Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/154/09. The contractual start date was in July 2016. The final report began editorial review in July 2019 and was accepted for publication in January 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Mike Crawford is Director of the College Centre for Quality Improvement at the Royal College of Psychiatrists (2011 to present) and was a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment General Committee (2018–19). He also reports that Imperial College London has received other research grants from the National Institute for Health Research and other funding bodies. Alan Quirk and Chloe Hood work at the Royal College of Psychiatrists (London, UK) and oversee the National Audit of Dementia, since 2013 and 2008 respectively. Peter Crome is chairperson of the Steering Group for the National Audit of Dementia and has been on the Health Technology Assessment Primary Care, Community and Preventive Interventions Panel and Health Technology Assessment Prioritisation Committee A (Out of Hospital) (2014–19). He also reports that University College London has received other research grants from the National Institute for Health Research and other funding bodies. Sophie Staniszewska has been on the following committees: Health Services and Delivery Research Associate Board Members (2012–17); and Health Services and Delivery Research Researcher Led – Associate Board Members and INVOLVE Board (2005–12). She also reports that University of Warwick has received other research grants from the National Institute for Health Research and other funding bodies. Kate Seers was a member of the Health Services and Delivery Research Commissioning Board (Researcher Led) (2010–18). She also reports that University of Warwick has received other research grants from the National Institute for Health Research and other funding bodies.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Sanatinia et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Context

The number of people living with dementia is increasing and it is expected that > 1 million people in the UK will have dementia by 2021. 1,2 The number of people with dementia who are admitted to acute hospitals is also increasing, with an estimated one in four beds occupied by a person with dementia at any one time. 3,4 People with dementia are more than twice as likely to be admitted to hospital than those without this condition. 5 Admission to hospital is rarely due to cognitive impairment. Most people with dementia have coexisting physical health conditions6 and admissions to hospital are precipitated by acute problems, such as hip fractures, stroke, urinary tract and respiratory infections. 7,8 In addition to higher rates of admission, people with dementia also spend longer in hospital once they are admitted and have higher rates of readmission once they are discharged. 9,10

Admission to hospital is very difficult for people with dementia. 7 Loss of contact with familiar surroundings and people, and disruption of regular routines, can be unsettling for patients and give rise to anxiety and agitation. 11,12 In one study,13 consisting of 230 inpatients with dementia in two acute hospitals in London, 57% of patients displayed signs of aggression and 35% of patients had significant anxiety during the course of their admission. 13 Problems that people with dementia may have in communicating their needs to staff may lead to poor pain management, which further increases the likelihood of agitated behaviour. 14 The likelihood of delirium, falls and other adverse events is also higher among inpatients who have dementia than those who do not. 3,15

Quality of care received by inpatients with dementia

Concerns have repeatedly been expressed about the quality of inpatient care that people with dementia receive. 16–19 Inquiries into poorly performing hospitals have highlighted the mismanagement of frail elderly people with dementia. 20 In its thematic review of the quality of care received by people with dementia in 2014, the Care Quality Commission reported that over half of hospitals had variable or poor practice when assessing the needs of people with dementia. 21 It also found variable or poor practice regarding staff knowledge and understanding of dementia in over half of hospitals. 21 Carers of people with dementia have reported dissatisfaction with the quality of care that people receive. 22

In an online survey of 570 carers of people with dementia, almost 60% of people felt that the person with dementia was not treated with dignity or understanding while in hospital. 7 A national audit of treatment received by people with dementia in general hospitals in England and Wales found that many people do not receive a comprehensive assessment of their needs and that carers are not sufficiently involved at the time of the admission or when planning for discharge from hospital. 23

Qualitative research conducted in acute inpatient settings has explored factors that influence the quality of care that people with dementia receive. Semistructured interviews with nurses working in a general hospital in southern Sweden identified a lack of time and other resources needed to care for people with dementia. 24 Nursing staff reported that they did not have the knowledge or skills to manage behavioural problems associated with dementia, leading to frustration and use of force and neglect in an effort to manage such problems. 24 Qualitative interviews with staff working on general medical and surgical wards in a general hospital in Queensland, Australia, revealed that nurses tended to focus on the safety of people with dementia, which led to an emphasis on monitoring patients at the expense of efforts to maintain their dignity and well-being. 25 In their literature review of the state of care of older people in general hospitals, Dewing and Dijk15 conclude that available evidence suggests that prioritisation of acute care for physical health conditions often means that staff do not deliver person-centred dementia care. 15

Concerns have also been expressed about the length of time people with dementia remain in hospital. It has been argued that failure to assess and respond to the needs of inpatients with dementia can lead to longer length of stay. 3,26 Follow-up studies have shown that, even when demographic and clinical conditions of patients are accounted for, people with dementia may stay in hospital for twice as long as those who do not have this condition. 10 Identifying steps that hospitals could take to avoid lengthy admissions of people with dementia has the potential to improve both the clinical outcomes and the cost of care for people with dementia.

Efforts to improve the quality of care that people with dementia receive

Concerns about poor health outcomes and negative experiences of inpatient care among people with dementia have promoted the development of a range of different policies and practices aimed at improving the quality of care that people receive. These efforts include better training for staff,27 deployment of specialist nurses,28 the expansion of mental health liaison teams29 and specialist units. 30–32 Although studies based in single wards or hospitals have shown that it may be possible to improve patient and carer experience and physical and mental health outcomes,30,31,33 there is very little understanding of the impact that efforts to improve quality of care at a national level have on the quality of care that people with dementia receive.

Specialist units have been designed to try to better meet the needs of inpatients with cognitive impairment. 34,35 Available evidence suggests that such units may increase carer satisfaction and reduce the incidence of adverse events, but may not have an impact on mortality or length of admission. 30,31,36 However, the vast majority of people with dementia who are admitted to an acute hospital are admitted to general medical and surgical wards, and there is limited evidence about what staff on these wards can do to ensure that people with dementia receive high-quality care.

Over the last 20 years, a number of hospitals have set up specialist posts in an effort to improve the quality of inpatient care that people with dementia receive. 37 Specialist nurses, such as those deployed in Cambridge,28 helped hospitals develop policy and practice guidelines, and trained and supported colleagues working on inpatient wards. In a survey of 75 dementia specialist nurses working in the UK, Griffiths et al. 38 reported that people working in these roles undertook a broad range of activities, including efforts to prevent adverse events, supporting successful and timely discharge of patients, and reducing the use of antipsychotic medications. 38 In a parallel scoping literature review, the team identified a number of interventions that may reduce the length of stay and rate of readmission of people with dementia, but did not find direct evidence for the impact of dementia nurse specialists on patient outcomes. 39

Regarding psychiatric liaison services, research into the impact of a service, which was set up to deliver ‘rapid assessment, interface and discharge’ in an acute hospital in Birmingham, used data from a matched sample of historical controls to calculate the impact of the service. 40 Although the mean age of referrals to the service was 65.7 years, only 18% of people referred to the team had dementia. The team found that length of stay of patients referred to the service was shorter than those of matched patients before the introduction of the service, raising the possibility that psychiatric liaison services can assist in facilitating the discharge of older adults with mental health conditions, including dementia. 41 National mental health policy published in England in 2014, called for all acute hospitals to have access to liaison mental health teams that include expertise in psychiatry of older adults by 2021. 42

The National Audit of Dementia

The National Audit of Dementia (NAD) was established in 2008 to provide comparative data on the quality of care that people with dementia receive from acute hospitals in England and Wales. The audit is funded by the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) on behalf of the NHS England and the Welsh Government. To date, there have been three rounds of data reporting, in 2011, 2013 and 2017. 8,23,43 The 2017 audit, combined a retrospective audit of clinical data obtained from case notes with a survey of carers of people with dementia who had been admitted to acute hospitals. Clinical data included information about whether or not assessment of patients had been conducted in accordance with national guidelines, as well as information about length of stay. In addition to this audit, leads in each hospital completed an ‘organisational checklist’, which quantified aspects of the organisation and delivery of care for people with dementia (e.g. involvement of senior managers in reviewing the care of people with dementia and the deployment of specialist dementia nurses).

The third round of the NAD generated benchmarked data for each hospital in England and Wales, which was used by local commissioners, providers and users of services to identify poor performance and support efforts to improve the quality of care they provide. 8 Although the audit was not designed to generate or test hypotheses about factors that influence the quality of care delivered to inpatients with dementia, data from the audit provides a rich source information about both the processes and the outcomes of care that inpatients with dementia receive. A secondary analysis of data from the second round of the audit found differences in the quality of assessment of patients according to the type of ward they were treated on. 44 However, data from the audit have not been used to examine the impact of the organisation and delivery of general hospital services on the length of stay or carer-rated quality of care for people with dementia.

