Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/115/82. The contractual start date was in August 2015. The draft report began editorial review in February 2021 and was accepted for publication in August 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Maheshwari et al. This work was produced by Maheshwari et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Maheshwari et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The study operated to a strict pre-agreed protocol, which has been published. 1

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from the published protocol, Maheshwari et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Infertility is common, affecting one in seven couples in the UK. 2 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends in vitro fertilisation (IVF) as the definitive treatment for prolonged unresolved infertility. 3 The number of IVF treatments in the UK has continued to rise each year, from 6609 in 1999 to > 64,000 in 2013, resulting in > 20,000 pregnancies. 4

In vitro fertilisation

In vitro fertilisation treatment involves a number of consecutive steps. Initially, each woman is given external hormone injections to develop multiple ovarian follicles. The growth of these follicles is monitored by serial transvaginal ultrasound scans and, when these follicles reach maturity, the eggs within them are harvested surgically. Retrieved eggs are mixed with sperm by one of two methods: IVF, where motile sperm are placed surrounding the eggs, or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), where a single sperm is selected and injected into the egg. Eggs mixed with sperm are then incubated to create embryos. Conventionally, these embryos are allowed to develop in the laboratory for a few days before one or two of them are selected for transfer into the uterus (i.e. fresh-embryo transfer) on day 3 (the cleavage stage) or day 5 (the blastocyst stage). Additional embryos are frozen and stored for replacement at a later date without the need for ovarian stimulation (i.e. frozen-embryo transfer).

Concerns with in vitro fertilisation

Despite being a widely used treatment in the UK and around the world, there are a number of concerns about conventional IVF.

Static success rates

In vitro fertilisation success rates remain modest, with a mean live birth rate of 25% per treatment involving a fresh-embryo transfer. Data for three consecutive years (2010 to 2012) from the American4 and European registries5 suggest that there was no improvement in IVF live birth rates over the 3-year period.

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome

Exogenous hormones used for ovarian stimulation are associated with a risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), which is exacerbated if a woman becomes pregnant following fresh-embryo transfer. Moderate to severe OHSS is a complication unique to IVF treatment, occurring in around 1–5% of treatments,6 and often requiring in-patient care, resulting in significant NHS costs. Severe OHSS is associated with significant morbidity (including ascites, pleural and pericardial effusion, respiratory failure and intensive care admission) and, rarely, death.

Poor obstetric and perinatal outcomes

Pregnancies resulting from IVF are associated with a higher rate of maternal and perinatal complications than pregnancies resulting from spontaneous conception. A systematic review7 has shown that babies, even singletons, conceived following IVF are more likely than babies conceived without IVF treatment to die during the perinatal period [risk ratio (RR) 1.87, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.48 to 2.37], to be delivered preterm (RR 1.54, 95% CI 1.47 to 1.62), to have a low birthweight (RR 1.65, 95% CI 1.56 to 1.75) and to have congenital anomalies (RR 1.67, 95% CI 1.33 to 2.09). Women who become pregnant as a result of IVF are more likely than those who become pregnant as a result of spontaneous conception to develop pre-eclampsia (RR 1.49, 95% CI 1.39 to 1.59), bleeding in pregnancy (RR 2.49, 95% CI 2.30 to 2.69) and diabetes (RR 1.48, 95% CI 1.33 to 1.66) and to require a caesarean section (RR 1.56, 95% CI 1.51 to 1.60).

Although the absolute number of women with OHSS and pregnancy-related complications associated with IVF is relatively small, the increasing number of women receiving IVF4 has meant that the NHS burden of dealing with its short- and long-term complications is a serious and growing problem.

A possible cause of suboptimal live birth rates, as well as adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes, following IVF is the impact of the exogenous hormones used for ovarian stimulation on the lining of the uterine cavity. High levels of oestrogen produced by the ovary in response to this treatment affect uterine receptivity, reducing the chances of successful implantation and placentation. Suboptimal placentation may lead to obstetric and perinatal complications. It has been suggested that avoiding embryo transfer when the uterus is less receptive could improve success rates and reduce complications in pregnancy and delivery. Such a strategy also reduces the risk of OHSS by ensuring that a pregnancy does not occur in the presence of hyperstimulated ovaries.

Evidence supporting frozen-embryo transfer

It is already known that the risk of severe OHSS is greatly reduced by a policy of freezing all embryos, followed by frozen-embryo transfer, compared with fresh-embryo transfer. 8 A systematic review of observational data9 showed that babies (singletons) conceived from frozen embryos have a reduced risk of perinatal morbidity (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.96) and preterm delivery (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.90), making IVF safer and more effective for women and babies.

Preliminary data from small randomised trials from the Islamic Republic of Iran10 and the USA11,12 in 2015 suggested that a strategy of not replacing embryos when they are created, but freezing them, followed by transferring thawed embryos into the uterus at a later date, improves pregnancy rates. A meta-analysis of data from these three randomised controlled trials (RCTs)8 has shown higher pregnancy rates following frozen-embryo transfer (odds ratio 1.32, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.59).

However, these existing trials have a number of significant limitations:

-

They reported implausibly high pregnancy rates (e.g. 84% per embryo transfer), which are far in excess of those reported by national and international registries. 4,5

-

Key outcomes, including healthy baby, live birth, costs, safety and acceptability, were not measured by any of the trials.

-

They were limited in terms of design, with highly selected populations, inadequate sample sizes and per-protocol analysis rather than intention to treat (ITT) and conduct, as all of the trials involved co-interventions that were not accounted for in the analysis.

One of the publications10 has been retracted on the grounds of serious methodological flaws. Hence, the evidence base, comprising two small trials, was not sufficiently robust to support a radical change in clinical practice. In addition, the results of these trials could not be directly applied to a UK setting because of very different regulatory and funding arrangements. There was, therefore, an urgent need to perform a definitive RCT in the UK evaluating elective freezing of embryos, followed by subsequent thawed frozen-embryo transfer, in terms of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

Objective

Primary objective

The primary objective of the trial was to determine if a policy of freezing embryos, followed by thawed frozen-embryo transfer, results in a higher healthy baby rate than the current policy of transferring fresh embryos.

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives of the trial were to assess if a policy of freezing embryos, followed by thawed frozen-embryo transfer, compared with the current policy of transferring fresh embryos, results in:

-

fewer complications associated with IVF treatment and pregnancy

-

greater cost-effectiveness from a health service and broader societal perspective.

Chapter 2 Methods

The study operated to a strict pre-agreed protocol1 and statistical analysis plan (SAP),13 both of which have been published.

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from the published protocol, Maheshwari et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this chapter have also been reproduced with permission from the SAP, Bell et al. 13 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Design

The elective freeze (E-Freeze) trial was a pragmatic, multicentre, two-arm, parallel-group, non-blinded RCT conducted in the UK, comparing the freezing of all suitable embryos, followed by frozen-embryo transfer, with the current policy of fresh-embryo transfer. We undertook both clinical effectiveness and economic analysis. Details of the economic analysis are reported in Chapter 4.

Ethics approval and research governance

The E-Freeze trial protocol was approved by the North of Scotland Research Ethics Service (NoSRES) Committee (study reference 15/NS/0114). Local approval and site-specific assessments were obtained from each participating site. The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) Registry as ISRCTN61225414.

Participants

Participants were couples undergoing their first, second or third cycle of IVF/ICSI treatment in the participating clinics in the UK.

Inclusion criteria

-

The female partner was aged between ≥ 18 and < 42 years at the start of treatment (i.e. start of ovarian stimulation).

-

Couples were undergoing their first, second or third cycle of IVF/ICSI treatment, where a cycle is defined as egg collection following ovarian stimulation.

-

Both partners were resident in the UK.

-

Both partners were able to provide written informed consent.

-

They had at least three good-quality embryos [as defined by the Association of Clinical Embryologists (ACE)14] on day 3 after egg collection (note that the day of egg collection is counted as day 0). Good-quality embryos on day 3 were defined as those with 6–8 cells of grade 3/3 or above using the agreed national grading scheme. 14

At the start of the trial, only the first cycle was included. However, after discussion with the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Monitoring Board, it was agreed that couples having their second or third cycle could also be included. This change to the eligibility criteria took effect from 12 April 2018.

A list of all amendments are described in Appendix 1.

Exclusion criteria

-

Couples were using donor gametes.

-

Pre-implantation genetic testing was planned.

-

Elective freezing of all embryos was planned for medical reasons (e.g. severe risk of OHSS).

-

Couples had been previously randomised to E-Freeze.

Setting

The trial was conducted in 18 IVF units across the UK. A list of all participating sites is presented in Appendix 2.

Participant selection and enrolment

Identifying participants

Potentially eligible couples were identified from clinic case notes. An invitation letter and participant information leaflet (PIL) were mailed to eligible couples prior to their clinic appointment. A PIL was also provided at patient information/open evenings attended by couples preparing for their IVF/ICSI treatment. This was usually at least 24 hours prior to their clinic appointment. Eligible couples were approached by a clinician involved in their care and were invited to participate in the trial. Those interested in participating were able to discuss the study with a research nurse on the same day or at a later date.

Consenting participants

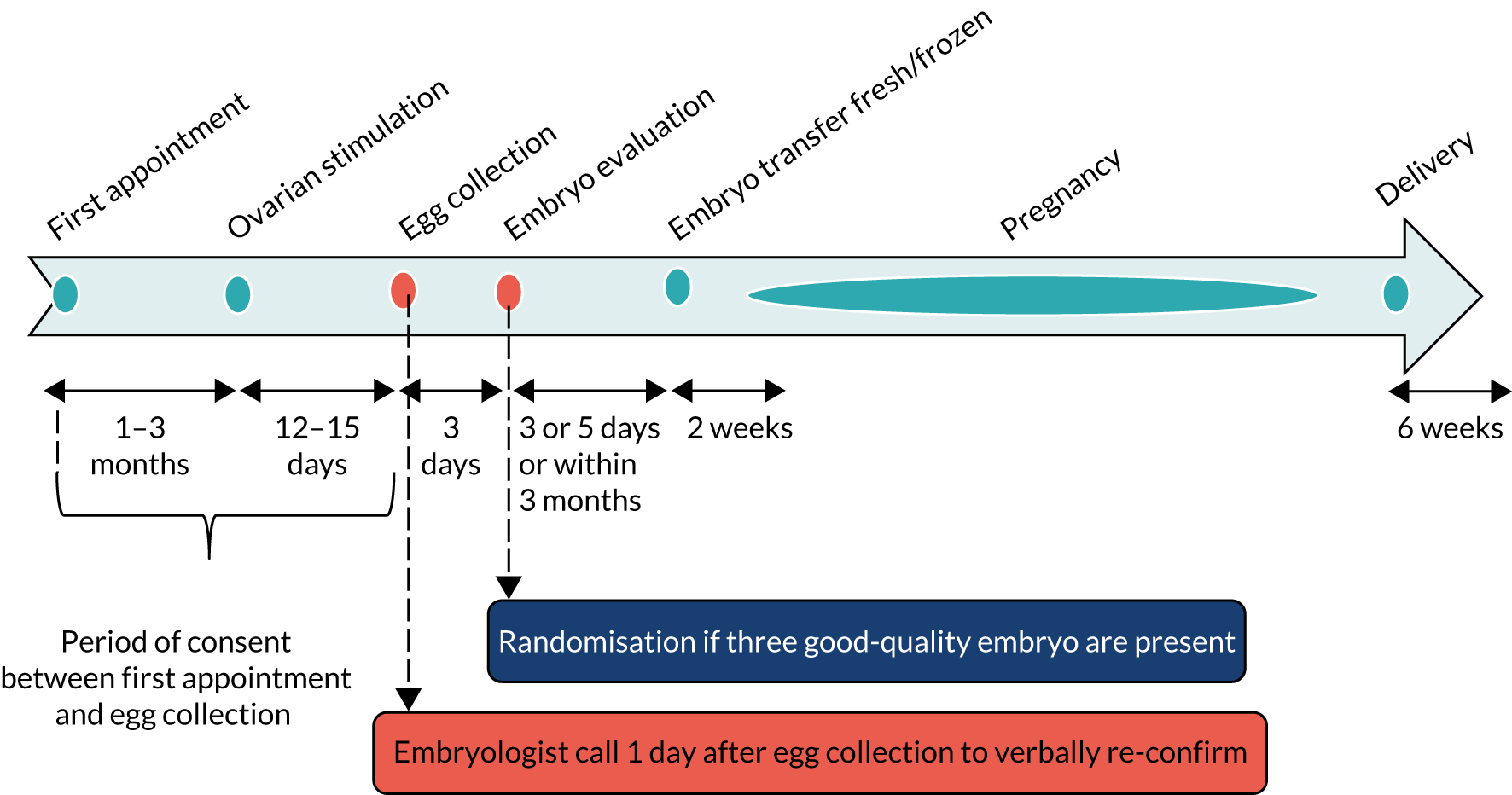

Informed consent from both partners was obtained by an appropriately delegated member of the study team. Contact details and baseline characteristics that were necessary for randomisation were recorded by the research nurse immediately after consent was obtained. Consent forms were signed by both partners; however, this could be undertaken at two different time points, as not all appointments were attended by both partners. This could be undertaken at their clinic appointment or at a subsequent visit until the procedure of egg collection; all consent forms had to be signed before the procedure of egg collection took place (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Process and timescale for consent and randomisation.

Couples who may have previously consented to take part in E-Freeze during their first or second cycle of IVF were still eligible to participate in E-Freeze if they had not been previously randomised into the trial. For couples who had previously consented but had not been randomised onto the trial, informed consent was reobtained for any participation during future cycles and a new study number was generated.

After consent, each partner completed a short questionnaire on how they were feeling emotionally (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Each participant sealed their questionnaire in an envelope after completion and questionnaires were destroyed (unopened) if the couple did not proceed to randomisation.

The data needed for randomisation were recorded in the bespoke consent and randomisation program developed by the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit (NPEU) Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) at the University of Oxford (Oxford, UK).

Confirmation of consent

A routine telephone call was made to couples 1 day after egg collection to inform them of the outcome of fertilisation (see Figure 1). Consent was confirmed during this routine telephone call from the embryologist or research delegate.

Screening for final eligibility

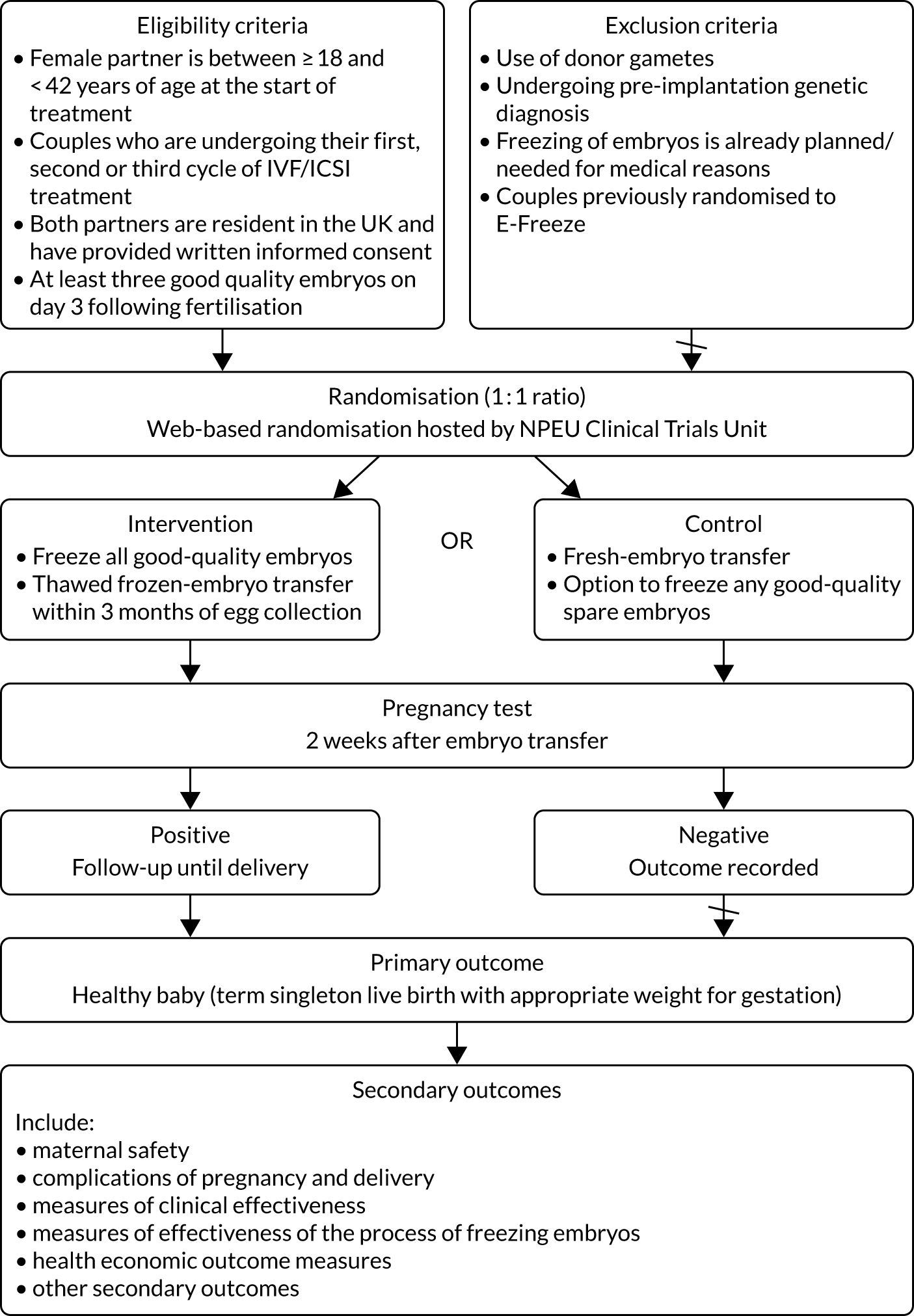

A final eligibility check was carried out on day 3 post egg retrieval. Couples with a minimum of three good-quality embryos were eligible for randomisation to receive either fresh-embryo transfer (i.e. the fresh-embryo transfer arm) or freezing of all good-quality embryos, followed by subsequent transfer of thawed embryos within 3 months (i.e. the freeze-all arm) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Final eligibility criteria.

