Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR131238. The contractual start date was in November 2020. The final report began editorial review in January 2022 and was accepted for publication in May 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 O’Cathain et al. This work was produced by O’Cathain et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 O’Cathain et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Demand for primary and emergency care in the UK

There is considerable pressure on general practices, emergency departments (EDs) and emergency ambulances in the UK. In 2019, the Royal College of General Practitioners highlighted intense resource and workforce pressure on general practice out-of-hours services and expressed concerns about decreases in the number of general practitioners (GPs) per head of population, despite rising demand for general practice. In 2021, the Royal College of General Practitioners highlighted the lack of GPs to meet demand. 1 In 2019, policy-makers reported on the NHS England website that there were 110 million urgent patient contacts in England each year, with around 85 million being same-day GP appointments, and the rest attendances at EDs and minor injury units. NHS England estimated that between 1.5 million and 3 million attendances at EDs could be managed by other parts of the urgent care system. Emergency ambulance services deal with around 11 million calls annually, and around one in eight are dealt with through advice from a clinician by telephone. 2 Patients having these ‘hear-and-treat’ calls, that is calls that do not result in an ambulance being despatched, are offered self-care advice or are recommended to contact lower-acuity services. NHS England is currently encouraging people to use NHS 111 to help them make decisions about which service, if any, to use, including self-care and pharmacy. Demand for NHS 111 also outstrips supply, and policy-makers have attempted to ease demand for this service by encouraging people to use NHS 111 Online to help them make decisions about where in the NHS to seek care. 3

There is a need to consider ways of reducing pressure on emergency and primary care services. Although primary care is a setting that provides a first point of contact in the NHS for patients, and includes general practices, community pharmacies and dentists, a focus on general practice is important because of the current pressure on this service.

Minor health problems

Some people need to use emergency and urgent care, and it is important to maintain access to services to meet their needs. However, some people do not need the clinical resources or acuity level of primary or emergency care services. Some patients could contact their GP instead of calling for an emergency ambulance or attending an ED. Other patients could self-care or seek advice from a pharmacist instead of contacting general practice, the ED or the ambulance service. A variety of terms are used to describe this type of service use, such as ‘clinically unnecessary’,4 ‘primary care sensitive problems’ in emergency care,5 non-urgent or low acuity. The prevalence of this type of use varies depending on the definition used, but it is likely to be high. For example, 15% of attendances were classed as non-urgent in an analysis of routine data from EDs in the UK. 6

Some of these contacts in primary and emergency care are for minor health problems, injuries or ailments that could be managed through self-care or contact with a pharmacist. Examples of minor health problems include raised temperature in a child, musculoskeletal pain, eye discomfort, gastrointestinal disturbance and upper respiratory tract-related symptoms. 7 Research has shown that people attend EDs, general practice or a pharmacy with these minor health problems. When contacts with different services for similar minor health problems are compared, they have similar resolution rates, but the cost per consultation is higher for EDs and GPs than for pharmacy: £147 and £82, compared with £29, respectively. 7 People may also attend general practice out-of-hours services, as well as daytime general practice, for minor health problems. 8

Reasons why people attend primary and emergency care with minor health problems

There are a wide range of reasons why people contact services for minor health problems. A recent study of ‘clinically unnecessary’ use of ambulance services, EDs and GPs in the UK explored this issue using a realist review, qualitative interviews with patients and a national population survey. 4 Ten reasons were identified in the realist review9 and qualitative interviews:10

-

uncertainty about symptoms, causing anxiety

-

heightened awareness of risk as a result of experience or knowledge of traumatic health events, leading to anxiety

-

fear of consequences when responsible for others such as children or elderly people

-

inability to get on with daily life, such as going to work or looking after children

-

need for immediate pain relief

-

waited long enough for things to improve

-

stressful lives so cannot cope with any health problem

-

following advice of trusted others from NHS staff, family, friends, colleagues

-

perceptions or prior experiences of services, for example positive experiences of EDs lead to further use of EDs

-

perceived poor access to a GP in the time frame wanted.

These issues were measured in a national population survey of the tendency to contact primary and emergency care for minor health problems. Other issues that were less commonly identified in the literature were also measured, including awareness of alternative services, beliefs about how busy emergency and primary care services are and health literacy levels. The effect of people’s health literacy levels on their decision-making was measured because researchers in the USA found that people who attended EDs with non-urgent problems had lower levels of health literacy. 11 It was also possible that poor health literacy might underlie some of the reasons for using primary and emergency care for minor health problems. For example, people with low levels of health literacy might be more anxious about minor health problems because they do not understand what symptoms are associated with serious problems, they may be less likely to know how to manage pain, they may be more likely to look to others for advice, they may not know how long it takes for some minor problems to resolve and they may be unaware of alternative services. When a range of variables were tested in a population survey to explain tendency to contact primary and emergency care for minor health problems, lower health literacy levels were associated with this use of emergency ambulances and general practice, even when all other variables were controlled for. 9,12

The importance of health literacy

Given the role of health literacy in explaining the tendency to use emergency ambulances and general practice, and its relationship with the use of EDs for non-urgent problems, it is important to understand what it is, how it is measured, its relationship with use of primary and emergency care, and how it can be addressed to reduce the use of primary and emergency care for minor health problems.

What is health literacy?

Health literacy is defined by the World Health Organization as the resources needed for people to access, understand and use information and services to make decisions about their health. 13 There are different types of health literacy: functional or basic health literacy (reading and writing skills); communicative health literacy (cognitive and social skills to extract information and apply it); and critical health literacy, which requires more advanced cognitive and social skills to analyse information. 14

People with limited health literacy struggle with:

-

finding information

-

reading and understanding information

-

knowing how to act on information

-

knowing how to communicate with health professionals

-

knowing which services to use and when. 15

Aligned with health literacy is digital or e-health literacy, which has been defined as ‘the ability to seek, find, understand, and appraise health information from electronic sources and apply the knowledge gained to addressing or solving a health problem’. 16

Health literacy may be viewed as an individual skill, but an individual’s social support system (e.g. partner, family, community) and the context in which they live (e.g. the health-care system available) are also likely to be relevant. 17

How is health literacy measured?

There are a number of validated measures of health literacy that either test health literacy (one might call these ‘objective measures’) or measure people’s perceptions of their health literacy (one might call these ‘subjective measures’). Examples include the objective measure Newest Vital Sign, used in a study of health literacy among parents attending a paediatric ED for non-urgent problems;11 the subjective measure the Health Literacy Questionnaire, which measures multiple domains of health literacy;15 and the subjective measure the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire, which is available in multiple European languages. 18

Policy initiatives on health literacy in the UK

Improving health literacy is important to policy-makers in the UK. National policy in England currently focuses on improving health literacy in the management of chronic conditions and health improvement, and on improving health literacy awareness among the health-care, social care and third-sector workforces. NHS England has a health literacy lead and multiagency initiatives to improve health literacy. 13 NHS Scotland has a long-term plan to improve health literacy. 19 Health Education England generates tools and leads initiatives to improve health literacy. 20

The relationship between health literacy and demand for primary care and emergency services for minor health problems

Primary care

There is evidence that a lower level of health literacy is related to greater use of primary care, including contacting a GP,21 frequency of doctor visits22 and use of out-of-hours primary care services. 23 There is also evidence that it is related to greater demand for general practice for minor health problems. A recent British population survey of the demand for same-day general practice for minor health problems identified that people with a lower level of health literacy had a greater tendency to contact their GP in a multivariable analysis testing a wide range of variables. 12

Emergency care

There is systematic review evidence from 2011 that a lower level of health literacy is associated with greater use of emergency services. 24 More recent studies support this conclusion. Examples include unnecessary use of the ambulance service in Japan,25 ED use for minor or non-urgent problems in the USA,26 ED return rates27 and use of EDs by first-generation Chinese immigrants in Australia. 28 A 2020 British population survey of demand for emergency ambulances and EDs for minor health problems identified that people with a lower level of health literacy had a greater tendency to contact emergency ambulances. 4

Reasons for the relationship

The relationship between health literacy and the use of primary and emergency care for minor health problems could be explained simply by the educational status of patients. There is a correlation between health literacy and educational attainment, but educational attainment does not explain all of the variation in health literacy levels. For example, 29% of people attending EDs for non-urgent issues were found to have a college education and a low level of health literacy. 11

There is evidence that people with a lower level of health literacy may overestimate the severity of an illness and seek care sooner than people with a higher level of health literacy. 29 They may also be harder to reassure when a symptom is not serious. A study30 of factors determining parental reassurance for a child with fever in rural general practice showed that parents who lacked knowledge about complications of fever had higher levels of concern before consulting a doctor and were less likely to be reassured after consultation with a doctor, leading to a recommendation that further education of parents is required.

