Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/195/02. The contractual start date was in January 2016. The final report began editorial review in January 2019 and was accepted for publication in October 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Vaughan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background and rationale

The rising number of older patients with multiple chronic conditions and/or more complex needs is considered to be one of the most pressing problems facing the NHS. 1 Although these patients receive the most resource-intensive care, their problems are less likely to be accurately diagnosed and they have more adverse outcomes than other age groups. 2–5 The emerging consensus is that current models of hospital care, which are heavily based around specialists delivering disease-specific care, serves these patients poorly, as it is often fragmented and poorly co-ordinated. A revival of medical generalism has been suggested to provide better and more cost-effective care. 6–10

On paper, this appears to be an excellent suggestion. However, it is based on the pervasive assumptions that what is meant by ‘medical generalism’ is clearly understood, that the patients who would benefit most from a revival of medical generalism have been identified and that current service models are uniform, well-delineated and that changing these will result in better outcomes. The reality is that there is a paucity of evidence and clinical consensus on which to base new models of medical generalism. As noted in the Australian ‘2020’ review, the policy discourse is heavily dominated by opinion and commentary. 11 Here, we will review the evidence across each of these aspects of the debate, professional, service model and patient need, beginning with the core driver of the debate, patient need.

Patients and generalism

Patient demography has been changing rapidly over the past two decades. The population is becoming older, with one in six people the UK now aged > 65 years. The latest projections have this figure doubling to around 19 million people by 2050. Within this total, the number of very old people is expected to grow even faster, with the number of those aged > 80 years set to reach 8 million by 2050. This group of the ‘oldest old’ are the biggest consumers of health and social services. 12 Almost 75% of those aged > 65 years have multiple chronic medical conditions,13 whereas 25–50% of those aged > 85 years are thought to have a frailty syndrome as a result of the general decline in their physical and psychological reserves. 14

The rising number of patients with comorbidities or complex disease is not confined to those aged > 65 years. A recent Scottish study15 found that around one-quarter of patients have two or more morbidities and that, although the presence of multimorbidity increases with age, the absolute number of comorbid patients is largest among those aged < 65 years. 15 Other studies have found that there are associations between multimorbidity and increased risk of mortality, disability, poor quality of life and adverse drug events. 16,17 Patients with multiple comorbidities also have substantially higher rates of general practice consultation, experience less continuity of care and are more dissatisfied with the care that they receive. 18

It is then, perhaps, not entirely unexpected that there has been a sharply rising demand for unscheduled medical care, with the number of English hospital admissions increasing by 2 million patients per year over the last 6 years. 19 These patterns of demographic change and the accompanying rise in health-care usage have led to calls for the whole system of medicine to be realigned with the needs of this patient population. 8,20 However, the impact of the changing patterns of age and disease on secondary care is not fully understood. Recent work by the Nuffield Trust, for example, found that there were 60% more hospital admissions than could be accounted for by the ageing population. 21 There is also an increasingly compelling body of evidence that poor outcomes for patients are more directly the result of poor processes of care contained within a model, rather than the model itself. Misdiagnosis is increasingly held at the international level to be the commonest cause of potentially preventable deaths,22–24 with adverse events relating to diagnostic errors being associated with the highest mortality rate. 25 Although National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD) reports have made clear that errors in processes of care antecede poor outcomes for most patients,26,27 there is a suggestion that the higher rates of morbidity and mortality suffered during hospital admissions by patients with complex disease are a result of their being, as a group, more susceptible to the impacts of below-average care than their less comorbid counterparts. 28 It also worth noting that there have been no high-quality studies relating to the secondary care of multimorbid patients and that a recent systematic review found very little evidence for primary care interventions in this group. 29

To our knowledge, the acceptability of generalist care to patients is yet to explored, a key consideration given that patients value and actively seek specialist care. 30

Professional concepts of generalism

The professional discourse around ‘generalism’ over the last few decades has suffered owing to the lack of a clear definition of what generalism actually is. This has hampered intelligent debate and has contributed to the lack of evidence on the benefits (or otherwise) of generalism and consensus on which to base change. 31 The Australian ‘2020’ review11 of generalism proposed a ‘continuum of generalism’ that used three overlapping dimensions to define a philosophy of practice: ‘ways of being, ways of knowing and ways of doing’. 11 A more recent review by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada31 argued for a clear delineation between the frequently conflated concepts of ‘generalism’ and ‘generalist’. They proposed that ‘generalism’ should be seen as a philosophy within medicine:

Generalism is a philosophy of care that is distinguished by a commitment to the breadth of practice within each discipline and collaboration with the larger health care team in order to respond to patient and community needs.

Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada31

The term ‘generalist’ should be used to refer to a subset of physicians who possess a unique group of competencies:

Generalists are a specific set of physicians and surgeons with core abilities characterized by a broad-based practice. Generalists diagnose and manage clinical problems that are diverse, undifferentiated, and often complex. Generalists also have an essential role in co-ordinating patient care and advocating for patients.

Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada31

Discussions of generalism have, almost invariably, been set alongside and reactive to shifts in the nature of ‘specialism’. Since the emergence of modern concepts of physiology and pathology in the late 19th century, there has been a tension between those who provide a broad scope of services to their patients and those who are specialists with a restricted range of expertise, usually focused on a single organ. 32 Although generalism dominated for much of the early 20th century, medical and technical advances have led to an almost continuous increase in the number of and variety of specialties and subspecialties, with 60 specialties now recognised in the UK and 80 specialties and a further 120 subspecialties recognised in the USA. 33 In parallel with these changes, concerns have been expressed about the increasing complexity of clinical services, rising costs and the fragmentation of care for patients. 34

In the mid-1990s, the debate between generalists and specialists became particularly heated. 35–37 The ‘overspecialised’ American physician workforce was seen as a threat to the provision of affordable, equitable and high-quality health care. 38,39 The resulting flurry of research noted that although generalist was often defined solely in terms of being ‘not specialism’,33 generalists had a strong sense of professional identity. 36 They were usually the first point of contact for the patient in their care pathway, were skilled at diagnosing illness and were able to provide comprehensiveness and continuity of care. 40,41 Contrary to the notion of generalists as ‘failed specialists’, they were found to have a better knowledge base, which was maintained for longer, than their specialist counterparts. 42,43 There was evidence of better outcomes for selected patient groups of receiving specialist care, such as the treatment of myocardial infarction by cardiologists,44,45 depression by psychiatrists,46 acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) by infectious diseases experts47 and some rheumatic conditions by rheumatologists. 48 However, generalist care was found to match or outperform specialist care in other areas. 49,50 More importantly, variations in quality of care between individual generalists and between individual specialists were often found to be larger than the variations between generalists and specialists as groups. 36

In the USA, policy-makers at the time interpreted the evidence to be in favour of increasing the number of medical graduates entering postgraduate training programmes in general internal medicine (GIM). 38,39 The response to this has been the advent of new forms of generalism. In the USA, ‘hospitalism’ focuses on the delivery of inpatient care that was previously provided by specialists or family physicians, whereas acute internal medicine, developed in the UK, provides the initial assessment and management of patients during the first 72 hours of hospital inpatient stay or in the acute ambulatory setting. 51 Despite the arrival of newer specialties that focus on generalist-type care, this has failed to shift the balance towards generalists in the overall medical workforce, with the eclipse of the traditional general physician who could provide care across the whole patient pathway and across a broad range of settings.

Initially, the gradual fading away of the general physician was not mourned, but there have been increasingly urgent calls for the revival of general medicine in the last 5 years. 6–8,52,53 Almost entirely this has been fuelled by the perceived gap between models of care and the needs of patients, leading to the concept of the generalist being both idealised and reimagined with little or no reference to either current models of care or ‘traditional’ general medicine. 11,54 However, although there is a strong policy and professional consensus about the importance of the generalist and generalism,8 it is the branches of medicine that are more generalist, such as acute internal medicine and geriatrics, that are experiencing some of the greatest difficulties recruiting staff. 55 These are also specialties that tend to contribute the most to the acute medical take. 56

Attempts to fill the space that was once occupied by general medicine has led to suggestions that acute physicians should extend their scope of practice beyond the first 72 hours of care,57 whereas the British Society of Geriatrics has suggested that all geriatricians should consider themselves as generalist physicians, rather than confining themselves to caring for patients with diseases relating to ageing and degeneration. 58

Service models and generalism

Until the early 1990s, the bulk of secondary care in the UK was delivered by general physicians. Unscheduled medical patients were admitted by the medical team on the day and remained under the care of the admitting general physician on a general medical ward until their discharge or referral to a specialist service; follow-up care was also frequently the responsibility of the admitting general medical team. 59,60

Alongside the evidence that certain patient groups fare better when cared for by specialists rather than generalists, a large number of observational studies reported that poor outcomes, particularly mortality, reduced as patient number increased. 61–66 These findings added weight to the NHS policy drive that was to reconfigure services in hospitals and centralise them across regions, shifting patients from generalist to specialist services and closing or merging smaller hospitals. 67 The underlying evidence and the assumptions around these drives towards centralisation are now being questioned. There is a recognition that much of the research that examines the relationships between health outcomes and numbers did not take sufficient account of the effects of differences in patient case mix or the additional resources that are often attached to specialist services. 36,68–70 Furthermore, mergers of hospitals have failed to produce gains in efficiency or save costs. 71,72

By the early 2000s, it was becoming clear that these changes were having an impact on the ‘front door’ of hospitals and the assessment of the acutely sick medical patient. The loss of the general medical beds meant that patients were being boarded for long periods in emergency departments (EDs)73 or being admitted directly to inappropriate beds in other parts of the hospital. 74 This, coupled with the erosion of the traditional medical ‘on take’ system,59,60 led to the development of acute medical units (AMUs) in Scotland. These units are designed to improve patient safety by cohorting newly admitted patients in a highly resourced, purpose-built space. 75 Although the initial studies demonstrated that there was a benefit to this,76 AMUs did not become widespread until the 4-hour waiting time ED target was introduced in 2004. It is now estimated that > 95% of acute hospitals in the UK have an AMU.

These twin drivers, the increasing specialisation of the medical workforce and the introduction of AMUs, have transformed the landscape of medical secondary care. Many factors have needed to be aligned with the new models of care,77,78 including:

-

consultant working patterns

-

undergraduate medical education

-

junior and middle-grade postgraduate training

-

the configuration and staffing of hospital wards

-

patient pathways

-

patterns of referral and investigation.

To our knowledge, there has been no wholescale evaluation of the impact of AMUs. The systematic review76 of AMUs in 2009 found that although studies on the introduction of AMUs all reported that there were positive improvements in patient and/or hospital-related outcomes, only nine studies from six hospitals were found. 76 Although guidelines do exist for the structure of and the processes contained in an AMU,79 several smaller studies have found that these are not uniformly adhered to and that the variability between AMUs may account for the differences in outcomes for patients and hospitals alike. 80,81 Concerns have been raised that although AMUs do benefit some patients, they disadvantage those patients with more complex needs by increasing the fragmentation of care, with nearly 30% of physicians considering that care in their own institutions lacks continuity. 82

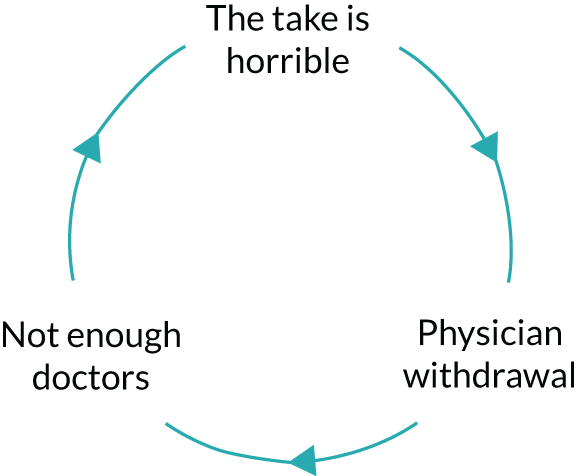

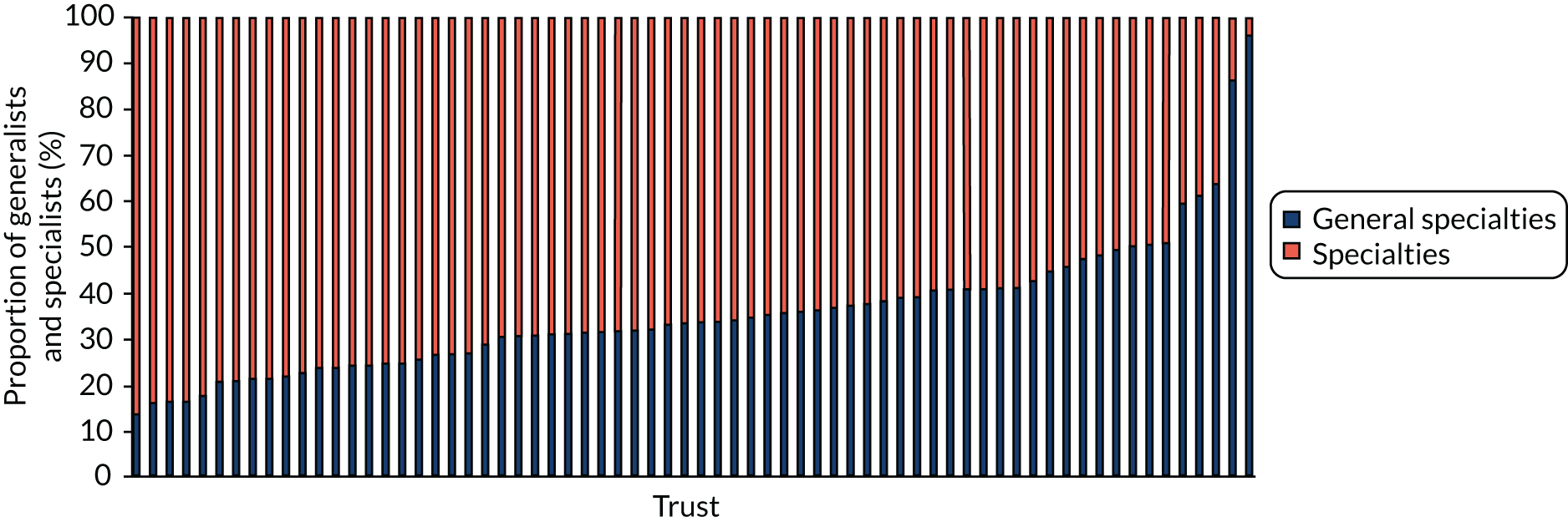

There is also a perception that management of the ‘acute take’ has become more onerous since the introduction of the AMU as a result in the loss of traditional ‘on take’ teams, driving further flight from generalist work. 83 The proportion of all consultant physicians who committed to the acute medical take fell from > 40% in 2012 to 33% in 2017/18, with the participation of consultants from the four largest specialties (geriatric medicine, respiratory medicine, endocrinology and diabetes mellitus, gastroenterology and hepatology) dropping from > 80% to < 60% over the same period. 84 To the knowledge of the research team, there is only one hospital in England that continues to operate a traditional ‘consultant of the take’ model of general medicine.

Despite their rapid spread, AMUs are not ubiquitous in the NHS. Around 5% of hospitals appear to have systems where patients are seen in the ED by acute physicians who act in a generalist-type role, before being triaged to specialty teams without a stay on an AMU. Explorations of unscheduled emergency care suggest that most hospitals operate some type of hybrid model, deploying medical staff across the ED and the AMU,85 although this has never been systematically investigated.

The increasing use of dedicated ambulatory care and frailty services to provide locations to assess the acutely sick medical patient, something that was encouraged by national policy guidance,86 also has significant consequences for the generalist medical workforce in hospitals. In common with the AMU, there are a wide variety of approaches in providing and staffing these services and little formal evaluation. 87 However, in most hospitals the medical leadership for these services comes from doctors who have more generalist skills, while the medical wards are generally led by specialists. 87

Why smaller hospitals?

From this overview of the literature, it is clear that there are a number of gaps in the evidence that need to be addressed. There is a lack of clarity around the meaning of ‘generalism’ in medicine, which has consequences for the professional identity and the role of the ‘general physician’. There is a paucity of information about the current models of care in England and the balance of care offered by generalists and specialists. Furthermore, there has not been an assessment of the impact of the wholescale changes driven by the increase in specialist care and the advent of a variety of services dedicated to the assessment of the acutely unwell patient. There has also been little exploration of what the case mix of patients presenting acutely to hospitals actually is and what the needs of patients actually are.

