Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/33/45. The contractual start date was in September 2014. The final report began editorial review in November 2017 and was accepted for publication in April 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Christopher Vernazza reports a grant from GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) (Brentford, London, UK) during the conduct of the study. Girvan Burnside reports a grant from GSK during the conduct of the study. Susan Higham reports grants from Unilever UK Limited (London, UK) and GSK and an Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (Swindon, UK) and GSK CASE (formerly known as Collaborative Awards in Science and Engineering) Studentship during the conduct of the study.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Harris et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background and introduction

Risk and responsibility in the NHS

Defining risk

Risk is the possibility that something unpleasant or unwelcome will happen. 1 Therefore, risk carries two elements: the probability of an adverse outcome happening and how important or troublesome the outcome would be. 2 Linguists have identified the word as originating from the world of navigation (the Latin word ‘risicum’ meaning sailing into uncharted waters, and the Greek ‘rhiza’ meaning the hazards of sailing too near to the cliffs, contrary tides, turbulent downdraughts, etc.). However, scholars have noted that the word risk is often used very loosely in everyday parlance and, as a conceptual phenomenon, is open to multiple interpretations. 3 Giddens, for example, argues that in traditional cultures, and in the Middle Ages, there was no such notion as risk (because troubles were understood to come from God, or simply to be part of a world that one takes as granted). 4 Rather, the idea of risk is ‘bound up with an aspiration to control and particularly with the idea of controlling the future’. 4 Lupton also identifies that the concept of risk in late modernity assumes that ‘something can be done’ to prevent misfortune. 5 She observes that ‘the notion of risk is associated with notions of choice, responsibility and blame, and has become a means by which institutions and authorities are held accountable and encouraged to regulate themselves’. 5 The term ‘risk society’ has been coined to describe modern ideas of the nature of and attitudes to risk. 6

General policy context: discourse on risk and individual responsibility

Public health in the UK and other Western countries currently operates within a neoliberal model. 7–10 Here, neoliberalism refers to a ‘system of thoughts and beliefs’7 about the role of the state that includes ‘shrinking state mandate, deregulation and privatisation, a faith in markets to govern social life, and an increased emphasis on personal choice and freedom’. 11 Using this definition to think about health, neoliberal approaches emphasise the role and responsibility of individuals to make healthy choices and, subsequently, to accept the blame for their failure in order to become a ‘good’ citizen. 12,13 As such, citizens have a duty to be well. 14 Neoliberal approaches to health in the UK are readily seen in governmental policy documents with references to an onus on the public ‘to take personal responsibility for their own health’. 15 Although the recent UK White Paper states that responsibility for health should be shared, it also emphasises the need for approaches to ‘empower individuals to make healthy choices’. 16

In a ‘risk society’ where personal responsibility for health is emphasised, experts are essential in order to provide knowledge to guide individual decision-making. Psychologists largely follow this tradition, tending to focus on risk behaviours and ways in which individuals’ responses to risks can be improved. 17 This, however, assumes that risk is an objective reality that can be measured, controlled and managed. 3 Although this ‘technicoscientific’ perspective18 on risk predominates in science and medicine, there is a danger that this approach overplays certainty when there is none. 6,19,20

An alternative standpoint is to understand risk as socially constructed within cultures,21–24 an approach emphasising that risk-taking is a form of social action that involves individuals facing challenges and making decisions that contribute to their social identity. 17 Anthropologists, for example, identify that there is often a bias ‘highlighting certain risks and downplaying others’. 21 For example, the focus on young people’s drinking in the context of excessive drinking among the middle-aged. 25 Advocates of the sociocultural perspective are concerned when, because risk tends to relate to danger and thus has a negative valence,21,26 objects, behaviours and groups are described as ‘risky’ and inevitably associated with badness, danger, being morally flawed7 and deviant. 27 Current policy discourse tends to encourage people to ‘define themselves in part by how well they succeed or fail in adopting healthy practices’. 28 Where certain groups are being defined as ‘high risk’, a rounded perspective on risk should therefore consider who is being judged, who is being blamed and who is labelling them as dangerous. 21

Rationing through risk assessment

Rationing (a process that restricts access to potentially beneficial but scarce resources) is inexorably linked to risk assessment; when professionals judge people to be at a ‘high risk’ of some disorder, they invariably seek to target scarce services at the selected population. 29 Being labelled ‘at risk’ can result in individuals being targeted for ‘expert advice, surveillance and control’. 30,31 ‘Low risk’ patients may be allocated proportionally fewer resources, even though they may have benefited from these. 29

Within a context of neoliberal responsibilisation, however, ‘high-risk’ individuals might also face restrictions on certain types of care. This is because a multiplicity of responsibilities exist. 11 Neoliberal ‘responsible’ citizens exist within a matrix of dependencies. While patients share responsibility with clinicians for their health, clinicians have wider responsibilities too, to other patients, to the state and to society in general for their use of scarce resources. Thus, fertility treatment is restricted for women over a certain body mass index,32 priority scoring tools including positive exercise tests, non-smoking habits are introduced to deal with elective surgical waiting lists,33 and root canal treatment, crowns and bridges are restricted for ‘red’ patients within prototypes of the new NHS dental contract being tested. 34 Risk is a notion that is relevant to almost every aspect of modern health care; its relevance extends beyond a means to improve the way patients look after their own health and it has a significant impact on the way health services themselves are delivered, especially in NHS dentistry.

Dental policy context

Since the 1990s, there have been various models of contract-governing work undertaken in NHS dental practice. All have been met with unintended consequences and have led to further reform. 35 Two prototypes of a new model contract are currently being tested in > 80 English dental practices. 34 Both are based on the principle of allocating patients to clinical care pathways according to an oral health risk assessment undertaken at a dental check-up. 36 Information on the patient’s medical history, social history (self-care, e.g. toothbrushing habits) and clinical examination findings determine whether the patient is categorised as red (high risk), amber (medium risk) or green (low risk) within the traffic light [red–amber–green (RAG)] system. In the prototypes and earlier pilot practices, software with a RAG algorithm was used to generate the red–amber–green rating of risk, which was then ‘fed back to the patient and used for appropriate advice and treatment’. 37 Data from new contract pilot practices indicates that 16% of adult NHS patients are green (have healthy mouths and virtually no signs of disease), 56% are amber and 28% are red. 37

Risk communication

Risk communication is something that most clinicians do every day. 38 In dentistry, risk communication is even recommended as something which ‘should form part of every patient interaction’. 39 This is because, first, patients’ risk perception, and how this balances with benefits, lies at the heart of helping patients make informed choices between treatment options and, second, because self-care and self-management behaviour is underpinned by how patients perceive threats to their health. 40,41 Risk communication is also the concern of public health practitioners, where it is seen as crucial to the prevention and co-operative management of health risks, and ‘at least equally essential to outbreak control as epidemiological training and laboratory analysis’. 42 While this study is concerned with risk communication with patients in a health-care setting to prompt improvements in self-care behaviour, its findings have relevance to other activities involving communication of health risk messages in other contexts.

Recent systematic reviews of risk work in health-care settings have found a deficit of research looking at how risk is acted on, and communicated, in routine practice. 1

Tailoring of risk information

‘Tailoring’ refers to methods of creating communications that are individualised to the receivers, with the intention that this increases impact. 43 Studies generally show that tailoring of information is beneficial. 43–45 Tailoring of risk information for health education purposes is thought to be especially important, because people are found to report their own risk of experiencing a health problem as less than that of an average person, even when given information about the average person’s risk or behaviour. 46 This systematic underestimate of personal risk is a barrier to the adoption of all types of precautionary health behaviour. 46

Individualised health communication can range from personalised generic communication (e.g. using someone’s name to personalise the message) to targeted communication (composing the message with a particular group or segment of the population in mind, an approach that is the basis of many public health education and social marketing campaigns), through to truly personalised communication that provides information based on characteristics that are unique to a person (e.g. as in brief counselling interventions). These approaches involve tailoring, which is based on characteristics beyond broad demographic categories such as age or gender and, therefore, depend on some sort of individual assessment. However, with the advent of computer-based tailoring, the population reach can still be wide. 47,48

Social marketing, which takes lessons from commercial marketing and applies them to the health and social sectors,49 takes a targeted communication approach out of concern that health messages, given inadequate understanding of the groups they are meant to serve, can result in a widening of health inequalities between the rich and poor. 50 It divides populations into ‘audience segments’ according to shared characteristics and behaviours, and then explores what each target audience prefers to do and what affects their behaviour and preferences. 51 The emphasis is on developing a whole understanding of consumers’ complexities of life, and how people choose to navigate these. 50 Pricing is a major device in the social marketing toolbox, which sums up the costs that the target audience will ‘pay’ for adopting the desired behaviour that leads to the promised benefits. Taking a ‘value to user’ approach as opposed to an ‘expert defined product’ approach lies at the heart of social marketing approaches that aim to design programmes which make changing behaviour easy. 49 Health information preferences is one way in which populations may be segmented, with this directly informing how health promotion approaches might be best applied. 52 Although many studies report area-based differences in oral health and behaviour, with application in identifying small areas that may benefit from health promotion activities,53 relatively little information exists concerning the value that people in deprived areas place on interventions that aim to improve their oral health. More work is also needed about the type and amount of information people want concerning their oral health, and whether or not this varies according to different psychographic (attitudes, values, lifestyle) groups. This study therefore has relevance, not just to inform the giving of risk information to individual patients in NHS dental practices, but in informing the design of risk communication messages to targeted segments of high-risk populations.

