Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HS&DR Evidence Synthesis Centre, contracted to provide rapid evidence syntheses on issues of relevance to the health service, and to inform future HS&DR calls for new research around identified gaps in evidence. Other reviews by the Evidence Synthesis Centres are also available in the HS&DR journal.

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project numbers 16/47/22, 16/47/17, 16/47/11. The contractual start date was in April 2017. The final report began editorial review in March 2021 and was accepted for publication in May 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Anderson et al. This work was produced by Anderson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Anderson et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Systematic reviews for policy and service improvement

For systematic reviews to be useful, rigorous and deliverable within given resources, they need to articulate a well-defined review question. The bold advice in one of the more authoritative methods textbooks in the field is ‘Never start a systematic review until a clear question (or clear questions) can be framed’. 1 Useful, deliverable systematic reviews also require an appropriately bounded set of inclusion criteria that together describe the nature of the evidence and types of studies that should answer the review question. 1–3 The review question and inclusion criteria form the core information of systematic review protocols, driving the specification of subsequent aspects of the methods (i.e. search strategies, data extraction plans, tools for study quality assessment and strategy for evidence synthesis). In turn, prespecified and registered systematic review protocols seek to assure rigour and transparency in the conduct of systematic reviews. 4

Policy-makers and service commissioners frequently express a desire to use evidence, but acknowledge that they often lack the time or relevant skills to explore and specify which type of research evidence would best inform a policy or service commissioning choice. Therefore, teams of experienced systematic reviewers and information specialists are often commissioned to undertake such responsive review work with and for them. The model of having university-based research centres, commissioned for a number of years to conduct highly applied work for the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC), National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) or the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), is a key feature of the applied ‘evidence ecosystem’ to inform UK health services and policy. For example, there are long-term arrangements for commissioning systematic reviews or model-based economic evaluations to support NICE technology appraisals and policy-making in the DHSC (e.g. Policy Research Programme evidence review facilities).

The NIHR’s Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme first commissioned two evidence synthesis centres in 2013, and then three centres from 2017 to 2020 [the University of Exeter (Exeter, UK), University of Sheffield (Sheffield, UK) and University of York (York, UK)-based teams that produced this report]. 5 The aim of these centres has been to ‘produce evidence syntheses which will be of immediate use to the NHS in order to improve the quality, effectiveness and accessibility of the NHS including delivery of services’. 5 The review topics are specified by the HSDR programme, and:

. . . will be areas of importance to the service, where there is a reasonable level of published evidence but these may be dispersed, with useful lessons for the NHS from other sectors, countries or a broad range of literature. The finished products are designed to summarise key evidence for busy managers and clinical leaders, while evaluating the quality of information and strength of findings. The aim is for an authoritative single-source document, which provides simple top-line messages in complex areas.

. . . The output will be an evidence synthesis – that is, a comprehensive review of published literature with explicit search strategy, appropriate range of sources and critical assessment of quality of evidence and strength of findings.

Between 2017 and 2020, our three research centres were commissioned to conduct evidence syntheses that respond to specific health policy-makers’ and service commissioners’ needs. Typically, we were tasked, at short notice, to conduct a systematic/rapid review of evidence on a service delivery/design health-care topic, following the identification of a need for evidence on that topic by a policy or commissioning lead or team within the DHSC or NHS England.

Scoping within systematic reviews

The scoping stage of a review comprises those initial processes that aim to establish or refine the review questions and determine the review’s scope, such as its area of focus, key terms and types of studies to be included. (It is potentially confusing that a scoping review is a particular type of review method and evidence end-product.) In general, the scoping stage seeks to reconcile the twin goals of asking the ‘right review question’ (to best address user needs) and making the best use of available research and other evidence. To be useful, systematic reviews frequently have to negotiate a compromise between these two goals, answering questions that are close to the user’s needs, but also being confident that evidence of adequate quantity and quality exists. This report aims to share the lessons learned from our varied experiences of managing this compromise within the NIHR HSDR programme’s remit, primarily to inform health-care commissioning and delivery in the UK.

This report's focus was initially suggested by the lead author (RA) at our annual HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centres meeting, in May 2019. After further discussion by e-mail, we chose this focus for our joint final report because we felt, collectively, that question formulation and review scoping are (1) critically important stages and processes in ensuring the quality and usefulness of responsive reviews, (2) review stages for which few explicit ‘methods’ or detailed guidance exists (see next section), and they are also (3) rarely described in journal articles or reports of reviews and systematic reviews. We also wanted to explore, for the benefit of our own teams and others that conduct policy-/service-responsive reviews, whether or not it is possible to specify ‘best practice’ principles and approaches to question formulation and review scoping on the basis of our experiences.

Established principles for scoping and developing review questions

This section summarises the guidance from established textbooks and guides on the methodology and conduct of high-quality systematic reviews in the health-care field or more broadly in the social sciences. Table 1 shows the degree of coverage of methods or principles for question formulation and scoping provided in the established textbooks and guides most used by and familiar to the members of the three review teams.

| Source | Coverage of how to develop or decide review questions? | Other guidance on best practice for scoping? |

|---|---|---|

| Boland et al.6 | Contains an 18-page chapter on ‘defining my review question and identifying inclusion and exclusion criteria’. Outlines a six-step process from identifying a topic of interest to writing a review protocol | ‘Consider contacting experts in the topic area’ is only step five of six scoping steps, revealing the student-oriented focus of the text |

| Booth et al.7 | Contains a 24-page chapter ‘Defining your scope’ (pp. 83–107), which includes defining your scope with an audience in mind, the specific requirements for complex interventions, further defining your scope (mapping and data mining) and challenges and pitfalls | Chapter 3 on ‘Choosing your review methods’ includes a box (box 3.1) on ‘what do we mean by scoping’? |

| Higgins et al.8 | Contains a chapter (chapter 2) on determining the scope of the review and the questions it will address (pp. 13–32) | Chapter 2 also includes brief coverage of involvement of stakeholders and use of conceptual models |

| CRD9 | Contains a four-page section on ‘Review question and inclusion criteria’ (under ‘Key areas to cover in a review protocol’), but describes how good effectiveness review questions should be framed and presented, rather than the process of how to develop them | Contains a section on conducting scoping searches to check that a systematic review of the same or overlapping question has not already been conducted |

| Gough et al.10 | Chapter 4, ‘Getting started with a review’, of Gough et al.10 (pp. 71–92) includes building the scope through use of conceptual frameworks and choosing review methods, scale and timescale | Includes a complete chapter on stakeholder perspectives and participation in reviews, and covers the entire review process, including clarifying the problem and question |

| Petticrew and Roberts1 | Contains a seven-page section on ‘Framing the review question’ (pp. 28–34) and includes a section on ‘Framing policy issues and answerable questions’ |

Chapter 2 is titled ‘Starting the review: refining the question and defining the boundaries’ Other sections in chapter 2 consider when a systematic review should be carried out and when they are most valuable |

Although most methodological guidance on the conduct of systematic reviews offer coverage and consideration of how to develop review questions and agree the scope of a review, others start with the review question as already given. For example, both the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination guidance9 on conducting systematic reviews in health care and the Cochrane handbook by Higgens et al. 8 give very little guidance on scoping and developing review questions, beyond the need to conduct searches to confirm that an identical or overlapping systematic review is not already published or in progress.

