Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR135079. The contractual start date was in July 2021. The final report began editorial review in January 2022 and was accepted for publication in September 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final manuscript document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this manuscript.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Cantrell et al. This work was produced by Cantrell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 et al.

Chapter 1 Background and introduction

Rationale

Suicide prevention is a key priority of the NHS Long Term Plan (NHS, 2019). 1 In the most recently available figures (from 2020) a total of 5224 deaths by suicide were registered in England and Wales (ONS, 2020). 2 The National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health (NCISH) annual report indicates that over a quarter of people who die by suicide have been in contact with mental health services within the last year (NCISH, 2021). 3 Suicide and self-harm represent the most acute forms of crises for children and young people.

Predicting and managing risk is an important element of mental healthcare planning in the UK. In mental health, risk is constructed as a potential negative outcome or behaviour arising from the unwanted actions of people using services. 4 This results in two main concerns: the risk the person presents to themselves in the form of suicide or vulnerability and the risk the person presents to others. 4 As mentioned above, the first of these risks is common. The risk of harm to others is rarer but adds substantial concerns for health staff and for the mental health system.

Throughout this report a distinction is made between the risk-assessment process and the tools that are used within the process. The risk-assessment process is used in response to many drivers and to meet many demands; these vary from offering a person-centred care approach through to seeking to predict the risk of future harm to self or others through risk screening. Some of these responses are considered to be appropriate and others are not. As a consequence, two broad types of tools can be identified; those that are designed with the intent of predicting risk, that is risk screening, specifically self-harm and suicide, and those that are intended for broader use in facilitating the risk-assessment process. Both of these approaches are explored in this report.

Approaches to risk assessment

Within the wider context of risk assessment, three main approaches have been identified: unstructured clinical judgement (based on professional gut feeling), actuarial (using validated tools to measure risk) and structured clinical judgement (a combination of the former two). 5 The current risk-averse climate, common to many areas of protection and safeguarding, has seen increased use of actuarial approaches to risk management. 6 Actuarial approaches utilise statistical techniques to generate risk predictors along with checklist approaches. Actuarial approaches seek to make it easier to demonstrate adherence with procedures and may simplify completion making the process little more than a tick-box exercise. Organisationally, checklists and scales facilitate standardisation of procedures and of documentation, particularly when included within integrated electronic records.

‘… Those advocating for their use suggest that they enrich assessment by providing “an anchor against the force of bias”,7 greater inter-rater reliability and scientific validity, greater transparency around decisions taken as well as providing documentation for review, audit and analysis should a negative event occur’. 5,8

Conversely, clinical approaches involve an assessment derived in part from the medical and mental health disciplines. Clinical approaches include the structured clinical approach, which uses prompts or checklists to guide and subsequently interpret the risk assessment. 9 Outside of a clinical context, this expertise-based approach may alternatively be labelled structured professional judgement. 10 Aside from these three reference points, additional terms are used to describe certain features or characteristics of approaches, either individually or collectively. Assessments that employ a theory-informed approach assume that, because the subsequent assessment is based on theory, it can prove superior to approaches that are simply determined by institutional requirements and the procedural structure of assessment guidelines. 11 Practitioners refer to a formulation process;12 in such circumstances they employ a systematic approach that identifies all factors critical to a specific risk assessment and considers the purpose of the assessment, scope and depth of the necessary analysis, analytical approach, available resources and outcomes, and overall risk-management goal. Others contrast a problem-orientated approach with a medical model approach. 13 Other descriptions may focus more on the intended aim of the assessment, as, for example, with the collaborative approach or therapeutic approaches. Approaches may reference the content, as in multifaceted approach or the overarching philosophy of care as in the interpersonal approach. Finally, increasing attention is being directed at a whole-system approach, recognising the complexity of the included interventions and of the context in which they are delivered. These diverse approaches can similarly be observed within the specific context of risk assessment for self-harm and suicide.

Although risk assessment remains contested within mental health care, efforts continue to focus on developing actuarial mechanisms for identifying and predicting future risk behaviours. The predictive accuracy of risk screening in mental health care falls short of the performance of commonly accepted tools from other branches of health care. 4 In the light of reviews that repeatedly document significant limitations of such scales, with consistent recommendations that scales are not used for routine clinical practice, there is a need to consider whether such scales truly meet the best interests of the individual child or adolescent mental health patient. 4

NICE guidance

NICE guidance describes risk assessment as:

a detailed clinical assessment that includes the evaluation of a wide range of biological, social and psychological factors that are relevant to the individual and, in the judgement of the healthcare professional conducting the assessment, relevant to future risks, including suicide and self-harm. 14

Risk assessments may be used as part of a broader assessment to inform treatment planning but have been frequently misused to guide clinician predictions of future behaviour. 15,16

Following submission of this review an update to the 2011 NICE guidance entitled Self harm: assessment, management and preventing recurrence [NG225] was published. This guidance is intended to fully update both: Self-harm in over 8s: short-term management and prevention of recurrence (CG16) and Self-harm in over 8s: long-term management (CG133), previously referenced within this report.

Risk-assessment tools and scales can form part of the risk-assessment process and are generally checklists to be completed by patient or health professional to give a quick and rough estimate of patient risk, for example high or low risk of suicide. However, concerns have been expressed about how risk assessments are undertaken across the UK. NICE guidance on long-term management of self-harm in the over-eights recommend the following ‘Do not use risk assessment tools and scales to predict future suicide or repetition of self-harm’ and ‘Do not use risk assessment tools and scales to determine who should and should not be offered treatment or who should be discharged’. 14 Risk screening may have unintended consequences in drawing the clinical encounter towards a focus on self-harm, which may itself have harmful effects. However, contrary to staff fears, there is little evidence to suggest that simply discussing the possibility of self-harm or suicide increases the chance that children or young people will contemplate such actions.

Suicides in children are very rare, and predicting them is difficult. The NICE Quality Standard on Depression in children and young people (NICE, 2019; NG 134) states that children and young people with suspected severe depression should be seen by a Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) professional within 2 weeks of referral, or within a maximum of 24 hours if at a high risk of suicide. Prompt access to services is essential if children and young people are to receive the right treatment at the right time. 17 Arrangements should be in place so that children and young people referred to CAMHS with suspected severe depression and a high risk of suicide are kept in a safe place and seen as an emergency, within a maximum of 24 hours, to help prevent injury or worsening of symptoms. However, CAMHS service are currently experiencing extreme pressure.

A mental health professional called to assess a child or adolescent during a crisis situation, either in Accident and Emergency, in a CAMHS outpatient service or at young person’s home, needs to assess her/his suicide risk quickly. Assessment is typically conducted via an interview. Checklists and assessment instruments have been developed to facilitate the clinical encounter. They also offer a structure within which to obtain the necessary information on which to base a comprehensive assessment. NICE (2011) guidance recommends that risk assessment is used as part of a broader assessment to inform treatment planning. 18 However, they have been frequently misused to guide clinicians’ predictions of future behaviour.

Concern has been expressed that risk assessments frequently fail to capitalise on their clinical value, being translated into a perfunctory exercise that occurs in isolation from an overall assessment of a young person’s biopsychosocial need. This is particularly the case given that a primary motivation for completion of risk-assessment processes is likely to be seeking to avert recriminations relating to likely risk to others. A relatively rare, and yet high-profile, risk (harm to others) has therefore come to dominate risk-management considerations ahead of the more frequent occurrences of child or adolescent self-harm or suicide. A UK Royal College of Psychiatrists report titled ‘Rethinking risk to others’19 raised concerns about a culture of blame and the proliferation of invalidated tick-box assessment forms that are produced as a means of ‘back covering’ and that represent ‘a lazy and authoritarian approach to delivering health care .…’. 20

Aims and objectives

Our initial research question is as follows:

‘Which risk-assessment tools for self-harm and suicide are currently in use in CAMHS services in the UK and other English-speaking high-income countries?’

The review then addresses the main research question:

‘For whom and in what circumstances do risk assessments for self-harm and suicide change the clinical encounter for children and adolescents and what effect does this have on their mental health outcomes?’

Our aim is to address the initial research question by mapping the literature and then to explore the main research questions by a resource-constrained realist-informed review of published and ‘grey’ literature.

The review objectives were as follows:

To review the factors within the clinical encounter that impact upon risk assessments for self-harm and suicide within CAMHS, specifically,

-

to conduct a realist synthesis to understand underlying mechanisms for risk assessment, why they occur and how they vary by context

-

to conduct a mapping review of primary studies and reviews to identify and describe the available tools of potential applicability to the UK for undertaking risk assessments for self-harm and suicide within CAMHS.

