Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HS&DR Evidence Synthesis Centre, contracted to provide rapid evidence syntheses on issues of relevance to the health service, and to inform future HS&DR calls for new research around identified gaps in evidence. Other reviews by the Evidence Synthesis Centres are also available in the HS&DR journal.

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/47/11. The contractual start date was in November 2018. The final report began editorial review in August 2019 and was accepted for publication in November 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Raine et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Objectives

-

To conduct a rapid scoping exercise to identify existing reviews on workplace-based interventions to promote health and well-being.

-

To produce a descriptive map of the extent and nature of the available research evidence, and assess the scope for further evidence synthesis work.

Chapter 2 Background

The health and well-being of staff working in the NHS is a significant and long-standing issue in UK health care. In 2019, NHS England reported that in the NHS the sickness absence rate (4%) is higher than in both other public sector organisations (2.9%) and the private sector (1.9%); the cost of sickness absence of NHS staff has been estimated at £2.4B. 1 In addition to having financial implications for the NHS through levels of sickness absence, there is strong evidence linking staff health and well-being with quality of care, safety and patient outcomes/experience. 2–5 More broadly, the NHS has a responsibility to protect the health of all its employees. 6 The NHS constitution makes a pledge to support staff in maintaining their health, well-being and safety. 7 Guidance produced by the Health and Safety Executive also addresses staff well-being, including work-related stress (e.g. Health and Safety Executive8).

Consistent with the situation in other occupational sectors, data reveal that musculoskeletal and mental health conditions are major causes of ill health and sickness absence among NHS staff. The Boorman review found that musculoskeletal disorders account for almost half of all sickness absence in the NHS. 9 Findings from the 2017 NHS staff survey revealed that 26% of respondents experienced musculoskeletal problems as a result of work activities in the previous 12 months. 10 A large proportion of musculoskeletal disorders cases result in long-term absence. 6

Approximately one-third of sickness absence in the NHS is a consequence of mental health issues. 11 The 2017 NHS staff survey found that 38% of all staff, and 49% of individuals working in ambulance trusts, had felt unwell because of work-related stress in the last 12 months. 12 As a professional group, doctors experience high levels of mental health problems and have one of the highest suicide rates. 4 The existence of a bi-directional relationship between mental and physical health is well recognised, and evidence suggests that poor mental well-being can negatively affect lifestyle behaviours. For example, a study conducted by the Nursing Standard of 3500 nurses, midwives and health-care assistants in the UK reported that workplace stress had a negative impact on the diet of 60% of respondents. 13

Health professionals, and nurses in particular, have been encouraged to promote healthy lifestyle choices among patients. 14 Emphasis has been placed on staff taking responsibility for their own health and acting as a positive role model for engaging in healthy behaviours. 15 Notably, a number of recent UK studies found that a large proportion of health-care staff do not themselves meet public health guidance in relation to healthy lifestyle behaviours including consumption of fruit and vegetables,16,17 consumption of fats,16 consumption of sugars,16 physical activity16,17 and alcohol consumption;17 for example, Mittal et al. 16 reported that 83% of all staff did not eat the recommended five or more portions of fruit or vegetables per day. Similarly, Schneider et al. 17 found that 68% of nurses, 53% of other health-care professionals and 82% of unregistered care workers (including nursing auxiliaries and assistants) did not eat five or more portions of fruit or vegetables daily. They also reported that 46% of nurses, 49% of other health-care professionals and 44% of unregistered care workers did not meet physical activity guidelines. 17 These figures for physical activity are consistent with the proportion reported by Mittal et al. 16 for all staff (44%). In addition, the proportion of UK health-care workers who reported being overweight or obese in four recent studies ranged from 44% to 69%. 14,16,18,19

Schneider et al. 17 raised concerns about the potential impact of nurses’ low personal adherence to public health guidance in relation to healthy lifestyles on their health promotion work with patients and its effectiveness. Furthermore, Kyle et al. 14 highlighted an increased risk of both musculoskeletal and mental health conditions from having excess body weight, which, as highlighted earlier, are leading causes of ill health and sickness absence among NHS staff.

The negative influence that organisational-level factors can have on the lifestyle behaviours of health-care staff has been highlighted in past UK studies; for example, 51% of the hospital staff who responded in the study by Mittal et al. 16 indicated that long working hours impeded their ability to stay fit. Furthermore, in the Nursing Standard study reported by Keogh,13 79% of respondents indicated that eating a healthy meal while at work was made difficult by a lack of breaks. Over half (56%) of respondents also reported that inadequate staff levels had a negative impact on their food choices. 13

Findings from the 2017 NHS staff survey showed that 15% of all staff, and around one-third (34%) of employees at ambulance trusts, had experienced physical violence from patients, relatives or the public in the previous 12 months. In addition, over one-quarter of all staff (28%) and nearly half of the staff at ambulance trusts (47%) also suffered harassment, bullying or abuse from patients, relatives, or members of the public in the last 12 months. Just under one-quarter of all staff (24%) experienced harassment, bullying or abuse from other members of staff. 12

The importance of improving the health and well-being of NHS staff has repeatedly been recognised in government and NHS England publications published within the last 10 years. The NHS Long Term Plan1 re-emphasises the key role that employers have in supporting staff to remain healthy, and provides a clear commitment to the continued promotion of positive physical and mental well-being among the NHS workforce. This includes reducing the level of violence and abuse experienced by staff.

Over a number of years, there have been various initiatives to improve the health and well-being of NHS staff. On a national level, the NHS Healthy Workforce Programme was established in 2016 to identify best practice in relation to promoting staff health. The focus within the programme was on the implementation of employer-led health and well-being initiatives as well as creating organisational practices and culture that are supportive of staff health. 11

The NHS Health and Wellbeing Framework20 introduced in 2018 was informed by the findings and learning from the NHS Healthy Workforce Programme. 6 The framework document includes guidance and actionable steps to enable all NHS providers to plan and implement a staff health and well-being strategy. 21 There is a focus within the framework on promoting healthy lifestyles in addition to addressing mental health and musculoskeletal health. Health and well-being interventions incorporated into the framework comprise prevention-/self-management-focused approaches (e.g. physical activity classes) and more targeted forms of support such as weight loss services, health checks, addiction support, counselling and physiotherapy. An accompanying diagnostic tool enables organisations to carry out self-assessment against the Health and Wellbeing Framework. 21

The NHS Staff and Learners’ Mental Wellbeing Commission report22 published in 2019 by Health Education England reviewed evidence of good practice in relation to organisational policies within NHS organisations that had made mental health and well-being of staff and learners a priority. A number of recommendations were made to improve support, including ensuring the provision of tailored in-house mental health support and signposting to clinical help.

A Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) payment was introduced in 2016 in order to provide financial incentives for NHS providers to support staff health and well-being. Payment is dependent on (1) the introduction of workplace health and well-being initiatives, with a particular focus on physical activity, and improving support for mental health and musculoskeletal issues, (2) encouraging healthier food choices and (3) increasing staff uptake of the influenza vaccination. 11

The York Health Services and Delivery Research Evidence Synthesis Centre was asked by NHS England to identify evidence relevant to the promotion of healthy lifestyles among NHS staff. For this piece of work, the term ‘NHS staff’ was conceptualised broadly as any individual working for the organisation in any post.

Chapter 3 Methods

Scoping and mapping of the evidence

This rapid scoping and mapping exercise was undertaken to provide a high-level overview of the available evidence from existing reviews and reviews of reviews (RoRs). The objective was to classify the evidence in terms of broad descriptive characteristics and it was not intended that the findings from the reviews or RoRs would be extracted, evaluated and synthesised.

Although we did not aim to conduct a full systematic review, aspects of systematic review research methodology were applied, wherever possible, to maintain the rigour, transparency and reproducibility of the mapping process.

Identification of evidence

Database searches were undertaken to identify systematic reviews about health and well-being at work. Results were limited by publication date (2000 to January/February 2019). No language or geographical limits were applied. The following databases were searched:

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR)

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE)

-

HTA database

-

Epistemonikos

-

Health Evidence

-

Database of Promoting Health Effectiveness Reviews (DoPHER)

-

PROSPERO

-

MEDLINE

-

Business Source Premier.

The search strategies are provided in Appendix 1. Searches were limited to the year 2000 onwards to maximise the relevance of the evidence identified.

Once it became apparent that database searches had identified a large number of potentially relevant reviews, it was decided not to undertake supplementary searching of specific websites to identify any additional relevant publications or grey literature.

Selection procedure

A sample of title and abstracts were initially pilot screened by two reviewers independently and their decisions compared. On achieving at least 90% agreement, the remaining title and abstracts were screened against the selection criteria by one reviewer only. If there was uncertainty regarding the eligibility of any record, it was discussed with a second reviewer. Records without an abstract were screened on title only.

