Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/196/04. The contractual start date was in September 2016. The final report began editorial review in March 2019 and was accepted for publication in September 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Sharon Spooner and Kath Checkland work as general practitioners in the English NHS. Ruth McDonald, Sharon Spooner and Kath Checkland are employed by the Centre for Primary Care and Health Services Research, which is part-funded by National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research (SPCR) funding. Ruth McDonald and Kath Checkland’s posts were part-funded by NIHR Greater Manchester Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) funding until September 2019. Kath Checkland's salary is part-funded by the NIHR Policy Research Unit in the Health and Care System and Commissioning. During the study, Ruth McDonald was joint principal investigator for the Policy Research Programme (PRP)-funded research Evaluation of strategies for supporting innovation in the NHS to improve quality and efficiency. Kath Checkland was principal investigator for the NIHR PRP-funded national evaluation of the Vanguard for New Care Models programme. Sharon Spooner’s NIHR grants during this period were for An investigation of the scale, scope and impact of skill mix change in primary care (Health Services and Delivery Research 17/08/25); An investigation into the career intentions and training experiences of newly qualified general practitioners (NCITE) (NIHR SPCR); An investigation of factors which are associated with successful transitions from GP Specialty Training Programmes to long-term careers in NHS general practice (FIT2GP) (NIHR SPCR); and An investigation of the factors behind the training choices of junior doctors which result in inadequate recruitment to general practice careers (FACSTiM) (NIHR SPCR).

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by McDonald et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

In England, most general practitioners (GPs) are based in general practices, which are, mostly, small professional partnerships independent of other general practices. However, recent decades have seen successive organisational reforms encouraging GPs from different practices to collaborate,1–10 particularly (but not exclusively) in relation to commissioning care for NHS patients. In addition to collaborating to commission care and provide out-of-hours services, GPs have started to come together to create new provider collaborations between practices. 11 These new organisational forms are sometimes referred to as GP federations, defined by the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) as groups of practices and primary care teams that work together, sharing responsibility for the development and delivery of high-quality, patient-focused services for their local populations. 12 In 2010, the RCGP, in conjunction with various organisations, published a primary care federations toolkit12 that includes advice, evidence, case studies and other resources intended to help practices navigate the changing organisational landscape.

General practitioner federations vary in scope, geographical reach and organisational form, from loose alliances of a small number of local practices to much larger organisations,11 some of which have been established as limited companies. Potential benefits of federations might include efficiencies of scale and scope, strengthening capacity to deliver services outside hospital (by either direct provision or contracting) and improving local integration. 12 Federations might also present many challenges including balancing the ways of working, autonomy and identity of individual practices with the requirements of more centralised and standardised procedures that interorganisational collaboration implies. Federations are substantially different from the traditional partnership model; however, little is known about how federations are working in practice and the implications of different organisational forms for the organisation of primary care.

The changing context of English general practice

The context for this report is England, as responsibility for health-care policy was fully devolved to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland in 1999. 13 Thereafter, health-care policy increasingly diverged across the four nations.

General practice as a profession

Traditionally, GPs in practices have enjoyed a high degree of autonomy with regard to their clinical practice. 14 As generalists, their professional identity narrative is based on a biographical approach to medical care,14 emphasising a ‘patient-centred’ approach to the patient consultation,15 although this aspiration is not necessarily matched by the reality. 16 This patient-centred narrative traditionally helped GPs to maintain clinical autonomy and control14 and involved GPs incorporating a range of diverse elements (e.g. time, organisation, knowledge of the patient, financial considerations) into their decision-making process. However, this idiosyncratic approach to decision-making, reflecting high levels of individual discretion, has been constrained over time by the state, peers, pharmacists, nurses and patients. 17,18 Furthermore, over time, there has been an increasing acceptance by GPs of the legitimacy of scrutiny and accountability in relation to their work. 19

The growth of and support for evidence-based medicine by professional elites has been described as justifying professional autonomy, legitimising GPs’ decisions on the basis of their access to this knowledge. Yet there is a tension between the preservation of the powers of the profession as a collective and the ability of individual practitioners to exercise clinical discretion. 14,18 As we discuss further in the following section, various initiatives have contributed to a move away from individualised decision-making and towards a more standardised and collaborative way of working. 19

General practice collaborative working: a recent history

These developments build on a rich, layered history of collaborative working and network arrangements in UK and English general practice. The first formalised initiative of note occurred in the form of Medical Audit Advisory Groups (MAAGs) in the late 1980s, which saw groups of practices in particular geographical areas working together to audit care across their patch and share best practice. 2,20 Evidence from attempts elsewhere to incorporate peer review and audit21 provided encouragement for those seeking to introduce greater conformity and co-operation within and between practices. 22 In the early 1990s, in the context of the creation of the internal market and the split between the purchasing and providing of care,23 general practitioner fundholding (GPFH) was introduced. This voluntary scheme allowed practices access to a portion of secondary and community care budgets to purchase certain services for their patients (e.g. various inpatient and outpatient services), with any surpluses generated available for reinvestment in the practices for patient benefit. 24 In many cases, groups of practices worked together in consortia or multifund groups to purchase care under the scheme. Total purchasing pilots,25 introduced in 1995, built on aspects of the GPFH model and allowed groups of practices to, in theory, purchase all secondary and community care for their patient population with the budget delegated to them by the Health Authority (which retained statutory responsibility for the spending).

In parallel with these developments in care commissioning, out-of-hours co-operatives (or GP co-operatives) emerged as a notable form of networked primary care provision in response to heightened pressures associated with delivering care out of hours. 6 GP co-operatives involved groups of practices coming together, often formally as a non-profit organisation, and jointly developing processes to provide out-of-hours services to all patients in their combined geographical area. A variety of models was employed, but common practices involved the use of a central telephone triage function and patient access ‘hubs’ in convenient locations.

In 1997, following a change in government, GPFH and MAAGs were formally abolished. The policy language used to describe the acquisition of care shifted from ‘purchasing’ to ‘commissioning’. A small number of GP commissioning pilots were launched to test different commissioning models. These were predicated on collaborative working between local clinicians to commission secondary and community care and included a role for public stakeholders. The pilots ran for 2 years but were superseded by Primary Care Groups (PCGs). These new organisations were intended to extend GP involvement in commissioning further than ever before. Each typically covered a patient population of 50,000–100,000 and it was compulsory for general practices to join one (although there was some flexibility in terms of their level of involvement). Within 3 years, however, all PCGs had evolved into primary care trusts (PCTs) and the level of GP involvement in these new, more autonomous organisations was significantly curtailed.

The emergence of the more managerially focused PCTs was one reason why, by the mid-2000s, collaborative activities between general practices had begun to wane significantly. 26 Other factors are also of importance in explaining this trend. Changes to payment mechanisms also meant that collective provision of additional services across more than one practice became more difficult, with the new general medical services (GMS) contract of 2004 supporting the individual provision by practices of what were called ‘Local Enhanced Services’. 27 This did not provide a straightforward mechanism for remunerating practices for offering additional services to patients beyond those registered on their practice list, and was associated with the disappearance of many GP co-operatives. By 2004, it was clear that collaborative activity between practices and engagement in the commissioning and collective provision of services had declined. 26 To remedy this, and to re-engage GPs in commissioning services, practice-based commissioning (PBC)28 was introduced in 2005. GP consortia formed, each becoming established as a subcommittee of a local PCT, and were allocated an indicative budget.

