Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number 17/99/85. The contractual start date was in April 2019. The draft manuscript began editorial review in July 2022 and was accepted for publication in June 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Adams et al. This work was produced by Adams et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Adams et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Introduction

This three-phased, qualitative, realist study aimed to identify and investigate the critical factors that underpin improvements in the disclosure and discussion of avoidable harm with families in NHS maternity care. This chapter describes the policy and research background on disclosure in health care and in NHS maternity care and outlines the structure of the report.

Open disclosure: policy and research background

Since the mid-2000s, the term ‘open disclosure’ has been adopted internationally by policy-makers and researchers to capture the process of ongoing communication with patients and families after adverse events. 1,2 Open disclosure (OD) is defined by Manser (2011) as: ‘the open and timely communication about adverse events to keep patients and family members informed, to acknowledge their suffering and grief and help in reducing feelings of abandonment’. 3–5 OD communication involves providing accurate information about the critical incident, its immediate consequences and appropriate remedial action, as well as providing an expression of regret and information about what will be done to avoid harm reoccurrence. 5

Internationally, OD of adverse events to affected patients and families has been recognised as an important ethical and patient safety concern for several decades. 6–13 Additionally, evidence suggests that OD reduces long-term emotional distress and injury to families and healthcare staff. 5,14–22 As an added benefit, greater openness with families post incident might enhance their confidence in service transparency, thereby reducing their need for investigatory and legal processes and, when practised routinely and in the longer term, may enhance the public’s trust in services. 14,19,23–29

Yet, services consistently providing OD that meets the needs and expectations of patients, families and staff remains a challenge. Barriers to OD are deeply rooted and widely documented, and include factors like physician management fears over loss of reputation or litigation and second victim trauma,11,12,30–33 fear of reprisals in punitive workplaces,34 lack of clarity over accountability for injury,15,35,36 varying perspectives on when disclosure is appropriate12 and heavy-handed procedural systems that can constrain empathic communication. 12,23,37,38 Furthermore, since the inception of OD policy initiatives, researchers have noted a tension between what patients and families expect after injury and what healthcare providers (HCPs) think that they should provide. 8,39,40 For HCPs, post-incident communication with families encompasses a complex array of legislative, policy, professional, organisational, local workplace and interpersonal considerations. 12,17,37 In the English NHS, and particularly in NHS maternity care since 2013, the development and implementation of a raft of legislative, policy and safety improvement initiatives have given rise to complex and sometimes contradictory OD improvement contexts. The following sections outline the rationales, components and effects of the most significant of these.

Open disclosure initiatives in the English National Health Service

The ‘Being Open’ framework

The ‘Being Open: Communicating Patient Safety Incidents’ best practice framework was launched to improve communication and ongoing support for patients and families injured during NHS care. 41 The guidance describes Being Open as a flexible, ongoing process, rather than a one-off meeting with a family and is underpinned by 10 principles. Among these, providing acknowledgement of the incident, taking patient reports seriously and reporting them as soon as possible and ensuring truthfulness, timeliness and clear communication to families throughout the investigation process in face-to-face meetings. The guidance highlights the importance of corporate and clinical governance (CG) structures for the support of staff reporting patient safety incidents, for the integration of Being Open into management and system improvements and for assuring ongoing care and confidentiality for all involved.

While this document remains an important reference for all health providers in England, the initial reception of this guidance by health service providers indicated a widespread lack of interest in implementation, including in staff training. 12 Birks et al. found that there was an ‘in-principle’ agreement of senior clinicians on the value of OD. However, in practice, it was expected that workplace attitudes and fear of litigation inhibited incident reporting, while the moral dilemmas over when and how to be fully open with patients inhibited efforts to invest in the guidance. 12

The statutory Duty of Candour

In 2014, the statutory Duty of Candour (DoC), Regulation 20 of the Health and Social Care Act42 was introduced for acute health providers following recommendation 181 of the Francis public inquiry. 43 It was to complement the existing professional DoC that applies to healthcare professionals.

The DoC obliges organisations to disclose to patients or families if there has been a notifiable safety incident during their care. Organisations that fail to comply are liable to criminal prosecution. The DoC also established expected disclosure standards, in particular, the timing of disclosure, how disclosure should be made (to include an apology that is ‘an expression of sorrow or regret’ regarding the incident) and documentation. A ‘two-stage’ approach to the DoC was written into the NHS contract in 2015. This made services responsible for ‘feedback of the findings of the inspection report to an appropriate person’. 44

In 2020, joint statements by the professional councils and regulators reiterated the professional DoC, with application of the duty to all situations of actual or potential harm. 45 The imposed (rather than negotiated) application of this duty has been questioned. 46 In 2021, the Care Quality Commission (CQC) (the arm’s length body of the Department of Health and Social Care with expertise in dispute, claims and resolution) reissued the Regulation 20 guidance to providers to emphasise the need for completion of the regulation for all notifiable safety incidents, for clarification of how these incidents can be defined and to emphasise that an apology is not an admission of fault on the part of individual or the service. 47

The effectiveness of the DoC in promoting honesty for injured patients and families has been widely debated. In particular, the emphasis on compliance (or ‘box ticking’) over a sensitive approach to patient or family needs has been contested. 48 Additionally, the higher threshold of statutory DoC reporting requirements, compared to professional DoC requirements, was anticipated to result in a downgrading of assessments of harm by organisations or HCPs. 12 This could confuse whether incidents meet the threshold for reporting or lead providers to neglect to report some cases. Furthermore, the effects of the DoC on litigation rates have also been debated. While honesty about an incident, as stipulated by the DoC, might reduce the need for some patients and families to initiate litigation action to find the answers they seek, disclosure might also encourage litigation as cases of avoidable injury are illuminated. 36 Regardless, there is evidence of varying compliance with the DoC,49 along with initially inconsistent inspection of compliance. 50 Despite this, across the NHS provision, the prosecution of organisations for breach of this duty has been infrequent. 51 At the time of research, the DoC did not apply to other NHS or independent investigating bodies. 52,53

Open disclosure in NHS maternity services

The Morecombe Bay Investigation Report made a powerful case for the need for disclosure of serious incidents (SIs) to affected families and for their involvement in incident review and investigation. 54 Concurrently, increasing costs of obstetric litigation claims were noted, with overall costs of settlement equating to 40% of the £1.1 bn paid by the NHS in 2016 and escalating to 50% in 2017 and 62% of all secondary claims in 2021–2. 55,56

NHS and professional bodies began to attend more closely to post-incident communication with families as a sign of wider and significant shortcomings in maternity safety, including incident investigation, and thus introduced multiple incentivised improvement programmes. 57 Since 2018, the Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts (CNST) administered by National Health Service Resolution (NHSR) (the arm’s length body of the Department of Health and Social Care with expertise in dispute, claims and resolution) requires participating Trusts to contribute an additional 10% of CNST premium that is then refunded if they can demonstrate that they have met all 10-of-10 identified safety actions (that range from workforce and training to completion of safety improvement programmes). 58 Safety improvement and parent engagement initiatives in maternity services are focused on both reviews, where the avoidability of some adverse events is not known, and on investigations, where avoidability is anticipated and the factors contributing to the event are unknown.

The most significant initiatives were:

Parent involvement in the Perinatal Mortality Review Tool (now UK-wide)

In 2017, an online, multidisciplinary reporting tool was developed by clinicians with families with the aim of improving and standardising all reviews of perinatal deaths across the NHS. The tool has three questions on parent involvement: if they have been notified of a review; if they have been invited to ask questions or raise concerns; and what responses to these questions were given. Bespoke implementation materials for parent engagement in NHS services include evidence-based timeline and flowcharts, and guidance on writing an effective report for parents. 59,60

Tool completion was financially incentivised by NHSR’s CNST as 1 of 10 actions requiring board-level reporting. In 2019, the reporting standard for the inclusion of parents in 95% of all perinatal deaths (from 22+ weeks gestation; stillbirths and neonatal deaths up to 28 days) in each Trust. 61 Findings from the Perinatal Mortality Review Tool (PMRT) are also thematically reviewed, with recommendations for clinical, service management and patient engagement published annually. 62–64 Up to 2021, of 9174 completed PMRTs, there was an overall increase in the number of parents told of a review. However, a more targeted investigation of parent engagement indicated that many parents (one in three) felt only partially heard by investigating clinicians. 65 Reported progress on family involvement facilitated by the PMRT is presented in Report Supplementary Material 1. Annual reporting on implementation progress of the PMRT in Trusts highlights the ongoing challenges on in-service resourcing, variability in multidisciplinary time or investment in reviews and weaknesses in action planning following review findings. 62–64

The Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch maternity investigation programme (England)

Initiated amid growing concerns with variations in the quality, rigour and timeliness of investigations conducted internally by Trusts, this programme was established for independent investigation of some serious maternity incidents in 130 NHS Trusts and 11 ambulance services in April 2019. 66 It was an extension of the wider HSIB, an arm’s length body of the Department of Health and Social Care that investigates harm to NHS patients. For families, this promised that investigations would not be biased by the defensiveness of service providers. The HSIB was funded to develop a standardised investigation and post-incident learning approach that was heavily influenced by human factors methodology. The primary purpose of the programme was to identify common themes and influence systemic change in clinical practice. 66

With parent consent (for the sharing of their data from the Trust), incidents that met certain clinical criteria (e.g. incidents affecting term babies, caused during labour or during the postnatal period, as well as some maternal deaths) were referred for investigation by the Trust to the HSIB. 67 Since 2020–1, 100% Trust reporting of these incidents to the HSIB has been incentivised under the NHSR CNST scheme.