It is the intention of this study to begin to fill-in these gaps in the evidence base and in particular concentrate on generalist care in smaller hospitals. The rationale for the focus on smaller hospitals is that:

-

A recent study88 suggests that the tensions in the wider health-care service around generalist care versus specialist care are concentrated in smaller hospitals.

-

As a group, smaller hospitals provide care for nearly half of all medical patients. 88

-

The patient populations are older, more vulnerable and have more complex needs in smaller hospitals and, hence, could be considered to require more ‘general medical’ than specialist-type care. 88

-

The trends towards subspecialty care have affected smaller hospitals significantly. With the shift of services to larger sites, smaller hospitals are often left struggling to balance inpatient services and the need to hit targets for outpatient specialist clinics and procedures. 89,90

-

Smaller hospitals are financially constrained and understaffed, with mismatches between service capacity and workload and difficulties in innovating services. 91

In short, smaller hospitals are an ideal microcosm in which to investigate what the needs of patients are, how well these needs are being met by different models of medical generalism and what medical generalism means to medical and other staff.

Chapter 2 Overview of methods

Design

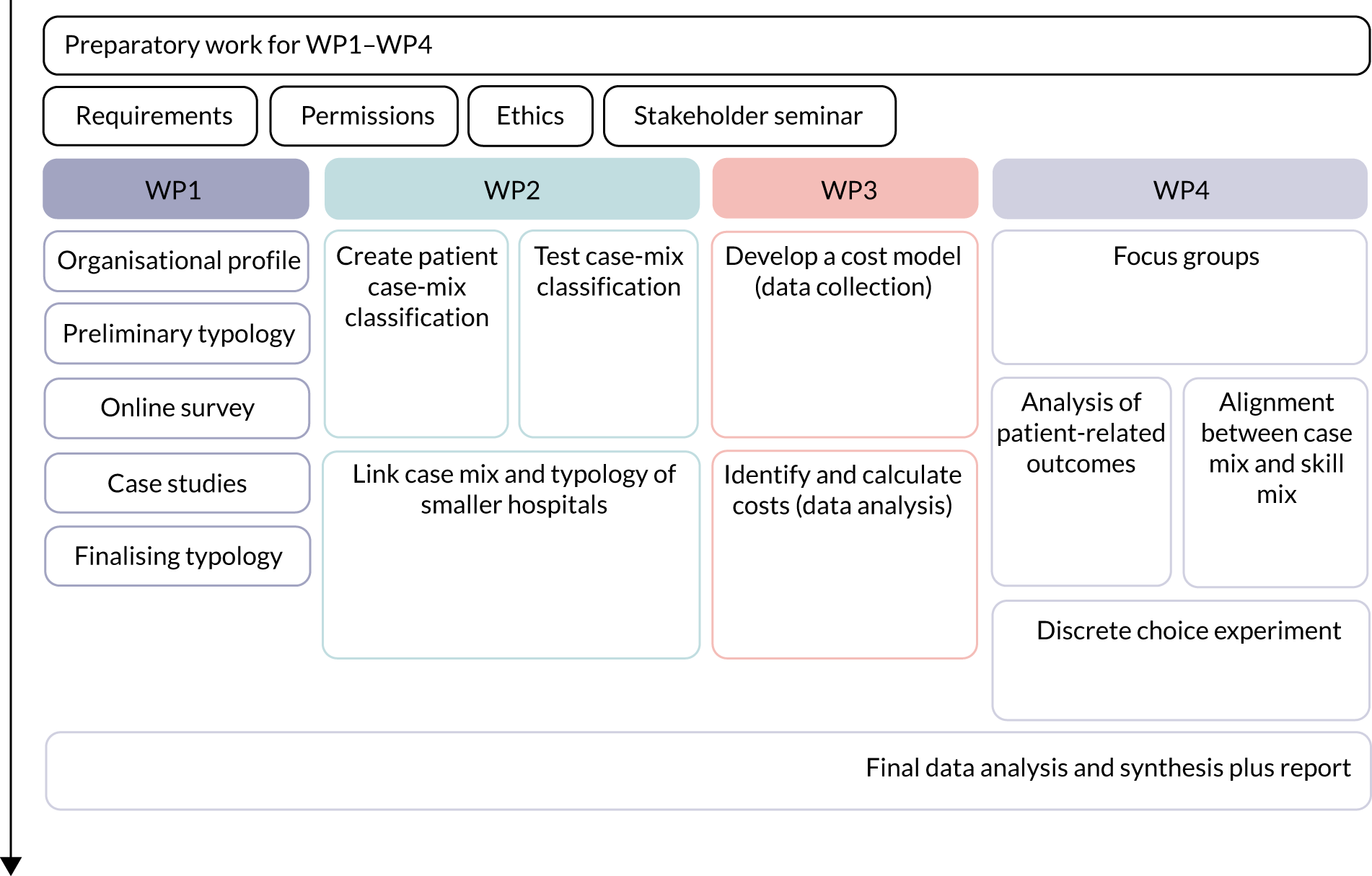

This study used a mixed-methods approach with five work packages (WPs) executed over four phases. The first WP used a variety of methods to map and characterise the models of medical generalism used in smaller English hospitals with a view to create a typology. The second WP used qualitative techniques to create a case-mix classification that identified patients who might benefit from generalist care and used this classification to describe and compare workload, resource utilisation and outcomes between hospitals and models of care. An assessment of the degree of alignment between the patient case mix and the medical generalist skill mix in smaller hospitals was also performed. The third WP explored the economic costs of the different models of generalist care. The fourth WP assessed the strengths and weaknesses of the different models of care using qualitative and semiquantitative approaches from patient, professional and service perspectives. The final WP, which ran across all four phases of the study, drew the results together into an overarching analysis and synthesis. The overall approach to the study allowed for both induction (data-driven generalisation) and deduction (theory-driven exploration of hypotheses), with each stage of the study able to inform the next. The aims and the methods of each WP are outlined in Table 1 and the design of the study is represented in Figure 1.

| Work package | Aims/research question | Methods/data source |

|---|---|---|

| WP1: describing models of medical generalism in smaller hospitals |

|

|

| WP2: understanding the case mix of generalist medical care in smaller hospitals |

|

|

| WP3: investigating the economic costs |

|

|

| WP4: understanding the strengths and weaknesses of current models of medical generalism |

|

|

| WP5: analysis and synthesis |

|

FIGURE 1.

Scheme of the study design.

Study design

Integration between the qualitative and quantitative components of the study was built into the design, which allowed us to robustly test and explore several underpinning hypotheses:

-

that the models of care deployed by hospitals would be shaped equally by theoretical considerations about medical generalism and the resources available to them, making size an important determinant of the model

-

that performance of the models of care would be dependent, at least partially, on an alignment between the hospital’s case mix and the available skill mix

-

that medical generalism provides a solution to the problem of rising numbers of patients with complex and/or multimorbid disease

-

that different models of care would carry cost implications.

Where these hypotheses were not upheld, the design allowed us to explore other potential explanatory factors and generate alternative theories.

Definition of smaller hospital

NHS Improvement (formerly Monitor) previously defined ‘smaller hospitals’ in England as providers with an operating revenue (income) of < £300M in the 2012/13 financial year. 88 This definition was adopted and updated to apply to the 2015/16 financial year.

Conceptual framework

Models of care in hospitals in England are not currently mapped with any level of detail. The literature suggests that medical generalist care has been driven by three main paradigms:92

-

general medical care as the default for all medical patients, unless/until a patient is referred to a specialist service

-

general medical care provided in response to patient needs

-

general medicine providing the ‘work left undone’ by specialists.

However, maps of pathways of emergency care suggest that the organisation of the care of acutely unwell patients tends to be parsed around the pragmatics of deploying available medical, nursing and other staff either on the AMU (where present) or on the downstream medical wards. Subsequently, systems of triage often reflect attempts to manage workload, rather than theoretical considerations. 93 This study attempted to bridge this gap between the theoretical aspects and the pragmatic aspects of general medical care.

Our theoretical framework of medical generalism was built on the Australian ‘2020’ conceptual model of generalism. 11 The resulting conceptual model views ‘ways of being’ (ontological frame), ‘ways of knowing’ (epistemological frame) and ‘ways of doing’ (practical frame) as a continuum that captures the attributes of ‘generalism’. 11 This sits with Abbott’s work,94 which considers that professional ways of working are ‘ecologically driven’ and situated in the context of actors, tasks, locations and the relationships between these. We, therefore, considered that hospital generalists and their ways of working are therefore not only ideologically or theoretically driven but also ‘ecologically’ determined by the locations in which they work, the tasks they are required to perform and the relationships between these and the professional identity and attributes of physicians. Our theoretical framework, therefore, addressed medical generalism in hospitals through three different perspectives:

-

the patient’ perspective – the needs of the patient and the tasks required to meet these

-

the ‘professional’ perspective – in particular, the knowledge and skills of the professional

-

the ‘service’ perspective – the context of the hospital in which they work, including their deployment, the configuration of beds and the allocation of resources.

This framework informed theoretical explorations of the essential dimensions of generalism in the English hospital context. We sought also to define and understand the duties and responsibilities of the general physician, the boundaries between generalist and specialist care and what is considered to constitute the ‘general medical patient’. These explorations were used to inform the body of the study, before being refined as part of the final study analysis.

Patient and public involvement

We were strongly committed through this project to active and meaningful patient and public involvement (PPI) and have been assisted throughout by the Engagement Team of the North-West London Collaboration for Leadership in Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) and the patient involvement unit of the Royal College of Physicians (RCP). The original proposal was developed in conjunction with two experienced patient representatives. The Study Steering Committee was led by a lay chairperson, with second PPI representative offering further input. A group of seven PPI representatives were recruited and then trained, using a co-design approach, to join the research team on the case study visits, review the coding of the patient focus groups and provide comment on findings. For this reason, the study has been heavily influenced by the patient voice in its shaping, the collection of qualitative data and the interpretation of overall findings.

Research ethics and other approvals

The case study visits were given a favourable opinion by the Yorkshire and The Humber – Leeds East Research Ethics Committee on 17 August 2016 (16/YH/0361) and final approval was granted by the Health Research Authority on 9 October 2016 (IRAS Project ID 191393).

A data-sharing agreement between NHS Digital and the Nuffield Trust for the purposes of this study was made on 9 March 2017 (NHS Digital reference DARS-NIC-384572-J7P6Y-v6.5).

Ethics approval for the discrete choice experiment (DCE) was granted by the joint chairperson of the University College London Research Ethics Committee on 8 May 2018 (Project ID 13187/001).

Changes to the protocol

The following changes to the original protocol were made:

-

In WP1, information on models of care was to be collected using two separate methods: telephone interview and online survey. The experience that was gained since the original proposal suggested that gathering information on models of care using online tools is problematic, so instead the decision was made to use telephone interviews for all sites. Interviews were conducted in three rounds.

-

In WP1, case study site selection was to occur at two time points: (1) after the telephone interviews and (2) after the online survey. Instead, case study selection occurred after each round of telephone interviews.

-

The case study interviews and the staff focus groups were to be analysed independently, in WP2 and WP4, respectively. However, as both methods collected information relevant to each of the WPs, it was decided to abandon this distinction and analyse all of the qualitative material in both WPs.

The following minor deviations from the protocol were made:

-

A single framework was intended to be used for the analysis of the case studies for WP1. Instead, the complexity of the material meant that the use of multiple separate frameworks was more pragmatic and allowed for better comparisons.

-

Testing of the typology was to be carried out using an expert consensus group convened for that sole purpose. We instead used a range of existing groups, including the New Cavendish Group, the steering group and the panel used to test the case-mix classification. This meant that the typology was tested on a wider group of clinicians and managers on more occasions, over a longer time period, ensuring its robustness.

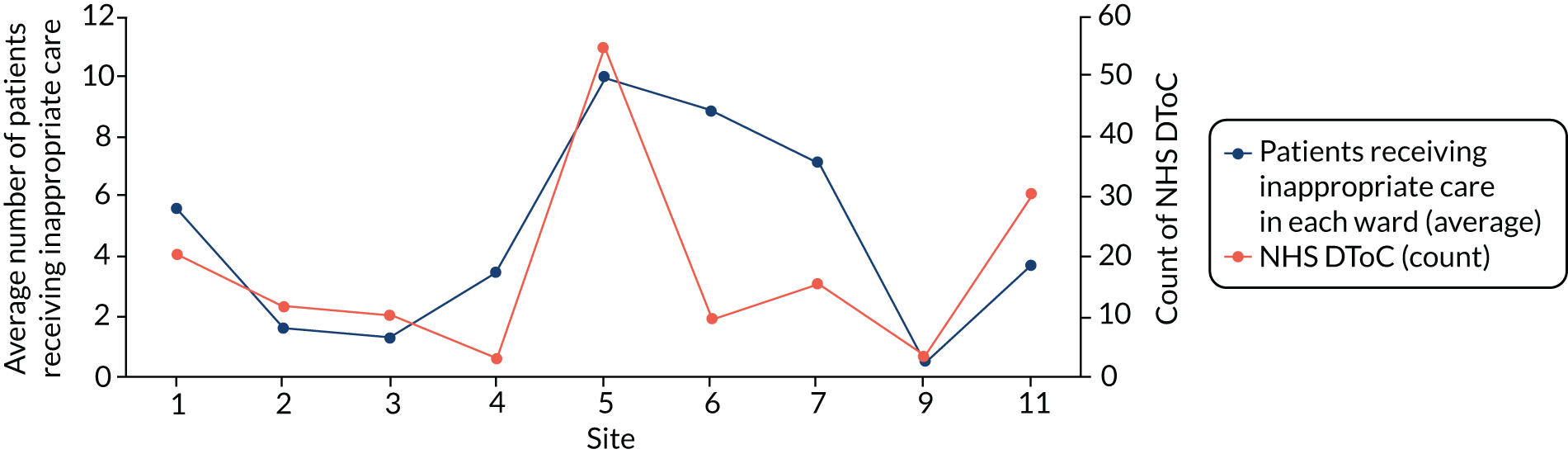

-

The Day of Care Survey (DCS) was included as an additional means by which the efficiency of models of care could be measured. However, we found that all hospitals were suffering from high numbers of delayed transfers of care (DToCs), meaning that inappropriate care was more often the result of shortfalls in local social provision rather than being related to the model of care. As a result, we did not use the results of the DCS as initially intended.

-

The descriptive analysis of workforce was to include specialist procedural and outpatient work. As this work varied markedly at the level of individual consultants, it was not possible to obtain sufficiently accurate information to include in the analysis.

-

The aims of WP2 have been altered to more accurately represent the work carried out. Notably, the assessment of the alignment between case mix and skill mix originally formed part of WP4. It was felt that this sat more naturally with WP2 and has been reported as such.

-

In WP3 we had planned to run a hospital-level cost analysis exploring the relationship between total staffing costs and hospital characteristics. We were unable to obtain data on total staffing costs. Rather than using total operating revenue as the dependent variable, which is an imperfect measure, we elected to forgo this analysis.

-

In WP3 we were unable to compare characteristics of smaller hospitals in our survey to all small hospitals (as we did not have analogous data for the latter) and consequently we were unable to investigate systematic differences between responders and non-responders and adjust for any differences using selection bias methods.

-

In WP4, a Delphi-style assessment of the alignment of case mix versus skill mix was to be performed. However, as there was no evidence of any relationship between hospital case mix and case mix, it was decided that this analysis would not provide any further useful information.

-

In WP4, responses to the DCE were to be analysed by subgroups. There were insufficient responses from managers for this to be meaningful but we did undertake analyses for the other two subgroups (hospital doctors, patients and public).

-

In WP4, the patient volunteer group was to assist with the coding of the patient focus groups. This was collectively thought to be too time-consuming by the volunteers, so they were asked to comment on the final analysis of the coding. One volunteer provided feedback.

-

The patient volunteer group was to provide comments on the final draft report. Time constraints did not permit this, although the Plain English summary was circulated to the lay members of the Study Steering Committee.

-

An open space was organised to obtain further PPI input into the study; this was cancelled owing to a lack of expressed interest despite heavy advertising.

Chapter 3 Concepts of medical generalism

Objectives

In this chapter, we describe our initial explorations of medical generalism. We conducted a literature review and held two stakeholder workshops to clarify the understanding of medical generalism and how this is currently enacted in the English NHS. As this took place outside the WPs and acted as necessary context for the rest of the study, we describe the methods and findings separately here.

