Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/46/19. The contractual start date was in September 2015. The final report began editorial review in June 2021 and was accepted for publication in December 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Fulop et al. This work was produced by Fulop et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Fulop et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Context and rationale for the research

Major system change in the context of specialist health-care services

Major system change (MSC) is an international issue of growing importance and relevance in health care. A review of the literature defined MSC (or large-system transformation) as a ‘coordinated, system-wide change affecting multiple organisations and care providers, with the goal of making significant improvements in efficiency of health care delivery, the quality of patient care, and population-level patient outcomes’. 1 There are long-standing recommendations in the English NHS and internationally to reorganise specialist services into integrated networks of services in which aspects of specialist care are delivered by a reduced number of larger units, treating a higher volume of patients and hosting a full range of experienced specialists and equipment to support care delivery. 2–6 It is argued that such changes (commonly termed ‘centralisation’) may improve care delivery and patient outcomes, and associations between higher volumes and better outcomes have been demonstrated in some clinical settings. For example, recent research7 indicates that centralising acute stroke services into ‘hub-and-spoke’ systems (i.e. a centralised model of care), in which a smaller number of high-volume units (i.e. hubs) provide specialist hyper-acute care and a larger number of units (i.e. spokes) provide ongoing acute rehabilitation closer to home, is associated with significantly better provision of evidence-based clinical interventions and significantly better clinical outcomes, including patient mortality. However, the strength of this relationship varies between specialties. 8

Recent guidance indicates that centralising specialist services will remain a priority in the English NHS in the future. 9–12 However, although this is a growing field of research, relatively little is known about the processes by which services are centralised, the impact of changes on patients and staff, the cost of implementing change13 and which factors influence implementation. 14–18

Centralisation of specialist cancer surgery services

This study evaluated centralisations addressing four cancer pathways that include complex surgery: (1) prostate cancer, (2) renal cancer, (3) bladder cancer and (4) oesophago-gastric cancer. In the UK, there are over 85,000 new cases of these cancers every year (i.e. prostate cancer, > 48,000 cases;19 bladder cancer, > 10,000 cases;20 renal cancer, > 13,000 cases;21 and oesophago-gastric cancer, > 15,000 cases22–24). Prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in men,25 and 5-year survival rates are around 50–60% for bladder and renal cancers,20,21 16% for gastric cancer and 12% for oesophageal cancer. 22

There are long-standing recommendations to centralise specialist services,2–4 citing the potential to reduce variations in access, increase patient volumes and improve patient outcomes by increasing the likelihood of patients receiving care in hospitals that have a full range of experienced specialists and equipment to support provision of care.

Higher volumes in specialist cancer surgery are associated with better outcomes for oesophago-gastric cancers22 and urological cancers. 26 Research indicates that there is limited evidence of the cost impact of centralising cancer services,27 and limited evidence on patient, public and professional preferences in relation to centralisations of this kind. 28,29 Research indicates that centralisation of cancer services is likely to place increased travel demands on patients and families, and may limit some people’s access to quality care. 30 A review of research evidence indicates that patients are willing to travel further for care for a number of reasons, including for specialist care, if a hospital has a good reputation, if a condition is serious or urgent or if the patient is of a higher socioeconomic status. In contrast, older patients and frequent users of services are less willing to travel further. 31 A recent study suggests that cancer patients are willing to make more frequent, but not longer, journeys to services if it means that they will receive care that is slightly more effective or associated with fewer side effects. 32

London Cancer and Greater Manchester Cancer

This research focused on two integrated cancer systems in the NHS in England: London Cancer and Greater Manchester Cancer. London Cancer (London, UK) covers north-central London, north-east London and west Essex (population 3.2 million). At time of writing, this area was covered by the North Central London Cancer Alliance (London, UK) and the North East London Cancer Alliance (London, UK). Greater Manchester Cancer (Manchester, UK) covers Greater Manchester and east Cheshire (population 3.1 million). At time of writing, this area was covered by the Greater Manchester Cancer Alliance (Manchester, UK). 33,34

London Cancer: context for changes

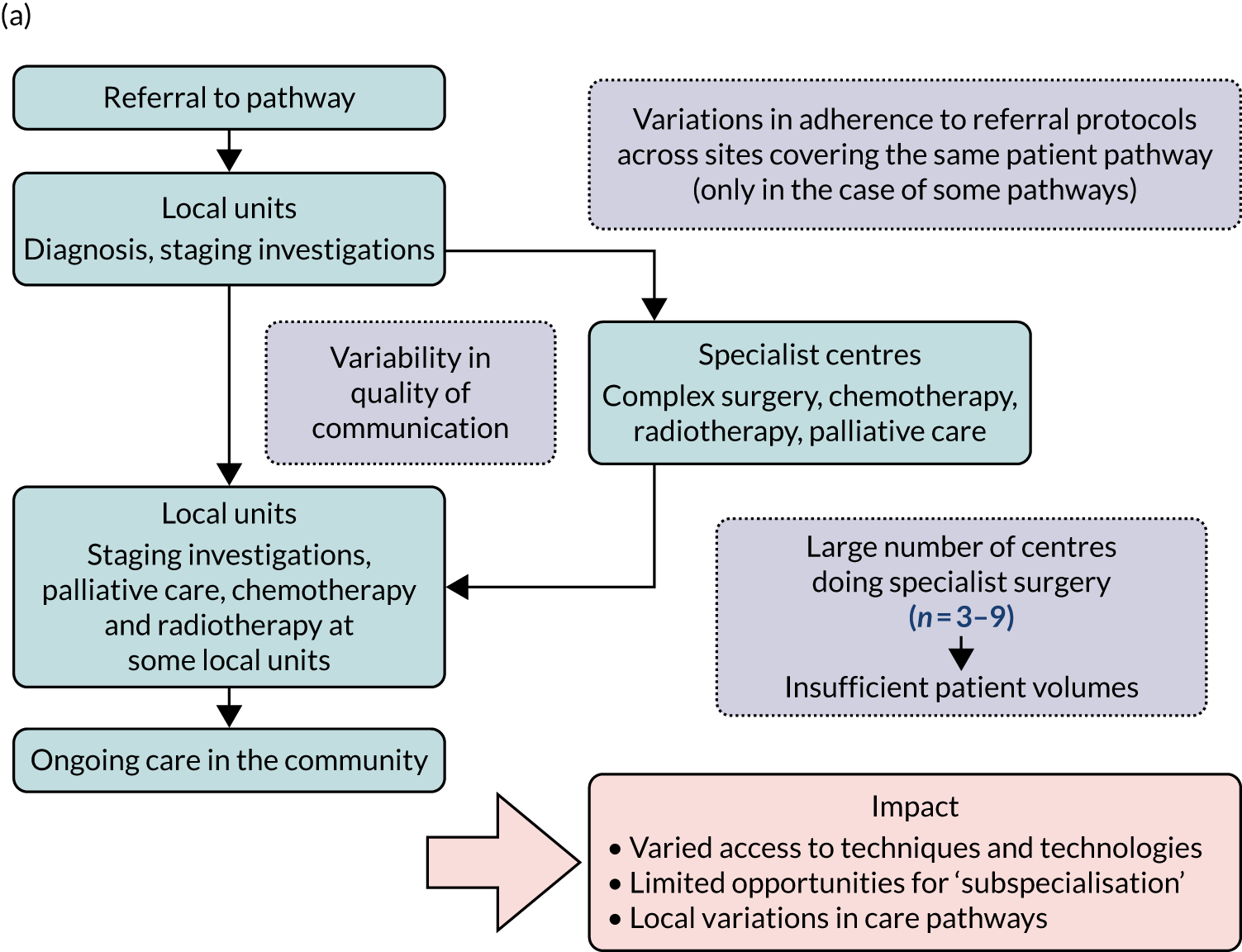

In London Cancer, when changes were being planned, potential cancer patients were referred to their local cancer centre for diagnosis and either remained there or were referred to a specialist centre (Figure 1a).

FIGURE 1.

Organisation of specialist cancer surgery (a) before planned changes; and (b) after planned changes. MDT, multidisciplinary team. Adapted with permission from Fulop et al. 18 This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited (see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Adapted with permission from Fulop et al. 18 This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited (see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

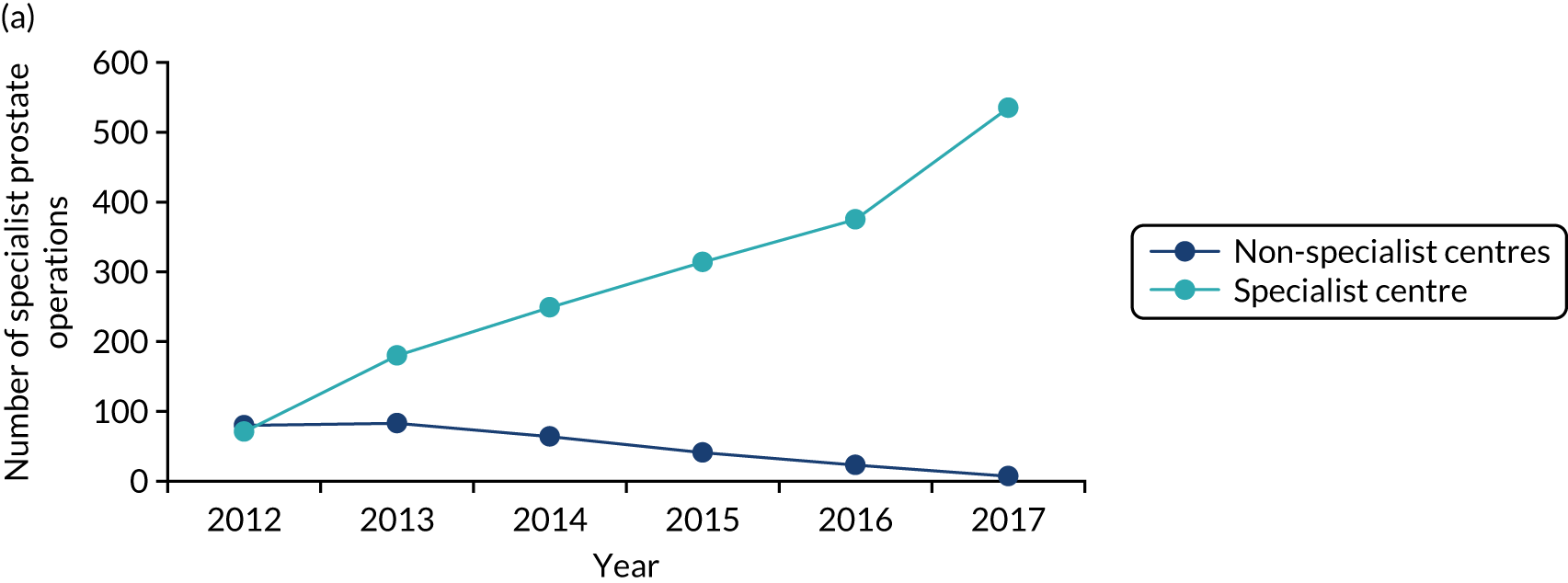

The care received by patients varied across centres providing cancer care, including specialist centres. For example, prostate and bladder patients could receive robotic surgery in only certain specialist centres; the majority of renal surgical patients underwent surgery in local non-specialist centres (performed by a specialist or general urologist), rather than in specialist centres (potentially limiting the surgical and other therapeutic options afforded these patients); and oesophago-gastric and urological cancer patients were not guaranteed to see a tumour-specific surgical specialist out of hours or at weekends. Variations existed in the protocols used for referral to specialist centres. Across specialist centres, patient volumes were substantially lower than recommended, and there were variations in access to technology (e.g. robotic surgery), innovative techniques and opportunities to participate in research. At the time, all surgeons provided all types of radical surgery within their specialty (e.g. urologists offered all specialist surgery for bladder, prostate and kidney) and there was limited opportunity for greater surgical ‘subspecialisation’ in specific techniques (e.g. robotic surgery).

Greater Manchester Cancer: context for changes

In Greater Manchester, at the time of planning the changes, patients were referred to a local cancer centre and, depending on diagnosis, either remained at that service for staging or palliative care or were referred to a specialist centre for specialist surgery, chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy (see Figure 1a). Specialist centres were located across the Greater Manchester region and took patients referred from nearby hospitals. Certain aspects of urological care (e.g. robotic surgery) were provided by The Christie Hospital (Manchester, UK). Similar to London Cancer, there was substantial variation in patient volumes across specialist centres.

Changes proposed by London Cancer and Greater Manchester Cancer

In both areas, work started in 2011/12 to create integrated cancer systems. It was proposed that specialist surgical services for these cancers should be centralised into hub-and-spoke systems, with a reduced number of specialist centres providing specialist surgery and local units providing most other aspects of pre- and post-surgical cancer care closer to patients’ homes (see Figure 1b).

Patient pathways to specialist cancer surgery were to be standardised, with the aim of reducing variations in access to care. Within specialist centres, it was anticipated that increased patient volume would permit greater specialisation of staff and greater experience and expertise across teams. In addition, specialist services would offer a full range of surgical technologies (e.g. robotics) and equal access to innovative techniques (e.g. less invasive procedures).

It was planned that local units would continue to provide much cancer care closer to home, including diagnosis, ongoing radiotherapy and chemotherapy. In addition, it was anticipated that local units would benefit from closer involvement of specialist centre staff [e.g. through joint multidisciplinary teams (MDTs)] and specialists providing training and delivering some outpatient care, thereby improving quality of care across the whole system. Both centralisations emphasised the importance of continuity of care (e.g. in terms of dedicated keyworkers to co-ordinate patient care and provide relevant information). 33,34 Table 1 provides an overview of the proposed changes in terms of the number of specialist centres for each type of cancer.

Timeline/progress of changes studied

Implementation of the London Cancer centralisations was completed between December 2015 and April 2016 (see Chapter 4). Implementation in Greater Manchester was delayed for a range of reasons (see Chapter 12). Centralisation of Greater Manchester Cancer’s oesophago-gastric cancer surgery services was completed in September 2018, whereas Greater Manchester Cancer’s planned centralisations of specialist surgery for urological cancers (i.e. bladder, prostate and kidney) were not implemented over the course of this study. Consequently, we were able to study the impact and cost-effectiveness of only the London Cancer changes, but we were able to study factors influencing the progress of implementation for both London Cancer and Greater Manchester Cancer. We provide details of our updated study design under Aims and objectives and Overview of the research, and in Chapter 2.

Over the course of this study, the National Cancer Vanguard was operational. The National Cancer Vanguard was a partnership that included London Cancer and Greater Manchester Cancer. 36,37 In 2016, incorporating the learning from the National Cancer Vanguard, the English NHS introduced cancer alliances (of which there are now a total of 21 covering the whole of the English NHS) ‘to bring together local senior clinical and managerial leaders representing the whole cancer patient pathway across a specific geography’. 37 In 2019, the geography covered by London Cancer reverted to two separate cancer alliances (i.e. the North Central London Cancer Alliance and the North East London Cancer Alliances) to align better with sustainability and transformation partnership footprints in the region. The split resulted from stakeholder decisions after a self-assessment process initiated by NHS England and Improvement and applied to all alliances nationally. The two alliances have continued to use the same pathway configurations, with single specialist cancer surgical centres serving both alliances.

Aims and objectives

This study aimed to use qualitative and quantitative methods to evaluate the centralisation of specialised cancer surgery services in London Cancer and Greater Manchester Cancer, and identify lessons that would guide centralisation work in other areas of specialist services.

The objectives of this study were to:

-

examine preferences for centralisation, the most important attributes of services that affect these preferences and how these preferences vary between patients, the public and professionals

-

identify factors influencing development, implementation and sustainability of centralisations of specialist cancer surgery

-

analyse the impact of changes on staff skill mix, patient choice, patient experience and continuity of care

-

analyse the impact of changes on patient outcomes and processes of care in London Cancer

-

analyse the relationship between processes of care and outcomes in London Cancer

-

analyse the incremental costs and cost-effectiveness of the changes in London Cancer

-

present lessons on centralising specialist cancer surgery services that might be applied in future centralisations of specialist cancer services and other specialist settings.

Overview of the research project

This evaluation was originally funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) (formerly the National Institute for Health Research) Health and Social Care Delivery Research (HSDR) programme from September 2015 to February 2019 to study centralisations of specialist cancer surgery for urological and oesophago-gastric cancers in London Cancer and Greater Manchester Cancer. This was part of the HSDR programme’s call to conduct research on the organisation of surgical services for the 21st century.

Our study protocol was amended several times over the course of the study. First, in 2018, in the light of limited progress of change in Greater Manchester Cancer, we agreed with the funder that the quantitative and cost-effectiveness analyses should focus on the impact of only the London Cancer changes and the project was extended (to August 2019) to ensure that these analyses could address sufficient numbers of patients passing through centralised services. Alongside this extension, additional qualitative work in London Cancer was agreed to focus on longer-term sustainability of the system. In addition, over the course of the study, we learned that it would not be possible to access oesophago-gastric national audit data and so this data set was removed from our analysis plan. There were also delays in obtaining other national data sets, which resulted in a number of no-cost extensions to the study, the last of which extended the study to 30 April 2021. We provide additional details of protocol amendments in Appendix 1, Table 17.

Structure of the report

-

Chapter 2 presents the evaluation design and an overview of the methods employed (note that greater methodological detail is presented within each findings chapter).

-

Chapters 3–13 present our key findings in terms of:

-

stakeholder preferences for MSC (see Chapter 3)

-

how network leadership approaches contributed to implementation of change in London Cancer (see Chapter 4)

-

interorganisational collaboration in London Cancer (see Chapter 5)

-

how learning from history contributed to implementing change to oesophago-gastric services in Greater Manchester (see Chapter 6)

-

the effects of losing services in London Cancer (see Chapter 7)

-

the cost of implementing the London Cancer changes (see Chapter 8)

-

the impact of the London Cancer changes on delivery and outcomes of cancer surgery (see Chapter 9)

-

the cost-effectiveness of the London Cancer changes (see Chapter 10)

-

factors contributing to different progress of changes to urological services in London Cancer and Greater Manchester Cancer (see Chapter 11)

-

wider impacts of London Cancer changes (see Chapter 12)

-

how lessons from this research might be adapted to different contexts (in cancer and non-cancer settings) (see Chapter 13).

-

-

Several findings chapters (see Chapters 3, 4 and 8) draw on papers published with full open access permissions. Details of publication status are provided at the beginning of each of these chapters. In addition, for coherence, we provide summary sections on ‘what is already known?’ and ‘what does this chapter add?’ for each findings chapter.

-

Chapter 14 presents our findings linked to our objectives, and implications for health services and research, in part informed by our stakeholder workshop.

-

Our appendices include the following: details of research governance and ethics approvals, a detailed summary of our approach to patient and public involvement (PPI), supplementary data for Chapters 9, 10 and 13, and details of our Study Steering Committee (SSC).

Chapter 2 Research methods

Overview

In this chapter, we provide an overview of this evaluation’s mixed-methods formative design and the quantitative and qualitative methods we used. We present our sampling and the overall approaches to collecting and requesting data, along with tables summarising the data that we collected and analysed in this study. We then discuss our overarching analytical approaches. Additional detail on analyses is presented within the relevant findings chapters. Finally, we provide details of ethics approvals and a brief summary of PPI (greater detail is provided in Appendix 2).

Design

This was a multisite study of centralisation of specialist surgical pathways for four cancers in two large areas in England. The study combined measuring the impact of centralisation in terms of clinical processes, clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness, using a controlled before-and-after design (i.e. ‘what works?’), with a parallel qualitative analysis of development, implementation and sustainability of the centralisations (i.e. ‘how and why?’).

Our research questions were:

-

What are patient, public and professional preferences in relation to centralisations?

-

What are the key processes in centralising specialist cancer surgery services in London Cancer and Greater Manchester Cancer, and what factors influenced progress of centralisation?

-

What is the impact on staff and health-care provider organisations, including ways of working, skill mix and approaches to collaboration?

-

What is the impact of the London Cancer centralisations on provision of care in terms of clinical processes and outcomes?

-

What is the impact of the London Cancer centralisations on patient experience, including choice and continuity of care?

-

What are the cost and cost-effectiveness of the London Cancer changes?

-

How might lessons from centralising specialist cancer surgery services be applied in future centralisations of specialist cancer services and other specialist settings?

