Notes

Article history

The contractual start date for this research was in January 2021. This article began editorial review in October 2023 and was accepted for publication in September 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Health and Social Care Delivery Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Massou et al. This work was produced by Massou et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2025 Massou et al.

Introduction

In view of the rising number of people living with multiple chronic conditions,1 reorienting healthcare services to achieve better outcomes is increasingly important. There is growing evidence that patients with chronic conditions can significantly benefit from managing both their biological and psychosocial needs. 2–5 Recognising the psychosocial components of illness – including personal, emotional, family and community factors – as equally important to the biological components has led to a more humanistic and patient-centred approach to care. 6 Effective delivery of this type of care requires collaboration among physicians, nurses, consultants, psychologists and other health professionals, rather than operating in isolation, to achieve better outcomes. 7

While this biopsychosocial model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding health and illness, it does not inherently imply integrated care. This is because the components of the model themselves do not define the level of co-ordination, communication or co-location needed for integrated care. Despite the ample evidence supporting the benefits of this holistic approach, there is a lack of conceptual consistency regarding the definition and implementation of integrated care. 4,8–10 Various organisations have developed different definitions and strategies of implementation influenced by national, regional and local contexts as well as differing perspectives, including patients’ versus managerial stakeholders’ perspectives. 11–13

For instance, the NHS defines integrated care as ‘partnership of organisations that come together to plan and deliver joined-up health and care services, and to improve the lives of people who live and work in their area’. 14 In the Netherlands, integrated care is defined as transmural care between traditionally separate sectors, referring to ‘care, attuned to the needs of the patient, provided on the basis of co-operation and co-ordination between general and specialised caregivers with shared overall responsibility and the specification of delegated responsibilities’. 15 According to a managers’ definition, integration is ‘the process that involves creating and maintaining, over time, a common structure between independent stakeholders … for the purpose of coordinating their interdependence in order to enable them to work together on a collective project’. 16 Social scientists describe integration as

a coherent set of methods and models on the funding, administrative, organizational, service delivery and clinical levels designed to create connectivity, alignment and collaboration within and between the cure and care sectors. The goal of these methods and models is to enhance quality of care and quality of life, consumer satisfaction and system efficiency for people by cutting across multiple services, providers and settings. Where the result of such multi-pronged efforts to promote integration leads to benefits for people, the outcome can be called ‘integrated care’. 17

A recent clinical review of the literature and existing services identifies three tiers of the concept of integration in health and social care. The first tier is that of co-ordinated care, which aims to promote communication for basic collaboration between providers of physical and mental health care. The second tier encompasses the co-location of services with some system integration. Beyond care co-ordination and co-location is the third tier of integrated care, which emphasises co-ordinated efforts, including shared medical records and multidisciplinary care, between physical and mental health services. 18 Examples include specialist paediatric eating disorder services where access to multidisciplinary care is increasingly the norm, or having psychologists based within epilepsy clinics as services become increasingly focused on outpatients. 19,20 For the health and social care system, the benefits of integrated care include financial sustainability,21 lower overall cost of services,22,23 improved service utilisation22,24 and a better working experience for staff. 25–27 From the patient’s perspective, benefits include greater satisfaction,8,22,24,25,28,29 improved access to care23,30,31 and higher quality of care. 22 These outcomes are facilitated by reducing fragmented care, confusion, repetition, delays, gaps in service delivery, and the perception of getting lost in the system. 7

Integrated care for children and young people

Arguably, children and young people (CYP) are particularly vulnerable if all of their care needs – mental and physical – are not properly identified and addressed. Their physical growth coincides with the development of cognitive, educational, social, emotional, behavioural and communication abilities. If these areas are adversely affected during development, the future potential of a child may be compromised. 9 Integrated care offers a promising solution to meet the health needs of this population. 10

A recent review that investigated the preferences of adolescents regarding the mental health care they receive highlighted the value of greater integration of mental and physical healthcare services. 18 The review identified several clinical conditions where a more integrated model of care is particularly beneficial. For instance, it emphasised the need for mental health support for children with life-limiting illnesses like cancer, and the high prevalence of psychiatric morbidities among children with brain disorders. The review observed also that children with psychiatric emergencies, such as deliberate self-harm, often present in medical rather than psychiatric settings even though they require care from both mental and physical health services.

Published evidence on the effect of integrated care models on psychiatric disorders in paediatric settings shows that this kind of care is associated with increased access to behavioural treatments and better mental health outcomes. 11 However, evidence on the implementation of integrated care models for children, adolescents and young people is still limited and available only for specific settings, and diseases, including children with chronic medical illness, children with mental health problems, children aged under 3 years with problems of early development, and mixed populations of children with mental health problems and long-term comorbidities. It is also limited in terms of the clinical outcomes that are considered, but these include access to mental and physical healthcare services, waiting times for first assessment in these services, early diagnosis, adherence to treatments, quality of life and clinical outcomes that are specific for each condition. Furthermore, the evidence on the effectiveness of integrated care for this population is of moderate quality and limited, indicating mixed results regarding clinical outcomes and acute resource utilisation. These inconsistencies are partially due to the varying interventions and outcomes examined across different studies. 12

Background

In this review, we discuss the integration of health care for CYP in two clinical conditions: eating disorders and functional symptom disorders. The selection of these two conditions is driven by two factors.

First, the high prevalence of these conditions in CYP underscores the importance of providing further evidence about them. The Mental Health of Children and Young People survey 2022 found that the proportion of children aged 11–16 years with possible eating problems increased from 6.7% in 2017 to 12.9% in 2022. 13 With regard to functional symptom disorders, the estimated incidence is 18.3/100,000. 14

Second, these two case studies represent opposite ends of the spectrum: eating disorders are traditionally treated as mental health issues, while functional symptom disorders are usually addressed as a physical health problem. Despite this prevalent one-dimensional approach, eating disorders can significantly impact a child’s or young person’s physical health, while functional symptom disorders may originate from mental health conditions. Therefore, appropriate management of these two conditions in CYP should involve both psychiatric and medical expertise.

Functional symptom disorders

‘Functional symptom disorders’, previously called ‘medically unexplained symptoms’, is the name given to physical symptoms for which there is no clear pathological explanation. 15,16 The term has been debated and criticised; alternative labels, including ‘somatisation’, ‘bodily distress syndrome’ and ‘persistent physical symptoms’, are sometimes used interchangeably. 32,33 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) subsumes all these labels in the category ‘somatic symptom disorders’ and emphasises that individuals with functional symptoms can also have organic disease. 34 Syndromes frequently found within the category of somatic symptom disorders include chronic fatigue, irritable bowel syndrome, functional neurological disorders such as non-epileptic seizures, fibromyalgia and chronic pain.

Most of the time, functional symptoms are temporary and resolve on their own, but sometimes they persist, prompting patients and general practitioners (GPs) to seek a diagnosis and treatment. Many GPs find patients with functional symptoms challenging and often refer them for further investigation. On the other hand, many affected patients who do not receive a correct diagnosis push for excessive diagnostic evaluations and treatment attempts. However, this management strategy might have more negative than positive effects on patients’ symptoms and concerns. 35 In addition, research indicates that the investigation of functional symptom disorders consumes considerable healthcare resources owing to the frequent utilisation of services, referrals for specialist consultations, numerous diagnostic tests and attempts at treatments. 15,36

Another management strategy focuses on the addressing the physical symptoms. Patients who seek help for these symptoms are given advice on self-care, including diet, exercise and lifestyle changes. However, this advice is often communicated unclearly and impractically, and GPs lack a variety of available strategies, leading to ineffective treatment. 37 Patients might also be advised to adopt a watchful waiting approach, which can cause additional distress.

