health service use or the impact of digital communication on patient demand. Stakeholder views or experience of alternative consultation methods or levels of satisfaction were reported in five reviews. 8,9,21,22,24 Five reviews8,20–22,24 also examined evidence in relation to patient health outcomes or clinical effectiveness. The potential impact of digital methods of consultation on health professionals (e.g. knowledge, behaviour, workload) or consultation dynamics was examined in four reviews. 8,9,20,21 Fewer reviews examined evidence in relation to financial costs or cost-effectiveness. 22,24 Chambers et al. 24 reported a number of other outcomes: diagnostic accuracy, accuracy of signposting and compliance with triage advice. A table presenting the characteristics of each review is provided in Appendix 3, Table 3.

Critical appraisal and limitations of the secondary data

The two systematic reviews conducted by Atherton et al. 21 and Chambers et al. 24 were methodologically rigorous. Both were supported by a comprehensive search of academic databases, as well as an online search for grey literature. Inclusion/exclusion criteria were clearly stated in each review and an appropriate quality and risk of bias assessment of included studies was conducted. An appropriate synthesis of findings was also conducted in both cases, and adequate study details reported. Two reviewers were involved at key stages of the review process, which reduced the potential for bias and error. Findings and conclusions of both reviews are potentially generalisable across countries. However, all of the included studies in the review by Atherton et al. 21 were assessed as being at risk of bias. Furthermore, the three studies based in primary care were assessed at risk of multiple sources of bias. Aside from two randomised trials, all studies in the review by Chambers et al. 24 were judged as having at least a moderate risk of bias. In addition, the overall strength of evidence was assessed by the review authors as being ‘weak’.

Reviews by Antoun,20 Castle-Clarke and Imison,8 and Hickson et al. 22 were assessed as being of low quality, owing to poor reporting. In all three reviews,8,20,22 there was limited reporting of both the methodological process and study details. However, the DARE criteria were not well suited to the appraisal of the Castle-Clarke and Imison8 report, which combined the findings of a literature review with case studies and expert interviews.

The lack of study details made it difficult to determine accurately the reliability or generalisability of many findings. However, given the technological focus of the reviews, it is likely that some findings potentially have relevance across countries.

The realist reviews conducted by Atherton et al. 9 and Huxley et al. 23 were assessed as ‘adequate’ or ‘good’ for the majority of the RAMESES quality standards criteria. However, it was possible to identify some limitations in both reviews, including a lack of study details. Findings in the review by Huxley et al. 23 also appeared to be based on a database search that was restricted to a very narrow date range, covering 1 year only (2013–14). Furthermore, the review by Atherton et al. 9 included opinion pieces, as well as primary studies, and many of the individual findings were drawn from a small number of studies of unknown design and origin. Although the country and setting of the included studies is uncertain, it is likely that the findings are potentially generalisable. The findings of the Huxley et al. 23 review related to various marginalised groups within high-income countries and are likely to be generalisable to a UK setting. See Tables 5 and 6 in Appendix 4 for critical appraisal assessments of included reviews.

Characteristics of included primary studies

The HSDR report by Atherton et al. 9 examined the potential of alternatives to face-to-face consultations in UK general practice. It comprised one conceptual review and three primary studies. The primary studies comprised (1) focused ethnographic case studies conducted in general practices in England and Scotland (qualitative data were collected from staff and adult patients/carers, with a particular focus on gaining the involvement of ‘hard-to-reach’ groups; (2) a quantitative cross-sectional scoping survey of general practices and individual GPs in England and Scotland; and (3) secondary analysis of patient health record data from general practices in England and Scotland. Each of the primary studies focused on a range of alternative consultation technologies, such as telephone consultation, e-consultations, e-mail, text messaging and video. The results of the scoping survey and case study research have also been published in journal articles. 10,11 Key outcomes of interest reported across the three primary studies included the extent of use of alternatives to face-to-face consultations; motives and rationale for use; stakeholder experiences or views, including on the types of patients who potentially benefit the most; characteristics of patients who use alternatives; and implementation issues. The methodology and methods used across the three primary studies were appropriate to the stated aims. The authors acknowledged some limitations to the research, but overall this UK-based report is highly relevant and addresses key questions of interest to the current review.

In total, five other primary studies were included. 25–29 Two of the studies were conducted in the UK25,29 and the other three were based in the USA. 26–28 Funding for the two UK studies25,29 was provided by the NHS Northern, Eastern and Western Devon Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG)25 and the Scottish Government/Chief Scientist Office. 29 Donaghy et al. 29 focused on video consulting (the Attend Anywhere system) between patients (aged ≥ 16 years) and clinicians for follow-up appointments in general practices in Lothian, Scotland. Carter et al. 25 evaluated webGP, which is an e-consultation and self-help web service for adult patients. The webGP e-consult service involves patients completing an online form which is reviewed by a practice GP. The patient then receives a response from the practice (e.g. they are asked to collect a prescription or offered a telephone or face-to-face consultation). Studies from the USA focused on adults’ use of e-visits28 and Teladoc (Westchester County, NY, USA; URL: www.teladoc.com). 26,27 Like webGP, the Teladoc system requires a patient to submit an online request for a consultation. A participating physician then reviews the patient’s medical history and contacts them to hold a consultation, which may be via telephone, internet or mobile app. It was reported that Teladoc physicians respond to requests 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. For e-visits, a patient submits information about their condition via an online portal. This information along with the patient’s medical record is reviewed by a physician who makes a diagnosis and then replies to the individual through the portal within several hours. 26

