Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 17/05/110. The contractual start date was in September 2018. The final report began editorial review in July 2021 and was accepted for publication in March 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Zoccatelli et al. This work was produced by Zoccatelli et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Zoccatelli et al.

Chapter 1 Context and research objectives

Some text in this chapter has been reproduced from Zoccatelli et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Enabling residents’ voices to be heard is vital for planning the provision of publicly funded health and social care services and ensuring that the wider systems – of which such services are a part – are accountable to the public, the communities and the patients they serve. National and international policies encourage the involvement of residents in health planning and provision. 2–4

In some countries, including England, there is a legal duty to consider public involvement in commissioning and providing health care, and at all stages in major health-care planning decisions,5,6 and this is a cornerstone of patient-centred health and care systems. There is increasing evidence of a positive association between public involvement and more ‘innovative, effective and efficient ways of designing, delivering and joining up services’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). 7 For instance, it has been argued that NHS managers and staff are more informed as to the needs of the community they serve and will make better decisions about how to use limited resources when they listen to what matters to residents. 7 Other rationales for incorporating public and patient voice into decision-making and care improvement are more broadly about enhancing legitimacy and building consensus around often contentious health-care reorganisations. 8–13

In England, state-sponsored patient and public involvement (PPI) dates to 1974, when community health councils were established as a new model through which to represent the views of the public and advocate for local patients in each area health authority. Subsequently, arm’s-length bodies fulfilling the function of representing the public in the sphere of health care have been a persistent feature of the English policy landscape. 14 Nevertheless, since 2000, there have been three major reorganisations of the statutory system for PPI in England. 15

Community health councils were replaced by PPI forums in 2002, which were themselves abolished and replaced by local involvement networks (LINks) in 2008. LINks operated for only 4 years before they were superseded by Healthwatch, which was established as part of the coalition government’s 2012 reform of health and social care. Each iteration of the formal PPI system in England has involved different duties, powers, funding, composition and mechanisms for accountability (Table 1). 16

| 1976–2002: CHCs | 2003–7: PPI forums | 2008–13: LINks | 2013 to present day: Healthwatch | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 185 | 572 | 151 | 150 |

| Funding | Regional NHS office | CPPIH | Local authority with funding from DHSC | Local authority with funding from DHSC |

| Cover | Locality | NHS and primary care trusts in England | Local authority | Local authority |

| Remit | NHS and public health | NHS and public health | Health and social care | Health and social care |

| Accountability | Unclear, but could be removed by nominating organisation | CPPIH | To be determined locally | Local authority |

| Staff | Selected by CHC members employed by the NHS | Employed through voluntary organisations who are contracted to support PPI forums | Employed by host organisations | Employed by Healthwatch independently or through its host organisations |

| Statutory powers | Request information, visit NHS premises, sit as observers on health authority boards, be consulted on major changes in health care, appeal to the Secretary of State | Request information and visit NHS premises | Request information, visit NHS premises, refer health and social care matters to local council’s overview and scrutiny committee | Request information, visit NHS premises, sit on local statutory health and well-being boards, signpost health and social care services, escalate issues to Healthwatch England or the CQC |

What is Healthwatch?

Originally conceived as a ‘consumer champion in health and care’, local Healthwatch is now ostensibly a major partner through which local government monitors the quality – and supports the design – of health and social care. 7,17 Healthwatch does this by providing NHS England, Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), provider organisations and local authorities themselves with information and advice based on the views of residents and service users.

As we write, there are 150 local Healthwatch bodies across England. This number does not quite correspond with the number of local authorities in England because Healthwatch Dorset, Healthwatch West Central London and Healthwatch Northamptonshire each cover more than one local authority area.

Local Healthwatch work is supported at the national level by Healthwatch England, an independent statutory subcommittee of the Care Quality Commission (CQC), which provides local organisations with guidance and advice and draws on evidence collected locally to highlight national trends and issues. Local Healthwatch organisations have statutory powers to advise local authorities and NHS commissioners about their communities’ needs and concerns relating to the provision of health and social care, and these are embodied in Healthwatch’s six statutory functions (Box 1).

-

Obtain the views of people about their needs and experience of local health and social care services. Make these views known to those involved in the commissioning and scrutiny of care services e.g. CCGs, local authorities, hospital trusts.

-

Write reports and make recommendations about how those services could or should be improved.

-

Promote and support the involvement of people in the monitoring, commissioning and provision of local health and social care services.

-

Provide information and advice to the public about accessing health and social care services and the options available to them.

-

Make the views and experiences of people known to Healthwatch England, supporting its role as national champion.

-

Make recommendations to Healthwatch England to advise the CQC to carry out special reviews or investigations into areas of concern.

Adapted from the Healthwatch England website (URL: www.healthwatch.co.uk/our-history-and-functions) and reproduced from Zoccatelli et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The box includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Healthwatch organisations are commissioned by each local authority in England with funding from the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). The money is provided by the DHSC through two separate funding streams: (1) the central government grant to local government (distributed through the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government) and (2) a supposedly smaller amount of funding provided directly to local authorities through the Local Reform and Community Voices (LRCV) grant. This funding is not ring-fenced. In addition to providing funding for Healthwatch, the LRCV grant is also used to fund deprivation of liberty safeguards in hospitals and the independent NHS complaints advocacy services. Although the bulk of Healthwatch funding is supposed to come from the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities grant, Healthwatch England has recently highlighted that ‘a total of 71 local Healthwatch, almost half the network, now get most of their funding via the LRCV grant . . . and six local Healthwatch [ . . . rely exclusively on the] money provided through the LRCV grant to fund their statutory activities’. 16 Funding for Healthwatch has also substantially decreased since its launch in 2013. Originally set at £40.3M in 2013/14, funding has fallen to an estimated £25.5M in 2019/20, which is in line with wider reductions in funding to local government. 18 In general, there is a well-recognised lack of transparency in the way that local authorities allocate funding to their local Healthwatch, leading to significant variability in Healthwatch budgets across England. 18

Although all Healthwatch organisations are required to be social enterprises and are expected to involve volunteers in their activities and governance structures, there is no nationally mandated model for Healthwatch. Such flexibility in terms of organisational arrangements contributes to the range of organisational models on which Healthwatch can draw. For instance, Healthwatch organisations can be registered as charities, community interest companies or private limited companies. Some organisations may function as standalone or so-called ‘independent’ organisations that do only Healthwatch work, whereas other organisations may be part of larger organisations that also do work unrelated to Healthwatch. This situation raises hitherto underexplored questions about the relationship between local Healthwatch and non-statutory Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) organisations, as well as how – and with what effects – their respective roles in the local health and social landscape are formed.

In terms of their institutional role, Healthwatch bodies are differentiated from earlier state-backed PPI systems – principally by their legally mandated functions and a statutory seat on local health and well-being boards. A cornerstone of the 2012 reforms, health and well-being boards were established to integrate health and social care and ensure the inclusion of a wide range of local stakeholders in the strategic planning of health care, social care and public health; they vary greatly in their role and operation. 19,20 Healthwatch’s membership of health and well-being boards was intended to provide Healthwatch organisations (and, therefore, patient and public voice) with a more extensive role in the local decision-making mechanisms through which health and social care services are commissioned and provided locally. However, the move to integrated commissioning and provision of care beyond local authority footprints and the role of health and well-being boards is increasingly unclear. 21 Nevertheless, as Gansu22 has stated, Healthwatch’s involvement in health and well-being boards points to an important, broader feature of its relationship to the local health and social care landscape:

. . . local Healthwatch are unique – they are the only organisation that has a helicopter view of an entire local Health and Wellbeing system. In the world of localism and integrated health and care this is key. 22

This ‘helicopter view’ is becoming more salient, given the transformation in NHS organisational structures towards integrated care at the regional, local and neighbourhood level in the years since 2013.

The organisation of health and care has changed dramatically since Healthwatch was conceived. Although the Health and Social Care Act 20125 prioritised the principles of competition and marketisation, the trend over the past 5 years has been towards greater collaboration and integration among NHS bodies and their partners. Of the many new structures that have emerged that affect the environment in which local Healthwatch work, integrated care systems (ICSs) are perhaps the most significant. ICSs are partnerships between NHS CCGs, providers and local authorities, together with VCSE organisations, across a given area (e.g. South East London or West Yorkshire and Harrogate). The NHS Long Term Plan23 envisaged that all areas in England would be covered by ICSs from 2021. Building on this, the government published a health and care white paper in February 2021. 24 The paper proposed that such ICSs be made statutory organisations with commensurate powers. However, although Healthwatch was mentioned in the 2021 White Paper as a way in which public and patient voice could be represented at the ICS level, its involvement was not formally mandated in the subsequent Health and Care Act 2022. 24

Studying Healthwatch

Although there have been several studies of Healthwatch’s predecessors,15,25–27 there has been little research into how local Healthwatch organisations are organised, how they build and maintain relationships with different stakeholders and, ultimately, whether or not they make a meaningful contribution as a key pillar of resident and patient involvement in the English NHS. In the period before Healthwatch became operational, a National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR)-funded study looked at how CCGs conduct PPI in relation to long-term conditions. 26 The study recommended that ‘further research is urgently required to examine how [PPI] is being developed within the reformed . . . NHS’. 26 However, since this report in 2014, there has been little research on the work of Healthwatch.

Related work has looked at public participation in large-scale health changes and has studied Healthwatch as one of many actors in that process. Although this work valuably explores how various iterations of PPI coalesce in situations of contest or controversy, Healthwatch itself is not its immediate focus. 28 Mixed-methods research commissioned by the DHSC examined the initial operations of local Healthwatch organisations in the first 18–21 months of their existence and noted the early variability of Healthwatch work, as well as its general reliance on positive relationships with local stakeholders to ‘build legitimacy, influence and create impact’ (contains information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). 27 The research also highlighted activities that made Healthwatch effective in its early days and proposed recommendations for change. 27 More recent qualitative research on local Healthwatch organisations in one English region has pointed to a lack of clarity as to Healthwatch’s role in the landscape of health and social care planning and provision. 15,29,30 Here, the authors identify what they term as the ‘jurisdictional misalignment’ between local Healthwatch organisations, local authorities, health and well-being boards and the NHS organisations with which they must work as a key challenge. 20,30,31 Other tensions include competition with other third-sector and PPI organisations and processes and constrained local authority budgets from which local Healthwatch contracts are awarded, typically for 2 or 3 years at a time. 15,29,30 Reflecting on the design of ‘local Healthwatch quality statements’ launched in 2016 to encourage local Healthwatch organisations to collect information about and assess the quality of their work, Gansu22 similarly highlighted the importance of local context and of good-quality relationships between service managers, local authority leaders, CCG members and local Healthwatch organisations.

Although these studies point to the challenges and tensions faced by local Healthwatch organisations, they do not explore the various institutional landscapes in which Healthwatch operates, the daily practices through which its influence is created and maintained, and the reasons for, and implications of, different approaches to collecting and communicating evidence about residents’ needs and experiences. It is essential to consider the interconnection of these various practices and concepts. To address this gap, our study uses the theoretical framework of actor network theory (ANT).

Actor network theory

Originating in science and technology studies, ANT focuses on the role of mutually influencing relations between various human and institutional actors, as well as the sociomaterial contexts (e.g. objects, documents, buildings, meetings, technologies, data, policies, strategies, contracts, ideas) in which they operate (Box 2). 32,33

-

ANT is a theory developed by Bruno Latour, Michel Callon and John Law as part of science and technology studies during the 1980s.

-

Although ANT carries ‘theory’ in its name, it is better understood as a range of methods for doing social science research.

-

ANT sets out to describe the connections that link together humans and non-humans (e.g. objects, documents, buildings, meetings, technologies, data, policies, strategies, contracts, ideas). Both humans and non-humans are understood as ‘actors’ that can have an influence on phenomena of interest.