Chapter 2 Research objectives

The overall aim of the study was to identify aspects of the organisation and delivery of general hospital acute care that are associated with better-quality care and shorter length of stay for people with dementia, and to understand how the organisation and delivery of hospital services influences the quality of care that people receive. To meet this aim, our objectives were to:

-

identify factors that are associated with higher quality of assessment, shorter length of admission and better carer-rated experience of care for inpatients with dementia

-

understand how aspects of organisational form and function of services impact on the quality of care that inpatients with dementia receive

-

examine how contextual factors, including organisational culture, can support and/or impede the delivery of effective care to inpatients with dementia

-

synthesise data on factors that may improve the quality of care for people with dementia, to make recommendations for commissioners, providers and users of acute inpatient services about the optimal organisation and delivery of inpatient services for people with dementia.

Although there is a considerable body of evidence that the quality and availability of community-based services has a significant impact on the length of stay and quality of care that inpatients with dementia receive, this study was designed to focus only on those factors that are under the direct control of those working in acute inpatient settings.

Aim of patient and carer involvement in the study

We set out to work closely with patients and carers throughout every stage of the study. A patient and a carer representative were members of the Project Management Group and patients and carers were also members of the Stakeholder Reference Group. Through working closely with patients and carers, we aimed to ensure that the study properly considered the experiences of people with dementia and their carers, and generated relevant and appropriate outputs that could improve patient and carer experience.

Chapter 3 Scoping review of the literature

Prior to the start of the study, we undertook a scoping review of the literature. We did not aim to systematically review the literature, as a comprehensive review of factors that affect the quality of care received by inpatients with dementia had already been published. 15 Instead, we aimed to identify any important new research that had been published following this review, to help guide the selection of items from the audit, which were to be included in the secondary analysis of data, and to inform the development of questions for the topic guide for the qualitative component of the study.

Dewing and Dijk15 searched electronic databases [PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), MEDLINE and PsycINFO] for papers on the acute care of older people with dementia in general hospitals, which were written in English and published between 2007 and 2013. They chose 2007 as the start date for their review, so as not to duplicate work already undertaken by Moyles et al. 45 who conducted an earlier review. Dewing and Dijk retrieved 278 papers, of which 53 met their inclusion criteria (written in English, published between 2007 and 2013, with a clear focus on care of older people with dementia in acute settings). In their narrative synthesis of data from these papers on factors affecting quality of inpatient care for people with dementia, Dewing and Dijk15 identified the following seven themes.

Care environment

Inpatient care on acute wards was generally considered unsuitable for people with dementia, because of the busy environment, the lack of familiar surroundings and personal objects, and too little or too much contact with staff. People with mild dementia who are able to discuss their experience of acute care described being ignored and being surrounded by noise and busy surroundings. 46,47

Cultures of care

Concerns expressed that senior managers often underestimate the needs of people with dementia. Front-line staff report inadequate training and a lack of time to spend with patients.

Attitudes

Observational evidence suggests that positive nursing attitudes have a positive effect on care and that attitudes of nurses may vary according to the type of ward people that are treated on (with nurses on medical wards tending to have more positive attitudes than those on surgical wards). There is also some evidence that the attitudes of front-line staff can have an impact on their willingness to use a person-centred approach.

Challenges for people with dementia as an acute patient

People with dementia experience disruption in their routines. ‘Challenging’ behaviours may be a response to a patient trying to assert control over a changing environment.

Challenges for carers

Descriptive accounts of how an admission to hospital can add to a carer’s physical and emotional exhaustion. 19 Evidence suggests that some staff find carers demanding and disruptive, which may further impede the delivery of effective care and discharge from hospital. 48

Challenges for staff

Clinical staff have reported feeling overwhelmed when having to deal simultaneously with medical emergencies and with ‘challenging behaviours’ of people with dementia. 48 Staff express concerns about not having adequate training to meet the demands of people with dementia. 25

Service models

Dewing and Dijk15 highlighted a number of service-level interventions that have aimed to improve the quality of inpatient care that people with dementia receive and concluded that mental health liaison services and specialist roles vary considerably, making it difficult to generalise findings from single-site studies; a number of studies have examined the impact of staff training; and several studies have found short-term improvements in knowledge and increased confidence in caring for people with dementia, but longer-term outcomes have not been examined.

To update this review, we searched two electronic databases [Web of Knowledge and Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA)] from January 2013 to April 2016, using the search terms related to ‘dementia/cognitive impairment’, ‘acute hospital care/general hospital’ and ‘quality of care/length of stay/experience of care/safety’. We included:

-

papers that reported the results of observational studies and described the quality of acute care for people with dementia, and experimental studies that tested the impact of interventions aimed at improving it

-

papers that were published after December 2012 and were written in English

-

papers that used a full range of research methods, including quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods studies.

We excluded:

-

papers that focused on care received by people with dementia outside acute care settings

-

opinion pieces and non-peer-reviewed publications.

The initial search generated > 17,677 papers. Examination of titles and abstracts of these papers led to 68 full-text articles being assessed for possible inclusion in the review. The main reason for excluding papers was that they did not examine acute care for people with dementia. Twelve of these 68 papers focused on factors influencing the quality of inpatient acute care that people with dementia receive. Details of these 12 papers are provided in Table 1. We started our analysis of the data by summarising the key features of the included papers and tabulating their results to identify patterns across different studies. We then grouped the papers together, based on the themes that Dewing and Djik used in their previous review. 15 Throughout this process, we attempted to find evidence that supported or challenged the results of Dewing and Djik’s review,15 as well as attempting to identify any aspects of the organisation and delivery of services that influenced the quality of acute care for people with dementia that the Dewing and Djik review15 did not report.

| Study | Study type | Study setting (country, clinical setting) | Study sample | Main aims | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banks et al.49 | Mixed-methods study | 113 health professionals from 14 NHS boards in Scotland | 78 nurses, 10 occupational therapists and 25 allied health professionals (physiotherapists, dieticians, one consultant physician) | To assess the impact of training new ‘dementia champions’ on staff perceptions, knowledge and understanding of dementia, and their ability to foster innovative practice | The training programme was judged to be effective and transferable to other staff groups, including community settings, etc. |

| Connolly and O’Shea50 | Case study | Discharge data from all acute hospitals in Ireland during 2010 | 6702 discharges for which there was a diagnosis of dementia | To identify measures to improve the experience of those with dementia in acute hospitals and reduced length of stay | Those with a dementia diagnosis had a longer inpatient stay than those without. Explanations for this were suggested by the authors |

| Goldberg et al.51 | Qualitative case study | Large hospital in the East Midlands region of UK | Field notes were analysed, and 360 hours of observations conducted from MMHU and standard care wards | To compare and contrast behaviours of staff and patients on each of the wards, to explain the link between structure, process and reported outcomes | MMHU offered distinctively different care, although good practice remained difficult to sustain |

| Griffiths et al.39 | Narrative literature review | Various | 71 papers included, mainly from Europe and North America | To identify the potential benefits of dementia specialist nursing and to inform the implementation of roles to support people with dementia during hospital admission | A skilled dementia specialist nurse can make a positive difference to the quality of care offered to those with dementia, but only if the role is clearly defined and they are permitted to work with patients and carers for a significant proportion of their time |

| Hynninen et al.52 | Qualitative study | Four surgical wards of a Finnish university hospital | Seven people with dementia and five close relatives | To describe the care of older people with dementia on surgical wards from the perspective of patients and their close relatives | Treatment of people with dementia in hospital improved when close relatives were involved in care planning |

| Hynninen et al.53 | Qualitative study | A surgical ward at a Finnish university hospital | 19 nursing staff and nine physicians | To describe the care of older people with dementia in surgical wards from the viewpoint of the nursing staff and physicians | Nursing staff believed that caring for people with dementia was physically and mentally demanding. Physicians and nursing staff had different views about patients’ challenging behaviour |

| Ibrahim et al.54 | Narrative literature review | Various | Papers mainly from Europe and North America | To examine domains of treatment effectiveness, burden of care, quality of life, and patient autonomy and capacity | Options identified for improving how limitations of care orders can be implemented more successfully at individual, organisational and societal levels |

| McPherson et al.55 | Qualitative study | Three inpatient dementia wards in UK | Qualitative interviews with 10 front-line nurses and health-care assistants | To explore the experiences of managing work pressures in the NHS when caring for older adults with dementia | Value-based recruitment is insufficient to deliver a high quality of care. Further attention should be paid to creating a culture of staff reliance and self-care |

| Scerri et al.56 | Qualitative study | Two geriatric hospitals in Malta | 33 care workers working in a geriatric hospital and 10 family members of patients with dementia | To explore the quality of inpatient dementia care | Five care processes identified: (1) role of other patients on the ward, (2) providing quality time, (3) providing care in time, (4) going the extra mile and (5) attending to needs with a human touch |

| Surr et al.57 | Case study | One NHS trust in the North of England | 40 acute hospital staff working in clinical roles (90% of whom were nurses) |

