Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number 16/116/03. The contractual start date was in September 2018. The draft manuscript began editorial review in June 2023 and was accepted for publication in January 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Walsh et al. This work was produced by Walsh et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Walsh et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSKDs) are the leading cause of disability in the UK with over 20 million people reportedly living with a MSKD;1,2 they account for approximately 30% of primary care consultations, with many patients repeatedly consulting due to non-resolution of their problem. 3,4 Lower-back pain is the most burdensome of these conditions1 and is the leading cause of years lived with disability in the UK. 5 The annual economic impact of MSKD more generally is vast, accounting for 23.3 million lost workdays in 2021,5 costing NHS England almost £5 billion6 and approximately £8.6 billion in personal independence payments in England, Scotland and Wales. 7

The volume of people with MSKD contributes to the significant financial and service delivery burden faced in primary care;8 2021–22 figures show that general practitioners (GPs) and other primary care staff delivered more appointments than in any other year on record9 and, given MSKD prevalence, a significant proportion will be attributed to these conditions. This is compounded by GP recruitment and retention difficulties10 which are likely to increase. Figures suggest that 13% of GPs under the age of 50 years, and 60% of those aged over 50 years expect to leave their position within the next 5 years. 11 The impact this is likely to have on patient care is substantial, and will inevitably affect waiting times, safety and levels of satisfaction, which are already causing concerns. 12 Given the exponentially increasing demand, coupled with the difficulties associated with GP recruitment and retention,8,10–12 alternative models of care that are implementable with relative ease, timeliness and affordability are essential. The pressing need for appropriate management is recognised by many integrated care boards, with primary care workforce initiatives representing an area of priority,13 and the area has been highlighted by the Primary Care Workforce Commission as requiring further evaluation and understanding. 10

By definition, GPs have an extensive knowledge of the initial and continuing management of multiple conditions. However, evidence suggests there is considerable variability in GP treatment of MSKDs, with care being offered that is inconsistent with national guidelines and under-use of cost-effective strategies, such as exercise and self-management. 14 Furthermore, data suggest that many referrals to secondary care orthopaedic and scanning services may be inappropriate, resulting in increased waiting times and the potential for delay in cases that do necessitate urgent attention. 14,15 There is a growing belief that GPs may not be the most appropriate healthcare professionals to manage the MSKD population, given their limited specialist musculoskeletal training. 16–18 By contrast, there is evidence that physiotherapists who are expert in MSKDs are effective in making diagnoses and achieving successful clinical outcomes, demonstrate good levels of patient satisfaction and save money on unnecessary referrals. 17,19–21 However, given the complexity of patients who may present with MSKD alongside multimorbidities, it is as yet unclear whether non-physician-led assessment and examination may lead to suboptimal management.

An emerging model and workforce development is first-contact physiotherapy, a rapidly developing approach to managing MSKD in primary care,22 whereby a specialist musculoskeletal first-contact physiotherapist (FCP) located within general practice undertakes the first patient assessment, diagnosis and management without the requirement for prior GP consultation. Furthermore, the expanding competency framework within physiotherapy means that in addition to the traditional skills of assessment, exercise provision, education and manual therapy, some first-contact physiotherapists can be accredited to prescribe medication, order scans, inject joints and list for surgery. 22 While FCP continues to expand across the UK, and is gaining significant commissioning momentum, there is limited evidence on the effectiveness of this approach and the context within which it is applied; local audits suggest that this model produces potential cost savings and service benefits. Pilot schemes throughout the UK indicate freeing-up of GP appointments, reduction in secondary care referrals, fewer scan requests, increased patient satisfaction and potential cost-savings within general practice. 23 Moreover, there is institutional support for the role evidenced by the investment in the Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme (ARRS), which aims to introduce 26,000 new roles into multidisciplinary teams (MDTs), of which first-contact physiotherapists are an integral part. 24

There is a lack of robust research evidence investigating the FCP service initiative, so further investigation is required. Of particular importance is the choice of model in relation to contextual variations within and across sites in the UK. Current audits of the various service delivery models suggest variables such as competency levels (i.e. whether or not clinics employ first-contact physiotherapists with additional qualifications), the extent of treatment provision (i.e. diagnosis and immediate treatment in surgery or diagnosis only with onward referral for treatment) and employment status (i.e. employed via single general practice, deployed from NHS physiotherapy departments or federation/cluster roles) impact upon their functioning within sites, which, we argue, is essential to study with robust methodology. The complexity of this emergent service delivery initiative, including the likelihood of intended and unintended outcomes, produces a compelling argument supporting the use of realist evaluation methodology; an approach that can manage an analysis of the variation between sites employing different FCP models as well as the mechanisms within each model. We believe the evidence gained from this methodological approach will expedite the impact this has on clinical and commissioning practice and will facilitate the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) ‘Push-the-Pace’ initiative. 25

Aim

To evaluate FCP in general practice for patients with MSKDs and to provide evidence for the adoption of appropriate service delivery models with potential to:

-

provide optimal patient management

-

show meaningful patient benefit

-

relieve GP workload pressures

-

promote better use of healthcare resources

-

positively impact on whole-system musculoskeletal practice.

Using realist methodology, the primary research question was to establish how FCP works in practice, for whom and why? Each phase provided cumulative insight into the primary research question stated above.

Objectives

-

Determine key characteristics of FCP provision in primary care (survey).

-

Analyse current literature to determine key aspects of service architecture that may impact provision and create initial programme theories regarding ‘how’ FCP may work in practice (realist review and stakeholder consultation).

-

Establish the clinical and cost-effectiveness of the FCP model of care compared with GP-led approaches (case study evaluation – quantitative).

-

Explore the views and experiences of patients, healthcare professionals and practice staff regarding the FCP model of care (case study evaluation – qualitative).

-

Determine the impact of new ways of remote working post-COVID-19 on FCP staff (survey and interviews).

-

Integrate data to provide insight into how and why the FCP service works in practice (case study evaluation – qualitative and quantitative).

Report structure

The report is presented with each phase included as a separate chapter, including the related methods, analysis and brief overview of findings. Chapter 7 then brings the quantitative and qualitative findings together and includes implications for implementation and practice. Chapter 8 summarises key findings and Chapter 9 includes strengths and limitations and recommendations for future research.

Chapter 2 Patient and public involvement and engagement

Ethos

Patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) is a core principle of our research and essential to ensure public accountability and transparency. For this study, PPIE directly improved the quality of our research, making it relevant to people affected by MSKD and to those who give them support. Patients and public have endorsed our research as important and have helped us refine our original proposal in a preapplication focus group. Continuing to support the research throughout each phase of work, our patient partners, present on the study steering committee and project management group, helped us to conduct the research using methodologies acceptable and sensitive to our patient groups, and assisted us in presenting findings in ways that are accessible to a range of audiences.

From the outset, people with MSKDs have made a valuable contribution in shaping and developing our work, and we continued to embed PPIE throughout. We had patient representation on the study steering committee, a white woman in her 40s who experienced chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain. Co-applicant Foster, a white man in his 70s with osteoarthritis in multiple joints, was a patient representative and was an integral part of the project management group. All time was reimbursed according to NIHR recommended rates.

Our project management group patient research partner and study co-applicant attended realist methodology training to support his involvement in the study planning and interpretation of findings. He attended monthly project management group meetings where possible and provided regular written feedback on all study decision-making processes. DF has also co-authored study outputs.

The study steering committee patient research partner attended the majority of our 6-monthly meetings, providing impartial feedback of study progress and supporting the team with problem solving and decision-making. Meaningful inclusion throughout the project also helped us understand patients’ ongoing service needs and make sure that the perspectives of those affected by MSKDs were represented in future service delivery decision-making.

Specific work package input

Work package 1: survey

Contribution to content and interpretation of data. The co-applicant patient representative was a co-author of the study output.

Work package 2: realist review and stakeholder engagement

Attended realist methods training and contributed to the development of FCP service architecture and initial programme theories. We recruited four additional patient representatives through People in Health West of England to attend our stakeholder event to provide feedback on our emerging initial programme theories. The co-applicant patient representative was a co-author of the study output.

Work package 3: case study evaluation

Contribution to all patient facing literature, interview schedules and advised on time to complete outcome measures. One patient research partner participated in a ‘practice interview’ to allow researchers to refine their questioning and techniques in advance of actual patient interviews. The co-applicant patient representative was a co-author of the study output.

Limitations

Despite considerable efforts, we had limited diversity within our PPIE; this was also reflected in the research itself. While this may have been influenced by the impact of COVID-19 and the disproportionate way in which the pandemic impacted people from underserved communities, we recognise this as a significant limitation of both our PPIE and the research itself. We relied on traditional means of recruitment for our PPIE, including social media and existing PPIE networks, which may have had limited reach. We have since changed our practice and have now established partnerships with local community organisations and champions within the community to ensure that we recruit a more diverse sample. The equality, diversity and inclusion within the research sample are discussed in the relevant chapters.

Summary

We integrated PPIE throughout the study and relied on the valuable contributions to ensure our planning and conduct had the patient at the centre. Our patient partners provided us with considerable insight and guided us on decision-making and data interpretation in the project’s entirety. We are grateful to all the patients and members of the public who have contributed to FRONTIER from the outset.

Chapter 3 National survey and identification of key first-contact physiotherapy service models

Reproduced with permission from Halls et al. 26 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text..

Aim

To conduct a survey to scope existing provision and key aspects of models of FCP provision across the UK. This information was used to inform the selection of models for in-depth evaluation in work package (WP) 3.

Study design

A survey was co-designed, piloted and subsequently distributed to individuals involved in FCP service provision.

Ethical approval

Prior to initiation of the study, an application for ethical approval was submitted to the University of the West of England Faculty Research Ethics Committee. Ethical approval to proceed with the study was given on 20 July 2018 (REC reference number: HAS.18.07.204).