The programme has invested in a detailed family engagement model, with regular, one-to-one contact with investigators that included an interview about the family’s experience, discussion of the investigation terms of reference (ToR), updating of investigation progress, access and explanation of a draft copy of the report, receipt of the final report with the possibility of a three-way meeting led by the Trust and invitation to feedback on the HSIB investigation process. 68 The Trust carries responsibility for families after their incident has been investigated and reported on.

The NHSR Early Notification Scheme (England)

Established in 2017, and incentivised since 2018, the Early Notification Scheme (ENS) incentivises the prompt initial investigation of incidents of suspected severe brain injury associated with birth. The scheme offers some financial assistance to families if it is agreed by an ENS panel (comprising doctors and midwives, solicitors and expert witnesses working independently of the Trust) that there is sufficient evidence for them to legal claim against the Trust. From 2020, investigation criteria for suspected cases were tightened to align with Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) established risk indicators. 69 The additional objective of the scheme is the thematic analysis of incidents for rapid dissemination of learning from incidents at Trust, regional and national levels, for the benefit of families and staff. The notification of families that an ENS investigation is ongoing was identified as important (and was incentivised) from 2020 to 2021; however, families are unable to access ENS investigation documents about their own case. 70 Since 2020–1, family consent has been required for ENS cases (as these are also reported to the HSIB). 71 Until 2020, communication with families after incident investigation under the NHSR ENS happened outside maternity services and after investigation completion. Therefore, the study is not directly focused on this intervention.

Interim summary of Chapter 1

Our brief overview of ongoing OD initiatives in place in 2021–2 indicates the complex background for service managers, as well as for front-line clinicians (doctors and midwives), involved in improvement efforts to engage with families post incident, along with the potential for confusion among families themselves.

We note that while regular reports on the progress on OD initiatives indicate a gradual, if uneven, overall improvement in post-incident communication with families, these reports are usually by organisations responsible for intervention development. We note that many of the long observed and widely noted challenges to OD improvement are evident in recent OD initiatives in the English NHS and NHS maternity care. These include professional and service concerns over litigation and reputational risk; differing perspectives on when and how far the exercise of openness with families should extend, including the application of different clinical thresholds by different improvement programmes for the incentivisation of openness with families; uncertainties over who is responsible for communication with families throughout the OD process; and the sometimes-unclear relationship between the imperative for family involvement and wider patient safety agendas. These questions underpin the fluid and uncertain conditions within improvements in post-incident communication with families unfold.

We note that while general and uneven improvements in OD processes have been described previously, these findings are most often drawn from progress reports on the implementation of interventions. Particularly in NHS maternity care, where multiple interventions to improve OD are ongoing and sometimes overlapping, there is limited understanding of how, in what circumstances, and to what effect OD happens in practice. More specifically, there is a need to identify what critical factors are required for improvements in OD.

Study aims, research question and objectives

The study aims were to:

-

identify and explore the critical factors underpinning OD improvements

-

capture the perspectives of national stakeholders, local service leads and practitioners, families, doctors and midwives (henceforth clinicians), and local managers during various situations of avoidable harm and their viewpoints on OD.

The overarching research question was: ‘What are the critical factors that can improve the incidence and quality of Open Disclosure in NHS maternity services?’.

We addressed this question and sought to achieve these aims through five sequential study objectives:

-

OBJECTIVE 1: To establish initial hypotheses to focus the realist investigation of OD improvements in NHS maternity services.

-

OBJECTIVE 2: To establish the scope of OD in NHS maternity services in England.

-

OBJECTIVE 3: To refine the initial hypotheses and conduct a stakeholder analysis with national and regional stakeholders, establishing a suitable dissemination and impact plan.

-

OBJECTIVE 4: To conduct an in-depth study of OD improvement interventions.

-

OBJECTIVE 5: To verify data interpretation and study output development with stakeholders.

Report structure

The following section details the contents of each of the upcoming chapters:

-

Chapter 2: Restates the study aims and objectives and describes the study design and methods.

-

Chapter 3: Details our scoping review of the changing assumptions that underpin policy about the purpose of post-incident involvement of injured families in NHS maternity service provision (2015–22).

-

Chapter 4: Details our realist synthesis and identifies the five initial hypotheses on the factors that underpin OD from the perspectives of families, clinicians and services.

-

Chapters 5–9: Examine and develop each of these five initial hypotheses. Each chapter includes findings from each study phase (SP) and explores the initial propositions from different viewpoints and fields of experience. The perspectives of national stakeholders, managers, front-line staff and families are included. We use these findings towards a ‘Best Practice Guidance Document’ draft (see Appendix 9).

-

Chapter 10: Discusses the overall study findings to identify the critical factors that underpin disclosure improvements, reconsidering the preliminary theories that guided our research questions, focusing on what works, in what contexts and for whom for OD to be successful. Here, we also reflect on the possibilities and constraints of our approach to the study question. Additionally, we briefly situate our findings in the wider national context of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and reflect on the impacts of the pandemic on our research.

-

Chapter 11: In the final chapter, we identify recent policy changes that will impact on OD in the UK, and identify implications from the findings for service managers, professional bodies, families, policy-makers and researchers.

Chapter 2 Research design, methods and data sources

Introduction

This report is based on findings from a three-phased evaluation of factors strengthening the disclosure and discussion of harm with families in NHS maternity care. We used a realist evaluation approach to understand how, for whom and in what contexts interventions to improve post-incident communication with injured families are effective. The aim of the research was to identify the critical factors that can improve the incidence and quality of OD in NHS maternity services to enable the generation actionable evidence for maternity providers on how to strengthen OD.

Overview of study

Following realist evaluation principles,72 a 36-month qualitative study was conducted in three sequential SPs. Families who had experienced injury in NHS maternity care were recruited into each of the SPs and acted as study advisors.

Our qualitative methods enabled us to meet the five study objectives as represented in Table 1. The overall study design is detailed in the research protocol. 73

| Study objective | Method | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Establish initial hypothesis to focus realist investigation of disclosure improvements in NHS maternity services | Realist synthesis with stakeholder consultation |

| 2 | Establish the scope of disclosure in NHS maternity services in England | Telephone interviews with national and regional stakeholders |

| 3 | Refine initial hypotheses and conduct stakeholder analysis with national and regional stakeholders | Telephone interviews with national and regional stakeholders |

| 4 | Conduct in-depth study of disclosure improvement interventions | Comparative ethnographic case studies of three services (Trusts or hospitals) |

| 5 | Conduct data interpretation and study output development with stakeholders | Interpretive forums |

Realist methodology

A realist, theory-driven approach underpins the study design. 74 Realism, as used in health service research, examines the interaction between a complex social intervention or ‘programme’ (e.g. a policy implementation, a programme of work or an operational system), the context in which it is implemented in everyday practices and the intended or unintended outcomes that are produced for different participants. 75,76 These interactions are examined by the identification of contingent and generative mechanisms (or critical factors) that trigger effects in particular contexts. 72 Realist evaluations approach understanding these interventions by asking ‘what works, for whom, in what circumstances, in what respects and why?’72,77 This is often expressed as a context–mechanism–outcome (C–M–O) heuristic. A summary of the realist terms and principles used in this study are in Report Supplementary Material 2.

A key aspect of the realist approach is the identification and later refinement of one or more initial hypotheses (in realist terms, ‘initial programme theories’) of how interventions have effect. Initial hypotheses are identified by literature scoping and realist synthesis and in discussion with different topic experts. 78,79 A realist evaluation generates a series of interconnected hypotheses on the critical factors that drive and direct improvement work. 80 The study design reflected this theory-driven approach as described below.

Study phase 1: scoping

Study phase 1a: policy scoping review and realist literature synthesis

Our scoping review examined guidance related to family involvement issued in the time between two landmark reports, the Kirkup report and the Ockenden report, to map what, if any, changes have occurred in this area. The aims of the review were to synthesise and examine key reports and policy documents to evaluate the evolution of recommendations for and discussion of family involvement in reviews and investigations in maternity care in England. A scoping review was selected as the approach to address the aims of this study because in contrast to systematic reviews, which aim to answer discrete questions, scoping reviews enable the researcher to collate a broad overview of a topic to synthesise evidence. 81

The scoping review aimed to address the following primary question: How has family involvement been conceptualised and how have recommendations for family involvement shifted over time in policy documents, reports and recommendations for reviews and investigations in English NHS maternity care?

To answer this question, we used three further questions to guide our review:

-

What language and terminology have been used to describe family involvement and how have these evolved?

-

What is the impetus for family involvement and has this changed over time?

-

What actions are suggested to improve family involvement and have these changed over time?

The policy review involved four steps: searching for key policy documents; searching within key documents for sections on family involvement; data extraction; and inductive thematic analysis. This process is detailed in Appendix 1, Section A: Stages of the policy scoping literature review and the findings of the policy review are reported in Chapter 3.