The timescale for this review was 3 months; its purpose is to provide an overview, description and summary of the available evidence, particularly in terms of identifying when particular approaches to conducting a clinical encounter for risk assessment for self-harm and suicide are most or least suitable.

Our approach involved the following:

-

Conducting systematic searches across the major medical, psychology and health-related bibliographic databases and additional ‘grey’ literature searches.

-

Descriptively mapping retrieved items meeting broad inclusion criteria plus any additional included items identified from the reference lists of review articles.

-

Coding the items according to the following elements: risk-assessment tools used (their features, validity), training, the clinical setting where the risk-assessment tools for self-harm and suicide are used, characteristics of the health professional and young people use of the tools within the clinical encounter, the short-medium term impact of the risk assessment and long-term impacts.

-

Coding the data for explanations of how the risk-assessment process is perceived to work (context–mechanism–outcome configurations or CMOCs) to inform the realist analysis.

-

Summarising the findings in a final literature review report.

Chapter 2 Methods

The review comprised two stages. The first involved an analytic realist logic within a realist review. A realist review is specifically designed to answer questions such as ‘how?’, ‘why?’, ‘for whom?’, ‘in what circumstances?’ and ‘to what extent?’ complex interventions, such as risk assessment for self-harm and suicide within a clinical encounter, actually ‘work’. 21 Through a review of the literature, the review team develops an overarching programme theory, which they gradually refine using data from documents identified as the review progresses. 22,23 The second review involved a mapping review to identify the quantity and quality of the literature on risk assessment in CAMHS.

Rationale for a resource-constrained realist review

Conventional systematic reviews assume that outcomes result from a linear progress of cause leading to effect. 24 However, clinical encounters do not take place within a controlled experimental setting but occur within a complex, continually-shifting context. 25 In seeking to explain the processes that are taking place it becomes necessary to use a theory-driven approach; focusing on explanations of how interventions ‘work’ (programme theories). 26 Within this programme theory, the team uses a realist logic of analysis to explore outcome patterns. 27 Realist synthesis represents a tried and tested methodology, frequently used within the NIHR Health Services & Delivery Research Programme to generate, explore and test such explanations by synthesising complex evidence from diverse sources and thus offering an understanding of why and how complex interventions work. 28

In brief, mechanisms cause outcomes to occur, but the relevant mechanisms are only activated within conducive contexts. 29 By examining the ‘mechanisms’, exploring the ‘contexts’ where the intervention occurred, and then linking these contexts and mechanisms to the ‘outcome’ of the intervention a review team is able to examine the relationships between these three components. 30 Each combination of context (C), mechanism (M), and outcome (O) is labelled a ‘C–M–O configuration’. 31 Where patterns of C–M–O configurations recur they offer semi-predictable patterns/paths of how a program functions – broad ‘rules’ for how and when certain outcomes most typically occur. 32

A realist review typically requires as much as 12 months of research endeavour; time spent in exploring the literature and in generating subsequent analysis. In recognition that policy windows may not always accommodate extensive analysis some have coined the term ‘rapid realist review’ for circumstances intended to support an accelerated transition from research to policy/practice. 33 The review team resists this terminology, not least because, in contrast to other rapid forms of synthesis, rapid realist synthesis variants offer no concessions to an abbreviated methodology. Instead, the report privileges ‘resource-constrained realist review’, recognising that constraints do not impact upon the methodology, as such, but may restrict the number of programme theories to be explored or, in the case of this review, constrain the quantities of evidence assembled to sustain or negate each theory. By exploring all the candidate theories the review team hopes to facilitate overall conclusions while acknowledging the potential for further nuance and explanation of the hypothesis underpinning each programme theory.

Prior to this resource-constrained realist review, a prespecified protocol was produced, which is available via the website of the funder, the National Institute for Health Research Health Service & Delivery Research Programme. This protocol incorporates both realist review and mapping review elements and includes the research question, search strategy, synthesis methodology, inclusion criteria for relevance screening, data-extraction form, quality-assessment tool, and plans for dissemination. This overview of methods offered a framework within which the specific realist review methods could be reviewed, revised and enhanced as relevant evidence became apparent. This section of the report follows the RAMESES (Realist and Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards) guidelines34 for reporting, modified to accommodate a resource-constrained realist review.

In addition to the data extraction to facilitate the review of tools, data were coded to inform the subsequent realist analysis. The codes were piloted with codes being refined based on emerging concepts throughout the analysis period. Coded text was selected according to its facility to address the following questions:

-

Does this section of text refer to context, mechanism or outcome?

-

How might this specific CMOC be described (whether partial or complete)?

-

(a) How does this (full or partial) CMOC relate to the clinical encounter? (b) Are there data that support how the CMOC relates to the clinical encounter? (c) In light of this CMOC and any supporting data, does the clinical encounter need to be changed?

-

(a) Is the evidence sufficiently trustworthy and rigorous to change the CMOC? (b) Is the evidence sufficiently trustworthy and rigorous to justify changing the clinical encounter?

Eligibility criteria

To be included in the mapping review a publication was required to meet the criteria provided in Table 1 and to not be excluded by the criteria given in Table 2.

| Primary list | ||

|---|---|---|

| Date | Evidence published between 1 January 2011 (year of NICE guideline) and 31 December 2021 | |

| Setting | Any setting in which structured formal child and adolescent mental health risk assessment for self-harm and suicide is conducted, which meets the above criteria (e.g. health or social care settings and child’s own home) | |

| Population | Child and adolescent mental health population (8 years and older to correspond with NICE guideline) and their family members and clinicians | |

| Study type | Systematic reviews OR Primary studies not restricted by study design (to include relevant audits or service evaluations in addition to formal research studies) but these must include quantitative or qualitative research or evaluation data |

|

| Model of care | Child and adolescent mental health and crisis care contexts | |

| Outcomes | Include any reported outcomes. Primary outcomes to include the following: health outcomes (suicide and self-harm, depression symptoms etc.), health service outcomes (admission, resource utilisation etc.) and individual outcomes (mood, anxiety etc.) | |

| Other | Individual studies from UK (for realist synthesis and review of tools). Discursive accounts, guidance and qualitative studies (realist synthesis) |

Systematic reviews that include studies from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, USA, UK and Ireland (review of tools) |

| Date | Evidence published before 1 January 2011 |

|---|---|

| Setting | Interventions/services that do not typically include structured formal risk assessment. Needs assessment as a form of psychological assessment. Studies only about self-harm were excluded as a single approach to self-harm/suicide is required |

| Population | Adults (18 years or older) and child under 8 years |

| Study type | Papers that describe interventions/services without providing any quantitative or qualitative data. Conceptual papers and projections of possible future developments |

| Model of care | Other first contact that does not involve risk assessment. Unstructured or informal approaches to risk assessment |

| Outcome | Studies that include no process (e.g. qualitative) or outcome (e.g. quantitative) data |

| Other | Studies conducted in low- or middle-income countries. Studies from non-Anglophone high-income countries. Papers not published in English |

Information sources

A broad search to identify published and peer-reviewed literature focused on how child and adolescent mental health risk assessment is delivered in the UK was conducted, including a search for relevant grey literature. The team sought to identify examples of current practice, pilots and other child and adolescent mental health initiatives carried out in the UK and review their robustness, applicability and scalability.

The search strategy combined thesaurus and free-text terms and relevant synonyms for the population (child and adolescent mental health population) and intervention [risk assessment (broad terms to retrieve research on the use of risk assessment, and risk-screening scales/tools; including terms for psychosocial assessment as the broad term for assessments including risk-assessment components)], using proximity operators where appropriate. Search terms were then combined using Boolean operators appropriately. Outcome terms were not included in the search as outcome information is not always included in the title or abstract, meaning that their use could impact negatively on the identification and retrieval of relevant studies. Similarly, the search strategy was not limited to self-harm and suicide with these inclusion criteria being assessed at the subsequent study selection stage (see Appendix 1, MEDLINE search strategy).

Once agreed with NIHR HS&DR and DHSC, the search strategy on MEDLINE was translated for other major medical and health-related bibliographic databases. The search was limited to research published in English from 2011–current to reflect developments since the NICE guidance (2011). Methodological search filters were not utilised to keep searching broad and ensure all relevant study types were retrieved. Geographical (i.e. UK)35 and review filters were used; first to restrict to the UK and subsequently, to retrieve systematic reviews.

