Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/53/17. The contractual start date was in January 2018. The final report began editorial review in July 2019 and was accepted for publication in April 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Baker et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

This chapter sets out the background and study context, explaining why it is important to enhance knowledge about restrictive practices in adult mental health inpatient settings and how the behaviour change technique (BCT) taxonomy can contribute to the development and understanding of interventions.

Restrictive practices in adult mental health inpatient settings

Incidents that threaten service user and staff safety, such as violence, aggression and self-harm, are not uncommon in mental health inpatient settings. 1 The Royal College of Psychiatrists’ (RCP) survey of violence in inpatient mental health settings in 20072 found violence and aggression to be commonplace, experienced by approximately three-quarters of all staff and one-third of service users. They are often managed using restrictive practices, which are defined by the Department of Health and Social Care as:

‘[. . .] deliberate acts on the part of other person(s) that restrict an individual’s movement, liberty and/or freedom to act independently in order to: take immediate control of a dangerous situation where there is a real possibility of harm to the person or others if no action is undertaken . . .’

Examples of restrictive practices include restraint (manual or mechanical holding of the service user), seclusion (isolating the service user in a locked room), coerced intramuscular injection of sedating drugs and constant observation (service user within eyesight or arm’s reach of one or more supervising nurses at all times).

Restrictive practices are widely used internationally4 although reliable prevalence data can be hard to find, and are influenced by discrepancies in definition and recording methods. 5 Cultural differences mean that across countries some forms of restrictive practice are more acceptable than others. For example, mechanical restraint is seen as an acceptable treatment in acute settings in the USA but unacceptable in UK acute settings. 6 Despite such differences, there is an emerging international consensus that restrictive practices are used too frequently. 7 Restrictive practices can cause serious physical and even lethal harm as well as psychological injury to service users and staff. 8 Face-down restraint has been associated with positional asphyxia. 8 Restrictive practices can also have a profoundly detrimental effect on therapeutic relationships between staff and service users. 9 Substantial costs arise from staff sickness10 and resource-intensive observation of service users. 11

Interventions to reduce restrictive practices

Restrictive practices began to attract wider attention following the occurrence of deaths attributed to their use. 12 In England and Wales, the Mental Health Units (Use of Force) Act 2018 has mandated that Mental Health Trusts must reduce the use of restrictive practices. 13 Despite a plethora of policies and initiatives in the UK and internationally to reduce the use of restrictive practices, there is no robust evidence to support the use of one intervention in preference to another. Furthermore, it has been noted that where one restrictive practice is reduced another might increase. 8,14 Safewards, an initiative to reduce conflict (violence, absconding, self-harm, rule breaking and medication refusal) and containment (restraint, seclusion and sedation),15 showed a reduction in incidences of both in the intervention arm. 16 It demonstrated that innovative, evidence-based interventions can reduce violence and containment usage in settings that are contending with the resource limitations characteristic of UK acute mental health services. A trial of Six Core Strategies17 demonstrated a reduction in ‘seclusion–restraint’ and observation days, although no differences in terms of violence.

Observation studies have reported the reduction of restrictive practices and violent behaviours after the delivery of interventions,18–20 although they are generally considered low quality, and other studies have reported no effect. 21 One study showed some evidence in favour of restraint training over de-escalation training. 22

In the UK, Safewards,16 Six Core Strategies23 and No Force First24 are examples of initiatives that have been promoted and adopted by some NHS Mental Health Trusts, while the National Coordinating Centre for Mental Health is promoting a quality improvement programme. However, the specific content of such initiatives and programmes has not been examined in detail; hence, the mechanisms through which they might change behaviour are not fully understood and, furthermore, it is not known whether or not interventions leading to reductions in the use of restrictive practices share common features.

Previous reviews14,18,25–31 have highlighted the paucity of research in this area and poor quality of the evidence. One study concluded that there is a lack of evidence from controlled studies to support the use of current non-pharmacological approaches to violent behaviour. 32 Although there is a clear imperative to identify the best-quality studies to reliably understand how effective an intervention is, this has little applicability in practice if the choice of interventions is extensive while awareness of their effectiveness is limited. Service providers thus require some way of knowing what interventions are available and how comparable they are.

There are repeated calls for restrictive practices reduction guidance to be based on robust transparent studies,33,34 and for interventions to be better described and better evaluated. A further challenge for reviewers of behavioural (non-pharmacological) interventions is how to synthesise content, especially when there are vast differences between procedures. Livingston et al. 18 reviewed training-based interventions to reduce restrictive practices. They highlighted the difficulty of reaching conclusions because of ‘different types of aggression management programs, which contain a variety of approaches’ [and that the] ‘focus, curriculum, and duration of the training vary substantially from one program to another’. 18 Another review found that only 39% of interventions were adequately described when published. 35 This does not necessarily mean that interventions are not described, but does suggest the absence of a common language with which to describe intervention components. 36,37

The behaviour change technique taxonomy

To address this issue, a taxonomy of BCTs was developed. 38 The taxonomy provides a reliable method of precisely specifying components of programmes in a transparent manner, using an established language. It is intended for application across theory-based programmes aimed at both patients and professionals.

The BCT taxonomy built on a previous taxonomy devised from content analysis of reports of interventions,39 and followed a series of context-specific taxonomies focusing on physical activity and healthy eating,40 and prevention of risky sexual behaviour,41 professional behaviour change,42 safe drinking43 and smoking cessation support. 44,45 It differed from these in that it was designed to be comprehensive and to encompass a wide range of behaviour change techniques. This taxonomy is widely used internationally to report on programmes and synthesise evidence. 46,47

The development of the BCT taxonomy involved an empirical approach aiming to achieve international consensus around content. Three distinct methodologies were employed: (1) Delphi methods were used to develop labels and definitions of the individual BCTs, (2) the reliability of coding these BCTs was tested and used to highlight BCTs requiring refinement by the study team, and (3) an open-sort grouping task was delivered via an online computer program, with statistical techniques, including hierarchical cluster analysis, applied to generate a hierarchical structure of technique clusters designed to increase the speed and accuracy of recall during use of the taxonomy.

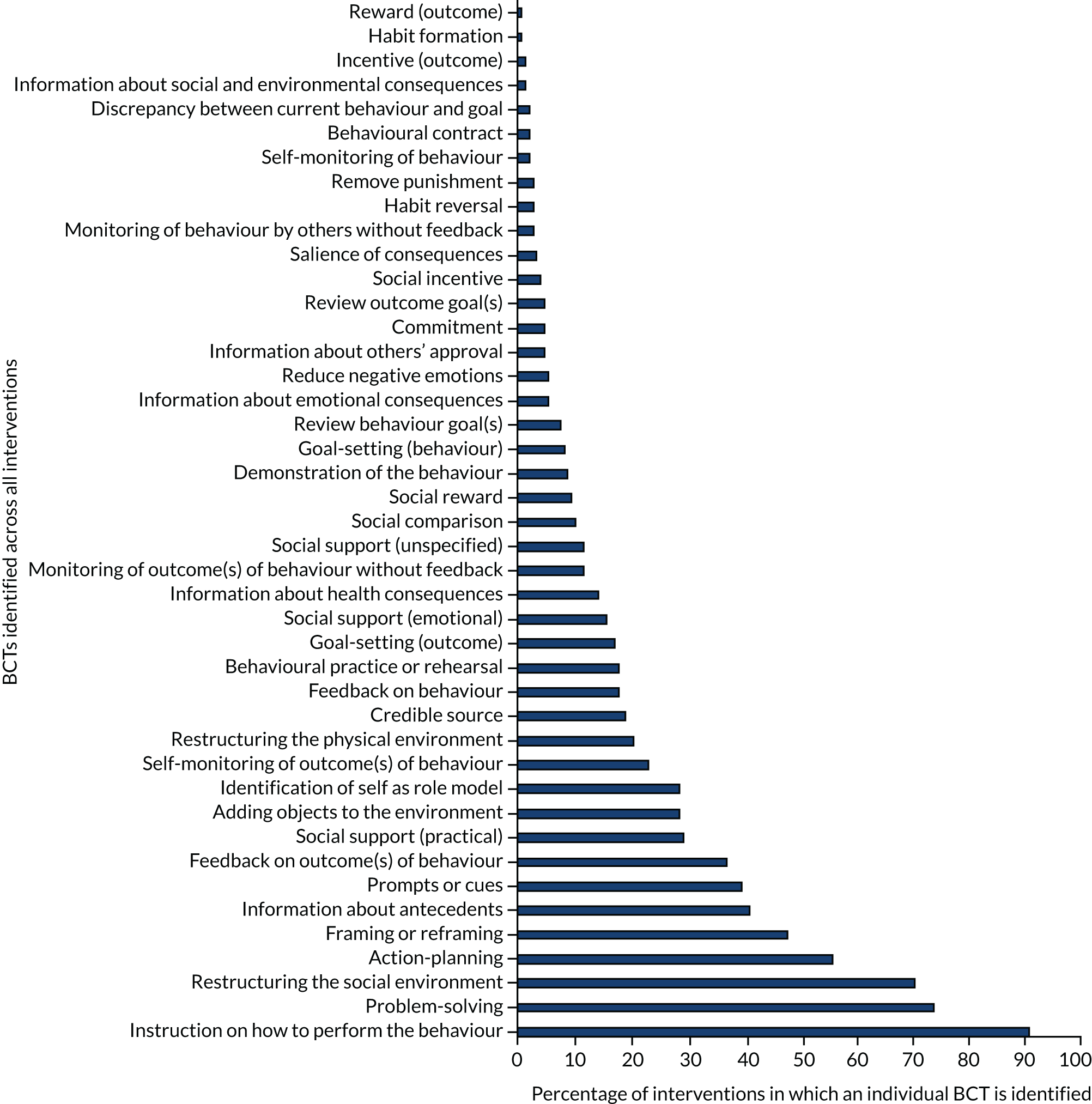

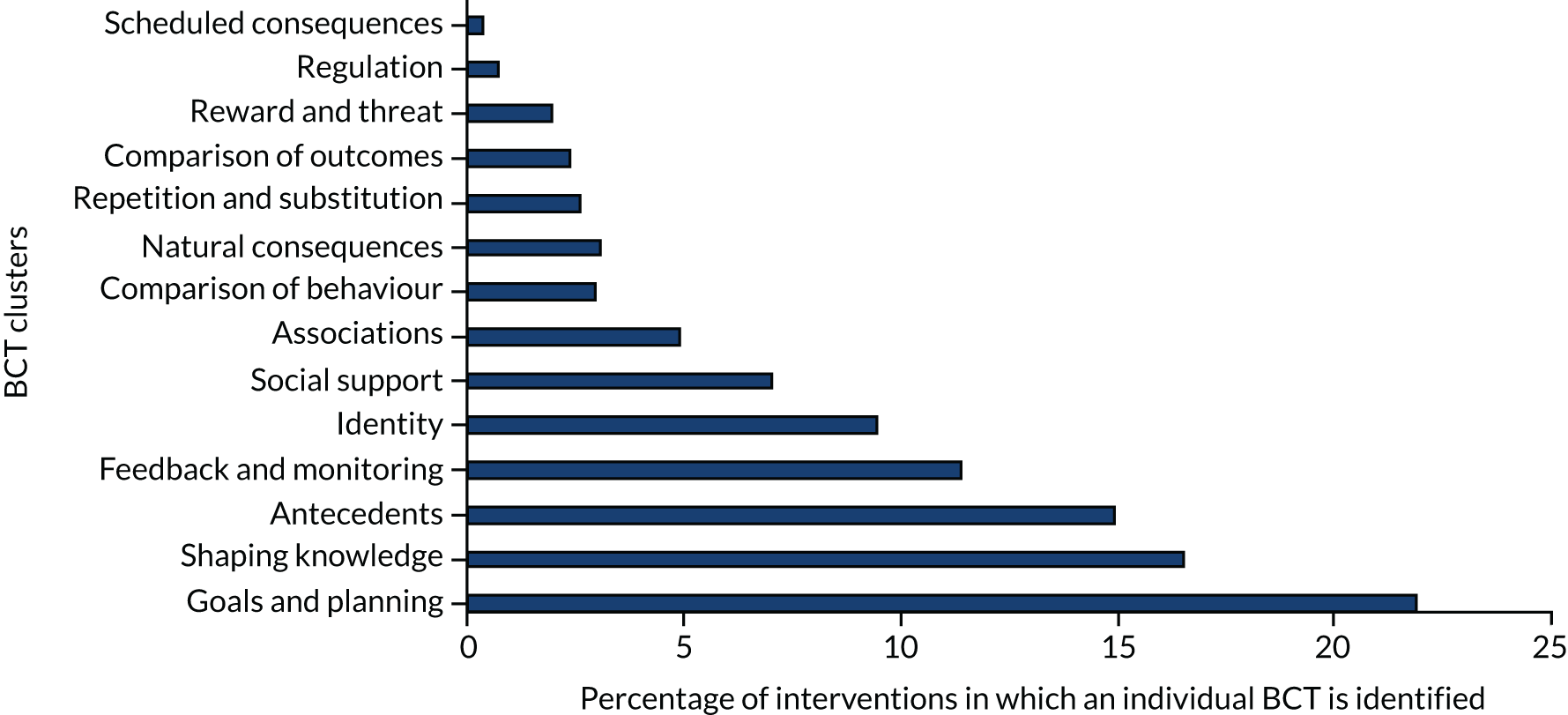

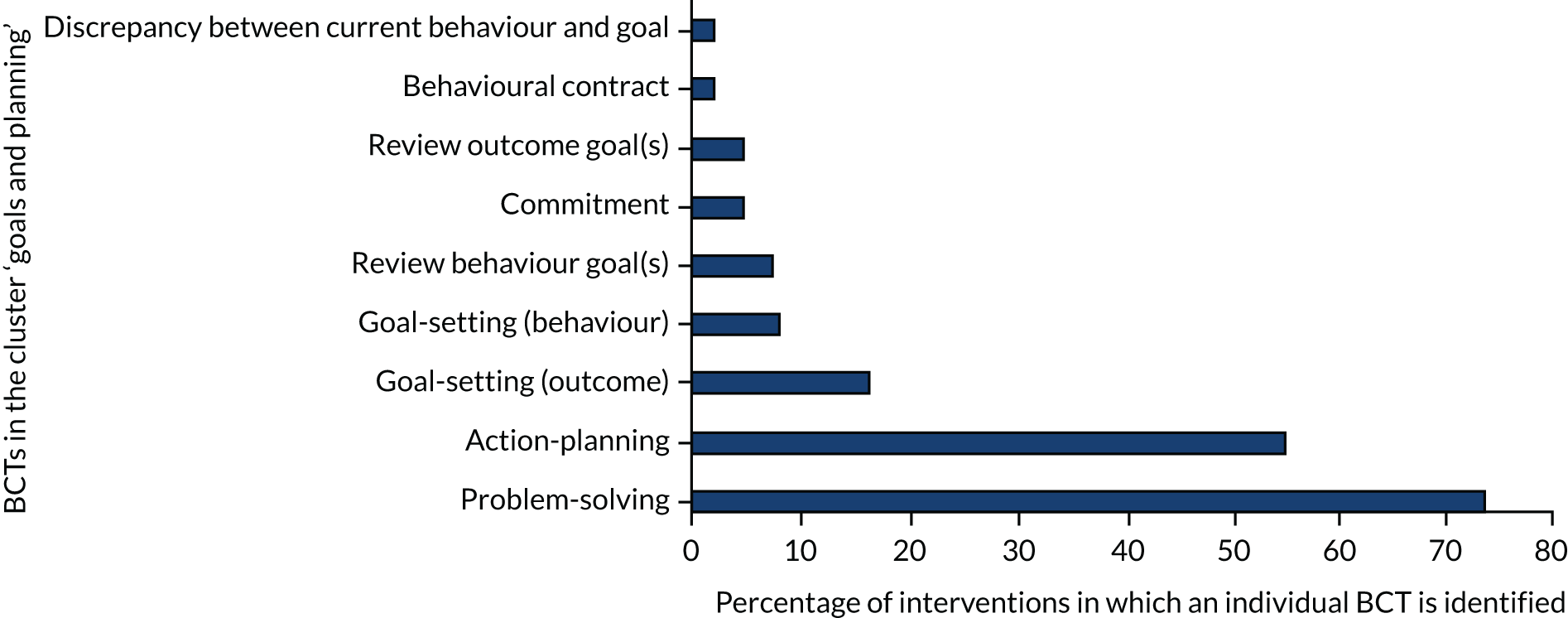

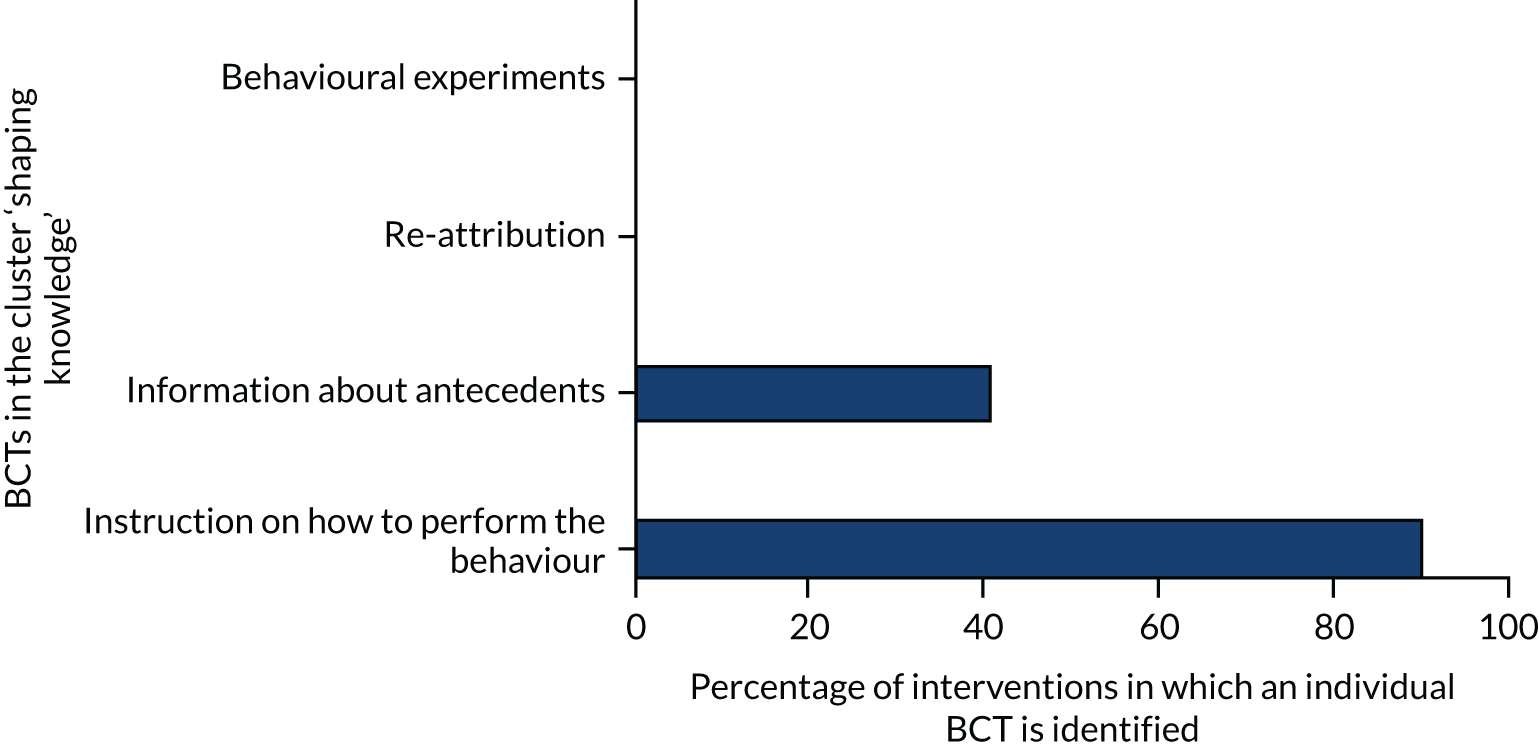

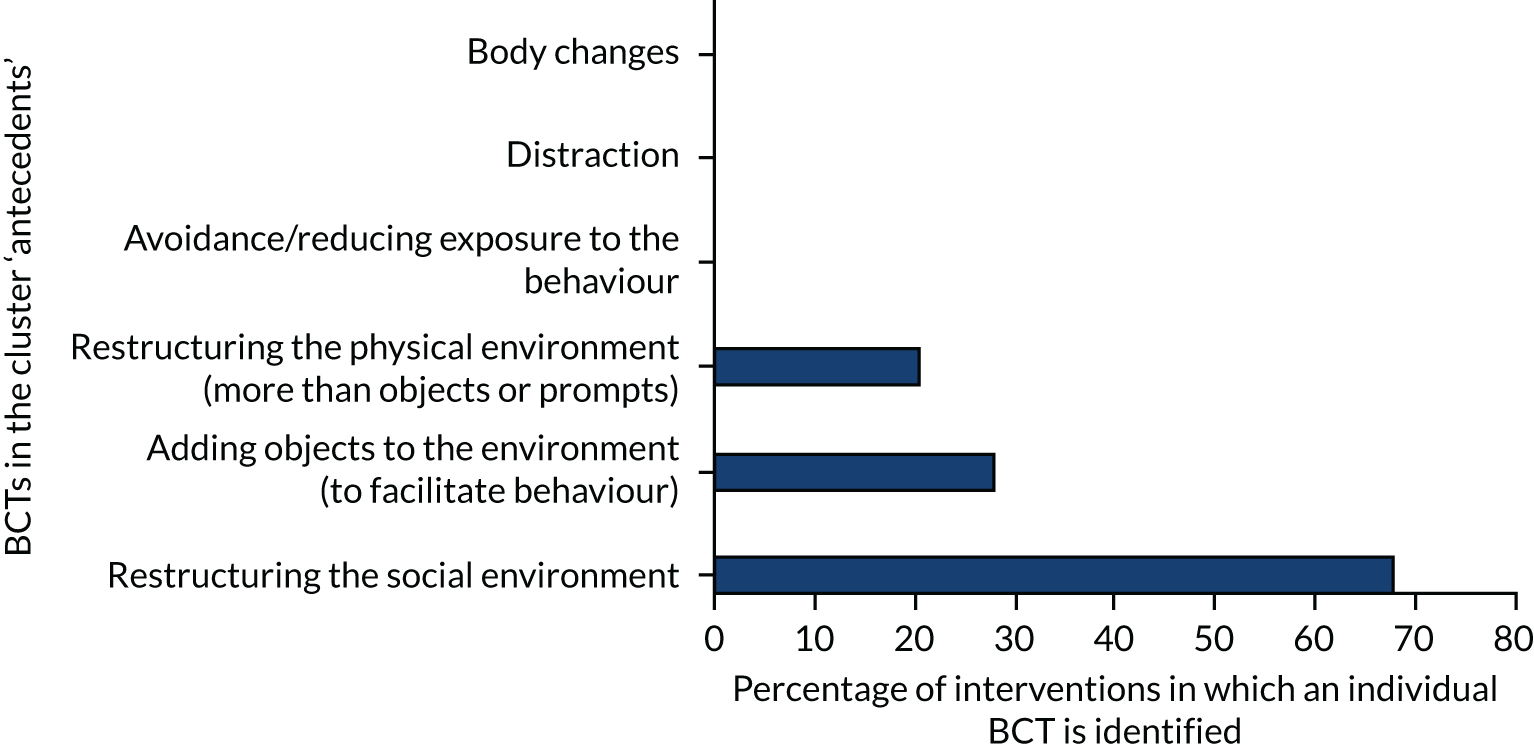

The BCT taxonomy enables the robust synthesis of evidence that has previously been problematic to unpick and compare. A BCT is defined as ‘an observable, replicable, and irreducible component of a programme designed to alter or redirect causal processes that regulate behaviour’. 38 The taxonomy comprises 93 BCTs (e.g. ‘problem-solving’, ‘instruction on how to perform the behaviour’, ‘social comparison’) in 16 thematic clusters, such as ‘goals and planning’ (solving problems by identifying actions required, and setting and reviewing goals) ‘shaping knowledge’ (including instructions on performing the behaviour and information about antecedents), ‘antecedents’ (including factors that could influence whether or not restrictive practices can be avoided) and ‘feedback and monitoring’ (including the monitoring of ward data, and whether or not and how feedback was given).