The refreshed role for GPs working collaboratively to commission care was a feature of a broader set of measures, including increased choice of providers for patients and the introduction of Payment by Results contracts (so funding would ‘follow the patient’). GPs were seen as key to fulfilling an aspiration to help create a more efficient system in which services were more local to patients and better suited to their needs. Like with GPFH, any profits realised from clinical commissioning could be reinvested by consortia for patient benefit. A review of GPs’ involvement in commissioning in the English NHS between 1991 and 2010 concluded that this focused on activities closest to general practice, such as prescribing, and developing general practice and community health services. There was little evidence that GPs’ involvement in commissioning had improved the delivery of secondary care services or overall outcomes. 8 This does not suggest that GP groups have been able to make meaningful system-wide change, despite working together, albeit in forms that differ from GP federations. By 2010, many consortia were considering formalising structures and relationships and developing formal provider organisations, using a variety of organisational forms such as Community Interest Companies. At around the same time, GP provider federations began to be promoted by organisations such as the RCGP,29 and many of these had a focus on collective provision by general practices.

In 2012, clinical commissioning and collaborative working between general practices became even more firmly established in the structure and operation of the English NHS in the form of Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs). These GP-led, compulsory membership organisations were allocated responsibility for around two-thirds of the total English NHS budget and charged with commissioning most secondary and community care. In their establishment, CCGs were initially afforded considerable flexibility when forming their geographical footprint and general practice composition, which, in many cases, reflected previous working arrangements relating to PBC and other prior collaborative arrangements. Initially, due to concerns about conflicts of interest, CCGs did not have a role in commissioning primary care services from their members, but, over time, this has been relaxed, with an increasing number taking on delegated responsibility for this function from NHS England. Through this co-commissioning of primary care, many CCGs have opted to reintroduce various incentives and peer audit processes developed through PBC to foster closer working between GPs. 30

Pressures on primary medical care and renewed support for collaborative working

The move towards creating and joining GP federations has taken place in the context of significant pressures on general practice in England. 31,32 These include rising patient demand in general practice and other NHS and social care sectors, NHS budgetary constraints, increasing expectations concerning quality and reduction of variations in general practice, and recruitment and retention issues. The recruitment and retention issues have been exacerbated, in the context of an ageing workforce, by incentives for GPs to retire early, created by tax changes affecting their pensions. 33 This has also happened during a period when traditional general practices have felt under threat from non-GP-owned private companies tendering to provide general practice services. 34 This was enabled with the ‘alternative provider of medical services’ (APMS)34 NHS contract route introduced in 2004 to increase capacity and broaden the range of providers of primary medical care, and subsequent ‘any willing provider’ and ‘any qualified provider’ policies.

Over the last decade or so, policy-makers have encouraged ‘primary care at scale’ working, viewing this as a solution to the problems in primary care. 35 (We use the term ‘at scale’ to cover arrangements that involve practices working together, which could include, but is not limited to, working in federations). Another policy strand has focused on new models of care, which included 50 ‘vanguards’36 focused on delivering the NHS Five Year Forward View. 37 Some of these involve new ways of working, with the intention being to bring together providers to collaborate on improving and integrating services. Other initiatives are aimed at helping an overburdened general practice, through policies such as funding pharmacists to work in general practices. 38 These three strands have existed alongside each other, rather than being integrated to focus on joining up potential solutions. Another initiative, Primary Care Home, developed by the National Association of Primary Care,39 aims to strengthen and redesign primary care, bringing together a range of health and social care professionals. The Primary Care Home initiative is cited as informing the new policy of encouraging and incentivising practices to work together across a geographical footprint in primary care networks (PCNs). 40 This is a complex policy, which we will return to in the discussion. However, it is noteworthy that, in their early stages, PCNs are being expected to address issues relating to extended access and broadening workforce skill mix.

There is, therefore, an array of policies directed towards the development of at-scale working in primary care. The intention is for practices to work collaboratively to provide enhanced care for their local community. Although policy-makers have acknowledged the need to expand the primary care workforce,35 they have also imposed targets for increasing access to general medical practice, adding to existing pressures on GPs and practice staff more generally. Furthermore, the emphasis on new collaborative structures implicitly assumes that structural reorganisation will go a long way to solving the problems, which leads to GPs leaving the profession and workforce shortages more generally. It also assumes the existence of sufficient knowledge, skills and human resources (HR), which will be required to staff these new structures. Although collaborative organisational forms offer the potential to strengthen the workforce,41–43 this would require substantial time and resources. Bringing together organisations that face problems may have an intuitive appeal but may not produce the desired results in a context of workforce shortages and rising expectations. 44 Although there are widespread perceptions that there has been a transfer of responsibilities from secondary to primary care, with practices expected to undertake tasks previously performed in secondary care, there has been no associated shift in resources or significant disinvestment in secondary care provision. This may act as an incentive for practices to come together to provide and draw on support, but it also raises questions about the capacity of practices to actively participate in emerging organisations, as well as the resource implications of doing so.

Furthermore, GP federations operate within a broader health system characterised by perverse and conflicting incentives and a range of diverse organisations involved in the provision and commissioning of health and social care services. This places significant constraints on their ability to engage in system-wide change. 8,45 In these circumstances, collaboration or at-scale working may begin to resemble an intrinsically idealistic46 solution that exists independently of a problem, becoming attached to it when a policy window presents an opportunity for this to happen. 47 Yet policies are likely to fail when these are formulated in denial of their contextual reality. 46 The collapse of federations and failures to deliver contracted services48–50 in a challenging context suggest that federating is, therefore, not a universal panacea.

In response to the pressures affecting the NHS more generally, NHS England has proposed a significant shift in the way that services are commissioned and provided, with integration between primary, secondary and community care services. 40,51 As part of the Five Year Forward View,37 NHS England divided England into 44 footprints, bringing together NHS, local authority and other health and care organisations to collaboratively determine the future of their health and care system. The systems were required to produce 5-year sustainability and transformation plans, intended to be place-based plans for the health and social care within their footprint. Subsequently, as NHS England has placed greater emphasis on system-wide working and integration, their name and nature have changed. In March 2017, these 44 systems were renamed sustainability and transformation partnerships (STPs),35 with their role being to enable services to be delivered in a more co-ordinated way, to decide system-wide priorities and to plan, collectively, how to improve citizens’ health. In some areas, STPs have evolved to form an integrated care system (ICS), involving even closer collaboration. In an ICS, NHS organisations, in partnership with local councils and others, take collective responsibility for managing resources, delivering NHS standards and improving the health of the population they serve. 51

The NHS Long Term Plan40 places great emphasis on integration and states that, by April 2021, ICSs will cover the whole of England, growing out of the current network of STPs. GPs working collaboratively will be a key element of these new arrangements. There is, however, little evidence that integrated care initiatives, comprising interorganisational collaborations and/or mergers, have reduced service use or produced cost savings. 52,53

