Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/52/25. The contractual start date was in October 2017. The final report began editorial review in March 2021 and was accepted for publication in November 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Chudleigh et al. This work was produced by Chudleigh et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Chudleigh et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Sections of this report have been reproduced from Chudleigh et al. 1–5 and Holder et al. 6 These are Open Access articles distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Context

Each year in England, almost 10,000 parents are informed about their child’s positive newborn bloodspot screening (NBS) result. This is likely to be around 2–8 weeks after birth, depending on the condition. 7,8 Currently, NBS in England tests for nine conditions: sickle cell disease (SCD), cystic fibrosis (CF), congenital hypothyroidism (CHT), phenylketonuria (PKU), medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MCADD), maple syrup urine disease (MSUD), isovaleric acidaemia (IVA), glutaric aciduria type 1 (GA1) and homocystinuria (pyridoxine unresponsive) (HCU). The last six conditions are collectively referred to as inherited metabolic diseases (IMDs). The purpose of NBS is to identify presymptomatic babies who have one of the nine conditions to allow early initiation of treatment. Most babies with initial positive NBS results for SCD and ≈ 10% of those with a positive NBS result for CF will later be confirmed as gene carriers of these diseases. Carriers are healthy children who carry a single faulty gene. After screening, further diagnostic testing is carried out to confirm whether or not a child is affected by one of the nine conditions or is a carrier of SCD or CF. In a small number of cases, the screening result will be a false positive, that is on further diagnostic testing the babies are found not to be affected or to be carriers. Therefore, of the almost 10,000 babies who receive a positive NBS result, most will be carriers of SCD, ≈ 120 will be carriers of CF, ≈ 1500 will be found to be affected by one of the nine conditions currently screened for and a small number will have a false-positive result. 7,8 Other outcomes include borderline CHT results and the designation of CF screen positive, inconclusive diagnosis (CFSPID).

The clinical spectrum in screen-positive cases varies enormously and, consequently, the message to parents needs to be carefully crafted to prepare them for a range of outcomes. The communication of positive NBS results is a subtle and skilful task that demands thought, preparation and evidence to minimise potentially harmful negative sequelae. 9–13

Current communication practices for positive newborn bloodspot screening results

The purpose of communication in health care is ‘to exchange information effectively and to build interpersonal relationships’. 14 The time frame for the communication of positive NBS results starts when the NBS card arrives in the NBS laboratory and continues until the parents are told their child’s definitive result.

Generic guidelines for breaking bad news exist,15–18 but research to support these guidelines is lacking. 19,20 Much of the literature about breaking bad news comes from adult oncology21–24 and paediatric palliative care settings. 25,26 Specific guidance regarding communication of positive NBS results currently focuses on the ‘chain of communication’ from NBS laboratories (NBSLs) to ‘appropriately trained health professionals’ and then to parents. 27,28 This guidance does not define what is meant by ‘appropriate’ training for health-care professionals in this context. Much of the literature to date has focused on the physician’s role when breaking bad news,29–31 but often the delivery of positive NBS results to parents is the role of other health-care professionals. Consensus guidelines for SCD state that babies who have received a positive NBS result should be referred to a paediatric haematologist, but how this information is delivered to parents is not considered. 32 Consensus guidelines for CHT state that detection of a high concentration of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) on screening should be communicated by an experienced person (e.g. the paediatric endocrine team) either by telephone or in person; however, again, the content of the communication is not considered. 33

Leaflets about each of the conditions covered by the NBS are available, and it is recommended that parents are given the appropriate leaflet at the same time as receiving a positive NBS result. 28 Guidance regarding the content and best mode of communication between health-care professionals and parents is variable for the different screened conditions27,28 and is often not evidence based. Consequently, communication occurs in a range of ways, which are not currently well defined. A quantitative stated-preference study indicated that parents have clear preferences for how information should be provided antenatally as part of the NBS programme (NBSP) and identified that these preferences differed from how this information is given in current practice in the UK. 34 This study suggested a need to identify specific models of communication for subgroups of parents and, therefore, a need for a stratified approach to communication strategies that may be dependent on parent characteristics or the type of NBS condition. 34 It is important, therefore, that these information preferences are also clarified after NBS when a positive screening result is being communicated indicating that a child may be a carrier of or affected by one of these life-changing conditions. 34

International newborn bloodspot screening communication practices

Much of the literature focuses on communication practices for children who are carriers of or affected by CF and/or SCD; fewer studies focus on other screened conditions. Several studies have identified the importance of both the knowledge and the experience of the person imparting the positive NBS result, as well as the content of the message.

Carriers

A study that explored genetic counsellors’ attitudes to the disclosure of carrier status generated by NBS found that 78% (n = 160) of counsellors supported disclosure, 14% (n = 30) opposed disclosure and 8% (n = 16) had no opinion; those with > 5 years’ experience of NBS were much more likely to strongly agree with one or more reasons for disclosure (p < 0.001), whereas those with ≤ 5 years’ experience were more likely to strongly agree with one or more reasons for non-disclosure (p = 0.031). The main motivating reasons for disclosure included helping parents to understand a positive NBS result and ensuring that parents were aware of reproductive risk; although genetic testing was viewed as a complex and ambiguous process, this did not justify non-disclosure. 35 Consensus guidelines for SCD32 also state that carrier status should be reported and counselling should be offered to carriers, as the knowledge of the carrier state in the family provides the opportunity for prevention of future affected births. Furthermore, in recent years genetic counselling has been advocated to highlight the emerging clinical risks of carrier status for SCD, including extreme exertional injury, kidney disease and venous thromboembolism. 36

In the USA, findings from telephone interviews with 270 parents following communication of carrier status after NBS for CF and SCD indicated that the content of the communication and knowledge of the person imparting the result were vital in terms of parental experience of the process. 37 Another recent study38 undertook telephone follow-up with parents of children aged 2–5 months who had been identified as carriers for either SCD (n = 426) or CF (n = 288). 38 Of these parents, 27.5% and 7.8% of parents of children who were carriers for SCD and CF, respectively, had no recollection of being informed of the NBS result. Of those who did recall receiving the result, 7.4% and 13.2% of parents of children who were carriers for SCD and CF, respectively, were dissatisfied with the experience; dissatisfaction was associated with failure to recall an explanation of the NBS result [SCD group: odds ratio (OR) 4.0, p < 0.01; CF group: OR 3.8, p < 0.01]. In addition, 27.5% and 7.8% of parents of children who were carriers for SCD and CF, respectively, held misconceptions that their children may develop the disease at some point in their life. This demonstrates that many parents either did not know about their child’s NBS result or misunderstood what their child’s NBS result meant. Further findings from the same study39 using an adapted version of the Vulnerable Baby Scale indicated that parental perceptions of child vulnerability were higher in the SCD group than in the CF group (p < 0.01). In addition, parental perceptions of child vulnerability were inversely correlated with parental age (p < 0.02) and lower health literacy for the SCD group (p < 0.015). These findings suggest that carrier status identification as part of the NBS programme can lead to misplaced parental perceptions of child vulnerability and that this was more marked in younger parents and parents of carriers of SCD with lower health literacy. This supports the findings of Wright et al. 34 in terms of the need for specific models of communication for subgroups of parents and stratified approaches to communication strategies that take account of parental characteristics and/or the type of NBS condition.

Affected

Other studies that have focused on children affected by CF or SCD have uncovered similar levels of uncertainty about the NBS result. A study in the USA that consisted of qualitative interviews with 28 parents following their child’s positive NBS result for CF demonstrated that the communication of the positive NBS result led to parental uncertainty and emotional distress. This was strongly influenced by the physicians’ approach to informing parents of the result, with face-to-face communication (as opposed to use of the telephone) and the physician having time and knowledge to explain the results in detail being preferable. 40 Findings from a recent questionnaire survey of 192 families in Germany,41 of whom 105 responded, following the implementation of NBS for CF in 2016 also supported the importance of there being an appropriate person with the ability to communicate relevant information effectively. Parents in this study who had received the screening result from a CF specialist were more satisfied than those who had received the screening result from staff on the maternity ward.

Other studies have focused on the content of communication. A questionnaire study in Switzerland42 that explored 138 parents’ perspectives of receiving a positive NBS for CF found that most parents (n = 98, 78%) felt troubled or anxious when the CF centre called to inform them of their child’s NBS result, but only 51 (38%) remained anxious after their visit to the CF centre. Interestingly, 19 of these were parents of children who were identified as not having CF (i.e. false positives). Parents who were dissatisfied with the information that they received by telephone said that the caller had not explained the test result and the disease (n = 9), or had provided superficial information only and instead focused on arranging the appointment (n = 5). The information received by telephone was less satisfactory for parents of children diagnosed with CF (OR 2.23; p = 0.044) or parents of younger infants (OR 0.93 per day older; p = 0.001). Negative feelings after the telephone call from a CF centre were more frequently observed in more highly educated parents (p = 0.003) and after a call from large CF centres (p = 0.005). Parents who were unhappy with the information that they received in the CF centre wanted to be told more clearly that a negative sweat test meant a healthy child (n = 3) or wished that they had been given more information at an earlier stage of screening (n = 3). Parents of a first child were more dissatisfied with the information from the CF centre (OR 0.21; p = 0.024). Negative feelings after the visit to the CF centre were more often found in families of foreign origin (p = 0.002) and in families whose infant had CF (p < 0.001). 42

A study in Australia43 investigated the information needs, priorities and information-seeking behaviours of 26 parents of infants during the education period following a positive NBS result for CF. The results indicated that parental information needs were variable and, to some extent, individual. However, most parents wanted to know about the treatment of CF, how to care for their child with CF and information about the disease pathophysiology and how the disease would affect the child. In addition, parents reported a preference for face-to-face consultations to deliver information as opposed to a telephone call owing to the perceived lack of sensitivity as to where the parent might be when they were having the telephone conversation and who might be with them at that time. All parents reported using the internet to search for more information after receiving their child’s positive NBS result. 43

Studies in the USA that explored parental experiences of receiving a positive NBS result for IMDs suggested that the communication of these results is highly stressful for parents and that improvements are needed. 44,45 One of the studies involved observation and audio-recording of clinical consultations, as well as interviews with parents regarding communication of their child’s initial positive NBS result for the metabolic conditions. It showed that the methods used to communicate the NBS result and the condition-specific knowledge of the individual imparting the result influenced parental dissatisfaction, anxiety and distress; results delivered over the telephone, by staff not known to the families or by staff without condition-specific knowledge were viewed less favourably. 45

Existing evidence supports the importance of ensuring that the initial communication of positive NBS results is handled sensitively and considers individual parent characteristics to minimise parental distress and consequences of this distress, and the importance of the knowledge and experience of the person imparting the result.

Communication practices in the UK

There is some evidence that there are regional variations in the UK with regard to the approaches used to communicate positive NBS results and, in particular, suspected carrier status for CF and SCD. 3 These approaches include receiving the result by letter and in-person communication during a home visit. 46,47 The findings of Kai et al.’s47 study informed the development of the first national guidelines for the communication process in the NBSP;27 these guidelines recommend face-to-face communication by an appropriately trained health-care professional. Despite these guidelines, a study reporting the findings from 67 interviews with parents about their experience of receiving CF or SCD carrier results following NBS found continued disparity in how the guidelines are implemented in practice. 9 The findings also revealed variability in the content of the communication and the way that the result was communicated, which led to increased parental anxiety and distress; it was the perceived lack of knowledge of the person communicating the result rather than the result itself that led to additional distress. 9

A scoping exercise at a national meeting of the CF NBS special interest group in 2014 and further informal discussion at the same group in 2016 indicated that communication of positive NBS results for CF in the UK continued to be variable. This ranged from initial telephone contact with a CF nurse specialist to face-to-face contact with a health visitor (who often did not have specific knowledge of CF) or a CF medical consultant, with the content not being clearly defined; this indicates that very little has changed since the original work of Kai et al. 47 The issue of guidelines being written for staff but not meeting the needs of patients (or parents, in this instance) is not unique to NBS. There is increasing recognition of the need to create guidelines that enable shared decision-making in health care by incorporating patient/parent experiences,48 especially where it is likely to affect the patient’s well-being and family relationships.

Recent studies have explored parental preferences and perceived information needs. One such study of five parents of children with GA1 found that, following diagnosis, parents wanted an approach that translated scientific information into practically focused, written information that would help them to manage the condition on a daily basis. 49 Clear parental preferences were also evident in a recent questionnaire survey50 that evaluated the communication of positive NBS results to 48 parents who had received a positive NBS for CF from a tertiary London paediatric centre. The results indicated that 40 out of 42 (95%) parents felt that the information could not have been given over the telephone; 39 out of 43 (91%) said that they wanted both partners present; 27 out of 42 (64%) said that it was helpful having the health visitor present; and 37 out of 40 (92%) felt that it was acceptable to wait until the next day for the sweat test. 50

Impact of communication practices

Poor or inappropriate communication strategies for positive NBS results can influence parental outcomes in the short term,9–12,42,45 but may also have a longer-term impact on children and families. 13 The evidence suggests that the distress caused can manifest in several ways, including arguments between couples (e.g. apportioning of blame),9,11,51 the alteration of life plans, an inability to conduct tasks of daily living, such as going to work or socialising,9 long-term alterations in parent–child relationships,13 and mistrust and lack of confidence affecting ongoing relationships with staff. 11 There is also evidence of increased parental distress that results in parents reducing their child’s interaction with others, particularly in the case of CF. 9 Parents also experienced poor intrapersonal and interpersonal relationships within their family system and more widely. 3,52 This, again, highlights the importance of creating guidelines that inform shared decision-making in health care by incorporating patient/parent experiences. 48

Studies with families who have received false-positive results have proved difficult to conduct, presumably because the children are no longer seen by health-care professionals. It has been suggested that false-positive screening results create undue anxiety and psychological harm in families and unaffected infants, as well as excess workload for staff. 53 A population-based cohort study that looked at the impact of false-positive results for CF and subsequent health-care use for all infants with false-positive CF results (n = 1564) and screen-negative matched controls (n = 6256) found that rates of outpatient visits and inpatient hospitalisations among children aged 3–15 months were significantly higher in the false-positive group than in the group of matched control infants whose screening results were negative. 54 Conversely, another study55 that compared anxiety, stress and depression in three sets of mothers who had received true-negative (n = 31), true-positive (n = 8) and false-positive (n = 18) NBS results for CF found no significant differences among the groups. However, the sample size for the study was much smaller and, therefore, may be less reliable than the larger population study. 55

As well as true-positive and false-positive NBS results, NBS for CF can also identify outcomes of uncertain clinical significance (CFSPID). 56 A recent qualitative study with five parents of four children who had been given a designation of CFSPID following NBS indicated that learning of their child’s CFSPID designation led to parental uncertainty and, for some, ongoing health concerns led to a significant negative psychological impact. For all parents, the initial communication of the results caused perceived heightened health risk and distress. Parents in this study struggled to understand CFSPID because it was incongruent with their preconceived illness and health-care beliefs. In addition, there was tension between individuals’ ability to understand and process the CFSPID designation, while managing uncertainty. 57

Cost-effectiveness

Although NBS for conditions such as CF has been deemed to be cost-effective,58 poor information provision when the initial positive NBS result is communicated to parents may lead to identifiable, quantifiable and measurable consequences for health-care systems and budgets. This could include additional consultations being requested by parents to allay additional fears and a negative impact on the health status of the parent. 9 In 2015, a systematic review59 summarised if and how information provision has been included in economic evaluations of NBSP. This review highlighted that only three studies included an estimate of the cost of information provision in their analysis, and none of the studies captured the impact of information provision after screening. 59 One of these studies60 referred to the costs related to the impact of poor information provision that were specifically related to false-positive results rather than poor information provision at the time of communicating the initial positive NBS result per se. The review also highlighted that evidence existed that poor information provision in relation to NBS affects parents but there have been few attempts to quantify the impact of information provision in economic evaluations of NBS to date. 59 Importantly, this review confirmed that there are no current data on the long-term impact of poor information provision and subsequent use of health-care resources and impact on parents’ health and well-being. Following this review, Ulph et al. 61 quantified the potential costs of different modes of information provision antenatally as part of the informed consent process for the UK NBSP using mixed methods, including telephone interviews and direct observation. This existing evidence base focused on the informed consent process and did not identify the long-term costs of information provision in terms of the follow-up use of health-care resources.

It is essential that the approaches used to deliver positive NBS results to parents are informed by the parents and are shaped to meet their needs. It may not be possible to remove parental distress completely from what is an upsetting time. However, it is important for staff to communicate positive NBS results in a manner that does not detrimentally affect parents’ relationships with their child and other family members. 62 Empirical evidence is lacking on the potential impact of information provision on parental well-being and decision-making strategies. Given the potential for the impact of information provision on the finite budgets available to provide communication strategies on a national level, there is a need to understand both the short- and long-term costs of different aspects of the NBSP. This includes the implications of providing positive NBS results, which have the potential to cause substantial parental distress, thereby affecting their well-being. A further consideration is ensuring that parents are informed well enough to facilitate communication within and between family members. Most of the screened conditions are genetic in origin and, therefore, positive NBS results can affect cultural beliefs, future reproductive decisions and family communication. 10,63–67 However, a recent scoping review67 that focused on family-planning decisions following diagnosis of rare genetic conditions, including CF, SCD, IMDs and spinal muscular dystrophy, found that most studies focused on pre-natal diagnosis and termination. Indeed, none considered the wider reproductive choices faced by parents when prenatal diagnosis and/or termination were not viable options or good health outcomes made these options less justifiable.

Aims and objectives

The overall aim of the project was to co-design, implement and evaluate new interventions to improve the delivery of initial positive NBS results to parents.

Research objectives

This study had the following research objectives:

-

explore current communication pathways for positive NBS results from the laboratory to the clinicians and then to families

-

identify and quantify the costs and benefits of approaches that are currently used to deliver positive NBS results to parents

-

select two case-study sites (NBSLs) in which to co-design interventions for communicating positive NBS results to parents

-

develop co-designed interventions in two case-study sites for improving the delivery of positive NBS results using experience-based co-design (EBCD) by –

-

exploring the experiences of parents receiving and staff delivering positive NBS results

-

producing a composite film of key themes or ‘touch points’ from parents’ perspectives

-

enabling parents and staff to identify together priorities for improving the delivery of positive NBS results

-

co-designing interventions for the delivery of positive NBS results.

-

-

implement the new interventions in selected case-study sites

-

undertake a parallel-process evaluation underpinned by Normalisation Process Theory (NPT)68,69

-

quantify the resources required to deliver the co-designed interventions in the selected case-study sites and compare these with the costs associated with current strategies

-

obtain consensus about the need for and potential design of an evaluation study of the co-designed interventions, including –

-

selection of which co-designed interventions to include in an evaluation

-

selection of relevant outcome measures

-

selection of relevant time horizon and resource use data to collect in a definitive evaluation

-

choice of future study design.

-

Structure of the report

This report is formed of six chapters. Chapter 2 details the methodological approach, including the theoretical framework used throughout the report and the methods for the four-phase mixed-methods study, including the national survey (phase 1), the co-design work (phase 2), the implementation and evaluation of the co-designed interventions (phase 3) and the work undertaken to design a future evaluation study (phase 4). The patient and public involvement (PPI) work is also outlined in Chapter 2. Chapter 3 presents the findings of phase 1, Chapter 4 presents the findings of phase 2 and Chapter 5 presents the findings of phases 3 and 4. Chapter 6 provides a discussion of the findings, including the strengths, limitations and recommendations for future research.

Chapter 2 Research methodology

Research design

Family Systems Theory (FST)62 underpinned the study design because of the potential vulnerability of family relationships if the initial positive NBS result is not shared as effectively and empathetically as possible. 70 This mixed-methods study used four phases with defined outputs. The principles and methods of EBCD underpinned intervention development. 71–77 NPT68,69 underpinned the process evaluation of the new, co-designed interventions to improve the delivery of positive NBS results to parents. An economic analysis was undertaken to determine resource use and the costs of current practice and of implementing the new co-designed interventions. Principles of the nominal group technique78,79 were used to identify future research priorities and inform the selection of suitable outcome measures for a future evaluation study. The study was approved by the London Stanmore ethics committee (17/LO/2102).

Theoretical framework

Our initial work11 and scoping of the literature showed that many parents were shocked to receive the initial positive NBS result. Despite consenting to the heel-prick test immediately after their baby is born, most parents assume that the test will come back negative. The initial positive NBS result can have a significant impact on parents, and this has implications for their relationship with each other,9,11,51 within their family system and more widely,52,80 with their newborn child13 and with health-care professionals. 11 Therefore, it is essential that when parents receive a positive NBS result they are helped to assimilate the information to enable them to cope and adapt as quickly as possible to minimise distress and disruption to their relationships.

With the positive NBS result having consequences for more than one individual, it was appropriate to use FST62 as the theoretical basis for the study. FST focuses not only on the relationships between family members, between parents and between the parents and the child, but also on external relationships, in this case their relationships with health care professionals, given that the professionals will also influence how the family functions.

Family Systems Theory evolved from General Systems Theory, one of the main tenets of which is holism, which states that a system (or, in this instance, a family) cannot be understood by merely studying each of its components (or members) in isolation from each other. Therefore, to understand the family and the way that it functions, it is necessary to consider all members of the family and how they relate to each other, as well as their responsiveness to external influences. 81,82 It is also vital to remember that the family system is ongoing in that it has a past, present and future that will affect family functioning; how the positive NBS result is delivered may trigger many stressors that will not be immediately apparent. 62,83

In FST, all components of the family are regarded as interdependent: what happens to one member will affect all other members of the family directly and indirectly. 70,83 However, change is considered to be an important and a normal part of families, which may result in both positive and negative consequences. 62 It is how families deal with the change that is important. This is particularly true when this change is because of potentially difficult news that family members may not be expecting to hear, such as initial positive NBS results. FST postulates that family functioning has the potential to be affected by an event, such as the communication of the initial positive NBS result; therefore, facilitating the coping mechanisms used and the adaptation of families to the NBS result is paramount. Therefore, the outcomes of the communications about positive NBS results were considered within the context of the family system; FST guided our choice of data collection tools and questions.

Experience-based co-design

Experience-based co-design is an approach that is used to improve health-care services that draws on participatory design and user experience to bring about quality improvements in health-care organisations. 75 EBCD involves focusing on and designing patient/carer experiences, rather than just systems and processes. 71,76,77 The ‘co-design’ process enables staff, patients and carers to reflect on their shared experiences of a service and then work together to identify improvement priorities, devise and implement changes, and then jointly reflect on their achievements. EBCD was first piloted in an English head and neck cancer service in 2005. 71 After a subsequent project72 in an integrated cancer unit, an online toolkit84 was developed as a free guide to implement the approach. An international survey of EBCD projects in health-care services identified 59 projects implemented in six countries (Australia, Canada, England, the Netherlands, New Zealand and Sweden) from 2005 to 2013 and a further 27 projects in the planning stage. 74,75,85 The design of these studies informed the sample size for the EBCD component of this work.

