Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/127/157. The contractual start date was in December 2013. The draft report began editorial review in April 2021 and was accepted for publication in March 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Abdel-Fattah et al. This work was produced by Abdel-Fattah et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Abdel-Fattah et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter are reproduced from Abdel-Fattah et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

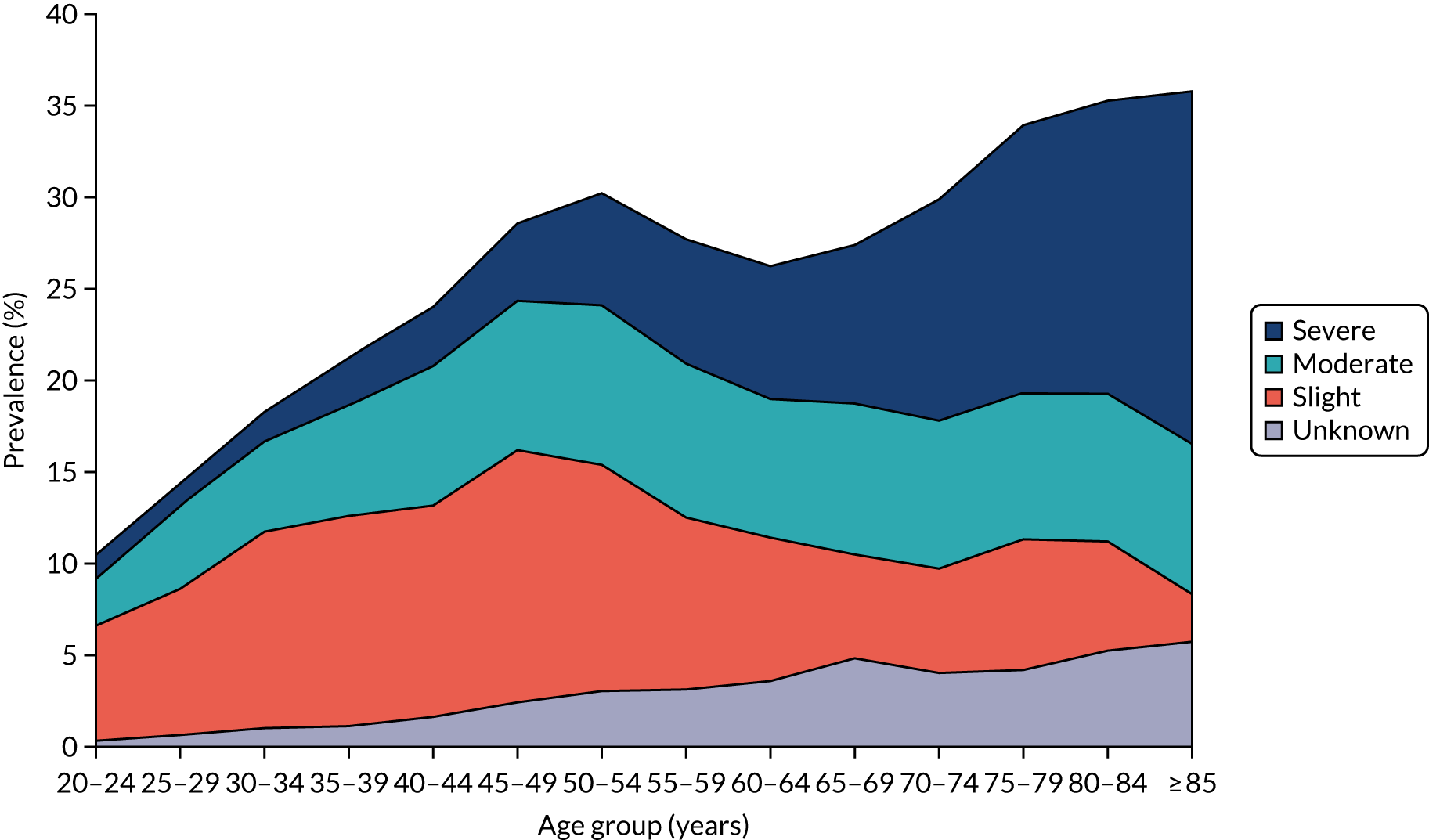

Urinary incontinence (UI) is involuntary leakage of urine. 2 It can affect both men and women, but it generally affects twice as many women as men. 3 The prevalence varies according to the population and the tool used. In a UK study published in 2009, 23% of the population reported UI. 4 Among women, the incidence of at least monthly UI is highest among those of white ethnicity (7.3/100 person-years), followed by those of Asian ethnicity (5.7/100 person-years). 5 The Leicestershire Medical Research Council Incontinence Study reported that over one-third of community-dwelling women aged ≥ 40 years had significant urinary symptoms, with 12% experiencing UI weekly. 6 The Epidemiology of Incontinence in the County of Nord-Trøndelag (EPINCONT) study among women aged > 20 years in Norway reported the prevalence of UI according to its severity within different age groups. 7 The authors7 reported that the prevalence of severe UI was 29% (range 11–72%) and affects more elderly women (Figure 1).

There are several types of UI according to the aetiology. The International Continence Society first published the definitions of the types of UI in 2002 and revised them in 2009. 8–10

The following are the most common types of UI:

-

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is involuntary leakage of urine on effort or on sneezing or coughing.

-

Urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) is involuntary leakage of urine associated with urgency. Urgency itself is a sudden compelling desire to pass urine that is difficult to defer.

-

Mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) is involuntary loss of urine associated with urgency and also with effort, sneezing or coughing.

-

Overactive bladder (OAB) is urinary urgency, usually accompanied by frequency and nocturia, with or without UUI, in the absence of urinary tract infection (UTI) or other obvious pathology. It is referred to as ‘OAB wet’ or ‘OAB dry’, depending on whether or not the urgency is associated with UUI. OAB is a symptom syndrome (clinical diagnosis) and can be diagnosed by cystometry with urodynamic findings of detrusor overactivity (DO).

Urinary incontinence can be progressive. The Nurses’ Health Study of almost 24,000 women aged 54–79 years showed that 9.2% of women leaked at least monthly. 11 After 2 years, 32% of these women progressed to report UI on a weekly basis. Wennberg et al. 12 compared two cross-sectional studies for the same cohort of Swedish women over 20 years (n = 2911) in 1991 and 2007 and found no significant differences in the prevalence of UI and/or the proportion of women seeking medical treatment for UI.

Burden of urinary incontinence

Although UI is not life-threatening, its effect on the physical and psychological well-being of women has been well demonstrated. 13 UI is a condition that causes personal and hygiene problems, with a detrimental impact on women’s quality of life (QoL). 12,14 UI in women is associated with low self-esteem and can lead to social disabilities and isolation. 6 Norton et al. 15 showed that 25% of women waited > 5 years before seeking help because of embarrassment or fear of surgery, 60% avoided leaving their home, 50% felt different from others and 45% avoided public transport because of fear of UI.

Urinary incontinence can affect health directly through skin irritation and ulceration, infection and the need for catheterisation (e.g. among the elderly) and its associated complications, or indirectly through the development of avoidance behaviour such as reduction of physical activity, social interaction and sexual activity and/or limitation in employment and productivity at work. UI also has a great impact on the psychological well-being of those experiencing it. 16 It is therefore not surprising to find UI associated with many comorbidities. In the national audit for continence care, those aged ≥ 65 years had comorbidities spanning the major organ systems. 17 Impaired mobility dominated the profile outside mental health and care home settings; within these settings, dementia, depression and recurrent falls were common. For those aged < 65 years, depression, neurological disease and hypertension predominated as associated conditions across the settings, and dementia and impaired mobility were common associated conditions within the mental health and care home settings. 17 Elderly people experiencing UI are twice as likely to be depressed. 18 Less than one-third of women experiencing ‘moderate’ or ‘severe’ UI were found to be receiving health or social services for their condition. 19

A number of studies showed a direct relationship between UI and women’s sexual function. In one study,15 50% reported avoiding sexual activity because of fear of UI, and 25–50% reported dyspareunia, lack of orgasm and/or negative impact on their marital status. The ability of surgery for SUI to improve sexual function has been debatable, especially given the poor level of evidence available. In a number of studies, women reported improvement in sexual function following continence surgery. 20–22 In other studies, it was associated with a risk of developing dyspareunia (up to 15% in some studies). 23–25

The financial burden of UI is immense, either directly to the individual through the need to buy incontinence products or medical care, or indirectly through limiting employment opportunities. The cost to the health-care system is even greater. In 2000, the annual cost to the NHS for the management of UI in women aged ≥ 40 years was £301M, equivalent to 0.3% of the total NHS budget. 26 In the same year, the annual costs borne by women were estimated at £230M, or £290 per woman per year. 14,27 In the Prospective Urinary Incontinence Research (PURE) study, the annual costs of treatment for female UI were estimated at €359 (£248) in the UK/Ireland. 28 Suboptimal continence management among the elderly often results in catheterisation and bedsores, with the associated health-care costs. In the UK, the harm resulting from the use of indwelling catheters costs the NHS between £1.0B and £2.5B and accounts for ≈ 2100 deaths per year. 29

Surgical treatment of SUI is costly. The lifetime risk for women having surgery for SUI is 3.6% in the UK and 13% in the USA. 30,31 Hospital Episode Statistics for England show that, between 2008 and 2017, > 100,000 continence procedures were performed in England. 32 Similarly, 165,000 surgical continence procedures were performed in the USA in 1995, which accounts for almost 2% of the US health-care budget. 33 In 2003, a systematic review of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different surgical treatments for the management of SUI in the UK showed a decrease in the cost of surgical treatment for every woman with UI owing to the development of mid-urethral sling (MUS) procedures, which necessitate a shorter hospital stay and are associated with more rapid recovery and return to normal activities than previous procedures, such as colposuspension and traditional slings. 34 More recently (2019), an updated systematic review and network meta-analysis reported that ‘over a lifetime, retropubic MUS is, on average, the least costly and most effective surgery. However, the high level of uncertainty makes robust estimates difficult to ascertain’. 35

Treatment of stress urinary incontinence

Stress urinary incontinence is the most common type of UI among women. 8 Treatment pathways for SUI generally start with lifestyle changes and pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT). A Cochrane systematic review of randomised trials found that, compared with no treatment or placebo, women treated with PFMT were more likely to report improvement or cure of UI. 36 In 2020, the Optimal PFMT for Adherence Long term (OPAL) study found no added value for biofeedback to augment PFMT. 37 Pharmacological treatment for SUI is generally not effective; there is one medication (duloxetine) that is licensed for the treatment of SUI, but its effectiveness is limited and its tolerability is poor. A Cochrane review of 10 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing duloxetine with placebo or PFMT showed that, when assessed subjectively, the cure effect size of duloxetine was only 3%; when assessed objectively, it resulted in no added benefit. 38

Other conservative treatment options include mechanical devices/pessaries (e.g. urethral plugs, vaginal devices) to support the bladder neck. 39,40 Among women with SUI or MUI, ≈ 50% treated with continence pessaries are satisfied at 1 year of follow-up. 41 Women who do not respond to conservative measures have the option of progressing to surgery.

Surgical treatment

Historically, there has been > 200 surgical operations described for treating SUI; the majority have come and gone with time. 42 They are generally classified as procedures that augment urethral closure by increasing outflow resistance (e.g. slings and urethral bulking) or that support the bladder neck/proximal urethra by elevating the bladder neck and proximal urethra to be intra-abdominal (e.g. Marshall–Marchetti–Krantz procedure, colposuspension). 43

Burch colposuspension

Up to the mid-1990s, Burch colposuspension (BC) was the most commonly performed continence procedure worldwide. BC is performed via a transverse lower-abdominal incision and had a reasonable success rate of ≈ 80% at 5 years’ follow-up. 44 BC is associated with an up to 30% risk of development of posterior wall prolapse, a 25% risk of postoperative voiding difficulties and an 18% risk of de novo OAB symptoms (urgency and UUI). 45

The first laparoscopic colposuspension (LC) was described in 1991. Several studies have reported patient-reported and objective success rates of 70–98%. 46–48 Kitchener showed that LC has a similar effectiveness to the open colposuspension, with shorter operating time. 49 LC has the advantage of less postoperative pain, a shorter hospital stay and shorter recovery time. 50 Interestingly, laparoscopic skills were not widely available in urology or gynaecology at the time LC was introduced, hence LC was offered only in certain centres. At the same time (1996), synthetic MUSs, namely retropubic tension-free vaginal tapes (RP-TVTs), were introduced.

Traditional slings

Traditional slings were first described by Aldridge51 in 1942; they require a combined abdominal and vaginal approach. Several studies comparing traditional MUSs with BC showed that the patient-reported cure rate was lower with the traditional slings at 1 year of follow-up [risk ratio (RR) 0.75, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.62 to 0.90). BC was associated with fewer perioperative complications, shorter duration of use of indwelling catheter and less long-term voiding dysfunction (VD). 52–54

Synthetic mid-urethral slings, mesh, tapes

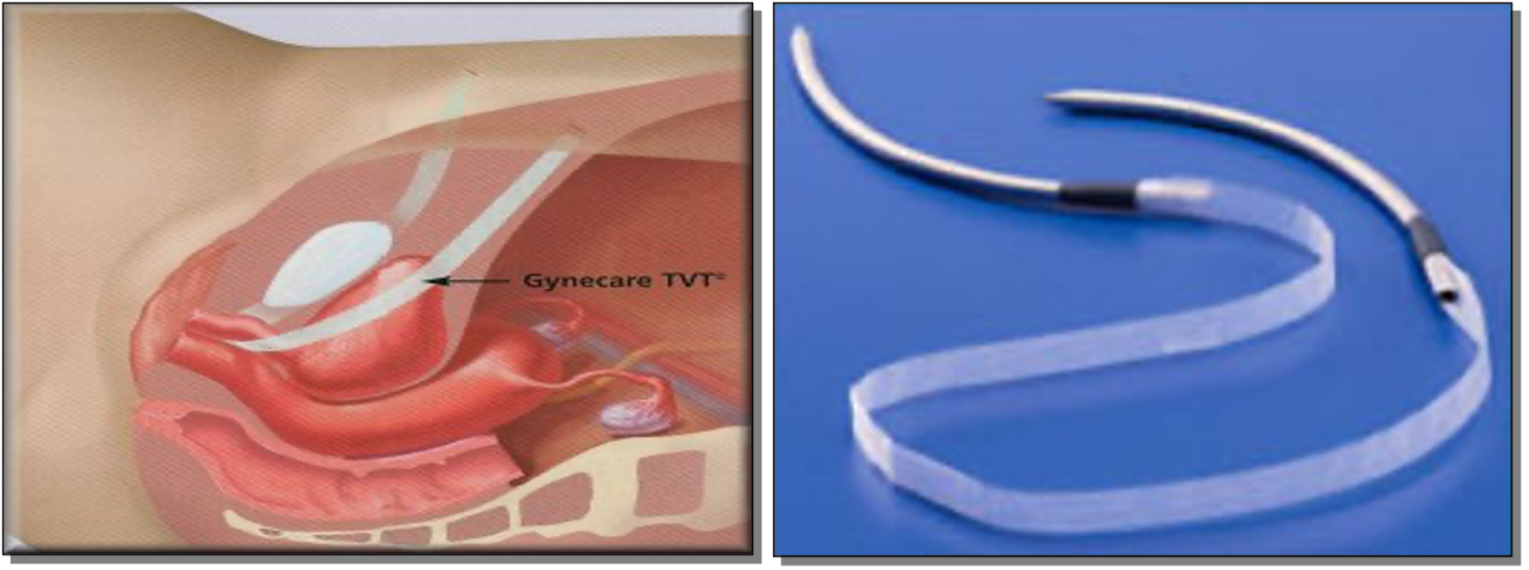

In 1996, Ulmsten et al. 55 presented the first MUS: the RP-TVT (Figure 2), which was revolutionary to continence surgery worldwide. MUS was developed with the aim of transforming continence surgery into a day case procedure. MUS primarily depended on the integral theory for continence which was first described by Petros and Ulmsten and later upheld by DeLancey’s hammock hypothesis. 56,57 In both, the pubourethral ligaments and the vaginal hammock structure constitute the main continence mechanism, disrupted in women with SUI, and require re-enforcement during surgical treatment.

FIGURE 2.

The RP-TVT needle and the position of its hammock.

The RP-TVT is considered the first generation of standard-length MUSs. It utilises a type-1 polypropylene mesh strip to create a suburethral hammock at the mid-urethral level. One main advantage of this procedure is that it is placed in a tension-free fashion (i.e. supporting the urethra). The RP-TVT procedure was easier to learn than LC, and soon evidence accumulated to show that it had a similar success rate and comparable pattern of postoperative complications to BC, and showing that subsequent prolapse development was much higher with BC. 58 RP-TVT was introduced as a day procedure under local anaesthetic (LA). However, the British Society of Urogynaecology (BSUG) surgical database in 2010 showed that 97% of MUS procedures in the UK were performed under general anaesthetic (GA). 59 The main concern with RP-TVT is bladder injury, with a reported rate of ≈ 6.3%, and is mainly attributed to the blind retropubic trajectory of the insertion needles/trocars. 58

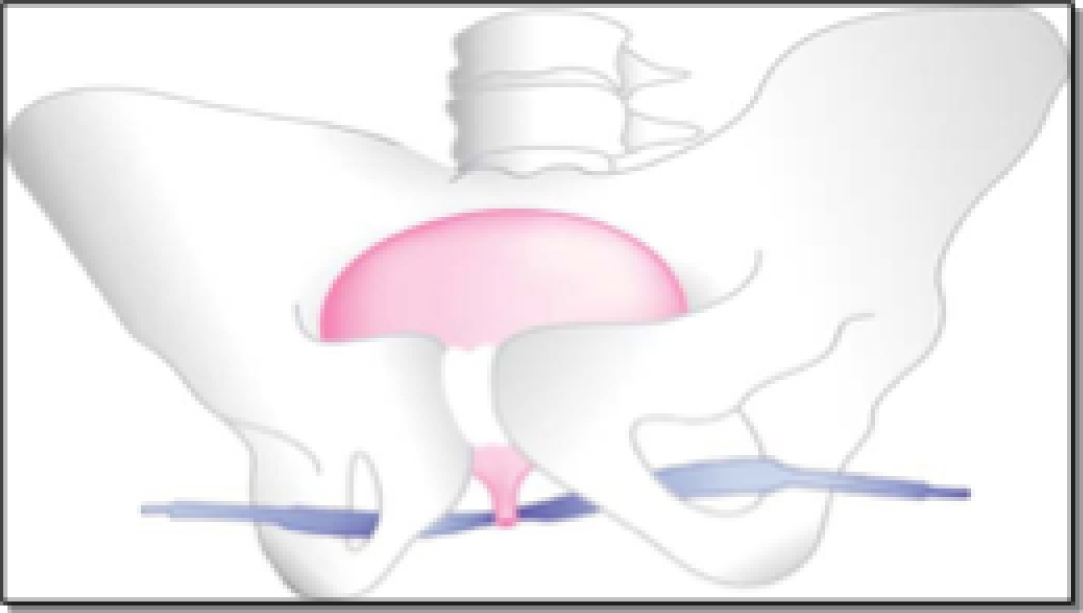

The second generation of standard-length MUSs, the transobturator tension-free vaginal tape (TO-TVT), (Figure 3) was developed as an outside–in TO-TVT by Delorme60 in 2001, followed by the introduction of the inside–out tension-free vaginal tape – obturator (TVT-O) TO-TVT by de Leval and Waltregny in 2003. 61 The main aim was to keep the concept and benefits of the RP-TVT (i.e. tension-free strip of polypropylene mesh supporting the mid-urethra), but to avoid the blind retropubic trajectory to reduce the risk of bladder injury and the more serious, but rare, bowel and vascular injury. In TO-TVT procedures, the insertion trocars pass in a more horizontal fashion (than they do with RP-TVT procedures) through the bilateral obturator complexes, with the skin incisions in the upper medial thighs. These theoretical benefits of TO-TVT materialised, with very low bladder injury rates and lower voiding difficulty rates than with RP-TVT. 62 However, more patients experienced groin/thigh pain with TO-TVTs, especially with the inside–out technique (i.e. TVT-O). 63 This was attributed to the passage of the mesh sling through the adductor muscles and the obturator complexes in the upper thigh (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

The TO-TVT.

At the time of the single-incision mini-sling (SIMS) trial design, a number of systematic reviews and the Cochrane review reported no evidence of significant differences, at 12 months’ follow-up, in the patient-reported and objective cure rates between TO-TVT (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.05) and RP-TVT (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.93 to 0.99). 63–69 Similarly, there were no significant differences in hospital stay (median 0.01 days, 95% CI –0.09 to 0.11 days) or recovery time (median 0.00 weeks, 95% CI –0.14 to 0.13 weeks). The TO-TVT procedure was significantly shorter in operative time (17 minutes, compared with 27 minutes for RP-TVT). Groin pain was more common (12%) with TO-TVT than with RP-TVT, but postoperative VD was significantly less with TO-TVT than with RP-TVT (4% vs. 7%, respectively, RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.89). No bladder injury occurred with TO-TVT; with RP-TVT, the rate of bladder injury was 7%. 70

Mid-urethral slings (both RP-TVT and TO-TVT) rapidly became the most common continence procedures worldwide. 30 Between April 2008 and March 2017, 100,516 MUS procedures were performed in England, compared with 1195 for all other procedures. 32 The Scottish independent review on transvaginal mesh implants71 analysed routinely collected data in Scotland and showed immediate postoperative adverse events (AEs) of 3.7% for RP-TVT, 2.5% for TO-TVT and 7.8% for colposuspension, with similar rates for repeat surgery or for later complications, when comparing standard mid-urethral sling (SMUS) procedures with open colposuspension. 71 The report recommended RP-TVT as the preferred mesh-based procedure for surgical treatment of SUI among women.