In March 2017, NHS England announced that practices were to be encouraged to work together in networks serving populations of at least 30,000 to 50,000. 35 Following on from this, the 2018 planning guidance for the NHS54 emphasised actively encouraging every practice to be part of a local PCN, with the goal of ensuring complete geographically contiguous population coverage of PCNs by the end of 2018/19, serving populations of at least 30,000 to 50,000. The NHS Long Term Plan40 added more detail on proposals for PCNs. It promised new investment to fund expanded community multidisciplinary teams aligned with new PCNs based on neighbouring general practices that work together typically covering 30,000–50,000 people. A set of multiyear contract changes will result in individual practices in a local area entering into a network [Directed Enhanced Service (DES)] contract as an extension of their existing contract, and have a designated single fund through which all network resources will flow. 40 (DES contracts involve additional services that GPs can choose to provide to their patients and that are financially incentivised by NHS England). PCNs will have a single clinical director, appointed from local general practices, and will be represented on the ICS partnership board. Their focus will be on population health management and on the provision of a wider variety of services in the community. The ‘network contract’ will bring together existing ‘enhanced’ services across a network area and will fund the appointment of new types of clinical workers (e.g. physiotherapists, pharmacists) across the network. Community services will be more closely aligned with networks, to support the provision of integrated care to defined geographical populations. Practices were required to join a network, and those unable to do this on a voluntary basis would be assigned to a network by NHS England. Importantly, it is envisaged that network practices will be geographically contiguous in their coverage. Networks had to be formed by July 2019. 40 Approaching the deadline, it was reported that 99% of practices were participating, with only 25 practices (of about 7000 practices nationally) actively deciding not to participate. 55

Primary care networks are different from federations, the latter being ‘bottom-up’ organisations. Although the terms network and federation have been used interchangeably on some occasions (e.g. General Practice Forward View38), the central policy of PCN creation, although allowing some local freedom, is fairly prescriptive in terms of the likely size of PCNs, their role and the need for a geographically consistent footprint. Therefore, federations, as they were not developed in response to an NHS England policy direction, have much greater freedom. However, the creation of PCNs in a landscape where federations have existed for some time raises questions about the ways in which these different types of organisations interact and develop over time.

Lessons from the literature

When considering successive waves of collaboration in primary care together, it becomes clear how influential previous arrangements have been in shaping local responses to, and the form of, subsequent arrangements. 56 For example, the legacies of specific local partnerships and networking footprints associated with MAAGs, GP co-operatives and GPFH can been seen expressed in the political dynamics of PCGs or the delineation of sub-CCG ‘neighbourhoods’. 57

Research also identifies a number of other issues of particular importance to networked arrangements in primary care:

-

General practitioners tend to work together most successfully when they have some agency over deciding with whom they collaborate and how they do so. 58,59

-

Successful collaborations tend to be in response to or focused on issues of particular salience to GPs and their everyday work. 26

-

Sufficient trust between parties is of crucial importance to successful collaborations – this can take time and effort to establish or build.

-

Historic issues between individuals and groups can mediate the success of this process. 60

A recent systematic review of new forms of large-scale general practice provider collaborations in England61 (see Appendix 1 for more detail) found that larger scale could contribute positively to sustainability in general practice through standardised processes and operational efficiency, maximising income, enhancing the workforce and deploying technology. However, it highlighted the significant levels of leadership and resources needed to create, develop and maintain these organisations. The quality of relationships with commissioners and local providers was found to be an important influence on the extent to which the GP organisations could go beyond the provision of core services.

Networks in health care

There is a literature that is concerned with organisational forms (called variously alliances, partnerships, networks and collaborations) in relation and as a response to problems facing public service provision. We use the term ‘network’ here for simplicity’s sake. Studies focusing on public services suggest that networks are particularly effective in tackling ‘wicked problems’62,63 and are able to respond rapidly to a changing environment. 64,65

Ferlie et al. 41 suggest that public networks with strong professions are characterised by a relatively benign ‘post bureaucratic’ style. This chimes with much of the literature on networks, which contrasts them with hierarchical, bureaucratic organisational forms. 66 Various commentators identify networks as embodiments of heterarchy that overcome weaknesses of hierarchical forms of organisation. 67–69 However, this raises questions about how and to what extent heterarchical and hierarchical forms interact in the context of formal organisations, such as federations, as well as the nature, location and mechanisms of accountability in these network forms. 70

Network structures and practices can vary widely, but Ferlie et al. 41 identify six continua to classify network forms, which are as follows: (1) the extent of complexity in the context; (2) mandated, hybrid or organic networks; (3) the extent of resourcing (including dedicated staffing time); (4) the extent to which roles, structures and governance are formalised; (5) the number and variety of stakeholder groups and the internal power balance; and (6) shared and accepted norms underpinning decision-making processes and management skills, which could enable collective decision-making or shared learning to occur.

Complexity of context

Smaller scale and simpler settings ‘have been identified as being “less challenging” ’,41 although to say that contexts are less complex because they are ‘simpler’ is a somewhat tautological explanation. ‘The dimension of “complexity” might include such indicators as: scale; the size of the population affected; challenging geography; extent of social deprivation or multi culturalism; number of teaching hospitals; degree of behaviour change sought’41 (contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0.).

Mandatory/hybrid/organic

Federations are bottom-up organisations and they are not mandated. One consequence of this may be to exacerbate inequalities, with only the more capable practices entering into at-scale working arrangements. Furthermore, voluntary participation means that even these well-placed practices may fall far short of implementing recommended behaviours if they involve managing clinical and financial risk. 71

Mandating collaborative working among health-care providers in a ‘top-down’ manner can provide a stimulus to develop new relationships. 72 However, this is likely to result in clinician disengagement compared with collaborations that emerge organically. 73,74 (It is worth mentioning that Guthrie et al. 45 found that distinctions between mandated and voluntary networks may overstate the extent to which these represent a dichotomy. Furthermore, they observed that, over time, initial advantages and disadvantages relating to the voluntary/mandated status of networks became less well defined as the mandated networks they studied matured.)

Degree of resourcing

Most commentators agree that organisations find autonomy preferable to dependence, but that they may sacrifice some of this to gain access to increased resources. Theories that focus on resource acquisition75–77 suggest that, by forming collaborative alliances, organisations will gain access to a wider range or volume of resources and/or capacity than would otherwise be the case. This may not be enough, however, to motivate organisations to actively engage in participation. 78–81 In the context of workforce shortages, whereby federations are successful in gaining access to resources, this may involve attracting staff from neighbouring federations, as the overall availability of care staff is fixed or limited in the short term at least. There is also the issue of who controls resources in federations, which we return to later.

The extent to which roles, structures and governance are formalised

Provan and Kenis82 see tensions arising from the need to maintain a stable and sustainable formal structure and avoiding bureaucratic hierarchical processes, which risk destroying the intent and purpose of the form and alienating network members. Informal and more flexible arrangements may be easier for smaller networks,72 but larger networks may be more able to influence the local health economy, bear financial risks and manage the administrative requirements of regulation. 81 There is no clear consistent relationship between the size of health-care organisations and their performance,72 but smaller collaborations may be able to exercise greater performance management accountability. 83 The size of the population needed to manage clinical risks and associated costs is another consideration, which depends on the range of services for which the organisation is responsible and the pre-existing health of the population. 11,53,84

According to Provan and Kenis,82 networks face tensions between the need for internal and external legitimacy and between the need for administrative efficiency and inclusive decision-making. These have implications for governance arrangements. Developing a governance structure that is both stable and flexible requires ongoing monitoring of structural mechanisms and procedures, and a willingness to make changes when necessary. 82 A perception of organisational legitimacy82 is important. For example, if practices wish to bid for resources, they may appear to have greater legitimacy to external funders if they are collaborating as part of a group than if they are bidding as individual entities. The building of trust with external stakeholders and members has been seen as important, as this has implications for autonomy. 81 Perceived trust has been shown to be linked to achievement of goals and increased interactions. 85 O’Leary and Blomgren Bingham78 suggest that, although organisations may relinquish control over some aspects of organisational business, they may develop new sources of autonomy, linked to new forms of power.