Framework for understanding major system change

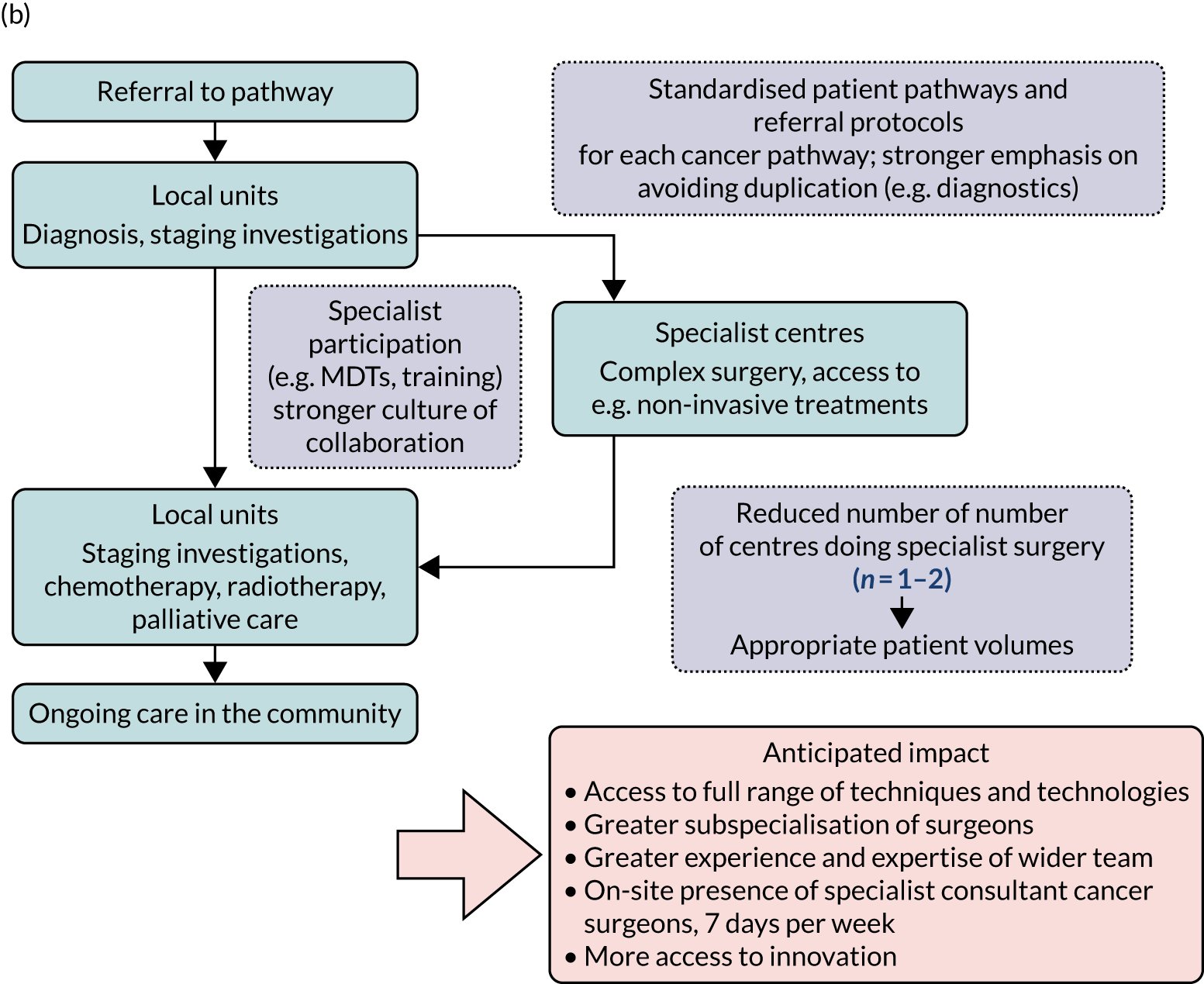

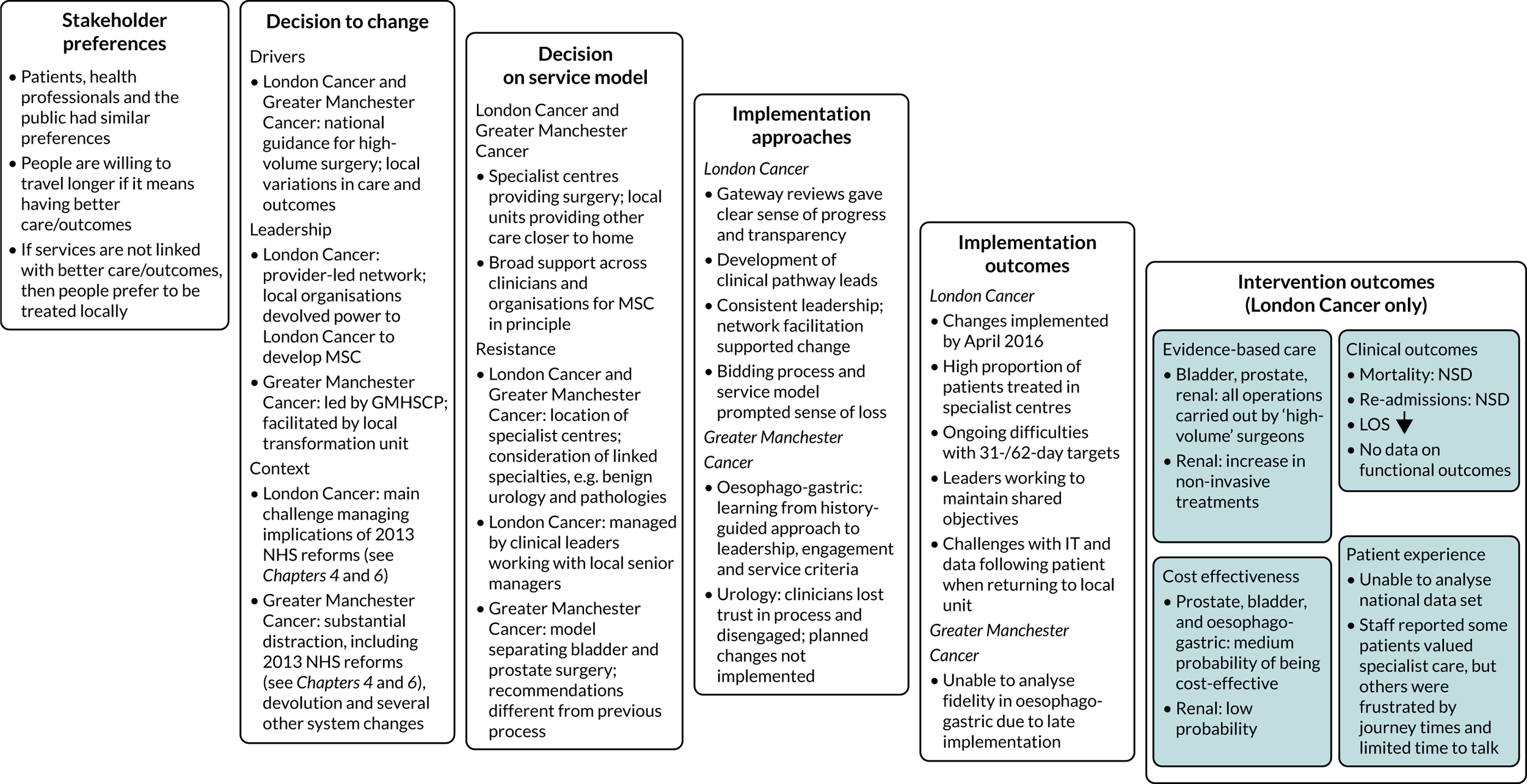

The approaches were combined using a framework that reflected key processes of MSC and how they are inter-related (Figure 2). This framework drew on several established conceptual frameworks, describing different aspects of the planning, implementation and outcomes of change,1,14,38–44 and was developed originally to support the evaluation of MSC in acute stroke services, with the potential for application in other contexts. 14 The framework covered (1) stakeholder preferences (note that this was an addition to the original framework), (2) reaching a decision to change, (3) developing and agreeing the new service model, (4) implementing the new model, (5) adherence to the new model throughout the system, (6) impact on provision of care and (7) impact on outcomes (including clinical outcomes, patient experience and cost-effectiveness) (note that the order of these factors should not be taken to imply a linear relationship between them).

FIGURE 2.

Framework for analysing MSC, adapted for the RESPECT-21 (REorganising SPECialisT cancer surgery for the 21st century) study. DCE, discrete choice experiment; HES, Hospital Episode Statistics; NCRAS, National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service; ONS, Office for National Statistics; RQ, research question. Adapted with permission from Fulop et al. 18 This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited (see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Adapted with permission from Fulop et al. 18 This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited (see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

There are important differences between the context in which this framework was developed and the context in which it was applied in this study. Stroke is a health-care event that requires immediate response, whereas specialist cancer surgical services operate at a different pace, affording greater opportunities for care-planning and engagement with the patient and family regarding treatment options. These contextual differences between stroke and specialist cancer surgery potentially introduced different considerations into the decision to change, model selection and implementation approaches (all with potential implications for progress of change).

Overview of methods and data sampled

In this section we set out the rationale for, and overall approach of, the methods used in this evaluation. Much data related to the areas undergoing centralisation (London Cancer and Greater Manchester Cancer). In addition, changes of this kind must be understood in a wider context and so, when appropriate, we collected/obtained national data as a control (Table 2).

| Study component | Areas covered |

|---|---|

| DCE (RQ 1) | London Cancer, Greater Manchester Cancer and national control |

| Documentary analysis, stakeholder interviews and non-participant observations (RQs 2 and 3) | London Cancer and Greater Manchester Cancer |

| Clinical processes and clinical outcomes (RQ 4) | London Cancer and national control |

| Patient experience (RQ 5) | London Cancer |

| Cost-effectiveness (RQ 6) | London Cancer and national control |

| Stakeholder workshop (RQ 7) | London Cancer, Greater Manchester Cancer and national control |

Stakeholder preferences for centralisation: London Cancer, Greater Manchester Cancer and national control (research question 1)

The centralisations had the potential to significantly change how care was organised and delivered, with implications for patient travel times, choice of treatments and, potentially, outcomes. To examine the acceptability of such changes to patients, the public and professionals, we conducted a discrete choice experiment (DCE). 45–47 The DCE examined stakeholder preferences for centralisation, the relative importance of attributes of surgical services and how preferences vary between stakeholder groups. The DCE was designed in line with international best practice guidelines (detailed methods are presented in Chapter 3 and Vallejo-Torres et al. 48).

Implementation and sustainability of change: London Cancer and Greater Manchester Cancer (research questions 2 and 3)

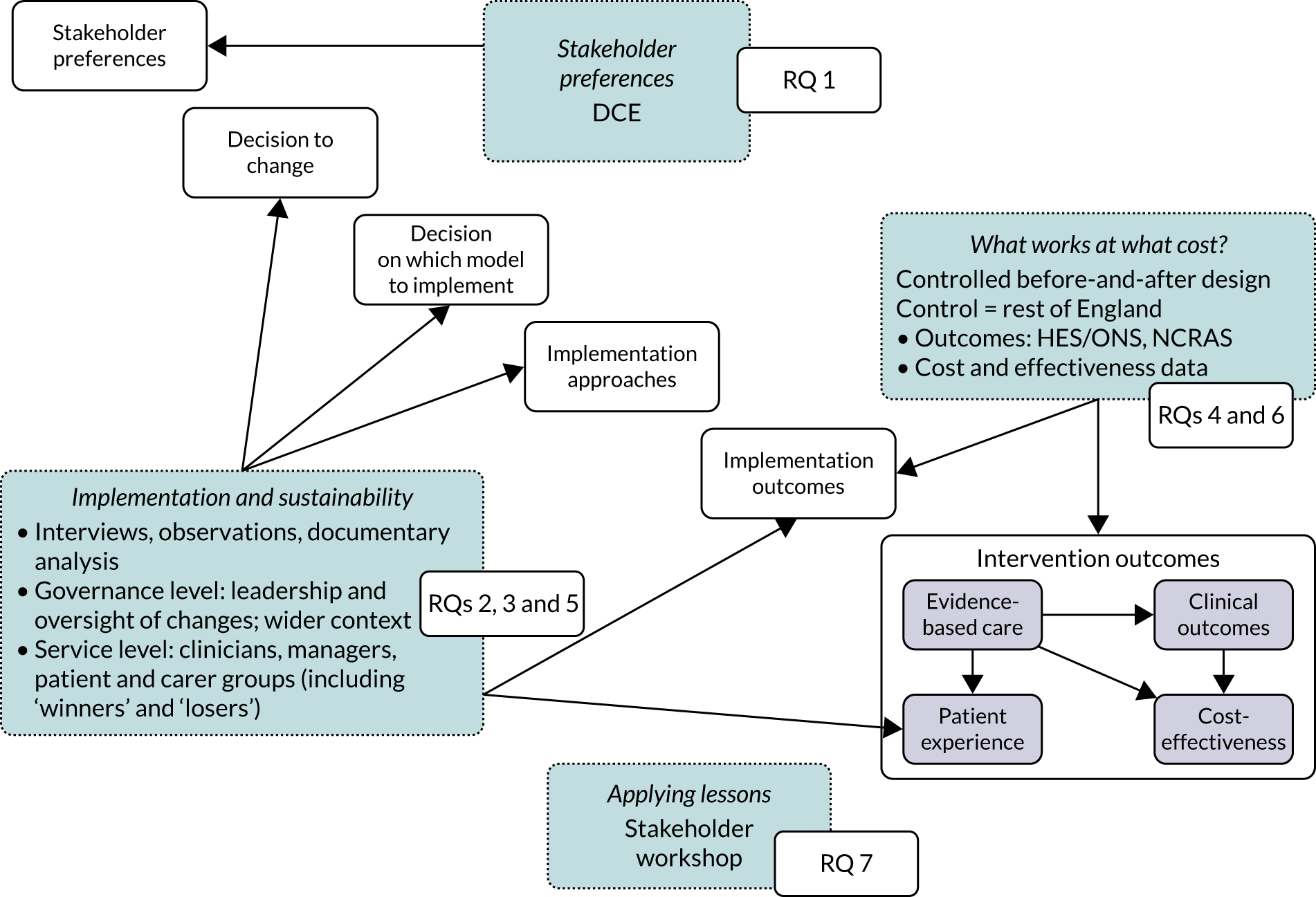

We used qualitative methods to understand how the London Cancer and Greater Manchester Cancer changes were planned and implemented, and to understand the progress and impact of changes (including factors contributing to non-implementation). We analysed key documents (e.g. project plans, meeting minutes and local press) to develop a timeline of which processes were carried out and when, in the planning and implementation of change. Documentary analysis was also used to supplement and extend understanding of findings emerging from other qualitative components. We interviewed a range of stakeholders related to the London Cancer and Greater Manchester Cancer changes to understand relevant perspectives on how and why change happened, and the implications of change for different groups. We used purposive sampling combined with snowball sampling to ensure a good range of perspectives. Figure 3 presents our sampling for qualitative work, which focused at the governance level (including programme teams, pathway boards and wider context, e.g. patient representative groups, payer organisations and NHS England) and the service level (including specialist centres, local units that had provided specialist surgery pre centralisation and local units that had not provided specialist surgery pre centralisation). Clinical staff interviewed included surgeons, specialist nurses, oncologists and allied health professionals (e.g. therapists, dieticians and radiologists).

FIGURE 3.

Sampling for qualitative research.

Reflecting previous research on evaluating MSC14,18 and our framework for analysing MSC (see Figure 2), our interviews were guided by semistructured topic guides that focused on such topics as drivers for change and factors influencing key stages of change (e.g. agreeing the case for change, selecting the service model, planning and implementing changes, and their impact on quality of care) (see Appendix 8). We conducted non-participant observations of events to obtain a direct understanding of key processes in action. Observations focused on governance and implementation of change (e.g. oversight and planning meetings, including the overarching London Cancer and Greater Manchester Cancer boards) and organisation and delivery of care post centralisation (e.g. MDT meetings).

To interpret these data, we used a comparative case study approach. 49,50 Our analysis was guided by our framework for understanding MSC, which we developed with reference to several other key conceptual frameworks for understanding implementation and outcomes of change. 51 In addition, to understand specific aspects of MSC, we drew on relevant literatures on networks and interorganisational collaboration (see Chapter 5), the influence of history (see Chapter 6), subtractive loss (see Chapter 7) and organisational context (see Chapter 12). In each case, the literature is introduced and discussed in the relevant chapter.

We organised interview transcripts and observation field notes with NVivo version 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) and Microsoft Excel® (Version 2205; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) software. Initial analysis and category-building was led by the London and Manchester qualitative researchers. The analysis was developed with a subgroup of co-investigators who have qualitative expertise and the whole research team contributed to the interpretation of findings. Ongoing iterative and thematic analysis of all data was undertaken, following established procedures of constant comparative analysis. 52

Table 3 presents the qualitative data collected and analysed. Summaries of interview data are disaggregated by organisation level (i.e. governance and service levels) and specifying the types of change services underwent (or anticipated undergoing) through centralisation.

| Data source | Data collected (n) |

|---|---|

| London Cancer: planning and implementation (see Chapters 4, 5, 7, 11 and 12) | |

| Stakeholder interviews | |

| Governancea | 28 |

| Service A (specialist oesophago-gastric) | 8 |

| Service B (specialist prostate/bladder) | 12 |

| Service C (specialist renal) | 9 |

| Service D (local renal) | 7 |

| Service E (specialist to local renal) | 5 |

| Service F (specialist to local oesophago-gastric) | 4 |

| Service G (local prostate/bladder) | 6 |

| Service H (specialist to local prostate/bladder) | 6 |

| Service I (specialist oesophago-gastric) | 3 |

| Service J (local oesophago-gastric) | 5 |

| Total stakeholder interviews | 93 |

| Total documents | 423 |

| Total non-participant observations | 64 |

| London Cancer: sustainability (see Chapters 5, 7, 11 and 12) | |

| Stakeholder interviews | |

| Governancea | 6 |

| Service A (specialist oesophago-gastric) | 2 |

| Service B (specialist prostate/bladder) | 3 |

| Service C (specialist renal) | 3 |

| Service D (local renal) | 3 |

| Service G (local prostate/bladder) | 3 |

| Service I (specialist oesophago-gastric) | 2 |

| Service J (local oesophago-gastric) | 2 |

| Total stakeholder interviews | 24 |

| Total non-participant observations | 12 |

| Greater Manchester Cancer: planning and implementation (see Chapters 6 and 12) | |

| Stakeholder interviews | |

| Governancea | 57 |

| Service K (specialist oesophago-gastric) | 12 |

| Service L (specialist to local oesophago-gastric) | 5 |

| Service M (specialist to local oesophago-gastric) | 12 |

| Service N (local oesophago-gastric) | 3 |

| Service O (specialist prostate and oncology) | 5 |

| Other oesophago-gastric services | 1 |

| Total stakeholder interviews | 95 |

| Total documents | 450 |

| Total non-participant observations | 109 |

| Grand totals | |

| Stakeholder interviews | 212 |

| Documents | 873 |

| Non-participant observations | 185 |

In conducting 212 interviews (including follow-ups), we interviewed a total of 176 stakeholders (Greater Manchester Cancer, n = 76; London Cancer, n = 100). Of those interviewed, 105 were clinicians working in oesophago-gastric and urological services (Greater Manchester Cancer, n = 44; London Cancer, n = 61), including consultant surgeons, consultant oncologists and pathologists, specialist nurses and allied health professionals (e.g. dieticians, occupational therapists, physiotherapists and radiologists).

Impact on clinical processes and clinical outcomes: London Cancer only (research question 4)

