Notes

Article history

The contractual start date for this research was in January 2022. This article began editorial review in May 2023 and was accepted for publication in February 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Health and Social Care Delivery Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Hawkins et al. This work was produced by Hawkins et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Hawkins et al.

Background

Social welfare legal needs in life-limiting illness

There is material within this section that has been reproduced from BMC Palliative Care under the Creative Commons licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Problems raising everyday legal needs are common in chronic illnesses. 1,2 They relate to social welfare matters for which the law defines rights, entitlements and protections, such as income security, suitable housing, employment rights, family issues, immigration, protection from abuse and the right to community care. 1–3 These social welfare legal (SWL) needs tend to cluster. People with multiple health needs, mental illness and/or social disadvantage are disproportionately affected, with a greater number and negative impact of SWL needs. 1–3 These groups are also least likely to access the help they need. 1,3 Unmet SWL needs become chronic stressors, generating morbidity in their own right and exacerbating chronic ill health. 1,4–6 Health and social inequalities have also been highlighted and exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic. 7

Serious illness impacts on financial security through increased living costs and loss of employment. 8 One in four terminally ill people of working age spend their final year of life in poverty with people in deprived areas of northern England at increased risk. 9 Welfare benefits should provide a safety net, but evidence shows it frequently fails to do so with many struggling to access entitlements. 8

Our previous research found that SWL needs are prevalent in the last 12 months of life,2,10 generating significant practical day-to-day challenges, and psychological and emotional distress affecting both patients and carers. 2 People with more complex health or social care needs, people living in deprived, marginalised or isolated communities and people with non-malignant diagnoses are more impacted by SWL needs. 10

Social welfare legal needs often present first to healthcare providers, meaning health professionals are ‘critical noticers’ of SWL needs and have a key role in facilitating access to support but this is often overlooked. 1,2 A wide range of agencies and services provide SWL advice and support, including councils and the not-for-profit advice sector, which includes voluntary and community services (VCS). 10 However, these actors are rarely connected and geographically variable making navigation to advice and support very difficult, resulting in battles to secure rights as well as unmet needs. 2,10

Co-production

Effective awareness of advice and support therefore relies heavily on a place-based, multiprofessional approach from engaged and informed healthcare professionals. 1,2,11,12 In order to support quality improvement in health care, attempts to understand the system of interest should be as comprehensive as possible, taking into consideration patients’ and professionals’ unique expertise, knowledge and experience. 13 Rather than viewing health care as a product, this approach reframes the relationship, and power dynamic, between professional and patient as a co-produced service. 13 We refer to place-based as meaning an approach to partnering and collaboration between organisations responsible for delivering services, as those within a place, in this case, the North East region. Our partnership frames issues, connections and subsequent coordinating action to improve the lives of those within the region, as being the concern of those serving communities in the North East region. More latterly, newer members of the partnership were focused within the Teesside area.

Such shared work should be collaborative across agencies and should integrate performance and learning to facilitate continuous change for improvement. 14 This requires a shift away from traditional approaches to leadership and performance management and measurement. At the level of practice, this shift evolves a move towards a culture where evidence is used to support shared decision-making to improve health care that better aligns with the patient’s needs. 13 At the service provider level, evaluative co-production work generates evidence that can be used to help proliferate learning through understanding the system levers which may facilitate or inhibit patient-centred practice. 15,16

Interprofessional learning

Interprofessional education is said to occur when ‘two or more professionals learn with, from and about each other to improve collaboration and the quality of care’. 17 The World Health Organization has developed a framework for action on interprofessional education and it is argued that learning across professional groups has a ‘significant role in mitigating many of the challenges faced by health systems around the world’. 18

This type of intervention has been linked with an increased awareness of the value of collaboration and development of skills around communication, leadership, conflict management and co-ordination. 11 Improved participant self-efficacy is also reported alongside intellectual resources to engage in a collaborative approach to person-centred care which could improve service delivery by responding to the increasing complexity of healthcare needs. 11 Finally, attitudinal change towards patients is also a potential outcome of interpersonal learning (IPL), as well as participants’ perceptions of role adequacy, role legitimacy and work satisfaction. 11

Further evidence in the context of legal issues in life-limiting illness suggests that IPL raises awareness of the breadth and relevance of SWL needs to end-of-life care and the need for interprofessional, cross-agency team working. 12 Therefore, IPL can be considered a route to relational working across agencies, smoothing cross-boundary care and support. 12,18

Aim and objectives

The aim of the research was to co-create a robust foundation for cross-agency research investigating the impact of IPL on SWL needs towards end of life in the North East England region. The potential of IPL to offer a scalable route to a relational place-based response for SWL needs is important to elucidate for current national policy discussion as well as its widespread impact on practice.

Objectives

-

Convene a research partnership group across academics, multiagency service providers and members of the public with lived experience.

-

Reach consensus on key issues for successful place-based multiagency research in this area, including access and engagement with the intervention (IPL); research capacity across stakeholders; defining and evaluating success.

-

Co-create a complexity-appropriate research proposal with IPL as an intervention.

Methods

Methodological approach

Complexity science is increasingly being used as a way to understand healthcare systems, and complexity of SWL work has been highlighted by previous funded work by the research team. 19 This research acknowledges that outcomes are often unpredictable and the relationships between cause and effect are non-linear. 20 Therefore, rather than relying on traditional, causality-focused measures of effectiveness that are decided with minimal input from service users and often aligned to service-level performance indicators, this research sought to start by identifying meaningful outcomes for and with service users.

Our approach also aimed to be emergent. Emergence is ‘the process by which individuals, through many interactions, create patterns or solutions that are more sophisticated than could be created by an individual’. 21 To embrace a fully emergent approach, the circle of agency must extend beyond traditional top-down approaches to enable the participation of actors from across the system. 21 Therefore, we sought to explore how to co-produce the delivery and evaluation of IPL from actors from across the North East region in a way that measures what matters to service users. This emergent and integrative approach to building the partnership and evaluating its activities is reflective of developmental evaluation, where the role of research facilitates real-time iteration through the surfacing and sharing of concepts and issues that all participants can frame and reframe together for the purposes of learning and development. Typical to developmental evaluation, methods are eclectic and flexible, capable of supporting changes in thinking and practice. 22

Research activities

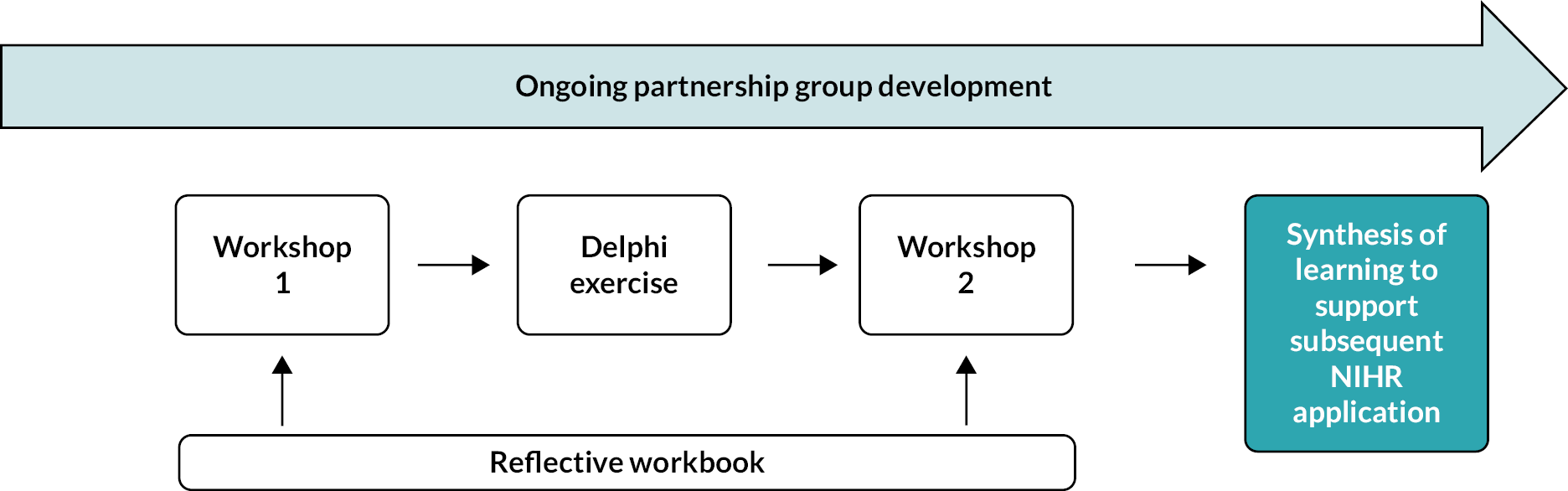

The project employed a range of methods to support the above objectives (see Figure 1 for project overview), described in Protocol v1.2.