Methods and analysis

Overview of methods

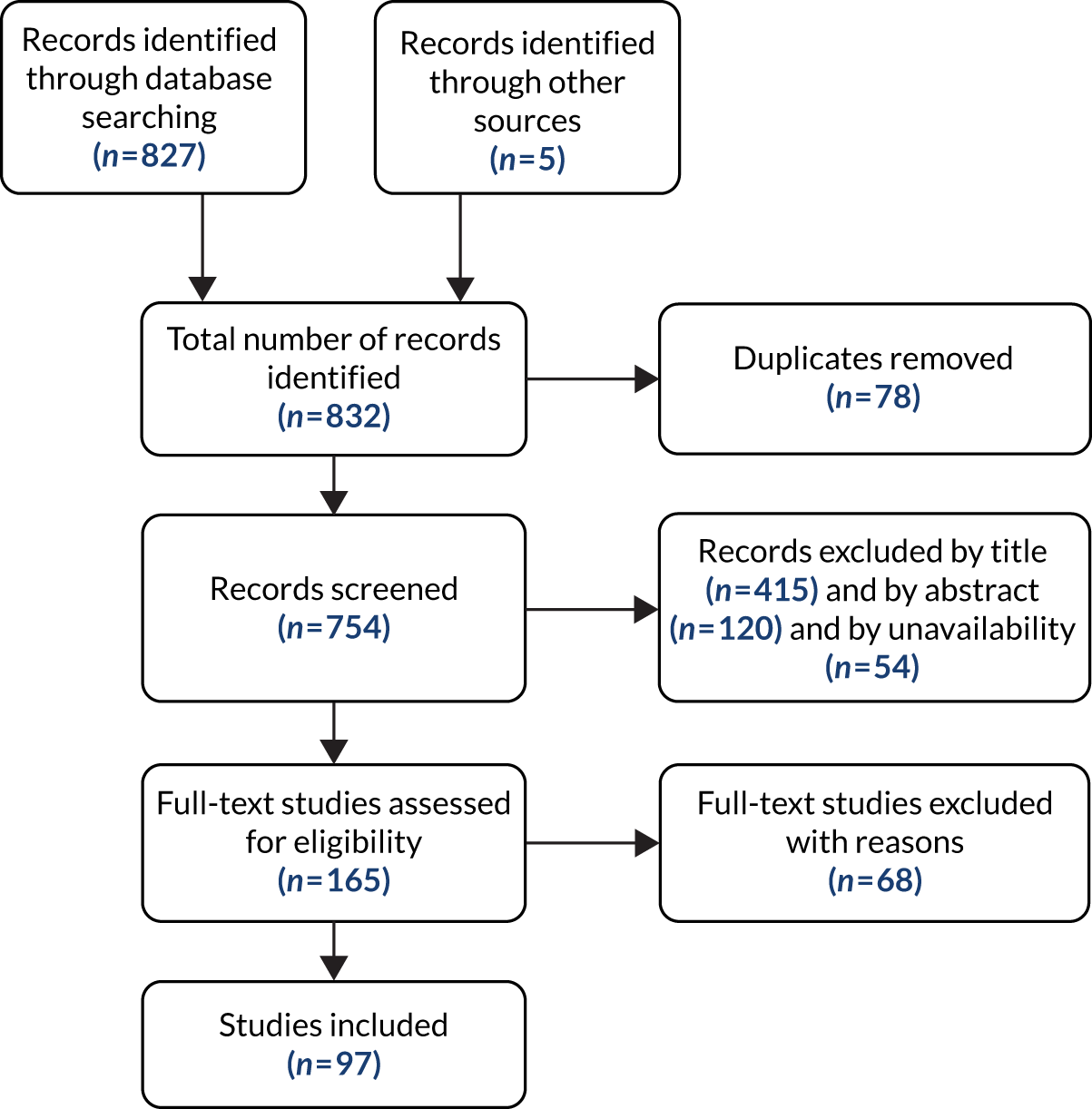

We conducted a systematised literature review with the aim of providing context for our discussion around the patient, public and professional views of medical generalism in the acute setting (see Appendix 1 and Report Supplementary Material 1). We were particularly interested any definitions or paradigms of medical generalism underpinning current models of care in the UK.

Two stakeholder workshops were undertaken to explore how theories of medical generalism influence models of care.

Initial development of theoretical models of acute care

The literature review failed to find any consistent or shared definitions of generalism or what constitutes a generalist, with a profound separation between any theoretical models of medical generalism and how these are enacted within clinical practice. It was hoped that with the construction of this study this divide would be crossed, by devising a classification scheme for typology that was primarily based on the realities of day-to-day service delivery but informed by an understanding of how theories of medical generalism shape the ways of working and influence decision-making about patient care.

To explore how the theories of medical generalism might influence models of care, we convened two typology workshops (10 June 2016 and 14 November 2016). The first workshop was designed to explore with both medical generalists and medical specialists the boundaries between disciplines, the approaches to triage and how one judges how ‘generalist’ a medical service actually is. The second workshop was designed to explore the contexts in which models of care operate and which aspects of the wider system are driving them. As the aims of the two meetings were different, participants in the first group consisted of generalist physicians, as well as representatives from subspecialty societies (such as rheumatology and neurology); participants in the second workshop were selected for their ability to provide insights into the workings of either smaller hospitals and/or insight into service configuration at a national level.

At each workshop, group discussions were facilitated by Louella Vaughan, Candace Imison and Anne Marie Rafferty. Whole-group discussions were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Additional notes were taken by team members to capture smaller group discussions. Data were discussed by the team on consecutive occasions, with attention paid to emerging themes and points of divergence. All quotes extracted have been fully anonymised.

Workshop 1

At workshop 1, the participants were asked to engage in a series of group exercises. For each, background information was provided and participants were asked to discuss a series of questions. The topics of interest were:

-

Potential dimensions of investigation for use in the construction of the typology.

-

Useful definitions of medical generalism.

-

Capturing models of service.

-

The rules for triage – what does a ‘general medical patient’ look like?

-

What does a ‘good’ medical service look like?

-

To what extent can whole pathways of care be characterised as ‘generalist’ or ‘specialist’?

Workshop 2

At the second workshop participants were asked to engage in a series of linked group exercises, which were based around the drawing of ‘Rich pictures’. Rich pictures are a tool developed by Checkland95 as part of soft systems methodology to capture the complexity, nuance and multiple perspectives that often characterise complex human systems. 95 Groups were first asked to draw a picture of the operations and processes that characterise the emergency/acute medicine pathway. They were then asked to consider what the key drivers of the pathway at the hospital and the external landscape-level (such as staffing, finances and policy directives) were and to indicate where and how these influence the pathways. For the final round, participants were asked to consider what underlies positive and negative experiences of the system from the perspectives of staff and patients.

