Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/177/04. The contractual start date was in July 2014. The final report began editorial review in November 2018 and was accepted for publication in July 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

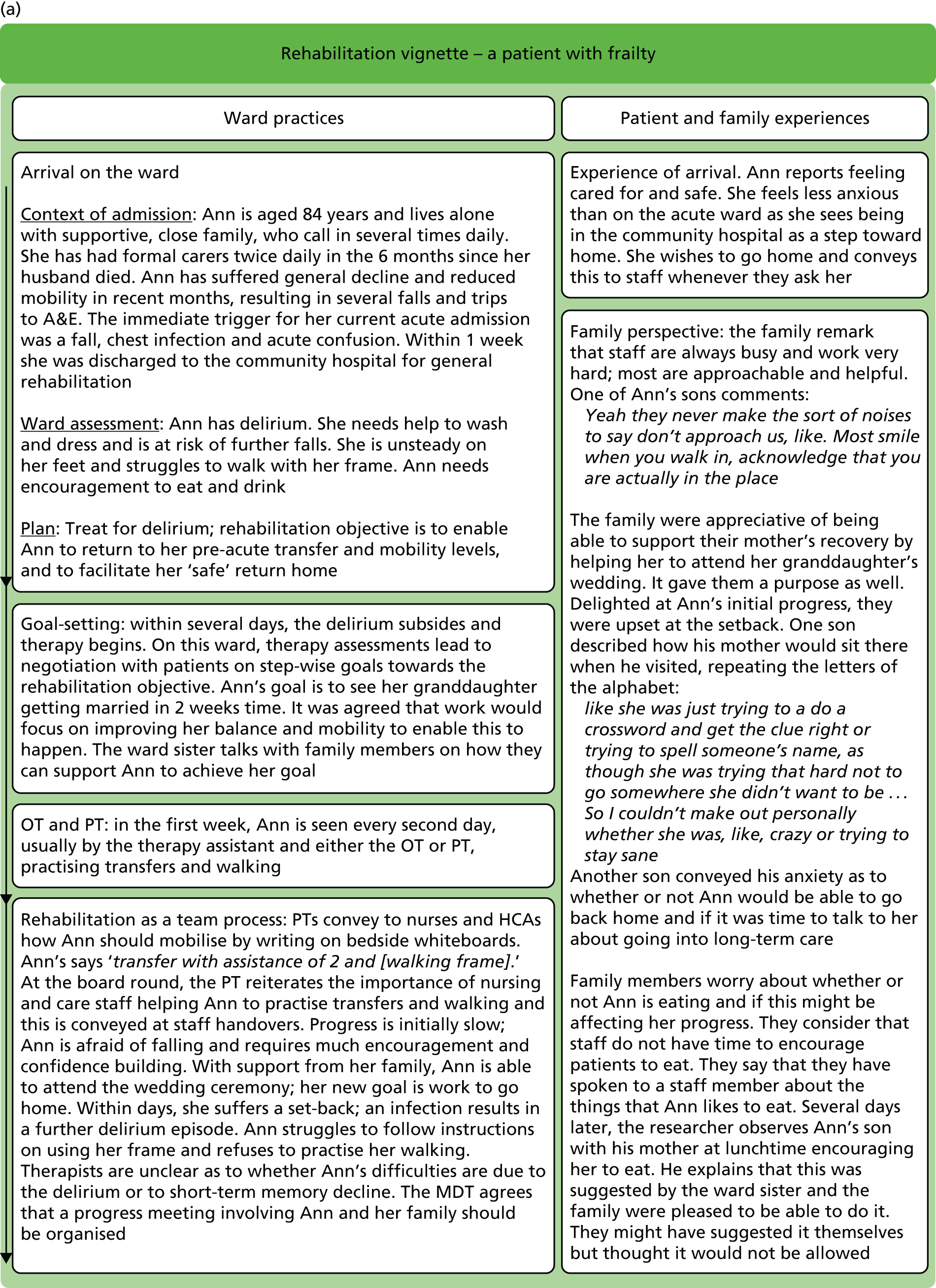

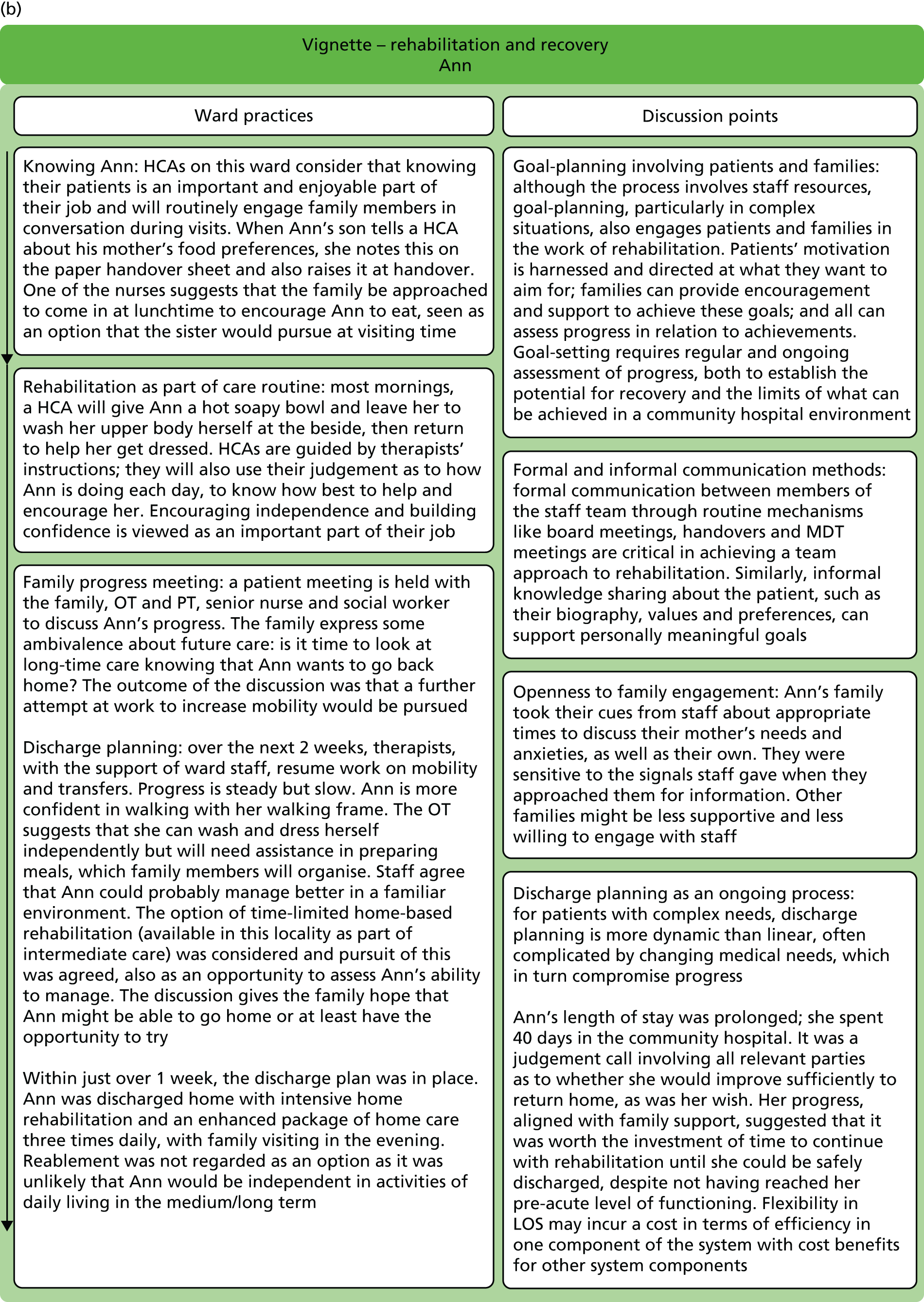

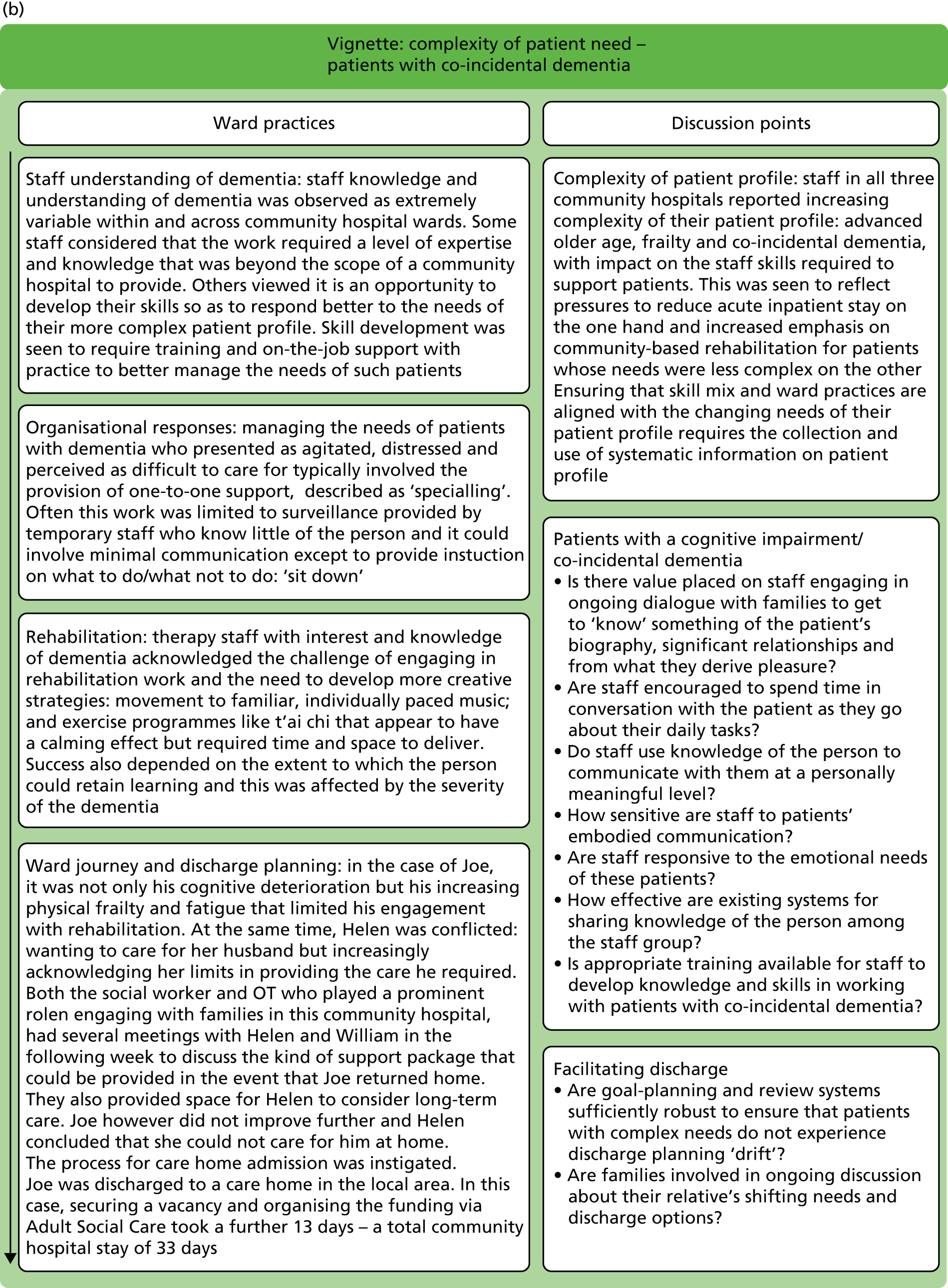

Claire Hulme was a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Commissioning Board over the life of the project (from 2013 to 2017). Mary Godfrey reports grants from NIHR for Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) 12/209/66, HSDR 12/5003/01, Health Technology Assessment 11/143/01 and Programme Grants for Applied Research RP-PG-1210-12017 during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Young et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale to study

Nearly 12 million people in the UK are aged ≥ 65 years, which is projected to increase by 5.5 million in the next 20 years, and the number of people aged ≥ 85 years is projected to double to 4 million. 1 An increasingly older population, along with improvements in the management of chronic conditions, will result in more people living to very old age with one or more chronic conditions. 2 As multimorbidity increases with age, over half of those aged ≥ 85 years will have four or more chronic conditions (complex multimorbidity). 3 Furthermore, among more than one-third of those with complex multimorbidity, the burden is exacerbated by mental ill health (e.g. depression and dementia). 3 Multimorbidity is associated with secondary care utilisation, complications during a hospital stay, reduced functional capacity and increased need for co-ordinated care and support to facilitate safe hospital discharge. 4 Multimorbidity therefore poses considerable challenges for appropriate models of treatment and rehabilitation during and following an acute illness and for ongoing support from health and social care services. This is a major issue and decision-makers across the NHS are attempting to reconfigure services to deal with the year-on-year increase in hospital admissions, often with inadequate evidence to inform their decisions.