All interventions to reduce restrictive practices use BCTs. For example, role-playing verbal de-escalation strategies could be coded as ‘rehearsal of relevant skills’ involving ‘social comparison’, ‘monitoring of emotional consequences’ and ‘feedback on behaviour’. An expert delivering information about the risks of restraint could involve ‘information about health consequences’ delivered by a ‘credible source’. The BCT taxonomy therefore provides a reliable method of precisely specifying intervention components and the mechanisms by which behaviour is changed. 36,37 Use of this standardised language promotes transparency through more accurate reporting and replication,45 as well as more successful implementation with proven effectiveness. 38

The taxonomy can be used prospectively in intervention design48,49 by assisting with the identification of BCTs potentially associated with effectiveness. 38 It can also be used retrospectively to describe completed interventions and has been used internationally to report interventions43 and synthesise evidence,41,50 including reanalysing existing interventions to explore their components. 40

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter sets out the study aim and objectives and describes the methods used in a three-stage study design including literature search, data extraction and analysis.

Aim and objectives

The aim of this study was to identify, standardise and report the effectiveness of components of interventions that seek to reduce restrictive practices in adult mental health inpatient settings using the BCT taxonomy. 39

The study objectives were to:

-

provide an overview of interventions aimed at reducing restrictive practices in adult mental health inpatient settings

-

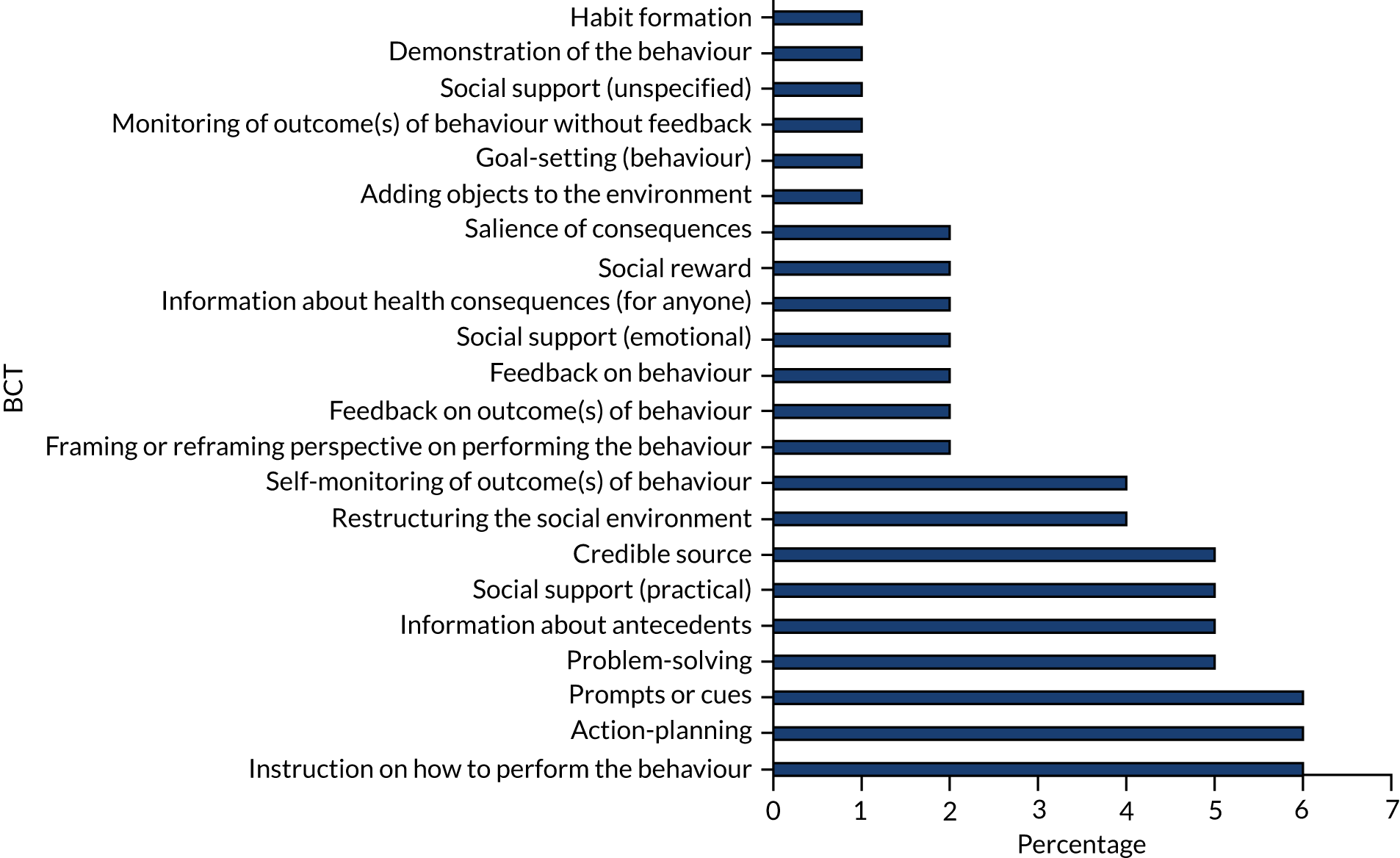

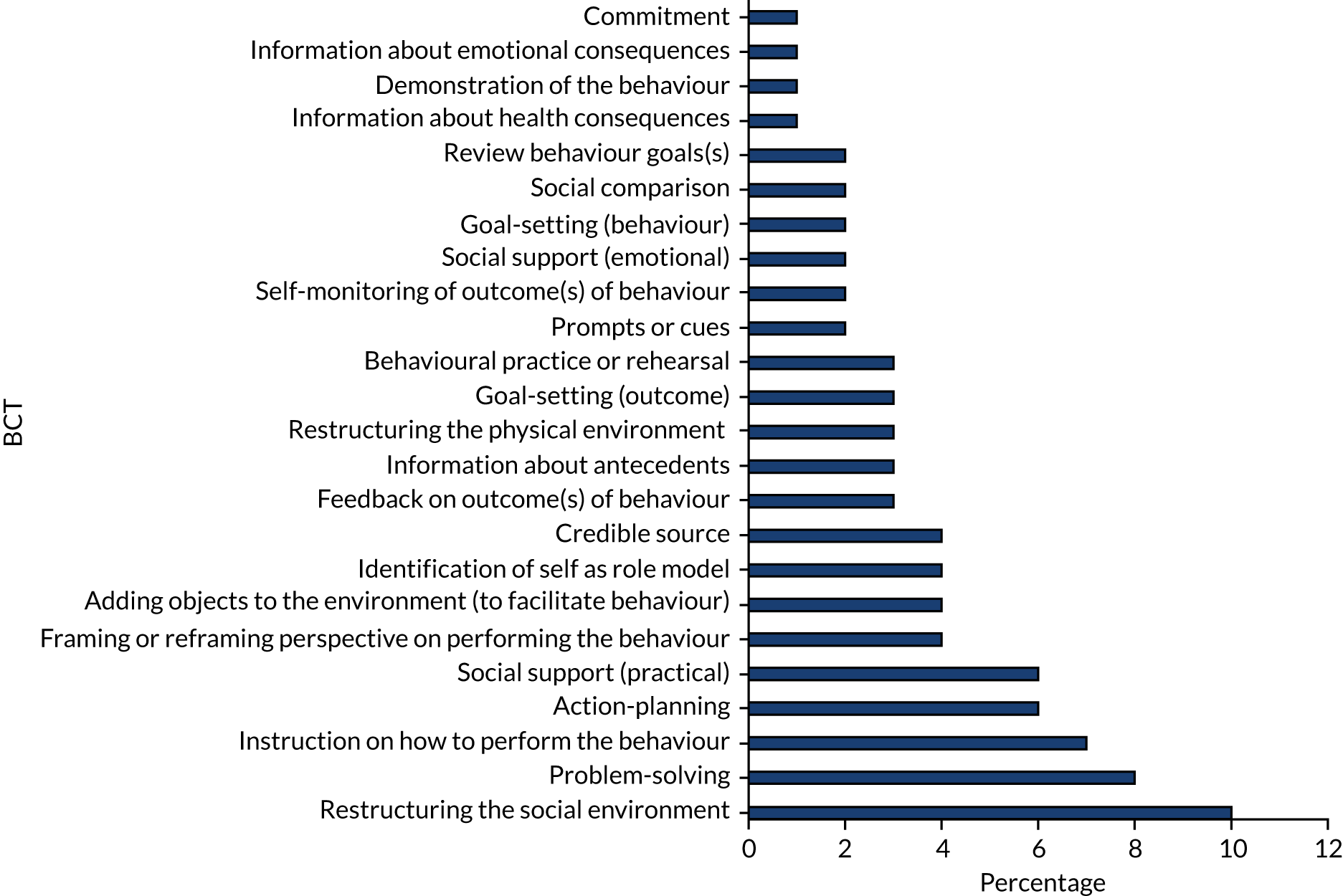

classify components of those interventions implemented in terms of behaviour change techniques, and determine their frequency of use

-

explore evidence of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness by examining behaviour change techniques and intervention outcomes

-

identify behaviour change techniques showing the most promise of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, and that require testing in future high-quality evaluations.

Design

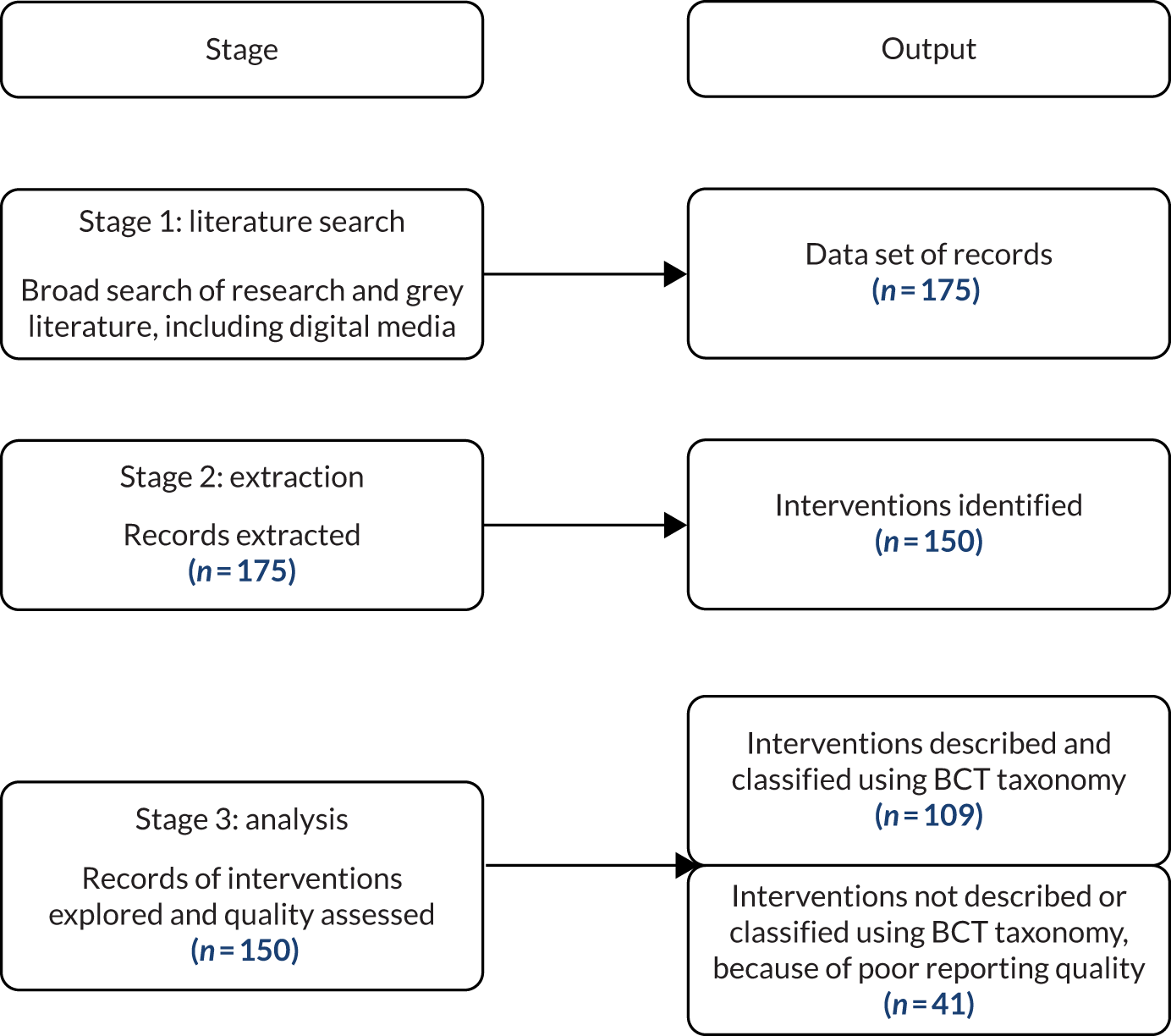

The study design comprised three stages. The purpose of stage 1 was to systematically search all English-language reports of interventions to reduce restrictive practices in inpatient mental health settings (objective 1). The aim of stage 2 was to extract data for analysis using the validated, structured BCT taxonomy to identify the content of the interventions (objective 2). The aim of stage 3 was to analyse the content of interventions using the BCT taxonomy, alongside a critical appraisal of all retrieved records using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), an appraisal tool specifically designed for mixed-methods reviews. 51 The application of the MMAT is described in Assessment of study quality using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. The study design is illustrated in Figure 1 (see Chapter 3).

Stage 1: literature search

Introduction

Stage 1 focused on ascertaining the range and characteristics of interventions, irrespective of evidence of effectiveness, which involved systematically searching and reviewing all reports of interventions seeking to reduce the use of restrictive practices.

The search strategy approach drew on the increasingly utilised method of mapping52–56 to inform the purpose and output of the review. It differed from the method described in Bradbury-Jones et al. 52 because of the broad scope of the search and the inclusion of interventions in the current study. It was known that in addition to a small number of well-known interventions reported in the academic literature, there were numerous small-scale, standalone initiatives available for implementation in services. Not all of these would appear in a search restricted to the published research literature as they may be reported in unpublished literature or ‘non-research’ publications.

The search for relevant interventions records was informed by an ‘environmental scanning’57 approach suggested by Judy Wright, the project Information Specialist. Environmental scanning is a search methodology familiar in business contexts but relatively little used in health research. It permits the identification of more diverse information about an area than could be retrieved solely from published literature. In health-care settings, environmental scans have been used to inform future planning, to document evidence of current practice and to raise awareness. 57 It was therefore an appropriate choice for expanding the scope of the search strategy. Environmental scanning may involve a ‘passive’ approach that focuses on published and unpublished existing data or an ‘active’ approach where additional knowledge is generated through primary data collection. 57 In this study, a passive approach was used.

In keeping with objective 1 (to provide an overview of interventions aimed at reducing restrictive practices in adult mental health inpatient settings), the search criteria targeted diverse reports of non-pharmacological interventions aimed at changing the behaviour of inpatient adult mental health service staff to reduce restrictive practices. The scope of the searches was necessarily broad to include all records of an intervention, whether it was an evaluation or a descriptive report. 55 In order to include as many interventions as possible within the scope of the search, no quality threshold was imposed either indirectly (by restricting the search to high-impact journals)52 or directly via the search criteria or by screening. 54,56 Inclusion was not restricted by study design. 42 Interventions that solely involved policy change and those that aimed to reduce the use of one type of restrictive practice by replacing it with another were not eligible for inclusion.

In addition to interventions intended to reduce or eliminate restrictive practices, reports of interventions designed to improve quality or reduce or manage violence were included if their procedures and/or outcome measures addressed restrictive practices. Eligibility criteria are shown in Table 1.

| Criterion | Include | Exclude |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adult (including older people) mental health inpatient settings (including acute, forensic and PICU services) | Children and Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services, learning disability and organic conditions |

| Date | 1999–2019 | |

| Interventions | Aimed at changing the behaviour of inpatient adult mental health service staff to reduce restrictive practices. Interventions may or may not have been implemented | Pharmacological only |

| Outcomes | Reduce restrictive practices | |

| Language | English language | Non-English language |

The starting date of 1999 was decided by the date of introduction of the UK National Service Framework for Mental Health,58 which precipitated new quality standards and a significant shift in the orientation of services. Because of the research team’s prior knowledge of the paucity of the evidence base, there were no restrictions on study design and no quality threshold was imposed. Searches were conducted from February until June 2018, and repeated in April 2019.

Two main searches were developed to identify interventions to reduce the use of restrictive practice in adults with mental health disorders. The first search aimed to identify reports from the academic bibliographic databases. The second search aimed to identify unpublished reports, including those occurring in the grey literature, social media and other digital resources.

Academic bibliographic databases search

The first search was conducted in February 2018. A wide range of academic bibliographic databases were searched for published studies, including:

-

British Nursing Index (BNI)

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CCTR)

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR)

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE)

-

EMBASE

-

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Database

-

HTA Canadian and International

-

Ovid MEDLINE®

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED)

-

PsycInfo®

-

PubMed.

For full details of the databases, see Appendix 1.

The rationale for the academic databases was to select databases with good coverage of mental health studies and those covering studies of the nursing workforce, because the restraint reduction interventions are particularly important to this group that are dealing with aggressive and difficult situations on a ward. Two nursing databases (CINAHL and BNI), two of the largest medical databases (EMBASE and MEDLINE), the largest mental health database (PsycInfo), an evidence-based health database with good coverage of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (Cochrane Library) and PubMed were searched to supplement the Ovid MEDLINE as they can contain some articles more recent than those included in Ovid MEDLINE. The team discussed and consented to this database selection, as proposed by the Information Specialist.

Search strategies were developed for the concepts: coercive interventions, mental health conditions and inpatients. Searches included subject headings and free-text words, identified by text analysis tools (PubReMiner), the Information Specialist (JW) and project team members. Further terms were identified and tested from known relevant papers. Searches were peer reviewed by a second Information Specialist. For full details of the search strategies, see Appendix 2 and Report Supplementary Material 1.

The search was updated and re-run in April 2019 in the same databases except for DARE and NHS EED, which were not searched as they had not received further content since the 2018 search. Owing to a change in database providers, BNI and HTA databases were searched via a different database host in 2018 rather than 2019. After checking index terms, two additional terms were added to the PsycInfo search: involuntary treatment/and psychiatric hospitalisation. All other searches remained the same.

Grey literature search

The second search was run from June 2018 to August 2018 to identify unpublished (grey) literature reports in databases, websites and social media sources. For full details, see Appendix 1.

The list of information resources to search was created collaboratively by the project team and information specialists. Websites for charities, government health departments, health-care organisations, health-care quality agencies, mental health organisations, professional societies/colleges and training providers were selected following an exercise to gather all potentially useful websites known by the project team, and those found by an information specialist scoping search. This large list was then organised into ‘types’ of organisations, such as health-care quality agencies, charities and government departments, and the team refined the list to include a set of 5–10 websites to search for each group that represented different countries/regions.

The team prioritised resources that were likely to provide relevant reports from North America, Australasia and Europe. Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) was used to search for interventions in 30 countries specifically identified in the 2016 Legatum Prosperity Index™ (a between-nations ranking system) as having the best health systems. A structured social media search incorporated YouTube (URL: www.youtube.com; YouTube, LLC, San Bruno, CA, USA), Facebook (URL: www.facebook.com; Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) and Twitter (URL: www.twitter.com; Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA).

The search strategies used in academic databases were adapted for use in grey literature databases, websites and social media sources. Website and social media searches used search terms similar to those used in the academic database searches, but fewer of them, and multiple short searches were run per resource, rather than one complex search. This ensured that the searches were consistent with the academic databases despite the limited ability of web and social media resources to process long strings of search terms or combine multiple searches. For further detail, see Appendix 2 and Report Supplementary Material 1.

In addition, an information request for unpublished interventions was sent to mailing lists for the health and medical community, clinical librarians and mental health librarians. No suggestions of restrictive practice reduction interventions were received from the mailing list information request. Project team members forwarded relevant reports they saw on their own social media accounts and through personal contacts with experts. When contact details were available, authors of identified interventions aimed at reducing the use of restrictive practices were contacted for further data. A request for information was circulated around Restraint Reduction Network members.

Backward citation searching of cited references and forward citation searching using Google and PubMed were used in order to access fuller descriptions of interventions, including development, procedures and implementation to supplement records with minimal detail, such as conference and poster abstracts, Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) slides and some non-research reports. This procedure was also used to identify journal publications associated with a dissertation/thesis and published reports associated with unpublished records and non-research reports. These strategies were also supported with a Google search for authors. Individual journals were hand-searched; however, because of the disparate nature of journals reporting the study topic, no key journals were identified.

The results of the published and grey literature database and website searches were stored and de-duplicated in EndNote (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) referencing software libraries. The results of the social media searches were stored in a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) file.

Screening

Free online citation screening software (Abstrackr beta version, Center for Evidence Synthesis in Health, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA) was used to assist with screening. Abstrackr uses artificial intelligence to help reduce screening time by determining the relevance of papers, based on inclusion and exclusion terms entered by reviewers, and subsequently displays references in order of predicted relevance. 59

Retrieved references were imported into Abstrackr and the following settings were selected: a pilot phase of 100, double-screening, display-all (i.e. title, authors, abstract, keywords) and order by relevance. Two researchers (KC and KB) independently screened the first 100 references, documenting their decision-making. Terms were discussed and shared to ensure maximum efficiency and coherence after screening the first 100 references, again after screening 600 and again after screening 1000. In total, 55 terms indicating relevance were entered, including restrain, intervention, psychiatry, inpatient, and the names of specific interventions of interest. In addition, 78 terms indicating irrelevance were entered, including child, community, dementia and learning disability. The full list is provided in Appendix 3. Once 1500 references had been screened, no further references appeared to be relevant. Following the recommendation of Rathbone et al. ,60 references without an abstract were screened separately (n = 998) to avoid compromising Abstrackr’s predictions. Screening conflicts were discussed and resolved between KC and KB. This process generated a subset of full texts to retrieve for further screening.

Stage 2: data extraction

Records were scrutinised to develop a sense of scope and content, and then extracted using a data extraction sheet informed by relevant data extraction tools.

A full list of extraction terms can be found in Appendix 4. Extraction was conducted using a standardised extraction tool supplemented with additional terms. The Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER) tool was used. WIDER was designed specifically to facilitate the identification and extraction of essential details of behaviour change interventions. 61 It comprises 20 recommendations under four broad headings for reporting behaviour change interventions: characteristics of those delivering the intervention, characteristics of the recipient, setting and mode of delivery. In order to capture the breadth of interventions identified in the retrieved records, the tool was adapted to include additional subheadings; for example, city, state/province, country, setting (type) and setting size (beds/wards) were added to subheadings under ‘setting’. These subheadings were developed inductively to reflect content, while retaining the validated structure of the WIDER recommendations. The subheadings under ‘setting’ are relatively descriptive, reflecting the different ways in which setting was reported.

Subheadings under ‘mode of delivery’ were developed in a more interpretive fashion, using the constant comparison technique62 to make judgements about whether one form of delivery was the same as or different from another. When a key detail of delivery mode was identified that did not fit under an existing subheading, another subheading was created for it.

Other headings for data extraction, for example publication type, year of publication and peer review, were drawn from modifiable Cochrane extraction templates63 and developed with reference to the study objectives. Extraction in stage 2 applied the first two screening questions in the MMAT to identify evaluation studies. Additional information using terms from the Cochrane template included, for example, funder (if any), design and outcome measures. The application of the MMAT is described in more detail in Assessment of study quality using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool.

Two researchers (KC and KB) extracted all data into a shared Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, where the data were stored and organised. Notes and clarifications were recorded directly on the spreadsheet. Decision-making during the process of extraction was documented for transparency.

Modification

Reports of modifications to the intervention protocol were recorded, including what was modified and how. 64 In this context, modification meant any planned deviation from the original intervention protocol.

Fidelity

When fidelity was recorded, it described reports of implementation as specified by the intervention protocol. 65

Theory

For the purposes of data extraction, theory was defined as a way of understanding, explaining and predicting behaviour, events and situations. Different scales of theory have been proposed:66 grand, mid and small.