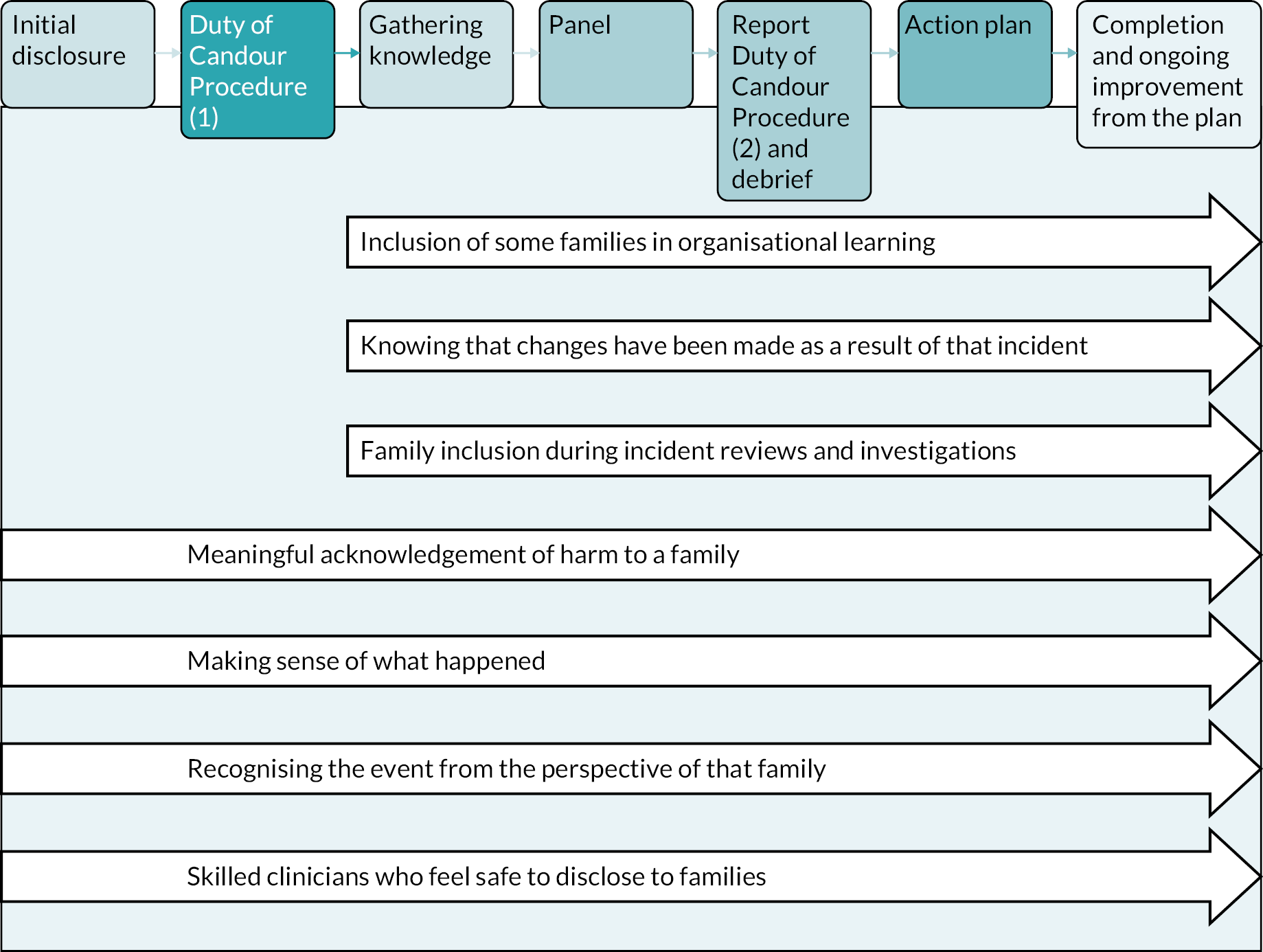

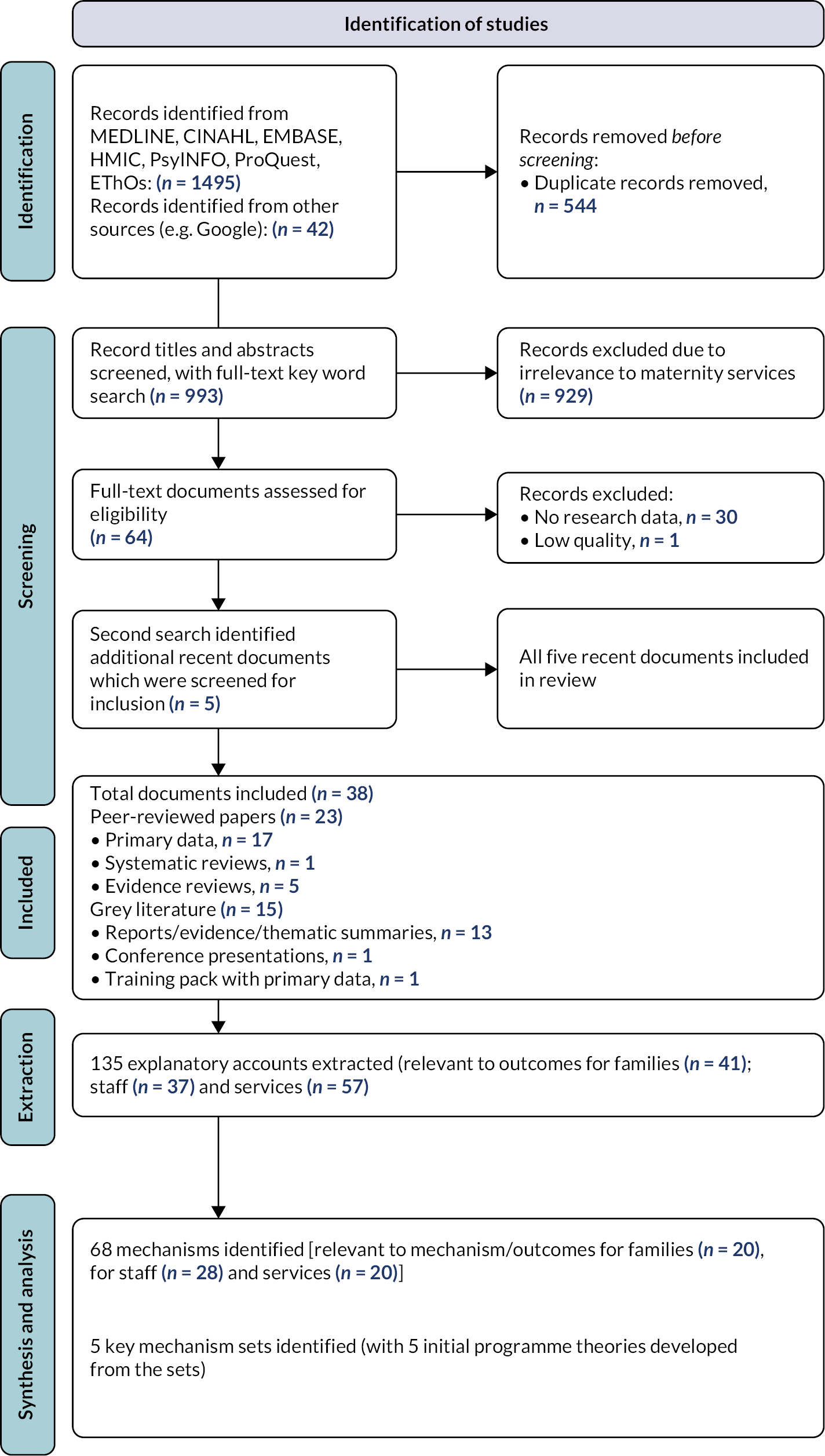

Our realist synthesis of the international literature on disclosure improvements in maternity services addressed the overarching research question of: ‘what are the critical factors that can improve the incidence and quality of disclosure in NHS maternity services?’ Recognising that diverse forms of evidence contribute to realist synthesis and theory development,82 the researchers sought the views and experiences of two mixed groups of expert stakeholders [from the established Project Advisory Group (PAG) and Co-investigator Group (CIG)] to help focus on the synthesis and prioritise the findings. The synthesis was conducted in five steps: a two-stage literature search; realist document appraisal; retroductive theorisation with data extraction; and consolidation of extracted data into Explanatory Accounts (EAs). The process is detailed in Appendix 1, Section B: Stages of the realist literature review and Figure 3. The findings of the realist synthesis are reported in Chapter 4. A comprehensive account of the realist synthesis methods is available in Adams. 83

Study phase 1b: national and regional interview study

We developed our SP1b interview topic guides following the SP1a programme theory findings. Sampling, approach and recruitment of national and regional stakeholders were designed to prioritise national policy-makers, including senior representatives from NHS Resolution; NHS England; HSIB maternity programme; PMRT design and implementation; the Royal Colleges; and third-sector organisations actively participating in national OD or safety improvement work within local or national services. This initial sample included 12 families who were actively participating in national- and local-level safety improvement work. As interviews progressed, this sampling framework was revised to include participants with more localised or informal experiences of OD improvement work (e.g. clinical fellows on rotation through national organisations and families without formalised roles in service improvement).

Participants were identified by purposive and snowball sampling. Following university-approved ethical procedures to protect research participants from coercion and identification, initial participants were identified and approached by PAG members. Next, snowball sampling through organisational networks was utilised to identify additional participants. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants prior to interview and each participant was given a unique identifier code to protect their anonymity and confidentiality. Both study information and the interview topic guides were forwarded in advance of all interviews to facilitate reflection and discussion. Advice on sources of post-incident support and a follow-up call were offered by the research team due to the sensitivity of the research topic. The interview topic guides, study information sheet and interview consent forms approved by university ethics panels are available as project documents (www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/99/85).

