Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HS&DR Evidence Synthesis Centre, contracted to provide rapid evidence syntheses on issues of relevance to the health service, and to inform future HS&DR calls for new research around identified gaps in evidence. Other reviews by the Evidence Synthesis Centres are also available in the HS&DR journal.

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/47/17. The contractual start date was in September 2017. The final report began editorial review in October 2018 and was accepted for publication in April 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Andrew Booth is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Complex Reviews Support Unit Funding Board (2015 to present), the Health Services and Delivery Research Funding Board (2018 to present) and the Systematic Reviews Programme Advisory Group (2019 to present).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Chambers et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Admissions to hospital increasingly contribute to pressure on health system resources internationally. In the UK NHS, changes to commissioning arrangements have increased the focus on reducing hospital admissions. 1 In 2016–17, there were 5.8 million emergency admissions to hospitals, costing approximately £13.7B. 2 This situation poses a significant challenge to health services delivery. Factors contributing to health service pressures include the high and rising unit costs of unplanned hospital admissions compared with those of other forms of care; increasing admissions of older people; and the disruption that emergency admissions cause to elective health care, most notably to inpatient waiting lists, and to the individuals admitted. 1

Unplanned hospital admission rates vary between geographical areas from 90 to 139 per 1000 people, and variation in emergency admission rates is even higher. 3 The existence of such variation across the NHS indicates that there is potential to reduce hospital admission rates. The way in which emergency admissions are recorded also varies between institutions and this makes it more difficult to get an accurate picture of the current situation.

Interest in reducing admissions focuses in particular on a group of ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSCs), defined as conditions for which hospital admission could be prevented with care delivered in the primary care setting. 4 These include asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, epilepsy, hypertensive disease, dementia and heart failure. 5

The terminology in this field is complex. Terms such as ‘unplanned admissions’, ‘inappropriate admissions’, ‘unnecessary admissions’, ‘preventable admissions’ and ‘avoidable admissions’ are widely used but not always in a consistent way. Unplanned admissions may be defined as admissions or re-admissions involving an overnight stay in hospital that were not previously planned or are defined as ‘elective’. 3 The term ‘avoidable admissions’ is often used to refer to admissions via emergency departments that could potentially be avoided through interventions in the urgent and emergency care system. The focus of this evidence synthesis project is on preventable admissions, defined as admissions for ACSCs and other long-term conditions that could potentially be prevented by provision of appropriate care and services in primary care and community settings. However, the two categories are not mutually exclusive and some interventions to reduce preventable admissions or re-admissions may be delivered in pre-hospital, emergency department or other hospital settings.

Over more than a decade, the NHS has explored community-, population- and policy-level interventions aimed at reducing preventable hospital admissions, but these have had little impact on admission rates. 1 In 2012, a series of systematic reviews by Purdy et al. 3 summarised the evidence regarding interventions that had exhibited success in reducing unplanned hospital admissions. In terms of services to reduce admissions, Purdy et al. 3 found evidence of effectiveness for education, self-management, exercise and rehabilitation, and for telehealth in certain patient populations, mainly respiratory and cardiovascular. 3 Case management, community interventions and specialist clinics showed effectiveness for heart failure only. However, case management and specialist clinics overall, care pathways and guidelines, medication reviews, vaccine programmes and hospital at home did not appear to reduce preventable admissions. The reviews found insufficient evidence on the role of service combinations or co-ordinated system-wide care services, emergency department interventions, continuity of care, home visits or pay-by-performance schemes. 3

Thus, although the pattern of findings was mixed, Purdy et al. ’s3 systematic reviews revealed a consistent picture of reduction across different interventions targeting two particular types of condition, namely cardiovascular and respiratory conditions, with some of the interventions being disease-specific. By way of comparison, one of the quality measures for accountable care organisations under the US Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act6 is to reduce preventable emergency admissions for three chronic medical conditions: COPD, congestive heart failure and asthma. 7 For this interpretative review, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme asked us to consider these as ‘proven interventions’ and to seek to provide an in-depth understanding of how interventions that have been shown to reduce admissions for cardiovascular and respiratory conditions work in practice. This includes both (1) how the interventions work to reduce unplanned admissions and (2) how they seek to ensure that admissions that are avoided are, in fact, unnecessary. The intention is also to identify some potentially transferable lessons that might determine how to achieve comparable success in other conditions or, at least, help in understanding factors that potentially explain when comparable success is not realised outside these two focal conditions.

The aim of this research was to fill a gap in the evidence base around successful implementation of admission reduction programmes by focusing on understanding what works for whom, why it works and in what contexts it works. 8 We first investigated interventions that are currently used in the NHS to manage cardiovascular or respiratory conditions using a systematic mapping approach. 9 We then used a realist approach8 to identify and explain factors that contribute to successful implementation of interventions to reduce preventable hospital admissions, looking at responses to interventions that involve different mechanisms and different contexts. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example of a realist-based approach exploring these aspects of implementation.

Chapter 2 Methods

Overall review strategy

The overall review comprised two main phases:

-

systematic mapping of cardiorespiratory intervention studies for reducing preventable admissions

-

realist review of implementation evidence.

The overall review commenced with the decision, agreed with the NIHR HSDR programme team, to focus exploration on those conditions revealed by the 2010 Purdy review1 to demonstrate effective interventions to prevent avoidable hospital admissions. A positive effect or positive indication was consistently found for cardiorespiratory conditions and this was a focus for systematic mapping of studies.

Based on these included studies, four complementary activities were conducted (Table 1):

-

generation of if–then–leading to statements from a conceptually rich set of empirical studies and theoretical papers and selection of candidate programme theories

-

analysis of implementation studies to identify intervention components using an abbreviated version of the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist

-

analysis of implementation studies using the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARiHS) framework

-

comparison of PARiHS templates with shortlisted programme theories.

| Review component | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Evidence base for effectiveness | 2. Intervention map | 3. Programme theory | 4. Empirical studies | 5. PARiHS analysis | 6. Realist analysis | 7. Integration of review outputs | |

| Review activity | Selection from Purdy et al.3 review | Systematic mapping of studies | Generation of if–then–leading to selection of candidate theories |

Identification of implementation studies for mapped interventions Use of TIDieR-Lite templates |

Analysis of implementation studies for mapped interventions | Analysis of PARiHS templates against shortlisted programme theories | Analysis of map, interventions, implementations and programme theories |

| Review deliverable | Search strategy for map | Map of interventions by study characteristics | Shortlist of intervention-independent programme theories | Sets of implementation studies for each intervention | PARiHS templates for each intervention | Identification of mechanisms linked to interventions | Final report |

| Location in report | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 2, Testing and refining the programme theory | Chapter 4, Number and type of UK studies sections | Chapter 4, Contextual factors sections | Chapter 4, Description of putative mechanisms sections, and Chapter 5 | Chapters 5 and 6 |

Finally, Chapters 5 and 6 provide the opportunity to integrate the diffuse review outputs.

The remainder of this chapter provides fuller details of the mapping and realist reviews.

Mapping review

The objective of the mapping review was to identify and map the literature on interventions that could be used to reduce preventable hospital admissions in the NHS, with a particular focus on cardiovascular and respiratory conditions. The included studies were to be used as a sampling frame, allowing the realist synthesis to examine the underpinning mechanisms that explain how the interventions work in practice, for whom and in what circumstances.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included in the mapping review if they met the following criteria:

-

Published in or since 2010 in the English language.

