Notes

Article history

The contractual start date for this research was in August 2021. This article began editorial review in November 2023 and was accepted for publication in March 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Health and Social Care Delivery Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Tierney et al. This work was produced by Tierney et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Tierney et al.

Background

The term ‘social prescribing’ describes an approach to addressing non-medical issues (e.g. social isolation, financial worries and housing problems) that can affect people’s health and well-being. 1 Social prescribing involves connecting patients to community resources (organisations, services and groups) often within the voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector, to address these concerns. Social prescribing has become part of the healthcare lexicon in recent years, on a global scale. 2 In England, the NHS Long Term Plan3 elevated social prescribing’s profile as an extended approach to traditional medical care; this document associated social prescribing with the idea of personalised care4 and with population-focused approaches to building community resilience and assisting people to self-manage their well-being. 5

Connecting patients to community support is not a new concept in primary care; it has been undertaken by general practitioners (GPs) for decades. This is because patients often present to general practice with concerns that could be better managed through non-medical routes, delivered by VCSE organisations. 6,7 What is new in England, as in other countries,2 is a non-clinical dedicated role in primary care – known as link workers (other terms are also used, such as social prescriber or community connector). In the 2019 Long Term Plan,3 NHS England made a commitment to provide allocated funding over 5 years for a social prescribing link worker to be attached to each primary care network (PCN). This was extended in the 2023 NHS Workforce Plan to increase link worker numbers from approximately 3000 in 2022 to 9000 by 2037. 8

Link workers are central to social prescribing. 9 They assist patients by actively listening to their challenging life circumstances, through which they identify what matters to individuals and their well-being goals. These goals can vary widely, from finding a purpose in life and enhancing self-confidence to addressing more practical problems. Ideally, link workers have current knowledge of local community assets to which they can connect patients. This could include, but is not limited to, exercise classes, arts and crafts groups, volunteering, as well as services that provide advice on housing or debt management.

There is no specific professional qualification required to be considered for this job; link workers come from a variety of backgrounds (e.g. VCSE, NHS, social care, local authority, education, volunteering)10,11 and will have experienced a range of training and education. Likewise, there is variation in how link workers are employed. For some, this is through a PCN to serve one or more GP practices, where they might work alone or alongside a health and well-being coach and/or care co-ordinator. Others are employed through a VCSE organisation as part of a bigger social prescribing team and deployed into GP practices. This reflects the fact that social prescribing through the VCSE sector pre-dates its roll-out in primary care in England.

Since the national roll-out of link workers into primary care in England, numerous guides and frameworks have been developed to inform their implementation in this setting. They typically emphasise role flexibility to meet local needs. 8,12 This paper examines one result of this local flexibility, namely the use of discretion by link workers at a micro (rather than meso or macro) level.

Discretion describes an individual’s freedom to choose what is done or how to act in a particular situation. Previous research suggests that discretion can be embraced by employees as an opportunity for independent decision-making and use of specialist skills or knowledge, but it can also be experienced as overwhelming and disorientating by staff encountering too little guidance or structure in their work role. 13 In healthcare settings, discretion is often bounded; for example, when multidisciplinary teams delineate the scope of practice of different professions. 14 This can result in boundary work, whereby distinctions between professional groups ‘are created, challenged or reinforced’. 15 Such boundary work is surfaced when new roles are created. 16

Aim and objectives

Building on our previous realist review on the link worker role in primary care,9 we conducted a realist evaluation on this topic. The realist evaluation addressed the question: When implementing link workers in primary care to sustain outcomes – what works, for whom, why and in what circumstances? In this paper, we explore discretion exercised by link workers in their role and its consequences. We also highlight how it relates to an existing substantive theory by drawing on the work of Lipsky17 on ‘street-level bureaucracy’.

Methods

A protocol for the realist evaluation has been published (researchregistry6452), outlining the key procedures associated with the research. Ethics approval was secured from East of England – Cambridge Central Research Ethics Committee. We followed RAMESES quality and reporting guidelines when conducting and reporting on this study. 18

Design

Realist evaluations are appropriate for exploring complex interventions,19 such as the implementation of the link worker role into primary care, which has multiple components and actors. Realist evaluations support the identification of causal factors through the iterative development of a programme theory – an explanation of how an intervention is thought to work. Realist evaluations involve developing context–mechanism–outcome configurations (CMOCs) that can be used to explain why, when and for whom an intervention may or may not work. Table 1 outlines some key concepts in realist evaluations.

| Context | Circumstances within which an intervention is delivered or executed. It can relate to individuals (characteristics of stakeholders), interpersonal relationships, institutional factors (e.g. norms, culture) or infrastructure (wider sociocultural factors).20 Interventions (e.g. the introduction of link workers into primary care) can change contexts to activate mechanisms that then lead to intended or unintended outcomes. |

| Mechanism | Underlying, often invisible causes of outcomes, ‘embodied in the subjects’ reasoning …’20 Mechanisms are a response (e.g. fear, reputation management, feeling valued) to resources provided by an intervention. In realist research, mechanisms ‘are features of the real world that we cannot change … they cannot be directly observed but are the deeper causes of actual events which are themselves latent, always possible, but which are made manifest only under certain conditions …’21 |

| Outcome | From a realist perspective, ‘it is not the programs that “work” but their ability to break into the existing chains of resources and reasoning [of individuals or groups] …’22 Hence, in this project we were interested in understanding how potential outcomes (expected and unanticipated) were produced, and patterns associated with this, rather than making a binary judgement about whether or not link workers were effective. |

| Context–mechanism–outcome configuration (CMOC) | A proposition that the intervention produces an outcome (O) ‘because of the action of some underlying mechanisms (M), which only comes into operation in particular contexts (C)’.20 In their simplest form, CMOCs are statements or causal claims that explain how a specific context can activate certain mechanisms to produce a particular outcome. |

Data collection

The study involved focused ethnographies23,24 conducted between November 2021 and November 2022. We purposively selected seven geographical areas in different parts of England that varied in their socioeconomic characteristics,25 and selected GP practices within these areas, which became our study sites. A link worker based at each practice constituted our study case, around whom we collected data. Maximum variation was sought in terms of link workers’ experience in the role and areas they served (Table 2). Researchers spent 3 weeks with each link worker, going to meetings with them, watching them consult with patients and interacting with healthcare staff and VCSE organisations. Researchers made field notes during this time. They also had a daily debrief with each link worker, asking them what they had done that day and whether these activities were a standard part of their role or if anything unusual had taken place. In addition, they interviewed link workers, patients they supported, and healthcare staff and VCSE representatives. Interviews lasted between 20 and 65 minutes. Some took place in-person, others via telephone or Microsoft Teams (dependent on participant preference and whether researchers were ‘on-site’ when an individual wanted to be interviewed).

| Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | Site 5 | Site 6 | Site 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Link worker time in role in months when data collection started | 24 | 2 | 16 | 8 | 32 | 31 | 38 |

| Link worker leading a team | No | No | No | No | Yes (officially) | Yes (officially) | Yes (informally) |

| Number of sessions with patients | < 6 | < 6 | < 6 | Open | 6–8 | Open | Open |

| Deprivation in area served | Medium | Low | Low | Medium | Medium | High | High |

| Location of site in England | South | Midlands | South | Midlands | South West | North | North |

| Employment of link workers | Funded through primary care but subcontracted to and managed by VCSE | Funded through primary care but subcontracted to and managed by VCSE | Funded through primary care but subcontracted to and managed by VCSE | Funded, contracted and managed by primary care | Funded, contracted and managed by primary care | Funded through primary care but subcontracted to and managed by VCSE | Funded, contracted and managed by primary care |

| Who set up the link worker service | VCSE, GP and link worker | GP led | VCSE and link worker | Mainly link worker | Practice manager and link worker | VCSE and link workers | Link workers |

| Management/supervision of link worker | Provided by VCSE manager | Provided by VCSE team leader and PCN Clinical Director | Provided by VCSE manager | Described as limited – responsibility of practice managers | Provided by practice manager | Provided by VCSE manager | Provided by operational manager |

Patients were invited to a second interview 9–12 months later (conducted between December 2022 and August 2023). Follow-up interviews sought to explore and understand how patients benefitted (or not), in the longer term, from seeing a link worker. We also reinterviewed (9–12 months later) link workers, to explore how the service had changed in the intervening months, to ask additional questions related to our emerging programme theory and to sense-check some of our thoughts on the data. Follow-up interviews were conducted via telephone or Microsoft Teams, and lasted between 10 and 50 minutes.

Analysis

Analysis was concurrent with data collection. The core research team held monthly analysis meetings to identify key concepts coming from the data, and weekly meetings to talk about the coding of data. After completing focused ethnographies for the first four sites, we developed an initial coding framework informed by our earlier realist review. 9 Data from these first four sites were coded deductively in NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK) (software that supports qualitative data analysis) using this framework. When data did not fit the deductive framework, new (inductive) codes were discussed and developed as a team (and the coding framework amended accordingly). Three members of the research team coded these data; one coded data for two sites, and the other researchers coded data for the remaining two. This analysis was used to revise CMOCs from our previous realist review9 and to develop new CMOCs that reflected the primary data we had collected. Data from the final three sites were coded against these revised and new CMOCs. Each researcher coded data from one of these sites. Follow-up interview data were used to strengthen and expand CMOCs, and helped with finalising core concepts from the data about the link worker role in primary care.

We applied a range of realist reasoning processes within the analysis20 – juxtaposing data, unpicking conflicting data and consolidating data – to explain why differences may arise across settings, and how and why identified outcomes occurred (or not). We developed diagrams to help us make sense of the data and to explain key elements of our programme theory.

In this paper, we describe specific micro-discretions – actions link workers take that may not reflect explicit guidance or expected procedures associated with the role. We also identify boundaries that constrained micro-discretions of link workers. We use the term micro-discretions to refer to actions and decisions taken by link workers themselves, often in relation to one-to-one interactions with patients and other stakeholders.

Patient and public involvement and stakeholder involvement

For sense-checking and to hear alternative perspectives on our interpretation of data, we discussed our findings with two patient and public involvement (PPI) groups (one composed of six members of the public with an interest in social prescribing who we met with on seven occasions; another involving 10 people with an interest in health research who we met with twice). In addition, we shared our thinking on the data with our study advisory group; it consisted of those delivering and/or funding social prescribing and VCSE organisations. We met with the advisory group five times during the project.

Results

The seven link workers who formed our cases were female, and six were White British. They ranged in age from 22 to 60 years (mean = 38.3 years, standard deviation = 15.6). They had been in post for between 2 and 38 months when data collection started at their site (mean = 21.5 months, standard deviation = 13.4). Interviews were conducted with 93 professionals (link workers, healthcare staff and VCSE representatives) (see Table 3 for details). Sixty-one patients were interviewed initially (Table 4) and, of these, 41 were reinterviewed. One link worker had left her role when it came to follow-up interviews, but we managed to talk to her replacement.

| Work roles | Link workers (seven were our cases and five were others with whom these cases worked) | 12 |

| VCSE staff and managersa | 20 | |

| GPs (including trainees) | 19 | |

| Practice managers/operations managers | 11 | |

| Nurses (including advanced practitioners) | 10 | |

| Care co-ordinators/health and well-being coaches | 6 | |

| Reception staff | 5 | |

| Clinical pharmacists | 2 | |

| Mental health practitioners | 2 | |

| Dietitian | 1 | |

| Occupational therapist | 1 | |

| Paramedic | 1 | |

| Physiotherapist | 1 | |

| Other | 2 | |

| Ethnicity | White British | 71 |

| Asian (including British Asian or Indian) | 7 | |

| White (non-British) | 5 | |

| Mixed ethnic groups | 4 | |

| Afro-Caribbean/Black British | 3 | |

| Chinese/Chinese Hong Kong | 2 | |

| Missing | 1 | |

| Gender | Female | 70 |

| Male | 23 | |

| Age | Range | 20–66 years |

| Mean (standard deviation) | 43.3 years (SD 12.2) |

| Involvement in the study | Observation only | 23 |

| Interview onlya | 49 | |

| Interview and observation | 12 | |

| Ethnicity | White British | 62 |

| White (non-British) | 6 | |

| Asian (including British Asian and Indian) | 5 | |

| Afro-Caribbean/Black British | 5 | |

| Mixed ethnic groups | 3 | |

| Other | 3 | |

| Gender | Female | 55 |

| Male | 29 | |

| Age | Range | 19–86 years |

| Mean (standard deviation) | 49.3 years (SD 19.5) | |

| Number of times spoken to/met with the link worker (in-person or remotely) | Range (eight people said they had seen the link worker ‘multiple times’ rather than a specific number, and three people could not remember. In addition, the PPG representative had not seen a link worker) | 0–30 times |

| Mean | 4.1 times (SD 4.9) | |

| Person who referred the patient to the link worker | GP | 60 |

| Nurse | 5 | |

| Mental health professional | 3 | |

| Pharmacist | 2 | |

| Unsure/can’t recall | 2 | |

| Self-referral | 2 | |

| Child’s school | 1 | |

| Receptionist | 1 | |

| Health visitor | 1 | |

| Physician associate | 1 | |

| Community worker | 1 | |

| Crisis team | 1 | |

| Healthcare assistant | 1 | |

| Took part as PPG member | 1 | |

| Missing | 2 |

Data highlighted key areas where discretion could be exerted by link workers (which we have defined as micro-discretions) (Table 5).