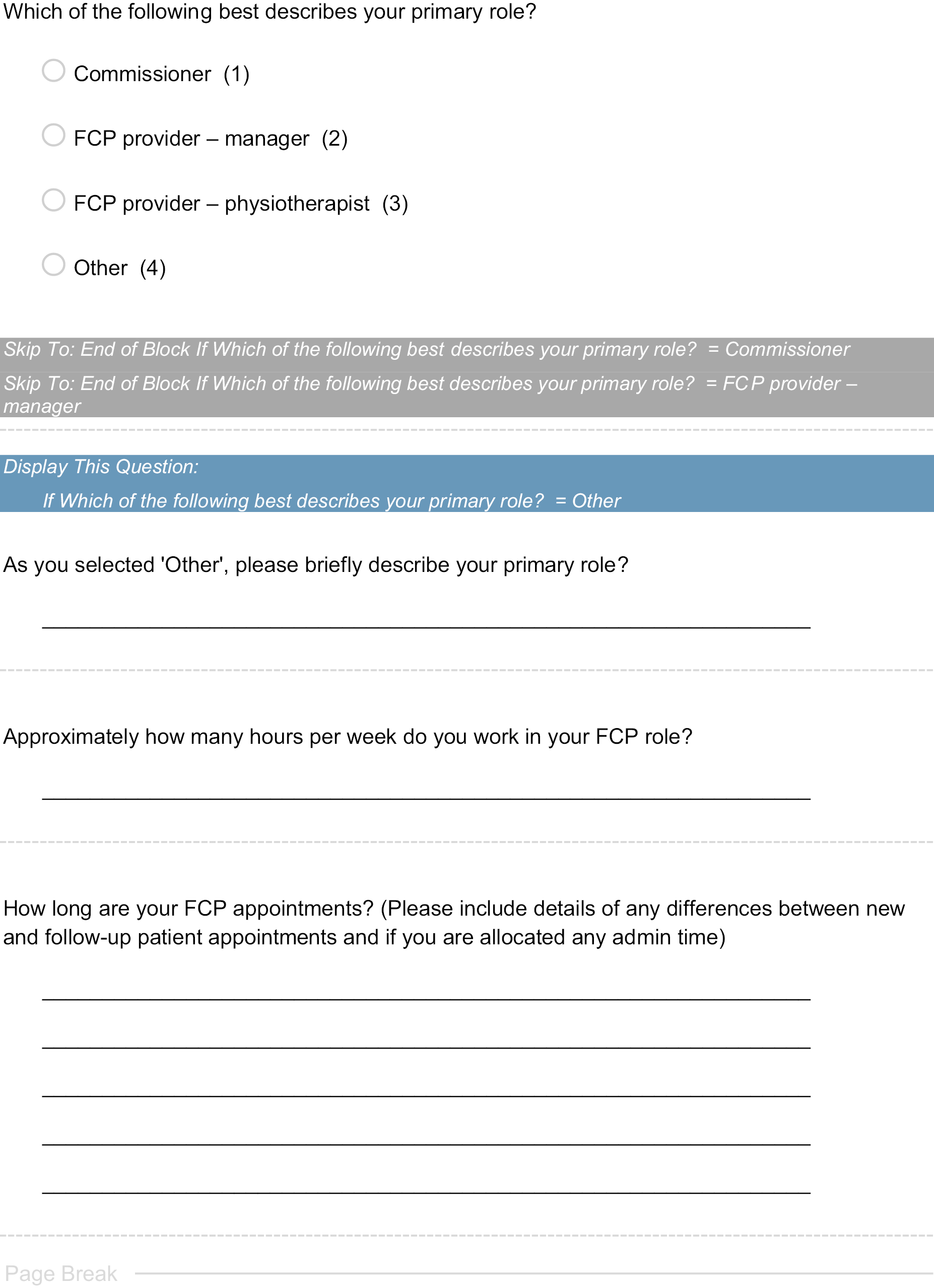

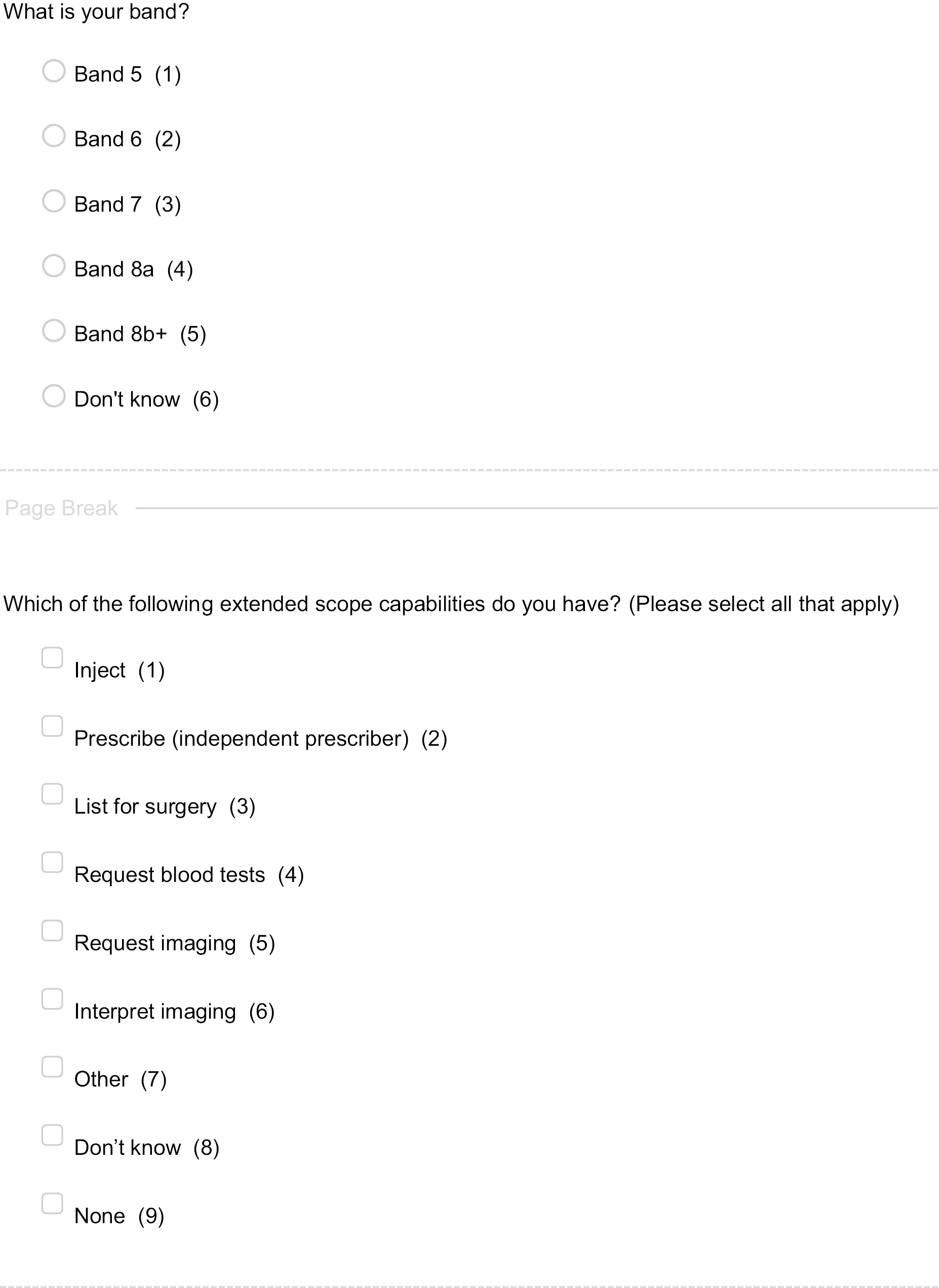

Survey development and pilot

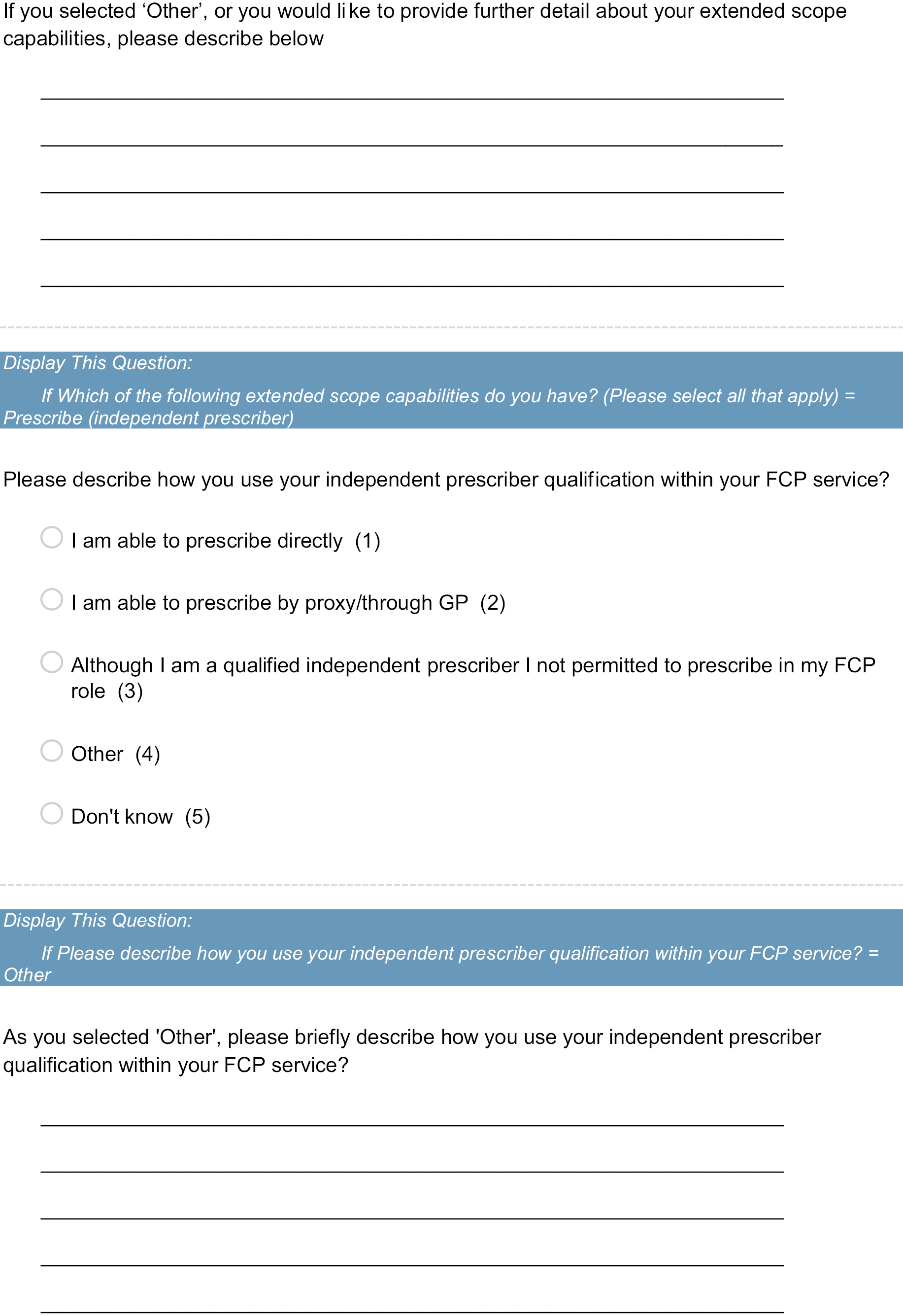

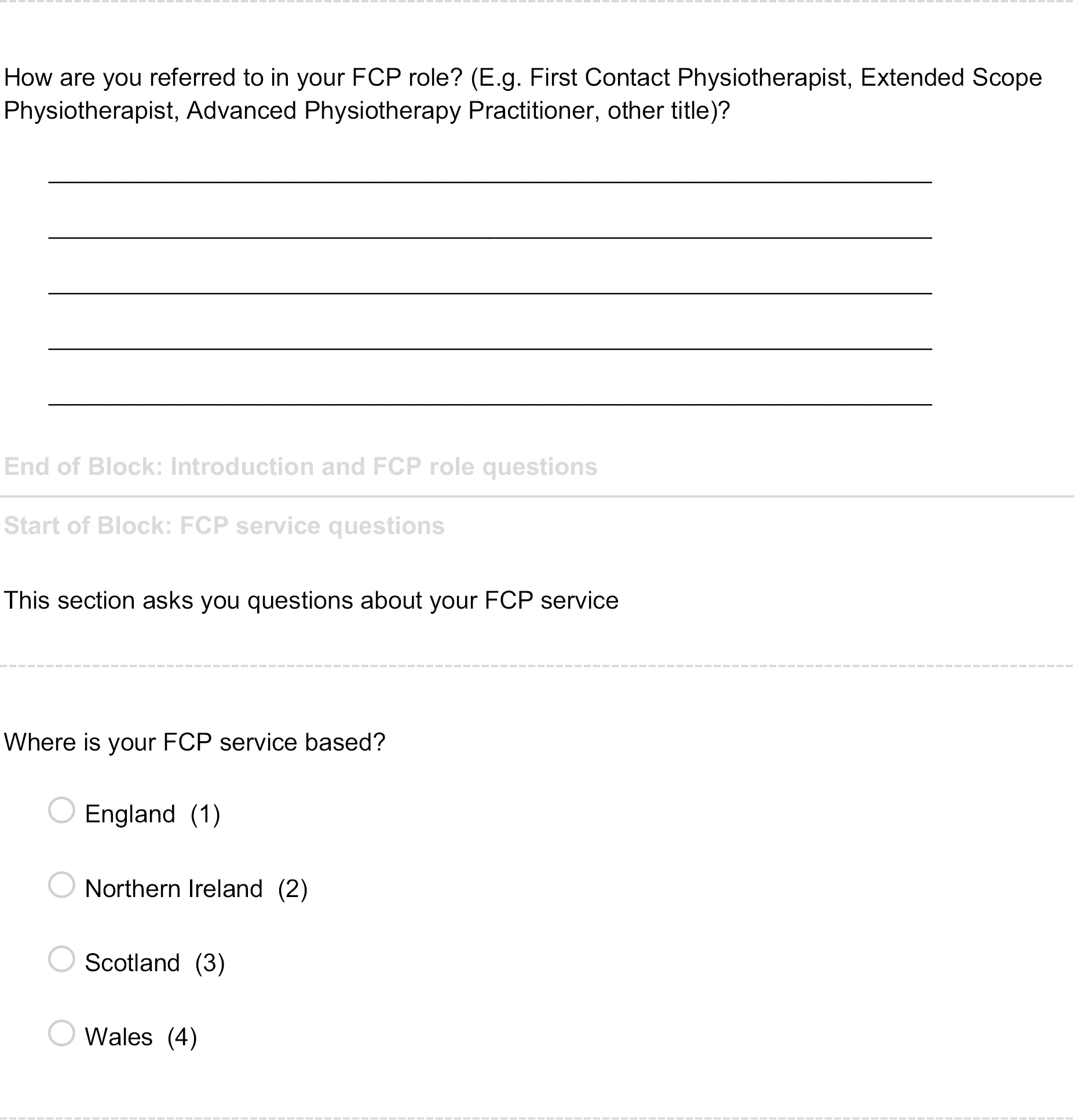

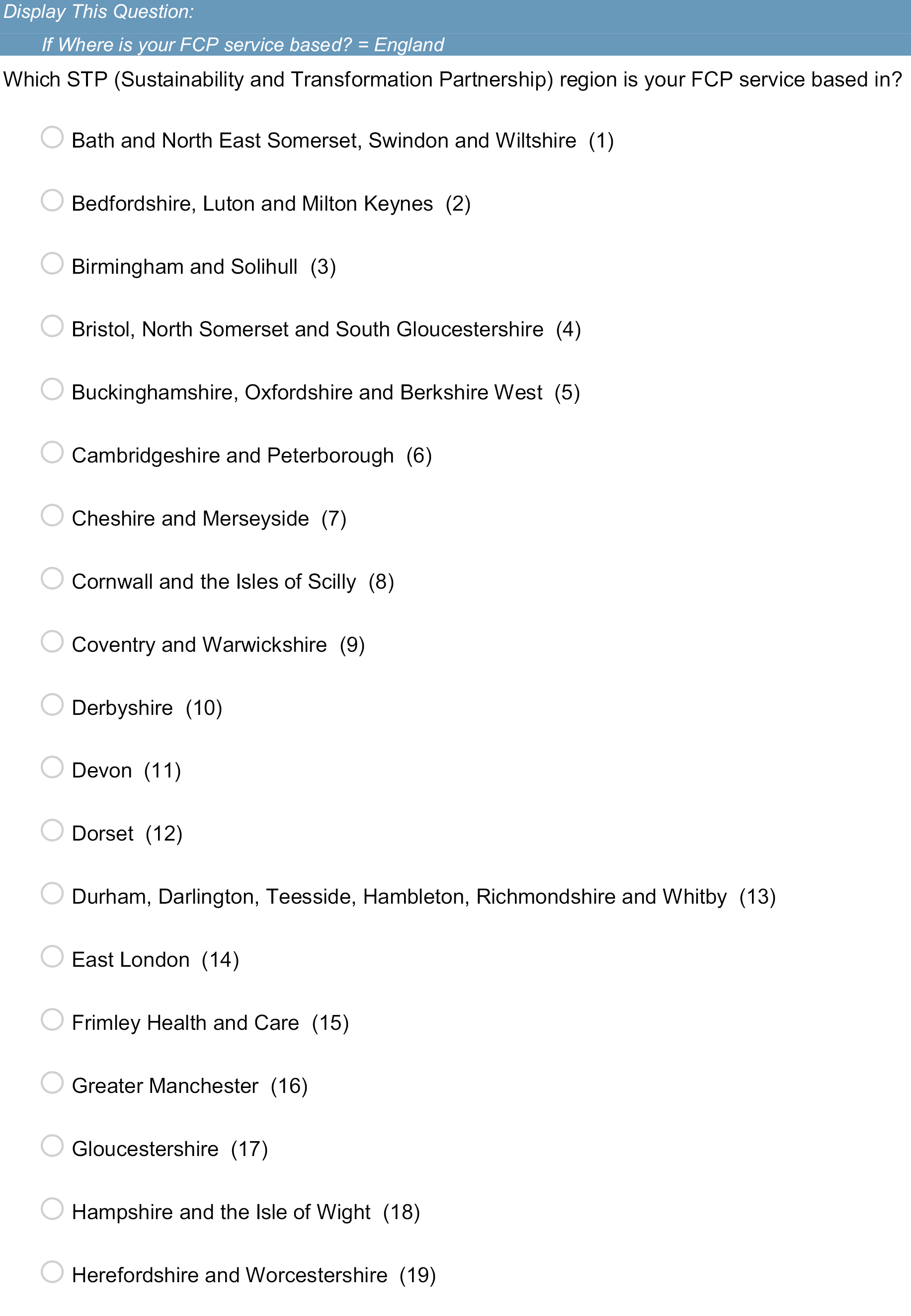

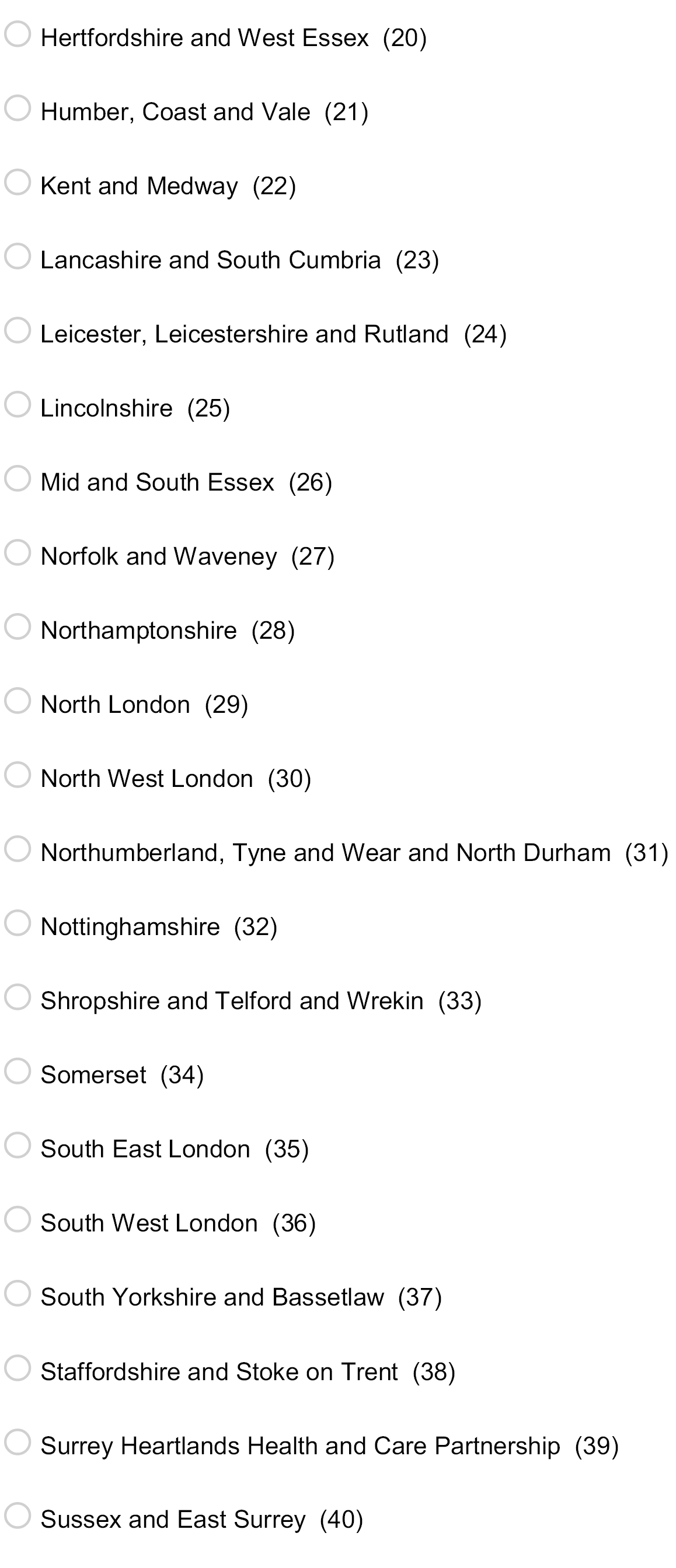

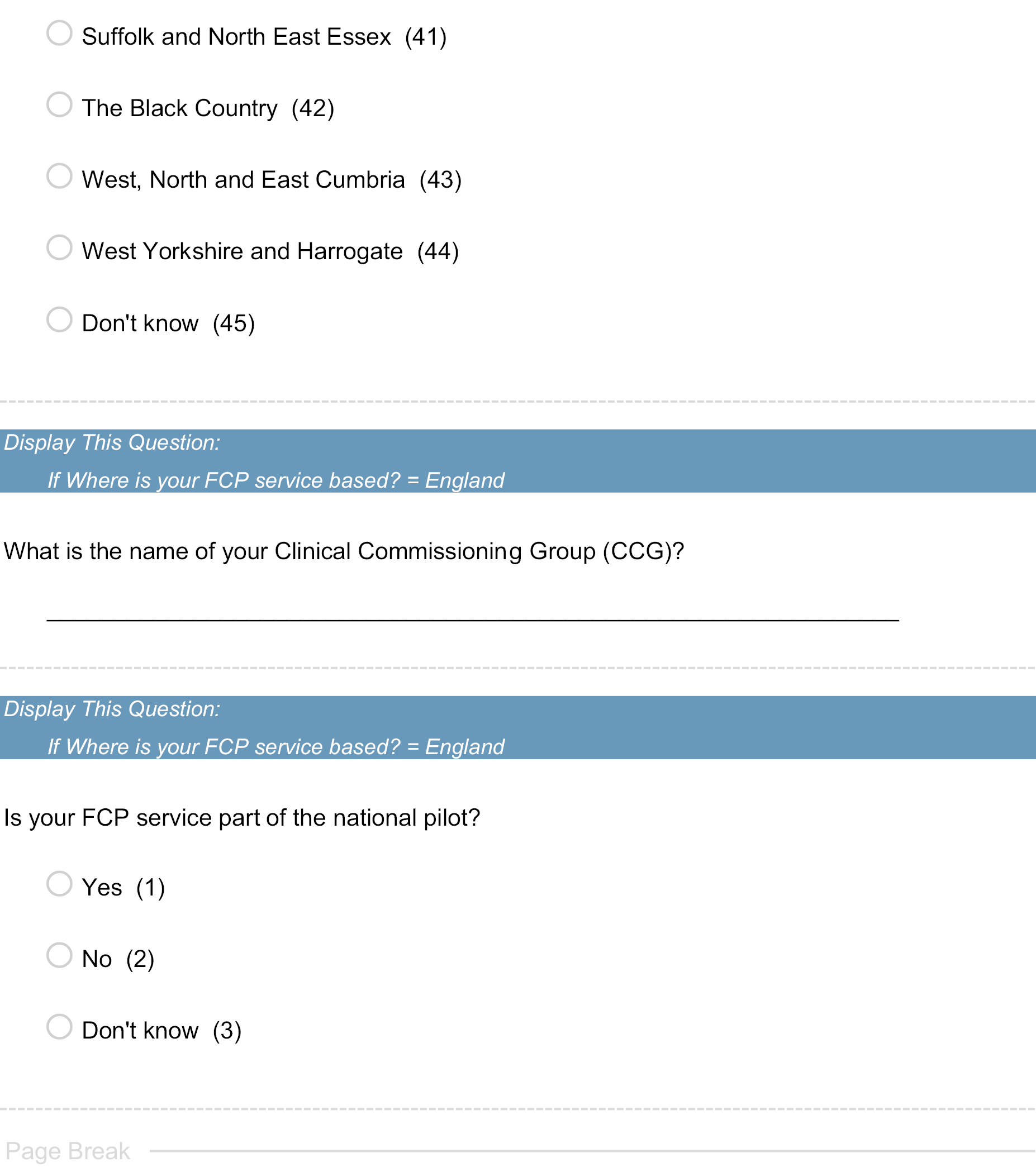

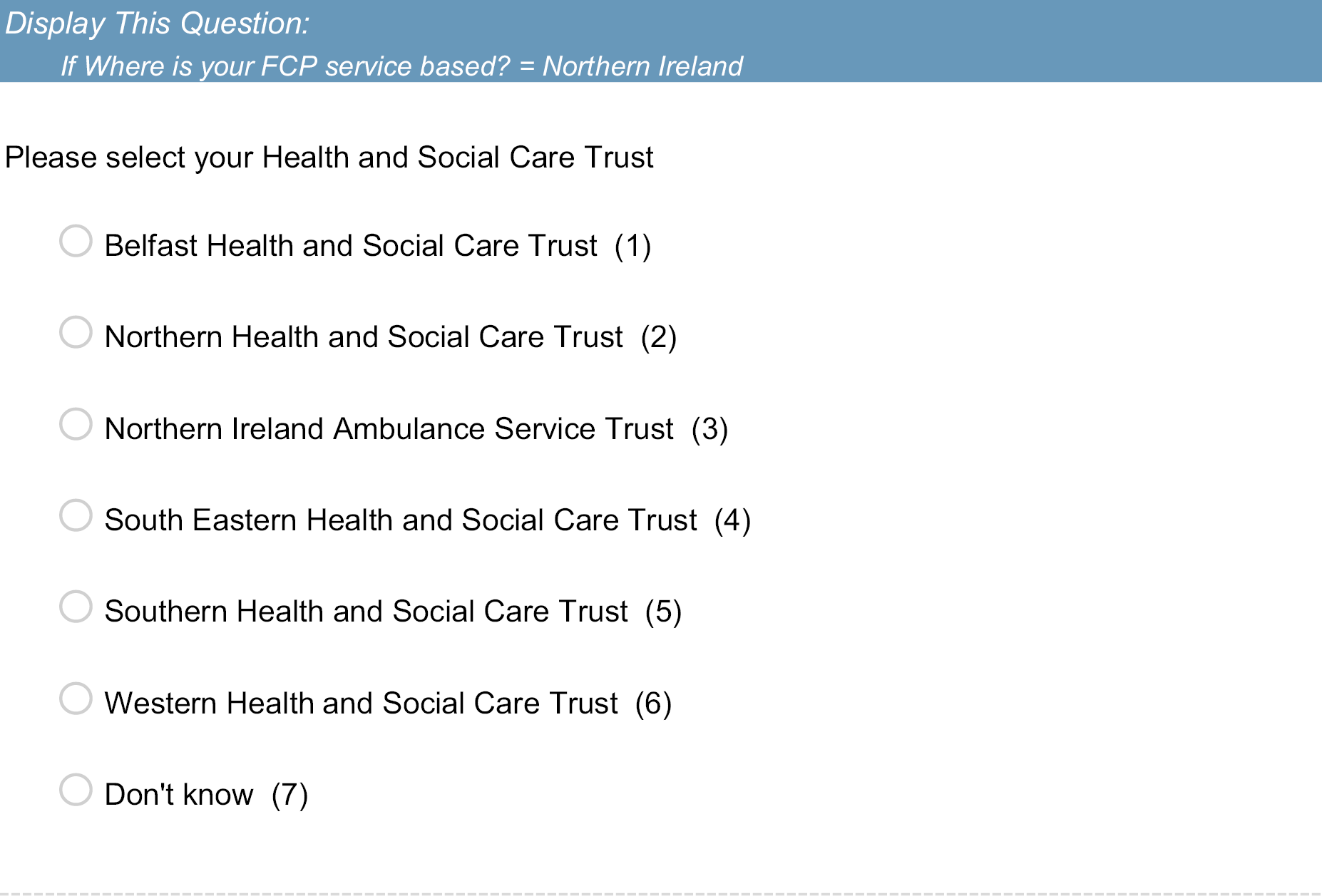

The survey was developed by the research team (including researchers, clinical commissioners, patients, physiotherapists and GPs). Initially, a draft survey was designed by the immediate study team. Although it was intended that the survey would be distributed using an online survey platform, the early drafts were developed in Microsoft Word® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) for ease of editing. The draft survey included open and closed questions regarding but not limited to geographical location, patient demographics, current service providers, referral pathways, staffing (numbers, grades and competencies), access to services, service aims and financial arrangements.

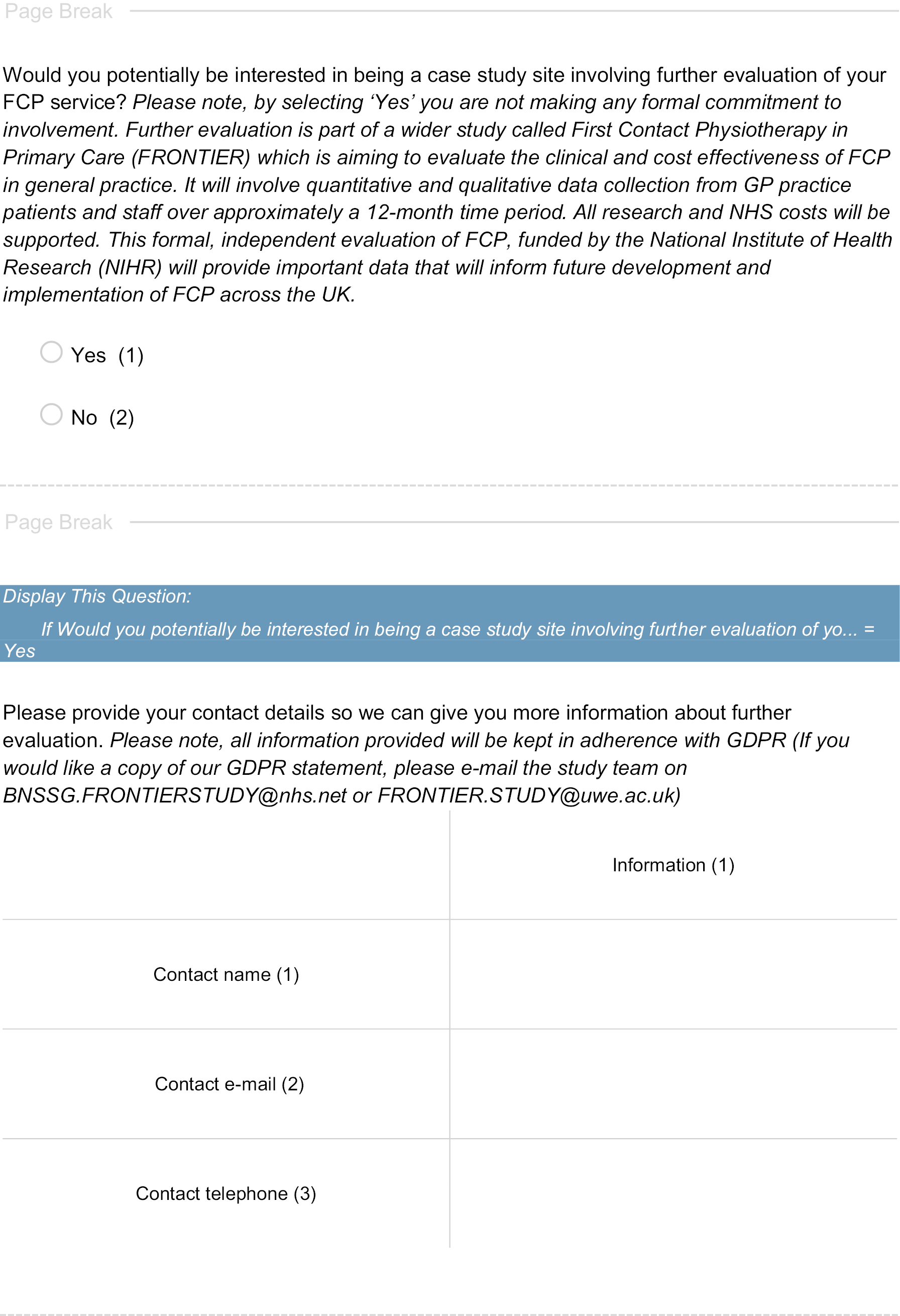

The draft survey was piloted with three individuals, known to the research team, who work in the areas of FCP and/or MSKD commissioning. Each pilot involved the draft survey being reviewed by the external individual and subsequently comments and feedback were provided via e-mail, via telephone conversation and in person. The draft survey was then edited based on this feedback. The revised survey was then discussed with the wider research team at the first project management group meeting. Following this, the survey was again edited based on the feedback received. It was then formatted using Qualtrics® (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA), an online survey platform. Once finalised, the online link to the 42-question survey (see Appendix 1) was sent to five individuals known to the research team to check that there were no problems accessing the survey (e.g. NHS firewalls or differences across the devolved nations) prior to wider distribution.