Single-incision mini-slings

Single-incision mini-slings were introduced in 2006 with the aim of keeping the advantages of SMUSs, but avoiding both the retropubic trajectory and the perforation of the adductor muscles to reduce the risks of bladder injury and upper thigh pain. 72 It also involves less surgical dissection and shorter mesh length (8–14 cm, compared with 17 ± 2.87 cm for TO-TVT and 20.4 ± 0.8 cm for RP-TVT). A number of small studies showed that the SIMS procedure was more likely to be performed under LA, and had lower incidence of immediate postoperative pain, shorter hospital stay and quicker recovery. 73–76

In 2008, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) produced interventional procedures guidance (IPG) on the SIMS procedure. It found no RCTs evaluating its clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, compared with those of other continence procedures. The NICE IPG recommended that SIMS procedures be confined to research and/or performed under special governance conditions (NICE IPG 262). 77 A Cochrane systematic review in 2011 reported lower patient-reported and objective success rates for SIMSs than for SMUSs, with 6–12 months’ follow-up, and higher incidences of repeat continence surgery and de novo UUI. However, SIMSs were associated with less operative time, less immediate postoperative groin pain and shorter recovery. 78

The introduction of SIMSs was associated with great enthusiasm as a truly ambulatory procedure. A number of SIMS devices (Figure 4) were introduced into clinical practice rather quickly, without any robust assessment of their effectiveness or safety. At the time of design of the SIMS trial, a number of SIMS procedures were used in clinical practice, such as Minitape® (Mpathy Medical Devices Ltd, Glasgow, UK), MiniArc® (American Medical Systems, Inc., Minnetonka, MN, USA), Ophira Mini Sling System (Promedon, Córdoba, Argentina), Zippere™ (ProSurg, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA), Contasure-Needleless® (NeoMedic Ltd, Watford, UK), Solyx™(Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA), Ajust™ (C.R. Bard, Inc., New Providence, NJ, USA), Altis® (Coloplast A/S, Humlebæk, Denmark) and Tissue Fixation System® (TFS) (Adelaide, SA, Australia) (see Figure 4). TVT Secur™ (Ethicon, Inc., Bridgewater, NJ, and Cincinnati, OH, USA) was withdrawn from clinical practice in 2013 by its manufacturer for ‘commercial reasons’.

FIGURE 4.

Types of SIMSs: TVT Secur (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ, USA), Minitape, Mini sling, Zippere and MiniArc, Solyx, Ajust, Epilog, Ophira, Needleless and Altis.

Single-incision mini-slings fundamentally differ from SMUSs because they have a shorter trajectory of insertion, and therefore need a robust anchoring mechanism to the obturator complex with a strong post-insertion pull-out force. 79,80 All clinically used SIMSs share the same mesh material (type-1 polypropylene) and the same insertion technique, through a single vaginal incision; however, they differ in the type/robustness of the anchorage mechanism used. 81 A number of more recently developed SIMSs, such as Ajust and Altis, have an added advantage in that they allow post-anchorage adjustment of the sling tension and have been shown in independent animal studies, assessing their immediate and delayed extraction forces, to be associated with the strongest and most robust anchoring mechanism to the obturator complex. 79,80

At the time of SIMS trial design, several observational studies have shown promising results for SIMSs. The objective and patient-reported success rates were 82–91% and 80–85%, respectively, at 12 months’ follow-up. SIMSs were associated with rapid recovery, low levels of postoperative pain and a short hospital stay. 73,74,82,83 There were, however, reports of potentially higher rates of postoperative voiding difficulty, vaginal exposure, de novo urgency and reoperation rate. 83–85

To our knowledge, our group was the first in the UK to evaluate the adjustable anchored SIMS (Ajust) in a series of interlinked projects. A multicentre prospective cohort study of the adjustable anchored SIMS Ajust among 100 women has shown its acceptability (75%) and feasibility (97%) under LA. 74 A multicentre prospective RCT comparing the SIMS Ajust with the SMUS TO-TVT, with a minimum of 12 months of follow-up, showed no significant differences in the patient-reported success rates [odds ratio (OR) 0.895, 95% CI 0.344 to 2.330; p = 1.000], the objective success rates (OR 0.929, 95% CI 0.382 to 2.258; p = 1.00) or the reoperation rates (OR 0.591, 95% CI 0.136 to 2.576; p = 0.721) between the two groups. 86 Comparable numbers of women in both groups reported significant improvement in QoL (p = 0.190) and sexual function (p = 0.699). Similar results were reached by a Dutch group in a similar small RCT. 87 In addition, a number of observational studies assessing adjustable anchored SIMSs, across multiple countries (UK, France, Italy, USA and Israel) and with varying cohort sizes and lengths of follow-up (6–12 months), have shown similar patient-reported and objective success rates of 85–91%. 73,88,89

Evidence on the longer-term outcomes of adjustable anchored SIMSs emerged. In July 2012, one RCT reported its 5-year follow-up comparing an adjustable anchored SIMS (TFS) with a SMUS. 90 The objective and patient-reported success rates were 83% and 89%, respectively, in the SIMS (TFS) group, compared with 75% and 78%, respectively, in the SMUS group (p = 0.16). Naumann et al. 91 reported their prospective observational study of 51 women who underwent a SIMS procedure (Ajust) with 20–29 months’ follow-up; the patient-reported success rate was 86%.

We conducted the first health economic analysis of the adjustable anchored SIMS Ajust, compared with the SMUS TO-TVT. 92 Results have shown an incremental total cost saving to the health service of £142 per procedure with the adjustable anchored SIMS, not counting the further potential economic gain of earlier return to work among these women. There were no significant differences in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) generated, compared with the SMUS.

An updated systematic review and meta-analysis comparing the effectiveness and complications of SIMSs with those of SMUSs for the surgical management of female SUI included a total of 26 RCTs (n = 3308 women). 81 The results showed that, after excluding RCTs evaluating TVT Secur, which was clinically irrelevant having been excluded from clinical practice, there was no evidence of significant differences between SIMSs and SMUSs in patient-reported success rates (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.00) and objective success rates (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.01) at a mean follow-up of 18.6 months. These results were sustained on comparing the SIMS with TO-TVT and RP-TVT separately.

In the same review, meta-analyses showed that SIMSs lead to significantly earlier return to normal activities and to work [weighted mean differences (WMDs) of –5.08 (95% CI –9.59 to –0.56) and –7.20 (95% CI –12.43 to –1.98), respectively], and to lower immediate postoperative pain scores (WMD –2.94, 95% CI –4.16 to –1.73).

Single-incision mini-slings had numerically higher rates of repeat continence surgery (RR 2.00, 95% CI 0.93 to 4.31), but this difference was not statistically significant. We urged caution in interpretation of results because of the heterogeneity of the small trials, including lack of blinding of the assessors, which can be a source of bias; the level of incomplete data, leading to attrition bias; and the relatively short term of follow-up.

The Cochrane review in 2014 included data from 3290 patients from 31 studies and showed that SIMSs were less effective than other tapes, but once data from the withdrawn TVT Secur were excluded, the difference was no longer statistically significant. 93 The authors concluded that there was not enough evidence to show difference between the SIMS and the SMUS, and recommended an adequately powered RCT with long-term follow-up to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of SIMSs, compared with those of SMUSs.

The SIMS trial compares the patient-reported success rate and cost-effectiveness of SIMSs with those of SMUSs.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter are reproduced from Abdel-Fattah et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this chapter are also reproduced from Beard et al. 94 Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

Trial design

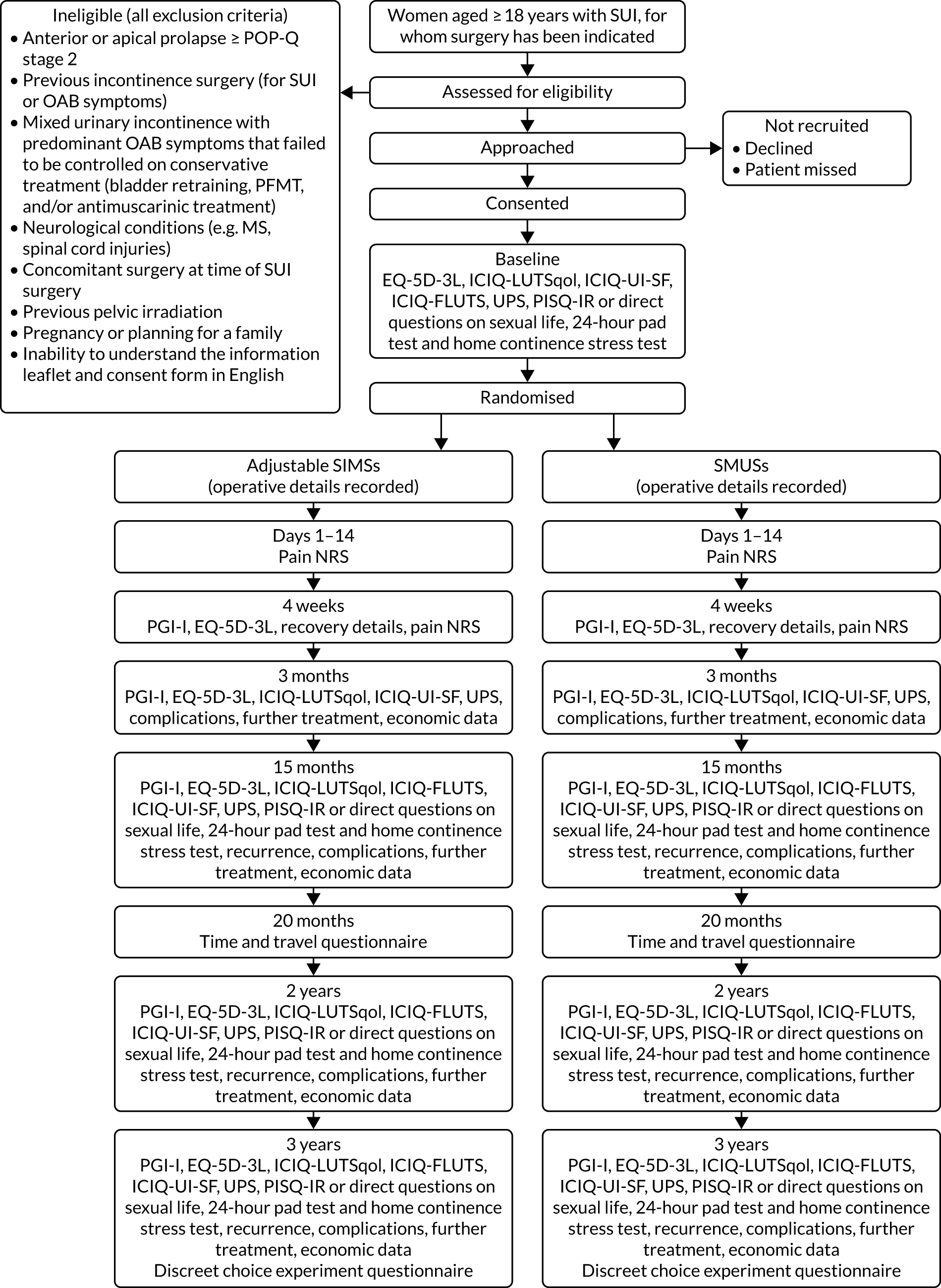

The trial was a pragmatic, multicentre non-inferiority RCT comparing adjustable anchored SIMSs with tension-free SMUSs in the surgical management of SUI among women. The trial protocol has been published in an open-access journal. 1

The trial design is presented in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5.

Trial design. EQ-5D-3L, EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version; ICIQ-FLUTS, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms; ICIQ-LUTSqol, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms-Quality of Life; ICIQ-UI-SF, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Urinary Incontinence-Short Form; MS, multiple sclerosis; NRS, numerical rating scale; PGI-I, Patient Global Impression of Improvement; PISQ-IR, Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire, International Urogynecological Association-Revised; POP-Q, Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System; UPS, Urgency Perception Scale.

Interventions

The interventions compared were tension-free SMUSs, including RP-TVT and TO-TVT, and adjustable anchored SIMSs, which fulfilled the following criteria of robust anchorage and post-insertion adjustability:

-

made of type-1 polypropylene mesh – monofilament and macroporous (pore size ≥ 75 µm).

-

robustly anchored to obturator complex (robust insertion is defined as immediate pull-out force of 12 N and/or 4-week pull-out force of 30 N).

-

fully adjustable sling post insertion/anchorage.

-

proven feasibility to be done under LA.

-

minimum of level-2 evidence showing their safety and short-term (minimum 3 months) patient-reported outcomes.

Two types of SIMSs used in the UK fulfilled these criteria at the time of the study: Ajust and Altis.

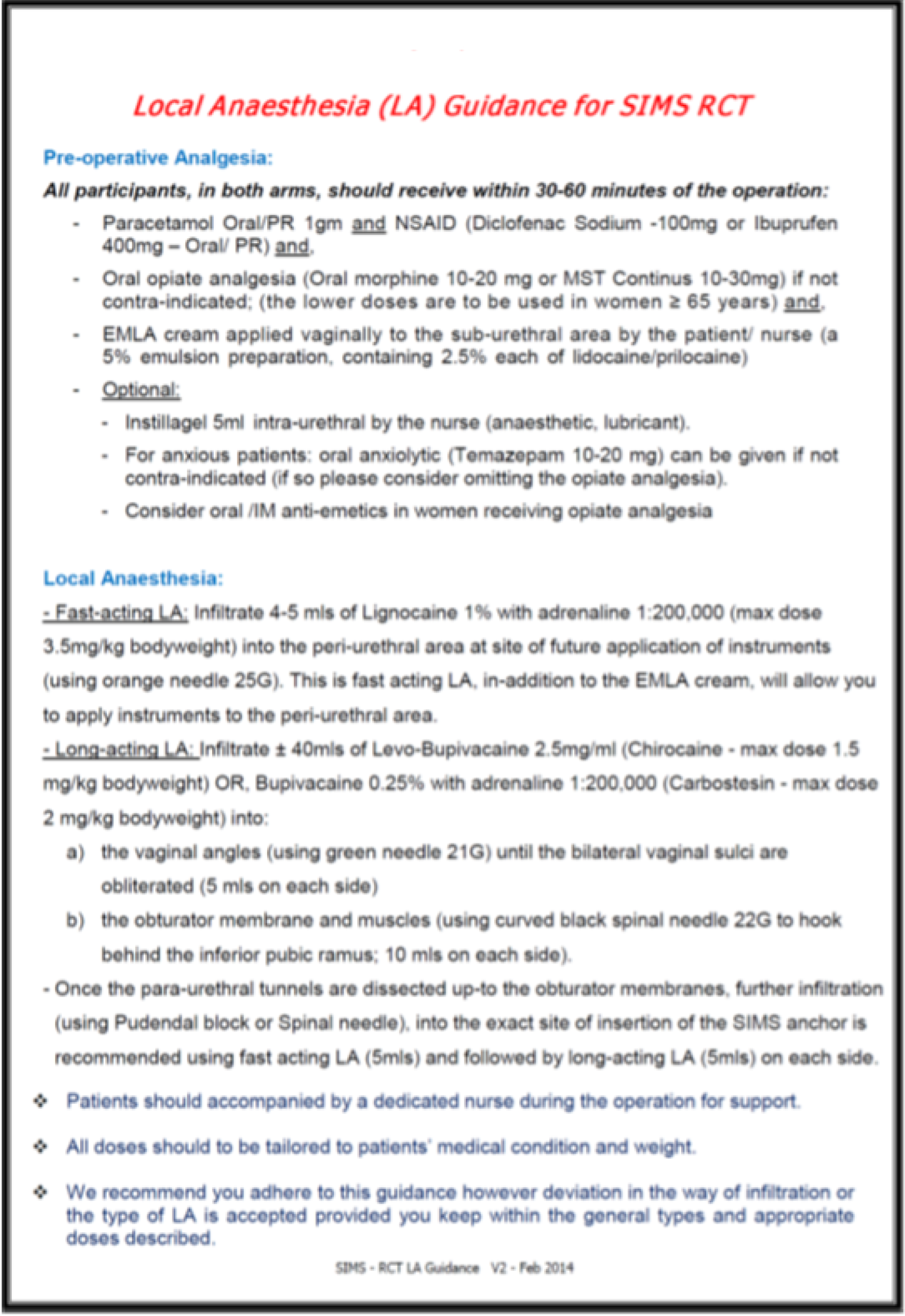

Standard MUS procedures were performed under GA or deep intravenous sedation, whereas SIMS procedures were offered under LA as standard, but all participants were informed that they could opt for GA. A participant’s request for a GA was respected at all stages of the trial/procedure. A standard LA protocol (previously published and successfully used in two previous studies74,86) was used as a LA guide (see Appendix 1).

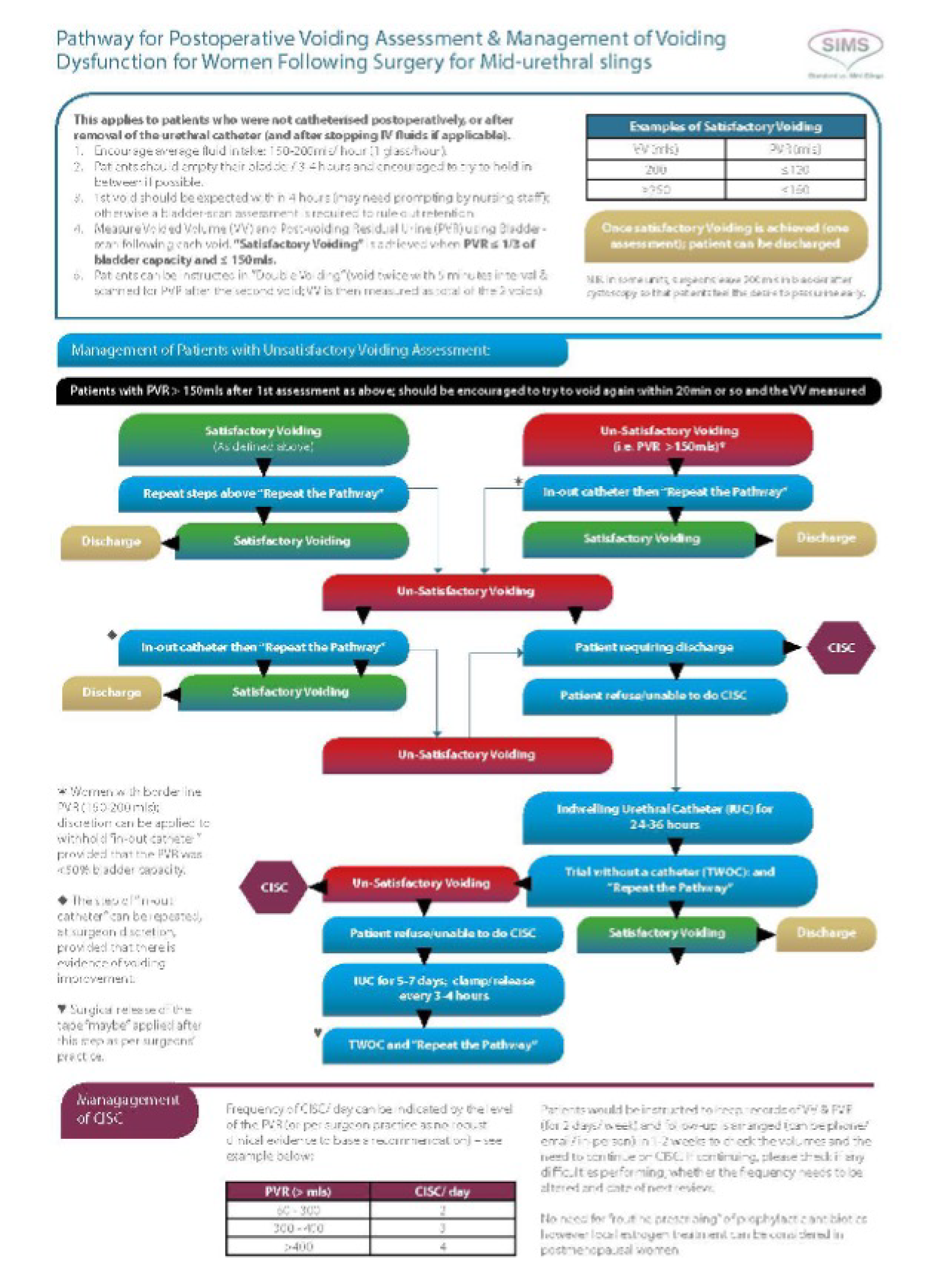

All participants received a preoperative analgesia (30–60 minutes prior to the operation): paracetamol and a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (diclofenac sodium or ibuprofen), a vaginal application of EMLA™ cream (AstraZeneca plc, Cambridge, UK) (a 5% emulsion preparation, containing 2.5% each of lidocaine and prilocaine) and an optional 10 ml of intraurethral Instillagel® (Almed GmbH, Berlin, Germany) (anaesthetic, antiseptic lubricant). All participants also received preoperative/intraoperative prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics. A cystoscopy (rigid or flexible) was performed in all women following insertion of the sling. Postoperatively, all participants underwent a voiding assessment, including assessment for post-voiding residual urine volume using a bedside bladder scanner, when available at the collaborating centre (see Appendix 1).

