Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR129209. The contractual start date was in March 2020. The final report began editorial review in January 2022 and was accepted for publication in August 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Duddy et al. This work was produced by Duddy et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Duddy et al.

Chapter 1 Background

This chapter introduces the National Health Service (NHS) Health Check (NHSHC), the existing evidence base that underpins the programme, recent developments that have affected its delivery, and the focus of this review project. The text below reproduces in part, and updates, the background information provided in our published protocol paper. 1

The NHS Health Check programme

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) causes one-quarter of all deaths in the United Kingdom (UK) and is the largest cause of premature mortality in deprived areas. Early detection and prevention of CVD are a priority for the NHS and the NHS Long Term Plan (2019) makes a clear commitment to early detection of risk factors and rapid initiation of treatment, with the ambitious aim of preventing over 150,000 heart attacks, strokes and dementia cases over 10 years. 2

The NHSHC programme is one pillar of England’s CVD prevention effort. Launched in 2009, the NHSHC aims to offer a five-yearly assessment of CVD risk factors to all adults in England aged between 40 and 74 years. The check involves the measurement of key CVD risk factors and calculation of an overall 10-year CVD risk (using QRisk®3), followed by advice, discussion and agreement on lifestyle and pharmacological approaches to manage and reduce risk. The latter steps may include the delivery of advice and ‘brief’ or ‘very brief’ interventions, signposting or formal referral to ‘lifestyle support’ services, such as stop-smoking and weight-management services, and clinical risk management (including prescribing) per relevant National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines. 3

The total eligible population for the NHSHC programme has been estimated at 15.5 million. 4 The largest and most recently published analysis of national data relating to the programme found that 10 million eligible people were offered a check between 2012 and 2017. 5 Of these, 52.6% (just over 5 million) received an NHSHC. Although national uptake rates have generally increased over time, there is significant regional variation, with uptake rates calculated for upper-tier local authority (LA) areas ranging from 25.1% to 84.7%. 5 These findings are in line with previous analyses that have identified significant regional variation in the invitation and uptake rates for the programme,6 as well as variation in other aspects of delivery and follow-up, including variation in the delivery of advice and onward referrals to lifestyle services. 7,8

History of the NHSHC programme

Originally commissioned by Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) across England, the NHSHC programme was developed to address high rates of death, disability and inequality in health outcomes associated with vascular disease. The programme was designed to build on success in secondary prevention, shifting the focus to early intervention and primary prevention,9 and supported by evidence compiled in a handbook produced by the UK National Screening Committee. 10 From the outset, the programme was intended not only to address individuals’ modifiable risk factors but also to address population-level health inequalities,9 and to do so via provision of pharmacological (e.g. statins and anti-hypertensives) and non-pharmacological (‘lifestyle’) interventions, focused on exercise, weight and smoking. 11

The original modelling for the programme estimated that it had the potential to deliver significant benefits, including the prevention of 1600 heart attacks and strokes, and 4000 new cases of diabetes each year. However, these modelled outcomes rested on key assumptions about the uptake of checks themselves, and of the uptake and compliance with interventions offered after the check. 11

The NHSHC programme was relaunched in 2013, when responsibility for commissioning many public health services was transferred from the NHS to LAs, and a new executive agency, Public Health England (PHE), was formed. 12 Minimum standards for the NHSHC delivery model became statutory requirements,13,14 and recommendations and guidance for programme delivery were produced and have since been regularly updated by PHE. 3 On 1 October 2021, following the disbandment of PHE, responsibility for oversight of the programme was formally transferred to the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID), a newly formed unit within the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC).

Although minimum standards for NHSHC delivery are in place, LAs have flexibility in how and whom they commission to provide NHSHCs. As commissioning and delivery decisions are taken locally, with the aim of meeting the needs of local populations, there is inevitable variation in programme delivery, uptake and outcomes. In practice, most NHSHCs are delivered in general-practice settings but even so, there is significant variation in NHSHC delivery. 15,16

A summary of key programme milestones and documents is provided as part of Appendix 1 in this report.

Covid-19 and the NHS Health Check

The Covid-19 pandemic had a major impact on delivery of the NHSHC. In April 2020, NHS England and Improvement (NHSE&I) issued guidance for the prioritisation of community health services as part of the pandemic response, which included guidance to stop delivery of NHSHCs altogether. 17 PHE’s April 2020 Health Check e-Bulletin confirmed this plan, and outlined a delayed schedule for routine data collection relating to the programme. 18 To support the resumption of programme delivery after this pause, PHE issued ‘restart preparation’ guidance for commissioners and providers in April 2021. This guidance made it clear that decisions to restart delivery of the programme should be taken by LAs, in light of local assessments of safety and capacity (especially taking into account the need for general practices to prioritise Covid-19 vaccination work). 19

In recognition of the potential ‘limiting factor’ of workforce capacity in general practice, this guidance explicitly recommends that LA commissioners consider ‘alternative’ delivery models for future provision. It is clear that the pause and restart of the programme provoked a range of responses at local levels, including the introduction of new delivery models in some areas. 20 In recognition of this fact, we designed the survey component of this project to gather information from LAs on the extent and nature of changes in programme delivery in response to Covid-19.

In addition to these operational changes, official communications from PHE have placed a new emphasis on the potential benefits of the NHSHC in relation to Covid-19 outcomes, recognising that many of the risk factors that the NHSHC is designed to assess are also associated with increased risk of severe illness and death from Covid-19. 21,22 The potential for the NHSHC programme to help address risk factors associated with severe Covid-19 is acknowledged in the UK government’s Covid-19 recovery plan. 23

The NHS Health Check Review (2021)

Plans for a major review of the NHSHC programme were announced by the DHSC in August 2019, with an emphasis on personalisation and consideration of potential digital delivery methods. 24 In August 2020, the NHSHC e-Bulletin confirmed that this review was being undertaken by PHE21 and formal terms of reference were published in November 2020. The scope of the review included an assessment of the existing programme’s effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and limitations, as well as consideration of evidence relating to potential changes that might be made to both the content and delivery methods for the check. 25

The review’s findings were published in December 2021 by the new OHID unit. 26 The report sets out a new ‘vision’ for the NHSHC and makes six recommendations to government to guide delivery of the programme over the next decade. We have taken these recommendations into account in developing our own set of recommendations based on the findings of this project, aiming to complement and add to the recommendations published by OHID (see Chapter 4, Discussion).

Overview of existing evidence

The NHSHC programme has been controversial since its inception, and the value of the evidence underpinning its design and demonstrating its effectiveness has been subject to dispute. 27 Opponents of the programme cite an absence of data from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrating the effectiveness of mass CVD screening and prevention programmes. 28,29 PHE have responded by commissioning and producing a range of evidence that aims to demonstrate the effectiveness of the programme, and by setting up the NHSHC Expert Scientific and Clinical Advisory Panel (ESCAP) to regularly review and support delivery of the programme. 30

Observational studies collated in two PHE-commissioned rapid reviews suggest that the NHSHC is associated with increased rates of the detection of CVD risk factors and disease, statin prescribing, and referrals to lifestyle support services (including smoking cessation, weight management, exercise and alcohol support services). However, regional studies demonstrate wide variation both in these outcomes and in service delivery across England. Evidence on behaviour change and improvements in CVD risk factors and outcomes post-HC is sparse. The rapid reviews identified only six primary studies examining behaviour change, assessing only smoking. A limited number of studies have assessed improvements in body mass index (BMI), diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol and overall CVD risk, but results are inconsistent and some studies found no evidence of an effect. 7,8

A more detailed overview of the existing evidence underpinning the NHSHC is available in our published protocol paper. 1

Project focus: what happens after the risk assessment in an NHS Health Check?

Our scoping searches and review of the existing research evidence identified a clear focus in the existing literature on the reach of the NHSHC programme, including on how to improve invitation, uptake and coverage. Less attention has been paid to what happens after the measurements and risk assessment have been undertaken, especially in relation to the delivery of advice, onward signposting or referral and ongoing support for lifestyle and behaviour change. In consultation with our key stakeholder, PHE (now OHID), we confirmed the value of a focus on these steps in this review. Our wider public and professional stakeholder groups (see Chapter 2) were also consulted on this proposed focus and confirmed the need for research in this area, reflecting their interest in the NHSHC as a programme with the potential to prompt and support behaviour and lifestyle change in attendees. The ability of the NHSHC to promote such behaviour change is a crucial underpinning assumption for the programme in relation to its aim to help attendees reduce their risk of experiencing a heart attack or stroke or developing some forms of dementia. 3 The rationale for choosing this project focus is further elaborated in Chapter 2 below (see Step 1: Locate existing theories).

What should happen after the risk assessment is completed in a Health Check?

PHE’s Best Practice Guidance3 and programme standards31 for the NHSHC make a number of clear recommendations in relation to what should happen after the measurements and risk assessments have been completed during a check. The documents are aimed at both commissioners and providers, and describe a range of advice and referral options, as well as clinical interventions that can be offered to attendees, with two objectives:

-

To promote and improve the early identification and management of the individual behavioural and physiological risk factors for vascular disease and the other conditions associated with those risk factors.

