Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/04/41. The contractual start date was in November 2015. The final report began editorial review in April 2019 and was accepted for publication in April 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Memtsa et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Clinical background

Early pregnancy complications are common and account for the largest proportion of emergency work performed in gynaecology departments across the UK. 1 The term ‘early pregnancy complications’ encompasses all types of miscarriage in the early pregnancy period (up to 12 weeks of gestation), ectopic pregnancies, trophoblastic disease and maternal complications such as hyperemesis gravidarum.

Miscarriage is the most common early pregnancy complication. Based on Hospital Episode Statistics,2 it is estimated that 15–20% of all pregnancies miscarry spontaneously; however, the actual loss may be much higher, as many cases remain unreported to hospital or are not recognised by women.

Even though the incidence of ectopic pregnancy is considerably lower than the rate of miscarriage (11 per 1000 pregnancies, according to Hospital Episode Statistics),2 every year 12,000 women in the UK are diagnosed with this condition. The mortality rate from ectopic pregnancy has remained fairly constant over the last 20 years and is around 0.47 per 100,000 maternities in the UK. 1

Early pregnancy assessment units in the UK

The early pregnancy assessment unit (EPAU) is a specialised clinical service for women with suspected complications during the first trimester of pregnancy. EPAUs are organisational structures unique to the NHS and there are only a few similar units operating in Europe, Canada and Australia.

Early pregnancy assessment units aim to provide comprehensive care to pregnant women, which includes clinical assessment, ultrasound and laboratory investigations, management planning, counselling and support. The main reported benefits of EPAUs are shortening of time to reach the diagnosis and reduction in the number of hospital admissions for women with suspected early pregnancy complications. 3

There has been a significant increase in the number of EPAUs in NHS hospitals since 1991, when Bigrigg and Read3 first published data on the role of the EPAU in improving quality of care and cost savings following the opening of a unit in Gloucestershire Royal Hospital.

According to the Association of Early Pregnancy Units (AEPU), there are currently an estimated 200 EPAUs and they operate in the majority of acute NHS hospitals in the UK. 4

Variations in the organisation of EPAUs in the UK

The National Service Framework: Children, Young People and Maternity Services5 recommends that EPAUs should be generally available, easy to access and set up in a dedicated area in the hospital, with appropriate staffing and ultrasound equipment, as well as easy access to laboratory facilities. EPAUs should also provide a suitable environment for women and their partners. There should be direct referral access for general practitioners (GPs) and selected patient groups, such as women who have experienced an ectopic or molar pregnancy in the past. In addition, Healthcare Improvement Scotland6 recommends that women presenting to EPAUs have access to ultrasound facilities with trained staff in secondary and tertiary services within 24 hours from initial presentation, as well as a choice of management options for miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy (i.e. surgical, medical and expectant).

The latest National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline on ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage (Clinical Guideline 154)7 aimed to establish how different models of care within EPAUs might have an impact on service outcomes, clinical outcomes and women’s experience of care. Fourteen studies were identified. 3,8–20 The majority of the studies (n = 10)3,8–16 were conducted in the UK. Of the studies included, two were cross-sectional studies,8,9 four were observational studies3,17–19 that compared outcomes before and after the establishment of an EPAU, and the remaining studies were descriptive. 10–16,20 The quality of the evidence was described as low or very low. 7

Evidence from the cross-sectional studies shows that in approximately half of the EPAUs ultrasound scans are performed by sonographers only, whereas in less than one-quarter of EPAUs the scanning is done by medical, nursing or midwifery staff. 7–9 Professionals from different disciplines perform ultrasound scanning in the rest of the EPAUs. Regarding access to services, all EPAUs accept patients referred from other health-care professionals, whereas only 51% of EPAUs accept self-referrals and the majority of units (70%) provide a weekday service only. 7–9 There is a paucity of data regarding the best indicators for clinical and service outcomes, and women’s views and experience of care were included in only two studies. 14,16

Given the considerable variation between different EPAUs in the levels of access to their services and the levels of care they provide, the best configuration of EPAUs for optimal balance between cost-effectiveness, clinical effectiveness, service- and patient-centred outcomes remains unknown. A key research recommendation of the NICE guideline7 was good-quality research to establish the effectiveness of different EPAU configurations.

Pilot study

A pilot study to test the feasibility of a large-scale service evaluation was conducted in selected EPAUs in London. Eight hospitals in Greater London were approached to participate in the study, seven of which agreed to take part. The EPAUs were selected on the basis of their size, staffing configuration and accessibility. Three of the EPAUs were located within teaching hospitals, with consultant presence in the EPAU for six or more dedicated sessions per week (≥ 60% of regular working hours; type A). The other four EPAUs were located in district general hospitals. Two of the EPAUs had named lead consultants who were present in the unit between three and five sessions per week (30–50% of time; type B). The remaining two EPAUs (type C) also had named lead consultants, but they had only a single or no dedicated sessions in the unit per week (≤ 10% of time). See Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 1, for the EPAUs’ opening hours and staffing levels.

As there are no auditable standards against which the EPAU service can be assessed, the main service outcomes examined were the proportion of women attending for follow-up visits, the proportion of non-diagnostic ultrasound scans, the proportion of visits for blood tests and the proportion of women admitted to hospital.

Data were collected prospectively using purposefully designed data collection forms. Prior to starting the study, two key members of the research team held a series of meetings with clinical teams in all participating hospitals to discuss the study methodology and to define outcomes of interest. Individual clinicians/nursing staff were identified in each unit who volunteered to take responsibility for the running of the study and to ensure contemporaneous data collection. The chief investigator visited each unit on a weekly basis to facilitate data collection and to ensure data quality.

The study was conducted over 2 calendar months. After excluding all duplicate entries, records from 3769 women who attended for a total of 5880 visits were included in the data analysis.

There were no significant differences in the mean gestational age recorded at the time of women attending for initial assessment between different types of EPAUs (p = 0.29). There were significant differences in the proportion of women attending for follow-up visits, the proportion of non-diagnostic scans and the proportion of women having blood tests between individual EPAUs. There were also significant differences in the proportion of admissions for the purpose of diagnostic work up (see Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 2). The pilot study confirmed that there are significant differences in the various clinical and service performance indicators between different EPAUs in a certain geographical area. However, it was not possible to determine the factors that may influence these results. The study also showed that it is feasible to conduct a larger-scale study involving women from a range of EPAUs to identify possible factors affecting outcomes in the delivery of early pregnancy care.

Aims and objective

Primary aim

The primary aim of our study was to test the hypothesis that the rate of hospital admissions for early pregnancy complications is lower in EPAUs with high consultant presence than in EPAUs with low consultant presence.

Secondary aims

-

To test the hypothesis that increased consultant presence in EPAUs improves other clinical outcomes, including the proportion of women having follow-up visits, non-diagnostic ultrasound scans, negative laparoscopies for suspected ectopic pregnancies and ruptured ectopic pregnancies requiring blood transfusion.

-

To assess the effect of variations in opening hours and service accessibility on the overall admission rates and other clinical outcomes.

-

To determine the optimal skill mix to run an effective and efficient EPAU service.

-

To examine the cost-effectiveness of different skill mix models in EPAUs.

-

To explore patient satisfaction with the quality of care received in different EPAUs.

-

To make evidence-based recommendations about the future configuration of EPAUs in the UK.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter reports the methods used to conduct the Variations in the organisations of Early Pregnancy Assessment Units in the UK and their effects on clinical, Service and PAtient-centred outcomes (VESPA) study.

Study design

The VESPA study employed a multimethods approach and included:

-

a prospective cohort study of women attending EPAUs (to measure clinical outcomes)

-

a health economic evaluation (including skill mix and cost–utility model development)

-

a patient satisfaction survey

-

qualitative interviews with service users

-

an EPAU staff survey

-

a hospital emergency care audit for women presenting with early pregnancy complications.

The study received a favourable ethics opinion from the North West Research Ethics Committee (reference 16/NW/0587) [see the relevant named documents for the full study approved protocol, patient and staff information leaflets and consent forms, data collection forms, unit data collection forms and unit protocol forms, URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/140441/#/ (accessed 2 June 2020)]. We recognised that women would be asked to participate in the study at their initial attendance at the EPAU with a lack of ‘cooling-off time’ before consent was obtained and the completion of questionnaires commenced. These issues are often encountered in studies of emergency medical care and in studies of pregnant women in labour. 21,22 The issue of ‘cooling-off time’ was addressed prior to commencing the study at the Study Steering Committee (SSC) meeting. We also consulted with a focus group of service users and the Miscarriage Association about the optimal timing to approach women about research. We concluded that because of the nature of the EPAU clinical service, which mainly looks after emergency patients, it would have been impossible to carry out this study without asking participants to engage with the research team at their initial presentation. However, as a part of the study eligibility criteria, women who presented with severe clinical symptoms or who were in severe distress were not approached. In addition, we emphasised the need to be sensitive, sympathetic and considerate in the approach to potential participants, and informed women that they could withdraw their consent for follow-up at any time. This information was also included in the participant information leaflet (PIL).

National survey of EPAUs

Information about existing EPAUs in the UK and their contact details are held by the AEPU. We used this information to conduct a UK-wide survey of all NHS EPAUs. Our aim was to determine the current set-up of EPAUs across the country and accurately sample potential participating units. An online questionnaire was sent to the named lead clinician of all EPAUs in the country, as it appeared on the AEPU database. A reminder e-mail was sent after 6 weeks in cases of non-reply or missing data. The survey results were used to classify each of the potential centres with respect to the following three key factors: (1) consultant presence, (2) weekend opening and (3) volume. To increase the response rate to the survey, all of the EPAUs that had not responded to the online survey were contacted individually by telephone and the clinician in charge (consultant/nurse) was asked to answer the same questions as the online survey.

The following algorithm was utilised to obtain a sample of 44 centres, ensuring that each key factor is equally represented:

-

The first centre was sampled at random.

-

A score was calculated for the remaining centres, with higher scores given to those centres that had characteristics that were under-represented in the sample.

-

The next centre was sampled using weighted random sampling (using this score).

-

Return to (b) until 44 centres were sampled.

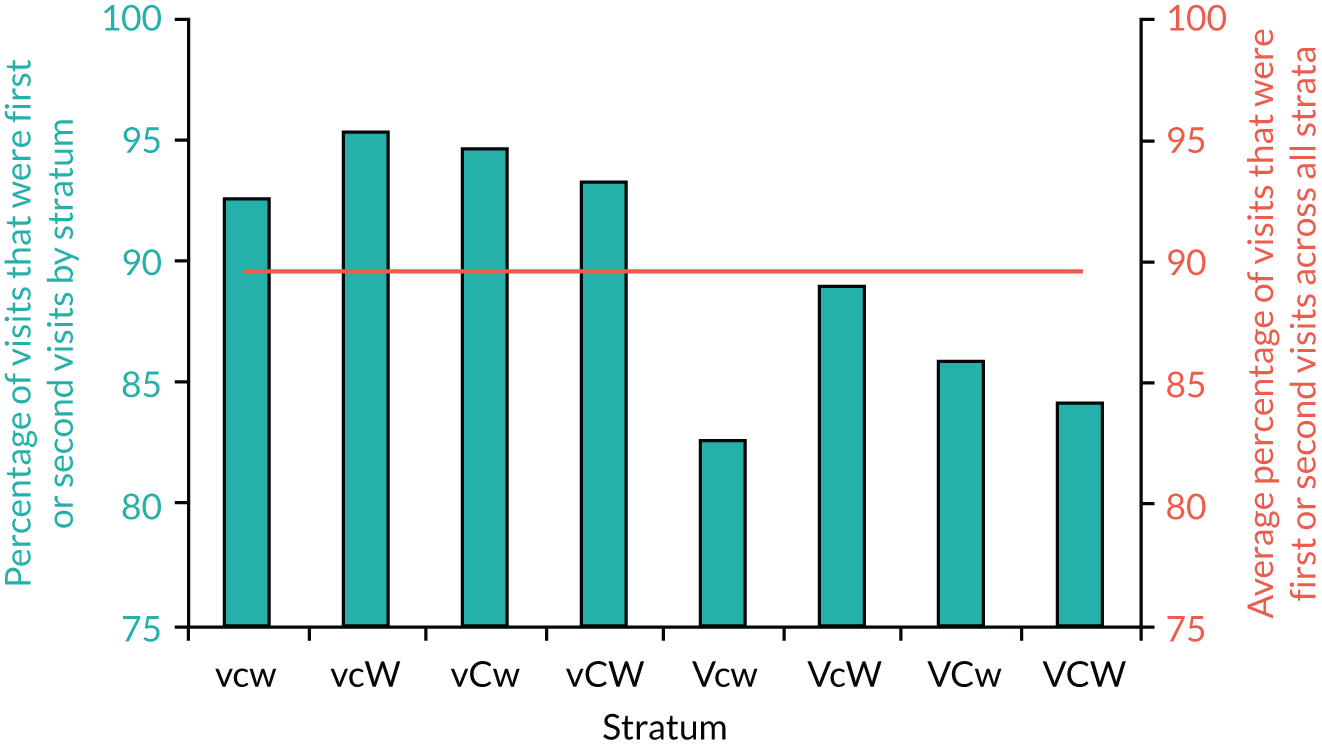

We then grouped the units in eight strata, all of which differed by at least one key factor. The results of the national survey are summarised in Chapter 3.

Recruitment of participating EPAUs

The responses to the national survey were summarised and the units were categorised according to three factors: (1) planned consultant presence (yes vs. no), (2) whether the unit was open at weekends (yes vs. no) and (3) the number of patients seen over 1 year, as reported by the clinicians in charge (low volume of < 3000 appointments annually vs. high volume of ≥ 3000 appointments annually). These cut-off points were chosen following analysis of the survey results. The cut-off point for number of patients was chosen so that there were equal numbers of low- and high-volume units.

Previous studies and the results of our own audit have shown that inpatient admissions could be significantly reduced when consultants are available to review patients in acute clinical settings, such as accident and emergency (A&E) departments or medical assessment units. 23,24 Weekend opening of the EPAU facilitates access to the ultrasound diagnostic service, which is essential for safe and effective management of early pregnancy complications. Without such access, it is likely that a number of women would be admitted as a precaution until potentially harmful early pregnancy complications, such as ectopic pregnancy, are ruled out. We have chosen the size of the unit as the third key confounding factor because the results of previous studies suggest that higher volume leads to better outcomes for certain groups of patients. This is likely to be because of greater exposure to more complex cases, which contributes to better collective team experience and learning, which translates into improved clinical outcomes. 25,26

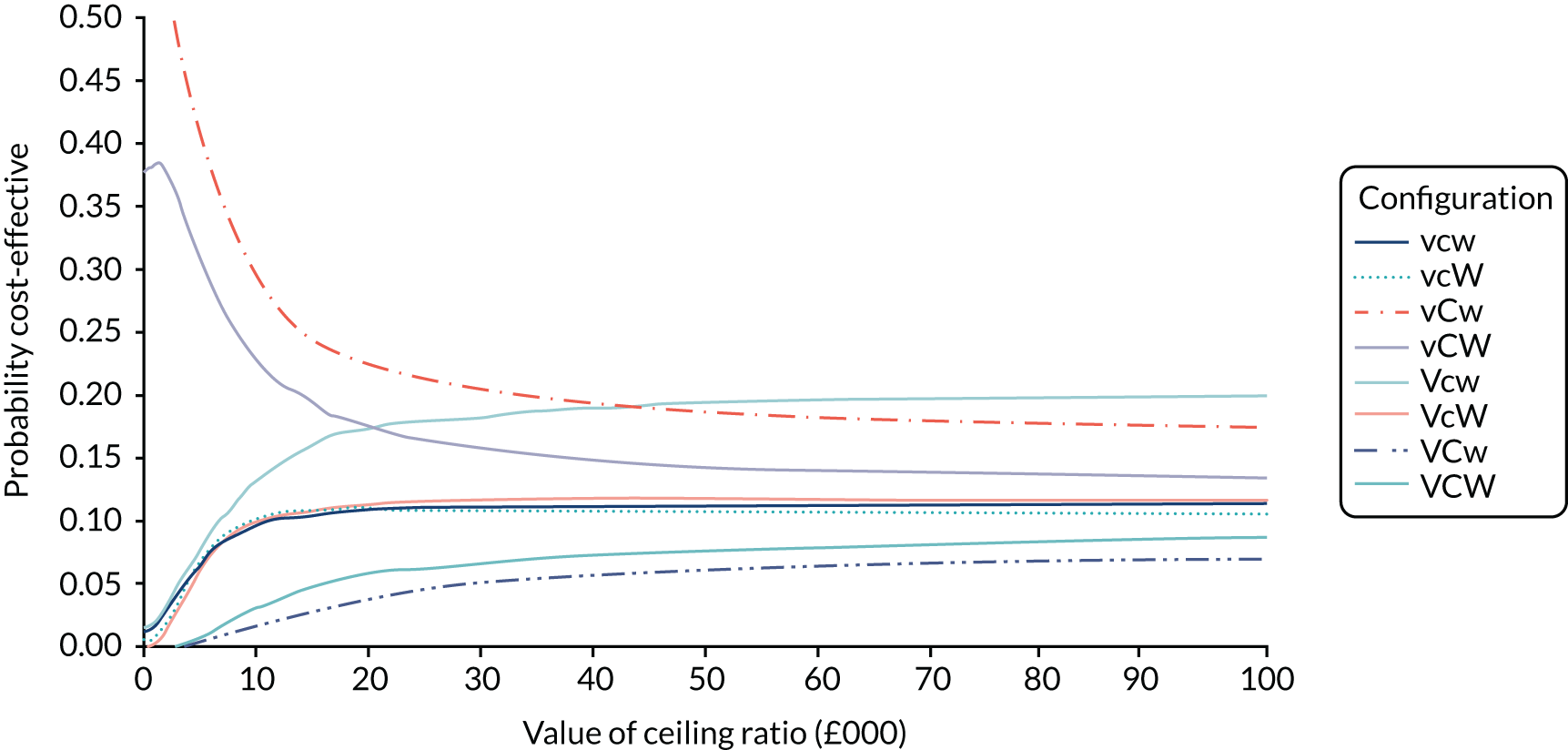

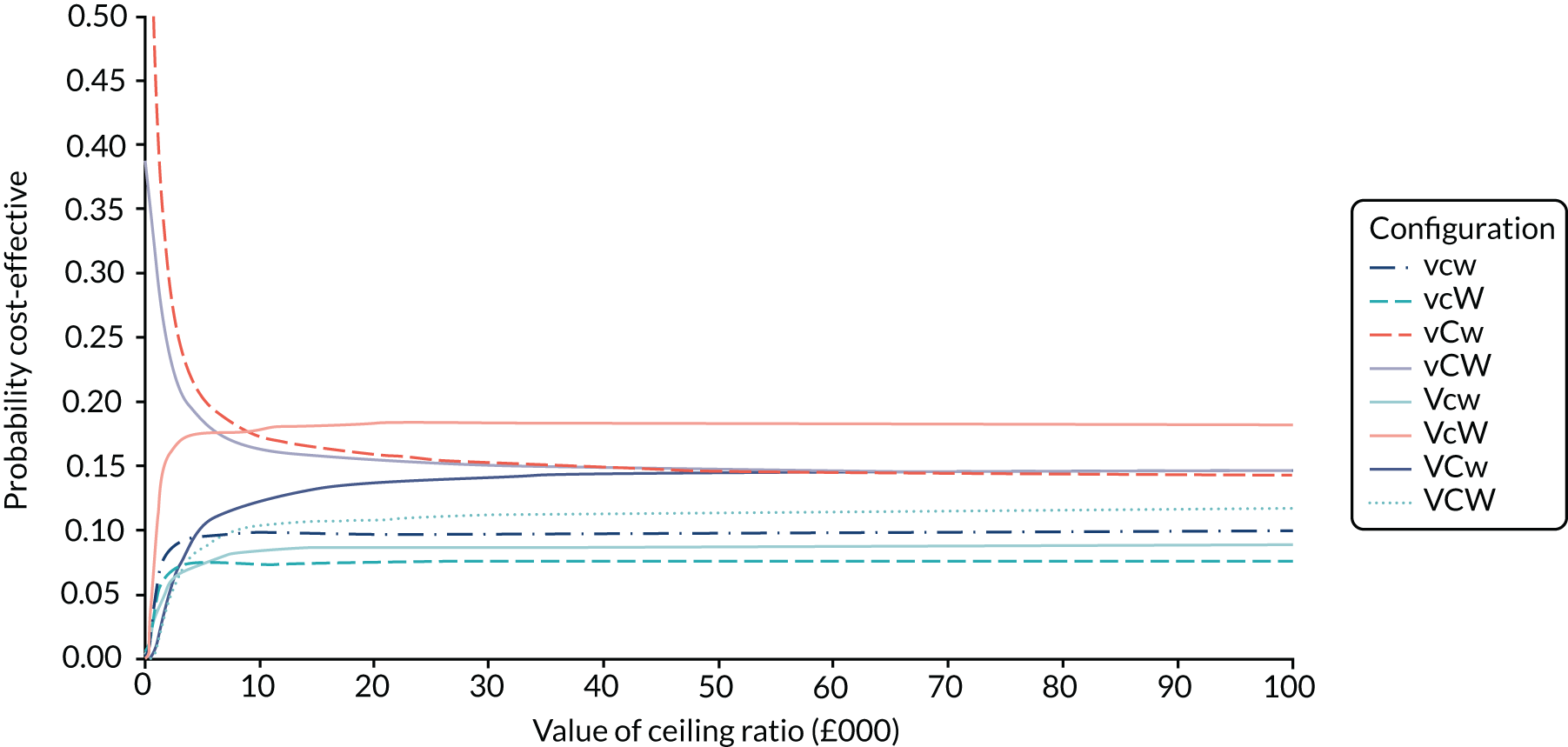

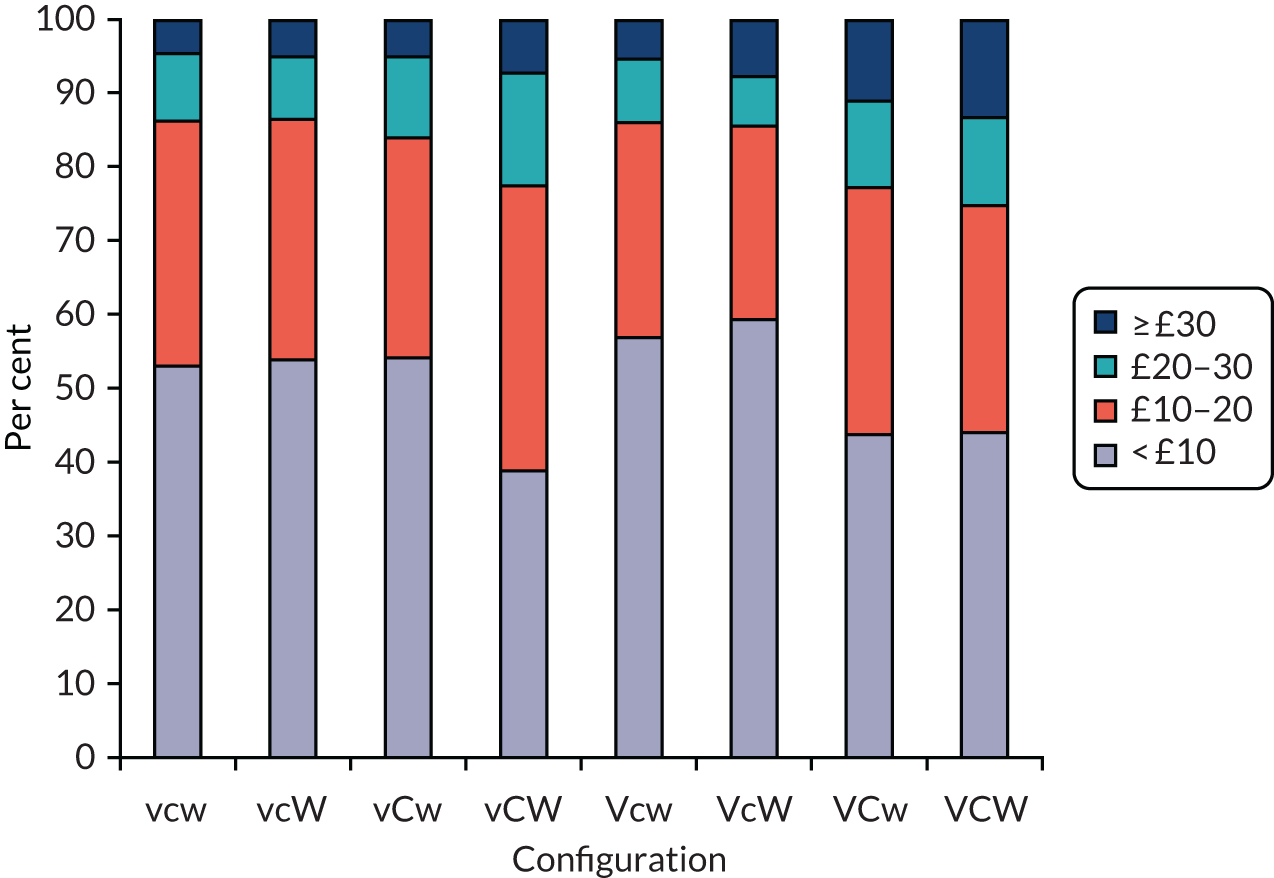

Eight unique EPAUs configurations were considered and were divided into the following strata:

-

low volume, no consultant presence, no weekend opening (vcw)

-

low volume, no consultant presence, weekend opening (vcW)

-

low volume, consultant presence, no weekend opening (vCw)

-

low volume, consultant presence, weekend opening (vCW)

-

high volume, no consultant presence, no weekend opening (Vcw)

-

high volume, no consultant presence, weekend opening (VcW)

-

high volume, consultant presence, no weekend opening (VCw)

-

high volume, consultant presence, weekend opening (VCW).

The formation of strata was employed to aid the random selection of the participating EPAUs and ensure that EPAUs from all configurations were accurately represented. A computer program randomly selected four or five EPAUs from each stratum. Once the 44 potentially participating EPAUs were identified, the central team contacted the clinician in charge of each EPAU or the research and development team of that trust and officially invited them to participate in the VESPA study. If an EPAU unit declined to participate or was deemed unsuitable to participate because of size (i.e. < 300 reported patient visits per year), another randomly selected unit was invited to participate. The detailed breakdown of all EPAUs randomly selected, whether they accepted or declined the invitation and if they were replaced is presented in Chapter 3. Once the participating EPAUs were confirmed and all the regulatory approvals obtained, site initiation visits were arranged to inform the local research and clinical teams of the study protocol and procedures. At the time of the site initiation visit, the unit characteristics were reconfirmed so that, at the time of data analysis, the EPAU was assigned to the correct stratum. To facilitate accurate data collection and troubleshooting, a member of the central VESPA research team was either present on site on the day that recruitment opened at each EPAU or available to provide advice remotely over the telephone. Staff members were also available to attend whenever any of the EPAUs required additional support. During patient recruitment we recorded the grade of all members of staff who were present in the EPAU during its opening hours, as well as the actual hours that each member of staff spent in the EPAU. Finally, during recruitment, we collected information about the EPAU referral policy regarding the minimum gestational age when women could be seen, as well as the management protocols of early pregnancy complications (including availability of medical/surgical/expectant management of miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy).

Data strands

Given the multimethods approach of the VESPA study, data collection was organised into seven data strands:

-

clinical outcomes in EPAUs

-

emergency hospital care audit

-

patient satisfaction

-

staff satisfaction

-

qualitative interviews

-

health economic evaluation

-

workforce analysis.

The questionnaire arm of the study, which will be routinely referred to throughout the report, includes the patient satisfaction and health economic evaluation data strands.

Eligibility (inclusion and exclusion criteria)

Clinical outcomes in EPAUs

All women (aged ≥ 16 years) attending the participating EPAUs because of suspected early pregnancy complications for the first time during the index pregnancy were included in this strand of the study. A gestational age limit was set at 13+6 weeks’ gestation to standardise recruitment from all EPAUs across the country. There were no exclusion criteria for this strand of the study.

Emergency hospital care audit

Routine data were collected for all women who attended hospital emergency services because of early pregnancy complications over a period of 3 months, following completion of clinical data collection from the EPAU.

Patient satisfaction

All pregnant women (aged ≥ 16 years) attending EPAUs because of suspected early pregnancy complications who agreed to sign a written consent form to participate in the questionnaire arm of the VESPA study were included. Women who were haemodynamically unstable or in severe pain and those who declined consent were excluded.

Staff satisfaction

All members of staff directly involved in providing early pregnancy care were eligible to consent to this data strand. Non-permanent members of staff and locum and agency staff were excluded.

Qualitative interviews

Women who had taken part in the patient satisfaction survey and who had provided consent to being approached later to participate in a telephone interview formed the sampling frame for the qualitative interviews. Using the EPAU location and strata configuration, pregnancy outcome and participants’ 2-week post-discharge satisfaction score [Short Assessment of Patient Satisfaction (SAPS)27], a sampling frame was created to select a maximum variation, purposive sample of women. Please see Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 3, for the strata of each component of the sampling frame.

Health economic evaluation

The health economic evaluation included pregnant women (aged ≥ 16 years) attending EPAUs because of suspected early pregnancy complications who agreed to provide signed consent to participate in the questionnaire arm of the VESPA study. Women who were haemodynamically unstable or in severe pain and those who did not consent to participate in the questionnaire arm of the study were excluded from this data strand.

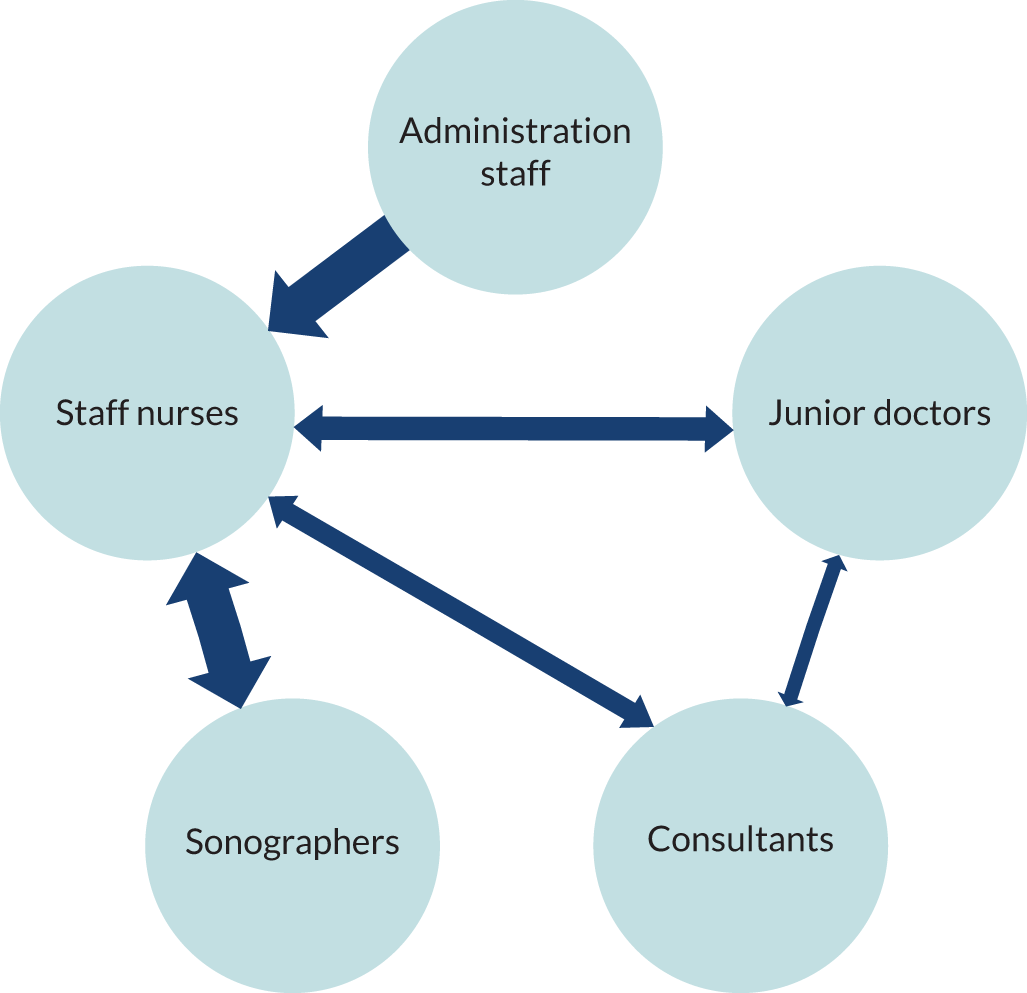

Workforce analysis

All interactions of women with any member of staff (i.e. administrative, nursing, medical) during their visits to the EPAU, and the duration and type of these interactions, were contemporaneously collected.

Participant flow

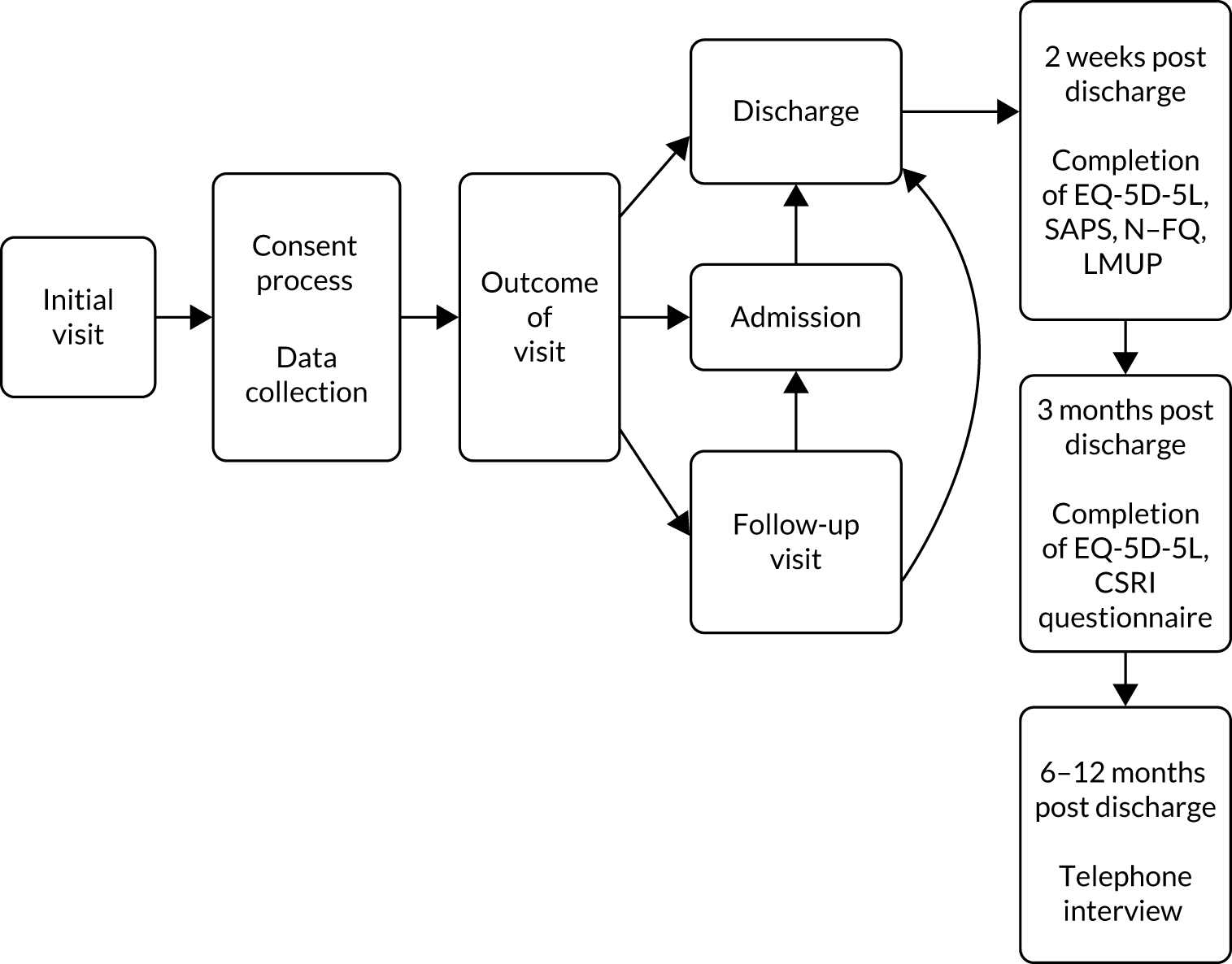

The participant flow is represented diagrammatically in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Participant flow diagram. CSRI, Client Service Receipt Inventory; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version; LMUP, London Measure of Unplanned Pregnancy; N–FQ, Newcastle–Farnworth questionnaire.

Recruitment process

The VESPA study recruited from the EPAU population. All eligible women were provided with the study information leaflet as they registered their attendance at the clinic reception. Once they had sufficient time to read the information leaflet, they were then approached by the triage (registered) nurse, midwife, research nurse, nurse sonographer, trial officer, research team lead, clinical research fellow or doctor and were asked to participate in the questionnaire arm of the study. At this point, the local recruiting team completed an enrolment log and women who agreed to participate signed a consent form. All women were informed that participation in the questionnaire arm of the study was entirely voluntary, with the option of withdrawing from the study at any stage. Women were also told that participation or non-participation in the study would not affect their clinical care. Ongoing consent was reconfirmed at every clinical follow-up visit, if applicable, and at any time that the research team made contact with the participating women.

Clinical outcomes in EPAUs

All women who attended the participating EPAUs were included in this data strand. Clinical follow-up of women was organised by the local clinical team based on clinical need; no additional clinical follow-up visits were arranged for the VESPA study.

Emergency hospital care audit

All participating sites were asked to provide data for this data strand.

Patient satisfaction

Women who attended the participating EPAUs and had consented to participate in the questionnaire arm of the study were recruited in this data strand.

Staff satisfaction

Staff (including the principal investigators) were approached by the local research teams and provided with a PIL. A limit of 15 consented members of staff was set per site. If staff members had agreed to take part in the survey they were asked to sign the designated consent form with the consenting member of the local research team. Only staff working at the participating EPAUs during the period of patient recruitment were approached.

Qualitative interviews

Women who attended the participating EPAUs and who had consented to participate in the questionnaire arm of the study were recruited in this data strand. Recruitment began by contacting women who had rare pregnancy outcomes (i.e. molar pregnancies, ectopic pregnancies, terminations) as these accounted for the smallest proportion of women in the VESPA study overall, and it was anticipated that these participants would be the most difficult to recruit. Women who had experienced miscarriages were also contacted, as were women who had ongoing pregnancies. The method of recruitment was determined by the contact details we had for each participant and, therefore, a combination of first contact by e-mail (preferred) or letter, followed by telephone calls, was used.

Health economic evaluation

Women who attended the participating EPAUs and who had consented to participate in the questionnaire arm of the study were recruited to this data strand.

Workforce analysis

All women who attended the participating EPAUs were included into this data strand.