Young people with functional symptoms who seek medical help may be reluctant to be referred to psychological services for fear of not being taken seriously, or of their symptoms being dismissed as ‘not real’. 38 Additionally, there is relatively little evidence on the perceptions and experiences of healthcare professionals caring for CYP with functional symptom disorders. This suggests that healthcare professionals may not always feel equipped to manage these cases. 38 This lack of confidence in capacity to support young people with functional symptoms and their families is partially due to limited time, communication skills, care protocols and expertise. 39,40

There is some evidence that implementing a multidisciplinary approach grounded in a biopsychosocial perspective for CYP with functional symptom disorders can result in cost savings, better recognition of underlying mental ill health, improved short-term functional outcomes and increased school attendance among affected children. 41

Eating disorders

‘Eating disorders’ is an umbrella term that encompasses a range of disorders related to eating and feeding. DSM-5 lists pica, rumination disorder, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder and eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) under eating disorders. 34 The NHS uses a similar classification.

The current national and international guidelines consider eating disorders as mental health disorders and suggest their treatment should be primarily through psychological/psychiatric interventions that are usually delivered in outpatient settings. 42 However, eating disorders can coexist with physical and mental health comorbidities, including anxiety, depression and obsessive–compulsive disorder, and can have extensive impact on physical functions. 43 For example, the effects of anorexia can affect the endocrine system, growth and body height, menarche and menstruation, bone density and brain volume, while the effects of binge-eating disorder and self-induced emesis can affect dental and oral health. 43,44 These complex cases are not efficiently treated through psychological therapies and require multidisciplinary care. Moreover, eating disorders have the highest mortality of any psychiatric disorder45 and, in severe cases, hospitalisation may be necessary to avoid collapse due to the physical impacts of prolonged starvation or repeated vomiting and purging. Physical and mental health problems can also persist even after the eating disorder has been successfully treated.

Consequently, patients with eating disorders are likely to be treated in both physical and psychological health settings, for different aspects of their condition. Mairs and Nicholls46 suggest that an effective integrated team approach may be more important for successful outcomes than the specific skills of individual practitioners, but they highlight the need for further research on the evaluation of treatments and understanding of outcomes.

Review questions

The present review is part of a larger study that will inform the development of a new children’s hospital in England. One pivotal aspect driving the service redevelopment for the new hospital is the enhanced integration between physical and mental health services, to be achieved through the co-location of services.

In summary, both eating disorders and functional symptom disorders may benefit from an integrated approach to health care; however, it is not clear what service models have been used to integrate care, what factors influence their implementation, and what effects these integrated models have on access to and outcomes from care. Therefore, this review aims to answer the following:

-

What are the service models and implementation approaches used to integrate physical and mental health services for CYP with eating disorders or/and functional symptoms?

-

Which factors influence how integration of these services is implemented?

-

How do these integrated health services influence CYP’s access to care?

-

How do these integrated health services influence the delivery of clinical interventions, patient outcomes, and cost-effectiveness?

Methods

Study protocol

The protocol of this systematic review was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42022349805), while our approach was guided by the Preferred Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement (Appendix 1). 47 This review was discussed regularly with public and patient representatives who contributed to the broader study.

Data sources

Our search was initially conducted in August 2022 and updated in July 2024, without any restrictions in terms of the date of publication or country, but it was restricted to papers in the English language. We identified eligible peer-reviewed papers through systematic searches of the MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycInfo® (American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA) electronic bibliographic databases. We also carried out hand-searching for studies that could be relevant (i.e. manual page-by-page examination of the entire contents of a journal issue to identify all eligible reports48), and we contacted expert consultants for further key publications that we might have missed.

Definitions

We defined the terms ‘integration of mental and physical health care’, ‘eating disorders’ and ‘functional symptom disorders’ in line with recent reviews and contacts with experts in these fields. More particularly, we defined ‘integration’ as the ‘[…] changes to health or both health and health-related service delivery which aim to increase integration (i.e. joining up) and/or co-ordination’. 49 The same definition has been used in a very similar review12 and it refers to the planning, commissioning and delivery of co-ordinated, joined-up and seamless services to support the public. 50

‘Eating disorders’ were defined as a range of disorders related to eating and feeding. DSM-5 lists pica, rumination disorder, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder and EDNOS under eating disorders. 51

‘Functional symptom disorders’ were defined as a range of conditions that present with physical symptoms for which there is no clear pathological explanation. 52 The term has alternative labels, including ‘somatisation’, ‘functional disorder’, ‘bodily distress syndrome’ and ‘persistent physical symptoms’, that are sometimes used interchangeably. 53,54 Syndromes frequently found under these labels and included in other reviews include functional abdominal symptoms, chronic fatigue syndrome, tension-type headache, fibromyalgia and pain. 55

Search terms

To capture the concepts of interest – that is, ‘integration of mental and physical health care’, ‘eating disorders’ and ‘functional symptoms’ – we used medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and synonyms (see Appendix 1, Table 5). The list of search terms was developed with support from experts in this field. We applied these search terms in subject headings and individual text words. The search strategies are available in Appendix 1, Tables 6 and 7. One researcher conducted the initial search, and another conducted the updated search, using the same strategy (JM and EM, correspondingly).

Study selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials, quasi-randomised controlled trials, controlled before-and-after studies, prospective cohort studies, cross-sectional studies and economic evaluations were eligible for our review. Qualitative studies, preprint studies and grey literature were also included.

Studies were included within our review if: (1) they were based on children or young people aged 0–18 years with an eating disorder and/or a functional symptom disorder; and (2) they investigated the effectiveness of integrated mental and physical health services versus any other type of services provided to CYP with eating disorders and/or functional symptoms. We focused on comparative studies since we wanted to know whether integration of physical and mental health had better outcomes than other types of care. Studies based on patients older than 17 years were excluded (Table 1).

| Key element | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Population | CYP aged 0–17 years |

| Population specification | Experiencing any eating disorder and/or any functional symptom disorder |

| Exposure | Integrated health and social care, as defined in this study |

| Comparator | Different service delivery model |

| Setting | Any setting involved in the delivery of integrated care |

| Outcomes | Primary:

|

Secondary:

|

|

| Study design | Randomised controlled trials, quasi-randomised controlled trials, controlled before-and-after studies, prospective cohort studies, cross-sectional studies and economic evaluations were eligible for our review. Qualitative studies, preprint studies and grey literature were also included |

| Country | Any country |

| Date | From the earliest available |

| Language | English |

Outcomes

We prioritised our main outcomes inclusion criteria to four primary and four secondary outcomes. 48 The primary outcomes were: (1) the characteristics of the approaches to integrating physical and mental health services for CYP with eating disorders and/or functional symptoms; (2) the effects on accessing and receiving care (including the effect on access to care, the effect on waiting times and the effect on access to treatment) compared to non-integrated care; (3) the effects of clinical interventions on outcomes and cost-effectiveness (including quality of life and occurrence of physical and mental health symptoms); and (4) barriers and facilitators to successful implementation. The secondary outcomes were: (1) a review of the measures that have been used to quantify integration; (2) a review of the relationship between integration and clinical outcomes; (3) users’ experience/satisfaction (including patients, carers, and healthcare professionals); and (4) provider perspectives on integrated health care. Studies focusing on other outcomes, for example beliefs and knowledge about the conditions of interest, or readiness to seek integrated care, were excluded.