Survey distribution

The survey was targeted at those providing FCP services as managers or physiotherapists. Two approaches to survey distribution were used: direct e-mail and online platforms. The direct e-mail approach involved sending a survey link to relevant individuals identified from the FCP development network e-mail list. This e-mail list contained predominantly those involved in England-based FCP services and the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP)-led English pilot, therefore contacts in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland assisted in distributing e-mails to their local contacts across the devolved nations. E-mails were addressed to individuals personally, provided a short description of the aim of the survey, invited them to participate by clicking the attached link, and provided study team contact details should they require further information.

The online platform approach used Twitter (now X; San Francisco, CA, USA) and the FRONTIER study website. The link to the survey was made available via these online platforms. Regular updates were posted and shared during the period that the survey was available. The aim of the survey was to achieve as large a sample as possible to determine the nature of service provision at that point in time.

Data management and analysis

Survey data were initially stored in Qualtrics. Following the closure of the survey, data were downloaded from Qualtrics into a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet for formatting and analysis.

Analysis involved basic descriptions (numbers and percentages) and graphical representation of survey data. Survey respondents also had the opportunity to provide free-text responses. These data were not analysed using formal qualitative methodology but, instead, were used to add context to responses provided to particular questions. Some survey respondents indicated potential interest in further case-study-based evaluation (WP3) and provided their names and contact details.

Results

Response

The survey received 102 responses; 81% (n = 83) provided fully complete data sets. Given the nature of distribution it was impossible to determine a response rate. Furthermore, NHS England primary care workforce returns were unable to explicitly or reliably identify FCP numbers at this stage.

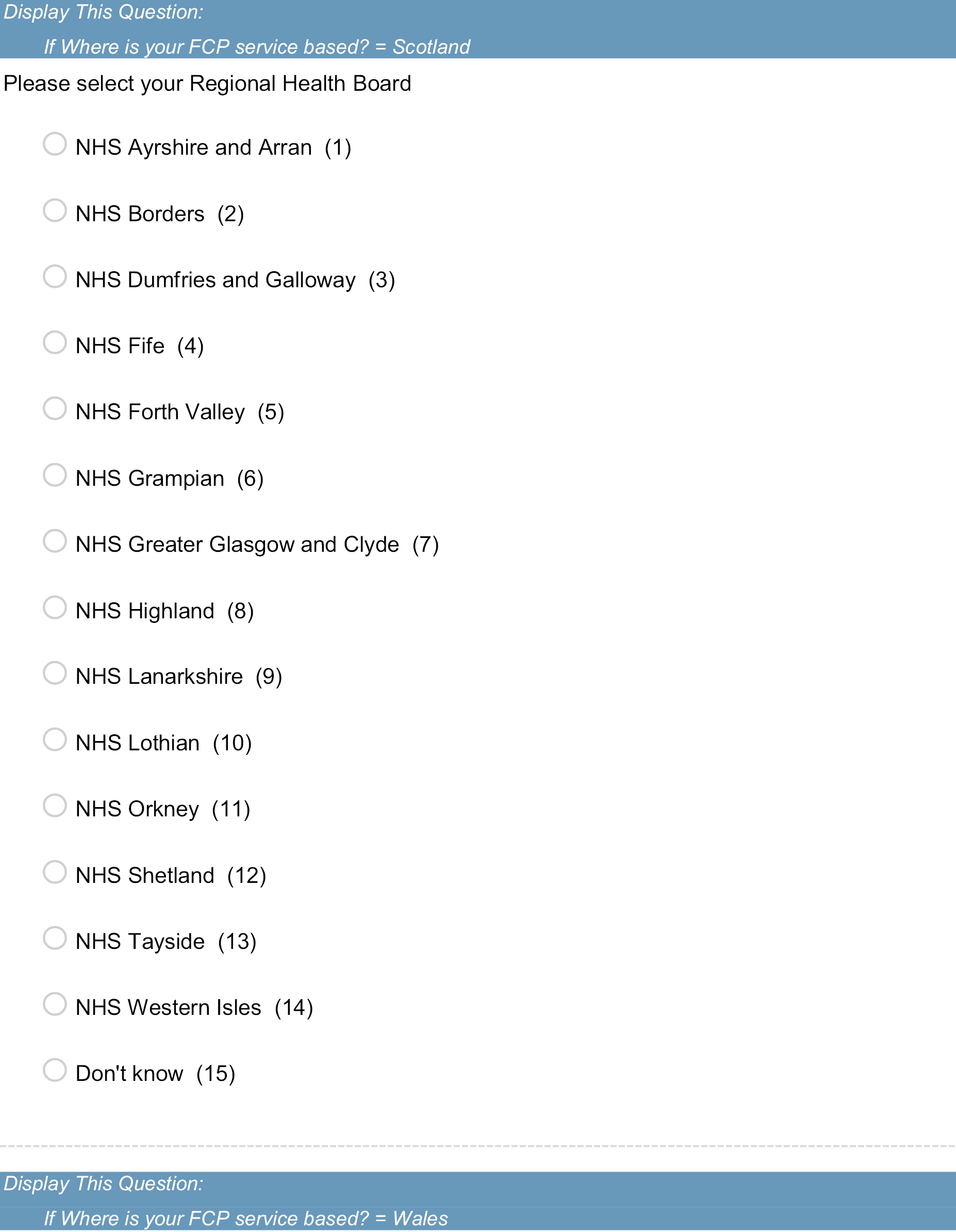

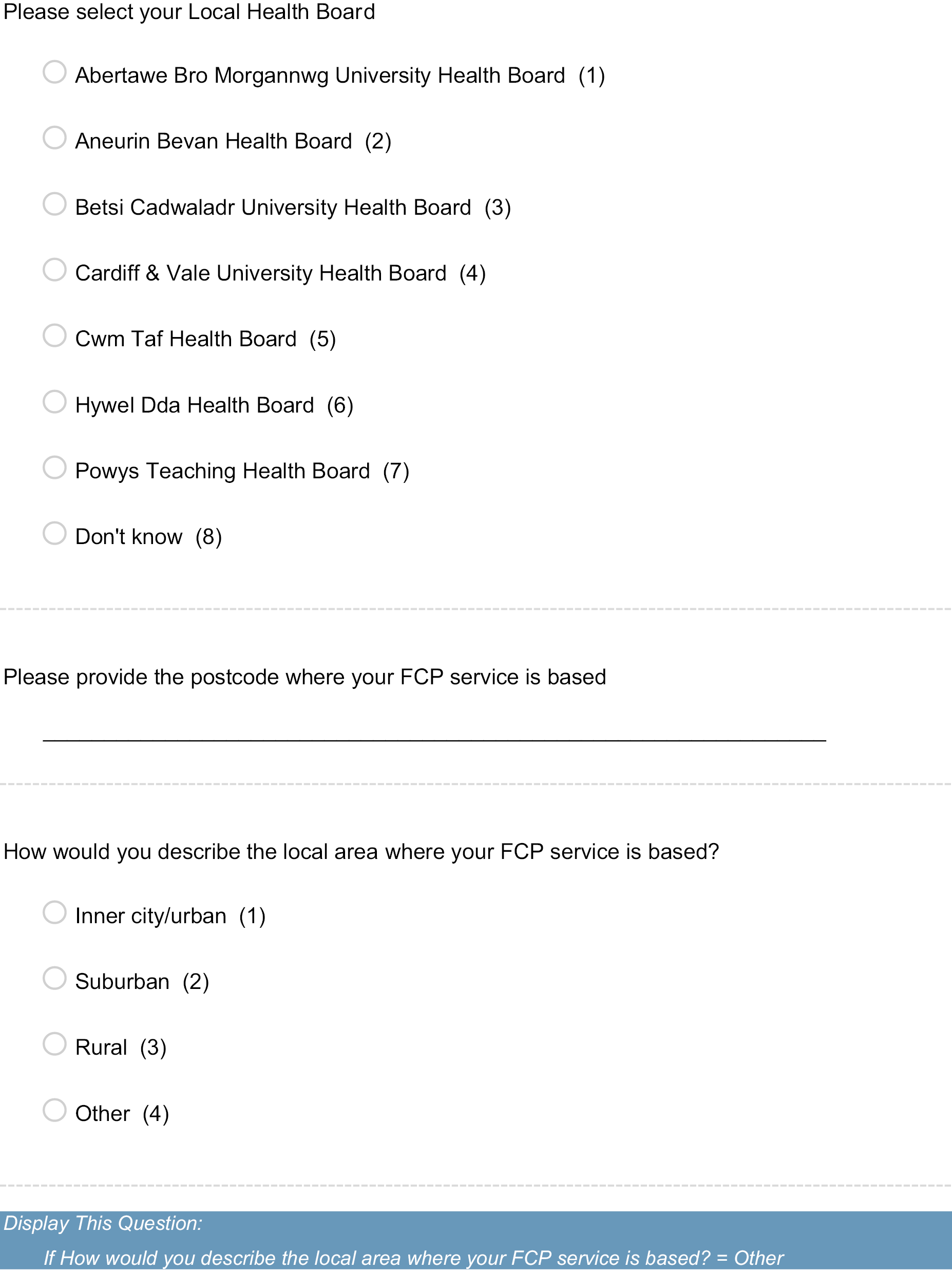

Respondent demographics

Of the 102 respondents, 31% (n = 32) identified themselves as ‘service manager’ and 63% (n = 64) as ‘FCP physiotherapist’. Six respondents indicated ‘other’ as their professional role. These responses included four individuals reporting different physiotherapist titles including advanced practitioner physiotherapist, consultant therapist, telephone triage physiotherapist and consultant physiotherapy. One respondent reported that their role was ‘director of clinical integration’ and one respondent left their role unidentified. The largest proportion came from those based in England (59%, n = 60). There were 22% (n = 22) responses from Scotland, 14% (n = 14) responses from Wales and 2% (n = 2) responses from those based in Northern Ireland. Four responses (4%) were unidentified in relation to geographical location. A total of 93 respondents described the local area where their FCP service was based, which included inner city/urban (35%, n = 33), suburban (33%, n = 31) and rural (20%, n = 19). Ten respondents (11%) indicated that their first-contact physiotherapist was based in an ‘other’ local area, which they described as a mixture of above options. Finally, 48 respondents (47%) provided information regarding the patient population that their FCP service covered. Reports of patient populations ranged from 1200 to 600,000. Of these, 12 (25%) had a patient population ≤ 10,000, 24 (50%) had a patient population between 10,001 and 99,999 and 12 (25%) had a patient population ≥ 100,000.

First-contact physiotherapy service provision by individual physiotherapists

Reports of the number of hours worked per week ranged from 0 to 37.5 hours, with a median of 16 hours. Responses indicate that 58% of respondents worked in their FCP roles up to 0.5 full-time equivalent (FTE), while 17% were working in FCP roles at 1.0 FTE. Appointment times for both initial and follow-up patient appointments ranged from 15 to 30 minutes, with 20-minute appointments being reported by most (71%, n = 50).

Some respondents specifically indicated that their service was only available to new patients or that they had no follow-up patient appointments. One respondent stated that their service has ‘no follow-ups but patients can request a call back if they have seen us before’. Some respondents also reported that they provide telephone triage (prior to face-to-face appointments). These were reported as 5–10 minutes, or that appointment times were 30 minutes, which included time for telephone triage and administration time.

Banding

A total of 69 responses were received, most reported being Agenda for Change band 7 (43%, n = 30) or 8a (48%, n = 33). Only one respondent reported being band 6 (1%) and five reported being band 8b+ (7%).

Additional skills

Of the 66 responses received, 7 (10%) reported having no additional skills, while 55 (83%) reported having two or more of the extended scope capabilities listed. The most frequently selected extended scope capabilities were the ability to request imaging (86%, n = 57), request blood tests (68%, n = 45), and the ability to inject (67%, n = 44); 19 (29%) reported that they were able to interpret imaging and 11 (17%) reported that they were able to list for surgery.

Of the 27 (41%) who indicated that they were independent non-medical prescribers, 20 (74%) reported that they were able to prescribe directly, 4 (15%) could prescribe through the GP via patient-specific or group direction pathways, 2 (7%) were not permitted to prescribe in their FCP despite being qualified independent prescribers, and 1 (4%) did not know.

First-contact physiotherapy service delivery models

Service duration

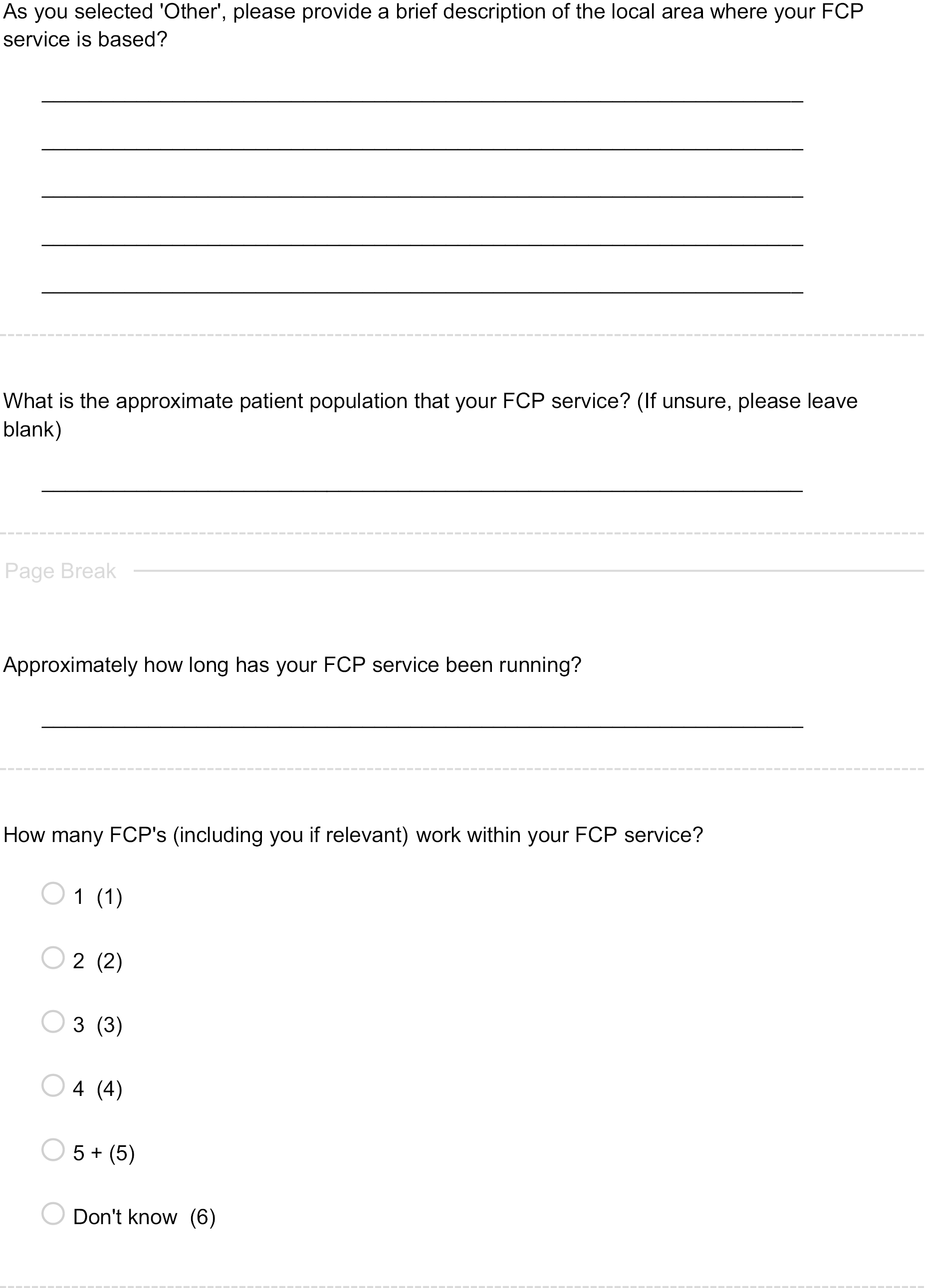

Responses were provided by 93 (91%) respondents. FCP service durations ranged from 0 months to 9 years. Of the 93 responses, 9 reported that their services were currently still in development or not yet up and running (10%). Approximately one third of FCP services were reported to have been running for < 1 year (n = 30, 32%); just under half of all FCP services were reported to have been running between 1 and 3 years (n = 43, 46%). Only seven (8%) FCP services were reported to have been running for longer than 3 years.

First-contact physiotherapist allocation

Respondents were asked about the number of first-contact physiotherapists working within their service. A total of 89 responses (87%) were provided, of which 5 (6%) indicated that they did not know; 13 (15%) reported that their FCP service was provided by 1 practitioner, 14 (16%) by 2, 7 (8%) by 3, 19 (21%) by 4 and 31 (35%) by 5 or more practitioners.

In relation to the total number of hours of FCP provision available per week, through current FCP services (note, not individuals), 88 (86%) responses were provided. Of these, 12 (14%) indicated that they did not know or the provided response was unclear or zero. The remaining responses ranged from 4 to 763.5 hours, with just under half of those between 30 and 187.5 hours (49%).

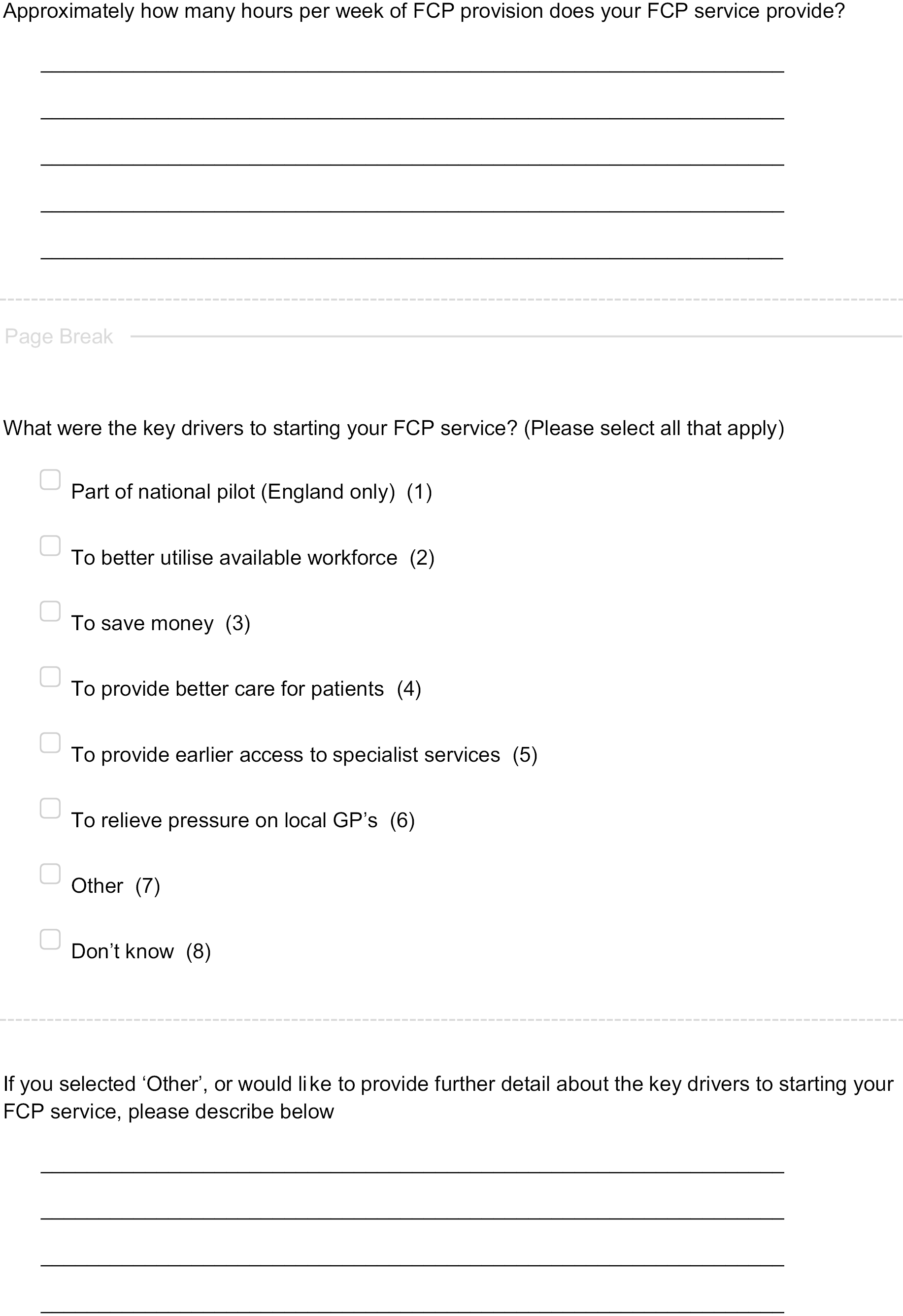

Key service drivers

For this question, 86 responses (84%) were given; multiple responses were permitted. Most respondents (90%) stated the main driver was to relieve GP pressure; 76% suggested it was to provide better care for patients and to provide earlier access to specialist services (59%). Other responses included better use of the available workforce, to save money and because they were part of an earlier national pilot in England.

