Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/35/29. The contractual start date was in February 2014. The draft report began editorial review in June 2020 and was accepted for publication in August 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 O’Connell et al. This work was produced by O’Connell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 O’Connell et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this report have been reproduced with permission from Harries et al. 1 © Article author(s) (or their employer(s) unless otherwise stated in the text of the article) 2017. All rights reserved. No commercial use is permitted unless otherwise expressly granted. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Parts of this report have been reproduced with permission from Cornish et al. 2 © 2016 The Author(s). Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Background

An incisional hernia (IH) is a common and potentially serious complication following abdominal surgery. An IH is a bulge in the abdomen through or close to a previously made incision caused by the patient’s intestines, organs and/or other tissue protruding through a weakening in the abdominal muscles as a result of surgery. The reported rates of IH range from 8.6% to 39.9% following open colorectal surgery and from 4.7% to 24.3% following laparoscopic surgery. 3–7 In a systematic review8 that included 14,618 patients, the incidence of IH was 12.8% at 2 years’ follow-up, with incidence rates as high as 35.6% among patients who had received a midline incision during surgery. In patients with colorectal cancer, the rate of IH has been reported to be as high as 39.9%. 5

A number of potential risk factors for IH have been identified, including male sex, increased age, increased BMI, history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, history of smoking and certain medications. Surgeon-modifiable risk factors include surgical technique and suture type for abdominal closure; however, although a number of studies have been conducted investigating different surgical methods, uncertainty remains around the impact of such surgeon-modifiable factors on IH rates, with several studies reporting conflicting results. For example, three meta-analyses9–11 concluded that non-absorbable stitches reduce the risk of IH, one meta-analysis12 reported that absorbable stitches are associated with a lower risk of IH and one meta-analysis8 reported no difference in IH rates when comparing absorbable and non-absorbable stitches.

Recent cost analyses have found that the treatment and repair of IH places a considerable strain on already-stretched health-care resources. Direct per-patient cost estimates range from €3497 to €16,367 in European countries13,14 and from US$6530 to US$16,889 in the USA,15–17 with hospitalisation and surgery costs, as well as complications, adverse events and recurrences, identified as the main cost drivers.

An IH can be diagnosed as a result of patient-reported symptoms, such as a lump, abdominal pain and symptoms of obstruction. If the hernia has become incarcerated or strangulated, then this can also lead to tissue necrosis.

Treatment can vary depending on the size and anatomy of the hernia, the general health of the patient and the desired level of physical activity post repair. However, it will generally require one of two types of surgery: an open or, sometimes, a laparoscopic hernia repair. In attempting to reduce the risk of hernia recurrence, there is an increasing reliance on the use of synthetic or biologic mesh to facilitate the repair.

Rationale

More than 30,000 patients are diagnosed with colorectal cancer in the UK each year. 18 Most of these patients will undergo surgery as part of their treatment, and the incidence of complications following surgery is high. 19 One common complication after abdominal surgery is the occurrence of an IH following the closure of the midline incision.

An IH may have a negative impact on a patient’s quality of life (QoL) and their overall experience. 20 The outcomes for patients with IHs are poor, and many will suffer with chronic pain or suffer a repeat hernia even after the first repair. This can, in turn, lead to increased NHS resource use as a result of additional or longer hospital stays. It is, therefore, important to identify surgical procedures and strategies that can reduce the risk of IHs in patients who undergo abdominal surgery.

The aim of this study was to assess the potential of Hughes abdominal repair, an alternative wound closure method, to prevent IHs. The study recruited colorectal cancer patients who were due to receive surgical treatment for their cancer. The care pathway followed its standard course, except at point of abdominal wall closure, when the patient was randomised to either Hughes abdominal closure or standard mass closure.

Literature update

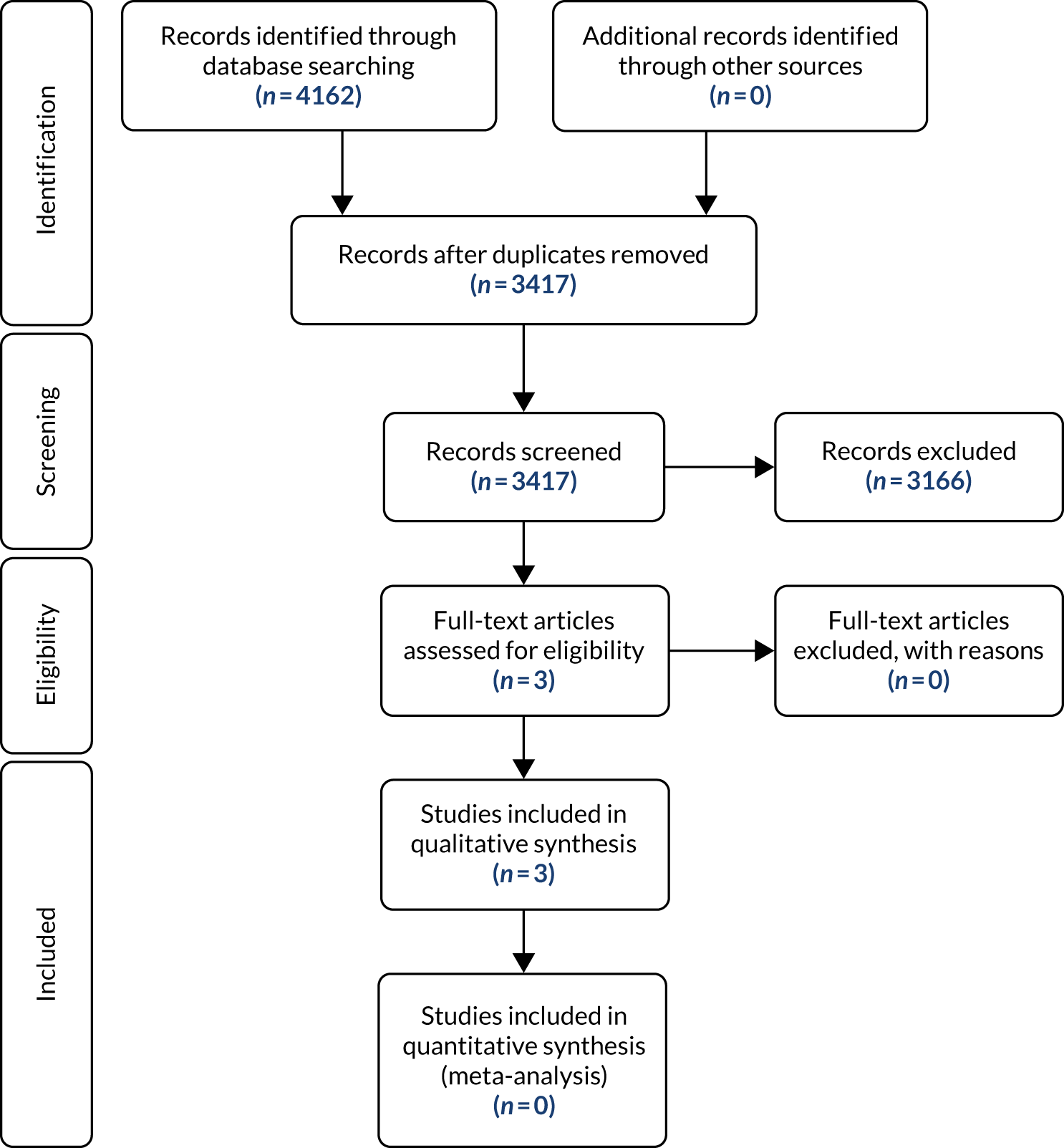

A review of the literature was conducted in key databases, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials. The review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA),21 and the PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1) details the amount of evidence sifted and excluded at each stage. Search strategies were developed in MEDLINE and adapted for other databases (see Appendix 1, Table 29).