-

In particular, ANT describes how these connections come to be formed, what holds them together and what they produce in particular contexts. This system of mutual influence between and among humans and non-humans is called an ‘actor network’.

-

To study an actor network, ANT researchers employ some key qualitative research methods as part of their data collection:

-

non-participant observation (i.e. spending time in the places where the interactions between actors, both human and non-human, happen and decisions about them are taken) and recording them as field notes

-

interviews with relevant human actors to discuss their opinions, frustrations, emotions, hopes and beliefs, as well as the reasons underlying their practices

-

collection and analysis of relevant documents, particularly if they play a part in interactions.

-

In studies of health-care service and delivery, ANT has typically been advanced as a framework for investigating health-care organisations and technologies,34–36 and it has been applied successfully in other NIHR-funded studies. 37–40 For instance, three of the authors of this report – Amit Desai, Giulia Zoccatelli and Glenn Robert – were recently involved in a NIHR-funded project that used ANT to investigate and optimise the use of patient experience data in acute NHS trusts. 40 This work explored the mutually influencing relationship between different forms of patient experience data and technologies and the people and institutions that use (or fail to use) them to improve the quality of patient care. 40–42 Thinking with ANT meant that we built ethnographic descriptions of how patient experience data came to be formed in any given hospital and how these data were entangled in relationships that enabled them to act to affect improvement.

Our study of Healthwatch similarly pays attention to these ‘mutually influencing relations’ between various human and non-human actors in shaping the practices and strategies through which Healthwatch promotes patient and public voice. 43 Using ANT adds to our understanding of Healthwatch in two main ways. First, we are able to expand the range of actors beyond merely human or institutional actors, which had been the focus of previous studies,15 and this allows us to give due consideration to the ways in which relationships between Healthwatch and its local stakeholders are shaped and mediated on a daily basis by artefacts, such as organisational and governance structures, funding arrangements, institutional landscapes, data, technologies and evidence-gathering mechanisms (i.e. non-human actors) (Box 3).

-

Healthwatch staff and volunteers.

-

Patients.

-

Carers.

-

Local residents.

-

Charities staff and volunteers.

-

CCG members.

-

Local authority officers.

-

Local councillors.

-

Local GPs and others in general practices.

-

Trust staff (e.g. patient experience managers, engagement managers, nurses, clinicians).

-

Documents (e.g. ‘enter and view’ reports, strategy documents, ICS plans, Healthwatch quality statements).

-

Technologies (e.g. computers, software, patient experience data, surveys, internet, e-mail, telephones).

-

Funding and funding applications.

-

Policies.

-

Buildings.

-

Contracts.

GP, general practitioner.

As we explore in the mode of analysis (see Chapter 3), findings (see Chapters 4–7) and discussion (see Chapter 8) chapters that follow, thinking with ANT allows us to see and analyse the entanglements of which Healthwatch is a part and which shape the possibilities of its work. Therefore, for example, we trace the ways in which the health and social care institutional landscape in any given Healthwatch area of operation intersects with funding arrangements or Healthwatch organisational structure, and how these need to be considered together to understand the nature of key Healthwatch activities, such as engagement or evidence-gathering and communication.

Second, existing studies rely primarily on interviews and surveys that can provide only post hoc accounts of events. 15,27,30 Our study, although incorporating a survey and interviews, also prioritised a broadly ethnographic approach (endorsed by ANT) to capture the processual nature of relations, therefore uncovering the emergent and unexpected ways in which local Healthwatch organisations enhance patient and public voice.

By examining the nature and quality of interaction between local Healthwatch organisations and key stakeholders, as well as the non-human elements that enable such interaction, our study provides, to the best of our knowledge, the first comprehensive exploration of these hitherto largely neglected organisations.

Research aims and objectives

The aim of our study was to explore and enhance the operation and impact of local Healthwatch organisations in ensuring effective patient and public voice in the commissioning and provision of NHS services. We have achieved this aim by pursuing the following four objectives:

-

to establish current priorities, activities (e.g. advocacy, signposting, surveys, inspections) and organisational arrangements (e.g. staffing, funding, nature of contract, jurisdictions) of local Healthwatch organisations in England [method: survey (phase 1)]

-

to explore the processes and interactions that link local Healthwatch organisations to a range of individual and institutional actors [e.g. commissioners, general practitioners (GPs), CCGs, trusts, patients, local authority staff, care homes, third-sector organisations and Healthwatch England] and to the wider contexts through which they operate (e.g. funding, contracts, reports) to assess their impact on local health-care commissioning and provision [method: ethnographic fieldwork at five local Healthwatch organisations and engagement with members from 15 other Healthwatch organisations (phases 2 and 3)]

-

to build consensus about what might constitute ‘good practice’ in terms of the operation of local Healthwatch organisations [method: joint interpretive forums (JIFs) (phase 4)]

-

to distil and then disseminate generalisable principles around what facilitates and/or limits the influence of local Healthwatch as a key element of patient and public voice in the NHS [method: small-group discussions and online interviews with the Healthwatch Involvement Panel (HIP) and JIF (phase 3)].

Pursuing these objectives helped us answer our two key research questions:

-

What are the strategies, practices and sociomaterial structures that enable Healthwatch to enhance patient and public voice in the NHS?

-

How is PPI made impactful for residents themselves, as well as commissioners, providers and other NHS actors, as they are brought together through the daily work of Healthwatch?

Structure of the report

In this chapter, we have set out the context and relevant literature for our study, including the theoretical lenses we chose to adopt, as well as the aims and objectives of the study. In Chapter 2, we discuss the methodology we used and the changes we made to the original protocol.

In Chapter 3, we detail our data sources and our modes of analysis across the four phases of the study.

Chapter 4 presents the findings of our national survey of local Healthwatch mapping organisational structures, relationships and impact across the network.

Chapter 5 presents the findings from 16 months of ethnographic fieldwork at five local Healthwatch study sites and explores key axes of variability in Healthwatch’s arrangements, strategies and practices. The chapter is organised into four sections: (1) organisational structures, (2) funding arrangements, (3) institutional landscapes and (4) strategies and practices of engagement.

Chapter 6 combines insights from phases 2–4 of the study to produce statements of good practice relating to the collection, analysis and communication of patient and public voice. The bulk of the data presented here were collected at local JIFs held remotely at four of the study sites, and focused on what constitutes good and useful evidence for Healthwatch organisations and key partners, such as the NHS and local authorities, and what most effectively presents the voice of residents.

Chapter 7 draws on our research in phases 2 and 3 and explores how local Healthwatch organisations responded to the COVID-19 pandemic in England.

In Chapter 8, we demonstrate how our findings provide significant new knowledge about the everyday practices and strategies of local Healthwatch organisations. Before concluding the report, we draw out the implications of our study for policy, practice and research.

The appendices contain additional information that the reader may find useful, including profiles summarising key features of each of the five local Healthwatch study sites (see Appendix 1) and resource documents we produced for the JIFs (see Appendix 4).