One-to-one, audio-recorded telephone interviews with national and regional stakeholders were conducted between September 2019 and November 2020 by author MA. These interviews were intended to capture perspectives and experiences of OD in different service settings and conditions with different interest groups. 84 Sixty-seven one-to-one interviews were conducted, lasting between 40 and 120 minutes each. One group interview, lasting 90 minutes, was conducted with four families. Fifty-eight of these interviews were with participants who had a national role in OD improvement and nine of the interviews were with families who had experience of any OD improvement (see Appendix 2, Table 4). The interview guides for families were adjusted reflexively for families depending on the family’s readiness to consider the perspectives of clinicians and services. 84

Study phase 2: ethnography

Identification of case-study services

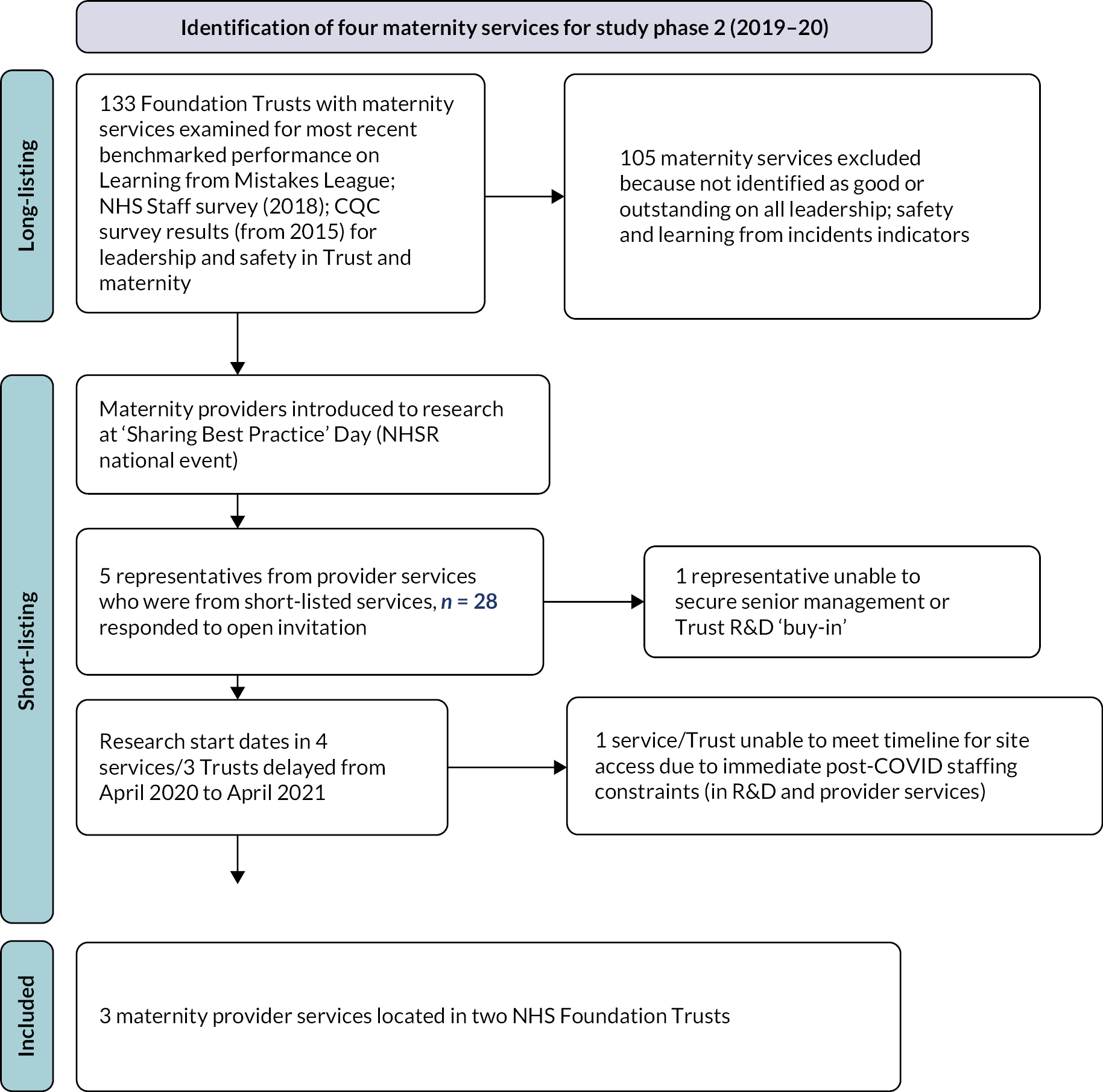

Three case-study services were selected for positive deviance85 using purposive sampling for maternity services that had high or improving performance in disclosure improvements. To select the case-study services, first we examined most recent CQC ratings of Trust and maternity service performance (2014–20) and 2019 NHS Staff Survey Results (Trust-level benchmark reports) to identify metrics that were indicative of an environment supporting disclosure improvements (e.g. metrics on transparency, incident reporting and staff-reported organisational or service responsiveness of incident reporting). We also included the rating from the 2015 to 2016 ‘Learning from Mistakes League Table’ as comparative case data. These surveys established a picture of how well all 134 Trusts in England were engaging in disclosure improvement work. Next, we shortlisted Trusts and services that indicated better performance for leadership and learning from incidents to be approached through an open call for study participation. Due to the sensitivity of the research topic and anticipated challenges with research engagement, we followed Stake’s principles of case-study sampling that prioritise (1) maximum changes of ongoing research engagement, (2) diversity of cases across contexts and (3) cases that provide learning about complexity and context. 86 Due to COVID-19-related delays in research engagement, the study team was obliged to prioritise criteria (1). The sampling process for case-study site selection is documented in Appendix 3, Figure 4.

The three services selected for case study had the following attributes:

-

Trust-level CQC ratings and Board minutes that indicated a notable emphasis on DoC improvement work or transparency (e.g. long-established practices of SIs in maternity reporting in Board minutes).

-

Service-level variation in the consistency and seniority of leadership.

-

Service and Trust-level variation in ongoing practices of listening to families (most notably, provision of postnatal and post-incident support for families).

Further general and topical features of the selected case-study sites are presented in Appendix 4, Table 7.

Ethnographic case studies

Following a series of one-to-one and group meetings at each case-study service, where the study was introduced and concerns and questions addressed, key informants and initial case-study interviewees were approached. Initial interviewees were identified using purposive sampling with assistance from service gatekeepers and site-specific principal investigators (PIs). Subsequent case-study interviewees were identified using snowballing techniques. After the identification and approach of clinicians with a central role in disclosure (notably, clinical and service leads and CG teams), the sampling approach was to maximise the diversity of interviewees with experience of disclosure. For clinicians, this was to explore variations in the clinicians’ experiences based on clinical and corporate roles, place of work, seniority and clinical profession. MA and JH conducted 75 interviews with clinicians in a range of front-line to senior management positions and across the three case-study services. For families, we sought to identify families that reflected social and ethnic diversity, as well as differences in clinical events and histories. To protect anonymity and confidentiality, if an individual decided to participate, they were asked to contact the research team directly. The realist topic guides from SP1 were reflexively adapted for use in SP2 to explore the initial programme theories. Informed, written consent was obtained from all interviewees. We conducted interviews with four families recruited from one service. Other services were reluctant or unable to facilitate family approaches. All services had challenges recruiting families that were socially or ethnically diverse. Appendix 2, Table 5 summarises participation in the case-study interviews by case-study service. The case-study services also included observations of formal and informal meetings and collection of relevant organisational documents. Appendix 2, Table 6 documents the formal meetings observed by the researchers at the case-study sites.

A detailed account of research processes employed in the case-study data collection, iteration and analysis is presented in Appendix 2.

Study phase 3: interpretation and output development

Finally, we facilitated five interpretive forums: one at each organisational case-study site (two online and one in-person), one national forum with the PAG and one online family forum (FF) (online due to COVID-19 travel concerns). The interpretive forum research process is described in Appendix 2. Appendix 2, Table 3 details participation at the interpretive forums.

Data organisation and analytical approach

Pseudonymised interview and forum transcripts, fieldnotes of observations and all redacted site documents were stored on a dedicated, password-protected drive hosted on a secure university server. Transcripts, notes and documents were analysed using NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK) (March 2020 release). A realist, retroductive, thematic analysis of the data was completed. This analytical approach is directed to the ‘unearthing of causal mechanisms’. 87 The approach starts with the empirical and seeks to explain events and outcomes by theorisation of the underlying mechanisms and structures that are likely to produce them. 88 This interrogation of the data and consideration of underlying generative possibilities was conducted by the researchers in several stages. This involved ongoing discussion with the CIG, who were topic and policy experts, and sense-checking the findings and interpretations during the interpretive forums.

This staged, iterative analysis of data generated more findings than could be accounted for in the five programme theories. Three additional programme theories were developed in retrospect using a thematic analytical approach and are described in Chapter 10. Additional findings that extended beyond the study aims included: family strategies of help seeking, including families investigating their own incidents; the personal careers of family support champions; and practices of epistemic injustice across perinatal care.

Further development of findings and dissemination

-

The development of formative practice guidance for OD improvement was generated from the analysis of findings in collaboration with our CIG and some interpretive forum participants (see Appendix 9). This guidance is to be further developed in collaboration with two PIs from our case-study services and with wider clinical (service) and corporate (Trust) governance teams.