Research that does not support this relationship

Not all studies have found a relationship between use of health services for minor health problems and health literacy. For example, health literacy was found not to be associated with GP consultations, only with home consultations. 31 A survey of the British population found no relationship between health literacy and tendency to use EDs for minor health problems when other variables were adjusted for. 4

Need for interventions to address health literacy in this context

Research exploring help-seeking behaviour for minor health problems sometimes concludes that patient education is needed. Physicians and nurses cite lack of education and self-care when exploring the related area of frequent attendance,32,33 and a lack of awareness of the availability and capability of alternative services to EDs. 10 When GPs in the UK were interviewed about strategies for coping with increasing workload, they identified the need to educate patients about self-care, stating that they preferred that the government rather than GPs to be responsible for this education. 34

Improving health literacy is one of many solutions needed

This review focuses on health literacy because it is an important factor affecting demand for primary and emergency care for minor health problems. However, it is one of many factors; as a 2020 study concluded, ‘There is unlikely to be a single solution to these multiple, inter-related reasons for “clinically unnecessary” use of services. Rather, a series of solutions, undertaken concurrently, may be necessary’. 4 It is important to keep in mind that service-related issues are important, as well as health literacy; for example, some people may have tried to get an appointment with their GP before going to an ED, but have been unable to get one in the time frame they wanted. Addressing health literacy is a potential solution to consider, complementary to other initiatives.

NHS initiatives to address demand for primary and emergency care

Given that there is a need for multiple interventions to address demand for primary and emergency care for minor health problems, it is useful to consider the range of interventions that policy-makers, commissioners and service providers have introduced. They tend to focus largely on service and workforce reconfigurations that offer alternatives to the three pressurised services of general practice, EDs and emergency ambulances, or on initiatives to manage minor problems efficiently within each of these three services. Examples of these initiatives include provision of a Community Pharmacy Minor Ailment Service, the provision of walk-in centres, the extension of the role of pharmacists, GPs working in EDs, paramedics working in general practices and redirection of people attending EDs. Initiatives also include the national telephone helpline NHS 111 for urgent care whereby non-clinical call-takers direct people to the most appropriate service for their need, or pass callers to clinicians who assess more difficult cases and offer self-care advice or referral to services.

Intervention further back in the pathway of help-seeking behaviour may offer a complementary approach to these initiatives. That is, it may be possible to reduce population need to seek advice from health professionals in pharmacy or NHS 111 for minor health problems and thereby reduce demand for pressurised services. This will be useful at any time, and especially during pandemics, when some people stop attending primary care and emergency services for minor health problems and need to self-care or be able to distinguish between minor and serious problems.

Reviews in related areas

Prior to applying for funding for this systematic review, we undertook a scoping exercise and found no similar systematic reviews. We continued to search for other reviews during the study. We found a number of reviews in related areas, but no review of the same territory.

Reviews of interventions to improve health literacy

There are numerous systematic reviews of interventions to improve health literacy,24,35,36 including for enhancing digital health literacy. 37,38 These reviews tended to focus on interventions with the intention of improving health literacy as their primary outcome, and often did not go beyond this point in the pathway to consider the impact of this improved health literacy on service use. When the reviews did go beyond this point, they considered improvement in health and changes in service use for self-management of chronic conditions, rather than for minor health problems.

Reviews of behaviour change

A review focusing on health behaviours39 looked relevant to our work because health literacy interventions can aim to change behaviour regarding service use. This review did not include the types of interventions of interest in our review. It concluded that interventions could improve health literacy and result in lifestyle changes.

Reviews of self-management of chronic conditions

Some reviews focused on self-management interventions for chronic conditions, with the aim of reducing ED attendances and hospital admissions. 35 These interventions aimed to educate patients on how to prevent serious exacerbations that necessitate an emergency response. That is, they aimed to reduce ED attendance for serious problems, rather than minor problems. It is possible that they also reduced ED attendance for minor problems, but this was not the primary purpose of the intervention and so these reviews did not include interventions relevant to our review. The term ‘self-management’ rather than ‘self-care’ is usually used in the context of chronic conditions such as asthma and diabetes, whereby the aim is to prevent exacerbations using self-management.

Reviews of patient-focused interventions

A review of patient-focused interventions included one type aiming to improve health literacy. 40 Again, the focus was on health literacy rather than changing service use.

Reviews of health literacy interventions to reduce use of primary or emergency care

Prior to seeking funding for this study, we found a review that focused on parental health literacy and paediatric ED attendance, in which seven out of eight studies showed that interventions reduced ED use. 26 This review considered one specific patient group (parents of young children), so we still believed that it was important to undertake our review. We intended to include the papers from this review in our review, but found that most of them focused on the chronic condition of asthma and the prevention of serious problems, rather than the management of minor health problems.

Andrews et al. 41 reviewed the specific area of respiratory illness among children. Part of the focus was on primary care consultations, for which they found nine papers about eight interventions aiming to increase health literacy. Six studies measured reductions in the number of consultations, with these reducing by 13–40% in three studies, although some studies relied on self-report of service use. They authors concluded that interventions were best if they occurred prior to an illness episode, highlighting the importance of the timing of an intervention. Again, this review focused on a specific illness in a specific age group, so there was still a need to undertake our review, and to ensure that we included relevant papers from this review.

Paudyal et al. 42 undertook a systematic review of pharmacy-based minor illness schemes aiming to reduce use of other services. Although pharmacy use can be viewed as ‘supported self-care’, this review was not relevant because interventions did not focus on improving health literacy, but instead on offering an alternative health professional for advice.

Reviews of digital health literacy interventions

Some of the interventions in our systematic review are likely to be delivered digitally. Of interest was a 2011 systematic review that concluded that there were not enough studies to identify effective interventions for enhancing digital health literacy. 38 A more recent (2020) systematic review of digital interventions for the specific area of parents of acutely ill children in primary care found three studies. 43 Interventions were applications (hereafter referred to as ‘apps’) or a website offering self-triage or advice. Parents did not find two of the interventions easy to use. None of these interventions demonstrated reduced use of services for minor health problems. One study showed no difference in non-urgent ED attendances; one did not measure this outcome; and one measured intended, rather than actual, service use. Donovan et al. 43 proposed that the way in which interventions were developed could affect their usability and their effectiveness, and that co-design with patients was important.

Reviews of self-care for minor health problems

Richardson et al. 44 undertook three systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative research on self-care for minor ailments. One review focused on evaluation of services/interventions and their impact on reduction of use of GPs and EDs. The focus of this review was much wider than that of our review, looking beyond health literacy and including interventions such as the use of NHS 111, pharmacies and walk-in centres. In addition, it focused only on the UK, rather than international literature. Richardson et al. 44 found that interventions using education only did not work and proposed that this was because a range of issues affected patient decision-making. They highlighted that people can be overwhelmed by anxiety. We included their education-based interventions in our review where relevant.

Reviews of self-triage/symptom checkers

An audit of self-triage interventions showed that most were risk averse and encouraged people to contact services when, in fact, self-care was reasonable. 45 This audit did not measure impact on service use.

The need for this review

Although a number of reviews have been undertaken in related areas, and some reviews addressed parts of the territory covered in this review, there was a research gap for a review of health literacy interventions aiming to reduce the use of primary and emergency care for minor health problems.

Chapter 2 Research aim, design, and patient and public involvement

Aim and objectives

The aim was to identify interventions that reduce the use of primary and emergency care for minor health problems by improving health literacy.

The objectives were to:

-

identify the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and safety of interventions

-

identify the contexts in which different types of interventions are effective

-

describe interventions

-

identify the mechanisms of action of interventions

-

construct a typology of interventions relevant to service use reduction

-

describe the development process and its impact on effectiveness

-

describe the literacy levels of information-based interventions and their impact on effectiveness

-

identify patient, carer and staff views on the feasibility and acceptability of interventions

-

consider how UK stakeholders could operationalise the evidence in terms of identifying a set of interventions that they would find feasible, appropriate, meaningful and effective within their localities.

These objectives are slightly different from those in the proposal. For example, we originally intended to consider the literacy levels of effective interventions only, but we subsequently decided to do this for all the interventions we could find because we were interested in whether or not the readability or ease of use of an intervention had an impact on its effectiveness.

Design

We undertook a systematic review with stakeholder involvement. First we held a stakeholder event to inform the systematic review, then we conducted a systematic review to identify and synthesise the evidence and, finally, we held another stakeholder event to consider how to implement the evidence. We attended to guidance on good practice when involving stakeholders in systematic reviews. We drew on the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public 2 (GRIPP2) framework to reflect on our patient and public involvement (PPI). 46 See Report Supplementary Material 1 for the GRIPP2 reporting guidance checklist.

Ethics approval

Some researchers may use research methods for stakeholder involvement, such as Delphi exercises,47 and this requires research ethics approval. Our stakeholder involvement was akin to PPI in that we held workshops to encourage research users to shape and interpret the systematic review. We did not require ethics approval for the stakeholder involvement or for the systematic review.

Patient and public involvement

Aim

We aimed to have patients and members of the public providing input to the development, conduct and dissemination of the review to ensure that the findings would be relevant and useful in supporting people making decisions about self-care or accessing health care.

What we proposed in the funding application

Margaret Ogden (a member of the Sheffield Evidence Synthesis Centre PPI group when we applied for funding) supported development of the funding application and was a co-applicant. We planned that Margaret would be part of the project management team, attending team meetings every couple of months and inputting into decision-making throughout the study.