Note on naming practices and pseudonyms

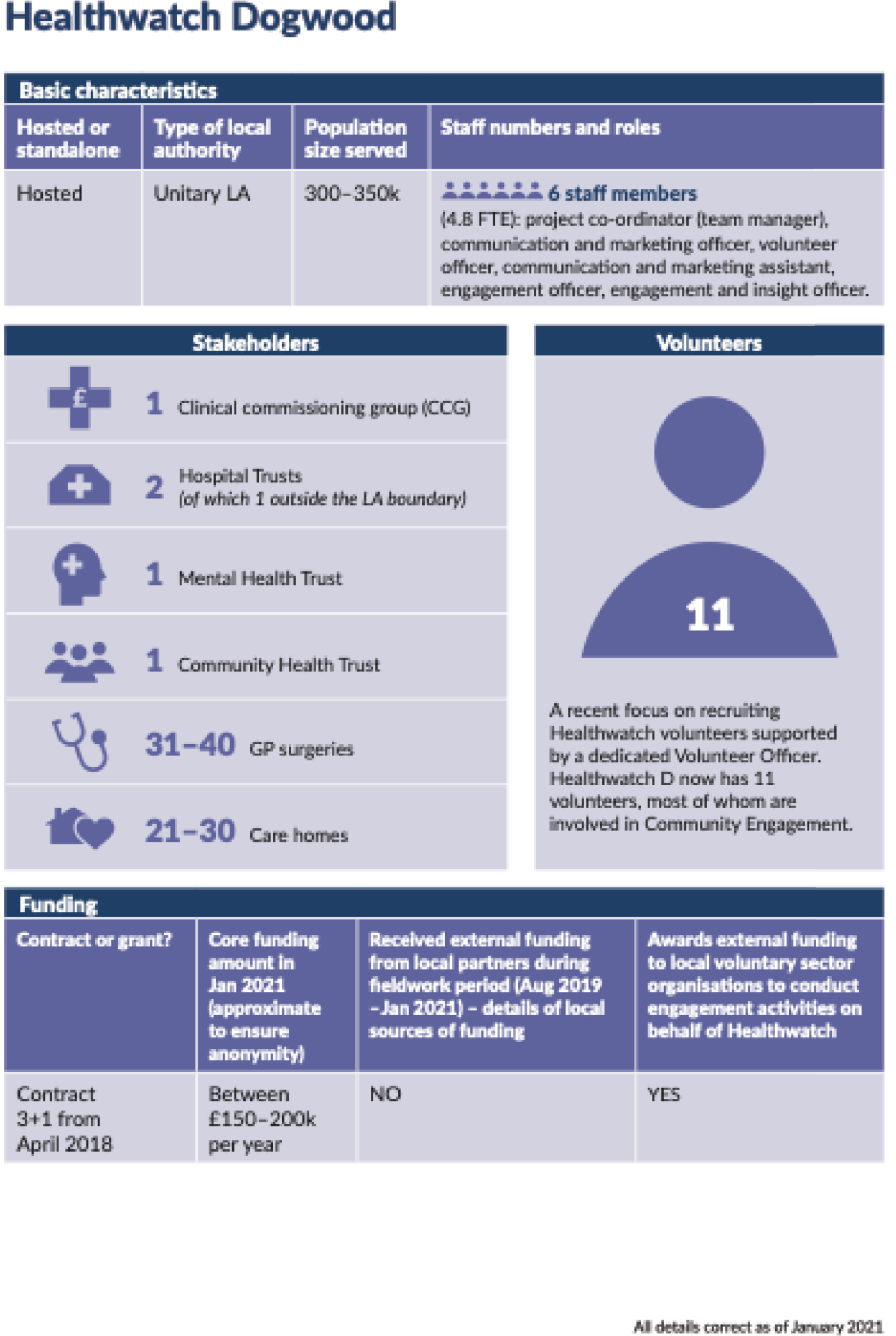

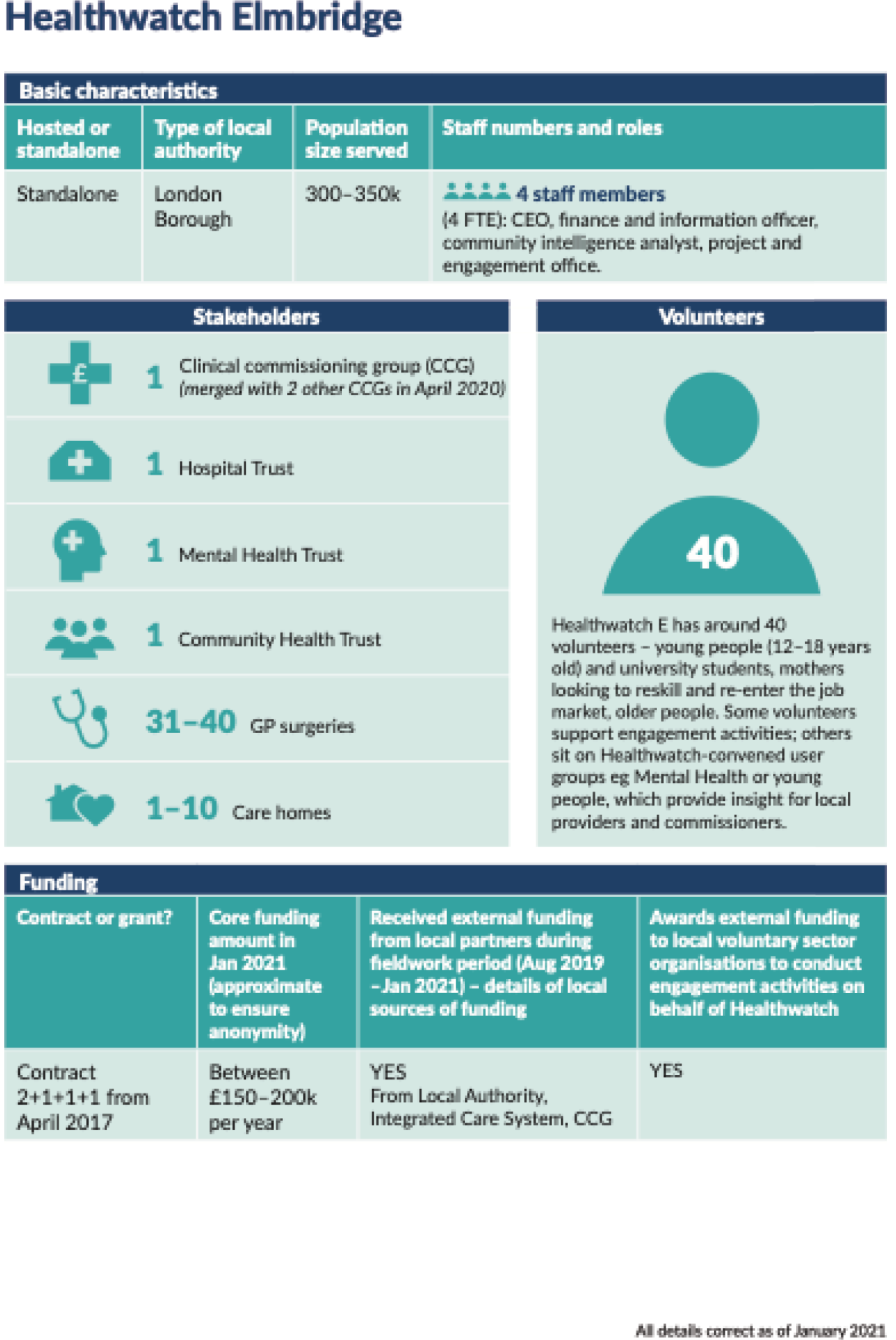

We have anonymised each of the study sites by giving them the following pseudonyms: Healthwatch Ashton, Healthwatch Beecham, Healthwatch Cherryburgh, Healthwatch Dogwood and Healthwatch Elmbridge. Similarly, the organisations that hosted three of our study sites are given the following pseudonyms: Achieve (Healthwatch Ashton), Community Together (Healthwatch Cherryburgh) and Direction Health (Healthwatch Dogwood).

Other Healthwatch organisations referred to in the report (e.g. those of HIP members) are also given pseudonyms. Where individual HIP members are quoted, they are not referred to by name but are, instead, given a number (e.g. HIP member 3).

Chapter 2 Methodology and changes to the protocol

Some text in this chapter has been reproduced from Zoccatelli et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

The study was organised in four phases.

-

Phase 1 (September 2018 to April 2019) comprised the design, development, distribution and analysis of our national survey of all local Healthwatch in England (objective 1).

-

Phase 2 (April 2019 to January 2021) included:

-

the recruitment of five case study sites and the recruitment of 15 members of the HIP

-

ethnographic data collection visits to gather documentary evidence, carry out observations and conduct interviews

-

a switch to virtual fieldwork in March 2020

-

data-gathering and iterative data analysis with the HIP (objective 2).

-

-

Phase 3 (March 2020 to April 2021) included online interviews and small-group discussions with HIP members to explore Healthwatch experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic and to generate statements of good practice (objective 4).

-

Phase 4 (January to June 2021) consisted of participatory sense-making workshops modelled on JIFs. 44 The first workshop was held virtually in January 2021 (with representatives from all five Healthwatch study sites) and it was followed by virtual workshops at four of the individual local Healthwatch study sites (May to June 2021) (objectives 3 and 4).

Phases 1–3 deepen our understanding of how Healthwatch organisations are structured and operate, whereas phase 4 is concerned with the related but separate issue of enhancing evidence-gathering strategies.

Phase 1: nationwide online survey

We conducted a national online survey between December 2018 and January 2019. The survey had the following three aims:

-

to explore the current organisational arrangements, relationships and impact of local Healthwatch organisations in England

-

to explore the extent to which these vary across local Healthwatch organisations

-

to use the data to help select our five study sites and members of the HIP in line with our broad sampling framework.

All local Healthwatch organisations in England were invited to take part in the survey. We obtained a list of 150 publicly available ‘info@’ e-mail addresses of local Healthwatch organisations from Healthwatch England and sent unique links to these addresses. We asked the local Healthwatch organisation chief executive, director or manager to complete it. The survey was conducted using the Jisc online survey platform (URL: www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk). We sent weekly reminders to potential respondents. We also reminded potential respondents through Facebook (URL: www.facebook.com, Meta Platforms, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) and Twitter (URL: www.twitter.com, Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) and asked Healthwatch England to publicise the survey through its communication channels.

The survey was designed in consultation with:

-

participants (mainly Healthwatch chief executives, chairpersons and managers) at the Healthwatch Annual Conference in October 2018, where we ran a workshop to identify areas the survey should explore

-

Healthwatch England, in relation to the surveys and data returns they already conduct and collate from local Healthwatch organisations (so as avoid duplication in our survey)

-

our independent Project Advisory Group

-

five former local Healthwatch chief executive officers (CEOs) or directors.

The final version of the survey had 47 questions and examined three facets of local Healthwatch work (see Report Supplementary Material 1). The first section focused on Healthwatch organisational structure, particularly funding arrangements and staffing. The second focused on local Healthwatch engagement with key partners, location of relevant stakeholders and level of co-operation. The third explored the types and qualities of the impact achieved (or intended) by local Healthwatch organisations. Based on suggestions made by the former local Healthwatch chief executives and directors who piloted our survey, in this third section we opted for descriptive questions about the types of impact achieved and about practical examples of successful or failed impact experienced by local Healthwatch organisations in the past 3 years. This approach allowed us to account for a broad range of factors involved in successful/failed projects (e.g. project topics, their length, stakeholders involved and systemic challenges encountered). We avoided more general questions about the overall impact of each organisation because we regard ‘impact’ as the outcome of a complex array of inter-related factors, which are better suited to the in-depth qualitative investigation we carried out in the second phase of this research project.

The survey used a combination of open- and closed-response questions. The questionnaire mainly comprised questions requiring ‘yes/no’ responses [e.g. ‘Does your Healthwatch award funding (e.g. grant, contract) to other organisations?’] or the selection of possible answers from a drop-down menu (e.g. ‘How would you describe the overall quality of co-operation among key health and social care stakeholders in your local area?’, with respondents asked to indicate their views on a five-point scale from ‘excellent’ to ‘poor’). Most closed questions in the survey included an ‘other’ option and allowed for free-text responses in the form of a brief description.

Open questions were limited to the last two sections of the survey. In these sections, we asked respondents to briefly outline two specific pieces of work they had carried out in the past 3 years that they regarded as (1) successful and (2) unsuccessful. In these final sections, we used a combination of closed and open questions, requiring text responses in the form of a brief description. Open-ended questions asked, for example, ‘What was the piece of work about?’, ‘How was the impact delivered?’ and, in the case of unsuccessful projects, ‘What barriers did your Healthwatch experience in its work?’. We coded answers based on topic, duration of the project (i.e. ≤ 1 year, between 1 and 2 years or ≥ 2 years) and barriers to impact. Closed questions in these final two sections included ‘type of impact achieved or intended to be achieved’ (covering 13 options, e.g. ‘improved access to care and treatment for members of our community’, and participants could select more than one option) and, in the case of successful projects, ‘most important stakeholders involved’ (covering 19 options, including an ‘other’ option, and participants could select up to three options).

For data about numbers of [total and full-time equivalent (FTE)] staff and volunteers and Healthwatch grant/contract values, we relied on data compiled by Healthwatch England in the period 2013–18. These data were shared with the research team in February 2019.

Based on the findings of phase 1 survey, the team wrote a report for circulation to the network and presented it at the Healthwatch conference (2019).

Phase 2: ethnographic study

Below we present a description of our sampling and data collection methods for the two main research elements of the research work in phase 2; that is, (1) the fieldwork at our five case study sites before and during the COVID-19 pandemic and (2) the work of the HIP.

