Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/54/55. The contractual start date was in June 2015. The final report began editorial review in June 2018 and was accepted for publication in April 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Reynish et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Dementia and cognitive impairment pose a major challenge to health services. Dementia prevalence is most strongly associated with age,1 and has risen sharply with increasing population longevity resulting, in part, from the medical advances made in reducing vascular mortality in mid-later life and early later life.

Current policy

The framework of policy that currently exists for guiding and improving the care and treatment of people with dementia is extensive. The importance of improving general hospitals’ response to dementia is frequently highlighted. In addition, the recognition that the measurement of outcomes, rather than only process measures, when aiming to improve quality of care is deeply rooted in governmental policy.

Dementia is on the policy radar at the global level. In December 2013, the UK hosted the G8 (Group of Eight) dementia summit. This concluded with the publication of a declaration setting out agreements that had been reached. Since this event, a World Dementia Council and World Dementia Envoy have been appointed to lead the global dementia action.

The UK Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge was launched in March 2012. 2 One of its three key domains was the ‘health and care’ of people with dementia.

The Dementia Challenge follows on from the individual nations’ dementia strategies. In England, objective 8 of the National Dementia Strategy3 prioritises the identification of leadership for dementia in general hospitals, defining the care pathway for dementia and the commissioning of specialist teams to work in general hospitals. In Scotland, improving care in hospitals was the second of two key improvement areas in the first Dementia Strategy. 4 The second Dementia Strategy states one of the key priorities to be that people with dementia in hospitals or other institutional settings are always treated with dignity and respect.

In 2006, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)/Social Care Institute for Excellence5 recommended that hospitals review their facilities and service function so that they promote independence and maintain function in people who have a dementia.

In 2010, the government published the White Paper Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS. 6 This outlined the intention to move the NHS away from focusing on process targets to measuring health outcomes.

In 2013, the Department of Health and Social Care published Dementia: A State of the Nation Report on Dementia Care and Support in England. 7 Once again, general hospitals’ response to people with dementia was highlighted as a priority.

The current NHS Outcomes Framework 2013–148 sets out the outcomes and corresponding indicators used to hold the NHS Commissioning Board to account for improvements in health outcomes. It states that:

Health outcomes matter to patients and the public. Measuring and publishing information on health outcomes are important for encouraging improvements in quality.

This sits alongside the Adult Social Care Outcomes Framework 2014 to 2015,9 which sets out the indicators for measuring adult social care outcomes, which have been recognised as being as important for people with dementia.

Current evidence

Dementia presents specific important challenges in acute hospitals. In 2001, the Department of Health and Social Care estimated that two-thirds of hospital beds were occupied by patients aged > 65 years,10 up to half of whom might have some kind of cognitive impairment, including dementia and delirium. 11 Poor identification of cognitive impairment, frailty, comorbidity and polypharmacy complicate the picture and make this a highly vulnerable but heterogeneous population. The commonest symptom of dementia is cognitive impairment, but, in the hospital setting, individuals with cognitive impairment due to dementia are difficult to distinguish from those with delirium. In a study by Sampson et al. ,12 which included a specialist clinical assessment for delirium, the prevalence of dementia in general hospitals was found to be 42.4% in patients aged > 70 years, but half of these individuals did not have a formal diagnosis. In acute hospital admissions, dementia is a common comorbidity but it is poorly recognised and poorly managed. In a systematic review, Mukadam and Sampson13 found that prevalence estimates for people with dementia in a general hospital setting varied from 12.9% to 63.0%, but it was not possible to estimate a pooled prevalence because of heterogeneity between studies in terms of the population studied (specialist geriatric medicine settings alongside unselected medical admissions), the assessment methods used and the majority of studies not screening for delirium or depression, meaning that the rish of misclassification was high.

Poor outcomes for people with dementia after hospital admission were highlighted by the 2016 Alzheimer’s Society (London, UK) poll of > 570 carers, families and friends of people with dementia. 14 Ninety per cent said that they felt that the person with dementia became more confused while in hospital. This was a follow-up from their 2009 staff and carer survey, which found that the health of most people living with dementia is worse when they leave hospital than when they are admitted. 15

The Alzheimer’s Society also reported from a Freedom of Information request that the average length of stay (LoS) in hospital in 2015 for someone aged > 65 years was 5.5 days, whereas for people with dementia it was 11.8 days. 14

Current knowledge concerning the outcomes of this hospital population with cognitive impairment can be divided into three distinct groups: reports look at the outcomes of (1) those with dementia, (2) those with delirium and (3) the broader population of those with cognitive impairment. Evidence-based documentation of outcomes for people with cognitive impairment in this setting is sparse. The 2011 systematic review by Mukadam and Sampson13 identified seven studies reporting outcomes for people with dementia who were admitted to an acute hospital. 16–22 The included studies mostly did not screen for delirium or depression, and a significant proportion of the ‘dementia’ identified may be misclassified. Included studies were generally small, with six having sample sizes of 100–375; the other study17 included 2000 patients. The review found that individuals with dementia have worse outcomes, including increased length of hospital stay, functional decline and likelihood of discharge to institutional care. It also found that the cost of treatment was higher for those with dementia. 13 The current understanding of the health economic impact of dementia is often defined by intervention rather than health-care setting, and estimates for cost of care for patients with dementia in general hospitals are sparse, despite some important existing work on dementia. 23

When looking at the outcomes of patients with delirium in general hospitals, there is substantial evidence that shows that outcomes are poor. 24 Delirium is a common condition, known for its acute onset in confusion, fluctuating course and inattention. Delirium affects up to 30% of older hospital patients, and people who develop delirium have high mortality. 25 As well as an increase in overall morbidity and mortality, delirium increases the lengths of hospital stays. 26,27 Delirium can also lead to significant functional decline; following an episode of delirium, patients are more likely to require social support, which can range from new or increasing home care input to an increase in the likelihood of admission to a nursing home. 24 There is also evidence that shows that cognitive function in elderly patients can be significantly worsened following a period of delirium, and may never return to its premorbid baseline. 28 People with a dementia have a fivefold risk of developing delirium. 11 There are estimates from over a decade ago that delirium cost the US health system > US$4B in inpatient costs alone. 29 In a study of delirium in elderly patients on general medical units during their initial hospitalisation and 1 year following their discharge, Leslie et al. 30 showed that delirium during a hospital stay was associated with higher mean total costs (at least US$69,498 vs. US$47,958), as well as 2.5 times higher costs per day (US$461 vs. US$166). This study concluded that delirium was responsible for between US$60,516 and US$64,421 additional health costs per year per delirious patient, which translates to a US$38B per year financial burden of delirium, with significantly higher figures (US$143B–152B per year) when the figure was processed using models that accounted for the fact that the data were right-censored. In 1986, Levkoff et al. 31 estimated that if the LoS of each delirious patient could be reduced by just 1 day, the savings to Medicare would amount to US$1B–2B annually.

In a randomised controlled trial of a specialist medical and mental health unit versus standard care for those admitted to hospital with ‘confusion’, the primary outcome measure used was the number of days at home beyond 90 days after randomisation. 32 Results showed no difference in this outcome between the two groups, although the intervention significantly improved patient experience and the satisfaction of family carers. Bradshaw et al. 33 examined outcomes for people with comorbid mental health problems (dementia, delirium and depression). This study showed a high mortality, high re-admission rate and high discharge to care home rate within the study population, but there was no comparison with a similar population without mental health disease and no subgroup analysis of different mental health conditions.

Why this study?

There is little doubt that outcomes for people with cognitive spectrum disorders (CSDs) admitted to hospital are worse than those for people without CSDs, and it is likely that these could be improved. Plausible interventions to improve the outcomes are necessarily complex because they have to address the multiple clinical and social scenarios encountered, but their development requires a good understanding of the population with CSDs in the acute general hospital, and their outcomes. Lack of or incorrect CSD diagnosis, frailty, comorbidity and polypharmacy complicate the picture and make for a heterogeneous population. There is initial evidence from the USA that holistic management of older adults can improve outcomes. 34 The Medical Research Council (MRC) Framework35 for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions recommends pre-intervention development work to understand the population receiving the intervention, and to inform the choice of appropriate outcomes. Current knowledge of how common CSDs are among older people admitted to hospital and their post-hospital outcomes is sparse owing to the difficulties (especially consent and external validity) of recruiting a large and representative patient cohort, but such epidemiology is a central first step (theoretical phase) in the development of interventions.

Reporting of health-care outcomes, such as LoS, mortality and re-admission, is difficult to capture in this population owing to underdiagnosis. This is compounded by the fact that ‘dementia’ per se is rarely recorded as the primary reason for admission and is unreliably recorded as a secondary reason.

The need for this research is all too apparent when reviewing the catastrophic impact that poor outcomes from a hospital admission may have on the lives of individuals with a CSD, their families and the health and social care systems. Decline in physical and mental well-being in the older population can happen at any time and an admission to general hospital is often the trigger for an irreversible acceleration in this decline. What happens in general hospitals can have a profound and permanent effect on individuals with CSDs and their families, not only in terms of their inpatient experience, but also in terms of their ongoing functioning, relationships, well-being, quality of life (QoL) and the fundamental decisions that are made about their future. 36

This research enables accurate documentation of these outcomes and provides a baseline from which to measure improvement. This documentation adds evidence to be used in future policy development to drive these changes.

The increased understanding resulting from this study is a component that is necessary for the next step in improving the quality of care for people with CSDs in general hospitals.

Chapter 2 Systematic reviews

Background

Older people admitted to the acute hospital present with CSDs including dementia, cognitive impairment, delirium and delirium superimposed on dementia (DSD). This study systematically reviewed the prevalence and outcomes of such disorders and highlights the varied range of prevalence estimates for each condition and the variation in methodology contributing to these findings.

Introduction

The literature review examined evidence that currently exists in the field of cognitive impairment in general hospitals. It covered the domains of cognitive impairment, dementia and delirium both separately and in a combined fashion, thereby summarising the majority of this subject area for the first time, and, in the case of dementia, updating the review compiled in 2008. 13 The primary aim of this current review was to systematically report the prevalence and outcomes of cognitive impairment in older people admitted to general hospitals across the spectrum of all cognitive disorders.

The research questions answered by this review are as follows:

-

What is the prevalence of CSDs (including cognitive impairment, dementia, delirium and DSD) in older people admitted to hospital acutely?

-

What outcomes have been reported/observed/studied and how have they been measured in this population?

-

What are the differences in the outcomes experienced by those with and those without CSDs following an acute hospital admission?

Methods

Protocol and registration

A protocol for the review was developed and registered with PROSPERO in 2015 (PROSPERO CRD42015024492) before work was started on defining search terms. 37

Eligibility criteria

An inclusive approach was adopted in the original search. Table 1 contains the full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria. The exposure of interest was CSD and how it was measured or diagnosed.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

Randomised controlled trials, intervention studies, quality improvement initiatives, before-and-after designs and narrative reviews were excluded as they do not provide general population (unselected) prevalence or outcome data. Systematic reviews were retained for review of their reference lists.

Other exclusions were made to remove non-general hospital settings, such as community hospitals, intensive and post-acute care units, rehabilitation hospitals, outpatient clinics, primary care, mixed settings (i.e. outpatients and inpatients) and inpatients who had been discharged home before data collection.

Outcomes of interest included mortality (in-hospital and at follow-up), length of hospital stay, hospital re-admission, admission to long-term care (nursing homes, etc.), health or social care costs, physical function [activities of daily living (ADL)], QoL and change in cognitive function. Any articles that did not report prevalence data or outcome data on any of the outcomes of interest were excluded.

No restrictions were made for date of publication in the search. Conference abstracts were included in the screening and a search was carried out based on title and first and last author to identify any subsequent full-text publication for inclusion in the review. Systematic reviews were not included in the full-text review. The results were restricted to publications available in the English language.

Information sources

The following databases were searched between 29 January and 1 February 2016:

-

Ovid MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Ovid MEDLINE (date range searched: 1946 to present)

-

Ovid EMBASE (date range searched: 1980 to 2016 week 4)

-

EBSCOhost Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Plus

-

Ovid PsycINFO (date range searched: 1806 to January week 4 2016)

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

See Appendix 2, Table 25.

Search

Initial scoping searches were undertaken in MEDLINE using keywords and medical subject heading (MeSH) terms both separately and combined in order to comprehend their coverage. The search was formed using three distinct concepts: (1) CSD (made up of searches for dementia, delirium and cognitive impairment), (2) hospital inpatient and (3) prevalence and/or outcomes. Search terms were combined within the concepts using OR and the three concepts were combined using AND.

Search strategy development drew on a range of existing published sources. The reviews conducted by Mukadam and Sampson13 and Siddiqi et al. 38 were consulted and search strategies were shared with the review team. The Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group search strategies for delirium and dementia were used to inform search strategy development. 39 Terms for cognitive impairment were expanded. Additional assistance and advice was given by an information specialist from the University of Stirling.

Multiple iterations of the search were tested to ensure that it identified all papers on a list of target publications constructed by the research team. The search strategy was circulated to the External Advisory Board for comment and then finalised. A copy of the complete search strategy is available in Appendix 2.

Study selection

All articles were uploaded into the online systematic review tool for screening and review (Covidence, VIC, Australia). Direct deduplication was carried out by the software. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by pairs of reviewers, one of whom was a senior reviewer, and all conflicts were resolved through discussion between two of the senior reviewers.

Prior to full-text screening, two senior reviewers reassessed all titles and abstracts and removed those that were not in the general or geriatric medical setting in order to limit the heterogeneity of study methods resulting from disease-specific hospital settings. A spreadsheet was developed to classify these so-called specialist populations for future use by one reviewer, and each entry was checked by a second reviewer to ensure consistency in classification. Any studies that did not meet the review exclusion criteria were removed at this stage with the agreement of the two reviewers.