Both Carter et al. 25 and Donaghy et al. 29 employed a mixed-method design, whereas the three studies26–28 from the USA adopted a quantitative approach and involved secondary data analysis. Mehrotra et al. 28 analysed the data of patients with sinusitis and urinary tract infection only. Similarly, the two studies26,27 by Uscher-Pines et al. were also restricted to patients with a small number of specific health conditions: acute respiratory illnesses, urinary tract infections and skin problems;27 or lower back pain, pharyngitis and acute bronchitis. 26 No restrictions were placed on the types of patients who participated in either of the UK-based studies.

All five studies25–29 reported on the characteristics of individuals utilising digital forms of consultation and/or which patients could potentially benefit the most from their use. Other outcomes reported included the extent of alternative technology use;25–27 stakeholder views and experiences/satisfaction;25,29 impact on quality of care;26 implementation issues, consultation content and health service use. 29 A table presenting the characteristics of each primary study is provided in Appendix 3, Table 4.

Critical appraisal and limitations of the primary study data

The studies by Carter et al. 25 and Donaghy et al. 29 used appropriate methodology for the research aims, and methods were clearly described. These two studies25,29 were conducted in the UK, so the results will have a high degree of relevance. However, data collection in both studies was limited to a small number of practices. Furthermore, practices participating in the study by Carter et al. 25 were located in only one CCG area and had a predominantly white British population. Donaghy et al. 29 stated that the case-mix variation between groups potentially limits the conclusions that can be drawn. Limiting the focus to follow-up appointments was justified by the authors on the grounds of helping to control case-mix variation. It was also reported that clinicians had difficulties in recruiting patients to video consulting. Consequently, this resulted in a self-selecting sample comprising mainly younger and more ‘tech-savvy’ individuals.

Both studies by Uscher-Pines et al. 26,27 were based on data from patients enrolled in one US health insurance programme. The authors cautioned, therefore, that the results may not be generalisable outside California or to different patient populations. Analyses in both studies also focused on a small number of health conditions only. In addition, almost all patients (98–99%) had a consultation via telephone rather than through video, internet or the Teladoc app and, consequently, the results are of limited direct relevance. Limitations of the study by Mehrotra et al. 28 included being restricted to patients in a small number of practices in Pittsburgh and focusing on only two health conditions. The generalisability of the results may again be limited, but the broad conclusions related to the types of patients who used the e-visits technology, which could potentially have UK relevance. See Table 7 in Appendix 4 for critical appraisal assessment of UK qualitative studies.

Stage 2: thematic synthesis of included evidence

A large proportion of material in this synthesis is derived from a recent NIHR-funded project by Atherton et al. 9 on alternatives to face-to-face consultation in general practice. This project included a conceptual review of the literature, a survey of UK general practice staff, a series of focused ethnographic case studies in eight UK general practices and an analysis of routine consultation data. Material throughout this report has been reproduced with permission from Atherton et al. 9,10

We have also included a second NIHR-funded project – a systematic review of digital and online symptom checkers and health assessment and triage services for urgent care – by Chambers et al. 24 This review includes evidence more closely aligned with the concept of ‘digital-first’ primary care, although does not focus on alternative consultation methods.

Taken together, these two publications9,24 represent the most robust, comprehensive and up-to-date source of evidence on this topic and include important evidence that could not be entirely reported here. The rapid synthesis below draws together some findings and conclusions from these publications, alongside other recent evidence of potential relevance to the research questions identified by NHS England. A summary of findings is available in Appendix 5.

Benefits of digital modes and models of engagement between patients and primary care

Absence of reliable evidence

It is clear from recent reviews that there is very little reliable data on the effects of alternative models of consultation. As will become apparent in this synthesis, much of the existing data are qualitative, providing some insight into the perceptions of patients and health professionals. However, objective measurement of the impact of alternative consultation models is lacking for most relevant outcomes.

The reviews undertaken by Atherton et al. 9,21 noted the dearth of evidence relating to alternatives to face-to-face consultations in general. They found little quantitative research either on the impact of e-mail on GP workload, or on analysis of the content of e-mails in comparison with face-to-face and telephone consulting for similar problems. A separate group of reviewers also reported a lack of robust evidence on the impact of e-mail on patient outcomes, health services outcomes (e.g. service use) or health-care professional outcomes (professional knowledge, behaviours and performance). 20 They also reported very limited evidence on safety, quality of care, privacy issues and appropriateness of e-mail communication.