Fieldwork at five local Healthwatch study sites

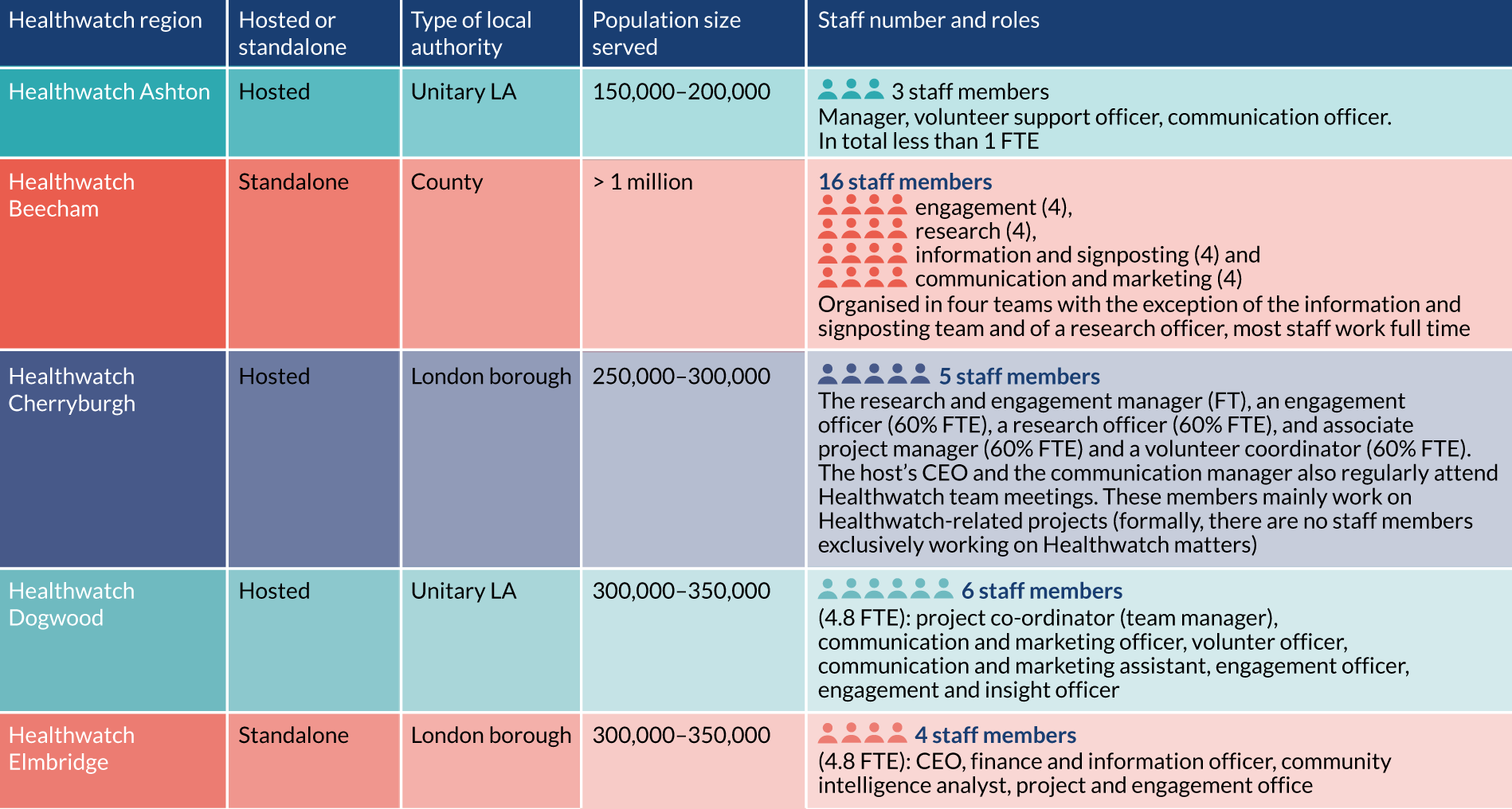

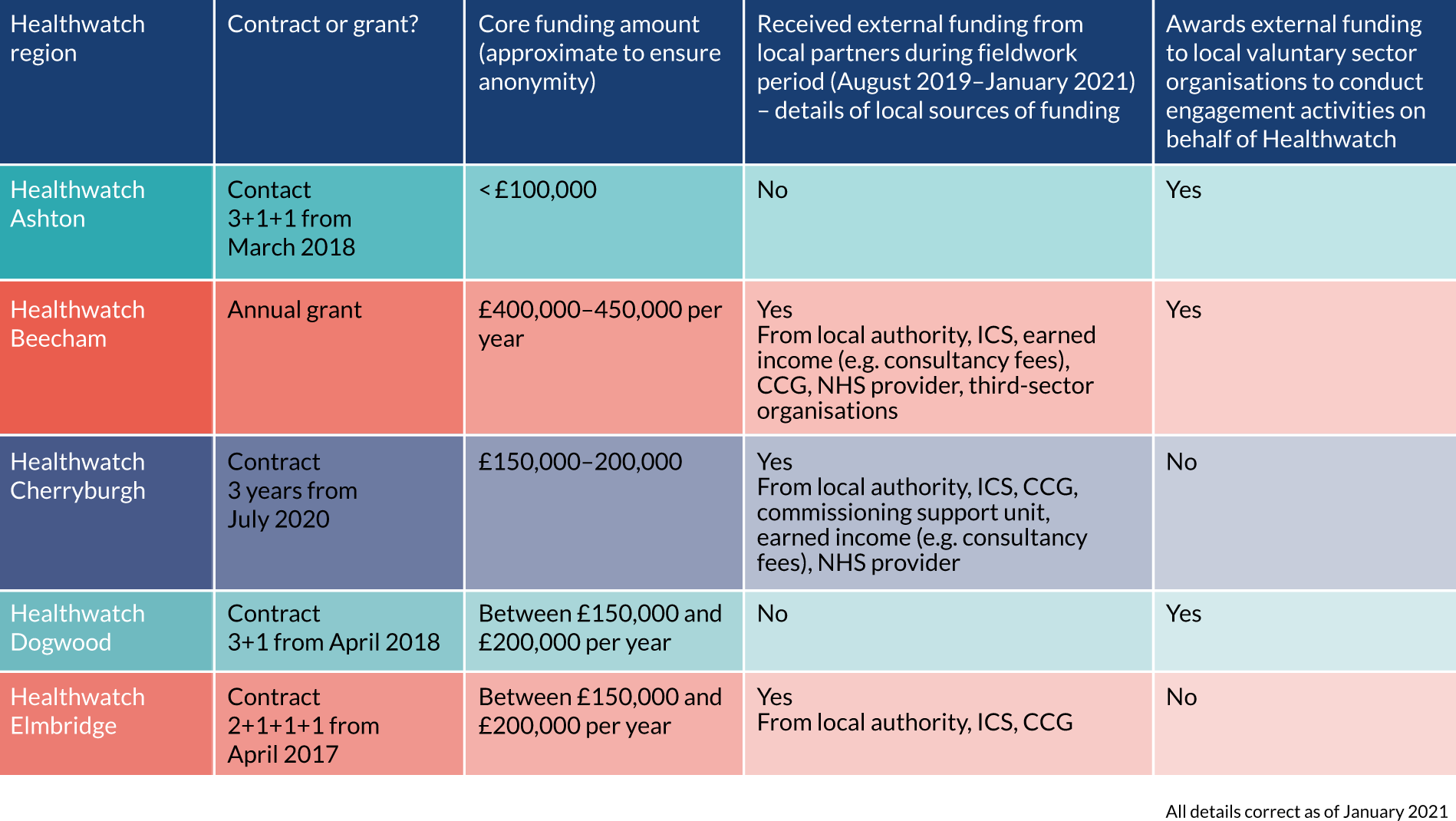

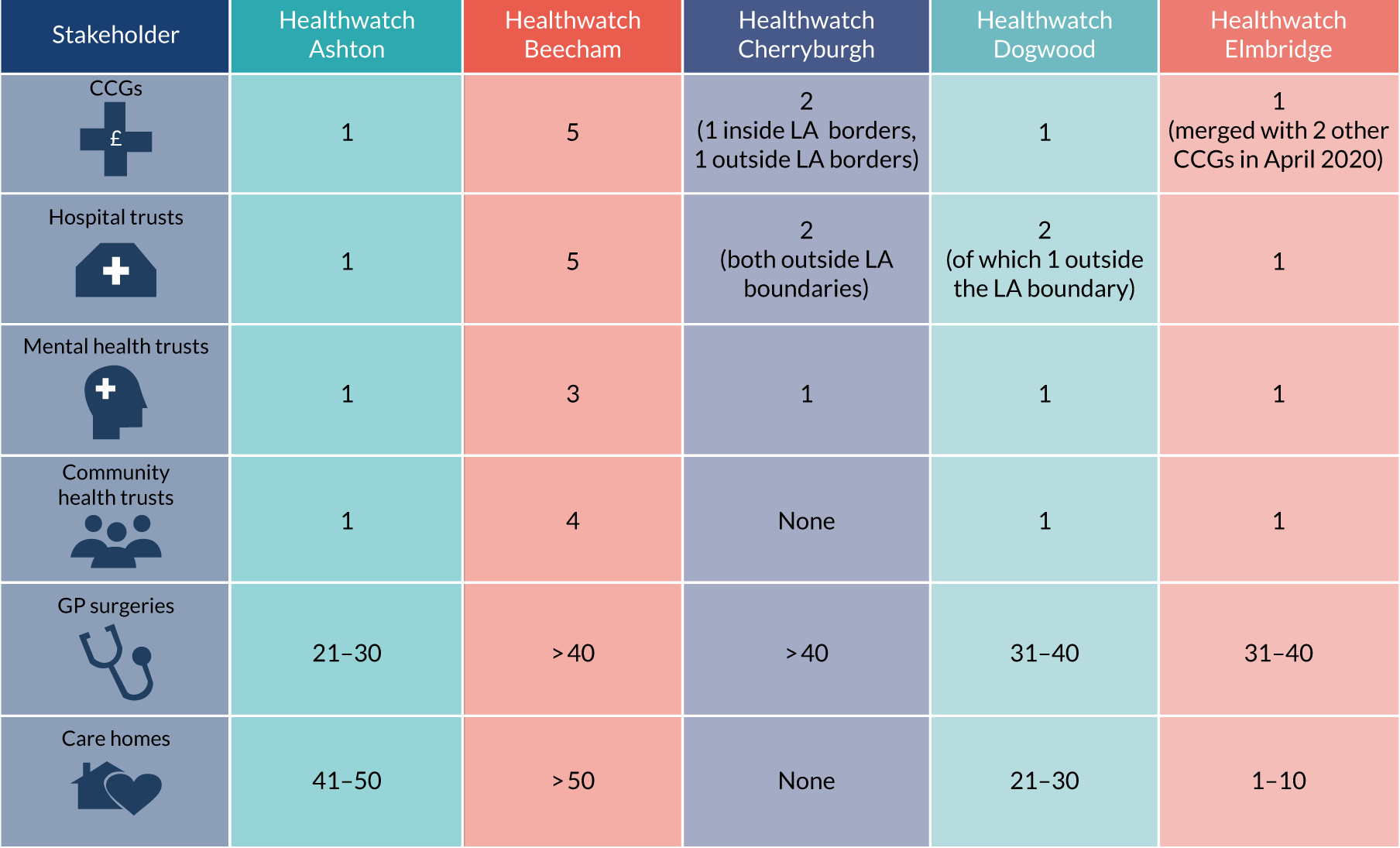

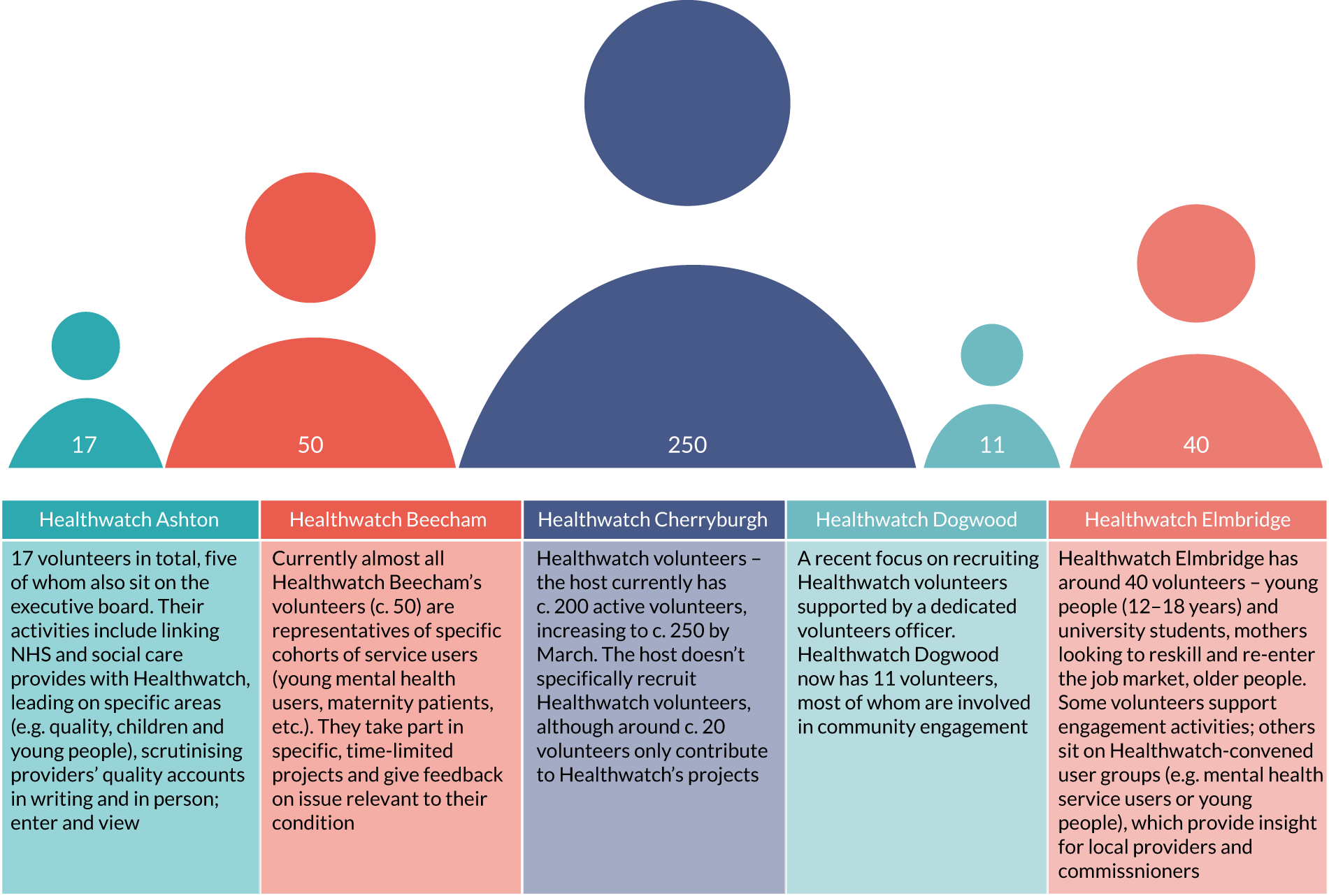

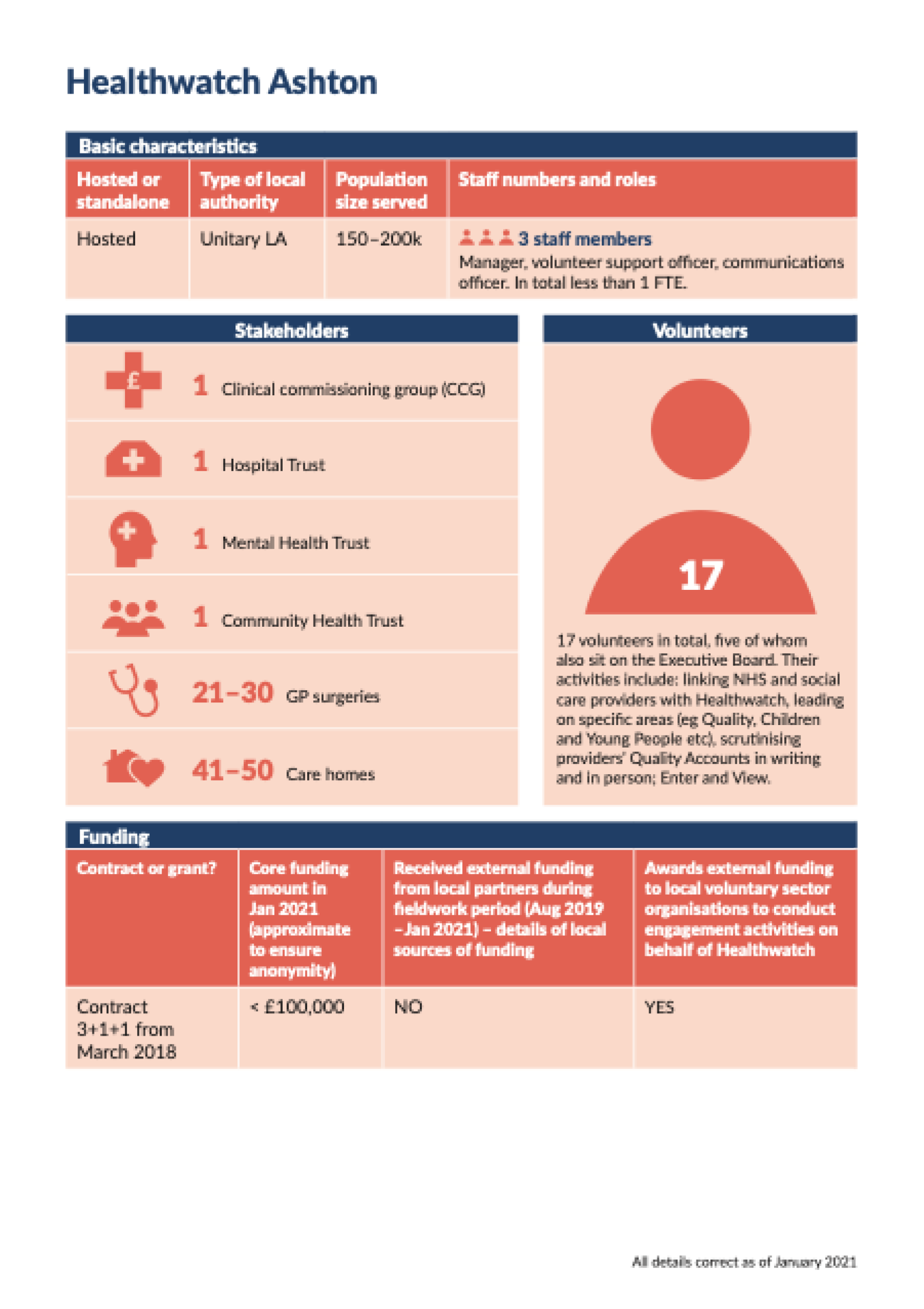

We carried out interviews, observations and documentary analyses at five purposively sampled local Healthwatch organisations over a 17-month period (August 2019 to January 2021) (see Appendix 1 for a summary of characteristics for each study site). Although the project proposal and first version of the protocol envisaged only four local Healthwatch study sites, as phase 2 developed through the involvement of the HIP, it became clear that we needed to recruit a fifth local Healthwatch site to have a sample that better reflected the variability of Healthwatch, as perceived by staff and volunteers of Healthwatch themselves.

Sampling

To identify potential Healthwatch study sites, we constructed and adapted our sampling frame through an iterative process that included the following stages:

Survey results analysis

We built our sampling strategy for the selection of five case study sites from the results of the phase 1 survey, focusing particularly on the findings associated with the intersection of organisational structure, funding arrangements and type of local authority. In doing