Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/5005/06. The contractual start date was in January 2014. The final report began editorial review in August 2018 and was accepted for publication in May 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Katherine L Brown is a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Clinical Trials Board (2017–21) and a member of the domain expert group of the National Congenital Heart Diseases Audit (2014–19). David L Barron is a member of the National Congenital Heart Disease Audit Steering Committee (2014–18). Monica Lakhanpaul is part of the following boards or panels: HTA Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health (MNCH) Methods Group, HTA MNCH Panel (2012–17) and Psychological and Community Therapies Panel (2012–15). Steve Morris has been a member of the following boards or panels: Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) Board Members (2014–18), HSDR Commissioned Board Members, HSDR Evidence Synthesis Sub Board 2016 and the Public Health Research Research Funding Board (2011–17). Thomas Witter was a member of the National Congenital Heart Disease Audit Steering Committee (2014–18).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Brown et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background and rationale

What is paediatric cardiac surgical morbidity?

Morbidity is defined as a state of being unhealthy or of experiencing an aspect of health that is ‘generally bad for you’. Morbidity associated with paediatric cardiac surgery is illness or lack of health that has a temporal connection to such an operation and, as such, may be regarded as an adverse outcome.

Although there has been considerable research on measuring, understanding and reducing perioperative mortality for paediatric cardiac surgery,1–4 there has been less attention on surgical morbidities. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) taskforce subcommittee on patient safety in the USA has defined a range of unwanted events that may contribute to postoperative morbidity, including complications, adverse events, harm, medical error, or injury and near misses. 5 This patient safety taskforce further noted that in the current era of falling mortality rates after paediatric cardiac surgery, improvement in health care as measured by reduction in adverse outcomes is more likely when unwanted events are acknowledged, measured and responded to in terms of health-care delivery. 5

The main focus of our study, which is set in five of the 10 paediatric cardiac tertiary centres in the UK, incorporating around half of the national cases, is on early paediatric cardiac surgical morbidities that are considered potentially avoidable or reducible or can be mitigated.

Why does morbidity after paediatric cardiac surgery matter?

Much of the previous research on surgical morbidities after paediatric cardiac surgery has focused on establishing their links with longer stays in hospital and establishing that children who experience prolonged hospitalisation and complications are also at greater risk of further adverse events and even death. 6,7 In addition, over the long term, children with specific heart conditions who experienced prolonged stays in hospital following surgery, which are often related to complications or morbidities, have been shown to develop higher levels of neurological disability. 8,9 Children who experienced the most difficult postoperative courses involving a period of mechanical circulatory support developed neurological disability in around 50% of cases. 10 Prolonged hospitalisation due to morbidities can be very expensive to manage, with mechanical circulatory support costing > £10,000 per day. 11,12

Morbidity, disability and quality of life are increasingly viewed as key outcomes by patients, families and clinical teams who are looking to deliver further improvements in service quality, partly owing to decreasing mortality rates. Although previous studies did not include patient perspectives to select morbidities for monitoring and were based on clinical opinion of what is important rather than the measured impact of morbidities, recent initiatives in the USA13 and Canada14 are illustrative of growing attention worldwide on the issue of surgical morbidity in this population. In the UK, a recent major review of the specialty highlighted the need to monitor outcomes in a timely and meaningful fashion,15 and commissioners of services are appropriately seeking evidence on outcomes and quality assurance from providers.

Previous relevant morbidity definitions and measurements

A series of detailed articles by professionals from the MultiSocietal Database Committee for Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease, based in the USA, profiled an extensive range of complications incorporating all organ systems, including examples such as kidney failure, deep-seated infections and failure of the original operation leading to reintervention. 16–23 The US STS database selected a narrower range of defined major complications that were retrospectively available within the registry, and demonstrated that rates varied from 1% to 38%, with greater prevalence at increased procedural complexity. 13 A Canadian study indicated that prospective monitoring of complications may lead to greater case ascertainment and, hence, a perception of higher complication rates. 14

Routine audit of postoperative mortality in paediatric cardiac surgery is well established in the UK via the National Congenital Heart Disease Audit (NCHDA),24 which has published centre-specific results of individual operations online since 2005 and programme-based 30-day mortality rates with case mix adjustment since 2012. Stakeholders, including children’s heart surgery programmes, congenital heart patient support groups and the NCHDA, share a goal of adding to these mortality outcomes by reporting morbidity. In 2015, at the start of our study, the NCHDA initiated the capture of preliminary morbidity measurements, which they based on our study protocols; however, those UK national audit data have yet to be analysed.

It is important to note that views may differ between professionals and non-professionals over what exactly the term morbidity refers to, and which morbidity events are most important. A recent study showed differing perceptions and priorities between clinicians and patients regarding chronic obstructive pulmonary disease services and outcomes. 25 Focus groups and formal consensus methods have been used to elicit patient and carer perspectives, and determine group priorities in many contexts. 26 The nominal group technique was successfully used among general practitioners (GPs) to identify prioritised lists of quality markers for the management of children in general practice26 and by kidney transplant patients in ranking outcomes by importance. 27 A recent National Institute for Health Research-funded study showed differing perceptions and priorities between clinicians and patients regarding chronic obstructive pulmonary disease services and outcomes. 25 Therefore, within our research we set out to combine patient and carers’ perspectives with those of professional groups in defining a prioritised list of outcomes for audit may be valuable to other specialties. We aimed to address these major gaps in current knowledge by setting out to establish robust definitions for, and the current incidence of, major morbidities and their impact in the UK paediatric population following heart surgery.

The particular case of neurological damage and child development

Neurological damage following cardiac surgery is considered crucial by patients, families and clinical staff. Systematic evaluation of infants undergoing common congenital heart repairs in the USA with a ‘gold-standard’ assessment indicated that neurological difficulties occurred in up to 25% of patients, making this the most frequent morbidity among children with heart disease. 28 However, at the time our project commenced, the UK national audit reported deterioration in cerebral performance category29 in 1.2% of children following surgery (Dr David Cunningham, National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research, London, UK, 2012, personal communication). This was almost certainly an underestimate, with data quality undermined by lack of expertise among cardiac specialists in assessing neurological development, exacerbated by the medical complexity and age mix of the patients. The importance of improving these assessments goes beyond audit and quality assurance: early detection of neurodevelopmental deficits can prompt timely intervention and improve outcomes.

The different types of neurodevelopmental abnormalities in survivors of cardiac surgery30 include motor deficits,31–34 seizures,35–38 poor executive functioning,39 communication problems,8,33,40 impairments in visual construction and perception,8,40–43 poor attention44,45 and learning difficulties. 33,34,45 Deficits can range in severity and may be subtle and therefore more easily overlooked, particularly in children with less complex congenital heart disease (CHD), and throughout the course of childhood and adolescence the presentation of neurodevelopmental abnormalities can change. Some deficits may resolve spontaneously; others may not be apparent until later childhood. Recent longitudinal evaluation of a cohort of preschool-aged children at high risk of developmental delay indicated an improving developmental trajectory in some, but approximately 20% had scores in one or more developmental domains which decreased over time. 46 Presentation of deficits can be obscured or confounded by a range of factors, including those related to cardiac surgery, the effects of hospitalisation and other comorbidities.

In 2012, the American Heart Association47 published guidelines for systematic surveillance, screening, evaluation and intervention to identify neurodevelopmental problems early and optimise outcomes in the short and longer term, building on earlier guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics. 48 They also highlighted the importance of continued monitoring because the level of risk for neurodevelopmental impairment can change over time, as different impairments become apparent during different periods of development. Furthermore, children at risk for poor late outcomes are frequently not identified from results of early testing. 49 It is therefore not surprising that increasing numbers of follow-up programmes for children with CHD and neurodevelopmental concerns are now being implemented, particularly in the USA50 and some countries in Europe.

Finding a solution for neurodevelopmental surveillance in an NHS context

Every child in the UK, irrespective of any known health problems, has an allocated health visitor (a community-based nurse or midwife) who should make a minimum of five key visits in which the child’s development is reviewed from birth up until the age of 2–2.5 years. However, the health visiting service is recognised to be overstretched, with not all children getting full access to this. Children with CHD are under follow-up with a paediatric cardiologist; however, such professionals are, in general, not trained to undertake developmental assessments, as their specialisation is focused on the heart. Children with CHD and other comorbidities, including known neurological events or developmental delay, may also be under the care of a paediatrician at their local hospital and may be referred by the cardiac centre or their paediatrician to local services based on suspicion of developmental delay, but there is seldom the opportunity or resources for any developmental testing to provide evidence to support those concerns. After an acute neurological event (ANE) post surgery, a child with heart disease in an NHS specialist centre will be assessed by a neurologist.

As stated in The particular case of neurological damage and child development, children with CHD are a particularly high-risk group for neurodevelopmental problems that may arise from multiple aetiologies and at all stages in their early lives and care pathways,30,31,35,38 hence these may be an issue prior to the age of 2–2.5 years. A formal standardised assessment of development using comprehensive tests, such as the Bayley Scales of Infant Development,51 the Griffiths Mental Development Scales52 or the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen),53 is considered to be the gold standard, but these are not tests that are used for early recognition of developmental delay. If a problem is identified and a child is referred for follow-up, such tests are usually undertaken by someone who has had specialist developmental training and has time dedicated to perform the testing. However, if a child is not referred, such tests are unlikely to be performed as they are not integrated into the routine follow-up of children. Moreover, this would not be feasible because the tests are time-consuming and not practicable with sick children or within the context of a busy ward or outpatients. Of note, children may require multiple cardiac interventions and the level of risk may change over time, thereby necessitating some mechanism for repeated routine monitoring and early recognition of developmental problems in all children with CHD.

Given this whole picture, and as we know anecdotally from our own clinical practice, developmental delay is often detected late – frequently not until a child starts school and education services become involved – thereby precluding the opportunity for early intervention and causing stress to families who may be aware that ‘something is wrong’.

With the above in mind, we determined that an early recognition tool would help to address some of the current shortcomings and facilitate appropriate and timely referral for further, more comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation for those in whom this is indicated. After reviewing existing tools and establishing that none would be fit for this purpose, we undertook the development of a new tool that had the potential to be routinely used within tertiary programmes for managing children with CHD. 54 One of the objectives of this study was to validate this new tool, which is called the brief developmental assessment (BDA).

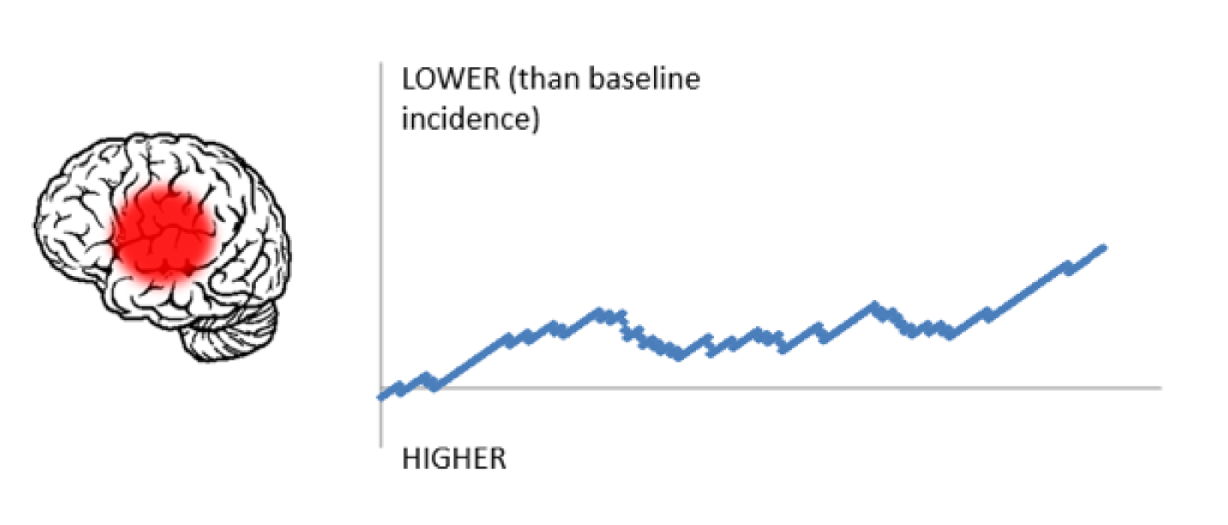

Methods for the reporting of morbidity outcomes

To enable routine monitoring of morbidities, approaches to data analysis and display are required. Analytical and graphical methods for the timely reporting of risk-adjusted mortality outcomes for the purposes of quality improvement are well established in adult cardiac surgery practice. 55 Our research group developed the method of variable life-adjusted display (VLAD), which is now used nationally in the UK to monitor contemporaneous risk-adjusted postoperative survival rates for paediatric cardiac surgery. 56 These approaches have received positive feedback and are judged useful by a range of stakeholders; hence, within the scope of this project we set out to develop something similar for the reporting of morbidity events.

Considering previously reported attempts at reporting of morbidity outcomes, two single-centre studies have attempted to generate an aggregate ‘Morbidity Index’ by assigning subjective weights to postoperative complications. 7,57 The STS in the USA has attempted a similar ‘Morbidity Score’. 13 Condensing diverse morbidities into a single score loses information, and recent work on using graphical methods to routinely monitor a range of morbidities14 highlighted the complexity of graphically summarising multiple morbidities (see also commentary by Utley et al. 58). The Pediatric Cardiac Critical Care Consortium (PC4) was set up in 2009, with the aim to improve the quality of care given to patients with critical paediatric and congenital cardiovascular disease in North America and abroad. The PC4 database provides partner sites with access to real-time, reliable and actionable data to be used for local quality improvements and has been the basis for a range of excellent publications related to postoperative complications after paediatric cardiac surgery. 59–62 However, membership of PC4 is voluntary for institutions on a subscription basis, the reported measures, although of great importance, have all been selected by clinicians and the reporting of outcomes is accessible only to subscribing member institutions.

Chapter 2 Aims and objectives

Aims

The research aims, as stated in the original study protocol, were to identify which surgical morbidities present the greatest burden on patients and health services following paediatric cardiac surgery and to establish how they should be routinely monitored.

Objectives

The objectives that were stated in the original study protocol as required to achieve these aims were to:

-

identify the key surgical morbidities following paediatric heart surgery, taking into account views from patients, carers, psychologists, nurses and clinicians, that together capture important aspects of the clinical and health economic burden

-

develop objective definitions and measurement protocols for the identified morbidities

-

determine which morbidities are suitable for routine monitoring and are amenable to service improvement

-

validate a tool suitable for routine screening of neurological disability perioperatively

-

measure the incidence of defined morbidities in the UK patient population and in subgroups defined by case complexity

-

evaluate the impact of defined morbidities on quality of life and estimate their clinical and health economic burden

-

develop and pilot sustainable methods for collection and feedback of surgical morbidity data for use in future quality assurance and for patient and carer information.

Chapter 3 Exploring patient and family perspectives on morbidity after paediatric cardiac surgery

Parts of this chapter are reproduced with permission from Rajagopal et al. 63 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

Morbidity associated with cardiac surgery can be very challenging for patients and families, and for those with the most severe morbidities the impact may be life-changing or, in some cases, life-limiting. As more children with increasingly complex CHD successfully undergo surgery, there are a growing number of children living with the impact of a range of morbidities. It is therefore imperative that information about morbidities is prospectively communicated in an empathic and clear way to ensure that there is an accurate understanding by those who will potentially live with the consequences.

In this chapter, we describe qualitative research undertaken in the first year of our study to explore family perceptions on the meaning of morbidity, family understanding of what different types of morbidity exist and family viewpoints about which morbidities are important. As parents are in general lay people who do not possess specialist knowledge about paediatric cardiac surgery, inevitably much of their information is gathered from health professionals. Therefore, in this section of our research we focused not only on what parents understood, but also on the manner and quality of health professional communication about morbidities. As set out in our original study protocol, we used two separate and complementary approaches to solicit parent and family viewpoints on the topic of interest: an online discussion forum and more traditional focus groups.