Petticrew and Roberts1 indicate the importance of asking the ‘right review question’ when deciding whether or not a new systematic review would be appropriate and useful. The authors also list situations when conducting a systematic review may not be appropriate (Box 1).

-

High-quality systematic reviews already exist on the same topic.

-

A systematic review on the same topic is already being conducted.

-

The review question is too vague/broad.

-

The review question is too narrowly scoped and, therefore, unlikely to be useful.

-

There are insufficient resources to conduct a reliable systematic review.

Summary of box 2.2 in Pettigrew and Roberts. 1

More positively, Petticrew and Roberts1 describe the importance of finding and using previous systematic reviews and, if resources allow, conducting scoping searches to see what sorts of studies and what number of primary studies exist in relation to a potential review question. They go on to assert that policy questions may often be quite broad and that work is usually required to decide which questions it would be most useful to answer. The authors imply that this often involves ‘working back’ from the types of available evidence and the disciplines that have produced them. 1

Advice offered by these texts often also includes breaking down the question into common components. Typically, for effectiveness review questions, these are its PICOS [population (or patient type), intervention, comparator, outcomes, study types] components. 2,3,7 This exploration and breaking down is also framed as developing a conceptual framework for a systematic review. 3 To give direction and corroboration to these decisions, several authors strongly suggest setting review questions jointly with the intended users of the review and also involving them in developing the review protocol. 1,3 However, beyond such general advice, the texts offer limited specific, practical guidance on the principles or process of negotiating a path to the ‘right’ review question and inclusion criteria. Our experience as systematic reviewers within our teams also underlines that we have never been ‘taught’ or learned ‘formal methods’ for conducting these important stages of reviews, but have mainly learned through experience of conducting many commissioned and responsive reviews and engaging directly with the intended review users/commissioners.

An initial model for understanding the scoping process

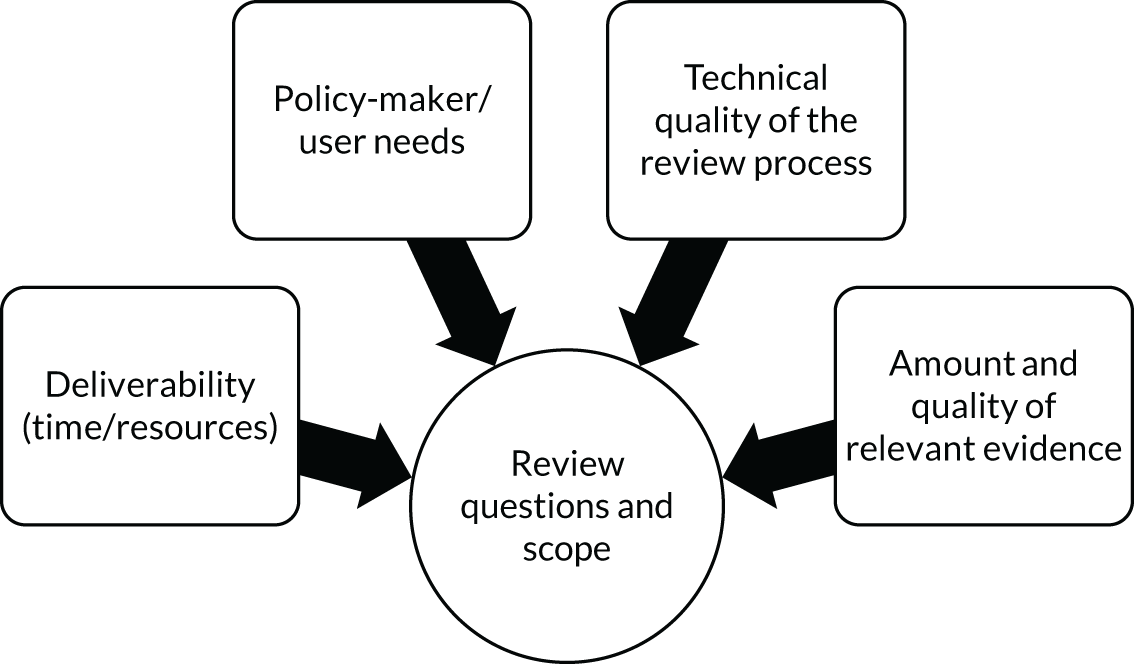

To help guide our descriptions, discussions and reflections on scoping processes, we devised a simple model to depict the interaction of the stakeholder and other main considerations that determine review questions and review scope (Figure 1). Essentially, this combines the drivers associated with rigour (i.e. technical quality) and relevance (to policy-maker and user needs), alongside logistic concerns relating to deliverability (i.e. time/resources) and empirical considerations (i.e. amount and quality of relevant evidence). Acknowledging that quality extends beyond technical quality to include the perceptions of the policy-makers and users of the utility of each review product, the model can be seen to partly embody a specific application of the reconciliation of time, quality and money (as previously identified in Booth et al. 7).

FIGURE 1.

Basic model of key factors in systematic review scoping.

Aim of this report

The aims of this work and report were to:

-

describe six or more varied examples of recent scoping processes that were required to shape and specify responsive systematic reviews conducted by the three HSDR evidence synthesis centres

-

provide reflective commentary on the different choices, sources of information and advice that shaped the review question(s) and scope for each review

-

provide an overarching summary and set of principles or lessons for effective scoping of rapid and responsive systematic reviews.

We intended that these principles would apply to reviews when they are commissioned at short notice and with limited time for completion, and to meet specific health-care policy/commissioning needs. We sought to compare these principles and lessons with current authoritative advice on developing review questions and the scoping stage of systematic reviews.

Discussion of these aims revealed a shared interest in the need to reconcile, on the one hand, technical or ‘data-driven’ aspects of scoping the evidence for potentially answerable questions and, on the other hand, the collective learning processes required to develop an understanding of a new topic, and to build relationships with stakeholders and potential users of the review. As one co-author framed it, we sought to cover:

. . . technical issues of scoping (e.g. scoping searches and preliminary desk research) and the softer issues of consultation as they specifically relate to topic identification and scoping and could include our relationships with variously the generator of the initial topics (as appropriate), the HSDR team, patient/public representatives and those delivering services.

Personal communication between authors (Anderson et al. ), 2020

At the same time, we were mindful that the previous report and paper, which was based on these centres’ work (from 2014 to 2017), had mainly reflected on the role of stakeholder engagement in such responsive and service-/policy-oriented reviews. 11 The main findings from that previous review of the HSDR centres’ earlier review projects are shown in Box 2.

Rapid production of high-quality outputs is facilitated by initial evidence mapping and topic scoping.

Barriers to prioritising the topic and defining the scope were: review team knowledge of the wider NHS/policy context; ability to define a scope that was both relevant and manageable.

Staying on track with the review was facilitated by: the ability in the team to deal with unexpected findings or problems; the commitment of individuals to support the project (especially external stakeholders).

Responsive working with stakeholders was also facilitated by: producing and disseminating appropriate outputs; the timeliness and topicality of outputs; producing or capturing evidence of impact.

Involvement of stakeholders at key stages maximises value and potential for impact but the impact of evidence on decision-making remains poorly documented.

Responsive evidence synthesis programmes should seek the optimum balance between decision-makers’ needs for rapid and efficient evidence synthesis and the time and resource requirements of rigorous systematic reviews.