this, we slightly modified the sampling strategy outlined in the protocol, where we had said that we would focus particularly on the findings associated with the ‘jurisdictional contexts’ variable. This choice was justified by the fact that in designing the phase 1 survey we were advised by the people we consulted (see the list above) not to include many questions about Healthwatch jurisdictional context, as these would have duplicated information already collected by Healthwatch England or otherwise publicly available. Following discussion with our Advisory Group, we, instead, decided to build our sampling strategy using the following formula:

We selected a study site with typical organisational arrangements for each of the three main local authority types (i.e. county, unitary and London/Metropolitan). We grouped London and Metropolitan local authority types together, as their answers in the surveys were largely consistent.

The typical arrangements we found (based on the survey return), which are explained in greater detail in Chapter 4, were as follows:

-

unitary + small number of relationships + contract + hosted (represented by Healthwatch Dogwood)

-

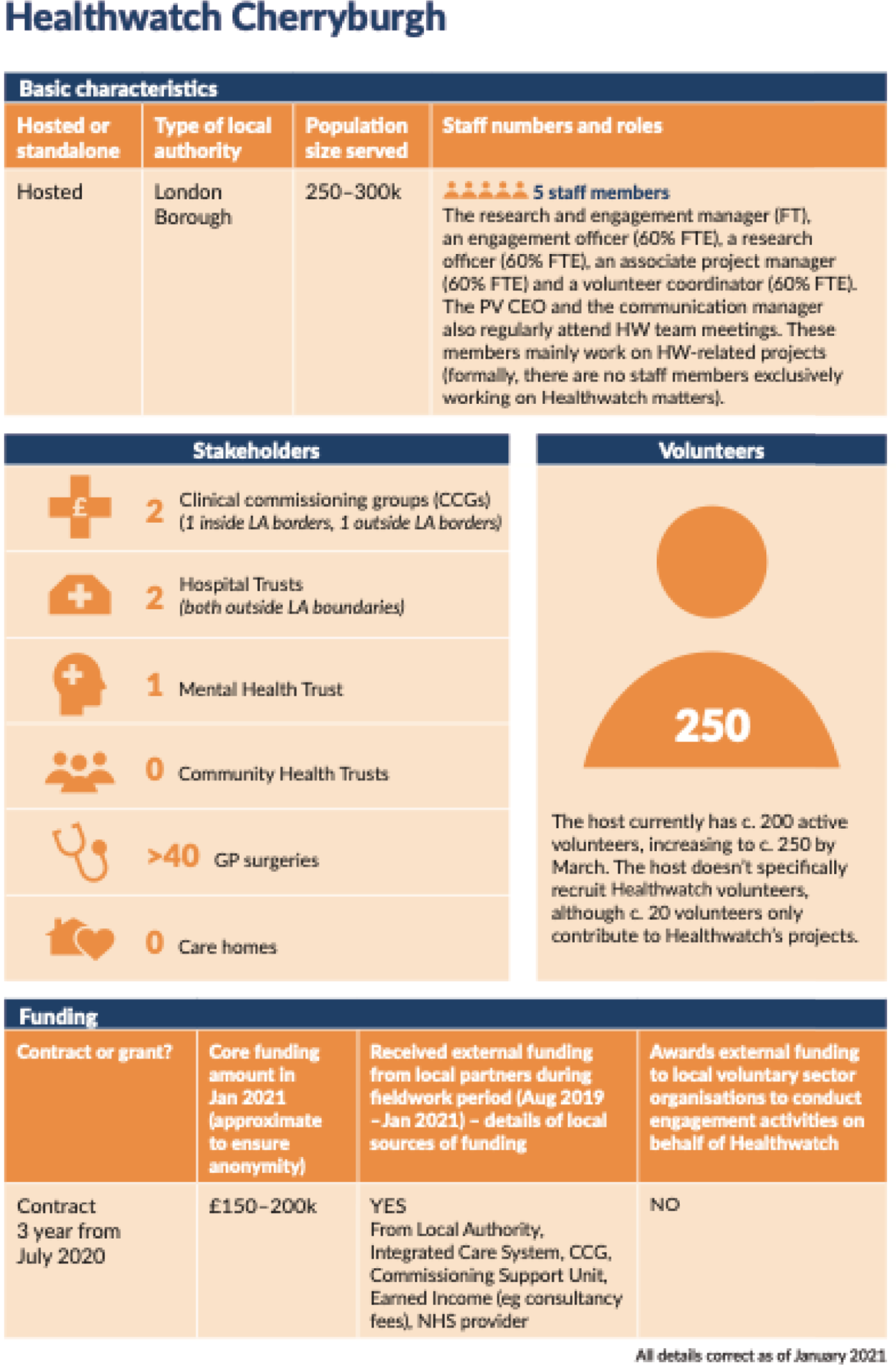

London or Metropolitan + average number of relationships + contract + either hosted or standalone (represented by Healthwatch Cherryburgh)