The rationale for an online discussion forum

Traditional methods of accessing parental views can limit access for some people, thereby impairing inclusivity. 64,65 Logistics, time and discomfort in face-to-face and group interaction may deter some individuals. As the use of the internet continues to increase, it represents a vital tool for the delivery of health-care information. Online forums are an important way in which internet users seek this information and communicate with others who have had similar health-care experiences, and there is an increasing focus on understanding the potential value of this method of data collection in qualitative research. 66,67 Forums have successfully been used in previous health-care research68–73 because they provide a flexible and safe space, where open and honest discussions can be held over a period of months, in a conveniently non-synchronous way for potentially large numbers of users in different geographical areas. 64,65,74 There is no burden on travel and participation results in minimal disruption to daily life. We therefore hoped that the inclusion of an online forum as a method of engaging with families, alongside more traditional approaches, might enable us to access the views of those who find it hard to attend in person or take part in interviews and focus groups, adopting a similar approach to that used by our group previously. 75

Online forum methodology

The Children’s Heart Federation (CHF), a national parent charity and co-applicant for the wider study, facilitated and moderated a closed, anonymous, online discussion group via their Facebook page (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA), following a similar approach to that reported in a previous study. 75 The discussion group was advertised on the charity’s home webpage and potential participants were directed to the charity’s Facebook page, where they could access more information about the study and the governance surrounding it. Any person who wished to participate was asked to provide some basic demographic details (age, sex, ethnicity and geographical region) and on completion of this information they were directed to the closed Facebook group, where they were able to respond to questions posted there. The research team provided questions to be posted on the forum at the start of the process and the charity were responsible for deciding when new questions should be posted or any prompts introduced, based on participant responses and the rate of responding. Questions posted on the forum are shown in Box 1. The forum ran continuously over a 3-month period in the spring of 2014.

1. When thinking about children’s heart surgery, what does the word ‘complication’ mean to you?

2. When thinking about children’s heart surgery, what does the word ‘morbidity’ mean to you? Can you give an example of how this affected you or your child?

3. As the experience of heart surgery becomes more distant and in the past, and your child is older, are there any difficulties that your child has now which you think may relate to the operation?

4. Thinking about yourself and your family, can you help us understand the impact that any complications had on you, your child or any other family members:

-

While your child was still in hospital?

-

After you got home?

5. We are thinking about measuring and recording how often complications happen, but we want to concentrate on the things that matter most to the child and family. Here is a list of problems that we know can happen:

-

Children who have heart problems may sometimes experience different types of brain damage and this may lead to disability ranging from loss of hearing to problems with learning or movement or all types of disability.

-

A child may sometimes need an extra operation during the same stay in hospital that was not planned at the start.

-

Infection may sometimes happen after heart surgery.

-

A child’s kidneys may stop working and need to be supported with a machine for a period of time.

-

The muscle that helps a child to breathe may be weakened because the nerve supplying it is bruised or damaged – sometimes an operation is needed to strengthen the breathing muscle (diaphragm muscle).

-

A child may need to stay in intensive care for a long time because he/she needed assistance with breathing or he/she needed tubes to remain in place.

-

A child’s gut may not digest milk or food and she/he may need to have nutrition via a drip.

-

A child’s heart may become very weak such that a machine to support the body called ‘ECMO’ was needed.

-

Damage can happen to the nerve supply of the heart so that the child needs to have a pacemaker put in to regulate the heartbeat.

Which of these complications seems the worst or most worrying to you?

6. We are thinking about measuring and recording how often complications happen, but we want to concentrate on the things that matter most to the child and family. Here is a list of problems that we know can happen:

-

Children who have heart problems may sometimes experience different types of brain damage and this may lead to disability ranging from loss of hearing to problems with learning or movement or all types of disability.

-

A child may sometimes need an extra operation during the same stay in hospital that was not planned at the start.

-

Infection may sometimes happen after heart surgery.

-

A child’s kidneys may stop working and need to be supported with a machine for a period of time.

-

The muscle that helps a child to breathe may be weakened because the nerve supplying it is bruised or damaged – sometimes an operation is needed to strengthen the breathing muscle (diaphragm muscle).

-

A child may need to stay in intensive care for a long time because he/she needed assistance with breathing or he/she needed tubes to remain in place.

-

A child’s gut may not digest milk or food and she/he may need to have nutrition via a drip.

-

A child’s heart may become very weak such that a machine to support the body called ‘ECMO’ was needed.

-

Damage can happen to the nerve supply of the heart so that the child needs to have a pacemaker put in to regulate the heartbeat.

Could you please tell us why you think one or more of these complications is ‘worse’ than other complications?

Are there things that happened to your child after their operation that you think ‘went wrong’ which should be on this list but is not?

7. Could you please let us know what information you were provided with regarding the complications of your child’s heart surgery?

8 (a). Do you feel you were provided with the right amount of information regarding complications before surgery?

8 (b). How much information would you like (more or less)? How much detail is helpful?

9. What visual (books, etc.) methods could be developed for letting families know the risk of complications to better inform them about what might happen after surgery?

10. What do you think about everyone being able to see (on the internet) the numbers of complications occurring after children’s heart surgery at different hospitals?

11 (a). Do you have any further comments regarding complications following heart surgery? Is there anything we should know to improve services? Is there anything else you can think of?

11 (b). Is there anything we could have done to improve the online study? Do you think we should have asked questions more frequently, for example? Any other suggestions?

ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Focus group methodology

We held three focus groups for patient families in the first 6 months of 2014, which took place in Glasgow, Birmingham and London. The focus groups were advertised via the CHF website and potential participants contacted the CHF if they wanted to take part. The CHF organised the groups, which were held on a Saturday and were moderated by an independent, experienced researcher who used the same questions that were used for the online forum as a topic guide (see Box 1). Focus group participants provided written consent for their participation, recording and the use of anonymised quotations in dissemination of the findings. Each focus group was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data management and analysis

Responses from the online forum were collated into a single transcript and each focus group formed a single transcript. The four transcripts from the online forum and the three focus groups were thematically analysed. 76 Transcripts were read and codes attached to segments of data independently by three members of the research team (JW, CP and VR). Similar codes were then brought together to create themes. The researchers met to discuss the themes and to agree the descriptive names assigned to them. Discussion continued until consensus was reached.

Participant demographics

The online discussion forum ran over 3 months and involved 72 participants (68 mothers, one father, one patient and two grandmothers, with an age range of 15–59 years). The vast majority of participants were white British (n = 70, 97%), and there was a spread of participants across England, Wales and Scotland.

The three focus groups each lasted for approximately 2 hours and comprised 13 participants in total (10 mothers, two fathers and one adult CHD patient). The ages of the parents’ children ranged from 14 months to 24 years (however, only one ‘child’ was an adult, the others all being aged ≤ 14 years, with a median age of 5 years at the time of the focus group). The sex ratio of the participants’ children was seven boys to five girls. Two children had recognised clinical syndromes and one of the mothers was bereaved.

Themes from analyses

A number of codes were identified from the online forum and focus group data, and collated to form three themes, with seven subthemes, relating to communication between health-care professionals and families about complications arising from cardiac surgery. The themes are shown in the first column of Table 1, with subthemes in the second column and illustrative quotations in the third column. These are discussed further as follows.

| Theme | Subtheme | Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Clinicians’ use of language | Comprehension/consistency | It’s just jargon . . . Please . . . English . . . so we can understand it!. . . some doctors are better than others . . . at explaining. . . they go into the usual doctor terminology. . . they use hypoplastic instead of small, stenotic instead of stiffIt’s really easy to get yourself tied up in knots with risks and percentages, when they’re really not explained properlyPercentages are rarely accurate anyway, so why do we – as parents – hang on to them so dearly (me included!!!!). We were given 13% but it wasn’t properly explained that this was risks (i.e. morbidity) not death aloneI think it’s assumed that parents have a basic understanding of statistics when it’s such a complicated measurement and it’s not properly explained to usMorbidity to me means deathJust to talk mum to mum . . . then you’re not getting the medical jargonI found a huge discrepancy between the way the cardiologists describe surgery, i.e. very optimistic, complications are rare, and the surgeons who spell it out in order to cover themselves. Personally I prefer the latter as it means when it does happen you are aware of it and know it has happened before, whereas the former makes you feel so unlucky and wondering why things have happenedWe were given very detailed information by the surgeons on the eve of our son’s op but . . . up until that time we had only seen cardiologists who were really quite blasé. . . We were told ‘he’ll be fine’ they do switches all the time. Turns out it was far from that . . . |

| 2. Being unprepared for complications | Differing priorities of health-care professionals and families/timing of consent | NG [nasogastric tube] feeding was never something I thought about when we considered the prospect of having a congenital heart disease childWe weren’t mentally prepared for the longer stay as we were told ‘in and out in 5 days’I really wish someone had prepared me for the psychological side effects . . . anything explaining how trauma and complications can have a negative impact on your child’s self-esteem and mental well-being. . . tell parents beforehand . . . This is very likely going to affect development in growth, height, learning and development and things like thatThey do tell you some of the physical things that might happen but not how it might affect . . . a person’s behaviour or emotionsYou know when they do the consent forms it’s usually the night before surgery which . . . is a bad idea, because you’re not taking that in . . . if you did it a week before . . . you take in a lot more . . . It’s easy for you to digest and understand |

| 3. Information needs of families | No right amount of information/types of information/access to staff/lay support | Some parents will want to know everything and others want to know as little as possibleIf we knew all the potential outcomes I think signing the consent would have been so much harderYou can’t have a blanket rule of ‘We must tell them every possible thing that could go wrong’ or, ‘We only tell them the most common’. You need to look at it case-by-caseIt’s such a delicate balance . . . you’ve got to try and test the waters with the patient’s parents and the patient’s themselves to find out how much information . . . you need to give this person. It has to be an individual case-by-case scenarioSomething to take away and look at and digest in your own timeEven a simple information sheet . . . you might not have internet access . . . you might need to go into your room or sit by the bed and have another look at it a bit laterLittle Hearts Matter . . . DVD pack for antenatal diagnosis. It was brilliantCommunity liaison nurses are very useful and parents should be given contact numbers as a matter of course. . . knowing who to ask . . . that there’s somebody you can ask about things you might spot . . . signposting |

Clinicians’ use of language

Immediate barriers to comprehension

Technical language used by clinicians about complications of surgery was often poorly understood by families. In particular, jargon (e.g. words such as ‘morbidity’, ‘stenotic’, ‘hypoplastic’) was used instead of lay language and percentages were used to communicate risk. These were often confusing to participants and led to misunderstandings with lack of information transfer. Some parents expressed the view that it would have been useful to hear from another parent who had been through a similar experience and could tell them ‘mum to mum’, with ‘no jargon’, what to expect.

Inconsistency of content

Participants described individual clinicians as giving different messages about what complications to expect following surgery. Although some individuals played down complications, others were seen as being more upfront and frank about complications during consent conversations. These inconsistencies between individuals led to mistrust and a perception that some clinicians were being more honest than others.

Being unprepared for certain complications

Differing priorities of health-care professionals and families

Clinical teams and families appear to have had some differences in the perception as to what was considered as key content for information sharing about morbidities. This appears to have led to the clinicians focusing on more immediate technical issues related to the heart and circulation, whereas the families wanted to know more about later events affecting the child at home, such as child development. For example, feeding difficulties and the need for a nasogastric tube to support milk intake after discharge were of huge significance to families; however, parents were frequently not made aware of this as a potential complication prior to surgery and were surprised when this transpired. Another important example identified by many of the parents was the unanticipated psychological side effects on their child, the siblings and themselves, which were reportedly not mentioned by professionals during the hospitalisation.

Timing of consent

The timing of the consent conversations was also highlighted as being suboptimal in order for morbidities to be explained and understood, thus leaving families unprepared for certain morbidities. Examples were given of consent being taken the night before surgery, when parents were feeling not only anxious but also left with little time to reflect on or think through what had been said.

Families information needs

There is no right amount of information

It was clear that there was no ‘right amount of information’ that suited every individual. Although some parents wanted to know about all possible morbidities or complications, others felt that too much information would have been overwhelming, potentially paralysing them in the consent process, when, in reality, faced by a child requiring paediatric cardiac surgery in order to survive long term, they often have little true decision-making power. Participants felt that the detail of information being conveyed should be tailored according to the needs of the individual receiving it, rather than using a ‘one size fits all’ approach.

Types of information

Written and audio-visual materials were reported as helpful supplements. Being able to take something back to their accommodation, that could be read and digested in their own time, was valued. As well as more high-tech information, simple leaflets were appreciated as something that could be read without the need for internet access and a telephone or computer.

Access to staff/lay support

Parents valued having access to a member of staff whom they could contact with further questions and who could signpost them to other information as needed. In addition, parents expressed that being able to speak to another parent who had gone through something similar, and who actually knew how it felt to be a parent going through this, would have been a source of comfort and help.

Discussion of findings

Overview

This section of our study provided a clear steer that parents consider longer-term events that on the surface may not appear to be directly related to the heart itself, such as difficulties establishing oral feeding after discharge home and parental psychological stresses, to be ‘legitimate morbidities’ linked to paediatric cardiac surgery. As such, these are suitable topics to cover during preparation for paediatric cardiac surgery, ideally backed up by appropriate data concerning incidence and impact. Furthermore, the analysis of parental comments highlighted clinician, parental and situational factors that may influence parental understanding of potential morbidities following paediatric cardiac surgery and, consequently, aspects of communication about morbidities that can be targeted for improvement. These are discussed further as follows.

Communication content

Clinicians’ use of jargon, the lack of consistency between clinicians and an individual clinician’s skill in communication have been previously identified as important factors in patient comprehension and adherence,77,78 and in the current study all of these aspects had an impact on the qualitative assessment of parental satisfaction and understanding. Individual communication skills vary, with one participant noting that some clinicians are ‘just better’ at it than others. Although this may be an innate strength or weakness for a given individual, clinicians may benefit from communication training and assessments as they undertake for other elements of practice.

Amount of information

The amount of information given by clinicians can have both positive and negative effects on parental anxiety. 79,80 Parents want their clinicians to be accessible, honest and caring and to use lay language at a pace that can be understood. 81 This was also reflected in our study data, which suggested that the information given needs to be tailored to the information needs of the individual receiving it. Taking the time to ascertain the best fit for an individual parent is an important investment not only in their understanding, but also in their ability to make decisions and cope with the situation that lies ahead. In addition, what the parents want to know is what is likely to happen to their child, such that the risk of complications would ideally be tailored to the individual characteristics of the child for whom surgery is being discussed. This is easier said than done, in as much as the population of cardiac children becomes increasingly complex, and as surgical and medical techniques evolve, we are constantly pushing boundaries meaning that uncertainty is inevitable. The approach taken to support parents and families in coping with uncertainty is an important part of the care we provide.

Time pressure

Stress and time pressure are barriers to informed consent. 82,83 Previous studies84,85 have indicated that levels of distress, time pressure and the quality of ‘clinician–parent communication’ can adversely affect parental understanding of information given, with the potential to limit parents’ ability to make informed decisions. 79 Children with CHD may at times be severely ill, which leads to discussions with clinicians occurring under pressure of time; however, this is not always the case. Our participants commented on the difficulties that they faced with consent the night before surgery. When possible, a staged consent approach86 should be used, such that an initial consultation will be used to just relay information, followed by a period of time allowing consideration by the parents, before a second conversation when consent is actually sought.

Limitations

The data we obtained relied on participants’ retrospective recall of conversations. An evaluation of clinician–parent communication in real time would provide a valuable insight into what is actually said and the interpretation at the time – not only of parents, but also of clinicians. What did the parents understand from the conversation and what did the clinicians believe the parents understood from the conversation?

Despite specifically choosing a data collection method to increase the accessibility of the research to potential participants, our participants did not reflect a broad range of ethnic groups or sex, therefore limiting the generalisability of our data to the wider population of parents of children with CHD in the UK. The challenges of including ethnically, culturally and linguistically diverse populations, as well as fathers, in paediatric research studies are well documented. 87,88 However, an innovative approach that successfully includes minority groups needs to be adopted to ensure the broadest capture of parental and family views. Finally, we did not collect the same demographic information from participants in the online forum and the focus groups, which limited our ability to describe certain aspects of our participants across both data collection approaches.

Conclusion and next steps

The importance of ‘good communication’ goes beyond just promoting understanding between parties. Meert et al. 81 ask whether or not the way in which clinicians communicate may impact on the psychological adjustment and functioning of parents and families. The feedback we obtained suggests that there is wide variability and lack of consistency in the way clinicians describe complications, much of which may not be absorbed or retained by parents, particularly during times of extreme stress and distress. 80,89 Hence, the participants commented on the feeling of being ‘unprepared’, in particular for morbidity events taking place further along in time after their child had gone home and events that were not ‘on the face of it’ immediately obviously linked to the heart (e.g. impaired child development, psychological stress and feeding difficulties). We suggest that future work should seek to understand whether or not clinicians are able to mitigate some of the short- and long-term distress experienced by families in this situation, through adjustments to communication to make this more consistent and less jargon heavy. These findings also provide motivation for a later section of our project in which we set out to develop parent information resources related to perioperative morbidities.