FIGURE 1.

Learning flow from research activities. NIHR, National Institute for Health and Care Research.

Building a partnership group (Objective 1)

Previous research had generated a network of stakeholders across a range of health, social care, local government, charities and community groups, advice and legal services and academics at regional (North East England) and national levels. Members of this network were selectively invited to this project, based on the need for diversity of perspectives and capacity to engage with previous work.

New stakeholders were identified through this network, increasing representation of services supporting disadvantaged people or communities in the most deprived areas of North East England. All stakeholders had involvement with people living towards end of life and had experience relating to SWL issues. Contacts were given information about the project by e-mail with the opportunity to discuss by video call with the corresponding author. Partnership organisations engaged at different stages of recruitment are listed in Appendix 1, Table 1.

Partners recruited before research activities were sent materials to orientate their understanding of the work and support active engagement: a 30-minute webinar and a project workbook to hold all research partnership details as a single resource. Partners recruited after completion of research activities had a video call with the corresponding author to discuss the work and ongoing partnership opportunities.

Workbook (Objective 2)

Prior to the first workshop, participants were sent a workbook in the form of a PowerPoint slide deck which could be completed digitally or printed. This served as a repository of general information about the project and invited participants to engage in activities which would support participation and reflection around the research questions. While offered as a personal tool, participants were also given the option to share with the project team as additional data (with written informed consent). Three participants chose to return their completed workbooks and provided consent for these data to be included in the analysis.

Workshop 1 (Objectives 1 and 2)

Workshop 1 aimed to review partnership representation, set the foundation for co-design and agree themes for the Delphi process of reaching consensus on what outcomes IPL could achieve. The 3-hour online workshop took place in month 3 and comprised a mix of full and subgroup discussions, facilitated by the core project team. Introductory information around the context of the research and proposed IPL was provided, with a definition of ‘end of life’, ‘social welfare legal issues’ and ‘interprofessional learning’.

Discussion considered participants’ views of representation across the partnership, respective contributions to the partnership and themes for the Delphi process of reaching consensus, with a particular focus on what ‘success’ of the IPL would look like. Previous IPL pilot experience was relayed to the group in order to inform discussion around meaningful outcomes of IPL.

Participants were informed and encouraged to take part in the Delphi process of reaching consensus via surveys, which was constructed by the core research group following this workshop, informed by learning from this session.

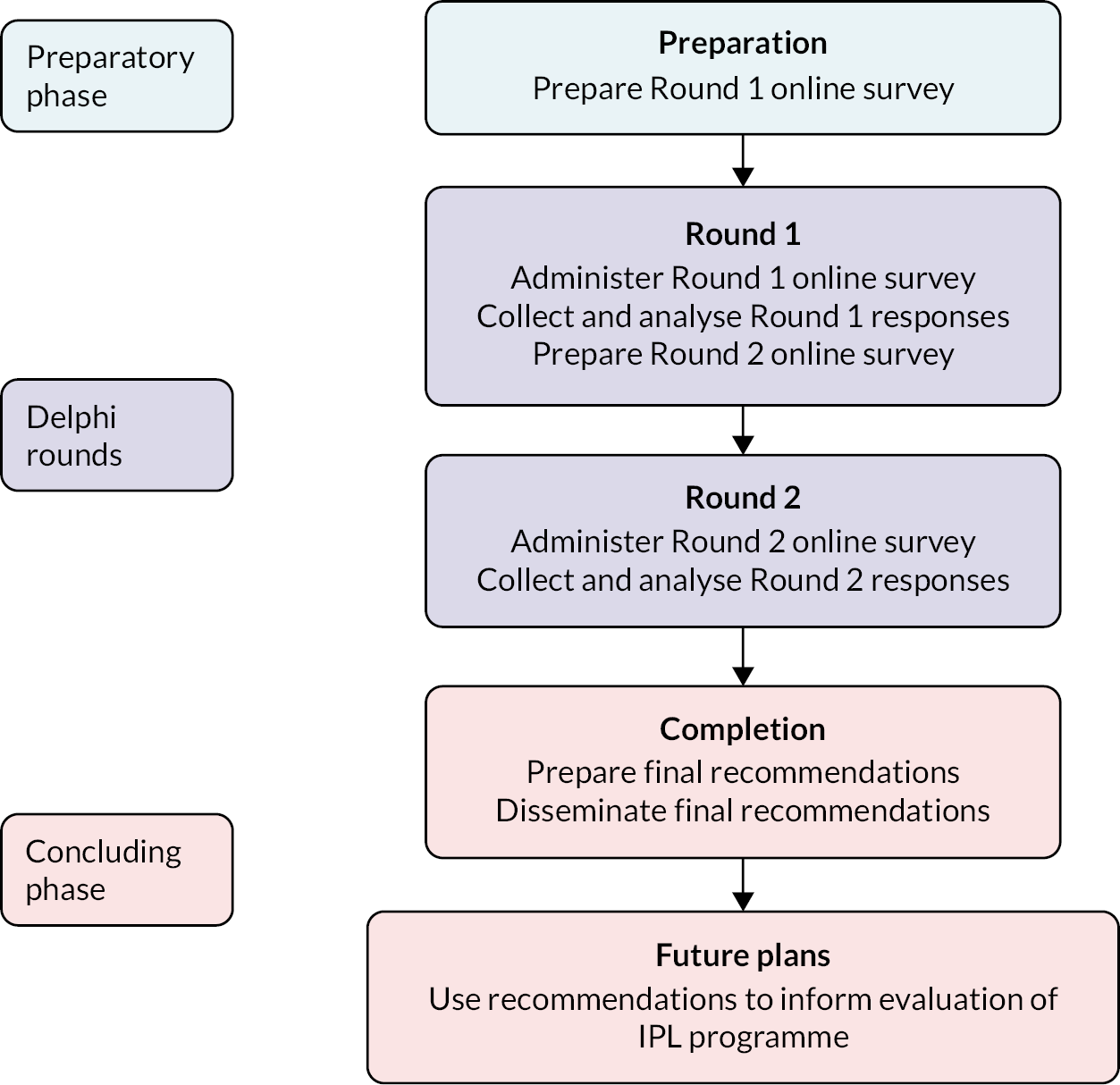

Modified Delphi technique (Objective 2)

In response to study objective 2, a two-round online modified Delphi technique was employed (Figure 2). The initial round was developed from existing evidence and workshop findings. The second round was to agree upon key issues identified from the initial round for successful research partnership focused on end-of-life research from key stakeholders. The Delphi technique is a well-established approach to seeking consensus of the opinions of a group of experts through a series of questionnaires and was employed to develop evidence- and consensus-based recommendations on the content and delivery of IPL. 23

FIGURE 2.

Overview of modified Delphi technique.

This Delphi technique is reported in line with recommendations for the Conducting and REporting of DElphi Studies (CREDES). 24

Expert panel

There are no established guidelines on the optimal Delphi study panel size. 25 At the time of this consensus exercise, the partnership comprised 10 project team members [1 a patient and public involvement (PPI) representative], 3 additional PPI representatives and 20 recruited participants from a range of organisations (see Appendix 1). All were invited to participate. Partners brought a range of expertise, including lived experience, support of underserved groups, support of people living towards end of life, SWL needs or support.

Data collection

Data from the Delphi technique were collected in months 4 and 5. Both surveys were hosted using online survey tools and administered via e-mail. A consent statement was included on each survey’s introductory page. Participants were required to complete the consent statement on each survey. Reminders were provided via e-mail to help maximise response rates. All individuals who completed Round 1 were subsequently e-mailed links to Round 2.