Good-quality embryos on day 3 were defined as those with 6–8 cells grade 3/3 or above using the agreed national grading scheme based on guidance from ACE in the UK. 14

Randomisation

Randomisation was performed after the creation of embryos, 3 days post egg collection, once all eligibility criteria were established, including ensuring that three or more good-quality embryos were available. This minimised the randomisation-to-intervention time interval as embryos were transferred at either the cleavage or the blastocyst stage (i.e. day 3 or 5 after egg collection, respectively). Couples were randomised (in an allocation ratio of 1 : 1) to a strategy of either fresh-embryo transfer or freezing of embryos, followed by thawing and replacement at a later date (typically 4–6 weeks later and almost always within 3 months of egg collection). Randomisation was undertaken by the research nurse or a delegated member of the research team using a secure web-based centralised system [with 24 hours per day, 7 days per week (24/7) telephone back-up, 365 days per year] hosted by the NPEU CTU (University of Oxford), ensuring allocation concealment. The randomisation employed a minimisation algorithm to balance across the following factors: fertility clinic, woman’s age (at the time of start of treatment, i.e. ovarian stimulation), primary/secondary infertility, self-reported duration of infertility, method of insemination (IVF, ICSI or a combination of both) and number of previous egg collections (i.e. cycles).

Communication of randomisation to couples

As part of routine practice, the embryologist contacted the couple by telephone to let them know the quality of their embryos (on day 3 after egg collection). The embryologist or research delegate confirmed to couples whether or not they fulfilled the final inclusion criteria (three or more good-quality embryos on day 3) and which arm they had been randomised to at the time of their routine telephone call on day 3. The research nurse then contacted the couple if they had not fulfilled the inclusion criteria to answer any queries and offer follow-up in the clinic.

Treatment plan

This study was a pragmatic, multicentre, two-arm, parallel-group, non-blinded RCT to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of the proposed intervention using the most rigorous gold-standard experimental methodology in real-life conditions. All clinical elements of IVF/ICSI treatment, apart from the randomised interventions, were carried out in accordance with local protocols. Blinding of the allocated intervention was not possible in this trial because of the nature of the treatments and statutory requirements of the regulatory body the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA). 15 The process is detailed in the subsequent sections.

Standard-care arm

Women underwent fresh-embryo transfer at the cleavage or blastocyst stage in accordance with local protocols.

Intervention arm

All good-quality embryos were frozen in accordance with local protocols. Couples who were randomised to the freeze-all arm were contacted by the research nurse or research delegate within 3 working days post randomisation and arrangements were made for frozen-embryo transfer within 3 months of the egg retrieval process. This could involve a few visits to hospital for blood tests and ultrasounds to prepare the endometrium prior to embryo transfer.

At embryo transfer (in both arms), couples were asked to complete a short questionnaire to assess the additional costs related to the treatment (see Report Supplementary Material 2) and to repeat the emotions questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 1) that they filled in when they provided consent.

Ineligible and non-recruited participants

Details of all consenting couples were entered in a dedicated secure online database. It was anticipated that a proportion of those consented may not proceed to randomisation; the reasons for this were recorded (if available) and included the non-availability of three good-quality embryos on day 3. Couples not proceeding to randomisation were offered the most appropriate standard treatment. All clinics have access to supportive counselling as a requirement of the regulatory authority.

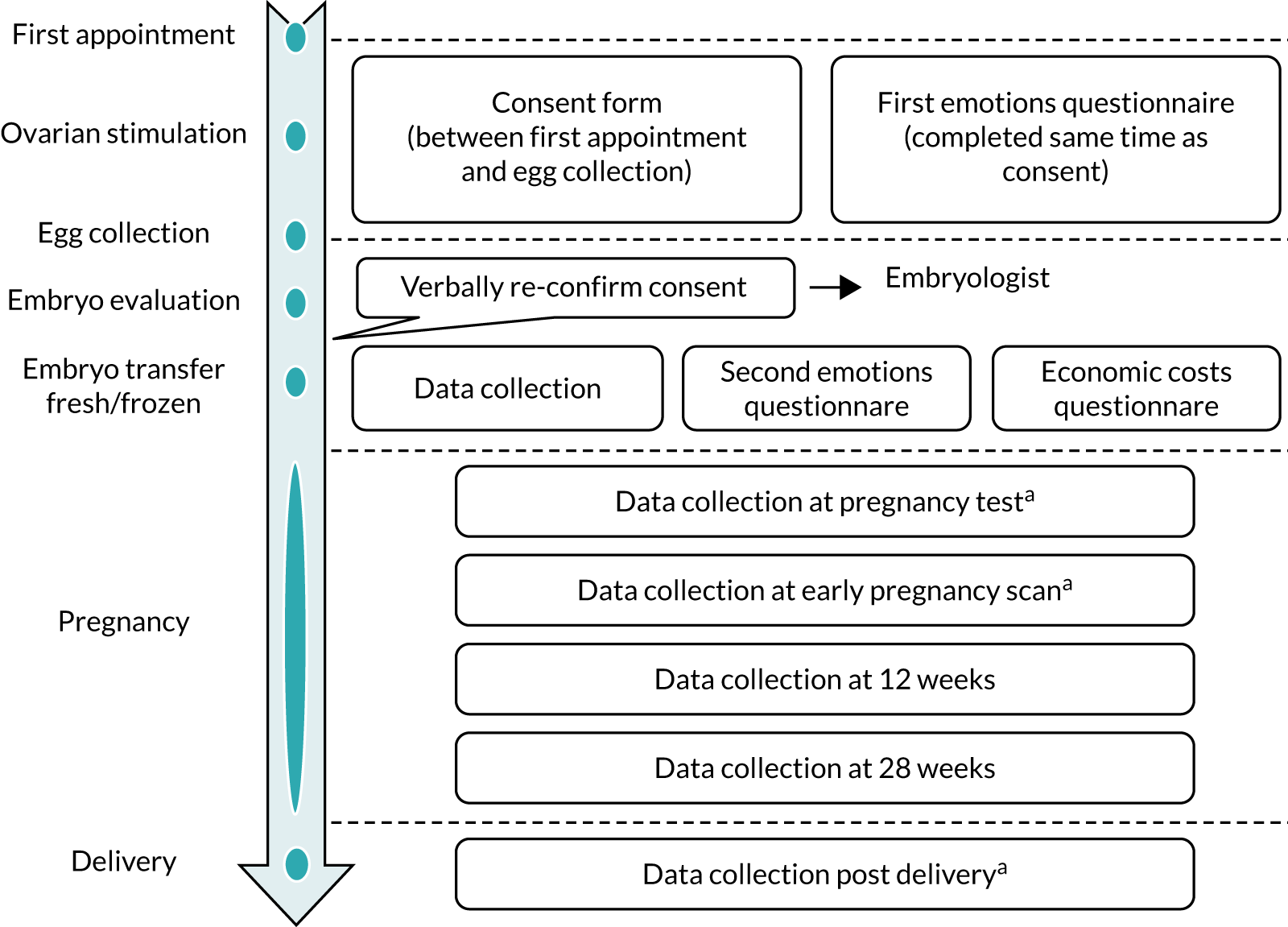

Follow-up

All randomised women carried out a pregnancy test 2 weeks (± 3 days) after embryo transfer. All women who had a positive pregnancy test at 2 weeks (± 3 days) underwent a transvaginal ultrasound scan afterwards (i.e. at 6–8 weeks of gestation) to identify the presence of a gestational sac with a fetal heartbeat, signifying an ongoing pregnancy.

Women who had an ongoing pregnancy were contacted by their research nurse (by telephone) to record pregnancy events and outcomes at 12 and 28 weeks of gestation and, again, at approximately 6 weeks after delivery. Outcomes presenting at ≥ 6 weeks post delivery were not recorded. All women who conceive by IVF/ICSI are followed up by their IVF centres routinely, as there is a mandatory requirement to report early-pregnancy outcomes, as well as delivery outcomes, including stillbirth, congenital anomalies and perinatal mortality, to the regulatory body (HFEA). Usually, this information is provided to each IVF clinic by the couples themselves. Alternatively, clinic staff contact couples by telephone to collect this information and report it to HFEA. In addition to data collected for reporting to HFEA, data were collected over the telephone at 12 and 28 weeks, and collected using questionnaires at embryo transfer for this trial.

Those who had a negative pregnancy test were not followed up any further as part of this trial.

Figure 3 presents a flow chart that explains the flow of participants through the trial.

FIGURE 3.

Flow chart for the study.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was a healthy baby. A healthy baby was defined as a live, singleton baby born at term (between 37 and 42 completed weeks of gestation), with an appropriate weight for gestation (i.e. weight between the 10th and the 90th centile for that gestation, based on standardised charts).

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were separated into maternal safety, complications of pregnancy and delivery, measures of clinical effectiveness, measures of effectiveness of the process of freezing embryos, and health economic outcome measures.

Maternal safety outcome

-

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, defined and classified as per the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG)’s Green-Top Guidelines. 6

Complications of pregnancy and delivery outcomes

-

Vanishing twin or triplet (defined as more fetal heartbeats than babies born, more gestational sacs than babies born or more gestational sacs than fetal heartbeats).

-

Miscarriage rate (defined as pregnancy loss prior to age of viability, i.e. 24 weeks of gestation).

-

Ectopic pregnancy.

-

Termination.

-

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

-

Multiple pregnancy (defined as more than one fetal heartbeat or more than one gestational sac).

-

Multiple births (including live and stillbirths).

-

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (e.g. chronic hypertension, pregnancy-induced hypertension, pre-eclampsia and eclampsia).

-

Most severe hypertensive disorder experienced (from least to worst severe: chronic hypertension, pregnancy-induced hypertension, pre-eclampsia and eclampsia).

-

Antepartum haemorrhage (i.e. any bleeding per vaginam after 28 weeks of pregnancy, including placenta praevia and placental abruption).

-

Onset of labour (i.e. spontaneous, induced or planned caesarean section).

-

Mode of delivery for each baby (i.e. normal vaginal delivery, instrumental vaginal delivery or caesarean section).

-

Preterm delivery (defined as delivery at < 37 completed weeks of gestation).

-

Very preterm delivery (defined as delivery at < 32 completed weeks of gestation).

-

Low birthweight (defined as weight of < 2500 g at birth).

-

Very low birthweight (defined as weight of < 1500 g at birth).

-

High birthweight (defined as weight of > 4000 g at birth).

-

High birthweight for gestational age (defined as birthweight > 90th centile for gestational age at delivery, based on standardised charts).

-

Low birthweight for gestational age (defined as birthweight < 10th centile for gestational age at delivery, based on standardised charts).

-

Congenital anomaly/birth defect (all congenital anomalies/birth defects identified to be included).

-

Perinatal mortality (stillbirth or late, as well as early, neonatal deaths, up to 28 days after birth).

Measures of clinical effectiveness outcomes

-

Live birth rate (this is a live birth episode, i.e. twins were counted as one birth).

-

Singleton live birth rate.

-

Singleton live birth rate at term.

-

Singleton baby with appropriate weight for gestation.

-

Pregnancy rate (defined as positive pregnancy test at 2 weeks ± 3 days after embryo transfer).

-

Clinical pregnancy rate (defined as the presence of at least one fetal heartbeat at ultrasound between 6 and 8 weeks’ gestation; ectopic pregnancy counts as a clinical pregnancy and multiple gestational sacs count as one clinical pregnancy).

Measures of the effectiveness of the process of freezing embryos outcomes

-

Total number of embryos frozen, thawed and transferred for all randomised couples.

-

Proportion of thawed embryos that were then transferred for all randomised couples.

-

No embryos survived thawing, leading to no embryo transfer.

Health economic outcome measures

-

Cost to the health service of treatment, pregnancy and delivery care.

-

Modelled long-term costs of health and social care, and broader societal costs.

Other secondary outcomes

-

Evaluation of emotional state (for both the female and the male partners).

Data collection

Data were collected at various time points, as shown in Figure 4. Data for both clinical and economic outcomes were collected using bespoke electronic case report forms (eCRFs) and entered directly into the study’s OpenClinica, version 3.0 (Waltham, MA, USA), electronic database by the centre’s research staff and trial team. Data were single entered only and, at the point of entry, the data underwent a number of checks to verify the validity and missingness of the data captured.

FIGURE 4.

Stages of data collection. a, Part of routine care.

After consent and at embryo transfer, each partner completed a short paper-based questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 1) asking them how they were feeling. This was based on the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). 16

A short questionnaire was provided to each partner for them to record the details of time and travel expenses accrued during their treatment as part of the economic evaluation (see Report Supplementary Material 2). This was completed at the time of embryo transfer.

Sample size

Sample size calculation

The proposed primary outcome for this trial was novel and is not currently reported by IVF clinics or national regulatory bodies. This meant that a number of assumptions were made to determine the expected event rate in the fresh-embryo transfer arm (receiving current standard treatment, i.e. fresh-embryo transfer).

Prior to commencing the trial, the most recent data from the HFEA,4 which collects data on all IVF cycles from all clinics in the UK, showed that 25% of all women undergoing one episode of IVF treatment involving a fresh-embryo transfer have a live birth and 20% have singleton live births. These values were for women of all age groups, not necessarily for women fulfilling the inclusion criteria for this trial in terms of the number of good-quality embryos in their IVF cycle. The live birth rate for first, second and third cycles was similar. 4 No data were available regarding the primary outcome for this study: the healthy baby rate (i.e. live singletons born between 37 and 42 weeks, with appropriate weight for gestation). For our trial population, we anticipated that the fresh-embryo transfer arm event rate was likely to be < 25% and possibly as low as 17%.

To provide relevant information regarding the event rate expected in the fresh-embryo transfer arm, we surveyed 10 IVF centres that expressed an interest in the study, collecting data on the number of live births in women aged < 42 years who were undergoing their first IVF treatment in 2012. The average live birth episode rate from this survey was 31% (95% CI 25% to 37%). Accurate data on the healthy baby rate in those with at least three good-quality embryos were not available. Although the live birth rate is expected to be higher in women with at least three good-quality embryos (who are likely to have a better prognosis), we anticipated that the healthy baby rate in our trial population would be towards the lower end of the CI, that is around 25%, taking into account the higher risk of preterm delivery and babies who are small for their gestational age following IVF. 9

The following assumptions were made for the sample size calculation.

We assumed a healthy baby rate of between 17% and 25% in women who were eligible for the trial (i.e. aged < 42 years, with three good-quality embryos) undergoing standard care (i.e. fresh-embryo transfer). Taking into account the extra time, effort and potential expense involved in freezing embryos, and the delay in embryo transfer of up to 3 months, a difference of at least 8% in absolute terms was considered to be clinically important by an expert panel of clinicians to recommend a change in clinical practice. With 90% power and using a two-sided, 5% level of statistical significance, a total of 1086 couples (i.e. 543 couples in each arm) would be required to be able to detect an absolute difference of 8% (from 17% to 25%) and 9% (from 25% to 34%) in the healthy baby rate in the fresh-embryo transfer arm and the freeze-all arm, respectively.

It is a regulatory requirement for clinics in the UK to report live birth outcomes (including number, weight and gestation) after all embryo transfers; hence, loss to follow-up was not anticipated. Therefore, we did not take into account loss to follow-up for these sample size calculations.