-

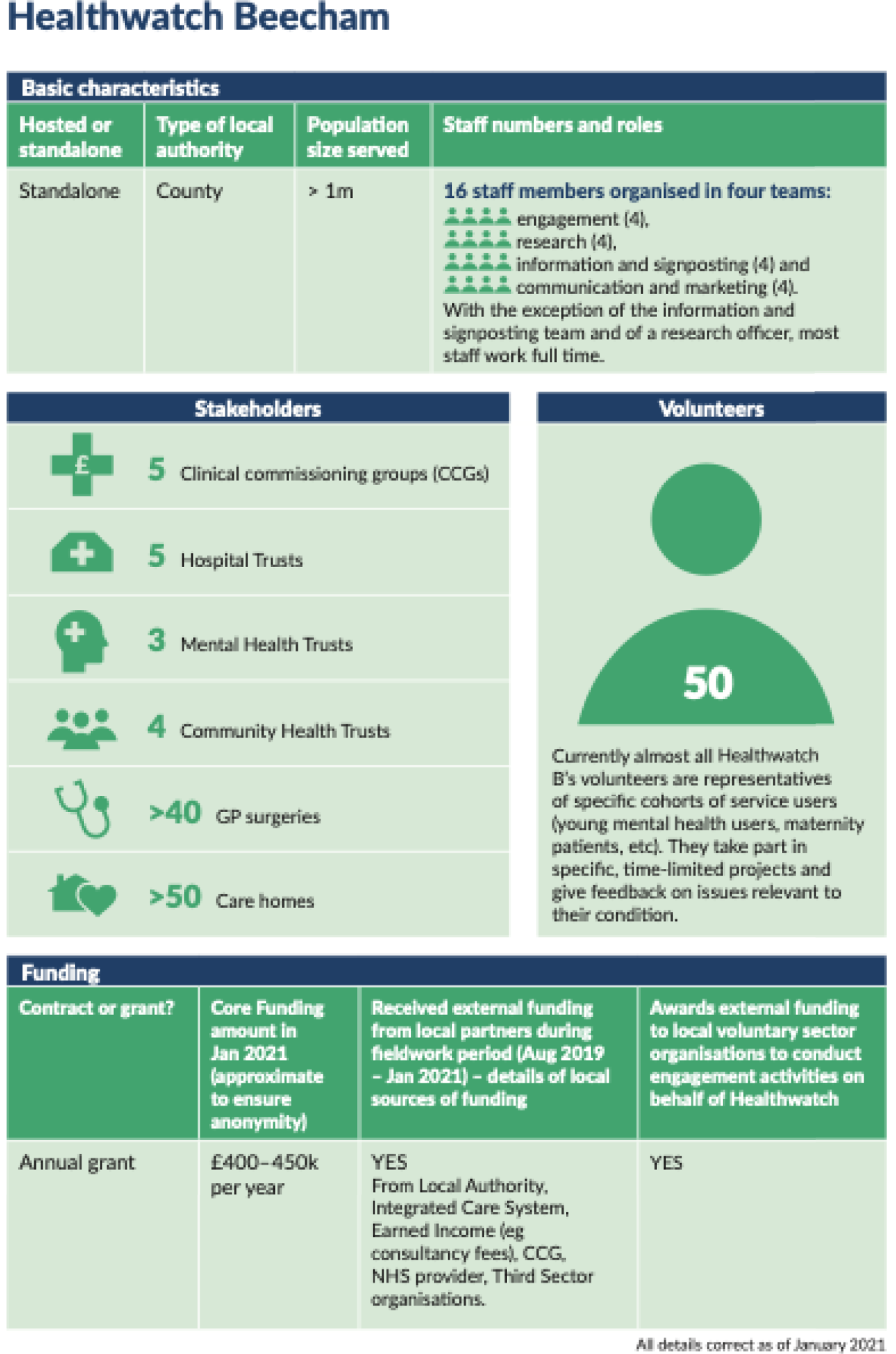

county + large number of relationships + grant + standalone (represented by Healthwatch Beecham).

Advisory group

We presented our sampling strategy to our Advisory Group. The Advisory Group approved the three Healthwatch sites, listed above. The study team discussed with the Advisory Group the criteria for recruiting the fourth study site and these included:

-

a Healthwatch in an urban area outside London

-

a Healthwatch with a host with more than one Healthwatch contract.

These characteristics were deemed to complement those of the three Healthwatch sites mentioned above and allowed for a rounded sample of study sites taken as a whole. In May 2019, we recruited a Healthwatch study site that, hosted by an organisation with four Healthwatch contracts and based in an urban area outside London, met these inclusion criteria. However, in August 2019, the host lost the contract for this Healthwatch. We then approached two other Healthwatch sites with similar characteristics. In discussion with the Advisory Group, we agreed on the recruitment of Healthwatch Ashton, that, hosted by an organisation with two Healthwatch contracts and based in a mixed urban/rural area outside London loosely met the above criteria. The selection of Healthwatch Ashton was regarded by the Advisory Group as particularly valuable by virtue of the small size of its core local authority contract (< £100,000 per annum) as this characteristic was not present in any of the other three Healthwatch sites we had already recruited.

Healthwatch Involvement Panel

We held our first HIP meeting on 17 July 2019, where we discussed our sampling strategy and presented the anonymised core features of the four Healthwatch sites we planned to recruit. The panel members suggested that our sampling still did not fully reflect the range of local Healthwatch organisations in England. The panel members noted that the only standalone Healthwatch study site recruited was operating at county level and had an unusually large budget compared with the median Healthwatch core local authority funding (i.e. > £500,000 per annum). Therefore, the HIP suggested the recruitment of an additional standalone Healthwatch study site with the following characteristics:

-

a Healthwatch site operating in a smaller area than a county

-

a Healthwatch site with a smaller local authority core funding than Healthwatch Beecham.

The study team agreed that this gap was important to fill and at the end of July 2019 recruited Healthwatch Elmbridge, which met these inclusion criteria.

Ethnographic data collection

We carried out 75 days of face-to-face ethnographic fieldwork at the five local Healthwatch study sites during the period preceding the COVID-19 pandemic (August 2019 to March 2020). The two researchers Giulia Zoccatelli and Amit Desai carried out fieldwork at two study sites each (GZ: Healthwatch Beecham and Healthwatch Cherryburgh; AD: Healthwatch Dogwood and Healthwatch Elmbridge) and shared fieldwork at the fifth site (Healthwatch Ashton). Fieldwork at this latter site started in January 2020 because of recruitment issues. The researchers visited each Healthwatch site for meetings, informal conversations and formal individual interviews. The researchers also observed the daily work in Healthwatch offices and accompanied Healthwatch staff and volunteers to relevant daily activities and meetings. Although we observed interactions between Healthwatch staff and members of the public, and had interviewed and spoke informally to local residents and volunteers at all of our study sites, the principal aim of the study was to explore and enhance the practices and strategies of local Healthwatch itself. Furthermore, although communicating the voice of residents is a key aspect of Healthwatch work, data collection did not focus on residents themselves (other than volunteers), as they were not involved (with a few exceptions) in Healthwatch’s everyday work.

In line with the study’s ANT-informed theoretical approach, we collected the following three forms of data:

-

Ethnographic field notes, which included notes made when attending meetings (e.g. health and well-being board meetings, ICS meetings, overview and scrutiny committee meetings), accompanying staff and volunteers on data-gathering, outreach and inspection activities (e.g. enter and view visits, stalls at community events, hospital trusts, local libraries, engagement activities with local residents and specific patient cohorts), observing the daily work in Healthwatch offices and having informal chats with Healthwatch staff, volunteers and local stakeholders.

-

Eight-four individual semistructured interviews were carried out face to face and online both before and after the pandemic with employed staff of all levels, volunteers and local stakeholders, including local authority staff, ICS staff, councillors, representatives of local third-sector organisations and relevant provider representatives. Fifty-six interviews were audio- or video-recorded and transcribed for analysis. For a breakdown of the interviewees’ characteristics, see Table 8. Potential participants for one-to-one semistructured interviews were selected based on our observations and their involvement with Healthwatch work. External stakeholders were identified and introduced by Healthwatch staff at each study site. No-one refused to participate or withdrew from the study once they had agreed to participate. Interview transcripts were anonymised at the point of transcription and assigned a composite numeric identifier. A template of the interview schedules is included on the NIHR Journals Library website [URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/1705110/#/ (accessed 27 May 2022)].

-

Documentary evidence, such as internal documents, reports, health and well-being board minutes, and local Healthwatch and Healthwatch England strategy documents.

At each local Healthwatch site, we paid particular attention to the interaction between human and non-human actors (e.g. strategy documents, funding applications, data, reports) and observed the practices in which these interactions are embedded. The researchers took detailed hand-written notes during observations and interviews, which were then typed or written up into detailed field notes soon after. Observations included office work, meetings, the production and circulation of reports, the collection of data and everyday interactions between Healthwatch members and external actors, such as the CCG and local authority staff, NHS provider trusts, ICS staff and third-sector organisations.

Ethnographic data collection during the COVID-19 pandemic

On 23 March 2020, the government issued a broad range of regulations intended to curb the spread of COVID-19 in England, including ‘stay at home’ instructions. When this happened, we moved our ethnographic data collection online. Between March 2020 and January 2021, we carried out a total of 114 virtual contacts (i.e. observations, catch-up chats, interviews) with the five Healthwatch study sites. The researchers were able to start virtual fieldwork almost immediately after the issuing of the ‘stay at home’ regulations at four (Healthwatch Ashton, Cherryburgh, Dogwood, Elmbridge) out of five study sites. On request of the then chairperson of Healthwatch Beecham, fieldwork was suspended at this site between March 2020 and July 2020, as the organisation was appointing a new CEO and recruiting new trustees and members of the staff. Fieldwork at Healthwatch Beecham resumed in June 2020 and continued until January 2021, when fieldwork formally concluded in all sites.

During our virtual ethnography (March 2020 to January 2021) we collected the following four types of data:

-

Observational data about both internal and external Healthwatch meetings, including virtual team meetings, board meetings, health and well-being board meetings, overview and scrutiny committee meetings, ICS-level meetings and Healthwatch and external stakeholders annual general meetings. As almost all Healthwatch engagement activities moved online, researchers also observed virtual engagement events carried out by Healthwatch staff and volunteers at all five study sites, including engagement with specific patient cohorts, volunteers’ meetings and roundtables to discuss residents’ experiences and needs during the pandemic.

-

Catch-up conversations and interviews with Healthwatch staff, board members and other volunteers.

-

One-off interviews with external stakeholders, including CCG chief operating officers (COOs), directors of public health, local authority Healthwatch commissioners and contract managers, hospital staff, ICS officers and members of the public involved in Healthwatch engagement activities.

-

Documentary evidence, such as internal documents, reports, health and well-being board minutes and local Healthwatch and Healthwatch England strategy documents.

Ethnographic data collection at the five Healthwatch study sites was complemented by an expanded role and involvement of the HIP. Below we outline the work we conducted with the HIP and describe its changing role during the COVID-19 crisis.

Healthwatch Involvement Panel

The HIP was a panel of 15 local Healthwatch staff and volunteers recruited from 15 local Healthwatch organisations that were not case study sites. The HIP was conceived as a group that would help us analyse the ethnographic data from the five study-sites.

The purpose of the HIP was therefore to ensure:

-

the ongoing generalisability of our findings by ensuring that local Healthwatch staff and volunteers have the chance to jointly reflect on the data presented and provide ongoing interpretation and explanation based on their own experience

-

that our study outputs are meaningful to local Healthwatch staff and volunteers, therefore, improving the likelihood of beneficial change in the way in which Healthwatch currently operates

-

appropriate PPI in this phase through engagement with Healthwatch volunteers.

The operation of the HIP changed substantially after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. We adapted our approach so that the HIP functioned as a data source about local Healthwatch work during the pandemic (as opposed to a data analysis partner). This way of working deepened our engagement with individual HIP members and we were able to ensure that the three purposes listed above were achieved.

Healthwatch Involvement Panel member selection

We recruited 15 HIP members over the course of spring 2019. The members comprised a mix of Healthwatch staff and volunteers.

The first HIP by role included nine senior staff [CEO/COO/director/manager], two other staff and three volunteers (including one board member); one member could not attend. Over the course of the HIP, there were several minor changes in composition by role (but not by organisation). One member in the ‘other staff’ category became a manager, one CEO began attending instead of a member of his staff, one manager left his organisation and was replaced on the HIP by his successor and one CEO left her organisation (at which point a board member attended instead).

The principal inclusion criterion for sampling for the HIP was a ‘yes’ response to question 46 in the survey (‘Would someone in your Healthwatch like to participate in the Healthwatch Involvement Panel?’). We also included those who approached us by e-mail to ask to be further involved in the study. In addition to wanting representation from each English geographical region, we also took account of the varieties of organisational structure (i.e. standalone or hosted, hosted by a large or small host, contract or grant) and institutional landscapes. For instance, we wanted to include a Healthwatch organisation from Greater Manchester, given the unique nature of the region’s devolved health budget. These considerations (except geographical region) reflected the same criteria as those used to select our five study sites. All HIP members’ Healthwatch organisations received funding from the local authority through a contract and none received a grant. In Tables 2–4 we present the composition of the HIP by organisation type, English region and type of local authority.

| Organisational type | Number of people in HIP |

|---|---|

| Standalone | 9 |

| Hosted | 6 (of which 2 were hosted by an organisation and 4 or more Healthwatch contracts) |

| English region | Number of people in HIP |

|---|---|

| London | 4 |

| South East | 2 |

| South West | 1 |

| East | 2 |

| West Midlands | 1 |

| East Midlands | 2 |

| North West | 1 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 1 |

| North East | 1 |

| Local authority type | Number of people in HIP |

|---|---|

| County | 5 |

| Unitary | 6 |

| London borough | 4 |

| Metropolitan borough | 3 |

We prepared a shortlist of possible Healthwatch candidates for the HIP and presented this to our Advisory Group. The Advisory Group endorsed our suggestions and noted that the Healthwatch candidates proposed would together form a panel of sufficient range and diversity.