Small theory or programme theory is how and why an intervention is proposed to work. It sets out the components of the intervention, the outcomes and how outcomes will be measured, often in the form of a logic model or driver diagram. 67 Although a 19-item measure for the assessment of the use of theory in interventions is available,48 it was apparent from screening and data extraction that few interventions made any use of theory, and most of the items in the measure would be recorded as ‘no’. Therefore, an adaptation was developed in which any interventions that explicitly referred to theory were examined for (1) whether or not they used theory to inform intervention design and implementation and (2) whether or not they related their findings back to the theory (this criterion was adapted from the theory coding scheme). 48 For example, a judgement would be made about whether or not a training intervention that was described as being informed by social learning theory had linked its training content and delivery back to the same theory, and subsequently whether or not the findings were discussed in relation to the theory.

Not reported

The term ‘not reported’ (NR) was used to indicate missing information, unless there was an explicit explanation of why the information was not provided, such as that costs were not recorded or a procedure was not followed. For example, if fidelity is not reported it can be assumed neither that fidelity was unmeasured nor that it was measured and unreported. The analysis and findings presented below therefore can reflect only what was reported.

Stage 3: analysis

The aim of stage 3 was to analyse the data by describing and classifying interventions using the BCT taxonomy, alongside quality assessment of those records which reported evaluations. The application of the BCT coding manual in this study is illustrated in Appendix 5.

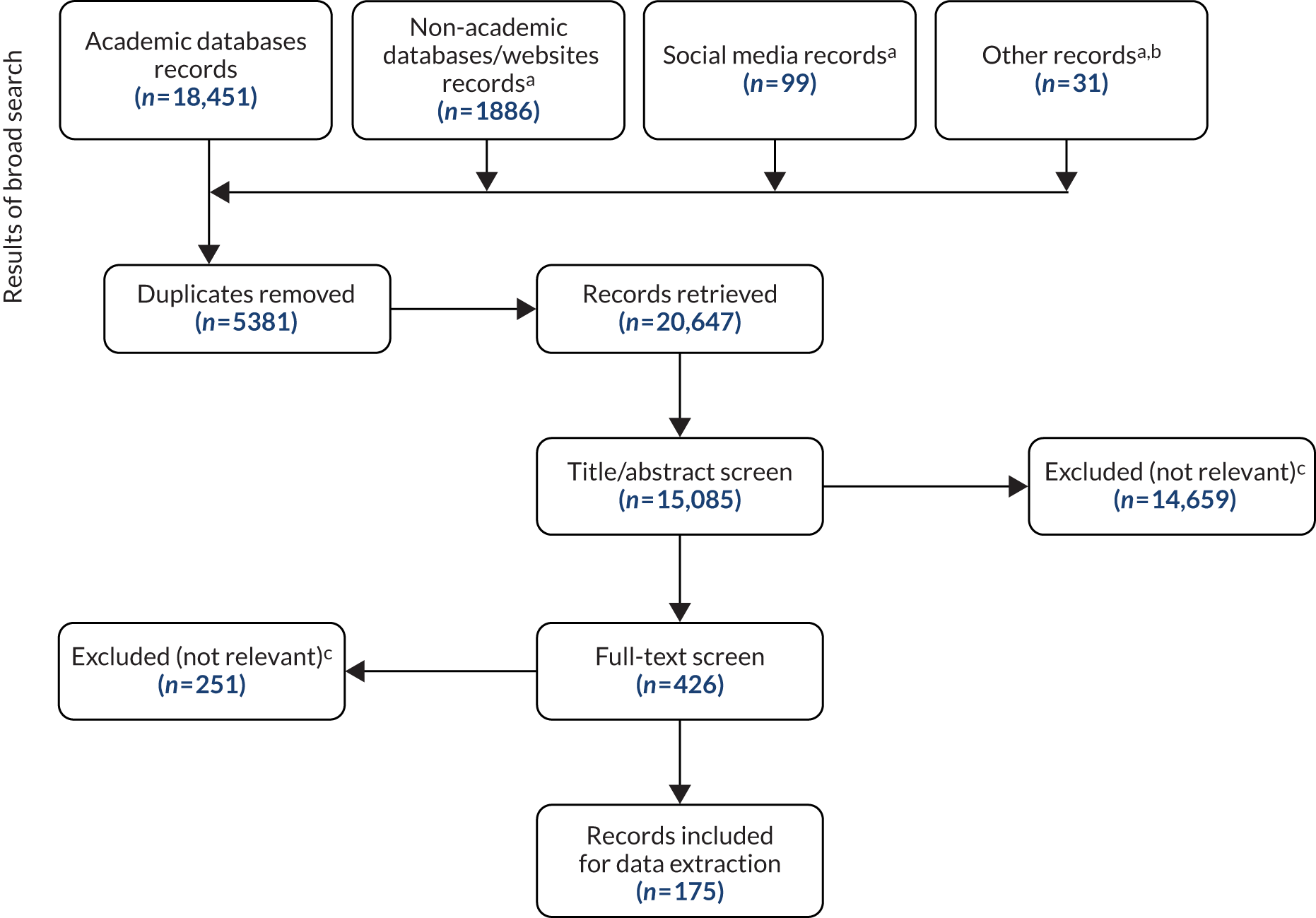

A single record could contain multiple interventions (e.g. NHS documents describing examples of good practice) and multiple records could refer to the same intervention (e.g. initial study, longitudinal study and replication study of an intervention). Records were used to complete the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (see Figure 2) and to report sources and formats. These are presented by type (e.g. research, tool), format (e.g. journal article, thesis) and year of publication to provide a general overview of the range of records captured by the search (see Chapter 3, Characteristics of records identified).

A distinction was made between interventions that had been reported/implemented only once (as far as could be ascertained) and others that had been reported/implemented multiple times, so that multiple records of the same intervention would not skew the analyses. Multiple reports of a single intervention were grouped together and termed an ‘intervention family’. Chapter 4 provides detailed descriptions of the interventions identified under headings corresponding to recommendations in WIDER,61 where that information was reported. As some records contained multiple interventions and the focus here was on the content of each report, the unit of analysis was instances where an intervention was mentioned.

Records were screened using the MMAT,68 as its first level of screening establishes whether or not a report can be categorised as an evaluation. In order to capture different evaluation designs, outcomes and findings, the unit of analysis was the evaluation. They are presented under headings corresponding to Cochrane guidance63 (see Chapter 4).

Describing intervention content using the behaviour change technique taxonomy

Interventions to reduce restrictive practices use a variety of behaviour change techniques to change staff behaviour. The BCT taxonomy was used to describe and compare the content of the interventions identified. As described above, the BCT taxonomy can be retrospectively applied to completed interventions41,46 and to synthesise evidence. 41,50

Behaviour change technique coding

Two researchers (KB and KC) acted as coders and independently coded the documents using the BCTv139 as the basis for a coding manual for the data. Both researchers were trained in application of the BCT taxonomy and are experienced qualitative mental health services researchers. The analysis was also supported by NVivo 12 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK) for qualitative data analysis. NVivo provided an efficient means of storing, coding, checking and reviewing throughout the analysis. The software enables the generation of audit trails including spreadsheets with clear links to original data sets.

Twenty interventions of varying types were coded independently by both researchers before discussion about how BCTs had been identified and coded. The coding manual was developed as the two researchers (KB and KC) discussed and recorded details about how they had coded BCTs and for what reasons. Once the researchers were satisfied with the coding of this set of 20, the remainder were independently coded by one coder and then reviewed by the second. The researchers conferred when there was uncertainty and sought advice from author Ian Kellar, an expert in BCT, as required. Changes were made to the coding manual and coding to ensure consistency. Formal measures of agreement were not used because of the novelty of applying the taxonomy in this area. Appendix 4 provides further details.

Development of the coding manual

The starting point for the coding manual was the BCTv1 taxonomy and its definition and examples of each BCT. 39 However, most of the examples in the taxonomy referred to behaviour of health-care service users rather than health-care staff. In response to this discrepancy the current study applied the approach reported in Presseau et al. 47 For example, regarding ‘reframing’ in the context of staff–patient interactions, staff are supported to think of aggression as a response to trauma, that is the communication of distress. Further examples specific to the literature were developed to consider the content of the interventions to be described. As the coding progressed, additional examples and clarification based on areas of both discrepancy and consensus were added.

There were no intervention components that did not fit into the taxonomy. Some BCTs detected were aimed at health-care staff, for example instructions on how to perform a behaviour via training. Others were aimed at mental health service users, for example using distraction to reduce feelings of aggression and some were aimed at both groups, for example generating emotional and social support by encouraging socialising on mental health wards. Again, taking the approach of Presseau et al. ,47 these were treated separately. In line with the study aims, the focus was BCTs targeting staff behaviour.

The taxonomy deals with BCTs concerning both behaviour and outcomes of behaviour. Outcomes can be the stopping of a behaviour (e.g. stopping smoking and improving health) or the commencement of a behaviour (e.g. exercising and reducing weight). These were distinguished by treating incidents of restrictive practices as ‘outcomes’ and ‘behaviour’ as the efforts made to reduce these (e.g. de-escalation). The interventions contained more focus on outcomes than on behaviour as these are easier to record and report; however, some interventions did encourage the examination of near-misses and successes (i.e. where restrictive practices had been avoided), perhaps through team meetings, and these were seen as examples of monitoring of behaviour rather than outcomes.

One problematic aspect of the taxonomy is its use of ‘self’ in terms of ‘self-monitoring’, ‘self-reward’, ‘self as role model’, ‘valued self-identity’ and ‘self-talk’. The initial screening of the literature had revealed that there was very little reference to individual health-care staff at all and no self-monitoring from individuals. Therefore ‘self’ was interpreted in a collective sense and was applied in instances in which the ward team were, for example, self-monitoring rather than being monitored at arm’s length via management. This interpretation was validated during coding, since no examples of individuals (rather than ward teams) were detected, and, in addition, many ward-based initiatives had been generated from the ward staff, rather than from management or at a broader policy level. Therefore, when it was reported that a ward recorded its own incident data, this was classified as ‘self-monitoring of outcomes’. When data were recorded centrally, this was recorded as ‘monitoring of outcomes’. The other opportunity for self-monitoring was in interventions that used debriefing after an incident. If it was specified that staff were encouraged to reflect on their role in the incident, this was coded as ‘self-monitoring of behaviour and/or outcomes’.

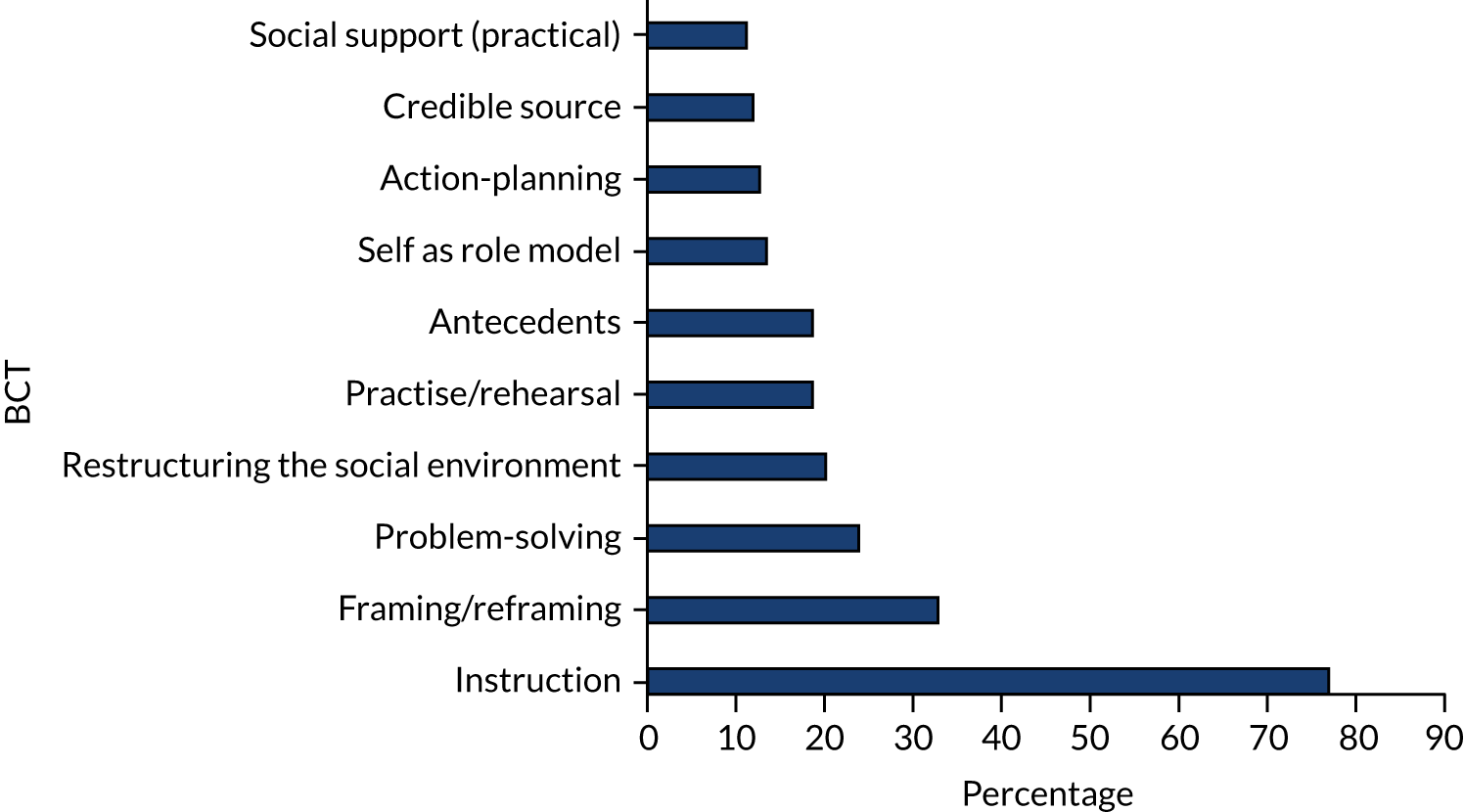

One coding decision made in relation to staff training was that, if this was mentioned at all, it was coded as BCT 4.1 ‘instruction on how to perform the behaviour’, regardless of the level of detail (following Presseau et al. 47). Sometimes, interventions referred only to staff training in de-escalation, with no further detail; it was agreed that, in this circumstance, an assumption could be made that, at the minimum, there would be instruction involved. This is not in keeping with the specified instructions for coding BCTs, but had the rationale that, if only those interventions that had gone on to describe the actual content of this training had been coded, the presence of training within the interventions would have been severely under-reported.

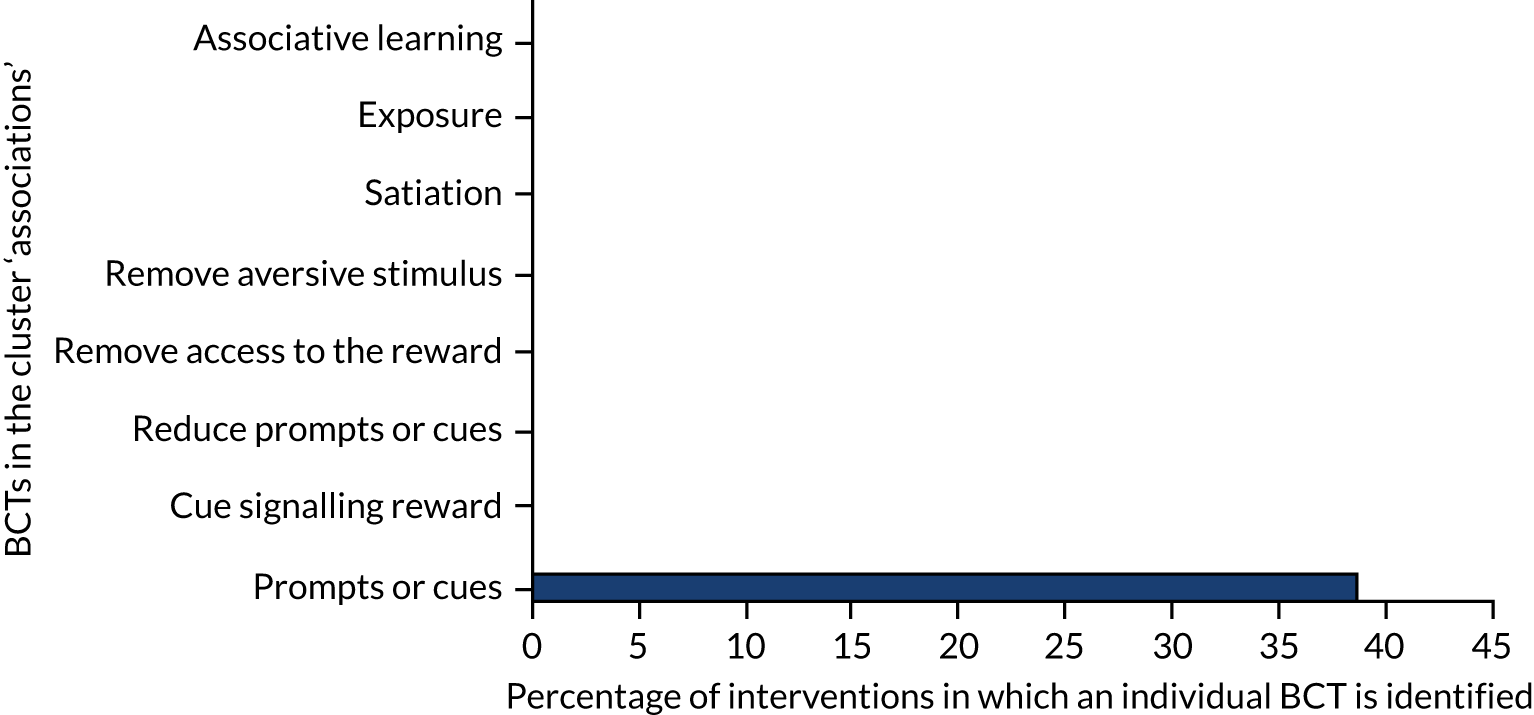

Several of the BCTs refer to prompts or cues. It was agreed that, where a checklist or tool had been implemented on a ward (e.g. during a risk assessment on admission), this would be coded as a ‘prompt’, as it prompted staff to carry out behaviour that had the intention of avoiding restrictive practices. Care planning or risk assessment were treated within the context of ‘goals and planning’. This was because, although they were focused on the service user, ‘goals and planning’ can also refer to agreement on how staff will respond to service users’ needs. ‘Problem-solving, goals and planning’ could also be identified in post-incident debriefing, depending on how the debriefing was described.

The difference between ward and service level in monitoring of outcomes was also seen in a number of other BCTs that could be applied at the individual staff/service user level, ward level, organisation level and policy level. For example, ‘goal-setting (outcome)’ was detected at all of these levels (see Appendix 6 for further details).