Adjustable anchored single-incision mini-slings

The choice of adjustable anchored SIMS (Ajust or Altis) was dependant on the device used as standard in the collaborating centre and/or surgeon preference and experience.

A standard combination of fast- and delayed-action LA (dose was dependant on participant’s body weight) was infiltrated vaginally into either side of the mid-urethra, the vaginal angles (sulci) and behind the inferior pubic ramus into the obturator complex (e.g. using a curved black spinal needle and/or pudendal block needle). When possible, women were accompanied throughout the procedure by a health-care professional for support. The women’s bladders were emptied with a catheter. An adjustable anchored SIMS (meeting the prespecified criteria described previously) was used. The standard insertion steps for the adjustable anchored SIMS (Ajust and Altis) were as follows: women were positioned in lithotomy position with hips flexed at 90–100 °; LA infiltration was conducted as above; a suburethral vertical vaginal incision (≈ 1.5 cm) was made; and bilateral paraurethral tunnels were created reaching to the posterior margin of the inferior pubic ramus, but without piercing the obturator membrane. Further infiltration of LA into the obturator complex was carried out; the SIMS, with the ‘fixed anchor’ end mounted on the applicator, was introduced through the pre-dissected paraurethral tunnel until reaching behind the inferior pubic ramus. The applicator then pivoted slowly behind the ramus, allowing the fixed anchor to maintain its position in the obturator complex (membrane and obturator internus muscle) at points equivalent to 10 and 2 o’clock in relation to the urethral orifice. The insertion steps were repeated on the other side, allowing the ‘adjustable anchor’ to be fixed in the contralateral side. With the SIMS now robustly anchored, the tension was then adjusted as required to achieve continence while avoiding voiding difficulty. The cough stress test (CST) was conducted when possible. For Ajust, the adjustable anchor was then locked (this was not required with Altis). A cystoscopy was then performed to exclude lower urinary tract (LUT) injury and the vaginal incision was closed.

Standard tension-free mid-urethral slings

The choice of RP-TVT or TO-TVT was dependant on the standard procedure and device used in the collaborating centre and/or surgeon preference and experience.

Retropubic tension-free vaginal tape

The RP-TVTs were type-1 polypropylene mesh (monofilament and macroporous, with a pore size of ≥ 75 µm). The procedure (developed by Ulmsten and Petros55,56) was done under GA or intravenous sedation as per the standard practice of each surgeon. Women were positioned in lithotomy position. The women’s bladders were emptied with a Foley catheter. Close to the superior rim of the pubic bone, two 1-cm long transverse incisions 3 cm either side of the mid-line were made after injection of LA into the abdominal skin just above the symphysis pubis, down along the back of the pubic bone to the retropubic space and vaginally into the periurethral area. An incision of ≈ 1.5 cm was made in the mid-line of the suburethral vaginal wall, followed by dissection of the periurethral tunnels to allow introduction of the RP-TVT needle. A stent was then inserted into the Foley catheter to deviate the uretherovesical junction away from the path of the needle. The RP-TVT needle perforated the urogenital diaphragm and was brought up to the abdominal incision as close as possible to the back of the pubic bone. The procedure was then repeated on the other side, and a cystoscopy was performed to exclude LUT injury. The CST was then performed, according to the surgeon’s standard technique; the sling adjusted in a tension-free fashion; and the incisions closed.

Transobturator tension-free vaginal tape

The TO-TVTs were type-1 polypropylene mesh (monofilament and macroporous, with a pore size of ≥ 75 µm). All procedures were performed under GA (as originally described by Delorme60 and de Leval and Waltregny61 for the outside–in and inside–out routes, respectively). The lithotomy position was used with hips hyperflexed at 100–110 °. LA was infiltrated into the vaginal angles in a similar regime to the one used in the adjustable SIMS insertion (see previous section). The women’s bladders were emptied with a Foley catheter. A suburethral longitudinal vaginal incision of ≈ 1.5 cm was made, and bilateral paraurethral tunnels were created, reaching to the posterior margin of the inferior pubic ramus. Bilateral groin incisions were made 1–2 cm lateral to the labio-femoral fold and 2 cm above level of the urethra. The TO-TVT trocar was inserted from groin incisions at 90 ° to pierce the groin muscles, obturator muscles and membranes, and then guided by the surgeon’s finger to the vaginal incision. The TO-TVT was then mounted on the trocar and the trocar was withdrawn in reverse order. The previous two steps were repeated on the contralateral side, achieving a horizontal suburethral placement, and the TO-TVT was then adjusted until tension free. For the inside–out technique of insertion, the TO-TVT was introduced in the reverse route, from the vaginal incision towards the groin, using the winged guide to protect the LUT. A cystoscopy was performed to exclude LUT injury. Vaginal and skin incisions were then closed.

Setting

Clinical centres

The trial was conducted in 21 secondary and tertiary care acute hospital settings across the UK. NHS Grampian was the clinical co-ordinating centre, housing the chief investigator.

Each collaborating centre had at least one participating surgeon who was competent in performing SIMS procedures under LA prior to enrolling in the RCT. This experience was demonstrated by the surgeons having performed an average of 12 adjustable anchored SIMS procedures (with six or more procedures performed under LA) in the preceding year. Clinical experts in the trial team watched the surgeons performing two SIMS procedures under LA in their local hospitals and deemed them eligible for the trial. All collaborating centres also had at least one participating surgeon who was experienced in at least one type of SMUS (RP-TVT or TO-TVT) and had performed an adequate workload (an average of 20 procedures) in the preceding 2 years. In 20 out of 21 centres, the same surgeon was experienced in both procedures (SIMS and SMUS procedures). In five centres, at least one additional surgeon participated in the trial and was experienced in either procedure.

Population

The population comprised women aged ≥ 18 years with SUI, who had been referred to one of the collaborating centres from across the UK, and for whom MUS surgery had been indicated. Women had completed their families and failed or declined conservative treatment: PFMT. All women had either urodynamic stress incontinence or urodynamic mixed incontinence with predominant SUI bothering symptoms. Women with pure symptoms and signs of SUI, and no symptoms of OAB or voiding difficulties, were included without urodynamic investigations, as per NICE clinical guidelines 171,19 at the time. Patients were discussed in the local multidisciplinary team meetings as per standard local practice.

Preoperative urodynamic investigations included free uroflowmetry, post-voiding residual urine volume assessment and subtracted filling cystometry. Other tests, such as urethral pressure profile and leak point pressures, were not mandatory.

We excluded women if they had one or more of the following:

-

anterior or apical prolapse ≥ stage 2 on the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification system

-

previous incontinence surgery (for SUI or OAB)

-

MUI with predominant OAB symptoms (defined as OAB failed to be controlled on conservative treatment, such as bladder retraining, PFMT and/or antimuscarinic treatment)

-

neurological conditions (e.g. multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injuries)

-

concomitant surgery at time of SUI surgery

-

previous pelvic irradiation

-

pregnancy or planning for a family

-

inability to understand the information leaflet and consent form in English.

There were 14 minor breaches to the exclusion criteria of concomitant surgery at the time of SUI surgery. These are detailed in Appendix 5, Table 35.

Identifying participants

Local procedures to identify participants at the participating centres were different, and the timing and mode of approach to patients and the consent process varied to accommodate both the variability at the centres and the needs of the patients. When possible, the patient information leaflet (PIL) was sent to patients together with their clinic appointments, ensuring that they had ample time (> 24 hours) to consider participating before being approached by the research team at the clinic.

Patients likely to require MUS surgery for SUI and who met the eligibility criteria were identified at the pre-assessment clinics, urodynamic clinics and outpatient urology/gynaecology clinics by their consultant, clinical team or a research nurse (RN).

A baseline invitation letter was available to centres to send to potential participants before they were approached at the centre. This contained local details and was personalised for each centre with the hospital trust logo. Patient address labels were then added, and the letters sent out with a copy of a PIL. Between February 2014 and June 2016, patients were also given a detailed surgical information patients’ leaflet, produced by the Scottish Pelvic Floor Network, on various MUSs. After June 2016, the surgical information was updated according to national guidelines and incorporated into the trial PIL.

Alternatively, these documents were given to patients attending clinics to read before the trial was discussed with them. The consultant or RN introduced the trial to the patient, provided them with the PIL and answered any queries. Patients whose first approach was at the clinic were given as much time as they required to consider participation. Patients could decide to participate during their hospital visit or take the recruitment pack home and decide later.

A log was taken of all potentially eligible patients assessed to document the reasons for non-inclusion in the trial (e.g. the reason why they were ineligible or declined to participate) to inform the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram. Brief details of potentially eligible patients were recorded in the screening logs at each centre (as an aid to monitoring potential participant inclusion). As the screening logs held personal data of potential participants, who had not given consent to participate, these screening logs were not shared with the trial office; they were seen only by the centre’s research staff.

If a patient decided to participate during the hospital visit, they signed the consent form and completed the baseline questionnaire at this visit. If required, the baseline questionnaire could also be completed at home and returned in the stamped addressed envelope (addressed to the centre) provided. At the hospital visit, they also received the 24-hour pad test and the home continence stress test (see Appendix 1) to complete at home 48 hours prior to admission for surgery, and returned them to the RN at the surgery appointment. 1

Some patients decided to participate during the hospital visit, whereas others agreed to be contacted at home by the local RN, taking home the recruitment pack containing the PIL, consent form, baseline questionnaire, stamped addressed envelope, the 24-hour pad test and the home continence stress test. In the latter case, typically, the patient was telephoned by the local RN to discuss any questions about participating in the trial. If the patient agreed to participate, they completed and signed the consent form, then completed the baseline questionnaire, and returned both to the centre in the stamped addressed envelope. The 24-hour pad test and the home continence stress test were completed at home (48 hours prior to admission for surgery) and returned to the RN at the surgery appointment.

The pads returned at the surgery visit for the 24-hour pad test were weighed, the weight and number of pads was recorded, and the pads were disposed of by the local team.

Informed consent

The PIL explained that the trial was investigating the use of adjustable anchored SIMSs and tension-free SMUSs for the surgical management of SUI among women. Signed informed consent forms were obtained from all participants. Patients who could not give informed consent (e.g. due to incapacity) were not eligible to participate. The participant’s permission was sought to contact them about any potential long-term follow-up for the SIMS trial and to inform their general practitioner (GP) that they were taking part in this trial.

Randomisation

Participants were allocated using a remote web-based randomisation service at the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT) in the University of Aberdeen. Participants were allocated 1 : 1 to either the SIMS or the SMUS (RP-TVT or TO-TVT) using a minimisation algorithm based on centre and previously supervised PFMT within the previous 2 years (yes/no). Participants were given a unique trial number on randomisation. An e-mail was automatically sent to the RN at the trial centre and to the trial office detailing the randomisation allocation and trial number.

Participants had to complete (and, if completed remotely, return) the baseline questionnaire before being informed of their allocated treatment.

Trial outcome measures and schedule of assessment

The SIMS trial outcomes and schedule of measurement are detailed in Table 1

| Measure | Baseline | Surgery details | Days 1–14 | 4 weeks | 3 months | 15 monthsa | 20 months | 2 years | 3 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical/surgery details | ○ | ○ | |||||||

| Pain NRS/daily text messaging | ● | ● | |||||||

| Recovery | ● | ● | |||||||

| PGI-I scale | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| EQ-5D-3L | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| ICIQ-LUTSqol | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| ICIQ-FLUTS | ○ | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| ICIQ-UI-SF and UPS | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| PISQ-IR or direct questions on dyspareunia and coital incontinence | ○ | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| 24-hour pad test | ○ | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Home continence stress test | ○ | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Health-care resource use/complications/recurrence/further treatment | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| Time and travel questionnaire | ● | ||||||||

| DCE | ● |

We collected data using participant questionnaires at baseline, at 4 weeks and 3 months postoperatively, and at 15 months and 2 and 3 years post randomisation. We chose 15 months post randomisation to reflect the average waiting time for surgery, which was up to 3 months.

Baseline assessment comprised the following:

-

demographic data – baseline use of anticholinergics/prophylactic antibiotics/clean intermittent self-catheterisation (CISC); the urodynamics diagnosis; any previous relevant surgery; 24-hour pad test and home continence stress test.

-

symptom severity questionnaires – International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Urinary Incontinence-Short Form (ICIQ-UI-SF), Urgency Perception Scale (UPS) and International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (ICIQ-FLUTS). 95–97

-

quality-of-life questionnaires – EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), and International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms-Quality of Life (ICIQ-LUTSqol). 98,99

-

sexual function – as part of a substudy comparing the two approaches to assessing sexual function:

-

half the cohort (50% selected at random; see the following paragraph for discussion) were given the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire, International Urogynecological Association-Revised (PISQ-IR)100

-

the other 50% received direct questions on dyspareunia and coital incontinence, derived and modified from the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Female Sexual Matters Associated with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (ICIQ-FLUTSsex). 101

-

At the time of the RCT design, the majority of the Project Management Group (PMG) members felt that the PISQ-IR was long and intrusive. In the interest of reducing participant burden, especially with potentially intrusive questionnaires, we decided to undertake a substudy to assess two approaches of assessing the impact of the procedure on participants’ sexual function: the PISQ-IR versus simple direct questions on sexual function. Hence, only 50% of participants (randomly selected) received the PISQ-IR; the rest received direct questions on dyspareunia and coital incontinence (derived and modified from the ICIQ-FLUTSsex). 100,101

Operative data were collected, comprising operative time, blood loss, intraoperative complications, postoperative voiding assessment and duration of hospital stay. We also collected pain scores and analgesia use in recovery, at hospital discharge and daily up to 14 days postoperatively.

Follow-up data comprised the following.

-

At 4 weeks post operation, participants completed the Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I) scale and the EQ-5D-3L, and provided information on pain (i.e. a pain score) and return to normal activities. At 3 months post operation, participants also completed the ICIQ-UI-SF and the ICIQ-LUTSqol, and provided information on AEs and additional treatments. At 15 months and 2 and 3 years post randomisation, they also completed the ICIQ-FLUTS and sexual function assessment as explained above.

-

On completion of the questionnaires at 15 months, 2 years and 3 years post randomisation, participants were sent the 24-hour pad test and home continence stress test to complete.

-

At 20 months, participants were asked to complete an additional health economic data questionnaire, which included the patient time and travel costs questionnaire. Sending this questionnaire at 20 months aimed to minimise participant burden when completing the primary outcome questionnaire at 15 months.

-

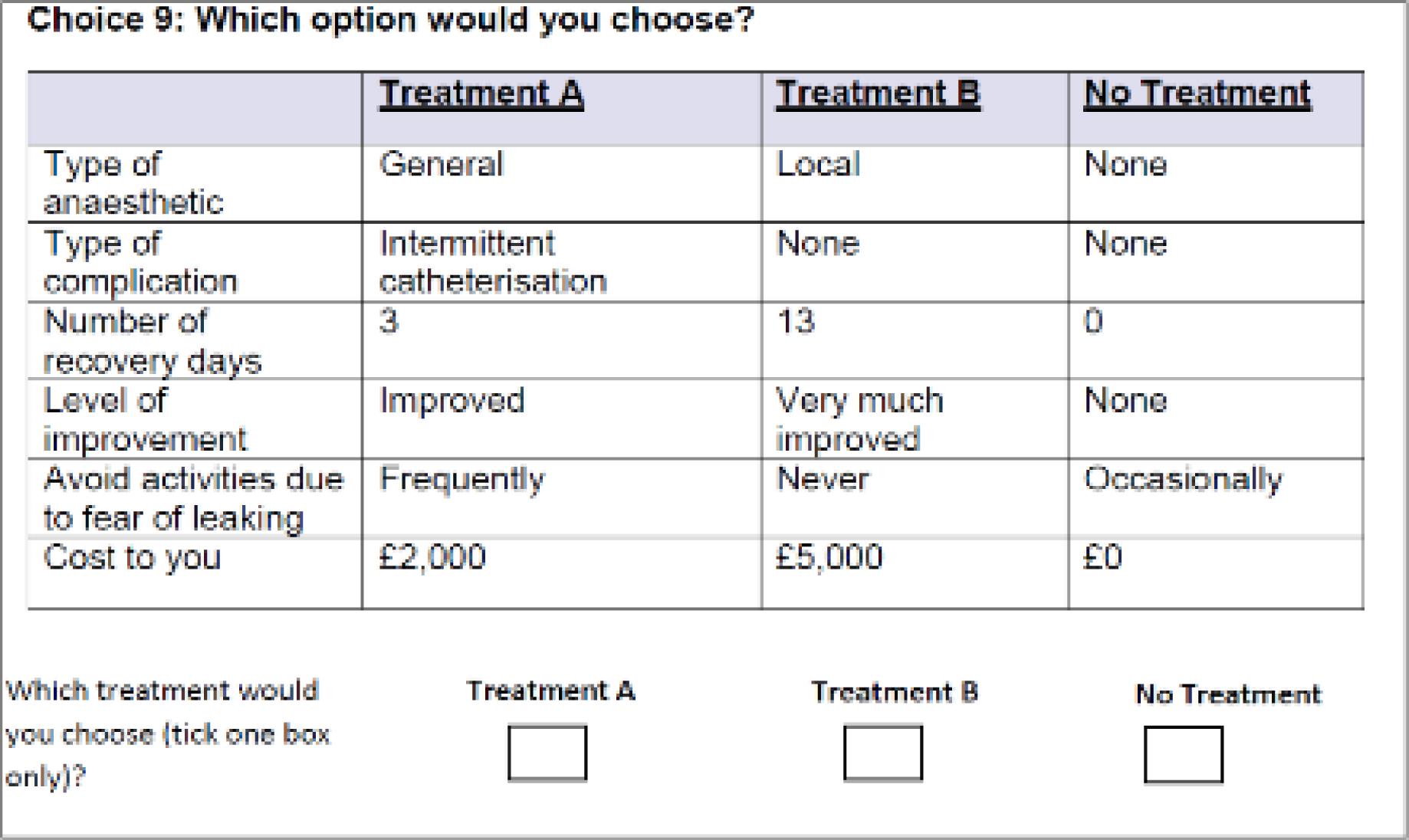

The discrete choice experiment (DCE) was sent to all participants on completion of their questionnaire at 3 years.

See Table 1 for the source and timing of measures.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was patient-reported success as measured by the PGI-I scale at 15 months post randomisation. We dichotomised the PGI-I scale responses: ‘success’ was defined as ‘very much improved’ or ‘much improved’, and the rest of the responses were defined as failures. This definition of ‘success’ is widely used within the research field of surgical treatment of SUI; therefore, it facilitates comparison of our results with those of other trials in the literature.

We chose patient-reported success rate as the primary outcome as it reflects patient experience, compared with the objective measures, which can overestimate the success of SUI surgery. The PGI-I scale is a simple, direct and easy-to-use scale that is intuitively understandable to clinicians and patients. It is widely used for assessment of patient-reported outcomes following surgical and conservative interventions for treatment of UI. It has excellent construct validity. 102

Secondary outcomes comprised the following: AEs, such as bladder/urethral injuries; blood loss of ≥ 200 ml; postoperative voiding difficulties; pain; mesh exposure; dyspareunia; long-term self-catheterisation; worsening urgency; postoperative pain using a pain numerical rating scale, assessed on days 1–14; objective success rates, assessed by the 24-hour pad test; LUT symptoms, as measured using the ICIQ-FLUTS and ICIQ-UI-SF; health-related QoL profile derived from the EQ-5D-3L, pain scores and ICIQ-LUTSqol; impact on sexual function, derived from the PISQ-IR; and reoperation rates for SUI. Operative AEs were collected from operative data collection sheets. Other AEs were collected at each time point as they were reported by participants, reviewed and confirmed by the relevant centre, and onward reported as appropriate. Data on participants receiving extra treatments as outpatients or inpatients were also collected as supplementary hospital visits’ reports.

Compliance with allocated treatment

The SIMS trial was designed as a pragmatic trial and compliance with trial intervention was monitored using a question on the surgery case report form (CRF).

Safety reporting

We defined AEs as any untoward medical event affecting a participant. AEs were recorded from the time of joining the trial until follow-up was complete. Each initial AE was considered for severity, causality and expectedness, and reclassified as a serious event when appropriate.