Chapter 4 Selection by a panel of clinicians and family representatives of important early morbidities with paediatric cardiac surgery

Parts of this chapter are reproduced from Pagel et al. 90 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

Our account of the selection of important early morbidities associated with paediatric cardiac surgery by a panel of clinicians and family representatives is based on the open access publication on this topic in BMJ Open. 90

Reporting of early morbidities associated with paediatric cardiac surgery has been driven largely by the data available within the databases of professional societies,91 clinical consortia61 or those available within data sets curated by individual clinical teams. 14 Quality assurance initiatives rooted in such data sets benefit greatly from considerable effort, often over many years, to agree definitions of the outcomes collected and design data collection processes. However, it is inevitable that the data sets agreed on, constructed and curated by clinicians (as individuals or via professional societies) focus largely on outcomes considered important from the perspective of that clinician or professional group. Research in other specialties has shown that patients and carers can have quite different perceptions to clinicians on what outcomes are important to monitor as part of service evaluation. 92

Selection panel process overview

We convened three meetings of a panel of family representatives, surgeons, liaison nurses and other health-care professionals to shortlist and then select surgical morbidities for routine monitoring.

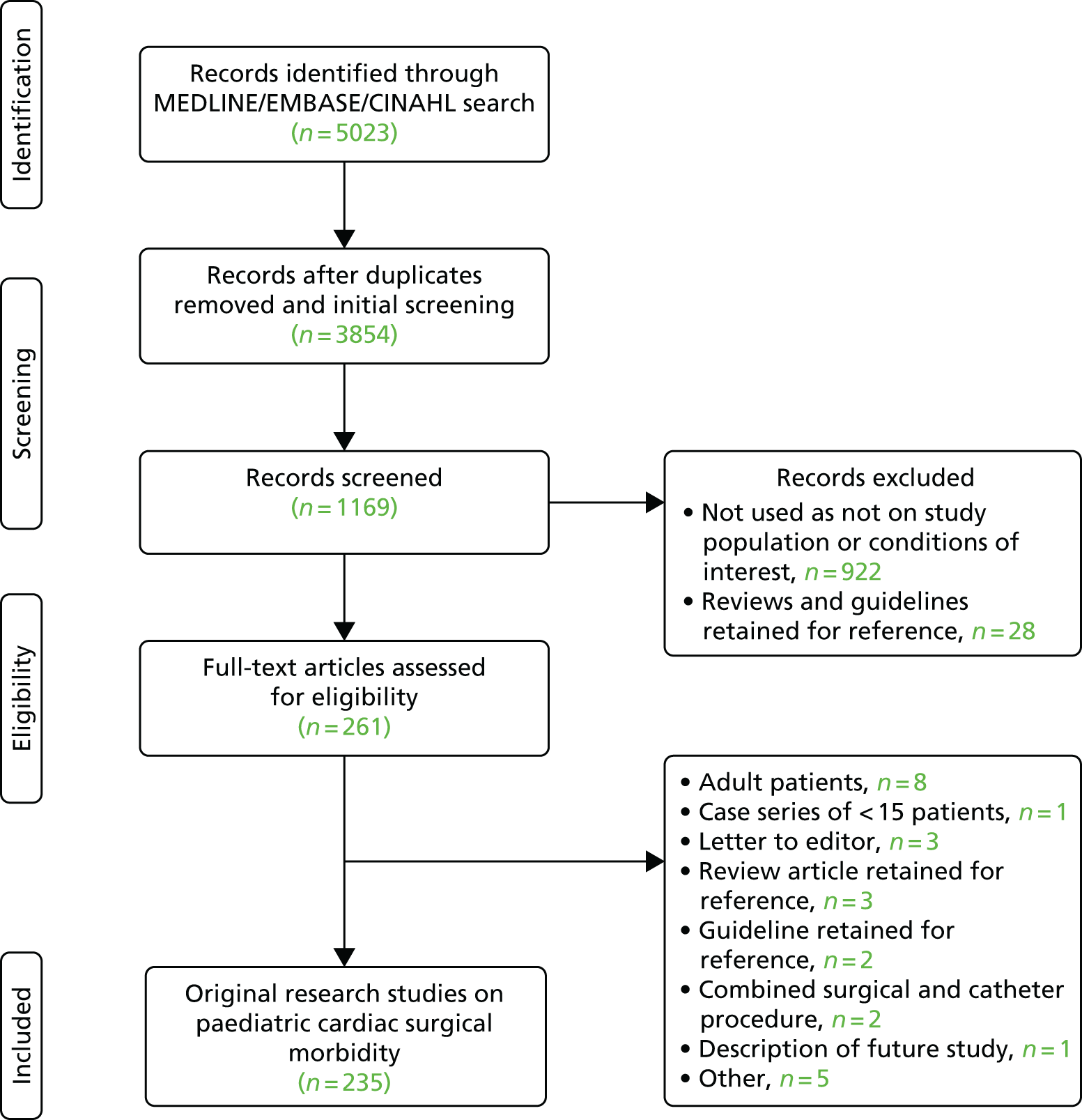

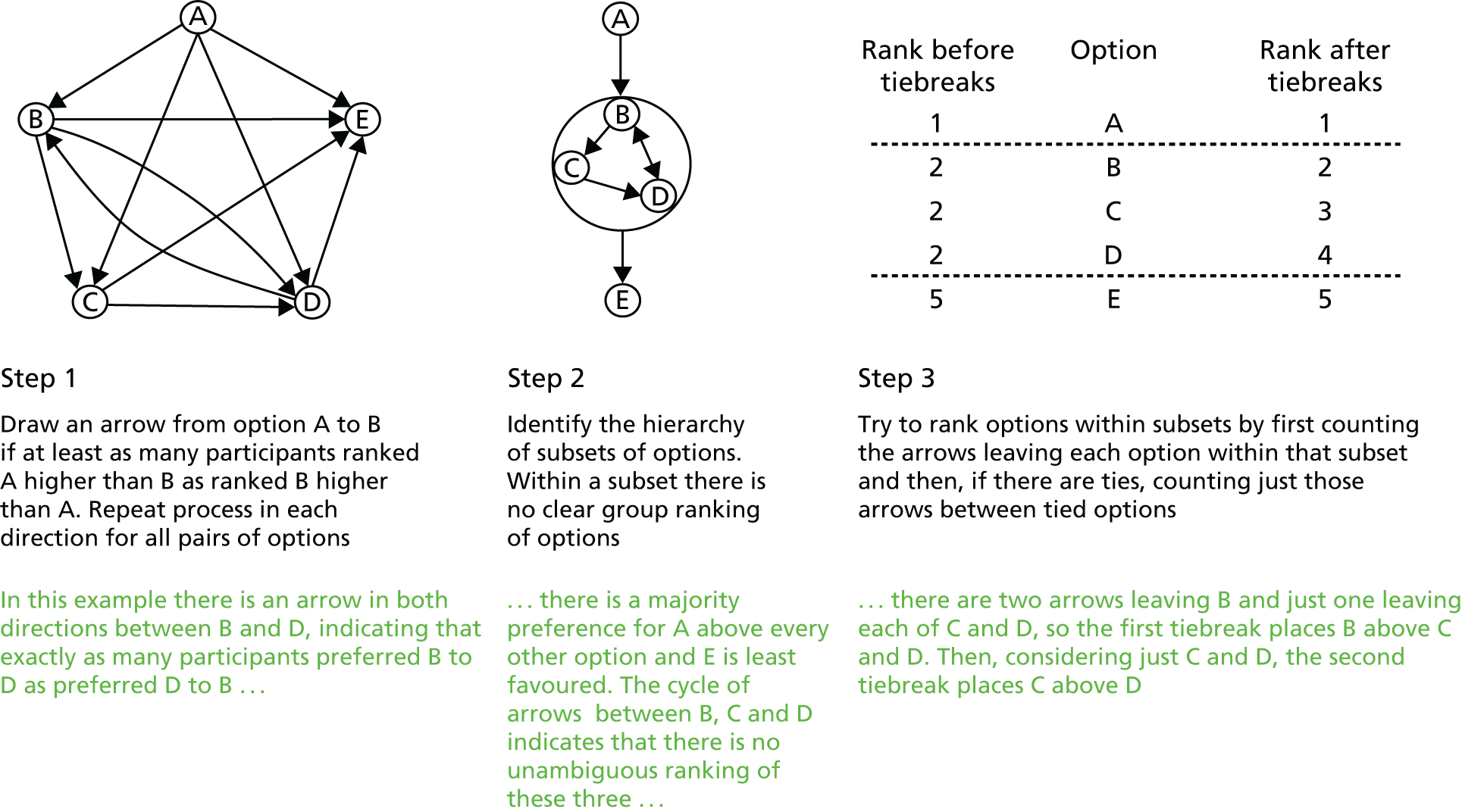

The shortlist of surgical morbidities was selected by the panel using a modified nominal group technique, informed by a comprehensive list of possible morbidities that can occur in relation to paediatric cardiac surgery that was generated by a systematic review [see the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram in Appendix 1, search terms and the list of references in Report Supplementary Material 1], and the parent focus groups and online forum information presented in Chapter 3. The question addressed by the panel was ‘What are the important surgical morbidities to monitor routinely following paediatric cardiac surgery?’ We assessed group preferences between options using the robust secret voting process developed by Utley et al. 93

We held three selection panel meetings over the course of the project: two during year 1 (April and September 2014) and a final meeting in year 4 (May 2018). At the first meeting of the panel, the emphasis was on shortlisting the morbidities considered important and potentially reducible, with participants encouraged not to self-censor owing to issues of definition and measurement. The output of this meeting was a prioritised list of 24 candidate morbidities with other, less-favoured options discarded at this stage. At the second meeting, informed by the definition group (see Chapter 5), the panel discussed issues raised by the definition group on the shortlisted morbidities before, again, individually ranking the remaining options in a secret vote, shortlisting nine morbidities for the incidence and matched cohort studies (objectives 4 and 5). A third and final round of discussion took place following completion of the incidence and matched cohort studies (in May 2018).

Composition of the selection panel

In forming the panel, we aimed to include clinicians from surgical centres, referring hospitals and primary care, as well as family representatives. We wanted a panel of enough people to provide a range of perspectives while also being manageable. The panel comprised 15 people: three family representatives, three paediatric cardiac surgeons, two paediatric intensive care doctors, two paediatric cardiologists, two paediatricians, one paediatric intensive care nurse, one clinical nurse specialist and one clinical psychologist who had experience of working with children with CHD and their families. The panel was chaired by a cardiothoracic surgeon with extensive experience of chairing multidisciplinary panels. We tried, but did not manage, to recruit a GP to the panel.

With the permission of panel members, year 1 selection panel meetings were recorded and professionally transcribed. Each selection panel meeting also had a predetermined seating plan to ensure that people from similar specialties were not grouped together.

Selection panel meeting 1: shortlisting

Preparation

The aim of the first meeting was to identify a shortlist of 15–20 candidate morbidities that would then be considered by the definitions group. Prior to the meeting, the panel was supplied with an extensive list of candidate morbidities identified through:

-

a systematic review of the literature – the search terms, a PRISMA diagram and an exhaustive list of morbidities (see Appendices 1 and 2) and the reference list are provided (see Report Supplementary Material 1)

-

three facilitated focus groups held in different UK cities, with parents recruited by the CHF

-

an online forum for patients and families hosted on the website of the CHF.

The panel was also sent an abridged version of the study protocol, a description of the role of the selection panel and an agenda. Each panellist was asked to identify among or beyond this list of candidate morbidities those they judged most important to monitor routinely according to a deliberately broad working definition of a surgical morbidity as:

Any health or emotional problem that arose as a result of the fact of surgery (whether directly caused by surgery/post-operative care or not).

For the first meeting, panellists were requested not to censor their suggestions on the grounds of the perceived difficulty of definition or measurement and it was stressed that another group would be making these judgements.

We used the nominal group technique,94,95 augmented by a robust voting process to determine group rankings of morbidities (see Appendix 3). The nominal group technique is designed to reduce the influence of perceived power differentials and of dominant personalities on group decision-making, while retaining the benefit of discussion absent from other systematic approaches to group decision-making, such as Delphi. 96 We inferred group preferences from individual rankings, using a method developed by Utley et al. ,93 which is briefly described in Appendix 3.

Structure of the first panel meeting

Each panellist was given the opportunity to speak uninterrupted for 2 minutes on the morbidities they considered important. Each suggestion was entered onto a spreadsheet, which was projected in the meeting room to ensure that there was accurate transcription. The panel was then given the opportunity to add to this initial list if they thought that something important had been missed.

The chairperson (TT) led a process of identifying suggestions that fell outside the working definition above (see Preparation): duplication among suggestions and merging of closely related suggestions. There was then a secret ballot in which panellists were asked individually to rank the resulting list of candidate suggestions in order of descending importance. The voting process and the method for generating group preferences from individual ranking data are described further in Appendix 3.

During a scheduled break, the group preferences were calculated from the individual rankings by CP and MU, who did not have a vote on which morbidities to measure. After the break, the group preferences were fed back to the panel. The chairperson then led a second round of discussion, focusing on the group preferences and giving panellists the opportunity to argue for specific morbidities being given greater importance, and for the group to further consolidate the list of morbidities.

There was a second round of secret ranking followed by feedback of group preferences, prior to a consensus being sought as to the prioritised shortlist of morbidities to be passed to the separate definition panel for an assessment on the feasibility of defining, measuring and monitoring each in routine practice.

Results of the first panel meeting

Of the 15 panellists, three could not attend. At this meeting, 66 morbidity terms were suggested during the round of 2-minute contributions from each panellist (see Appendix 3). In the discussion that followed, seven terms were removed as being irrelevant to our study, related to impacts of post-surgical morbidity that would be measured as part of our empirical study, were too long term in nature to be captured within our study or redundant given other terms suggested.

Of the remaining 59 terms, seven were accepted as candidate morbidities as they were and a further five terms were simply relabelled before being accepted. The remaining 47 terms were mapped onto 16 groups of two to eight terms, with each group considered to relate to a sufficiently similar phenomenon for them to be single candidate morbidities. Members of the panel confirmed that they wanted the term ‘extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)/mechanical support’ to feature on its own, as well as being an indicator of a ‘major adverse event’ (MAE). A new term (‘liver injury’) was added as a candidate at this stage, with the agreement of the panel. This gave 29 candidate morbidities.

These candidate morbidities and the group ranking of importance among them in the first round of voting are shown in Table 2. It is worth noting that, in this first round of voting, the group ranked ‘new global permanent neurological impairment’ as the most important morbidity. After that, there was a group of 22 candidate morbidities that could only be separated by applying tie-breaks, with the other six candidate morbidities [including ‘necrotising enterocolitis’ (NEC)] ranked as less important.

| Morbidity | Rank | |

|---|---|---|

| Before tie-breaks | After tie-breaks | |

| New global permanent neurological impairment | 1 | 1 |

| New impaired cognitive function more than a month after surgery | 2 | 2 |

| Unplanned reoperation/reintervention | 2 | 3 |

| Developmental delay | 2 | 4 |

| MAE | 2 | 5 |

| Problems feeding (graded) | 2 | 6 |

| Mental health consequences | 2 | 7 |

| Length of ICU stay | 2 | 8 |

| New focal permanent neurological impairment | 2 | 9 |

| Low cardiac output (categorised) | 2 | 10 |

| Poor communication between clinical team and family | 2 | 11 |

| ECMO/mechanical support | 2 | 12 |

| Acute kidney injury (graded) | 2 | 13 |

| Prolonged pleural effusion | 2 | 14 |

| Complications during surgery | 2 | 15 |

| Hospital acquired infection (graded/categorised) | 2 | 15 |

| Prolonged hospital length of stay | 2 | 17 |

| Complete heart block (categorised) | 2 | 18 |

| Surgical bleeding (graded) | 2 | 19 |

| Questionable clinical team decision and diagnosis | 2 | 20 |

| Level of support from hospital available at home | 2 | 21 |

| Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy | 2 | 21 |

| Phrenic nerve injury | 2 | 23 |

| Necrotising enterocolitis | 24 | 24 |

| Vascular thrombosis (graded) | 25 | 25 |

| Junctional ectopic tachycardia | 26 | 26 |

| Elevated pulmonary vascular resistance | 27 | 27 |

| Liver injury (graded) | 27 | 27 |

| Sensory neural deafness | 27 | 27 |

In the discussion that followed the first round of voting, the panel merged the two items describing neurological impairment and individual panellists expressed surprise at the low ranking of ‘NEC’ and ‘vascular thrombosis’, leading to a discussion of these particular morbidities and their impact.