Full-text screening of 422 articles was undertaken independently by pairs of experienced reviewers. Of these articles, 73 were reviewed twice independently by pairs of reviewers and consensus was reached over any conflicts. Full-text screening for the remaining 349 articles was completed by at least one independent senior reviewer. Eighty per cent of the 349 articles reviewed were cross-checked by two senior reviewers to ensure consistency and evaluation of judgements about relevance. There was strong consistency in judgements between both reviewers, and any conflicts between the reviewers were resolved. The final number of included articles was 146. Sixty-four foreign-language papers were not considered for review.

An exclusion hierarchy was developed for full-text screening, recognising that there may be multiple reasons to exclude a single study:

-

non-human study

-

paediatric population (aged < 18 years)

-

duplicate record

-

specialist population

-

wrong study design

-

wrong setting

-

wrong population

-

conference abstract (with no subsequent full text)

-

no prevalence/outcome data reported

-

foreign-language publication

-

insufficient information to evaluate.

Data collection

A data extraction form was developed using Google Docs (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). This was piloted with the data extraction team to improve consistency of approach. It was developed in line with Stirling University Literature Review and Evaluation Methodology. Data extraction was carried out by two independent reviewers. To ensure consistency of data extraction, all articles were cross-checked by each reviewer. Particular attention was given to articles for which a second opinion was sought. All conflicts were resolved by consensus between the two reviewers and did not require the opinion of a third reviewer.

Data items

Data were extracted on the following items: emerging issues, population, setting, type of study, age range, sample size, sex of participants, coverage, the country that the study was conducted in, inclusion and exclusion criteria, start date of the study and study duration. For each CSD covered in the article, data items included the definition of CSD used in the paper, assessment tools or diagnostic criteria, number of cases, size of underlying population, quoted prevalence and quoted incidence. For associated outcomes, the following data items were extracted: LoS; QoL; mortality; nursing/care home admission; functional status/ADL; change in cognitive status; health-care costs; hospital re-admission; other outcomes; and covariates. All outcomes were reported on.

Quality assessment of studies

Quality assessment was conducted based on the tool developed by Boyle40 and adapted by Mukadam and Sampson. 13 This was integrated into the data extraction form.

A maximum quality score of 18 could be assigned in the context of each diagnosed condition. When evaluation questions were not applicable to the study (e.g. when studies did not address all conditions), the maximum score was adjusted to reflect this and to ensure that quality was measured equitably for all studies.

Risk of bias across studies

To ensure consistency of judgements about the quality of evidence, the second independent reviewer assessed 20% of the included studies; this has been found in previous work to be sufficient to ensure consistency. These studies were identified randomly and any identified disagreements were resolved.

Summary measures

Studies were included if they reported quantitative data on the prevalence of any of the CSDs in an unselected hospital population and/or if they reported quantitative data on the outcomes of interest, based on CSD category or comparing a CSD with no CSD.

Results of the systematic review

Study selection

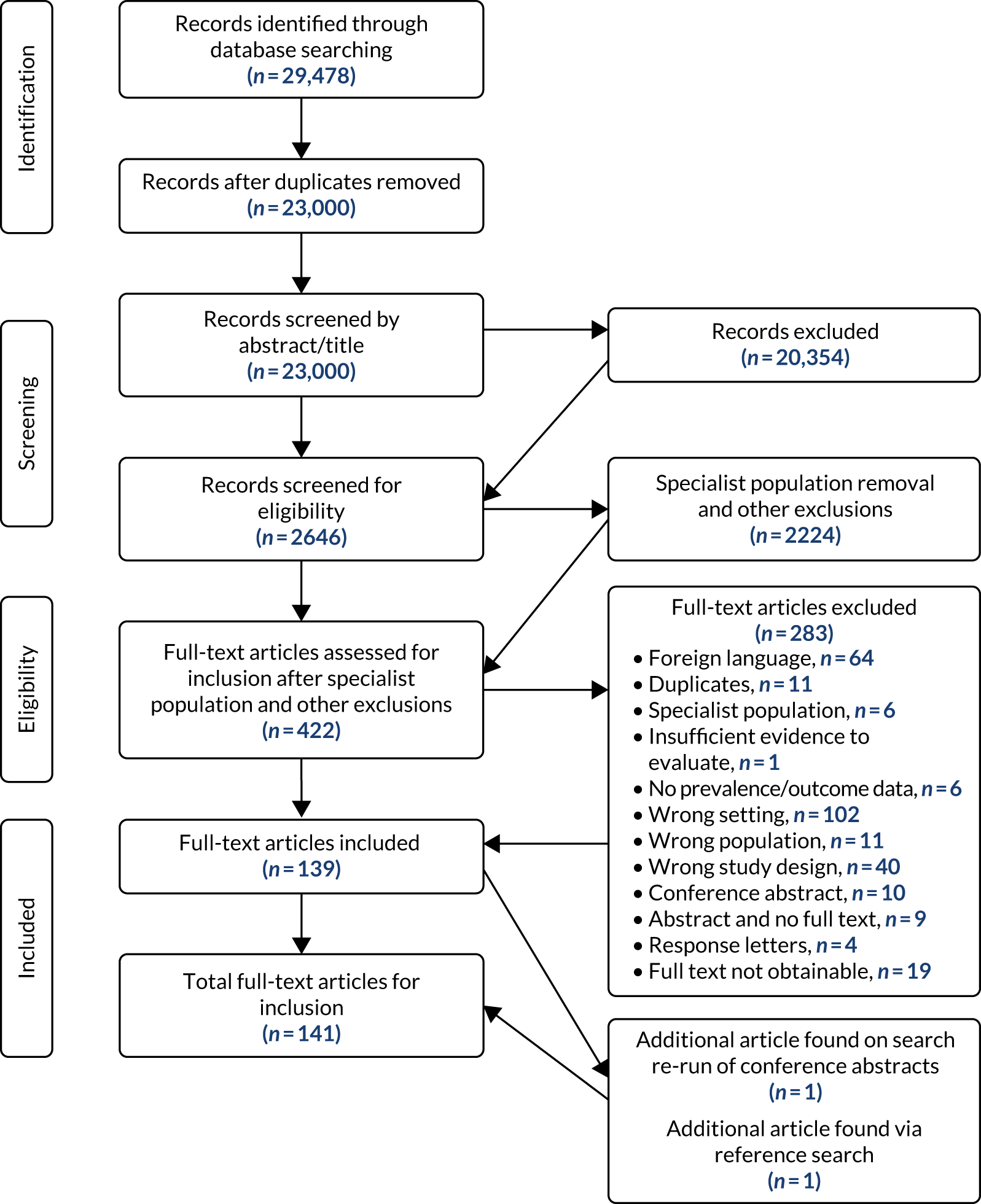

The initial search identified 23,000 records after initial deduplication. Following title and abstract screening, 2646 records remained. Specialist population removal removed a further 1553 articles (Table 2). In addition, 671 identified articles did not comply with the original study eligibility criteria and so were removed, resulting in 422 for full-text review. A total of 277 records were excluded from the review on full-text screening (see the exclusion hierarchy in Study selection). The search was re-run to identify any conference abstracts available as full-text articles, which yielded one additional full text for inclusion. A total of 141 articles were included in the review (Figure 1).

| Category | Number of articles removed |

|---|---|

| Emergency department | 133 |

| Haematology and oncology | 81 |

| Orthopaedics and trauma | 290 |

| Cardiovascular and cardiac surgery | 262 |

| Postoperative | 134 |

| Stroke and brain injury | 148 |

| Palliative care | 32 |

| Disease or condition specific | 320 |

| Nutrition and electrolytes | 48 |

| Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy | 22 |

| Care home | 21 |

| Psychological liaison | 33 |

| Unclassified | 29 |

| Total number of specialist populations removed | 1553 |

| Total number of other exclusionsa | 671 |

| Total number of exclusions | 2224 |

FIGURE 1.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Studies excluded from the review

A total of 283 studies were excluded. Studies were excluded for the following reasons: foreign language (n = 64), duplicates (n = 11), specialist population (n = 6), insufficient evidence to evaluate (n = 1), no prevalence or outcome data (n = 6), wrong setting (n = 102), wrong population (n = 11), wrong study design (n = 40), conference abstract (n = 10), abstract identified and no full text available (n = 9), response letters (n = 4) and full text not obtainable (n = 19).

Included study characteristics

A total of 141 studies were included in the review. A summary of the characteristics of the included studies is provided in Appendix 3, Table 26.

The sample size varied significantly, from 1841 to 1,135,42342 participants. Fifty-five per cent of the studies were conducted in Europe. A total of 127 (89%) of the included studies were reported as cohort designs, 12 of which were retrospective and 113 of which were prospective. There was one descriptive cohort study.

Five retrospective studies were reported as secondary analyses and two were reported as case–control studies. There were seven cross-sectional studies. 19,43–48

Participants in one study had a mean age of < 65 years; 13 studies did not report the average age of participants. 49–52

Study duration varied, with data ranging from 1 month to 17 years. Seventy-three studies represented the acute general setting, with 65 in the acute/geriatric setting, and three studies encompassed both acute general and geriatric settings. 53–55

Twelve studies evaluated participants for both cognitive impairment and dementia. Sixteen studies evaluated dementia alone and 21 studies evaluated only cognitive impairment. Delirium was evaluated in 89 studies, DSD was evaluated in 18 studies, 46 studies screened for both delirium and dementia, and delirium, dementia and cognitive impairment were screened for in 11 studies.

There was heterogeneity in terminology used to describe the acute hospital setting, which encompassed terminology including ‘teaching hospital’, ‘university hospital’ and ‘internal medicine’.

Screening and prevalence of delirium

A total of 89 included studies reported delirium prevalence. Delirium prevalence ranged from 5% to 85.5% (see Appendix 3, Table 27), reflecting the range of diagnostic tools and methodological approaches used. 56,57 Demographic characteristics of the cohort and differences in study design may also have influenced prevalence estimates; for example, Jitapunkul and Hanvivadhanakul49 included an all-female sample. Goldberg et al. 58 used a sample that disproportionately included patients who had carers living locally and who had longer hospital stays.

Adamis et al. 59 included those with less severe delirium – in parallel with other studies demonstrating selection biases – and required participant consent, thus potentially underestimating delirium prevalence.

There were eight retrospective studies and three secondary analyses. These designs can lead to underestimates of prevalence figures and depend on quality and availability of medical data. Prevalence figures may also have been influenced by not routinely diagnosing delirium but using only a single assessment in which it is difficult to differentiate between new and existing cases of delirium (e.g. Edlund et al. 60). Four studies included only incident cases; thus, prevalence could not be reported. 61–64

The term ‘acute confusion’ was used to describe delirium in five studies. 49,50,65–67 Five studies reported prevalence of subsyndromal delirium (SSD): Bourdel-Marchasson et al. 68 (20.6% SSD), Cole et al. 69 (65% SSD), Lam et al. 70 [66.2% residual subsyndromal delirium (rSSD)], Martínez-Velilla et al. 71 (22.3% SSD) and Zuliani et al. 48 (37.9% SSD). Six studies reported prevalence figures for subtypes of delirium: mixed, hypoactive and hyperactive delirium. 19,57,60,70,72,73

The most common tools adopted to diagnose delirium (see Appendix 3, Table 27) were the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM)/Confusion Assessment Method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU) (41 studies) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) (21 studies). There was considerable heterogeneity across studies in the diagnostic tools used. Basic and Khoo74 and Basic and Hartwell75 did not specify how diagnosis was made. Díez-Manglano et al. 76 defined delirium presence from any cause during the previous hospitalisation, and relied on medical notes to diagnose delirium.

Screening and prevalence of dementia

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), (21 studies) and the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (21 studies) were the most commonly used tools to diagnose dementia (see Appendix 3, Table 28). There were five case-only studies. 12,77–80 Prevalence in the remainder of studies varied greatly: from 1.33%81 to 74.4%,70 probably owing to sample selection biases and heterogeneity in screening tools and methodological approaches used to diagnose dementia. Five studies did not specify the criteria used to diagnose dementia. 41,72,75,82,83 Variations in demographic characteristics of the studied population also may have affected prevalence figures; for example, Di Iorio et al. 84 conducted a study in multiple hospital sites.

Six studies appeared to use the terms ‘cognitive impairment’ and ‘dementia’ interchangeably. 59,62,68,85–87

Several studies were selective in the approach used. For example, Sampson et al. 12 excluded people with persistent delirium, so may have underestimated the prevalence of dementia, and Aminoff77 used a case-only study to include only patients with severe dementia.

Five studies reported the prevalence of subtypes of dementia. Erkinjuntti et al. 17 found vascular dementia to be the most common (72.4%), then primary degenerative dementia (PDD) (23%) and then other causes (4.6%). Erkinjuntti et al. 18 reported prevalence of PDD as 16.1% and prevalence of vascular dementia as 69.4%, and 14.5% of patients had specific causes of dementia. Jackson et al. 88 reported Alzheimer’s disease (AD) prevalence to be 66%, vascular dementia prevalence to be 26% and mixed dementia prevalence to be 6%, followed by dementia with Lewy bodies at 21%. Lorén Guerrero and Gascón Catalán44 reported AD prevalence to be 40.74%. Wancata et al. 21 reported AD prevalence to be 61.8%, multi-infarct dementia prevalence to be 21.6%, pre-senile dementia prevalence to be 2.5% and unidentified dementia prevalence to be 14.1%.

There were 11 retrospective studies, including five secondary analyses. These study designs are likely to produce an underestimate of prevalence of dementia, as estimates were derived from medical notes or discharge codes, rather than from assessment actively undertaken by a researcher. In retrospective studies, validity depends on the quality of the discharge reports used as well as access to other data, including re-admissions. Furthermore, five prospective studies relied only on medical records to diagnose dementia. 49,67,79,89,90 Six prospective studies and one retrospective study did not specify how dementia was diagnosed. 41,54,63,72,75,82,91 Hsieh et al. 92 prospectively assessed dementia using a researcher-led approach but did not specify the diagnostic tool used.

