Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/10/86. The contractual start date was in September 2014. The final report began editorial review in April 2019 and was accepted for publication in March 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Beresford et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background and study overview

About autism

Autism is a spectrum of developmental conditions that change the way people communicate and experience the world around them. 1 Diagnostic characteristics are pervasive difficulties since early childhood, including reciprocal social communication and restricted, repetitive interests and behaviours. 2 Around half of autistic adults have learning disabilities (LDs). Earlier diagnostic classifications imposed diagnostic labels according to the presence of learning disabilities or functional ability (e.g. Asperger syndrome, high-functioning autism). Although no longer used as diagnostic labels, some autistic people choose to continue to use them for themselves. Improved recognition and awareness of autism over the years has seen a substantial rise in the estimated prevalence from 4 out of 10,000 people in the mid-1960s to the current estimate of ≈ 1% of the adult population,3 with around half diagnosed as autistic without LDs.

The health and well-being of autistic adults

There is now a robust evidence base on the health and other outcomes of autistic adults. Autistic adults without LDs experience poorer outcomes than the general population in many areas of their lives,4,5 including mental health, particularly anxiety and depression;6–11 social isolation;12–15 employment;16–19 and achieving independent living. 20 More recent evidence also points to poorer physical health outcomes and increased risk of suicide. 21,22 Co-occurring mental health problems may be the primary source of impairment23 and in themselves may directly impact other outcomes, such as managing everyday life, work and independent living. Other studies have highlighted potential impacts on family members, particularly parents, with reports of unmet information and support needs, and negative impacts on health outcomes. 24

Despite this evidence, a number of studies conducted in different countries report difficulties accessing diagnostic services and wide-ranging unmet needs. 25,26 A lack of specialist autism adult services, particularly for autistic adults without LDs, is a key reason for this. 27 Indeed, it has been estimated that not providing long-term, low-intensity, holistic support for this population is likely to result in higher costs to individuals and society. 28

The notion of a Specialist Autism Team

In England, widespread concern about the health, social and economic outcomes of inadequately supporting autistic adults culminated in the cross-government Autism Act (2009)29 and Autism Strategy (2010). 30 These placed responsibility on the NHS and local authorities (LAs) to improve support and services for autistic adults. Both the Autism Act29 and the Autism Strategy30 stipulated the need for autism-specific provision, including specialist community-based, multidisciplinary teams to develop, co-ordinate and deliver services. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance published shortly after31 also recommended that each locality had such a team, referring to them as Specialist Autism Teams (SATs), and further specified their multidisciplinary nature and roles (Box 1).

In each area a specialist community-based multidisciplinary team for adults with autism (the specialist autism team) should be established. The membership should include:

-

clinical psychologists

-

nurses

-

occupational therapists

-

psychiatrists

-

social workers

-

speech and language therapists

-

support staff (e.g. staff supporting access to housing, educational and employment services, financial advice, and personal and community safety skills).

The specialist autism team should have a key role in the delivery and co-ordination of:

-

specialist diagnostic and assessment services

-

specialist care and interventions

-

advice and training to other health and social care professionals on the diagnosis, assessment, care and interventions for adults with autism (as not all may be in the care of a specialist team)

-

support in accessing, and maintaining contact with, housing, educational and employment services

-

support to families, partners and carers where appropriate

-

care and interventions for adults with autism living in specialist residential accommodation

-

training, support and consultation for staff who care for adults with autism in residential and community settings.

NICE, 201231

Reproduced with permission from NICE. 31 © NICE [2012] Autism spectrum disorder in adults: diagnosis and management. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg142 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication.

The term used by NICE to describe this type of provision in its more recently published Guidance Implementation Resources (GIRs),32 and by the government in its updated strategy for autism (Think Autism. Fulfilling and Rewarding Lives, the Strategy for Adults with Autism in England: An Update),33 is ‘multi-agency local autism team’. Overall, the proposed functions or roles of these teams were generally unchanged. However, compared with the NICE 2012 guideline,31 the 2014 GIRs32 appear to place additional emphasis on particular roles or functions, namely, ‘up-skilling’ professionals in other services and the provision of autism-specific, preventative social inclusion and well-being interventions. These are interesting developments that reflect a wider re-emphasis on supporting self-management and prevention. The 2014 GIRs32 also appear to signal a recognition that, for a condition emerging as more prevalent than previously thought, exclusively ‘specialist’ provision is not a sustainable model and an important part of the role of a specialist service should be upskilling other professionals and services.

The lack of evidence underpinning policy and practice

The Guideline Development Group (GDG) that was responsible for the NICE guideline31 on management of adults with autism5 made the following comment:

. . . while there is no doubt that guidance on the development and organisation of care for people with autism is needed, it is nonetheless very challenging to develop. In significant part this relates to the very limited evidence base . . .

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. 5

Reproduced with permission from The British Psychological Society

Indeed, the group noted that the evidence base was even more limited with respect to autistic adults without LDs than that for autistic adults with LDs and autistic children.

Thus, in terms of its recommendation for the development of SATs, the GDG drew on the Common Mental Health Disorders Guideline34 and studies that explored the views and experiences of autistic adults, carers, partners and other family members. 5 As a result, although advocating the broad principles and role of SATs, the GDG could not advocate a particular structure or model of service delivery.

The dearth of evidence faced by the NICE GDG in 2012 remains a significant issue and barrier to evidence-informed care, management, service development and policy development. 27,32,35,36 A number of reports identify the relative underinvestment of health and care services research concerning the care and support of autistic adults compared with other lifelong conditions. 36,37 Other reports make the point that, historically, within autism research, the attention and investment has been on neurobiology and cognitive research, which has had little or no impact on the lives of autistic people. 38

The call to develop an evidence base on Specialist Autism Teams

The Autism Act29 and NICE guidance’s31 recommendation that localities have a ‘Specialist Autism Team’ has tasked commissioners and practitioners with developing a new type of provision in the absence of any robust evidence about what it should look like in terms of its organisation, service structure, delivery and practice characteristics. The NICE GDG recognised this, and one of its key research recommendations was that as SAT provision emerged and developed this should be evaluated, with particular attention paid to identifying service characteristics associated with positive outcomes (Box 2). This study was developed specifically in response to this call for evidence. To our knowledge, this remains the only study of this sort of provision for autistic adults without LDs. 32

The Department of Health’s autism strategy (2010) proposes the introduction of a range of specialist services for people with autism; these will usually be built around specialist autism teams. However, there is little evidence to guide the establishment and development of these teams.

There is uncertainty about the precise nature of the population to be served (all people with autism or only those who have an IQ of 70 or above), the composition of the team, the extent of the team’s role (for example, diagnosis and assessment only, a primarily advisory role or a substantial care co-ordination role), the interventions provided by the team, and the team’s role and relationship with regard to non-statutory care providers. Therefore it is likely that in the near future a number of different models will be developed, which are likely to have varying degrees of success in meeting the needs of people with autism. Given the significant expansion of services, this presents an opportunity for a large-scale observational study, which should provide important information on the characteristics of teams associated with positive outcomes for people with autism in terms of access to services and effective co-ordination of care.

NICE, 2012 p. 4231

Reproduced with permission from NICE. 31 © NICE [2012] Autism spectrum disorder in adults: diagnosis and management. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg142 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication.

Study aims

This was the first study of ‘Specialist Autism Team’-type provision. The overall aim was to generate an evidence base on this novel model of care and support service for autistic adults that would be pertinent and valuable to commissioners, practitioners and the autism community and could support evidence-informed implementation of national policy, and service and practice development. Although specific to the English context, the dearth of provision for autistic adults means that the findings may be a useful resource more widely, as other countries seek to improve services and support for autistic adults. 27

The key research questions the study sought to address were:

-

What models of providing SATs currently exist?

-

Is there a particular service model(s) that performs better in terms of achieving positive outcomes for its users?

-

What characteristics of SATs are associated with positive outcomes?

-

What is the ‘added value’ to individuals of the support and care functions of a SAT beyond the diagnostic assessment process?

-

What is the service user experience and does it differ between SATs?

-

What are the costs of the different models of SATs, how are they being funded and how do they compare in terms of costs and cost-effectiveness?

Study design and structure

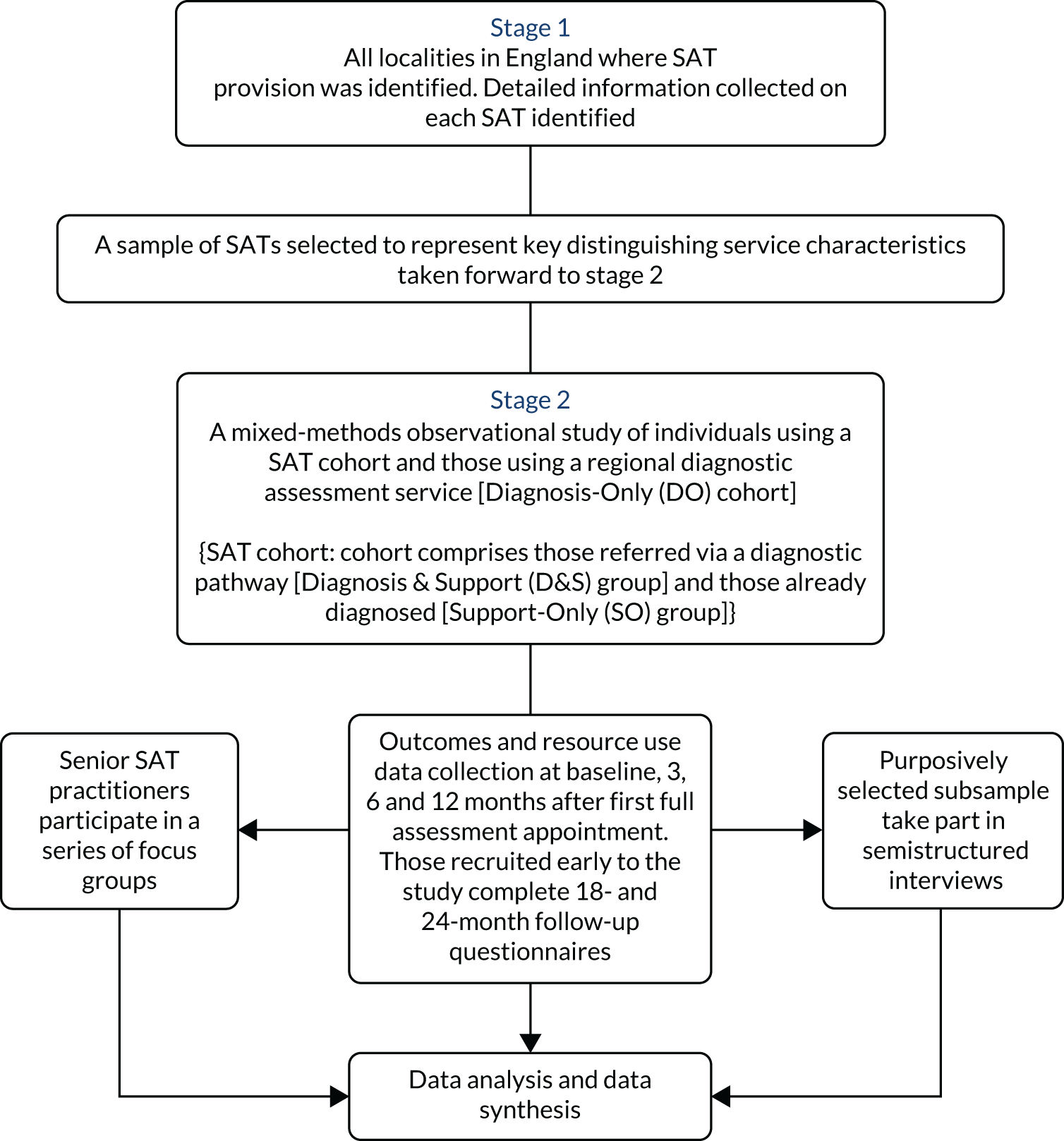

To address these questions, a two-stage study was conducted.