Risk presentation, format and information visualisation

Previous literature on risk communication has concentrated on information framing, the interpretation of numerical information54,55 and whether presenting information numerically or in different graphical forms has greater impact. 56,57 Rothman and Kiviniemi46 group these investigations as ‘probability-based approaches’, comparing them with contextually based communication strategies. They conclude that probability-based approaches alone are unlikely to be successful, not just because people generally have difficulty understanding and using quantitative information, but because risk perceptions are ‘imbued by emotion’ and ‘always interpreted via a social and cultural lens’. 58 As an alternative, they outline contextually based approaches to risk communication, which are better at recognising that lay conceptions of risk are based on a rich mixture of cognitive and affective beliefs, and enable people to develop a mental model that delineates the personal relevance of a given risk. 46 An example of a contextually based approach would be to direct individuals to imagine themselves experiencing a symptom of a disease in order to heighten their perception of personal vulnerability.

Information visualisation is important here. It assists sense-making, which is the process of finding meaning from information. 59 For example, a study including digital photographs to contextualise and augment glucometer readings for people living with diabetes mellitus, found that the images carried deeper meaning than purely looking at the readings, and helped participants to address the social and psychological challenges of living with the condition. 60 Patients are known to use heuristics (simplified ‘rules of thumb’) to allow them to understand and make decisions. 61,62 Although heuristics may be biased by non-relevant information, such as cultural expectations and emotional responses, they are still important in allowing patients to process large amounts of complex and novel information and make decisions. 63,64 The traffic light (TL) categorisation of patients’ oral health risk is an example of an information format that provides a simple portrayal of complex sets of information, which may be useful and valuable to patients (although this has never been tested).

People’s understanding of risk is thought to be enhanced when information is presented in a vivid way, holding their attention. 65 Although all patients can benefit when pictures are used, people with low literacy skills are especially likely to benefit. 65 Very vivid and highly personalised information is increasingly available as risk communication tools, given recent advances in technologies, scans and radiographs now available that show, for example, body fat, heart function and osteoarthritis of joints. Previous studies have shown that medical imagery that gives a vivid representation of the consequences of unhealthy behaviour can enhance risk communication, although these have used general rather than personalised images, which provide less personalised information about risk status. 66–68 None of these studies investigated the extent to which patients appreciate and value this type of information.

Developments in dental photography technology allow a vivid and highly personalised way of presenting risk information to dental patients. A Quantitative Light-Induced Fluorescence (QLF™) camera (Inspektor Research Systems BV, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) can produce images of teeth showing tooth mineral loss before it is visible to the naked eye and before cavities develop. 69 Demineralised areas show up as dark spots on QLF photographs, where loss of fluorescence correlates with mineral loss in the lesions (when teeth demineralise there is a loss of fluorescence due to an increase in tooth porosity, which in turn leads to a decrease in the refractive index of the carious lesion) (Figure 1). Camera software allows changes in fluorescence of dental enamel to be quantified to estimate mineral content and, as such, can be used to evaluate changes in level of dental caries, although this requires dental plaque to be removed from teeth before the image is taken.

FIGURE 1.

Example QLF image of early tooth decay: dark patches on the image.

Quantitative light-induced fluorescence also highlights mature dental plaque in a relatively vivid way. Mature dental plaque (present for ≥ 48 hours) contains porphyrins, a by-product of the bacteria that appear as bright red/orange areas (red fluorescence)70 under QLF conditions (Figure 2). QLF images can therefore be a useful means of monitoring patients’ toothbrushing behaviour over several days rather than just behaviour related to the day of the oral examination itself. Plaque Percentage Index data gathered from QLF photographs permit plaque assessment on an interval scale and show excellent reliability when repeated measurements of the same image are analysed. 70 The tooth surface area of red autofluorescence of dental plaque can also be measured using software associated with the QLF equipment.

FIGURE 2.

Example QLF photographic image of plaque coverage: red fluorescence highlighting plaque present in the mouth for > 48 hours.

Quantitative light-induced fluorescence images can be stored in clinical records for subsequent reference and shared with the patient (digitally or as a hard copy). Images can be discussed at the dental chair-side on a computer screen or tablet, with the option of e-mailing images to patients’ mobile devices or computers as material to support the message given.

Quantitative light-induced fluorescence offers an alternative risk communication tool to TL graphics currently being used in new dental contract prototype practices. Although possibly more expensive as a higher-technology option, its potential benefits and whether or not patients value information in this form has never been properly explored. Incorporating QLF technology into the study also allows us to gather objective measures of oral health (demineralisation of teeth and plaque coverage).

Traffic light and QLF imagery have contrasting features as risk communication tools:

-

TL image –

-

simple information

-

individuals grouped by category

-

image is pictorial but not vivid

-

low technology.

-

-

Quantitative light-induced fluorescence (QLF) –

-

detailed information

-

personalised to individuals

-

vivid

-

high technology.

-

Risk work

Previous research on risk in the health context has focused mainly on either the perspective of patients or on the governance of risk by organisations. 71 By contrast, very little work has been conducted which takes a service delivery perspective. For example, dealing with how frontline health-care workers undertake activities concerned with identifying and managing risk. Against a backdrop of a ‘risk society’,6 Gale et al. 71 used the term ‘risk work’ to denote ‘working practices framed by concepts of risk’. Despite a drive from evidence-based medicine for consistent application of externally produced knowledge, dealing with uncertainty remains part and parcel of medicine, which is both an art and a science,72 so ‘risk work’ is central to everyday health care.

‘Translating’ risk information into different contexts is a common health-care activity. 71 Some of this work involves translating ‘up’, identification of individuals and creating auditable records to ensure accountability (e.g. as in the RAG categorisation of NHS dental patients in prototype practices). Translation work is also required, when clinicians take population-level data and converse with patients, translating the data into meaningful information for the individual in order to bridge the gap between scientific and lay perspectives of risk. 73

Talking to patients about risk can in itself be risky: first, balancing uncertainties in risk makes talk difficult73 (some risks may be open to medical uncertainty); second, ‘risk talk’ can be threatening for patients who may experience shame or embarrassment as a result; and, third, risk does not automatically concern an actual deviance in the patient’s body, but rather indicates a probability of something happening in the future, and hence risk talk can be anxiety inducing for patients. Risk talk can even result in a deterioration of a patient’s health: ‘once a person knows that she or he is at risk, the person often starts to feel uneasy and it is possible that she or he begins to feel sick and indeed becomes sick’. 73 While previous studies have investigated risk talk using discourse analysis,73 contextual, extraneous information in interpreting discourse data (ethnographic methods) is recommended. 74

Theoretical model of risk perception and behaviour change

Imagery and numeric risk estimates are thought to influence people’s reaction to risk messages by increasing patients’ perception of the said threat to their health and well-being, thus heightening fear regarding any negative consequences of inaction. 75 The extended parallel process model (EPPM) is therefore relevant in this context because it predicts that people engage in defensive behaviours when they perceive themselves to be at risk of a threat. 76 The EPPM model is based on the concept of ‘fight or flight’. It supposes that a person is likely to ‘flee’ if they perceive that the threat is great and that they have little hope of overcoming the obstacle, whereas they are more likely to ‘fight’ where they believe that (1) the challenge is important enough (perceived threat) and (2) they can win (perceived efficacy).

According to the EPPM, ‘perceived threat’ has two components (threat susceptibility and threat severity), as does perceived efficacy’ (response efficacy and self-efficacy). Self-efficacy refers to individuals’ subjective beliefs that they can complete behavioural changes. 77 Response efficacy relates to the person’s belief about how effective the recommended behavioural change will be to reduce the threat. The EPPM model hypothesises that when both threat and efficacy levels are high, danger control processes ensue, which lead to aversive action, whereas when threat appraisal is high and efficacy appraisal is low, this can lead people to a maladaptive action, such as rejecting the message. The EPPM, therefore, theorises that when someone is presented with information at their dental check-up appointment (e.g. about their risk of tooth decay or gum disease), they may either sense no threat and do nothing/become fearful and ignore the message or begin a danger control process, which drives them to accept the challenge and adopt the recommended course of action.

The course of action which the patient takes is therefore thought to be influenced by the extent to which the message given conveys how serious the threat is (e.g. pain, spoilt appearance from tooth decay), and how susceptible they are to such problems. The form in which information on risk is given is particularly relevant here. Imagery, in particular, has been associated with defensiveness. 78 The EPPM opens the possibility that certain risk communications can have negative as well as positive effects on individuals. 79 The EPPM will therefore be used as a framework to help understand why TL or QLF supplements to usual verbal risk communication at dental check-ups are or are not effective, and how effectiveness of risk communication may be improved.

Overview of the project

Aims and objectives

Our aim is to describe how patients value and respond to information on their oral health status and risk, and to compare the value of three different methods of presenting information on patient’s oral health and risk: verbal communication only, verbal supported by information presented as a TL graphic, or a QLF image of the patients’ own mouth.

Objectives

-

Describe what type of information patients want, need and prefer when having a dental check-up and how they use this information.

-

Describe how patients interact with the three different forms of information.

-

Investigate whether or not and how the clinician–patient relationship is influenced by patients having access to different types of information.

-

Measure individuals’ preferences, by using the economic, preference-based valuation methodology [willingness to pay (WTP)] for each of the three different methods of giving information.

-

Identify differences in preference for different types of information by differing demographic, behavioural and psychographic groups.