In Round 1, participants were presented with statements detailing potential IPL outcomes (see Appendix 2, Table 2) and were asked to rate each item on a nine-point Likert scale from ‘least meaningful’ to ‘most meaningful’. Where appropriate, items included an ‘other’ option so participants could provide more relevant information and/or explanation. Free-text options were included at the end of each item to allow participants to suggest additional items. Round 1 also included questions on panellists’ characteristics. Separate sets of questions were included for PPI panellists (sociodemographic and clinical characteristics) and professional panellists (their workplace, role and experience).

A second round of the survey included the initial items from the original survey which reached agreement from at least 70% of participants, as well as additional recommendation items generated from Round 1. In Round 2, participants were asked to rate how meaningful they thought the different outcomes are to participants of the IPL programme (see Appendix 2, Table 3), organisations (see Appendix 2, Table 4) and patients and carers (see Appendix 2, Table 5) A summary of the results of the preceding round was shared and explained to panellists with the opportunity provided to reconsider their judgement.

Data analysis

The free-text responses from Round 1 were examined using directed content analysis. 26,27 All recommendations were assessed and coded inductively. Those sharing similar meanings were clustered into sections, each forming a primary category. Codes that did not align with these subcategories were integrated into newly formed subcategories generated through the inductive process. Subsequently, these subcategories were merged into broader, generic categories. These generic categories were reviewed with the research team to ascertain if any additional primary categories were needed.

There are no established guidelines on how to define consensus in Delphi studies. 28 Consensus levels of published Delphi studies were taken into account and the level of consensus for this Delphi study was set at 70%. 29–31 Consensus was therefore defined as at least 70% of respondents rating an item as ‘critically meaningful (score 7–9)’. Participant characteristics and importance ratings were analysed descriptively using Stata 17 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). All items that reached consensus in Round 2 among all respondents considered together were included in the final set of recommendations.

Workshop 2 (Objectives 1 and 2)

Workshop 2 aimed to agree on the future research strategy and continued the dialogue around partnership representation and engagement. This 3-hour workshop, a mix of facilitated full and small group discussions, was held online in month 6.

The rationale for IPL as an intervention and its format were described. The findings from the modified Delphi technique were presented followed by an introduction to evaluation. Facilitated discussion, framed by the Delphi findings, refined priorities for evaluation and debated approaches to collection of meaningful data. This included consideration of process and impact evaluation, engagement with IPL and how the partnership could be a resource for future research. A digital whiteboard (Jamboard) was used to facilitate this discussion. The session closed with the plan to use the data collected to formulate a proposal for the next phase of the research.

Audio recordings of Workshops 1 and 2 were transcribed and collated alongside facilitator notes made during the sessions, online chat recorded from the sessions, completed workbooks and collaborative materials including Jamboard notes. These data were then inductively coded using NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK) software to identify the key themes from the data.

Project governance

A study advisory group, including the research team and sponsor research and development representatives, met twice during the project to review progress against protocol timelines, review budget and troubleshoot problems. The core research team (CH, HH, AP, YF, AW) met every month to keep tasks on track and learnings updated.

Patient and public involvement

Four PPI participants contributed at every stage of the project. They were recruited as patients and/or carers with lived experience of life-limiting illness and SWL needs and recruited through Newcastle Voice (https://voice-global.org/). One is a heart failure patient and current carer, one is a current carer, two are bereaved carers. One of this group has been a project co-applicant and is an author of this report (and subsequent publications), the other three are partnership group members. PPI participants brought important experiences and insights relating to inequalities in end-of-life care, including non-malignant diagnosis (including mental health issues), social deprivation, ethnicity and sexuality. PPI participants were paid for their time and made aware of the NIHR Benefits helpline and Department for Work and Pensions letter template to avoid impact of research participation on financial benefits.

The Research Design Service PPI panel was consulted as part of preparation of the follow-on research proposal; this led to key changes in our approach to public engagement in the next project.

Equality, diversity and inclusion

The partnership engaged a range of stakeholders to create a collaboration between academic organisations and organisations that are generally outside of health system research. A core activity of convening the partnership group was to focus on locations with significant social inequalities, poor health outcomes and high need for palliative care. Services supporting people in deprived communities or representing people experiencing homelessness and/or addictions, people with learning difficulties or mental ill health, asylum seekers and refugees, were engaged in order to extend the reach of the partnership group to underserved groups. This engagement is an ongoing activity.

Workshops were held online to maximise access and participation; partnership group members were encouraged to contact the core project team by e-mail or phone with any comments or feedback outside research events.

Results

Results are presented thematically under each objective but in the order of research activities. Thus, Workshop 1, the Delphi technique findings and Workshop 2 findings are integrated under the themes, as this reflects the emergent nature of the narrative from the partnership group.

Objective 1: building a partnership

Partnership engagement

At project commencement, the partnership group comprised a research team of 10 people [7 academics with expertise in executive education, co-production, health economics, public health and sociolegal studies, 1 public representative with lived experience (PPI), 1 palliative medicine clinician, 1 social prescribing and VCS lead] alongside existing contacts from previous projects including 3 further PPI representatives.

Partnership building was a continuous exercise throughout the project, as new links were identified (see Appendix 1). New stakeholders were recruited from: regional VCS support group, public health, primary care, carers group, advocacy service, community action groups (Middlesbrough and County Durham), Citizens Advice, Middlesbrough adult social services, food bank and debt advice service, complex social needs, learning disability social care, community housing support, asylum and refugee services and substance misuse services. All services approached wanted to be involved in the project; there were no refusals at recruitment.

All recruited partners were invited to contribute to the research activities remaining at the time of recruitment.

At completion of the project, 37 different services/organisations had been recruited to the project, alongside the 10 project team members. Of these 37, 14 were research naive (VCS, social care, advice service), 15 had participated in research to some extent (NHS, local government and some VCS services) and 4 had a primary research role. Seven recruited participants were unable to contribute to any of the research elements, six because of capacity (NHS and VCS) and one because of funding constraints (VCS). Of the remainder, all participated in at least one research activity. The workshops included discussions around partnership engagement and involvement. The key findings are presented below:

-

Workshop 1 attendance: 22 (2 clinicians, 7 academics, 5 PPI representatives, 4 people from VCS, 1 from the Council, 1 from Department of Work and Pensions, 1 from social care and 1 from Advice Services Alliance).

-

Workshop 2 attendance: 15 (2 clinicians, 6 academics, 2 PPI representatives, 3 people from VCS, 1 person from Law Centres Network and 1 person from addiction services).

Service providers attending Workshops 1 and 2 were all senior staff members within their organisations.

Capacity for partnership engagement

Over the course of the project, representatives of 37 different organisations/services were invited to participate in this partnership alongside the research team. While there was universal interest and recognition of the value, capacity to contribute to research activities was variable, and limiting for many.

Discussion in Workshop 1 considered the capacity for partnership engagement. Lack of time was the main reason cited for non-participation in research activities. This was particularly problematic for participants from clinical services and small VCS organisations. Enablers for participation included allocated time, funding, leadership support and perceived value.

I’m very, very aware how challenging it has been for the health service, over the last sort of a few years and obviously with COVID.

P8, NHS, Workshop 1

Value of the partnership

Workshop 1

During the initial workshop, expectations about contributions to the partnership were inconsistent, with some participants appearing to think they would be advising on a proposal, rather than co-producing as part of a team. There was also some confusion between delivery of IPL and research evaluation of IPL.

I don’t really know what it is we’re trying to achieve. So you know, I’m not a researcher.

P2, VCS, Workshop 1

Therefore, greater clarity around the partnership and the objectives of the research were provided and the value of the diverse expertise that members could bring to the project emphasised.

However, there was a strong sense that partnership participants wanted to be part of sustainable practice change, connecting the research with action, and avoiding becoming another ‘talking shop’ (P2, VCS, Workshop 1).

That’s the thing that always worries me is the sustainability and I’ve seen a number of projects in my 31 years that come and go.

P6, Person with lived experience, Workshop 1

Workshops 1 and 2

Across both workshops, participants expressed enthusiasm to contribute to this work, with a shared vision that a multiagency approach gave an opportunity to do things differently. The variety of experience and expertise across the partnership was stimulating and positive; the potential to use multiagency partnership to ‘map’ the system and shine a light on the barriers and opportunities to system working was clear.

When the problem’s been identified, we need to look at which agencies could have helped or should have helped, or might have helped to address that problem whether social care or somebody in the hospital or voluntary sector organisation.