MEDLINE (including Epub Ahead of Print & In-Process), PsycINFO, EMBASE, CINAHL, HMIC, Science and Social Sciences Citation Index and the Cochrane Library were all searched in September 2021. Targeted ‘grey’ literature searches were carried out in October 2021 to identify reports/case studies in websites including the following: Mental Health Foundation www.mentalhealth.org.uk, MindEd for Families www.mindedforfamilies.org.uk/young-people, Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health www.rcpch.ac.uk/, Royal College of Psychiatrists www.rcpsych.ac.uk and Young Minds www.youngminds.org.uk. Additional evidence was identified from the reference lists and/or citation searching of included studies.

We also utilised expertise of colleagues working in mental health including Scott Weich and Elizabeth Taylor Buck and input from Dr Bernadka Dubicka, consultant and research lead in Pennine Care Foundation Trust, Greater Manchester and Chair of the Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCPsych) Child and Adolescent Faculty to identify additional documents and initiatives being carried out within a UK context to ensure that the review is as inclusive as possible.

Data management/data selection

Search results were downloaded to Endnote bibliographic management software.

Selection process

A pilot-study selection exercise involved members of the review team independently coding a small sample of records (200 each). Verdicts were compared and inter-rater reliability was rated as acceptable. The remaining records were distributed between the review team (AC, KS, ABo and DC) and then subject to independent single review. A sample of excluded records was reviewed to minimise the likelihood of exclusion in error. Where a verdict of unsure was recorded by one reviewer these records were passed to a second reviewer for agreement to be resolved by consensus. In the event of continued disagreement a third reviewer (ABo) arbitrated on eventual inclusion.

Data-collection process

Following piloting of a data-extraction form, a user-friendly Google form interface was used to input data into a Google Sheets/Excel spreadsheet. Summary tables were inserted within the final report and summarised data were produced for the summary report. In accordance with most rapid reviews, duplicate data extraction was not considered possible. However, data were iteratively checked and rechecked during writing of the final report.

Data items

Data to be extracted included the following:

-

year and place of study

-

the tool and risk-assessment method

-

the population included (age group, clinical characteristics and setting)

-

study design and outcomes measured [any outcomes measured by studies relevant to patient mental health (e.g. status of condition, risks and care planning as a result of the risk assessment) were included]

-

main findings

-

key messages including limitations.

Quality assessment

In line with realist-informed approaches, that privilege richness of data and relevance over rigour, preliminary quality assessment of each study focuses on generic limitations of study design, although specific design limitations were documented where identified. Given the diverse evidence to be included, the review team made the decision to only apply quality assessment to studies evaluating an actual tool. This allowed for the use of insights from qualitative data and process evaluations as well as implementation studies.

For the mapping review the team compiled published assessments relating to the different aspects of validity for the individual tools and documented these according to systematic methods (Table 8). Quality appraisal was then conducted independently using the appropriate sections (quantitative or qualitative or both) of the MMAT tool, and disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Data synthesis

Synthesis takes the form of descriptive, narrative approaches – such as textual, tabular and graphical presentation. However, following a mapping process, the team utilised a realist-based approach. A realist review seeks to explore the underlying causes for observed outcomes and when these might occur by reviewing published and grey literature.

Using the analytic building blocks known as CMOCs [i.e. propositions that describe what works (or happens), for whom and in what contexts and why] the team explored these contexts. 36 Contexts are conditions that activate or modify the behaviour of mechanisms. 22 This realist review seeks to identify and understand the contexts that impact on factors that determine the outcome of the risk-assessment process, whether that clinical encounter is successful or suboptimal. Realist methods offer an optimal vehicle for exploring the complex and dynamic nature of the clinical encounter.

The resource-constrained realist review sought to explore the contexts that influence risk assessment for mental health for children and adolescents by seeking to answer the following questions:

-

Which factors within the clinical encounter impact positively or negatively on risk assessment for self-harm and suicide in children and adolescents within CAMHS?

-

What are the underlying mechanisms, why do they occur and how do they vary in different contexts?

This resource-constrained realist review supports exploration of risk-screening tools and risk-assessment processes in child and adolescent mental health, including a descriptive analysis of tools most commonly used within the UK. As a result, this review focuses on the processes of risk assessment while acknowledging known limitations to the design and utilisation of specific risk-screening tools. The question on underlying mechanisms involved exploring key components and processes within risk assessment for self-harm and suicide and constructing programme theory statements for each stage or component – for assessment against the identified evidence. Individual team members extracted data from each allocated study and coded the context, mechanisms and outcomes within the studies.

Synthesis followed a pathway approach, as used in previous realist-based reviews for primary care and social care. 22,37 Resultant CMOCs were discussed within the research team. Comments from patient representatives and clinical experts were fed into the iterative, cyclical process of searching, data extraction, analysis and programme theory development.

The scope of the resource-constrained realist review was clarified through regular team meetings to discuss the protocol, review process and synthesis outputs. The agreed review question was ‘For whom and in what circumstances do risk assessments for self-harm and suicide change the clinical encounter for children and adolescents and what effect does this have on their mental health outcomes?’.

Although findings for CAMHS in general are privileged, the review team sought to identify specific age differences between children and adolescents where these may exert an influence on the conduct or outcome of the clinical encounter. Where contextual differences relate to the setting of the risk assessment these were also highlighted in the review findings.

Searching for relevant evidence: search strategy and eligibility criteria

To test the programme theory, a qualified information professional developed and implemented a search strategy to retrieve relevant primary studies and discursive contributions from both academic and grey literature. This complemented the overall search strategy as implemented for the mapping review and executed across multiple bibliographic databases (see Information sources). Items informing the programme theories were identified from the full bibliographic searches. Supplementary subject searches and forward citation were then executed on Google Scholar using the Publish or Perish desktop search engine. These electronic searches were complemented by innovative use of the scite tool to view ‘within publication citations’ in context and to establish whether the citation provides supporting or contrasting evidence for cited claims.

Relevance confirmation, data extraction and quality assessment

A single reviewer assessed each study to determine its relevance to the review question and to extract pertinent detail. Given the nature of the question and the available evidence (non-research designs) no attempt was made to appraise the quality of included studies. Assessment of relevance involved studies being assigned one of three categories based on conceptual relevance:

*** Directly relevant – evidence derived from a child and adolescent risk-management context.

** Partially relevant – evidence derived from a wider mental health risk-management context, which may or may not include child and adolescent populations.

* Indirectly relevant – evidence on risk assessment more generally (e.g. risk assessment for violence).

Patient and public involvement (PPI)

Patients and members of the public have been involved in this review through the Sheffield Evidence Synthesis Centre PPI group. This PPI group advises on the plain language summary and other relevant outputs and provides perspectives on relevant contextual factors and key messages for NHS staff.

Chapter 3 Results

This section begins by characterising the main approaches that feature in risk assessment. Both generically and specifically. Thereafter, the Results section falls into two subsections. First, programme theory components are examined and explored within a resource-constrained realist review. Second, the report presents a review of approaches to assessment and tools used specifically in the UK context.

The pathway to intervention

The risk-assessment process is clearly defined in NICE documentation and other guidance (Table 3; Box 1). Within this overarching structure latitude exists with regard to the purpose of risk assessment, how exactly it is performed, what scales or tools are used, if any, and how the outputs and outcomes from risk assessment are used.

| Stage | Detail |

|---|---|

| 1. Child presents to service | Presentations to accident and emergency departments, primary care, acute paediatric care etc. |

| 2. Initial triage and care | Initial assessment for risk (e.g. by paediatrician or registered children’s nurse) and assignment of immediate (e.g. physical) care |

| 3. Risk formulation | Brings together an understanding of personality, history, mental state, environment, potential causes and protective factors, or changes in any of these to provide a narrative of individual risk |

| 4. Development of care plan and risk-management plan | A risk-management plan should be included in the overall care plan |

| 5. Regular review of care plan | Plans should be updated, to include monitoring changes in risk and specific associated factors for the service user, and evaluation of impact of treatment strategies over time |

See Appendix 2 for an expansion of the stages of the risk-assessment pathway offering further detail on each of these processes.

-

Methods and frequency of current and past self-harm.

-

Current and past suicidal intent.

-

Depressive symptoms and their relationship to self-harm.

-

Any psychiatric illness and its relationship to self-harm.

-

The personal and social context and any other specific factors preceding self-harm, such as specific unpleasant affective states or emotions and changes in relationships.

-

Specific risk factors and protective factors (social, psychological, pharmacological and motivational) that may increase or decrease the risks associated with self-harm.

-

Coping strategies that the person has used to either successfully limit or avert self-harm or to contain the impact of personal, social or other factors preceding episodes of self-harm.