Reproduced with permission from Chambers et al. 11 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The box includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original.

We aimed for our new collective methodological reflection to complement rather than duplicate that work. We believed that new and valuable insights might emerge from a systematic focus on the processes of topic scoping and review question formulation, which are rarely described in academic outputs of systematic reviews.

For the purposes of this reflective exercise, the scoping processes of a review were specified as those that occurred between the time of first notification of a new review topic and the final agreement of the review protocol (with the NIHR HSDR programme and policy customer), including final review questions, inclusion criteria and the type of planned evidence synthesis.

Chapter 2 Methods

Overview

This report presents, discusses and reflects on the experiences of the three research centres that conducted evidence syntheses to inform health and social care service organisation and delivery in the UK between April 2017 and June 2020. These responsive and often rapid reviews were commissioned by the NIHR HSDR programme, although the direct customers and audiences of different reviews included policy-makers, service commissioners, service providers and managers, or particular types of care professionals working in the UK health and social care sector.

This discussion and reflection on our experiences of the process of review scoping and review question formulation is based on the following:

-

the collation and writing of eight descriptive case studies of selected reviews within each of the three teams

-

a broad and basic thematic analysis of key issues or common considerations that shaped the processes of review scoping and question formulation

-

a discussion and reflection on the overall process and practice of scoping for such policy, service and practice-responsive evidence syntheses.

The process comprised within-centre reviewing of documents, review team recollection, reflection and discussion (to produce the descriptive case studies) and between-centre discussion and reflection on our shared experience of scoping selected review topics, primarily through consideration of each other’s experiences, as written in the case studies.

We did not explicitly aim to document how our centres and teams differ in academic experience, team organisation or working practices; however, from past collaborations and experience (e.g. on public health reviews and technology assessments) we typically learned that we worked in similar ways in most respects. The HSDR centres at Exeter and York had smaller core teams that conducted most of the work on every review project; however, the Sheffield team typically made use of a wider group of researchers, with different people working on different reviews. Otherwise, we were not aware of major differences in how review teams within the three centres worked.

Choice of case study reviews

In May 2020, all researchers (the co-authors) in each of the three centres were e-mailed and asked to select two or three examples of their reviews, commissioned since April 2017, where ‘the scoping was challenging, interesting, and demonstrates a variety of approaches, or where the teams believe it was particularly critical to the ultimate delivery, quality and usefulness of the review’. The final number provided by each centre reflected the diversity of topics covered and challenges faced, but also the capacity and time resources of the researchers within teams to create these retrospective accounts of scoping. All case studies suggested by centres were written up and included.

Data sources and process

Exploration of the scoping processes for each case study drew on a combination of researcher recollection, review of notes and meeting minutes (e.g. with expert stakeholders) from within teams, e-mail correspondence with stakeholders, scoping searches and search results, from first allocation of a review topic through to review protocol agreement (with the NIHR HSDR programme or the policy customer). However, the extent to which the case study was grounded in or checked against documentary evidence (e.g. notes of meetings with service commissioners or HSDR contacts), rather than the recollections of review team members, was not rigorously documented. In most cases, the initial draft was written by one lead researcher, before elaboration and revision by other members of that review’s team.

Case study content

To simplify the process of writing and to best enable cross-case comparisons, we sought a similar structure and level of content for each case study. A draft case study was prepared by the Exeter team and shared across all three teams with a proposed set of headings and content:

-

introduction of the basic context and origin of each review and topic (identifying the review team, the supporting protocol and main academic output)

-

a statement of the final review questions or aims

-

a description of the key challenges or choices during scoping, plus key decisions made in response to them, to illustrate how the team moved from an original review topic to specific review questions and the detailed review approach

-

a (within-case) reflection and discussion section.

This broad structure was agreed by all co-authors for use in all case studies, although identification of key challenges and key decisions was not constrained to the subheadings.

Thematic analysis

Drafts of all eight case studies were shared across the three teams prior to a joint teleconference. One of the co-authors (AB) drafted a provisional thematic analysis based on reading these drafts. This framework of 14 distinct scoping considerations was informed by earlier conversations on the focus of the report, which had identified the combined influence and inter-relationships between stakeholder-/user-related factors and review team/technical factors. It also drew on factors identified in a systematic review of evidence use by policy-makers12 and sought to reflect the twin emphases of an associated report for policy-makers and systematic reviewers. 13 Finally, the conceptual model was informed by the RETREAT (Review question, Epistemology, Time/Timescale, Resources, Expertise, Audience and purpose, Type of data) framework of review considerations, with review question, epistemology, and audience and purpose collectively reflecting the user-related factors; and time, resources, expertise and type of data capturing the technical requirements. 14 The RETREAT framework was developed (by co-author AB) from an analysis of the attributes of qualitative evidence synthesis methods in 26 methodological papers, and has been shown to both distinguish and inform selection of synthesis approaches. 15

The initial tabulation of scoping considerations organised themes according to whether or not they primarily related to:

-

consultative issues (i.e. externally generated issues relating to input from commissioners, stakeholders, experts and patient groups to inform the planned evidence synthesis product)

-

interface issues (i.e. issues relating to the interaction between the technical processes of the review team and the requirements of the review user)

-

technical issues (i.e. internally managed issues relating to the conduct of the review, as experienced within the review team).

The first draft of the thematic framework was shared with all co-authors and commented on using e-mail and tracked changes. It was also discussed in a teleconference. This led to several revisions of wording and clarified definitions, but all 14 originally suggested considerations in the framework were retained and no new ones added. The framework was used by the lead author to allow similarities and differences in scoping processes and outcomes to be more easily identified as a basis for drafting this report’s discussion. Co-authors were also encouraged to consider the framework in relation to reviews that they had contributed to, which enabled further mapping of these scoping considerations to the case study reviews.

Ethics considerations

As this report is not based on any formal process of data collection and analysis, and did not formally recruit any participants from which data were obtained (e.g. interviews), it would not be defined as research and, therefore, did not require research ethics approval. The main contributors were the team members and co-authors of this report. Nevertheless, the scoping processes described in this report sometimes closely involved other individuals within the NIHR, DHSC and other national and regional organisations linked to NHS service commissioning and delivery. Although such individuals are potentially identifiable from the report and the underlying review reports of the eight case study reviews, in all cases, we ensured that the degree of anonymity in this report was the same as in the report already in the public domain.