Screening and prevalence of delirium superimposed on dementia

Typically, the term ‘delirium superimposed on dementia’ is used when an acute change in mental status (e.g. fluctuating course, inattention, altered level of consciousness and disorganised thinking) occurs alongside pre-existing dementia. 93 Across all papers, there was considerable heterogeneity in the operationalisation and measurement of DSD and the diagnostic criteria applied (see Appendix 3, Table 29). Five studies did not explicitly reference the term ‘delirium superimposed on dementia’, but included patients who presented with both conditions concurrently. Faezah et al. 72 did not clearly assign prevalence estimates to differentiate the subjects in the cohort under study.

Prevalence varied widely, from 0.5% to 76%, which probably reflects the range of diagnostic approaches and the variation in the populations assessed. McCusker et al. 94 reported the highest prevalence of DSD across all prospective studies, at 76% (based on 164/217 patients).

The DSM-IV was used in nine studies in conjunction with other tools to diagnose DSD, but there was no consensus approach to measure DSD. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition (ICD-9), coding was used in two studies: Bellelli et al. ,55 who reported the lowest prevalence of DSD, and Gallerani et al. 95 Bellelli et al. 55 did not document pre-existing dementia using a separate, validated tool, which limited the ability to differentiate deficits associated with delirium from those in dementia. Rockwood83 did not specify how dementia assessment took place. Several papers did not distinguish prevalent and incident cases of delirium as delirium assessment was undertaken on the day of admission only. 60,79,96,97 Single assessments also make it difficult to differentiate delirium from dementia as they share many symptoms. McCusker et al. 26 assessed prevalent and incident delirium separately but did not report the relative number of cases.

Screening and prevalence of cognitive impairment

A total of 21 studies screened for cognitive impairment but did not report prevalence estimates.

The range of prevalence was 8.9%59 to 80%. 62 The majority of studies defined cognitive impairment as distinct from ‘dementia’, and, in 45 studies, the MMSE was used to diagnose cognitive impairment (see Appendix 3, Table 30). There was heterogeneity in the assessment tools used across studies, potentially biasing prevalence estimates.

Five studies focused on ‘mild cognitive impairment (MCI)’. Bickel et al. 98 reported ‘mild cognitive impairment’ as patients diagnosed using International Working Group on MCI criteria and fulfilling criteria for cognitive impairment but not dementia; Orsitto et al. 46,99,100 used the Petersen criteria101 to diagnose ‘mild cognitive impairment’. Jackson et al. 88 defined MCI as when the person is neither normal nor demented with some evidence of cognitive decline, and ADL largely intact.

Two studies did not describe the diagnostic approach used to screen cognitive impairment. 102,103 There was some heterogeneity in the terminology used to define cognitive impairment, with six studies appearing to use the terms ‘cognitive impairment’ and ‘dementia’ interchangeably. 59,62,68,85–87

Freedberg et al. 104 used ICD-9 coding to diagnose delirium and/or dementia under the umbrella term ‘cognitive impairment’, and did not report separate prevalence figures for delirium or dementia.

Esmayel et al. 43 evaluated a cohort with a high level of illiteracy and did not adequately distinguish between educational attainment levels that would potentially affect MMSE scores.

Dementia outcomes

Mortality

Outcomes in respect of dementia are summarised in Appendix 3, Table 31. Mortality was reported as an outcome in respect of dementia in 16 studies. 12,42,55,56,77,90,97,105–113

Nine studies reported in-hospital mortality. 42,55,77,90,97,105,106,110,111 Seven studies reported post-discharge mortality. 56,105,107–109,112,113

One study reported a statistical difference in in-hospital mortality rates between patients with dementia and delirium, with a higher mortality rate among delirious patients. 97 Four studies found that in-hospital mortality was independently predicted by dementia. 12,42,77,110 Aminoff77 examined the role of suffering in patients, as measured by the Mini Suffering State Examination (MSSE), with advanced dementia in relation to mortality. Significantly higher MSSE scores were reported in the non-surviving patients than in the surviving patients. A higher MSSE score was a significant risk factor for mortality in multivariate analysis.

Forasassi et al. 111 found no statistically significant association between dementia and in-hospital mortality in univariate analysis. Dementia did not predict in-hospital mortality using multivariate analysis in four studies. 55,90,105,106

Three studies did not find a significant association between dementia and discharge mortality after adjusting for confounders. 105,112,113 Zekry et al. 105 noted vascular or severe dementia to be associated with short- and long-term mortality. However, when vascular dementia was adjusted for in multivariate analysis, the effect of dementia (regardless of its aetiology) was not associated with in-hospital, 1-year post-discharge or 5-year post-discharge mortality.

Two studies found a significant relationship between dementia and post-discharge mortality. 107,108 Sampson et al. 107 found an association for dementia and post-discharge mortality and an association for patients with moderately severe and severe dementia after multiple adjustment. However, after adjusting for Waterlow (pressure sore risk) score, this association was no longer significant. Ponzetto et al. 108 reported a significant difference in mortality up to 5 years post discharge stratified by dementia status.

Length of hospital stay

Nine studies reported length of hospitalisation as an outcome in respect of dementia. 17,18,20,21,74,81,97,109,114 All but one study established an association between LoS and dementia. 109 Two studies did not report associations. 74,81

Wancata et al. 21 found that LoS was predicted by dementia in patients grouped into two subtypes of dementia displaying either cognitive or non-cognitive symptoms. Saravay et al. 114 reported each of eight behavioural and mental manifestations and complications associated with delirium, dementia and cognitive impairment to be significantly associated with increased LoS. McCusker et al. 109 did not find a significant association between presence of dementia and LoS in a cohort of delirious patients.

Nursing/care home admission and hospital re-admission

Five studies reported admission to care/a nursing home as an outcome for dementia. 21,45,78,94,115 All studies, with one exception,94 found a significant association between dementia and nursing/care home admission. McCusker et al. 94 specifically found increased odds of long-term institutional transfer for at least 12 months after admission when patients presented with both delirium and dementia compared with dementia alone. Marengoni et al. 45 reported that admission to a nursing home or rehabilitation were each independently predicted by dementia after adjustment for confounders. Di Iorio et al. 85 reported that hospital re-admission within 3 months of discharge was associated with dementia, after adjustment.

Functional status

Five studies examined the relationship between dementia and functional status. 71,94,99,109,116 McCusker et al. 94,109 reported poorer functional status among demented patients than among non-demented patients at the 12-month follow-up with both the independent activities of daily living (IADL) and the Barthel Index (BI). Orsitto et al. 99 reported functional status to be worse in those with dementia than in those with MCI or no dementia. Dementia was associated with poorer functional status in all studies except McCusker et al. ,109 which did not examine any associations.

Cognitive status

McCusker et al. 94 reported that patients with dementia had worse MMSE scores over time than those without the condition. The effect of delirium on MMSE scores at follow-up was significant among patients with and patients without dementia. At enrolment, patients with only delirium had worse MMSE scores than those with only dementia, but patients with only delirium showed more improvement at follow-up than those with only dementia. McCusker et al. 109 found that MMSE scores were significantly lower at the 12-month follow-up in the dementia group.

Other

Two studies reported health-care costs as an outcome for dementia. 20,81 Torian et al. 20 reported no significant difference in net hospital profits and losses between patients with and patients without dementia. Briggs et al. 81 reported average hospital care costs as being three times higher per patient with dementia than per patient without dementia.

Delirium outcomes

Mortality

Outcomes in respect of delirium are summarised in Appendix 3, Table 32. A total of 38 studies reported mortality, which was expressed differently depending on the study: chiefly in-hospital and/or post-discharge mortality. 49,55–57,59,60,63,66,69,70,73,90,92,94–97,109,112,113,116–131 It was also reported as a composite outcome and, less frequently, as survival rates/mean number of days survived.

Sixteen papers examined the unadjusted association between delirium and in-hospital or post-discharge mortality. Of these, 12 studies reported higher in-hospital death rates in presence of delirium, all of which reached statistical significance. 49,59,60,92,95–97,123–125,127,130 The remaining four studies examined delirium and post-discharge mortality rates, all of which reported a significant association. 60,63,92,130 McAvay et al. 63 revealed statistically significant higher death rates for patients whose delirium was not resolved at discharge than for patients with resolved delirium on 1-year discharge, and a significantly higher mean number of days of survival in resolved cases.

Kolbeinsson and Jónsson97 found a higher in-hospital mortality rate among patients with delirium than among those with dementia. Reports of mortality were not unanimously higher in patients with delirium. Boustani et al. 129 reported no significant difference in survival rates between those with and those without delirium at 30 days post discharge. O’Keeffe and Lavan122 found no statistically significant difference in in-hospital mortality rates between subtypes of delirium. Adamis et al. 130 found no significant difference in in-hospital mortality rates delirious patients and non-delirious patients (incident or prevalent). This was the same at 6 months post discharge, at which point delirium severity also failed to show an association with mortality. Two studies reported relative death rates in delirious patients and non-delirious patients, but did not examine an association between delirium and in-hospital mortality. 66,94

Delirium independently predicted post-discharge mortality in eight studies after adjustment for confounders. 26,63,69,113,119,124,126,128 In five studies, delirium did not independently predict post-discharge mortality after adjustment for confounders. 112,116,120,121,123

Delirium was a predictor of in-hospital mortality after multiple adjustments in five studies. 90,118–120,126 Eeles et al. 126 reported in-hospital and post-discharge mortality, and established an association between index admission, 1-year and 2- to 5-year post-discharge mortality and delirium. Jitapunkul and Hanvivadhanakul49 observed ‘history of acute confusion’ as a significant predictor for mortality after controlling for multiple confounders. Delirium did not independently predict in-hospital mortality in three studies. 55,73,121

White et al. 117 found that low levels of plasma esterase activity in delirious patients – regardless of whether delirium was acquired in hospital or present on admission – were significantly associated with increased in-hospital mortality. Two studies used a predictive model to predict mortality in delirious patients. 56,130 Adamis et al. 130 found no relationship between in-hospital and post-discharge mortality and delirium.

Seven studies examined mortality as a composite outcome. 63,69,70,92,122,127,128 Cole et al. 69 used a composite outcome (death and institutionalisation post discharge) to examine its association with non-recovery from SSD. Non-recovered SSD predicted death and institutionalisation at 6 and 12 months post discharge. Lam et al. 70 reported that rSSD on discharge was predictive of inpatient mortality or incident institutionalisation on discharge. O’Keeffe and Lavan122 examined the percentage of deaths among subtypes of delirium (hypoactive, agitated, mixed or no delirium) and found no significant difference in mortality between these groups. Buurman et al. 128 found the composite outcome (mortality or functional decline) to be independently predicted by delirium. Dasgupta and Brymer127 reported that delirium severity as measured by the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (mDAS) was independently predictive of poor recovery (functional decline, institutionalisation or death). Hsieh et al. 92 established one episode of delirium as independently associated with increased odds of unanticipated intensive care unit (ICU) admission or in-hospital mortality. In addition, delirium persisting for all 3 days of admission was independently associated with decline in discharge status (defined as discharge to care or in-hospital mortality). Using a composite outcome of nursing home placement and mortality, McAvay et al. 63 reported a greater risk for delirious patients at discharge of dying or being institutionalised than for those who were never delirious and those whose delirium resolved.

Length of hospitalisation

Twenty-eight studies55,59,60,63,66,70,73,74,79,83,92,96,97,109,119–122,124–127,129,131–135 examined LoS as an outcome. Twenty studies established a statistically significant association between delirium and length of hospitalisation. Five studies79,120,121,132,133 that adjusted for confounders reported delirium as independently predictive of duration of hospitalisation. One study134 found incident delirium and non-prevalent delirium to be predictive of LoS after adjustment. Basic and Khoo74 reported that absence of delirium predicted a short LoS.

Functional status

Thirteen studies66,70,71,83,94,109,112,116,121,124,125,131,136 reported functional status as an outcome for delirium, expressed as ADL scores. An additional three studies69,127,128 reported on functional status as a composite outcome. One further study120 reported care needs after discharge.

Two studies83,125 reported no significant difference in functional dependency scores between delirious patients and non-delirious patients. González et al. 124 found a significant association between functional status (ADL) and delirium. Lam et al. 70 observed that patients without rSSD had significantly higher functional independence at admission and discharge and showed a faster rate of improvement in functional status than those with rSSD. However, the magnitude of change in functional recovery observed at discharge was not statistically different between those with and those without rSSD. McCusker et al. 109 reported that patients with transient delirium had significantly worse BI/IADL scores at follow-up than those with recovered delirium, and those with persistent delirium had worse functional outcomes than recovered patients. Wakefield66 showed a decline in discharge functional status in patients who developed acute confusion during hospitalisation, although this did not reach significance.

Seven studies94,109,112,116,120,121,136 used multivariate analysis to examine the relationship between delirium and functional status. All but two studies94,136 reported delirium as independently predictive of functional dependency.

Cognitive impairment

Seven studies69,70,94,109,112,125,137 that examined cognitive impairment (measured with the MMSE) as an outcome for delirium reported a significant difference in those whose MMSE scores improved compared with those who showed no improvement, according to delirium severity rather than delirium status. Feldman et al. 125 found a significant difference in MMSE score stratified by delirium status on discharge, compared with premorbid scores, and Lam et al. 70 found that cognition improved more slowly in those with rSSD. Cole et al. 69 established that MMSE score – a constituent item of a hierarchical composite outcome – was independently predicted by non-recovery from rSSD. Francis and Kapoor112 found that cognitive status declined more significantly in delirious patients than in non-delirious patients in adjusted multivariate logistic regression. McCusker et al. 94 found that, over time, patients with both delirium and dementia had the worst MMSE scores and those who had neither condition had the best MMSE scores. On enrolment, patients with delirium only had worse MMSE scores than those with dementia only, but patients with delirium only showed greater improvement at follow-up than those with dementia only. After adjusting for covariates, all four groups showed small but statistically significant declines in MMSE scores from 2 to 12 months. McCusker et al. 109 found that those with persistent delirium had significantly worse MMSE scores at follow-up than those with recovered delirium. In terms of the clinical course of delirium, McCusker et al. 109 differentiated between transient, recovered and persistent symptoms of delirium present at discharge. Lam et al. 70 reported that rSSD patients improved more slowly in delirium severity than non-rSSD patients. Martínez-Velilla et al. 116 reported persistent delirium at follow-up as being significantly associated with previous episodes of delirium.