It was anticipated that a proportion of those who consented may not reach randomisation (e.g. those who did not have three good-quality, day 3 embryos or who required all embryos to be frozen for medical reasons); therefore, a larger number of participants would need to be consented. It was anticipated that the number of participants who did not have three good-quality embryos would be 50% out of those consented.

Statistical analysis

A detailed SAP was agreed and published13 prior to data lock. The analysis and presentation of results followed the most up-to-date recommendations of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) group. 17

Descriptive analysis

The flow of participants through each stage of the trial was summarised by trial arm. Demographic factors and clinical characteristics were summarised for all couples at trial entry, and separately for couples who delivered. Counts and percentages were reported for categorical variables, means [with standard deviations (SDs)] were reported for normally distributed continuous variables, and medians [with interquartile ranges (IQRs)] were reported for other continuous variables. No tests of statistical significance were performed and CIs were not calculated for differences between randomised arms on any baseline variable.

Primary analysis

All participants were analysed in the arms to which they were assigned, regardless of deviation from the protocol or treatment received under the ITT analysis principle. To perform the analyses for all outcomes on the ITT analysis population, the couple was included in the denominator once for all outcomes regardless of whether a pregnancy or a live birth occurred. Where this was a perinatal outcome, the woman was included once in the denominator. For neonatal secondary outcomes, the unit of analysis in the ITT analysis was the mother, and in cases of multiple pregnancy for which the infants’ outcomes differ, the worst outcome was reported.

Binary outcomes were analysed using a log-binomial regression model or a Poisson regression model with a robust variance estimator if the binomial model failed to converge. Linear regression was used for normally distributed continuous outcomes and quantile regression was used for skewed continuous outcomes. All comparative analyses were adjusted for the minimisation factors where possible. Fertility clinic was treated as a random effect in the models, where possible, and all other factors were treated as fixed effects. Both unadjusted and adjusted estimates are presented, but the primary inference is based on the adjusted analyses.

Comparative analyses entailed calculating the adjusted RR and 95% CI for the primary outcome, adjusted RRs and 99% CIs for all binary secondary outcomes, adjusted mean differences (MDs) and 99% CIs for normally distributed continuous secondary outcomes, or median differences and 99% CIs for skewed continuous secondary outcome variables. To account for the number of hypothesis tests performed, 99% CIs were used for all analyses of the secondary outcomes.

Customised birthweight centiles to calculate low weight for gestational age and high weight for gestational age were based on an existing, published, British model. 18

The following secondary outcomes were described only, and no formal statistical analysis comparing the arms was conducted:

-

chronic hypertension, pregnancy-induced hypertension, pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

-

most severe hypertensive disorder experienced (from least to worst severe: chronic hypertension, pregnancy-induced hypertension, pre-eclampsia and eclampsia).

Secondary analysis

The primary analysis for all primary and secondary outcomes was by ITT. Secondary analyses were performed to include clinically relevant denominators, such as the total number of women with a positive pregnancy test at 2 weeks ± 3 days after embryo transfer (for miscarriage), the total number of pregnant women with an ongoing pregnancy resulting in delivery (for pregnancy complications) and the total number of babies born (for birthweight and congenital anomalies). The adjusted analyses per total number of babies also accounted for the anticipated correlation in outcomes between multiple births. The rate of embryos not surviving after thawing (per embryo thawed) was reported for the intervention arm only.

Subgroup analysis

We performed subgroup analyses of the primary outcome on the following, as prespecified in the SAP:13

-

fertility clinic

-

woman’s age (at the time of start of treatment, i.e. ovarian stimulation): < 35, 35 to < 40 and ≥ 40 years

-

blastocyst-stage compared with cleavage-stage embryo transfer

-

single embryo transfer compared with multiple embryo transfer

-

number of previous embryo transfers: 0 compared with ≥ 1 (the groups 0, 1–3 and ≥ 4 were prespecified, but were reduced to two groups in the analysis because of low frequencies).

The consistency of the effect of type of embryo transfer across specific subgroups of couples was assessed for the primary outcome using the statistical test of interaction, in addition to the adjusted model. The results are presented in forest plots, with RRs, 95% CIs and the results of the interaction test.

In addition, for those receiving frozen-embryo transfer, the primary outcome was summarised for the following subgroups using numbers and percentages only:

-

natural cycles compared with hormone replacement cycles

-

vitrification compared with slow freezing.

Additional analysis

The following prespecified analyses were carried out for the primary outcome only:

-

per protocol – restricted to those who complied with the allocated intervention

-

as treated – grouping couples according to the intervention that they actually received (i.e. those randomised to frozen-embryo transfer but who received fresh-embryo transfer were in the fresh-embryo transfer arm in this analysis)

-

complier-average causal effect (CACE) analysis.

To assess the impact of non-compliance with the randomised allocation, that is women randomised to the frozen arm receiving fresh-embryo transfer (non-compliers), a CACE analysis was conducted. This analytic technique provides a robust estimate of the treatment effect among compliant participants. 19,20

The baseline characteristics of women randomised to the freeze-all arm were reported by compliance status, and the unadjusted event rate for the primary outcome was calculated for the observed compliers and non-compliers in the freeze-all arm. The CACE analysis assumed that the proportion of non-compliers in the fresh-embryo transfer arm (i.e. couples in the fresh-embryo transfer arm who would not have complied had they been randomised to the freeze-all arm) was the same as the proportion of non-compliers in the freeze-all arm. It also assumed that the event rate among the non-compliers in the freeze-all arm was the same as the event rate among the non-compliers in the fresh-embryo transfer arm. Applying these two assumptions, the unadjusted event rate for the primary outcome was calculated for the would-be compliers and would-be non-compliers in the fresh-embryo transfer arm. The unadjusted CACE RR with 95% CIs for the primary outcome was calculated using the event rates for compliant groups only (i.e. the observed compliers in the freeze-all arm and the would-be compliers in the fresh-embryo transfer arm). The CIs for the CACE-estimated RRs were calculated using bootstrapping methods. 21

Analysis of emotions questionnaire

The emotions questionnaires at randomisation and post embryo transfer captured responses to the STAI. 16 The response at randomisation was used as a covariate in an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model. Hypothesis testing investigated if there was a post-embryo transfer difference in the means of the two treatment arms after adjustment for responses at randomisation. To avoid bias, maximise the power of the study and obey the ITT principle, the missing-indicator method22 was used to replace missing baseline scores. This method replaces all missing baseline observations with the same value and an extra indicator variable is added to the model to indicate whether or not the value for that variable is missing. For any partially completed questionnaires, if one or two items were omitted, then the prorated score was obtained by calculating the mean weighted score for the completed items, multiplying by 20 and rounding to the next whole number. If three or more items were omitted, then the whole questionnaire was analysed as missing. Models were fitted separately for the female and male partners.

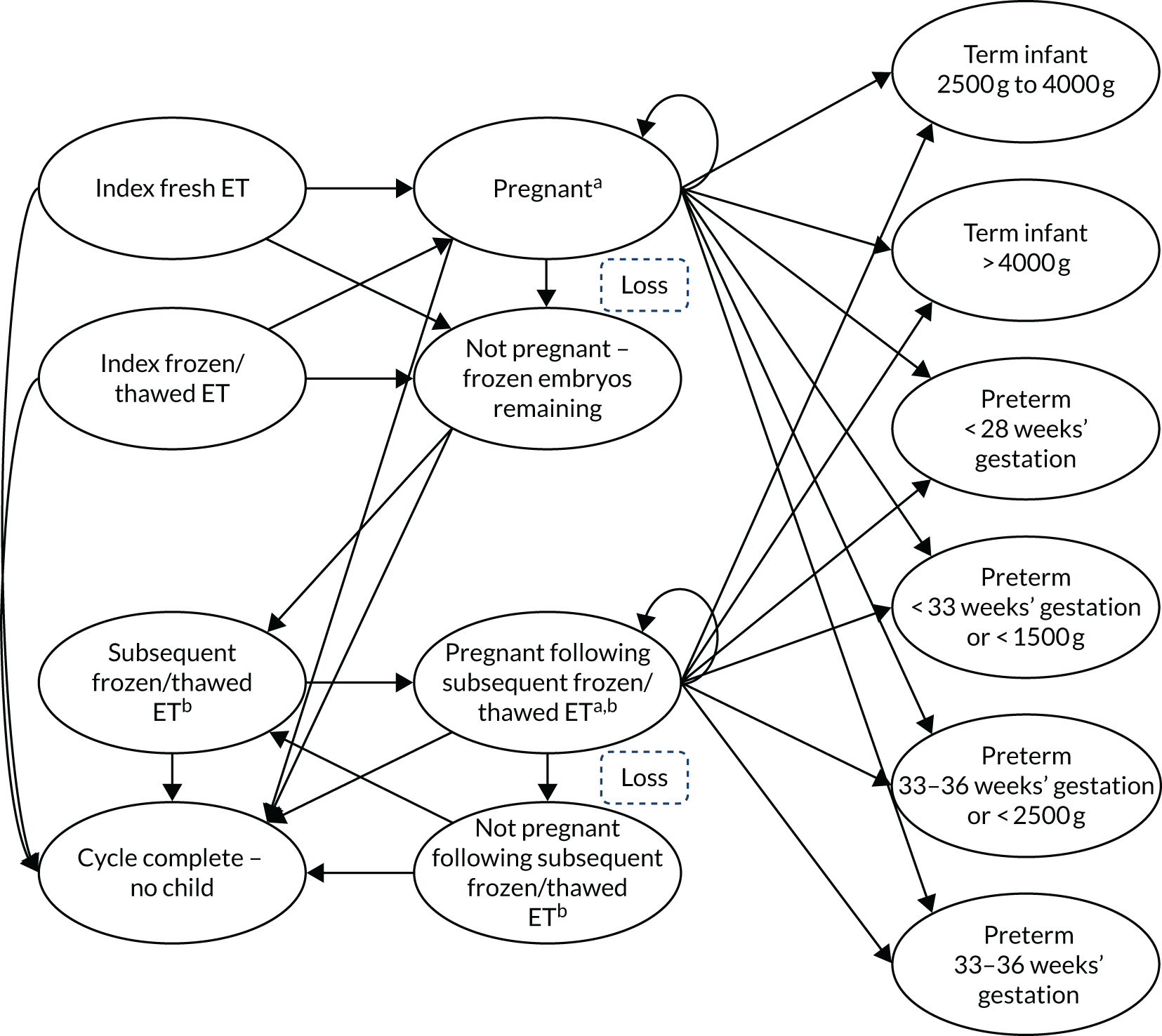

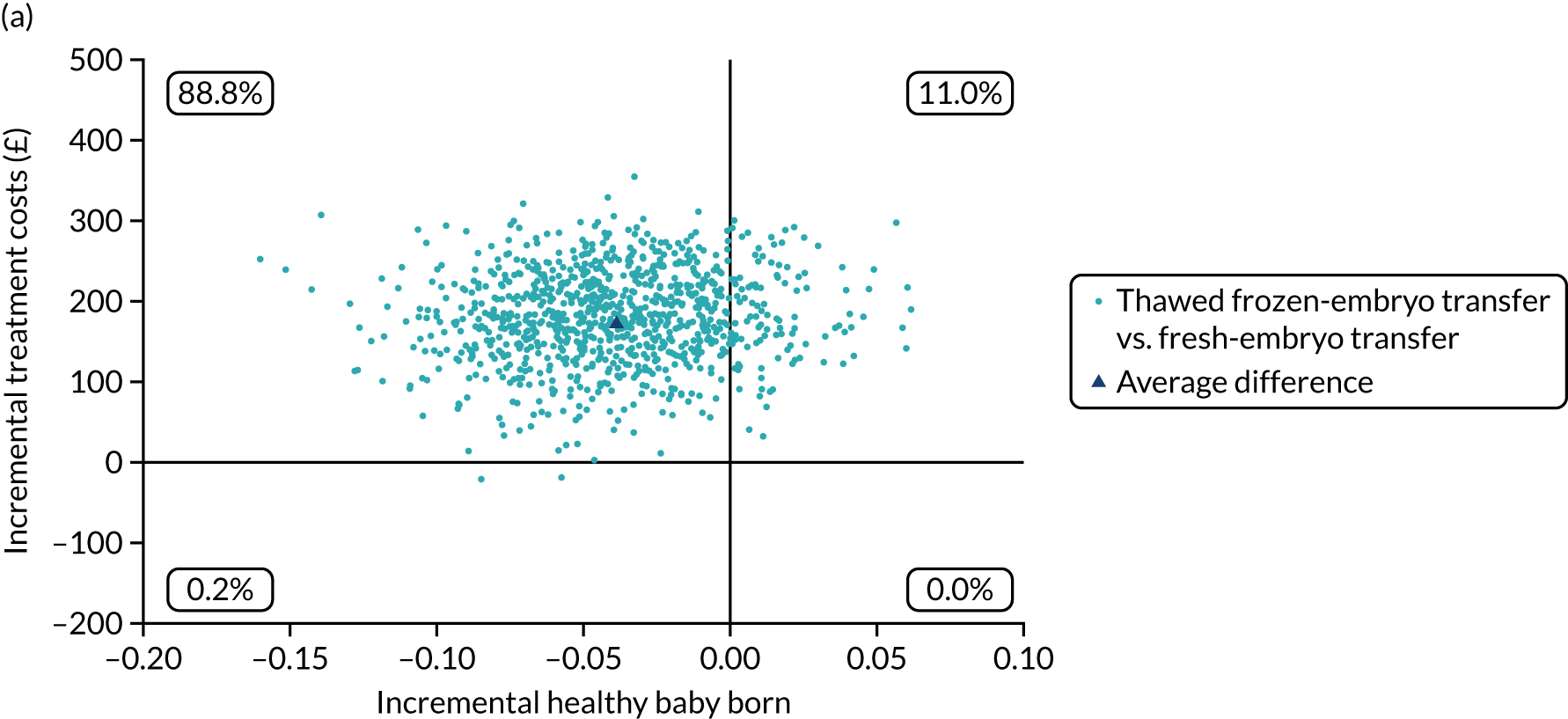

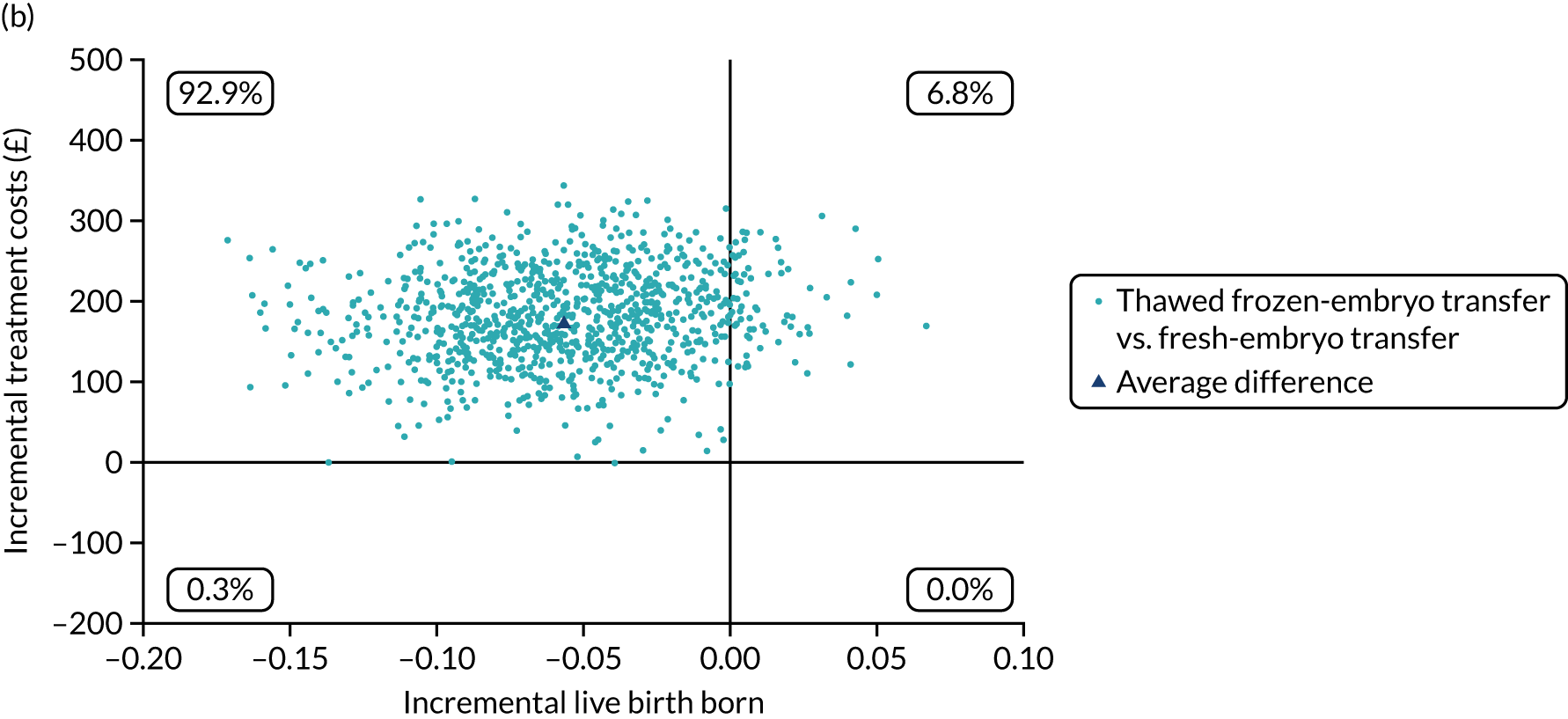

Economic evaluation

A formal economic evaluation was undertaken to assess the cost-effectiveness of the alternative approaches to treatment used in the trial.