Chapter 3 Results

The eight case studies feature the scoping stages of evidence syntheses conducted by the HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centres between 2017 and 2020: three cases from the University of Exeter, three from the University of Sheffield and two from the University of York. Table 2 shows the considerable diversity of topics and types of synthesis method that these case studies covered. Please note that for ‘synthesis type’ we have used the terminology used in the source project and report, and that there is some variation and overlap in use of terms. In particular, evidence maps and mapping reviews are essentially the same in purpose and final product, and scoping reviews (as a defined product) should be distinguished from the scoping stage and processes that are the focus of all of the case studies. In addition, most of these named subtypes of evidence synthesis are also systematic reviews (in the sense that they had clearly defined questions and explicit methods for identifying, assessing and summarising included evidence sources). We have decided to retain the terms as used in each case study review, rather than to retrospectively impose a standardised typology. Further details of the specific synthesis methods used in each case study review, the rationale for their choice and any patient and public involvement (PPI) are in Appendix 1, Table 13.

| Short name | Centre | Population | Intervention/phenomenon | Comparator | Outcome/domain of performance | Study or publication types included | Synthesis type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Digital-First Primary Care | York | Primary care medical staff and patients (or their caregivers) | Digital/non-face-to-face systems for accessing primary care and receiving care | Conventional systems | Effectiveness and safety, patient access/convenience, system-level efficiencies and related issues, such as workforce retention, training and satisfaction | Systematic reviews, meta-analyses and other forms of evidence syntheses |

Scoping evidence map Rapid evidence synthesis |

| 2. MHA | Exeter | People detained under the MHA, their family and carers and the individuals involved with their care | Specific legal provisions for involving trusted relatives or friends in decisions about detention or care | Not applicable | Experiences of care, especially dignity, confidentiality and feeling supported | Qualitative research studies | Rapid framework synthesis |

| 3. Integrated care regulation and inspection | York | Any users of integrated health and social care | Regulation and inspection of integrated care, including integration between primary and secondary care | No/less regulation/inspection (implicit) |

Effectiveness (any outcome relevant to integrated care) Implementation (barriers and enablers) Description of innovative regulatory models or frameworks |

Empirical publications (qualitative and quantitative) and non-empirical publications | Rapid scoping review and evidence map |

| 4. Social care access and diversity | Sheffield | Ethnic minorities and LGBT+ people with social care needs | Personal, social and cultural factors | Any or no comparison | Access to social care | Any study design | Rapid realist review |

| 5. Strengths-based approaches | Exeter | People being supported by social workers or adult social care teams | Strengths-based approaches to social work practice | Any area, service or teams of social workers that have not adopted the given strengths-based approach |

Any effectiveness measure used (intended outcomes) Markers of implementation |

Comparative empirical evaluations (question 1) Qualitative or mixed-methods studies (question 2) |

Framework synthesis |

| 6. Reducing length of stay | Exeter | Hospital inpatients (planned admissions) aged ≥ 60 years | Multicomponent hospital-led interventions that aimed to reduce length of stay or enhance recovery | Any type of control group or comparator (e.g. usual hospital care) | Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness | RCTs, controlled before-and-after studies and interrupted time series | Systematic review of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness |

| 7. Interventions to reduce preventable hospital admissions | Sheffield | Adults with a cardiovascular or respiratory condition (not cancer) | Implementation of evidence-based interventions to reduce preventable hospital admissions (or re-admissions, or combinations of these interventions) | Any or no comparator | Implementation in the context of the NHS at the patient, GP and health system level (e.g. barriers and facilitators, staff or patient views/experiences) |

UK experimental intervention studies Sampling from mapping review and wider evidence base (including controlled/uncontrolled observational studies, qualitative studies and systematic reviews) |

Mapping review and realist synthesis |

| 8. Access to services for adults with IDs | Sheffield | People aged ≥ 16 years with IDs | Actions, interventions or models of service provision in primary health-care services | The general population | Access to primary health-care services and barriers to and facilitators of accessing and using services | Qualitative research, comparative literature, evaluation studies and systematic reviews | Mapping review and systematic review |

The case studies that started with a clearly known policy customer/decision-maker and with a clearly stated review question or evidence gap/need are presented first, through to those that had neither a clearly stated policy customer nor a clear initial question. In this way, the order of presentation of the case studies should, in principle, move from those with clearer predefined initial scopes to those with more open-ended and uncertain scopes. The classification of case studies according to these two criteria is presented in Table 3.

| Degree of clarity in initially stated review question | Known main policy customer/decision-maker | Unspecified main policy customer/decision-maker |

|---|---|---|

| Very clear |

Digital-First Primary Care (York HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre) MHA16 (Exeter HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre) |

Integrated care regulation and inspection (York HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre) |

| Some clarity |

Social care access and diversity (Sheffield HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre) Strength-based approaches (Exeter HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre) |

|

| Unclear (just a topic area) |

Reducing length of stay (Exeter HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre) Interventions to reduce preventable hospital admissions (Sheffield HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre) Access to services for adults with IDs (Sheffield HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre) |

Case study 1: rapid evidence synthesis of ‘Digital-First Primary Care’

This topic was given to the HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre at York, having been identified as an urgent topic from an NHS England primary care workshop that focused on digital aspects of care. The York team had not been involved in the workshop and so sought further information from NHS England about evidence requirements and scope. Following initial clarification and discussion with representatives from NHS England in June 2018, the team undertook a rapid, responsive evidence synthesis between July and December 2018. Throughout the project, the York team maintained e-mail and telephone contact with a senior policy lead in the new business models team of NHS England’s Strategy and Innovation Directorate. This person co-ordinated the involvement of representatives from other teams (e.g. primary care).

The protocol was posted on the team’s webpage,17 as it was not eligible for registration in PROSPERO. The final report was published in full18 and a brief evidence summary produced. 19

The original questions articulated at the workshop were as follows:

-

What are the most effective automated systems management approaches that result in high levels of general practitioner (GP) engagement?

-

How do you present data to ensure change in practice?

-

What are the barriers to and motivators of using digital technology that drive cultural and behavioural change within primary care practitioners?

Following initial discussions with NHS England, which identified a broad and far-reaching list of themes and questions, an iterative production process was agreed to undertake the work in stages. We presented the findings after each stage to discuss progression onto the next stage. After the discussions that followed the second stage, the work was concluded and the report completed.

The rapid responsive evidence synthesis was undertaken to inform NHS England policy in ‘Digital-First Primary Care’. The principles and some aspects of systematic review methodology were applied to ensure transparency and reproducibility. The two stages of the synthesis consisted of (1) scoping the published review evidence and (2) addressing a refined set of questions produced by NHS England from the evidence retrieved during the scoping stage. Given that ‘a full systematic review was not possible, given the time and resources available’, the team ‘conducted a rapid synthesis of the most relevant evidence identified during the scoping exercise (stage 1) to establish if and to what extent these questions can be answered by the identified research’. 18 Patient and public representatives were not directly involved in the development of the synthesis aims, methods or interpretation.

The following questions were addressed in the second stage:

-

What are the benefits – to patients, GPs and the system – of digital modes and models of engagement between patients and primary care?

-

As GP workload and workforce is the main threat to primary care, how do we use these innovations to alleviate this, rather than only increasing patient convenience and improving their experience?

-

Which patients can benefit from digital (online) modes and models of engagement between patients and primary care?

-

What channels work best for different patient needs and conditions?

-

Are there differences in synchronous and asynchronous models?

-

-

How do you integrate ‘digital first’ models of accessing primary care within wider existing face-to-face models?

-

How do you contract such models and how do you deliver them (what geography size, population size)?

The final inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

population – any primary care medical staff and patients (or their caregivers) of any age and/or other medical professionals

-

interventions – as the known literature rarely conceptualised interventions as ‘digital primary care’, any form of non-face-to-face interaction, including e-mail, online/video, messaging and artificial intelligence-led systems or triage (or any of these alongside telephone consultation)

-

outcomes – impact on care in terms of effectiveness and safety, patient access/convenience (including which patients are able to use digital consultations and what conditions are appropriate for non-face-to-face engagement), system-level efficiencies and related issues, such as workforce retention, training and satisfaction

-

study design – systematic reviews, meta-analyses and other forms of evidence syntheses (any related primary studies encountered were included where relevant, although primary research evidence was not systematically searched).