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram. Reproduced with permission from Moher et al. 21 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

The study team was aware of a published systematic review and meta-regression that reported on factors affecting rates of midline IH in 14,618 patients from 56 individual studies, as well as the prevalence of IH at the 2-year follow-up. 8 The quality of the studies included was variable. All study types were considered for inclusion in the meta-analysis if they described a population of adult patients undergoing primary suture closure of a midline laparotomy wound. The review included a literature search up to March 2013. For this reason, it was decided to update the literature searches from this point. Initial database searches were carried out for the period from January 2013 to November 2018, with update searches carried out in September 2019 and again in April 2020 to ensure completeness. Following the removal of duplicate records, searches identified 3417 potentially relevant records (see Figure 1).

During the initial sifting of the updated literature search results, a Cochrane review published in 2017 was identified, entitled ‘Closure methods for laparotomy incisions for preventing incisional hernias and other wound complications’. 22 Assessment of the Cochrane review indicated that the searches were comprehensive and directly relevant to this study. As this provided a thorough review of relevant evidence up to February 2017, the authors decided that a full literature review was not required at this time. The decision was made to limit the evidence review for this report to new evidence and to include only relevant evidence published after the date of the searches in the Cochrane review.

Although an earlier systematic review8 had included all study types, the decision was also made to limit the searches to randomised controlled trials (RCTs) reporting the primary outcome, incidence of IH following abdominal surgery, in line with the Cochrane review,22 as it was considered that there were sufficient RCTs available.

As this was not a full systematic review of the literature, it was not registered on the PROSPERO database.

In addition, a review of clinical trial databases was conducted to identify any relevant ongoing clinical trials. Five additional relevant ongoing trials were identified, three of which have corresponding trial protocols published. 23–25 Ongoing trials include:

-

the ESTOIH study,23 investigating the influence of stitch length, using an elastic, extra-long-term absorbable monofilament suture, on the long-term clinical outcome of abdominal wall closure

-

the HULC trial,24 investigating whether or not a combination of small stitched fascial closure and onlay mesh augmentation after elective midline laparotomies reduces the risk of IH

-

the CONTINT trial,25 comparing continuous slowly absorbable sutures with interrupted rapidly absorbable sutures for abdominal wall closure after midline incisions for emergency laparotomy

-

the E-STITCH trial,26 comparing the small-tissue-bite technique with the large-bite technique for the closure of emergency midline laparotomy

-

the Rein4CeTo1 trial,27 comparing the IH incidence 1 year after planned colorectal cancer surgery performed through a midline incision that is closed either by a standardised small stitch 4 : 1 technique or with the same technique plus a reinforced tension-line suture.

Full details of these additional studies can be found in Appendix 2.

Based on the adjusted criteria for inclusion in the review, only two additional studies not covered by the Cochrane review were identified as relevant: the STITCH trial28 and the HART feasibility trial. 1

In total, three studies are included in the literature review. 1,22,28 The methods and results of each of the studies are detailed in the following sections.

STITCH trial28

A total of 540 patients were randomly assigned to large bites (1 cm every 1 cm) or small bites (5 mm every 5 mm). IH was reported in 21% (n = 57) of patients in the large-bites group and in 13% (n = 35) of patients in the small-bites group (p = 0.0131). Radiological (using ultrasound) and physical follow-up assessments were carried out in 62% (n = 338) of patients, and IH was identified in a total of 26% (n = 87) of patients. In 49% (n = 43) of patients, IH was identified by both radiological and physical examination, in 47% (n = 41) of patients it was identified by radiological examination only and in 3% (n = 3) of patients it was identified by physical examination only. Re-admission rates and the number and type of adverse events did not differ significantly between the groups.

No significant differences in pain scores, as measured with the visual analogue scale, were reported in the first week postoperatively, and no significant difference was observed between the arms for any patient-reported outcomes, as measured with the Short Form-36 items (SF-36) subdomain or the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D).

Patients who developed IH reported lower general health scores [mean 60.16 (SD 18.27) vs. mean 64.84 (SD 48.7); p = 0.0326] and reported more problems in the EQ-5D dimension of mobility [mean 1.46 (SD 1.06) vs. mean 1.36 (SD 0.46); p = 0.0318] than those who did not develop IH.

HART feasibility study1

A 30-patient feasibility trial demonstrated that a RCT comparing Hughes abdominal closure with standard mass closure would be acceptable to patients, achieve adequate recruitment and present no early safety concerns. Patient participation rates were high, with 69% of all eligible patients consenting to take part. The feasibility study recruited 30 patients over a 5-month period, suggesting that the proposed sample size of 800 patients for a full trial would be achievable.

The importance of having adequate numbers of approved consenting staff on the delegation log was highlighted, as nine consenting patients could not be randomised because of staff shortages.

Rates of serious adverse events (SAEs) were similar between the arms [34% for Hughes (10 SAEs in five patients) vs. 31% for mass closure (six SAEs in five patients); p = 1.00], and no suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions were reported.

Cochrane review main findings22

For the primary outcome, namely the proportion of participants who developed IH at ≥ 1 year of follow-up, the authors did not find evidence that suture (absorption moderate), closure method (very low-quality evidence) or closure technique (moderate-quality evidence) resulted in a difference in the risk of IH. They did, however, find evidence to suggest that monofilament sutures reduced the risk of IH when compared with multifilament sutures (moderate-quality evidence).

Considering the secondary outcomes, the authors reported that none of the interventions under investigation [suture absorption (moderate-quality evidence), closure method (low- to moderate-quality evidence) or closure technique (moderate-quality evidence)] reduced the risk of wound infection or wound dehiscence.

Absorbable sutures reduced the risk of sinus or fistula tract formation compared with non-absorbable sutures, but this was based on low-quality evidence. None of the other comparisons showed a difference in risk of sinus or fistula tract formation (very low- to low-quality evidence). Table 1 provides a summary of the results by comparison and outcome.

| Comparison | Risk ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IH | Wound infection | Wound dehiscence | Sinus/fistula tract formation | |

| Absorbable vs. non-absorbable sutures | 1.07 (0.86 to 1.32) | 0.99 (0.84 to 1.17) | 0.78 (0.55 to 1.10) | 0.49 (0.26 to 0.94) |

| Slow vs. fast absorbable sutures | 0.81 (0.63 to 1.06) | 1.16 (0.85 to 1.57) | 1.55 (0.92 to 2.61) | 0.88 (0.05 to 16.05) |

| Mass vs. layered closure | 1.92 (0.58 to 6.35) | 0.93 (0.67 to 1.30) | 0.69 (0.31 to 1.52) | 0.49 (0.15 to 1.62) |

| Continuous vs. interrupted | 1.01 (0.76 to 1.35) | 1.13 (0.96 to 1.34) | 1.21 (0.90 to 1.64) | 1.51 (0.64 to 3.61) |

| Monofilament sutures vs. multifilament sutures | 0.76 (0.59 to 0.98) | |||

In summary, the authors reported that, based on their review of the evidence, a number of factors, including closure type and suture material, may have an impact on patient outcomes, such as IH rate, wound complications and QoL, following a midline incision. However, in their conclusions the authors note that the quality of the evidence ranges from moderate to very low, and there is a need for larger, high-quality trials. The conclusions of the authors also recommend that future studies ensure that proper randomisation and allocation techniques are performed, wound assessors are blinded and the duration of follow-up is adequate. 22

The authors note that it is important that only one type of intervention is compared between arms. In addition, they suggest that a homogeneous patient population would allow for a more accurate assessment of the interventions. 22 The STITCH trial,28 conducted in the Netherlands, is one such trial, in which patients were randomly assigned to large bites (1 cm every 1 cm) or small bites (5 mm every 5 mm). This well-conducted, double-blind, randomised controlled trial included all patients scheduled to undergo midline incision for any condition, not just colorectal cancer. IH rates differed significantly between the two arms (p = 0.0131).