Findings

Theoretical models of medical generalism

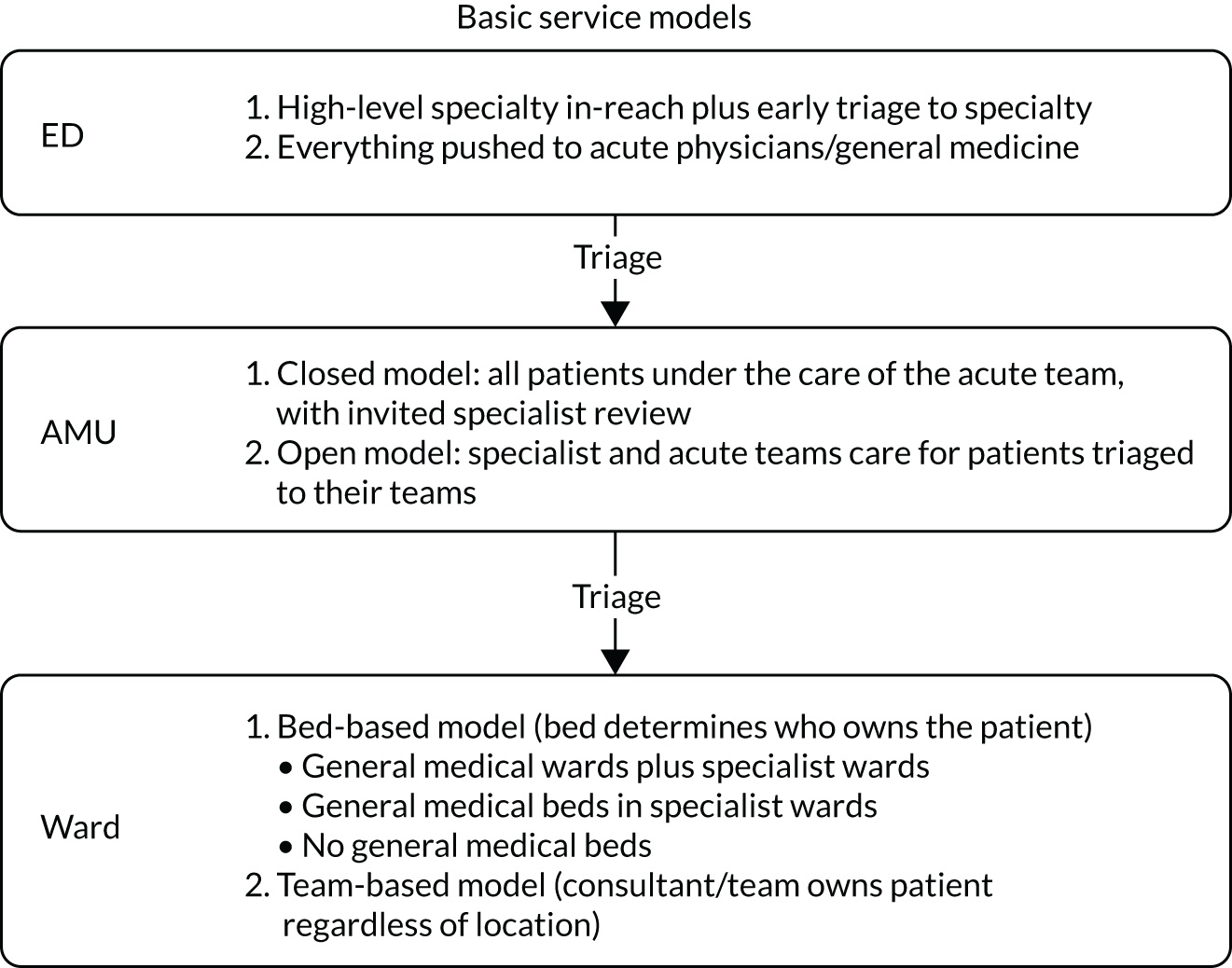

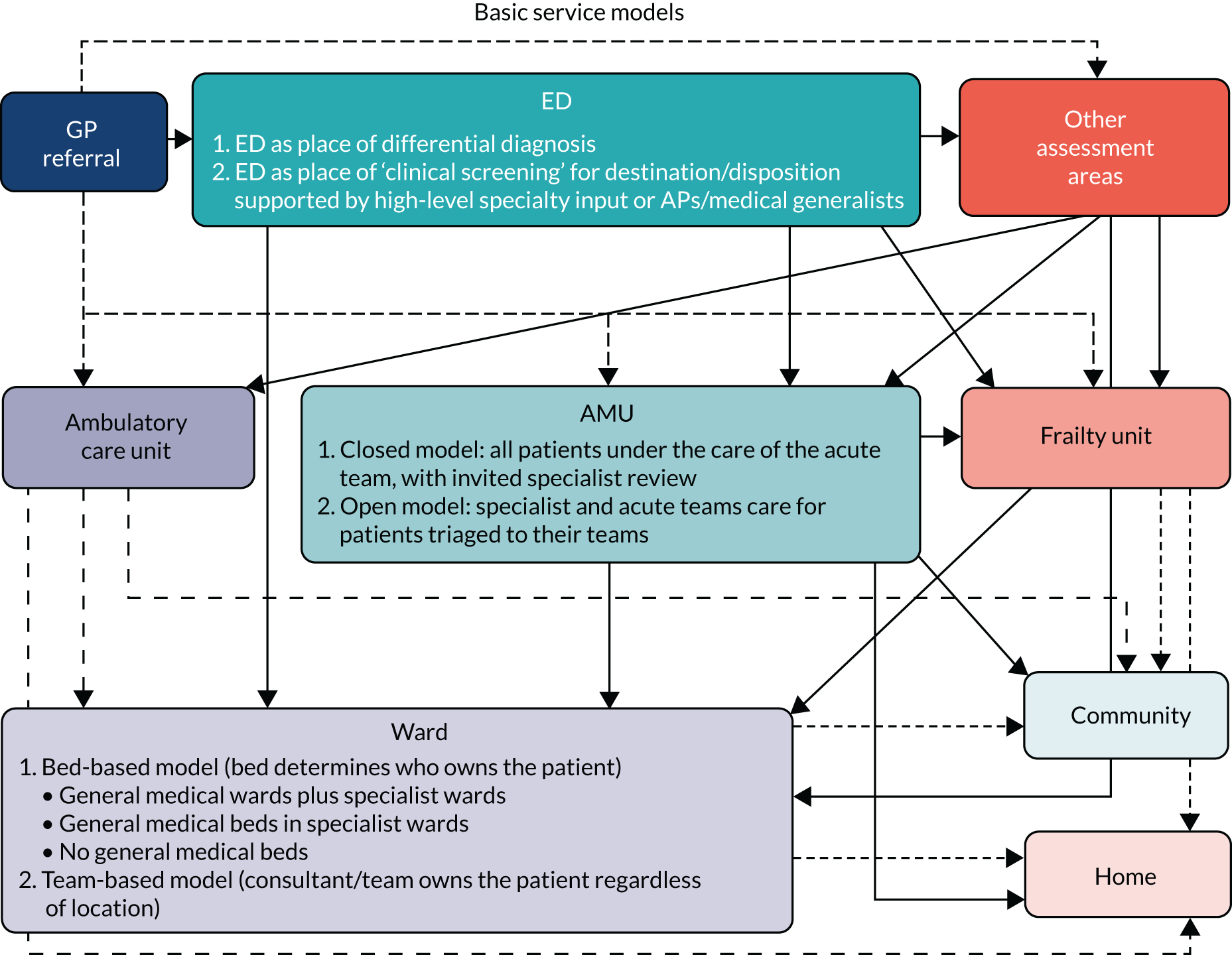

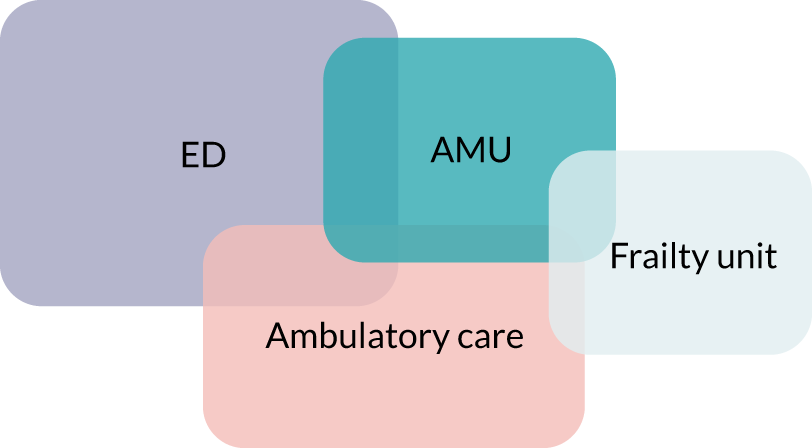

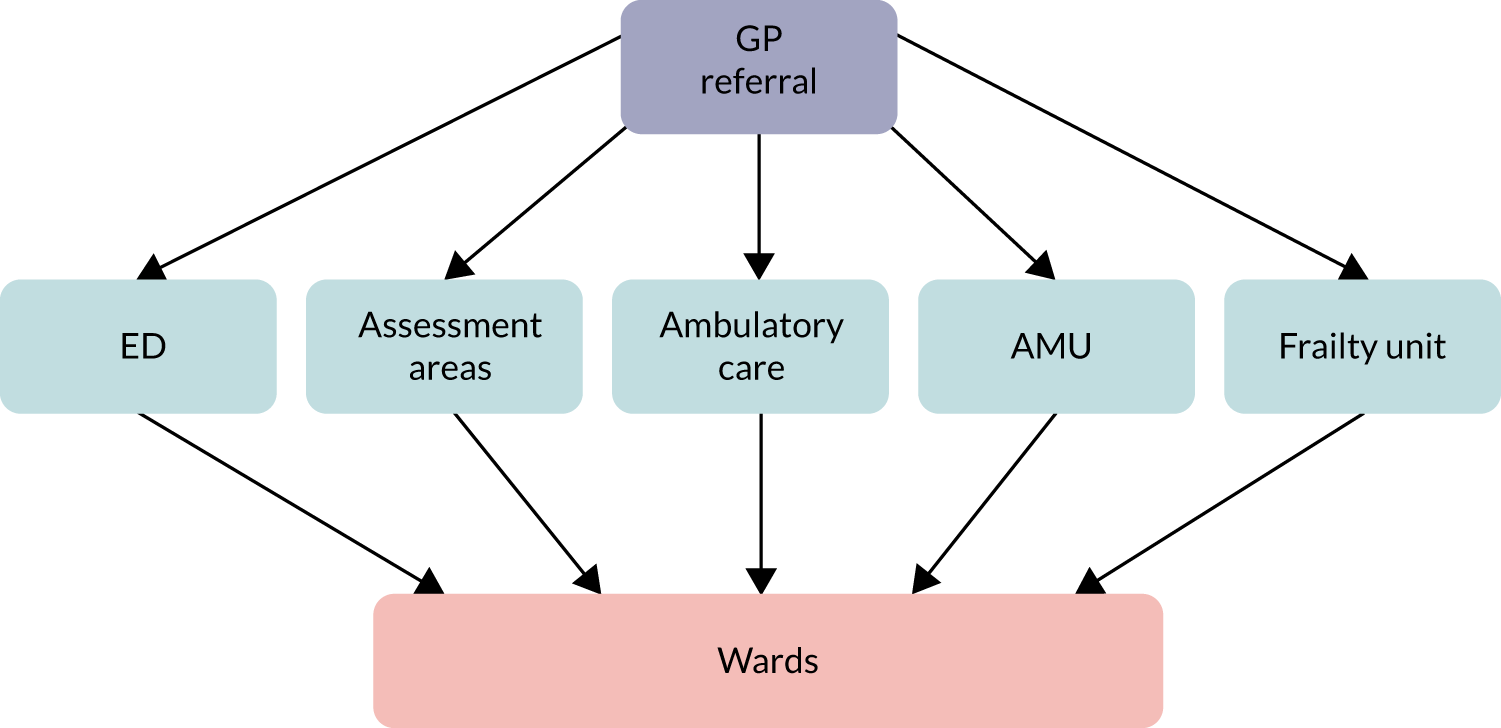

The first workshop was useful in honing the theoretical construction of the emergency and acute medicine pathway. The team had initially assumed that patients would pass in a relatively uniform way between the ED, the AMU and the downstream medical wards (Figure 2). Intelligence from the participants suggested that models have become substantially more complex over the past 2–3 years, with the spread of services such as ambulatory/emergency care and frailty services, which has led to revision of the model (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Assumed basic service model for the delivery of emergency/acute care.

FIGURE 3.

Revised service model (v3.0) for the delivery of emergency/acute care. AP, acute physicians; GP, general practice.

There was no consensus among participants, however, on how to characterise either the system components or the whole system as specialist or generalist.

The views expressed in the workshop confirmed that, rather than attempting to explore both service issues and professional issues in the telephone interviews, these should concentrate on capturing systems and processes of care, whereas the case studies should explore in more depth the issues that relate to professional identity and hospital culture.

Professional aspects of medical generalism

The first workshop also focused on professional aspects of medical generalism: who are the general physicians and what are their attributes? The following key themes emerged from the discussion.

Complex definitions

There was general agreement with the primary underlying assumption of the study: that more ‘generalists’ are required to meet the needs of the growing numbers of multimorbid patients. However, participants agreed that there was no universal definition of general medicine, that it was unclear which doctors deliver generalist care and that it was unclear what might actually constitute generalist care. Indeed, it was argued that attempting to nail down definitions may be counter-productive for the purposes of the study. The boundaries between specialist and generalist practice emerged as permeable and partially located at the level of the individual doctor, rather than being neatly and consistently drawn at system level:

General physicians have the use the expertise they have from where they recognise that they can manage the problem and when they recognise they can’t manage the problem they find someone who can.

Workshop participant

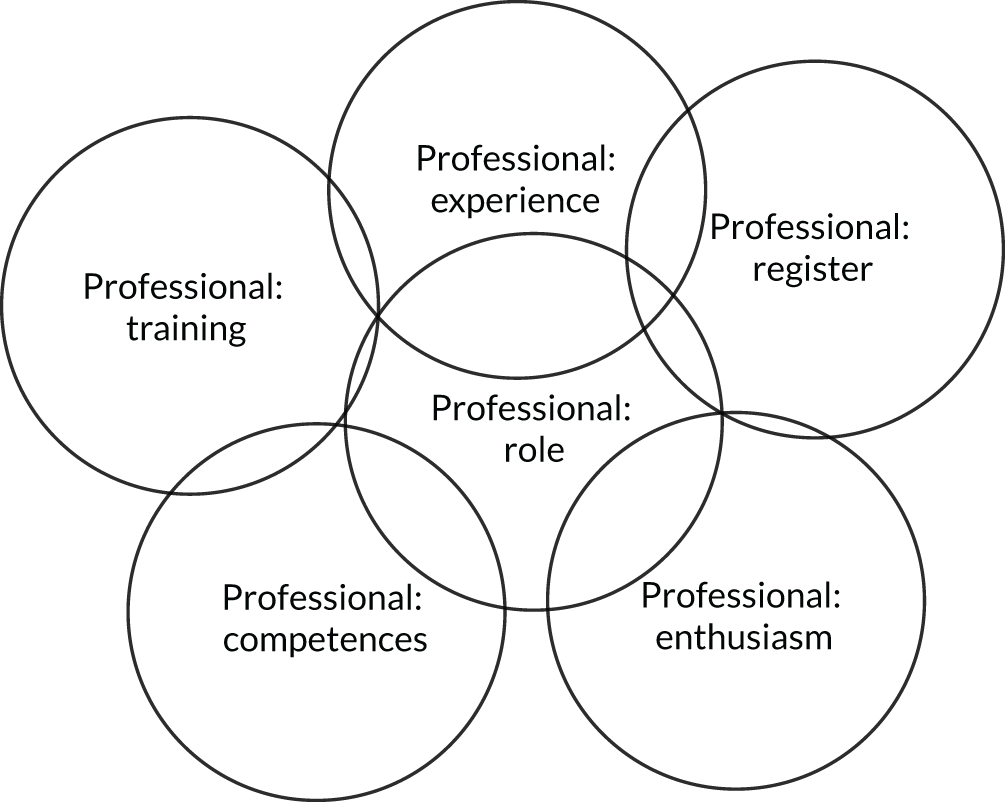

A complex mosaic of overlapping factors that might constitute the general physician as a professional emerged and are shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

The general physician as a professional: identified factors.

Skills versus role versus identity

Participants drew distinctions between the skills required to be an effective general physician, the role of the general physician in providing care and the extent to which a consultant identified as being a general physician.

The skills and competencies that were required were considered to be a function of training, which were sanctioned by general medical council certification, as well as maintenance over time:

You may have had the ticket for general medicine . . . but what is at issue is people’s skills atrophy.

Workshop participant

The role of the general physician was considered to be determined largely by service needs, particularly the acute medical take and the provision of downstream care to ‘general medical patients’:

Modern general medicine largely is . . . the first 2 or 3 days for young and non-frail people or in the deeper wards it is generally older people with complex needs.

Workshop participant

The distinctions between skills and role were repeatedly emphasised, given that the role of the general physician was heavily context driven and was dependent on factors such as type of organisation (teaching vs. non-teaching), location in the hospital (AMU vs. ward) and the case mix:

So what people’s training is and what their skillset is, is one thing, but what their actual role is, is another.

Workshop participant

We have been talking a lot about roles and training which actually defines a general physician whereas general medicine is what you actually practice, it’s the medicine that you actually do.

Workshop participant

Moreover, the skills of general medicine were not seen to be professionally contained. Although many specialists might no longer explicitly act as general physicians, that is they no longer contribute to the medical take or look after general medical inpatients, they were still capable of providing generalist care to their specialist patients:

If you are a neurologist who has a patient who comes in with hypertension . . . [that makes you someone] who is practising general medicine even if you are not a general physician.

Workshop participant

The split between skills and role was also seen to be a by-product of the nature of training as a physician in the UK. With standalone GIM training being almost completely replaced by dual accreditation in both a specialty and GIM over the past two decades, virtually all younger physicians have specialist skills and generalist skills and competencies and are capable of adopting more than one clinical role. This duality of medical training alongside the gradual disappearance of consultant physicians without a specialty was also considered to play a major role in the fact that although many doctors practised general medicine, they no longer primarily identified themselves as general physicians:

There aren’t many doctors left who would call themselves [general physicians] . . . they might say ‘I’m a consultant in geriatrics and general medicine or chest and general medicine’. But there aren’t many doctors left who call themselves a general physician when they are describing what they do.

Workshop participant

The degree to which consultants self-identified as a generalist or a specialist emerged partially as a function of the degrees to which professional and personal satisfaction were derived from the different roles. Notably, satisfaction with meeting the needs of patients and a diagnostic challenge were associated with general medicine, whereas prestige and advancement were attached to specialist medicine:

We get a different buzz out of [general medicine] . . . It’s the job satisfaction that you get from doing general medicine.

Workshop participant

Your specialty consumes you. Your ability to distinguish yourself, become famous and all that sort of stuff depends largely on how you perform in your specialty.

Workshop participant

The profound aversion that some specialists feel towards practice as a general physician, particularly in the context of the acute take, was also commented on:

Some people are doing [the acute take] . . . [it] is their idea of hell so they are not going to do it well if they are not committed to it.

Workshop participant

The cases of acute medicine and geriatrics

Participants touched on the issues of whether or not the specialties of acute medicine and geriatrics were fully generalist in nature. This was considered of relevance given that neither discipline routinely provides care across the whole patient pathway, with acute medicine focusing on the first 3 days of inpatient care and geriatrics focussing on the wards. Although it was agreed that both specialties provide generalist care, the group was split on whether or not either specialty could be considered to be a branch of general medicine. The nature of the debate highlighted that ‘true’ general physicians were capable of meeting the broadest spectrum of patient needs, regardless of their location of practice or their point in the patient journey:

In our hospital, [geriatrics] is aged-based and therefore by definition actually our care services are offering general medicine to those over the age of 75 is a specialist service.

Workshop participant

Conclusions

These findings suggested that the study team should refrain from imposing hard definitions of what constituted generalist practice for the purposes of the study. Instead, attempts should be made to explore further the boundaries between generalism and specialism and the contexts of practice.

Contexts of models of care

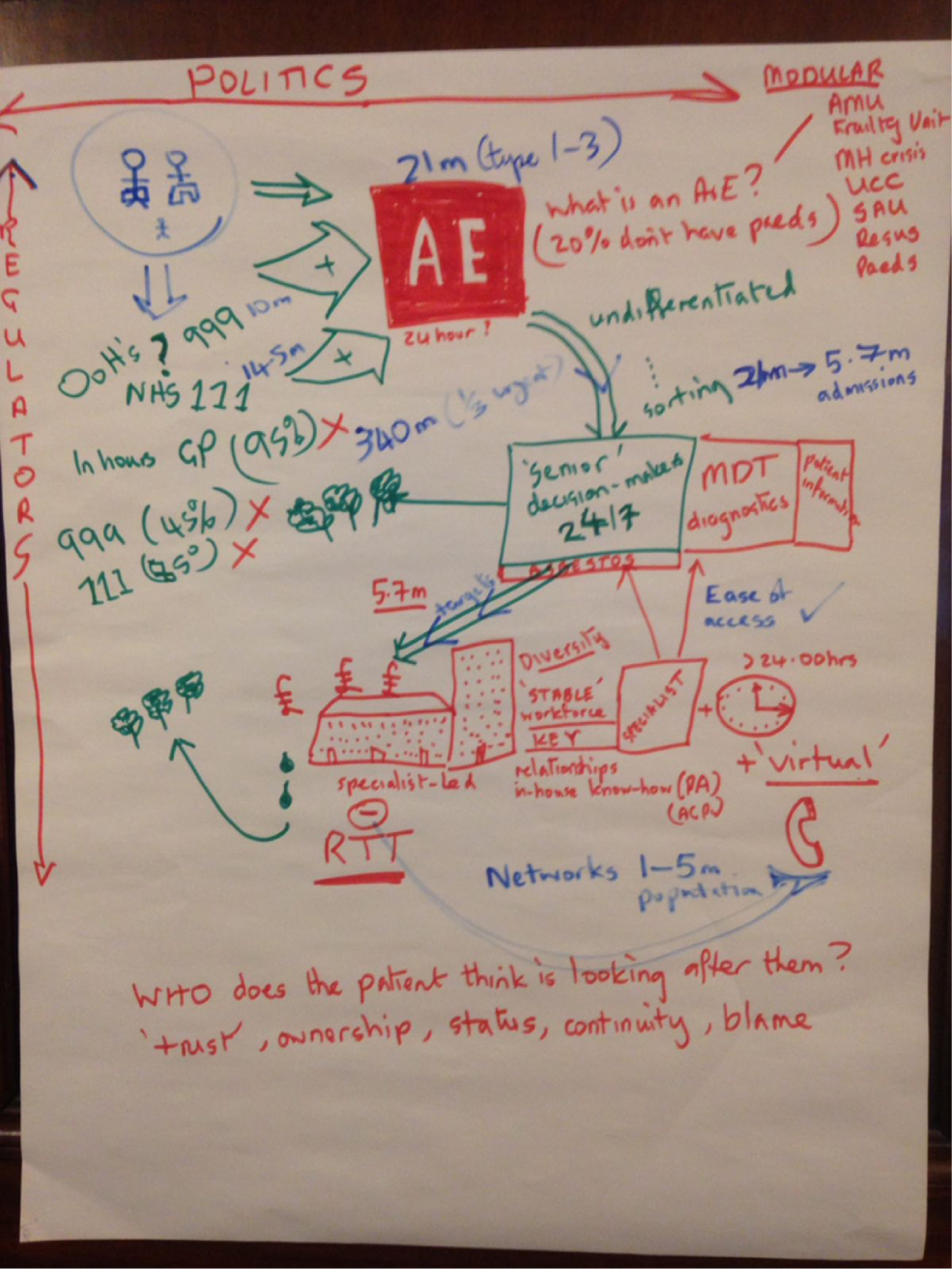

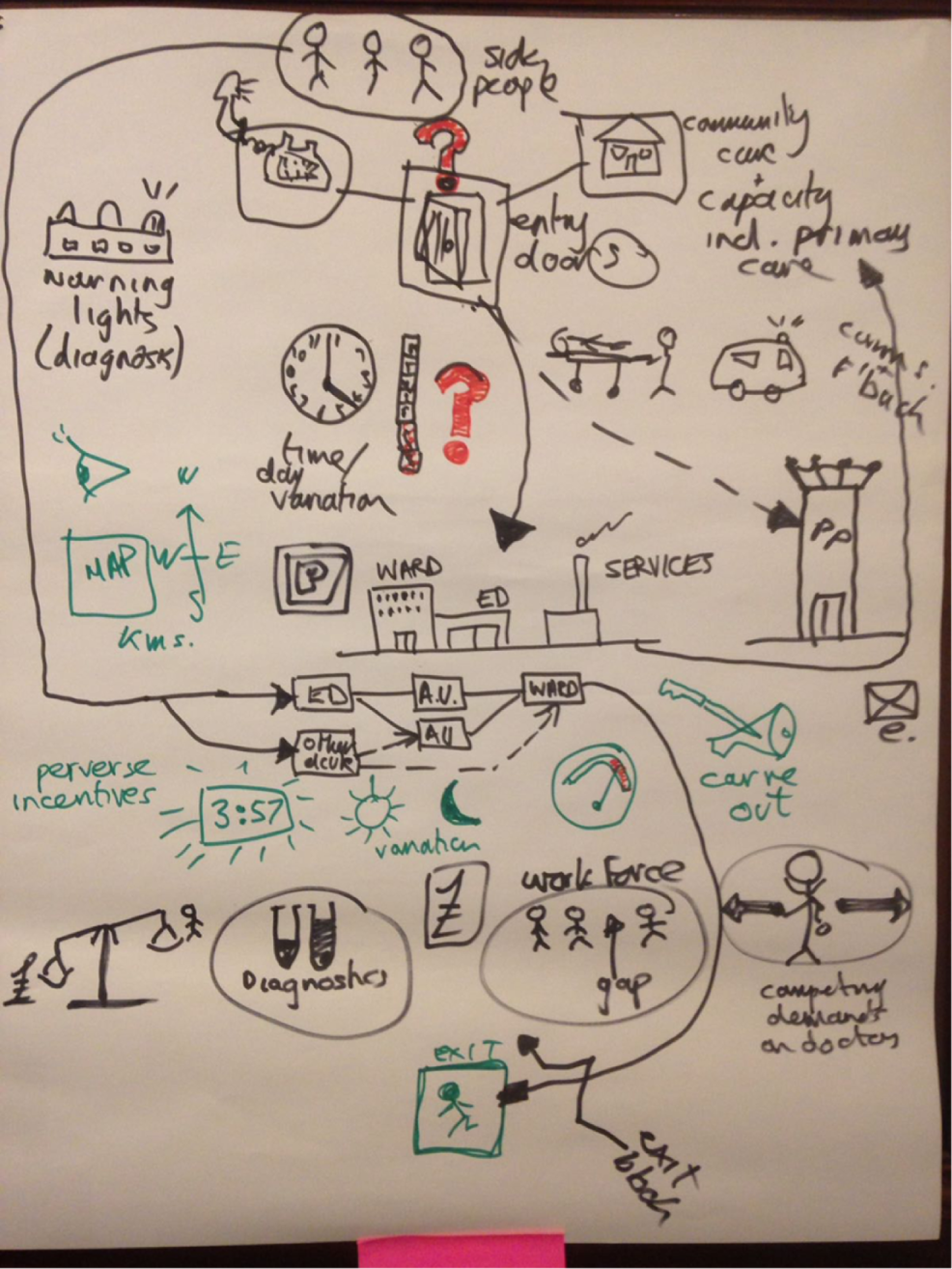

The second workshop explored the extent to which the emergency and acute medicine pathway is shaped by factors at multiple levels. Examples of the resulting rich pictures are given in Figures 5 and 6.