Screening

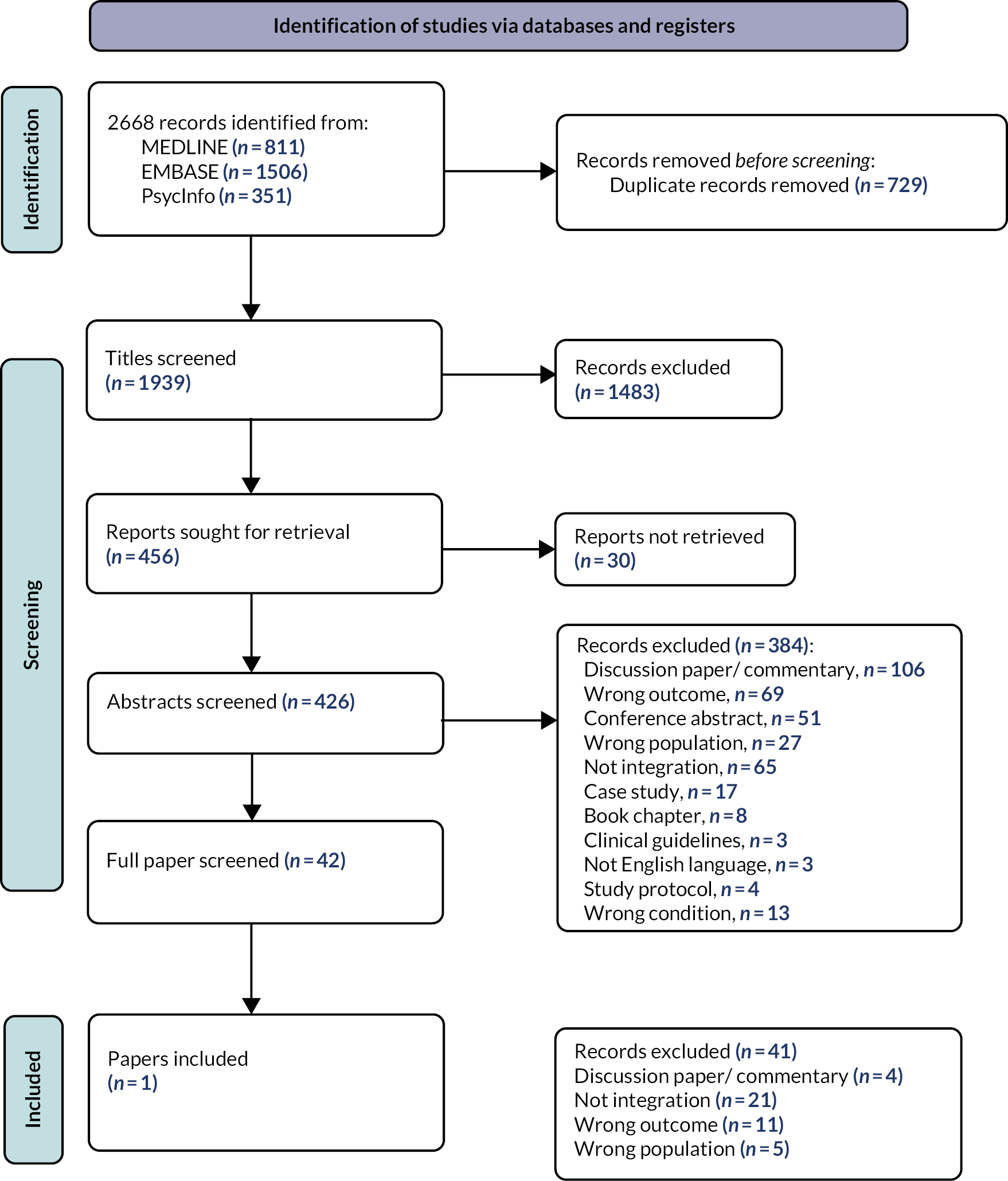

Screening was managed using the EndNote v.21.0 (Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA) and Rayyan (Qatar Computing Research Institute, Doha, Qatar) reference software56. All studies retrieved through the searches were merged, and duplicate studies were removed. The unique studies were screened in three phases: (1) title, (2) abstract/executive summary and (3) full text. Due to the large number of records (1939 titles and 426 abstracts) and time constrictions (this was a rapid systematic review aimed at informing the empirical workstreams of a broader study), we were unable to conduct dual screening of all records. Two reviewers (EM and JM) independently screened the title, abstract and full text of the studies, and a subsample of 10% of studies were dual-screened to ensure that the screeners applied the inclusion criteria consistently [agreement level from 94% (abstract screening) to 100% (full-text screening)]. 57 In cases where the two reviewers disagreed, a senior member of the research team (SM) was asked to make the final decision. The studies that met the inclusion criteria summarised in Table 1 were considered for full-text screening.

Quality assessment

We used the Effective Public Health Project Practice (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (https://merst.ca/ephpp) to appraise the quality of the included quantitative studies. 58 Six domains (selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection method and withdrawals and dropouts) are assessed and rated as strong, moderate or weak, resulting in a global quality score. The tool was applied independently by two reviewers (EM and JM) and then compared (agreement level 100%). No qualitative studies were appraised and hence we did not use the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme qualitative checklist (https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/) as described in the protocol.

Data extraction

Using a data extraction form developed in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), we extracted the following information from studies that were eligible for inclusion into the review following full-text screening: title, author(s), year of publication, country/origin, aims, type and design of study, population (e.g. children of a specific age group), study comparator, time period covered, aspects of integration captured, type of health care (i.e. primary, secondary, social), questions/scales used to quantify integration, pathways used, health-related outcomes, findings (these could be reported e.g. as mean difference, absolute values, or risk ratio). Information was identified using an extraction form developed a priori specifically for this review (see Appendix 1, Table 8). Extraction of data was performed by EM and JM and was independently verified by other co-authors.

Strategy for evidence synthesis

A numerical summary of existing evidence and narrative description of findings in relation to the research questions was provided. We reported year of publication, country of interest and study design. To summarise evidence from both quantitative and qualitative studies, we carried out a narrative synthesis. 59 This framework comprises four main stages: (1) developing a theory of how the intervention works, why and for whom; (2) developing a preliminary synthesis of findings in included studies; (3) exploring relationships in the data; and (4) assessing the robustness of the syntheses. Findings were described separately for each research question, and overall summary and conclusions were provided.

The PROSPERO protocol of this study includes details about the strategy of qualitative evidence synthesis – which, however, was not needed in practice, as shown below.

Results

Selection of studies

We identified 2668 citations from our searches, which resulted in 1939 papers eligible for title screening after the extraction of duplicates. Of these, 456 papers met our criteria in the title screening, and the corresponding abstracts were sought for retrieval. It was not possible to retrieve the abstracts of 30 studies, leaving 426 abstracts for screening. We excluded papers at abstract screening stage for the following reasons: commentaries (n = 106), conference abstracts (n = 51), book chapters (n = 8), study protocols or guideline documents or not available in English (n = 10), case studies (n = 17), non-integration (n = 65), research on adults (n = 27), different health conditions (n = 13), non-inclusion of our outcomes of interest (n = 69). For example, we excluded a study focused on participants’ knowledge about diagnostic criteria, treatment approaches and ways in which clinicians can collaborate with each other to provide appropriate care for people with a specific eating disorder. 60 A total of 42 studies were eligible for full-text review, and 41 of these were excluded for the following reasons: commentaries (n = 4), non-integration (n = 21), non-inclusion of our outcomes of interest (n = 11), research on adults (n = 5) (see Figure 1). Therefore, only one study was included in our review. 61 That single-site Australian evaluation of an integrated care model for CYP with eating disorders based on data in 1990, and its main elements in population, intervention, control/comparison, outcome (PICO) format, are summarised in Table 2.

| Study elements | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | CYP with eating disorders, seen at the eating disorders assessment clinic during a 39-month period |

| Intervention | Integration of health services |

| Control or comparison | Children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa admitted to the hospital during a 39-month period that was earlier than that of the participants |

| Outcome | Hospital admissions for eating disorders per year,

|

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for systematic review on integrated services for eating disorders and functional symptoms in CYP.

