Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/52/52. The contractual start date was in February 2018. The final report began editorial review in September 2019 and was accepted for publication in March 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Gwernan-Jones et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

People living with dementia in the acute care setting

Demographic ageing is associated with increased rates of acute general hospital admissions among older people with multiple comorbidities and complex care needs. 1 The estimated 850,000 people living with dementia in the UK are over-represented in this inpatient population: around 40% of patients over the age of 70 years who are admitted to hospital have dementia, and only half of these have a prior diagnosis. 2 Those admitted to hospital with dementia experience more complications and adverse outcomes, including longer length of stay, greater mortality rates and increased risk of institutionalisation post discharge, than those without dementia. 3,4 An Alzheimer’s Society report5 based on Freedom of Information request responses from 73 trusts showed that in 2015 the average length of stay in an acute hospital for someone aged > 65 years was 5.5 days, whereas for people living with dementia it was twice as long, at 11.8 days. Longer length of stay translates into additional costs to the NHS,6 with health-care costs (including hospital costs) summing to £1.2B per year. 7 Although 20% of hospital admissions of people living with dementia are potentially preventable,8 some unplanned admissions are unavoidable, and it is important that hospital care supports the needs of those affected by dementia.

The importance of the care of people living with dementia in hospitals has been reflected in recent government policy and initiatives around the UK. 9–15 These include aspirations and commitments to transform hospitals into dementia-friendly health-care settings, to welcome and support family and friends (i.e. informal carers) of people living with dementia on wards, and to promote workforce education and training to meet the needs of people living with dementia using a person-centred care (PCC) approach. Hospitals are fast-paced environments striving towards fast and effective responses, assessment, diagnosis, intervention and discharge. Services operate on the assumption that patients will be able to express their wishes, acknowledge the needs of other patients and move through the system as required. However, for people living with dementia, particularly when they are ill or have had an accident, hospital settings, with all their noise, changing staff and unfamiliar surroundings, can be overwhelming and confusing, which can further impact their well-being and the ability to optimise their care. Furthermore, what happens in hospitals can have a profound and permanent effect on individuals and their families in terms of not only their inpatient experience, but also their ongoing health and the decisions that are made about their future. 16,17 In 2011, the Royal College of Nursing published five principles for improving dementia care in hospital settings: staff, partnership, assessment, individualised care and environments (SPACE). 18,19 The Royal College of Nursing SPACE principles have helped promote a key objective of the national dementia strategy, namely to improve hospital care for people living with dementia. 20 Although these principles have been detailed and set out as a resource for those involved in care, providing effective acute care services to people living with dementia remains an ongoing challenge,21,22 and there is uncertainty about the best way to do this.

There are many potential interventions or approaches that could be important in improving the experience of being in hospital for people living with dementia. For example, enhanced training and integration of specialist mental health staff has been shown to improve best practice and carer experience in the acute hospital setting. 23 Similarly, the introduction of a dementia activities co-ordinator in an acute hospital ward has been shown to improve the experience for both people living with dementia and their families. 24 There are also initiatives that have received widespread attention, such as the Alzheimer’s Society’s ‘This is Me’ tool (a simple leaflet that can help health-care professionals build a better understanding of a person living with dementia when they move to a new care setting), John’s Campaign (a campaign to give carers the right to stay with people living with dementia in hospital) and the National Dementia Action Alliance’s charter (a document outlining the principles of what a dementia-friendly hospital should look like and the recommended actions that hospitals can take to fulfil these),25 which has been widely adopted by acute hospitals across the UK.

Patient experience is one of the three pillars of quality of care and should be given the same emphasis as clinical effectiveness and safety. 26 Improving the experience of care for people in the hospital setting with dementia is among the top priorities in dementia research for the Alzheimer’s Society and the recent James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership with the Alzheimer’s Society. 27 Discussions with carers and local health-care providers during meetings in preparation for this project also highlighted that this issue was a priority. Examining experience of care may benefit current hospital care practice, resulting in better care for those with dementia and support for those involved in their care, as well as highlighting areas in which we have limited understanding of how to achieve best practice. The incorporation of experience of care may provide a more holistic perspective that is not automatically available when measuring discrete clinical effectiveness or patient safety outcomes. To improve the experience of hospital care, it is necessary to (1) understand the issues faced by people living with dementia, their carers and those who provide care in this complex setting; (2) identify effective best practices in this area; and (3) establish the critical factors that promote or hinder best practice.

Defining experience of care

For the purposes of this report we have defined ‘experience of care’ as ‘the extent to which a person perceives that the needs arising from the physical and emotional aspects of being ill are met’. The NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement28 refers to patient experience as what the process of receiving care feels like for the patient, their family and carers. Experience is one of the key elements of quality of care: if clinical excellence (or effectiveness) and safe care are the what of health care, then experience is the how. We took both views of experience of care into account.

Aim and research questions

Although there is evidence from numerous qualitative and quantitative reviews around experience of care and effectiveness of potentially relevant interventions, some of the reviews do not focus solely on the hospital setting,29,30 and others do not use robust systematic methods. 31,32 Importantly, to our knowledge, no review to date has sought to address our specific research questions33–36 combining both qualitative and quantitative evidence on experience of care from the perspectives of all of those affected by dementia: people living with dementia, carers and hospital staff.

Our aims were to (1) explore the experience of care for people living with dementia in hospital from the perspectives of those giving and receiving care, namely people living with dementia, carers and hospital staff; and (2) evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions to improve the experience of care in the hospital setting for these groups. The reviews address the following research questions.

Review 1

-

What is the experience of people living with dementia and their carers of receiving care in a hospital setting?

-

What is the experience of hospital staff of caring for people living with dementia?

Review 2

-

Which factors are important in the successful delivery of approaches to improve the experience of care?

Review 3

-

What evidence is available to inform on the most effective and cost-effective ways to improve the experience of care for people living with dementia in hospital?

-

What is the impact of such interventions on the health and well-being of hospital staff and the (family and informal) carers of those with dementia?

In consultation with stakeholders both internal and external to the project, we aimed to use the evidence to identify and co-develop areas of practice or process that could help improve the experience of care for people living with dementia in hospital. We have developed these into the DEMENTIA CARE ‘pointers for service for change’.

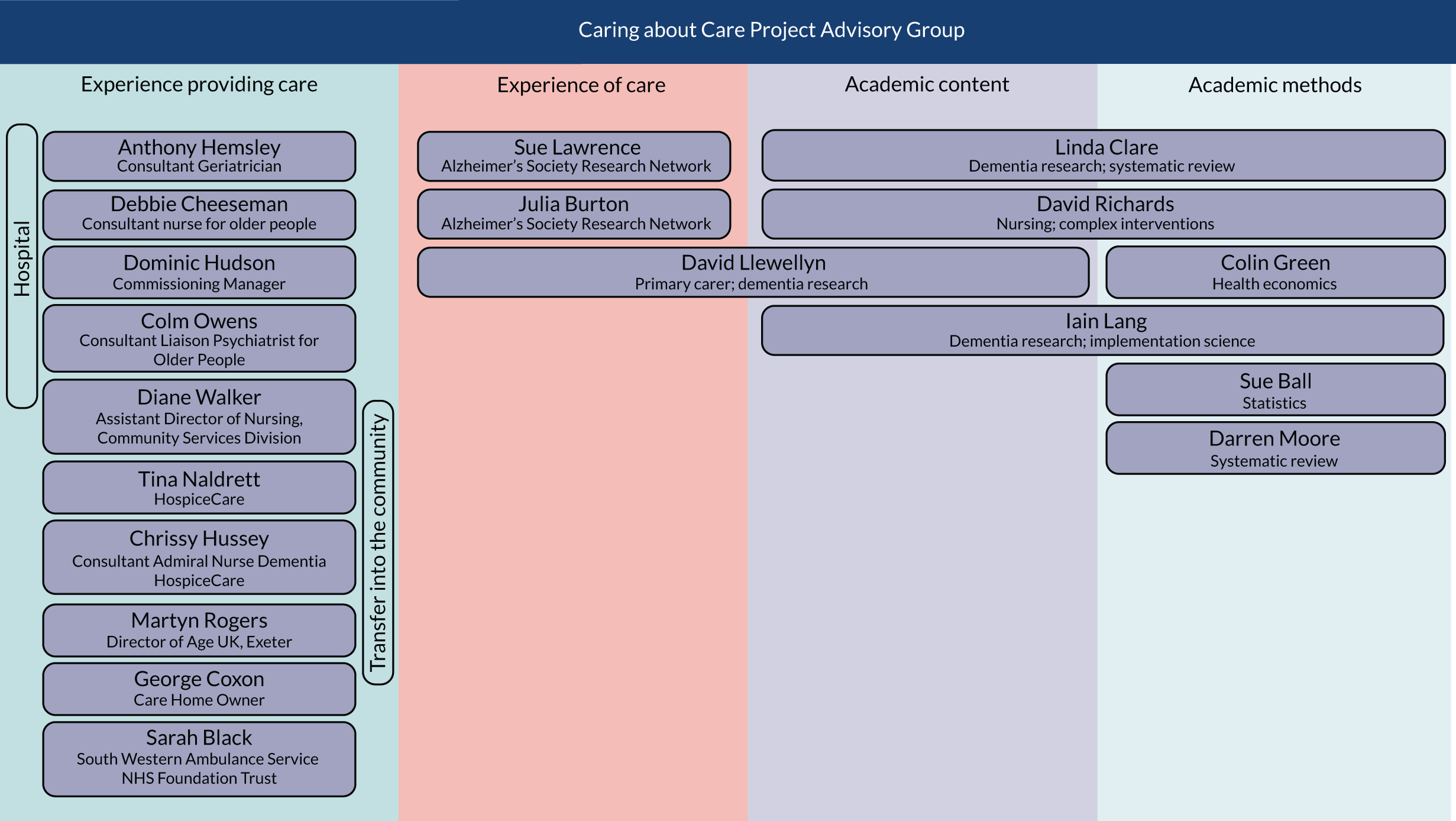

Project Advisory Group and stakeholder involvement

We held four whole-team meetings during the course of the project, each attended by between 12 and 17 individuals. All members of the co-applicant team, the core research team and all members of the Project Advisory Group (PAG) were invited to all meetings. The aim of these meetings was to ensure that our findings were relevant to the people who would eventually use them to make a difference to the experience of care for people living with dementia in hospital, namely staff and family carers. The PAG had input at all stages of the review process. The key discussions, activities and impact of this stakeholder involvement at the different stages of the reviews, from planning through to development of the pointers for service change, are described in the relevant chapters. The members of the PAG and a full list of the dates, event, attendees, activities and impact are provided in Appendix 1, Figure 10 and Table 3. Towards the end of the project, we took our findings to three key meetings (the National Dementia Action Alliance Task Force, the South West Mental Health Clinical Network’s Dementia Improvement Group and the Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust ‘Care Matters’ meeting) to share these and to discuss the context and implications. We also shared our findings and gathered feedback while presenting at the British Geriatrics Society, the Health Services Research UK conference, the Alzheimer’s Association Annual Meeting and the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Report structure

The structure of the report is as follows. Chapter 2 describes the methods of and findings from reviews 1 and 2 synthesising the perceptions and experience of people living with dementia and their carers of receiving care in hospital, the hospital staff members’ experience of giving that care, and the factors affecting experience of care at both the personal and the institutional level. Chapter 3 describes the methods and findings from review 3, synthesising the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions to improve experience of care for people living with dementia while in hospital, and the impact of those interventions on the well-being of their carers and hospital staff. Chapter 4 brings together the evidence from reviews 1, 2 and 3 in an overarching synthesis. It also describes the presentation and dissemination of findings with internal and external stakeholders, and the co-development of the DEMENTIA CARE pointers for service change. Chapter 5 provides a brief summary of the findings of each review and the overarching synthesis, outlines the strengths and limitations of the reviews, and presents implications for research, policy and practice.

Chapter 2 The experience of care and factors that may enhance or hinder the experience of care in hospital for people living with dementia

Research questions

In this chapter we will be drawing from qualitative data exploring the experiences of care in hospital for people living with dementia and their carers, and the hospital staff who care for them (review 1), and how participants perceived that interventions improved the experiences of care in hospital (review 2). Some processes of synthesis between the two reviews were independent, but many were linked (see Chapter 4, Methods for the overarching synthesis). Because of congruence between the findings of the included studies in reviews 1 and 2, we have chosen to report the two reviews together to reduce repetition and to optimise the potential for explanation available as a result of the links between the two reviews. The research questions for review 1 are:

-

What is the experience of people living with dementia and their carers of receiving care in hospital?