The results of the second round of voting are shown in Table 3. Although the panel’s view of the top three morbidities [including the merged item of ‘new permanent neurological impairment (global or focal)] was clear, there was a large group of 21 candidates that could only be separated by applying tie-breaks. This group included ‘NEC’ and ‘vascular thrombosis’. Given the lack of unambiguous group preference among these 21 candidates, the panel decided to request that the separate definition panel considered the 24 candidate morbidities given in bold in Table 3, with the remainder discarded.

| Morbidity | Rank | |

|---|---|---|

| Before tie-breaks | After tie-breaks | |

| New permanent neurological impairment (global or focal) | 1 | 1 |

| New impaired cognitive function more than a month after surgery | 2 | 2 |

| Unplanned reoperation/reintervention (categorisation) | 3 | 3 |

| Length of ICU stay | 4 | 4 |

| MAE | 4 | 5 |

| Problems feeding (graded) | 4 | 6 |

| Developmental delay | 4 | 7 |

| ECMO/mechanical support | 4 | 8 |

| Low cardiac output (categorised) | 4 | 8 |

| Mental health consequences | 4 | 10 |

| NEC | 4 | 11 |

| Hospital acquired infection (graded/categorised) | 4 | 12 |

| Prolonged hospital length of stay | 4 | 13 |

| Acute kidney injury (graded) | 4 | 14 |

| Prolonged pleural effusion | 4 | 15 |

| Poor communication between clinical team and family | 4 | 16 |

| Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy | 4 | 17 |

| Vascular thrombosis (graded) | 4 | 18 |

| Surgical bleeding (graded) | 4 | 19 |

| Complications during surgery | 4 | 20 |

| Complete heart block (categorised) | 4 | 21 |

| Questionable clinical team decision & diagnosis | 4 | 22 |

| Phrenic nerve injury | 4 | 23 |

| Level of support at home | 4 | 24 |

| Junctional ectopic tachycardia | 25 | 25 |

| Sensory neural deafness | 26 | 26 |

| Elevated pulmonary vascular resistance | 27 | 27 |

| Liver injury (graded) | 27 | 27 |

Between panel meetings 1 and 2

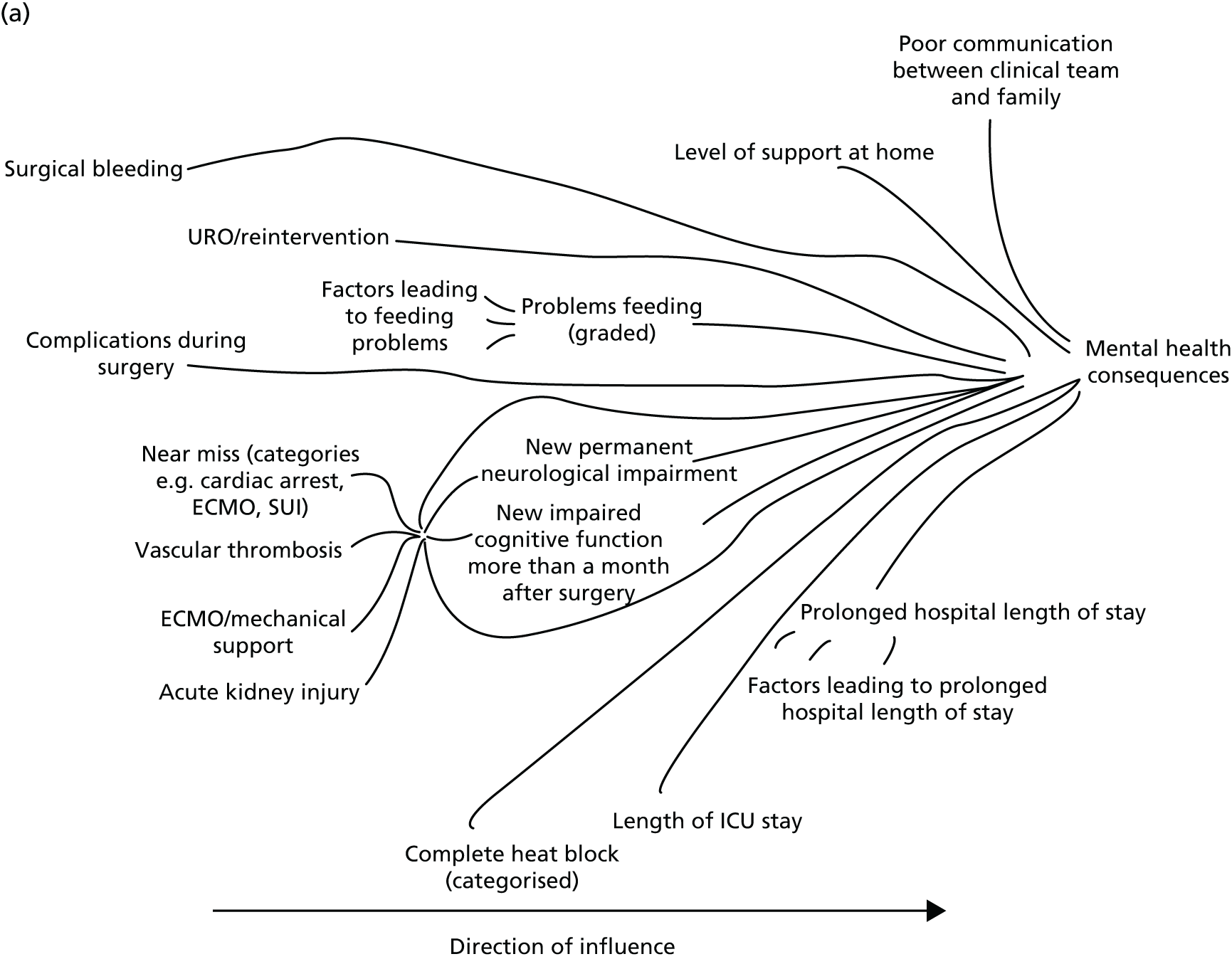

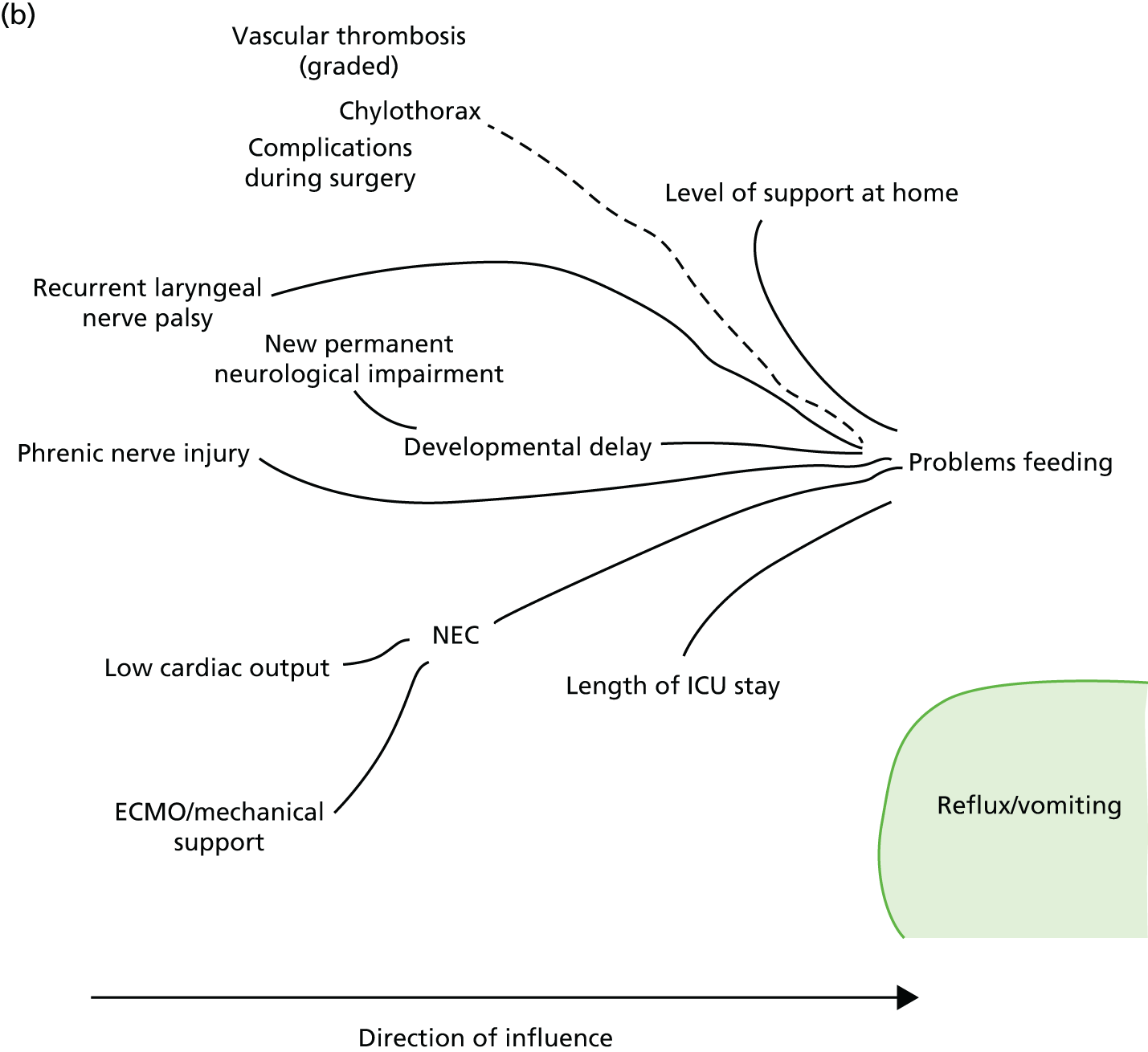

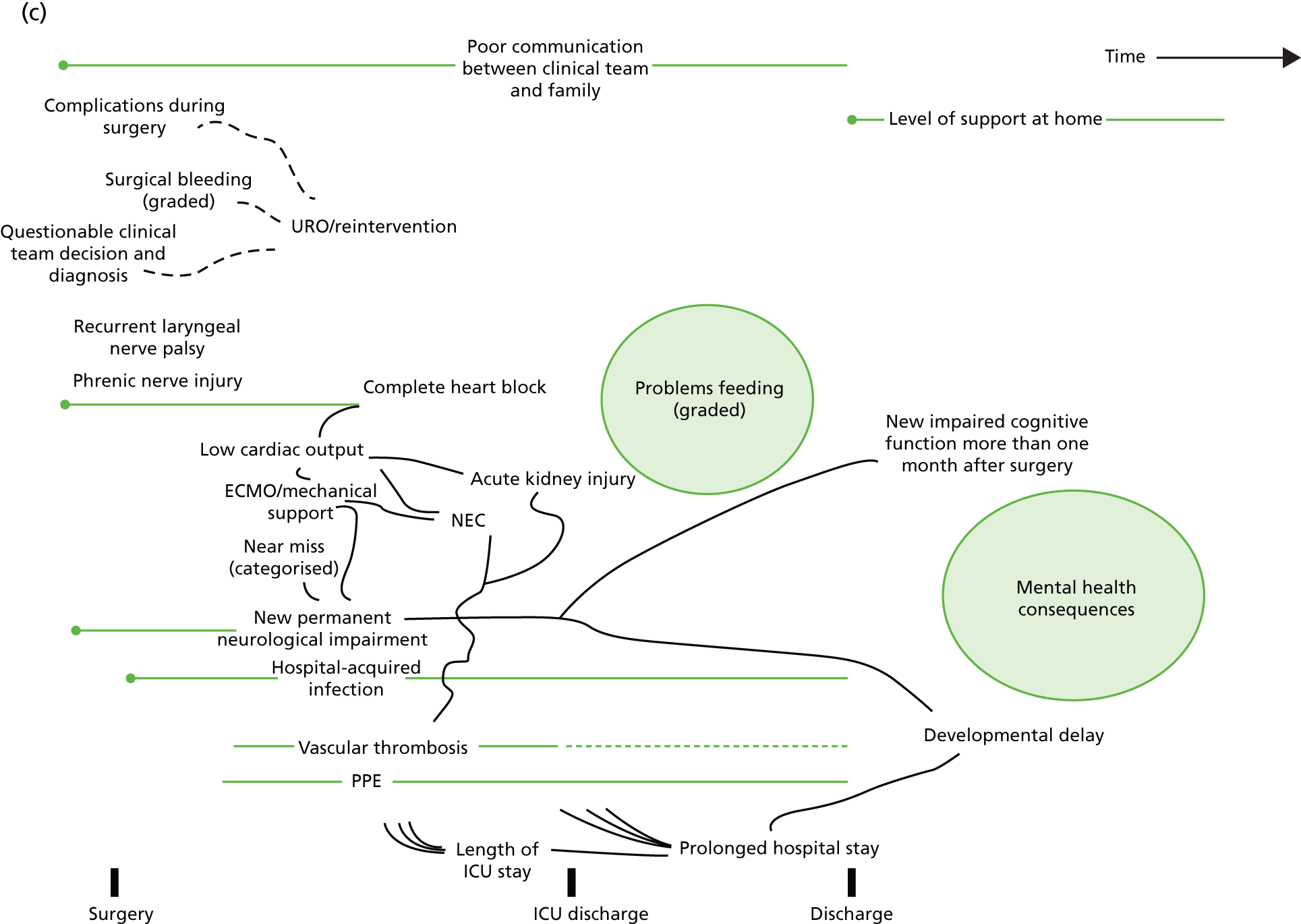

Causal mapping

Following the first selection group meeting, it was decided that it might be useful for non-clinical members of the panel to have an accessible summary of any causal relationships among candidate morbidities so that, when choosing the best set of morbidities to monitor, any overlap or redundancy among candidates could be accounted for. To this end, a set of causal mapping exercises was conducted by one of the facilitative team (MU) separately with two of the panellists (IM and HJ). In each exercise, cards representing shortlisted morbidities were placed on a large sheet of paper and arranged left to right, with lines drawn to indicate potential causal relationships. Photographs were taken of these causal maps, which were then converted to diagrams (see Appendix 4).

Selection panel meeting 2: incorporating feasibility and overlap

Preparation

Prior to the second panel meeting, panellists were provided with a pack of materials containing:

-

a summary of any estimates of incidence and impact of candidate morbidities from the systematic review

-

the judgement of the definition panel on the feasibility of defining, measuring and monitoring routinely each candidate morbidity

-

a summary of potential long-term impacts of each candidate morbidity from the definition panel

-

a summary of the parent and family focus groups and the online forum

-

diagrams generated through the causal mapping exercise provided in Appendix 4

-

minutes from the first meeting

-

a statement of the purpose of the second meeting and its agenda.

Structure of the second panel meeting

At the beginning of the second meeting the panel were given a brief reminder of the scope of the overall project, the remit of the selection panel and the time scales we were working to.

The panel were tasked with narrowing the list of shortlisted candidates to a selection of 6–10, the incidence and impact of which would be measured in five centres over 18 months. It was explained that the upper limit of 10 morbidities was a result of the sample size required for measuring the impact of distinct morbidities. It was explained that we could measure just the incidence of other morbidities, if possible, from routine data. Panellists were also alerted to the (then) recently launched ‘NHS England consultation on the future of Children’s Heart Services in England’, which highlighted the possibility of future national audit of surgical morbidities.

Panellists were asked to consider the following.

Feasibility of measurement including time scales

Given our plans to measure the impact of morbidities, the project team stressed that selected morbidities needed to be identifiable in a timely manner. This aspect was the special consideration of the definition panel (see Chapter 5).

Overlap and redundancy among selected morbidities

The project team made the point that selecting morbidities that almost always occur with other selected morbidities would pose problems in terms of measuring their individual impact. It highlighted that length of stay measures are particularly problematic in this respect.

Incidence

Selected morbidities needed to have an incidence of at least 1.5–2% to measure their impact over 18 months, owing to sample size considerations.

A summary of the judgements of the definition panel was presented to the panel, consisting of an array showing the shortlisted candidates placed vertically based on the group ranking of importance from meeting 1 and horizontally in terms of the feasibility of monitoring that morbidity (this is shown in Chapter 11). The panel were then asked in a secret ballot to nominate morbidities for exclusion and others for inclusion, without further discussion. The panel discussed the remaining morbidities as a group.