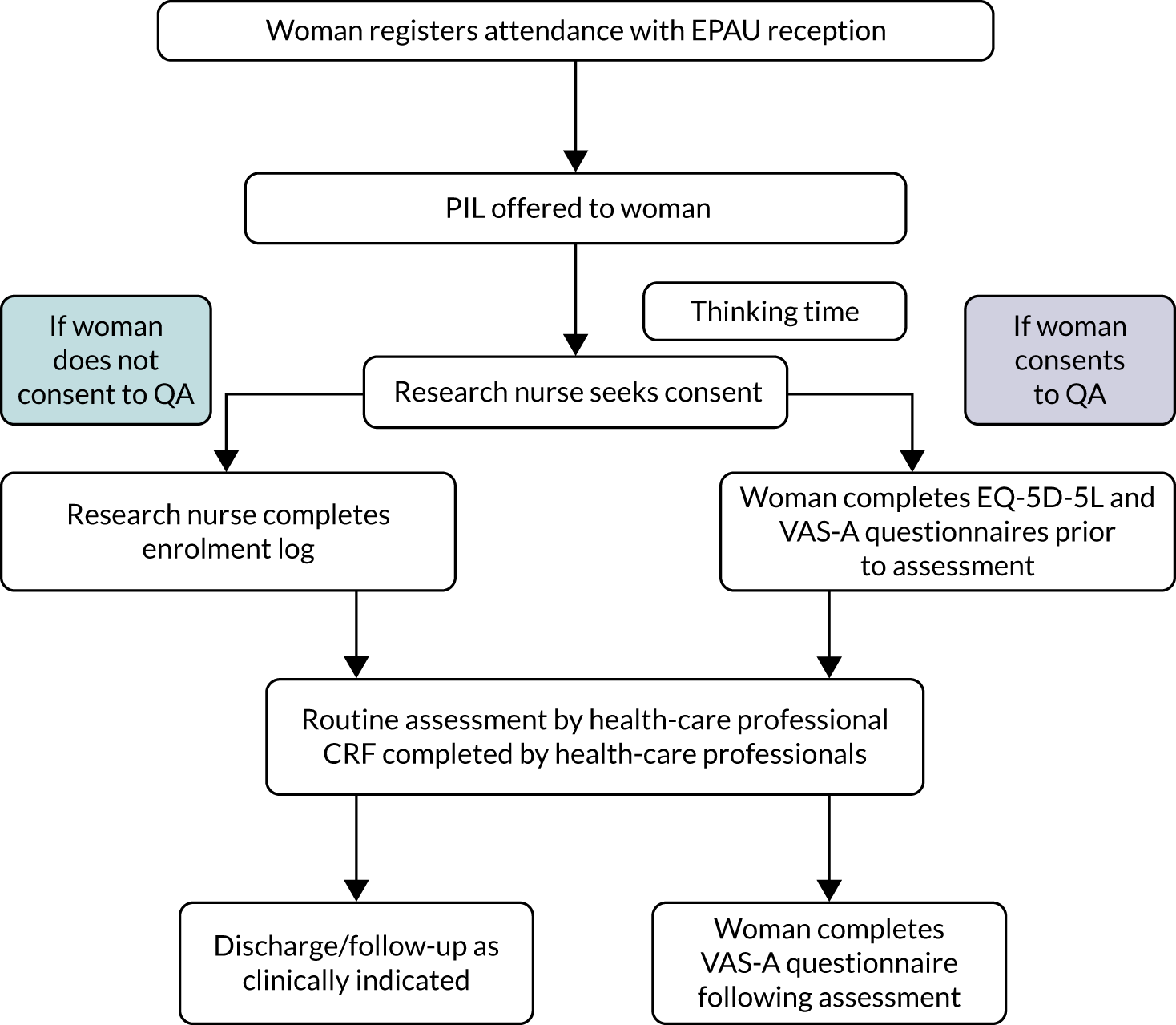

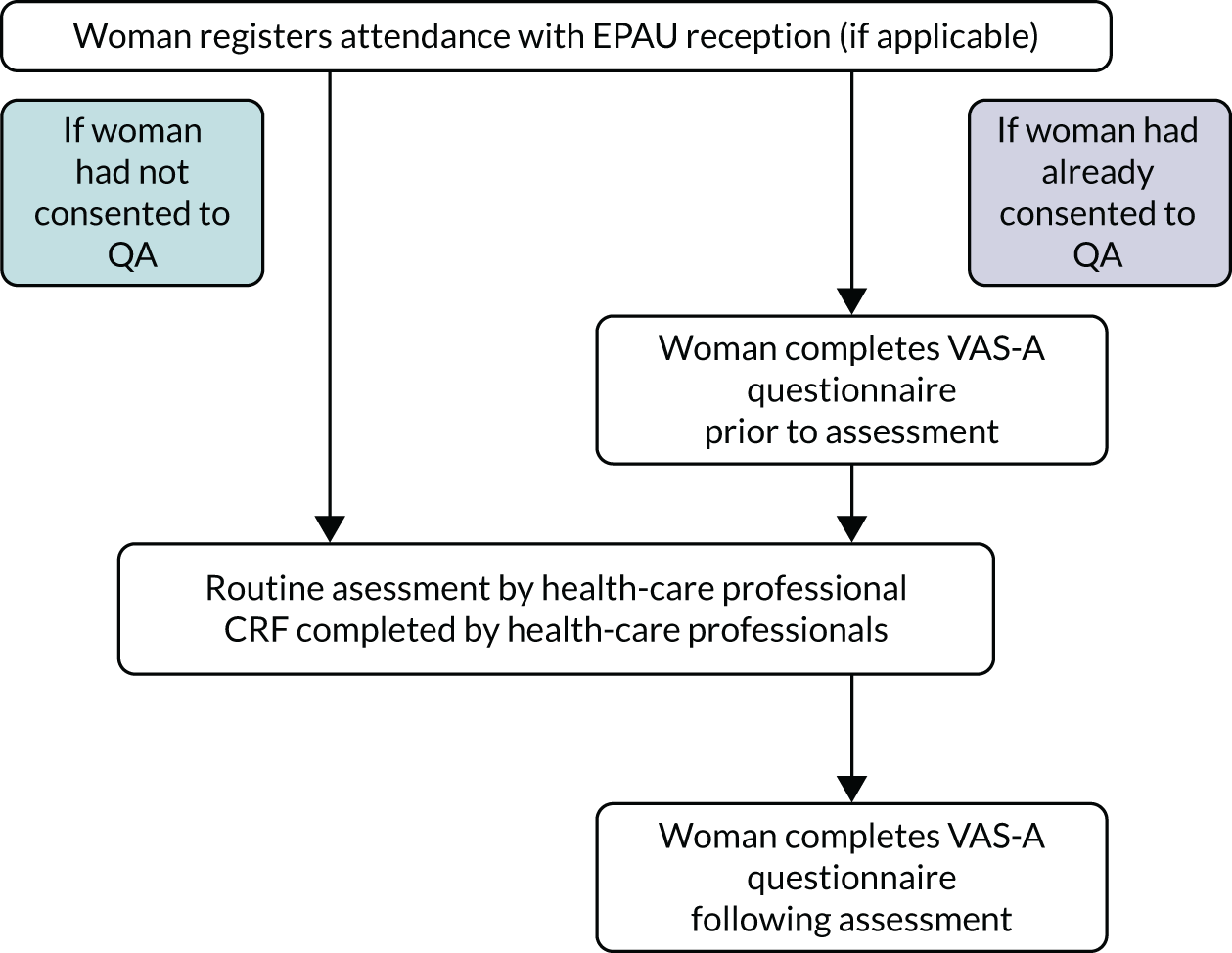

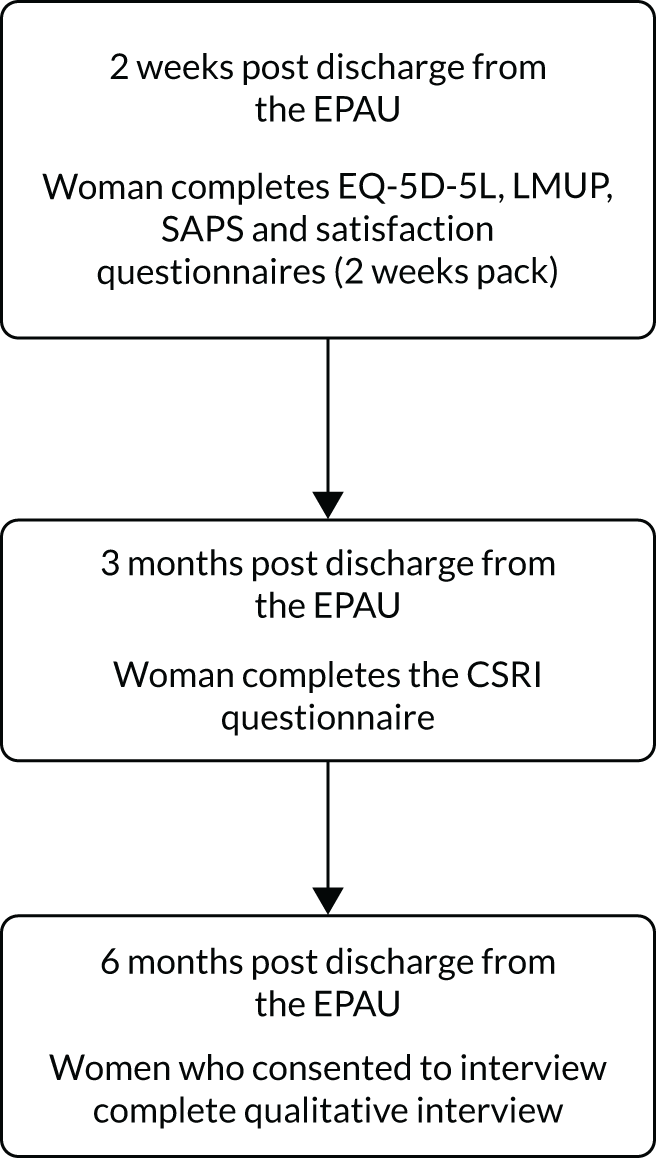

Diagrammatic representations of the journeys that women may have followed are shown in Figures 2–4. Figure 2 shows the journey of women at the initial visit, Figure 3 shows the potential journey of women at clinical follow-up visits and Figure 4 shows the journey of women following discharge from the EPAU.

FIGURE 2.

Journey of women at initial visit. CRF, case report form; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version; QA, questionnaire arm of the study; VAS-A, visual analogue anxiety scale.

FIGURE 3.

Journey of women at clinical follow-up visits (if applicable). CRF, case report form; QA, questionnaire arm of the study; VAS-A, visual analogue anxiety scale.

FIGURE 4.

Journey of women following discharge from the EPAU. CSRI, Client Service Receipt Inventory; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version; LMUP, London Measure of Unplanned Pregnancy.

Data collection

Demographic and routine clinical data were collected from all women attending the EPAUs. For women who provided consent to complete the questionnaires, clinical data and questionnaires were linked using the woman’s study number. The clinical data from women who did not consent were anonymised, and the data collection forms containing any identifiable data remained on the individual hospital premises and were archived locally following the end of the study.

Clinical outcomes in EPAUs

Demographic and routine clinical data were collected from all women attending the EPAUs [see case report form (CRF), URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/140441/#/ (accessed 2 June 2020)]. It was designed by the study team based on the CRF used for the pilot study, and modified in accordance with the feedback provided by the researchers and clinical staff who conducted the pilot study. All participating sites were provided with paper CRFs; however, the CRFs were also available online on the secure VESPA study website, hosted by MedSciNet (London, UK), in case sites opted to use the online version. CRFs were uploaded to the secure VESPA study website by a member of the local research team, either concurrently or retrospectively.

Emergency hospital care audit

Data for this data strand were collected following collaboration with the information services departments in participating hospitals to retrieve already collected data (from routine hospital systems). We collected data about the total number of A&E attendances for pregnant women under 14 weeks’ gestation. We also asked for data about the total number of emergency admissions, emergency operations and their outcomes, the number of women receiving blood transfusions and the number of admissions to intensive care units. Wherever possible, all data relating to hospital admissions that were provided by the information services departments were cross-checked by the site principal investigator or the lead local researcher, with support from a member of the central VESPA study research team, against ward admission books/databases, to ensure the accuracy of the data obtained.

The aim of the audit was to capture emergency activities of the hospital with regard to early pregnancy care, looking at A&E attendances for women in early pregnancy and emergency admissions (from A&E and other settings, e.g. outpatient clinics). The time frame covered at each unit was set at 3 months. The data were collected retrospectively, with the end of the 3-month period corresponding to the date when the last woman recruited to the clinical outcome data strand was discharged from EPAU care. The central team contacted the local research teams as soon as the last follow-up visit was established. The teams were provided with a Microsoft Excel® file and a Microsoft Word® document (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The documents listed the criteria to be included in the data set and showed the model search that was conducted at the host site as an example of the methodology for extracting the data.

Patient satisfaction

Women who consented to this arm of the study were asked to complete the SAPS27 measure, as well as a condition-specific patient satisfaction questionnaire (i.e. the modified Newcastle–Farnworth Questionnaire) [see modified Newcastle–Farnworth questionnaire, URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/140441/#/ (accessed 2 June 2020)] and the London Measure of Unplanned Pregnancy (LMUP)28 at 2 weeks post discharge from the EPAU. The SAPS questionnaire was chosen as it is a short, validated, well-established measure of patient satisfaction of hospital care. However, as it is generic and applicable across disciplines, it was supplemented by a pregnancy-specific measure. Given that a validated satisfaction questionnaire specific to early pregnancy care was not available, we modified and used, with permission from the key researcher, the ‘Patient Satisfaction Survey’ that was developed by Allison Farnworth and the team at Newcastle University as part of a Knowledge Transfer Partnership review of the Early Pregnancy Care Policy. The original questionnaire is specific to women who have experienced a miscarriage. The modified Newcastle–Farnworth questionnaire was developed by the co-investigators of the VESPA study for women who had been reviewed in EPAUs, irrespective of clinical outcome. As it is not a validated measure, the score was calculated as the average of the individual component scores. The LMUP, a short, validated measure, was used to define unplanned pregnancies and control for patient satisfaction (as there is emerging evidence that women with unplanned pregnancies report different levels of satisfaction with health-care services). Following careful consideration by the VESPA co-investigators and after consultation with women, through our links with the Miscarriage Association and The Ectopic Pregnancy Trust, the timing of the questionnaire was set at 2 weeks.

Staff satisfaction

Eligible members of staff who had consented were asked to complete a confidential and anonymous online shortened version of the standard NHS staff satisfaction survey. 29 We contacted Picker (Oxford, UK) to obtain permission prior to use; however, it was confirmed that, as the survey was intended for use for an NHS study, additional permissions were not required. To the best of our knowledge, the annual NHS staff satisfaction survey is the largest survey of staff opinion in the UK. The survey gathers views on staff experience at work and includes key areas such as (1) appraisal and development, (2) health and well-being, (3) staff engagement and involvement and (4) raising concerns. The VESPA study staff survey was based on the 2015 NHS staff survey [see VESPA staff survey, URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/140441/#/ (accessed 2 June 2020)]. Once valid consent was obtained and the designated consent form signed, the local research team would securely e-mail the central VESPA study e-mail account with the e-mail address of each consenting member of staff. The central team set up accounts for each staff member to complete the survey online, on the MedSciNet database system, and sent login details to the staff members individually. Sites had the option to complete the surveys on paper and return them by post to the central VESPA study office, where the responses were uploaded by the central team onto the database and the paper forms were disposed of in a confidential manner.

Qualitative interviews

As soon as fully informed consent was obtained, interviews were conducted with 39 participants over the telephone. The interviews lasted between 20 and 78 minutes. Participants were asked a series of questions as per the topic guide [see topic guide URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/140441/#/ (accessed 2 June 2020)], relating to the beginning of their pregnancy, their experience of attending the EPAU, their care following discharge from the EPAU, and their suggestions to improve quality of care and women’s experiences of the EPAU.

Two particular research questions were highlighted for this investigation:

-

How do women’s experiences of EPAU services vary by unit configuration?

-

How do women’s experiences of EPAU services vary by clinical outcome?

Health economic evaluation

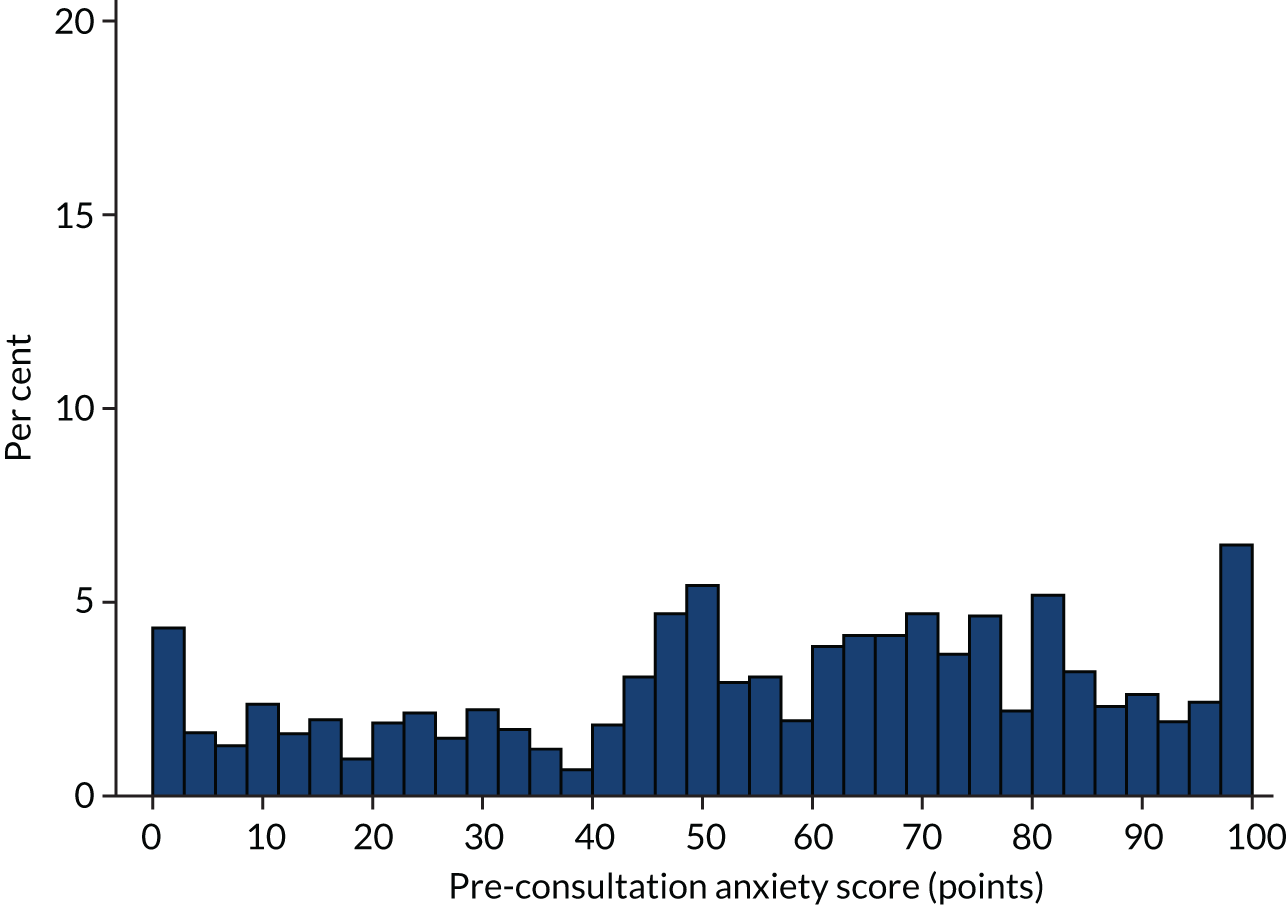

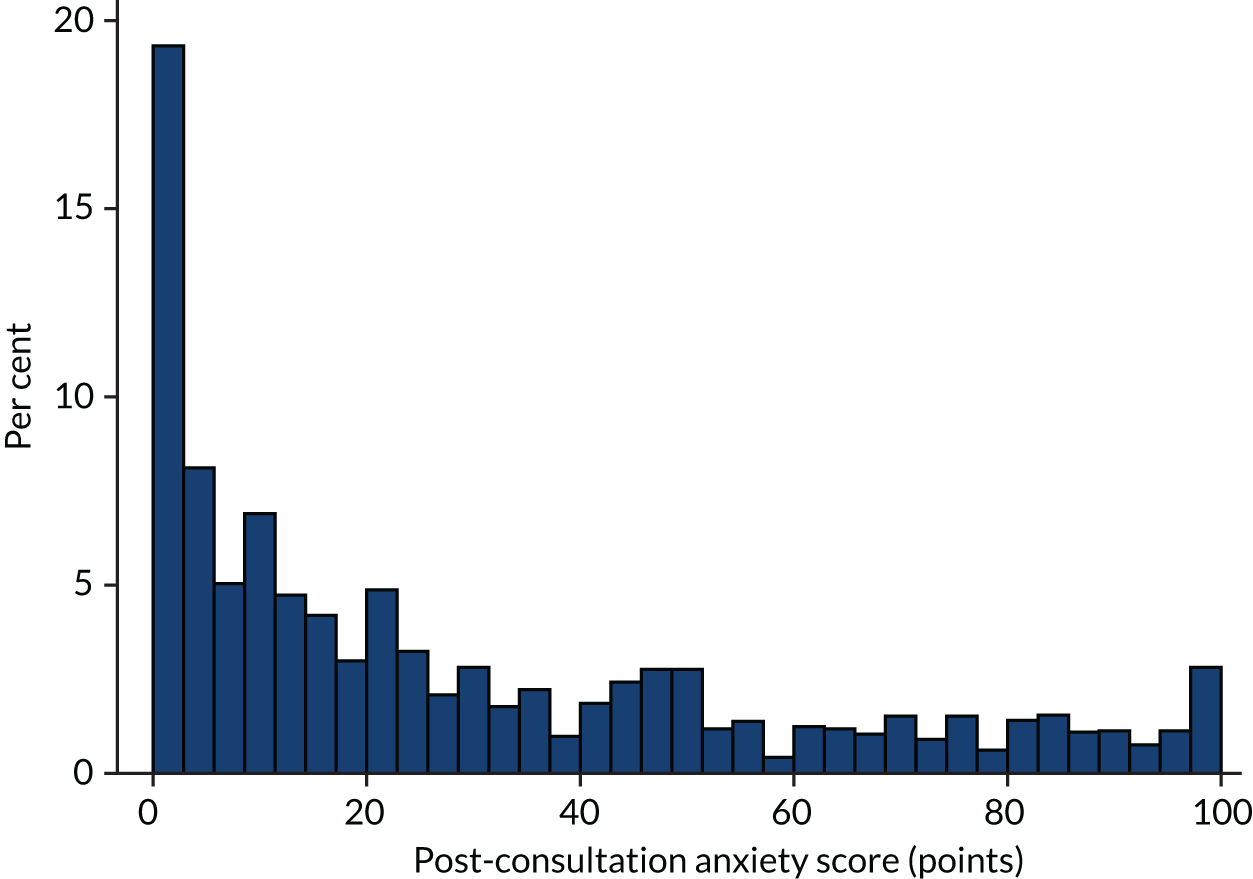

Data were collected at up to three time points during the study. Quality-of-life [EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)30] data were captured before the consultation at the initial visit and then at two time points post discharge from the EPAU (planned at 2 and 12 weeks, but actually at 4 and 18 weeks; see Chapter 3 for clarification). Anxiety data were collected prior to clinical assessment for every visit (whether initial or clinical follow-up visit) using the visual analogue anxiety scale. 31 Patients also completed the same scale at the end of every visit. Data on resource use during visits (e.g. staff contacts, diagnostic tests) were collected as part of the study CRF. Data on additional resources used after the visit were collected from a sample of patients at a planned time point of 3 months.

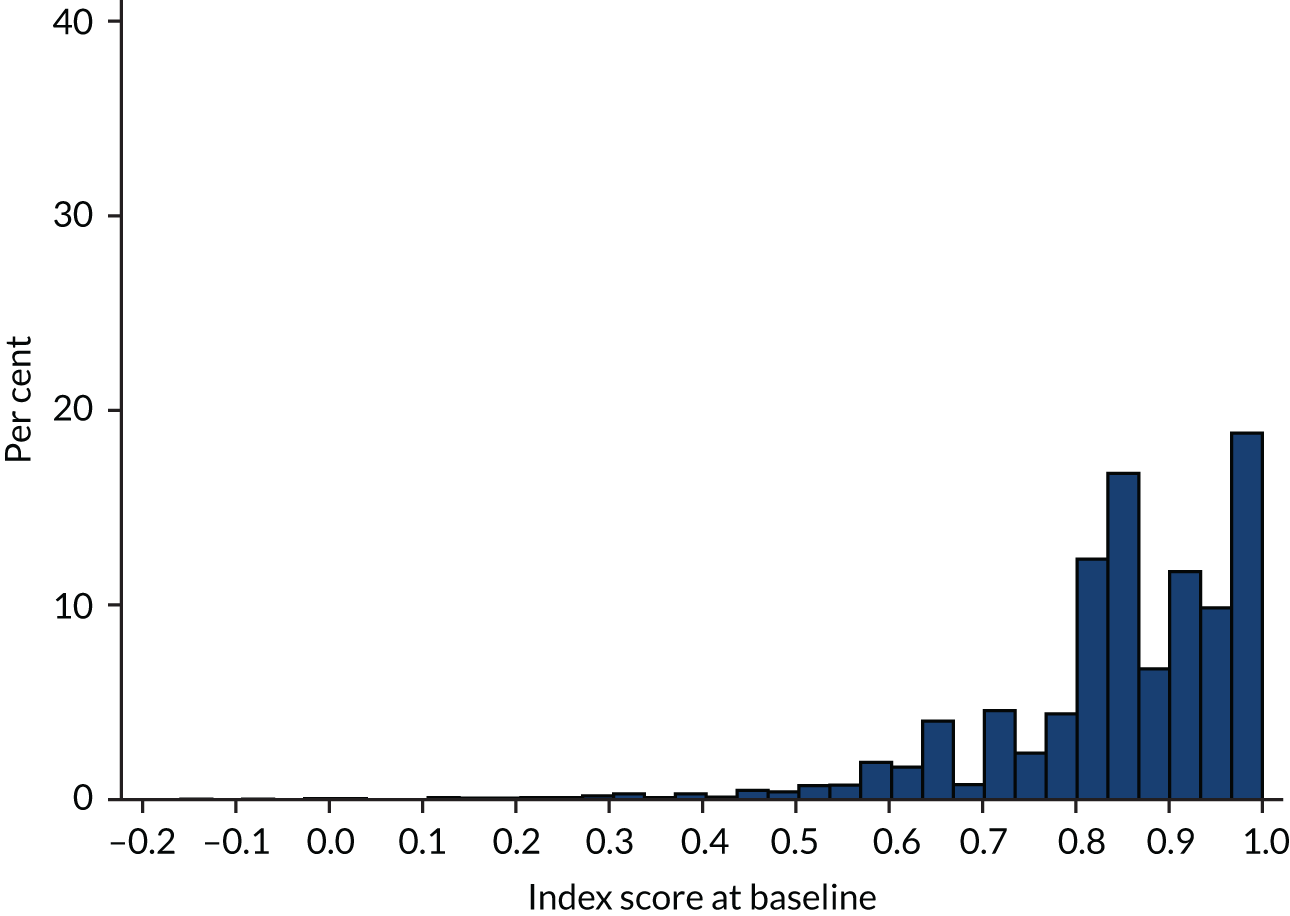

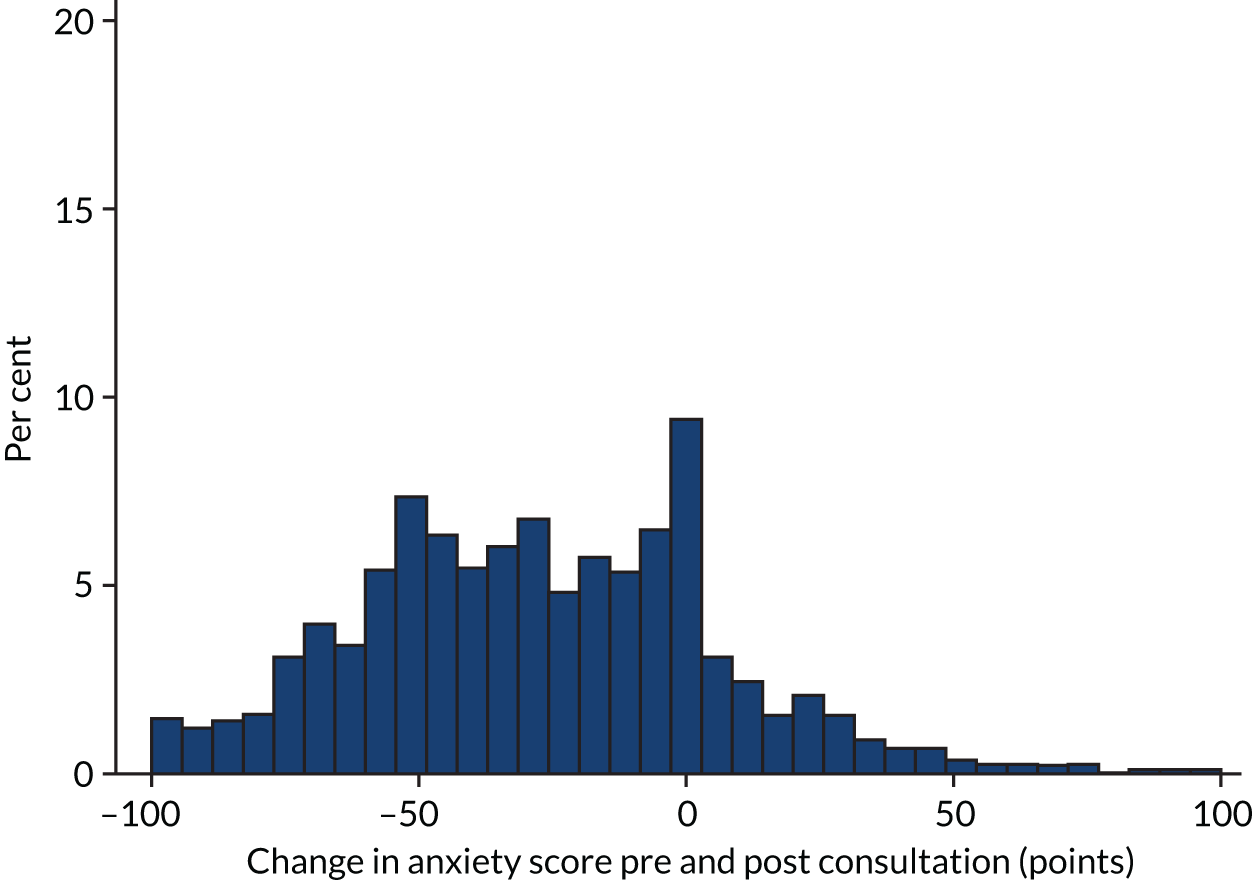

Health outcomes

Outcomes collected and analysed for the economic analysis included quality of life and anxiety. Quality of life was measured using the EQ-5D-5L at baseline in all eligible patients and at two follow-up time points in a subset of patients. This questionnaire asks patients to score their own health based on five dimensions: (1) mobility, (2) self-care, (3) usual activities, (4) pain/discomfort and (5) anxiety/depression. Each dimension has five levels: (1) no problems, (2) slight problems, (3) moderate problems, (4) severe problems and (5) extreme problems. This decision results in a five-digit number that is converted into a number between 0 (equivalent to death) and 1 (full health) and expresses the patient’s self-reported health at each time point. The replies were then converted to an index score using the value set for England reported by Devlin et al. 32 Index scores were in turn, used to calculate quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). Anxiety data were collected using the visual analogue anxiety scale, as described above. Patients were asked to indicate how anxious they felt at that moment on a line with marks going from 0 to 100, with a mark at the extreme left indicating not at all anxious and a mark at the extreme right indicating that they were the most anxious they could ever imagine. Pre- and post-assessment scores were then compared.

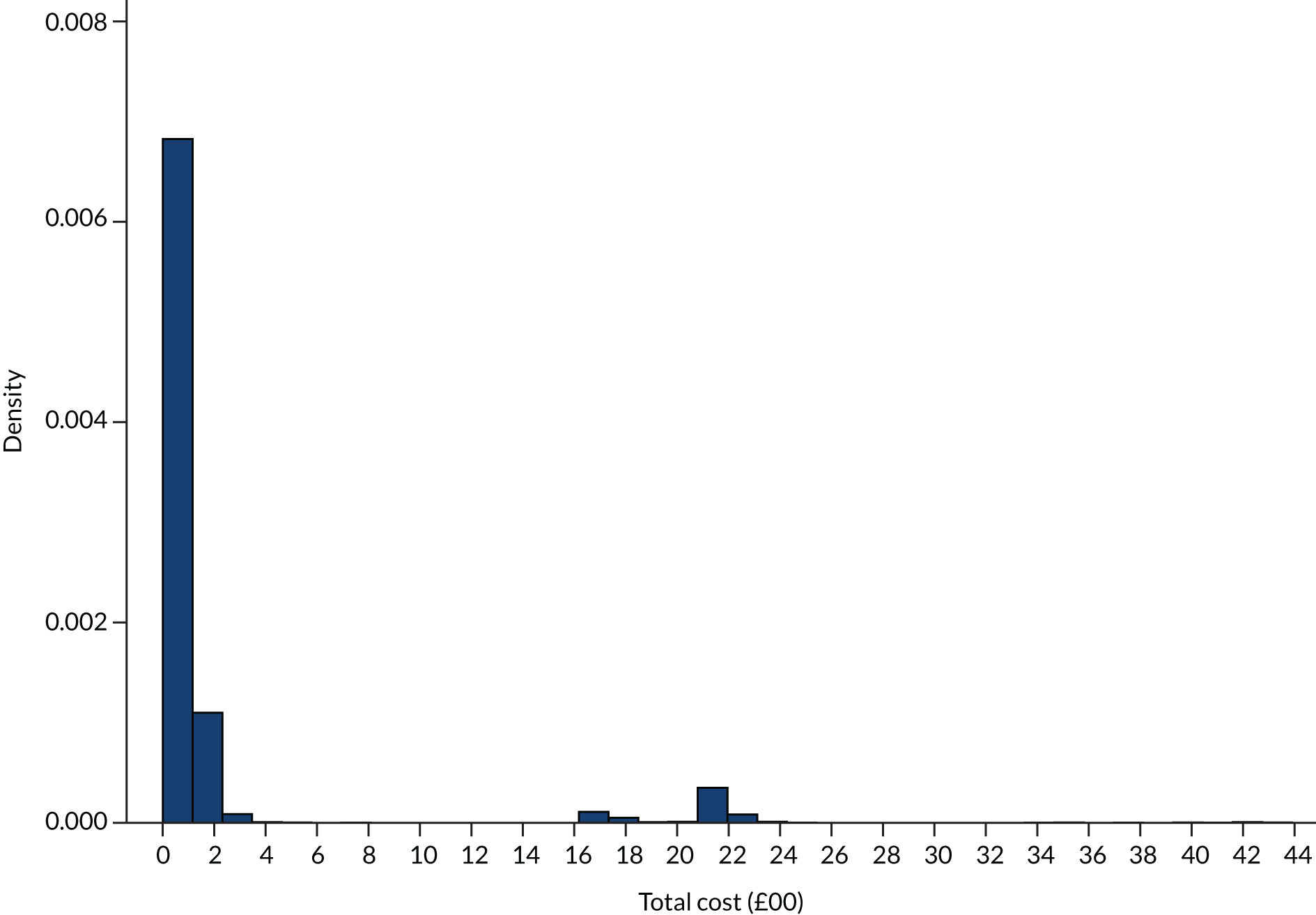

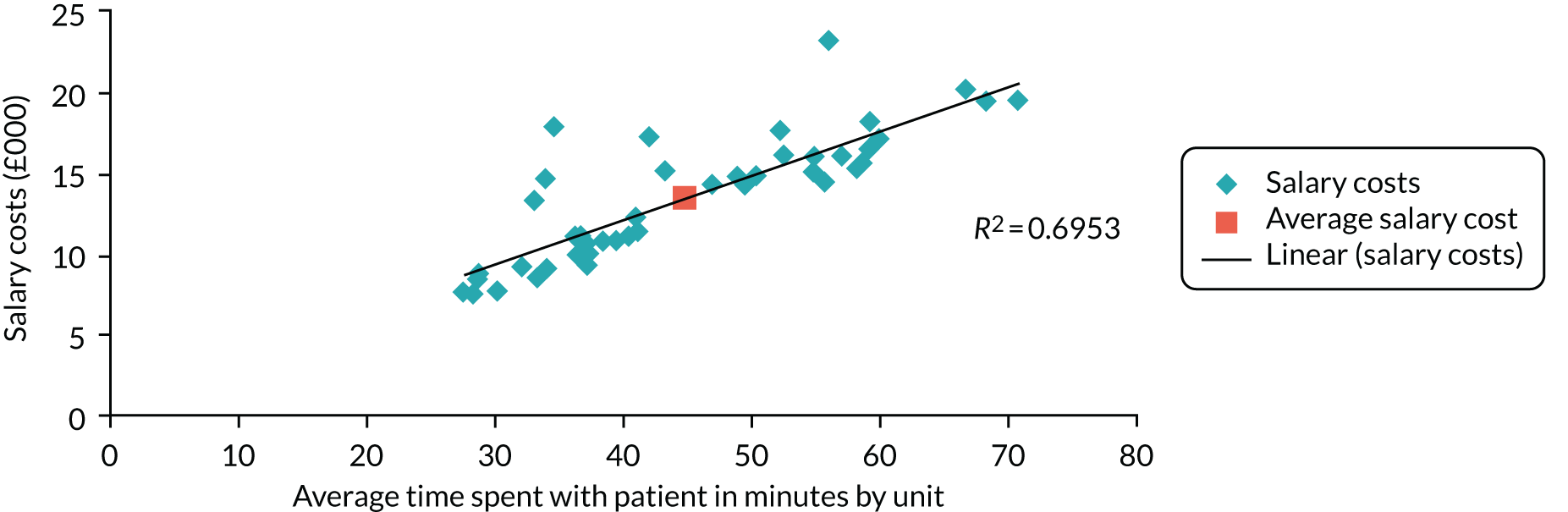

Resource use and costs

Data were captured on resource use relating to EPAU visits. Resource use during the visit(s) included staff contact time, blood tests ordered, ultrasounds conducted and admissions for surgery or observation. Staff costs were taken from the workforce analysis. This provided an exact salary cost for each patient based on the salary cost of the staff who provided care and assistance to that patient during their EPAU appointment(s). The entire care pathway of each patient was analysed.

The unit cost of an ultrasound associated with an EPAU visit was estimated by the finance team at University College Hospital, London, as £49.21. The cost of a blood test was based on a study by Czoski-Murray et al. 33 and the cost of admissions for surgery or observation was taken from the NHS Reference Costs 2016–17. 34 See Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 4, for the sources for the costs used in the primary analysis.