It had been intended that the full text of potentially relevant reviews would be retrieved and screened for inclusion, but because of the large number identified, this was not practical within the available time frame. A pragmatic post-protocol decision was taken to adjust the approach and select reviews for inclusion in the evidence map based on information in the title and abstracts of records only. However, the full text of all RoRs identified during the selection process was retrieved in order to conduct a more detailed examination of these publications.

Selection criteria

Records were screened for potential inclusion against the following selection criteria:

-

Population – adult employees (aged ≥ 18 years) in any occupational setting and in any role. Any reviews focusing solely on self-employed workers or including participants from other settings (e.g. school students) were not eligible for inclusion.

-

Interventions – any intervention aimed at promoting or maintaining physical or mental health and well-being (however conceptualised). Interventions could also be focused on early intervention and reducing the incidence or symptoms of common mental health conditions (stress, anxiety or depression) among staff. Reviews of interventions addressing violence against staff, workplace bullying or harassment were also eligible for inclusion. Occupational health interventions and those aimed at returning employees to work after absence were considered beyond the scope of the review. Occupational health interventions were conceptualised as those with a predominate focus on promoting safer working environments and practices, and reducing injuries and workplace health risks.

Interventions could be either or both (1) individual-level interventions, for example, initiatives focused on individual behaviour modification, (2) organisational-level interventions aimed at modifying the workplace environment, culture or ethos.

-

Outcomes – any outcome related to the effectiveness of interventions. Relevant outcomes could include, (but were not limited to) staff satisfaction, sickness absence, mental resilience, staff uptake of flu vaccination, lifestyle choices (smoking rates, alcohol consumption, physical activity levels, sedentary behaviour, dietary behaviour), coping skills, symptom reduction, levels of violence against staff and levels of bullying. Reviews could also report on outcomes related to the implementation of initiatives.

-

Study design – any form of evidence synthesis including systematic reviews of effectiveness, systematic reviews of implementation, meta-analyses, qualitative reviews or realist reviews. Reviews could include primary studies of any design or other reviews (i.e. RoRs).

All RoRs also met the following additional study design criteria: authors (1) searched at least two sources, and (2) reported inclusion/exclusion criteria. One of the sources searched must have been a named database. Other acceptable sources were conducting internet searches, hand-searching journals, citation searches, reference checking, contacting other authors.

It was stated in the protocol that all forms of evidence synthesis would have to meet the two criteria above to be included in the map; however, as the full text of reviews was not retrieved, this stipulation could not be implemented. In most cases, there was insufficient detail reported in title and abstracts alone to complete an assessment.

Data extraction

For each included review, data on key characteristics were extracted from titles and abstracts into a spreadsheet, including type of document, focus of the review, intervention type (where identifiable), population(s) and whether the review had a primary focus on effectiveness, costs/cost-effectiveness or implementation. A sample of reviews were extracted independently by two reviewers to ensure consistency of coding and decisions compared. Once there was a high level of agreement, data extraction was conducted by one reviewer.

For the included RoRs, data on key characteristics were also extracted by one reviewer. In addition, comments by the RoRs’ authors reflecting on the included evidence were noted. One reviewer checked to ensure that relevant reviews reported in the RoRs had been identified in the searches and included in the mapping of the evidence. Data extraction was not checked by a second reviewer, which represents another post-protocol change necessitated by the large number of relevant publications identified and the limited time available.

Summary of post-protocol changes

As indicated previously, it was necessary for the review team to make the following post protocol changes:

-

No supplementary searching of specific websites was conducted to identify any additional relevant publications or grey literature.

-

Reviews and meta-analyses (RMAs) were selected for inclusion in the evidence map based on information in the title and abstracts only.

-

It was not possible to assess whether or not RMAs were conducted using a systematic methodology.

-

Data extraction was not checked by a second reviewer.

Synthesis

Data from the spreadsheet were imported into the software package IBM SPSS Statistics version 25(IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and descriptive statistics for key characteristics generated (counts and percentages). Data from the reviews and RoRs were then used to produce a map and descriptive summary of the evidence. This provided an overview of the extent and nature of the current evidence base relevant to promoting healthy lifestyles in NHS staff. Reviews and RoRs were grouped by topic focus (e.g. lifestyle behaviour, mental health, violence/bullying) and briefly described.

External engagement

This mapping work was conducted for NHS England, which was consulted at the start and end of the process. The research team initially received a very brief outline of the topic area of interest via the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). A teleconference with NHS England and NIHR colleagues was subsequently held to establish the goals and scope of the work. Based on this discussion, the research team produced a review protocol, conducted the mapping exercise and produced an interim report for NHS England.

Following the submission of the interim report, a second teleconference was held between the York research team, NHS England and NIHR in order to discuss the interim results, conclusions and scope for further evidence synthesis work. During this teleconference, the York research team gave a presentation of key findings and answered any questions arising. On the basis of this discussion, no additional evidence synthesis work was requested from the research team. Three regional medical directors at NHS England were involved over the course of the work. Owing to the rapid and responsive nature of the work, patient or public representatives were not asked to be involved.

Chapter 4 Results

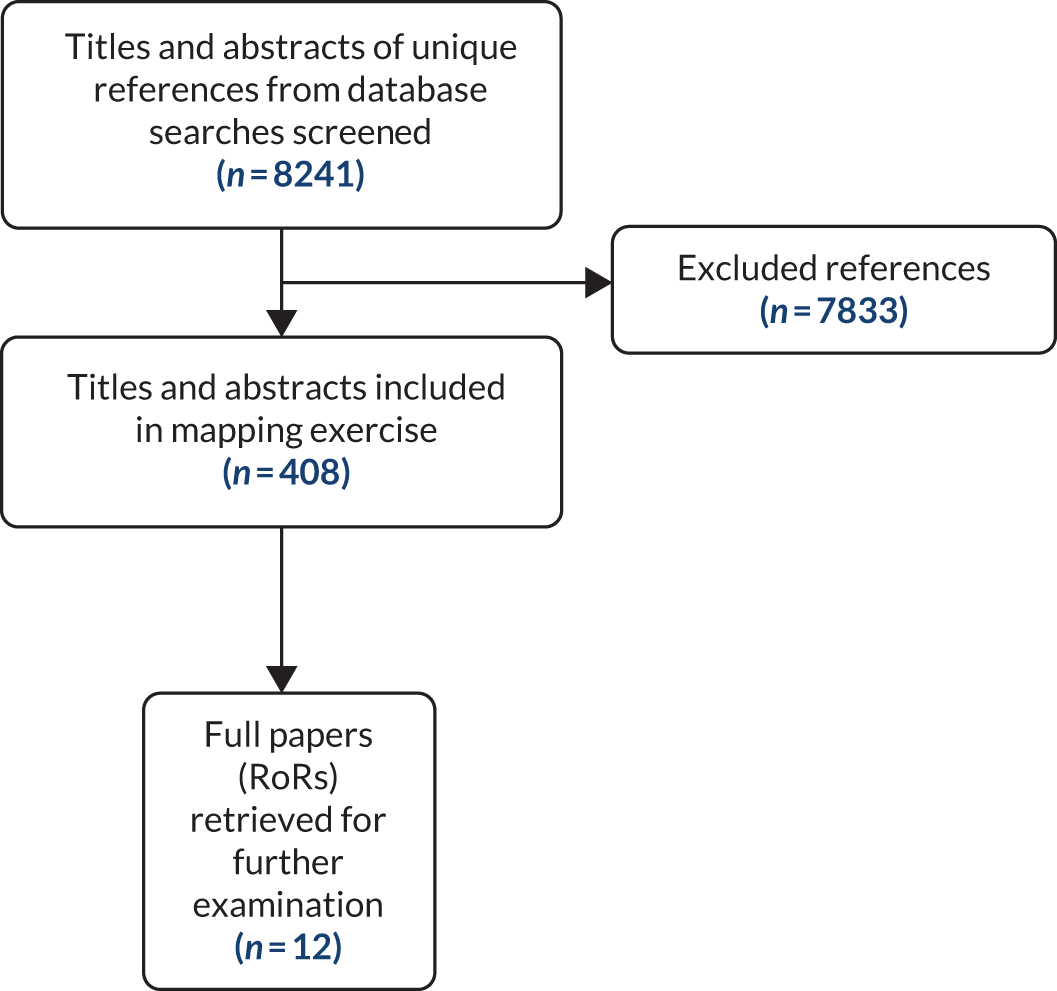

In total, 9622 search results were downloaded and imported into a reference management software package. After deduplication there was a total of 8241 unique records. In total, we identified 408 potentially relevant reviews of workplace-based interventions focused on the health and well-being of staff. The flow of literature through the review is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart.