After the panel meeting, a written summary of the discussion was circulated and an online poll conducted to obtain the group ranking of importance among the shortlisted candidate morbidities. The poll was conducted to elicit the views of panellists who were not able to attend and to identify replacement morbidities if any of those selected were judged to be infeasible to monitor in routine practice. We used the online voting tool (URL: www.crankit.io; accessed 22 September 2014), which uses the same algorithm for robustly inferring group preferences from individual preference data that was used in the selection meetings and which is outlined in Appendix 3.

Results of the second panel meeting

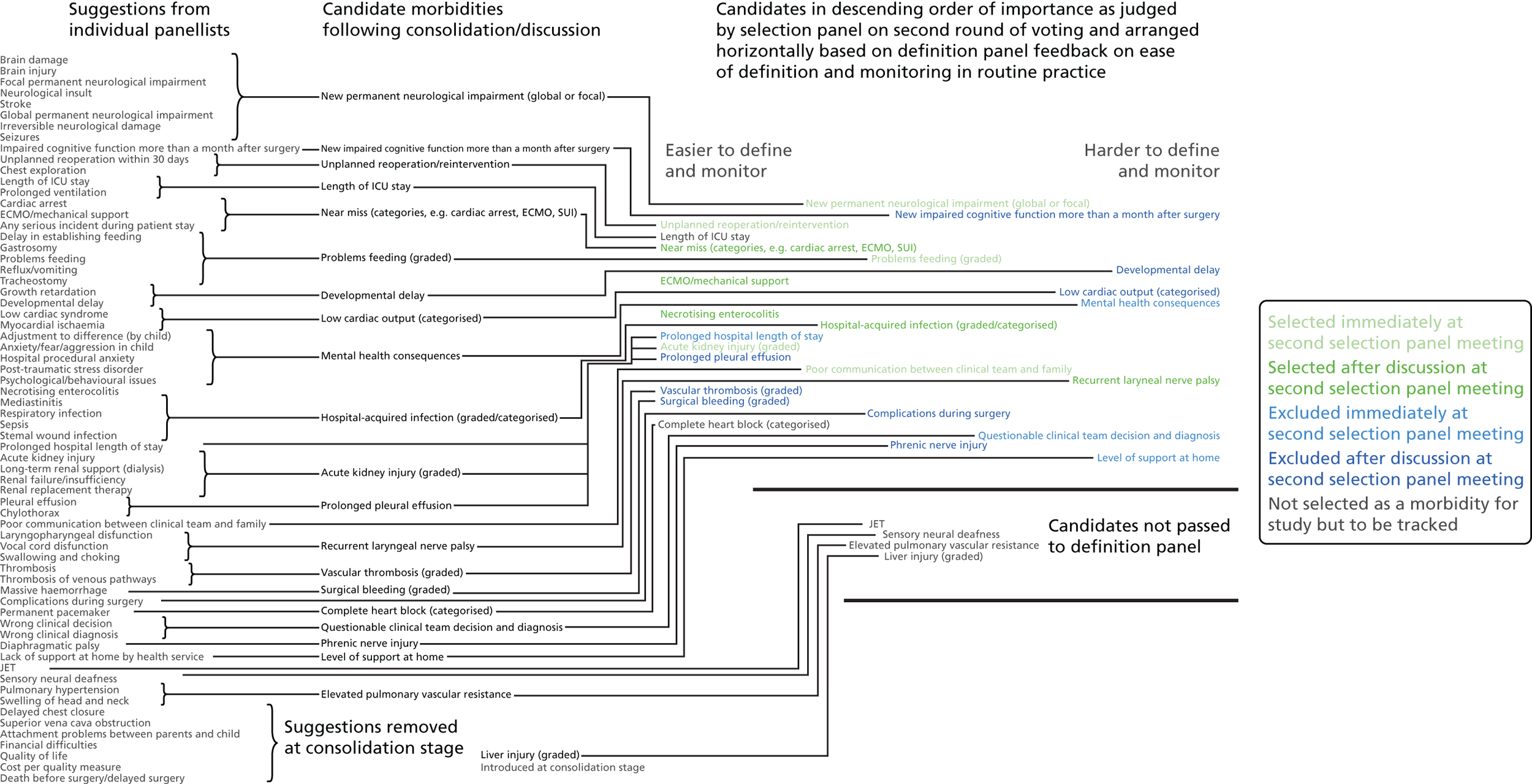

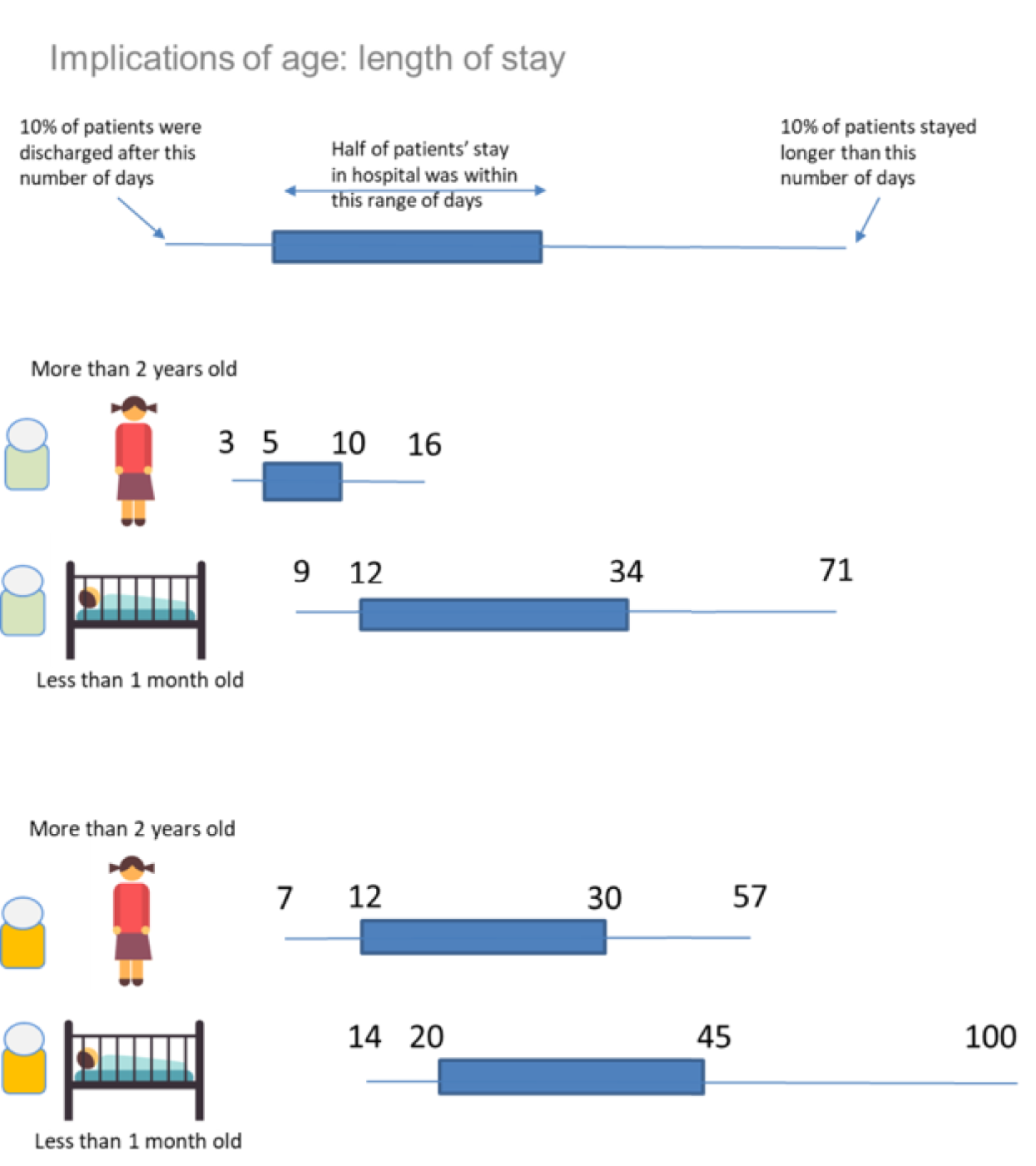

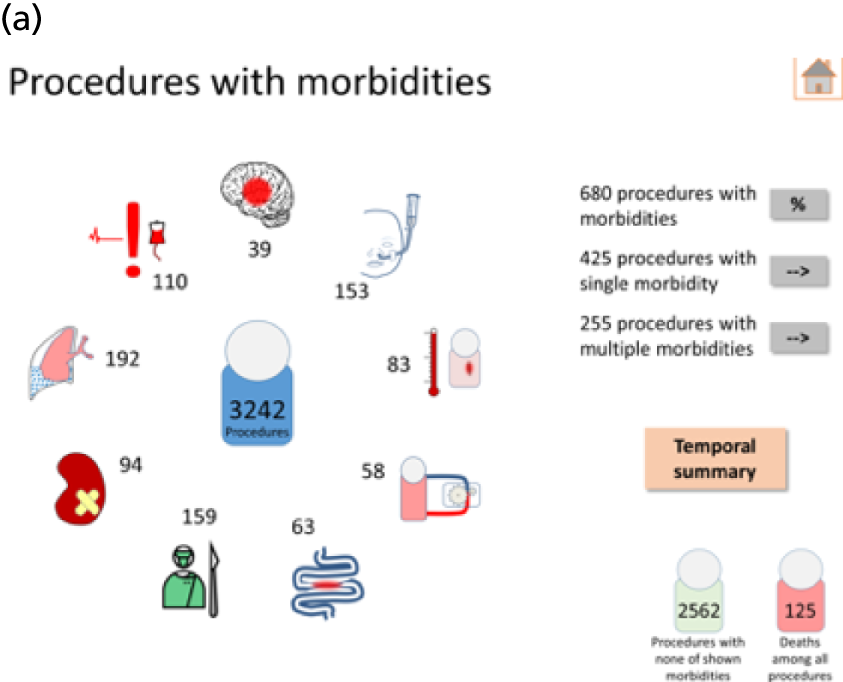

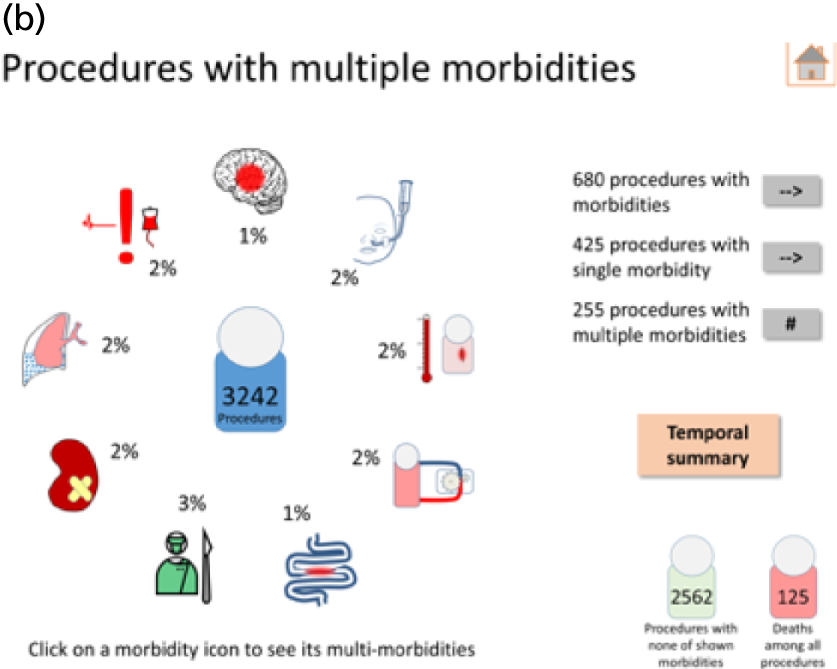

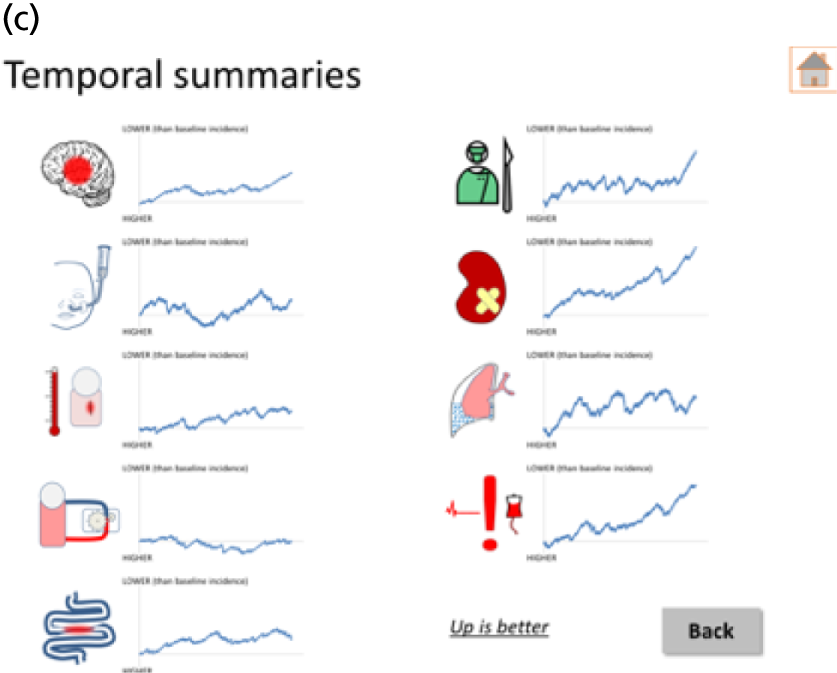

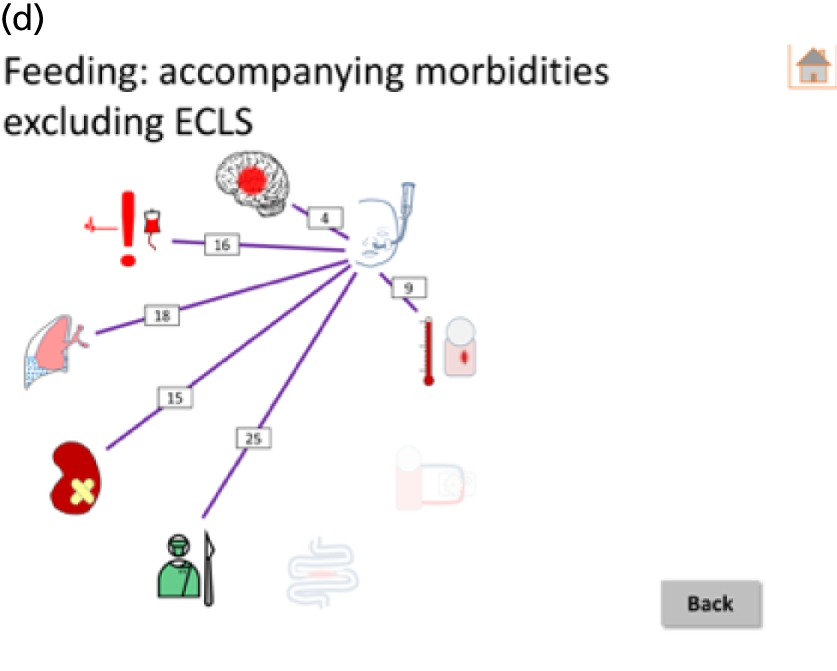

Of the 15 panellists, six could not attend. An overview of the results of the first year’s selection process is given in Figure 1. The initial assessment of the definition panel as to the feasibility of defining and monitoring each of the candidate morbidities still in contention after the first selection panel meeting is shown to the right-hand side of Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of results as presented to the selection panel. ICU, intensive care unit; JET, junctional ectopic tachycardia; SUI, sudden unforeseen incident. Reproduced from Pagel et al. 90 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