Normalisation Process Theory

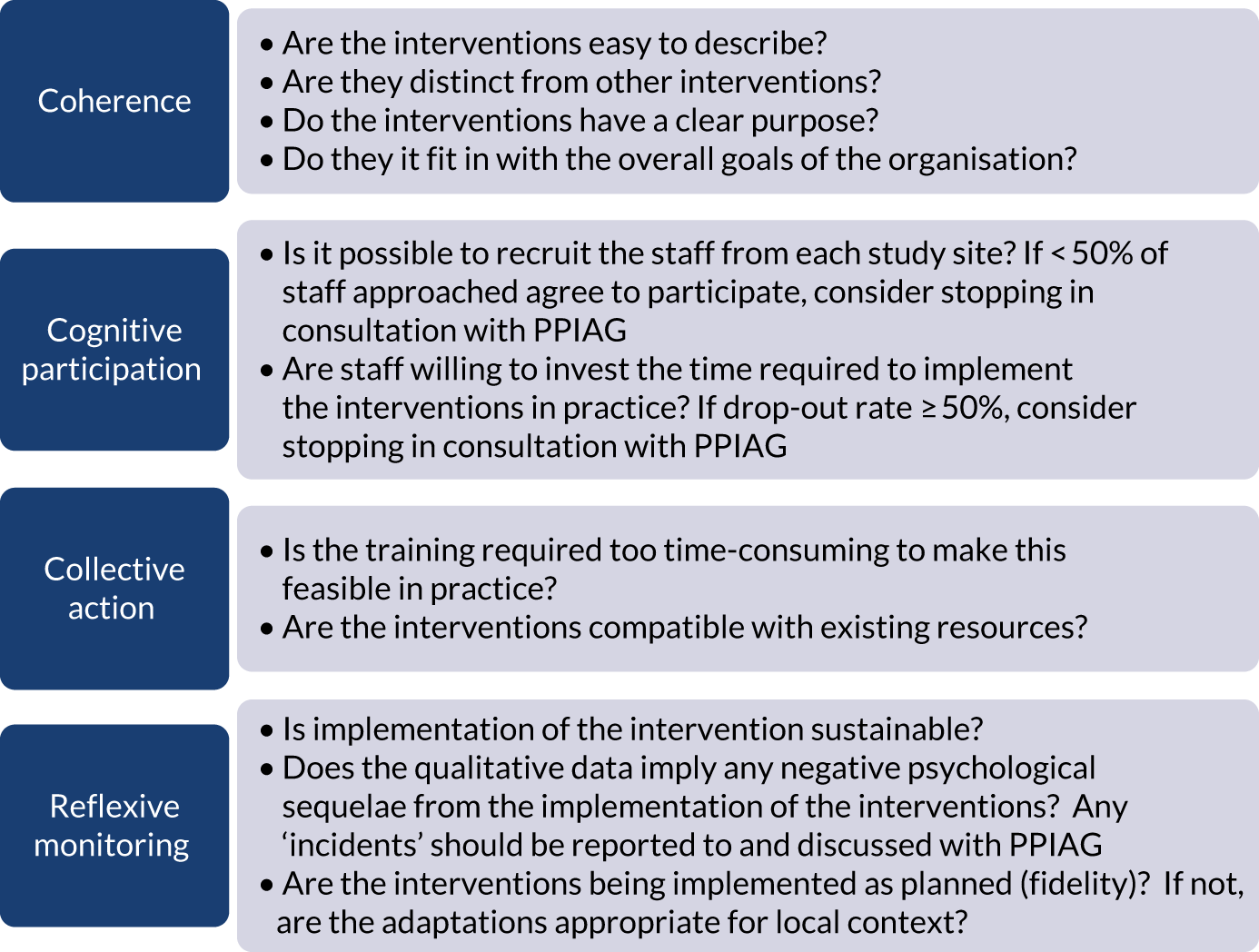

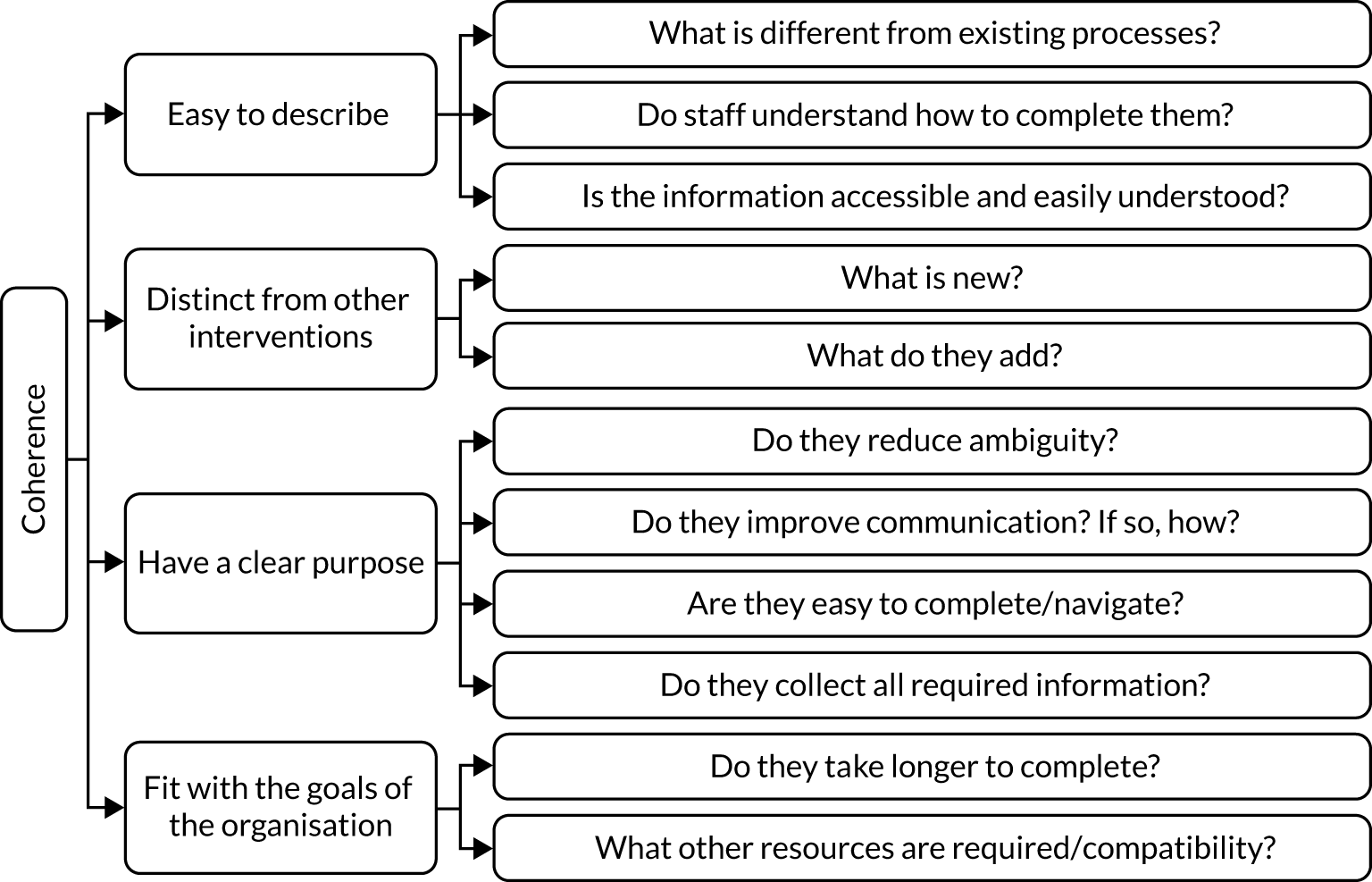

Research evidence needs to be translational; interventions can have a significant impact on health and health care only if they are shown to be effective and capable of being widely implemented and can be normalised into routine practice. 68 For this reason, NPT68,69 was used to study the implementation and assimilation of the co-designed interventions into routine practice in the two case-study sites (NBSLs). NPT consists of four components that explain how interventions are embedded and ‘normalised’ into routine care. These are coherence (how participants make sense of the new/different way of doing things), cognitive participation (committing to working in the new/different way), collective action (making the effort and working in that way) and reflexive monitoring (undertaking continuous evaluation and making adjustments if needed so that what was once a new intervention becomes a normal part of everyday practice). We used NPT to guide and evaluate the translation of the co-designed interventions into routine practice and as a framework for the analysis of related data.

Semistructured interviews undertaken during the process evaluation were used to determine parents’ views and, where relevant, experiences of the co-designed interventions. Data from interviews were also used to identify potential outcome measures for a future evaluation study by focusing on the impact on parents in terms of anxiety, stress, distress and well-being caused by communication of the positive NBS result. In addition, principles of the nominal group technique78,79 were used during phase 4 to rank the components of the proposed outcome measures to determine their relevance and importance from a stakeholder perspective.

Economic analysis

The aims of the economic analysis were to (1) calculate the costs of the proposed and current communication strategies (in phase 3, but also using data collected in phase 1) and (2) inform the economic evaluation that would accompany a full trial, including identifying potential sources of data and how best to collect these data.