-

Use variables from derived established models of the behavioural change process to predict the likelihood that different forms of communication will lead to behaviour change; and to measure any actual behavioural changes and link these with differences in valuations.

-

Conduct a cost–benefit framework analysis of the three different methods and to explore financial implications for NHS dentistry.

Research plan and outline of chapters

In order to frame our research within the wider health-care context, and help address objective 1, we undertook a systematic review to identify and summarise any previous research undertaken in clinical settings concerned with how patients value and respond to health risk information given in different forms. This was focused on giving personalised feedback about health states or health risks in different forms (for example, but not limited to verbal, written, diagrammatic, photographic information), and investigated the following outcomes: patients’ preferences and economic valuations, objectively verified behavioural change, self-reported behavioural change and potential mediators of change including behavioural intentions and risk perceptions, as well as having an impact on patient-carer communication and patient satisfaction. Methods and results are given in Chapter 2.

To help address the first three objectives, we undertook an ethnographic study. This began before the experimental stage of the research [a randomised controlled trial (RCT) in NHS dental practices] and continued as a piece of qualitative research alongside the trial. The purpose of ethnography is to provide in-depth accounts of people’s views and behaviours as well as the significance of the inhabited space of the interaction. 80 As well as collecting qualitative data by interviewing patients and dental staff, we collected a wealth of ethnographic data, which included non-participant observations of dental appointments. We did this in recognition that dental staff and patients may behave differently during the dental appointment (or the ‘front stage’ according to Goffman81) than in other spaces and interactions (back stage). Cross-examining dental team and patients’ accounts with observations of everyday practices allowed us to investigate discrepancies between what patients and dental staff said and what they actually did to become apparent; this allowed us to more fully explore objectives 1–3 using the concept of ‘risk work’82 as a framework. Risk work is concerned with working practices that occur under the guise of risk, for example what do discussions of risk do in NHS dental practice, how dentists translate risk information to patients, how dentists amplify or minimise risk when giving patients information and how dentists provide care to patients when addressing risk. 71,82

The qualitative research component of the study is described and reported in Chapter 5. The qualitative component of the study was also used to identify negative outcomes from poor dental health which were important to patients, for inclusion in RCT data collection as measures to investigate potential mechanisms related to behaviour change (see Chapter 3, Secondary outcomes).

Objectives 4–7 are addressed in a RCT undertaken in four NHS dental practices, the methods and results of which can be found in Chapter 3 and 4, respectively. This research was undertaken with the active participation of four people who have a patient and public perspective in the formulation and conduct of the research, as well as in its reporting. Chapter 6 is written by this group and outlines their involvement and perspective. Chapter 7 brings together the various research components in a discussion of findings and implications for policy and practice. We also identify future research needs in this area.

Ethics and NHS Research Governance approvals

Liverpool Health Partners was the research sponsor (approval reference number UoL001042). Favourable ethics opinion for the study was confirmed by the North West – Liverpool East National Research Ethics Committee (REC) on 1 August 2014 (REC reference number 14/NW/1016). A subsequent substantial amendment in ethics approval was obtained on 18 March 2016 pertaining to the RCT [to allow a prize draw of 10 lots of £25 (amounting to £250 in total) for patients completing follow-up data collection at 6 months and, again, at 12 months]. NHS Research Governance approval was obtained from The Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust on 20 August 2014 (reference number 4819).

All participants in the study (dental staff and patients) received a written information sheet relating to their aspect of the study, written and signed consent was obtained before their involvement in the study. The information sheet provided details of the study, information on right to withdraw at any time, anonymity and confidentiality, along with contact details of the research team. Participants were given the opportunity to ask questions before consent was taken.

Records identifying participants used a system of identification (ID) numbers to preserve anonymity, with all data stored under the guidelines of the 1998 Data Protection Act. 83 No patient-identifiable information was sent via electronic means (use of coded study number, patient’s gender and age only). Details of patients participating in the RCT were recorded in a recruitment log and this was held by the NHS dental practice where they were recruited. This information was later collected in person by a member of the research team, rather than transmitted electronically, in order to conduct follow-up data collection.

Chapter 2 Systematic review

To enable us to understand the contribution of our research in the NHS dental practice context to the wider context of health care more generally, we undertook a systematic review to identify previous work that had focused on the form of risk information given to patients in a clinical setting. Our review focused on research that provided personalised feedback to patients about health states or health risks in different forms and in clinical settings (e.g. verbal, written, diagrammatic and photographic information). We also focused on research that investigated the following outcomes: patients’ preferences and economic valuations, objectively verified behavioural change, self-reported behavioural change and potential mediators of change including behavioural intentions and risk perceptions, and impact on patient–carer communication and patient satisfaction.

Review methods

Search strategy

We adopted an iterative search strategy, which involved electronic literature searching of nine databases (including grey literature and dissertation databases) and hand-searching eight specialist journals (see Appendix 1, Table 24). To strike a balance between literature search sensitivity (finding all articles in the topic area) and specificity (finding only relevant articles), we initially developed electronic search terms using TerMine ATR software (using the GENIA Tagger version 2.1 POS tagger, which is customised for texts from biomedical science) provided by The National Centre for Text Mining, University of Manchester (www.nactem.ac.uk), applying this to 35 papers previously retrieved through pilot searches undertaken in Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). 84 We then broadened the search strategy with general topic search terms (e.g. health education) as is customary to systematic review methods. 85 Search terms used for an example (MEDLINE) search are found in Appendix 1, Table 25. We also used forward and backward citation searches, that is, reviewing references cited in articles identified earlier in the review process and searching for publications which cited papers that met study inclusion criteria. Because we were originally only commissioned to do a scoping review, rather than a systematic review, we did not contact authors for the full article where only abstracts were available either online or via interlibrary loan. The search was last updated on 10 October 2017.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Literature searching was limited to publications about adults receiving risk information in clinical settings. We were aware that this was a developing field and wanted to include reports which might be likely to lead on to experimental work in the near future (we had originally been commissioned to do a scoping review). Therefore, we included all types of study design, including qualitative work and protocols, although intervention study designs were limited to those comparing delivery of tailored risk information in one form with usual care or verbal risk messages, or with a different form of risk information. We included studies involving giving tailored information about an individual’s level of health with reference to likely negative consequences, as well as those involving risk terminology and health outcome probabilities (i.e. studies involving lay concepts of risk as well as risk defined in scientific terms). We precisely defined personalised (tailored) information as that ‘given to patients which is reliant on a pre assessment of the patient’ to mirror the situation that underpins new models of NHS dental care (oral health assessments at check-ups) and the design of the RCT component of our research. Complete inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in Appendix 1.

Data extraction and analysis

Quality assessment of included RCTs was undertaken using Cochrane risk-of-bias methodology at the study level. 86 Data extraction items consisted of type of study, intervention type, study populations, methodology, outcome measures and key results. The limited number and heterogeneity in the design and outcomes of included studies meant that meta-analysis was not undertaken. We therefore used narrative synthesis methods to summarise and synthesise findings, juxtaposing data extracted from all included studies to identify common findings. 87

