Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR133884. The contractual start date was in November 2021. The final report began editorial review in November 2022 and was accepted for publication in March 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Chambers et al. This work was produced by Chambers et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Chambers et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Residents in care homes for older people include a high proportion of people with complex health and care needs, including frailty and dementia. 1 Consequently, they are at high risk of experiencing unplanned hospital admissions. While they are often necessary, such admissions can be distressing for the residents, their families and friends, and care home staff, and can also be costly. A report by the Health Foundation concluded that around 40% of unplanned admissions from care homes may be avoidable (conditions potentially manageable outside hospital). 2

Action to reduce unnecessary and/or unhelpful/potentially harmful unplanned admissions among people in care homes and the wider community is an important priority for health and social care both in the UK and internationally. The recent UK government White Paper Integration and Innovation set out plans to promote greater cooperation between health and social care. 3 The COVID-19 pandemic further demonstrates the need for health and social care systems to work together. An additional concern in the UK is ‘delayed discharge’ when patients admitted to hospital are unable to be discharged because of lack of social care support, which in turn affects patients requiring admission from emergency departments (EDs). 4 Reduction of unplanned admissions from care homes can help to alleviate this pressure on the wider health-care system and enable more holistic person-centred place-based care to be provided in the person’s home setting.

Interventions to reduce unplanned admissions from care homes or the community can potentially be implemented at various points in the health and social care system. 5 The University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) conducted a scoping review on the topic for Northumberland Clinical Commissioning Group in 2014. 6 This review focused on interventions that were categorised as community geriatrician services, case management, discharge planning, integrated working between primary care and care homes, medicines management, the prevention of delirium and end-of-life care. The key finding of the CRD report was that ‘there is little good quality comparative evidence to inform strategies for reducing unplanned admissions from care homes’. The authors noted, however, that closer working between health-care and care home staff, training for care home staff and advanced care planning at end of life all appeared promising.

A systematic review of interventions to reduce admissions from care homes was published by Graverholt et al. around the same time as the CRD report. 7 This review included 4 systematic reviews and 5 primary studies, covering 11 different interventions. These were categorised as interventions to structure or standardise clinical practice, geriatric specialist services, and influenza vaccination. Both the CRD report and Graverholt et al. concluded that the quality of evidence was low but some interventions [e.g. advance care planning (ACP), palliative care, care pathways and ‘geriatric specialist services’] represent promising approaches that require further research. The need for an update is justified by the substantial volume of new research. An initial scoping search of Medline, the Cochrane Library and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (January 2014 to January 2021) identified 647 unique references.

We were not aware of any subsequent broad reviews of this topic at the outset of our review, which was commissioned in 2020. However, initial literature searching identified a more recent review by Buck et al. published in 2021. 8 We compare our findings with those of Buck et al. in the Discussion section of this review but our systematic treatment of issues related to implementation and applicability gives our work a broader focus.

The aim of this systematic review was to update the literature on health and/or social care interventions that might support home-based care for people living in care homes with or without nursing. Relevant interventions could be delivered in care homes, hospitals, or a mixture of the two, and could involve many different health and social care professionals. This means that the research evidence identified and synthesised in this review is of key importance in enabling further development of integrated working between health and social care.

Chapter 2 Methods

Patient and public involvement

The project was planned to incorporate public involvement led by a public co-applicant (Lynne Wright, who replaced Cynthia Atkin) supported by regular meetings of a public advisory group. The strategic public advisory group of the Sheffield Health and Social Care Delivery Research Programme (HS and DR) Evidence Synthesis Centre also discussed the review at an early stage and advised on recruitment of the public advisory group.

The topic-specific public advisory group and review team had four one-hour meetings, covering:

-

introductions and discussion of the project context, the methods used (including the public involvement plan and offer of optional training on evidence synthesis methods) and the objectives

-

discussion of ‘emerging’ findings

-

further discussion of review findings

-

focus on dissemination of the review findings and production of the final report (including plain language summary and reporting public involvement).

Members of the group contributed to the review by

-

highlighting issues from their own experience, primarily related to how services work in practice, for example inadequate needs assessment of people with complex problems leading to placement in a care home that is unable to meet their needs and hence increasing risk of unplanned hospital admission. Members also discussed examples of paramedic assessment and decision-making about taking people to hospital, and raised awareness of pressures on some care home managers to adopt a ‘risk averse’ approach to managing residents’ health

-

providing details of potentially relevant research based on involvement in other research projects, specifically a tool for identifying people at risk of deterioration

-

suggesting channels for disseminating review findings outside academia, for example charities such as Age UK, local carers’ groups (with links to both the NHS and local authorities), the Care Quality Commission and possibly Parliament (Health and Care Select Committee or All-Party Parliamentary Groups)

-

suggesting that many carers were unlikely to access material on academic websites even when this was labelled as being in plain language. Short printed summaries were seen as being more suitable for decision-makers than for carers, care home residents and the general public.

We also made contact with an existing group based in Leicester with an interest in older people’s health and care and we hope to work with them on the dissemination of the research findings.

We encountered a number of challenges:

-

The public co-applicant was unable to participate as planned for personal reasons. A member of the patient and public involvement (PPI) group, Lynne Wright, took on the role and attended meetings with the research team and clinical experts as well as contributing to the report.

-

Despite our best efforts, we were only able to recruit three active members for the topic-specific PPI group. This was obviously not ideal, although the members were knowledgeable and enthusiastic, represented different geographical areas and had diverse experiences of the care home sector.

-

We were unable to attend a meeting until late in the project with the existing PPI group based in Leicester but the group was interested in the project and we hope to work with them on dissemination of the review findings.

Statement by Lynne Wright

I joined this research project because I am very concerned about the present state of social care and the availability of care homes in the UK that are able to offer care to frail elderly people with complex needs. I am also concerned about the increasing number of care home residents being sent to accident and emergency (A&E) or ‘shipped off to hospital’ because their care needs are not being fully met. I feel that this research is extremely worthwhile and will hopefully be a valuable source of information.

The meetings have been productive and well run, and I feel that myself and my fellow PPI members have been listened to and given the opportunity to put across our own thoughts and perspective on the research.

I was the carer for my husband, who sadly died earlier this year; he had Parkinson’s with Lewy body dementia and other comorbidities. Three and a half years ago, as I was no longer able to meet my husband’s care needs at home, we made the sad joint decision that he should move into residential care. As a family, we put much thought and effort into finding a suitable care home that was close to our home, where he would be happy and that was able to meet his needs at that time. As my husband had a degenerative condition, we did realise that, as his condition progressed, he would probably need to move to a home that could offer more specialised care.

From my experience it is very important to find the right type of residential care to meet the resident’s specific care needs. This has been made more difficult of late due to the COVID-19 crisis.

Sending residents to A&E following minor injuries – where a paramedic or GP is called out – is something that should, if at all possible, be avoided. Residents are often taken alone by ambulance. The home may try to contact a relative, but it is not always possible for someone to get to A&E to be with their relative. This can be extremely upsetting and confusing for the resident. In the south-west, we now have two paramedics who are able to carry out minor interventions in situ. On two occasions one of these paramedics attended my husband and was able to treat minor cuts (by stitching or glueing) thus avoiding a visit to A&E. Hopefully, more paramedics will be trained and available to carry out these procedures.

More and more elderly people are being admitted to acute hospitals because a suitable care home cannot be found or their care package fails at the residential home they are living in. They are not ‘ill’ as such – they need care. This is not an ideal situation. There is a lack of elderly care wards and people find themselves on a busy acute ward where staff have little training in the needs of someone with multi-morbidity and also sometimes mild or severe dementia. Often, they do not understand why they are in hospital and for many due to lack of stimulation and help with mobilising their condition can quickly deteriorate. It is a similar scenario for many elderly people who after completing inpatient treatment are fit to be discharged but are no longer able to be safely discharged back to their home.