-

What is the experience of hospital staff caring for people living with dementia?

The research question for review 2 is:

-

Which factors are important in the successful delivery of approaches to improve the experience of care?

Methods

Search strategy

Two database searches covering quantitative and qualitative studies were designed by our information specialist (MR). The search strategies combined terms for dementia with terms for hospital settings, terms for interventions, and either terms for study type (quantitative search) or terms for experience (qualitative search). The qualitative search strategy was run on 4 March 2018 using MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Social Policy and Practice and Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) (via OvidSp), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (via EBSCOhost), British Nursing Index and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) (via ProQuest), Social Science Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Citation Index (via Web of Science) and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. The quantitative search strategy was run on 9 May 2018 using MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, HMIC and Social Policy and Practice (via OvidSp), CINAHL (via EBSCOhost), British Nursing Index (via ProQuest), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (via the Cochrane Library), NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database (via the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination database), Social Science Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Citation Index (via Web of Science) and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. No date restrictions were used for any of the searches. The MEDLINE search strategy (see Appendix 2) was adapted for all other search strategies (see Report Supplementary Material 1). The citation lists of included references were checked, and forwards citation chasing was carried out using Web of Science and Scopus.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria for qualitative studies

Articles were included or excluded according to the following criteria.

-

Population: studies of older adults with dementia, their carers or professionals delivering care. Studies that focused on older adults with delirium or acute confusion were excluded. Studies that focused on older adults with cognitive impairment or chronic confusion were included.

-

Setting: studies focused on hospital settings, which encompassed inpatients/outpatients in a hospital, hospital day centres and rehabilitation wards. Non-hospital day-care centres were excluded. Interventions that supported carers to care for people living with dementia outside hospital were excluded. Studies conducted outside OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries were excluded because societies and medical systems fundamentally different from that of the UK were likely to have an impact on applicability in important ways.

-

Outcomes/aims: studies focused on the experience of care or improving the experience of care. Studies that explored clinical aspects of dementia (e.g. prevalence, assessment or diagnosis) were excluded.

-

Design: primary studies collecting qualitative data (e.g. by conducting interviews, focus groups and observation using field notes) that were analysed qualitatively. Open questions on surveys or questionnaires were excluded.

-

Language: only studies written in English were included.

Study selection

The titles and abstracts of records returned in the search for qualitative studies were screened by two reviewers independently (three reviewers conducted this screening: RGJ, HJ and RA). The records and reviewer decisions were organised in EndNote software version X8 (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA). Two reviewers resolved disagreements, referring to a third reviewer when needed (RGJ, HJ, RA). The records whose titles and abstracts met the inclusion criteria were obtained at full text through the University of Exeter library, through general web searching or from The British Library. Full texts were screened by two reviewers independently (RGJ and RA) according to the inclusion criteria, and reasons for exclusion were documented (see Report Supplementary Material 2). Two reviewers resolved disagreements, referring to a third reviewer when needed (RGJ, RA, JTC).

Methods of analysis/synthesis

The methods of data extraction, quality appraisal, data analysis and synthesis were the same for both reviews, except where specified.

Data extraction

We developed and piloted a data extraction template in Microsoft Word 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Two reviewers (RGJ and RA) independently extracted data for three included studies and then compared and discussed the data extracted, refining the template in response. The data extracted for review 1 included study details and setting, population characteristics, methods, reviewer evaluation of the study and findings (thematic structure). The same data extraction template was used for review 2, with additional information extracted about the intervention studied. Following our second whole-team meeting in September 2019, two additional items were extracted in response to stakeholder feedback: reason for hospital admission and dementia status (e.g. diagnosis, suspected dementia, reported confusion, cognitive impairment, Mini Mental State Examination score). Finally, the portable document format (PDF) files of included papers were uploaded into NVivo, version 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK), so that the findings could be extracted.

Quality appraisal

We conducted quality appraisal in parallel with data extraction using an adapted form of the Wallace checklist. 37 The purpose of the checklist was to draw reviewers’ attention to a range of study aspects to consistently familiarise the reviewers with the methodological content of each study. Fourteen questions probed the reporting of research questions, explicitness and impact of the theoretical/ideological stance, study design, description of context, sample, data collection/robustness, analysis, relationship between data and findings, limitations, claims to generalisability, ethics and reflexivity. Each question was answered ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘can’t tell’ (see Appendix 3). Two reviewers (RGJ and RA) conducted quality appraisal independently. Disagreements were discussed, with a third reviewer (JTC) consulted when necessary.

Prioritisation of papers in review 1 (experience of care)

Because of the unexpectedly large number of papers that met the inclusion criteria for review 1, prioritisation of papers was conducted. Inclusion of too many studies in evidence synthesis of qualitative studies can make sufficient familiarity difficult to achieve38 and can prevent anything more than surface analysis. 39

Data extraction and quality appraisal was conducted for all included papers, and during these processes two reviewers independently evaluated the usefulness of each included paper according to three criteria: (1) richness of text, (2) methodological quality and (3) conceptual contribution. These judgments aimed to evaluate the ability of each paper to contribute to the review, prioritising papers that were (1) best contextually situated to support synthesis, (2) most methodologically robust and (3) most able to provide the conceptual themes necessary to conduct meta-ethnography. Criteria 1 and 3 were evaluated in relation to the aims of the review.

Richness of text was scored along a four-point continuum of ‘poor’, ‘some’, ‘good’ or ‘very good’. The criterion for scoring followed Geertz’s concept of thick description,40 and involved judgement of the extent to which participants and researchers provided background information necessary to understand and interpret experience. Methodological quality was assigned according to the number of ‘yes’ responses during quality appraisal, with a good paper scoring ≥ 10 ‘yes’ responses. Conceptual contribution was scored along a four-point continuum of ‘poor’, ‘some’, ‘good’ or ‘very good’. The criterion for scoring involved judgement of the extent to which the study authors drew from or developed concepts relevant to the questions of the review through use of existing theory, development of theory and/or conceptual models.

Papers that were judged to be ‘good’ and/or ‘very good’ in all three categories were prioritised. Medium-priority papers were those evaluated as ‘good’ or ‘very good’ in two of the three categories. Papers judged to be least likely to contribute to the review were those evaluated as ‘good’ or ‘very good’ in none or one of the three categories. Following prioritisation, we compared prioritised and medium-priority papers to establish how well they were able to represent the full body of papers.

Categorisation of interventions for review 2

Interventions were categorised to identify similarities between interventions to support reporting and synthesis. Categorisation involved an iterative process that developed over the initial months of the study through discussion between reviewers (RGJ and IL). The reviewers independently categorised interventions according to focus and content for their own reviews, and then met to establish the consistency of categories across the reviews. Both had found that some of the interventions were complex and that identification of categories was not straightforward. To clarify the similarities and differences between interventions, reviewers independently created a table identifying the intervention components of each study. They then met and agreed a set of intervention categories that was able to represent interventions across the two reviews.

Data analysis and synthesis for reviews 1 and 2

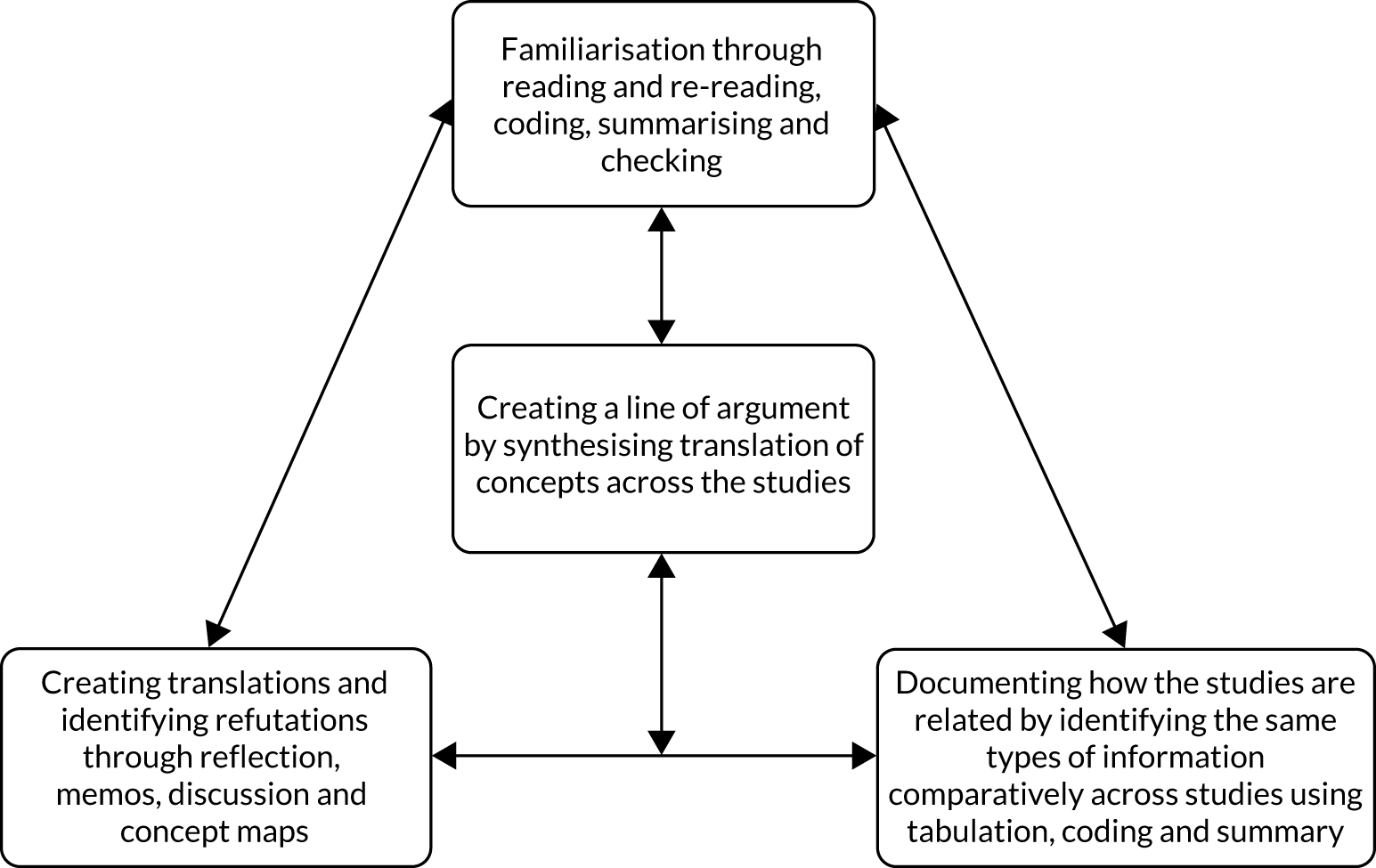

Data analysis and synthesis broadly followed the approach of meta-ethnography. 41 Meta-ethnography is a process of synthesising qualitative studies by analysing the ‘concepts, themes, organizers, and/or metaphors that the authors employ to explain what is taking place’. 41 Meta-ethnography involves activities that do not proceed linearly but are repeated across the review in tandem, during which time review concepts are developed and refined in an ongoing, iterative cycle (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Activities of meta-ethnography.

Reading and re-reading

Beginning at the full-text screening stage and continuing into the final stages of synthesis, two reviewers (RGJ and RA) read and re-read included papers during processes of familiarisation, coding, summarising and checking.

Identifying relationships between studies

During data extraction and the creation of tables summarising study characteristics, the same information about each study was documented in the same way, supporting the systematic identification of similarities and differences in study aims, location, design, interventions and findings. The initial process of coding also contributed to establishing relationships between studies.

