Notes

Article history

The contractual start date for this research was in January 2022. This article began editorial review in April 2023 and was accepted for publication in April 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Health and Social Care Delivery Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Cook et al. This work was produced by Cook et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Cook et al.

Background

Providing timely and effective palliative and end-of-life care (PEoLC) has become a ‘gold’ quality standard for patients diagnosed with an incurable illness. 1 The Better Endings report ‘Right Care, Right Place, Right Time’2 states that patients who receive specialist PEoLC tend to have a ‘better death’ than those without access to this care, through improved symptom management, experience less distressing symptoms and are more likely to receive supportive care in their own homes in their last month of life, a key aspiration for many. 3

The UK has become increasingly diverse, with non-White British representing > 25% of the UK’s total population. However, inequalities persist, whereby minority ethnic groups remain under-represented across PEoLC service provision,2,4,5 consequently experiencing poorer symptom management, more intensive treatments at end of life (EoL) and more likely to die in hospital. 5,6 Timely access to PEoLC can address the holistic care needs of patients and families, allow adequate care planning, facilitate treatment choices and reduce distress among patients and families. 7 This can improve pain and symptom management, enable informed decision-making and improve the quality of life for patients and their families. 8

Reducing inequalities and improving access to PEoLC among ethnically diverse populations is a national and international priority. 9 The James Lind Alliance and the Palliative End-of-Life Priority Setting Partnership10,11 identified improving access to PEoLC should be a national priority. Further, fair access to care represents a core ambition in the recent update of the ‘Ambitions for Palliative and End of Life Care’ national framework for 2021–612 alongside National Palliative and End of Life Care Partnership and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidance and Quality Standards for Palliative and End of Life Care. 1,13 This is also reinforced by the NHS Long Term Plan (2019) which is committed to the delivery of PEoLC which is personalised and accessible to all sections of the population. 14 These inequalities are yet to be addressed, and without action, we risk these inequalities continuing to be exacerbated. 15,16

Evidence reveals a complex interplay of factors which have been shown to influence access and experiences of PEoLC among the UK’s diverse population. Ethnic minority groups can be reluctant to be referred for PEoLC due to negative perceptions,5 lack of awareness,17–19 and differing care preferences based on cultural and family expectations and religious practices around dying. 5,20 PEoLC is also often viewed as culturally inappropriate5,17,18,20,21 with language barriers5,17,19 alongside limited cultural and religious sensitivity in how services are delivered, with many patients experiencing discrimination. 17–19,22,23 Many professionals can also lack confidence, knowledge and skills to interact and deliver effective PEoLC to minority ethnic populations. 23,24

Research is needed to understand how these inequalities can be addressed so that all sections of the population can access the care they need. 25 However, to facilitate this, there is a need to develop capacity and capability, particularly within underserved communities that are under-represented in research, to provide an infrastructure that can stimulate and deliver research activity to benefit the populations they serve. Research partnerships can facilitate this, bringing together multiple stakeholders to share and collectively address common goals and challenges which impact access to PEoLC,26 which can play a significant role in improving health and addressing health inequalities. 27 Developing inclusive and representative research partnerships can also help build social capital and cohesion by cementing new ways of working, building trust and providing a platform for knowledge exchange to help understand the local context and capacity. 25,28 Through developing the research infrastructure at a local level, research partnerships can create research capacity and capability to drive community-driven ‘bottom-up’ research activity, which has increased relevance and impact that can inform effective policies and interventions that can serve to address these inequalities.

Aims and objectives

This research programme aimed to develop a research partnership network (RPN) to build research capacity and capability in PEoLC in Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire and Milton Keynes (BHMK). The RPN, funded by National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), represented the first phase in a research programme designed to address the research question: How can access to PEoLC services be improved to reduce inequalities among the ethnic minority populations who reside in BHMK?

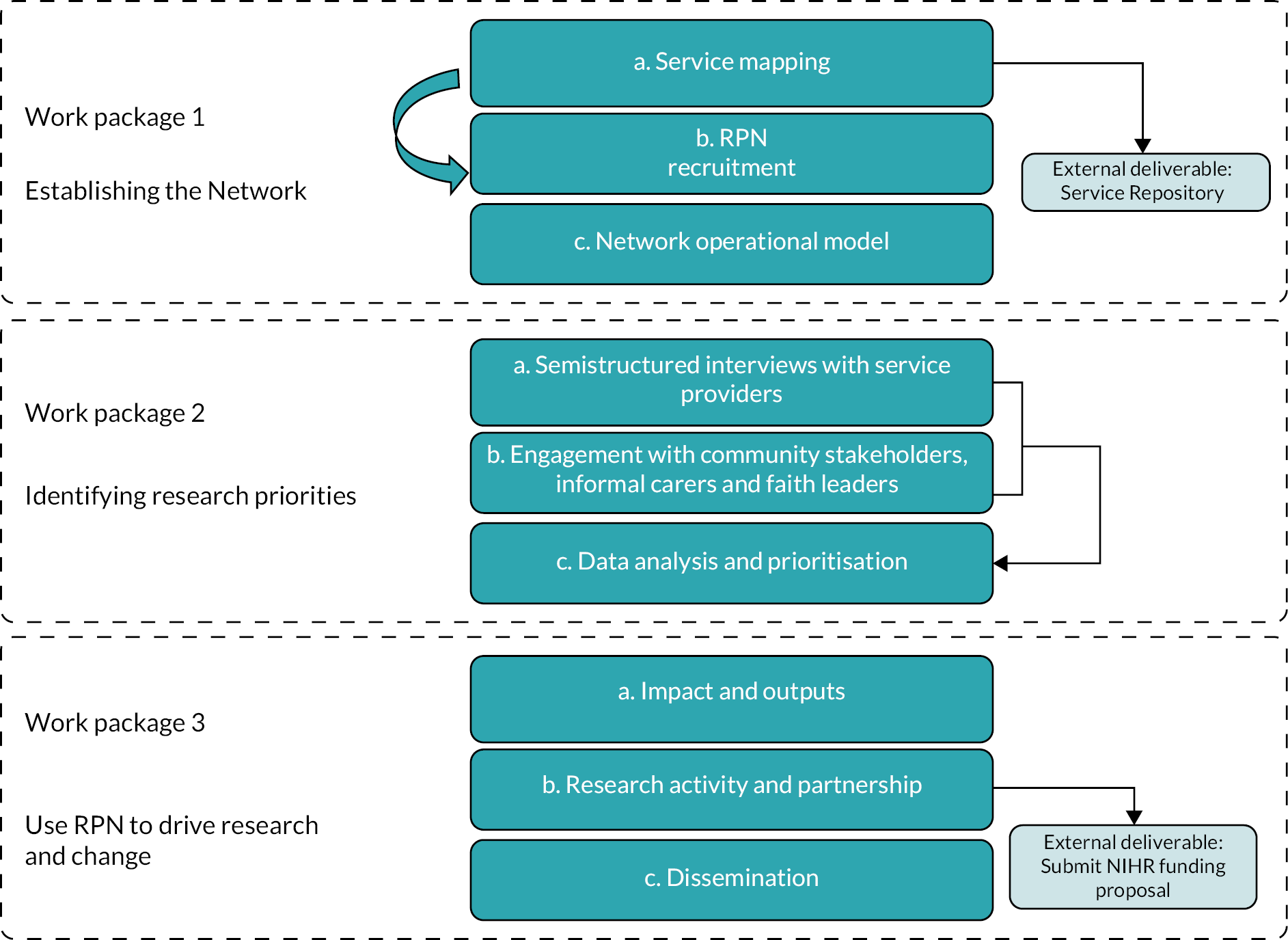

To achieve this aim, the research programme had three objectives (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Project plan.