-

Conducted in a relevant country (UK, USA, Canada, Australia or New Zealand). Canada, Australia and New Zealand were included as the countries with health systems most similar to that in the UK, and the USA was included because of the high volume of good-quality health research conducted there. We took a pragmatic decision to exclude as far as possible studies from other European countries because of differences in health service organisation. We recognise that this could involve excluding potentially relevant studies from some countries, but consider that the impact on the structure of the evidence map was likely to be relatively minor.

-

Recruited adults with a cardiovascular or respiratory condition (not cancer).

-

Evaluated or described an intervention that could reduce preventable hospital admissions or re-admissions. Based on the work of Purdy et al. ,3 the following interventions of interest were specified in advance: case management, specialist clinics, community interventions (not fitting into any other relevant category), patient education, self-management, pulmonary rehabilitation, cardiac rehabilitation and telehealth. Programmes involving combinations of these interventions were also eligible for inclusion.

-

Reported admissions/re-admissions or prevented admissions as an outcome and/or reported on implementation of the intervention (e.g. barriers and facilitators, qualitative studies of staff or patient views/experiences) in the context of reducing admissions.

The main study designs of interest were experimental studies (e.g. randomised and non-randomised trials), controlled and uncontrolled observational studies, qualitative studies and systematic reviews. We attempted to exclude editorials, letters, study protocols, papers discussing study rationale and design and other papers not reporting substantive data. Given that inclusion was based on titles and abstracts, published conference abstracts were eligible for inclusion.

Literature search

Formal bibliographic searches of MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Health Management Information Consortium, EMBASE, Web of Science and The Cochrane Library were conducted in September 2017 and October 2017. The search was developed from initial scoping searches and previous systematic reviews, with search terms adapted for each information source. The search comprised terms for ACSCs combined with intervention terms and terms around admissions, implementation and research dissemination. The MEDLINE search is documented in Appendix 1. The ACSCs included the following: angina, hypertension, COPD and asthma. Intervention terms were derived from The King’s Fund report Avoiding Hospital Admissions: What Does the Research Evidence Say?. 1 The search was limited to studies published from 2010, when the Purdy report1 was published, to July 2018 and research published in the English language. Focusing on this narrower time frame is further justified by the specific focus of this review on implementation; an implementation context is a continually mutable backdrop within which to evaluate the introduction of a complex intervention.

Recent initiatives and, specifically, those that have been evaluated within a UK context were prioritised. Nevertheless, the review methodology preserved the potential to engage with the wider literature through coverage of reviews that extend the time and geographical limits beyond the formal sampling frame. The UK focus was strengthened by examination of the catalogues of the Health Services Management Centre at the University of Birmingham, The King’s Fund Library and Health Management Online (NHS Scotland).

Screening of search results and coding of included records

Bibliographic records identified by the literature research were imported into EPPI-Reviewer 4 (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre, University of London, London, UK) for screening and data extraction. Records were screened for inclusion or exclusion by one reviewer, with a 10% sample being screened by two reviewers to check for consistency. Screening of search results was based on information in database records (title or title and abstract) only; we did not systematically screen full texts.

Data extraction (coding) was carried out by one reviewer in EPPI-Reviewer 4 using a mixture of tick-box selection and manual data entry. Table 2 summarises the extracted data items. We did not extract study findings or authors’ conclusions because the purpose of the review was to map interventions and not to evaluate their effectiveness.

| Data to code | Options | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Include or exclude | Include; exclude; query |

Initial code set Include if: |

| Included studies only | ||

| Study identifier | Author, year, EndNote (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) number | |

| Study design | Experimental; controlled observational; uncontrolled observational; qualitative; literature review; other; unclear | Broad categories for simplicity |

| Population/condition | Coronary heart disease; heart failure; hypertension; asthma; COPD; multiple; other cardiovascular; other respiratory | Coronary heart disease includes angina and post MI |

| Sample size | Number of participants | |

| Intervention | Case management; specialist clinics; community interventions; patient education; self-management; pulmonary rehabilitation; cardiac rehabilitation; telehealth; multiple; other; unclear |

Community interventions = those that do not fit into other relevant categories (Purdy et al. 3) This is based on Purdy et al. ’s3 findings of interventions with evidence of positive effect; can be added to if necessary |

| Comparator | Alternative intervention; usual care; baseline; not applicable; unclear/not reported | |

| Country | UK; USA; Canada; Australia; New Zealand; multiple countries; not applicable; unclear/not reported | |

| Access route | General practitioner; other general practice staff; emergency department; paramedic; telephone advice; outpatient appointment; hospital discharge; community service; patient-initiated; other; unclear/not reported | Who acts as ‘gatekeeper’ for the intervention? |

| Data type | Quantitative; qualitative; mixed | |

| Outcomes assessed | Admissions/re-admissions;3 prevented admissions;1 patient reported; staff reported; costs/cost-effectiveness; workforce outcomes; health system outcomes; qualitative outcomes; other | Statistical data;3 audit/judgement on specific cases1 |

| Length/period of study | Length of study | Years/months |

Mapping review synthesis

We produced a descriptive summary of key characteristics of the body of included studies as reported in Chapter 3. Summary tables were developed using the search, cross-tabulation and reporting functions of EPPI-Reviewer 4.

Realist synthesis

The mapping review revealed the coverage by journal literature of each of the main intervention types identified by Purdy et al. ,1,3 including the existence of systematic review evidence and UK-based quantitative and qualitative studies. This helped to inform the sampling frame for the subsequent realist synthesis. In contrast to a conventional systematic review, a realist synthesis is not required to examine a comprehensive and exhaustive sample from the literature; instead, it explores a judiciously and purposively selected sample favouring richer, more informative data.

The practical focus of this review required exclusion of evidence with limited transferability to the NHS, such as avoidable admissions in low- and middle-income countries. Through systematic review-level evidence, we accessed studies from four countries in addition to the UK, namely the USA, Australia, Canada and New Zealand. We also engaged with the wider evidence base (using supplementary searches) through systematic reviews, opinion pieces and direct reference to individual study reports, particularly when authors themselves established a connection to the UK context. Explicit inclusion criteria were implemented in our sampling frame to ensure consistent study selection by the review team across the nine intervention types.

Data extraction

In contrast to the mapping review, data extraction for the realist synthesis was based on the full text of each item. Purpose-designed data extraction forms drew on appropriate frameworks as structures by which to interrogate the theories and the empirical evidence. We used an experimental methodological development, previously tried in another NIHR HSDR realist synthesis,10,11 which combined use of realist synthesis methods with elements of best-fit framework synthesis. Best-fit framework synthesis involves identification of an appropriate ‘good-enough’ framework to operate as both a vehicle for data extraction and, subsequently, an analytical lens for examination of extracted data. 12 Best-fit framework synthesis is believed to expedite the data extraction process,13 with a majority of the data being handled deductively using the framework before a subsequent inductive phase to code data not explained by the categories derived from the original framework. 14

The focus of this realist synthesis on implementation encouraged the review team to focus on frameworks or models specifically derived in an implementation, knowledge translation or evidence-based health-care context. Instead of embarking on an extensive parallel process of framework identification, which was typically the case in previous uses of best-fit framework synthesis,15 the team used the sourcebook, Models and Frameworks for Implementing Evidence-Based Practice: Linking Evidence to Action,16 and rapidly reviewed the pictorial models and accompanying textual descriptions for ‘fit’ to the purpose and context of the review. A short list of candidate models was subsequently narrowed down to the PARiHS framework. Within the PARiHS framework, successful implementation is represented as a function of the nature and type of evidence (to be examined from the mapping review), the qualities of the context in which the evidence is being introduced and the way the process is facilitated17 (to be extracted from included UK studies, both quantitative and qualitative).