Atherton et al. 9 noted that much of the literature on video consulting in primary care was focused on the potential of the technology, rather than exploring its impact on the content of the consultation or on GP workload or patient satisfaction. Although uptake of alternative consultation technologies in primary care was found to be low, it was unclear if this was due to GPs applying the use of alternatives selectively, patients not being aware of their availability or not wishing to use them, or problems with implementation. The authors also noted a lack of evidence relating to the roles of team members, such as reception staff, in delivering alternatives to the face-to-face consultation. 9

In 2015, Hickson et al. 22 noted that the delivery of primary care via e-visits on mobile platforms was still in its adolescence, with few methodologically rigorous analyses of outcomes of efficiency, patient health or satisfaction. No significant new evidence appears to have been found in subsequent reviews or in this current rapid evidence synthesis.

Looking specifically at digital and online symptom checkers and health advice/triage services, Chambers et al. 24 noted the weakness of existing evidence, being based largely on observational studies. In particular, Chambers et al. 24 highlighted that major uncertainties surround the likely impact of ‘digital 111’ services on most outcomes.

Uptake of alternative consultation models

From a scoping survey of UK GPs and practice managers, Atherton et al. 9 found that the majority of practices routinely offered telephone consultations (211/318, 66%) and few (6%) reported facilitating e-mail consultations (20% of practices intended to offer e-mail consultations in the future, but 53% had no such plan). None of the respondent practices reported offering internet video consultations and very few (4%) reported any plans to do so in the future. There was also evidence that 21% of practices had previously offered e-mail and that 10% had previously offered internet video, but that they had subsequently withdrawn these services. 9

Most GPs reported personally providing telephone consultations on most working days or every working day (79%). Only 8% of GPs reported providing e-mail consultations on most working days or every working day, whereas 45% did so rarely or sometimes and just under half (47%) never provided e-mail consultations. Furthermore, 99% stated that they never conduct consultations via internet video. Provision of telephone, e-mail or video consultations did not vary by GP age or sex, or by study site. 9

The authors concluded that unless, or until, uptake of e-consultations or video consultations increases, it will be impossible to measure their impact. 9 They added that these systems incur a subscription charge, and, to be cost-effective, would have to be both widely used and reduce practice workload considerably. 9

A 2016 review similarly concluded that physicians’ use of e-mail with patients is low and lags behind the willingness of patients to communicate with their physicians through e-mail. 20

When Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) video consultations were first introduced in a Manchester primary care practice in 2013, there was an initial increase in overall demand, with the same number of face-to face appointments being provided alongside additional Skype consultations. 8 However, increasing access to face-to-face appointments reduced the uptake of Skype consultations, as patients preferred face-to-face consultation. 8

A US study reported that ‘Teladoc’ visits accounted for a very small proportion of health-care use. Thirty-four per cent of all Teladoc visits occurred on weekends and holidays, in contrast to 8% of office visits. The timing of Teladoc visits closely resembled the timing of emergency department visits. 27 However, almost all (98–99%) Teladoc visits occur by telephone. Therefore, results are of limited direct relevance to digital modes of engagement.

Impact on clinical practice and patient health outcomes

The Atherton et al. 9 conceptual review noted evidence of ‘safety-netting’ behaviour, in which, for example, primary care doctors were more likely to prescribe antibiotics during an e-visit than a face-to-face consultation. The review authors suggested that this may reflect uncertainty about the medico-legal consequences of this form of prescribing. 9 A US primary study26 reported a similar finding, in which face-to-face office consultations more frequently avoided inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics for acute bronchitis than did Teladoc consultation (telephone, internet or mobile app).

Only two studies included in the Chambers et al. 24 review of digital symptom checkers and health advice and triage services reported on clinical effectiveness outcomes, making it difficult to draw conclusions. One study indicated that users of the ‘Internet Doctor’ website had longer illness duration and more days of illness rated moderately bad or worse than the usual care group, but the difference was not statistically significant. 24 Several patients using the ‘webGP’ system were reported to have received advice to seek treatment for serious symptoms that might otherwise have been ignored. 24 Evidence on patients’ reactions to online triage advice and whether they follow the advice or seek further help or information was very limited. Only two of the included studies reported specifically on patients’ compliance (or intention to comply) with advice received. The authors state that preliminary evidence from NHS England evaluation of NHS 111 online suggested that patients may be more likely to seek further advice for more urgent conditions. 24

Safety, harms and quality-of-care outcomes

A 2012 Cochrane review21 of e-mail consultation found that trials did not report any harms, though this is not the same as stating with confidence that no harms occurred. In their 2018 conceptual review,9 the same authors stated that much more work is required to identify potential patient safety issues and mitigate any associated risks.

None of six included studies reporting on safety-related outcomes identified any problems or differences in outcomes between digital/online symptom checkers and health professionals. 24 However, studies evaluating safety were generally short term and small scale. Some were limited to people with specific types of symptoms (e.g. influenza-like illness or respiratory infections) and others recruited from specific population groups (e.g. students) that were not representative of typical users of urgent care services. Like Atherton et al. ,9 Chambers et al. 24 advised that the evidence should be interpreted as a lack of evidence on harms rather than evidence showing no harm.