We might expect that governance structures are designed to meet the functions of the network. However, Shortell and Addicott86 suggest that governance structures are not necessarily designed with a clear definition of network functions in mind. Instead, new organisational forms emerge in response to problems associated with existing forms, and functions are worked out later, based on activities that these new forms can enable. They also suggest that governance through networks requires leadership, rather than authority, as well as ‘bargaining, negotiation, guidance and facilitation’. 86 These new organisational forms are characterised by high-risk interdependent relationships, which require accountability mechanisms that clearly locate responsibility for actions and allow for the exercise of professional judgment. 70

Provan and Kenis82 hypothesise that, as networks develop, their governance arrangements will tend to shift from relatively participative, democratic, egalitarian forms to more centralised, brokered, formal governance. These formal arrangements may go some way to addressing concerns about accountability of network forms. 70 Collaborative forms, especially where these are not mandated, offer the potential to exercise greater control over professionals,19,41,87 with a more hierarchical structure helping to focus network activities on their strategic goals. 70 Of course, even where formal structures and processes exist, we cannot assume that they are necessarily followed to the letter, so it is important to go beyond the formal structures to understand how governance is manifest in practice.

With regard to networks involving general practices, Sheaff et al. 52 highlight that accountability operates by concertive control, ‘legitimation of collective decisions by appeal either to an organisational culture or to technical knowledge; and as a last resort expulsion of non-compliant members’; ‘members or partners monitor each other’s work and through peer pressure prevent shirking’ (contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0.). Concertive control involves workers reaching a consensus about how to manage their work, and collaborating to develop the means of their own control. 88 This results in a shift from management to workers controlling themselves in a way that constrains organisation members more tightly than under traditional bureaucratic control, relying for its effectiveness on close working within teams of peers. This raises questions about the feasibility and effectiveness of this approach in federations, which comprise large numbers of staff from a range of groupings and member organisations. The issue of compliance and accountability may be important when federations seek to standardise processes and meet key performance indicators. However, GP federations also need to engage member practices, especially because, in many cases, they are reliant on them for their existence, and hierarchical governance can leave individual GPs feeling alienated. 89 Furthermore, in some cases, practices have a choice of federations and participation is not mandated in a top-down manner.

In terms of governance and ownership, Pettigrew et al. 72 suggest that non-hierarchical and hierarchical organisations are likely to bring about change through different internal mechanisms. They are likely to have different organisational goals and require different levers to maximise performance. 52 However, this dichotomy ignores the fact that change may be best achieved using a combination of top-down and bottom-up mechanisms. 90

With regard to specific governance issues, conflicts of interest can emerge when providers also act as commissioners of services, which could happen if/when GPs sell their practice to a larger group. 91,92 According to Pettigrew et al. ,72 this could also pose the risk of creating an organisation that becomes ‘too big to fail’,72 thereby needing public funds to bail it out. 93,94

The number and variety of stakeholder groups and internal power balance

Federations operate within a broader landscape populated by a range of stakeholders and influenced by a collection of regulatory and other policies and mechanisms. Their activities and fortunes will be subject to the constraints imposed on them by local and national policy-makers, which may distort their purpose and practices. 95–97 In addition, the divergent performance frameworks characterising organisations and stakeholders within health economies act to inhibit collaboration. 98

Studies that have examined networks involving groups of people from different types of organisations have identified power differentials, among other things, as inhibiting network progress. 98,99 Specialists, particularly hospital surgeons and hospital physicians, enjoy an elevated status compared with GPs,98 GPs being dubbed the ‘subalterns’ of medicine. 100 This means that the views of hospital surgeons and hospital physicians are likely to prevail, regardless of any formal arrangements ostensibly embodying parity across network members. 41,97,99 Federations are composed of practices as opposed to more diverse groups of stakeholders. However, within practices hierarchies exist based on professional status and practice ownership, resulting in power asymmetries, which may be reproduced in collaborative ventures. These power differentials are also likely to inhibit lay and service user representatives involved.

With regard to lay and/or service user input into networks, in many cases this is reported as being absent or limited,41,45 although this is not always the case. Sheaff et al. 52 suggest that service user involvement in voluntary networks will be more extensive, but also more uneven, than in mandated networks. They describe public and patient participation being used as an ‘add on’ to networks, after the networks’ main function and membership were established. They specify two necessary conditions for extensive and influential involvement of users in health networks: users (1) dominate the co-ordinating body and (2) are integral to the network’s core process.

Shared and accepted norms underpinning decision-making processes and management skills that could enable collective decision-making or shared learning to occur

A number of studies emphasise the importance of a shared vision of purpose, trusting relationships and good leadership, in particular the importance of clinical–managerial hybrid leaders with ‘soft’ skills. 11,41,45,52,101 Boundary-spanning roles and the ‘capacity to hold multiple perspectives within the federation’102 are also seen as contributing to network effectiveness. 41,45 In part, these roles are necessary because of the absence of formal authority and power over staff and/or resources in a context of diverse network membership. In these circumstances, networks rely on co-operation and co-ordination, rather than a strong mandate and/or statutory status. 41,45

With regard to effective network processes, it is advisable to avoid too strong a focus on business-dominated meetings. This means that networks should create opportunities for network members to come together to exchange ideas and influence decisions. 41

In the networks literature, the distinction between the terms ‘leader’ and ‘manager’ is not always clear. However, heroic leadership11 is seen as unsustainable, with leadership by small teams (‘duos and trios’41) viewed as preferable to a highly individualistic approach. Many of the positive attributes of managers and/or leaders (e.g. ability to combine soft and ‘hard’ approaches to management,41 span boundaries,41 draw on social capital,52 communicate effectively43) in networks might plausibly be applied to managers and leaders in organisations more generally.

Several authors highlight the importance of culture,52 with some suggesting that an ‘inclusive organisational culture’43 is a key feature of effective networks. This is defined in one study as involving widespread engagement and participation. 43 However, it could be argued that this is an aspect of a management or leadership style, rather than being a ‘culture’ that is shared by all members. General practice has been described as predominantly characterised by a clan culture. 103 However, at the level of the individual practice there is no discernible relationship between culture and performance,103 which raises questions about the mechanisms by which culture is assumed to be influential at a network level. A pragmatic and widely used definition of culture as ‘the way we do things around here’104 raises questions about who ‘we’ are in the context of federations. Furthermore, a shared culture will take time to evolve. For federations in their early stages of development and where practices are members of organisations whose members may have little involvement with the central authority function of the federation, it is not clear how useful the notion of a shared culture would be. In addition, if practices work together at the subfederation level, then they may develop shared ways of relating and acting, which are different from, but not necessarily incompatible with, those of the federation. Rather than exploring the extent to which there is a shared federation culture, therefore, it may be more useful to examine the degree to which members are encouraged to and do engage with the federation and how this influences their attitudes and behaviours. Sheaff et al. 105 suggested that ‘network macroculture’ can be used to manage the formation and operation of health networks, but acknowledge that the main limitation of their argument is the absence of a standardised definition of (network or organisational) ‘culture’ and the existence of > 100 dimensions of ‘organisational culture’. It may be preferable, therefore, to describe structures and processes, and to use this in providing explanations, rather than to invoke ‘culture’, with all its problematic connotations. Regarding inclusive communication and engagement style, this issue can be explored without recourse to concepts such as culture, which may not be helpful in federations, particularly in their early stages of development.