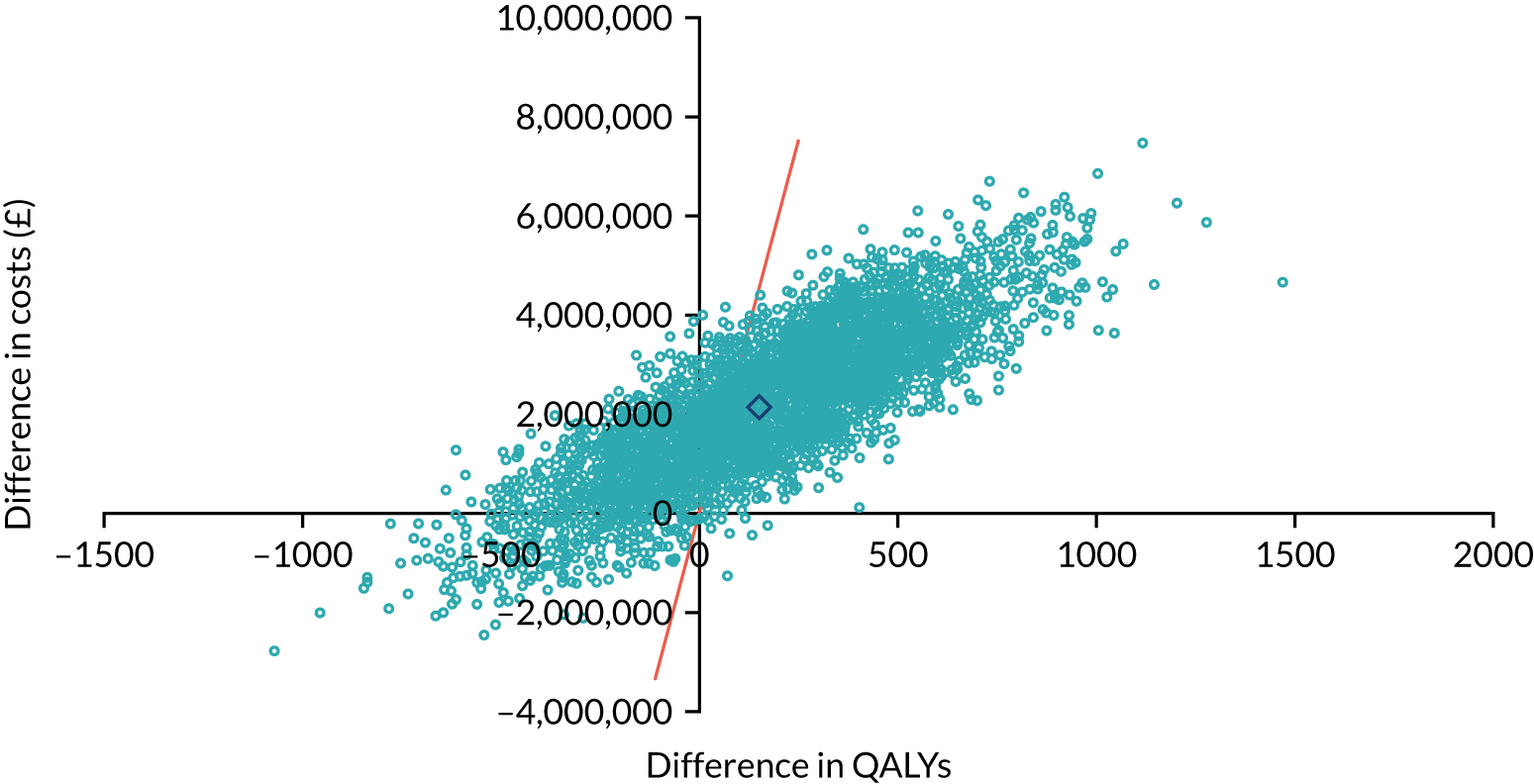

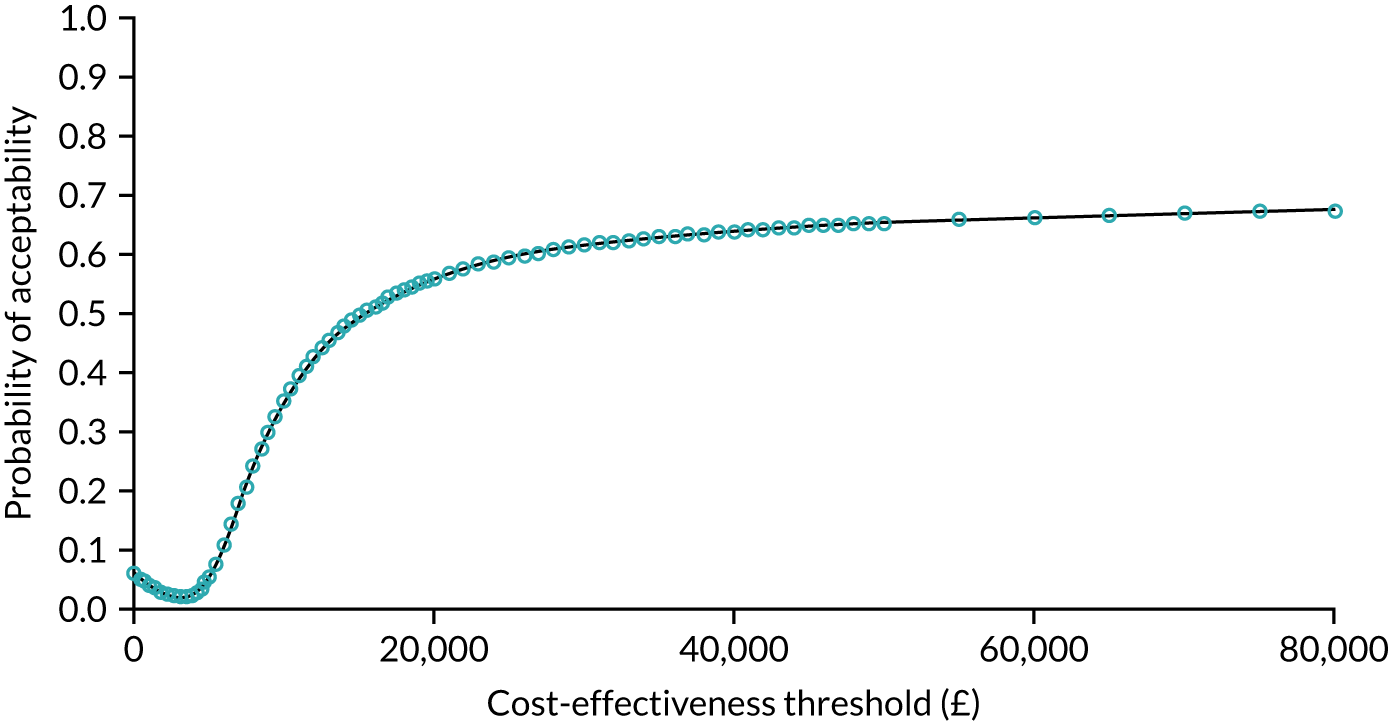

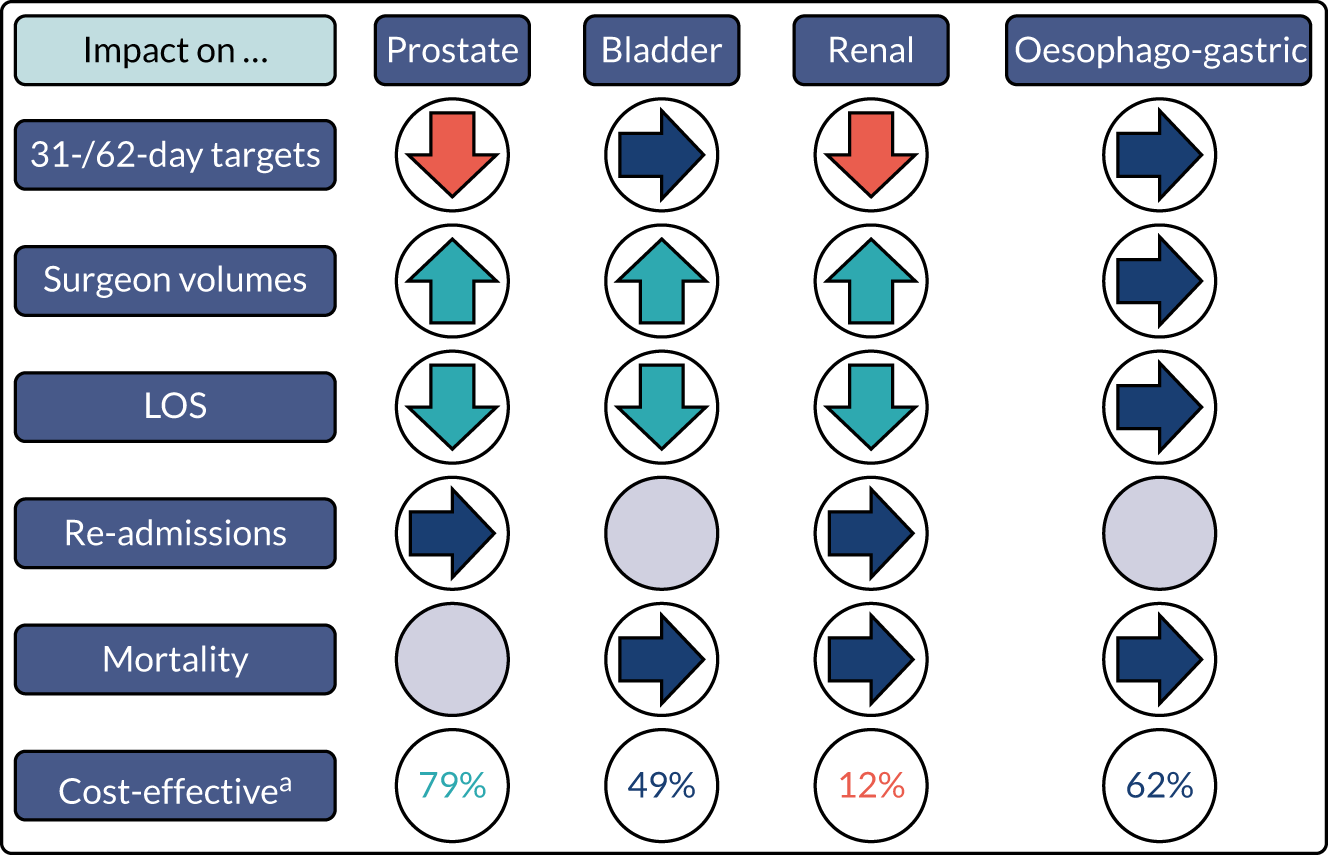

The proposals for change in London Cancer and Greater Manchester Cancer identified the potential for significant improvements in care and outcomes. Therefore, we analysed a range of national data sets that captured clinical outcomes and delivery of clinical interventions. We assembled data from the National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service (NCRAS) data linked to Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) and Office for National Statistics (ONS) mortality data to analyse the impact of selected cancer surgery service centralisations on a range of outcomes [e.g. mortality, re-admission, length of stay (LOS)] and impact on care process measures (e.g. surgical complications, surgical technique). We used a difference-in-differences approach, evaluating the changes in the outcomes over time following centralisation in London Cancer, accounting for changes seen during the same time period in the rest of England (see Chapter 9 for further details of the data, measures and methods used).

Impact on patient experience (research question 5)

Patient experience was a priority for London Cancer and Greater Manchester Cancer change planners. We originally planned to study the impact on key aspects of patient experience as part of our quantitative analysis, drawing on National Cancer Patient Experience Survey (NCPES) data. However, owing to issues with this data set (e.g. it was not possible to distinguish patients who had surgery from other types of management, nor disaggregate by specific cancer types addressed by the London Cancer changes) we were unable to analyse quantitatively the impact of London Cancer changes on patient experience. In lieu of quantitative data, we analysed qualitative interviews to establish London Cancer staff perceptions of how MSC influenced patient experience.

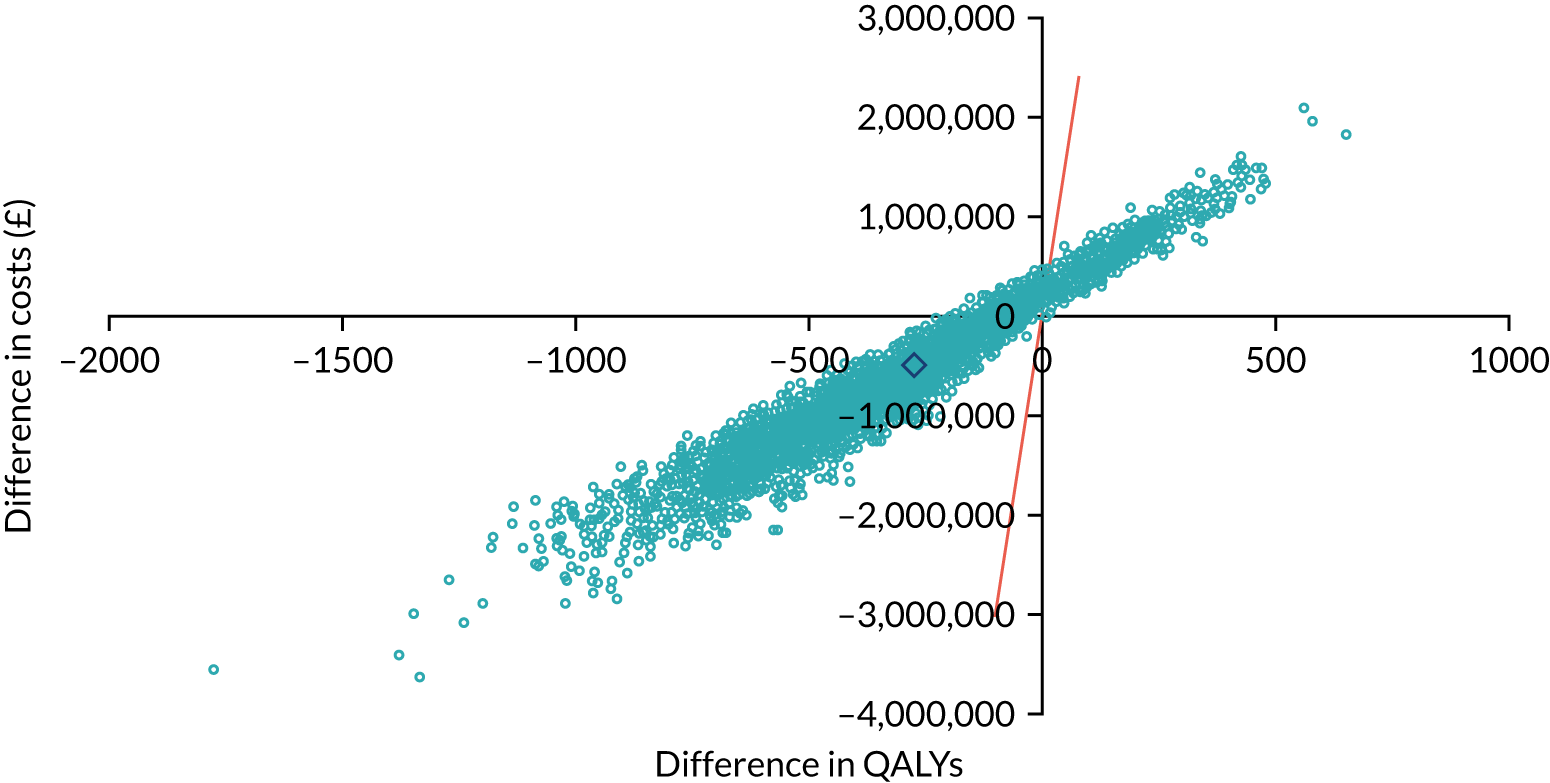

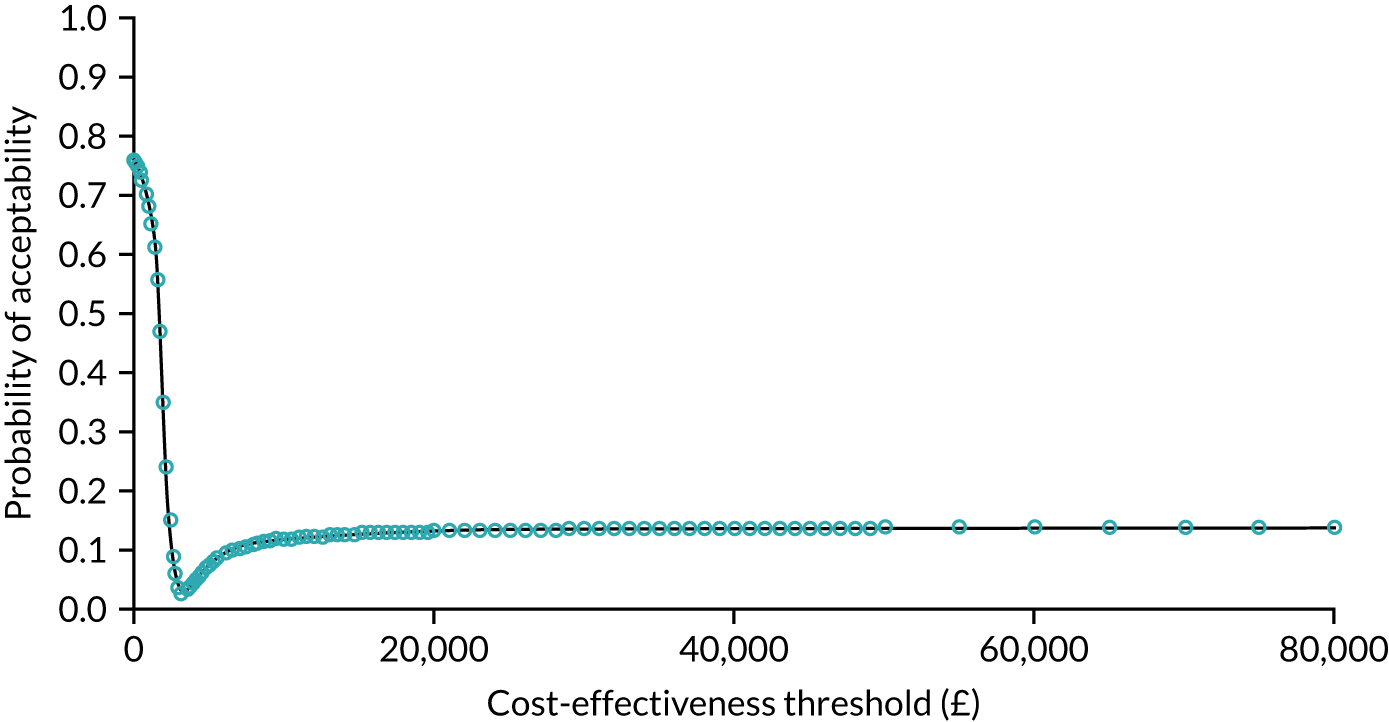

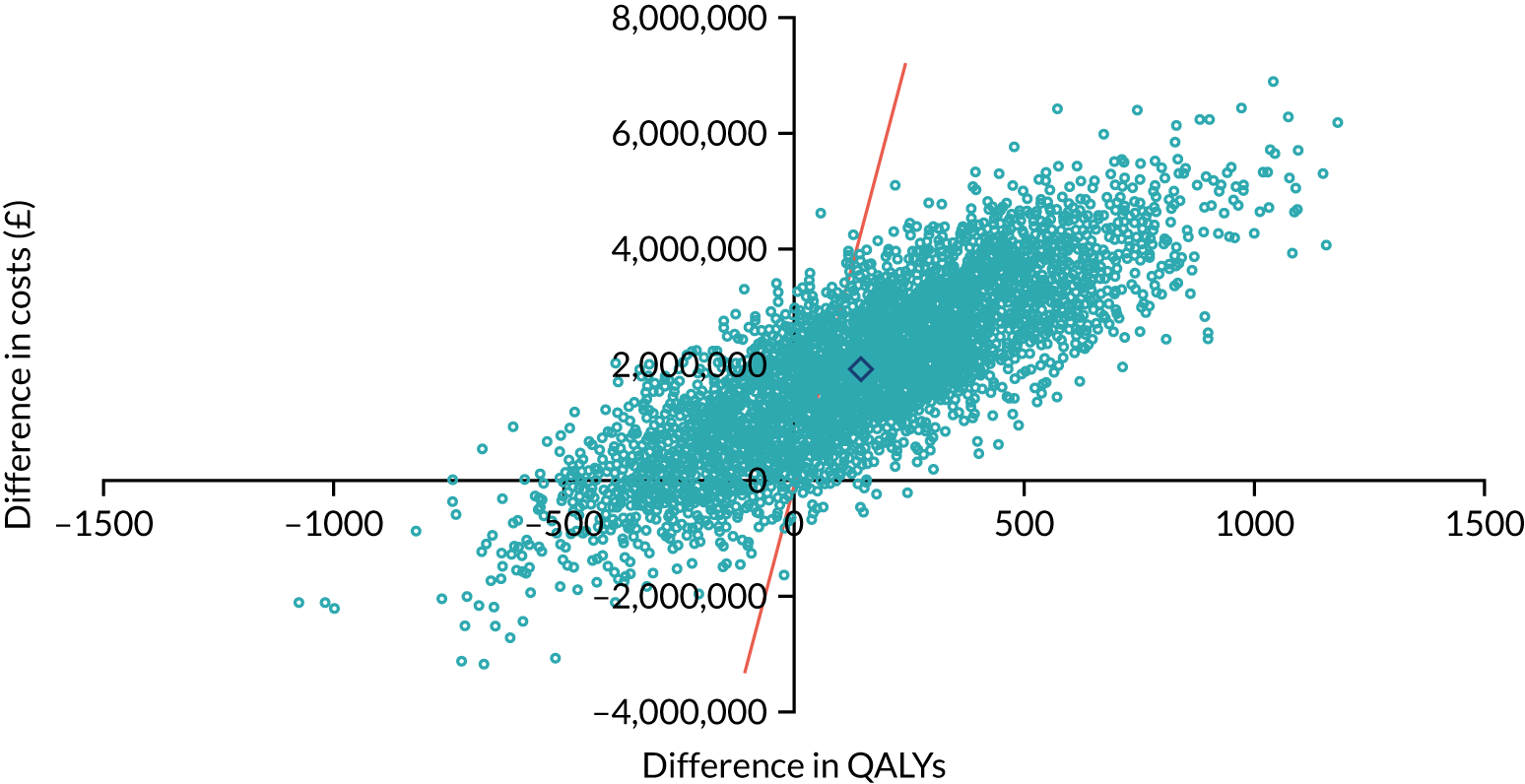

Implementation costs and cost-effectiveness: London Cancer only (research question 6)