| Time spent with patients | The first meeting was often 45–60 minutes, although this could be less if undertaken remotely (10–20 minutes at Site 1). Follow-up meetings could be as short as 10 minutes and as long as an hour. This depended on the problem(s) being addressed. Also, some link workers conducted ‘check-in’ telephone calls with patients, which did not address a specific issue but were keeping in touch with individuals considered vulnerable. These tended to be relatively short. |

| How often patients were seen | Data referred to a maximum number of appointments with a patient in some sites (around 6–8). However, there seemed to be flexibility here, with link workers extending this number or re-referring someone if they felt they had new difficulties requiring attention. A couple of services had a relatively open-ended approach, with some patients remaining in touch with a link worker for years. We asked sites involved in the study to indicate how many referrals a link worker received in the month of fieldwork. Information provided was as follows: Site 2 = 15; Site 3 = 19; Site 4 = 31; Site 5 = 12; Site 6 = 34; Site 7 = 13 (Site 1 did not provide this information). Variation in the number of patients link workers saw in a month could relate to the time of year, the ‘newness’ of their role or the fact that some served more than one surgery. In addition, some link workers were part of a team so might have had a smaller workload as a consequence. |

| Where patients were seen | Home visits were permitted in some sites, but others had a clear remit of only seeing patients in a surgery or remotely (e.g. via telephone or video conferencing). Location for appointments called for consideration of lone working procedures (e.g. going to visit patients in pairs) and time taken for home visits versus additional information acquired from talking to a patient about their non-medical needs in a non-medicalised setting. |

| Referral types | Referral criteria were mentioned at some sites. These usually excluded people exhibiting suicidal ideation or severe mental health problems (although data suggested that, in reality, individuals with such difficulties were referred to a link worker), or with cognitive problems that would make engagement difficult. Such cases could be jointly managed between health professionals and the link worker. Other link workers described broad criteria for acceptance into their service; generally, the individual was over 16 years of age. |

| Referral routes | Some link workers engaged in a triage system, having an initial conversation with a patient to identify if their needs (1) could be met quickly, (2) required a more intensive social prescribing approach or were (3) best addressed by another professional. Other referrals were made via an electronic system. Link workers in some sites received referrals from a wide range of professionals (including pharmacists, care co-ordinators and nurses). Others were limited to GP referrals. Some reception staff we interviewed would have liked to refer directly to a link worker because they believed they could identify patients who would benefit from social prescribing. One site that allowed this to happen had to then restrict referrals to clinical professionals only, due to an overwhelming demand. There were a few instances of patients self-referring to social prescribing in the data, but this was uncommon. |

| Training undertaken | There was no standard training undertaken by link workers across sites. Most had completed online modules on the role provided by NHS England, and some VCSE employers described additional training opportunities for their staff (e.g. in counselling skills). Interviewees talked about encountering problems when in the role that highlighted training needs (e.g. around trauma, domestic abuse, suicidal ideation). They suggested that training should be general as link workers were not set up to be experts in, for example, housing issues or claims for welfare benefits; rather, their role was identified as enabling people to open up about their non-medical needs, which might lead to signposting into community activities. How much flexibility link workers had over training was subject to outside influences (such as resources), as well as whether they had a specialist role (e.g. supporting children and young people or individuals with drug and alcohol problems). |

| Feedback and data collection | Some link workers were clear that they avoided completing questionnaires with patients about outcomes if they felt this could hamper them from building rapport with someone. Conversely, others used them as a tool to structure discussions. There were differences in whether link workers shared feedback with patients on how they were progressing based on these data. There were also differences about how any feedback was reported to others (e.g. to GPs and other referrers). |

We identified three broad types of micro-discretions, which are described in detail below, around:

-

tailoring support for and interactions with patients

-

employing and developing link workers’ skills and capabilities

-

scope and remit of the link worker role.

We used this analysis to produce a set of CMOCs (Table 6). These are reflected in the sections below, which include data extracts. Abbreviations used with these data extracts are: LW = link worker, P = patient, HCP = healthcare professional and VCSE = a representative from the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector.

| Context | Mechanism | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | When link workers feel they have discretion in how they interact with a patient | It enables them to create an environment that facilitates disclosure | Allowing them to access issues that are most important to a patient |

| 2 | When link workers use discretion to respond to an individual and their needs | Patients feel heard and valued | Prompting them to engage and to open up |

| 3 | When link workers can use their skills and knowledge as they see fit | It produces a sense of accomplishment and agency | Contributing to job satisfaction |

| 4 | Having discretion within their role to develop connections with the VCSE sector | Allows link workers to build an understanding of a range of available support | Which helps them to respond to the various needs with which patients present |

| 5 | When link workers accept there are structural factors over which they have no discretionary power (e.g. housing) | They can be open and clear about the scope of their role | This avoids raising patients’ expectations |

| 6 | When link workers have come from different professional and personal backgrounds | They will draw on what they know, can do and believe in | Which contributes to variation in how the role is executed |

| 7 | When link workers are able to shape training around gaps in their knowledge and skills | They feel confident to perform their job | So they are best able to support patients and do their role effectively |

| 8 | Having confidence to decline referrals they see as inappropriate | Link workers feel in control of their work situation | Meaning they can work within their capabilities and capacities |

| 9 | If link workers believe they should be able to assist everyone referred to them | They can feel they have failed if unable to do so | Reducing their sense of job satisfaction |

| 10 | When there is clear communication about what the link worker role entails | These employees know what is expected of them | So they feel able to execute their job with confidence |

| 11 | Receiving appropriate support and supervision in the role | Provides some boundaries for link workers | To practise in a way that enables them to feel safe in what they do |

| 12 | When link workers who prefer structure have managers who are ‘hands off’ | They may be uncertain about discretionary acts | Leaving them feeling daunted by the role |

| 13 | A lack of explicit guidelines around the link worker role | Can mean they experience uncertainty around what they should do | Putting them and patients at potential risk |

| 14 | When working in an environment that supports autonomy and being innovative | Link workers have scope to be creative and flexible | This allows them to meet individual patient needs |

| 15 | Involving link workers in shaping a social prescribing service | Allows them to offer a realistic perspective of its scope and remit | So the service is set up in a way that reflects the reality of their skills and capabilities |

Three types of micro-discretions

Discretion to tailor support for and interactions with patients

There was variation in how far link workers were able to exert discretion in managing their interactions with a patient (e.g. for how long and where they were seen). Having flexibility in how to work with patients was described as helping to create a conducive atmosphere, in which individuals could discuss their needs (e.g. not feeling rushed, being seen in a familiar setting). A structured approach to interactions with patients was not regarded as possible by link workers because they had to respond to a range of problems. Being responsive to patient needs might entail link workers drawing on their personal or previous professional experience if appropriate; some link workers described having been through difficult life circumstances (e.g. bereavement, unemployment) that they might share in a meeting with a patient, if they felt it would help develop rapport (CMOC1). ‘I’m never afraid of bringing in my lived experience if I think it’s relevant and appropriate and not insensitive … It really eases a patient when it’s not a them and us scenario...’ (Site 7 LW01).

Observations for the study highlighted that link workers varied in how they communicated with patients. There was no set way in which they opened up a conversation. Some started along the lines of ‘I see the GP referred you because you have been feeling depressed’. This could restrict the range of topics covered. In contrast, a more open discussion was facilitated when link workers started with a statement such as: ‘Tell me how you are and what your situation is like at the moment’ or ‘What would you like support with?’ This type of opening allowed the conversation to focus on issues of importance to patients. This could contribute to the control patients felt they had in their interaction with a link worker, as illustrated in the following quotation (CMOC2).

I think she let me talk more than anything. And answered my questions. Yes, no she wasn’t pushy, she’s a good listener, and she was very kind. And I think she waited for me to suggest to her what we needed. She didn’t say, ‘Oh, you can do this’.

Site 6 P10

When link workers felt they had tailored support to enable patients to make changes to their life, it contributed to a sense of role fulfilment (CMOC3). ‘I enjoy that feeling that you’re … well in the … ideally when you’re empowering a patient to make positive changes that things actually do change in their lives’ (Site 3 LW01). However, tailoring support could be curtailed by the range of community offers link workers were aware of and had access to. Discretion could be exerted on how much time link workers dedicated to seeking out and making connections with local groups or organisations. In addition, there was the opportunity, in some sites, for link workers to set up activities or community support. This ability to invest time in developing connections with local partners could be lost when demand for social prescribing escalated (CMOC4).