P7, Researcher, Workshop 1

The partnership was also seen as a route to uniting a diverse group of actors to achieve positive outcomes and bridge gaps between services. Diversity was seen as a strength as well as an opportunity to confront inequalities.

We really need to put equality, diversity and inclusion at the heart of this … because our population is diverse.

P16, Person with lived experience, Workshop 2

Partnership representation and roles

Workshop 1

The first workshop emphasised the importance of the research being informed by lived experience and including a diverse membership, including representation from clinical, voluntary and legal organisations.

Participants shared their interests and experiences to reflect on what they might bring to the partnership.

Workshop 2

Workshop 2 extended this discussion to consider the nature and extent of various roles that might be useful. The group dynamic was considered, particularly the value of viewing PPI participants as experts in their own right and on an equal footing with professional participants.

I am a lay person and PPI member … what we can offer is … the public perspective in research and public involvement as a critical friend … we can play a role of ensuring that it’s going to work, because … whatever you’re researching is going to have an impact on the public and carers. Then we can help ensure it will work because we will be able to give the first-hand perspective from the onset.

P16, Person with lived experience, Workshop 2

… Carers and people with experience, like me are also professionals in their own right …

P4, Person with lived experience, Workshop 2

The blurring of professional and personal insights went further, with a recognition that professionals also bring personal lived experience. A non-hierarchical partnership was welcomed.

Nearly all professionals will have personal, lived experience in some form or another, and maybe tapping into this is an important factor in building the relationships of trust that are required to build a more fluid multi-disciplinary approach

P19, NHS, Workshop 2

Participation in research required clarity around who would do what. Being specific and realistic was seen as a mechanism to engage organisations struggling with limited capacity, offering support by defined and appropriately costed research roles.

Objective 2: agreeing on key issues for successful multiagency research

While there was strong interest in the research, with all approached organisations agreeing to be part of the partnership, interpretation of Workshop 2 and Delphi technique showed that contributions had to account for the variable and flexible participation noted at the start of the findings section. The findings from the workshops and modified Delphi technique are presented below.

Modified Delphi technique

Responses: 26/33 (78%) Round 1; 16/26 (62%) Round 2.

Round 1 survey was sent to a total of 33 project group members, 26 (78%) completed it. Round 2 was completed by 16 (62%) of those who completed Round 1.

Out of 26 participants who completed Round 1, 31% (n = 8) were from university or a research network, followed by 23% (n = 6) from a charity, 15% (n = 4) were patients, carers or a member of the public and 12% (n = 3) from NHS. Others were from hospice (n = 2), council (n = 1), government organisations (n = 1) and commissioned substance misuse service (n = 1).

Out of 16 who completed Round 2, 31% (n = 5) were from a university or a research network, 31% (n = 5) were from a charity, 13% (n = 2) were patients, carers or a member of the public, 13% (n = 2) from NHS, 6% (n = 1) from hospice and 6% (n = 1) from commissioned substance misuse service.

Outcomes of interprofessional learning to be measured

Ten items were included in Round 1 (see Appendix 3, Table 6). Five items were included with the revised phrase by the project advisory group in Round 2. Four items were included in the final set of recommendations as critically meaningful (see Appendix 3, Table 7):

-

awareness of the relevance of SWL needs to end-of-life care

-

building a coherent understanding of the system that delivers and manages SWL needs

-

multiagency/multidisciplinary approach to care

-

increased engagement with other services

When separating items specifically for participating organisations and for patients/carers needing support, no consensus was reached for any outcomes of IPL for participating organisations (see Appendix 3, Table 8); however, four items were included in the final set of recommendations as critically meaningful for patients/carers needing support (see Appendix 3, Table 9):

-

ability to access appropriate support/advice

-

income

-

quality of life

-

well-being

Methods for data collection

Qualitative (interview, focus group and observation) and quantitative methods (questionnaires) were proposed in Round 1 and both were rated in Round 2.

-

individual interviews and focus groups were considered critically important for collecting data on participants of the IPL programme.

-

individual interviews and questionnaires (with open and closed questions) were rated critically important for participating service/organisational leads.

Workshops

The findings from the two workshops were largely overlapping and are therefore presented below by theme.

Language

Both workshops surfaced the need to develop a shared understanding of key terms to facilitate participation across the partnership.

Workshop 1

During the first workshop, jargon and academic language limited full participation; participants not familiar with research provided a valuable challenge to ensure plain English was used.

I’m finding this very academic … I know this background is needed but does it need to be explained in such detail?

P2, VCS, Workshop 1

Workshop 2

As the discussion moved on to consider how the research might be operationalised, the definition of key terms was explored. For example, one participant asked,

What do you mean by ‘your system’?

P13, VCS, Workshop 2

‘Integration’ and ‘collaborative/partnership working’ were initially used interchangeably but discussion identified the former as potentially unrealistic, with different organisational remits, funding and governance risking success; issues that were felt to be less relevant to the latter.

If I have to integrate, am I sharing my data? Am I integrating my IT … or am finding social systems which are allowing me to do better at my work?

P20, Academic, Workshop 2

Evaluation of interprofessional learning

Workshop discussion and Delphi engagement clarified approaches to the evaluation of IPL as part of future research.

Workshop 1

The initial workshop provided insight into the context of the problem as a precursor for defining what success might look like. Key findings were the need to use IPL to challenge attitudes and cultures as well as raising awareness of SWL needs, inequalities and connecting fragmented services.

Workshop 2

The second workshop extended the discussion, to co-design how success might be evaluated. Both process evaluation (did IPL achieve what we thought it would for staff?) and impact evaluation (did IPL make a difference in people’s lives?) were felt to be important.

A non-traditional approach to evaluation was encouraged, including exploring culture and system dynamics, factors influencing access by disadvantaged groups, understanding barriers and incentives to engagement with IPL and cross-agency working, and capacity issues across the system.

Mixed-methods evaluation was preferred, proposing interviews and/or focus groups alongside questionnaires with both open and closed questions.

The Delphi achieved consensus around evaluation of professional learners as well as patients/carers but not at organisational level. Workshop 2 discussion provided more detail around these levels of evaluation.

Impact on professional learners

Professional outcomes related to awareness of SWL needs and local system players, increasing connections to offer a multiagency approach to care.

There was a sense that the IPL intervention might provide an opportunity to expand networks among services that previously had not collaborated.

… would be good to understand … those relationships, and the collaborations that are formed … you’re more likely to phone them if you’ve met them at an interprofessional learning event.

P17, Academic and former nurse, Workshop 2

Responses in the workbooks indicated that broadening networks or ‘reach’ would be beneficial at both organisational and individual learner levels. Additional connections with peers could perhaps result in learners feeling less isolated.

… whether there was any way of you being able to measure, whether they felt as though the learning had given them an opportunity to feel more integrated with other services.

P4, Person with lived experience, Workshop 2

It was recognised that frontline staff often did not have an opportunity to reflect on their practice given the pressure services were under but that the IPL intervention offered this space. This could benefit the individual learner directly and could also help embed learning practices into service delivery.

Impact on patients and carers

Generating impact on the lives of patients and carers was an outcome measure that was deemed important and relevant by all stakeholders. Consideration of how this might be measured, in Workshop 2, acknowledged that this would be complex and needed to be driven by first-hand experience.

For instance, it was noted that the standard methods of measuring quality of life (e.g. the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version favoured by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) may not be appropriate for use at the end of life, as they do not measure the things that are seen to be important to people in this position. 32 Other quality-of-life tools, such as the ICECAP-SCM, may be more appropriate, despite the other challenges this may bring up:33

… the tools which you would use in a traditional economic evaluation have been shown … they don’t cover the topics which are important to people at the end of life. So therefore, in that sense we’d have to kind of think about slightly different … different outcome measures

P14, Academic, Workshop 2

Access to advice or support, general well-being, financial well-being and quality of life were identified as important in the Delphi.

Impact on organisations

The Delphi technique did not generate consensus around the impact of IPL on organisations providing services, although workshop discussions acknowledged that cross-agency connections were likely to impact at organisational level, as well as individual professional level.

Workshop themes included staff outcomes: improved job satisfaction and reduced sickness or turnover rates.

And if there was any reduction in sick leave because they’re both huge issues … it would be a measure of job satisfaction.

P4, Person with lived experience, Workshop 2

Capacity concerns fed into discussion around the economic implications of the IPL. More effective management of SWL needs around the end of life could impact on healthcare utilisation and costs, but direct attribution to IPL would be challenging.