-

Significant relationships that may either be supportive or represent a threat (such as abuse or neglect) and may lead to changes in the level of risk.

-

Immediate and longer-term risks.

Results 1: Programme theories for risk assessment

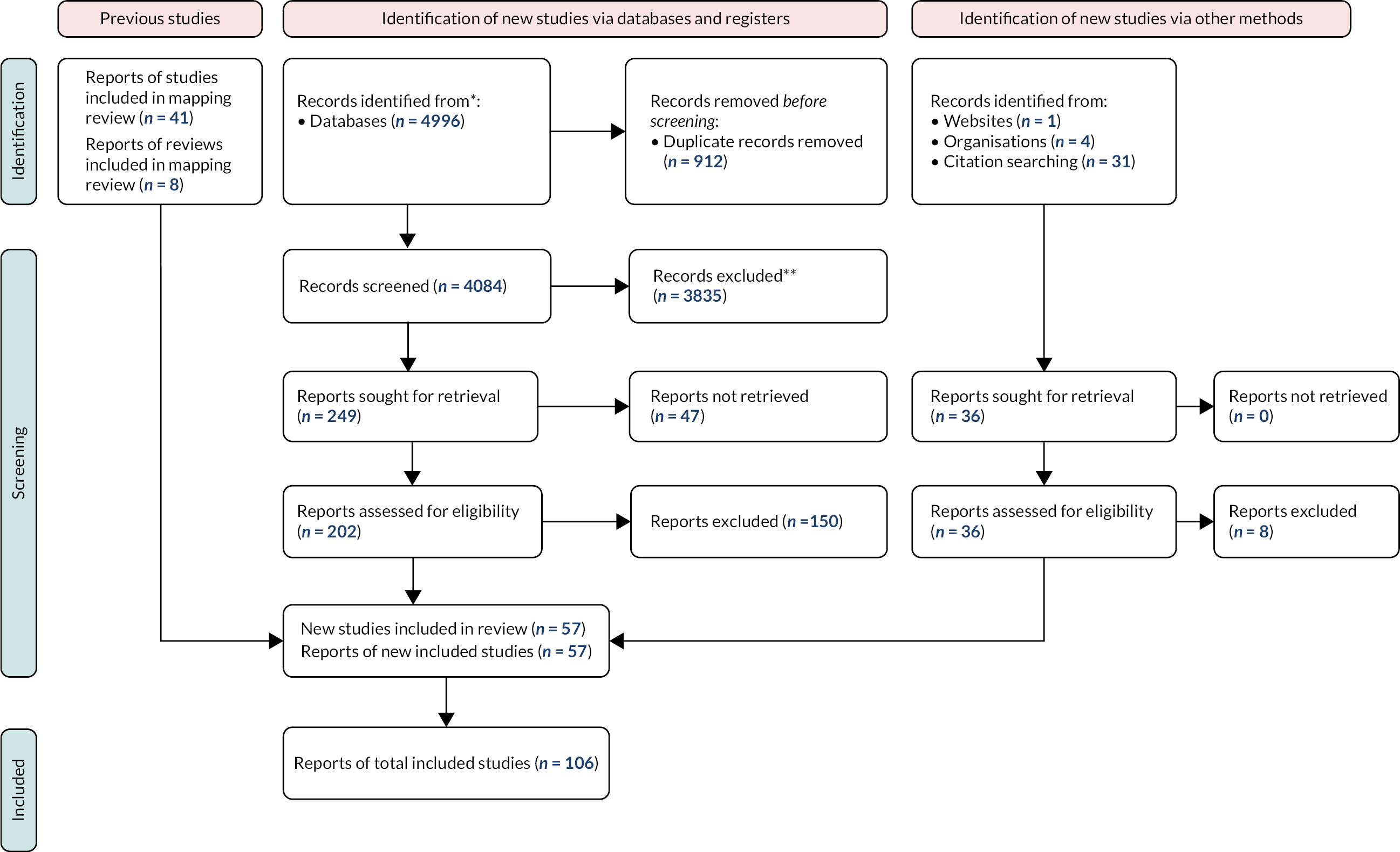

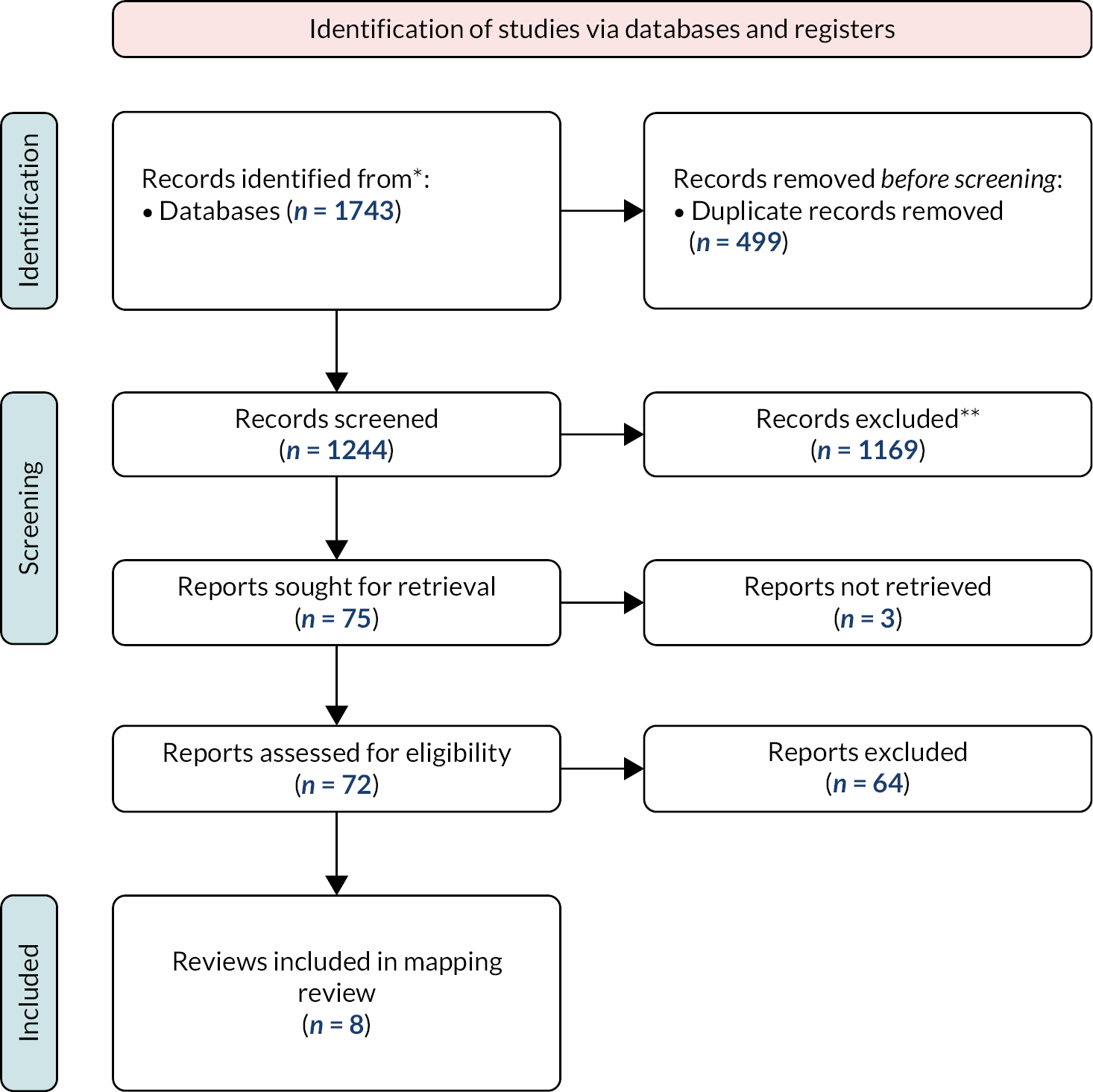

This section reports a resource-limited realist review of risk-assessment tools and processes in child and adolescent mental health. 57 papers were identified for inclusion in the realist review. These comprised 7 systematic reviews, 1 randomised controlled trial (RCT), 6 quantitative studies, 18 qualitative studies and 9 surveys with 7 discussion papers, 3 conventional literature reviews, and 1 opinion piece. There were two case studies and a further two case studies that combined case studies with qualitative research. Finally, there was a single case note review. The flow of information through the resource constrained realist review process is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis flow chart for the realist review. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.n71

Initial theory

Initial theory for how, when and why risk assessment is intended to work within the clinical encounter in child and adolescent mental health was identified by undertaking a detailed examination of The assessment of clinical risk in mental health services. National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health (NCISH). 38 This report asked 85 mental health trusts and health boards in the UK for details of the main risk-assessment tools and approaches that they currently used. Information on the nominated tools was documented, including structure, content and symptom profile. The Inquiry contacted clinicians, patients and carers asking them to share their experiences of tools via an online survey targeted across mental health services in general. 38 Importantly, it sought to represent clinician, patient and carer viewpoints as required when exploring a complex adaptive system. While this confidential inquiry was not specific to a child and adolescent population, the team considered it a suitable starting point because

-

the focus of the review question is not on the population but on the context of assessment within a mental health service (in its broadest sense) and

-

evidence would be privileged according to its relevance to the review question, meaning that the team would particularly seek and highlight nuances from a specific child and adolescent mental health context.