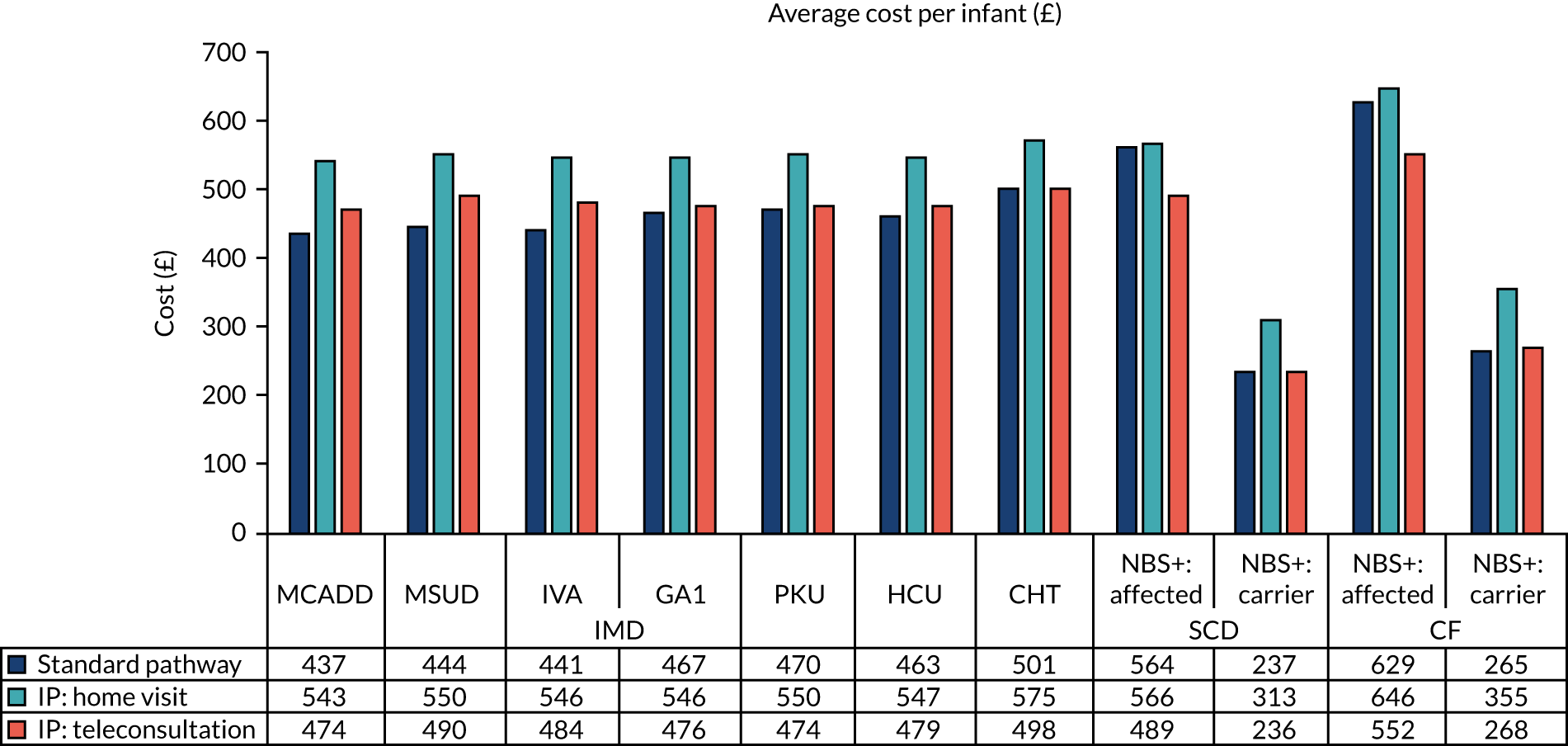

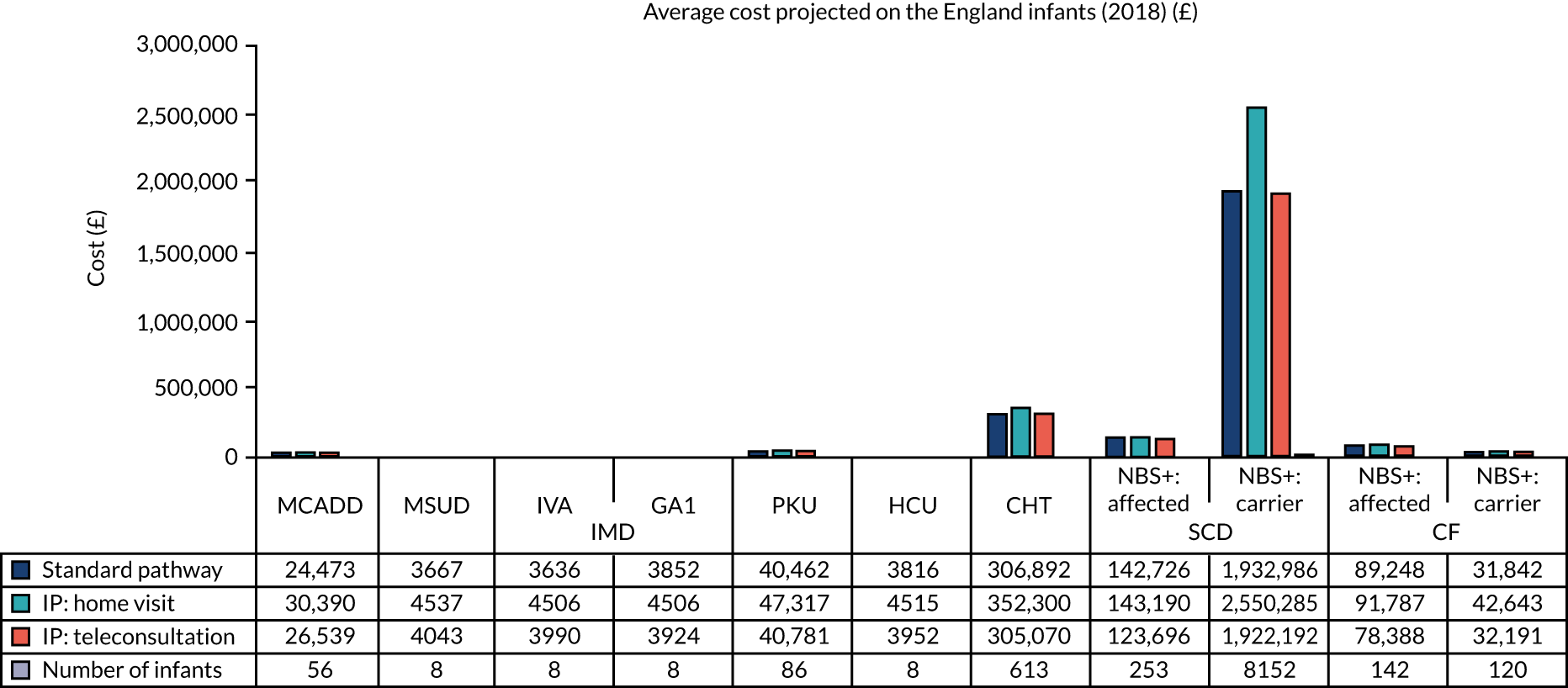

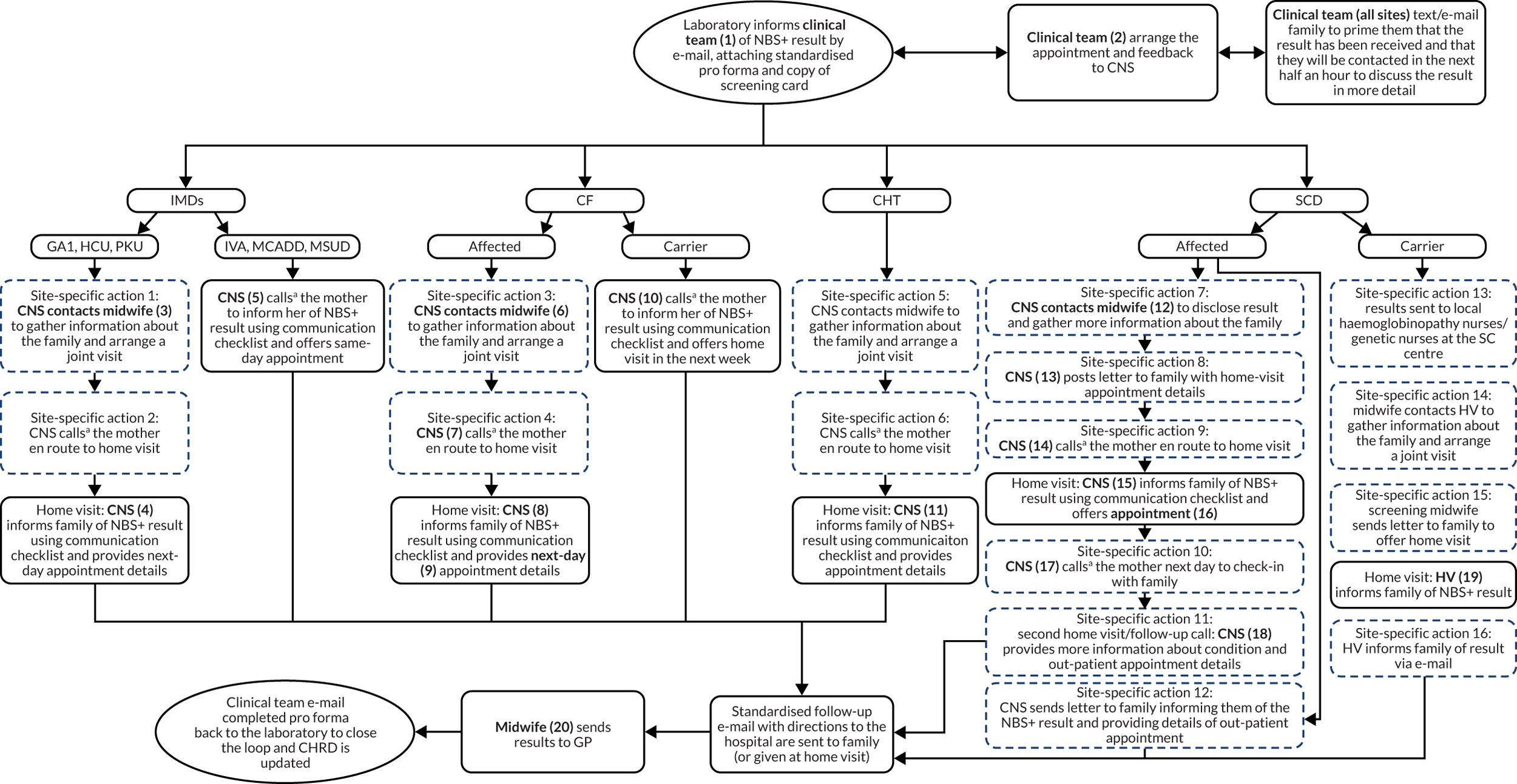

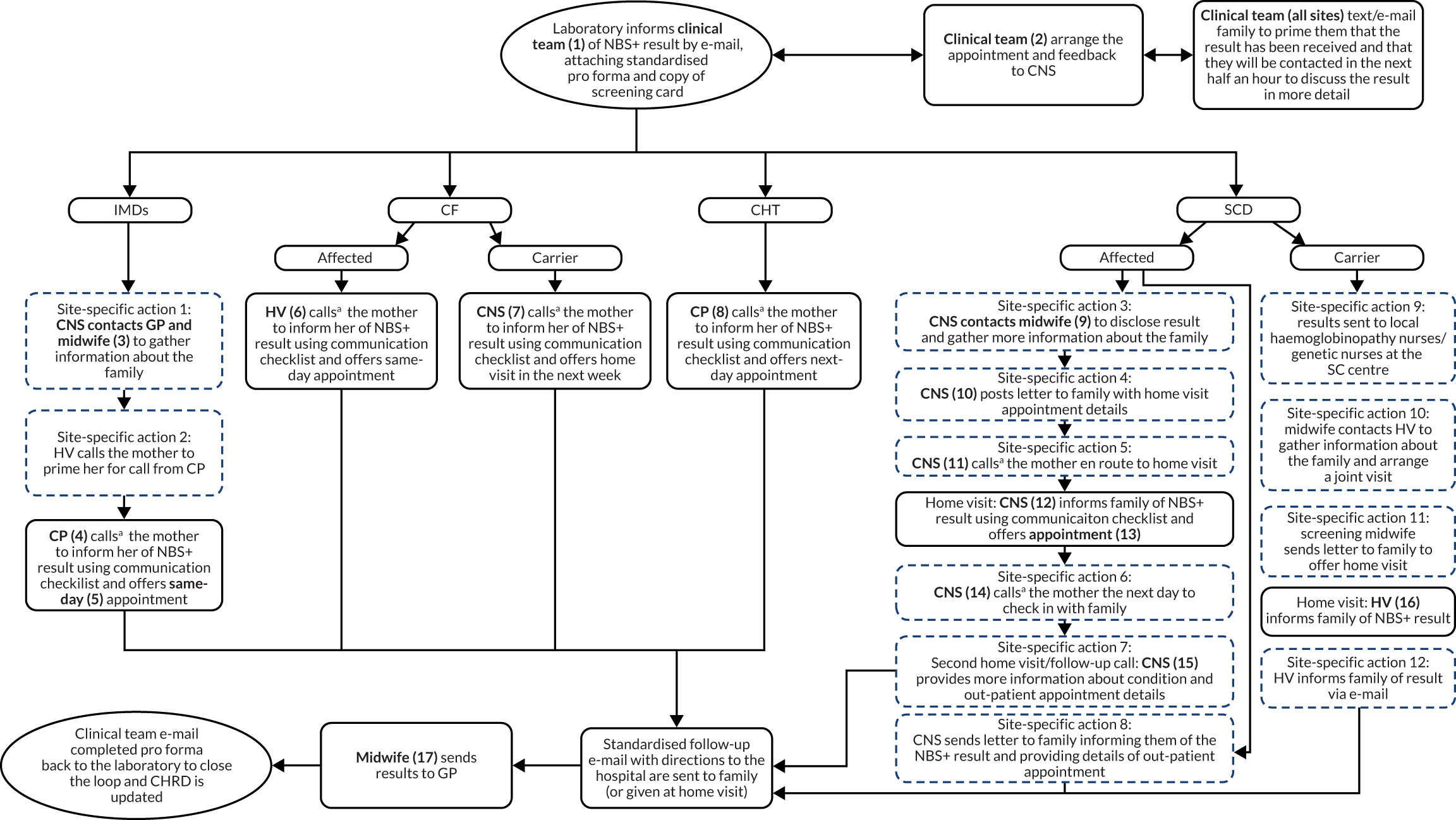

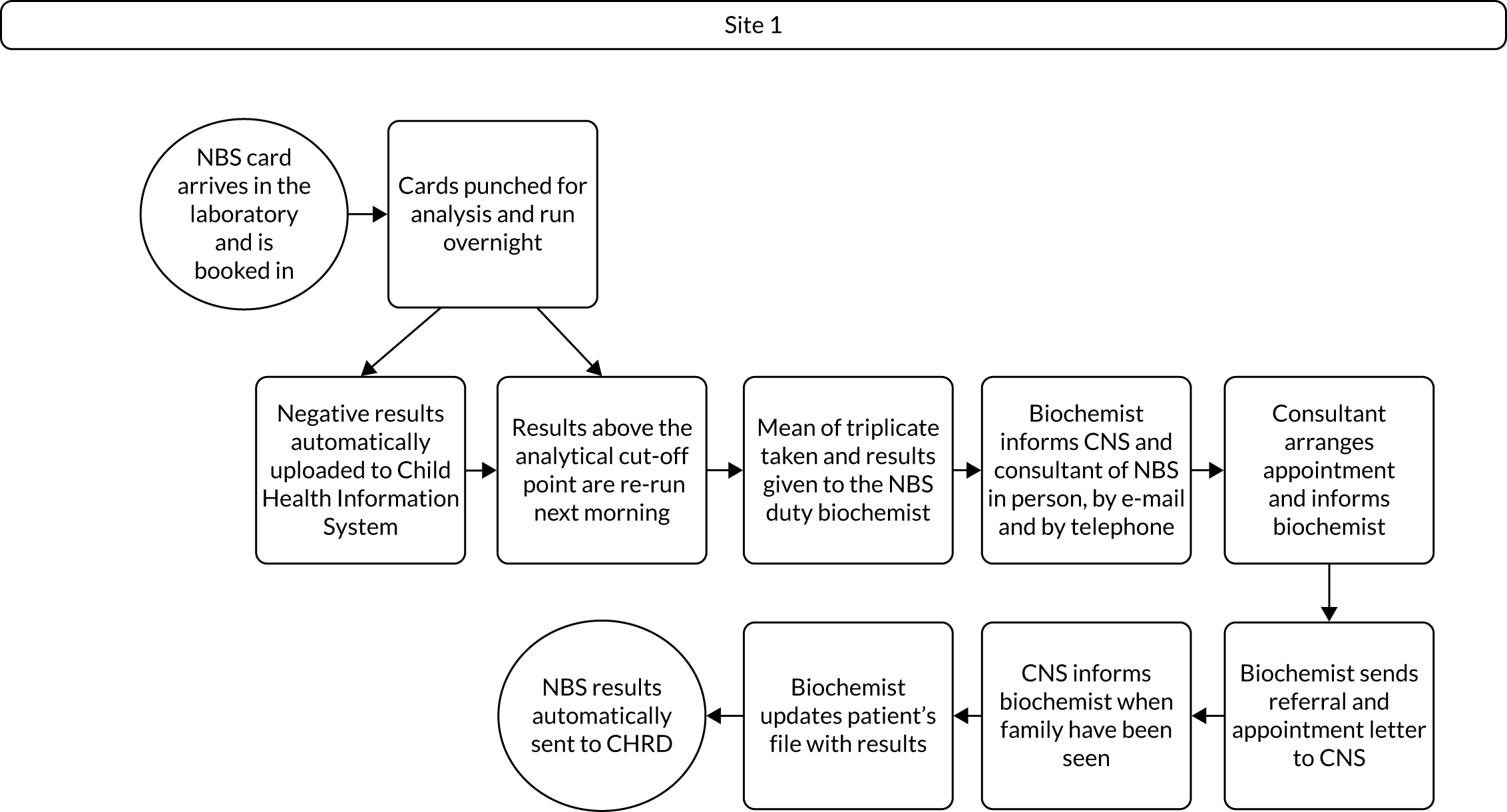

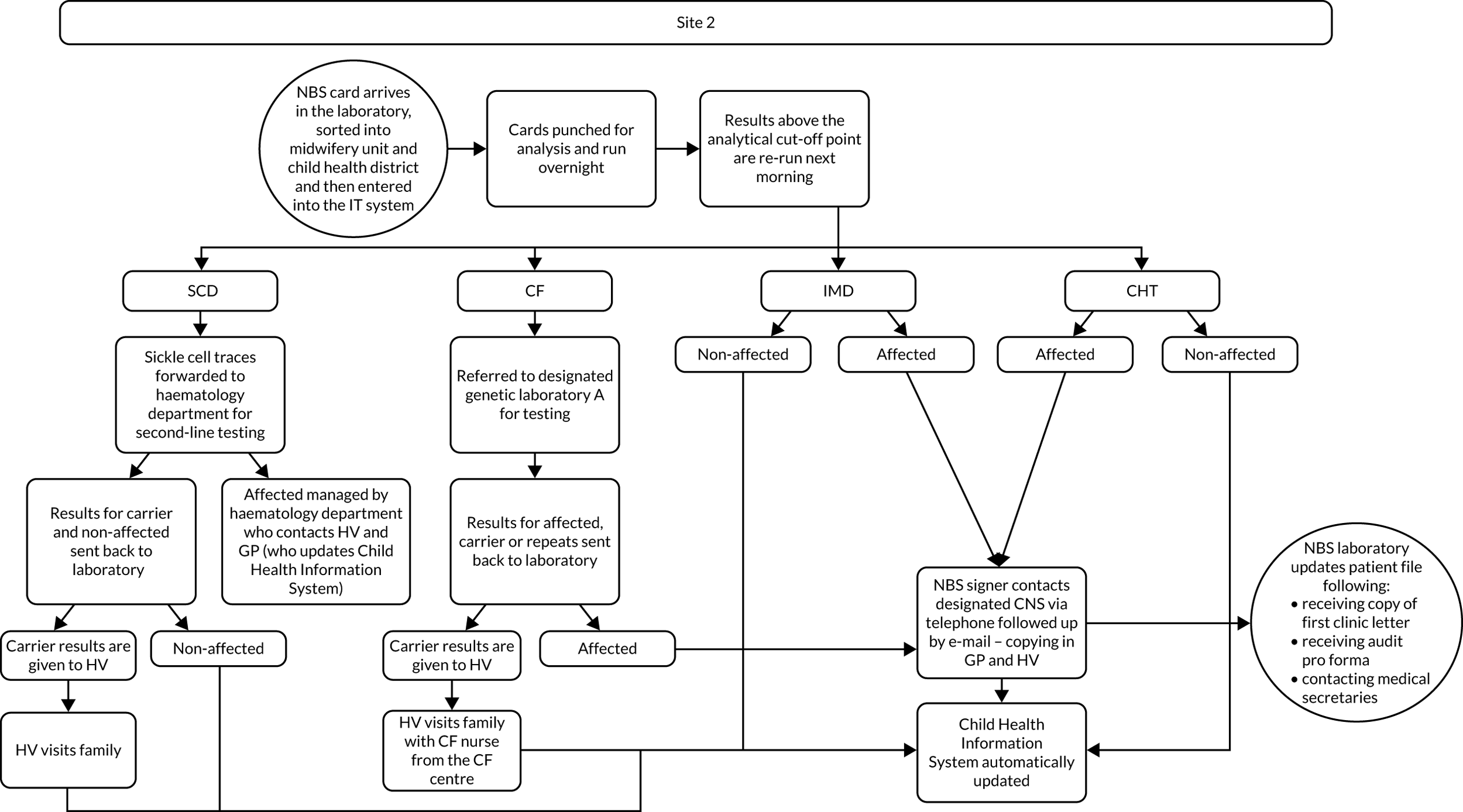

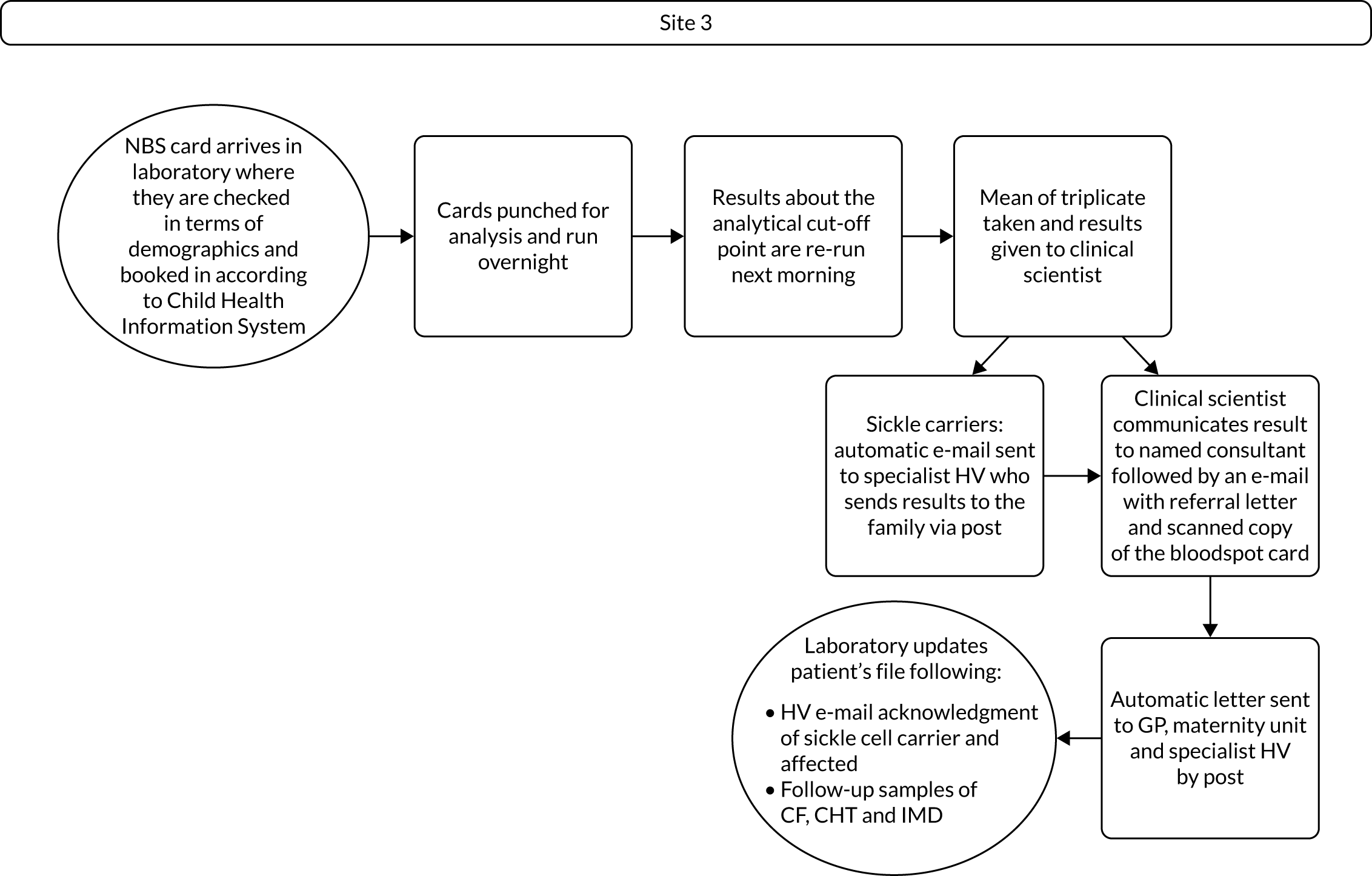

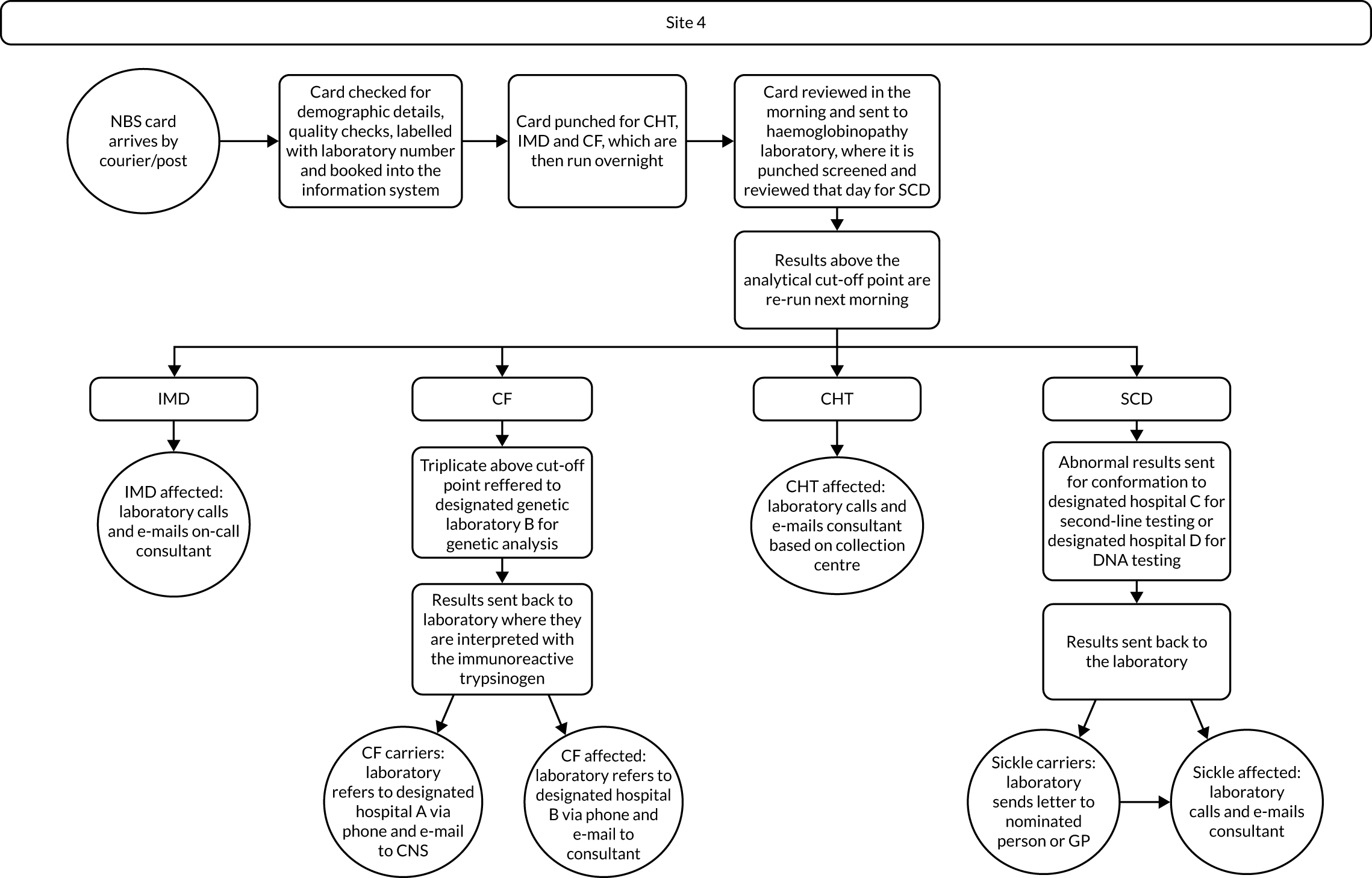

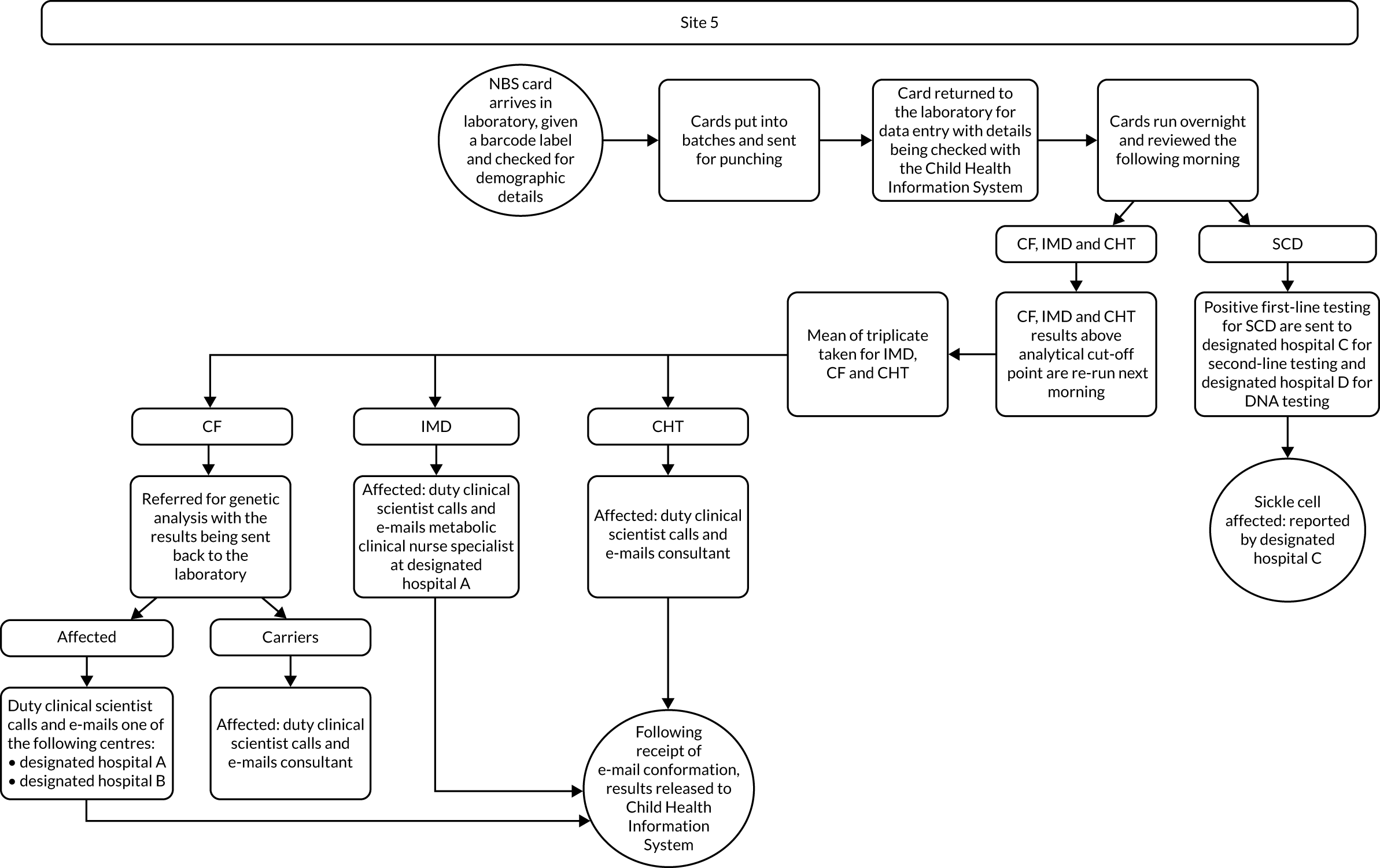

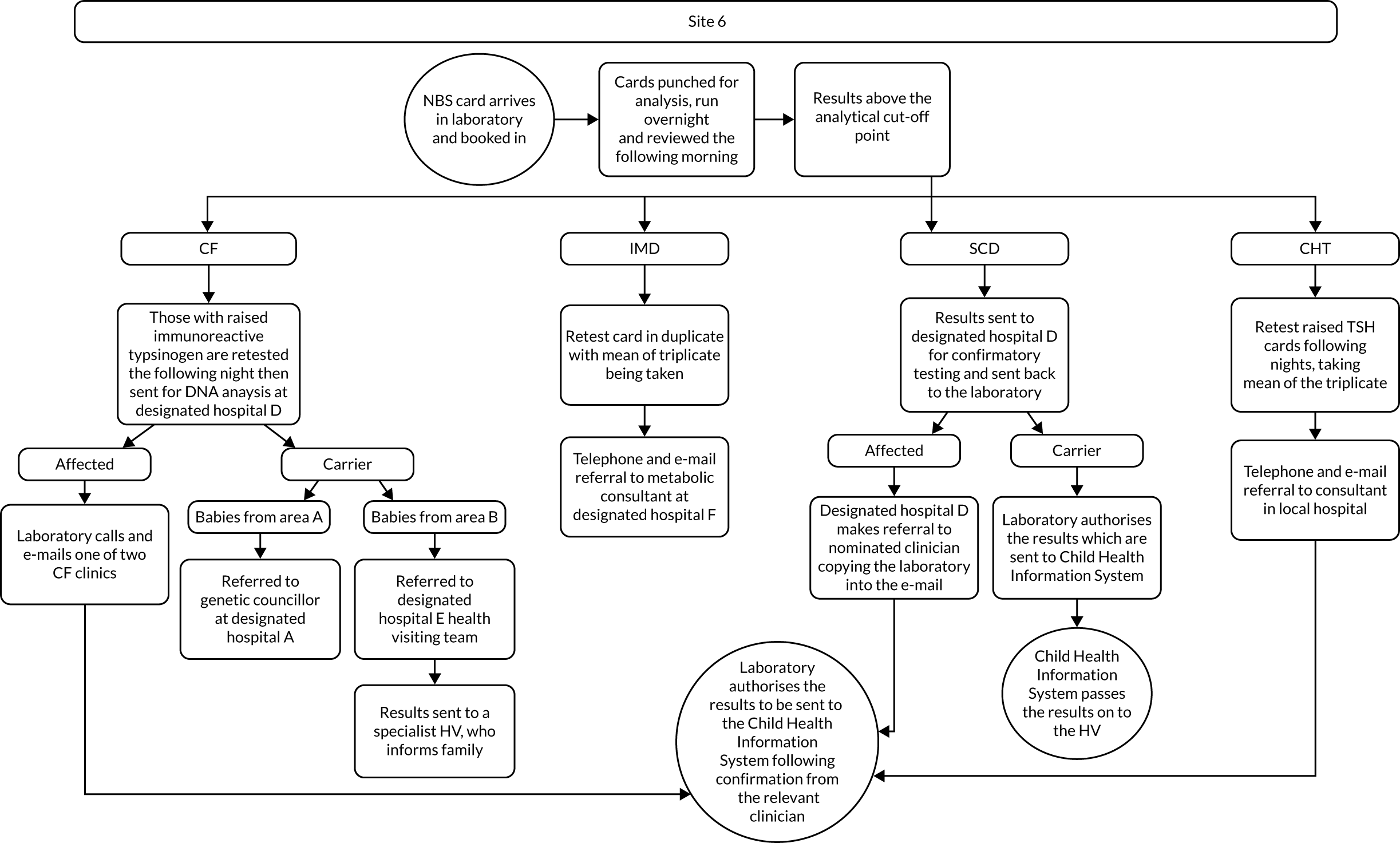

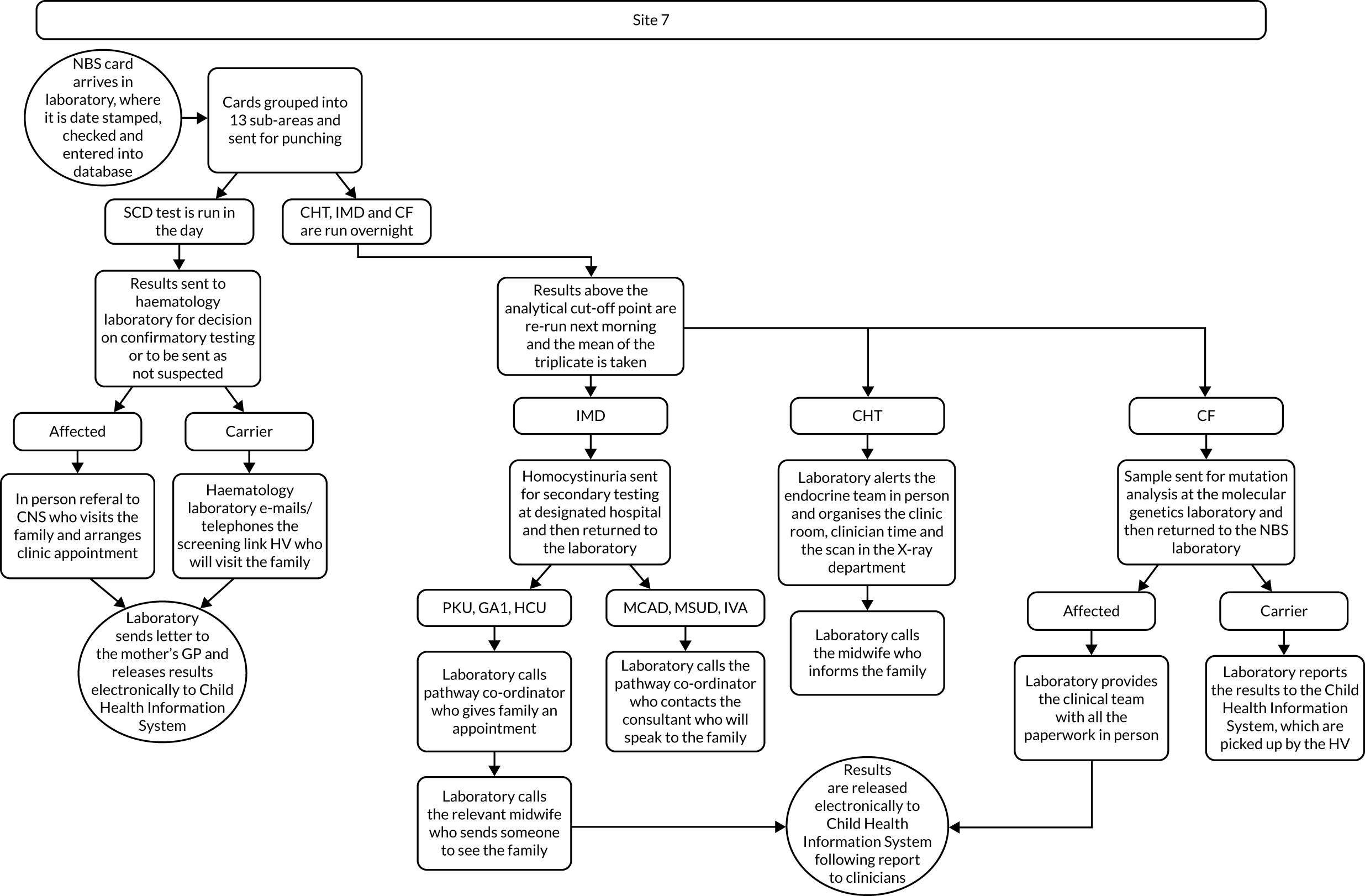

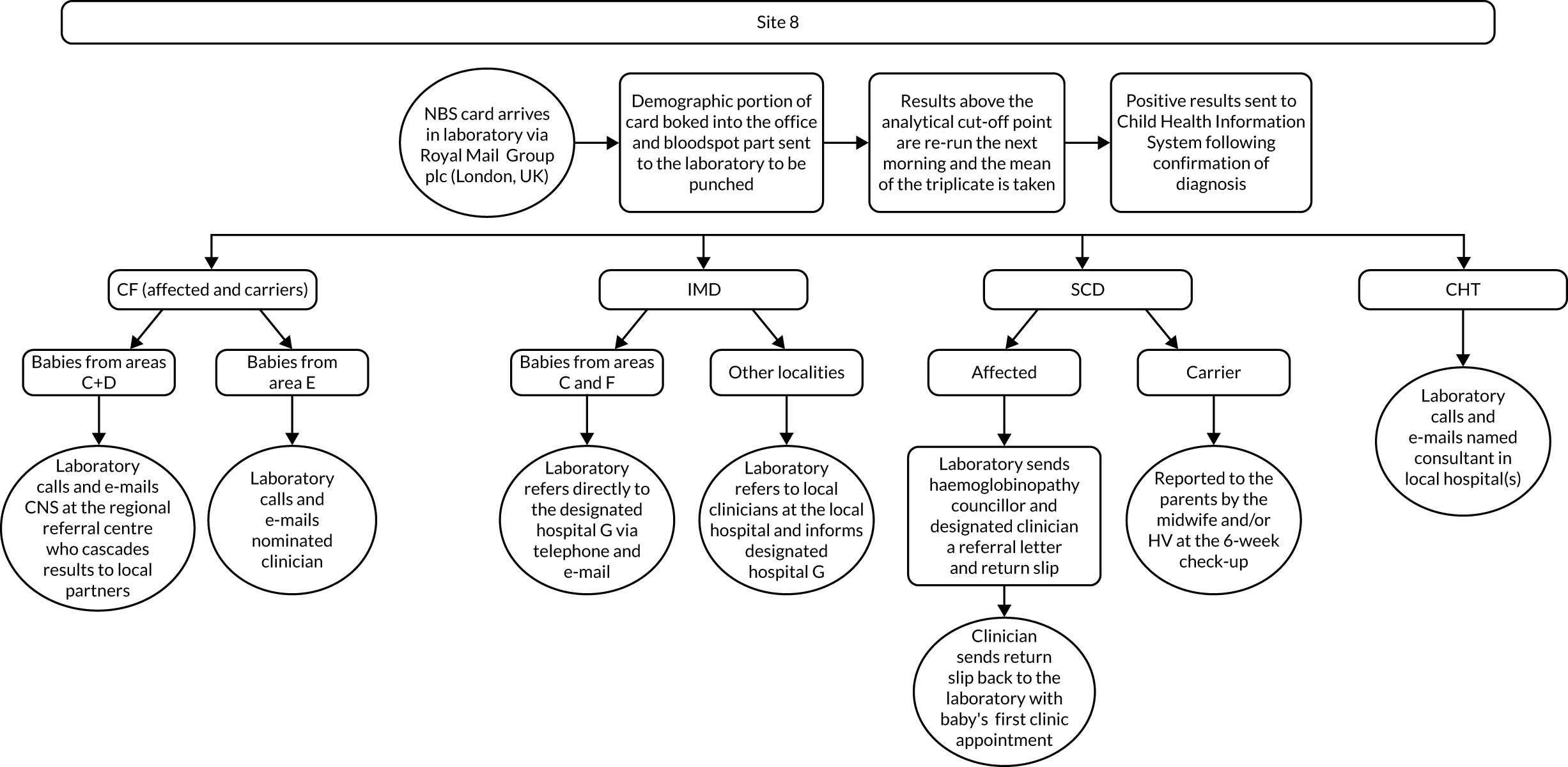

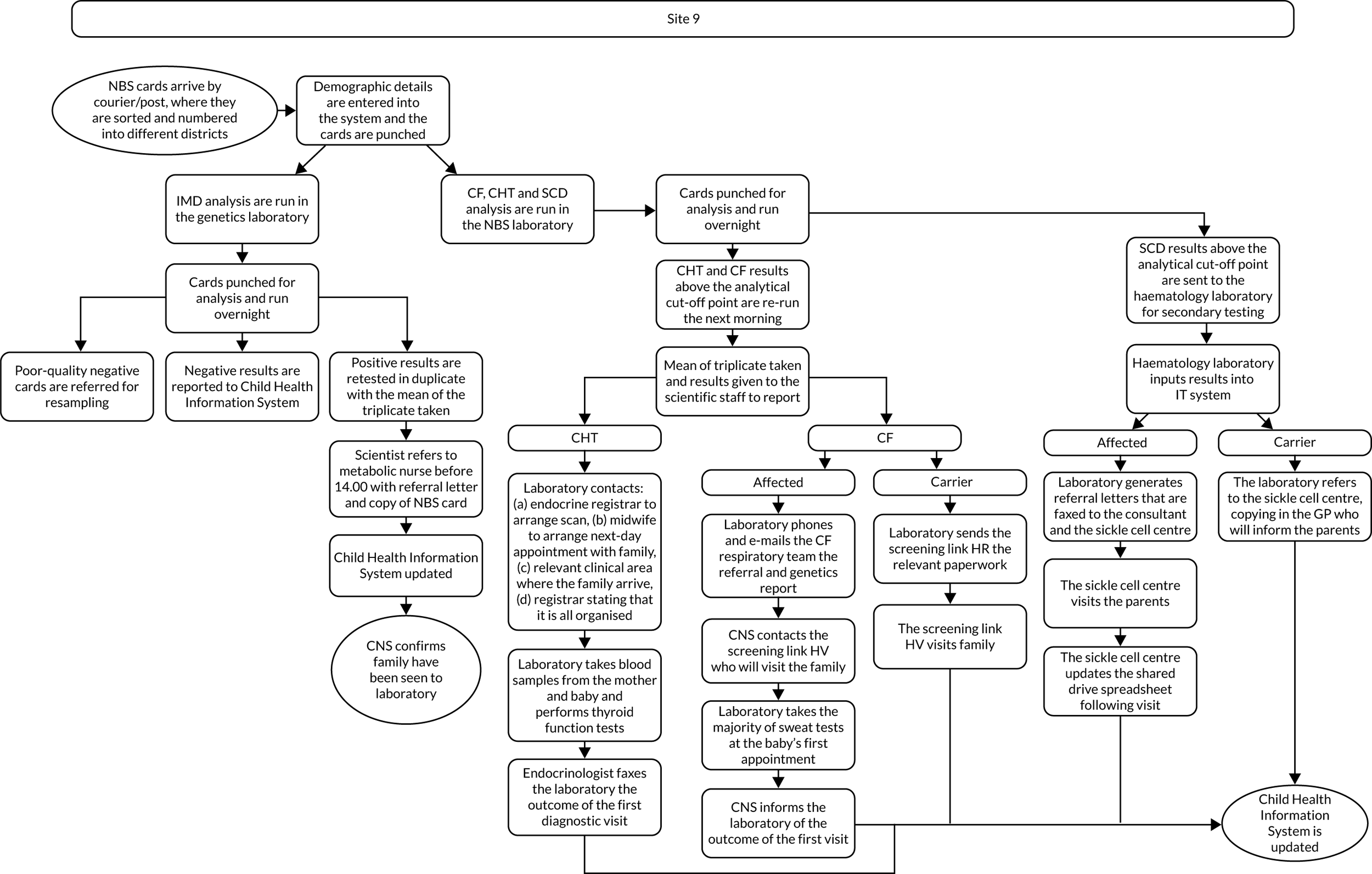

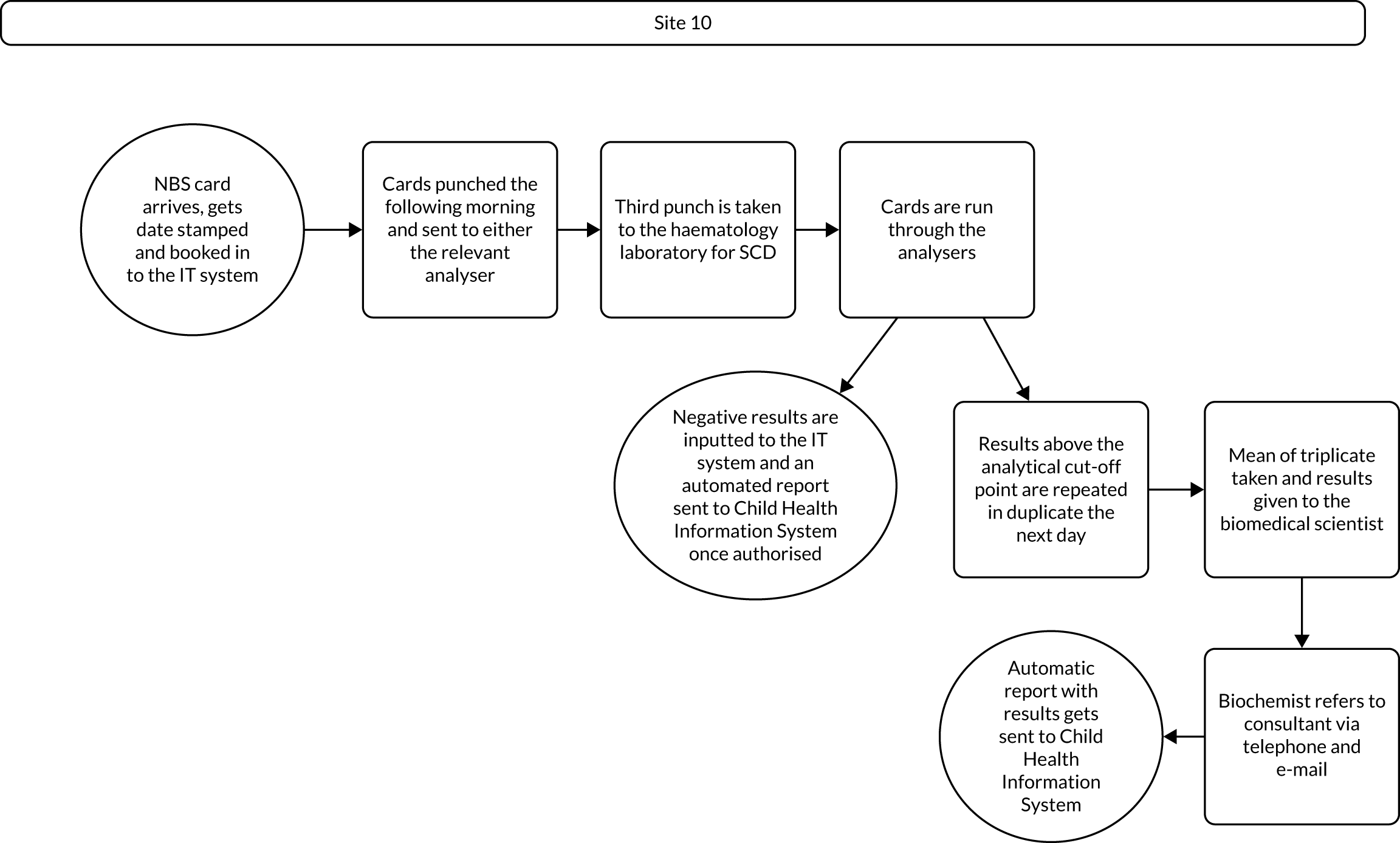

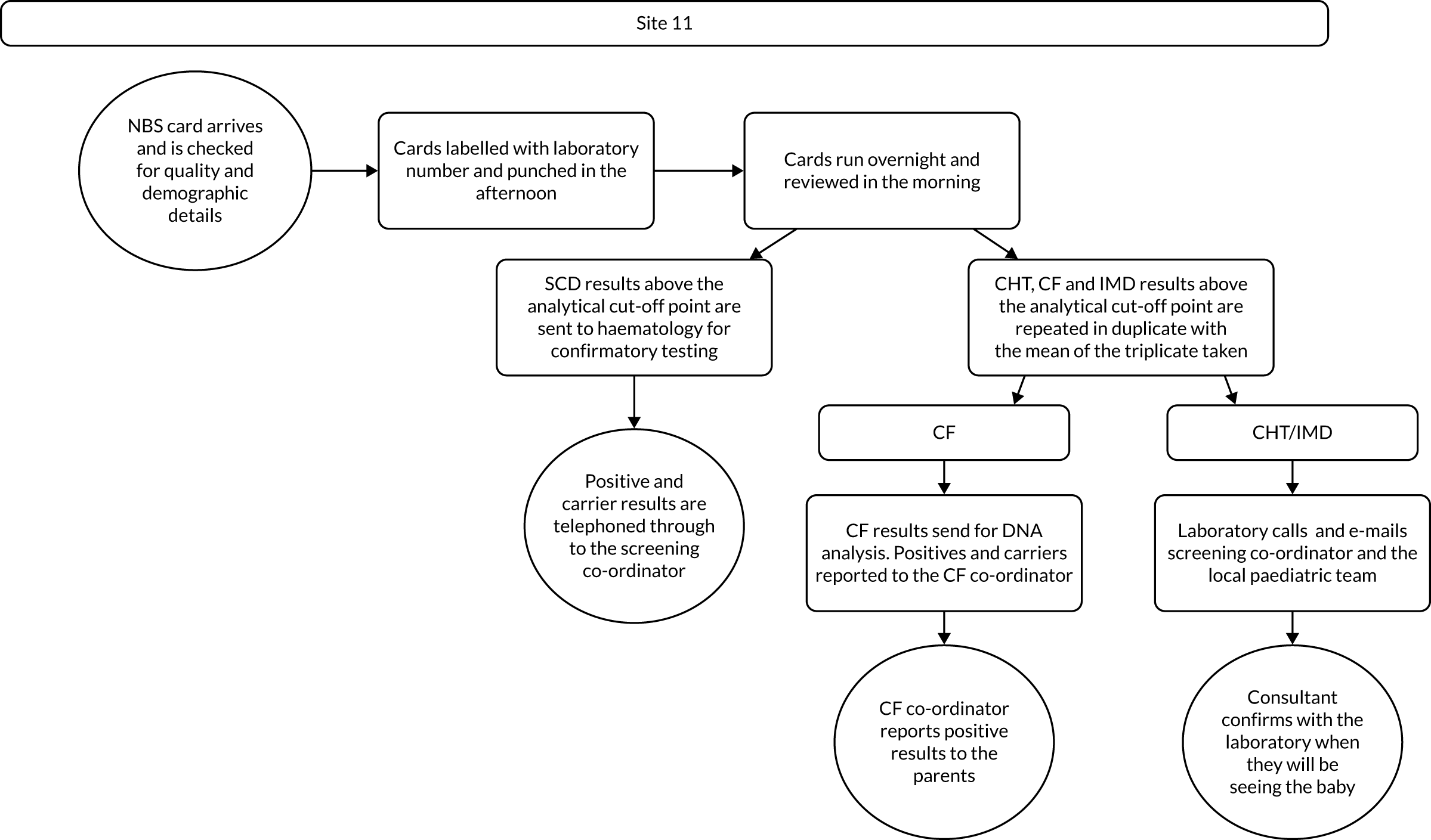

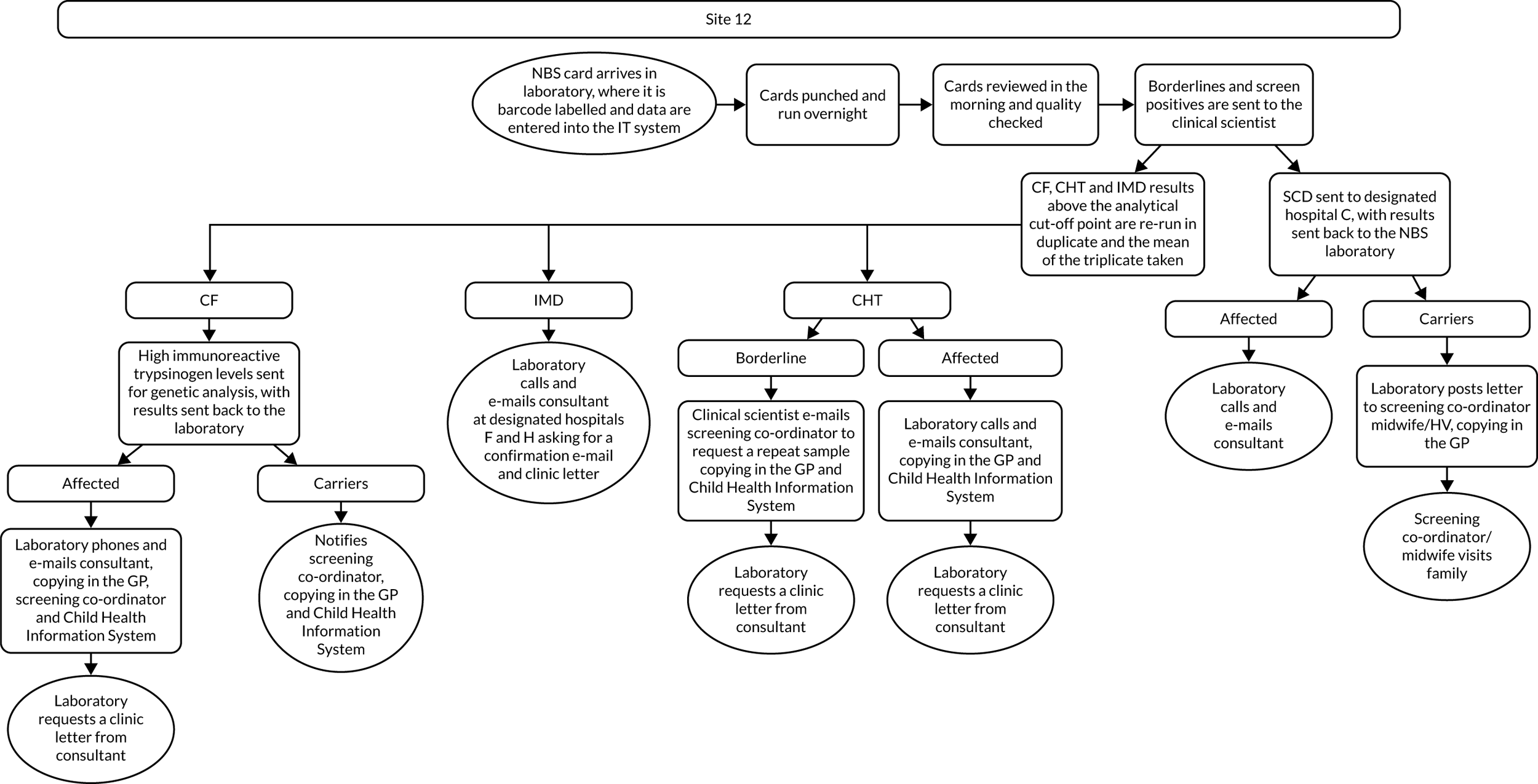

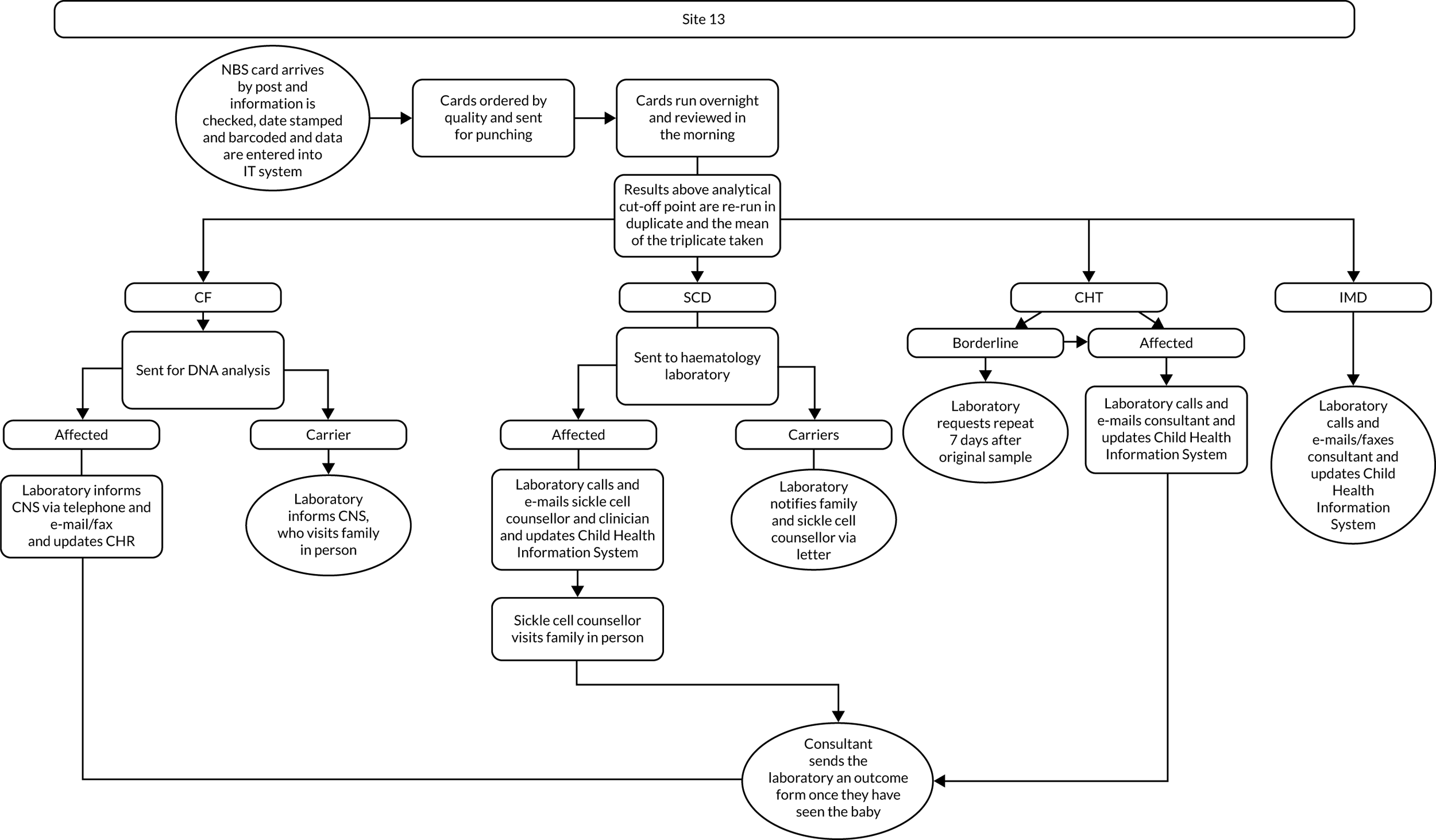

To meet the first aim, we estimated the cost incurred for each communication strategy, including their potential monetary impact at the national level. A microcosting approach was used to take into account the number of contacts made by medical staff and the parents of infants who had received a positive NBS result. 86 The schematics of the communication pathways were used to measure the number of activities performed across these pathways (see Appendix 1, Figure 13). We included the interactions between medical staff and their communications with parents. An estimate of the time required for each of these activities was obtained from the interviews with the clinical teams. This was converted into costs from an NHS perspective by applying publicly available unit costs. This process resulted in an estimate of the cost of each communication pathway. We then applied the number of infants affected by the relevant diseases to obtain the projected costs of implementing the communication strategies at the national level.

Identifying the relevant resources

Given the primary focus of this part of the study to ascertain the costs to the NHS of the different communication strategies, we took an NHS perspective for our analysis. Additional costs incurred by parents are considered separately.

The schematics of the communication pathways (see Appendix 1, Figure 13) were used to identify the relevant activities. These activities involved a range of medical staff, including, but not limited to, nurses, doctors and health visitors. Activities requiring a face-to-face interaction with the parents were categorised by their setting (home or clinic). Similarly, all of the activities that did not require a face-to-face interaction (e.g. telephone calls and e-mails) were categorised by whether they happened between medical staff or between medical staff and parents. We assumed that the time for drafting an e-mail corresponded to the time needed for a telephone call.

Measuring resource use

Once the relevant items of resource use were identified, the schematics of each communication strategy (see Appendix 1, Figure 13) were examined to count the number of relevant resource items. If the schematic indicated that the contact could have been performed by different types of staff, for example a nurse or a health visitor, we assumed an equal distribution, for example a nurse 50% of the time and a health visitor 50% of the time. Based on the interviews with the clinical teams, it was possible to derive data on the average time needed to perform each of the activities considered in the schematic.

Travel costs for parents of each baby were based on costs incurred for a one-off return visit from their home to the study centre for the initial appointment with the clinical team after receiving the positive NBS result. These data were collected over a 12-month period, that is for all babies who received a positive NBS from January to December 2020. It was not possible to collect data regarding subsequent general practitioner (GP) consultations, outpatient appointments and consultations with NHS services, such as emergency departments and emergency hospital admissions, owing to the impact of COVID-19 on these services.

Valuing costs

Unit costs were obtained from the Personal Social Services Research Unit. 87 The cost of leaflets was taken from a previous study. 88 Travel costs were valued for four scenarios involving different modes of transport: (1) private car, (2) public transport (e.g. bus, train), (3) taxi and (4) other means of transport (i.e. walking and cycling). All scenarios assumed that the appointments were scheduled to start at 09.00. In scenario 1, travel costs comprised 4 hours of hospital parking fees based on the average of the costs at each centre (mean £9.36, range £4.00–12.80) plus a cost of £0.14 per mile travelled by the parents. Scenario 2 was developed assuming that parents travelled using bus, train or tube from their home and was costed using publicly available websites (e.g. National Rail Enquiries; URL: www.nationalrail.co.uk/; accessed 4 January 2021). The costs of scenario 3 were calculated using the online estimates of Minicabit, a private taxi company (URL: www.minicabit.com/; accessed 28 February 2021). Scenario 4 assumed that parents incurred no travel cost. No data on the mode of transport were collected in the study; therefore, we assumed that means of transport followed the same distribution as that observed for parents attending antenatal tests. 89

Calculating costs per strategy and national costs

The overall cost for each of the existing and new communication strategies was obtained by multiplying the time spent by each staff member by the relevant unit cost and summing the cost for all staff members involved in the pathways. This provides an estimate of the cost of each strategy per infant. These were converted to national costs by multiplying the cost per infant by the overall number of infants who had received a positive NBS result in England. 90

Scenario analysis

Given the variability of communication practices across the study sites and the disease pathways, a scenario analysis was implemented to assess the impact of informing the parents on their infant condition exclusively by (1) home visits [intervention pathway (IP): home visit] or (2) teleconsultations (e.g. telephone call, video call) (IP: teleconsultation).