There is a shortage of homes, particularly nursing/dementia homes that are able meet the needs of someone with multimorbidities and dementia. My husband’s care package failed three times and he was admitted to an acute hospital twice. The second time he spent six months on an acute hospital ward (where his condition drastically deteriorated) before we were offered a placement that could meet his complex care needs and give him the care and support he needed and also give me ‘peace of mind’ knowing that he was in a safe and caring environment.

Equity, diversity and inclusion

As a systematic literature review, this project did not involve care home residents, family carers or members of the public as research participants. The research team included a public co-applicant (Lynne Wright, who replaced Cynthia Atkin) with extensive experience of the care home sector as carer for her late husband (see Patient and public involvement). The strategic and topic-specific public advisory groups included people from a diverse range of backgrounds (age, ethnicity and place of residence), although those involved in the topic-specific group tended to be older. We also discussed the project with a Leicester-based PPI group with a specific focus on health of older people (see Patient and public involvement).

Direct involvement of care home residents with appropriate capacity and interest would have made the project more inclusive but would have required considerable time and resources. The project was a systematic review, which meant that most of the research team had backgrounds in this field and lacked informal links with the care home sector. This probably acted as a barrier to including funding for this type of work in the research proposal.

The academic members of the research team were all highly experienced in their respective fields, reflecting the knowledge and experience required to gain funding and deliver the research. The overall team was balanced in terms of gender. The project was a development opportunity for the principal investigator (a late entrant to academic research) who undertook this role on a separately commissioned project for the first time.

Reflections on equity, diversity and inclusion arising from the review findings are presented below (see Chapter 5).

Review questions

The overall research questions were:

-

What interventions are used in the UK health and social care system to minimise unplanned hospital admissions of care home residents?

-

What candidate interventions used in other applicable settings could potentially be used in the UK?

-

What can we learn from research studies and ‘real-world’ evaluations about the effects of such interventions on admissions?

-

What is known about the feasibility of implementing such interventions in routine practice and their acceptability to care home residents, their families and staff?

-

What is known about the costs and value for money associated with these interventions?

Identification of evidence

A broad search was conducted to identify published and peer-reviewed literature on interventions to reduce unplanned admissions from care homes in the UK and other high-income countries. Additionally, a search was undertaken to retrieve relevant grey literature.

The search strategy was developed on MEDLINE and then agreed with the research team (see Appendix 1). The search includes thesaurus and free-text terms and relevant synonyms for the population (residents in care homes for older people) and intervention (interventions to reduce unplanned admissions and named interventions) and makes use of proximity operators where appropriate and the different terms for each concept were combined using the Boolean operator OR. Population and intervention search terms were then combined using the Boolean operator AND. Outcome terms were not included in the search as information on outcomes is not always included in title or abstracts, so including these terms could mean that relevant studies would potentially not be retrieved. The search was limited to research published in English from 2014 to December 2021 to reflect developments since the previous review. Methodological search filters were not applied to keep the search broad and to ensure that all relevant study types were retrieved. However, an attempt was made to remove non-empirical research using the Boolean operator NOT for letters, editorials, news, historical articles, comments and case reports. Additionally, to ensure that studies retrieved were on humans not animals, the Boolean operator NOT was used to remove terms likely to be in studies on animals not humans. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence filter for Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries was used to aid retrieval of studies from UK and other high-income countries. 9

Once the MEDLINE search had been agreed it was translated to the other major medical and health-related bibliographic databases in December 2021.

The following databases were searched:

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

-

EMBASE

-

PsycINFO® (American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

-

Science and Social Sciences Citation Indexes

-

Health Management Information Consortium

-

Social Care Online

-

Social Service Abstracts.

Following the main search, an extra focused search was conducted to identify studies investigating interventions to reduce falls in care homes in January 2022. The search used the MeSH term Accidental Falls/pc (Prevention and Control) and free-text terms, and was then combined with the main search population terms; the MEDLINE search is provided in Appendix 1.

Targeted grey literature searches were carried out to identify reports, guidelines and policy in January 2022. The websites of the following organisations were searched:

-

Department of Health and Social Care (https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-of-health-and-social-care)

-

Health Foundation (www.health.org.uk)

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (www.nice.org.uk)

-

Nuffield Trust (www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk)

-

The database OpenGrey (https://easy.dans.knaw.nl/ui/advancedsearch) was searched, although it is now an archive and no new items are being added.

Citation searching of the 49 initially included studies, from the screen of the main and extra falls searches, was undertaken on Web of Science on 9 March 2022.

Reference checking of included studies and relevant existing reviews was completed. Search results were downloaded to a bibliographic management database (EndNote X9, Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and deduplicated. Records were exported to EPPI-Reviewer (EPPI Centre, University College London, London, UK) systematic review software for coding and analysis.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Population and participants

The population of interest is residents of care homes for older people, including both those with and without nursing. Studies in which the main participants belong to other groups (e.g. families and social networks of residents; care home staff, other health and social care professionals providing services for care home residents, and health and social care policy makers/service commissioners) were included if they met the other criteria with a focus on reducing residents’ unplanned hospital admissions. We also included residents in assisted living or extra-care housing (with a wide range of services available on-site).

Studies involving residential care for children/young people and vulnerable working age adults (e.g. people with learning disabilities) were excluded, as were studies of older adults living in the community, including sheltered housing and those receiving care at home. Studies of mixed samples with a separate subgroup analysis of care home residents were eligible for inclusion.

Interventions

Interventions delivered in care homes or hospitals to reduce unplanned admissions were included. The taxonomy used to classify interventions is presented in Table 1. The final version was modified from the provisional version presented in the protocol based on discussion among the review team during the study selection process.

| Type of intervention | Setting | Definition | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| QI programme | Care home | Complex intervention centred on improving staff skills and processes of care | |

| Integrated working | Care home | Complex intervention centred on improving links between external health care providers and care homes | |

| Training and workforce development | Care home | General training courses; vocational/educational qualifications | Simpler than QI programmes |

| Dealing with specific problems | Care home | Management of common causes of unplanned admissions (e.g. delirium, inappropriate prescribing, hydration and nutrition) | Includes specific training courses |

| Paramedic assessment/non-conveyance | Pre-hospital | Paramedic assessment and possible treatment at the scene | Includes qualitative studies of decision-making |

| ED interventions | ED | Specialist treatment during and shortly after admission | |

| ACP | Care home | Interventions to encourage ACP by residents and/or family carers | |

| Palliative/end-of-life care | Care home | Access to specialist palliative care services | |

| Other | Any | Relevant interventions not included elsewhere (e.g. protective flooring) |

Comparator/control

Optimally, included studies compared an intervention with an alternative (such as continuing current practice) using an experimental (e.g. a cluster randomised trial comparing two groups of care homes)10 or quasi-experimental design such as interrupted time series. We also included before/after studies with or without a control setting and noncomparative qualitative or mixed-methods studies.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were measures of impact on unplanned admissions among care home residents (e.g. absolute numbers or statistical effect measures from comparative studies), perceived feasibility of implementing the intervention in UK settings (barriers/facilitators), and acceptability to care home residents, their families and staff involved in delivering the intervention. Secondary outcomes included other measures of admissions, costs/resource use and any measure of ‘cost-effectiveness’ (value for money). Patient-reported outcome measures (i.e. those reported directly by the patient or carer without interpretation by clinicians or others) were included where available.

Study types

We included studies of any design providing data on the outcomes of interest. This includes:

-

quantitative research studies of any design

-

qualitative research involving interviews, focus groups, etc.

-

mixed-methods studies

-

service evaluations from the UK only

-

UK-relevant guidelines, policy documents and grey literature.

We also included systematic literature reviews but in view of the volume of primary literature retrieved these were used for reference checking only.