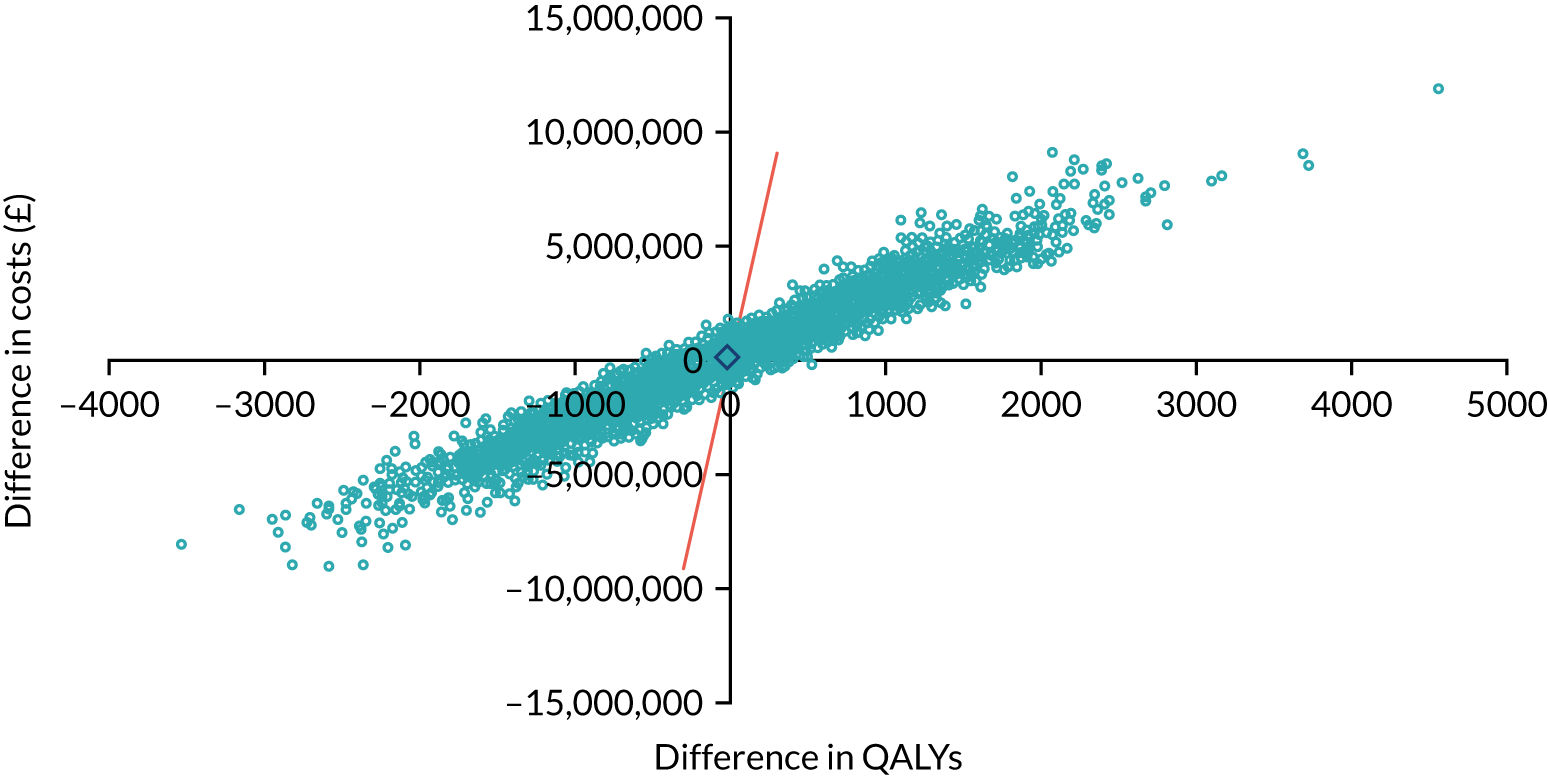

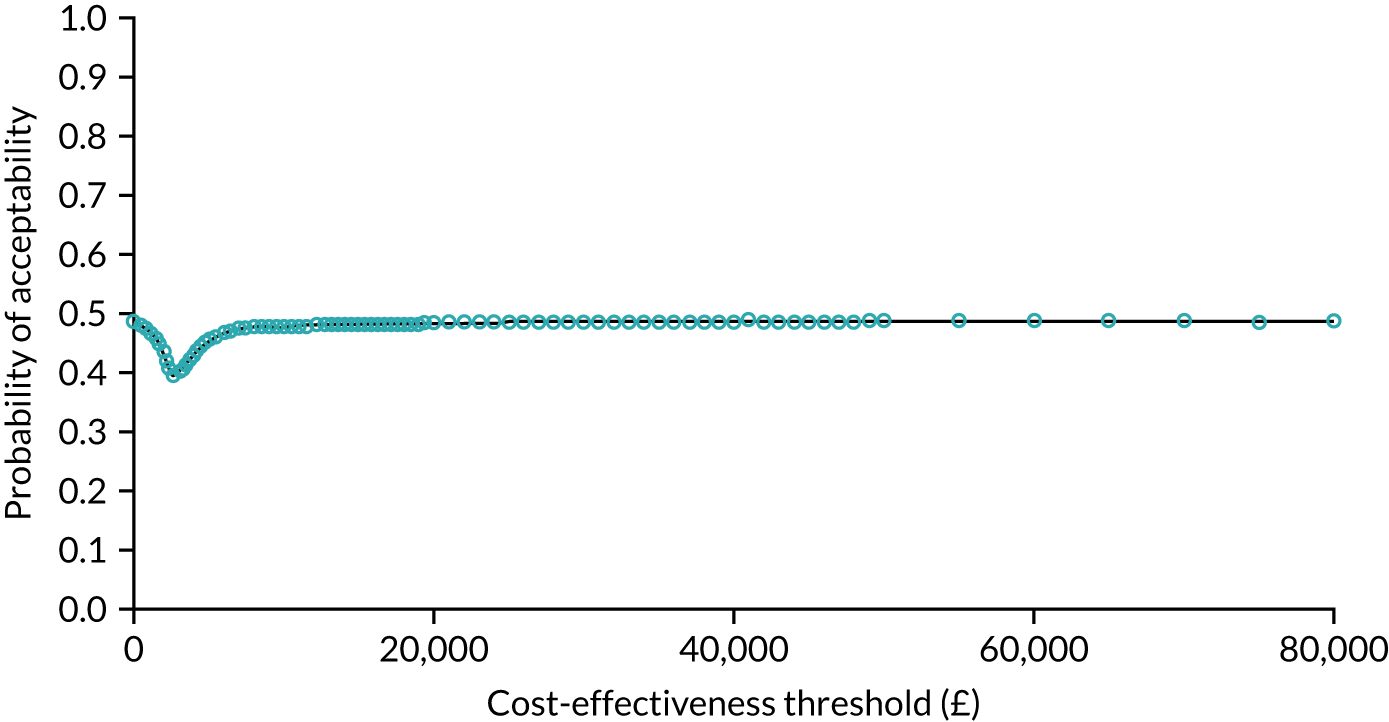

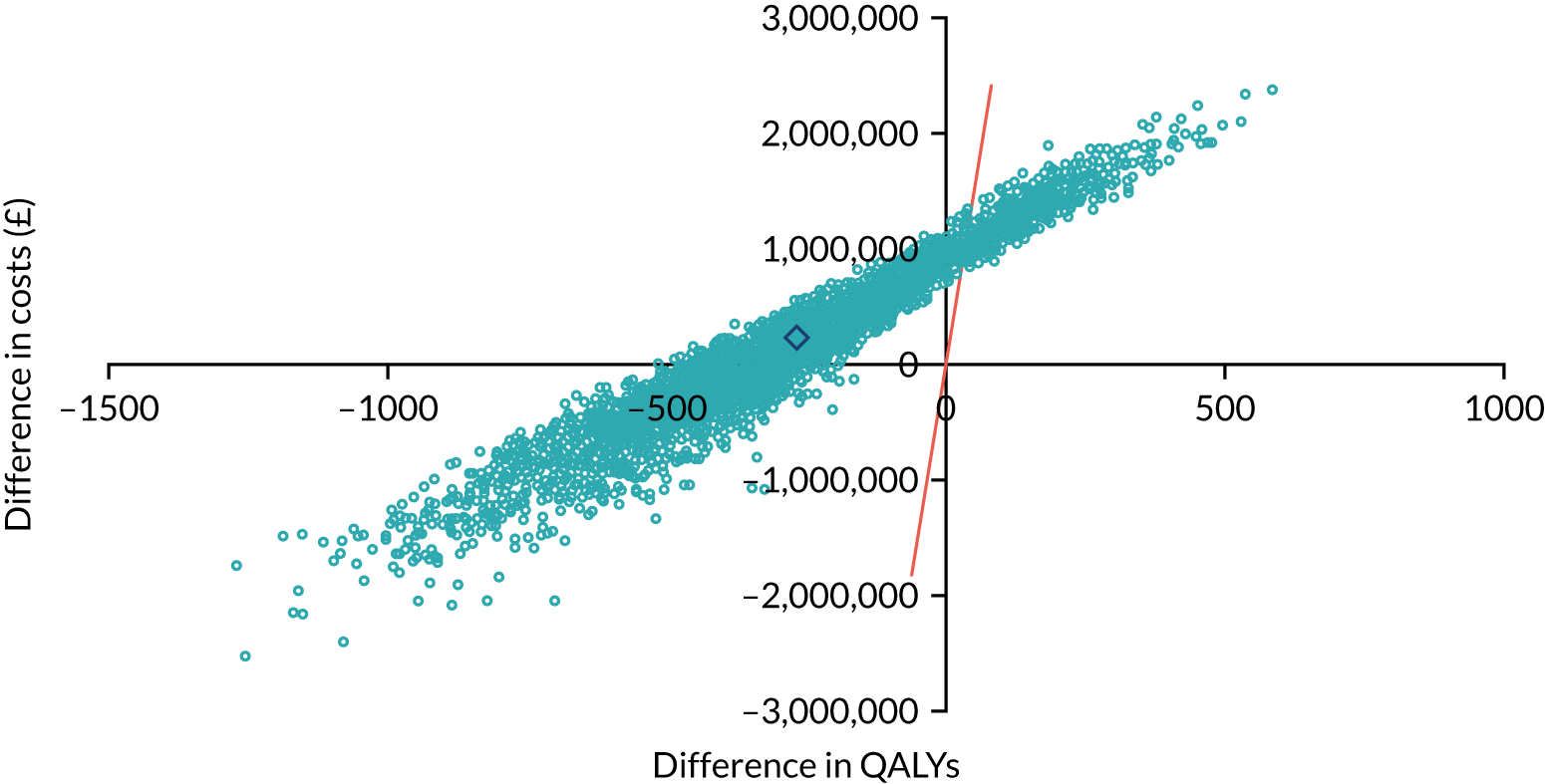

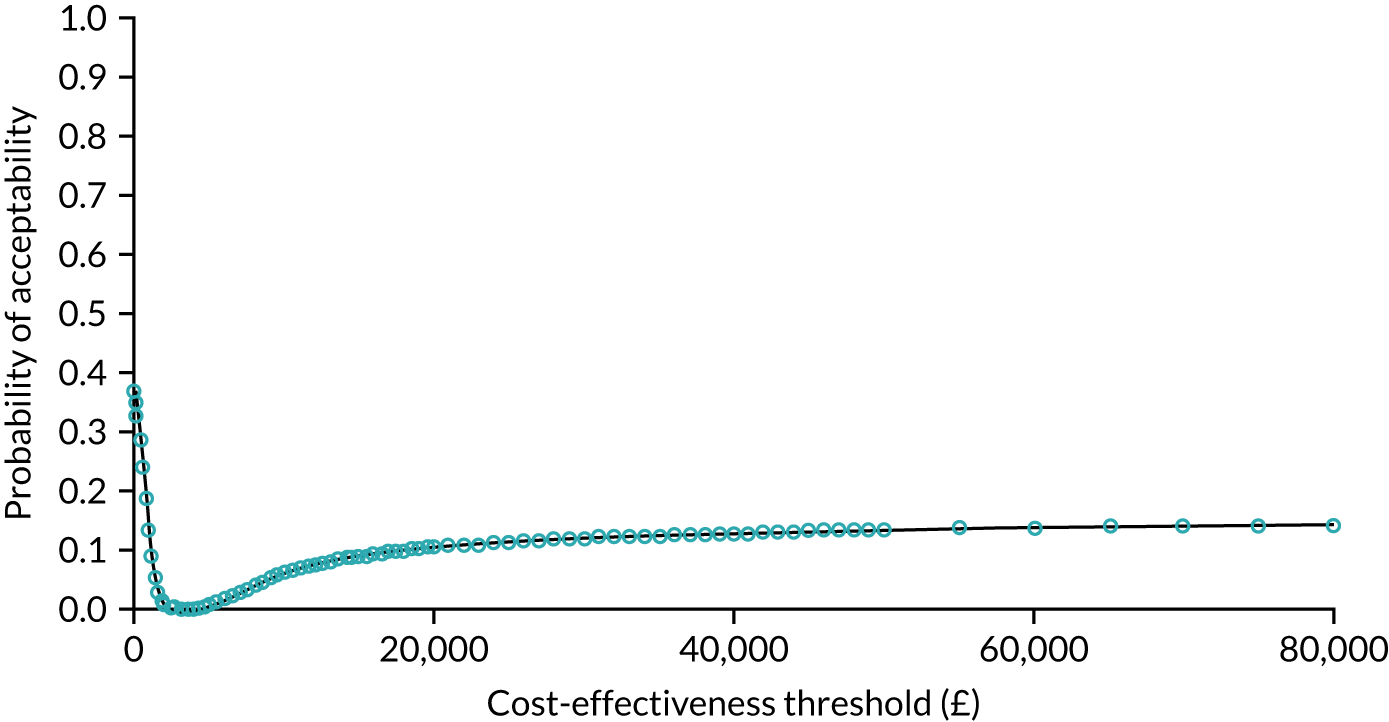

As noted in Chapter 1, little is known about the cost-effectiveness of MSC, and the implementation costs of MSC are rarely evaluated and even more rarely incorporated into incremental cost-effectiveness analyses. To address these gaps, we studied the cost of implementing the London Cancer changes (see Chapter 8), analysing key supports of change (e.g. meetings, events, clinical and managerial staff time, and programme team costs) and costs of new services (e.g. staffing, space and technology). To assess overall value for money of the London Cancer changes, we conducted a cost-effectiveness analysis (see Chapter 10). We analysed clinical processes and patient outcome data, alongside national and local cost data, incorporating implementation costs, to generate an incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained in the reconfigured services in the London Cancer region compared with the equivalent scenario without these specific changes, based on the difference-in-differences analysis framework used in Chapter 9.

How lessons might apply in other contexts: London Cancer, Greater Manchester Cancer and national control (research question 7)

We anticipated that lessons from this research would be of interest and use to people planning MSC in both cancer and ‘non-cancer’ specialist settings. However, we also recognised that stakeholders in different contexts would have valuable perspectives on how lessons may be adapted to enhance their applicability to other contexts. Therefore, we conducted a workshop both for people involved in planning centralisations of specialist cancer services elsewhere and for those involved in planning centralisation of non-cancer specialist services (see Chapter 13). Through this workshop we explored factors influencing applicability of the lessons to different settings and developed lessons that could be of use in these settings.

Data collection and recruitment

Stakeholder preferences for centralisation: London Cancer, Greater Manchester Cancer and national control (research question 1)

Recruitment to the DCE was arranged by the research team and Quality Health (Chesterfield, UK) (which, at the time, administered the NCPES). The DCE questionnaire included a cover letter and an information sheet that included study details, what participating would entail and information on data management and storage. We recruited the three stakeholder groups as follows.

Patients (postal or online survey)

Quality Health used the NCPES database to identify cancer patients who had agreed to take part in further research. A sample of these patients were sent a copy of the DCE questionnaire and study information by post, and were invited to return the questionnaire by post or online.

General public (online survey)

Quality Health recruited members of the public by advertising the survey through health-related (but non-cancer) charities’ websites, newsletters and e-mail listservs. Advertisements included a link to the online questionnaire and associated study information.

Professionals (online survey)

The research team identified organisations associated with relevant professionals (including surgeons, nurses, dieticians and physiotherapists) in London, Greater Manchester and nationwide, including Royal Colleges, professional organisations and National Cancer Research Institute (London, UK) Clinical Study Groups. We advertised the study through these organisations’ websites, newsletters and e-mail listservs. The advertisements included a link to the online questionnaire and associated study information.

Finally, we provided links to the online questionnaires for our stakeholder groups in the RESPECT-21 (REorganising SPECialisT cancer surgery for the 21st century) newsletter.

Implementation and sustainability of change: London Cancer and Greater Manchester Cancer (research questions 2 and 3)

Potential interviewees were identified using documentary evidence and ‘snowball’ sampling, and were contacted via e-mail or telephone. Interviewees were given at least 48 hours in which to consider the study information and interviews were conducted only after fully informed and written consent had been obtained. Interviews lasted approximately 50 minutes and were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. Non-participant observations were conducted with fully informed consent from the chairperson and members. All documents analysed were either in the public domain or obtained from local stakeholders.

Data collection for other research components

Our approach to data requests for the quantitative and cost-effectiveness analyses is presented in the relevant findings chapters (see Chapters 8, 9 and 10), and our approaches to recruitment and data collection for our stakeholder workshop are presented in Chapter 13.

Synthesis of approaches

We employed a mixed-methods case study approach to combine the above methods. The case study method permits development and testing of theories on how change processes interact with the context in which they take place. In our cases, we considered governance of the changes in both areas (i.e. overarching and at pathway level), and a number of services for each cancer pathway, covering specialist centres, local units that lost specialist surgery activity through centralisation and local units that had not been providing specialist surgery before centralisation (see Figure 3). A multiple case study approach – in this case, the overarching governance and implementation of change and the impact on organisation of services in Greater Manchester Cancer and London Cancer – allowed the analysis to be conducted in different organisational contexts.

The analysis was designed to enhance understanding of MSC in specialist cancer surgical services from several important perspectives. First, the DCE was developed to provide insights on stakeholder priorities for changes of this kind and this helped to inform the focus of the quantitative analyses of the impact of the London Cancer changes on provision of care, clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness. We used in-depth qualitative analysis of planning, implementing and sustaining change to develop explanations of these effects, while focusing on contextual influences (both within the analysis and through our stakeholder workshop) to support generalisability beyond the settings under investigation.

Presenting qualitative data

When presenting interview quotations, we use anonymised participant identifiers. The identifiers for each level of our sample are presented in Table 3. For each quotation, we also present a short statement of the individual’s role (e.g. urological cancer surgeon, clinical nurse specialist) and geographic location in which they were based. For document quotations, we state the document sources. For quotations from non-participant observations and documents we state the event and date on which it took place (e.g. project board meeting, 25 December 2010).

Changes from our final protocol

We summarise protocol amendments in Chapter 1, Overview of the research project. In addition, following our final protocol amendment, it emerged that because of issues with the NCPES data set we could not analyse patient experience quantitatively as originally planned (see Chapter 9 and Appendix 4, Table 20). Instead, we used our qualitative data set to explore staff perceptions of patient experience (see Impact on patient experience).

Ethics approvals

Given our proposed methods (i.e. a national survey for the DCE, along with stakeholder interviews and non-participant observations for our analysis of implementation and sustainability), we believed that this study warranted full NHS ethics review and we obtained full ethics approval from the National Research Ethics Service Ethics Committee Yorkshire & Humber – Leeds East (reference 15/YH/0359) in July 2015.

Three substantial amendments to our ethics approval were requested:

-

In June 2016, we provided additional detail on the DCE survey tool and recruitment activity (for both DCE and qualitative work). This amendment was approved in June 2016.

-

In November 2018, changes were made to the study design (including focusing quantitative analyses on London Cancer only and extending qualitative work in London Cancer for a longer period). This amendment was approved in December 2018.

-

In August 2019, the data set analysed in the quantitative study and details of research team were changed. This amendment was approved in September 2019.

In addition, we requested non-substantial amendments in February 2016 (i.e. updates to recruitment documentation) and in May 2019 (i.e. notification of study extension). In support of data collection in our studied areas, we obtained local research governance permissions for all relevant organisations (see Appendix 1, Table 18).

Patient and public involvement

From the planning stage onward, PPI played a pivotal role in this study. We worked with several named cancer survivors since 2015, and these patients shaped our research questions, approach to data collection, interpretation of findings and dissemination of findings. We provide a detailed summary of our approach to PPI and the many ways in which it enhanced our work in Appendix 2.

Dissemination

This was a formative evaluation. Over the course of the study, we shared findings, as they developed, with a wide range of local and national stakeholders. One important mechanism for this was through our research management and governance arrangements. We met quarterly with our Research Strategy Group (RSG), which included all RESPECT-21 study collaborators, including clinical leaders of London Cancer and Greater Manchester Cancer, and the relevant pathway leads and patient representatives who had been involved with planning the changes. We shared our findings as they developed, which both strengthened our interpretation and supported our approach to dissemination. Similarly, our SSC included a wide range of national clinical and patient stakeholders (see Appendix 9). On an annual basis, we shared developing findings to ensure wider awareness and uptake of our findings.

In terms of wider dissemination, we presented our developing findings on stakeholder preferences, implementation and costs of implementation at relevant research conferences. We published our findings (open access) in high-impact peer-reviewed journals, and produced accessible one-page summaries of published analyses (see Acknowledgements, Publications). We shared these publications with our dissemination list of over 200 stakeholders. We also presented findings to meetings of relevant stakeholders, including the participating cancer networks, patient representative groups and wider system governance (e.g. regional NHS England bodies).

To develop broader ownership of the research, we shared a quarterly newsletter with our stakeholders, which detailed progress of the work, key updates on team activity and interviews with team members (including clinical and patient representatives).

As outlined above [see How lessons might apply in other contexts: London Cancer, Greater Manchester Cancer and national control (research question 7)] and in Chapter 13, toward the end of our study we shared and discussed our key findings with a wide range of cancer and non-cancer stakeholders at an online workshop.

Finally, all of these outputs were made permanently available to the public via our regularly updated website.

Chapter 3 A discrete choice experiment to analyse preferences for centralising specialist cancer surgery services

Overview

Parts of this chapter are reproduced or adapted with permission from Vallejo-Torres et al. 48 This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited (see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

What is already known?

-

Centralising specialist cancer surgical services is expected to reduce variations in quality of care and improve patient outcomes.

-

One disadvantage of centralisation is that it leads to an increase in travel demands on patients and families.

-

Aligning system changes with stakeholders’ preferences might increase the likelihood of successful implementation.

What does this chapter add?

-

Patients’, health professionals’ and the public’s preferences were particularly influenced by the risk of complications, the risk of death and the access to specialist MDTs, whereas travel time was considered the least important factor.

-

Individual preferences were found to be consistent with the major goals of centralising cancer surgery services.

Background

The rationale for centralising specialist cancer surgery services is to reduce unacceptable variation in quality of care and to improve patient outcomes. 33 However, one disadvantage of centralisation is that it leads to increased travel demands, limiting access to high-quality care and to support from family and friends. 53 Therefore, there are advantages and disadvantages of centralising specialist cancer surgery services. These trade-offs need to be taken into account when assessing the implementation of MSCs of this kind.

The aim of this chapter was to examine preferences of patients, health professionals and the general public for the characteristics associated with centralising specialist cancer surgery services in England, including the relative importance of different service characteristics and how preferences varied between groups.

Method

Preferences were explored using a DCE. 54 In DCEs, respondents are typically presented with a series of questions, asking them to choose between two or more alternatives that describe a service in terms of a set of characteristics (i.e. attributes). The DCE allowed the evaluation of both the attributes service respondents would prefer to receive and the trade-offs that respondents are willing to make between attributes.

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Proportionate Review Sub-committee of the National Research Ethics Service Committee Yorkshire & the Humber – Leeds. DCE guidelines were followed for study design and analysis. 47,54

Sampling and recruitment

Discrete choice experiment responses were obtained from three groups: (1) cancer patients (target sample size n = 200), (2) members of the public (n = 100) and (3) health professionals involved in the treatment of patients with cancer (n = 100). Data were collected by hard-copy postal questionnaires (which were sent to patients) and online surveys (which were made available to the public, patients and health professionals). The sample was recruited through a number of routes (see Chapter 2 for more details).

