Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 08/1815/234. The contractual start date was in October 2008. The final report began editorial review in October 2012 and was accepted for publication in February 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimers

This report presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HS&DR programme or the Department of Health. If there are verbatim quotations included in this publication the views and opinions expressed by the interviewees are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HS&DR programme or the Department of Health.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Ridsdale et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Introduction to epilepsy in the context of the NHS

The stated policy of the NHS is to empower and support people with long-term conditions to understand their own needs and self-manage them. 1 In UK surveys of people with epilepsy (PWE), there has been a consistent demand for better provision of information. 2–5 One survey of patients with poorly controlled epilepsy found that one-third reported not being told what epilepsy was, > 90% wanted more information about the disease and ∼ 75% felt that they had not been given enough information about the side effects of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Over 60% wanted to talk to someone other than a consultant about epilepsy. 4 PWE (and their carers) frequently lack the confidence, however, to seek out such information. 6 To date, the NHS has not implemented a routine programme of education or rehabilitation for PWE.

The National Service Framework for Long-Term Conditions7 includes epilepsy as a long-term condition. Most adults with epilepsy experience paroxysmal loss of consciousness, and between attacks they do not have obvious signs such as weakness, rigidity or incoordination that might benefit from physiotherapy. Disability between attacks is likely to be cognitive, psychological and social and so is largely hidden. Perhaps this is why rehabilitation and advice on self-care have not generally been given a high profile in research or in practice.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) advocates self-management education for adults with epilepsy, aiming to achieve improvement in seizure frequency, increase individuals' understanding of epilepsy and adherence to medication, decrease fear of seizures and reduce hazardous self-management strategies. 8 A Cochrane review9 concluded that so far there is some evidence of benefit from self-management approaches, but there is insufficient evidence of improvement in health. Further research in this area has been recommended. 10,11

Poor epilepsy control is associated with unnecessary hospital admissions,12 which NHS policy aims to prevent. 13 Self-management education is designed, amongst other things, to reduce this, and providing information should receive high priority. 8 Improving health-related quality of life (HRQoL) for people with long-term conditions and ensuring that people feel supported to manage their conditions are NHS outcome targets. 13 In the UK, self-management programmes have been tested and adopted for other chronic conditions [e.g. diabetes: Dose Adjustment for Normal Eating (DAFNE),14 Diabetes Education and Self Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed (DESMOND),15 X-PERT;16 arthritis17,18].

What is the epidemiology of epilepsy?

The World Health Organization and the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) reported that epilepsy is the most common serious neurological condition, affecting approximately 50 million people worldwide. 19 With 0.6–1.0% of adults affected at any point in time,20–22 there are approximately 315,000 adults with epilepsy in England. The lifetime prevalence of seizures is 2–5%. 23 Epilepsy attacks are intermittent and their frequency and severity are variable. After diagnosis most people achieve control of attacks – studies show that 50–70% of PWE have had no attacks in the previous year. 24,25 Although these people have a long-term condition, most are able to participate in their social setting and adjust to the initial distress of a potentially stigmatising condition. 26–28

The impact of poor epilepsy control

On an individual level

The same studies found that 30–50% of PWE have had an epilepsy attack in the previous year and 40% have two or more seizures per year. 24,25 People with poorly controlled epilepsy face restrictions in activity, such as driving, which in turn affects work and social participation. Indeed, epilepsy alone accounts for 1% of all global disability, as measured by productive life-years lost. 29 Poor epilepsy control is also associated with higher rates of psychological distress, including anxiety and depression, and perceived stigma. 30,31

On acute hospital service use

One study24 found that 18% of PWE had attended a hospital emergency department (ED) and 9% had been admitted to hospital for epilepsy in the previous year. A different study32 found that 13% of PWE attended an ED for epilepsy, with a mean number of visits of 0.3. Shohet et al. 33 explored this issue using data from the 2004 Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF). 34 The QOF operates as a means of linking the income of English primary care general medical practices to care quality. As part of this, practices annually report the percentage of PWE (aged ≥ 16 years) registered on AEDs who were seizure free in the last 12 months. Shohet et al. found that poor epilepsy control measured according to the QOF34 was strongly associated with higher levels of emergency epilepsy-related hospitalisations. For those PWE-related emergency admissions, the mean number of admissions was 1.3. There is a gap in the evidence with regard to the frequency of ED use by PWE. However, use of health-care services is often not evenly distributed. 35 Some people attend infrequently or not at all, whereas others use services frequently.

Moore et al. 36 examined reattendance within a 12-month period to an inner London hospital ED amongst the general ED population. Reattendance was unusual – only 24% reattended, most doing so on one occasion only. In contrast, those with chronic conditions with episodic relapse reattend more frequently. International evidence shows that up to 67% of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)37 and 42% with asthma37 or diabetes38 reattend within a 12-month period.

The distribution of ED use is unknown in epilepsy. However, there is evidence that it is the most frequent neurological reason for emergency readmission into hospital. 39 If some people do attend EDs more frequently, there is a gap in the evidence about what their characteristics are, whether this service use is appropriate or preventable and, if so, by what means.

What is the association between poor epilepsy control, deprivation and acute hospital service use?

There is a strong correlation between the prevalence of epilepsy and social deprivation. 40 Using evidence derived from the QOF, Ashworth et al. 41 found that patients with epilepsy living in socially deprived areas were less likely to have had seizure control in the previous year. Gladman et al. 42 found examples of some neurological conditions that were better managed in major cites, particularly those with specialist rehabilitation services. The implication is that, for some conditions, specialist rehabilitation can and has achieved better outcomes. However, despite the presence of specialist services in English cities, we know of no evidence showing that better epilepsy control has been achieved. Neurologists see patients referred for diagnosis. After diagnosis there has not been a strategic approach to systematically identify people in the catchment area with recurrent seizures, for example by their attendance at EDs. Less than one-quarter of epilepsy-related ED attendees are referred for follow-up,43 and patients with poorly controlled epilepsy may not expect much or ask for follow-up. Majeed et al. 44 found that there are a greater number of hospital emergency admissions amongst those living in deprived areas in London. Reactive acute services are not linked with rehabilitation services.

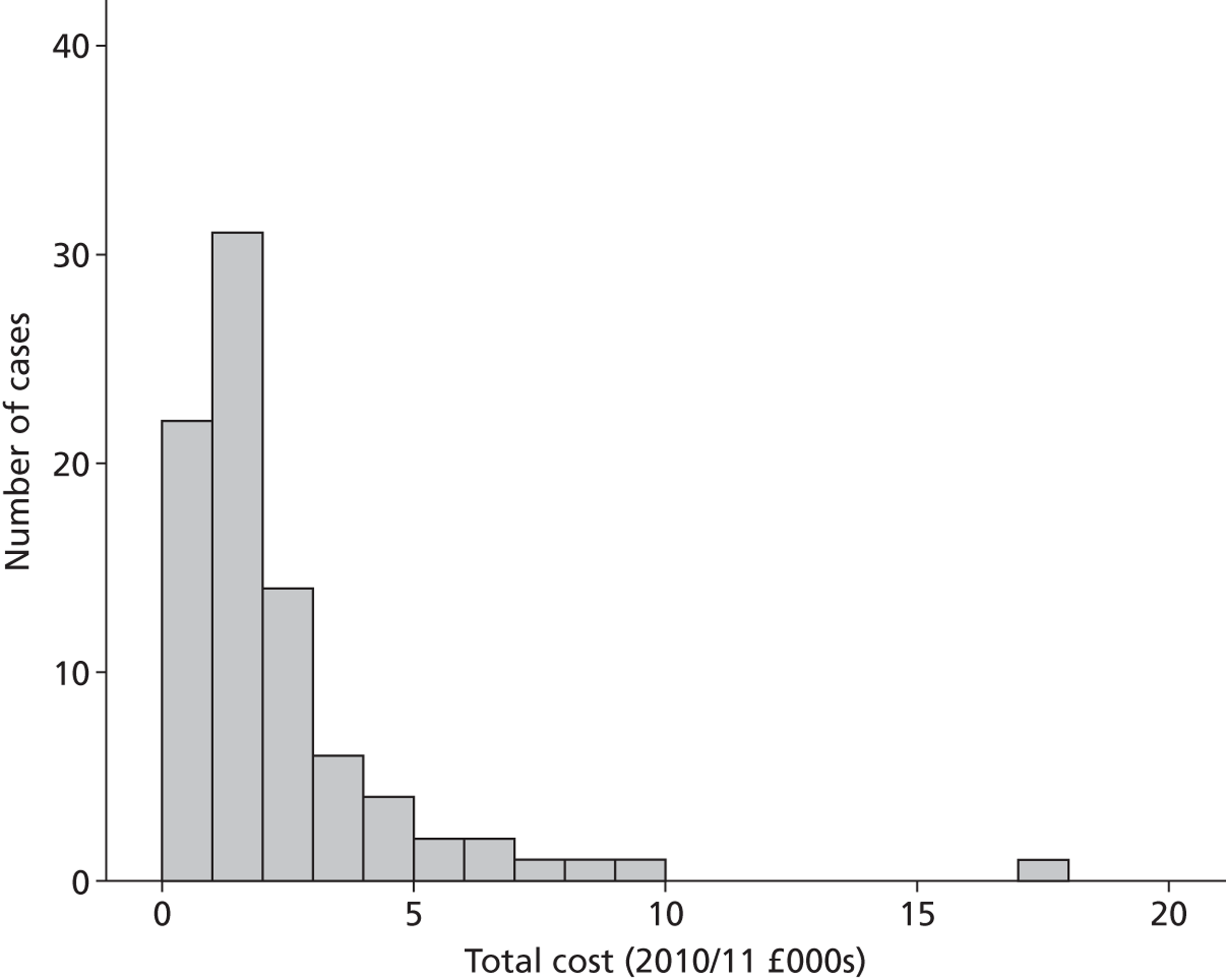

What is the consequence of poor epilepsy control in terms of NHS cost?

Epilepsy is costly. In the EU, the total cost of epilepsy was £15.5B in 2004,45 with the total cost per case being £2000–11,500. The largest element of health-care cost has often been found to be hospitalisations. 32,46 Six out of seven admissions for epilepsy are on an emergency basis. 47 Of all neurological conditions, epilepsy is associated with the highest rate of emergency readmissions within the same year. 39 In 2008–9, there were 37,140 NHS hospital admissions for which epilepsy was the primary diagnosis. 12 The average episode cost was £1514,48 indicating a total annual inpatient cost of £56.2M. There may also be significant indirect societal costs through lost/absent employment. 49

The costs are likely to be distributed unevenly because of differences in deprivation. 44 These costs are all estimated from research and national data sets with no in-depth research in specific areas of low or high service use. The health economic gain from any intervention may be greater when there are low epilepsy QOF scores, with high non-planned epilepsy admissions. On the other hand, when indicators suggest that epilepsy control is very poor, step-up care might need to be highly intensive. If the ratio of cost to benefit is low, new services may be deemed too expensive in the current economic climate.