Community hospitals are a long-established health-care facility in the UK, as well as internationally. They can be loosely defined as small hospitals that provide a wide range of locality-based outpatient and inpatient services such as health promotion, rehabilitation, day hospital and diagnostic services. Specific service configurations differ between community hospitals as a result of local history, proximity to a larger general acute hospital and perceived need. The policy direction for community hospitals was contained in the white paper Our Health, Our Care, Our Say: A New Direction for Community Services. 5 It was expected that primary care trusts would engage in an ‘ambitious’ shift of resources from secondary care to community services over a 10-year period. A new generation of community hospitals was proposed as an important component of the vision for community services within the umbrella term, ‘intermediate care’. The new format for the community hospital was that they should be locally led, of high quality and focus on older people. It was expected that they would provide new care pathways, adopt new technologies, minimise acute hospital admissions, promote integrated solutions and be affordable for the whole health economy. 5

There is high-quality evidence that supports the community hospital as an effective bed-based rehabilitation service for older people. A multicentre study in England randomised patients (n = 490) either to remain in a general hospital ward or to transfer to one of seven community hospitals. 6 The main finding was a significantly greater functional independence at 6 months for the patients allocated to the community hospital group,6 with similar cost-effectiveness. 7 A similar single-centre randomised controlled trial in Norway (n = 142) reported lower mortality and indirect evidence for increased independence for the community hospital group than for the group receiving continued care in a general hospital. 8 There is also evidence that older people are in favour of and, if given the choice, would prefer community hospital ward care. 9–11

This evidence suggesting superior outcomes for older people receiving rehabilitation in a community hospital, at an affordable cost, is encouraging, particularly as most of ≈400 community hospitals in the UK provide inpatient rehabilitation. 12 Thus, community hospitals remain an important provision for health care in the NHS. Considerable additional information describing the contemporary community hospital is available from two other national surveys from the NHS Benchmarking Network (NHSBN): the NHSBN Community Hospitals Project (begun in 2012);13 and the National Audit of Intermediate Care (NAIC). 14 These complementary surveys provide information on 180 community hospitals (approximately two-thirds of all community hospitals in England). Two findings are prominent. First, it is clear that a core function of the contemporary community hospital is rehabilitation for older people: ‘general rehabilitation’ is provided in 97% of the community hospitals. This is in accord with strong policy directives from the Department of Health and Social Care relating to intermediate-care services for older people. 15,16 Second, the contemporary community hospital is characterised by extreme variation in provision [e.g. bed provision per 100,000 weighted population (range < 10–70); clinical leadership (50% nurse led; 50% consultant led); average length of stay (LOS) (11–58 days); cost per admission (£3700–17,500); and cost per day (£140–450)].

This variation in the community hospital was highlighted by the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement but, despite provider engagement with their Productive Community Hospital initiative,17 the wide variations have continued. There is evidence that some features might be associated with performance, for example the lack of ward leadership,18 excessive waiting times for admission19 and underprovision of the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment. 20 However, our knowledge of the features that characterise optimum community hospital ward performance is incomplete as no large-scale study has been designed to systematically investigate the issue. In addition, there is a paucity of information available to service planners about the comparative outcomes and efficiencies of community hospitals in relation to alternative forms of community services, such as home-based rehabilitation and social service enablement services. Thus, when this study began, nearly 10 years on from the white paper Our Health, Our Care, Our Say: A New Direction for Community Services,5 the ‘ambitious’ shift of care focus for older people from secondary care to the community had not been realised. 21

Community hospitals and intermediate care

A prominent and sustained health-care policy for older people during the last decade has been that of intermediate care. Consistent with the established policy direction of increasing the provision of community-based services for older people, intermediate-care policy has been partly driven by the acknowledgement that large general hospitals comprise an environment in which unintended harms (e.g. increased risk of falls, delirium and increased dependency) are common for this vulnerable patient group, and the proposition that intermediate care might be less expensive.

Intermediate care comprises a range of service models designed to provide community-based, short-term rehabilitation with the aim of preventing admission to hospital and/or facilitating early discharge. Intermediate care was first proposed in the National Beds Inquiry,22 became a formal health-care policy in the NHS Plan of 2000,23 and was implemented as part of the National Service Framework for Older People in 2001. 15 Subsequently, intermediate care formed part of a wider health and social care policy loosely summarised as care closer to home. 16 The new role for community hospitals was specifically highlighted in these policy documents and, later, in implementation guidance. However, despite the successful achievement of intermediate-care expansion targets, and release of substantial capital monies for community hospital new-builds, the strategic objective of intermediate care to reduce pressures on acute hospital beds was not realised. ‘Refreshed’ guidance was produced that, once again, encompassed community hospital provision. 24 Acute services continue to be hard pressed, largely owing to a continuing year-on-year increase in acute admissions of older people. 25,26 Despite a decade of consistently applied policy, investment in intermediate-care services to provide short-term rehabilitation for older people appears to have stalled. The NAIC obtained information in 2014 from 62 commissioning and 112 provider organisations (327 intermediate-care services). 27 An important finding was that intermediate-care capacity nationally was around half that required to address the anticipated need for inappropriate admissions and post-acute care for older people. This mismatch of demand and supply has been a constant finding in the subsequent rounds of the national audit. 28,29 In addition, it was apparent that there is considerable scope to free up capacity in many services by simply addressing excessive lengths of intermediate-care stay. The average LOS was considerably longer than those given in the Department of Health and Social Care guidelines: ‘They (intermediate care) are time-limited, normally no longer than six weeks and frequently as little as 1 to 2 weeks or less’ (© Crown copyright 2009. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). 24 In the national audit,27 75% of patients in bed-based intermediate care had a LOS of > 2 weeks, and 9% of patients had a LOS of > 90 days. Specifically, for a community hospital with 20 beds and 90% occupancy, if the hospital is performing at the 75% quartile (LOS = 31 days) and improved to the 25% quartile (LOS = 21 days), it would be able to treat approximately 100 more patients per year (48% increase). Alternatively, if a 20-bedded community hospital is performing at the 75% quartile for cost per occupied bed-day (£200 per day) and improves to the 25% quartile (£110 per day), the annual cost saving is approximately £650,000.

From a whole-systems perspective, subsequent rounds of the NAIC reported no relationship between the scale of local intermediate-care provision and its impact on secondary care utilisation. 28,29 It was concluded that the case for further investment required new local evaluations to provide better evidence that future increases in intermediate-care capacity would indeed favourably affect secondary care utilisation. Until, and unless, this evidence is available, it will be difficult for commissioners to justify pro-active reductions in the secondary care bed base. In relation to community hospitals, this means that capital investment in new community hospitals will continue to be sporadic and opportunistic rather than strategically planned, and that some community hospitals will close or have bed reductions because of uncertainty over their contribution to the whole-system approach.

Community hospitals are part of this general uncertainty about intermediate care. Indeed, even producing a unifying definition for community hospitals has proved problematic, mostly because there are different models or subtypes of community hospital. This lack of agreement for community hospitals is important because it limits the potential of the commissioning process to shape the service to be delivered and leaves unanswered questions such as ‘what are the critical parameters of a community hospital?’ and ‘what are the tolerances to these parameters?’. For example, some community hospitals are nurse led and some medically led, but nurse-led rehabilitation units (where the admission, assessment, monitoring and discharge of patients are organised by senior nurses, and doctors have an advisory role) have been associated with weak evidence of increased mortality, and may operate at considerably higher unit costs. 18 Not surprisingly, this leads to uncertainty among commissioners and planners about the possible contribution of community hospitals. The number of community hospitals declined slightly between 1998 and 2008 (334 to 296),12 and again up to 2017, but this headline finding disguises a mixed picture of closures offset by newly opened facilities, which reflects an inconsistent approach to the provision of community services for older people.

A popular alternative bed-based form of intermediate care is the model of care home-based rehabilitation. Although widely used (as evidenced in the NAIC), little is known about its effectiveness, cost-effectiveness or safety. Only one randomised controlled trial has been conducted. 30 The NAIC reported that care home-based intermediate care was provided at considerably lower unit costs than community hospital care (£136 compared with £252 per day). 28

Robust comparison studies of different models of community hospital care are needed to provide confidence to patients, practitioners and commissioners in an evidenced-based selection approach that favours community hospital with specific criteria known to be associated with cost-effectiveness. Improved understanding of the role, external relationships, staffing structures and care processes in community hospitals providing intermediate care would clarify their contribution.

Aims and objectives of the research programme

Aims

The Models of Community Hospital Activity (MoCHA) study addressed deficiencies in the existing community hospital evidence base. This study aimed to explore the core unifying function of the contemporary community hospital: rehabilitation for older people. Thus, the key aim was to understand the features that optimise or detract from efficiency of community hospital ward care.

Objectives

-

To measure the current relative performance (cost efficiency) of community hospital inpatient care for older people (studies 1 and 2).

-

To identify the characteristics of community hospital inpatient care for older people that optimise performance (studies 1 and 3).

-

To develop web-based interactive toolkits for use by local commissioners and community hospital teams that support operational changes to optimise performance (study 4).

-

To investigate the current impact of community hospital inpatient care for older people on secondary care and the potential impact if the community hospital care was optimised to best practice nationally (study 5).

-

To determine if there is an association between the configuration (capacity and proportions) of short-term, community-based services (i.e. community hospital wards, home-based rehabilitation, care home rehabilitation and enabling services) and reduction in secondary care bed utilisation by older people (study 5).

Overview of method

The underpinning objectives of the project were addressed through a mixed-methods project design, consisting of five interdependent studies. This approach used existing data alongside complementary prospective data to produce insights that could not be achieved by the study of the components alone, and represents an efficient and effective research design.

-

Study 1: an analysis of cost efficiency of community hospitals (see Chapter 2).

-

Study 2: a national survey of community hospitals (see Chapter 3).

-

Study 3: comparative case study of community hospitals (see Chapter 4).

-

Study 4: development of toolkits for commissioners and community hospital providers to optimise performance (see Chapter 5).

-

Study 5: an analysis of the impact of intermediate-care services on secondary care utilisation (see Chapter 6).

Study team

The co-applicants comprised a team of health economists and efficiency analysis experts led by Claire Hulme; the Patients Association (led by Heather Eardley); the Community Hospitals Association (CHA) (led by Helen Tucker); a social scientist with experience in older people’s services (Mary Godfrey); and academic clinicians with experience in community hospital care delivery (John Young, John Gladman, Elizabeth Teale and Pam Enderby).

Patient and public involvement

Through the participation of the Patients Association and CHA, patient and public involvement was an integral feature of the study from conception and development of the research design to conduct of the research and interpretation and development of the interactive toolkit. Representatives of both (Heather Eardley and Helen Tucker) were co-applicants in the research and their contributions were critical in ensuring that the study engaged with the needs of patients and current quality and performance issues in this service sector. We worked with the Patients Association to produce a ‘primer’ that described the concepts that underpinned the economic efficiency work, concepts that would be unfamiliar to most people (see Appendix 1). This was used as an introduction during two workshops we held at consecutive CHA annual conferences during 2015 and 2016 attended by practitioners and NHS managers.

For all aspects of the study, we engaged with members of the CHA through sequential participation in their annual conferences from 2015 to 2017, where we delivered presentations and workshops, inviting feedback to inform the content and format of the interactive toolkit. Study progress was also conveyed on the CHA website.

In addition, for study 3, we involved our well-informed local older person’s group (approximately 15 people) with which we have a long-standing relationship. This is a subgroup of a forum established by the local authority that comprised approximately 300 retired local people who have been consulted on health and social policy issues. The subgroup has been acting as an advisory body in all aspects of our research with older people since July 2007. Meetings of the group took place to inform data collection methods and contribute to the ethics application, and following conclusion of data collection to reflect on the emerging findings and their implications. We also presented our initial findings to staff groups involved in each of our three case study sites towards the end of the study to further inform our interpretations and conclusions.

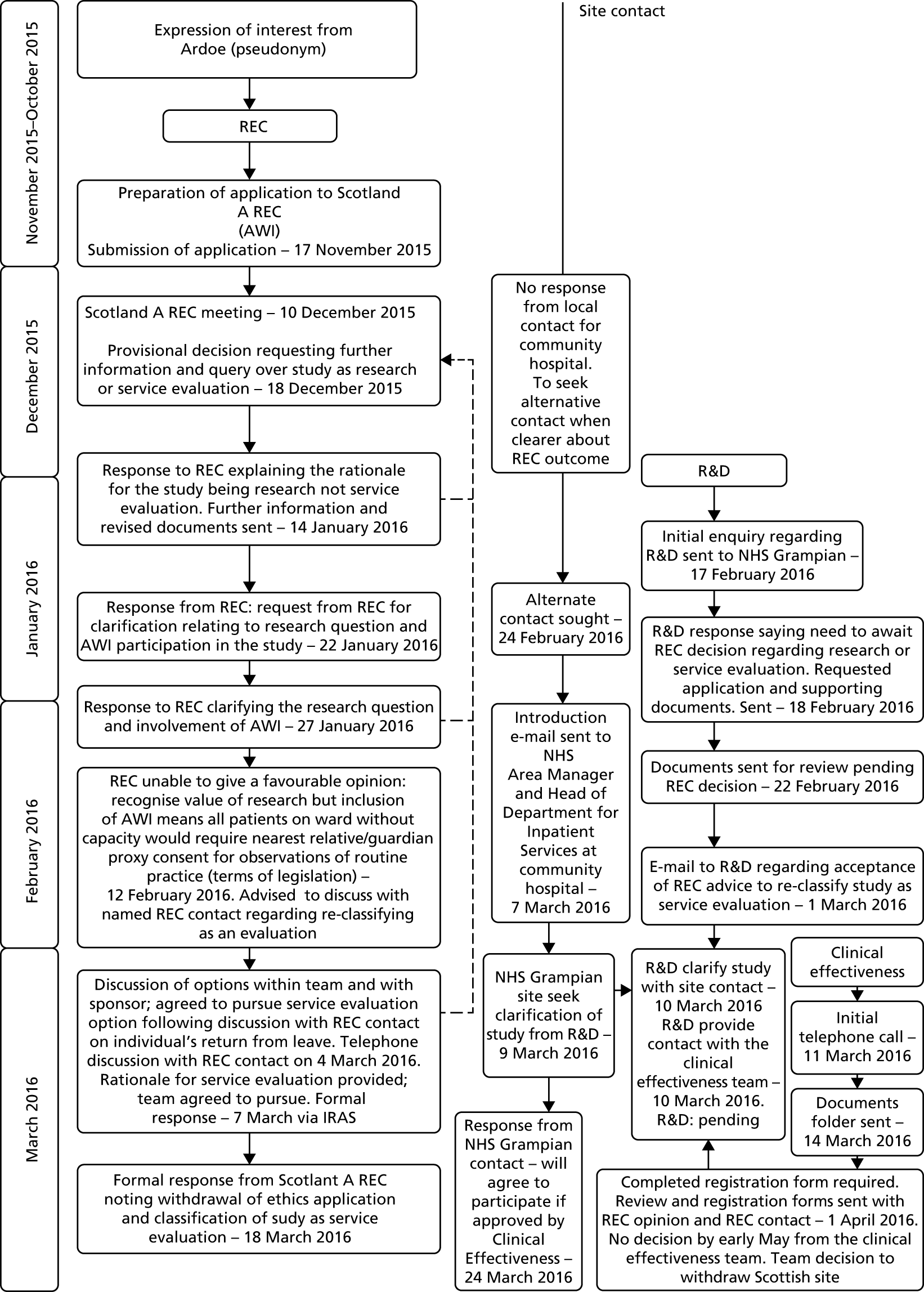

Ethics

Ethics approval was required only for study 3 (ethnographic case studies); all of the other studies were based on anonymised, aggregate data. Ethics approval was obtained via the Health Research Authority that governs research ethics in the UK (reference number: 15/YH/0062). The main ethics issues were securing the consent of patients to take part in specific ward observations, conversations and interviews, especially those who might lack capacity on account of dementia or delirium; not seeking formal consent for the general observations of ward routines; and maintaining anonymity of hospitals, wards, trusts/health boards, staff and patients.