Nursing/care home admission and discharge status

Eleven studies59,68,92,94,96,97,115,120,121,126,129 examined nursing/care home admission post discharge. Four papers63,69,70,127 included nursing/care home admission as a composite outcome. Hsieh et al. 92 examined the rate of nursing home discharge in both delirious patients and non-delirious patients in addition to multivariate analysis examining the decline in discharge to a higher level of care, in discharge to a hospice or in-hospital deaths. Two papers66,83 examined the outcome of discharge status. Two papers60,73 examined home discharge as an outcome. Pendlebury et al. 120 examined hospital re-admission within 30 days as an outcome.

Three studies60,96,129 reported higher rates of discharge to home among non-delirious patients than among delirious patients. Eeles et al. 126 reported higher rates of care home placement post discharge among delirious patients, which were statistically significant for up to 2 years from admission. One study97 did not find differing institutionalisation rates between patients with dementia and delirium.

In nine studies, delirium predicted institutionalisation after adjustment for confounders. Discharge status decline was independently predicted by persistence of delirium for 3 days after adjustment for age and premorbid cognitive impairment in Hsieh et al. 92 However, after multiple adjustment, this association failed to reach significance. Bourdel-Marchasson et al. 68 established prevalent, incident and subsyndromal delirium as independent predictors of institutionalisation. Lam et al. 70 found rSSD to independently predict nursing home admission or mortality. Four studies59,73,120,121 reported delirium as independently predictive of care home placement. Cole et al. 69 reported death or institutionalisation at 6 months post discharge as independently predicted by non-recovery from SSD. McAvay et al. 63 and Lam et al. 70 reported delirium as independently predictive of nursing home admission or mortality. Dasgupta and Brymer127 reported that delirium severity predicted institutionalisation as part of a composite outcome, and reported a significant difference in care home admission rates between delirious patients and non-delirious patients. Two studies94,115 did not identify delirium as independently predictive of nursing home admission after adjustment.

Other outcomes

No papers examined health-care costs in respect of delirium. O’Keeffe and Lavan121 found that in-hospital delirium was the strongest predictor of developing a hospital-acquired complication. Hsieh et al. 92 reported a number of outcomes in respect of delirium (see Appendix 3, Table 32).

Cognitive impairment outcomes

Mortality

Outcomes associated with cognitive impairment are shown in Appendix 3, Table 33.

A total of 13 studies reported mortality as an outcome for cognitive impairment, six of which examined in-hospital mortality and six of which examined post-discharge mortality. 12,105,108,138–142 One study104 examined death rates per person per year in respect of in-hospital, post-discharge and cumulative mortality. One study143 reported probability of survival for up to 5 years after discharge. The MMSE was the most frequently used diagnostic tool for cognitive impairment, with lower scores representing greater impairment.

Three studies12,138,140 reported an association between cognitive impairment and in-hospital mortality even after multiple adjustment for confounders. In addition, Freedberg et al. 104 reported in-hospital death rates per person per year, establishing a significant association with cognitive impairment after adjustment for confounders. Two unadjusted analyses108,139 revealed an association between mortality and cognitive impairment. Zekry et al. 105 reported only death rates among cognitively impaired patients.

Of six studies investigating post-discharge mortality and cognitive impairment, one140 found no association. Torisson et al. 142 found that cognitive impairment independently predicted post-discharge mortality. Espallargues et al. 138 reported an unadjusted association between cognitive impairment and the composite outcome of in-hospital mortality and mortality 1 month after discharge. Fields et al. 139 did not examine an association but reported mortality rates among cognitively impaired patients. Freedberg et al. 104 reported a significant association between post-discharge and cumulative death rates per person per year and cognitive impairment, after adjustment. Conde-Martel et al. 143 reported that post-discharge survival for up to 5 years was independently predicted by normal cognitive status.

Length of hospital stay

Eight papers44,84,86,114,138,139,144,145 reported LoS as an outcome. All papers except Forti et al. 145 found a significant association between cognitive impairment and length of hospitalisation.

Composite outcomes

Two papers138,145 used composite outcomes that included mortality. Espallargues et al. 138 used a composite of in-hospital mortality and mortality 1 month post discharge and Forti et al. 145 used unfavourable discharge (death plus any other ward discharge disposition other than return home). In both studies, cognitive impairment was significantly associated with a worse outcome.

Functional status

Three papers54,99,146 examined the association between cognitive impairment and functional status. Two papers54,146 established an association between cognitive impairment and poor functional status. Marengoni et al. 146 examined this association between two age groups and found that low MMSE scores, high depression rates and high disease severity rates predicted functional status in the oldest old age group. Low MMSE scores and depression rates showed an additive association with functional disability, particularly in younger patients. Orsitto et al. 99 examined functional status (ADL and IADL) in those with dementia and those with MCI, reporting functional status as significantly poorer in those with dementia than in those with no dementia or MCI.

Discharge destination, nursing home admission and hospital re-admission

Marengoni et al. 45 examined discharge destination to nursing home, rehabilitation unit or home, and three papers139,147,148 examined admission to a nursing/care home post discharge. Two papers85,138 reported hospital re-admission.

Helvik et al. 147 recorded an association between low MMSE score and care home admission. Joray et al. 148 found an adjusted association between institutionalisation and cognitive impairment in detected cases of cognitive impairment, and not when cognitive impairment was present but previously undetected, which represented the less severe cases of impairment. Fields et al. 139 did not examine associations and reported only rates of nursing home admission stratified by cognitive status. For hospital re-admission post discharge, Espallargues et al. 138 found no association for post discharge (collective follow-up period: 4 months). Di Iorio et al. 85 reported an adjusted association between early re-admission (within 3 months) and cognitive impairment. Marengoni et al. 45 reported that cognitive impairment determined admission to a rehabilitation unit but only in functionally impaired patients.

Cognitive decline

Two studies98,141 examined the course of cognitive impairment. Inouye et al. 141 reported that higher educational level, pre-admission functional impairment and higher illness severity were predictive of recoverable cognitive dysfunction (RCD) after adjusting for MMSE score. Bickel et al. 98 noted the positive predictive value of MCI in determining cognitive impairment at discharge, particularly for those with multiple-domain MCI.

Delirium superimposed on dementia outcomes

Appendix 3, Table 34, outlines outcomes for DSD. Two studies examined outcomes for DSD. 79,94 McCusker et al. 94 showed that those presenting with both delirium and dementia had a poorer cognitive status and were more likely to be admitted to long-term care than those with neither condition. Lang et al. 79 identified DSD as a marker for prolonged hospital stay.

Methodological limitations

Quality of studies

Variation in the quality of studies in a systematic review is a limitation. From the assessment of the quality of the 141 selected studies, we would recommend that future studies in related areas ensure that, from the outset, they give a clear description of the population, the method of sampling and the condition(s) studied, with adjustments for any confounding factors; that a standardised tool for diagnosis of dementia and other risk factors is used; and, finally, that the study clearly explains statistical methods and clinically significant associations.

We defined a high-quality study as one that dropped no more than 1 point in our assessment. From the 141 studies, 63 studies12,21,45–48,53,56,61,64,65,69,70,74,84,98,103–105,107,110,112–115,118,120,121,123,124,128–132,134,136–162 scored high in our quality assessment. A further 22 studies57,58,62,67,68,73,78,88,94,100,109,111,119,126,133,163–169 were classified as good, which we defined as dropping 2 or 3 points. The remaining 56 studies17–20,26,41–44,49–52,54,55,59,60,63,66,71,72,75–77,79–83,85–87,89–92,95–97,99,102,108,116,117,122,125,127,135,170–177 dropped ≥ 4 points, scoring low in our quality assessment. A review of these studies showed that the most common study deficiency is a lack of or insufficient description of presence of condition and/or adjustment for confounding factors. Twenty-four studies did not contain this description and 16 studies gave only partial information about this. Apart from this, the study factors most commonly in need of improvement were clear explanation of statistical methods and clinically significant associations (10 did not and 22 only partially); use of a structured/standardised tool for definition of dementia and other risk factors (11 did not and eight only partially); clear description of the process of sampling and selecting patients (five did not and 26 only partially); and clear and detailed description of the characteristics of the population (five did not and 23 only partially).

Prevalence of delirium and delirium superimposed on dementia

There was considerable heterogeneity in the diagnostic tools used to assess delirium. In addition, some studies did not distinguish between prevalent and incident cases as assessment of delirium was conducted in one session rather than routinely. 60 This variation in approaches and tools used can affect the reliability of prevalence estimates.

Delirium has previously been reported to be under-recognised in older hospitalised patients. 93 The reliance on discharge codes in retrospective studies also typically leads to a higher underestimation risk. Underdiagnosis of delirium may also arise from lack of awareness of the fluctuative course of delirium and its potential overlap with dementia; thus, comprehensive cognitive assessment is necessary for distinguishing disorders with overlapping symptoms. Forty-nine studies that screened for dementia also screened for delirium, increasing the overall reliability of prevalence estimates, but when studies did not separately screen for each condition, an underestimate of delirium may have arisen in favour of dementia diagnosis.

Delirium superimposed on dementia is typically characterised by premorbid dementia followed by an acute mental change in which delirium is suspected. Previously, studies reported that delirium is underdetected in older hospitalised patients. 93 The potential risk factors for under-recognition of delirium by nursing staff are dementia and the hypoactive form of delirium, the onset of which does not necessarily elicit a distinctly recognisable change in mental status. 178

The variation in assessment tools used to detect delirium and dementia also influences the wide range of prevalence estimates for DSD reflected in the included studies. For example, Bellelli et al. 55 reported that the ICD-9 has poor diagnostic accuracy for delirium, and Johnson et al. 179 found the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition (DSM-III), to have greater diagnostic accuracy than the ICD-9. Of the included papers reviewed in which DSD was formally documented, one study did not assess the premorbid existence of dementia using a validated tool, such as the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE), which meant that neurocognitive deficits attributed to delirium could not be reliably differentiated from those in dementia. 55

Although the majority of studies used validated tools to assess delirium, there was no comment specifically on the diagnostic accuracy of those tools in the context of patients with dementia. In addition, when studies did not continually assess delirium to record incident cases, it was difficult to assess the epidemiological impact of delirium on those with dementia had there been serial cognitive testing.

In summary, to recognise cases of DSD it is important to conduct a baseline assessment of dementia, whereby medical staff have full clarity and recognition of the symptoms pertinent to dementia. This must be supplemented with the ability to differentiate between this baseline status and symptoms characteristic of an acute mental change attributed to delirium. Dementia is a risk factor for delirium and the co-existence of these conditions leads to poor prognostic outcomes. It is thus imperative that consensual, comprehensive assessment approaches are undertaken using validated tools in the context of DSD in order to improve diagnostic accuracy in these groups.

Prevalence of dementia

Of 80 studies that screened for dementia, 49 also screened for delirium. The prevalence of dementia may be overestimated in studies not also screening for delirium.

Studies not including patients who were too ill to give informed consent or without proxies may exclude those at most risk of having pre-existing dementia, leading to selection bias, which affects prevalence estimates.

The high prevalence of mixed and vascular dementia reported in studies can be attributed to hospital setting; for example, more stroke patients are likely to be admitted to acute hospital settings or exhibit higher cardiovascular comorbidity. 13

Prevalence of cognitive impairment

Seven papers used inconsistent terminology to distinguish ‘cognitive impairment’ and ‘dementia’, used the terms interchangeably or did not make separate diagnoses for each condition. According to the majority of studies screening for cognitive impairment, there is a consensus that cognitive impairment is diagnostically exclusive of dementia or delirium, despite the fact that the three conditions share common characteristics and thus present with overlapping symptoms. Inconsistencies in the terminology adopted across studies can thus give rise to unreliable estimates of prevalence for cognitive impairment.

There is overlap in the assessment of cognitive impairment and dementia given their shared characteristics and, when studies explicitly excluded subjects with dementia from their analyses, a more reliable prevalence estimate for cognitive impairment could be achieved. When studies did not explicitly report cut-off scores in the MMSE, prevalence estimates for cognitive impairment could be biased as criteria by which cognitive impairment is diagnosed are not reported. 62 Other factors that can lead to overestimates of prevalence are the potentially inadequate conditions to appropriate detection inside a hospital setting, presence of other clinical conditions or performance difficulties not related to cognitive impairment, which can yield unreliable cognitive evaluations, for example patients failing to use glasses/hearing aids while being assessed with the MMSE. 156

Discussion

Clinical implications

Dementia and cognitive impairment

From this review, CSDs appear to result in unfavourable outcomes for patients acutely admitted to general hospitals, including in-hospital and post-discharge mortality, increased LoS and functional impairment. The variation in diagnostic methodology used can influence the strength of the observed association between dementia and mortality. Sampson et al. 12 excluded delirious patients to focus on the relationship between mortality and dementia, potentially underestimating the prevalence of those with pre-existing dementia who later presented with delirium, an established risk factor. 93 Thus, mortality may be underestimated in studies adopting similar approaches. Equally, the association may be overestimated in studies using single sites for their analyses.

One study105 did not establish dementia (of any aetiology) as a predictor of mortality after controlling for vascular dementia. It is thought that vascular dementia is associated with cardiovascular comorbidity, which could explain mortality in these populations. 105 The complexity of the relationship between dementia and poor outcomes thus requires further scrutiny.

In this review, cognitive impairment was associated with poor outcomes of increased risk of mortality, LoS, functional impairment and nursing home admission at discharge. It was also revealed that cognitive impairment is an important risk factor for the development of delirium. The routine diagnosis of cognitive status in hospital assessments would thus help identify acutely administered patients at risk of delirium.