The resource use and costs were primarily estimated from a health and personal social services perspective. However, personal time and travel costs associated with any additional treatment-related visits that were not part of standard, routine data collection were also estimated using a short questionnaire administered at the time of embryo transfer (see Report Supplementary Material 2). This was completed by both partners.

Trial data collected using eCRFs were used to capture participant-level resource use associated with treatment up to the trial end points of delivery or failure to become pregnant following the initial transfer. The appropriate unit costs were used to value resource use events recorded in the case report forms (CRFs). The detailed methods of economic evaluation are described in Chapter 4.

Adverse event reporting

A Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) was established to ensure the independent monitoring of the data and the well-being of study participants. The DMC periodically reviewed study progress and outcomes, as well as reports of unexpected serious adverse events (SAEs). The DMC made recommendations regarding the continuance of the study or modification of the study protocol.

Adverse events

As per the protocols of the trial unit, an adverse event (AE) was defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a participant, which did not, necessarily, have to have a causal relationship with the intervention. Owing to the high incidence of AEs routinely expected in this patient population (e.g. abnormal laboratory findings, new symptoms), only those AEs identified as serious were recorded for the trial.

Serious adverse events

A SAE was any untoward medical occurrence that:

-

resulted in death

-

was life-threatening

-

required participant hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

resulted in persistent or significant disability/incapacity

-

was a congenital anomaly/birth defect

-

was an important medical event.

The term ‘severe’ was often used to describe the intensity (i.e. severity) of a specific event; however, the event itself may have been of relatively minor medical significance. This was not the same as ‘serious’, which was based on participant/event outcome or action criteria, usually associated with events that posed a threat to a participant’s life or functioning.

The term ‘life-threatening’ in the definition of serious refers to an event in which the participant was at risk of death at the time of the event; it does not refer to an event that hypothetically might have caused death had it been more severe. Medical and scientific judgement was exercised in deciding whether or not an AE was serious in other situations.

Foreseeable serious adverse events

Foreseeable SAEs were events that were expected in the patient population or as a result of the routine care/treatment of a patient. The events were foreseeable in women or couples undergoing IVF treatment and, therefore, did not need to be reported as SAEs. Data on foreseeable SAEs were collected on the eCRF as part of routine data collection.

The foreseeable events relating to the female partner or couple were:

-

OHSS

-

miscarriage

-

hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

-

antepartum haemorrhage

-

GDM

-

multiple pregnancy

-

no embryos surviving thawing.

The foreseeable events relating to the baby when born were:

-

low birthweight

-

very low birthweight

-

low weight for gestational age

-

high weight for gestational age

-

preterm delivery

-

very preterm delivery.

Unforeseeable serious adverse events

An unforeseeable SAE was any event that met the definition of a SAE and was not detailed as foreseeable. The following unforeseeable SAEs were reported:

-

maternal death

-

stillbirth

-

congenital anomaly detected antenatally or postnatally

-

neonatal death.

Unforeseeable SAEs were reported up to 6 weeks post delivery. They were reported to the NPEU CTU as soon as possible after staff at the site became aware of the event. The SAEs were reported in one of the following ways:

-

Using the clinical database OpenClinica – only staff with access to OpenClinica could report SAEs in this way; site staff were required to print the OpenClinica SAE form and obtain the information and signature of the study clinician carrying out the causality assessment. The completed and signed SAE form was e-mailed or faxed to the NPEU CTU. NPEU CTU staff were automatically informed by e-mail of any SAEs reported electronically.

-

By completing a SAE form that was e-mailed or faxed to the NPEU CTU. Paper copies were available with the trial documentation to enable anyone to report a SAE. Guidance for the research site was provided on the paper SAE reporting form.

-

If it was not possible to report a SAE using the methods detailed in points 1 and 2, the unforeseeable SAE could be reported by telephone and the SAE form was completed by staff at the NPEU CTU.

If any additional information regarding the SAEs became available, this was detailed on a new SAE form and e-mailed or faxed to the NPEU CTU or reported electronically using OpenClinica. The SAE forms were sent to the sponsor by the NPEU CTU as soon as possible after they were received. The chief investigator assessed whether or not a SAE was ‘related’ (i.e. resulting from administration of any of the research procedures) and ‘unforeseeable’ in relation to those procedures. Any reports of related and unforeseeable SAEs were submitted to the following places, in line with the protocols of the trial unit: the North of Scotland Research Ethics Committee (which gave a favourable opinion of the study), the sponsor and the centre at which the SAE occurred within 15 working days of the chief investigator becoming aware of the event. All recorded SAEs were reviewed by the DMC at regular intervals. The chief investigator informed all principal investigators (PIs) concerned of relevant information that adversely affected the safety of the participants.

Governance and monitoring

To ensure oversight and governance of the trial, a DMC and a Trial Steering Committee (TSC) were established, and a Project Management Group (PMG) was responsible for the day-to-day running of the trial.

Trial Steering Committee

The role of the TSC was to provide overall supervision of the study. The TSC monitored the progress of the study and conduct, and advised on its scientific credibility. The TSC considered and acted, as appropriate, on the recommendations of the DMC and, ultimately, carried the responsibility for deciding whether or not the trial needed to be stopped on grounds of safety or efficacy.

The TSC consisted of an independent chairperson and two other independent members. The committee members were deemed to be independent if they were not involved in study recruitment and were not employed by any organisation directly involved in the study’s conduct. Representatives from Fertility Network (London, UK) (patient/public involvement groups), the chief investigator and other investigators/co-applicants were joined by observers from the NPEU CTU. A TSC charter was prepared in advance of and agreed on at the first TSC meeting to document how the committee operated.

Data Monitoring Committee

A DMC that was independent of the applicants and the TSC reviewed the progress of the trial at frequent intervals and provided advice on the conduct of the trial to the TSC, which reported to the HTA programme manager. The committee periodically reviewed study progress and outcomes. The timing and content of the DMC reviews were detailed in a DMC charter, which was agreed on at its first meeting.

Project Management Group

The study was supervised on a day-to-day basis by the PMG. This group reported to the TSC, which had overall responsibility for the conduct of the study. The core PMG met regularly (i.e. at least monthly). The Co-Investigators Group (CIG) met at regular intervals during the trial, and comprised all co-applicants and the members of the core PMG. The full membership of the committees is listed in Appendix 5.

Trial management

The trial co-ordinating centre was the NPEU CTU, University of Oxford, where the trial manager was based. The NPEU CTU was responsible for trial oversight; information technology (IT) system/functions, such as randomisation, clinical and administrative databases; all programming and statistical analyses; servicing both the DMC and the TSC; and, in collaboration with the chief investigator and the local research nurse, the general day-to-day running of the study, including the recruitment of sites and training of staff. A 24/7 (365 days per year) emergency helpline was available for out-of-hours queries related to the trial. The economic analysis was conducted at the University of Aberdeen (Aberdeen, UK).

Risk assessment and monitoring

A study risk assessment and monitoring plan was completed as part of the development of this study by the NPEU CTU. This risk assessment and monitoring plan was reviewed at regular intervals during the study to ensure that appropriate and proportionate monitoring activity was performed.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were involved at every step of the trial. At the conception of the trial, the Chief Executive of Fertility Network UK, Mrs Claire Lewis Jones, was consulted. She was involved in every meeting from the submission of the outline application to the NIHR HTA programme and the full application. Once funding was awarded, patient involvement continued during the design of the protocol and all patient facing information, including leaflets. Multiple members of Fertility Network UK were involved in publicising the trial, especially when recruitment was suboptimal and non-compliance was higher than expected. Patient representatives advised on recruitment strategies and the conduct of the trial at each step. They were part of both the DMC and the TSC. They were consulted when the inclusion criteria were amended from first cycle of IVF/ICSI to first, second and third cycle. We also took their advice when it was recommended to stop the trial, as communication to participants was crucial at that time. Patient representatives have been fully involved in the interpretation of the results, writing of this report and dissemination strategies.

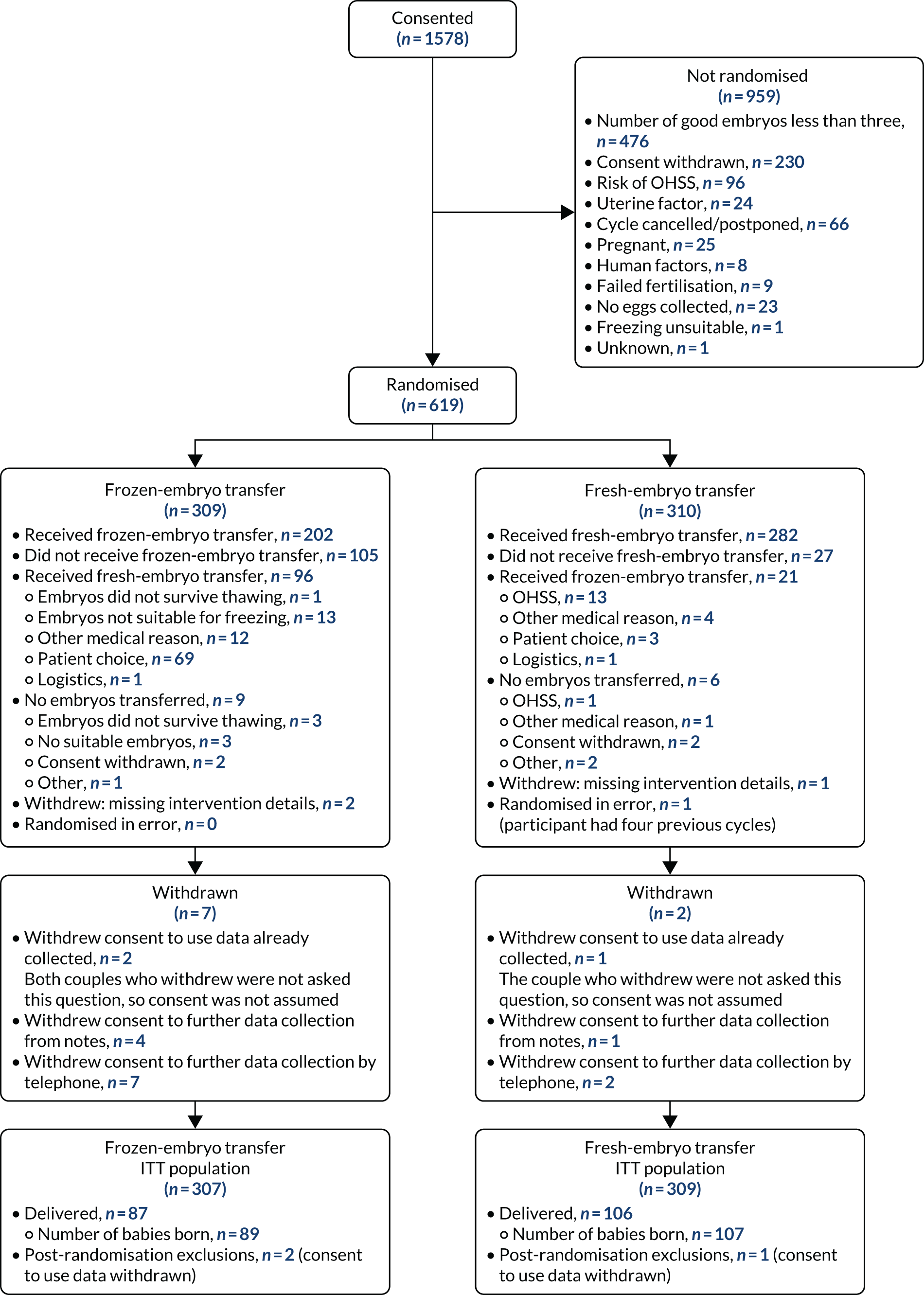

Chapter 3 Results

Between February 2016 and April 2019, 1578 participants consented and 619 couples were randomised: 310 to the fresh-embryo transfer arm and 309 to the freeze-all arm (Figure 5). One couple in the fresh-embryo transfer arm and two in the intervention arm withdrew consent to use their data; hence, the ITT analysis included 309 participants in the fresh-embryo transfer arm and 307 participants in the freeze-all arm.

FIGURE 5.

Flow of participants. Reproduced from Maheshwari et al. ,23 Elective freezing of embryos versus fresh embryo transfer in IVF: a multicentre randomized controlled trial in the UK (E-Freeze), Human Reproduction, 2022, deab279, by permission of European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology.

Recruitment and retention

When the trial initially started, in 2016, only the first cycle of IVF/ICSI was included. Owing to suboptimal recruitment (and after discussion with the funders), it was agreed that we could include the second and third cycles as well (decided on 12 April 2018).

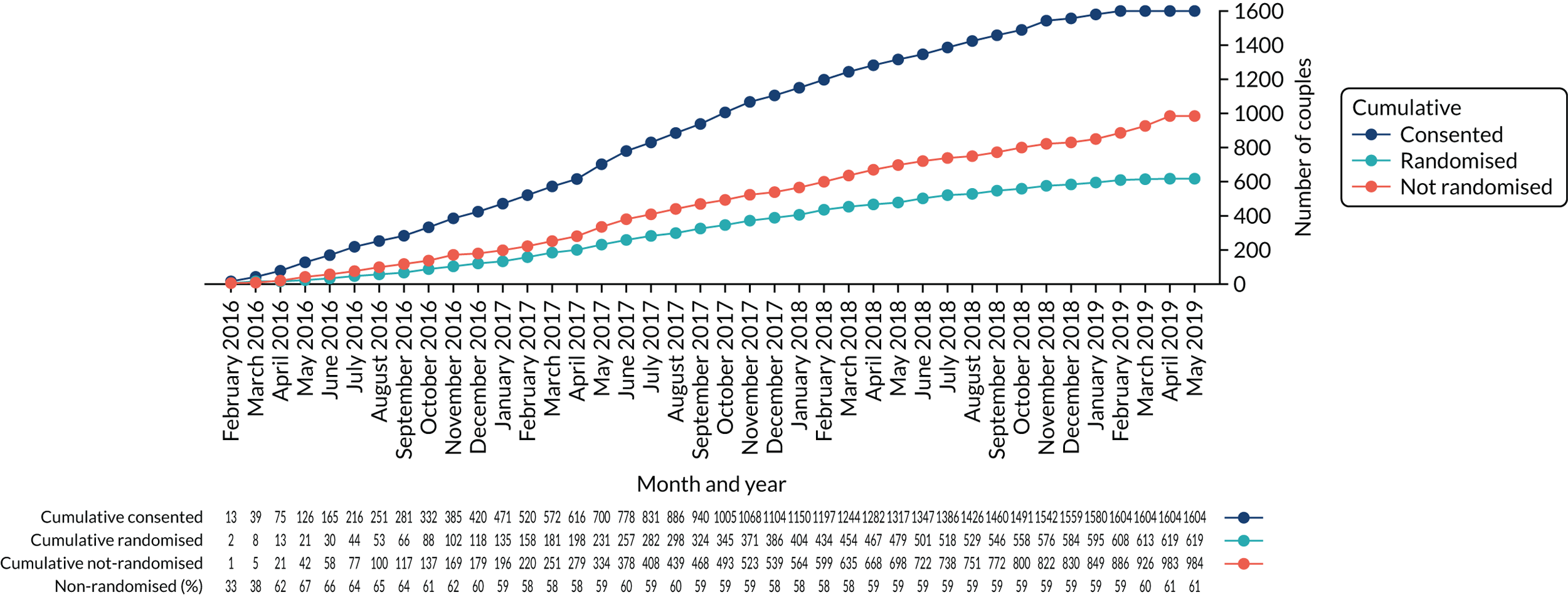

A total of 1578 couples provided consent to be enrolled in the trial. The time between consent and randomisation varied from 10 to 80 days, with a mean of 55.5 days. A total of 959 (60.8%) couples who provided consent were not randomised; the main reason for this (49.6%) was not meeting the final eligibility criterion of at least three good-quality embryos on day 3. Other reasons are described in the flow chart in Figure 5. Some couples (n = 25) became pregnant spontaneously during the time between consent and randomisation.