Quality appraisal

When assessed with the EPHPP quality assessment tool, the study had significant weaknesses in terms of confounders, blinding, data collection methods and withdrawals and dropouts, and moderate scores in terms of selection bias and study design. Applying the global rating, this study scored weakly (Table 3).

| Rating section | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, year, country | Study design | A: selection bias | B: study design | C: confounders | D: blinding | E: data collection methods | F: withdrawals and dropouts | Global rating |

| McDermott et al. 2001, Australia61 | Cohort | Moderate | Fair | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

Outcomes

Research question 1

What are the service models and implementation approaches used to integrate physical and mental health services for CYP with eating disorders or/and functional symptoms?

The included study describes an integrated healthcare model implemented as a fully government-funded service in the only paediatric eating disorders team in a regional capital city. According to this, referrals from parents, school nurses, counsellors, and paediatric and mental health practitioners were accepted by the eating disorders team. After an initial assessment by telephone triage, parents and children attended the assessment clinic for two consecutive mornings. During these visits they had a semistructured psychiatric interview, an eating disorders research interview, and a medical examination by a gastroenterologist with specialty in CYP and a dietitian. Their visits also included anthropometric assessments (measurement of height and weight). An assessment protocol was developed by the multidisciplinary team, and all the relevant clinicians reached a consensus diagnosis. Consent on the protocol was sought from parents and children. A plan on how to manage the case was also developed by the same team. Further information about the location and organisation of the services that comprise this integrated model is not reported in the study.

Research question 2

Which factors influence how integration of these services is implemented?

This was not stated in the study.

Research question 3

How do these integrated health services influence CYP’s access to care?

Access to care was not among the outcomes of interest of this study and no qualitative or quantitative data were included for this purpose. However, it is claimed that a ‘centre of excellence’ approach facilitates interaction with other national and international eating disorders services, allowing better access to current best practice.

Research question 4

How do these integrated health services influence the delivery of clinical interventions, patient outcomes and cost-effectiveness?

The study reported significant differences in hospital admissions. More specifically, prior to integration, most of the inpatient admissions were to the psychiatric unit, including those of patients transferred to and from psychiatric and medical wards (75%), while the admissions to medical wards accounted for only 8.5%. After the integration, only 2.5% of the inpatient admissions were to the psychiatric unit; most of the inpatient admissions were to medical wards (97%), and these were admissions from psychiatric wards that occurred prior to the intervention, or admissions for urgent nutritional resuscitations.

The integration of health services led also to a reduction, by approximately half, in the duration of the hospital admission [mean 51.72 days, standard deviation (SD) 44.04 days, range 1–174 days prior to integration vs. mean 23.80 days, SD 12.97 days, range 1–84 days after integration] and decreased variation in admission length, since fewer patients had multiple admissions. This was because patients with severe eating disorders requiring urgent inpatient services usually receive this care during the acute phase of the condition, and partial hospitalisation services may decrease the length of inpatient stay.

After the integration of the services, bed-days increased by 2.3 times, but this burden was shifted from child psychiatric wards to medical wards, leading to an increase in the total inpatient admissions cost by AUS$1.39. However, the cost per admission decreased by 40%, which could be interpreted as a reduction by 48% in the cost per inpatient (Table 4). This was because in the integrated scheme, most psychological therapy was provided in outpatient services while more than 95% of all inpatient admissions were to medical wards for nutritional resuscitation or other physical complications.

| Primary outcomes | Secondary outcomes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, year, country | Integration approach | Effects of accessing and receiving care | Effects of clinical interventions on outcomes and cost-effectiveness | Barriers and facilitators to successful implementation | Measures used to quantify integration |

| McDermott, B et al., 2001, Australia61 |

|

Allows better access to current best practice |

|

Medical wards’ staff had less appropriate training in dealing with children and adolescents with eating disorders than psychological medicine staff 117.693 pt | |

|

|||||

There was no evidence on the other predefined outcomes – that is, the relationship between integration and clinical outcomes, users’ experience, and providers’ perspective – in the reviewed study.

Discussion

Key findings

In this study, we reviewed the literature on integration of mental and physical health services for CYP in the management of eating disorders and functional symptoms. The review identified only one study investigating integrated services in secondary care, for children and adolescents with eating disorders, comparing them with generic services. No similar studies were found for CYP with functional symptom disorders. A single-site study conducted in Australia thoroughly describes the development and implementation of interventions for CYP with functional symptom disorders, but further research is needed in terms of their effectiveness and to promote their adoption as standard treatment plans. 62

The reviewed study showed a significant shift in the type of admissions, moving from admissions to psychiatric units to admissions to medical wards. This change was accompanied by a reduction in the cost per admission and cost per inpatient stay, despite the increase in bed-days. This was because, in the integrated scheme, most psychological therapy was provided in outpatient services while most inpatient admissions were to medical wards for nutritional resuscitation or other physical complications. However, further outcomes were not assessed in that study.

Our findings align with previous research on the integration of physical and mental health services, though it may not specifically address the two conditions of interest. Notably, integrated care has been associated with better utilisation of primary care and psychiatric outpatient services,63,64 as well as cost savings. 65 Other studies that have assessed eating disorder units – even if they are not explicitly labelled as integrated models and thus may have been excluded from the review – demonstrate the benefits from aspects of integrated care such as the involvement of multidisciplinary teams66,67 and closer co-ordination of healthcare services. 68 Additionally, our findings corroborate earlier evidence12 and highlight that, despite various studies describing aspects of integrated care, the integration of physical and mental health services for CYP with eating disorders and/or functional symptoms is underexplored, with the limited available evidence being of weak quality. To the best of our knowledge, no other studies quantitatively describe the lack of evidence in this specific research area. For instance, a study on the development of a joint working model for restrictive eating disorders on paediatric wards lacks quantitative evidence and comparisons between the proposed model and the generic models. 69

Two key challenges emerged during the screening process. The first challenge concerns the definition of integration and integrated care. Previous studies have acknowledged the inability to reach a consensus about this definition. 12 Consequently, the terms ‘integration’ and ‘integrated care’ are often used interchangeably with co-location or multidisciplinary teams, whereas true integration in health care goes beyond simple co-location or co-ordination of multidisciplinary teams.

The second challenge lies in defining functional symptoms. As mentioned in the introduction, this term refers to physical symptoms without clear pathological explanation. This makes it difficult to distinguish between functional symptoms and other chronic conditions, such as chronic abdominal pain, for which there is no clear pathological explanation.

The fact that the study meeting our eligibility criteria used children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa as the comparison group, instead of a broader group with various eating disorders, is in line with the existing evidence indicating that the current research focuses on very specific conditions and lacks broader conclusions about integrated care.

Strengths and limitations

Our systematic review adds to the limited evidence about the integration of physical and mental health services for CYP and highlights the gap that exists in the relevant research. Apart from the population of interest, which is underexplored in the literature, this review extended the outcomes of interest that are used in other studies by including a wide variety of outcomes. The identification of a single study indicates the dearth of evidence, even though no specific outcomes are used.

Another strength of our review is the focus on two highly prevalent conditions that capture different types of symptoms, and which were traditionally treated using different approaches; that is, eating disorders are traditionally addressed using mental health services, and functional symptom disorders using physical health services. This might be interpreted as an attempt to investigate integrated care starting from different starting points, in the sense of different prevalent perspectives.