-

To support individuals to effectively manage and reduce behavioural risks and associated conditions through information, behavioural and evidence-based clinical interventions. 3

For commissioners, the Best Practice Guidance document makes some limited recommendations in relation to providing and ensuring clear referral pathways to other services that may be commissioned to support lifestyle and behaviour change. For example, in relation to smoking cessation, it suggests that LAs ‘may wish to’ put in place pathways to refer smokers to local stop-smoking services. However, it is also made clear that clinical follow-up remains the responsibility of primary care, and there is an emphasis placed on LAs’ legal responsibilities in relation to NHSHC delivery and data reporting – both focused on invitation and uptake. There is no legal requirement to ensure that NHSHCs include the provision of advice or referrals beyond the requirement to ‘ensure the individual having their NHS Health Check is told their cardiovascular risk score, and other results are communicated to them’, and that relevant data are recorded and sent to general practices to ensure appropriate clinical follow-up as required. 13,14

Despite this, PHE’s guidance documents aim to provide a level of standardisation in setting out recommendations for the steps following the mandatory measurements and risk assessments. The recommendations are not new or specific to the NHSHC programme; instead, the guidance invokes relevant NICE guidelines and so reflects what should be ‘usual care’, at least for those providers based in general practice. Both the Best Practice Guidance and the programme standards explicitly echo the ‘Making Every Contact Count’ competencies, intended to promote the opportunistic delivery of ‘brief’ and ‘very brief’ lifestyle interventions during routine interactions with health and care staff. 32 The NHSHC encounter is positioned as a means of extending the opportunity to deliver these interventions to an otherwise healthy population who may not otherwise have contact with healthcare services. 3

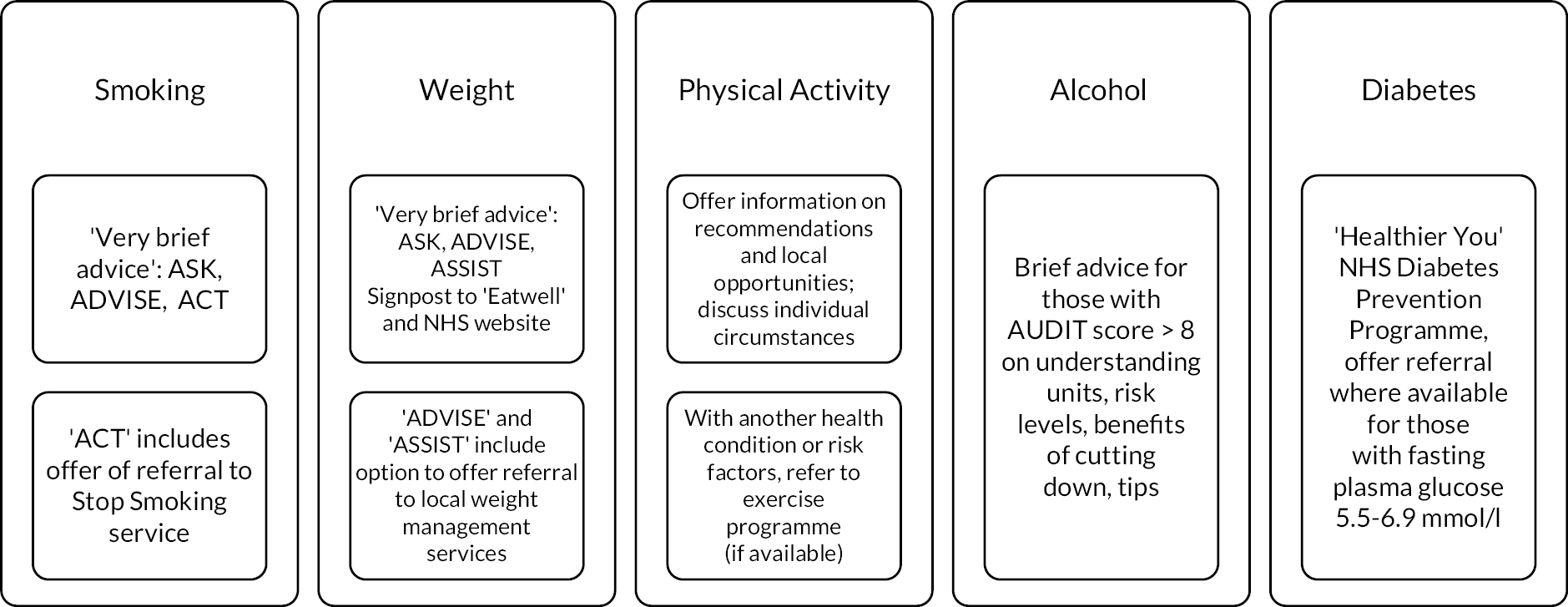

A summary of the recommendations in relation to advice, brief interventions and referrals in relation to each risk factor assessed during an NHSHC is provided in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Recommendations for advice, brief intervention and referral.

Data on these potential activity outcomes for attendees of the NHSHC are not routinely collected or reported to PHE. A recent cross-sectional observational study of the NHSHC extracted data from primary care records in 90% of English general practitioner (GP) practices for the 5-year period 2012–2017. 5 The findings included data on the percentage of NHSHC attendees recorded as receiving advice, information or a referral after a check, in relation to each risk factor assessed. Table 1 reproduces Table 3 from this study, showing the percentage of all NHSHC attendees who received advice, information or referrals, as well as the percentage of all NHSHC attendees meeting the threshold for these interventions who received them.

| Intervention type | All attendees n (%) | Attendees with the CVD risk factor above threshold for intervention: n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol consumption | 792,761 (15.5) | 46,611 (38.4) |

| Diet | 1,189,986 (23.3) | 766,521 (25.1) |

| Physical activity | 1,501,103 (29.4) | 434,326 (39.3) |

| General lifestyle/behaviours | 814,611 (16.0) | 211,571 (20.1) |

| Smoking cessation | 865,913 (17) | 467,119 (57.3) |

| Weight loss and obesity | 821,414 (16.1) | 599,380 (19.6) |

| Diabetes prevention programme | 4551 (0.1) | 3348 (0.9) |

| Total | 2,501,565 (49.0) | 565,047 (53.7) |

Although it is likely that data recording (coding into primary care records) for these activities is incomplete, the available data indicate that the rates at which they are delivered vary widely for different risk factors and appear to fall well below what the recommended thresholds for intervention suggest would be appropriate. These data also provide no detail on the nature of the advice, information and referrals offered, and the extent to which the specific recommendations made in the guidance are followed. These findings echo those from existing systematic reviews, which have also identified regional variation in ‘post-delivery management’ following an NHSHC. 7,8 In addition, this study and another recent observational study make it clear that most NHSHC attendees do not receive any treatment or referral after a check, and that statin prescribing in particular is much lower than guidelines recommend. 5,33 The rates recorded also fall short of those estimated in the initial economic modelling for the NHSHC programme. 34

Aims and objectives

Aim

The aim of this project was to understand how the NHSHC programme works in different settings for different groups, in order to recommend improvements to maximise intended outcomes. Following scoping searches and consultation with our stakeholders, we focused on the steps that follow the measurements and risk assessment undertaken during the check.

Objectives

-

To map how the programme is currently delivered across England, using findings from a PHE survey (October 2020) and data we collect using our own online survey of LAs (with a specific focus on what happens after the measurements and risk assessment and on Covid-19 related changes to delivery models).

-

To conduct a realist review to enable understanding of how the NHSHC programme works in different settings, for different groups, to achieve its outcomes (with a specific focus on what happens after the measurements and risk assessment).

-

To provide recommendations on tailoring, implementation and design strategies to improve the current delivery and outcomes of the NHSHC programme in different settings, for different groups.

Chapter 2 Methods

The project had two main strands – a survey of LAs and realist review – both supported by strong stakeholder engagement. This chapter begins with a section describing the role of our stakeholder groups throughout the project, before describing the methods used in our survey and realist review.

We conducted a survey of LAs with the aim of providing a comprehensive overview of how different localities across England implement the NHSHC programme. In addition, the survey aimed to gather additional material (including local knowledge, unpublished evaluations and examples of best practice and Covid-19-related innovation in delivery) for the review.

Our survey asked questions about current NHSHC delivery models (in 2021/2022, following the Covid-19-related pause to the service) and questions related to options for onward referral and follow-up of attendees after the Health Check encounter. It sought to identify the extent to which commissioners and providers had changed the way they commission and deliver the NHSHC programme in light of the Covid-19 pandemic. It also identified the extent to which services are available to support those identified as having modifiable risk factors, which has helped us to address our review focus on what happens after a Health Check, especially in relation to follow-up, onward referral and ongoing support for lifestyle and behaviour change. Our survey findings were considered alongside those from the previous PHE survey of LA commissioners, conducted in October 2020 as part of the wider review of the NHSHCs programme. 16

In addition, we conducted a realist review to enable us to better understand the important contexts that influence NHSHC delivery, and the mechanisms which produce both intended and unintended outcomes. Realist review is an interpretive, theory-driven approach to evidence synthesis that aims to develop an in-depth understanding of how, why, when and for whom complex interventions (such as the NHSHC) ‘work’. We chose this approach because existing research clearly demonstrates that the NHSHC programme is a complex intervention with context-sensitive outcomes, that is, the programme’s outcomes are highly dependent on the circumstances in which the NHSHC is delivered and received by attendees. There is significant heterogeneity in commissioning and delivery of the programme across England and wide variation in key outcomes, including rates of attendance, follow-up, and the provision of advice, onward referral and prescribing post-NHSHC. 7,8 Our review sought to improve understanding of this variation, via developing a programme theory that identifies the important contexts and mechanisms that produce NHSHC outcomes, with a specific focus on what happens after the measurements and risk assessment are complete.

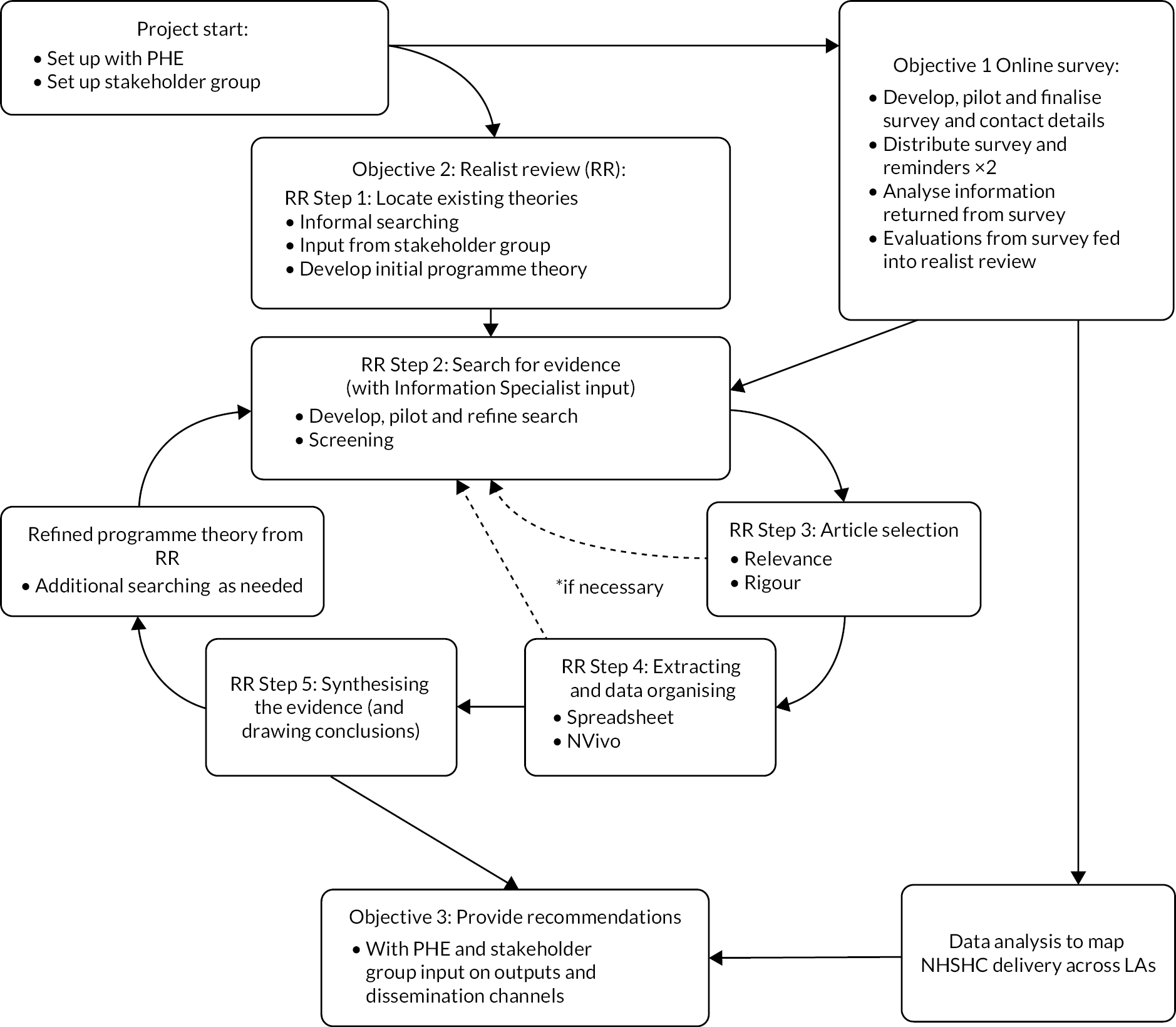

The full project plan is presented in Figure 2. The project was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020163822) in January 2020. The start date of the project was delayed to October 2020 due to Covid-19, and the project was conducted over 15 months, completed in December 2021.