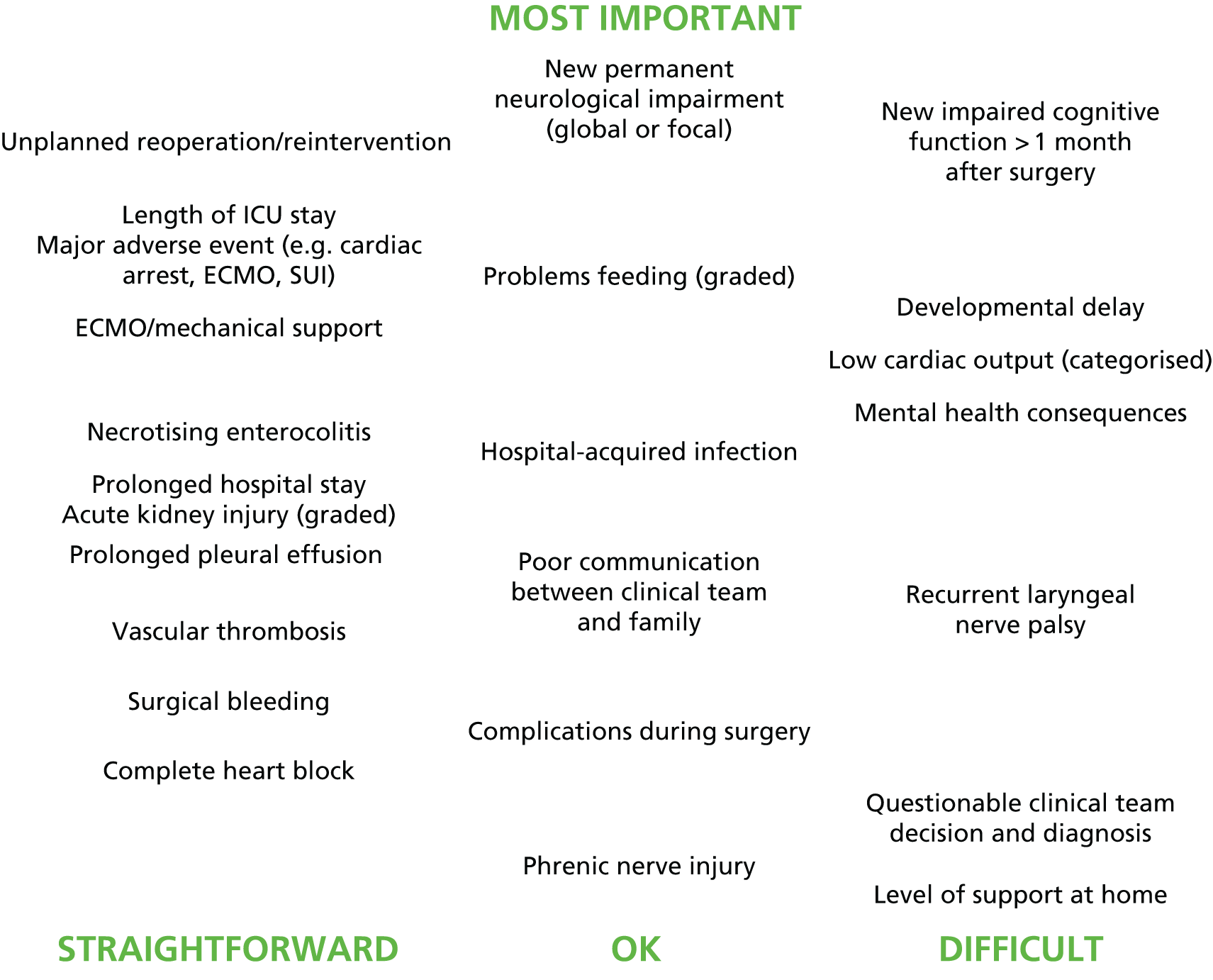

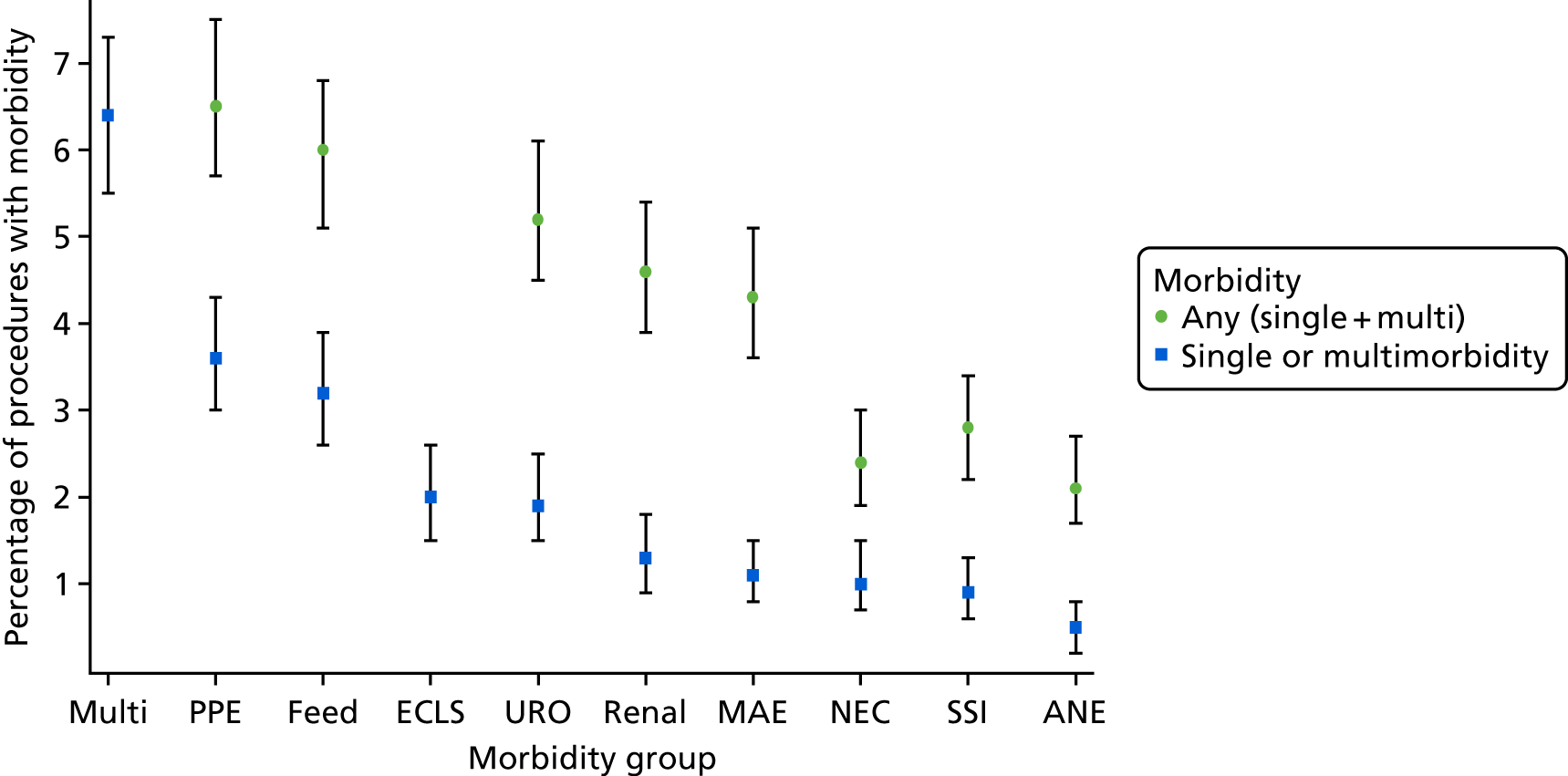

Eleven candidate morbidities were considered straightforward to define and monitor in routine practice: (1) ‘unplanned reoperation (URO)/reintervention’; (2) ‘length of intensive care unit (ICU) stay’; (3) ‘MAE (e.g. cardiac arrest, ECMO, serious untoward incident)’; (4) ‘ECMO/mechanical support’; (5) ‘NEC’; (6) ‘prolonged hospital length of stay’; (7) ‘acute kidney injury’; (8) ‘prolonged pleural effusion (PPE)’; (9) ‘vascular thrombosis’; (10) ‘surgical bleeding’; and (11) complete heart block’.

Six candidate morbidities were considered less straightforward: (1) ‘new permanent neurological impairment (global or focal)’; (2) ‘problems feeding’; (3) hospital-acquired infection’; (4) ‘poor communication between clinical team and family’; (5) ‘complications during surgery’; and (6) ‘phrenic nerve injury’.

The remaining seven candidate morbidities were deemed difficult to define and monitor in routine practice: (1) ‘new impaired cognitive function more than a month after surgery’; (2) ‘developmental delay’; (3) ‘low cardiac output’; (4) ‘mental health consequences’; (5) ‘recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy’; (6) ‘questionable clinical team decision and diagnosis’; and (7) ‘level of support at home’.

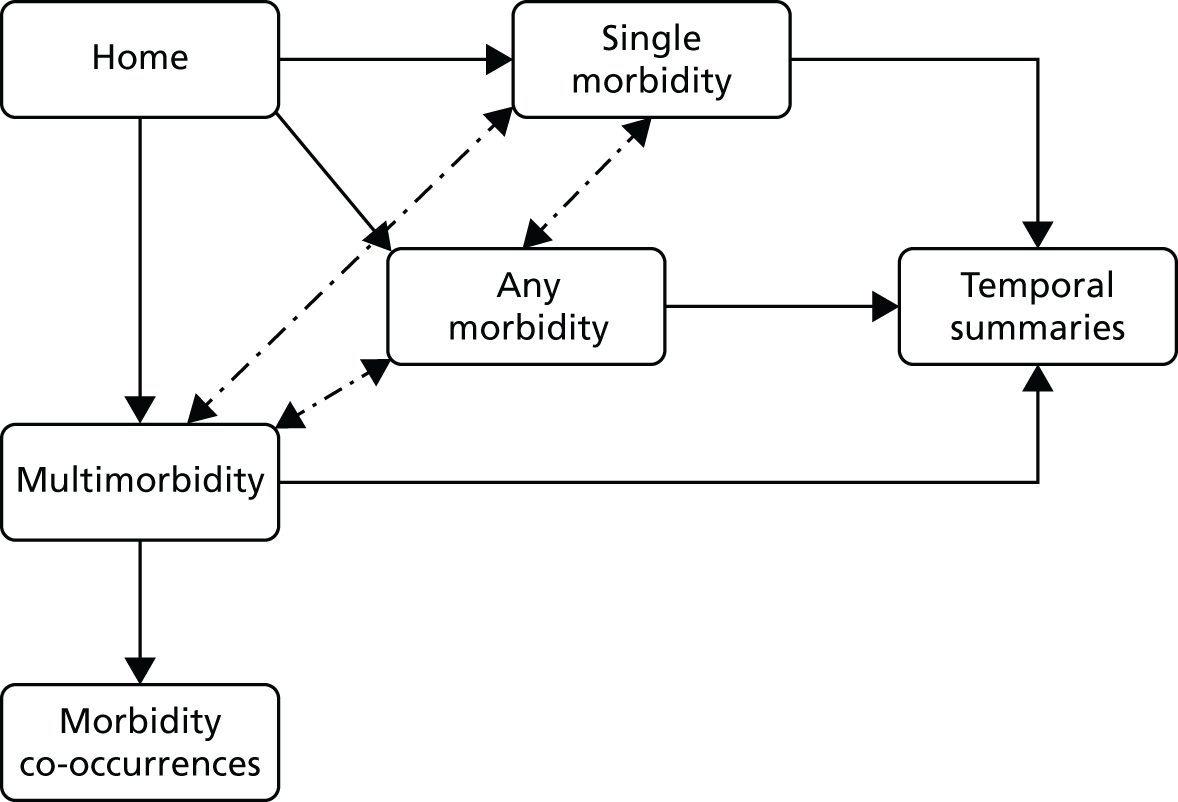

The output from the causal mapping exercises given (see Appendix 4) highlighted how ‘mental health consequences’ could be a result of several other candidate morbidities, how the majority of candidate morbidities could result in prolonged stay in the ICU or hospital and how ‘low cardiac output’ could become manifested in several of the other candidate morbidities.

Based on these assessments and the selection panel’s own previous assessment of the importance of these morbidities, it was agreed that the following candidate morbidities would be selected without further discussion: ‘new permanent neurological impairment (global or focal)’; ‘URO/reintervention’; ‘problems feeding’; ‘acute kidney injury’; and ‘poor communication between clinical team and family’.

The following candidate morbidities were discarded at this point without further discussion: ‘mental health consequences’; ‘prolonged hospital stay’, ‘questionable clinical team decision and diagnosis’; and ‘level of support at home’.

The remaining 15 candidate morbidities were then discussed, with the panel reminded of the need to select at most five from these 15. Group decisions were made to select ‘ECMO’, ‘MAE’, ‘NEC’, ‘hospital-acquired infection’ and ‘recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy’. Note that the group accepted that ‘MAE’ should not include ECMO, as this had been selected as a distinct morbidity.

Group decisions were made to discard at this stage ‘new impaired cognitive function more than one month after surgery’, ‘developmental delay’, ‘low cardiac output’, ‘PPE’, ‘vascular thrombosis’, ‘surgical bleeding’, ‘complications during surgery’, ‘phrenic nerve injury’ and ‘length of ICU stay’.

The online poll conducted after the second panel meeting identified ‘recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy’, ‘phrenic nerve injury’, ‘complete heart block’ and ‘PPE’ as potential substitute morbidities in the event of the definition panel vetoing any of the selected morbidities in routine practice.

Review of selected morbidities by definition panel and chief investigators

The selected morbidities were then reviewed by the definition panel, which could veto inclusion of a selected morbidity if, after careful consideration and discussion with the chief investigators (VT and KB), it was deemed infeasible to define and monitor in routine practice.

Of the morbidities selected by the panel, two (‘poor communication between clinical team and family’ and ‘recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy’) were removed from the final list. In each case this was carried out on the grounds that the morbidity concerned would be too problematic to measure in routine practice. The morbidity ‘PPE’ was added to the final list of morbidities as a substitute, as this was the next ranked morbidity, at number 10. Feeding problems due to symptomatic recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy were then included under ‘problems feeding’. The definition panel and the project team decided to monitor the incidence of phrenic nerve injury and complete heart block by using routinely collected cardiac audit data. These changes were shared with the selection panel.

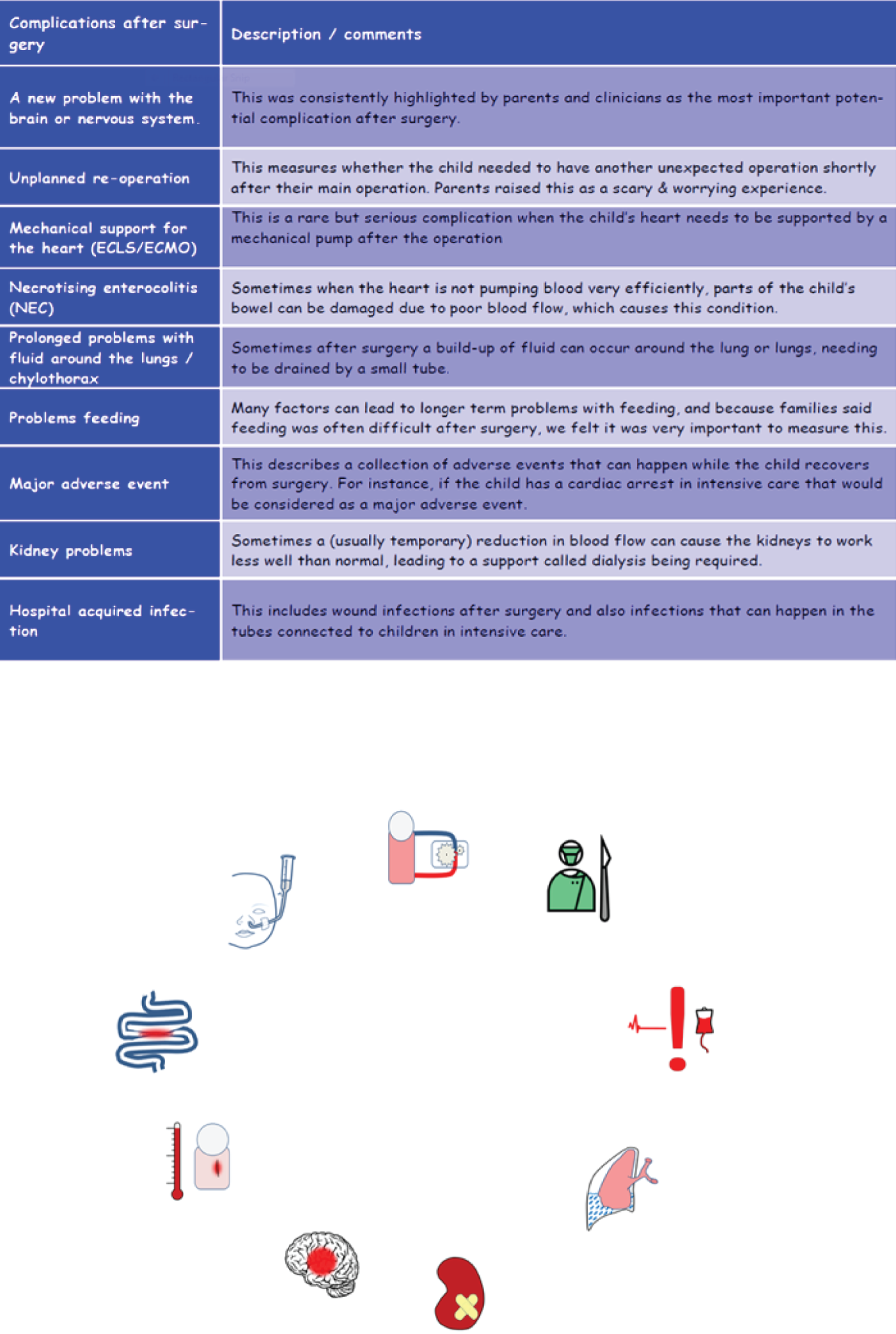

The final nine morbidities chosen for inclusion in the study, using the revised labels provided in the final selection, are listed in Box 2.