To evaluate a specialist training programme for acute hospital staff to deliver more person-centred care Impact on self-reported attitudes and behaviour was assessed 4 months later |

Positive change noted on all outcome measures following completion of intermediate training. Significant positive effect found on ‘approaches to dementia’ measure, but not in staff experiences and ‘caring efficacy’, after the foundation training |

| Whittamore et al.58 | Randomised trial | General wards and a specialist MMHU in a general hospital in England | 600 cognitively impaired individuals aged ≥ 65 years and 488 related caregivers | To identify patient and caregiver characteristics associated with caregiver dissatisfaction with hospital care of cognitively impaired elderly adults | Dissatisfaction was associated with carer strain and their response to behavioural and psychological symptoms of the patient, but was lower among those admitted to the MMHU |

| Yevchak et al.59 | Mixed-methods case study (in the context of a RCT) | Three clinical sites: an academic centre, a regional trauma centre and a regional medical centre in the USA | Acute care staff, including registered nurses, nursing assistants and other staff |

To determine whether or not there are differences in nursing rounds across three diverse settings, with regard to number and staff attendance To assess barriers to and facilitators of conducting nurse-led rounds |

A unit champion was present on 64% of all nursing rounds in each site, the only obstacle to their presence being ‘busy on the unit’ Barriers to care that were identified via qualitative research were ‘busy on the unit’, ‘lack of awareness’ and ‘no study patients’ |

Summary of the results of the scoping literature review

Care environment

Lack of privacy, including the impact of noise, was regarded by service users and their families as a significant issue that compromised patients’ basic care on occasions, as well as their sense of identity and self-esteem. 51 Organised activities were regarded as contributing to the creation of a homely and comfortable environment conducive to quality care. 51,57 Basic safety and cleanliness, as well as other inexpensive but effective touches, were identified as important in making the patient feel more comfortable, which, in turn, were believed to ameliorate fear and anxiety. 57

Cultures of care

The frenetic nature of activity on the ward, combined with a sense of professional abnegation of responsibility, were viewed as barriers to assessing the mental health needs of the patients. 52 Staff felt as if there was insufficient time to care for patients, resulting in a focus on task management.

Patients were often excluded from decision-making, which, aside from leading to inaccurate judgement calls in relation to patients’ needs, led to a fractured caring relationship with professionals. 54

Attitudes

The resilience of staff to manage their workloads was significantly undermined by the lack of organisational training, access to pastoral and professional support, and time for emotional processing. 56 When person-centred training had been offered to staff, positive changes in approach to work were observed, in terms of a professional’s approach both to their work and to the patients. 59

Challenges for people with dementia as an acute patient

Lack of consultation with patients often made them feel frustrated, which had an impact on their ability to function in a non-aggressive way on the ward. 54 Patients often coped better when they were able to access family support, instead of relying entirely on staff, particularly in circumstances when the family felt welcomed and were provided with feedback as to how to manage the care needs and welfare of the patient. 57 Patients often felt insecure without family support and missed them. 39

Challenges for carers

Carers’ dissatisfaction was found to be mostly associated with discharge planning, clinical management and poor communication. When patients were treated on specialist medical and mental health units, carers were less dissatisfied. 58 Carers who were allowed to become more involved with their loved one while they were a patient helped bridge the difficulties in communication about welfare needs between patient and staff. This was even more beneficial when visiting hours were flexible and staff were not rotating frequently. Greater consistency in staffing was viewed as improving rapport between patients and staff. 57 When carers were not involved appropriately, this led to significant strains, especially around discharge planning. Care diaries, family meetings and routine engagement by staff (including consultants overseeing a patient’s care)39 with family members were all considered helpful and inexpensive methods to achieve a joined-up experience of care for patients and their family. 52

Challenges for staff

Nursing staff on surgical wards reported that providing care for patients with dementia was demanding and that they felt that they did not have the skills needed to effectively manage challenging behaviour. 53 The importance of assessing capacity and knowing how to manage care in consultation with the patient was highlighted in the research undertaken by Ibrahim et al. 54 The ability of staff to identify and manage delirium was considered a barrier to the assessment of capacity. 49,50 Staff reported wanting to have better information about what community-based services they can involve or refer people on to. 50 In their analysis of qualitative comments from front-line staff working with people with dementia, Banks et al. 49 reported that some staff had positive experiences of using patient-held documents. These documents summarise a person’s history, cultural and family background, and their preferences.

Service models

Specialist nurse involvement improves patient experience and outcomes, in terms of both cost and delivery of specialist care. Specialist nurses can also assist in training other staff and thus enhance the general levels of skills and care afforded to patients with dementia. 55 The dementia champions training programme was also assessed to lead to positive changes in confidence, aptitude and work satisfaction in staff dealing with patients who have dementia. 56

Unit champions were considered to promote the welfare of patients, particularly if they had a strong interest in gerontology, and were prepared to act in a mediation-type role between staff, patients, family support and administrative leadership. 59

Specialist units were found to provide more consistent and enduring attention to a patient’s mental health needs, despite a need to concentrate more time to basic physical health care,51 which was enhanced even more so if the patient was cared for on a specialist mental health ward. 52

The results of the scoping review of the literature provided additional evidence to support the roles that the ward environment, staffing levels and staff training, and supervision and support for staff and carer involvement play in the quality of inpatient care that people with dementia receive. We also found, largely qualitative, evidence supporting the deployment of specialist nurses and patient-held records. The results of the scoping review led to our decision to include the deployment of specialist staff and the availability of personal information as items in our secondary analysis of quantitative data from the NAD. We also enquired about these elements of care in the subsequent qualitative case studies.

Chapter 4 Methodology

We used a mixed-methods approach to examine factors associated with the delivery of high-quality acute care for people with dementia. The study consisted of two work packages: a secondary analysis of data from the third round of the NAD (work package 1), followed by nested comparative case studies of hospitals and wards that provide the most and least effective care using a ‘realist’ approach (work package 2). This ‘sequential’ approach to mixed-methods research has been recommended as a means of understanding the significance of quantitative associations between interventions and outcomes, and has been used to develop a better understanding of how, and in what circumstances, positive outcomes of interventions can be delivered. 60,61

We used the results of the scoping review of the literature to help select items for inclusion in the quantitative analysis in work package 1 and the development of topic guides used in work package 2.

Work package 1

Work package 1 consisted of a secondary analysis of data, primarily from the third round of the NAD. 8 We obtained data for work package 1 from the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ (RCPsych’s) Centre for Quality Improvement. We applied, via the HQIP’s Data Access Request Group, for access to password-protected copies of two databases that contained the results of the case note audit and the carer survey. Neither database contained any identifiable data, such as name or contact details of patients or carers. Hospital names were replaced by codes.

Data on provision of psychiatric liaison services were not collected in the third round of the audit. We therefore used data from the second national survey of liaison psychiatry services for working-age adults and for older adults in England, which was conducted by Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry, on behalf of NHS England. 62 The two sources of data were linked using the name of the hospital. The survey was limited to acute hospitals in England that had an emergency department at the time when the survey was conducted.

Study setting and sample

The setting for the study was acute hospitals in England and Wales. We analysed data from all acute hospitals that took part in the third round of the NAD. Overall, 203 hospitals were asked to take part in the audit and 200 (98.5%) participated. Each hospital that took part in the audit was asked to submit anonymised data on a consecutive sample of at least 50 people (and a maximum of 100 people) admitted to the hospital from 1 April 2016. To be eligible to take part in the audit, patients had to have been given a diagnosis of dementia and to have been in hospital for ≥ 72 hours. Case notes were identified by hospitals using a list of International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, codes for dementia. When patients had more than one admission during the data collection period, data from the first admission only were used.

Data collection methods

Each hospital that took part in the audit was asked to collect and submit five different sets of data:

-

a hospital-level organisational checklist

-

a retrospective case note audit of at least 50 sets of patient records

-

an examination of the availability of personal information on 10 people with dementia

-

a survey of carers of people with dementia

-

a staff survey.

Data from the first four sets of data were included in this analysis. Data from the staff survey were not included.

A senior member of staff at each hospital was asked to complete the organisational checklist. The checklist consisted of 42 questions on topics including collection and reporting of data to the executive board; staff training; carer engagement; environmental review; the collection of personal information about patients with dementia; and food provision. The audit team asked for the member of staff who completed the organisational checklist to be aware of how senior managers and front-line staff aimed to support people with dementia, and that they consulted with colleagues in the hospital to ensure that the information they provided was accurate. Data were entered by staff in each hospital via a secure online survey portal.