… I think I do have a good relationship with some of them [community organisations], especially those I refer patients to a lot but it’s just that I don’t think I have enough time to network with them as often as I should or finding time to look at what are the needs at the moment.

Site 1 LW01

Structural barriers limited how far link workers could tailor support and the discretion they could exert. Housing was a particular issue raised here. Hence, it was noted that clarity with patients about what link workers could assist with was important from the start, to avoid unrealistic expectations (CMOC5). Such clarity was sometimes clouded in the way that referrers described the link worker’s role to patients. ‘…GPs are setting patients up to come to us thinking that we’re going to get them rehoused really easily … based on … we’ve had a really positive outcome with another patient of theirs …’ (Site 6 LW01 [follow-up interview]).

Discretion to employ and develop skills and capabilities

Link workers entered the role from different backgrounds (e.g. the VCSE sector or healthcare). Data highlighted that having discretion to draw on existing skills or knowledge helped link workers to feel valued and able to make a unique contribution to patient care. A link worker’s personal characteristics could shape how far they engaged in micro-discretions; some appeared more confident to work in a way that reflected their skills and enabled them to best meet a patient’s needs (CMOC6).

… I’m just a person who likes to take charge … I’ve been allowed to mould the role to fit my strengths and my passions and my interests … the absolute perfect job for me right now. I can signpost people, and that’s what is expected of me … but also I can push the boundary…have more therapeutic conversations and use therapeutic worksheets … I’m able to do that because I want to.

Site 2 LW01

Some healthcare staff expressed concern around the lack of standardised training for link workers, and the potential discretion they could exert in this respect. The following quotations came from clinicians responsible for managing link workers who had differing perspectives on this issue.

… link workers have very little experience in care or health … yes, in their own lives, they’re obviously involved in voluntary work previously or were volunteers … but the qualifications are quite thin … the populations they’re dealing with are often the most deprived or most damaged …

Site 7 HCP04

There are things that they [link workers] need to know, like record keeping and confidentiality and safeguarding and stuff like that. Suicide prevention or risk assessment, things like that. Do they need to do a level three in social prescribing? I’m not convinced they do. It looks good on your CV, but is it actually – does it make you a better social prescriber? Does it make you more safe, more agile worker? I don’t – I’m not a big fan of education for education sake …

Site 6 HCP11

Link workers saw some elements of training (e.g. safeguarding, data protection, health and safety) as mandatory. They thought that other training should be shaped around existing skills. Hence, having some discretion was depicted as important, so training could address gaps rather than covering knowledge or expertise already gained from previous roles or experiences (CMOC7). An area in which link workers often required initial training was in using GP electronic reporting systems. These tended to be a primary route for referrals, although instances were identified when referral systems were circumvented by referrers (e.g. a GP asking a link worker over coffee to see a patient who was coming to the practice that day). In these cases, link workers might decide to accommodate such a request to foster positive working relationships, particularly when starting out in the role. At the same time, having the ability to decline referrals was seen as an important discretionary act, as suggested in this quotation from a link worker (CMOC8).

I am getting better at actually referring them back to the GP and saying, ‘I don’t think I’m the right person to be working with this patient’… I wouldn’t want to make their situation worse … by saying the wrong thing…triggering any sort of negative emotions … Whereas when you begin … you don’t necessarily know those things so you could just take anybody.

Site 3 LW01

A lack of clear referral criteria, and a desire to be inclusive, left some link workers feeling a sense of responsibility to try and do something for everyone. This could limit their ability to exercise discretion over how they approached the role, prompting them to work outside their skill set. At the same time, discretion involved some recognition of the extent to which they could help people, and accepting this was not always possible. Data suggested they might need support to do this in a way that did not make them feel they had failed (CMOC9).

… you have to remember what your role is … you’re not supposed to be specialised in one service. You can know a bit about housing but … there are other services, and your job is there to help them along. So it’s just to keep reminding yourself of that. As long as you’ve done all you can, I think that’s what’s important because you can only do your best … it’s just making sure you have those boundaries set as well with patients.

Site 5 LW03

Discretion around scope and remit of the role

Data showed variability in the range of activities undertaken by link workers. Some might go to organisations and groups with patients or assist them with form filling; others were clear that this was not part of their job. There were examples of link workers mentioning a need for greater steer around their remit, to stop them feeling overwhelmed (CMOC10); others were keen to retain independence around their day-to-day activities. As outlined in the comments from study participants below, having a social prescribing lead or manager was helpful, who could act as a buffer between different demands that link workers experienced, although this was not the case for everyone (CMOC11; CMOC12).

I know that for some social prescribers who maybe haven’t had such a clear remit, they’ve ended up being utilised by PCNs for things like the vaccine programme and various other things which we didn’t do, even if we were asked to do it, it wasn’t our remit.

Site 2 VCSE01 (manager)

… to be employed by an outside organisation to work in different surgeries and managed by a manager outside, yeah, and the manager won’t know 100% what we go through in a way, and what kind of day-to-day stuff and that can create some issues … our manager is not very proactive in terms of engaging with the surgery, so certain things we have to deal with the surgeries ourselves.

Site 1 LW01

The possibility of link workers acting outside their remit, and who was accountable for such actions, was raised during interviews. Healthcare staff, in particular, highlighted the potential danger of link workers practising in a way that put them or others at risk. This included working with patients who self-harmed, were suicidal or who had committed sex offences (CMOC13).

I’ve heard from the GPs they like the idea … that this person could dive into deeper aspects where they may not have time to. They’re a little bit apprehensive with: ‘is the person trained enough to deal with certain tricky situations?’ because obviously the GPs will have lots of training to do with mental health …

Site 2 HCP03

… they [link workers] deal with troubled teenagers in a lot of cases and my worry is that rather than being a signposting service, that the young person becomes attached to them … and if something goes wrong with that young person who has mental health problems, where will that … link worker be if things haven’t gone well?

Site 7 HCP04

Fear of being rebuked for going outside of their remit was rarely raised by link workers, who talked about being reassured by having other healthcare professionals they could draw on for assistance (particularly GPs), and being aware of safeguarding rules and procedures.

We have a safeguarding lead at [surgery]. An adult safeguarding lead and then a children’s safeguarding lead as well … We’ve got protocols and we also have a duty doctor who would then call them immediately or go out to them immediately … I think in the surgery I feel that you’re fairly well backed up … because you can share that risk.

Site 3 LW01 (follow-up interview)

Observations undertaken for the study suggested that where link workers were employed could shape what was expected of them and the degree of discretion they could exercise. Those managed within the VCSE sector appeared able to adopt a relatively flexible approach to interactions with patients in terms of frequency, location and duration. Conversely, when services were managed within primary care, a focus on boundaries was more evident, especially on how often and for how long patients were seen (CMOC14). Healthcare managers seemed to focus on the number of people seen and social prescribing’s impact on the wider patient population and GP workload. This was contested by some link workers, who perceived success in terms of improvements for individual patients, whatever that took to achieve.