-

Study findings are being used to inform a 5-minute animation for families, front-line clinicians and service managers to illustrate what many families and clinicians experience during post-incident communication.

The study was assessed against RAMSES II reporting standards for realist evaluations (see Report Supplementary Material 3).

Summary

This chapter reports on the methods used in the study. The SPs conducted were:

-

SP1a. Realist synthesis of the literature and policy review of family involvement in OD.

-

SP1b. Interview study with national and regional stakeholders. This SP also included interviews with nine families recruited through support associations.

-

SP2. Ethnographic case studies in three maternity services in two English NHS Trusts that included clinician interviews, family interviews and ethnographic observations.

-

SP3. Interpretive forums conducted in the case-study services, with a national PAG, and with a family group.

Governance arrangements included steering committee meetings and reporting, as well as PAG meetings. During the research period (April 2019–March 2022), the research scope and timelines were adjusted, with a 9-month extension including a 3-month costed extension, so that all study objectives were met despite two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Chapter 3 Scoping review of policies and interventions informing disclosure and discussions with injured families

Introduction

This chapter situates the study within recent policies designed to foster family involvement in maternity safety, focusing particularly on the inclusion of families after incidents affecting them. Our policy review traces two trajectories, the first related to the DoC and the second to maternity safety, to describe the various ways that the involvement of harmed families has been envisaged and prioritised post incident.

Family involvement in disclosure and maternity safety

Independent investigations54,89–91 have exposed several system failures that led to potentially avoidable harm in maternity care in NHS Trusts in the UK. Although these investigations span incidents occurring over two decades of maternity care, during which time many recommendations and improvements have been advised by various stakeholders, common themes persist. One area that is emphasised in investigation reports is that families’ voices were not heard, both during their care and in the aftermath of harm during incident reviews and investigations. 54,89–91 The importance of increasing support for families, personalised care and family involvement in decision-making, reviews and investigations is recurrently highlighted. Despite this, recent studies have shown that family involvement in reviews and investigations is not yet consistently taking place in practice. 59,60,92–94 The lack of translation of these recommendations into changes in practice could be due, in part, to the inconsistency of recommendations over time and the lack of actionable recommendations provided. Accordingly, the aim of this review was to synthesise and examine key reports and policy documents to evaluate the development of recommendations and discussion of family involvement in reviews and investigations in NHS maternity care in the time since the statutory DoC requirement came into effect.

Results

We identified two overlapping policy trajectories (see Report Supplementary Material 4): one related to the DoC (see Report Supplementary Material 5) and one related to maternity safety more generally (see Report Supplementary Material 6).

Ten total documents were included in the DoC trajectory. Of these, nine discussed family involvement in reviews and investigations42,49,95–101 and one document did not. 102 Forty-three documents were included in the Maternity Safety Trajectory. Of these, 31 discussed family involvement in reviews and investigations54,55,57,68,90,93,94,98,103–125 and 12 documents did not. 66,126–136 Within and across each of these trajectories, we identify shifts and continuities in how service user (SU) and family involvement are understood. The language, priorities and recommendations surrounding family involvement over time are discussed.

Building trust in organisations

In 2014, the impetus for involving SUs in reviews and investigations was to build individual and public trust in organisations. 95,101 A shift from ‘paternalism’ to ‘partnership’ and the ability to have candid conversations were emphasised for improving trust. 101 Recommendations related to SU involvement were focused on organisational obligation to provide patients and families their rightful access to their health information101 and to notify, acknowledge and apologise for what happened. 95,101 This was described not only as a professional obligation, but also as ‘the right thing to do’; a key priority was creating an organisational culture of openness. At the time, SUs were one-directional recipients of information about their case. Care Quality Commission Guidance recommended a single point of contact in case of SU questions or queries about what happened, but the emphasis was on organisational communication rather than SU involvement. 95 The CQC recommended the provision of emotional support and other relevant assistance for SUs, but details on how this should be facilitated were not provided. 95

Improving systems of care and ensuring accountability

The Kirkup report, published in early 2015 on the independent investigation into Morecambe Bay NHS Trust, uncovered numerous failures in safety, care and respect for injured families within the Trust. 54 Recommendations addressed organisational failings in admission of the ‘extent and nature’ of injuries caused to families. The Trust was instructed to review family involvement practices, particularly with respect to complaint procedures. It was noted, for the NHS more widely, that there was a ‘strong case’ for standardising the internal investigation process to include input and feedback from families, with families offered the opportunity contribute evidence to their investigation. Shortly after the Kirkup report, strategy documents began to highlight the importance of reducing stillbirths and neonatal deaths. 105,107 These documents did not include SU involvement recommendations for when harm occurred, but did suggest that post-mortem examinations were important in the event of stillbirth or neonatal death so that counselling could be provided for future pregnancies. 105,107

Around the same time, the rationale for conducting investigations into incidents of injury shifted from building and restoring public trust in the NHS to improving systems of care while encouraging public accountability. 96,98,106 Although documents did not make explicit recommendations for family involvement, they still warned that the relationship between patients and organisations was in danger of remaining merely ‘transactional and contractual’ without changes and improvements in leadership. 104 When involvement was included, it was envisaged as more two directional than in previous documents, with a language shift from ‘apologising, acknowledging, providing and telling’42,99 in earlier documents to ‘engaging’,96,98 ‘hearing’106 or ‘involving families’97,98 as ‘active participants’96 ‘at the centre’ of investigation processes98 from ‘start to finish’. 106 Policy documents continued to advise on the provision of a single point of contact for families during the investigation process,96–99 along with the opportunity for SUs to ask questions. 98,99 For the first time, the importance of establishing family expectations and preferences for communication96,98 was described as part of active engagement. Although little detail was provided on how to achieve active engagement or involvement,106 the unique perspective SUs offer on their adverse events was acknowledged and it was noted that these perspectives should be shared and listened to as part of the review process. 96,98 The specifics on how these contributions were to be garnered and used remained unclear.

Notably, the serious incident framework (SI Framework), which involved some families in its production, was the first document to detail specific actions and resources to produce meaningful involvement (e.g. the provision of letter templates to facilitate the initial communication with families). 98 The SI Framework suggested the following actions: arranging meetings with families, ensuring that investigation teams have expertise in facilitating family involvement, keeping families informed of investigation progress, providing support and opportunity to express concerns and questions, enabling families to inform ToR and give evidence, sharing findings with families, giving media advice as appropriate and providing the opportunity for families to comment on findings and recommendations. 98 The SI Framework included expectations that investigation reports include a description of how families have been engaged in the investigation process and how they were supported following the incident. Finally, after the conclusion of the investigation, the framework recommended that families be offered opportunities for continued involvement should they wish. The rationales for family involvement were to ensure accountability and build service-user confidence that the investigation findings were ‘robust, meaningful and fairly presented’. 98

Improving the safety of maternity care and saying sorry

Most documents in 2016 were focused on improving the safety of maternity care, rather than improving the processes after harm has happened. 126–129 However, in the Better Births National Maternity Review, where recommendations for improving family involvement were made, the language used to describe this involvement matched the shift in late 2015. 108 Recommendations focused on improving communication with families, putting families at the centre of processes and enabling informed decision-making. In addition to informing families of what was involved in reviews and investigations, the importance of individualised, relational care in maternity care and in investigation practices was foregrounded. 108 The importance of a single point of contact, especially in the wake of trauma, was described as essential to communicating family involvement options. 108

Despite these recommendations, evidence from the CQC in 2016 suggested SU involvement in investigation processes was still inadequate. 49 SUs reported that they were not always told that an investigation was happening, what their rights were in this process, what an investigation involved or how to access support and advocacy. 49 Family involvement was perceived by families as ‘tokenistic’ rather than ‘meaningful’. 49 This suggests that, although the language had shifted towards promoting meaningful involvement after publication of the Kirkup report, there was a lag in translating these priorities into practice. To combat this, the CQC review recommended production of a complementary family engagement framework, developed in partnership with families, for learning from deaths.

Throughout this period, a central concern was how to manage NHS staff concerns with liability and organisational obligations to meet the DoC. In 2016, the NHSR ‘Saying Sorry’ poster was released for circulation through Trust services. Its purpose was to encourage more NHS staff to apologise to injured families. The poster sought to clarify the difference between an apology and an admission of liability. 100 It also alerted staff to their obligations, as employees and professionals, to ‘apologise’, ‘acknowledge’, ‘share information about what went wrong’, ‘provide truthful information’ and ‘inform’ families after an incident. 100 In addition to this reminder of obligations, NHS staff were encouraged to see that apologising had a wider moral basis, in that it is ‘the right thing to do’. The poster also touched on the challenges of standardising communication with injured families, suggesting the ‘tailoring the apology’ to individual patient’s needs. 100

Shifting to individualised, relational care

In 2017, the shift to individualised, relational care was even more pronounced. A new vocabulary was adopted: rather than ‘active participants’ as in previous publications, families were described as ‘equal partners’. 109,110 This was captured in the recommendations, which were extended to incorporate individual choice. In addition to communicating openly and honestly about what happened, services were advised to communicate investigation and complaint procedures with families55,109,110,112 and to involve families to whatever extent they wish in these processes. 55,109–112 This involvement was envisaged as providing the opportunity for families to ask questions and voice concerns during reviews,55,109,110 inviting families to contribute to evidence, inform ToR and comment on findings and recommendations,55,110 providing families a meaningful, plain English explanation of what happened and what could have prevented what happened,112 and finally, offering the option of involving families in service learning efforts after the conclusion of the review or investigation. 109,110 However, it was also noted that it should be made clear that SU feedback may not be included if was not considered ‘relevant or appropriate’. 110 Who determines what is ‘relevant or appropriate’ was not described in this guidance, which was produced for Trust Boards. However, this creates an interesting paradox: families cannot truly be considered equal partners if their contributions to reviews can be dismissed.