However, critical differences combine to make the application of an assessment of child or adolescent suicide and self-harm unique. 39 Power differentials, which will exist for both populations, are particularly amplified for younger children. Furthermore, a child at risk exists in a complex care system that includes both protective and risk factors. Assessment of young people in many contexts is conducted by non-mental health experts who lack specialist knowledge and experience to inform clinical decisions. 40 Further differences may relate to the focus of assessments, for example in acute paediatric care assessment typically takes place within an immediate (i.e. hours or days) window for potential self-harm or suicide. 39 In such contexts, assessments are performed in time-limited circumstances with children and adolescents with potentially dynamic and fluctuating mental health. In the UK, NICE (2004) guidelines advocate that children and adolescents who self-harm should be assessed for risk. 41 This assessment is intended to identify psychiatric illness and its relationship to self-harm, assess personal and social context together with any specific factors predicting self-harm. It is further required to recognise any significant relationships, either supportive or representing a threat. Such an assessment needs to consider the relatively immediate risk of self-harm or suicide in order to make time-critical risk-management decisions.

We formulated 14 programme theory components derived from the clinical implications of the NCISH report. In each case, the intention was to represent context (signified by IF), mechanisms (represented by THEN) and outcomes (designated by LEADING TO). When programme theory components were either underspecified or incomplete other sources of evidence are used to complete the CMOCs. A single reviewer extracted the following information from the source documents:

-

The activities associated with the risk-assessment process.

-

The setting in which the risk-assessment process took place, including physical environment, social setting, and wider social and economic climate (if specified).

-

The outcomes of each intervention, including both clinical outcomes and responses by adolescent or carer.

Through this preliminary review, successful interventions are considered to require the following:

-

IF risk-assessment approaches are simple, accessible and part of a wider assessment process THEN staff are able to generate standardised, informative and clinically useful assessments LEADING TO appropriate use of support and services.

-

IF clinical staff focus clinical risk-assessment processes on building relationships THEN clinicians and adolescents trust each other LEADING TO frank and open communication within the clinical encounter.

-

IF the emphasis of clinical risk-assessment processes is on gathering good-quality information on (i) the current situation, (ii) past history and (iii) social factors THEN staff use information to inform a collaborative approach to management LEADING TO coordinated and integrated care.

-

IF staff are comfortable asking young patients about suicidal thoughts THEN young service users share relevant information concerning their circumstances LEADING TO an appropriate service response.

-

IF risk-assessment processes are conducted consistently across mental health services THEN the quality of response to young service users does not depend upon each individual contact LEADING TO the availability of consistent information across services.

-

IF staff are trained in how to assess, formulate and manage risk, including appropriate referral THEN staff feel equipped to manage the risks for children and adolescents who present to health services LEADING TO an emphasis on positive risk taking.

-

IF staff are supported by on-going supervision THEN staff feel able to deliver a consistent approach to risk assessment LEADING TO a reduction in adverse events.

-

IF families and carers are involved in the assessment process THEN families and carers are given an opportunity to express their views on potential risk LEADING TO a collaboratively developed risk-management plan.

-

IF mental health staff communicate risk assessments with primary care THEN young people are directed to appropriate care LEADING TO successful health outcomes.

-

IF the management of risk is personal and individualised THEN young people don’t see their care as ‘protocol driven’ and won’t feel alienated LEADING TO their engagement with care.

-

IF organisations involved in risk assessment utilise a whole-system approach THEN this strengthens the standards of care for everyone, LEADING TO the safe management of supervision, delegation and onward referral.

As a complementary activity, the review team identified three ‘counter programme theories’, which relate to how the risk-assessment process might result in unintended consequences:

-

IF staff view risk-assessment tools as a way of predicting future suicidal behaviour THEN they incorrectly interpret individual levels of need for care LEADING TO inappropriate use of restrictive practices such as involuntary hospitalisation, restraint, sedation and seclusion (for the service user).

-

IF clinicians use risk-screening tools and scales in isolation within the risk-assessment process THEN treatment decisions are determined by a score LEADING TO incorrect interpretation of individual need for care and inappropriate utilisation of CAMHS (for the service).

-

IF staff develop tools for risk assessment locally THEN checklists and scales lack formal psychometric evaluation LEADING TO limited clinical utility of tools for risk assessment and unnecessarily restrictive treatment options.

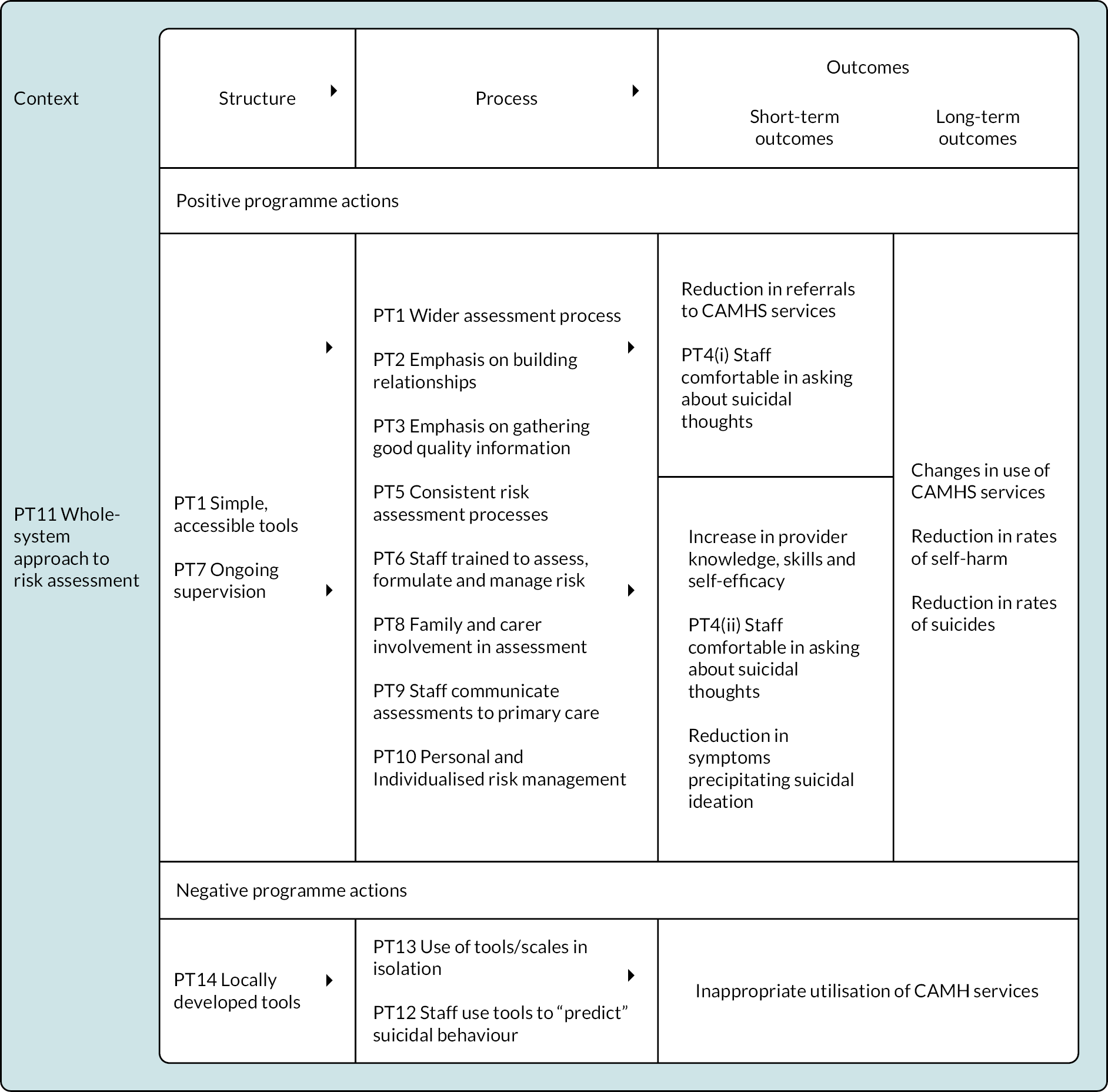

Following identification of programme theory components the team decided to construct an overall logic model as a ‘conceptual map’ within which to locate the diverse programme theories. An initial version was identified from a Screening and Referral Logic Model derived from a relevant publication from the RAND Corporation (Figure 2). 42 The team then overlaid the 14 programme theories on the initial logic model to create a logic model for the realist review (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Logic model developed for the realist review.