We proposed that four members of the School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR) Evidence Synthesis Centre PPI group would be involved in different parts of the review process, including attending the two stakeholder events and supporting the development of the protocol (e.g. ensuring the salience of the search strategy, supporting the development of a dissemination strategy and providing feedback on the plain English summary included in the final report). We promised that we would keep the group informed throughout the project.

We proposed that we would also take our early findings to the Yorkshire and Humber Deep End Patient Panel. This is a panel of 10–15 people living in the most socioeconomically deprived areas in Sheffield, established by a local GP. We would also invite them to the second stakeholder event, expecting a maximum of five to attend.

What we did

Although our activities were in keeping with what we proposed, we had to respond to COVID-19 restrictions by quickly amending our plans to meet virtually, rather than face to face. This provided an opportunity to involve people from a wider geographical area while keeping within allocated costs. We also involved members of the Deep End Patient Panel from the start of the systematic review, rather than only at the findings stage. We involved PPI members in all stages of the review, including developing the funding application, deciding the scope of the review, designing the user-friendliness assessment and considering the implications of the findings.

Who was involved

We aimed to work with people representing the general public, rather than seeking out people with lower levels of health literacy or a history of using primary or emergency care for minor health problems.

Margaret Ogden was actively involved in the review. She supported the development of the funding application and was a co-applicant. She was a member of the project team, attending team meetings and supporting the development of the stakeholder events. She co-led the PPI group with Alexis Foster, seeking out new members to ensure diversity. She helped with developing the User-Friendliness Assessment Tool (UFAT) and undertaking assessments of the user-friendliness of included interventions (see Chapter 3). She commented on and edited the plain English summary in the final report. Using Pollock et al. ’s48 involvement framework, Margret Ogden’s involvement was categorised as both ‘controlling and influencing’: she was part of the research team, contributed to decision-making and undertook review activities by assessing the user-friendliness of interventions.

In the application for funding, we said that we would work with the Sheffield Evidence Synthesis Centre PPI group, but this ceased to exist by the start of the review. Instead we developed a new PPI group for the review, with membership expanding over time. We invited some members of the disbanded Sheffield Evidence Synthesis Centre PPI group to be involved; in addition to Margaret Ogden, one person agreed to be involved. As some of the potential interventions included in the review were aimed at parents of young children, we wanted to have representation from this demographic. Through our networks, we identified two people to be involved who had young children, one of whom had not undertaken PPI work before. We also invited members of the Deep End Patient Panel to join our PPI group. We did this because the Deep End Patient Panel was not meeting at the time because of COVID-19. A member of our team (AF) had links with several of the members, and so was able to support them to become involved in our group. As the review progressed, Margaret Ogden recruited three more experienced PPI members who were based in different parts of country, two of whom were carers. We took an open, flexible approach to PPI,48 recruiting people throughout the review and involving them in the review in different ways.

Although not all PPI members attended all the events, throughout the review 14 different people were involved and 10 people attended (or provided input into) each of the four PPI meetings. The PPI members were relatively diverse. Although the majority of people were based in Sheffield, we also had people based in the north-east of England, London and Gloucestershire. People were at different stages of their lives: some were retired whereas others had young children. We had a mix of males and females. People had different life experiences including being carers, being a refugee, being community activists and living in socioeconomically deprived areas. The involvement was categorised as ‘contributing’: PPI members influenced the review, for example by contributing to the scope of the review and interpretation of the findings. 48

Patient and public involvement meetings

We held four events attended by PPI members. Ten PPI members contributed to each of the two stakeholder events either by attending or offering insights after the event. In between the two stakeholder events, there was a PPI meeting to develop the UFAT and a meeting to discuss the preliminary findings of the review. After each meeting, we wrote up notes that documented points made and the actions the team would take based on these points.

Owing to COVID-19, all meetings were held virtually. The advantage was that it enabled people to participate from across the country. Furthermore, it meant that we were able to involve a larger number of PPI members because the budget could be used for remuneration rather than for travel and refreshment costs. The disadvantage was that some people found the technological aspect of virtual meetings difficult. For these people, a team member (AF) held discussions with some PPI members outside the meetings to enable them to share their views and/or supported them with using the technology such as having trial sessions on the technology. Over time, members became more confident at participating virtually. For example, one person went from having to speak outside the meeting by telephone to actively engaging in later PPI events virtually. Having ‘break-out rooms’ in the first stakeholder event helped to give an opportunity for everyone to participate. We did not do this in the second stakeholder event, which may have reduced participation from less confident members.

Keeping people informed between meetings

The team wanted to ensure that PPI members (and other stakeholders) were kept informed of the progress of the review between meetings. We did this through producing newsletters periodically throughout the project. These were written in plain English by a team member (AF) and Margaret Ogden reviewed them to ensure that they were easy to understand. Margaret Ogden also wrote part of one of the newsletters. We received positive feedback about the newsletter and intend to do this in future studies.

Remuneration and skills development

Patient and public involvement members were remunerated by direct transfer to their bank accounts. We generally paid £50 per attendance at a 2-hour meeting. People were also remunerated for supporting the UFAT work (explained in Chapter 4). To support skills development, we delivered training on using social media at the request of some PPI members. They wanted to learn how to use Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) to support their PPI work and promote the findings from the review. We delivered this training to five people. The technological support and trial sessions for using technology for virtual meetings are likely to increase people’s skills and confidence in participating in future virtual meetings.

Chapter 3 First stakeholder event

Background

In the first month of the study (November 2020), we held a virtual stakeholder event. It had to be virtual because of COVID-19. We aimed to involve representatives from the following groups: patients, carers and members of the public; Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs); NHS England Emergency and Urgent Care directorate; the NHS England Health Literacy Lead; general practice; EDs; and emergency ambulance services. The aim was to elicit stakeholders’ perceptions of key issues that might further shape the review, such as suggestions about the key types of interventions to include. The virtual format facilitated people from different parts of the UK to attend the event.

Stakeholders attending the event

Fourteen stakeholders attended the event, along with research team members:

-

seven PPI representatives (three others provided input outside the event)

-

one urgent care commissioner from a CCG

-

one representative from NHS England

-

one ED consultant

-

one GP

-

one academic pharmacist

-

one representative from NHS Digital

-

one representative from the third sector.

We designed the event with our PPI co-applicant Margaret Ogden to ensure that PPI representatives were supported to engage in the event. Our stakeholder lead on the team (AF) contacted all of the PPI representatives by telephone or e-mail before the stakeholder event to discuss the review and to support people to attend by explaining how the virtual platform worked. Alexis Foster also facilitated input from three PPI representatives who could not attend the event. Two did not feel confident with the technology and one person could not make the date. Alexis Foster sent them the notes from the event and then had a telephone call with each of them to discuss the event and get their input. We ensured that we included their viewpoints in the write-up of the event. This additional involvement was important because we did not want to exclude people from the event because of lack of technical skills.

The event

The event was held on 10 November 2020 and lasted 2 hours. It was a mixture of presentations and discussions. Alicia O’Cathain delivered two short presentations (each < 10 minutes) to explain the review, to justify why the research was needed and to discuss how the research fits within research on help-seeking behaviour in emergency and primary care. Jonathan Berry, the health literacy lead from NHS England, also presented on initiatives being delivered within the NHS to increase health literacy.

The group was split into two smaller groups to facilitate discussion, with each small group facilitated by a member of the research team and including a mix of stakeholders. In the discussion we focused on potential factors we needed to consider in the review. We also discussed potentially relevant interventions. Attendees gave us potential sources of grey literature such as work undertaken by the World Health Organization Healthy Cities initiatives, and by specific CCGs in England.

The issues raised and actions taken

After the event we recorded the points made by stakeholders and our comments on how we would address each point in the review (Table 1). We circulated our write-up to the stakeholders so they could add to the document. Comments from people who had been unable to attend the meeting were added at this stage (this is indicated by ‘post meeting’ in Table 1).