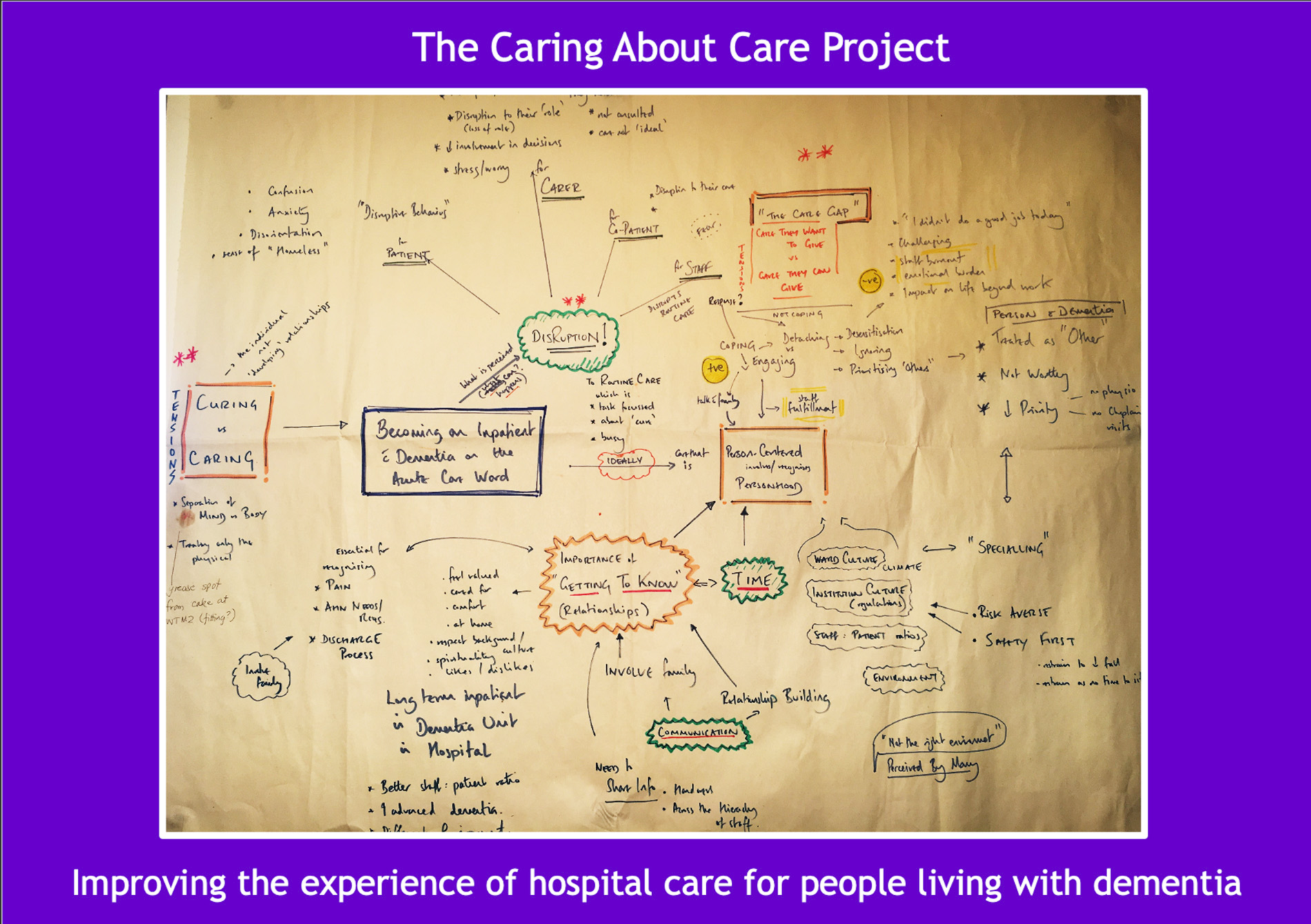

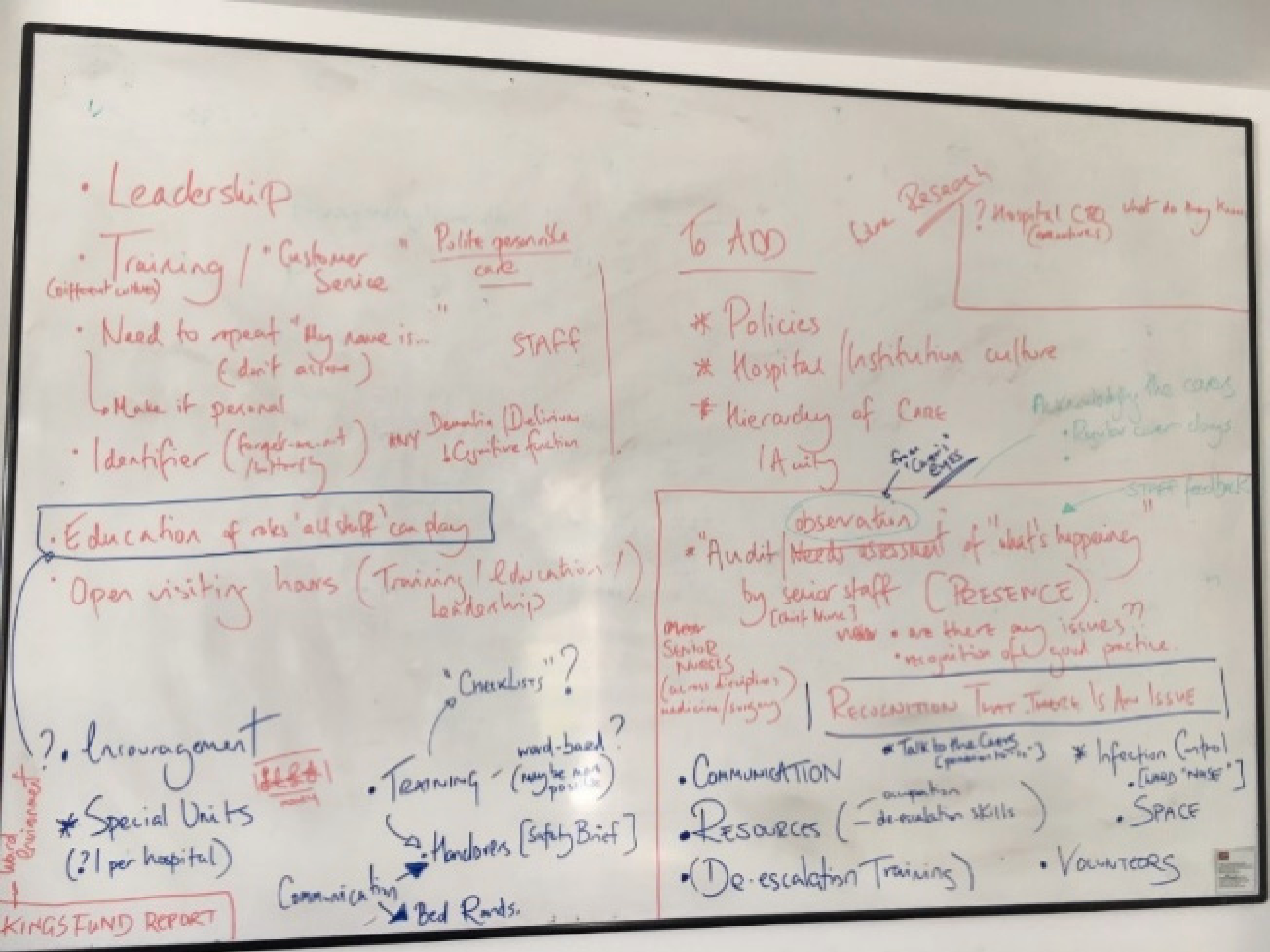

Creating translations and identifying refutations

Translation and refutation of study themes within each review occurred throughout the review process. Relationships between review 1 study themes, and how these linked to the interventions reported in reviews 2 and 3, were discussed regularly between core reviewers (RGJ, RA, IL, JTC, MR). Study concepts were discussed more broadly with the PAG at the four whole-team meetings (February 2018, September 2018, May 2019 and July 2019) and at consultation meetings (see Stakeholder involvement in reviews 1 and 2).