The HART study proposed a large, multicentre, pragmatic clinical trial comparing only one type of intervention, Hughes abdominal closure method (hereafter referred to as Hughes repair), with standard mass closure exclusively in colorectal cancer patients. Although the population was limited to patients having surgery for colorectal cancer and the intervention arm was tightly defined with no variance in approach allowed, it should be noted that, in the control arm, the approach to standard mass closure allowed surgeon preference and this may have introduced an element of heterogeneity.

Hypothesis

The null hypothesis states that, in patients having midline abdominal wall closure following elective or emergency colorectal cancer surgery, there is no difference in the rate of IH over 1 year between those undergoing Hughes repair and those undergoing standard mass closure.

The alternative hypothesis states that, in patients having midline abdominal wall closure following elective or emergency colorectal cancer surgery, Hughes repair alters the incidence of IH over 1 year when compared with standard mass closure.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) was an integral part of the HART study. A minimum of two PPI representatives were involved at any given time throughout the study, one of whom had experience of colorectal surgery for a colorectal cancer. PPI representatives had previous experience of working with research groups and sat on the Trial Management Group for the study. In addition, a PPI representative sat on the Steering Committee for the trial. PPI began at the protocol development stage and continued right through to the interpretation, discussion and dissemination of results.

Patient and public involvement representatives were paid honoraria and out-of-pocket expenses in line with Health Care Research Wales and INVOLVE guidelines for attending meetings.

Although the impact of PPI was not an outcome of the study, feedback was sought from the patient representatives at all stages of the study and their experience of being part of a clinical study is reported.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

This was a multicentre, single-blinded randomised controlled trial. The patients were randomised 1 : 1 to enable the comparison of two suture techniques for the closure of the midline abdominal wound following surgery for colorectal cancer.

Changes to trial design

The study was split into three phases: feasibility, pilot and main. The feasibility phase assessed recruitment, randomisation, deliverability and early safety of the surgical technique. Following a successful feasibility phase, the trial was approved by the independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) and progressed to the pilot and main phases. No changes were adopted in the trial design specified during the feasibility phase and the study finished its primary end point as per the published study protocol. 1,2

Conduct of the study: approvals and trial registration

The trial was conducted in compliance with the protocol, the Declaration of Helsinki as currently revised29 and the principles of Good Clinical Practice (GCP),30 and in accordance with all applicable regulatory guidance.

The study protocol and all subsequent amendments were reviewed and approved by the Wales 3 Research Ethics Committee (REC) (MREC 12/WA/0374) and the research and development offices of the participating NHS sites. A list of key protocol amendments can be found in Appendix 3.

Annual progress and safety reports were submitted to the REC.

The trial was registered in the ISRCTN registry and the trial registration number is ISRCTN25616490.

Participants

The study identified patients who were due to undergo abdominal surgery for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Patients undergoing emergency surgical treatment and patients receiving elective surgical treatment were screened. Patients were not excluded if they had undergone previous abdominal surgery for conditions other than the new colorectal cancer. To be eligible for inclusion, patients had to be considered suitable for either Hughes repair or standard mass closure. Patients had to have a midline incision at least 5 cm in length or they were excluded from the study.

Surgery was carried out as per standard surgical procedure in a general surgical unit within the NHS across the UK. Prior to commencing closure and provided that the patient still met the inclusion criteria, the closing surgeon accessed the telephone randomisation system and the patient was allocated to either Hughes repair or standard mass closure.

An initial feasibility phase in which 30 participants were randomised to Hughes repair or standard mass closure was conducted at University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, only. Following the feasibility phase, which demonstrated that a RCT comparing Hughes repair with standard mass closure would be acceptable to patients,28 the study moved into the pilot and main phases. Patients were randomised to the pilot (n = 80) and main (n = 722) phases of this study (Hughes repair, n = 401; standard mass closure, n = 401) over a period of approximately 3 years and 5 months. No changes were made to the inclusion and exclusion criteria from the feasibility study to the full trial. Data from the pilot and main phases of the study were combined and are referred to as the main study phase in the rest of this report.

Inclusion and exclusion

Eligibility assessment

Eligible patients were identified through a screening process that identified whether or not patients met the initial pre-surgery inclusion criteria. Potentially eligible patients included both those undergoing elective surgery for colorectal cancer (identified via a multidisciplinary team meeting) and those undergoing emergency surgery for suspected colorectal cancer.

Eligibility for inclusion in the trial was assessed at two stages: first at screening and again at the point of surgical closure (which was the point of randomisation). The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the trial were as follows.

Inclusion criteria

At screening:

-

patients aged ≥ 18 years

-

able to give informed consent

-

both standard mass closure and Hughes repair were suitable closing techniques for the patient

-

patient was undergoing elective colorectal cancer surgery following full staging investigations including abdominal computed tomography (CT) scanning OR patient was undergoing emergency colorectal surgery because of a strong suspicion of colorectal cancer based on admission CT scanning.

At the point of surgical closure/randomisation:

-

midline abdominal incision (open or laparoscopic assisted/converted)

-

incision of ≥ 5 cm in length.

Exclusion criteria

At screening:

-

unable to provide informed consent.

At point of surgical closure/randomisation:

-

insertion of a mesh as part of abdominal closure

-

undergoing musculofascial flap closure of perineal defect in abdominoperineal wound closure.