Settings

The setting of interest is the UK social care and health system. Studies from other high-income countries (as defined by the World Bank) were included but synthesised separately and assessed for relevance to the UK context using the Framework for Intervention Transferability Applicability Reporting (FITAR) tool. 11

Additional exclusion criteria

Editorials, commentaries, opinion surveys, news and discussion articles, books, book chapters, theses and conference abstracts were excluded, as well as articles in languages other than English.

Study selection

Selection of studies for the review was carried out in stages. In view of the large number of records retrieved, keyword searching of EPPI-Reviewer for relevant terms in titles and abstracts was used as a preliminary filter. Search terms included ‘care home(s)’, ‘nursing home(s) (NHs)’, ‘assisted living’, ‘extra-care’, ‘ambulance’, ‘paramedic’, ‘skilled nursing facility’ and ‘residential aged care facility (RACF)’. Records that contained relevant terms but were obviously not relevant based on their title were excluded by a single reviewer. Titles and abstracts of remaining records were screened by two reviewers independently using the inclusion criteria above. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and, if necessary, by reference to a third reviewer. Full-text items that appeared potentially to meet the inclusion criteria were obtained and evaluated by two reviewers independently, with disagreements resolved as above. Records of the process were maintained in EPPI-Reviewer.

Data extraction and quality (risk of bias) assessment

Data were extracted from included studies in EPPI-Reviewer Web (EPPI Centre, University College London, UK) using a customised set of codes covering the study characteristics, key findings/conclusions and strengths/limitations. Effect measures were extracted as reported by study authors. Data on intervention components and delivery were extracted using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDiER-Lite) checklist. We used the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework to support extraction of relevant data on implementation of interventions from included UK studies and the FITAR tool to assess applicability of international evidence to the UK context. PARIHS incorporates domains covering evidence, context and facilitation. 12 FITAR covers elements of the intervention/initiative, features of workforce, features of services, systems leadership, financial and commissioning processes and patients/populations. 11

We assessed risk of bias for studies using recognised research designs using the following tools:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute checklists for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi-experimental studies. 13

-

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute checklist for cohort and cross-sectional studies. 14

-

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool for mixed methods and qualitative studies. 15

Assessments were performed by two reviewers independently, with discrepancies resolved by consensus or referral to a third reviewer.

In addition to risk of bias assessment, we extracted data on the strengths and limitations of each included study. Strengths and limitations were those reported by study authors and/or identified by members of the review team. Evidence sources with major limitations, namely absence of a control group and/or a small sample size (judged qualitatively) were described as low quality to reflect the need to treat such studies with caution as evidence of intervention effectiveness. This does not mean that the research was poorly conducted or not of value in its own setting.

Synthesis of evidence

The synthesis of evidence adopted a narrative synthesis approach as specified in the review protocol. Narrative synthesis has been described as ‘an approach to the systematic review and synthesis of findings from multiple studies that relies primarily on the use of words and text to summarise and explain the findings of the synthesis’. 16 Narrative synthesis typically involves four stages: developing a theoretical model of how the intervention(s) of interest might work; developing a preliminary synthesis; exploring relationships in the data; and assessing robustness of the synthesis (strength of evidence). 16

Interventions to reduce unplanned hospital admissions of care home residents are diverse and involve different health and care professionals intervening at different stages of residents’ care pathways. Our taxonomy of interventions (see Table 1) identified these and formed the theoretical model for the narrative synthesis.

We grouped studies by type of intervention and setting (UK or international) and the preliminary synthesis was performed within these groups. We summarised study characteristics, findings and study quality (risk of bias assessment where applicable plus strengths and limitations) for each group, together with any general issues about implementation or applicability to the UK setting using the PARIHS and FITAR tools, respectively. For studies that reported sufficient detail, we extracted information on intervention characteristics and delivery using the TIDiER-Lite checklist. Studies were assigned to one intervention group, but the synthesis took account of links between intervention types; for example, ACP can be a stand-alone intervention, part of a quality improvement (QI) programme or linked to an approaching need for palliative/end-of-life care. We used the totality of extracted data for each type of intervention to seek to identify factors that might make the interventions more or less effective and/or influence their implementation in routine practice (described as ‘exploring relationships in the data’ by Popay et al. ). 16

We classified the overall strength of evidence for intervention effectiveness as ‘stronger’, ‘weaker’, ‘very limited’ or ‘inconsistent’ based on the following criteria:17

-

‘stronger evidence’ represents generally consistent findings in multiple studies with a comparator group design

-

‘weaker evidence’ represents generally consistent findings in one study with a comparator group design and several noncomparator studies or multiple noncomparator studies

-

‘very limited evidence’ represents an outcome reported by a single study

-

‘inconsistent evidence’ represents an outcome for which less than 75% of the studies agree on the direction of effect.

Evidence on effectiveness was considered alongside that on feasibility, acceptability and ‘cost-effectiveness’ to assist decision-makers in forming an overall assessment of the value of the intervention. We specifically aimed to identify which interventions are best supported by UK evidence and which interventions in use elsewhere may be suitable for adaptation and evaluation in the UK context. All studies included in the review were included in the analysis of the overall strength of evidence, with no exclusions based on study design or risk of bias.

Evidence summary tables are presented in the main text. Detailed tables on intervention characteristics, implementation and applicability are presented in (see Appendices 2 and 3, Tables 33–41). Risk of bias tables for different study designs are presented in Appendix 4, Tables 42–45.

Variations from protocol

As noted above, keyword searches were undertaken to prioritise records for screening in EPPI-Reviewer because of the large number of records retrieved by the search. A random 10% sample of remaining records was checked and no further references were selected for abstract or full-text screening. One relevant reference that would have been overlooked was subsequently discovered by chance as part of a separate EPPI-Reviewer search.