Hospital staff were asked to enter data extracted from clinical records for between 50 and 100 patients with dementia. This approach meant that larger hospitals with greater numbers of admissions could submit more data if they chose to. The case note audit covered 36 items, including the person’s admission, their assessment, use of personal information, care planning and delivery, and the discharge process. Data were submitted by audit leads from each hospital, with input from colleagues from audit departments, junior doctors and dementia champions. Data from patient records were entered by staff in each hospital via a secure online survey portal.

Staff at each participating hospital were also asked to examine the extent to which personal information on people with dementia was available to front-line clinical staff. To establish this, the audit lead at each hospital was asked to select three acute adult wards with the highest admissions of patients with dementia. They were then asked to identify 10 patients with dementia on these wards and to check whether a personal information document (e.g. the Alzheimer’s Society’s This is Me document63) was present at the bedside or in the patients’ clinical notes.

A median of 10 patients were checked per site. Of the patients checked at each site, a mean average of 49% had a personal information document present. This ranged from 0% to 100% of patients checked.

The carer questionnaire was developed specifically for the NAD by staff at the Patient Experience Research Centre at Imperial College London. The questionnaire consisted of 10 items, out of which eight were ranked high in terms of relevance to the care of people with dementia, by a panel of carers. The panel thought that all carers and family members who might visit people with dementia would answer these questions. The questionnaire also incorporated the Friends and Family Test question for validation and comparison,64 and a final question, added at the suggestion of the audit reference group, on support provided by the hospital to the carer. Paper versions of the carer questionnaire were distributed by staff to both paid and family carers visiting patients during June to September 2016. Questionnaires were returned directly to the audit team at the RCPsych. Carers could also complete an online version of the questionnaire, which was publicised via social media and on posters displayed around participating hospitals. The questionnaire did not include personal identifiable information and could not be linked to individual patients. All tools used in the audit were piloted by 10 hospitals in 2015 and changes made prior to the full audit in 2016.

Data for the second national survey of liaison psychiatry services for working-age adults and for older adults in England were collected between 14 January 2015 and 30 April 2015.

The team conducting this survey contacted liaison psychiatry teams at all acute trusts in England that included an emergency department. Data were returned on 179 hospitals in England. 62 The questionnaire included 27 items, covering the composition of teams and the hours that the liaison service covered.

Outcome measures

We set out to examine factors influencing three aspects of the quality of acute care that people with dementia receive: (1) length of admission, (2) carer-rated quality of care and (3) quality of patient assessment. The date of a patient’s admission and discharge from hospital was included in the case note audit. We used this to calculate the length of admission for each patient.

We used scores on carer-rated quality of care for each hospital, which had been calculated for the third round of the NAD. This score was derived from responses carers made to a single item, ‘overall, how would you rate the care received by the person you look after during the hospital stay?’, which could be rated excellent, very good, good, fair or poor. The maximum rating for a hospital was 100 (awarded if all carers rated the hospital as excellent) and the minimum rating for a hospital was 0 (if all carers rated the hospital poor). Details of how carer responses were used to calculate the aggregate hospital score can be found at URL: www.rcpsych.ac.uk/improving-care/ccqi/national-clinical-audits/national-audit-of-dementia/nad-reports-and-resources (accessed 18 March 2020).

We used data from the case note audit records to assess the quality of assessment that each patient received. 44 Each patient was given a score of between 0 and 7, according to whether or not seven components of a high-quality assessment had been conducted (mobility, nutritional status, pressure ulcer risk assessment, continence needs, presence of any pain, a structured assessment of functioning and assessment of delirium). These seven items were selected because they are included in the guidelines produced by the British Geriatrics Society. 65 Failure to assess these aspects of health care have also been shown to be associated with the likelihood of early readmission to hospital of people with dementia. 33,66

Predictor variables

We used a three-stage process to generate a list of predictor variables for work package 1. We selected these variables from those assessed in the dementia audit and survey of psychiatric liaison services. In the first stage, we used data from our scoping review of the literature and from our previous research examining factors associated with the quality of assessment of people with dementia who are admitted to acute hospital beds,44 to draw a long list of items that we judged could influence one or more of our three study outcomes. We presented this long list to the Project Management Group and Stakeholder Reference Group for their views (see Patient and carer involvement). This generated a short list of variables paired with each outcome. Having examined the distribution and frequency of these measures, we noted that in some instances there was very little variation and excluded any predictor variables that were present or absent in > 90% of hospitals. In all instances, variables were excluded from the analysis because they were nearly always present. A list of these variables is provided in Appendix 1. The final list of variables included in the main analysis is presented in Tables 2–4.

| Predictor variable | Source of data | Audit item |

|---|---|---|

| Type of ward | Case note audit | Q5 |

| Primary diagnosis | Case note audit | Q6 |

| Discharge planning within 24 hours of admission | Case note audit | Q34 |

| Evidence of discussing discharge with carers | Case note audit | Q29b |

| Executive board reviews delayed discharge | Organisational checklist | Q2b |

| Evidence of discussing discharge with consultant responsible for the patient | Case note audit | Q29c |

| Dementia specialist nurse | Organisational checklist | Q6 |

| Social worker or other designated person | Organisational checklist | Q34 |

| Dementia care pathway/bundle | Organisational checklist | Q1 |

| Liaison hours | Liaison survey | Q21 |

| Older adult consultant | Liaison survey | Q14 |

| Demographic variable | ||

| Age of the patient | Case note audit | Q1 |

| Gender of the patient | Case note audit | Q2 |

| Ethnicity of the patient | Case note audit | Q3 |

| Predictor variablea | Source of data | Audit item |

|---|---|---|

| Evidence of discussing discharge with carers | Case note audit | Q29b |

| Social worker or other designated person | Organisational checklist | Q34 |

| Strategy or plan for carer engagement (e.g. triangle of care) | Organisational checklist | Q7 |

| Hospital provides finger food for people with dementia | Organisational checklist | Q35 |

| 24-hour food service | Organisational checklist | Q36 |

| Carer visit at any time (carer passport) | Organisational checklist | Q13 |

| Availability of personal information (mini audit) | Organisational checklist | Q16 |

| Carer received notice of discharge (< 24 hours and ≥ 24 hours) | Case note audit | Q35 |

| Documented assessment of carer needs prior to discharge | Case note audit | Q36 |

| Care assessment contains section dedicated to information from carer | Case note audit | Q22 |

| Demographic variables (patient) | ||

| Age of the patient | Case note audit | Q1 |

| Gender of the patient | Case note audit | Q2 |

| Ethnicity of the patient | Case note audit | Q3 |

| Demographic variable (carer) | ||

| Gender of the carer | Carer survey | Q1 |

| Age of the carer | Carer survey | Q2 |

| Ethnicity of the carer | Carer survey | Q3 |

| Predictor variable | Source of data | Audit item |

|---|---|---|

| Type of ward | Case note audit | Q5 |

| Length of stay | Case note audit | Q11 |

| Dementia care pathway in place | Organisational checklist | Q1 |

| Dementia champion (at directorate level) | Organisational checklist | Q5 |

| Dementia specialist nurse | Organisational checklist | Q6 |

| Liaison hours | Liaison survey | Q21 |

| Older adult liaison psychiatry consultant | Liaison survey | Q14 |

| Primary diagnosis | Case note audit | Q6 |

| Demographic variable | ||

| Age of the patient | Case note audit | Q1 |

| Gender of the patient | Case note audit | Q2 |

| Ethnicity of the patient | Case note audit | Q3 |

Carer-rated quality of care was measured at the hospital level; therefore, all variables needed to be aggregated at hospital level. We were therefore unable to include primary diagnosis and type of ward in this analysis.

Data management and analysis

A number of the predictor variables included large numbers of categories with small numbers of patients in them. To simplify the analysis, we combined some categories prior to data analysis. When possible, we used categories that were developed by the audit team. Case notes included > 100 descriptions of primary diagnosis. These were grouped together in 11 categories, such that myocardial infarction was combined with other vascular conditions, and kidney and urological conditions were grouped together. Ethnicity was not well recorded in the case notes. The majority of the sample were recorded as white or white British (82.1%) and 12.4% of the sample were recorded as ‘other’. Less than 2% of records indicated other ethnicities (black/black British 1.2%, Asian/Asian British 1.9%, Chinese 0.1% and mixed 0.1%). We therefore combined these groups with ‘other’ to create a dichotomous variable white and white British, or black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME).

We used univariate tests to conduct preliminary analysis of the relationship between dependent variables (length of admission, carer-rated quality of care and quality of assessment of patient needs) and patient-level (age, gender, presenting complaint), ward-level (type of ward) and hospital-level (access to liaison mental health services, deployment of specialist dementia nurses, etc.) predictor variables. Further exploratory analyses were carried out to look at which combinations of these exploratory variables could best explain the variations in dependent variables.