-

To establish a Palliative and End of Life RPN to represent the diverse multiethnic and multifaith communities across BHMK (work package 1).

-

Understand the experiences of the key stakeholders and identify and prioritise the issues that need research to be addressed effectively (work package 2).

-

Use findings from work package 1 and work package 2 to drive research activity and change (work package 3).

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) was embedded throughout the study to ensure that KEEch research Partnership NETwork (KEEP-NET) is inclusive and representative, and that research activity is informed by the concerns and experiences of patients and families from ethnically diverse communities across BHMK. PPI informed our recruitment strategy, interpretation of the data, and outputs, including the co-developed funding application and dissemination of findings.

Methods and results

This research was situated in BHMK, located in the Southeast of England. BHMK has a combined population of 1.5 million, projected to grow to 2 million by 2035, with the number of people aged 85 and over projected to double by 2035 and a higher-than-average growth in adults aged 65 and over. Towns in BHMK counties have high rates of ethnic diversity and pockets of high deprivation.

Luton, located in Bedfordshire, is the most urban, deprived and ethnically diverse town across the three counties. The demographic characteristics of Luton are complex, characterised by high levels of migration, both from overseas and within the UK, significant population turnover, and one of the most ethnically diverse populations in England. 29 Referred to as ‘super diverse’,30 Luton hosts significant long-standing Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, African-Caribbean and Irish communities, and more recent immigration from countries that joined the EU in 2004 and 2007, Turkey, Afghanistan and African countries. Luton also recently became a Marmot Town,29 hosting five of the most deprived Wards in England, where large sections of the ethnically diverse community reside. Bedford Borough, Milton Keynes and Hertfordshire are also urban, with pockets of deprivation and ethnically diverse populations.

Work package 1: establishing the research partnership network

The first work package aimed to establish and launch a PEoLC RPN representing the diverse multiethnic and multifaith communities across BHMK.

Mapping of palliative and end-of-life care services and organisations

Previous local mapping exercises of PEoLC, such as the one conducted by Luton Palliative Care Network,31 have only achieved partial success. This has been due to the fragmentation of services across different geographical boundaries and the multiple agencies involved. Therefore, rather than defining services by commissioning groups, a patient-centric approach was created to reflect the range of services available to people in the last year of life. This represents a novel approach that aimed to provide a structure for a comprehensive review of all PEoLC services across BHMK, which had not been attempted before. A service list was created from those services already included within the Luton Palliative Care Network31 and also informed by the NICE guidelines32 and the Gold Standards Framework Proactive Identification Guide. 33 This process identified around 36 services organised into five categories: medical treatment and advice, personal and domiciliary care, psychological and counselling services, alternative therapies, and practical services.

An online survey was created on a Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA) survey platform, which asked for details on the type of organisation, the services provided, geographical areas served in BHMK, the main source of referrals, and identified perceptions around the level of service use by people from ethnic communities alongside faith and translation services offered. This survey was shared with the initial 36 services identified alongside the research team’s existing known networks, stakeholders and relevant mailing lists. In parallel, web searching was used to identify potential service providers and organisations. Personal contacts were made with these organisations to introduce the project and encourage them to participate in the mapping survey. We also sent regular chaser e-mails and reminders to encourage participation. Snowballing techniques were also used whereby known contacts alongside those who took part were asked to disseminate the survey to other relevant services/organisations who were omitted and provide PEoLC to the local communities across BHMK. The survey was also widely disseminated online through social media, for example Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA), WhatsApp and Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA). The survey remained live throughout the project (February 2022–December 2022).

A total of 21 additional service providers responded to the survey, primarily including medical PEoLC service providers, such as hospices, hospitals and community nurses (N = 57). There were, however, challenges in getting responses from non-medical service providers, which reinforced findings of previous attempts at mapping services that identified PEoLC provision as complicated and fragmented, with only hospice providing a central co-ordination point for people in the last year of life. While non-institutionalised service providers, such as community groups, are essential for understanding and improving PEoLC experiences of diverse populations, many organisations that provided support in these non-medical areas did not perceive themselves as a PEoLC service provider. Therefore, we proactively approached potential services and organisations across the non-medical categories to introduce the project and supported them in completing the survey. We would then ask them to introduce us to other relevant services and organisations. These conversations were an essential step in creating the network’s visibility.

An additional aim of the mapping exercise was to build a searchable open-access online database of PEoLC services across BHMK that enables the public and professionals to search for specific services in their area. The website uses an algorithm that enables an individual to search for services based on their locality, whether the service relates to an adult or child and what type of support they are looking for with options including (1) faith and spiritual, (2) medical advice and treatment, (3) personal care and home help, (4) practical assistance, psychology and counselling, and finally and (5) well-being and alternative therapies. All available providers are shown to the individual with links that direct them to their contact information [including website, address and telephone number, details on how to access their service(s), that is whether they need a professional referral or not and whether the service is free or paid]. There are future plans to continue to develop this website to build in translated versions and provide information on translation services available by the service providers. An annual survey will be sent to all services held on the repository to ensure that all information about their service is accurate and, where relevant, provide any changes to provision. In addition, services will be asked to identify if they know any new services that should be included within the repository.

Research partnership network recruitment

A ‘whole system’ and inclusive approach34 was used to recruit key partners, professional groups and stakeholders across health and social care from a diverse range of third-sector organisations, including charities, voluntary and formal and informal community organisations and networks that deliver PEoLC across the region. To facilitate this, a mapping exercise was conducted to identify providers and stakeholders of PEoLC across BHMK who would be invited to join the RPN. To ensure that we developed an inclusive RPN representing the ethnically diverse communities across BHMK, we adopted a flexible and pragmatic approach to aid recruitment, using direct contacts and networks, snowballing alongside a solid social media presence.

Network operational model

The launch of KEEP-NET was initiated through a face-to-face event at the University of Bedfordshire on 31 March 2022. All services and organisations identified through the mapping survey were invited. Adverts were also created and shared via existing networks, with known services and attendees invited to share to their wider networks. The event gained substantial interest and was attended by 32 members who represented a range of health, social care and community stakeholders across the BHMK region. Hospices, community and hospital health and social care providers attended alongside representation from Grassroots community organisations and informal networks across BHMK, including Equality in Diversity CIC, local mosque funeral services and local community health forms, including Healthwatch representatives. Academics and community members also attended the event with an active interest and/or lived experience of PEoLC.

The launch of the network was a symbolic and important starting point for the RPN to develop ground rules in which the RPN would operate alongside an agreed shared vision to set out the common values underpinning the network. Working towards shared values and goals was an important step in developing a network that facilitates more effective working relationships through increased trust, transparency and respect. 35–37 The agreed ground rules are presented in Table 1, which centred around six guiding principles: (1) a shared vision, (2) all voices are equal, (3) inclusivity, (4) acceptance that issues exist, (5) accountability and (6) building mutual trust.

| A shared vision | The RPN should collectively identify objectives and research priorities. Specifically, the network should:

|

| All voices are equal |

|

| Inclusivity |

|

| Acceptance that issues exist |

|

| Accountability |

|

| Build mutual trust |

|

Work package 2: identifying research priorities

The mapping exercise and launch event identified that the key stakeholders involved in identifying research priorities should include service providers, faith leaders and informal carers. Therefore, a series of activities were designed to identify the research priorities of these groups as follows:

-

Interviews with service provider professionals (hospices, community services and hospitals).