Meta-organisations

As discussed, the term network has been used to denote a broad and diverse range of organisational forms, leading some to suggest that it has been used to describe far too many phenomena. 106 Networks have been contrasted with meta-organisations (MOs)107 and federations resemble MOs. An advantage of using the term MO is that the organisational form is clearly defined and this definition is very applicable to federations. According to MO theorists, there are large and significant differences between networks and MOs. 107–109 Networks are often based on differences (different types of organisations such as hospitals and primary care organisations), with the network providing opportunities for interactions that bring mutual advantages:

The collaboration itself is based on trust and reciprocity – on the assumption that those included in the network give, and that they receive in return. In most meta-organizations, on the other hand, the members take similarities as their starting point and there are efforts to clarify and manifest these similarities in making decisions about common rules. [. . .] Networks among organizations are embedded in a set of other social relationships (Thompson 2003: 144), and their boundaries are blurred [. . .] Meta-organizations, on the other hand, create boundaries between themselves and the world around them. They make decisions about who is a member and who is not. Instead of being embedded, meta-organizations strive to create autonomy and distinctions.

Ahrne and Brunsson107

Meta-organisation relationships are characterised by disembeddedness, as staff in the different member organisations may not meet in person. Instead, the foundation for creating trust is the MO’s striving towards similarity and shared status among its members, whereas network participants may develop trust via face-to-face interaction. Networks are viewed as less hierarchical than traditional organisational forms, but MOs are hierarchical in nature:

They possess an authoritative centre called a board, management, government, leadership, or some such term; and the people who comprise these units have the right to issue commands and rules prescribing their members’ actions [. . .] The right to enforce compliance with commands and rules requires organization; such rights do not exist outside organizations.

Ahrne and Brunsson107

Traditional forms of organising rely on hierarchical mechanisms to control and co-ordinate the activities of organisational employees,110,111 yet the members of MOs are not individual employees but organisations. 107 Although organisational employees are relatively dispensable, MOs are dependent on certain organisations being willing to join. This dependence of MOs on its member organisations to constitute its organisational identity contrasts with individual-based organisations, in which skill sets, as opposed to recruitment of certain individuals, are much more likely to influence the search for organisational members. 107 Combined with the important fact that MO membership is voluntary, this contributes to relations of interdependence, which are very different from those characterising both traditional organisations and networks. In MOs, member organisations retain their identity and a high degree of autonomy. 107,109 There is a potential tension, therefore, between the MO’s requirement for a degree of authority to organise its members and each member organisation’s need to organise itself.

There may be financial costs to member organisations that contribute to the central authority function, but often these costs are not high relative to members’ turnover. MO theory suggests that free-riding will be low because the benefits of membership relative to costs make membership attractive. However, this also means that organisations may join because they do not wish to be left out of the MO, rather than from a genuine interest in the MO’s purpose and activities. This contrasts with network studies that often depict members as actively engaged, even if they are, at times, constrained by power asymmetries in the network. Furthermore, whereas studies of networks have emphasised the danger that the network will be captured by powerful stakeholders, MO theory highlights the threat to the MO central authority from its member organisations. Combined with the absence of mandatory membership (unlike mandated networks and PCNs, which contain strong incentives to comply) the result can be that MOs become organisations for the weak, rather than the strong. 107 MOs are viewed as aiming for 100% membership and monopoly strengthens their position, yet competition can be a feature of the MO landscape, whereas this is usually absent in network contexts. However, as we elaborate on later, we suggest that competition for members between MOs can also have strengths, insofar as members being able to make an active choice between options can enhance legitimacy and compliance.

A key aspect of the attraction of MOs for individual organisations is strength in numbers far beyond that enjoyed by individual organisations. As part of this process, MOs can be seen as creating a protected zone,112 restricting the influence of other, at times more hostile, organisations outside the MO. This explicit rationale may mean that they are less vulnerable to pressures from the external environment than health networks. ‘Fear of the future’113 as an explicit driver for federation formation also suggests that to understand MOs we should, rather than asking what they are for, try to understand what it is that they are against. It also highlights the importance of emotion in motivating federation creation, whereas many network studies focus on rational, instrumental aspects neglecting the emotional dimension. In addition, although (implicit) support for the creation of a protected zone may be seen as a goal around which member organisations can coalesce, this does not imply collective support for all MO policies.

It has been suggested that MOs have specific characteristics, such as the need for member approval of decisions and development of an elitist identity, which make them prone to avoiding risk and uncertainty. 114 However, another view is that MOs encourage the development of organisational capabilities for sustainable innovation, by virtue of their ability to combine multiple stakeholders with reporting and accountability mechanisms. 115

Despite the emphasis on similarity, MO member organisations are characterised by dissimilarity (for federations all members are practices), but practices differ markedly in many respects. 116 To survive, MOs must manage differences between members and between the MO and its members. This involves continually having to balance their own identities (e.g. small-town GP federation) with those of its members (e.g. small-street practice). Members join MOs because they feel weaker without membership. The diverse membership of MOs means that they face trade-offs in terms of standardisation versus local freedom. 102 Furthermore, within MOs we would expect to see an avoidance of top-down directives, as these involve an element of constraint and inflexibility, thereby curbing member autonomy. 107 If MOs are to introduce and enforce clear rules, then it is easier to do this at their inception. 107 They may employ staff (‘direct’ resources), but they may also draw on ‘indirect’ resources,117 relying on staff from member organisations to undertake some of the MO’s work. Although the latter may cost less and involve staff who understand the local member context, it runs the risk that those staff will prioritise their employing organisation over the MO.

With regard to service users, the formation of a MO is aimed at reducing what members perceive as disorder, thereby increasing predictability and control, for themselves and their customers as well as other interested parties. We would not necessarily expect customers (or, in the NHS, patients or service users) to be involved in a MO’s activities, therefore, but they should be beneficiaries of the new more stable environment that the MO strives to create. 107

The foregoing provides useful and important lessons, as well as raising questions about how and to what extent these apply to federations working in practice today and the implications of these different organisational forms for the organisation of primary care.

Aims

The aims of the research were to:

-

provide a wide-ranging and in-depth exploration of GP federations in England

-

strengthen the evidence base on the organisation and management of general practice for the twenty-first century.

The second of these aims was based on an assumption that GP federations would endure for several years. However, recent policy announcements about PCNs raise questions about the future role of federations. Furthermore, PCNs are very different from federations in many respects and are still in the early stages of development, which makes it difficult, at this stage, to discern how these two organisational forms will interact with each other.

Research questions

This research focus was intended to allow us to provide answers to the following questions:

-

Managing practice processes – how does federation affect the way practices organise themselves internally, and which governance arrangements best enhance practices’ ability to work co-operatively with others?

-

Workforce – how does federating affect the way practices use their staff, skill mix, etc., and what impact does federating have on the general practice workforce?

-

Innovations in practices and interface with health-care and social care stakeholders – to what extent and how is the federation enabling or inhibiting integration with community and social care?

In addition to asking these ‘how’ and ‘to what extent’ questions, we also sought to provide answers that explain why these things happen in the way they do at each of the study sites.