Stage 1 (the mapping study) identified services in England that fulfilled the NICE criteria of a SAT, described the service characteristics and investigated whether or not it was possible to create a typology of different SAT service models.

Stage 2 (the evaluation study) was a mixed-methods investigation of SATs that sought to:

-

describe the implementation and delivery of SATs

-

describe the outcomes of using SATs at 12 months after entry into the service and, where possible, at 18 and 24 months after entry into the service

-

identify and explore features of service organisation, delivery and practice, and individual characteristics, that are associated with user outcomes

-

estimate the costs of different models of SATs and investigate cost-effectiveness

-

describe the experiences of using a SAT

-

conduct an initial comparison of outcomes for individuals diagnosed and then supported by a SAT with a cohort of individuals who received a diagnostic assessment only.

Figure 1 illustrates the overall design and flow of the study.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the study.

Stage 1: the mapping study

Multiple data sources [survey of Autism Leads across England, searches of Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) and local authority (LA) websites and published reports] were used to identify services in England that, potentially, fulfilled the NICE guideline31 description of a SAT in terms of functions and staffing. All identified services were subject to a two-stage screening process, with additional data collected directly from the services potentially fulfilling the NICE criteria after the first stage of screening. Data on services identified as SATs were subject to structured content analytical techniques to describe them, to identify service characteristics that distinguished them and to test whether or not they could be organised into a typology of SAT service models. Purposive sampling techniques were used to identify SATs to act as research sites for stage 2. Stage 1 took place in late 2014 and 2015.

Stage 2: the evaluation of Specialist Autism Teams

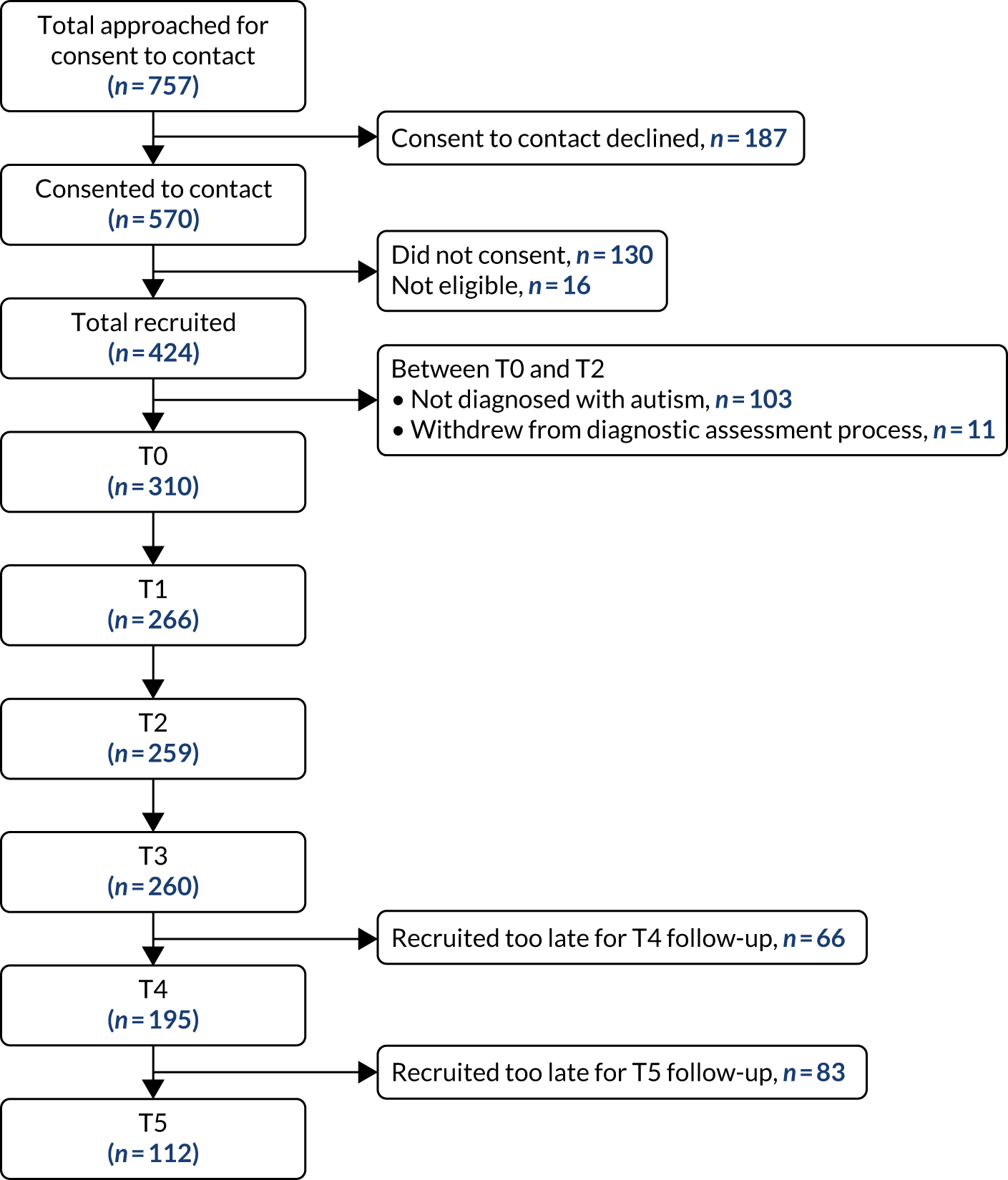

Stage 2 comprised a mixed-methods observational study of two cohorts [the SAT cohort and the Diagnosis-Only (DO) cohort] and a nested qualitative study of the views and experiences of senior members of SATs.