-

Roundtable stakeholder workshops with (1) community and provider stakeholders, (2) faith leaders and (3) informal carers.

Semistructured interviews with service providers

A qualitative study using semistructured interviews was conducted with service providers/professionals to explore their experiences working with ethnic minority communities, including experience and perception of inequalities. Health professionals/service providers who work across health and social care from a wide range of PEoLC services, including charities and voluntary and community organisations across BHMK, were purposively recruited to participate in this study.

Information and promotional materials about the study were e-mailed to all existing contacts identified through the service mapping alongside contacts made through the RPN. RPN members were also asked to share the recruitment materials through their networks and with known contacts/services who they felt may be eligible. A total of 11 health professionals/service providers agreed to take part in an interview, who represented hospital (n = 3), community (n = 3) and third-sector organisations (n = 5) across the four geographical regions in BHMK, including Luton (n = 3), Milton Keynes (n = 4), Central Bedfordshire (n = 2) and Hertfordshire (n = 2).

An interview topic guide was developed collaboratively as part of the multidisciplinary research team, informed by the literature and discussions from the KEEP-NET launch event. The topic guide used open-ended questions to explore key priorities for research and experiences of providing PEoLC care to ethnic minority communities, including experience and perception of inequalities, the role of communication and translation, the role of planning for death, approaches to faith and resource planning (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Probes were also used to generate further explanations where relevant.

Before participation, all participants were provided with a participant information sheet which clearly explained the nature and purpose of this research, with written informed consent obtained through the completion of a consent form. A trained and experienced research assistant with a postgraduate qualification in Health Psychology facilitated all interviews. All interviews were conducted online using video conference software (Microsoft Teams) and lasted approximately 60 minutes each (46–83 minutes). The interviews were video-/audio-recorded with permission and were stored securely on a secure password-protected laptop. All participants were provided an opportunity to verify their transcript, and once this process was complete, the video files were destroyed. Participants were provided pseudonyms to maintain confidentiality, with all names of organisations removed to ensure any direct quotes could not be linked back to the individual. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institute of Health Research at the University of Bedfordshire (REF: IHREC979).

The interviews were analysed using the Framework Method,40 which provides a highly structured and systematic approach to generating themes and through the development of a ‘matrix’, which can identify commonalities and differences within the data. 41 An inductive approach was used to guide the analysis, whereby transcripts were read several times to identify emerging themes. A working analytical framework, comprised of the research team and lay members, was presented to the steering group for comment. The agreed analytic framework was then applied to all transcripts using specialist software [NVivo v12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK)]. The coded data were then synthesised and summarised into a Framework Matrix with case nodes representing the different settings where PEoLC services are delivered (hospitals, hospices and NHS community) [including general practitioners (GPs) and community nurses] and coded nodes representing the themes.

The findings uncovered three main themes, which included (1) access to services, (2) uptake of services and (3) experiences of engaging with services. The high-level findings are presented in Appendix 1, Table 2, which details the extent to which people from ethnic minorities are affected by the barriers and facilitators identified, that is (1) everyone is affected in the same way; (2) everyone is affected, but people from ethnic minorities are affected more; and (3) only affects people from ethnic minorities (see Appendix 1, Table 2).

There was a clear need to co-ordinate research, with all interviewees stating that they were very supportive of the objectives of KEEP-NET and recognised that addressing inequity based on ethnicity was a high priority. However, some interviewees were also keen to understand not only inequity relating to other underserved groups who were also identified as not always receiving the services they need, including those who are homeless, LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning or any other sexual identity that exists outside of heterosexuality), people in the criminal justice system and those with learning difficulties. Nonetheless, it was recognised that this was a valuable and innovative approach that could put PEoLC on the agenda, which could develop trusting relationships in the local communities and further extend to address inequity among other underserved populations.

The findings uncovered a wide range of barriers and facilitators that were perceived to impact the access and uptake of PEoLC among ethnic minority groups. It was felt that barriers relating to communication, particularly terminology and lack of translation, impacted the access to many services. It was felt that patients’ needs were not being identified early enough, whereby more effective strategies are needed to identify those in the last year of life, with clearer referral pathways to ensure patients are referred to services earlier and can receive more timely support. While it was acknowledged that a more diverse workforce in PEoLC would make services more culturally inclusive, all services echoed the challenge of being unable to attract and retain staff from ethnic minority communities.

A range of cultural barriers were perceived to impact the uptake of PEoLC among ethnically diverse communities. There was a consensus across all services that attitudes to death and dying among minority ethnic groups differ from the mainstream and are not widely understood. It was also felt that service providers lack knowledge and confidence on how to talk about death and dying with minority groups from non-Western cultures. It was also felt that negative perceptions towards hospices impact uptake, where assumptions and biases exist for those who use hospice services. It was further felt that hospices/hospice staff were not always viewed as medically competent as hospital staff by professionals and/or the public.

In relation to patient experience, ethical and legal challenges were noted, particularly among participants representing community and hospice settings, where they felt that patients’ cultural and faith needs could often conflict with medical procedures and legal requirements. There was also a perception that PEoLC lacked compassion and focused on medical procedures rather than care. Language barriers also impact patient experience, where professionals/service providers feel that information is not often translated or translated effectively. It was also felt that while medical information was widely shared, non-medical information was either not shared or not shared enough.

Engagement with community stakeholders, informal carers and faith leaders

A guiding principle of community-based participatory research (CBPR) is that it is necessary to partner with the communities that will ultimately benefit from the research42 with co-production and the engagement of communities and individuals critical when designing person-centred care, especially for marginalised minorities. 43 To achieve this, we facilitated three roundtable workshops, one with (1) community and service provider stakeholders, which formed part of our launch event and additional separate workshops with (2) faith leaders and (3) informal carers. All events were centred on two main topics. Firstly, to identify the needs, challenges and priorities at the end of life and, secondly, to consider what ideal support looks like and recommendations. After each event, a report capturing the major themes, experiences and suggestions was shared and sent to all attendees to verify and make any suggested changes/additions. Attendees were invited to comment on the report and encouraged to add anything else they would like to add. The reports were updated as and if necessary and then widely disseminated to the RPN.

Workshop 1: community/provider stakeholders

As part of the launch event, we asked the community stakeholders and service providers who attended to identify the most pressing issues and concerns and identify the big questions that need answering. An overview of the key themes is illustrated in Figure 2, with more detailed findings in Appendix 2. The discussions centred on the cultural appropriateness of institutional settings in providing PEoLC and how relevant these services are in meeting the cultural and faith needs of ethnically diverse communities that live in BHMK. There was a concern that training healthcare providers to become more culturally aware, while helpful, might not be the answer. Rather, there is a need to better understand existing end-of-life care provided by informal carers and faith communities to understand what additional support is needed.

FIGURE 2.

Frequency of words used in discussions with community stakeholders and service providers.

Workshop 2: faith leader’s event

To ensure representation for all faiths, we approached the council of faiths of Luton, Bedford and Milton Keynes and e-mailed 75 individual places of worship and their faith leaders who were identified as providing faith in the local communities across BHMK. We also shared invitations through our networks and the wider RPN. E-mail invitations and follow-ups were then sent to all institutions identified. A total of 14 faith leaders representing Christian (Pentecostal, Baptist, Catholic, Orthodox), Muslim and Sikh faiths attended the workshop on 6 July 2022. Leaders from the Hindu and Jewish faiths were missing from the event, although representatives of both had expressed interest in attending.