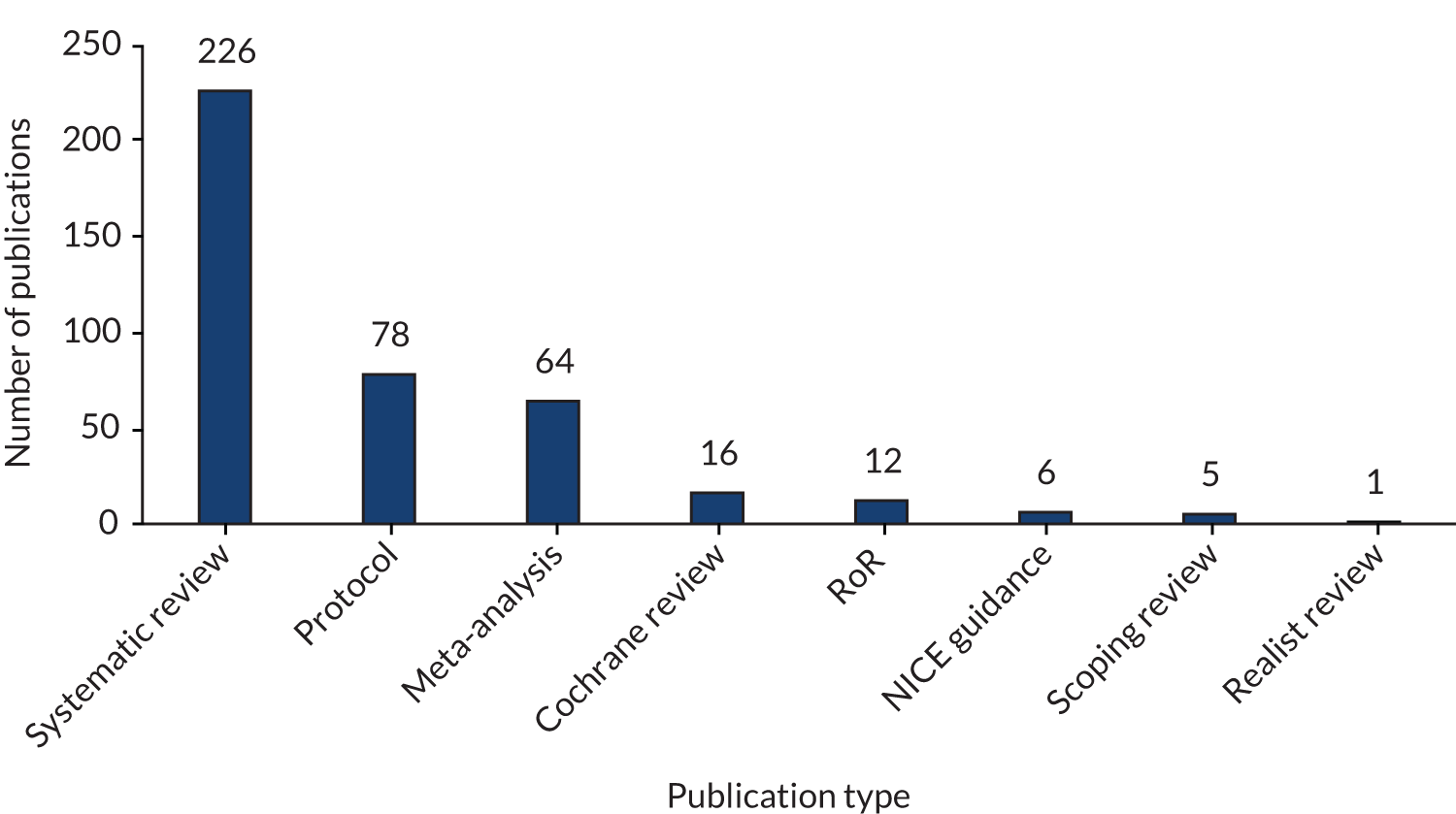

Figure 2 shows the different types of publications identified from the scoping searches of key databases.

FIGURE 2.

Type of publication (n = 408). NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Results are presented below by the following categories of publication type: RoRs; Cochrane reviews; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance; a merged grouping of systematic reviews, scoping reviews, realist reviews, and meta-analyses, which has been labelled as ‘reviews and meta-analyses’ (RMAs); and protocols.

‘Reviews of reviews’

It can be seen from Figure 2 that there is a sizeable number of existing RoRs (n = 12). These have examined the effectiveness of workplace interventions targeting both physical and mental health. Two reviews addressed interventions focused on employees in the health sector. 23,24 The primary topic addressed in each of the 12 RoRs is outlined below:

General health and lifestyles/mixed physical and mental health

-

Health promotion and primary prevention, including interventions focused on stress, physical activity, nutrition and smoking. 25

-

Smoking cessation. 26

-

‘Healthy lifestyles’ focused on physical activity, healthy weight and good nutrition. 27

-

‘Workplace health programmes’ for improving both physical and mental health. This review addressed implementation issues as well as effectiveness. 28

-

Organisational-level interventions in the ‘health sector’ to improve health. 23

-

Physical activity. 29

-

Dietary change. 30

Mental health

-

Stress management with a particular emphasis on preventing common mental health disorders (anxiety and depression). 31

-

Mental health including stress management and the prevention of psychological disorders. 32

-

Common mental disorders (depression and anxiety). 33

-

Interventions to prevent mental health problems and absenteeism. 34

-

Physician burnout (including medical students and residents). 24

A more detailed description of the 12 RoRs is provided in Review of reviews: full-text scoping.

Cochrane reviews

Out of the 16 Cochrane reviews identified,35–50 eight were targeted at general health, physical health or lifestyle behaviour. This included reviews related to improving physical activity through the use of pedometers,37 decreasing sitting time at work,46 sex risk behaviour and preventing human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection,43 and smoking cessation. 36 The latter review examined the effectiveness, costs and cost-effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions. 36 Strategies to improve the implementation of workplace-based policies/practices aimed at lifestyle behaviours (diet, physical activity, obesity, tobacco use and alcohol use) have also been examined in a Cochrane review. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of such strategies were also assessed as secondary outcomes. 50

Four Cochrane reviews examined the effectiveness of interventions to prevent or reduce workplace stress/burnout, two of which were focused on health-care workers. 45,49 One other review that was also focused on the well-being of health-care personnel, reported on the psychological effects of making changes to the physical workplace environment, although only one primary study met the authors’ inclusion criteria. 48 One Cochrane review on the prevention of workplace bullying was identified. In addition, there are Cochrane reviews of interventions addressing sleepiness and sleep disorders among shift workers; the effects of flexible working interventions on the health and well-being of employees and their families; breastfeeding support at work; alertness and mood in daytime workers; and absenteeism among workers with inflammatory arthritis.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has produced evidence-based guidance on a number of workplace health issues including the promotion of mental well-being,51 physical activity52 and encouraging employees to stop smoking. 53

Reviews and meta-analyses

Workplace settings

In total, 296 reviews (systematic reviews/scoping/realist reviews) and meta-analyses were identified, which focused on primary studies with 23 different groups of workers. For a full list of all 23 population groups/workplace settings in the 296 RMAs, see Appendix 2, Table 13. The largest proportion of RMAs had a focus on generic ‘workplace’ interventions, and did not state a specific target group of workers (n = 155, 52%). There were 31 RMAs focused on primary studies with nurses of all types, and a similar number were focused on ‘health-care’ workers (n = 28). A further 36 RMAs had a specific focus on other groups of health-care workers, and these are shown in Table 1. Out of the 296 RMAs identified, a total of 95 (32%) focused on individuals working in a health-care setting in some capacity. Among RMAs not focused on health care, the groups of workers most frequently studied were individuals who work shifts (n = 9), those based in offices (n = 7) and female workers (n = 7).