Previous experience of realist synthesis within complex service delivery contexts had also revealed the value of using the TIDieR as a formal framework for identifying and describing the components of included interventions. 18 We therefore decided to use a version of this template, abbreviated in recognition of both the time constraints and the generic level at which interventions have been characterised, as a structure for describing the nine intervention types. The 12-item TIDieR checklist [brief name, why, what (materials), what (procedure), who provided, how, where, when and how much, tailoring, modifications, how well (planned), how well (actual)] was therefore abbreviated in the form of the five-item ‘TIDieR-Lite’ (by whom, what, where, to what intensity, how often). Importantly, this was to be used to summarise the generic characteristics of each intervention type across multiple intervention reports, although significant areas of variation across each generic type were prompted for identification by the framework.

Finally, data relating to programme theory were extracted using an ‘if–then–leading to’ realist logic structure, pioneered by other research teams and used in previous reviews by team members. This enabled the generation of multiple programme theory statements [ultimately five in number: programme theories (PTs) 1–5; see Programme theory development] to be used to examine data from included empirical studies and to communicate programme logic to stakeholders in the form of narrative scenarios.

In summary, data extraction comprised use of:

-

an implementation framework, PARiHS, as a structure for examining how interventions are delivered

-

an intervention template, TIDieR, as a format for describing intervention components

-

a realist logic template, if–then–leading to, to elicit programme theory on how interventions might work.

Initial logic model

The team deliberated regarding whether or not logic models would be required for each intervention type, ultimately concluding that the focus on mechanisms, as opposed to outcomes, would facilitate a single inclusive logic model that could explain multiple points within the overall complex adaptive system. 19 Using barriers and facilitators identified from a rich subset of the literature, supplemented by input from team members and from the patient and public involvement (PPI) group (see Patient and public involvement), the team identified three systemic ‘problem points’:

-

Patient uncertainty about appropriate admission. This would have a direct effect on patient-centred interventions such as self-management, but also a secondary effect on health-care professional (HCP)-mediated interventions as patients attempted to resolve their initial uncertainty.

-

HCP uncertainty about appropriate admission. This revolves around the HCP’s gatekeeper role and may relate to the severity of patient symptoms, the risk-averse culture within which HCPs might operate and awareness of alternative service provision.

-

Structural barriers to appropriate admission. Patient or HCP current or previous experience of health service delivery may have an impact on the decision pathway. For example, if patients or HCPs have previously experienced delays in arrival of ambulance transport, they may factor in such delays by initiating call-out earlier than the patient’s symptoms might otherwise justify.

Based on these three potential problem points, the teams mapped the different interventions to those points that each sought to address. For example, telehealthcare may offer a ‘feedback’ loop to a patient on whether or not their current physical signs or symptoms should trigger admission and/or can offer more data to the HCPs to help them make a more informed and ‘real-time’ referral judgement. This map of barriers and the mechanisms by which interventions might address them became the initial logic model and contributed to the development of programme theories focusing on how inappropriate admissions may be facilitated or prevented at the three problem points listed above.

Programme theory development

Five programme theory components were identified following a review of published barriers, consultation with the PPI group and analysis of a rich subset of intervention studies for preventable admissions (Box 1). These are expressed in the form of hypotheses to be tested against the empirical data.

People with chronic conditions are frequently admitted to hospital when hospital is not the optimal destination for them. They may have symptoms that could be self-managed or anxieties that could be addressed by patient education or information.

Programme theory 2People with chronic conditions lack knowledge about alternative health provision and therefore draw disproportionately on well-signposted channels, such as their GP or the emergency department. Alternatively, patients perceive that presentation to an emergency department holds relative advantage (e.g. quality, ease of access, response) over GP-based or other primary or community care services. Patients pressure HCPs to admit them to hospital.

Programme theory 3HCPs lack confidence in their own diagnoses or may lack confidence in, or knowledge of, alternative sources of health-care provision and so may refer people with chronic conditions or admit them directly to hospital. HCPs feel under pressure to admit people with chronic conditions directly to hospital.

Programme theory 4People with chronic conditions use health services inappropriately, delaying their presentation to HCPs or hospital because of perceptions of the service either anticipated or based on the past experience of either themselves or others.

Programme theory 5General practitioners and other HCPs are influenced by the wider context of the health-care system, and the availability or otherwise of support and incentives may influence their adoption of interventions and pathways designed to avoid preventable referrals and admissions to hospital.

GP, general practitioner.

Synthesis

Following identification of the initial programme theories, the review team extracted data into evidence tables. The resultant hypotheses operationalised synthesised statements around which we developed an explanatory narrative referenced to the underpinning evidence base. Additional searches for mid-range theories (conceptual models or frameworks relevant to one or several of the interventions covered by the review) and overarching theories (theories relevant to the phenomenon of inappropriate admissions as a whole) were conducted using Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). The aim of searching for these higher-level theories was to elucidate how previous researchers have understood factors underlying inappropriate admissions and their prevention at a relatively high level of abstraction. Our EPPI-Reviewer map, reference management database and accompanying data extraction spreadsheets collectively offer a comprehensive evidence base relevant to interventions to reduce unplanned hospital admissions.

Testing and refining the programme theories

Searches for programme theories relevant to avoidable admissions were conducted using Publish or Perish 6™ software. 20 This desk-based tool offers an auditable interface to searching of the Google Scholar resource as well as allowing construction of semicomplex search strategies.

The first set of Google Scholar searches combined the term ‘ambulatory sensitive’ with terms for preventable admissions and different programme theory terms. The second set of searches combined the term ‘preventable admissions’ with ‘hospitalisation or hospitalization’ and different programme theory terms. Full details of the search terms used for each individual search and the number of results retrieved are provided in Appendix 2.

Papers retrieved from the programme theory searches were reviewed by one reviewer with experience of harvesting programme theories. Prioritising conceptually and contextually rich papers, the reviewer drafted preliminary if–then–leading to statements21 [known technically as context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations] for discussion with the review team. The aim of this process was not to generate an exhaustive list of possible explanations but to generate a selection of theories of change operating variously at patient/carer, health provider and health system levels. When several programme theory components seemed to be interrelated, these were combined into a more overarching explanation.

From the papers retrieved from the programme theories searches and from the papers included in the mapping review, we developed five programme theories to guide the realist review. Details of the generic programme theories are given in Box 1. Details of the programme theories expressed as if–then–leading to statements and the probable types of evidence identified by the team by which programme theories might be supported or negated are provided in Table 3. In Chapter 4, the programme theories are considered in the specific context of each of the included interventions.