Summary of key challenges/choices and scoping decisions

Challenge 1: clarifying the questions of interest and deciding the most appropriate method of synthesis

The brief topic outline we were given at the start of the project was broadened and expanded during the initial communications with NHS England. They were interested in patient-focused digital innovation in primary care and identified four broad themes and nearly 20 separate questions for which they wanted answers. The questions were wide-ranging, covering issues of contracting and implementation, as well as effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, benefits and risks. They reflected the interests and priorities of the various sections of NHS England involved in implementing ‘Digital-First Primary Care’.

It became clear in these discussions that it was not possible, at that stage, to identify a clear and focused research question (or questions) of high priority to NHS England that was amenable to evidence synthesis. Instead, we identified the need for a responsive and iterative approach to support the needs of the policy-makers.

We adopted a multistage approach to the work. We began by searching the research literature to scope available evidence syntheses. We extracted the key characteristics of all included documents and produced an interactive database of published and ongoing evidence that could be ordered or filtered according to these characteristics, incorporating links to the full-text versions where available. We produced an interim report that summarised the key evidence identified in this scoping exercise, along with an annotated bibliography and the interactive spreadsheet.

We presented the interim report to NHS England and asked them to decide whether it provided the information they needed or if a gap remained to be addressed by further rapid evidence synthesis. NHS England responded with seven questions that reflected specific ‘live’ policy areas in which they were most interested. Therefore, we undertook a second stage and conducted a rapid synthesis of the relevant evidence identified from the stage 1 scoping exercise with the seven research questions identified by NHS England, forming the basis of a thematic framework. Critical appraisal of included evidence was facilitated by relevant assessment tools and reporting standards used to inform judgements about the internal and external validity of included research results presented in the thematic synthesis.

We produced a report that combined both the initial scoping exercise and the rapid synthesis undertaken at stage 2. Again, we presented the findings through a summary report and teleconference to representatives from various NHS England teams (e.g. new business models, primary care, digital and workforce). Following this presentation, and the subsequent discussions, the topic was concluded.

Summary of response to challenge

We needed to adopt an iterative, responsive approach to this topic and revise our methodology accordingly. The initial scoping exercise was undertaken to provide a high-level overview of the available evidence, followed by a rapid evidence synthesis. A full systematic review was not possible, but aspects of systematic review research methodology (such as a priori inclusion criteria, critical appraisal of included evidence, and process measures to avoid bias and errors) were applied to introduce a level of transparency and reproducibility.

Challenge 2: identifying and incorporating recent and ongoing research

As a result of the initial scoping exercise and discussions with other researchers working in the field, we became aware of recent and ongoing projects, as well as two open NIHR calls for a proposal relevant to the topic. Although we searched for evidence syntheses, we incidentally identified some recent or ongoing primary research studies.

We were keen to ensure that we did not duplicate effort and also to alert NHS England to academic groups actively researching the topic. Therefore, we made contact with the researchers who were eager to engage, providing early sight of their draft reports in confidence to be included in our work. They were also keen to engage further with NHS England to inform ongoing policy work.

Summary of response to challenge

To avoid duplication of effort and to ensure that policy was informed by the most recent research, we highlighted the ongoing work alongside review evidence and facilitated contact between NHS England and the research authors.

Reflections and lessons

Multiple stakeholders from different areas within the same organisation identified a broad and far-reaching list of themes and questions that reflected the differing remits and priorities of the stakeholders. This required an iterative production process, undertaking the work in stages and presenting the findings at each stage to support their needs. We identified a tension between ongoing engagement with busy and changing stakeholders and fast-moving policy in an area of rapid and ongoing innovation. This required pragmatic adaptation of methods to meet the needs of stakeholders to balance methodological rigour with the usefulness of outputs, while maintaining transparency. In addition, in an area of rapid and ongoing innovation where peer-reviewed evidence may not be currently available, it was helpful to highlight ongoing work and academic colleagues working in the area for further direct dialogue with the stakeholder.

Disseminating the outputs from this multistage project was problematic. To respond to the stakeholder needs, we produced an interactive database of published and ongoing evidence (i.e. enabling sorting and filtering of the evidence base on key characteristics, accessing direct links to full publications and/or contact details of researchers). Reducing this to a final textual HSDR report stripped away this functionality and obscured much of the underlying work.

Case study 2: review of experiences of the ‘nearest relative’ provisions of the Mental Health Act 1983

Origin and context of the review topic

This evidence review topic was initially notified by the NIHR HSDR programme in direct response to an urgent request for help in gathering evidence for the independent review of the Mental Health Act 1983 (MHA),16 which was being conducted during 2018. In the UK, the MHA16 is the central piece of legislation that determines the circumstances and processes for when and how people experiencing mental distress can be compulsorily detained for assessment or treatment.

For the Exeter centre, it was the most rapid of the rapid systematic reviews that we had conducted during the contract period, as well as our first review project that was specifically about a piece of legislation (rather than a health-care intervention or model of health service delivery). We got our first indication of the review topic on 3 January 2018 and submitted the final report by the end of March 2018. The scoping process was, therefore, compressed and pragmatic, for example relying closely on the knowledge and stated needs of the main policy contact within the team conducting the independent review. Although we could identify a time point when the review questions and inclusion criteria were agreed, in other respects the scoping stage was less distinguishable from the main searches and review. In effect, it was a ‘live’ review protocol and the review was shaped and delivered through regular ongoing contact with the policy customer.

The scoping and systematic review was conducted by the HSDR evidence synthesis team at Exeter, and the full review protocol was published on the PROSPERO database (CRD42018088237). 20

The review topic was initially stated as one of several very brief issues or aspects of the MHA16 sent to the team by NIHR. The subtopics that the policy leads initially prioritised as ‘the most pressing’ were:

-

the rights of relatives

-

consent and capacity

-

the criminal justice system (tribunals and restricted patients)

-

legal clarifications.

Our work was steered towards the first topic and, specifically, the ‘nearest relative’ provisions of the MHA. 16 These are the legal requirements and associated practices that govern the involvement of the spouse or close biological relatives (i.e. the ‘nearest relative’) of a person who is being detained compulsorily for mental health reasons under the MHA16 (sometimes referred to as ‘being sectioned’). These persons are involved primarily as an advocate and support for the person in mental distress, especially in relation to decisions about care.

Although we had no specific review question, the remit of the independent review of the MHA16 included specific questions that it wanted to answer (Box 3) and these usefully shaped the possible directions of our rapid evidence review.

Overarching question: are the powers of the nearest relative within the MHA16 appropriate?

What is the role of the nearest relative under the MHA?16

What rights are available for nearest relatives and are these appropriate?

What are service users’ and carers’ experiences of nearest relative provision?

What is the impact on (1) service users’ access to family and carer support and (2) the experiences of families and carers involved in a person’s care?

How does this role impact information sharing and confidentiality?

Are there any possible alternative models (e.g. international best practice)?

Our contact person in the independent review team expressed the purpose of the needed review as the following main review question:

-

Are the powers under the MHA16 relating to the appointment and involvement of the nearest relative appropriate (i.e. working)?