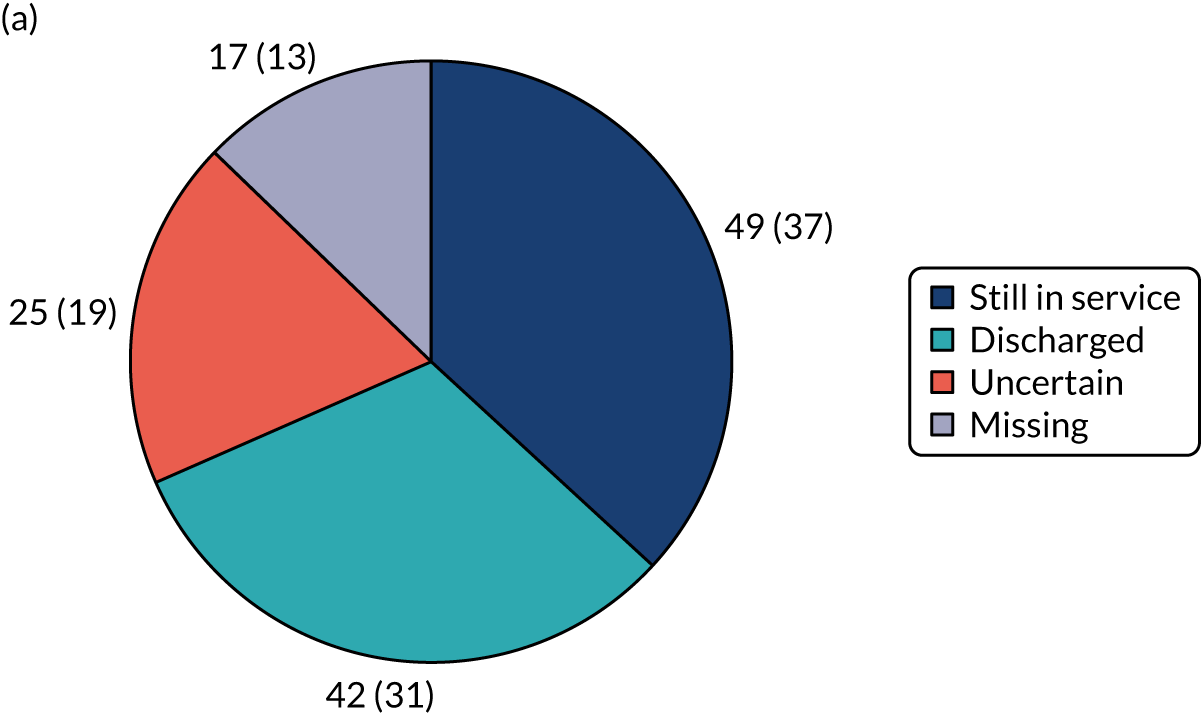

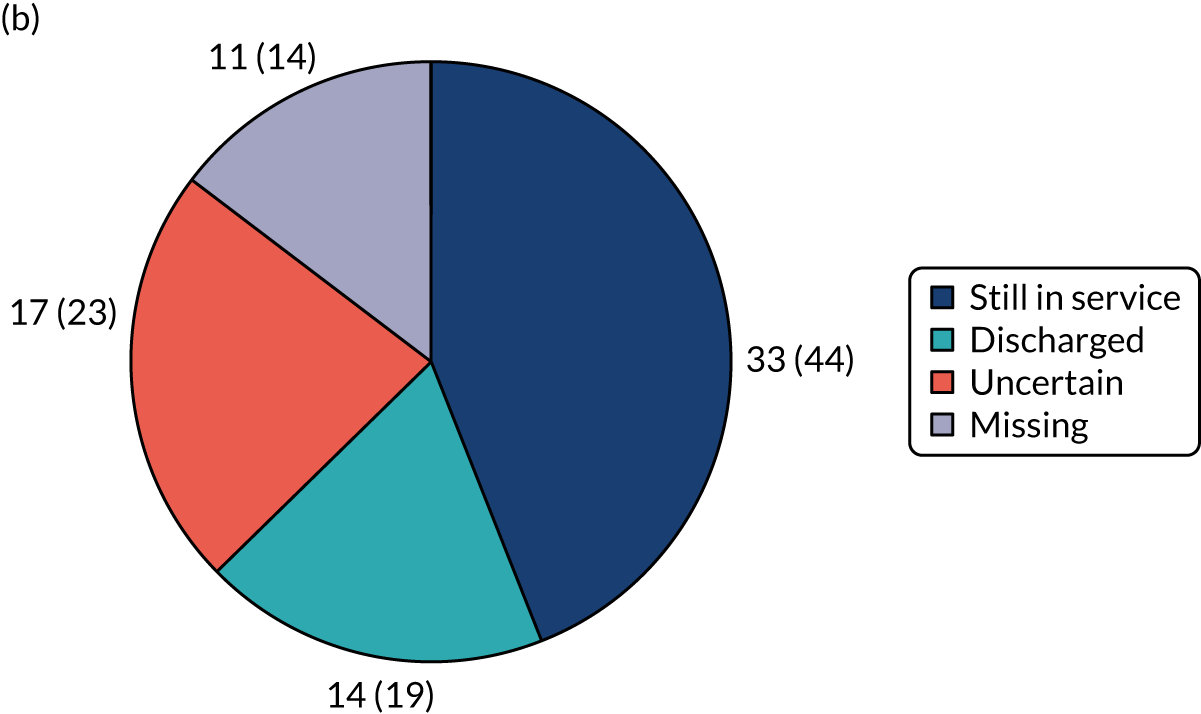

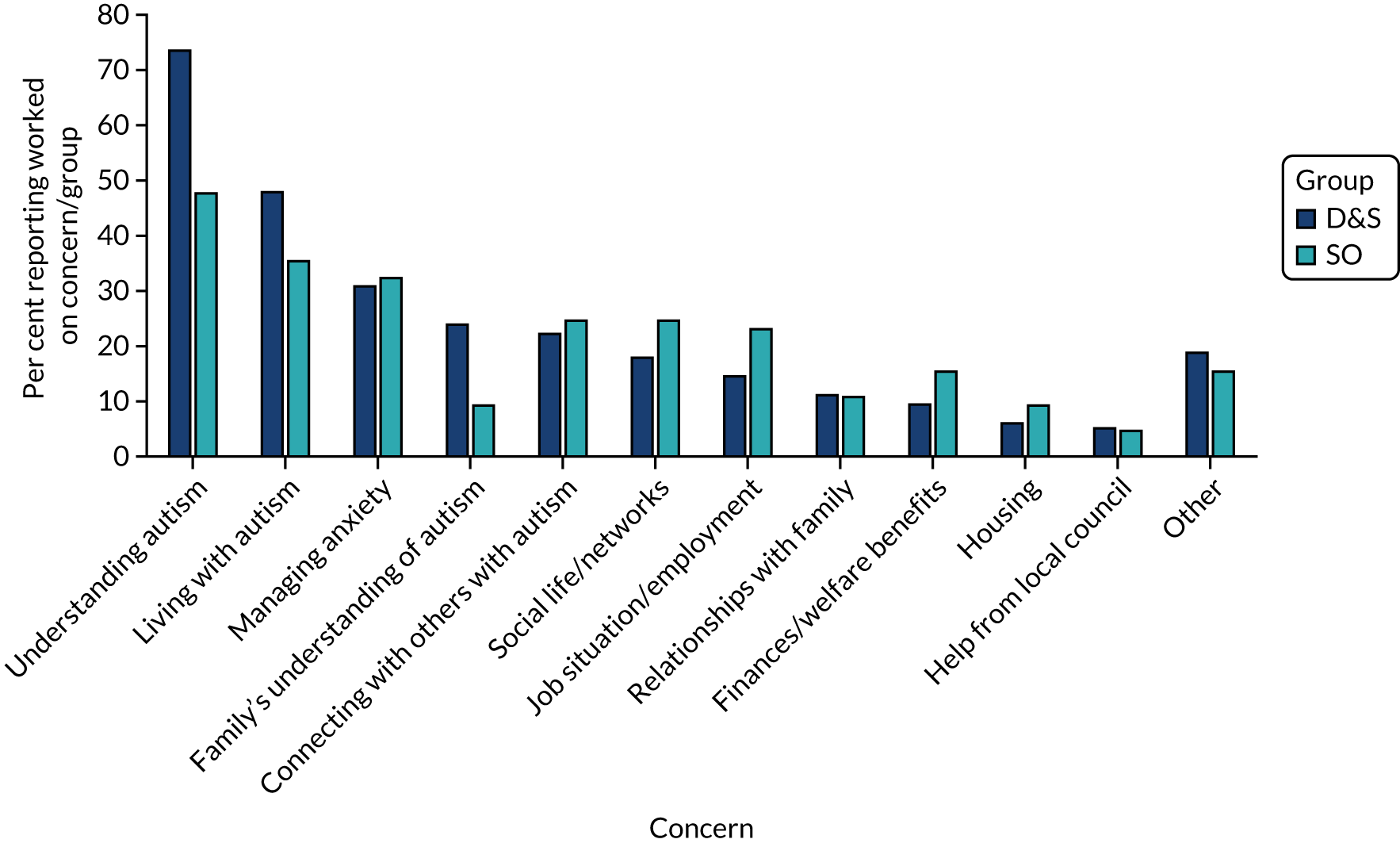

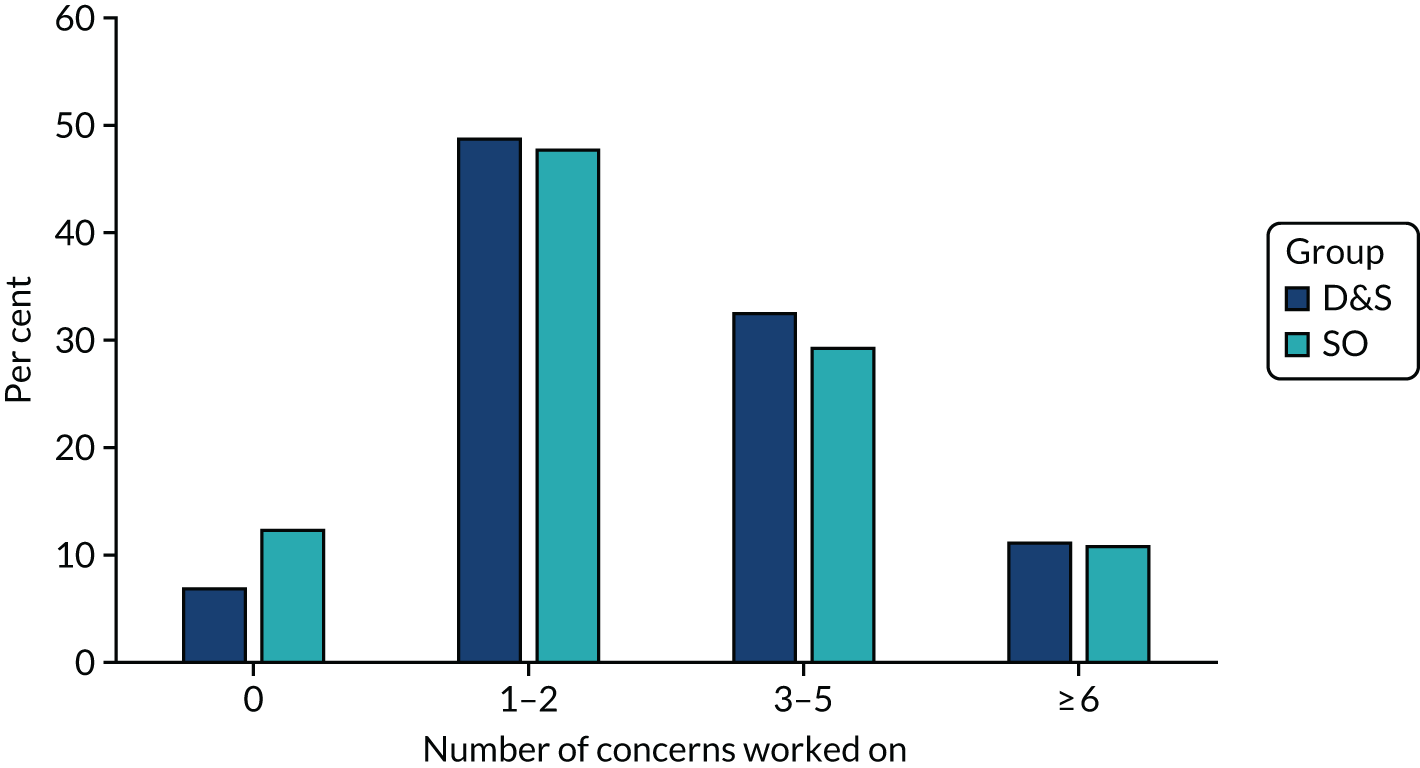

The SAT cohort comprised users of SATs, who were recruited at the time of their first full assessment appointment. Individuals in this cohort included those referred to the SAT who were already diagnosed with autism [the ‘Support-Only’ (SO) group] and those referred for diagnostic assessment and ongoing support [the ‘Diagnosis and Support’ (D&S) group].

Three of the research sites also provided a regional or national diagnostic assessment service for individuals living outside its CCG/LA boundaries via block contracts with neighbouring CCGs or on a case-by-case basis. The DO cohort comprised individuals who accessed the diagnostic assessment service at these sites via this pathway. Thus, these individuals did not receive any post-diagnosis support from the SAT.