FIGURE 2.

Project flow diagram.

Our protocol was published in BMJ Open in April 2021. 1 The conduct and reporting of the review were informed by the Realist and Meta-narrative Evidence Synthesis: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) quality35 and publication36 standards. Ethical approval for the survey component of the project was granted by the University of Kent’s SRC Research Ethics Committee (SRCEA ID 0367) in February 2021.

Stakeholder groups

We recruited two stakeholder groups to provide us with content expertise and a range of perspectives throughout the project.

Throughout the project, our strategy for patient and public involvement (PPI) was informed by our PPI lead (VH). VH is an experienced PPI contributor (via the Public Involvement in Pharmacy Studies at Medway School of Pharmacy Group) and brought her valuable perspective as a member of the public and skills in group facilitation. In particular she supported us in developing lay summaries, advertising for further PPI contributors and supporting our PPI group throughout the project.

Our PPI group involved 10 members of the public from six different English regions, all of whom are eligible to receive the NHSHC. 37 This group was recruited by advertising via the Oxford Biomedical Research Centre website and the University of Kent’s Centre for Health Services Studies’ Opening Doors to Research group. We offered PPI contributors a shopping voucher as a token of our appreciation for their involvement, and covered any expenses they incurred in taking part. From those members of the public who came forward, we purposely selected a group who were as diverse as possible in relation to gender, age, ethnicity and geographical location, with the aim of capturing a range of different perspectives from individual members of the public.

Our ‘professional’ stakeholder group were recruited via our project team’s existing networks and snowballing from these, and included LA commissioners, NHSHC providers, an NHSHC trainer and representatives from relevant health charities. In addition, we maintained close contact with PHE’s (latterly OHID’s) CVD Prevention Programme lead throughout the project.

Both groups were consulted via regular online meetings throughout the project, using Microsoft Teams (Version 1.0, Microsoft Corporation) and Zoom (Version 5, Zoom Video Communications, Inc.) video conferencing software. Our approach to facilitating our meetings was driven by the need to work to ensure that these online discussions – necessary due to the Covid-19 pandemic – were as open and inclusive as possible. Based on the recommendation of our PPI lead (VH) we met with our PPI and professional stakeholder groups separately, to help ensure that members felt able to speak openly about their experience of receiving and/or commissioning/providing the NHSHC and to reduce the number of people in each meeting, giving individuals more opportunity to contribute. However, CD attended all meetings of both groups and, where relevant, reported discussions from the PPI group to the professional group and vice versa. Our PPI stakeholder group meetings were chaired by VH and our professional stakeholder group meetings by GW. To facilitate more in-depth discussion and give each participant more time to contribute, our PPI group was split into two smaller groups for the last two meetings.

Our final professional stakeholder group meeting was augmented with additional contributions from 36 individuals. They came from a range of professional backgrounds (LAs, Public Health, OHID and providers) and from geographically diverse parts of England. Individuals were recruited via OHID’s existing networks. These additional contributions were sought to ensure that we would get broader feedback and advice on our findings and recommendations.

We consulted the stakeholder groups in relation to the focus of the project and asked them to provide feedback on our emerging findings as they developed. To help facilitate discussion on our findings, we circulated summary material before each meeting and provided an overview slide presentation at the beginning of each meeting. We initiated discussions with sets of simple questions to help guide the participants; for example, we asked stakeholders how our findings related to their own knowledge and/or experience of commissioning, providing or attending the NHSHC, and we asked them about important influences on NHSHC delivery or the response to the NHSHC that seemed to be missing from our findings. Our aim was both to identify those findings with particular resonance for stakeholders, but also to highlight any important aspects of NHSHC delivery that are not well represented in the literature. We consulted the professional stakeholder group on the development of our survey questions, to ensure their relevance and importance, and on our survey design, with the aim of maximising clarity, validity and the likelihood of achieving a good response with full completion of questions.

The discussions held during these meetings helped to shape our analysis as the project progressed. Input from both the professional and PPI groups influenced the analysis of our survey responses and our interpretation of the data included in the review. For example, input from the professional stakeholder group informed the development of a typology of NHSHC delivery models and the identification of relevant factors to consider in our analyses. In discussions of the review’s emerging findings, our PPI group members emphasised the need for NHSHC attendees to have more control over what happens during and after a check, especially in relation to the discussion of ‘lifestyle’ advice and opportunities for referral to other services. As a result, we reconsidered our data on attendee responses to what providers offer or discuss at the end of an NHSHC encounter, to consider whether it could tell us more about potential mechanisms producing these important outcomes for attendees. (see e.g. CMOCs A16–A17, A30–32 in Chapter 3). Similarly, PPI members’ repeated observations on the ‘mismatch’ of the focus of the NHSHC with their own health needs and priorities helped us to shape our findings (see e.g. CMOCs A9–A11) and recommendations in this area. Overall, our PPI group felt strongly that they needed more clarity on the purpose of the NHSHC programme and the group’s in-depth discussions on this point are represented strongly throughout our findings and in our subsequent recommendations for policy and practice (see Chapter 3 and Chapter 4).

In the last meetings with each group, we asked the participants for their input to help us to develop and refine practical recommendations for NHSHC delivery based on our findings and to inform our dissemination strategies, to help us to develop tailored outputs and identify the key ‘players’ for dissemination amongst different audiences. We refined our recommendations and developed plans for dissemination activities and project outputs on the basis of feedback from both groups.

A summary of the stakeholder group meetings and important input from these groups is provided in Table 2.

| Date | Stakeholder members | Key discussion topics |

|---|---|---|

| 29/01/2021 | Professional group: seven attendees (one GP, one pharmacist, one trainer, two LA commissioners, two charity representatives) | Introduction to the project. Discussion focused on the potential gap between commissioning and delivery and the reality of NHSHCs delivery and on the project focus. On the survey, discussion focused on timing to ensure good response rates, clarity on the time periods referred to in survey questions, knowledge of the intended respondents (in LAs) and the balance between capturing detail while minimising burden for respondents. |

| 23/04/2021 | PPI group: 10 contributors | Introduction to the project. Discussion focused on contributors’ personal experiences of NHSHCs and included reflection on their awareness of the programme, negative and positive experiences of NHSHCs. |

| 21/05/2021 | PPI group: 10 contributors | Presentation of an initial set of emerging review findings focused on contexts influencing referral to other services as an outcome of an NHSHC. Discussion focused on the appropriateness of referrals, availability of services and the limitations of the NHSHC CVD focus. |

| 11/06/2021 | Professional group: six contributors (two GPs, one trainer, two LA commissioners, one charity representative) | Presentation of an initial set of emerging review findings focused on commissioner and provider perspective. Discussion focused on local variation in delivery, enthusiasm and engagement, leadership, workforce competencies and skills and the impact of Covid-19. |

| 10/09/2021 | PPI group: 10 contributors (split into meetings with five in each) | Presentation of review findings focused on attendee experience and response to the NHSHC. Discussion focused on medical versus ‘lifestyle’ interventions, the importance of follow-up, the need for personalised advice and support, and on the potential value and risks of digital checks. |

| 17/09/2021 | Professional group: four contributors (one GPs, one trainer, one LA commissioner, one charity representative) | Presentation of review findings focused on attendee experience and survey results. Discussion focused on the purpose of the HC, what ‘good’ looks like and what training is needed to achieve this, plus data and monitoring issues. Feedback was provided on emerging findings and the survey’s findings, typology and how it might be meaningfully described and analysed. |

| 05/11/2021 | PPI group: eight contributors (split into meetings with four in each group, follow up with two other members by email and separate online meeting) | Presentation of recommendations based on findings. Discussion focused on the need to recognise the impact of Covid-19 on individuals, variation in delivery between local areas and the need to clarify and communicate the purpose of the programme to the public. Contributors suggested outputs should include illustrative examples of good practice and a range of formats that could be appealing or accessible to different audiences (e.g. magazine articles, animations, social media posts). |

| 12/11/2021 | (Augmented) Professional group: 36 contributors (range of professional backgrounds – LAs, Public Health, OHID and providers and from geographically diverse parts of England) | Presentation of recommendations based on findings. Discussion focused on whether the recommendations resonated with them and on: tensions between case-finding and behavioural change; services to refer attendees onto after the NHSHC; challenges for providers; and wider issues impacting on NHSHC delivery. |

Survey methods

Survey aims and objectives

The aim of the survey was to enable us to gather additional material (local knowledge, unpublished evaluations and examples of good practice and Covid-19-related innovation) for the project, and to provide a comprehensive overview of how different localities across England implement the NHSHC programme. The objectives were:

-

To describe how NHSHCs are delivered across England, particularly in relation to what happens after the measurements and risk assessment.

-

To determine how the Covid-19 pandemic has changed the way NHSHCs are delivered in some areas.

-

To categorise, as far as possible, different models of NHSHC delivery employed across England.

-

To determine any associations between NHSHC delivery models and other variables, based on relevant publicly available data.