The faith leaders from Luton, Bedford and Hertfordshire who attended the event revealed that patients and their families have unmet faith support needs exacerbated by the recent pandemic. There is a perception that spiritual and faith care in PEoLC is not prioritised, with professionals lacking the awareness and skills to facilitate this. The discussions further uncovered faith support within the community; however, there is a disconnect with institutional services that provide PEoLC. An overview of the priorities, needs and recommendations are presented in Appendix 3.

Workshop 3: informal carers event

Engaging with diverse informal carers who can represent the ethnically diverse communities across BHMK was pivotal in understanding the needs, challenges and priorities of ethnically diverse families to access PEoLC. There was an initial attempt to run a workshop event with informal carers in July 2022; however, despite providing 2 months’ notice, the event failed to attract attendees, so the event was rescheduled. The challenges in engaging informal carers in research are well documented,44,45 with competing demands, lack of time and resource limitations impacting involvement. We liaised with several carer networks who supported us with recruitment, and with their support, we readvertised and changed the location to a more central location in BHMK to make it more accessible, with an afternoon tea included for all attendees. We also adopted a more ethnographic approach to advertising; we drew on our trusted and established informal networks in the local communities through word of mouth and snowballing approaches. This change of approach was met with good success, particularly among the Muslim communities of BMMK, with a rescheduled workshop attended by 15 informal carers from Bangladeshi, Pakistani and Kashmiri. Despite these efforts, there remained a lack of representation of informal carers from black African, Caribbean and Eastern European communities. While the reasons for the lack of engagement were unclear, hosting more targeted events at more convenient and neutral locations across BHMK may have increased engagement.

The informal carers forum was highly emotional, where people shared raw and painful experiences in the hope that they could improve the situation for others in their communities in the future. There was a consensus that help and support from PEoLC service providers were needed; however, this should complement rather than the family’s role. Discussions also uncovered a wide range of cultural, religious and structural barriers that impacted access to PEoLC in their communities, including a lack of awareness of what support exists and how this can be accessed, the perception that PEoLC does not have the spiritual and religious understanding to meet the needs of the communities, and a disconnect between service providers and community support. A more detailed overview of the priorities, needs and recommendations is presented in Appendix 4.

Data analysis and prioritisation

The triangulated findings from the interviews and stakeholder discussion groups revealed that barriers vary across settings, and while some issues affect everyone equally, there are significant barriers that negatively impact ethnic minorities more than their White British counterparts. There was also consensus around some of the most pressing issues and potential solutions across the stakeholder workshops, with the core themes presented below.

Awareness of palliative care services

Families and the wider community did not understand what PEoLC support is available, particularly non-NHS institutions such as hospices and how this support can be accessed. There was a preconception that the services available were focused on taking the individual way from their home and family. Informal carers were unaware that community-based hospice at-home support is available, and they were particularly open to understanding more about this support. Families were unsure what was available, which they needed to know to enable them to make a judgement of if this support would fulfil a required need. This finding supports previous research which has identified low awareness and negative perceptions as a barrier to accessing PEoLC,5,46 particularly towards hospice care. 20 To address this, it was felt that services needed to be more proactive in their efforts to increase access by offering services to families by reaching out to communities to increase awareness of services and support available. It was also acknowledged that patients are not identified early enough and are not provided the information they need when they need it. Therefore, clear processes are needed earlier in the end-of-life pathway to ensure families are aware of available services and support before reaching a need and/or crisis point.

Perceived need for palliative care services available

While it was acknowledged that people need to understand the services available, it was also felt that providers also need to understand what services are needed and wanted by the communities they serve. The consideration of need is fundamental to explaining demand and supply variations of healthcare delivery and can exacerbate inequity, particularly when services do not allow for variations in need between and within population groups. 47 Families want services that fit with the community’s understanding of caring for people who are dying rather than trying to replace the care families provide. This is particularly important when services are perceived not to be congruent with cultural and social expectations around caring for loved ones, with a concern that services will over-ride the family’s role or remove the dying person from their loved ones. 48

Disconnect between institutional and non-institutionalised routes

While ‘institutionalised’ services (e.g. hospices) are available, minority ethnic groups often depend upon informal carers, faith and community support, that is ‘non-institutionalised’ routes that focus on providing love and care but have limited medical expertise. Conversations centred on the disconnect between these routes with an acknowledgement that service providers and diverse ethnic communities need to engage more with each other; they are, however, far less certain about how. This uncovers the need for a more holistic understanding of the pathways and integration between ‘institutionalised’ and ‘non-institutionalised’ routes to understanding how these services can work better across the wider provision and how services can better fit with the community’s understanding of caring for patients and their families.

Person-centred approaches to end of life

Person-centric care requires medical institutions to promote compassion and encourage the initiation of broad conversations about death and dying that give weight to non-medical needs through effective processes to capture and share this information. This is true for everyone. However, it is more important to people, particularly those from multifaith communities whose beliefs about death are far from Western medical practices. The findings revealed that service providers often lack knowledge and confidence on how to talk about death and dying with minority groups from non-Western cultures. Care delivered in hospitals and the community was perceived to lack compassion, focusing more on the medical procedure than care. Treatment plans were viewed as rigid and based on the primary medical diagnosis and comorbidities, not on the capabilities and wishes of the patient or their families.

Medical, ethical and legal challenges in PEoLC can impact access and experience among ethnically diverse communities. 21 The findings revealed that service providers can often find themselves in ethical dilemmas when the cultural and faith needs of minority ethnic patients and their families can conflict with medical procedures and legal requirements. All stakeholder groups cited examples of distressing conflict, and while it exists in all settings, conflict is more extreme when medical rules are employed rigidly. There is, therefore, a need to move beyond medical procedures to care more holistically for the patient and their family through building rapport and trusted relationships with flexibility and person-centric approaches considered necessary to reduce the incidence and intensity of conflict.

Religious and cultural needs

Palliative and end-of-life care was perceived as not acknowledging the important role that faith and spiritual care play in the diverse communities they serve, with a lack of policy and process that puts spiritual or faith needs on par with medical interests. While community stakeholders recognised that service providers understand patients’ medical and sometimes emotional needs, they felt that there is limited value placed on the importance of faith and spiritual care. It was felt that ethnic minority communities need spiritual care from someone who will familiarly care for them, with PEoLC services perceived to lack the spiritual and religious understanding to support the needs of minority ethnic patients and their families. More person-centric and culturally sensitive approaches are needed to address spiritual and faith care for patients and families, where individual cultural and spiritual beliefs, priorities and wishes are acknowledged and respected. 24,49 Pathways to better integrate PEoLC with spiritual and faith support that exists in the community will provide more familiar support and care that can better meet the faith needs of patients and their families.

Language and communication barriers

Language was viewed as a barrier to the use and experience of PEoLC services by people with ethnic minority backgrounds, both in terms of translation and terminology. While the former is an issue that only affects people from ethnic minority communities, terminology is a problem for all. However, it is undoubtedly worse for people for whom English is not their first language and whose first languages do not have effective translations for common terms, including: ‘End of Life’, ‘Palliative Care’ and ‘Hospice’. Providing on-demand translation for the most used languages in the region is essential, and recruiting staff from these communities to make services feel more culturally relevant was expected to improve the situation significantly.