| Issue | Detail | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Making connections with others doing similar work | People are doing a lot of work related to this area | We need to talk to people who may be doing work on this issue such as the Scottish Government and NHS Sheffield CCG |

| Type of literature | Initiatives will be happening in the real world so search websites (e.g. World Health Organization reports) and speak to people rather than just searching research published in academic journals | We are already planning to do this but we have made it more central to our search now and intend to start this early in our study, for example search websites of NHS Scotland and the World Health Organization Healthy Cities initiative |

| Focus of our review | Are we including in our review:

|

We are focusing on interventions that improve health literacy for minor problems and, by doing this, reduce the need for people to use urgent general practice services, A&E and ambulance for minor problems |

| A lot of this list is relevant to our work. Some of the list is not relevant to our specific study, but is important to the wider topic of health literacy | ||

| It is useful to have this list so that when we identify interventions we can think about what we have not found information on, as well as what we have found | ||

| International literature | Focus beyond high-income countries | We are already planning to look at all countries. We did not make this clear in our meeting. We agree that some health literacy interventions will be used in low- and middle-income countries, so will make sure we search for and value those |

| Framework of types of interventions | Level of interventions: focus on individuals or systems? (e.g. school curriculum would be a systems approach) | This helped us to think about our framework for interpreting findings. We are going to be focusing on both individual- and system-level interventions |

| Timing of intervention and relevance to people’s lives: makes more of an impact if given at the right time so people are receptive and interested? | We will include ‘timing/relevance’ in our framework now | |

| Language used in interventions | Simple ‘living-room speak’ is needed in any intervention | We are planning to assess the literacy levels of information-based interventions in our review. Some may not have been effective because they required people to have high levels of literacy or knowledge |

| When are people receptive to interventions | We spoke about when people are most receptive to interventions. For example, we wondered whether or not it is when someone is feeling ill and accessing services, rather than when they are well | We will check when the studies provide the intervention to people. For example, is the intervention provided to people when they access health-care service or to children at school? |

| People felt that school children and people moving into an area (e.g. students) need to be taught health literacy and also taught about local services as each area is different (systems approach) | ||

| Level of trust in who is giving the information | The success of interventions may depend on how much people trust the source/person delivering the intervention. For example, people may trust community workers they have an established relationship with more than doctors | We will explore whether or not any of the studies we find consider the influence of trust on the results of their research |

| People have a lot of trust in urgent care services (e.g. A&E). They are consistent throughout the country and people know a doctor will see them, even if they have to wait | ||

| People are increasingly getting information from social media and may get lots of opinions on, for example, ‘what is this rash?’. They may choose to believe those with similar health beliefs | ||

| Who people are making the decision for | People may be more likely to access urgent care for minor problems because they are worried about their child or someone they care for more than if it had been for themselves | We will consider who the interventions are aimed at, for example patients directly, parents, informal carers. We will reflect on how this may influence a study’s findings |

| COVID-19 | How and when people access services may not return to normal after the COVID-19 pandemic | We will need to reflect on the UK context when we meet in the second stakeholder event to consider which interventions are relevant |

| It is about more than health literacy | People struggle to get GP appointments and other types of services, and so may access urgent care services because they cannot get help from other sources | We totally agree that other things are important. Health literacy is only one piece of a bigger picture. We will make sure that this is explained when reporting our findings and also reflect on whether or not studies have considered these issues within their research |

| There are logistical challenges to accessing some services, such as public transport | ||

| People are becoming increasingly used to 24/7 access to things (e.g. online shopping), and so may expect this in terms of accessing support for their health | ||

| Some people are more pessimistic/worriers by nature and may worry that a symptom is serious, which influences how they access services | ||

| It was suggested that people may access urgent care services because of previous experiences. For example, someone may have tried to access a pharmacist before about a condition but been directed to urgent care, so they feel they might as well go straight to urgent care. Likewise, if someone has a positive experience of accessing other services, this may give them the confidence to do this again | ||

| Training and knowledge of health professionals | It is not just about individual patients/carers, but also the role of health professionals to support people to have conversations, signposting to services, etc. | We are looking at interventions aimed at patients, not health professionals. (Originally our response to this issue was to say we would include these interventions. We changed this response after reflecting that we needed to stay focused on our plan) |

| Post meeting: studies not written up in the English language | There may be research on the topic that has been published in languages other than English | Unfortunately, for this study we do not have the resources to translate articles not written in English. However, we will be recording how many studies we have not included because of this and if there are some, then we will recommend that further research is needed that does consider these studies |

| We will also feed back to reviewers more generally about the need to have the resources to translate studies in future reviews | ||

| Post meeting: how was the intervention designed? | It will be important to consider how the intervention was designed, especially in terms of whether or not people who may receive the intervention were involved in the design process. For example, who are the authors of the paper? | We will consider within the review how the interventions are designed, especially in terms of involving people who may receive the support |

Ongoing communication

Following the event, we circulated newsletters to keep stakeholders informed about the progress of the review and to give people the opportunity to provide further feedback.

Chapter 4 Systematic review methods and results

Design

We undertook a multicomponent review49 of quantitative and qualitative research. We registered the review on PROSPERO (registration number CRD42020214206). The funders played no role in the review.

Methods

Searches

We searched the following databases from inception to 11 January 2021: Ovid MEDLINE, The Cochrane Library (via Wiley Interscience), EMBASE (via Ovid), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (via EBSCO), PsycINFO (via Ovid), Web of Science and Sociological Abstracts. We also searched for evidence in other sources including Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) and web-based review databases, such as Epistemonikos, PROSPERO and the Joanna Briggs Institute database.

We undertook a structured grey literature search by searching websites including Social Care Online, Health Literacy UK (https://healthliteracy.org.uk/), Public Health England, NHS England, NHS Scotland, The Kings’ Fund and the Royal College of Nursing. We also undertook targeted Google searches of domains including ‘.gov.uk’ and ‘.org.uk’ (and their international counterparts). In addition, we searched the websites of specific organisations known to have run local initiatives (e.g. Sheffield CCG, Stoke CCG) and the websites of international projects, including Optimising Health Literacy and Access (OPHELIA) (Australia) and the World Health Organization Healthy Cities initiative. Finally, we compiled a list of known authors on the topic of health literacy and searched for their conference papers, reports and papers, as well as researchers citing their work on Google Scholar (Google Inc.).

Given that this review was multicomponent, we had proposed, if needed, to undertake supplementary searches after our initial search to ensure that we met the aims and objectives of the review. As the initial search progressed and synthesis began, we did not need to undertake further searches for different components. We did however undertake one further search in August 2021 to identify additional studies reporting evaluations of navigation tools because we had identified tools only from the USA in our original search.

Search terms

A professional information specialist within the information resources team in the ScHARR (MC) developed the search strategy using the standard search strategy of population, intervention, comparator, outcomes and setting/context.

-

Population. No search terms in relation to population were used because we wanted to include all populations.

-

Intervention. Interventions with the primary purpose of reducing primary or emergency service use for minor health problems by improving health literacy. ‘Minor health problems’ was not used to limit the initial search because researchers may not use this term (or similar terms), or explicitly articulate a focus on minor health problems. Instead we searched widely and then screened for interventions to reduce service use for minor health problems. We were not interested in interventions to improve health literacy for chronic conditions, where the aim is to reduce use of emergency care and hospitalisation through prevention of health problems. These chronic condition interventions tend to focus on self-management to prevent serious exacerbations, hence the interest in hospitalisation. We removed these at the screening stage. Nor were we interested in interventions in which health professionals made decisions about whether or not, or where, to seek health care and gave self-care advice as part of this (e.g. NHS 111).

-

Comparator. A range of study designs. When a design was a randomised controlled trial (RCT), the comparator could be usual care or a control assumed not to have the active intervention being tested.

-

Outcomes. (1) Changes in use of general practice, GP out-of-hours services, emergency ambulance, EDs, paediatric EDs (using a range of international terms for these services). (2) Changes in use of services overall or specifically for minor health problems. (3) Rate of adverse events, that is missed serious health problems for which people would otherwise have sought care. (4) Patient acceptability and health-care feasibility. (5) Changes in other outcomes, for example knowledge, health literacy, confidence.

-

Setting/context. We were interested in interventions that might work in the UK context. We searched for evidence without limiting the country/setting.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used on 11 January 2021.

Further inclusion/exclusion criteria

We limited the search to English-language literature. We limited the search to articles published between 1990 and 2020 to ensure relevance to the current health-care system.

Screening

We downloaded references into EndNote [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA]. We piloted the screening process by having three reviewers (AOC, AF and CC) independently screen the titles and abstracts (when available) of the same 100 records retrieved from the searches to determine whether or not a study met the predefined inclusion criteria and whether or not the criteria were being interpreted by all reviewers in the same way. We discussed and clarified any differences of interpretation and then one reviewer (CC) screened all the titles and abstracts, tagging each as ‘include,’ ‘exclude’ or ‘unclear’. We retrieved the full texts of all ‘include’ or ‘unclear’ articles and classified them as ‘include’, ‘exclude’ or ‘unclear’ (CC and AOC), with differences resolved through discussion. When this discussion did not lead to resolution, we consulted a fourth reviewer (LP). One reviewer (LP) screened the reference lists of relevant systematic reviews for further primary research studies. One reviewer (CC) checked the references of included studies to identify additional relevant studies.

Data extraction

Louise Preston developed a data extraction form to meet the study objectives. Four reviewers (CC, AOC, AF and LP) independently extracted data from three studies and discussed the process to ensure that we were clear about what we needed to extract and the level of detail required. Then one reviewer (CC) independently extracted data from each included study. The data extracted included the following.

-

General description (author, year of publication).

-

Study design.

-

Context. Although this was not a realist review, we were interested in characteristics of context that might contribute to reductions in use of primary care and emergency services. Contexts included the country where the research was conducted and the target population.

-

Delivery setting (emergency care, primary care, community, workplace, other).

-

Headline message.

-

Description of the intervention using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) framework. 50

-

How the intervention was developed. Given that patient involvement in the development of interventions is noted as good practice to create usable and helpful interventions,51 we documented how authors of papers described the intervention development process. We did not search beyond the included papers.

-

Mechanisms of action of the intervention (see the next section about how we identified these).

-

Changes in service use: ED, general practice and emergency ambulance overall or for minor health problems. We also extracted how they were measured (actual use from patient records or patient-reported use) and time period of measurement (e.g. 6 months).