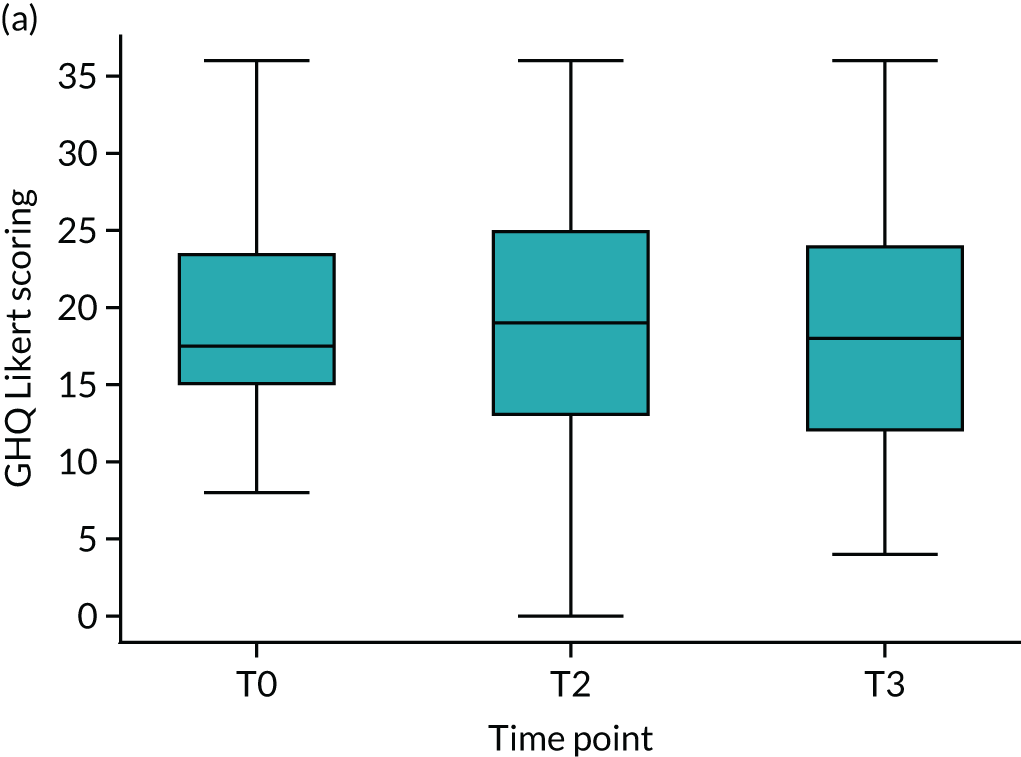

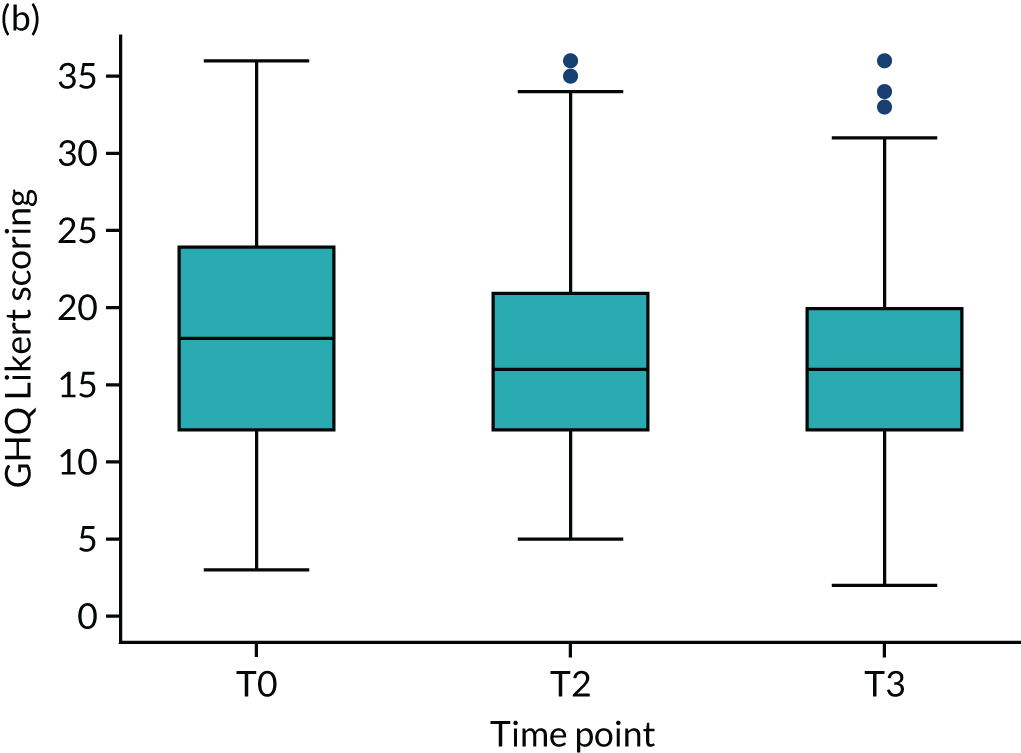

The SAT and DO cohorts were followed up for 12 months from the point of the first full assessment appointment (T0). Outcomes and resource use data were collected at 3 (T1), 6 (T2) and 12 months (T3) for the whole cohort. T3 was our primary outcome time point. For those recruited early to the study, it was decided that outcome data would also be collected at 18 (T4) and 24 (T5) months, as this would provide initial data on longer-term outcomes.

A purposively selected subsample of service users from both cohorts was recruited to take part in a semistructured, in-depth interview about their experiences as service users, perceived outcomes and views on factors (service-level and individual-level characteristics) that affected outcomes. Where the interviewee gave permission, a family member (e.g. a parent or partner) nominated by the interviewee was also invited to take part in an interview.

The nested qualitative study of senior SAT practitioners used individual interviews and focus group discussions to collect data on their views and experiences of setting up, managing and delivering a SAT; factors affecting outcomes; and ensuring sustainable developments and improvements in the care and support for autistic adults without LDs.

Finally, for the economic evaluation element, SAT service leads were asked to provide relevant financial information.

Study delivery

Stage 2 recruitment and data collection took place between February 2016 and November 2018, with all study participants followed up to at least the 12-month follow-up time point.

We encountered two obstacles in delivering the study. First, recruitment of research sites to the study, which was originally scheduled to take 4 months, took over 1 year. Reasons for this included (1) needing to bring additional sites on board to replace a large research site that withdrew well into study set up because of capacity and commissioning issues; (2) two sites having to pause study set up because of recommissioning processes; and (3) in some sites, limitations to the local research and development support available and/or a lack of autism expertise among clinical studies officers. Second, resource limitations meant that the majority of sites could not collect or provide data on service-level outcomes (e.g. intervention take up and retention) for stage 2 of the study.

On a separate note, a proposed element of stage 2 (i.e. seeking views on support, training and advice from services/staff who refer to the service and/or care for adults with autism in residential and community settings) was not pursued. This was for a number of reasons. SATs were providing services only to autistic adults without LDs, almost all of whom lived independently. The two research sites that provided the most extensive consultancy and supervision of other services/professionals withdrew from the study prematurely owing to capacity (and a third site also operating in this way failed to open); therefore, accessing referrers/services with the experience of using the SAT for more than one case was significantly affected. In addition, the majority of referrals were via the diagnostic pathway or self-referral.

Ethics considerations

Stage 1 (the mapping study) was defined as a service audit by the Health Research Authority and did not require ethics approval. The Health Research Authority’s North West – Greater Manchester West Research Ethics Committee reviewed and approved stage 2 (Research Ethics Committee reference 15/NW/0708) and all substantial amendments.

Public and service user involvement

When developing the funding application, we surveyed members of the National Autistic Society (London, UK) to ascertain their interest and support for the project, and their views on the key questions that the research should address. Strong support for the study was expressed; this appeared to be driven by experiences of high levels of unmet need and the lack of specialist autism services.

A project advisory group (PAG), comprising autistic adults without LDs, was appointed. PAG members were recruited through an advertisement that was placed on the National Autistic Society’s website that provided details of the application process, including hyperlinks to an information sheet (explaining the project, its objectives and what being on the PAG would involve) and a short application form. The application form collected information that allowed us to ensure that a range of experiences and characteristics were represented on the PAG (e.g. age, age at diagnosis, experience of using any autism-specific services and geographical location). Over 70 individuals applied. Applications were reviewed by the research team and 14 individuals were invited to an afternoon ‘project advisory group recruitment event’ that was held at the head office of the National Autistic Society. The purpose of this event was for applicants to meet the research team and experience some of the tasks and activities that they might be expected to do as a member of the PAG (e.g. reviewing information sheets, small group tasks and discussions). It also provided the research team with the opportunity to observe the group working together. Eleven individuals attended the event and, at the end of the event, all indicated they were willing be on the PAG.

We used face-to-face meetings to consult with the PAG. These were held in a central London venue that was routinely used by the National Autistic Society and was previously checked as being suitable for use by autistic adults. Those unable to attend meetings had the opportunity to share comments and views via a telephone call with a member of the research team or via e-mail. In between meetings, we consulted with the group via a closed Facebook group (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; URL: www.facebook.com). This was something that the majority of individuals asked to be created in preference to using e-mail for communication. We also provided project updates via Facebook.

All elements of the project were discussed with the group, with particular attention paid to those elements in which autistic adults without LDs were directly involved as research participants. Examples of the sorts of issues that we brought to the group included:

-

content and layout of all stage 2 recruitment materials

-

the wording of questions for the demographic and the resource use questionnaires used for the outcomes evaluation

-

formatting and layout of the outcomes evaluation questionnaire

-

the reminder process when questionnaires were not returned

-

content and ordering of the topic guide for the user interviews (process evaluation)

-

tools to use to facilitate interviews

-

issues to consider when recruiting to and setting up interviews for the process evaluation (reported in Appendix 6)

-

adjustments required to interview technique

-

minimising anxiety associated with anticipating and during interviews.

In addition, individual members of the PAG met with the member of the research team who conducted the service user interviews. These meetings were used both to review draft topic guides and as a training experience for the researcher with respect to interacting with and interviewing autistic adults without LDs. We cannot emphasise enough the contribution the PAG made to this project.

Chapter 2 Stage 1: identifying and describing ‘Specialist Autism Team’ services

Introduction

Stage 1 was a necessary preliminary to the evaluation stage of the project. It identified and described services across England that fulfilled the NICE’s31 definition of a SAT (see Box 1), thus allowing us to identify our research sites. It also generated important standalone evidence regarding the way and extent to which localities are implementing SAT provision.

The key objectives were to:

-

identify SATs currently operating in England

-

describe their characteristics (structure, delivery and ways of working) and examine the differences and similarities between them

-

test whether or not service characteristics cluster together in such a way that a typology of SAT service models can be recognised.

Methods

Identification of services potentially fulfilling Specialist Autism Team criteria