The proportion of couples not randomised after providing consent remained constant throughout the trial (Figure 6), even after changing the inclusion criteria to incorporate second- and third-cycle treatments.

FIGURE 6.

Proportion of consented and randomised participants.

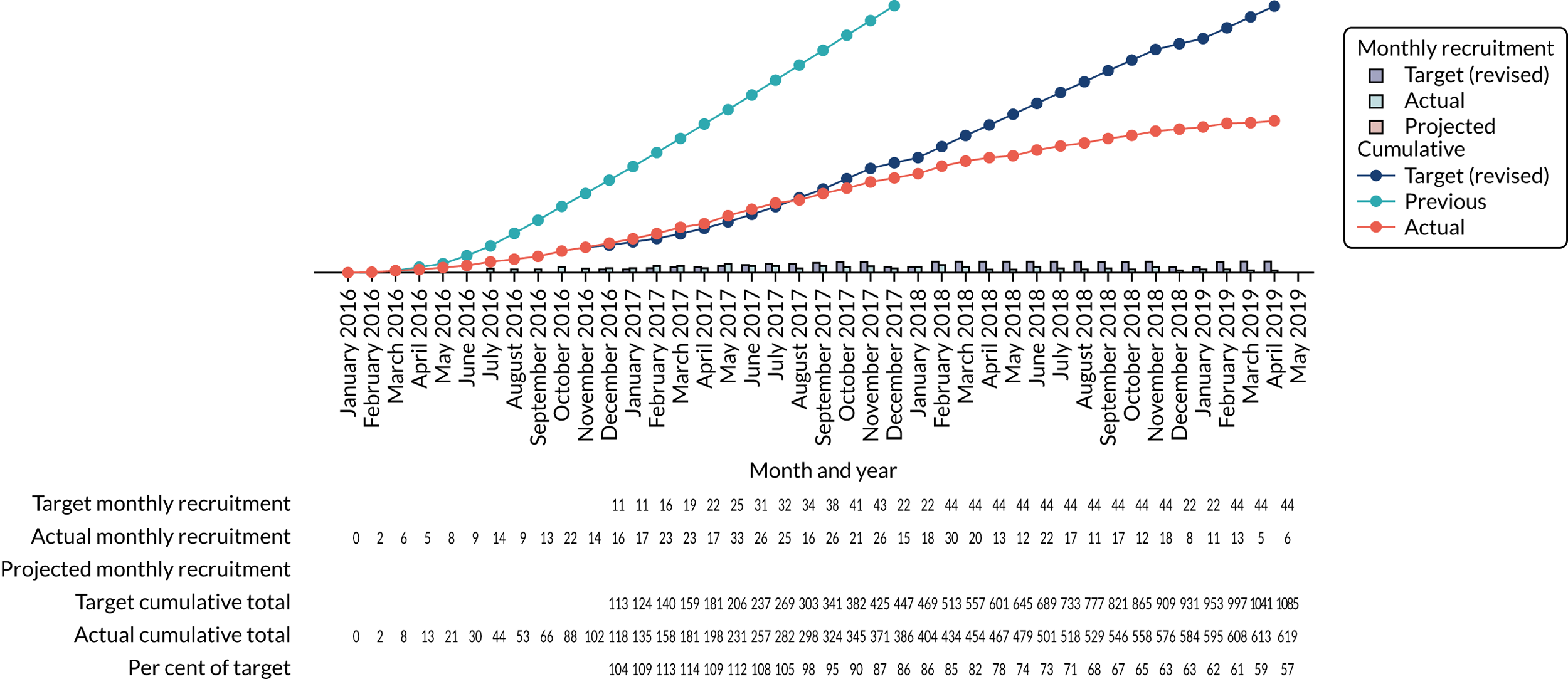

The monthly recruitment figures lagged behind target and plateaued after October 2018 (Figure 7). On 9 November 2018, the DMC recommended to the TSC that the trial should be halted, owing to the shortfall in recruitment and the high level of non-adherence. Following this recommendation, a joint meeting of the TSC and DMC was convened on 17 January 2019, with an independent chairperson because of disagreement between the TSC and the DMC, to agree scenarios for a monitoring meeting. After a monitoring meeting with the NIHR HTA programme on 29 January 2019, it was agreed that the trial would stop recruitment on 30 April 2019. It was felt that continuing the trial further would yield no benefit, as an adequate sample size was unlikely given the slow recruitment, compounded by non-adherence, which was particularly evident in the intervention arm (see Table 1).

FIGURE 7.

Final recruitment figures.

One-fifth of couples included in the analysis (117/616, 19%) did not adhere to their allocated intervention: 21 out of 309 (6.8%) in the fresh-embryo transfer arm and 96 out of 307 (31.3%) in the freeze-all arm. Non-adherence varied across clinics, with the rate in the intervention arm ranging from 0% to 86%. One clinic had a for-cause monitoring visit and was closed early in its recruitment, with non-adherence reaching almost 100%.

Table 1 shows the reasons for non-adherence in the trial arms. The most common reason for non-adherence in the freeze-all arm was patient choice (72% of those who did not receive their allocated intervention).

| Clinical characteristics | Freeze-all arm (N = 307) | Fresh-embryo transfer arm (N = 309) |

|---|---|---|

| Received frozen-embryo transfer, n (%) | 202 (65.8) | 21 (6.8) |

| Time from egg collection to frozen-embryo transfer (days), median (IQR) | 63 (33–97) | 105 (84–138) |

| Received frozen-embryo transfer within 3 months of egg collection,a n (%) | 145 (71.8) | 7 (33.3) |

| Received fresh-embryo transfer, n (%) | 96 (31.3) | 282 (91.3) |

| Reason embryo transfer type is different from allocation, n (%) | 96 | 21 |

| Embryos did not survive after thawing | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| OHSS | 0 (0.0) | 13 (61.9) |

| Not suitable to freeze | 13 (13.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other medical reason | 12 (12.5) | 4 (19.0) |

| Patient choice | 69 (71.9) | 3 (14.3) |

| Logistics | 1 (1.0) | 1 (4.8) |

| Received no embryo transfer, n (%) | 9 (2.9) | 6 (1.9) |

| Reason no embryos were transferred, n (%) | 9 | 6 |

| Embryos did not survive after thawing | 3 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| OHSS | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| No suitable embryos | 3 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other medical reason | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) |

| Consent withdrawn | 2 (22.2) | 2 (33.3) |

| Other | 1 (11.1) | 2 (33.3) |

Recruitment by sites

Eighteen clinics across the UK signed up for the trial. Only 13 clinics randomised any participants, of which four randomised > 50 participants. The number of recruited participants from each clinic is presented in Table 2.

| Fertility clinica | Number of participants (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Freeze-all arm (N = 307) | Fresh-embryo transfer arm (N = 309) | |

| 1 | 11 (3.6) | 11 (3.6) |

| 2 | 14 (4.6) | 11 (3.6) |

| 3 | 90 (29.3) | 92 (29.8) |

| 4 | 49 (16.0) | 48 (15.5) |

| 5 | 31 (10.1) | 30 (9.7) |

| 6 | 21 (6.8) | 29 (9.4) |

| 7 | 11 (3.6) | 11 (3.6) |

| 8 | 24 (7.8) | 23 (7.4) |

| 9 | 7 (2.3) | 7 (2.3) |

| 10 | 10 (3.3) | 8 (2.6) |

| 11 | 29 (9.4) | 30 (9.7) |

| 12 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| 13 | 9 (2.9) | 8 (2.6) |

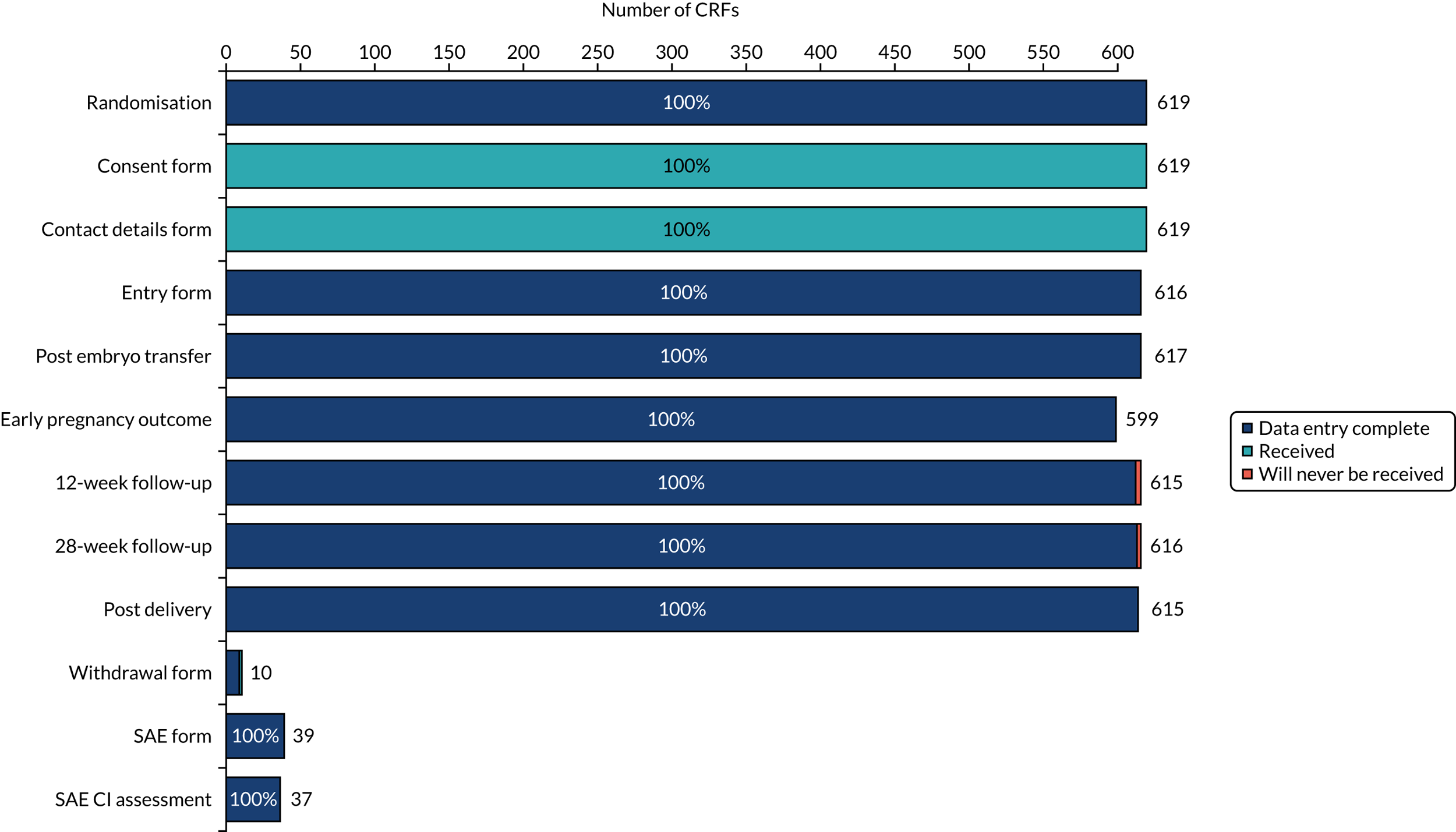

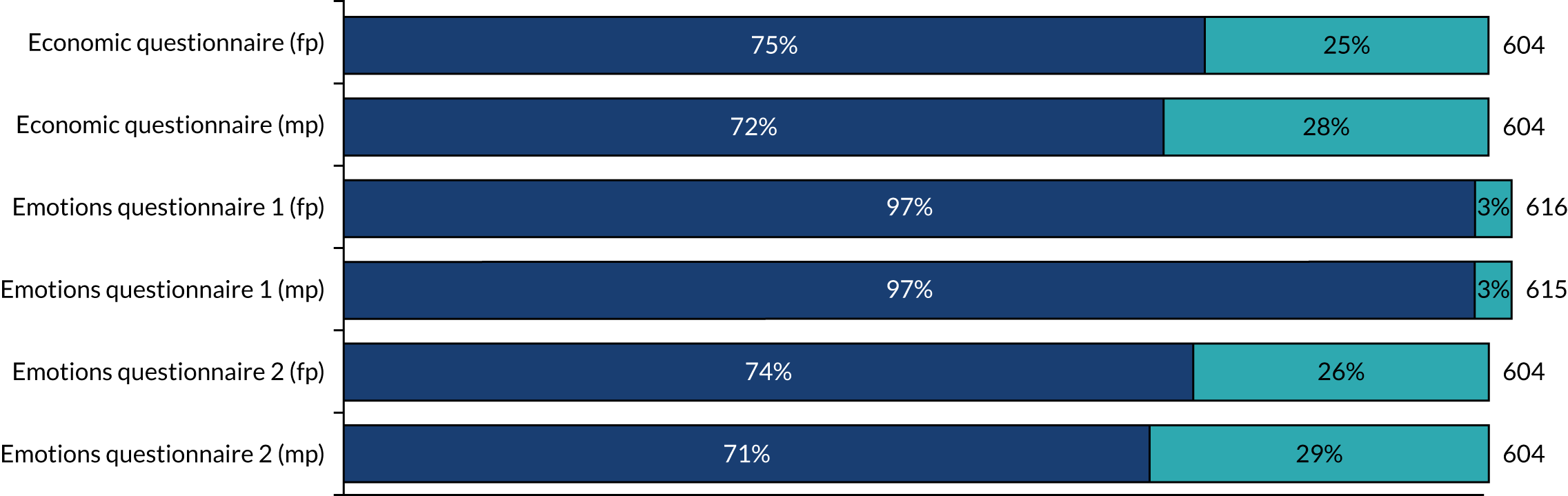

Data missingness

As is clear from Figures 8 and 9, there were very few missing data for all clinical outcomes. The emotions questionnaires were completed at consent and, again, at embryo transfer. The return rate was 97% for the first emotions questionnaire and > 70% for the second emotions questionnaire. Patients also completed an economics questionnaire, which had a return rate of > 70%.

FIGURE 8.

Data missingness on CRFs.

FIGURE 9.

Data missingness for patient-completed questionnaires. fp, female participant; mp, male participant.

Statistical analyses

Baseline comparability of randomised arms

The demographic and clinical characteristics at trial entry are described for all couples in the ITT population by trial arm.

Demographic characteristics at consent

Demographic characteristics at consent are described in Table 3.

| Characteristic | Freeze-all arm (N = 307) | Fresh-embryo transfer arm (N = 309) |

|---|---|---|

| Woman’s age at ovarian stimulation (years) | ||

| < 35, n (%) | 153 (49.8) | 157 (50.8) |

| 35 to < 40, n (%) | 137 (44.6) | 139 (45.0) |

| ≥ 40, n (%) | 17 (5.5) | 13 (4.2) |

| Mean (SD) | 34.7 (3.8) | 34.6 (3.6) |

| Woman’s ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 237 (82.0) | 221 (78.4) |

| Black | 8 (2.8) | 13 (4.6) |

| Asian | 28 (9.7) | 40 (14.2) |

| Mixed | 6 (2.1) | 5 (1.8) |

| Other | 10 (3.5) | 3 (1.1) |

| Not known | 12 | 16 |

| Missing | 6 | 11 |

| Woman’s smoking status, n (%) | ||

| Never smoked | 276 (89.9) | 282 (91.3) |

| Past smoker | 30 (9.8) | 26 (8.4) |

| Current smoker | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Woman’s BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| Underweight (< 18.5), n (%) | 5 (1.6) | 5 (1.6) |

| Healthy weight (18.5–24.9), n (%) | 195 (63.7) | 187 (60.7) |

| Overweight (25–29.9), n (%) | 91 (29.7) | 102 (33.1) |

| Obese (30–34.9), n (%) | 12 (3.9) | 14 (4.5) |

| Very obese (> 35), n (%) | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 24.1 (3.4) | 24.1 (3.2) |

| Missing, n | 1 | 1 |

| Type of infertility, n (%) | ||

| Primary | 237 (77.2) | 241 (78.0) |

| Secondary | 70 (22.8) | 68 (22.0) |

| Woman’s previous pregnancies, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 214 (69.7) | 220 (71.2) |

| 1 | 65 (21.2) | 63 (20.4) |

| 2 | 18 (5.9) | 16 (5.2) |

| > 2 | 10 (3.3) | 10 (3.2) |

| Woman’s previous live births, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 292 (95.1) | 295 (95.5) |

| 1 | 15 (4.9) | 12 (3.9) |

| 2 | 0 | 2 (0.6) |

| Main cause of infertility, n (%) | ||

| Ovulatory | 40 (13.0) | 32 (10.4) |

| Tubal | 29 (9.4) | 27 (8.7) |

| Endometriosis | 13 (4.2) | 11 (3.6) |

| Unexplained | 119 (38.8) | 131 (42.4) |

| Male factor, n (%) | 102 (33.2) | 102 (33.0) |

| Uterine | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Low ovarian reserve | 2 (0.7) | 4 (1.3) |

| Other | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) |

| Duration of infertility (months) | ||

| < 12, n (%) | 3 (1.0) | 3 (1.0) |

| 12 to < 24, n (%) | 31 (10.1) | 37 (12.0) |

| 24 to < 36, n (%) | 106 (34.5) | 99 (32.0) |

| 36 to < 48, n (%) | 80 (26.1) | 81 (26.2) |

| 48 to < 60, n (%) | 37 (12.1) | 38 (12.3) |

| ≥ 60, n (%) | 50 (16.3) | 51 (16.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 36 (24–48) | 36 (24–48) |

Age

The mean (SD) age of the female partner was 34.7 (3.8) years in the freeze-all arm and 34.6 (3.6) years in the fresh-embryo transfer arm. Most women (95.1%) were aged < 40 years and half (50.3%) were aged < 35 years. Age was a minimisation criterion.