Additional new recommendations, such as providing a sympathetic environment for disclosure, also surfaced at this time. 109,110 Improved communication between healthcare professionals across services was also recommended, for instance, increasing communication with outside facilities during transfer and with the family’s general practitioner (GP), to improve continuity and handover. 109,110 Although these recommendations were more actionable than their predecessors, it was still suggested that more detailed guidance on family involvement was required. 109,111 In some cases, recommendations signposted to existing outside guidance, such as that by the stillbirth and neonatal death charity (Sands). 55,111,112 Concurrently, two consultation documents were produced to inform policy development in ways that aligned the interests of families and HCPs. 57,113 These stated that both parties value the opportunity for meaningful apology,57 increased family involvement in reviews and investigations,57 a single point of contact57 and continuity of carer. 113

Enhancing communication

Despite mounting recommendations in previous years for increasing family involvement, in 2018, a progress update on the Each Baby Counts (EBC) programme revealed that only 41% of parents were invited to be involved in reviews. This was an increase from 34% in the previous EBC report, but still startlingly far from involvement ambitions. 116 The EBC recommendations that followed these statistics were mainly focused on procedural compliance, but reiterated that families should be informed of any reviews and investigations taking place and be invited to contribute according to their wishes. 116 The Maternity Safety Training Fund (MSTF) Fund, one of the other mechanisms set out for achieving the national maternity ambitions, also released an evaluation report in 2018 which listed the training opportunities provided to staff around maternity safety. Disappointingly, none of the offered trainings were related to family involvement or disclosure, other than training on the DoC. 130 The content of this training was not described, and it was not one of the ‘popular’ courses selected by the Trust. The course was also not featured in the MSTF catalogue, but rather was included as a course funded by the programme in the ‘other’ category.

Also in this year, National Health Service Improvement (NHSI) launched their scheme for ‘Maternity Safety Champions’ operating at the front-line, regional and national levels. 114 Maternity Safety Champions are representatives who act as ambassadors for improving safety in maternity care by learning and sharing best practice. Notably, this programme does not include a SU representative; however, the guidance recommends that champions ‘work with service users to address their needs, particularly in the redesign of new services’ (p. 10). Although no advice on how to achieve this work is given, it is the first time that a co-design approach to family involvement in maternity safety/service improvement is recommended.

The year 2018 did not yield many new recommendations for SU involvement; however, NHSI produced a document on promoting effective spoken communication between clinicians and patients. 115 This highlighted factors like providing the right environment for communication, ensuring information is accurate and understood, listening, conveying an attitude of respect and aligning expectations as facilitators to effective communication. 115 Although not specifically about disclosure, these principles can be applied to the practice. However, as Iedema et al. pointed out the following year in their report on the findings of this initiative, translating these principles from work-as-imagined to work-as-done presents a number of challenges. 137 Namely, there are differences between factually accurate communication and cultural, emotional and situationally sensitive communication, between imagined calm contexts for communication and the reality of the hospital setting, and between structured, evidence-based communication templates and individual, flexible, situated judgement. As such, it is unsurprising that these recommendations were not carried into future policy documents.

Conceptualising families as active partners rather than passive recipients

In mid-2019, the publication of the new NHS Patient Safety Strategy (PSS) marked a significant shift in the potential for patient and family involvement. 120 Transparency, providing opportunity for families to raise concerns and the use of the Patient Safety Incident Response Framework (PSIRF) and ENS were emphasised, and family involvement was embedded in a wider national strategy. The first ENS progress report, published in 2019, highlighted that the programme would enable families to receive answers, support and compensation more quickly. The ENS report did not reflect any of the developments in family involvement recommendations since 2015, instead integrating the original DoC steps of apology, openness, candour and providing support. 121 The biggest addition to existing recommendations in the PSS was the explicit recommendation to approach patients not as ‘passive recipients’ but ‘active partners’. In other publications published that year, the language matched that of 2017, employing phrases like ‘meaningful engagement’ and family as ‘equal partners’. 118 The PSS differentiated itself terminologically, opting for the word ‘active’ instead of ‘equal’. This new status was to be embodied by the ‘Patient Safety Partner’ who was to represent patient interests in their work with innovators on co-production, safety, strategy and policy developments. 120 Other publications signposted to existing recommendations for family involvement from the SI Framework, Sands or HSIB rather than producing new recommendations. 117,119 A report of qualitative findings on the implementation of the learning from deaths national guidance was published, reporting that good practice involved engaging families. 118 The report revealed that environments where there is a culture of openness and staff are supported/trained help with achieving engagement, but did not give specific recommendations beyond that. Several reports published between 2019 and 2020 on maternity safety topics by NHS England, NHSI, NHSR and HSIB did not include any sections on family involvement. 66,125,131–136

Enabling families to guide the process

As in previous years, 2020 policy recommendations by professional, NHS and inspection bodies focused on reminding services of the importance of informing families that a review or investigation was taking place,93,94,122 offering an opportunity for families to share their perspective on their care and raise any questions that they have,93,94,122 enabling families to contribute to evidence,68 personalising care123 and providing a point of contact. 124 Interventions that include family notification, such as the PMRT93,122 and ENS,122 were also signposted. The impact of the gradual recommendation changes and specification on steps for boosting involvement was evidenced in the EBC progress reports published in 2020, which revealed that invitations for family involvement in reviews had increased from 40% to 51% from 2016 to 201793 and to 70% by 2018. 94 These results were approximated in PMRT annual review reports (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