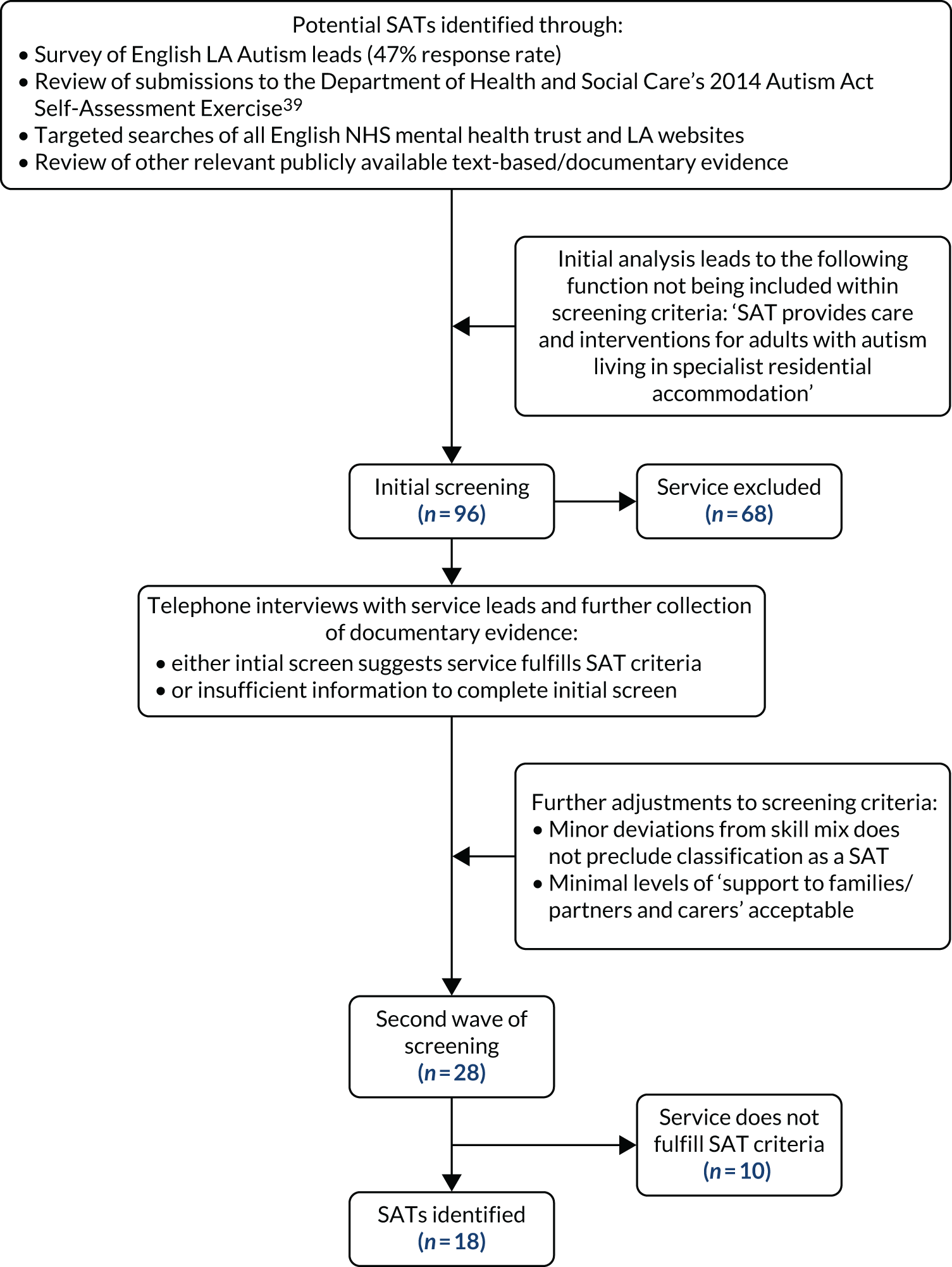

An overview of the process by which SATs were identified is shown in Figure 2. Data collection instruments are available in Report Supplementary Material 1.

FIGURE 2.

The process of identifying SATs.

A survey of Autism leads across England, web searches and reviews of documentary evidence identified services that, potentially, fulfilled the NICE description of a SAT in terms of functions and staffing. Information gathered on identified services (n = 96) was independently scrutinised by at least two members of the research team. It soon became apparent that the predominant population served by potential SATs were autistic adults without LDs. In response, one of the functions of SATs set out in the NICE guidance31 – ‘care and interventions for adults with autism living in specialist residential accommodation’ – was not used as an inclusion criterion (NICE 2012 Autism spectrum disorder in adults: diagnosis and management. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg142 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this product/publication). Where insufficient information had been identified to allow a screening decision, services were taken forward to next stage of data collection. Twenty-eight services were taken through to this stage. The main reasons why services were lost at this screening stage were that they provided (1) diagnostic assessment service only or (2) social care provision with no integrated pathway to/from a diagnostic assessment service.

Structured telephone interviews with service leads of ‘potential SATs’ (n = 28) gathered further data. These interviews were conducted from late 2014 to mid-2015. Interviews, lasting 50–75 minutes, were audio-recorded and a detailed summary was subsequently generated. The topics covered included:

-

commissioning and funding arrangements

-

the population served and eligibility criteria

-

the structure of the service

-

the service/team composition

-

the diagnostic assessment process

-

the approach to meeting health, social care and other needs (e.g. deliver interventions, refer on and/or ‘up-skill’ other services)

-

the wider service context (local availability of other specialist autism provision, including third sector).

The interviewees were asked to supply any relevant publicly available documentary evidence (e.g. annual reports/audits, service commissioning briefs and invitations to tender for services) that was not already collected. Where interviews were not achieved (n = 6/28), further extensive efforts were made to gather publicly available documentary evidence.

Using the data gathered, a detailed ‘service description’ of each potential SAT was created and organised under the following high-level headings:

-

service history and overview

-

staffing, skill mix and location

-

structure of the service and commissioning and funding arrangements

-

eligibility criteria and referral

-

services/interventions offered

-

ways of working

-

the care pathway

-

discharge and caseload.

Before the final screen and informed by an initial analysis of the data, further adjustments to the inclusion criteria were made. First, minor deviations in skill mix from the NICE guidance31 were not used as exclusion criteria. Second, any degree of intensity of ‘support to families/partners and carers’ was acceptable.

‘Service descriptions’ were independently scrutinised by at least two members of the research team. Where necessary, follow-up telephone calls/e-mails with services were carried out to gather additional information. Final decisions regarding whether or not a service (or configuration of services) was classified as a SAT were made in the context of a review of evidence and discussion involving two or more members of the research team.

Data analysis

We had proposed to use cluster analysis to analyse the data and support the generation of a typology of models of service delivery. However, a first look at the data made it apparent that this was neither feasible nor appropriate. First, there were just 18 SATs in our sample. Second, it was clear that these were complex and highly idiosyncratic services and there were no patterns in the co-occurrence of certain features or characteristics. Third, and related to the previous point, no relevant existing evidence was available that could inform selecting certain service characteristics/organisational features to prioritise in the development of a typology.

Service descriptions were, therefore, subject to structured content analysis. 40 Qualitative data were interrogated for descriptive evidence on service characteristics and explanations given for service characteristics or ways of working, etc. Data were also extracted into Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheets to facilitate comparison between SATs and the identification of any consistent clustering of service characteristics or features. Analytical writing, with iterations shared and commented on by all members of the research team, supported data analysis and conclusion drawing. We also carried out a brief descriptive analysis of all relevant quantitative and qualitative data that were collected to generate high-level information about specialist autism provision in localities without a SAT.

Results

Services identified as SATs varied in a number of service characteristics. There were no consistent patterns in the way certain characteristics co-occurred and, as a result, it was not possible to develop a typology of SAT service model into which services could be allocated.

The number of Specialist Autism Teams identified and their broad characteristics

Eighteen localities in England were identified as having a SAT (based on the revised inclusion criteria reported in Methods).

A number of factors influenced both the original ‘design’ of services and the changes to service features/characteristics over time. External influencers were the funding available, the service specifications set out in commissioning briefs and the nature and extent of multiagency working. These were, to some extent, interdependent. Internal influences were personal clinical opinion and cumulative clinical experience acquired through running a SAT.

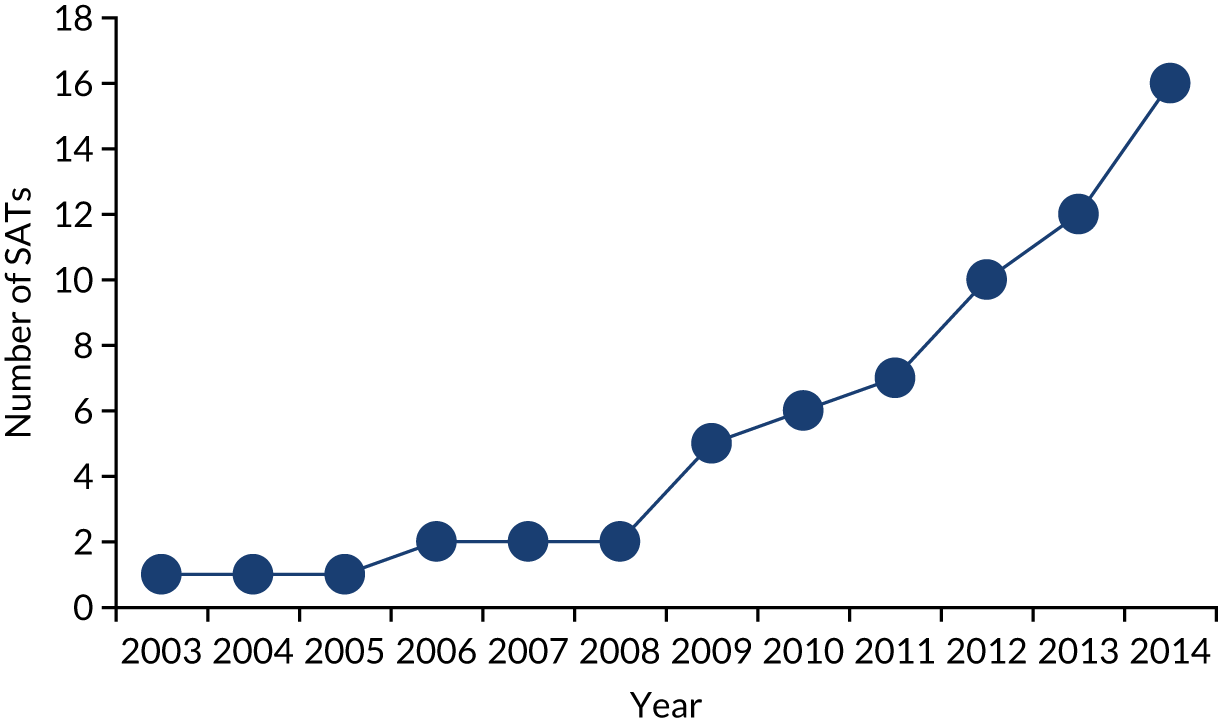

The majority of SATs came into existence from 2009, with only two existing prior to that date (Figure 3). For those more recently established, the Autism Act,29 Autism Strategy30 and 2012 NICE guidance31 were identified as providing the impetus or justification for the development of the SAT.

FIGURE 3.

The number of SATs in existence by year (missing data, n = 2).

The loss of Specialist Autism Teams

A very small number of services were identified that, previously, would have been regarded as fulfilling the criteria for a SAT. Owing to a reduction in NHS funding and/or a loss of LA involvement, services had constricted to being a diagnostic service.

Population served

Entry into the service was commonly via a diagnostic assessment. The majority of SATs (n = 16/18) also accepted referrals of adults without LDs who were already diagnosed with autism. The proportion of ‘already diagnosed’ referrals within these services varied from < 10% to around half. Only one-quarter of SATs accepted self-referrals. All SATs operated an eligibility criterion of an IQ of > 70. The explanation for this selective approach was a perceived gap in support for autistic adults without LDs, and a belief that there were significant differences in the types of provision and expertise needed for autistic adults with LDs compared with those without LDs.

Organisational features

Autism-specific versus neurodisability service

The majority of SATs were autism-specific services (n = 15), but three were based within a wider neurodisability service.

Organisational structure and funding arrangements

A number of different organisational structures and funding arrangements were identified. Within each, different commissioning and funding arrangements were observed.

The majority of SATs were a single service (n = 12), typically based in the local community mental health trust. A number of different commissioning and funding models were reported:

-

CCG sole commissioner with a SAT fully funded from the health budget.

-

CCG sole commissioner with a LA-seconded social worker post.

-

CCG lead commissioner in joint health/social care commissioning arrangement; SAT mainly funded by CCG, and LAs contributing a relatively small proportion of funding for a social work post.

-

LA-led commissioner (as per role of autism lead for locality) in joint health/social care commissioning arrangement; approximately equal financial contributions from health and LA.

Where the CCG had geographical boundaries that covered more than one LA, financial contributions and involvement by LAs varied.