… in terms of health care costs to people at the end of life; we know that these costs can be huge, having something that could even change these costs and rein them in slightly could have quite a big impact.

P14, Academic, Workshop 2

Workshops 1 and 2

An interesting debate, in relation to the organisational level, emerged across both workshops. In Workshop 1, it was suggested that a potential outcome of the IPL might be some form of accreditation or quality standard.

I did wonder whether organisations that undergo some training could get some sort of like quality mark, if that makes sense, that they could then display as an organisation which is signed up to people’s welfare rights, and that’s something that it could be quite standard

P6, Person with lived experience, Workshop 1

This notion was also considered in Workshop 2, with a discussion around whether the training should be mandatory and ‘drip fed or force fed into organisations’ (P12, Academic, Workshop 2).

However, ultimately, a culture of learning as ‘core business’ and continuous improvement was desired, as opposed to required educational activity.

I’m not sure what I personally think about that because there’s something about a system that will pre-develop a culture of people wanting to come together and learn from one another as opposed to, you know, you have to go to this.

P19, NHS, Workshop 2

Need for leadership engagement

Sponsorship at a senior level, facilitating access to IPL, endorsing its value and supporting translation of learning to practice emerged as a strong theme across the workshops.

Workshop 1

In Workshop 1, the group considered the sustainability of the project, with leadership engagement identified as a route to policy change:

I think about who we are missing here. And I think those people are the senior people in organisations that commission the services.

P6, Person with lived experience, Workshop 1

Workshop 2

In Workshop 2, the need for influence within organisations and systems was highlighted by a PPI participant, addressing the potential tension with the group’s vision for a non-hierarchical partnership:

If you’re genuinely wanting to do a bottom-up change, then it needs to start at the top funnily … by getting the right people involved in that first discussion and then targeting as the learner group, the people who have a high enough status within their organisations to be listened to when they want to disseminate that information further down.

P4, Person with lived experience, Workshop 2

Objective 3: co-creating a complexity-appropriate research proposal with interprofessional learning as an intervention

Following Workshop 2, we co-produced a research proposal in collaboration with members of the partnership group. The aim of the proposed research is to test feasibility, scalability and impact of IPL, through engagement with public, professionals and organisational leaders. This proposal was submitted for further NIHR funding in April 2023 [22/561 Palliative and End of Life Care (HSDR Programme)].

Discussion

Principal findings

The findings provide evidence for the mechanisms which support the convening of a multidisciplinary research partnership, encompassing academics, multiagency service providers and members of the public with lived experience. Partnership recruitment was a positive experience, with overwhelming enthusiasm to be involved in addressing an issue which all participants could identify with. Participants shared a desire for change, relating to identification of SWL issues, timely access to support and better links between services. Impact at practice and policy levels was desired.

Engagement with research activities was very variable with seven recruits unable to participate at all. Capacity and funding were key barriers. However, our previous research experience in cross-agency collaborations has shown that, once aware of a project, partners are willing to be called on for specific input or one-to-one discussion.

Impact of patient and public involvement

The four PPI participants involved in the partnership group provided insights which shaped this project and the proposal for subsequent research. These are further described below, but the overarching perspective was that inclusion of public representation is critical to development and evaluation of services if they are to meet needs in an appropriate and accessible way. A ‘them’ and ‘us’ approach was challenged by PPI participants identifying as experts in their own right and also by recognition that partnership members, and service providers generally, are service users as well. Involvement of the RDS PPI panel shaped our planned involvement of the public in our follow-on proposal. They ensured we did not offer involvement which might be confusing, with participants thinking they would be getting personalised help, rather than attending partnership events.

Equality, diversity and inclusion

Building the partnership group involved extending membership to people with lived experience, organisations supporting underserved groups in the context of end-of-life care, and engaging organisations with varying, or no, experience in health service research. This led to a diverse group, revealing facilitators and barriers to partnership working, which are important in considering widely inclusive partnerships.

Facilitators of place-based multiagency research

Effective partnership engagement was facilitated by clarity in relation to the nature and purpose of the research and the nature and intention of the IPL. Language proved both a facilitator and barrier and the need for accessible, shared language was clear. Additionally, given the diversity of participants’ backgrounds, exploring opportunities for participants to utilise their strengths was important to engage members of the partnership and capitalise on diversity. Public participants encouraged the group to view them as experts and value them on equal terms. The group recognised the importance of an inclusive and mutually respectful culture within the partnership as a foundation for co-production. The partnership continues to evolve, facilitated through word of mouth across partnership members who share a commitment for appropriate representation, particularly in relation to underserved groups.

Providing multiple methods of participation, such as verbal and written feedback mechanisms, seemed to be beneficial, with participants engaging in both modes. Very few participants chose to submit their reflective workbooks. Although concrete conclusions cannot be drawn about the use of such workbooks for non-respondents, those that were returned can provide interesting insight. All respondents were from the PPI group, which perhaps indicates a difference in their availability to participate flexibly. Themes from workbooks mirrored those discussed in workshops, perhaps indicating that workbooks served a preparatory function or that PPI participants were more engaged in voicing their opinions when offered different options.

In terms of engagement with the research partnership, a shared commitment to meeting SWL needs more effectively was clear, but capacity constraints restricted engagement by some participants, notably clinicians who necessarily prioritised clinical activity and representatives of small VCS organisations, who articulated the need to justify involvement in research through allocated funding.

In terms of engagement with the IPL, pressures on healthcare staff were noted again. The importance of organisational endorsement and sponsorship at a senior level was emphasised as facilitators to engagement.

A structure for research provision

Much of the partnership discussion was focused on the ‘system’. As participation was so multiagency, the ‘systems’ in question needed some interpretation. From a previous NIHR Applied Research Collaboration funded programme in the same region, local stakeholders produced their versions of where they thought system boundaries were. While this was not assumed to be adopted by the partnership participants in this project, it gives an indication of the wide and varied place-based multiagency landscape of services that are being referred to. However, in addition to this service landscape, we expect that each participant may have a slightly varying definition of ‘system’, which is bespoke to their position relative to other services. In this respect, we can use the service landscape image as a proxy, but assume that ‘systems of interest’ are unique to each participant, in line with Jackson’s version of systems of interest: this is an articulation of a constructivist position on systems thinking. 34 Any system under discussion is essentially imagined (and therefore created) by the people in that conversation. Potential ways to navigate research capacity issues and facilitate involvement in ‘system-wide’ research were discussed, clarifying a partnership structure.