We organised five HIP meetings in total between July 2019 and February 2021. Two of these meetings were held in London. Details of the meetings are presented in Appendix 2. The final three meetings were held online. The final meetings discussed a combination of findings from the ethnographic work conducted at the five case study sites (phase 2) and from the semistructured interviews and small-group discussion (phase 3).

Phase 3: online interviews and small-group discussions with Healthwatch Involvement Panel members

Lessons emerging from COVID-19 pandemic

National restrictions to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic were imposed in England from mid-March 2020 onwards. As we described above, face-to-face fieldwork at our study sites was no longer possible. Similarly, we could no longer convene the HIP in person or hold long meetings with them as we had pre-pandemic. With the approval of our Advisory Group, we decided to modify the protocol to adapt the operation of the HIP to these new circumstances. Our fieldwork data showed that the pandemic was highlighting and catalysing existing Healthwatch practices and relationships. Understanding Healthwatch’s role in the pandemic response, therefore, represented a new and important part of achieving our study’s aims and objectives.

Alongside our ongoing data collection from the five study sites, we used the HIP as a key source of data about the work of local Healthwatch organisations during this time. This significantly expanded the role of the HIP in our study beyond its original scope as a partner in analysing data from the study sites. In addition, using the HIP in this way allowed us to access a broader range of insights from different organisations, as well as different roles, within Healthwatch. This change in HIP structure and role helped mitigate some of the challenges of conducting online fieldwork with our existing study sites. Data collection at these sites – although ongoing and valuable – had become less time intensive, and the benefits of the ethnographic method in conducting observations and informal conversations with study participants were attenuated in an online format. Moreover, as work had moved online, HIP members were accessible regardless of geographical location.

Over three panel meetings (in April 2020, October 2020 and February 2021), we developed a model for working with the HIP (see Table 10). We carried out semistructured individual or small-group online interviews with panel members 2 or three 3 in advance of a panel meeting. These interviews were recorded and transcribed. Amit Desai and Giulia Zoccatelli analysed the transcripts together and highlighted key findings and themes. At the online HIP meeting, the study team presented key themes emerging from both these interviews and small-group discussions and from fieldwork at the five study sites. We organised a plenary discussion around prepared questions based on the initial data analysis. The online HIP meeting was video- and audio-recorded and transcribed, the chat box saved and the transcript and chat box further analysed.

Production of emerging statements of ‘good practice’

We used data from the fieldwork at the five study sites (in phase 2), from the online interviews and small-group discussions (in phase 3) and from the JIFs (in phase 4) to draft a series of statements of ‘good practice’ about the practices and strategies used by local Healthwatch organisations to collect, organise and communicate patient and public needs to key stakeholders and the contexts where they might apply and work best. The emerging list of these statements of good practice was discussed and refined through an interactive process with HIP members and the participants at the local JIFs (see Phase 4: joint interpretive forums). In the last part of this interactive process (in July 2021) we circulated via e-mail a draft list of these statements to all HIP members and asked for their insights on their generalisability and usefulness. We obtained comments from five HIP members, which were incorporated to generate the final set of statements of good practice (see Chapter 6).

Phase 4: joint interpretive forums

In phase 4, we carried out a series of multistakeholder workshops in the format of JIFs (i.e. a type of group discussion aimed at encouraging ‘perspective taking’ and joint decision-making). 44 We organised five JIFs in total: one cross-site JIF (January 2021), which brought together representatives from each Healthwatch study site, and four local JIFs, one at each study site (May 2021–June 2021). The JIFs were attended by members of the Healthwatch team, Healthwatch board and key local stakeholders identified by each Healthwatch study site. Despite repeated attempts, we were unable to organise a local JIF with Healthwatch Ashton because of significant staff changes and work pressures at the organisation in May and June of 2021. All JIFs were held virtually over Microsoft Teams (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Cross-site joint interpretive forum

Our first workshop was held in January 2021 and was attended by up to three representatives from all five Healthwatch study sites, as well as the study team (Table 5 shows a breakdown of JIF participants by roles in their respective local Healthwatch organisation).

| Healthwatch organisation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashton | Beecham | Cherryburgh | Dogwood | Elmbridge | |

| Role | Manager | CEO | CEO | Manager | CEO |

| Volunteer co-ordinator | Office manager | Chairperson | Chairperson | Chairperson (volunteer) | |

| Healthwatch volunteer | Engagement manager | Board member | Research analyst | ||

The 2-hour workshop concluded the data collection at the five case study sites. The workshop aimed to allow participants to share information about key features of their Healthwatch organisation to enable discussion of early analytical themes (discussion was elicited with the aid of four deliberately provocative statements prepared by the research team based on our emerging findings) and provide a space for the presentation and discussion of preliminary findings from the study. Ahead of the workshop, we circulated a document outlining emerging themes from our analysis (see Appendix 4).

The cross-site JIF comprised three inter-related activities that were organised around a structure carefully planned to maximise participation and dialogue. These three activities were:

-

a discussion of pre-circulated Healthwatch profiles

-

a presentation of emerging themes from our fieldwork

-

a provocations activity.

We detail these activities in Appendix 3.

Local joint interpretive forums held at each Healthwatch study site

The local JIFs aimed to provide a platform for the sharing of perspectives between three broad groups of people (i.e. the study researchers, staff and officers of local Healthwatch study sites and key institutional stakeholders of these study site Healthwatch organisations). In May 2021, we held four local JIFs in total, each involving one of our study sites and their principal stakeholders, such as CCG, local authority, provider trust and VCSE representative (Table 6).

| Healthwatch | Participants by professional role |

|---|---|

| Beecham |

|

| Cherryburgh |

|

| Dogwood |

|

| Elmbridge |

|

We used local JIFs as part of the iterative process through which we generated statements of ‘good practice’ about the daily work of local Healthwatch organisations. To tailor the discussion to the needs and interests of our local Healthwatch study sites, in the planning phase (April 2021), we discussed with the Healthwatch CEO or manager at each study site the structure and content of the local JIFs. In dialogue with the Healthwatch CEO or manager, we developed three key questions that we used to guide the discussion during the meeting:

-

What evidence from Healthwatch about public and patient needs and experiences of local services do health and social care partners find most useful?

-

How can the collection and communication of such needs and experience be improved?

-

How can Healthwatch and its local health and care partners work better together to effect positive change for local people?

The CEOs or managers at all Healthwatch study sites were involved in planning the JIFs at their respective organisations and in the recruitment of participants among their health and social care partners. Participants for the JIF workshops were purposively selected by each local Healthwatch organisation based on their role in the organisation, relevance in Healthwatch daily work, participation in earlier phases of the study and their willingness and availability to participate. All four local JIFs were held remotely via Microsoft Teams and lasted between 90 and 120 minutes. Three local JIFs (i.e. Beecham, Dogwood and Elmbridge) were video- and audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis. Technical difficulties meant that the Cherryburgh local JIF was not recorded. Amit Desai and Giulia Zoccatelli took detailed notes.

Local JIFs were organised around two inter-related activities:

-

a presentation about Healthwatch history and statutory functions and about the aims, objectives, methods and outputs of the study

-

a plenary discussion of the current and potential practices used by Healthwatch to gather and communicate evidence about residents’ needs and experiences.

We describe these activities in Appendix 3.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement was an integral element throughout the study. The involvement of patients and members of the public in the study aimed to ensure that they could share their experiences about local Healthwatch organisations and contribute to the discussion about how Healthwatch might work better to serve their needs and interests.

In the planning phase, PPI shaped the formulation of the research questions, the study design and the plans for dissemination. During the study, patients and the public (including volunteers at local Healthwatch organisations) were involved in various ways across the four phases in an ongoing and embedded fashion:

-

In pre-study phase meetings, we involved 17 patients and members of the public to refine the research questions and the study design.

-

In phases 2 and 3, we involved local Healthwatch volunteers in the HIP. These Healthwatch volunteers helped us with the analysis of ethnographic data from the case study site during the first two HIP meetings and provided valuable insights about volunteers’ involvement in Healthwatch activities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

In phase 4, two Healthwatch volunteers attended the cross-site JIF and several Healthwatch volunteers (mainly board members) attended the local JIFs.

-

Our Advisory Group included two members of the public (recruited from the attendees to our pre-study phase focus groups).

-

In addition to this face-to-face PPI engagement, the study team established Twitter and Facebook accounts for the project through which we shared research activities and emerging findings.

Patients and members of the public who took part in the study were offered full support to contribute effectively to the study. This support included reimbursement of travel costs to face-to-face meetings, accommodation and subsistence (where appropriate) for HIP members, and training in qualitative methods during phase 2. In addition, we provided payments to PPI participants in accordance with INVOLVE guidelines.

In the sections that follow, we detail the four principal ways in which patients and the public were involved in our research.

Patient and public involvement meetings (pre-study phase, completed April 2017)

People involved

-

Meeting A: Research Expert Group at the Centre for Public Engagement, Kingston University (London, UK) and at St George’s University of London (London, UK):

-

Ten members of a standing ‘Research Expert Group’, including former and current NHS patients, carers, and former and current local Healthwatch volunteers.

-

-

Meeting B: local Healthwatch organisations and Healthwatch England, held at King’s College London (London, UK):

-

Nine people, including staff and volunteers from several London local Healthwatch organisations and Jacob Lant (Head of Policy and Partnerships at Healthwatch England).

-

Aims

-

To refine research questions, study design, objectives and pathways to impact and dissemination.

-

To identify the need for the research.

Methods

A presentation of the proposed study followed by general discussion.

Outcomes

The PPI meetings emphasised the need for this research, but rejected our initial proposal to focus exclusively on local Healthwatch organisation’s dementia-related work, which the group said would not be representative of the work of all local Healthwatch organisations in England. The group suggested that we adopt a broader focus by means of the phase 1 survey to account for the variability of each local Healthwatch organisation’s annually agreed priorities and identified variables. The group approved and refined our recruitment strategy for the HIP (see below) and suggested a Delphi phase (see Changes to protocol) to build consensus around ethnographic data analysis.

Healthwatch Involvement Panel (phase 2)

People involved

-

Four volunteers with local Healthwatch organisations that were not case study sites.

-

The HIP was chaired by Sally Brearley, who is an experienced patient and public representative and facilitator.

Aims

-

To involve Healthwatch volunteers, as well as staff, given that volunteers play a significant role in local Healthwatch organisations.

-

To ensure that volunteers, as well as staff, assist the analytical work of the study team based on their own experience and knowledge of local Healthwatch.

-

To look for points of similarity and difference with their own organisational practices to help build a broader picture of local Healthwatch activity across England.

-

To guide the research team with detailed suggestions on how to develop the ethnographic work in accordance with short- and medium-term fieldwork objectives.

-

To share with the research team their experiences of, and insights about, Healthwatch volunteering in the first year of the COVID-19 crisis.

Methods

All HIP members (including volunteers) took part in a qualitative research methods training delivered by the study team at King’s College London on 17 July 2019. At the first two HIP meetings, HIP members were presented with data from phase 1, the sampling strategy for the five case study sites and some emerging findings from the phase 2 ethnography. HIP members were asked to participate in activities and joint discussions in line with the aims articulated above. During the COVID-19 pandemic, HIP members (including volunteers) were invited to take part in two one-to-one interviews and one focus group to discuss their personal experience of the work of Healthwatch in this time. We conducted and recorded a total of six interviews with our volunteer HIP members and one focus group. The latter explored the experience of volunteering at Healthwatch during the pandemic. HIP member volunteers also took part in the activities and discussion during plenary HIP meetings.

Outcomes

The involvement of volunteers in the HIP helped us broaden our focus to include the experiences of non-staff members of local Healthwatch organisations. In addition, the involvement of volunteers provided an inclusive forum for engagement and joint reflection between staff and volunteers on the everyday practices and strategies of local Healthwatch work.