For the analysis of self-reported health-care usage costs at follow-up, cost estimates were taken from the Unit Costs of Health and Social Care provided by the Personal Social Services Research Unit. 35

Workforce analysis

Data for this data strand were collected as part of the study CRF. All members of staff, including administrative and clinical staff, who had contact with women attending the early pregnancy service were asked to record the type of interaction, the start and end time of their interaction, as well as their staff type. The duration of the interaction was then calculated and recorded on the study database at the time of uploading the CRF information to the VESPA study database.

Summary of data collection methodology

See Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 5, for a summary of the data collection tools used to collect data from the different data strands, the sources and the planned timings of data collection.

Data analysis and reporting of results

Clinical outcomes in EPAUs

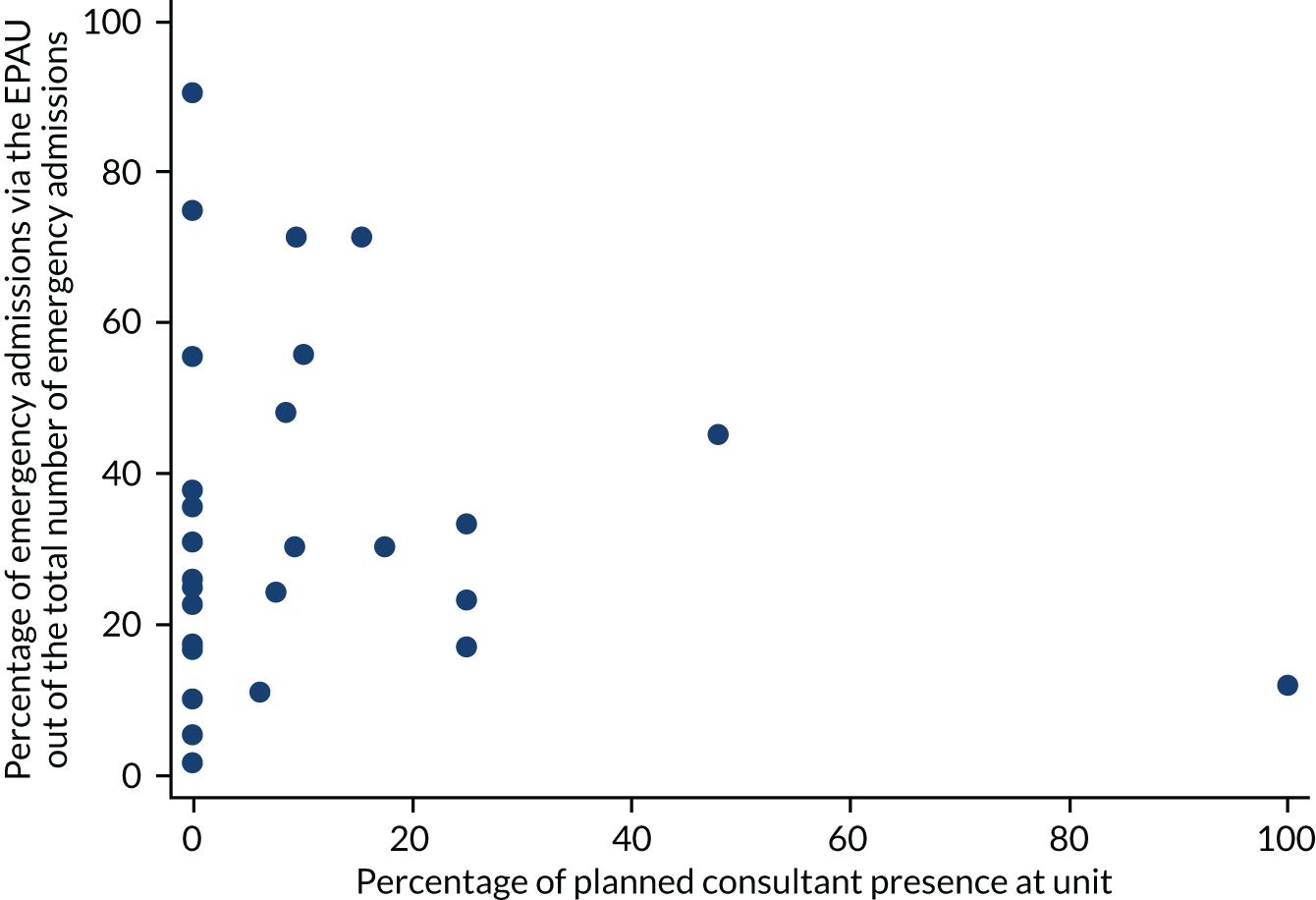

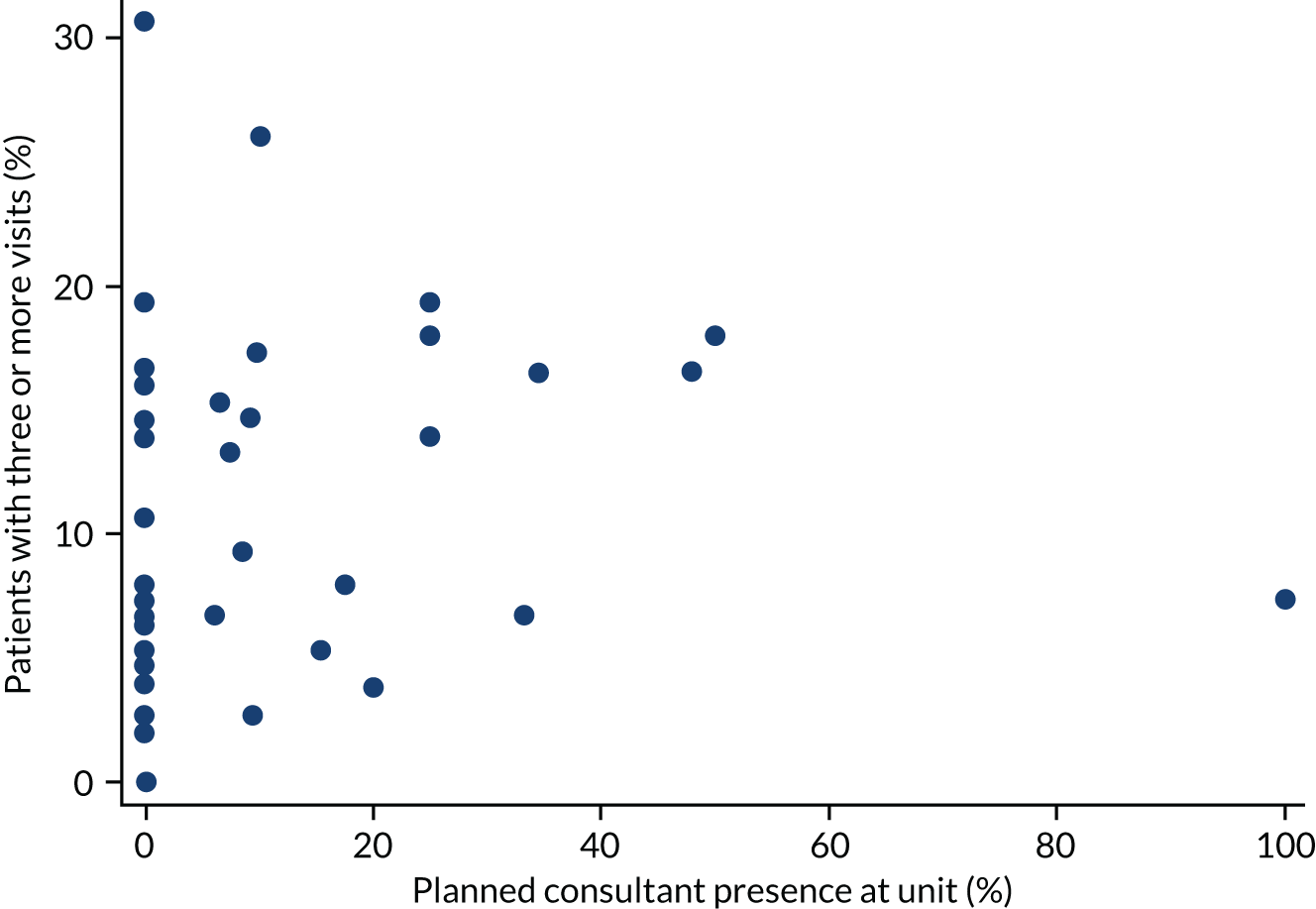

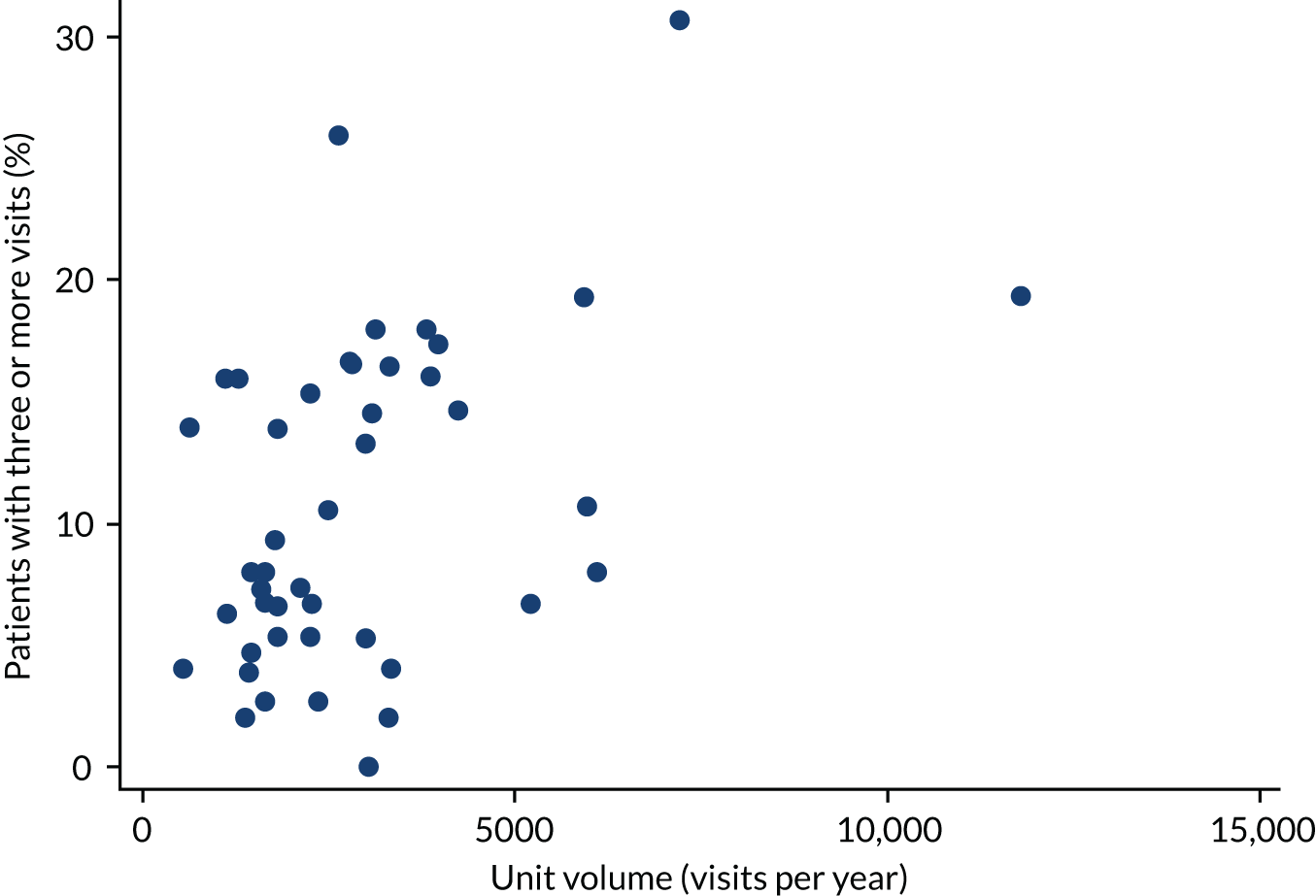

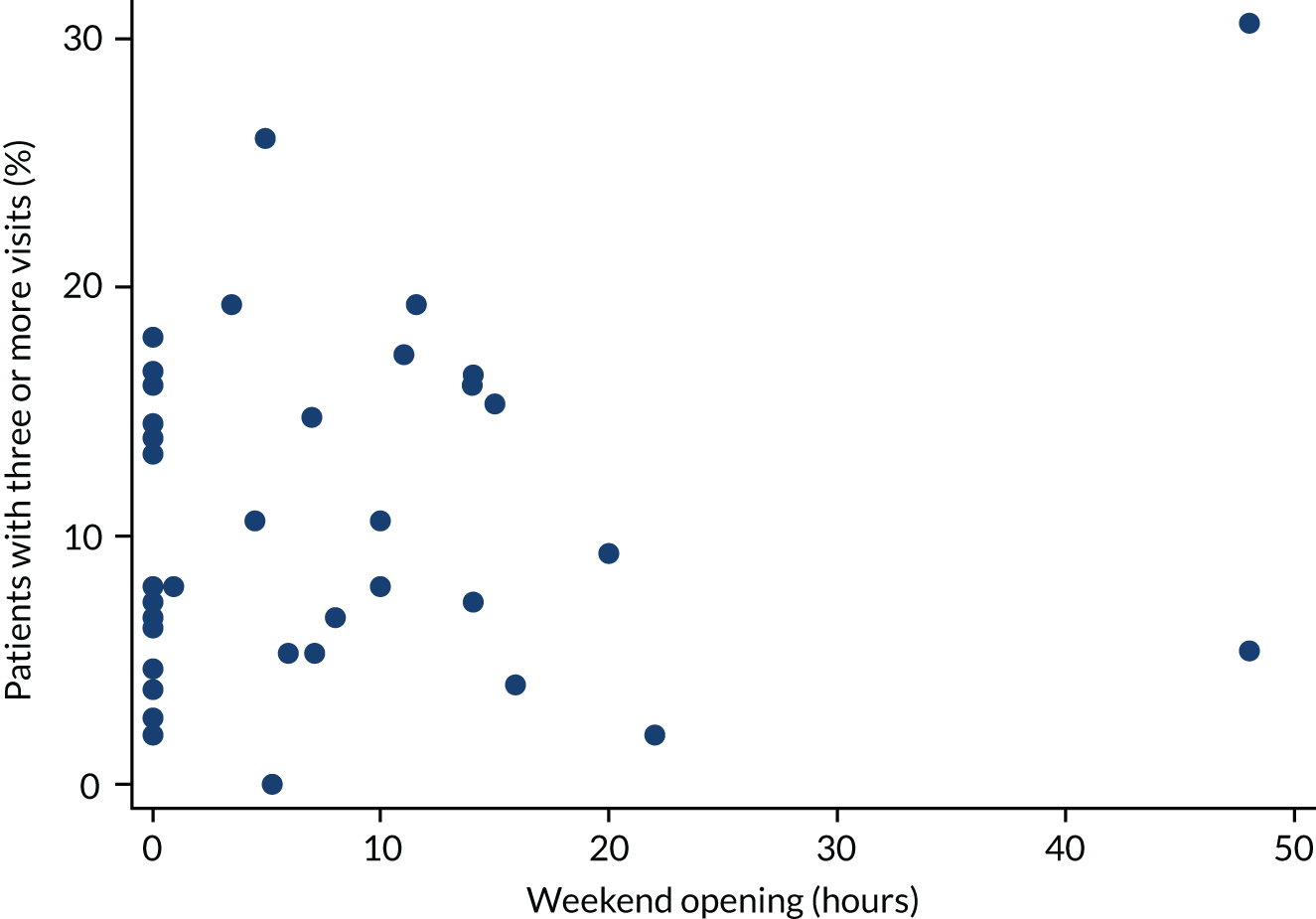

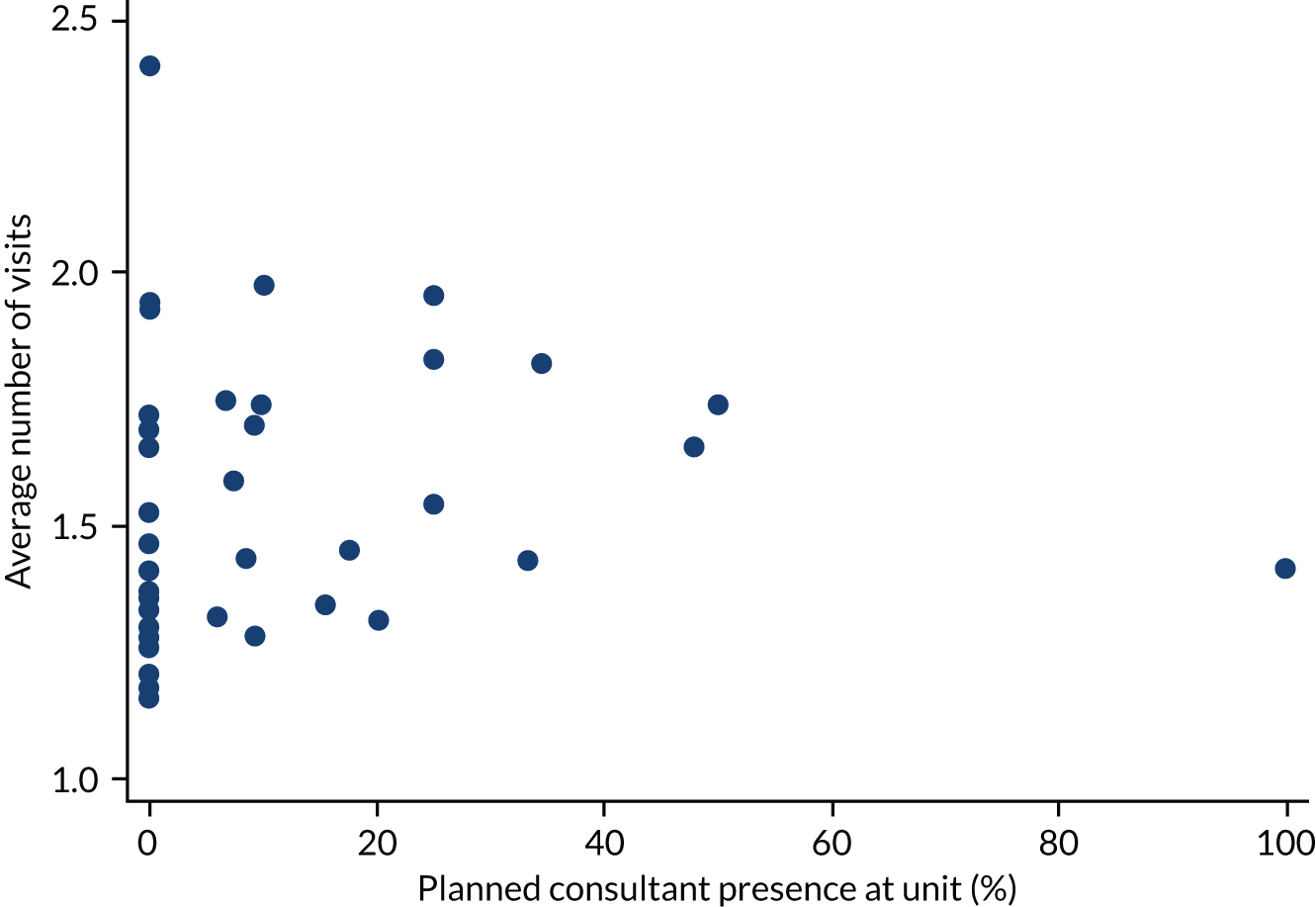

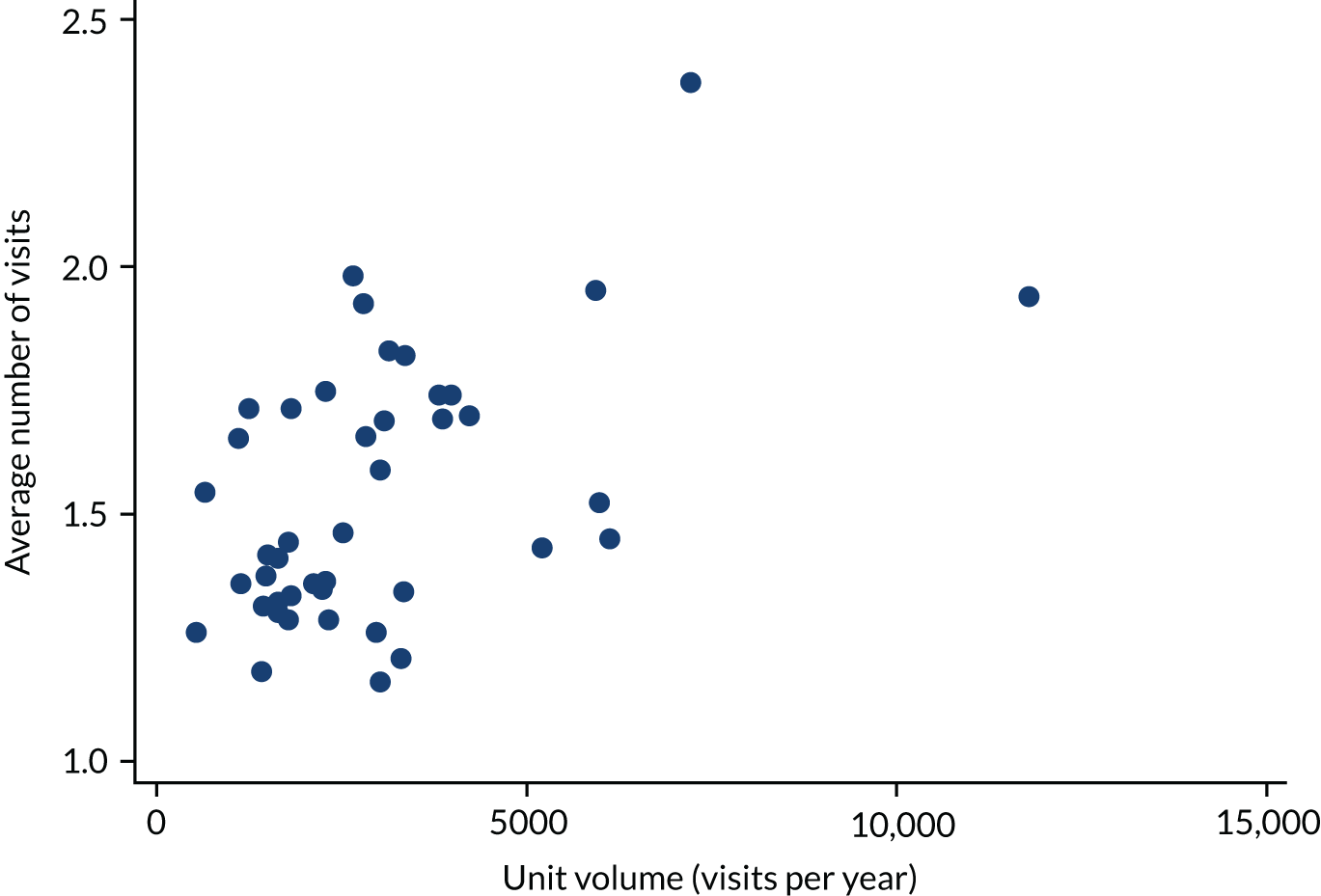

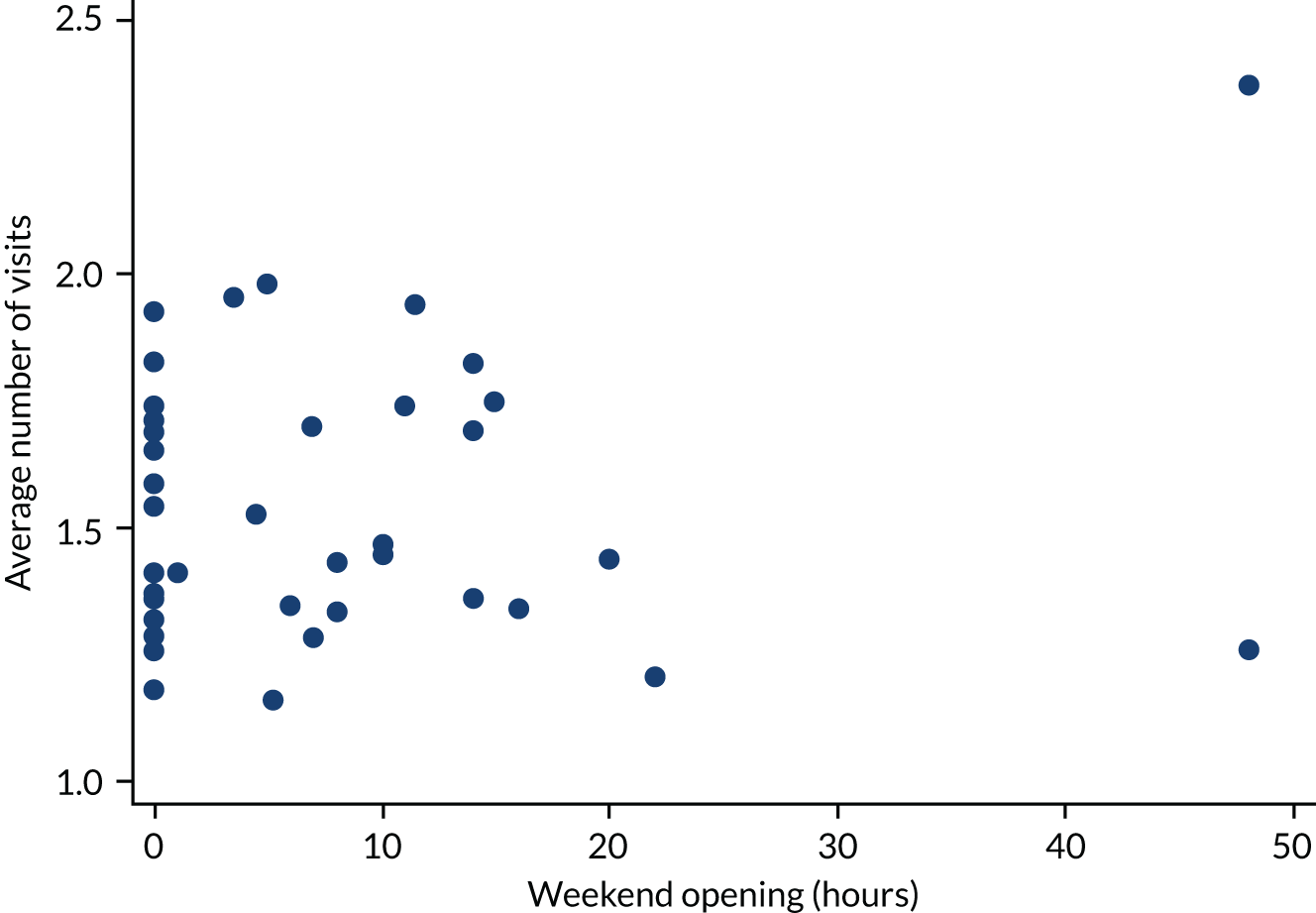

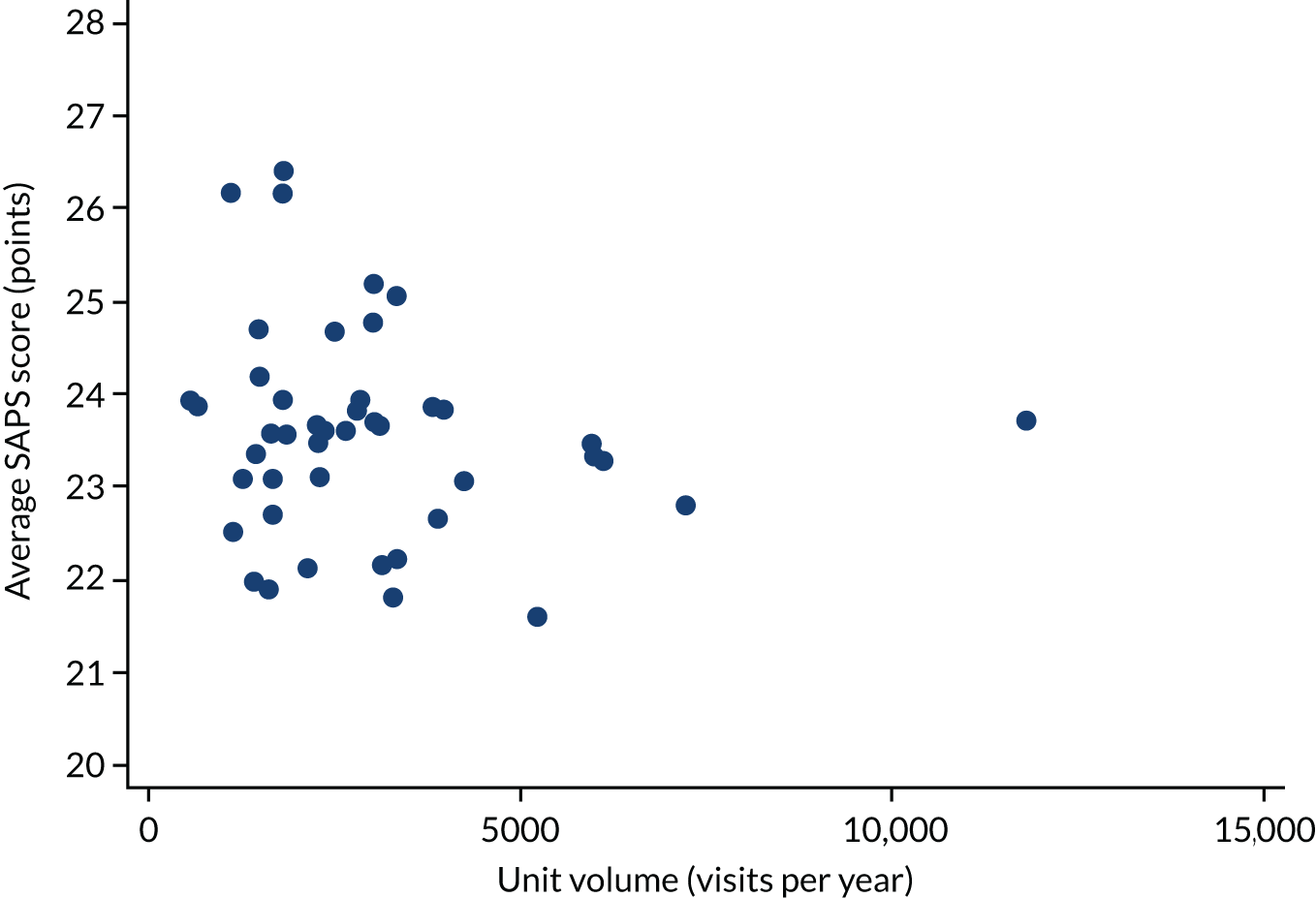

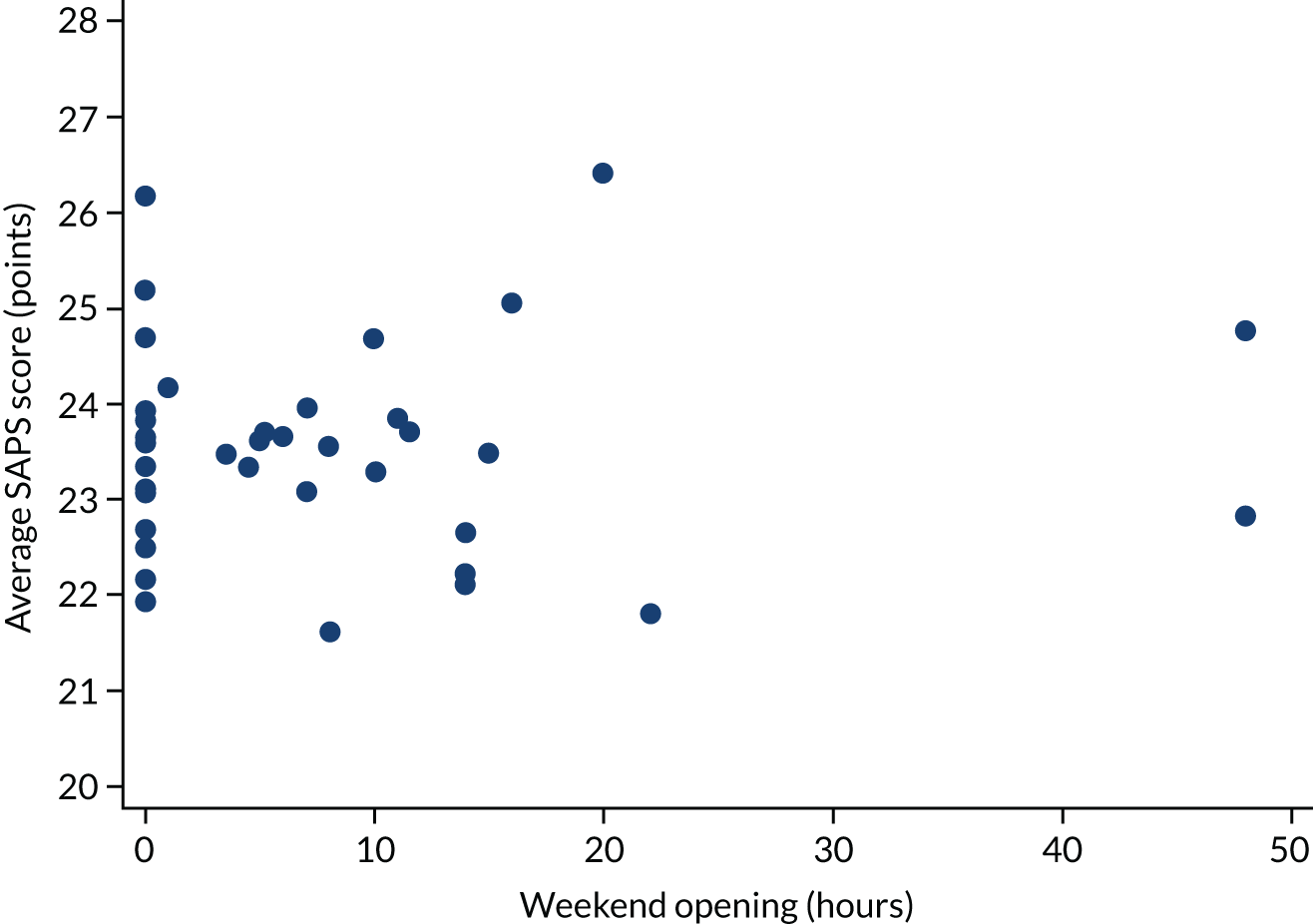

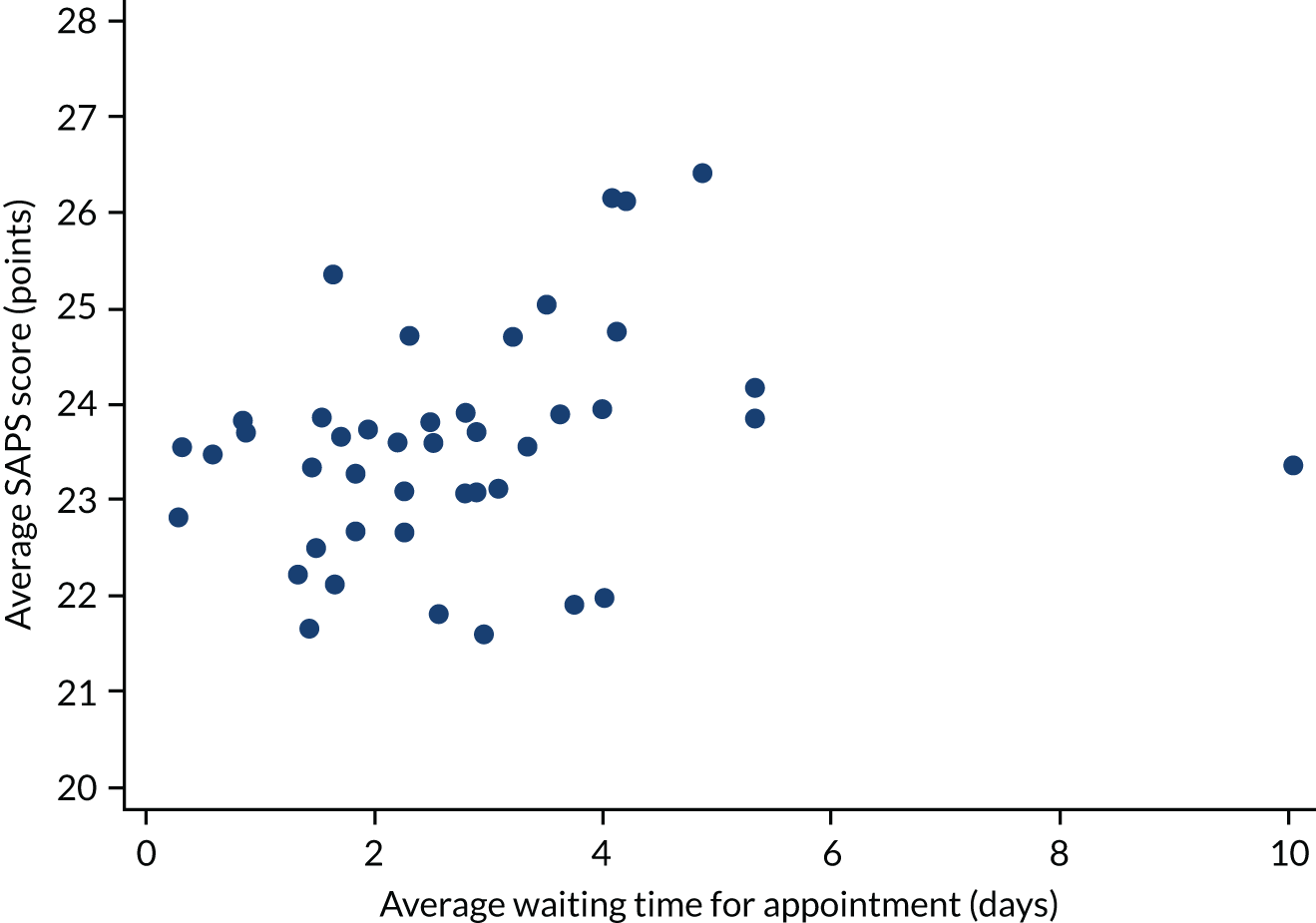

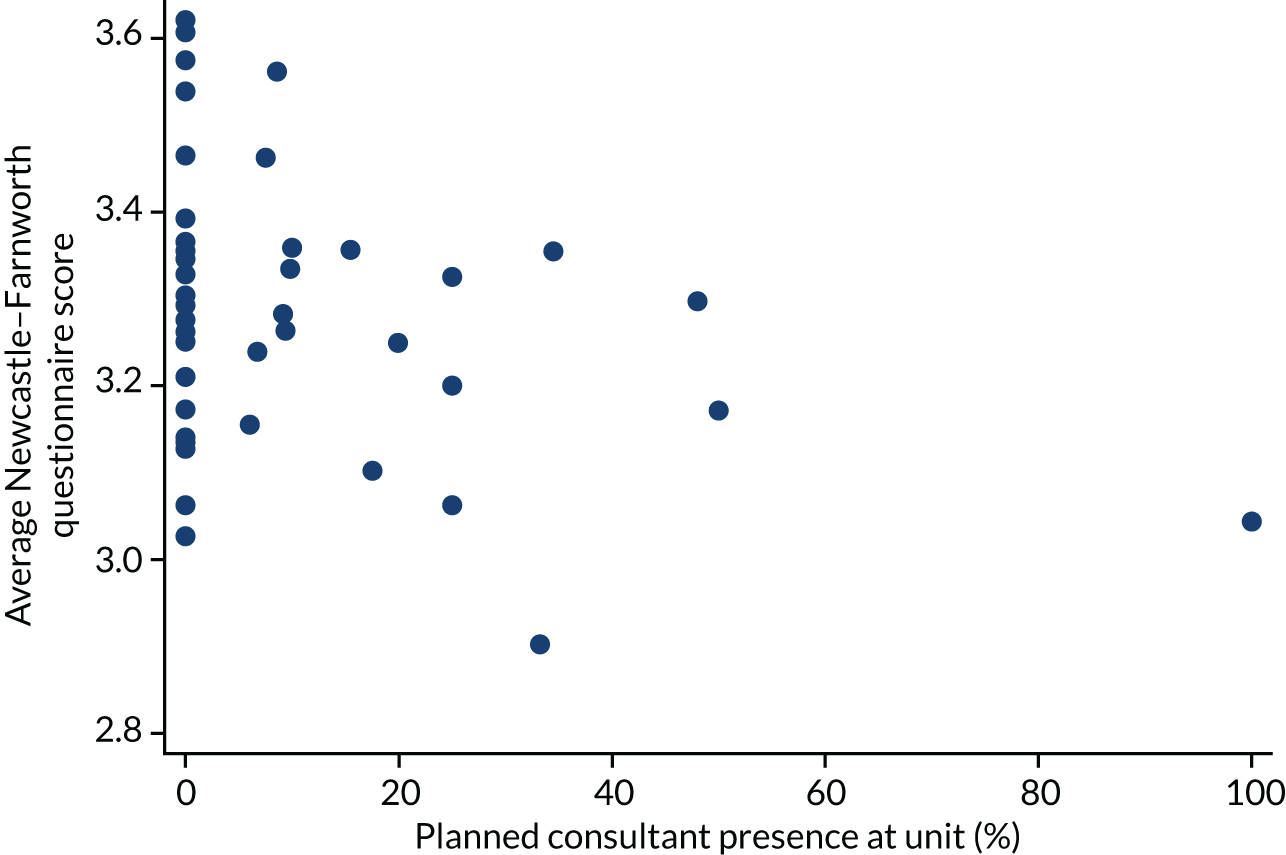

We investigated the relationship between outcomes and consultant presence, unit volume and weekend opening hours using appropriate regression models (i.e. linear models for continuous outcomes, logistic models for binary outcomes and Poisson models for count outcomes). Hierarchical models were used when analysing patient-level data. Unit-level data were analysed using standard regression models.