Given the nested structure of the data (patients within hospitals), the final analysis was carried out using hierarchical models. 67,68 Traditional regression methods were not deemed appropriate because they assume independent observations. For instance, measurements taken from patients in the same hospital can no longer be assumed to be independent (i.e. they are correlated). Hierarchical models take this into account to draw valid statistical inferences. 69 Using hierarchical modelling made it possible to compare hospitals in terms of patient outcomes. This was achieved by testing cross-level interactions, which combine the effects of explanatory variables at the patient and hospital level. Interactions between explanatory variables within each level were also tested.

Using this methodology, we combined the information across hospitals with patient-level information to identify predictors that may have an impact on length of admission and quality of assessment of needs. Unlike length of admission and quality of assessment, which were measured at the patient level, carer-rated quality of care was measured at the hospital level. Therefore, for this analysis, variables that were not at the hospital level were aggregated. Multiple linear regression was used for this analysis.

Patient-level scores on quality of assessment were not continuous; they were ordered categorical variables, ranging from 0 (no items completed) to 7 (all items completed). We therefore used ordered logistic regression applied to hierarchical models to analyse these data. Most patients (n = 9260, 91.6%) had a score of ≥ 5 on this measure. We therefore collapsed the seven categories to create a variable with four categories: 0 (zero to four items completed), 1 (five items completed), 2 (six items completed) and 3 (seven items completed).

All data were analysed using statistical packages Stata® (version 13; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and SPSS 23 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

The outcome measure, length of admission, was skewed so transformation of data on length of admission was required. For the outcome measure, we excluded all those who died during their admission from all analyses, including the sensitivity analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

In addition to examining factors associated with mean length of stay among the entire audit sample (excluding those who died during their admission to hospital), we conducted two sensitivity analyses. In the first of these, we repeated the analysis in a subsample of people who were admitted to hospital with fracture of the hip and related injuries. In the second, we restricted the analysis to the 50% of hospitals that had higher carer-rated quality of care.

By limiting the sample to those with hip injuries we sacrificed study power, but aimed to provide a more precise estimate of the association between practice and outcomes, by reducing confounding resulting from differences in case mix across study sites. 70 We selected hip injuries for this analysis following consultation with front-line clinicians and other stakeholders, as it is prevalent among people admitted to acute hospitals with dementia and because they are relatively easy to diagnose. 26,70

We conducted a sensitivity analysis among the hospitals that were in the top half of carer-rated quality of care because of concerns from members of our Stakeholder Reference Group that hospitals could achieve shorter average lengths of stay by discharging patients prematurely. We therefore wanted to check that any factors assorted with shorter lengths of stay were not at the cost of low carer-rated satisfaction.

Work package 2

Work package 2 consisted of six comparative case studies of dementia care in acute hospitals. Hospitals were sampled to include pairs of hospitals that organise and deliver care in a similar way, but which achieve different outcomes. The overarching aim of this study was to identify aspects of organisation and delivery of general hospital services associated with the three key outcomes measured for the third round of the NAD: (1) carer-rated experience of care, (2) length of stay and (3) quality of assessment.

Theory development: a ‘twin-track’ approach

To optimise the contribution of work package 2 to the study, we designed and implemented a ‘twin-track’ approach to theory development. 71

Track A: qualitative exploration of factors associated with patient outcomes

In parallel with a realist evaluation [see Track B: theory testing and refinement (realist evaluation)], we explored factors associated with patient outcomes in work package 1. For example, we found that initiation of discharge planning within the first 24 hours of admission was associated with shorter length of stay. In work package 2, we were interested in finding out how and why that might be the case.

Track B: theory testing and refinement (realist evaluation)

We conducted a realist evaluation of the delivery of acute care for people with dementia. 72,73 Realist research design employs no single standard ‘formula’, other than producing a clear theory of programme mechanisms, contexts and outcomes, and then using appropriate empirical measures and comparisons. We considered the most effective approach for this study to be a comparative case study design. The selection of hospitals, methods and research questions was theory driven (i.e. driven by the research team’s theory for how interventions for improving dementia care bring about change and how organisational culture shapes the response of hospital staff).

At the outset of the study, we developed programme theories for aspects of dementia care assessed by the NAD (see Appendix 2). These theories were informed by the results of our scoping review of the literature and results from earlier rounds of the audit and, thus, summarise our initial thinking about how aspects of hospital care, such as dementia-friendly food provision, can make a difference in favourable contexts to outcomes, such as carer-rated quality of care.

Realist evaluation can be used to test theory for how change occurs (if the evaluators already have a fairly well-developed theory) or to formulate and develop theory through a more exploratory approach. 72 We considered our programme theories to be only moderately well developed, so after testing the theories in the main 18-month phase of fieldwork in four hospitals, we sought to refute or refine them in a second 4-month phase of fieldwork in two additional hospitals. By interviewing staff and carers in contrasting hospitals, we sought to understand better why something that can work well in one context may make little difference in another.

Over the course of the fieldwork period we progressively focused data collection and analysis on two main context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations. We chose to do this because it became apparent very early on in the fieldwork that attempting to address all CMO configurations associated with the delivery of care to this patient group would result in an unacceptably superficial research report. The two CMO configurations selected for in-depth analysis were chosen because they had emerged as key issues for interviewees and were considered by them to be areas that were amendable to quality improvement.

Work package 2 thus has two distinct analytic foci: exploring the nature of the relationship between specific predictor variables and outcomes (track A), and testing and refining programme theories in the context of a realist evaluation (track B).

This is reflected in the design of the data collection and data management tools, which have clearly demarcated sections for each track of the study. It is also reflected in the approach we adopted for analysing the qualitative data, which involved asking distinctly different analytic questions of the same data set. 74 These two tracks were then brought together in the discussion.

Selection of case study sites

Case study sites were selected from hospitals participating in the NAD. We thought that there was likely to be a complex relationship between service organisation and delivery, experience of care and length of stay, so hospitals were carefully chosen for detailed case study analysis based on their capacity to (1) provide insights into this relationship, and (2) provide a better understanding of what works for whom and under what circumstances.

We had planned to use data from work package 1 to help select the first four case study sites. However, time constraints required us to select the first site before the results of the third round of the NAD had become available. Our selection of the first hospital was based on its performance in previous rounds of the audit and other intelligence, which led us to predict (correctly) that it would score comparatively highly in relation to carer-rated quality of care. Findings from interim analysis of the qualitative data from this first site clearly demonstrated that, despite lack of governance infrastructure, this hospital scored highly on carer-rated quality of care. After discussions with the project working group it was decided that governance score should be chosen as the other main criterion for selecting sites. This would provide the opportunity to explore how and why governance infrastructure might or might not result in desirable patient outcomes and whether or not there are some other organisational and/or contextual factors that lead to high-quality care.

When the audit results subsequently became available, we reviewed those results alongside other data sources, such as Care Quality Commission reports, and undertook telephone interviews with key stakeholders, before selecting three further hospitals. A paired sampling approach was used to help us understand similarities and differences between sites (Table 5).

| Site | Governance audit score | Carer-rated quality of care |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Low | High |

| 2 | High | Low |

| 3 | Low | Low |

| 4 | High | High |

| 5 | Average | Not available |

| 6 | High | Average |

Members of the Project Management Group and Stakeholder Reference Group informed us about hospitals that had put measures in place to reduce length of stay. We were also interested in collecting data from hospitals that were geographically different from our four main study sites, which were all in London or the South East/West. Selecting two additional study sites in the south-west and north of England allowed us to test our theories in hospitals with different characteristics to the first four study sites.

Our sampling approach resulted in the inclusion of hospitals with differing levels of performance. We define good performance or ‘outcome’ in realist evaluation terms, as comparatively positive carer-rated experiences of care plus shorter admissions. It also resulted in the inclusion of hospitals operating in differing contextual conditions for delivering good-quality acute care for people with dementia, including key components in the organisation and delivery of care identified through the third round of the NAD, such as adequate staffing levels and access to liaison mental health services.

Data sources

At each hospital we conducted in-depth interviews and assembled documentary evidence at three key organisational ‘levels’ relating to the quality of care: (1) clinical governance, (2) middle management and (3) the staff–patient interface.

In-depth interviews

The main source of data was in-depth interviews, with a total of 56 staff and seven carers. The interviews were undertaken by the lead researcher and two managers from the NAD, who had been trained in qualitative interviewing.