There is a gap in the evidence with regard to the actual costs of ED use by PWE, particularly in deprived areas where use is likely to be high. As NHS commissioning becomes increasingly decentralised, this cost information will be important for commissioners. This will be weighed against the potential cost-effectiveness of any proactive intervention that is designed to improve the self-management of PWE.

What evidence is there with regard to usual care provided for people with epilepsy who attend the emergency department?

In England all PWE are expected to have a structured medical review of their epilepsy at least yearly by either a generalist or a specialist. 50 Evidence nationally is that 95% of adults on drug treatment have had their epilepsy reviewed in primary care in the last 15 months. 51 In contrast, there is no currently accepted care for those with established epilepsy who have visited an ED. NICE guidelines for epilepsy,50 however, indicate that, when seizures are not controlled or treatment fails, it is expected that a patient will be referred to tertiary services for assessment. The 2012 UK-wide National Audit of Seizure Management in Hospitals (NASH)52 showed that UK EDs initiated this for only one-third of PWE attending EDs.

The NASH also found that only a minority of PWE who had attended an ED had a basic neurological examination and that advice was not typically given to patients or their carers on seizure management. These findings suggest that there has been little change in care since a survey of usual ED care for PWE was carried out in the late 1990s by Reuber et al. 43 The NASH also found that there was great variability between hospitals, and some consensus is emerging that ED attendance is a lost opportunity to identify and help PWE who have poor control and self-management (Association of British Neurologists Conference, 2012, personal communication).

The need to know

All people with long-term conditions may benefit from some self-help education, especially when first diagnosed; however, this does not always occur. In a previous qualitative study of PWE53 one person said:

They didn't give me hardly anything (information), just sort of said, please take these tablets.

Female, 56 years

Another summarised the lack of information and support:

I was left high and dry.

Male, 59 years

In epilepsy the need is particularly great when the person's knowledge of epilepsy is low54 or when he or she experiences a negative psychological response to the diagnostic label or subsequent life events. The reaction to loss, whether it be to a disease with negative consequences or any other loss, has been characterised as including a range of responses such as fear, denial, anger, bargaining and depression as well as acceptance. 55 Negative psychological reactions to the diagnostic label of epilepsy, such as denial, may considerably limit an individual's ability to take on new information needed to manage his or her condition. Initial and subsequent experiences of seizures, with unconsciousness and possible injury, may trigger fear. This was described by people following other conditions involving a sudden loss of consciousness, such as subarachnoid haemorrhage, who also fear recurrence. 56,57 In this condition fear and catastrophic thinking has been conceptualised as a post-traumatic stress syndrome. 58 PWE, particularly those from minority ethnic groups, experience more than an internal struggle. Cultural beliefs in evil spirits may be associated with epilepsy, and this may have negative consequences for PWE and their quality of, and opportunities in, life. 59,60 When ethnic groups represent multiple small diverse minorities as they do in the UK, their special needs may not be recognised, as has been described for other conditions. 61

Our research group54 found that, after diagnosis by a neurologist, the median score for PWE using Jarvie et al.'s62 epilepsy knowledge questionnaire was 43 out of a maximum of 55, with a wide range of 12–51. Not having general education qualifications [General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE)], normally undertaken at 16 years in the UK, was associated with a lower knowledge of epilepsy (one-third of the general population have no qualifications). Compared with those in the highest knowledge of epilepsy quartile, those in the lowest quartile had a median score that was 12 points lower on the knowledge of epilepsy scale (26 vs. 48). 54 It is arguable that, after diagnosis, a course of learning should be tailored to the educational level of the PWE, with duration inversely related to educational attainment.

In another study we found that people with long-term epilepsy (average 23 years) did not have a higher median knowledge score (42.5) than those with newly diagnosed epilepsy. 63 As with those with new epilepsy, educational attainment was predictive of epilepsy knowledge. Specifically, those with no GCSEs had lower epilepsy knowledge scores (median score 39) than those with GSCEs or a higher qualification (median score 43). Lower epilepsy knowledge scores were also found in older people (37 vs. 43 in younger people), in those who left school earlier rather than later (40 vs. 43) and in those not belonging to an epilepsy self-help group (42 vs. 45). Multiple regression analysis showed that these predictors had independent effects and so the additive consequences of social disadvantage for knowledge of epilepsy are considerable.

Some people are affected more by their epilepsy than others. Like people with so-called ‘brittle’ diabetes, these people can have difficulties controlling their epilepsy. They may benefit from step-up care and advice, which might be called rehabilitation. The specific characteristics of those whose condition impacts on them more, in terms of distress to themselves and their families, reduced social participation and possibly inappropriate service use, need to be identified. The study investigators responded to a NHS call for research on rehabilitation. The research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and allocated to a self-help research group. We have used the terminology of self-help generally here, but the issue of specific needs that may require specific services will become clear in the results and will be taken up in the discussion.

What is self-management?

There is no universally agreed definition of self-management. The US Institute of Medicine proposed that self-management is ‘the tasks that individuals must undertake to live with one or more chronic conditions. These tasks include having the confidence to deal with medical management, role management and emotional management of their conditions’ (p. 57). 64

Self-management can be enhanced by ‘self-management programmes’. ‘Self-management programmes’, as defined by the Department of Health, ‘are not simply about educating or instructing patients about their condition. They are based on developing the confidence and motivation of patients to use their own skills and knowledge to take effective control over life with a chronic illness’. 65 Self-management therefore aims to enhance patients' self-efficacy by helping to solve identified problems, with benefits for patients' clinical outcomes and quality of life (QoL) and reduced hospital utilisation. 66

Epilepsy self-management can be conceptualised as a range of actions and skills that help PWE feel more confident about making decisions about their epilepsy, acting to improve seizure control, their use of medication and living with epilepsy. 49 Good self-management therefore involves PWE working in partnership with health-care professionals to decide the best treatment and care plan for their epilepsy and to assist them in developing confidence and problem-solving skills and strategies to manage the emotional and physical challenges of epilepsy. 49

What is rehabilitation?

A critical review has been undertaken of evidence from the UK to support the concept of developing a rehabilitation strategy. 6 A rehabilitation service is not simply physical therapy. Rather, it can comprise a multidisciplinary team of people who work together towards common goals for each patient, involve and educate the patient and his or her family, have relevant knowledge and skills and can resolve most of the common problems faced by their patients. Here the rehabilitation process aims to maximise the participation of the patient in his or her social setting and minimise distress experienced by the patient and distress and stress experienced by the patient's family and carers. 67 As epilepsy is common, it is important to identify those who will benefit more specifically from rehabilitation services.

How should needs be matched with services for people with epilepsy?

Is it self-care or rehabilitation?

Individuals have described their experiences of epilepsy movingly. 68–71 Once diagnosed with epilepsy, people vary in their ability to manage their condition and participate fully in daily life. The needs of people and the skills of care providers need matching,72 with the addition of an overarching strategy. 73 Health services can be conceptualised as promoting and providing for self-help and/or rehabilitation. This includes prevention of death and disability by the comprehensive and systematic care of established disease. This is sometimes more a vision than a reality; nevertheless, care models lie on a continuum, which attempts to provide a theory about how services might match people's needs.

What is the current evidence on epilepsy self-management?

Two Cochrane reviews9,10 found only three self-management studies targeting adults with epilepsy. 74–76 A fourth study77 was published later. Psychological interventions have also been reviewed. 11 None of the interventions was trialled in the UK. Helgeson et al. 75 reported the 2-day Sepulveda Epilepsy Education (SEE) programme for adults in the USA. The Modular Service Package Epilepsy (MOSES)74 was evaluated in Europe and offered over 2 days. Olley et al.'s76 psychoeducational therapy programme was run in Nigeria. Pramuka et al. 77 trialled six weekly sessions of a psychosocial self-management programme in the USA.

Differences in study methodology prevented a direct comparison of findings in a meta-analysis. 18 Of the four self-management approaches for adults, MOSES74 has been evaluated in the greatest number of participants, across 22 epilepsy centres (mainly specialist epilepsy hospital units). Its evaluation was the most robust, with benefits in terms of improved knowledge about epilepsy, better seizure control and coping, and greater tolerance of, and fewer reported, side effects of AEDs. MOSES was delivered on an inpatient basis to groups of PWE by a pair of educational facilitators drawn from a medical/nursing and psychosocial background. An inpatient hospital course might facilitate access for PWE who cannot predict when they will have seizures, but would be costly to provide. In the current economic climate it is likely that NHS interventions need to be developed on an outpatient basis. Courses or sessions might also be targeted only at those PWE who have the greatest needs, in terms of poor epilepsy control and high service use.

What is the current evidence of the impact of epilepsy nurse specialist-led advice on self-management for people with epilepsy in ambulatory care?

Bradley and Lindsay9 reviewed specialist education and advice for neurological conditions and identified three previous trials of the impact of epilepsy nurses, two undertaken by our own group. 54,63,78 These trials were undertaken in areas that were not deprived. As most people achieved good seizure control, the trials focused on outcomes such as satisfaction with information provided, psychological distress and knowledge of epilepsy. In the trial of an epilepsy nurse specialist (ENS)-led self-management intervention for people with chronic epilepsy, there was improved patient satisfaction with the information provided and reduced depression scores in the group who had experienced no recent seizure. 53,63,79 Again, it was PWE with lower educational levels who were found to have the least knowledge of epilepsy. 63 In the trial of patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy, those who were in the lowest knowledge quartile at baseline improved their knowledge of epilepsy following an ENS-led self-management intervention. 63

A small US study with ‘hard’ outcomes

There is evidence from a US study80 that a nurse-led intervention can help patients manage their epilepsy and reduce hospital admissions. Nurses led on helping patients who had been hospitalised for epilepsy to manage their condition, and this was associated with a reduction in seizure-related readmission at 90 days (0/23 patients in the intervention group and 3/19 in the control group). This was a small but interesting trial. Results from some case series also suggest that nurse interventions may reduce ED visits and admissions. 81,82

An epilepsy nurse specialist-led self-management intervention in an area of poor epilepsy control

From the evidence, the potential for demonstrating change in outcomes and cost-effectiveness from ENS-led rehabilitation might be greater in the context of high levels of deprivation, poor epilepsy control and less social participation. We planned to achieve this by carrying out a study with patients in three London boroughs, namely Lambeth, Southwark and Lewisham. These boroughs are in the top 10% of English authorities for deprivation. 83 The mean level of practice-reported seizures in 2007 was lower (50%) than the national average (60%) [Mark Ashworth, general practitioner (GP) and Clinical Senior Lecturer, Department of Primary Care and Public Health Sciences, King's College London, 22 December 2011, personal communication]. There are three hospitals in this area: one lies in the north of Lambeth and Southwark, one in the south and one in Lewisham. One hospital had two ENSs who previously only saw patients referred by neurologists and neurosurgeons. They co-ordinate a multidisciplinary team approach to managing problems experienced by patients. The other hospitals had no ENSs. A sample of patients with poor epilepsy control could be identified by recruiting ED attendees for epilepsy at each hospital. In a previous audit we found that one out of 60 attendances were for epilepsy, with 40% of patients being admitted. The plan was for the nurses to offer clinic appointments following discharge for those PWE attending the ED for epilepsy, and lead on providing advice and support. The other hospitals would continue to provide usual medical care.