| Staff groups | Number of RMAs |

|---|---|

| Nurses | 31 |

| ‘Health-care’ staff | 28 |

| Staff working in mental health care | 8 |

| Medical students | 7 |

| Doctors | 7 |

| Nurses/nursing students | 4 |

| Nursing students | 3 |

| Emergency medical service personnel | 3 |

| Midwives/obstetricians and midwives | 2 |

| Doctors/medical students | 1 |

| Health-care students/professionals | 1 |

Health focus of reviews and meta-analyses

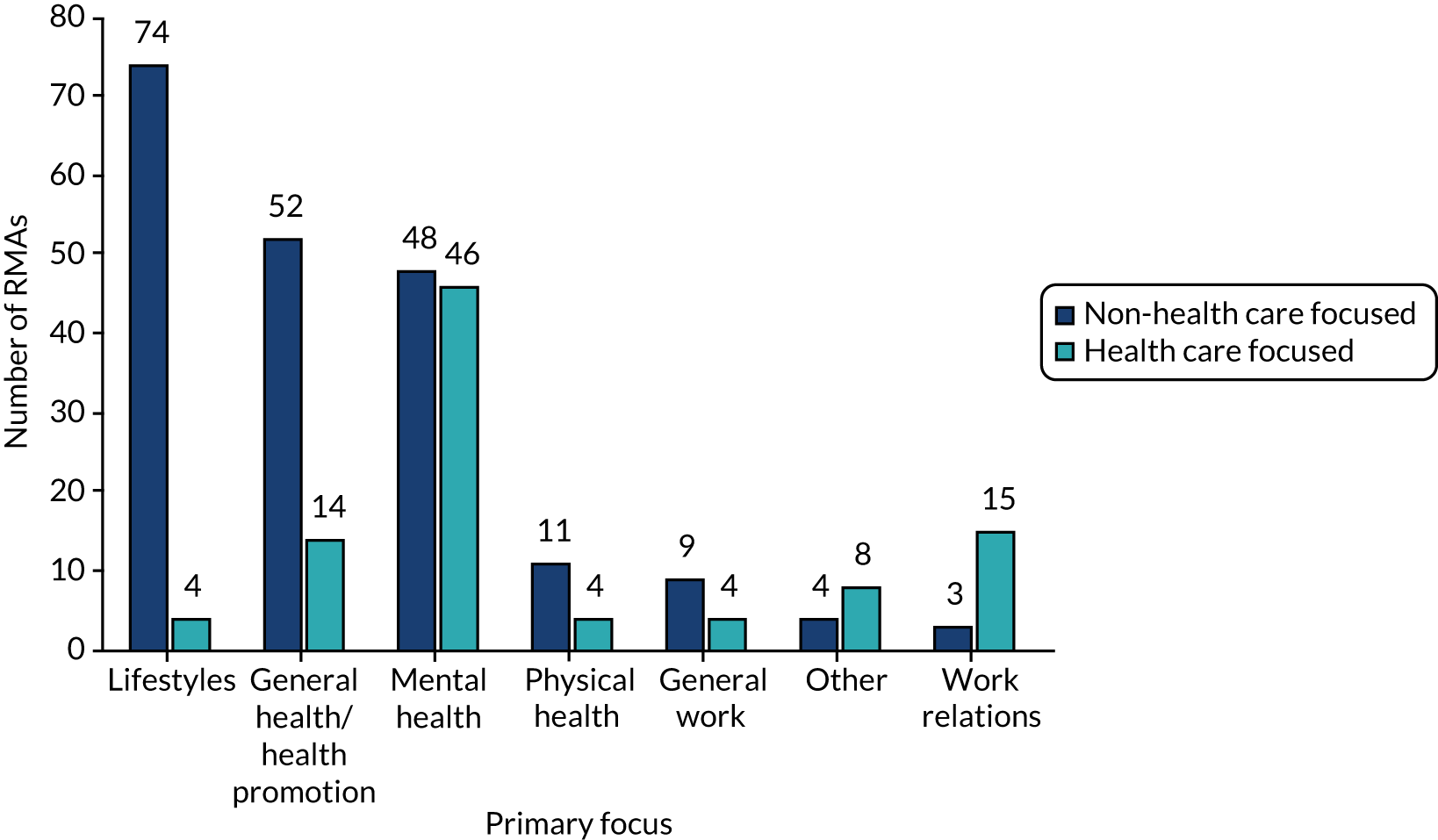

The primary health focus of each review or meta-analysis was categorised into seven broad groupings: lifestyles, general health/health promotion, mental health, physical health, work relationships, general work and ‘other’ health-related interventions. As the grouping of RMAs was based on information in titles and abstracts only, it should not be considered a definitive categorisation of health focus. It is also important to recognise that there is potentially considerable overlap between some of the groups depending on the specific aims of interventions, and particularly the general health/health promotion and lifestyles categories.

Figure 3 shows the primary health focus of the 296 identified RMAs. In order to retain pertinent information, RMAs have been separated into those that had a specific focus on health-care settings (health care focused) and those that did not (non-health care focused). However, it should be recognised that some of the RMAs without a health-care focus could, depending on the inclusion criteria applied, have also potentially included primary studies conducted with staff in health-care settings. A full bibliographic list for the 296 RMAs by primary health focus and setting is provided in Appendix 3.

FIGURE 3.

Primary focus of RMAs (n = 296).

Lifestyles

In total, 78 out of the 296 RMAs addressed lifestyles and lifestyle behaviour, of which four were focused on staff in health-care settings. As Table 2 reveals, the largest proportion of the non-health-care focused RMAs addressed physical activity, sedentary behaviour or sitting time (n = 29). Five RMAs included interventions that examined both physical activity and/or dietary behaviour/nutrition. It can also be seen from Table 2 that a total of 22 non-health-care-focused RMAs were on obesity/weight status (n = 11), general diet/nutrition (n = 7), fruit and vegetable consumption (n = 3) or dietary behaviours and adiposity (n = 1). A further nine RMAs addressed smoking cessation or employees’ smoking behaviour. The four RMAs related to health-care staff were focused on physical activity and/or dietary behaviour (n = 2), weight status (n = 1) and dietary behaviour (n = 1). Of these four RMAs, two were focused on nurses and two on a broad grouping of ‘health-care’ staff.

| Health focus | Number of RMAs | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-health care focused | Health care focused | |

| Physical activity/sedentary/sitting time | 29 | 0 |

| Obesity/weight | 11 | 1 |

| Smoking cessation | 9 | 0 |

| Diet/nutrition | 7 | 1 |

| Physical activity/diet/nutrition | 5 | 2 |

| Alcohol | 3 | 0 |

| Fruit/vegetable consumption | 3 | 0 |

| Diabetes | 2 | 0 |

| Substance use | 2 | 0 |

| Dietary behaviours/adiposity | 1 | 0 |

| Physical activity/diet/weight | 1 | 0 |

| Substance use and HIV-risk behaviours | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 74 | 4 |

In terms of interventions, it was possible to determine from information provided in the abstracts that at least 12 of the non-health-care-focused RMAs had included both individual- and organisational-level interventions. These addressed weight status (n = 5); physical activity, sedentary behaviour or sitting time (n = 3); alcohol (n = 1); smoking (n = 1); physical activity/diet/weight (n = 1); and diet/nutrition (n = 1). It was not possible to make a similar determination for the four RMAs conducted in health-care settings.

Eight lifestyle RMAs (seven non-health care focused and one health care focused) examined organisational-level interventions or policies only. The one health-care-based review was commissioned by Public Health England to examine the evidence on environmental (choice architecture) interventions to increase the purchase and consumption of healthier food and drinks by NHS staff. 54

Interventions evaluated in six other RMAs (all non-health care focused) were aimed at reducing sedentary behaviour in office workers through desk-based changes such as the use of active workstations, and cycle and treadmill desks.

Among the 74 non-health-care-focused RMAs, one had a primary focus on the costs and financial return of worksite programmes aimed at improving various lifestyle behaviours rather than effectiveness. Furthermore, four other RMAs (addressing physical activity and smoking) focused primarily on implementation and process-related issues.

General health/health promotion

The scoping searches identified 66 RMAs that were concerned with general health promotion or interventions to promote the health and well-being of workers in broad terms. Of this total, 14 had a specific focus on health-care staff.

The most common intervention type that was identified among the 52 non-health-care-focused RMAs was various forms of ‘workplace health promotion programmes’ (n = 18). Other specific types of intervention that were also identified included:

-

alterations to the jobs or work patterns of employees; for example, changing shift patterns, task restructuring, increasing employee control and job redesign (n = 5)

-

organisational-level interventions including improving the social or psychosocial work environment (n = 4)

-

digital-/technology-based interventions (n = 2)

-

mentoring, training or support (n = 2).

One of the 14 RMAs of general health promotion in health-care settings was commissioned by the Department of Health and Social Care in the UK and examined whole-system approaches to improving the health and well-being of health-care workers. 55

Where a specific intervention type could be determined, three out of the other 13 health-care-focused RMAs addressed alterations to jobs or work patterns. Other RMAs examined clinical supervision; mentoring, training and support; Schwartz Center Rounds; exercise interventions to promote both physical and mental health; and health promotion programmes to improve behavioural health-risk factors. Table 3 provides details of the specific groups of staff that were the target population in the 14 health-care-focused RMAs.

| Staff groups | Number of RMAs |

|---|---|

| Nurses | 7 |

| Health-care workers | 3 |

| Medical students | 2 |

| Doctors | 1 |

| Mental health-care workers | 1 |

Reviews and meta-analyses of general health/well-being were largely focused on effectiveness outcomes, but several had a primary aim of evaluating the costs and economic impact of worksite health promotion programmes. One RMA focused solely on process issues and the factors that influence the implementation of workplace health promotion interventions. Similarly, one RMA, focused on health-care staff, examined barriers to promoting the health and well-being of Brazilian health-care workers.