Adverse events did not include the following:

-

continuous and persistent disease or symptom, present before the trial, which failed to improve, such as urgency, urgency incontinence, VD, pain or dyspareunia

-

treatment failure – persistence or recurrence of UI.

Worsening pain or the site of pain changing were AEs.

We identified the following as potentially expected AEs linked to surgery.

-

Intraoperative complications: bleeding, bladder/urethral injury, bowel injury, nerve injury (obturator/dorsal nerve of clitoris), injury to blood vessels, hypersensitivity to the LA or GA and/or any of the medications or materials used, pain, shaking/dizziness, change of procedure or device and/or type of anaesthesia.

-

Immediate postoperative complications: pain in the hip/thigh or the vagina, infection (chest, urinary tract), bleeding, fever, haematuria, syncope, dizziness, voiding difficulties/urinary retention and thromboembolism.

-

Later postoperative complications: pain in the hip/thigh or the vagina, vaginal mesh exposure, mesh erosion to the LUT, haematoma, abscess formation and nerve injury. In addition, new onset or worsening of any of the following: dyspareunia, vaginal discharge, voiding difficulties/urinary retention, long-term self-catheterisation (CISC) and urgency/urgency incontinence.

We adhered to the standard definition of serious adverse events (SAEs) as those leading to death or life-threatening, unplanned hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation (except for social/geographical reasons),leading to persistent or significant disability or incapacity, or otherwise considered medically significant.

Hospitalisations for treatment planned prior to randomisation and hospitalisation for elective treatment of a pre-existing condition, or complication arising from either, were not considered to be AEs or SAEs.

Adverse events were assessed in respect of seriousness to determine if they were a SAE by the local principal investigator (PI), the chief investigator or their deputies.

A total of 27 SAEs were reported during the trial, (see Appendix 5, Table 34). All SAEs were reviewed by the sponsor from 11 September 2014. The two SAEs reported prior to this date were sent to sponsor on 19 September 2014 for their review. The Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) reviewed all SAEs annually at first, but from September 2017 to the end of the trial, it reviewed all SAEs as they occurred.

Blinding

Baseline data were collected prior to randomisation using self-completed questionnaires. It was not possible to blind the participants, given the nature of the procedures (SIMS procedure under LA and SMUS procedure under GA). Surgeons could not be blinded for obvious surgical reasons. Outcome assessment was primarily through participant-completed postal questionnaires.

Sample size

The aim of the trial was to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of adjustable anchored SIMSs, compared with those of tension-free SMUSs, and so the trial was designed to show non-inferiority. If SIMSs were superior in having shorter hospital stays, less postoperative pain, earlier recovery and greater cost-effectiveness, then 10% was the maximum inferiority margin acceptable, as determined by expert clinicians.

Published literature at the time of the trial design suggested that the 15-month success rate was approximately 85% for the SMUS arm. Several smaller studies indicated a similar success rate for SIMSs. Power estimates were obtained by simulating trials of a fixed sample size and using the proportion of simulated trials where the lower bound of a two-sided 95% CI for the difference in success rates (SIMS – SMUS) was > –10%. These simulations showed that 275 women randomised to each arm would give 90% power. Adjusting the total of 550 participants to allow for 15% dropout gave a required sample size of 650 participants. In November 2016, this was reduced to 600 owing to difficulties completing recruitment within time and budget. Under the same assumptions, this reduced the power to 88%. There was no interim analysis of the primary outcome to inform the re-estimation of statistical power.

Statistical analysis of outcomes

Predefined statistical analyses were included in the published protocol. 1 All statistical analyses were based on all randomised women, regardless of whether they complied with their randomised surgery. The comparisons were between those who were randomised to receive a SIMS and those who were randomised to receive a SMUS.

The primary outcome was the PGI-I dichotomised to success and failure. Success was defined as a response of ‘very much improved’ or ‘much improved’; all other responses were classed as failure. The primary outcome was analysed using a generalised linear model (GLM) with binomial family and log-link function. Fixed effects were included for the treatment (receiving a SIMS procedure) and having received supervised PFMT within the previous 2 years. Robust variances were used to adjust for clustering by centre. Statistical significance was at one-sided 2.5%, as standard for a non-inferiority design, with CIs calculated at the usual 95% width. An intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was performed with all participants remaining in their randomised group. A prespecified per-protocol analysis was also carried out of participants who received their allocated randomised surgery. The adjusted difference is obtained from the difference between the predictive margin of the SIMS and SMUS groups.

The primary outcome was tested in a non-inferiority framework with a margin of 10%. The null hypothesis was that SIMSs were inferior to SMUSs by at least 10%; a p-value of < 0.025 would indicate that the null hypothesis could be rejected, thereby suggesting that SIMSs were non-inferior to SMUSs.

The prespecified statistical analysis plan did not provide precise details on dealing with missing data; post hoc, we have chosen to use multiple imputation using chained equations to account for missing data on the primary and secondary outcomes. The imputation model used the treatment variable; the baseline characteristics of age, body mass index (BMI) and receipt of PFMT; number of previous deliveries; and the responses to the questions at baseline on how often a participant leaks, the amount leaked and how much urinary leakage interferes with daily life. Collected outcomes for other participants and the baseline measures of the outcomes were also used in the imputation model. If baseline data were missing for a participant, they were imputed with the centre mean or median, as appropriate.

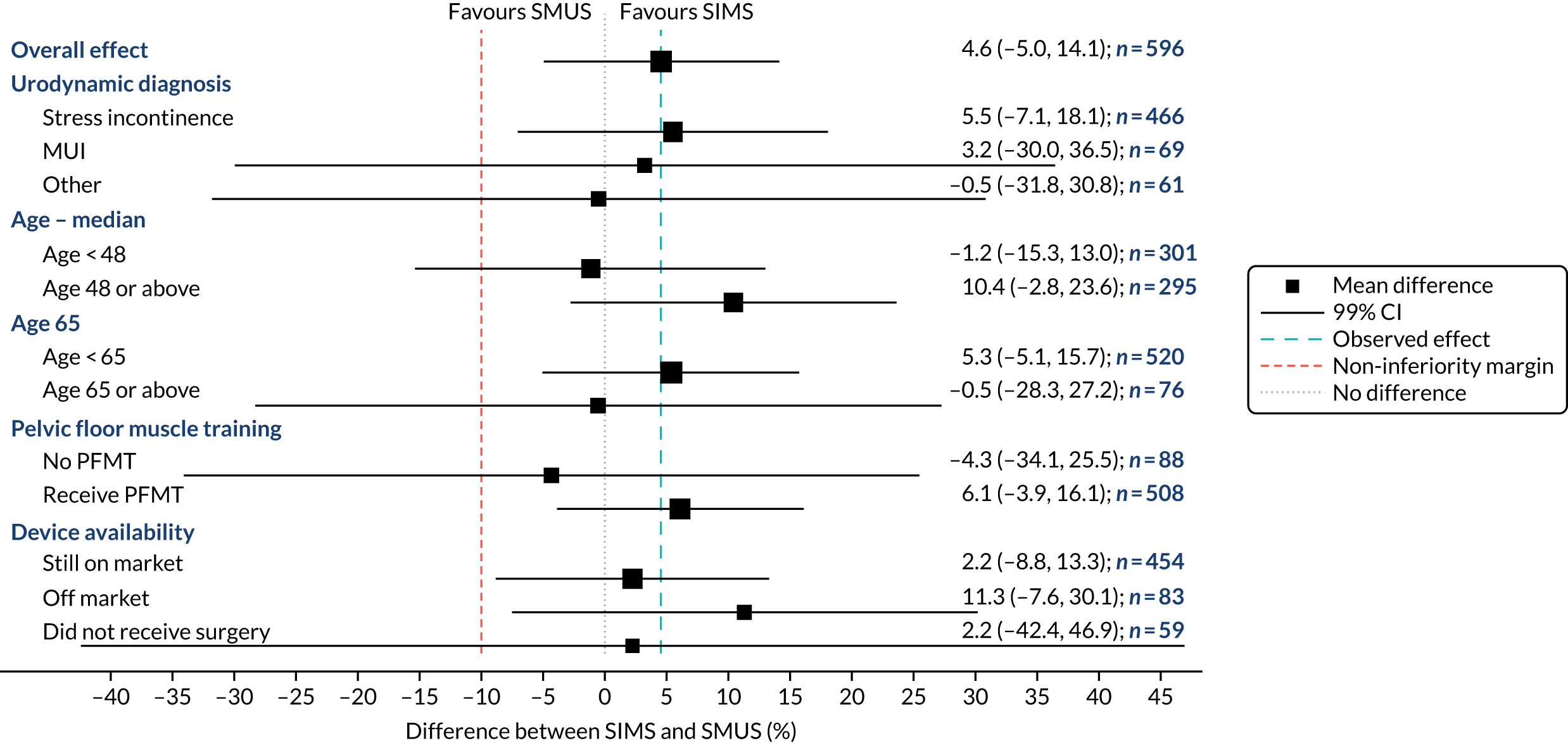

Subgroup analyses of the primary outcome between the following groups were carried out at the stricter one-sided 0.5% level, and are therefore summarised with 99% CIs:

-

urodynamic stress incontinence versus urodynamic mixed incontinence

-

types of adjustable anchored SIMS (Ajust and Altis) versus each type of SMUS (i.e. RP-TVT and TO-TVT, separately)

-

age – above and below the observed median age of the recruited women

-

a post hoc analysis for age – < 65 years, compared with those aged ≥ 65 years

-

a post hoc comparison between devices withdrawn from clinical use and those still available

-

a post hoc comparison between those who had received supervised PFMT in the previous 2 years and those who had not.