Coding and concept development

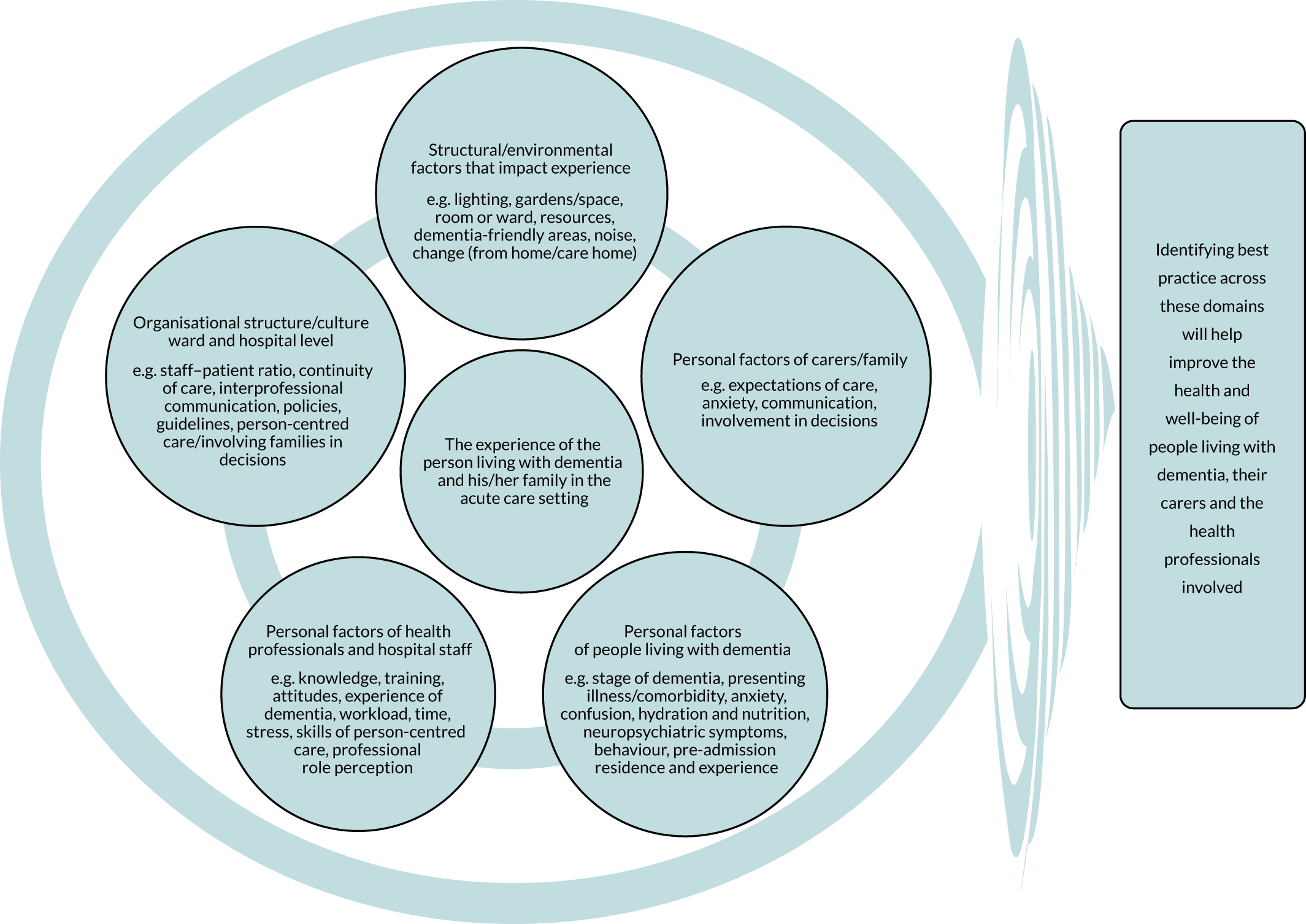

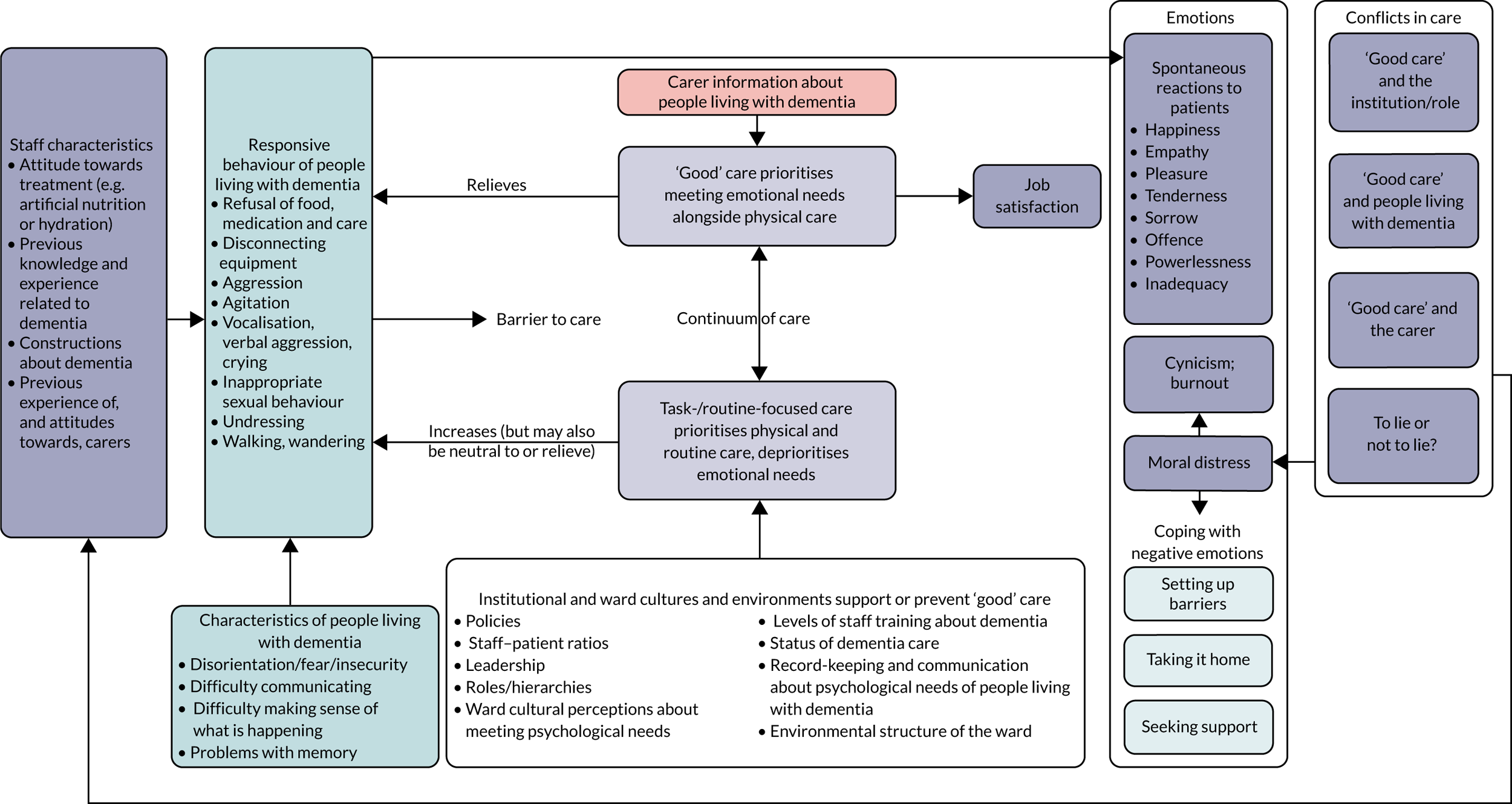

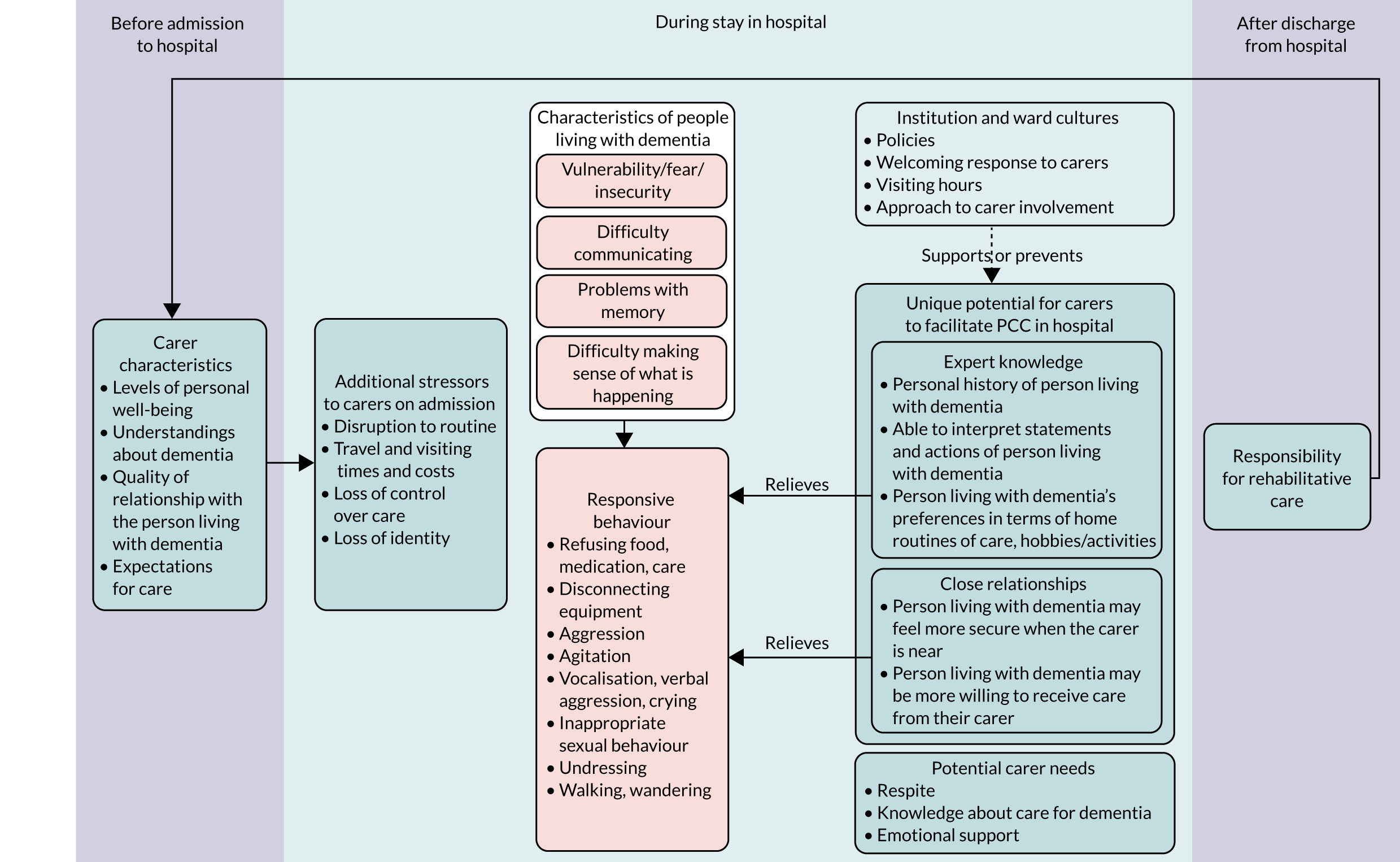

During data extraction, one reviewer (BA) extracted themes for each study using Microsoft Word, and one reviewer (RGJ) uploaded a PDF file of each study into NVivo software. Where searchable PDF files were not available,42–48 the findings and discussion were typed into a Microsoft Word document and these were uploaded into NVivo. Findings and discussion sections were coded deductively according to a preliminary conceptual framework developed before the start of the review to support our application for funding (Figure 2). The model was put together from a scoping of the literature and drew on previous published models and frameworks of dementia care. 49–52 Coding was undertaken inductively where findings were not represented by this initial conceptual framework. Each code was organised using ‘participant/researcher subcodes’ that identified whose perspective the coded text represented (e.g. staff, people living with dementia, carer, researchers). Memos were kept about references made in papers to existing theory, interpretations of how papers linked with or refuted each other, and emerging categories/themes.

FIGURE 2.

Preliminary conceptual framework describing the nature and complexity of possible factors that may influence the experience of hospital care for someone with dementia.

Following coding, it was decided that the findings differed in significant ways by participant type and they were, therefore, synthesised separately. Noblit and Hare41 suggest using a pre-existing framework for conceptual development, for example by adopting the thematic structure from a key paper to guide the synthesis. However, we adopted the approach proposed by Spicer,53 who posits the development of concepts through an inductive process of interpretation across studies. RGJ, in consultation with RA, conducted translation of studies by further regrouping and refining concepts from the coded text by perspective [people living with dementia: subreview A (see Subreview A: findings from reviews 1 and 2 about the experience of care for people living with dementia in hospital – feeling afraid and insecure), staff: subreview B (see Subreview B: findings from reviews 1 and 2 about the experience of care for people living with dementia in hospital – feeling prevented from being able to give ‘good’ care); carers: subreview C (see Subreview C: findings from reviews 1 and 2 about the experience of carers of people living with dementia in hospital – feeling stressed and desiring inclusion)] to create subreview conceptual maps. These conceptual frameworks were then used to organise how the findings were communicated for both reviews 1 and 2.

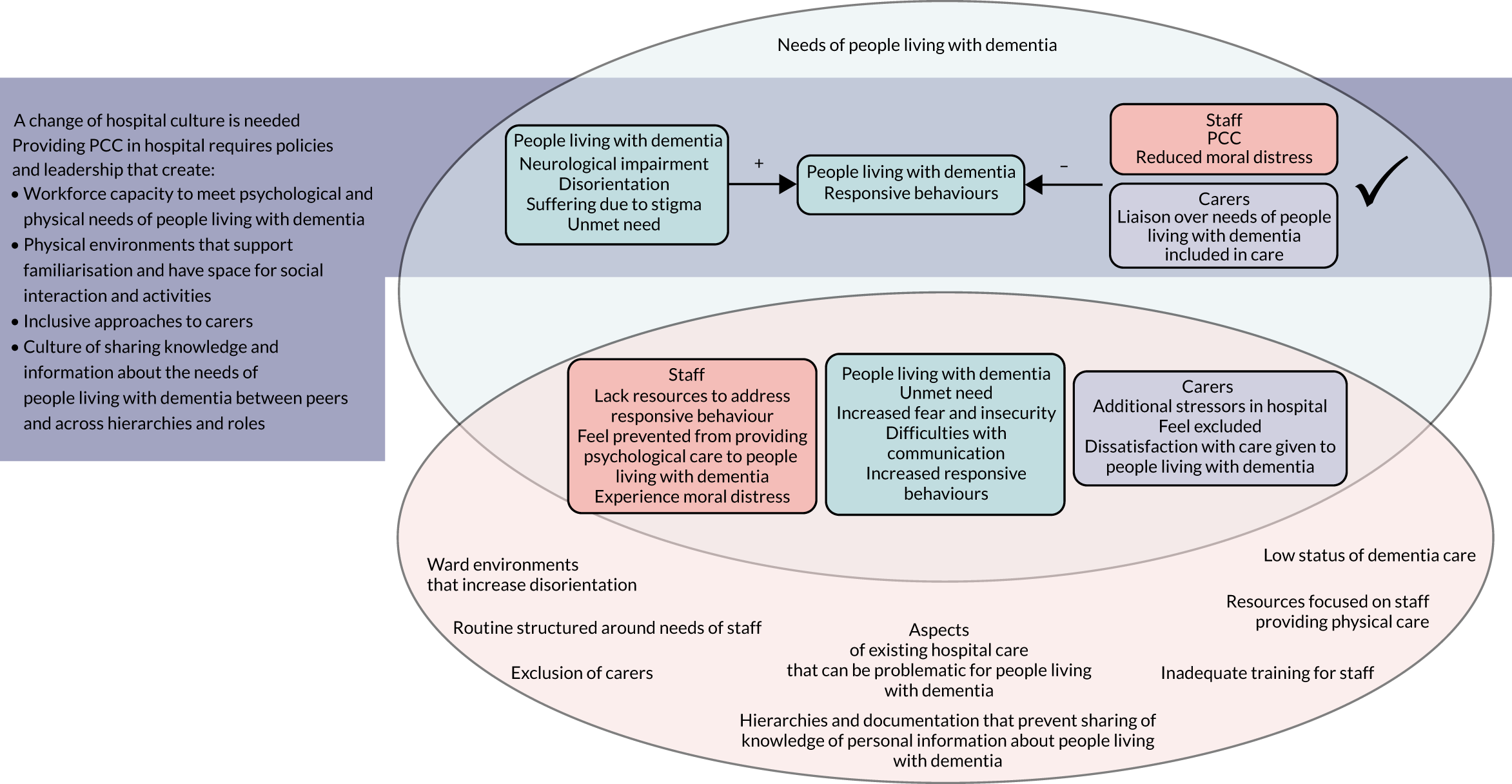

‘Line of argument’: synthesising translations/refutations

Noblit and Hare41 suggest that it is possible to make inferences based on the concepts translated from multiple studies to create a structure that represents the concepts as a whole. To do this, translations and refutations are synthesised to provide an overall narrative linking the issues identified across studies. To create a line of argument (LoA) in this review, RGJ and RA considered the relationships and overlap between the models representing the perspectives of people living with dementia, carers and hospital staff, and the findings around institutional-level factors. To further support theory development, the three subreview concept maps were printed out and cut up, asking of each separate issue ‘what is really going on here?’, with the answer written on the back. These slips of paper were grouped and named according to the answers and then arranged according to the relationships between them. This more concrete task supported us to think through concepts and identify relationships we had been considering for some time, and resulted in a concept map depicting the findings across subreviews [see Line of argument: synthesis of findings from review 1 (experience of care) – a change of hospital cultures is needed before person centred-care can become routine].