FIGURE 5.

Rich picture produced for workshop 2, example 1.

FIGURE 6.

Rich picture produced for workshop 2, example 2.

Factors at the hospital level

The factors at the hospital level that were thought to have a major influence on the shape of models of care included the:

-

capacity of the hospital, as well as individual services (such as the ED)

-

size and skills of the hospital workforce

-

access to diagnostics, in terms of both hardware and staffing

-

access to allied health-care services

-

financial position of the hospital

-

provision of ‘turnaround’ services at the front door

-

level of consultant cover, especially at weekends

-

‘carve out’ versus streaming allocations at the front door (siloed working vs. allocation of patients to appropriate flows)

-

slickness of transfers between clinical areas

-

organisational culture

-

relationships between clinicians, especially between specialists and generalists.

Factors at the regional level

The factors at regional level that were thought to have a major influence on the shape of models of care included the:

-

geography, especially the time to the next ED

-

number, capacity and quality of local general practice (GP) services

-

ease of access to and the quality of out-of-hours services

-

capacity and quality of local ambulance services, especially paramedical teams with the ability to treat onsite rather than transfer

-

presence and use of networked services

-

social care provision

-

integration with community services

-

relationships with relevant Clinical Commissioning Group (CCGs) and local authorities.

Factors at the national/policy level

The national policy and regulatory frameworks were thought be critical in informing almost every aspect of care in smaller organisations. Key policies and factors included:

-

the 4-hour target

-

24/7 consultant working

-

the review and recommendations of the Care Quality Commission (CQC)

-

Health Education England’s attitudes towards training in smaller organisations

-

directives from NHS England (NHSE) and NHS Improvement (NHSI) on acute service provision.

Other factors

The question of ‘who owns the patient’ and the associated issues around trust, ownership, status, continuity and blame were seen as important drivers of clinician and system behaviour.

Conclusions

These findings pointed to models of care shaped by numerous factors at multiple levels, with interactions between each level. At one end, individual hospitals were located in a complex regulatory and policy environment, which influenced almost every aspect of service provision. At the other end, the cultural, organisational and behavioural factors moulded services in hospitals. This suggests that models of care cannot be considered as independent of the contexts in which they sit and that the study would need to take account of these factors in the conduct of the research.

Chapter 4 Describing models of medical generalism in smaller hospitals

Objectives

In this chapter, we describe the models of medical generalism used in smaller hospitals and recount the creation of a typology of the different models of care. We then explore the models of generalism through case studies and other methods, with a focus on the medical workforce, their roles, skill mix and the boundaries between specialist care and generalist care.

Methods

Overview of methods

We outline here the methods used; a fuller description is contained in Appendix 2.

This study aimed to explore medical generalism through the perspectives of the patient, the professional and the service. WP1 was designed primarily to define and explore the service perspective, as well as elements of the professional perspective, namely how doctors define and experience medical generalist work.

We used a multistep approach to investigate models of care in smaller hospitals and understand how and why these models of care are deployed. This was carried out by:

-

identifying and creating organisational profiles of all smaller trusts in England (n = 69)

-

undertaking telephone surveys of all smaller trusts that agreed to participate in the study (n = 48 trusts; 50 hospital sites) with a view to map processes of medical care across the acute/emergency pathway

-

creating a typology of the models of medical generalism used by smaller hospitals, based on the telephone surveys

-

carrying out case study visits (n = 11) to examine in more detail the similarities and differences between main models of care identified by the typology and to evaluate the broader contexts in which the models of care sit, as well as the definitions, boundaries and meanings of medical generalism as theoretical concepts and lived experiences

-

undertaking a descriptive analysis of workforce, combining data obtained from the interviews and case studies with national workforce data from NHS Digital.

We considered the service perspective in two ways. First, we considered that the emergency and acute medicine pathway could be considered a closed system, boundaried by the patient’s presentation to and discharge from hospital, and therefore amenable to a general systems approach, which seeks to define and understand systems in terms of the functions and processes of each component within systems and the relationships between these. 96 Emergency and acute medicine pathways have also undergone radical change over the past two decades, with the introduction of AMUs, ambulatory care and the maturing of emergency medicine as a specialty. 76,97,98 It was therefore considered that emergency and acute medicine pathways in individual organisations were the result of serial rounds of innovation and improvement, mediated by contextual factors at multiple levels. 99 The Consolidated Framework for Improvement Research was adopted so as to better conceptualise and explore how and why hospitals operationalise their services and the contexts in which these services exist, particularly at the levels of the team provider, hospital and external landscape/policy. 100

Identification of smaller hospitals

NHS Improvement (formerly Monitor) has previously defined ‘smaller hospitals’ in England as providers with an operating revenue (income) of < £300M in the 2012/13 financial year. 88 Of the 142 general acute trusts, 75 of these in the 2012/13 financial year were found to fit into this category. Following review of financial information for 2015/16, six trusts were removed from the sample on the grounds that their operating revenues now exceeded that which might be expected from natural growth and were likely the result of major service reconfiguration. This left a sample of 69 smaller hospitals in England. This definition captures trusts that are predominantly single site, minimising the problem of attempting to distinguish Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data at the hospital level in multisite trusts. It also ensures that there is a reasonable geographical distribution of sites, including hospitals in urban, provincial and rural settings.

Organisational profiles

Organisational profiles were constructed for all smaller trusts (n = 69) from a combination of publicly available data (e.g. trust and CQC reports) and hospital-level data that were collected by Monitor88 (later NHSI) and the Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC), now known as NHS Digital.

Exploring models of care in smaller hospitals

Semistructured telephone interviews were used to gather data on the models of medical generalism deployed in smaller hospitals. Guides for the semistructured telephone interviews were constructed, following the work of Reid et al. ,101 to explore the following:

-

hospital department characteristics across the emergency and acute medicine pathway (ED, AMU, ambulatory care, frailty services, downstream wards and any other relevant spaces)

-

local triage rules for determining patient journeys

-

construction of the acute medical take

-

cover of the downstream medical wards

-

networking arrangements.

Constructing the typology

As discussed in Appendix 3, the marked differences between organisations with regard to almost every aspect of service delivery across the emergency and acute medicine pathway made meaningful classification and comparison of the models of care difficult.

The classification scheme that was ultimately adopted focused on the AMU and the downstream wards, the components of the system through which the majority of patients with medical conditions flow. The classification also limited the analysis to the categories that best express splits between generalist medicine and specialist medicine:

-

AMU – unit openness (closed/partial/open)

-

AMU – patterns of consultant working [acute physician dominant (APD), mixed, specialist dominant (SpD)]

-

wards – unit openness (closed/partial/open)

-

wards – patterns of ward distribution within the hospital (some designated general medical wards, SpD wards only).

Using this scheme, distinct models were visible for the AMUs and the wards. However, there were still no consistent relationships between the models used on AMUs and the models used on the downstream wards. For this reason, some aspects of the analysis have been carried out using the typologies of AMUs and wards separately.

Analysis

Full details of the analysis can be found in Appendix 2.

Case studies: investigating the typology

The purpose of the case studies was threefold:

-

to examine in more detail the operational aspects, such as the processes of care and staffing, with particular reference to the similarities and differences between models of care

-

to evaluate the contexts in which the models of care sit at provider team, hospital and external landscape/policy level

-

to explore concepts of medical generalism and how these may relate to the development and deployment of the different models of care.

Case studies were chosen so as to explore the different models of care that emerged from the typology. Care was taken to ensure that there was appropriate representation of trusts according to geographical location (urban vs. rural), size (small vs. ‘smallest’) and case mix. Three pairs of adjacent trusts were chosen, providing an opportunity to explore the contribution of external landscape and case mix to model development.

Case study visits were conducted over 1–2 days and involved the following activities:

-

Semistructured interviews with key clinical, managerial and nursing staff. Topics included processes of care and triage, past and present organisational strategies, local networking arrangements, tensions between generalists and specialist workloads.

-

Mapping patient flows by ‘walking’ through the emergency and acute medicine patient journeys. 102

-

DCSs103 that allow insight into the appropriateness of inpatient care.

-

Observations, with particular interest in unwritten rules, that influence how patients pass the emergency and acute medicine pathway.

-

Staff focus groups (at half of the sites), exploring themes around processes of care, organisational culture and views of medical generalism.

-

Document review, with a particular interest in standard operating policies for the AMU and downstream wards.

The case study interview guides and other materials can be found in Report Supplementary Material 2.

Testing the typology

There were two concerns about the typology: (1) whether or not clinicians and managers would recognise the models described and (2) whether or not the typology would be sufficiently pragmatic, as opposed to theoretical and abstracted, to be useful. To this end, the typology was presented, in various stages of development, for expert consideration by convened groups of senior managers and clinicians. It was presented twice to the New Cavendish Group and to the expert convened to look at case mix (see Chapter 5). It was also iteratively reviewed by the Study Steering Committee.

Construction of case studies

Case studies for each site were constructed, which were supplemented by material from the telephone survey and publicly available data such as trust annual reports. The studies aimed to combine detailed information about the processes of care at the unit level, while also providing contextual information about the hospital’s internal and external environments. Sankey diagrams, which depict flow through systems, were constructed for each organisation (Density Design Research Lab, Milan, Italy, URL: https://rawgraphs.io).

Framework analysis

Five separate sets of coding frameworks were used for all of the material generated by the case studies and relevant portions of the telephone surveys:

-

models of care – descriptions of mechanics of care were grouped by system component

-

the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR),100 which explores the contexts in which systems exist through five major domains – intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of the individuals involved and the process of implementation

-

medical generalism and specialism

-

smaller hospitals

-

workforce.

‘Pattern matching logic’ was used to look for emerging themes, with an emphasis on convergent and divergent evidence between data sources. 103 An iterative approach was taken, with regular discussions used to confirm important themes and guide further rounds of analysis.

Day of Care Survey

The DCS was analysed according to methods described elsewhere. 104

Findings

For ease of reading, the findings are presented in the following way:

-

We describe the key characteristics of the 69 trusts that were included in the study.

-

We describe the key characteristics of the 50 hospitals that participated in the telephone interviews.

-

We provide an overview of Emergency and Acute Medicine pathways in smaller hospitals in England.

-

We present the typology.

-

We relate the typology to the demographics of the study hospitals.

-

We provide an outline of the case study organisations.

-

We describe the factors, based on the case studies, that shape model development.

-

We explore the definitions and meanings of general medicine.

-

We provide a description of the workforce deployed by the study organisations.

Description of participation

Table 2 describes the participation of NHS staff in the study.

| Activity | Number of NHS staff participants |

|---|---|

| Telephone interviews (48 trusts) | 57 |

| Site A | |

| Staff interviews | 7 |

| Staff focus group | 7 |

| Walk around | 2 |

| Site B | |

| Staff interviews | 8 |

| Staff focus group | 10 |

| Walk around | 4 |

| Site C | |

| Staff interviews | 4 |

| Walk around | 1 |

| Site D | |

| Staff interviews | 7 |

| Staff focus group | 5 |

| Walk around | 3 |

| Site E | |

| Staff interviews | 5 |

| Staff focus group | 8 |

| Walk around | 3 |

| Site F | |

| Staff interviews | 6 |

| Staff focus group | 8 |

| Walk around | 4 |

| Site G | |

| Staff interviews | 7 |

| Walk around | 2 |

| Site H | |

| Staff interviews | 5 |

| Staff focus group | 9 |

| Walk around | 2 |

| Site I | |

| Staff interviews | 5 |

| Walk around | 5 |

| Site J | |

| Staff interviews | 5 |

| Walk around | 1 |

| Site K | |

| Total staff interviews | 5 |

| Total walk around | 4 |

| Total participants | 199 |

What do smaller acute hospitals in England look like?

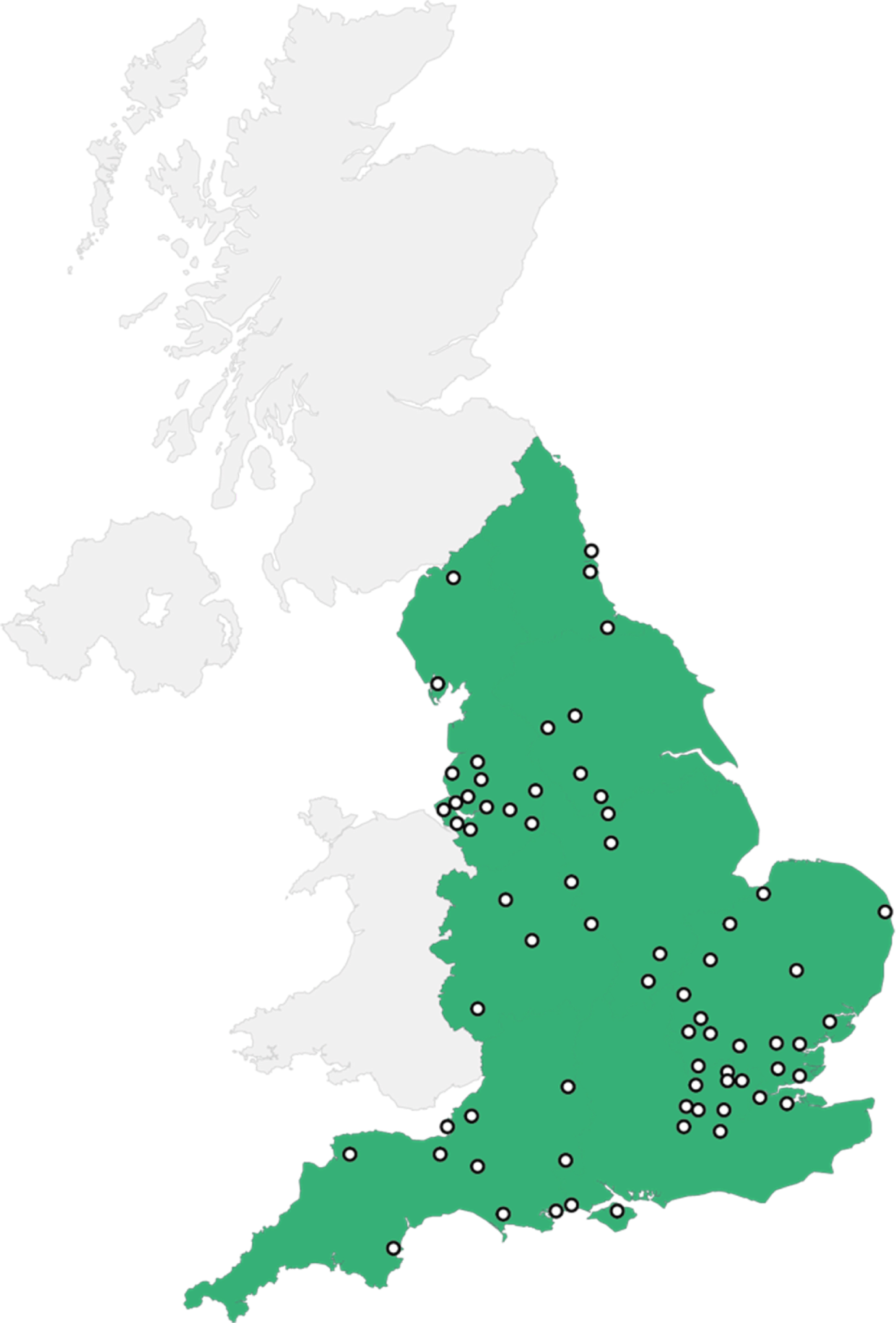

Using the definition of ‘smaller’ equating to an operating revenue of < £300M per annum,88 we identified 69 smaller trusts in England in 2015/16. Six of these trusts had more than one acute site. The geographical distribution of trusts is shown in Figure 7. Organisational profiles, detailing the number of beds, catchment population, distance to the next ED, ED attendances, medical admissions and CQC ratings, are given in Report Supplementary Material 3.