| Programme theory | Types of evidence |

|---|---|

| PT1: IF patients are equipped with knowledge/information for self-management, including seeking help as appropriate, THEN they will access hospital/health services as required LEADING TO appropriate utilisation of health resources and a reduction in unplanned admissions |

|

| PT2: IF patients feel confident and satisfied with non-secondary-care health provision THEN they will not consider it necessary to access/request secondary care services LEADING TO appropriate utilisation of health resources and a reduction in unplanned admissions |

|

| PT3: IF GPs/primary care staff feel confident in their own ability to diagnose and/or refer patients appropriately and have confidence in and knowledge of services available within primary and community care THEN they will not refer patients to hospital LEADING TO an increase in use of self-management and non-secondary-care health service provision and a reduction in unplanned admissions |

|

| PT4: IF patients delay/are delayed in accessing health services THEN patients may experience exacerbation of symptoms LEADING TO a higher level of clinical input or resource use when they finally access health care and an increase in unplanned admissions |

|

| PT5: IF clinicians and other health service staff perceive that the wider health system provides appropriate support and incentives THEN they will feel confident in implementing (and evaluating) interventions that involve changes to practice and professional roles LEADING TO appropriate utilisation of health resources and a reduction in unplanned admissions |

|

The initial programme theories were tested from the theoretical literature, empirical studies and insights from the PPI group. Programme theories were examined against the nine individual intervention types and collectively as a set. A subsequent activity involved seeking to map the elements of the programme theory to potential mid-range theories that might add greater transferability to review findings. 22 Mid-range theories could be identified serendipitously, when reviewing the empirical evidence, but more typically were identified from Google Scholar searches that combined the intervention (e.g. ‘case management’) with terms relating to models or theories (i.e. ‘theor*’ or ‘model*’ or ‘framework*’ or ‘concept*’). 23

Patient and public involvement

Members of the pre-existing Sheffield HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre Public Involvement Advisory Group provided input to the study at various stages, including exploration of the study parameters, discussion regarding the meaning and interpretation of the study findings, drafting of the Plain English summary and help with disseminating the findings and maximising the impact of the research. The group comprised nine members, mainly from the Yorkshire and Humber region, with two members from other regions of England. Members were recruited by contacting other existing PPI groups and via a PPI website.

The project was discussed at three meetings of the advisory group. At the first meeting, the researchers introduced the topic and also provided a brief introduction to the concept of a realist review. We then discussed pathways that could potentially lead from a patient perceiving a problem to an avoidable admission or avoidance of admission. Advisory group members gave their perspective on factors that could influence patient behaviour at various stages of the pathway (e.g. ‘Patients lack confidence in their ability to self-monitor and self-manage their condition’ and ‘Patients perceive that they need to be treated in hospital’). This discussion was helpful to the research team in developing programme theories for analysis in the realist synthesis.

Before the second meeting, the researchers ‘translated’ aspects of the programme theories into ‘scenarios’ (see Appendix 3) and discussed these with the advisory group. Group members provided input on both the credibility of the scenarios and the appropriateness of the language used to describe them. Some scenarios were significantly modified as a result and this was reflected in a change in the researchers’ understanding of the corresponding programme theory.

The third advisory group meeting coincided with near-completion of the draft final report. The main findings were presented and the advisory group members discussed the draft plain English summary and channels for disseminating the research and achieving wider impact.

Changes to the protocol

Time and resource constraints meant that we were not able to engage with HCP stakeholders to the extent outlined in the protocol. Because we did not invite HCPs to participate in interviews or focus groups, we did not need to obtain ethics approval as envisaged in the protocol.

Chapter 3 Results of mapping review

Screening of literature search results

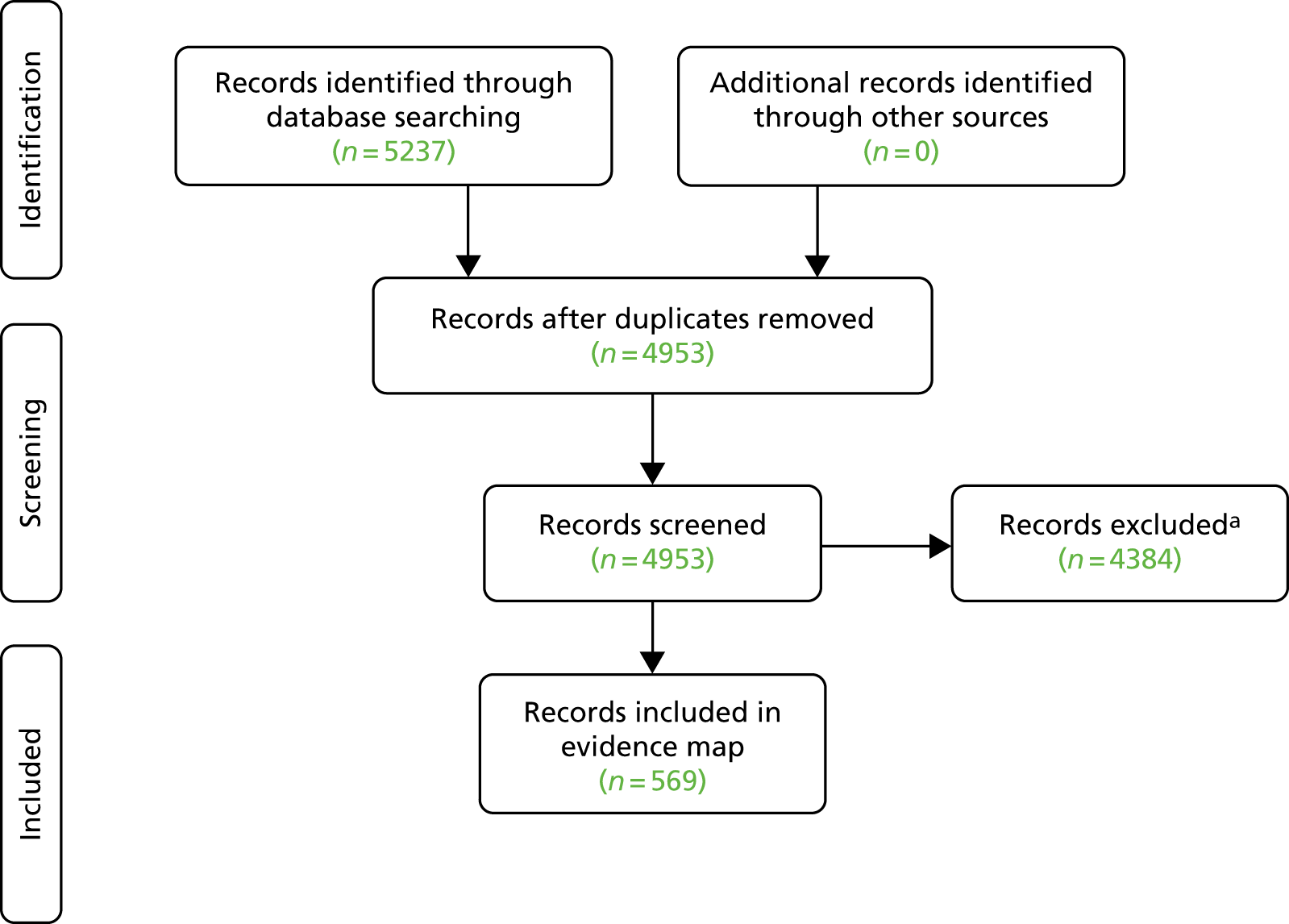

Figure 1 [adapted from the standard Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram] summarises the results of the screening process. A total of 569 publications were judged to meet the inclusion criteria (based on titles and abstracts) and were coded in EPPI-Reviewer 4. The total numbers in the following sections do not always add up 569 because of studies being coded for more than one item within a category or because studies could not be fully coded with the information available in the abstract.

FIGURE 1.

Flow of studies through the mapping review. a, Irrelevant, not country or date range of interest or additional duplicates.

Populations

The most commonly studied conditions were heart failure (238 studies) and COPD (212 studies). Other conditions with significant numbers of studies were asthma (65 studies), hypertension (44 studies) and coronary heart disease (CHD) (25 studies). Thirty-two studies were coded as covering multiple (generally three or more) conditions. Some of these studies included patients with chronic conditions outside the main focus of the mapping review (e.g. diabetes).