Role of family caregivers

The informal carers we spoke to revealed that there is a cultural expectation in South Asian families to provide care for relatives, with stigma and guilt associated with any other course of action. However, some informal carers felt excluded from key decisions about their loved one’s care and lacked confidence or were fearful of challenging experts and professionals. This reinforces previous findings, which highlight the importance of engaging with the wider family when making decisions surrounding palliative care. 50 While this may be the case for many families, several community members felt that the assumption that certain communities look after their own is not always accurate, particularly for those who live alone or do not live near family or have children. 5 Therefore, having sensitive conversations early with the patients to understand the role of their family in their care is crucial, while avoiding cultural assumptions that may negatively impact access. 5

Informal carers voiced their concerns about the lack of support and care they received following the death of their loved ones. Many family caregivers cited experiences of depression but were offered no support. Families felt that the system required them to fight for the counselling/help that they needed at a time when they were least able to do so. It was also felt that when the support was accessed, it was generic and not culturally relevant. These findings reinforce gaps in bereavement care and support that is being provided to minority ethnic populations. 51 Further research is therefore needed to understand the important role friends, family and the community play in providing bereavement support in ethnically diverse communities and understand what bereavement care is needed and how this can be successfully integrated to complement existing support and better meet the needs of the family.

There is considerable agreement about the issues and how they impact the use and experience of PEoLC by people from ethnic minority communities. However, service providers and the communities need guidance and to share best practices to learn quickly and avoid repeating the same mistakes.

Work package 3: use findings from work package 1 and work package 2 to drive research activity and change

Research activity and partnership

KEEch research Partnership NETwork has addressed a significant gap in research infrastructure through the development of a robust, inclusive and representative RPN, which has brought together over 80 partner organisations, including commissioners, service managers, providers and clinicians who work across primary care, palliative care services and community, hospice, and hospital settings, academics alongside community stakeholders, including faith leaders, community networks, third-sector organisations, carers and community members and academics that represent the diverse and multifaith communities of BHMK.

A key aim of the funding was to support the development and growth of partnerships and collaborations, which could facilitate the submission of a high-quality proposal which could be submitted to a forthcoming NIHR research commissioned call on PEoLC. Research priorities were identified through the triangulation of the experiences of the major stakeholder groups, including service providers, community groups, faith leaders and informal carers, as outlined in work package 2. These priorities were then used to co-develop a research funding proposal with formed work packages based on an agreed topic by the RPN to address inequality in access and uptake of PEoLC for ethnically diverse communities.

KEEch research Partnership NETwork uncovered that while service providers and communities acknowledge they need to engage with each other more, they remain uncertain of the best way to achieve this. A funding application will, therefore, seek to adopt a proactive approach to create a more holistic understanding of the pathways and integration between ‘institutionalised’ and ‘non-institutionalised’ PEoLC. This research, if funded, will seek to adopt a system-wide approach and provide the evidence base for a multifaceted intervention comprised of co-designed tools and resources aimed at health professionals, health providers and community stakeholders to increase engagement and interactivity that seeks to address existing inequalities. Through improved interactions between ‘non-institutional’ and ‘institutionalised’ settings, this research seeks to make an impact through increased referrals, access and engagement of PEoLC among minority ethnic groups, provide PEoLC that meets the needs of diverse minority groups and provide increased awareness of barriers to access to PEoLC among minority ethnic groups across stakeholders at a national and international level.

As KEEP-NET has begun to grow and partnership relationships have matured, it has provided a platform for further unplanned spin-off research projects and collaboration. 52 For example, the research team were awarded funding to conduct a pilot and process evaluation funded by the Bedfordshire, Luton and Milton Keynes (BLMK) Integrated Care System to evaluate if a ‘Community Connector’ intervention programme is feasible, acceptable to beneficiaries and implementers, and appropriate for the local cultural context within the cancer and end-of-life care pathway for minority ethnic communities. KEEP-NET has also been invited to collaborate on several research projects that focused on engaging diverse populations in PEoLC and has become a study site for a recently funded NIHR bereavement study that seeks to explore improving bereavement services for ethnic minority communities. These sustained efforts will be crucial in developing long-term working relationships through the RPN.

Impact and outputs

While the key aim of KEEP-NET was to drive research activity, there were additional notable outcomes from this project that have the potential to impact the local communities significantly. Through an extensive mapping exercise, we developed a searchable PEoLC service repository for BHMK, which has provided a useful front-facing tool for the local community to understand what services exist, what support they provide and how they can be accessed. There are plans for how this can be further maintained and developed. The service repository was demonstrated as part of the KEEP-NET dissemination event, with details on how it can be used, accessed and shared. This resource will also be widely shared with key stakeholders identified in KEEP-NET, including service providers, community and faith leaders and informal carers, to ensure that it can be made available and accessible to the communities that will benefit from it.

In addition, an unanticipated activity which resulted since the launch of KEEP-NET was the implementation of a new ‘Community Connector’ role, crowdfunded by the community, to engage with Luton’s Muslim communities as a conduit between institutional PEoLC and the community to build networks and increase capacity in PEoLC. Community connectors have become an important community asset and are integral to the CORE20PLUS553 strategic approach to addressing inequalities in underserved populations across England. This innovative role has the potential to facilitate better integration of community and voluntary services in PEoLC, which may enhance the community’s stage of readiness to address disparities in access to PEoLC. 54 Further research is needed to evaluate the implementation of this role to understand if and how this initiative can address disparities in access to PEoLC and how it may enhance other community-facing peer-led roles, which will provide useful evidence for local and national commissioners and policy-makers.

Dissemination

Dissemination and engagement have been integral in maintaining KEEP-NET. Soon after the project started, a local and national press release featured the launch event on numerous TV channels. An interactive web page, hosted on the University of Bedfordshire server, was developed, which provides information about the network, shared network vision and common values underpinning the group, blogs about named members, events and meetings, research activity, outputs and dissemination. We have also provided regular updates, including details of outputs, progress and events, shared via social media networks, including X (formerly Twitter) and mail distribution lists.

At the end of 2022, we also hosted a dissemination event, which presented the key findings and progress from the RPN alongside future steps and recommendations. It was held at the University of Bedfordshire on 1 December 2022. This event included sessions on the new Keech Community Connector role, the service repository tool, the themes and questions generated from the launch, faith leader and informal carer events, and the progress and achievements made in relation to research activity. Feedback was also sought and captured on the tangible initiatives of KEEP-NET and research priorities, which were then fed into the NIHR research funding proposal. This event was well attended (N = 24), including representatives from hospices, hospital trusts and community nursing (n = 11); representatives from community groups (n = 6); informal carers (n = 3); and academics (n = 4).

Discussion

An inclusive and representative RPN, comprised of over 80 key partners, professional groups and community stakeholders representing the ethnically diverse communities of BHMK, was successfully launched. Through this network, we have developed a research infrastructure that has provided a supportive environment for research collaboration facilitated through networking and collaboration committed to reducing the inequalities of PEoLC. The RPN successfully achieved all three objectives, including the co-production of a research funding proposal submitted to a NIHR commissioned call with formed work packages that seek to improve access and uptake to PEoLC for ethnically diverse communities.

The development of KEEP-NET was rooted in the principles of CBPR,55 bringing together researchers, practitioners, community stakeholders and the public to share power and responsibility to ensure research remains committed to tackling the issues identified by the community. 56 The value of community-based research in reducing inequities has been widely documented,57,58 alongside an increased recognition of the role community and faith groups play in improving health outcomes among disadvantaged populations. 59 The lessons learnt throughout this process also offer insight into the challenges faced and provide recommendations on what can strengthen equitable partnerships based on what has worked and what has not. This research, therefore, contributes to the wider evidence base to help understand how community research partnerships can be successfully developed and built in an ethnically diverse community within the context of PEoLC.