Access

In relation to how patients access FCP services, respondents could select ‘triage at reception’, ‘self-booking (e.g. online appointments)’ or ‘other’ or could select multiple responses if that was more relevant. Some 85 responses (83%) were provided; of these, approximately half selected a combination of responses (n = 45, 53%). The majority were triaged at reception (40%) or triage at reception and other strategies such as self-booking.

Service funding

The following three questions asked about how FCP services are commissioned, funded and provided. In relation to how FCP services were reported to be commissioned, 86 (84%) responses were provided. Of these, eight respondents (10%) did not know, but a range of other responses across the provided response options were given including commissioned by the Clinical Commissioning Group (17%) or funded by a practice group (15%).

Within ‘other’, respondents added detail about commissioning of their FCP services. Some respondents used other terms for group of GP practices to describe how FCP services were commissioned including ‘super GP partnership’ or ‘GP federation’. Others described that FCP services were commissioned by systems and funding relevant to different devolved nations, including health and social care partnerships (Scotland), health boards (Wales) and integrated joint boards (Northern Ireland).

In relation to how FCP services were reported to be provided, 82 (80%) responses were given. The response ‘NHS provider’ accounted for over 80% of responses. Few additional free-text responses were provided here to elaborate on ‘other’; those provided described that FCP services were funded by health and social care partnerships, physiotherapy services and a GP stakeholder company.

Additional information

A total of 27 respondents (26%) provided additional information about their FCP service or role. Some of these respondents commented about how their services were further expanding.

Appointment length and content was mentioned by three respondents:

15 mins session does not work, especially if you have an interpreter patient and you have to use language line.

I feel moving forward 20 min appointments would be better, allowing more time with patients, better Assessment and able to do all admin for patient within the slot. Would negate need for admin slot at end of session.

FCP banding and advanced practice capabilities were mentioned by two respondents, who both questioned the necessity and cost-effectiveness of advanced practice capabilities:

Banding currently at 7 but trying to re band as 8a given the service provided. In my view physiotherapy is making the same mistakes as ANP [advanced nurse practitioners] first did when starting the advanced role.

More than 95% of patients do not require any advance practice intervention.

Challenges with FCP services were also discussed, including recruitment and information technology (IT) systems:

The XX [IT system named] does not work well at all within a cluster setting. It is the single biggest problem we have with the role.

Study implications

This WP used a survey approach to identify FCP service provision across the UK. This section considers results specifically in relation to the objectives of this WP, which included understanding the models of FCP service provision available across the UK, understanding the key aspects of ‘standard’ and additional capabilities models and scoping potential interest in WP3.

The 102 responses received within the 29-day window that the survey was available indicated that there was considerable interest in the topic of FCP. Although as expected, most responses (59%) came from those based in England, the largest of the devolved nations, responses were received from all devolved nations, in particular in Scotland and Wales. Interest from outside England may have resulted from their lack of involvement in the CSP-led English pilot and evaluation. The interest and engagement in this work at the early stage from the devolved nations provided positive indicators for the next phases of the FRONTIER study considering the wider project aim to engage with and involve UK-wide FCP services. It also met the WP objective of identifying potential interest in WP3.

In relation to responses regarding geographical location, within each devolved nation apart from Northern Ireland, over half of the sustainability and transformation partnerships/health board regions that make up each nation were represented in survey responses. Limited response from Northern Ireland may have been due to the lack of availability of FCP services when the survey was conducted, but this service has subsequently developed.

The survey responses also provided the opportunity to identify key aspects of ‘standard’ [non-pharmacological (medication and/or injection) and ‘additional competency’ (prescription and/or injection) models of FCP provision for WP3].

In our survey sample, 91% (n = 66) of FCPs reported that they were either band 7 or 8a. Only seven (10%) reported having no additional capabilities, while 86% (n = 57) reported that they could request imaging, 67% (n = 44) reported that they could inject and 41% (n = 27) reported that they could prescribe.

The survey also allowed enhanced understanding of FCP models and service provision available across the UK. In relation to how long FCP services have been running, the survey sample revealed that 9% (n = 9) of FCP services were currently still in development, nearly one quarter (23%, n = 22) were < 5 months old and only seven (8%) were reported to have been running for longer than 3 years. These figures, together with additional free-text comments provided, indicate the future development and expansion of services and demonstrate the new and evolving nature of FCP.

With regard to the key drivers for FCP service initiation, nearly all those who responded to this question (90%, n = 77) selected ‘To relieve pressure on local GPs’. Although a common justification for FCP service initiation, this response was surprisingly high, given that the majority of respondents were not GPs. Other highly selected responses included ‘to provide better care for patients’ and ‘to provide earlier access to specialist services’. Interestingly, ‘To save money’, a commonly cited justification for FCP service initiation, was only selected by one third of respondents (30%, n = 26). These responses are likely a reflection of the majority of respondents being FCP service physiotherapists or managers rather than commissioners. The qualitative work within the WP3 case studies was able to draw out more detail regarding the perspectives on this from a range of staff. It also provided an opportunity to explore reasons for initial FCP service initiation and service development and continuation.

A commonly reported benefit of FCP is appointments are typically longer than GP appointments (typically 10 minutes or less). This was confirmed in the survey responses, with 71% (n = 50) reporting that their FCP services offered 20-minute appointments, with all ranging from 15 to 30 minutes. Some additional free-text comments indicated that FCP service appointment times may change, which was a consideration for WP3 in terms of understanding the context at individual sites, but also potentially in terms of site recruitment to ensure inclusion of services running a range of appointment durations.

With regard to how patients access FCP services, there were a few aspects of note. First, it was very common that patients were triaged into FCP services. However, this role was not only performed by reception staff, but also by clinical GP practice staff. Second, very few respondents selected ‘self-booking’ either as an individual response or in combination with another response option. Both these aspects may be a result of the relatively ‘new’ nature of many of the services represented in this survey. It may be the case that clinical staff identify appropriate patients during routine consultations until services become established and patients become aware of its availability and purpose. Additionally, despite suggestions that standardised scripts can be used for musculoskeletal triage, this was only mentioned by one respondent. When thinking about WP3, survey responses indicated that it may be that multiple approaches to patient access are in operation in GP practices. It was therefore important for the study team to be able to record ‘footfall’ from all patient access routes.

Finally, in terms of FCP service commissioning, funding and providers, there were a number of points of note. First, the providers of FCP services were clear with over three quarters (83%, n = 68) of respondents describing that their FCP service was provided by the NHS. Service commissioning and funding questions were less clear. Respondents reported across all the response options provided for the commissioning question and, in addition, nearly one quarter (n = 24) reported ‘other’ commissioning approaches. However, many comments related to how services were paid for or financed, rather than how they were planned and monitored. The subsequent question about how FCP services were funded had a poor response rate, potentially due to respondents feeling that they had answered this in the previous question. Despite the effort that went into designing the questionnaire, and these three questions in particular, question wording may have been a limitation.

Limitations

We were unable to identify how many individuals saw the questionnaire and chose not to respond. Equally, it was not possible to determine the potential number of participants and therefore report our sample size as a percentage of the potential sample. Given the relatively small numbers of respondents to this survey, this is recognised as a limitation of this work.

Conclusions and summary

In summary, an online survey was used to identify and understand models of FCP service provision across the UK. A total of 102 responses were received from physiotherapists, managers and others involved in the provision of FCP based across the devolved nations. A number of considerations and implications for the FRONTIER project were identified. First, the interest and engagement with WP1 was promising, particularly with the identification of 62 respondents who indicated potential interest in participation in WP3. Second, recruitment of sites for WP3 needed to consider inclusion of services with a range of appointment durations and representation of FCP services commissioned in different ways. Third, consideration needed to be given to how best understand the educational, resource and cost implications of different models of FCP. Fourth, areas for further contextual understanding were identified including perceptions of the FCP role from a range of stakeholders and reasons for initial service initiation and continued service development. These areas were therefore included in the development of preliminary programme theory and realist synthesis as part of WP2 and explored in depth in WP3. Finally, practical considerations for WP3 included ensuring that all patient access routes into FCP services could be captured in data collection, and that processes were in place to manage practices using no or multiple clinical data systems.

Chapter 4 Rapid realist scoping synthesis regarding provision of first-contact physiotherapy in primary care

Reproduced with permission from Jagosh et al. 27 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Aim

To develop initial programme theories to inform in-depth case-study evaluation.

Objectives

-

Conduct a rapid realist review to produce a set of realist initial programme theories regarding what works, for whom, in what context and with what resources.

-

Engage with key stakeholders to validate the programme theories and gather further evidence about how FCP models are currently working.

Research questions

-

Does FCP improve patient management over usual GP care? And if so, how?

-

Does FCP show meaningful patient benefit? And if so, how and for whom?

-

Does FCP relieve GP workload pressure?

-

Are there unintended consequences to GP workload that need to be understood?

-

Does FCP promote better use of healthcare resources? If so, how?

-

Does FCP positively affect whole systems musculoskeletal practice? If so, how?

-

Are there risks associated with FCP models? If so, what are they and how do they accrue?

Study design

Realist synthesis and stakeholder consensus.

Ethical approval

Prior to initiation of the study, an application for ethical approval was submitted to the University of the West of England Faculty Research Ethics Committee. Ethical approval to proceed with the study was given on the 20 July 2018 (reference number: HAS.18.07.204).

Methods

Methodological approach

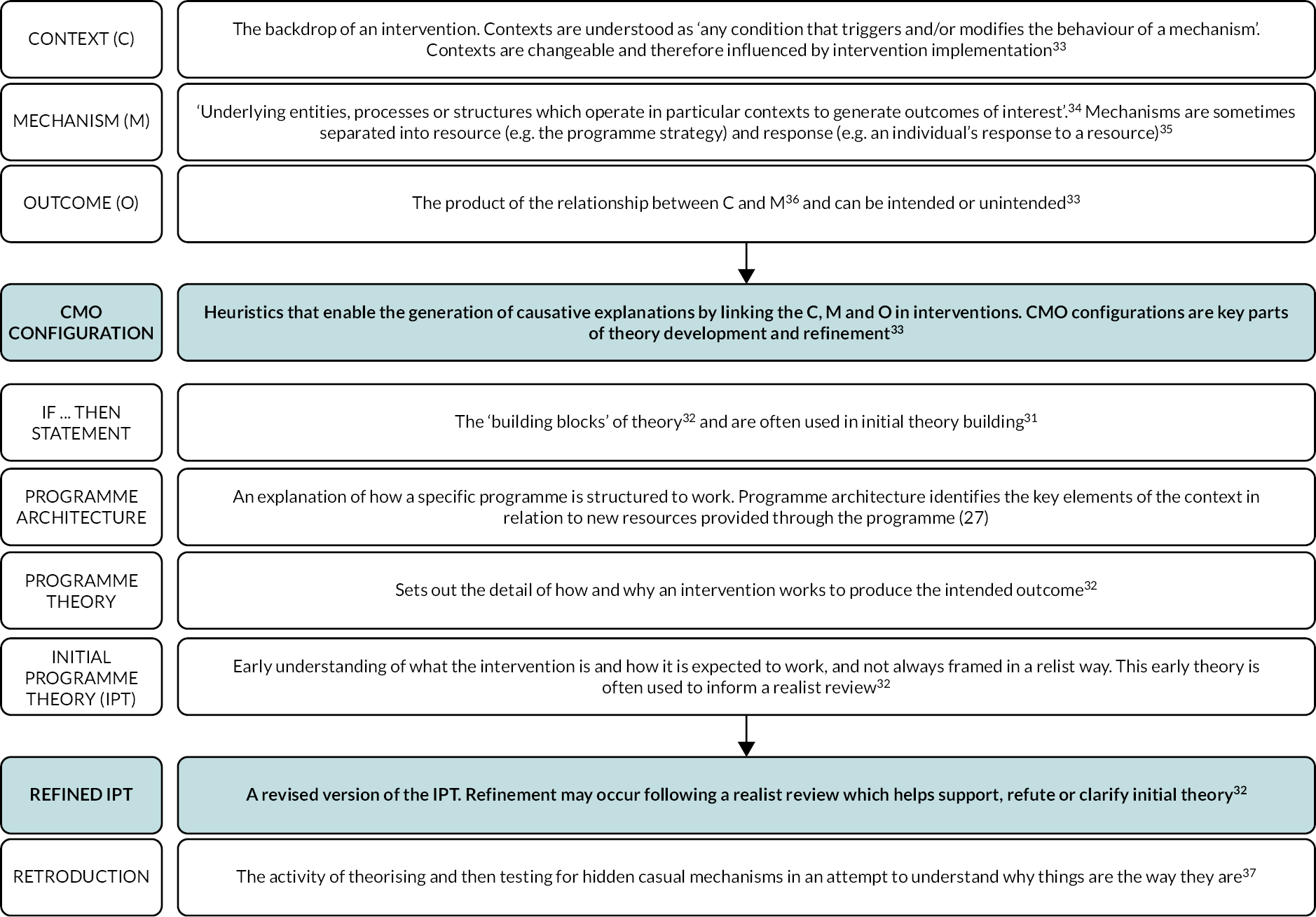

A realist-informed scoping synthesis was performed. Realist synthesis is a theory-driven approach designed to investigate complex social interventions. 28–30 It is described as being focused on understanding ‘what works (or does not work), for whom under what circumstances, how and why’. 28–30 Rather than assuming that interventions are the direct and linear cause of outcomes, the realist approach posits that ‘mechanisms’ are the causal explanations that result in outcomes. 28–30 As such, realist approaches look to identify relationships between contexts, mechanisms and outcomes (CMO) to allow explanation of how and why interventions are effective or not. 28–30 The key definitions relating to the realist approach used in this synthesis are shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Realist definitions. C, contexts; IPT, initial programme theory; M, mechanisms; O, outcomes.

The realist approach was chosen for this synthesis for its value in investigating complexity, and the recognition that FCP is in itself a complex intervention, being implemented in a complex system (NHS). 31 Prior to commencement, the realist methodological expert on the team (JJ) completed a 2-day in-person training event with the co-applicant team to develop realist skills. NW had previously attended realist methodological training in advance of study application.

Finally, and importantly, the use of a realist informed approach was also necessary to develop initial programme theory to take forward as the theoretical foundation of the FRONTIER realist evaluation (WP3).

Search process

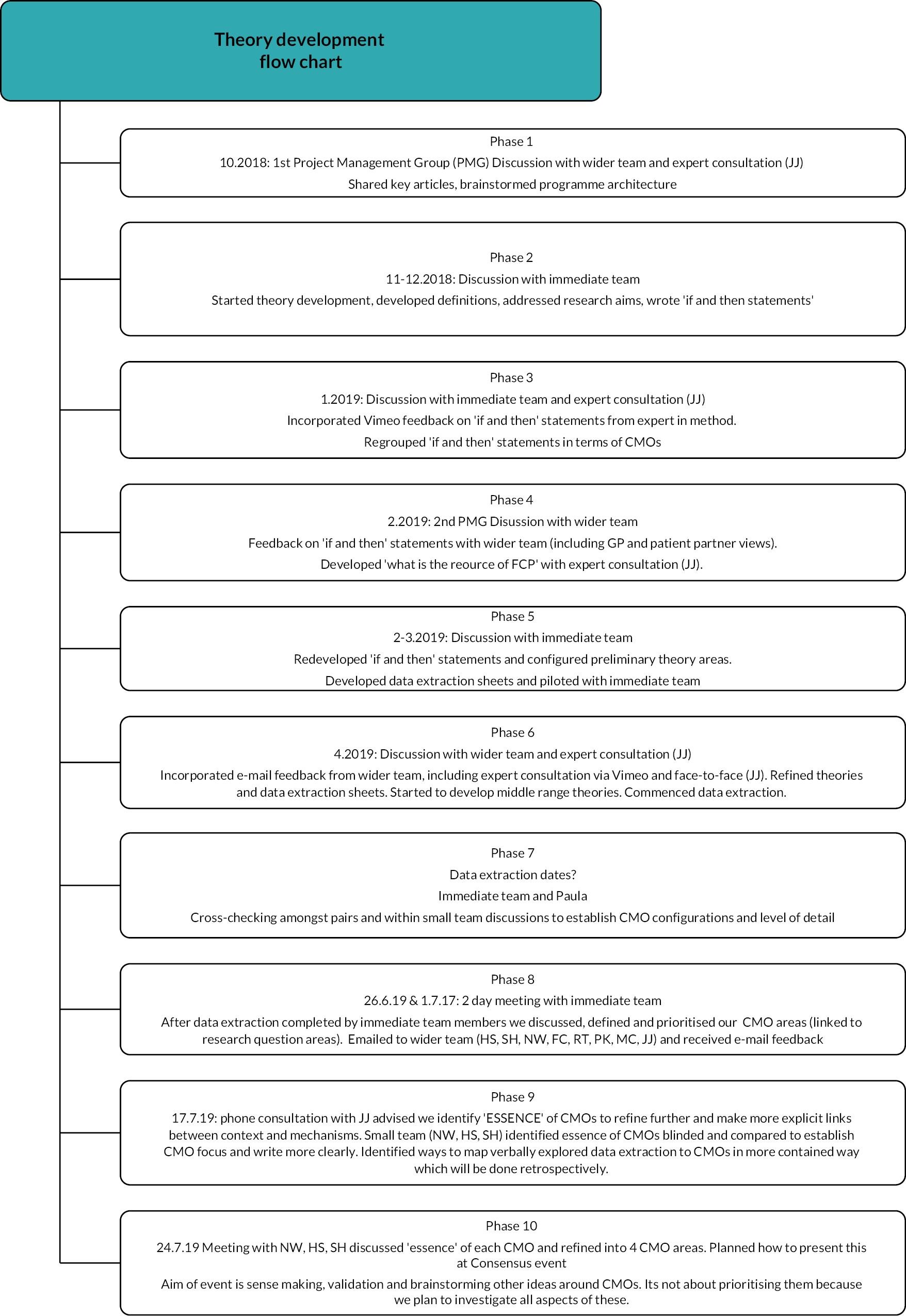

We adhered to the steps outlined in RAMESES (Realist And MEta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards) guidelines32 in performing realist reviews or syntheses: (1) identifying potential theories; (2) searching for evidence; (3) appraising primary studies; (4) extracting data; (5) analysing and synthesising evidence; (6) consultation with key stakeholders and (7) theory refinement. Stages 6 and 7 were included to provide further validation of the emerging theories from key external stakeholders, naïve to the proposed theories38 (see Appendix 2 outlines theory development processes).

Step 1: identifying potential theories

To facilitate initial theorising, an exploratory scoping review of the FCP literature was undertaken in October 2018. Initial theories were developed through a series of iterative discussions with the full academic and MDT and conceptualised from the perspective of key stakeholders involved in the FCP model, at all levels of service provision (i.e. patients, physiotherapists, commissioners).

Although this and subsequent steps are described as a linear process, the theorising that occurred at each step was iterative and thus overlapped with other steps; considerable numbers of iterations of theory were generated, revised and refined throughout the synthesis process.

Step 2: searching for evidence

Following initial theorising, and in consultation with library services, an iterative literature search was performed in January 2019 to identify primary and grey literature. The search was deliberately broad to ensure the identification of a range of sources which could contribute information on this emerging topic area.

All study designs were eligible and no exclusion criteria were imposed other than English language sources only. Databases searched included the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, MEDLINE, SPORTDiscus, PsycInfo® (American Psychological Association, Washington DC, USA, via EBSCO), EMBASE (via OVID), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials.

The core synthesis team filtered the identified literature for inclusion in full-text review informed by consideration of the scope and breadth of the synthesis and for pragmatic reasons. The process involved duplicate removal, title screening and then rigorous, iterative rounds of abstract screening performed in synthesis team pairs who discussed abstracts with an independent synthesis team member in the event of disagreement. In addition to empirical literature, grey literature sources were also searched using basic search terms (e.g. first contact physiotherapy). Sources included the CSP and Royal College of General Practitioners websites and YouTube (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). A CSP FCP discussion forum and e-mail list and a discussion forum from Twitter (now X) focused on FCP (#PhysioTalk) were also included.

Step 3: appraising primary studies

Appraisal of identified sources was informed by consideration of their richness, relevance and rigour. Sources that contained detail to elucidate initial theories were considered conceptually rich and relevance pertained to the insight into the topic of investigation. 39 The core synthesis team was mindful of the relevance of non-UK derived literature given the unique context of the NHS, the timeliness of publication given the emerging nature of the FCP model and the recognised definition of FCP as co-located in primary care. Rigour was addressed through methodological appraisal of source credibility. No sources were excluded but considerations were documented which informed source influence on the developing theory.

Step 4: extracting data

All records were managed in an Excel database. Initially, information about each source including title, authors, date, type and abstract were extracted before assigning to members of the team. For consistency, a data extraction process was designed and piloted.

For data extraction, team members were asked to follow six steps for each assigned source: (1) source familiarisation and note taking; (2) consider the contribution of the source (e.g. the insight it generates, whether it illuminates initial theory) and its overall value; (3) write a summary capturing thoughts from step 2; (4) reread each source to identify causal links and CMO configurations; (5) extract specific data related to CMO if only partial information is available directly from the source (e.g. no mechanism stated), fill gaps with ‘hunches’ to propose logical causal hypotheses to complete the CMO configuration; and (6) add any additional comments about the source not captured elsewhere. Approximately 10% of sources were cross-checked by synthesis team pairs, who discussed sources in relation to relevance, reviewed source data extracted in the above six steps and resolved any differences in opinion through discussion.