Elsewhere, Hickson et al. 22 reported evidence that e-visits can improve quality of care, access to care and continuity of transitions in care, but provided no further details.

The Atherton et al. 9 conceptual review noted that patient privacy and confidentiality are described as being important, but reports of privacy and confidentiality breaches are few and collection of these data is uncommon.

Impact on consultation dynamic

The Atherton et al. 9 conceptual review noted that alternatives to face-to-face communication can change the dynamic of consultations, so that elements may be lost or may need to be expressed in different ways or at different times for the doctor–patient relationship to be maintained. Some studies in this review noted particular uncertainty around the ‘rules of engagement’ for e-mail and video consultations. Other publications noted that typical face-to-face consultations allow for diagnostic cues, such as smelling a patient’s breath, noting how a patient walks into the room, as well as using casual contact, such as shaking hands, that enables assessment of skin temperature and tone. The loss of non-verbal communication may also diminish the ability to check a patient’s understanding. However, authors report that there is little research indicating whether misunderstandings are increased or diminished with alternatives to the face-to-face consultation. 9

Conversely, some responders to Atherton et al. ’s scoping survey9 described benefits of digital consultations, such as patients being able to send pictures of a transient rash or an audio file of a child’s cough. Other respondents preferred to use e-mail because of communication difficulties or disabilities that made it difficult to get to the surgery.

Huxley et al. ’s review23 focusing specifically on the impact of digital communication on marginalised groups included a study reporting that both clinicians and patients need the rich stimuli (e.g. auditory, visual, tactile and olfactory) of face-to-face contact to build the therapeutic relationship. One included review suggested that face-to-face consultations are essential for communication about emotional states, though evidence from single studies suggested that patients do communicate their emotional states with GPs via e-mail and are able to discuss embarrassing or sensitive questions. One study suggested that patients consulting for physical problems can feel less intimidated via video link and feel able to ask more questions.

There was some evidence to suggest that reducing the need for patients to engage with receptionists and other health centre staff may reduce apprehension for some patients. 23

A recent unpublished study, conducted in a Scottish primary care setting, reported that face-to-face consultations were longer and more problems were raised and addressed than in telephone and video consultations of similar duration. 29 The types of problems addressed were similar across the three consultation types and were typical of general practice.

During face-to-face consultations, patients’ health understanding was more likely to be sought and the problem placed into a psychosocial context at least once than in telephone or video consultations. Face-to-face consultations were also associated with more overall ‘information giving’ by both patients and clinicians (but this may partly reflect the number of problems raised). The authors noted that increased confidence and experience with video consultations might lead to different consultation dynamics in the future. 29

Financial costs or cost-effectiveness

Evidence on cost or cost-effectiveness is largely absent from the identified literature.

The review of digital and online symptom checkers and health advice and triage services for urgent care identified cost-effectiveness data from two studies (both produced by digital system manufacturers). 24 Based on 6 months of pilot data, webGP was estimated to provide £11,000 savings annually for an average general practice (6500 patients) compared with current practice. A saving to commissioners equivalent to £414,000 annually for a CCG covering 250,000 patients was also suggested. The Babylon Check app (Babylon, London, UK) claimed to provide average savings of over £10/triage compared with NHS 111 by telephone, based on a higher proportion of patients being recommended to self-care. A third study found that potential savings to practices from using e-consultation depended on the percentage of face-to-face appointments avoided. 24

One review identified a limited number of US data on costs-applied reimbursements for e-visits to a fee-for-service model of patient payment, but this is not generalisable to an NHS funding model. 22

Diagnostic accuracy

One review suggested that digital and online systems have yet to achieve a high level of accuracy in the diagnosis of specific conditions. This applies both to ‘general purpose’ symptom checkers and to those limited to particular conditions. 24 Most studies reported that the diagnostic accuracy of symptom checkers was poor in absolute terms, though two studies found evidence that symptom checkers performed relatively well when complaints were generally common and uncomplicated. 24

Another overview concluded that diagnosis apps are not always accurate, which may encourage patients to use the health system unnecessarily. 8

Information, triage and signposting

The accuracy of signposting of patients to the most appropriate level of service was inconsistent between studies evaluating digital and online symptom checkers and triage services. 24 Algorithm-based triage tended to be inferior and more risk averse than that of health professionals, with 85% of respondents being advised to visit their doctor in one study. 24 The only studies to find clearly equal or superior accuracy of triage and signposting to appropriate services using an automated system were the evaluations of ‘Babylon Check’ produced by the company that developed the system. The app gave an accurate triage outcome in 88.2% of cases, compared with 75.5% for doctors and 73.5% for nurses (one study). 24

The realist review by Huxley et al. 23 found no evidence that digital communication will improve knowledge about health services and how to access them.