FIGURE 7.

Geographical distribution of the smaller hospitals in England.

Characteristics of the participating trusts

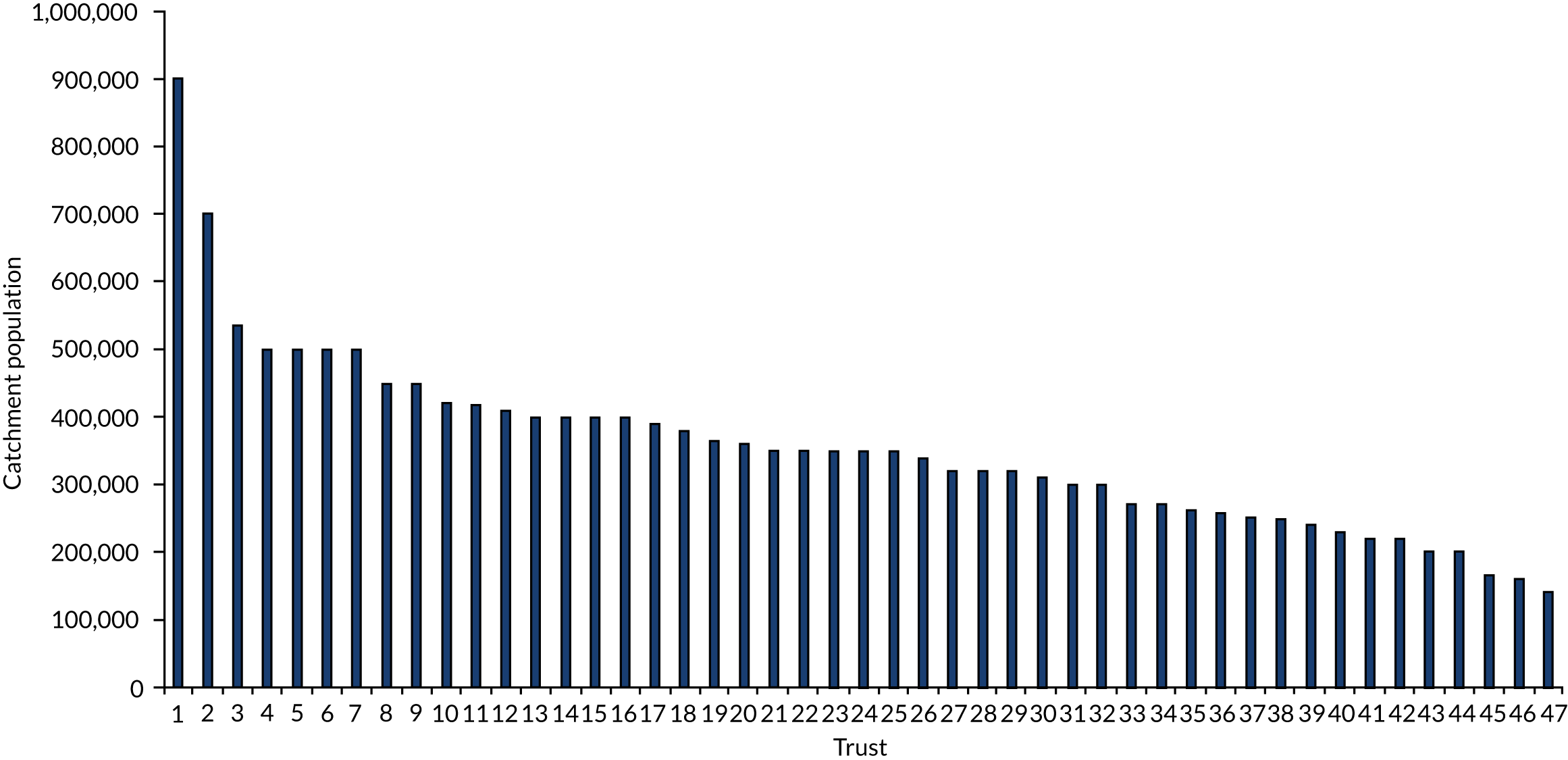

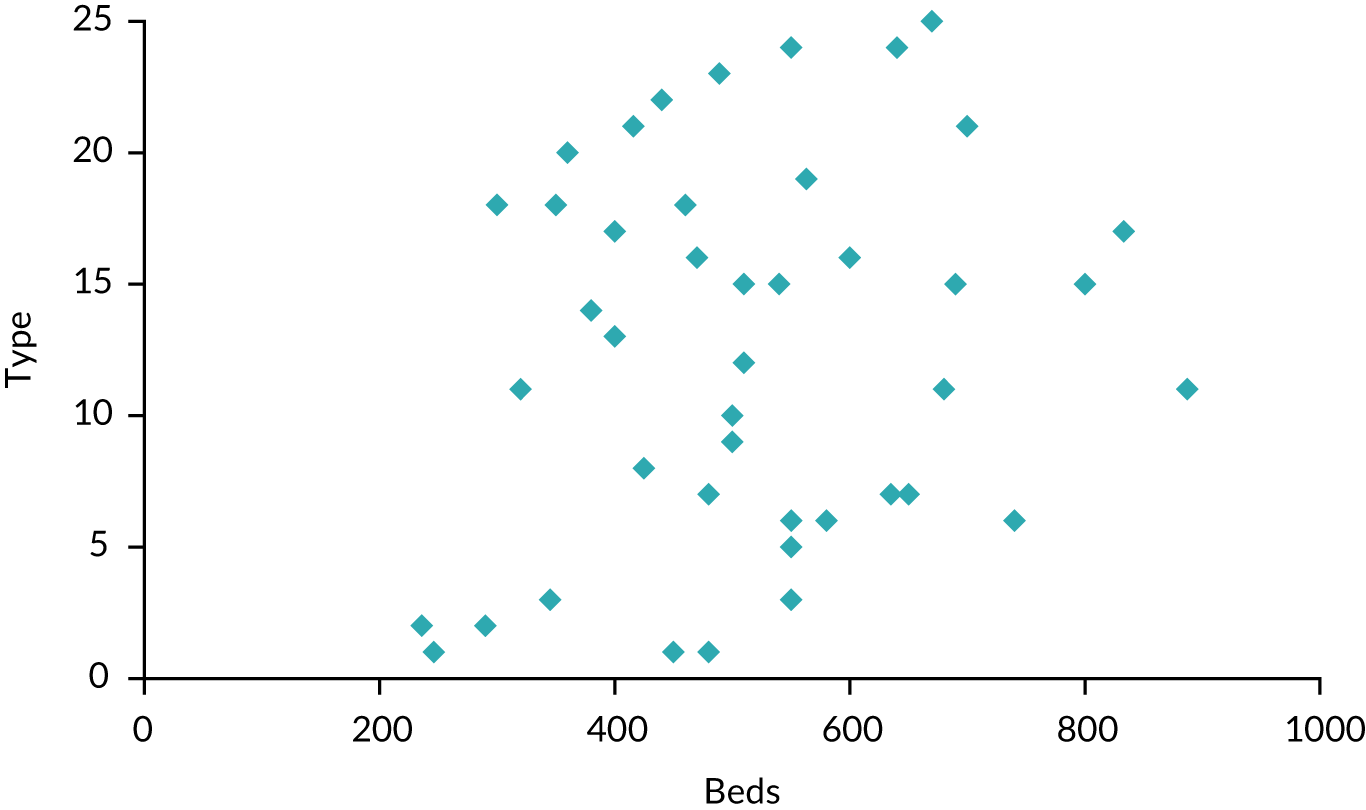

In total, 48 trusts, with 50 hospitals, agreed to participate in the study (including 70% of all smaller hospitals). The average population served by these was 300,000 people, compared with an average of 54,000 people for a ‘general hospital’ elsewhere in the European Union. The catchment populations varied from 140,000 to just over 500,000 (Figure 8), of which only 17 trusts had catchment populations of under 300,000. The average distance to the next nearest acute hospital was 17 miles; four hospitals were > 30 miles to their closest neighbour. The majority of hospitals were located in urban or well-populated rural areas.

FIGURE 8.

Trusts by catchment population.

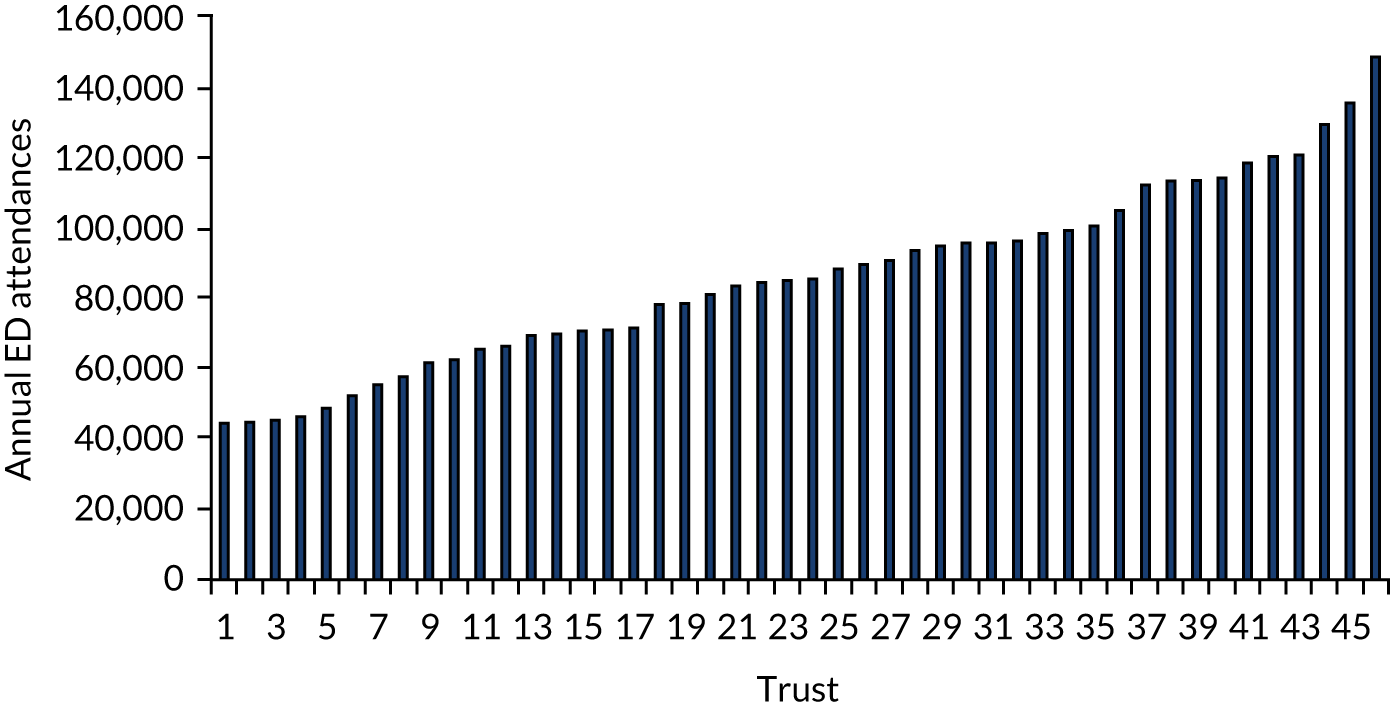

There was wide variation in the level of ED activity across the sites, from just over 40,000 attendances per annum to nearly 150,000 attendances (Figure 9).

FIGURE 9.

Annual ED attendances 2015/16 by trust.

Overview of models of acute medical care in smaller hospitals in England

The raw results of the telephone interviews are in Report Supplementary Material 4. These results have been the basis for two publications. 67,87

A system in flux

The original structure of the study had assumed that systems were in evolution but had stability in their underlying structures and degrees of coherence, with similarities between dominant models of care. However, the telephone interviews found that no two hospitals employed models of care that were similar across the three main components of the emergency and acute medicine pathway (ED, AMU and downstream wards). All of the organisations, with the exception of two, described major organisational change to emergency and acute medicine services within the last 12 months, with some engaged in a near frenzy of reorganisation and expansion of acute services. Many of the organisations also reported their usual systems and processes of care being overwhelmed at points either by spikes in patient demand or by external pressures to meet centrally mandated targets. Interviewees frequently framed their responses as ‘we should do A, but now we usually do B and we are planning to move to C’. All organisations, with the exception of one, declined to submit standard operating policies for analysis on the grounds of redundancy.

Although this flux in itself led to problems for interviewees to describe the systems in which they work, this was compounded by the fact that many organisations did not appear to have a coherent vision for the whole emergency and acute medicine pathway and that most interviewees, despite being selected on the basis of seniority, tended to be siloed within their own divisions with limited insight into other parts of the system. Almost all interviewees had to seek help from colleagues to answer all of the survey questions; some had managers from other departments join the telephone interviews.

Variation at every level

Our stakeholder engagement had suggested that emergency and acute medicine pathways in England have changed markedly over the past 5 years, with the expansion of ambulatory/emergency care and the introduction of frailty units (see Figure 3).

The reality did not quite match this theorised model. Although all hospitals by definition had an ED and downstream wards, there was marked variability in the numbers and types of other emergency and acute medicine components between hospitals (Table 3).

| Component of emergency/acute care | Percentage of hospitals (%) |

|---|---|

| AMU | 100 |

| Ambulatory care unit | 96 |

| Frailty unit | 56 |

| GP assessment area | 26 |

| Other assessment area | 41 |

Within each of these areas, there was marked variability between organisations with respect to the size, function(s) and, for certain components, criteria for accepting patients.

The relationships between these components of the system also varied markedly. Most organisations had a mosaic of services at the front door (e.g. ED, ambulatory care and GP assessment), all providing some form of primary assessment function, with patients moving from these areas to the AMU and then to the downstream wards. In other organisations, there were two discernible trends: towards either ‘acute hub’ or ‘hyperstreaming’ models of care. The acute hub, as suggested by the Future Hospital Commission,8 looks to co-locate and streamline all services with a primary assessment function into a single ‘hub’ (Figure 10). Although no hospital had fully achieved this, four hospitals reported moving towards this.

FIGURE 10.

Schematic of the acute hub model of emergency/acute care.

By contrast, ‘hyperstreaming’ models had moved the bulk of the work outside the ED into a series of parallel places of assessment (Figure 11). Seventeen hospitals reported having more than four places for the initial assessment of patients, with one organisation reporting eight.

FIGURE 11.

Schematic of the ‘hyperstreaming’ model of emergency/acute care.

Although this schematic shows the AMU in parallel, the rules for where patients should proceed varied by organisation, with some hospitals requiring all patients to pass also through the AMU and others allowing patients, after primary assessment (regardless of location), to be admitted directly to a ward. Other organisations conceded that patient flow through the system was wholly contingent on the availability of ward beds.