Our review inevitably comes with a number of limitations. First, the lack of conceptual consistency about the definitions of integration and integrated care may have driven false screening and loss of some evidence. This could be addressed by analysing, for instance, the 21 papers that we identified as relevant but not featuring integrated services. For example, among these papers is a study by Blécourt et al. which describes a multidisciplinary pain management programme for children and adolescents with chronic musculoskeletal pain. 70 However, this programme does not address integration of care and does not include a comparator. To include such studies, we would need to redefine the term ‘integration’ and include studies on aspects of integration and multidisciplinary approaches which would be out of the scope of the current study. In addition to this, recently published reviews of integrated healthcare services for CYP did not find any studies about either condition. This suggests that we have not overlooked any key studies. The same limitation applies in terms of the definition of functional symptom disorders. Again, it is possible that we have missed some evidence considering that there is a pathological explanation, whereas the described condition might be only a symptom of the functional symptoms.

Apart from the number of eligible studies that we identified (i.e. only one), we should also acknowledge the fact that the study uses data collected in the 1990s. Given that an integrated care model takes into consideration, among other things, social factors that might affect an individual’s physical and mental health, this might be a limitation about the power of its conclusions in the current circumstances.

Finally, we acknowledge that double-screening only a proportion of the identified records may have caused inconsistent application of the inclusion criteria. However, the level of agreement between the two screeners was very high.

Implications

The lack of concrete evidence that our review showed highlights the need for further understanding and evaluation of integrated healthcare services for specific populations and conditions. The findings from the unique study that we included are encouraging and can be used to increase awareness about the impact of integrated care on CYP with eating disorders.

Future research

This work is paving the way for more empirical research on integrated care for CYP living with eating disorders or functional symptoms. The currently available research indicates the dearth of evidence regarding the integration of physical and mental health services. Future research should set as a priority the conceptual consistency regarding the definition of integrated care. Our review showed that the term ‘integrated health care’ is usually interchangeable with that of ‘interdisciplinary/multidisciplinary teams’, indicating the broad and usually vague nature of integrated health care. To understand and assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of this type of care, clear definitions are required.

Given the specific characteristics that CYP face, conclusions about integrated care in paediatric settings should be based on research on this population instead of research focused on integrated care for adults or elderly people. Thus, future research needs to consider the developmental challenges that CYP face and to focus particularly on them for the investigation of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of integrated physical and mental health services.

The multifaceted needs that CYP and their families face highlight the need for research focusing on different health conditions. The complexity of their needs is such that it might be very difficult and challenging to draw definitive conclusions that will apply to all conditions. The risk of fragmented evidence underlies this approach. However, the thorough investigation of integrated care for specific conditions allows better understanding and more reliable evidence.

Future research needs to also address the challenge of different settings. In integrated care models, it is usually difficult to distinguish the hierarchies and the organisation of the involved parties. In the literature, we meet different levels of integration and taxonomies. Further understanding of the implementation of integrated care will allow comparisons between different models and further development of this type of care. Future research needs to address the definition of functional symptom disorders. As mentioned above, this term covers a wide range of health conditions that usually overlap or are difficult to distinguish.

Last but not least, future research needs to identify clinical, social and economic outcomes and agree on how these will be measured. This is particularly challenging when the population of interest is CYP, where the parents’ or carers’ involvement is needed more. Agreement on these issues will allow the evaluation of better models of integrated care that enhance the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of physical and mental health services for CYP.

Conclusion

In conclusion, even though we focused on two highly prevalent conditions that are traditionally71 treated using different pathways of care, and we included a wide range of outcomes of interest, we identified only one eligible study. The review of this study supports the findings from other studies regarding the limited evidence on the clinical and cost-effectiveness of integrated care for CYP. The challenges and the big gaps in literature that this review shows up can be used as inductions for future researchers.

Additional information

CRediT contribution statement

Efthalia Massou (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0488-482X): methodology (equal), investigation (lead), software (lead), formal analysis (lead), data curation (lead), writing - original draft, review and editing (lead)

Josefine Magnusson (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5116-6153): methodology (equal), investigation (lead), software (lead), formal analysis (lead), data curation (lead), and writing - original draft (lead).

Naomi J Fulop (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5306-6140): methodology (equal), and writing - original draft (equal).

Saheli Gandhi (https://orcid.org/0009-0000-9850-5370): methodology (equal), writing- original draft (equal), project administration (lead).

Angus IG Ramsay (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4446-6916): methodology (equal), writing - original draft (equal).

Isobel Heyman (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7358-9766): methodology (equal), writing - original draft (equal).

Sara O’Curry (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4132-5827): methodology (equal), writing - original draft (equal).

Sophie Bennett (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1076-7112): methodology (equal), writing - original draft (equal).

Tamsin Ford (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5295-4904): methodology (equal), writing - original draft (equal).

Stephen Morris (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5828-3563): conceptualization (lead), methodology (lead), formal analysis (equal), writing - original draft, review and editing (equal), supervision (lead).

All authors approved the final version of the article and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Dr Mike Basher, Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust, member of the Project Advisory Group, who contributed to development of the search strategy and made critical revisions to earlier versions of this article. They would also like to thank Pei Li Ng, Research Project Manager, Department of Applied Health Research, University College London, London, UK, who provided administrative support.

This systematic review was part of a wider project on centralisation of specialised services (NIHR136239), which run through the NIHR Rapid Service Evaluation Team programme. The centralisation project held regular meetings with patient representatives. The review was discussed regularly in these meetings, and patient and public representatives provided feedback throughout the process, including during dissemination. Their feedback helped ensure the review focused on the importance of integrating physical and mental health services for CYP with eating disorders and functional symptoms; ensure that its focus was reflected in our aims, objectives and research questions; and finally ensure that our findings were disseminated effectively and in a manner that is meaningful to patients, carers and the public.

Data-sharing statement

Evidence reported in this systematic review is included in the referenced literature and tables. Requests for more information about data from the study as a whole should be submitted to the corresponding author for consideration. Access to anonymised data used for other parts of the study may be granted following review.

Ethics statement

The study as a whole was reviewed by the East Midlands – Nottingham 1 Research Ethics Committee and received ethical approval from the Health Research Authority and Health and Care Research Wales on 25 January 2023 (REC reference: 22/EM/0277). This article derives from the systematic review of existing literature and as such does not require ethics approval. No research data were collected for the project.

Information governance statement

There were no personal data involved in the production of this report.

Disclosure of interests

Full disclosure of interests: Completed ICMJE forms for all authors, including all related interests, are available in the toolkit on the NIHR Journals Library report publication page at https://doi.org/10.3310/ELPT1245.

Primary conflicts of interest: Naomi J Fulop is an NIHR Senior Investigator, the UCL-nominated non-executive director for Whittington Health NHS Trust (2018–24), a non-executive director of the organisation Covid Bereaved Families for Justice, and a trustee of Health Services Research UK (to November 2022). Naomi J. Fulop was formerly a member of the following: the UKRI and NIHR College of Experts for COVID-19 Research Funding (2020), the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research (HS&DR) Programme Funding Committee (2013–18), and the HS&DR Evidence Synthesis Sub Board (2016).

Angus IG Ramsay is a Trustee of Health Service Research UK, and formally an NIHR HSDR Associate Board Member (2015–8).

Sophie Bennett is the Principal Investigator of an Epilepsy Research UK grant, and Co-investigator of an NIHR PGfAR Great Ormond Street Hospital Children’s Charity funded studies. She is an editor of the Oxford Guide to Brief and Low Intensity Interventions. Sophie Bennett is a Trustee of HOPE for Paediatric Epilepsy London. She is a psychologist at the Mind and Body London.

Tamsin Ford’s research group receives funding for research consultancy to Place2Be, a third-sector organisation that provides mental health training and interventions in schools.