Aims

The aims of the study were to provide:

-

a description of people attending the ED for epilepsy, their use of the ED and their psychological state, knowledge of epilepsy, perception of stigma, QoL and needs

-

an economic evaluation of people attending the ED for epilepsy to determine the cost both for PWE and for society

-

quantitative evidence from a comparison of two groups, one receiving treatment as usual (TAU) and the other receiving TAU and an ENS-led self-management intervention

-

qualitative evidence of PWE's experiences of emergency services, the way in which services meet/do not meet their needs and their explanations of the process of, and rationale for, attendance

-

qualitative evidence from the group receiving the ENS-led self-management intervention

-

an economic evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of services both for an ENS-led self-management intervention and comparison groups before and after the ENS-led intervention.

Justification for use of mixed methods, staging and reporting in three streams

We will describe the work in three major streams: the first used quantitative methods, the second used qualitative methods and the third used health economic methodology. We gave priority to identifying those PWE with poor control and evaluating step-up care. There is some evidence that use of emergency medical services may be a proxy for poor control. Currently, there is comparatively little evidence on the characteristics of PWE who attend EDs, and no evidence from the PWE themselves about what the process is. In the current climate of recession the Department of Health and hospital medical services have strong drivers to identify the reasons why six out of seven epilepsy admissions are unplanned, to reduce these admissions, and to provide evidence on what the costs of reactive and proactive services might be.

We therefore used mixed methods to describe not only the demographic, psychological and social characteristics of PWE who use EDs but also their views of why and how they use EDs. We planned to describe not only whether an ENS-led self-management intervention reduces the use of EDs but also whether PWE regard the intervention as useful or as not useful and why.

To avoid the interviews contaminating the responses to the questionnaires, the qualitative component was scheduled to be carried out after the return of the final questionnaires, 1 year after recruitment of the participants. This sequence has a methodological advantage in terms of the prevention of contamination. We realise that the results of neither of the two enquiries about reasons for calling the ED and participants' views of the intervention can inform the intervention retrospectively; however, the results can be used to inform future interventions, which might as a consequence be designed differently.

Chapter 2 Quantitative component

We recruited people with established epilepsy from the EDs of three inner London hospitals and conducted a non-randomised trial (ISRCTN06469947). Those recruited from two of the hospitals formed a TAU cohort, whereas those attending the ED of the remaining hospital were offered the outpatient ENS-led self-management intervention plus TAU. Participants in both cohorts were assessed on recruitment (baseline) and then at 6 and 12 months following recruitment.

This chapter is split into two sections. In the first section we present the results from the baseline assessments, which occurred before any differences had occurred in the care given to the two cohorts. Results from this assessment are used to describe the characteristics, needs and previous service use of PWE attending EDs for epilepsy.

In the second section we describe the effects of the ENS-led self-management intervention by comparing the psychosocial outcomes and subsequent ED use of the two cohorts, adjusting for differences between them at baseline.

STUDY 1: THE CHARACTERISTICS OF PEOPLE WHO ATTEND HOSPITALS FOR EPILEPSY

The information collected from the baseline assessments was used to answer four specific questions concerning the characteristics, needs and previous service use of PWE attending EDs for epilepsy:

-

What is the pattern of use of EDs by PWE?

-

What are the characteristics of this population?

-

What standard of outpatient epilepsy care have they been receiving?

-

What factors are most associated with frequent ED visits (cross-sectional analysis)?

Methods

Recruitment

From May 2009 to March 2011 we prospectively recruited PWE attending the EDs of three London hospitals because of their condition. The hospitals were King's College Hospital (KCH), St. Thomas' Hospital (STH) and University Hospital Lewisham (UHL). These are inner London facilities with comparable EDs. Each is consultant led and offers a 24-hour service with full resuscitation facilities. Together they serve 1 million residents in the surrounding London boroughs of Southwark, Lambeth and Lewisham. 84 The prevalence of epilepsy in adults in this population is 0.51%. 85

Each of the boroughs has high levels of social deprivation and ethnic diversity, similar rates of emergency epilepsy admissions and a level of epilepsy control that is worse than the national average. 85,86 Epilepsy control is defined here as the percentage of PWE prescribed AEDs in the local population who were seizure free in the previous 12 months as recorded by primary care doctors in the boroughs as part of England's 2009–10 QOF. 85 According to this measure, 68% of PWE in the three boroughs were seizure free during the period of recruitment, whereas the national average was 74%.

Inclusion criteria

People with epilepsy may visit a hospital ED for a variety of reasons. These include for acute seizures, status epilepticus and seizure-related accidents (e.g. head injuries, burns) and causes (e.g. rash from anticonvulsants). To identify PWE visiting the ED with a wide range of presentations, we convened an expert panel of two emergency medicine and two neurology consultants to identify those symptoms and diagnoses by which the three EDs classified attendances that they considered potentially indicative of an epilepsy-related attendance. During the recruitment phase a research worker (AN) and a neurology consultant (LR) reviewed for eligibility ED records of patients falling into these categories.

People with established epilepsy were invited to participate in our study as long as their attendance was caused by their epilepsy and they were aged ≥ 18 years, had had epilepsy diagnosed for ≥ 1 year, could independently complete questionnaires and had no life-threatening or serious comorbidity (e.g. psychosis). For the purposes of the subsequent trial phase of the project, we also excluded those who had seen an ENS in the previous year, those referred to neurology for an outpatient appointment by the ED and, to maximise the comparability of patients in the two cohorts, those visiting the ED who did not reside within the local boroughs of Southwark, Lambeth or Lewisham.

Invitation letters were sent to eligible PWE shortly following their discharge from the ED. The Joint South London and Maudsley and the Institute of Psychiatry NHS Research Ethics Committee approved the study (08/H0807/86). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Assessment

On recruitment, during a face-to-face appointment with a researcher (AN), participants completed validated generic and epilepsy-specific self-report questionnaires. 62,87–92 These included measures of their epilepsy-related ED visits and care over the previous 12 months, epilepsy-related QoL, seizure frequency, medication management skills, psychological distress, felt stigma, confidence in managing epilepsy (i.e. mastery) and epilepsy knowledge. Table 1 details the specific measures used.

Information collected on participants' epilepsy was restricted to that which was recorded in their primary and secondary care medical records. Deprivation levels were estimated by linking their postcodes to the Index of Multiple Deprivation. 93 As noted by previous studies,43,103,104 information on the seizures that led to the participants' ED attendances was not consistently reported in their ED records and so we do not present this information here.

| Purpose | Assessments used ina | Measure | Information | Range/interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epilepsy characteristics | 1 | Medical records | Information collected on participants' epilepsy was restricted to that recorded in their medical records, which were coded using the ILAE's 1989 classification system94 | – |

| Social deprivation | 1 | Index of Multiple Deprivation93 | Deprivation was estimated by linking participants' home postcodes to the Index of Multiple Deprivation | – |

| ED and health service use | 1, 2, 3 | Client Services Receipt Inventory95 | Examines contact (proportion, appointments number, duration) with different services for epilepsy, including the ED, neurology, ENSs, other hospital outpatient services and primary care doctors and nurses, and medications prescribed in the previous 12 months for assessment 1 and the previous 6 months for assessments 2 and 3 | – |

| Seizure frequency | 1, 2, 3 | Frequency scale96,97 | How many attacks have you had in the last 12 months (assessment 1)/6 months (assessments 2 and 3)? | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, ≥ 10 |

| Seizure severity | 1, 2 | Liverpool Seizure Severity Scale 2.087 | Patient rates ‘most severe seizure/s’ in the previous 4 weeks against 12 items concerning loss of consciousness, confusion, postictal sleepiness, time to recovery and injury. Linear transformation of sum of responses produces a total score | Range 0–100; higher = increasing severity |

| Psychological distress | 1, 2, 3 | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale98 | Patient rates experience of seven anxiety and seven depression symptoms in the previous week. Symptoms of anxiety or depression relating also to physical disorders, such as headaches, insomnia, anergia and fatigue, are excluded | Range 0–21 for each scale; higher score = more disturbance. For each scale, 8–10 = borderline, ≥ 11 = valid case88 |

| QoL | 1, 2, 3 | Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory-1092 | 10-item measure of QoL in the previous 4 weeks. Covers epilepsy effects (memory, physical and mental effects of AEDs), mental health (energy, depression) and role functioning (seizure worry, work, driving, social limits) | Range 10–50; higher = lower QoL |

| Felt stigma | 1, 2 | Stigma of Epilepsy Scale99 | Patients asked to what extent, because of their epilepsy, they feel that some people (1) are uncomfortable with them, (2) treat them as inferior, (3) would prefer to avoid them. Each item is responded to using Taylor et al.'s90 scale: 0 = ‘not at all’; 1 = ‘yes, maybe’; 2 = ‘yes, probably’; 3 = ‘yes, definitely’ | Range 0–9; higher = more stigma; 0 = no felt stigma, ≥ 1 = stigmatised |

| Medication management | 1, 2, 3 | Epilepsy Self-Management Scale – medication subscale89b | Examines the frequency, over the previous 12 (assessment 1)/6 (assessments 2 and 3) months, with which patient performed behaviours associated with optimum adherence. Covers intentional and non-intentional non-adherence. Items rated on a scale ranging from ‘never’ to ‘always’ | Range 10–50; higher = better management |

| Information satisfaction | 1, 2 | Satisfaction with Information about Medicines Scale100 | 17-item scale asks patients to rate the amount of, and satisfaction with, medication information received. Items 1–9 address action and usage of their AEDs and 10–17 concern the potential problems of their medications. Items rated on a scale ranging from 1 = ‘none needed’ to 5 = ‘too much’ | Range, post recording, 0–17; higher = more satisfied |

| Epilepsy knowledge | 1, 2 | Epilepsy Knowledge Profile – General62 | 55-item true/false questionnaire (34 medical knowledge items, 21 social knowledge items). Social knowledge scale contains items on first aid for epilepsy | Range: medical knowledge scale 0–35, social knowledge scale 0–21; higher = more knowledge |

| Mastery | 1, 2, 3 | Epilepsy Mastery Scale101 | Epilepsy-specific six-item adaptation of Pearlin and Schooner's102 internal vs. external locus of control measure. Patients rate extent to which they perceive their epilepsy as being under their control. Example of item: ‘Sometimes I feel helpless in dealing with my seizures’. Items rated on a scale ranging from 1 = ‘strongly agree’ to 4 = ‘strongly disagree’ | Range 6–24; higher = greater perceived mastery |