Consultant presence was defined as the percentage of planned hours which consultants were expected to spend in the unit divided by the planned opening hours. We also defined a binary variable indicating planned consultant presence (yes/no), which was used in sensitivity analyses.

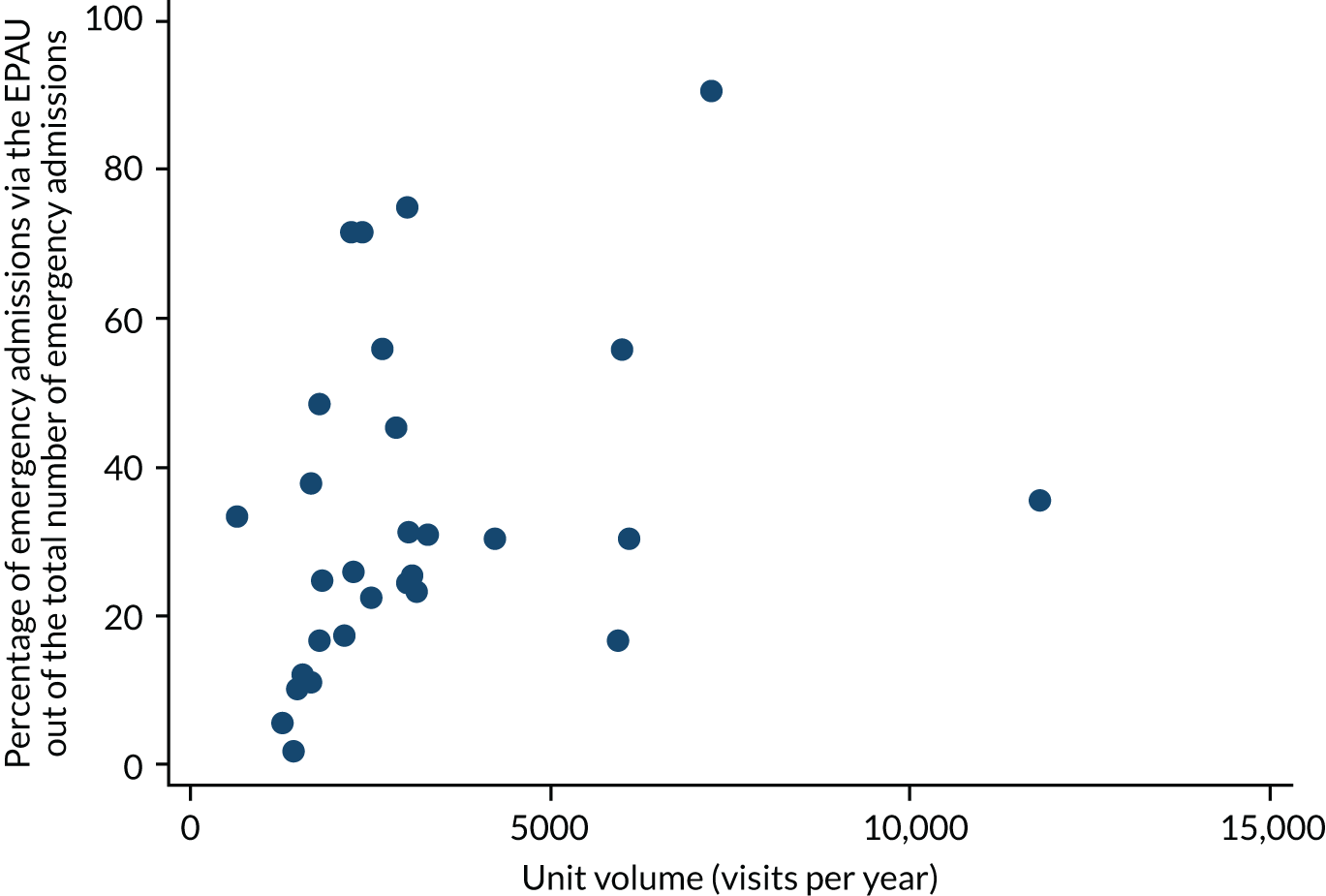

Volume was defined as the number of patient visits per year and was estimated using the time taken to obtain data on 150 patients and the average number of visits per patient. We also defined a binary variable indicating whether or not the yearly number of visits was greater than the median of 2500 (yes/no) for sensitivity analyses. This cut-off level was defined based on the data analysis, which showed that half of the EPAUs have a yearly visit volume of < 2500 visits per year.

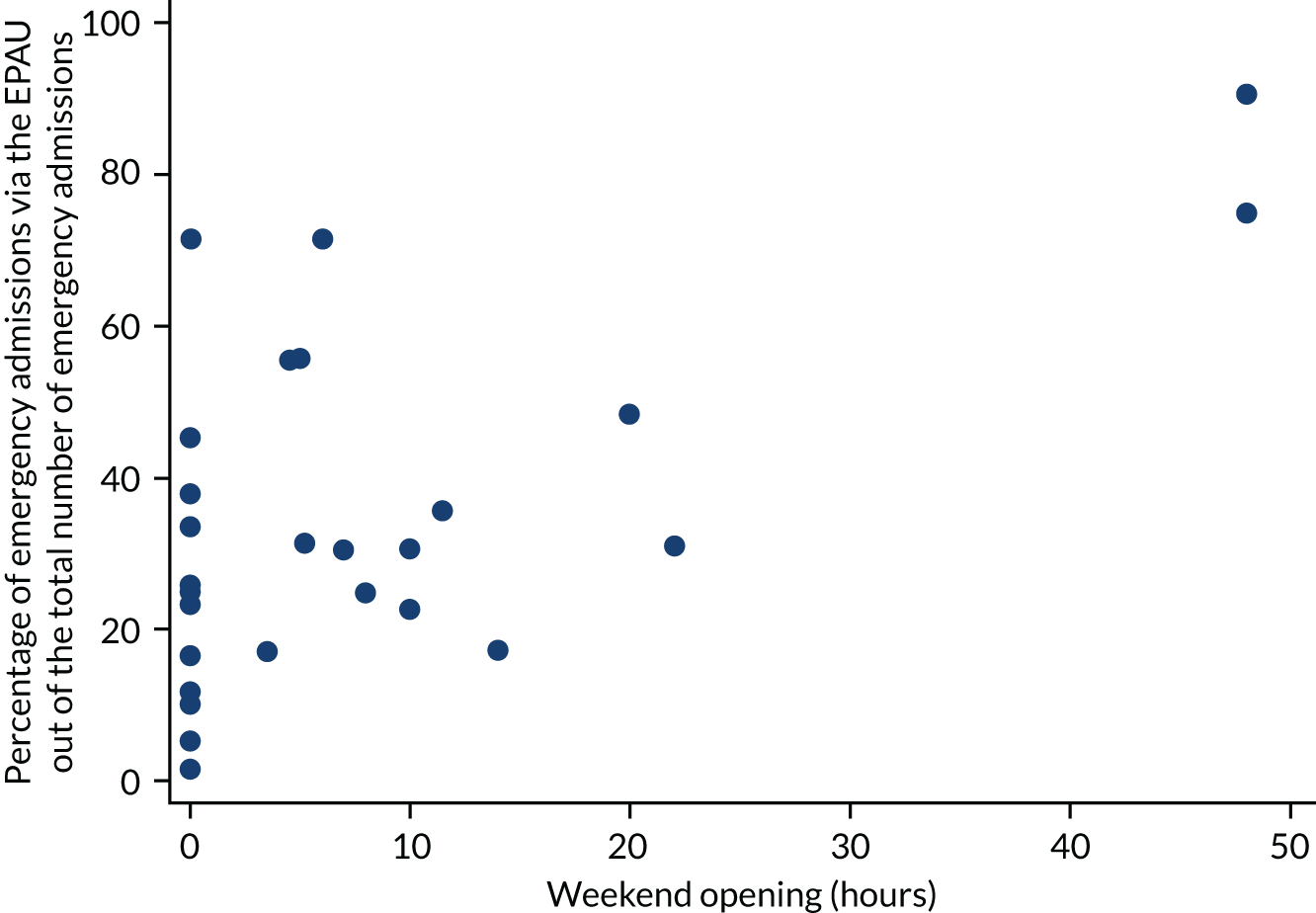

Weekend opening was defined as the total number of opening hours per weekend. We also defined a binary variable indicating whether or not an EPAU was open at weekends (yes/no). In addition, a three-level weekend opening variable was defined: no/Saturday, only/Saturday and Sunday. The latter variables were used for sensitivity analyses.

Most models were adjusted using two sets of potential confounder variables:

-

final diagnosis (FD) and maternal age at initial visit (MA)

-

FD, MA, deprivation score (DS) and Gestational Age Policy (GAP).

Two sets were used because the DS (10 decile groups) and GAP had a reasonable number of missing data. Analyses based on the first set are described first in each instance.

Most of the statistical models are adjusted for FD (five groups), MA, DS (10 decile groups) and GAP. The FD and GAP groups are defined as follows.

Final diagnosis (five groups):

-

early intrauterine and normal/live intrauterine pregnancy

-

early embryonic demise, incomplete miscarriage, complete miscarriage, retained products of conception

-

ectopic pregnancy

-

inconclusive scan

-

other (molar, twin, not pregnant, etc.).

Gestational Age Policy (two groups):

-

< 6 weeks

-

≥ 6 weeks.

The main analyses modelled consultant presence, unit volume and weekend opening hours using continuous variables. Sensitivity analyses were performed by replacing these continuous variables with the corresponding binary or categorical variables.

Emergency hospital care audit

The relationship between emergency admissions from A&E and consultant presence, unit volume and weekend opening hours was investigated by fitting multivariable logistic models. ‘Emergency admissions from A&E’ was defined as a binary outcome to indicate whether or not a patient had an emergency admission from A&E. Data from 29 EPAUs were used for this analysis. Models were either unadjusted or adjusted for GAP.

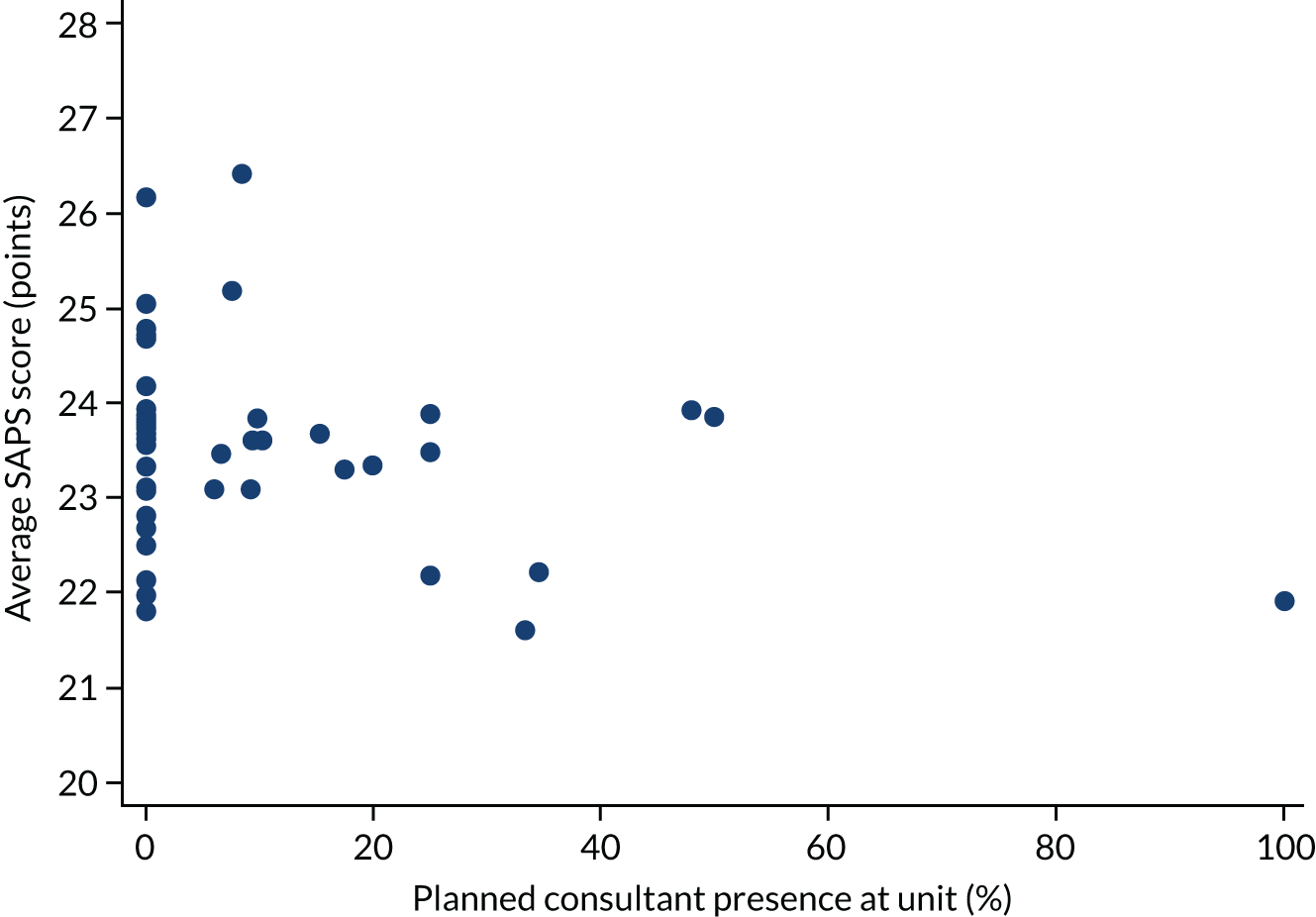

Patient satisfaction

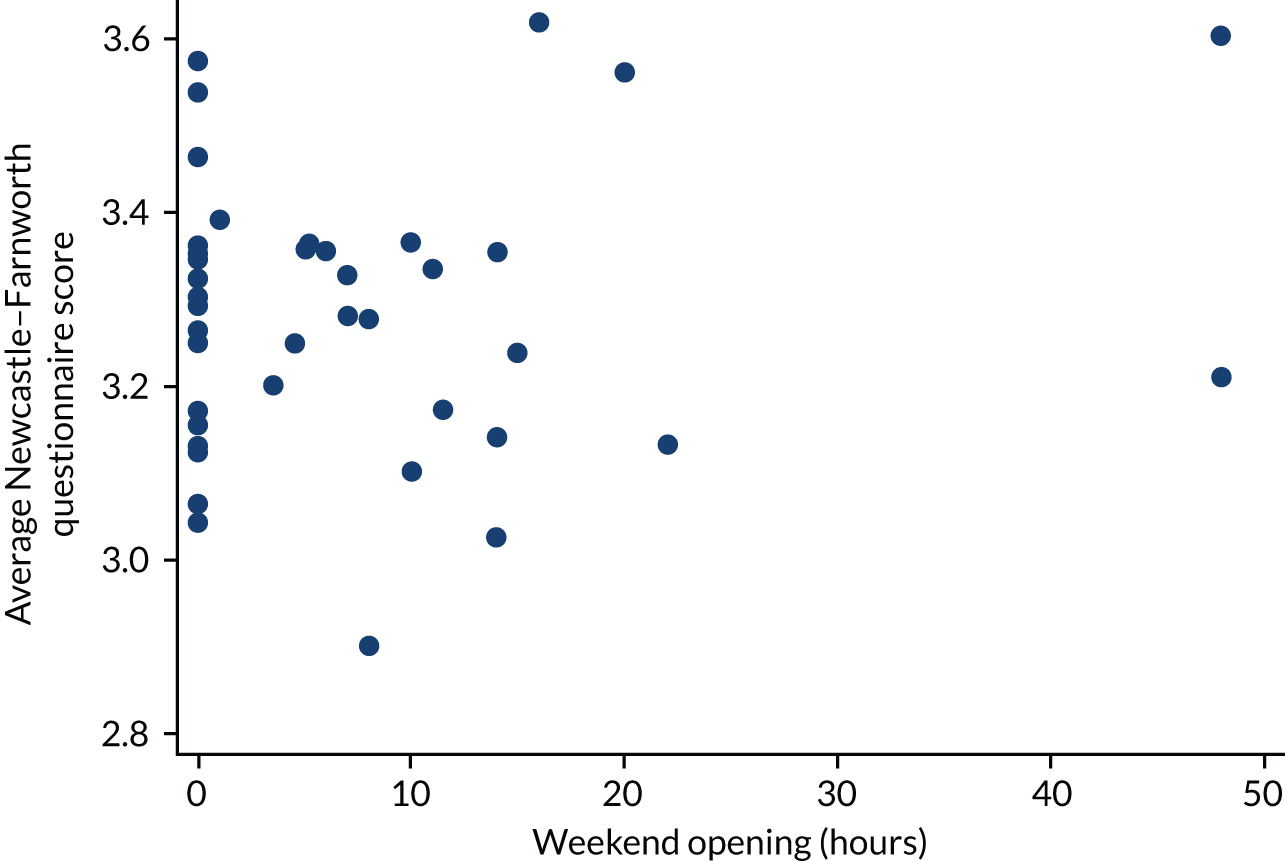

We investigated patient satisfaction by exploring the relationship between the SAPS or the modified Newcastle–Farnworth score and consultant presence, unit volume and weekend opening hours [see modified Newcastle–Farnworth questionnaire; URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/140441/#/ (accessed 2 June 2020)].

The SAPS questionnaire consists of seven questions, with most of them having the following categorisation: 0 ‘very dissatisfied’, 1 ‘dissatisfied’, 2 ‘neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’, 3 ‘satisfied’ and 4 ‘very satisfied’.

Based on the above, the SAPS score may range between 0 and 28 points. 27 The modified Newcastle–Farnworth score was calculated as the average of the individual component scores.

Models were adjusted using three sets of potential confounder variables, two of which are defined in Clinical outcomes in EPAUs (FD + MA and FD + MA + DS + GAP). The third set of confounders was FD, MA, DS, GAP, ethnicity, parity, gravidity and LMUP score.

Staff satisfaction

The association between staff experience of providing early pregnancy care and consultant presence, unit volume and weekend opening was explored using descriptive statistics.

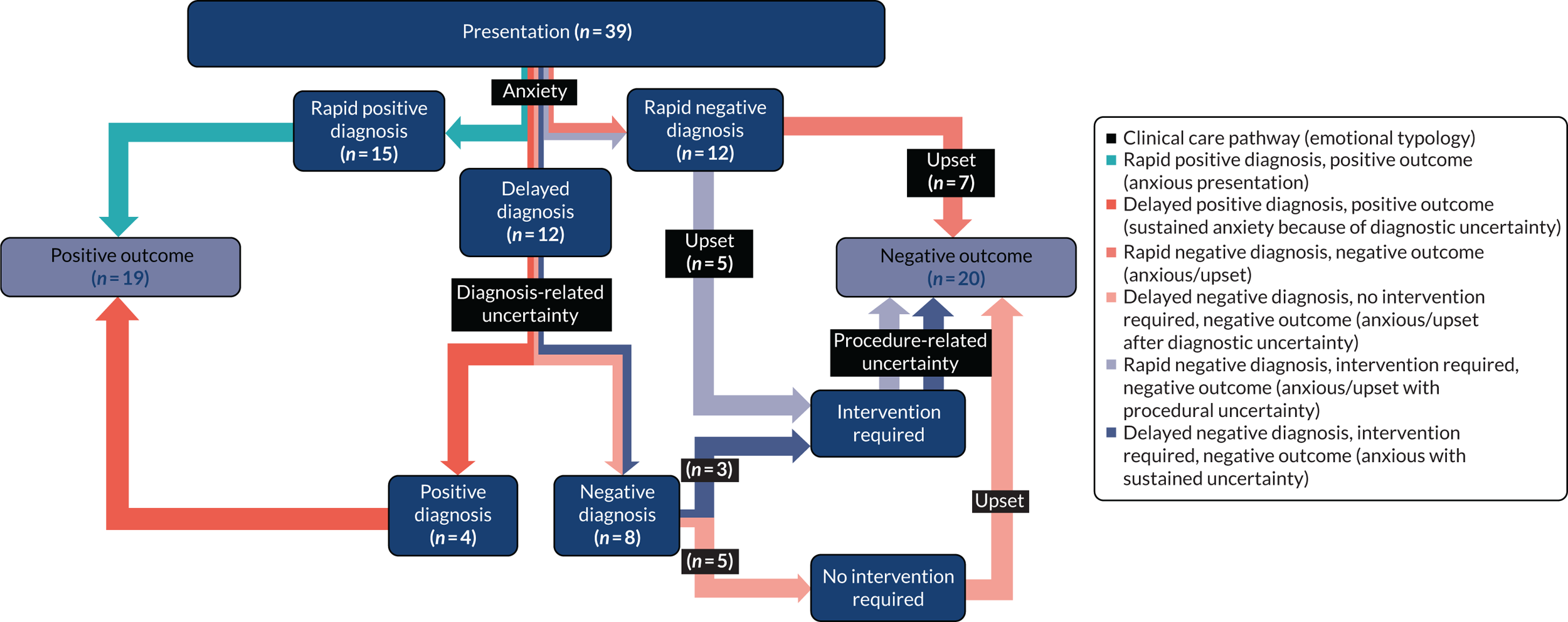

Qualitative interviews

Thirty-nine interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysis was conducted by members of the qualitative team, in an iterative and consultative manner,36 cross-checking with members of the wider VESPA study team for clinical and other facts related to other data collection strands, when appropriate. The data were analysed using a thematic framework analysis,37,38 focusing on women’s clinical and emotional pathways through their care experience at the EPAU, and how these were influenced by the configuration and practices of the service they used. The thematic framework was devised and agreed for the preliminary analysis. It was produced from the interview guide, the researchers’ knowledge of the content of each interview and the associated memo writings for each interview, as well as notes made during the refamiliarisation process.

In accordance with a thematic framework analysis approach appropriate for multidisciplinary health research,39 the interview transcripts were first read in their entirety to achieve refamiliarisation with the interviews and uploaded to NVivo software (QSR International, Warrington, UK) for management and analytical work up. Coding was initially broad and used text from within the transcript data as the preliminary codes, before the merging or splitting of some codes to form more defined strata. The second coding was more granular and further refined subthemes were generated, leading to a hierarchical structure of themes and subthemes which aligned with the pre-existing thematic framework.

All transcripts were coded by two members of the qualitative research team independently, and regular meetings were held to discuss and revise the coding thematic framework. Any discrepancies between researchers were resolved through explanations, debate and revisiting the data, to ensure that they had been completely coded and that the analysis satisfied a psychological, clinical and public health perspective40 for a dynamic health-care system (as in Zubairu et al. 41). We explored recommendations made by women for improvements to service and drew additional recommendations from our analysis.

Particular attention was paid to women’s emotional experience. These data were first coded to demarcate them as relating to an experience of emotions and then were refined with specific codes to reflect the emotion being expressed (e.g. ‘anxious’, ‘concern’, ‘worried’, ‘upset’, ‘uncertainty’). These codes were then grouped into four strata: (1) anxiety, (2) procedure-related uncertainty; (3) diagnosis-related uncertainty; and (4) upset. We also noted when women expressed feeling ‘guilty’ or ‘vulnerable’, or when women drew positives from a negative situation. Through iterative coding, reworking of the data regarding women’s emotions and comparison between interviews, we produced six robust and distinct emotional typologies which mapped to different care pathways through the EPAU.

For each of the other main themes we undertook a process of charting, creating a matrix for each theme for which text from each transcript was summarised, allowing retention of the original sense and meaning of each transcript. We then looked for patterns within the theme in accordance with strata or emotional typology to see how these factors influenced women’s experiences. If relevant, we linked back to the satisfaction score from the 2 weeks post-discharge SAPS score.

Health economic evaluation

The analysis takes that of an NHS health and social care payer perspective. Personal and productivity costs collected from a subsample of patients were analysed separately.

We analysed costs and outcomes at baseline and each follow-up time point. Costs were analysed, adjusting for the site-level stratification variables, as well as age and FD. We used a multilevel model to estimate adjusted costs. Multilevel models have been recommended for use in health economics as they are able to incorporate the hierarchical structure of data, including patients within centres, and provide more appropriate estimates of patient- and centre-level effects than ordinary least squares models. 32

We examined mean total costs and mean QALYs for each stratum, as well as mean change in anxiety pre and post consultation. We also carried out a probabilistic sensitivity analysis, which reflects uncertainty around the estimates of costs and QALYs. As the probabilistic analysis requires simulated samples from the mean cost and utility estimates, Monte Carlo simulation was performed within Microsoft Excel to obtain 10,000 simulated samples.

For each stratum we analysed the expected total QALYs and expected total cost, averaged over the simulation sample, together with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We also computed net benefit for a given willingness to pay per QALY, λ (ceiling ratio), where net benefit is defined as:

This converts utilities to a monetary scale, so that the costs and QALYs can be compared directly. Expected net benefit is the average net benefit over the simulation samples. For a given willingness-to-pay threshold, λ, the optimal stratum is that with the highest expected net benefit. We present expected net benefit for λ = £20,000.

We allowed for the uncertainty in the optimal stratum by plotting the probability that each stratum is the most cost-effective (has highest net benefit) against willingness to pay per QALY, using cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs).

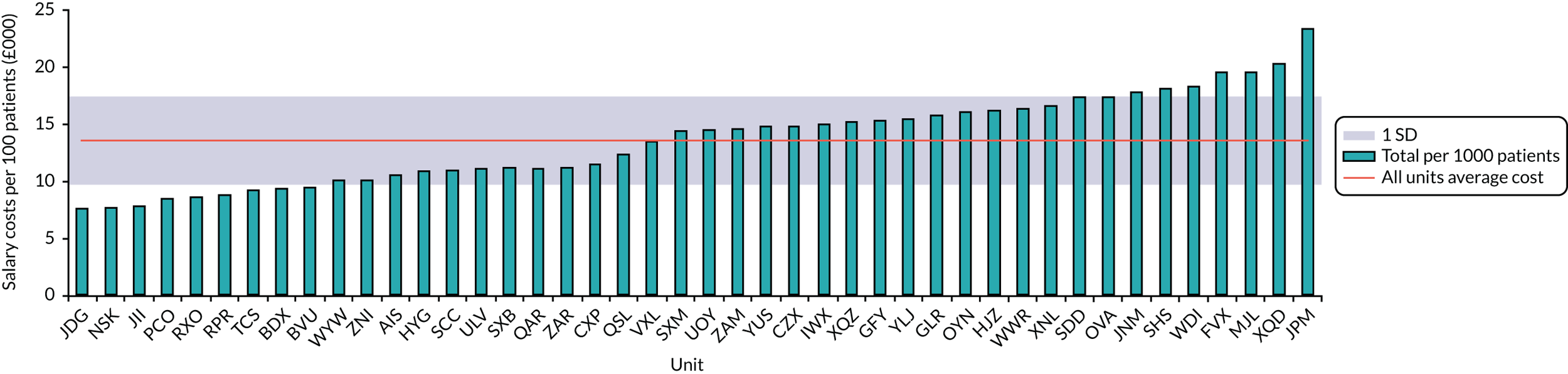

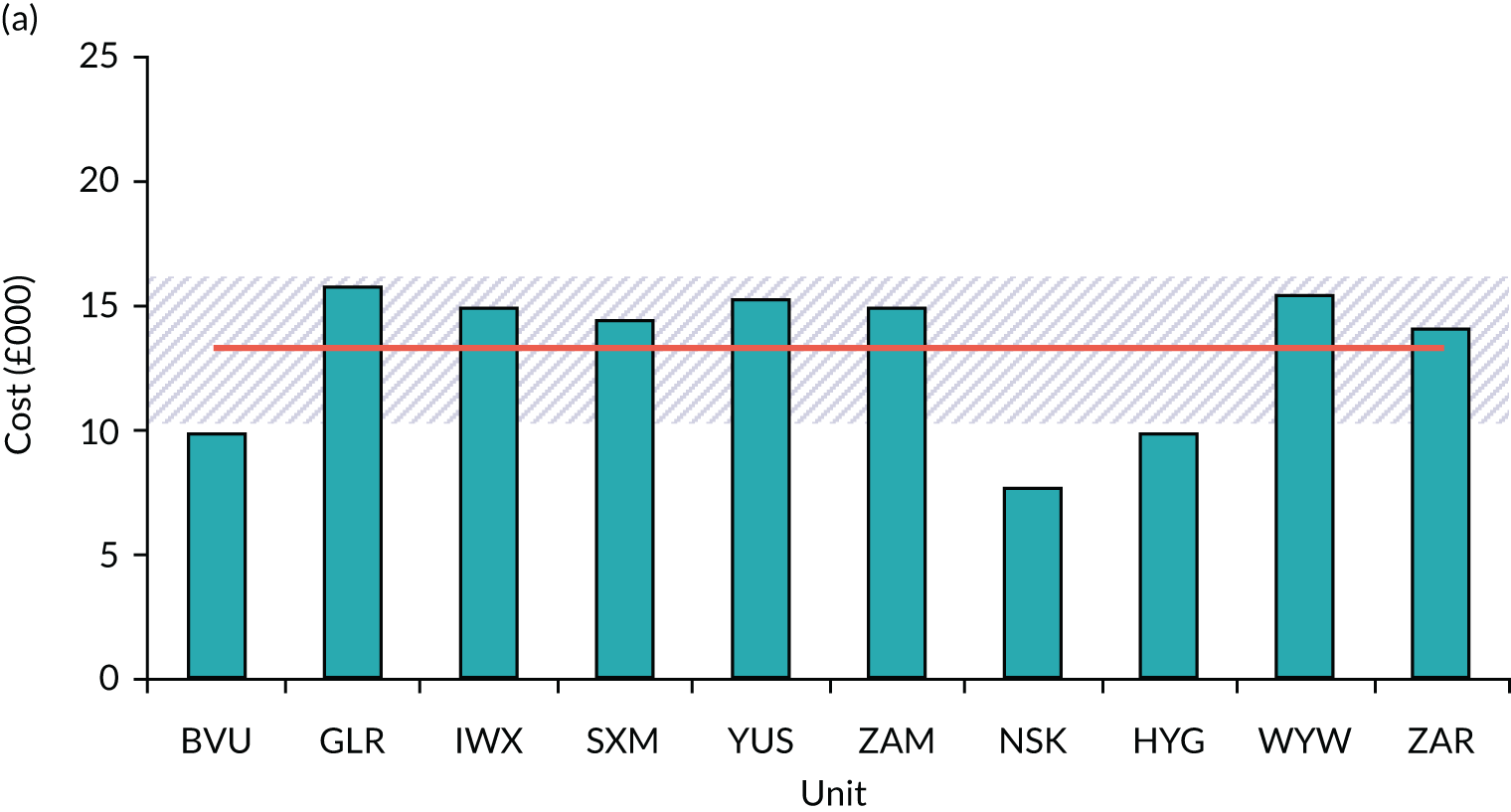

We also analysed mean total costs, QALYs and anxiety change at the unit level.