Health professional experience and satisfaction

Atherton et al. ’s ethnographic case studies9 in eight UK general practices found that clinicians use e-mail to share and gather information when co-ordinating complex health-care packages. For nurses, telephone and e-mail consultations were valued in the management of diabetes (e.g. for discharge checks and medication reviews). For GPs, the main motivation for using alternatives to face-to-face consultation was to help manage their workload.

On the basis of a survey of over 300 UK general practices, the authors concluded that:

Despite policy pressure to introduce consultations by email and internet video, there is a general reluctance among GPs to implement alternatives to face-to-face consultations. This identifies a substantial gap between rhetoric and reality in terms of the likelihood of certain alternatives (email, video) changing practice in the near future.

Clinicians from a recent study conducted in Scottish general practice reported that video consultation appeared to be of less utility in managing patient problems, largely because of technical issues (B McKinstry, personal communication). Overall, 62% of clinicians rated video consultation as ‘very useful’ (29/47), compared with 85% for face-to-face consultations (29/47) and 76% for telephone consultations (38/50). In addition, 62% of clinicians would ‘absolutely’ choose video consultations, again compared with 94% for face-to-face consultations and 90% for telephone consultations. In contrast to other more positive views, some clinicians felt that video consultations did not add anything advantageous to telephone consultations. Interviews confirmed findings from the other data collection methods that face-to-face remained the ‘gold standard’ and that, like telephone consultations, video consultations tended to be limited to a single problem. Furthermore, the lack of a physical examination prevented clinicians from spontaneously addressing other health issues. 29

Another recent primary study, evaluating the ‘webGP’ e-consultation approach in Devon, found that in the majority of cases (37/61, 63%), the GP reported being ‘not at all familiar with the patient’, with only three (5%) reporting being ‘very familiar’. In virtually all cases (58/61, 97%), GPs reported feeling either ‘very confident’ or ‘confident’ about managing the e-consult request. 25

Patient experience and satisfaction

Two studies in the Atherton et al. 9 conceptual review reported that when patients had been offered an alternative to the face-to-face consultation, they usually report liking them. 9 Patients viewed the removal of the necessity to attend the GP or nurse’s professional space as a benefit of e-mail and telephone consultations. Other reported benefits included the convenience of being able to consult while at work, to choose when and how to consult, and the perceived advantage of avoiding the practice receptionist. 9

Patients interviewed in the 2018 UK case studies were interested in using these technologies (particularly telephone and e-mail), which they saw as a means of reducing the time they had to expend arranging to see and consult clinicians (particularly for what they termed ‘simple’ problems). 9 The use of alternatives to the face-to-face consultation could also be much more convenient, as well as time saving, for people who have difficulty physically getting to a surgery, either for geographical reasons or because of illness. The asynchronous nature of some alternatives, such as e-mail, meant that patients could send a message at a time that suited them and then read the response later, rather than having their diary dictated by appointment availability. 9

One overview noted that the developers of webGP and askmyGP reported patients being satisfied with their services. 8 It was suggested that patient satisfaction may be related to the use of professional review in the service. 8

In uncontrolled studies identified in one systematic review, study participants generally expressed high levels of satisfaction with digital and online triage services. 24 These studies appeared to be rating usability rather than satisfaction with the advice received or the degree of reassurance provided. One study identified in the review, an evaluation of NHS 111, reported that patients tend to be less satisfied with triage services when they have been auto-routed from another health service, such as a GP out-of-hours service. 24

Patients in the recent Scottish primary care study reported that they were generally happy with all available forms of consultation, which were considered equally useful, but face-to-face scored consistently higher than video and telephone consultations in a number of domains: health professionals giving enough time; asking about symptoms; listening; explaining tests and treatments; involving patients in decisions; treating patients with care and concern; and taking problems seriously. 29 Technical problems were more common with video consultations: some patients had significant problems with insufficient bandwidth and occasionally the connection failed and telephone consultation was used instead. The biggest perceived advantage for patients of video consultation was time saving. 29

The recent evaluation of webGP by Carter et al. 25 reported substantial differences (> 10% between groups) between e-consulters and face-to-face consulters for reported problem resolution (55% vs. 33% ‘completely resolved’, respectively) and seeing or speaking to a GP following the consultation request (52% vs. 93.8%, respectively). e-consulters also reported being less satisfied than face-to-face consulters with their ability to consult their preferred GP (44% vs. 57%, respectively). Although satisfaction rates were generally high, some patients had concerns about confidentiality, particularly around reception staff reading confidential medical information submitted via web requests. 25

Issues relating to general practitioner workload and workforce

Impact on service use and professional workload

The Atherton et al. 9 conceptual review of alternatives to face-to-face consultation found limited evidence from three studies suggesting that the availability of e-mail consultations had not ‘opened the floodgates’ for patient demand and these alternatives have not been widely used where patients have been able to e-mail family doctors for some time. 9 In one US study, patient use of secure e-mail with clinicians was not found to be associated with an increase in the use of clinical services 7–18 months after first use. Although it was associated with an initial increase in activity by e-mail users, this did not persist beyond 6 months (though it is unclear if this study relates to primary care). 9 Although studies have examined the association between e-mail and outcomes, there is limited evidence about the organisational and relational dynamics that contribute to change. 9

Interviews with UK primary care staff reported that alternative consultation methods could offer flexibility to both staff and patients depending on how practices organised the working day, with GPs and nurses being able to choose when, and in what order, to reply to messages or make telephone calls. 9 Other themes included telephone consultations taking longer than expected, lengthening the working day; some telephone consultations were converted to face to face, increasing the overall number of consultations with that patient.