Three SATs comprised two services jointly delivering SAT provision to a locality. Diagnostic assessment was provided by an NHS service, and support for social/everyday living support needs was provided by the LA (adult social care teams) and, in one locality, in partnership with a third-sector provider. Two types of commissioning arrangement were observed. First, the SAT was jointly commissioned (LA as the lead commissioner) with approximately equal financial contributions coming from CCG and LA. Second, the two services were separately commissioned by the CCG and LA, but had established joint-working practices.

Finally, a ‘hub and spoke model’ was observed. Here, three localities had commissioned a neighbouring, well-established (single-service) SAT to deliver diagnostic assessment, mental health intervention and advice services. Different commissioning arrangements (CCG as the sole commissioner vs. CCG as the lead commissioner with LA involvement) meant that there were differences between localities in terms of LA social work/social care involvement. In two localities these staff were seconded into the service, in the other a joint-working arrangement was in place.

Staffing and skill mix

The size of the team (in terms of whole-time equivalents) did not necessarily reflect the size of a locality’s population. Constraints in funding were reported. The NICE guidance31 recommended a multidisciplinary team, with a range of professions represented. All SATs were multidisciplinary, but considerable variation in approaches to staffing were observed.

Clinical psychology was the only profession represented in all SATs, with diagnostic assessment the dominant aspect of that role. Within each SAT, the proportion of staffing resource assigned to clinical psychology ranged from < 15% to 50%. Differences in the time requirements of diagnostic assessment protocols and whether or not the SAT delivered specific mental health interventions, rather than referring to another service, appeared to determine this. Typically, if psychiatry featured in the staff team it represented a small proportion of staffing resource. The exception was one service in which the diagnostic assessment was led by psychiatry and not clinical psychology.

Around two-thirds of SATs had a (mental health or social care) social work post. Many SATs also had generic posts in which a set of competencies and autism expertise, rather than a particular professional qualification, were required. Speech and language therapists (SLTs), social workers, mental health nurses and/or occupational therapists occupied these posts. The whole-time equivalent of total staffing resource allocated to generic posts ranged between 25% and 35%. Specific SLT and occupational therapist posts were unusual, although in some SATs had relatively high whole-time equivalents.

Around two-thirds of SATs also employed staff who did not hold a professional qualification. These were typically assistant psychology posts, but other ‘support’ posts were also used. The roles that they assumed included initial/screening assessments, supporting diagnostic assessments and co-facilitating group-delivered interventions. Support workers were more likely to be involved in meeting social/social care needs, such as being involved in running ‘drop-in’ sessions/support groups and providing individuals with community-based ‘low intensity’ support. A few SATs also employed ‘employment support workers’. The proportion of staff resource assigned to ‘support worker’ posts ranged between 20% and 50%.

The diagnostic assessment

Specialist Autism Teams differed in their diagnostic assessment protocols and each was unique. Protocols varied in terms of the:

-

use of published diagnostic tools and/or clinical interview protocols [e.g. Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication Disorders (DISCO)]41

-

approaches involving informants for the developmental history

-

number of sessions (from one to around four)

-

number of professionals involved (between one and three)

-

decision-making process

-

process by which the outcome of the assessment was shared with the client.

There was wide variation in reported rates of diagnosis between SATs, ranging from < 50% to > 80%. SAT professionals believed that this variation could be attributed to a number of factors, including referrals to longer-established services potentially being ‘harder’ to diagnose (i.e. present more subtly), between-clinician differences and differences in diagnostic assessment protocols.

Psychoeducational support regarding diagnosis

All SATs offered a psychoeducation intervention after diagnosis. As an approach, such interventions integrate psychotherapeutic and educational elements. Their objective is to develop understanding and acceptance of autism, address information needs and support the development of adaptive strategies to manage everyday life. The content of psychoeducation interventions was broadly similar across SATs. Some SATs used a multisession, group-delivered intervention, others used two or more individually delivered sessions and a few offered flexibility regarding mode of delivery, which was based on the individual’s needs.

Needs assessment and ‘care planning’

All SATs conducted a comprehensive needs assessment (covering mental health, social care, employment, housing and sensory needs). This took place either within the diagnostic assessment process or when ‘already diagnosed’ referrals entered the service. This resulted in a ‘care plan’ that incorporated the ‘offer’ from the SAT in terms of interventions and support, and any planned onward referrals or signposting. Services varied in the extent to which the care plan was co-produced with the service user.

Types of care provided by Specialist Autism Teams

The interventions being delivered by SATs could be organised as two ‘levels’ of care, both of which were included in the care plan:

-

supporting self-management – interventions that increase knowledge and understanding of autism, improve or develop coping/problem-solving skills and self-efficacy, and develop informal support networks

-

managing or addressing specific mental health and/or social needs in which the specialist nature or severity of needs and/or the individual’s capacity to self-manage mean that professional support/intervention is required.

Most SATs did not manage forensic cases or individuals with significant or ‘high-risk’ mental illnesses. If involved, they typically assumed an advisory/consultancy role.

Supporting self-management

A range of interventions to support self-management were reported (Table 1). Information provision and psychoeducation were provided by all SATs, and almost all offered informal support groups. Provision of other self-management interventions was idiosyncratic.

| Intervention | Notes/further information | Prevalencea |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting knowledge and understanding of autism | ||

| Psychoeducation intervention | Typically manualised, group-delivered interventions | Universal |

| Written information | One service also provided DVDs (digital versatile disks) | Universal |

| One-off seminars/workshops | Programme of topic areas covered | Unusual |

| Facilitating connections with peers and wider autism (or other) community | ||

| Signpost to third-sector/user-led autism groups | Verbal recommendations and provision of written information. Includes local community-based, virtual and national groups | Universal |

| Informal support group | Regular, informal gatherings, often held in a public venue (e.g. local café). ‘Hosted’ by SAT staff. (One SAT occasionally introduced social outings and another organised a walking group) | Common |

| ‘Drop-in’ serviceb | Regular (weekly, bimonthly or monthly) service comprising advice/information provision, and an opportunity for informal contact with staff and other autistic people. May offer one-to-one appointments. Social activities (e.g. social/interest groups) may also take place | Less common |

| Support peer-led social/interest groups | SAT supports initial set up (e.g. introducing potential members) and/or maintenance (e.g. venue and administration support) of a peer-led interest/activity group (e.g. badminton, music or theatre) | Unusual |

| Signpost to local mental health recovery group | Achieved through information provision and advice nearing discharge | Unusual |

| Developing coping/problem-solving skills | ||

| Psychoeducation intervention | Typically manualised, group-delivered interventions | Universal |

| Training in problem-solving/coping skills | Often delivered as manualised group intervention. One SAT also offered mindfulness classes | Universal |

| Information and advice about services/sources of support | ||

| Written information | For example, contact details and information leaflets about other services and benefit entitlements | |

| Informal support group | See earlier notes in table | Common |

| ‘Drop-in’ serviceb | See earlier notes in table | Less common |

| Telephone advice serviceb | If available staff cannot provide information, referred as ‘duty query’ to team meeting for discussion | Less common |

| Facilitating inclusion/access to mainstream/community activities | ||

| Support inclusion in ‘mainstream’ group/club | Staff actively support ‘introduction’ into existing mainstream/community-based groups/clubs (e.g. local arts project or sports club) | Unusual |

Specialist Autism Teams differed according to the priority given to offering interventions that supported self-management. Commissioning arrangements, clinical opinion and/or availability of autism-specific voluntary sector groups/services in their locality accounted for this. A small number of SATs were distinctive in the relative high priority and investment that was given to this aspect of their service. Others reported that they had plans to expand this aspect of their work. Although psychoeducation was delivered soon after diagnosis, other self-management interventions were not confined to a specific time point in the care pathway. Practitioner judgement (particularly in terms of clients’ readiness) and, in the case of rolling programmes of group-delivered interventions, the availability of an intervention influenced when an individual might access such interventions. In some SATs, self-management interventions were explicitly used as a way of ‘stepping down’ care.

Management of specific mental health and/or social needs

Where identified mental health, social care, employment, housing and sensory needs were sufficiently severe to require direct therapeutic intervention from a suitability qualified professional, there were substantial differences in the ways that this was approached:

-

One-to-one work – as well as direct work with the individual, this could also include contact with other agencies/organisations (e.g. employer, landlord or LA housing department) in an advocacy role.

-

Manualised, group-delivered interventions.

-

‘Supported referral’ to another service. By ‘supported referral’, we mean that SAT staff support the engagement of an individual with the service (e.g. attending assessments, supporting an individual to complete application for benefits, co-working with the service during assessment and care planning). Services/agencies that SATs referred to included:

-

community mental health services for psychological well-being interventions

-

LAs for assessment of eligibility for statutory social care provision

-

secondary adult mental health services (more severe mental health difficulties)

-

specialist employment support services (statutory and third sector)

-

welfare/benefits services.

-

Specialist Autism Teams differed in the types of need that were managed within the team and those that were routinely managed through a ‘supported referral’. This variously depended on commissioning arrangements, the perceived suitability of mainstream services, an individual’s ability to engage or cope with a mainstream intervention, the skills/competencies of the team and, in terms of accessing statutory assessment of social care need, the nature of the involvement of the LA in the SAT.

In some SATs, management of employment, welfare and/or housing needs occurred only when significant mental health needs were also present. Where this was not the case, signposting (e.g. providing information about sources of support and contact details for agencies) was used.

For mental health needs, a small minority of SATs reported that it was highly unusual for them to undertake direct work. More common was a time-limited intervention (e.g. cognitive–behaviour therapy for anxiety). Sometimes this preceded a referral to a mainstream psychological well-being service. In one SAT, mental health interventions were spot purchased, as the CCG commissioned the diagnostic assessment only. In terms of social needs (i.e. social care, employment, housing and welfare needs), commissioning arrangements and the skill mix of the team determined whether a SAT was directly involved or used a supported referral to address a need. Finally, SATs varied considerably in the extent of resources directed to specialist sensory processing interventions; this reflected differences in clinical opinion regarding their effectiveness.

Management and oversight of the care plan

There were two broad approaches to overseeing implementation of the care plan: managed care and episodic involvement.

In the majority of sites (n = 14), a named member of the team held responsibility for co-ordinating and overseeing implementation of the care plan; we refer to this as ‘managed care’. In some SATs, this individual was also presented to the service user as their ‘named contact’ while they were in the service. In 12 SATs, there was no predefined duration for an individual to be in the service, but there was an aspiration to achieve discharge (or for the client to use drop-in type provision only) for the majority of clients within at least 1 year. However, in two SATs all referrals were eligible to receive up to a maximum number of sessions (11 or 12 sessions). In one of these SATs, there was no time limit by which these sessions had to be delivered. Both of these SATs used ‘named contacts’, and one-to-one work was a core feature of both.

A second approach was ‘episodic involvement’. Here, the individual is placed on waiting list(s) for each intervention identified in the care plan, receiving each intervention when it becomes available, should they choose to. Two SATs adopted this model. There is no review prior to discharge, rather the individual is regarded as no longer ‘in the service’ once the last intervention has been delivered/offered.