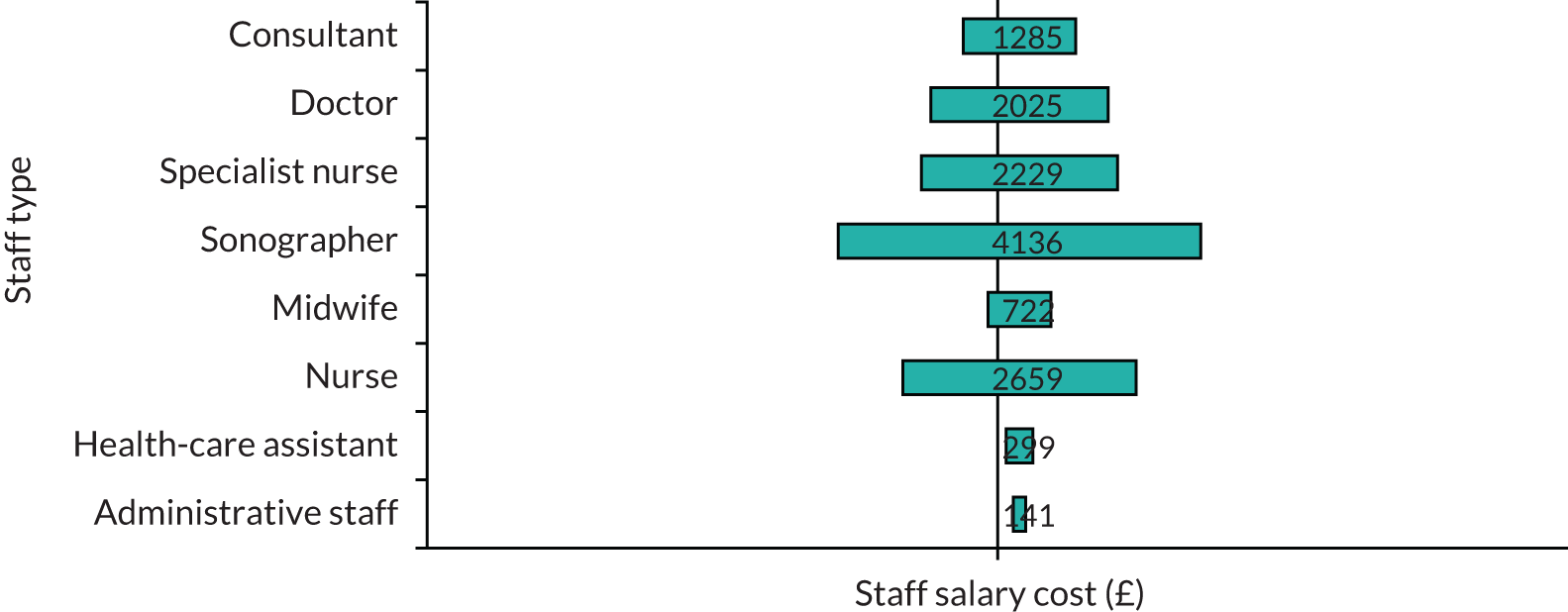

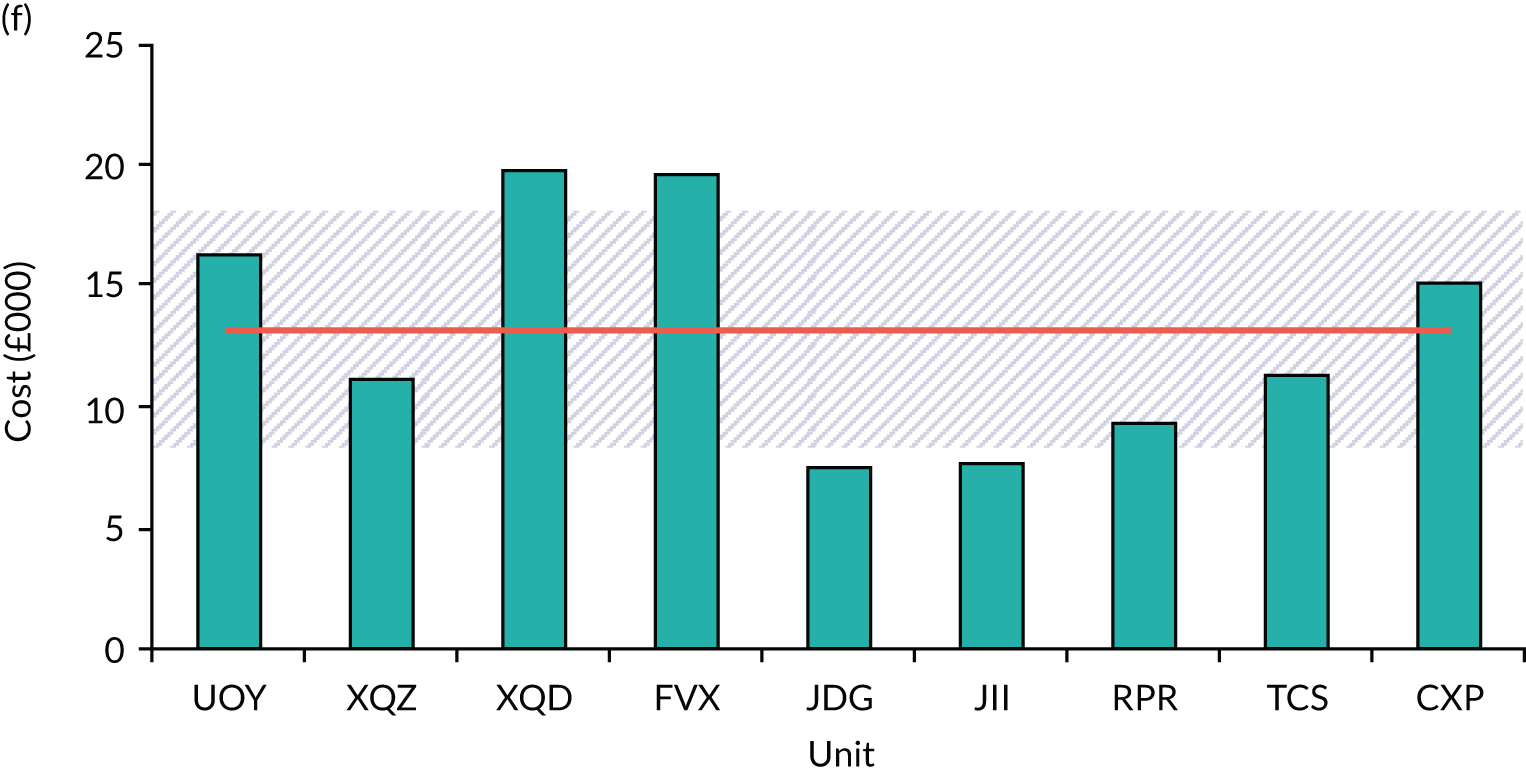

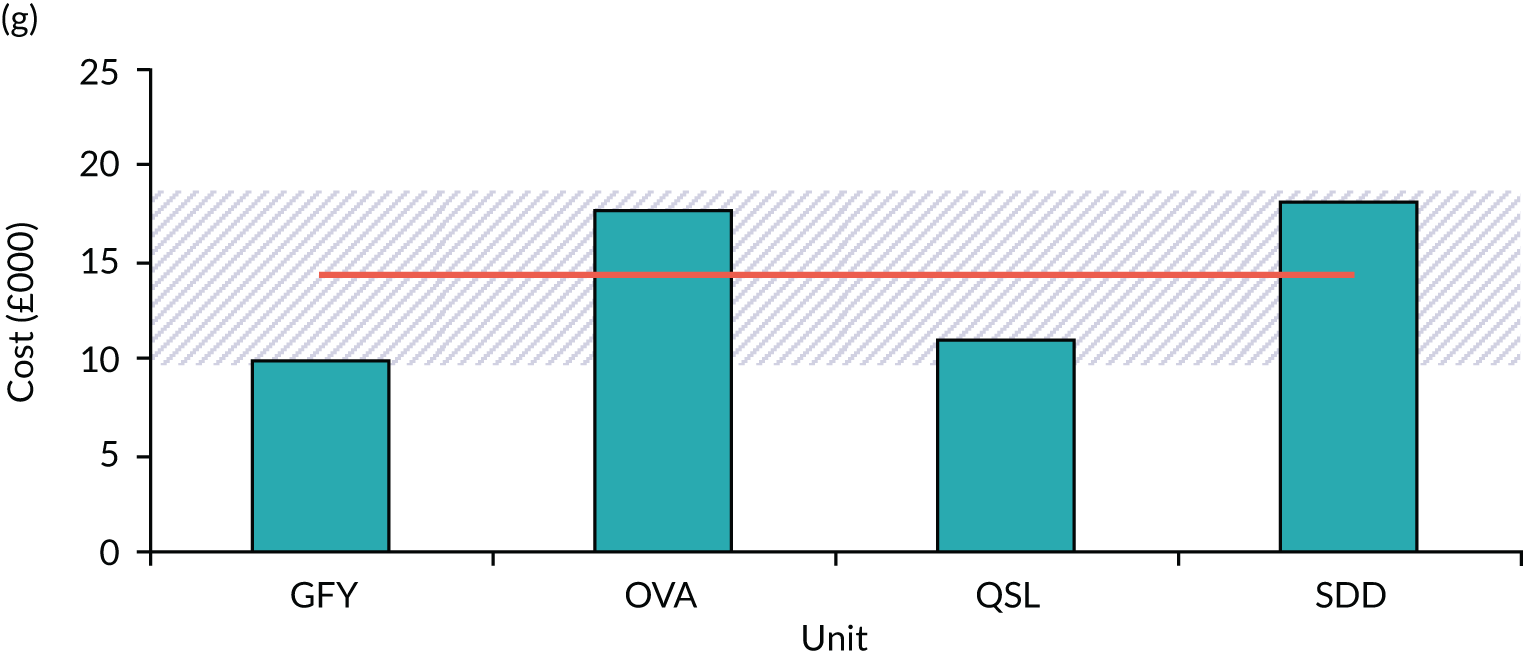

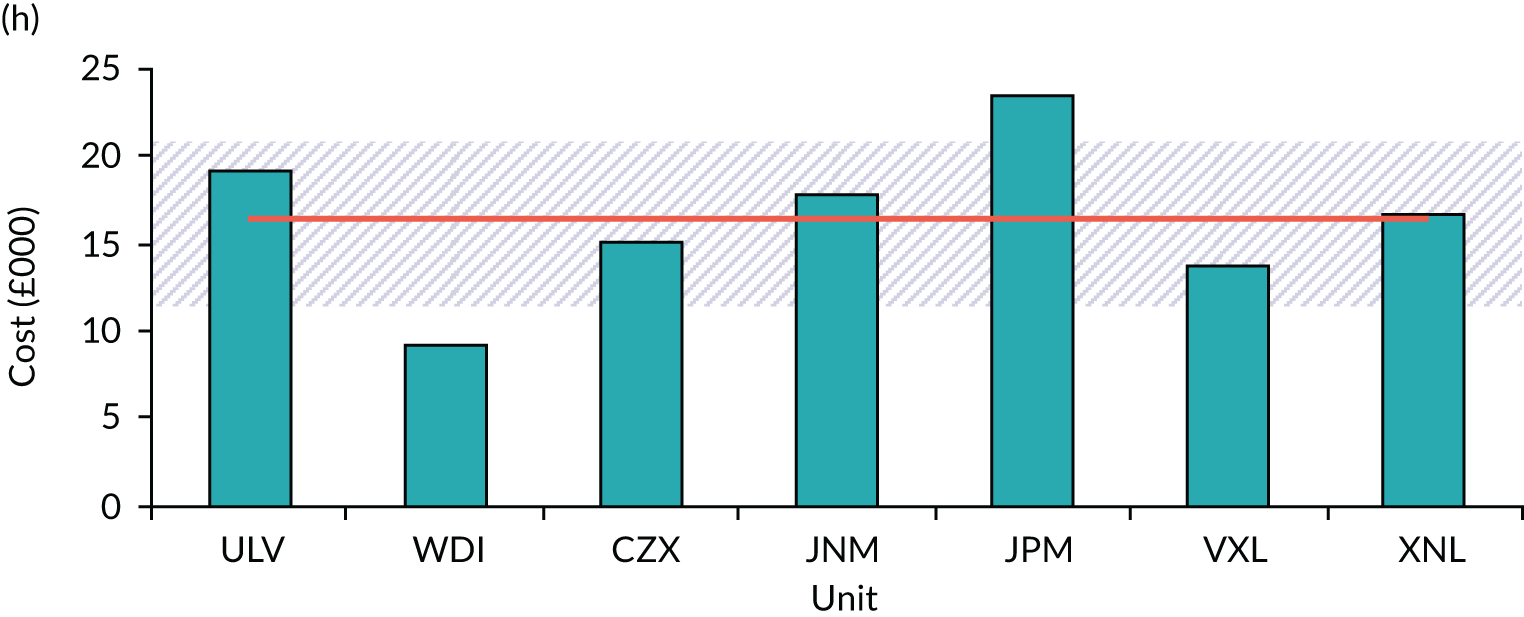

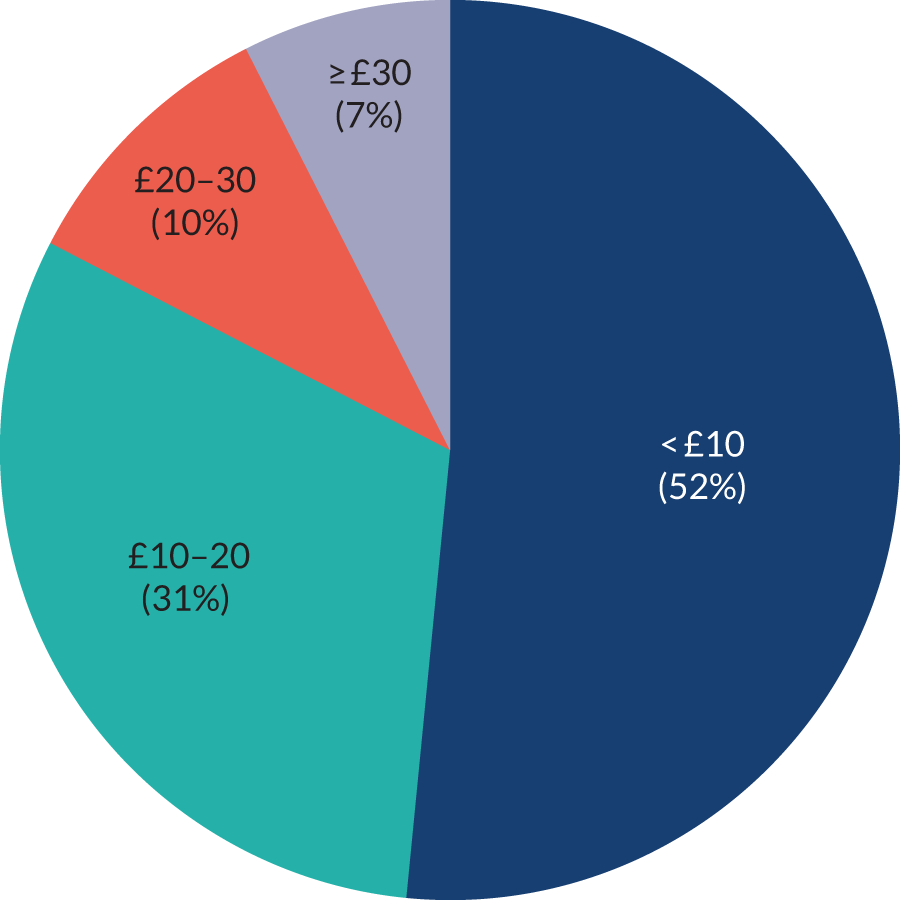

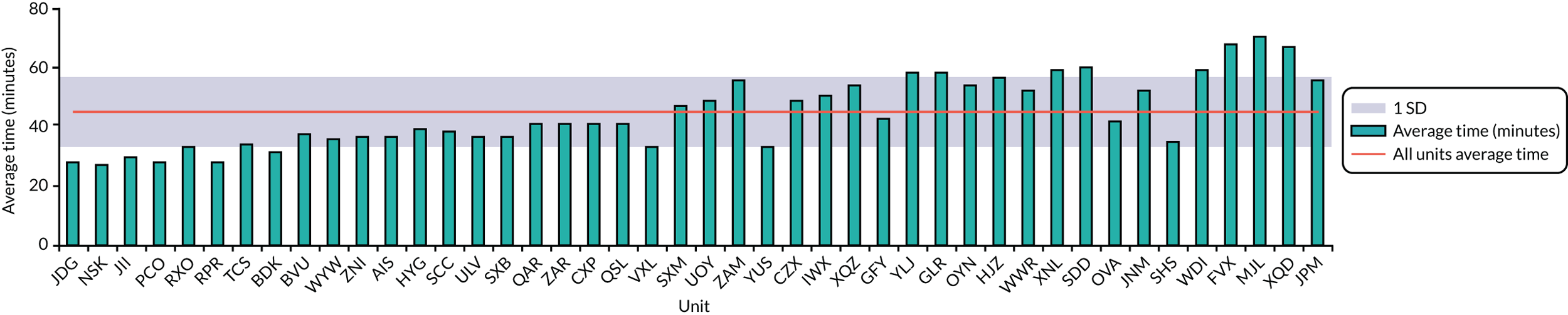

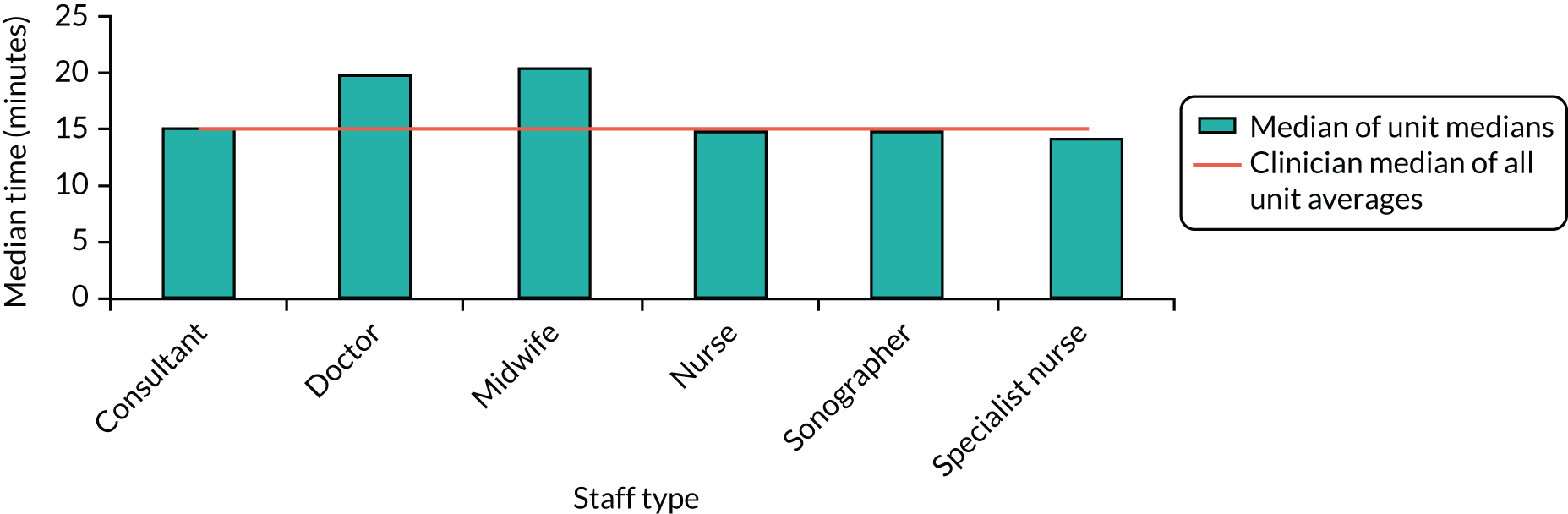

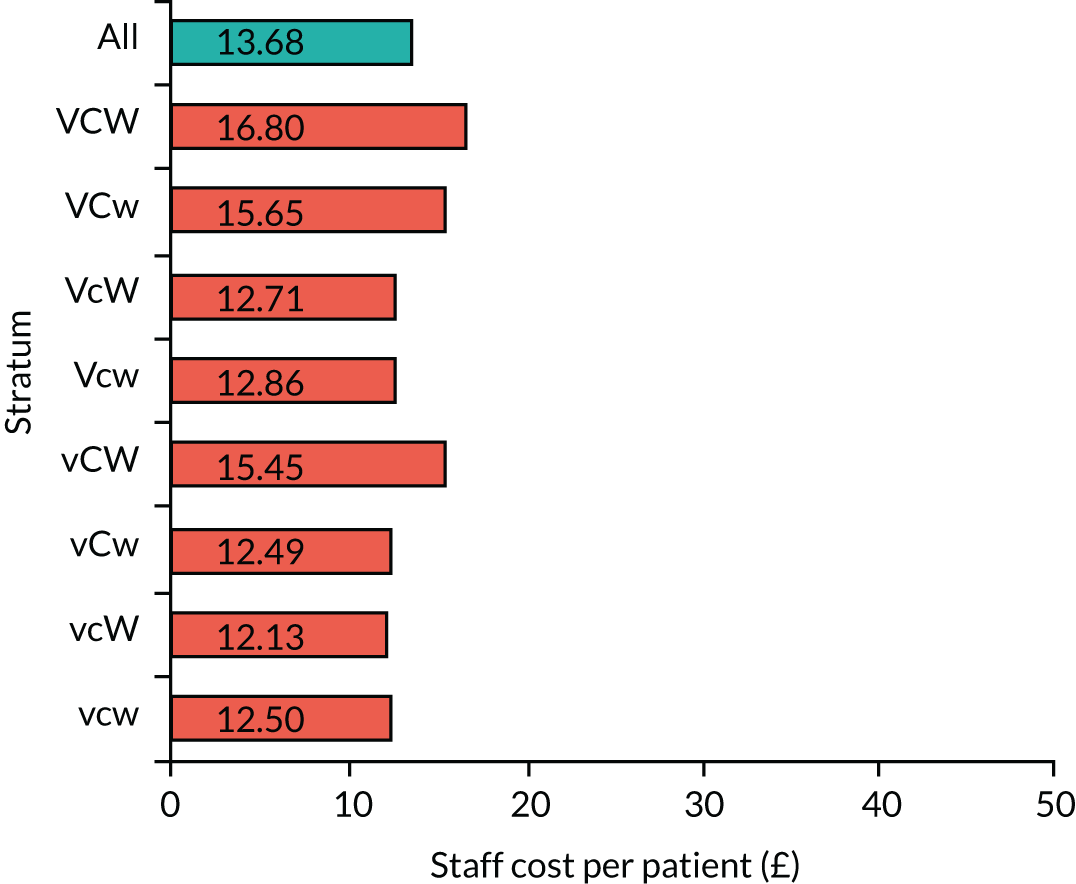

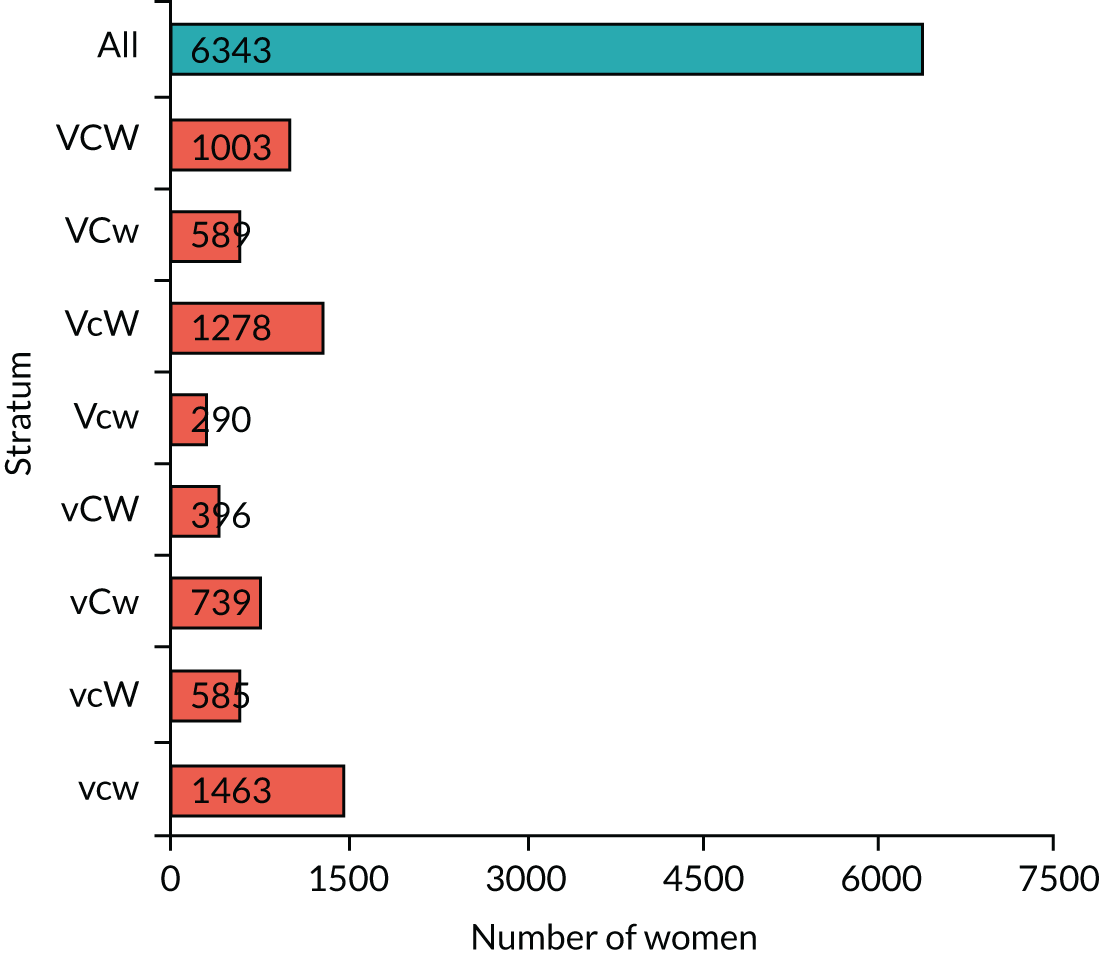

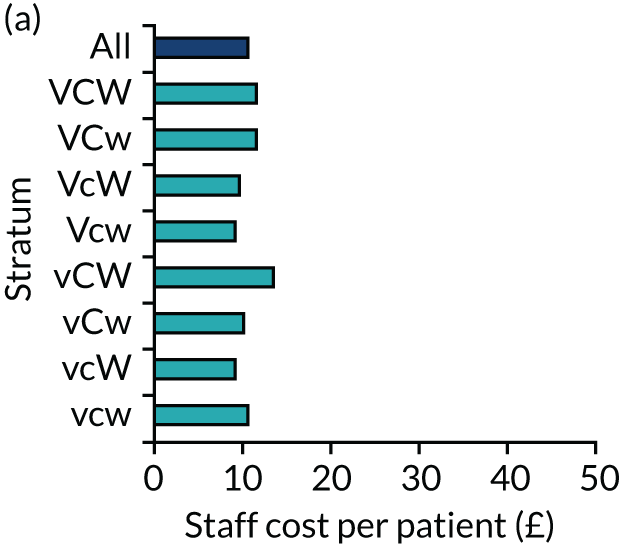

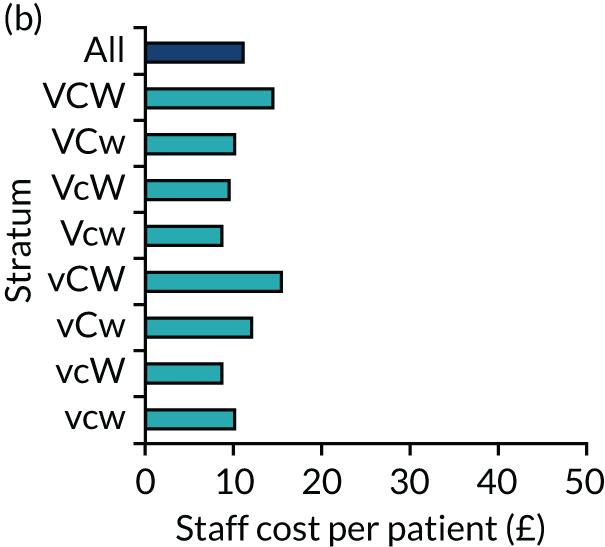

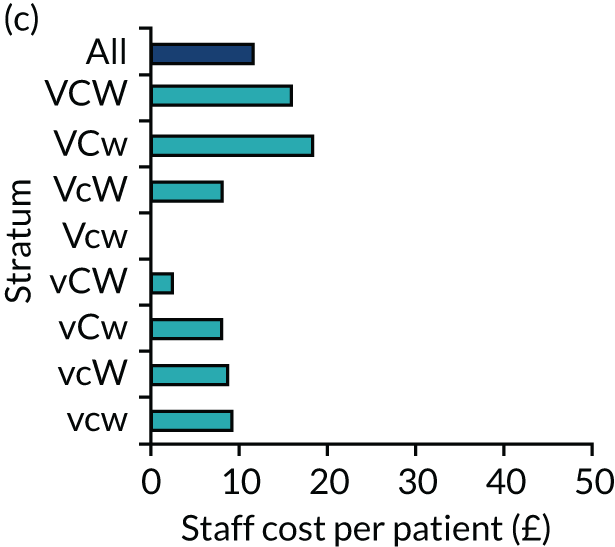

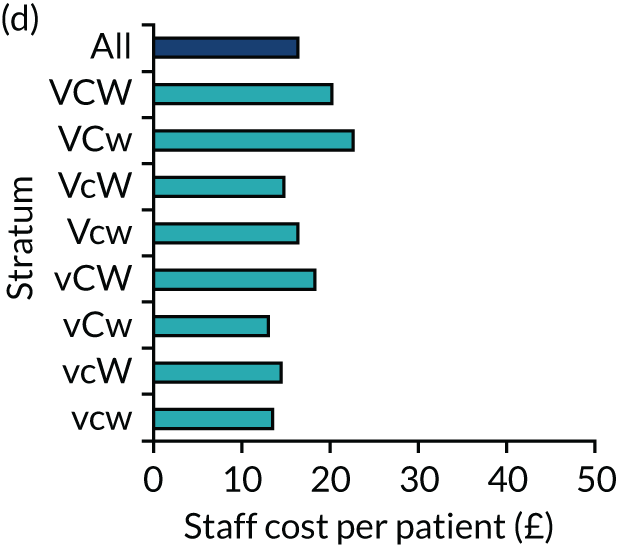

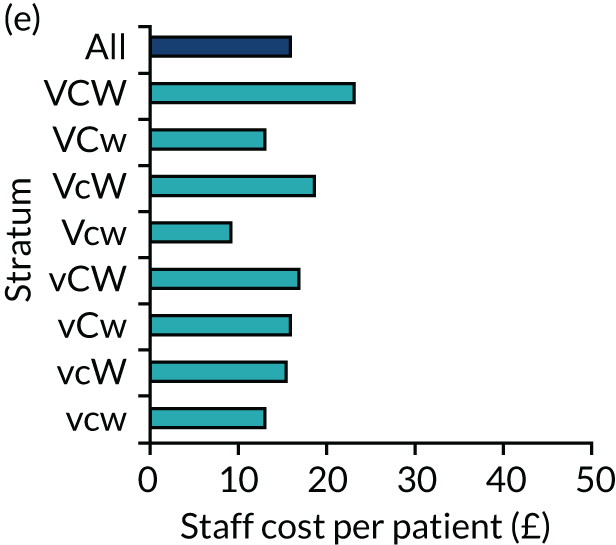

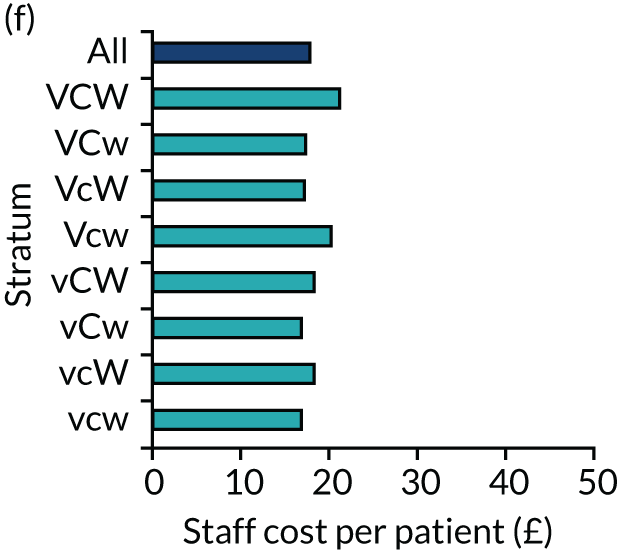

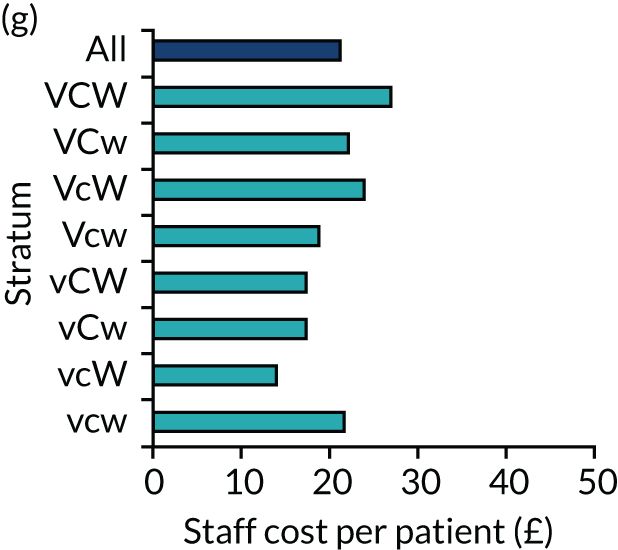

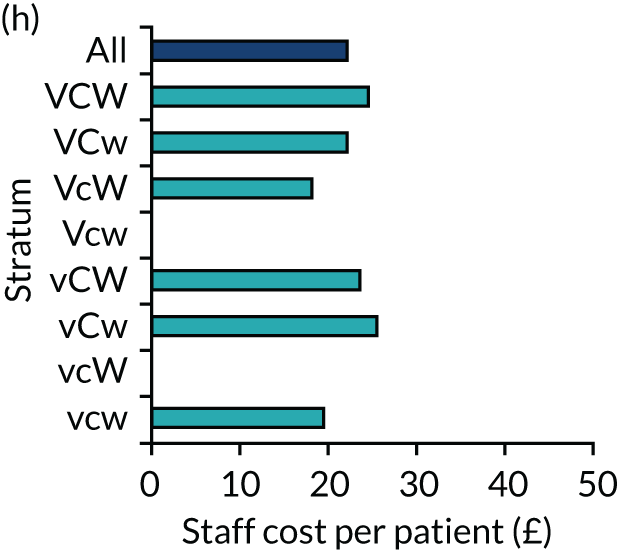

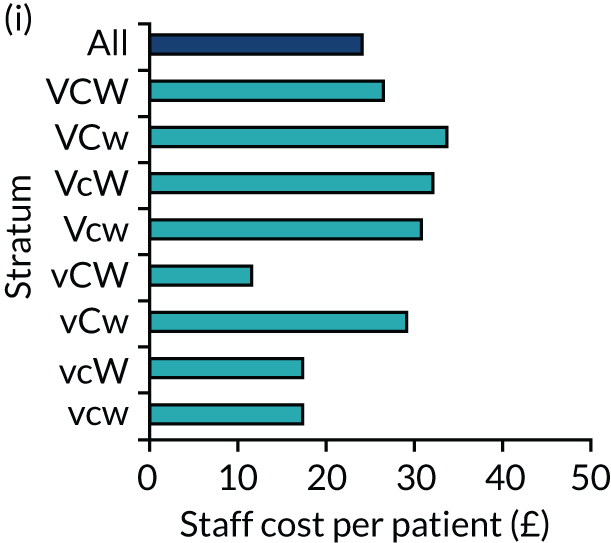

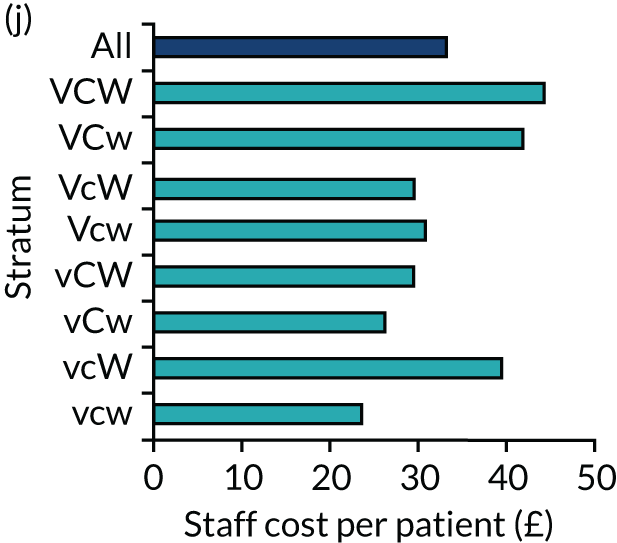

Workforce analysis

The workforce analysis calculated the time spent with each staff type for each visit and interaction, and used this time to calculate the salary cost for each staff type. The total cost for each staff type for each EPAU was amalgamated into a stratum. In this way, the staff cost profiles (showing each EPAU’s staff type makeup) could be presented by individual unit and stratum per 1000 patients. This also allowed comparisons between salary cost of staff types across EPAUs and strata.

The staff salary costs were further examined by FD, allowing further analyses. The average, median and standard deviations (SDs) of salary cost by diagnosis were computed and presented. Any statistically significant variations were identified using two-way analysis of variance. Other breakdowns/categorisations of staff salary costs, such as the number of patients seen and the time spent per patient, by each staff type, were also studied.

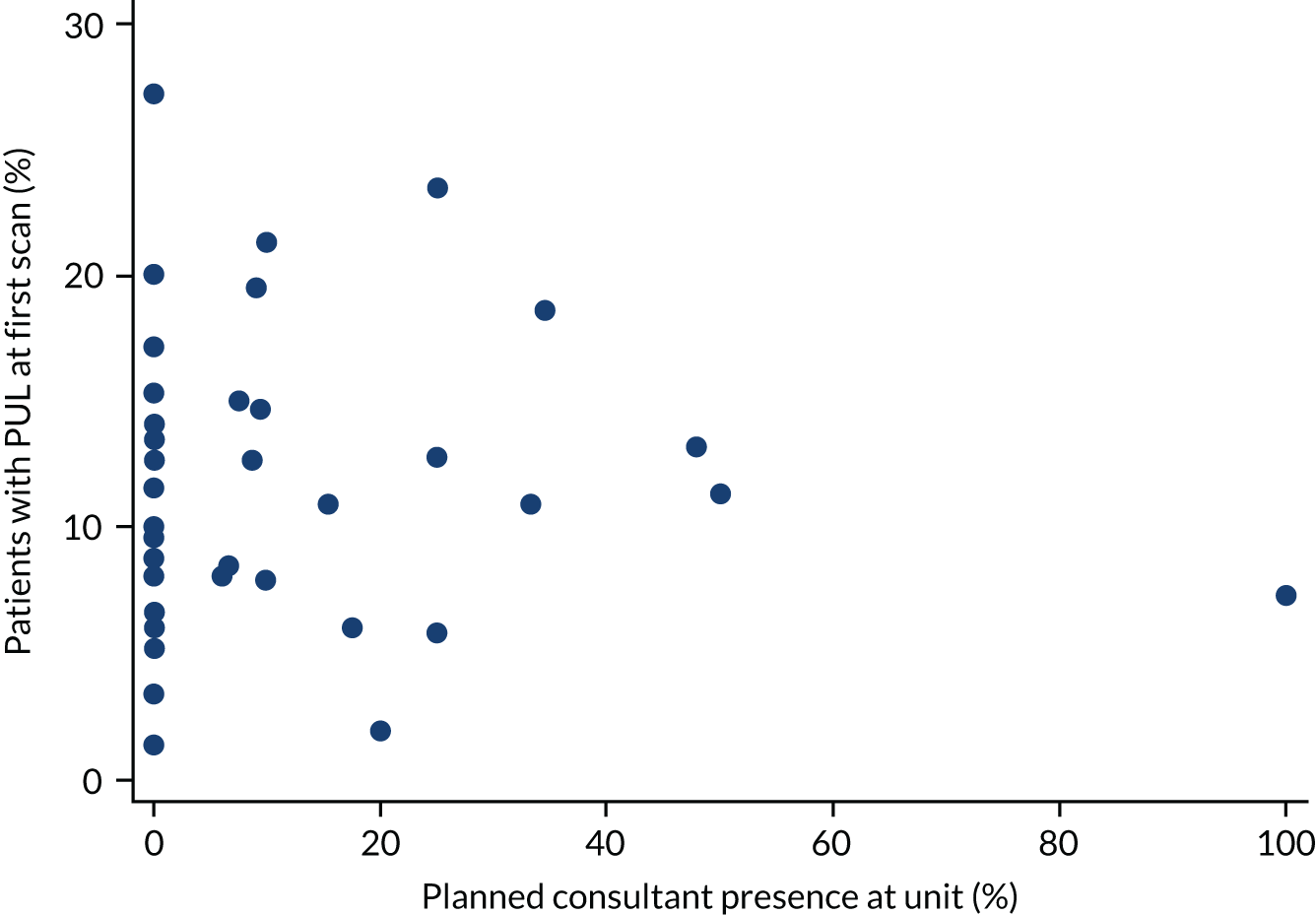

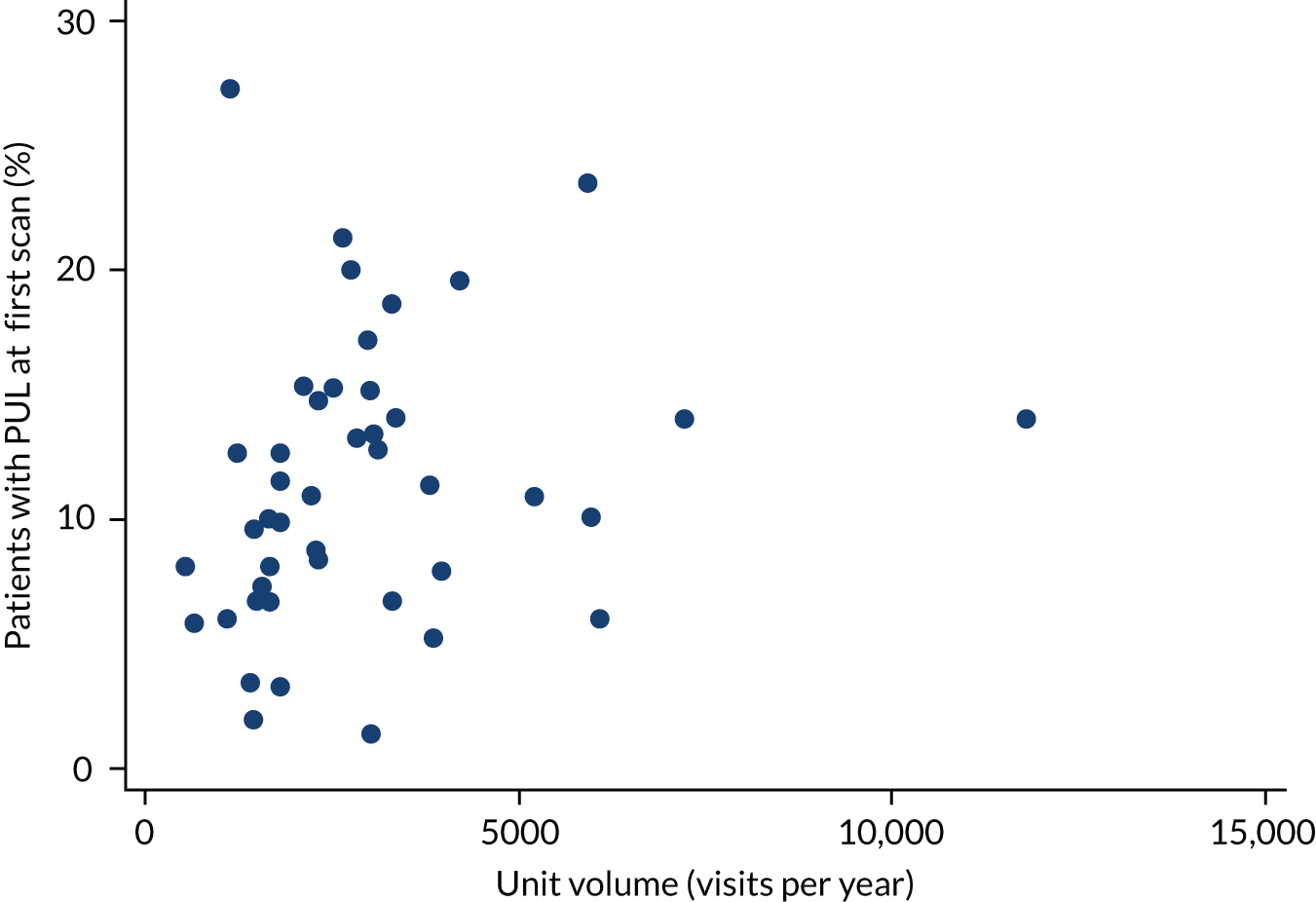

Among the final diagnoses, the number of inconclusive scans [pregnancies of unknown location (PULs)] was determined to be a useful indicator of the quality of an EPAU’s patient care: the higher number of PULs, the lower the level of care, and the lower number of PULs, the better the care. Number of admissions and number of visits were also identified as useful indicators. The analysis focused on the six clinical staff types: (1) consultant, (2) specialist nurse, (3) sonographer, (4) doctor, (5) nurse and (6) midwife. These indicators were investigated using correlation coefficients and ratios to determine if any of the staff types had an effect on them.