Stephen Morris is currently (2022–) a member of the SBRI Healthcare panel. He was formerly a member of the NIHR HS&DR Programme Funding Committee (2014–6), the NIHR HS&DR Evidence Synthesis Sub Board (2016), the NIHR Unmet Need Sub Board, the NIHR HTA Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board (2007–9), the NIHR HTA Commissioning Board (2009–13), the NIHR PHR Research Funding Board (2011–7), and the NIHR PGfAR expert subpanel (2015–9). His post is funded in part by RAND Europe, a non-profit research organisation.

Department of Health and Social Care disclaimer

This publication presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, MRC, NIHR Coordinating Centre, the Health and Social Care Delivery Research programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

This synopsis was published based on current knowledge at the time and date of publication. NIHR is committed to being inclusive and will continually monitor best practice and guidance in relation to terminology and language to ensure that we remain relevant to our stakeholders.

Publications

Ramsay AIG, Tomini SM, Gandhi S, Fulop N, Morris S. Centralisation of specialised healthcare services: a scoping review of definitions, types, and impact on outcomes. Health and Social Care Delivery Research {HSDR NIHR133613 RSET – RA1 Scoping review).

Magnusson J, Fulop NJ, Ramsay AIG, Massou E, Gandhi S, O’Curry S, Heyman I, Bennett SD, Ford T, Morris S. Integration of physical and mental health services for children and young people with eating disorders and functional symptoms: a qualitative study of staff and parent perspectives. (Submitted to BMC Health Services Research).

Massou E, Basher M, Bennett SD, Ford T, Gandhi S, Heyman I, Magnusson J, Mehta R, Ng PL, O’Curry S, Ramsay AIG, Fulop NJ, Morris S. Integration of physical and mental health services for children and young people with eating disorders and functional symptom disorders: discrete choice experiments (Submitted to BMC Health Services Research).

Morris S, Massou E, Magnusson J, Gandhi S, Ng PL, Ramsay AIG, Fulop NJ. Centralisation of specialised health care services (CENT): integration of specialised services for eating disorders and functional symptom disorders in children and young people, a mixed methods study. (HSDR NIHR136239 RSET – Synopsis).

Study registration

This study is registered as PROSPERO CRD42022349805.

Funding

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health and Social Care Delivery Research programme as award number NIHR133613.

This article provided an overview of the research award Centralisation of specialist health care services: a mixed-methods programme. Other articles published as part of this thread are: [LINKS to other articles]. For more information about this research please view the award page www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/NIHR133613.

About this article

The contractual start date for this research was in January 2021. This article began editorial review in October 2023 and was accepted for publication in September 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Health and Social Care Delivery Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Copyright

Copyright © 2025 Massou et al. This work was produced by Massou et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

List of abbreviations

- CYP

- children and young people

- DSM-5

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition

- EDNOS

- eating disorder not otherwise specified

- EPHPP

- Effective Public Health Project Practice

- GP

- general practitioner

- SD

- standard deviation

References

- Goodwin N, Curry N, Naylor C, Ross S, Duldig W. London: The Kings Fund; 2010.

- Sheaff R, Halliday J, Ovretveit J, Byng R, Exworthy M, Peckham S, et al. Integration and continuity of primary care: polyclinics and alternatives – a patient-centred analysis of how organisation constrains care co-ordination. Health Serv Delivery Res Volume 2015;3:1-148.

- Murtagh S, McCombe G, Broughan J, Carroll A, Casey M, Harrold A, et al. Integrating primary and secondary care to enhance chronic disease management: a scoping review. Int J Integr Care 2021;21:1-15. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.5508.

- Flanagan S, Damery S, Combes G. The effectiveness of integrated care interventions in improving patient quality of life (QoL) for patients with chronic conditions. An overview of the systematic review evidence. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017;15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0765-y.

- Nuño R, Coleman K, Bengoa R, Sauto R. Integrated care for chronic conditions: the contribution of the ICCC Framework. Health Policy 2012;105:55-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.10.006.

- Kodner DL, Spreeuwenberg C. Integrated care: meaning, logic, applications, and implications – a discussion paper. Int J Integr Care 2002;2. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.67.

- NHS Improvement . Guidance, Delivering Better Integrated Care 2015. www.gov.uk/guidance/enabling-integrated-care-in-the-nhs.

- Cameron A, Bostock L, Lart R. Service user and carers perspectives of joint and integrated working between health and social care. J Integrated Care 2014;22:62-70. https://doi.org/10.1108/JICA-10-2013-0042.

- Backes EP, Bonnie RJ. The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2019.

- Wolfe I, Lemer C, Cass H. Integrated care: a solution for improving children’s health?. Arch Dis Child 2016;101:992-7. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2013-304442.

- Burkhart K, Asogwa K, Muzaffar N, Gabriel M. Pediatric integrated care models: a systematic review. Clin Pediatr 2020;59:148-53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922819890004.

- Pygott N, Hartley A, Seregni F, Ford TJ, Goodyer IM, Necula A, et al. Research review: integrated healthcare for children and young people in secondary/tertiary care – a systematic review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2023;64:1264-79.

- Newlove-Delgado T, Marcheselli F, Williams T, Mandalia D, Davis J, McManus S, et al. Mental Health of Children and Young People in England. Leeds: NHS Digital; 2022.

- Yong K, Chin RF, Shetty J, Hogg K, Burgess K, Lindsay M, et al. Functional neurological disorder in children and young people: incidence, clinical features, and prognosis. Dev Med Child Neurol 2023;65:1238-46.

- Rosendal M, Olesen F, Fink P. Management of medically unexplained symptoms. BMJ 2004;330:4-5.

- Berezowski L, Ludwig L, Martin A, Löwe B, Shedden-Mora MC. Early psychological interventions for somatic symptom disorder and functional somatic syndromes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 2022;84:325-38.

- Goodwin N. Understanding Integrated Care. Int J Integr Care 2016;16. 10.5334/ijic.2530.

- Fazel M, Townsend A, Stewart H, Pao M, Paz I, Walker J, et al. Integrated care to address child and adolescent health in the 21st century: a clinical review. JCPP Adv 2021;1.

- Hughes EK, Le Grange D, Court A, Yeo M, Campbell S, Whitelaw M, et al. Implementation of family-based treatment for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. J Pediatr Health Care 2014;28:322-30.

- Plevin D, Smith N. Assessment and management of depression and anxiety in children and adolescents with epilepsy. Behav Neurol 2019;2019.

- Shortell SM, Addicott R, Walsh N, Ham C. The NHS five year forward view: lessons from the United States in developing new care models. BMJ 2015;350. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h2005.

- de Bruin SR, Versnel N, Lemmens LC, Molema CC, Schellevis FG, Nijpels G, et al. Comprehensive care programs for patients with multiple chronic conditions: a systematic literature review. Health Policy 2012;107:108-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.06.006.

- Jha S, Moran P, Blackwell A, Greenham H. Integrated care pathways: the way forward for continence services?. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2007;134:120-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.07.028.

- Julian S, Naftalin NJ, Clark M, Szczepura A, Rashid A, Baker R, et al. An integrated care pathway for menorrhagia across the primary–secondary interface: patients’ experience, clinical outcomes, and service utilisation. Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:110-5.

- Jackson GL, Powers BJ, Chatterjee R, Bettger JP, Kemper AR, Hasselblad V, et al. The patient centered medical home. A systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:169-78. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00579.

- MacLean A, Fuller RM, Jaffrey EG, Hay AJ, Ho-Yen DO. Integrated care pathway for Clostridium difficile helps patient management. Br J Infection Control 2008;9:15-7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469044608098324.

- Roberts S, Unadkat N, Chandok R, Sawtell T. Learning from the integrated care pilot in West London. London J Prim Care 2012;5:59-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/17571472.2013.11493376.