Aim

Following Pawson75 and Manzano,76 our interviews were theory driven, in that they were designed to inspire, validate, falsify or modify our hypotheses about how dementia care programmes and interventions work (track B), while in parallel exploring with participants their views on factors associated with patient outcomes (track A). 75,76

Inclusion criteria for staff interviews

-

Aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Experience of working directly or indirectly with patients with dementia in acute hospital settings.

-

Willingness to provide written informed consent to take part in an interview.

-

Agreement that the interview is digitally recorded.

Sampling strategy

The associations found in work package 1 guided our plans for data collection in work package 2. Most of the associations we found in work package 1 related to the way that staff and managers organised services. After discussions with the Project Management Group, it was decided that the main focus of data collection in work package 2 should be on interviewing a wide range of managers and front-line staff. This was because it seemed unlikely that carers would have direct experience of the decisions that hospital staff made about the organisation of the service. Staff members were purposively sampled to include a mix of those with professional and non-professional backgrounds (nursing, medical, professions allied to medicine, nursing assistants), and a mixture of junior and senior staff, including those who hold management responsibilities and those who do not. We also sought to interview staff who had specific responsibility for overseeing care for people with dementia, such as a dementia ‘champion’, a specialist dementia nurse and a member of the trust board who is responsible for care of people with dementia.

The carers who took part were identified, with support from staff, and approached for their consent to be interviewed.

Topic guides

Following Manzano’s guiding principles76 for realist interviews, we produced separate topic guides for staff (see Appendix 3) and carers (see Appendix 4). The guides were drafted by the study team and presented to the Project Advisory Group, which included a patient and a carer, for their comments. The guides were designed to be used flexibly to allow researchers to be responsive to issues raised by participants.

Interview procedure

All interviews were conducted using a topic guide. With consent, the interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed, or handwritten notes were made during the interview and subsequently typed up as a fieldnote.

After each interview, the researcher noted reflections that might be analytically useful, along with two or three high-level bullets about interview content, to help with navigating managed data later. The researcher also carefully documented sampling characteristics. All this information was collated in a central location [a Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA)] and updated after each interview, to give the research team a good sense of the sample as it developed.

Staff and carer participants were offered a choice over whether they would like to be interviewed face to face at the NHS participating site, over the telephone or by video chat. Carers were also given the option of being interviewed at a place of their convenience, for example in their home.

Documentary evidence

We obtained and studied documentary data prior to visits to case study sites. This included data from recent Care Quality Commission reports, which were examined to identify any areas of achievement or concern about care for frail elderly patients in the hospital. We also asked each hospital to provide policy documents relevant to care of frail elderly patients, including (when available) their dementia care pathway, service-level agreements for the mental health liaison service and policy on the management of vulnerable patients. Other documents included work unit guidelines, any information provided to staff regarding working with frail elderly, guidance in relation to working with carers, and assessment and treatment protocols.

None of the documents was subjected to any form of content or discourse analysis. Rather, the documents were gathered to familiarise the researcher with the context and information derived from them was fed into interview questions as appropriate.

Data management and analysis

Data management

We had 62 interviews transcribed in full by an external transcribing agency. One interviewee did not consent to their interview being recorded, so for that interview the researcher took notes and typed them up later.

We coded the transcripts in NVivo Pro 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK), using the final version of the coding scheme shown in Appendix 5. The coding scheme reflects the study’s twin-track approach, with the first part of it being used to code data for the realist evaluation and second part for track A.

We incorporated a framework approach, which involved creating a case and theme-based matrix in NVivo, and systematically summarising the data into relevant cells. 77 The aim was to ensure that no data were lost in the process of condensing them into a more manageable, summarised form, and the end result was a series of populated matrices that could be viewed in multiple configurations. After the first few interviews had been summarised, we reflected on how the framework was working and revised it.

Managing data in this way made it easier to identify patterns in the data and then interrogate the data to explain them. Doing this in NVivo made it possible to maintain links to the raw data.

Data analysis

We analysed data using a thematic analysis approach to detect the most salient patterns from a realist perspective. 78 The analysis and write-up focused on the relationship between service organisation and delivery, experience of care, carer involvement and length of stay. We addressed questions such as:

-

What hinders hospitals from performing as well as other similar hospitals?

-

How do hospitals operating with minimal governance infrastructure manage to deliver good-quality care?

-

Why do certain predictors, such as discharge planning in the first 24 hours of admission, lead to shorter length of stay?

The lead researcher met regularly with the research team throughout the fieldwork process to share and reflect on what had been observed, which fed into theory development.

Patient and carer involvement

With support from the team co-ordinating the NAD, we co-opted members of the Audit Advisory Group to comment on the methods and results of this study. Throughout the report, we refer to this group as the Stakeholder Reference Group. We took this approach because the Advisory Group was an established group of people with relevant expertise who provided and used acute care for people with dementia. Members of the group were already engaged in discussing the quality of care that people with dementia receive while in hospital, and they were aware of and interested in this study. We added a regular item on the agenda of the Advisory Group to discuss the design of this study and discuss emerging findings. In addition to this, a patient and a carer representative on the Project Management Group provided a range of comments and suggestions about the design and conduct of the study. Recommendations of patients and carers on these two groups were used to:

-

select which predictor variables to include in work package 1 from among the long list that we initially developed

-

help us develop the content of the topic guides that we used in work package 2

-

help us to interpret the results of the findings of the study.

In addition to this, Gemma Zafarani (carer representative) helped us prepare this report and write the lay summary for the study.

Ethics issues

We received approval for the secondary analysis of data from the National Clinical Audit and Patient Outcomes Programme from the HQIP prior to the start of work package 1 (reference HQIP162). We obtained ethics approval for work package 2 from the proportionate review subcommittee of the South West – Frenchay Research Ethics Committee prior to the start of data collection for work package 2 (reference 17/SW/0038).

All clinicians, managers and carers were provided with written and verbal information about the study before being asked if they were willing to take part in the study. Only those people who provided written informed consent were interviewed.

Changes to the study protocol

In work package 1, data on access to mental health liaison services at acute hospitals in England and Wales were not collected in the third round of the NAD. However, we were able to access data on the provision of liaison mental health services in England from a separate survey, conducted by the University of Plymouth on behalf of NHS England (see Work package 1).

Although we were able to collect data on the type of ward that patients were admitted to, we were unable to obtain accurate information on the identity of the ward. This meant that our original plan to conduct three-level modelling (patients within wards within hospitals) was not possible. Instead, we used a two-level model of patients in hospitals.

For work package 2, we originally proposed collecting data from ‘up to 15’ hospitals. However, feedback from the commissioning board was that these plans were overambitious and we were encouraged to reduce the number of case study sites. Following discussions within the Project Management Group, we modified our original plans and focused, initially, on collecting data from four sites, adding two further hospitals following an initial analysis of data, which suggested that we needed to capture more data from carers of people with dementia.

We originally proposed analysing qualitative data from work package 2 purely from a realist perspective. This approach proved helpful for developing an understanding of the CMOs of particular ‘programmes’ operating in hospitals (e.g. staff training). To optimise the contribution of the qualitative component to the study, we used a ‘twin-track’ approach to theory development. In parallel with a realist evaluation, we used a broader thematic approach to analyse data arising from associations identified in work package 1 (see Work package 2 for details).

Chapter 5 Results: work package 1

Two hundred (98.5%) of 203 acute hospitals in England and Wales took part in the third round of the audit. All 200 hospitals submitted an organisational checklist. Data from the clinical records of 10,106 patients were also submitted and 4688 carer questionnaires were received. A summary breakdown of the number of participating hospitals and data submission is provided in Table 6.

| Audit tool/questionnaire | Hospitals participating, n | Data received, n | Average per hospital, n | Range per hospital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organisational checklist | 200 | 200 | N/A | N/A |

| Case note audit | 196 | 10,106 | 52 | 22–99 |

| Carer questionnaire | 197 | 4688 | 24 | 1–104 |

| Liaison psychiatry | 176 | 176 | N/A | N/A |

Data on predictor (explanatory) variables extracted from the organisational checklists submitted by the 200 hospitals are presented in Table 7.

| Predictor variable | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Executive board reviews delayed discharge | ||

| Yes | 63 | 31.5 |

| No | 137 | 68.5 |

| Dementia specialist nursea | ||

| Yes | 64 | 32 |

| No | 136 | 68 |

| Dementia care pathway/bundle | ||

| Yes | 121 | 60.5 |

| No | 26 | 13 |

| In development | 53 | 26.5 |

| Dementia champion at directorate level | ||

| Yes | 164 | 82 |

| No | 35 | 17.5 |

| In development | 1 | 0.5 |

| Social worker or other designated person | ||

| Yes | 152 | 76 |

| No | 48 | 24 |

| Strategy or plan for carer engagement | ||

| Yes | 153 | 76.5 |

| No | 47 | 23.5 |

| Hospital provides finger food for people with dementia | ||

| Every day/4–6 days | 133 | 66.5 |

| Sandwich or wraps only | 167 | 33.5 |

| 24-hour food service | ||

| Yes (full range/simple food supply) | 166 | 83 |

| No | 34 | 17 |

| Carer visit at any time (carer passport) | ||

| Yes | 177 | 88.5 |

| No | 23 | 11.5 |

Data from the case note audit

Of the 200 hospitals that took part in the audit, 152 (76%) submitted data from the recommended minimum of 50 case notes and 186 (93%) submitted data from at least 40 sets of case notes. Demographic and clinical details of patients who were included in the audit sample are presented in Table 8 and data on predictor variables extracted from the case note audit are presented in Table 9. The youngest patient in the audit was 34 years and the oldest was 108 years.