Patient consent

The consent procedures adhered to the Mental Capacity Act (2005)31 and accompanying Code of Practice. 32 Consent was an ongoing process. The researchers repeatedly checked with participants that they were happy to continue and were sensitive to any signs of distress or unwillingness to proceed. If any such signs, verbal or non-verbal, were present, we discontinued.

General ward observations

As observations were unobtrusive, carried out in public or semi-public spaces, and did not identify individual staff, patients or visitors by name, we considered that it would be impractical and probably more intrusive to seek formal written consent from all those present. Instead, we sought informal, verbal consent. Prior to each observation, the researcher reported to a senior staff member and introduced themselves to staff not previously met at an opportune moment so as not to interfere with the work flow. At the end of each observation period, the researcher ‘signed out’ with the senior staff member. Emphasis throughout was that observations were conducted with the full knowledge, support and co-operation of ward staff. If anyone appeared unhappy, distressed or uncomfortable, we did not include them in the observation.

Privacy and anonymity

We have used pseudonyms throughout for community hospitals, wards, trusts/health boards, staff, patients and caregivers, and have altered some biographical details to protect anonymity, privacy and confidentiality.

Summary

Community hospitals continue to provide an important function for the NHS. There is high-quality evidence that supports the community hospital as an effective bed-based rehabilitation service for older people. Nevertheless, the contemporary community hospital is characterised by extreme variation in provision and there is evidence that some features may be associated with ward-level performance. Our knowledge of the features that characterise optimum community hospital ward performance is incomplete. In a number of sequential and overlapping studies, and employing mixed methods, this research aimed to understand the features of community hospital ward care that optimise or detract from optimum performance, through the lens of rehabilitation for older people, the core unifying function of the contemporary community hospital, and to provide a resource for community hospitals to inform practice. It also sought to investigate the impact on secondary care of community hospital inpatient care for older people. Patient and public involvement was an integral feature of all aspects of the study through the participation of the Patients Association and CHA and a local older person’s group.

Chapter 2 An analysis of the cost efficiency of community hospitals (study 1)

Introduction

As discussed in Chapter 1, there is a growing body of evidence to support community hospitals as an effective bed-based alternative to rehabilitation in the acute setting in terms of patient outcomes. However, in terms of economic outcomes, the evidence base is much weaker. One study reported community hospital rehabilitation to be cost-effective relative to secondary care in England. 7 Elsewhere, a national study of 180 community hospitals found considerable variation in the provision of services. 26 However, there is only speculation as to the causes of the variation. Finally, on the basis of cost comparisons, it was estimated that there were achievable savings of £1.2–1.8B in community services in general. 33 With a total spend of £8.4B across these services, this represents a potential for cost reduction of around 15%.

In the study presented here, we sought to extend the understanding of community hospitals in respect of the drivers of costs, economies of scale and bed occupancy. Furthermore, we assessed the relative efficiency of ward providers. In collaboration with the NHSBN, we made use of the NHSBN Community Hospital Programme data set encompassing hospitals in England, Scotland and Wales. 13 We adopted a stochastic frontier framework approach, which allowed both the cost structure and cost efficiency to be analysed.

Specifically, study 1 considered the following objectives:

-

study objective 1 – to measure the current relative performance (cost efficiency) of community hospital inpatient care for older people

-

study objective 2 – to identify the characteristics of community hospital inpatient care for older people that optimise performance.

We start with a general description of cost efficiency analysis based on frontier techniques that includes a discussion of the econometric approach to efficiency analysis. We then describe the data and categorisation of the variables to construct the final data set used for modelling. The specific methods and empirical specification of models are described in detail. Finally, we report the results of the analyses and diagnostic statistics with a discussion of interpretation and limitations.

Stochastic frontier analysis for community hospital costs and efficiency

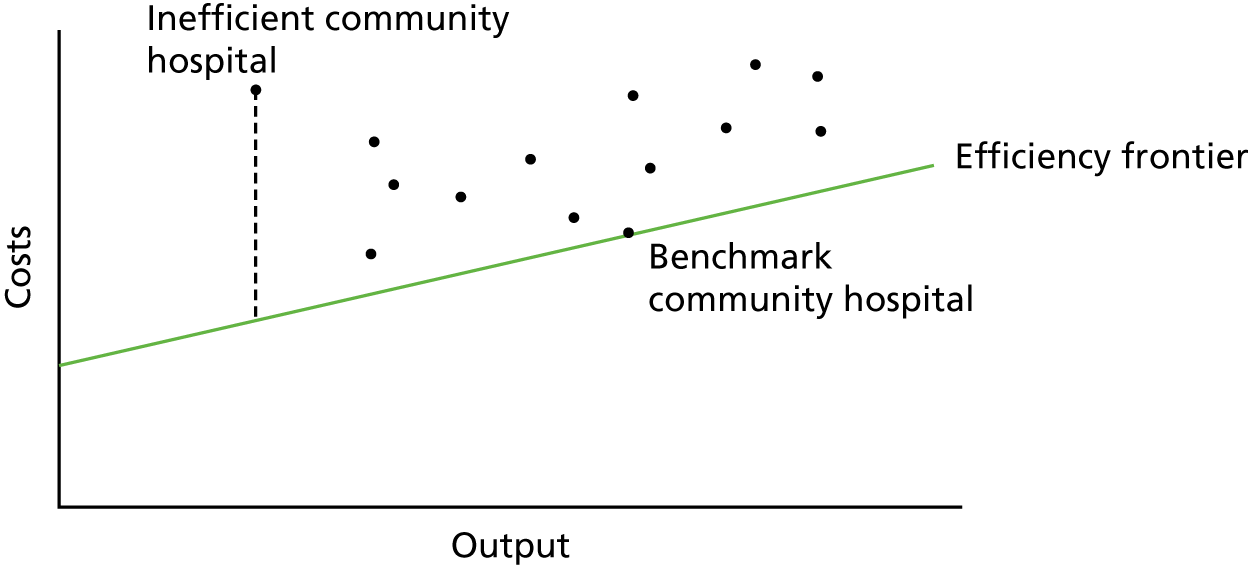

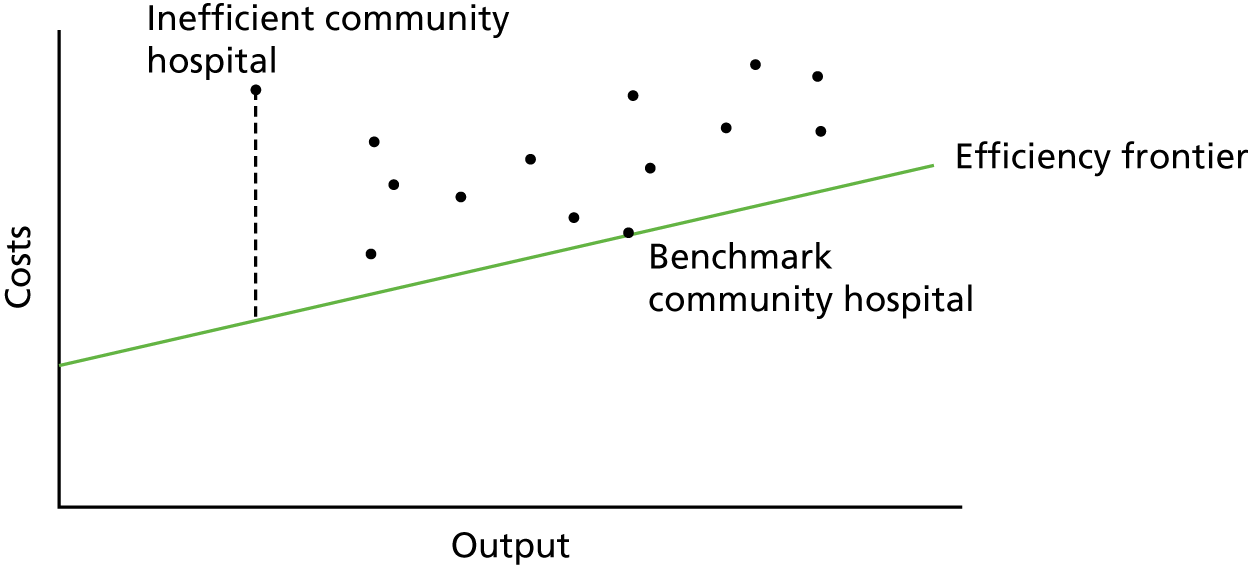

Frontier techniques have a long history of use in efficiency analysis, following pioneering work by Farrell. 34 The principle behind frontier techniques is very simple: an efficiency or ‘best-practice’ frontier is defined, representing full efficiency, and then distances from the frontier are measured, representing inefficiency. That is, the further from the frontier, the higher the inefficiency. This is shown for the case of community hospitals in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual features of frontier-based efficiency analysis as applied to community hospitals.

Frontiers are regarded as the foremost hospital efficiency analysis tool and are seen to have great potential in health-care markets more widely. 35,36 Frontier techniques have been applied widely in health for measuring efficiency. 36–41 There are, broadly, two approaches to frontier analysis, both of which have been deployed repeatedly to analyse efficiency in health-care markets. The first is an approach based on mathematical programming, data envelopment analysis (DEA), and the second is based on econometric estimation, stochastic frontier analysis (SFA). We make use of SFA in this study because, unlike DEA, it enables us to analyse both costs and efficiency, which are of interest to managers and policy-makers. Furthermore, it enables removal of statistical noise from the predictions of efficiency, which is a key advantage over DEA. 41

The stochastic frontier (SF) model for costs defines the efficiency frontier as a cost function (based on outputs, input prices, environmental variables and quality, thus allowing for variables not in control of the decision-making unit. The frontier assumes the shape of the cost function. The frontier represents the minimum attainable cost for a firm, given its levels of outputs and input prices (and other features defined by the cost function noted above). Deviations of firms from the frontier are considered to be, in part, due to inefficiency, where the distance to the frontier represents the magnitude of the inefficiency. In addition, the SF model allows for the removal of random statistical noise in the data from inefficiency estimates.