Interventions

The largest groups of interventions were those coded as self-management (122 studies) and telehealth (119 studies). Patient education (72 studies) was frequently linked with self-management. Pulmonary rehabilitation (53 studies) was more commonly studied than cardiac rehabilitation (24 studies). A large group of studies (87 studies) evaluated multiple interventions, notably those characterised as transitional care programmes. There were 50 studies of community-based interventions and 37 studies of case management.

Nature/amount of evidence

The numbers of included studies coded by intervention for each condition are listed in Table 4. In general, the frequency of included studies reflected the findings of Purdy et al. 3 Interventions and populations for which Purdy et al. 3 found evidence of positive effects were generally well represented in the map, as illustrated in Table 4. Examples were patient education and telehealth for heart failure (46 and 66 studies, respectively), self-management of asthma (37 studies) and pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD (59 studies). Interventions considered to have evidence of no effect (as distinct from no evidence of effect) were less well represented: we included 15 studies of case management for COPD but only three studies of community interventions for CHD and two studies of specialist asthma clinics.

| Condition | Number of studies per intervention | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case management | Specialist clinics | Community interventions | Patient education | Self-management | Cardiac rehabilitation | Pulmonary rehabilitation | Telehealth | Multiple | Other | Unclear | |

| CHD | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 12 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Heart failure | 18 | 10 | 16 | 46 | 44 | 12 | 2 | 66 | 37 | 14 | 0 |

| Hypertension | 2 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Asthma | 2 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 37 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 0 |

| COPD | 15 | 1 | 24 | 6 | 27 | 2 | 59 | 57 | 36 | 17 | 1 |

| Multiple | 7 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Other cardiovascular | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Other respiratory | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Evidence by study design

Interventions not rated by Purdy et al. 3 but covered by substantial numbers of studies (≥ 20) in the mapping review included self-management for heart failure (44 studies, although many of these also included patient education) and community interventions (24 studies) and telehealth (57 studies) for COPD.

Literature reviews (including systematic reviews, narrative reviews and some conceptual or discussion papers based on literature reviews) were the most common type of literature included in the mapping review (156 studies), followed by experimental studies [randomised and non-randomised controlled trials (117) and uncontrolled observational studies (115)]. We also identified 47 controlled observational and 61 qualitative studies. As this was a mapping review, the quality of individual studies was not assessed. In the following sections, we briefly describe the composition of the main groups of included studies.

Key systematic reviews included in the mapping review are listed in Table 5. Up-to-date (2016 or 2017) systematic reviews were found for most key combinations of condition and intervention. Several were Cochrane reviews or overviews of reviews, which use standard methods and are likely to be of high quality. Although some reviews focused purely on effectiveness of interventions, other reviews attempted to assess that features were most essential to intervention effectiveness or to identify barriers to and facilitators of implementation. This latter group of reviews was most useful for the realist synthesis.

| Condition | Key reviews |

|---|---|

| CHD |

Cardiac rehabilitation: Anderson et al. (2016),24 Anderson and Taylor (2014),25 Huang et al. (2015)26 and Karmali et al. (2014)27 Telehealth: Huang et al. (2015)26 |

| Heart failure |

Case management: Huntley et al. (2016)28 and Van Spall et al. (2017)29 Specialist clinics: O’Neill et al. (2017)30 and Thomas et al. (2013)31 Community interventions: Coffey et al. (2017),32 Health Quality Ontario (2017)33 and Van Spall et al. (2017)29 Patient education: Casimir et al. (2014)34 and Zarea Gavgani et al. (2015)35 Telehealth: Clarke et al. (2011),36 Gorst et al. (2014),37 Graves et al. (2013),38 Inglis et al. (2015),39 Kitsiou et al. (2015),40 Klersy et al. (2016),41 Kotb et al. (2015),42 Lin et al. (2017),43 Pandor et al. (2013)44 and Vassilev et al. (2015)45 |

| Hypertension | Telehealth: Harrison and Wild (2017)46 |

| Asthma | Self-management: Denford et al. (2014),47 Marcano Belisario et al. (2013),48 Morrison et al. (2014),49 Pinnock et al. (2015),50 Pinnock et al. (2017),51 Ring et al. (2011)52 and Ring et al. (2012)53 |

| COPD |

Case management: Martínez-González et al. (2014)54 Self-management: Baker and Fatoye (2017),55 Clari et al. (2017),56 Harrison et al. (2015),57 Howcroft et al. (2016),58 Jonkman et al. (2016),59 Jordan et al. (2015),60 Lenferink et al. (2017),61 Wang et al. (2017)62 and Zwerink et al. (2014)63 Pulmonary rehabilitation: Alison and McKeough (2014),64 Cox et al. (2017),65 Jones et al. (2017),66 Keating et al. (2011),67 Meshe et al. (2017),68 Moore et al. (2016)69 and Puhan et al. (2016)70 |

Experimental studies generally compared an intervention with ‘usual care’. Usual care was generally not defined at all in the abstracts that we used for coding, making it difficult to compare studies. A few studies compared different interventions, although these tended to be variations of a common intervention (e.g. more vs. less intense or different durations) rather than distinctly different interventions. The distribution of experimental studies across conditions/interventions broadly reflected that of the whole group of included studies.

Controlled observational studies were less frequent in the map than experimental studies were, with no combination of condition/intervention having more than seven such studies. Similar to the experimental studies, the majority of this group compared the intervention with a ‘usual-care’ control group. By contrast, most uncontrolled observational studies (65 studies) used baseline values as a comparator, although 14 such studies also included a ‘usual-care’ group.

Qualitative studies are an important source of evidence for understanding the implementation of interventions in practice, as the views and perceptions of HCPs and patients have a strong influence on if and how interventions work in practice. The 61 qualitative studies included in the map covered the range of relevant populations and interventions, the largest single group being studies of pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD (13 studies). Other populations and interventions were covered by up to seven qualitative studies. Studies using recognised methods of qualitative analysis, such as thematic analysis, were included in this group, although the quality of individual studies was not assessed.

Setting

Most studies were conducted in the USA (207 studies), followed by the UK (103 studies), Canada (46 studies) and Australia (43 studies). Just two studies from New Zealand were included. There were 91 studies, primarily literature reviews, in which the concept of study country was considered to be not applicable, and 59 studies were conducted in multiple countries. Finally, the country was coded as unclear/not reported for 23 studies in which the reviewer’s judgement was that the setting was likely to be one of the countries included in the map. We did not systematically check the full texts of included studies to identify the authors’ country of origin, so it is possible that this group includes a few studies from outside our defined settings of interest.

In terms of how patients accessed the intervention, the largest single group was studies in which the access route was not reported or was judged as unclear (213 studies). The most common identified ways of accessing interventions were via community-based services (134 studies) and at the time of hospital discharge to reduce risk of re-admission (122 studies). General practitioners (GPs) or equivalent primary care doctors were the access route in 45 studies, and other general practice staff were the access route in 22 studies. Less frequent ways of accessing interventions were outpatient appointments (24 studies), emergency departments (15 studies) and paramedic and telephone advice (two studies each). There were no included studies in which access to the intervention was initiated by the patient.

UK evidence

We included 103 studies from the UK. The majority of these focused on a small number of interventions: self-management of COPD (12 studies), pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD (15 studies) and telehealth for COPD (26 studies) and heart failure (15 studies). Almost half of the included UK studies (49 studies) dealt with interventions classified as telehealth, primarily remote monitoring and consultation. This concentration on telehealth probably reflects strong backing for the technology from the Department of Health and Social Care through initiatives such as 3 Million Lives and the Whole System Demonstrator trial. 71 Interventions classed as effective by Purdy et al. 3 but with limited evidence from the UK included cardiac rehabilitation and telehealth for CHD (one study each), case management (one study), specialist clinics (no studies), community interventions (two studies), patient education for heart failure (two studies) and self-management of asthma (six studies).