Consent

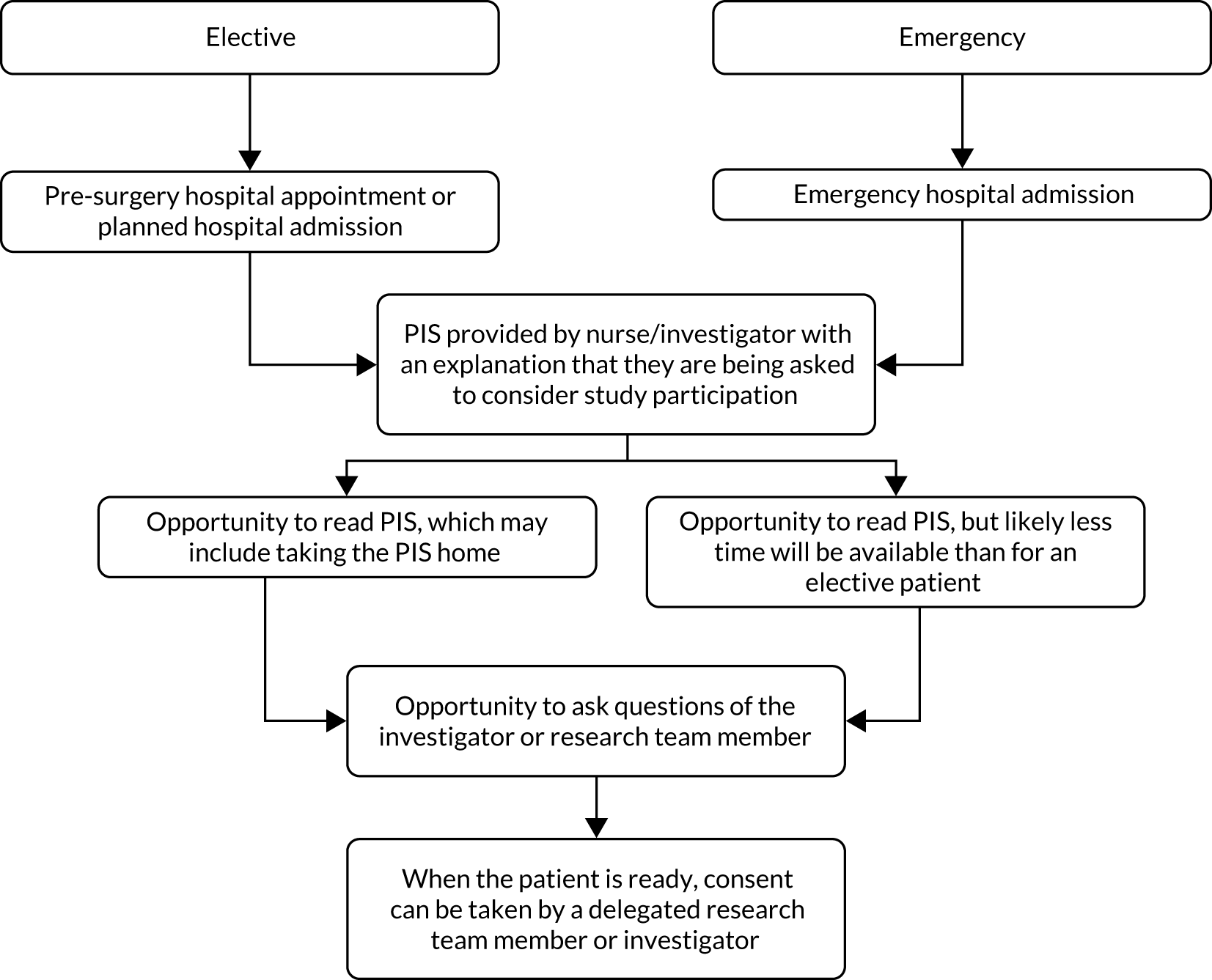

Patients identified as eligible were approached by a member of the research team to discuss taking part in the study. Interested patients were given a patient information pack containing a letter of invitation, a consent form and a patient information sheet for the study. Patients were given time to review the information and ask questions. Patients who agreed to take part in the study were consented prior to their surgery (Figure 2). In 2018, an updated consent statement was implemented to meet with GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) requirements. This was sent to each site for their records.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram of consent process. PIS, participant information sheet.

The mean time from signing the consent form to randomisation (surgery) was 2.5 days [standard deviation (SD) 7.2 days]. The maximum time was 91 days and the minimum time was 0 days. For patients undergoing elective surgery, the mean time from consent to randomisation (surgery) was 2.7 days, and for patients undergoing emergency surgery, the mean time from consent to randomisation was 0.4 days.

Study settings

The main study phase was conducted across 28 sites in England and Wales, with the University Hospital of Wales (Cardiff and Vale University Health Board) acting as the lead site and governance sponsor. Recruitment began in August 2014 and stopped in January 2018. A list of all participating sites and their level of recruitment can be found in Appendix 4, Table 30.

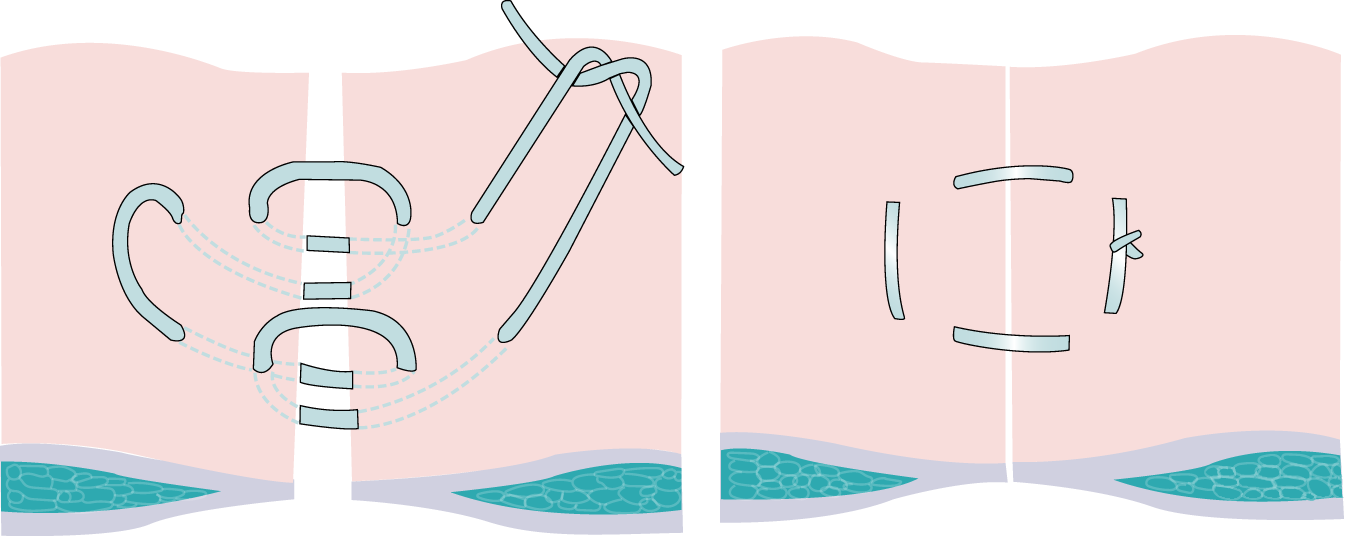

Interventions

The Hughes abdominal repair technique involves the use of ‘near and far’ sutures to close the abdominal wall. The technique combines a standard mass closure [two-loop 1-polydioxanone (PDS) sutures] with a series of horizontal and two vertical mattress sutures within a single suture (1 nylon), theoretically distributing the load along the incision length as well as across it (Figure 3). Surgeons use loop 1-PDS for the mass closure element of the Hughes repair, with the multiple nylon sutures used for the ‘near and far’ sutures. The principles of the technique are to ensure that only sound normal tissues are used for repair, to use graduated tension for easy approximation and to use a monofilament nylon suture, which has the advantage of slipping easily through tissues to create a pulley system. 2 This was a standardised intervention arm with no variation permitted.

FIGURE 3.

Hughes repair. Reproduced with permission from Cornish et al. 2 © 2016 The Author(s). Open Access. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Standard care (control arm) comprised standard mass closure. This involves closing all layers of the abdominal wall (excluding the skin), usually using non-absorbable sutures, although ‘slow-resorbing’ sutures, such as PDS, are also widely used. Variation was allowed in this arm according to surgeon preference, but the technique used was recorded on the patient case report form (CRF).

All patients were given the same postoperative rehabilitation advice regardless of study arm.

Standardisation and training in intervention

Training in the Hughes repair (arm A) technique was undertaken by either the chief investigator or the co-investigator, both of whom were colorectal surgeons, as part of each site induction. This training involved both a 6-minute instructional video31 and a Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) presentation describing the background to the trial and the trial outline, followed by a practical clinical skills session with subsequent formal assessment. This practical clinical skills session involved either the chief investigator or the co-investigator demonstrating the Hughes repair technique on an abdominal wall simulation jig using the same sutures as used in the trial (loop 1-PDS and 1 nylon). Those being trained (surgical consultants and trainees) were then able to practise the technique until they were confident in it. A formal assessment in technique competence was then completed for each of those being trained at the site induction.

With regard to other members at each site who did not attend the site induction but were to be on the delegation log and performing abdominal wall closure as part of the trial, the site principal investigator was given responsibility for their training and formal assessment (once the principal investigator was deemed competent themselves).

Primary outcome

The primary outcome measure was the incidence of IH at the 1-year clinical examination.

The clinical presence of a hernia was assessed by an independent surgeon who was blinded to the closure technique wherever possible. In some centres, this examination was carried out by a nurse specialist who had appropriate accreditation for patient examination and was also blinded to the closure technique. The CRF included explicit details/instructions on how to carry out the examination. The presence of a hernia was detected as a reducible, palpable mass, usually with a cough impulse, which may cause pain or discomfort.