Systematic review results

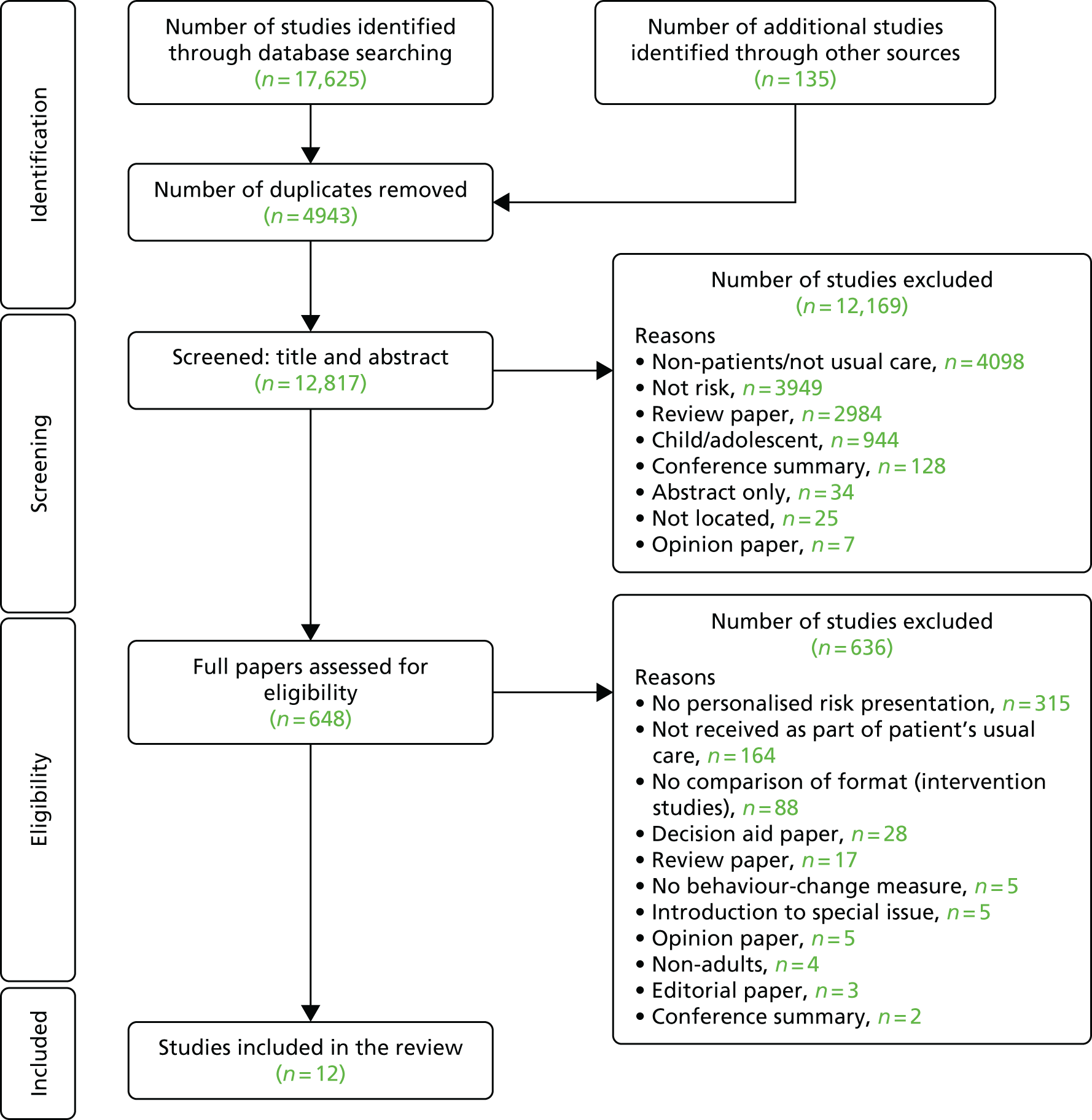

Electronic searching and hand-searching identified 17,625 papers, of which 4943 were duplicates. A further 135 papers were identified through backwards and forwards citation-chasing. Title and abstract screening was undertaken by two independent reviewers, with the full paper retrieved when at least one of the reviewers identified the study as potentially meeting inclusion criteria. This identified 648 potentially relevant papers that were then subjected to independent screening by the two reviewers, with any disagreements resolved by discussion. This identified 12 papers88–99 as being eligible for inclusion (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Nine of the included studies were RCTs, although two of these were feasibility studies91,94 and two were pilot RCTs93,95 (Table 1). Of the three remaining publications, one was an intervention description,99 one was a protocol98 and the other was an iterative exploratory study that involved developing an intervention, with a qualitative analysis relating to the type of information patients preferred. 97 The quality assessment of included RCTs indicates that some of the studies were rated as having a low risk of bias in many domains (Table 2). There were no intervention studies that were not RCTs.

| Study (name, year of publication and type) | Participants (characteristics and location) | Intervention (n of participants and method of delivery) | Control (n of participants and usual care) | Follow-up (time) | Outcome measures (behaviour, communication and risk perception) | Results summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Dapp et al. (2011) 88 RCT Patients randomised by computer |

Non-disabled Aged ≤ 60 years 21 medical practices Hamburg |

n = 878 (14 practices) Written risk reports: |

n = 1702 (14 practices) Usual care: with physician training and checklists with preventative recommendations n = 746 An additional seven concurrent ‘comparison’ practices with untrained GPs |

1 year | Behaviour:

|

Adherence: ↑ in PCUB (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.4 to 2.1) and ↑ in PHB (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.6 to 2.6), but subgroup analyses suggest a favourable effect only with personal reinforcement NS health outcomes Preferences: Majority selected group rather than home visit reinforcement Group reinforcement is promising |

|

Harari et al. (2008) 89 RCT Patients randomised by computer |

Aged ≤ 65 years Four general practices UK 26 GPs |

n = 940 patients (18 GPs) Written risk reports: |

n = 1066 Usual care (18 GPs): Concurrent comparison group (one practice, eight GPs) |

1 year | Behaviour:

|

Adherence: ↑ in 1 PCUB (OR 1.2, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.5) and ↑ in 1 PHB (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.0 to 2.0) NS health outcomes or patient self-efficacy Lower than expected effect attributed to lack of face-to-face reinforcement |

|

Kreuter and Strecher (1995) 90 RCT Randomisation unreported |

1317 adult patients aged 18–75 years from eight US medical practices |

n = not reported Graphical and numerical presentation of patients’ 10-year mortality risk Group 1: HRA feedback Group 2: HRA feedback plus behaviour-change information Results combined groups 1 and 2 and only given for participants recalling the intervention |

n = not reported Usual care |

6 months | Risk perception of mortality:

|

↑ in optimistic bias for risk perception of stroke mortality only (OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.02 to1.60), i.e. intervention groups were 27% more likely to have an ↑ in risk perception at follow-up ↓ in pessimistic bias for cancer risk perception only (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.73), i.e. intervention groups 36% more likely to an ↓ in risk perception at follow-up |

|

Zullig et al. (2014) 91 Feasibility study Block randomisation |

US points with CVD + a modifiable risk factor Mean age 65 years |

n = 96 Web-based intervention: |

n = 49 Usual care with general health education information |

3 months | Behaviour:

|

NS Web interventions may be ineffective without guidance and accountability from clinician interactions |

|

Welschen et al. (2012) 92 RCT Patients randomised by computer |

T2D points Netherlands |

n = 131 Verbal ± pictorial: |

n = 130 Usual care |

12 weeks | Risk perception:

|

↑ in risk perception (β between-group difference 0.48, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.95) after 2 weeks, but not at 12 weeks (β between-group difference –0.03, 95% CI –0.43 to 0.37) NS risk anxiety/worry NS ICB There is no evidence that risk communication, besides an improved risk perception, will motivate patients to adopt a healthier lifestyle |

|

Hess et al. (2014) 93 Pilot RCT Cluster randomised by doctor |

Attending a single US general practice Mean age 29 years |

n = 51 (16 doctors) Computer-generated immediate feedback of risk (e.g. tobacco use, physical activity, HRQoL) before clinical appointment, to prompt initiation of discussion |

n = 48 (14 Doctors) Usual care (completing health questionnaire without feedback) |

At the end of the visit | Communication:

|

NS Patient initiation of health-related discussion but ↑ in number of doctor reports of PID on physical HRQoL only for patients with low physical HRQoL (OR 4.6, 95% CI 1.3 to 16.3) Preference: NS patient perceived discussion to be useful |

|

Neuner-Jehle et al. (2013) 94 Feasibility RCT Cluster randomised by doctor |

Swiss general practice Median age 47 years 27 GPs |

n = 114 patients Verbal ± numbers ± pictorial risk message GPs using ‘quit smoking tool’ and individualised CVD risk calculation training presented in numbers and coloured charts and training and guidelines including Motivational Interviewing (MI) |

Verbal GPs using a ‘quit smoking tool’ and training and guidelines including MI |

Not reported | Behaviour:

|

NS patients estimated motivation NS comprehensiveness, satisfaction NS counselling duration, self-confidence Feasibility and acceptability of adding a visual element is ‘equally high’ |

|

Shahab et al. (2007) 95 Pilot RCT Patients randomised by computer |

23 CVD outpatients UK |

n = 11 Print of ultrasound image of their carotid artery alongside a disease-free artery and leaflet linking smoking and CVD |

n = 12 Routine verbal feedback |

Immediately after and at 4 weeks | Behaviour:

|

All outcomes NS except ‘perceived susceptibility’ Mean difference of high perceived susceptibility = 8.04 (95% CI 5.58 to 10.50) Interviews: Only patients in the intervention group reported that the visit made them think seriously about giving up smoking High self-efficacy may be necessary to translate higher risk perception into intention to change behaviour |

|

Mauriello et al. (2016) 96 RCT Patients randomised by computer |

English/Spanish-speaking pregnant women, up to 18 weeks’ gestation |

n = 169 patients iPad-delivered tailored guidance grounded in the transtheoretical model of behaviour-change during prenatal appointments, with goal-setting, a printed report and a booklet on behaviour targeted |

n = 166 patients A March of Dimes brochure |

1 month and 4 months post partum | Behaviour:

|

Stress: NS at 1 and 4 months Fruit and vegetable consumption: at 1 month 4.31 cups in the treatment group vs. 3.32 cups in the usual care group (OR 2.74); at 4 months 4.43 cups in the treatment group vs. 3.70 cups in the usual care group (OR 2.16) |

|

Saver et al . (2014) 97 Mixed methods study |

English/Spanish-speaking adults with T2D and at least one CVD risk factor Two general practices in one US city |

n = 56 patients Verbal ± pictorial risk message First 38 patients randomised to receive bar chart/crowd chart Final 18 patients receive bar chart/crowd chart sequentially Patients were asked to explain their thinking about any changes in the ranking of risks before and after receiving the intervention |

N/A | N/A | Qualitative data on reasons for changing/not changing, motivations for change, incongruence in perceptions |

Although 80% felt that some/all of the data applied to them personally, < 40% felt it motivate changes; 75% report ‘their own body experiences’ as their motivator; 20% report a ‘warning shot’ event or a specific instance when provider urging resulted in engagement of healthy behaviours Personalised risk estimates have limited salience |

|

Ahmed et al. (2011) 98 RCT protocol Block randomisation |

18- to 69-years old Asthma patients from tertiary care pulmonary clinics, Canada |

n = 80 Web-based self-management system with asthma status presented as red (be careful), amber (needs improvement), green (keep up the good work) plus links to online educational resources tailored to patients’ gaps in knowledge and clinical information |