Ethnicity

Women’s ethnicity was included in the eCRFs only part-way through the trial, on 12 April 2017. All attempts were made to collect these data retrospectively, but data were missing for some couples who were recruited prior to this date (freeze-all arm, n = 6; fresh-embryo transfer arm, n = 11). Most participants were of white ethnic background (80.2%) and 11.9% were Asian. A small proportion in both arms were of black, mixed or other ethnic backgrounds.

Woman’s smoking status

Regarding smoking status, 89.9% of women in the freeze-all arm and 91.3% in the fresh-embryo transfer arm had never smoked. A small proportion were previous smokers (9.8% in the freeze-all arm and 8.4% in the fresh-embryo transfer arm).

Woman’s body mass index

The mean body mass index (BMI) of the female partner was 24.1 kg/m2 (SD 3.4 kg/m2) in the freeze-all arm and 24.1 kg/m2 (SD 3.2 kg/m2) in the fresh-embryo transfer arm. Just over 60% were in the healthy weight category (as per internationally agreed criteria). 24 Almost one-third of female participants were overweight and 4.2% were obese. Overall, 95.3% had a BMI of < 30 kg/m2.

Type of infertility

Most women (77.2% in the freeze-all arm and 78% in the fresh-embryo transfer arm) had primary infertility. One-fifth had secondary infertility in both arms (22.8% vs. 22% in the freeze-all and fresh-embryo transfer arms, respectively). The type of infertility was a minimisation criterion.

Previous pregnancies

Over two-thirds of the participants (69.7% in the freeze-all arm vs. 71.2% in the fresh-embryo transfer arm) had had no previous pregnancy. In both arms, most participants (> 95%) had not had a previous live birth.

Main cause of infertility

The male factor and unexplained infertility constituted > 70% of the causes of infertility (72.0% in the freeze-all arm and 75.4% in the fresh-embryo transfer arm), followed by ovulatory factor (13.0% in the freeze-all arm and 10.4% in the fresh-embryo transfer arm). In both arms, a large proportion of participants had unexplained infertility (38.8% in the freeze-all arm and 42.4% in the fresh-embryo transfer arm).

Duration of infertility (months)

The median (IQR) duration of infertility was 36 months (24–48 months) in both arms. Overall, 28.6% of patients had a duration of infertility of > 48 months.

The demographic characteristics of participants randomised to the freeze-all arm were similar whether or not they complied with the allocated intervention.

Characteristics of treatment pre randomisation

The characteristics of the IVF treatment pre randomisation are described in Table 4. All proportions were similar in both arms unless specified.

| Characteristic | Freeze-all arm (N = 307) | Fresh-embryo transfer arm (N = 309) |

|---|---|---|

| Endometrial scratch performed, n (%) | 4 (1.3) | 3 (1.0) |

| Stimulation regimen used, n (%) | 299 (97.4) | 301 (97.4) |

| Long | 73 (23.8) | 64 (20.7) |

| Short | 42 (13.7) | 48 (15.5) |

| Ultrashort | 7 (2.3) | 4 (1.3) |

| Antagonist | 177 (57.7) | 185 (59.9) |

| Total stimulation dose of FSH (IUs), mean (SD) | 2540 (1257) | 2543 (1259) |

| Adjuvants used (non-exclusive), n (%) | 9 (2.9) | 7 (2.3) |

| Aspirin | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Heparin | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Steroids | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Growth hormone | 7 (2.3) | 6 (1.9) |

| DHEA | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Blood test performed on day of trigger injection, n (%) | 135 (44.0) | 142 (46.0) |

| Trigger injection used, n (%) | ||

| Agonist | 19 (6.2) | 28 (9.1) |

| Dual trigger | 31 (10.1) | 32 (10.4) |

| HCG | 257 (83.7) | 249 (80.6) |

| Total number of eggs collected | ||

| 3–5, n (%) | 14 (4.6) | 16 (5.2) |

| 6–9, n (%) | 73 (23.8) | 77 (24.9) |

| 10–15, n (%) | 141 (45.9) | 121 (39.2) |

| > 15, n (%) | 79 (25.7) | 95 (30.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 12 (9–16) | 12 (9–17) |

| Method of insemination,a n (%) | ||

| IVF | 158 (51.5) | 159 (51.5) |

| ICSI | 139 (45.3) | 138 (44.7) |

| Split (IVF and ICSI) | 10 (3.3) | 12 (3.9) |

| Number of eggs fertilised normally (two pronuclei) | ||

| 3–5, n (%) | 69 (22.5) | 69 (22.3) |

| 6–9, n (%) | 139 (45.3) | 137 (44.3) |

| 10–15, n (%) | 76 (24.8) | 81 (26.2) |

| > 15, n (%) | 23 (7.5) | 22 (7.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 8 (6–11) | 8 (6–11) |

| Time lapse used, n (%) | 124 (40.4) | 126 (40.8) |

| Good-quality embryos created on day 3 | ||

| 3 or 4, n (%) | 131 (42.7) | 112 (36.2) |

| 5 or 6, n (%) | 70 (22.8) | 84 (27.2) |

| 7–10, n (%) | 80 (26.1) | 88 (28.5) |

| > 10, n (%) | 26 (8.5) | 25 (8.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 5 (3–7) | 5 (4–8) |

| Number of previous egg collections,a n (%) | ||

| 0 | 284 (92.5) | 286 (92.6) |

| 1 | 19 (6.2) | 17 (5.5) |

| 2 | 4 (1.3) | 5 (1.6) |

| ≥ 3 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Number of previous embryo transfers, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 284 (92.5) | 288 (93.2) |

| 1–3 | 22 (7.2) | 20 (6.5) |

| ≥ 4 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

Stimulation regimen and dose

The most common protocol used was an antagonist protocol (used in 58.8%), followed by a long protocol (used in 22.2%). The total stimulation dose was similar, with a mean dose of 2542 (SD 1257) international units (IUs). Most participants (> 80%) had human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG) as a final booster injection, followed by dual trigger (10.2%) and, in a small proportion of participants, agonist trigger.

Adjuvants

Most treatments did not have add-ons or adjuvants, including endometrial scratch. A total of ≈ 40% used time lapse as the incubator, but this was similar in both arms.

Number of eggs collected

The median (IQR) number of eggs collected was 12 (range 9–16 eggs), with > 10 eggs collected from 70.8% of participants and > 15 eggs collected from 28.2%; in the case of 30 participants, fewer than six eggs were collected.

Method of insemination

The eggs and sperm were mixed by IVF or ICSI, with an almost equal split between the two methods (IVF, 51.5%; ICSI, 45%). The method of insemination was a minimisation criterion.

Number of embryos

The median number of embryos created was 8 (IQR 6–11), with 45 couples having more than 15 embryos. The median number of good-quality embryos created on day 3 was 5 (IQR 3–7) in the freeze-all arm and 5 (IQR 4–8) in the fresh-embryo transfer arm. The number of good-quality embryos created on day 3 was a minimisation criterion.

Number of previous treatments

Despite the inclusion of second and third cycles, most couples recruited had not previously undergone egg collection (92.5%) or embryo transfer (92.9%).

The clinical pre-randomisation characteristics of those randomised to the freeze-all arm were similar whether or not they complied with the allocated intervention.

Clinical characteristics post randomisation

The clinical characteristics of the embryo and the endometrium, which were collected post randomisation, are described for the ITT population by trial arm in Table 5.

| Characteristic | Freeze-all arm (N = 307) | Fresh-embryo transfer arm (N = 309) |

|---|---|---|

| Had embryo transfer, effective, n | 298 | 303 |

| Stage of embryo at transfer, n (%) | ||

| Cleavage (day 3) | 11 (3.7) | 14 (4.6) |

| Cleavage (day 4) | 5 (1.7) | 6 (2.0) |

| Blastocyst (day 5) | 270 (90.6) | 281 (92.7) |

| Blastocyst (day 6) | 12 (4.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| < 3 days | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Number of embryos transferred | ||

| 1, n (%) | 249 (83.6) | 247 (81.5) |

| 2, n (%) | – | 55 (18.2) |

| 3, n (%) | 49 (16.4) | 1 (0.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) |

| Number of remaining frozen embryos after transfera | ||

| 0, n (%) | 68 (22.8) | 61 (20.1) |

| 1, n (%) | 46 (15.4) | 52 (17.2) |

| 2, n (%) | 55 (18.5) | 55 (18.2) |

| ≥ 3, n (%) | 129 (43.3) | 135 (44.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) |

| Endometrial appearance, n (%) (percentage is of effective N: frozen, effective N = 167; fresh-embryo transfer, effective N = 169) | ||

| Triple layer | 152 (96.2) | 157 (96.3) |

| No triple layer | 6 (3.8) | 6 (3.7) |

| Unknown | 140 | 140 |

| Endometrial thickness (mm), mean (SD) (mean is of effective N: frozen, effective N = 188; fresh-embryo transfer, effective N = 189) | 9.3 (1.9) | 10.2 (2.3) |

| Not recorded, n | 119 | 120 |

Of those randomised, 298 out of 307 participants underwent embryo transfer in the freeze-all arm and 303 out of 309 participants underwent embryo transfer in the fresh-embryo transfer arm. Most transfers (93.8%) were at the blastocyst stage. Overall, > 80% of participants in both arms underwent single embryo transfer; the remaining participants had two embryos, except for one participant, who had three embryos.

The endometrial appearance was recorded in only half of the cases in both arms; in 96.3% of these cases, it was triple layer, with a mean thickness of > 9.3 mm (SD 1.9 mm) in the freeze-all arm and 10.2 mm (SD 2.3 mm) in the fresh-embryo transfer arm.

The number of embryos remaining frozen (i.e. spare embryos) after the first embryo transfer was similar in both arms (median 2, IQR 1–4); 78.5% of couples had at least one remaining embryo frozen after embryo transfer.

The clinical characteristics post randomisation of those randomised to the freeze-all arm were similar whether or not they complied with the allocated intervention.

Post-randomisation characteristics of those who received frozen-embryo transfer

As shown in Table 6, 202 couples in the freeze-all arm and 21 couples in the fresh-embryo transfer arm received frozen-embryo transfer. Most couples had embryos frozen by vitrification (88.1% in the freeze-all arm and 95.2% in the fresh-embryo transfer arm). Most embryos were frozen at the blastocyst stage. The median number of embryos frozen among those who underwent frozen-embryo transfer was 4 (IQR 3–6). The median number of embryos thawed was one. One-fifth (19.8%) of those randomised to the freeze-all arm and 14.3% of those randomised to the fresh-embryo transfer arm who underwent frozen transfer had more than one embryo thawed. Very few embryos were thawed and discarded (i.e. this occurred in a total of 19 couples). The most common method used for endometrial preparation was artificial cycle with oestrogen and progesterone, or downregulation with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist.

| Characteristic | Freeze-all arm (N = 307) | Fresh-embryo transfer arm (N = 309) |

|---|---|---|

| Received frozen transfer, n | 202 | 21 |

| Method of embryo freezing, n (%) | ||

| Vitrification | 178 (88.1) | 20 (95.2) |

| Slow freezing | 24 (11.9) | 1 (4.8) |

| Number of embryos frozen | ||

| 1, n (%) | 16 (7.9) | 1 (4.8) |

| 2, n (%) | 34 (16.8) | 2 (9.5) |

| ≥ 3, n (%) | 152 (75.2) | 18 (85.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 4 (3 to 6) | 4 (4 to 6) |

| Number of embryos thawed | ||

| 1, n (%) | 162 (80.2) | 18 (85.7) |

| 2, n (%) | 34 (16.8) | 2 (9.5) |

| ≥ 3, n (%) | 6 (3.0) | 1 (4.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 1 (1 to 1) | 1 (1 to 1) |

| Number of embryos thawed and discarded | ||

| 1, n (%) | 15 (7.4) | 0 |

| 2, n (%) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (4.8) |

| ≥ 3, n (%) | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0 to 0) | 0 (0 to 0) |

| Number of embryos thawed and refrozen, n (%) | ||

| ≥ 3 | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Number of embryos remaining frozen | ||

| 0, n (%) | 28 (13.9) | 1 (4.8) |

| 1, n (%) | 33 (16.3) | 4 (19.0) |

| 2, n (%) | 40 (19.8) | 1 (4.8) |

| ≥ 3, n (%) | 101 (50.0) | 15 (71.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 3 (1 to 4) | 3 (2 to 5) |

| Method of endometrial preparation for transfer, n (%) | ||

| Natural cycle | 6 (3.0) | 6 (28.6) |

| Natural cycle with HCG | 4 (2.0) | 0 |

| Artificial cycle with oestrogen and progesterone | 130 (64.4) | 7 (33.3) |

| Artificial cycle with oestrogen and progesterone and downregulation with GnRH agonist | 47 (23.3) | 6 (28.6) |

| Artificial cycle with oestrogen, progesterone and antagonist | 14 (6.9) | 2 (9.5) |

| Other | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Time from egg collection to embryo freezing, n (%) | ||

| Cleavage (day 3) | 14 (6.9) | 0 |

| Cleavage (day 4) | 3 (1.5) | 0 |

| Blastocyst (day 5) | 175 (86.6) | 19 (90.5) |

| Blastocyst (day 6) | 10 (5.0) | 1 (4.8) |

| < 3 days | 0 | 1 (4.8) |

Primary outcome

Intention-to-treat analysis

The ITT analysis (Table 7) showed that the healthy baby rate (i.e. term singleton live birth with appropriate weight for gestation) was 20.3% in the freeze-all arm and 24.4% in the fresh-embryo transfer arm (p = 0.28). There was no statistical difference with/without adjustment of confounding factors (adjusted RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.15). The proportion of singletons born was 27.7% in the freeze-all arm and 34.0% in the fresh-embryo transfer arm. The proportion of babies born at term was 25.4% in the freeze-all arm and 30.2% in fresh-embryo transfer arm. Similarly, the proportion with an appropriate weight for gestation was 22.5% in the freeze-all arm and 26.9% in the fresh-embryo transfer arm.

| Outcome | Freeze-all arm (N = 307) | Fresh-embryo transfer arm (N = 309) | RR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | ||||

| Singleton baby born at term with an appropriate weight for gestation, n (%) (percentage is of effective N: frozen, effective N = 306; fresh-embryo transfer, effective N = 308) | 62 (20.3) | 75 (24.4) | 0.83 (0.62 to 1.12) | 0.84 (0.62 to 1.15) | 0.275 |

| Missing, n | 1 | 1 | |||

| Singleton, n (%) | 85 (27.7) | 105 (34.0) | |||

| Born at term, n (%) (percentage is of effective N: frozen, effective N = 307; fresh-embryo transfer, effective N = 308) | 78 (25.4) | 93 (30.2) | |||

| Missing, n | 0 | 1 | |||

| Appropriate weight for gestation, n (%) (percentage is of effective N: frozen, effective N = 306; fresh-embryo transfer, effective N = 308) | 69 (22.5) | 83 (26.9) | |||

| Missing, n | 1 | 1 | |||

Sensitivity analysis by compliance status of the freeze-all arm

When the analysis for the primary outcome was undertaken by compliance status of those randomised to the freeze-all arm, there was no difference in the outcome healthy baby rate between those who complied and those who did not comply with the allocated intervention (21.3% vs. 20.0%, respectively) (Table 8).

| Outcome | Treatment received, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Frozen-embryo transfer (N = 202) | Fresh-embryo transfer (N = 96) | |

| Singleton baby born at term with an appropriate weight for gestation | 43 (21.3) | 19 (20.0) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 |

| Singleton | 56 (27.7) | 29 (30.2) |

| Born at term | 52 (25.7) | 26 (27.1) |

| Appropriate weight for gestation | 46 (22.8) | 23 (24.2) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 |

Sensitivity analysis: complier-average causal effect

The CACE RR was 0.77 (0.204/0.264). This was calculated for participants with no missing primary outcome data.