Through bringing together key stakeholders, including service providers, informal carers, and community and faith leaders, KEEP-NET provided a unique and holistic understanding of the factors influencing access to PEoLC for minority ethnic communities in BLMK. Triangulated findings uncovered a complex interplay of demographic, institutional, psycho-social and cultural factors5,23 that influence access and uncovered the important, yet under-utilised, role community and faith groups play in supporting the mixed healthcare economy in ethnically diverse communities. The findings further support recent theoretical developments, which acknowledge the importance of mobilising communities to engage with PEoLC services, which can help improve access. 54 The implementation of ‘community connectors’ as an innovative role to create opportunities for integration will provide useful evidence for local and national commissioners and policy-makers on how community-facing peer-led roles can be embedded within the complex system and across the patient pathway to address inequity in PEoLC. 60

Lessons learnt

Through KEEP-NET, we have listened to, engaged with and empowered local communities in BHMK to share, which has created a strong, robust infrastructure for collaboration. While this partnership has facilitated numerous benefits, the journey has not been without its challenges, and thus, we outline some of the lessons learnt, including the ongoing uncertainties.

Developing KEEP-NET required a flexible and agile approach to engage effectively with institutionalised and non-institutionalised stakeholders. There was a need to understand what motivates different stakeholders across the system to want to become partners within the network. Representatives from institutionalised settings understood the concept of KEEP-NET and recognised the need for a RPN specifically focused on ethnic minority inequalities in the region. It was clear that there was a clear motivation among service providers to gain an understanding and insight into the problems faced by ethnic minorities in engaging with PEoLC services. Many of the services were aware of the significant barriers for diverse communities and were actively seeking support to better understand how to develop strategies to address inequity.

Community stakeholders, in contrast, were clear that research in and of itself was not enough of a benefit for them to want to be involved. While they valued that community voices were being heard, many felt they had said the same things before and nothing had changed. Community representatives, therefore, wanted tangible actions in return for their participation and wanted to understand what has or will change as a consequence of this network. Therefore, there was a need to balance the delivery of quick, actionable results with the more time-consuming outputs such as research publications and grant applications. Managing differing stakeholder expectations has been identified as an important factor when developing new partnerships to ensure success and long-term sustainability. 61 We therefore sought to adopt a more flexible understanding of what could be changed which enabled a more realistic judgement of what could be achieved within the partnership to address the complexity of the wider problems. 28

It is important to highlight the context in which KEEP-NET was formed. Launched in March 2022, the communities across BHMK were still recovering from the recent COVID-19 pandemic, many of whom had been disproportionately impacted. There were heightened tensions and increased distrust, particularly towards government bodies and health providers. 62 Dealing with these tensions early in the process was paramount to building trust. Laying the foundations for KEEP-NET with the development of ground rules was an essential step in building trusting relationships. Bringing together partners with diverse assumptions, perspectives and experiences can cause tension;63 therefore, sharing a joint purpose of learning to achieve the same goal was able to facilitate equal partnership working alongside increased transparency and trust. 35–37

Transparency and accountability between all partners are important to ensure equitable partnerships. 64 KEEP-NET unearthed difficult and, at times, confrontational conversations where service providers’ ways of working were challenged. The success of these discussions was dictated by the service providers’ ability to bring their expertise to the RPN with a level of openness that issues with accessing and using PEoLC services by people from ethnic minority backgrounds exist. While at times challenging, service providers gained from and contributed the most to the network when they resisted natural responses to be defensive, with an acknowledgement that embraced the founding principle of KEEP-NET that every person’s voice was equally valid and valuable. These open and honest discussions enabled community stakeholders to move beyond ‘mistrust’ and ‘scepticism’ to a place of mutual respect and partnership centred on a shared vision and commitment from all.

Strengths and limitations

This research partnership successfully brought together over 80 organisations and services, including commissioners, service providers, faith leaders, community networks, third-sector organisations, informal carers and academics representing the diverse and multifaith communities of BHMK. By taking a flexible and agile approach, we were able to convene a range of workshops. Our key learning point is that building trust in ‘often-ignored’ communities takes time and flexibility.

We know that there are many examples of unmet needs and that the voice of the informal carer is pivotal in understanding how we can improve access and uptake of PEoLC. Despite wide advertising, allowing plenty of time to plan to attend, and putting the event at a time that might make it easier for others to attend (during school hours), factors we were told were important, we were still met with challenges in engaging with informal carers that can represent the diverse communities across BHMK. While we successfully engaged Muslim informal carers (N = 15), which uncovered insightful experiences of accessing PEoLC, we acknowledge that the views heard may not reflect those of all ethnic minority groups in BHMK. We expect that while some commonalities exist, some distinct barriers may impact ethnic communities differently. Therefore, future engagement should centre on having multiple workshops hosted in community settings and targeted at different community groups to ensure that all sections of the community feel empowered to share their views and experiences. Additionally, the inclusion of alternative and convenient methods, such as surveys and online workshops, may also enhance participation, particularly among informal carers.

Summary and next steps

An inclusive and representative RPN was established, comprised of over 80 partner organisations bringing together commissioners, service managers, providers and clinicians who work across primary care, palliative care services and community, hospice, and hospital settings, academics alongside community stakeholders, including faith leaders, community networks, third-sector organisations, carers and community members and academics that represent the diverse and multifaith communities of BHMK.

This partnership addressed a significant gap in research infrastructure through the development of a robust, inclusive and representative RPN, which has facilitated improved research activity that included the co-production of a recent funding application meeting the existential objective of the RPN. Beyond that, KEEP-NET has provided insight into factors that can facilitate the successful collaboration between different stakeholders, alongside some of the challenges we faced that are particularly pertinent to multifaith and diverse communities. We offer our observations through KEEP-NET as an opportunity for shared learning to consider when in the planning stages of developing and building a RPN.

Moving forward, the longer-term sustainability of KEEP-NET will remain dependent on continued funding, time and commitment from all stakeholders to ensure the relationships, infrastructure and benefits developed in this project are preserved. 65 The university has made a strong commitment to support KEEP-NET and will continue to work with new and existing partners to enable mutually beneficial research collaborations with those who share the same mission and commitment to reducing health inequalities in PEoLC. We will continue to feedback to the RPN on research activity, including the recently funded evaluation of the new community connector role implemented within BLMK, to ensure that we remain accountable and can continue to build trust with the community. Developing a clear operating structure for KEEP-NET, alongside ongoing monitoring,64 will be crucial to ensure continued engagement and progression, particularly without ongoing funding and resources. The mutual benefit of developing this partnership and working collectively with communities to address inequalities in accessing PEoLC could provide a useful approach and way of solving other important priorities to reduce wider health inequalities.

Additional information

CRediT contribution statement

Erica J Cook (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4369-8202): Conceptualisation (equal), Formal analysis (lead), Funding acquisition (equal), Investigation (lead), Methodology (equal), Project administration (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – editing and reviewing (lead).

Elaine Tolliday (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1875-3206): Funding acquisition (supporting), Investigation (supporting).

Nasreen Ali (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2017-8482): Investigation (supporting), Methodology (equal).

Mehrunisha Suleman (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8819-0659): Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting).