Type of discharge

The majority of SATs operated closed discharge. Two SATs used an open discharge system in which individuals could re-refer themselves to the service within the first 12 months post discharge. A further two SATs used stepped discharge, offering monthly contact from the service for the first 6 months post discharge.

Changes in delivery models and practice

Many, and, particularly, the longer established, SATs reported ways in which their service had changed or evolved. These were driven by one of more of the following factors:

-

unprecedented levels of demand for the service caused by unanticipated numbers of referrals and/or high levels of unmet need

-

changes in commissioning arrangements

-

reductions in funding

-

observing existing practices (e.g. open-ended involvement) were creating a dependency on the service

-

cumulative clinical experience of working with adults with autism.

Changes implemented included introducing triaging of referrals in terms of level of need, shifting from individual to group-delivered interventions, the introduction of, or increased investment in, preventative and low-intensity support in terms of social inclusion and self-management.

Advice and training to mainstream services and professionals

One of the functions of SATs stipulated in government strategy and clinical guidance is to upskill other professionals and services in their locality. All SATs were delivering on this, although the resource and priority allocated to this varied according to whether or not such activities were included in service specification and the staff views on the suitability of mainstream services/interventions for autistic adults.

Some delivery models were fundamentally based on upskilling and co-working with other services to deliver care and support to autistic adults. Here, clinical leads believed that this was the only sustainable way to meet demand for specialist autism provision. Aside from this, SATs reported upskilling a wide range of professionals/services, including mental health learning disability (LD) teams, adult social care mental health and LD teams, general practitioners (GPs), police, prison service, employers and local industry. Box 3 summarises the types of upskilling work that SATs undertook.

Design and/or delivering of training to staff working in services that interact with/support adults with autism.

Routinely provide other agencies/professionals opportunities for consultation with a team member/whole team regarding management of a particular case or more strategic supervision/advice. Most SATs provided this in a responsive way; one SAT offered bookable, 30-minute consultation slots with the whole team (two available each week).

Supporting mainstream services to deliver interventions (e.g. statutory social care assessments, employment support, mental health therapies), or co-delivering intervention with mainstream staff.

Co-creation of autism-suitable interventions/adaptation of generic interventions delivered by mainstream services (e.g. well-being interventions delivered by primary care/community mental health teams).

Access to the Specialist Autism Team by the wider community of autistic adults

To make themselves available for low-level support and advice to the wider population of autistic adults without LDs living in their locality, a small number of SATs offered an open drop-in service. However, service leads reported that it was highly unusual for someone not previously known to them to attend or, indeed, this had never occurred. One SAT ran a programme of open workshops/seminar on various topics related to autism.

Support to family members and supporters of autistic adults

Supporting family members is the final identified function of SATs. This aspect of provision was not prioritised and SATs undertook limited or no direct work in this area. Where it was provided, the types of support offered included:

-

provision of written information

-

responding to simple requests for advice (raised at drop-in or via telephone calls to the service)

-

leading informal ‘family member’ support group meetings

-

enabling and hosting a peer-led support group

-

extending an existing drop-in services for use by family members

-

organising and hosting occasional social events for autistic adults and their families

-

at diagnosis, offering the opportunity to attend an individually delivered post-diagnosis psychoeducational intervention with the individual being diagnosed.

Many SATs regarded local third-sector groups and peer-led networks as an important source of support for family members. Where this was the case, SATs signposted and promoted them. There were instances of joint work with these organisations (e.g. support groups and social events). Some SATs, however, reported such partnerships were not available in their locality.

Specialist autism provision for adults with autism/no learning disabilities in localities without Specialist Autism Teams

In localities that did not have a SAT service, one or both of the following types of provision were observed.

Diagnostic services

Autism diagnostic assessments were reported as being provided by one of the following arrangements:

-

non-specialist autism local NHS service

-

service-level agreement with specialist autism diagnostic assessment service in the region

-

spot purchasing of specialist autism diagnostic assessments.

Some of the specialist autism diagnostic services for which we collected data during stage 1 reported a frustration at the limitations placed on them, and the services and support they could provide, by funding/commissioning arrangements.

Services solely commissioned/provided by local authorities

As expected, we identified a large number of specialist services for autistic adults solely commissioned/provided by LAs. Sometimes these services were delivered in-house, or specialist autism third-sector providers had been commissioned. These included organisations specific to a locality and national organisations (e.g. National Autistic Society). They included both ‘autism without LDs’ and ‘whole spectrum’ services. None of these services, on their own, fulfilled the criteria for a SAT. If an specialist autism diagnostic/mental health service existed in their locality (which was unusual), there were no joint-working arrangements.

Summary

This mapping study has revealed whether or not, and how, localities in England have implemented the Autism Act29 and NICE’s recommendation for a SAT. We did not identify a single instance of the NICE ‘Specialist Autism Team’ model being fully implemented with respect to all autistic adults. Rather, it has stimulated the development of new provision specifically for autistic adults without LDs. Indeed, many services reported that the decision to focus on this population arose from the recognition of a (total) lack of specialist autism services for this group and significant concerns about their outcomes/well-being. Their situation was contrasted to autistic adults with LDs who were perceived to be (relatively) well served by NHS and LA LD services.

Given the specific focus of SATs on autistic adults without LDs, it is not surprising to find that the SATs identified did not wholly align with the NICE guidance31 on SATs. First, although always multidisciplinary and delivering multiple functions, they are not typically multiagency. However, all SATs reported systems or pathways that connected them to other agencies, particularly LA social care and housing departments, and specialist autism third-sector organisations. Second, except for individuals with complex mental health problems, their emphasis was on delivery of care and support, referring onto and supporting access to other services, rather than assuming a care co-ordination role. Finally, their work with carers/supporters was typically minimal. This might simply reflect prioritisation of work within the context of constrained resources and/or may indicate lower levels of need among family members of autistic adults without LDs than family members of autistic adults with LDs. Alternatively, it may reflect a lack of understanding or recognition of the support needs of this group.

An objective of stage 1 was to discover if SATs could be classified according to a typology of service models based on their structural and organisational characteristics and ways of working. Our work has revealed the complexity of SATs. This partly arises from the fact that the functions and roles of SATs are so wide ranging. Thus, there is potential for differences between SATs both in the emphasis given to the different roles/functions and, within each role/function, differences in practices and ways of working. Furthermore, staffing of a service is often one of the dimensions used to define service model typologies. 42 However, we found that, for some posts, generic competencies and an expertise in autism were more important than specific professional qualifications. Layered on top of these issues, but not necessarily influencing them, are the more ‘straightforward’ organisational dimensions (such as commissioning arrangements and the organisational location of the service).

A consequence of this complexity, and the relatively small number of SATs currently operating, meant that a distinct typology that was meaningful across the entire set of roles/functions of a SAT was not identified. It is, however, very clear that there are a number of service-level characteristics (as well as some higher-level structural/organisational characteristics) on which SATs differ.

In our study protocol, based on work carried out to support development of the funding application, the following service characteristics were identified as potentially distinguishing between SATs. These were:

-

caseload – autism without LDs versus all autism

-

‘virtual’ versus co-located teams

-

professional composition

-

extent of diagnostic assessment

-

to deliver interventions versus consultation/support to other services

-

the wider service context (local availability of other specialist autism provision, including third sector)

-

the level and nature of partnership between health and social care.

Findings from this mapping work indicate that many of these characteristics did indeed serve to distinguish between SATs. The exceptions are that SAT provision is for autistic adults without LDs only and diagnostic assessment is consistently a core and substantive aspect of provision and, in a minority of SATs, the only pathways into the service.

The implications of these findings for stage 2 of this project were that, in the absence of a typology of service models, the focus shifted from a comparison of service models to exploring the impact of service-level (and some individual) characteristics on outcomes, costs and cost-effectiveness. Indeed, this had always been a key research objective as set out in the protocol.

Chapter 3 The research sites

Introduction

This chapter describes the services that acted as research sites for the evaluation study. We focus on reporting whether or not research sites represented service characteristics that were identified by the mapping study (see Chapter 2) and distinguished between services.

Characteristics of the sites

Sociodemographic and population characteristics

Sites varied in the size of the population they served and their geographical size. Most were localities representing a single CCG and LA. They represented a range of deprivation and urban/rural characteristics (see Appendix 1, Table 24).

Organisational characteristics

Four sites were neurodevelopmental services and the remainder were autism-specific services (Table 2). Two (sites D and H) were multiteam services, with separate teams delivering the diagnostic assessment and ongoing support functions; these teams were not co-located. One multiservice SAT (site D) was commissioned entirely by the local CCG. In the other (site H), the diagnostic assessment service was commissioned by the CCG and the ongoing support service by the LA. Close joint-working arrangements ensured continuity of care between the services.

| Site ID | Year established | Autism or ND service | Commissioner | LA funding/resource contribution | Single vs. multiteam | Hold and co-ordinate complex cases? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2003 | Autism only | CCG | Part-fund social inclusion hub (via carers grant)a | Single | No |

| B | 2014 | Autism only | CCG | None | Single | No |

| CAb | 2009 | ND | CCG | None | Single | No |

| Dc | 2009 | Diagnostic assessment service is ND | CCG | None | Multi | Yes |

| E | 2011 | ND | CCG | None | Single | Yes |

| F | 2012 | Autism | CCG | In some districts, part-time social work post seconded to serviced | Single | No |

| H (Ha and Hb)e | 2013 | Diagnostic assessment service is ND | Ha: CCG Hb: LA | Funds Hb | Multi | No |

| IAb | 2014 | ND | CCG lead | LA social work posts seconded to service | Single | No |

| J | 2014 | Autism | Joint, LA lead | Joint funded by LA and CCG | Single | No |

The different patterns of commissioning and funding identified in the mapping study (see Chapter 2) were represented in the research sites. Among the single-service SATs, three out of the seven had no LA involvement. In another (site A), the LA contributed to the funding of the drop-in service. One (site J), however, was jointly commissioned (with relatively equivalent levels of funding) by the LA and NHS. In two other sites (sites F and IA), the CCG was lead commissioner, with the LA seconding social work posts. However, in site F, which had three LAs within its boundaries, LAs varied in whether or not they invested in the service.

Thus, the range of organisational characteristics observed across all SATs identified in the mapping study (see Chapter 2) were represented in the sites recruiting to the study.

Service lead and skill mix

Seven research sites were clinical psychology led and the remaining two sites were nurse led (site CA) and psychiatry led (site J) (see Appendix 1, Table 25). The only profession represented across all sites was clinical psychology. In the majority of services (n = 7), the staff team included four or more professional disciplines (e.g. psychiatry, clinical psychology, mental health nursing, speech and language therapy, and occupational therapy) or roles (e.g. autism clinical specialist and specialist autism support worker). The remaining two services both had clinical psychologists and autism clinical specialists/support workers, with the latter working across a range of needs. Sites varied in the relative resource allocated to staff with the same professional qualification. However, as reported in Chapter 2 (and also discussed in Chapter 5), care should be taken when interpreting this given that services reported, on occasion, prioritising autism expertise and a generic skill set over discipline-specific expertise. Overall, research sites represented the different patterns of staffing and skill mix observed in the mapping study (see Chapter 2).