By the time we completed scoping the topic and finalised our review protocol, the planned systematic review aimed to address the following question:

-

What are the experiences of services users, family members, carers and professionals of the use of the ‘nearest relative’ provisions in the compulsory detention and ongoing care of people under the MHA?

However, the remit and context of the independent review, together with guidance from the policy customer about the main perceived problems with the current legislation, revealed specific stages or aspects of these provisions that were of particular interest. These included the processes of identification of the nearest relative, displacement (i.e. replacement) of the assigned nearest relative, decisions about care, service users having access to support from those carers and loved ones who they wanted support from, and issues of patient confidentiality and information sharing. These stages/aspects were expressed in the PROSPERO protocol under the ‘outcomes’ of interest (see Table 8). 20

We aimed to answer this question by identifying, summarising and synthesising evidence from studies that met specific inclusion criteria. Table 4 summarises how the scoping process refined review questions and defined the inclusion criteria, compared with the initial, briefly stated review topic. The ultimate choice of a rapid form of qualitative evidence synthesis (i.e. framework synthesis) was mainly dictated by the review question’s focus on people’s experiences, combined with the very short time frame. Although there was some PPI in interpreting and writing up this rapid evidence synthesis, people or carers who had been directly affected by the nearest relative provisions were not involved in scoping the review or its questions.

| Criterion | Original topic or question | Final question about experiences of the nearest relative provisions |

|---|---|---|

| Population/sample | People affected by the MHA16 |

People detained under Section 2 or 3 of the MHA,16 their family and carers and the individuals involved with their care who work within the remit of the MHA16 Excluding those detained for criminal purposes |

| Intervention/phenomenon of interest | The MHA16 | Experiences of or attitudes towards the application of the nearest relative provision of the MHA.16 This includes any experiences in relation to the involvement of relatives, carers or professionals in the care of or decisions about a compulsorily detained person |

| Comparator | Uncertain if relevant | Not applicable |

| Outcomes domain of interest | Patient and carer experiences |

Explore experiences:Issues related to decisions about care during detention and after discharge, including to a community treatment order Issues related to service users having access to support from those carers and loved ones who they want to be involved with or informed about their care Issues relating to patient confidentiality and information sharing, relating to all aspects of compulsory detention |

| Study designs | Not stated | Qualitative research studies (e.g. based on analysing data from interviews or focus group discussions with patients) |

| Geographical scope | Not stated | UK-only evidence (i.e. legal jurisdictions of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland) |

| Date limits | Not stated | Evidence published from 1998 onwards |

Summary of key challenges/choices and scoping decisions

Key challenge 1: uncertainty about the type of evidence that would best answer the questions

The first question was whether or not any prior research had focused on patient and carer experiences of the nearest relative provisions within UK legislation. The questions of interest seemed so specific that we doubted if research would address them. Our review group’s contract and work remit extended to the potential for primary research or surveys, where such methods best answer policy-maker or NIHR HSDR questions. However, two early discoveries enabled us to focus on the evidence review component, rather than primary research. First, we identified a 2017 survey of people’s experiences of the MHA by the Mental Health Alliance and Rethink Mental Illness (London, UK). 21 Second, we learned that the independent review team were, themselves, conducting a survey of carer experiences.

It became important to know early on whether the policy customer expected the review team to summarise research evidence or, given the distinct possibility of finding no or very little research, to extend coverage to other relevant non-research forms of evidence in the public domain (e.g. blogs, online discussion forums). Our first teleconference with the policy customer revealed a clear preference for research-based evidence, if available. This was to ‘reduce possible bias’ and achieve a breadth of evidence in the review process, given the other information sources and consultation on which the independent review processes would be drawing.

Therefore, the policy customer gave us a clear and early steer to search for and synthesise research evidence only. Nevertheless, at that time, we were not sure if there would be sufficient, or even any, good-quality UK-based research evidence on patient and carer experiences of the nearest relative provisions. Therefore, we also noted that, later, we might need to extend the scope to grey literature and less research-based sources of evidence, or include evidence from beyond the UK. This highlights pervasive uncertainty about the available evidence for answering alternative potential questions, and the motivation to make best use of a review team’s core skills and resources in responsive, commissioned policy-informing reviews.

Decision 1: to limit to research evidence only

The response of the team was to commit to reviewing evidence from research only. However, we also made some aspects of the review scope and protocol conditional (i.e. on the amount and quality of research evidence found). For such reviews, the scope and protocol are live and adjustable plans that are expected to change in response to the evidence that is found. They often lay out sequences of possible scopes, iteratively refined, realigned and renegotiated. Had the team found only one or two includable research studies, this decision may have been revisited. This kept options open within a very rapid review timescale.

Key challenge 2: deliverability within 8 weeks

This was the overarching challenge and a non-negotiable constraint, against which the other challenges and decisions were all weighed. The deliverability of any review would critically depend on the number, richness/quality and, therefore, amenability to formal synthesis of the studies found, and this would not be known until 4–6 weeks before the report submission deadline. Concerns about this were compounded by our awareness that synthesising qualitative research, usually being an interpretative process, takes time and requires a team approach. We had team discussions about the value of also searching for and including survey research (i.e. which may not be qualitative). However, having found enough qualitative research, we did not ultimately search for survey studies. (In any case, such a review would be unlikely to provide more recent and relevant evidence than a reanalysis of the 2017 Mental Health Alliance survey responses.)

Decision 2: manage expectations of the policy customer through regular contact and review of progress

We had teleconferences with the policy customer every 1 or 2 weeks, at a minimum, during the first half of the review. This was not so much a decision, but a direct response to our uncertainty (i.e. to keep open communications with the policy customer about whether or not we were finding evidence and what evidence we were finding). Had there been too much evidence to synthesise, there would be discussions during these teleconferences as to what evidence we should focus on. The short time frame of the review, undoubtedly, also played a part in us choosing not to look for evidence from beyond the UK or prior to 1998 (see Key challenge 3: how old and from which other jurisdictions would evidence be relevant to experiences of the UK Mental Health Act? and Decision 3: to include only UK evidence and evidence after 1998).

Key challenge 3: how old and from which other jurisdictions would evidence be relevant to experiences of the UK Mental Health Act?

As mentioned, this was our first review of an aspect of legislation. Although people in other countries might have experience of equivalent legislation and practices for including family members of close friends in decision-making for people experiencing severe mental distress, only people from the UK (i.e. the jurisdiction of application of the MHA16) would have directly relevant experience of the nearest relative provisions.

Decision 3: to include only UK evidence and evidence from after 1998

This was an early and relatively easy decision (i.e. to not include evidence from beyond the UK). The legislation and the nearest relative provisions within it were so specific to the jurisdiction of the UK that evidence from elsewhere would have very little applicability to the UK legislative and mental health-care context. It was also because the broad context of this review – and the scope of the interim report of the independent review of the MHA16 that it was to inform – was the creation of a fuller understanding of the current and past problems with legislation and its use. Had the review context required a stronger understanding of potential alternatives and legislative solutions, then perhaps an international and comparative review of equivalent provisions in mental health legislation in other countries may have been useful. Another factor that may have informed this decision was that we knew that some research evidence would originate from Scotland, where an alternative to the nearest relative provisions was already current practice. It was, therefore, likely that this evidence, and its comparison with studies in England and Wales, would be more likely to inform the independent review than studies from mainland Europe or North America.