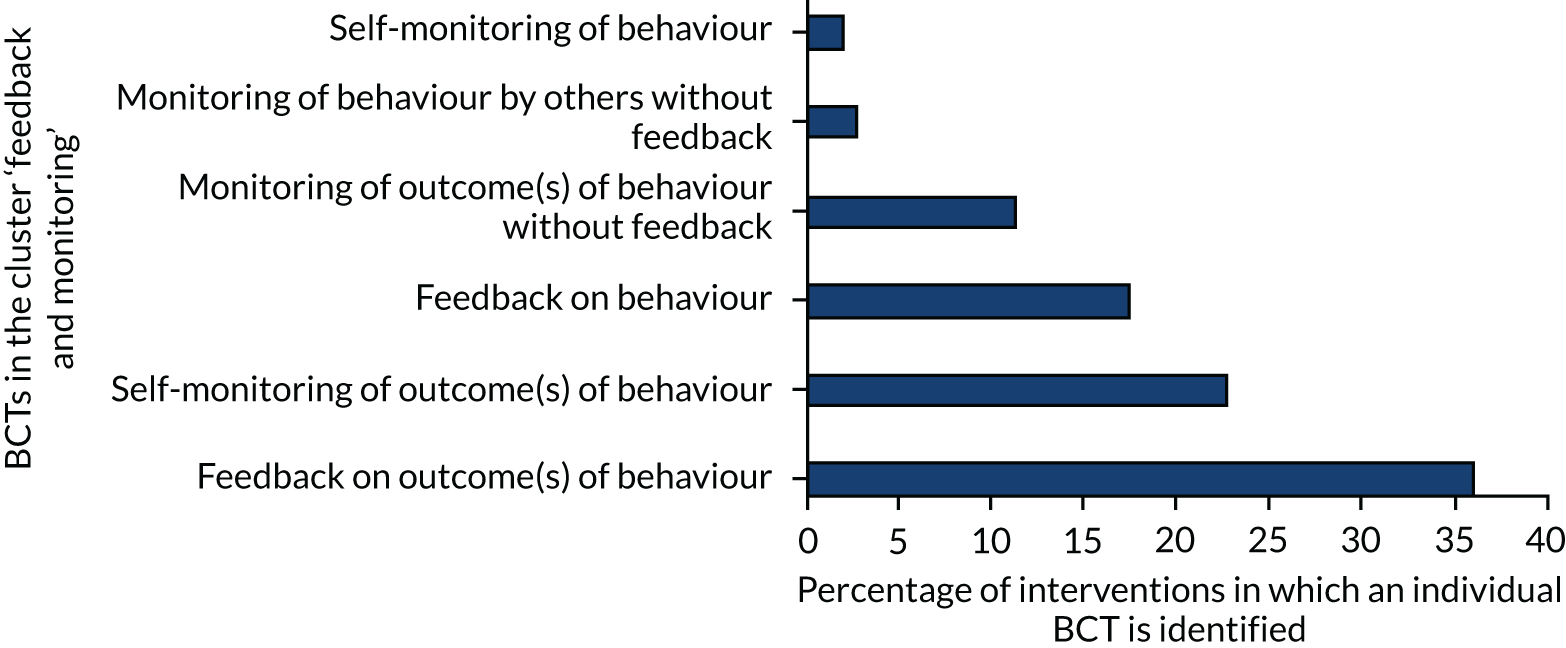

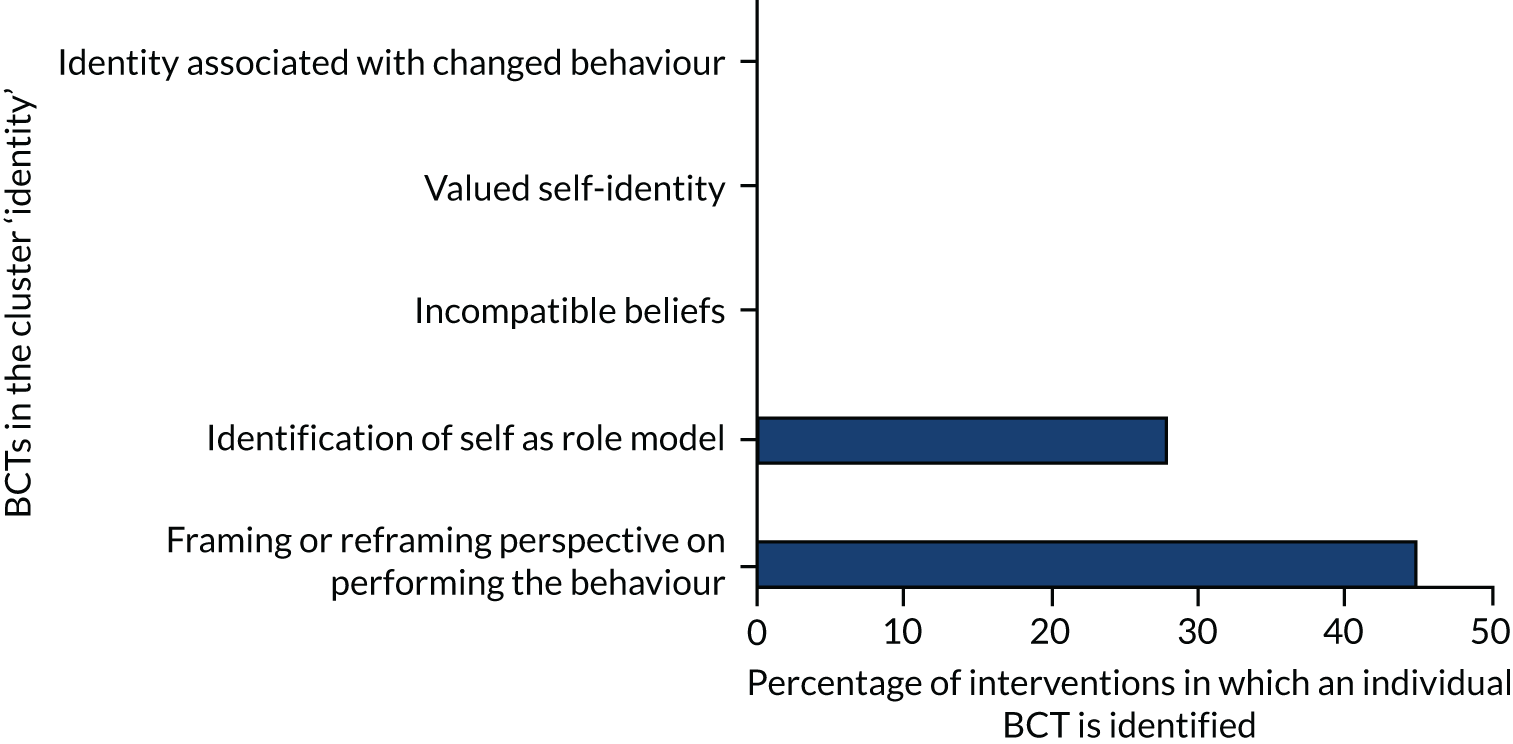

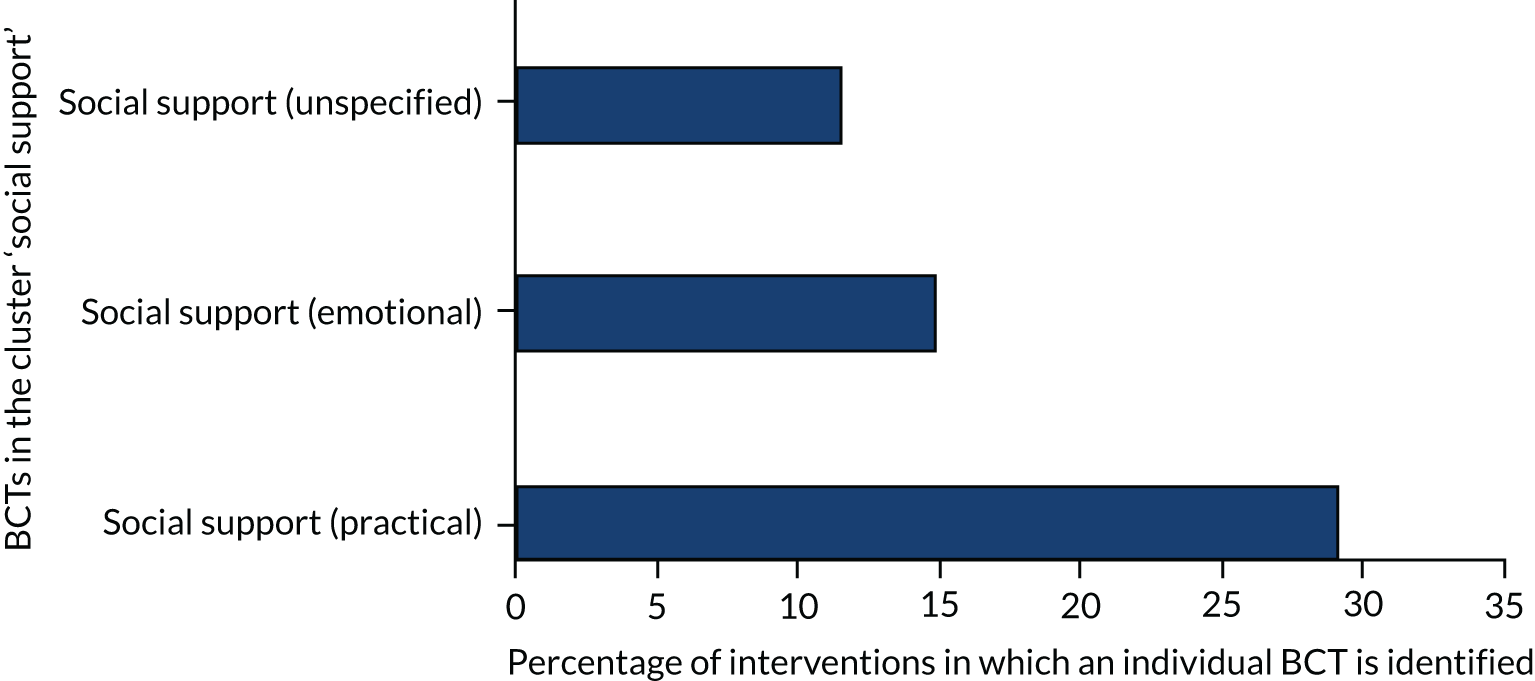

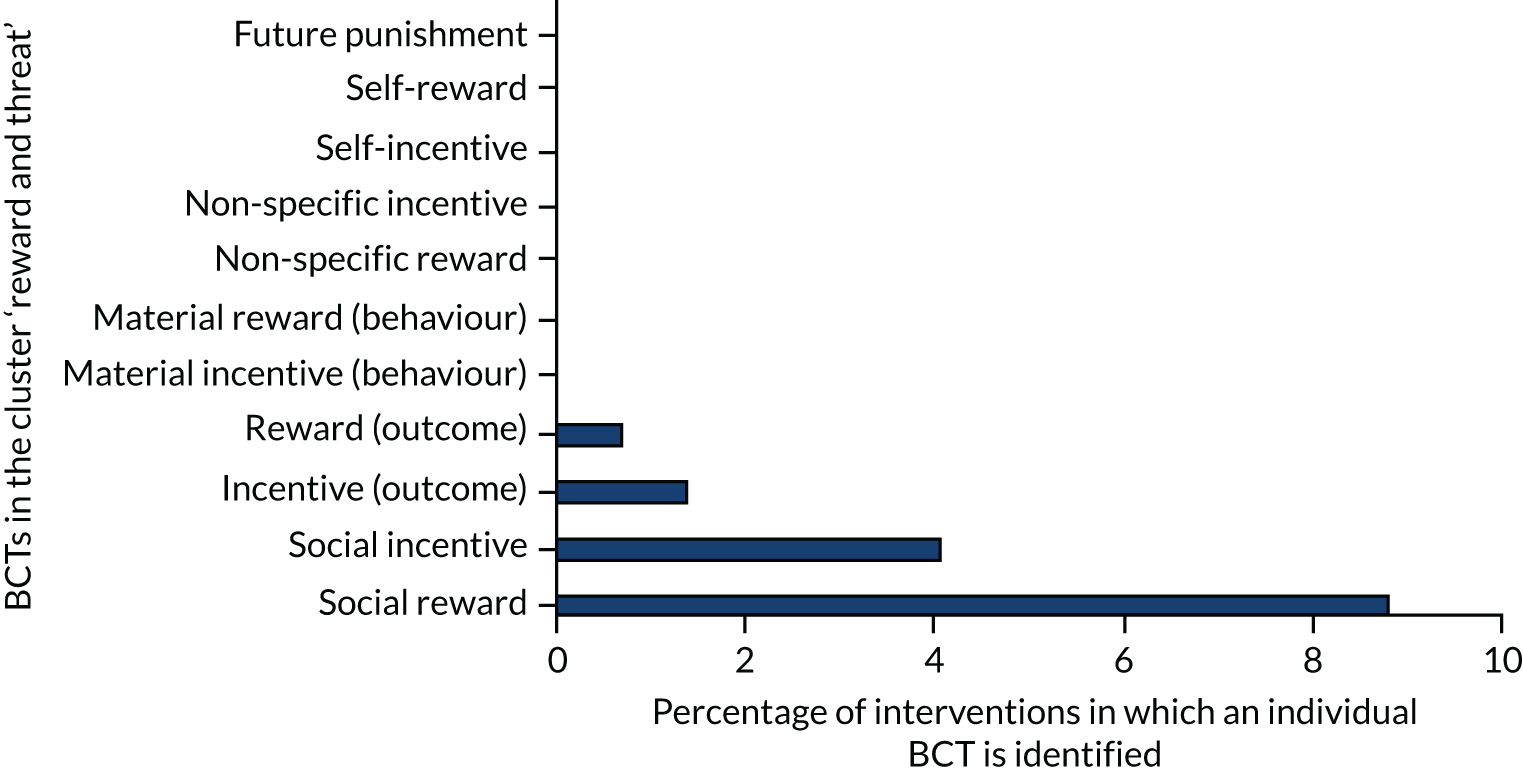

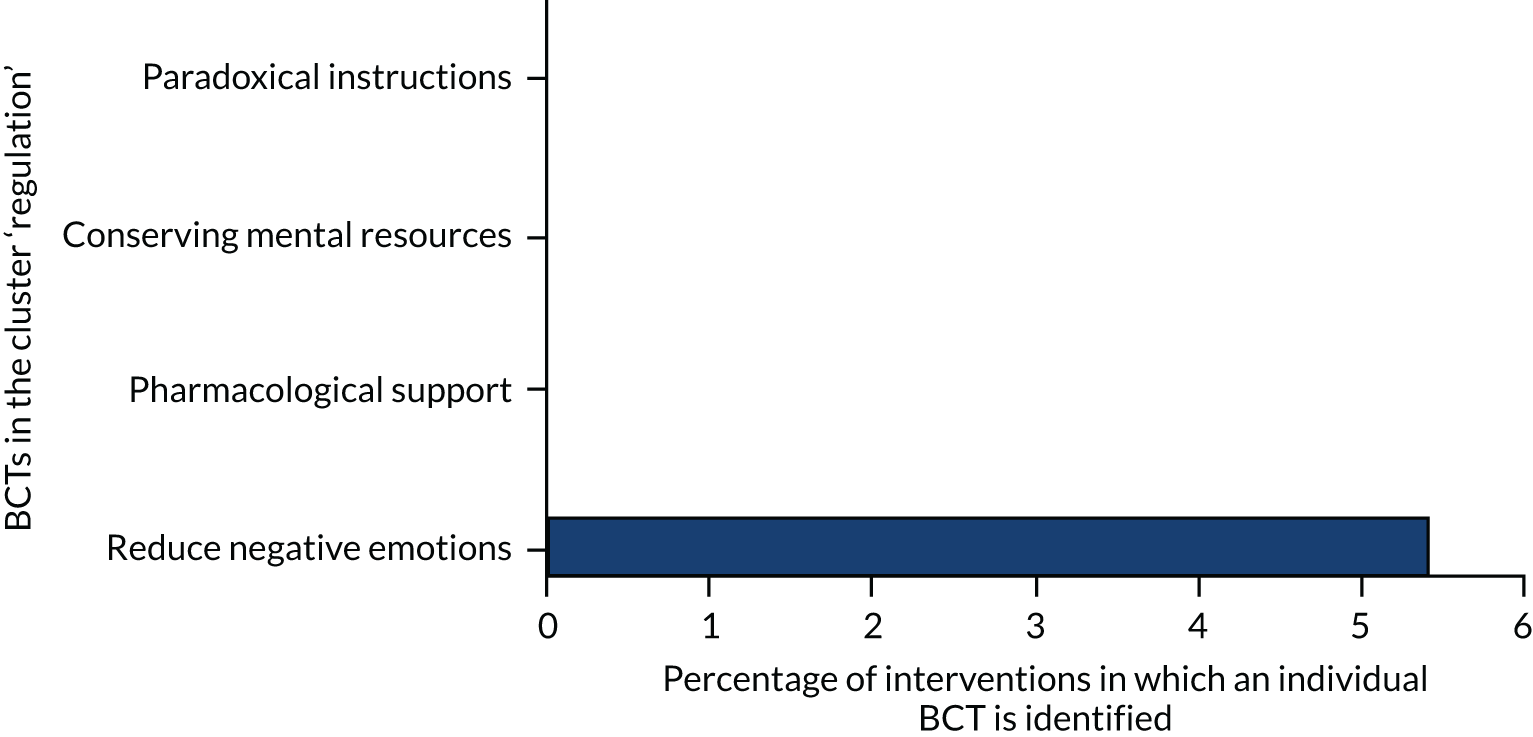

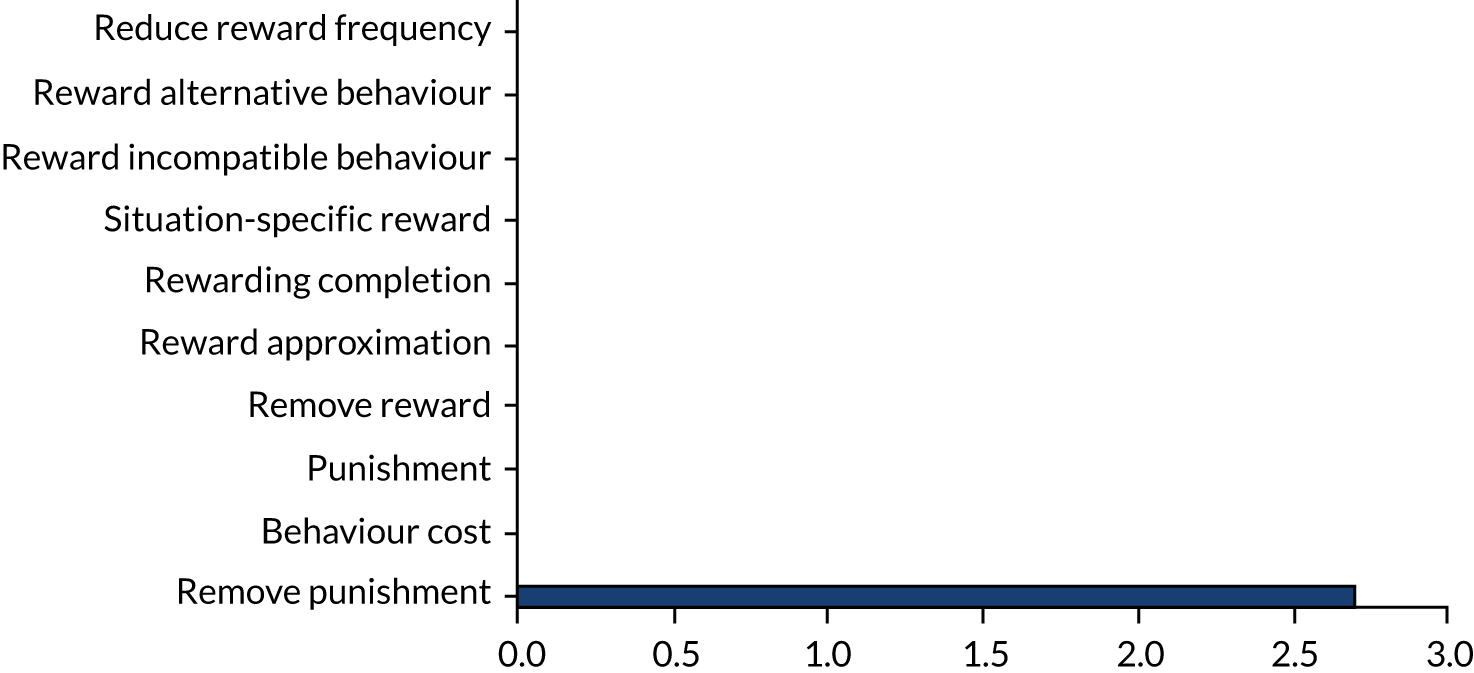

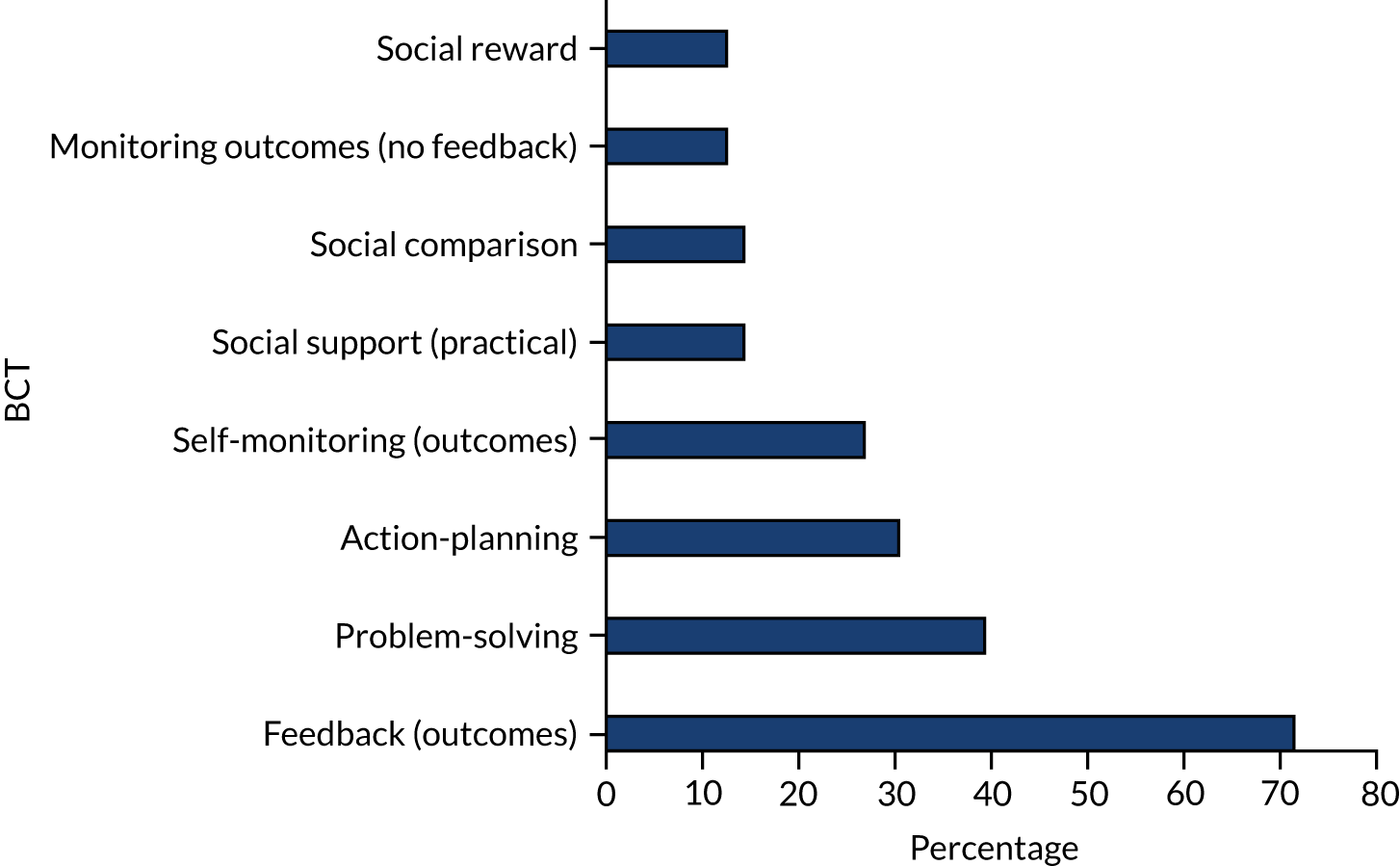

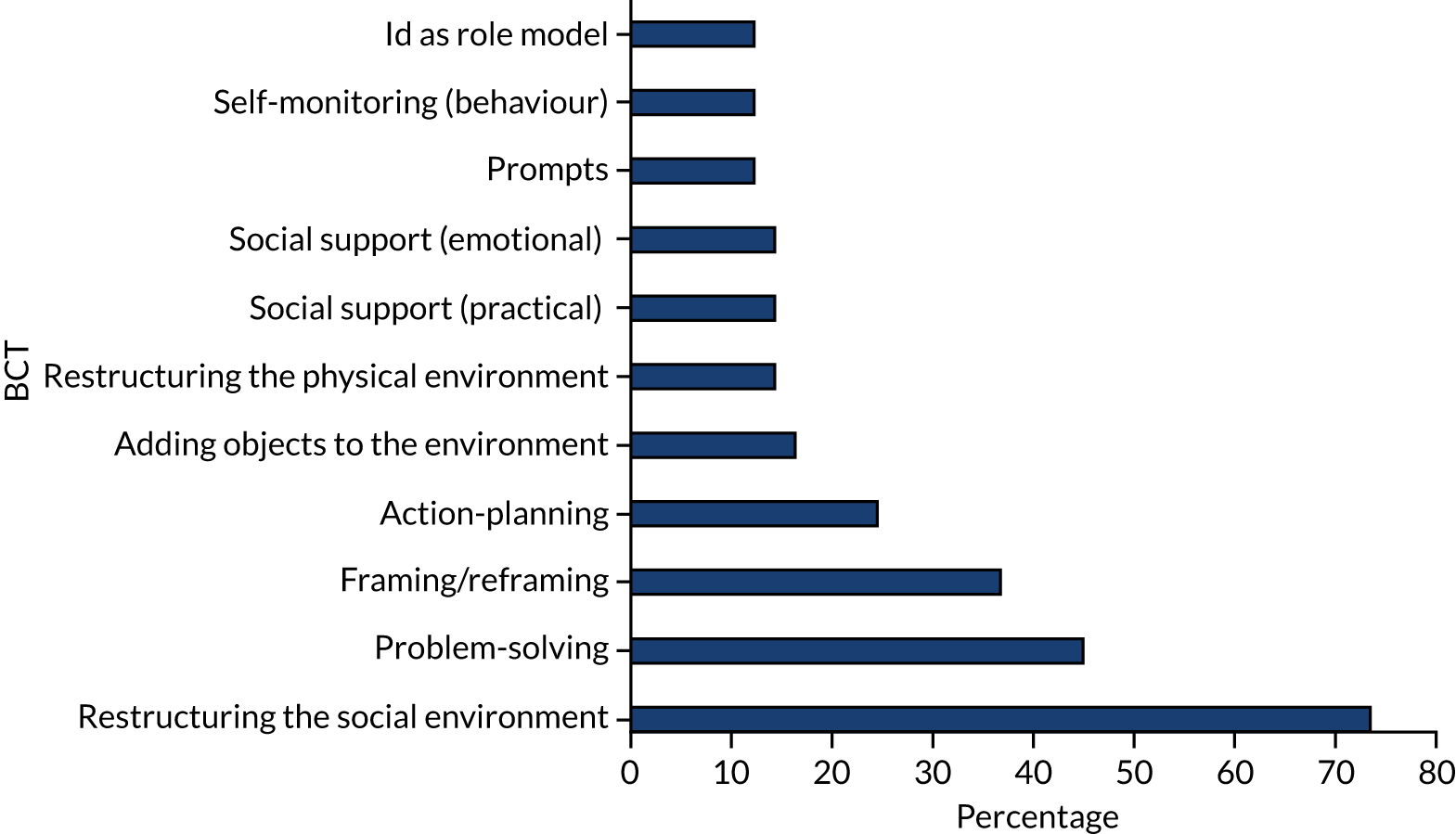

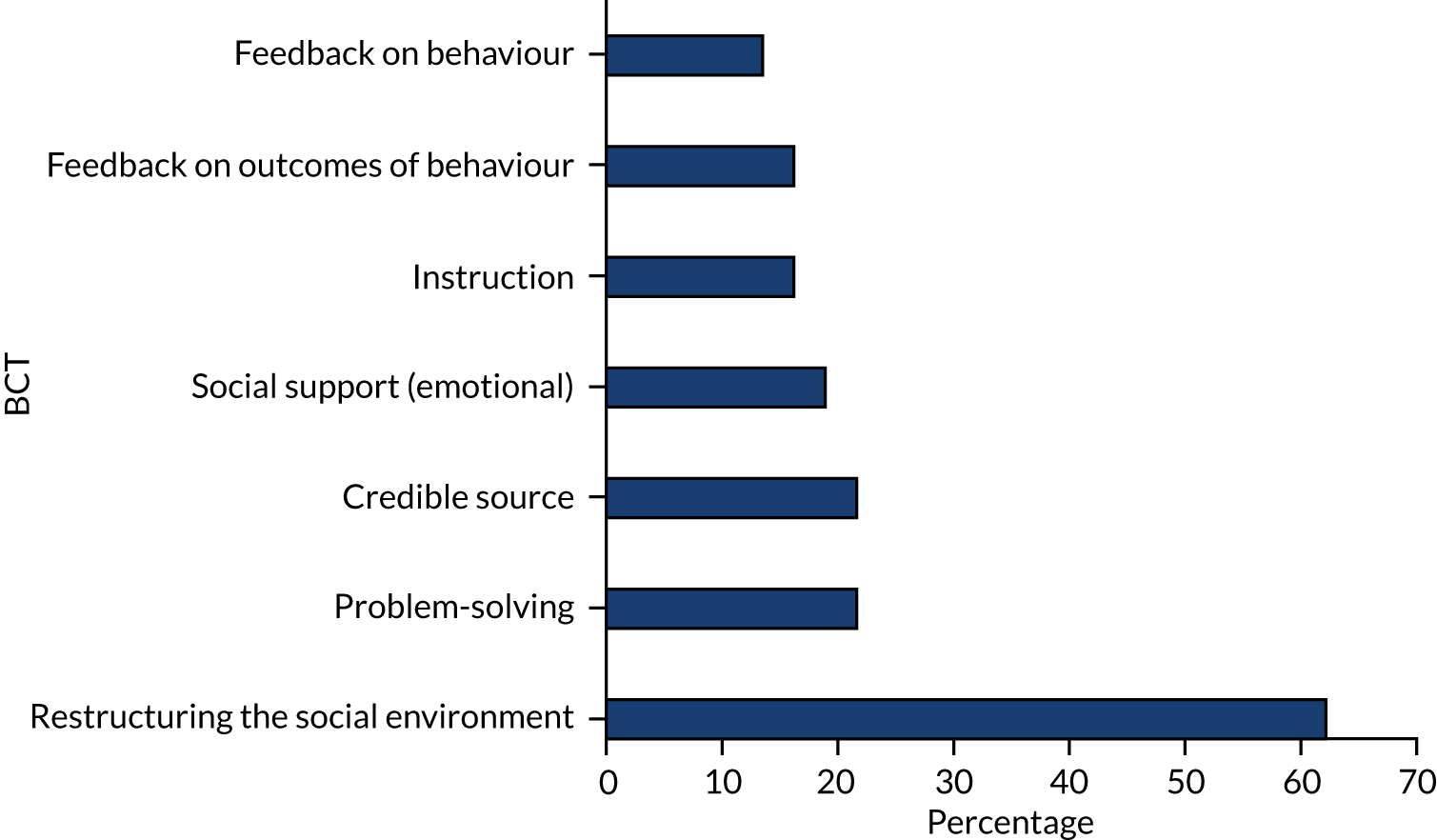

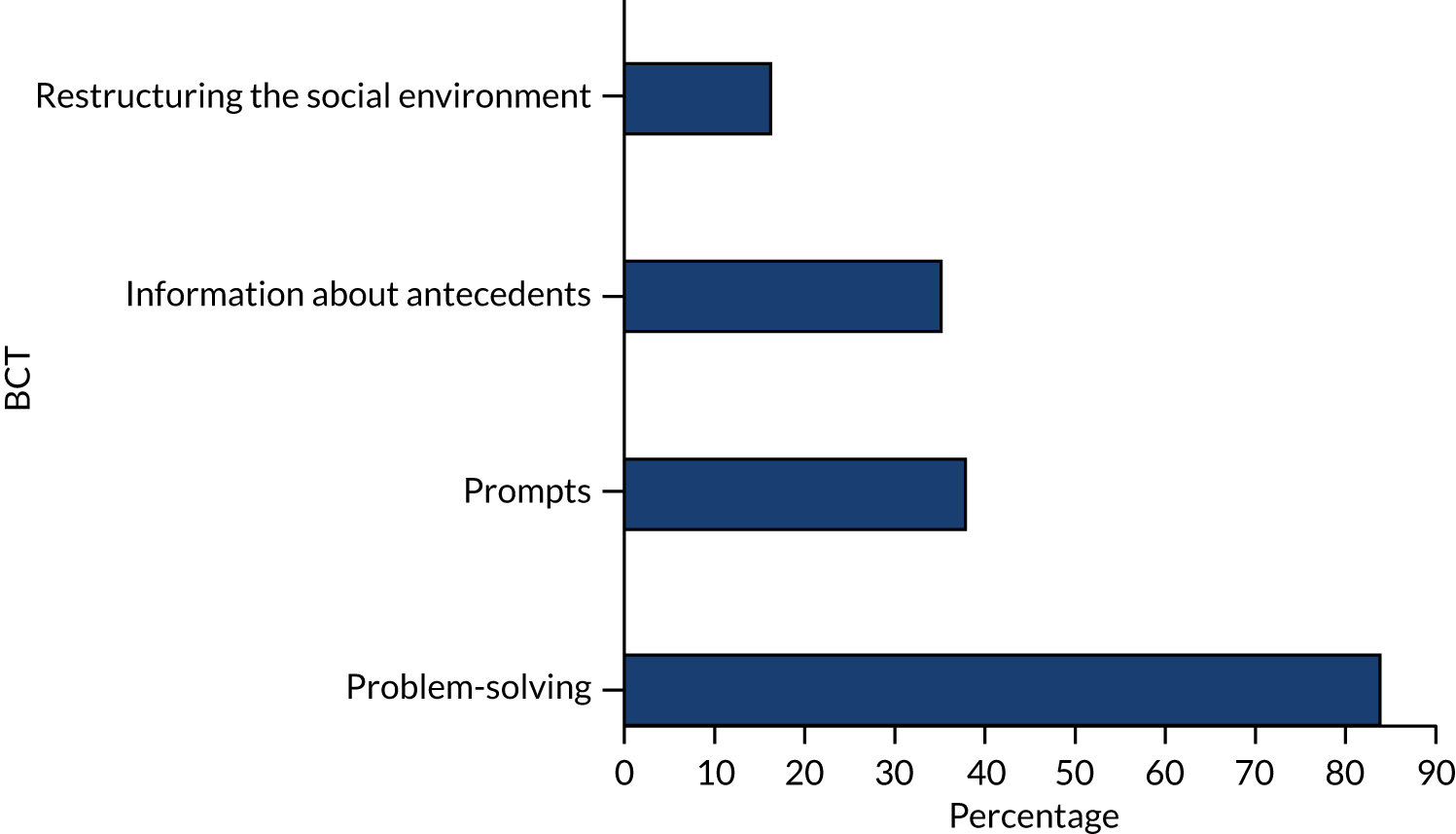