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement was instrumental in the design and conduct of this study. Eight parents of babies who had received a positive NBS result for one of the nine screened conditions formed a Patient and Public Involvement Advisory Group (PPIAG), which met every 6 months for the duration of the study, including prior to, during and following data collection. Their suggestions were incorporated into the study design, the data collection tools and the data analysis and presentation. The PPI group was presented with data from the annual reports of the NBS programmes and it made suggestions as to which sites should be used in phases 2 and 3 of the study. The PPI group also suggested clarifying that positive NBS results indicated an ‘abnormal’ result, whereas negative NBS results indicated a ‘normal’ result during data collection, as they had found this confusing when they received their child’s NBS result. Initial findings were presented to members of the PPI group during the regular 6-monthly meetings, and drafts of manuscripts were also shared with PPI members to ensure that these were presented in a readable format. In addition, we obtained the views of representatives from charities for the screened conditions, including Metabolic Support UK (Chester, UK), the British Thyroid Foundation (Harrogate, UK), the Cystic Fibrosis Trust (London, UK) and the Sickle Cell Society (London, UK).

Ethical considerations

The study included parents who had received a positive NBS result, which can be extremely distressing. The research team is highly experienced at working with families in this situation and always proceeded with due care and sensitivity for the potential participant.

In addition, the research team consisted of a consultant clinical psychologist who was available to provide advice to the research team if and when any issues of this nature arose. Time was spent debriefing parents at the end of the parental interviews; this included ensuring that parents were aware of additional sources of support, including their relevant clinical team and appropriate charities.

Observing health-care professionals delivering positive NBS results to parents in phase 2 involved accompanying a health-care professional and entering the parents’ home. Advice was sought on each occasion from the health-care professional concerned prior to this happening to ensure that they felt that it was appropriate. During the limited observations that took place, the researcher was introduced to the parents by the health-care professional. The researcher did not participate in the discussion between the health-care professional and the parent, but observed the interaction and made notes after the event.

Written informed consent was sought from participants prior to any data collection procedures taking place. When data were collected remotely [by telephone or Microsoft Teams (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA)], written informed consent was sought by e-mail prior to the data collection event.

Phase 1: existing communication practices nationally

Data collection

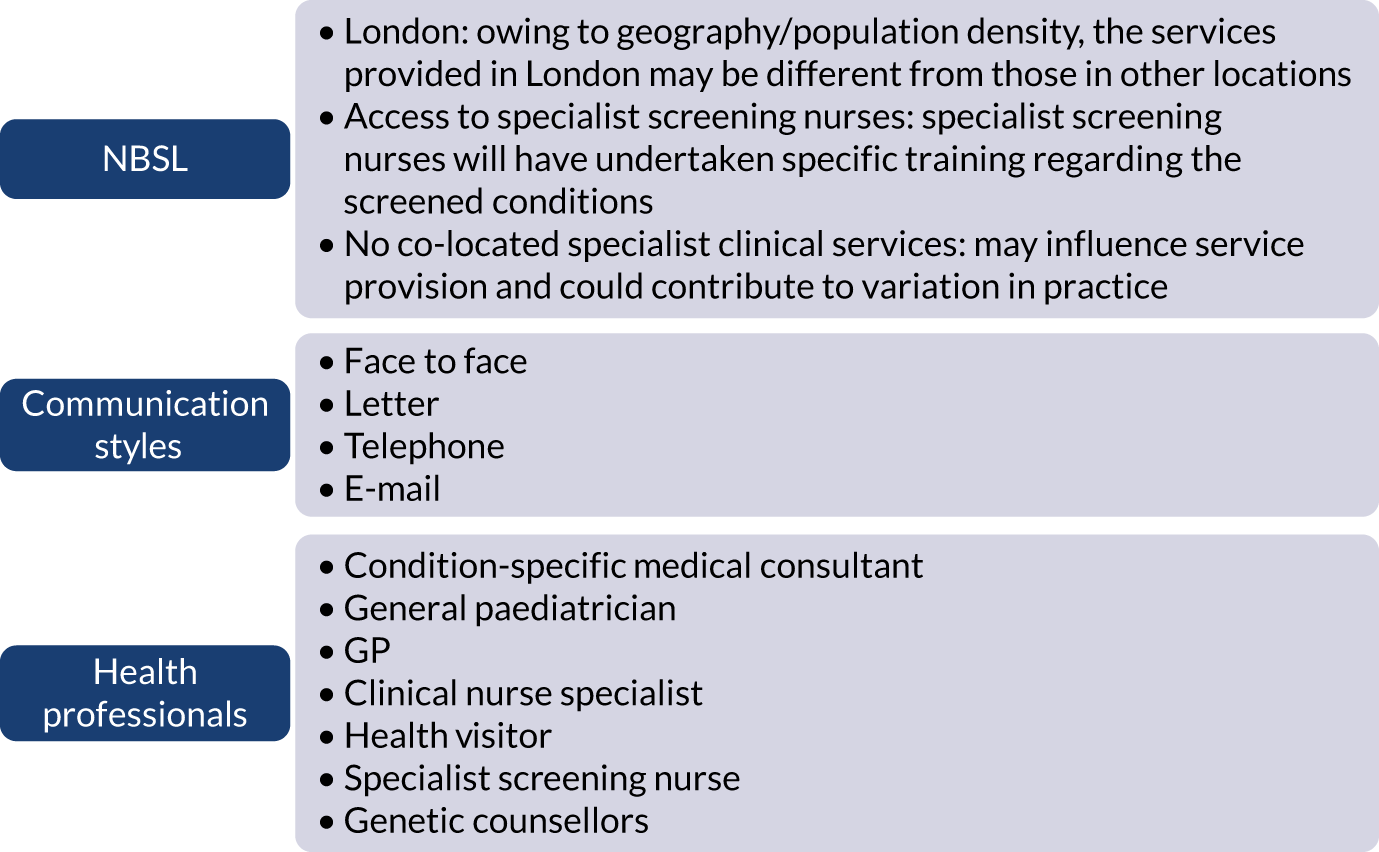

Semistructured telephone interviews were undertaken by Jane Chudleigh between June 2018 and February 2019 to ascertain the existing pathway(s) used to communicate positive NBS results, and associated resource use. Written consent was obtained by e-mail prior to the telephone interviews taking place. All telephone calls were recorded using a telephone pick-up microphone, which was plugged into an encrypted recording device. For all 13 laboratories, for each condition included in the NBSP in England, the time frame extended from the time the NBS card arrived in the laboratory to when the parents were told the definitive result. Directors of NBSLs, laboratory staff involved in processing results and members of relevant clinical teams, including medical consultants, general paediatricians, nurse specialists, health visitors, specialist screening nurses and genetic counsellors, who were involved in receiving positive NBS results from laboratories and/or communicating positive NBS results to parents were interviewed.

The information gathered included the mode of communication (face to face, letter, telephone, e-mail), the resources involved in each communication strategy, who provides the information and their role, and the location (co-located or alternative site) of relevant services for each condition.

Sampling

A two-stage sampling approach was employed. In the first stage, participants were sampled purposively based on their experience of the phenomena of interest. In the second stage, snowball sampling, participants from the first stage suggested other relevant clinical colleagues. Directors of all 13 NBSLs in England were invited to participate. The directors were identified through the UK NBSL Network (www.newbornscreening.org/site/laboratory-directory.asp; accessed 28 February 2021) and were contacted by e-mail by a member of the research team. Directors of newborn screening laboratories were invited to be the local principal investigator for their study site and were asked to provide the names and contact details of staff in the laboratory who met the inclusion criteria for the study. These staff members were contacted by e-mail and invited to participate.

Representative members of local clinical teams (medical consultants, general paediatricians, nurse specialists, health visitors, specialist screening nurses and genetic counsellors) were identified through individual trust websites and invited by e-mail to participate. Those who agreed to participate were also asked to identify other members of their team who they thought should be interviewed to provide further information about the NBS process. These additional potential participants were also contacted by e-mail and invited to participate. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data analysis