Results

1. Usability

-

Programme Theory 1. IF risk assessment approaches are simple, accessible and part of a wider assessment process THEN staff are able to generate standardised, informative and clinically useful assessments LEADING TO appropriate use of support and services.

Supporting evidence

This programme theory component is based on the NCISH report, which promotes an assessment process that goes beyond strict actuarial approaches. 38

Evidence base: three systematic reviews, one NICE guidance document, one feasibility study, one qualitative study, one narrative review, one survey, five commentaries, and one textbook.

Risk-assessment scales are commonly used in clinical practice to quantify the risk of suicide, with 85% of NHS mental health trusts using checklist-style approaches. 38 Currently, no standardised risk-screening tool is available for use within clinical practice in the UK. 39 Furthermore, risk-screening tools that exist possess questionable validity, reliability and acceptability (see Validity and Table 8).

In contrast, NICE guidance (CG133) recommends that risk assessment should take place within a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s needs. 14 A recent systematic review43 concludes that current evidence is not yet sufficient to recommend that structured diagnostic assessments should be universally adopted as an adjunct to clinical practice. However, the reviewers suggest that structured diagnostic assessments could be applied cautiously and mindfully pending further evaluation. A minority of users of the Davies’ structured interview for assessing adolescents in crisis expressed concern that ‘having a form to fill in’ hampers the development of rapport and a relationship between the young person and the professional.

Critics of actuarial approaches comment on the paucity of empirical evidence to support the ability of tools to predict accurately. 16,44–46 See Programme Theory 12. Many argue that tools are based on information about groups, which is of limited value in predicting the behaviours of an individual. 5,44,47 Within adult mental health care the literature consistently affirms that the focus of mental health organisations is now on risk management,48,49 quality assurance and patient safety. 49 Recent studies suggest that this may also be true for CAMHS. 50,51 Risk assessment in isolation from the development and implementation of clinical judgment frameworks becomes potentially ineffectual. Clinicians should not shelter behind the ‘fallacy’ of risk assessment, instead of acknowledging that assessment tools are likely to serve the organisation more than the patient. 52

A possible corollary to Programme Theory 1 is that development of simple assessment tools within a complete assessment process could result in higher rates of referral for risk of self-harm and suicide, thereby increasing utilisation of CAMHS services.

2. Trust

-

Programme Theory 2. IF clinical staff focus clinical risk-assessment processes on building relationships THEN clinicians and adolescents trust each other LEADING TO frank and open communication within the clinical encounter.

Supporting evidence

This programme theory component on building relationships is based on the NCISH report, which found that clinicians believed that an important focus of risk assessment involved building a rapport such that the assessment flowed smoothly. 38

Evidence base: one NICE guidance document, five qualitative studies, two surveys, one case study, and one commentary.

NICE guidance 133 states that ‘health and social care professionals working with people who self-harm should: aim to develop a trusting, supportive and engaging relationship with them’. Such a recommendation is further informed by qualitative research using interviews with nurses on wards of four psychiatric hospitals. 53 Professionals are concerned about how risk assessment may influence their relationship with service users. Often mental health nurses tend to emphasise risk avoidance to maintain safety. 5,54,55 Literature describing nurses’ perceptions of safety in acute mental health reports that nurses perceive their role as mainly risk management. 5 Most packages focus on assessment skills, risk screens and risk-factor tools but do not address tensions between divergent views of people in distress and professionals involved and how to build empathic partnerships5 in time- and resource-poor environments.

A further tension relates to working environments that privilege ‘task-based nursing over therapeutic care’ and those that create ‘conditions for open and genuine communication’. Task-based working environments, exemplified by a preoccupation with tick-box risk assessment, often prove detrimental to person-centred care. Furthermore, within a mental health service context, a focus on risk management ‘inherently erodes the formation of a therapeutic relationship, as patients who are viewed as risky are not trusted’. 56

In contrast, where ‘conditions for open and genuine communication’ exist staff members seek to focus on ‘developing an accurate and meaningful picture of patients’. 53 As a consequence staff members can enhance their capacity for compassionate and considerate contact and communication with patients experiencing suicidal ideation.

Compassionate care is particularly important – unlike their feelings for the self-harm population in general, staff typically hold positive attitudes towards self-harm specifically in adolescents and young children. 40,57 If done well in an unhurried, empathetic and non-judgmental manner, the interview can be therapeutic and encourage the patient to seek future help. By contrast, negative attitudes and a focus on the patient’s physical needs might result in the patient avoiding emergency services in the future. A healthcare professional should not give false reassurance, because patients may doubt that they are taking their situation seriously. 58 If possible, they should seek to obtain a corroborative history of the event from a third party. 58

Assessing young people requires engagement, empathy and a genuine curiosity about what has happened to bring the young person to a point of acute risk. Such an approach seeks to increase the chances of openness and honesty and a collaborative risk assessment. Otherwise, young people will keep risky thoughts and plans hidden, particularly if they think they will be judged or punished.

When presenting to their GP, young people feel that it is important that their GPs initiate the conversation about mental health, suicide and self-harm. 59 If a GP asks directly about such topics this may overcome some of the barriers to disclosure of suicidal thoughts, depressive symptoms or mental health problems more generally.

In the context of risk assessments for suicidal behaviour and/or self-harm, young people dislike labels such as ‘risk’ and ‘risk assessment’. 59 They perceive such labels to be potentially stigmatising and problematic. Young people may be especially vulnerable to labels that could increase stigma; language and terms related to suicidality or self-harm may be perceived as ‘pathologising’. Awareness of these attitudes may help in a shift away from professional-focused terms such as ‘at-risk’ and ‘risk assessment’, to patient-focused language such as ‘coping assessment’. 60 However, participants in one qualitative study disliked the term ‘assessment’, suggesting the inclusion of language relating to ‘well-being’. 59

Young people endorse the need for ‘comprehensive psychosocial-based assessments that prioritise collaboration and the therapeutic alliance, are holistic, acknowledge that risk is dynamic over time, and are needs-driven’. 59 Individualised, needs-based approaches to assessment are key for young people. 59

A collaborative dialogue facilitates empowerment and creates opportunities for young people to be involved in decision-making and to meet their growing needs for autonomy, agency and control. 59 Such a dialogue is concordant with principles of patient-centred care, shared decision-making and patient engagement. Furthermore, patient-centred care is fundamental to a biopsychosocial approach and recognises the pivotal role of the family. Young people may be particularly sensitive to power disparities and condescension. A friendly, non-judgemental attitude is critical; poor attitudes and body language and impersonal, overmedicalised approaches impede the therapeutic alliance and the disclosure of suicidal behaviour/self-harm. 59

Young people’s views of self-harm services have not been extensively studied. 61 A recent study has explored the views of young people in relation to the role of GPs. 59 GPs have been found, in one study, to be the most frequent healthcare practitioner source for urgent referrals of children and young people for self-harm, suicidal thoughts or following overdose. Families may prefer to access their GPs when worried about these issues. GPs can feel dependent on specialist support and feel the need for increased training in supporting children and young people with mental health issues. 62 Young people expect GPs to be skilled and knowledgeable in providing practical resources and support for presentations of suicidal behaviour and self-harm, including crisis support. 59 Assistance from the GP with accessing crisis resources or using a safety plan is viewed as highly beneficial. 59 GPs taking the time to demonstrate resources to the young person was another expression of care and connection to assist a positive relationship. 59 Young people may have little previous experience of how the healthcare system is structured, and therefore might require more ‘scaffolding’ than adults. 63

Young people are typically ambivalent when seeking help. They may isolate themselves, feeling that it is not safe, or that they are not ready to disclose their suicidal thoughts and feelings (e.g. as a consequence of feeling shame). In response, nurses describe how they try to enable patients to communicate in an open and genuine way. 53 By presenting themselves as accessible and approachable, reaching out to patients, and encouraging patients to approach them and talk to them nurses are able to work on creating an open and communicative environment. 53 Nurses highlight the need to develop a trusting relationship, respect the emotions of patients and reassure patients that they can disclose suicidal ideation. 53

All the above suggests that ‘… policy makers and hospital leaders should aim to create environments where [staff] can be involved in multifaceted and interpersonal approaches to suicide risk assessment’. 64 In such environments organisations could create relationships between children and young people and professionals that release preventive and therapeutic potential, rather than encouraging impersonal observations and ineffective checklist approaches. See Programme Theory 1.