Based on the evidence as a whole, Atherton et al. 9 concluded that there is little quantitative research on the impact of e-mail on workload and on the analysis of the content of e-mails in comparison with face-to-face and telephone consulting for similar problems. The authors did not find evidence to determine whether or not the provision of alternatives to face-to-face consultation leads to supply induced demand. 9

Hickson et al. 22 found studies with conflicting findings on the impact of e-visits on face-to-face consultation rates and Castle-Clarke and Imison8 reported mixed evidence on the capacity of online triage tools to manage demand. Some evidence suggested that interactive symptom checkers are often risk averse, recommending professional care when self-management is appropriate, and inaccurate diagnosis apps might potentially encourage patients to use the health system unnecessarily. 8

Chambers et al. 24 provided more detailed evidence on the influence of symptom checkers on the pattern of service use. One randomised controlled trial (RCT) focused on promoting self-care and covered respiratory symptoms only. The results showed that the intervention group had fewer contacts with doctors (but more contact with NHS Direct) than controls, despite having a longer duration and greater severity of illness. It was unclear if this finding is generalisable to systems covering the full range of urgent care. An NHS England evaluation of NHS 111 online found that online/digital triage was associated with a small shift towards self-care when compared with telephone triage (18% vs. 14%). In addition, online and digital triage directed a smaller proportion of patients to other primary care services, such as GPs, dental and pharmacy (40 vs. 60%). A pilot evaluation of the webGP system by its developers reported that 18% of patients had been diverted away from requesting a GP appointment for that consultation. In addition, 14% of patients reported that they would have attended a walk-in centre or other urgent care service if they had not had access to the webGP system. However, the report provides few details of the methodology used. Data provided by the manufacturer of the ‘Babylon Check’ app indicated that patients were more likely to be triaged to self-care by the app than with NHS 111 by telephone (40% vs. 14%). One further study suggested that students had a stronger intention to seek treatment for a hypothetical illness when the diagnosis was made using WebMD or Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) than with no electronic aid.

The recent UK study by Donaghy et al. 29 reported that video consultation was generally time neutral for clinicians.

Some UK primary care respondents suggested that webGP had increased the workload for GPs and administrative staff, whereas others suggested that webGP was shifting workload from the GP to the patient. 25

Impact on follow-up consultations

The analysis of routinely collected UK primary care data by Atherton et al. 21 found that most consultations by telephone, e-mail or e-consult are followed by another consultation (around 62%, often face to face) within 14 days, and this is more common than after an initial face-to-face consultation (48%). Therefore, the authors concluded that any analysis of the use of alternatives to face-to-face consultations needs to take account of knock-on effects in the following 2 weeks. 21

In the 2014 US evaluation,27 initial Teladoc visits were less likely than emergency department or physician office visits to result in a follow-up visit for a similar condition in any setting (6% vs. 20% vs. 13%, respectively). It could not be established whether fewer follow-up appointments with Teledoc was attributable to higher rates of clinical resolution, or to an increase in initial consultations for minor complaints that would not require follow-up. 27

The UK study25 of webGP reported that, in 72% of e-consults, the GP suggested a subsequent face-to-face or telephone consultation with a GP or nurse.

Atherton et al. ’s 2012 Cochrane review21 reported inconsistent findings on the impact of e-mail consultation on subsequent consultations of different types.

Data on the duration of follow-up consultations were sparse. One study of telephone triage in a general practice reported that, despite a clinician speaking with patients during a telephone triage encounter, the subsequent face-to-face consultation was no shorter. 21

Patients subgroups that can(not) benefit

Compared with patients using traditional face-to-face consultations, evidence from multiple sources indicates that users of alternative methods are more likely to be younger,8,9,20,25,27–29 healthier,20,27 female8,25,27 and have higher levels of education, employment or income. 8,9,20,25,27

Patients who used video consultations in primary care in Scotland were more likely to be working and to have experienced other video technologies, such as Skype and FaceTime (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA), and clinicians stated that, while trying to be inclusive of all patients, they were more likely to attempt to recruit patients who were more technology savvy. 29

Although health professionals raise concerns that older patients, disabled patients, people without literacy skills and patients who are less educated may be disadvantaged through alternatives to the face-to-face consultation,10 there is some evidence that, among those who have internet access, patients who are disabled, elderly, less confident or living at some distance from the practice are often among those who are particularly keen to use e-mail consultations. 10