Joint interpretative forums (phase 4)

People involved

-

Of the 15 total participants at the cross-site JIF, two were volunteers.

Aims

-

To engage patients and the public as key stakeholders in joint reflection and interpretation of the findings from phases 1–3.

-

To discuss what forms of evidence and what dissemination strategies by local Healthwatch organisations would be more useful in affecting positive change for residents.

Method

The cross-site JIF involved one 2-hour virtual meeting involving three representatives from each study site (including volunteers). The meeting involved a mix of interactive activities, presentation of emerging research findings and joint discussion among participants.

Outcomes

The JIFs ensured that the patient and public voice was considered in the interpretation of study results, building the basis for collaboration to guarantee that patient and public voice was involved in the creation of resulting action at the local level.

Advisory Group (all phases)

People involved

-

Members of our Advisory Group included two patients and members of the public who were recruited among the participants of the PPI focus groups held in the pre-study phase.

Aims

-

To ensure that patient and public views are considered throughout the research process, along with those of academics, policy-makers and practitioners.

-

To ensure that patient and public perspectives contribute to the dissemination of research findings and recommendations.

Method

We held five 2-hour meetings over the course of the study, during which the study team consulted the Advisory Group about the sampling and recruitment of participants and research plans during the following months.

Outcomes

Patient and public involvement in the Advisory Group enabled us to consider the perspective of lay people on emerging research findings from the study and to tailor the planning of research outputs to various intended audiences.

Ethics approval

Following advice from our sponsor and the Research & Development Office at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust on behalf of King’s College London – and with the agreement of the NIHR – we initiated two separate ethics approval processes with separate protocols. Phase 1 was split from the later phases. This was to ensure that phase 1 (i.e. the survey) could proceed on schedule without being unduly delayed by the more complicated ethics approval processes required for ethnographic fieldwork at specific study sites.

The survey phase was judged to pose a minimal ethics risk by King’s College London and received Research Ethics Minimal Risk Registration (MRA-18/19-8494) on 14 September 2018.

Ethics approval for the rest of the study was organised through Integrated Research Application System and Health Research Authority processes (Integrated Research Application System number 252993). As the study was largely non-NHS based and did not require the recruitment of NHS patients, it was judged to fall outside the purview of NHS Research Ethics Committee review. Therefore, we proceeded to apply for King’s College London ethics review and this was granted by PNM Research Ethics Panel on 12 July 2019 (reference LRS-18/19-12587). The Health Research Authority granted approval on 5 August 2019.

Changes to protocol

The following three substantive changes to our original protocol were made and agreed with the NIHR Health and Social Care Delivery Research programme.

First, the addition of a fifth case study site was a result of discussions with our HIP in July 2019 and following the successful completion of our national survey in phase 1. We presented a sampling frame to the HIP together with anonymised details of the four Healthwatch case study sites we proposed would become the focus of our ethnographic fieldwork in phase 2. The HIP felt that limiting ourselves to four sites would inevitably mean not being able to explore an important additional type of Healthwatch organisation and asked us to carefully consider whether or not we could add a fifth site that would enable us to include this additional type of Healthwatch organisation. Following discussions among the research team and with the chairperson of our Advisory Group, we added a fifth site. This was acknowledged by NIHR in its response to our second progress report (August 2019):

Thank you for explaining the two separate ethical approvals and both KCL [King’s College London] and HRA [Health Research Authority] approvals are now uploaded to the MIS [Management Information System]. This is good news as you can now commence your fieldwork. Your Healthwatch Improvement Panel is providing value, includes volunteers and have recommended that you recruit a fifth case study site, which you have added.

Communication from the funder's monitoring department, 2019, personal communication

Second, we replaced our proposed Delphi study with the greater involvement of our HIP (in combination with the end of study JIFs). The purpose of a Delphi is to reach consensus. Through the early phases of our empirical fieldwork, however, we discovered that the huge (and unexpected) variability of the 150 Healthwatch organisations in England and their activities would make consensus around uniform principles of good practice difficult to achieve and, arguably, inappropriate (this is also reflected in the important addition of the fifth case study site as outlined above). ‘Good practice’ principles achieved via a Delphi process would also be difficult for local Healthwatch organisations to implement, given their diversity. Instead, we used the JIFs together with the enhanced involvement of the redefined HIP (with a membership of 15 Healthwatch organisations) to formulate, test and refine more nuanced, tailored and targeted principles of good practice, which would be better able to take account of the diversity of Healthwatch organisations:

The Research Team proposed that the Delphi process (phase 3) be replaced with regional workshops based on emerging research findings, which would involve the HIP and possibly existing regional networks. The Advisory Group agreed that a Delphi would not be suitable at that point in the project because it would truncate the emerging complexity. They felt that the research team’s proposal would increase the value of the research.

Advisory Group meeting minutes, 6 November 2019

Third, the decision to explore the impact of COVID-19 on Healthwatch practices was discussed and agreed with the Advisory Group at a subsequent meeting. In addition to the 13 one-to-one interviews already carried out with HIP members, the study team proposed continuing direct engagement with panel members through virtual small-groups discussions and/or semistructured interviews with panel members. The two remaining HIP meetings, originally scheduled for phase 2, were eventually carried out alongside these new forms of engagement in the months following the end of fieldwork in January 2021. At the meeting on 21 May 2020, the study team remarked that the expanded role of the HIP throughout the study would enable a more nuanced understanding of the variability of Healthwatch work, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Chapter 3 Data sources and modes of analysis

Some text in this chapter has been reproduced from Donetto et al. 40 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

In addition, some text in this chapter has been reproduced from Zoccatelli et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Phase 1

Data sources

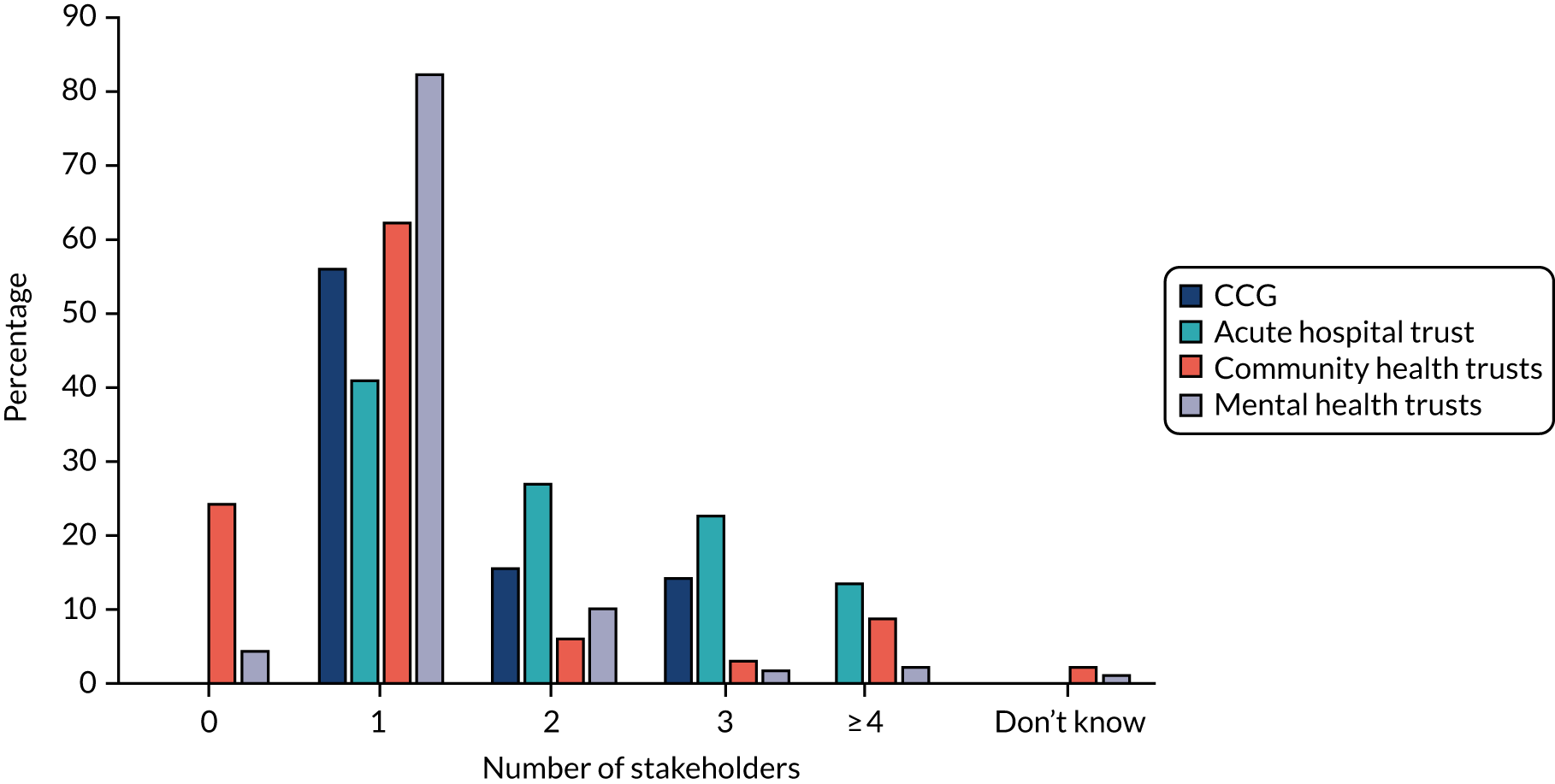

We received responses to our survey from 96 local Healthwatch organisations, achieving a response rate of 68% (note that eight Healthwatch organisations responded on behalf of two or more Healthwatch organisations that they operated as a combined organisation). Nineteen (19.8%) of our respondents were commissioned by county councils, 16 (16.6%) by London boroughs, 23 (24%) by metropolitan districts and 38 (39.6%) by unitary authorities. Table 7 presents a breakdown of the responses we obtained based on the geographical region.

| Region (na) | Total number of Healthwatch organisations | Number of survey respondents |

|---|---|---|

| East (1) | 11 | 9 |

| East Midlands (2) | 10 | 6 |

| London | 32 | 16 |

| North East | 12 | 6 |

| North West (2) | 23 | 12 |

| South East (1) | 18 | 15 |

| South West (1) | 15 | 11 |

| West Midlands | 14 | 13 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 15 | 8 |

| Total | 150 | 96 |

Modes of analysis

The survey data and analysis comprised descriptive statistics consisting of single variables and included frequency and percentage response distributions, measures of central tendency and dispersion measures, such as the range and standard deviation. All open comment responses were analysed using open coding and constant comparison. The survey was conducted using the Jisc online survey platform.

Phase 2

Data sources

Data sources include documents collected at the Healthwatch study sites [e.g. agendas and minutes from board meetings, committees and panel discussions, strategy documents, PowerPoint® presentations (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), leaflets, feedback forms], transcripts of video- and audio-recorded interviews, ethnographic field notes from informal conversations and observations at each study site and written ethnographic notes and transcripts of HIP meetings. In Table 8, we present a breakdown of fieldwork data sources (observations and interviews) at each of the five study sites. Table 9 outlines the number and roles of attendees at the five HIP plenary meetings.

| Healthwatch | Days of fieldwork pre pandemic (n) | Contacts (e.g. online observations, catch-up chats, interviews) (n) | One-to-one interviews (total): (n) | Formal interviews recorded and transcribed (n) | Interview participants (n) (recorded and transcribed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashton | 8 | 15 | 15 | 8 |

2 Healthwatch staff 2 Healthwatch board members 2 Healthwatch volunteers 2 VCSE representatives |

| Beecham | 17 | 26 | 28 | 18 |

8 Healthwatch staff 4 Healthwatch board members 2 Healthwatch volunteers 2 council staff (Healthwatch commissioner and council senior commissioning officer) 1 ICS programme director 1 CEO of neighbouring Healthwatch |