3. Credible information

-

Programme Theory 3. IF the emphasis of clinical risk-assessment processes is on gathering good-quality information on (i) the current situation, (ii) past history and (iii) social factors THEN staff use information to inform a collaborative approach to management LEADING TO coordinated and integrated care.

Supporting evidence

This programme theory component is based on the NCISH report,38 which found that clinicians believed that an important element of risk assessment is the quality of the information gathered. The clinicians interviewed noted the importance of gathering a thorough history of previous incidents, and having an awareness of triggers for distress, for example significant anniversaries. They reported that a good risk history should include details of the incident and its consequences as well as the likelihood of the incident being repeated. However, some highlighted the difficulty of predicting suicide. 38

Evidence base: two quantitative studies, one multicentre study, three qualitative studies, three surveys and three commentaries.

Critics argue that tools tend to focus on historical (static) risk factors thus ignoring the dynamic or situational variables, which impact on the person. 5,8 The Functional Analysis of Care Environments–Child and Adolescent Risk-Assessment Suite (FACE–CARAS) suite of tools promotes use of schedules that enquire about both historical (static) and current (dynamic) risk factors. 65

Key to risk assessment is a collaborative dialogue, which encompasses the provision of adequate, detailed information across all aspects of a young person’s care, including treatment options and confidentiality. 59 Assessment tends to focus on risks people with mental health diagnoses pose, which marginalises consideration of other risks like living in inadequate accommodation. 66 It constructs individuals as risks who need interventions rather than identifying issues within particular communities, such as those with higher levels of poverty, substance abuse and unemployment. 48 It may also obscure risks that come from accessing mental health services, which potentially include loss of liberty, forced treatment or negative experiences. 67,68

Young people value the protection of their privacy, particularly for sensitive issues. 59 However, this should not be interpreted as a reason not to ask them about their thoughts of self-harm or suicide. Health professionals should also be aware that different types of self-harm may be viewed differently by children and young persons (CYP). For example, stigma associated with cutting may make a child or young person more secretive whereas attempted suicide frequently signals that the young person has reached a point where they are no longer able to cope at all. 61 Young people also express concerns regarding the privacy and confidentiality of their medical information relating to mental health and suicidal behaviour/self-harm. 59

Challenges exist in relation to incompleteness of information. A survey of outpatient and inpatient adolescents in the UK showed that 20% reported at least one episode of self-harm on the questionnaire that was not recorded in the clinical record. 69 The authors concluded that ‘using a combination of clinical interviews (with multiple informants), paper-and-pencil tools and comprehensive clinical records’ keeping afford the best chance of identifying adolescents who self-harm’. 69 A multicentre study of self-harm in England70 reported that psychosocial assessment occurred in only 57% of presentations in the study, even though the three centres (six hospitals) involved had well-established specialised self-harm services. The authors concluded that this ‘low rate of completion demonstrates the extent to which hospitals fall short of implementing the national guideline recommendation that all self-harm patients should receive a specialist assessment’. 70 They suggest that this low completion requires further investigation, particularly as ‘non-assessment may have several causes (e.g. self-discharge, patient refusal, unavailability of staff, emergency department policy). 70 They argue that this is particularly critical given what they claim as ‘accumulating evidence that psychosocial assessment is associated with reduction in risk of repetition of self-harm’ and the fact that ‘provision of appropriate psychiatric and social care is unlikely in the absence of an assessment’. 70

The FACE–CARAS tools are predicated on a stepped approach to completion – such that subsequent tools are only completed when indicated by the overall risk profile – but even within the context of research and evaluation completion of subscales was found to be unacceptably incomplete. 65

While advances in computerisation and clinical records have shifted the exact nature of this challenge the need for multiple and complementary approaches remains as pressing as ever. Specific challenges relate to conducting suicide risk assessment. Self-report measures of suicidality are limited by reporting biases (e.g. young people may conceal suicidality to avoid anticipated negative consequences) and high temporal variability (i.e. self-reported suicidal ideation may fluctuate from moment to moment). 71

When patients feel able to communicate in an open and genuine way, nurses are able to get to know patients, can assess suicidal ideation and also identify risk and protective factors. Strategies used to characterise the presence and severity of suicidal ideation, include listening to and observing patients, asking patients about the presence of suicidal thoughts and plans, and checking with colleagues. 53 Nurses must be alert to expressions that might be indicative of suicidal ideation (e.g. self-harm and social isolation). Nurses describe how they depend upon their intuitive senses, and that their own emotional responses, including ‘feeling anxious about the potential of a suicidal attempt’, provide cues to emerging suicidal ideation. Conversely, such emotional responses may also make nurses more likely to assess suicide risk as higher than it actually is. 53

4. Communicative environment

-

Programme Theory 4. IF staff are comfortable asking young patients about suicidal thoughts THEN young service users share relevant information concerning their circumstances LEADING TO an appropriate service response.

Supporting evidence

This programme theory component is based on the NCISH report38 in which patients recommended that risk-assessment tools should incorporate a focus on suicidal thoughts, i.e. ‘to encourage staff to confidently tackle difficult questions’.

Evidence base: one meta-analysis, one quantitative study, one service improvement project, five qualitative studies, five surveys and one editorial comment.

Mental health nurses who are confident can make responsible decisions related to risk management. 5 Some nurses seem to have the interpersonal qualities and skills to move beyond checking and controlling suicide risk and instead make efforts to acknowledge and connect (with) the patient as a person, even during standardised assessments and observations. 53 These nurses adopt a focus that transcends a reductionist focus on static risk and protective factors and seems to open doors to a holistic picture of patients by being attentive to their needs and hopes and trying to understand the nature of their suicidal expressions. 20,72

One possible source of discomfort for staff members, particularly those who do not specialise in mental health, is the fear that asking patients about suicide might induce suicidal ideation. In general, nurses favour ‘daring to discuss’ suicidal ideation to support the patient’s communication. However, they also felt that they must not ‘force the conversation’. 53 Thirteen studies (2001–13) have examined whether asking about suicide induces suicidal ideation. 73 With samples including both adolescents and adults and both general and at-risk populations, none of the identified studies found a statistically significant increase in suicidal ideation in participants as a result of being asked about their suicidal thoughts. Findings suggest that acknowledging and talking about suicide with adolescent populations may in fact reduce, rather than increase suicidal ideation, with a suggestion that repeat questioning may benefit long-term mental health. 73 Studies in treatment-seeking populations suggest that asking people who are or have been suicidal about suicidality can lead to improvements in mental health. 73 Review findings suggest that recurring ethical concerns about enquiring about suicidality could be relaxed.

The fear that asking about suicide itself precipitates action (so-called iatrogenic risk) persists, especially among clinicians with a non-psychiatric background. A meta-analysis quantitatively synthesised 13 studies that explicitly evaluated the iatrogenic effects of assessing suicidality via prospective research designs. When pooled the overall effect of assessing suicidality did not demonstrate significant iatrogenic effects in terms of negative outcomes. A key strength of this study is that the review authors stratified studies according to the timing of their follow-up assessments, concluding that assessing suicidality did not result in any significant negative effects on immediate, short-term, or long-term follow-up assessments. The authors conclude that their findings support the appropriateness of universal screening for suicidality, and state that this should allay the fears of clinicians that assessing suicidality is harmful. 74

Clinicians’ anxieties may increase the reliance on undertaking an assessment based upon a checklist of phenomenological or epidemiologically valid items that provide few opportunities to account for individual differences that may provide a more accurate and richer suicide risk assessment. 75 Use of risk-assessment tools may provide false reassurance, assuaging the clinician burden and sense of dyscontrol, while giving the impression of effective working and so mediating corporate risk.