-

Costs and cost-effectiveness (see Costs and cost-effectiveness for explanation).

-

Safety or adverse events.

-

Displacement. We documented whether or not studies of interventions to reduce the use of primary care also measured any effect on EDs to ensure that we considered displacement of service contacts to higher-acuity services.

-

Any other outcomes measured, for example change in health literacy levels or knowledge of minor illness management.

-

Patient/carer and staff views on the feasibility or acceptability of the intervention.

-

Copy of written components of the intervention.

A second reviewer (LP) independently extracted data from 10% of the included studies and resolved differences by discussion with Christopher Carroll and Alicia O’Cathain. Discrepancies were related to the level of detail of extraction, rather than the accuracy of extraction.

Mechanisms of action

We began the review with three potential mechanisms in mind (information, education and empowerment), identified from reading background literature and some of the included intervention studies. An information mechanism might include ‘take your temperature’, education might include ‘this is how you take your temperature’ and empowerment might include ‘engendering confidence in making decisions based on a temperature reading’. One reviewer (CC) extracted authors’ stated mechanisms or assigned mechanisms based on this list of three mechanisms and the description of the interventions.

As we read existing reviews on self-care and health literacy, and read more of the included studies, we reconsidered the list of mechanisms. Richardson et al. 44 was particularly helpful in this endeavour. In their systematic review of self-care for minor ailments, they explored mechanisms using the theoretical domains framework. 52 They described the need to affect people’s willingness to self-care, which might be compromised by a lack of knowledge and skills to manage self-care. They identified the need to address people’s capability (knowledge, skills, beliefs about capabilities, decision-making processes) and motivation (beliefs about consequences, e.g. persuasion that EDs are overcrowded or that pharmacists are competent). Some authors of the included studies explicitly discussed the need for an intervention to address people’s anxiety about a specific symptom as a barrier to self-care. 53 Some interventions in the included studies also tailored the intervention to individuals’ symptoms and situations, rather than offering the same advice to all. We constructed an extended set of mechanisms and one reviewer (AOC) extracted these when the basic data extraction had been completed by Christopher Carroll. Authors of papers were rarely explicit about mechanisms; we identified them by interpreting text from the description of the intervention, or the background or discussion sections of a paper in which authors discussed the intervention aims, rationale or development. The six mechanisms are listed and described in Results.

Constructing a typology of interventions

We expected to see different types of interventions for improving health literacy with the aim of reducing the use of primary and emergency care. We planned to synthesise the evidence by type. We could find no existing framework of types of interventions, so we read a selection of included papers and papers in the wider health literacy literature. We inductively constructed a typology. We have used this inductive approach to developing taxonomies and frameworks successfully in other reviews. 54,55 We drew on Coulter and Ellins,40 who identified different types of health literacy interventions as written health information, alternative format resources, low literacy initiatives and targeted mass media campaigns. When we read a selection of included papers, we identified the following types: written information to navigate the health-care system, written information on managing illness, educational workshops, one-to-one health coaching and digital self-triage. These interventions came in different formats (paper; digital, including mobile phones; human; or mixed). They were also delivered at different times [to people who had used emergency or primary care for a minor health problem (‘specific’) or made available to the people at any time (‘general’)]. Although we had a number of other intervention characteristics to choose from, and we discussed the potential to use these (e.g. setting of delivery, target population aimed at, group vs. one-to-one delivery, tailored vs. not), we wanted to keep the typology simple. We constructed a typology of interventions based on the aim of the intervention (navigation, education or self-triage), how the intervention was delivered (e.g. written, person, digital) and when it was delivered (when a patient had used a service for a minor health problem, or it was offered to everyone). We selected timing of the intervention because a related review drew attention to its importance,41 and this was also raised in our first stakeholder event. We discussed the typology as a team and tested it on a range of included studies. When we were happy with the typology, one reviewer (AOC) coded each included study to it. A second reviewer (CC) checked the application of this typology and highlighted a few discrepancies. Alicia O’Cathain returned to the highlighted papers to double-check the coding of each study (see Results for the typology).

Quality assessment: risk of bias and risk to rigour

Given the wide variety of study types included in this review, we used a hybrid approach to risk-of-bias assessments. For RCTs, we used the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. 56 For non-randomised studies, we used the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (case–control and cohort studies). 57 For qualitative studies, we assessed risk to rigour using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool,58 and for mixed-methods studies we used the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). 59 We did not use our assessment of risk of bias or of risk to rigour to exclude evidence from the review, but to assess the overall evidence base and the confidence with which we could use the evidence. One reviewer (CC) undertook the quality assessment. Another reviewer (LP) undertook an independent assessment of 10% of studies and identified minor differences, which were resolved via discussion with Christopher Carroll.

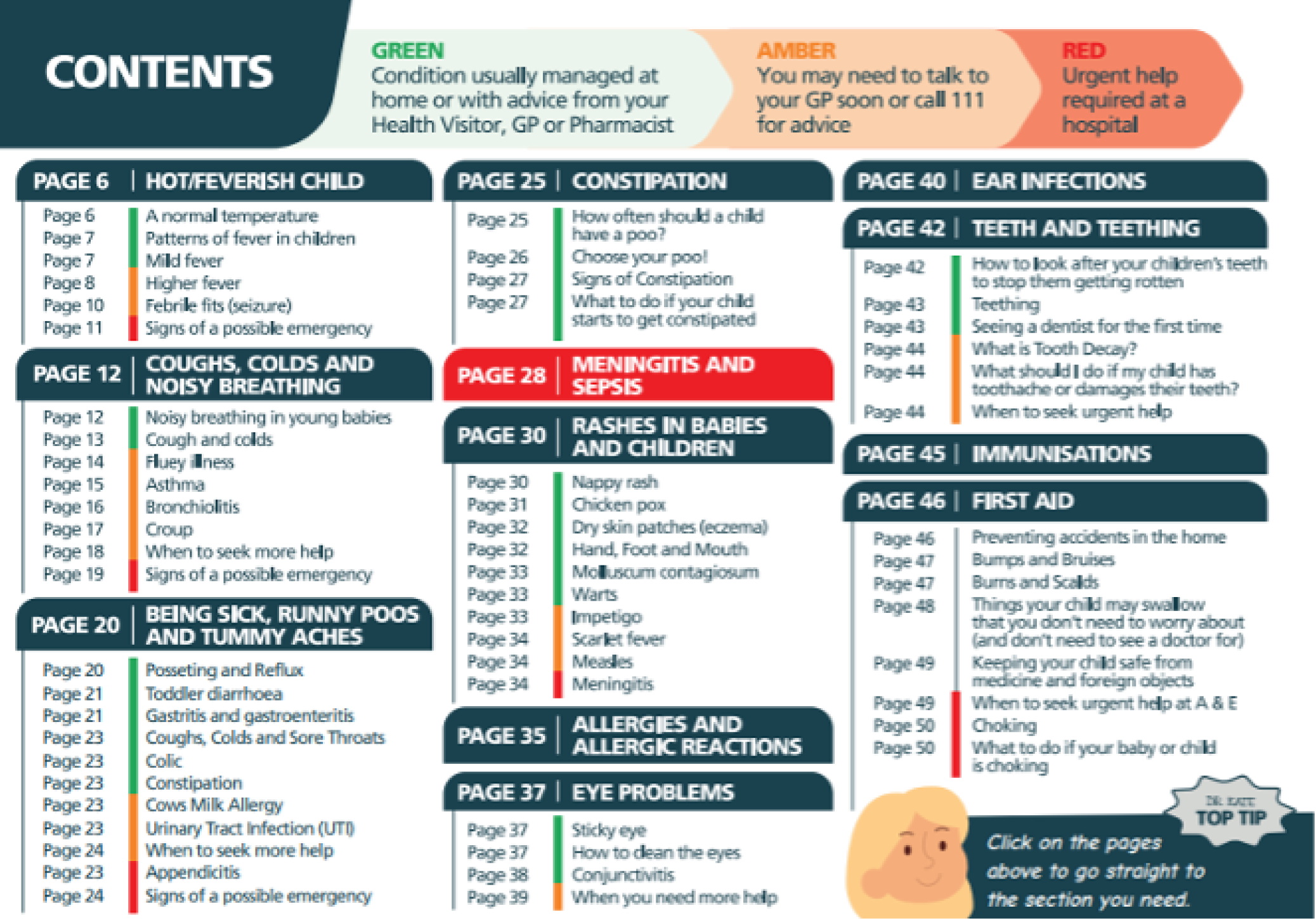

Assessment of readability and user-friendliness of written components of interventions

An important concern arising from the first stakeholder event was that interventions aimed at improving health literacy needed to be written in plain English and designed in a way that made it easy for the reader to comprehend what was written. For example, interventions using medicalised language or with long chunks of condensed text would be difficult for people to understand and act on. At least 43% of written materials containing health information are too complex for most adults to understand. 60 We decided to assess both the readability and the user-friendliness of the written components of included interventions.