Secondary outcomes

-

Quality of life (QoL) measured using SF-12 and FACT-C. Questionnaires were administered at baseline and at 30 days, 6 months, 1 year and 2 years following randomisation. QoL was compared between arms (Hughes repair vs. standard mass closure) and between patients who developed IH and patients who did not develop IH.

-

Cost-effectiveness of Hughes repair compared with standard mass closure in the first year from the perspective of the NHS. Information regarding health-care resource use (including surgery-specific resources) was collected using a Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI) questionnaire at baseline, 6 months and 1 year.

-

Postoperative full thickness abdominal wall dehiscence (burst abdomen) within 30 days of surgery, as well as details of any repair surgery and closing sutures used.

-

Identification and characterisation of patient and surgical factors associated with an increased risk of developing an IH.

-

Prevalence of hernia at 1-year clinical examination.

Tertiary outcomes

-

Prevalence of clinically detectable IH at 5 years from surgery.

-

Effect of Hughes repair and standard mass closure over the 5 years from surgery.

-

Cost-effectiveness of Hughes repair compared with standard mass closure over 5 years from the perspective of health and social care.

-

Sensitivity and specificity of CT image identification over 2 years compared with clinical examination over 2–5 years from surgery.

-

Quality of life between patients with IH and patients with no IH in both arms over 5 years.

Sample size

A clinically important difference between the study arms was deemed to be a reduction in the IH rate from 30% in the standard mass closure arm to 20% in the Hughes repair arm. To detect this difference, it was calculated that a total of 640 patients would be required, providing 80% statistical power with a 5% level of significance. Assuming loss to follow-up of about 20% at 1 year, as seen in similar trials, HART aimed to recruit a total of 800 patients. A completed sample of 640 participants was calculated to yield 80% power of detecting (with a 5% significance level) a standardised difference (differences in means scaled by SD) of 0.225 in QoL (the principal secondary outcome).

Interim analyses and stopping guidelines

No interim analysis was planned in this study. Primary analysis was performed when all 1-year visits had been completed, data had been collated and the database had been locked. A separate analysis was carried out on data collected in year 2 of follow-up. The statistician received unblinded data after the database was locked for the final data analysis at year 1 and again at year 2.

The study followed the principle of allowing for early stopping were there to be a safety concern. During the study, the DMC and the study sponsor were responsible for stopping the study early had continuation of the trial been considered not in the patients’ best interest. Study data were reviewed by the DMC approximately every 6 months and reports were made to the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). The sponsor was ultimately responsible for trial progression after the consideration of recommendations by the DMC and TSC. The TSC also monitored recruitment and study progress to inform any decision to halt the study were it to be considered that the study had failed to deliver its objective as a result of delayed recruitment or lack of data besides any safety concern for the patients.

Randomisation and treatment allocation

We used an adaptive randomisation design to allocate the eligible patients to arms of similar sizes using an allocation ratio of 1 : 1. The sequence was created by a computerised random number generator and the allocation of participants was balanced by controlling the stratification variables. This dynamic randomisation stratified by operation type (elective or emergency) and site. 1 The principles of the randomisation design can be found in Russell et al. 32 The customised randomisation process was hosted by Sealed EnvelopeTM (London, UK; www.sealedenvelope.com; accessed March 2021), an independent company registered with the Information Commissioner’s Office, which provided a validated and fully automated 24-hour access telephone service for this dynamic randomisation. Randomisation was performed by the closing surgeon and took place as close as possible to commencement of closure. HART study surgeons were provided with training on the use of the telephone randomisation system.

Blinding

Study participants were informed prior to surgery that they would be randomised to receive one of the two closing techniques. Both the study participants and the post-surgical clinical assessors were blinded to the closure techniques. To attempt to maintain blinding, the method of closure was not documented in the operating notes and/or the clinical assessor was asked to complete the hernia examination (CRF) before reviewing the patient notes. The surgeon could not be blinded to the arm allocation because they were to undertake the closure as per randomisation. The data entry staff, the trial manager and the data manager were not blinded because of their central role in data collection and collation. The trial statisticians were blinded until the point of data lock during the final analysis stage.

Data

All data, including those on screening, eligibility, randomisation, surgery and follow-up, were collected on a patient CRF and managed using the MACRO database (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; www.elsevier.com/en-gb/solutions/veridata/macro; accessed March 2021), a secure electronic data capture system recording the information collected on CRFs and allowing rapid data extraction.

Radiology data (CT scans and related data) were managed in REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture; www.project-redcap.org; accessed March 2021), a secure web application for data collection.

The data collection comprised pre-surgery data, intraoperative data and post-surgery follow-up data. For detailed information of the data collected in the CRF, see Report Supplementary Material 1.

Patients were assessed for eligibility using the study inclusion and exclusion criteria, and eligible patients who gave informed consent were recruited to the trial. Once they were recruited, and prior to surgery, patients’ baseline demographic information, medical history, surgical history, hernia status and QoL were collected. Intraoperative data were collected immediately post surgery and included the surgery type, grade of surgeon, details on the materials used and surgical outcomes.

Quality-of-life data were collected using the validated SF-1233 and FACT-C questionnaires. 34 Questionnaires were given to patients to complete while they were waiting for follow-up visits or, where necessary, were sent by post. The SF-12 is a short version of the SF-36 item health survey. It is a general health questionnaire capturing information on both physical and mental health across eight domains. FACT-C is a 37-item colorectal cancer-specific tool that adds a subset of 10 colorectal cancer-specific items to the original 27-item FACT-G (which is used for any cancer population). FACT-C consists of five subscales: physical well-being, social and family well-being, emotional well-being, functional well-being and the Colorectal Cancer Subscale. Both SF-12 and FACT-C can be self-administered by the patient or completed in an interview with the patient. Both tools are used widely in research, and a review of available generic and colorectal cancer-specific patient-reported outcome measure tools35 suggests that the SF-12 and FACT-C were appropriate choices for this study.

The MACRO database was locked for year 1 data collection in March 2019 and for year 2 data collection in April 2020. The REDCap database was locked for year 1 data in September 2019. The later datalock for REDCap was to allow all CT scan images and data to be transferred from individual sites via the Picture Archiving and Communications System (PACS) and entered into the database to be reviewed independently by two radiologists.

Following data lock, data were checked for completeness. Any outstanding queries were raised with individual sites and resolved, and SAE coding was completed and reviewed.

Year 1 data analysis included data collected at 12 months ± 2 months (i.e. 10–14 months) and year 2 data analysis similarly included a 2-month window either side (24 months ± 2 months; range 22–26 months). If a patient’s treatment course and clinical requirements meant that no CT was undertaken during this window, the CT scan closest to the 1-year time point was used. In total, 86.5% of CT scans were recorded within 14 months, with 95% recorded within 16 months.

Follow-up

Patients consented to be followed up at 30 days, 6 months and 1 year and annually thereafter. Postoperative follow-up data included data from clinical examination, CT scanning, patient-completed SF-12 and FACT-C quality-of-life forms and patient diaries. Full details of the data collected at individual follow-up points are reported in Appendix 4, Table 31.

Safety

As part of the monitoring of adverse events, information related to surgical site infection (SSI) and postoperative burst abdomen was collected. Colorectal cancer stage information was collected within 30 days post surgery.

Statistical methods

The trial analysis was carried out in accordance with the statistical analysis plan (SAP) using treatment allocated [intention to treat (ITT)], with participants in the arm allocated at randomisation. QoL data were collected using recognised and validated patient-reported outcome measure tools, namely the generic SF-12 and the condition-specific FACT-C.

Continuous variables that follow an approximately normal distribution were summarised using n (non-missing sample size), means, SDs, minimums and maximums. Skewed continuous variables were summarised using medians and interquartile ranges. Categorical variables were summarised using frequencies and percentages. All hypothesis testing was planned to be two-tailed with a 5% significance level and no adjustment for multiple testing.