A case study conducted in a Manchester primary care practice found that Skype consultations most benefited patient groups with additional needs (e.g. those with mobility problems and parents of autistic children who find attending the practice distressing) and those not in the local area (e.g. students wanting ongoing care from their usual GP). 8 For some patients in the recent Scottish study, video consultation was less stressful and more practical (e.g. patients with mobility problems or anxiety disorders). 29 A UK study of webGP reported similar findings. 25

Huxley et al. 23 concluded that digital communication technology offers marginalised groups increased opportunities to access health care. The removal of the patient ‘being seen’ seeking help potentially removes the embarrassment, social disapproval and stigma that some patients may experience at health-care centres, and anonymity of digital communication could encourage groups who wish to remain hidden to seek help. Digital communication provides an increased feeling of privacy when an interpreter is not physically present, which increases patient willingness to discuss sensitive issues; however, loss of visual information can reduce interpretation quality. People who do not have English as a first language are not heavy users of digital communications in English-speaking countries, so the advantages may be lost. In addition, the authors concluded that, as benefits of digital communication also apply to non-marginalised groups, patient–clinician communication could potentially be monopolised by those who are already well able to access services. 23

Atherton et al. 9 noted that much of the evidence about potential benefits and disadvantages for patients and particular subgroups of patients has been written from the health-care professional perspective and credible empirical evidence from patients is very limited.

The effects of different channels for different groups and settings

There is little direct evidence on the differential effects of different consultation channels and how these vary among groups and settings.

Routine data reported by Atherton et al. 9 indicated that face-to-face consultation rates were slightly higher in the least deprived areas and telephone consultations slightly higher in the most deprived areas, but otherwise there was no strong relationship with deprivation for these consultation types. 9 However, for electronic consultations, some of these patterns were reversed, with the highest rates in young adults and white patients. There was also a clear trend towards higher rates of e-mail consultations in the less deprived areas. 9 The demography of patients using telephone consulting was largely similar to that of patients attending the surgery and there were insufficient instances of use of video consulting to determine the demography of users with confidence.

As might be expected, telephone consultations are more challenging for people who have communication difficulties (primarily those who did not use English as a first language or who had hearing or speech problems), learning difficulties or cognitive impairment. 9

For some of these groups, written communication, such as webmail or e-mail and e-consulting systems, might be helpful. 9 e-mail exchanges can provide a consultation record, and possibly clearer explanations and subsequent understandings than information obtained during face-to-face contact. This may be particularly advantageous to those who are less articulate or confident in person, those who wish to discuss their consultation with others and those who need help with translation. 9

Some patients may be more willing to disclose intimate or sensitive information via an e-mail than in person or over the telephone, especially if they are at work or in a public place. 9

One overview mentioned studies indicating that patients are often more honest with digital tools than with a professional, but no further details were reported. 8

Atherton et al. 9 note that that practice staff, and sometimes patients, can blur the distinction between telephone consultation and telephone triage, and it is unclear whether or not policy-makers have made the distinction.

Differences between synchronous and asynchronous models

Conceptually, asynchronous text-based models of communication, such as e-mail and e-consultation, have been recognised as useful for people who are very anxious, find face-to-face contact difficult, have hearing or communication difficulties or struggle to express themselves. 9 Asynchronicity allows both patients and health-care professionals to send and act on contacts at a time that suits them, enabling health-care professional to draw on external resources or check evidence and providing sources of information for the patient. With e-mail, patients can also attach photographs and other digital files, such as audio recordings. For patients preparing for a hospital visit or recovering afterwards, these forms of consultation provide a way to communicate without having to visit. 9

Although asynchronous models work poorly for health conditions that require urgent care,22 they can potentially reduce the need to negotiate with receptionists, deal with appointment systems, travel to surgery and use waiting rooms. 23 Whereas synchronous models, such as video consultation, can retain some aspects of face-to-face consultation through real-time interpersonal interaction, these aspects are lost with asynchronous approaches. However, as elsewhere in the literature, quantification of the purported advantages and disadvantages of synchronous and asynchronous methods is largely absent.

Integration of digital-first models within wider existing face-to-face models

The identified publications did not provide information on how to integrate digital models into primary care, but a number of barriers to implementation of digital modes and models of engagement have been identified.

Health professional concerns about alternative consultation models

A possible barrier to implementation of alternative consultation or digital-first models is concern among primary care staff about possible adverse consequences.

Concerns about increases in demand and workload (both in terms of increased consultations and administrative load) were commonly reported in the literature. 9,20,22 Specific concerns included ‘lowering the bar’ to consultation, inappropriate use of e-mail as a means of fast-tracking a face-to-face appointment and concerns about introducing a new means of accessing a service that is already failing to cope with patient demand. 9 As mentioned in Issues relating to general practitioner workload and workforce, evidence on the actual impact of alternative models on demand and workload is extremely limited.