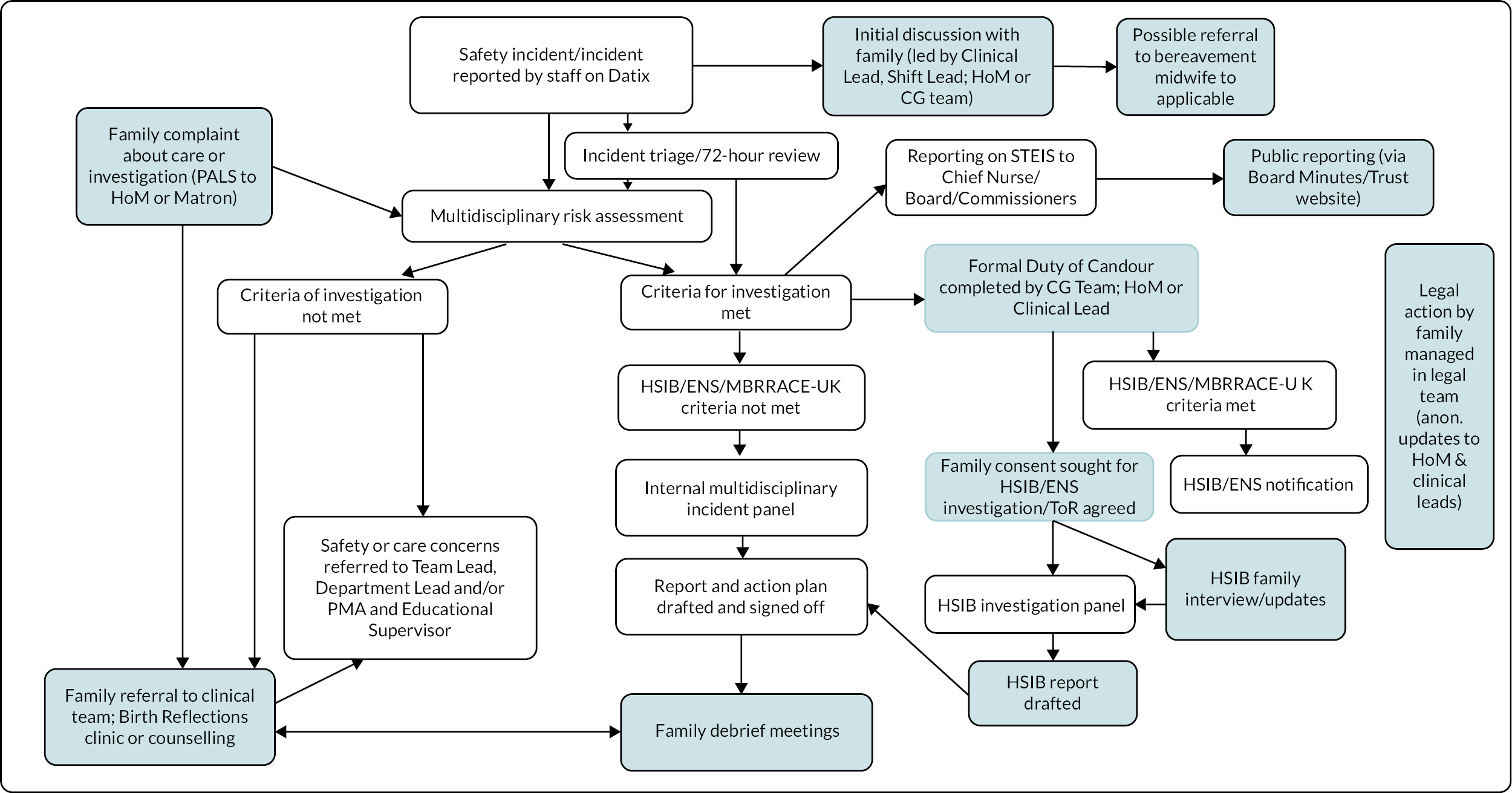

The language shifted slightly in some documents from ‘partnership’ and ‘active engagement’ to allowing patients and families to ‘guide’ their own engagement122,124 with flexibility, inclusivity and transparency during the review process. 93,94 The transition of SUs from recipients to equal partners, to active partners, and finally to guides, demonstrates the changes in perception of family involvement over time. HSIB stressed that families offer unique perspective as the only individuals with insight into what transpires at all stages of the healthcare journey and that families should have continuous involvement. 68 Fittingly, new recommendations at this time included encouraging and instructing patients, families and carers on how to record and share information about patient safety incidents,124 proactively seeking feedback about service openness and transparency,124 having a discussion with families about incidents124 and helping families to understand reports and recommendations. 68 Although national guidance remained the same, HSIB published a diagram illustrating the different steps for family involvement throughout HSIB-led reviews and investigations, illustrating their process for continuous engagement. 68 The process spans the initial contact with the family through investigation completion, with opportunities for family engagement at each stage. Each step has a section with additional information on questions to ask families, considerations to keep in mind and advice for where, when and how meetings with families should take place. 68 For the first time, this process involves giving the family access to a draft report for their input in addition to shaping ToR. 68

Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch reports on their progress for involving families in their investigations indicates the success of organisational investment in an adequately staffed, systematic and flexible family involvement strategy. It also indicates the neglected interests of many families in involvement. In 2019–20, 88% of families were involved in HSIB maternity investigations, whereas, in that same year, 34% of families were involved in Trust investigations. 103

In late 2020, the preliminary findings of the Ockenden report were published with immediate actions and recommendations. 89 Disappointingly, as in Kirkup,54 few of these recommendations were related to processes of family involvement. While Ockenden reports that families want their questions answered and want systems to learn, the only recommendation related to families made is that family voices must be heard and that families must have an advocate. 89 This advocate is to provide an oversight of meetings that happen with families in services. The final Ockenden report, published in 2022, builds on these recommendations to some degree, adding that families should be the primary concern during incident investigations, that families must be actively involved, that feedback must be shared with families openly and transparently by senior team members, that governance teams must work with the Maternity Voices Partnership (MVP) and that bereavement care and other support should be provided. 90 In 2021, an inquiry report published by the House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee recommended that families should be involved in a ‘compassionate manner’ and acknowledged that investigations have often failed to involve families in a ‘meaningful’ way. 103 It was again stressed that families need to be heard and that lessons need to be learnt; HSIB’s family engagement pathway68 was cited as a programme that had boosted family involvement. The report concludes that: ‘… it is important that [HSIB] continue to pursue improvements in this area to ensure that all investigations are informed by the experience of families’ (p. 22). 103 What improvements were needed, or how these might be achieved, were not noted.

Conclusions

This review of policy and report recommendations for family involvement in reviews and investigations in maternity care has several key findings. The first is that many recommendations have remained consistent over time but with limited guidance or resourcing for their implementation in NHS Trusts or maternity services. The importance of providing each family with a sincere apology, information about the review and open and honest communication throughout the investigation or review process, and of facilitating their access to the service with a single point of contact has been reiterated over time. Recommendations have also gradually extended to stress the need for continuous family engagement and for the provision of multiple opportunities for families to ask questions and raise concerns. The reimagining by policy-makers of injured families from those who passively receive information to those who can actively contribute evidence is notable. In policy terms, the recognition that families offer a unique and valuable perspective on patient safety has resituated them as subjects whose experiences of harm might become useful resources for learning and safety improvement. These additions evidence the fact that progress has been made in promoting the active and meaningfully involvement of families in documentation. Yet, there is still work to be done to meaningfully action these aspirations at the service level. Critically, this review also highlights that, in practice, families are not as involved as they would like to be, that different stakeholders in reviews and investigations (for instance, NHS England, NHSR, NHSI, HSIB, various charities and the NHS Trusts themselves) may have different perspectives on what family involvement entails and thus, the complete application of the principles for involving families is inconsistent.

Chapter 4 Realist literature synthesis of open disclosure in international maternity services

Introduction

This chapter reports the results of our realist synthesis and is the first step to meeting research objective one: to establish initial hypotheses to focus realist investigation of OD improvements in NHS maternity services. The research question guiding this synthesis was: ‘What key factors (resources and relationships) underpin successful disclosure in maternity care for different social groups, families, clinicians and managers of services in different circumstances?’

Identification of the literature

The documents included in the synthesis were identified using a two-stage literature search that included consultations with stakeholders. This process is detailed in Appendix 1.

In total, 39 documents were identified. After quality appraisal of the 39 documents for ‘fitness for purpose’ by relevance and rigour,75,138 38 documents were included in the realist synthesis (see Report Supplementary Material 7). A summary of our realist assessment criteria to establish ‘fitness for purpose’ is in Report Supplementary Material 8.

Realist data extraction and synthesis

Following RAMESES guidance,78 a data extraction tool was developed and piloted incorporating C–M–O configurations. For each paper, the rationales for interventions discussed or investigated were extracted as sets of ‘if …, then … ’ propositions using the tool.

This data extraction yielded 135 EAs from the 38 papers and were reported separately for families, staff and services. These EAs were organised by two researchers into a series of themes based on semi-predictable patterns in the accounts. 139 Following realist review principles,138 neither reported EAs nor reported intervention outcomes were necessarily the primary study focus of the papers. These EA statements were then mapped across two pathways: the ‘ideal-type’ temporal trajectory of OD (from event to resolution) and in relation to context/mechanism relationships that could be identified in relation to this trajectory. The outcomes of this data extraction for families, staff and services are available in Report Supplementary Materials 9, 10 and 11, respectively.

This data extraction from the perspectives of three distinct interest groups (families, staff and services) helped us to surface points of divergence and commonality in how OD was envisaged (its purpose, benefits and how it might be achieved). For example, OD as a service imperative to protect or enhance organisational reputation and to manage litigation may be antithetical to OD envisaged by families as greater transparency. These documents were discussed with our CIG and some members of our PAG. The PAG included national policy experts (n = 5), senior clinicians (n = 4) and family members with lived experience (n = 5). These stakeholder groups advised on the consolidation and prioritisation of the mapped EAs (or partial C–M–Os). They directed our attention towards key elements of OD experiences for families and staff, for example:

-

the initial responses of staff to a catastrophic incident and how this is felt by the parents or family

-

the significance of family involvement in reviews or investigations over time

-

the importance of understanding what happened and why for families

-

the complications of this work for staff during periods of rapid procedural change

-

the different ways in which some relief from the injury of harm happens for a family, including:

-

sincere recognition by clinicians of the effects of the incident on the family

-

knowing that changes have been made because of what happened to them

-

the value of clinicians’ OD skills.

-

-

the immediate and ongoing social and emotional effects of OD on healthcare staff as being fundamental to the ongoing quality and extent of disclosure with families

-

and finally, given the diversity of interventions identified, that an overview of intervention outcomes would deepen our understanding of the assumptions underpinning these programmes of work.