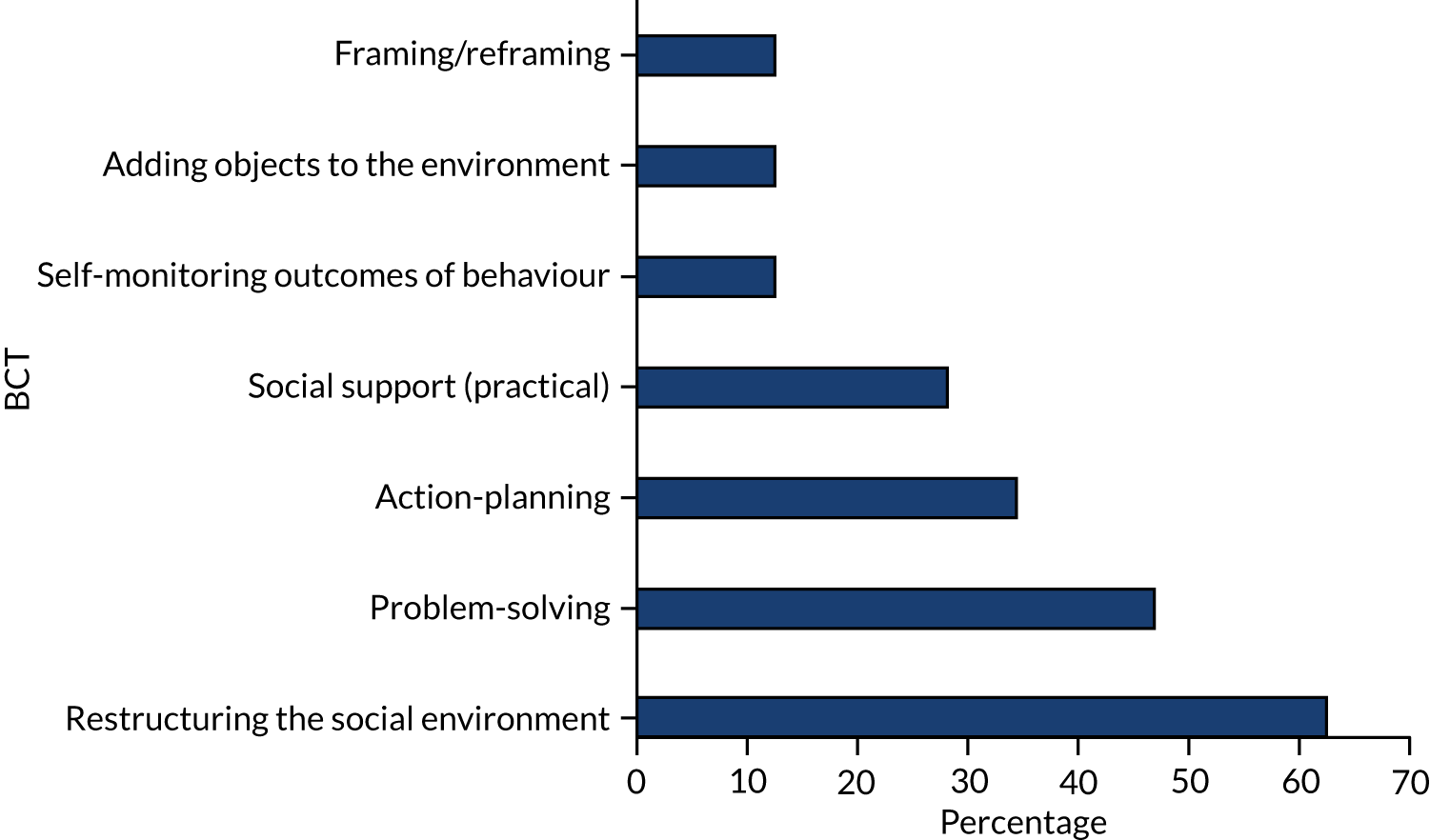

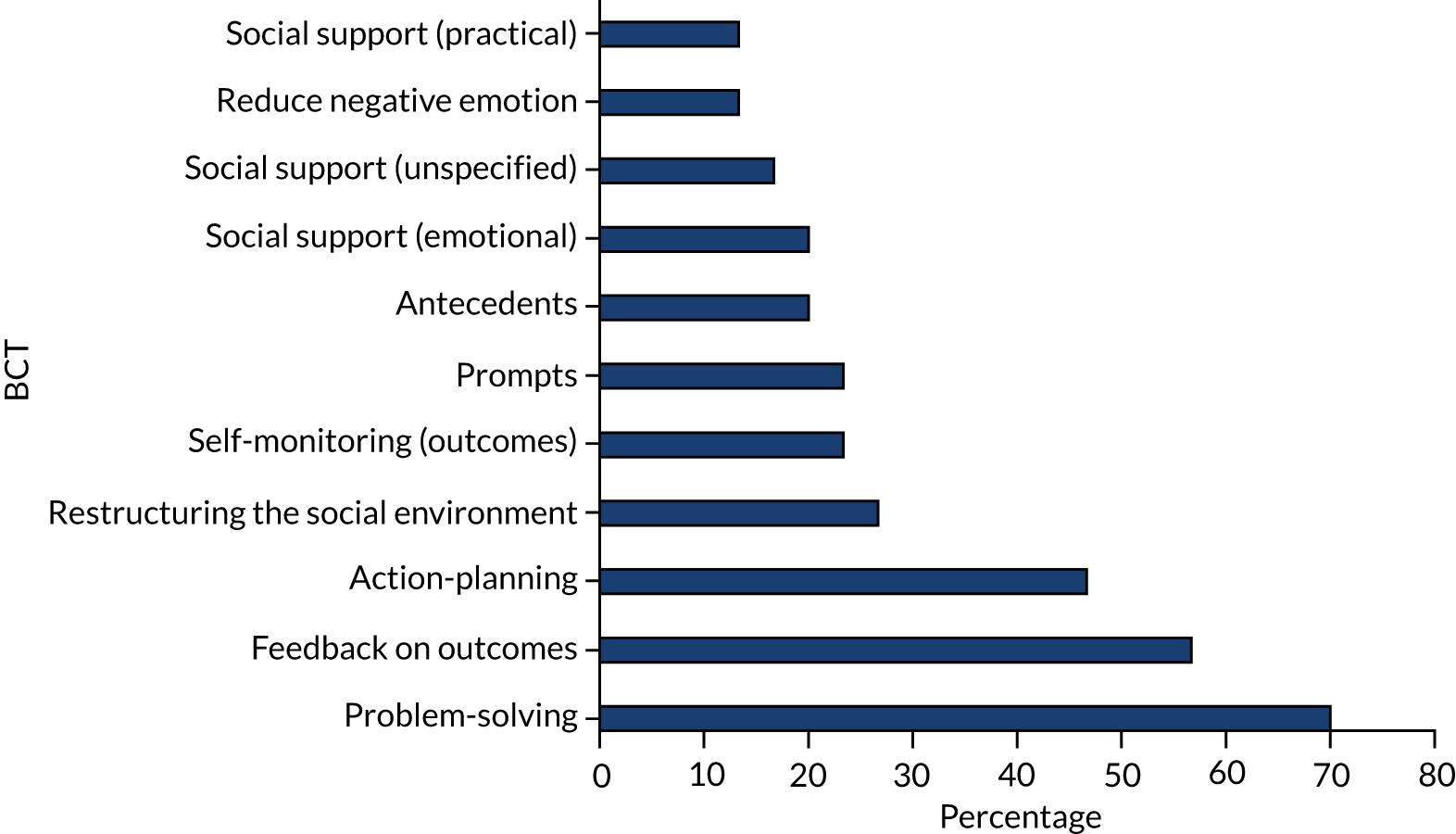

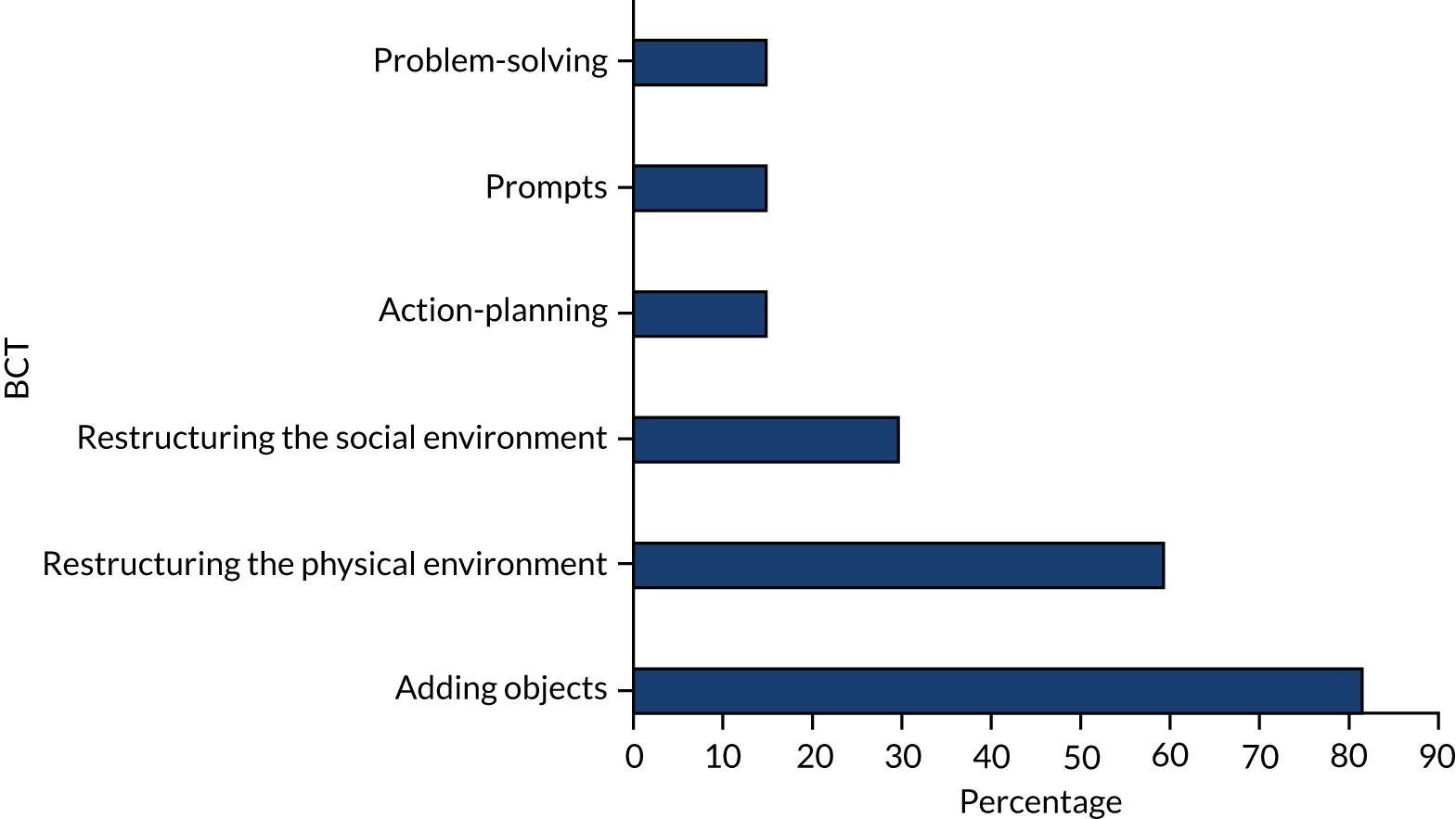

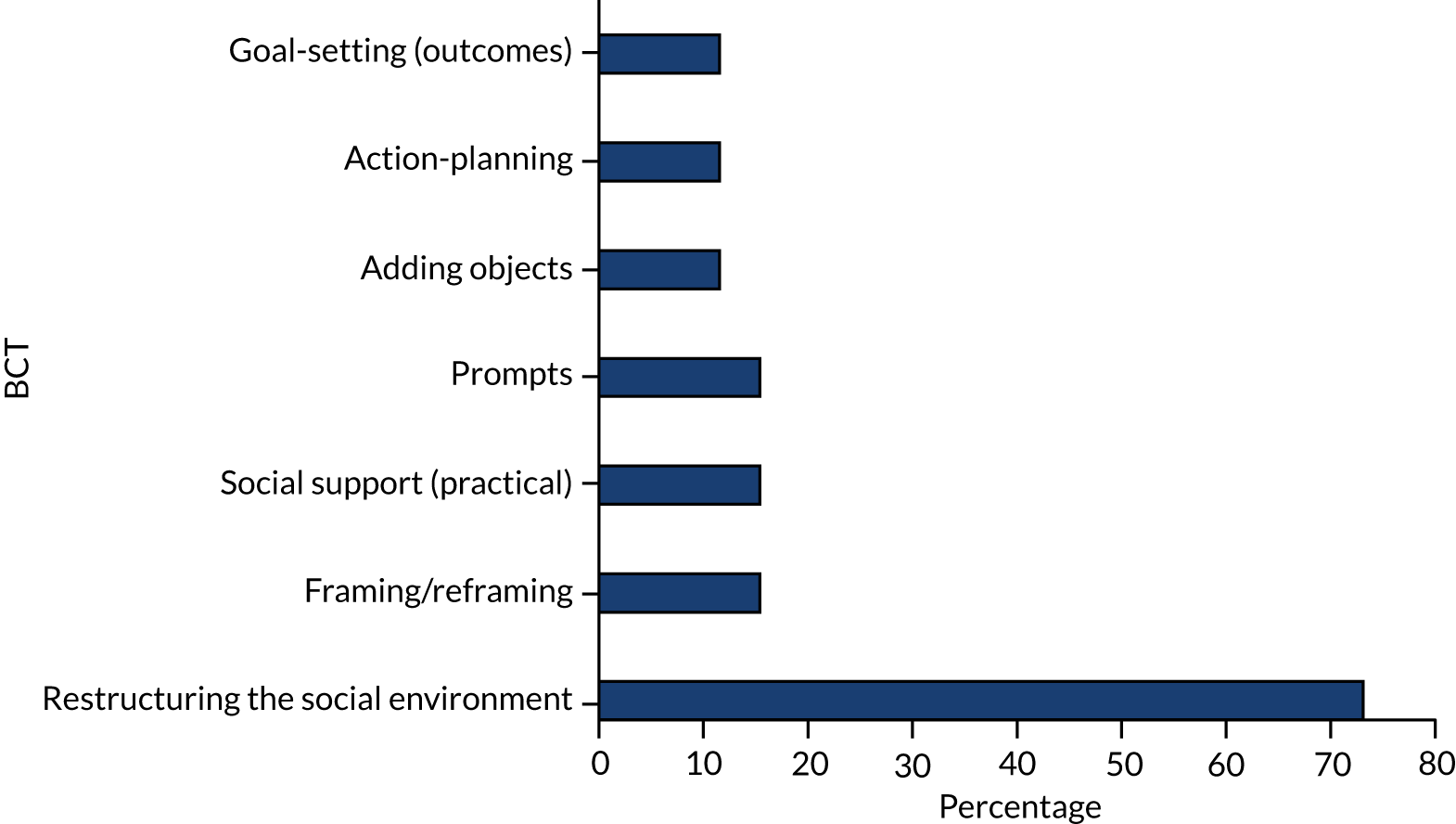

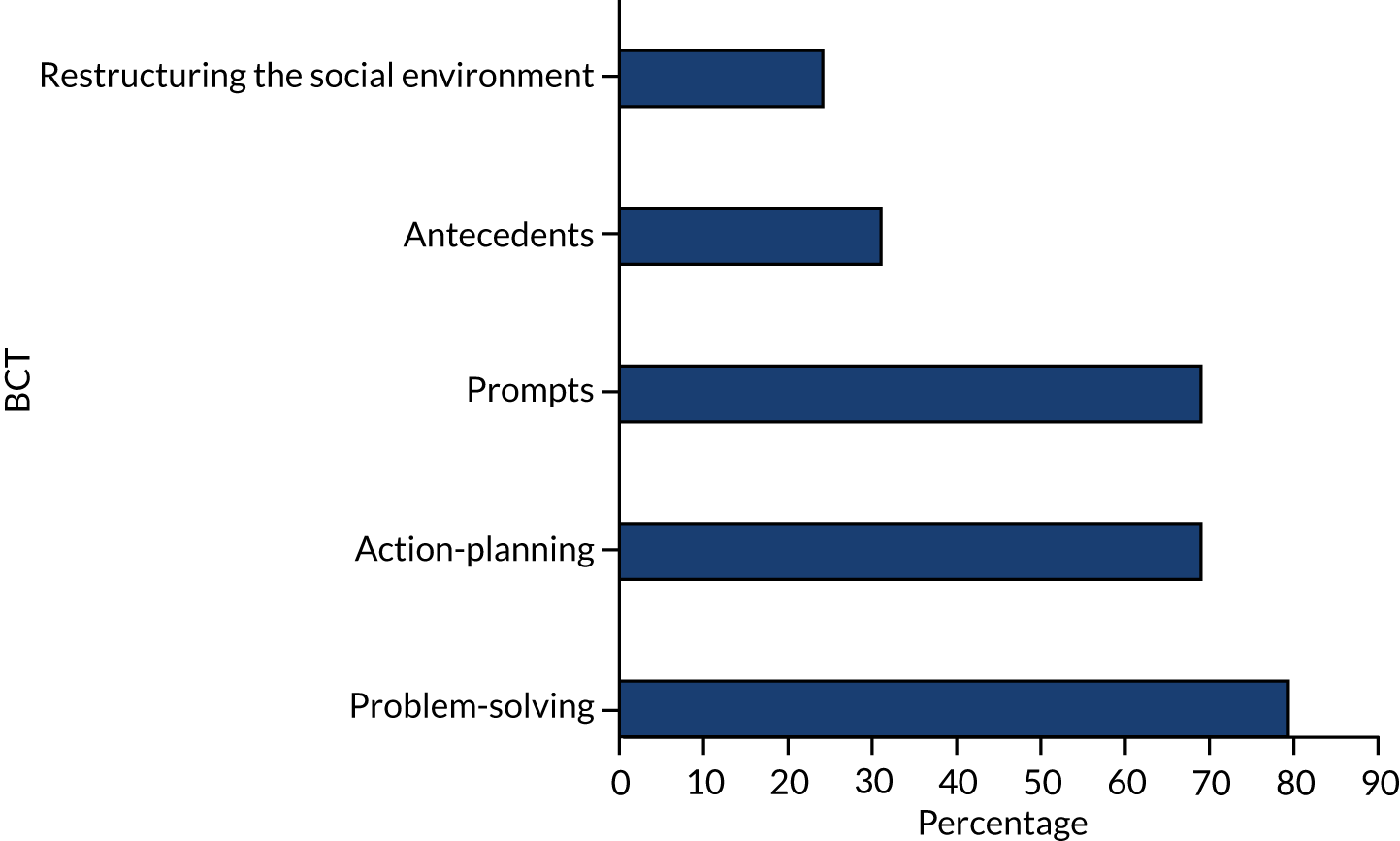

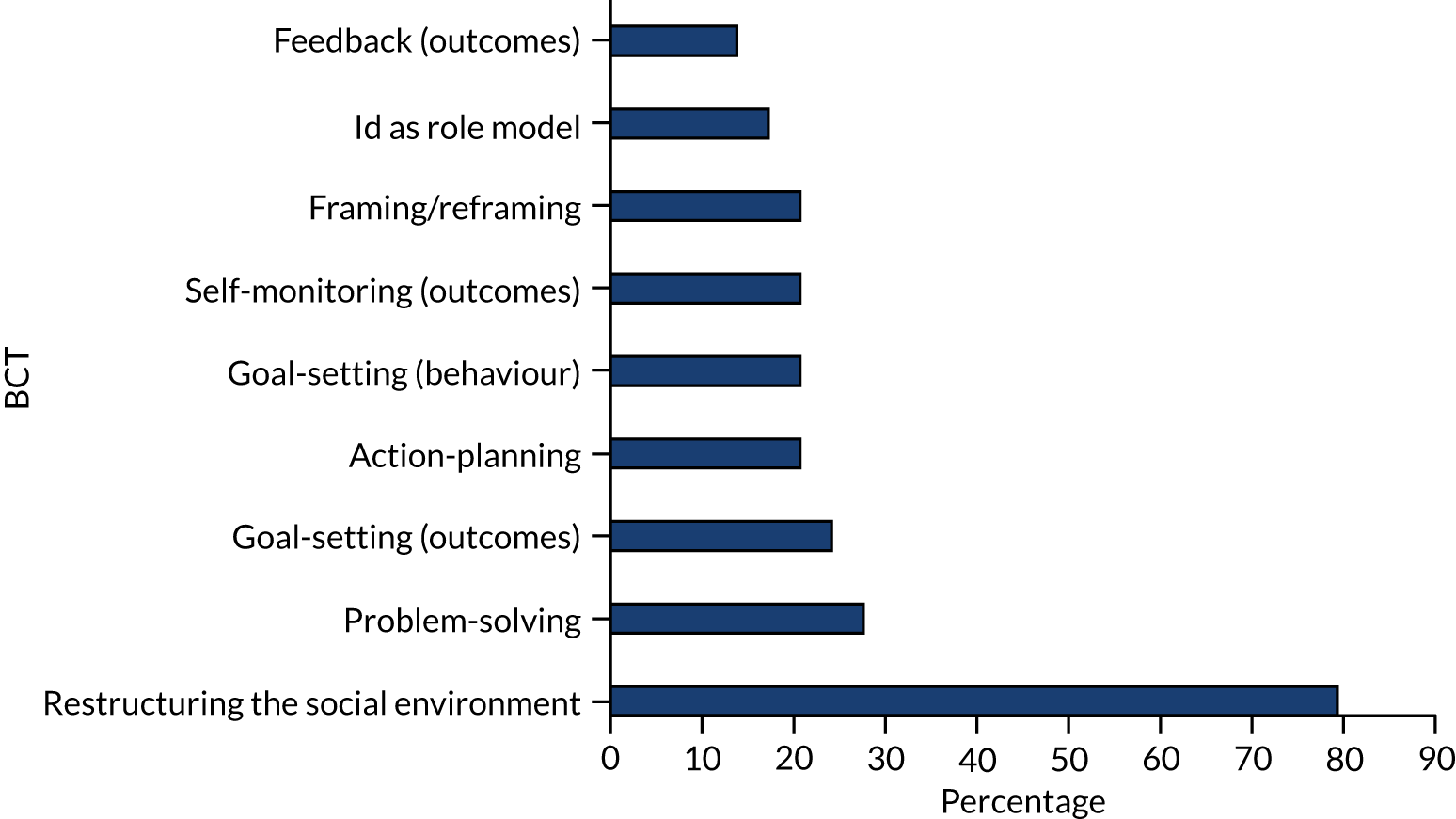

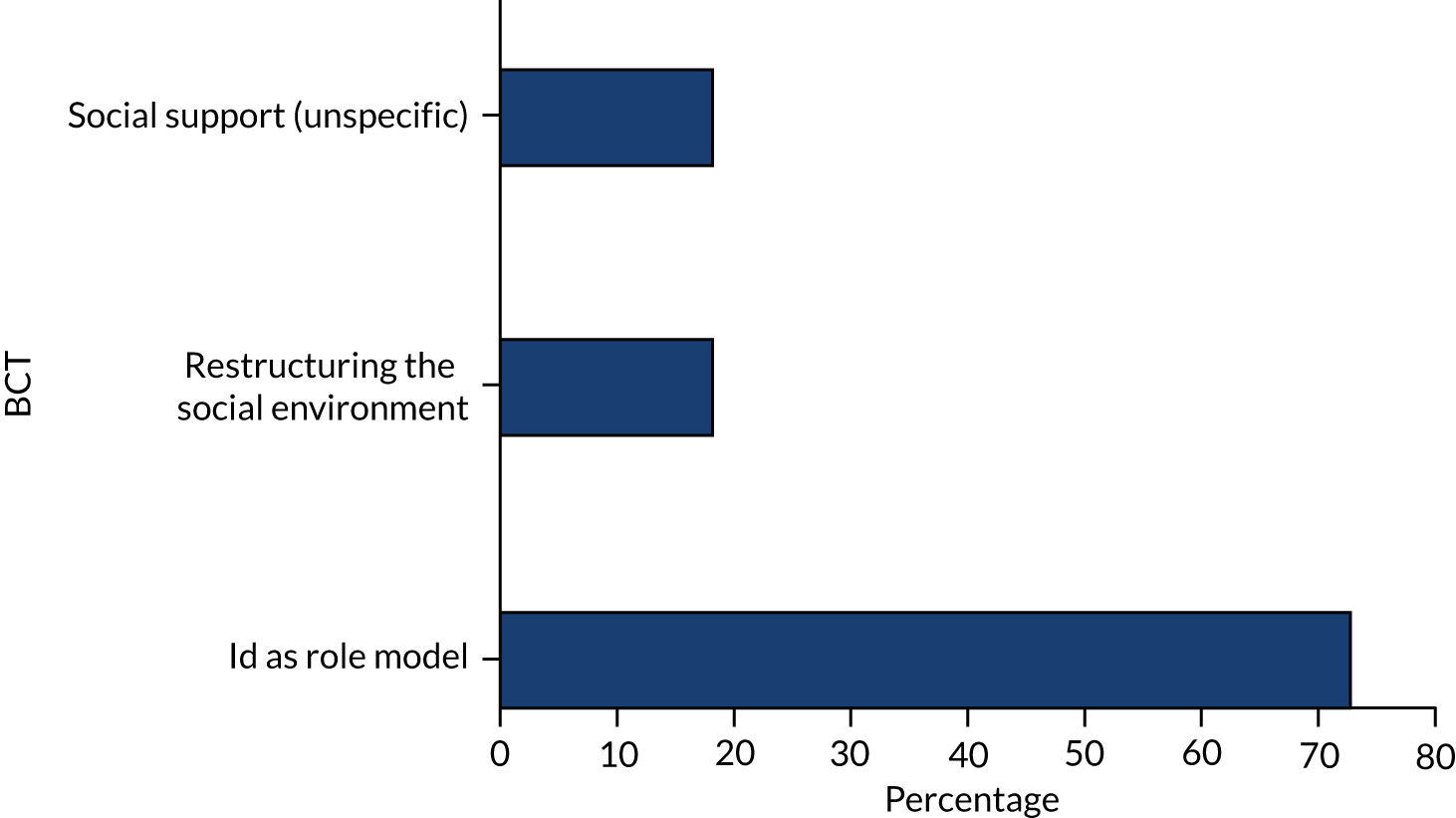

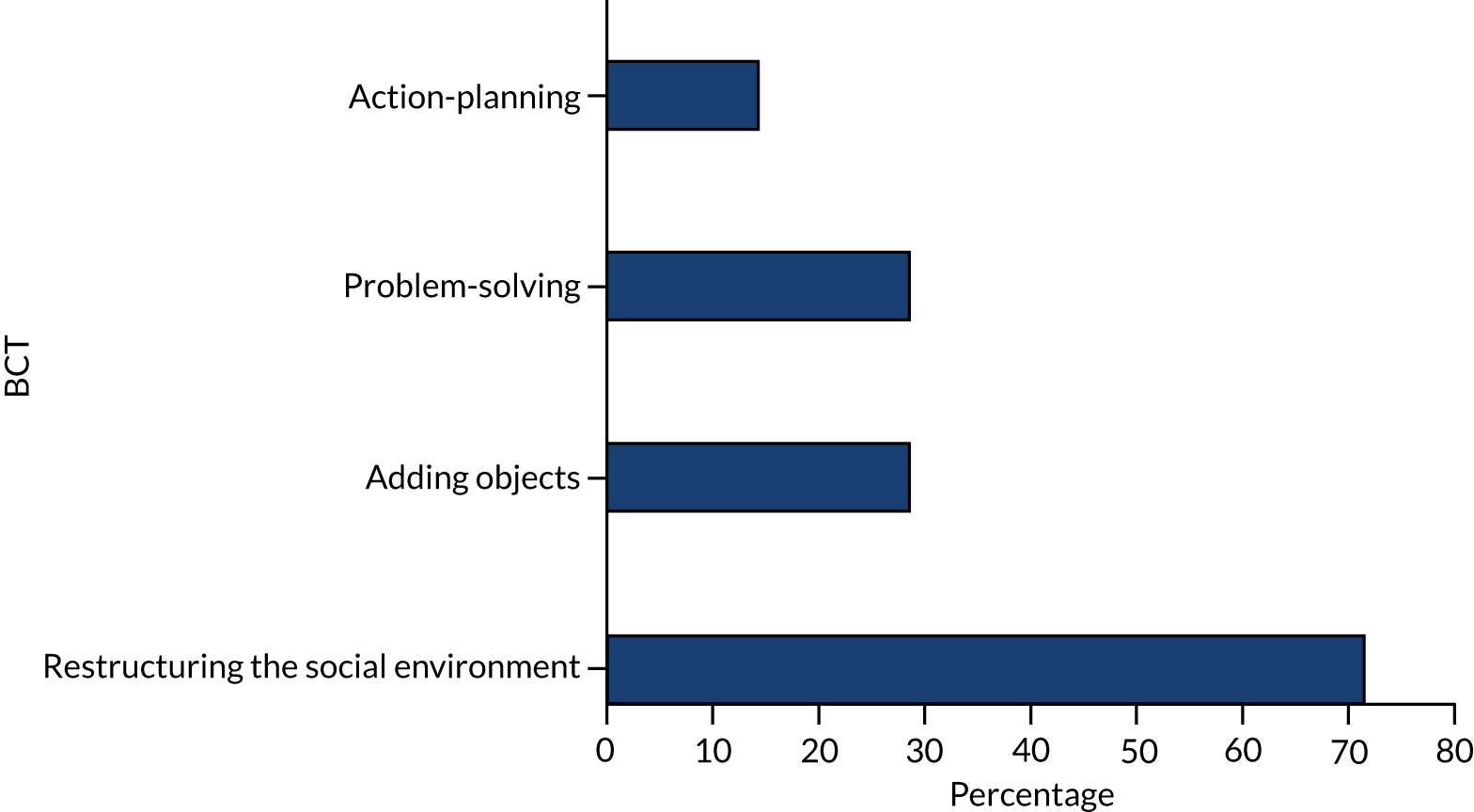

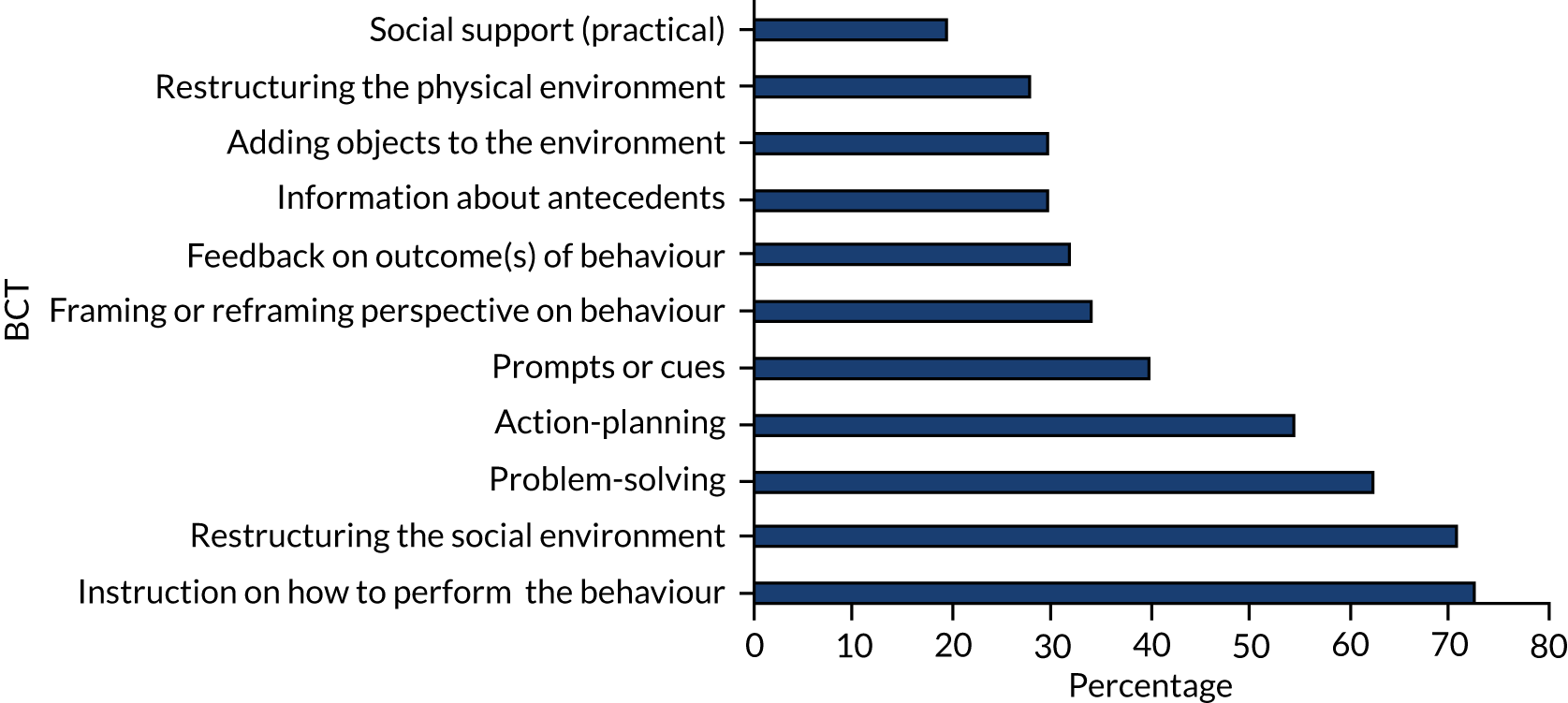

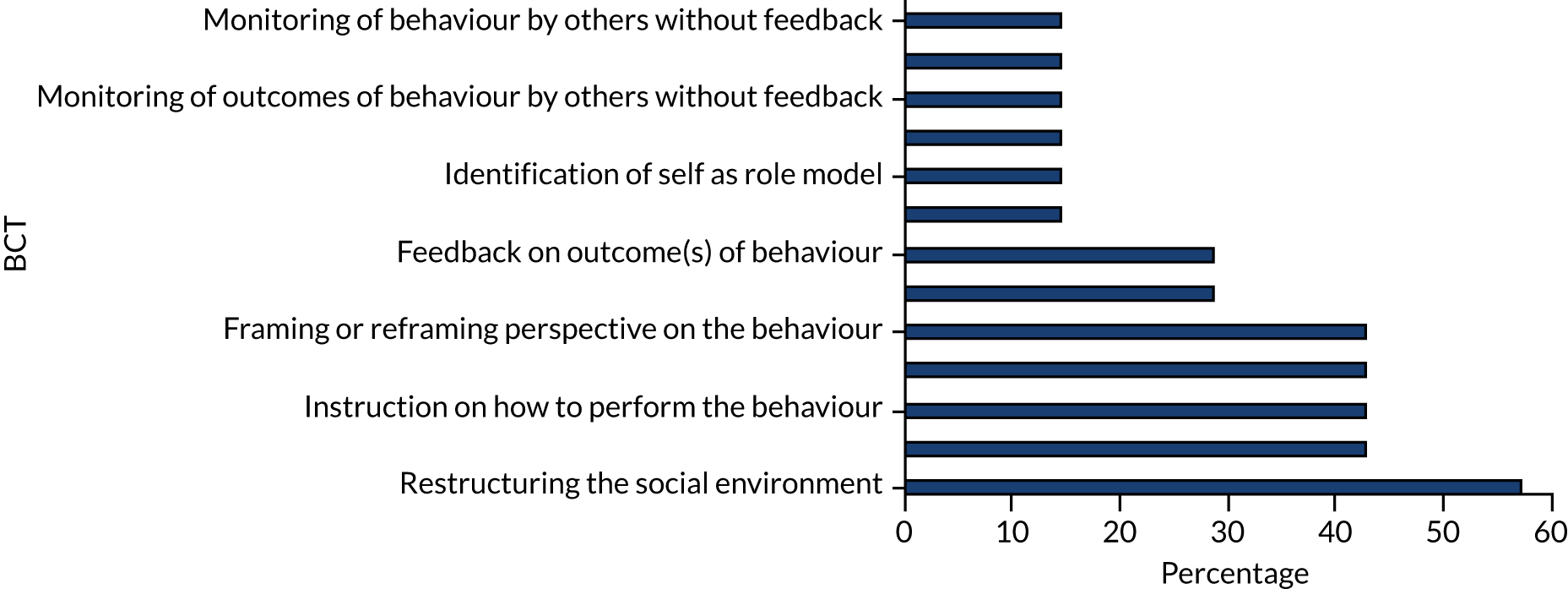

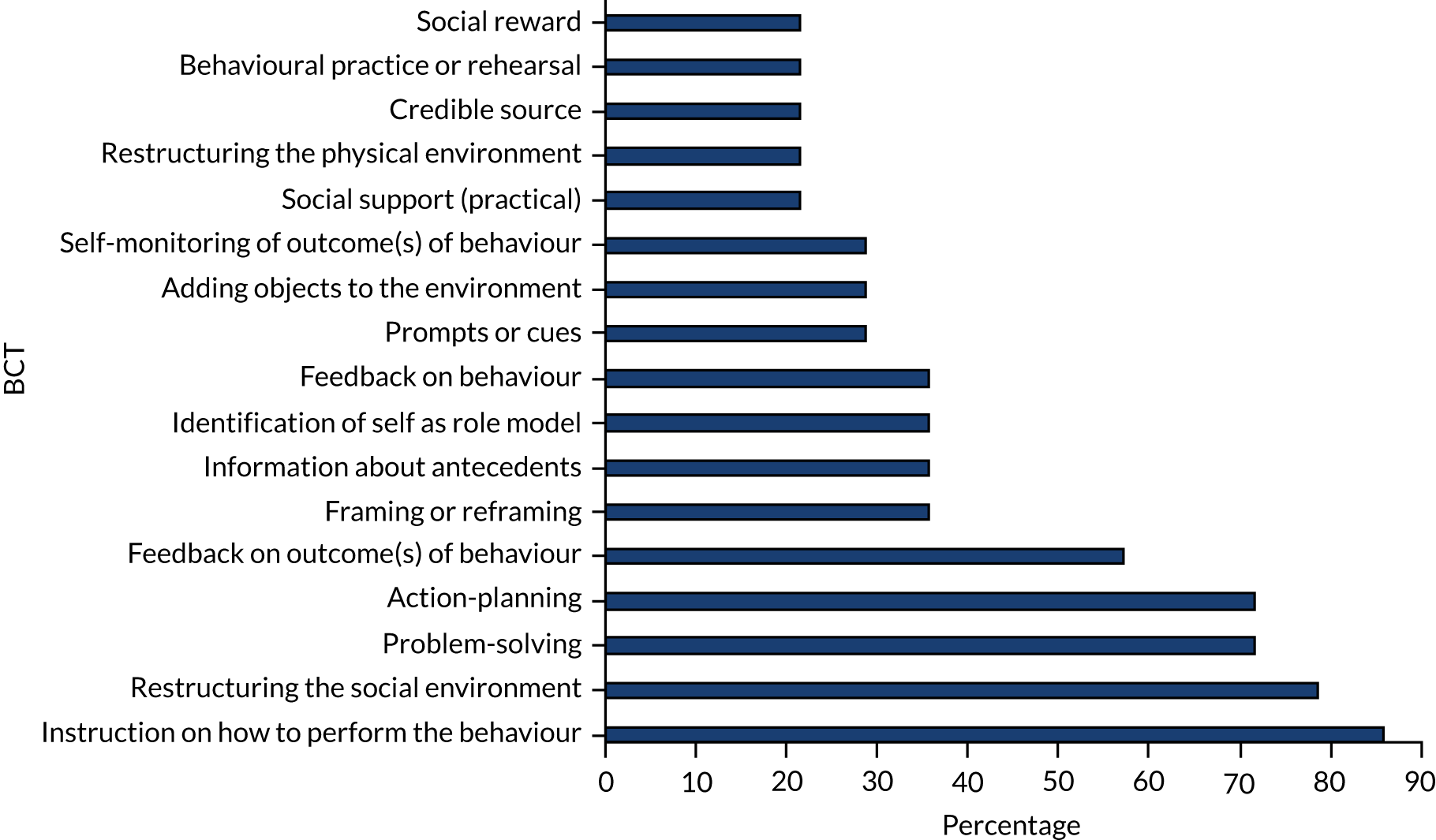