Binary logistic regression analysis for the outcome variable IH was adjusted for all of the important baseline covariates. As this was a variable selection method, we employed a stepwise backward selection search starting with the full model, considering all of the adjusting covariates and removing the least significant, and repeating until only statistically significant covariates and the arm indicator remained in the model. The initial list of variables was arm indicator, age, gender, ethnicity, BMI, diabetes, any chemotherapy, radiotherapy, history of high alcohol use, history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), any IH present clinically, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, whether the patient was from a high (≥ 50 enrolled participants) or a low (< 50 enrolled participants) recruiting site, baseline QoL measures [i.e. the SF-12 Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS) and FACT-C score] and baseline Physiological and Operative Severity Score for understanding Mortality and Morbidity (POSSUM) score.

Data processing and analyses were performed using Stata® version 16 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Baseline data

Baseline characteristics, including demographics, medical history, specific conditions (e.g. COPD and diabetes), chemotherapy, radiotherapy, abdominal aortic aneurysm, abdominal surgery history, current hernia status (incisional, non-incisional), baseline POSSUM score and QoL measures (FACT-C and SF-12), were summarised by treatment arm using appropriate descriptive methods for all randomised participants. Full details can be found in the statistical and health economic analysis plan (see Report Supplementary Material 2).

Primary end point

The primary outcome was the incidence of IH, and we tested the null hypothesis that there is no difference between the two surgical procedures (i.e. Hughes repair and standard mass closure) at 1 year (the primary end point). Patient and surgical factors associated with a risk of IH were identified via binary logistic regression models.

Secondary end points

Quality of life

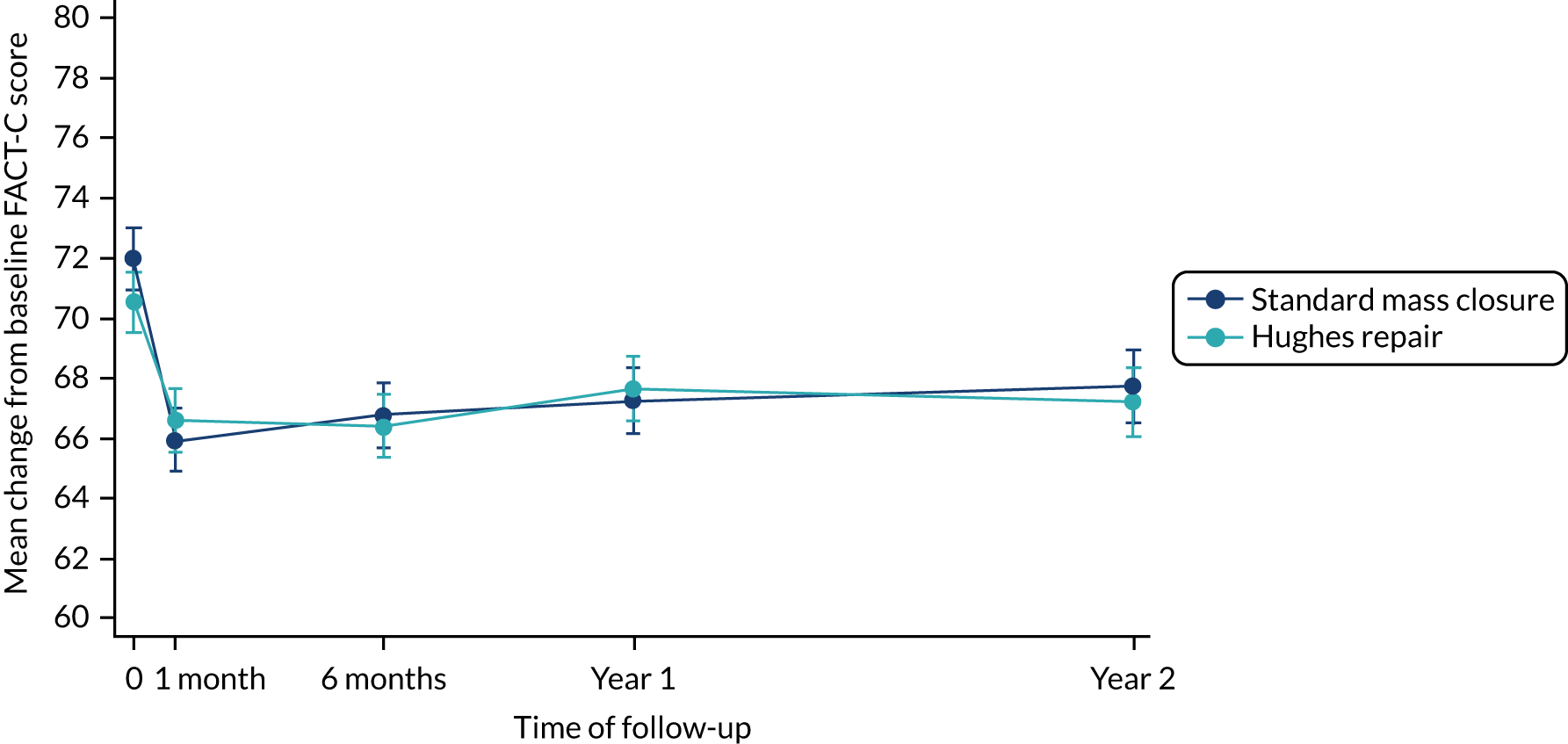

Patient-reported outcome measures measure a patient’s health status or health-related QoL at any specific time point. They are collected using patient self-reported questionnaires about their symptoms, conditions and overall QoL. We used SF-12 and FACT-C and measured patients’ QoL at baseline, 30 days, 6 months and 1 year, and annually thereafter. The PCS score and MCS score were calculated from the SF-12. Scores on both of these range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better physical activity and better mental health, respectively. The FACT-C score ranges from 0 to 136, with higher scores indicating better health. In accordance with licence agreements, we followed the standard manuals to score these outcome measures and used standard methods for dealing with missing responses when scoring. We scored the summary statistics of the PCS, MCS and FACT-C scores at all time points by arm and have explored whether or not there was any statistically significant difference at any time point between the arms. Following this descriptive analysis, we performed an adjusted analysis using mixed-model repeated measures to explore the changes in PCS, MCS and FACT-C scores over time (baseline to 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 1 year and 2 years). We used all of the covariates as confounding factors in this adjusted analysis [e.g. age, gender, ethnicity, BMI, COPD, any baseline chemotherapy, radiotherapy, ASA class 2 and ≥ 3 (reference: class 1), smoking history and visit time (1 month, 6 months, 1 year and 2 years; reference: baseline)]. The outcome of this analysis enabled us to explore whether or not any changes in score (e.g. PCS) from baseline were significantly different by arm after adjustment for all of the factors considered.

Postoperative wound dehiscence

The postoperative full thickness wound dehiscence rate at 30 days following surgery was calculated for each arm and compared using Fisher’s exact chi-squared test with 95% confidence interval (CI) for any significance difference.

Prevalence of incisional hernia

The prevalence of IH was calculated at 1 year following surgery for each arm as the proportion of IH cases at 1 year of the total number of patients.

Sensitivity and specificity of computed tomography image compared with clinical examination at 1 year

Abdominal CT images (both preoperative and postoperative) were independently reviewed by two radiologists who were blinded to both the type of abdominal wall closure and the IH clinical finding. All cases of disagreement were resolved by consensus. The sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative predictive values of detecting IH by CT image were calculated with respect to clinical examination. The index test was CT scanning and the reference standard was clinical examination. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was calculated to provide the area under the curve and detect the best combination of sensitivity and specificity of CT image identification of hernias over 1 year compared with clinical examination data following surgery.