Structure of the report

In Chapter 2, we describe the methods used in our study, as well as outlining changes to the original protocol and reasons for these changes. Chapter 3 contains in-depth descriptions of the case study sites and compares their differing approaches. It also draws out key drivers influencing relationships, events and attitudes at those sites. In Chapter 4, we explore the ways in which federation members worked together, as well as using the Improving Access to General Practice (IAGP)38 policy as a tracer issue to compare and contrast the ways in which the case study sites approached the requirement to increase access by 1 October 2018. Chapter 5 examines the working relationships between federations and a range of stakeholders in their environment. Chapter 6 synthesises and discusses the findings of the empirical chapters (see Chapters 3–5) using concepts from literature on MOs and networks to extrapolate beyond the detail of individual sites. Finally, Chapter 7 presents implications for policy and practice.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

There is a growing interest in the topic of general practices working together,61 with various researchers seeking to add to the knowledge on this topic. We designed this study to be different from, but also complementary to, other approaches that emphasise large-scale data collection via surveys118 and/or that focus on federations, which may be more developed than is typical, nationally. 13

We used a qualitative comparative case study design that was longitudinal in nature. We chose this approach because we envisaged that it was not possible to quantify the impact of changes on health (proxy) outcomes, given the diverse objectives of federations and the evolving nature of the organisations concerned. This design was appropriate to our research aims and research questions outlined in Chapter 1, as it enabled us to examine organisational process over time. It also allowed for an element of induction to identify aspects that had not been reported in previous studies. We planned for 200 interviews during the study (i.e. approximately 50 per case), including repeat interviews to capture development over time when indicated. This was because federations comprise large numbers of organisations, which employ a variety of staff types and include GP partner owners. In addition, we expected that federations would interact with other organisations (e.g. NHS trusts, local authorities) and we planned to interview staff from those external organisations too, as well as interviewing patients. As there was already a large literature on collaborative working and networks in health generally, it was also important to provide sufficient detail from case study sites to enable readers to make judgements about the extent to which federations did or did not resemble networks already described in the literature. This meant that observation was a key aspect of the design, as it was important to watch interactions and events generally, as opposed to relying on retrospective accounts.

We made a number of changes to our initial design, as we explain in the following section.

Key changes to the initial design

Case selection

We intended to undertake a national mapping exercise of federations and to include a non-federation case study site. Appendix 2 explains why we did not undertake these.

We planned to select four case studies to reflect a range of types of organisations, defined according to their form and function. In addition to one non-federation case study, we planned to select:

-

a set of general practices with collaborative arrangements but without a significant provider function (sharing back-office functions, staff or premises)

-

the creation of a provider entity separate to, but owned by, general practices

-

a formal merger of general practices into a super-practice.

This was based on our understanding of the landscape at the time of the bid. In addition, we were keen to avoid sites where federations were participating in other qualitative studies and those involved in national large-scale change initiatives, such as NHS vanguards, as overlapping initiatives involving the same practices would make it difficult to tease out the specific impact of the federation. We planned to use the mapping exercise to inform the selection of sites, but this was abandoned after several months. However, during this process, a staff member at one federation expressed an interest for their organisation to be included. This site partially met the criteria for category 1 above. It did not share back-office functions, but it did have a management team. We also recruited a site that intended to create a provider entity as described in point 2 above. An additional site was committed to standardising systems across practices in a way that differed from the other sites. It did not formally merge practices, but it did obtain registration with the Care Quality Commission (CQC), which meant pooling risk insofar as it was accountable to the CQC for the performance of all member practices. The other site was evolving from an informal collaborative organisation to one involved in bidding for contracts and providing new services.

All the sites were federations with a central authority function. Box 1 summarises key features of each.

-

One provider for CQC purposes, developing centralised systems for finance, payroll and intranet, and aiming to pool staff and share risk across the federation.

-

Bidding for service contracts, but without shared functions across practices.

-

Federation with provider entity created to run small number of practices and joint vehicle to deliver community health services with a local trust.

-

No significant provider function; less developed compared with other sites.

In all cases, we observed changes over time as goals, tactics and organisational forms underwent a process of evolution and adaptation. We explain more about these processes of evolution and adaptation in our empirical sections in Chapters 3 and 4. Therefore, rather than seeking to understand federation forms in terms of a snapshot at a point in time, we traced their ongoing journeys in the context of an evolving external environment.

The selection of sites was a more pragmatic and opportunist process than originally intended. We did not include a super-practice, but, based on our telephone survey, these are relatively rare. Furthermore, by selecting cases that had some features in common (e.g. employment of a management function, formal agreements), we were able to explore differences in processes and outcomes and the factors influencing these in terms other than differences in organisational forms. We also envisaged that factors such as whether or not there were other federations in the same geographical footprint competing to recruit member practices might influence events.