Outcomes and assessment

Primary outcome measure

-

The proportion of emergency hospital admissions for further investigations and treatment, as a proportion of women attending the participating EPAUs (data strand 1).

Secondary outcome measures

-

Total number of emergency admissions of women presenting with early pregnancy complications (data strands 1 and 2).

-

Ratio of new to follow-up visits (data strand 1).

-

Rate of non-diagnostic ultrasound scans (PUL). This has traditionally been used in early pregnancy as an indicator of quality of care (data strand 1).

-

Proportion of laparoscopies performed for a suspected ectopic pregnancy with a negative finding (data strand 2).

-

Ruptured ectopic pregnancies requiring blood transfusion (data strand 2).

-

Estimated blood loss at operation (data strand 2).

-

Patient satisfaction with the quality of care received (data strands 3 and 4).

-

Staff experience of providing care in EPAUs (data strand 4).

-

Proportion of women diagnosed with miscarriage and treated surgically, medically or expectantly (data strand 1).

-

Proportion of women diagnosed with ectopic pregnancy and treated surgically, medically or expectantly (data strand 1).

-

Visits to A&E departments (data strand 2).

-

Admissions to intensive therapy units (data strand 2).

-

Duration of admissions (data strand 2).

-

Waiting times from referral to assessment (data strand 1).

-

Quality-of-life measures before and after assessment of women at the EPAU during initial and follow-up visits (data strand 6).

-

Anxiety before and after assessment of women at the EPAU during initial and follow-up visits (data strand 6).

-

Cost-effectiveness of different staffing models (data strand 7).

Definition of end of study

The end of the study was defined as the last 3-month follow-up visit for a participating patient at each individual site. The study was considered closed when the last patient reached this time point, all data were complete and all data queries were resolved.

Withdrawal from study

Participants who gave consent to provide data were able to voluntarily withdraw from the study at any time. If a participant did not return a questionnaire, two attempts were made to contact her using the preferred method of contact (indicated by the participant at the time she provided consent). If a participant explicitly withdrew consent to any further data collection, then this decision was documented on the database and no further contact attempts were made.

Statistical considerations

Sample size

Clinical outcomes in EPAUs

We planned to recruit 44 EPAUs, each contributing the required 150 patients. This gave us 90% power to detect a difference in admission rates of 5% (8.5% vs. 3.5%) between units with a low consultant presence and units with a high consultant presence, at the 5% significance level. The results from our pilot study suggested that such a difference in admission rates was both clinically relevant and plausible.

This sample size calculation was based on a simplified analysis for which EPAUs were classed as having either low or high consultant presence based on a dichotomisation at the median level of consultant presence. The admission rates for the patients in the 22 EPAUs with ‘high’ consultant presence could then be compared with those from EPAUs with ‘low’ consultant presence. A basic sample size calculation (that assumes no clustering) suggested that we required 946 patients in total (or 22 patients per EPAU). However, assuming a moderate level of clustering (intracluster correlation coefficient = 0.04), we required 150 patients per EPAU. Data collection for each unit was for a minimum of 7 days to ensure that weekday/weekend variation was captured.

Emergency hospital care audit

Results from the pilot study and the national survey of EPAUs showed that the average number of women reviewed in different EPAUs across the country is 105 per week. Collecting hospital statistics data over 3 months would enable us to detect differences in rare outcomes, such as the proportion of negative laparoscopies for suspected ectopic pregnancy, transfusion rates and intensive therapy unit admissions.

Patient satisfaction

Our study population comprised 6600 women (150 for each of the 44 EPAUs). With a response rate of 30%, a 95% CI (for a yes/no question) would have a margin of error of, at most, 2.2%. If the response rate was just 10%, then the error would have been, at most, 3.8%.

Staff satisfaction

We expected that there would have been approximately 200 staff members in the sample of 44 EPAUs. If our response rate was 50%, then a 95% CI (for a yes/no question) would have a margin of error of, at most, 10%.

Qualitative interviews

Forty interviews with EPAU service users were planned. This calculation was based on the needs of the intended maximum variation sample42,43 (enabling representation by region, pregnancy outcome and reported level of satisfaction) to provide a wealth of qualitative data for analysis.

Health economic evaluation

In the absence of prior knowledge of the expected values and SDs of costs and effects (in this case, QALYs) it was not possible to formally estimate a required response rate. Therefore, we took a pragmatic approach to determining the number of resource use questionnaires to collect. Our aim was to balance the collection of sufficient data to make inferences about cost-effectiveness against the burden on women of being asked to complete data collection forms potentially soon after experiencing a pregnancy loss.

Questionnaires were sent to randomly chosen women from each stratum. The women selected were those who had given consent at their first visit for further contact, who had not withdrawn their consent and who had been discharged within 2 months. The sample was stratified using the same criteria as were used to select participating EPAUs. We anticipated that 320 completed questionnaires would provide sufficient data, based on the assumption of 40 completed questionnaires per stratum.

An algorithm and approach to sampling similar to that used to select units for participation in the study were used to select women who were approached to complete the resource use questionnaire. The key factors used to sample were the level of consultant presence, weekend service and number of patients attending. Each stratum of each key factor was equally represented. The breakdown for consultant presence consisted of 80 women in strata 1—4. Likewise, the breakdown for weekend opening was 160 women for strata 1 and 2, and similarly for number of patients attending a unit similarly for number of patients attending a unit. Women were approached to complete the resource use questionnaire until we achieved the target of 320 responses balanced across factors and strata.

Workforce analysis

To accurately capture the workforce resources needed to run each EPAU, we prospectively collected data on members and the grades of staff involved in providing care, as well as the time spent providing this care. Consultant presence was collected prospectively for each session/day that data were collected for (i.e. a record of whether or not a consultant was physically present in the unit reviewing patients was collected for every session for which we collected data).

The staff salary costs were further examined by the FD, allowing additional analyses. The average, median and SDs of salary cost by diagnosis were computed and presented. Any statistically significant variations were identified using two-way analysis of variance. Other breakdowns/categorisations of staff salary costs, such as the number of patients seen and the time spent per patient, by each staff type, were also studied.

Among the final diagnoses, the number of inconclusive scans (PULs) was determined to be a useful indicator of the quality of a EPAU’s patient care: the higher number of PULs, the lower the level of care. Number of admissions and number of visits were also identified as useful indicators. The analysis focused on six clinical staff types: (1) consultant, (2) specialist nurse, (3) sonographer, (4) doctor, (5) nurse and (6) midwife. These indicators were investigated using correlation coefficients and ratios to determine if any of the staff types had a measurable effect on them.

Study oversight

Study oversight was provided by a SSC and an Expert Reference Group. The SSC provided independent supervision for the study, advising the chief investigator, co-investigators and the sponsor on all aspects of the study throughout. The SSC met at regular intervals during the study period and the Expert Reference Group provided advice at the planning and data analysis stage.

Chapter 3 Results

This chapter presents the results of the VESPA study.

EPAU and patient recruitment

EPAU recruitment

A national survey was undertaken with the help of the AEPU. We approached 212 EPAUs and we received responses from 205. Each responding EPAU provided information about the key factors: planned weekly consultant presence, yearly number of attendances and weekend opening hours. Using a random sampling methodology we recruited 44 EPAUs with equal distribution of planned weekly consultant presence (yes/no), volume (< 3000 and ≥ 3000 attendances) and weekend opening (yes/no). The recruitment of the EPAUs was completed between December 2015 and April 2016. Following site initiation visits, four hospitals were moved to different strata as a result of changes in their configuration.

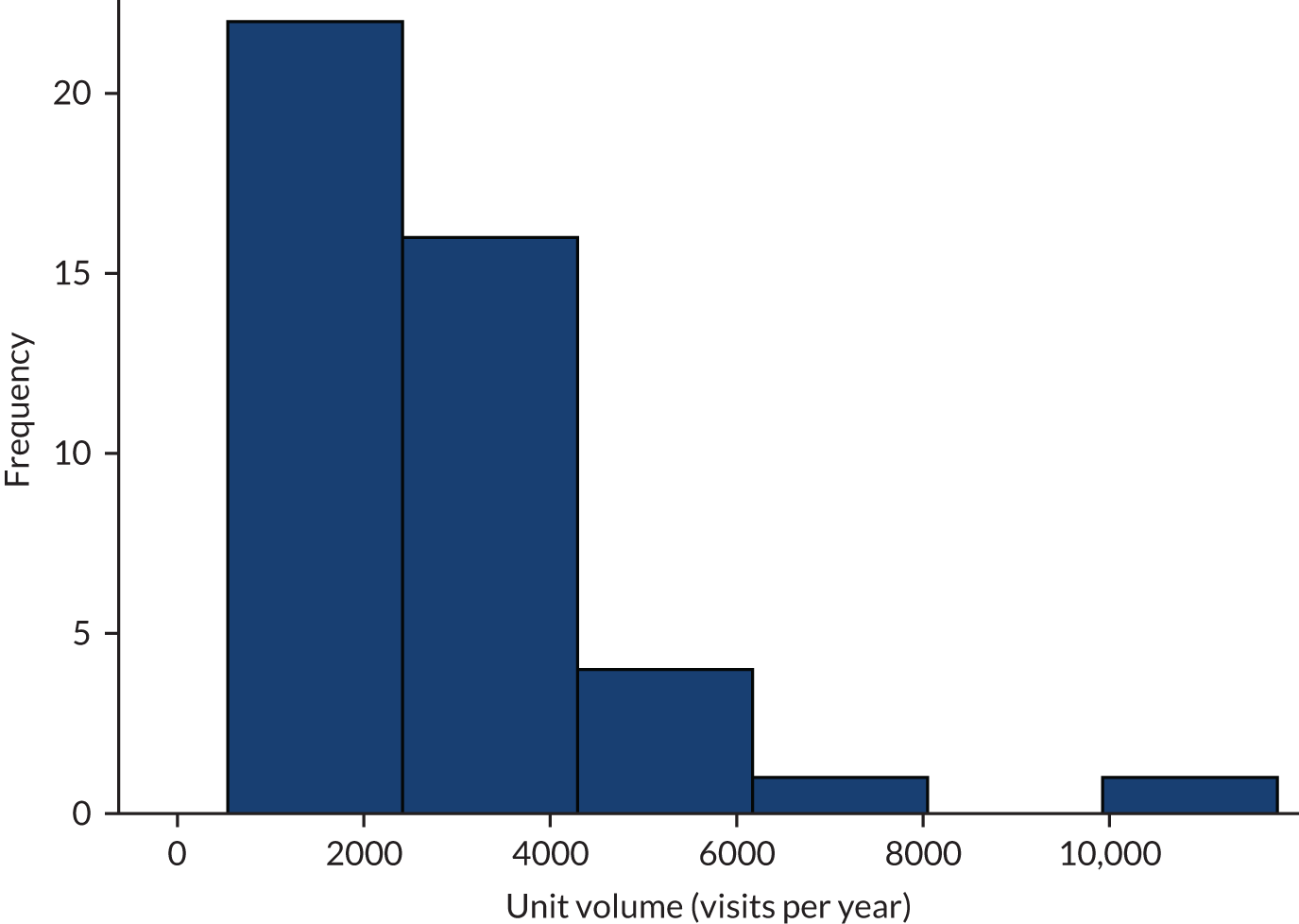

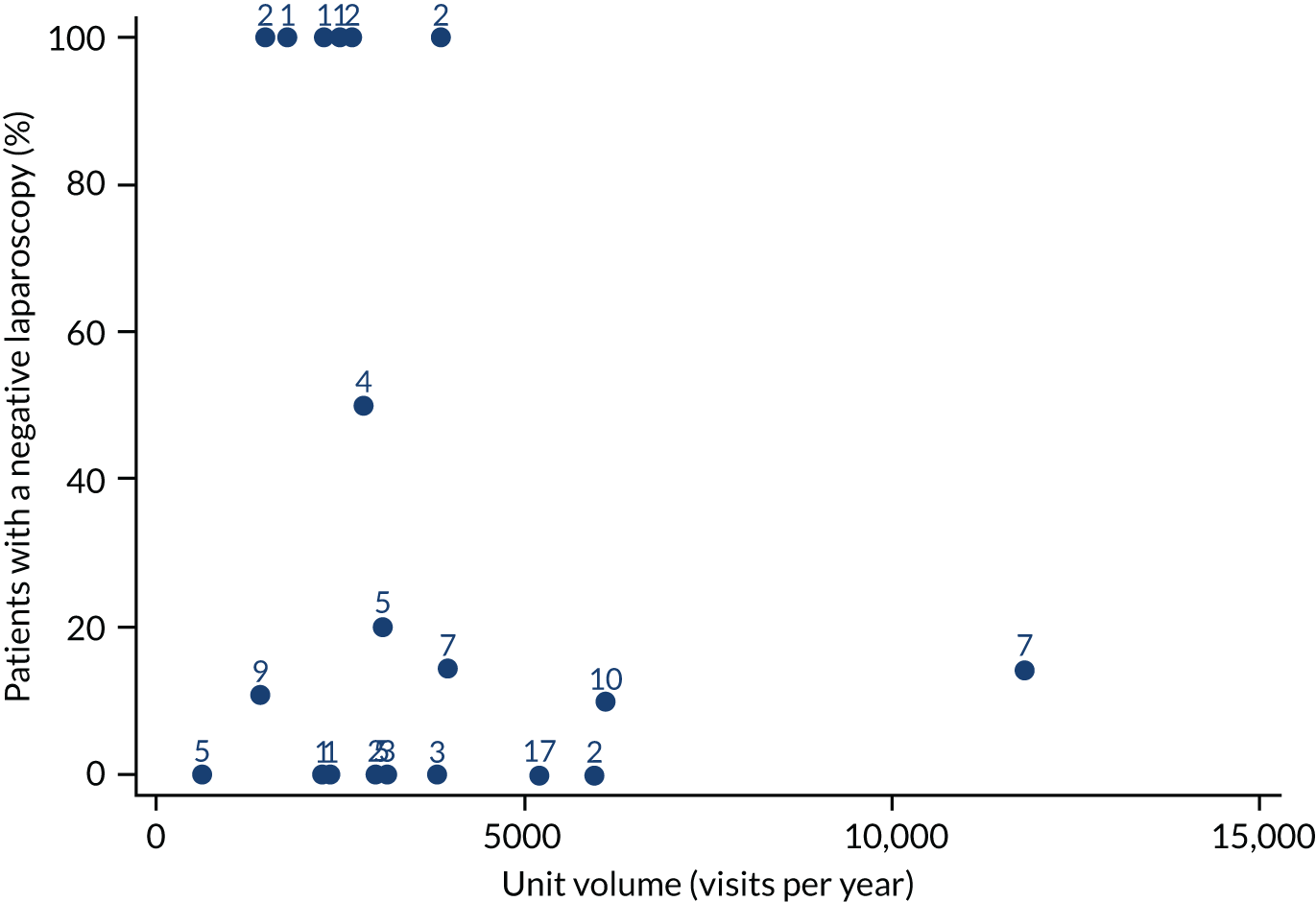

When data collection was complete, we reviewed the level of activity in all EPAUs. The volume of each EPAU was defined as the number of patient visits per year, and was estimated using the time taken to obtain data on 150 patients and the average number of visits per patient. The majority of the EPAUs (37/44) had a unit volume of < 4000 visits per year and 22 EPAUs had a yearly visit volume of < 2500 visits per year. In view of this, we used a cut-off point of 2500 visits to describe the units as high or low volume in the final data analysis.

See Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 6, for all participating EPAUs and their characteristics. Random three-letter codes were generated for each EPAU and used to anonymise data in accordance with our study protocol.