Some would only be a couple of sessions … Some might take ages … Some surgeries weren’t as busy as others, so I was able to see people more often and see them for a lot longer. I know there’s this rule, you’re supposed to see people no more than six times…as far as I’m concerned rules are there to maybe be broken, so I would see people for two years plus and they found that beneficial …

Site 1 LW02

For several sites (see Table 2), it was clear that link workers were instrumental in designing the service, so had some control over its remit and scope (CMOC15). This was intentional at some sites but more ad hoc at others, as link workers were left by practices to get on with setting up. Link workers liked the freedom to shape a social prescribing service in line with the needs of patients being referred, but there were instances when this responsibility could feel too broad and unwieldy.

At the interview, they were quite clear that part of the job was going to be shaping how the role worked … I wondered if there might be some guidance from my supervisors and managers as to what I needed to do … There wasn’t really any of that, which was like a blessing and a curse, because it meant that they didn’t really have any expectations of me … I just didn’t have the guidance … If there had been more guidance, it would have taken away … feeling daunted …

Site 4 LW01

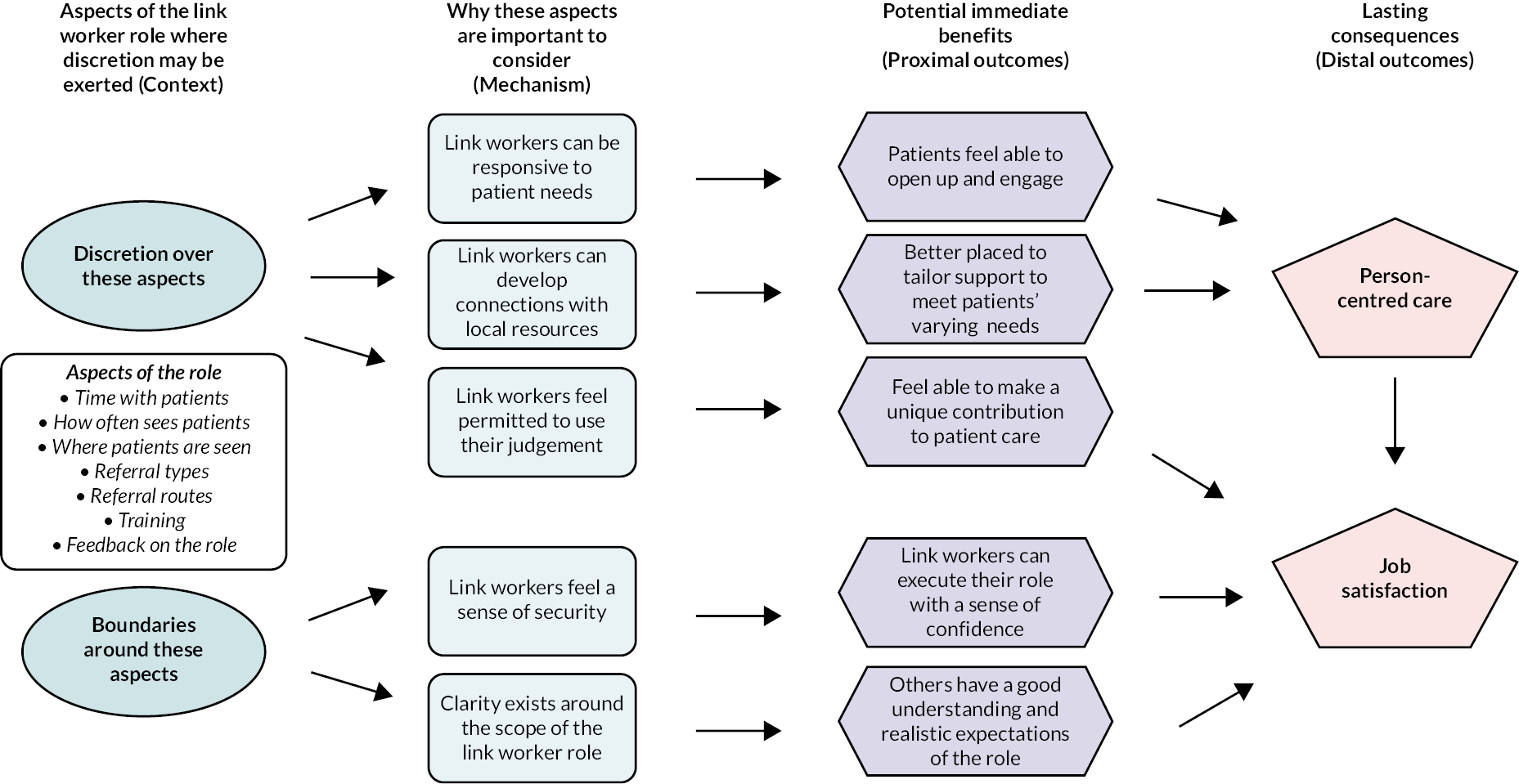

Programme theory around micro-discretions

Our analysis suggested that link workers’ reasoning for exerting discretion related to a desire to offer patients person-centred support, and to perform their job in a way that was fulfilling. This understanding underpinned the programme theory we created from our analysis (Figure 1), which highlights outcomes associated with the exercise of discretion by link workers. Discretionary acts tended to be undertaken by link workers to create positive connections with patients and healthcare staff. These acts demonstrated flexibility, which in turn enabled link workers to feel they were providing person-centred care and were making a difference to patients’ lives. It was a way to exert autonomy in a biomedical setting (where link workers could feel like outsiders) and a means to best use their skills and knowledge. This contributed to job satisfaction. However, link workers could also feel overwhelmed if their caseloads escalated due to having too much flexibility and too few boundaries, reducing job satisfaction.

FIGURE 1.

Programme theory (with selected higher level CMOCs) showing the links between person-centred care and job satisfaction and the influence of discretion and boundaries on the link worker role.

Boundaries could offer clarity of purpose and role coherence. Some link workers wanted more frameworks and guidance when starting out. Boundaries helped with managing expectations, which was important when others (e.g. healthcare staff, patients) were unfamiliar with the link worker role. Our analysis highlighted that opinions about how social prescribing works (and for whom) were not always shared across stakeholder groups, so clear boundaries may help with ‘buy-in’ to the link worker role and more purposeful adoption. Yet, although boundaries provided a sense of structure and safety, they could curtail link workers’ ability to be responsive to individual patient circumstances.

Street-level bureaucracy as a substantive theory related to discretion

During the analysis, we considered existing theories that were related to our findings; in realist research, it is common to do this to augment understanding. 26 We felt that our data fit with this reference on street-level bureaucracy.