Reflexivity

Reflexivity in health research involves bringing to awareness how a researcher’s previous experiences may impact processes of interpretation54 and, in relation to reviews, making reviewer reasoning processes explicit. 55 The lead reviewer for reviews 1 and 2 (RGJ) has a background in research in education and health-care services, exploring perceptions and models of disability and how these relate to personal experience. She does not have experience as a health-care practitioner, which might have limited the extent to which she was able to understand the experiences of these practitioners. She has had close relationships with people who have experienced problems with mental health, including dementia. These experiences support her ability to understand what it is like to care for a person living with dementia, but her experiences may have also acted as a source of bias. The iterative nature of the concept development process, involving the full core reviewer team plus interaction with our PAG, supported minimisation of such bias.

Findings

Study selection

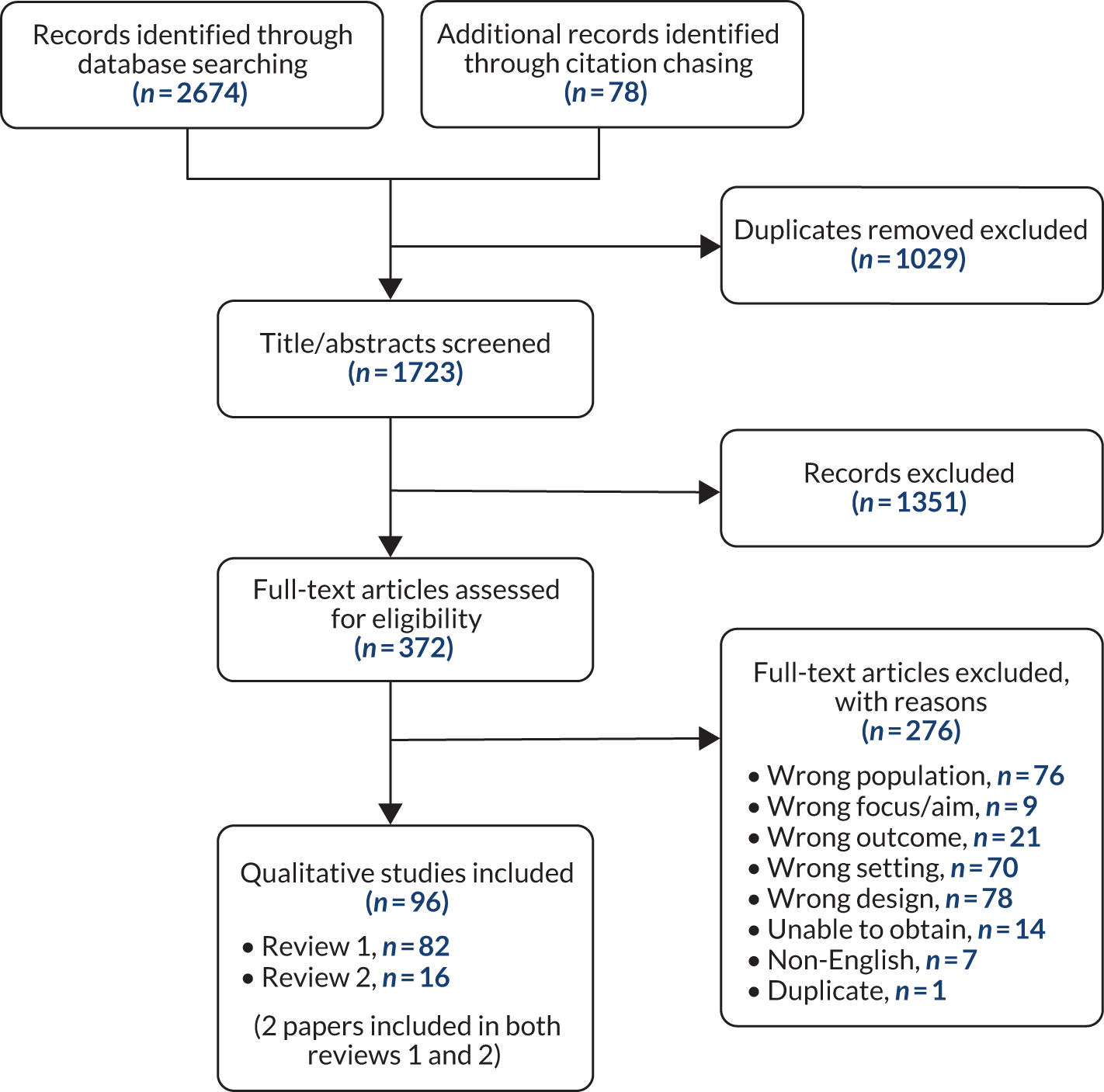

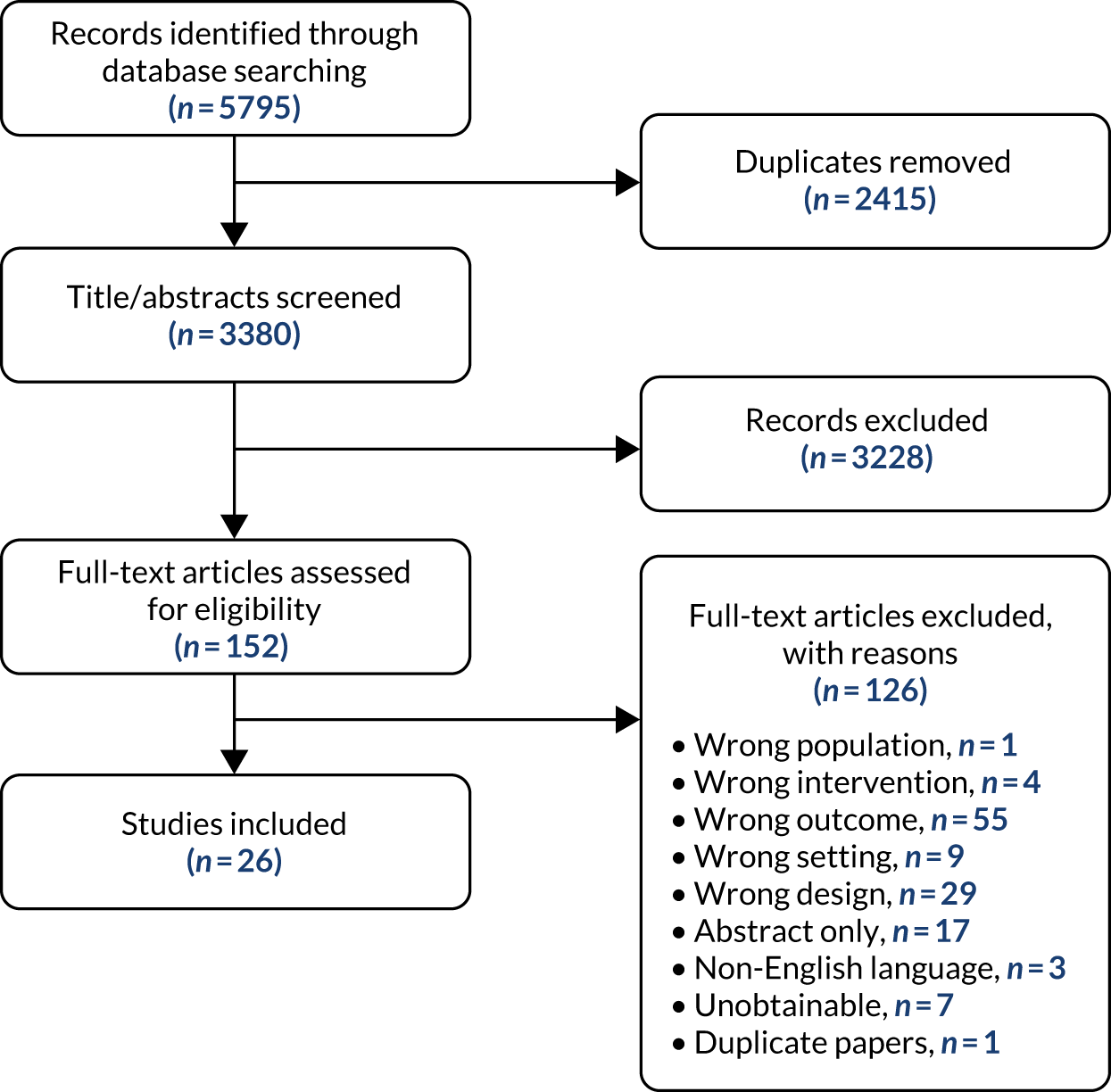

Appendix 4, Figure 11, provides the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram showing the process of study selection. Database searches returned 2674 records, with a further 78 records found during forward and backward citation chasing. After removing 1029 duplicates, the titles and abstracts of 1723 records were screened according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and after excluding 1351 records, the remaining 372 were sought at full text for further screening. Reasons for exclusion of papers at full text are given in Report Supplementary Material 2. Of the total 96 papers included at full text, 82 were included in review 142–47,56–132 and 16 were included in review 2. 23,48,87,116,133–144 Two papers87,116 were included in both reviews 1 and 2.

In review 1, 63 studies were reported in 82 papers. Fourteen studies were represented by more than one paper: nine studies were reported in two papers each;43,58,59,62,75,76,79,82,89,90,92,95,98,99,102,109–111,113,129 three studies were reported in three papers each;60,65,66,72–74,84,125 and one study was represented in five papers. 69–71,96,114 In review 2, 14 studies were reported in 16 papers: one study was reported in three papers. 23,87,142 To signify the singular nature of these studies, although we included all the papers in the syntheses, the journal article first published from each study will be cited when reporting number of studies with a particular finding;43,58,60,62,66,69,73,76,79,82,90,92,99,110 when quoting an extract or reporting specific findings, the paper of origin will be cited.

Study characteristics

Review 1 (experience of care)

Appendix 5, Table 4, summarises the characteristics of the studies included in review 1. Studies were conducted in 15 countries; 2842,44,45,56–58,63,64,69,73,76,79,82,87,88,90,99,106,110,116–122,131,132 (44%) studies were conducted in the UK, 1246,60–62,78,93,97,104,105,126–128 (19%) studies were conducted in Australia, and seven80,81,83,100,107,108,123 (11%) studies were conducted in Sweden. All included papers were published in peer-reviewed journals, except six dissertations47,63,75,89,98,117 at PhD level. Three studies45,46,123 were published before 2000, and 6444,47,56–61,63–66,68–71,73–79,81,82,84,85,87,88,90–94,96–105,107,108,112–122,124–132 (almost 80%) were published from 2010 onwards.

Twenty-four studies43,56–58,62–64,66,67,76,83,85,88,90,97,100,101,104,108,112,116,120,123,128 (38%) reported the experiences of hospital staff, students and/or volunteers only; 14 studies42,44–47,60,61,77,86,93,105,117,124,130 (22%) reported the experiences of carers only; and two studies78,80 reported the experiences of people living with dementia only. Twenty-two studies68,69,73,79,81,82,87,91,92,94,99,106,107,110,115,118,119,121,122,126,127,132 (35%) reported the experiences of mixed types of participants. Together, studies reported the experiences of 293 people living with dementia, 524 carers and 1135 hospital staff (see Appendix 6, Table 5, for a breakdown of roles) for a total of 1952 participants.