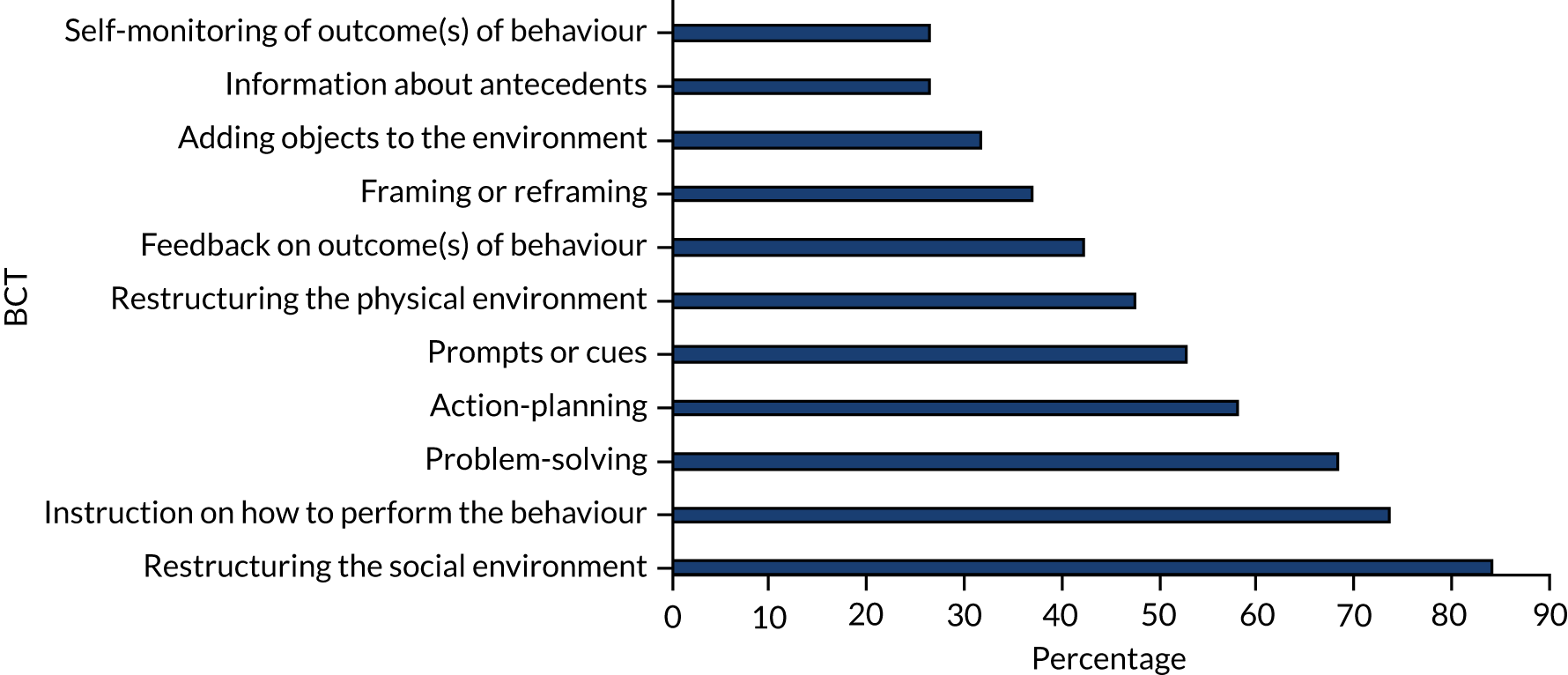

Descriptive statistics were used to count which BCTs featured in each intervention to provide an overall frequency of the most commonly occurring BCTs across the data set, and what clusters they were from. It was further established which BCTs were used in interventions with particular components, for example training, or audit and review, or service user involvement.