Emma Wilkinson (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8672-5277): Methodology (supporting), Investigation (supporting).

Gurch Randhawa (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2289-5859): Conceptualisation (equal), Funding acquisition (equal), Methodology (equal), Supervision (lead), Writing – original draft (supporting).

Data-sharing statement

All data requests should be submitted to the corresponding author for consideration. Access to all anonymised data may be granted following review by the data-sharing officer and completion of a data-sharing agreement.

Ethics statement

This research has been conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institute of Health Research Ethics Committee at the University of Bedfordshire on 14 March 2022 (REF: IHREC979).

Information governance statement

The University of Bedfordshire is committed to handling all personal information in line with the UK Data Protection Act (2018) and the General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR) 2016/679. Under the Data Protection legislation, University of Bedfordshire is the Data Controller, and you can find out more about how we handle personal data, including how to exercise your individual rights and the contact details for our Data Protection Officer here www.beds.ac.uk/about-us/our-governance/public-information/data-protection/.

Disclosure of interests

Full disclosure of interests: Completed ICMJE forms for all authors, including all related interests, are available in the toolkit on the NIHR Journals Library report publication page at https://doi.org/10.3310/MWHY5612.

Primary conflicts of interest: Mehrunisha Suleman declares being a Trustee for Arthur Rank Hospice, Cambridge.

Department of Health and Social Care disclaimer

This publication presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, MRC, NIHR Coordinating Centre, the Health and Social Care Delivery Research programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

This article was published based on current knowledge at the time and date of publication. NIHR is committed to being inclusive and will continually monitor best practice and guidance in relation to terminology and language to ensure that we remain relevant to our stakeholders.

Funding

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health and Social Care Delivery Research programme as award number NIHR135381.

This article reports on one component of the research award KEech End of life research Partnership NETwork (KEEPNET): A partnership network to enhance research capacity and capability to improve access of palliative and end-of-life care among the ethnic minority population across Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire, and Milton Keynes. For more information about this research please view the award page (https://www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/NIHR135381).

About this article

The contractual start date for this research was in January 2022. This article began editorial review in April 2023 and was accepted for publication in April 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Health and Social Care Delivery Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Copyright

Copyright © 2024 Cook et al. This work was produced by Cook et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

Notes

Supplementary material can be found on the NIHR Journals Library report page (https://doi.org/10.3310/MWHY5612).

Supplementary material has been provided by the authors to support the report and any files provided at submission will have been seen by peer reviewers, but not extensively reviewed. Any supplementary material provided at a later stage in the process may not have been peer reviewed.

List of abbreviations

- BHMK

- Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire and Milton Keynes

- BLMK

- Bedfordshire, Luton and Milton Keynes

- CBPR

- community-based participatory research

- EoL

- end of life

- GP

- general practitioner

- KEEP-NET

- KEEch research Partnership NETwork

- NICE

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- NIHR

- National Institute for Health and Care Research

- PEoLC

- palliative and end-of-life care

- PPI

- patient and public involvement

- RPN

- research partnership network

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Care of Dying Adults in the Last Days of Life 2017.

- National Institute for Health and Care Research . Better Endings: Right Care, Right Place, Right Time 2015.

- Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, Hannon B, Leighl N, Oza A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:1721-30.

- Ahmed N, Bestall JC, Ahmedzai SH, Payne SA, Clark D, Noble B. Systematic review of the problems and issues of accessing specialist palliative care by patients, carers and health and social care professionals. Palliat Med 2004;18:525-42.

- Evans N, Meñaca A, Andrew EV, Koffman J, Harding R, Higginson IJ, et al. PRISMA . Systematic review of the primary research on minority ethnic groups and end-of-life care from the United Kingdom. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012;43:261-86.

- Evans N, Meñaca A, Andrew EV, Koffman J, Harding R, Higginson IJ, et al. PRISMA . Appraisal of literature reviews on end-of-life care for minority ethnic groups in the UK and a critical comparison with policy recommendations from the UK end-of-life care strategy. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11.

- Meier DE. Increased access to palliative care and hospice services: opportunities to improve value in health care. Milbank Q 2011;89:343-80.

- Lalani N, Cai Y. Palliative care for rural growth and wellbeing: identifying perceived barriers and facilitators in access to palliative care in rural Indiana, USA. BMC Palliat Care 2022;21.

- Hasson F, Nicholson E, Muldrew D, Bamidele O, Payne S, McIlfatrick S. International palliative care research priorities: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care 2020;19.

- Marie Curie . Does Current Palliative and End of Life Care Research Match the Priorities of Patients, A Grant Mapping Analysis of the UK Clinical Research Classification System Dataset 2014.

- James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnerships . Palliative and End of Life Care Top 10 2023. www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/priority-setting-partnerships/palliative-and-end-of-life-care/top-10-priorities/ (accessed 5 April 2023).

- National Palliative and End of Life Care Partnership . Ambitions for Palliative and End of Life Care: A National Framework for Local Action 2021–2026 2021.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . End of Life for Adults 2011.

- National Health Service . The NHS Long Term Plan 2019.

- Mayland CR, Mitchell S, Flemming K, Tatnell L, Roberts L, MacArtney JI. Addressing inequitable access to hospice care. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2022;12:302-4.

- Todd-Fordham F, Candy B, McMillan S, Best S. Does current UK research address priorities in palliative and end-of-life care?. Eur J Palliat Care 2016;23:290-3.

- Dixon J, King D, Matosevic T, Clark M, Knapp M. Equity in Palliative Care in the UK. London: London School of Economics/Marie Curie; 2015.

- Worth A, Irshad T, Bhopal R, Brown D, Lawton J, Grant E, et al. Vulnerability and access to care for South Asian Sikh and Muslim patients with life limiting illness in Scotland: prospective longitudinal qualitative study. BMJ 2009;338.

- Katbamna S, Ahmad W, Bhakta P, Baker R, Parker G. Do they look after their own? Informal support for South Asian carers. Health Soc Care Community 2004;12:398-406.

- Tobin J, Rogers A, Winterburn I, Tullie S, Kalyanasundaram A, Kuhn I, et al. Hospice care access inequalities: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2022;12:142-51.

- Siriwardena AN, Clark DH. End-of-life care for ethnic minority groups. Clin Cornerstone 2004;6:43-8; discussion 49.

- Calazani N, Koffman J, Higginson I. Palliative and End of Life Care for Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Groups in the UK. London: Kings College London; 2013.

- Fang ML, Sixsmith J, Sinclair S, Horst G. A knowledge synthesis of culturally- and spiritually-sensitive end-of-life care: findings from a scoping review. BMC Geriatr 2016;16.

- Brooks LA, Bloomer MJ, Manias E. Culturally sensitive communication at the end-of-life in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. Aust Crit Care 2019;32:516-23.

- Mitchell S, Turner N, Fryer K, Beng J, Ogden ME, Watson M, et al. A framework for more equitable, diverse, and inclusive Patient and Public Involvement for palliative care research. Res Involv Engagem 2024;10:1-11.

- Corbin JH, Mittelmark MB. Partnership lessons from the Global Programme for Health Promotion Effectiveness: a case study. Health Promot Int 2008;23:365-71.

- Godoy-Ruiz P, Cole DC, Lenters L, McKenzie K. Developing collaborative approaches to international research: perspectives of new global health researchers. Glob Public Health 2016;11:253-75.

- Matheson A, Howden-Chapman P, Dew K. Engaging communities to reduce health inequalities: why partnership?. Soc Policy J N Zeal 2005;26.