Outcomes

We mapped two measures of effect on admissions: (1) admissions (or re-admissions) per se, based on aggregated data from trials or routinely collected data, and (2) prevented admissions, based on audit of individual cases; these outcomes were reported in 311 and three studies, respectively. This suggests that in most included studies there was an implicit assumption that admissions were prevented appropriately (i.e. the intervention did not lead to patients not being admitted when admission was the most appropriate course of action) but this was not investigated directly.

Other commonly reported outcomes were patient-reported outcomes such as quality of life (211 studies), health system outcomes such as length of stay or emergency department visits (91 studies), qualitative outcomes (themes identified by qualitative analysis) (85 studies) and costs or cost-effectiveness (73 studies). Other outcomes, including mortality, were reported in 133 studies.

Summary of findings

The mapping review allowed identification and description of a large number of studies relating to interventions to reduce preventable hospital admissions for people with cardiac or respiratory conditions. A limited number of descriptive outcomes are reported here but the features of EPPI-Reviewer allow the data to be analysed in a wide variety of ways. Unsurprisingly, the interventions identified by Purdy et al. 3 as having the best evidence of effectiveness (or no effect) were well represented in the map. The largest group of studies originated from the USA; differences between health-care systems mean that care should be taken in extrapolating the results of such studies to the UK setting. Regarding the included studies from the UK, a similar distribution of studies was shown by intervention and population to that of the map as a whole but there was evidence of some country-specific features, such as the prominence of studies of telehealth. We excluded studies from non-UK European countries based on lack of similarity between most countries’ health systems and the UK NHS. This means that some studies of interventions that could be implemented in the UK were omitted from the mapping review. However, it is unlikely that this would have led to any significant intervention being omitted from the mapping review altogether. Furthermore, studies from European countries were included indirectly via the inclusion of relevant systematic reviews in our mapping review.

Mapping reviews use systematic methods to identify, screen and code studies, but a mapping review is not a systematic review. Mapping reviews generally omit some standard features of systematic reviews, for example study quality assessment, and do not attempt to assess effectiveness. The role of mapping reviews is to provide a descriptive account of the published literature and this should be taken into account when assessing the findings of this part of the overall evidence synthesis.

The studies coded for the mapping review and stored in EPPI-Reviewer 4 represent a broad sampling frame of UK studies for use in the accompanying realist synthesis. In view of the number of studies screened for inclusion and included, we cannot rule out the possibility that some studies were included or excluded in error. Inclusion decisions were taken on the basis of information in the title and abstract only and, in some cases, important information (e.g. the study country) was not available. However, it is unlikely that any errors regarding study inclusion or exclusion would have a major effect on the overall shape of the evidence map.

Chapter 4 Analysis of UK studies

Case management

Summary

Exploration of case management reveals that the role of the specialist nurse is key to its success. The impact of the role is determined by issues relating to responsiveness (as seen in response times) and availability (as seen in the demand for 24-hour access), which themselves can be moderated by the size of the nursing caseload and the competing demands of the administrative workload. A tension may be identified between the intrinsic advantages of continuity of care, as especially evidenced in a knowledge of a patient’s symptoms and the need to provide round-the-clock coverage to patients with more severe manifestations of cardiorespiratory conditions. Case management is therefore seen to require substantive re-engineering of the health system in which it is intended to operate.

Definition

Case management is a generic term, with no single definition, described as the process of planning, co-ordinating and reviewing the care of an individual. The Case Management Society of America provides a definition on its website (www.cmsa.org; accessed 4 April 2019). This definition was operationalised by Purdy et al. 3 in their series of NIHR reviews. The literature reflects confusion between case management as an ongoing process and as an intensive time-limited intervention. 72

Case management within the NHS has been largely configured as community-based programmes, set up and funded by primary care trusts and typically (but not always) staffed by community matrons. 72 In recent years, UK initiatives have focused on multidisciplinary team (MDT)-led case management but have demonstrated little or no reduction in use of secondary care. 73 Increasingly, attention has focused on the ‘added value’ of benefits for patients and professionals. 74 Interest in case management has been revived by the new models of care initiatives, with their focus being on integrated care.

Intervention components

Rather than comprising a single intervention, case management typically describes a package of care that covers activities that vary widely between programmes; it is described as a ‘prototypical example of a complex intervention’. 75 Such variation makes case management both difficult to describe and challenging to evaluate. TIDieR-Lite components of self-management interventions are summarised in Table 6.

| Question | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| By whom? | Health-care professionals, typically specialist nurses with medical support |

| What? |

|

| Where? | May be delivered face to face in a patient’s home or in a clinic setting or via the telephone |

| To what intensity? | Frequency and duration of contacts varies according to need |

| How often? | At intervals determined by case manager; may also be patient initiated |

Several commentators72,76,77 identify the following core components as particularly important to case management programmes:

-

case-finding

-

assessment

-

care planning

-

care co-ordination (usually undertaken by a case manager within the context of a MDT), including but not limited to –

-

medication management

-

self-care support

-

advocacy and negotiation

-

psychosocial support

-

monitoring and review

-

case closure (in time-limited interventions).

-

Case management can include components such as self-management, patient education and disease management programmes,72 making it more challenging to distinguish this intervention from others reviewed in this report. Case management may be delivered in diverse ways that vary according to intensity (frequency and duration of the contacts), degree of embeddedness in the local care network, the background and training of case managers and the extent to which they work alone or within a team. Further variation is exhibited in whether or not the case manager is supported through reflexive group meetings with peers or supervisors, how the target population is identified and how the case management intervention is initiated.

Number and type of UK studies identified

The effectiveness review by Purdy1 drew on only one UK study of case management. 78 This randomised controlled trial (RCT) in a COPD population in West London found no difference between case management and usual care in terms of numbers of hospital admissions. Indeed, the primary impact of the intervention seemed to be a reduced need for unscheduled primary care consultations. For every one COPD patient receiving the intervention and self-management advice, there were 1.79 fewer unscheduled GP contacts. 78

The mapping review identified two further quantitative UK studies (three papers) of case management for cardiovascular or respiratory conditions published since 2010. One study examined a COPD population in a single general practice79 and the other study73,80 presented data on 20 ACSCs. The six conditions of relevance to this review were asthma, atrial fibrillation, CHD, COPD, heart failure and hypertension.

Three UK qualitative studies were identified (four papers/reports). One of these studies examined patients with heart failure and staff involved in their care81 and the other two initiatives targeted case management in ‘high-risk’ populations including conditions eligible for this review.

Details of the studies included in the analysis are presented in Appendix 4, Table 25.

Operating programme theories

Programme theory 2 proposes that IF patients feel confident and satisfied with non-secondary care health provision THEN they will not consider it necessary to access/request secondary care services LEADING TO appropriate utilisation of health resources and a reduction in unplanned admissions. Case management affects a patient’s perceived capability of staying in their own home. 82 Crisis situations can be anticipated, if not averted; this is particularly important in the context of exacerbations as, for example, with COPD.