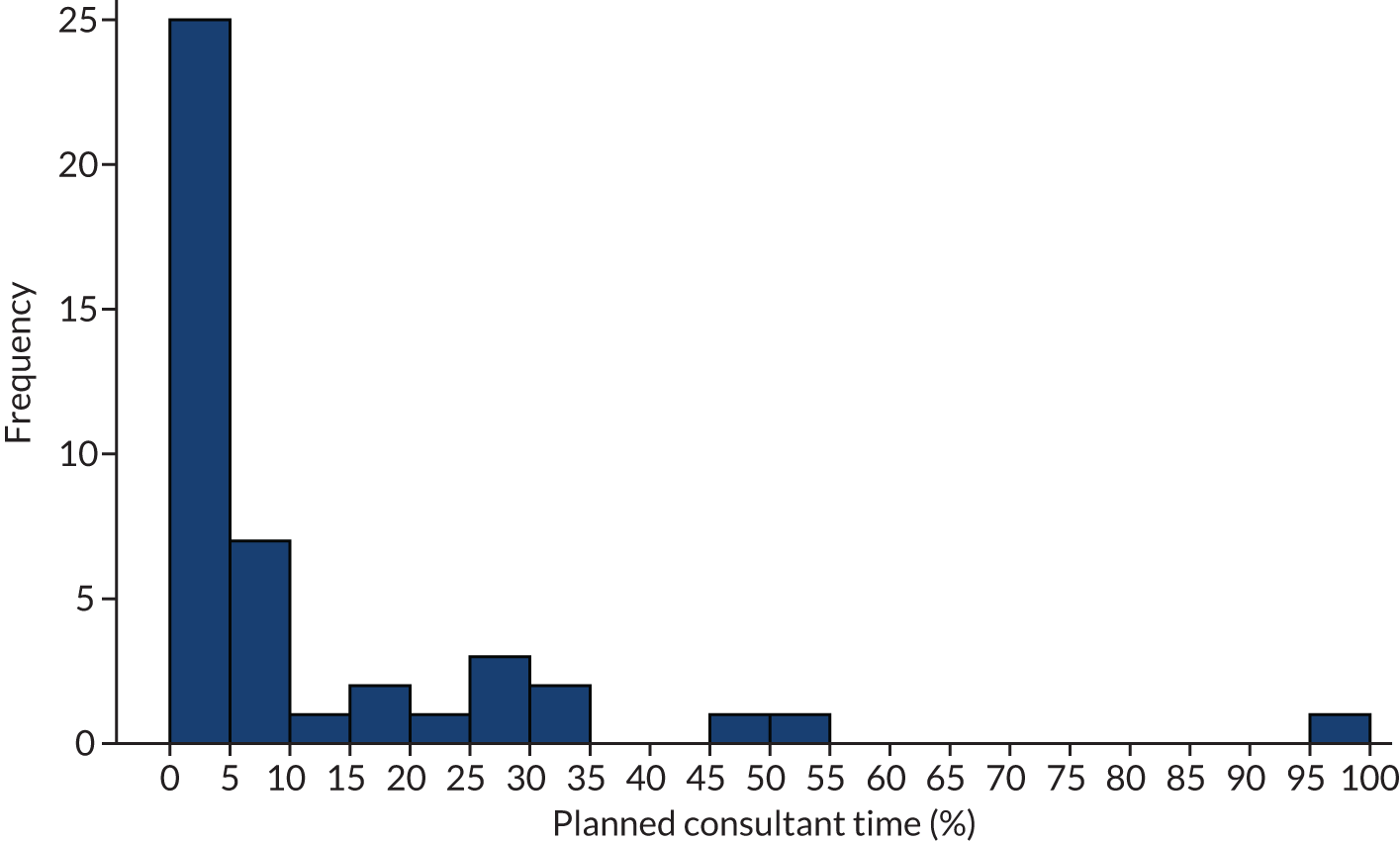

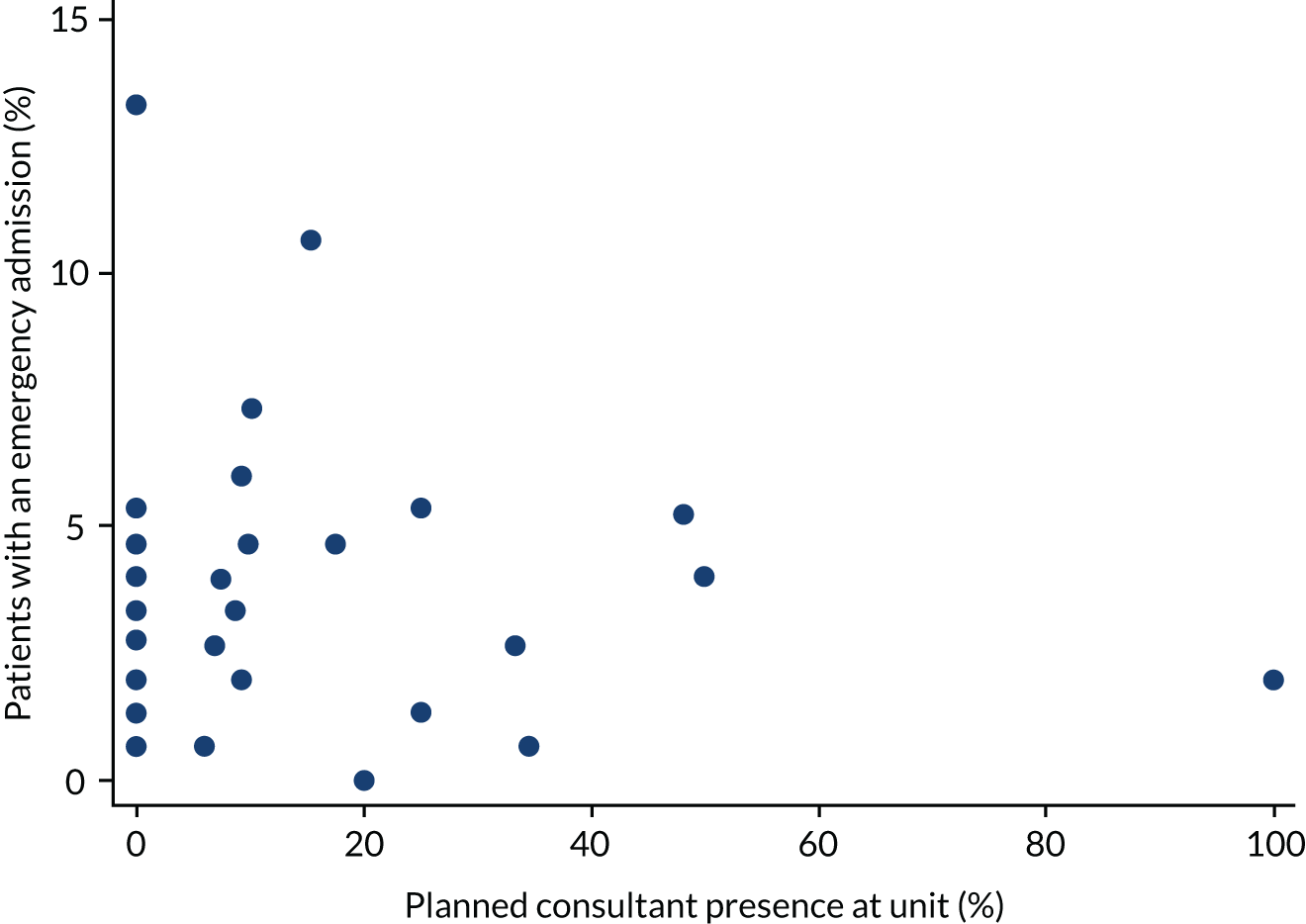

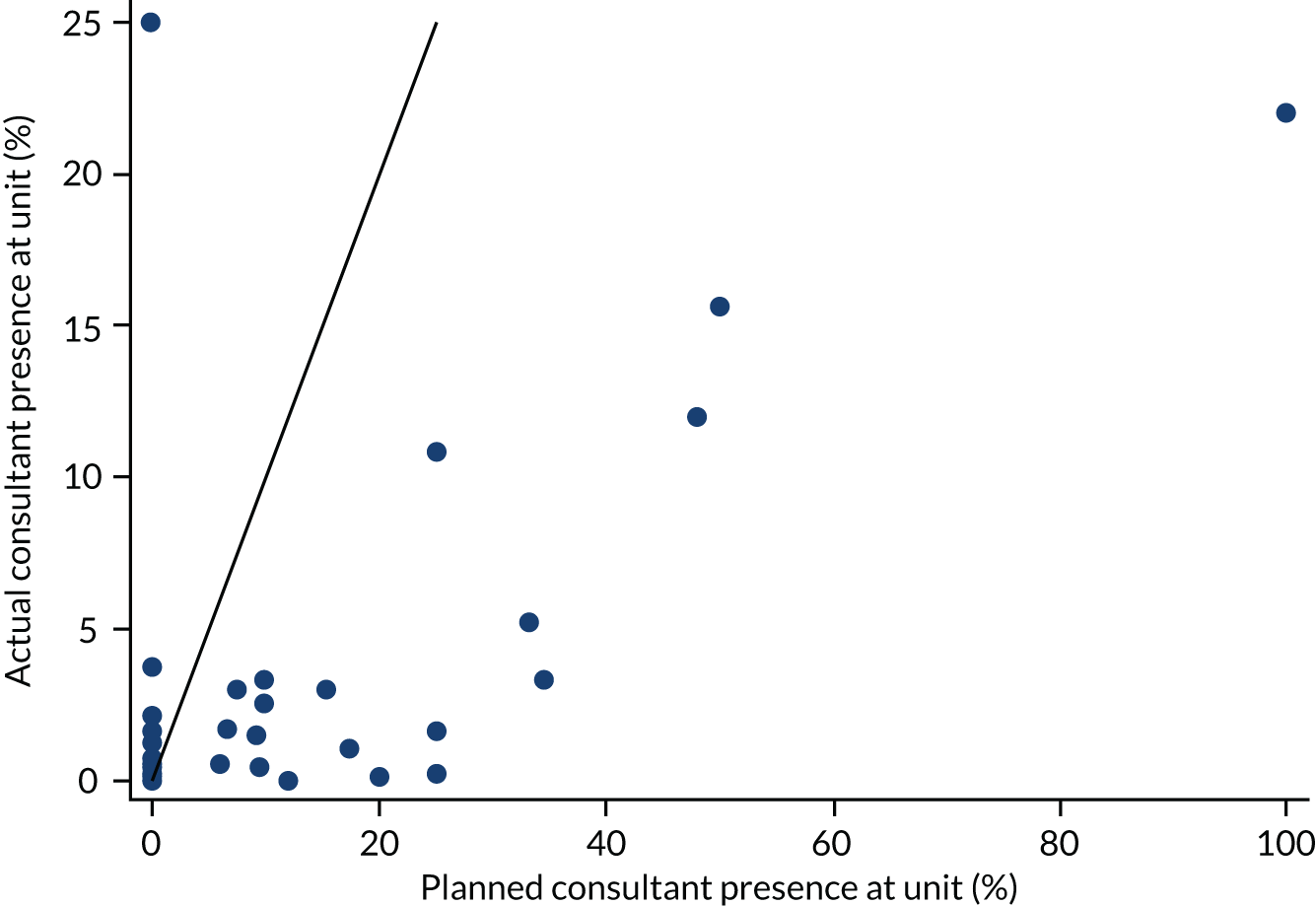

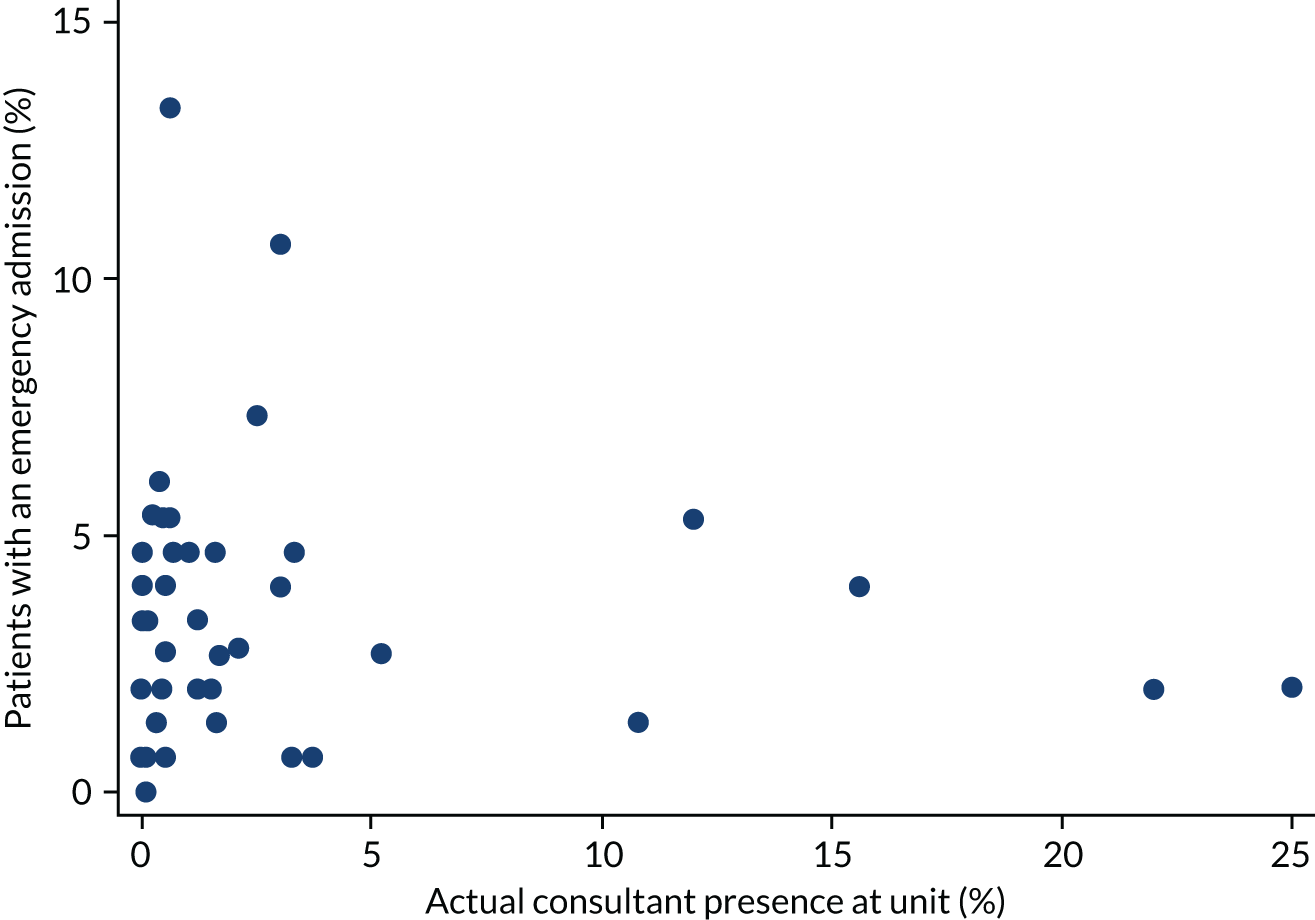

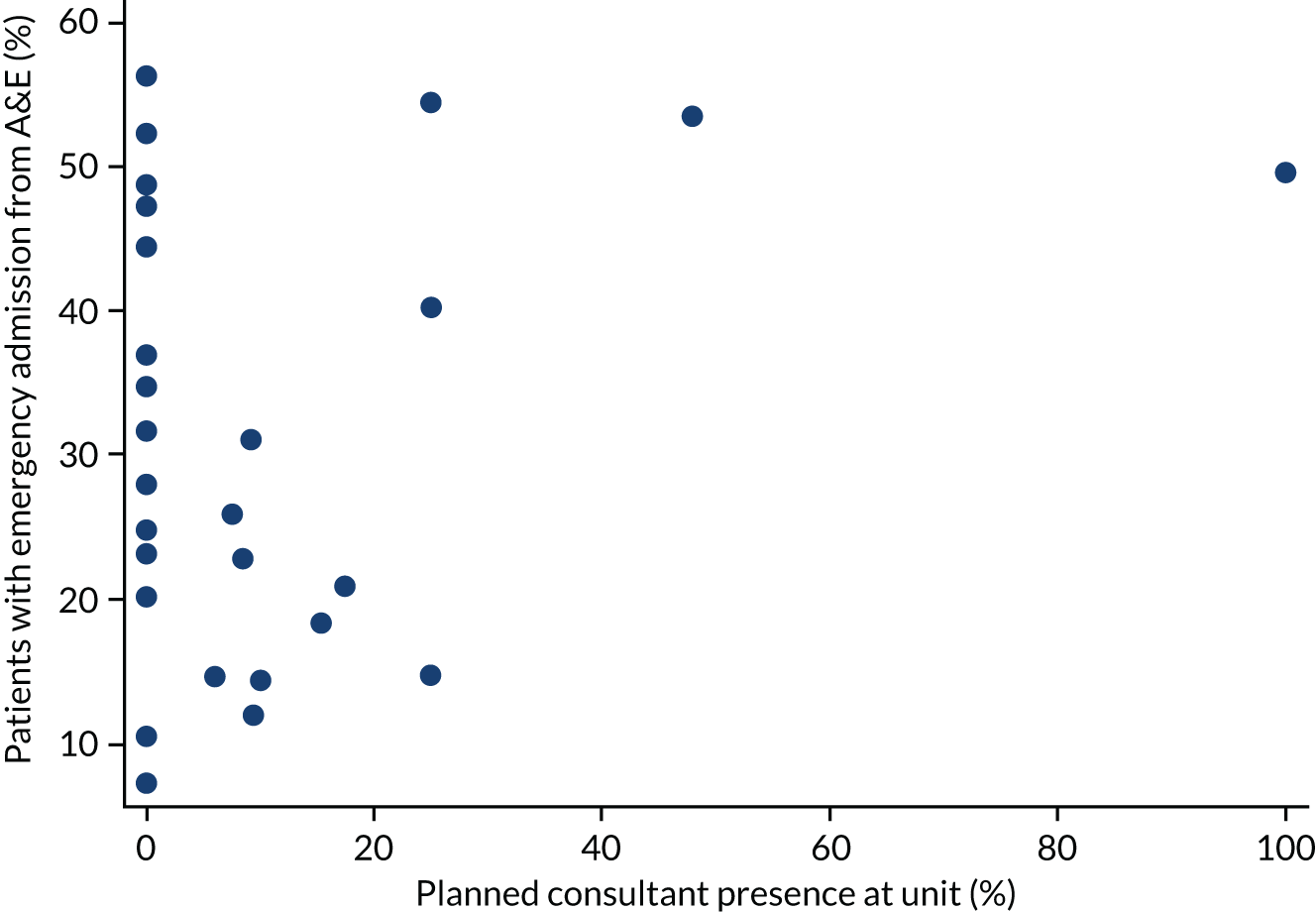

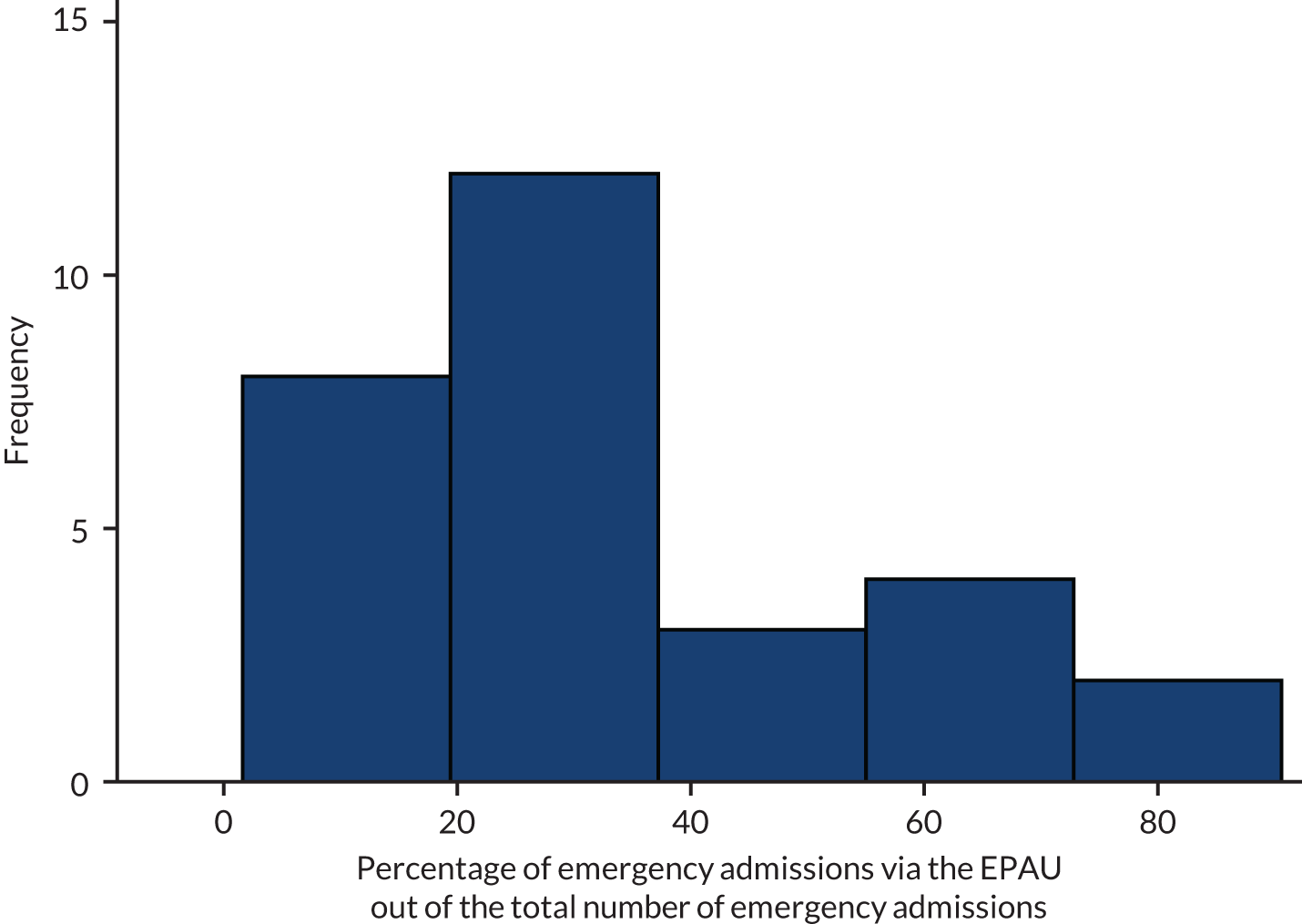

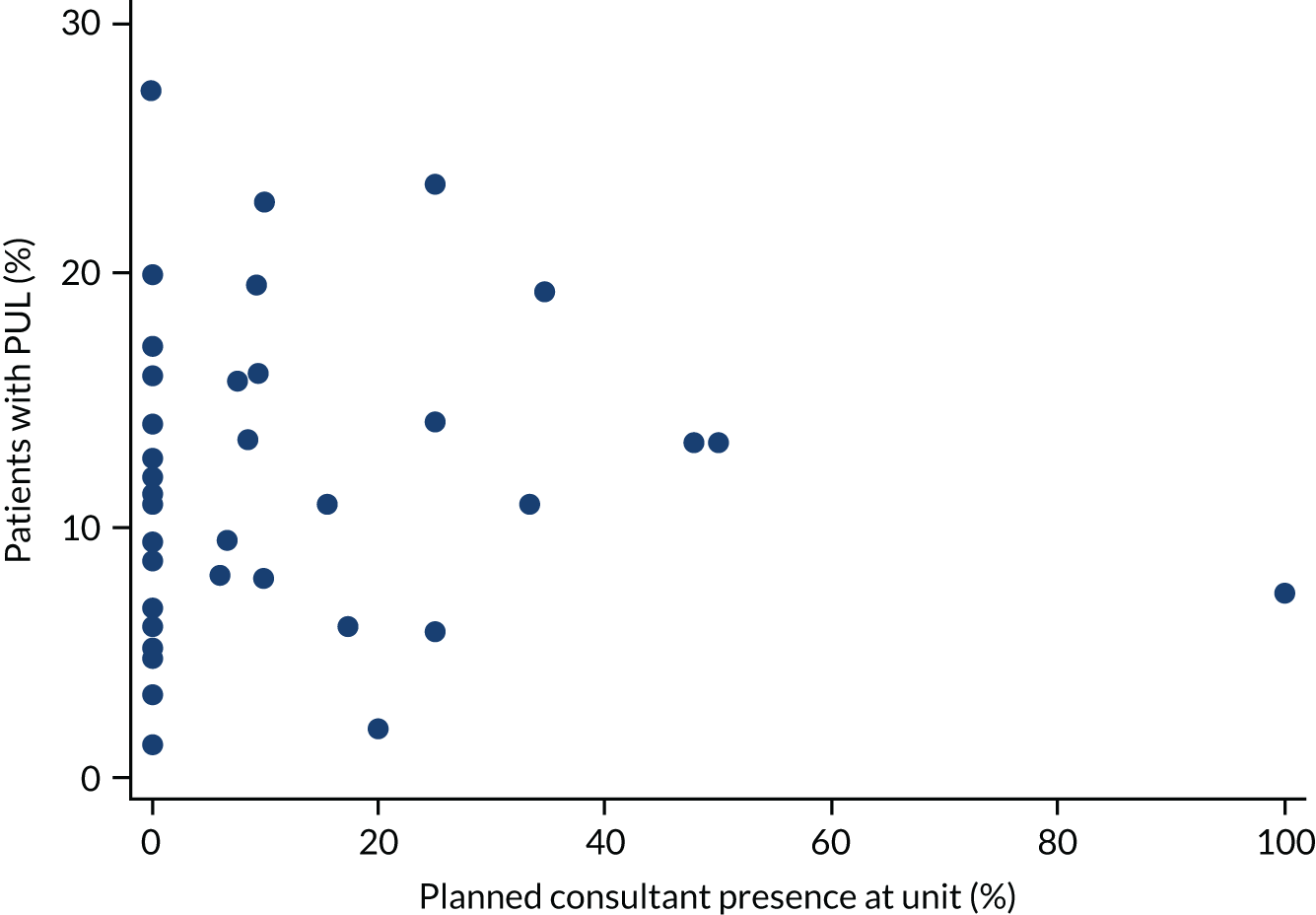

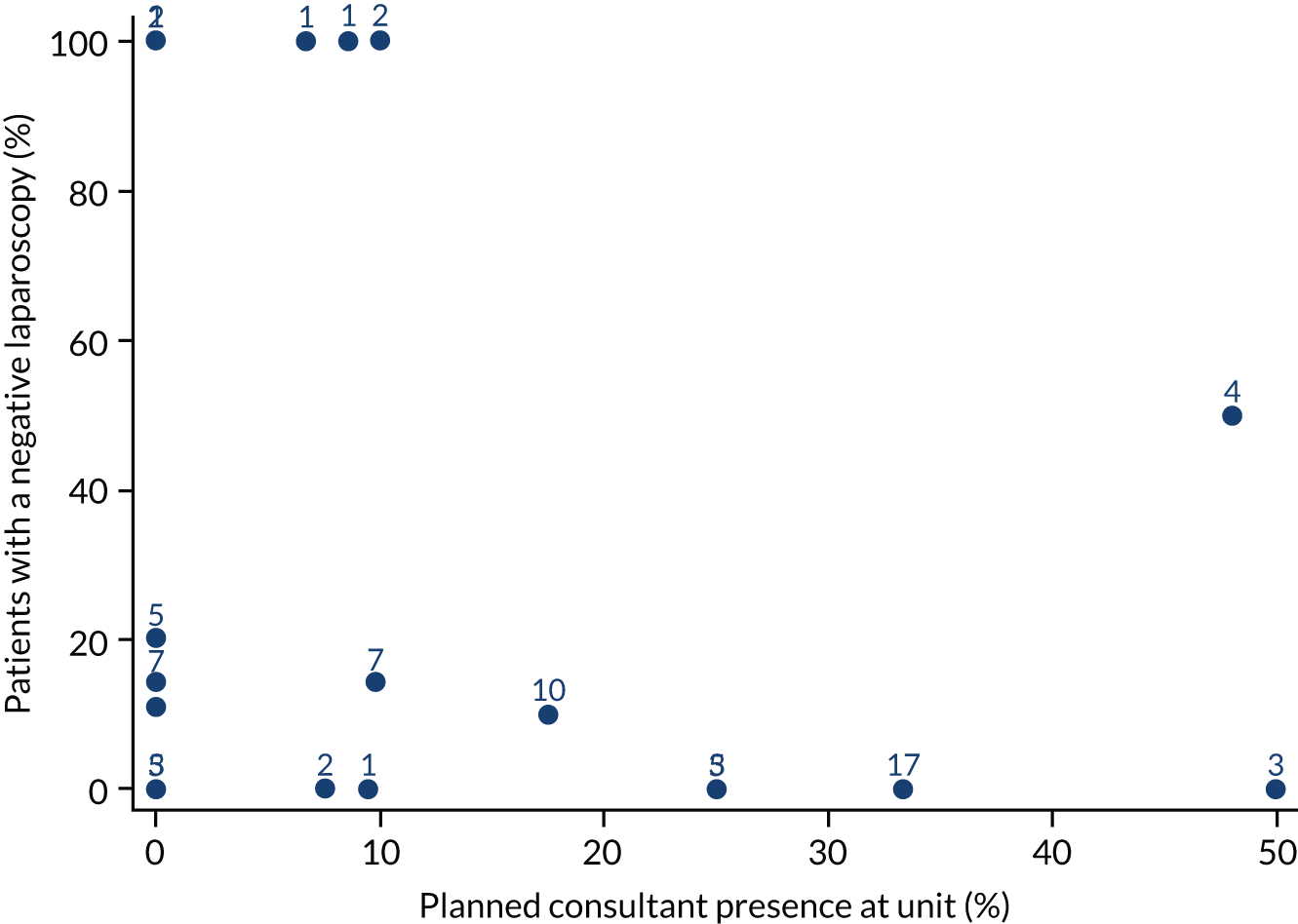

The distribution of planned consultant presence in the recruited units is shown in Figure 5. The majority of the EPAUs (41/44) had a planned presence of < 35% of opening time and 25 EPAUs had no planned consultant presence.

FIGURE 5.

Planned consultant presence at EPAUs, expressed as percentage of opening hours across 44 EPAUs.

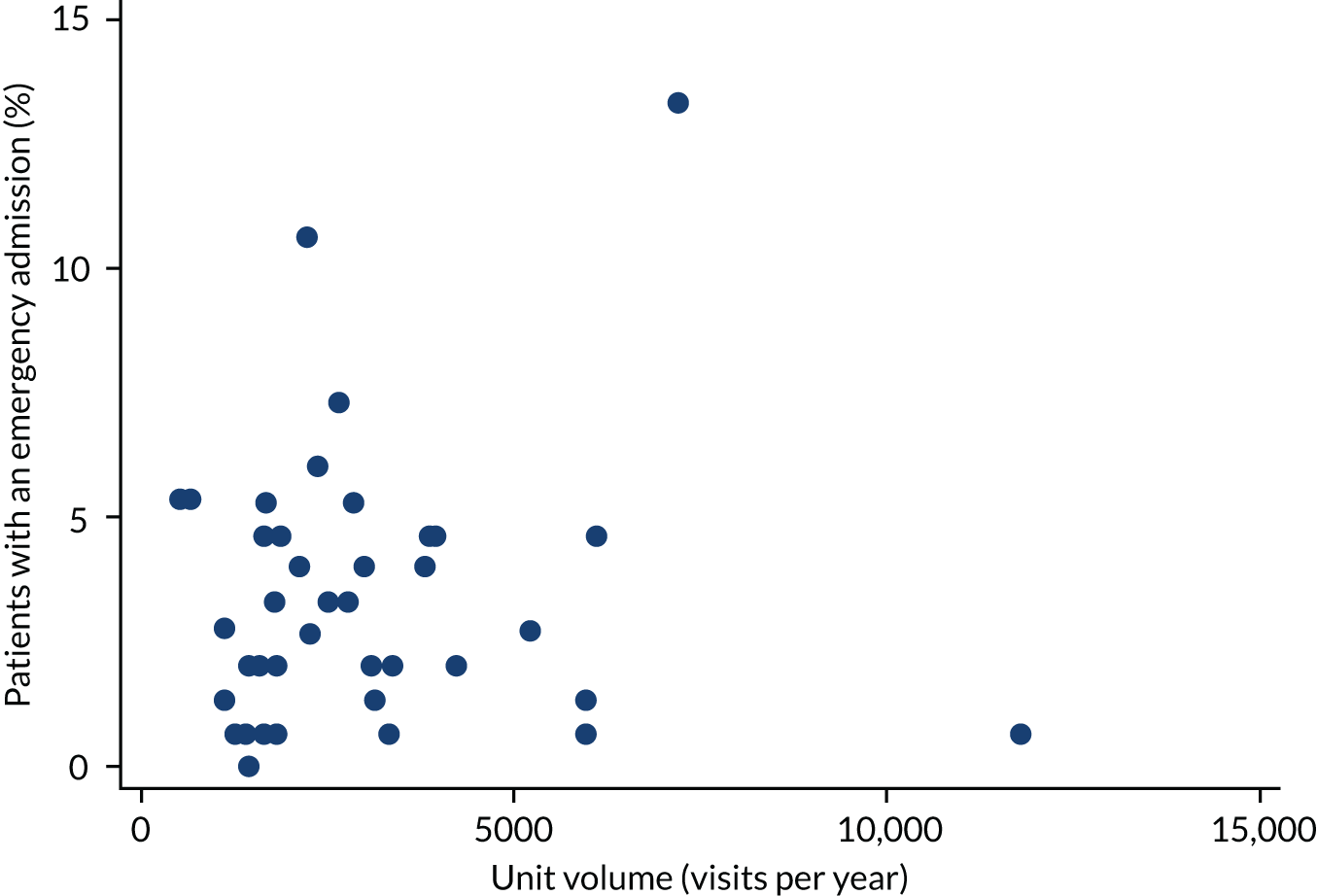

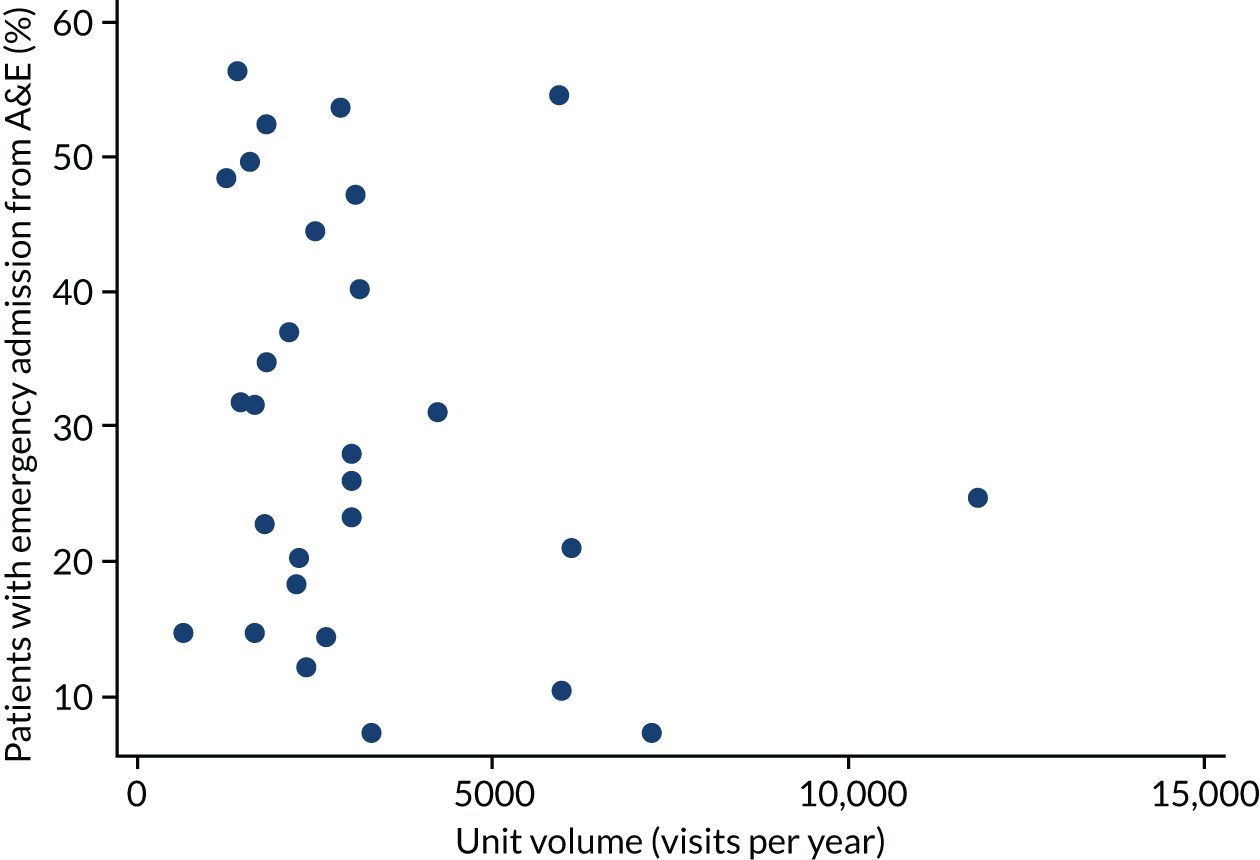

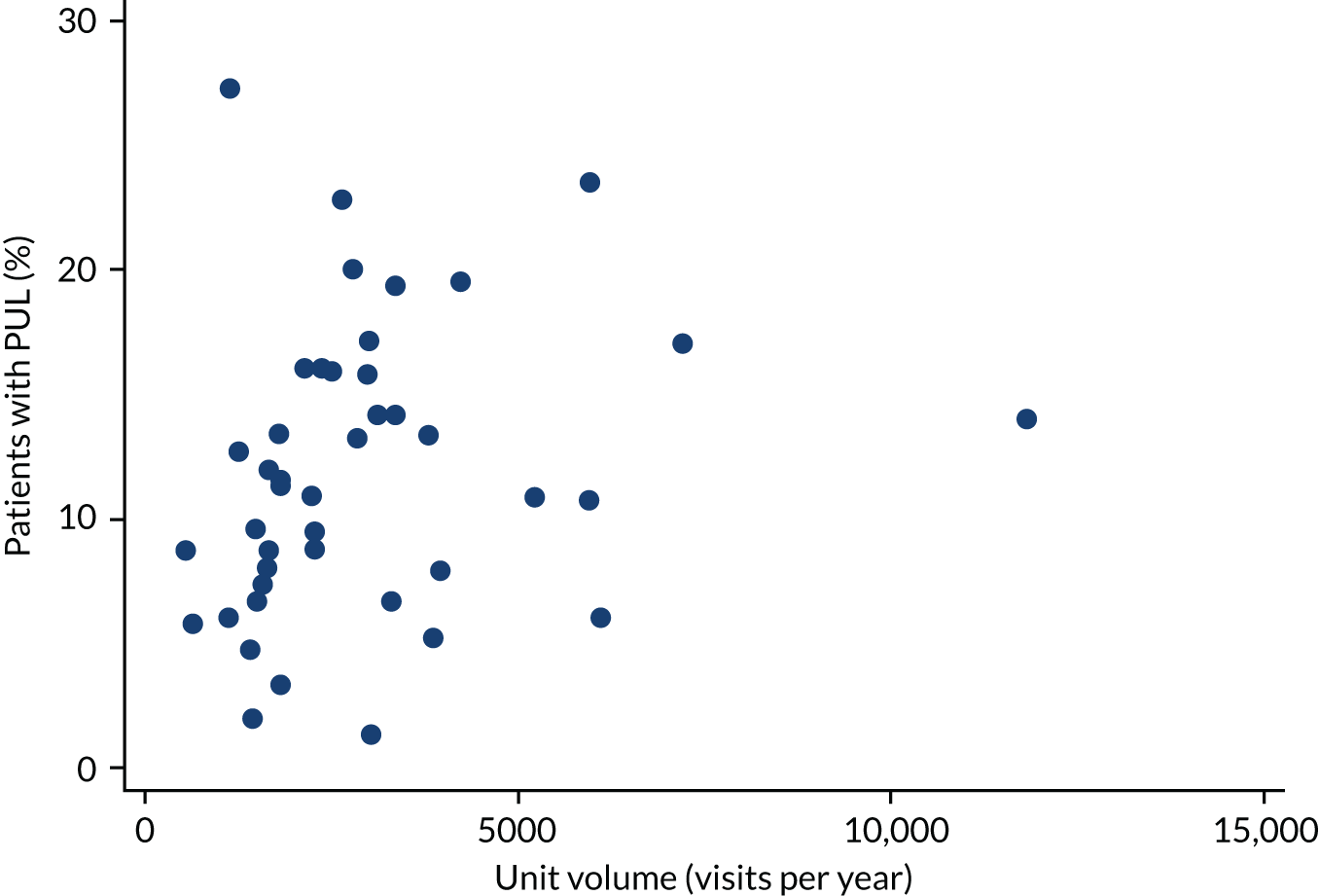

The distribution of unit volume is shown in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6.

Estimated number of visits per year across the 44 participating EPAUs.

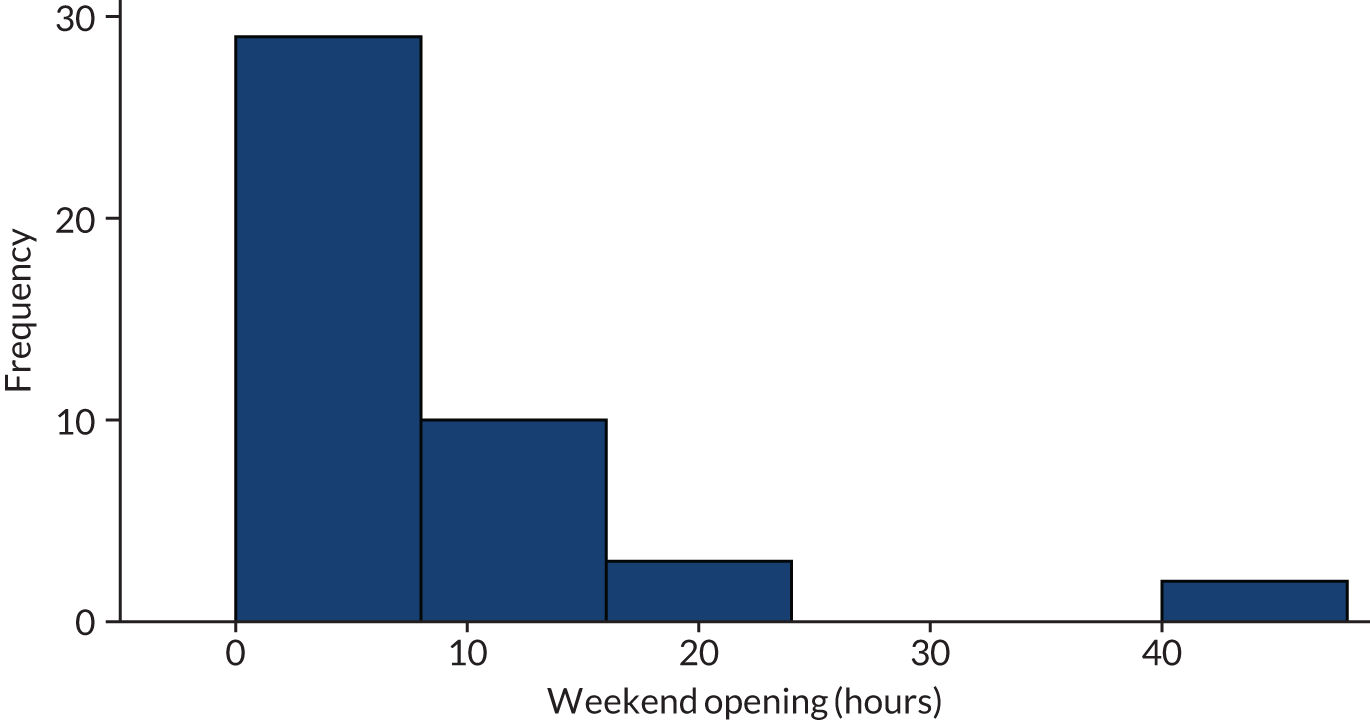

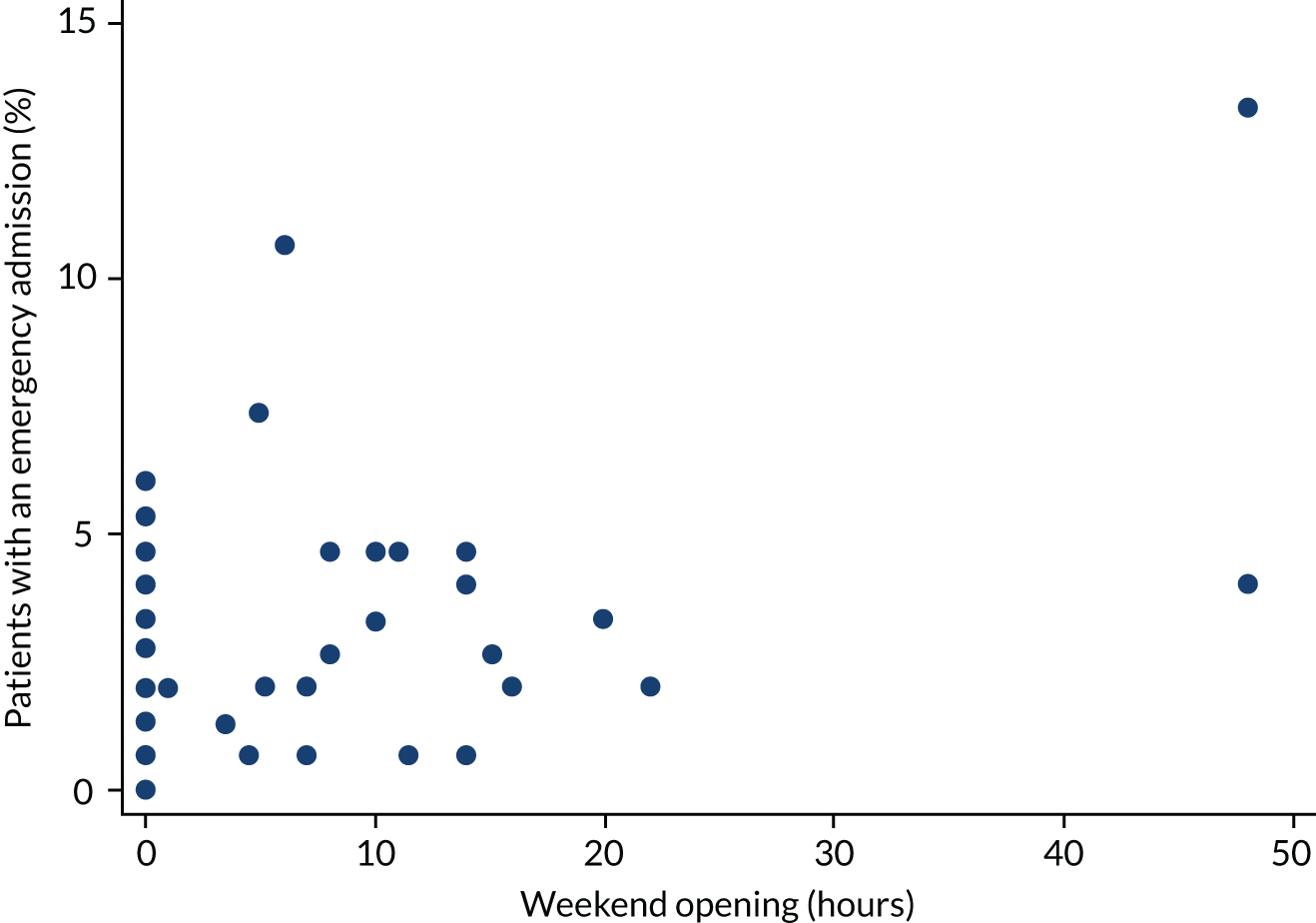

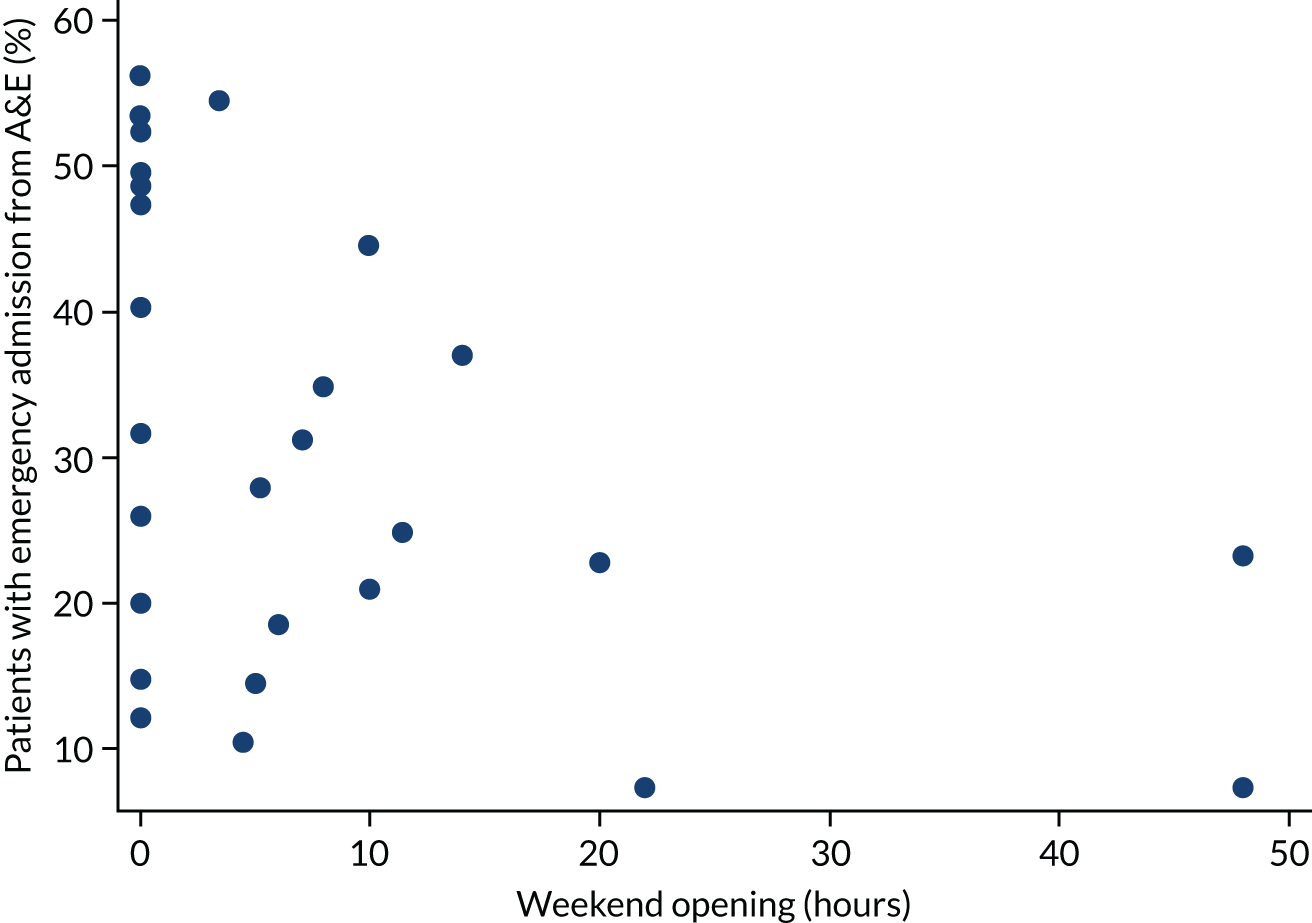

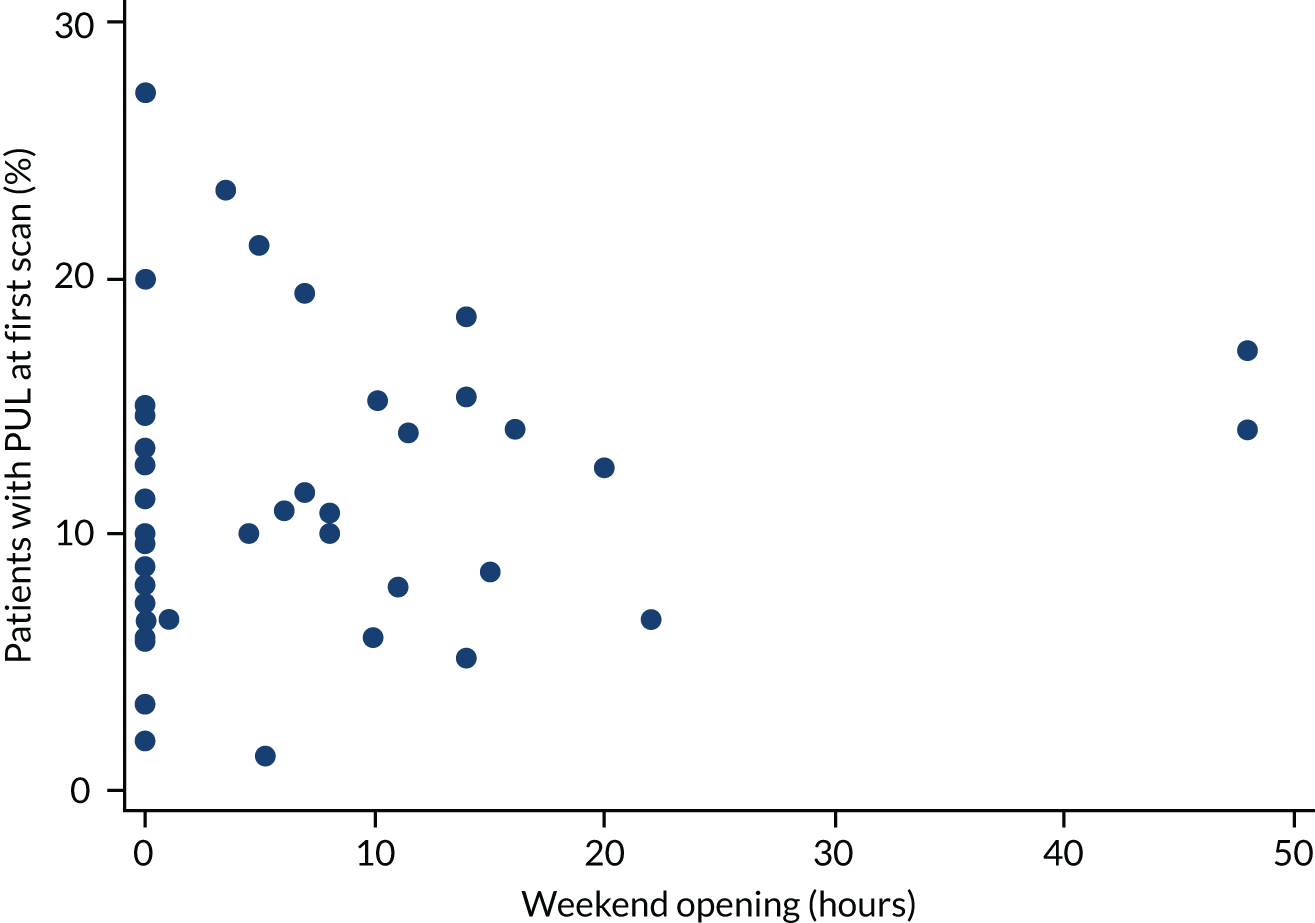

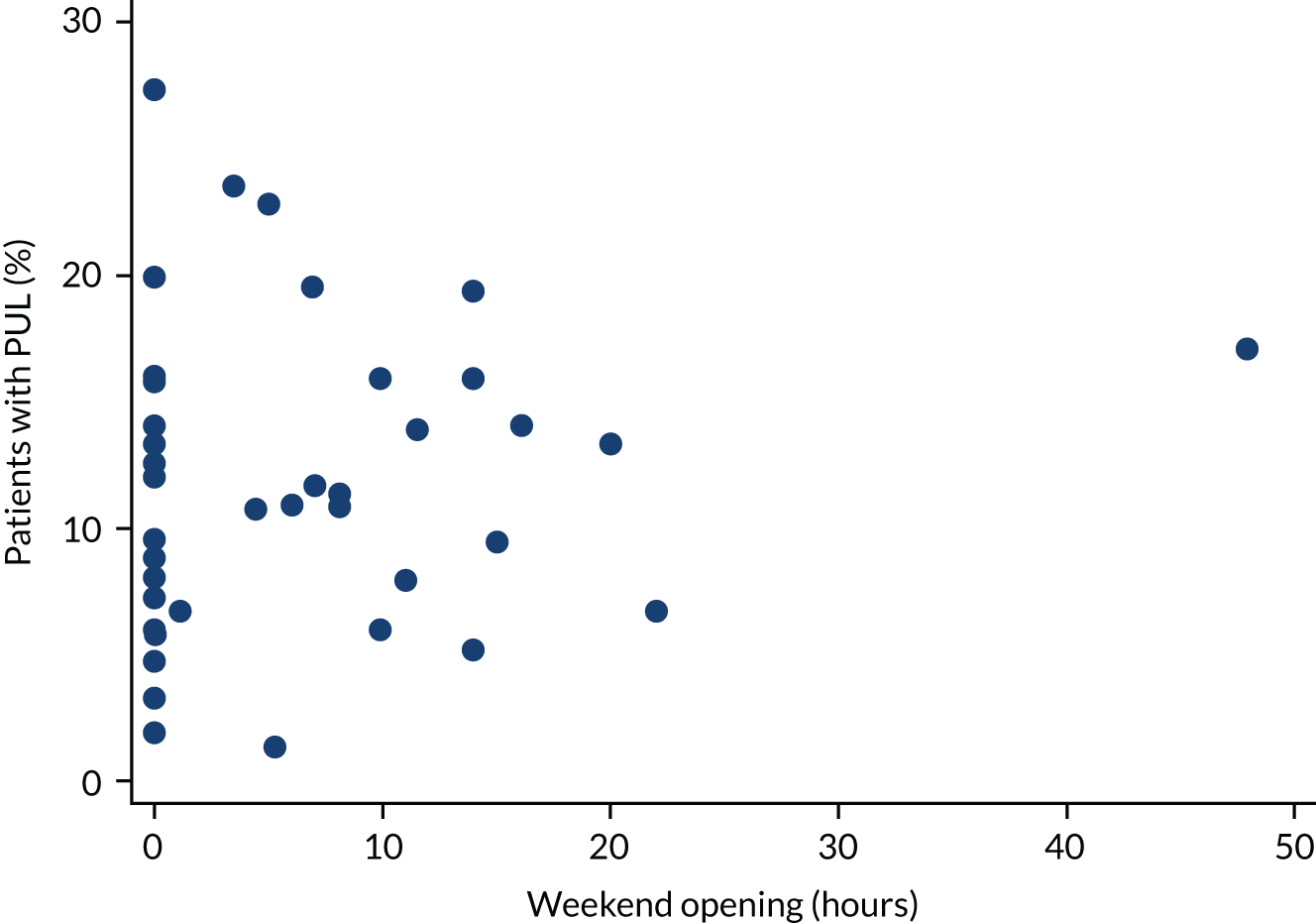

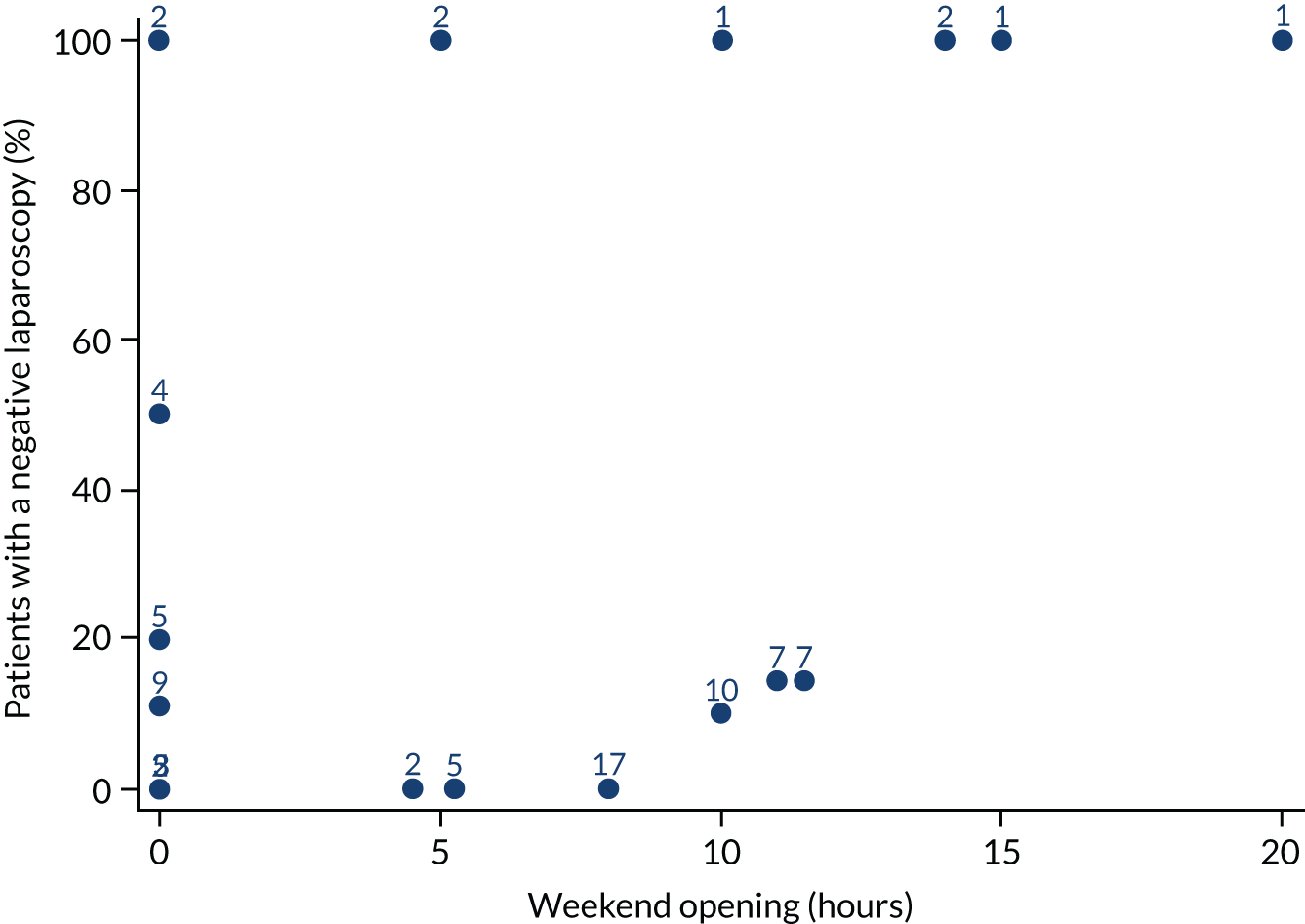

The distribution of weekend opening hours is shown in Figure 7. Approximately half of the EPAUs (23/44) were open at weekends, but the majority of these EPAUs (12/23) were open for < 10 hours.