Mental health issues

In total, 94 RMAs had a focus on mental health issues. Notably, almost half of all RMAs focused on health-care staff were related to mental health (n = 46, 49%). The largest proportion of RMAs (38/94) comprised primary studies that were aimed at improving psychological health or well-being outcomes (non-health care focused, n = 23; health care focused, n = 15). The remaining 56 RMAs had a primary focus on more specific mental health issues, and these are shown in Table 4. The majority of the 56 RMAs concerned interventions targeting stress and/or burnout among workers (n = 39). Stress and burnout-related interventions were a particular focus of RMAs in health-care settings (26/31). In addition, nine of the RMAs on stress and/or burnout were based on primary studies with nurses.

| Focus | Number of RMAs | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-health care focused | Health care focused | |

| Stress | 8 | 11 |

| Burnout | 5 | 12 |

| Compassion fatigue/secondary traumatic stress/vicarious traumatisation | 0 | 2 |

| Stress/burnout | 0 | 2 |

| Compassion fatigue | 1 | 1 |

| Coping/resilience | 0 | 1 |

| Depression | 6 | 1 |

| Stress/burnout/depression/suicide | 0 | 1 |

| Anxiety | 1 | 0 |

| Depression/anxiety | 1 | 0 |

| PTSD | 1 | 0 |

| Suicide prevention | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 25 | 31 |

It is likely that a number of the issues in Table 4 were also outcomes of interest in at least some of the 38 broad RMAs of mental health interventions in the workplace. Consequently, the table potentially underestimates the frequency with which issues have been addressed in RMAs.

Eleven mental health-related RMAs had an identifiable focus on mindfulness-/meditation-based interventions (health care focused, n = 6; non-health care focused, n = 5). Four addressed digital or web-based interventions including apps (applications). In addition, two RMAs examined the effectiveness of physical activity interventions to improve mental health outcomes. It was further possible from the abstracts to determine that 19 other RMAs included both individual and organisational-level interventions. In terms of outcomes, nearly all RMAs synthesised evidence in relation to the effectiveness of interventions; however, one had a primary focus on the financial return and cost-effectiveness of mental health interventions in the workplace, and another examined process-related outcomes in workplace stress management intervention studies. Finally, one review reviewed workplace guidelines to prevent, detect and manage mental health issues.

Physical health issues

Fifteen RMAs addressed a number of other issues related to the physical health of the workforce, and these are shown in Table 5. The largest group (8/15 RMAs) was focused on issues around fatigue, sleep, sleepiness, insomnia and alertness, particularly among shift workers. Interventions included changing shift patterns and length, napping, restorative breaks, fatigue training and other non-pharmacological measures. Three RMAs had a specific focus on reducing cardiovascular risk, one of which evaluated lifestyle-targeted interventions. Another addressed internet-based cardiovascular wellness and prevention programmes.

| Focus | Number of RMAs | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-health care focused | Health care focused | |

| Sleep/fatigue | 4 | 4 |

| Cardiovascular risk | 3 | 0 |

| Cervical cancer screening | 1 | 0 |

| Headaches | 1 | 0 |

| Hearing difficulties | 1 | 0 |

| HIV/tuberculosis | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 11 | 4 |

Work relations

Eighteen RMAs were related to violence, bullying or other unacceptable behaviour in the workplace. Fifteen RMAs were focused on health-care settings, 12 of which addressed violence/aggression prevention or management. The other three health-care-focused RMAs addressed bullying, violence and/or incivility. Approximately half (n = 8) involved interventions conducted with nursing staff, and two focused solely on nurses working in emergency departments. Some of the health-care-focused RMAs evaluated specific forms of interventions including de-escalation techniques training and aggression management programmes. The prevention of bullying, incivility or unprofessional behaviour was the focus of three RMAs of non-health-care settings.

General work issues

Table 6 shows the primary focus of 13 RMAs that addressed general work issues. It can be seen that an equal number of RMAs were related to sickness absence (n = 4) and absenteeism (n = 4), and a further two had a focus on presenteeism. Three of these 11 RMAs examined the role of physical activity in reducing sickness absence, absenteeism or presenteeism. Two health-care-focused RMAs synthesised evidence on the effectiveness of interventions and strategies to support student well-being during their transition to becoming qualified nurses.

| Focus | Number of RMAs | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-health care focused | Health care focused | |

| Sickness absence | 3 | 1 |

| Absenteeism | 3 | 1 |

| Transition to work | 0 | 2 |

| Presenteeism | 1 | 0 |

| Presenteeism and mental health | 1 | 0 |

| Work ability | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 9 | 4 |

Other health-related issues

Four RMAs of workplace interventions aimed to promote or support breastfeeding. Eight RMAs were also identified that addressed influenza vaccination among health-care workers. Five examined interventions to improve vaccination uptake and two focused on implementation issues. This included exploring factors that may influence the success of strategies to increase uptake, as well as exploring the views and experiences of health-care staff. One other review investigated both barriers to health-care staff getting vaccinated and components of effective programmes.

Review protocols

The scoping searches identified 78 protocols for reviews, of which 19 had a health-care focus and 59 did not. A bibliographic list of all 78 protocols is provided in Appendix 3. As Table 7 details, approximately 83% (65/78) were published on PROSPERO or elsewhere from 2016 onwards.

| Year of publication | Number of protocols | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-health care focused | Health care focused | |

| 2009 | 0 | 1 |

| 2010 | 1 | 0 |

| 2013 | 0 | 3 |

| 2014 | 2 | 0 |

| 2015 | 3 | 3 |

| 2016 | 8 | 3 |

| 2017 | 19 | 4 |

| 2018 | 25 | 5 |

| 2019 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 59 | 19 |

The two protocols from 2014 were registered on PROSPERO, and the records indicate that both have been completed. One examined environmental interventions for changing the eating behaviours of employees, and the other evaluated the effectiveness of height-adjustable desks for decreasing sedentary behaviour among office workers. Both these reviews were included in the current evidence map. The status of reviews relating to the other 11 protocols published between 2009 and 2015 is unclear.

The status of reviews based on the more recent protocols published since the end of 2015 is also currently unknown. Nonetheless, the focus of the 65 protocols (53 non-health care focused and 12 health care focused) that were published between 2016 and 2019 is shown in Table 8.

| Focus | Number of protocols | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-health care focused | Health care focused | |

| General health/health promotion | 14 | 4 |

| Mental health and well-being | 12 | 2 |

| Physical activity/sedentary/sitting | 10 | 0 |

| Cardiovascular health | 4 | 0 |

| Alcohol | 2 | 0 |

| Breastfeeding | 2 | 0 |

| Absenteeism and presenteeism | 1 | 0 |

| Depression (prevention) | 1 | 0 |

| Dietary behaviour | 1 | 0 |

| Musculoskeletal problems | 1 | 0 |

| Physical activity/diet/sleep | 1 | 0 |

| Resilience | 1 | 0 |

| Self-confidence | 1 | 0 |

| Sleep/fatigue | 1 | 0 |

| Work/life balance | 1 | 0 |

| Violence/aggression | 0 | 5 |

| Violence/harassment/bullying | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 53 | 12 |

Approximately half of the non-health-care-focused protocols were related to general health and well-being or lifestyle-related behaviours, such as physical activity, sedentary behaviour, sitting time, dietary behaviour and alcohol consumption. These protocols have targeted effectiveness, financial outcomes or process-related outcomes including:

-

digital [mhealth (mobile health)] interventions to promote physical activity and reduce sedentary behaviour

-

return on investment for workplace chronic disease prevention programmes

-

factors influencing the implementation of interventions to improve workplace health and well-being.

The largest number of health-care-focused protocols (6/12) were on the prevention of violence or bullying/harassment. Two protocols published recently (2018) focused on the effectiveness of general health and lifestyle interventions. One aimed to synthesise evidence on the effectiveness of interventions to improve the health and well-being of hospital staff, with a specific focus on nutrition, physical activity, stress and musculoskeletal interventions. The other was targeted at improving the health risk of nurses using behavioural and/or educational interventions. Finally, two other health-care-related protocols were published in 2018, which addressed the following issues:

-

health, well-being and support interventions for UK ambulance service personnel

-

use of technology to provide social or emotional support to nurses.

Review of reviews: full-text scoping

The full texts of all 12 RoRs were retrieved and key characteristics examined in greater depth. 23–34 The reviews were published between 2009 and 2019, seven of which had been published since 2016. There was variation between the RoRs in terms of focus, interventions and outcomes; therefore, the RoRs have been described individually below. Table 9 shows the main focus of the reviews.

| Focus | Number of RoRs | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-health care focused | Health care focused | |

| Lifestyle | 3 | 0 |

| General health/health promotion | 3 | 1 |

| Mental health | 4 | 1 |

| Total | 10 | 2 |

Workplace settings

Only two RoRs explicitly stated that they had a health-care focus. One RoR evaluated interventions to improve mental health by reducing physician burnout. 24 The other evaluated interventions that facilitate sustainable jobs and have a positive impact on the health of workers in health-sector workplaces. However, the included RMAs evaluated interventions in a range of workplace settings, only some of which were in the health sector. 23

The remaining RoRs reported little information on workplace setting. Some did incorporate RMAs that included staff in the health sector; however, other workplace settings were included and findings were not reported separately.