Readability

The Flesch Reading Ease (FRE) and Flesch–Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL) are established approaches to readability assessment. 61 Readability is about the complexity of language being used, and thus the level of literacy someone may need to have to understand a document. 62 We used the FRE and the FKGL because they have been used in previous studies that consider health literacy and are the most commonly used assessments because they can be measured using Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). 63 Both the FRE and the FKGL consider the number of syllables in words and the average number of words per sentence. They differ in terms of the weightings they give to different parts of the formula. Therefore, there may be some differences in how an intervention is scored on the two assessments. 63

The readability assessments are automatically calculated using Microsoft Word. We needed to type the interventions into Microsoft Word. Rather than typing in the whole document, we followed an established procedure of choosing a selection of text from each intervention. 62 The selection was drawn from the first 100 words (excluding title/headings), 100 words from the middle and the last 100 words of a written component of an intervention. It is possible that an intervention may have been scored differently had the full text been assessed.

The FRE score ranges between 100 and 0, where 90–100 = very easy, 80–89 = easy, 70–79 = fairly easy, 60–69 = standard, 50–59 = fairly difficult, 30–49 = difficult and 0–29 = very confusing. A document scoring ≥ 70 is considered suitable for most adult readers. A score of 30–69 is considered somewhat difficult and suitable for only some adults. Anything scoring < 30 is considered difficult and inappropriate because it is written at a university graduate level. 64 More generally, documents are considered to be written in plain English if they have scores of at least 60. 65

The FKGL relates to the USA education grade a document is suitable for. The score ideally needs to be grade 8 or lower, as this reflects the reading level of most adults. Scores are categorised as follows: ≤ 8 (suitable for most adults), 9–12 (fairly difficult because it is written at a level suitable for high school students aged 14–18 years) and > 12 (difficult because it is written at a level suitable for university students).

Development of a User-Friendliness Assessment Tool

At the first stakeholder event, people raised the issue that interventions need to be user-friendly so that people feel able to understand and act on the information they contain. Stakeholders gave examples of text-heavy leaflets full of jargon, which would be barriers to people understanding and acting on the information provided. This would then have implications on the effectiveness of those leaflets. Consequently, as a research team, we wanted to assess the ‘user-friendliness’ of interventions, focusing on medicalised language/jargon, font and text style; whether or not content was broken down into short paragraphs/bullet points; and whether or not the intervention was written by someone patients trusted. We had to develop our own UFAT because we could not identify an existing tool. We found guidance from credible sources that recommended good practice for health literacy interventions. These were from the NHS in the UK66 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the USA. 67 We drafted a tool and shared this with our PPI members for feedback. Some PPI members also tested the UFAT on two interventions. We held a meeting in June 2021 with PPI members to discuss their feedback, and revised the tool substantially based on their feedback. Key changes included ensuring that at least two people assessed an intervention because of the divergence in views about the interventions, having four response options per item so that the tool was more sensitive, and adding additional questions on trustworthiness and confidence in the information provided. We also agreed that PPI members would be involved in assessing the user-friendliness of interventions. The UFAT is in Appendix 2. The tool consists of 14 items, each of which produces a score of 0–3. The scores from each question are combined to produce a maximum overall score of 42. Interestingly, Rughani et al. 63 published a paper assessing GP websites during our review and included a similar ‘design factors’ assessment tool in their work.

Process of assessment

Health literacy interventions can come in a range of formats including person-delivered, leaflets, websites and posters. The readability and user-friendliness assessments could be undertaken only on interventions that included a written component. Furthermore, we could only assess interventions that were in English and publicly available. For example, some of the websites were subscription only or in Dutch. Some papers showed an extract from the intervention rather than a link to, or copy of, the whole intervention; therefore, we used this extract. We were able to locate 13 interventions related to 20 articles included in the review; some interventions were reported in a number of papers. Some of the interventions were impossible to find because they were more than 20 years old, for example leaflets developed in 1991.

In addition to assessing the interventions in the review, we also assessed an intervention identified by PPI members and stakeholders that is currently in use in the NHS: The Little Orange Book. 68 This is an information resource aimed at parents of young children in the north-east of England to support them with understanding common childhood illnesses.

We calculated the FRE and the FKGL for each intervention. At least two people applied the UFAT to each intervention, typically two PPI members and one researcher (LP). The scores of the different assessors were combined and a mean calculated. We compared scores on readability and user-friendliness to assess their relationship. Very high levels of correlation would suggest that only the readability scores were necessary for use in our synthesis.

Synthesis

Presentation of the studies

One reviewer (CC) reported the included studies in alphabetical order in four tables: (1) context/characteristics, (2) description of the intervention (including mechanisms and typology), (3) service use outcomes and (4) other outcomes. A second reviewer (AOC) read the papers independently and checked the presentation of each study.

Synthesis of outcomes

We used the typology of interventions to identify common types and then we presented a narrative synthesis of service use outcomes for each common type, with data summarised in tables. We ordered studies in these tables in alphabetical order, or, if there was a subset of the type, we ordered by this subset and then alphabetically.

We could not use meta-analysis because of the heterogeneity in how service use outcomes were measured. We did not measure heterogeneity in reported effects because it was clear from the data extraction that there was considerable variation in the way the outcomes were measured and the time periods over which they were measured. We planned to use the typology to synthesise other outcomes and processes, but numbers were too small. Instead we undertook a narrative synthesis of all the studies for each outcome or process. We followed the synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) reporting guidelines. 69 The SWiM checklist can be found in Report Supplementary Material 2. When drawing conclusions from the synthesis, we gave weight to studies that used RCTs in preference to other designs, measured the impact on service use using routine data/records rather than self-reported service use, were assessed as being of higher quality, and had greater relevance to the UK because the research was undertaken in the UK or a country with a similar health-care system to that of the UK.

Costs and cost-effectiveness

We knew from scoping the evidence base that there would be few economic evaluations for synthesis. We intended to follow the ‘brief economic commentary’ for synthesis, rather than the ‘integrated full systematic review of economic evidence’ as set out in the Cochrane Handbook. 70 We planned to follow methods used by Angus et al. 71 to summarise any directly reported costs associated with interventions as reported in the literature and convert them to Great British pounds for a specific year. We planned to aggregate these data across intervention types to report costs for comparison and narratively synthesise cost-effectiveness and report the relationship between cost-effectiveness and context. Unfortunately, the cost data and cost-effectiveness analyses were often poorly undertaken or reported. Instead we undertook a simple narrative synthesis.

Qualitative research

We intended to analyse qualitative research using qualitative synthesis methods. 72 There were only four articles reporting qualitative research, focused mainly on digital interventions, so synthesis was limited.