Usual care | 3, 6 and 9 months | Behaviour:

|

|

|

Weymann et al. (2013) 99 Outline of an intervention |

T2D patients | Tailored web-based interactive health communication application. Personalisation involves mirroring what the user says, conveying esteem and empathy, building individualised bridges, content matching and presenting users with information on themselves | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Risk domain | Study (year of publication), level of bias | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dapp et al. (2011)88 | Harari et al. (2008)89 | Kreuter and Strecher (1995)90 | Zullig et al. (2014)91 | Welschen et al. (2012)92 | Hess et al. (2014)93 | Neuner-Jehle et al. (2013)94 | Shahab et al. (2007)95 | Mauriello et al. (2016)96 | |

| Selection bias | |||||||||

| Random sequence generation | Low | Low | Unclear | Medium | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Allocation concealment | Low | Low | Unclear | Medium | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Performance bias | |||||||||

| Blinding of participant and personnel | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | High |

| Detection bias | |||||||||

| Blinding of outcome assessment | High | High | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | High | High | Low |

| Attrition bias | |||||||||

| Incomplete outcome data | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Medium |

| Reporting bias | |||||||||

| Selective reporting | Low | Low | High | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Other bias | |||||||||

| Bias other than those above | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

There were no studies of oral health. Most studies involved the giving of information on cardiovascular risk. 91,92,94,95,97 One study concerned asthma risk information98 and the rest covered broader ‘healthy life-check’ information. Three studies involved information for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. 92,97,99

Computerised information was the most common form of information studied. 88–91,93,98,99 This reflects an expanding area of technology which is starting to have an impact on clinical practice. Computers can generate customised messages on risk, including, for example, patients’ health literacy, locus of control, internet experience, attitude to self-care, decision preferences and current health knowledge. 99 After patients enter details into a database, computerised capacity (including several hundred text files, graphics and photographs) can potentially correspond with tailored options to each survey response and all possible response option combinations. 99

Two studies reported RCTs involving computerised health risk appraisals (HRAs) used in a general medical practice. 88,93 The earlier of these integrated computerised risk appraisals into practice-based information technology systems, and generated individualised feedback for both patients and general practitioners who had been trained on current care and behaviour recommendations relating to the risk domains covered. However, it was left to the discretion of doctors and patients as to how any issues identified were addressed in consultations, if at all. 89 Results showed minimal improvement in patients’ health behaviour or uptake of preventative care across the domains studied89 (see Table 1). It is interesting to note that, in the later study,88 a face-to-face reinforcement component was added (albeit outside the clinical appointment; participants were given a choice of group sessions or home visits), and a subgroup analysis showed favourable effects for HRAs delivered along with personal reinforcement, but not without. A further study of HRAs with outcomes limited to risk perception rather than clinical outcomes found that adjustments in optimistic and pessimistic bias occurred in only some disease domains studied. 90

A recent RCT96 used iPads (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) to deliver a tailored intervention while pregnant women were waiting for their antenatal appointment. The computer activity included interactive components and incorporated feedback messages, quizzes, calculators, support messages and recipe ideas. This RCT found that this intervention increased the amount of fruit/vegetables consumed but did not increase the engagement with stress-reducing activities. However, a RCT involving a web-based intervention that gave personalised cardiovascular risk information to patients found no significant differences in health outcomes or behaviour between intervention and control groups after 3 months91 (see Table 1). In summary, although several studies conclude that computerisation makes tailoring of risk information possible100 and enables simple and visual representation of complex risk information, further reinforcement seems to be needed to interpret and discuss the information;88–91 evidence in this area is limited and more work needs to be conducted.

Studies testing other forms of presenting risk information to patients also found limited evidence for effectiveness. Studies in the clinical setting presenting risk information by way of population diagrams,92,97 coloured charts94 or photographs95 conclude that risk information presented in this way alone is insufficient to prompt patients to adopt healthier lifestyles, or even to enhance clinical communication (see Table 1). The only effect found was a short-term increase in risk perception. 92,95 Welschen92 concludes that risk communication is insufficient on its own, but should be a first stage in a more complex lifestyle intervention.

The closest previous study to the PREFER (presenting information on dental risk) study is a pilot RCT involving the use of ultrasound images to show the extent of blockage in carotid arteries (alongside contrasting photographs of a healthy artery) to cardiovascular clinic outpatients. 95 The basis for the intervention is empirical evidence, such as a study drawn from a community-based sample, showing that providing smokers with photographs of atherosclerotic lesions, together with relevant explanations, increases quit rate at 6 months compared with counselling alone (22% vs. 6%). 101 Although the pilot RCT based in outpatients showed no effect of intervention in smoking behaviour after 4 weeks, the study includes EPPM variables to investigate possible behaviour-change mechanisms. 95 The study found, first, an increase in perceived susceptibility in the intervention group and, second, that the intervention increased intentions to stop smoking only in patients with high self-efficacy (p < 0.03) and not in those with low self-efficacy (p > 0.35). This led the authors to conclude that, because their study was probably underpowered, the intervention may have the potential to alter both motivational and behavioural outcomes, and that the moderation effect may be important and could mean that such interventions may need to include procedures that increase self-efficacy in order to achieve optimal results. 95

Limitations

All systematic reviews must balance sensitivity with the precision of the literature search. In the first instance, we used text mining based on a selection of sample papers to design a precise search and then broadened this to increase sensitivity, supplementing with hand-searching. It is possible that by using text mining in the initial stages, the added precision may have limited the sensitivity of the search and some relevant papers may have been missed. To make the search manageable within the time and resources allowed, it was limited to English-language articles and the authors were not contacted for the full article where only the abstract was available online or through interlibrary loan. As a result, a few relevant papers may have been missed.

Summary

Although various studies have compared the different ways that risk messages can be framed and presented to people (e.g. comparing graphs or charts with numerical presentations), even in an era where risk profiles can be generated in the course of electronic clinical record-keeping and graphic imagery produced from scan technology with potential applications in health improvement, very few studies have been undertaken in the clinical setting. Studies that are available indicate that risk information itself may have a limited impact on health behaviour; discursive practices to define ‘who and what is normal, standard, and acceptable’ and to create meaning from the information are also needed46 (see Chapter 1, Risk presentation format and information visualisation).

Chapter 3 A randomised controlled trial in dental practice: methods

This chapter draws on the article by Harris et al. 102

Trial design, setting and population

This was a pragmatic, multicentre, three-arm, parallel-group patient RCT.

Dental practices

Patients were recruited from four NHS dental practices (practices 1–4, Table 3), located in north-west (NW) (n = 2) and north-east (NE) (n = 2) England, which were not involved in testing new models of the NHS dental contract. 103 Following pragmatic trial design principles, practices were invited to participate by sequential invitation based on random selection from a list of NHS dental practices within the two areas of England. Single-handed practices were excluded to ensure that sufficient numbers of patients could be recruited to the trial per practice. All four practices were in urban areas, with three of the four in relatively deprived areas. Practice 5 took part in qualitative work only (see Chapter 5, Observations in dental settings).

| Practice | NHS case mix (% patients) | Dental team | Location (UK) | IMD decile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70% NHS, 30% private | 1 principal dentist | NE, Urban | 9 (20% least deprived) |

| 2 FT dentists; 1 PT dentist | ||||

| 1 FT hygienist; 5 dental nurses | ||||

| 1 practice manager | ||||

| 2 | 95% NHS, 5% private | 1 principal dentist | NE, Urban | 1 (10% most deprived) |

| 1 FT dentist; 1 dentist in VT | ||||

| 1 FT HT | ||||

| 6 dental nurses | ||||

| 3 | 70% NHS, 30% private | 1 principal dentist | NW, Urban | 1 (10% most deprived) |

| 3 FT dentists; 1 VT dentist | ||||

| 1 FT HT; 6 dental nurses | ||||

| 2 receptionists; 1 practice manager | ||||

| 4 | 80% NHS, 20% private | 2 PT dentists | NW, Urban | 2 (20% most deprived) |

| 1 PT HT; 1 FT dental nurse | ||||

| 1 trainee dental nurse | ||||

| 1 receptionist; 1 practice manager | ||||

| 5 | 60% NHS, 40% private | Multi-dentist practice, dental team not disclosed to preserve anonymity (involved in qualitative work only) | New contract prototype practice | 9 (20% least deprived) |

Participants

Participants were adults attending a NHS dental check-up judged to be at high/medium (red/amber) risk for poor oral health according to a nationally developed algorithm used in practices testing new models of NHS dental contract. 104,105

The algorithm, which uses a combination of social and medical history (both patient-reported) and clinical information, was applied by the recruiting dental practice. 105 Patients underwent an initial eligibility screening when making the check-up appointment (e.g. patients reporting symptoms when making the appointment could be classified as red/amber), although eligibility could be fully determined only after the dental examination by a dentist, just prior to intervention delivery. For example, categorisation of the patient as amber risk might depend on the dentist rating the patient’s dental plaque control (toothbrushing) as poor after the clinical examination.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion:

-

aged ≥ 18 years

-

high/medium (red/amber) risk of poor oral health

-

NHS patients

-

new patients or regular attenders

-

any level of literacy.

Exclusion:

-

low (green) risk based on the absence of either clinical- or patient-related factors

-

patients attending for an emergency appointment (they do not usually receive a full check-up)

-

edentulous

-

private patients

-

patients requiring an interpreter for routine care.

Interventions

The trial had two intervention arms and a third ‘usual care’ arm.