FIGURE 7.

Distribution of weekend opening hours across EPAUs.

Patient and staff recruitment

Clinical outcomes in EPAUs

Patient recruitment and collection of clinical data were carried out over a period of 8 months between December 2016 and July 2017. All EPAUs were asked to recruit a minimum of 150 women each. Forty EPAUs met this target and four EPAUs recruited between 143 and 149 women (see Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 7). The median time for units to complete recruitment was 33 (interquartile range 24–47) days.

Data cleaning was carried out by the central study team to resolve any discrepancies in the data set and to ensure data completeness. Several duplicate patient entries were identified, and some patients were identified who did not fulfil the eligibility criteria. These entries were removed from the database and relevant sites were asked to meet their recruiting target of 150 patients by collecting anonymous data about the next patient who would have been seen in the EPAU at the end of recruitment. We were unable to complete this process at all sites, which explains the small shortfall in the number of recruited patients at four sites.

The total number of recruited patients was 6606.

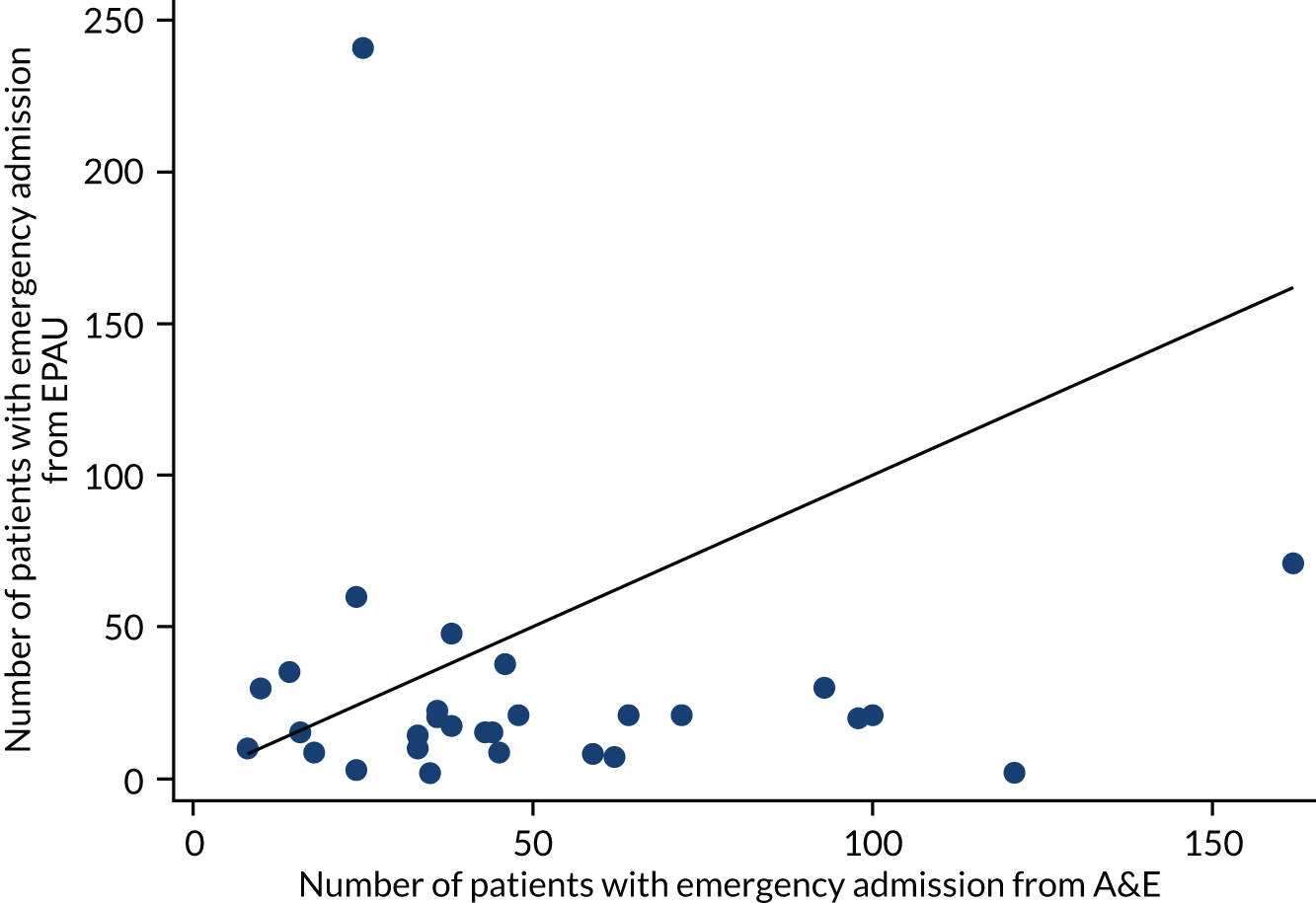

Emergency hospital care audit

Audit of emergency care was carried out in 42 EPAUs operating in acute hospitals with functional A&E departments. The aim of the audit was to capture emergency hospital activity with regard to early pregnancy care, by looking at A&E attendances for women in early pregnancy and at emergency admissions which were not generated from EPAUs (i.e. admissions from A&E departments, any of the outpatient clinics and other settings). The time frame covered at each EPAU was set to 3 months. The data were collected retrospectively, with the end of the 3-month period corresponding to the date of when the last woman recruited to the clinical outcome arm of the study was discharged from the EPAU.

Forty-one sets of data were received between June 2017 and September 2018. One site was unable to provide data. Data quality and completeness varied between the sites. Coding practices differed between trusts and obtaining high-quality and complete audit data was a difficult and complex task. Extensive data checks were carried out to assess for discrepancies between data sets and local admission lists and to assess the reliability of the data.

Of the 41 sets of data received, 10 EPAUs provided data for all emergency admissions, 19 EPAUs provided data for admissions from A&E only, six EPAUs provided data for emergency admissions from sources other than A&E, and the remaining six EPAUs provided data considered to be unreliable. In view of this, data from only 29 EPAUs were used to assess factors associated with emergency admissions from sources other than the EPAU.

Patient satisfaction

All eligible women were approached to consent to take part in the questionnaire arm of the study. This involved women completing the SAPS and the modified Newcastle–Farnworth questionnaires 2 weeks after their attendance at the EPAU. A total of 4217 women agreed to take part, with 414 women subsequently withdrawing consent and the remaining 3803 women completing the questionnaires.

Staff satisfaction

The staff satisfaction survey was carried out between February 2017 and July 2018. A total of 338 staff members were approached to take part. A total response rate of 52% was achieved, with 158 surveys fully completed and 18 surveys partially completed.

Qualitative interviews

A total of 153 women were contacted between January and May 2018 and asked to take a part in the qualitative interviews. Of the 60 women who responded, 17 declined to take part and four withdrew. Thirty-nine women were interviewed, but one woman was excluded from the analysis because of the content of her interview (which focussed on other clinical experiences outside her time at the EPAU). Therefore, the final analysis was of 38 women.

We achieved a fairly even distribution across the sampling frame for all components (see Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 8). We deliberately sampled more women with pregnancy losses than women with ongoing pregnancies, as we expected these women to provide richer data. Of the women included in this study, 17 had ongoing pregnancies, 15 had experienced miscarriages, two had a PUL, two received treatment for ectopic pregnancies, one experienced a molar pregnancy and one underwent a termination of pregnancy. Women in this study were mostly aged 30–39 years at the time of interview. The majority were married, although some were single with a partner and one woman was single with no partner. Six women in our sample were unemployed, many were currently on maternity leave and most women reported having planned the pregnancy they discussed in the interview.

Health economic evaluation

The health economics protocol specified two follow-up time points for data collection: at 2 weeks and 3 months after the participant’s final visit to the EPAU. A total of 3803 women were requested to complete the 2-week pack containing the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire; 1576 questionnaires were returned (giving a response rate of 41%). Of the questionnaires returned, 573 were returned between 2 and 6 weeks after women visited their EPAUs. The remaining questionnaires were returned after 6 weeks and up to 26 weeks after the initial visit. The median number of days between baseline and follow-up was 42 days.

We had estimated that for the secondary analysis we needed 320 women to complete the EQ-5D-5L questionnaires 3 months after their last hospital visit. We sent out a total of 1415 questionnaires and received 364 responses (a response rate of 26%). This exceeded our original target. The median number of days between baseline and second follow-up was 104 (range 8–259).

Many patients returned either the 2-week or 3-month questionnaires late. Strict adherence to the analysis plan in the protocol would have excluded many of the data, particularly around the 2-week questionnaire and outcome. To maximise use of the data, we made the following changes to the timings of the follow-up analysis. The 2-week follow-up became a 4-week follow-up and all EQ-5D-5L responses received between 2 and 6 weeks post visit were included in this analysis. This gave a total sample size for analysis of 573. If we included only responses received between 2 and 3 weeks, the total sample would have been 228. Including responses received between 2 and 4 weeks would give a sample of 347. The 3-month follow-up time point became an 18-week follow-up time point. Any EQ-5D-5L responses received between 12 and 24 weeks post visit were then included in this analysis. This gave a total of 316 responses to the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire.

Workforce analysis

Timing data, which included the length of women’s interactions with different EPAU staff members, were collected during each visit. A total of 6531 complete records were used for the workforce analysis

Demographic characteristics of the study population

See Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 9, for the demographic characteristics of women included in the study across the EPAUs.

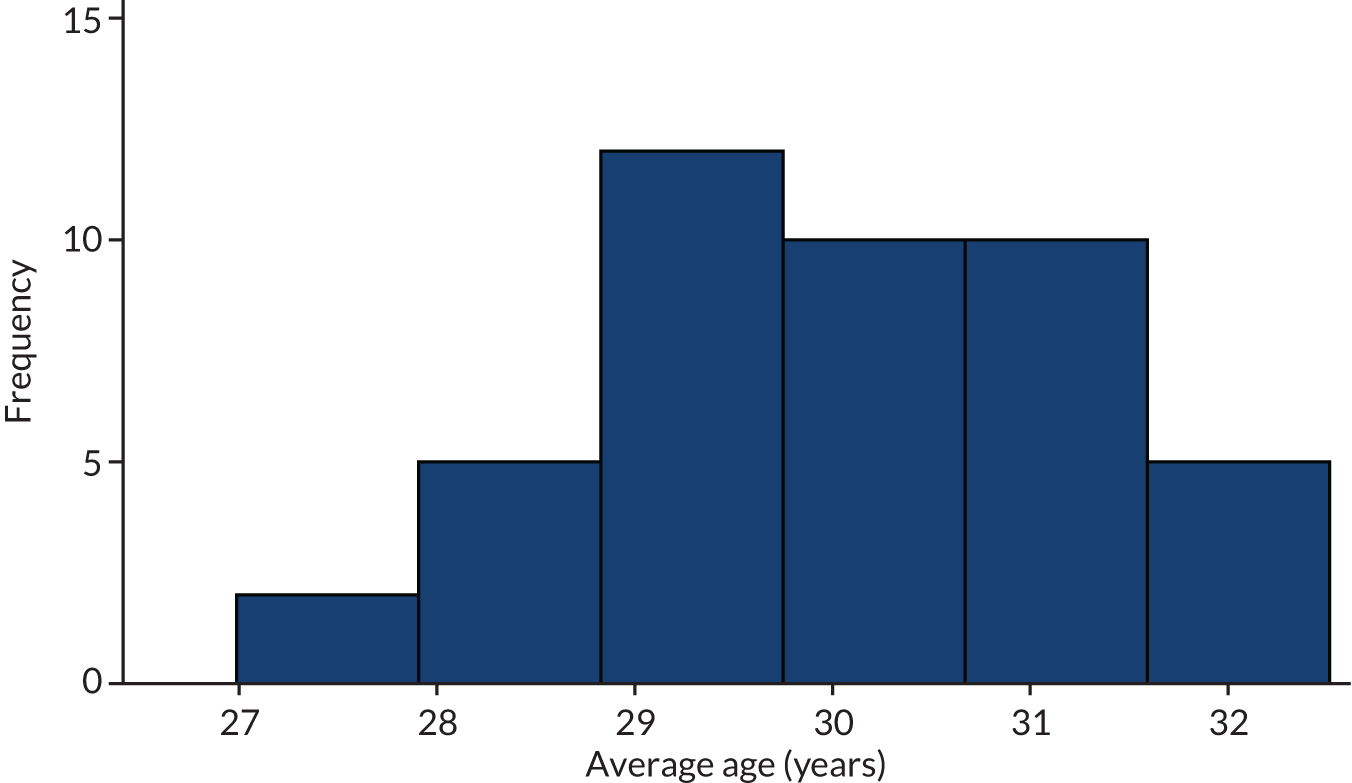

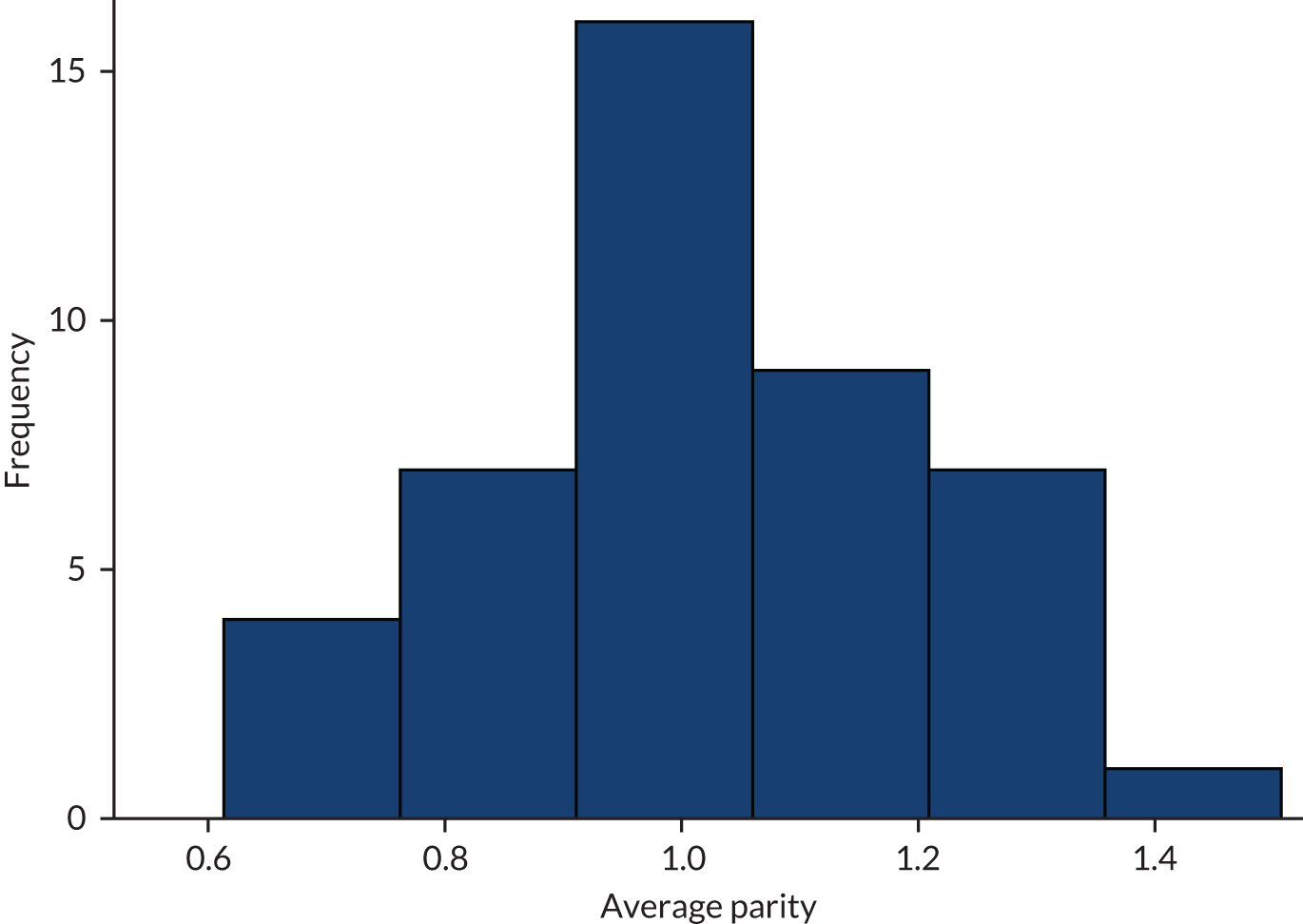

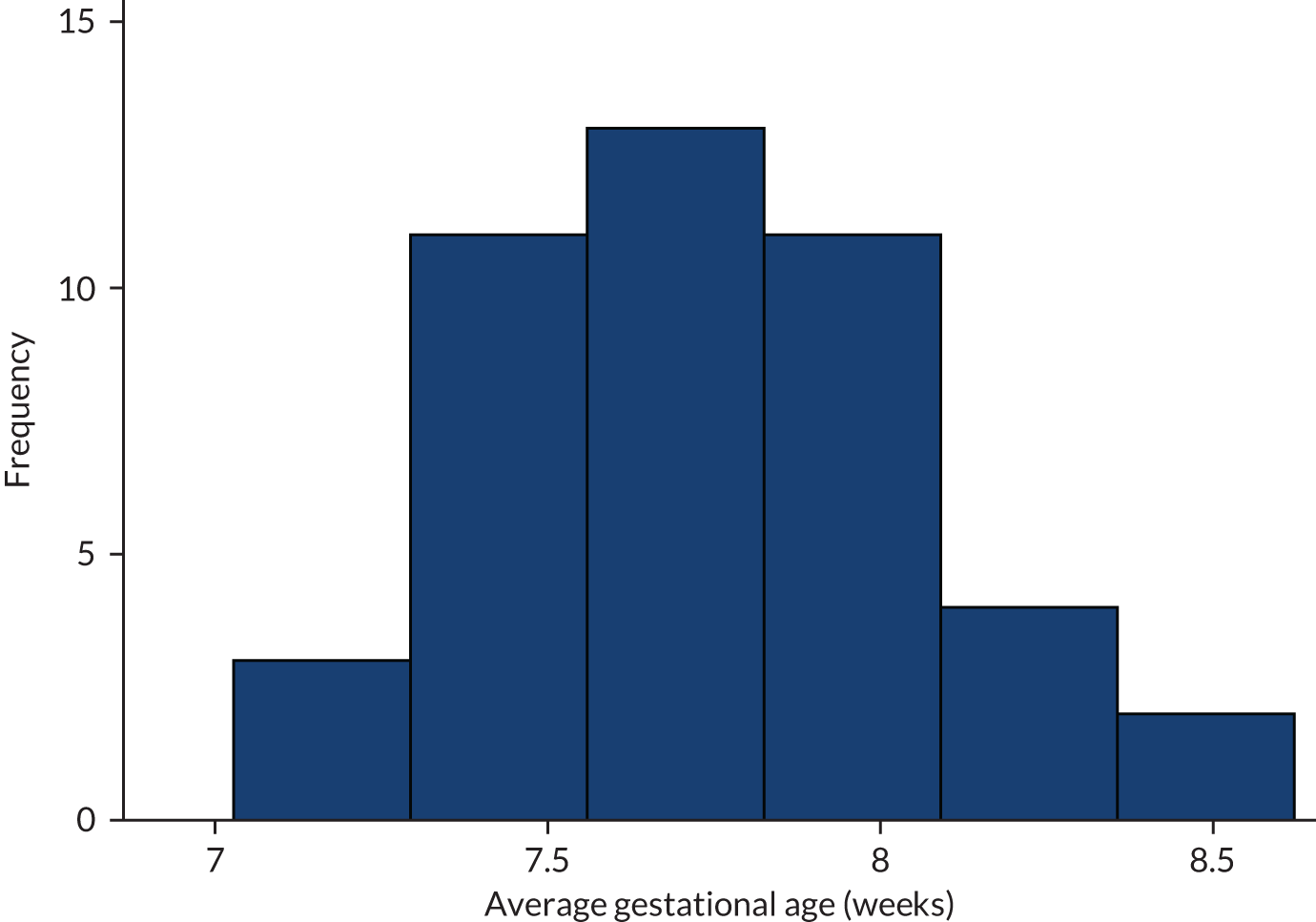

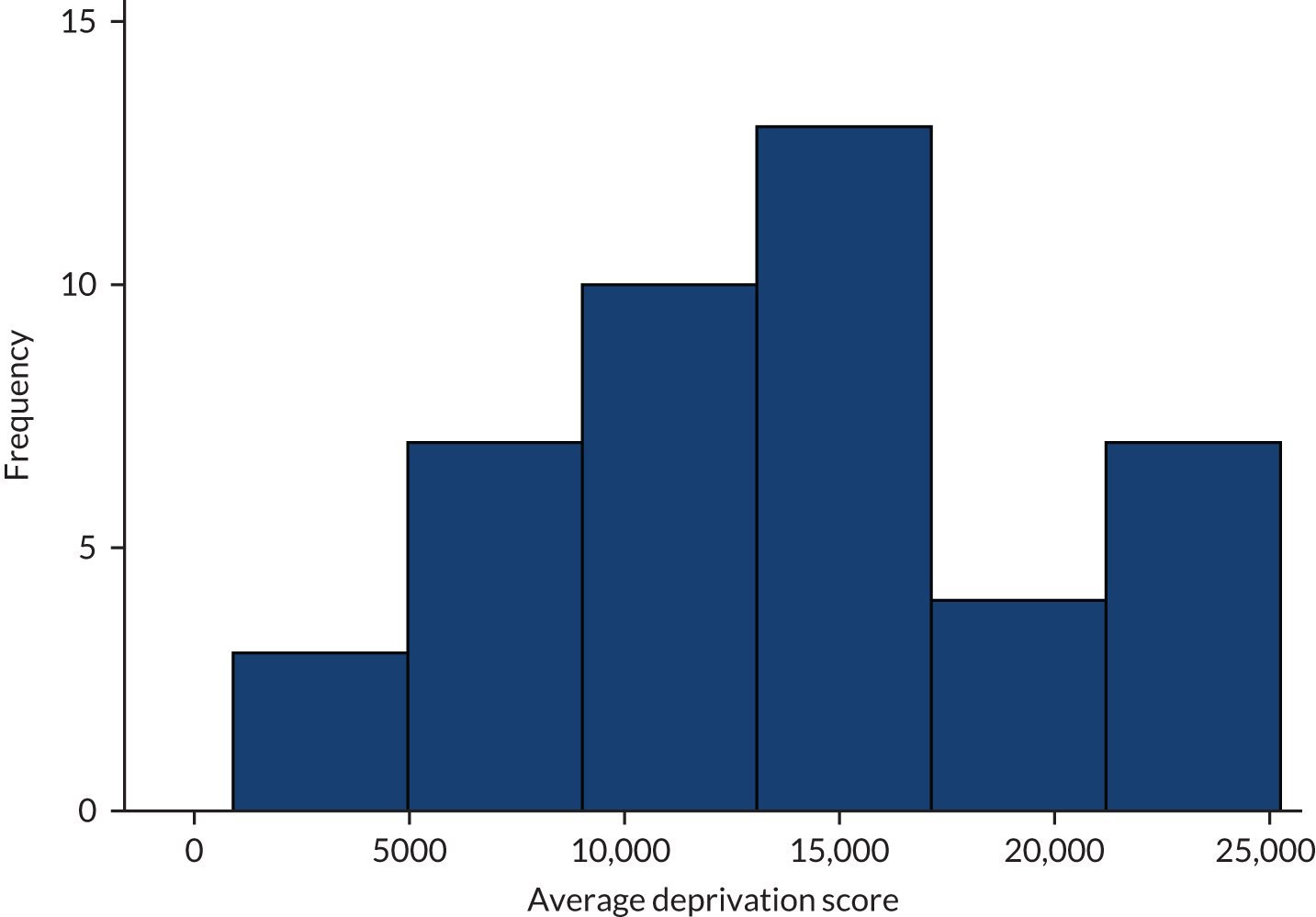

The distribution of women’s average age, parity and gestational age at presentation across the EPAUs are shown in Figures 8–10. The average DSs across the units are shown in Figure 11.

FIGURE 8.

Distribution of women’s average age across units.

FIGURE 9.

Distribution of average parity across units.

FIGURE 10.

Distribution of average gestational age at presentation across units.

FIGURE 11.

Distribution of average DS across units.

Summary of clinical data

We collected clinical data from 6606 women. A total of 2422 (36.7%) women attended EPAUs for follow-up visits. Of those who had a follow-up visit, the median number of follow-up visits was 1 (range 1–14) visit. The overall ratio of new to all follow-up visits was 6606 to 3512 (1.88).

We then compared the units in terms of follow-up visits adjusted for MA and FD. The majority of women [5891/6606 (89.2%)] attended for one or two visits. We postulated that higher numbers of follow-up visits (i.e. three or more visits) is more likely to reflect the quality of clinical care, and we decided to use it as a basis for our comparisons (Table 1).

| Unit | n | Follow-up visits (three or more visits), n (%) | Ranka |

|---|---|---|---|

| JDG | 150 | 0 (0) | 1 |

| RPR | 150 | 3 (2) | 2 |

| OYN | 150 | 4 (2.7) | 3 |

| BVU | 150 | 3 (2) | 4 |

| HYG | 150 | 4 (2.7) | 5 |

| NSK | 150 | 6 (4) | 6 |

| RXO | 156 | 6 (3.8) | 7 |

| TCS | 150 | 6 (4) | 8 |

| YUS | 150 | 7 (4.7) | 9 |

| SXM | 143 | 9 (6.3) | 10 |

| QAR | 151 | 8 (5.3) | 11 |

| BDX | 150 | 8 (5.3) | 12 |

| CXP | 150 | 8 (5.3) | 13 |

| WYW | 149 | 10 (6.7) | 14 |

| SXB | 151 | 10 (6.6) | 15 |

| VXL | 149 | 10 (6.7) | 16 |

| PCO | 149 | 10 (6.7) | 17 |

| HJZ | 150 | 11 (7.3) | 18 |

| SHS | 150 | 11 (7.3) | 19 |

| GLR | 150 | 12 (8) | 20 |

| AIS | 150 | 12 (8) | 21 |

| ULV | 151 | 12 (7.9) | 22 |

| MJL | 150 | 14 (9.3) | 23 |

| XQZ | 151 | 16 (10.6) | 24 |

| JII | 150 | 16 (10.7) | 25 |

| QSL | 150 | 20 (13.3) | 26 |

| JPM | 150 | 22 (14.7) | 27 |

| ZAR | 151 | 21 (13.9) | 28 |

| SCC | 151 | 21 (13.9) | 29 |

| ZNI | 151 | 22 (14.6) | 30 |

| XNL | 150 | 26 (17.3) | 31 |

| GFY | 151 | 25 (16.6) | 32 |

| OVA | 150 | 27 (18) | 33 |

| YLJ | 150 | 25 (16.7) | 34 |

| UOY | 150 | 24 (16) | 35 |

| IWX | 150 | 24 (16) | 36 |

| CZX | 152 | 25 (16.4) | 37 |

| ZAM | 150 | 24 (16) | 38 |

| JNM | 150 | 29 (19.3) | 39 |

| SDD | 150 | 27 (18) | 40 |

| FVX | 150 | 29 (19.3) | 41 |

| WWR | 150 | 23 (15.3) | 42 |

| WDI | 150 | 39 (26) | 43 |

| XQD | 150 | 46 (30.7) | 44 |

A total of 6122 (92.7%) women had an ultrasound scan at their initial visit. Most follow-up visits also involved ultrasound scans, but the proportion of visits that included scans decreased with increasing numbers of visits (Table 2).

| Initial visits | Initial (N = 6606), n (%) | Follow-up visit | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (N = 2252), n (%) | 2 (N = 715), n (%) | 3 (N = 271), n (%) | 4 (N = 120), n (%) | 5 (N = 65), n (%) | 6 (N = 43), n (%) | 7 (N = 27), n (%) | 8 (N = 19), n (%) | ||

| Ultrasound scan | 6122 (92.7) | 1697 (75.4) | 507 (70.9) | 180 (66.4) | 58 (48.3) | 22 (33.8) | 14 (32.6) | 6 (22.2) | 2 (10.5) |

The majority of women (68.9%) were diagnosed with normal or early intrauterine pregnancies at the initial visit. However, the proportion of abnormal pregnancies increased with the number of follow-up visits. This trend was particularly strong with ectopic pregnancies, which were diagnosed in 1.3% of women at the initial visit and in 7.6% of women at the fourth follow-up visit (Table 3). Out of a total of 109 ectopic pregnancies, 80 (73%) were diagnosed at the initial visit.

| Ultrasound diagnosis | Initial (N = 6190), n (%) | Follow-up visit | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (N = 1812), n (%) | 2 (N = 549), n (%) | 3 (N = 197), n (%) | 4 (N = 66), n (%) | 5 (N = 26), n (%) | 6 (N = 16), n (%) | ||

| Early intrauterine pregnancy | 1460 (23.6) | 218 (12.0) | 75 (13.7) | 24 (12.2) | 7 (10.6) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (6.3) |

| Normal/live intrauterine pregnancy | 2802 (45.3) | 784 (43.3) | 162 (29.5) | 56 (28.4) | 12 (18.2) | 4 (15.4) | 1 (6.3) |

| Early embryonic demise | 511 (8.3) | 260 (14.3) | 85 (15.5) | 35 (17.8) | 11 (16.7) | 3 (11.5) | 3 (18.8) |

| Incomplete miscarriage | 205 (3.3) | 141 (7.8) | 46 (8.4) | 19 (9.6) | 7 (10.6) | 5 (19.2) | 2 (12.5) |

| Retained products of conception | 59 (1.0) | 67 (3.7) | 32 (5.8) | 11 (5.6) | 8 (12.1) | 4 (15.4) | 3 (18.8) |

| Complete miscarriage | 352 (5.7) | 233 (12.9) | 90 (16.4) | 25 (12.7) | 8 (12.1) | 3 (11.5) | 2 (12.5) |

| Ectopic pregnancy | 80 (1.3) | 28 (1.5) | 19 (3.5) | 13 (6.6) | 5 (7.6) | 4 (15.4) | 3 (18.8) |

| Inconclusive scan (PUL) | 697 (11.3) | 76 (4.2) | 39 (7.1) | 13 (6.6) | 8 (12.1) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (6.3) |

| Other | 13 (0.2) | 4(0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 1 (3.8) | 0 |

The overall proportion of PULs was 11.3% at the initial visit, decreasing to 7% at the third follow-up visit. However, the proportion increased again to 12.1% at the fourth follow-up visit. The rate of inconclusive scans differed between the EPAUs, ranging from 1.3% to 27.3%. Observed and ranked data at the unit level for PUL diagnosis are shown in Table 4. Ranking was adjusted for MA.

| Unit | n | PUL at first scan, n (%) | Ranka |

|---|---|---|---|

| JDG | 150 | 2 (1.3) | 1 |

| SCC | 138 | 8 (5.8) | 2 |

| RXO | 156 | 3 (1.9) | 3 |

| BVU | 147 | 5 (3.4) | 4 |

| ZAR | 151 | 5 (3.3) | 5 |

| UOY | 135 | 7 (5.2) | 6 |

| HYG | 150 | 10 (6.7) | 7 |

| RPR | 149 | 10 (6.7) | 8 |

| IWX | 150 | 9 (6) | 9 |

| NSK | 149 | 12 (8.1) | 10 |

| SHS | 150 | 11 (7.3) | 11 |

| AIS | 150 | 10 (6.7) | 12 |

| ULV | 150 | 9 (6) | 13 |

| XNL | 139 | 11 (7.9) | 14 |

| WYW | 148 | 13 (8.8) | 15 |

| GLR | 150 | 15 (10) | 16 |

| WWR | 106 | 9 (8.5) | 17 |

| OYN | 150 | 22 (14.7) | 18 |

| SXB | 151 | 15 (9.9) | 19 |

| PCO | 149 | 12 (8.1) | 20 |

| YUS | 146 | 14 (9.6) | 21 |

| BDX | 147 | 16 (10.9) | 22 |

| VXL | 147 | 16 (10.9) | 23 |

| XQD | 135 | 19 (14.1) | 24 |

| OVA | 150 | 17 (11.3) | 25 |

| QAR | 147 | 17 (11.6) | 26 |

| JII | 149 | 15 (10.1) | 27 |

| ZNI | 149 | 20 (13.4) | 28 |

| MJL | 150 | 19 (12.7) | 29 |

| QSL | 146 | 22 (15.1) | 30 |

| HJZ | 150 | 23 (15.3) | 31 |

| GFY | 151 | 20 (13.2) | 32 |

| CXP | 128 | 22 (17.2) | 33 |

| ZAM | 142 | 18 (12.7) | 34 |

| SDD | 149 | 19 (12.8) | 35 |

| FVX | 143 | 20 (14) | 36 |

| JPM | 149 | 29 (19.5) | 37 |

| XQZ | 151 | 23 (15.2) | 38 |

| TCS | 149 | 21 (14.1) | 39 |

| YLJ | 145 | 29 (20) | 40 |

| CZX | 140 | 26 (18.6) | 41 |

| WDI | 136 | 29 (21.3) | 42 |

| SXM | 143 | 39 (27.3) | 43 |

| JNM | 149 | 35 (23.5) | 44 |

A total of 1295 (19.6%) women had a blood test at their initial visit. The proportion of women having a blood test showed the opposite trend to ultrasound scans, with the number of blood tests increasing with increasing number of visits (Table 5).

| Initial visits | Initial (N = 6603), n (%) | Follow-up visit | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (N = 2242), n (%) | 2 (N = 715), n (%) | 3 (N = 271), n (%) | 4 (N = 120), n (%) | 5 (N = 65), n (%) | 6 (N = 43), n (%) | ||

| Blood test | 1295 (19.6) | 476 (21.2) | 194 (27.1) | 85 (31.4) | 48 (40) | 30 (46.2) | 23 (53.5) |

The majority of blood tests were carried out in women with PULs and ectopic pregnancies. A relatively large proportion of women who were diagnosed with a miscarriage [369/1126 (32.8%)] also underwent blood tests. A total of 513 blood tests were carried out in women with a conclusive diagnosis of an intrauterine pregnancy (513/1143, 44.9%) (Table 6).

| Ultrasound diagnosis (n) | Blood test, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Early intrauterine pregnancy (1459) | 81 (5.6) |

| Normal/live intrauterine pregnancy (2802) | 63 (2.2) |

| Early embryonic demise (511) | 235 (46.0) |

| Incomplete miscarriage (204) | 42 (20.6) |

| Retained products of conception (59) | 21 (35.6) |

| Complete miscarriage (352) | 71 (20.2) |

| Ectopic pregnancy (80) | 59 (73.8) |

| Inconclusive scan (PUL) (697) | 562 (80.6) |

| Molar pregnancy (8) | 5 (62.5) |

| Other (16) | 4 (25.0) |

The FD in the majority of women was a normal intrauterine pregnancy, whereas 29.9% of women were diagnosed with a miscarriage and 1.7% with an ectopic pregnancy. There was little variation in the final pregnancy outcomes between the units (Table 7).

| Unit (n) | Diagnosis, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal intrauterine pregnancya (N = 4202) | Miscarriageb (N = 1919) | Ectopic pregnancy (N = 109) | Other (N = 179) | |

| AIS (150) | 102 (68.0) | 46 (30.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| BDX (147) | 98 (66.7) | 42 (28.6) | 3 (2.0) | 4 (2.7) |

| BVU (147) | 108 (73.5) | 37 (25.2) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| CXP (128) | 72 (56.3) | 50 (39.1) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (4.7) |

| CZX (140) | 92 (65.7) | 41 (29.3) | 4 (2.9) | 3 (2.1) |

| FVX (143) | 91 (63.6) | 49 (34.3) | 2 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) |

| GFY (151) | 101 (66.9) | 40 (26.5) | 5 (3.3) | 5 (3.3) |

| GLR (150) | 103 (68.7) | 37 (24.7) | 4 (2.7) | 6 (4.0) |

| HJZ (150) | 93 (62.0) | 47 (31.3) | 3 (2.0) | 7 (4.0) |

| HYG (150) | 93 (62.0) | 51 (34.0) | 1 (0.7) | 5 (3.4) |

| IWX (150) | 108 (72.0) | 38 (25.3) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.0) |

| JDG (150) | 97 (64.7) | 48 (32.0) | 3 (2.0) | 2 (1.4) |

| JII (149) | 103 (69.1) | 45 (30.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) |

| JNM (149) | 93 (62.4) | 49 (32.9) | 3 (2.0) | 2 (1.3) |

| JPM (149) | 75 (50.3) | 63 (42.3) | 4 (2.7) | 7 (4.7) |

| MJL (150) | 102 (68.0) | 45 (30.0) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.3) |

| NSK (149) | 106 (71.1) | 35 (23.5) | 1 (0.7) | 7 (4.7) |

| OVA (150) | 89 (59.3) | 53 (35.3) | 3 (2.0) | 4 (2.7) |

| OYN (150) | 86 (57.3) | 44 (29.3) | 6 (4.0) | 14 (9.4) |