Survey development and piloting

An online survey (available in full on our project website www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/NIHR129209/#/) was developed using Jisc Online Surveys, chosen as it is designed to generate professional academic survey formats. The survey was to cover all LAs in England with responsibility for commissioning the NHSHC programme (i.e. upper-tier and unitary). Given the timing of the survey – during the second year of the Covid-19 pandemic, and less than a year since PHE’s own survey on NHSHC programme delivery – we were concerned that our survey would add an unwanted and unwarranted burden, unless it asked new questions and was able to provide new information. The survey was therefore designed to capture (1) changes in delivery in response to the pandemic and (2) detail about the delivery of the programme with a focus on what happens after the measurements and risk assessment are complete.

We also used the survey to find out whether LAs had commissioned, conducted or been part of any assessments of the NHSHC programme in the previous five years (including evaluations, collection of attendee feedback, health equity audits, or any other type of study), and to request copies of these to be included in our review.

The survey questions were designed in collaboration with our stakeholders, who helped us to ensure that the content of the questionnaire addressed the objectives of the research, the instructions and questions were clear and concise, and the survey was straightforward and quick to complete (i.e. in less than 15 minutes).

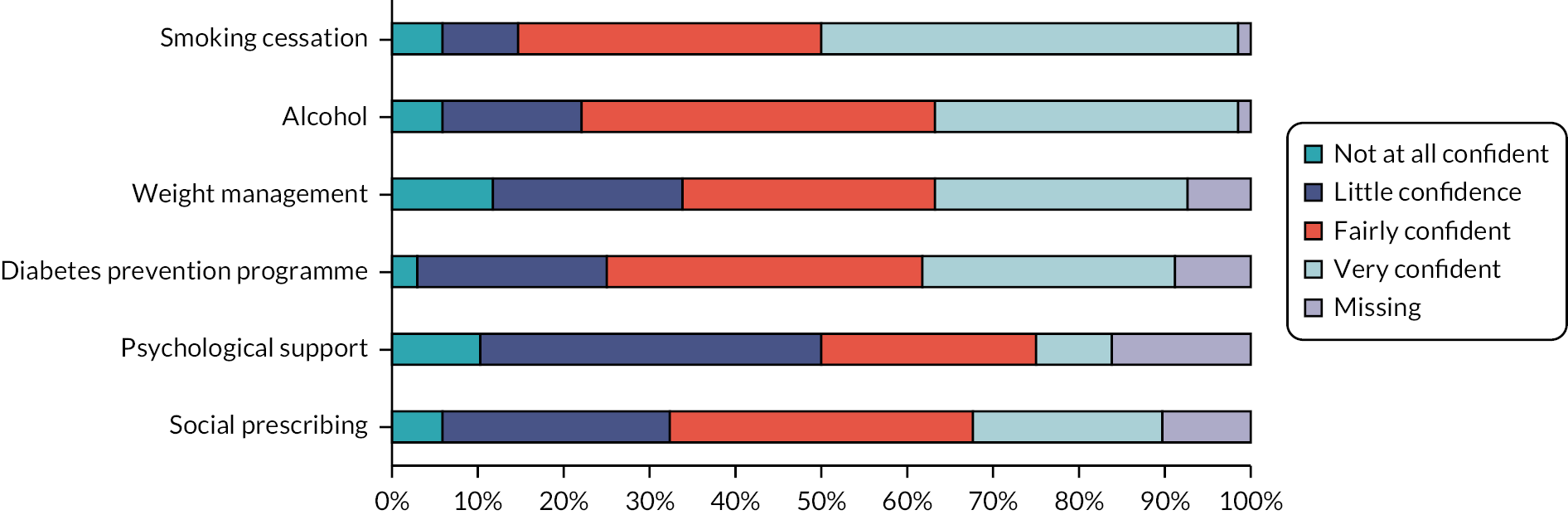

The survey included a mix of simple closed- and open-ended questions. The latter were included to enable respondents to both explain their responses to closed questions and add any further information about commissioning and delivery. Four-point rating scales were used to obtain level of confidence in capacity, accessibility and usage of support services (where 1 means ‘not confident at all’, and 4 means ‘very confident’).

The resulting online survey was sent to seven LAs (NHSHC/Cardiovascular Health leads) on 30 April 2021 to ‘test’ the system in advance of full roll-out. The survey was completed in full by three respondents, and feedback on the survey itself was positive. One subsequent change was made to the survey prior to the main launch. This was to include a single additional question at the start (Q3: Has the delivery of NHSHCs in your area resumed since the Covid-19 pause? Yes/No).

Administering the survey

To ensure a maximal response, and to ensure the survey was correctly targeted to those best placed to answer it, we worked closely with PHE to distribute the survey and make use of their tried-and-tested processes for dissemination. PHE sent the survey on our behalf to two of their governance groups: the PHE regional NHSHC Leads, and their Local Implementor National Forum, which includes LA NHSHC implementers representing all of the PHE regions. These groups were then asked to disseminate the email to their networks (e.g. the regional leads were asked to cascade the message to contacts for the LAs in their area). PHE also publicised the survey through their established NHSHC programme webinar series. Following the launch on 17 May 2021, a first reminder was sent on 4 June, and another on 18 June (announcing an extension to the deadline). On 2 July, targeted reminders were sent to leads in regions with a response rate of less than 35% (West Midlands, North East, East of England and London), for further cascading to all LAs in their regions. The survey closed on 18 July 2021.

Data handling

Survey responses were recorded online then downloaded into Microsoft Excel and a statistical software package (IMB SPSS Statistics 27) to aid analysis. Respondents were allocated unique identifying codes (R01–R68). Respondents were asked to name the LA(s) on behalf of which they were responding. Where one respondent was responding on behalf of multiple LAs, responses to all remaining questions were copied for the relevant LAs. Each LA was then allocated a unique identifying code (LA01–LA74). Qualitative responses given in free-text boxes were used to clarify or amend responses where relevant. For a few responses that appeared confusing or limited, we conducted a search of that council’s website in order to double-check information given (e.g. with regard to where NHSHCs are made available).

Data analysis

Simple descriptive statistics were used to analyse quantitative responses to the questionnaire. Where relevant, qualitative responses were categorised to enable descriptive analysis; for example, the venues where the NHSHC was offered. Qualitative responses were also used to illustrate the quantitative data throughout, for example by contributing to case examples of delivery types.

In order to develop a typology of LAs based on delivery of the NHSHC, data from responses to several questions were combined. This enabled categories to be devised, based on how LAs were delivering NHSHCs before the Covid-19 pause and their use of remote methods after the pause. The following responses were used to categorise delivery models:

-

number and type of venues pre-Covid-19 pause

-

number and type of providers delivering face-to-face and/or remote health checks

-

number of remote methods used post-Covid-19 pause.

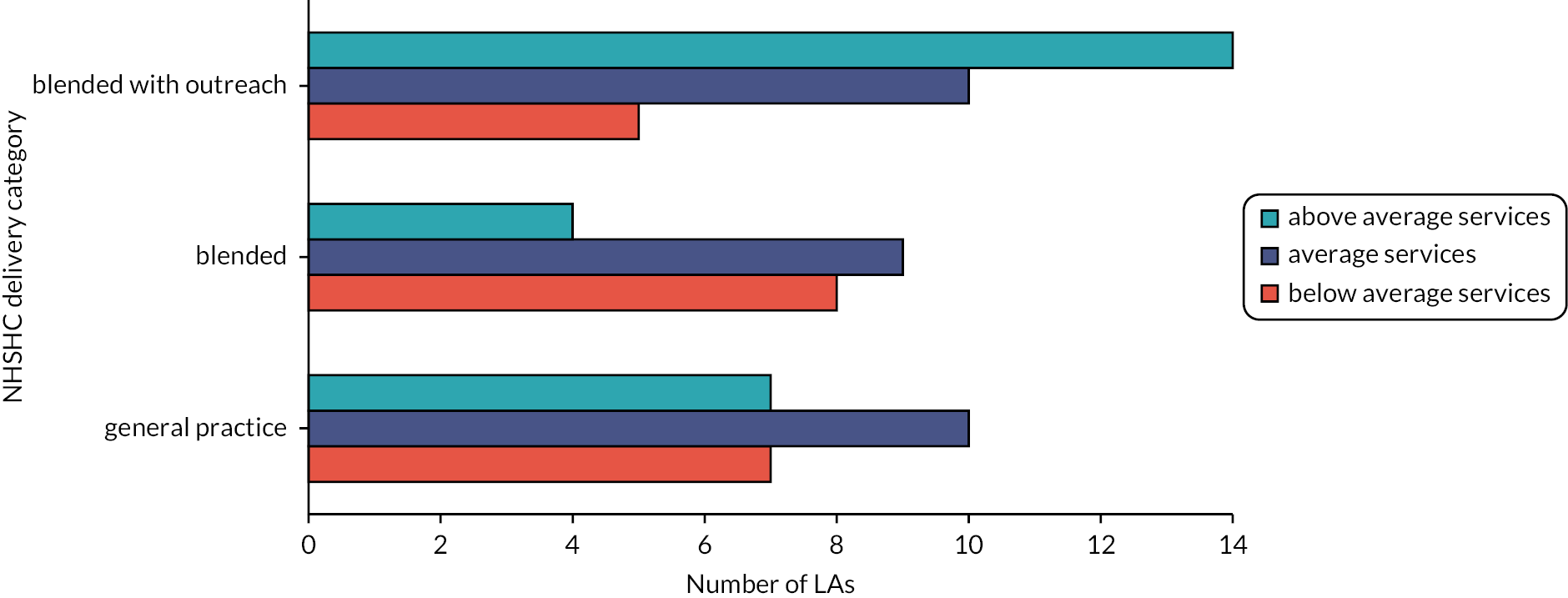

Based on their responses to these questions, LAs were grouped into three categories as outlined in Table 3.

| Category | Number of venues | Number of providers | Number of remote methods used post-Covid |

|---|---|---|---|

| General-practice delivery | Delivery in general practice only | All general-practice staff | No remote delivery |

| Blended delivery | Delivery in general practices plus/minus pharmacies. No other community provision. | General-practice staff plus/minus pharmacy staff | No or limited remote delivery post-Covid |

| Blended with outreach delivery | Delivery in multiple venues, including community settings | Mix of providers, including general-practice and non-general-practice staff | No or limited remote delivery post-Covid |