Safety data

All enrolled patients were included in the safety analysis. Safety data included adverse events, SAEs, serious adverse reactions and suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions. A number of adverse events and SAEs were expected in patients in this study, including lower respiratory tract infection, urinary tract infection, anastomotic leak, intra-abdominal sepsis, deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolus, wound infection, SSI, wound breakdown, paralytic ileus, bleeding, myocardial infarction and stoma complications. All SAEs within 30 days of surgery and all deaths (regardless of time after report) were reported by the site staff and reviewed weekly by the chief investigator. Events reportable to the REC were identified during the weekly review and submitted by the chief investigator and trial manager (or delegate). Six-monthly reports were also provided to the REC. SAEs were summarised by the total number and the number of patients involved in each arm. SAEs were graded using the Clavien–Dindo classification36 and SAE types were classified using MedDRA. 37

Patient and public involvement

Two PPI representatives were involved in this study at any given point. Both representatives had previous experience of working with research groups and sat on the Trial Management Group for the project. A PPI representative sat also on the Steering Committee for the trial.

The PPI representatives were involved throughout this study from protocol development stage to study conclusion.

Patient and public representatives co-participated with the study team in areas such as designing patient materials and promoting the study to patients. PPI representatives worked with study team members to produce a patient information pack introducing the trial and explaining the aims of the research. The PPI representatives were involved with the development of the patient information sheets, patient questionnaires and contributed extensively to the writing of the Plain English summary for the study.

Patient and public representatives were in attendance at all Trial Management Group meetings and actively contributed to any discussions and decision-making processes. Over the course of the study, PPI representatives joined the clinical team at a number of public events giving presentations about public involvement in research to nurses and medical students. They were also involved with providing feedback to trial participants throughout the study and keeping sites up to date with trial progress via a study newsletter and designed a thank-you card giving information about the trial and details of where the results would be posted, which was sent to all surviving participants following the completion of the trial.

The PPI representatives were paid honoraria and out-of-pocket expenses in line with Health Care Research Wales and INVOLVE guidelines for attending meetings.

Patient representatives will have further input into the dissemination of the final results.

Chapter 3 Results

Participant flow

Recruitment

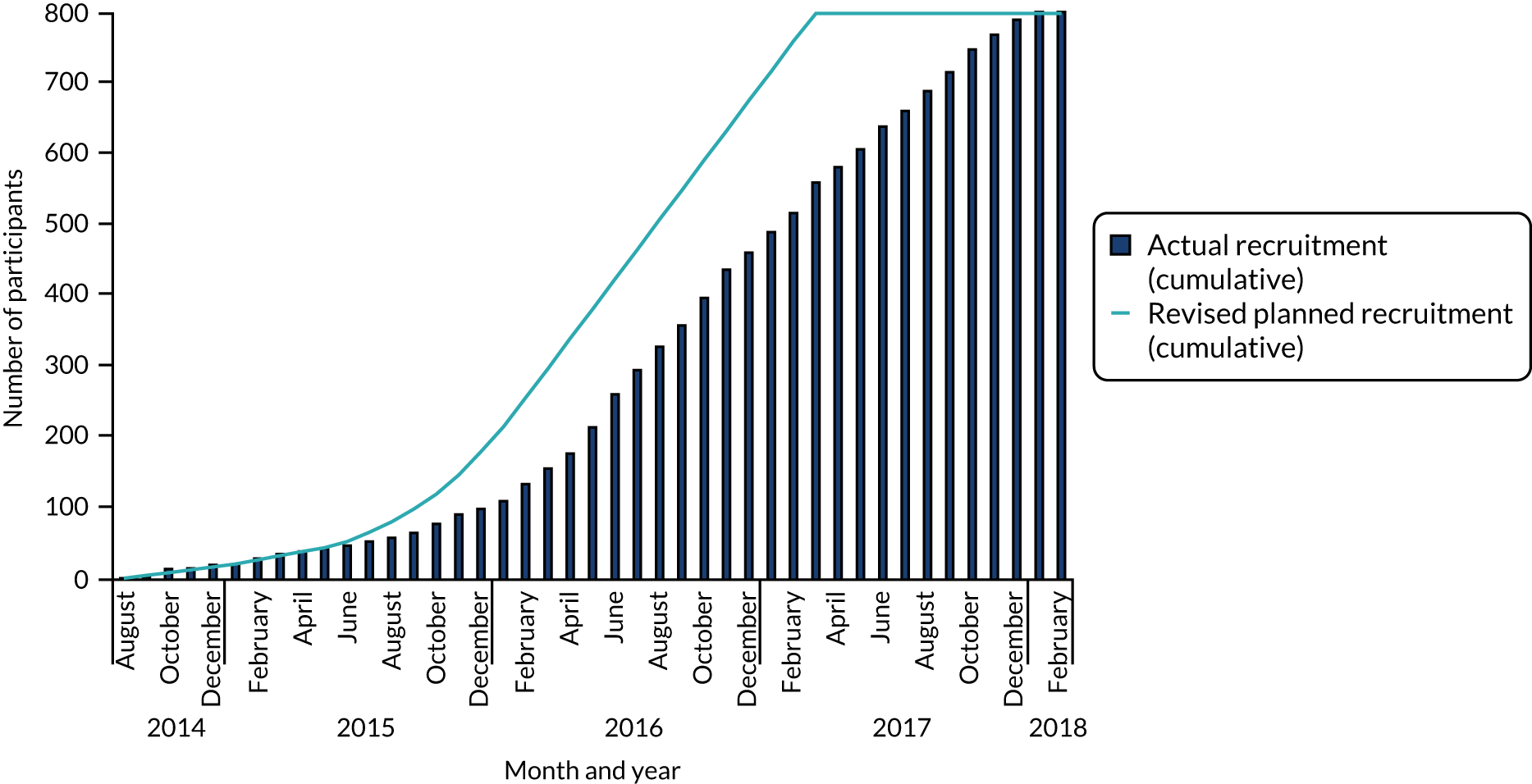

The first study site opened for recruitment in August 2014 and the last site opened in December 2016. A total of 28 sites opened for recruitment; one proposed site did not open and one site, although open for recruitment, did not recruit any patients to the study. Recruitment was planned to be completed by March 2017. However, owing to slower than anticipated recruitment, the recruitment phase of the study was extended and recruitment was completed in January 2018 (Figure 4). Detailed recruitment by site is reported in Appendix 3, Table 30.

FIGURE 4.

Cumulative recruitment.