-

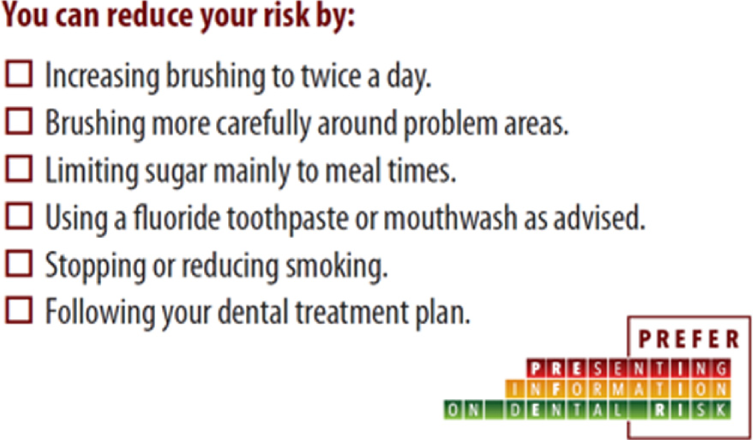

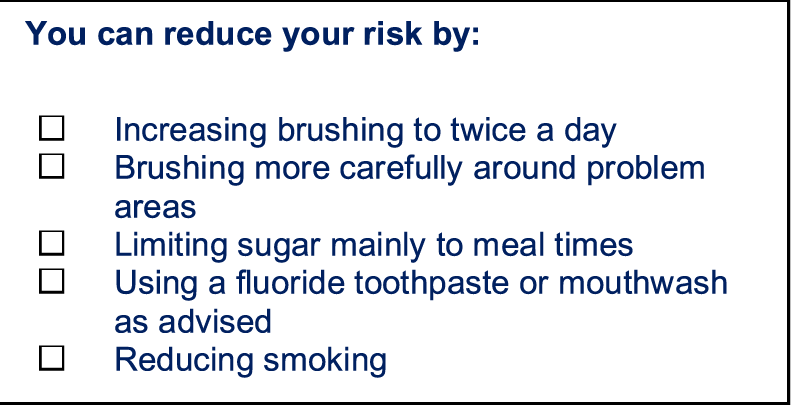

Verbal information only (usual care): dentists gave verbal information on risk in the usual way. Patients were also given a printed, credit-card-sized card with six key messages about recommended health behaviour (Figure 4). The dentist marked any messages they had covered with the patient, giving the patient the card to take away as reinforcement of advice given. When the dentist marked ‘Following your dental treatment plan’, this related to any advice about returning for further dental visits.

FIGURE 4.

Intervention card with six possible oral health behaviours (with the areas of advice covered at the check-up marked by the dentist). Reproduced with permission from Harris et al. 102 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

-

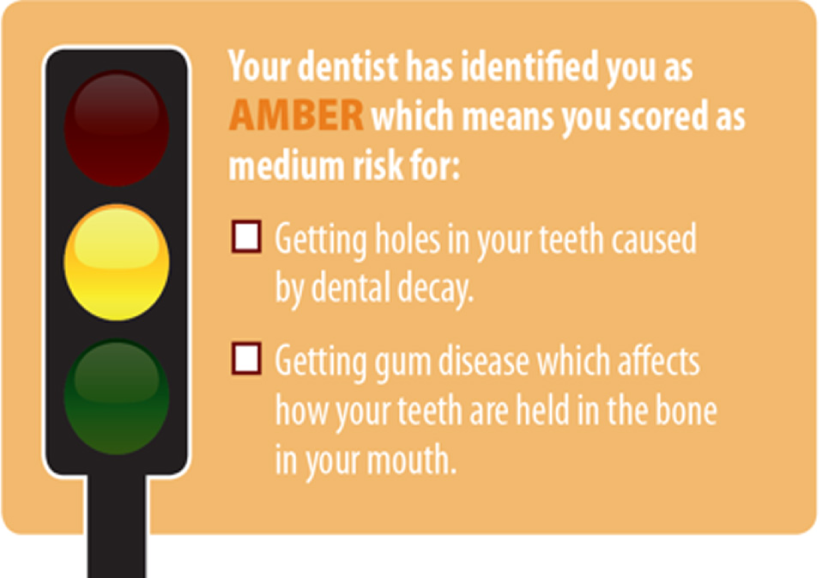

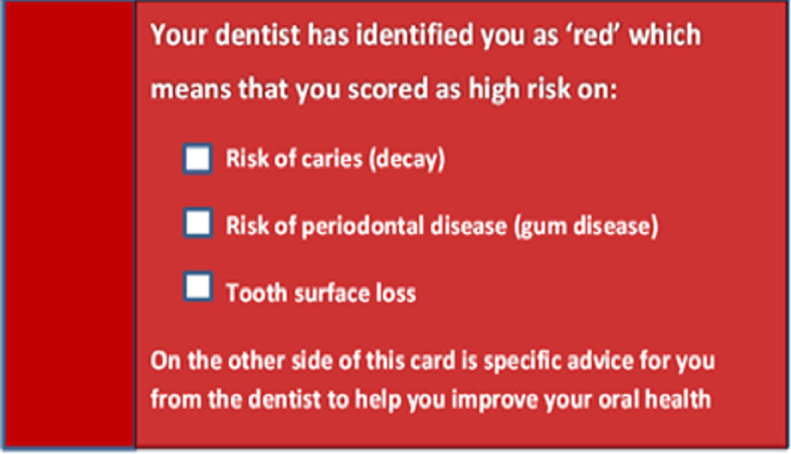

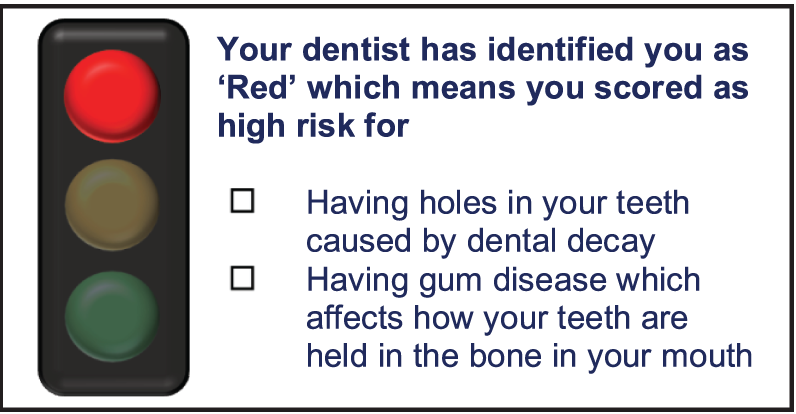

Verbal information plus TL graphic: dentists allocated the patient to one of the three RAG categories and gave them a credit card-sized card that described their risk group (Figure 5). The reverse of the card was identical to the reverse of the card given to group 1 (see Figure 4). The verbal advice covered the meaning of the RAG categorisation and oral health behaviours, as recommended by the dentist, to address any issues (which were also marked on the reverse of the card).

FIGURE 5.

Traffic light graphic cards to support verbal advice (group 2). Reproduced with permission from Harris et al. 102 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

-

Verbal information plus QLF photograph: Dentists gave advice supported by QLF images of the patients’ anterior six (canine to canine, top and bottom) teeth. Patients received a credit-card-sized colour copy of the QLF photograph showing either demineralisation areas (see Figure 1) or plaque coverage (see Figure 2), whichever the dentist thought was most important for the patient. On the reverse of the printed photograph a sticker was placed, replicating the credit card-sized card provided to group 1, with any messages covered regarding recommended oral health behaviours marked by the dentist (see Figure 4).

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome measure was the mean valuation for each of the three interventions in terms of WTP. This is a common approach to the valuation of health care elicited either by observing consumer choice (the revealed preference approach) or through an expressed preference (the contingent valuation approach). 106 We used the latter method. In economics, the value of a good or service is thought of in terms of what an individual is willing to sacrifice to obtain it. A common unit of sacrifice that is well understood globally is money. If the maximum amount of money that an individual is willing to pay for a series of services or goods can be determined, then the relative values of these goods or services are revealed. In health, it is often the case that services are not paid for, or are subsidised or insured against, and so monetary payments cannot be directly observed. In these situations, values are determined by constructing a hypothetical market for the service and eliciting the maximum an individual would be willing to pay in theory, if payment was necessary.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were collected in three ways: (1) self-reported by patients (see Report Supplementary Material 1), (2) clinical data recorded at the check-up [visit 1 (V1) – baseline] and at subsequent dental treatment visits [short-term follow-up: visit 2 (V2) and/or visit 3 (V3)], and (3) clinical outcome data extracted from QLF photographs taken at baseline and at V2 and/or V3. If clinical data were available for both V2 and V3, the V2 data were used. Secondary outcomes concerned with self-reported oral health behaviour focused on data collected 6 months post intervention (medium-term follow-up) and 12 months post intervention (long-term follow-up):

-

Clinical communication measured by the Communication Assessment Tool (CAT),107 completed by patients after receiving the risk information at V1.

-

Self-reported behaviour change between baseline and 6 and 12 months post intervention.

-

Oral hygiene –

-

Use of fluoride –

-

fluoride toothpaste prescribed by the dentist

-

fluoride mouth-rinse.

-

-

Dietary sugar intake –

-

Smoking status –

-

-

Clinical outcomes:

-

Self-rated oral health108 – change between baseline and 6 and 12 months.

-

Basic periodontal examination (BPE) score collected by dentists concentrating on conversions between codes 1 (bleeding) and 0 (healthy) between baseline V1 and V2/3.

-

Plaque Percentage Index70 [as measured on QLF images (ΔR30)] – change between baseline and V2/3.