The standard of epilepsy care reported to have been received by each of the participants in the 12 months preceding recruitment was compared with the following three NICE criteria for good epilepsy care. 8 The first concerns access to specialist services: ‘[i]f seizures are not controlled and/or there is diagnostic uncertainty or treatment failure, individuals should be referred to tertiary services . . . for further assessment’ (p. 44). The second relates to medical review: ‘[a]ll individuals with epilepsy should have a regular structured review . . . this . . . should be carried out at least yearly by either a generalist or specialist, depending on how well the epilepsy is controlled’ (p. 44). The third concerns prescribed AEDs: ‘individuals should be treated with a single antiepileptic drug . . . wherever possible’ (p. 56). The Clinical Standards Advisory Group104 further recommends that ‘Monotherapy should be the rule . . . in at least 50% of those with established or severe epilepsy’ (p. 44).

Statistical analysis

Representativeness

To examine how representative our sample was of the population from which it was recruited, the characteristics of the sample were compared with those of the group with established epilepsy who attended the EDs for epilepsy during the recruitment period but who were not recruited. The recruited sample was also then compared solely with those people who were eligible but who declined participation.

Information on the non-recruited patients' characteristics was limited to that available in their ED records, as wider access to their medical records was not ethically permissible. We were able to compare the age, gender profile, deprivation status and ethnicity of participants in the groups, as well as the clinical urgency of the ED presentation as measured by the triage category that each patient was assigned to on arrival at the ED. 105 To permit an examination of the recruited and non-recruited groups' epilepsy and care generally, we also extracted information recorded by their primary care practices for the 2009–10 QOF. 106

As noted in the previous chapter, the QOF operates as a means of linking the income of primary care practices to care quality. For epilepsy, participating practices annually report (1) the percentage of PWE (aged ≥ 16 years) registered on AEDs who were seizure free in the last 12 months (indicator 8); (2) the percentage of PWE on AEDs who had a medication review in the last 15 months (indicator 7); and (3) the percentage of PWE on AEDs with a record of seizures in the last 15 months (indicator 6). There is variability between practices on these criteria. 41

Mann–Whitney, Kruskal–Wallis and chi-square tests were used to compare groups on the variables noted. Because information in ED records is often incomplete, each analysis was restricted to those without missing data. When missing data exceeded 5%, those with and without missing data were compared.

Pattern of emergency department use, attendees' characteristics and standard of epilepsy care

Descriptive statistics described the level of ED use, the standard of epilepsy care and the characteristics of the recruited patients. When data were not normally distributed, the median and interquartile range (IQR) were used to describe central tendency.

Association between level of previous emergency department use and baseline factors

Regression analyses were used to estimate relationships between the frequency of previous ED use reported at baseline and the other baseline variables. Coding of the variables is described in Table 2.

Unadjusted regression models were first run to determine the relationship between each of the baseline measures and the level of ED use in the previous 12 months. Variables significantly associated with ED use were then simultaneously entered into multiple regression analysis to identify parsimonious predictors.

Overdispersion and exclusion of zero values in baseline ED visit data meant that zero-truncated negative binomial regression (NBR) was the most appropriate regression technique. 35 Relative ED use is described in incidence rate ratios (IRRs), with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The likelihood ratio test examined overdispersion and the Wald statistic provided the statistical significance of variables.

All p-values are two-sided and alpha set at 5%. Analyses were performed using Stata 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), SPSS 17.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and StatsDirect 2.7.8 (StatsDirect, Cheshire, UK).

Results

Participants

During the recruitment period, 943 people attended the EDs because of established epilepsy. Of these, 315 were eligible and 85 (27%) were recruited. We found no significant difference in the acceptance rates between ED sites.

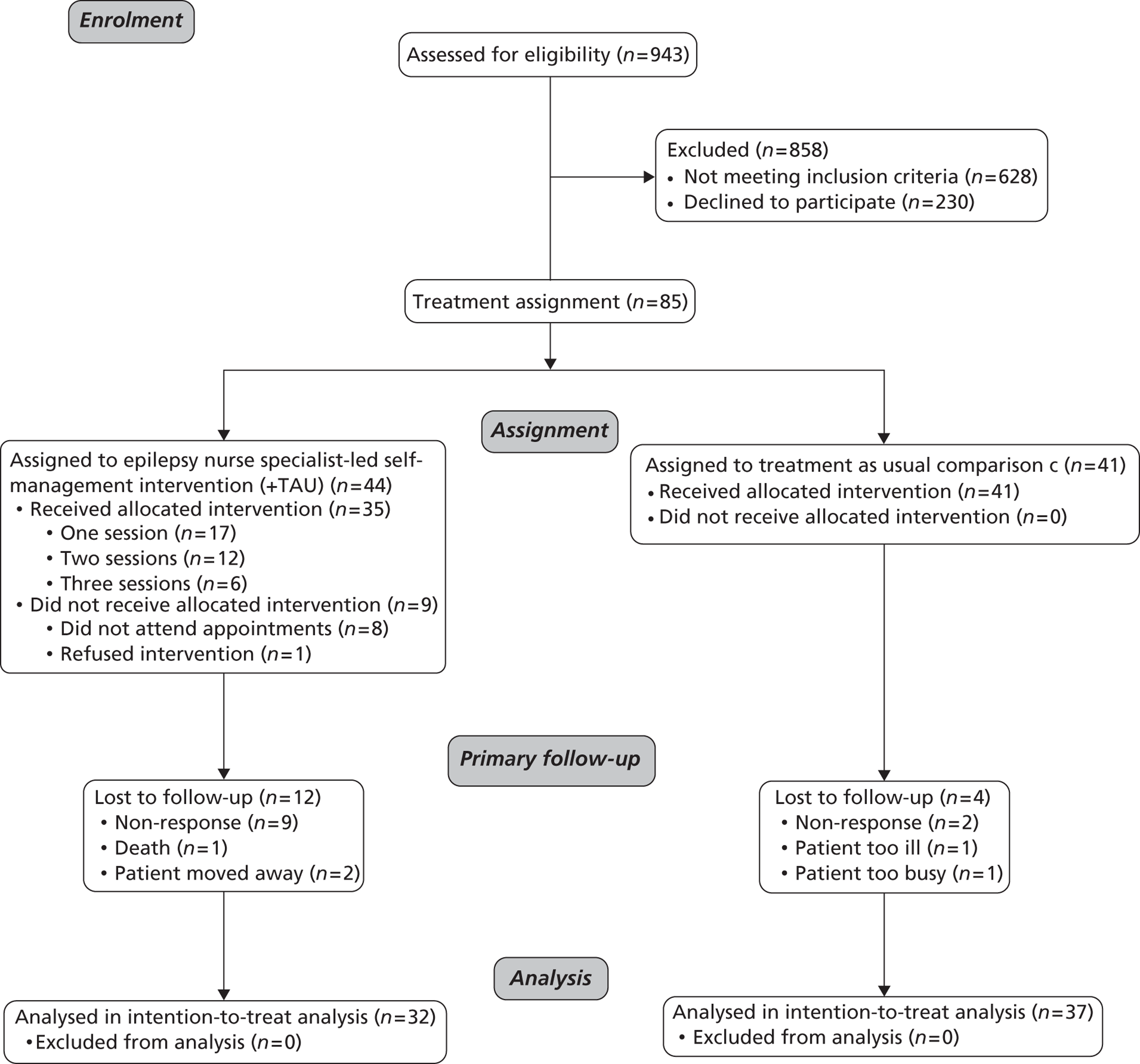

Reasons for exclusion were not living within one of the local boroughs served by the hospital (n = 352, 56.1%), unable to independently complete questionnaires (n = 115, 18.3%), having a serious comorbidity (n = 83, 13.2%), having consulted an ENS < 1 year previously (n = 43, 6.8%) or having been referred to neurology by the ED (n = 35, 5.6%) (Figure 1).

For those recruited, the median age at which epilepsy was diagnosed was 19 years (IQR 13.0–32.5 years) and the median time since diagnosis was 11 years (IQR 6–28 years). In total, 34% lived in areas with a deprivation score in the most deprived quintile for England. 84

The longstanding nature of the participants' diagnoses meant that their epilepsy tended to be described in their wider medical records according to the ILAE's older 1989 system of classification. 94 Specifically, 37 patients (43.5%) were recorded as having experienced both focal and generalised seizures, 37 (43.5%) only generalised seizures and six (7.1%) only partial seizures; for five patients (5.9%) no seizure type was recorded.