Attributes and attribute levels

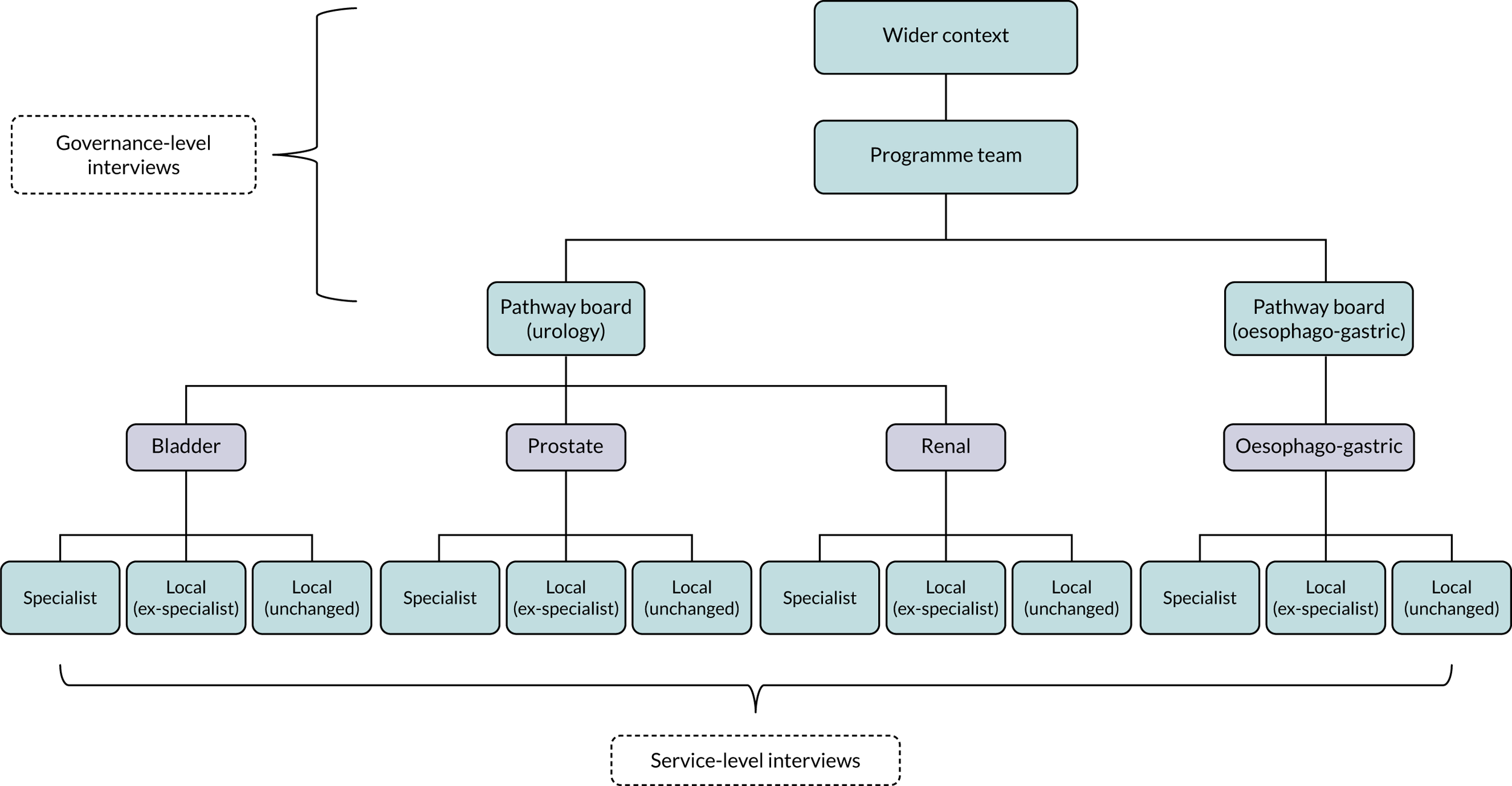

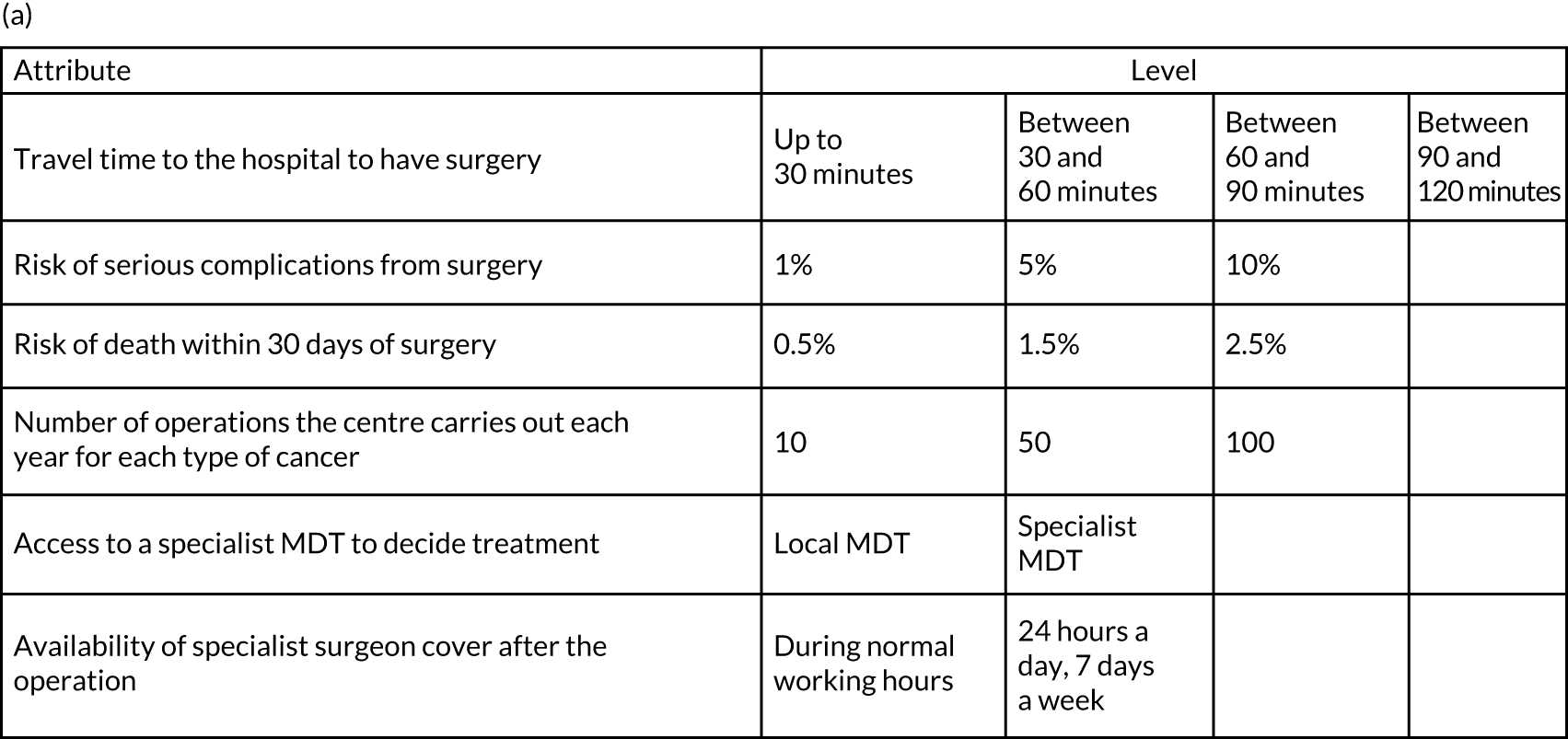

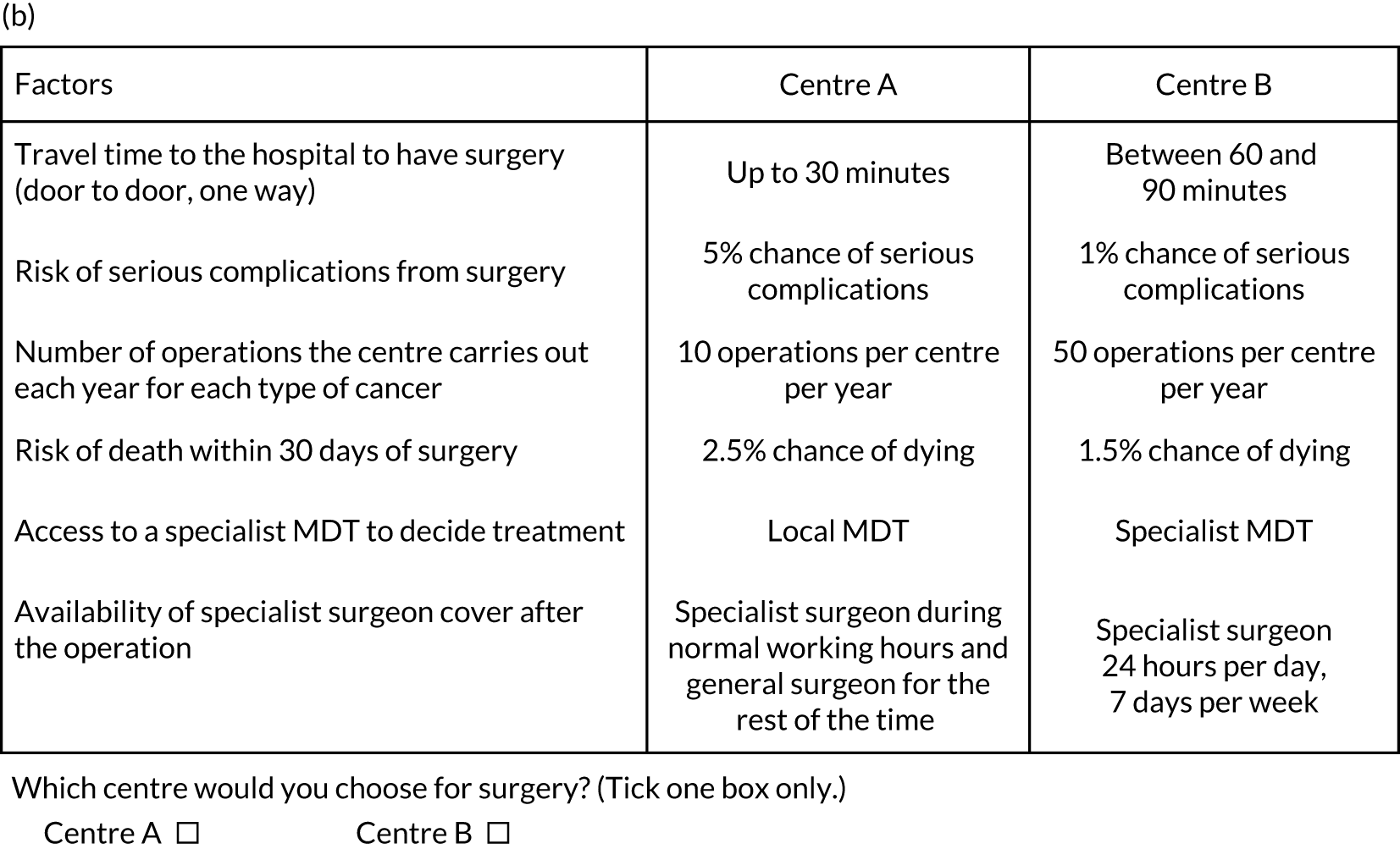

Analysis of the information from planning documents, covering development, planning and implementation of the changes33,34,55,56 and responses from the questionnaire,57 identified the following six attributes as those that are most likely to be important to respondents and likely to change as a result of centralising specialist cancer surgical services: (1) travel time to hospital, (2) risk of serious complications from surgery, (3) risk of death within 30 days of surgery, (4) number of operations the centre carries out each year, (5) access to a specialist MDT and (6) availability of specialist surgeon cover after the operation (Figure 4). The levels of each attribute were based on planning documents (as above) and input from the RESPECT-21 RSG. Descriptions were developed for each of the attributes to help participants understand the nature of each attribute that they were being asked to consider (note that the complete questionnaire is available in supplementary material for Vallejo-Torres et al. 48).

FIGURE 4.

Discrete choice experiment survey design and format. (a) Attributes and levels used in the DCE; and (b) example of a DCE choice set. Adapted with permission from Vallejo-Torres et al. 48 This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited (see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Adapted with permission from Vallejo-Torres et al. 48 This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited (see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Questionnaire design

Respondents were asked to choose their preferred option from a series of pairwise choices (i.e. in which of two fictitious centres would they prefer to have surgery). Similarly, health professionals were asked in which centre they would prefer their patients to have surgery. Each centre was described by a unique combination of different levels of the attributes (see Figure 4 for an example of a DCE question).

In addition, the questionnaire included an initial question that asked respondents to rank the six attributes according to their overall importance, from 1 (most important) to 6 (least important). Information on demographics, socioeconomic status and cancer-related experience was also collected.

Data analysis

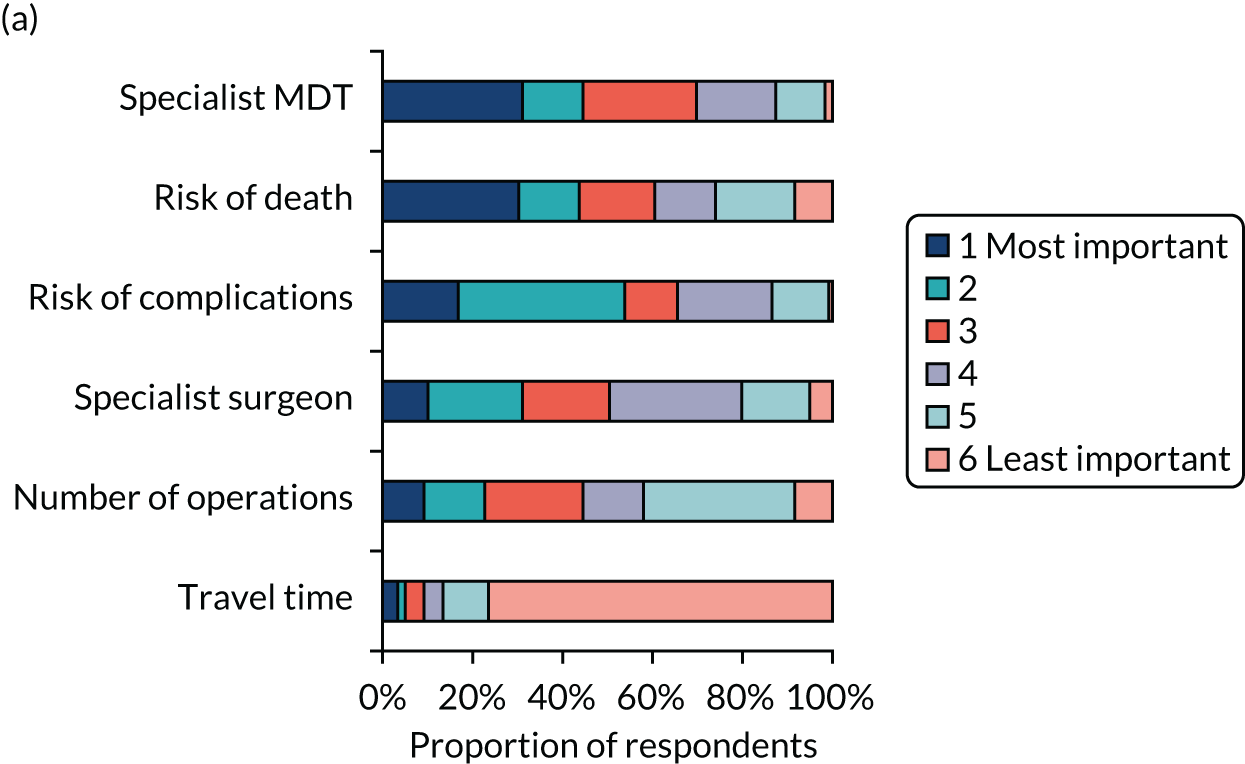

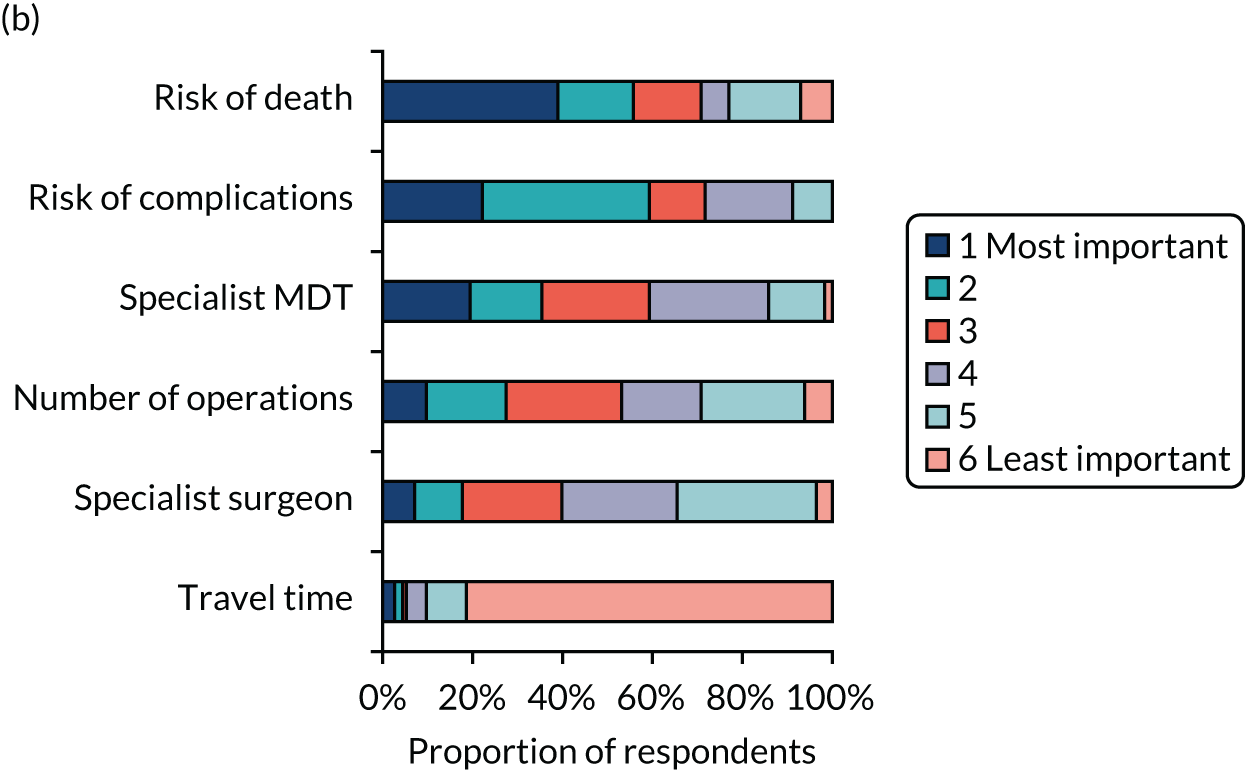

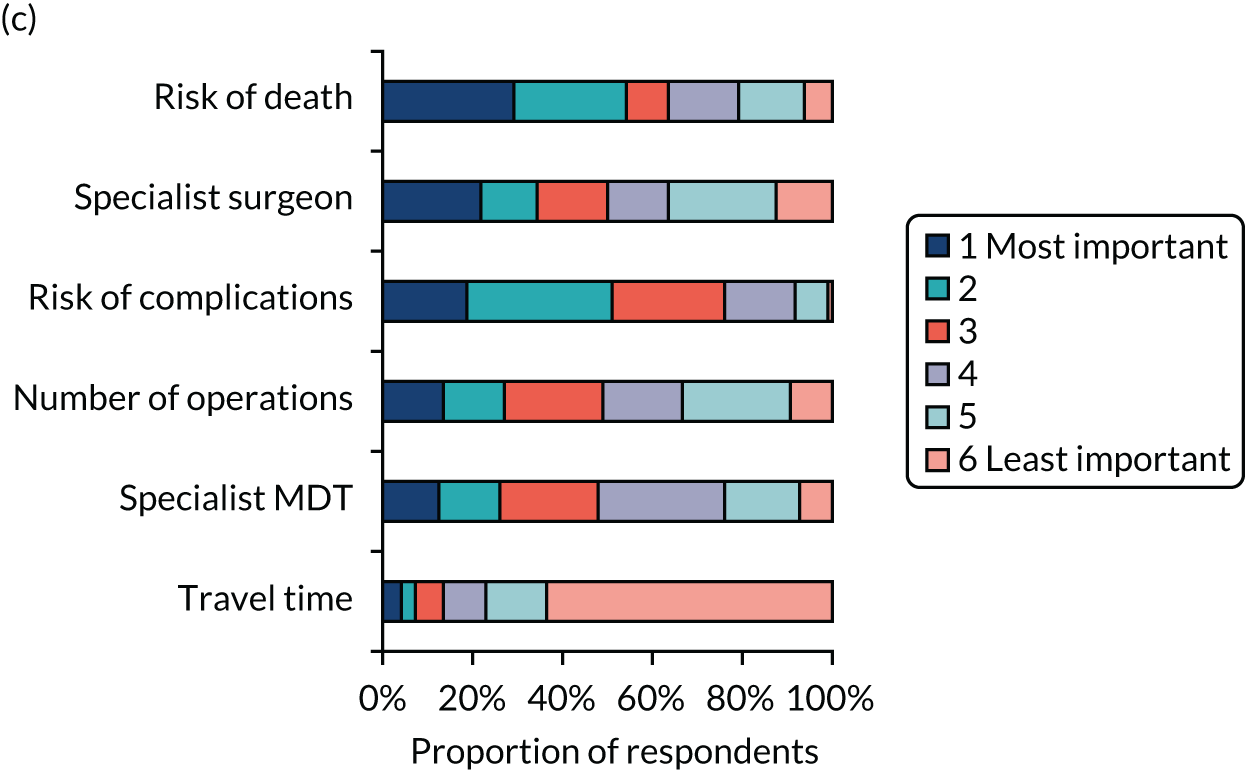

Responses to the ranking questions are presented graphically (Figure 5) and we measured inter-rater agreement using kappa statistics. 58

The DCE data were analysed using a conditional logit regression model in which the outcome was centre preference (i.e. A or B) and the variables in the equation were the individual attributes. We ran the model on the whole sample, as well as stratifying participants by the three groups. We tested for differences in preferences between the groups using chi-squared tests.

We included the travel time attribute as a continuous variable, taking the higher-end value of each interval (i.e. 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes). This specification allowed marginal rates of substitution with respect to this variable to be computed.

In addition, we used the regression analysis results to calculate the predicted probabilities of choosing cancer surgical services with attribute levels corresponding to the goals of centralisation, compared with a non-centralised service. Specifically, we compared the probability that a respondent would choose a hypothetical non-centralised service [which was defined as 30 minutes’ travel time, 10 operations carried per year at the centre (for both attributes these were the lowest levels included in the study), no access to a specialist MDT, specialist surgeon cover during normal hours only, a 5% risk of complication and a 1.5% risk of death] against various different centralised service scenarios. In each case, travel time was fixed at 120 minutes and the number of operations at the centre was increased to 100 operations per year (i.e. the highest levels included in the study). In addition, the following characteristics were added individually and then jointly: (1) access to a specialist MDT, (2) access to specialist surgeon cover 24 hours per day, 7 days per week (24/7), (3) risk of complications reduced to 1% and (4) risk of death reduced to 0.5%.

All analyses were undertaken using the software package Stata® version 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Respondents’ characteristics

From July to November 2016, we obtained 444 responses (patients, n = 206; health professionals, n = 111; members of the public, n = 127). DCE questions were completed in full by 199 patients, 109 health professionals and 125 members of the public. Our analysis was a complete-case analysis using only these respondents’ answers. Table 4 provides a summary of demographic characteristics by group.

| Characteristic | Respondent type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Public | Health professionals | |

| Sex: female, n (%) | 41 (21) | 85 (68) | 45 (41) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 69 (9) | 46 (16) | 48 (8) |

| Ethnicity: white, n (%) | 186 (94) | 107 (86) | 87 (80) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Prostate cancer | 67 (34) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Bladder cancer | 61 (31) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Kidney cancer | 46 (23) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Oesophagus and stomach cancer | 38 (19) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) |

| Other type of cancer | 17 (9) | 19 (15) | 5 (5) |

| Time from diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| This year | 0 (0) | 5 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Last year | 107 (54) | 6 (5) | 2 (2) |

| 2 years | 45 (23) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) |

| 3 years | 11 (6) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| 4 years | 9 (5) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| ≥ 5 years | 14 (7) | 11 (9) | 1 (1) |

| Current stage of treatment, n (%) | |||

| Waiting for decision | 4 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Scheduled for surgery | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Schedule for other treatment | 4 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Already had surgery | 115 (58) | 17 (14) | 5 (5) |

| Other treatment | 64 (32) | 9 (7) | 4 (4) |

| Prefer not to have treatment | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Educational qualification, n (%) | |||

| No formal qualifications | 43 (22) | 1 (1) | |

| O Level or GCSE | 40 (20) | 6 (5) | |

| Ordinary National Certificate or BTEC | 12 (6) | 1 (1) | |

| A Level | 9 (5) | 2 (2) | |

| Higher education qualification | 26 (13) | 11 (9) | |

| Degree or higher degree | 44 (22) | 100 (80) | |

| Other educational attainment | 9 (5) | 1 (1) | |

| Employment status, n (%) | |||

| Full-time employed | 26 (13) | 59 (47) | |

| Part-time employment | 16 (8) | 13 (10) | |

| Homemaker | 4 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| Student (in education) | 0 (0) | 9 (7) | |

| Retired | 135 (68) | 30 (24) | |

| Unemployed and seeking work | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Unemployed and unable to work for health reasons | 4 (2) | 4 (3) | |

| Other employment status | 7 (4) | 5 (4) | |

| Health professional specialty, n (%) | |||

| Surgeon | 61 (56) | ||

| Oncologist | 6 (6) | ||

| Nurse | 22 (20) | ||

| Other specialty | 20 (18) | ||

| Place of residence, n (%) | |||

| London | 39 (20) | 63 (50) | 27 (25) |

| Greater Manchester | 50 (25) | 8 (6) | 14 (13) |

| Rest of England | 103 (52) | 52 (42) | 65 (60) |

| Sample size, n | 199 | 125 | 109 |

Simple attribute ranking

A total of 328 respondents (patients, n = 119; members of the public, n = 113; health professionals, n = 96) provided full responses to the ranking question. Figure 5 shows graphically the responses for each of the three groups separately. The kappa statistic overall was 0.1166. For each subgroup, the kappa statistics were 0.0765, 0.1268 and 0.1501 for health professionals, patients and the general public, respectively, representing ‘slight’ agreement among rankers in each case. 59

FIGURE 5.