- Wedel R, Kalischuk RG, Patterson E, Brown S. Turning vision into reality: successful integration of primary healthcare in Taber, Canada. Healthc Policy 2007;3:80-95.

- Beacon A. Practice-integrated care teams–learning for a better future. J Integrated Care 2015;23:74-87.

- Mason A, Goddard M, Weatherly H, Chalkley M. Integrating funds for health and social care: an evidence review. J Health Serv Res Policy 2015;20:177-88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1355819614566832.

- Wilberforce M, Tucker S, Brand C, Abendstern M, Jasper R, Challis D. Is integrated care associated with service costs and admission rates to institutional settings? An observational study of community mental health teams for older people in England. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016;31:1208-16. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4424.

- Creed F, Guthrie E, Fink P, Henningsen P, Rief W, Sharpe M, et al. Is There a Better Term Than ‘Medically Unexplained Symptoms’? Journal of psychosomatic research. 2010.

- Marks EM, Hunter MS. Medically unexplained symptoms: an acceptable term?. Br J Pain 2015;9:109-14.

- Asken MJ, Grossman D, Christensen LW. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- Rolfe A, Burton C. Reassurance after diagnostic testing with a low pretest probability of serious disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:407-16. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2762.

- Ibeziako P, Bujoreanu S. Approach to psychosomatic illness in adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr 2011;23:384-9.

- Gol J, Terpstra T, Lucassen P, Houwen J, van Dulmen S, Hartman TCO, et al. Symptom management for medically unexplained symptoms in primary care: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2019;69:e254-e61.

- Hinton D, Kirk S. Families’ and healthcare professionals’ perceptions of healthcare services for children and young people with medically unexplained symptoms: a narrative review of the literature. Health Soc Care Community 2016;24:12-26.

- Furness P, Glazebrook C, Tay J, Abbas K, Slaveska-Hollis K. Medically unexplained physical symptoms in children: exploring hospital staff perceptions. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2009;14:575-87.

- McWilliams A, Reilly C, Heyman I. Non-epileptic seizures in children: views and approaches at a UK child and adolescent psychiatry conference. Seizure 2017;53:23-5.

- Pales J, Street K. 1604 A biopsychosocial model of care for children and young people (CYP) with persistent, unexplained, physical symptoms (PUPS) J Pales*, K Street, R Howells. Arch Dis Child 2021;106:A426-A7. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2021-rcpch.741.

- Hilbert A, Hoek HW, Schmidt R. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for eating disorders: international comparison. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2017;30:423-37.

- Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Dahmen B. Children in need – diagnostics, epidemiology, treatment and outcome of early onset anorexia nervosa. Nutrients 2019;11.

- Rosen DS. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence . Identification and management of eating disorders in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2010;126:1240-53.

- Edakubo S., Fushimi K. Mortality and risk assessment for anorexia nervosa in acute-care hospitals: a nationwide administrative database analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2020;20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-2433-8.

- Mairs R, Nicholls D. Assessment and treatment of eating disorders in children and adolescents. Arch Dis Child 2016;101:1168-75.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

- Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.0 (Updated August 2019). Hoboken: Wiley; 2019.

- Baxter S, Johnson M, Chambers D, Sutton A, Goyder E, Booth A. The effects of integrated care: a systematic review of UK and international evidence. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3161-3.

- Department of Health and Social Care . Health and Social Care Integration: Joining Up Care For People, Places and Populations 2022. www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-and-social-care-integration-joining-up-care-for-people-places-and-populations.

- Sarmiento C, Lau C, Carducci BJ, Nave CS, Fabio A, Saklofske DH, et al. The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences: Personality Processes and Individual Differences. Wiley: Wiley Online Library; 2020.

- Rosendal M, Olesen F, Fink P. Management of medically unexplained symptoms. BMJ 2005;330:4-5. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.330.7481.4.

- Creed F, Guthrie E, Fink P, Henningsen P, Rief W, Sharpe M, et al. Is there a better term than ‘medically unexplained symptoms’?. J Psychosom Res 2010;68:5-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.09.004.

- Marks EM, Hunter MS. Medically unexplained symptoms: an acceptable term?. Br J Pain 2015;9:109-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463714535372.

- Bonvanie IJ, Kallesøe KH, Janssens KA, Schröder A, Rosmalen JG, Rask CU. Psychological interventions for children with functional somatic symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr 2017;187:272-81.e17.

- Mourad Ouzzani, Hossam Hammady, Fedorowicz Zbys, Elmagarmid Ahmed. Rayyan — a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 2016;5. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4.

- Polanin JR, Pigott TD, Espelage DL, Grotpeter JK. Best practice guidelines for abstract screening large‐evidence systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Res Synthesis Methods 2019;10:330-42.

- Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Cummings GG. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract 2012;18:12-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x.

- Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. ESRC Methods Programme 2006;1.

- Derenne J. Eating disorders in children, adolescents, and transition-age youth: assessment, diagnosis, and treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2020;59.

- McDermott B, Gullick K, Forbes D. The financial and service provision implications of a new eating disorders service in a paediatric hospital. Australas Psychiatry 2001;9:151-5. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1665.2001.00322.x.

- Kozlowska K, Chudleigh C, Savage B, Hawkes C, Scher S, Nunn KP. Evidence-based mind–body interventions for children and adolescents with functional neurological disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2023;31:60-82. https://doi.org/10.1097/hrp.0000000000000358.

- Gaglioti AH, Barlow P, Thoma KD, Bergus GR. Integrated care coordination by an interprofessional team reduces emergency department visits and hospitalisations at an academic health centre. J Interprof Care 2017;31:557-65.

- Bird SR, Noronha M, Kurowski W, Orkin C, Sinnott H. Integrated care facilitation model reduces use of hospital resources by patients with pediatric asthma. J Healthc Qual 2012;34:25-33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1945-1474.2011.00143.x.

- Wolfe I, Satherley R-M, Scotney E, Newham J, Lingam R. Integrated care models and child health: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2020;145. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3747.

- Sharp WG, Volkert VM, Scahill L, McCracken CE, McElhanon B. A systematic review and meta-analysis of intensive multidisciplinary intervention for pediatric feeding disorders: how standard is the standard of care?. J Pediatr 2017;181:116-24.e4.

- Brown L. Nutrition Masters Projects. Georgia State University; 2020.

- Gould S, Hendrickson K. Coordination of care and early adolescent eating disorder treatment outcomes. J Multidiscip Res 2016;8:5-14.

- Street K, Costelloe S, Wootton M, Upton S, Brough J. Structured, supported feeding admissions for restrictive eating disorders on paediatric wards. Arch Dis Child 2016;101:836-8. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2016-310506.

- Blécourt AD, Preuper HR, Van Der Schans CP, Groothoff JW, Reneman MF. Preliminary evaluation of a multidisciplinary pain management program for children and adolescents with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Disabil Rehabil 2008;30:13-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280601178816.

- Archibald HC, Tuddenham RD. Persistent stress reaction after combat: a 20-year follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry Ther 2007;45:2317-25.