| Predictor variable | Number | Percentage or SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (n = 10,096) | ||

| Mean | 84.3 | 7.9 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 4052 | 40.1% |

| Female | 6054 | 59.9% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 8274 | 81.9% |

| BAME | 1622 | 16% |

| Not documented | 210 | 2.1% |

| Specialty of the ward | ||

| Cardiac | 248 | 2.5% |

| Care of the elderly/complex care | 4125 | 40.8% |

| Critical care | 23 | 0.2% |

| General medical | 2397 | 23.7% |

| Nephrology | 52 | 0.5% |

| Obstetrics/gynaecology | 41 | 0.4% |

| Oncology | 22 | 0.2% |

| Orthopaedics | 906 | 9.0% |

| Stroke | 457 | 4.5% |

| Surgical | 686 | 6.8% |

| Other medical | 1000 | 9.9% |

| Other | 136 | 1.3% |

| Unknown | 13 | 0.1% |

| Primary diagnosis (n = 10,048) | ||

| Respiratory | 2005 | 19.8 |

| Fall | 1346 | 13.3 |

| Urinary/renal | 906 | 9.0 |

| Hip fracture/dislocation/other fractures/trauma | 886 | 8.8 |

| Sepsis | 635 | 6.3 |

| Delirium/confusion/cognitive impairment | 1204 | 11.9 |

| Gastrointestinal | 595 | 5.9 |

| Cardiac/vascular/chest pain | 518 | 5.1 |

| Stroke + neurological | 750 | 7.4 |

| Other | 1239 | 12.3 |

| Missing | 22 | 0.2 |

| Predictor variable | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Carer received notice of discharge (n = 7385) | ||

| < 24 hours | 1446 | 14.3 |

| 24 hours | 899 | 8.9 |

| 25–48 hours | 1090 | 10.8 |

| > 48 hours | 1902 | 19.7 |

| No notice at all | 35 | 0.3 |

| No carer, family or friend | 129 | 1.3 |

| Not documented | 1786 | 17.7 |

| Patient specified information to be withheld | 3 | 0.0 |

| Could not contact | 5 | 0.0 |

| Missing | 2721 | 26.9 |

| Evidence of discussing discharge with carer (n = 7385) | ||

| Yes | 5628 | 55.7 |

| No | 1359 | 13.4 |

| N/A | 398 | 3.9 |

| Missing | 2721 | 26.9 |

| Evidence of discussing discharge with consultant (n = 7385) | ||

| Yes | 5529 | 54.7 |

| No | 1856 | 25.1 |

| Missing | 2721 | 26.9 |

| Care assessment contained a section dedicated to collecting information from a carer or next of kin | ||