Delirium

This review presents compelling evidence that delirium in acutely admitted older inpatients generally confers negative outcomes, such as increased risk of mortality, reduced functional status, increased LoS and referrals to care home at discharge. However, not all studies found an association between delirium and mortality. This may be attributed to the methodological heterogeneity between studies, including issues of generalisability, attrition rates, study duration, diagnostic heterogeneity (different use of tools and approaches used, including retrospective analyses), sample size variation and ensuring adequate controlling of potential confounders.

The association between rSSD/SSD and unfavourable clinical outcomes suggests that diagnostic screening should be encompassed by a multifactorial approach in consideration of its prognosis and management. In addition, our review showed that delirium was predicted by demographic factors, infections, nutritional status, illness and cognitive impairment. A standardised clinical diagnostic method would thus help identify the broad range of factors that place hospitalised patients at risk of delirium.

In addition, it is clear in this review that patients with delirium frequently present with low cognitive function and, over the clinical course, cognitive status improves. However, clarification is required on the complex relationship between the clinical features associated with delirium and changing cognitive function. Cognitive recovery is not simply explained by an improvement in delirium status but by a combination of factors, including demographic factors (sex), delirium severity, illness severity or change in presence of circulating biological markers. 137 The relationship between delirium and mortality may also be complex; for example, Martínez-Velilla et al. 71 reported that delirium was not independently associated with post-discharge mortality after controlling for illness severity, a significant risk factor for delirium. This suggests that delirium is a good indicator of comorbidity and that interventions require a multidisciplinary and broad factorial approach to elucidate the range of prognostic factors and aetiologies associated with delirium.

Functional decline was frequently independently associated with delirium; however, variations in the length of follow-up across studies could influence these associations as unpredicted, uncontrolled events unfold. Furthermore, when studies could not establish delirium as independently predictive of functional decline, it is possible that biological factors associated with delirium may mediate this relationship. For example, Adamis et al. 136 established that functional status was significantly affected by the biological markers apolipoprotein E (APOE), interleukin 1 alpha (IL-1α), interleukin 6 (IL-6), leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and not by delirium itself. Thus, the pathophysiology of delirium may be complex and requires consideration. 165 Accordingly, clinical interventions for delirium management necessitate a broad multifactorial approach to address the range of co-existing factors accompanying delirium.

Delirium superimposed on dementia

Few studies examined the association between DSD and outcome; thus, it was difficult to draw meaningful conclusions. Previous studies have highlighted that delirium is poorly recognised in patients with dementia. 93 DSD can be defined as pre-existing dementia accompanied by an acute mental change typical of delirium, and it can be difficult to recognise hypoactive forms of delirium, which typically manifest more ‘quiet’ symptoms of delirium and share many overlapping symptoms with dementia. 93 Early recognition and prevention of delirious symptoms in people with dementia is imperative.

Conclusion

This study systematically reviewed the prevalence and outcomes of a range of CSDs, including dementia, cognitive impairment, delirium and DSD.

There was considerable methodological heterogeneity across studies reviewed, with relatively few reporting high-quality investigations. The narrative review revealed that delirium, dementia and cognitive impairment present significant problems for acutely admitted older hospital patients. Their admissions to hospital are associated with increased mortality, low functional independence, longer hospitalisation periods and higher risk of re-admission or nursing home admission. However, it is clear that, to improve the prognosis of acutely admitted patients diagnosed with CSDs, a broad, multifactorial approach to case finding, diagnosis and subsequent management is required.

Chapter 3 Quantitative study: the Older Persons Routine Acute Assessment data set

Context

Cognitive impairment of various kinds is common in older people admitted to hospital, but previous research has usually focused on single conditions in highly selected groups and has rarely examined associations with clinical outcomes. This study examined prevalence and outcomes of cognitive impairment in a large, unselected cohort of people aged ≥ 65 years who underwent an emergency medical admission.

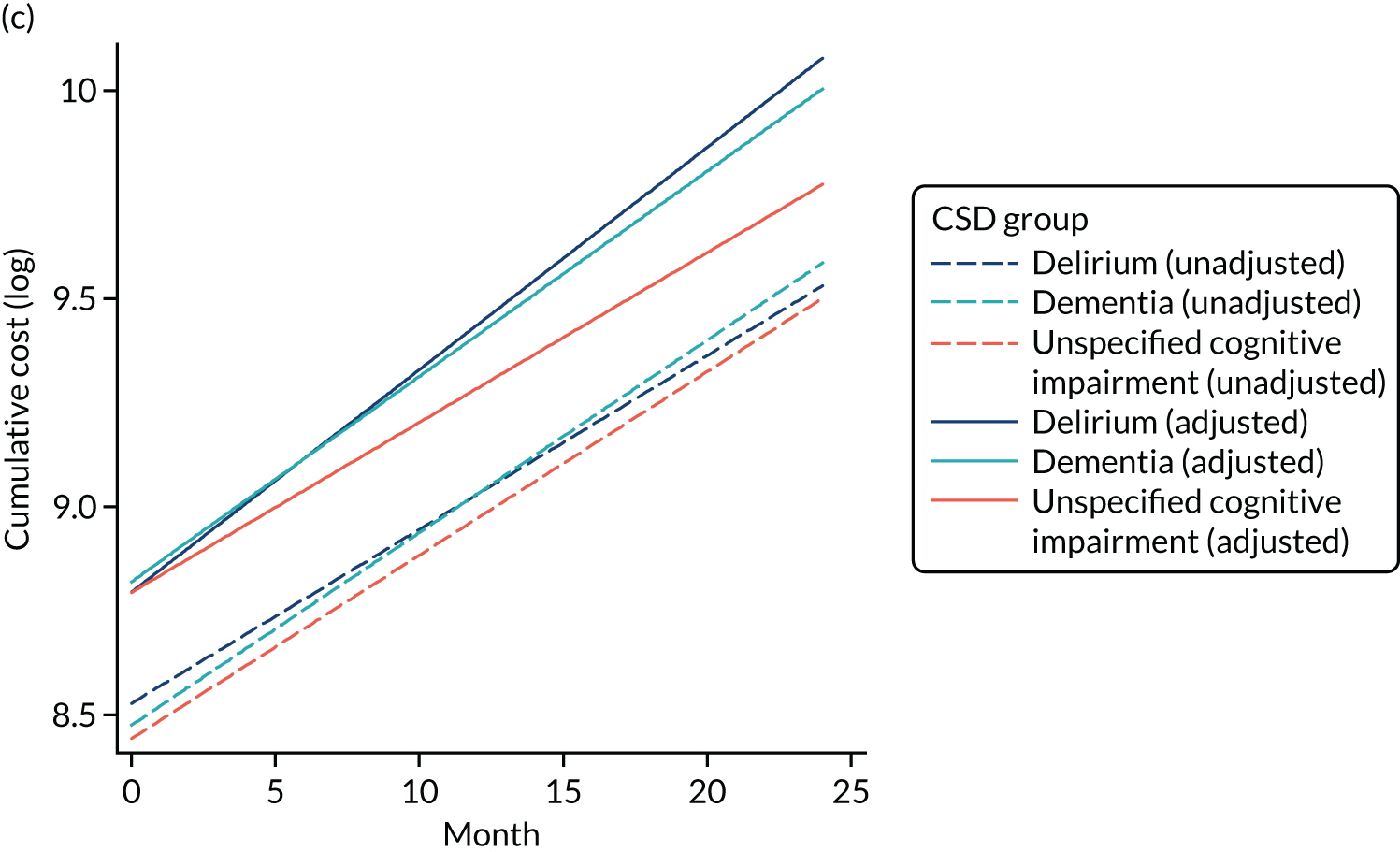

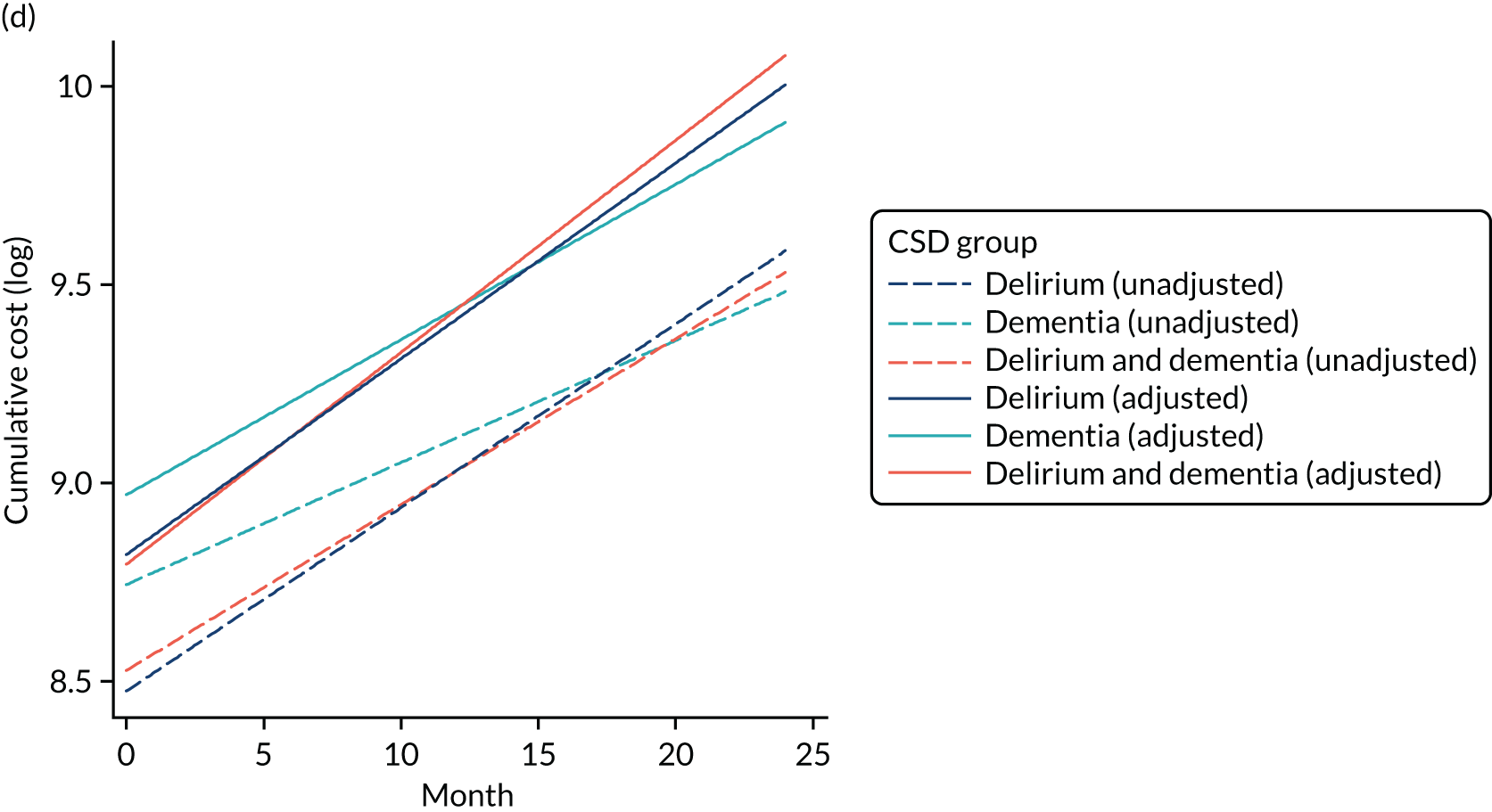

Research objectives

As stated in the protocol, the aim of this element of the work was to ‘analyse routine population-based health-care data to examine health-care and economic outcomes following hospital admission of older people with and without cognitive impairment and dementia’. This chapter reports health-care outcomes and Chapter 4 reports economic outcomes.

Data and data methods

The population studied and the Older Persons Routine Acute Assessment data set

NHS Fife provides medical care to a varied urban and rural population of ≈ 360,000 people. From January 2011, all emergency medical admissions within the health board from any source were via a single acute medical unit (AMU) at the research hospital (the only exceptions are acute stroke and acute ST segment myocardial infarction, for which admission is via specialist services). The research hospital is a district general hospital with 640 beds and a full range of health-care specialties. After AMU admission, patients are usually discharged or stepped down to appropriate medical wards after 12–24 hours. Orthopaedic trauma patients requiring surgery are admitted via the surgical admissions unit and non-operative trauma patients are admitted via the AMU.

Starting in 2009 and funded by the Scottish Government Joint Improvement Team, this health board’s Dementia Co-ordinating Group designed and implemented the Older Persons Routine Acute Assessment (OPRAA). From 2011, OPRAA was offered routinely to all people aged ≥ 65 years admitted as an emergency to a NHS hospital in this health board. By design, individuals with a predicted LoS of < 24 hours, for whom death was expected or with an acute illness requiring critical care intervention did not undergo an OPRAA.

The cohort

The design is a cohort study of all people aged ≥ 65 years with an acute medical admission to one district general hospital in Scotland, prospectively recruited to undergo an OPRAA. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in Table 3.

| Inclusion criteria (patients meeting all of the criteria below) | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Aged ≥ 65 years | |

| An emergency medical admission via the study hospital AMU under an acute medicine, general medicine and geriatric medicine specialty | Had a medical admission in the 6 months prior to the start of the study |

| Received an OPRAA | Did not receive an OPRAA (individuals with a predicted LoS of < 24 hours, for whom death was expected or with an acute illness requiring critical care intervention) |

Data for all emergency medical admissions of people aged ≥ 65 years were identified from Scottish Morbidity Records (SMR) 01 data, which is a validated NHS Scotland routine data set providing information on the date of admission and discharge, type of admission, admission and discharge destination and the patient’s main and other conditions [in the form of International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes]. An emergency medical admission was defined as an admission via the study hospital AMU under an acute medicine, general medicine or geriatric medicine specialty. Admission and final discharge date and the Community Health Index (CHI) number (the NHS Scotland unique patient identifier) were then used to link all eligible admissions in SMR01 to the OPRAA data set and to determine eligible admissions whereby patients underwent an OPRAA.