Step 5: analysing and synthesising evidence

Following data extraction, a 2-day meeting was held with the core synthesis team where all data extracted during step 4 were discussed and reconfigured for clarity. Here, the extracted data refined the initial programme theory and were grouped into overarching research priority areas – person, place and time.

Step 6: consultation with key stakeholders

To consolidate and validate understanding and further refine theory development, an event with key stakeholders was held. The event was attended by stakeholders (n = 10) representing commissioners (n = 1), practice managers (n = 2), physiotherapists (n = 3), professional body (n = 1) and members of the public (n = 3). The event was facilitated by the research team (n = 6) who presented the candidate CMOs within each of the three priority areas (person, place and time) and facilitated small group discussions based on a modified nominal group technique approach.

The group was divided into two smaller subgroups for ease of discussion before reconvening into a larger whole group meeting. Each group was provided with the candidate CMOs and asked to discuss for their relevance, indicate their levels of agreement and to prioritise. The two groups then reconvened in a single group to present their individual findings, discuss any amendments and reprioritise as a whole group.

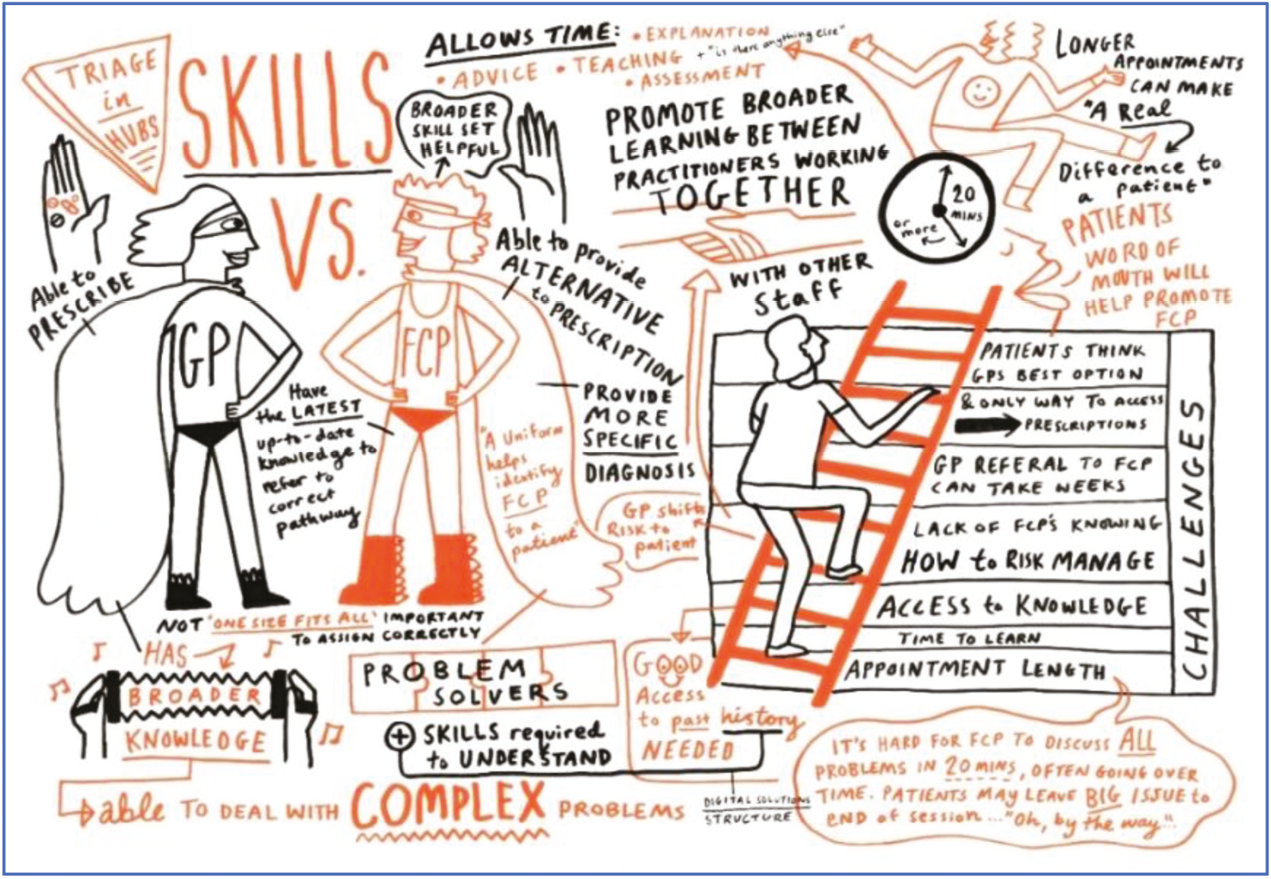

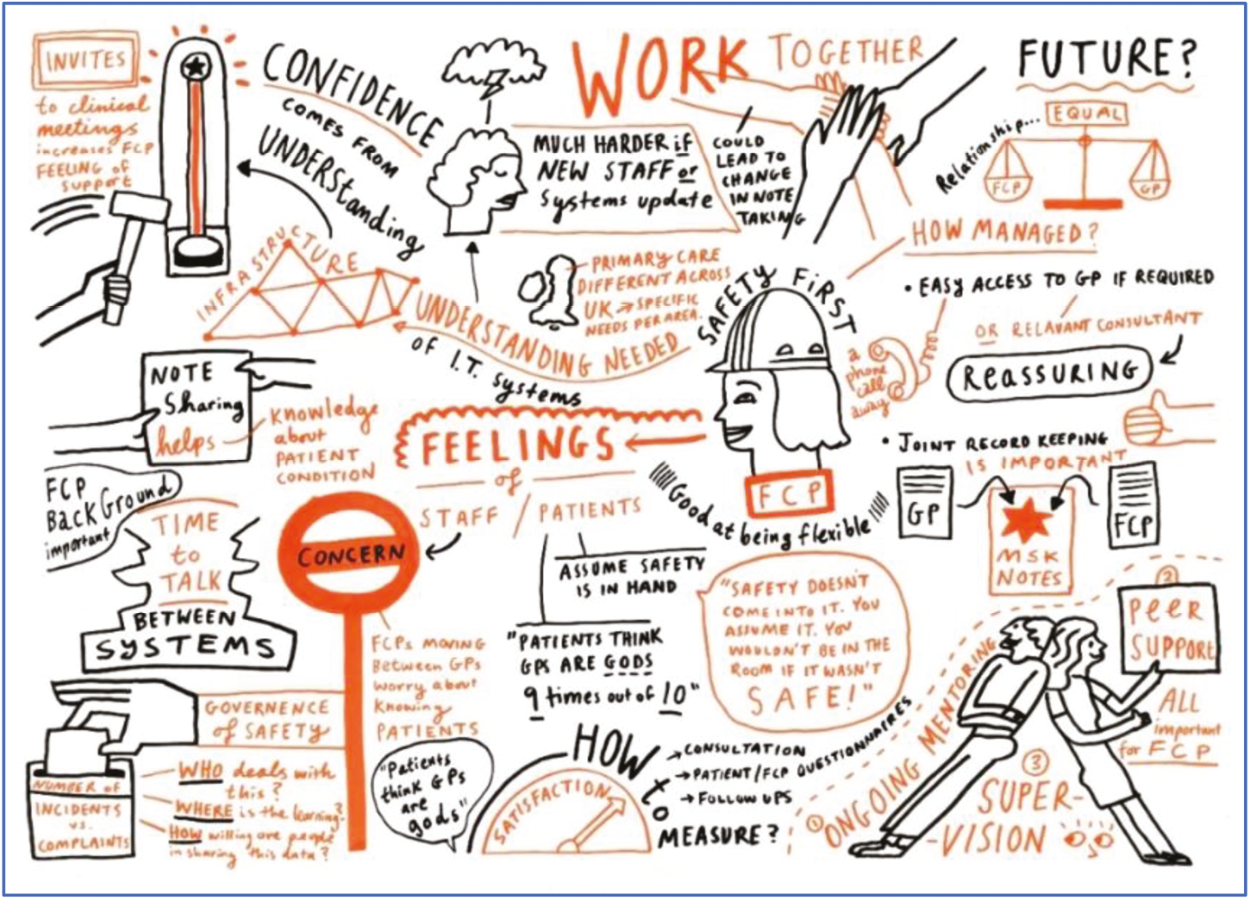

Discussions were audio recorded and field notes collected. In addition, discussions were professionally illustrated in real time to provide an accessible representation to the whole group and permit further discussion and group validation.

Step 7: theory refinement

Following the stakeholder event, three team meetings were held to consolidate theory refinement and reflect on stakeholder prioritisation to inform later project work.

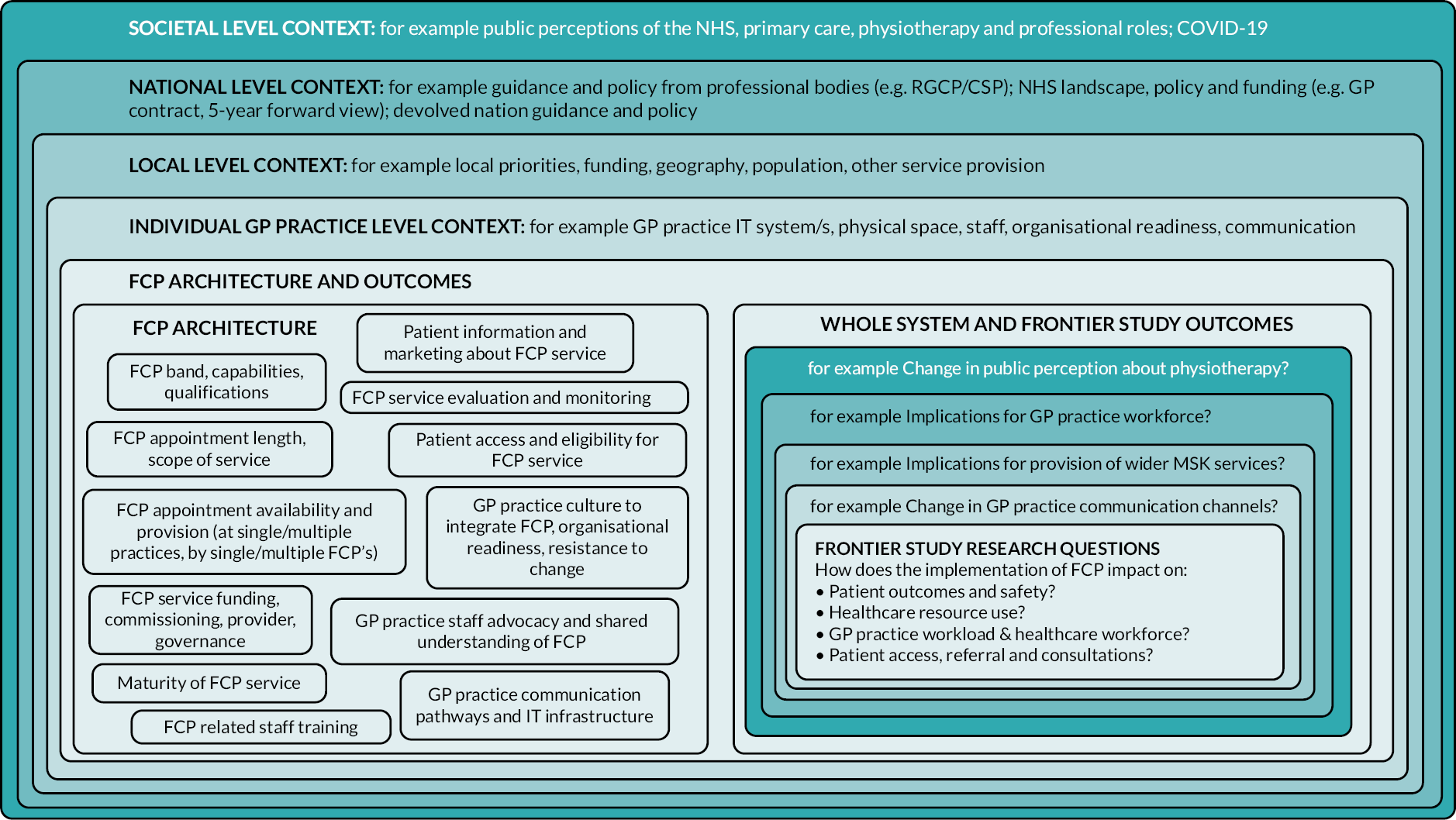

Results

Initial programme theory and first-contact physiotherapy architecture

Initial theorising through iterative team discussions identified key components of the ‘architecture’ of the FCP intervention, creating initial programme theories of how FCP may ‘work’. This was conceptualised at multiple levels of service provision, including broad ‘societal’ level contexts through to ‘individual GP practice’ level contexts (Figure 2). This provided understanding and appreciation of the wider context in which the FCP model was operating and how this may influence its functioning, for example by considering how funding streams, local models of delivery or public perceptions of primary care impact FCP delivery. It also developed an awareness of how outcomes resulting from the FCP model may impact on systems at a wider level; for example, if FCP reduces referrals to secondary care, then there may be implications on funding and provision in secondary care MSK services.

FIGURE 2.

Early conceptualisation of first-contact physiotherapy architecture. CSP, Chartered Society of Physiotherapy; RCGP, Royal College of General Practitioners.

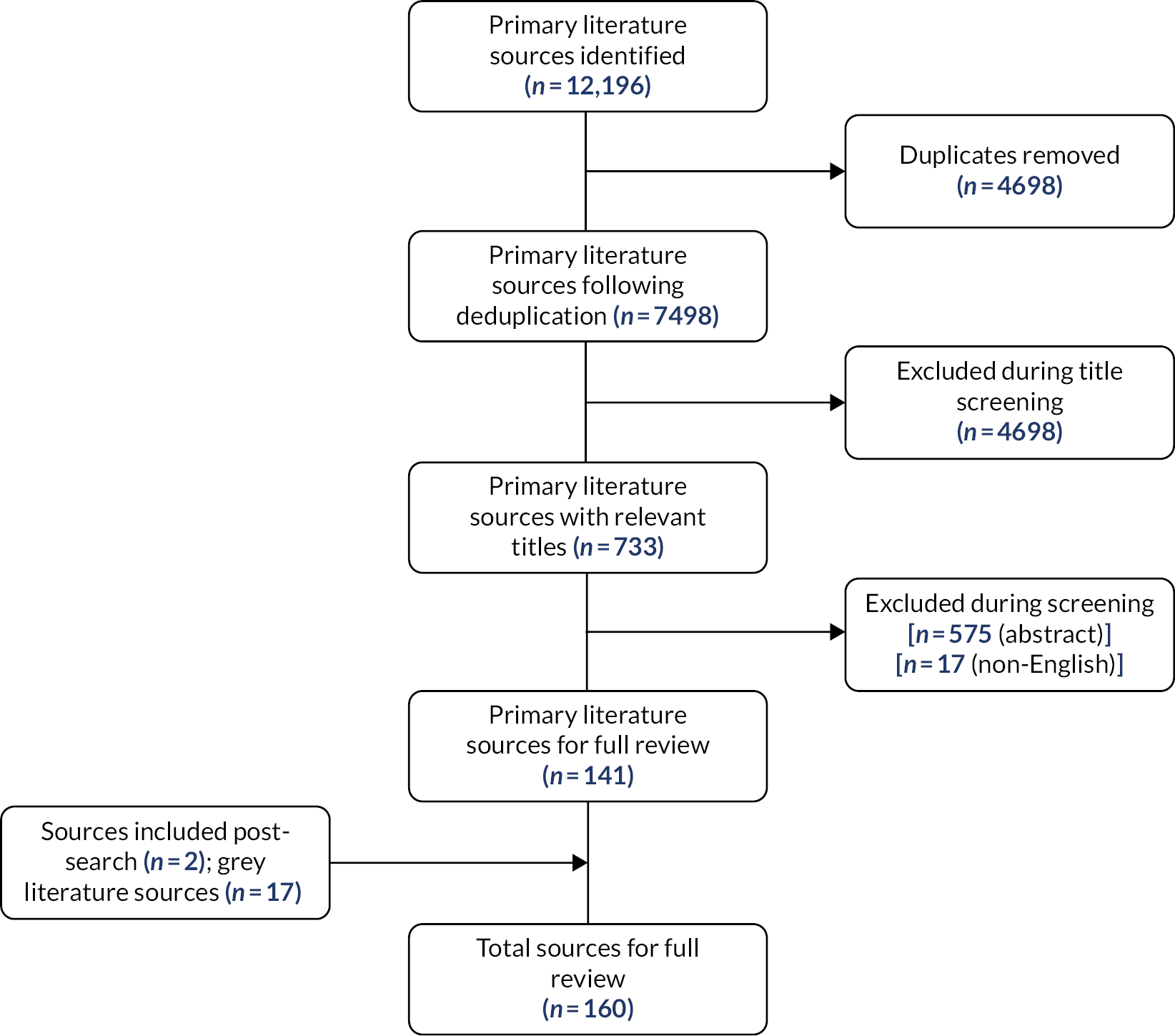

Summary of sources for synthesis

The sources identified and excluded during searching are detailed in Figure 3. The primary literature search identified 12,196 sources, which were reduced to 143 sources, including journal articles (n = 46), abstracts (n = 29), magazine articles (n = 63), letters (n = 4) and theses (n = 1). Grey literature searching identified 17 sources, CSP discussion fora and e-mail list (n = 3), Royal College of General Practitioners website (n = 1), YouTube videos (n = 12), Twitter (now X) #physiotalk discussion (n = 1). Searching totalled 160 sources for full-text review.

FIGURE 3.

Flow diagram of search process and source identification.

Preliminary programme theory synthesis and refinement

During the team meeting to reconfigure the extracted data, the initial programme theories (developed before the synthesis) were considered alongside 300 preliminary CMO configurations resulting from data extraction. CMO configurations were grouped by theme, refined to remove duplication and prioritised to meet the research objectives. This led to the development of CMO configurations which were grouped under three overarching research priority areas:

-

Awareness of and access to FCP: covering the approaches to sharing information about FCP (e.g. marketing, advocacy), accessing FCP services and how these considerations influence staff and patient feelings and perceptions about FCP.

-

FCP skills and knowledge: covering the unique value of the FCP role, skills and knowledge (and the distinction from GP role, skills and knowledge) and how these considerations influence staff and patient feelings and perceptions about FCP.

-

Safety and FCP: covering how patient safety are managed and performed in the FCP role and how this influences staff and patient feelings and perceptions about FCP.

Development of programme theory through the stakeholder event

At the stakeholder event, participants were presented with a refined and accessible version of the theory, presented using the overarching research priority areas described above.

Illustrations were produced that captured small group discussion and whole-group feedback of each of the three priority areas. Following the stakeholder event, the synthesis team met to deliberate the discussion points using field notes and illustrations as reminders. The event discussion points highlighted and prioritised three main areas (awareness and access to FCP; FCP skills and knowledge; patient safety and FCP), enhanced understanding of some of the issues surrounding the FCP model and clarified areas of uncertainty. This fed into the refined initial programme theory described below. Throughout the stakeholder event, an illustrator was employed to visually document discussions. This provided an accessible means of relaying information to participants and other groups thereafter. Summary illustrations are presented in Figures 4–6.

FIGURE 4.

Awareness of and access to the first-contact physiotherapist (person and place).

FIGURE 5.

Skills and knowledge of the first-contact physiotherapist (person and time).

FIGURE 6.

Patient safety (person).