Describing intervention outcomes and relating back to behaviour change technique content

The outcomes of evaluations were extracted and described. These outcomes were then related back to the BCTs contained in the intervention subject to evaluation. The BCTs in evaluations with both positive and negative findings were identified and described.

Assessment of study quality using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

In stage 1, the primary objective was to identify and document all interventions in records that met the eligibility criteria. The quality of the records was of interest; however, although it was anticipated that the records would be diverse in quality, it was also expected that the data set would contain valuable information about the range of interventions being considered for use in practice. Therefore, no records were excluded on the basis of quality.

In the current study the MMAT51 was used at two levels: to identify records of interventions that had been evaluated and to assess the quality of the evaluation reports. To get a sense of the quality of the evidence, the screening questions of the MMAT51 were used during data extraction to establish whether or not the intervention had been subject to an evaluation. The MMAT was again used for further examination of evaluations during data analysis.

The MMAT was designed for use in complex systematic literature reviews that include quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods studies. The MMAT was developed from theory and a literature review, and has been found to have good validity. 51,68 Quantitative and qualitative studies are judged against four criteria and mixed-methods studies are judged against three. Scores are between 0% and 100%, although caution is advised against relying solely on the score, and reviewers are encouraged to provide a narrative description of the study features that lead to that score. The quantitative domain is split into three subdomains: randomised controlled, non-randomised and descriptive. The characteristics of the MMAT meant that it was selected as the most suitable tool with which to judge study quality in the context of wide-ranging research methods.

Chapter 3 Results of the literature search and a detailed description of records

This following sections present the results of each of the three stages of the review. Figure 1 illustrates the study design with outputs.

FIGURE 1.

Study design with outputs.

This chapter provides an overview of the literature search results, including a PRISMA flow diagram to indicate the extraction process. It describes in detail the records identified and highlights key characteristics of the data set.

Overview of the literature search results

As illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 2, the search of academic databases identified 18,451 records, and a further 1985 records were found in the grey literature (1886 in databases and websites, 99 in social media). Backward and forward citation searches, and contact with authors generated an additional 31 records. After removal of duplicates, 15,085 records were subject to title and abstract screening, which excluded 14,659. A total of 426 records were retrieved, of which 251 were excluded following full-text screening. The final data set consisted of 175 records for extraction. Further details are available in Appendices 1 and 2.

FIGURE 2.

The PRISMA flow diagram. a, Grey literature: non-academic databases and websites, social media and ‘other’ records; b, ‘other’ records: forward citation searches, contact with authors; c, excluded because not relevant (e.g. record does not describe an intervention, generic policy change, replacement of one restrictive practice with another).

The data set of 175 records was diverse in terms of how interventions were reported. Some interventions occurred in more than one record, some records reported more than one intervention and some reports were mentioned in more than one record. Overall, within the data set were 221 separate records of interventions, referring to 150 interventions in total. Of these, 109 had been evaluated and 41 had not been evaluated. This detail is illustrated in Figure 1.

The approach to analysis was designed to address study objectives 3 and 4, that is to explore evidence of effectiveness by examining behaviour change techniques and intervention outcomes, and to identify behaviour change techniques showing most promise of effectiveness and that require testing in future high-quality evaluations. Therefore, following extraction, the reports were organised into groups according to the intervention or interventions they described. This allowed for a primary focus on the evidence for each intervention, rather than the evidence per se.

Characteristics of records identified

Records were organised by type, the most common of which was research reports (Table 2 and see Appendix 8). The remaining records included brief descriptions of interventions presented in reports by organisations such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the Care Quality Commission (CQC), NHS, Mind, the RCP (practice examples), and NHS trusts and hospitals (service reports); these non-research reports focused on interventions rather than a service setting (intervention reports), instructions for the performance of an intervention (instructions), links to training organisation websites (training links) and tools used as part of an intervention (tools). The majority of these were journal articles but they also included websites, leaflets, theses,69–75 abstracts,76–81 booklets,82–87 slides,84,88–92 videos,93–96 a podcast97 and a course syllabus. 98

| Record characteristic | Number of records (n = 175) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Record type | ||

| Research reports | 121 | 69 |

| Service reports | 15 | 9 |

| Tools | 14 | 8 |

| Training links | 9 | 5 |

| Intervention reports | 7 | 4 |

| Practice examples | 6 | 3 |

| Instructions | 3 | 2 |

| Format | ||

| Journal article | 116 | 66 |

| Website | 16 | 9 |

| Leaflet/handout | 10 | 6 |

| Booklet | 8 | 5 |

| Thesis/dissertation | 7 | 4 |

| Slides | 6 | 3 |

| Abstract | 6 | 3 |

| Video | 4 | 2 |

| Podcast | 1 | 1 |

| Syllabus | 1 | 1 |

| Year of publication | ||

| 1999–2004 | 21 | 12 |

| 2004–9 | 24 | 14 |

| 2009–14 | 49 | 28 |

| 2015–19 | 61 | 35 |

| No date | 20 | 11 |

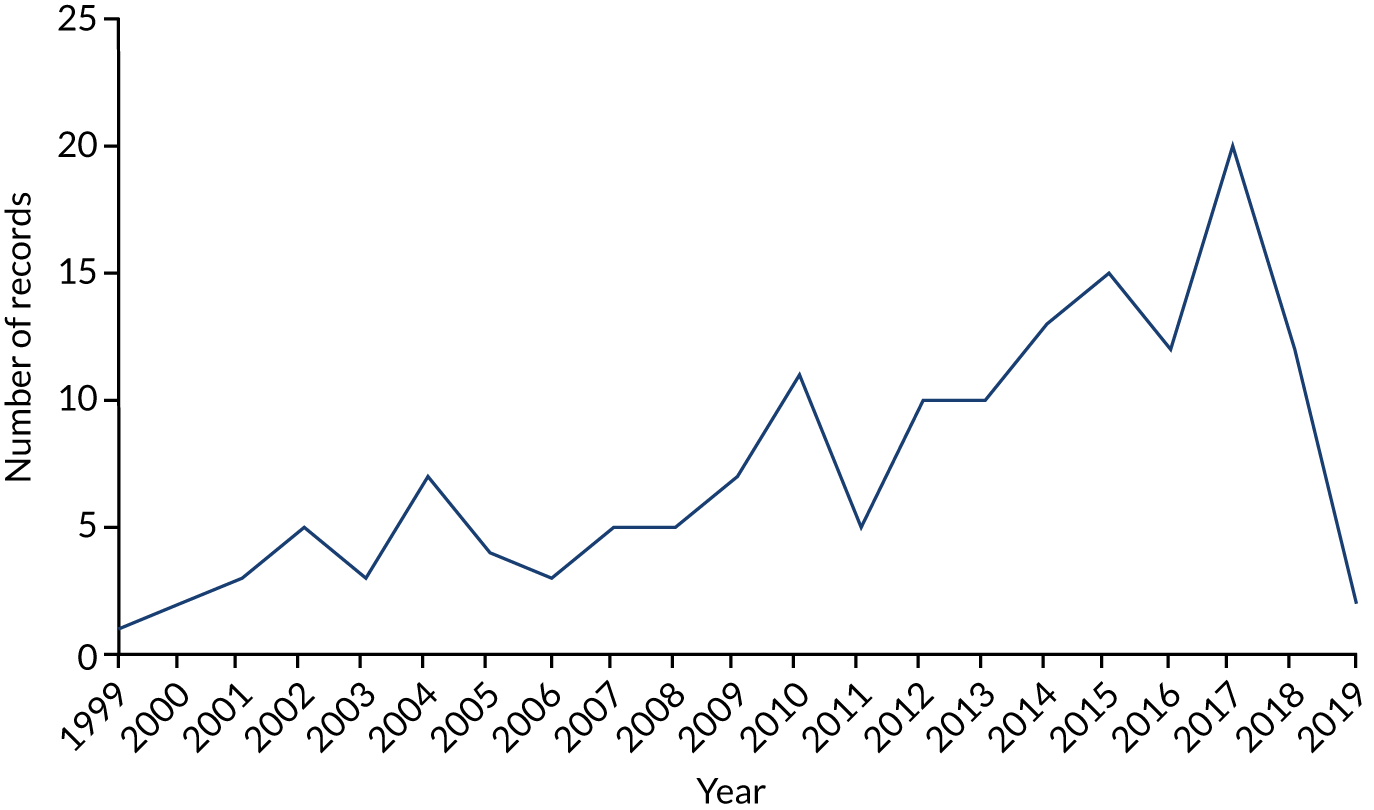

The number of records available steadily increased over the search period (i.e. 1999–2019), peaking at 20 in 2017, as illustrated in Figure 3. More than double the number of records in the period 2009–19 (n = 111) were identified compared with the previous 10-year period (n = 45). Twenty records were undated. These comprised all instructions, an intervention report and a service report (both in slide format), six tools (three of which were websites), the case examples on the AHRQ and RCP websites, and seven training links (three of which were videos). The context and content of these records indicated that they fell within the inclusion criteria.

FIGURE 3.

Records by year.

The distinction between records, standalone interventions and intervention families

The 175 records that were identified reported a total of 150 unique interventions (see Figure 1). Of these, 121 records reported standalone interventions. The remaining 54 records contained 100 references to 29 intervention families. Intervention families consisted of interventions with multiple records, sometimes in different formats and some of which have been implemented (and evaluated) multiple times (see Appendix 7). The intervention for which the most records were identified was Six Core Strategies (n = 18), including research reports, intervention reports, service reports and tools. With the exception of four records that pertained to two studies respectively,23,99 all other records were unrelated to each other – there were no follow-up or replication studies. Similarly, 10 records were identified for Safewards, which were unrelated research reports except for two that reported the same study in different formats. 88,100 Just three interventions had replication studies: City Nurse,101,102 Patient Focused Nursing103,104 and Review. 105,106 Two interventions had follow-up studies: Initiatives to Reduce Seclusion and Restraint107,108 and Open Door Policy. 109–111 One intervention (Brøset Violence Checklist112–114) had been evaluated in a pilot and a subsequent study. In the case of six interventions (Beacon Project,115,116 Recovery Based Principles,6,117 Early Recognition Method,118,119 REsTRAIN Yourself,22,85,87,120,121 Scottish Patient Safety Programme for Mental Health91,122–124 and Talk First83,86,125,126), the multiple records related to the same application or study of that intervention, often in different formats.

Chapter 4 Description of the interventions and evaluations

As per objective 1, and in keeping with the mapping approach, this chapter documents the overarching characteristics of the 150 interventions identified, including their scope and common features.

Comprehensiveness and consistency of reporting

A great deal of information was missing from the records about key aspects of the interventions. Recipient, setting, mode of delivery and aims were well reported but often lacked detail, whereas development, dose, who it was delivered by, and modification and fidelity were poorly reported (Table 3). Only 12% did not report setting. Remarkably few details were provided about who delivered the intervention, to whom, how, for how long or how often. These were usually ambiguous, describing implementation in a ward/unit, hospital or trust/administrative area without providing details of whether the sample consisted of staff and/or service users, front-line and/or managerial/administrative staff or how many of each were exposed to the intervention. Few specified whether the intervention was aimed at one or multiple professions. Most records did not include information regarding modification of or fidelity to the intervention protocol or the assumed change process that informed the intervention development (see Table 3).

| Reported (N = 221) | WIDER recommendation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detailed description of interventions | Assumed change process and design principles | Access to manuals/protocols | |||||||

| By whom delivered | Recipient | Setting | Mode of delivery in implementation | Dose: intensity and duration | Modification and fidelity | Aims/targets | Development | Materials | |

| Not applicable, n (%) | 17 (8) | 21 (9) | 32 (15) | 42 (19) | 29 (13) | 16 (7) | – | 18 (8) | 85 (39) |

| Not reported, n (%) | 99 (45) | 19 (9) | 27 (12) | 49 (22) | 130 (59) | 173 (78) | 46 (21) | 138 (63) | 84 (38) |

| Reported (including partial reporting), n (%) | 105 (47) | 181 (82) | 162 (73) | 130 (59) | 62 (28) | 32 (15) | 175 (79) | 65 (29) | 52 (23) |

Intervention setting

Clinical setting

Sixty-seven interventions (45%) did not provide any detail about the clinical setting other than it being adult inpatient (see Appendix 9). A further 27 interventions (18%) did not report clinical setting as they were not reporting implementation, for example training links. The intervention that has been applied in the widest clinical settings is Six Core Strategies. Six standalone interventions127–132 had been implemented in multiple settings within the same intervention/study, as had four intervention families (i.e. interventions with multiple records): Six Core Strategies (in acute and secure wards); Brøset Violence Checklist [in acute wards and psychiatric intensive care units (PICUs)]; Tower Hamlets Violence Reduction Collaborative (in multiple acute settings); and Initiatives to Reduce Seclusion and Restraint (in multiple, unreported settings). A further five interventions had been applied across various clinical settings: the Scottish Patient Safety Programme for Mental Health had been implemented in acute, PICU and forensic settings, the Dynamic Appraisal of Situation Aggression – Inpatient Version (DASA-IV) had been implemented in acute and high-dependency wards, the Novel Seclusion Reduction Program in acute and forensic wards, and Sensory Modulation and Sensory Rooms had both been implemented in acute wards and PICUs.

The most common setting for implementing interventions to reduce restraint and seclusion was acute wards (n = 40/150; 27%). Nevertheless, interventions had also been implemented on PICUs (n = 11), and on forensic (n = 10), secure (n = 8) and specialist geriatric (n = 6) wards. The least common settings were admission wards (n = 1) and high-dependency units (HDUs) (n = 1).

Geographical setting

Just five interventions (3%) had been implemented in different countries, with Six Core Strategies23,75,133 having the widest geographical spread covering six countries (i.e. Canada, England, Finland, New Zealand, Spain and the USA). No Force First24,134 had been applied in three countries (i.e. Australia, England and the USA), as had Sensory Modulation135–137 (Australia, Denmark and New Zealand) and Sensory Rooms138 (Australia, England and the USA). The Brøset Violence Checklist114 (Canada and Switzerland) and Patient Focused Nursing104,139 (Australia and the USA) had each been applied in two countries. Safewards16 was applied in three countries (Australia, Denmark and England). Overall, the countries applying the widest range of interventions were the USA (n = 60) and the UK (n = 59). The origins of two interventions were not reported (see Appendix 10).

Assumed change process and design principles

Intervention aims and targets

Three intervention aims were identified to (1) reduce, eliminate or prevent, (2) improve and (3) manage or monitor.

One hundred and five of the 150 interventions (60%) had a single aim, 35 (23%) had two aims and five (3%) had three aims88,131,133,140–142 (Table 4). The remaining 14% did not report an aim or target. 77

| Target | Standalone intervention | Intervention family | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple restrictive practices | |||

| Seclusion and restraint | 31 | 22 | 53 (24) |

| PRN and security involved in restraint | 1 | – | 1 (0.25) |

| PRN and restraint | – | 1 | 1 (0.25) |

| PRN, seclusion and restraint | – | 3 | 3 (1) |

| Single restrictive practices | |||

| Restraint only | 15 | 10 | 25 (11) |

| Seclusion/long-term segregation only | 7 | 14 | 21 (9.5) |

| Chemical only | 4 | 2 | 6 (2) |

| Generic | 8 | 21 | 29 (13) |

| Patient focused | |||

| Aggression/violence/assault | 14 | 12 | 26 (11) |

| Patient care/outcomes | 4 | 4 | 8 (3) |

| Early identification | 1 | 2 | 3 (1) |

| Patient experience | 3 | 3 | 6 (2) |

| Ward focused | |||

| Safety | 3 | 15 | 18 (8) |

| Quality | 6 | 5 | 11 (5) |

| Collaboration/communication | – | 4 | 4 (2) |

| Staff focused | |||

| Knowledge and skills | 12 | 2 | 14 (6) |

| Staff outcomes | 3 | – | 3 (1) |

As seen in Table 4, 81 interventions reported a single target, 29 had multiple targets and the remainder did not report a target. The most common target was seclusion and restraint (n = 53 interventions), followed by restraint only (mechanical, physical or prone restraint) (n = 25 interventions), seclusion [including long-term segregation (n = 21 interventions)] and generic terms [e.g. ‘restrictive practice’, ‘conflict and containment’, ‘coercive measure’ (n = 29 interventions)]. Another common target was service user behaviour [e.g. aggression, violence, ‘problem behaviour’ (n = 26)]. Just 11 interventions included pro re nata (PRN) medication or chemical restraint as a target: in six it was the sole target. One of these interventions specified eliminating unsupervised PRN medication (and reducing PRN medication overall),143 another aimed to replace PRN medication with ‘other clinical strategies’ (no further explanation provided),131 and another to reduce restraint associated with PRN medication and security involvement. 69 None of the interventions explicitly reported targeting the use of rapid tranquillisation, although Beckett et al. 130 referred to reviewing its use (in their procedures) and Sarkar78 examined the impact of their intervention on their use of rapid tranquillisation (reported in their outcome measures). Some interventions specified the type of restrictive practice they wanted to address, whereas others specified frequency115,131,144 or duration. 115,145,146

The most common aim for improvement was quality (e.g. environment, ward functioning, staff presence, service user to staff ratios, quality of care, ‘communication’) (n = 11). Other common targets for improvement included safety (n = 18), service user behaviour (‘dangerous’, ‘disruptive’, ‘risk’, ‘challenging’, ‘problem’, ‘aggression’) (n = 26),20,78,112–114,118,129,136,137,141,147–156 and staff skills and attitudes (n = 14). Three interventions targeted staff injury,129,157 anxiety141 and burnout,70 whereas 14 targeted service user outcomes and experiences, including service user harm,114 the service user experience (e.g. feeling of safety158), experience of care79,159 and service user outcomes. 160 Others targeting harm or safety did not specify service user or staff (e.g. Bell and Gallagher161) or included both (e.g. Lo74). In addition to those targeting quality of care (and implicitly targeting staff behaviour), five specifically targeted staff behaviour in terms of staff attitudes and perceptions,162 knowledge and efficacy,21,141,163 and culture. 132

Reference to theory

Mention of theory was absent from many interventions. Three interventions referred to having a ‘theory of change’85,153 but provided no further detail about what this was, how it had been developed and how it was tested and refined. Many of the ‘quality improvement’ interventions used a plan, do, study, act (PDSA) cycle: a mechanism to repeat and adjust interventions until they achieve the desired effect. 12,16,17

Some interventions130,137 made explicit cited reference to programme-level theories that had informed their intervention procedures, such as Sensory Modulation or Trauma-Informed Care. Other programme-level theories cited sought to explain staff behaviour, service user behaviour, therapeutic relationships and organisational change. These studies often sought to test or modify not the actual theory but rather the impact of using interventions based on them in relation to the reduction of restrictive practices.

The most frequently cited theory related to staff behaviour was social learning theory,71–73,152,164 which was used to support training interventions that sought to improve the self-efficacy of individual staff and staff teams.

Bonner’s theoretical model for debriefing and post-incident review165 informed one intervention166 and the general aggression model167 informed another that sought to reduce aggression via Sensory Modulation. 152 Kernberg’s theory of personality organisations and transference-focused psychotherapy168,169 informed clinical guidelines that aimed to reduce restraint. 170 Other theories mentioned included those seeking to explain care giving processes: Peplau’s interpersonal relations171 and Watson’s caring theory. 172 Both Safewards173 and City Nurse102 were based on the theoretical work of Bowers et al. 101 regarding conflict and containment, and the interaction between service users and staff.

Five interventions were informed by broad organisational change theories. Kanter’s structural empowerment theory sees organisational empowerment and potential for change as being influenced by the individuals within the organisation having access to information, resources and opportunities to learn. 174 The transtheoretical model of change175 is generally applied to individuals, explaining how people prepare for and enact change, although Colton176 applies it to organisations to structure a tool kit to prepare to reduce restrictive practices. Schein’s model of organisational culture177 informed the development of the Six Core Strategies. 178 This focuses on publicly espoused values and assumptions. Senge179 focuses on the capacity of organisations and, by extension, the individuals within them to learn and focuses on a common goal. 133 The Iowa Model of Evidence Based Practice was used to guide the implementation of a rapid response team. 74 The full analysis of behaviour change techniques used in the interventions can be found in Chapter 5.

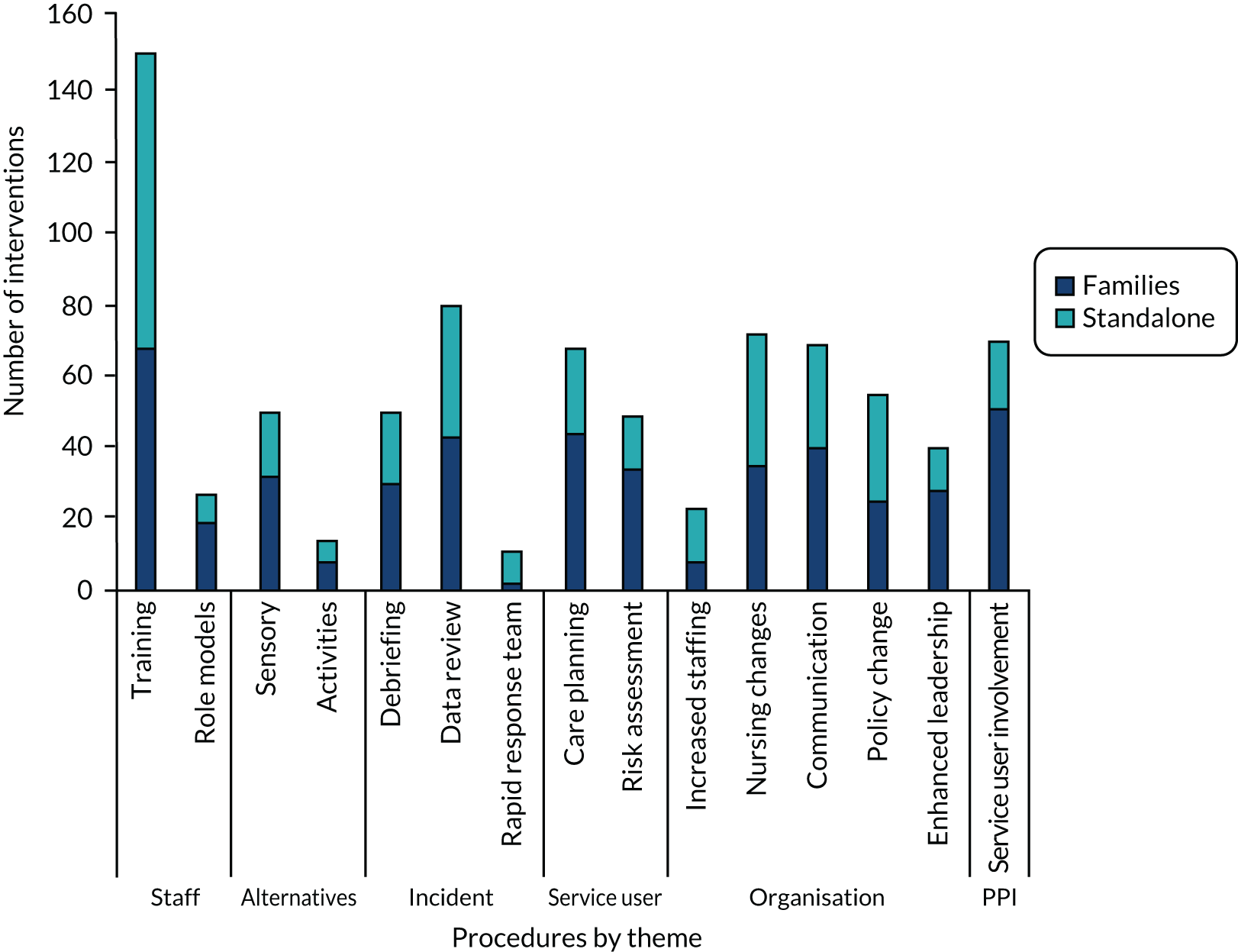

Mode of delivery: intervention procedures

The extraction process highlighted the procedures used by each intervention to address restrictive practices. A total of 15 unique procedures were identified from the analyses and these were organised into six themes (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Intervention procedures by theme. PPI, patient and public involvement.