The SF model can be computed mathematically as:

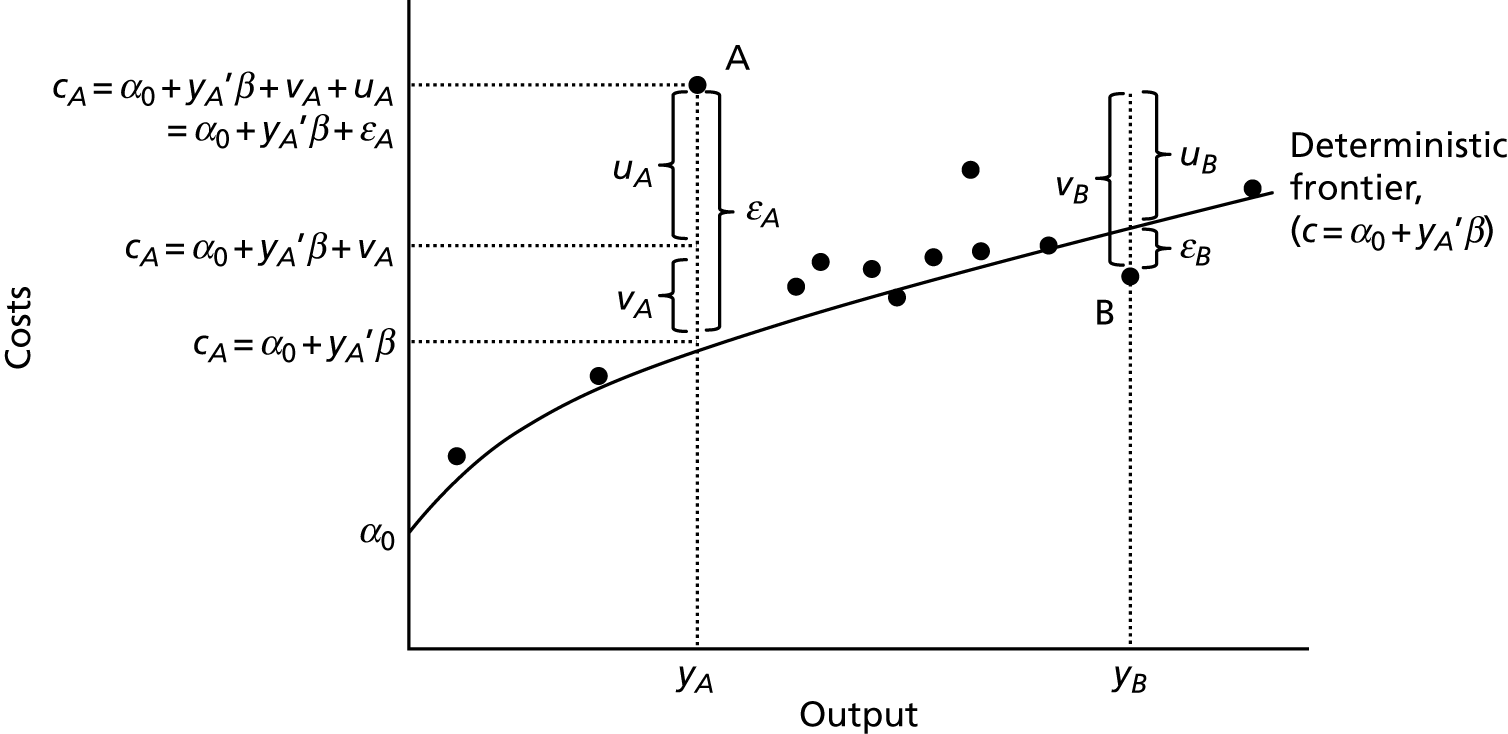

where care costs are a function represented as f (. . .) in Equation 1 of output (y), input prices (w), environmental influences (z) and quality (q). The ε term is the observed deviation from the frontier; it comprises both inefficiency (u) and random noise (v) to a firm’s (in this context, a hospital ward’s) production that impinges on its costs, as in Equation 2. Figure 2 shows the conceptual features of the SF model.

FIGURE 2.

Diagrammatic representation of the stochastic cost frontier model.

The gradient of the frontier in Figure 2 is defined according to the cost function and is the deterministic element of the model. In this case, costs (c) are defined as a function of outputs (), namely c=α0+y’β.

We consider observation A, representing a specific community hospital A. Here, as shown, community hospital A has output yA, at which the minimum attainable costs for community hospital A (shown via the cost frontier) are cA=α0+ y’Aβ. The observed value is in fact point A, which is higher than the deterministic frontier for community hospital A, given its level of output. Then, the community hospital-specific observed deviation ϵA comprises both the community hospital’s inefficiency uA and random statistical noise vA. In this case, both noise and inefficiency have a positive influence on costs.

In some cases, community hospitals are observed to be below the deterministic frontier, as in observation B for which the observed deviation from the frontier εB is negative. This is the result of a noise component vB, which is negative and greater than the community hospital’s (positive) inefficiency uB. Here, community hospital B has output yB at which the cost frontier is cB=α0+y’Bβ.

Random noise can encompass a number of features. In non-health-care settings, these typically comprise random ‘shocks’ to production that include untoward events, such as strikes, unusual weather, force majeure, etc. In addition, this component can account for measurement error and approximation error (from the choice of functional form). 41 The defining feature of the SF model is its ability to remove these factors so that they do not distort the underlying metric of interest: inefficiency.

Although we had originally planned to use DEA as a cross-check for ranking efficiency scores, we did not apply DEA because the method does not deal well with random noise in the data and also because we were interested in establishing the relationship between costs and cost drivers, which DEA does not support. We therefore decided to focus on econometric methods as the most appropriate method for the research objectives.

NHS hospital efficiency studies

Although there is no previous evidence on cost efficiency for community hospital wards, there is a wealth of econometric evidence for the general hospital setting. We did not undertake a full systematic review. Instead, a scoping search was carried out in MEDLINE in 2015. The search included all relevant publications published up to 30 September 2015. In addition, research papers already known to the authors of this study were included and citation tracking of identified papers used. A list and summary review of these studies42–53 is provided in Table 1. This will facilitate later comparisons between the two types of inpatient ward provision.

| Year | Authors | Methods | Unit of analysis | Sample size (n) | Years | Observations (n) | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | Harper et al.42 | COLS | General surgery specialties | 31 | 1998/9–1999/2000 | 62 | No efficiency predictions reported; rank correlations only, which were highly correlated between models |

| 2002 | Street and Jacobs43 | COLS; SFA | Whole hospital | 217 | 1999 | 217 | Average inefficiency: 0.74 COLS; 0.90–0.92 for SFA |

| 2003 | Street44 | COLS; SFA | Whole hospital | 236 | 1999 | 236 | Average inefficiency: 0.69 COLS; 0.87–0.90 for SFA |

| 2006 | Ferrari45 | SFA (distance function approach) | Whole hospital | 52 | 1991/2–1996/7 | 312 | Productivity gain average 3% per annum; no time-varying inefficiency; no efficiency estimates reported |

| 2006 | Jacobs et al.46 | COLS; SFA | Whole hospital | 185 | 1994/5–1997/8 | 740 | Mean efficiency across range: COLS 0.69; SFA cross-section 0.87–0.90; panel 0.61–0.92 |

| 2010 | Laudicella et al.47 | 2SLS cost function | Obstetrics | 136 hospitals; 952,273 patients | 2005/6 | 952,273 | More and less efficient units identified; efficiency itself not quantified explicitly |

| 2012 | Cooper et al.48 | Difference-in-differences | Individual procedure | 161 hospitals; 1,882,750 patients | 2002/3–2010/11 | 1,882,750 | Competition appeared to induce efficiency improvements |

| 2013 | Daidone and Street49 | 2SLS cost function | Specialised services | 163 hospitals; 12,154,599 patients | 2008/9 | 12,154,599 | Some variation in hospital efficiency but not reported |

| 2013 | Gutacker et al.50 | Multilevel cost function | Individual procedure | 147 hospitals; 194,570 patients | 2009/10 | 194,570 | For hip replacement, 95% of providers within a range of –£2740 to £3690 (mean £6335) |

| 2015 | Buckell et al.51 | SFA | Pathology laboratories | 57 hospitals | 2006/7–2010/11 | 187 | Efficiency of around 0.87; efficiency decreased over time; multifactor productivity increased over time |

| 2015 | Moran and Jacobs52 | Ordered probit; linear model | Mental health | 58 providers; 185,281 patients | 2011/12–2012/13 | 342,288 | Performance based on outcomes; variation of around 11% in ordered probit and around 2% in linear model attributable to providers |

| 2015 | Smith et al.53 | SFA | Pathology laboratories | 57 hospitals | 2006/7–2010/11 | 187 | Variation in efficiency at different levels in the organisation; average efficiency around 0.77 |

We note the link between the cost function methods used and the SFA literature. In several studies, a hospital-specific effect from a cost function is used as the measure of hospital efficiency (some authors use the term performance). 47,49,50,52 In this sense, they are akin to the panel data SF models that measure time-invariant inefficiency. 41,47

Community hospital data set

The NHSBN is the in-house benchmarking service of the NHS. The Network has 270 members including Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), acute and mental health trusts and community providers, and runs a range of benchmarking projects across all sectors of NHS provision. Members submit locally collected data to participate in the projects. Participation is not compulsory and incomplete data submissions are accepted.

The NHSBN Network Community Hospital Programme was instigated at the request of the network members to provide a structured comparison using key metrics that include workforce, activity, investment levels and quality measures. However, the granularity of the NHSBN Network Community Hospital data set at the ward level for older people was insufficient for the analysis. Further questions were therefore added to the data collection process for the 2013/14 survey13 to enable capture of data at a level to facilitate the analyses, namely at ward level. However, this meant that only this version of the Community Hospitals Project was used for this study, which collected data on 158 community hospitals from the financial year 2013/1413 (not the 3 years originally anticipated).

We started by categorising the variables into general features of the community hospital, information on patient access, services provided, workforce characteristics, activity of community hospitals, financial data and service quality. The nature of the variables includes continuous, categorical, binary and qualitative data.

Our unit of analysis was the community hospital ward for older people. Provision of services on older people’s wards is the core activity of community hospitals. We adopted this approach for a variety of reasons. First, it allowed us to maximise the sample size, as there was a high number of missing data for variables at the whole-hospital level (Table 2 shows a variable summary of missing data). Second, this allowed us to better control for the issue of heterogeneity between providers than would be the case at the whole-hospital level 54 (there is less heterogeneity in the provision of services on the ward). This is important as we have a limited number of variables on patient characteristics, quality, hospital characteristics and input prices. Third, following an initial modelling exercise, results indicated that models at the whole-hospital level yielded questionable results in terms of parameter estimates and, consequentially, efficiency predictions, probably because of the high number of missing data. Fourth, by focusing on wards, managers are better placed to understand the source of inefficiency than with whole-hospital analysis, in which the source of inefficiency may be unclear.

| Variable | Description | Categorya | Variable type | Wards (n) | Missing (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community hospital older people’s ward costs (£) | Operating costs for older people’s wards | c | Continuous | 129 | 28 |

| Total number of admissions to all older people’s wards in this community hospital (2013/14) | Total admissions | y | Continuous | 143 | 15 |

| Occupied bed-days (all older people’s wards) (2013/14) | Total occupied bed-days | y | Continuous | 139 | 19 |

| Materials input prices (£) | Non-staff operating costs divided by the number of beds | w | Continuous | 119 | 39 |

| London weight | Binary variable taking the value of 1 if the London wage supplement is received | w | Binary | 113 | 45 |

| Staff mix (average annual salary of clinical staff, £) | Total staff costs divided by the number of staff in whole-time equivalent terms | z | Continuous | 130 | 28 |

| Bed occupancy (%) (all older people’s wards) (2013/14) | Ratio of used to available beds | z | Continuous | 138 | 20 |

| Average LOS for older people’s wards (2013/14) | Average number of days patients stay on the ward | z | Continuous | 139 | 19 |

| Number of services | Number of services provided by the community hospital | z | Continuous | 158 | 0 |

| Number of beds on older people’s wards | Number of beds on wards | z | Continuous | 158 | 0 |

| Approximately how old is your community hospital? (< 20, 20–50, 50–100, > 100 years) | Age of the community hospital, years, by category | z | Categorical | 141 | 17 |

| Does this community hospital have specific admission criteria set out in a formal policy or service level agreement? (Y/N) | Patient selection criteria, may be indicative of higher-severity patients where true | z | Binary | 120 | 38 |

| Diagnostics (Y/N) | Diagnostic services provided – proxy for case mix | z | Binary | 114 | 44 |

| Proportion of senior staff (%) | Ratio of senior staff to total staff | q | Continuous | 142 | 16 |

| Proportion of physiotherapists and occupational therapists (%) | Ratio of physiotherapists and occupational therapists to total staff | q | Continuous | 141 | 17 |

| MDT meetings weekly? (Y/N) | Proxy for quality | q | Binary | 133 | 25 |

| Has the community hospital been involved in any research programmes during the previous year? (Y/N) | Proxy for quality | q | Binary | 120 | 38 |

| Frequency of clinical governance meetings (no meetings, monthly, quarterly, annually) | Proxy for quality | q | Categorical | 137 | 21 |

Our data set comprises 158 community hospital wards from 158 NHS providers and 18 variables per ward. Of these, 11 were continuous variables, five were binary variables and two were categorical variables. The continuous variables comprise what can be seen as core variables (i.e. the dependent variable and variables on outputs and input prices) and some environmental variables (these include, for example, patient selection policy and provision of diagnostic services). There are also continuous quality variables. See Table 2 for the list of variables, their descriptions, classification and missing data.

Some of the variables we used were constructed from other variables in the data set. Materials input prices were defined as the non-labour operating costs divided by the number of beds. Staff costs were calculated by the total labour costs divided by the number of staff, in whole-time equivalent (WTE) terms. The proportion of physiotherapy/occupational therapy staff and senior staff was defined as the ratio of each of these to the total number of staff.

We removed 14 outliers from the data set. For materials input prices, there were two clear outliers (around £100,000; the mean for this variable is around £9000). For staff mix, observations in excess of £50,000 were removed (i.e. where average wages were > £50,000). In this case, 12 observations were removed. All other variables appeared to have plausible distributions. Furthermore, we tested models that included the outliers and estimates did not appear to be sensitive. After cleaning the data set for missing values and outliers (some remained unverified), 101 community hospital wards were available for analysis. Thus, we undertook a complete-case analysis (having also removed outliers from the data set).

Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics for the 101 community hospital wards are presented in Table 3. For each variable, the category (see Equation 1), mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum and number are reported.

| Variable | Mean | Standard deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH ward costs (£) | 2,255,170 | 1,504,690 | 624,526 | 7,970,050 |

| Number of admissions to CH ward | 417 | 254.65 | 107 | 1499 |

| Occupied bed-days | 10,671 | 7324.06 | 2886 | 47,295 |

| Materials input prices (£) | 9293 | 9855.11 | 1989 | 50,998 |

| London weighting | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Staff mix (average annual salary of clinical staff, £) | 31,617 | 9646.70 | 5291 | 48,935 |

| Bed occupancy (%) | 89.69 | 6.59 | 68.90 | 100 |

| Average LOS (days) | 26 | 7.82 | 12 | 53 |

| Number of services provided by CH | 14 | 5.99 | 3 | 27 |

| Number of beds in ward | 31 | 20.49 | 4 | 130 |

| Approximately how old is your CH? (< 20, 20–50, 50–100, > 100 years) | 2.50 | 1.08 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Does this CH have specific admission criteria set out in a formal policy or service level agreement? (Y/N) | 0.71 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Diagnostics available (Y/N) | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Proportion of senior nursing staff (%) | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.46 |

| Proportion of physiotherapists and occupational therapists (%) | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.91 |

| MDT meetings weekly? (Y/N) | 0.88 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Has the CH been involved in any research programmes during the last year? (Y/N) | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Frequency of clinical governance meetings (no meetings, monthly, quarterly, annually) | 2.93 | 0.49 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

We can see that, on average, the annual expenditure for the provision of a community hospital ward is £2.3M.

For the output variables, on average, 417 patients were treated each year, accounting for around 11,000 occupied bed-days.

The London weighting variable suggests that around 10% of our sample are based in London (we do not have any further geographical information).

For the environmental variables, average bed occupancy reveals that community hospital wards are close to capacity, with an occupancy rate close to 90%. The National Audit Office (NAO) suggest that bed shortages may occur when bed occupancy is in excess of 85%. 55

Community hospital age is a categorical variable for which categories reflect incrementally older community hospitals.

The remaining environmental variables show various environmental aspects of the sample of community hospitals. Around 70% have a patient selection policy, and around half provide diagnostic services.

For the measures of quality, on average, senior staff occupy 16% of the workforce. There is a range from around 2% up to around 46%. Although the mean is approximately the same for the ratio of physiotherapy and occupational therapy (18%), the range is much greater: from 0% up to 91%. It appears that most community hospitals hold regular governance meetings (88%) and that around one-quarter have been involved in research programmes (24%).

Methods for model specification and estimations

Functional form and inefficiency

Having specified the form of our economic model (see Equation 1), and detailed the data, we now move to the specification of our econometric model. We begin with a Cobb–Douglas functional form. The Cobb–Douglas form allows the estimation of a linear function when log-transformed. Thus, the Cobb–Douglas realisation of Equation 1 is:

where:

-

ci – operating costs of older people’s wards for community hospital i

-

yi – output of older people’s wards for community hospital i

-

wi – input prices of older people’s wards for community hospital i

-

zi – environmental variables of older people’s wards for community hospital i

-

qi – quality of older people’s wards for community hospital i

-

ui – inefficiency of community hospital i.

α0 is the intercept and vi is the random noise in the data. ln(·) denotes that the variable is in natural logarithms.

To retrieve community hospital-specific predictions of inefficiency, ui above, it is necessary to make distributional assumptions about both ui and vi.The standard assumptions are that inefficiency is distributed with half-normal truncated at zero, and noise is normally distributed with zero mean. This is referred to as the normal-half normal model.

Then, using the method of Jondrow et al. ,56 community hospital-specific prediction of inefficiency, u^i, can be computed as:

where i is the number of observations, σ2=σu2+σv2 and λ2=σu2/σv2. When λ2 = 0, the variance is due solely to random noise – there is no inefficiency. 39 The disturbance is defined as εi=vi+ui=c−α0−x’β. Φ(x) is the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal variable evaluated at x. ϕ(x) is the corresponding probability density function.

Finally, the estimate of cost efficiency from the SF model is:

The βs are the first derivatives of cost with respect to each variable and so, for example, in the case of output ∂ln(c)∂ln(y)=β1. This allows direct interpretation of the parameter estimates as cost elasticities. Using the coefficient on output, we can observe the economies of scale properties in the provision of services. In addition, using natural logarithms is useful for technical issues, such as helping to reduce heteroscedasticity. 57

It is possible to examine the properties of the cost function in greater detail by using more complex functional forms. A common form used in the literature is the transcendental logarithmic, or translog. 46 As with the Cobb–Douglas form, natural logarithms are taken. This form differs through the addition of both higher order and interaction terms between variables. A translog has some appealing empirical and economic features: its flexible nature means it provides a second-order differential approximation to any unknown function (.);58 it does not impose restrictions on substitution possibilities and allows economies of scale to vary with output levels. This is likely to provide a better empirical approximation of the unknown cost function than the Cobb–Douglas form. The price is the addition of variables, which may affect the precision of estimates. The translog realisation of Equation 1 is:

where variables are as in Equation 7.

An appealing feature of these specifications is that the translog nests the Cobb–Douglas form. That is, the Cobb–Douglas form is a special case of the translog in which the squared and interaction terms are all equal to zero. In the empirical setting, it is possible to use a Wald test to test this restriction and, thus, as a means of deciding between specifications. We report the results of these tests in the following section.

Estimation results, community hospital ward costs and efficiency

Estimation outputs

Table 4 reports the six estimated models. Although we tested the complete set of variables in Table 3, we did not find that all variables were significant. We began with a full model and tested down to arrive at a parsimonious specification including only variables that were significant. Four variables were retained as statistically significant, namely the number of occupied bed-days (that relates lengths of stay and number of admissions), bed occupancy rate, nursing staff skill mix and materials input prices. We report models after having applied a Wald test to decide between specifications. In all cases, the translog was rejected, meaning that the Cobb–Douglas form was adopted in all cases. The exception to this was that the higher-order term for bed occupancy was retained as it was found to be significant.

| Regressors | COLS | Half normal | Truncated normal | Exponential | Gamma | Rayleigh | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Significance | Coefficient | Significance | Coefficient | Significance | Coefficient | Significance | Coefficient | Significance | Coefficient | Significance | |

| Constant | 1.57243 (0.869) | * | 1.20133 (0.926) | 1.23144 (0.998) | 1.42859 (1.056) | 1.54492 (0.904) | * | 1.10161 (0.989) | ||||

| Log-(occupied bed-days) | 0.8451 (0.050) | *** | 0.851935 (0.051) | *** | 0.846839 (0.0540 | *** | 0.853875 (0.051) | *** | 0.852711 (0.051) | *** | 0.846726 (0.054) | *** |

| Log-(materials input prices) | 0.19074 (0.040) | *** | 0.197202 (0.038) | *** | 0.193506 (0.039) | *** | 0.203948 (0.039) | *** | 0.205231 (0.038) | *** | 0.195717 (0.038) | *** |

| Log-(staff mix) | 0.29368 (0.062) | *** | 0.34732 (0.069) | *** | 0.346611 (0.062) | *** | 0.32774 (0.076) | *** | 0.320843 (0.056) | *** | 0.346643 (0.061) | *** |

| Log-(bed occupancy) | –1.24419 (0.511) | ** | –0.943673 (0.511) | * | –0.998334 (0.642) | –0.9678 (0.547) | * | –0.98829 (0.560) | * | –1.00774 (0.601) | * | |

| [Log-(bed occupancy)]2 | –13.5702 (3.081) | *** | –13.2466 (2.946) | *** | –13.6751 (2.817) | *** | –12.6519 (3.090) | *** | –12.6581 (2.573) | *** | –13.7243 (2.670) | *** |

| λ/θ | 2.0511 (0.519) | *** | 2.08783 (1.256) | * | 6.337 (2.527) | ** | 5.51691 (2.578) | ** | ||||

| σ | 0.36822 (0.003) | ** | 0.32454 (0.109) | *** | 0.20249 (0.039) | *** | 0.21320 (0.032) | *** | 0.34629 (0.069) | *** | ||

| μ | 0.199992 (0.451) | |||||||||||

| Probability | 0.61667 (0.235) | *** | ||||||||||

| R 2 | 0.79 | |||||||||||

| Log-likelihood | –5.0826 | –4.06141 | –4.03529 | –4.27569 | –3.49423 | –4.007 | ||||||

| AIC | 24.1 | 26.1 | 24.6 | 25.0 | 24.0 | |||||||

| Log-likelihood vs. OLS | 2.043 | * | 2.095 | 1.614 | 3.443 | * | 2.151 | * | ||||

| Degrees of freedom | 6 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 8 | ||||||

Number of log-likelihood versus ordinary least squares is a statistical test of the stochastic frontier model versus the basic cost function

Cost elasticities

We now consider the cost elasticities. Elasticity refers to the relative rate of change of outputs and costs. If the cost elasticity with respect to outputs is < 1, then outputs are rising at a faster rate than costs. This implies that there are economies of scale present. If the elasticity is > 1, then costs are rising at a faster rate than outputs. Here, diseconomies of scale are present.

The parameter estimates appear to be consistent with each other and with the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates in the corrected ordinary least squares (COLS) model. This is important as the COLS model does not impose the distributional assumptions that the SF models do, meaning that the parameter estimates are more reliable. Moreover, the parameter estimates appear to be in a plausible range and consistent with expectations, which we discuss below. The R2 for the COLS model reveals that the model has good explanatory power, accounting for 79% of the cost variation in the sample, even with a fairly limited number of variables.

The cost elasticity with respect to output is highly significant and consistent across all models, at around 0.85. This suggests that a 1% rise in output is associated, on average across the sample, with a 0.85% increase in costs. This, in turn, suggests that output is rising (in terms of proportion) more quickly than costs, implying that there are some economies of scale in the provision of services in older people’s wards. One outstanding issue is that no evidence was found to support variation in economies of scale across the output range: higher-order terms were not found to be significant. It was suggested that the economies of scale properties were likely to vary between community hospitals, but no evidence was found to support this.

Cost elasticity with respect to input prices is, as with output, highly significant and consistent between models, at around 0.20. This suggests that, on average, an increase in materials prices of 1% is associated with a 0.2% rise in costs, all other things remaining equal. Prices are similar for different regions across the country.

For staff mix, the parameter estimates are all positive and highly significant, reflecting that use of a higher proportion of staff on higher bands inflates costs, which is unsurprising. There is slight variation between models, where coefficient estimates are in the range 0.29–0.35. This suggests that a 1% increase in spend per staff is associated with a 0.29% to 0.35% increase in costs.

Bed occupancy has been specified with the addition of a higher-order term, which was the preferred specification in all cases. The variables have been mean-scaled to allow direct interpretation of the first-order term (they represent the cost elasticity at the sample mean). Therefore, the parameter estimates on the bed occupancy variables can be discussed directly. The coefficients suggest that a 1% increase in bed occupancy is associated with a 0.94–1.24% decrease in operating costs. That the data supported a second-order term implies that the relationship is non-linear. The results suggest that the second-order term is negative. Then, the second derivative is also negative, implying negative concavity in the relationship. This implies that the elasticity at the higher end of the range will be lower than at the lower end of the range. This suggests that the effect on costs of having higher bed occupancy is greater for community hospitals with bed occupancy levels that are at the lower end of the range.

Overall, that the parameter estimates are reasonable, the R2 value is high and that the parameter estimates are consistent between models suggest that the models are good representations of the underlying cost function.

Model testing

For functional form, as noted, we made use of a Wald test to decide between a Cobb–Douglas and translog specification. The joint test on the higher order and interaction terms rejected their inclusion. We further tested down by individually testing each of the translog terms. The only term that we found to be significant was the second-order term on bed occupancy. We therefore retained this variable in our final specification.

We used a likelihood ratio procedure (LR) to test for the presence of inefficiency. 59 This involves a test of the SF against its OLS counterpart (the SF nests the OLS model). The LR test statistic is:

which has an asymptotic distribution, which is a 50 : 50 mixture of χ02 and χ12. 46 LOLS is the log-likelihood for OLS, and LSF is the log-likelihood for the SF model at hand.

Rejection of the null, H0 : LOLS = LSF, in favour of the SF indicates that the SF model is a better fit of the data. Our interpretation of this result is the presence of inefficiency.

This procedure was applied to the full set of models estimated and the results are reported in Table 3. With the exceptions of the truncated-normal and normal-exponential SF, all null hypotheses are rejected at the 10% level (given the relatively small sample size). That is, three out of five of our models support the presence of inefficiency in the data.

Although it is not possible to statistically test between SF models directly (they are not nested), it is possible to use information criteria to identify a preferred model. In this case, using the Akaike information criterion (AIC) (see Table 3), the Rayleigh SF is preferred as its AIC value is lowest. We note, however, the similarity between SF models in respect of LR, AIC and parameter estimates, rendering this choice somewhat irrelevant. This is one reason why we use the full range of efficiency estimates in making judgements about community hospital efficiency.