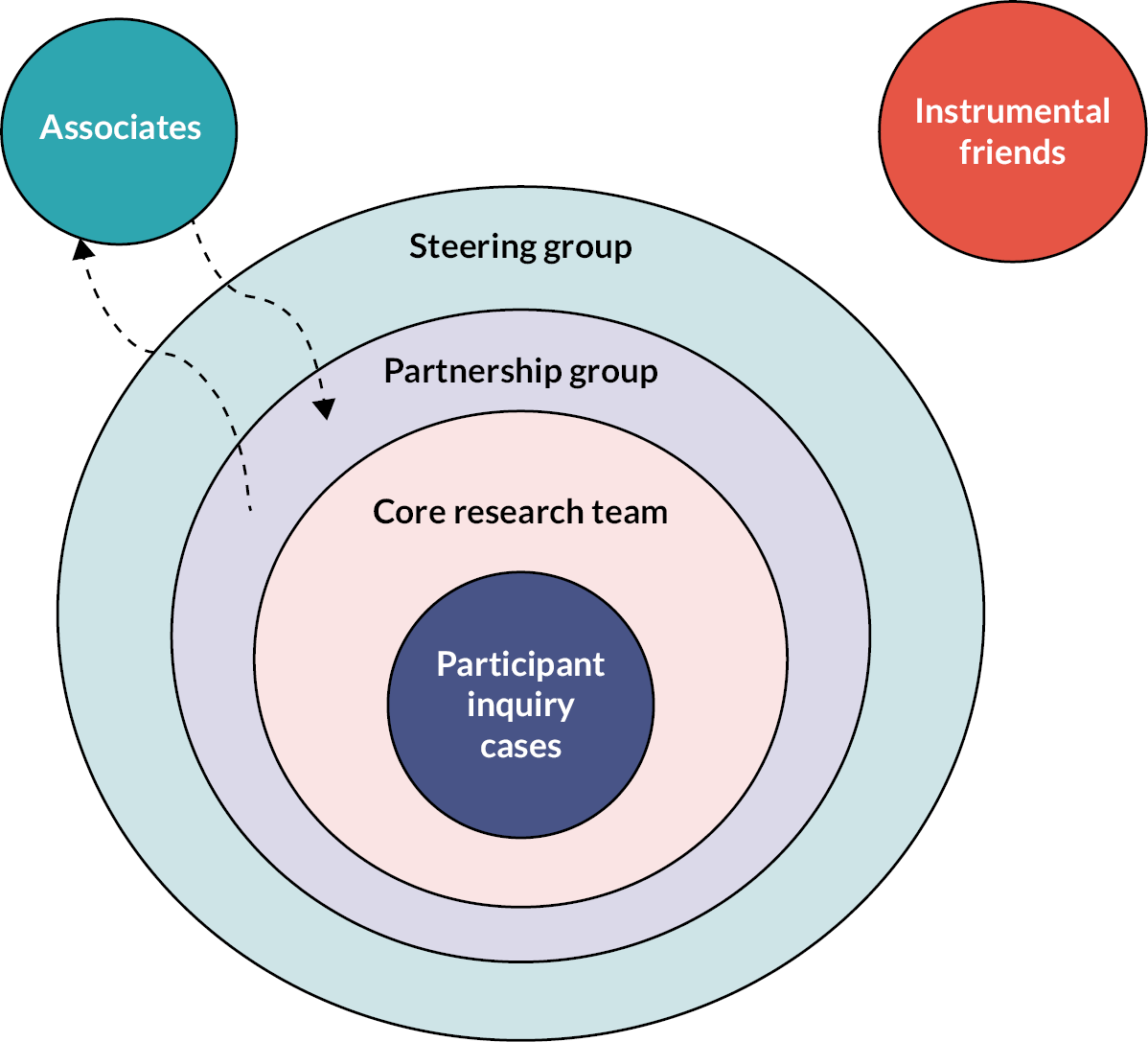

The partnership needs to allow various levels of participation (Figure 3), with some members being more instrumental in the design and delivery of the research (core research team) and those having less intensive involvement, but nevertheless valuable contributions via the wider participant group and steering group. Additionally, those with limited capacity might be called upon for specific contributions (associates) or indirectly support the research (instrumental friends) such as acting as a critical friend. The voice of lived experience was seen as significant in all layers of the research partnership.

FIGURE 3.

Structuring the research partnership.

Defining and evaluating success

Both process and impact evaluation of IPL were favoured, spanning multiple levels: public (patient/carer), individual professional learner and organisation. Attributing outcomes directly to the IPL intervention generated some challenges, particularly in relation to patient/carer impacts and health economic considerations.

Impact of IPL on professional learners was more straightforward, with measures around awareness, of both SWL needs and available services, and connectedness described. These identified measures are consistent with the extant literature on the value of IPL interventions. 11,12,18 In addition, participants described the capacity to reflect as being a meaningful measurement of the success of the IPL programme, reframing IPL as a continuous, iterative process of co-production rather than a static product. 13,14

Success of the IPL programme was also considered at the organisational level. However, this was more nuanced, and the Delphi technique failed to generate consensus around how this be evaluated. Organisations were seen to have differing, often conflicting, priorities, highlighting the difficulty of finding measures which would engage across the system. Given the backdrop of austerity and the importance of services being cost-effective for the NHS and social services, demonstrating value for money was often seen as important, which jarred slightly with some of the other outcomes identified.

Questions remain about the benefit and risk to organisations offering a more connected place-based response to SWL needs. There is potential to increase demand in some areas (e.g. VCS and advice services) while potentially reducing demand in others (e.g. unplanned health contacts). The exponential rise in unplanned hospitalisation towards end of life makes this an important consideration for future research. 35

Potential accreditation of IPL could raise credibility, but there was concern that this might move away from creating a collaborative learning culture, labelling IPL as a required task, rather than an approach to care. The importance of leadership engagement and endorsement of IPL was identified repeatedly as a route to validating the IPL approach and facilitating engagement.

Sustainable change at a system level was deemed important. However, there was some scepticism among participants around how achievable this might be, with a sense of frustration around the capacity for change.

Strengths and limitations

Although the research met its objectives, it was not without limitations. Attrition and flux within the partnership group were expected given capacity issues and this was indeed a feature of the research with variation in participation across the various elements of the project. There were strengths and limitations with this approach. The dynamic nature of the partnership group meant that a diverse range of perspectives were considered, and the group expanded over the duration of the research. However, this also meant that the depth of the discussion may have been hindered at times, with participants entering discussion at various levels of awareness about the project. The use of supplementary materials such as a video overview of the background of the research provided some mitigation.

Increased representation of underserved groups was achieved; however, this was by no means exhaustive. This project has catalysed an ongoing process of engagement through a shared commitment for inclusion and diversity across partnership members.

Also, inclusion of all the items in the Delphi technique was determined solely by expert consensus rather than empirical data. All panellists were required to be able to use/access the internet and e-mail and the patient panellists were not necessarily fully representative.

As this is a place-based study which is orientated to be highly contextualised, generalisability is not a concern for this approach. However, the use of developmental evaluation and systems of interest builds in a degree of default transferability such that any assembled group could adopt the approach detailed in the report and co-produce their own basis for partnership research. We expect our learning around convening a multiagency partnership, including a wide range of research experience from significant, to none, will provide insights for others looking to make research more inclusive.

Lessons learnt and next steps

This project sets the foundation for further partnership research. An inclusive, diverse and non-hierarchical partnership group is needed to drive change at the system level. Facilitators to engagement, including accessible language and payment for participation by small voluntary or community groups, will be incorporated into future research. PPI participation continues to impact positively on the research and inclusion in the partnership on equal terms has been appropriate and comfortable.

In addition to public representation, the influence of organisational leads has been recognised as necessary to endorse learning activity, facilitate access to staff and embed learning into standard practice. The inclusion of a multiagency leadership group in our next project will shed light on the impact of this in practice. This group will also build our understanding of the impact at organisational level of a more connected cross-agency system.

Learning from this project has informed a co-produced proposal for further NIHR funding. This will test feasibility, scalability and impact of IPL, through engagement with public, professionals and organisational leaders. We will continue to reach into local communities and increase representation of underserved groups. Filmmaking will be used to capture perspectives, telling the story of SWL needs around end-of-life and service connectedness from multiple perspectives. This will provide a powerful narrative to engage policy-makers and publicise the IPL, providing an evidence-based model for implementation at scale.

Conclusions

A multiagency partnership group is a positive and appropriate approach to potential system-wide research, providing participants are enabled to engage and all are valued equally. Clear language, expectations and roles facilitate this, with funding made available for participation by VCS organisations.

A follow-on project, evaluating IPL as an intervention to improve support for SWL needs around end of life, is planned. Learning around engagement with IPL and measures of success have been adopted into the new proposal.

Additional information

Contributions of authors

Colette Hawkins (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1177-3319) Academic Consultant, Palliative Medicine. Co-led the study, contributed to the study design, convened the partnership group, supported delivery and analysis of project elements and helped draft the report.

Amy Wheatman (https://orcid.org/0009-0001-4613-0949) Senior Research Assistant. Supported data analysis and drafted the report.

David Black, PPI Co-applicant. Led the PPI work, advised on project design, attended workshops and helped draft the report.

Alexis Pala (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8933-8283) Research Associate. Provided co-design expertise, co-led workshops, developed the workbooks, supported data analysis and reviewed the project report.

Yu Fu (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4972-0626) Senior Research Associate. Led the Delphi technique and analysis, co-led workshops and helped draft the report.

Tomos Robinson (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8695-9738) Research Fellow, Health Economics. Provided health economics expertise, attended workshops and reviewed the project report.

Jonathan Ling (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2932-4474) Professor, Public Health. Provided public health expertise, attended workshops and reviewed the project report.

Sarah Gorman, NHSE Regional Social Prescribing Learning Co-ordinator and Community Partnership Lead, Edbert’s House. Provided VCS and social prescribing expertise and attended workshops.

Sarah Beardon (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8716-6211), PhD Researcher. Provided social welfare research expertise, attended workshops and reviewed the project report.