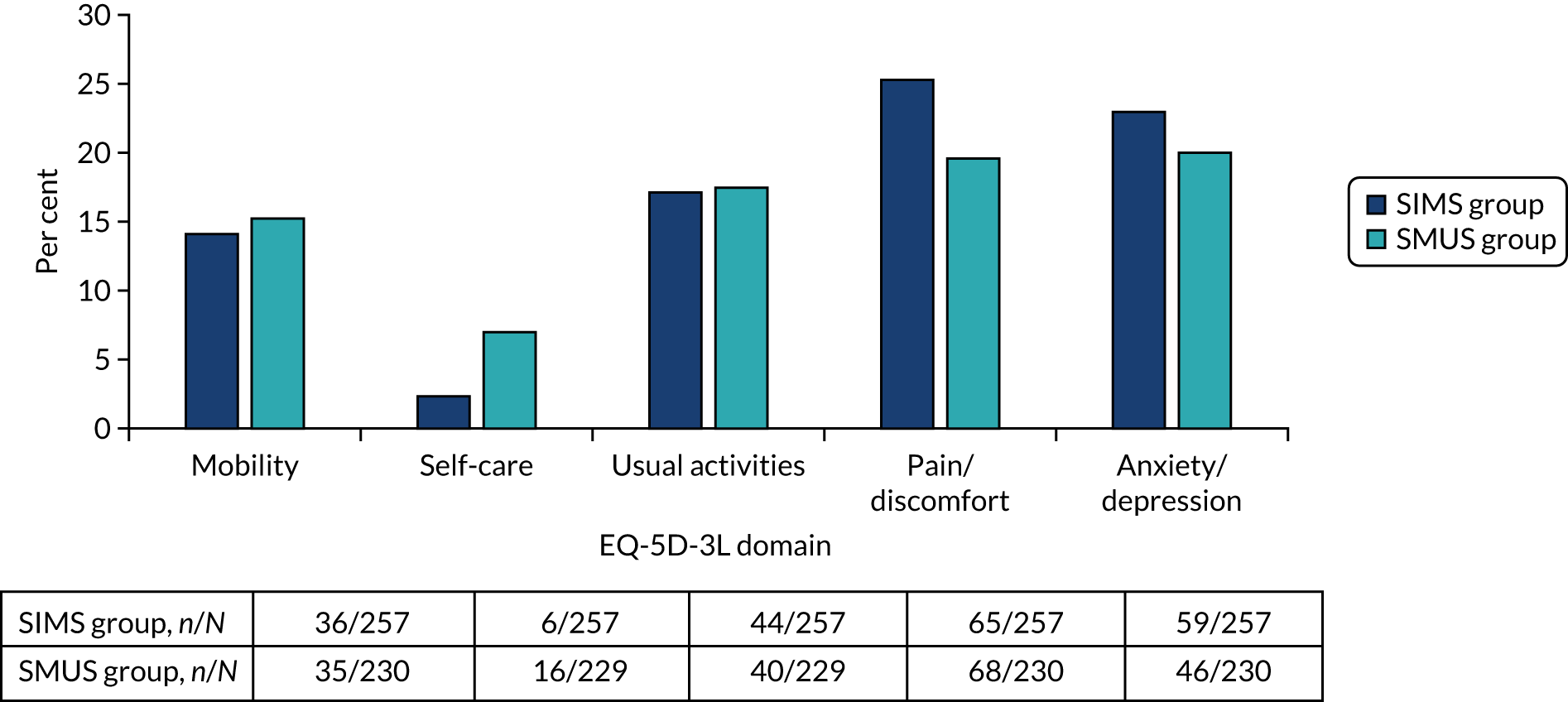

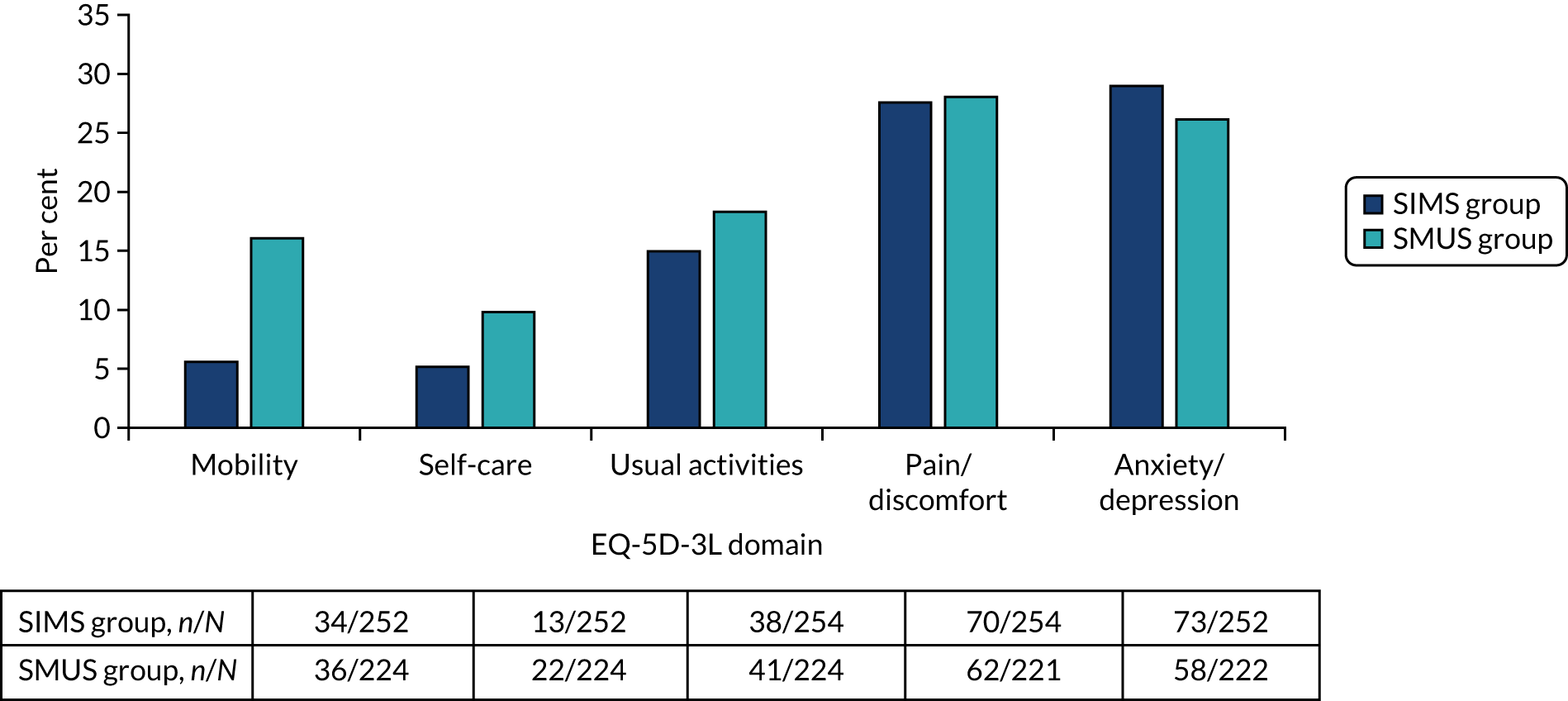

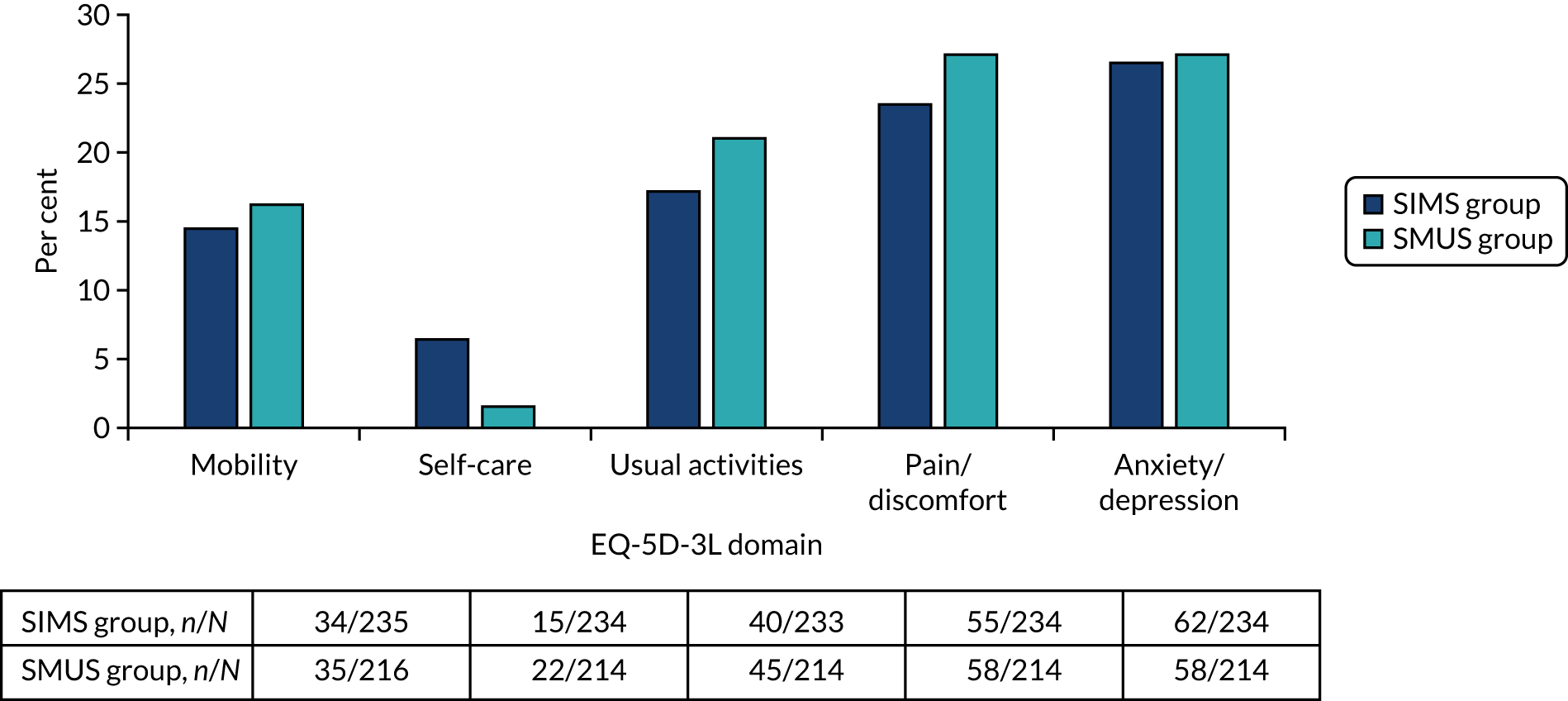

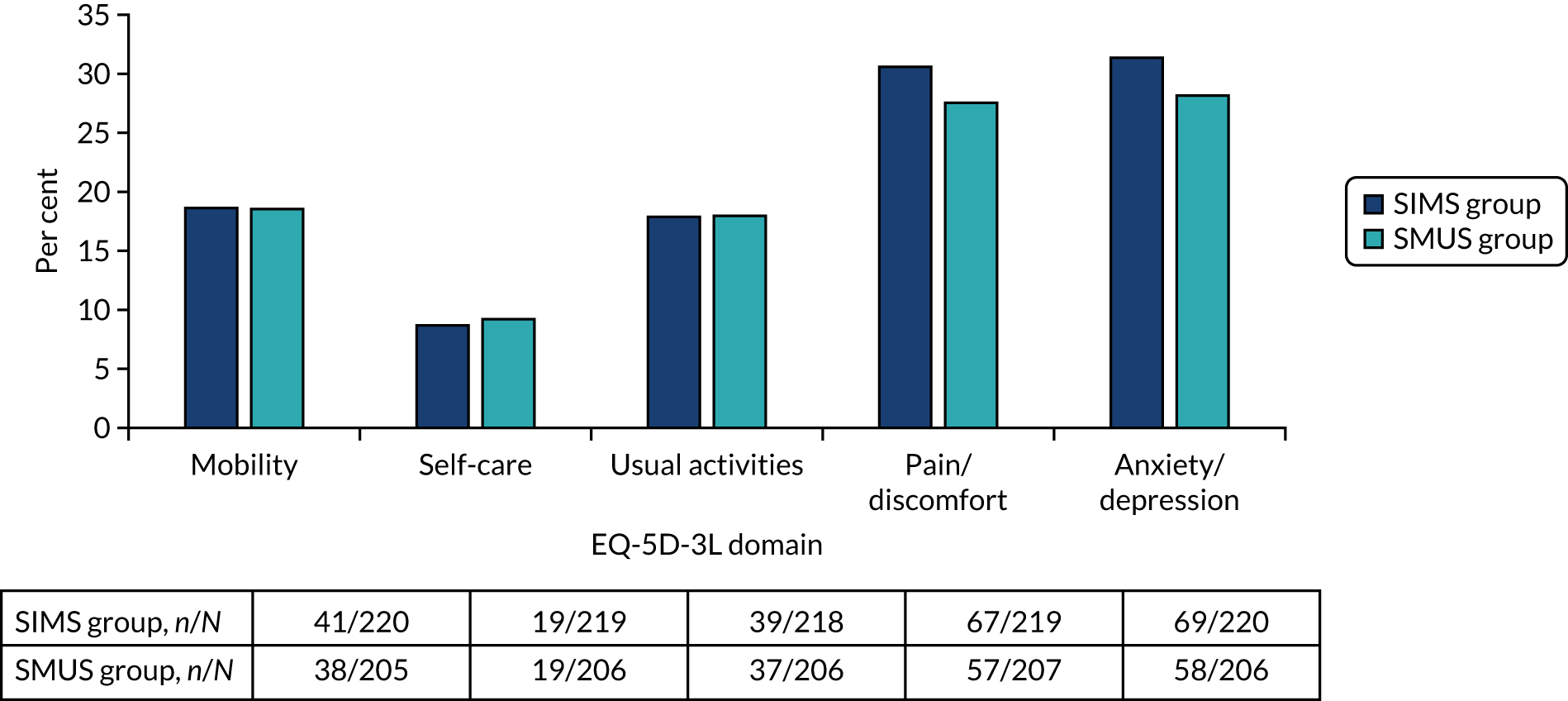

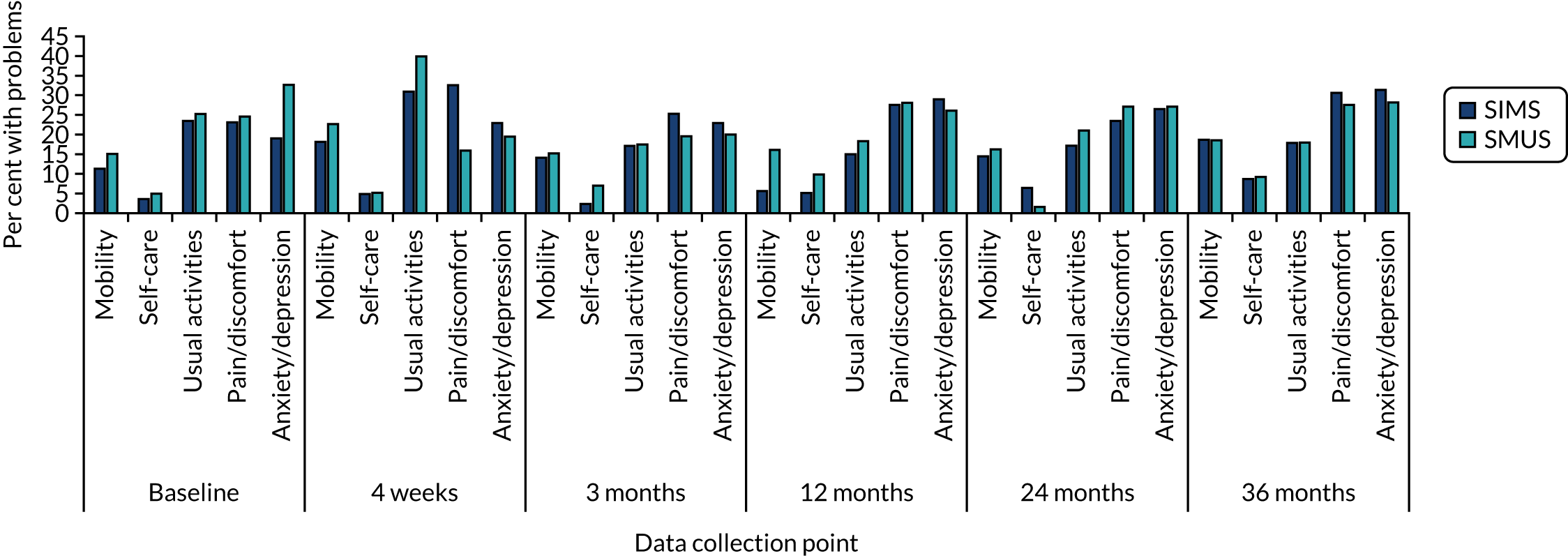

Secondary outcomes with multiple categories (such as satisfaction categories) were analysed using ordered logistic regression clustered by centre and with adjustment for PFMT. Secondary outcomes that are continuous outcomes and measured repeatedly (such as the EQ-5D-3L; the ICIQ-UI-SF; the ICIQ-FLUTS filling, voiding and incontinence scores; the ICIQ-LUTSqol and the PISQ-IR) were analysed using a mixed-effects repeated time model, with random effects for centre and participant and fixed effects for the treatment, the respective outcome at baseline and PFMT.

Secondary outcomes that measure QoL, such as EQ-5D-3L, or incontinence secondary outcomes, such as the ICIQ-UI-SF, the three ICIQ-FLUTS outcomes, the specific QoL measure ICIQ-LUTSqol and the PISQ-IR, were tested under a superiority framework.

Non-responder analysis

Descriptive data comparing the baseline characteristics of participants who did respond with those of participants who did not respond at 15 months are displayed in Appendix 2, Table 29; the t-test (continuous outcomes) and chi-squared test (categorical outcomes) were used to estimate the statistical significance of the differences between responders and non-responders.

Sensitivity analyses

The secondary outcomes (i.e. ICIQ-UI-SF score; ICIQ-FLUTS filling, voiding and incontinence scores; ICIQ-LUTSqol score; and PISQ-IR score) were all measured at baseline and the repeated measures mixed-effects model included a fixed effect for the baseline measure. The GLM for objective success using the 24-hour pad test has a fixed effect for the pad test weight at baseline. For participants for whom follow-up measures were recorded but the baseline measure was missing, the baseline measure was imputed by the centre mean.

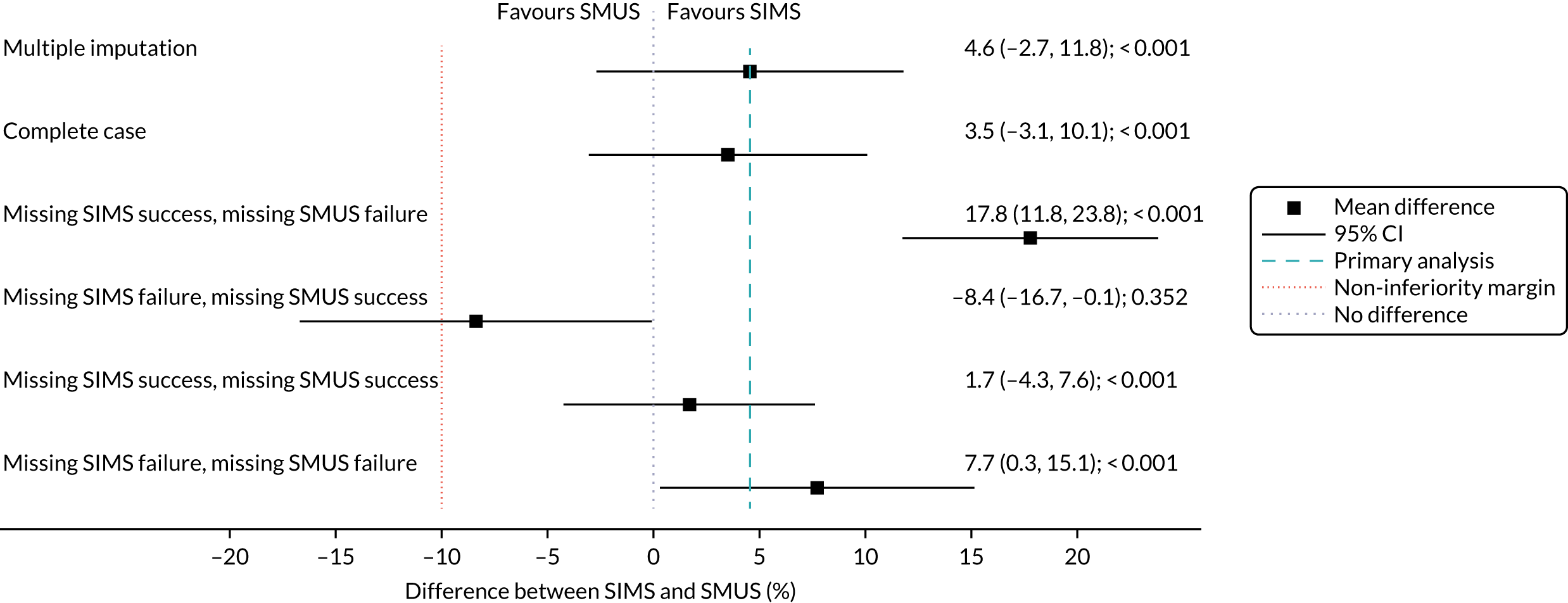

When the primary outcome was missing, it was imputed by pattern-mixture modelling; this is presented with the effect size from the multiple imputation using chained equations and a complete-case analysis. The results from the imputations are shown along with the observed effect size on a forest plot (see Figure 8).

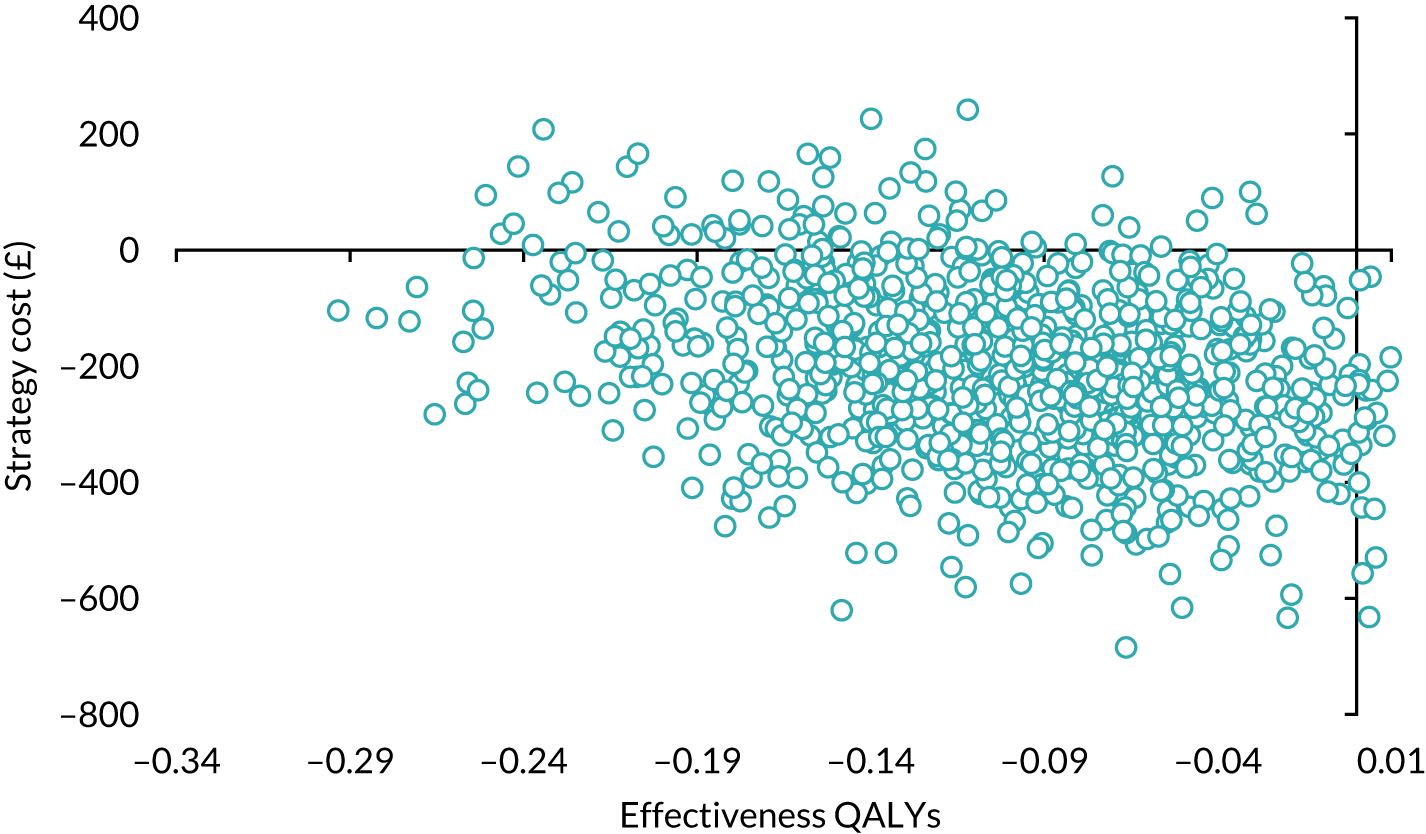

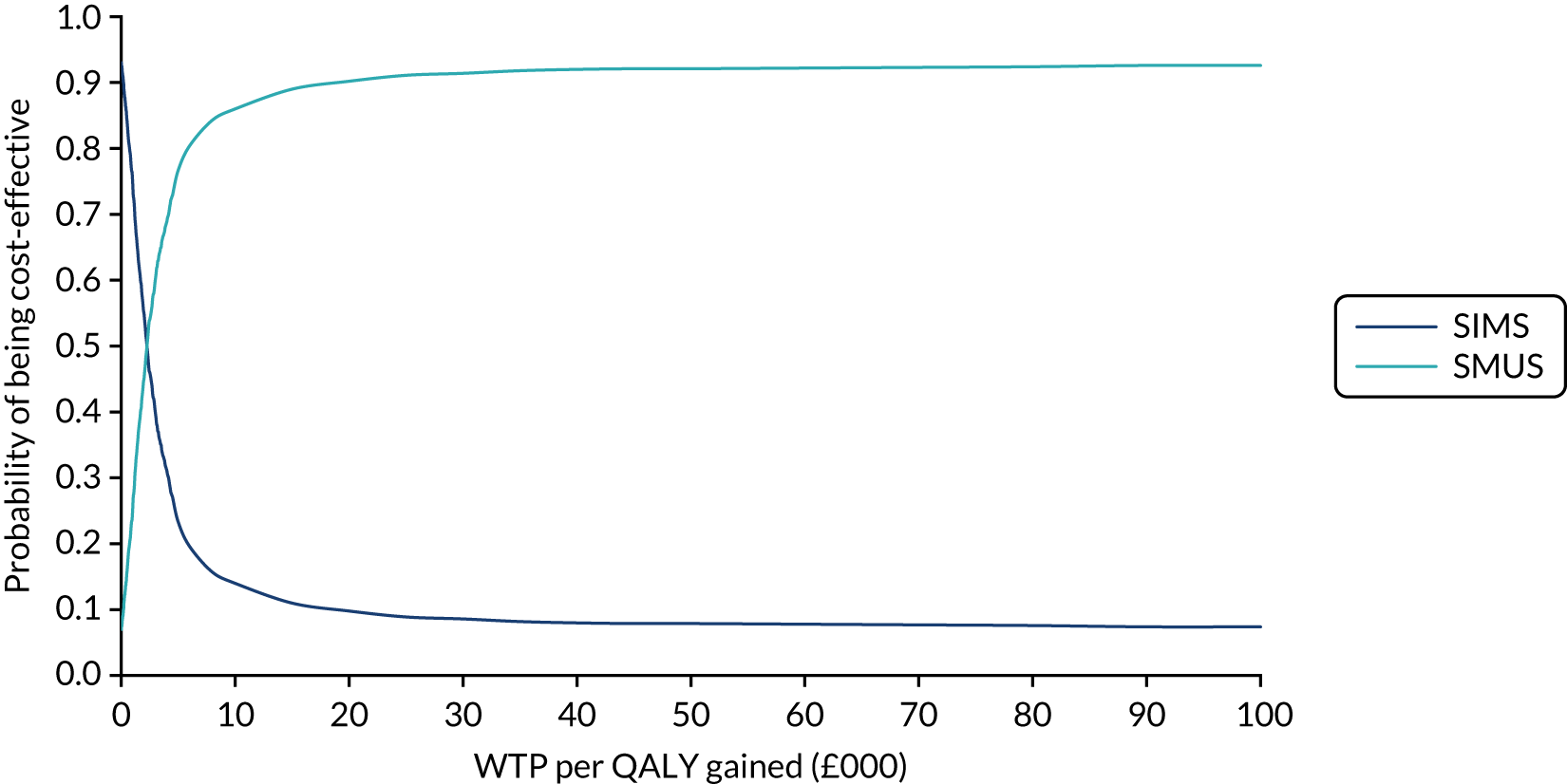

Economic evaluation

A cost–utility analysis was conducted alongside the RCT and a cost–benefit analysis was also conducted using the results from the DCE. Our primary health economic evaluation is from a health service provider’s (NHS) perspective; however, we also present data from a wider societal perspective. These data include costs to patients of time and travel, costs to carers and family members and costs to society as a whole, estimated from lost productivity as a result of time off work/away from normal activities. Full details are given in Chapters 7 and 8.

Research ethics and regulatory approvals

The SIMS trial received a favourable ethics opinion from the North of Scotland Research Ethics Committee (REC) on 12 December 2013 (REC reference number: 13/NS/0143).

Protocol amendments

There were seven protocol amendments; these are summarised in Appendix 2. All amendments were reviewed by the sponsor. Substantial amendments were then submitted for approval to the REC. Amendments involving changes to the protocol were reviewed by the funder and the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) before being submitted to the REC for approval. Non-substantial amendments were submitted to the REC when the next substantial amendment was submitted for review or included in the annual REC report.

Management of the trial

The trial management team, based in the CHaRT at the University of Aberdeen, provided day-to-day support for the recruiting centres led by a local PI. The PIs, in most cases supported by RNs, trial co-ordinators or dedicated staff, were responsible for all aspects of local organisation, including recruitment of participants, delivery of the interventions and notification of any problems or unexpected developments during the trial period.

Recruitment pauses

Recruitment to the trial paused at participating Scottish centres in June 2014 for 3 weeks when the Scottish Health Secretary requested the suspension of mesh implant surgery in Scotland. It was also paused briefly at all participating centres in December 2014 when the chief investigator was temporarily changed to John Norrie and James N’Dow, jointly, for a period of 8 months to allow sponsor investigation into a media report. The investigation did not find evidence of any inappropriate behaviour. The findings were accepted by the National Institute for Health and Care Research and Mohamed Abdel-Fattah resumed as chief investigator.

Trial oversight committees

Study Management Group

The Study Management Group was responsible for the day-to-day management of the trial. This group was chaired by the chief investigator and consisted of the trial manager, senior trial manager, data co-ordinator, health economist and statistician.

Project Management Group

The PMG was responsible for overseeing the management of the trial. This group consisted of the Study Management Group plus grant applicants, a patient and public involvement (PPI) representative and a senior programmer. Membership of the PMG is listed in the Acknowledgements.

Trial Steering Committee

The TSC was responsible for monitoring and supervising the progress of the SIMS trial. The committee met seven times between April 2014 and September 2020, at intervals agreed by the TSC. The TSC consisted of independent experts, a PPI representative, the chief investigator and key members of the PMG. Membership of the TSC is given in the Acknowledgements.

Data Monitoring Committee

The DMC was independent of the trial and responsible for monitoring safety and data integrity. The committee met nine times between April 2014 and September 2020, at intervals agreed by the committee. The trial statistician provided the data and analyses requested by the DMC prior to each meeting. The committee consisted of three independent experts. Membership of the DMC is given in the Acknowledgements.

Patient and public involvement

One of the trial PPI representatives was a grant holder and an active member of the PMG. As part of this role, she contributed extensively to the development and review of trial materials, including the protocol, PIL, questionnaires and participant newsletters, as well as to the trial processes, the 6-monthly funder reports and the final report. There was also an active PPI member of the TSC.

Chapter 3 Baseline data and operative details

This chapter describes how the trial population was formed, the clinical characteristics of the participants and the baseline measures used. We also describe the baseline operative details.