Chapter 3 Results

Results of literature search

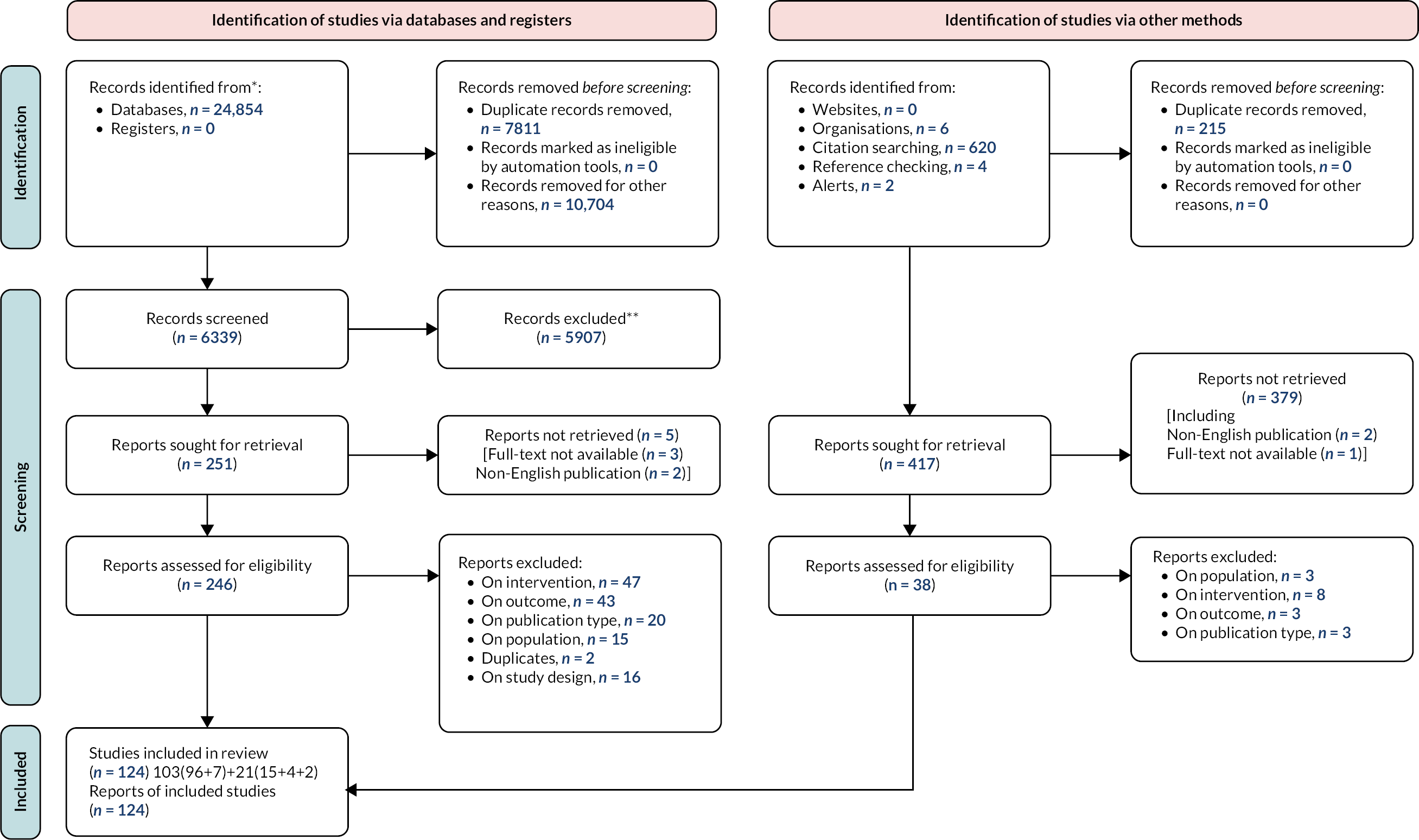

The database searches retrieved 24,656 references which were imported into Endnote X9. After the removal of 7691 duplicates there were 16,965 unique references. The unique references were then imported in EPPI-Reviewer systematic reviews software and a check for duplicates found a further 120 duplicates leaving 16,845 unique references. The large number of references would have taken up too much time and resources to screen; thus keyword searches were undertaken on EPPI-Reviewer to prioritise references for screening (see Variations from protocol). Single-reviewer title screening was then undertaken on 6141 references and 576 were then screened on abstract by two reviewers with 234 included for full-text screening. A total of 96 references were included in the full review from the original database search.

The extra focused database search for falls prevention retrieved 198 references after duplicates within the falls and from the original search were removed. All 198 references were screened on title and 22 were included for abstract screening; 17 references were included for full-text screening and 7 were included in the review.

Citation searches retrieved 620 references. After deduplication within the citation search results and the Endnote library, 406 references were imported into Endnote for screening. Title screening included 84 of these references for abstract screening and 32 were included for full-text screening with 15 included in the final review.

Reference checking of included studies found four further studies for inclusion in the review. A further two included studies were found from alerts. Search of websites of relevant organisations retrieved six potential additional publications, none of which were included.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram18 (see Figure 1) illustrates the study selection process. In summary, 124 publications were included in the review. Given that some interventions/programmes were represented by multiple publications, and that we included qualitative and implementation research as well as trials and service evaluations, the term ‘study’ is used to refer to any type of publication (primarily peer-reviewed journal articles) or report (primarily grey literature).

Summary of included studies

Of the 124 studies from which we extracted data, 30 were from the UK, 44 from the USA, 24 from Australia, 4 from New Zealand, 20 from other countries and 2 from multiple countries (see Table 2). The most common types of intervention were integrated working (particularly in the UK and Australia) and QI programmes (particularly in the USA).

| UK (n) | Australia (n) | USA (n) | New Zealand (n) | Other (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QI programme | 3 | 1 | 19 | 4 | 1 |

| Integrated working | 13 | 15 | 4 | 0 | 5 |

| Training/workforce development | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Management of specific problems | 4 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 4 |

| Paramedic assessment/non-conveyance | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| ED interventions | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Advance care planning | 4 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 5 |

| Palliative/end-of-life care | 4 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 3 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

In terms of study design, the largest single group was cluster RCTs (17 studies), followed by uncontrolled before–after (15), controlled before–after (13), non-RCTs (11), qualitative studies (11) and mixed-methods studies (10). Four studies used a step-wedge design, involving randomisation to introduce the intervention at different times during the study. Thirty-two studies used other designs, including cohorts and secondary data analyses. The studies reported a wide range of quantitative and qualitative outcomes but no patient-reported outcome measures were recorded.

Quality improvement programmes

UK evidence

We included three studies of interventions in UK settings that were classified as QI programmes. 19–21 The key feature of QI programmes is an emphasis on developing skills and expertise within the care home. Studies in which the intervention included elements of QI but the main emphasis was on integrating health and social care using expertise from outside the care home are discussed under Integrated working.

Two of the studies were regionally based and involved around 30 care homes each,19,20 while the third was smaller, with just three care homes involved. 21 Care homes in the study by Damery et al. 19 were predominantly care homes with nursing, while the study by Giebel et al. 20 included a mixture of care homes with and without nursing. All three studies used a before–after type of design with no separate control group. Formal risk of bias assessments were not performed because all the studies were potentially at high risk of bias. Study characteristics are summarised in Table 3; Appendix 2, Table 33 gives more details of the interventions. Two studies reported a significant improvement in at least one outcome following implementation of the QI intervention, while one reported a small increase in admissions. 1 These mixed results, together with the weak design of the included studies, suggest that evidence for the effectiveness of QI programmes in the UK is both weak and inconsistent.

| Study ID | Study type | Type of care home | Sample size | Comparator | Outcomes | Intervention effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Damery et al.19 | Mixed methods | Nursing home: 28/29 provided nursing care | Care homes: 29 care homes from two localities in the West Midlands. Individuals: over 1000 care home staff received QI training | Standard care (before/after) | All admissions; transport to ED; feasibility of intervention | No effect: non-significant increase in admissions (p = 0.052); no effect on ED attendance |

| Giebel et al.20 | Interrupted time series | Nursing home: 15; residential home: 17 | Care homes: 32 care homes with 1314 beds. Individuals: unclear (no individual patient data were collected) | Standard care (before/after): 1 year pre and 4 years post implementation | Unplanned/preventable admissions: conveyance to hospital appears to be considered as a ‘potentially avoidable admission’; transport to ED; other (specify); emergency calls | Significant positive effect: 19% reduction in conveyance to hospital |

| Steel et al.21 | Uncontrolled before–after | Residential home | Care homes: 3 residential homes. Individuals: 34 care home residents | Standard care (before/after) | All admissions; costs/cost-effectiveness; other (specify); advance care planning; polypharmacy | Significant positive effect: 75% reduction in admissions at one care home |

Implementation

The two larger studies reported in some detail on implementation of the programmes while information was more limited for the smaller study by Steel et al. 21 (see Appendix 2, Table 34). Barriers to implementation centred around high staff turnover and resistance from some care home managers. Factors that acted as facilitators included active facilitation by programme staff, an emphasis on opportunities for career progression in one study20 and a policy environment in which reducing unplanned admissions is a high priority.

International evidence

The international evidence on QI programmes comes mainly from the USA (18 studies), with additional evidence from New Zealand (4 studies), Australia and Switzerland (1 study each).

The 18 US studies mainly reported on three QI programmes: Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT); Missouri Quality Initiative (MOQI); and Optimising Patient Transfers, Impacting Medical Quality and Improving Symptoms: Transforming Institutional Care (OPTIMISTIC). Two studies summarised the results of an initiative launched by the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in 2012. 26,36 This initiative covered QI programmes in seven US states, including MOQI and OPTIMISTIC (Indiana).