-

Number of tooth surfaces affected by early caries – change between baseline and next dental visit measured on QLF images. 70

-

Where early carious lesions are present – change in lesion volume (ΔQ) between baseline and next dental visit measured on QLF images. 70

-

Predictor and moderator variables

-

Socioeconomic characteristics:

-

Education:

-

Patient dental visiting behaviour:

-

Oral health:

-

number of natural teeth at baseline.

-

-

Dental provider characteristics:

-

dental practice

-

clinical ID.

-

-

Behaviour-change variables (EPPM):76

-

perceived threat (severity)

-

perceived threat (susceptibility)

-

self-efficacy

-

response efficacy

-

message fear

-

affect regarding threat

-

danger control response

-

fear control response – (1) defensive avoidance, (2) perceived manipulation, (3) message derogation

-

intention to change behaviour.

-

Sample size calculation

Because valuation is the primary outcome, differences in mean and median WTP values between the three forms of information were the primary drivers of sample size. The sample size needed to be sufficiently high to detect differences between any of the three arms, either between the two intervention groups, TL and QLF photograph, or between one of these groups and the control. The sample size calculation is therefore based on a need to detect significant differences in the primary outcome (WTP) between the three arms at 80% power with an α of 0.05.

Sample size calculations for stated preference surveys, such as contingent valuation studies, are complicated by two factors. First, often no similar ‘goods’ have been valued in the past and so reliable variance estimates are impossible to determine. Second, if such data are absent, applying any effect-size estimate or minimally important difference would be arbitrary. Given these problems, and the fact that, to our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind, we calculated the samples required to show different effect sizes between any of the three groups based on numbers of standard deviations (SDs) rather than absolute numbers, as per Cohen,116 who suggests using a value of 0.5 SDs for a medium effect size where neither SD nor effect size is known. Thus, to detect a difference of 0.5 SD, 63 people were calculated to be required per arm. To detect 0.33 SD, 145 people per arm would be needed. Accepting a detectable difference of between a half and a third of a SD, and allowing for around 20% refusal to answer WTP questions (protest responses), gave a number of 133 people in each arm or a total sample size of 400 people.

We then considered the implications of this size on the detection of clinical outcome effects, particularly plaque coverage. Published data on a group of 38 college students showed a mean Plaque Percentage Index of 14.8, with a SD of 7.7. 117 As this is likely to be a more homogeneous population than that in our study, a more conservative estimate of a SD of 10 has been used to calculate a sample size of 133 people per group, which would allow us to detect a mean difference of 3.5 in the Plaque Percentage Index between groups, with 80% power at 0.05 significance level.

Trial processes

Dental practice training

Before setting up the study, whole dental teams (including the receptionist and anybody who had contact with study patients and/or procedures) at each recruiting dental practice received two sets of face-to-face training by the research team:

-

Good clinical practice training including taking informed consent, adverse event records, recruitment logs and study document and data management.

-

Study-specific training relating to the study protocol, including data collection procedures, flow of patients through the study, taking and the interpretation of QLF photographs (arm 3), the categorisation of patients to TL categories (see Report Supplementary Material 2: Study materials) and the use of intervention materials (arm 2).

The dentists or hygienists who delivered the interventions to the patients were trained in the use of the TL algorithm. Written instructions (laminated copies) on the application of the algorithm for categorising patients were provided to the dental teams. The algorithm took into account both patient and clinical factors and provided step-by-step guidance.

Specific training concerned taking QLF images to measure clinical outcomes of plaque and dental caries and included instructing staff to ask patients to clean their teeth between QLF photograph 1 (plaque) and photograph 2 (caries). If red deposits of plaque were still visible on the QLF image after brushing, the dental teams were instructed that they should ask the patients to brush their teeth again until all plaque had been removed and a further image should be taken in order to measure dental caries.

Training was supported by study materials, including a video and quick guide of how to use the QLF system, and crib sheets that included a participant procedures flow diagram (see Report Supplementary Material 2). Training on or calibration of undertaking a BPE was not provided.

Training logs were kept. Training was repeated when there was dental team staff turnover.

Randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding

Once consent was taken, dental staff took a sequentially numbered, sealed envelope containing group allocation information. The allocation sequence was prepared by the trial statistician using the ralloc procedure in Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Allocation was stratified by practice with random block sizes of three and six. Patients were allocated with equal probability to each group.

Allocation was revealed by opening the envelope just prior to the information being given (i.e. by the dentist, witnessed by the dental nurse in the dental surgery), after the check-up had been carried out, including baseline clinical outcome data collection (BPE score).

The researcher extracting clinical outcome data from QLF photographs was blind to group allocation. Patients and dental staff were not blinded to allocation, neither was the researcher undertaking 6- and 12-month follow-up data collection nor the trial statistician (the same statistician who generated the allocation was involved in the analysis).

Piloting, trial set-up and support

The study was set up in the four practices sequentially. This meant that experience from early practices taking part was used to inform the training of later ones. Two members of practice 4 NW travelled to practice 2 NE to take part in the study training of practice 2. All dental practices received considerable support in training and during the trial (Table 4), particularly in some practices where staff turnover was high. Seven dentists per practice participated in the trial from practices 1 and 3 and three dentists in each of practices 2 and 4 (see Table 3). Study recruitment started on 17 August 2015 and ended on 5 September 2016.

| Training/support type | Practice | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Number of separate training sessions | 5 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Number of trial monitoring and support visits | 13 | 7 | 7, plus a period of 3 weeks with a researcher in the practice | 16 |

| Number of requests for support regarding QLF equipment failures | 5 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

Some practices particularly required support regarding issues associated with the use of the QLF camera; practice 1, for example, required the camera cable to be replaced three times. QLF software freezing was another complaint. Camera troubleshooting instructions were developed to tackle possible issues and support was provided both by telephone and by visits to practices.

Piloting included testing to see how well the use of the QLF camera to measure clinical outcomes would work in a practice setting, how well the dental teams were able to operate the camera and which members of the teams were best placed to take the QLF photographs. The pilot phase lasted 2 weeks in one practice. The pilot lasted until the dental team was happy with study processes and was deemed able to undertake them. A researcher attended the practices to provide support during this period. A total of 10 patients were involved in the pilot. As a result of the pilot, it was decided that the photographs would be taken by the dental nurses, not dentists, because of time constraints/availability issues. Patient-held dental retractors (for lips) were introduced following the pilot period. We also reduced the number of images taken per participant, related to the measurement of clinical outcomes. We had initially planned that both a central anterior and also a right and left posterior images would be taken from the buccal aspect but reduced this to taking anterior (buccal) images only.

The use of the QLF camera proved challenging for the NHS dental teams and so a simpler, less technical, version of the camera was used as a consequence of piloting. The initial version used for the pilot was the QLF-D (QLF-Digital™) Biluminator 2 system (Inspektor Research Systems BV, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) originally designed for research use (Figure 6). This customised SLR Canon 550D (Canon Ltd, Surrey, UK) camera has a polished metal tube attached to a lens with four white and 12 high-powered blue light-emitting diodes around the lens aperture.

FIGURE 6.

The QLF-D Biluminator 2 system.

Experience after a week of training in a pilot practice (practice 5) was that the dental team had found the heat and light from the camera off-putting, making them reluctant to use the device with patients. Dentists reported that it felt inappropriate to use with new patients, because the initial appointment was about developing rapport and a relationship based on mutual trust. The equipment itself was considered bulky for use in a practice setting (trailing cables, etc.) (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

The QLF-D system in a practice setting: camera, laptop computer, printer and cables. (a) Trailing wires from the QLF-D camera across the dental surgery; (b) photograph showing bulky equipment associated with the QLF-D camera system occupying a significant area of the dental surgery workspace.

It was decided to replace the QLF-D camera (see Figure 6) with a Q-Ray™ camera (Inspektor Research Systems, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) (Figure 8), which had been recently developed for use in the dental practice setting. The system is more like a simple camera than a sophisticated SLR camera.

FIGURE 8.

The Q-Ray camera.

Extracting clinical outcome data from quantitative light-induced fluorescence images

A single researcher, blind to allocation, first scrutinised all images for quality (focus, excessive ambient illumination, parts of teeth obscured by lips, retractors or operator’s fingers, or any other artefacts that could affect the analysis). Good-quality images were judged as photographs which were taken at a sufficiently close distance (lower and upper front teeth filling the majority of space in the middle of the frame), with the absence of excessive ambient light (lips and gums appear as dark/black), focused and not blurred due to fogging, without any object (e.g. lips, tongue, lip retractors, fingers) blocking the view of the buccal surface of any of the 12 front teeth and with tip to tip contact of opposite teeth.

Images which were out of focus, had obscured tooth surfaces and/or with excessive ambient light present were classified as unacceptable for analysis purposes and were excluded from the statistical analyses. Presence of early caries lesions and dental plaque was calculated automatically using QA2 software, version 1.26 (Inspektor Research Systems, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). If early lesions were detected, these were manually mapped by drawing a contour patch (including sound enamel) around the lesion. The software then automatically calculated the percentage of fluorescence loss (ΔF,%) within the contour patch and the area of the white spot. Multiplying both values gave the estimated volume of the lesion as Δ.