Trial recruitment

Between 4 February 2014 and 7 September 2017, we recruited 600 participants from 21 centres (see Appendix 3, Table 31). A total of 300 participants were allocated to receive an adjustable anchored SIMS and 300 were allocated to receive a tension-free SMUS. All centres recruited to both arms of the trial. The trial database was locked on 15 October 2020.

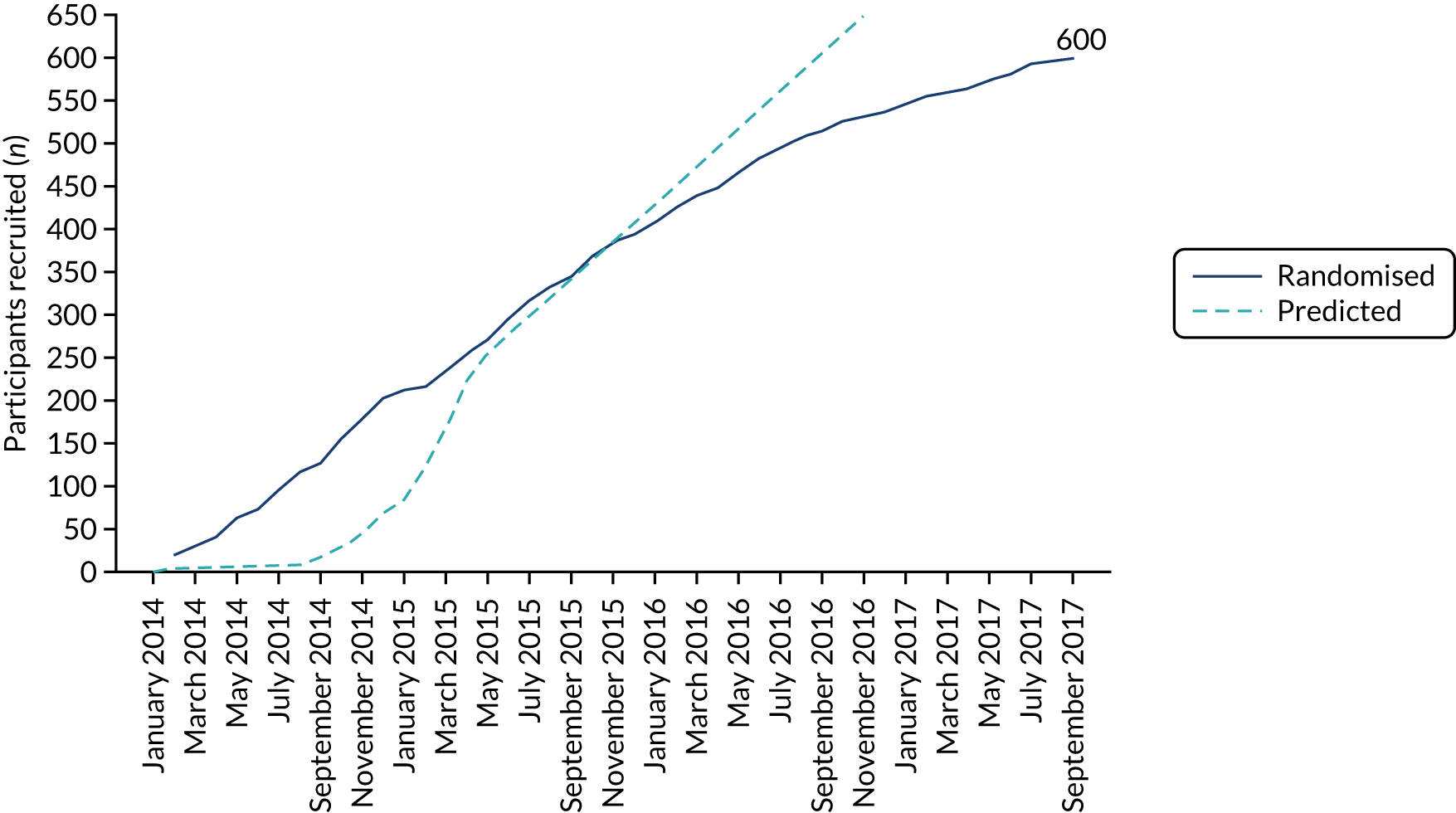

Appendix 3, Table 31, shows the number of participants randomised at each site to receive a SIMS and those randomised to receive a SMUS. The data show that there was no dominant site in the trial and that all sites allocated participants to both interventions. Figure 6 shows the monthly recruitment to the trial, compared with what was predicted. Although the trial required an extension to the recruitment period, Figure 6 shows that recruitment was at a consistent rate.

FIGURE 6.

Recruitment graph.

Participant flow

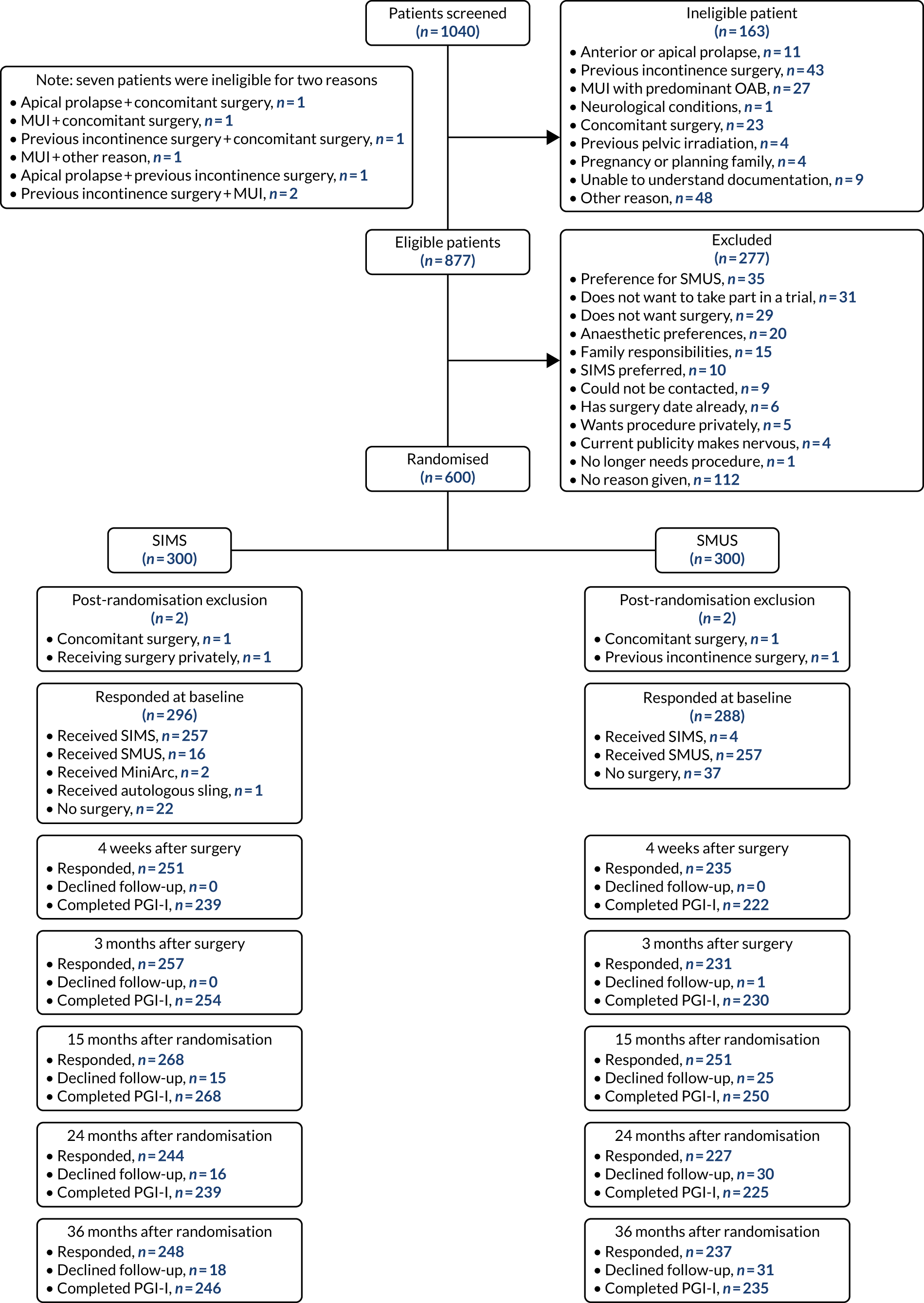

The progress of participants through the stages of the trial to the follow-up stages is shown in the CONSORT diagram (Figure 7). In total, 1040 participants were considered for entry to the trial. Of these participants, 163 (15.7%) failed to meet one or more of the eligibility criteria. Of the 877 who were eligible, 277 were excluded; the majority of these were excluded because the patient wanted a particular surgery or anaesthetic.

FIGURE 7.

The CONSORT diagram.

Four participants were excluded from the trial after entering. Two of these were in the SIMS group and were excluded for the following reasons: one was receiving concomitant surgery and one wanted to receive their surgery privately. In the SMUS group, one participant was excluded because of previous incontinence surgery and another because she was receiving prolapse surgery concomitantly.

The time from randomisation to intervention and the time from randomisation to each of the follow-up points were similar between the two randomised groups. These are shown in Appendix 3, Table 32.

Participant and sociodemographic factors

The mean age of participants was between 50 and 51 years. The mean BMI was similar in both groups, at very slightly < 29 kg/m2. Approximately 85% of participants in both groups had received PFMT within the previous 2 years. A slightly higher percentage of participants in the SIMS group than in the SMUS group were smokers [17.2% (n = 52) and 14.4% (n = 43), respectively]. There was a difference between the two groups in the percentage of participants on anticholinergic drugs at baseline: 20.1% (n = 60) in the SIMS group, compared with 11.7% (n = 35) in the SMUS group. Previous history of use of anticholinergic drugs was similar between the two groups. Previous gynaecology surgeries were similar between the two groups, although previous abdominal hysterectomy and anterior repairs had slightly higher percentages in the SIMS group. Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of participants in both groups.

| Characteristic | Trial group | |

|---|---|---|

| SIMS (N = 298) | SMUS (N = 298) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 50.4 (11.0) [n = 298] | 50.7 (10.9) [n = 298] |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 28.9 (5.5) [n = 297] | 28.7 (5.6) [n = 292] |

| Received PFMT in previous 2 years, n (%) | 254 (85) | 254 (85) |

| Obstetric history, n (%) | ||

| Parity | ||

| 0 | 10 (3.4) | 9 (3.0) |

| 1 | 41 (14) | 35 (12) |

| 2 | 130 (44) | 130 (44) |

| 3 | 81 (27) | 81 (27) |

| ≥ 4 | 34 (11) | 39 (13) |

| Missing | 2 (0.67) | 4 (1.3) |

| At least one forceps delivery | 38 (13) | 37 (12) |

| At least one vacuum delivery | 20 (6.7) | 21 (7.0) |

| All deliveries were caesareans | 9 (3.0) | 10 (3.4) |

| Manual job (heavy lifting), n (%) | 84 (28) | 84 (28) |

| Smoker, n (%) | 52 (17) | 43 (14) |

| Current or previous hormone replacement therapy, n (%) | 29 (9.7) | 26 (8.7) |

| On anticholinergic drugs at baseline, n (%) | 60 (20) | 35 (12) |

| Previous use of any anticholinergic drugs, n (%) | 49 (16) | 50 (17) |

| Experience recurrent UTIs, n (%) | 10 (3.4) | 11 (3.7) |

| Performing CISC, n (%) | 4 (1.3) | 1 (0.34) |

| On prophylactic low-dose antibiotics, n (%) | 2 (0.67) | 2 (0.67) |

| Previous gynaecology surgery, n (%) | 98 (33) | 87 (29) |

| Abdominal hysterectomy | 42 (14) | 30 (10) |

| Vaginal hysterectomy | 17 (5.7) | 20 (6.7) |

| Sacrospinous fixation | 1 (0.34) | 1 (0.34) |

| Anterior repair | 14 (4.7) | 6 (2.0) |

| Anterior mesh repair | 2 (0.67) | 5 (1.7) |

| Posterior repair | 6 (2.0) | 6 (2.0) |

| Sacrohysteropexy | 1 (0.34) | |

| Posterior mesh repair | 1 (0.34) | |

| Manchester repair | 1 (0.34) | |

| Other previous gynaecology surgery | 35 (12) | 31 (10) |

Clinical assessment and health status

Most women underwent preoperative urodynamics (95%, n = 571). The preoperative urodynamic diagnosis was urodynamic stress incontinence for 79% (n = 235) and 78% (n = 231) of the SIMS and SMUS groups, respectively, and mixed urodynamic UI was diagnosed for 12% (n = 36) and 11% (n = 33) of the SIMS and SMUS groups, respectively. A clinical diagnosis of pure SUI was used (without urodynamics) for only 4.7% (n = 14) and 3.7% (n = 11) of the SIMS and SMUS groups, respectively. For 77% (n = 459) of participants, the uroflowmetry diagnosis was normal. Although the ICIQ-FLUTS filling and voiding scores were low on average, some women had scores at the top of the scale, indicating the worst possible score. The ICIQ-UI-SF score, ICIQ-FLUTS incontinence score and ICIQ-LUTSqol score all suggested that women’s lives were negatively affected by their UI. Both coital incontinence and dyspareunia had higher frequencies at baseline among women in the SIMS group.

The EQ-5D-3L results showed a wide range of values, including the maximum score of 1.0; both the mean and median were > 0.8, suggesting very good health on average. There were also some very low scores, indicating that some women rated their health as very poor. The patient-reported baseline scores were similar between the two groups; this is also the case for the ICIQ-LUTSqol.

Table 3 shows the baseline questionnaire scores and Table 4 shows the urodynamics diagnoses for both groups. The urodynamic diagnosis by device is shown in Appendix 6, Table 38.

| Questionnaire | Trial group | |

|---|---|---|

| SIMS (N = 298) | SMUS (N = 298) | |

| ICIQ-UI-SF score, mean (SD) | 14.4 (3.3) [n = 284] | 14.4 (3.6) [n = 285] |

| Median (IQR) | 15.0 (12.0–17.0) | 14.0 (12.0–17.0) |

| ICIQ-FLUTS filling score, mean (SD) | 4.5 (2.7) [n = 291] | 4.9 (2.8) [n = 284] |

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0–6.0) | 5.0 (3.0–7.0) |

| ICIQ-FLUTS voiding score, mean (SD) | 1.9 (2.0) [n = 293] | 1.7 (2.0) [n = 286] |

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (0.0–3.0) | 1.0 (0.0–3.0) |

| ICIQ-FLUTS incontinence score, mean (SD) | 11.0 (3.0) [n = 284] | 11.4 (3.1) [n = 286] |

| Median (IQR) | 11.0 (9.0–13.0) | 11.0 (9.0–14.0) |

| ICIQ-LUTSqol score, mean (SD) | 46.9 (11.7) [n = 286] | 46.6 (10.7) [n = 276] |

| Median (IQR) | 46.0 (38.0–55.0) | 45.0 (38.5–54.0) |

| EQ-5D-3L | 0.860 (0.200) [n = 286] | 0.834 (0.249) [n = 284] |

| PISQ-IR, mean (SD) | 3.3 (0.6) [n = 87] | 3.3 (0.6) [n = 91] |

| Median (IQR) | 3.3 (2.9–3.9) | 3.3 (2.9–3.8) |

| Coital incontinence, n/N (%) | 60/145 (41) | 52/145 (36) |

| Dyspareunia, n/N (%) | 25/145 (17) | 21/145 (14) |

| Urodynamics diagnosis | Trial group, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| SIMS (N = 298) | SMUS (N = 298) | |

| Cystometry diagnosis | ||

| Urodynamic stress incontinence | 235 (79) | 231 (78) |

| Urodynamic mixed incontinence | 36 (12) | 33 (11) |

| Equivocal | 3 (1.0) | 3 (1.0) |

| Not interpretable | 1 (0.34) | 1 (0.34) |

| Other | 2 (0.67) | 2 (0.67) |

| Clinical diagnosis SUI (no urodynamics performed) | 14 (4.7) | 11 (3.7) |

| Missing | 7 (2.3) | 17 (5.7) |

| Uroflowmetry diagnosis | ||

| Normal | 233 (78) | 226 (76) |

| Obstruction | 6 (2.0) | 4 (1.3) |

| Suboptimal | 12 (4.0) | 17 (5.7) |

| Equivocal | 4 (1.3) | 4 (1.3) |

| Not interpretable | 5 (1.7) | |

| Not recorded | 19 (6.4) | 10 (3.4) |

| Other | 18 (6.0) | 21 (7.0) |

| Missing | 6 (2.0) | 11 (3.7) |

Symptom severity

There were a wide range of pad test results, but the median in both groups was similar at 39 g and 40 g in the SIMS and SMUS groups, respectively.

The total ICIQ-UI-SF score was comparable between both groups, indicating similar symptom severity and impact on women’s QoL. There were also similar percentages of women in both groups describing severe symptoms (i.e. a score of ≥ 13). The participants’ responses to individual questions of ICIQ-UI-SF are shown in Table 5.

| Symptom severity | Trial group | |

|---|---|---|

| SIMS (N = 298) | SMUS (N = 298) | |

| Pad test weight (g), mean (SD) | 51.0 (58.1) [N = 234] | 56.4 (58.5) [N = 204] |

| Median (IQR) | 39.0 (24.0–60.0) | 40.0 (24.0–67.0) |

| ICIQ-UI-SF score, mean (SD) | 14.4 (3.3) [N = 284] | 14.4 (3.6) [N = 285] |

| Median (IQR) | 15.0 (12.0–17.0) | 14.0 (12.0–17.0) |

| How often do you leak urine?, n (%) | ||

| Once or less per week | 8 (2.7) | 7 (2.3) |

| Two or three times per week | 31 (10) | 37 (12) |

| Once per day | 29 (9.7) | 24 (8.1) |

| Several times per day | 192 (64) | 183 (61) |

| All the time | 33 (11) | 37 (12) |

| Missing | 5 (1.7) | 10 (3.4) |

| How much urine do you leak?, n (%) | ||

| Small amounts | 122 (41) | 106 (36) |

| Moderate amounts | 125 (42) | 131 (44) |

| Large amounts | 41 (14) | 50 (17) |

| Missing | 10 (3.4) | 11 (3.7) |

| How much does urinary leakage interfere with day-to-day activities?, mean (SD) | 7.3 (2.1) [N = 289] | 7.1 (2.2) [N = 286] |

| ICIQ-UI-SF severity, n (%) | N = 284 | N = 285 |

| Mild/moderate (< 13) | 79 (28) | 80 (28) |

| Severe (≥ 13) | 205 (72) | 205 (72) |

| Urgency perception: baseline, n (%) | ||

| No urgency | 49 (16) | 40 (13) |

| Mild urgency | 80 (27) | 85 (29) |

| Moderate urgency | 115 (39) | 117 (39) |

| Severe urgency | 49 (16) | 45 (15) |

| Not answered | 5 (1.7) | 11 (3.7) |

Operative details

Of the women allocated to receive an adjustable anchored SIMS, 92.6% (n = 276) received surgery, whereas 87.6% (n = 261) of those randomised to the tension-free SMUS group received surgery. Compliance with the allocated intervention/surgery was high: 86.2% (n = 257) in both groups.

The comparison between both groups for operative data collected is provided in Table 6 (for operative outcomes, see Table 12). In terms of the actual device received, 70.7% (n = 195) in the SIMS group received Altis and 22.5% (n = 62) received Ajust. Slightly more SMUS devices were TO-TVT [52.9% (n = 138)] than RP-TVT [45.6% (n = 119)]. Owing to the nature of the procedure, there were some differences between the two groups, for example in the type of anaesthesia and adjustment of the sling. More women in the SMUS group had their procedure by a senior trainee who was deemed competent by their consultant/local PI. In all such cases, the procedures were performed under supervision of the consultant.

| Operative data | Trial group, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| SIMS (N = 298) | SMUS (N = 298) | |

| Received any surgery | 276 (93) | 261 (88) |

| Type of procedure | N = 276 | N = 261 |

| Ajust | 62 (22) | – |

| Altis | 195 (71) | 4 (1.5) |

| RP-TVT | 7 (2.5) | 119 (46) |

| TO-TVT | 9 (3.3) | 138 (53) |

| Autologous fascial sling | 1 (0.36) | – |

| MiniArc | 2 (0.72) | – |

| Grade of surgeon | ||

| Subspecialist urogynaecologist | 65 (24) | 46 (18) |

| Consultant gynaecologist | 183 (66) | 160 (61) |

| Consultant urologist | 23 (8.3) | 9 (3.4) |

| Associate specialist/staff grade | 1 (0.36) | 3 (1.1) |

| Senior trainee | 4 (1.4) | 43 (16) |

| Type of anaesthesia | ||

| GA | 70 (25) | 238 (91) |

| Spinal | 5 (1.8) | 7 (2.7) |

| LA with IV sedation | 47 (17) | 14 (5.4) |

| LA with oral sedation | 26 (9.4) | 1 (0.38) |

| Local anaesthesia only | 128 (46) | 1 (0.38) |

| Local anaesthesia received during the procedure | 270 (98) | 235 (90) |

| Sling adjusted under CST guidance | 180 (65) | 15 (5.7) |

The majority of participants [91% (n = 238)] in the SMUS group had the procedure under GA, whereas the majority in the SIMS group [73% (n = 201)] had the procedure under LA, with or without sedation. Most participants received LA infiltration during the procedure. More women in the SIMS group had their sling adjusted under guidance of a CST.