Hazel Genn (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0612-7649) Professor, Socio-Legal Studies. Provided social welfare law and policy expertise.

Hannah Hesselgreaves (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6877-8199) Professor, Executive Education. Co-led the study, contributed to study design, led and co-ran the workshops, supported data analysis and helped draft the report.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to all our partnership colleagues for contributing time, experience and expertise to this project.

Data-sharing statement

All available data can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee at Northumbria University (reference number: 44920; 6 March 2022). Prior to both workshops, participants were provided with information about the purpose of the workshop and an agenda for the session via e-mail and the workbook described above. Participant consent was sought via e-mail prior to all data collection methods.

Information governance statement

This project comprised a partnership group in order to co-produce a follow-on research proposal. Since this acted as a collaboration, there was no traditional participant recruitment and therefore no data protection consequences.

Disclosure of interests

Full disclosure of interests: Completed ICMJE forms for all authors, including all related interests, are available in the toolkit on the NIHR Journals Library report publication page at https://doi.org/10.3310/YGRA9852.

Primary conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Department of Health and Social Care disclaimer

This publication presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by the interviewees in this publication are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, MRC, NIHR Coordinating Centre, the HSDR programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Funding

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health and Social Care Delivery Research programme as award number NIHR135276.

This article reports on one component of the research award Meeting social welfare legal needs in end-of-life care: co-creation of a system-wide research partnership. For more information about this research please view the award page (https://www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/NIHR135276).

About this article

The contractual start date for this research was in January 2022. This article began editorial review in May 2023 and was accepted for publication in February 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Health and Social Care Delivery Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

This article was published based on current knowledge at the time and date of publication. NIHR is committed to being inclusive and will continually monitor best practices and guidance in relation to terminology and language to ensure that we remain relevant to our stakeholders.

Copyright

Copyright © 2024 Hawkins et al. This work was produced by Hawkins et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution, the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

Glossary

Interprofessional learning/interprofessional education Professionals learning with, from and about each other within academic and work-based settings to support collaboration. (Lowe T, French M, Hawkins M, Hesselgreaves H, Wilson R. New development: responding to complexity in public services—the human learning systems approach. Public Money Manage 2021;41(7):573–6.)

Patient and public involvement Within the context of this research, participants from the patient and public involvement group had experience of some form of social welfare legal needs relating to end-of-life care.

Social welfare legal needs Everyday matters with rights, entitlements and protections defined by law. These include finances, suitable housing, employment rights, family issues, immigration, protection from abuse and the right to community care (Close H, Sidhu K, Genn H, Ling J, Hawkins C. Qualitative investigation of patient and carer experiences of everyday legal needs towards end of life. BMC Palliat Care 2021;20:47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00739-w).

List of abbreviations

- IPL/IPE

- interprofessional learning/interprofessional education

- PPI

- patient and public involvement

- SWL needs

- social welfare legal needs

- VCS

- voluntary and community services

References

- Genn H. When law is good for your health: mitigating the social determinants of health through access to justice. Curr Legal Probl 2019;72:159-202.

- Close H, Sidhu K, Genn H, Ling J, Hawkins C. Qualitative investigation of patient and carer experiences of everyday legal needs towards end of life. BMC Palliat Care 2021;20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00739-w.

- Balmer N. English and Welsh Civil and Social Justice Panel Survey: Wave 2. Legal Services Commission; 2013.

- Pleasence P, Balmer NJ, Buck A, O’Grady A, Genn H. Civil law problems and morbidity. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:552-7.

- Citizens Advice . Helping People Find a Way Forward: A Snapshot of Our Impact in 2015 16 2016. www.citizensadvice.org.uk/Global/Public/Impact/Citizens-Advice-Impact-report-2015_16_digital.pdf (accessed 31 August 2021).

- Tobin-Tyler E, Conroy KN, Fu CM, Sandel M. Poverty, Health and Law. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press; 2011.

- Bambra C, Lynch J, Smith KE. The Unequal Pandemic COVID-19 and Health Inequalities. Bristol: Policy Press; 2021.

- Macmillan Cancer Support . Cancer and Social Security 2021. www.macmillan.org.uk/dfsmedia/1a6f23537f7f4519bb0cf14c45b2a629/3918-10061/welfare-and-work-report (accessed 16 October 2023).

- Marie Curie . Dying in Poverty: Exploring Poverty at the End of Life in the UK 2022. www.mariecurie.org.uk/globalassets/media/documents/policy/dying-in-poverty/h420-dying-in-poverty-5th-pp.pdf (accessed 16 October 2023).

- Hawkins C, Kirby M, Genn H, Close H. Legal needs of adults with life-limiting illness: what are they and how are they managed? A qualitative multiagency stakeholder exercise. Integr Healthc J 2020;2. https://doi.org/10.1136/ihj-2019-000029.

- Ojelabi AO, Ling J, Roberts D, Hawkins C. Does interprofessional education support integration of care services? A systematic review. J Interprof Educ Pract 2022;28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2022.100534.

- Hawkins C, Rothwell C, Close H, Emmett C, Hesselgreaves H. Legal issues in life-limiting illness: can cross-agency, interprofessional education support integration of care?. J Law Med 2021;28:1082-91.

- Batalden P. Getting more health from healthcare: quality improvement must acknowledge patient coproduction—an essay by Paul Batalden. BMJ 2018;362. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k3617.

- Jabbal J. Embedding a culture of quality improvement. The Kings Fund; 2017.

- Dixon-Woods M. How to improve healthcare improvement—an essay by Mary Dixon-Woods. BMJ 2019;367. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l5514.

- Lowe T, French M, Hawkins M, Hesselgreaves H, Wilson R. New development: responding to complexity in public services—the human learning systems approach. Public Money Manage 2021;41:573-6.

- Barr H, Freeth D, Hammick M, Koppel I, Reeves S. The evidence base and recommendations for interprofessional education in health and social care. J Interprof Care 2006;20:75-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820600556182.

- Gilbert JH, Yan J, Hoffman SJ. A WHO Report: framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. J Allied Health 2010;39:196-7.

- Churruca K, Pomare C, Ellis LA, Long JC, Braithwaite J. The influence of complexity: a bibliometric analysis of complexity science in healthcare. BMJ Open 2019;9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027308.

- Preiser R, Biggs R, De Vos A, Folke C. Social-ecological systems as complex adaptive systems. Ecol Soc 2018;23.

- Darling M, Guber H, Smith J, Stiles J. Emergent learning: a framework for whole-system strategy, learning, and adaptation. Foundation Rev 2016;8. https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1284.

- Patton MQ. Developmental Evaluation: Applying Complexity Concepts to Enhance Innovation and Use. Guilford Press; 2010.

- Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs 2000;32:1008-15. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.t01-1-01567.x.

- Jünger S, Payne SA, Brine J, Radbruch L, Brearley SG. Guidance on conducting and REporting DElphi studies (CREDES) in palliative care: recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med 2017;31:684-706. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216317690685.

- Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, McKee CM, Sanderson CF, Askham J, et al. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess 1998;2:1-88.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277-88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Assarroudi A, Heshmati Nabavi F, Armat MR, Ebadi A, Vaismoradi M. Directed qualitative content analysis: the description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. J Res Nurs 2018;23:42-55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987117741667.

- Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, Pencharz PB, Ling SC, Moore AM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:401-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002.

- French SD, Bennell KL, Nicolson PJ, Hodges PW, Dobson FL, Hinman RS. What do people with knee or hip osteoarthritis need to know? An international consensus list of essential statements for osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2015;67:809-16. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22518.

- Robinson KR, Leighton P, Logan P, Gordon AL, Anthony K, Harwood RH, et al. Developing the principles of chair based exercise for older people: a modified Delphi study. BMC Geriatr 2014;14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-14-65.

- Wells C, Kolt GS, Marshall P, Bialocerkowski A. The definition and application of Pilates exercise to treat people with chronic low back pain: a Delphi survey of Australian physical therapists. Phys Ther 2014;94:792-805. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130030.

- Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen MF, Kind P, Parkin D, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20:1727-36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x.

- Sutton EJ, Coast J. Development of a supportive care measure for economic evaluation of end-of-life care using qualitative methods. Palliat Med 2014;28:151-57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216313489368.

- Jackson MC. Critical Systems Thinking and the Management of Complexity. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2019.