Health focus of reviews of reviews

Lifestyles

Three RoRs addressed lifestyles and lifestyle behaviours but each evaluated different interventions. 26,29,30 None of the RoRs was explicitly set in a health-care sector. The RoRs were published from 2013 to 2019 and included RMAs published from 1994 to 2017. The main focus of the RoRs are listed in Table 10.

| Focus | Number of RoRs | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-health care focused | Health care focused | |

| Dietary change | 1 | 0 |

| Physical activity | 1 | 0 |

| Smoking cessation | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 3 | 0 |

Schliemann and Woodside30

The most recent RoR,30 published in 2019, included 21 RMAs and evaluated the effectiveness of dietary workplace interventions. However, authors reported that only one component of a workplace intervention had to be dietary and, therefore, RMAs also reported other components that were largely general wellness programmes (e.g. physical activity, smoking cessation, alcohol use). As well as reporting effects on dietary behaviour, such as fruit and vegetable consumption, some environmental aspects (e.g. catering policies, healthy choices, labelling healthy options) were reported together with economic outcomes (e.g. absenteeism, productivity and health-care costs). In their discussion section, authors reported a lack of consistency across the results due to variation of the RMAs and the included primary studies. They noted many of the outcomes were self-reported rather than objectively measured and there were a lack of process evaluations.

Jirathananuwat and Pongpirul29

One RoR published in 201729 included 11 RMAs and aimed to categorise interventions into factors that could optimise improvements in physical activity in the workplace. The factors were classified as enabling (e.g. information, self-motivation, programme training), predisposing (e.g. instrument resources such as pedometers), reinforcing (e.g. incentives, social support), policy regulatory (e.g. organisational action) and environmental development (e.g. break rooms, signage). The interventions addressed multiple health behaviours of which promoting physical activity was just one part; others included diet, stress management, weight control and smoking cessation. Workplaces included health service, government, industry, factory, educational and private sectors, but results were not reported separately for the health-service settings.

Fishwick et al.26

A RoR evaluating smoking cessation was published in 201326 and included six RMAs. The journal article also included a summary of a systematic review of relevant published qualitative literature, two case studies and findings from an expert focus group. Interventions included workplace cessation programmes (including behavioural, self-help and pharmacological) as well as legislative smoking bans. Specific workplace settings were not described by the RoR authors. Outcomes included rates of cessation, abstinence, quit rates and costs.

General health/health promotion

Four RoRs had a more general health focus;23,25,27,28 one of which evaluated interventions aimed at improving the health of health-sector employees, although RMAs in a non-health-care setting were also included. 23 RoRs were published between 2010 and 2016 and included RMAs published between 1997 and 2014. The main focus of the RoRs is listed in Table 11.

| Focus | Number of RoRs | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-health care focused | Health care focused | |

| Workplace health programmes for both physical and mental health | 1 | 0 |

| Organisational level to improve health | 0 | 1 |

| ‘Healthy lifestyles’ (physical activity, weight and nutrition) | 1 | 0 |

| Health promotion and primary prevention | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 3 | 1 |

Brunton et al.28

The Department of Health and Social Care (UK) commissioned a report, published in 2016,28 to understand whether or not workplace health programmes are effective for improving health and business outcomes and to identify characteristics that potentially influence their success. As well as a RoR, the authors included research on stakeholders’ views and experiences and a summary of key workplace health policy documents. Although the RoR identified a large number of RMAs (n = 106), the authors chose to include only those providing pooled effects sizes (n = 24). Interventions were multicomponent including education, exercise, counselling, screening, change to company regulations or policy, and risk assessments. Health-related outcomes included body mass index, diabetes risk, stress and physical activity. Business outcomes included absenteeism and related costs, health-care costs and productivity. The RoR authors did not report details of the types of workplace included in the RMAs. They did report that interventions differed across varying types of workplace making it difficult to judge the applicability of interventions to other settings. They also commented that physical activity interventions predominated and there were few data on other public health topics. Costs were rarely evaluated and few RMAs reported on the follow-up of interventions, therefore, making it difficult to assess the sustainability of the interventions.

Haby et al.23

One RoR23 published in 2016 (containing 14 RMAs) evaluated interventions to facilitate sustainable jobs and promote the health of workers in health-sector workplaces. However, the included RMAs evaluated interventions in a range of workplace settings, only some of which were in the health sector. Interventions included flexible work arrangements, compressed working week and task restructuring. Reported outcomes varied widely between RMAs and included disease incidence and prevalence, health-service use, and health and socioeconomic inequalities. Authors commented that interventions were not well described, which made it difficult to fully understand important factors such as delivery of the intervention and whether it was supported by employees or managers.

Schröer et al.27

A RoR published in 201427 included 15 RMAs and evaluated interventions promoting healthy lifestyles, preventing disease and reducing health-care costs. Physical activity and/or dietary interventions at the individual and/or organisational level were assessed. Details of workplaces and employees were not described in the RoR. Outcomes of interest were weight, physical activity and nutritional, together with some limited economic data. The authors reported a lack of consistency in the findings, and noted that few outcomes were evaluated long term.

Goldgruber and Aherns25

A RoR conducted in 201025 with 17 RMAs focused on the effectiveness of workplace health promotion and primary prevention interventions. The authors did not report details of workplace settings. The interventions targeted stress reduction, physical activity and nutrition, organisational development, smoking cessation, as well as ergonomics and back pain. Multiple outcomes were reported including psychosocial, physical and mental health, and economic indicators.

Mental health

Five RoRs focused on mental health,24,31–34 one of which evaluated interventions aimed at health-care staff. 24 RoRs were published between 2009 and 2016 and included RMAs published between 1996 and 2016. The main focus of the RoRs are listed in Table 12.

| Focus | Number of RoRs | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-health care focused | Health care focused | |

| Physician burnout (including medical students, residents and fellows) | 0 | 1 |

| Common mental health disorders (anxiety and depression) | 1 | 0 |

| Prevention of mental health problems and absenteeism | 1 | 0 |

| Mental health including stress management and prevention of psychological disorders | 1 | 0 |

| Stress management | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 4 | 1 |

Kalani et al.24

Reductions in physician burnout was the focus of one RoR published in 201824 with four RMAs. Participants included medical students, interns, physicians, residents and fellows. One of the three RMAs also included nurses. Most of the interventions were at an individual level including counselling, support groups and mindfulness. Organisational-level interventions included duty standards, shift-work staffing and change in workload. The authors commented that there were conflicting findings across RMAs at both individual and organisational level. It was suggested by the review authors that this could be owing to primary studies including different groups of physicians or other mediating or moderating factors that were not investigated. Sample sizes were also reported to be small in some primary studies and interventions differed across reviews.

Joyce et al.33

Workplace interventions for common mental health disorders were the focus of a RoR published in 201633 containing 20 RMAs. Interventions were aimed at primary, secondary and tertiary prevention, but details of workplace settings were not reported. Primary prevention interventions aimed to reduce the onset of a condition as well as reducing the impact of related risk factors; for example, through increasing employee control, physical activity and workplace health promotion. Secondary prevention interventions aimed to identify early symptoms and risk factors to reduce progression and included screening, counselling, stress management programmes and post-trauma debriefing. Tertiary prevention interventions aimed to provide therapy and rehabilitation to those formally diagnosed with a mental health condition and included cognitive–behavioural therapy, exposure therapy and medication. Outcomes included changes in physical activity, symptom reduction and occupational outcomes (e.g. sickness absence). The authors commented that few RMAs explored the impact of interventions on work-related aspects such as absenteeism and presenteeism.

Wagner et al.34

A RoR also published in 201634 and including 14 RMAs aimed to determine the level of evidence supporting mental health interventions relating to work outcomes such as absenteeism, productivity and cost. Workplace settings varied widely, where reported. Interventions also varied and many were multicomponent. Others included cognitive–behavioural therapy, exercise and injury prevention.

Dalsbø et al.32

Workplace interventions for employees’ mental health was the subject of a RoR published in 201332 in Norwegian with an English summary. Only three RMAs were included. Employees included health-care workers, law enforcement officers as well as ‘all employees’ in workplace settings. Interventions included stress management, mental image training and flexible working. Outcomes were stress, mental strain, self-image, quality of sleep and alertness. The RoR authors commented that no outcomes were reported for productivity, absence, sick leave, costs or adverse events.

Bhui et al.31

A synthesis of evidence on the effectiveness of different workplace stress management interventions was the focus of a RoR published in 2012,31 which included 23 RMAs. Interventions varied and included those at the individual (e.g. stress management, cognitive–behavioural therapy, relaxation, mindfulness) and organisational level (e.g. wellness programmes, support groups, problem-solving committees, work redesign). However, details of workplaces were not reported by the RoR authors. Outcomes were anxiety, depression and absenteeism. Authors reported that interventions differed in their components, mode of delivery and whether they targeted individuals or organisations. This made it difficult to compare benefits from any single intervention across a number of primary studies both within a RMA and across RMAs. Furthermore, outcomes of anxiety and depression were measured in different ways and there was not always clarity within RMAs as to which outcomes were included in meta-analyses. It was also reported that although many RMAs appeared to be reviewing the same evidence, they did not all identify the same primary studies and, therefore, did not always reach the same conclusions.

Further details about the characteristics of the 12 RoRs are provided in Appendix 4, Table 14.