Highly complex systems

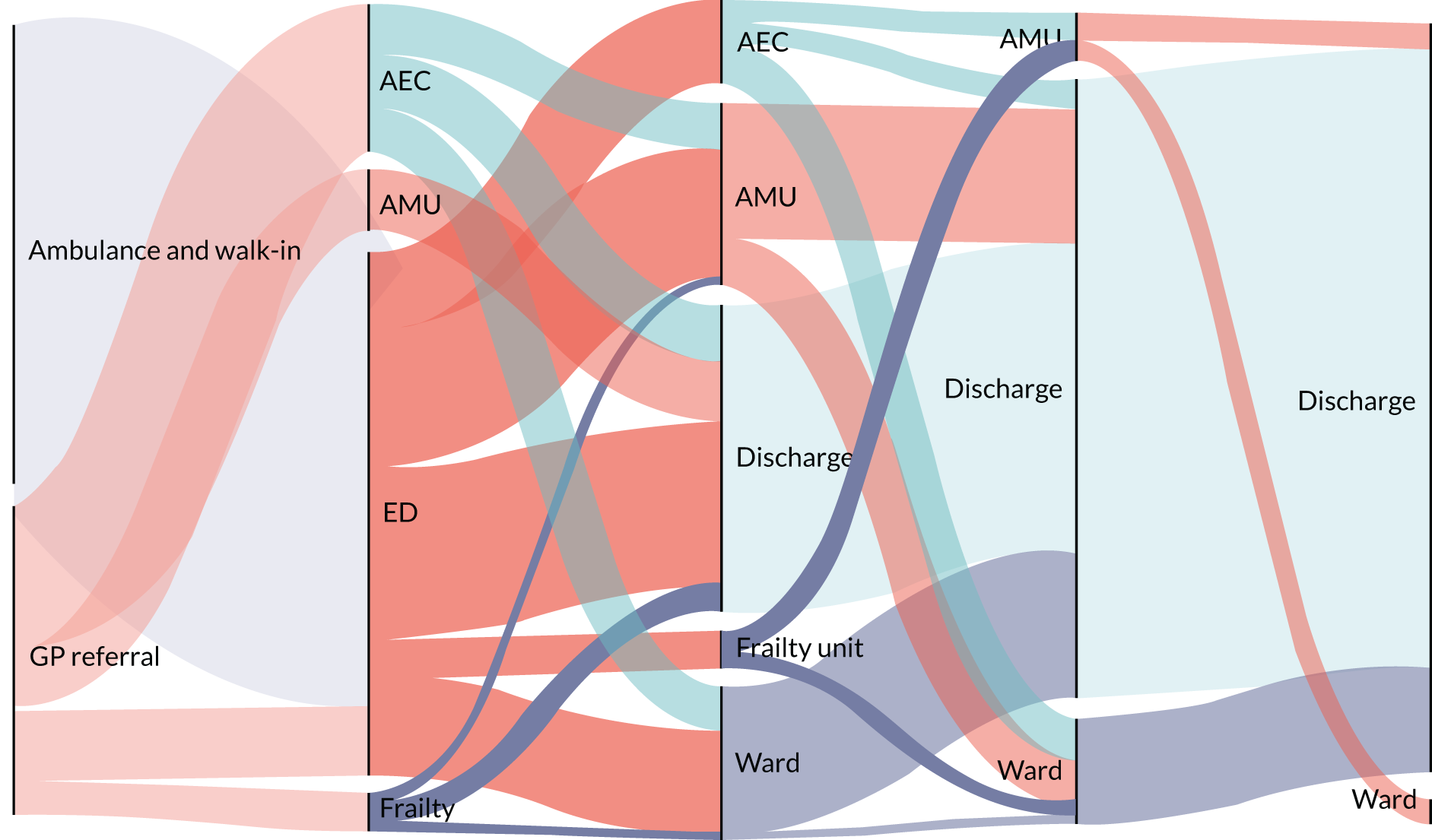

The result of the multiplication and the diversity of services at the front door has resulted in highly complex flows through the emergency and acute medicine pathway. Figure 12 shows the Sankey flows for a smaller rural hospital with 350 beds (Sankey flows for all case studies are given in Report Supplementary Material 5). Patients usually undergo multiple moves, through up to five different components of the system before finally being discharged. Considering that each move between the different components (denoted by the solid black lines) will be accompanied by a change of treating team, this visualises the fragmentation and complexity of the emergency and acute medicine pathway used in many hospitals.

FIGURE 12.

Sankey flow diagram of emergency/acute care at a 350-bed rural hospital.

Typology of models of medical generalism

The intention was to define and classify the degree to which each component of the emergency and acute medicine pathway was generalist or specialist, and then use this to form a judgement of how generalist or specialist the whole system of medical care in each organisation was. However, because of the extreme complexity and variability at almost every level, this was not feasible (see Appendix 3).

The RCP defines general medical work in two ways: (1) participating in the unselected acute medical take and (2) the care of general medical patients on the ward. 105 Therefore, we decided to focus on the patterns of consultant working on the AMU and the medical wards and the issue of who looks after the general medical patient: the generalist or the specialist? Our initial analysis of the data found that ‘ownership’ of a patient by a named consultant had the potential to occur at three specific time points in the patient journey: admission, first morning post admission and change of geographical location (predominantly the move from the AMU to the downstream wards). At each of these points, patient ownership could be considered a function of:

-

patterns of the contribution of medical consultants to the acute take (specialist vs. generalist)

-

patterns of the contribution of medical consultants to the post-take (specialist vs. generalist)

-

patterns of the contribution of medical consultants to ward work.

In all organisations, the patterns of work were also determined by the degree of permeability of the boundaries between the different components of the system, that is whether the service delivery unit is ‘closed’, with all patients within that space cared for by a single clinical team, or the service delivery units are ‘open’, with the allocated consultant caring for the patient regardless of their geographical location.

The other factor that emerged from the interviews as a key organising principle for medical work was the arrangement of downstream wards. Two dominant patterns were observed. Hospitals either had some wards designated as being ‘general medical’ or had all wards designated as being ‘specialty’.

It is acknowledged that the determination of whether a patient should be cared for by a generalist or a specialist is partly a function of the needs of the individual patient. However, the unwritten rules at each hospital for labelling patients were not visible in the telephone interviews, and so this dimension was not included in the creation of the typology. The issue of which patients were considered to be generalist was explored during the case study visits (see The general medical patient).

Acute medical units: definitions of generalist and specialist models of care

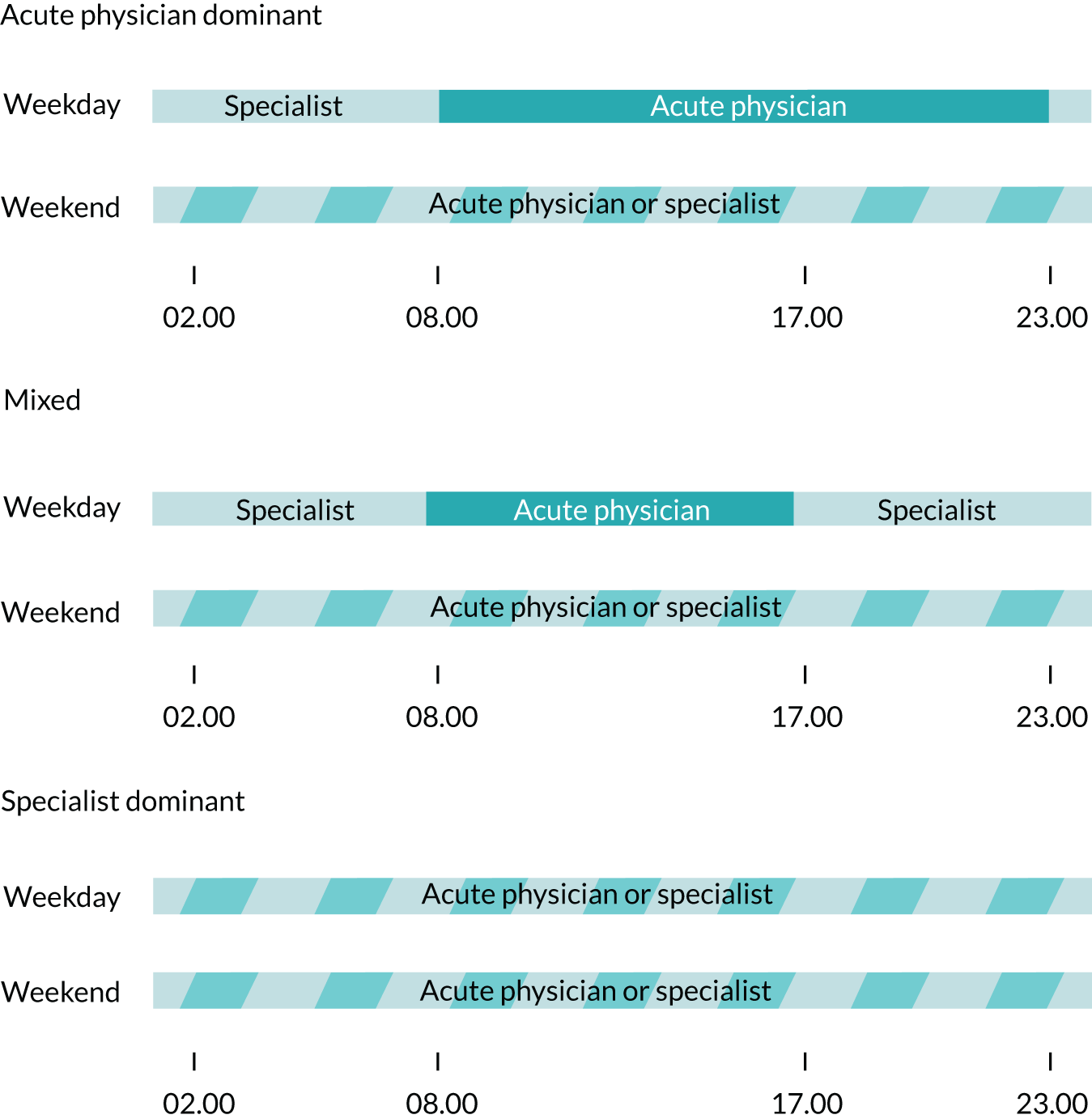

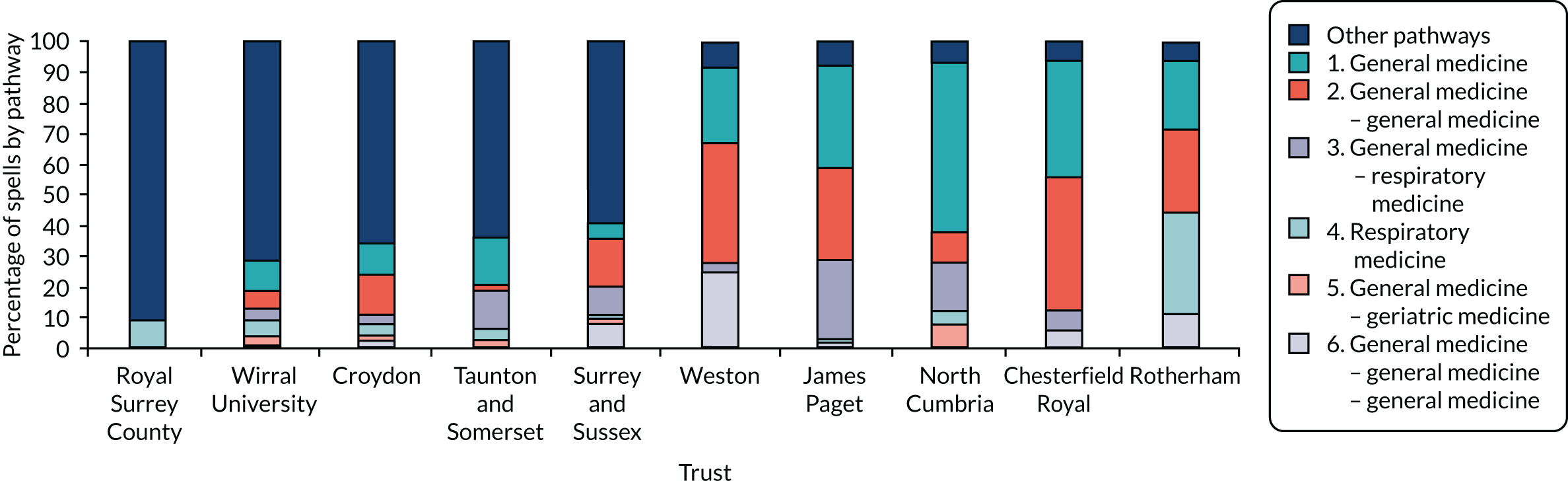

Two categories were chosen to classify the generalist nature of AMUs: the permeability of boundaries (Table 4) and the patterns of contribution of the medical consultants to the acute take (Table 5), a schematic of which is given in Figure 13.

| Type | Definition | Descriptive code | Type code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Closed | All patients on the AMU are under the care of the acute medical team | Clos | A1 |

| Partial | Most patients remain under the care of the acute medical team, with the exception of a small number of specific patients. This applies to models where one or two groups of patients routinely have their care transferred to a specialist team (e.g. care of a patient with myocardial infarction is routinely carried out by cardiology) | Part | A2 |

| Open | Newly admitted patients initially remain under the care of the acute medical team but are then triaged to a specialist team, which may include general or acute medicine | Open | A3 |

| Type | Definition | Descriptive code | Type code |

|---|---|---|---|

| APD | Acute physicians provide the majority of input into the acute take. SAG contribution is limited to acute take on the weekends and/or overnight on-call. This does not include models where the SAG are physically present in the evening | APD | B1 |

| Mixed | SAG consultants make a regular contribution to the acute take across the whole working week | Mix | B2 |

| SpD | SAGs provide the majority of input into the acute take | SpD | B3 |

FIGURE 13.

Schematic for the patterns of consultant working on the AMU.

These definitions come with a number of important caveats:

-

They are based on usual patterns of care, rather than behaviour in exceptional circumstances (such as a patient belonging to a specialist consultant needing to remain on a closed AMU owing to nursing needs).

-

They do not capture all transfers of patient care between individual consultants, only those when the care has the potential to change from being generalist to specialist.

-

The closed/openness of an AMU ignores the issue of who leads the acute medical team at any point in time.

As all patients on a closed AMU will remain under the care of a single physician who co-ordinates their care, these units can be considered to be the most generalist. Conversely, the system operating in open units, commonly known as ‘take triage’ (patients are assigned or ‘triaged’ to specialty services as part of the admitting process), were specifically created to bring specialists as close to the front door as possible, rather than patients being assigned to specialist teams only at the point of transfer to the wards. 106

Prior to the fieldwork, it was assumed the balance between acute physicians and specialists and generalists would correlate with how generalist the unit was in its approach to patient care. Although during the course of the fieldwork it held that hospitals with an APD model viewed their care as being more generalist, hospitals with SpD models often viewed themselves as being highly generalist.

Downstream wards: definitions of generalist and specialist models of care

Two categories were chosen to classify the generalist nature of downstream medical wards: (1) the permeability of their geographical boundaries (Table 6) and (2) whether or not any wards were labelled as ‘general medical’ as opposed to all medical wards in a hospital being labelled as ‘specialty’ (Table 7).

| Type | Definition | Descriptive code | Type code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Closed | All patients on a given ward are cared for by a single team based on that ward. Transfers between wards necessitates a change of team | Clos | C1 |

| Partial | Most patients on a ward belong under the care of the ward team, with the exception of a small number of patients who belong under the care of other specialty teams | Part | C2 |

| Open | Patients belong to named consultants, rather than ward-based teams. Transfers between wards do not necessitate a change of team | Open | C3 |

| Type | Definition | Descriptive code | Type code |

|---|---|---|---|

| General medical wards | Wards that were explicitly designated as ‘general medical’ and/or wards where admittance was based around criteria other than medical specialty need, e.g. short-stay wards, medically fit for discharge wards, slow stream wards and rehabilitation wards | GMW | D1 |

| Specialty wards | All medical wards are allocated to a given specialty | SpW | D2 |

These definitions contain a number of important caveats:

-

They are based on usual patterns of care, rather than behaviour in exceptional circumstances.

-

They do not capture all transfers of patient care between individual consultants, only those when the care has the potential to change from being generalist to specialist.