Attribute rankings by (a) patients (n = 119); (b) members of the public (n = 113); and (c) health professionals (n = 96). Adapted with permission from Vallejo-Torres et al. 48 This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited (see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Adapted with permission from Vallejo-Torres et al. 48 This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited (see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

When using this method of ranking, risk of death and risk of complications were ranked highly in each sample, and travel time was consistently considered to be the least important factor by each group. However, we did observe some differences across groups. For example, patients appeared to consider the availability of a specialist MDT highly important, whereas health professionals considered the availability of a specialist surgeon 24/7 more important.

Discrete choice experiment analysis

We found no statistically significant differences in the effects of the attributes between groups, except for the risk of complications, which had a slightly larger impact in the public sample compared with the patient sample. Therefore, we focused on the model conducted on the whole sample (Table 5).

| Attribute | Level | Coefficient (95% CI) | Willingness to travel to the hospital (minutes): MRS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Travel time to the hospital to have surgery | Minutes | –0.002 (–0.003 to –0.0002) | |

| Risk of serious complications from surgery | Percentage | –0.132 (–0.149 to –0.116) | 75 |

| Risk of death within 30 days of surgery | Percentage | –0.544 (–0.615 to –0.473) | 307 |

| Number of operations the centre carries out each year for each type of cancer | Number | 0.009 (0.007 to 0.010) | 5 |

| Access to a specialist MDT to decide treatment | Local MDT | ||

| Specialist MDT | 0.414 (0.322 to 0.507) | 234 | |

| Availability of specialist surgeon cover after the operation | Specialist surgeon during normal working hours and general surgeon for the rest of the time | ||

| Specialist surgeon 24/7 | 0.308 (0.219 to 0.397) | 174 | |

| Sample size: observations/respondents | 6834/433 |

We observed that, as expected, individuals preferred to have surgery in a centre requiring shorter travel time, where the risk of complications and the risk of death were lower, the number of operations carried out each year was larger, and there was access to a specialist MDT and specialist surgeon cover 24/7. We found that participants were willing to travel 75 minutes longer to reduce the risk of complications by 1% and over 5 hours longer to reduce their risk of death after surgery by 1%. Participants’ willingness to travel increases by 5 more minutes for every additional surgery carried out by the centre each year, and by approximately 4 and 3 hours to have access to a specialist MDT and access to specialist surgeon cover, respectively.

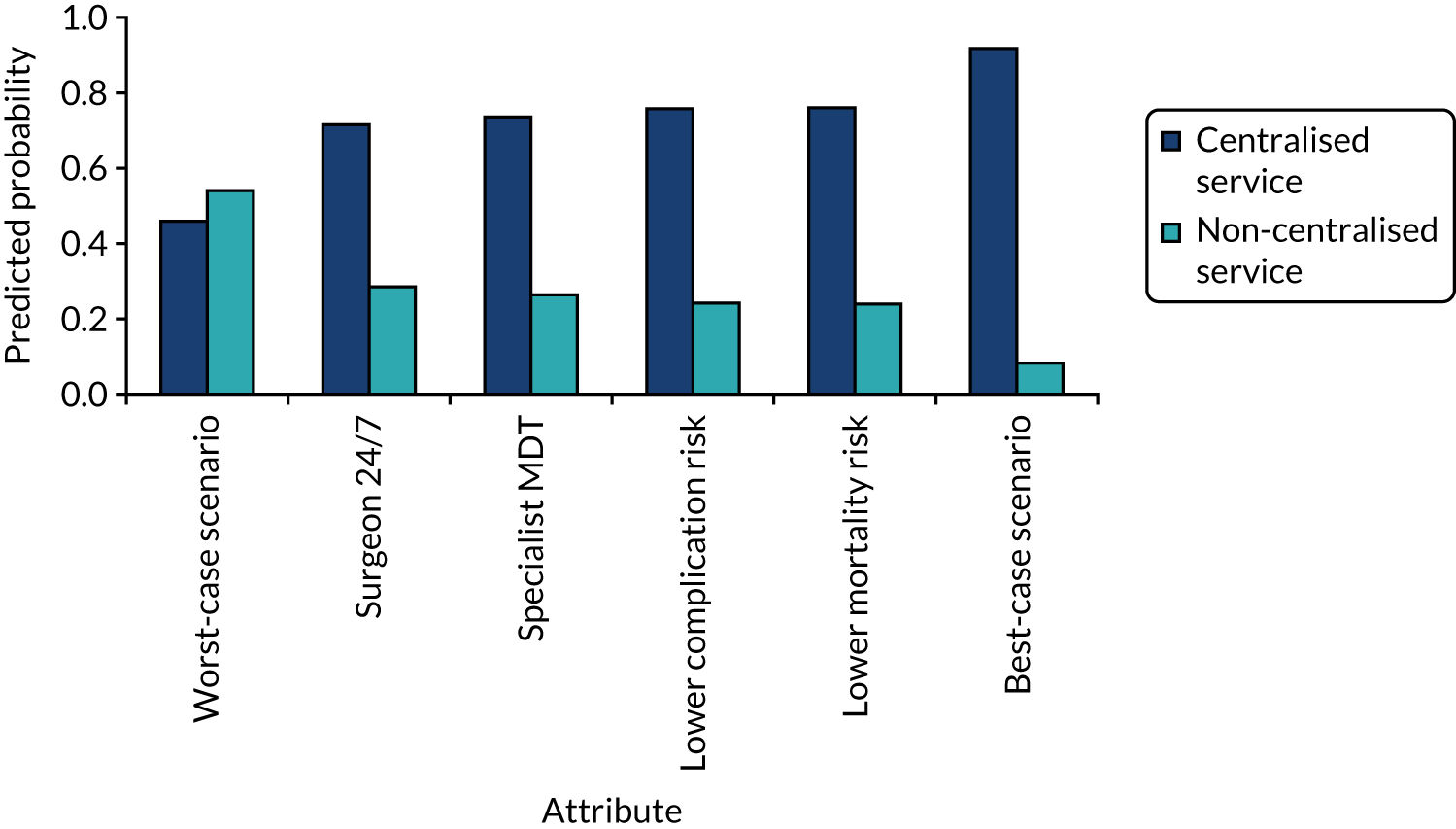

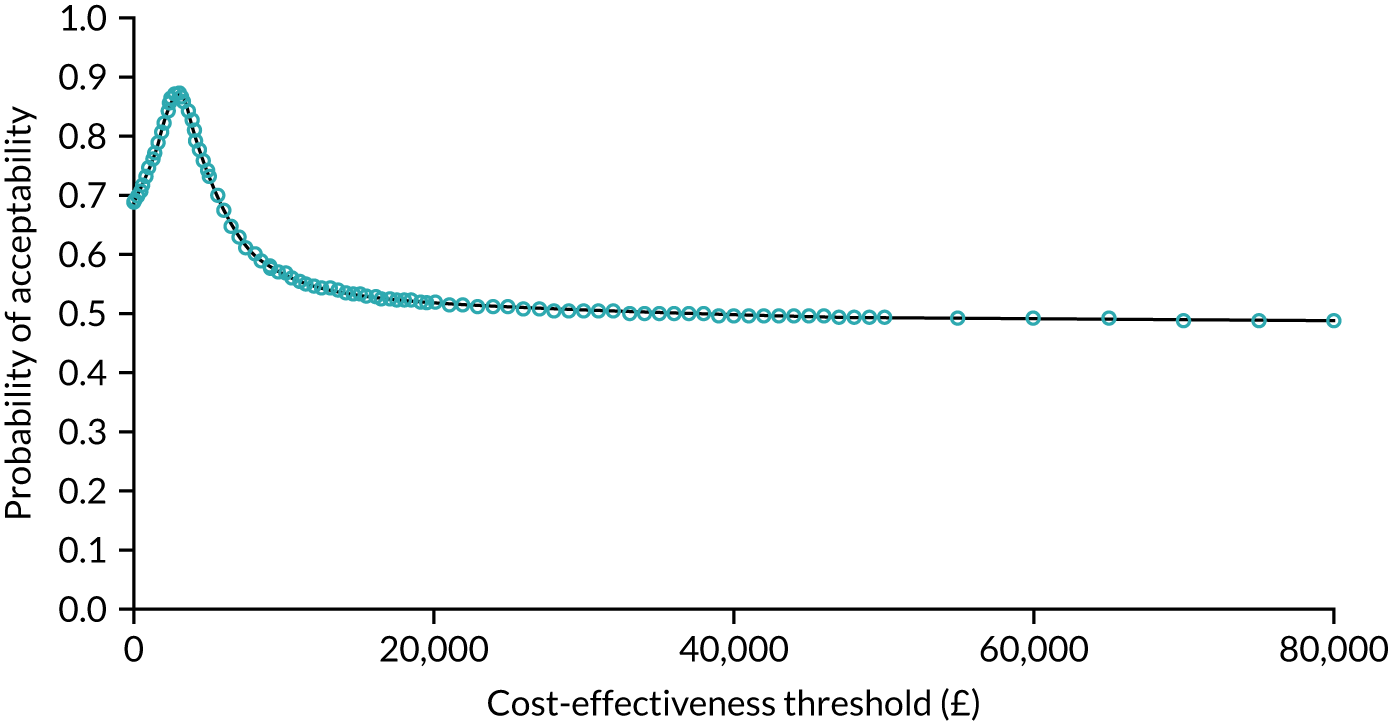

The probability that respondents would choose a centre with attribute levels corresponding to a centralised service compared with a non-centralised service is presented in Figure 6. Compared with a centre requiring 30 minutes’ travel time that carries out 10 operations per year (i.e. a generic non-centralised service), respondents are less likely to choose a centre that carries out 100 operations a year, but for which the travel time increases to 120 minutes, holding the rest of the attributes constant (i.e. ‘worst-case scenario’). However, the probability that respondents would choose the centralised service increases if the centre also achieves the goals with respect to each of the other attributes. The probability that respondents would choose the centralised service is 72% if the centre provides access to specialist surgeon cover 24/7, 74% if there is access to a specialist MDT, 76% if the risk of complications is reduced from 5% to 1% and 76% if the risk of death is reduced from 1.5% to 0.5%. If the centralised service achieves all of these changes in the attributes, at the expense of increasing travel time from 30 minutes to 120 minutes, defined as the ‘best-case scenario’ in Figure 6, then the probability that respondents would prefer to have surgery in the centralised service reaches 92%.

FIGURE 6.

Predicted probabilities of choosing centralised cancer surgery services. Adapted with permission from Vallejo-Torres et al. 48 This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited (see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Adapted with permission from Vallejo-Torres et al. 48 This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited (see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Discussion

Principal findings

In this study, we explored patients’, health professionals’ and the public’s preferences for centralising specialist cancer surgery services using a DCE. We found that, consistently across the three groups, respondents’ preferences behaved as expected. Individuals preferred attributes with better values (e.g. shorter travel times; lower risk of death and of complication; and access to more specialised centres, teams and surgeons). We also found that preferences were particularly influenced by the risk of complications, the risk of death and the access to a specialist MDT. Travel time was considered the least important factor. Preferences were, therefore, found to be consistent with the goals of centralisation.

The estimated probability that participants would choose to have surgery in the best-case scenario, with a centre meeting the changes corresponding to the aims of centralisation, was very high, estimated at 92%. However, it is important to note that the impact on mortality and complications in this best-case scenario might not be achieved. Furthermore, if centralisation of cancer surgery services implied an increase in travel time to attend a hospital that carries out a larger number of operations in a year, but that does not offer the additional benefits associated with centralisation, then participants would prefer to have surgery in a non-centralised centre.

Strengths and weaknesses

The analysis applied a DCE that allowed the evaluation of both attributes service respondents would prefer to receive and the trade-offs that respondents are willing to make between attributes.

The analysis was undertaken with responses from over 400 participants, including patients with each type of cancer under evaluation, health professionals and members of the general public. Content validity of the DCE was obtained by grounding the attributes and levels of the changes expected from centralisation based on careful reviews of planning documents and on responses from initial questionnaires to identify the most important factors. The questionnaire was carefully tested and revised during piloting.

We acknowledge several limitations. DCEs elicit hypothetical choices and, therefore, might lack external validity if individuals do not make the same choices in real-life situations. The representativeness of the sample responding to the questionnaire might be limited, as the generalisability of the findings depends on individuals elsewhere having similar preferences. Although the selection of attributes included in the DCE was carefully considered, we acknowledge that there might be other factors affected by centralisation not included in our analysis that may also be considered important for individuals. Similarly, we explored patients’, health professionals’ and the public’s views, but the views of other groups might also be important in the planning, implementation and delivery of MSCs, such as hospital managers and health-care decision-makers.

Another limitation is that in this study we have analysed preferences for specialist cancer surgery services in general, and these preferences might vary by different types of cancer.

Comparison with other studies

This study provides, to our knowledge, the first evaluation of individual preferences with respect to changes associated with the centralisation of cancer surgical services. Previous studies have explored the impact of travel on cancer patients’ experiences of treatment, finding a paucity of research in this area and inconclusive evidence. 53

Implications

There are several implications of our study. First, planners who are redesigning services might consider and measure the impact of the reorganisation on the factors identified as being important in this study. Health policy in England has focused on improving access to services; however, our findings highlight that, in the context of centralising specialist surgery services for cancer, people are willing to trade travel time for better outcomes and quality of care. For centralisation to be judged favourably by patients, the public and health professionals, compared with a non-centralised model, it needs to demonstrate improvements in outcomes (e.g. complications and mortality) and/or delivery (e.g. in terms of postoperative surgeon care and specialist MDT input). In addition, although travel time was identified as the least important factor, the DCE analysis showed that this factor still plays a role in people’s preferences for care and, therefore, plans for transport support and parking facilities for patients and their families would also improve individuals’ views towards centralisation.

Chapter 4 Implementing major system change in specialist cancer surgery: the role of provider networks

Overview

Parts of this chapter are reproduced or adapted with permission from Vindrola-Padros et al. 60 This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited (see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

What is already known?

-

MSC has multiple, sometimes conflicting, goals and involves implementing change processes across a number of organisations.

-

Evidence of networks has demonstrated their capability to attempt to address ‘wicked problems’ that are characteristic of MSC in complex, although not uncontested, ways.

What does this chapter add?

-

This chapter provides a new understanding of MSC by discussing the strategies used by London Cancer to facilitate MSC in a health-care context in the absence of system-wide authority.

-

MSC was a contested process in London Cancer. Actors across the network, including clinicians and patients, questioned the rationale for the changes, the clinical evidence behind them and the ways in which the changes were made.

-

A core central team composed of network leaders, managers and clinical–manager hybrid roles was able to drive changes forward by developing different forms of engagement with provider organisations, distributing leadership across vertical and horizontal layers, and maintaining constancy in central leadership over time.

Background

One example of MSC is the centralisation of specialist services. There are long-standing recommendations to centralise specialist services,3,4 citing the potential to reduce variations in access, increase patient volumes and improve patient outcomes by increasing the likelihood of patients receiving care in hospitals that have a full range of experienced specialists and equipment to support provision of care. In the case of cancer, there is evidence that higher volumes of surgical cases are associated with improvements in clinical outcomes. 3,4 Despite these potential benefits, little is known about the processes by which centralisations of this kind are planned and implemented, the impact of changes on patients and staff, and which features influence implementation.

Implementing MSC is hard, as it has multiple, sometimes conflicting, goals and involves change processes across numerous organisations,61,62 for instance the reconfiguration of patient pathways, which might depend on the co-ordination of care across many organisations. 63 Despite growing evidence of the impact of centralisation in different areas of health-care delivery,51,61 there are still considerable gaps in knowledge regarding how MSC is planned and implemented. Recent papers have highlighted the potential negative consequences of MSC, as clinical teams, therapeutic relationships and collective identities may be disrupted, possibly without generating promised health-care benefits for the population. 64

In this chapter, we seek to develop a new understanding of MSC implementation by analysing the centralisation of specialist cancer surgery across four pathways (i.e. bladder cancer, prostate cancer, renal cancer and oesophago-gastric cancer) developed and implemented by a network of NHS provider organisations across a large part of London and neighbouring areas. Previous evidence on MSC has indicated that a combination of top-down and bottom-up leadership is required to implement changes at the system level. 1,61,62 However, the centralisation of specialist cancer surgery in this area was implemented during a wider context of profound organisational restructuring in England that removed key sources of top-down leadership. The Health and Social Care Act 201265 abolished the regional system-wide organisations identified as playing a central role in the implementation of MSC in other areas of health-care delivery. 61 Despite these changes, the provider-led network was able to complete the changes it sought to implement.

Method

Design

The study built on previous research exploring network leadership and evidence on the strategies used by networks to implement MSCs in health care. In this chapter, we focus on the role of the network in implementing the planned changes. 66

Data collection and sampling

We conducted a qualitative study of the centralisation of specialist oesophago-gastric, prostate, bladder and renal cancer surgery in London. The qualitative study focused on 10 sites. We combined documentary evidence (n = 100 documents), non-participant observations (134 hours) and interviews with stakeholders (n = 81) (sampling is shown in Table 6).

| Interviewee group | Number (n) |

|---|---|

| Network managers and other network staff members | 8 |

| Local context (e.g. commissioners, staff driving the centralisation and health-care leaders) | 9 |

| Patient representatives | 3 |

| Urology pathway board members | 4 |

| Oesophago-gastric pathway board members | 4 |

| Oesophago-gastric clinicians from provider organisations (specialist and local centres) | 14 |

| Urology clinicians from provider organisations (specialist and local centres) | 30 |

| Oesophago-gastric managers from provider organisations (specialist and local centres) | 2 |

| Urology managers from provider organisations (specialist and local centres) | 7 |

Data analysis

Interview transcripts, observation notes and documentary evidence were analysed using thematic analysis. 67

Results

Central network leadership drove the changes forward

The role of chief medical officer at a local academic health science partnership was established to oversee the design, planning and implementation of the changes. The chief medical officer was a clinician by background, but her clinical specialty was not involved in the centralisation. The chief medical officer was also based at an ‘independent’ organisation, in the sense that it was not a part of any of the provider organisations in the network. A network board (i.e. an independent skills-based board formed of experts external to London and chaired by a former cancer patient) was created to make clinically led recommendations for the model of care. The network board oversaw a bidding process in which provider organisations stated how they would host services as specialist centres and how they would work with the other providers in the network. Where prior consensus was not achieved and competing bids were submitted by provider organisations, the proposals were reviewed externally. These recommendations were agreed by the chief executives and medical directors of the network provider organisations. The chief medical officer and chairperson of the board were perceived by many managers and clinicians across the network as providing strong and objective leadership, with a clear vision and mandate to implement the changes outlined in the model of care.

The relative independence of the chief medical officer role and the board was seen by some members of the network as a factor that allowed the central leadership of the network to be seen as ‘neutral’. However, other actors in the network associated central leadership figures with dominant provider organisations, that is those organisations that obtained most of the specialist cancer workload as a result of the reconfiguration. Constancy in network leadership over time was also perceived to have enabled the implementation of changes, even in the light of the profound organisational restructuring of the health-care system during and after the 2012 reforms.

The central leadership team drew from existing evidence on the potential benefits of the centralising specialist cancer surgery and previous experiences of centralisation as a way to justify the need for the changes. Data were not always readily available and some interviewees spent a considerable amount of time searching for and collating data, and developing new sources when these were not available. There were some discussions about the quality, veracity and inclusivity of the data used to guide decisions on the reconfiguration. Some local surgeons expressed doubts about how the data were used.

Network managers supported leaders

The chief medical officer and the chairperson of the board played a central leadership role, but staff members in managerial and clinical roles across other layers of the network also played important roles. The network managers played an instrumental role in supporting leaders, mediating relationships across sites and facilitating the day-to-day requirements of the changes. The board appointed clinical leads to chair pathway boards and design the integrated cancer care pathways. 68

The network core team designated, arranged training for and supported leaders from each of these pathway boards and these leaders became a core leadership team that remained beyond the implementation of the changes. Leaders were selected for their skills in leading teams, engaging with a wide range of stakeholders and building relationships. Leaders needed to act in hybrid roles, that is having clinical knowledge, as well as managerial skills. An early planning document stated: ‘as we interview pathway directors, we will carefully screen for those with the leadership competencies to spread our culture quickly through the community’. 69 The screening process was based on the use of competency models and role-play simulations. 69 The appointed leaders took part in personal leadership development sessions.

Engagement across provider organisations

The network encouraged pathway leads to engage with a wide range of stakeholders within the network and ‘develop relationships with colleagues across the care pathway’. 69 These relationships were considered central aspects of their role objectives and the leadership development programme. Leaders used their own styles to create change. Successful implementation of changes was associated with leaders who were viewed as trustworthy, as having a clear vision and showing dedication, and as good at building relationships.

Planning the changes entailed the inclusion of representatives from all provider organisations. There was an expectation that if all organisations were involved during early stages, then the implementation of the changes would be smoother, as all organisations would have a sense of ownership of the new pathways, building momentum to drive the changes forward and sustain the changes over time.

This expectation of engagement, however, was practised in a context that was interpreted by some as infused with a spirit of competition for future surgical activity. There was also a concern that specialist centres would be ‘taking over’ the network and absorbing all of the specialist care, leaving local centres without the ability to retain surgical expertise and recruit new members of staff.