The cut-off date of 1998 was partly to limit the size of the screening task (i.e. to address deliverability in 8 weeks) and partly because our stakeholders confirmed that the experience of the nearest relative provisions would have differed before and after the adoption of the Human Rights Act 199822 in the UK. Therefore, only evidence about experience of the mental health legislation after 1998 was judged as relevant to future possible legislation.

Key challenge 4: conducting rapid synthesis of qualitative research evidence

Given the extremely tight timelines, and the researcher-intensive nature of qualitative evidence synthesis, we were very nervous about the possibility of finding too many studies that met our inclusion criteria. This would have risked making the review undeliverable, rushed and of reduced quality, or having to retrospectively exclude studies.

Decision 4: using ‘framework synthesis’ and prioritising conceptually richer studies within the synthesis

Although a full thematic synthesis would have been the preferred approach, this would not have been possible within the limited time frame of this review. However, committing to conducting a rapid synthesis of qualitative research was less risky and more feasible because a streamlined, pragmatic approach to qualitative evidence synthesis was available, which could be applied to a modest number of studies. Fortunately, we found 35 papers from 20 studies; however, 22 papers provided only half a page of qualitative evidence relevant to the five study objectives.

This meant that we could, with some adaptations and innovations to the method, conduct a pragmatic, rapid, best-fit framework synthesis of the qualitative studies within the 6-week time frame. Within the method, a three-stage approach was used. First, relevant data were extracted according to the research objectives of our review from the 22 papers with half a page of relevant qualitative evidence. This process identified the six richest studies that contained the most data relevant to our research questions. Themes were selected from these studies to further refine the framework. In the third and final stage of the synthesis, thematic synthesis of the data enabled the corroboration and extension of the framework. 23

Reflection and lessons

In this review, where review scoping and the conduct of the review overlapped almost completely, regular contact with the policy customer was an important way of staying responsive to the state of the evidence as it emerged. Fine-tuning of the review in response to the evidence needed to be in keeping with the overall protocol and fit with the available time and resources. These were decisions that could largely be manage from our side. However, the review also needed to be relevant to the policy customer’s needs, which demanded a close working relationship in such a rapidly evolving review.

The development of search strategies to scope the literature and identify pockets of evidence that were amenable to review underpinned many of the decisions that were made in the early stages. Scoping searches using Google Search and Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), and the initial bibliographic search development, played a key role in the decisions to exclude experiences of the MHA16 via criminal justice proceedings and to focus on research published after the 1998 Human Rights Act. 22 Throughout this process, the integration of the information specialist in the review team was crucial. The pressing requirement to rapidly scope the available literature meant that our bibliographic database search strategy was developed and ready to run as soon as the final focus of the review was agreed. Supplementary searches were iterative and responsive to the emerging literature, within the prespecified boundaries set out in the protocol. In particular, this included iterative citation searching or ‘snowballing’ of key primary studies. Indeed, this approach to searching is a core part of qualitative searching, but the rapid nature of this review brought to the foreground the importance of this type of searching.

The searches also determined that there were no available frameworks or theories directly relevant to our research objectives that we could use to inform the initial framework for our framework synthesis. This informed our decision to structure our initial framework based on our initial research objectives, and then refine the framework using the themes from the primary studies included in our reviews, followed by thematic synthesis.

Case study 3: regulating and inspecting integrated health and social care in the UK

In 2018, the NIHR conducted a topic identification exercise within the broad area of professional regulation in UK health care. The exercise generated approximately 30 possible research topics, with some articulated as research questions and others as stated areas thought to be lacking in evidence. The NIHR assessed each topic and prioritised the following questions for referral to the York HSDR review team:

-

What factors enable delivery of an effective system of regulation and inspection in an environment where services are increasingly being provided on a multiagency (including third sector) and local basis in or close to people’s own homes?

-

How can we overcome the barriers to delivering effective joint regulation and inspection in a way that makes sense from the perspective of the individual accessing the care and services? To what extent is it possible to achieve this without the need for major legislative or structural change?

The research team conducted extensive stakeholder consultation to shape these questions into research questions, define terms and adapt the scope where necessary (see Summary of key challenges/choices and scoping decisions). There was some PPI in the review project, but at the report-writing and dissemination stages only. Ultimately, we planned to conduct a rapid scoping review to identify and classify published material that could potentially address four key questions:

-

What models of regulation and inspection of integrated care have been proposed (including approaches taken in other countries)?

-

What evidence is available on the effectiveness of such models?

-

What are the barriers to and enablers of effective regulation and inspection of integrated care?

-

Can barriers to effective regulation and inspection be overcome without legislative change?

The rationale for conducting a scoping review was based on these mainly descriptive, rather than evaluative, review questions (especially questions 1–3). The protocol was posted on the team’s webpage,24 as it was not eligible for registration in PROSPERO. The final report was published in full25 and a brief evidence summary produced. 26

As can be seen by the above contrasting sets of questions, consulting with diverse stakeholders resulted in a broader scope, with a series of research questions focusing on the extent and nature of the evidence that were best suited to a scoping review. A map of the evidence was created, underpinned by the following inclusion criteria:

-

Publication type – both empirical and non-empirical publications were eligible for inclusion. Empirical studies could be of a qualitative or quantitative design. Non-empirical publications could include discussion or theory papers, as well as other descriptive pieces, such as editorials. Letters or news articles were excluded, as were publications that reported the findings from inspections of care services.

-

Setting – publications were primarily focused on the integration of health and social care provision, for example services delivered jointly by NHS providers and local authorities. However, publications could also focus on care provision that is delivered across other settings/sectors by different professional groups working together, for example across primary or secondary care. Care providers could be in the public, private or third sector, and services could be aimed at both adults and children.

-

Focus – publications needed to have a primary focus on the regulation and/or inspection of integrated care. Reference to the governance of services more broadly was not sufficient for inclusion. Integration could be either horizontal or vertical in type and be at a macro-, meso- or micro-level.

-

Outcomes – empirical studies could report on any outcome relevant to the regulation and/or inspection of integrated care. This could include issues related to implementation, such as views about barriers and enabling factors. Non-empirical publications could focus on any relevant issue, including proposed models of regulation or outcome frameworks.

Each included publication was coded on various key characteristics, including topic (i.e. regulation or inspection), country, population/setting and document type (e.g. empirical research, models or frameworks, or theoretical). This information was used to produce a high-level descriptive overview, which characterised the nature of current literature on the regulation and inspection of integrated health and social care in the UK, as well as identifying research gaps.

Summary of key challenges/choices and scoping decisions

Key challenge 1: reconciling multiple independent stakeholder consultations

The original questions prioritised by the NIHR originated from Health Inspectorate Wales (Merthyr Tydfil, Wales). A teleconference held between the York team and representatives of both Health Inspectorate Wales and Care Inspectorate Wales (Merthyr Tydfil, Wales), provided background and context to their proposed questions. However, before this teleconference could be arranged, the research team had already consulted other key stakeholders about the proposed questions.