Community hospital ward efficiency

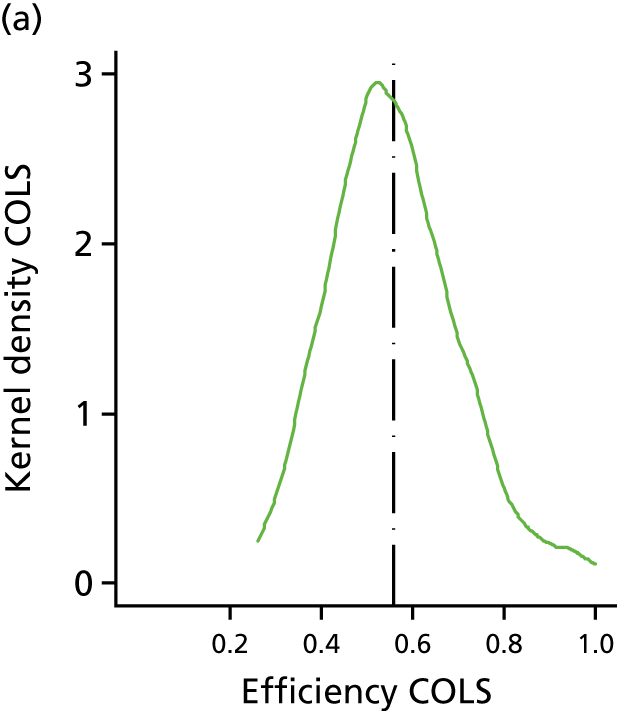

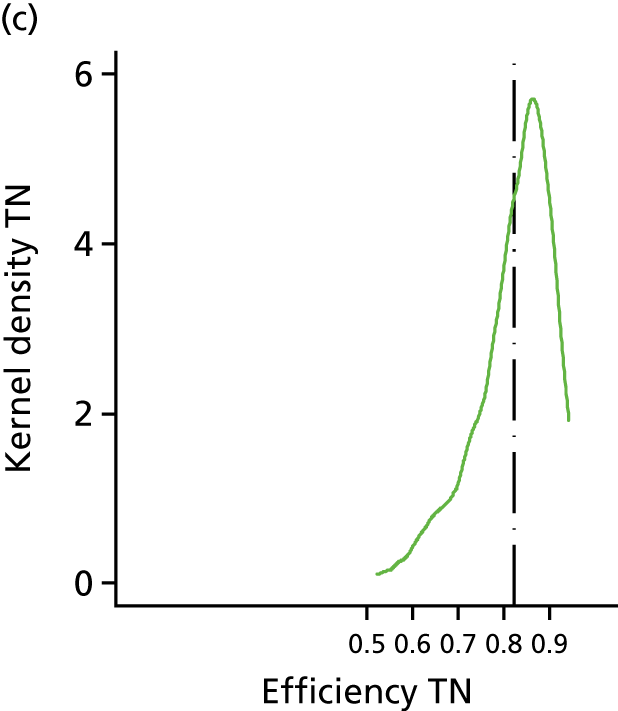

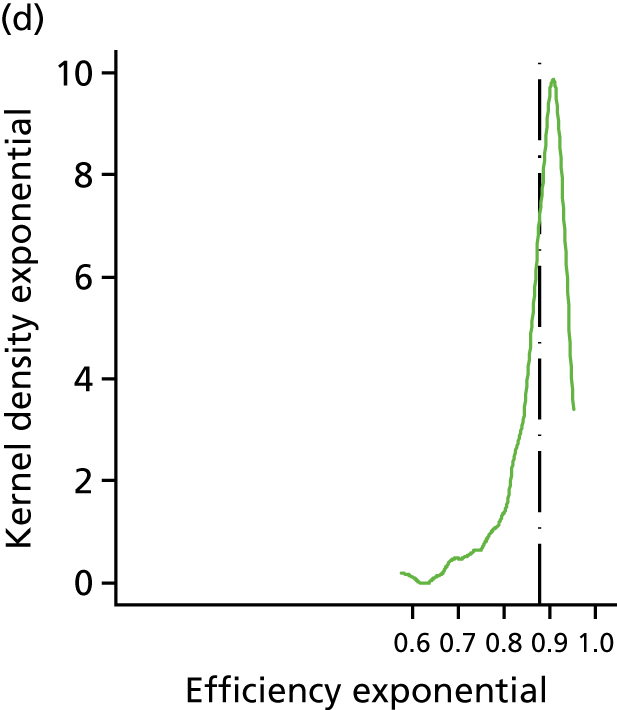

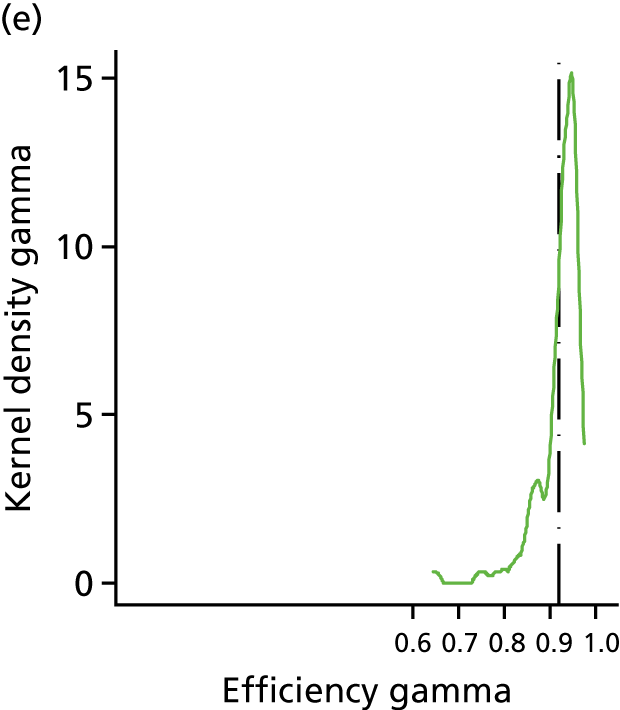

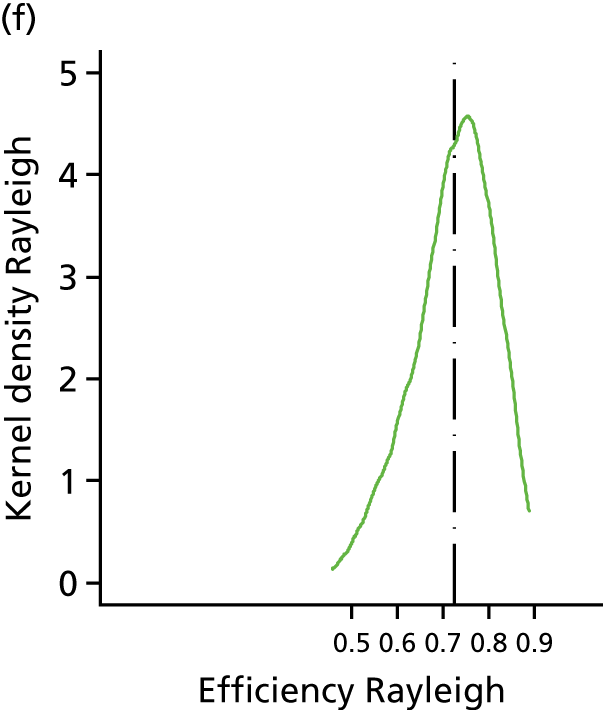

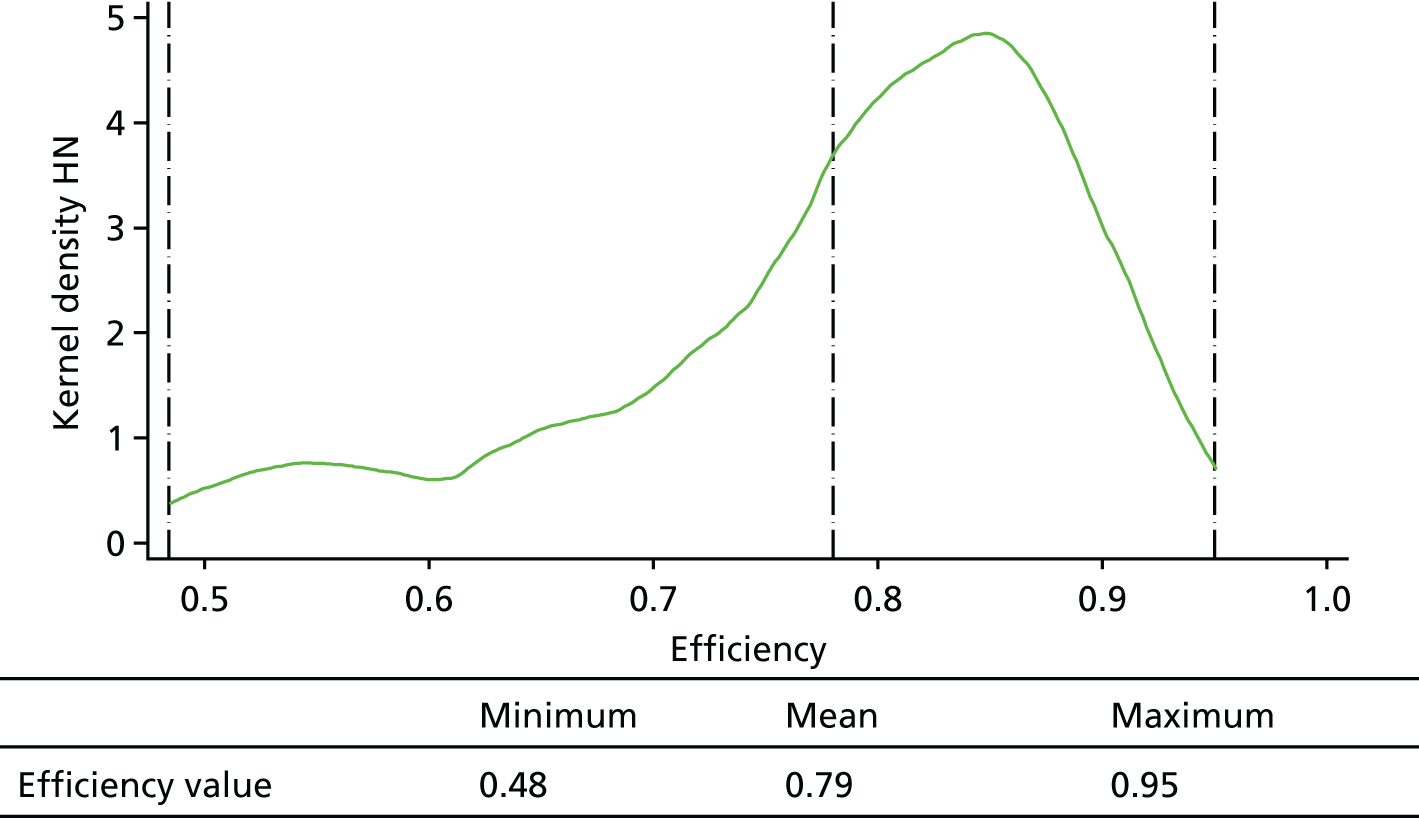

Descriptive statistics for efficiency predictions from the range of models are presented in Table 5. Corresponding kernel densities are presented in Figure 3.

| Efficiency specification | Meana | Standard deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COLS | 0.560 | 0.138 | 0.263 | 1.000 |

| Half normal | 0.808 | 0.087 | 0.514 | 0.940 |

| Truncated normal | 0.823 | 0.083 | 0.524 | 0.943 |

| Exponential | 0.878 | 0.063 | 0.575 | 0.952 |

| Gamma | 0.921 | 0.049 | 0.645 | 0.975 |

| Rayleigh | 0.724 | 0.087 | 0.458 | 0.888 |

| Mean | 0.831 | 0.543 | 0.939 |

FIGURE 3.

Kernel densities for efficiency predictions. HN, half normal; TN, truncated normal.

In Table 4 we can see that, in three out of five specifications, the SF model was preferred to OLS. As expected, the COLS average efficiency is much lower than the remaining models, owing to the failure to separate statistical noise from efficiency. Indeed, the minimum value is much lower than those of comparator models. Specifically, a value of 0.26 suggests that this community hospital ward could reduce its costs by 74% if it brought its performance in line with best practice. This result seems rather implausible, particularly as the analysis is focused on the ward rather than the whole community hospital. For these reasons, the efficiency predictions from the COLS model have been discarded.