An incident cohort was further defined, comprising people aged ≥ 65 years who had received an OPRAA during their first acute medical admission within the study period, providing that they had not had an acute medical admission in the 6 months prior to the start of the study.

The study period was chosen to reflect a period when OPRAA was routine. Between 1 January 2012 and 30 June 2013, > 80% of all acute medical admissions for those aged ≥ 65 years underwent an OPRAA.

Data extracted

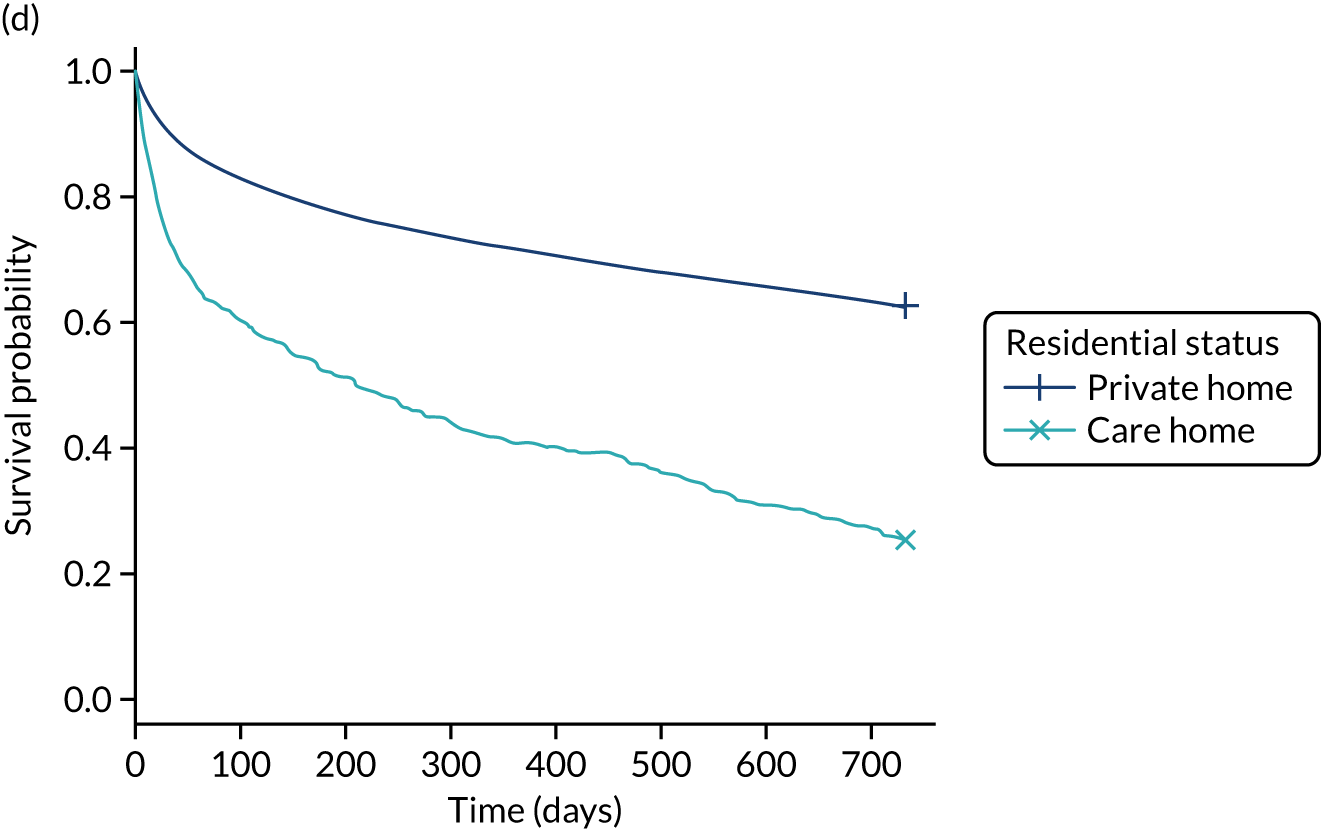

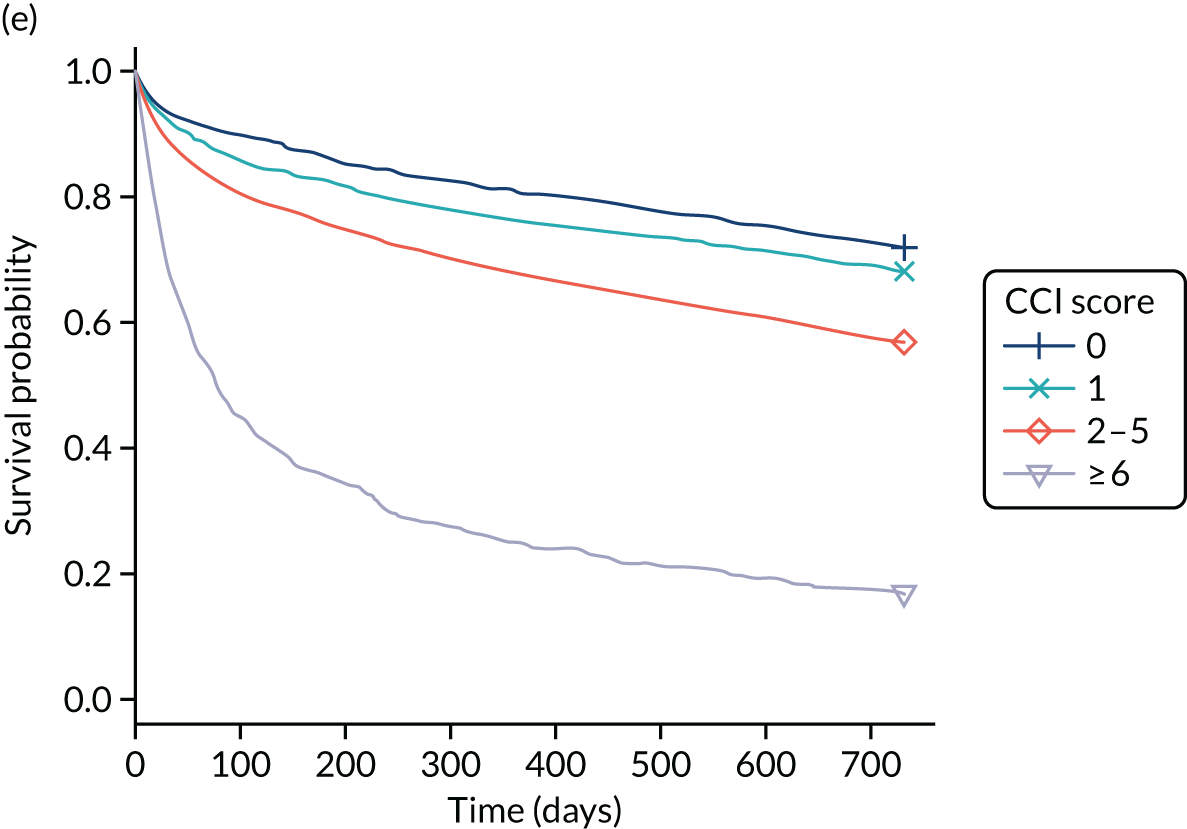