Interview data were managed manually. Quantitative data collected from the closed-ended questions were analysed using descriptive statistics. Qualitative data from the open-ended questions were analysed using thematic analysis91 using an inductive approach. Data from laboratory staff and clinical staff were analysed separately. Seven interview transcripts from laboratory staff were coded by two members of the research team (JC and HC) to aid coding comparisons and to inform and align code development. 92 A code book was developed based on these jointly coded transcripts. A further seven laboratory transcripts were then coded separately by the same two members (JC and HC) of the research team using the code book. These separately coded transcripts were compared; the intercoder reliability was 95%. A similar process was followed for the transcripts for clinical staff; the intercoder reliability was 92%. Following this, the same two members of the research team (JC and HC) coded the remainder of the laboratory and clinical staff transcripts using the relevant code books. This was an ongoing iterative process; new codes were developed and the definition of codes was refined as the analysis progressed. 93 Once this initial coding had been completed, these codes were then collapsed into themes. Process maps (see Appendix 2, Figure 15) were developed for each NBSL to describe how positive NBS results were communicated to clinical teams and how clinical teams communicated the results to parents. These data were also used as a baseline for calculating costs associated with existing communication strategies and following implementation of the co-designed strategies in phase 3.

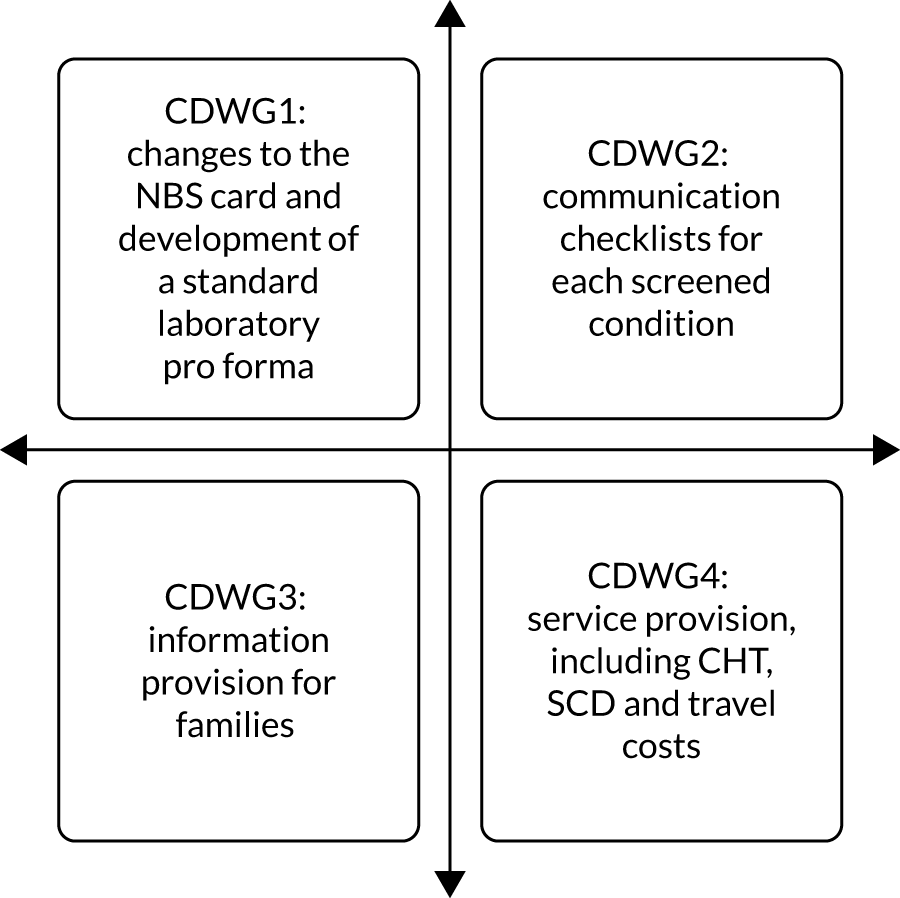

These data were considered by the study team in the first instance and then presented to the PPIAG alongside data regarding how many screen-positive cases each NBSL processes annually7,8 and the predetermined exemplar framework (Figure 1) to determine which NBSLs would be included in phases 2 and 3. The study team narrowed the study sites down to four potential sites that fulfilled the criteria set out in the exemplar framework and processed similar numbers of positive NBS results annually. These were presented to the PPIAG, who selected the final two case-study sites included in phases 2 and 3.

FIGURE 1.

Exemplar framework: features of the process for communicating positive NBS results to parents.

Phase 2: co-design of interventions to improve communication of positive newborn bloodspot screening results

This phase consisted of implementing the EBCD approach73,76 and was guided by the online EBCD toolkit. Study sites consisted of three NHS provider organisations (trusts) in England served by two NBSLs (study sites) that process comparable numbers of positive NBS reports annually for each of the nine conditions currently included in the NBS programme. These consisted of two trusts in Greater London served by one NBSL processing 128 positive NBS results in 2017/18, and one NBSL in the West Midlands processing 129 positive NBS results in 2017/18.

Stage 1: engaging patient/carers and gathering experiences

Data collection

Two members of the research team (JC and HC) undertook filmed narrative interviews with parents (ensuring representation of all screened conditions) across the two study sites between September 2018 and March 2019. Written consent was obtained by e-mail prior to the interviews taking place. These explored parents’ experiences of receiving positive NBS results to identify key themes (touch points). Parents were identified as potential participants by health-care professionals communicating positive NBS results, as this has previously been shown to be an effective recruitment method. 11 Questions were guided by the principles of FST and focused on the impact of receiving a positive NBS result on their relationships with each other, their child and their wider support network, including their friends and family. 62 For this reason, parents were asked to talk about their experience of receiving their child’s positive NBS result in terms of both the process and any emotions or feelings this caused and why.

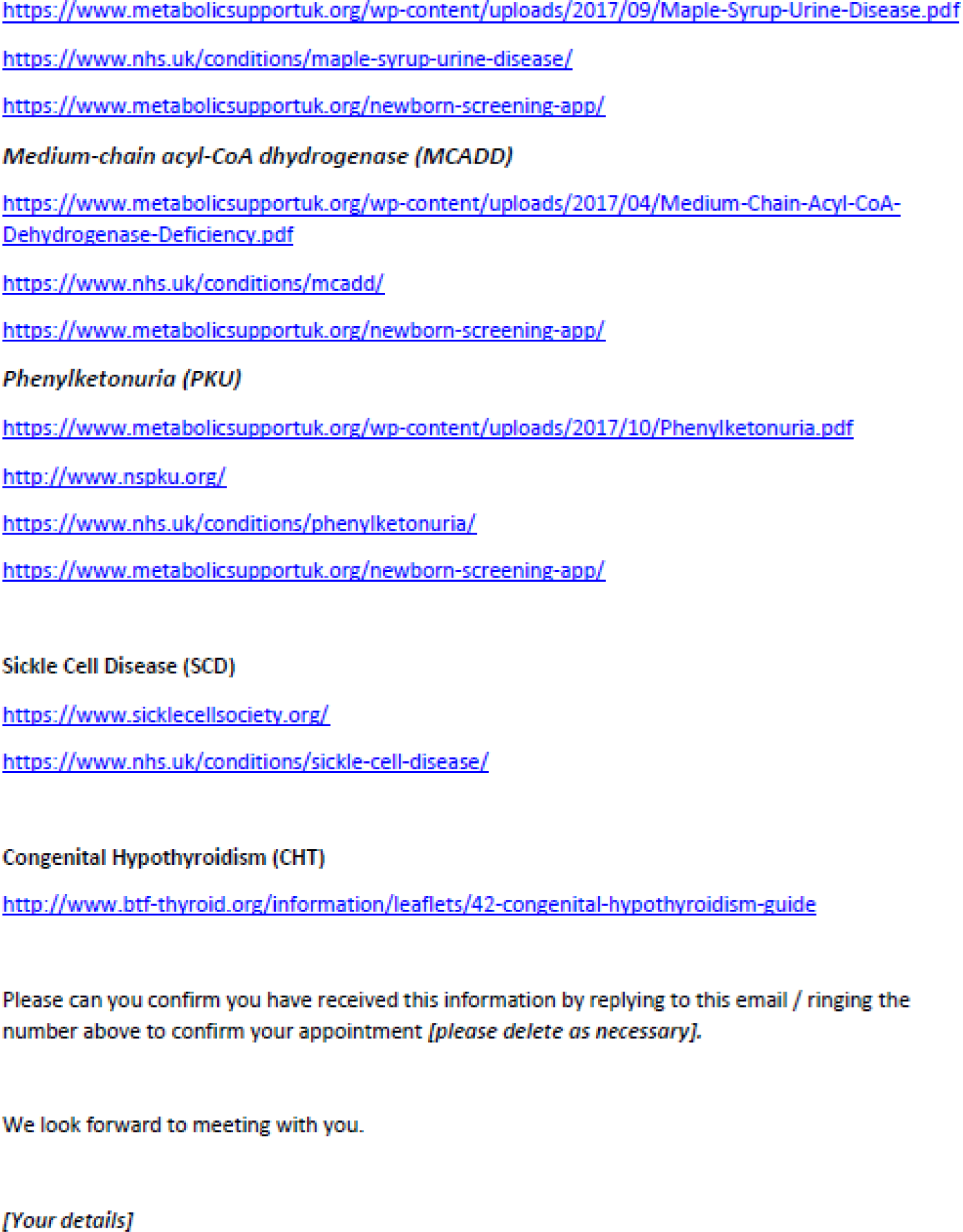

Following the interviews, parents at each study site were invited to a parent feedback event in April/May 2019. These events were guided by the online EBCD toolkit and accompanying online resources, including the invitation and the agenda template. Parents who were involved in the filmed narrative interviews were invited to view the composite film of their interviews to ensure that it was a fair and valid representation of their shared experiences. This was used to inform a facilitated group discussion to highlight emerging issues and priorities for improvement, and an emotional mapping exercise to highlight their ‘touch points’. Parents were also asked to review an informational application (app) that was developed by members of the research team (JB and LM) in conjunction with Metabolic Support UK to provide parents with key information about inherited metabolic diseases and the screening journey, to provide recommendations for further development of the app and to explore the usability and acceptability of the app with parents. The app had been developed as part of a separate co-design process but was felt to be relevant given that this parallel work also focused on communication. In addition, it was felt that this could form part of the interventions and, therefore, potentially be part of the trial designed in phase 4. This required permission for a substantial amendment from the Health Research Authority (HRA)/Stanmore Research Ethics Committee (REC) and associated changes to the study protocol (protocol v4).