The 18 included studies are listed in Tables 4 and 5, which summarise the key reports (those providing original data on intervention effectiveness). Table 6 summarises details of the INTERACT, OPTIMISTIC and MOQI interventions as extracted from the key study reports.

| Reference | Programme name | Effect? | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blackburn et al. 22 | OPTIMISTIC | Yes | Before/after; highlights variation across facilities |

| Ersek et al.23 | OPTIMISTIC | Qualitative study | |

| Galambos et al.24 | MOQI | Stakeholder surveys | |

| Huckfeldt et al.25 | INTERACT | Yes | Varies by degree of implementation |

| Ingber et al. 26 | Summary of 7 initiatives | Yes | Relative to comparison groups |

| Kane et al. 27 | INTERACT | No | RCT of implementation support |

| Ouslander et al.28 | INTERACT | Secondary data analysis | |

| Ouslander et al.29 | INTERACT | Secondary data analysis | |

| Popejoy et al.30 | MOQI | Evaluates use of INTERACT tools | |

| Rantz et al.31 | MOQI | Yes? | Single-facility before–after |

| Rantz et al. 32 | MOQI | Yes | Before–after; main results paper |

| Rantz et al.33 | MOQI | Implementation, role of advanced practice registered nurse | |

| Rantz et al.34 | MOQI | Estimated cost savings | |

| Tappen et al.35 | INTERACT | No negative effect on safety | |

| Vadnais et al. 36 | Summary of 7 initiatives | Yes | Follow-up to Ingber et al.25 |

| Vogelsmeier et al.37 | MOQI | Analysis of avoidable transfers | |

| Vogelsmeier et al.38 | MOQI | Implementation: role of support team | |

| Vogelsmeier et al.39 | MOQI | Yes | 6-year follow-up before/after |

| Study ID | Study type | Type of care home | Sample size | Comparator | Outcomes | Intervention effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blackburn et al.22 | Uncontrolled before/after | Nursing home | Care homes: 19 facilities in Indiana enrolled in OPTIMISTIC programme October 2012 | Standard care (before/after) | All admissions: Kaplan–Meier curves estimating the probability of a resident being hospitalisation-free from time of eligibility were calculated overall and separately for each facility | Significant positive effect: probability of having no hospitalisations within 1 year, increasing from 0.51 to 0.57, which was statistically significant (p < 0.001) |

| Ingber et al.26 | Controlled before–after, mixed methods | Nursing home | Care homes: 7 ECCP organisations, 143 ECCP facilities, 262 comparison facilities. Individuals: 61,636 facility residents, 22,442 from 143 ECCP facilities, 38,194 from 262 comparison facilities | Standard care (before–after) | Unplanned/preventable admissions: all admissions; feasibility of intervention; processes, successes, challenges, lessons learned, and unintended consequences; acceptability to residents/families; costs/cost-effectiveness; Medicare expenditure | Significant positive effect |

| Kane et al.27 | Cluster RCT | Nursing home | Care homes: 85 (33 intervention, 52 control). Individuals: 23,478 (9050 intervention, 14,428 control) | Standard care (parallel control group) | Unplanned/preventable admissions: based on Medicare/Medicaid criteria; all admissions; transport to ED; ED visits without admission; other (specify); 30-day readmissions | No effect: effect for avoidable admissions not robust after correction for multiple comparisons |

| Rantz et al.32 | Uncontrolled before–after | Nursing home | Care homes: 16 within 80 miles of a major city in Missouri. Individuals: 5186 enrolled; average 1750 each day |

Standard care (before–after) | Unplanned/preventable admissions; all admissions | Significant positive effect: for all-cause admissions in some quarters |

| Vadnais et al.36 | Controlled before–after: pooled evaluation of 7 separate QI programmes in different US states under the CMS initiative to reduce avoidable hospitalisations among nursing facility residents | Nursing home | Care homes: not reported but target of 15–30 intervention homes per state. Individuals: baseline period intervention 24,978, comparison 41,986. Intervention period: intervention 67,315, comparison 117,383 | Standard care (before–after) | Unplanned/preventable admissions; all admissions | Significant positive effect: reduction in all-cause and potentially preventable hospital transfers compared with controls |

| Study ID | By whom | What | Where | To what intensity | How often |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blackburn et al.22 | Full-time registered nurses working with care home staff | Working together to assess changes in resident condition and implement QI measures. Additionally, OPTIMISTIC nurse practitioners provide in-person evaluations, and management of residents with acute condition changes. Evidence-based processes implemented under OPTIMISTIC include coordination of care through collaborative care reviews, advance care-planning facilitation, and the use of tools from INTERACT | Nursing home | Nurses employed full time | Not applicable |

| Kane et al.27 | INTERACT study team; INTERACT champion and co-champion in each NH | Training and support (primarily telephone/online) for implementing INTERACT, including tools to help nursing home staff identify and evaluate acute changes in nursing home resident condition and document communication between physicians; care paths to avoid hospitalisation when safe and feasible; and ACP and QI tools | Participating nursing homes | 1-year intervention period (March 2013 to February 2014) | Not reported |

| Rantz et al.32 | APRN (nurse practitioner or clinical nurse specialist) at each nursing home; project medical director; other MOQI team members, including QI coach, care transitions coach (coordinating ACP and end-of-life care) and health information technology coordinator; other stakeholders, including social services, primary care and nursing staff (see also Vogelsmeier et al.)38 | Early recognition, assessment and management of residents’ condition (APRNs); education of APRNs, advice to MOQI team, liaison with participating physicians (medical director); use of INTERACT tools, including root cause analysis for all hospital transfers; regular feedback to nursing home leadership; proactive discussions about end-of-life care and ACP | Participating nursing homes and other treatment settings | Full-time APRN in each nursing home supported by MOQI team | Not reported |

Initial evaluations of OPTIMISTIC22 and MOQI32 used a before–after design with no control group, placing them at high risk of bias. Subsequently, Ingber et al. 26 and Vadnais et al. 36 strengthened the evidence base by using administrative data to create comparison groups (matched by propensity scoring) for both intervention groups, together with five other initiatives funded by the CMS (see Table 5). INTERACT was the only programme to undergo a randomised trial, as well as a number of secondary data analyses (see Table 4). The trial was subject to unclear risk of bias as key details including method of randomisation were not reported in the paper. 27

The main component of INTERACT is a series of tools for care home staff to recognise acute changes in residents’ condition, document communication with physicians and use care pathways to avoid hospital admission when safe to do so. The trial performed by Kane et al. 27 compared implementation support for INTERACT with standard care in nursing homes that could be using INTERACT tools without support. By contrast, OPTIMISTIC and MOQI both involved study nurses working in nursing homes to improve staff skills and promote best practice. The MOQI programme also involved use of some of the QI tools developed by INTERACT (see Table 6).

In terms of effectiveness, the trial of implementation support for INTERACT27 reported a reduction in avoidable admissions that was not robust after correction for multiple comparisons. Subsequent analyses revealed that nursing homes in the intervention or control group reporting high usage of INTERACT achieved reductions in potentially avoidable admissions of 0.221 per 1000 resident‐days, representing an 18.9% relative reduction. 25 The MOQI and OPTIMISTIC studies reported reductions in unplanned admissions, but both were at high risk of bias, as noted above.

The initial analysis of the seven CMS-funded initiatives with a controlled before–after design reported mixed results for reductions in potentially avoidable admissions. 26 Three of the seven programmes reported statistically significant reductions against matched controls in 2014 and four did so in 2015. Only two programmes (MOQI and OPTIMISTIC) reported significant reductions in both years. These findings suggest the existence of ‘publication bias’ in the reporting of this initiative, with only the more successful programmes publishing their results in full. In a subsequent analysis, Vadnais et al. combined data from 2014–16 for all intervention and control groups to produce a single effect estimate. 36 The combined analysis reported an annual decrease in potentially avoidable admissions of 2.01 percentage points [95% confidence interval (CI) 2.86 to 1.15], representing an 18% relative reduction. Reductions in potentially avoidable acute care transfers and ED visits were also reported.

In summary, the studies of QI programmes implemented in US nursing homes broadly meet the criteria for ‘stronger’ evidence but the findings should be interpreted with caution because of possible confounding factors in uncontrolled studies and unclear risk of bias. The inclusion of MOQI and OPTIMISTIC as separate publications and as part of the combined analysis should also be taken into account.