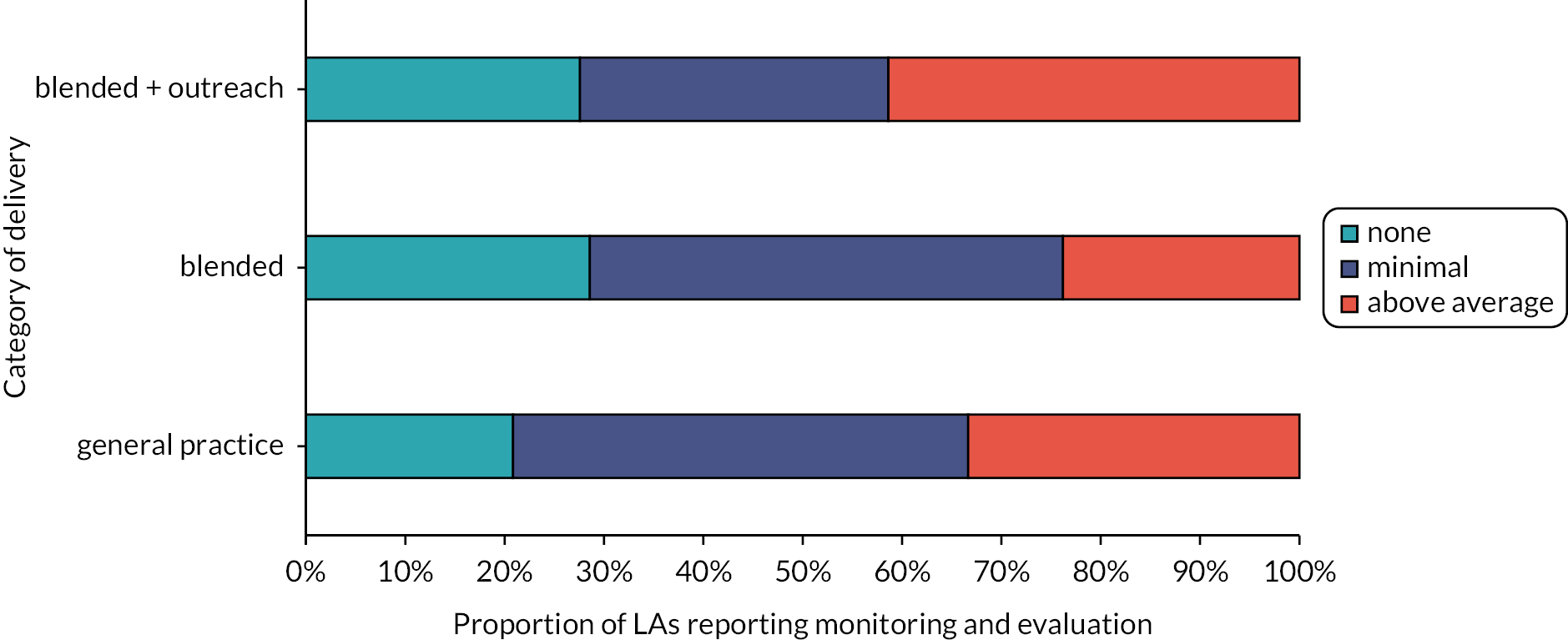

Associations between category of delivery and other factors

Associations with the following other survey responses were assessed:

-

total number of commissioned services reported

-

total number of referral processes reported

-

total number of methods used to prioritise invitations pre- and post-COVID pause

-

average reporter confidence in capacity and accessibility of support services, confidence in their usage (rating scale)

-

total number of monitoring aspects plus evaluation reported (categorised as none, minimal, above average).

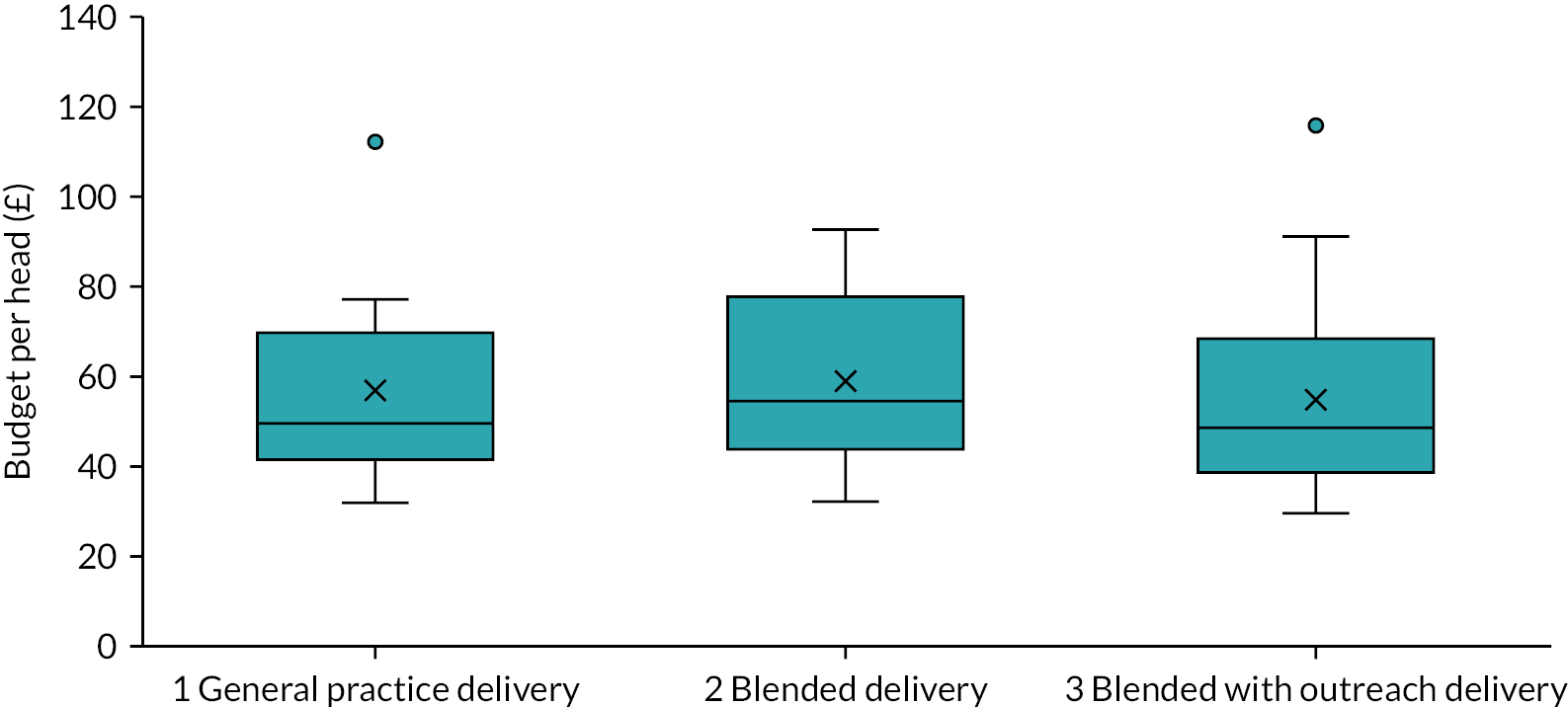

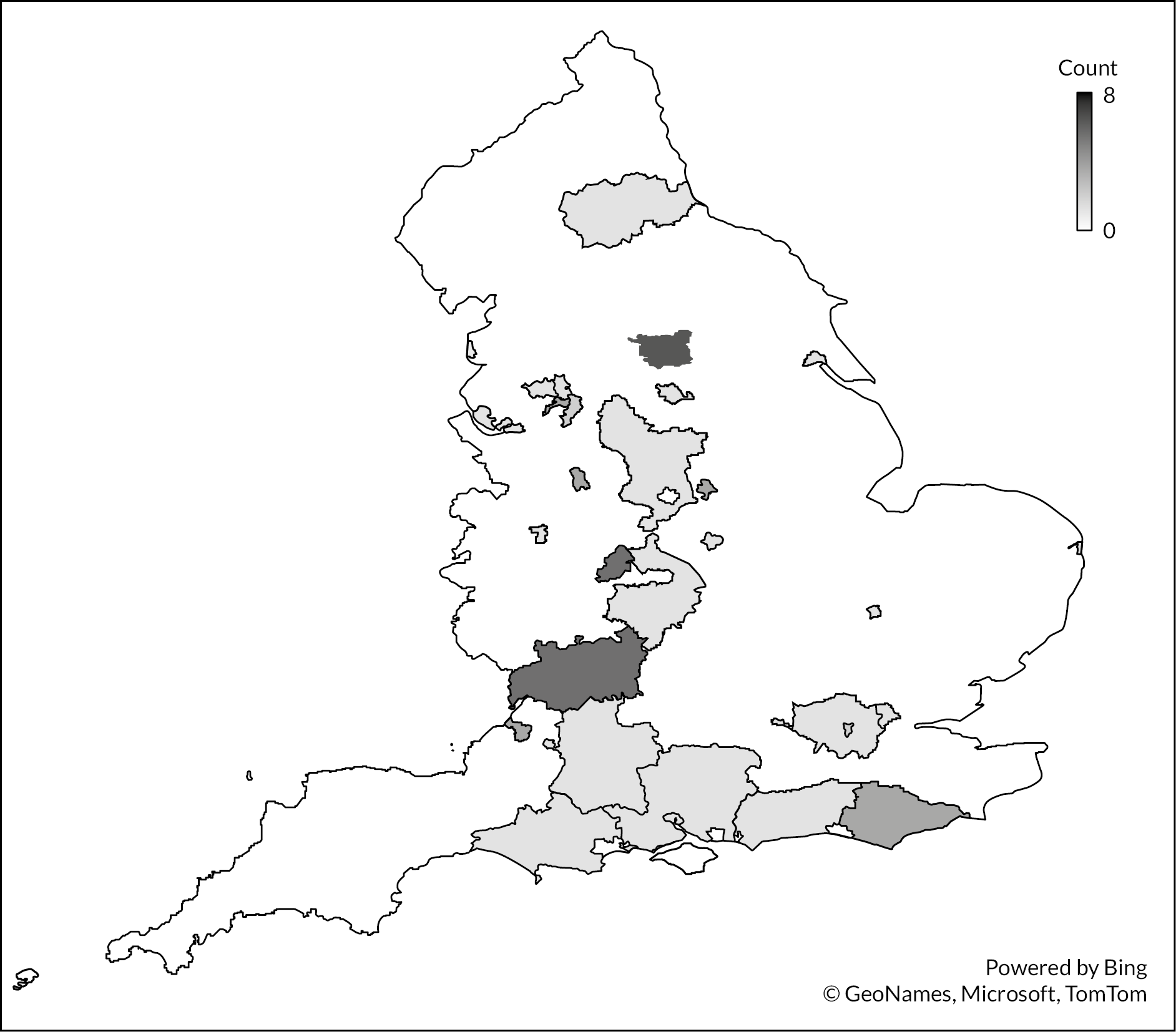

In addition, key statistics related to the public health function, populations, and performance measures for NHSHC programme delivery at LA level were obtained from publicly available data. For each responding LA we recorded:

-

geographic region: PHE centres38

-

size: estimated population, 201939

-

budget: Public Health budget per head, 2019/2039

-

deprivation: Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 201940

-

NHSHC programme delivery performance: proportion of eligible people receiving an NHSHC between 2015/16 and 2019/20. 41

On the request of our stakeholder group, we also explored the possibility of including the rurality index in our analysis, as an external factor that is likely to influence NHSHC delivery. However, this was found to be problematic since rurality is classified at district level, meaning no classifications are available for the large county (upper tier) councils (of which there are 19 in our dataset). In addition, due to the number of classifications (six), and the exclusion of the county councils, there were very few responding LAs within any of the more rural classifications.