Studies were conducted in a range of hospital settings, including general acute wards (accident and emergency, acute longer stay, subacute and acute wards) in 29 studies;44–46,56–58,60–62,90,93,117,118,132 older persons’ wards (geriatric, dementia, psychogeriatric, geriatric rehabilitation, geriatric acute, geriatric subacute, geriatric long stay) in 24 studies;43,65,68,69,73,76,78–82,87,88,98,101,106,115,116,121–123,126,127,131 general rehabilitation wards in four studies;79,82,130,131 general wards in two studies;47,120 admission in one study;111 palliative care ward in one study;65 respite care ward in one study;86 and ambulances in one study. 64 Nine studies were conducted on more than one type of ward47,65,69,79,82,87,88,110,131 and 13 studies did not specify the type of ward. 44–46,56–58,60–62,90,93,117,118

Qualitative data were collected most often using semistructured interviews, with 53 studies42–47,56,57,60–63,65,67–69,73,76–80,82,83,85,86,88,90–93,98,100,104,105,107,108,110,115–120,122–124,126–128,130–132 drawing on this approach. Seventeen studies68,69,73,79,81,82,87,91,94,98,106,107,110,121,122,127,132 made use of observation; nine studies58,64,82,97,101,110,112,118,122 held focus groups; and two studies98,108 conducted document analysis. Thirteen studies combined methods, using a combination of interviews and observation;68,69,73,79,91,127,132 interviews, observation and focus groups;82,110,122 interviews, observation and document analysis;98,108 and interviews and focus groups. 118

The focus of included papers related to different aspects of the experience of care. The aim of some papers was to explore the experience of care more generally,71–74,87,110,111,114,115,117 whereas other papers focused on aspects of the experience of care for specific participant types such as porters and cleaners,57 health-care assistants,122 student nurses/paramedics, 58,59,64,131 nurses and/or health-care professionals generally,43,62,63,65–67,75,76,83,85,88–90,95,97,100,101,104,108,109,112,116,120,123,125,128 carers42,44–47,61,69,70,77,86,93,96,98,99,105,124 and people living with dementia. 78,80,91,106,127 Finally, the aims of some papers involved a focus on particular topics such as admission,93 communication,75,76,91,100,121,125 end of life,56,65,66,119,125 discharge,60,82,84,97,103,113 PCC,68,70,107 ward environment/design,81,91,126 medication/managing pain,79,94,102 responsive behaviour,89,90,132 specific types of ward,86,92,129,130 delirium superimposed on dementia,47,118,130 the role of carers128 and the use of truth and deception. 120

Characteristics of prioritised papers and their relation to the remaining included papers in review 1

In review 1, we conducted a prioritisation process to manage the large number of included papers [see Prioritisation of papers in Review 1 (experience of care)]. We prioritised 21 studies66–68,79–82,86,87,94,96,99,104,107,108,110,118,120,122,123,127 reported in 29 papers65–71,79–82,86,87,94,96,99,102,104,107,108,110,111,113,114,118,120,122,123,125,127 as most able to meet the questions of review 1. Thirty-six papers43,46,47,57,60,61,63,64,73–76,78,83,84,88–91,95,97,98,100,103,106,109,112,115–117,119,121,126,128,131,132 were identified as medium priority, and 17 papers42,44,45,56,58,59,62,72,77,85,92,93,101,105,124,129,130 were identified as least able to provide answers to the review 1 research questions.

Following synthesis of the three subreviews, the contribution of prioritised studies was tabulated against the findings from medium-priority studies in relation to each subreview main theme and subcategories (see Appendix 7, Tables 6–8). During this comparison, it was found that the majority of medium-priority studies supported the structure and content of the subreviews. One study132 interpreted responsive behaviour as resistance, rather than unmet need as we have done in this synthesis. However, we considered these to be compatible interpretations. One study106 structured findings around psychoanalysis and infant theory. Although the conclusions of this work were interesting, because the methods were poorly reported, and the findings differed from those of the remaining studies, we did not incorporate these findings into review 1. It was determined unnecessary to compare prioritised papers with the studies judged as least likely to contribute to the review, as it has been found that such studies tend not to have an impact on syntheses because of their sparse or descriptive findings. 38

Review 2 (experience of interventions)

Appendix 8, Table 9, summarises the characteristics of the studies included in review 2. Studies were conducted in six countries. Nine out of 14 studies (64%) were conducted in the UK,23,48,116,133,134,138,139,141,143 two studies (14% each) were conducted in Canada135,140 and Australia136,144 and one study was conducted in Switzerland (7%). 137 All included papers were published in peer-reviewed journals. One paper was published before 2010,137 with the remaining 15 (94%) published after 2010. 23,48,87,116,133–136,138–144

Seven studies116,133,138–141,143 reported the experiences of hospital staff, students and/or volunteers only; and seven studies23,48,134–137,144 reported the experiences of mixed types of participants. Together, studies reported the experiences of 83 people living with dementia, 62 carers and 213 hospital staff (see Appendix 9, Table 10, for a breakdown of roles), a total of 358 participants.

Interventions were conducted in a range of hospital settings, including general acute wards (n = 3),138,140,141 dementia wards (n = 4),23,133,135,137 geriatric acute wards (n = 3),23,134,136 geriatric wards (n = 2)116,139 and a rehabilitation ward (n = 1). 144 One study involved supporting junior doctors to become dementia champions while they were completing a rotation on a geriatric ward, a role they continued in during subsequent ward rotations,143 and one study was conducted from an Alzheimer’s Society stand in the hospital foyer. 48

Qualitative data were collected most often using semistructured interviews, with 10 studies23,48,116,134–138,141,144 drawing on this approach. Seven studies133,136,138–140,143,144 held focus groups, and three studies23,134,137 made use of observation. Seven studies combined methods, including a combination of interviews and observation;23,134,137 interviews and focus groups;136,138,144 and interviews, observation and focus groups. 138

Intervention characteristics

Intervention characteristics are summarised in Report Supplementary Material 3 using the TIDieR checklist. 145 Most of the interventions involved a combination of components including institutional level support, therapeutic support to carers, information/education for carers, inclusive approach to carers, activities for people living with dementia, training off wards, training on wards, existing specialist knowledge utilised, documentation to improve individualised care, new approach adopted to guide caring for people living with dementia, specialist capacity added, non-specialist capacity added, and structural changes to ward environments (see Report Supplementary Material 4). The study with the smallest number of components involved two components;137 the most common number was four,133,135,136,139,141,144 and the greatest number was seven. 23 Interventions were categorised (see Categorisation of interventions for review 2) according to intervention focus into six categories: improving staff information, knowledge and skills (n = 5),136,139–141,143 increasing ward capacity (n = 2),138,144 activity-based or tailored interventions (n = 2),116,134 changes to ward environment (n = 2),133,137 support for carers (n = 2),48,135 and special care units (n = 1). 23

Quality appraisal

The results of the quality appraisal of included studies for reviews 1 and 2 are given in Appendix 10, Tables 11 and 12. Although we aimed to conduct a Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (CERQUAL) assessment, we decided that this was unnecessary because the synthesis was conducted with only high-quality, prioritised studies, and the volume of evidence identified meant that it would have been unfeasible to do this in the time frame of the project.

Review 1 (experience of care)

Eleven57,62,82,90,91,99,108,110,118,123,127 out of 63 studies rated a ‘yes’ response to all 14 sensitising prompts. A further 3743,46,47,60,61,63,64,66–68,76,78–81,85–88,93,94,96,97,100,104,107,115–117,119,120,122,124,126,128,131,132 were rated with 10 or more ‘yes’ responses, demonstrating that the majority of included studies scored fairly highly. The remaining 15 studies scored relatively lower than the rest, with the lowest two42,44 of these papers scoring ‘yes’ for five out of the 14 prompts answered.

The quality criteria against which studies most often scored ‘yes’ were clear research questions, appropriate study design and rigour of data collection. The quality criteria against which studies least often scored ‘yes’ related to reporting reflexivity, making theoretical/ideological perspectives explicit and the extent to which theoretical/ideological perspectives influenced the research process.

Review 2 (experience of interventions)

None of the studies in review 2 rated a ‘yes’ response to 13 or 14 out of the 14 sensitising prompts. Nine studies rated a ‘yes’ response to 10, 11 or 12 of them,23,116,133–135,137–139,144 and five studies scored lower than 10, with one study scoring 5. 141 Of the lower-scoring studies, two140,143 contributed substantially to the synthesis.

The quality criteria against which studies most often scored ‘yes’ probed the presence of clear research questions, appropriate study design and findings that were substantiated by the data. The quality criteria against which studies least often scored ‘yes’ related to reporting limitations, generalisability claims and reflexivity.

Qualitative synthesis

We report findings of reviews 1 and 2 according to each participant perspective and the LoA. To illustrate these findings, we quote participant extracts from included studies. Where extracts are followed by ‘author edits’, the study authors changed information from the original transcripts; extracts followed by ‘reviewer edits’ refers to changes made by reviewers. Changes include the removal of some words, denoted using ellipses, and explanation of issues referred to by the participant as [*]. We found no process evaluation studies linked to the randomised controlled trials (RCTs) included in review 3.

Subreview A: findings from reviews 1 and 2 about the experience of care for people living with dementia in hospital: feeling afraid and insecure

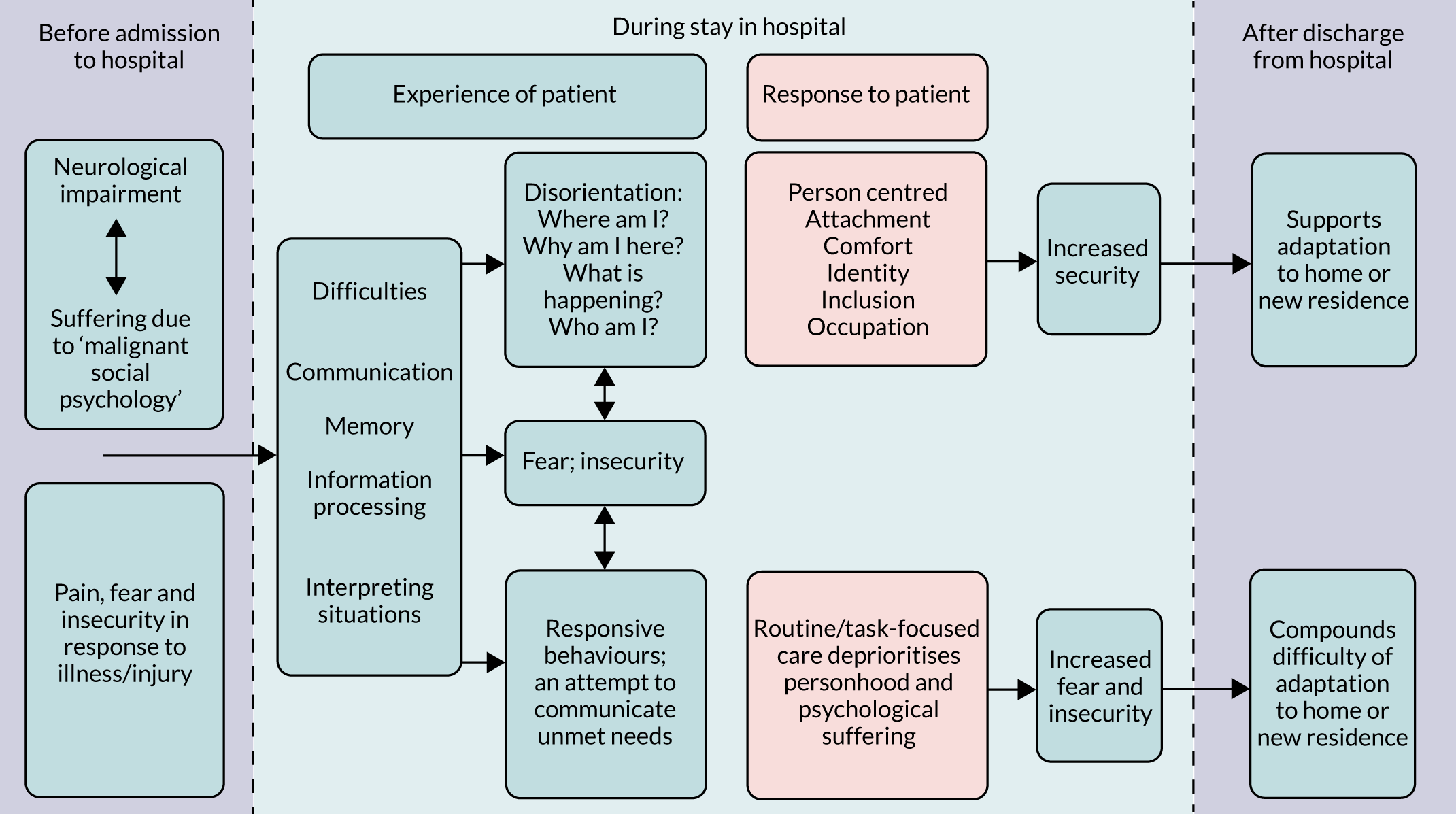

Because of the repeated role of theories of PCC in relation to patients with dementia in included studies from both reviews 1 and 2, we organised the synthesis of subreview A around PCC. Thirteen68,80,81,87,94,96,102,107,108,110,118,122,127 out of 20 prioritised studies included in review 1 drew on theories around PCC to make sense of findings, and six studies23,116,133,139,140,144 included in review 2 drew on theories around PCC in the rationales for their interventions. Another six prioritised studies66,67,82,104,120,123 from review 1 and another four intervention studies135,138,141,143 from review 2 made reference to values promoted by PCC, such as dignity and individualised care.