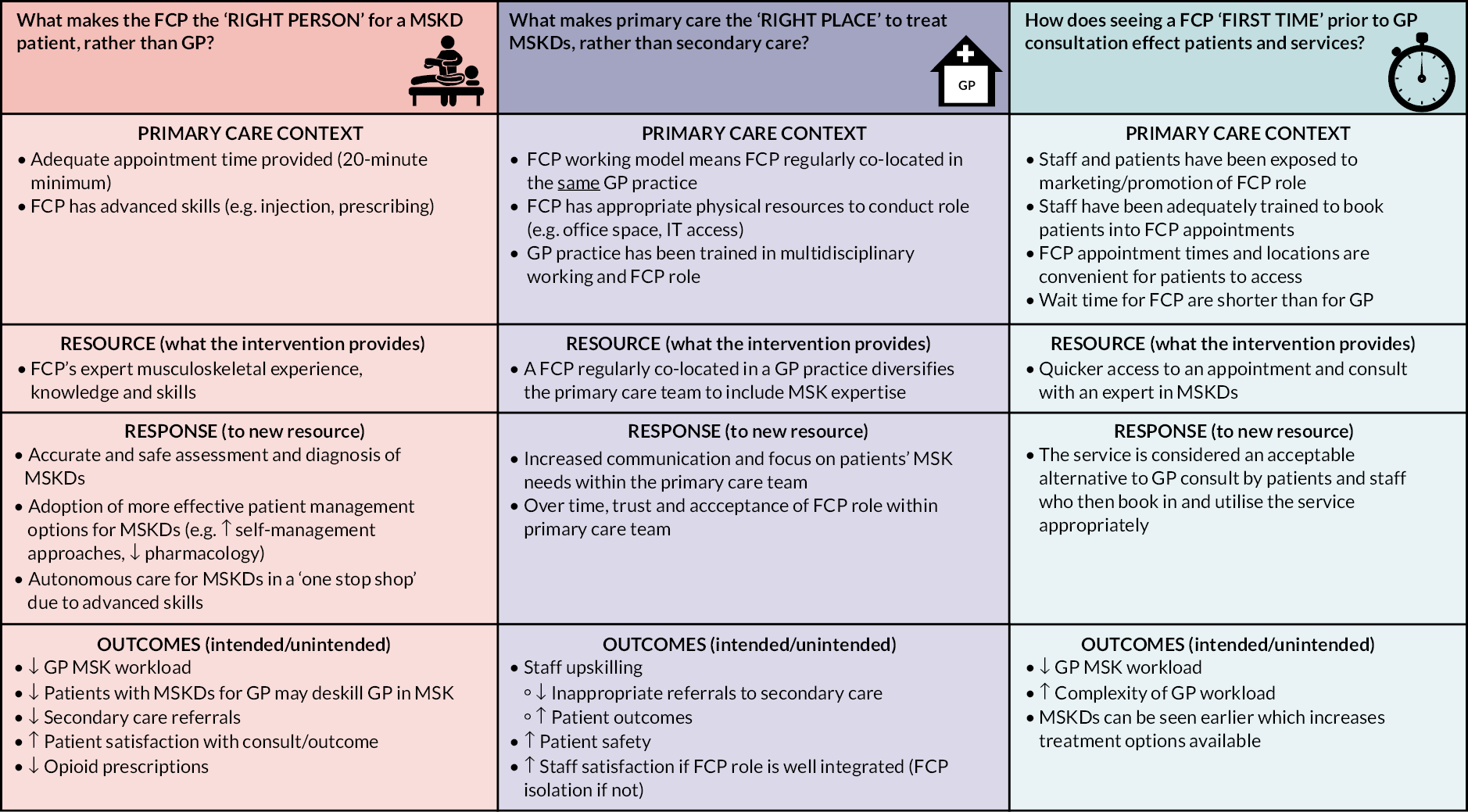

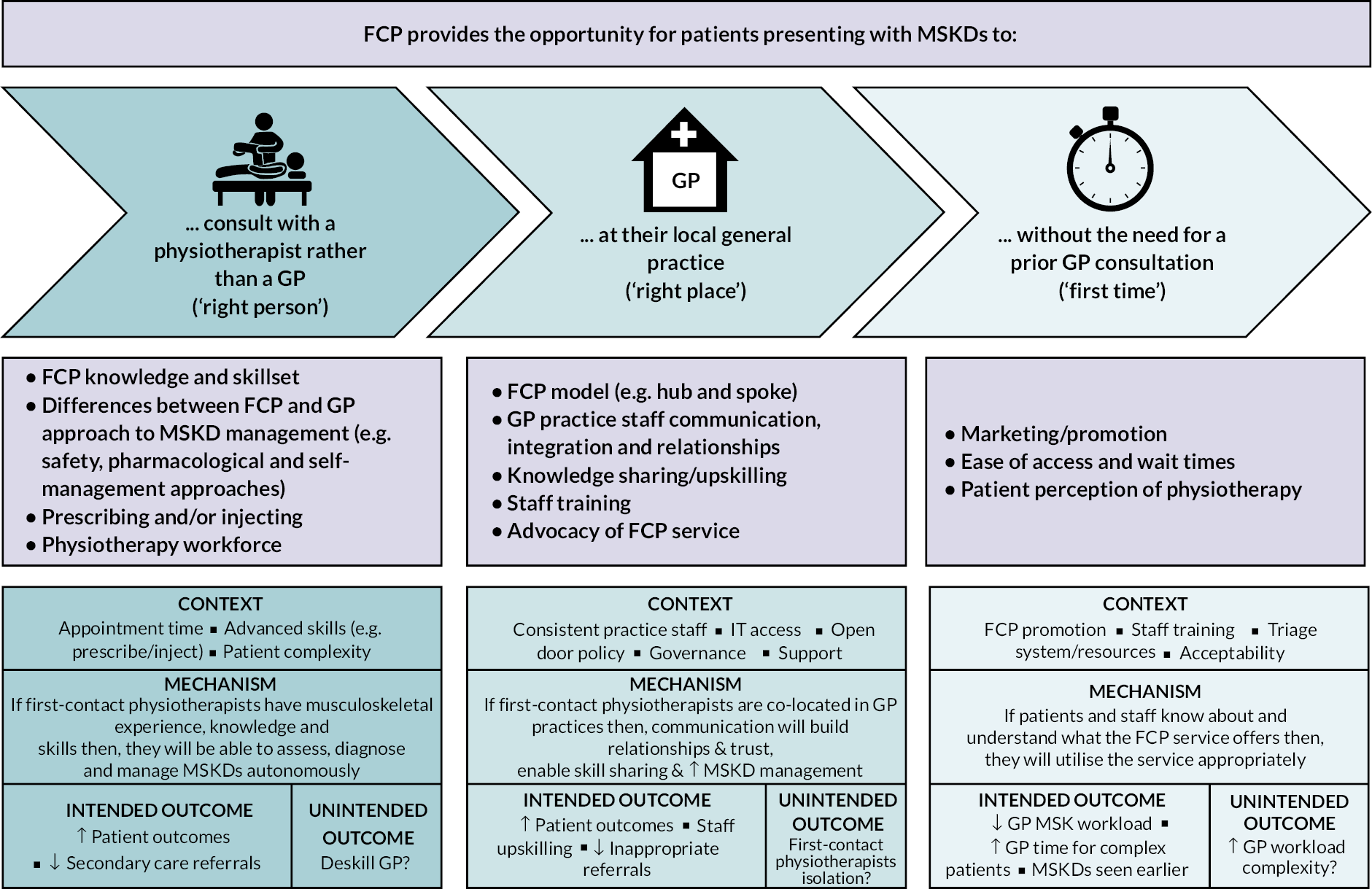

Refined initial programme theory

The stages of initial theorising, source synthesis and stakeholder event all systematically fed into the refined preliminary programme theory. This process was also influenced by the continually evolving wider context of FCP, which saw the model become more prominent during the study period and undergo its own refinement and adjustments to implementation. FCP was identified within NHS strategy as a high-impact intervention, the underpinning principle of which are that ‘patients should be seen by the right person, in the right place, first time’. 40 This underpinning principle was felt to summarise how the FCP programme was intended to work, while demonstrating the inextricable link between the FCP programme and the wider NHS and was therefore used to conceptualise the refined programme theory, considering all of the previous aspects of the work, including consultation. This conceptualisation proposed that FCP provides the opportunity for patients presenting with MSKDs to consult with a FCP rather than a GP (‘right person’), at their local GP practice (‘right place’), without the need for a prior GP consultation (‘first time’; Figures 7 and 8). See Appendix 2 for early theorising.

FIGURE 7.

Right person, right place, first time.

FIGURE 8.

Refined initial programme theories with hypothesised contexts, mechanisms and outcomes.

The key theory aspects relating to each of the three headings have been summarised under the main heading represented by (either ‘right person’, ‘right place’, or ‘right time’). However, there is a natural overlap across headings and key theory aspects; therefore, although visually represented by a single heading, the key theory aspects are in reality more interlinked.

Right person

The ‘right person’ component conceptualises that the FCP model provides patients presenting with MSKDs to consult with a first-contact physiotherapist rather than a GP. Key aspects relating to ‘right person’ include expert musculoskeletal skills and knowledge of the first-contact physiotherapist, how the FCP model compares with the traditional model of GP-led care, safety of the FCP model, additional training and qualifications relevant to FCP roles, and the impact of FCP on the wider physiotherapy workforce.

Right place

The ‘right place’ component conceptualises that the FCP model provides patients presenting with MSKDs the opportunity to consult with a first-contact physiotherapist at their local general practice. Key theory aspects relating to ‘right place’ include model of primary care provision, communication, staff integration and knowledge sharing. Although overlapping, aspects relating to patient awareness of and access to FCP services are captured within ‘first time’.

Right/first time

The ‘first time’ component conceptualises that the FCP model provides patients presenting with MSKDs the opportunity to consult with a first-contact physiotherapist without the need for prior GP consultation. Key theory aspects relating to ‘first time’ include service awareness, promotion and training, and acceptability.

A summary of the areas for further investigation is provided below. These are categorised into overarching areas rather than specific ‘if–then’ statements.

-

practice understanding of the role

-

integrating the first-contact physiotherapist into general practice

-

knowledge and skills of the physiotherapist

-

appointment structure

-

practice endorsement of FCP

-

patient acceptability of the first-contact physiotherapist role

-

employment and management of the first-contact physiotherapist role

-

impact of FCP on practice workload and wider resource use.

Implications for the FRONTIER project

The purpose of WP2 was to identify initial programme theories for further investigation in the qualitative aspect of WP3 (mixed-method realist evaluation). However, this phase of the work coincided with a rapidly evolving initiative to implement FCP, with service configurations changing constantly, including implementation toolkits and educational frameworks, all of which impacted on the architecture of FCP. Therefore, theories developed in this phase were useful for sensitising the team to the issues of interest, but possibly elucidated fewer established theories due to the changing contexts of FCP provision. Indeed, this was further impacted during the evaluation resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic that had significant impact on delivery of FCP models, namely to remote consultation from in-person contact.

The benefits of the realist methodology however allowed fluidity between the synthesis and consensus exercise (WP2), with the qualitative aspect of the evaluation (WP3), this is discussed further in Jagosh et al. 27

Limitations

The stakeholder consultation exercise was limited in numbers and did not include GP representatives or practice nurses who may have provider greater insight into the theorising and validation. Further challenges were the rapidly moving landscape of FCP which meant service initiatives were changing constantly. We addressed this issue in part by retaining some fluidity between our synthesis and consensus approach, and later stage qualitative evaluation, to ensure the theorising reflected on contemporary thought and practice. Furthermore, the literature base was developing at a rapid pace and some publications may have been missed; we also acknowledge there was very little literature at the time (and indeed at present) on the wider impact of FCP implementation on different levels of population deprivation.

Given the novelty of the service and the involvement of multiple stakeholders, we needed to provide some focus to our work to retain manageability and ensure it was completed within the project time and budget. We therefore adopted the ‘right person, place and time’ approach. This could be considered reductive and not representative of the full landscape and architecture of FCP. We recognise this as a limitation of our work but believe it does provide a useful insight to support implementation, and further research can explore the wider issues influencing and influenced by FCP implementation.

Conclusions and summary

The rapid realist synthesis identified multiple candidate initial programme theories and early CMO configurations. Theories that were related to service implementation were carried forward for further investigation in WP3. Hypothesised initial programme theories were used to inform interview schedules and iterative thinking in the case study evaluations.

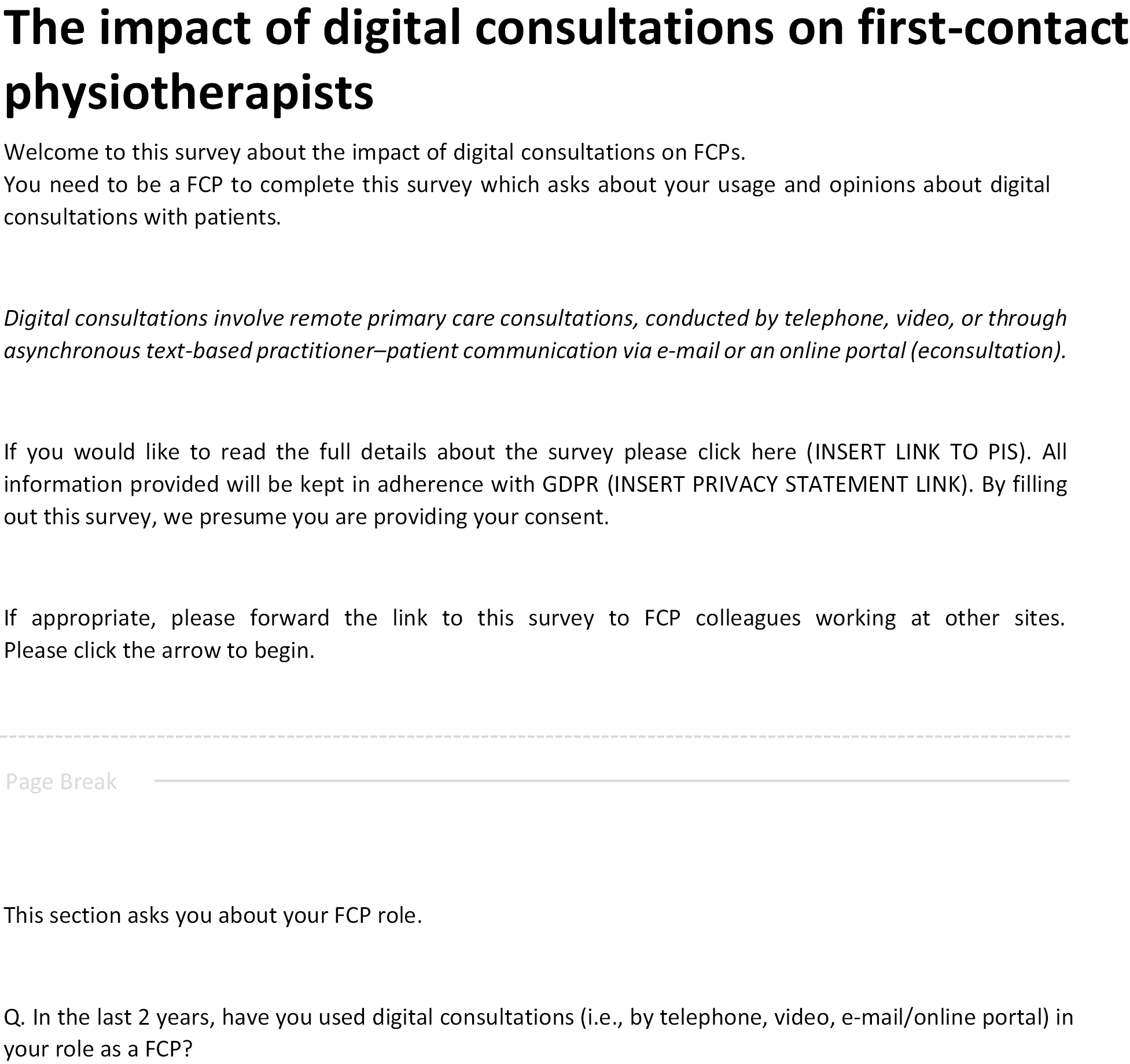

Chapter 5 Surveying the impact of remote consultations on the first-contact physiotherapist’s mental health

Reproduced with permission from Anchors et al. 41 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

In response to a NIHR call for an additional WP for current studies that could investigate mental health issues, we undertook a study investigating the impact of remote consultations, imposed by COVID-19, but integral to the NHS Long Term Plan drive for digital first. 42

Aim

To explore the health and well-being issues experienced by first-contact physiotherapists as a result of remote consultations.

Study design

A mixed-method sequential explanatory study was undertaken consisting of: (1) a nationwide e-survey with FCPs and (2) qualitative interviews with FCPs.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval to proceed with the study was given by the University of the West of England Faculty Research Ethics Committee HAS.19.06.204 on 15 December 2021.

Methods

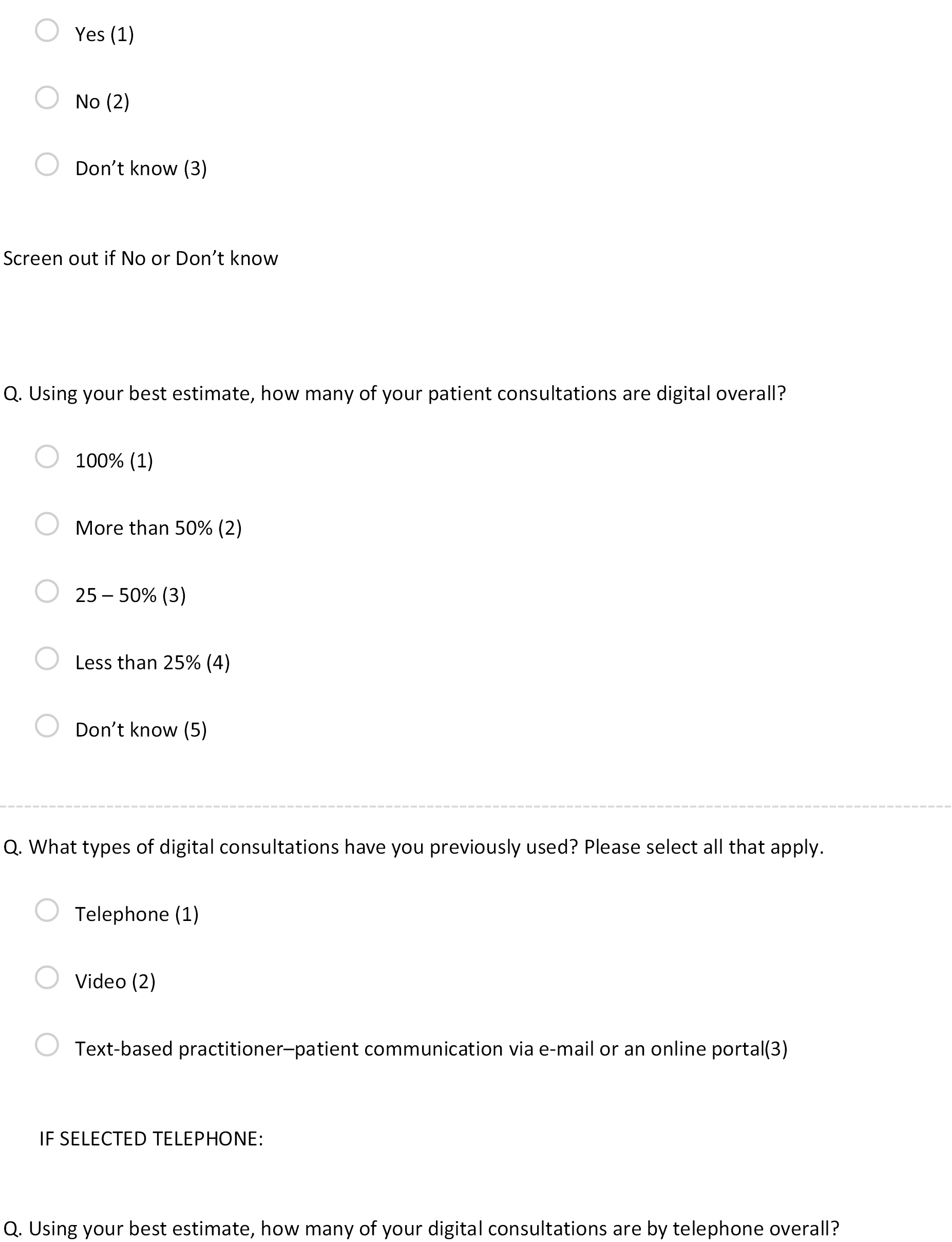

Survey development

The draft survey was developed within the MDT. The attitude statements were derived from reanalysing transcripts described in Chapter 6 in relation to remote consultations. Nvivo (Lumivero, Denver CO, USA) was used to undertake a keyword search related to remote consultations, then attitude statements derived from the coded transcripts. Existing literature was also searched to identify any novel areas not represented in the transcripts.

The identified areas and related challenge statements were within the following domains:

-

isolation

-

increased workload

-

professional anxiety

-

frustration and job satisfaction

-

IT issues

-

mental strain

-

physical impacts.

The benefits statements were within the following domains:

-

improved access for patients

-

flexibility

-

expedited access

-

improved management of acute presentations

-

patient acceptability and satisfaction

-

increased productivity.

The draft was piloted once on a FCP and a research fellow at the University of West England to check the content, logic, routing and timing of the survey. Only minor changes were made to wording as a result.

Survey content

Instructions at the beginning of the survey included a link to the participant information sheets; participants were explicitly informed that responding to the survey constituted consent. Respondents were asked to provide a contact e-mail if they wished to be interviewed in phase 2 of the study.