Initial contact with representatives from the Professional Standards Authority (London, UK) and Care Quality Commission (London, UK) provided the team with an overview of health-care regulation in the UK and associated research. They expressed a willingness to assist with the proposed work and arranged for researchers to attend (1) the Professional Standards Authority’s Policy and Research Forum and (2) a meeting of the health and social care regulators. The former included representatives from the Professional Standards Authority and various regulatory organisations [e.g. the General Pharmaceutical Council (London, UK), the General Chiropractic Council (London, UK), the Health and Care Professions Council (London, UK), the General Optical Council (London, UK), the General Osteopathic Council (London, UK), the General Medical Council (London, UK), the General Dental Council (London, UK) and the Nursing and Midwifery Council (London, UK)]. The latter included senior managers from the Care Quality Commission, DHSC, the General Dental Council, the Health and Care Professions Council, the Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman (Coventry, UK), the Nursing and Midwifery Council, the General Pharmaceutical Council, the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (London, UK), the Professional Standards Authority, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (London, UK), Social Work England (Sheffield, UK) and the General Medical Council. The research team also held a separate teleconference with a representative of the General Medical Council.

In each case, different stakeholders emphasised slightly different areas of interest, deviating to a greater or lesser extent from the original questions. The Health and Social Care Regulators suggested that interdisciplinary regulation of online primary care was the topic of interest. The diverse disciplines and regulatory organisations providing online care provoked questions about effective regulatory oversight and complaints related to care. The potential relevance and utility of the international evidence was particularly emphasised.

The General Medical Council agreed that, even given the differences in the regulatory architecture and frameworks across countries, there was scope to learn from other health and social care systems that face similar issues and potential risks. Of particular interest was multidisciplinary team working: understanding the barriers to, enablers of and issues around responsibility, given joint working and multidisciplinary collaboration.

The representatives of Healthcare Inspectorate Wales and Care Inspectorate Wales described recent policy initiatives to promote the integration of health and social care in Wales and the implications of such policies for regulators. They elaborated on their initial questions to pose a series of fundamental questions about the regulation and inspection of integrated health and social care provision, including what models exist, their effectiveness, the barriers to their implementation and non-legislative means of overcoming these barriers.

Decision 1: share all scoping conversations among the stakeholders and encourage ongoing engagement

It can be seen that – when given exactly the same information to scope a rapid evidence review – different stakeholders proposed differing but inter-related research questions. As these stakeholders are the likely audience for the review, we felt it crucial that they remain engaged with its development. Consequently, as part of the protocol development process, we shared our individual stakeholder discussions with the wider group. An introduction to the draft protocol outlined how these shared discussions informed the basis of a draft scope, which the stakeholders were then invited to further comment on and amend, as appropriate. Each of the stakeholder groups responded positively to this invitation.

Beginning with two detailed questions derived from a prioritisation exercise may have been a barrier to initial engagement from some stakeholders. Some stakeholders would defer to the questions as worded, focusing on interpreting the authors’ intentions rather than expressing their own perception of research priorities. The research team, therefore, encouraged stakeholders to use the initial questions as a starting point for the discussion about research priorities.

Key challenge 2: not all stakeholders are familiar with rapid evidence synthesis

It was clear that stakeholders’ experience and knowledge of rapid evidence synthesis varied widely, particularly in relation to formulating implementable research questions. We wanted to avoid the potential hazard of arriving at a scope that was simply amenable to evidence synthesis rather than reflecting a genuine stakeholder knowledge need.

Decision 2: empower stakeholders to take advantage of the available resource

The research team began each stakeholder group consultation with a presentation to ensure a common level of understanding before beginning the scoping work. This presentation covered:

-

the nature of the work conducted by the HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centres

-

the types of evidence synthesis and the related research processes

-

the role of stakeholder involvement in evidence synthesis

-

required stakeholder input for this specific project [e.g. helping develop the scope of the research question(s)].

The presentation aimed to create conditions in which stakeholders could lead the discussion, speak with confidence about their evidence needs and describe how rapid evidence synthesis might serve those needs. The research team could outline the types of research method that might be feasible or suitable for proposed research questions, but were careful not to influence topic-specific discussions. It became clear that stakeholders’ information needs were best served by quickly identifying and organising the apparently diffuse and disparate literature on regulation and inspection of integrated care. Consequently, a rapid scoping review was considered the most appropriate starting point.

Reflections and lessons

Successful scoping of rapid evidence synthesis questions requires the involvement of stakeholders who are knowledgeable, enthusiastic and engaged. However, it also requires researchers to developa framework in which stakeholders can lead conversations about the scope while remaining within the parameters of what can be achieved by a rapid evidence synthesis. This requires researchers to focus on listening and facilitation in the early stages of consultation, moving towards providing stronger guidance on possible methodologies once a level of consensus among stakeholders has been achieved. The time and effort required to develop these processes and practise these skills should not be underestimated.

Case study 4: social care access for BAME and LGBT+ populations – a rapid realist review

This evidence review topic was initially proposed by the Research Programmes Branch – Health and Care Section within the UK’s DHSC. The scoping and subsequent rapid realist synthesis was conducted by the HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre at the School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR), University of Sheffield. The protocol was published on PROSPERO (CRD42019158250) and was also made publicly accessible on the NIHR’s published Sheffield Evidence Synthesis Centre web page (URL: https://njl-admin.nihr.ac.uk/document/download/2031791; accessed 21 June 2021). The review was conducted between November 2019 and the end of June 2020 and was published in 2021. 27

The review focus was initially stated as the following topic:

-

addressing diversity and inequalities in access to social care services.

Access to social care services had featured as a dominant theme within the James Lind Alliance’s Adult Social Work Top 10,28 reflecting a recent priority setting exercise. Rather than representing a specific priority from the James Lind Alliance exercise, this theme encapsulated several priorities. It was, therefore, felt by the NIHR and the DHSC that coverage of these priorities could be interpreted and understood by targeting the review at groups for whom access to social care could be particularly challenging. Initial discussion with the contacts at the DHSC focused on two particular groups of interest: ethnic minorities, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender plus (LGBT+) people with social care needs. This process emphasises how a broad theme may be refined to particular populations, both as a specific target for policy initiatives and in the assumption that by addressing issues in access for specific groups, this can have wider implications for other population subgroups.

Rather untypically, the review customer (the DHSC) had already conducted a preliminary literature scoping around race disparities in the use of social care. The review team, therefore, faced two particular challenges: (1) how to add value to the initial literature review by complementary activity and (2) how to inform the social care access literature from the extensive work completed in health care. Both of these considerations shaped our subsequent approach to scoping the literature. In addition, the review scope and the perceived relevance of the review was discussed with members of the Sheffield Evidence Synthesis Centre’s PPI Group.

Although classic scoping of effectiveness review questions involves population (or patient type), intervention, comparator and outcomes, with the subsequent addition of study types (i.e. PICOS), once the quantity and quality of available literature has been established by scoping, we have identified the need for addition of a further ‘S’ [population (or patient type), intervention, comparator, outcome, study types, synthesis method (PICOSS)]. This additional ‘S’ relates to the type of ‘synthesis’ (i.e. a preliminary assessment of the literature allows us to identify what type of synthesis will be possible and useful to match the requirements of the topic to the needs of the commissioner). In this instance, we identified that realist methods would extend the evidence base beyond the descriptive literature review that the DHSC team had already explored to gain an understanding of how ‘access’ worked (or did not work) for different groups.