Other studies

Three studies (four publications) described QI programmes evaluated in New Zealand care homes (see Table 7). The studies were performed by the same group of authors, were relatively large and performed in a diverse range of settings. Two studies were cluster RCTs and one was a repeated measures before/after study. The study by Boyd et al. 40 was at unclear risk of bias because of limited reporting and lack of blinding. The Aged Residential Care Healthcare Utilisation Study (ARCHUS) trial41 was better reported and appeared to be at lower risk of bias, although as usual with this type of intervention, only limited blinding was possible. The third study was at high risk of bias because there was no control group. 42

| Study ID | Study type | Type of care home | Sample size | Comparator | Outcomes | Intervention effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boyd et al.40 | Cluster RCT | Nursing home, residential home | Care homes: intervention facilities 29, comparison facilities 25. Individuals: intervention facilities 1425 residents, comparison facilities 1128 residents. | Standard care (parallel control group) | Unplanned/preventable admissions. Medical admissions considered as potentially preventable. All admissions. All resident hospitalisations | No effect. Acute hospitalisation rates increased for both groups, although less for intervention group |

| Connolly et al.41 | Cluster RCT | Nursing home; mixture of ‘private hospital care’ for those requiring assistance with activities of daily living and 24-hour nurse availability; dementia care (secure rest homes); and psychogeriatric care (for those with dementia and additional needs). Residential home: ‘rest homes’ not providing 24-hour nursing care | Care homes: 36 (18 in each group). Individuals: 1998 (1123 intervention; 875 control) | Standard care (parallel control group) | Unplanned/preventable admissions (defined as ambulatory-sensitive hospitalisations; i.e. admission for specific conditions); all admissions (all acute admissions); length of hospital stay; other (specify); mortality | No effect. No difference in avoidable admissions (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.36) or mortality |

| Connolly et al.42 | Uncontrolled before–after | Nursing home; residential home; similar to Connolly 201541 | Care homes: 21 facilities with higher than expected ED presentation/admission rates. Individuals: 1296 beds | None: repeated measures before–after | Unplanned/preventable admissions; emergency admissions for specific conditions; paper appears to use presentation and admission interchangeably (authors note ED presentation more directly under control of care home staff); transport to ED | Significant positive effect: 25% reduction in ED admissions after intervention |

The interventions used in the three studies are summarised in Table 8. The first study involved a relatively simple intervention with gerontology nurse specialists providing on-site support to care home staff. 40 The ARCHUS study added a wider multidisciplinary team (MDT)41 and this intervention was also evaluated in the third study with some minor changes. 42

| Study ID | By whom | What | Where | To what intensity | How often |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boyd et al.40 | GNS working with care home staff and primary and secondary health care services | Clinical support; education and clinical coaching; and care coordination for high-risk residents | Care home | The GNS was on site at each facility for a mean of 1.9 hours per month. GNSs provided care coordination and comprehensive geriatric assessments for residents of concern as needed (mean 2.6 assessments per facility in 12 months). The GNS also provided care coordination for residents transitioning across healthcare settings, although much of this work was not well captured in GNS records | On-site visits every other month and delivery of standardized gerontology education sessions for nurses and care assistants (mean 5.5 sessions per facility in 12 months). Ad hoc on-site clinical coaching to discuss residents of concern (mean 2.3 sessions per facility in 12 months) occurred at the request of facility staff |

| Connolly et al.41 | GNS and study MDT | Facility baseline assessment and care plan; monitoring and benchmarking of indicators linked to care quality; MDT meetings to review individual residents’ needs; gerontology education and clinical coaching for care home nurses | Care home/facility | GNS support/education began with weekly visits and gradually reduced in intensity over the 9-month intervention period | Benchmarking: 3 times during the intervention period; MDT meetings monthly for the first 3 months at each site |

| Connolly et al.42 | GNSs and study MDT | Facility baseline assessment; clinical coaching for nurses and care givers; MDT meetings, including medication review | Care home/facility | Increased clinical coaching time at each facility (relative to ARCHUS) | Three 1-hour MDT meetings at each facility |

Neither of the randomised trials found that the intervention reduced potentially preventable admissions compared with standard care. A subsequent ‘post hoc’ analysis of the ARCHUS data reported a reduction in admissions for a group of five conditions (cardiac failure, ischaemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke and pneumonia) responsible for many admissions among care home residents43 but as an unplanned analysis this should be treated with caution. Connolly et al. 42 reported a reduction in admissions post intervention but causality is uncertain in the absence of a control group. This suggests that the evidence for QI programmes involving gerontology nurse specialists with or without MDT support in New Zealand is at best inconsistent.

Turning to single studies in other countries, the Early Detection of Deterioration in Elderly residents (EDDIE) programme was evaluated in a before/after study in Queensland, Australia. 44 The intervention involved advanced clinical skills training, decision support and access to additional diagnostic equipment, plus targeted collaboration with a wide range of external stakeholders. Implementation was supported by an on-site clinical lead and ‘clinical champions’. The EDDIE programme was associated with a 19% reduction in annual hospital admissions and a 31% reduction in the average length of stay from baseline, comparable to effects reported in other studies but with a relatively high risk of bias. One additional study evaluated a QI programme in Switzerland using a stepped-wedge design. 45 The intervention, designated INTERCARE, was similar to the US programmes described above, with a nurse appointed to each participating care home as a link between care home staff and physicians. INTERCARE also used tools from the INTERACT programme. As this was a non-randomised study, the risk of bias was higher than for similar stepped-wedge studies with randomisation. The study reported a significant reduction in unplanned hospital transfers compared with the pre-implementation period, thus strengthening the international evidence base for QI programmes of the INTERACT type.

Applicability

Three of the US studies of QI programmes (four publications) provided data relevant to assessing applicability to UK settings: a summary of the 2012 CMS initiative,26 one of its component studies (MOQI32,33) and the trial of implementation support for INTERACT. 27

The major differences between the US and UK health systems (insurance-funded vs. publicly funded) are less acute for care home research because many US care home residents are covered by the publicly funded Medicare (for older people) and/or Medicaid (for people on low incomes) programmes. Both the CMS initiative and the INTERACT trial stated that included participants were Medicare/Medicaid recipients, although MOQI included some privately paying residents in state-licensed beds.

A further difference from the UK is that many US care homes include a mixture of long-term residents and those admitted for short-term rehabilitation following hospital treatment – although this difference is becoming less marked over time with the widespread commission of short-term ‘discharge to assess’ beds in the care home sector. The CMS initiative included only long-stay residents, increasing applicability to the UK, but this was unclear for the INTERACT study.

Other relevant factors captured by the FITAR framework for assessing intervention transferability/applicability were:

-

Population (residents seemed to be comparable to UK populations in terms of age and sex or gender and representative of the general US population)

-

Organisation/finance (Medicare financial penalties for readmissions; not currently relevant to UK setting)

-

Leadership:

-

supportive and stable nursing home leadership was associated with success in reducing admissions

-

a high level of facilitation in the INTERACT study (which was a trial of implementation support)27 and MOQI (intervention support team)

-

-

Services/workforce/initiative:

-

care homes participating in MOQI had high standards of care and high admission rates (comparable to some UK care homes)

-

INTERACT largely provided support to existing workforce

-

MOQI was heavily dependent on advanced practice registered nurses and other specialist nurses working full-time in care homes (difficult to apply in UK with current workforce shortages)

-

legal restrictions affected services provided by advanced practice nurses in some states26

-

NH staff turnover limited buy-in to QI initiatives26

-

the CMS initiative lasted four years but researchers reported that attitudes and practices were only beginning to shift at the end of the study period.