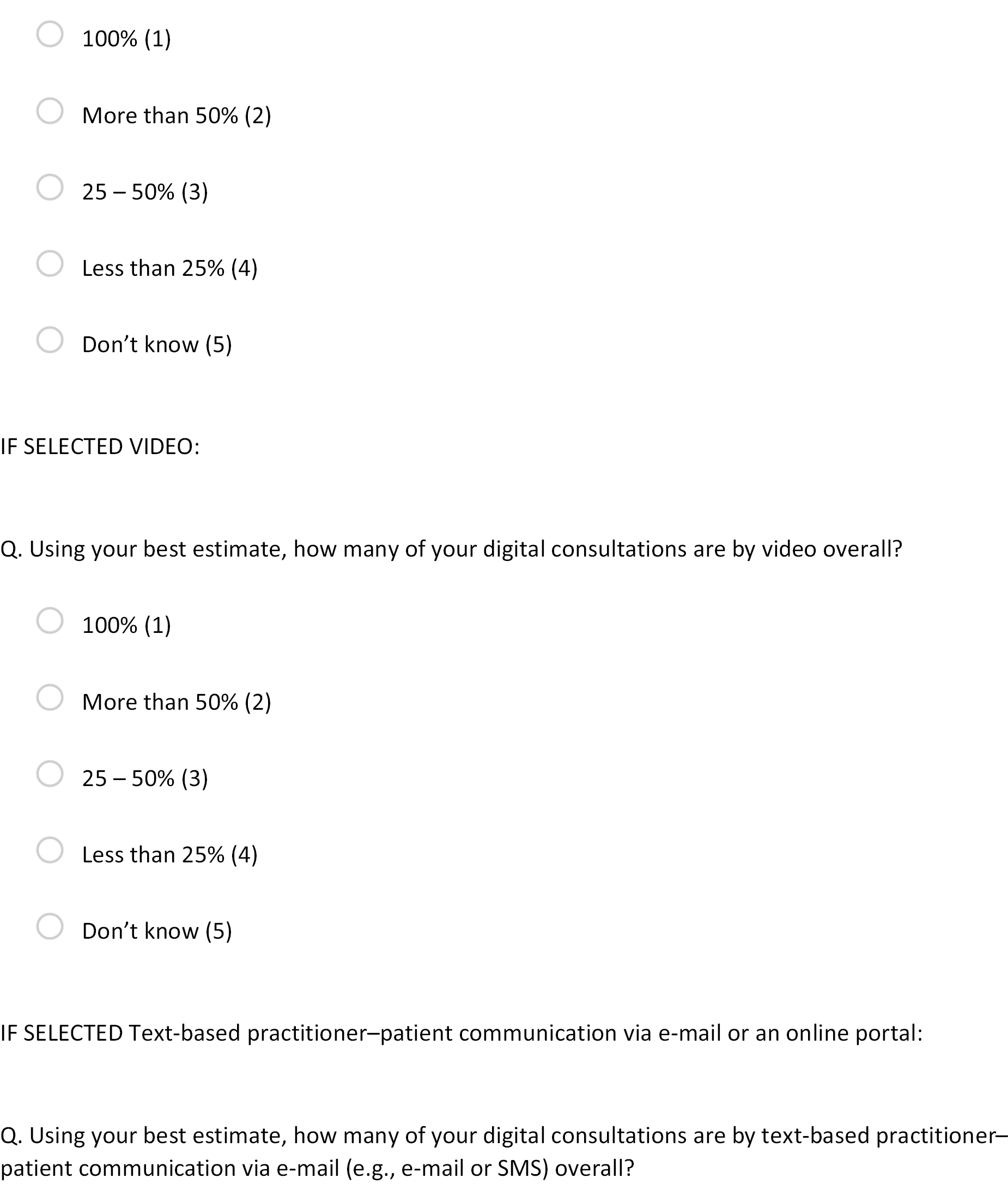

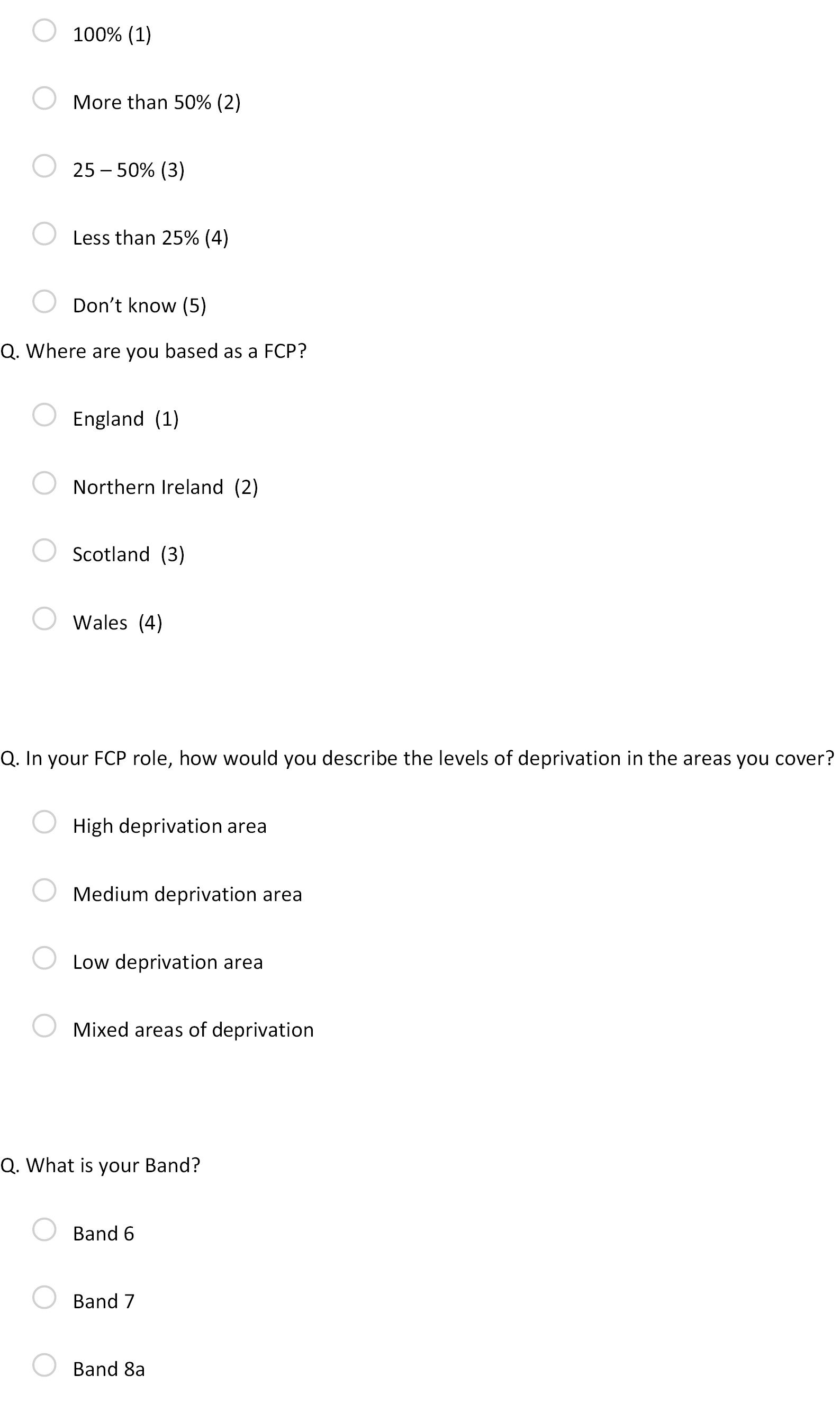

Demographics

Work location (nation), deprivation level of work location, professional banding, professional experience, details regarding FCP employment model and number of practices worked at, and any training to undertake remote consultations.

Remote consultation usage

Types of remote consultation used and estimated time allocation for each.

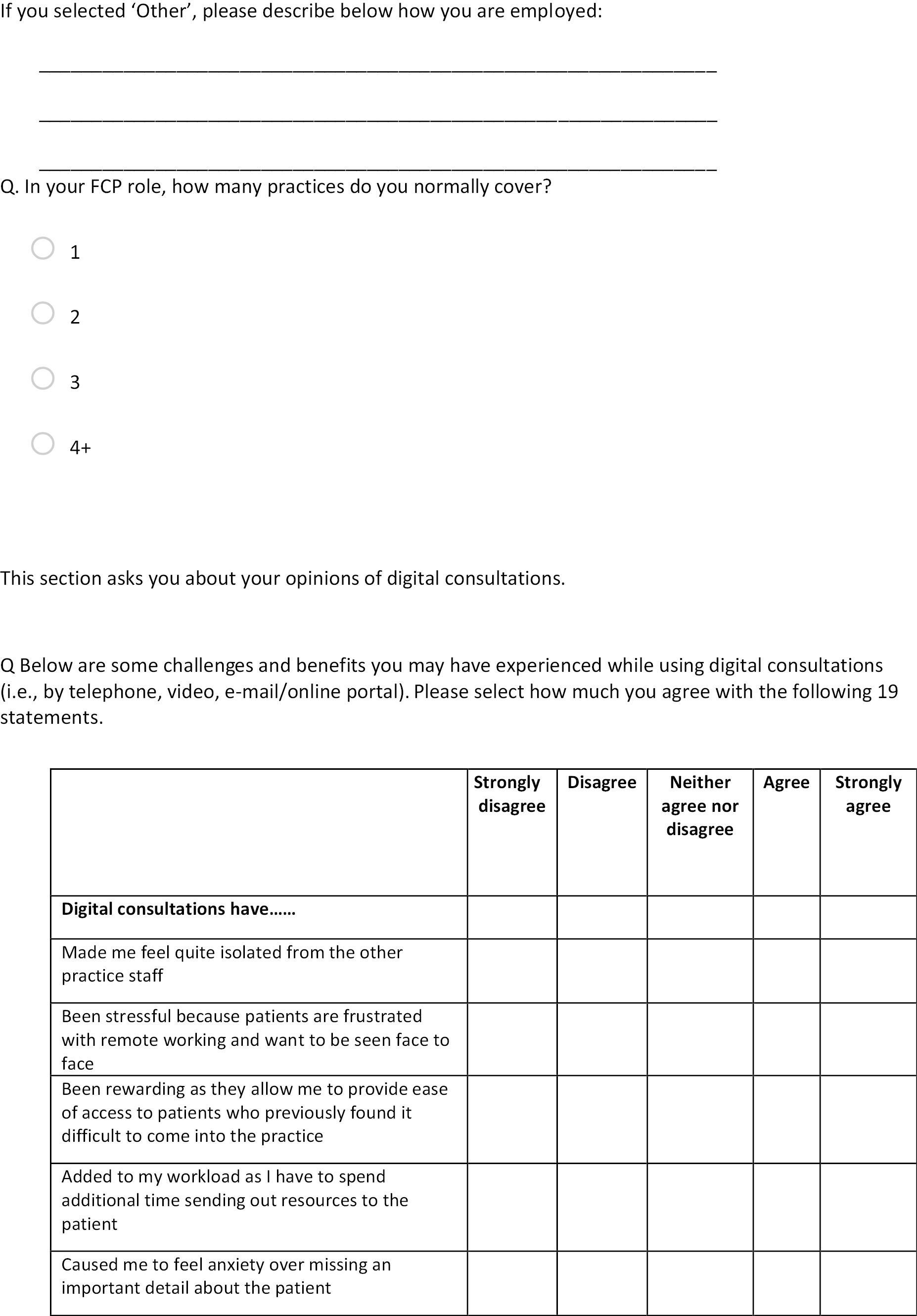

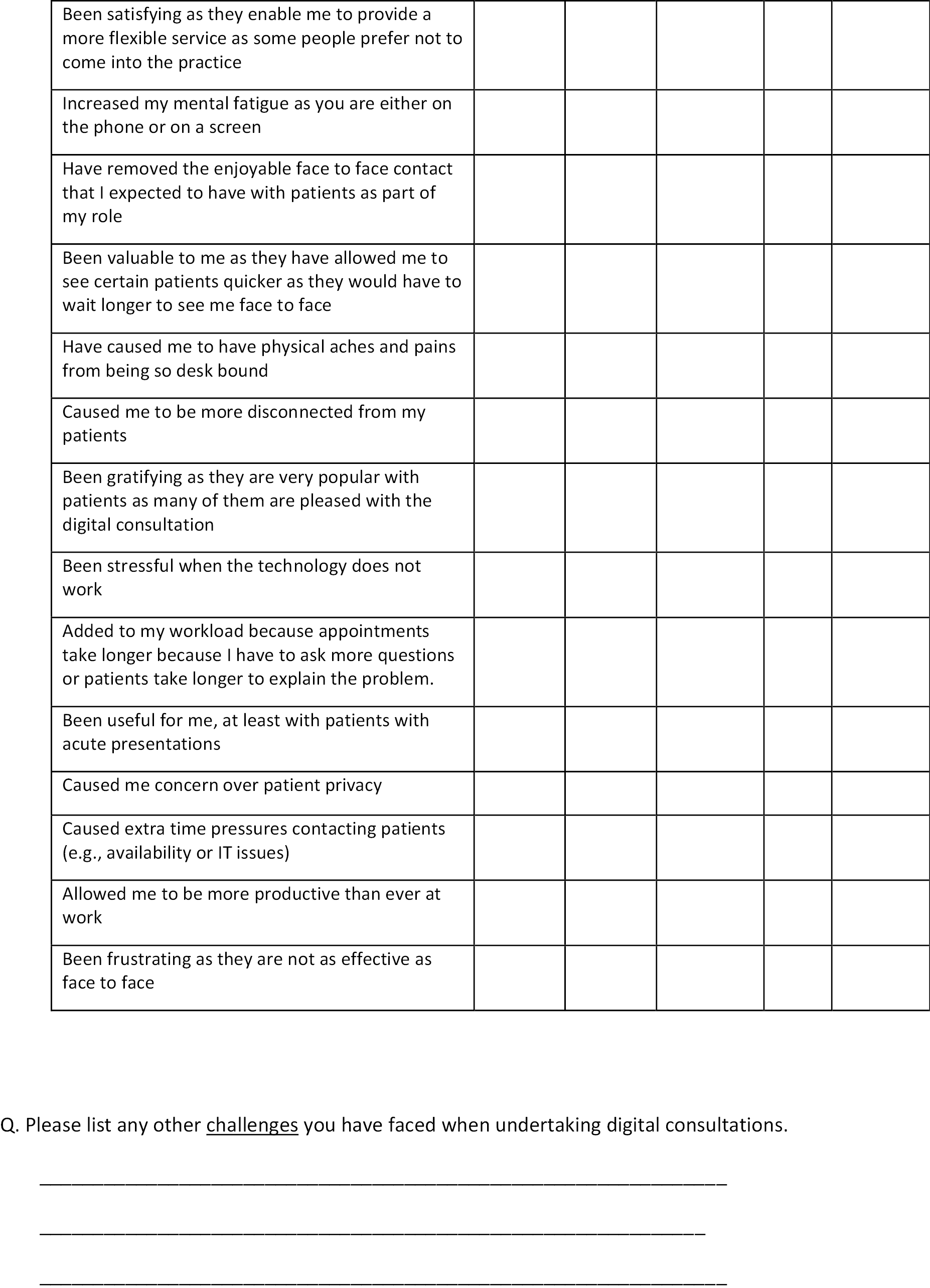

Challenges and benefits of remote consultations

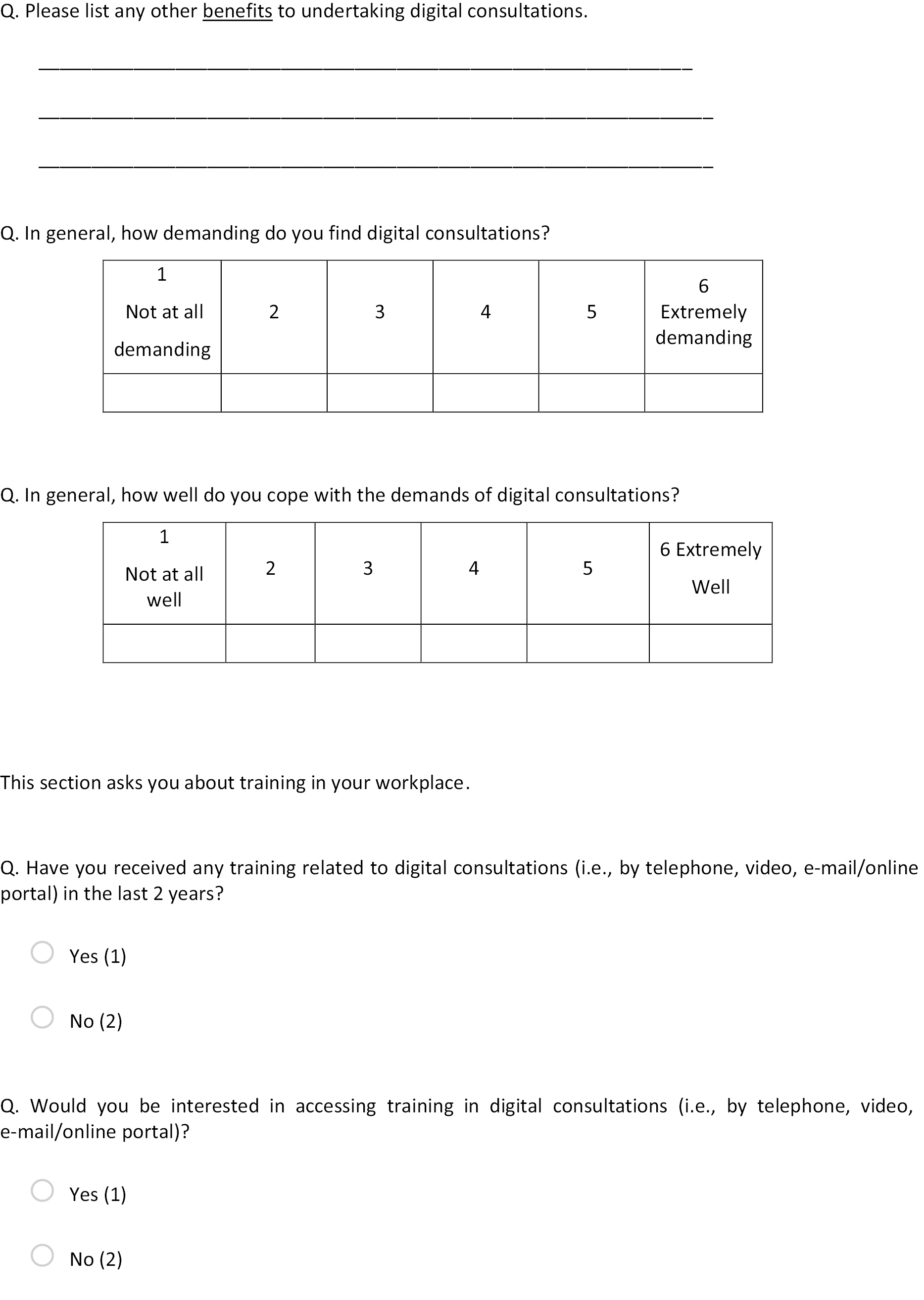

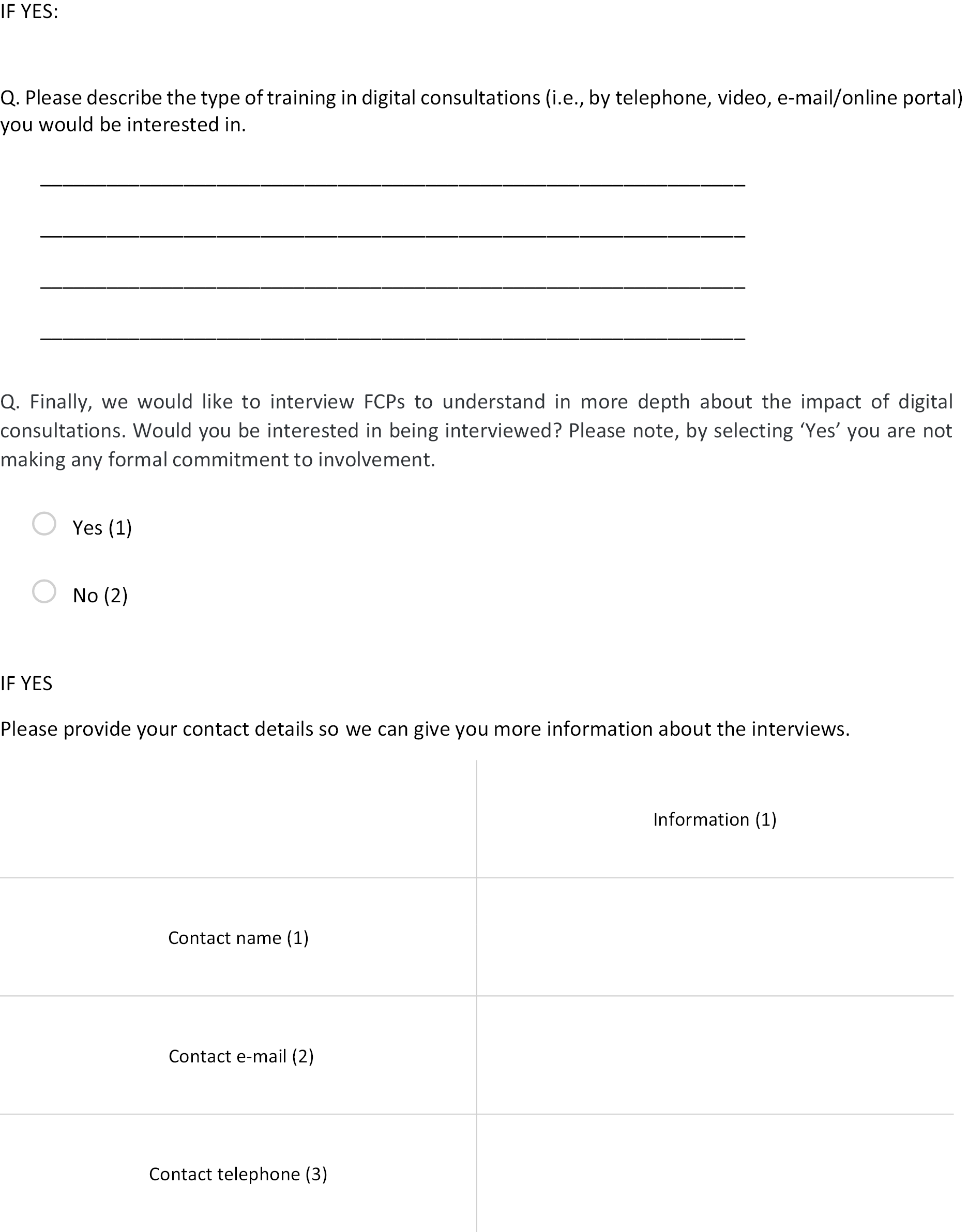

Participants rated their agreement with 19 attitude statements that related to either to a challenge (e.g. ‘Digital ways of working have made me feel quite isolated from the other practice staff’) or a benefit (e.g. ‘Digital ways of working have been useful for me, at least with patients with acute presentations’) of remote consultations on a five-point rating scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The attitude statements were created from re-analysing transcripts described in Chapter 6 and from existing literature. Open-ended questions about benefits and challenges of remote consultations were also included.

Stress appraisal

Rated on a six-point Likert scale anchored between 1 (not at all) and 6 (extremely), two self-report items from the cognitive appraisal ratio were adapted to assess evaluations of task demands and personal coping resources towards remote consultations. 43 Specifically, demand evaluations were assessed by the item ‘In general, how demanding do you find digital consultations?’, while resource evaluations were assessed by the item ‘In general, how well do you cope with the demands of digital consultations?’. A stress appraisal score was calculated by subtracting demands from resources (range: −5 to 5), with zero and a positive score suggested to be reflective of a challenge state (i.e. coping resources match or exceed task demands) and a negative score representative of a threat state (i.e. task demands exceed coping resources). 44

The survey was open from 27 June to 1 August 2022. A copy of the survey can be found in Appendix 3.