… street-level bureaucrats must make judgments about how to act in a given situation because guiding policies speak to general rather than specific cases … they can exercise discretion in some situations to resist or transform systemic conditions, which can lead to increased job satisfaction and more meaningful client outcomes … 27

Street-level bureaucracy was introduced by Lipsky. 17 It is based on the idea that public servants (e.g. teachers, police officers, social workers, healthcare staff) shape and enact policies related to their role (rather than simply following them). It involves the use of discretion in work tasks as a coping mechanism, to manage contradictions encountered from imposed time frame, high caseloads and shortage of resources, which can affect employees’ sense of control over their work. In response to such stressors, street-level bureaucrats resist or reframe systems they regard as problematic to better align with their goals and values, deviating from policy as a consequence. Hence, street-level bureaucracy positions those responsible for implementing policy as active agents; they have to respond to varying circumstances and try to build meaning around their role, normalising what they do when facing uncertainty and ambiguity in the workplace. 28

Discussion

Summary of the findings

The important role of micro-discretions in the activities and decisions taken by link workers has been surfaced in this paper, which identifies considerations for these employees, their managers and commissioners of social prescribing services. Data emphasised potential outcomes from having more or less discretion in the role and showed that link workers undertake micro-discretions, on a daily basis, to (1) engender positive connections with others involved in social prescribing (patients, healthcare staff, the VCSE sector), (2) promote buy-in to their role, (3) deliver person-centred care and (4) experience job satisfaction. At the same time, boundaries may sometimes be sought to avoid being overwhelmed by the role’s demands and others’ unrealistic expectations. However, boundaries can curtail link workers’ ability to be responsive to individual patient needs. This could be seen as a ‘Goldilocks Conundrum’; too much discretion may overstretch link workers and put them in a precarious working situation, while too many boundaries risk stifling their judgement and response to an individual’s situation, potentially reducing job satisfaction. An informed and explicit balance of boundaries to discretion is required, which reflects the context and skills and needs of a link worker undertaking the role.

Comparison with the existing literature

Research involving other health and care professionals (e.g. GPs, nurses) has referred to this balance between working within boundaries and exerting discretion;13,29–31 hence, it is not unique to link workers. Yet, as a relatively new role, without a clinical background, link workers lack the protection (or shackles) of a professional identity – with its standardised training, knowledge and regulations. A lack of professional status for link workers may explain inconsistencies among stakeholders’ perspectives, reflected in our data, of where boundaries around the role start and end. This can be seen as offering both disadvantages (e.g. lack of support structures) and advantages (e.g. opportunities to negotiate boundaries).

The topic of professionalisation of link workers has been debated. 32 In a qualitative study involving link workers in England, Moore et al. 10 reported that professional registration could give the role more legitimacy in the eyes of others (including healthcare professionals), and provide equity of service provision so that patients received a similar level of support. However, concerns were also expressed, by interviewees in their study, that professional registration could remove individuality and flexibility, and act as a barrier to those suitable for the role who were unable or unwilling to undertake steps required for professional qualification.

It has been noted that a strong professional identity can foster resilience and fulfilment in a role,33,34 while at the same time providing protection through formal policies and standards. 29 Professional boundaries can highlight areas of responsibility, providing clarity around what is expected in a role, offering indicators of good practice. 35 Yet good practice can also be delineated as the ability to employ professional judgement, to work in a way that best serves patients.

Link workers in our study, as in others,10 described entering the role to help others; this could explain their willingness to use their discretion when required to achieve this outcome. A willingness to work around rules within a workplace has been associated with length of experience in a post. 36 This relates to the idea of gaining wisdom in how to practise with discretion through performing a job. 37 Our study suggested that time in the role could shape link workers’ willingness to deviate from organisational procedures, but so too could personality and employment history. These are factors that we also see in research examining healthcare professionals perceived willingness and ability to work beyond guidelines. 38 It reflects the fact that link workers, although not having a qualification in this role, come to it with past workplace and/or personal experiences that support them in their jobs.

Practice and policy implications

Link worker services are being delivered differently across the country. This means that, in a way, there is no such thing as ‘a’ link worker, especially given the discretion that may (or may not) be exercised by those in the role. The writing of Lipsky17 around street-level bureaucracy is helpful in this respect. Street-level bureaucrats have been described as ‘inventive strategists’ who adapt and shape what they do to overcome excessive workload, complex cases and unclear performance targets. 39 Link workers can be seen as inventive strategists who employ discretion, when required and possible, to meet the needs of patients and to maximise job satisfaction. This understanding has contributed to the recommendations listed in Table 7 around micro-discretions and link workers, drawn from our data. We know from knowledge exchange events we have held across England, at which we described our findings, that some of our recommendations are already being undertaken within certain social prescribing services. We present these recommendations as reflective prompts to trigger discussion and action at a local and national level.

| Recommendation | Target group | Related CMOC(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Policy-making (local and national) related to link workers needs to be codeveloped with these employees, to ensure it fits with the issues they are experiencing in the role, and reflects their skills, knowledge and capacity. | Policy-makers | No. 1 No. 2 No. 15 |

| Explicit discussions with key stakeholders about how link workers are implemented in a local setting are required. Discussions should consider issues related to discretion and boundaries in the role. These discussions need to be regular and ongoing (rather than one-off) given that the circumstances within which link workers support patients are highly dynamic; in recent years in England, link workers have faced COVID-19, the cost of living crisis and seen the introduction of other roles in primary care through the Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme. | PCNs, integrated care system | No. 10 No. 13 No. 14 |

| Link workers require adequate supervision (clinical and emotional) that helps them to explore issues and any confusion related to discretion in their role. This should include support with accepting that there are some circumstances affecting patient well-being that are outside their sphere of influence. | GPs, managers | No. 5 No. 9 No. 10 No. 11 No. 12 |

| Peer support and an opportunity to exchange views and experiences of the role, and activities undertaken within it, are important to enable link workers to compare their everyday practice with their peers. | Link workers, managers | No. 1 No. 3 No. 6 |

| Link workers should have scope within their role to develop connections with the VCSE in a way that fits with patient needs and fits alongside the other work they do in the role. | PCNs, managers | No. 4 |

| Clarity around the role and how it is delivered in a local area is needed for multiple stakeholder groups; for patients to manage expectations in terms of what link workers can achieve given their skills and available resources, and for practitioners to avoid inappropriate referrals. | Staff who communicate about social prescribing | No. 10 No. 13 |

| A system should be in place for link workers to decline referrals they feel are inappropriate, and to communicate reasons for this decision to the referrer. | Link workers, PCNs, managers | No. 8 |

| Link workers need training on topics that they have not covered in previous jobs and that they feel are important for them to carry out their roles safely and effectively. Joint decision-making around training can be supported through regular supervision. | Link workers, PCNs, managers | No. 7 |

Future research

Retention of link workers can be challenging;40 therefore, understanding how best to promote job satisfaction is important. This might be supported by ensuring a good ‘fit’ between the individual link worker and scope for discretion in their role. We were unable, in this study, to explore if there was a different view of discretion depending on the background of link workers, but it is something that would be interesting to explore in the future. For example, if link workers come from a health background (e.g. healthcare assistants, occupational therapists, nurses), do they feel more in need of boundaries to reflect the working conditions to which they are accustomed? Retention could also be affected by the degree of supervision/support experienced in the role, which might affect link workers’ discretion and confidence to undertake their jobs. This is an area some of the authors are exploring in a new study. 41

Further understanding of the risks associated with the link worker role, and how discretion may contribute to this, is required. Likewise, more research is warranted on how link workers convey to patients the scope of their role and discuss with them a decision to end the support they receive from the service. This is important for appreciating the impact that withdrawing support given to a patient may have on their experiences of social prescribing.

Our research highlighted how the role represents a myriad of services that are often delivered in different ways in order to meet patient needs. This has implications for evaluation – you cannot treat all link workers as undertaking the same activities, in the same way, within the same infrastructure and support. More exploration of how best to evaluate the link worker role, which considers the diversity and flexibility outlined in this paper, is required.