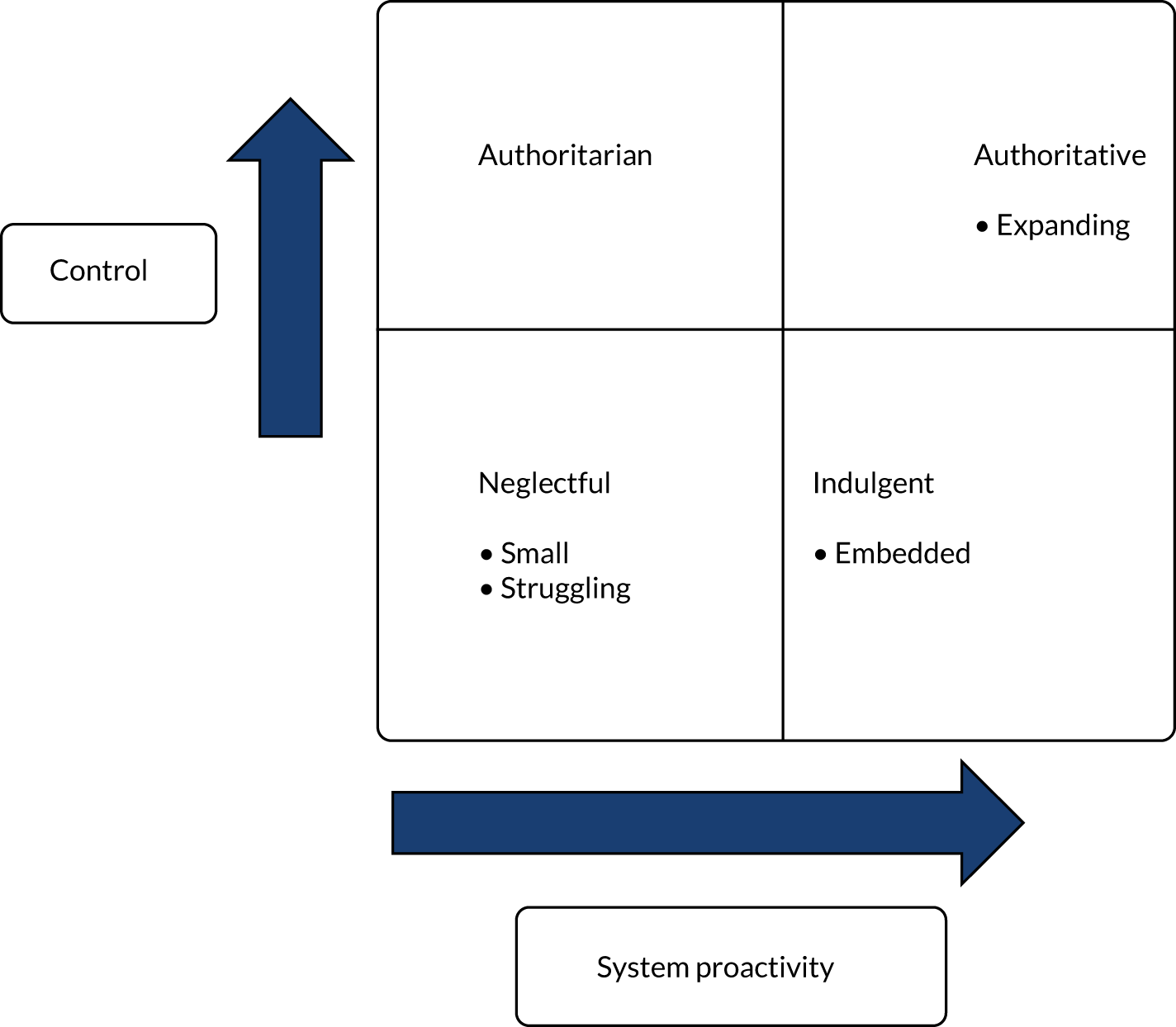

Case study data collection and analysis

Following four organisations over time enabled us to understand how federations were emerging and operating and allowed us to produce early lessons to inform their future development. To protect the identity of the sites, we use pseudonyms, which are indicative of the findings and of the broader characterisation of each site. These are Expanding, Embedded, Struggling and Small. We chose ‘Expanding’ because this site increased its membership over time and expanded its geographical coverage. ‘Embedded’ reflects the embedded nature of the federation, with close links to the CCG and no competing federations in its geographical footprint. The other two pseudonyms reflect the fact that Struggling experienced difficulties during the fieldwork that were much greater than those at the other sites and Small was chosen because of the size of the federation generally and, in particular, in relation to the other sites. We elaborate on this in Chapter 3. We also use pseudonyms in the vignettes included in Appendix 3 featuring individuals at case study sites.

Data collection

We used qualitative methods to explore the stated aims of federations and the mechanisms by which such aims were intended to be achieved, as well as assessing progress against these aims. Other foci included the perceptions of member practices, their motivations for joining, the mechanisms by which practices were working together within the federation, enabling and constraining factors regarding establishment and operation of the federation, and the impact on the constituent practices (in the widest possible sense, including practical impacts on their work and impacts on practice identity). We interviewed staff to explore the creation of the federation and its history and context, how the federation was intended to achieve its aims, as well as views on progress towards these aims. We recognised, from our earlier work and the literature, the difficulty in assessing the performance of federations,60 in part because of the different goals of different federations and the tendency for goals to shift in the light of changes in the wider policy environment. Nonetheless, we examined performance claims by federations, seeking to understand the mechanisms underlying any claimed benefits. In addition, we explored patient perceptions in our case study sites using interviews and focus groups.

Data collection involved attending and observing meetings and conducting documentary analysis in case study sites. We identified the meetings where federation leaders came together and focused, in all sites, on board meetings and other meetings of federation leaders. As time went on, we also observed meetings relating to IAGP, as well as any events to which the broader membership was invited [i.e. annual general meetings (AGMs) and open forums]. In total, 139 meetings were observed (Expanding, n = 43; Embedded, n = 28; Struggling, n = 39; and Small, n = 29), equating to almost 320 hours of observation (Table 1). In terms of documents, we examined business plans, shareholder agreements and documentation relating to governance structures and processes. These enabled us to gain an understanding of the formal structures and processes of the federation at each site.

| Site | Type and number of meeting observed | Total (n) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Federation | Federation services | Practice | Other | ||

| Federation A (Expanding) |

|

|

|

One strategy | 43 |

| Federation B (Embedded) |

|

IAGP was covered during other meetings |

|

|

28 |

| Federation C (Struggling) |

|

|

One CCG Patient consultation | – | 39 |

| Federation D (Small) |

|

Two IAGP |

|

|

29 |

| Total (n) | 77 | 25 | 29 | 8 | 139 |

Field notes taken during observation of meetings were added to at the earliest opportunity following the end of the meeting. These were typed in Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) documents by the observing researcher to enable easy access for analysis by core research team members. Interviews (n = 205) were conducted with a range of stakeholders and were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim (Table 2). We used a standard interview schedule, but varied the questions according to the role and background of the interviewee. In some cases, the questions were informed by observations undertaken prior to interview. In addition, the patient members of the advisory group helped to inform the interview topic guide, as well as the data collection and analysis more generally. We expected that federation activities would affect a range of different staff (for example, standardisation of software and/or documentation may result in changes for clinicians, managerial and administrative staff). We therefore aimed to interview a range of different types of staff and included a range of practices for staff interviews. Selection of interviewees was, in part, informed by the aims and activities of the federation, but, as a minimum, we aimed to interview clinicians (doctors, both partners and salaried GPs and nurses), practice managers (PMs), administrative staff and local providers (hospital and/or community). We interviewed patients and carers in a targeted way, namely we used the plans and activities of federations to identity potential impacts on patients, and chose relevant respondents. However, we also interviewed patients to ascertain their views and priorities in relation to their health care, comparing these with those of the federation.

| Site | Interviewee type (n) | Total interviews (n) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinicians | PMs | Federation staff | Patients | CCG | Other | ||

| Federation A | 17 | 5 | 11 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 45 |

| Federation B | 22 | 9 | 6 | 21 | 3 | 7 | 68 |

| Federation C | 23 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 43 |

| Federation D | 12 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 40 |

| National perspectives | 9 | ||||||

| Total | 74 | 24 | 27 | 45 | 10 | 16 | 205 |

Data collection time scales

We started our observations of meetings at the first two sites (Expanding and Struggling) in December 2016, and we commenced observations of meetings at the other two sites (Embedded and Small) in April 2017. All observation had ceased by the end of November 2018, although two interviews were conducted in January 2019. We lost access at one site (Struggling) where our meeting observations ceased in September 2017, but we conducted a small number of interviews at the site after that date that enabled us to fill in gaps in our knowledge of their story.

Data analysis

Owing to the need to capture events at federations as they were unfolding, we concentrated initially on data collection, with analysis comprising regular team meetings to discuss researchers’ experiences and reflections. After several months, we constructed a coding framework drawing on themes arising from the data. We used some of the concepts from the literature on GP working at scale, organisational networks, MOs and organisational behaviour to inform our understanding of the data. This literature also helped provide a focus for data collection. This was an iterative process, with periods of researchers coding independently, interspersed with regular meetings and discussion to address areas of disagreement to obtain consensus. We used NVivo 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to code data and this process helped to identify initial themes. Having identified relevant first-order codes, we conducted further analyses to refine what was a large number of codes to consolidate findings in a smaller number of second-order codes, which, although grounded in the data, reflect a higher level of abstraction. This process was aimed at providing generalisable lessons beyond the immediate cases.

After the initial 4 months focusing on data collection, we undertook data collection and analysis concurrently. In addition to observations recorded and reflected on, and interview transcripts, we used documentary analysis and relevant quantitative data produced and discussed in these settings to provide understanding, seeking out systematic relationships and patterns. We have attempted to reflect this in the presentation of data. Rather than insert short extracts from meeting notes, we use vignettes, based on observation and interviews, to convey key aspects of context, activities and interaction. Owing to their length, they are included in Appendix 3. We do use quotations from interviews in the main body of the report.