- Marmot M, Alexander M, Allen J, Egbutah C, Goldblatt P, Willis S. Reducing Health Inequalities in Luton: A Marmot Town. London: Institute of Health Equality; 2022.

- Office for National Statistics . Births by Parents’ Country of Birth, England and Wales: 2020 2021. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths/bulletins/parentscountryofbirthenglandandwales/2020 (accessed 30 August 2023).

- Barron L, Luton PCN. Luton Clinical Commissioning Group Children and Young People’s Palliative Care Strategy Edition 2. Luton: Luton Clinical Commissioning Group; 2015.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . End of Life Care for Adults: Service Delivery 2019.

- National Gold Standards Framework Centre . The Gold Standards Framework 2023. https://goldstandardsframework.org.uk/proactive-identification-guidance-pig (accessed 3 March 2024).

- Farmer E, Weston K. A conceptual model for capacity building in Australian primary health care research. Aust Fam Physician 2002;31:1139-42.

- Jehn KA. Enhancing effectiveness: an investigation of advantages and disadvantages of value‐based intragroup conflict. Int J Confl Manage 1994;5:223-38.

- Jehn KA, Mannix EA. The dynamic nature of conflict: a longitudinal study of intragroup conflict and group performance. Acad Manage J 2001;44:238-51.

- Whitworth A, Haining S, Stringer H. Enhancing research capacity across healthcare and higher education sectors: development and evaluation of an integrated model. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12.

- Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health. Stockholm: Institute of Future Studies; 1991.

- Fletcher C. Community-based participatory research relationships with Aboriginal communities in Canada: an overview of context and process. Pimatisiwin J Aborig Indig Community Health 2003;1:27-62.

- Ritchie J, Lewis J. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2003.

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13.

- W.K. Kellogg Foundation . Logic Model Development Guide 2004 2021. https://wkkf.issuelab.org/resource/logic-model-development-guide.html (accessed 21 December 2021).

- Acha BV, Ferrandis ED, Ferri Sanz M, García MF. Engaging people and co-producing research with persons and communities to foster person-centred care: a meta-synthesis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18.

- Oldenkamp M, Wittek RP, Hagedoorn M, Stolk RP, Smidt N. Survey nonresponse among informal caregivers: effects on the presence and magnitude of associations with caregiver burden and satisfaction. BMC Public Health 2016;16:1-11.

- Malm C, Andersson S, Kylén M, Iwarsson S, Hanson E, Schmidt SM. What motivates informal carers to be actively involved in research, and what obstacles to involvement do they perceive?. Res Involv Engagem 2021;7.

- Wilkinson E, Randhawa G, Brown EA, Da Silva Gane M, Stoves J, Warwick G, et al. Communication as care at end of life: An emerging issue from an exploratory action research study of renal end-of-life care for ethnic minorities in the UK. J Ren Care 2014;40:23-9.

- Goddard M, Smith P. Equity of access to health care services: theory and evidence from the UK. Soc Sci Med 2001;53:1149-62.

- Dosani N, Bhargava R, Arya A, Pang C, Tut P, Sharma A, et al. Perceptions of palliative care in a South Asian community: findings from an observational study. BMC Palliat Care 2020;19.

- Braun UK, Ford ME, Beyth RJ, McCullough LB. The physician’s professional role in end-of-life decision-making: voices of racially and ethnically diverse physicians. Patient Educ Couns 2010;80:3-9.

- Shabnam J, Timm H, Nielsen DS, Raunkiaer M. Palliative care for older South Asian migrants: a systematic review. Palliat Support Care 2020;18:346-58.

- Mayland CR, Powell RA, Clarke GC, Ebenso B, Allsop MJ. Bereavement care for ethnic minority communities: a systematic review of access to, models of, outcomes from, and satisfaction with, service provision. PLOS ONE 2021;16.

- Jagosh J, Pluye P, Wong G, Cargo M, Salsberg J, Bush PL, et al. Critical reflections on realist review: insights from customizing the methodology to the needs of participatory research assessment. Res Synth Methods 2014;5:131-41.

- NHS England . CORE20PLUS5 2021. www.england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality-hub/national-healthcare-inequalities-improvement-programme/core20plus5/core20plus5-community-connectors/ (accessed 5 February 2023).

- Moss RH, Hussain J, Islam S, Small N, Dickerson J. Applying the community readiness model to identify and address inequity in end-of-life care in South Asian communities. Palliat Med 2023;37:567-74.

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health 1998;19:173-202.

- Butterfoss FD, Goodman RM, Wandersman A. Community coalitions for prevention and health promotion. Health Educ Res 1993;8:315-30.

- Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel JG, Minkler M. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2017.

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA. Introduction to methods in community-based participatory research for health. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health 2005:3-26.

- Cyril S, Smith BJ, Possamai-Inesedy A, Renzaho AM. Exploring the role of community engagement in improving the health of disadvantaged populations: a systematic review. Glob Health Action 2015;8.

- Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, Annandale E, Arthur A, Harvey J, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006;6:1-13.

- Dean L, Njelesani J, Smith H, Bates I. Promoting sustainable research partnerships: a mixed-method evaluation of a United Kingdom–Africa capacity strengthening award scheme. Health Res Policy Syst 2015;13.

- Charles G, Anderson-Nathe B. The Way Ahead Past COVID: Worse than Before. London: Taylor & Francis; 2021.

- Nyström ME, Strehlenert H. Advancing health services collaborative and partnership research comment on ‘experience of health leadership in partnering with university-based researchers in Canada – a call to “re-imagine” research’. Int J Health Policy Manag 2021;10:106-10.

- Kajumba T. Exploring Equity in Partnerships: Lessons from Five Case Studies. London: International Institute for Environment and Development; 2023.

- Ross LF, Loup A, Nelson RM, Botkin JR, Kost R, Smith GR, et al. The challenges of collaboration for academic and community partners in a research partnership: points to consider. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2010;5:19-31.

Appendix 1

| Themes | Hospital | Hospice | Community | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access | Knowledge |

|

||

| Communication |

|

|

|

|

| Operational barriers |

|

|

|

|

| Recommendations |

|

|

||

| Uptake | Knowledge and perceptions |

|

|

|

| Communication |

|

|

|

|

| Operational barriers |

|

|

|

|

| Recommendations |

|

|

|

|

| Experiences | Faith and cultural barriers |

|

|

|

| Communication |

|

|

|

|

| Operational barriers |

|

|

|

|

| Recommendations |

|

|

|

Appendix 2 Feedback from community/provider stakeholders

| Needs, challenges and priorities |

|---|

| Language/terminology |

|

|

| Access to information and services |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Navigating the system |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Applicability of services |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Service provider challenges |

|

|

|

| Talking about end of life |

|

|

|

|

|

| Communicating with health professionals |

|

|

|

Appendix 3 Feedback from faith leader stakeholders

| Needs, challenges and priorities |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Suggestions for improvement |

| Give non-medical support equal standing and resource to medical |

|

|

|

| Start talking about spiritual needs early |

|

|

|

| Support spiritual and faith needs of informal carers/families |

|

|

| Utilise and connect providers of different services with each other |

|

| Provide education and information on services to faith communities |

|

Appendix 4 Feedback from informal carers

| Needs, challenges and priorities |

|---|

| Help is wanted and needed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cultural and religious barriers |

|

|

|

|

| Structural barriers |

|

|

| Navigating the system is difficult, if not impossible |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Suggestions for improvement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|