Sampling

Originally, we had intended to interview parents who had received a positive NBS result in the preceding 3–12 months. However, during a meeting with the PPIAG, PPI members requested that we increase the age range of the baby when recruiting parents from 3–12 months to 3–36 months. PPI members felt that this was important to allow parents time to adjust to their child’s diagnosis and have time to participate in the study. This required permission for a non-substantial amendment from the HRA/Stanmore REC and associated changes to the study protocol (protocol v3). Following this, informed by previous successful EBCD projects,74–76 we recruited a purposeful sample of parents across the two study sites who had received a positive NBS result for their child in the previous 3–36 months, ensuring representation of all screened conditions.

Data analysis

Family Systems Theory62,70,82,83 informed the development of themes identified from parental interviews. This included consideration of parental reactions to receiving the positive NBS result and consideration of how this had affected them as parents, individuals and partners, as well as the impact of the diagnosis on family and friends, reflecting the tenets of holism and interdependence that are fundamental to FST. These themes were developed into a composite film during April 2019. Touch points were gathered from the composite film and the emotional mapping exercise to highlight priorities and share with staff.

Stage 2: engaging staff and gathering experiences

Data collection

We intended to observe up to 10 staff in each study site on four occasions each (up to 40 observations) communicating the initial positive NBS result for all of the screened conditions to parents. The purpose of this was to gather data on the process of communicating the result, the parents’ initial reactions, how the health-care professional responded, questions asked and information and resources provided. However, it became apparent that the timing of this was difficult for staff members involved; staff endeavour to contact families as soon as possible after receiving the positive NBS result from the NBSL. Often, the process of trying to reach families, sometimes after trying to contact the family’s midwife or health visitor, could be challenging and time-consuming. Despite repeated attempts and reminders, only 13 observations were undertaken by Jane Chudleigh and Holly Chinnery. These were written up as field notes immediately after completion of the encounter, and a separate reflective researcher diary was kept to record personal views or thoughts. However, the quantity of data collected was limited and it was not possible to undertake any meaningful analysis.

Semistructured interviews and staff feedback event

Semistructured telephone interviews comprising closed and open-ended questions were conducted between September 2018 and March 2019 (JC and HP) to identify the approaches used to communicate positive NBS results from NBSLs to health-care professionals. Written consent was obtained by e-mail prior to the telephone interviews taking place. All calls were recorded using a telephone pick-up microphone, which was plugged into an encrypted recording device. Data were collected on the mode of communication strategy (face to face, letter, telephone, e-mail), the resources involved in each communication strategy, who provided the information and their role, and the location (co-located or at alternative site) of relevant services for each condition.

After the interviews, during April/May 2019, staff at each site were invited to attend a staff event to review the themes arising from the interviews and identify their priorities for improving delivery of positive NBS results. These events were guided by the online EBCD toolkit and the accompanying online resources, including the invitation and the agenda template. The findings of the staff interviews were presented in PowerPoint® (Microsoft) and included many direct quotations to illustrate the points made. This was followed by a facilitated discussion to identify issues needing service improvement, which were then narrowed down by participants to a shortlist of potential areas for the co-design working groups (CDWGs) to focus on. We also asked staff to review the informational app that had been developed by members of the research team (JB and LM) in conjunction with Metabolic Support UK.

Sampling

We aimed to recruit a purposeful sample of 15 staff across the two study sites involved in communicating positive NBS results in the preceding 6 months. A two-stage sampling approach was employed. Participants were first sampled purposively based on their experience of the phenomena of interest. This was followed by a second stage, snowball sampling, during which participants from the first stage suggested other relevant clinical colleagues. Members of relevant clinical teams (medical consultants, general paediatricians, nurse specialists and specialist screening nurses) were initially identified through individual trust websites and were contacted by e-mail and invited to participate. If no response was received, a follow-up e-mail was sent after 1 week. Identified health-care professionals were asked if there were any other members of the clinical teams who the research team should contact to ensure that views were representative. All potential participants were given the choice to participate or not and were reminded of their right to withdraw from the study at any time.

Data analysis

Interviews were analysed thematically; an inductive approach to data analysis was used and themes were generated using a latent approach to provide a deeper understanding of the approaches used to communicate positive NBS results to families. 91 Two members of the research team (JC and HC) coded one interview transcript separately. These codes were then compared to inform and align code development92 and a code book was developed. 93 A further four transcripts were then coded separately by the same two members of the research team (JC and HC) using the code book. These separately coded transcripts were then compared; the intercoder reliability was 84%. Following this, the same two members of the research team (JC and HC) coded the remainder of the transcripts using the code book. Once this initial coding had been completed, all data for each code were compared to ensure consistency in coding and to enable the codes to be collapsed into themes. All quotations for each theme were collated to inform theme development. This was an ongoing, iterative process; new codes were developed and the definition of codes were refined as analysis progressed.

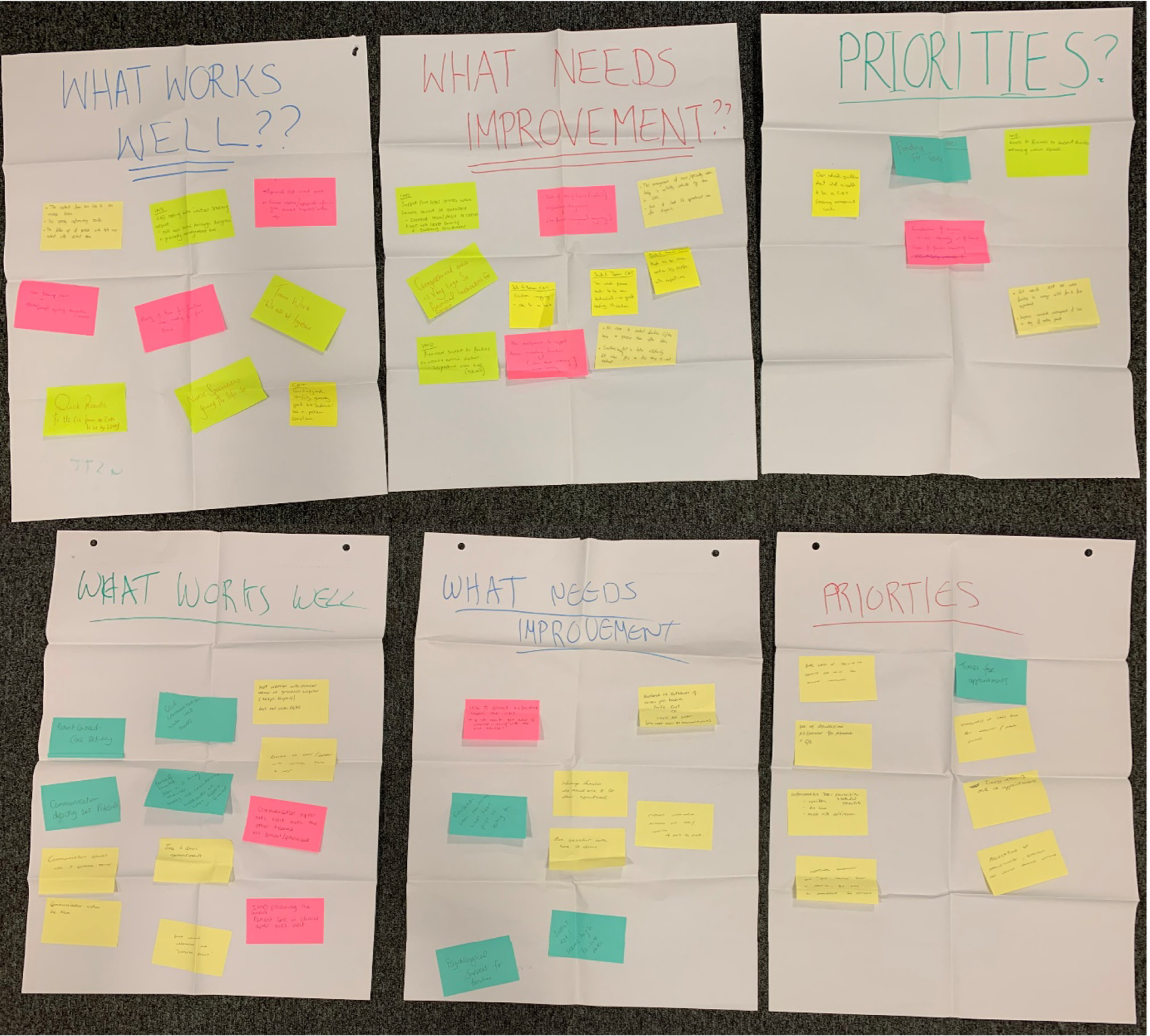

Stage 3 (14–18 months): bringing staff and patients/carers together

Data collection

We held mixed staff and parent events94 in each of the study sites in June 2019. These events were guided by the online EBCD toolkit and the accompanying online resources, including the invitation and the agenda template. During these events, a parent representative (discussed and agreed prior to the meeting) was invited to share the composite film with staff. As per the EBCD toolkit, an unstructured discussion followed to analyse the issues highlighted in the film, and priorities were identified during the separate staff and parent meetings. This was followed by a facilitated discussion (JC and HC) to help to reach consensus on joint priorities and four key target areas for improving delivery of positive NBS results. 74,75,85

Sampling

All staff and parents involved in the previous interviews were invited to participate in the focus groups.

Analysis

During the joint staff/parent feedback event, shared priorities were established and key target areas were identified for the improvement of communication of positive NBS results to parents. In addition, parents and staff identified which co-design group(s) they would like to join for the next stage of the project.

Stage 4: co-design working groups

Data collection

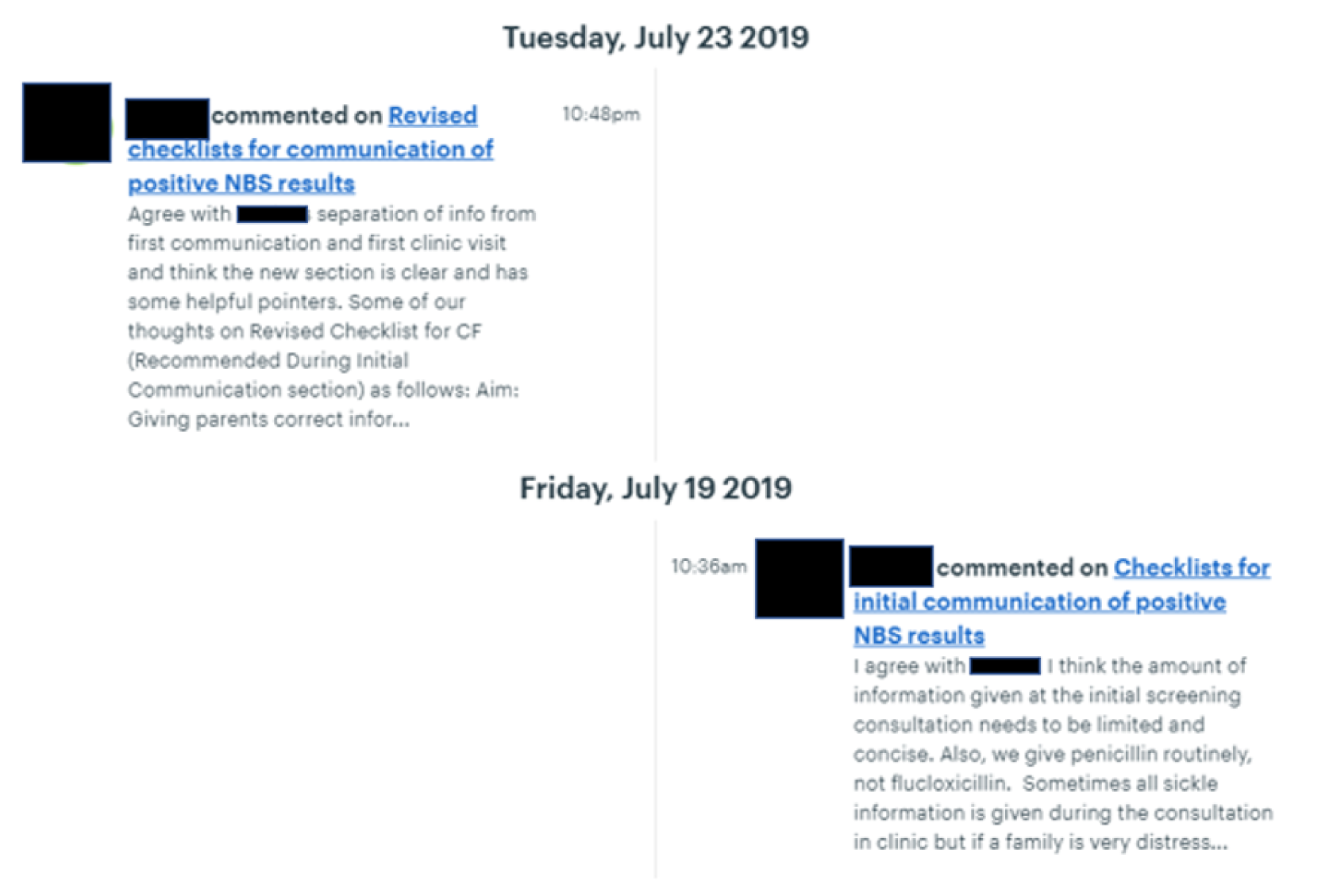

The original plan was for parents and staff from both study sites to come together in four face-to-face CDWGs (six to eight members each), which would each meet on three or four occasions to consider how different components might be combined to produce interventions for improving communication of positive NBS results to parents to reduce potential deleterious effects on family functioning in line with FST. 62 However, during stage 3, staff and parents requested that the CDWGs take place online to offer them more flexibility to share resources, and facilitate communication and negotiation between staff and parents regarding the proposed co-designed interventions. This required permission for a non-substantial amendment from the HRA/Stanmore REC; no changes to the study protocol were required.

The online platform Basecamp (https://basecamp.com/; accessed 28 February 2021) was used to host the online CDWGs. Each CDWG was set up as a different group and those who had indicated that they would be interested in the particular CDWG were invited by e-mail to participate. Ground rules were set and the message board was used to invite participants (a mixture of staff and parents in each CDWG) and remind them of the purpose of the groups.

The composite film and the PowerPoint presentations from the separate parent and staff events were uploaded to the online portal, as well as the priorities identified by both parents and staff at the end of these events. Example interventions based on discussions held during stage 3 were uploaded to the online portal, and members of the CDWGs were asked to provide feedback and comments.

Participants were asked, over a period of 8 weeks during July and August 2019, to post comments on documents and files that were uploaded, as well as to use the discussion boards to develop the co-designed interventions. Members of each group were sent a message approximately weekly or when new/revised documentation was uploaded to the online portal that asked them to review the information and provide feedback.

Sampling

Informed by previous successful EBCD projects,74,75,85 four online CDWGs consisting of parents and staff from stages 1–3, each comprising 12–18 members, took place. Staff and parents were permitted to be part of more than one CDWG if they wished.

Data analysis

Parents and staff used data collected in stages 1–3 to work on their designated work stream to produce interventions for improving delivery of condition-specific positive NBS results to parents; these groups were facilitated by two members of the research team (JC and HC).