Ethics approval

We received ethics approval from the South East Scotland NHS Research Ethics Committee. As part of this process, we used generic job titles to describe individuals’ roles and, in some cases, to alter certain contextual details to preserve anonymity. We also did not quote directly from minutes of meetings to avoid the possibility that doing so would enable the individuals and/or organisations to be identified.

Conclusion

For each federation, we produced an in-depth description of organisational form, processes and activities, factors that influenced events and actions and a description of the extent to which ‘success’ (in terms of its stated aims) was achieved. We compared sites to look at common and site-specific factors to generate wider learning. We also examined the ways in which, and extent to which, the federations were involved in responding to the IAGP policy. We discuss this in more detail in Chapter 4, but before that, in Chapter 3, we provide detailed information on each of the case study sites.

Chapter 3 Case study sites: an in-depth discussion

Introduction

Federations differed in a number of respects. In this chapter, we draw on our observations, documentary analysis and interviews to describe formal structures and processes. We also discuss the findings in relation to the ways in which these evolved over time, and compare the formal arrangements with the day-to-day realities of how these worked in practice. As MOs, each federation had their own ‘central authority function. By central authority we mean a combination of structures and processes for making decisions and, when relevant, holding member organisations to account.

We found that a number of factors were important in influencing events at each site. These were the styles adopted by federations, historical context, the relationship between the federation and the CCG, the extent of competition between federations locally, money, size and geography, and leadership and management.

In this chapter, we aim to provide sufficient detail to convey the activities and processes in which federations participated. At the same time, word constraints and the need to protect the identities of our sites mean that we have been selective in what follows.

The characteristics in Table 3 are based on the position at the start of the fieldwork. We use rounding to avoid identification of sites.

| Characteristic | Federation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expanding | Embedded | Struggling | Small | |

| Size (n organisations) | 40 | 50 | 90 | < 10 |

| Size (n patients) | 330,000 | 335,000 | 500,000 | 90,000 |

| Competition for members | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Local geography | Predominantly urban | Predominantly urban | Predominantly urban | Rural and urban |

| Deprivation | Above average | Above average | Above average | Below average |

| Single local authority | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

These characteristics remained unchanged throughout, apart from changes to membership, which we describe in more detail in the following sections.

Site A: Expanding

History and geography

The federation was based in a largely urban area, in a major conurbation. At the start of the fieldwork, federation practices were located in one CCG, in which there was a history of working together in a number of geographical ‘localities’. In 2014, in the context of growing pressures and vulnerability, GP partners in two separate localities began discussing closer working and, in response, the CCG funded a series of ‘working-at-scale’ workshops, providing venues and facilitation consultants with influential key GPs invited to participate. During this period, the General Practice Forward View38 was published. In interviews, the founding board members were keen to highlight that their discussions around setting up the federation were clarified by the publication, rather than being a knee-jerk reaction to it.

Expanding had competition for members from three other local federations, two of which had expanded nationally. Their co-existence meant that the city’s CCG was keen not to be seen to favour any one GP federation, so initial support was limited to start-up workshops. During our fieldwork, the federation expanded its operations into a second geographical area, which was more rural in nature.

The majority of practices in the city had previously been involved in a provider collaboration that had ceased to exist. In terms of other forms of collaborative working, there was an existing ‘locality alliance’ situated within the federation itself. Before the federation began to bid to deliver services, the locality alliance had previously successfully bid alone to deliver services.

Core aims

Expanding aimed to help practices to retain their autonomy, providing leadership and support, and enable the delivery of high-quality care. As part of this process, it attempted to provide efficient centralised processes and systems to reduce the operational burden on practices. These included a single CQC registration, accounting and payroll, intranet system and staffing solutions. To facilitate this aim, all constituent practices were expected to convert to using these standard systems and related software as part of the joining process.

Structure, governance and decision-making

Structure

The federation formally commenced in November 2015, as an overarching umbrella organisation under which all the constituent practices retained their individual GP partnerships, ensuring their autonomy and the preservation of their individual GMS contracts.

Expanding was set up as a traditional partnership, with each partner being equal and having one vote at partner, or other, events. A detailed deed of partnership was drawn up by a legal firm and governed the rights and responsibilities of constituent practices. GP partners from member practices retained their income and autonomy with regard to the running of their practices. Two GP partners from the board were added to each of the constituent practice’s local partnership agreement, to protect smaller single- or two-handed practices from closure.

Governance

A transitional board was tasked with establishing the federation over a 6-month period (May–November 2015). Nominations were then sought from within the federation for the full board, and the election process was contracted to, and overseen by, an independent organisation. Partners were asked to vote for directors; the candidate securing the most votes was appointed chairperson of the board of directors.

Board of directors

The board of directors comprised seven directors (including the board chairperson); the board also included three non-voting officers: a part-time managing director (MD), a full-time chief operating officer (COO) and a full-time finance director (FD), all of whom were salaried. The board was chaired by a GP partner and, initially, all board directors were GP partners from constituent practices.

In May 2017, two additional directors were co-opted onto the board to represent constituent practices from the new second area.

In addition, a PM, who had previously had a non-voting role as a HR advisor during the ‘transition’ board, joined the board in December 2017, following competitive interview.

Central team

Day-to-day work and roll-out of the standard systems and processes to constituent practices were undertaken by a central team, which was under the direction of the three non-voting board officers. These officers formed the management team, which met weekly with the board chairperson.

Governance team

The governance team met fortnightly to oversee data collated centrally from the practices and reviewed complaints and compliments as part of the process of ensuring adherence to standardised policies and processes. Members were a GP from the board who was responsible for governance, the project manager responsible for governance from the central team and a practice nurse from one of the constituent practices.

Decision-making

The board were authorised to make strategic decisions, with each director holding one vote in elections. During the observation period, decisions were made by discussion rather than formal voting within the board. Board meetings were held monthly and were live-streamed for access by partners. GP partners and PMs were invited to attend, although only one GP partner and PM attended during our observation period.

Any variation in the partnership deed, approval of accounts or dissolution of the board had to be approved by the partners with a special resolution via a partners’ meeting. Partners’ meeting approval was necessary for change in directorships to be announced and new nominations to be sought for board positions. Elections were held by postal vote from individual partners within the federation to allow maximum involvement, including those unable to attend partners’ events.

Monthly informal board meetings were held as a closed meeting 2 weeks ahead of the formal board meetings. The former were used to collate and discuss ideas and strategies, as well as to finalise information to be shared with partners at the formal board meetings. The board chairperson met weekly with the MD to discuss strategic direction and approaches from practices wishing to join the federation.

Membership and recruitment

Expanding began within a single CCG and it intended to recruit practices in this CCG area. Board members were each allocated a geographical area (not necessarily their practice area) to recruit ‘non-constituent’ practices via (1) providing a point of contact and (2) reporting feedback on the federation and other federations.

The board discussed many strategies to encourage more practices to join the federation and the central team supported these aspirations by identifying more lucrative practices (e.g. list size, locality, previous contact with the federation) that could be approached first. However, growth in membership failed to meet that required to offset running costs.

The initial growth strategy to focus on recruiting local CCG practices in the city changed following an approach by a group of nine practices in another much more rural (second) area some distance from the CCG boundary. This resulted in six of these practices joining in May 2017.

Business model and finance