Our findings reveal the knowledge work undertaken by link workers in general practice – the work done to critically and creatively make sense of and action complex problems in context. 42 We highlight both the importance of and challenges in this work; this resonates with issues experienced by healthcare professionals working in primary care. Future research examining the knowledge work of boundaried and discretionary professionals in primary care settings may offer valuable insights into achieving culture shifts to enable provision of truly person-centred health care.

Equity, diversity and inclusion

Our study PPI group supported us to ensure that language used in information for recruitment purposes was clear and understandable. We looked to involve patients of various ages, genders and ethnicities, which we achieved (see Table 4). We also included sites that varied in terms of deprivation (see Table 2). Our study team ranged from early career researchers through to senior academics; it comprised of both women and men, people from different ethnic backgrounds and people with a disability. All had the opportunity at monthly meetings to contribute to the study’s execution, analysis and dissemination. We involved two PPI groups, so we had diversity in terms of ethnicity, age and socioeconomic status. Both groups challenged our thinking about the data and provided alternative thoughts on this, and prompted us to explain our findings in plain language.

Strengths and limitations

We collected a wealth of data from seven different sites and link workers in England. A range of participants took part (including patients, healthcare professionals and VCSE representatives). This gave us an in-depth understanding of the topic raised in this paper. Through spending time with link workers at their place of work, we came to appreciate the nuances associated with this role. It also enabled us to follow-up issues that had not been considered when planning the study. The link workers involved were mainly White British and female. Whether ethnicity or gender would make a difference to experiences of micro-discretions is not clear from the data we collected. Furthermore, we focused on research with link workers attached to primary care. Whether issues related to discretion are the same for those undertaking similar activities in more community settings needs to be further explored.

Conclusion

Our research has brought to the fore the function of discretion and boundaries for link workers in primary care, and the consequences for both those undertaking the role and patients they support. Micro-discretions appear to allow for responsiveness in social prescribing and for the service to be led by the needs of an individual patient, but can result in uncertainty and to link workers feeling overstretched. There may be limits to how flexible link workers can be; discretion will be shaped by community-based resources available, socioeconomic circumstances of the local area and the power link workers have within primary care. Developing a professional identity could lead to more boundaries around the role, offering consistency of delivery and security, but could affect link workers’ ability to deliver person-centred care if too confining.

Additional information

CRediT contribution statement

Stephanie Tierney (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2155-2440): Conceptualisation (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Funding acquisition (equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (lead), Writing original draft (lead), Editing and reviewing (equal).

Debra Westlake (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6927-5040): Formal analysis (equal), Investigation (equal), Editing and reviewing (equal).

Geoffrey Wong (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5384-4157): Conceptualisation (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Methodology (equal), Editing and reviewing (equal).

Amadea Turk (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5139-0016): Formal analysis (equal), Investigation (equal), Editing and reviewing (equal).

Steven Markham (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0564-3158): Formal analysis (equal), Investigation (equal), Editing and reviewing (equal).

Jordan Gorenberg (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2723-8786): Formal analysis (equal), Investigation (equal), Editing and reviewing (equal).

Joanne Reeve (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3184-7955): Conceptualisation (equal), Editing and reviewing (equal).

Caroline Mitchell (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4790-0095): Conceptualisation (equal), Editing and reviewing (equal).

Kerryn Husk (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5674-8673): Conceptualisation (equal), Editing and reviewing (equal).

Sabi Redwood (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2159-1482): Conceptualisation (equal), Editing and reviewing (equal).

Anthony Meacock: Conceptualisation (equal), Editing and reviewing (equal).

Catherine Pope (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8935-6702): Conceptualisation (equal), Editing and reviewing (equal).

Kamal R Mahtani (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7791-8552): Conceptualisation (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Funding acquisition (equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Editing and reviewing (equal).

Data-sharing statement

Due to the consent process for data collection with participants, no data can be shared except for quotations in reports, journal articles and presentations. All data requests should be sent to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was secured from East of England – Cambridge Central Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 21/EE/0118). This was provided on 4 May 2021.

Information governance statement

The University of Oxford is committed to handling all personal information in line with the UK Data Protection Act (2018) and UK General Data Protection Regulation. This is specified in the University’s data protection policy and in the research protocol. The University of Oxford, as sponsor of this research, is the data controller. You can find out more about how we handle personal data, including how to exercise your individual rights and can access the contact details for the University of Oxford Data Protection Officer here: https://compliance.admin.ox.ac.uk/individual-rights.

Disclosure of interests

Full disclosure of interests: Completed ICMJE forms for all authors, including all related interests, are available in the toolkit on the NIHR Journals Library report publication page at https://doi.org/10.3310/JSQY9840.

Primary conflicts of interest: Stephanie Tierney: Part of the of the Academic Partnership for the National Academy for Social Prescribing. Geoffrey Wong: HTA Prioritisation Committee A (Out of hospital) 1 January 2015 to 31 March 2022; HTA Remit and Competitiveness Group 1 January 2015 to 31 January 2021; HTA Prioritisation Committee A Methods Group 21 November 2018 to 31 March 2021; HTA Post-Funding Committee teleconference (POC members to attend) 1 January 2015 to 31 March 2021.

Caroline Mitchell: Chair of NIHR in Practice Fellowship Award 2023; HTA Prioritisation Committee A (Out of Hospital) – 2022–6.

Kerryn Husk: HS&DR Researcher-Led – Panel Members 1 December 2018 to 30 June 2020; HS&DR Funding Committee (Bevan) 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2022. Part of the Academic Partnership for the National Academy for Social Prescribing.

Catherine Pope: NIHR HS&DR Researcher-led panel member 1 July 2017–31 July 2021; HS&DR Funding committee (Bevan) member 1 November 2020 to 31 July 2021; Academy panel 2019–present.

Kamal R Mahtani: NIHR HTA Prioritisation Committee A (Out of hospital) 1 March 2018 to 31 March 2023; NIHR Remit and Competitiveness Group 1 March 2018 to 31 March 2023; NIHR HTA Prioritisation Committee A Methods Group 1 March 2018 to 31 March 2023; NIHR HTA Funding Committee Policy Group (formerly CSG) 1 March 2018 to 31 March 2023; NIHR HTA Programme Oversight Committee 1 March 2018 to 31 March 2023.

Department of Health and Social Care disclaimer

This publication presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by the interviewees in this publication are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, MRC, NIHR Coordinating Centre, the HSDR programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Study registration

This study is registered as researchregistry6452 (www.researchregistry.com/browse-the-registry#home/registrationdetails/5fff2bec0e3589001b829a6b/).

Funding

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health and Social Care Delivery Research programme as award number NIHR130247.

This article reports on one component of the research award Understanding the implementation of link workers in primary care: A realist evaluation to inform current and future policy. For more information about this research please view the award page (https://www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/NIHR130247).

About this article

The contractual start date for this research was in August 2021. This article began editorial review in November 2023 and was accepted for publication in March 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Health and Social Care Delivery Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

This article was published based on current knowledge at the time and date of publication. NIHR is committed to being inclusive and will continually monitor best practice and guidance in relation to terminology and language to ensure that we remain relevant to our stakeholders.

Copyright

Copyright © 2024 Tierney et al. This work was produced by Tierney et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

List of abbreviations

- CMOC

- context–mechanism–outcome configuration

- GP

- general practitioner

- NHS

- National Health Service

- PCN

- primary care network

- PPI

- patient and public involvement

- VCSE

- voluntary, community and social enterprise

References

- Muhl C, Mulligan K, Bayoumi I, Ashcroft R, Godfrey C. Establishing internationally accepted conceptual and operational definitions of social prescribing through expert consensus: a Delphi study. BMJ Open 2023;13.