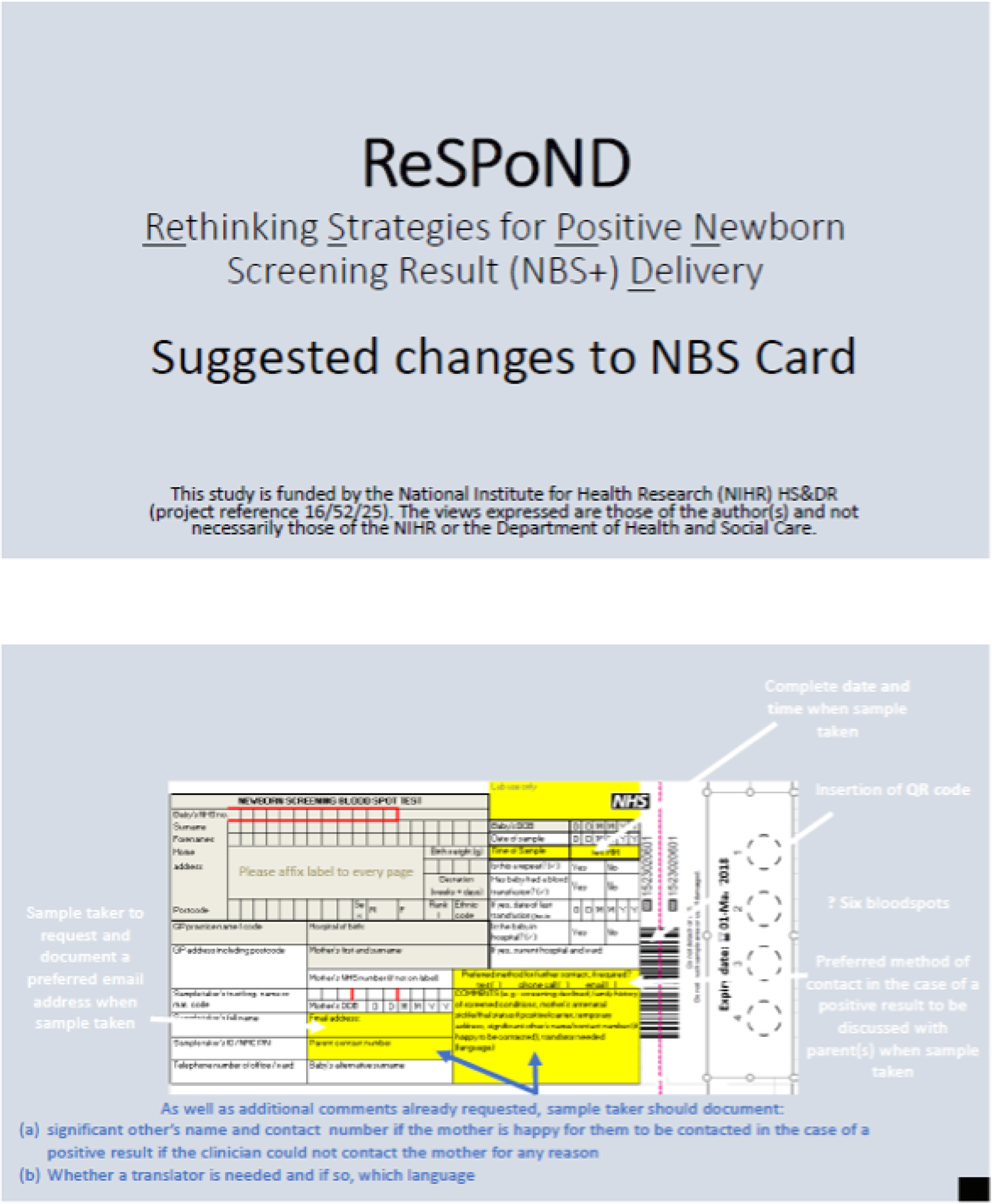

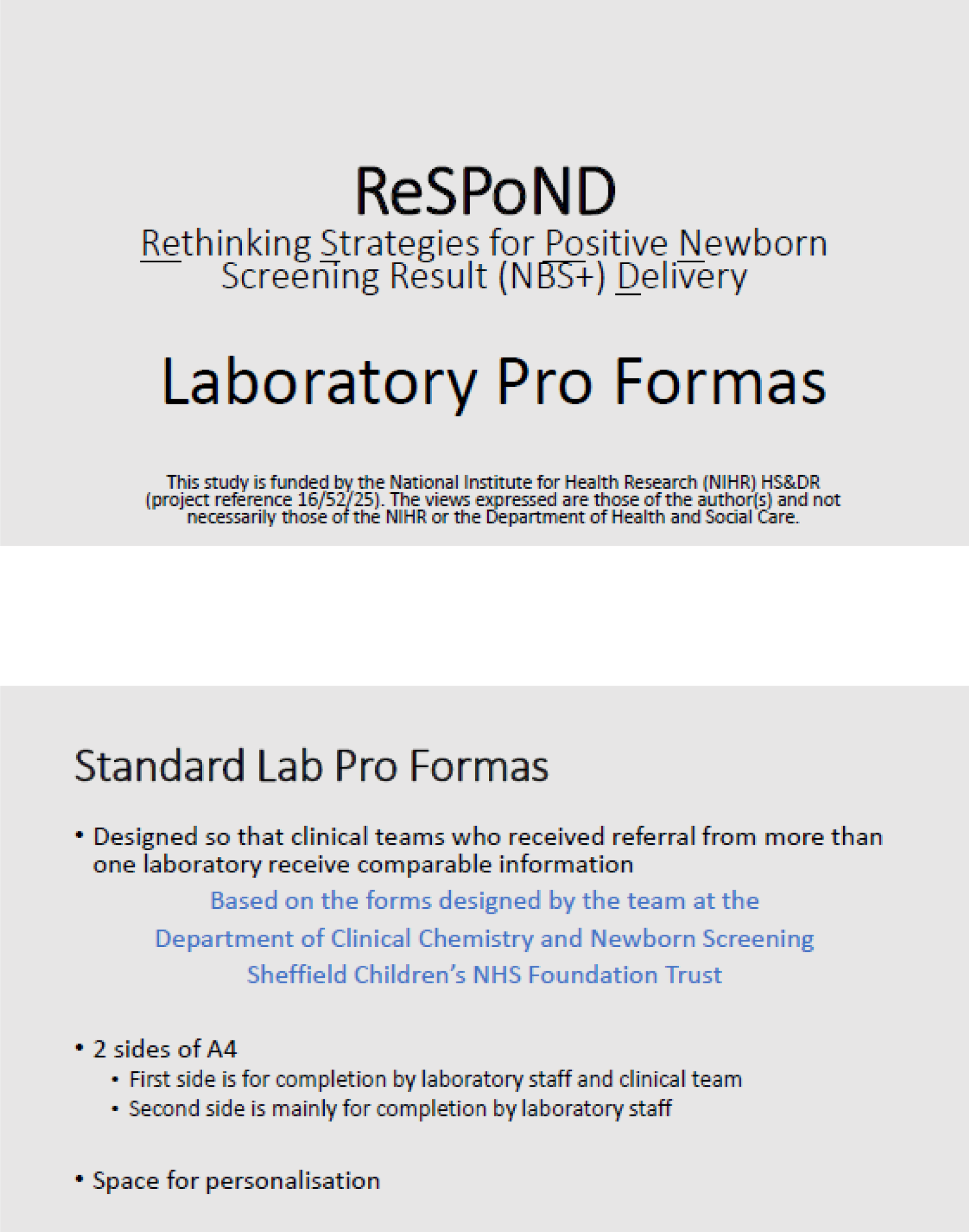

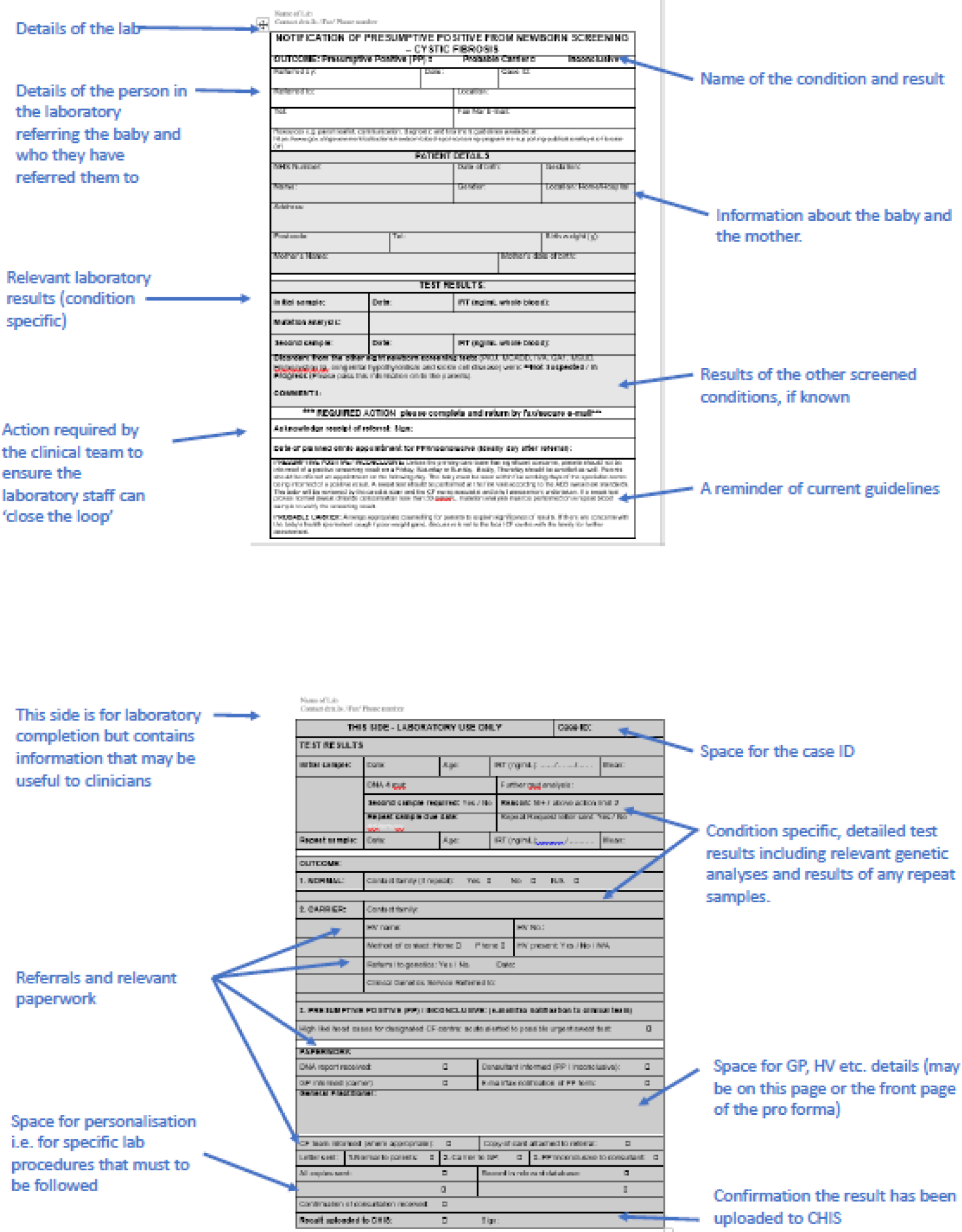

Phase 3 (24–33 months): training, implementation and evaluation of the new co-designed interventions

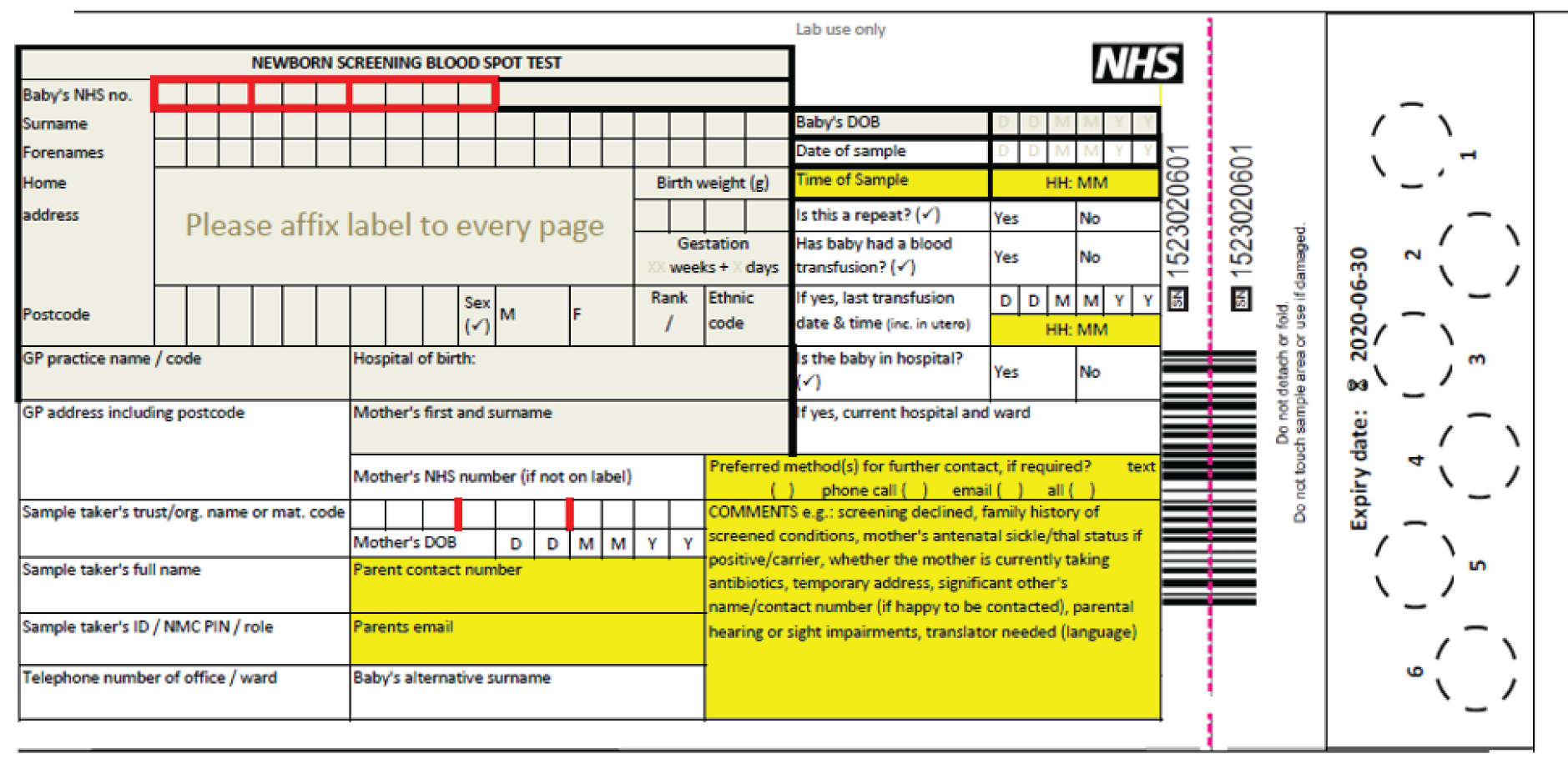

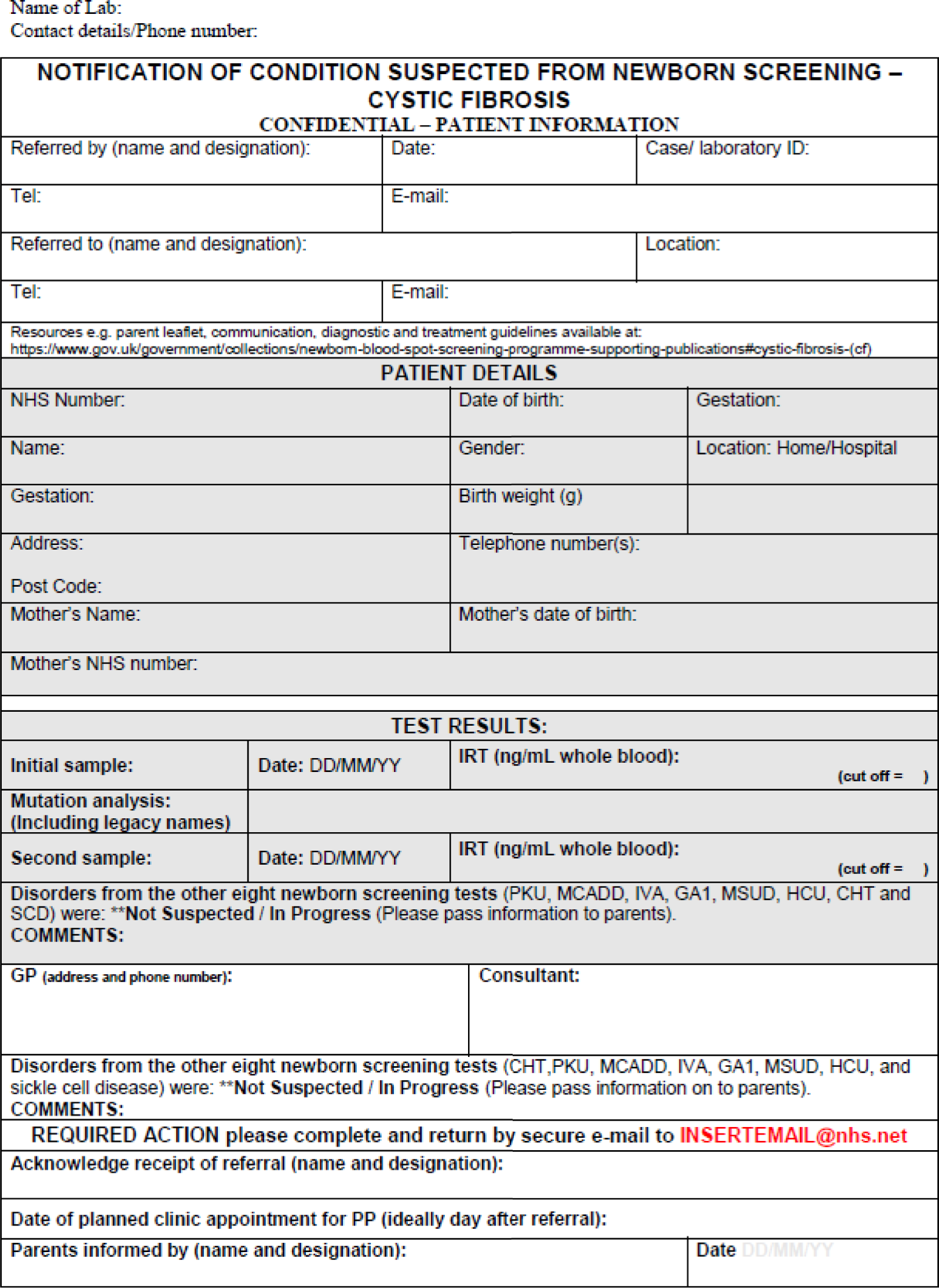

In early September 2019, a meeting was held between the study team and the relevant members of the NBSP, Public Health England (PHE), to discuss the co-designed interventions and if and how these might be implemented in practice during phase 3. One of the proposed interventions related to changes to the NBS card (CDWG 1), and another included suggested changes in service provision specifically related to CHT and investigation of potential cost implications for families who need to travel to see clinical teams either the same day or the next working day following a positive NBS result (CDWG 4). However, the NBSP felt that even modest changes to the NBS card and any changes in service provision for any of the conditions currently included in NBS would require considerable consultation and, therefore, it did not feel that it would be appropriate to implement these interventions as part of the present study.

However, the NBSP stated that it would be interested in the collection of further evidence from a range of stakeholders (including midwives and parents who had received either a positive or a negative NBS result) regarding the proposed changes to the NBS card, suggestions in relation to service provision for CHT and data regarding travel costs incurred by families following a positive NBS result as part of the process evaluation (phase 3). Furthermore, the NBSP stated that it would be keen to include the results, particularly in relation to the NBS card, in the NBSP’s 5-year plan.