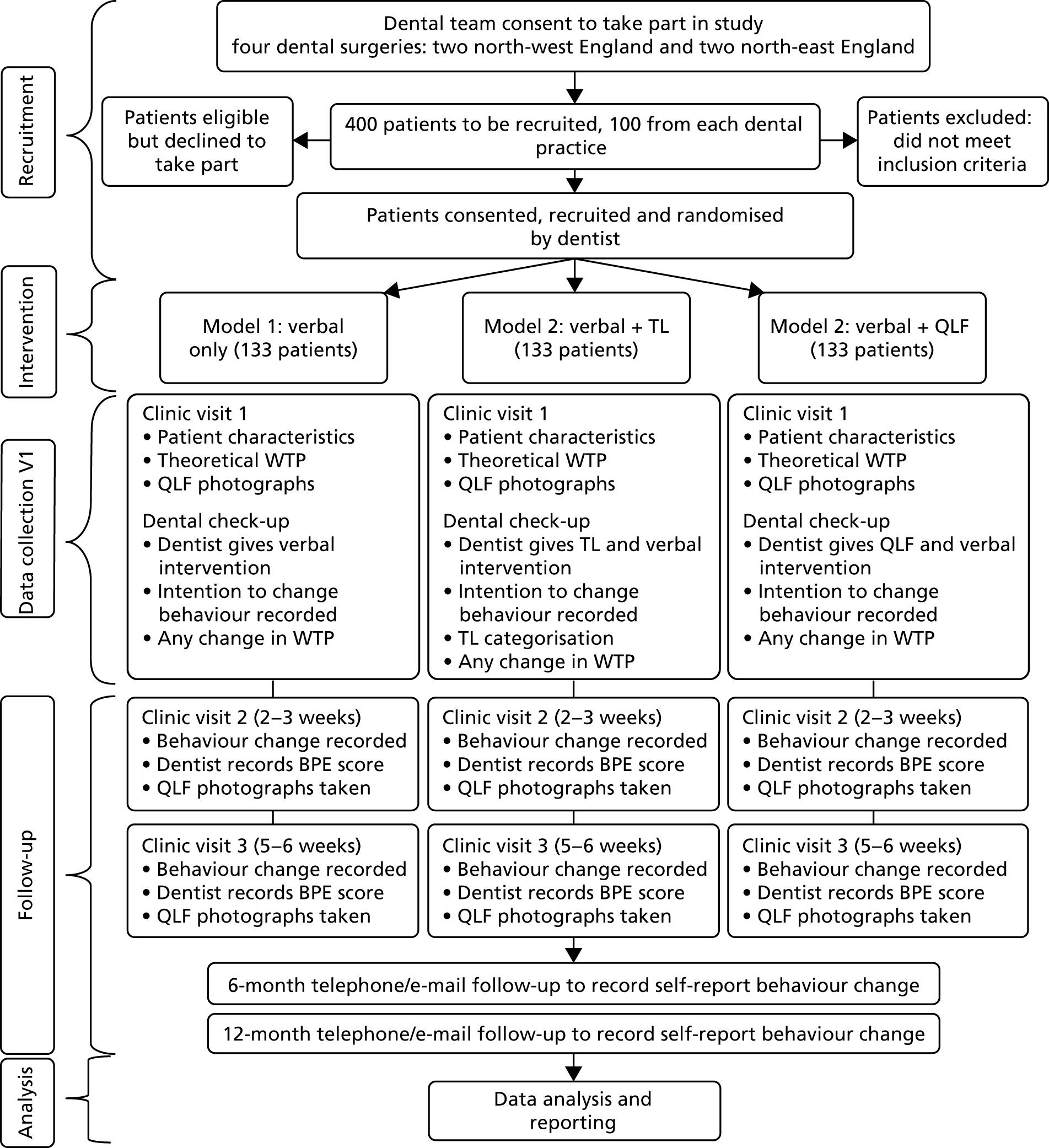

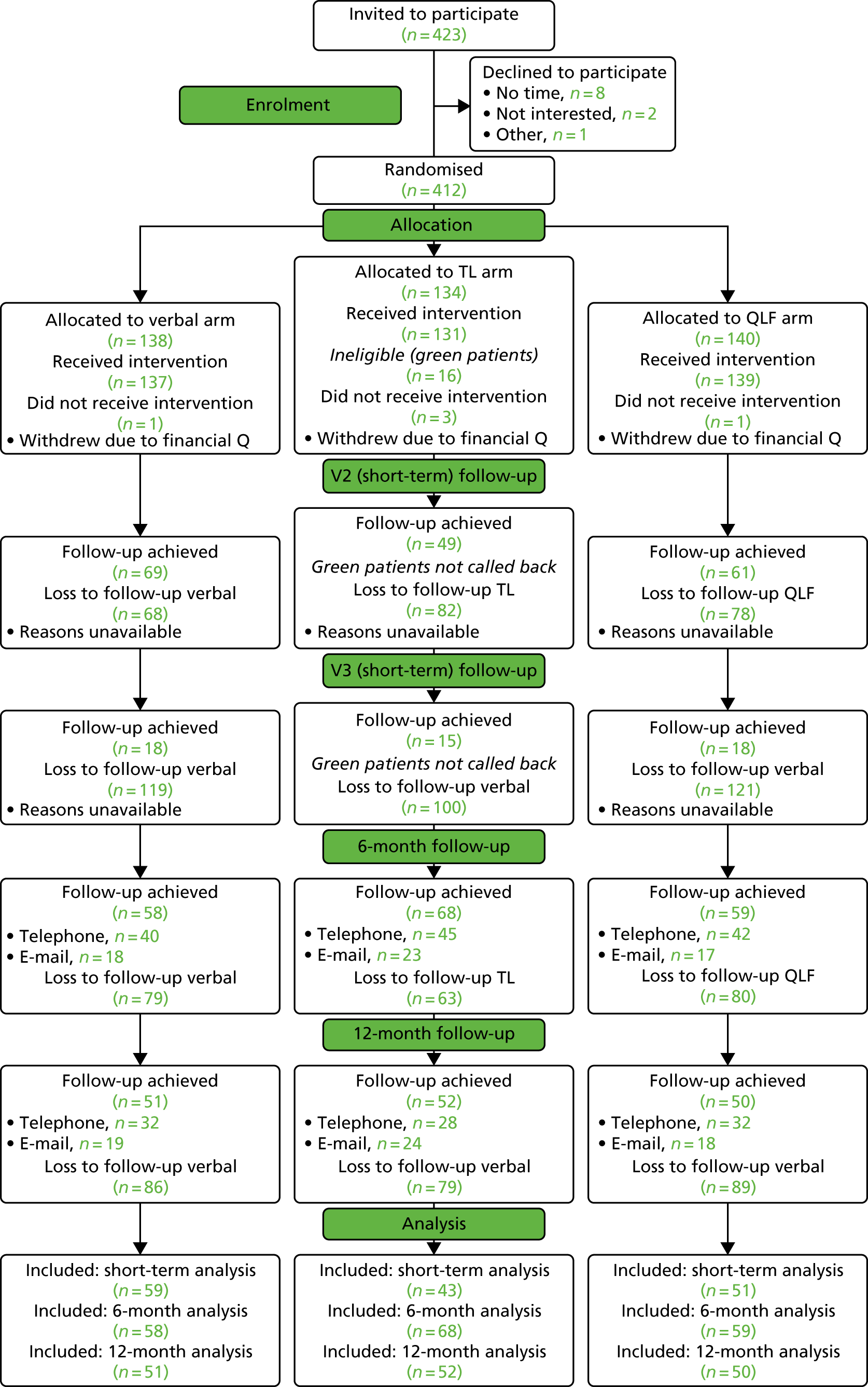

Study flow diagram

Figure 9 outlines the patient flow through the trial, with details on the study intervention arms and procedures.

FIGURE 9.

Study flow diagram.

Data collection schedule

Data were collected at baseline and at short-term (V2/V3), medium-term (6 months) and long-term (12 months) follow-up. Table 5 shows the data collection schedule and the sequence of measures collected. At each dental practice, data were entered directly onto a tablet PC computer (Samsung, Seoul, South Korea) using Qualtrics survey software [version 092017 © 2017 Qualtrics® (Provo, UT, USA)]. Trained dental nurses started by entering patients’ sociodemographic data fields and then undertook an assessment of patients’ literacy using a laminated card with REALM-R words. The tablet was then passed to the patients, who then entered data onto the tablet, including the completion of the WTP task, assisted by the dental nurse when required.

| Event | Completed by | Time point | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | V2 | V3 | 6 months | 12 months | ||

| Demographics | Dental nurse | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| REALM-R | Dental nurse | ✗ | ||||

| WTP | Patient | ✗ | ||||

| Demographics | Patient | ✗ | ||||

| Self-assessed oral health | Patient | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| MDAS | Patient | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Demographics | Patient | ✗ | ||||

| QLF photo | Dental nurse | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| BPE | Dentist | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| WTP revision | Patient | ✗ | ||||

| EPPM and behaviour change | Patient | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| CAT | Patient | ✗ | ✗ | |||

Quantitative light-induced fluorescence photographs were taken by the dental nurse (with the patient brushing their teeth between the two photographs taken for plaque/caries purposes). Patients then went into the surgery with the tablet, the dentist entered the BPE score and the number of natural teeth data, and after that the check-up was completed. Once group allocation was disclosed, only patients in the QLF arm received a copy of their photograph. Patients completed the remaining fields (including CAT) on the tablet after leaving the surgery.

Because participants were patients at high/medium risk of poor oral health, all would have been scheduled for return/treatment visits. Further data were collected during the initial follow-up visit (V2 at 2–3 weeks post intervention) and at a further follow-up visit (V3, 5–6-weeks post intervention) where these occurred. At V2 and V3, dentists entered data on the BPE score and further QLF photographs were taken (not shown to the patient) as a follow-up clinical outcome measure. Patients completed other fields related to behaviour at V2/V3.