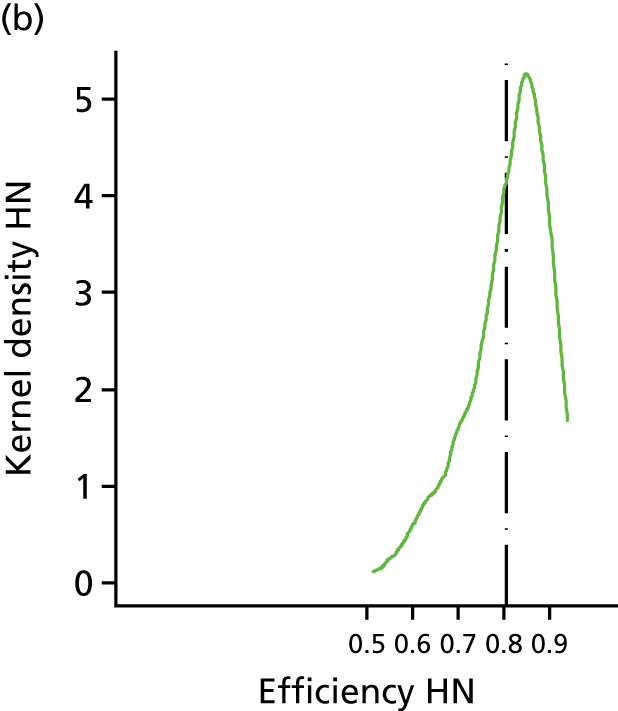

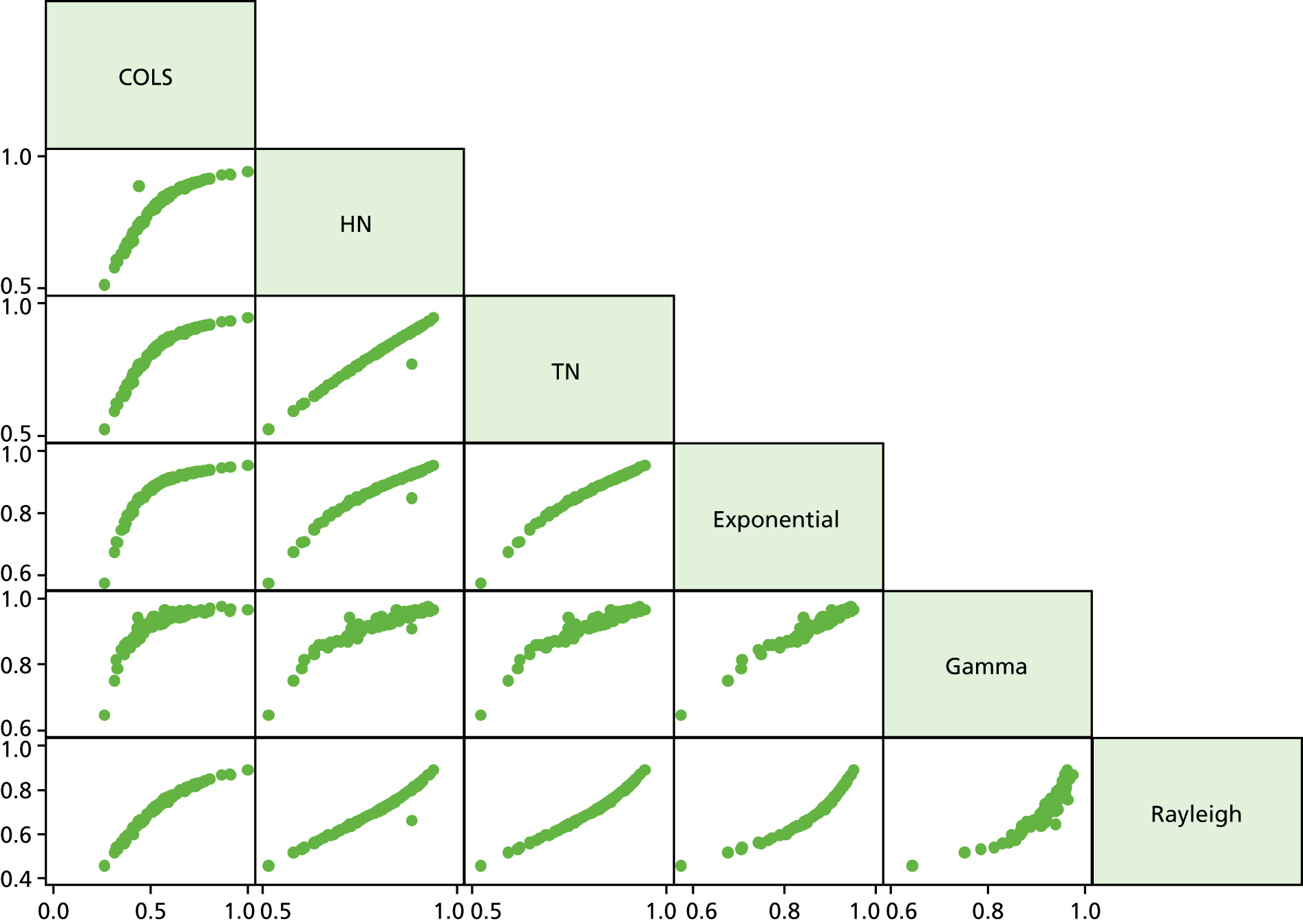

For the remaining models, the mean efficiency predictions are in the range of 0.72–0.92, with an average of 0.83. The interpretation of this number is that, on average, community hospital wards could reduce operating costs by 17% if the performance of all community hospitals was brought in line with best practice. The minimum ranged from 0.46 to 0.58 with an average of 0.54, and the maximum ranged from 0.89 to 0.98 with an average of 0.94. There was some variation in the standard deviations between model predictions, which can be seen in the kernel densities in Figure 3. Some of the models yield predictions with similar average efficiency, whereas others do not. The range in mean predictions of efficiency of 20% (0.72–0.92) is rather large. Therefore, there is a question as to how the efficiency predictions correlate between models. We examine this issue in detail in Tables 5 and 6, by looking at models’ efficiency prediction correlation in terms of absolute values and rank. Figure 4 shows the correlation matrix graphically.

| Correlation | COLS | Half normal | Truncated normal | Exponential | Gamma | Rayleigh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COLS | ||||||

| Half normal | 0.91 | |||||

| Truncated normal | 0.91 | 0.99 | ||||

| Exponential | 0.84 | 0.96 | 0.98 | |||

| Gamma | 0.77 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.97 | ||

| Rayleigh | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.89 |

FIGURE 4.

Correlation matrix absolute efficiency predictions. Note that all of the cells in the figure are actually an individual graph themselves. All are showing efficiency: both x- and y-axes. HN, half normal; TN, truncated normal.

It is unsurprising that the Rayleigh model predicts the lowest efficiency given that this distribution allows for a non-zero modal value. Although this is also true for the truncated-normal model, this does not appear to be the case. We note, however, that the mu parameter is not significant in this model, which may explain this finding. Indeed, using the LR test, the half-normal model is preferred to its truncated-normal alternative.

Tables 6 and 7 and Figure 4 show pairwise correlation between the predictions of efficiency, which is high. Farsi et al. 54 suggest that values in excess of 0.90 denote concordance between models. That almost all pairs of efficiency predictions are over 0.90 in Table 6 reflects similarity between models’ predictions. Moreover, in terms of rank correlation, as shown in Table 7, not only are correlation coefficients high, they are statistically significant across all pairs of predictions. This high correlation is visible in Figure 4. These results hold for the COLS model, which may be expected to give different results because of its composed error. We do not find any evidence of this in this instance.

| Kendall’s tau | COLS | Half normal | Truncated normal | Exponential | Gamma | Rayleigh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COLS | ||||||

| Half normal | 0.93*** | |||||

| Truncated normal | 0.95*** | 0.97*** | ||||

| Exponential | 0.96*** | 0.96*** | 0.99*** | |||

| Gamma | 0.80*** | 0.77*** | 0.80*** | 0.80*** | ||

| Rayleigh | 0.95*** | 0.97*** | 0.99*** | 0.98*** | 0.80*** |

Overall, although the average predicted efficiency spanned a range of 20%, the correlation, and in particular the ranks, between model predictions were very similar. The ranks of the predictions are particularly important because the goal of this exercise is to identify high and low performers. We turn to this issue in the discussion.

Discussion

Results from the models are, overall, encouraging from several perspectives. First, the parameter estimates are sensible and plausible. Importantly, the results appear to be consistent over a range of specifications and with the OLS base case, which does not impose the distributional assumptions that the SF models do. The base model, a limited number of variables notwithstanding, had considerable explanatory power, which is a good sign for the reliability of the estimates.

Our testing procedure indicated that our functional form was appropriate. All but one of the models detected the presence of inefficiency. Predictions of inefficiency are within a plausible range, and the models’ predictions of inefficiency are highly correlated. This finding supports previous studies in that ranks are not affected by distributional assumptions. This is key here: our cross-sectional results appear robust to the specification of efficiency distribution. This further implies that models agreed as to high and low performers and it proved possible to rank-order the cost efficiency of the included community hospital wards, but the rank-order was not declared as we received deidentified data for this research study. Nonetheless, in a situation of formal benchmarking, providing a rank order would be a simple procedure based on the models and data inputs described here. In terms of other efficiency studies, the results from our SFA analysis were comparable with those from previous studies43,44,46,51,53 of NHS general hospital efficiency (0.61–0.92; see Table 1). This suggests that the cost efficiency of community hospital wards is similar to that of general hospital wards. The COLS estimates were below those presented in studies elsewhere. Our COLS result was 0.56; results from other studies42–44,46 ranged from 0.69 to 0.74. However, the COLS models are more susceptible to outliers. Moreover, our testing procedure favoured the use of SFA, the results of which accord with prior studies. Importantly, the results here seem to accord with those of community hospitals more generally. 33

There are some methodological points for discussion. First, being a cross-sectional analysis, there are concerns over uncertainty; as we have one observation only per ward, we do not see the precision of the efficiency estimates increase per ward as the sample size increases. 44,60 We did not calculate prediction intervals around our estimates, although this may be an important avenue for future development so as to assess the extent of the uncertainty. However, that the ranks of providers are consistent across models helps to allay this issue insofar as we are able to assess the general level of efficiency and identify high and low performers.

Second, there is an issue around unobserved heterogeneity (when the variance, or standard deviation, of a variable varies across the range of the variable), particularly as the model did not support the inclusion of variables as proxies for case mix, patient severity and quality. We note that we are analysing costs at ward level, where there is likely to be much less heterogeneity than if we were modelling at the whole-hospital level. Indeed, the OLS results indicate that much of the variation has been explained. Moreover, by allowing for noise and removing it from our measure of inefficiency, it may well be that some unobserved influences are captured here. 41

We were able to utilise a unique data set on community hospitals that facilitated an econometric efficiency analysis on this part of the NHS for the first time. The data set suffered, to an extent, from missing values leading to a reduced sample with which to estimate models. We do not know the reason for the missing data; we have assumed it to be missing at random for the purposes of this analysis. We attempted an imputation exercise in preliminary work, which did not yield plausible results.

There may also be other more practical considerations. For example, although the NHSBN Community Hospital Programme included WTEs for staffing levels, there is the potential for over- or underestimation for staff who have responsibilities across sites or hospitals.

We considered that there might be selection effects of hospitals that chose deliberately not to report on the basis of their own poor performance. But to know this, they would need to have an intimate knowledge of their own and other wards’ operations in order to make a reasonable determination of this. Thus, it seems unlikely that they would be able to do this (although they might have considered themselves to be a poor performer). Moreover, if this was the case, we surely would not observe the range of efficiency estimates that we did: those that genuinely performed poorly would drop out of the sample.

The restricted sample size may be one reason why it was not possible to use a translog functional form and, thus, allow some flexibility in the cost function. In particular, no evidence was found to support variation in the cost elasticity over the output range. Of course, it may be that the cost elasticity is constant over the output range, but this view was not supported by community hospital staff. The other complication to this issue is the lack of a capital component in our cost variable. We note that, in this regard, we are not truly measuring the economies of scale, more a measure of size. This may an explanation for the finding on the cost elasticity with respect to output.

Our general view is that, given the data available, the models are well specified and are a good approximation of the underlying cost function. We thus have confidence in our predictions of inefficiency. The level of efficiency is high and the results are in keeping with those found elsewhere in the general hospital sector. Furthermore, we are able to identify high and low performers from the models, meaning that managerial effort can be targeted effectively to maximise gains across the sector.

The average predicted efficiency among community hospital wards was 0.83, implying that, on average, community hospitals could reduce operating costs in the provision of service on older people’s wards by 17% if performance was in line with best practice. If community hospitals were able to extinguish this inefficiency, there would be around £47M of available gains; total spend is around £227M. There was a range of performance, with the lowest-performing community hospital operating at around 0.55, whereas the highest-performing community hospitals were operating at around 0.94. That is, the models indicate that all community hospitals can improve efficiency on their wards.

Using a price year of 2013/14, in terms of input prices and staff mix, the results were unsurprising. Those community hospitals that faced higher input prices appeared to have higher costs; those community hospitals that employed a more experienced staff force also appeared to have higher costs. In terms of output, the results appeared to suggest that there were reasonable economies of scale at the sample mean, with a beta coefficient on output of around 0.85. This suggests that, for wards with bed size below the mean, marginal costs can be reduced by increasing the scale of the operation; for those above the mean, the scale at which the all-important cut-off point of 1 is reached is unclear. We note a slight limitation here, which is that, as suggested by staff working in community hospitals at a workshop held at the 2016 CHA conference (13–15 May, Bristol, UK)), we did not find variation in economies of scale between smaller and larger community hospitals (we did not find a statistically significant squared term on the output variable). However, the main finding was in keeping with what had been proposed: that there were economies of scale present. For bed occupancy, it appears that increasing bed occupancy rates are associated with lower costs. This may reflect that spare capacity is costly. However, this needs to be balanced against the effect on the service of high occupancy, which may be disruptive to service provision; we note that our sample mean is around 90%. Indeed, the NAO have suggested that services in which bed occupancy levels are in excess of 85% may experience disruption (in the general hospital setting). 55 This would be an interesting area for future work.

Summary

In the analyses described in this chapter we have applied econometric techniques to NHS community hospitals for the first time using a unique data set collected by NHSBN. The analyses suggest the potential for economies of scale in the provision of community hospital services for older people. As expected, higher input prices and a more experienced staff mix were associated with higher costs, and costs appeared to be lower when bed occupancy was higher.

We used a range of models to predict efficiency in our sample of community hospitals. Under differing assumptions, models’ predictions varied somewhat. Their average was 0.83, implying that, on average, community hospitals could reduce operating costs in the provision of service on older people’s wards by 17% if performance was in line with best practice. There was a range of performance, with the lowest-performing community hospital operating at around 0.55, whereas the highest performing community hospitals were operating at around 0.94. The predictions of efficiency were found to be highly correlated between models, in terms of both absolute values and ranks. Policy implications of our findings are discussed in Chapter 7.

Chapter 3 National survey of community hospitals (study 2)

Introduction

According to the CHA, there are > 500 community hospitals in the UK: 346 in England, 101 in Scotland, 44 in Wales and 13 in Northern Ireland. However, not all community hospitals have inpatient beds and the numbers fluctuate because of closures and newly commissioned facilities. 12 From this national pool of community hospitals, 158 elected to participate in the Community Hospitals Project run by the NHSBN for the financial year of 2013/14. 13 Of these 158 hospitals, 101 returned questionnaires with the required information for the health economics analyses to determine key performance features (see Chapter 2, Community hospital data set). This sample comprises approximately 25% of community hospitals across England. Community hospitals across England will have a range of (unknown) reasons to participate in the NHSBN Community Hospitals Project and this may lead to a sample bias, for example over-representation of more adventurous community hospitals with high cost efficiencies. To address this, and to obtain more generalisable estimates of cost efficiency, we designed a national survey of community hospitals.