In Kitwood’s51,146 seminal work on PCC for people living with dementia, he argues that, rather than focusing on physical aspects of dementia as a cause for understanding behaviours associated with dementia, acknowledging the unity of mind and brain can open up constructive approaches to treatment. In this original work and a recent edition with further commentary from other authors on the issues he raises,146 Kitwood details multiple ways that the personhood of a person living with dementia is undermined in society in a manner that goes beyond the impact of neurological impairment, for example because of neglect, invalidation, stigma and banishment, calling this ‘malignant social psychology’. He posits that deterioration during dementia results from the combination of neurological impairment and malignant social psychology, so by meeting the psychological needs of people living with dementia it is possible to enhance the personhood of people living with dementia, thereby optimising the quality of life of people living with dementia despite the consequences of neurological impairment.

The main theme representing the experience of care in hospital for people living with dementia was Feeling afraid and insecure and the six subcategories were:

-

disorientation and responsive behaviour

-

identity

-

comfort

-

inclusion

-

attachment

-

occupation.

How studies included in reviews 1 and 2 contributed to the main theme and subcategories is shown in Appendix 7, Table 6. In this subreview, we found that, for people living with dementia in hospital, care that was orientated around supporting personhood was crucial because it acted to decrease fear and insecurity (Figure 3). Although any person admitted to hospital may experience this, it is particularly relevant to people living with dementia. The experience of loss of personhood related to malignant social psychology, difficulties experienced communicating with others and problems making sense of what was happening around them meant fear and insecurity in hospital was particularly intense. If personhood was undermined further in hospital this could create a negative cycle, whereby people living with dementia responded by acting in ways that attempted to communicate their distress [called ‘responsive behaviour’ in this review; see Experiences of disorientation and responsive behaviour: review 1 (experience of care) and Experiences of disorientation and responsive behaviour: review 2 (experience of interventions)]. Such behaviour could increase negative responses from staff, making the fear and insecurity of people living with dementia even more intense. PCC, by contrast, worked to decrease fear and insecurity, and therefore increased the psychological well-being of people living with dementia.

FIGURE 3.

Concept map depicting subreview A: the experience of care in hospital for people living with dementia. Main theme: feeling afraid and insecure.

We start by presenting findings from studies that described the increasing levels of fear and insecurity in people living with dementia that arose from disorientation. We then describe findings relating to approaches to decreasing fear and insecurity and increasing feelings of being safe by establishing familiarity, which were taken across aspects of PCC. Finally, we explore how aspects of PCC, or lack of PCC, had an impact on the experience of care for people living with dementia in hospital, how interventions made changes to improve these and how well participants perceived that the interventions worked.

Experiences of disorientation and responsive behaviour: review 1 (experience of care)

Studies that explored the experience of care in hospital for people living with dementia commonly described it as one of disorientation. 80,82,86,94,96,102,118,122,123,127 People living with dementia expressed uncertainty about who they were,80 where they were, 80,82,86,94,123,127 what time of their life it was80,123 and/or why they were in hospital:80,127

Am I at the geriatric unit? But I have never worked within geriatrics?

Aren’t you retired?

Yes, of course, you’re right. And I used to work in an office.

Person living with dementia80

In two studies86,127 people living with dementia understood themselves to be imprisoned:

I saw Gina being led back to her room. She was shouting at the nurses and looked very agitated. I asked the ward clerk what had happened and she said that Gina had taken the phone and rung the police to report that she was being kept imprisoned.

Researcher observation of a person living with dementia127

This quotation demonstrates that the intensity of distress is in keeping with the sense the person has made of their situation, and many studies attributed the behaviour of people living with dementia to an attempt to communicate such distress. 81,87,94,96,102,104,107,108,110,118,122,123,127 Porock et al. 114 found that hospitalisation created difficulty and distress by disrupting known and reassuring routines:

. . . with Alzheimer’s they’ve got to stay in a routine, that’s the most important thing, that’s the only thing they feel comfortable with, is keeping them in a routine, so going to the hospital was out of her routine.

Daughter (reviewer edits)114

A few studies noted experiences that alleviated disorientation by linking to, or establishing, familiarity:80,127

That wall over there, bricks or whatever they are called, I see that wall every day immediately when I wake up in the morning. Then I know where I am and that gives me a feeling of safety.

Person living with dementia80

Staff themselves could become the basis for familiarity as relationships grew between them and people living with dementia over time. 68 People living with dementia sought clues to explain where they were from the environment, for example using room numbers and nameplates above beds. 80 The environment could also increase their disorientation,80,127 for example because of the similarity of design between rooms and fixtures,80 or, paradoxically, when the ward was adapted to be ‘dementia-friendly’ by making it look more home-like because of the reduction in cues that might have helped people living with dementia understand they were in hospital. 80

Experiences of disorientation and responsive behaviour: review 2 (experience of interventions)

A number of studies included in review 2116,134,137,139,140 attributed the responsive behaviour of people living with dementia to their distress about unmet physical and psychological needs. In one of the studies providing training to staff,140 the authors drew from this perspective in their rationale for training content. The authors described a common clinical discourse around perceptions of behaviour of people living with dementia, where repeated vocalisation, wandering and protesting care [behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD)]147 were attributed to neuropathy. Within the training, ‘gentle persuasive approaches’, staff were taught to reframe responsive behaviour as unmet need in the patient. This change in attribution led to a change in practice, because staff were encouraged to seek why the person living with dementia was agitated and attempt to resolve the cause, rather than dismissing such behaviour as an untreatable aspect of dementia.

Two intervention studies133,137 included in review 2 suggested that changes to ward environments could reduce disorientation by increasing a feeling of security and familiarity. One intervention137 involved installing access technology that meant that people living with dementia could only enter their own rooms. The authors found that the combination of being able to find their own room and being able to have privacy helped people cope with the disturbance they experienced from being admitted to hospital:

They use their room as the place they can isolate themselves for a while, to rest, or to refresh themselves, find new resources, new strength to cope with the situation.

Hospital staff137

The authors concluded that the access technology created a sense of security for both patients and staff. Staff knew that people living with dementia could not enter other patients’ rooms, and that they could not ‘escape’ from the wards. This reassured them, and not only was that sense of security created for people living with dementia because they had their own room to escape to, but the authors suggested that staff’s sense of security was communicated to people living with dementia. The other intervention that adapted a hospital ward involved a dementia-friendly ward. 133 Staff thought that the more home-like colours and spaces produced an improvement in the behavioural and psychological well-being of the patients with dementia, who were perceived to be generally less agitated.

Having reported findings from reviews 1 and 2 that describe general experiences of care for people living with dementia including disorientation, behaviours in response to disorientation and the benefit of establishing familiarity to decrease disorientation, below we describe aspects of PCC and discuss how they link to findings in included papers.

Identity

Kitwood146 describes identity as ‘having a sense of who one is, in thought and emotion, in relation to others’. A person’s narrative of life to the present moment provides a sense of identity, including roles and the contexts in which people have lived over time. Identity can be maintained for people living with dementia through knowing personal information about a person’s past life, and through empathy, when it is possible to respond to the individual as a unique person: ‘thou’ rather than ‘it’.

Identity: review 1 (experience of care)

Identity was addressed in three ways within included studies: respect for personal preferences, space being made for personal items and respect for dignity and personhood. Simple respect for personal preferences, for example what someone liked to be called, what songs or hymns they liked, or what their usual routines were, could mean a lot. 65,68,70,99 Being able to have personal items such as family photographs by the bed not only helped people maintain their sense of identity, but talking about a past that they could remember was easier than expressing their identity in the disorientating present. 80 Both carers and staff noted that it was often small personal things that could make a person living with dementia ‘feel like a person’; it might be someone spending a few moments with them or engaging them in conversation as they walked past, or often something as simple as being acknowledged. 68,69,81

Contrasting these positive experiences, people living with dementia sometimes felt unimportant, a nuisance or ignored. 87,110,127 In addition, there were observations of personal preferences not being sought or being actively ignored:69,87,110,122

I kept saying to them that, although he’s down as Lewis Brown, he’s always from a little boy been called Roger, so I always said his name is Roger . . . they always spoke to him as Lewis and I said well you’ll not get a connection.

Carer (author edits)70

A lack of respect for the personal preferences of people living with dementia was also shown when staff woke individuals to serve them meals at times that fitted into ward routine rather than suiting the person living with dementia, did not defer to food choices, or did not offer drinks outside the ‘drinks round’. 87,122,127 Similarly, mealtimes, the giving of medications and personal hygiene were areas of care in which personal autonomy was often ignored. 94,110,122 For example, there were instances where the choice of people living with dementia to refuse medication was actively circumvented by concealing medications within food. 94

Identity could also be compromised by a lack of respect for dignity. Limited spaces between beds in bays often resulted in a lack of privacy. The personhood of people living with dementia was ignored when staff communicated briefly or not at all with people living with dementia about what was about to happen or happening, or when staff carried out routine care while talking to each other and ignoring the person for whom they were caring:81,87,107,127

They literally charge in. Very rarely announce themselves let alone explain what they are or who they are . . . I think that they don’t want to know you because you’re going to be a nuisance.

Person living with dementia127

Delays to individuals’ personal care needs were also not uncommon, and instances were observed of these being actively ignored. 71,87,107,127 Such experiences are consistent with Kitwood’s146 suggestion that people living with dementia are sometimes interacted with more as objects than as people, with consequent harm to their already vulnerable sense of who they are.

Identity: review 2 (experience of interventions)

Interventions in included studies supported the identity of people living with dementia in two ways following from Kitwood’s description: becoming familiar with their personal preferences and histories, and respecting their dignity.

A number of interventions involved the use of a tool completed by carers or assessment by a specialist to gather personal information about people living with dementia that could then be used by staff. 87,133,143,144 Participants across studies talked about the benefits of knowing personal information about people living with dementia. For example, in the participatory music intervention, music that was meaningful and therefore most therapeutic to people living with dementia often linked to their past experiences. 134 Volunteers found that knowing personal information about a person living with dementia not only supported the development of rapport, but also could be used to soothe distress:

So we kind of redirected the conversation towards, ‘Well, I’m writing some reports. I know you used to write lots of reports [patient was former teacher],’ and then it led on to a discussion about her work and my work so we kind of distracted her away from her worries.

Volunteer, p90 (author edits)139

Staff found that by understanding the likes and dislikes of people living with dementia they were often able to resolve disruption without medication or restraints, because they were better able to meet the needs of people living with dementia. 140 Staff on the dementia-friendly ward133 felt that the changes to the environment made it easier to provide individualised care and to support emotional needs. However, individual needs meant that some of the environmental changes could actually cause distress:

The environment changes impact on patients differently . . . we had a patient with dementia and an acute delirium, who was really scared of the picture opposite her . . . she kept asking ‘who is standing there, is that my dog?’ She must have a pet at home.

Health-care assistant (author edits)133

Carers attending a carer support group135 perceived that the psychoeducation they received sensitised them to the wishes of the person living with dementia, and the authors of the study concluded that the group helped both carers and staff to reflect on the identity and personhood of people living with dementia. 135 Two of the studies explicitly discussed how interventions supported the dignity of people living with dementia. One study raised awareness in staff of the need to consider dignity through staff training,23 and found that carers perceived fewer staff failed to consider dignity on this special care unit. This suggests that training may have supported the dignity of people living with dementia. On the ward where access technology was installed,137 staff perceived that the technology fostered dignity for people living with dementia through privacy, autonomy and capability:

This [the chip card] helps me find my room, I know I can try out all the doors, so I can forget my room and still find it; I don’t have to worry and I don’t have to interrupt and ask the people in white to show me my room.

Person living with dementia (author edits)137

The privacy of their room also created a place where people living with dementia were free to keep personal possessions which were often strong prompts for past identity, for example by sharing photographs with staff, without the fear of another patient taking them.