However, because of its personalised, tailored nature and the involvement of multiple health and social care professionals, case management may be considered overly intrusive. 82 Others patients report that the case manager was perceived as an impediment to accessing their GP. 83 Furthermore, if a patient feels supported, they are less likely to feel a need to access sources of support from secondary care. One patient with respiratory problems74 reported past and probable future occasions when her needs might be best met in hospital. This patient perceived the hospital as a means for meeting not just her medical needs but also her holistic needs, making her feel safer and therefore less anxious. Other participants described their ‘confidence’ in local hospitals should circumstances arise in which they feel that some of their needs may be better met in hospital.

Case management also engages with PT3: IF primary care staff (in this case the case manager) feel confident in their own ability to refer patients appropriately and have confidence in and knowledge of services available within primary and community care THEN they will not refer patients to hospital LEADING TO an increase in use of self-management and non-secondary care health service provision and a reduction in unplanned admissions. In this context, the detailed knowledge of a patient’s condition and circumstances and the holistic perspective of their care enables the case manager to calibrate and negotiate appropriate thresholds for secondary care intervention. Previously, the Evercare evaluation found that, as advanced primary nurses’ knowledge of available services increased over time, they referred their patients to an increasing range of resources for support. 84 Gowing et al. 74 report that some patients may be content to trust the case manager’s judgement, but others may resolutely insist that hospital is the best place for them. A major issue was the lack of adequate social care support, although isolated instances of providing overnight care following hospital discharge were reported. 74

An important contextual variable is the need for adequate training to strengthen the case managers’ self-efficacy and confidence in the appropriateness of their situational assessments. 82 This confirms that, as case managers become more experienced, GPs are likely to spend less time liaising with other services and case managers are able to provide more patient care themselves. 85 One potential unintended consequence of case management is increased levels of case finding resulting in a non-reduction in hospital admissions. 85

Detailed knowledge of a patient’s condition and circumstances (embracing both clinical and social contextual factors) also mitigates operation of action according to PT4, that is the patient does not perceive a need to delay presentation to secondary care services; they feel empowered to elicit information from their case manager as and when required. The triad of case manager, patient and informal carer only perceives a need to escalate action when the personalised threshold has been exceeded. A key contextual factor here relates to case manager caseload: if a case manager holds responsibility for an excessive number of cases then they will be unable to determine appropriate personalised thresholds and will either admit a patient unnecessarily or cause/contribute to delays in seeking treatment. Delays in accessing services have been shown to lead to deterioration in patients’ health and are a probable cause of future hospital admission. Lack of available community-based services constitutes a major challenge to effective case management. 84,86

Description of putative mechanisms

Possible mechanisms for case management are summarised in Box 2. In theory, case management seeks to increase efficiency by reducing unnecessary contacts with the health system. 87 Such contacts include fragmented routine contacts, as well as emergency contacts caused by potentially preventable exacerbations. The goal of case management is ‘to better co-ordinate care, offering individually-tailored contacts and care planning’. 87

-

Accurate case finding; identification of top 2% of at-risk patients on at-risk register.

-

Single point of assessment.

-

[May use MDT to case manage.]

-

Joint care planning.

-

Care co-ordination.

-

Contact between case manager and patient/caregiver.

-

Regular monitoring.

-

Knowledge of referral options.

-

Incentives.

-

‘Green tape’: clear guidelines and algorithms relating to resource allocation by patients.

-

[Self-management.]

-

Knowledge and motivation of health and social care staff.

-

Clarity of role.

-

Access to training.

-

Optimised caseload levels (may not be achieved).

-

Regular and longer contact/visits.

-

Organisational structure of the programme.

-

Financial and regulatory framework.

-

Available physical and human resources.

-

Information systems to support communication.

-

Accountability of individual or team to patient (named case manager).

-

Confidence in ability to determine appropriate personalised thresholds.

-

Identification of barriers to patient remaining at home and primary, community and social care resources required to address these barriers.

-

Reduced fragmentation among services.

-

Confidence in personalised thresholds.

-

Belief in capability for self-care and remaining at home.

-

Prompt and open communication to health-care professionals of exacerbations or barriers to self-care.

-

Acceptance of care and services offered.

-

Self-efficacy (health-care professional).

-

Self-efficacy (patient/informal caregiver).

-

Increased case finding.

-

Changes to medication (to avoid adverse effects) in conjunction with GPs.

-

Case management seen as another add-on service competing for NHS resources.

-

Patients reluctant to be discharged from case management.

-

Improved functional status.

-

Improved quality of life.

Green font denotes outcomes that could be detrimental in the context of reducing inappropriate hospital admissions.

The case management model is predicated on the presence of so-called ‘super utilisers’: ‘high-risk’, high-need patients, typically with multiple health conditions, who utilise a disproportionate amount of health-care resource (with a high cost). 88 The idea behind case management is that by targeting additional and individually tailored primary care at these patients, more costly secondary care admissions (particularly emergency admissions) can be avoided. 89

However, research suggests that case management does not meet its primary aims for the patients involved, although it is associated with increased patient satisfaction. 87,90 In practice, MDT case management tends to target those identified as ‘high risk’ using a selected statistical algorithm that is validated to predict patients who are likely to have substantial future health-care use. 80 These tools generate a heterogeneous group of patients, and it may be that there are subgroups for which the direct effects of the intervention are more effective. However, as papers by Stokes et al. 73,80 reveal, it can be extremely challenging to identify so-called ‘super utilisers’ both in terms of the ‘safe’ margin of those who can be appropriately managed in primary care and, equally, in terms of those for whom the complexity of their comorbidities renders secondary care an appropriate option.

Systematic review evidence identifies continuity of care as an important influence on admissions for long-term conditions. 91 Commentators seek to distinguish continuity of relationship (a continuous caring relationship with clinicians) from continuity of management (all aspects of integration, co-ordination and sharing of information). Both mechanisms can be considered important in the context of preventable admissions. A patient must feel that they can trust the judgement of the HCP and that the HCP has a sufficient understanding of their unique personal circumstances. Practically, continuity of management is important in the context of 24-hour care and delivery of services across organisational and professional boundaries.

Case management is centred on the premise that targeted, proactive, community-based care is more cost-effective than downstream acute care. Delivering such care requires that an intervention is integrated across care providers to avoid overlap and to ensure that each care provider knows and realises what each other care provider does. Wagner et al. ’s92 chronic care model (CCM) has been proposed as a framework to restructure the health system towards integrated, proactive, consistent and continuous care, and, thus, anticipate acute exacerbations or lessen their consequences. 93 The CCM draws on six interacting elements: links with the community, the health system, self-management support, tailored delivery system design, help for decision support and adequate clinical information systems. 94 Case management for people with complex care needs offers a potential strategy for delivering this type of integrated care.

Time-limited case management targets those with the greatest risk of emergency admission. A stepped approach means that people at lower risk of admission can be targeted with disease management programmes or supported in self-management. Case management shares the patient orientation of self-management75 (see Self-management). Indeed, patients in the study by Gowing et al. 74 reported being able to take a more active role in their own planning and care, thereby promoting independence. However, independence appears context dependent: a respiratory patient in the same study described being given a rescue pack for COPD and struggling with her own judgement about when to use it. 74

Previous evaluations report that policy-makers assumed that case management would stimulate ‘service redesign beyond the introduction of case management itself’. 85 However, evidence of wider local re-engineering of primary and secondary care for older people has proved challenging to establish.

Conceptually, case management can be understood in the context of integrated care. The six dimensions of services integration suggested by the National Collaboration for Integrated Care and Support (2013)95 are:

-

consideration of patient and family needs

-

communication with the patient and between HCPs

-

access to information

-

involvement in decision-making

-

care planning

-

transitions between various HCPs.