The intention of the survey was to augment the NHSBN Community Hospitals Project data set through a greater representation of community hospitals not only in England but across the UK. This study therefore contributed to the following project objectives:

-

to measure the current relative performance (cost efficiency) of community hospital inpatient care for older people

-

to identify the characteristics of community hospital inpatient care for older people that optimise performance.

Method

The focus of the national community hospital survey was to collect data from a larger and more representative sample of community hospitals that provide rehabilitation to older people in the UK. The aim was to develop a brief postal survey instrument that focused only on the four key cost efficiency parameters identified in study 1: bed occupancy, input prices, LOS and staff mix (see Chapter 2). Questions relating to these four parameters were extracted from the existing items in the NHSBN Community Hospitals Project, to ensure comparability. The survey instrument therefore comprised a covering letter and four questions presented in four A4 pages (see Appendix 3).

Sampling frame for the national community hospitals survey

The sampling frame used for the piloting and administration of the national community hospitals survey was developed using a three-stage process.

Stage 1

The first stage entailed the receipt of a list of community hospitals in the UK from the University of Birmingham community hospitals project team. The list had been sourced by the University of Birmingham from NHS Digital (formerly known as the Health and Social Care Information Centre) and was an accurate listing of community hospitals in 2012/13. This initial list contained 404 hospitals (559 rehabilitation/older people’s wards) of which 258 were in England, 11 were in Northern Ireland, 40 were in Wales and 95 were in Scotland.

Stage 2

The second stage involved a reconciliation process to ensure that the list excluded hospitals that had been closed or lost their beds or changed ownership. This was done in conjunction with the CHA, which provided business intelligence on recent hospital closures, and supplemented through internet searches and telephone calls to 291 individual community hospitals. The final list to be used for the postal survey contained 423 community hospitals (284 in England, 10 in Northern Ireland, 91 in Scotland and 38 in Wales), and an estimated 582 rehabilitation/older people’s wards in the UK.

Stage 3

To develop a contact list for the community hospitals, we sought the name of the matron/charge nurse/ward manager at each of the 423 sites. This information was obtained through internet searches and telephone calls.

The intention of this was to personalise the covering letter that accompanied the survey to facilitate improved completion and return rates.

Survey pilots

The survey instrument was sense-checked using 10 community hospitals selected at random from the ‘CHA Research Group’ (a list of community hospitals interested in research). We requested feedback on content and format. The feedback received was incorporated into a revised version of the survey instrument and then sent to a random selection of 10 community hospitals from the study sampling frame. The community hospitals used in the piloting of the questionnaire were selected using random number generating in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The pilot sample was weighted according to the number of community hospitals in each country (five in England, one in Northern Ireland, three in Scotland and two in Wales).

The covering letter that described the rationale for the survey accompanied the questionnaire and a request for feedback on the individual questions was included also.

The pilot sites that did not respond were contacted again after 2 weeks. All information received was included in the final version of the study survey.

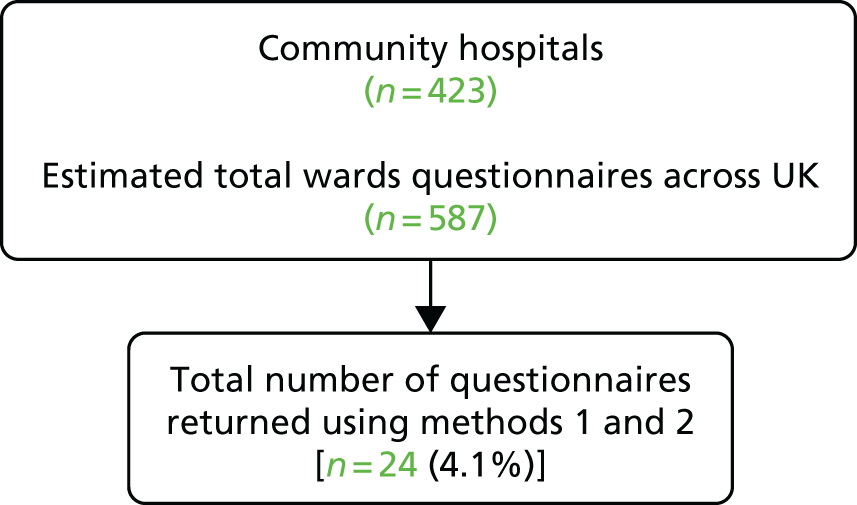

Main survey

The covering letter and survey instrument (see Appendix 3), addressed to the persons identified in stage 3, were posted to the 423 community hospitals (587 rehabilitation/older people’s wards) identified during stage 2. The covering letter and questionnaire were accompanied by a stamped addressed envelope, for the return of completed survey instrument to the study team. A reminder letter was sent to non-responding sites at 2 weeks from the initial mail-out.

Returned questionnaires were logged and the information they contained entered on a central secure database for analysis.

Results

The pilot of the questionnaire had three returns (response rate 33.3%) from a sample of 10 community hospitals.

The initial mailing of the questionnaires to 587 rehabilitation/older people’s wards (423 community hospitals) resulted in only 17 responses (2.9%). We therefore contacted, by telephone, the ward managers/matrons for a selection of the non-responding sites to establish reasons for not completing the survey. The reasons provided included:

-

‘too busy on the ward to keep up with “non-essential” admin[istration]’

-

‘survey isn’t a priority’

-

‘no incentive to complete the survey’

-

‘don’t have information readily available to enable easy completion’

-

‘financial information not immediately available’

-

‘terminology (e.g. what do we mean by indirect costs?)’

-

‘needed manager‘s approval to complete survey’

-

‘information requested on finances is confidential’.

We subsequently modified the administration method by adopting a more focused approach that included only the non-participants of the NHSBN Community Hospitals Project. In this way, we hoped to learn something about these ‘non-responders’ and to determine if they were systematically different from the responding hospitals across our four key variables.

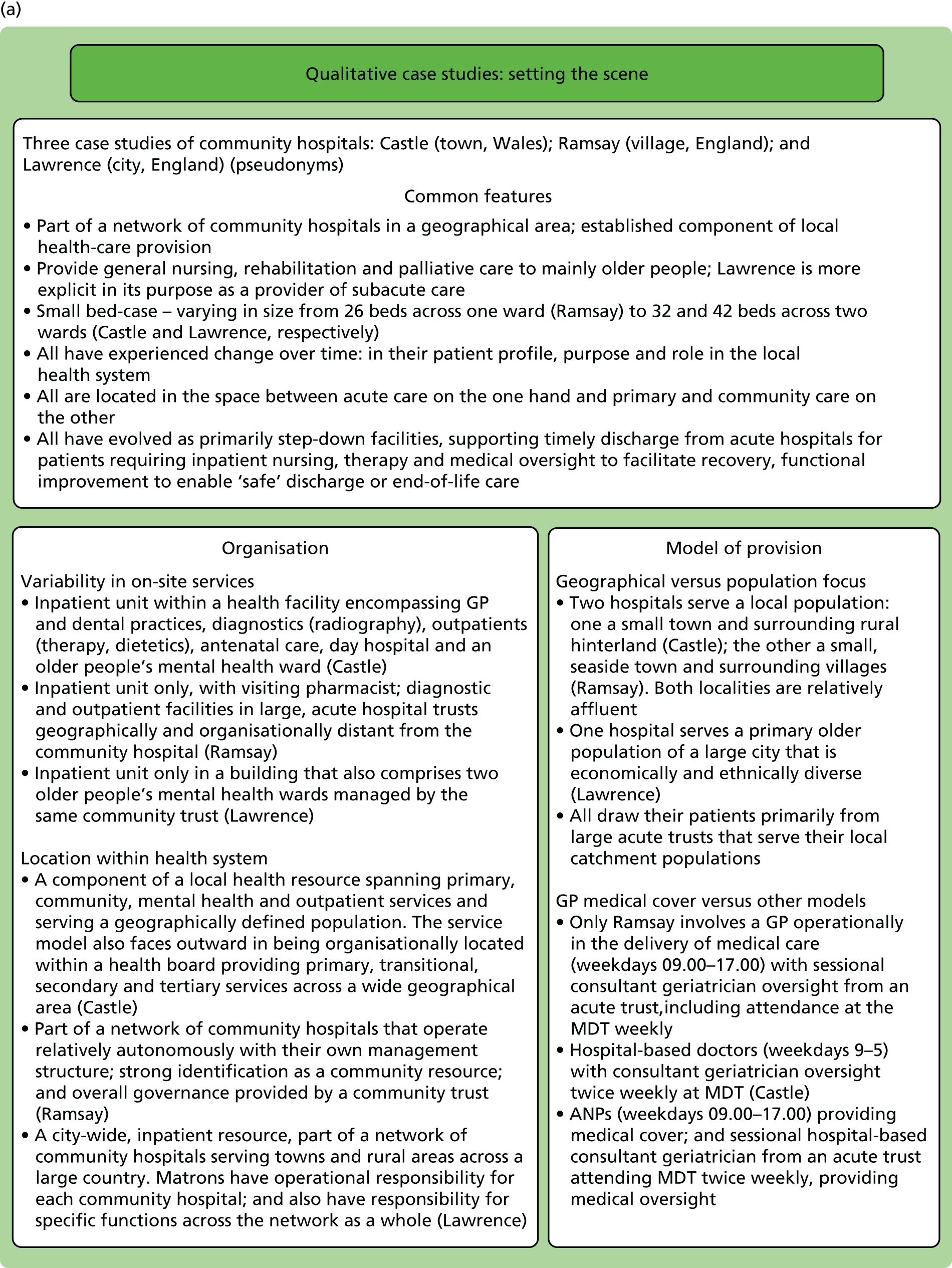

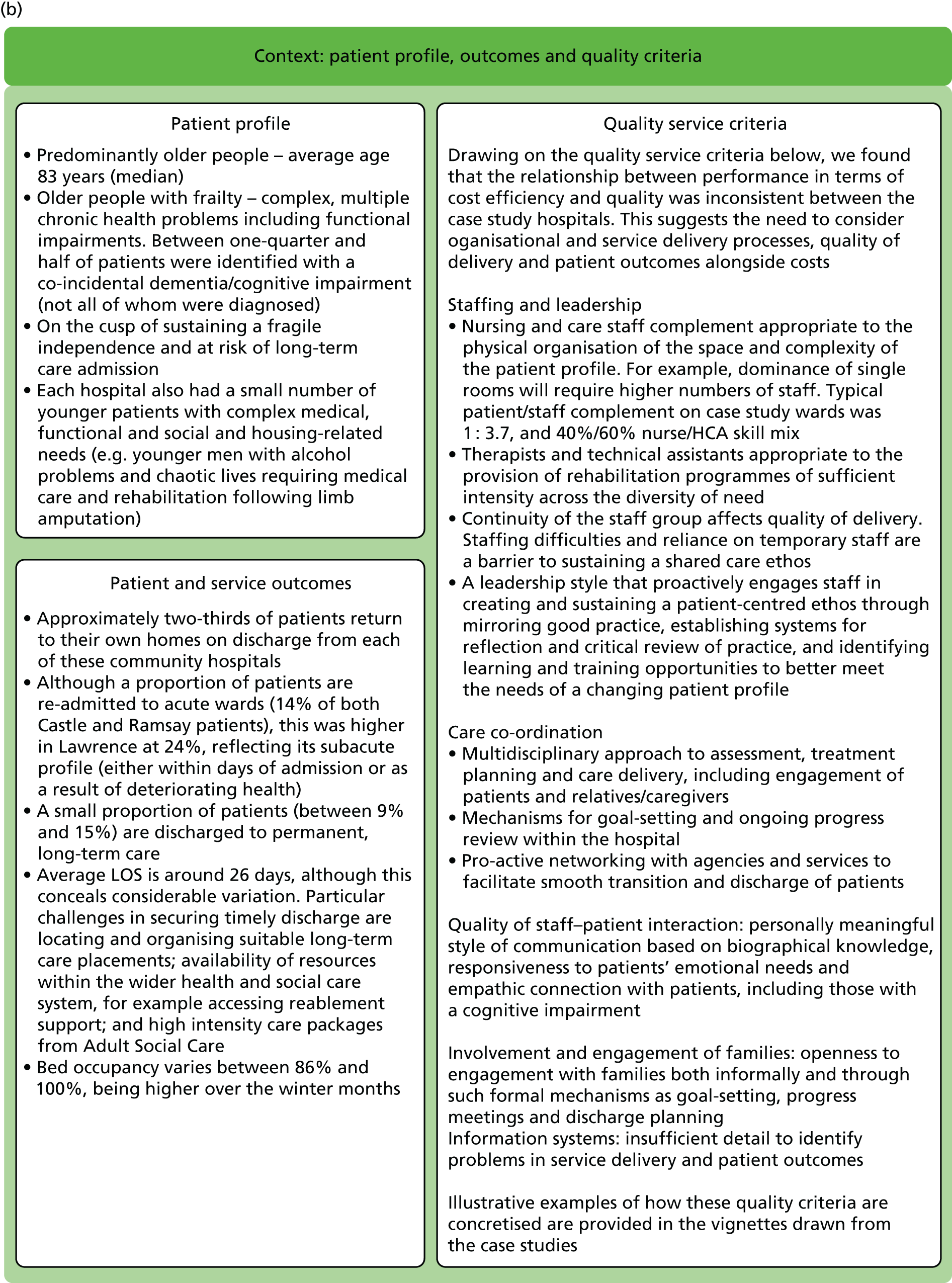

As part of this method we contacted approximately 10% of the non-responding hospitals (30 in England, 11 in Wales and 27 in Scotland). This resulted in an additional seven questionnaires from wards being returned.