Chapter 4 Patient-reported clinical outcomes

This chapter compares the clinical outcomes of the adjustable anchored SIMS with those of the tension-free SMUS at 4 weeks and at 3 months after surgery, and at 15, 24 and 36 months after randomisation.

Analysis populations

A total of 600 participants were randomised to receive either a SIMS or a SMUS device. There were two post-randomisation exclusions in each group; this chapter reports on the results from 596 participants.

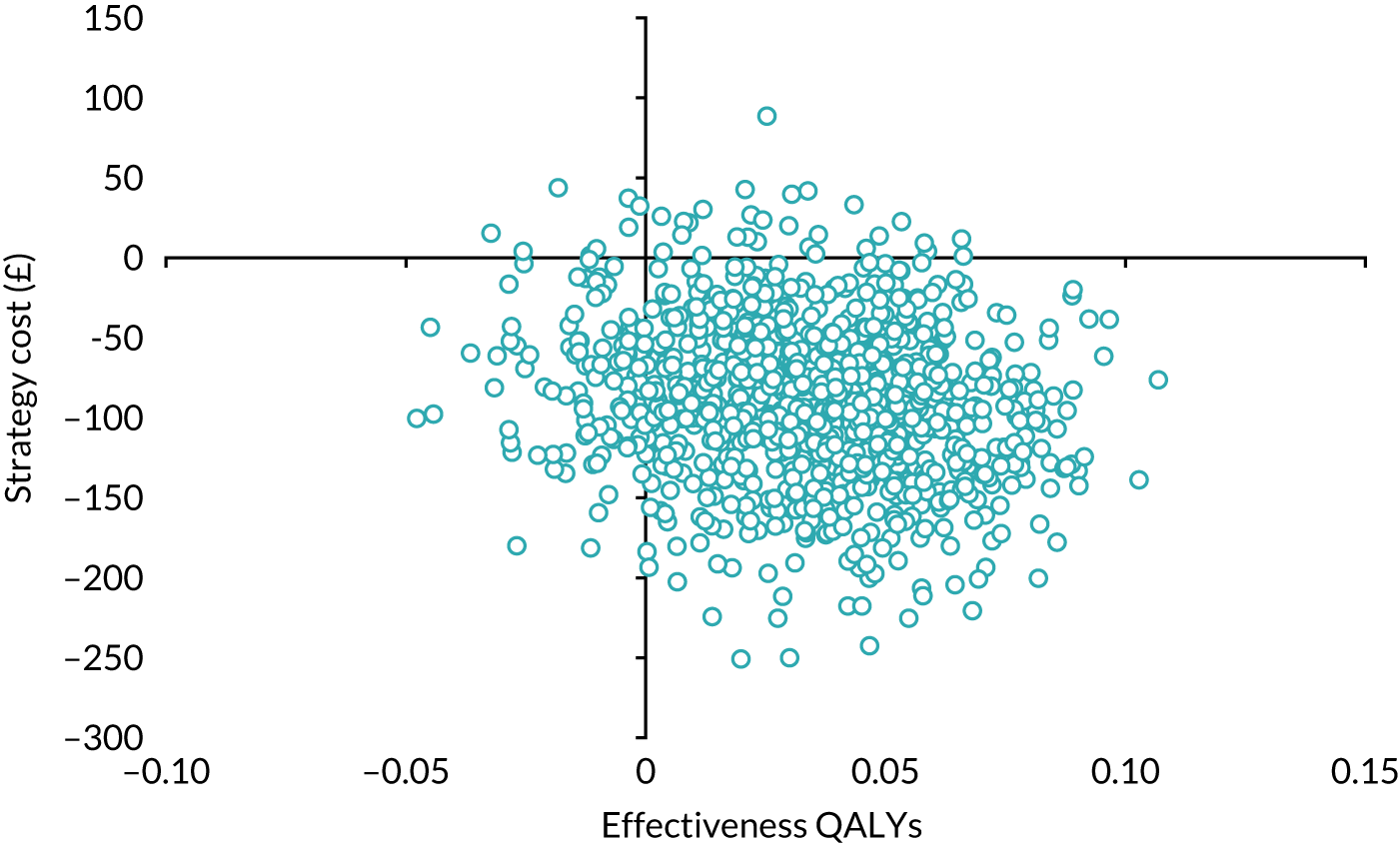

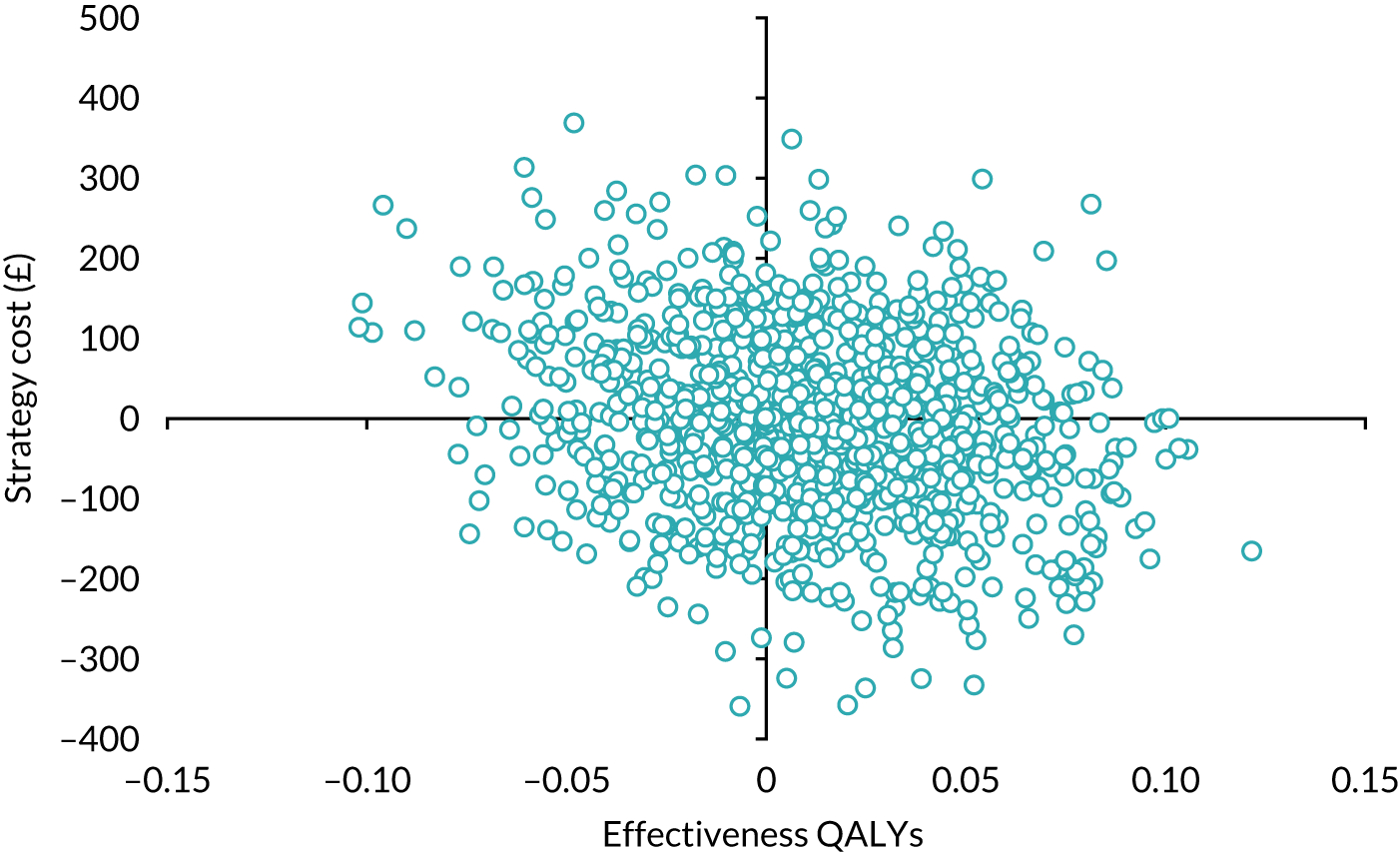

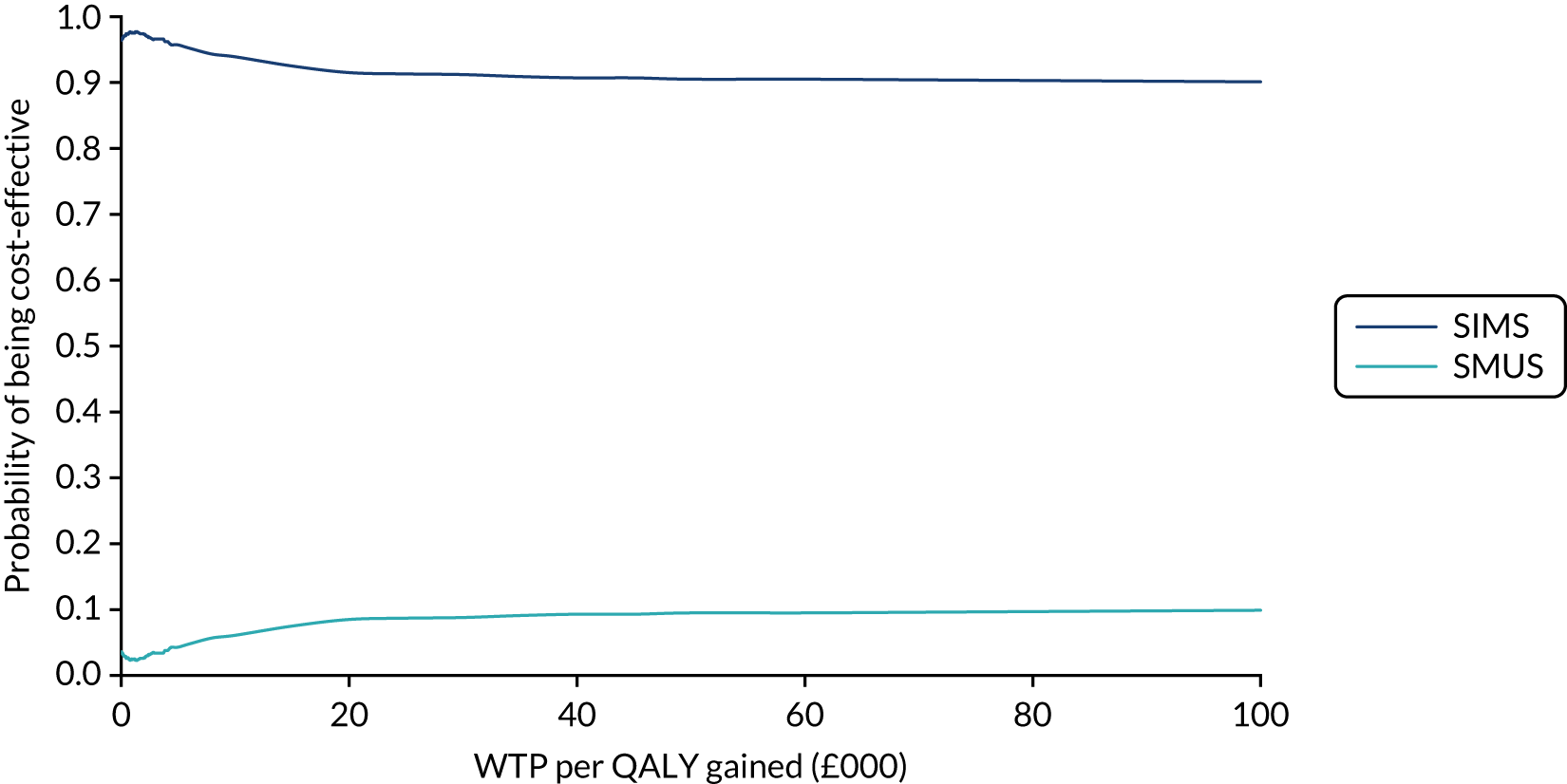

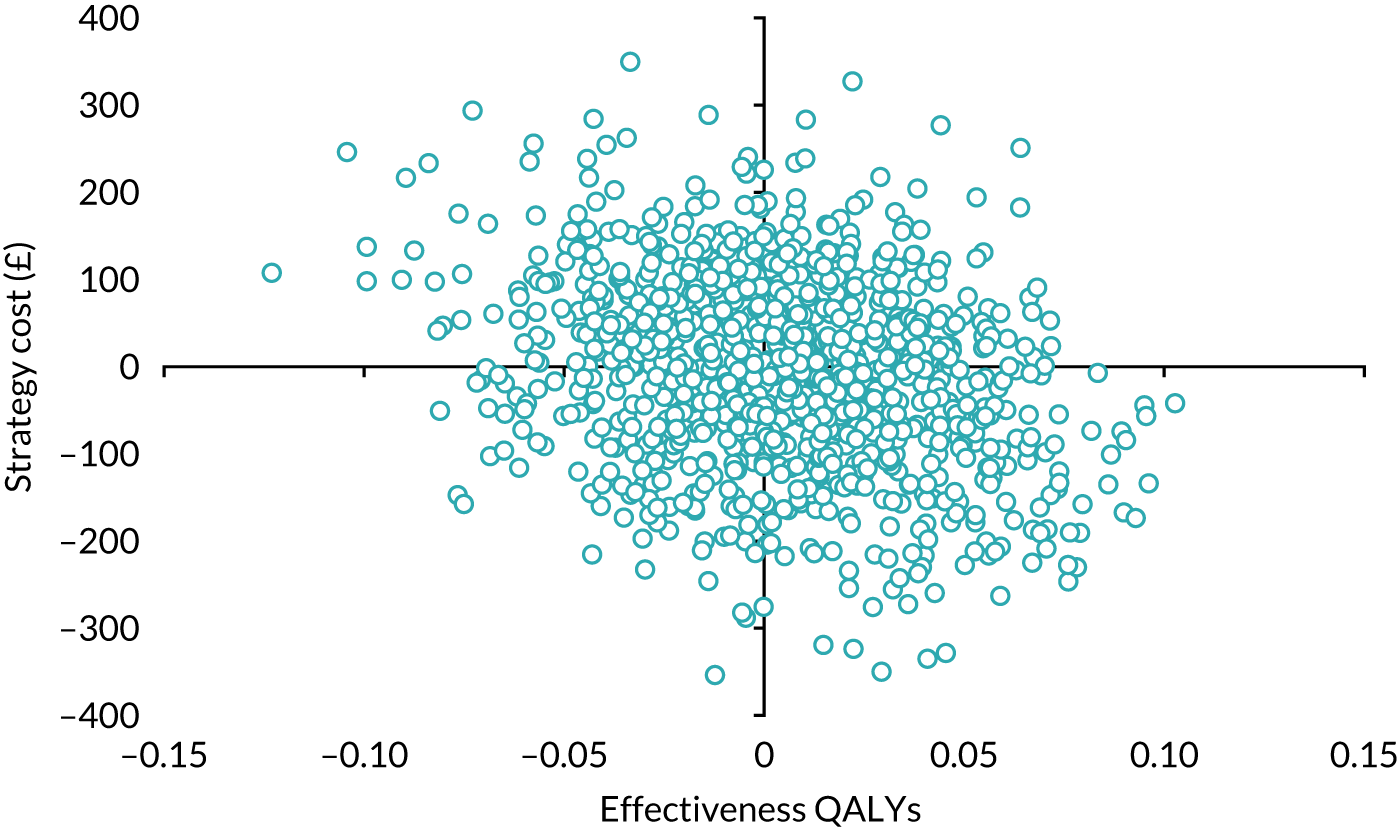

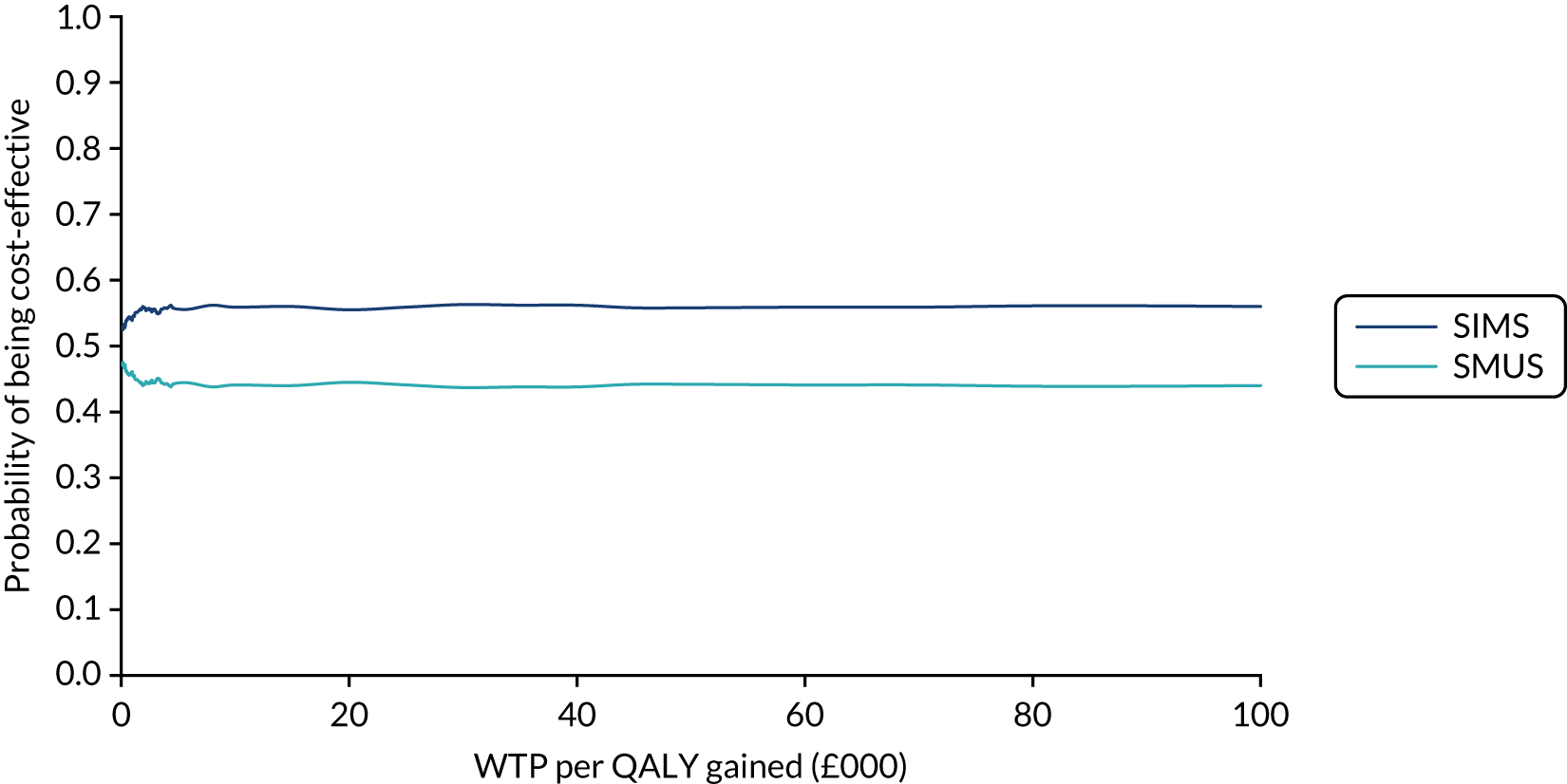

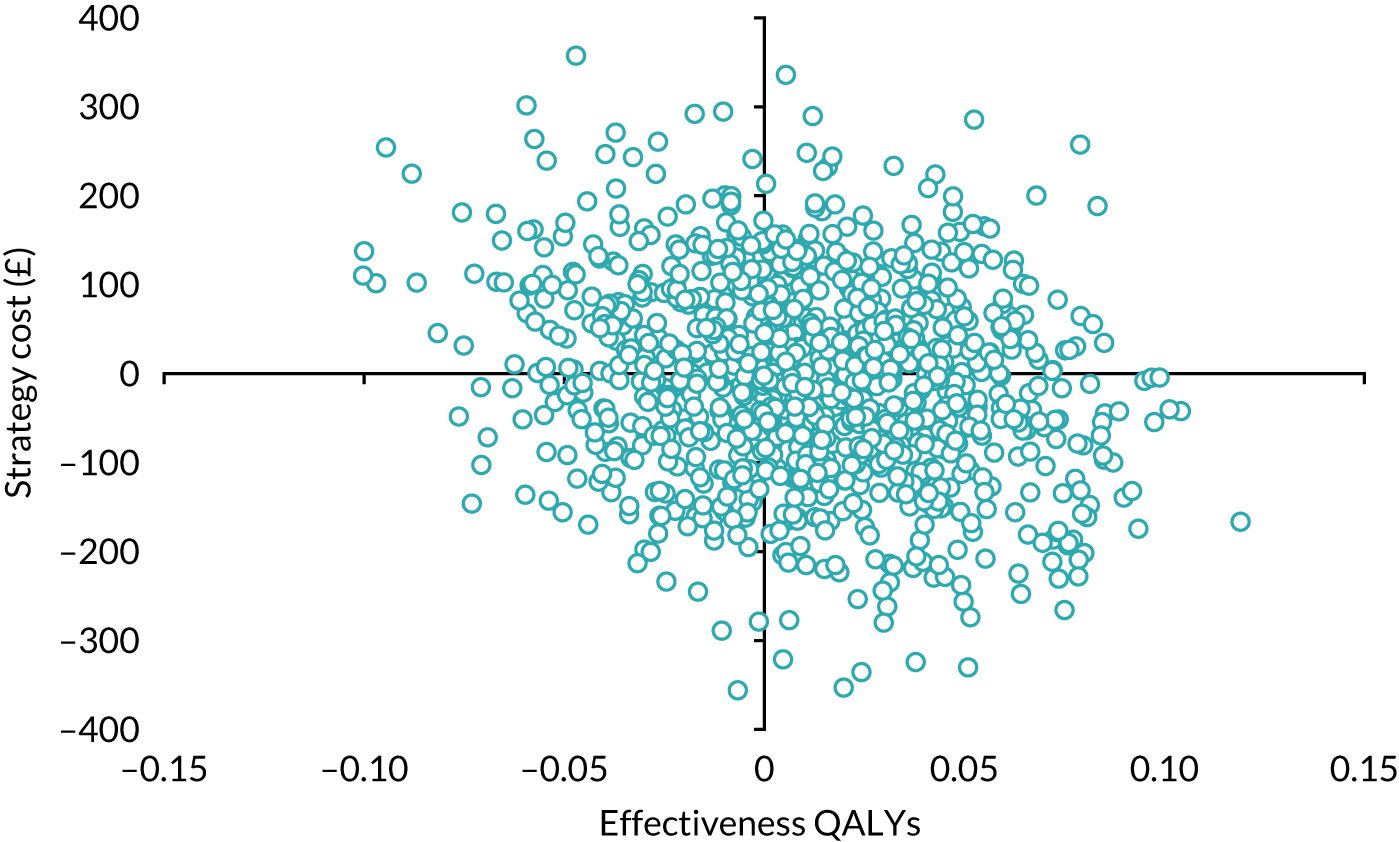

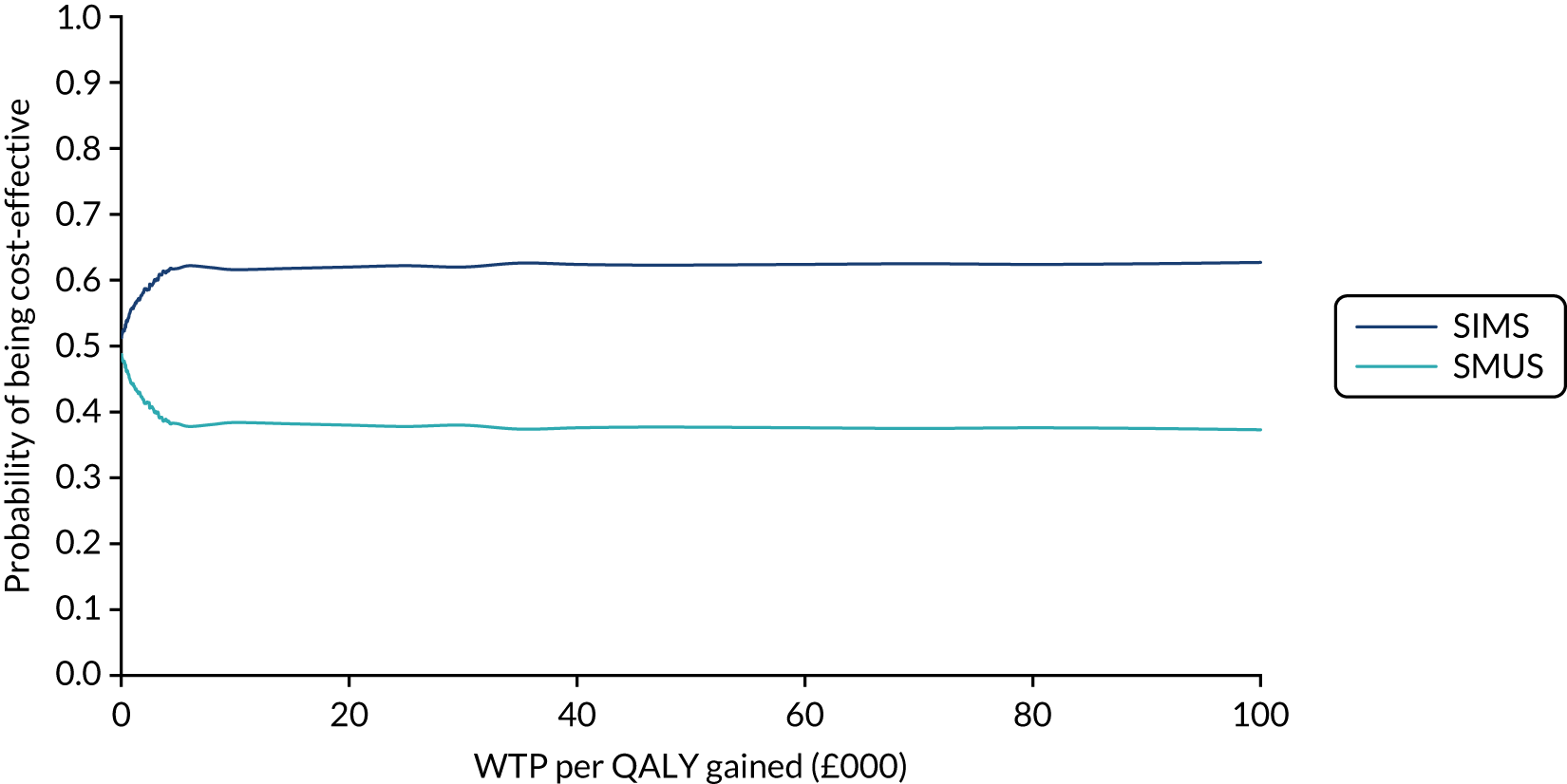

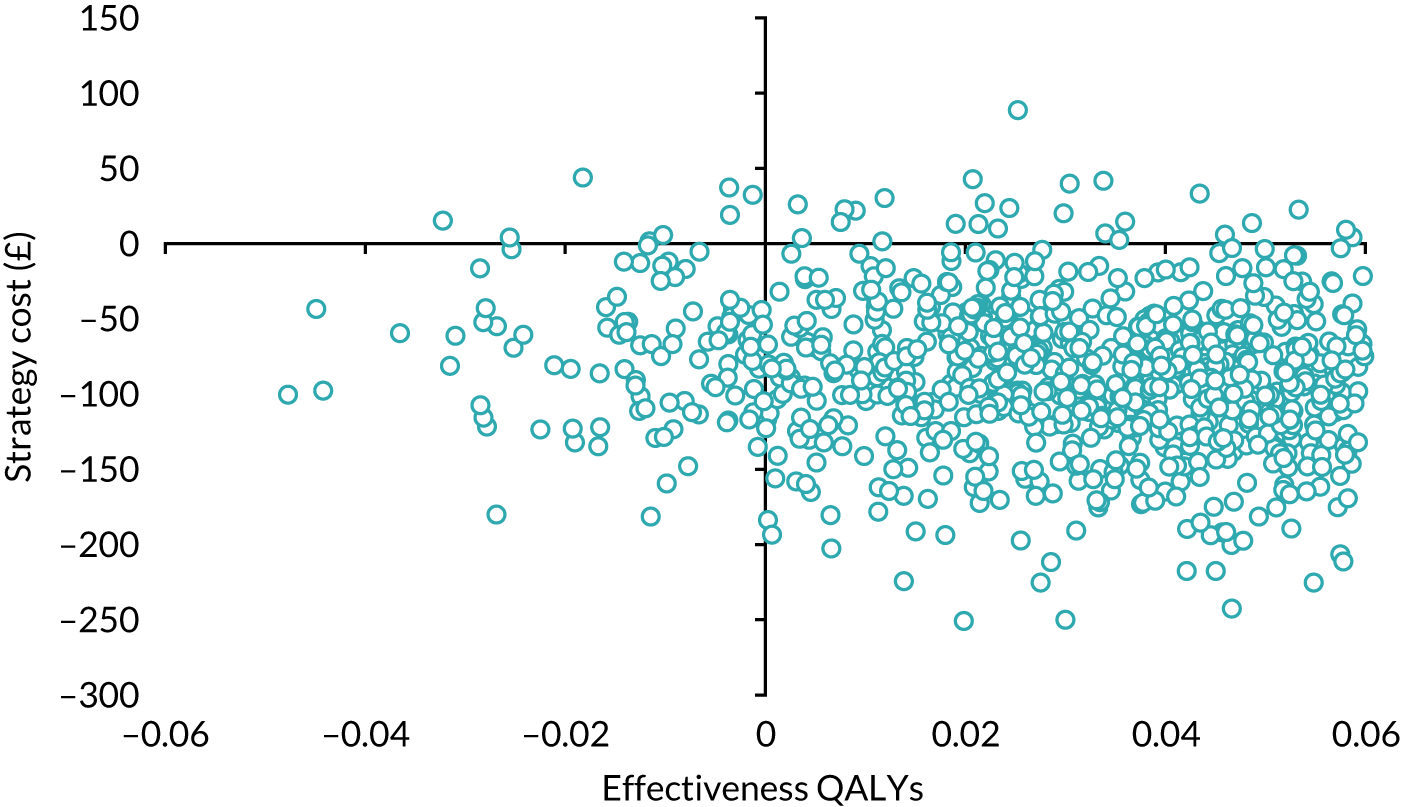

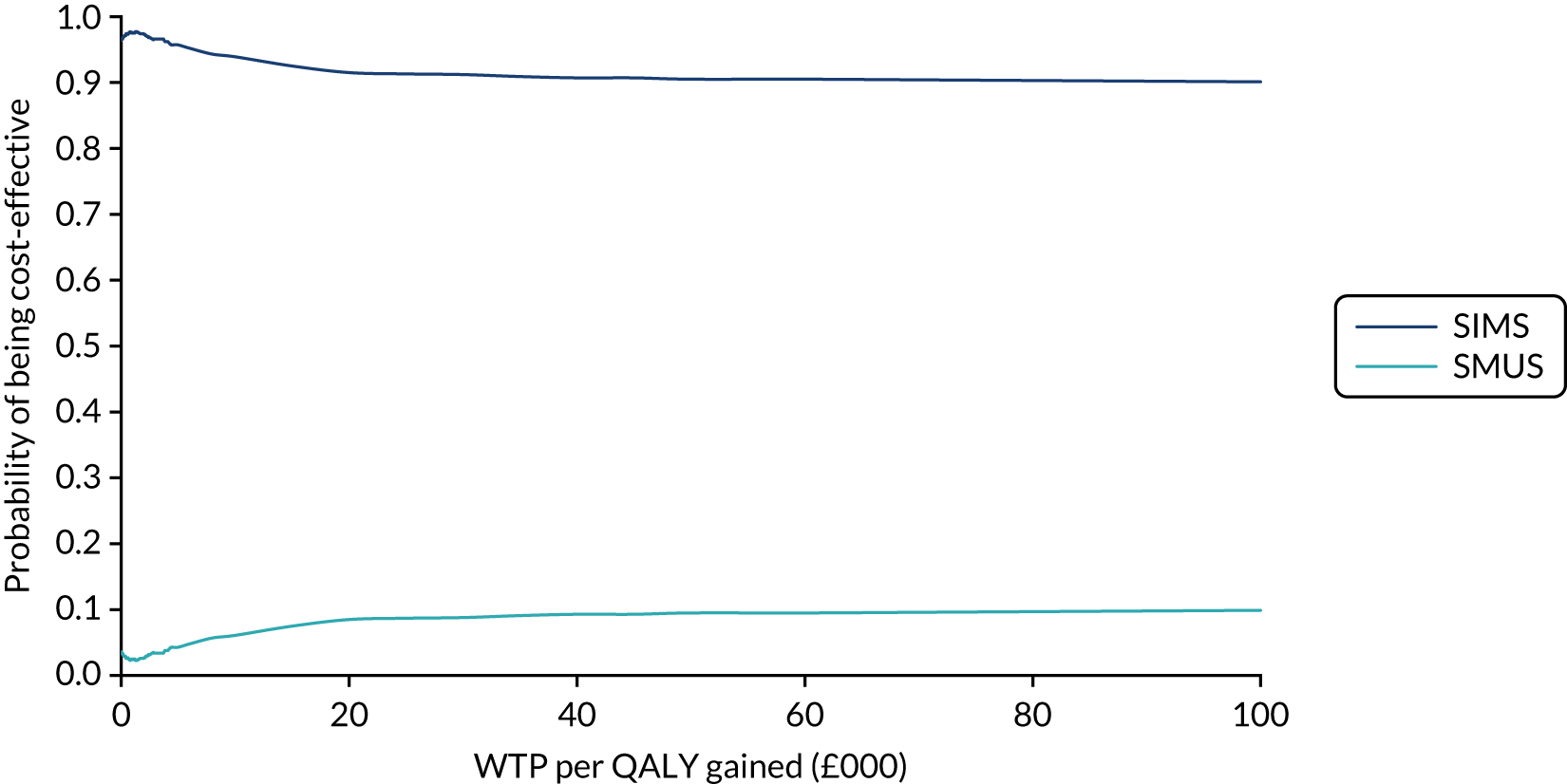

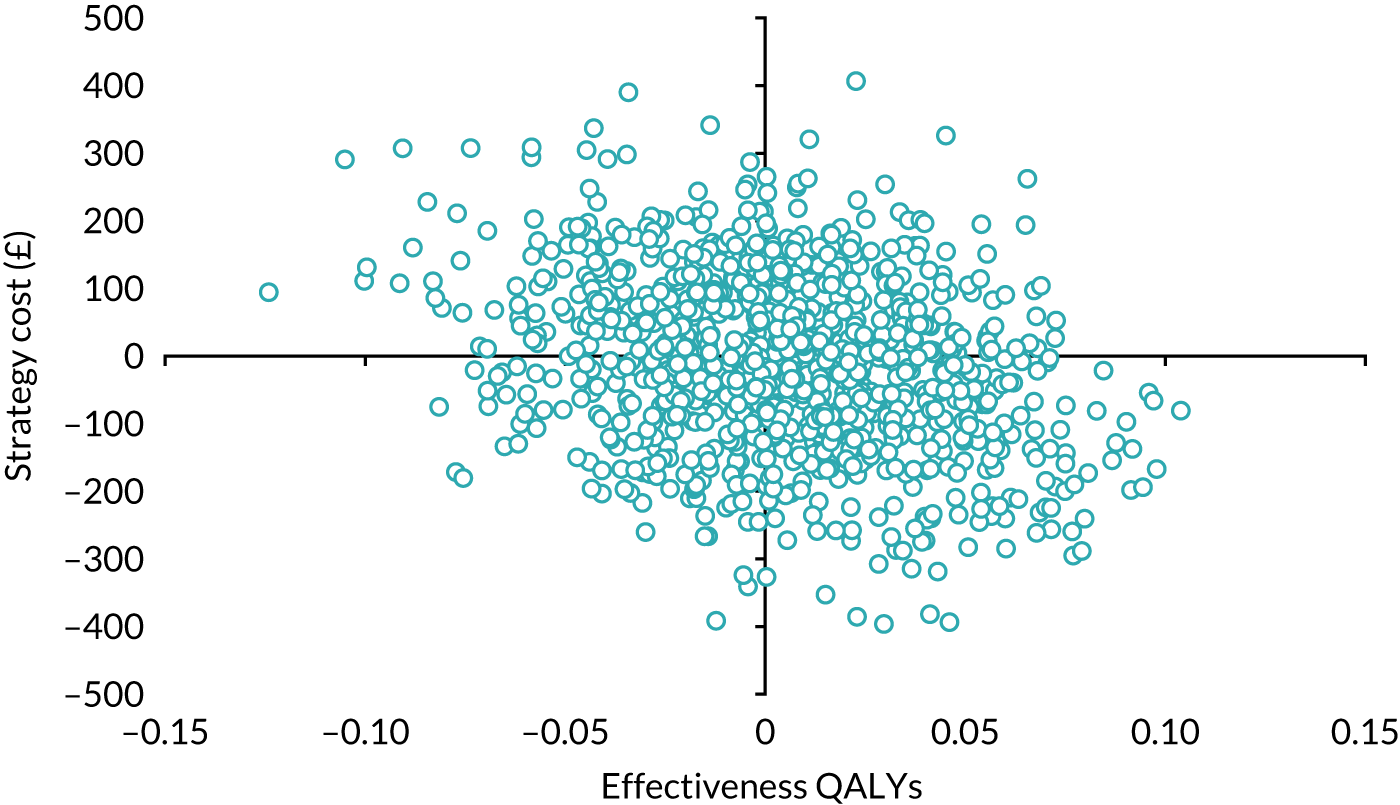

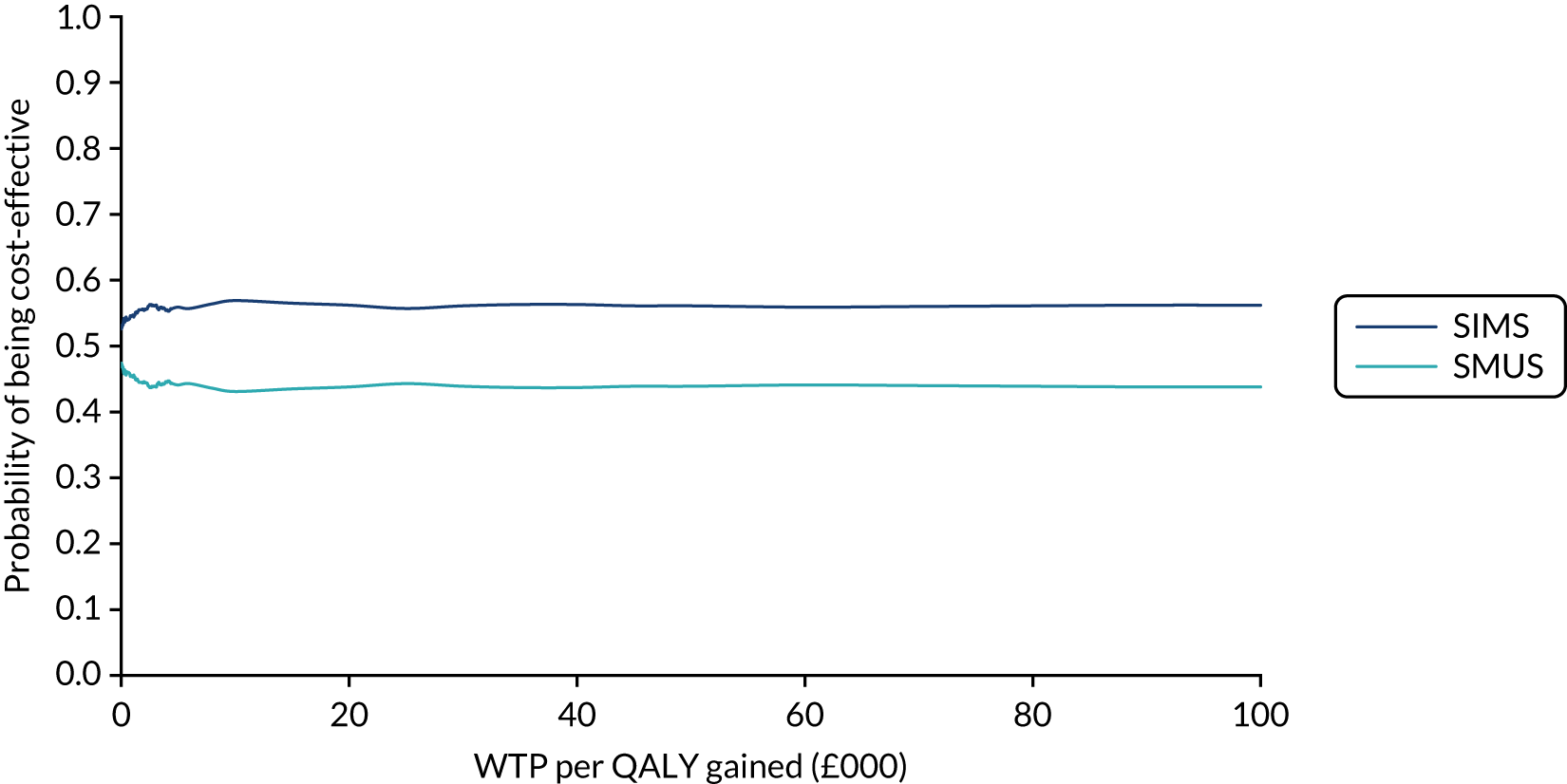

Primary outcome