-

Acute neurological event (ANE).

-

Unplanned reintervention (URO).

-

Feeding problems (Feed).

-

Need for renal replacement therapy (Renal).

-

Major adverse event (MAE).

-

Extracorporeal life support (ECLS ECMO).

-

Necrotising enterocolitis (NEC).

-

Post-surgical infection (SSI).

-

Prolonged pleural effusion or chylothorax (PPE).

Alongside these nine morbidities, the study team committed to measuring poor communication between the clinical team and the family among the patients entering the matched cohort phase of our study, and to conducting secondary analyses to identify the impact of longer stays in the ICU above and beyond the impact of the selected morbidities.

Selection panel meeting 3: review of the selected morbidities

The final definition panel took place (January 2018) before the final selection panel, so that the final definition panel views on feasibility could feed into the final selection panel meeting. The final selection panel meeting was held in May 2018, with seven panellists being unable to attend. Panel members were given the preliminary results of the incidence and impact study data which are covered, in full, in Chapters 7–9.

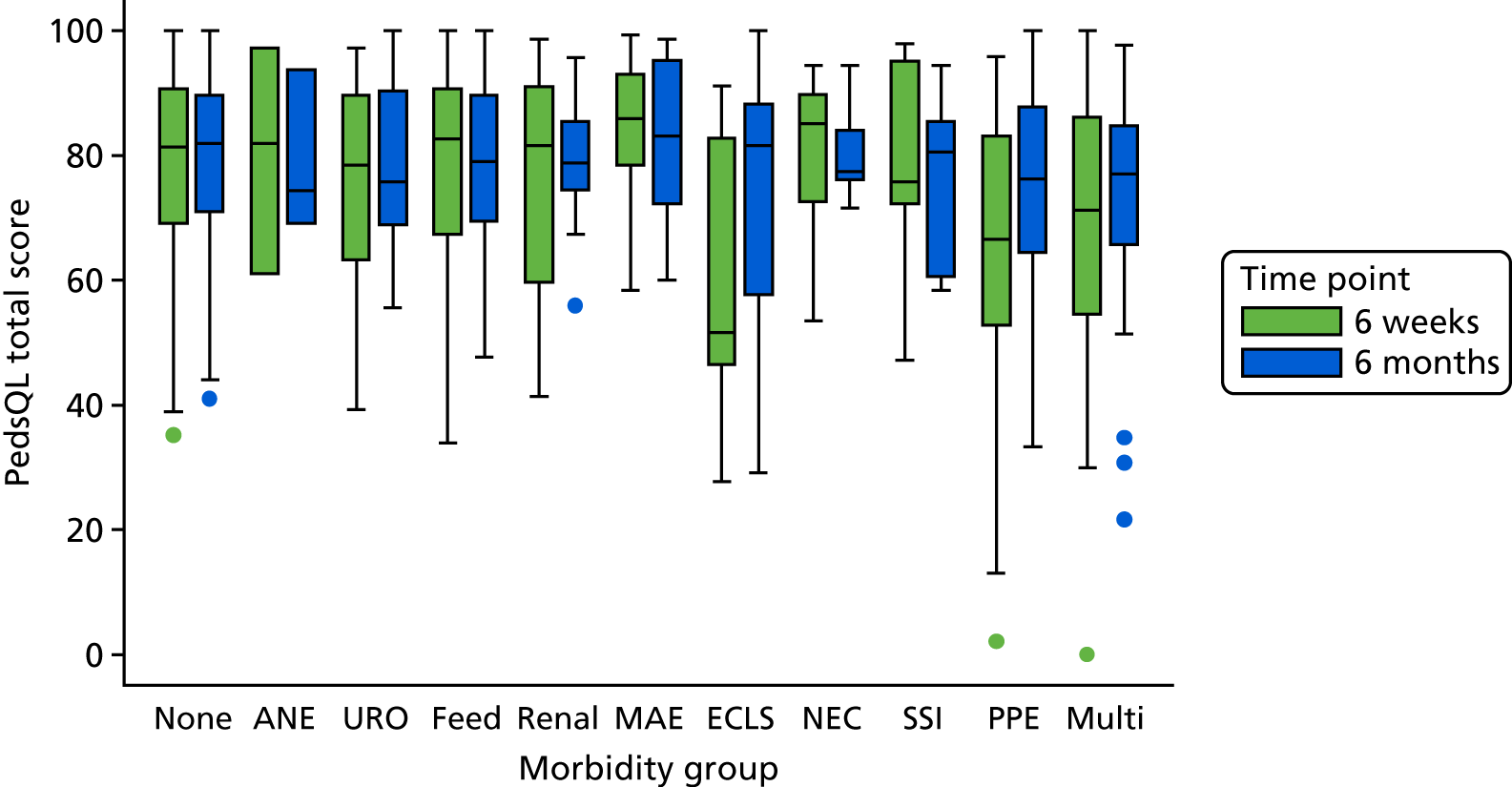

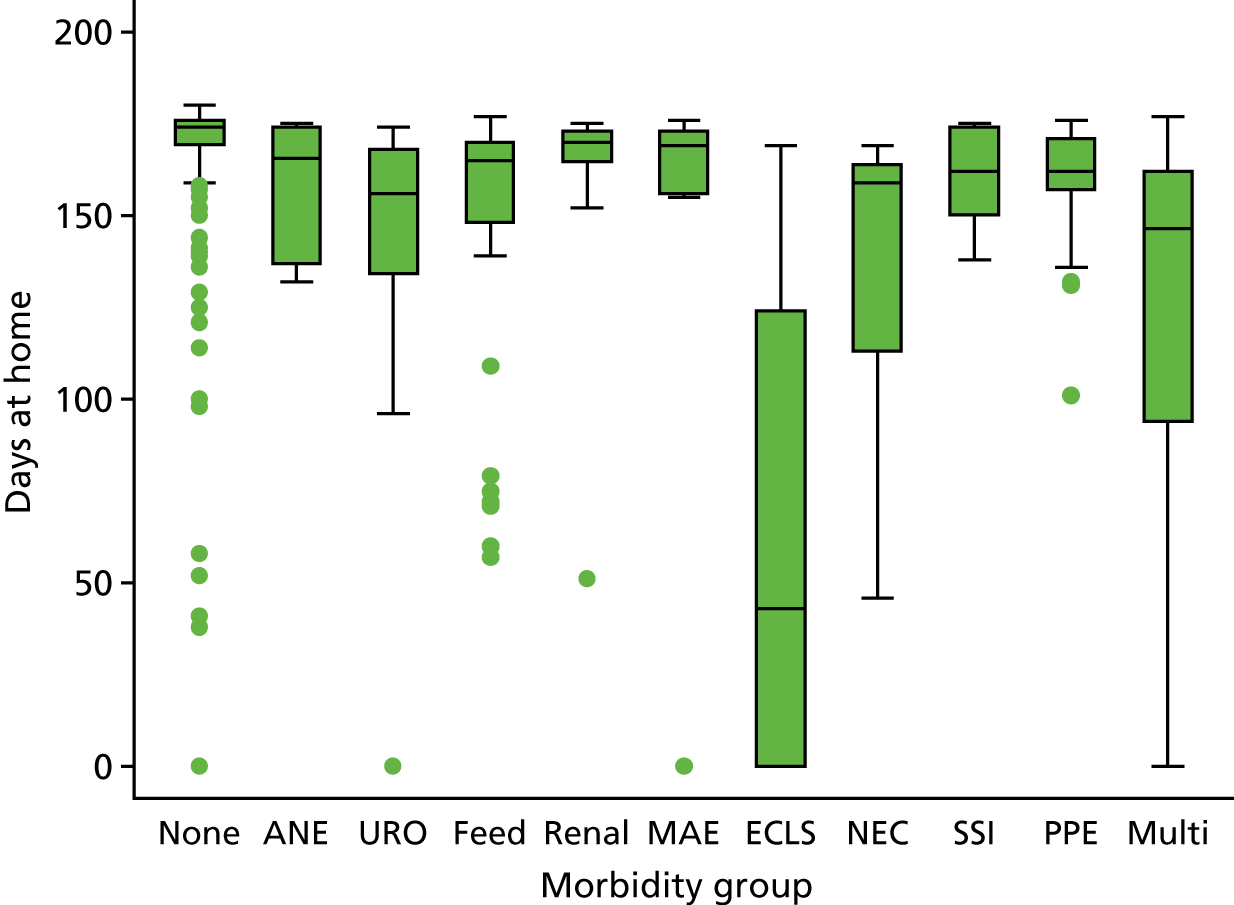

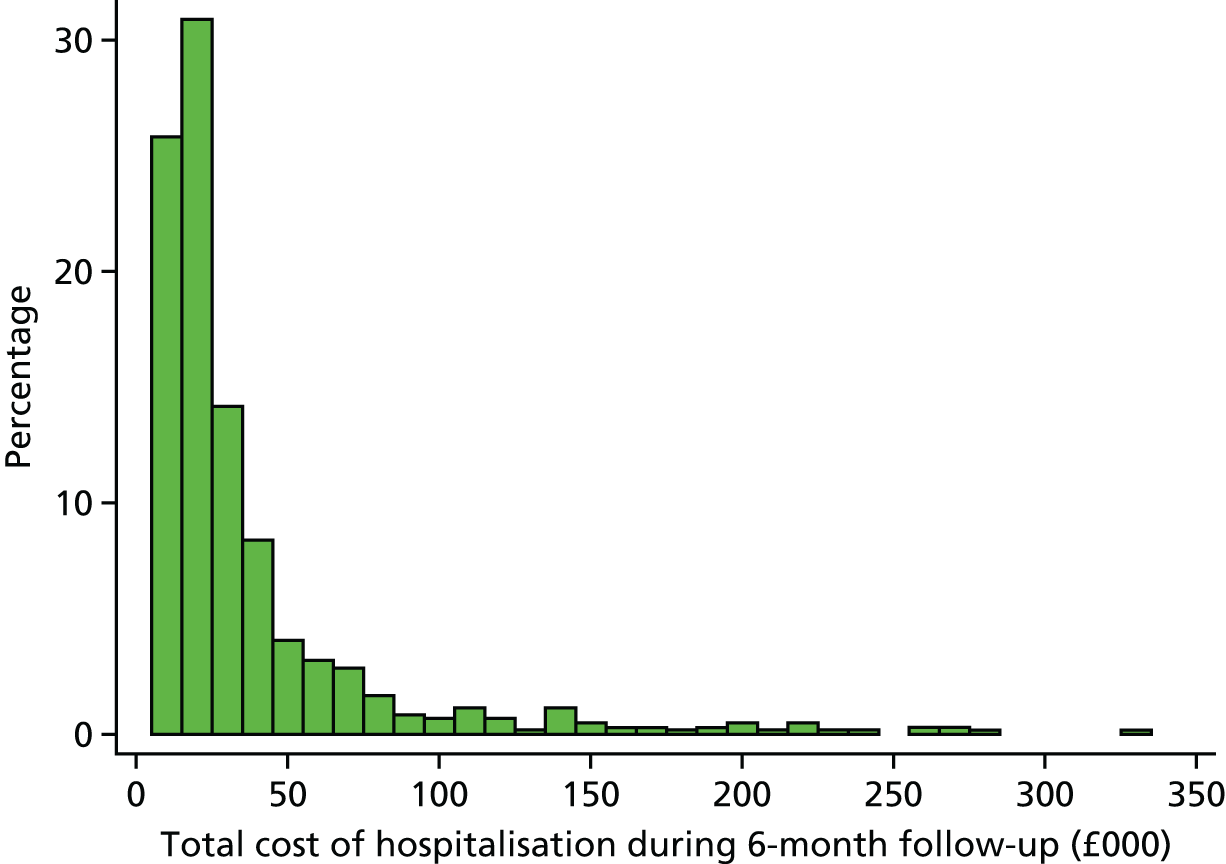

Members who could not attend were given the opportunity to provide comments to the chairperson beforehand for inclusion in the discussion, which three absent members did do before the meeting. During the meeting, CP presented the overall results to the group and the group discussed each of the morbidities in turn in terms of its suitability for routine monitoring within hospitals. Members were told that at this stage no morbidities needed to be dropped and that morbidities should be considered in terms of:

-

the incidence of each candidate morbidity as measured in the study

-

the experience and any difficulties that teams had in capturing the relevant data

-

partial/preliminary analysis of the impact that each morbidity has in terms of quality of life, length of stay in hospital and other outcomes at 6 months

-

the extent to which monitoring each of the morbidities studied could support improvement initiatives.