Some GPs expressed concerns about patient access and equity: although some had experience of some vulnerable and older people who preferred alternative consultation methods, others thought that these same groups would be disadvantaged. 9 In interviews, staff and patients concurred that alternatives to face-to-face consultation might be unsuitable if a new health problem was being presented, if the patient was older or confused, or if the patient was using a complex array of medicines. Clinicians varied in their views about which patients were most likely to be suitable for an alternative consultation; in some cases these decisions were based on age, socioeconomic status or ethnic group. 9

Security, confidentiality and privacy issues have also been identified as important concerns for physicians that act as barriers to implementation. 9,20 In one e-mail study,20 some physicians feared receiving spam e-mails, viruses or being hacked. Others were concerned about the uncertainty of e-mail receipt by patients and the lack of integration with medical records. 20

Concerns around medico-legal issues in handling sensitive and urgent matters have also been raised by clinicians. 9,20 These include concerns about content and the suitability of e-mail for discussing sensitive issues and addressing new or urgent symptoms using an asynchronous method. Some physicians reported fear of medical errors owing to the absence of physical examinations, as well as potential miscommunication and litigation for medical negligence. 9

Infrastructure and logistics

One barrier noted by Atherton et al. 9 was the technical difficulties that may be encountered ‘working within the heavily firewalled, low bandwidth systems of the NHS’. 9 Examples included inadequate technology and long set-up times, resulting in some planned video consultations defaulting to telephone. 9 The authors noted the importance of reliable contingencies being in place in case of technological failure, as there may be clinical consequences (e.g. it may be particularly distressing for people with mental illness). 10

The recent UK study of video consultation concluded that rising ownership of smart devices and experience of video calling will increase demand for such services, but further investment in information technology (IT) infrastructure in general practices would be required to enable video consultation to become a routine service. 29 Video consultation may also require practices to allocate a well-lit, private area for staff to use. 9

Beyond having adequate IT infrastructure to provide digital consultations, primary care staff felt that any future implementation of these systems should be properly integrated with desktop personal computers used for consulting, as well as with current appointment and electronic record systems. 22,25,29

Patient–professional relationships

Clinicians reported that having an established relationship with the patient is an important facilitator of implementing alternative consultation models, including video consultation,29 telephone and e-mail. 9 Continuity also mattered to patients: for certain health problems, it might be important to know the clinician who would be consulted remotely. 9 There was some evidence that patients try to see trusted GPs for mental health issues rather than the most available GP, thereby prioritising relationship over convenience. 23 Huxley et al. 23 reported that text-based communication leaves room for interpretation; therefore, communication between patients and clinicians with well-established relationships is more likely to be successful than that between strangers. 23 One study noted potential inequalities in delivery of care in which clinicians chose which patients they would consult with on this basis. 9

Professional identity

Atherton et al. 9 noted the role of professional identity as an implementation issue in both their conceptual review and case studies. Some interviewees perceived the core tenet of general practice as the doctor–patient relationship, as conducted in the face-to-face consultation, ‘Medicine’s about relationships really and getting to know your patient as a person’. 9 Other research suggests that any new technology needs to be seen to enhance what the professional sees as their core role, otherwise it is unlikely to be accepted into practice. 9

Similarly, the few studies that have collected the views and experiences of practice nurses on alternative consultation models suggested that nurses feel that their role requires proximity to the patient. 9 In a study of a telehealth self-care support system for people with chronic health problems, the nurses who were providing the service positioned their work as ‘proper nursing’, whereas nurses who were using the telecare system suggested that the calls with patients were ‘just chat’ and doubted that real nursing could be delivered via the telephone. 9 A Norwegian study of nurses working in emergency medicine found that the approach of nurses changed when they consulted remotely; they were more assertive and gave more advice. 9

Two studies found that some health-care professionals were worried that their lack of confidence with technology might be exposed and that such exposure may undermine their authority. 9 One study reported that the balance of power within the consultation may change if the primary care professional’s skills come under patient scrutiny. However, it was suggested that this would not necessarily be damaging and could result in a helpful shift in relationship dynamics over the longer term. 9

Policies and procedures around the implementation of alternative consultation models

There is some evidence that the effective implementation of alternative consultation models can be hindered by the absence of relevant policies, procedures and guidance. In the UK case study practices observed by Atherton et al. ,9 policies about e-mailing patients were not in place, not known about or not followed. Contradictions were evident; for example, one GP explained that their practice was trying to discourage patients from engaging in two-way e-mail communication with the practice, yet the GP used e-mail with ‘selected’ (trusted) patients. 9 The authors concluded that robust systems for handling e-mail have not been established in practices and this would be difficult to achieve using standard e-mail (e.g. establishing with confidence the identity of patients using the system). Even when more secure alternatives can be provided by practices, effective triage systems would need to be implemented to determine the suitability of the medium (e.g. urgency of response, need for physical examination). 8,9 If patients can choose from a range of consultation options that are equally available, then the patient group using each type of consultation will be determined by patients themselves. If use of alternatives to the face-to-face consultation is mandated by the practice as the default way to gain access to care, it will be important to facilitate other routes to care to avoid marginalisation of groups with particular needs. 9

It was also observed that e-mail consultations were not consistently recorded in the medical record. 9 Three studies reported potential inefficiencies that included duplicate consultations for patients who consult remotely and then attend the practice or require a home visit. 9