Staff-focused procedures

Staff-focused procedures were those that were aimed at and undertaken solely by staff with a view to influencing staff use of restrictive practices. One procedure was training, which could cover, among other topics, de-escalation (e.g. Laker et al.,21 Sullivan et al. ,104 Lee et al. 127 and Jonikas et al. 180) or crisis management (e.g. Steinert et al. 20 and Melin69). Another staff-focused procedure was role modelling, which could involve supervision or mentoring (e.g. Fletcher et al. 181 and Noorthoorn et al. 182) and identifying champions, experts or specialists (e.g. Bowers et al. ,102 Tully et al. 90 and Lombardo et al. 159) to set an example to ward staff.

Service user-focused procedures

Service user-focused procedures were those that focused on and sometimes involved service users but always involved staff. One of these procedures was risk assessment – whereby service users’ triggers would be recorded – which was often undertaken using a tool designed for this purpose (e.g. Brøset Violence Checklist114 or the Early Detection Plan118). Another related procedure was care planning, in which service users and/or staff planned appropriate and preferred strategies to prevent or respond to distress and/or incidents. These sometimes involved service users in identifying their own triggers and forming their own plans, for example a ‘personal safety plan’132 and also included PDSA. 161

Alternative approaches

Two further procedures were classified as alternative approaches because they proposed alternative ways of either preventing or responding to service users’ distress. Sensory approaches included Sensory Modulation via the installation of sensory or Comfort Rooms (e.g. Novak et al. ,183 Barton et al. 184) and/or the availability of sensory equipment (e.g. Lee et al. 127) and/or use of Sensory Modulation techniques (e.g. Yakov et al. 185).

Incident-focused procedures

Other procedures were incident focused, that is, they were responses to incidents of restrictive practices. These included incident review procedures, in which organisations (staff and managers) conducted retrospective chart audits (e.g. Qurashi et al. 186) or collected and monitored their incident data (e.g. Donat106 and Friedman et al. 131) to establish baseline and progress rates, or to identify patterns for targeted intervention. In contrast to this whole-system review, debriefing was conducted immediately or soon after an incident, and included the staff and service users involved and possibly others who witnessed the incident (e.g. Duxbury et al. 120). The final procedure was rapid response, where specially trained rapid response teams were formed to respond to and provide support to incidents when they happened [e.g. psychiatric emergency response teams (PERTs); see Smith et al. 142 and Prescott et al. 128].

Organisation-focused procedures

We also identified several organisation-focused procedures. These were system-wide structural and cultural changes including making changes to staffing levels (e.g. Parasurum et al. 77), increased one-to-one nursing (e.g. Jungfer et al. 109) and/or staff availability to/contact with service users (e.g. Beezhold et al. 79 and Lewis et al. 132). Another procedure involved changing nursing approaches [e.g. such as implementing the City Nurse model,101 the Bergen model,129 a recovery approach (e.g. Repique et al. 187) or a trauma-informed approach (e.g. Madan et al. 108)]. This theme also included improvements to communication (e.g. Stead et al. 188), community meetings (e.g. Mistral et al. 189), de-escalation (e.g. Cowin et al. 163) and safety huddles (e.g. Taylor-Watt et al. 153 and Stead et al. 188). Another procedure involved policy change (e.g. Short et al. 157 and Sullivan et al. 190). Finally, leadership-related procedures involved senior management being involved in meetings, making statements of commitment.

Service user involvement in interventions

Forty-eight interventions involved service users in some way, but the type and extent of involvement varied greatly. In some cases, service users were involved in multiple ways, whereas in others they had limited roles. A number of interventions involved service users in a consultation or advisory role, for example as committee representatives,133 participants of project teams158 (e.g. working group on medicines and rapid tranquilisation130), service user panels,160 or advisory committees. 88,115,140,163 Service users were consulted for their views16 and feedback on rules,116 sensory rooms116,140 and research. 17,140 Others described involving service users in the design or co-production of parts of the intervention, such as safety plans,116 information leaflets,130 comfort rooms,23,191 training16,115,163 and the selection of intervention components. 16,116 Service users were involved in intervention delivery, for example in ward/community meetings,17,23,186,191 delivering activities,116 and training,88,116,137,163,182,192,193 displaying their positive messages for current service users,181,192,194,195 and as peer advocates,142 counsellors196 and support workers. 99,193 Only two interventions specified that service users were paid for their involvement. 24,197 The remainder that reported service user involvement provided no further detail.

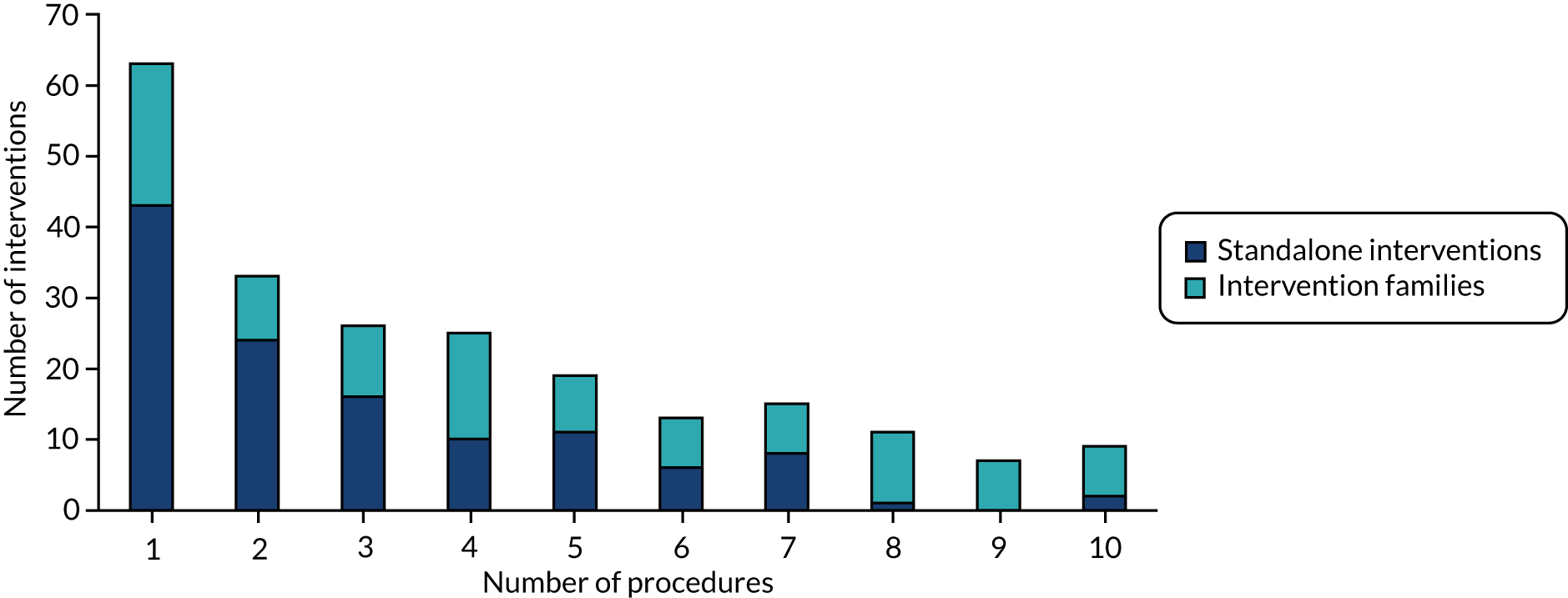

Seventy-one per cent (n = 158) of interventions involved multiple procedures, which ranged from 2 to 10 procedures (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Number of procedures per intervention.

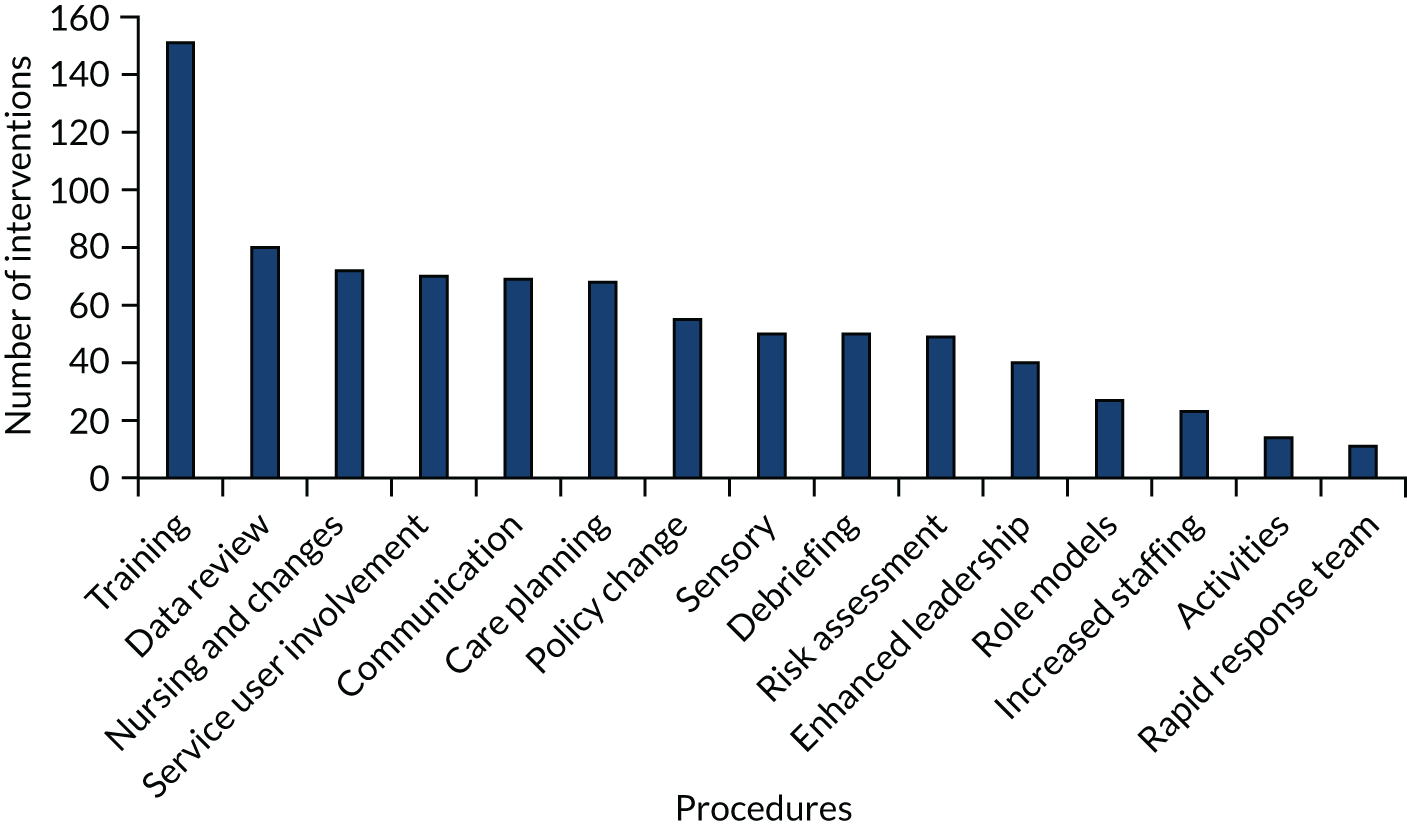

The most common procedures were training/education (n = 151), changes to nursing approaches (n = 72) (e.g. implementing Trauma-Informed Care or the Recovery Approach) and reviewing incident data (n = 80). Least mentioned were rapid response teams (n = 11) and activities (n = 14) (see Appendix 11).

As illustrated in Figure 6, although most interventions involved staff training, few reported the content, mode of delivery or training provider in any detail. The documentation reporting 89 interventions did not report any detail at all. The most common mode of delivery was group training or workshops (n = 37). Six reported using e-learning or online training and a further five reported multimedia components (e.g. video, PowerPoint) to their training. Four interventions reported using a train-the-trainer model. Others described training as one to one (n = 2), face to face (n = 3) or on the job (n = 1). Two interventions mentioned using champions and exchange visits respectively. Training was specified as provided in-house in 64 interventions and, of these, only seven specified the provider (these included quality improvement team, occupational therapists, unit manager or researcher). Training was delivered by external providers in 24 interventions, and 20 of these specified the provider. Providers mentioned included Bergen Model Representatives, Centre for Creative Leadership, City Nurse, Crisis Prevention Institute (CPI), ePsychNurse, Omega, Safewards, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA), National Enforcement Training Institute, JKM Training, AQUA and Recovery Innovations. The remaining interventions did not report any information about the training provider.

FIGURE 6.

Distribution of procedures.

Intervention dose: duration and intensity

Many evaluations did not report details about the duration and intensity of the intervention. Partial details, such as overall duration of the intervention or of an individual component (usually training), were sometimes, but not always, provided. Often, the evaluation period and the duration of intervention implementation were not distinguishable. Similarly, the duration of individual intervention components was often not reported. With this proviso, interventions ranged in length from 10 months to 5 years. Some interventions described providing standalone training sessions, whereas others were conducted over a short period of time (e.g. 1 week) or longer (e.g. several months). One evaluation described offering refresher sessions. 152

Intervention materials

Interventions reported using various materials in the implementation of the intervention, including training materials, guidelines, multimedia resources, tools, posters, slides and policies. Some referred to materials that are publicly available on the internet (i.e. the Six Core Strategies, Safewards, Brøset Violence Checklist).

Costs and funding

Eighteen interventions referred to the cost of implementing the intervention or its financial impact. Costs were reported in the currency relevant to the study setting. Several studies provided details of the costs of one or more elements of the intervention, for example: US$10,000 for a Snoezelen room,198 US$11,456.98 for two Sensory Rooms,191 US$4000–5000 for sensory equipment,136,198 £70,000189 and £2000154 for environmental improvements, US$600 for PERT including office supplies and digital pagers,74 £69,285.25 for staff de-escalation and restraint training including replacement costs and overheads21 and US$20,000 for consulting fees. 198 Others referred to costs incurred but did not specify the amount, for example sensory equipment;127,196 camera, television monitor, three two-way radios;149 or staff training. 23,196 Putkonen et al. 17 reported the costs of their intervention as the equivalent to two person-years per year. Bell and Gallacher161 stated that their interventions incurred no costs.

Seven interventions reported who funded the intervention. Three reported receiving funding from the hospital where the intervention was implemented,23,74,127 whereas Mistral et al. 189 received funding from the mental health care trust. Putkonen et al. 17 specified that funding came via the hospital performance improvement project from research funding from the National Institutes of Health and Welfare. McEvedy et al. 137 reported receiving funding from the Victorian state government-funded programme. Lloyd et al. 136 reported that they received funding but did not specify the funder.

Nine interventions reported some cost–benefit analysis. Mistral et al. 189 reported a 62% reduction in time lost to staff short-term illness. Laker et al. 21 recommended further analysis, having been unable to draw conclusions from insufficient data regarding the costs of incidents, specifically damage to property, staff or service users and injury-related absence. Brown et al. 154 reported savings of 49% associated with reduced staff absence and injury (from £119,988 prior to implementation to £61,376 post implementation). Short et al. 157 reported a decrease of 77% in lost work days due to staff injury (90% of which were attributable to physical interventions). Lo74 argued that because the PERT intervention did not require any additional staffing resources it was likely to bring economic benefits. Finally, Putkonen et al. 17 reported 75% reduction in the number of sick days in the information period and 65% reduction in the intervention period, compared with the previous year; and in addition, reported 80–82% shorter duration of sick days.

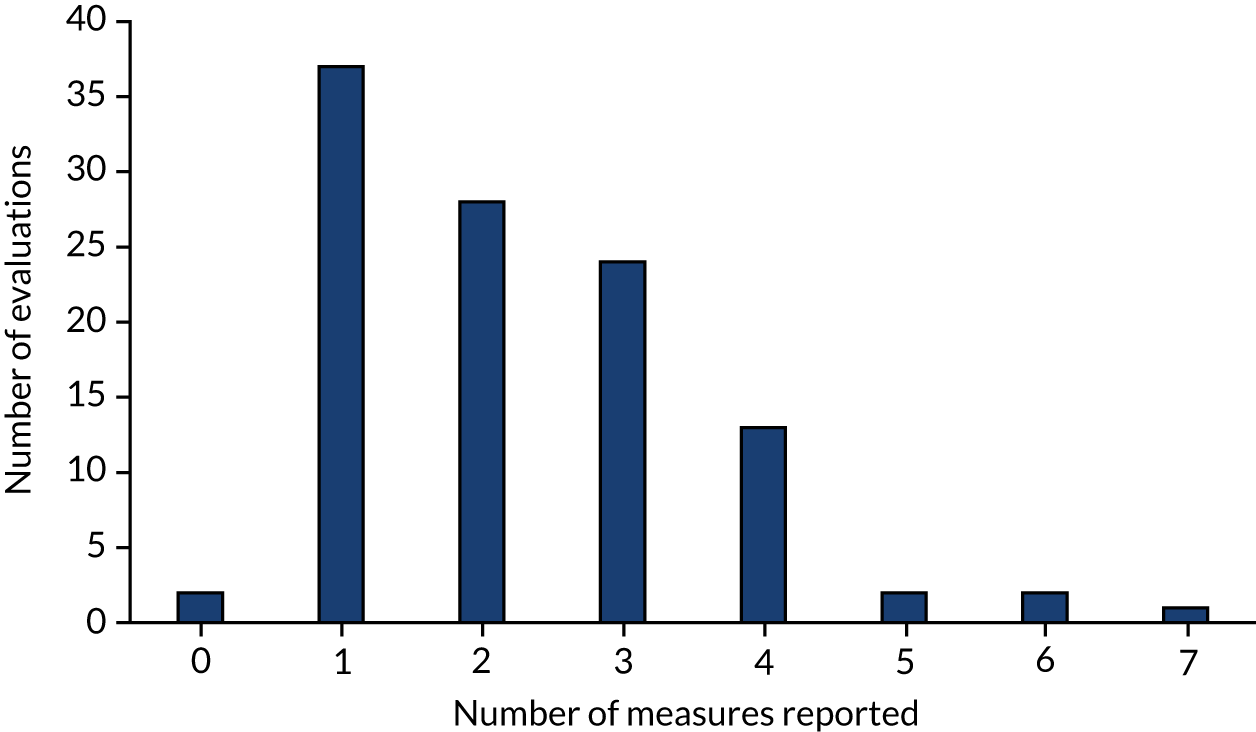

Evaluations of interventions

Evaluations were identified using the screening questions of the MMAT: the presence of a research question and the collection of data required to answer that question. Those reports that passed the screening were then appraised using the MMAT to be given a score in the form of a percentage.

Of the 109 evaluations that we identified, 106 were research reports and there was one intervention report,92 one service report156 and one practice example. 159 Six theses and five abstracts were included. Most evaluations (n = 95) were published in 42 peer-reviewed journals spanning mental health, nursing, psychiatry and quality. The most common publication titles were Psychiatric Services (n = 12), Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing (n = 7), Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services (n = 5), International Journal of Mental Health Nursing (n = 6) and Psychiatric Quarterly (n = 7). The remaining journals featured between one and four records.

Evaluation design

Evaluation design was often not described and, when it was reported, a variety of terms were used. Accordingly, design had to be inferred from other study details in some cases. Most evaluations were non-randomised studies (n = 103) (see Appendix 12). Based on the MMAT screening questions, all of these evaluations were considered to have recruited participants who were representative of the target population and used suitable outcome measures. Several were not considered to have reported complete outcome data and only two-thirds adequately accounted for confounders. There was very little reporting of modifications and fidelity to the intervention protocol, with only 11% of evaluations reporting this. There were six RCTs, four of which were cluster RCTs (Table 5). The MMAT scores of these six RCTs varied from 0% to 80%. Five out of the six RCTs reported complete outcome data and four did not describe any deviation from the protocol. Only three had comparable groups at baseline and described rigorous randomisation processes. Two reported that outcome assessors were blinded.

| Study authors and year of publication | Design | Sample | Intervention | Control | Outcome measuresa | Findingsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bowers et al. 201516 | Cluster RCT | 16 intervention wards, 15 control (mean number of beds per ward was 19) | Safewards | Physical health intervention | Rates of (1) total conflict and (2) total containment (Patient–staff Conflict Checklist) | Rate of conflict reduced by 15% (95% CI 5.7% to 23.7%); rate of containment reduced by 23.2% (95% CI 9.9% to 35.5%; not significant) |

| Kontio et al. 2014199 | Cluster randomised trial | 5 intervention wards, 5 control wards | E-learning course | Treatment as usual | Rates and duration of seclusion and restraint | Duration of mechanical restraint decreased (p < 0.001) |

| Putkonen et al. 201317 | RCT | 2 intervention wards, 2 control wards | Six Core Strategies | Treatment as usual | Rates of seclusion, restraints, or room observation, duration of seclusion or restraint | Rates of seclusion, restraints and room observation decreased from 30% to 15% (IRR 0.88, 95% CI 0.86 to 0.90; p < 0.001). Duration of seclusion/restraint decreased from 110 to 56 hours per 100 patient-days (IRR 0.85, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.92; p < 0.001) |

| van de Sande et al. 2011200 | Cluster RCT | Two intervention wards, two control wards | Structured short-term risk assessment (Brøset Violence Checklist, Crisis Monitor, Kennedy–Axis V scale, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, Dangerousness Scale, Social Dysfunction and Aggression Scale) | Treatment as usual | Rates and duration of seclusion, number of secluded patients | Duration of seclusion decreased (p < 0.05) |

| Parasurum et al. 201177 (abstract) | RCT | Four intervention wards, four control wards | Nursing staffing level and care | Not reported | Physical restraints | No restrictive practice outcomes reported |

| Abderhalden et al. 2008113 | Cluster RCT | Four wards randomised to intervention, five wards randomised to control, five wards introduced intervention without randomisation | Structured short-term risk assessment (Brøset Violence Checklist) for every patient admission | Treatment as usual | Incidence rates of (1) severe aggressive events (SOAS–R) and (2) coercive measures (yes/no) | Coercive measures decreased by 27% (p < 0.001) |

Four qualitative studies were identified72,137,152,201 (Table 6), as were a further six that used mixed methods15,140,166,187,189,203 (Table 7). Goulet et al. 166 and Chandler201 reported using case study methodology. These evaluations used the following data collection and analytical methods: interviews,72,137,140,152,201 focus groups,15,152,166,187 document (policy) review,201 observation,201 thematic analysis15,72,140,152,187 and qualitative content analysis. 137,166,201 All of these studies evaluated different types of interventions, except McEvedy et al. 137 and Sutton et al. ,152 which both evaluated Sensory Modulation.

| Study authors and year of publication | Design and methods | Research question(s) | Setting and sample | Intervention | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sutton et al. 2013152 | Qualitative: narrative analysis | To examine the potential of using sensory-based approaches to develop the theory and practice of preventing, minimizing, and managing aggression in mental health settings | 4 units: 40 staff, 20 patients | Sensory Modulation (Six Core Strategies) | Identified three factors that contributed to the management of distress and agitation:

|

| Chandler 2012201 | Qualitative: case study appreciative inquiry approach,202 inductive content analysis | How has the unit decreased use of restraints and seclusion? | 20-bed unit: 11 staff | Six Core Strategies; TIC | Rates of seclusion and restraint decreased from 27 to 6; identified three factors that played a key role:

|