The values in Table 9 are calculated for the would-be non-compliers and would-be compliers of the fresh-embryo transfer arm, assuming the same non-compliance rate and event rate as the non-compliers of the freeze-all arm. 20 The CACE RR suggests that there is no difference in the healthy baby rate between the two arms.

| As per compliance status | Freeze-all arm (N = 306) | Fresh-embryo transfer arm (N = 308) | CACE RR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compliance, n (%) | Primary outcome (n/N) | Event rate (%) | Primary outcome (n/N) | Event rate (%) | ||

| Compliers | 211 (69.0) | 43/211 | 20.4 | 56/212 | 26.4 | 0.77 (0.44 to 1.10) |

| Non-compliers | 95 (31.0) | 19/95 | 20.0 | 19/96 | 20.0 | |

| Total | 62/306 | 20.3 | 75/308 | 24.4 | ||

Exploratory analysis on primary outcome

In both arms, the healthy baby rate did not differ depending on whether the analysis was restricted to those who had received the allocated intervention (p = 0.45) or the analysis was undertaken as treated (p = 0.59) (Table 10).

| Analysis | Freeze-all arm | Fresh-embryo transfer arm | RR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | ||||

| Restricted per-protocol | |||||

| Total couples, excluding those who did not receive their allocated intervention, n | 202 | 282 | |||

| Singleton baby born at term with appropriate weight for gestation, n (%) (percentage is of effective N: frozen, effective N = 202; fresh-embryo transfer, effective N = 281) | 43 (21.3) | 70 (24.9) | 0.85 (0.61 to 1.19) | 0.87 (0.59 to 1.26) | 0.453 |

| Missing, n | 0 | 1 | |||

| As treated | |||||

| Total couples receiving each allocation, N | 223 | 378 | |||

| Singleton baby born at term with appropriate weight for gestation, n (%) (percentage is of effective N: frozen, effective N = 202; fresh-embryo transfer, effective N = 376) | 48 (21.5) | 89 (23.7) | 0.91 (0.67 to 1.24) | 0.91 (0.64 to 1.29) | 0.593 |

| Missing, n | 0 | 2 | |||

Subgroup analysis

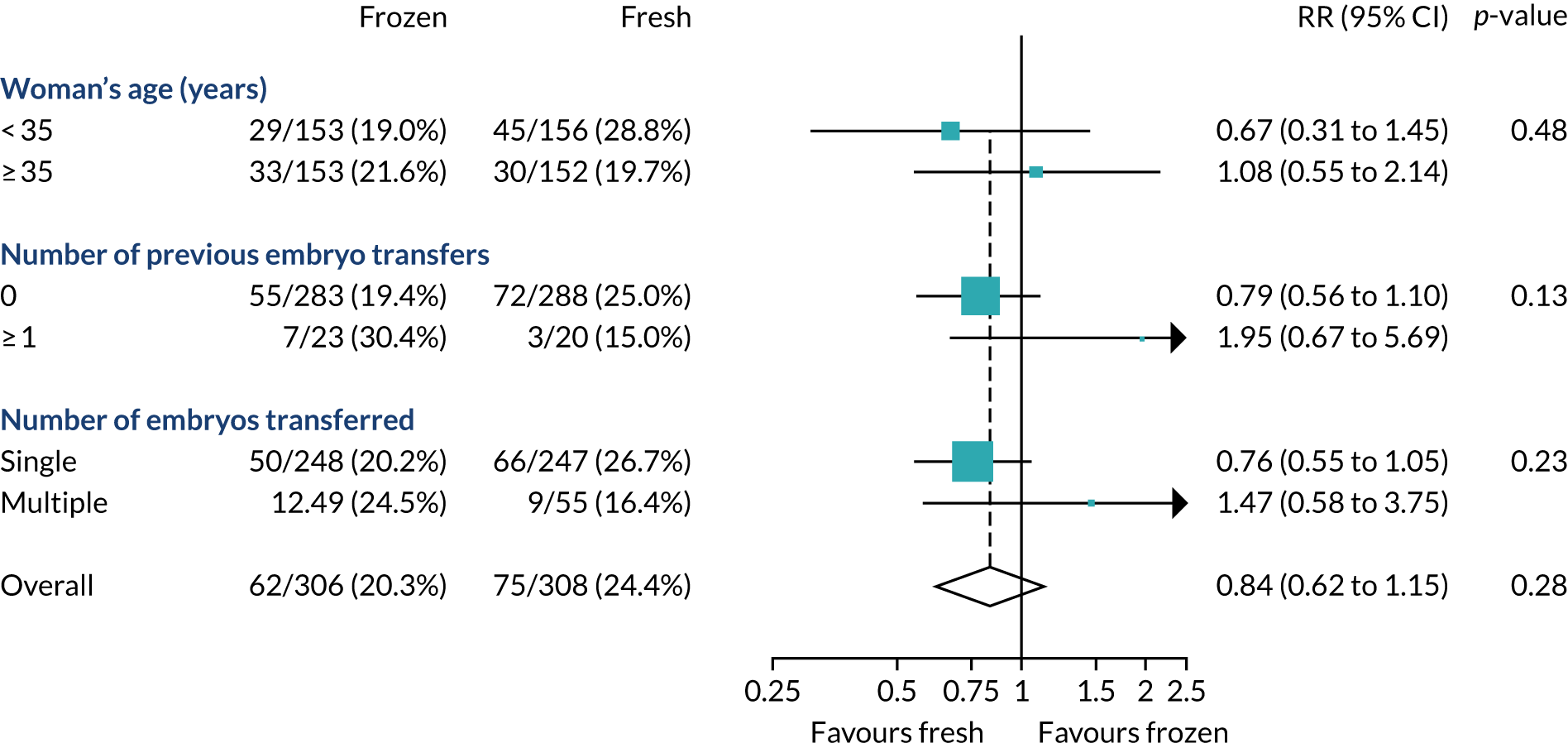

The prespecified subgroup analysis for the primary outcome of healthy baby rate was undertaken based on the age of the female partner, number of previous embryo transfers, stage and number of embryos, and fertility clinic. As shown in Figure 10, there was no statistical difference in the healthy baby rate in different age groups (< 35, 35 to < 40 and > 40 years), number of previous embryo transfers (0 or ≥ 1), whether the transfer was undertaken at the cleavage or blastocyst stage, or whether one or two embryos were transferred (Table 11). There was a difference in the healthy baby rate between clinics; however, this is unlikely to be meaningful because of the very small numbers recruited by most clinics. Exploratory analyses were undertaken for method of endometrial preparation and type of freezing. Most frozen-embryo transfers were hormonally mediated and most embryos were frozen by vitrification.

FIGURE 10.

Subgroup analysis of the primary outcome. Adjusted for minimisation factors at randomisation. p-values from test of heterogeneity. Reproduced from Maheshwari et al. ,23 Elective freezing of embryos versus fresh embryo transfer in IVF: a multicentre randomized controlled trial in the UK (E-Freeze), Human Reproduction, 2022, deab279, by permission of European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology.

| Subgroup analysis | Freeze-all arm (N = 307) | Fresh-embryo transfer arm (N = 309) | RRa (95% CI) | Interaction p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woman’s age (years), n/N (%) | 0.100 | |||