| Yes | 5759 | 57.0 |

| No | 4347 | 43.0 |

| Discharge planning initiated within 24 hours of admission (n = 7385) | ||

| Yes | 2499 | 24.7 |

| No | 2791 | 27.6 |

| N/Aa | 2095 | 20.7 |

| Missing | 2721 | 26.9 |

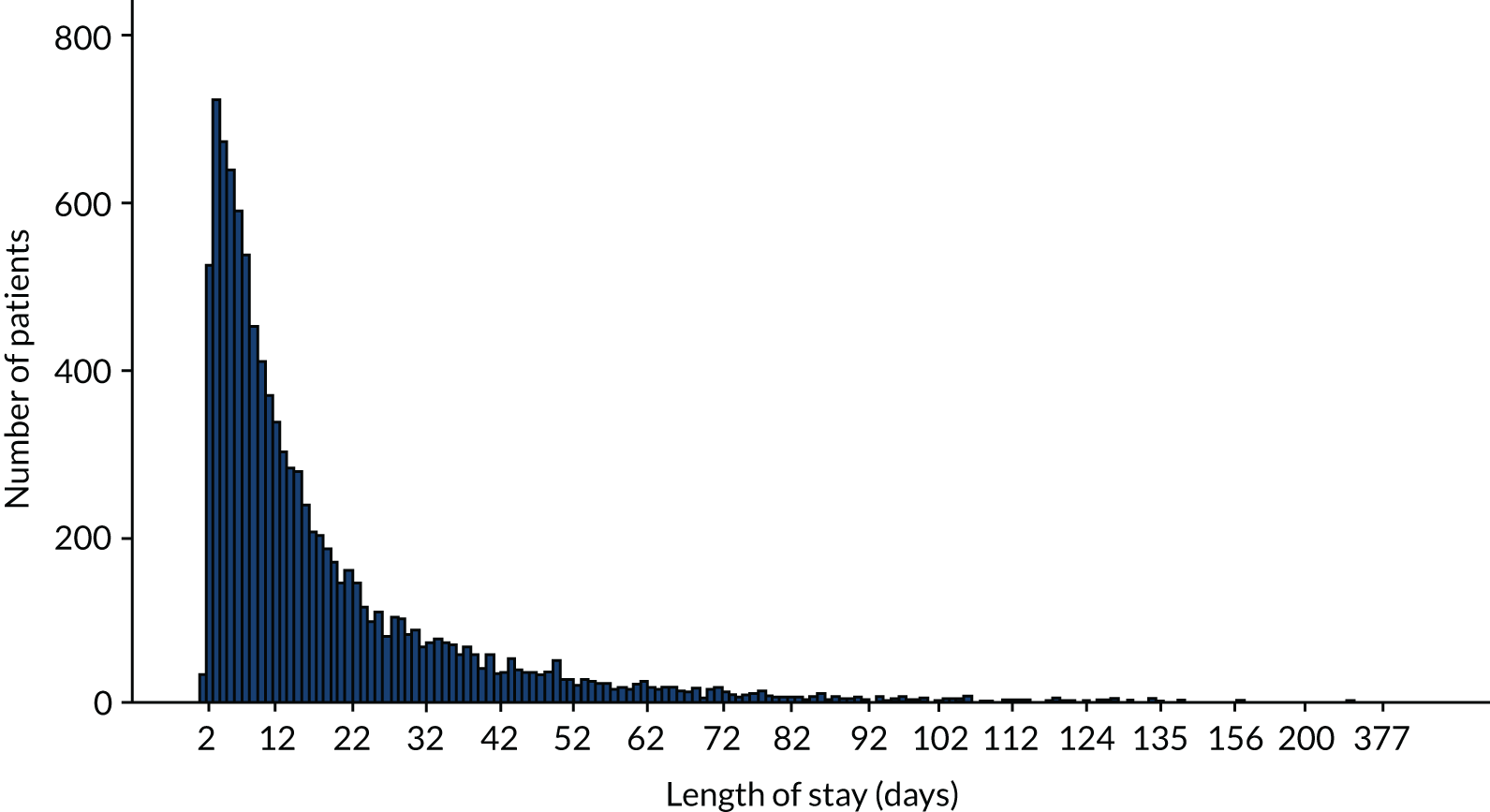

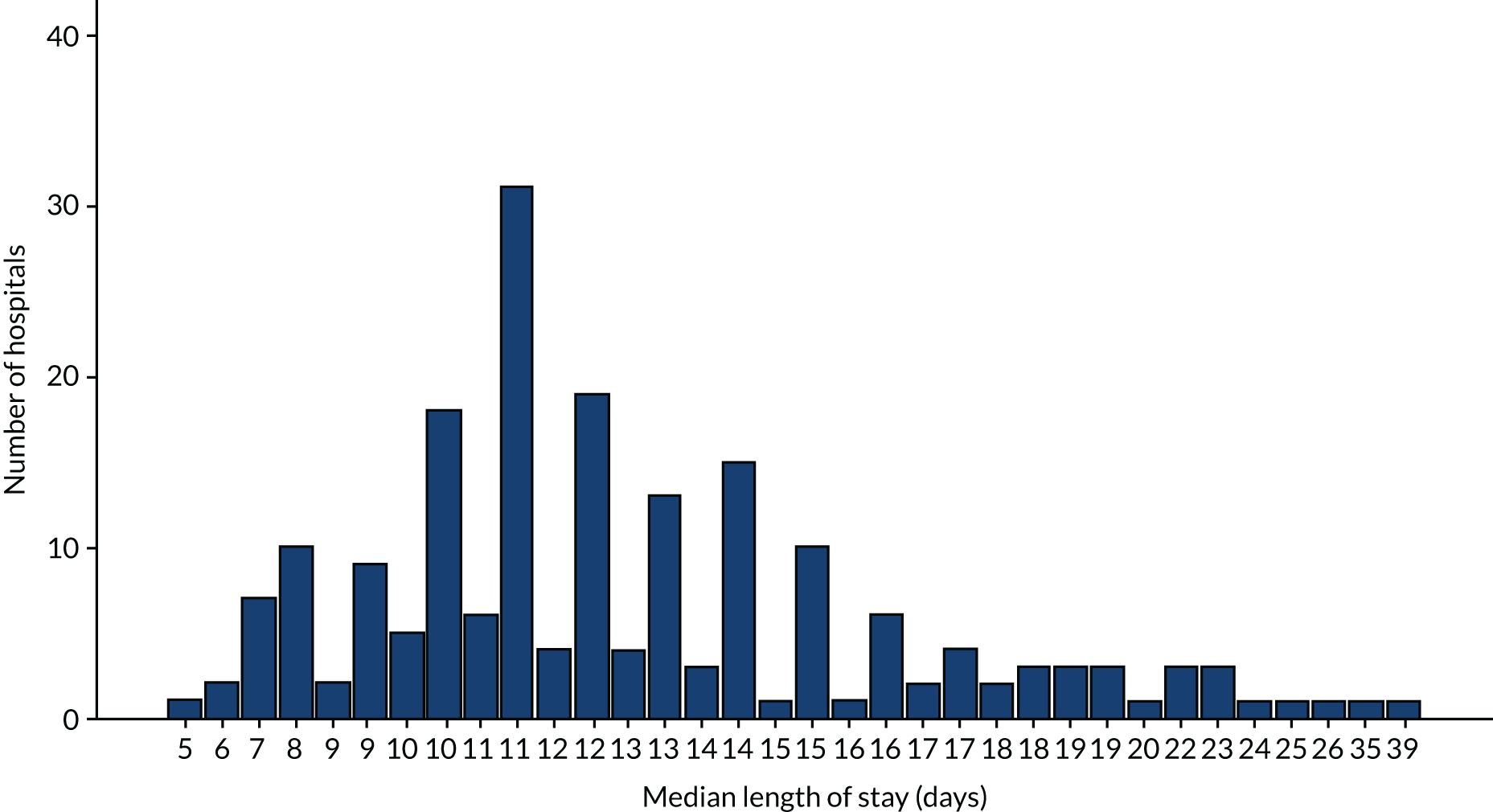

Valid data on length of stay were recorded for 10,105 patients. Variation in length of stay is illustrated in Figure 1. The median length of stay was 12 days [interquartile range (IQR) 6–23 days]. As seen in Figure 2, the median length of stay varied between different hospitals, ranging from 5 to 39 days (IQR 10–14 days).

FIGURE 1.

Length of inpatient stay among 10,105 patients in the case note audit.

FIGURE 2.

Median length of stay of people with dementia at 200 hospitals in England and Wales.

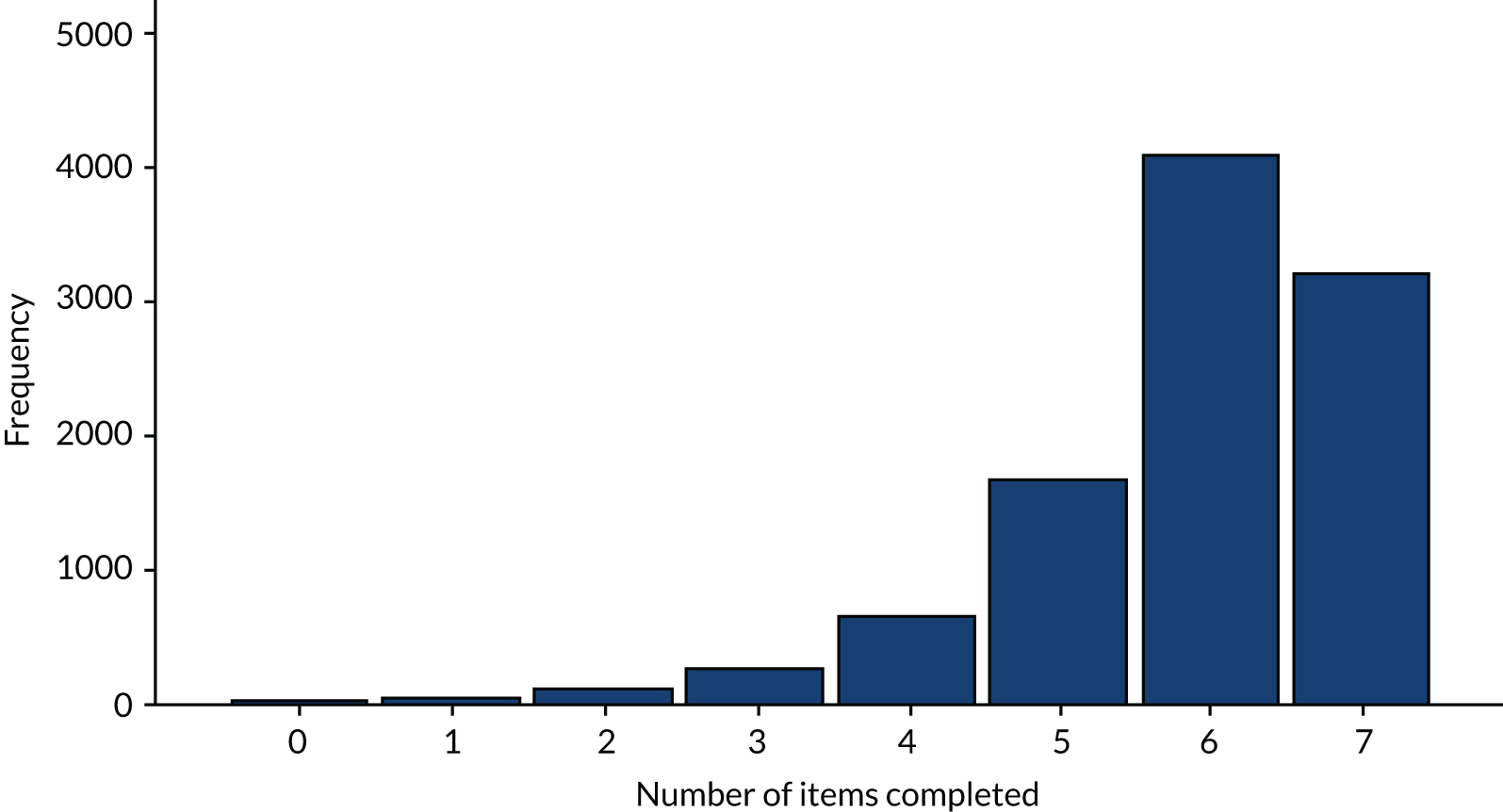

Data on quality of assessment were recorded for all 10,106 (100%) patients in the audit. Variation in the quality of assessment of patients is illustrated in Figure 3. The median number of items of assessment that were completed for each patient was six (n = 4093, 40.50%) and ranged from zero (n = 26, 3.0%) to seven (n = 3210, 31.8%).

FIGURE 3.

Number of items of assessment completed in 10,106 (100%) patient records.

Carer-rated quality of care

In total, 197 hospitals returned a total of 4688 carer questionnaires. Demographic characteristics of the carers who took part in the survey are presented in Table 10.

| Variable | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–24 | 48 | 1.0 |

| 25–34 | 135 | 2.9 |

| 35–44 | 259 | 5.5 |

| 45–54 | 753 | 16.1 |

| 55–64 | 1200 | 25.6 |

| 65–74 | 965 | 20.6 |

| 75–84 | 891 | 19.4 |

| ≥ 85 | 343 | 4.0 |

| Missing | 94 | 2.0 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1418 | 30.2 |

| Female | 3168 | 67.6 |

| Other | 4 | 0.1 |

| Missing | 98 | 2.1 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 4102 | 87.5 |

| BAME | 410 | 8.7 |

| Prefer not to say | 124 | 2.6 |

| Missing | 52 | 1.1 |

Forty-eight hospitals returned fewer than 10 carer questionnaires and data from these hospitals were excluded from subsequent analysis. Among the 149 hospitals that returned useable data from the survey, the median aggregate score for carer satisfaction was 72.3, ranging from a minimum score of 21.8 to a maximum score of 93.3 (mean 71.84, standard deviation 10.14).

Liaison psychiatry data