Chapter 5 Discussion and conclusions

Summary of process

This evidence map provides a descriptive overview of the extent and nature of the available research evidence relevant to the promotion of healthy lifestyles among NHS staff. It was conducted to meet the requirements of NHS England, which was consulted at the start and end of the mapping process. It was not the aim of this piece of work to extract, evaluate and synthesise findings from individual publications.

In total, the title and abstracts of over 8000 records were screened and 408 potentially relevant publications were identified. Such a large number of potentially relevant reviews meant that it was necessary to map reviews based on details provided in titles and abstracts rather than on the full text of publications.

Summary of key findings

Workplace interventions targeting health and well-being, including the promotion of healthy lifestyle behaviours, have been reviewed extensively in the literature. Existing reviews have largely addressed effectiveness, but some have focused primarily on cost-effectiveness and/or implementation.

Evidence relating to a broad range of physical and mental health issues was identified across 12 RoRs and 312 other reviews, including 16 potentially relevant Cochrane reviews, published since 2000. Cochrane reviews are systematic reviews that are recognised to be methodologically rigorous and have high standards of reporting. Furthermore, there exists NICE guidance addressing multiple issues of potential relevance. NICE public health guidance is developed through a rigorous process and is based on the best available evidence in relation to effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. 56 In addition to published reviews of all types, RoRs and NICE guidance, protocols for a further 65 potentially relevant reviews were published between 2016 and 2019.

In terms of the health issues addressed in publications, some differences were identified between reviews that had a specific focus on health-care settings (health care focused) and ones that did not (non-health care focused). In total, 144 RMAs addressed aspects of lifestyle or general health/health promotion. Out of the 144 RMAs, most (n = 126, 88%) were non-health care focused. Furthermore, approximately 63% of all non-health-care RMAs addressed lifestyle and general health/health promotion (n = 126/201). In comparison, lifestyle and general health/health promotion reviews/meta-analyses constituted a relatively small proportion of all health-care-focused RMAs (19%, n = 18/95). The largest proportion of health-care-focused RMAs addressed mental health issues (n = 46/95), and stress and burnout in particular (n = 26/46).

Physical activity, sedentary behaviour or sitting time was the issue most commonly addressed in lifestyle-focused RMAs. In total, 37 RMAs were identified that addressed physical activity/sedentary behaviour/sitting time either as the sole focus of a review or in combination with other issues such as diet and nutrition. Multiple RMAs also examined the effectiveness of physical activity interventions to improve broader outcomes including those related to mental health, sickness absence and presenteeism.

Sixty seven out of the 95 health-care-focused RMAs involved a specific group of workers. However, the roles and settings examined were quite limited in scope, and nearly all RMAs were focused on nurses of various types, nursing students, doctors, medical students or staff working in mental health settings.

On a general level, it is unclear to what extent findings from reviews of studies conducted in non-health-care settings or in other countries are generalisable to the NHS workforce. There could be factors specific to UK health-care settings that impact on the ability of staff to adopt healthier behaviours, which limit the generalisability of findings from existing reviews; for example, differing organisational structures and practices, or the working conditions of staff. Most reviews are likely to have synthesised international evidence, and some may have drawn conclusions that are broadly generalisable across countries. Others could have taken local context into consideration when interpreting findings from primary studies.

Several publications identified in the scoping searches were commissioned by agencies in the UK. One RoR and one other review were commissioned by the Department of Health and Social Care. 28,55 A third review was conducted on behalf of Public Health England. 54 The RoR by Brunton et al. 28 examined workplace health programmes for improving health and business outcomes in any occupational setting. In contrast, the two reviews by Al-Khudairy et al. 54 and Brand et al. 55 included approaches to promoting health or health-related behaviour among health-care staff. The study by Al-Khudairy et al. 54 evaluated environmental level interventions to promote healthier food and drink choices. Brand et al. reviewed interventions to improve the health of health-care workers that adopted a whole-system approach. A considerable number of other reviews have also evaluated organisational-level interventions, or a combination of both individual and organisational-level interventions. Evidence on the effectiveness of interventions that integrate workplace health promotion and occupational health and safety activities has also been evaluated; for example, integrated ‘Total Worker Health’ programmes.

Multiple reviews were identified that focused on the same broad health issue, and in the case of physical activity, obesity and stress/burnout in particular, a large number of potentially relevant RMAs were mapped. It is possible, therefore, that there was considerable overlap in the primary studies included across RMAs (i.e. the same primary studies being included in multiple RMAs), which increases the potential for bias. If an in-depth synthesis were to be conducted on a subset of the evidence, it would be important to assess the extent of overlap in primary studies included across reviews.

A more in-depth examination was conducted of the 12 RoRs. These focused predominantly on evidence of effectiveness, with little information reported on costs or the delivery of interventions. Review questions, inclusion criteria and included publications differed across RoRs. There was also variation within individual RoRs in terms of interventions assessed, outcomes and length of follow-up (most were short term). It is worth noting that 5 of the 12 RoRs were over 5 years old (at the time of inclusion), and several RoRs, regardless of their publication date, included reviews from before 2000. This could have implications for the current relevance of some of the findings reported. The same issue could also apply to the RMAs in the evidence map as some may have included primary studies that were conducted prior to 2000.

Limitations of the scoping and mapping review

A pragmatic search strategy was developed for this mapping exercise, which was designed to identify key reviews related to the promotion of health and well-being in all types of workplace settings. It involved searching six databases with a primary focus on indexing evidence reviews. A more focused search of two other databases was also conducted specifically to identify additional reviews of interventions in health-care settings only. Although the search process was extensive and clearly effective at identifying relevant publications, the strategy used may not have identified every potentially relevant review; however, this is not a significant concern given the very large number of publications that were identified. Any reviews that the searches failed to capture would not have impacted significantly on the broad results of this evidence map.

Including publications in the evidence map based only on information in titles and abstracts should be recognised as a limitation. Without examining the full text of publications, it was not possible to verify that all reviews met the inclusion criteria. It also prevented a definitive determination being made about the health focus of reviews, and little detail was reported in title and abstracts about the specific type of intervention being examined. In addition, some of the reviews included in the map may not have been conducted in a systematic way; for example, a proportion may have been non-systematic literature review style publications, which are potentially at a high risk of bias and have poorer reliability.

Implications for additional synthesis work

The current mapping exercise was conducted on behalf of NHS England shortly after the introduction in 2018 of the NHS Health and Wellbeing Framework. 20 The framework exists to enable NHS providers to develop a staff health/well-being strategy, and it has a key focus on promoting both healthy lifestyles and positive mental health. The framework was the product of a multiorganisation collaboration and incorporated ‘best practice, research and insights’. 21

In addition, NICE has produced evidence-based public health guidance on a number of relevant issues. These were not examined in depth for the mapping exercise, but the guidance documents are appropriate for all employers, including the NHS. NICE routinely reviews its guidance and produces updates as required. Information provided on the NICE website indicates, for example, that:

-

The guidance on workplace smoking cessation was last checked in 2014 and no major evidence that would affect the recommendations was identified. 53

-

The guidance on promoting physical activity in the workplace was last checked in January 2019. It was assessed as still being largely relevant, but an update is being planned for 2021 to incorporate evidence on sit-stand desks. 57

-

The guidance on mental well-being at work was last checked in March 2018, and NICE is planning to update some recommendations in order to incorporate new evidence around certain issues including the effectiveness of educational and well-being interventions at an organisational level; the effectiveness of specific interventions such as mindfulness, cognitive–behavioural therapy and stress management. 58

The review team is doubtful that further evidence synthesis work at this stage would be of value to NHS England and add substantially to the existing knowledge base. Additional synthesis work may be useful if it addressed an identifiable need, and it was possible to identify one of the following:

-

A specific and focused research question arising from the current evidence map. It may then be appropriate to focus on a smaller number of reviews only, and provide a more thorough and critical assessment of the available evidence.

-

A specific gap in the literature (i.e. an issue not addressed by existing reviews or guidance). It may then be possible to undertake further literature searching and conduct a new evidence review; for example, the limited number of reviews focused specifically on groups of health-care staff other than doctors, nurses or medical/nursing students could indicate a potential research gap.

Conducting a ‘meta-review’ of evidence would not be appropriate as there was a considerable degree of heterogeneity between RoRs, for example in terms of focus and interventions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank NHS England colleagues for their input and feedback over the course of this piece of work.

Contributions of authors

Gary Raine (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0354-0518) (Research Fellow, Evidence Synthesis) drafted the protocol and carried out study selection, data extraction, and write up of the report.

Sian Thomas (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0917-0068) (Research Fellow, Evidence Synthesis) carried out study selection, data extraction, and write up of the report.

Mark Rodgers (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5196-9239) (Research Fellow, Evidence Synthesis) contributed to the write up of the report.

Kath Wright (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9020-1572) (Information Specialist) conducted all searching, wrote the search sections of the report and commented on the draft report.

Alison Eastwood (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1079-7781) (Professor, Research) oversaw the project, contributed advice and expertise and commented on all drafts of the report.