The recruited sample was representative of the population from which it was drawn (Table 3), with no significant differences being found between those who were recruited and those who were not recruited. However, when compared solely with those who were eligible but who declined participation, a significant difference was that more white than non-white ED attendees agreed to participate (p < 0.03).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of participant recruitment, treatment allocation and retention.

| Factor | PWE attending the ED who consented to participate (n = 85) (group A) | PWE attending the ED who were not eligible to participate (n = 628) (group B) | PWE attending the ED who were eligible but who declined to participate (n = 230) (group C) | Difference (95% CI) group A vs. group B | Difference (95% CI) group A vs. group C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 41.1 (16) | 40.9 (17) | 38.8 (16) | −0.27 (−4.11 to 3.57) | −2.36 (−6.37 to 1.65) |

| Males, n (%) | 45 (52.9) | 349 (55.6) | 140 (60.9) | −0.03 (−0.14 to 0.08) | −0.08 (−0.20 to 0.04) |

| Median triage priority (IQR)a (1 = see immediately, 5 = non-urgent) | 3 (3–3) | 3 (3–3.75) | 3 (3–3) | 0 (0 to 0) | 0 (0 to 0) |

| White ethnicity, n (%)b | 51 (60) | 270 (55.1) | 78 (45.6) | −0.05 (−0.16 to 0.07) | 0.14 (0.01 to 0.27)c |

| Median deprivation score (IQR)a (score closer to 1 = more deprivation) | 32.1 (24.3–37.7) | 29.5 (21.1–37.0) | 32.7 (28.7–38.3) | 2.3 (0.01 to 4.67) | −1.8 (−3.92 to 0.31) |

| Median score QOF indicator 8 (IQR)d (higher = more seizure free) | 70.4 (61.1–78.2) | 71.4 (62.2–78.8) | 67.9 (56.4–77.8) | −0.9 (−4.1 to 2.1) | 2.5 (−1.1 to 6) |

| Median score QOF indicator 7 (IQR)d (higher = better epilepsy care) | 96.2 (93.3–100) | 95.7 (93.5–100) | 96.8 (94.6–100) | 0 (0.0 to 0.7) | 0 (−1 to 0) |

| Median score QOF indicator 6 score (IQR)d (higher = better epilepsy care) | 97.2 (94.1–100) | 96.5 (93.3–100) | 97.1 (94.1–100) | 0 (0.0 to 1.1) | 0 (−0.3 to 0.4) |

Pattern of use of emergency departments by people with epilepsy

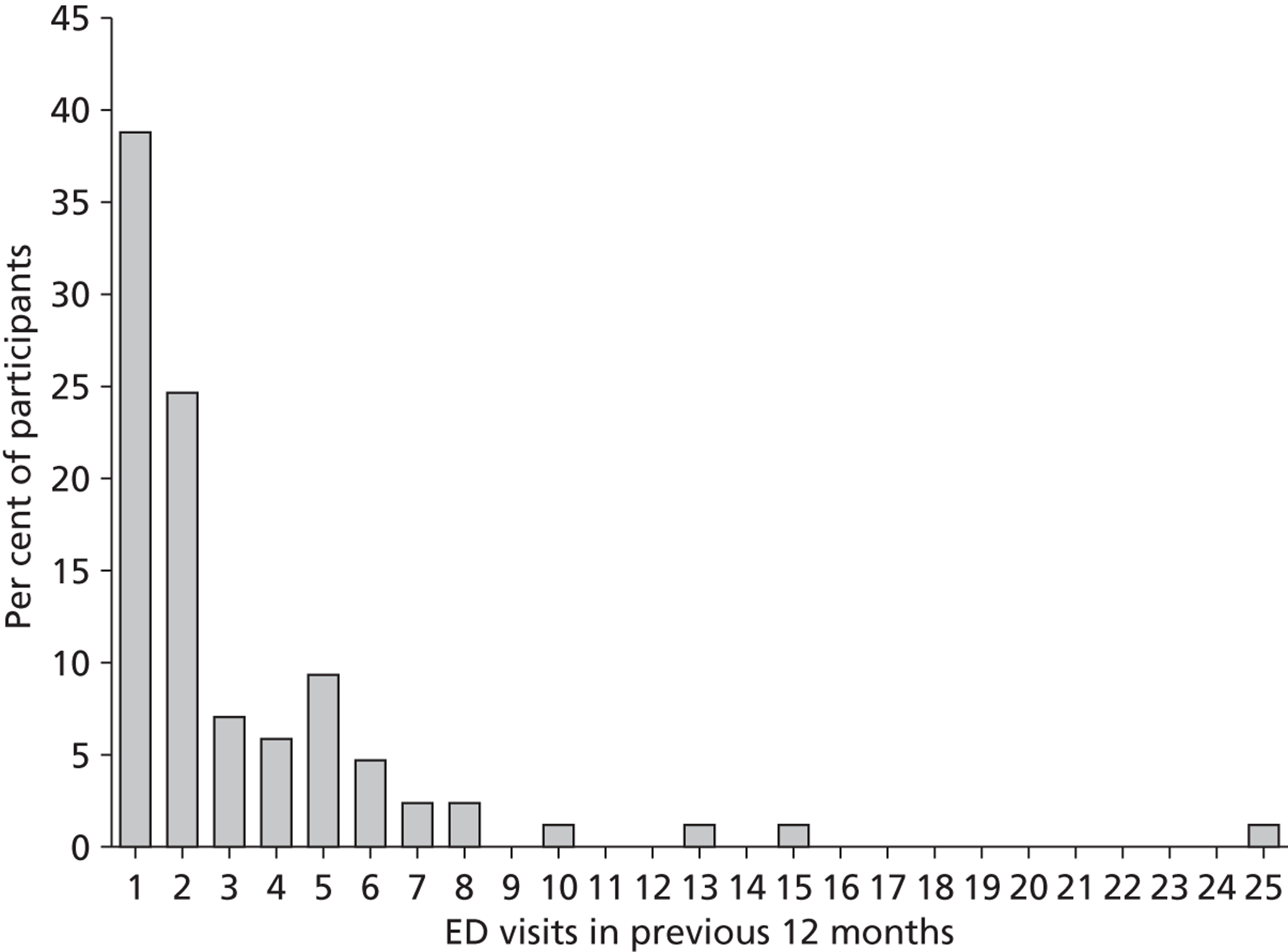

In the 12 months before the baseline assessment, the 85 PWE recruited from the EDs had together made 270 ED visits for epilepsy. Frequency of ED use amongst these PWE showed a strong positive skew (Figure 2). The median number of visits in the previous year was two (IQR 1–4, range 1–25), with 61% of participants reporting reattendance within 12 months. Specifically, 33 (39%) participants attended only once, 21 (25%) attended on two occasions and the remaining 31 (36%) attended on three or more occasions. This last group accounted for 72% of all ED visits. The median number of visits made by this subgroup was five (IQR 4–7).

Characteristics of people with epilepsy attending emergency departments

Seizures

All of the participants had experienced an epileptic seizure in the previous year. In total, 39 (46%) of the participants had experienced from two to nine seizures and 36 (42%) participants had experienced ≥ 10 seizures in the previous 12 months (Table 2). The median seizure severity score for the 54 (64%) participants who had a seizure in the 4 weeks preceding the baseline assessment was 57.5 (IQR 43.1–72.5).

Quality of life

Epilepsy-specific QoL, as represented by the mean total 10-item Quality of Life in Epilepsy (QOLIE-10) score, was 26.30 (SD 7.95). Higher scores on this measure indicate poorer QoL, and participants who reported having visited an ED the most in the previous 12 months reported the worst QoL. The mean QoL score was 28.30 (SD 8.7) for those PWE who had visited an ED on three or more occasions in the previous 12 months, 26.04 (SD 7.9) for those who had attended on two occasions and 24.57 (SD 6.9) for those who had visited once only.

Psychological distress

In total, 29 participants (34%) had a ‘case’ level of anxiety and/or depression, 28 (33%) had a ‘case’ level of anxiety and eight (9.4%) had a ‘case’ level of depression. Days since last seizure were not significantly associated with anxiety or depression score.

FIGURE 2.

Histogram of the number of participant-reported ED attendances in the previous 12 months. The distribution shows a positive skew (+3.40). In total, 39% of participants attended an ED once only.

Felt stigma

In total, 58 participants (68.2%) reported feeling stigmatised because of their epilepsy.

Epilepsy knowledge

Expressed as the mean per cent of correct answers, which is standard for this measure, the sample's scores on the different epilepsy knowledge scales were 70.7 (SD 10.8) for total score, 68.2 (SD 9.9) for social knowledge and 73.4 (SD 11.6) for medical knowledge. As an example, 24 (28.2%) of the participants stated incorrectly on the social knowledge scale that it was always necessary to call a doctor or ambulance if a person with epilepsy has a seizure, even if it occurred without complications.

| Factor | All participants (n = 85), n (%) | ED use, median (IQR) | Association with ED use, IRR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 41.12 (16) | ||

| Youngest quartile (18–26 years) | 23 (27.1) | 2 (1–5) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Second quartile (27–42 years) | 21 (24.7) | 2 (1–4) | 1.29 (0.44 to 3.81) |

| Third quartile (43–51 years) | 20 (23.5) | 2 (2–5) | 1.07 (0.43 to 2.66) |

| Oldest quartile (52–89 years) | 21 (24.7) | 1 (1–2.5) | 0.42 (0.16 to 1.12) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 45 (52.9) | 2 (1–4.5) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Female | 40 (47.10) | 2 (1–4) | 0.86 (0.39 to 1.89) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White British | 51 (60) | 2 (1–4) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Other | 34 (40) | 2 (1–5) | 1.36 (0.59 to 3.10) |

| Social deprivation, median (IQR) | 32.07 (24.31–37.66) | ||

| Least deprived quartile (13.97–24.38) | 22 (25.9) | 1 (1–2.25) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Second quartile (24.39–32.07) | 21 (24.7) | 3 (1–6) | 2.37 (0.54 to 10.36) |

| Third quartile (32.08–37.62) | 21 (24.7) | 2 (1–4) | 1.12 (0.24 to 5.33) |

| Most deprived quartile (37.63–47.46) | 21 (24.7) | 2 (2–4.5) | 1.26 (0.28 to 5.69) |

| Epilepsy type | |||

| Focal | 49 (57.6) | 2 (1–3.5) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Generalised | 17 (20.0) | 2 (1–5) | 1.59 (0.69 to 3.70) |

| Undefined | 19 (22.4) | 2 (1–5) | 2.21 (0.89 to 5.49) |

| Seizure type | |||

| Partial and generalised | 37 (43.5) | 2 (1–4) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Generalised only | 37 (43.5) | 2 (1–4.5) | 0.64 (0.27 to 1.53) |

| Partial only | 6 (7.1) | 2 (1–3.75) | 0.54 (0.16 to 1.87) |

| Unknown | 5 (5.9) | 5 (1.5–7) | 2.16 (0.84 to 5.54) |

| Seizures in last year, median (IQR) | 6 (3–10) | – | 1.22 (1.08 to 1.37) |

| Medication management, median (IQR) | 36.0 (32.5–38.0) | ||

| Highest management quartile (39–40) | 24 (28.2) | 2 (1–3) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Second quartile (37–38) | 24 (28.2) | 1 (1–4.5) | 1.97 (0.49 to 7.97) |