Appendix 1

| Patient care team/ |

|---|

| “Delivery of Health Care, Integrated”/ |

| ((multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary or collaborative hospital-managed or coordinat*) adj3 (care or healthcare or service* or clinic* or team* or management)) |

| “medical home” |

| “(hospital-based and (“home care” or “case management”)).” |

| “multisystemic therapy” |

| integrated delivery system |

| integrated health care system* |

| integrated healthcare system |

| adolescent/ or exp child/ |

| ((young and (people or person* or girl* or boy*)) or adolescen* or teen* or youth or minor* or child* or infant*) |

| Rumination Syndrome/ |

| “Feeding and Eating Disorders”/ |

| Anorexia/ or Anorexia Nervosa/ |

| Bulimia/ or Bulimia Nervosa/ |

| Binge-Eating Disorder/ |

| Rumination disorder* |

| (Avoidant or restrictive food intake disorder*) |

| Anorexia |

| “Bulimia.” |

| (Binge-eating adj (disorder* or syndrome)) |

| Pica |

| “Eating disorder*.” |

| “Purging disorder*.” |

| Restricted eating |

| Somati?ation |

| “(Functional disorder* or functional somatic syndrome*).” |

| “((Bodily distress or bodily stress) adj (syndrome* or disorder*)).” |

| “Somatic symptom disorder*.” |

| “((Psychophysical or psychophysiological or Psychosomatic or Somatoform or Conversion) adj disorder*).” |

| “(Symptom defined adj (illness or syndrome)).” |

| ((Persistent physical or Functional or Complex physical) adj symptom*) |

| Chronic idiopathic pain |

| (Non-specific functional and somatoform bodily complaints) |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome |

| Myalgic encephalomyelitis |

| “Fibromyalgia.” |

| exp Somatoform Disorders/ |

| Fatigue Syndrome, Chronic/ |

| “medically unexplained symptom*.” |

| Medically Unexplained Symptoms/ |

| irritable bowel syndrome |

| psychosomatic disorder |

| somatoform pain disorder |

| chronic headache |

| ‘chronic limb pain’ |

| chronic back pain |

| chronic neck pain |

| “chronic musculoskeletal pain.” |

| “chronic abdominal pain.” |

| chronic pain/ |

| “unexplained complaint*.” |

| unexplained illness |

| psychosomatic illness |

| psychosomatic complaint |

| chronic benign pain |

| functional pain |

| psychogenic pain/ |

| longstanding pain |

| idiopathic pain |

| “recurrent abdominal pain.” |

| “functional abdominal pain.” |

| functional gastrointestinal symptoms’ |

| functional gastrointestinal disorder* |

| functional headache |

| non specific headache |

| tension headache |

| idiopathic musculoskeletal pain |

| chronic widespread pain |

| nonspecific musculoskeletal pain |

| non specific musculoskeletal pain |

| hyperventilation syndrome/ |

| non cardiac chest pain.mp. or noncardiac chest pain/ |

| “persistent fatigue*.” |

| prolonged fatigue*. |

| musculoskeletal complaints |

| (Chronic abdominal (complaints) or (symptoms)) |

| unexplained complaint |

| somatoform pain |

| somatoform complaint |

| idiopathic headache |

| nonspecific musculoskeletal complaints |

| Nonspecific musculoskeletal symptoms |

| Nonspecific musculoskeletal disorder* |

| tension-type headache |

| tension type headache |

| recurrent headache |

| pediatric or pediatrics/ |

| paediatric |

| Database | APA PsycInfo 1806 to July Week 3 2024 |

|---|---|

| 1 | ((multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary or collaborative hospital-managed or coordinat*) adj3 (care or healthcare or service* or clinic* or team* or management)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 2 | “medical home”.mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 3 | (hospital-based and (“home care” or “case management”)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 4 | “multisystemic therapy”.mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 5 | integrated delivery system*.mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 6 | integrated health care system*.mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 7 | integrated healthcare system*.mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 8 | integrated program* of care.mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 9 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 |

| 10 | exp Adolescent Psychiatry/ or exp Adolescent Psychotherapy/ or exp Adolescent Psychology/ or exp Adolescent Psychopathology/ or exp Adolescent Health/ |

| 11 | ((young and (people or person* or girl* or boy*)) or adolescen* or teen* or youth or minor* or child* or infant*).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 12 | 10 or 11 |

| 13 | exp “Rumination (Eating)”/ |

| 14 | exp Eating Disorders/ or exp Feeding Disorders/ |

| 15 | exp Anorexia Nervosa/ |

| 16 | exp Bulimia/ |

| 17 | exp Binge Eating/ or exp Binge Eating Disorder/ |

| 18 | Rumination disorder*.mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 19 | (Avoidant or restrictive food intake disorder*).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 20 | Anorexia.mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 21 | bulimia.mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 22 | (Binge-eating adj (disorder* or syndrome)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 23 | exp Pica/ |

| 24 | exp Eating Disorders/ |

| 25 | Eating disorder*.mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 26 | Purging disorder*.mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 27 | exp “Purging (Eating Disorders)”/ |

| 28 | Restricted eating.mp. or exp Dietary Restraint/ |

| 29 | 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 |

| 30 | 9 and 12 and 29 |

| 31 | limit 30 to English language |

| 32 | Somati?ation.mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 33 | (Functional disorder* or functional somatic syndrome*).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 34 | ((Bodily distress or bodily stress) adj (syndrome* or disorder*)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 35 | exp Somatization/ or exp Somatoform Disorders/ or exp Somatization Disorder/ or Somatic symptom disorder*.mp. |

| 36 | ((Psychophysical or psychophysiological or Psychosomatic or Somatoform or Conversion) adj disorder*).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 37 | (Symptom defined adj (illness or syndrome)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 38 | ((Persistent physical or Functional or Complex physical) adj symptom*).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 39 | exp Somatoform Pain Disorder/ or exp Chronic Pain/ or Chronic idiopathic pain.mp. |

| 40 | (Non-specific functional and somatoform bodily complaints).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] |

| 41 | Chronic fatigue syndrome.mp. or exp Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/ |

| 42 | Myalgic encephalomyelitis.mp. |

| 43 | exp Fibromyalgia/ or Fibromyalgia.mp. |

| 44 | 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 |

| 45 | 9 and 12 and 44 |

| 46 | limit 45 to English language |

| 47 | 31 or 46 |

| Databases | EMBASE < 1974 to 2024 July 17 > Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL < 1946 to July 17, 2024 > |

|---|---|

| Search string | |

| 1 | Patient Care Team/ |

| 2 | “Delivery of Health Care, Integrated”/ |

| 3 | ((multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary or collaborative hospital-managed or coordinat*) adj3 (care or healthcare or service* or clinic* or team* or management)).tw,kf. |

| 4 | “medical home”.tw,kf. |

| 5 | (hospital-based and (“home care” or “case management”)).tw,kf. |

| 6 | “multisystemic therapy”.tw,kf. |

| 7 | integrated delivery system*.tw,kf. |

| 8 | integrated health care system*.tw,kf. |

| 9 | integrated healthcare system*.tw,kf. |

| 10 | integrated program* of care.tw,kf. |

| 11 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 |

| 12 | adolescent/ or exp child/ |

| 13 | ((young and (people or person* or girl* or boy*)) or adolescen* or teen* or youth or minor* or child* or infant*).tw,kf. |

| 14 | 12 or 13 |

| 15 | Rumination Syndrome/ |

| 16 | “Feeding and Eating Disorders”/ |

| 17 | Anorexia/ or Anorexia Nervosa/ |

| 18 | Bulimia/ or Bulimia Nervosa/ |

| 19 | Binge-Eating Disorder/ |

| 20 | Rumination disorder*.tw,kf. |

| 21 | (Avoidant or restrictive food intake disorder*).tw,kf. |

| 22 | Anorexia.tw,kf. |

| 23 | Bulimia.tw,kf. |

| 24 | (Binge-eating adj (disorder* or syndrome)).tw,kf. |

| 25 | Pica.tw,kf. |

| 26 | Eating disorder*.tw,kf. |

| 27 | Purging disorder*.tw,kf. |

| 28 | Restricted eating.tw,kf. |

| 29 | or/15-28 |

| 30 | 11 and 14 and 29 |