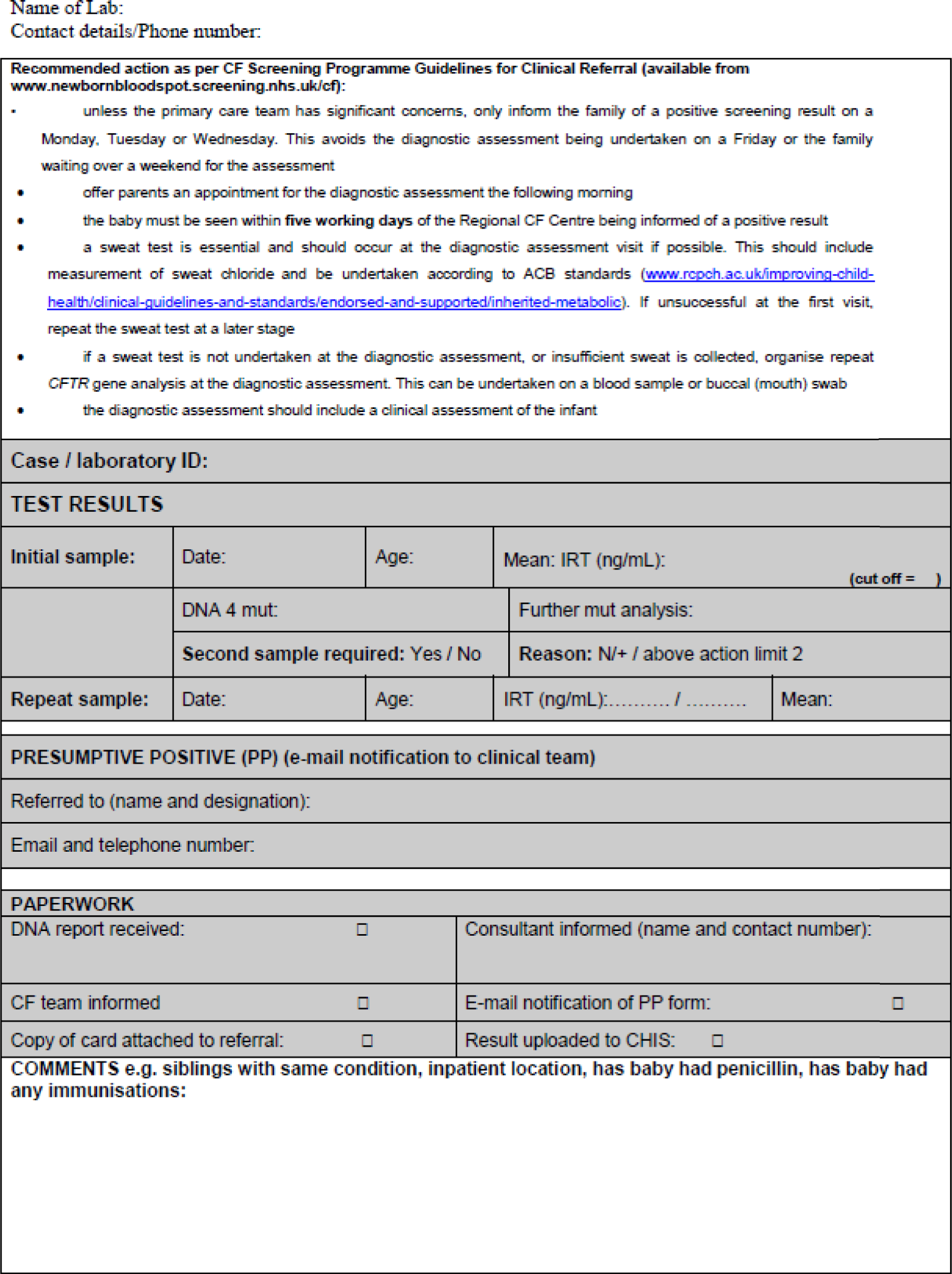

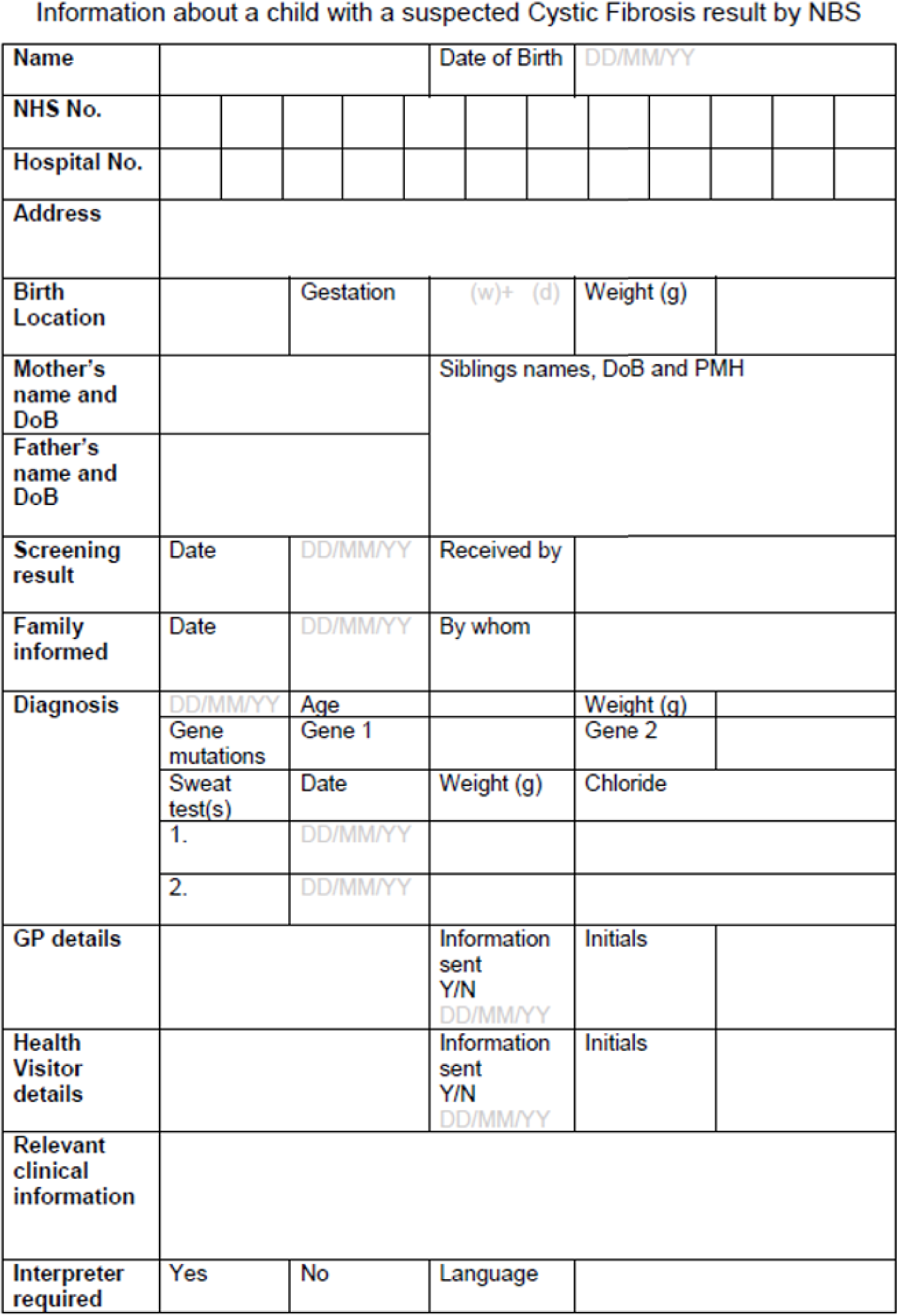

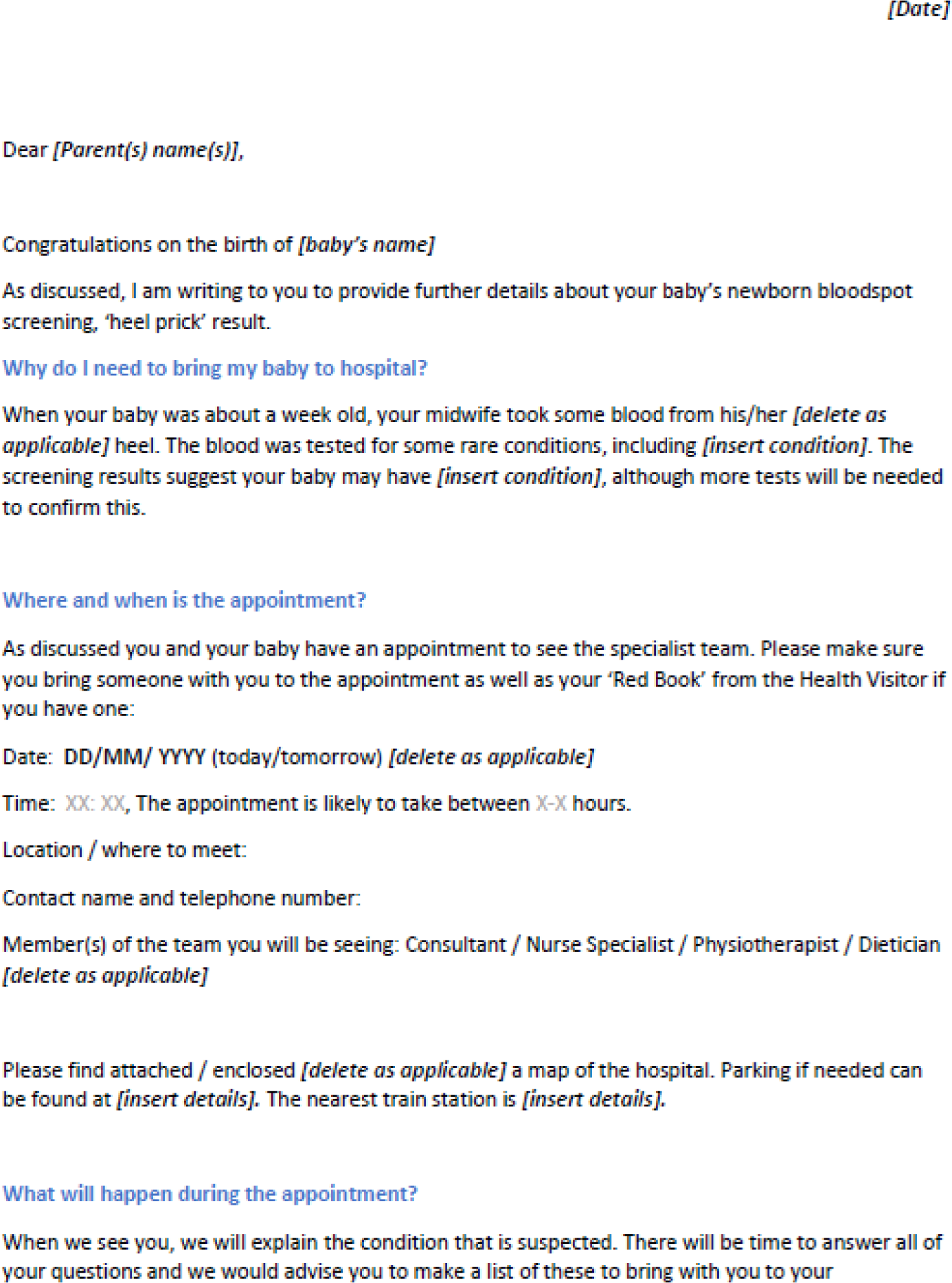

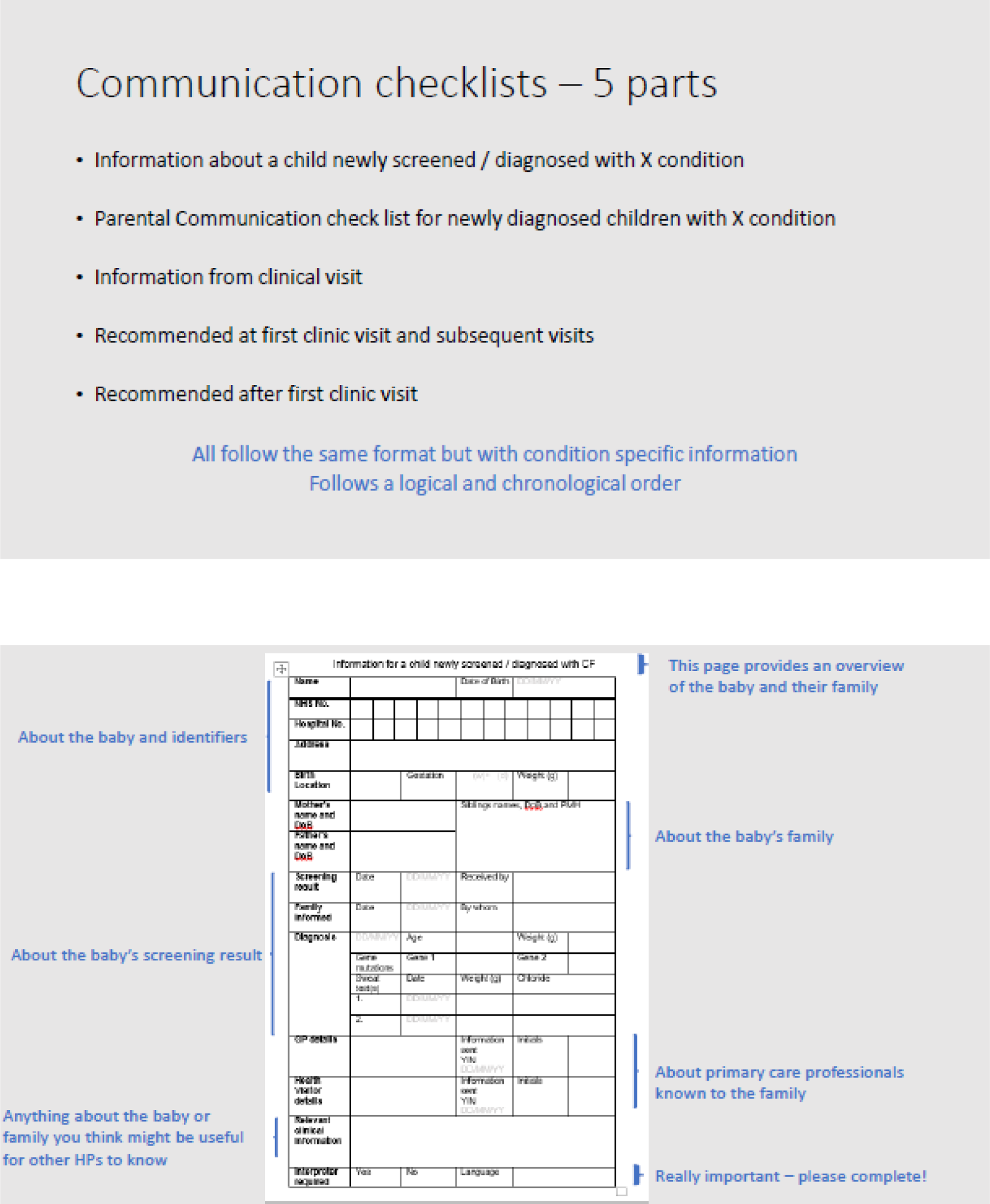

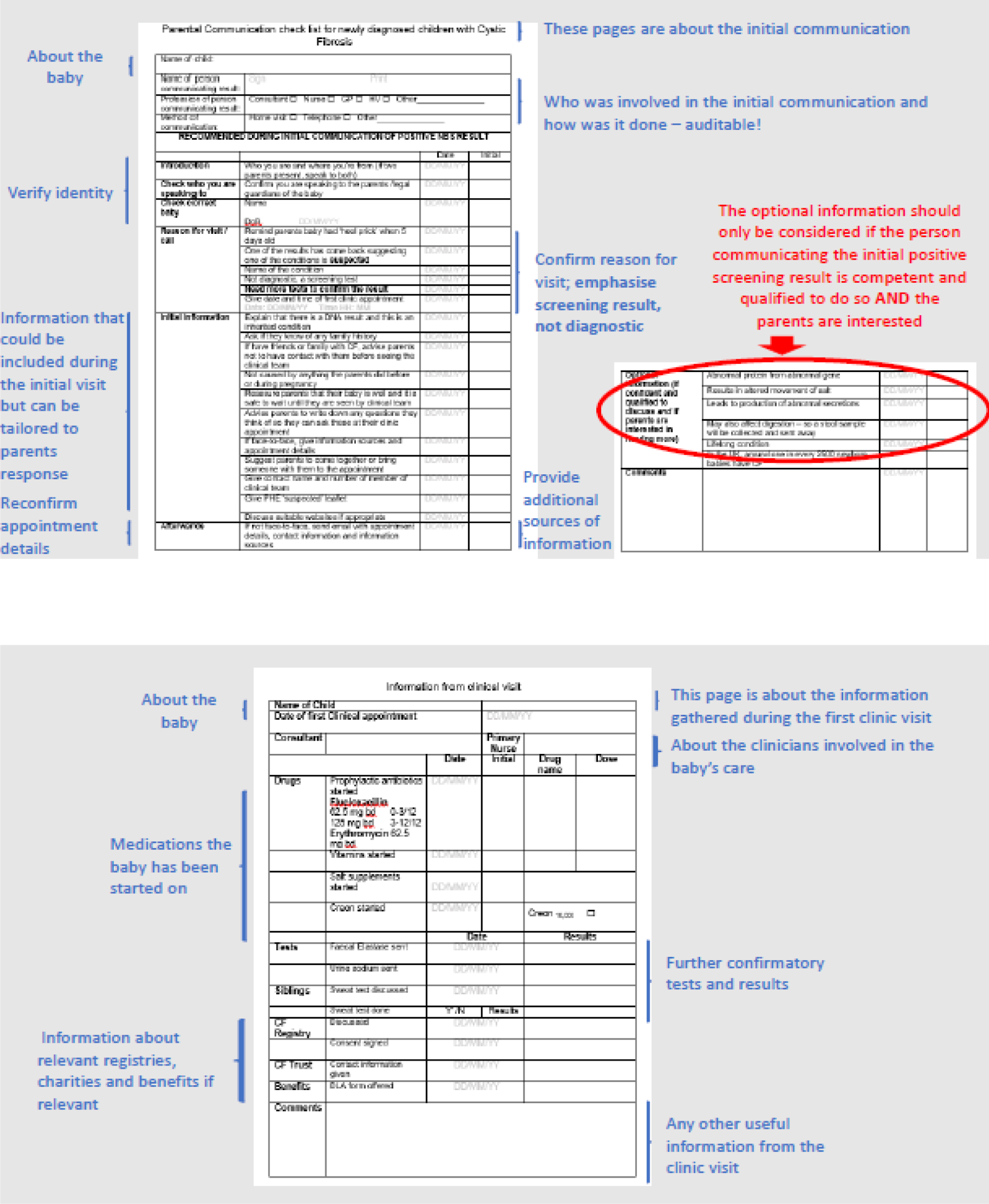

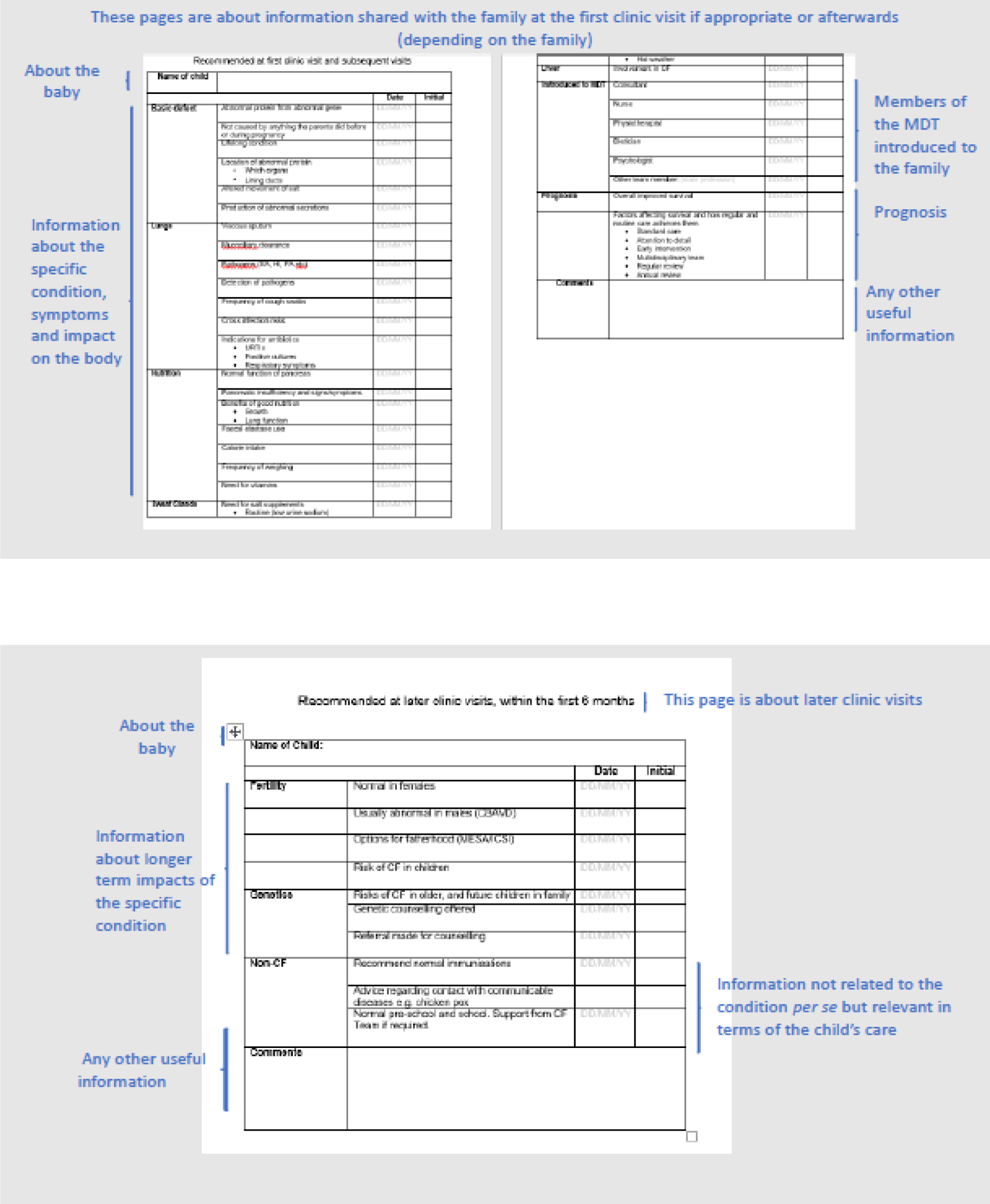

Consequently, it was decided that, during this phase, only the following new co-designed interventions would be implemented in practice: condition-specific, standardised laboratory pro formas (CDWG 1); condition-specific communication checklists (CDWG 2); and an e-mail/letter template to provide information to families following communication of a positive NBS result (CDWG 3). In addition, further evidence from a range of stakeholders would be gathered regarding the proposed changes to the NBS card (CDWG 1) and service provision (CDWG 4). This phase of the study was conducted in the same three NHS trusts in England served by two NBSLs (case-study sites) used in phase 2. By employing EBCD, the project was adopting a user-centred approach. This advocates for testing and iteration prior to final evaluation. 73 Testing at the same two study sites enabled assessment of the extent to which the interventions met the needs of those involved in the prioritisation, specification and development of the interventions.

During this phase, we sought permission for a substantial amendment from the HRA/Stanmore REC and associated changes to the study protocol (protocol v5) to enable us to collect the following additional data: interviews or focus groups with parents who had received a negative (normal) NBS result to explore how they felt about additional information being collected when the NBS sample was taken, in line with the suggestions from members of the NBSP; and the ability to undertake either interviews or focus groups with parents whose child had received a positive (abnormal) NBS result, parents who had received a positive NBS result who had not experienced the interventions and midwives (the latter was again in response to the suggestions made by relevant members of the NBSP). We already had permission to interview staff who had implemented the co-designed interventions and parents who had received a positive NBS result and had experienced the co-designed interventions. We also sought permission to collect information about the town that the child resided in and the hospital that the child was referred to following their positive NBS result to collect information about travel costs incurred to attend the initial appointment after receiving the positive NBS result. During the implementation stage, we also sought permission for a substantial amendment from the HRA/Stanmore REC and associated changes to the study protocol (protocol v6). This included permission to audit redacted copies of completed standard laboratory pro formas (CDWG 1) and the communication checklists (CDWG 2). These protocol changes (protocol v5 and v6) represented additional work that was not included in the original funding application.

Impact of COVID-19

Stage 1 of phase 3 took place between October 2019 and January 2020. Stage 2 commenced in February 2020. The first lockdown due to COVID-19 began in the UK on 23 March 2020, which meant that the study had to be paused with immediate effect. In July 2020, we sought permission to reopen the study remotely, which was granted in all study sites by August 2020. Given that the study had been paused, we spent August 2020 refamiliarising participants with the purpose of the study and the co-designed interventions. Staff began to reimplement the co-designed interventions in the study sites in September 2020. Owing to COVID-19, data collection regarding the implementation, acceptability and feasibility of the co-designed interventions was restricted to being undertaken remotely in all sites. Furthermore, the additional pressure on staff because of COVID-19 meant that many study participants struggled to implement the co-designed interventions alongside changes in practice and staff redeployment that occurred as a result of the pandemic, which, understandably, had to be prioritised. Not implementing the co-designed interventions fully and consistently during this period also reduced the number of parents we were able to speak to about their experiences of these. This also meant that we were unable to conduct the interviews and focus groups face to face; instead, these took place by telephone or Microsoft Teams, depending on the preference of the participant.

Stage 1: training staff in the new co-designed interventions

Training for the new interventions was developed in September 2019 and was delivered in the study sites from October 2019 to January 2020; refresher sessions were offered remotely and were provided in August 2020. Staff in each study site were able to choose from a variety of training options, including face to face (in person or remote), individual or group training (this was condition specific to ensure that the correct interventions were presented to the relevant staff) using narrated PowerPoint presentations and/or annotated PowerPoint presentations (see Appendix 3, Figure 28). These training materials were also made available on the study blog (https://blogs.city.ac.uk/respondnbs/what-is-respond/; accessed 28 February 2022).

Stage 2: implementing the new co-designed interventions

Following training, the final versions of the co-designed interventions were e-mailed to each clinical team. Follow-up e-mails were sent monthly between January and March 2020 and then, following the pause due to COVID-19, from September to December 2020 to ensure that staff could still access the documents. In addition, copies of the final co-designed interventions were placed on the study blog and on Basecamp. One study site chose to continue using the laboratory pro formas during the COVID-19 pause out of preference and were, therefore, able to provide data for the whole 12-month period.

Stage 3: evaluation of the new co-designed interventions

A parallel-process evaluation underpinned by NPT68,69 was conducted from September to December 2020. Success criteria (Figure 2) were defined to ensure that the implementation of the co-designed interventions was acceptable and feasible.

Data collection

Audit of completion of co-designed interventions

The fidelity of the co-designed interventions was assessed in both study sites. Staff were asked to send the research team redacted copies of all laboratory pro formas and communication checklists that had been completed during stage 2 so that these could be audited in terms of accuracy and completeness.

Non-participant observation

It was not possible to observe staff using the co-designed interventions owing to restrictions related to COVID-19; researchers were not allowed to be physically present in the trusts for the purpose of data collection.

Semistructured interviews and focus groups

Prior to lockdown, a face-to-face focus group was conducted with midwives in one of the study sites and was facilitated by two members of the research team (JC and PH) in line with the suggestions made by members of the NBSP. The purpose of this was to gain views and opinions regarding the proposed changes to the NBS card. Following lockdown, between September 2020 and December 2020, all interviews were undertaken by two members of the research team (JC and PH) by telephone or on Microsoft Teams (depending on participant preferences) owing to data collection restrictions imposed by the study sites because of COVID-19. Written consent was obtained by e-mail prior to the interviews and focus groups taking place. All calls were recorded using a telephone pick-up microphone, which was plugged into an encrypted recording device. The audio of interviews undertaken on Microsoft Teams was recorded on separate encrypted recording devices.

Subsequent interviews with midwives also explored the views and opinions of the proposed changes to the NBS card. Parents who had received a negative screening result were invited to take part in semistructured interviews to discuss the feasibility of the proposed changes to the NBS card, as per the suggestions of members of the NBSP. Parents who had received a positive NBS result for whom the new co-designed interventions were not used were also invited to take part in semistructured interviews to discuss the feasibility of the proposed changes to the NBS card and their value from their perspective of the communication checklists and the information provision. Parents who had received a positive NBS result for whom the new co-designed interventions had been used were also invited to take part in semistructured interviews to ascertain their views and experiences of the communication process. NBSL staff and members of relevant clinical teams interviewed in phase 1 or new staff identified as being involved in the delivery of initial positive NBS results across the two study sites were invited to take part in interviews to ascertain their views of the new co-designed interventions following implementation.

The interview questions were guided by NPT68,69 and the success criteria (see Figure 2). The purpose was to explore the views of the interventions and perceptions of factors that were influential (mechanisms of impact and context). 95,96

Economic data

Data collected in phase 1 regarding the costs associated with current communication practices were compared with costs associated with the new co-designed interventions. The same time horizon was used for both: the time from the point at which the laboratory produces the test result to when the parents receive the definitive result. This is consistent with the purpose of the study to co-design, implement and evaluate new interventions to improve delivery of initial positive NBS results to parents.

Sampling

Audit of completion of co-designed interventions

Staff were asked to share redacted copies of all completed interventions so that they could be audited in terms of accuracy and completeness.

Focus groups and semistructured interviews

During phases 1 and 2, it became apparent that the communication of positive NBS results is a process rather than an event, and starts at the point when the bloodspot is taken by midwives. In addition, members of the NBSP also suggested that midwives should be included in this process because they are usually the professional group who collect the NBS sample. This led to us including midwives in phase 3 to ensure that their views were also represented when considering the acceptability and feasibility of the proposed changes to the NBS card. A purposeful sample of midwives from the two study sites involved in collecting NBS data was, therefore, recruited to discuss the proposed changes to the NBS card.

Parents who had received a negative NBS results as per the suggestions made by members of the NBSP, were recruited using posters in GP surgeries in the vicinity of the study sites and by health visitors and midwives in the study sites. We also invited to interview a purposeful sample comprising parents who had received a positive NBS result for their child but for whom the interventions had not been used; parents who had been given their child’s positive NBS result using the co-designed interventions; and staff (NBSL staff, nurse specialists, consultants) who had used the co-designed interventions to deliver the NBS result to parents in the two study sites.

Data analysis

Audit of completion of co-designed interventions

The accuracy and completeness of redacted copies of the completed co-designed interventions were audited in terms of their completion based on the training and guidance provided.

Semistructured interviews and focus groups

All interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interviews with the parents of children with a positive result who had or had not experienced the interventions, and with the parents of children with a negative result, were analysed thematically; an inductive approach to data analysis was used and themes were generated using a latent approach to provide a deeper understanding of opinions regarding the proposed interventions. 91 Two members of the research team (JC and PH) coded one interview transcript separately. These codes were then compared to inform and align code development92 and a code book was developed. 93 A further two transcripts were then coded separately by the same two members of the research team using the code book. These separately coded transcripts were then compared; the intercoder reliability was 85% for the interviews conducted with parents of children with a positive NBS results but for whom no interventions had been used, 87% for interviews conducted with parents of children with a positive NBS results who had experienced the interventions and 89% for parents of children who had received a negative NBS result. Following this, the same two members of the research team coded the remainder of the transcripts using the code book. Once this initial coding had been completed, all data for each code were compared to ensure consistency in coding and to enable the codes to be collapsed into themes. All quotations for each theme were collated to inform theme development. This was an ongoing, iterative process; new codes were developed and the definition of codes was refined as the analysis progressed.

Qualitative data collected during the semistructured interviews with parents were used to identify factors that influence experiences during the delivery of positive NBS results. These were compared with the content of measures, including the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9), Parenting Stress Index,97 EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) and ICEpop CAPability measure for Adults (ICECAP-A),98 to determine where most overlap occurred and, therefore, which outcomes might be most suitable in a future evaluation study during phase 4.