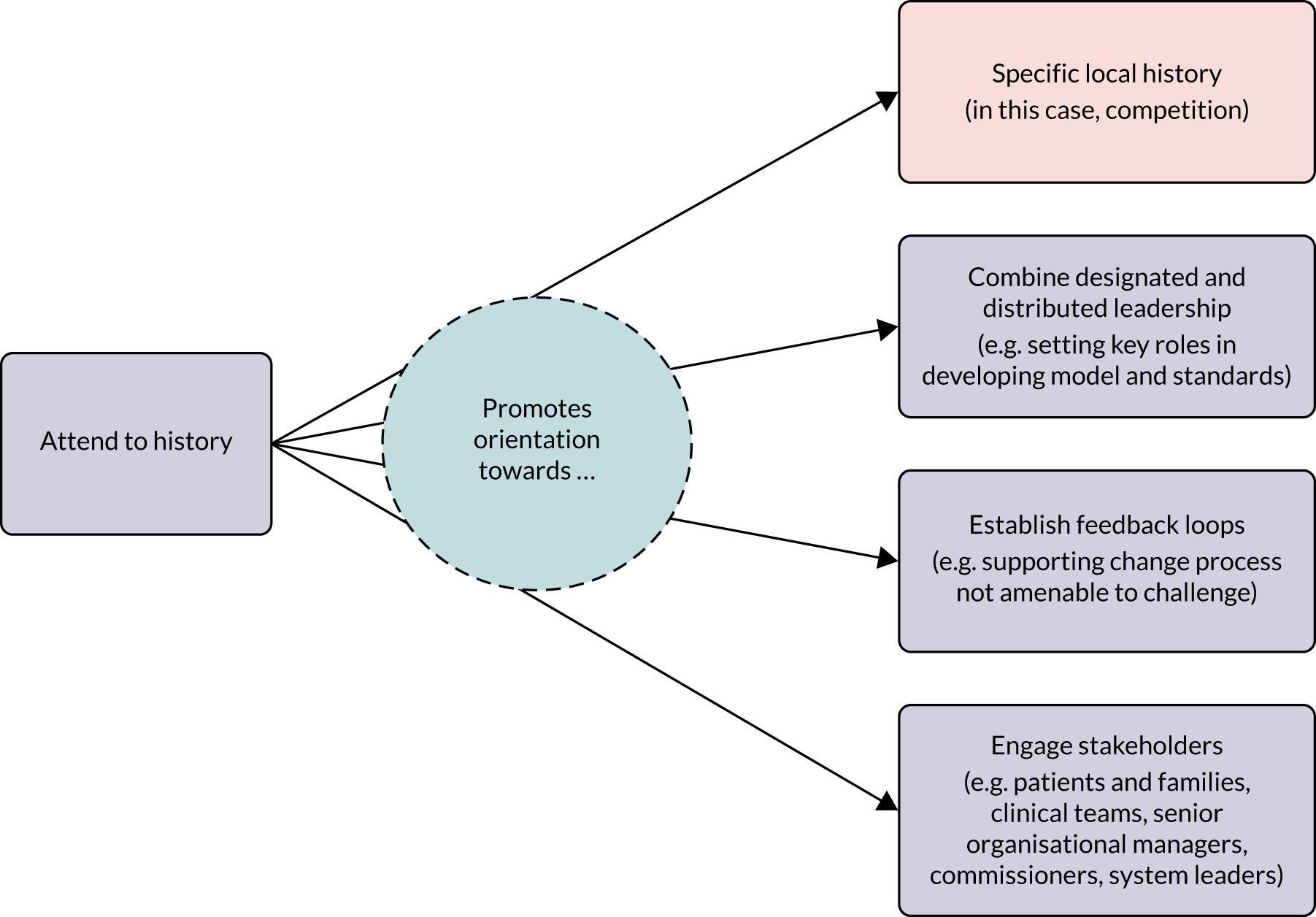

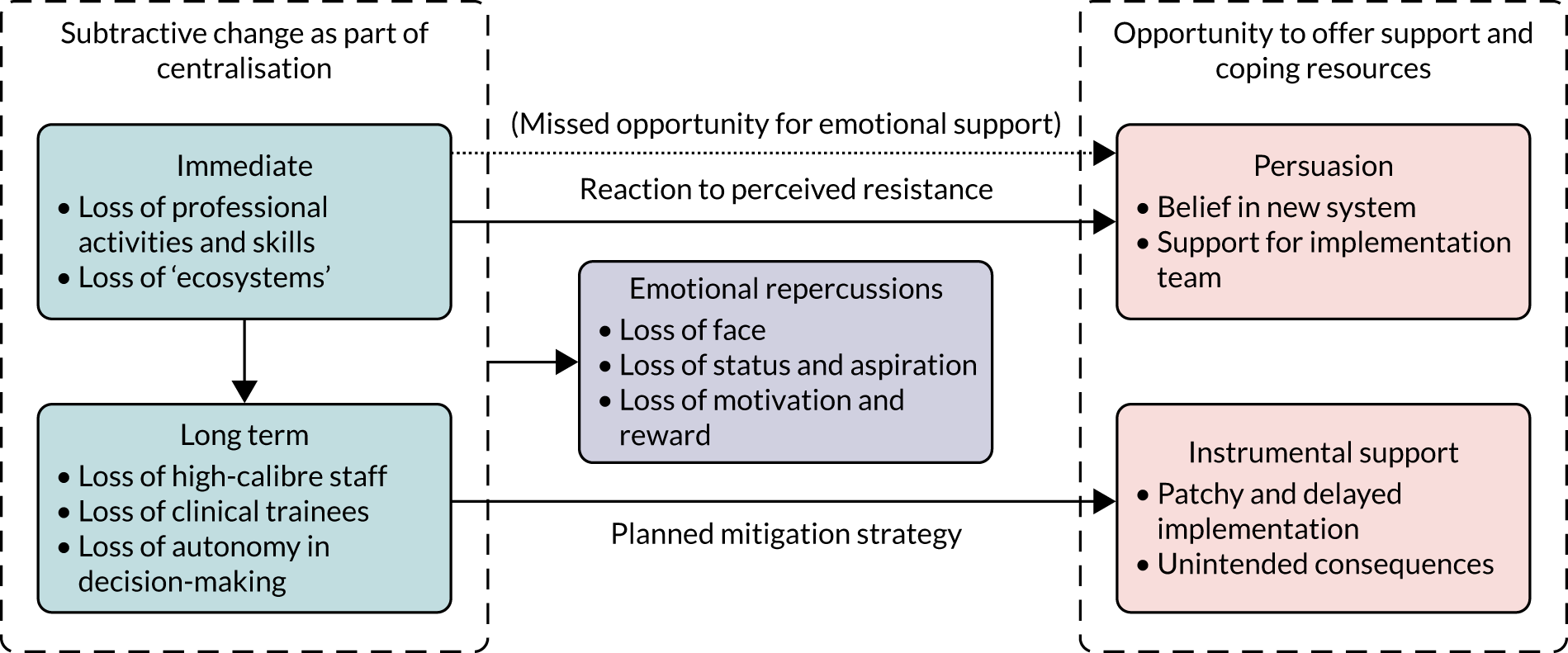

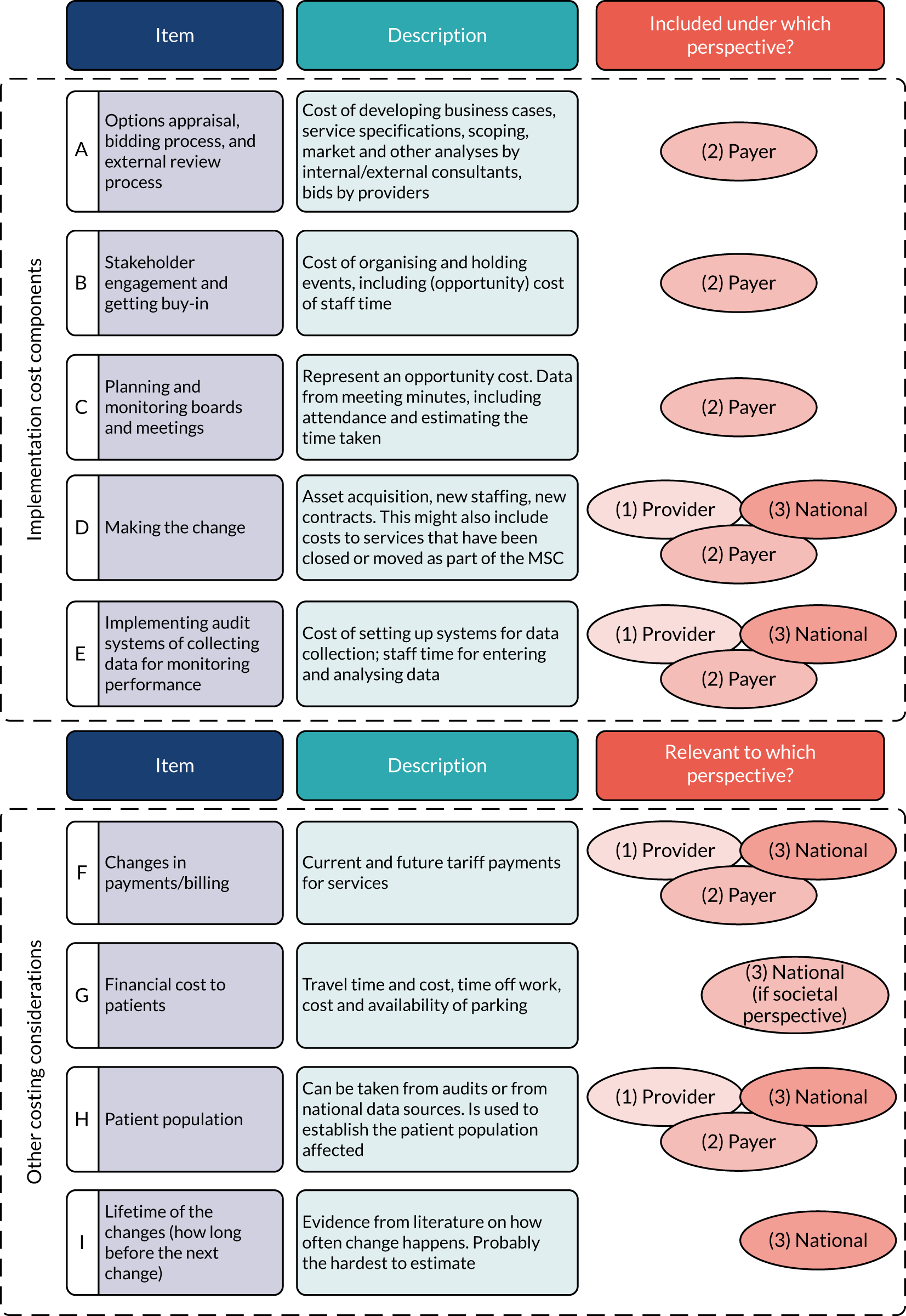

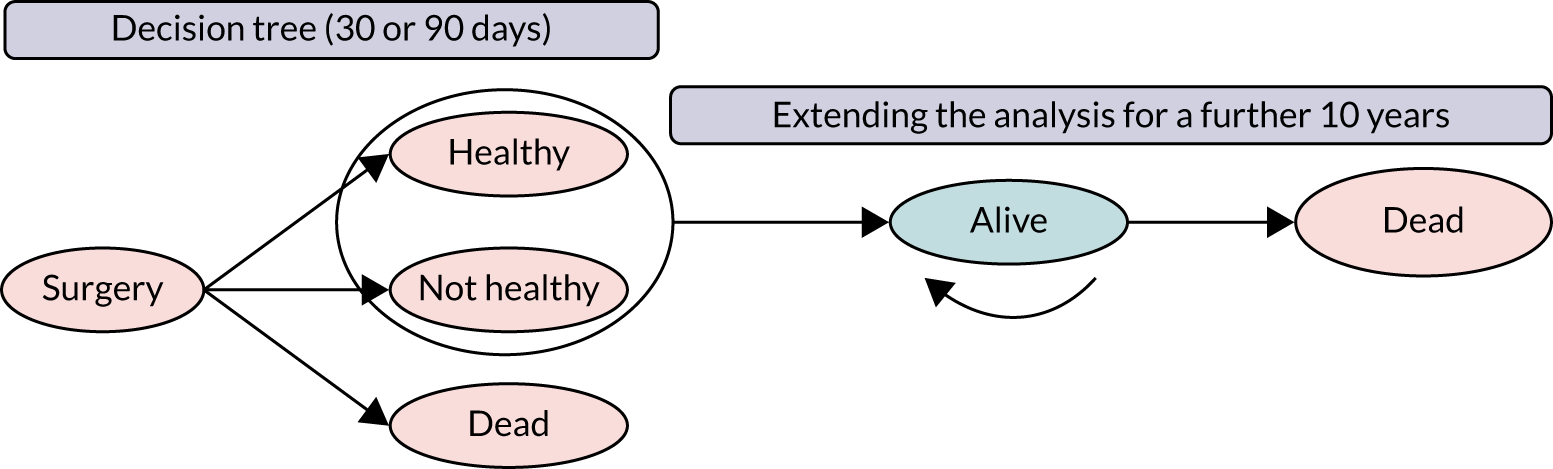

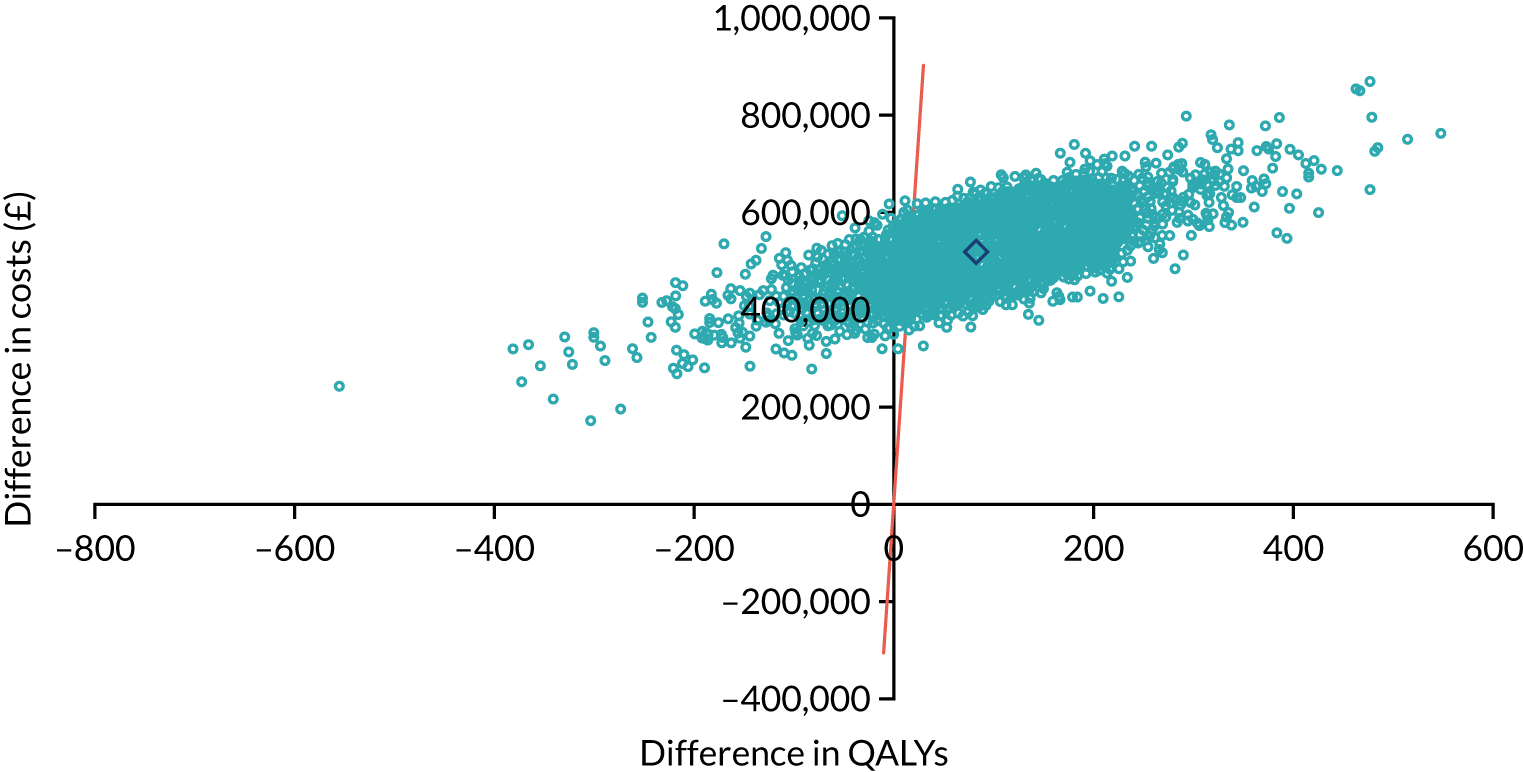

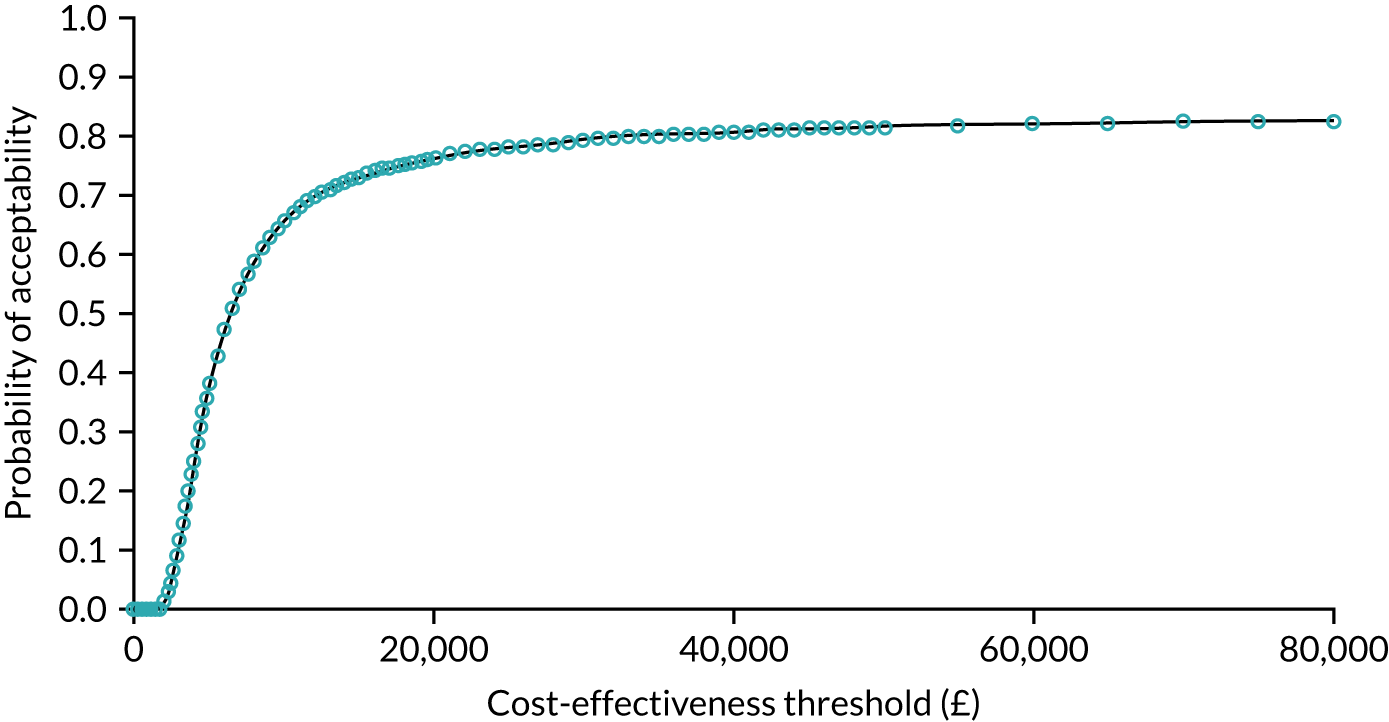

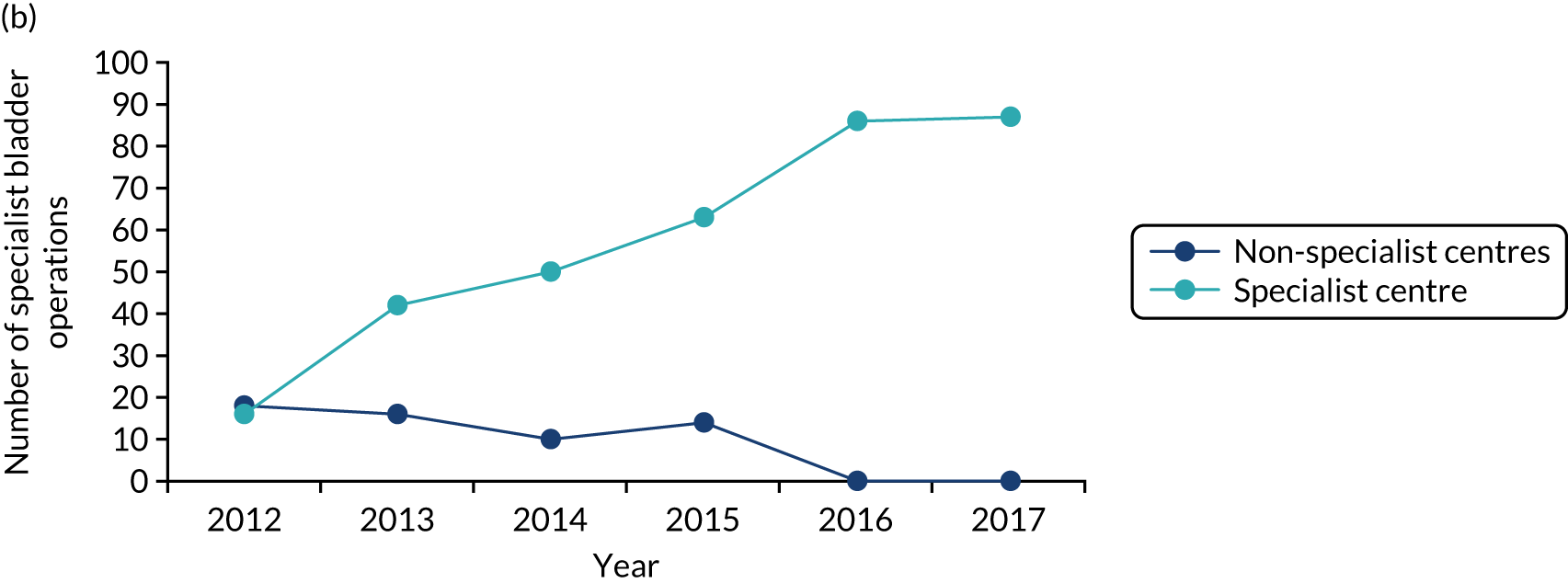