Roland et al. 96 advance possible explanations as to why using case management to improve care integration is not guaranteed to improve outcomes. The first is a potentially faulty underlying programme theory (i.e. because supply-induced demand increases appropriate admissions and does not simply decrease inappropriate admissions). Alternatively, the implementation of case management interventions may be wanting – an explanation on which Goodwin97 and Ling et al. 98 draw to explain suboptimal achievement of effects.

Efforts to strengthen coping capability are closely linked to the self-efficacy theories propounded by Bandura99 (see Self-management).

Contextual factors

In common with other complex interventions, case management studies generally lack contextual detail. As a complex intervention, case management includes various components interacting in a non-linear way to produce outcomes that are highly dependent on context and variables across settings. Attention should focus on analysing not only if and how case management works for frequent users of health-care services, but also in what contexts it works.

Role of patient preference

Several studies reveal that patients are generally satisfied with individual case manager-led case management approaches. 87,100,101 Patients particularly appreciate increased contact with HCPs and greater proactive input85,102 and reassurance that care was being co-ordinated. 102 In their qualitative study of the Northumberland High-Risk Patient Programme (NHRPP), Gowing et al. 74 recorded that patients were generally unaware of the exact composition of the programme but, nevertheless, observed such individual features as a named GP, regular review and the occurrence of MDT meetings.

Sheaff et al. 85 report that patients and carers valued case management for improving access to health care, increasing psychosocial support and improving communication with HCPs. They also report that ‘patients were often anxious that no-one should “take their nurse away” and were often reluctant to be discharged from case management’. 85

Role of culture

This section refers primarily to organisational culture within the health-care system. See also the following section, Role of leadership.

In most cases, case management requires significant cultural change. 1 In fact, much of the relative lack of attributed success relates to the inability of case management approaches to stimulate the radical scale of change required to realise its full benefits. Ross et al. 72 observed that case management is most effective as part of a wider programme of care in which various strategies are used to integrate care. These include good access to primary care, support for health promotion and primary prevention, and co-ordinated community-based packages for rehabilitation and reablement. 72 Where these features are not present, case management may not demonstrate effects on emergency admissions. 84 In their thematic analysis of key factors of case management interventions, Hudon et al. 103 highlight how the scale of innovation must be achieved across multiple levels, including in organisational culture.

Role of leadership

Leadership and culture are closely linked, so this section should be considered in conjunction with the previous one.

Good leadership skills are required to secure the support of other members of the MDT for the case management model. In their thematic analysis, Hudon et al. 103 highlight how leadership effectiveness is a key factor of case management interventions.

Role of evaluation/measurement

Many individuals undergo repeated monitoring and review as well as further assessment and care planning until they are fit to exit the case management system (note previous discussion about time-limited vs. ongoing definitions of case management; see Definition). 72 A well-written care plan enables case managers to monitor and review whether or not an individual is receiving an appropriate package of care. Frequency of monitoring will depend on the individual’s level of need:84 daily, weekly or monthly, and directly, in the individual’s home and/or through remote monitoring (e.g. by telephone or through telemonitoring of blood pressure or other vital signs). Such monitoring can be undertaken by a MDT.

Care plans must be constantly reviewed and changed when necessary. The NHRPP incorporated a key area of monitoring: patients were to be followed up promptly within 3 days of discharge from hospital. It should be recognised that telephone contacts are likely to be under-reported because of the burden of recording. 104

Role and characteristics of facilitation

The case manager typically operates within a MDT. It is vital that those in the team, and beyond, are engaged in the programme. Primary care professionals and social care staff generally welcome the role of case managers once they have a better understanding of what they do. 105 They particularly appreciated the role of the case manager in:

-

regular monitoring of patients

-

making diagnoses and changes to medication regimens

-

addressing patients’ social isolation by spending time with them

-

co-ordinating the overall care process

-

providing a link between primary, secondary and social care.

Case managers need to work proactively with diverse health and social care professionals, requiring good working relationships and effective communication. 106

Qualitative research supports personal aspects of the case manager role; community matrons were typically perceived as ‘friends’ in the case manager role. 83 This finding corresponds to data from corresponding roles in which empathy and compassion are regarded as important attributes.

Case management facilitates access to support and care as and when required. The patient, and their informal caregiver if present, feels able to call for adequate and appropriate help. 82 There is evidence of case managers (specifically community matrons) conducting low-skill roles initially, but with the aim of these being delegated to other professionals in time or absorbed within self-care. 83 If, on the other hand, a patient feels uncertain about their capability to remain at home, notwithstanding the information with which they have been provided, they feel empowered to access relevant secondary care-based help. Initially, the case manager occupies a role as a facilitator and gatekeeper to accessing appropriate help. Over time, however, the patient and informal caregiver feel increasingly able to assess when a personalised threshold for accessing secondary care services has been crossed.

Role/skills of implementation facilitators

Care planning includes many components and may cross multiple settings rather than be episode based. Fragmentation of care remains a persistent threat given the need to co-ordinate care plans for patients with complex chronic health conditions across multiple care contexts and professional groups. Given the frequent lack of consensus among professionals, relatives, carers and clients about the proposed care plan, good negotiation and communication skills are essential.

In addition to the pivotal role of the case manager, the care plan is typically seen as an essential component of the case management process. The initial assessment is translated into the development of a care plan and then facilitated and co-ordinated by the case manager. Published studies, although agreeing on the importance of this component, typically lack detail on how this process should be undertaken.

Case management as an intervention may display considerable variation in the intensity with which it is delivered. Resource provision and the expertise of the case managers in their facilitation role are important contextual variables that may have an impact on the success of the intervention. Further important variables include the balance of the case managers’ time between co-ordinating health and community-based services and interacting directly with the patient, the time spent on administrative tasks as opposed to direct work with patients, caseload size and role conflicts associated with combining the case management role with other clinical responsibilities.

Crucial to the effective implementation of case management is case manager control over the form and content of the services provided. Does the case manager exert some control over the supply or availability of services or other resources? Alternatively, are resources allocated on a team basis or is the success of the intervention dependent on referrals to other services? This latter ‘brokerage model’ has been considered insufficient on its own to exert the requisite influence to achieve effectiveness. However, even case management programmes with relatively more budgetary control may achieve only limited success when delivered within a wider resource-constrained environment. 107

Supporting evidence

This is a brief summary of evidence from systematic reviews, concentrating on hospital (re)-admission as the outcome of interest. Key results from UK studies included in this analysis are also presented.

Case management is an area that is rich in systematic reviews and evidence syntheses. Small numbers of systematic reviews briefly addressed enabling factors of successful case management interventions in the discussion sections of their papers. In a review of the effectiveness of case management among frequent emergency department users, Kumar and Klein108 noted that ‘frequency of follow-up, availability of psychosocial services, assistance with financial issues and active engagement of the case manager and the patient were important characteristics of CM [case management] interventions’.

Huntley et al. 109 conducted a systematic review to identify observational studies conducted at a practice level that describe factors and interventions that have an impact on levels of utilisation of unscheduled secondary care. Their review was limited by the challenges of trying to review across different health systems in different contexts. They found a benefit from seeing the same HCP, thus informing debates about continuity of care. Proximity to health-care provision was another major factor. However, they found it difficult to determine factors affecting quality of care.

Huntley et al. 109 subsequently conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of case management interventions for heart failure. They included case management within a hospital context and also studies targeting nursing homes and long-term care settings. None of their included UK studies therefore met our tighter inclusion criteria. They identified four studies of community-initiated case management versus usual care (two RCTs and two non-RCTs), with only the two non--RCTs showing a reduction in admissions. 109