Distribution

The e-survey targeted UK based first-contact physiotherapists and was distributed electronically via Qualtrics to FCP networks, the CSP FCP special interest group and personal contacts. E-mails were also sent to training hub contacts to share with local FCPs. E-mails provided a short description of the aim of the survey, invited them to participate by clicking the attached link, and provided study team contact details. The online platform approach used Twitter (now X) and the FRONTIER study website (frontierstudy.co.uk). Here, the link to the survey was made available via these online platforms. The link was redistributed on two occasions to promote further returns.

Eligibility

First-contact physiotherapists currently practicing in the UK and able to read and respond in English language. No other eligibility criteria were required.

Semistructured interviews

Survey respondents who expressed an interest in being interviewed, were contacted via e-mail and provided with an information sheet and consent form in advance of arranging. Interviews were conducted online via Microsoft Teams® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were double-checked for accuracy against the audio recording and anonymised before being imported into NVivo version 1.6.1.

Discussion guide

The interviews explored FCP experiences of remote consultations including implementation and usage, benefits and demands associated with remote consultations, impacts of remote consultations (on performance, health and well-being and burnout), coping responses, and training (past, current and level of interest).

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analysed descriptively in SPSS version 28 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The qualitative data were analysed in NVivo by three team members using Braun and Clarke’s45 six-phase reflexive thematic analysis.

Results

Quantitative component

Participants

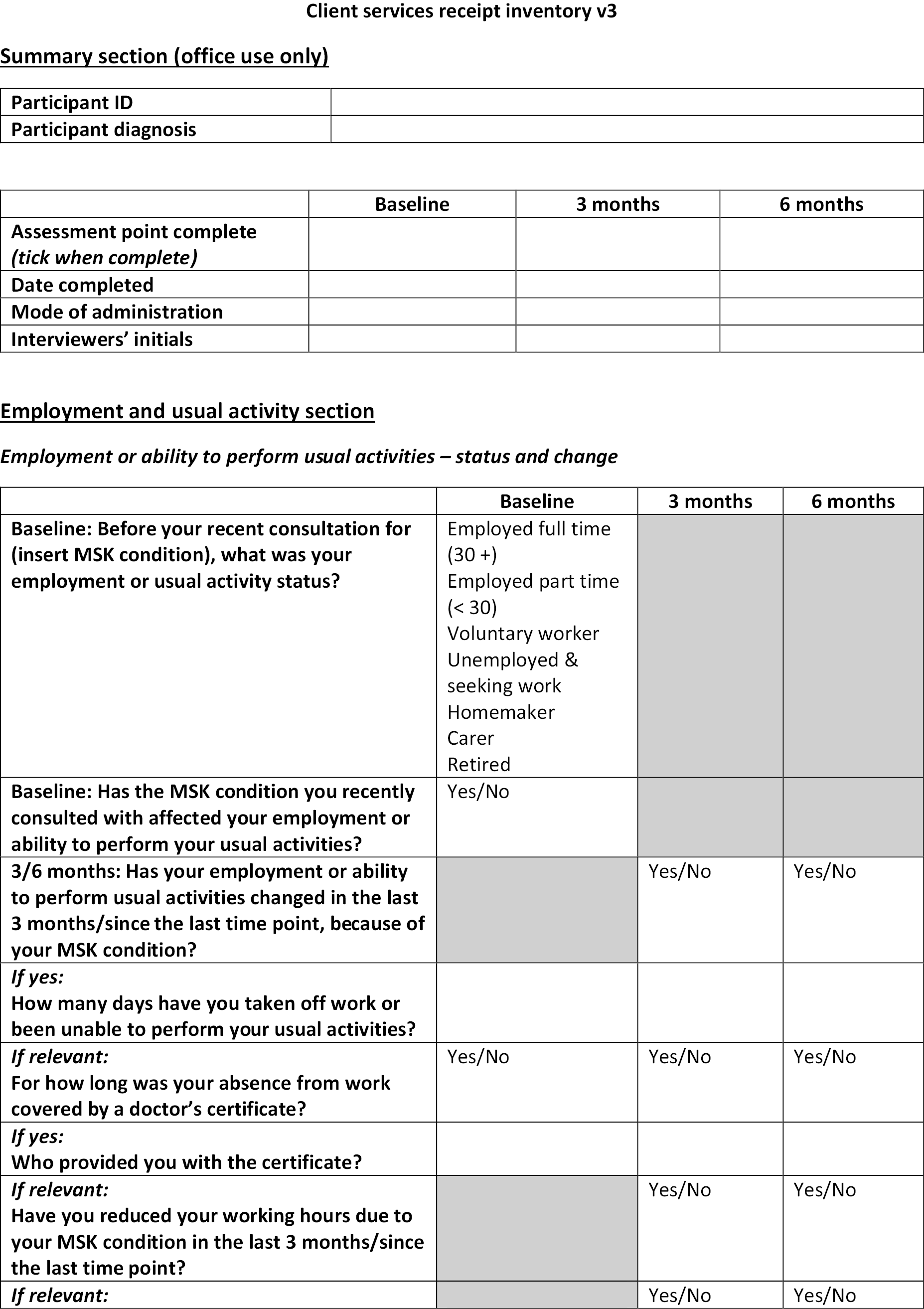

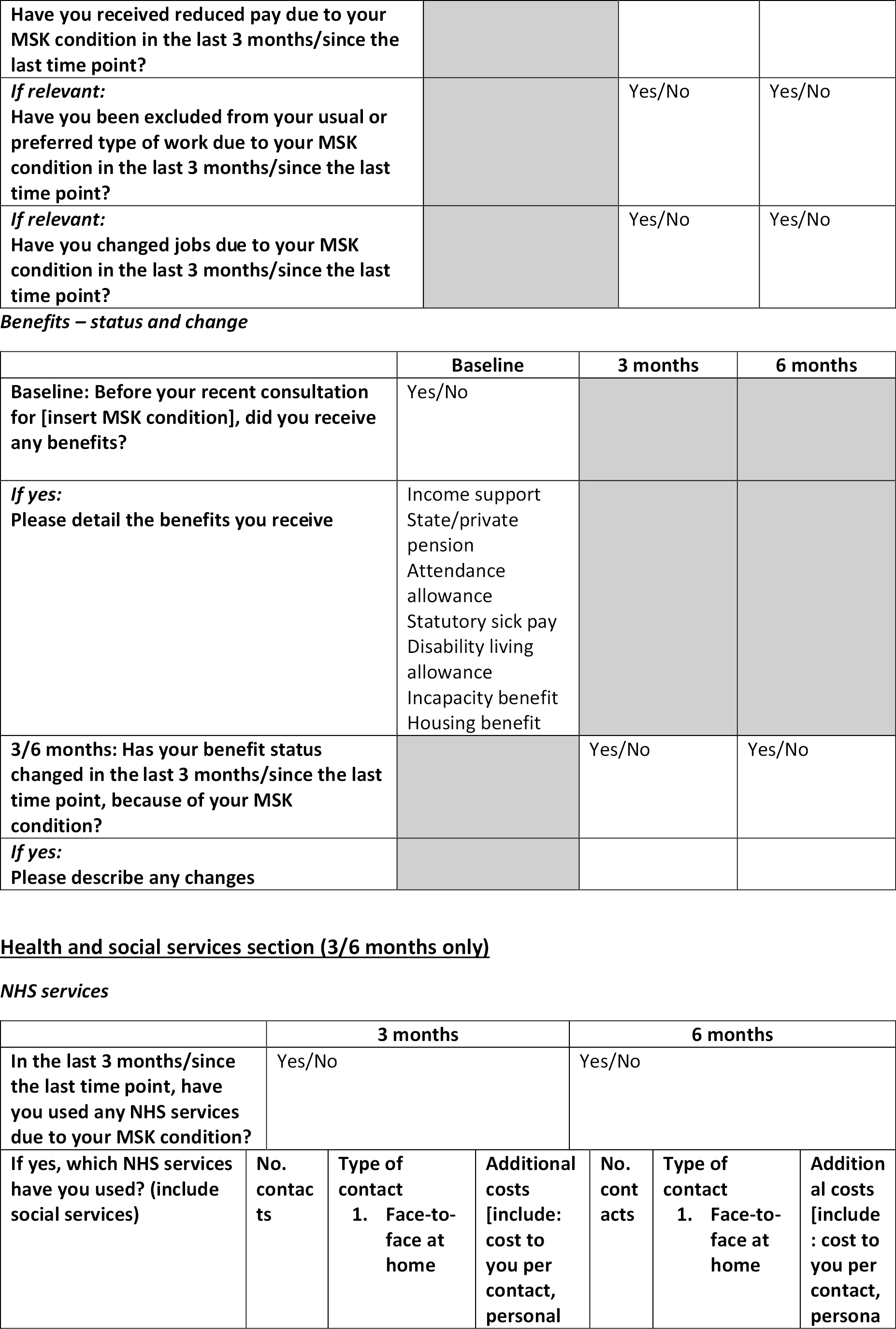

The survey was completed by 109 FCPs and included complete data sets (Table 1). Eleven others opened the survey and completed the first question, but provided no further data; they were therefore not included in the analysis. Almost half (46.8%) were based in England, with 39.4% in Scotland and smaller numbers based in Northern Ireland (8.3%) and Wales (5.5%). The areas of deprivation in which FCPs were working were evenly split, with 27.5% working in areas of high deprivation, 27.5% in low deprivation, 24.8% in mixed deprivation and 20.2% in areas of middle deprivation. The majority of participants had either 2–5 years (41.3%) or 1–2 years of experience (33.0%), with a smaller number having > 5 years (12.8%) or < 1 year of experience (12.9%) as a first-contact physiotherapist. Participants tended to be employed by an NHS community service provider (44.0%) or an NHS acute service provided (29.4%). Fewer were directly employed by the primary care network (PCN) (13.8%) and only 1 (0.8%) was employed by a single GP practice. Nearly 40% (39.4%) were working at two practices, one-fifth (20.2%) at one practice, one-fifth (20.2%) at three practices and one-fifth (20.2%) at four or more practices.

| Characteristic | Respondents (N = 109), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Work location | |

| England | 51 (46.3) |

| Northern Ireland | 9 (8.3) |

| Scotland | 43 (39.4) |

| Wales | 6 (5.5) |

| Description of deprivation area | |

| High | 30 (27.5) |

| Middle | 22 (20.2) |

| Low | 30 (27.5) |

| Mixed | 27 (24.8) |

| Band level | |

| 7 | 75 (65.1) |

| 8a | 36 (33.0) |

| 8b | 2 (1.8) |

| Length of time as a first-contact physiotherapist (years) | |

| < 0.5 | 3 (2.8) |

| 0.5–1 | 11 (10.1) |

| 1–2 | 36 (33.0) |

| 2–5 | 45 (41.3) |

| 5–10 | 14 (12.8) |

| Employment model | |

| Single GP practice | 1 (0.9) |

| Primary care network | 15 (13.8) |

| NHS community service provider | 48 (44.0) |

| NHS acute service provider | 32 (29.4) |

| Other | 11 (10.1) |

| Don’t know | 2 (1.8) |

| Practices employed (n) | |

| 1 | 22 (20.2) |

| 2 | 43 (39.4) |

| 3 | 22 (20.2) |

| ≤ 4 | 22 (20.2) |

Remote consultation usage

Of the 109 respondents who had used remote consultations in the past 2 years, 62.4% (n = 68) were using them for < 25% of their patient consultations. The majority of respondents (98.2%, n = 107) used telephone consultations, with 55.5% (n = 60) using a combination of other formats including video and 28.4% (n = 31) using text based remote consultations.

Benefits of remote consultations

Most agreed with the key benefits of the ease and flexibility of access of remote consultations for patients who found it difficult to come into the practice (64.2%, n = 70) and for those who preferred not to come into the practice (67.0%, n = 73). Half (50.5%, n = 55) agreed in the value of remote consultations allowing them to see certain patients quicker and 55.1% (n = 60) found them useful for patients with acute presentations. However, 44% (n = 48) did not agree that remote consultations allowed them to be more productive at work and 37.6% (n = 41) did not agree that remote consultations were popular with patients. Level of agreement responses are included in Table 2.

| Statement | Respondents, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly disagree | Somewhat disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Somewhat agree | Strongly agree | |

| Been rewarding as they allow me to provide ease of access to patients who previously found it difficult to come into the practice | 4 (3.7) | 10 (9.2) | 25 (22.9) | 65 (59.6) | 5 (4.6) |

| Been satisfying as they enable me to provide a more flexible service as some people prefer not to come into the practice | 3 (2.8) | 9 (8.3) | 24 (22.0) | 61 (56.0) | 12 (11.0) |

| Been valuable to me as they have allowed me to see certain patients quicker as they would have to wait longer to see me face-to-face | 13 (11.9) | 19 (17.4) | 22 (20.2) | 44 (40.4) | 11 (10.1) |

| Been useful for me, at least with patients with acute presentations | 8 (7.3) | 20 (18.3) | 21 (19.3) | 51 (46.8) | 9 (8.3) |

| Been gratifying as they are very popular with patients as many of them are pleased with the digital consultation | 11 (10.1) | 30 (27.5) | 41 (37.6) | 24 (22.0) | 3 (2.8) |

| Allowed me to be more productive than ever at work | 20 (18.3) | 28 (25.7) | 36 (33.0) | 22 (20.2) | 3 (2.8) |

Challenges of remote consultations

Seven challenge themes were measured: isolation, increased workload, anxiety, frustrations and job satisfaction, IT issues, mental strain and physical impacts. The key challenge of remote consultations with the most agreement (81.6%, n = 89) was stress caused by technology not working correctly. This was followed by the challenges linked to frustrations and job satisfaction, where over 60% of respondents agreed that patients are frustrated with remote working and want to be seen face to face (65.2%, n = 47); remote consultations are not as effective as face to face (61.5%, n = 67); and that these types of consultations have removed the enjoyable face-to-face contact (61.4%, n = 67). Results are presented in Table 3.

| Statement | Mean (SD) | Strongly disagree, n (%) | Somewhat disagree, n (%) | Neither agree nor disagree, n (%) | Somewhat agree, n (%) | Strongly agree, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation | ||||||

| Made me feel quite isolated from the other practice staff | 3.31 (1.18) | 8 (7.3) | 21 (19.3) | 27 (24.8) | 35 (32.1) | 18 (16.5) |

| Caused me to be more disconnected from my patients | 3.39 (1.05) | 4 (3.7) | 22 (20.2) | 23 (21.1) | 47 (43.1) | 13 (11.9) |

| Increased workload | ||||||

| Added to my workload as I have to spend additional time sending out resources to the patient | 3.00 (1.19) | 12 (11.0) | 31 (28.4) | 21 (19.3) | 35 (32.1) | 10 (9.2) |

| Added to my workload because appointments take longer because I have to ask more questions or patients take longer to explain the problem | 3.36 (1.14) | 5 (4.6) | 24 (22.0) | 25 (22.9) | 37 (33.9) | 18 (16.5) |

| Anxiety | ||||||

| Caused me to feel anxiety over missing an important detail about the patient | 3.41 (1.21) | 8 (7.3) | 20 (18.3) | 21 (19.3) | 39 (35.8) | 21 (19.3) |

| Caused me concern over patient privacy | 2.33 (0.92) | 20 (18.3) | 46 (42.2) | 31 (28.4) | 11 (10.1) | 1 (0.9) |

| Frustrations and job satisfaction | ||||||

| Been stressful because patients are frustrated with remote working and want to be seen face to face | 3.68 (1.09) | 3 (2.8) | 17 (15.6) | 18 (16.5) | 45 (41.3) | 26 (23.9) |

| Have removed the enjoyable face-to-face contact that I expected to have with patients as part of my role | 3.74 (1.06) | 2 (1.8) | 13 (11.9) | 27 (24.8) | 36 (33.0) | 31 (28.4) |

| Been frustrating as they are not as effective as face to face | 3.72 (1.05) | 3 (2.8) | 11 (10.1) | 28 (25.7) | 39 (35.8) | 28 (25.7) |

| IT issues | ||||||

| Been stressful when the technology does not work | 4.17 (0.94) | 2 (1.8) | 5 (4.6) | 13 (11.9) | 41 (37.6) | 48 (44.0) |

| Caused extra time pressures contacting patients (e.g. availability or IT issues) | 3.37 (1.08) | 3 (2.8) | 29 (26.6) | 14 (12.8) | 51 (46.8) | 12 (11.0) |

| Mental strain | ||||||

| Increased my mental fatigue as you are either on the phone or on a screen | 3.52 (1.18) | 7 (6.4) | 16 (14.7) | 24 (22.0) | 37 (33.9) | 25 (22.9) |

| Physical impacts | ||||||

| Have caused me to have physical aches and pains from being so desk bound | 3.42 (1.25) | 11 (10.1) | 18 (16.5) | 14 (12.8) | 46 (42.2) | 20 (18.3) |

Stress appraisal of digital consultations

Although respondents did rate the demands of digital consultations to be fairly high [mean 3.45, standard deviation (SD) 1.21], they rated their coping resources to be higher (mean 4.33, SD 0.82), therefore revealing a positive stress appraisal score (mean 0.88, SD 1.63). This positive score suggests that first-contact physiotherapists view digital consultations as a challenge type stress (i.e. their coping resources exceed the required demands) rather than a threat type stress (i.e. the task demands exceeded their coping resources).

Training

Nearly two-thirds (64.2%, n = 70) had not received training and over half (55%, n = 60) were interested in further development, particularly associated with IT and software training and remote assessment guidance. Participants also requested training on how to complete digital consultations in ‘general’ to ensure they can be more effective. Likewise, several references were made to improved communication techniques to ensure effectiveness.

Qualitative component

Participants

A total of 39 (35.8%) FCPs expressed an interest in taking part in an interview; 16 responded to follow-up e-mails and consented to take part in the qualitative component of this study. Interviews lasted for an average of 47.37 minutes (SD 9.29). Table 4 displays their characteristics. The sample was reviewed throughout data collection and considered sufficient when coding resulted in no further development.

| Participant pseudonym | Work location | Description of deprivation area | Consultations that are remote (%) | Remote consultation usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matt | England | Low | < 25 | Telephone, video and text |

| Justine | England | Low | < 25 | Telephone, video and text |

| Simon | England | High | 25–50 | Telephone, video and text |

| Lorraine | England | Low | < 25 | Telephone, video |

| Grace | England | Middle | > 50 | Telephone, text |

| Anna | Northern Ireland | High | 25–50 | Telephone only |

| Joanne | England | Mixed | < 25 | Telephone only |

| Sally | Scotland | Mixed | < 25 | Telephone, video and text |

| Damian | Scotland | High | < 25 | Telephone, video and text |

| Diane | Wales | Mixed | < 25 | Telephone, video |

| Vanessa | Scotland | Middle | < 25 | Telephone only |

| Lucy | Scotland | Mixed | < 25 | Telephone only |

| Abbie | Scotland | Middle | 25–50 | Telephone only |

| Paul | Northern Ireland | High | 25–50 | Missing data |

| Harriet | England | High | > 50 | Telephone only |

| Maxine | England | High | > 50 | Missing data |

Themes

Five overarching themes were identified through analysis of the interview data.

Theme 1: remote consultations provide logistical benefits to the patient

FCP participants perceived remote consultations as beneficial for the patient rather than for themselves and predominantly for logistical reasons. They were deemed useful for meeting the needs of patients who required flexibility with appointments because of employment, mobility issues, COVID-19 restrictions, holiday or preference for remote consultations:

To me it’s about them, not about me, it’s what suits them, but lots of patients are really happy with a phone consultation because they don’t have to take time off work. They can fit it in, it makes life a lot easier for them in lots of ways.

Grace

Likewise, remote consultations were considered useful for ‘simple’ presentations and for certain stages of the patient pathway, such as follow-up, providing results, sending information on exercises through e-mail and in certain circumstances, screening. However, there was no consistency where in the patient pathway remote consultations should be used, with some FCPs arguing that the first appointment should be face to face and others using the telephone to screen patients first.

Fewer references were made with regard to the benefit of remote consultations for the first-contact physiotherapist. However, some participants did agree that these types of appointments could offer them efficiency when dealing with participants:

They can be timesaving … if I run over, it is not the end of the world for the telephone. I just feel there’s not as much pressure on you with a telephone call, because you don’t have somebody sitting there in the waiting room for their appointment time. It is more efficient, generally.

Joanne

Other participants appreciated the control they experience when conducting remote compared with face-to-face appointments with regard to the ‘flow’ of the conversation and questioning:

I think as a clinician there is some ease in being remote in that you have time … If you have a problem you don’t know the answer to, you can say to somebody I need to go and ring and speak to somebody … It gives me time to go and do those things and come back. So, it’s quite flexible to my needs as a developing FCP.

Harriet

Theme 2: compromised efficacy is the key challenge of remote consultations

Perceived poor efficacy

Poor efficacy was seen as the key challenge of remote consultations. Reasons included: (1) problematic for certain patients; (2) inability to perform tests; (3) likelihood of missing red flags and (4) inability to build rapport.

-

Problematic for certain patients

Remote consultations were considered to be unsuitable for the elderly, people hard of hearing, patients with ‘complex’ presentations, male patients who some considered to be less open on the telephone and patients who were unable to access the phone or video.

-

Inability to perform tests

Participants readily discussed the inability to perform certain diagnostic tests in remote consultations that they used to aid their decision-making, consequently, gaps in clinical reasoning reduced effectiveness in some cases, with the potential for safety issues:

You can’t do any special tests, you can’t test for ligament integrity or you can’t fully assess muscle power remotely, it’s just not possible, it was an educated stab in the dark sometimes and that didn’t feel comfortable at all.

Lucy

-

Likelihood of missing red flags

Nearly all participants cited concerns about missing an important diagnosis or a ‘red flag’ when using remote consultations.

I suppose there’s always that wondering if you’ve missed something sinister and important, when you are taking your patient’s word for it, rather than being able to see anything.

Joanne