| Third quartile (34–36) | 17 (20.0) | 2 (1–2.75) | 1.01 (0.41 to 2.49) |

| Lowest management quartile (21–33) | 20 (23.5) | 3 (1–6.75) | 2.58 (1.06 to 6.27) |

| Anxiety, median (IQR) | 8 (5.5–12) | ||

| Not anxious | 36 (42.4) | 2 (1–2) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Borderline | 21 (24.7) | 2 (1–5.5) | 2.29 (1.16 to 4.51) |

| Caseness | 28 (32.9) | 3 (1–5.75) | 3.67 (1.67 to 8.09) |

| Depression, median (IQR) | 5 (2–7) | ||

| Not depressed | 66 (77.6) | 2 (1–3) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Borderline | 11 (12.9) | 4 (1–6) | 2.45 (1.19 to 5.03) |

| Caseness | 8 (9.4) | 4 (2–13.25) | 5.07 (2.03 to 12.63) |

| Felt stigma, median (IQR) | 2 (0–3) | ||

| Least stigmatised quartile (0) | 27 (31.8) | 1 (1–2) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Second quartile (1–2) | 20 (23.5) | 2 (1–2.75) | 1.64 (0.67 to 4.02) |

| Third quartile (3) | 18 (21.2) | 2 (1–4) | 1.82 (0.84 to 3.93) |

| Most stigmatised quartile (4–8) | 20 (23.5) | 5 (2–7.75) | 5.88 (2.62 to 13.19) |

| Social knowledge, median (IQR) | 15 (13–16) | ||

| Most knowledgeable quartile (17–20) | 26 (30.6) | 1 (1–3) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Second quartile (16) | 37 (43.5) | 1 (1–2.5) | 1.41 (0.26 to 7.63) |

| Third quartile (14–15) | 13 (15.3) | 2 (1–3) | 1.07 (0.33 to 3.44) |

| Least knowledgeable quartile (8–13) | 9 (10.6) | 4 (1.75–6.25) | 3.55 (1.04 to 12.17) |

| Medical knowledge, median (IQR) | 26 (22–28) | ||

| Most knowledgeable quartile (29–32) | 26 (30.6) | 1 (1–2.5) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Second quartile (27–28) | 24 (28.2) | 2.5 (1–5) | 2.80 (0.98 to 8.03) |

| Third quartile (23–26) | 18 (21.2) | 2 (1–2.75) | 2.46 (0.59 to 10.12) |

| Least knowledgeable quartile (15–22) | 17 (20.0) | 2 (1–5) | 3.46 (1.21 to 9.88) |

Characteristics of emergency department attendees compared with those of the wider epilepsy population

Table 4 presents a comparison of the ED attendees and the wider epilepsy population on some of the key variables. In descending order of effect, this provides some evidence that ED attendees have experienced more seizures, perceive more epilepsy-related stigma, have recently experienced more anxiety and have a lower knowledge of epilepsy and its management.

Standard of outpatient epilepsy care that attendees had been receiving

Access to tertiary epilepsy services

Most participants (n = 68, 80%) considered their main epilepsy carer to be a hospital doctor rather than a primary care doctor. Forty-three (51%) were being seen in general neurology clinics, 23 (27%) in specifically named ‘epilepsy clinics’ and two (2%) by neuropsychiatry or neurosurgery services.

Frequency of medical review

Nearly all participants (n = 82, 96%) had received a medical review of their epilepsy in the previous 12 months, with 60 (71%) reporting attendance at a hospital clinic and 72 (85%) reporting attendance in primary care. The median number of outpatient appointments for epilepsy was four (IQR 2–9).

Number of antiepileptic drugs prescribed

In total, 44 participants (52%) were taking monotherapy and 38 (45%) were taking polytherapy (median 2, IQR 2–2.25); three were not taking AEDs at all.

Factors associated with frequency of emergency department visits

Because the dependent variable ED use was overdispersed (mean 3.17 < variance 12.89), we adopted a negative binomial model. With use of unadjusted regression analysis, we found that in descending order of importance increased felt stigma, increased depression, increased anxiety, lower social and medical epilepsy knowledge, reduced medication self-management skills and increased seizure frequency were each significantly associated with increased use of EDs by PWE (see Table 2).

| Factor | ED participants (n = 85) | Wider epilepsy population | Reference study details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seizures in last year, n (%) | |||

| (n = 1630) | Moran et al.25 Postal survey of adults with active epilepsy identified through 80 primary care practices, geographically distributed across the UK | ||

| No seizures | 0 (0.0) | 843 (51.7) | |

| One seizure | 10 (11.8) | 129 (7.9) | |

| Two to nine seizures | 39 (45.9) | 280 (17.2) | |

| ≥ 10 seizures | 36 (42.4) | 378 (23.2) | |

| Epilepsy type, n (%) | |||

| (n = four studies) | Forsgren et al.107 Review of epidemiology of epilepsy type in European studies | ||

| Focal | 49 (57.6) | (33–65) | |

| Generalised | 17 (20.0) | (17–60) | |

| Undefined | 19 (22.4) | (2–8) | |

| Seizure type, n (%) | |||

| (n = four studies) | Forsgren et al.107 Review of epidemiology of epilepsy type in European studies | ||

| Partial and generalised | 37 (43.5) | (55–83) | |

| Generalised only | 37 (43.5) | (6–32) | |

| Partial only | 6 (7.1) | – | |

| Unknown | 5 (5.9) | (8–20) | |

| Anxiety, n (%) | |||

| (n = 1176) | Thapar.108 Survey of 82 adults (77 face-to-face, five postal) with active epilepsy from a epilepsy clinic in Glasgow, UK | ||

| Not anxious (0–7) | 36 (42.4) | 429 (36.5) | |

| Borderline (8–10) | 21 (24.7) | 487 (41.4) | |

| Caseness (≥ 11) | 28 (32.9) | 260 (22.1) | |

| Depression, n (%) | |||

| (n = 1185) | Thapar et al.109 Postal survey of adults with active epilepsy from a random selection of 82 primary care practices in Greater Manchester, UK | ||

| Not anxious (0–7) | 66 (77.6) | 878 (74.1) | |

| Borderline (8–10) | 11 (12.9) | 170 (14.3) | |

| Caseness (≥ 11) | 8 (9.4) | 137 (11.6) | |

| Felt stigma, n (%) | |||

| (n = 1571) | Taylor et al.90 Postal survey of adults with newly diagnosed epilepsy from UK hospital outpatient clinics recruited for SANAD trial comparing standard and new AEDs | ||

| None (0) | 27 (31.8) | 729 (46.4) | |

| Mild to moderate (1–6) | 50 (58.8) | 746 (47.5) | |

| High (7–9) | 8 (9.4) | 96 (6.1) | |

| Epilepsy knowledge, mean % correct | |||

| (n = five studies) | No single population reference is available. However, Elliot and Shneker110 identified and reviewed five previous European studies using the measure in the wider epilepsy population and reported the arithmetic mean scores. Three studies had recruited from hospital clinics, two from primary care and one from user support groups | ||

| Social knowledge scale | 68.2 | 71.8 | |

| Medical knowledge scale | 73.4 | 75.0 | |

| Total knowledge score | 70.7 | 74.3 | |

Multiple regression was performed for ED visits using those baseline variables that proved significant in the unadjusted analyses. The likelihood ratio test for alpha confirmed that the data were significantly overdispersed [χ2(1) = 21.68, p < 0.001]. The model predicting ED visits using the reduced list of variables remained statistically significant [χ2(9) = 81.03, p < 0.001]. Having a level of social epilepsy knowledge in the lowest quartile (p < 0.005), a sense of stigma in the highest quartile (p < 0.005), increased seizure frequency (p < 0.005) and less than optimal medication self-management (lowest quartile) (p < 0.05) remained significant in the adjusted model and predicted more frequent ED use.

Based on their respective IRRs, it was lack of social epilepsy-related knowledge (2.10, 95% CI 1.31 to 3.35) and greater perceived stigma (2.08, 95% CI 1.32 to 3.25) that were found to be most highly associated with ED use. On average, those with a social knowledge score in the lowest quartile had visited an ED in the previous year on two occasions more than those with more knowledge. Those with a felt stigma score in the highest quartile had visited an ED on three occasions more than those with lower felt stigma scores. Holding other variables constant, compared with those with better self-reported medication management, ED use was increased by 65% in those in the lowest quartile (IRR 1.65, 95% CI 1.02 to 2.67), and ED use increased by 11% for each category on the ordinal seizure frequency scale compared with the one below (IRR 1.11, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.19).

Summary

In total, 85 patients were recruited. The mean age of participants was 41 years and 53% were male. A total of 61% of participants reported reattending an ED within 12 months. PWE reported a mean of 3.2 and a median of two ED attendances in the last year. The rate of ED reattendance by PWE exceeds that of ED users in general and those with most chronic conditions. However, ED use was not homogeneous amongst participants, with some attending more frequently.

Compared with the wider epilepsy population and in descending order of effect, our results indicate that PWE attending the ED have experienced more seizures, perceive more epilepsy-related stigma, have recently experienced more anxiety and have lower knowledge of epilepsy and its management.

In the previous 12 months, the epilepsy outpatient care of most patients was consistent with standard criteria for quality.

Our cross-sectional analysis showed that, in descending order, lower epilepsy knowledge, higher perceived stigma, poorer self-medication management and higher seizure frequency were associated with the patient having made more ED visits.

STUDY 2: A COMPARISON OF THE GROUPS OF PEOPLE RECEIVING USUAL CARE AND AN EPILEPSY NURSE SPECIALIST-LED SELF-MANAGEMENT INTERVENTION, AND A COHORT STUDY OF PREDICTORS OF SERVICE USE

In this section we test the hypothesis that, compared with TAU alone, an ENS-led self-management intervention can reduce reattendance at the ED and improve well-being (ISRCTN06469947).

In the previous section we described how PWE were recruited from three similar inner London hospital EDs and completed self-report questionnaires on their service use and psychosocial well-being. To evaluate the effect of the ENS-led self-management intervention on well-being and subsequent ED use, participants who had attended the ED of one of the hospitals, KCH, were offered the intervention plus TAU whereas those attending the EDs of the two remaining hospitals, STH and UHL, were offered TAU alone. Participants in both groups were then reassessed 6 and 12 months later and the responses of the groups and their care were compared to determine the effect of the intervention. The similarity of the EDs made comparison of the patients' outcomes reasonable.

Methods

Treatment arms

The epilepsy nurse specialist-led self-management intervention (plus treatment as usual) group

Those from KCH were offered two one-to-one intervention sessions delivered on an outpatient basis at the hospital. The initial session was scheduled to last for 45–60 minutes and the second session for 30 minutes. The intervention was planned to be responsive to a patient's individual needs and so the number of sessions completed was permitted to vary slightly.