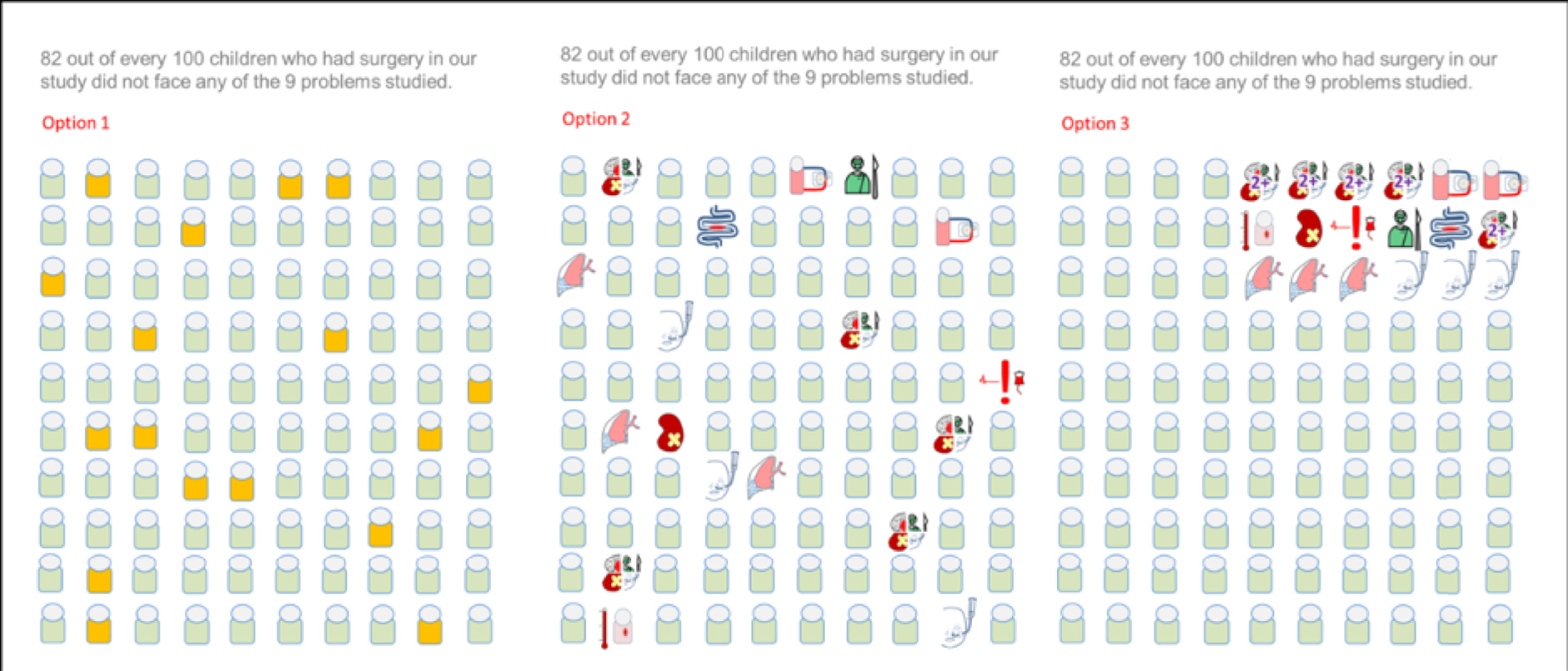

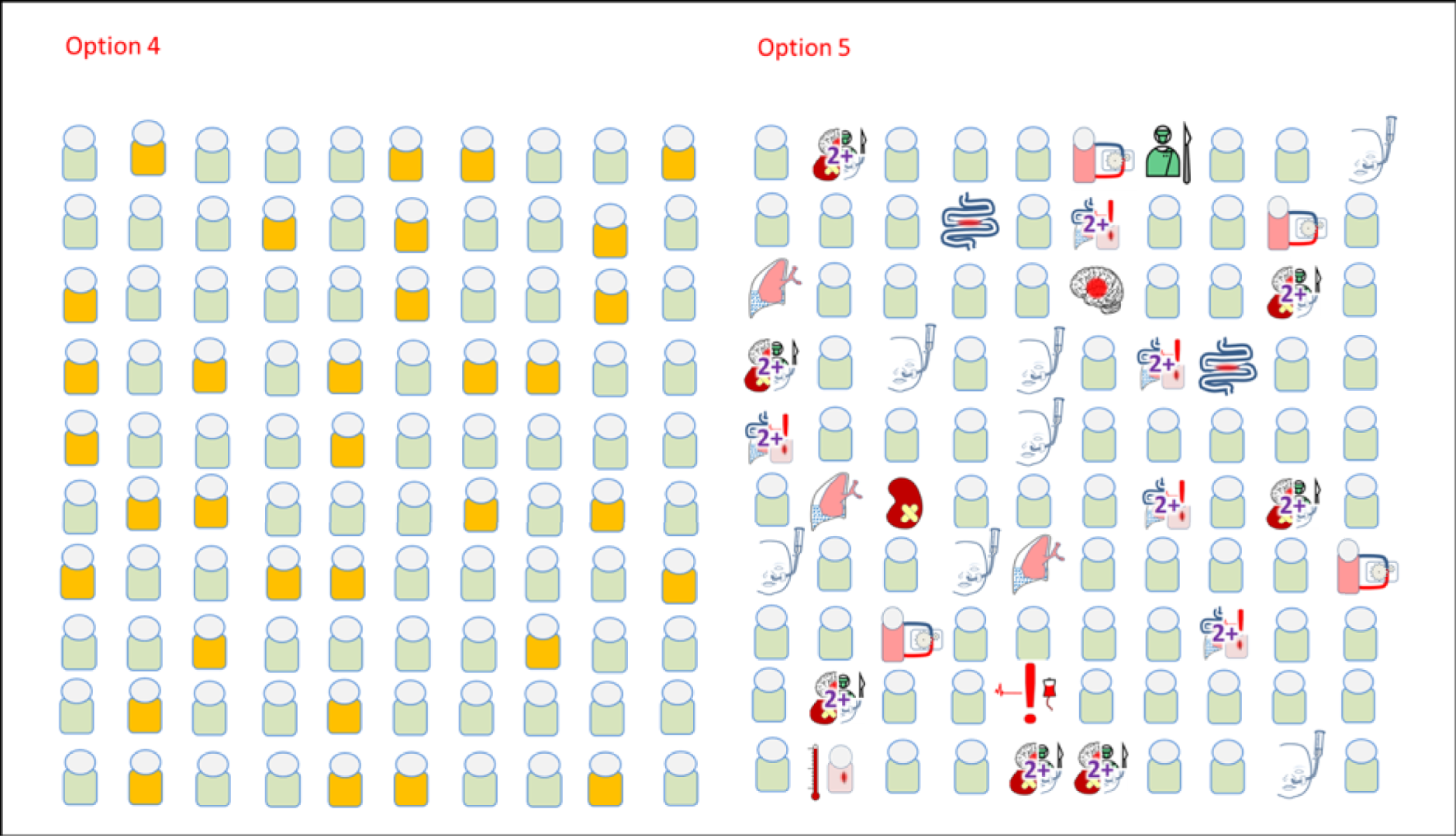

The panel also noted the low mortality rates and lower lengths of stay among children who had none of the nine measured morbidities, giving confidence that the main morbidities were indeed captured within the study.

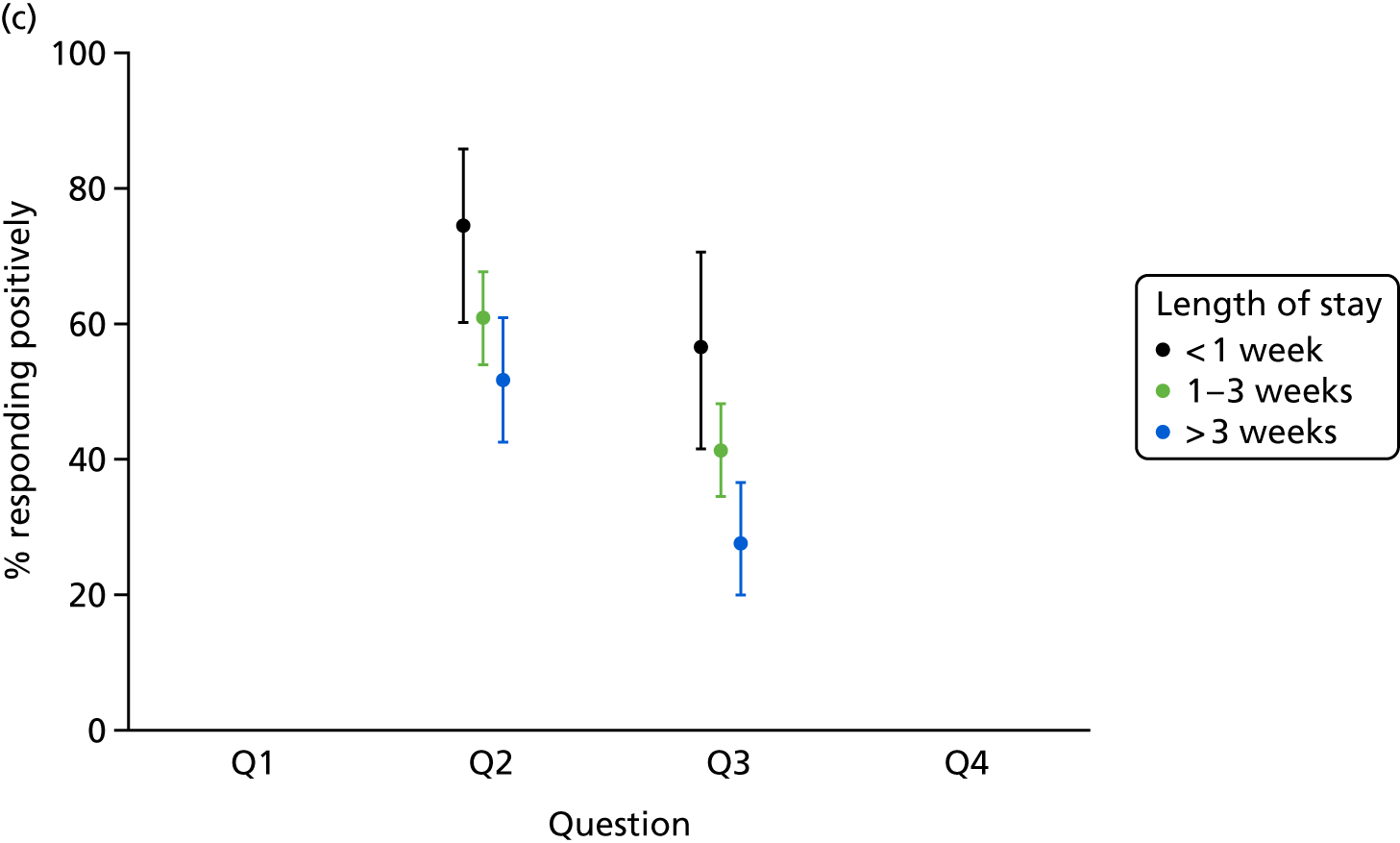

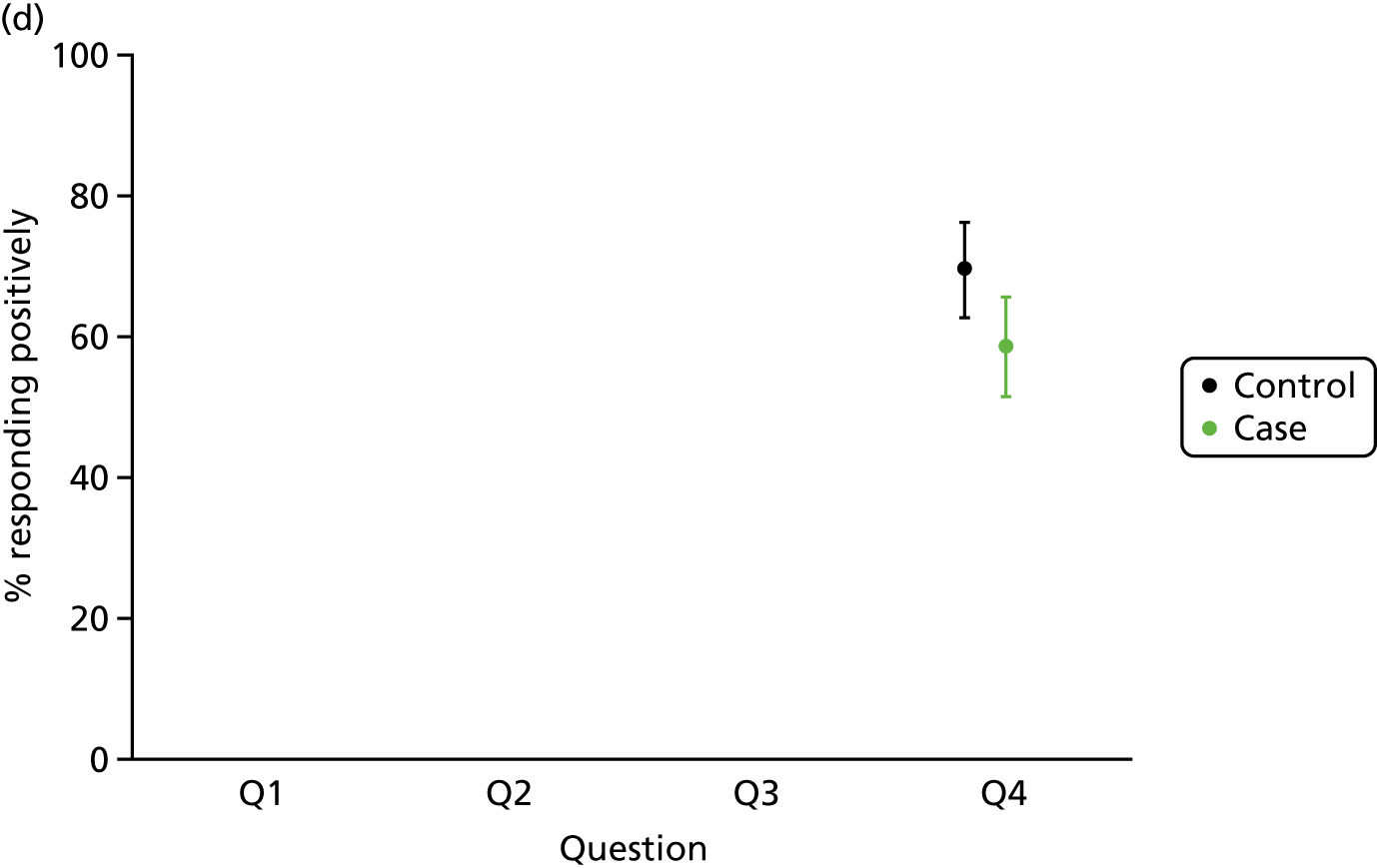

Finally, the panel discussed the initial results from the communication questions from the impact substudy (see Chapter 8). The panel thought that the results were very interesting and although they considered measuring communication routinely within hospitals infeasible, they suggested that NHS England could be asked to consider including the six communication questions within their parent congenital survey that is run every few years and to report results back to each unit. The panel recommended that future funding should be sought to better understand the communication and interaction between families and clinical teams.

Summary, limitations and future steps

Neurodevelopmental outcomes

At each stage of selection, the morbidity that was ranked of greatest importance by the panel was neurological impairment. This came as little surprise to the study investigators and vindicates the inclusion in our overarching programme of research of a parallel evaluation of the BDA, which it is hoped will provide a tool that can be deployed by nursing staff to identify patients who would benefit from referral to specialist neurological or other developmental services.

Differing priorities between health-care professionals and lay people

We found that opening up the process of choosing the metrics by which services should monitor their performance to include the perspectives of patients and family representatives, which is in line with policy initiatives in England,97 brought challenges. Throughout our work, there was a tension between choosing a ‘clean’ set of ‘clinical’ measures that most closely matched the understanding of ‘surgical morbidity’ among the tertiary clinicians on the panel, and the inclusion of arguably murkier phenomena considered hugely important by families and those working in secondary care. It is fair to say that inclusion on the panel of family representatives and clinicians from outside the tertiary surgical centres brought other issues, such as problems feeding and poor communication between clinical teams and families, to greater prominence than if the panel had consisted solely of tertiary clinicians, or if the study investigators had chosen the morbidities themselves.

Attribution of cause

In particular, those working in surgical centres were more concerned than family representatives and others with the attribution of morbidity to the surgical act, keen to include morbidities that may be related in part to surgical technique (laryngeal nerve palsy and phrenic nerve injury) and degree of success (low cardiac output), and were anxious to avoid the attribution to surgical teams of morbidities that are currently considered to ‘come with the territory’ of CHD and its surgical treatment. Family representatives and others highlighted the value of gathering information on the incidence and impact of key morbidities, even if they were not caused by surgery, not least as some of them may be reducible through interventions at other points in the care pathway.

Benefits and limitations of the methodology we used

We consider that the features of our study design were vital in terms of drawing out and balancing the differing perspectives. The nominal group technique, starting as it does with an opportunity for each panellist to speak without interruption and within an embedded democratic process, is specifically designed to minimise the influence of perceived power differentials and dominant personalities within a group. This was reinforced by the use of a secret ballot process to determine group preferences, allowing panellists to record their disagreement with the positions stated by others without that being openly declared. The voting tool used distinguishes between unambiguous group preferences and those that rely on tie-breaking. This acceptance and presentation of lack of consensus helped to focus discussion on where it would be most valuable to the task of selecting a group of morbidities and divert unnecessary debate focused on achieving a false consensus through attrition. Nonetheless, we recognise that the final selection of morbidities inevitably reflects the composition of the panel. In choosing panel members we wanted to keep the numbers down to a manageable number for an in-person group; we took the view that a group of > 14–18 participants would be too many for a constructive discussion to be feasible. Moreover, we also wanted a balance between project partners and independent panel members from non-study sites. We were disappointed that despite our best efforts we were unable to recruit a GP to the panel.

In addition, our choice to separate the process of identifying which morbidities are most important from the process of assessing the feasibility of defining and monitoring morbidities prevented all parties from self-censoring and clinical panellists from unconsciously using or claiming privileged knowledge of measurement processes to strengthen the case for morbidities that they wanted to include.

Firm and expert chairing was essential to maintaining this discipline. Having a chairperson conversant with the clinical area but also experienced in working with multistakeholder groups, including patient and family representatives, was also key. Although it meant that the chairperson brought their own clinical perspective to the table, the panel benefited from the chairperson’s ability to distinguish between the wheat and chaff of clinical discussions and summarise for non-clinical participants. It is also questionable whether or not a chairperson that was not an accomplished surgeon and clinical researcher would have held the respect of all parties through the process.

Separating the processes of judging the importance and the feasibility of routinely monitoring morbidities did, however, risk some of the subtlety of discussions slipping through the gaps between two panels of people. Although the preparation of detailed summaries of panel meetings and the presence of the same facilitating team (CP and MU) at all meetings reduced this risk, we acknowledge that the defined morbidities that will be monitored do not correspond exactly in all cases to the phenomena deemed important by the selection panel.

Chapter 5 Definition of important early morbidities after paediatric cardiac surgery