- Morse DF, Sandhu S, Mulligan K, Tierney S, Polley M, Chiva Giurca B, et al. Global developments in social prescribing. BMJ Glob Health 2022;7.

- NHS England . The NHS Long Term Plan n.d. www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan/ (accessed 1 November 2023).

- NHS England . Comprehensive Model of Personalised Care n.d. www.england.nhs.uk/publication/comprehensive-model-of-personalised-care/ (accessed 1 November 2023).

- NHS England . Population Health Management n.d. www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/population-health-management/ (accessed 1 November 2023).

- Citizens Advice . A Very General Practice: How Much Time Do GPs Spend on Issues Other Than Health? n.d. www.citizensadvice.org.uk/Global/CitizensAdvice/Public%20services%20publications/CitizensAdvice_AVeryGeneralPractice_May2015.pdf (accessed 1 November 2023).

- Ferguson K, Hogarth S. Social Prescribing in Tower Hamlets: Evaluation of Borough-Wide Roll Out n.d. https://towerhamletstogether.com/resourcelibrary/2/download (accessed 1 November 2023).

- NHS England . Workforce Development Framework: Social Prescribing Link Workers n.d. www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/workforce-development-framework-social-prescribing-link-workers/ (accessed 1 November 2023).

- Tierney S, Wong G, Roberts N, Boylan AM, Park S, Abrams R, et al. Supporting social prescribing in primary care by linking people to local assets: a realist review. BMC Med 2023;18.

- Moore C, Unwin P, Evans N, Howie F. Winging it’: an exploration of the self-perceived professional identity of social prescribing link workers. Health Soc Care Community 2023;2023.

- NHS England . Online Webinar Series: Career Development, Progression, Retention of Social Prescribing Link Workers n.d. https://cptraininghub.nhs.uk/event/splw-webinar-series-career-development-progression-retention-of-social-prescribing-link-workers/ (accessed 6 July 2023).

- NHS England and NHS Improvement . Social Prescribing and Community-Based Support: Summary Guide. n.d. www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/social-prescribing-summary-guide-updated-june-20.pdf (accessed 1 November 2023).

- Nickelsen NCM. The infrastructure of telecare: implications for nursing tasks and the nurse–doctor relationship. Sociol Health Illn 2019;41:67-80.

- Fournier V. Professionalism, Boundaries and the Workplace. London; New York: Routledge; 2000.

- Grant S, Guthrie B. Between demarcation and discretion: the medical-administrative boundary as a locus of safety in high-volume organisational routines. Soc Sci Med 2018;203:43-50.

- Baird B, Lamming L, Beech J, Bhatt R, Dale V. Integrating Additional Roles into Primary Care Networks n.d. www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/integrating-additional-roles-into-primary-care-networks (accessed 1 November 2023).

- Lipsky M. Street-level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1980.

- Wong G, Westhorp G, Manzano A, Greenhalgh J, Jagosh J, Greenhalgh T. RAMESES II reporting standards for realist evaluations. BMC Med 2016;14.

- Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist review: a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10:21-34.

- Pawson R. The Science of Evaluation: A Realist Manifesto. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2013.

- Hawkins AJ. Realist evaluation and randomised controlled trials for testing program theory in complex social systems. Evaluation 2016;22:270-85.

- Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic Evaluation. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 1997.

- Bikker AP, Atherton H, Brant H, Porqueddu T, Campbell JL, Gibson A, et al. Conducting a team-based multi-sited focused ethnography in primary care. BMC Med Res Methodol 2017;17.

- Cruz EV, Higginbottom G. The use of focused ethnography in nursing research. Nurse Res 2013;20:36-43.

- Westlake D, Tierney S, Turk A, Markham S, Husk K. Metrics and Measures: What Are the Best Ways to Characterise Our Study Sites? n.d. https://socialprescribing.phc.ox.ac.uk/news-views/views/metrics-and-measures-what-are-the-best-ways-to-characterise-our-study-sites (accessed 1 November 2023).

- Greenhalgh T, Pawson R, Wong G, Westhrop G, Greenhalgh J, Manzano A, et al. ‘Theory’ in Realist Evaluation: The RAMESES II Project n.d. www.ramesesproject.org/media/RAMESES_II_Theory_in_realist_evaluation.pdf (accessed 1 November 2023).

- Aldrich RM, Rudman DL. Occupational therapists as street-level bureaucrats: leveraging the political nature of everyday practice. Can J Occup Ther 2020;87:137-43.

- Checkland K. National Service Frameworks and UK general practitioners: street-level bureaucrats at work?. Sociol Health Illn 2004;26:951-75.

- Evans T. Organisational rules and discretion in adult social work. Br J Soc Work 2013;43:739-58.

- Hoyle L. ‘I mean, obviously you’re using your discretion’: nurses use of discretion in policy implementation. Soc Policy Soc 2014;13:189-202.

- Geng EH. Doctor as street-level bureaucrat. N Engl J Med 2021;384:101-3.

- National Association of Link Workers . NALW Response to the Personalised Care Group at NHSE I’s Request for Consultation on the Professional Registration Health and Wellbeing Coaches, Care Coordinators and Social Prescribing Link Workers n.d. www.nalw.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/NALW-Professional-Register-Consultation-Response-Survey-Report-20th-April-2021.pdf (accessed 1 November 2023).

- Ashby SE, Adler J, Herbert L. An exploratory international study into occupational therapy students’ perceptions of professional identity. Aust Occup Ther J 2016;63:233-43.

- Cowin LS, Johnson M, Wilson I, Borgese K. The psychometric properties of five professional identity measures in a sample of nursing students. Nurse Educ Today 2013;33:608-13.

- Robinson G. Technicality and indeterminacy in probation practice: a case study. Br J Soc Work 2003;33:593-610.

- Banks S. Ethics, Accountability and the Social Professions. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan; 2004.

- Hunt G. The human condition of the professional: discretion and accountability. Nurs Ethics 1997;4:519-26.

- Reeve J, Britton N, Byng R, Fleming J, Heaton J, Krska J. Identifying enablers and barriers to individually tailored prescribing: a survey of healthcare professionals in the UK. BMC Fam Pract 2018;19.

- Cooper MJF, Sornalingam S, O’Donnell C. Street-level bureaucracy: an underused theoretical model for general practice?. Br J Gen Pract 2015;65:376-7.

- National Association of Link Workers . Care for the Carer: Social Prescribing Link Workers Views, Perspectives, and Experiences of Clinical Supervision and Wellbeing Support n.d. www.nalw.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/NALW_Care-for-the-Carer_-Report_8th-July-2020-Final.pdf (accessed 1 November 2023).

- Tierney S. Embarking on Research to Explore Issues Related to Retention of Social Prescribing Link Workers in Their Role n.d. https://socialprescribing.phc.ox.ac.uk/news-views/views/embarking-on-research-to-explore-issues-related-to-retention-of-social-prescribing-link-workers-in-their-role (accessed 12 March 2024).

- Reeve J. Medical Generalism, Now! Reclaiming the Knowledge Work of Modern Practice. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2023.