One-way analysis of variance was used to compare service provision, referral processes and delivery performance across delivery categories. Chi-squared tests were used to assess associations between delivery category and other variables. Spearman’s correlation was used to assess relationship between variables.

Review methods

Review questions

-

What are the mechanisms by which the current NHSHC programme produces its intended outcomes after the measurements and risk assessment?

-

What are the important contexts which determine whether the different mechanisms produce intended outcomes?

-

In what circumstances are such interventions likely to be effective?

Our realist review followed Pawson’s five iterative stages42 as outlined in our protocol. 1 The steps we followed are summarised below.

Step 1: Locate existing theories

The goal of this step was to identify existing theories that explain when, how and for whom the NHSHC programme is supposed to ‘work’, to achieve its desired outcome of reducing CVD risk and mortality. The rationale for this step is that interventions and programmes like the NHSHC are underpinned by implicit and explicit assumptions and theories about how they should work in practice. 43 To locate existing theories that might offer explanations for NHSHC processes and outcomes, we undertook two iterative processes:

-

We drew on the knowledge and experience of our own project team (including in general practice, pharmacy, public health and lived experience), and consulted with our stakeholders.

-

We informally searched the literature to identify:

-

existing theories, consulting both grey literature in the form of NHSHC programme documentation, and published research studies that employed formal or substantive theories to understand the NHSHC

-

existing reviews and evidence syntheses focused on the NHSHC programme to develop our understanding of the existing research landscape and identify gaps in knowledge.

-

For step (b), we identified NHSHC programme documentation via searching and browsing the NHSHC website (www.healthcheck.nhs.uk) and the UK DHSC website (http://dh.gov.uk), and archived versions of these websites (via the UK Government Web Archive (http://nationalarchives.gov.uk) and the Internet Archive WayBack Machine (http://archive.org/web/)). We identified existing theoretical literature by running searches in PubMed and Web of Science (Core Indexes – SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, ESCI, AHCI), using a slightly modified version of Booth and Carroll’s BeHEMoTh approach for searching for theory. 44 We searched for the health context (the NHSHC) and terms relating to ‘theory’ and used citation tracking to identify additional studies. To identify published reviews, we consulted bibliographies produced by PHE, who have undertaken regular literature searches for evidence relevant to the NHSHC programme since 2015 (www.healthcheck.nhs.uk/commissioners-and-providers/evidence/literature-review/). The full details of the searches employed are available in Appendix 2.

Overall, we consulted 60 programme documents (policy papers and guidance) and identified 19 existing studies of the NHSHC that employed six formal theories or theoretical frameworks, and 10 existing reviews and evidence syntheses. Details of these documents are provided in Appendix 1.

In reviewing the existing research evidence relating to the NHSHC programme by consulting existing reviews and evidence syntheses, we identified an existing focus on the early steps of the initial programme theory (IPT) as outlined above, and especially on the processes involved in invitation and uptake of the NHSHC. Conversely, less research attention has been paid to later stages, and especially to what happens after measurements and risk assessment at the end of a check, in relation to advice, onward signposting and/or referral and ongoing support for lifestyle and behaviour change. As described above in Chapter 1 (see Project focus: what happens after the risk assessment in a Health Check?) we determined (in consultation with our stakeholder groups) to focus our own review on these later steps.

We combined our understanding of the programme from the literature reviewed with our own knowledge to develop and refine a coherent IPT for our realist review and to inform the subsequent stages of searching, data extraction and analysis. The IPT is presented in Figure 3; it maps out the steps involved in the delivery of an NHSHC and highlights our particular areas of focus and questions we considered in the course of the project.

FIGURE 3.

Initial programme theory for the realist review with project focus highlighted.

In recognition of the complex nature of the NHSHC programme, and the possibility (captured in our IPT) that important interactions and feedback loops may exist with earlier steps in the delivery of the check, we determined that we should not exclude evidence relating to other programme steps. Instead, we decided to focus initially on identifying those documents that could provide data relating to the later steps, and subsequently draw on data that may shed important light on relationships with other steps in the programme as necessary.

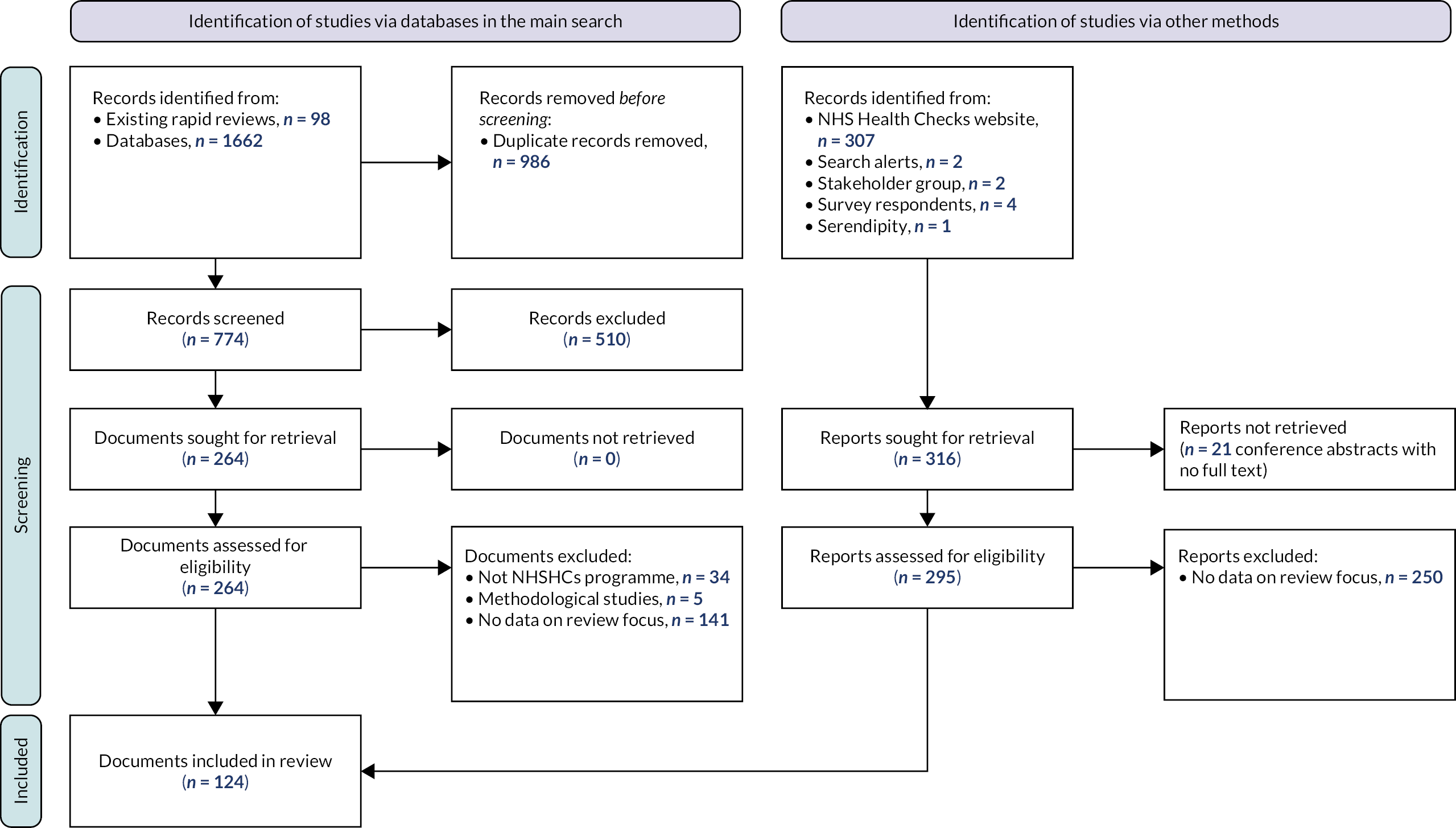

Step 2: Search for evidence

The aim of this step was to identify a relevant body of literature containing data that could be used to develop and refine the IPT developed in Step 1.

At the outset of this project, we were aware that PHE regularly undertakes literature searching for new evidence relating to the NHSHC. These regular searches employ a comprehensive search strategy across 13 relevant sources (PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Global Health, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, NHS Evidence, Google Scholar, Google, Clinicaltrials.gov and the ISRCTN registry). These searches have been used in previous review projects commissioned by PHE to identify and synthesise evidence relating to the NHSHC. 7,8 These published reviews have included additional searches in OpenGrey and/or Web of Science (Science Citation Index, SCI-EXPANDED); the most recent of these PHE-commissioned reviews captured studies published until the end of December 2019.

As described in our protocol, we did not duplicate this existing work, but aimed to re-use and extend it. As such, we identified documents to consider for inclusion in three main categories:

-

Documents included in two existing rapid reviews commissioned by PHE, as well as additional studies identified using the same search strategies and included in PHE’s published quarterly literature reviews. These were empirical (quantitative and qualitative) studies of the NHSHC. The eligibility criteria that were employed in the rapid reviews (and so determined our inclusion of documents from these sources) are summarised in Table 4.

-

Documents retrieved via additional focused searches that we ran to identify additional material that may have been excluded from the existing reviews and bibliographies. This included, for example, relevant commentary or opinion, which may still be included in a realist review where data from these documents may contribute to theory-building. 45 Our more specific search strategies focused on identifying documents focused on the NHSHC in England. We ran these more targeted searches in MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, HMIC and Web of Science (SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI indexes). These searches used specific free-text terms describing the NHSHC alongside relevant subject heading terms as appropriate. The full search strategies used are reproduced in Appendix 2.