-

Applicability data were extracted from three publications from New Zealand. 40–42 The setting was urban (Auckland) and participating care homes had a higher than expected level of potentially preventable admissions. Most participating facilities were equivalent to residential care homes, although the ARCHUS study also included some ‘private hospitals’ providing higher levels of long-term care. 41 The health and care system appeared to be more closely integrated than in the UK, with a district health board responsible for supporting and certifying care homes and also providing acute hospital services. Few details of leadership and facilitation were provided, although the ARCHUS study achieved good ‘buy-in’ from participating facilities. 41

Workforce is a key factor in evaluating the applicability of this New Zealand research to the UK. The interventions were led by gerontology nurse specialists with at least 10 years of gerontology experience who were employed by the district health board. 40 The ARCHUS study authors noted that nurse practitioners, most of whom can prescribe medications, might be able to provide a faster response for some conditions, but the study was unable to employ nurse practitioners. Boyd et al. 40 pointed out that employment of nurse practitioners in the care sector in New Zealand was low. Nurse practitioners are not currently employed in UK care homes, but they are increasingly employed by NHS providers, mainly as advanced clinical practitioners, to support care homes as part of the Enhanced Health in Care Homes (EHCH) model. However, Boyd et al. 40 noted that their intervention was relatively low in intensity compared with other interventions involving nurse specialists.

The one QI programme study from Australia44 shared some features with the English EHCH model and other initiatives, being initially developed by care home nursing staff with input from community healthcare providers. The presence of active implementation support in this study should be taken into account in assessing its applicability to the UK. Finally, the Swiss INTERCARE study45 involved an urban care home population with a median age and sex or gender distribution similar to the UK. Participating care homes were highly motivated and committed to implementing the complex study intervention, based on the use of registered nurses in extended roles.

Integrated working

UK evidence

We used ‘integrated working’ to cover interventions in which the central feature was enhanced health service support for care homes, albeit often as part of a complex intervention with several elements, for example staff training and patient advocacy. We included 13 UK studies in this group, most of which were part of the Care Home Vanguard Initiatives, which developed the model of care now delivered nationally through EHCH. 2,46–53 Data from these studies were analysed by the Health Foundation, Nuffield Trust and other independent organisations. The remaining publications described or evaluated local initiatives and were mainly published as grey literature. 54–56

Five of the Care Home Vanguard studies (six publications) reported on initiatives in specific English cities or districts (Nottingham, Sutton, Rushcliffe, outer East London and Wakefield) with support from local commissioners and health and social care organisations. Details of the interventions varied (see Appendix 2, Table 35) and all had multiple elements but strengthening links between care homes and local general practices was a key feature. One intervention differed from the others by including availability of support from a geriatrician. 51

Characteristics of these studies are summarised in Table 9. The studies used linked care home and hospital data to compare outcomes of residents in participating care homes with those of a matched control group in homes with similar characteristics but not receiving enhanced support. This means that the comparison was not randomised and limited data on resident characteristics were available. A further study used administrative data to estimate the effect of new integrated care models (including the Care Home Vanguards) on hospital admissions at the national level. 50

| Study ID | Study type | Type of care home | Sample size | Comparator | Outcomes | Intervention effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brine et al.46 | Controlled before–after | Nursing home, residential home | Care homes: 15 nursing and 23 residential care homes. Individuals: 782 residents | Standard care (before–after) | Unplanned/preventable admissions; all admissions; transport to ED; length of hospital stay; other (specify); proportion of deaths that took place outside hospital (as a proxy for dying in preferred place of death) | Significant positive effect: emergency admissions were 18% lower for the intervention group and potentially avoidable emergency admissions 27% lower. Differences were only significant for residential homes. There was no difference between groups in ED attendance |

| Conti et al.47 | Controlled before–after | Nursing home, residential home | Care homes: intervention group – 17 nursing homes and 11 residential care homes; matched control group – 97 care homes. Individuals: intervention group – 297 residents; matched control group – 243 individuals, 296 records |

Standard care (before–after) | Unplanned/preventable admissions: subset of ‘potentially avoidable’ emergency admissions, based on a list of conditions considered to be manageable in community settings or preventable through good quality care; emergency admissions; transport to ED; ED attendances; length of hospital stay; hospital bed days; other (specify); outpatient appointments; admissions with urinary tract infection as principal diagnosis; proportion of death occurring outside hospitals (taken indicator of successful end-of-life planning) | No effect |

| Lloyd et al.49 | Controlled before–after | Unclear or not available ‘care homes’ | Care homes: 23 Principia care homes; comparison group was from 64 care homes. Individuals: 588 residents from Principia care homes, 588 residents in comparison group |

Standard care (before–after) | Unplanned/preventable admissions; emergency admissions; all admissions; transport to ED; length of hospital stay; other (specify); outpatient attendances; death | No effect: significant reduction in emergency admissions only |

| Lloyd et al.48 | Controlled before–after | Nursing home, residential home | Care homes: nursing homes 10 intervention, 27 control; residential homes 13 intervention, 47 control. Individuals: 68 in each group |

Standard care (before–after) | Unplanned/preventable admissions; potentially preventable emergency admissions; all admissions; emergency admissions; transport to ED; length of hospital stay; other (specify); proportion of deaths outside hospital | Significant positive effect: residential care homes only |

| Morciano et al.50 | Controlled before–after | Nursing home, residential home | Care homes: not reported (care homes participating in 6 care home Vanguards were included). Individuals: not reported (residents in care homes participating in 6 care home Vanguard pilot projects were included) | Standard care (parallel control group); compares data from care home Vanguard sites with non-Vanguard sites; appears to be total hospital admissions and bed days | All admissions; emergency admissions; length of hospital stay; hospital bed days | Significant positive effect: significant reduction in rate of emergency admissions for care home Vanguard vs. non-Vanguard areas |

| Sherlaw-Johnson et al.51 | Mixed methods | Nursing home | Care homes: 4 [intervention (Health 1000) group]; 19 (comparator group). Individuals: 431 (intervention group); 1495 (comparator group) | Standard care (before–after) | All admissions; emergency admissions; transport to ED; length of hospital stay; acceptability to care home staff; costs/cost-effectiveness | Significant positive effect: 35% marginal reduction in emergency admissions (95% CI 6% to 55%) |

| SQW Ltd 201752 | Mixed methods | Nursing home, residential home | Care homes: all Sutton (CCG and local authority) care homes invited to participate. Individuals: not reported | None | Unplanned/preventable admissions; non-elective admissions; emergency admissions; transport to ED; length of hospital stay; acceptability to residents/families; costs/cost-effectiveness; other (specify); preferred place of death | No effect |

| Vestesson 201953 | Controlled before–after | Nursing home; residential home; assisted living/extra care housing; 2 supported living schemes received some parts of the support given to care homes | Care homes: 15 in intervention (Vanguard) and 30 in matched control group. Individuals: 526 residents in each group | Standard care (parallel control group); matched controls in similar care homes | Unplanned/preventable admissions; emergency admissions for specific conditions; emergency admissions; transport to ED; length of hospital stay; emergency and elective hospital bed days; other (specify); deaths in hospital | Significant positive effect: significant but not conclusive evidence for potentially avoidable admissions |

| Wolters 20192 | Other (specify): summary of learning from Health Foundation evaluations of initiatives in Sutton, Rushcliffe, Nottingham and Wakefield | Nursing home, residential home | Care homes: not reported (see reports on individual initiatives). Individuals: not reported (see reports on individual initiatives) | Standard care (before–after) | Unplanned/preventable admissions; emergency admissions; transport to ED; feasibility of intervention | Significant positive effect: varied across sites/outcomes |

Four of the five local interventions reported a decrease in emergency admissions, potentially preventable emergency admissions or both compared with matched control groups. The exception was the initiative in Sutton, which the authors suggested may have been evaluated too early for any effect to be detected. 5 Relative reductions of between 18% and 39% were reported but CIs suggested a range of effects from less than 5% to over 50%. A subgroup analysis of the Rushcliffe study indicated that the reduction in admissions was present for residential homes but not for nursing homes,48 possibly because the lower baseline level of support in these homes gave more scope for improving outcomes. Overall, this group of studies constitutes ‘stronger’ evidence for the effectiveness of integrated working initiatives but with uncertainty about the size and clinical significance of any effect.