The intervention was informed by the premise that PWE, as opposed to medical care providers, are responsible for their day-to-day epilepsy management. As such, PWE need the knowledge, support and skills to mitigate disability and improve outcome. 111 Sessions were delivered by either one of the two ENSs based at KCH. Carers accompanied patients when PWE requested this.

To guide the intervention's delivery and record the information given and actions taken by the ENS during sessions, a comprehensive checklist was developed (see Appendix 2). The intervention started with the ENS reviewing the patient's epilepsy and checking that the AED(s) and dose that the patient reported taking was aligned with his or her prescription. The ENS identified any self-management problems that the patient was having, and factors relevant to their resolution. The ENS developed personalised care plans with the patient, helped the patient set goals (e.g. to socialise more, be comfortable talking about epilepsy, be less fearful about seizures), evaluated progress, provided the patient with the opportunity to ask questions and provided information.

Information provision formed a large component of the intervention. The information that could be provided included the causes of epilepsy; seizure first aid; the role and mechanism of action of AEDs; the importance of adherence to their medication and of taking the same brand; prescription charges; what to do if a dose is missed; potential seizure triggers; safety in the home; legal rights of, and benefits available for, PWE; and the contact details of support organisations. The ENS also informed patients about the name of their seizures and syndrome and, having reviewed their existing medical records, the probable cause of their epilepsy.

With regards to advice concerning seizure first aid, the ENS informed the patient what should and should not be done when a seizure occurs and, as a permanent record, provided the patient with an information pamphlet developed by the Epilepsy Society on first aid management of seizures. 112 As per these guidelines, participants were informed that, usually, when a person has an epileptic seizure, there is no need to call an ambulance. Emergency medical care is recommended only when any of the following apply: (1) it is the person's first seizure; (2) the person has injured him- or herself badly; (3) the person has trouble breathing after the seizure has stopped; (4) one seizure immediately follows another with no recovery in between; (5) the seizure lasts for 2 minutes longer than is usual or the seizure lasts for > 5 minutes and you do not know how long the person's seizures usually last for.

The ENS could make referrals through normal pathways to other services, tailored to the patient's requirements (e.g. counselling, social services, emergency rescue medication clinic). Any advice given and actions taken were communicated to the patient's primary care doctor. At appointments, participants had direct access to either of two ‘expert patients’ in the waiting room who were trained by the UK's Epilepsy Society, and were invited to join a service users group.

Before the trial, for reasons of limited service capacity, the ENSs accepted only direct referrals from neurologists and neurosurgeons. They ran clinics but, as for this study, did not independently prescribe AEDs. At the time of the intervention, one nurse had 8 years' experience working as an ENS and the other had 10 years' experience.

Treatment-as-usual comparison group

Following recruitment, no restrictions were placed on the services that TAU participants could access. At the time of the study no ENS services were part of TAU at STH or UHL.

Baseline and outcome assessments

Following their baseline assessment (assessment 1), the results of which were described in the previous section, participants were assessed again at 6 months (assessment 2) and 12 months (assessment 3) post recruitment. As at baseline, measures included those of their epilepsy-related ED visits and care, health-related QoL, seizure frequency, medication management skills, psychological distress, felt stigma, confidence in managing epilepsy (i.e. mastery) and epilepsy knowledge. Table 1 details the measures used at each assessment.

As for assessment 1, the questionnaires at assessment 2 were completed during a face-to-face follow-up appointment with AN, who was not blind to treatment allocation. However, assessment 3 was completed by post. Questionnaires on care received, service use and seizure frequency referred to the previous 12 months at assessment 1 and the previous 6 months at assessments 2 and 3.

Sample size

Jacoby et al. 32 found that 27% of PWE in the UK with uncontrolled epilepsy (more than one seizure a month) make at least one ED visit per year. We considered that the intervention might reduce this to 7% (rate ratio 0.26), partly by more effective self-management and partly by more frequent and appropriate use of non-emergency services. Following Parmar and Machin's113 formulae, full data on 60 participants in each treatment group would give 80% power to detect such a difference. We planned to recruit 160 subjects to allow for 25% loss to follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Treatment group equivalence and care received

Descriptive statistics describe the characteristics of those recruited into each of the treatment arms, those retained at each follow-up assessment and the epilepsy care that patients received following recruitment. Logistic regression tested for the significance of differences between the groups. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs are presented.

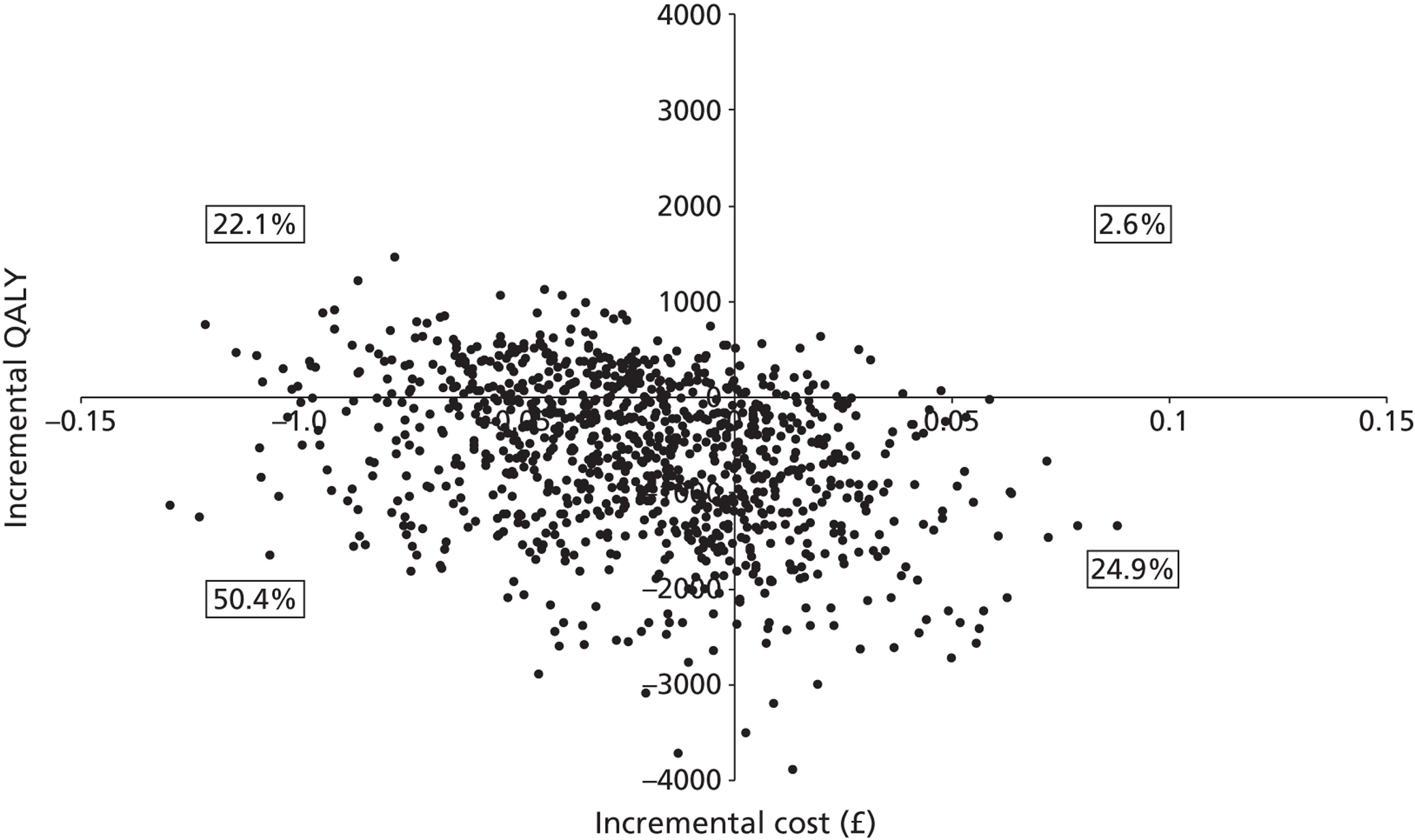

Effect of intervention on emergency department use

Analyses were performed using an intention-to-treat approach. The primary outcome was the number of ED visits that participants reported making over the previous 6 months at assessment 3. Secondary measures were ED visits reported to have been made over the 6 months preceding assessment 2 and psychosocial outcomes at assessments 2 and 3. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant for outcome analyses, with no adjustments made for multiple comparisons.

To examine the effect of the ENS-led self-management intervention on ED visits compared with TAU alone, NBR was used to determine whether treatment allocation predicted ED visits made over follow-up. Overdispersion of ED visits meant that NBR, with robust standard errors, was appropriate. 35

Unadjusted NBR analyses were first completed. However, to account for imbalances in baseline characteristics between the treatment groups, which may have confounded the estimated association between condition and subsequent ED use, we also completed adjusted NBR analyses. This involved first undertaking a process of model building, in which we examined the association between scores on each baseline measure and ED visits at assessments 2 and 3. Those covariates with a marginal statistical association (p < 0.10) were then included in the applicable adjusted NBR analyses. The adjustments made for each model are indicated in the table notes.

Estimates of treatment effect are presented in the form of IRRs with 95% CIs. IRRs < 1 represent a lower ED visit rate in the intervention group relative to TAU, whereas IRRs > 1 indicate a higher ED visit rate in the intervention group relative to TAU.

Effect of intervention on secondary outcome measures

For secondary outcomes, scores were treated as continuous, and linear regression, with robust standard errors, tested for treatment effects. Results from unadjusted and adjusted analyses are presented, with treatment effect estimates given in the form of unstandardised coefficients. Positive coefficients indicate an increase in the score on the outcome variable associated with receiving the ENS-led self-management intervention, whereas negative coefficients indicate the opposite.

All analyses were performed using Stata 11.

Results

Participants

Recruitment and baseline condition equivalence

Of the 85 recruited PWE, 44 were recruited from KCH and formed the intervention group and 41 came from STH and UHL and formed the comparison group. Figure 1 depicts their recruitment and retention.