-

Documents retrieved via a trawl of the NHSHCs website (www.healthcheck.nhs.uk/), including case studies, local evaluations and abstracts and posters presented at the Health Checks/Cardiovascular Disease Prevention annual conferences from 2014 to 2020. These sources represent an important source of data on local implementations of NHSHC and additional research studies that have been excluded from previous reviews. Our realist approach provides the opportunity to supplement and structure the informal collaborative knowledge-sharing that has been facilitated by these spaces. 46

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Intervention: NHSHC | Editorials, commentaries and opinion pieces |

| Study design: guidelines; RCT, cluster RCT, quasi RCT, cluster quasi RCT; controlled and uncontrolled pre–post studies with appropriate comparator groups; interrupted time series; cohort studies (prospective and retrospective); case-control studies; qualitative studies from any discipline or theoretical tradition with recognised qualitative methods of data collection and analysis; economic and health outcome modelling |

This main phase of searching and gathering documents was undertaken in October 2020. At the same time, a regular email alert for (NHS (‘health check’ or ‘health checks’)) was set up using Google Scholar, to help capture research studies and grey literature published over the course of the review. Some additional documents were provided by our professional stakeholder group members and by respondents to our survey, in response to our request for local evaluations or similar documents, as described above.

All documents identified via these processes were stored and deduplicated using Endnote X9 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) reference management software.

Additional searching

Additional searches for data may be undertaken in a realist review, for example, to help to develop and test particular aspects of the programme theory. Although we had anticipated that additional searches for documents containing empirical data may have been required for this review, the project team agreed that the material had been identified via the searching processes described above were sufficient to meet the needs of this project.

We conducted a small number of focused searches (in Google Scholar) to identify material related to one substantive theory, ‘street-level bureaucracy’,47 which has been used to help to frame and illuminate our final programme theory and discussion, and is described in more detail below (see Chapters 3 and 4). These searches are also reproduced in Appendix 2.

Step 3: Article selection

Documents were exported from Endnote X9 and imported into Rayyan QCRI (Qatar Computing Research Institute (Data Analytics), Doha, Qatar), a web-based tool designed to support screening for systematic reviews. Initially, CD and GW screened a small sample of documents (n = 25) in a pilot process to check for consistency in the application of our initial inclusion and exclusion criteria.

We then screened the full set of documents retrieved in Step 2 using a three-step process. CD screened the titles and abstracts (where available) of the documents retrieved via our searches and the NHSHC website following the eligibility criteria specified in our review protocol and outlined in Table 5. GW screened 10% of each of these sets of documents in duplicate (n = 67 documents retrieved via searching; n = 25 documents retrieved from the NHSHC website), and CD and GW discussed discrepancies in decision-making as a means of ensuring consistency in how the inclusion criteria were applied.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Intervention: NHSHC programme (all delivery models) Focus criteria: later steps in NHSHC delivery, including the provision of advice, signposting, referral, prescriptions |

Cardiovascular screening programmes run in countries other than England |

| Study design: all study designs | Other NHS screening programmes |

| Setting: any setting providing NHSHCs in England | Routine health checks offered to specific target populations by the NHS which are not part of the NHSHC programme |

| Participants: commissioners and providers of NHSHCs; all adults eligible for NHSHCs | |

| Outcome measures: all outcome measures related to NHSHCs Focus criteria: all outcomes relating to later steps in NHSHC delivery, including rates of provision of advice, signposting, referral, prescriptions, and behaviour and lifestyle change |

When this initial screening process was complete, CD re-screened all remaining documents in light of the review’s chosen focus, seeking to identify documents that were likely to include data on what happens after the measurements and risk assessments are complete in an NHSHC. This additional inclusion criterion was applied to identify documents that described, for example, the offer or delivery of advice, signposting or referral, ongoing support or prescriptions following an NHSHC. Where the coverage of any particular document was unclear from the title or abstract, it was included for full text screening. The application of this additional inclusion criterion permitted us to efficiently prioritise documents that were likely to contribute relevant data on our chosen focus.

For the documents included in the existing PHE-commissioned rapid reviews, we relied on the screening processes undertaken by these review teams. We therefore included for consideration in full text all of the documents included in these reviews that related to review questions which focused on the appropriate stage of the NHSHC, as follows:

-

How is primary care managing people identified as being at risk of CVD or with abnormal risk factor results? (Objective 4 in the rapid reviews)

-

What are patients’ experiences of having an NHSHC? (Objective 5 in the rapid reviews)

-

What is the effect of the NHSHC on disease detection, changing behaviours, referrals to local risk management services, reductions in individual risk factor prevalence, reducing CVD risk and on statin and anti-hypertensive prescribing? (Objective 6 in the rapid reviews).

In the final stage of screening, CD read all documents in full text, to assess whether or not they contained relevant data that could contribute to the development and refinement of the programme theory. This process continued and was repeated during Steps 4 and 5 (see below), as the documents were read and re-read closely multiple times and the analysis evolved over the course of the review.

All excluded documents were stored in an Endnote reference library so that they could be consulted later in the review as required.

At all stages, wherever we identified documents that included relevant data, we also considered the rigour or trustworthiness of those data at the point of inclusion. We did not apply a standard checklist to assess each study. Instead, each piece of extracted relevant data was first assessed in relation to the methods that were used to produce it (where applicable). We did not automatically exclude data that were judged to be of limited rigour, or data that were not produced directly by a specific research method, as we also made an overall assessment of rigour at the level of the programme theory developed over the course of the review. 45 Our overall assessment of rigour took into account the role that each piece of data played in the developing programme theory and focused on our judgement of the explanatory value of the theory produced. To make this assessment, we considered both the volume and the nature of the data that underpinned each part of our developing programme theory. We also assessed the plausibility and coherence of each aspect of the programme theory (each context-mechanism-outcome configuration (CMOC)), as well as the relationships between these and the programme theory as a whole. To do so, we applied three interrelated criteria to each of these levels45 (see Step 5 below for more detail):

-

Consilience: We considered the extent to which the theories explained the included data, and considered theories that explained more of the data to be more plausible than those that could only account for some data (while bearing in mind that the aim in realist research is to identify and explain ‘demi-regular’ patterns of outcomes, i.e. we anticipated some data may point to ‘exceptions to the rule’).

-

Simplicity: We considered the extent to which the theories were simple and did not require special assumptions to be added to ‘help’ them explain the data.

-

Analogy: We considered the extent to which the theories fit with what is already known from existing research and substantive (formal) theory and the extent to which the component parts of our theories fit with each other.

All of the review findings presented below were judged by our project team to meet these criteria and so represent our assessment of plausible and coherent theories that explain important outcomes related to what happens after the measurements and risk assessment are completed in an NHSHC. Some aspects of the programme theory are stronger and more plausible than others, being based on a greater volume of more trustworthy data. To ensure transparency, the findings are accompanied by a full account of the data underpinning them: see Table 21, Table 22 and Table 23. A separate data appendix with full details of all extracted data is available on request from the authors.

Step 4: Extracting and organising data

We extracted the main characteristics (bibliographic details and information relating to study design, participants, settings and main findings) of each included document into an Excel spreadsheet. These details are presented in Table 20 in Chapter 3.

The full text of included documents was uploaded into the qualitative data analysis software, NVivo (Version 12, QSR International, Warrington, UK). CD coded relevant sections of text in these documents where they were interpreted as being relevant to what happens after the measurements and risk assessment are completed in an NHSHC. Some coding was deductive (some codes were anticipated in advance of data extraction and analysis, based on the IPT and background reading) but most coding was inductive (codes were created to categorise data in the included studies during the data extraction process) and some was retroductive (codes were created based on an interpretation of the data extracted, where we inferred what the causal force was that generated observed outcomes, i.e. mechanisms). Each new element of data was incorporated into our analysis (as described below in Step 5) and as the analysis progressed and the programme theory was refined over the course of the review, documents were re-scrutinised to ensure that all relevant data were captured. The final version of the coding frame is reproduced in Appendix 3.

As with screening, a 10% set of documents were coded in duplicate. CD and EG coded 10% of documents (n = 22) independently and GW provided an additional check for this coding by reviewing a merged NVivo file. The coding decisions and coding frame were discussed by the wider project team to resolve discrepancies and ensure consistency in how codes were understood and applied. Following this, CD coded the remaining documents following the processes described above. This process is a slight deviation from the process planned in our protocol, which indicated that 10% checks would be conducted by GW alone. This change permitted an additional member of the research team (EG) to provide an additional independent check on data coding, while increasing her familiarity with the data included in the review.

Step 5: Synthesising the evidence and drawing conclusions

We used a realist logic of analysis to make sense of the data included in the review. This process began and moved in parallel with the decisions taken in Step 4, as data were included wherever they were considered sufficiently rigorous and were understood to have relevance to our focus in the NHSHC. When coding of the included documents was complete, the data contained within individual or across closely related categories were read and considered together. We interpreted the extracted data as relating to important contexts, mechanisms or outcomes (or the relationships between these) and used them to build CMOCs, describing why (by which mechanisms) particular outcomes were generated in particular contexts.

To do this, we compiled and interpreted data both within and across included documents. We used cross-case comparison to draw parallels wherever the data demonstrated that similar contexts and mechanisms were in operation to produce patterns of outcomes, and to understand when and how different outcomes were produced. Based on our interpretations, we constructed theoretical explanations in the form of CMOCs for the range of outcomes we observed in the data, where these were relevant to our focus on what happens after the measurements and risk assessment are completed in an NHSHC. We aimed to develop the CMOCs at an appropriate level of abstraction, such that they embodied potentially transferable explanations that encompassed a range of specific circumstances and outcomes. In practice, this meant that our interpretation focused on identifying the salient features of the circumstances described in the data that could be understood as functioning as context, and identifying the specific, proximal outcomes that were produced in those contexts, rather than focusing solely on the intended overall outcomes of the NHSHC. As our theories were refined, more specific CMOCs were merged, whenever they were understood to articulate specific cases of a more abstract phenomenon, while others were separated, when it became clear that more than one active context, mechanism or resulting outcome was in operation. Where mechanisms were not explicitly articulated in the included data, we used retroductive reasoning to infer likely causal forces, with a focus on the reasoning and responses of different participants involved in the NHSHC programme (commissioners, providers and attendees).

Our application of this process to an example CMOC is set out below, to help to illustrate what we did in more detail.

CMOC C1: When commissioners view the NHSHC programme as a means to improve people’s lives through behaviour change (C) they will try to exert their influence over providers to ensure that the programme is delivered with this in mind (O) because they believe this will maximise the potential benefits of the programme (M).

This CMOC is underpinned by data extracted from 12 documents: two research articles (one cohort study and one qualitative interview study), four local evaluations of the NHSHC, three conference abstracts or presentations, one unpublished working document provided by a LA who responded to our survey and two other reports focused on LA roles in programme delivery. The specific data underpinning this CMOC included:

-

Statements from the commissioners’ perspective (from local evaluations and reports focused on LA roles, which include local case studies) that illustrate the role of engagement and close working relationships with providers to ensure that NHSHCs are delivered as envisioned. For example:

There should be a dedicated programme team … to address, for example, day-to-day running, timely monitoring, provider quality control (especially training and audit), marketing and programme evaluation. 48

Data presented in this report reflect a high-performing [local] authority that works closely with general practices, stakeholders and patient representatives within it. 49

The commissioning body … has enthusiastically taken up the findings from their evaluation and created an information package for the participating GP Practices and has also held an information day…50

[The] importance of communications and relationship building should not be underestimated … it is important to build effective, collaborative working relationships between Commissioners and Providers. 51

-

Further statements from the same and additional sources draw attention to the potential for LA commissioners to use their influence and relationships to work to ensure providers retain a focus on the behaviour change purpose of the NHSHC. For example: (All our emphasis.)