Comfort

Kitwood146 defines comfort in terms of tenderness, closeness, soothed physical and psychological discomfort, and a sense of security. Comforting someone means providing warmth and strength in the face of vulnerability. People living with dementia can need a great deal of comfort. In addition to the disorientation experienced upon admission to hospital, they face many other losses: relationships, the failing of abilities and an end to old, known routines. In the following paragraphs we will discuss the experience of care for people living with dementia in relation to comfort, and the ways in which interventions did or did not help to support comfort for people living with dementia in hospital. In the following sections we first discuss findings from review 1 according to physical comfort separate to psychological comfort, and then discuss findings from review 2 generally around comfort.

Physical comfort: review 1 (experience of care)

A number of studies referred to physical discomfort from unmet needs due to pain, hunger, thirst or constipation/incontinence. 70,87,96,107,114 Discomfort was often linked to difficulties people living with dementia had with memory and communication. For example, authors of studies which focused on managing pain for people living with dementia in hospital observed that because of issues around memory, when asked questions, a person living with dementia was likely to only be able to respond according to his or her present state. 79,102 This meant that pain management could easily be inadequate because staff commonly relied on self-reports of pain. 79 Staff and carers said that it was possible to interpret pain levels of people living with dementia according to their gestures, posture, body movements, behaviour and/or metaphor, and that these could augment straightforward reports of pain. 79,123

Physical discomfort could also result when people living with dementia were left on their own or were not in their own bed, for example being left on a trolley for a long period of time despite acknowledging this was not good care. 70 Finally, discomfort occurred when staff either delayed care or overtly ignored the problem:

My mum’s lips kept sticking together because she wasn’t drinking and we had to constantly say ‘Can somebody please swab them and clean them?’ . . . and I feel, may be, if someone could have just been a bit more on the ball there.

Son70

Psychological comfort: review 1 (experience of care)

Despite observations from studies that suggested physical care was prioritised over psychological care of people living with dementia,69,87 some studies documented positive experiences of care for emotional comfort of people living with dementia. Staff were observed to respond sensitively when people living with dementia appeared in distress and to be sympathetic to those in pain or who were frail:66,70

Phyllis continued to cry . . . the housekeeper went over to Phyllis ‘Phyllis, now don’t cry. It does you no good love’ . . . The housekeeper wrapped both arms around Phyllis and rocked with her like a child, gradually slowing until the sobbing ceased.

Researcher observation70

A caring approach through touch was observed to calm or reassure people living with dementia, although comfort from touch was dependent on the relationship between the person living with dementia and staff,122 and in fact touch was not always comforting. 111 Some studies found that the general ambiance of a ward could improve emotional comfort by instilling a sense of security for people living with dementia, or add to a sense of insecurity. 68,81,123,127 Edvardsson et al. 81 attributed the behaviour of people living with dementia to the presence and ‘ways of being’ of staff members on the ward; when staff were present and engaged with people, and even when staff were present but not engaged, this supported a sense of security in people living with dementia. When staff were absent, people living with dementia became more anxious and this could easily be communicated to others in a sort of ‘collective escalation’. 81

Other aspects of ward environments were found to distress people living with dementia. Moving wards, or being moved for tests, and often being moved at very short notice or with little explanation, was seen to be challenging for people living with dementia. 107,118 Carers and staff across several studies reflected on the fact that the noise and general busyness from telephones, alarms, buzzers, surveillance equipment, staff talking (around people living with dementia and not to them), and patients calling out could be quite distressing to people living with dementia:87,107,118

Our environment isn’t good . . . in a big ward room there is a lot of movement and talk between the patients and noise from the TV, and there are many other unfamiliar sounds from buzzing signals etc., that can create anxiety, especially at bedtimes.

Nurse (reviewer edits)107

Included papers commonly described experiences of psychological discomfort. 69,79,81,87,96,107,113,118,122,127 Experiences of disorientation, discussed above, could create high levels of psychological discomfort for people living with dementia, and a lack of familiarity or meaningful connection was noted to add to fear, worry or anxiety. 66,99 Unmet needs relating to the other aspects of personhood, including attachment, inclusion, identity and occupation, could all create emotional distress.

People living with dementia appeared to express discomfort in a number of ways. Some examples included simply telling people they were unhappy – ‘I hate it [in here]’127 – but many authors linked a range of responsive behaviour to psychological and/or physical discomfort. Responsive behaviours included refusing food,66,108,122 refusing medication,122 refusing care (e.g. washing or toileting),96,108,110 removing/disconnecting medical equipment,105,107 aggression,81,87,96,104,108,120,122,123,127 agitation,66,81,96,107,118,120,127 vocalisation/verbal aggression/crying,68,80,81,87,96,108,122,123,127 undressing,96,104 walking/wandering,81,96,104,107,108,110,123,127 and/or rummaging/invading other patients’ space/moving furniture. 80,81,96,123 Finally, people living with dementia were perceived to express discomfort through withdrawal: by closing their eyes when staff approached or by closing their mouth and looking the other way when they did not want to eat or take medicines. 94,99,110

Comfort: review 2 (experience of interventions)

Findings from review 2 intervention studies linked to comfort in relation to companionship/relationship; meeting unmet needs; the senses; the structural environment, privacy and security. 116,133,138–140,144

Three studies found that providing companionship could support comfort for people living with dementia. 138,139,144 The two studies that focused on improving ward capacity by bringing in volunteers138,144 both found that the companionship provided by volunteers, whose primary role was to talk to people living with dementia, had a settling effect. Volunteers were also able to provide comfort during intensely vulnerable times when others were not able to:

She sat with the patient, was holding their hands and there were no relatives around, like they were abroad and they just couldn’t be there on time, and she was there holding hands while the patient was dying and with tears in her eyes.

Medical consultant138

Validation, Emotion, Reassurance, Activity (VERA) training for nursing students139 took an approach that drew on theories of PCC in that it emphasised the personhood of the person living with dementia and the importance of relationships between those providing care and people living with dementia. Students prioritised getting to know people living with dementia in order to promote comfort, and reported that getting to know patients by finding out about their personal histories, likes and dislikes helped them provide comfort, for example by knowing how to distract the person living with dementia from worries.

On a ward adapted to create a dementia-friendly environment,133 one of the adaptations was to remove the central nursing station; instead nurses completed paperwork on the wards in close proximity to the patients. Staff did not comment on how this change impacted their relationship with people living with dementia. The authors comment that the staff were not encouraged to change how they interacted with patients and carers, so while the opportunity for connections with people living with dementia was not optimised, it is possible that the constant companionship of having a nurse on the ward could have offered additional comfort to people living with dementia as was suggested in review 1.

Participants involved in three interventions referred to providing comfort through meeting unmet needs. 116,134,140 In the intervention using gentle persuasive approaches,140 staff were taught to interpret responsive behaviour as unmet need, leading to changes in practice [see Experiences of disorientation and responsive behaviour: review 2 (experience of interventions)]. Similarly, in the intervention Namaste Care,116 where people living with dementia were provided soothing sensory stimulation at the end of life, staff said that when the activities did not calm agitation, this led them to seek other causes for the behaviour. These staff viewed agitation as information that could help them meet the needs of the patient. Staff found that a Namaste Care approach supported comfort through touch:

There’s something about touching the skin. You are connecting with that person. I find it very soothing especially if you have a patient that’s very agitated.

Health-care support worker116

Stimulation of other senses could also be comforting. A health-care support worker trained in Namaste Care116 told about a patient who loved church hymns, and when he played them on his phone, ‘it calmed him completely. It took him back to a place where he was happier, content’ (p359).

Attachment

Kitwood146 draws from theory on attachment148,149 to suggest that any person, regardless of age, is unlikely to be able to function well without the security and reassurance that attachment to another person provides. People living with dementia constantly experience situations as strange, and this increases the importance of and their need for attachment.

Attachment: review 1 (experience of care)

Only a few studies referred indirectly to attachment and mainly through the sense of maintaining or fostering close relationships. The importance to the person living with dementia of maintaining family connections was observed across a couple of studies:96,99 either through the opportunities afforded or encouraged at visiting time or through families maintaining the familiarity of care practices:

I used to put me mum her nighty on [in hospital] and see to her and do her teeth and tuck her in . . . I think she felt better me doing that . . . It was more like being at home, when she stays with me.

Daughter or son (author edits)99

This extract suggests that familiar people in hospital are able to support a person living with dementia’s sense of security because they help maintain connections to prior routines, abilities and caregiving relationships. In one study, a person living with dementia was observed comforting a family member, giving the person living with dementia the opportunity to maintain their caregiving role to a loved one. In this extract Alma waited for a long period of time with her mother Patricia, a person living with dementia, during admission:

Even when I was standing next to her she’d say, ‘I bet your legs are really hurting you, because I couldn’t stand all that time’. And then she’d say to me, ‘Would you like to go and have a drink?’

Daughter114

Familiarity with staff could also develop into a sense of attachment. Consistency of staff was observed to foster more positive relationships with people living with dementia:

I think it may have been because . . . they did longer shifts and . . . my mother was under their wing so they developed a relationship to her which, to her, is very important. Whereas the other staff that I saw . . . they hadn’t got such a close relationship with her.

Daughter (author edits)70

A lack of opportunity for family members to maintain relationships with or be with the person living with dementia, either through limited space on the ward107 or through limited visiting hours, was noted in several studies. 96,99,118

Attachment: review 2 (experience of interventions)

None of the included papers in review 2 directly discussed supporting the needs of a person living with dementia to have contact with those with whom they had an attachment. A few studies, a special care unit23 that adopted a proactive and inclusive approach to carers and a ward fitted with access technology to which carers were given key cards,137 could potentially support attachment by allowing access to a person living with dementia for carers, however perceptions about this were not reported.

Inclusion

All people, including people living with dementia, need to belong socially, and if this need is not met a person is likely to decline and retreat and may feel they are living in a ‘bubble of isolation’. Kitwood146 describes how people living with dementia can be excluded on a personal and structural level, through ageism, stigma around ‘senility’ and inadequately informed or resourced public services. When socially included, people living with dementia are supported to expand back into ‘person’ status.

Inclusion: review 1 (experience of care)

Reference to inclusion in review 1 prioritised studies involved support for social interaction, or issues around respecting the rights of a person living with dementia to be involved in decisions about their own care. Direct inclusion by involving people living with dementia in decisions about their care was not commonly reported, but was referred to in one study; a clinician specifically asked that a person living with dementia be in the room while their care options were discussed with their family. 70 Inclusion was, however, experienced indirectly through interactions that helped create a sense of companionship and reassurance, for example when staff showed understanding of someone’s cultural beliefs. 68,69,87,99,110,123,127 Inclusion was also apparent through the togetherness found between people living with dementia. People living with dementia in shared living spaces were able to give support to and befriend each other:80,114

Mike walks back onto the bay. Alan calls to him ‘Wanna look at this Mirror [newspaper]?’ ‘Ay’ replies Mike ‘I’ll look at the local scandal. This football?’ Alan tells him ‘No, it’s local history’. ‘I’ll be in it then if it’s local history’ quips Mike.

Researcher observation, standard care ward87

They also provided comfort and gave physical assistance to each other, and called for nurses on someone else’s behalf as and when needed. 87

By contrast, the ward environment could also make people living with dementia feel excluded as a result of the physical location of their bed if they were isolated in a side room. 69,87,99 People living with dementia described not being asked to join in social activities that occurred on the ward,69 and talked about how the meals offered were not familiar to them or something they would usually eat. 127 Feelings of exclusion were also experienced by people living with dementia who perceived that they were not receiving the care that others were given or were not being asked their thoughts about the care options available to them:

. . . that physio he goes from room to room asking whether you want to do physio. Nobody asked me . . . Everybody do this or do that and I’m not asked [Larry looked very downcast, shoulders slumped, looking down].

Researcher observation of a person living with dementia (author edits)127

Decisions around discharge and assessment of capacity in particular seemed to be an area from which people living with dementia often felt excluded82,127 or, as in the following case, were likely to be excluded from if they did not agree with the team’s assessment of their capacity:

At follow-up, he expressed unhappiness because he felt ‘tricked’ by the social worker and doctors into accepting a trial discharge; but there had been no review or sign of any attempts to get him home.

Author82

Inclusion: review 2 (experience of interventions)

A number of interventions included in review 2 involved components that might potentially increase inclusion or a sense of belonging, for example those that encouraged interactions between staff or volunteers and people living with dementia,23,138–140,144 or between groups of people living with dementia and staff, for example through activities,23,116,134 social dining spaces133 and day rooms. 23 Participants from intervention studies rarely talked about aspects of inclusion explicitly. However, staff did notice how the mood and behaviour of people living with dementia improved because of interaction with volunteers:138,144