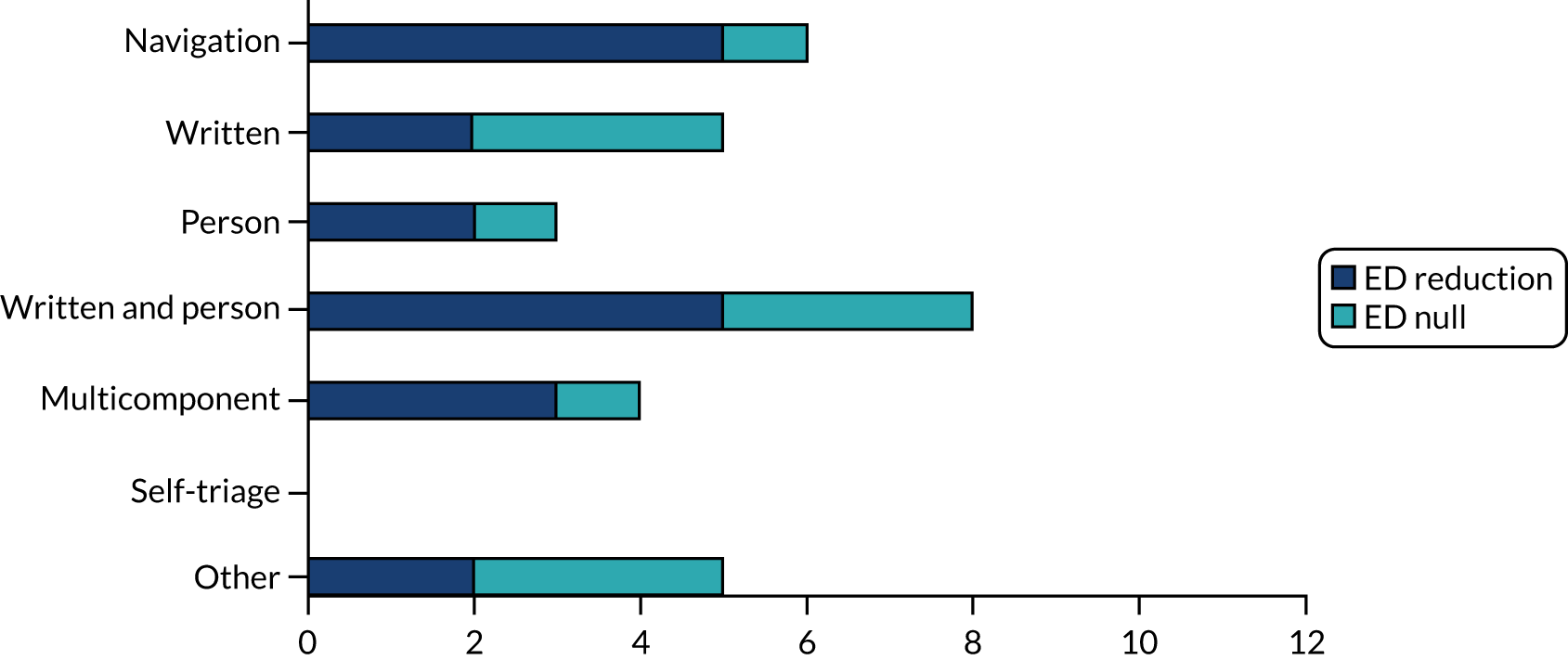

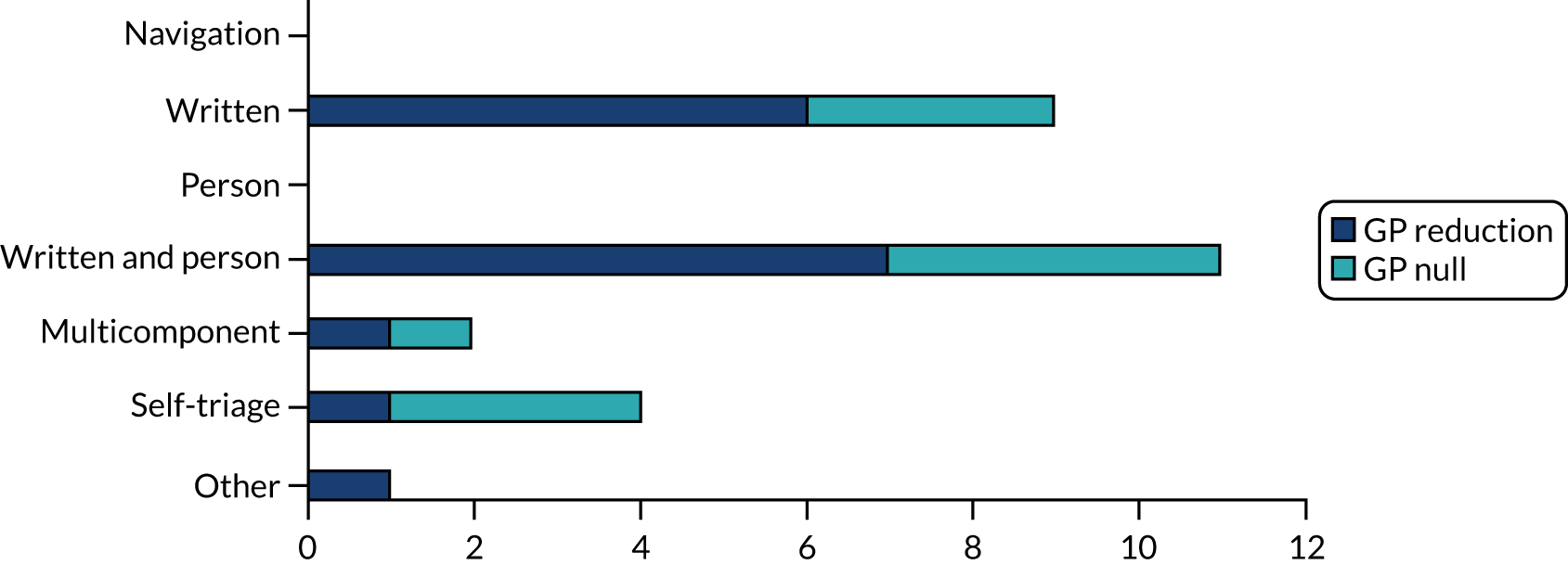

Explaining variation in impact on service use

Ideally we would have identified size of effect of each intervention within a meta-analysis, but, as explained previously, this was not possible because of heterogeneity in outcome measurement. We might also have considered a meta-regression to explain size of effect. 73 Instead, we identified whether or not studies that measured service use in a full evaluation (as opposed to pilot studies, which are underpowered statistically) had statistically significant reductions for impact on use of different services. Then we used IBM SPSS Statistics 27 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) to test whether or not different characteristics of the study, context and intervention explained reductions in service use.

An alternative way of explaining variation in an outcome is to consider the relationship between context, mechanisms and outcomes by identifying context–mechanism–outcome chains associated with understanding messy complex interventions. 74 We did this by considering mechanisms within the narrative synthesis by type of intervention.

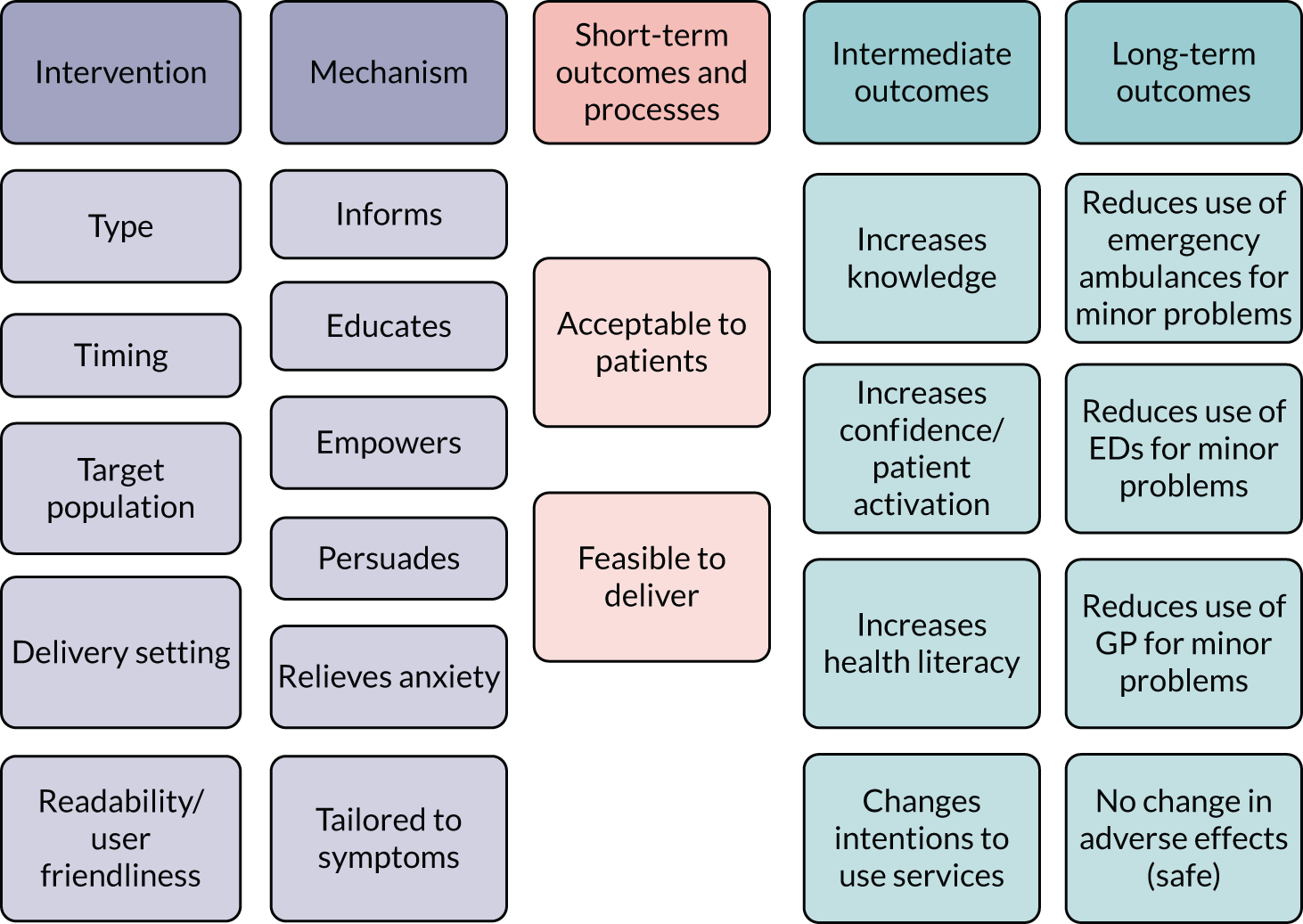

Articulating a programme theory

We constructed a logic model to present a programme theory of how characteristics and mechanisms of interventions might produce short- and intermediate-term outcomes that lead to long-term outcomes. We did this to facilitate interpretation of the synthesis (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Logic model of health literacy interventions to reduce use of primary and emergency care.