Liaise with NHS England [Local Area Team] to ensure the information gained from an NHS Health Check is used by … General Practitioners to improve the health of the patient by ensuring there is appropriate: incorporation of the NHS Health Check results into patient records; follow up with their GP; referral to lifestyle interventions as required. 48

The results we are most proud of relate to bringing all our primary care practices together to deliver consistency of approach, re-invigorating staff to enable them to feel they can assist people to make the changes. 52

‘Softer’ measures of success are seen as: ensuring there is provision of appropriate follow-up lifestyle services to help those with health issues identified during the NHS Health Check. Many commissioners believe this is imperative to the spirit of the programme, even though there are no targets around this. 51

Taken together, our data represent multiple local examples where there was recognition of the importance of a route for LA commissioners to exert influence over NHSHC providers in relation to programme delivery, and that this influence may be used in particular to try to ensure that advice and referrals relating to the programme’s aim to support behaviour change are delivered. By including these observations in local evaluation reports, conference presentations and case studies, commissioners and evaluators have drawn attention to the importance of this role for LAs, and, by implication, a potential disconnection in commissioner and provider priorities that could affect programme delivery. This latter implication is borne out in other CMOCs developed from the commissioner (e.g. CMOCs C2–C10) and the provider perspective (e.g. CMOCs P1–P8), lending further support to CMOC C1 as part of our overall understanding of how the programme operates, as captured in our final programme theory.

Only six of the documents reported research or evaluation work that was undertaken using specific methods, and therefore an overall judgement of the quality and strength of the evidence collated here was required. Our judgement centred on the criteria outlined above in Step 4. We considered that, taken together, our data were consilient, in that CMOC C1 captures a causal explanation for the observed outcome that LA commissioners may work to exert influence over NHSHC programme delivery; simple, in that we did not feel there was need to specify any additional assumptions to support our explanation; and supported by analogy. 45 In this case, we did not draw on substantive theory during the development of this CMOC, but we draw attention to our observation that this CMOC makes sense when considered in relation to other CMOCs developed over the course of the review, as summarised in our final programme theory (see Chapter 4).

CD undertook this step and developed and shared sets of developing CMOCs, accompanied by explanatory narratives and their underpinning data, with the wider project team. Following discussion within the team, the CMOCs were refined and re-organised to help develop their explanatory value. This included re-ordering and grouping similar CMOCs together – considering the relationship of each CMOC to a developing overall programme theory – as well as consideration of the level of abstraction at which CMOCs were presented and discussion of potential mechanisms where these were unclear. Emerging findings were also shared with our PPI and professional stakeholder groups (see section Stakeholder groups and Table 2 above) and feedback from these discussions also informed the project team’s discussions and refinement of the CMOCs.

In the later stages of the review, we also considered whether substantive theory could play a role in supporting or developing our analysis. A small number of documents included in the review included theoretical perspectives, reflecting what we found during IPT development (see Appendix 1), but most of the literature that contributed data to our review was atheoretical. We considered whether substantive theory from various disciplines could help to support or illuminate aspects of our findings during project team discussions.

Overall, analysis and synthesis of the data was an interpretive and iterative process, involving returning to the documents and data and interpreting and re-interpreting their meaning, seeking additional data as needed and ongoing discussion within the project team throughout.

Chapter 3 Findings

This section describes the findings of both the survey and realist review components of this project. The findings of the survey are presented first, including descriptive information about our respondents, before quantitative and qualitative analysis of responses and a typology of NHSHCs delivery models are presented. For the review, a description of the included documents is followed by an overview of the CMOCs developed, accompanied by a narrative detailing the findings of the synthesis of the data extracted from those documents. The overall final programme theory is outlined and illustrated in Figure 18 in the final part of this section. The findings of the survey and review together underpin the conclusions and recommendations presented in Chapter 4.

Survey findings

Respondent details

In addition to the three pilot responses, we received 69 from the main survey launch, giving a total of 72. Four responses were duplicates from the same LA, one from the pilot and three within the main survey. The pilot respondents asked us to ignore their first response, which was therefore removed, while the second responses from the remaining three duplicates were removed, leaving 68 responses for analysis.

Five of these respondents were reporting on behalf of multiple LAs. Therefore, the total number of LAs represented by these 68 respondents was 74. These varied proportionally by region (Table 6).

| Geographic region | Number of LAs | Number of responding LAs | % of responding LAs |

|---|---|---|---|

| East Midlands | 9 | 5 | 56 |

| East of England | 12 | 8 | 67 |

| London | 33 | 18 | 55 |

| North East | 12 | 4 | 33 |

| North West | 23 | 9 | 39 |

| South East | 18 | 13 | 72 |

| South West | 15 | 6 | 40 |

| West Midlands | 14 | 4 | 29 |

| Yorks & Humber | 15 | 7 | 47 |

| Total | 151 | 74 | 49 |

Delivery of the NHS Health Check

Responses representing 64 councils reported that delivery of NHSHCs in their area had resumed since the Covid-19 pause. The remaining respondents, representing 10 councils, said the programme hadn’t yet been resumed in their area.

Face-to-face delivery of NHS Health Checks before and after Covid pause

Face-to-face delivery in most venues reduced following the Covid-19 pause, but particularly in community settings and pharmacies. One respondent indicated a Covid-19 vaccination centre was used after the pause (Table 7).

| Venue | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| GP practice | 73 (99%) | 65 (87%) |

| Pharmacy | 16 (26%) | 9 (12%) |

| Mobile unit | 6 (8%) | 6 (8%) |

| Community setting: | 30 (41%) | 15 (20%) |

| Workplaces | 11 | |

| Community centres | 9 | |

| Places of worship | 4 | |

| Leisure centres/sports halls | 3 | |

| Libraries | 4 | |

| Wellbeing centre/hub | 3 | |

| Council offices | 2 | |

Alternative methods of delivery

The use of alternative (remote) methods of delivery increased significantly following the Covid-19 pause, with the telephone being the most frequently used means of communication (Table 8).

| Method | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| Telephone | 2 | 26 |

| Video | 1 | 11 |

| Self-completion online | 2 | 5 |

All 11 LAs that use video consultations for elements of the NHSHC also use telephone; two of these also indicated using self-completion online. Two LAs were trying out online self-completion tools before the Covid-19 pause. One was carrying out a ‘Pilot of a remote digital check, bloods were not taken but the question was asked if they know their values. Digital check just used to garner a risk score to encourage attendance at F2F [face-to-face] for higher-risk patients’ (R61). This LA did not continue with this method after resuming following the Covid-19 pause, while the second did:

[the online self-completion tool] wasn’t available to all practices ‘before’. However, the offer is available to all practices now, but some have not engaged or decided not to take up the offer. (R32)

Eleven of the LAs offering partially remote NHSHCs (in a two-part service) require that the NHSHC attendee attends the practice for blood tests. However, six use data on file, as long as it is within three or sometimes six months. One respondent representing two LAs described a drive-through blood-testing service in the community, set up by the hospital (R08).

Fifty-four respondents (75%) said they would consider using remote methods in future, mostly in combination with face-to-face testing. Digital options that allowed a lifestyle questionnaire to be completed online were seen as a potential way of reducing the length of a subsequent physical appointment within the practice (which would include risk assessment and advice/referral) (R01), or as a way of helping providers to prioritise or target those most in need (R17, R31), or to focus the face-to-face appointment on risk communication, personal support and advice (R50, R66):

Online assessments prior to appointment, or some digital intervention to capture some basic information, but having the main consultation face-to-face – communicating the risk. (R66)

Alternatively, some saw the value of a two-part model in which an initial brief face-to-face appointment for physical measurements was then followed up by phone to discuss results and interventions (e.g. R04, R07, R20).

Looking at doing physical measures face to face and follow up appointment including risk management part of the check remotely. (R07)

This is in contrast with at least one LA which allows their providers to use their own judgement about how to use remote delivery, but ‘insist they [patients] need to come in to take their measurements and collect their results’ (R11). One respondent (on behalf of two LAs) suggested that their preference for face-to-face delivery was ‘to achieve best behaviour change results’ (R15).

There were some other novel proposals, and a high degree of uncertainty about what will work best in the future:

We are testing the feasibility and acceptability of remote blood testing using a kiosk in community setting and then linking back to an online questionnaire tool. This system would be for lower-risk patients predominantly. (R61)

The provider of our lifestyle service is developing an online health check model that we may pilot. (R25)

[We are] concentrating on community options to ease pressure on primary care and consider[ing] any remote options that are presented to us. (R47)

Many indicated they were wanting to learn how other areas got on with this hybrid model of providing NHSHCs, or were hoping to take part in a PHE-led pilot. One respondent expressed a concern about the ‘need to stick to the contents of the NHS Health Checks in order for interventions to be counted as a Health Check’ (R09). This respondent was therefore dissuaded from looking at digital alternatives. Comments from other LAs also suggested that they would be waiting for the lead to come from PHE/national guidance.

Which health professionals are commissioned to deliver the Health Checks?

None of the respondents told us they didn’t know which health professionals are commissioned to deliver the NHSHC. However, in later comments, respondents said that:

We commission GP practices to deliver it through suitably qualified, trained (and overseen) staff. It is then up to them who that actually is. (R30)

It’s often difficult to monitor Health Check activity from start to finish. Lack of contract monitoring meetings and data wrapped up in other service provision. (R03)

Healthcare assistants (HCAs) and/or nurses deliver the NHSHC in most (61) of the responding LAs. These same staff have also been used to deliver NHSHCs remotely. Respondents said that GPs deliver the NHSHC in 48 of the LAs, and also deliver remotely in 12 (Table 9).

| Provider | Face to face | Remotely |

|---|---|---|

| HCA | 61 | 19 |

| Nurse | 61 | 18 |

| GP | 48 | 12 |

| Pharmacist | 17 | 1 |

| Pharmacy assistant | 14 | 1 |

| Health trainer | 14 | 5 |

| Other | 9 | 3 |

Other providers included wellbeing advisers, health improvement practitioners, lifestyle coaches and paramedics. No respondents reported delivery via a ‘drive-through’ service.