Eligibility and referral pathways

The research sites represented both open and closed referral processes observed in the mapping study (see Chapter 2). Four out of the nine sites operated an open referral process, including self-referrals (Table 3). The majority (n = 6) accepted referrals of those already diagnosed. A further two accepted such referrals, but only for those on their complex care pathway. This represented a very small minority of their caseload. Only one service triaged referrals at the intake assessment stage, prioritising referrals in terms of severity of mental health symptoms or social need.

| Site ID | Does the service accept self-referrals? | Which services are able to refer? | Does the service accept those already diagnosed? | Does the service triage referrals? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Yes | Open | Yes | No |

| B | Yes | Open | Yes | No |

| CAa | No | Any statutory health/social care | Yes | Exceptionally |

| Db | No | Any statutory health/social care | No, except complex care pathway | No |

| E | No | Any statutory health/social care | No, except complex care pathway | No |

| F | No | GP | Yes | Yes |

| H (Ha and Hb)c | Yes | Open | Yes | No |

| IAa | No | Any statutory health care | Yes | No |

| J | Yes | Open | No | No |

Diagnostic assessment processes

The majority of research sites were using a standardised diagnostic assessment tool (Table 4). The number of sessions used to complete the diagnostic assessment process ranged from one to four or more. Rates of diagnosis ranged from 36% to 90%. Where the assessment was completed in a single session, this tended to be a half-day appointment. Practice varied in terms of the number of staff involved and when service users learnt the outcome of the assessment. The majority of services conducted a single feedback appointment, after which service users were offered a psychoeducational intervention. In one site (site D), the mental health and social needs assessments were split between the two teams delivering the service. This range in approach to diagnostic assessment in the research sites was expected given that findings from the mapping study indicated services were idiosyncratic in their approach and practice. Work soon to be completed by Newcastle University45 on diagnostic assessment practices in England provides further analysis of this issue.

| Site ID | Typical number of sessions | Standardised assessment tool? | Staff involved | Were referrals told diagnosis at assessment appointment? | How report of diagnostic (and needs) assessment (and care plan) shared with individual | Timing of feedback appointment(s) | Typical number of feedback appointments | Proportion diagnosed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | One | DISCO | One clinician (clinical psychologist, specialist autism nurse or autism clinical specialist), then consult team | No | Posted to service user before feedback appointment | Not specified | One | 60% |

| B | One | ADOS-2, ADI-R | One clinician (clinical psychologist or specialist autism nurse), then consult team | No | Posted to service user before feedback appointment | Not specified | One | 90% |

| CA | One | ADOS-2, ADI-R | Two members of the team (clinical psychologist, nurse consultant, SLT) | Yes. Unless need to consult with team | At feedback appointment | Specify 4 weeks | ‘User-determined’ | 53% |

| D | Approximately four | See site E | Threea | 61% | ||||

| E | Approximately four | ADOS-2 | Two members of team (including clinical psychologist). If necessary, consult team | No | At feedback appointment | Not specified | Two/three | 47% |

| F | Three | No | One clinician (clinical psychologist). Then consult team | No | Draft report sent to service user | Not specified | One | 85% |

| H | Approximately four |

ADOS-2 DISCO (if complex) |

One clinician (clinical psychologist) | No | At feedback appointment | Specify up to 4 weeks | One | 47% |

| IA | One | No | One clinician (clinical psychologist), SLT may also be involved | Yes. Unless need to consult with team | Posted to service user before feedback appointment | Within weeks | One | 50% |

| J | One | No. Plan to introduce ADOS-2 | Two members of team, led by psychiatrist. Then consult team | No | Posted to service user before feedback appointment | Within weeks | One | 36% |

Delivery of the care plan: key features

A range of delivery and practice characteristics were represented in the research sites (Table 5). The three approaches to the management and oversight of the care plan identified in the mapping study (see Chapter 2) and approaches to addressing specific presenting needs (direct work vs. supported referral) were represented. The range of intensity of involvement with supported referrals that was reported by the mapping study was not fully represented by the research sites. Unfortunately, the service that had invested the most in supporting non-specialist services to deliver care and interventions had to withdraw from being a research site.

| Site ID | Management and oversight of care plan | Dominant mode of delivering psychoeducation | Routinely do one-to-one work regarding mental health problems | Management of presenting social care needs (daily living skills, community care assessment) | Communication/social skills interventions (one to one and/or group) | Approach to employment support | Type of discharge | Drop-in-type provision while in service? | Drop-in-type provision after discharge? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Managed, no named contact | Group | Yes | Supported referral | No | Supported referral | Stepped | Yes | No |

| B | Managed, no named contact | Group | Yes | Supported referral | No | Supported referral | Stepped | No | No |

| CA | Managed and named contact | One to one | Yes | Supported referral | Yes, SLT led | Supported referral | Open | No | No |

| Da | Managed and named contact | One to one | Yes | In house | Yes, not led by SLT | Direct work | Open | Yes | No |

| E | Episodic | One to one | No | Supported referral | Yes, not led by SLT | Supported referral | Closed | No | No |

| F | Episodic | Group | Yes | Supported referral | No | Direct work | Closed | No | No |

| H (Ha and Hb)b | Managed and named contact | Group | No | In house | Yes, not led by SLT | Direct work | Open | Yes | Yes |

| IA | Managed, no named contact | Group | Yes | In house | Yes, SLT led | Supported referral | Closed | No | No |

| J | Managed and named contact | One to one | Yes | In house | Yes, SLT led | Direct work | Closed | Yes | No |

In terms of group-delivered interventions, each service had developed its own; none was a published, manualised intervention. With respect to communication/social skills interventions, in some services this was led by a SLT, in others this was not the case.

The research sites also represented the three types of discharge observed in the mapping study (see Chapter 2), and the use or non-use, of drop-in provision. Unfortunately, the service in which drop-in provision was (perhaps) the most developed had to withdraw from acting as a research site.

Provision for carers

The research sites varied in provision for carers (see Appendix 1, Table 26). This ranged from signposting to receiving care and support alongside the family member, where appropriate (site CA). Three services (sites D, E and H) described their provision as being limited to a psychoeducational intervention post diagnosis. Another service (site IA) provided limited access to a more general support group-type provision. A couple of services noted that take-up of carers support was higher among parents than other family members. All but one service (site J) reported that there were active local autism carers groups to which they were routinely signposted. This sort of provision was not available in site J’s locality. This range of provision for carers and, overall, its limited nature is representative of the wider findings from the mapping study (see Chapter 2).

Training and consultancy

Training and consultancy was a core element of the range of services provided by the SATs acting as research sites. All but one site were commissioned to routinely deliver autism awareness training and/or more specialist training in their trust and, often, to other statutory services (see Appendix 1, Table 27). Less common, reported by only three sites, were autism awareness activities in the local community among the public. All sites reported providing advice to services/professionals in their locality on a case-by-case basis, although one site reported that this was unusual. Such input was not restricted to NHS or LA services. One site (site F) also offered an ‘advisory clinic’ (two appointments available per week) whereby individual professionals or whole teams could consult with the SAT. Again, this was used by a range of statutory agencies. In addition to these services and activities, one site (site C) had developed e-learning packages for its trust and LA.

Summary

This chapter reports the characteristics of the research sites. Overall, it demonstrates that the range of service characteristics identified as serving to distinguish between SATs in England (see Chapter 2) were represented in our research sites. However, some elements of service delivery and practice were not fully represented, including the full range of drop-in provision and the more intensive approaches to ‘upskilling’ professionals working in mainstream services [e.g. GPs, community mental health teams (CMHTs) and improving access to psychological therapies (IAPT)]. This was principally because of the withdrawal of a research site during study set-up.

Chapter 4 Leading and delivering a Specialist Autism Team

Introduction

This chapter concerns senior practitioners’ views and experiences of leading and delivering a SAT. The material reported in this chapter was collected during interviews with service leads during stage 1 and a workshop for senior practitioners (see Appendix 2 for the methodological report). A unique identifier system is used in this and the following chapter to ensure anonymity of services while allowing scrutiny of representativeness of quotations. We divide the chapter into three main sections:

-

the challenges facing SATs

-

aspects of services working well

-

sustainability.

The challenges facing Specialist Autism Teams

Increasing numbers of referrals

A very significant concern for all services was the number of referrals. All services reported a year-on-year increase. In addition, all reported an increase in the proportion of referrals who had complex needs. Critically, none had received an equivalent increase in funding. Indeed, a minority had experienced a constriction in available resources (e.g. loss of funding for posts, post being frozen, withdrawal or reduction of LA involvement):

We’ve constantly historically doubled over [the 4 years existed] . . . And pretty much the same amount of money.

SAT1

. . . the number of referrals are constantly increasing. We thought 7 years ago that we’d have a mass input and then it would slow down. Unfortunately it hasn’t, and we’ve got no more staff than we had to start with.

SAT2

As well as the increasing rates of autism diagnoses in children, services believed that there were three main reasons for this situation. First, mainstream/generic services could be unwilling to work with this population, even with supervision from a SAT. Second, other services were referring to the service as means of managing their own caseload. Third, the absence of any other non-LD, specialist autism provision in the locality.

Issues with service throughput

Services operating a more open-ended care pathway were, unsurprisingly, more likely to identify issues with service throughput. More generally, a reluctance of mainstream services (e.g. CMHT and IAPT) to accept referrals and the absence or loss of low-level community support services, such as third-sector services, peer-led groups/networks and LA provision, were identified as adversely affecting throughput:

. . . the [third-sector organisation] withdrew everything . . . virtually all their volunteering services and all that sorta stuff, which was a big loss . . . and unfortunately the cutbacks in terms of the voluntary sector and local authority and all of those sorts of thing (means) virtually all support has gone.

SAT2

Services acting as care co-ordinators for those with complex needs reported the additional difficulty of being unable to discharge these service users because of the complexity of their needs or the absence of another specialist autism service on which to refer. This further compounded the issue of long waiting lists:

We’re only supposed to care co-ordinate eight people. We’ve got 11 people at the moment and a lot waiting . . . massive pressure of people coming through who are very, very complex, that do need specialist care co-ordination but we can’t do it. And it’s a real area of stress for us trying to find out where those people can go. It’s very difficult to ‘review and move on’ the people that we have got because their needs remain constant and they don’t get better . . . so it’s really difficult, that.

SAT4

Increasingly constrained resources

Increasing numbers of referrals and growing caseloads within the context of unchanged levels of resource meant that all services reported an increase in wait times, both at referral to the service and in the delivery of the interventions set out in the care plan. Inadequate financial resources were attributed to both commissioners’ demands and within-trust cost-improvement programmes:

They [commissioners] are putting a lot of pressure on us to change our practice and looking at really limiting what interventions we’re going to be able to do.

SAT3