| < 35 | 29/153 (19.0) | 45/156 (28.8) | 0.67 (0.31 to 1.45) | |

| 35 to < 40 | 32/136 (23.5) | 28/139 (20.1) | 1.15 (0.60 to 2.18) | |

| ≥ 40 | 1/17 (5.9) | 2/13 (15.4) | 0.41 (0.04 to 4.10) | |

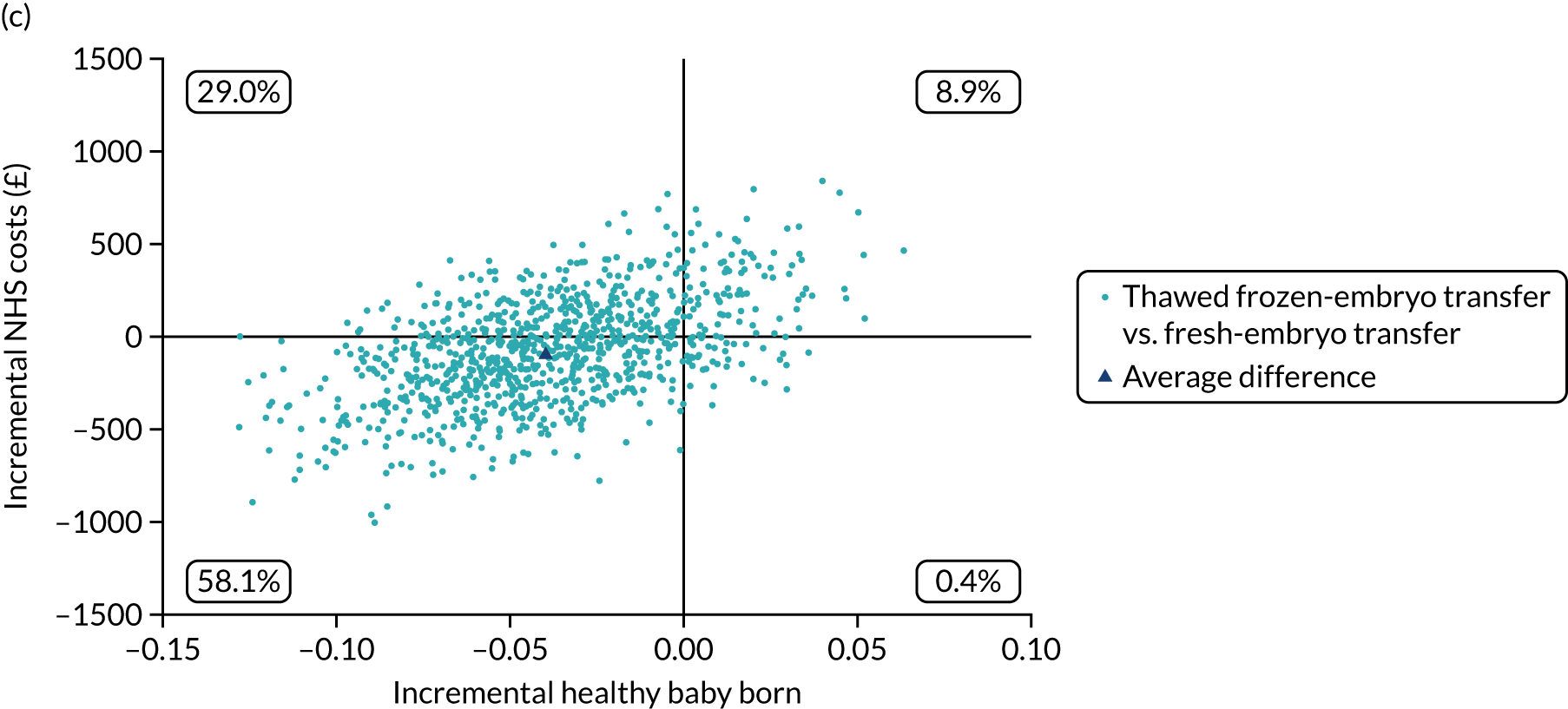

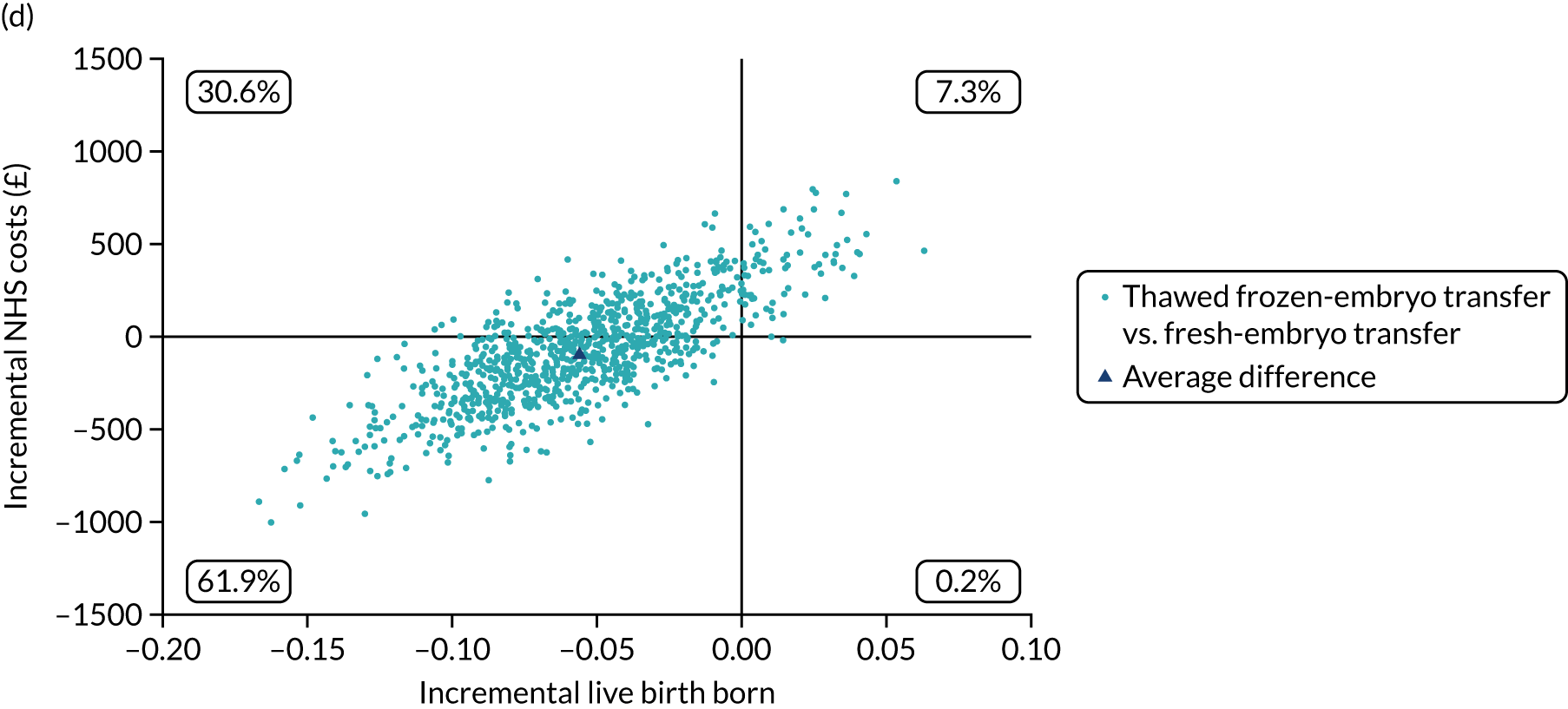

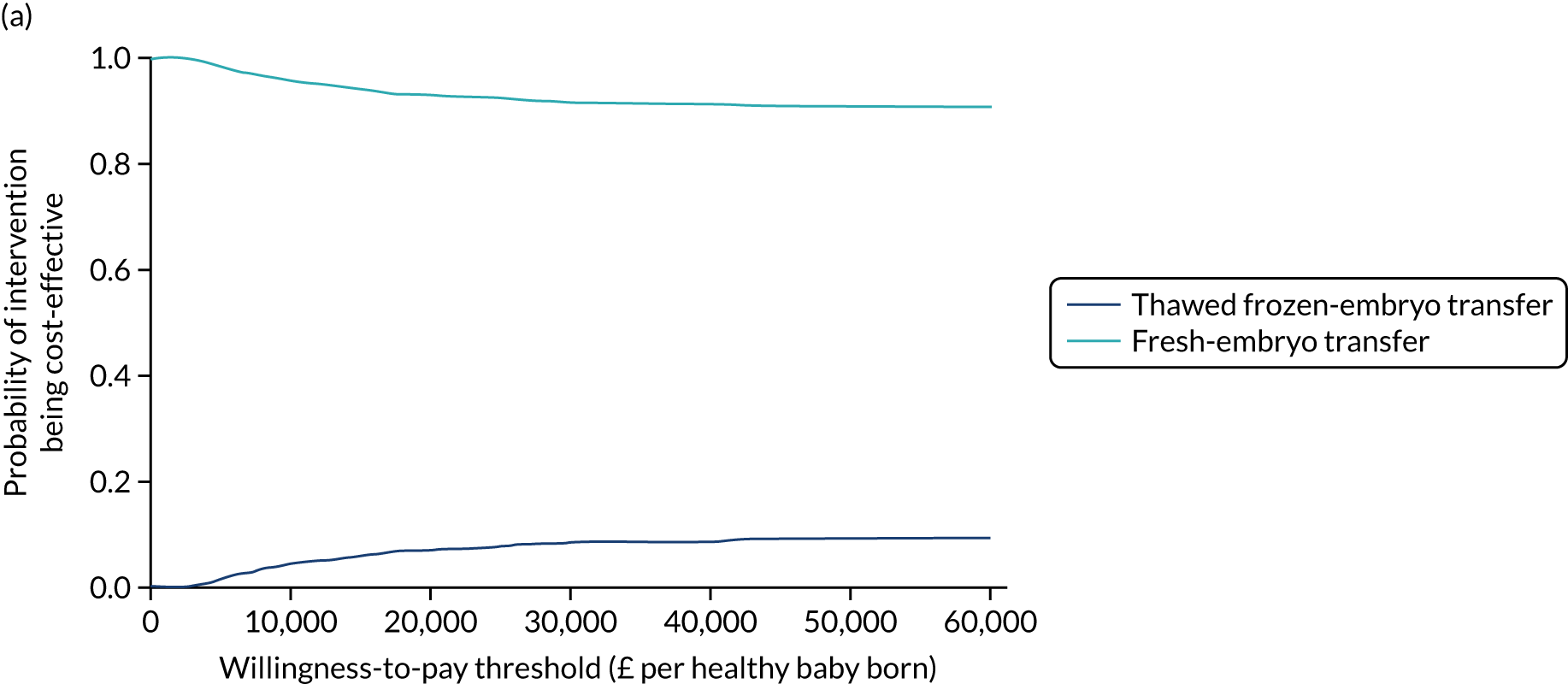

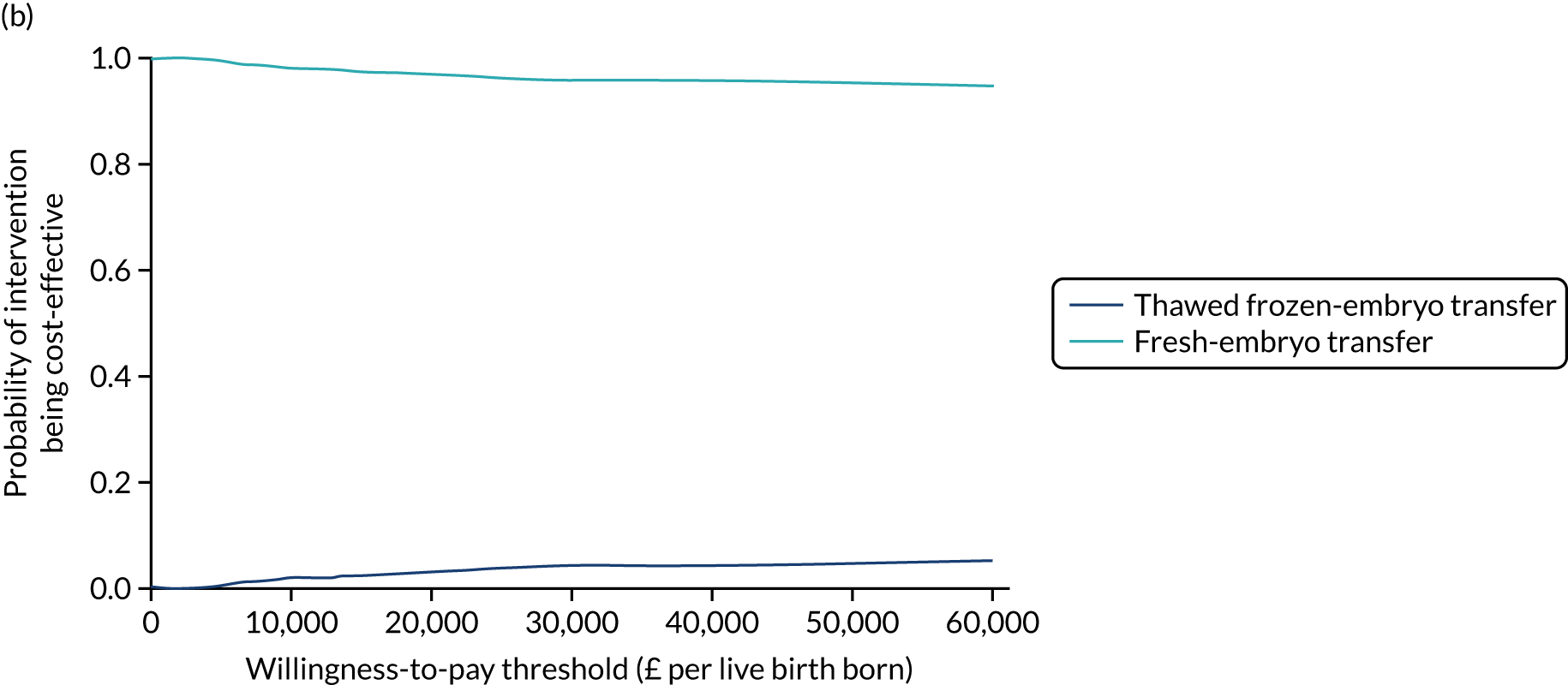

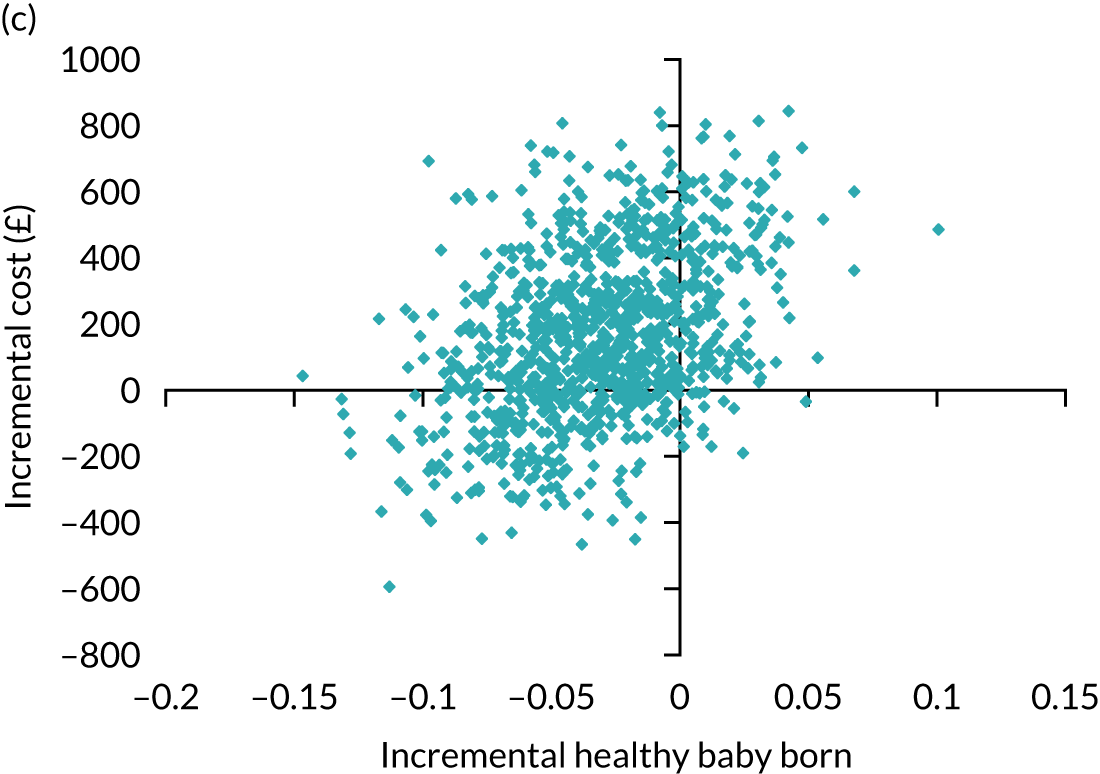

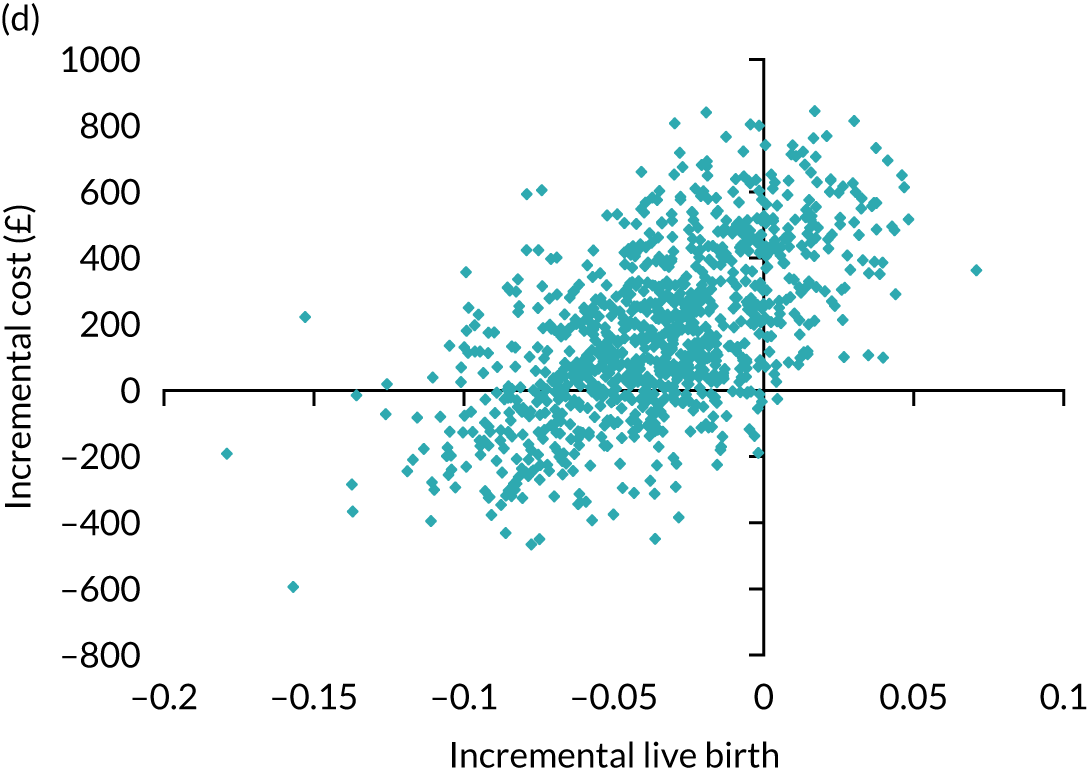

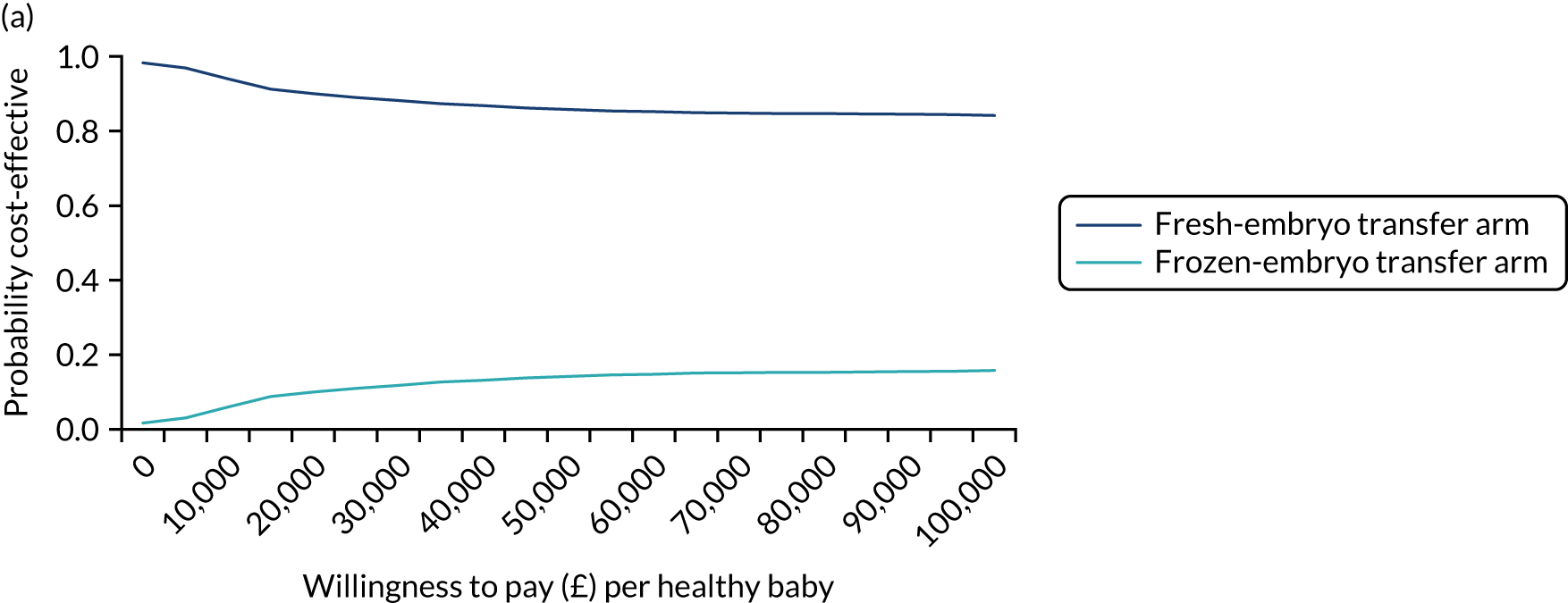

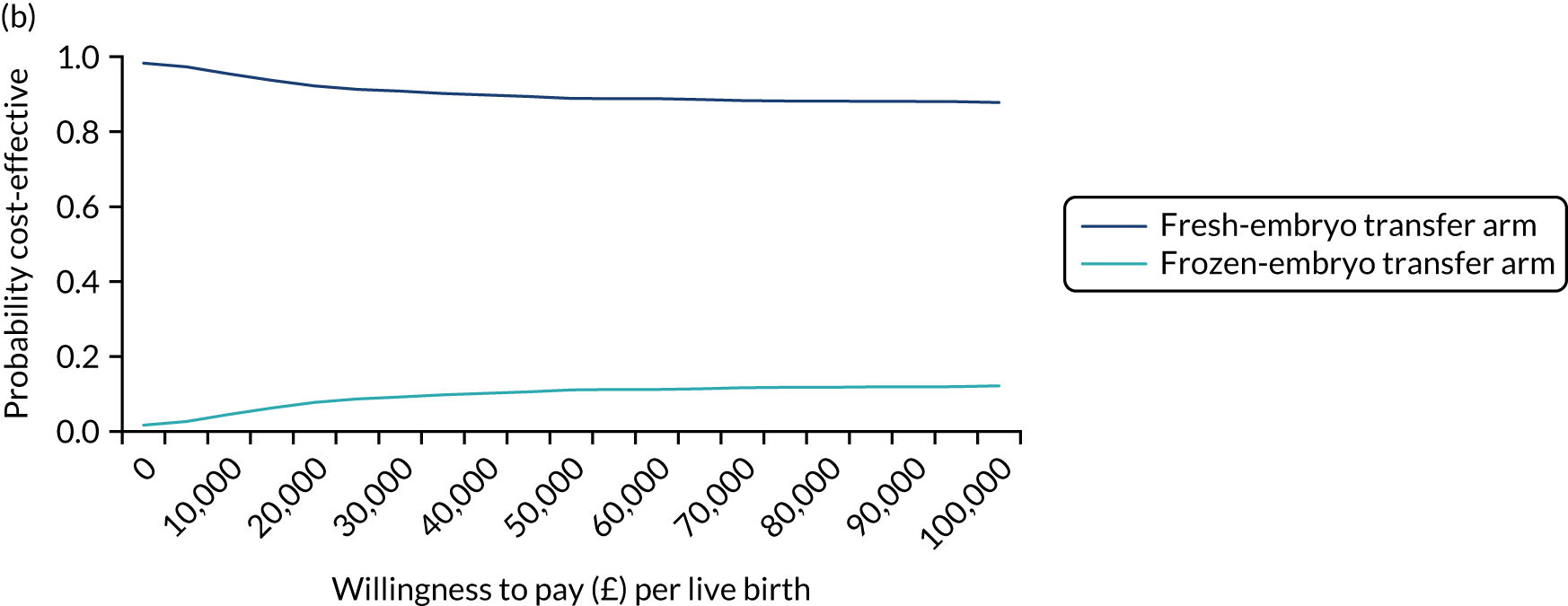

| Fertility clinic, n/N (%) | < 0.001 | |||