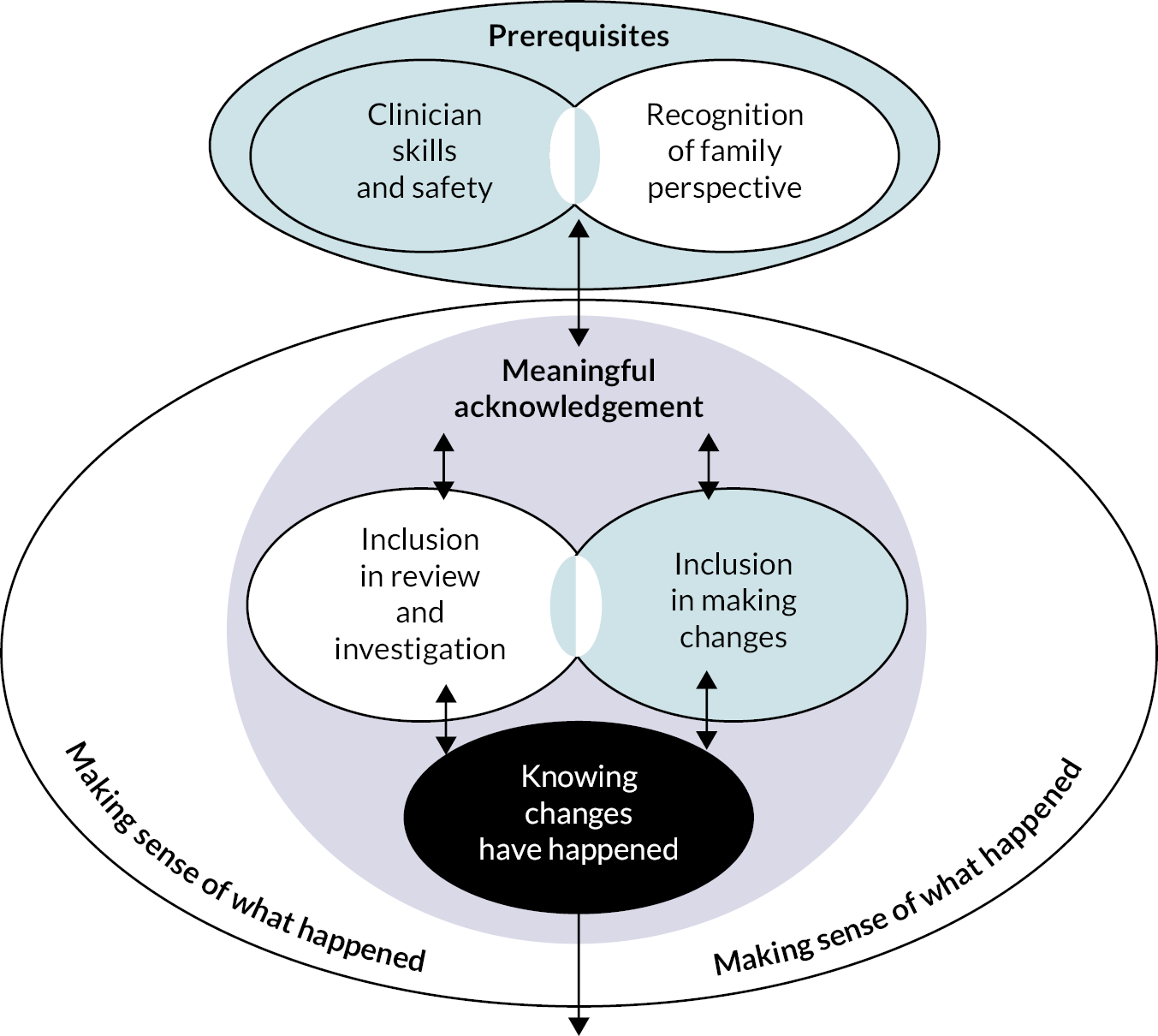

The outcome of these discussions was a honing of the synthesis into 68 consolidated EAs across the three interest groups: families (n = 20), staff (n = 28) and services (n = 20). These consolidated EAs were further synthesised into C–M–Os or elements of C–M–Os through independent analysis by two researchers (MA and JH) and in discussion with the CIG. CIG discussions refined the five ‘when/then’ mechanism sets. These were identified as C–M–Os expected to have a notable and identifiable effect on OD.

Results

Realist data extraction of the 38 documents identified 135 underlying assumptions or theories about what is required for effective OD events. The 38 identified documents include peer-reviewed publications (n = 22), policy research (n = 14) and evidence-based improvement updates with training resources (n = 2). They included findings from England (n = 18), the USA (n = 7), Australia (n = 4), ‘High-Income Countries’ (sic) (n = 3), Scotland (n = 2), Ireland (n = 1), France (n = 1), Europe (n = 1) and ‘International’ (sic) (n = 1). One paper was a systemic review, and two papers were evidence reviews. The complete list of included documents, organised by comparable interventions, publication details, realist quality appraisal ratings and key study characteristics, is presented in Report Supplementary Material 7.

Across all papers, there was limited primary research investigating families’ experiences of OD and what families consider necessary for OD in maternity services (with the exception of Iedema,37 Quinn140 and Stanford and Bogod141). Only two papers considered social diversity as a factor that might influence experiences of OD and felt outcomes. 37,142 Evidence of the direct use of family experience for practice or systems change was limited to one paper. 141 ‘Culture change’ towards either ‘no blame’ or ‘fair’ behavioural or organisational principles was often mentioned as an overarching cause49,55,92,121,140,143,144 or effect49,143 of OD improvements.

The empirical studies and reports documenting the effects of OD interventions (n = 21) were reviewed for descriptions of intervention design and intervention outcome. These fell into three broad categories of intervention and the nature of the evidence on outcomes varied between studies. First, three quantitative and mixed-methods studies examined the outcomes of simulated training sessions for individual trainees or professionals that were designed to enhance clinical communication skills. 145–147 These studies all suggested that there was an improvement in individual or team skills to conduct OD conversations after the interventions, with one identifying some of the benefits from the use of an evidence-based cognitive aid. 147 However, these clinical educational studies were small scale (n = between 15 and 60 participants), conducted in simulated environments and, most significantly, did not include patients or the public perspectives on the study design or assessments of outcomes.

The second group of studies (n = 5) included progress reports and one qualitative study. These documented the progress of parent or patient involvement in safety improvement interventions, including consideration of perinatal mortality reviews (PMRs) or audits62,63,148 and SI investigations. 49,118 These studies indicated the slow progress in improving parent involvement when doing so as one element of a wider safety improvement initiatives.

Third, a series of studies and reports (n = 8) documented the effects of multifaceted interventions to strengthen OD practices across a sector, service or hospital. 9,37,140,149–153 These interventions were often described as including the development and dissemination of faculty-tailored protocols and guidance, formation of CG revisions, introduction of general and more specialist clinician training and wider awareness-raising across staff teams. Overall, these studies acknowledged the long-term, uneven quality and extent of OD. A few individual, positive experiences of honest apologies in clinician–patient relationships were described. In many cases, the tension between clinicians’ support for OD in principle and their apprehension about reputational risk was captured. One study described a widespread increase in OD practices following a hospital-based quality assurance audit. 151 The increase was attributed to a long-term (at least 27-month) consequence of dedicated resourcing and focus by senior leadership, consistent messaging throughout the organisation, investment in enthusiastic and established champions working close direct care provision and insurer-approved protocols and specialist OD leads. However, with few exceptions,9,140 the views and experiences of patients, families and staff on the quality of OD events and their felt consequence were not a focus of these accounts of service-based OD improvements.

Initial programme theories hypothesised

The following sections describe the synthesised underlying factors for OD as a series of generalised hypotheses and explore how these are considered in the included papers. We summarise the realist data extraction findings in relation to the five identified programme theories in Appendix 5, Table 8.

The five identified programme theories are summarised as:

-

receiving a meaningful acknowledgement of the harm that has happened

-

being involved during the review/investigation process

-

making sense of what happened

-

receiving care from clinicians who are skilled and feel safe during post-incident communication

-

knowing that things have changed because of what has happened.

Receiving a meaningful acknowledgement of the harm that has happened

When a family feels that their experience of harm and its aftermath has been acknowledged in a meaningful way, their trust in clinicians and the service is more likely to be rebuilt, clinicians involved feel some relief and ongoing care and communication post incident is more likely.

Early and meaningful acknowledgement of harm, irrespective of questions of whether the harm was avoidable, was significant to families (24 papers) and staff (5 papers). Three studies stressed the importance of a family-centred perspective on the severity of harm and its aftermath. 49,141,154 Meaningful acknowledgement was emphasised as including recognition of the uniqueness of the experience on a family. This interpretation involved clinicians recognising and understanding the experience of the family and was additional to professional and regulatory duties. 49,121 The rationale for this acknowledgement differed from the organisationally and professionally prescribed OD tasks of giving honest information and explanation of what happened. This was also different from family involvement guidance, in which the clinician’s primary responsibility was to ensure that the family was invited to ask questions or raise concerns. 62,149 Only one paper considered the possibility that injured families could introduce clinicians to alternative perspectives on harm when involved. 153

As part of the meaningful acknowledgement of harm, the value of an honest and direct apology to a family during initial and subsequent OD conversations was noted in many studies. 37,118,141,149,155,156 Sometimes, a sincere expression of regret was found to enable some restoration of trust in a clinician or the service for the family. 37,141 Indeed, clinicians expressed surprise and relief that a family may offer understanding after an honest expression of regret. 9,149 Several studies indicated the disappointment of families when these apologies did not translate to their subsequent experiences of care. Many harmed families felt the injustice of poor ongoing care and expressed that they felt insensitivity from general maternity staff to their trauma and loss. Several papers suggested that the lack of ongoing recognition of harm may be because clinically defined incidents fall below procedural or regulatory thresholds of severity deemed to merit investigation;49,141,154 however, studies noted that clinicians also require information, time and determination to understand and discuss these ‘less severe incidents’. 141,157 Three studies explored the experiences of families after stillbirth, noting experiences of marginalisation, unrecognised distress and ignoring of their distinctive needs. 142,156–158

When evidence of harm was clinically uncertain and so interpretation of the extent or presence of harm gradually evolved, meaningful acknowledgement by a clinician was more complex and sometimes involved expert diagnosis and discussion with families and a wider clinical team. 156,158,159 Additionally, maternal harm or significant harm to babies could be identified weeks or months after the incident; in these circumstances, OD was initiated by clinicians or services far removed from the originating events and the clinicians involved. 121,141,154 These aspects of multiprofessional, multiservice OD work raise challenges around maintaining trust and communication with affected families. 141

Two papers from the same study found that the timing and conduct of OD meetings were often interpreted by those affected as indicators of how seriously the event was taken by the service. 37,153 Creating the space and time for exploration and discussion of events and their consequences communicated acknowledgement of the family’s situation. 153 Family preference for the presence of particular clinicians at their OD meeting also suggests the importance of personalising these events from the perspective of the family. While families more often wanted to meet with a senior clinician already known to them,159,160 some also wanted to meet those directly involved in the incident so that this family better understand events and their aftermath37,147 or can receive a more personal expression of regret. 37 A recognised barrier to meaningful acknowledgement during OD meetings was the inhibiting effects of clinicians’ worries about the risk of disciplinary action or litigation following OD. The distorting effects on conversations where legal or organisational representatives were present, or where legally protected ‘safe spaces’ were uncertain, limited the possibility for openness and honesty. 49,140