Implementation

Studies with data extracted on implementation are summarised in Table 10. In terms of the PARIHS framework, none of the studies reported evidence as a barrier to implementation. By contrast, numerous barriers associated with the background context in the UK were identified. Some general practitioners (GPs) were opposed to alignment of specific GP practices with care homes,46 and in another study alignment proved difficult for reasons connected to organisational boundaries. 51 In Bradford and Airedale, some GPs preferred direct referral rather than referral via a telehealth hub and some care homes continued to turn to GPs first rather than contacting the telehealth service. 57 Several studies reported barriers arising from within the care home, including resistance from managers and staff,57 difficulties in ensuring that staff had time to attend training,52 low levels of information technology literacy, internal processes that conflicted with study protocols51 and high staff turnover. 57

| Study setting | Evidence as barrier | Context as barrier | Evidence as facilitator | Context as facilitator | Role of facilitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nottingham City46 | Not reported | Inconsistent implementation across area; GP and resident resistance | Not reported | CCG supported initiatives to improve health in care homes from 2007 | Evaluation covered a range of existing services |

| Sutton47,52 | Not reported | Difficulties arranging staff time for training; lack of information technology literacy; e-learning underused; some staff unfamiliar with link nurse role | Intervention components based on evidence of what works elsewhere | Some intervention components already existed in some form; small group of committed senior staff did initial groundwork | Facilitation by steering group and programme staff; funding from NHS England to support spread of Vanguard |

| East and North Hertfordshire57 | Not reported | Lack of baseline data; time and resource demands of information governance | Not reported | Single trade association providing training across area; pre-existing collaboration between local authority and CCG | ‘Complex care champions’ appointed; homes received funding to backfill posts |

| Bradford and Airedale57 | Not reported | Some reluctance to use remote service; care homes continued to contact familiar GPs or community teams | Use of highly trained staff as first point of contact rather than relying on pathways or algorithms | Involvement of all staff, including those not directly using the service; telehealth hub as single first point of contact | Not reported |

| Rushcliffe46,49 | Not reported | Varying standard of ‘usual care’ within and between homes | Residential home residents identified as potentially more likely to benefit from additional support | Area with relatively low levels of admissions and socioeconomic deprivation | Residential home staff received additional training compared with nursing home staff |

| Outer east London51 | Not reported | Nursing homes in ‘geographically difficult’ locations, difficult to align with general practice; homes privately owned, potential conflict between existing practice and intervention procedures | Model of care based on Wagner’s chronic care model | Mutual trust between care homes and GPs; high staff turnover not seen as a problem locally | Initiative driven forward by a group of committed individuals providing ‘strong leadership and clear vision’; support from prime minister’s Challenge Fund |

| Wakefield53 | Not reported | One GP practice per care home model was not implemented | Not reported | Care home Vanguard formed in March 2015 | Not reported |

At the organisational level, implementation of the intervention across the Nottingham city area was inconsistent. 46 The East and North Hertfordshire care home vanguard encountered barriers associated with recruitment and time/resources required to obtain information governance approval. 57 Evaluation was also hampered by a lack of baseline data for comparison.

Implementation of support for integrated working was supported by cited evidence of similar interventions proving effective in other settings51,52 and evidence of variation in use of hospital services between care homes, suggesting potential for improvement. 2

Contextual factors that favoured implementation were generally based on pre-existing services or partnerships (see Table 10). Rushcliffe and outer East London benefited from low baseline levels of socioeconomic deprivation and relatively low levels of staff turnover which reduced care home sector instability, respectively.

Some details of facilitation of implementation were reported from Sutton, Hertfordshire, Rushcliffe and outer east London (see Table 10). Two studies highlighted the role of committed individuals in key positions47,51,52 and these sites also received funding to support implementation of their interventions.

International evidence

The largest body of international evidence on integrated working interventions comes from Australia (15 studies), followed by the USA (4) and other countries (4).

The 15 publications from Australia reported on 10 different interventions. Of these, seven were delivered by hospital-based teams. The studies used a wide range of designs (see Table 11). Sample size for quantitative studies ranged from 1 to 81 care homes. The number of participants involved also varied widely but was less clearly reported, for example as the number of beds rather than the number of individuals recruited or analysed. Many of the studies were at high risk of bias because of weak study designs or small sample sizes. Of the RCTs included, one was small (45 participants)58 and the other used a step wedge rather than a parallel control group design. 59 Details of risk of bias for individual studies can be found in Appendix 4.

| Reference | Intervention | Delivered from | Study design and sample size | Effect measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amadoru et al.64 | Residential in-reach | Hospital | Qualitative; 8 care homes, 40 staff | N/A |

| Chan et al.65 | Acute geriatric outreach | Hospital | Before–after; 12 nursing homes | Rate ratio 10% reductiona |

| Cordato et al.58 | Post-discharge visits (REAP) | Hospital | RCT; 21 care homes, 45 residents | Readmissions, ⅔ reductiona |

| Craswell et al.60 | Nurse practitioner candidate: enhanced primary care | Primary care | NRCT 1 intervention site |

ED admissions 44.6 vs. 59%a |

| Dai et al.62 | Acute geriatric outreach | Hospital | ITS; 12 care homes | Admissions 42.8 to 27.1/montha |

| Dwyer et al.61 | Nurse practitioner: community-based residential acute care service | Community | Qualitative; 10 care homes, 15 interviewees | N/A |

| Fan et al.63 | HiNH | Hospital | CBA; 1 hospital catchment area, > 2000 beds | Admissions rate ratio 0.62a |

| Fan et al.67 | HiNH | Hospital | Economic evaluation of Fan et al.63 | Reduction in net costs to health servicea |

| Haines et al.59 | In-house GPs | Primary care | Step wedge RCT; 15 care homes | Unplanned hospital transfers rate ratio 0.53; admissions 0.52a |

| Hullick et al.68 | ACE; nurse-led telephone triage+ | Hospital (ED) | CBA; 4 intervention, 8 control homes | 40% reduction in ED admissionsa |

| Hullick et al.69 | ACE | Hospital | Stepped wedge; 81 facilities, 9 EDs | ED admissions rate ratio 0.79a |

| Hullick et al.70 | ACE + video-telehealth | Hospital | CBA; 5 intervetion, 8 control homes | No difference in ED visits and admissions |

| Hutchinson et al.71 | Geriatrician-led outreach service (RECIPE) | Hospital | Cohort/ITS; 73 facilities in hospital catchment area | Reduction in admissions from 3.03 to 2.4/resident/quartera |

| Kwa et al.72 | Residential in-reach (linked to Amadoru et al.63) | Hospital | Uncontrolled before–after; 52 care homes | Unplanned ED presentations 2.4 vs. 0.8%a |

| O’Neill et al.65 | Hospital avoidance | Care home collaborating with specialist in-reach team and other specialists | Qualitative; 1 care home, 21 interviewees | N/A |

Table 12 summarises the interventions evaluated in the Australian studies. Interventions delivered by hospital-based teams were described as ‘residential in-reach’, ‘acute geriatric outreach’, ‘regular early assessment post-discharge’ (REAP), ‘hospital in the nursing home’ (HiNH), ‘aged care emergency service’ (ACE; with or without telehealth) and ‘geriatrician-led outreach service’ (Residential Care Intervention Program in the Elderly). Services described as ‘in-reach’ and ‘outreach’ overlapped in terms of intervention content and the distinction between them was unclear. The REAP programme differed from the others by being delivered after discharge with a view to reducing unplanned readmissions.

| Study ID | By whom | What | Where | To what intensity | How often |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|