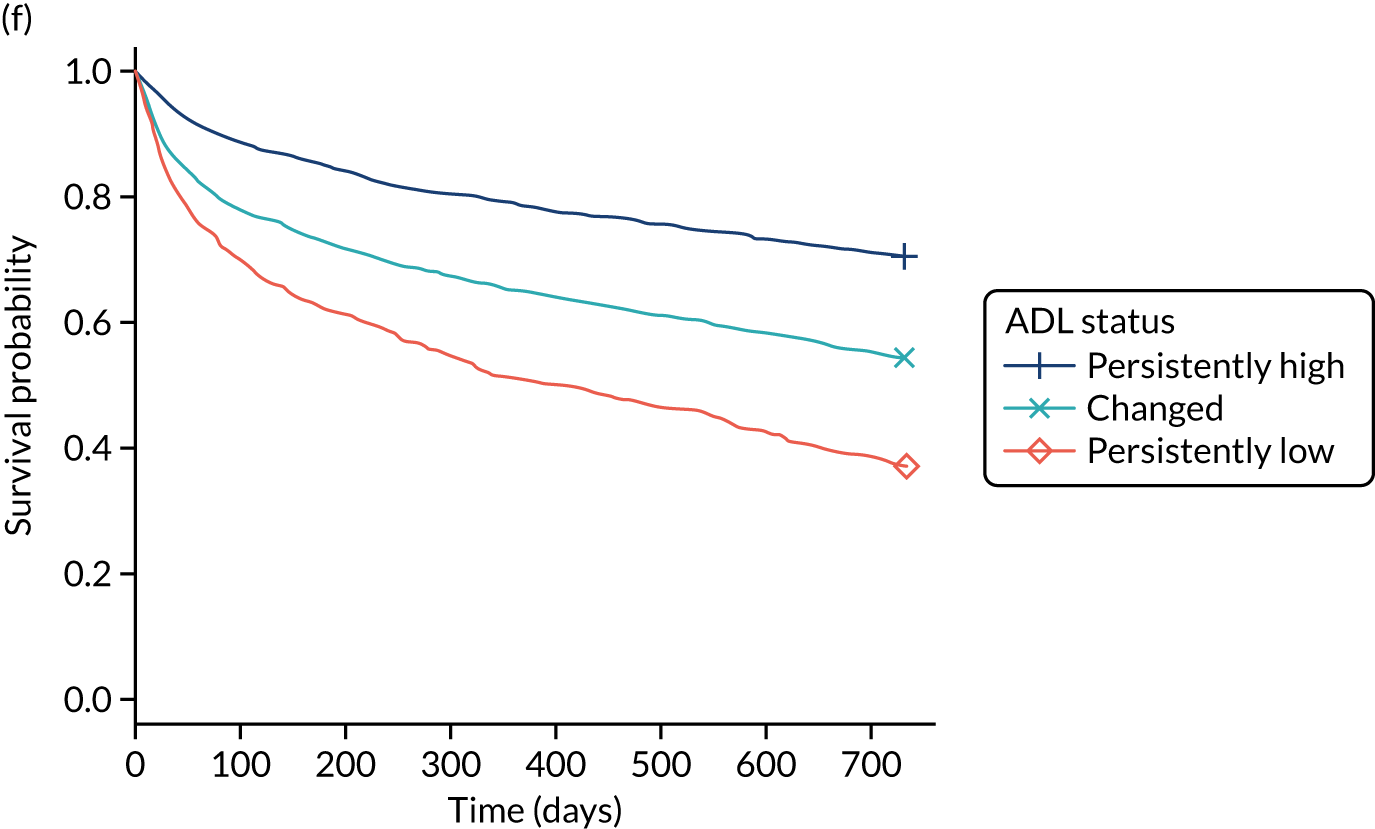

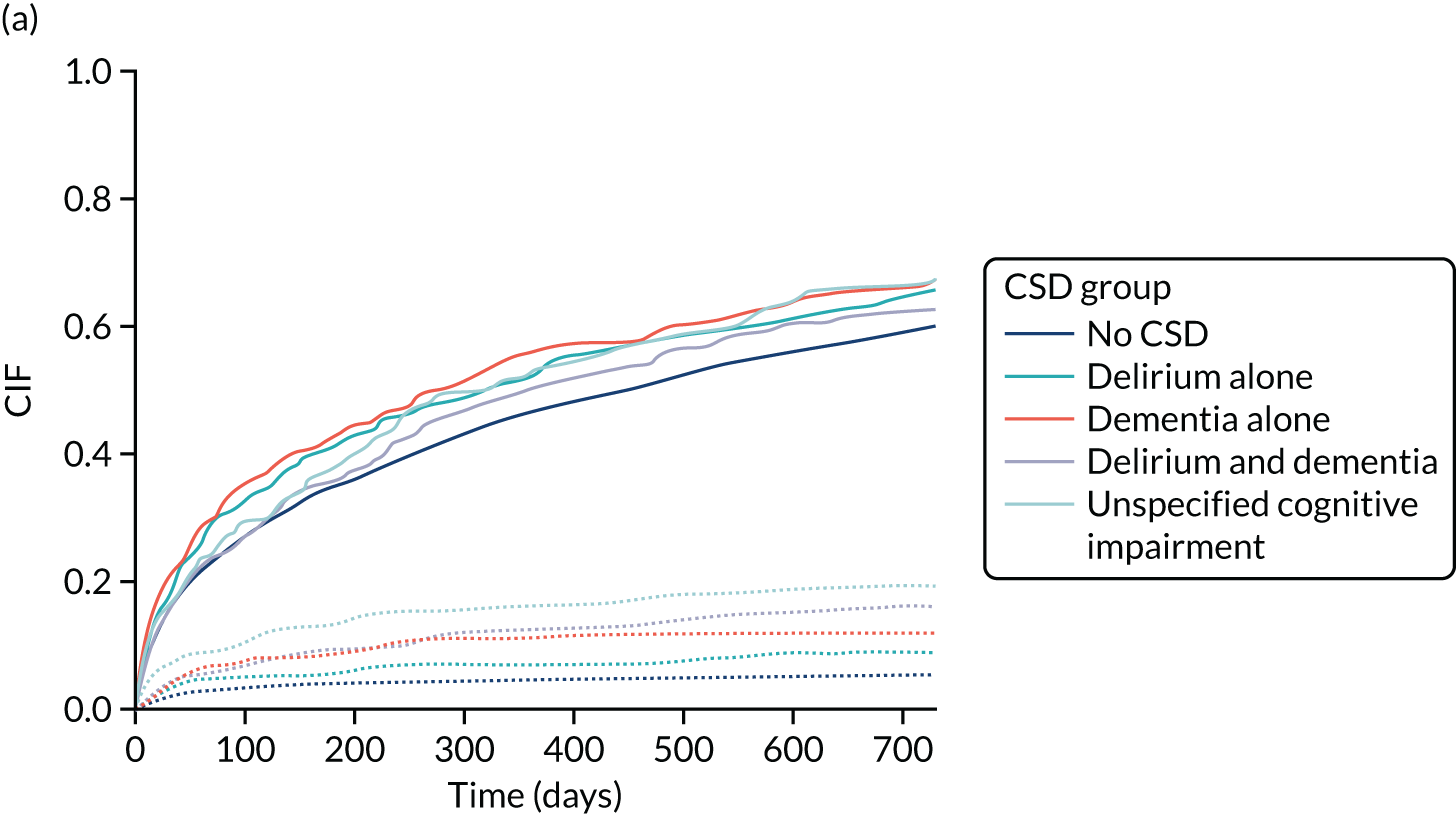

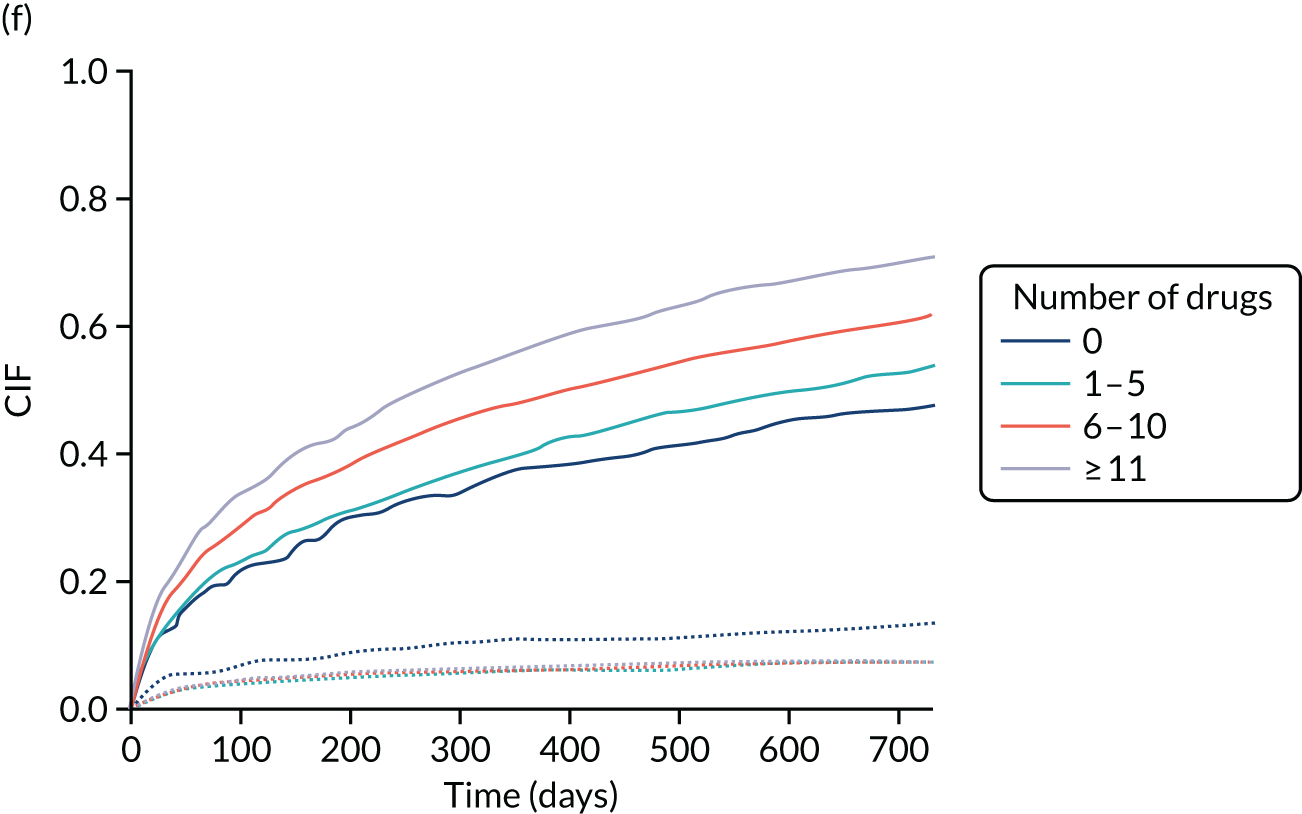

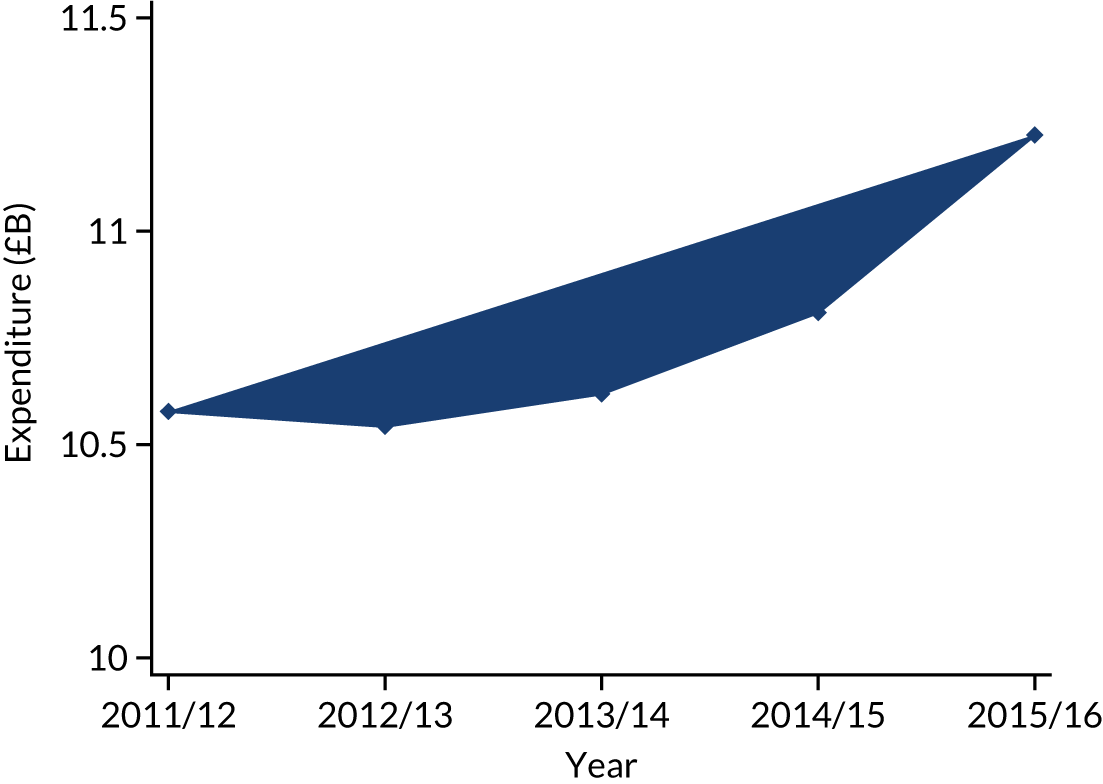

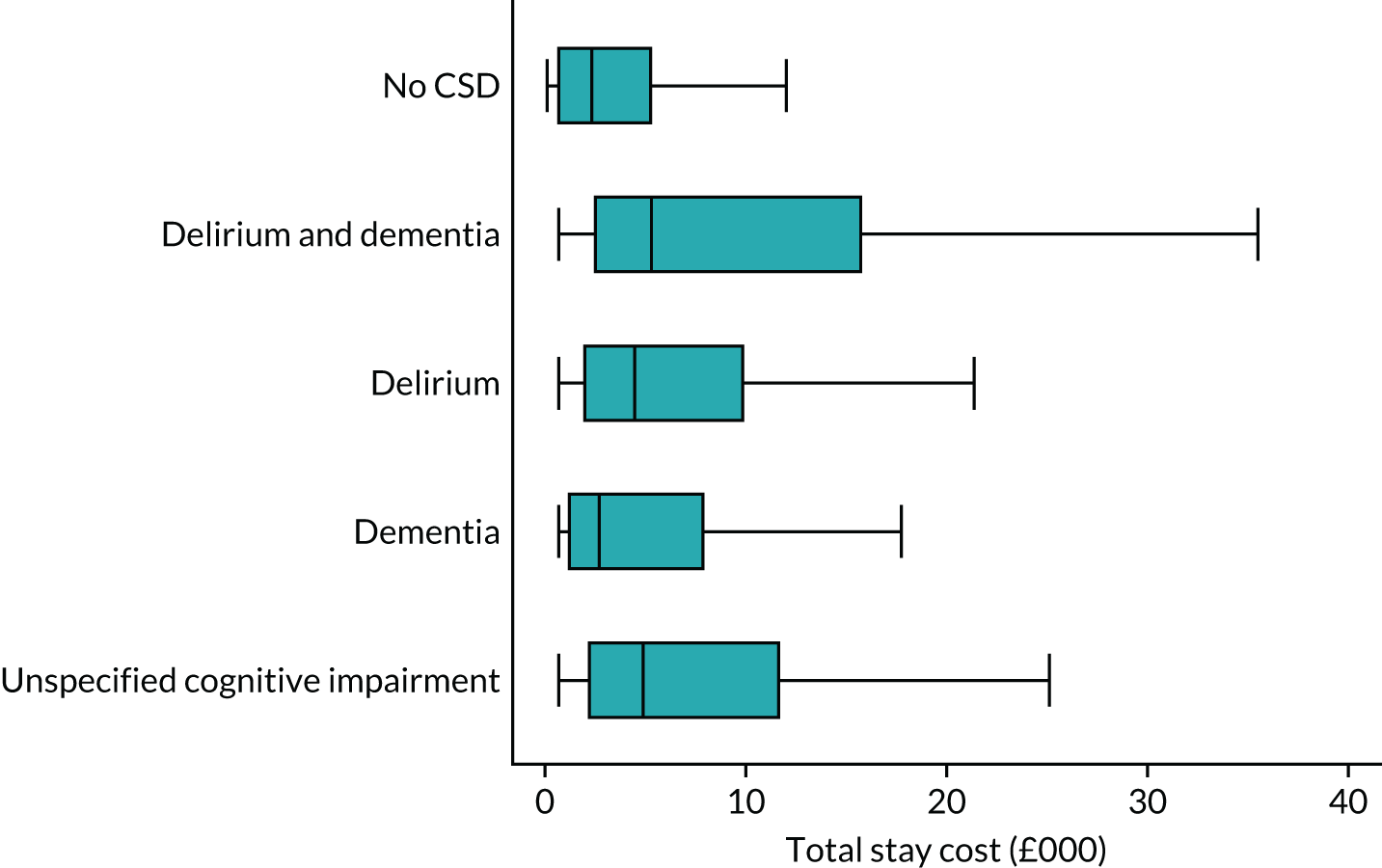

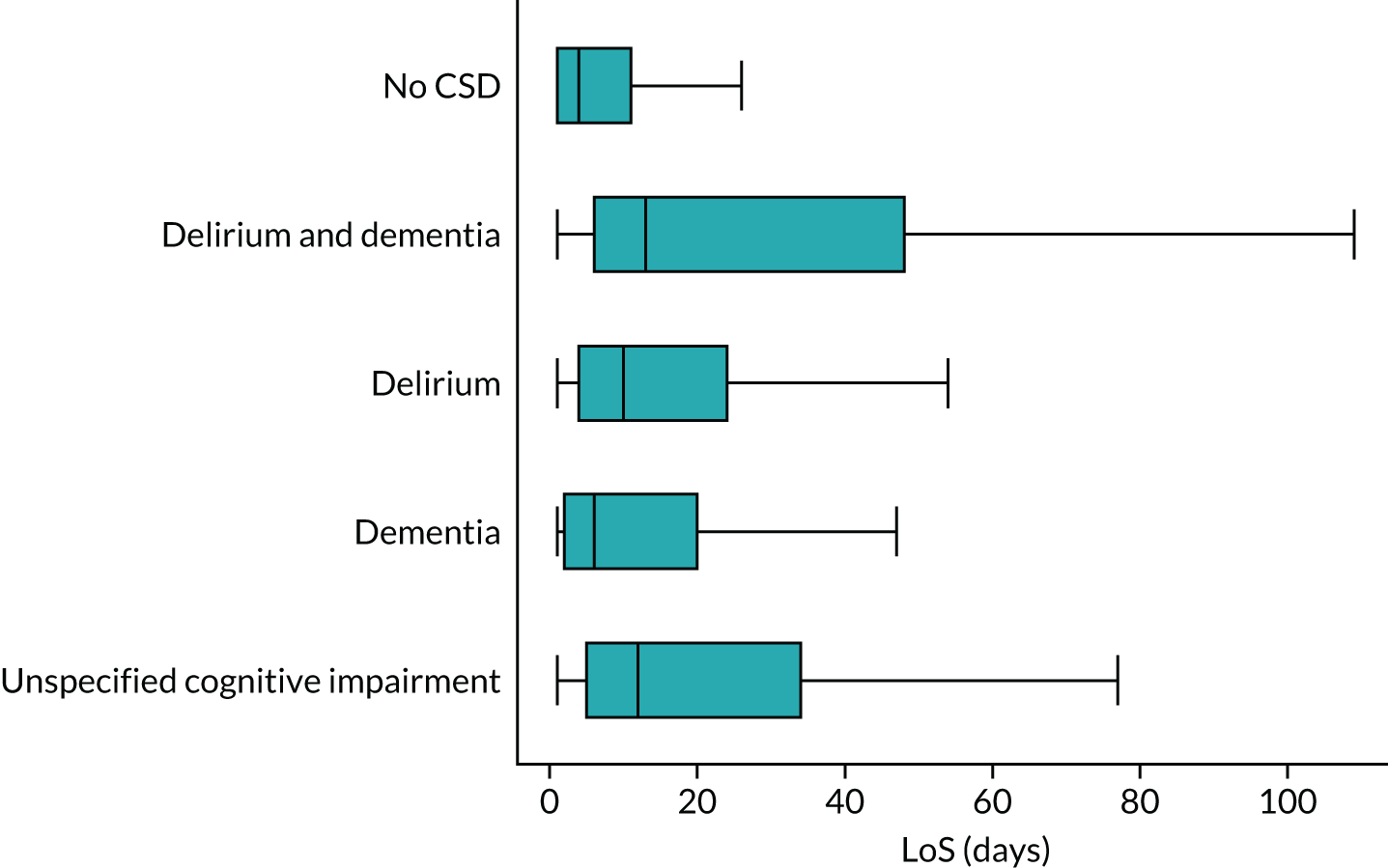

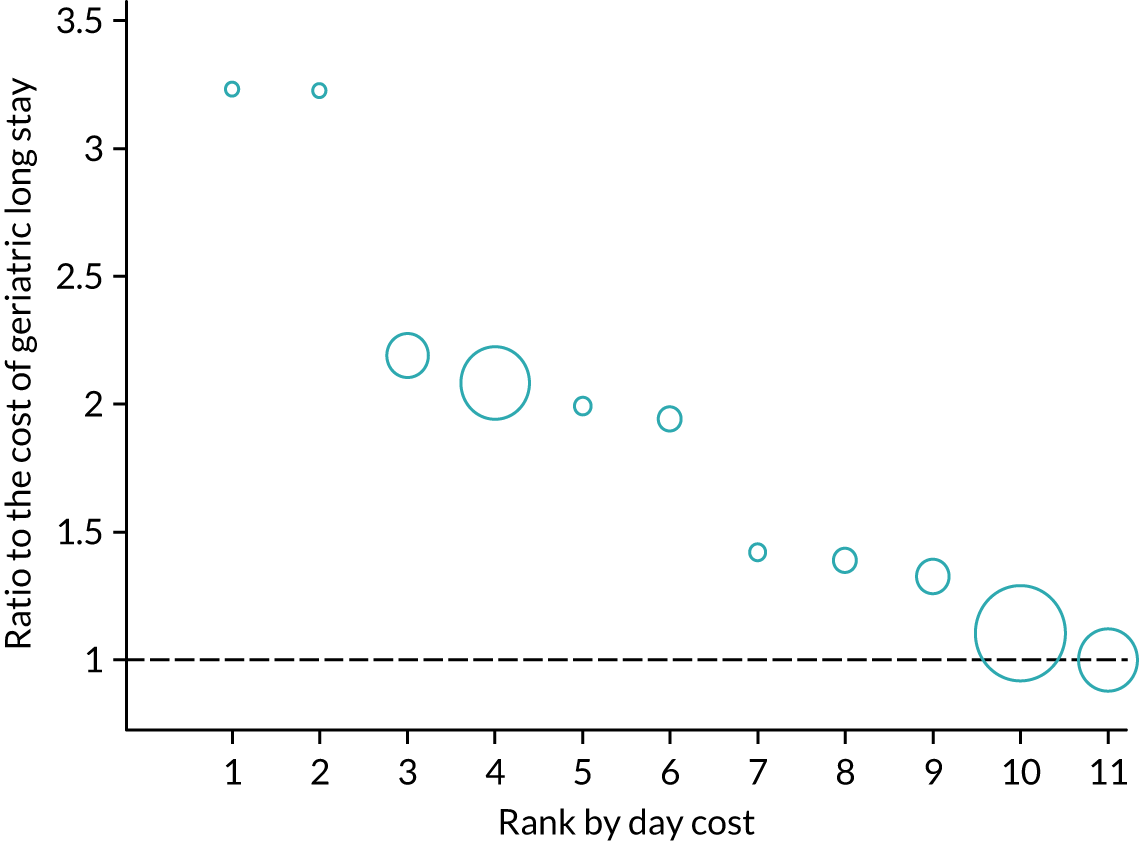

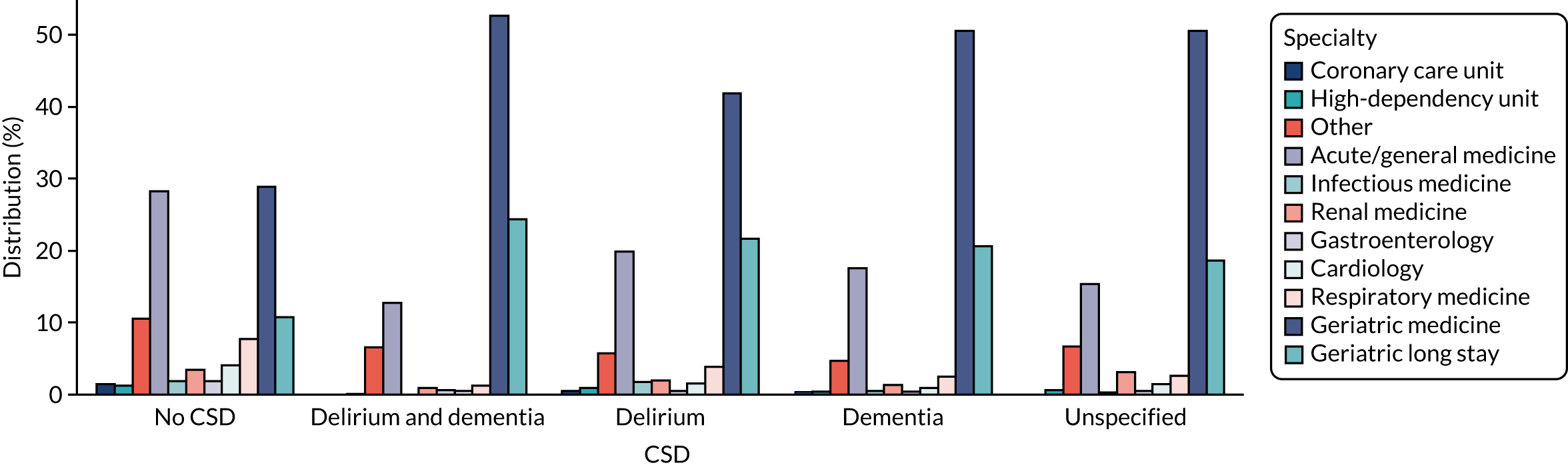

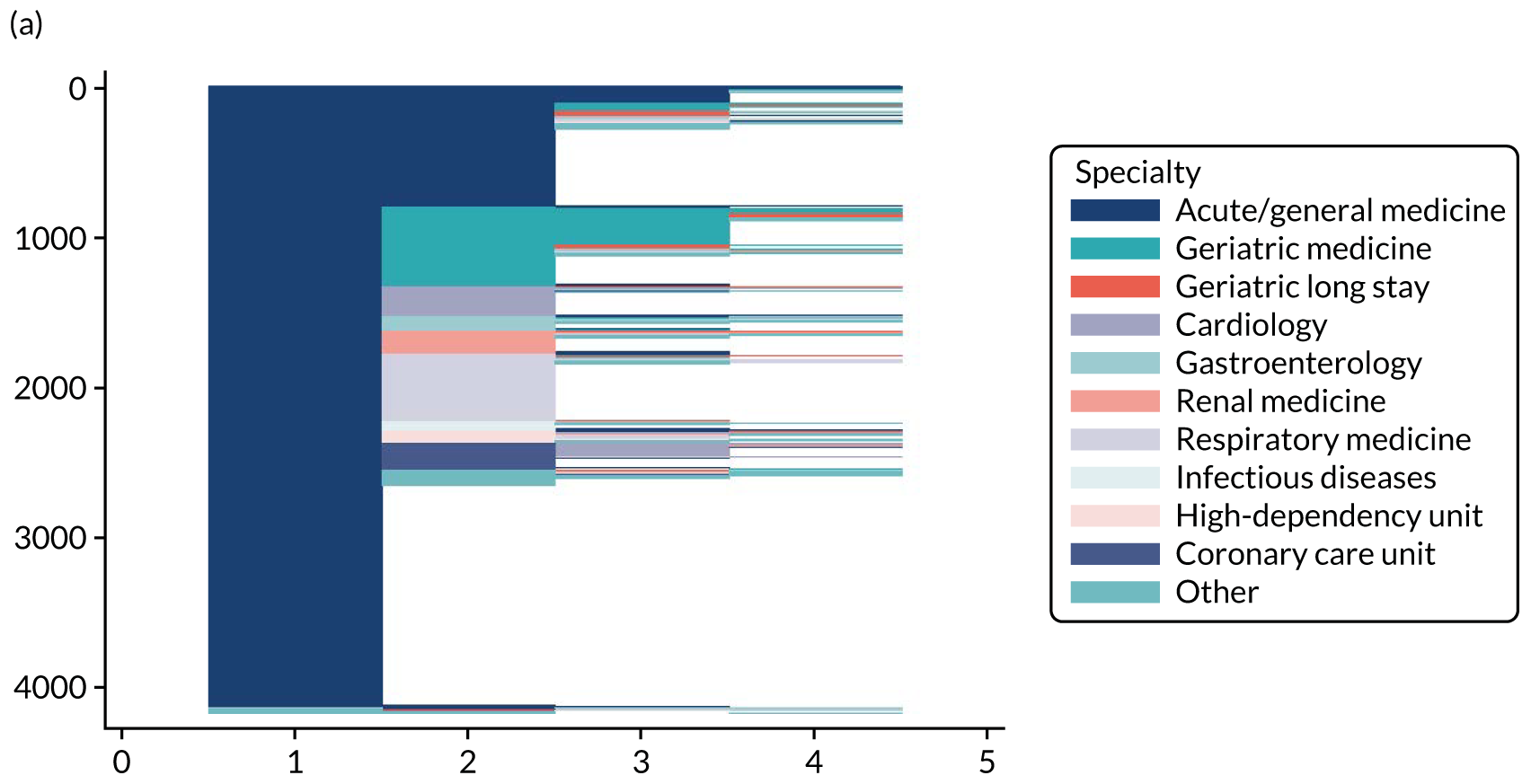

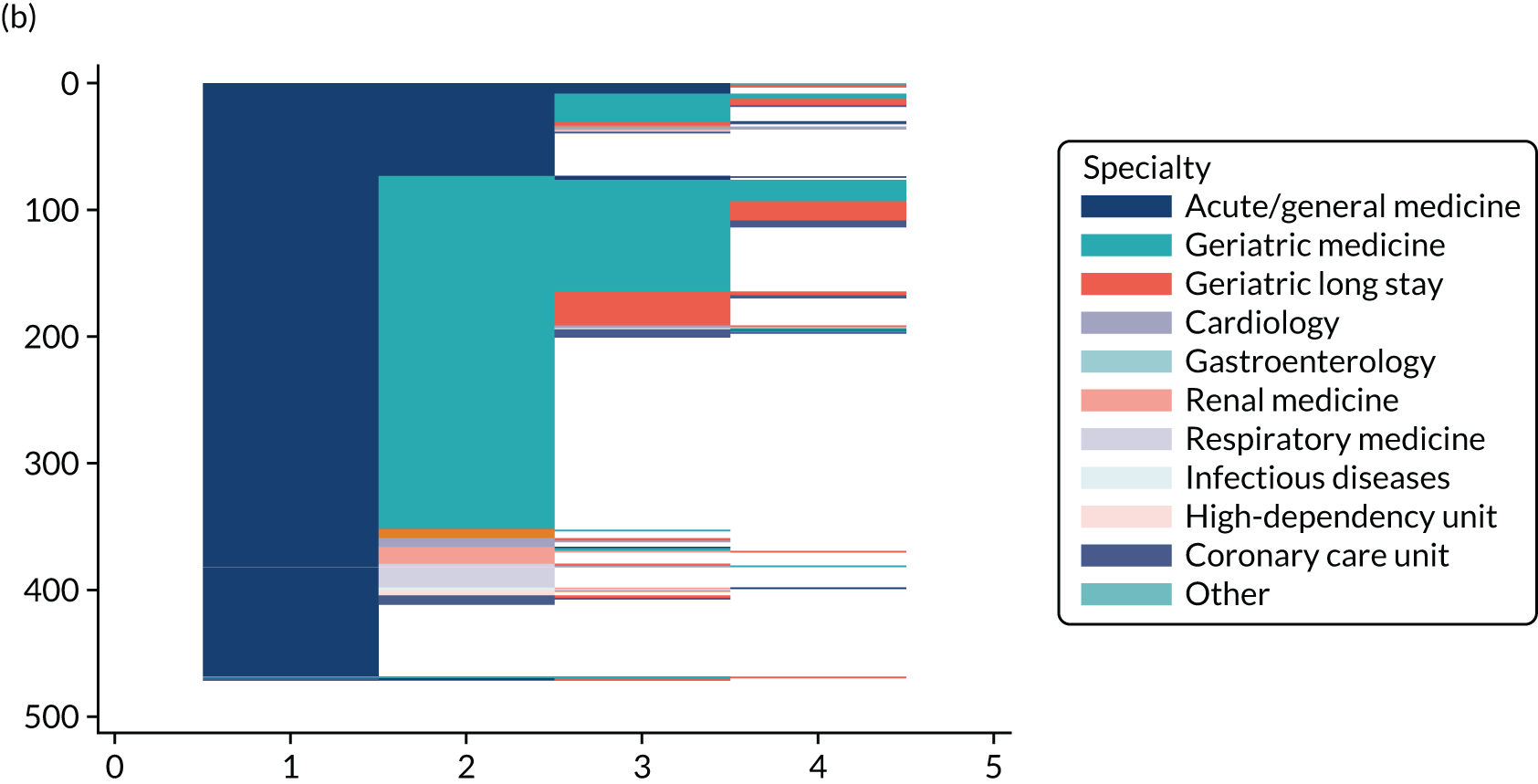

For eligible patients, discharge diagnosis (excluding dementia) from all previous admissions recorded in SMR01 were used to calculate each participant’s Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) at each eligible admission. 180 The CHI data set was used to define participant age, sex and postcode-defined socioeconomic status [measured using quintiles of the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD)] on admission. 181 Data on all community-dispensed prescriptions were used to create an additional multimorbidity score for case-mix adjustment, calculated as the number of drugs (defined as the number of distinct British National Formulary182 subsections) prescribed to the patient in the 84 days prior to admission. 183