All authors commented on the protocol.

Data-sharing statement

All data requests should be submitted to the corresponding author for consideration. Access to available anonymised data may be granted following review.

Disclaimers

This report presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HS&DR programme or the Department of Health and Social Care. If there are verbatim quotations included in this publication the views and opinions expressed by the interviewees are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HS&DR programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References

- NHS England . The NHS Long Term Plan 2019.

- Boorman S. NHS Health and Well-Being: Final Report 2009.

- Department of Health and Social Care . NHS Health &Amp; Well-Being Improvement Framework 2011.

- Royal College of Physicians . Work and Wellbeing in the NHS: Why Staff Health Matters to Patient Care 2015.

- Sizmur S, Raleigh V. The Risks to Care Quality and Staff Wellbeing of an NHS System Under Pressure. Oxford: Picker Institute Europe; 2018.

- NHS England . NHS Staff Health &Amp; Wellbeing: CQUIN 2017–19 Indicator 1 Implementation Support 2018.

- NHS England . The NHS Constitution: The NHS Belongs to Us All 2015.

- Health and Safety Executive (HSE) . Tackling Work-Related Stress Using the Management Standards Approach: A Step-by-Step Workbook 2017.

- Boorman S. NHS Health and Well-Being: Interim Report 2009.

- NHS Survey Coordination Centre . NHS Staff Survey 2017 – National Weighted Data 2018. www.nhsstaffsurveys.com/Page/1064/Latest-Results/2017-Results/ (accessed 10 January 2019).

- NHS England . NHS Staff Health and Wellbeing: CQUIN Supplementary Guidance 2016. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4023.

- NHS Survey Coordination Centre . NHS Staff Survey 2017: National Briefing 2018.

- Keogh K. Eat Well, Nurse Well survey reveals stress at work leads to poor diets. Nurs Stand 2014;29. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.29.8.7.s2.

- Kyle RG, Wills J, Mahoney C, Hoyle L, Kelly M, Atherton IM. Obesity prevalence among healthcare professionals in England: a cross-sectional study using the Health Survey for England. BMJ Open 2017;7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018498.

- Malik S, Blake H, Batt M. How healthy are our nurses? New and registered nurses compared. Br J Nurs 2011;20:489-96. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2011.20.8.489.

- Mittal T, Clegnorn C, Cade J, Barr S, Grove T, Bassett P, et al. A cross-sectional survey of cardiovascular health and lifestyle habits of hospital staff in the UK: do we look after ourselves?. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2018;25:543-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487317746320.

- Schneider A, Bak M, Mahoney C, Hoyle L, Kelly M, Atherton I, et al. Health-related behaviours of nurses and other healthcare professionals: a cross-sectional study using the Scottish health survey. J Adv Nurs 2019;75:1239-51. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13926.

- Bakhshi S, Sun F, Murrells T, While A. Nurses’ health behaviours and physical activity-related health-promotion practices. Br J Community Nurs 2015;20:289-96. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2015.20.6.289.

- Kyle RG, Neall RA, Atherton IM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among nurses in Scotland: a cross-sectional study using the Scottish Health Survey. Int J Nurs Stud 2016;53:126-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.10.015.

- NHS England . Workforce Health and Wellbeing Framework 2018. www.nhsemployers.org/-/media/Employers/Publications/Health-and-wellbeing/NHS-Workforce-HWB-Framework_updated-July-18.pdf (accessed 10 January 2019).

- NHS Employers . NHS Health and Wellbeing Framework 2018. www.nhsemployers.org/your-workforce/retain-and-improve/staff-experience/health-and-wellbeing/the-way-to-health-and-wellbeing/health-and-wellbeing-framework (accessed 20 December 2018).

- Health Education England . NHS Staff and Learners’ Mental Wellbeing Commission 2019.

- Haby MM, Chapman E, Clark R, Galvão LA. Interventions that facilitate sustainable jobs and have a positive impact on workers’ health: an overview of systematic reviews. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2016;40:332-40.

- Kalani SD, Azadfallah P, Oreyzi H, Adibi P. Interventions for physician burnout: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Int J Prev Med 2018;9. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_255_18.

- Goldgruber J, Ahrens D. Effectiveness of workplace health promotion and primary prevention interventions: a review. J Public Health 2010;18:75-88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-009-0282-5.

- Fishwick D, Carroll C, McGregor M, Drury M, Webster J, Bradshaw L, et al. Smoking cessation in the workplace. Occup Med 2013;63:526-36. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqt107.

- Schröer S, Haupt J, Pieper C. Evidence-based lifestyle interventions in the workplace – an overview. Occup Med 2014;64:8-12. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqt136.

- Brunton G, Dickson K, Khatwa M, Caird J, Oliver S, Hinds K, et al. Developing evidence informed, employer-led workplace health. London: Department of Health Reviews Facility; 2016.

- Jirathananuwat A, Pongpirul K. Promoting physical activity in the workplace: a systematic meta-review. J Occup Health 2017;59:385-93. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.16-0245-RA.

- Schliemann D, Woodside JV. The effectiveness of dietary workplace interventions: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Public Health Nutr 2019;22:942-55. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018003750.

- Bhui KS, Dinos S, Stansfeld SA, White PD. A synthesis of the evidence for managing stress at work: a review of the reviews reporting on anxiety, depression, and absenteeism. J Environ Public Health 2012;2012. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/515874.

- Dalsbø TK, Thuve Dahm K, Austvoll-Dahlgren A, Knapstad M, Gundersen M, Merete Reinar L. Workplace-based Interventions for Employees’ Mental Health. Oslo: Knowledge Centre for the Health Services at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH); 2013.

- Joyce S, Modini M, Christensen H, Mykletun A, Bryant R, Mitchell PB, et al. Workplace interventions for common mental disorders: a systematic meta-review. Psychol Med 2016;46:683-97. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002408.

- Wagner SL, Koehn C, White MI, Harder HG, Schultz IZ, Williams-Whitt K, et al. Mental health interventions in the workplace and work outcomes: a best-evidence synthesis of systematic reviews. Int J Occup Environ Med 2016;7:1-14. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijoem.2016.607.

- Abdulwadud OA, Snow ME. Interventions in the workplace to support breastfeeding for women in employment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;10. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006177.pub3.

- Cahill K, Lancaster T. Workplace interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;2. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003440.pub4.

- Freak-Poli RL, Cumpston M, Peeters A, Clemes SA. Workplace pedometer interventions for increasing physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;4. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009209.pub2.

- Gillen PA, Sinclair M, Kernohan WG, Begley CM, Luyben AG. Interventions for prevention of bullying in the workplace. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;1. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009778.pub2.

- Hoving JL, Lacaille D, Urquhart DM, Hannu TJ, Sluiter JK, Frings-Dresen MH. Non-pharmacological interventions for preventing job loss in workers with inflammatory arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;11. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010208.pub2.

- Joyce K, Pabayo R, Critchley JA, Bambra C. Flexible working conditions and their effects on employee health and wellbeing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;2. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008009.pub2.

- Kuster AT, Dalsbø TK, Luong Thanh BY, Agarwal A, Durand-Moreau QV, Kirkehei I. Computer-based versus in-person interventions for preventing and reducing stress in workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;8. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011899.pub2.

- Naghieh A, Montgomery P, Bonell CP, Thompson M, Aber JL. Organisational interventions for improving wellbeing and reducing work-related stress in teachers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;4. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010306.pub2.

- Ojo O, Verbeek JH, Rasanen K, Heikkinen J, Isotalo LK, Mngoma N, et al. Interventions to reduce risky sexual behaviour for preventing HIV infection in workers in occupational settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;12. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005274.pub3.

- Pachito DV, Eckeli AL, Desouky AS, Corbett MA, Partonen T, Rajaratnam SM, et al. Workplace lighting for improving alertness and mood in daytime workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;3. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012243.pub2.

- Ruotsalainen JH, Verbeek JH, Mariné A, Serra C. Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;4. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002892.pub5.

- Shrestha N, Kukkonen-Harjula KT, Verbeek JH, Ijaz S, Hermans V, Pedisic Z. Workplace interventions for reducing sitting at work. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;12. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010912.pub5.

- Slanger TE, Gross JV, Pinger A, Morfeld P, Bellinger M, Duhme AL, et al. Person-directed, non-pharmacological interventions for sleepiness at work and sleep disturbances caused by shift work. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;8. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010641.pub2.

- Tanja-Dijkstra K, Pieterse ME. The psychological effects of the physical healthcare environment on healthcare personnel. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;1. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006210.pub3.

- van Wyk BE, Pillay-Van Wyk V. Preventive staff-support interventions for health workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;3. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003541.pub2.

- Wolfenden L, Goldman S, Stacey FG, Grady A, Kingsland M, Williams CM, et al. Strategies to improve the implementation of workplace-based policies or practices targeting tobacco, alcohol, diet, physical activity and obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;11. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012439.pub2.