At assessment 1 (baseline), participants in the two groups were broadly comparable (Table 5). The comparison group did, however, report having experienced significantly more seizures in the previous year [median seizure number 10 (IQR 1.2–4.5) vs. 5.5 (IQR 1.0–3.0) in the intervention group]. The groups also differed on the related seizure frequency indicator of the 2009–10 QOF measure. 85

Retention at follow-up

In total, 69 participants (81%) were retained at assessments 2 and 3. Loss to follow-up was not equal between the treatment arms and those lost differed from those retained in terms of baseline characteristics. A total of 37 participants (90%) from the comparison group were retained compared with 32 intervention participants (73%). This further imbalanced the baseline characteristics of the two groups (Table 6). As well as the intervention group still having had fewer seizures, it also now had fewer participants who felt highly stigmatised by epilepsy at baseline. At the same time, however, there were more in the intervention group who had a comorbid condition.

Reasons for loss are presented in Figure 1. Of note, one participant died of sudden unexplained death in epilepsy. This patient was allocated to the intervention study arm but failed to attend any appointments with the ENS.

Epilepsy care received by participants following recruitment

Assessment 2

No significant differences existed between the two groups in the proportion of participants who reported having consulted with a neurologist or a primary doctor, or who had accessed other hospital outpatient services for epilepsy over the 6 months preceding assessment 2 (all p > 0.05). However, significantly more participants in the intervention group (n = 27, 84%; median number of appointments 1, IQR 1–2) than in the comparison group (n = 2, 5%; OR 94.5, 95% CI 16.80 to 531.72) had seen an ENS in this time. The median appointment duration was 45 minutes (IQR 30–60 minutes).

Significantly more participants in the comparison group (n = 19, 51%; median number of appointments 1, IQR 1–2) than in the intervention group (n = 7, 22%; OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.77) had had an appointment with a nurse within their primary care medical practice. Participants frequently cited the reason for these appointments as being for AED level testing. The median duration of these appointments was 10 minutes (IQR 5–15 minutes).

| Baseline measure | Treatment groups at baseline, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison (n = 41) | Intervention (n = 44) | ||

| Age at baseline (years) | |||

| 18–24 | 6 (14.6) | 8 (18.2) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 25–34 | 8 (19.5) | 12 (27.3) | 1.55 (0.56 to 4.31) |

| 35–45 | 7 (17.1) | 7 (15.9) | 0.92 (0.29 to 2.91) |

| 46–53 | 12 (29.3) | 8 (18.2) | 0.54 (0.19 to 1.50) |

| 54–89 | 8 (19.5) | 9 (20.5) | 1.06 (0.36 to 3.09) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 22 (53.7) | 24 (54.5) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Female | 19 (46.3) | 20 (45.5) | 0.97 (0.41 to 2.28) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Other | 17 (41.5) | 17 (38.6) | 1.00 (reference) |

| White British | 24 (58.5) | 27 (61.4) | 0.89 (0.37 to 2.13) |

| Years of formal education | |||

| 10 (least educated) | 2 (4.9) | 1 (2.3) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 11 | 24 (58.5) | 19 (43.2) | 0.54 (0.23 to 1.28) |

| 12 | 2 (4.9) | 2 (4.5) | 0.93 (0.12 to 7.00) |

| 13–15.5 | 6 (14.6) | 10 (22.7) | 1.72 (0.56 to 5.28) |

| 16–24 (most educated) | 7 (17.1) | 12 (27.3) | 1.82 (0.63 to 5.24) |

| Deprivation score | |||

| 13.97–22.70 (least deprived) | 5 (12.2) | 12 (27.3) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 23.36–28.98 | 9 (22.0) | 8 (18.2) | 0.79 (0.27 to 2.31) |

| 29.75–33.46 | 7 (17.1) | 10 (22.7) | 1.43 (0.48 to 4.22) |

| 33.56–38.31 | 11 (26.8) | 7 (15.9) | 0.52 (0.18 to 1.50) |

| 38.76–47.46 (most deprived) | 9 (22.0) | 7 (15.9) | 0.67 (0.22 to 2.02) |

| Comorbidity | |||

| None | 23 (56.1) | 20 (45.5) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Psychiatric and/or medical | 18 (43.9) | 24 (54.5) | 1.53 (0.65 to 3.63) |

| Years epilepsy diagnosed | |||

| 2–4 | 5 (12.2) | 10 (22.7) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 5–8 | 9 (22.0) | 7 (15.9) | 0.67 (0.22 to 2.02) |

| 9–15 | 7 (17.1) | 13 (29.5) | 2.04 (0.72 to 5.80) |

| 16–34 | 9 (22.0) | 8 (18.2) | 0.79 (0.27 to 2.31) |

| 35–67 | 11 (26.8) | 6 (13.6) | 0.43 (0.14 to 1.31) |

| ED visits last 12 months | |||

| 1 | 15 (36.6) | 18 (40.9) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 2 | 12 (29.3) | 10 (22.7) | 0.71 (0.27 to 1.90) |

| 3–4 | 3 (7.3) | 8 (18.2) | 2.82 (0.69 to 11.55) |

| 5–25 | 11 (26.8) | 8 (18.2) | 0.61 (0.22 to 1.71) |

| Seizures last 12 months | |||

| 1–2 | 7 (17.1) | 10 (22.7) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 3–5 | 6 (14.6) | 12 (27.3) | 2.19 (0.73 to 6.56) |

| 6–9 | 6 (14.6) | 8 (18.2) | 1.30 (0.41 to 4.15) |

| ≥ 10 | 22 (53.7) | 14 (31.8) | 0.40 (0.17 to 0.98) |

| Primary care QOF 8 score | |||

| 0.00–56.4 (fewer seizure free) | 6 (14.6) | 11 (25.0) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 58.3–65.4 | 10 (24.4) | 7 (15.9) | 0.59 (0.20 to 1.73) |

| 65.5–73.6 | 10 (24.4) | 6 (13.6) | 0.49 (0.16 to 1.51) |

| 75.9–78.9 | 10 (24.4) | 8 (18.2) | 0.69 (0.24 to 1.97) |

| 80.0–91.7 (more seizure free) | 5 (12.2) | 12 (27.3) | 2.70 (0.85 to 8.56) |

| Seizure severity score | |||

| 0–5 (least severe) | 13 (32.5) | 20 (45.5) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 7.5–50 | 10 (25) | 6 (13.6) | 0.47 (0.15 to 1.46) |

| 52.5–67.5 | 9 (22.5) | 8 (18.2) | 0.77 (0.26 to 2.24) |

| 70–90 (most severe) | 8 (20) | 10 (22.7) | 1.18 (0.41 to 3.38) |

| Seizure onset | |||

| Generalised or unknown | 19 (46.3) | 17 (38.6) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Focal | 22 (53.7) | 27 (61.4) | 1.37 (0.58 to 3.27) |

| AEDS prescribed | |||

| 0 | 1 (2.4) | 2 (4.5) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 1 | 18 (43.9) | 26 (59.1) | 1.85 (0.78 to 4.39) |

| 2 | 16 (39.0) | 13 (29.5) | 0.66 (0.27 to 1.62) |

| 3–5 | 6 (14.6) | 3 (6.8) | 0.43 (0.10 to 1.85) |

| Depression score | |||

| 0–1 (least symptoms) | 11 (26.8) | 2 (4.5) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 2–3 | 11 (26.8) | 26 (59.1) | 0.70 (0.26 to 1.93) |

| 4–5 | 4 (9.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2.72 (0.77 to 9.56) |

| 6–7 | 7 (17.1) | 13 (29.5) | 1.43 (0.48 to 4.22) |

| 8–19 (most symptoms) | 8 (19.5) | 3 (16.8) | 1.38 (0.49 to 3.88) |

| Anxiety score | |||

| 0–4 (least symptoms) | 7 (17.1) | 7 (15.9) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 5–7 | 10 (24.4) | 12 (27.3) | 1.16 (0.44 to 3.10) |

| 8–9 | 8 (19.5) | 6 (13.6) | 0.65 (0.20 to 2.09) |

| 10–12 | 9 (22.0) | 10 (22.7) | 1.05 (0.37 to 2.92) |

| 13–19 (most symptoms) | 7 (17.1) | 9 (20.5) | 1.25 (0.42 to 3.76) |

| QoL score | |||

| 13–18 (highest QoL) | 9 (22.0) | 7 (15.9) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 19–23 | 7 (17.1) | 11 (25.0) | 1.62 (0.56 to 4.71) |

| 24–26 | 6 (14.6) | 8 (18.2) | 1.30 (0.41 to 4.14) |

| 27–33 | 11 (26.8) | 8 (18.2) | 0.61 (0.22 to 1.71) |

| 34–36 (lowest QoL) | 8 (19.5) | 10 (22.7) | 1.21 (0.42 to 3.47) |

| Felt stigma score | |||

| 0 (least stigma) | 12 (29.3) | 15 (34.1) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 1–2 | 9 (22.0) | 10 (22.7) | 1.05 (0.37 to 2.92) |

| 3–4 | 8 (19.5) | 13 (29.5) | 1.73 (0.63 to 4.77) |

| 5–9 (most stigma) | 12 (29.3) | 6 (13.6) | 0.38 (0.13 to 1.15) |

| Medication management | |||

| 13–39 (lowest skills) | 5 (12.5) | 11 (25.0) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 40–44 | 6 (15.0) | 10 (22.7) | 1.90 (0.65 to 5.54) |

| 45–46 | 9 (22.5) | 10 (22.7) | 1.18 (0.44 to 3.16) |

| 47–48 | 8 (20.0) | 7 (15.9) | 0.93 (0.32 to 2.72) |

| 49–50 (highest skills) | 12 (30.0) | 6 (13.6) | 0.48 (0.16 to 1.41) |

| Satisfaction with medication information | |||

| 1–4 (least satisfied) | 7 (17.5) | 7 (16.3) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 5–7 | 8 (20.0) | 10 (23.3) | 1.21 (0.42 to 3.48) |

| 8–9 | 6 (15.0) | 9 (20.9) | 1.50 (0.48 to 4.71) |

| 10–11 | 8 (20.0) | 10 (23.3) | 1.21 (0.42 to 3.48) |

| 12–17 (most satisfied) | 11 (27.5) | 7 (16.3) | 0.51 (0.18 to 1.50) |

| Social knowledge | |||

| 8–12 (lowest knowledge) | 10 (24.4) | 5 (11.4) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 13–14 | 13 (31.7) | 13 (29.5) | 0.90 (0.36 to 2.29) |

| 15 | 9 (22.0) | 13 (29.5) | 1.49 (0.56 to 4.01) |

| 16–20 (highest knowledge) | 9 (22.0) | 13 (29.5) | 1.49 (0.56 to 4.01) |

| Medical knowledge | |||

| 15–21 (lowest knowledge) | 11 (26.8) | 7 (15.9) | 1.00 (reference) |