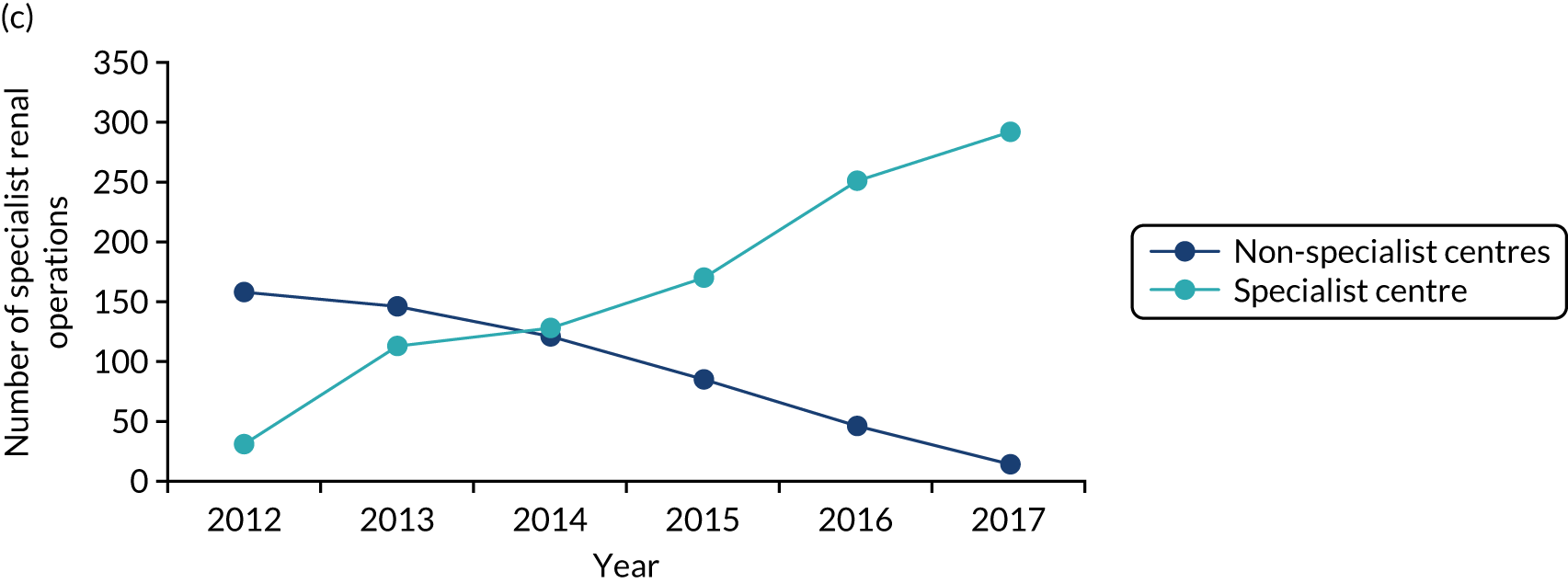

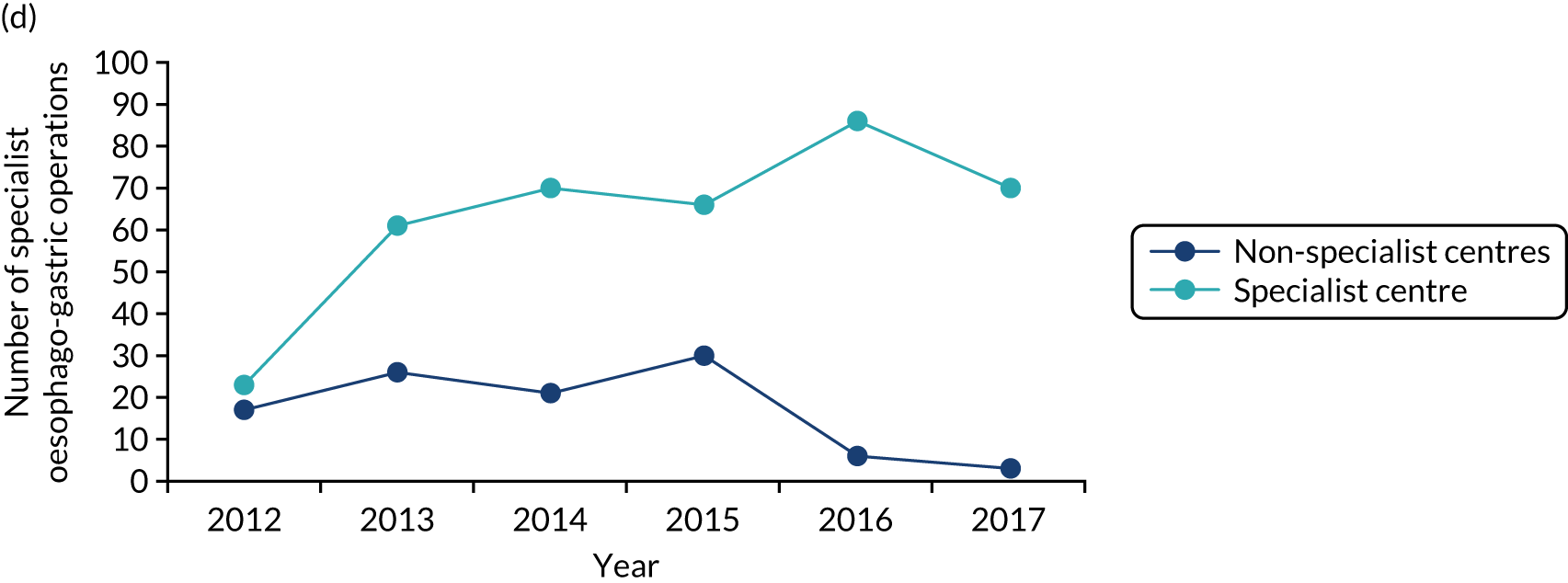

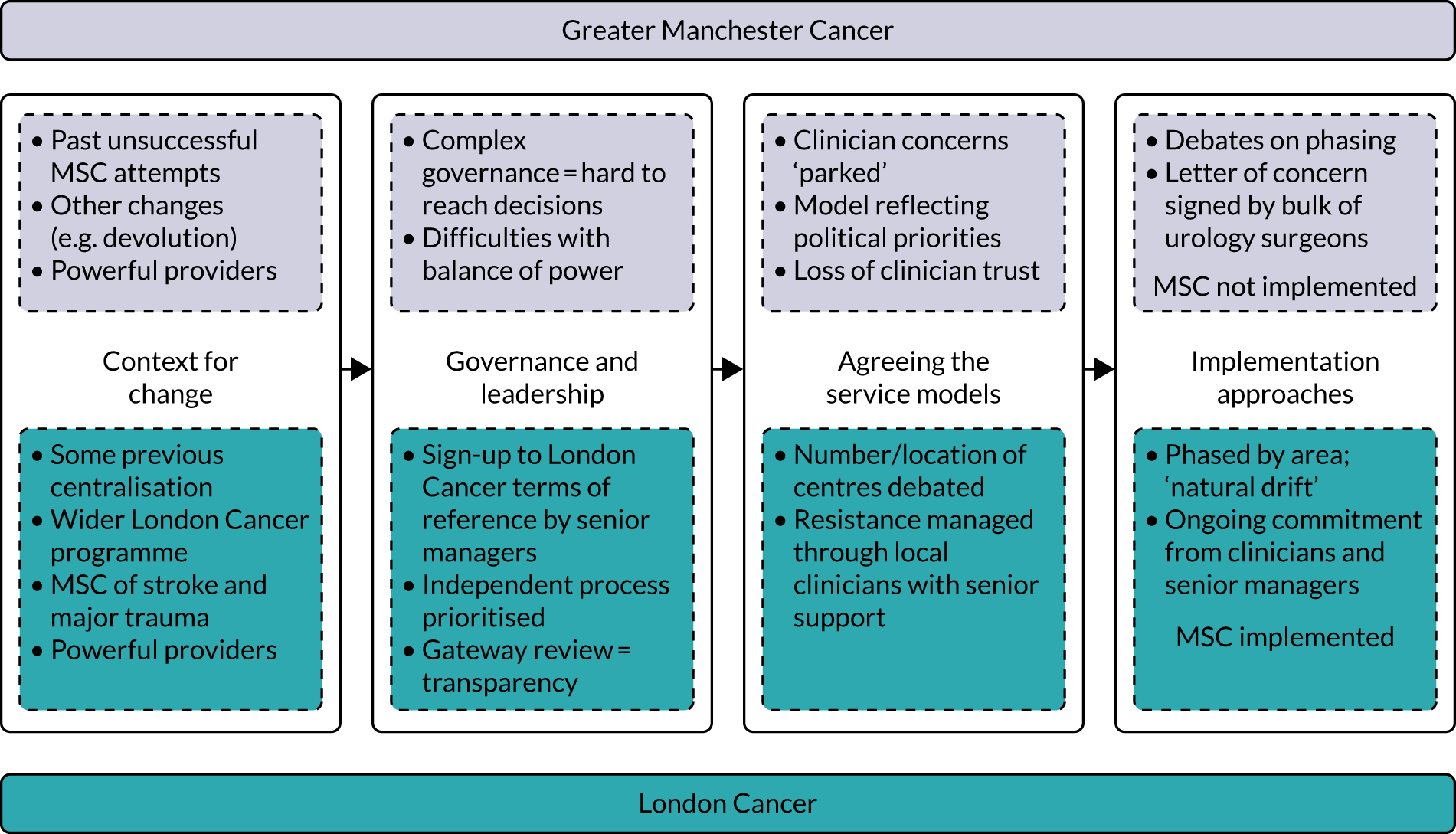

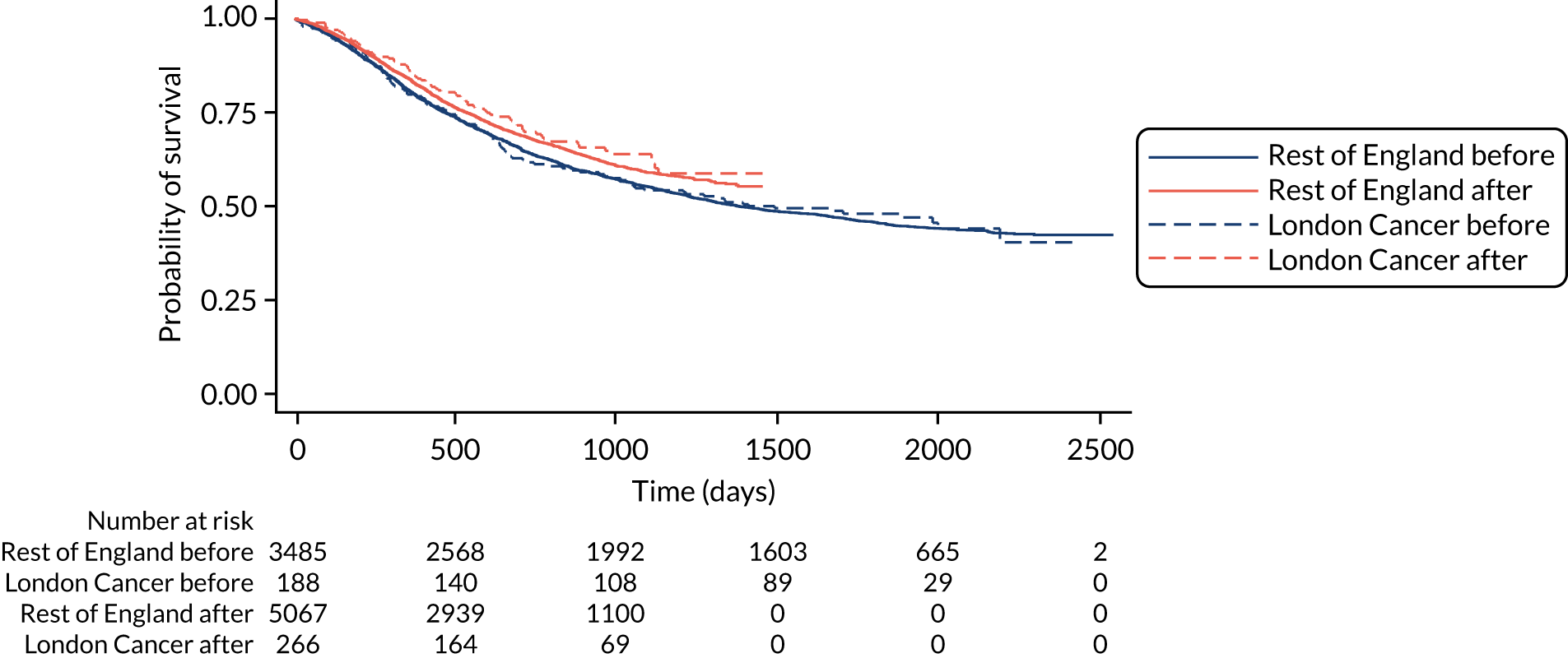

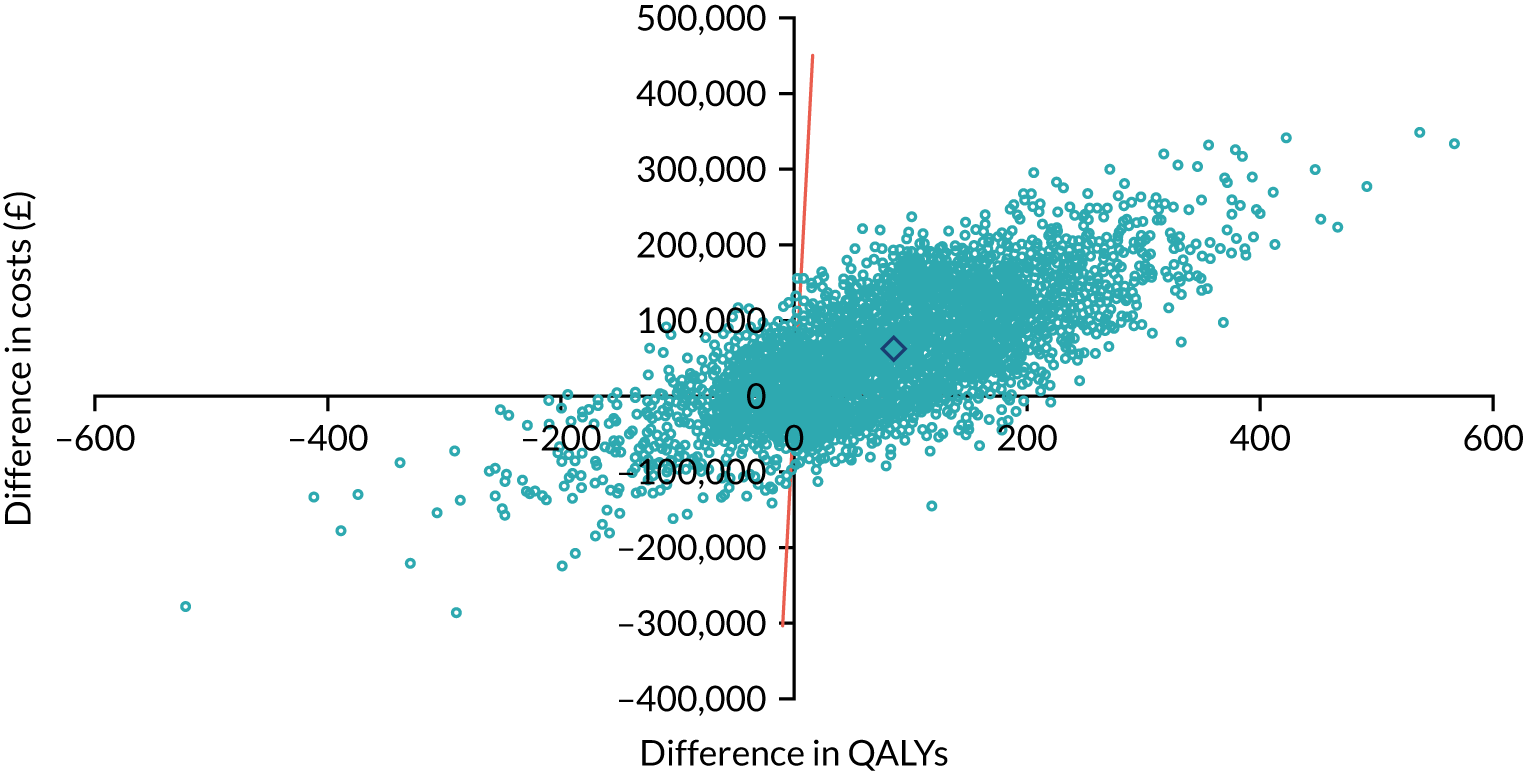

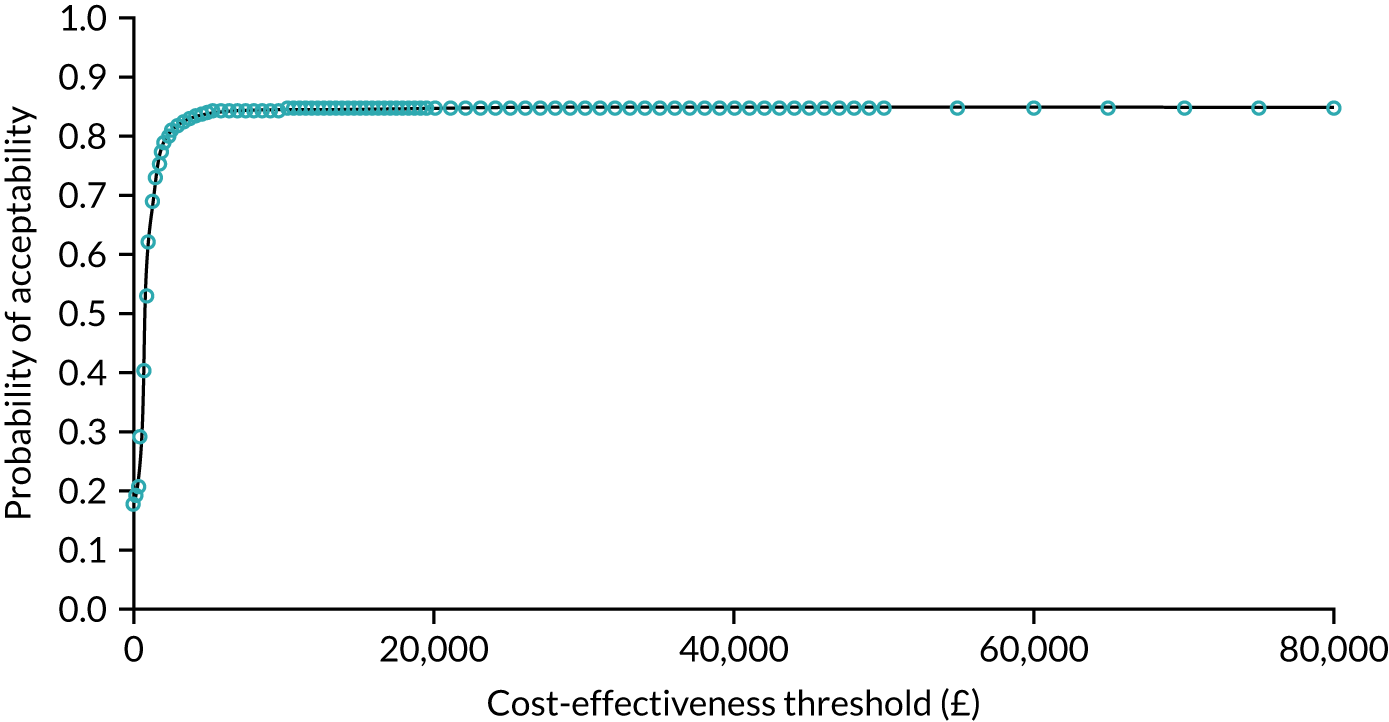

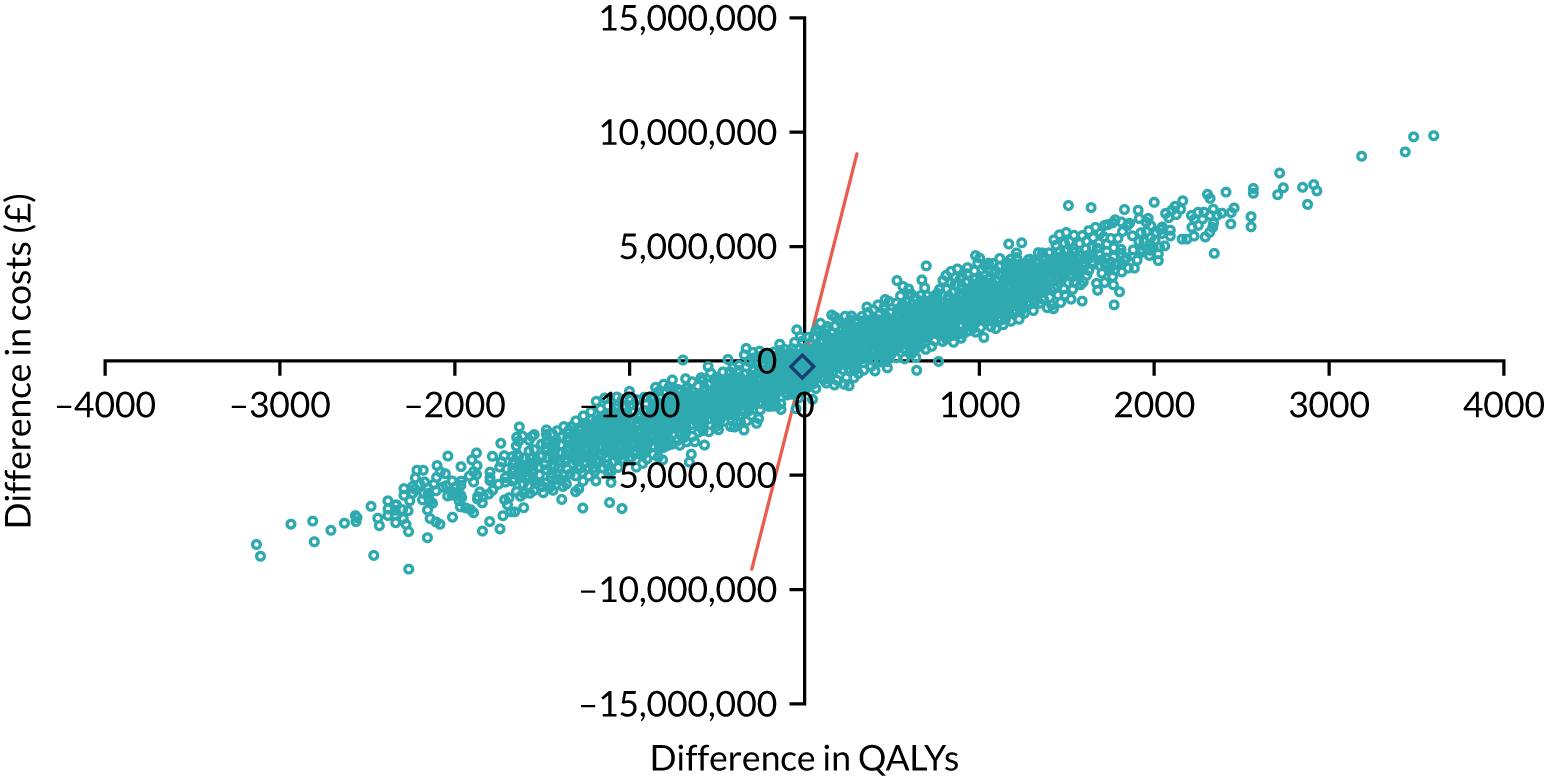

Engagement of other stakeholders