Results

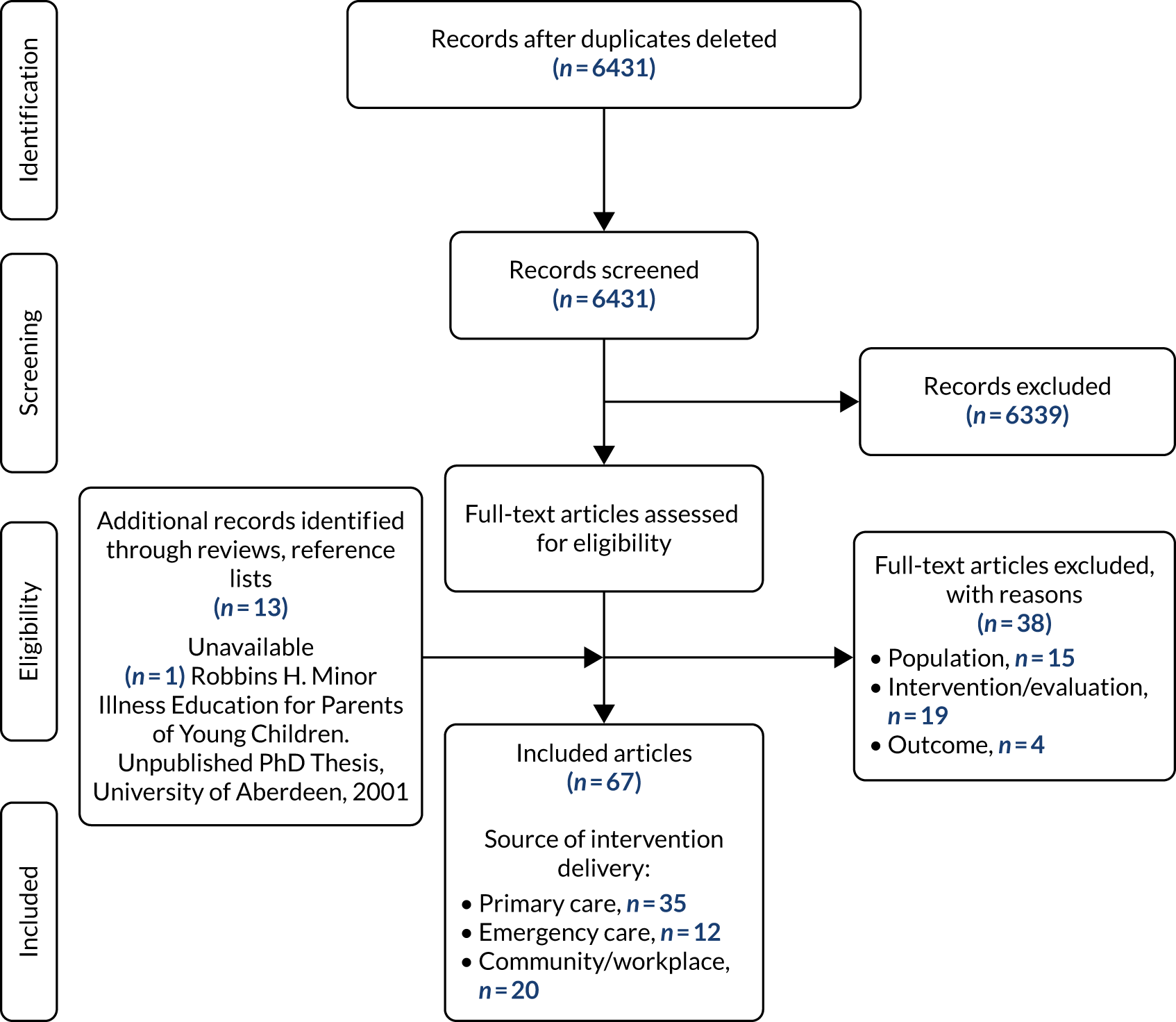

Included articles

We identified 67 articles that met our inclusion criteria (Figure 2). The decision about inclusion was challenging when studies met some, but not all, of the inclusion criteria. We excluded 38 articles at the full-text stage (see Appendix 3). Articles about frequent users of EDs tended to be excluded at the full-text stage because these studies focused on a population of people identified as having serious problems such as homelessness and substance abuse, rather than minor health problems. Articles about self-management of chronic conditions such as asthma were excluded when they were about prevention of acute severe problems, rather than management of minor health problems. Case management interventions tended to be excluded because they did not focus on minor health problems, but on serious problems that resulted in hospitalisations.

FIGURE 2.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

Characteristics or context of articles

The characteristics of each study are presented in Appendix 4. We describe each characteristic in the following sections.

Time of publication

The 67 articles were published over the three decades between 1990 and 2020, with half of articles published in 2010 or later (n = 32). In particular, interventions delivered in emergency care and community/other settings were undertaken more recently (e.g. 8/12 emergency care articles were published after 2010). This indicates the ongoing interest in this issue over time, and the more recent interest in interventions delivered in emergency care or community/other settings.

Country

The articles reported studies undertaken largely in North America (n = 37), the UK (n = 16) and the rest of Europe (n = 12). The Netherlands featured highly in the European group, specifically for interventions delivered in primary care. Only two articles were from the rest of the world (Taiwan and Australia). Most of the interventions delivered in emergency care were from North America (11/12), as were most of the community/other setting articles (15/20). This raises a potential concern about transferability of parts of the evidence base to the UK because of the role of payment and insurance for services in North American health-care systems, particularly in the USA.

Place of delivery of the intervention

The articles reported interventions delivered to users of primary care (n = 35), users of EDs (n = 12) and within community/other settings (n = 20). No intervention was delivered to ambulance service users.

Target population

Around half the articles were aimed at parents of young children (n = 32), some of which were aimed at parents of children aged < 5 years (14/32). Most articles about interventions delivered in EDs were aimed at parents of young children (9/12), demonstrating a paucity of evidence about interventions aimed at adults attending EDs. Some articles specified that the population aimed at, or the sample included in the study, was (1) socially deprived and/or (2) mainly from an ethnic minority group associated with poverty in that country and/or (3) had low health literacy levels (21/67).

Articles reporting the same study

Some articles reported different aspects of the same study or data set: Plass et al. ,75,76 Rutten et al. ,77,78 and Hibberd et al. 79 and Wagner et al. 80 There were 64 studies in total. Other articles were written by the same author, testing the same intervention in different ways on different populations,81–83 with Herman and Mayer82 undertaken as a pilot for Herman and Jackson. 81 Yardley et al. 53 was an exploratory RCT for Little et al. ’s84 full RCT.

Study design

The authors used a range of designs in the articles, mainly RCTs (n = 30), and single-arm or controlled cohort studies (n = 33). A few articles reported qualitative or mixed-methods research (n = 4). The cohort studies included controlled before-and-after studies (n = 11), before-and-after studies (n = 8) and non-RCTs (n = 4).

Description of interventions

The interventions reported in the 67 articles were described using TIDieR guidelines (see Appendix 5). This description included the rationale for the intervention; what was delivered and by whom, how, where, when and how much; and any tailoring/personalisation. The items of ‘modifications’ and ‘fidelity’ were also extracted, but were rarely reported and so are not presented in Appendix 5. Instead, these items are described in narrative form in the following sections Modifications and Fidelity. Appendix 5 also includes a summary of how the interventions were developed, their proposed mechanisms of action (subjective assessment by our team) and their type according to our typology.

Rationale for the intervention

The reported rationale for many interventions, whether delivered in primary or emergency care, was to reduce emergency care use for non-urgent complaints, including directing patients to primary care,83,85–95 and to reduce any and all health service use. 96–98 Some interventions were specifically designed to reduce reconsultation for a similar minor health problem, especially in primary care,99–101 and, in some cases, the interventions sought to modify patients’ and carers’ consultation behaviour related to specific minor problems, such as childhood fever,102,103 respiratory tract infections84 and cough. 77,78

Other primary and emergency care-delivered interventions were explicitly designed to improve patients’ and carers’ knowledge and confidence sufficiently to enable minor problems to be self-managed96,102,104–109 and/or to enable the selection of the appropriate service, for example primary instead of emergency care. 108–112 Many such interventions reported the corollary rationale of reducing unnecessary primary or emergency care use as a result of improved knowledge. 53,75,76,103,113,114

Unlike the primary and emergency care interventions, the majority of community and workplace-based interventions had the specific aim of improving self-care and participants’ knowledge, both of illnesses (including some specific minor problems such as childhood fever or cough)79–82,115–121 and when to access what service. 122,123 A smaller number of such studies explicitly reported that the aim of an intervention was to reduce use of primary care,124 emergency care125,126 or health services generally. 127–129

What was delivered and by whom, how, where, when and how much

The interventions were delivered either by a specific individual or designated team of health-care staff, (e.g. a GP, paediatric ED physician or nurse),75–78,88,99–102,107,109,112,130,131 a service generally (e.g. the primary care practice)84,86,92,106,132,133 or, in the case of some workplace or community interventions, an employer or an external organisation. 79,80,120,121,127,128 In some cases, the interventions were delivered by the researchers only. 83,85,89,94,110,134

Some interventions were delivered face to face to target groups of patients or carers at pre-set time points, in particular regular monitoring visits for babies and infants (e.g. Well Child Visits). 90,111,119,134,135 However, the majority of interventions directed at specific groups of patients or carers were delivered in direct response to a potentially unnecessary primary care or emergency care consultation and with the explicit purpose of preventing future, similar consultations. Such interventions were delivered principally at the time of the index consultation,75–78,83,85,94,95,99–103,109,130,131,136 but could also be delivered a little time later. 88,89,92,108,112,137