- Diernberger K, Luta X, Bowden J, Fallon M, Droney J, Lemmon E, et al. Healthcare use and costs in the last year of life: a national population data linkage study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2024;14:e885-92. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002708.

Appendix 1 Recruitment of partnership group

| Recruitment activity | Organisations engaged (single representative unless otherwise stated) |

|---|---|

| Existing contacts engaged through previous projects | Gateshead Council Adult Social Services Connected Voice (VCS) Primary Care Department of Work and Pensions NIHR Applied Research Collaboration North East and North Cumbria (PPI lead and Research Fellow) Fulfilling Lives (VCS) Advice Services Alliance Law Centres Network |

| Additional services approached for inclusion | Teesside Hospice South Tees NHS Foundation Trust (Clinical Educator and Care of the Elderly) County Durham and Darlington FT (Community Palliative Care) Newcastle University/Gateshead Council (Embedded Researcher) Empowerment (VCS) East Durham Trust (VCS) Carers Together (VCS) Marie Curie (national team, 2 participants) Accept Social Care (Learning Disabilities community support) |

| Post Workshop 1 engagement | START Hartlepool (addictions, complex needs) Tees Valley End of Life General Practice lead |

| Post Workshop 2 engagement | Homeless lived experience researcher from Newcastle University Oasis Community Housing (VCS) (2 participants) Public Health Middlesbrough, Redcar & Cleveland Middlesbrough Council Asylum seekers expertise (Leicester University and Gateshead Primary Care) North East Deep End GP Practice Network: education lead and project lead Middlesbrough social prescribing lead Redcar and Cleveland social prescribing lead Redcar and Cleveland Citizens Advice Redcar and Cleveland Financial Inclusion Group North East and North Cumbria Integrated Care System Health Inequalities Advisory Group North East Commissioning Support – Public Health Management Strategic Lead Access Social Care (VCS) South Tees NHS FT Health Inequalities group Mental health services, Tees, Esk and Wear FT |

Appendix 2 Delphi survey items

Round 1 survey included an initial set of outcomes of IPL which were based on existing evidence and covered 10 items as presented in Table 2.

| 1 | Better knowledge of social welfare issues faced by people who may be towards end of life |

| 2 | Better awareness of local services supporting social welfare issues |

| 3 | Clearer pathways into services so professionals can direct people onto the right place |

| 4 | Clearer pathways into services so people can find the right support themselves |

| 5 | Better inclusion of underserved groups, such as people experiencing homelessness or people with learning difficulties |

| 6 | Learning together, with and from each other, to create a dynamic system |

| 7 | Reduced anxiety among patients and carers around active social welfare issues |

| 8 | Better-quality measure/inspection reports |

| 9 | More timely and effective resolution of social welfare |

| 10 | Reduced contact with health services (primary care or acute services) when the issue relates to an active social welfare problem |

Potential measurement methods were also included:

-

engagement with IPL

-

staff member confidence level

-

impact on people using the services.

Round 2 survey specified outcomes for different groups. Respondents were asked to rate how meaningful they thought the different outcomes are to participants of the IPL programme (see Table 3), to participating organisations (see Table 4) and to patients and carers (see Table 5).

| 1 | Awareness of the relevance of SWL needs to end-of-life care |

| 2 | Building a coherent understanding of the system that delivers and manages SWL needs |

| 3 | Building confidence in assessment and accessing advice/support for SWL needs |

| 4 | Multiagency/multidisciplinary approach to care |

| 5 | Increased engagement with other services |

| 1 | Increased contacts with other organisations |

| 2 | New pathways of care |

| 3 | Referral patterns |

| 4 | Reduced health contacts with patient/carer, for example earlier discharge, fewer consultations |

| 5 | Gaps in service availability |

| 6 | Capacity (identifying increased or decreased service capacity) |

| 7 | Impact on inspection reports |

| 8 | Quality of service measured by inspection reports |

| 1 | Ability to access appropriate support/advice |

| 2 | Time to access social welfare advice/support (increased or decreased) |

| 3 | Reduced health contacts, for example fewer consultations |

| 4 | Income |

| 5 | Quality of life |

| 6 | Well-being |

Methods of data collection were also explored. Respondents were asked to rate the importance of the following methods in relation to collecting data on IPL participants and service/organisational leads:

-

questionnaire with open and closed questions

-

interview

-

focus group

-

observation.

Participant characteristics were also collected via both surveys, as well as information about how respondents might be involved in the research and the resources that would support their organisation’s involvement.

Appendix 3 Delphi Round 2 results

| Limited meaningful (1–3), N (%) | Meaningful but not critical (4–6), N (%) | Critically meaningful (7–9), N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Better knowledge of social welfare issues faced by people who may be towards end of life | 2 (7.69) | 4 (15.38) | 20 (76.92) |

| 2. Better awareness of local services supporting social welfare issues | 1 (3.85) | 4 (15.38) | 21 (80.77) |

| 3. Clearer pathways into services so professionals can direct people onto the right place | 1 (3.85) | 4 (15.38) | 21 (80.77) |

| 4. Clearer pathways into services so people can find the right support themselves | 2 (7.69) | 3 (11.54) | 21 (80.77) |

| 5. Better inclusion of underserved groups, such as people experiencing homelessness or people with learning difficulties | 2 (7.69) | 3 (11.54) | 21 (80.77) |

| 6. Learning together, with and from each other, to create a dynamic system | 2 (7.69) | 7 (26.92) | 17 (65.38) |

| 7. Reduced anxiety among patients and carers around active social welfare issues | 2 (7.69) | 6 (23.08) | 18 (69.23) |

| 8. Better-quality measures/inspection reports | 6 (23.08) | 10 (38.46) | 10 (38.46) |

| 9. More timely and effective resolution of social welfare issues | 2 (7.69) | 3 (11.54) | 21 (80.77) |

| 10. Reduced contact with health services (primary care or acute services) when the issue relates to an active social welfare problem | 2 (7.69) | 11 (42.31) | 13 (50) |

| Limited meaningful (1–3), N (%) | Meaningful but not critical (4–6), N (%) | Critically meaningful (7–9), N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Awareness of the relevance of SWL needs to end-of-life care | 1 (6.25) | 3 (18.75) | 12 (75) |

| 2. Building a coherent understanding of the system that delivers and manages SWL needs | 1 (6.25) | 1 (6.25) | 14 (87.5) |

| 3. Building confidence in assessment and accessing advice/support for SWL needs | 3 (18.75) | 2 (12.5) | 11 (68.75) |

| 4. Multiagency/multidisciplinary approach to care | 1 (6.25) | 2 (12.5) | 13 (81.25) |

| 5.Increased engagement with other services | 1 (6.25) | 2 (12.5) | 13 (81.25) |

| Limited importance (1–3), N (%) | Important but not critical (4–6), N (%) | Critical importance (7–9), N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Increased contacts with other organisations | 1 (6.25) | 4 (25) | 11 (68.75) |

| 2. New pathways of care | 3 (18.75) | 2 (12.5) | 11 (68.75) |

| 3. Referral patterns | 2 (12.5) | 4 (25) | 10 (62.5) |

| 4. Reduced health contacts with patient/carer, for example earlier discharge, fewer consultations | 3 (18.75) | 4 (25) | 9 (56.25) |

| 5. Gaps in service availability | 2 (12.5) | 4 (25) | 10 (62.5) |

| 6. Capacity (identifying increased or decreased service capacity) | 4 (25) | 5 (31.25) | 7 (43.75) |

| 7. Impact on inspection reports | 6 (37.5) | 6 (37.5) | 4 (25) |

| 8. Quality of service measured by inspection reports | 5 (31.25) | 6 (37.5) | 5 (31.5) |

| Limited importance (1–3), N (%) | Important but not critical (4–6), N (%) | Critical importance (7–9), N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ability to access appropriate support/advice | 0 (0) | 2 (12.5) | 14 (87.5) |

| 2. Time to access social welfare advice/support (increased or decreased) | 0 (0) | 5 (31.25) | 11 (68.75) |

| 3. Reduced health contacts, for example fewer consultations | 2 (12.5) | 4 (25) | 10 (62.5) |

| 4. Income | 0 (0) | 4 (25) | 12 (75) |

| 5. Quality of life | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 16 (100) |

| 6. Well-being | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 16 (100) |