Losing a patient by suicide can impact on professional practices, including issues around objective clinical decision-making. It may lead to behaviours likened to learned helplessness, such as increased vigilance when dealing with future suicidal patients and avoidance of treating suicidal patients. 76,77 These in turn may lead to an ongoing reliance on the same systems for assessment and treatment. 75

One feature that might influence staff’s comfort and willingness to ask young people about suicidal ideation relates to whether young people themselves feel comfortable with such questioning. Increasing numbers of qualitative studies have found that, contrary to the beliefs of many, young people do not mind being asked about the presence or absence of suicidal thoughts. 78–81 Several tools utilise self-report approaches. For example, the developers of the Risk-Taking (RT) and Self-Harm (SH) Inventory for Adolescents (RTSHIA) point out how the quality of data produced by self-report measures is comparable to those obtained through clinical interviews. 82 They state that people may feel more comfortable admitting to sensitive thoughts and acts when they are asked to circle a response or write a brief explanation instead of providing a verbal report, which may be influenced by interpersonal reactions to interviewers. Reassurance of the confidentiality and anonymity of self-reports is also important for young people. Pragmatically, few alternatives to self-report data exist when requesting personal and sensitive information from young people.

5. Consistency of approach

-

Programme Theory 5. IF risk-assessment processes are conducted consistently across mental health services THEN the quality of response to young service users does not depend upon each individual contact LEADING TO the availability of consistent information across services.

Supporting evidence

Programme Theory 5 is based on the NCISH report,38 which found ‘little consistency in the length, content or use of risk tools, although there was greater consistency in some places than others’. Risk assessment also needs to be consistent across mental health services. 38

Evidence base: one systematic review, one mixed-methods study, one interrupted time series, one case series, one service improvement project and two surveys.

As articulated the programme theory relates to inconsistencies in the role and personal characteristics of the staff member making the contact and to inconsistencies resulting from contact with multiple, uncoordinated individuals. Patients who were critical of the assessment process felt that there was inconsistency between teams. 38 It is noteworthy that one of the strengths of the Wales Applied Risk Research Network (WARRN) initiative, as identified by clinicians, is the development of a consistent approach, within and between organisations. 83 Clinicians acknowledged that different agencies had created a common language and understanding that improved communication both across and between agencies. 83 These benefits have been similarly realised by a consistent two-step risk assessment and management process (Comp RA) within Northern Ireland. 38 Benefits can also extend to the development of standardised training and supervision procedures and processes, seen in the WARRN83 and the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS) training programmes. 75

Programme Theory 5 is further supported by a mixed-methods study,84 which examined which risk-assessment tools were currently in use in the UK, and collected views from clinicians, service users and carers on the use of these tools. Findings showed little consistency in the use of these instruments. 84 Clinicians, patients and carers expressed both positive and negative views of the featured instruments. Findings attest to the need for assessment processes to be consistent across mental health services. Many professionals using the Davies’ structured assessment for adolescents in a crisis thought that it was good for a professional to have some structure and framework within which to operate so that ‘nothing would be missed’. Significantly, this view was not shared universally. Ongoing supervision is another provision to support consistency of approach. Care for self-harm within emergency departments appears to be particularly variable, with research showing it to be ineffective and delayed. 85

Areas where compliance needs to be improved include appropriate completion of the risk assessment. 86 A recent study extracted anonymised data from CAMHS at two time points. Data were compared with prevalence and population data and then a subsample was evaluated against NICE guidelines. Between time points there was a significant decrease in the number of cases that had a risk assessment completed appropriately and the number that had a full risk screen completed. 86 It is unlikely that this result was due to either a genuine reduction in the level of risk seen in CAMHS87 or that it represents a change in reporting practices. Even where a risk screen is completed somewhere in their notes, consistency needs to be improved to standardise risk monitoring and communication between services. For example, if a young person transitions to adult services having readily accessible information on risk is crucial.

Further variation relates to the experience of the clinician; experienced clinicians tend to use a positive risk-taking approach, whereas recently qualified clinicians do not feel as confident with suicidality cases unless they are routinely confronted with such cases (such as those working in a crisis team). 75

6. Self-efficacy

-

Programme Theory 6. IF staff are trained in how to assess, formulate and manage risk, including appropriate referral THEN staff feel equipped to manage the risks for children and adolescent who present to health services LEADING TO an emphasis on positive risk taking.

Supporting evidence

This programme theory component is based on the NCISH report,38 which found that healthcare professionals do not feel confident in being able to implement care plans, within which immediate risks can be mitigated, if they lack appropriate support and guidance to inform their assessment. 39

Evidence base: one systematic review, one RCT, three quantitative studies, one mixed-methods study, one qualitative study, one pre–post study, one service-improvement project, three surveys and one commentary.

Nurses with good confidence can make responsible decisions related to risk management. 5 Continuing education about the use of risk-assessment tools is needed to demonstrate that their use is compatible with therapy. 5 Staff need training if they are to use risk assessments in such a way that ensures their reliability. 88 A mixed-methods study in the UK reported little consistency in the use of instruments and highlighted a need for adequate training. 84 Nearly a third of clinicians surveyed in UK mental health services reported poor levels of training, highlighting practical issues in the use of tools and the poor quality of documented information. 84 Noticeably, training is a substantive component of both the Davies’ structured assessment for adolescents in a crisis and for the WARRN formulation-based approach83 – both indicating that familiarity with a structured process and how it integrates within clinical judgement should be considered more important than technical mastery of a tool or checklist. Over 2 days, the WARRN training modules cover basic clinical skills, such as how to conduct a clinical interview and what should be covered, techniques for asking difficult questions, how to formulate, and how to produce risk-management plans. The essential need for documentation and communication of presenting risks and the reasons underpinning these risks are highlighted. The value of co-production with the service user and family/carer is also covered. Standardised paperwork and forms to record the WARRN assessment and formulation are provided for use by clinicians following training. 83

Typically, healthcare professionals within emergency department environments have limited mental health training, and as such, feel ill equipped to assess and manage the associated risks apparent for children or adolescents presenting following an episode of self-harm or attempted suicide. 89 The limitations of these prediction methodologies likely impact on clinicians’ confidence when assessing suicide risk. Dealing with patients who self-harm and/or are suicidal is perhaps one of the most difficult challenges faced by clinicians. 75 One study estimated that 88% of mental health professionals have at least some level of fear relating to a patient dying by suicide, as well as discomfort around working with suicidal patients. 90 More than two-thirds of doctors practising emergency medicine believe that they are insufficiently trained at assessing those attempting self-harm. The limited training that health professionals receive relating to the assessment and management of suicidality may contribute to the burden felt by clinicians working in healthcare settings. Learned helplessness may result as suicide rates remain unaffected and predictive data have little impact on reversing this rate. The checklist-style structure of risk assessment within many NHS mental health services forms an ‘aide memoire’ of items characteristic of many suicide risk prediction tools.

Evidence highlights that training focusing specifically on the management of the suicidal drivers, or factors mediating the cognitions, emotions and behaviours augmenting suicidal risk, resulting in suicidal behaviours, can have a positive effect on clinicians’ confidence, clinical skills and implementation of evidence-based practices. 91,92 Greater awareness and accurate knowledge can de-stigmatise self-harm behaviour by staff enabling them to develop a greater understanding of contextual issues. 93 Additionally, education and attitude awareness may equip professionals with alternative explanations for self-harm behaviour that can help them to become more empathic and, subsequently, to alter their behaviours. 89,94

Training was a major component of a service-improvement initiative aimed at improving suicide prevention in North East Lincolnshire. 75 Three phases of training were delivered across the organisation: ‘suicide risk triage’ training, CAMS training, and CAMS concordance. All qualified staff were required to attend a mandatory 1-day training course entitled ‘risk triage training’ in groups of approximately 12 staff. Besides providing an overview of how the ‘suicide risk triage’ model was to be implemented within services, training collected data on factors that clinicians felt impacted on their confidence during the suicide risk assessment. The mandatory training also ensured all clinicians met a baseline level of ability and knowledge and was delivered to all new and newly qualified clinicians. Anecdotal feedback from the training highlighted the positive impact of a clear, structured approach to clinical risk decision-making to help clarify the most appropriate pathways to care for suicide risk presentations and the benefit of having support available for decision-making around challenging risk cases. The authors highlight evidence that CAMS training can significantly decrease clinician’s anxiety about working with suicidal risk and increase confidence, with results sustained at 3-month follow-up. 95 However, they acknowledge that the CAMS approach has yet to be evaluated in the UK.

Evidence from another study suggests that while training may help in ensuring staff can engage with the theoretical aspects of the situation they need additional provision for practical implementation. 96 Reflective peer review is suggested as one mechanism by which to help staff to reflect on their risk assessments, consider the knowledge and information that has informed their risk-management plans and discuss this with their peers in a supportive environment. 96 The authors claim that such a programme improved staff skills, confidence and documentation. 96