Closed wards were considered as more specialist, whereas open wards were considered more generalist. Hospitals with some general medicine wards were considered to be more generalist than their counterparts with specialty wards only.

Classifying hospitals according to the typology

In total, 48 hospitals could be classified; two sites could not be categorised with sufficient accuracy. A total of 25 models were identified as being in use in the 48 organisations; the descriptive and numerical codes used to assist with the analysis can be found in Appendix 3.

The distribution of models of care is given in Table 8.

| AMU | Downstream wards | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 D1 | C1 D2 | C2 D1 | C2 D2 | C3 D1 | C3 D2 | Total | |

| A1 B1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 8 | ||

| A1 B2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 8 | ||

| A1 B3 | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||||

| A2 B1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 | |||

| A2 B2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 13 | ||

| A2 B3 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| A3 B1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | |||

| A3 B2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| A3 B3 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Total | 12 | 13 | 7 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 48 |

There were no more than four hospitals using any one type of AMU or ward model, with eight hospitals operating models not used by any other organisation.

Testing the typology

The typology was reviewed on several occasions by both clinicians and managers. The standard response was that, although aspects of the typology were complicated, it did capture the critical differences between the most common ways of working across the acute/emergency care pathway and was clinically meaningful.

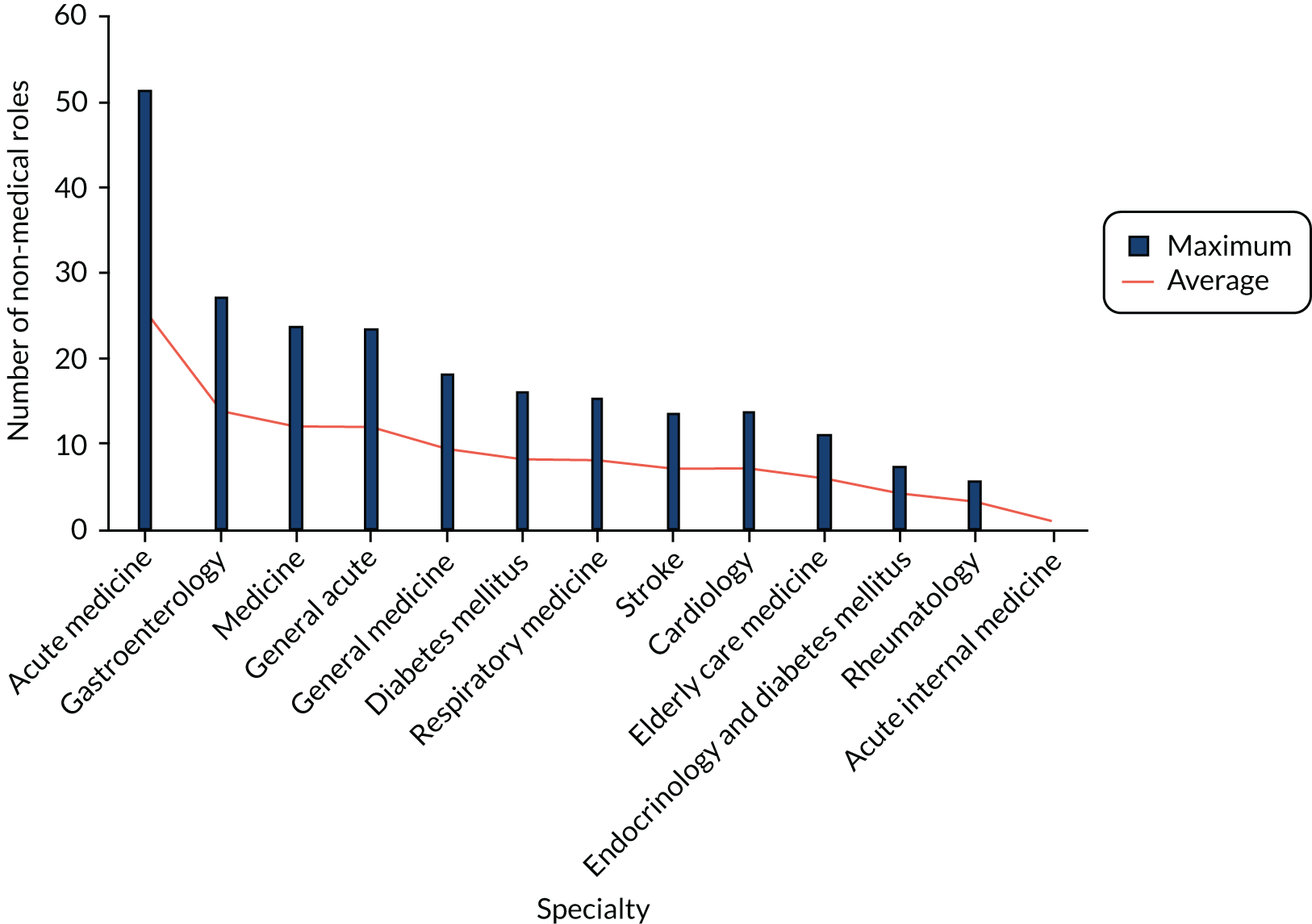

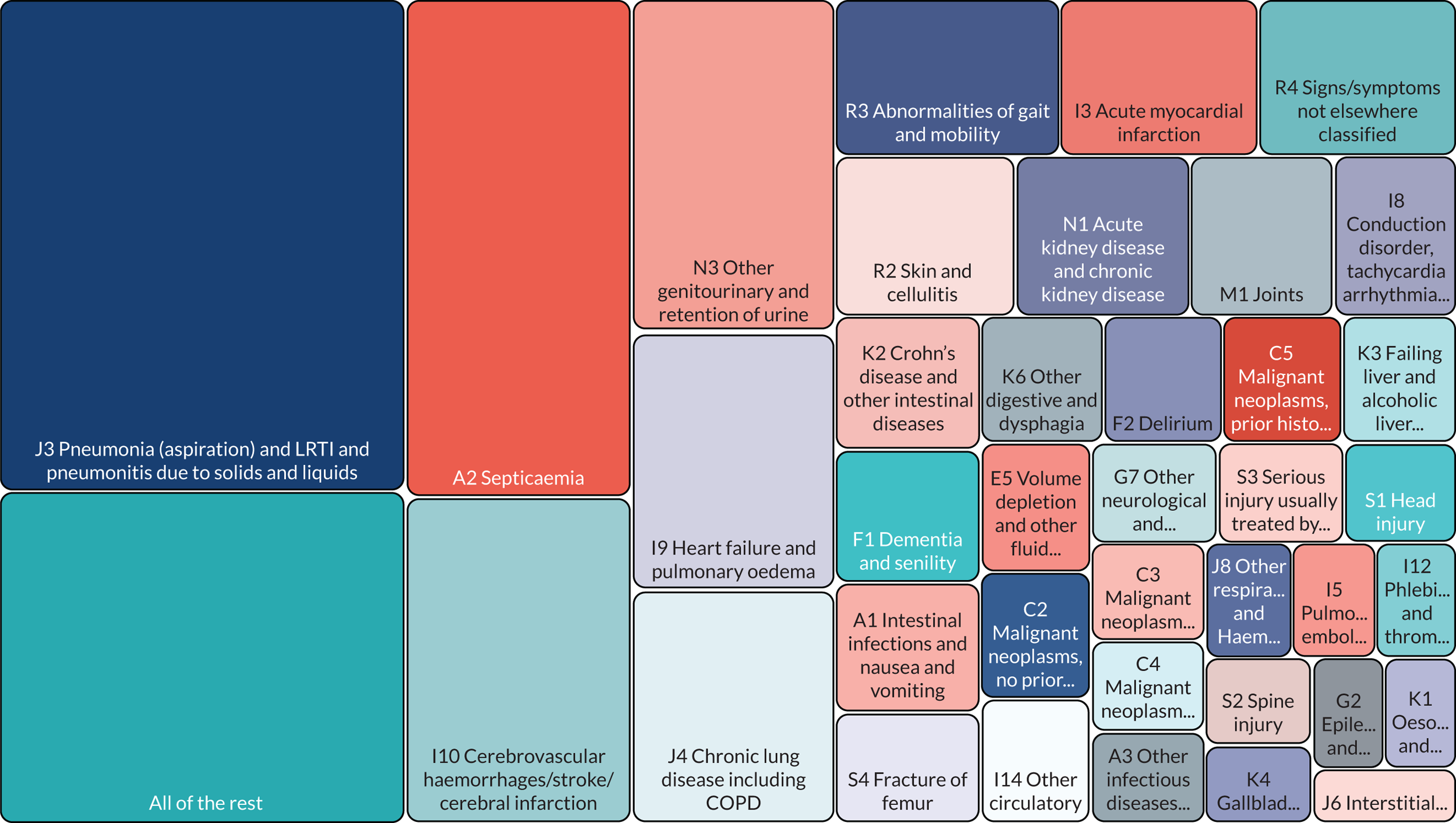

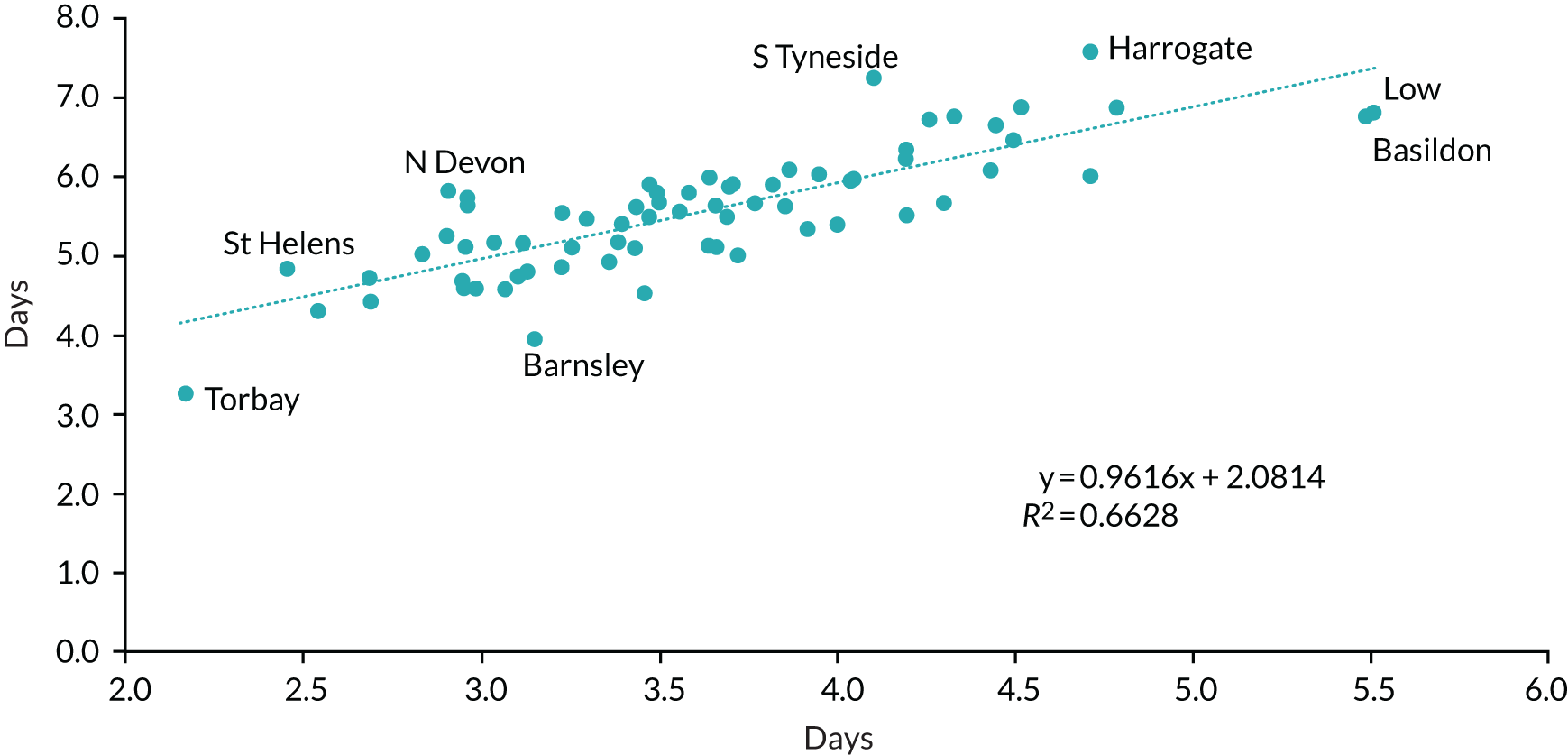

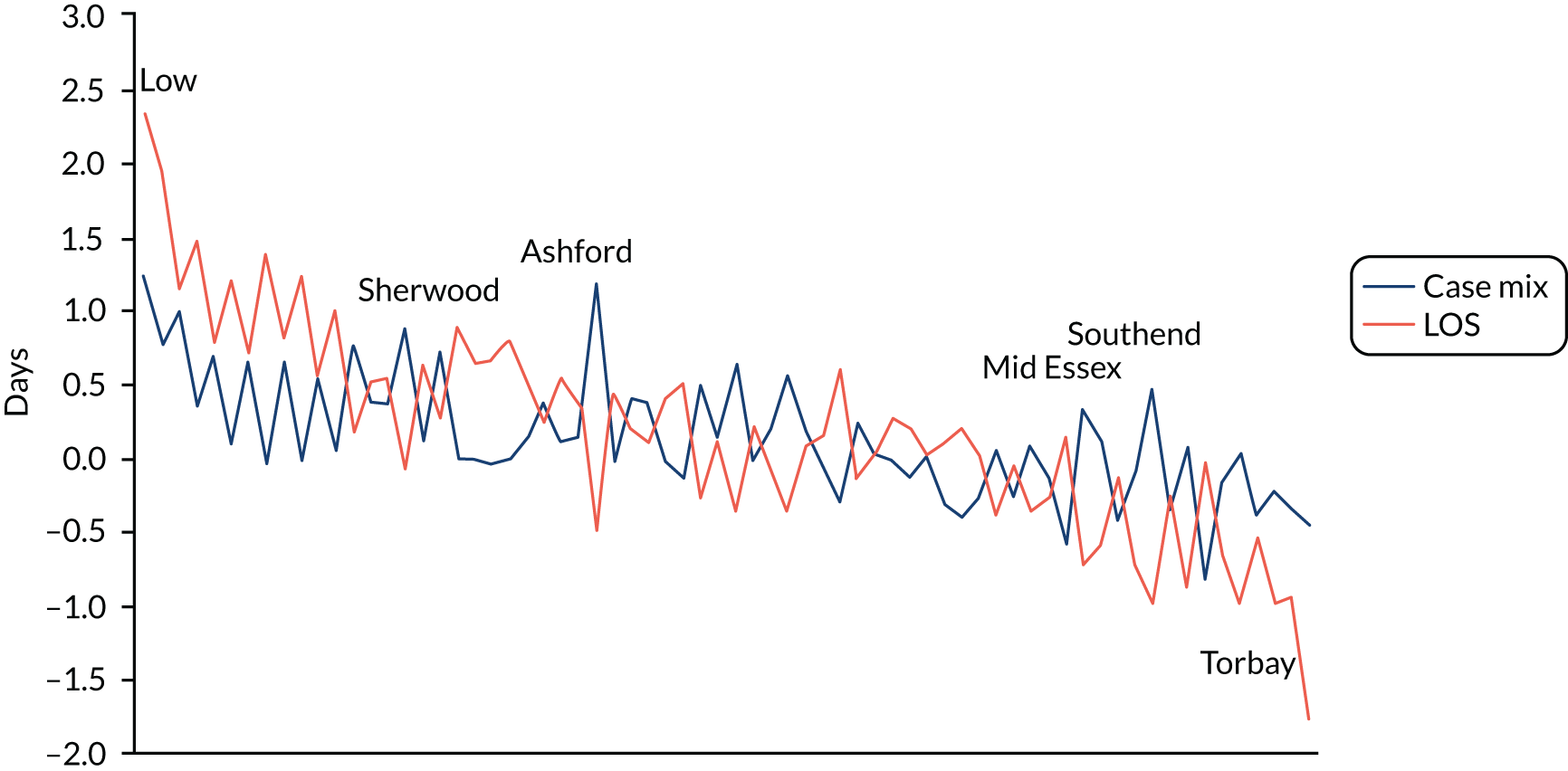

Are models of care contingent?