Screening and eligibility

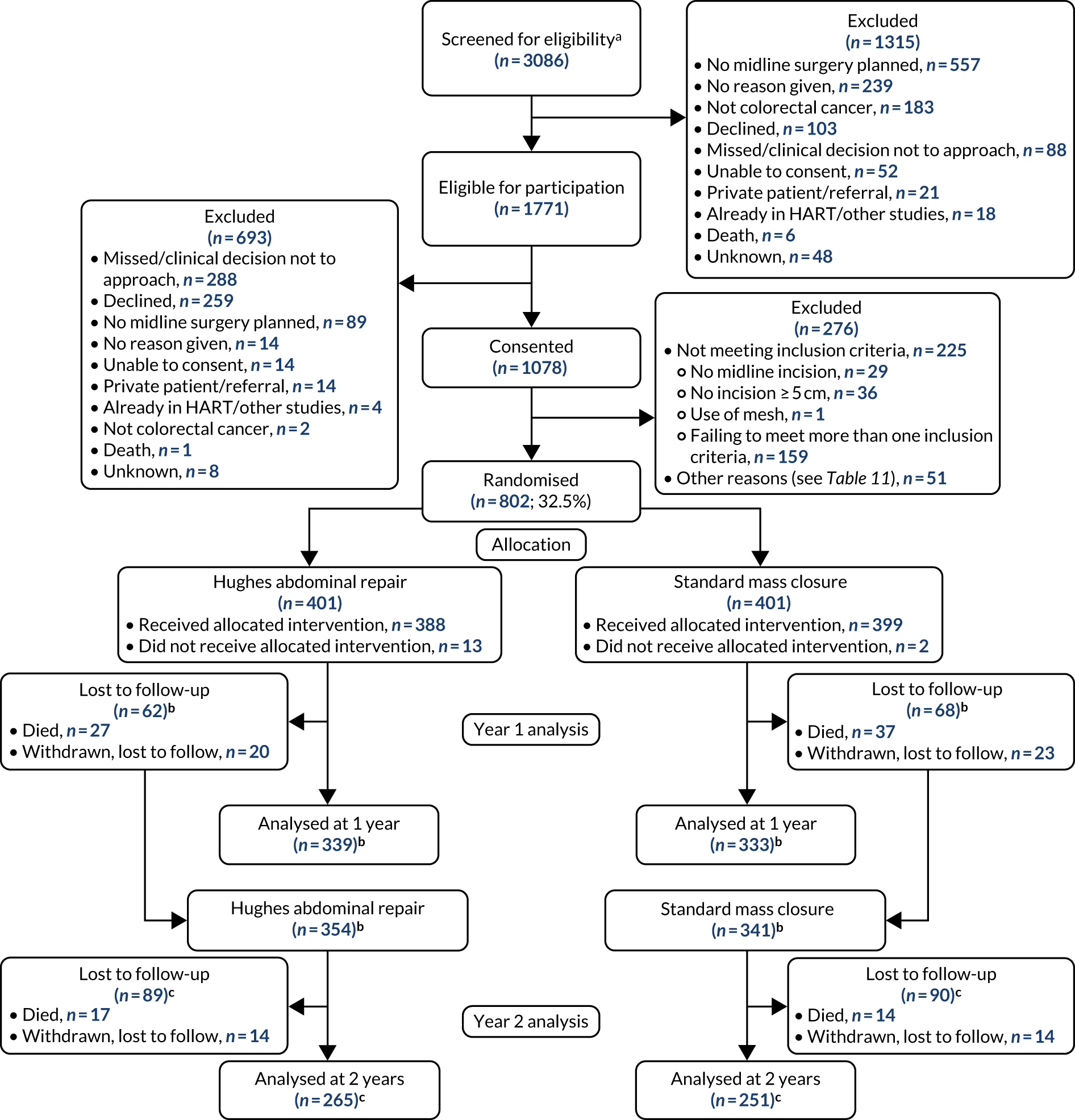

Screening logs showed that 3086 patients across 28 sites were screened for eligibility, with 1771 patients deemed to be eligible for study inclusion. Primary reasons for non-eligibility included not having a midline incision, not having colorectal cancer and declining to take part in the study. In a large number of cases, screening logs did not report a reason for non-eligibility (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

The CONSORT flow diagram of consented and randomised patients. a, Some sites included only eligible patients on their screening logs; therefore, the number screened is likely to be larger; b, a small number of patients (Hughes repair, n = 15; standard mass closure, n = 13) reported no year 1 data and could not be included in year 1 analysis, as no study discontinuation form had been completed. Of these 28 patients, eight were seen at year 2 (four in each arm), with five having no IH; c, 58 patients in Hughes repair arm and 62 patients in standard mass closure arm reported no year 2 data and could not be included in year 2 analysis. As no study discontinuation form had been completed, these patients could not be considered lost to follow-up in year 2.

Losses and exclusions

Eligible patients were asked to give their informed consent to take part in the study. Primary reasons for exclusion following eligibility assessment included not being approached for consent because of either nurse or physician unavailability, or declining to take part (see Figure 5).

Consent was obtained from 1078 patients and, of these, a total of 802 were randomised at the point of surgical incision closure (standard mass closure, n = 401; Hughes repair, n = 401). Most of the 276 participants excluded at this stage no longer satisfied the inclusion criteria, with 159 failing to meet more than one inclusion criterion (see Figure 5). Other reasons for the non-randomisation of consented patients are categorised in Table 2, with full details in Appendix 4, Table 32.

| Category | Count (n) |

|---|---|

| Logistical issues [e.g. operation took too long/complications in theatre/problems with surgery times (delayed/brought forward/busy)/equipment unavailable] | 18 |

| Surgeon decision | 17 |

| Patient eligibility | 14 |

| Reason not stated | 1 |

| Consent withdrawn | 1 |

| Total | 51 |

Following randomisation, 15 patients (Hughes repair, n = 13; standard mass closure, n = 2) did not receive their allocated treatment.

A total of 107 patients were lost to follow-up at year 1 (Hughes repair, n = 47; standard mass closure, n = 60). Of these, 64 died (Hughes repair, n = 27; standard mass closure, n = 37) and 43 withdrew (Hughes repair, n = 20; standard mass closure, n = 23).

Numbers analysed

A total of 672 patients were included in the year 1 analysis (Hughes repair, n = 339; standard mass closure, n = 333) and 516 patients were included in the year 2 analysis (Hughes repair, n = 265; standard mass closure, n = 251) (see Figure 5). For a number of patients (Hughes repair, n = 15; standard mass closure, n = 8), data were available for year 2 but no year 1 results were recorded and no discontinuation information was available and, therefore, these patients were not considered in the year 1 analysis but were included in the year 2 analysis.

Missing data

The study team made every effort to capture a full data set. The frequency of missing data is summarised for each variable. The statistical analysis plan and study protocol necessitated that if data were not missing completely at random, then the trial statistician and chief investigator would discuss the findings and agree on an approach to handle the missing data. The trial statistician identified no reason to indicate that data were not missing completely at random; therefore, protocol procedures for handling data not missing completely at random were not needed. For the key primary outcome, participants with no follow-up data were automatically excluded from the analysis. We scored the QoL measures (i.e. SF-12 and FACT-C) using their scoring algorithms. After this scoring, 20% of data were missing in the outcome scores of these QoL measures at baseline. For those missing, we adopted a multiple imputation method to impute the outcome scores outcome scores.

Short Form questionnaire-12 items questionnaire in the pilot phase

It was observed from SF-12 responses that 33 patients in the initial pilot phase were given a hybrid version of SF-12 version 1 and version 2 to complete for a total of 76 visits (33 visits at baseline, 26 at 1 month and 17 at 6 months). This affected four questions (3a, 3b, 4a and 4b), which offered two response categories from version 1 (i.e. yes and no) instead of five categories from version 2 (ranging from ‘all the time’ to ‘none of the time’). To resolve this issue, an imputation method for estimating the responses based on the distribution of their other responses was adopted.

The scoring software Procore 1.4 (https://support.procore.com; accessed March 2021) calculates SF-12 scores based on eight domains (i.e. general health perceptions, physical functioning, role limitations owing to physical health, role limitations owing to emotional problem, bodily pain, mental health, vitality and social functioning). For missing data, the maximum data recovery method (missing data estimation) from Procore was used. Under this missing data estimation, the software imputes a scale value if at least one item in the scale has valid data. PCS scores are calculated when the physical functioning scale and at least six of the remaining seven scale values are known or can be estimated. For MCS, the mental health scale and at least six of the remaining seven scale values must be known or able to be estimated.

FACT-C questionnaire

We followed the method for scoring FACT-C as per the FACT-C scoring manual, as described in their guidelines. 38 In accordance with the manual, FACT-C outcome scores were calculated only for patients who responded to at least 50% of the questions at a specific time point.

Baseline data

A summary of the baseline data for the study cohort is presented in Table 3 and a detailed summary of intraoperative characteristics is given in Table 4. The two arms were well balanced, with no differences observed between the arms in any of the baseline characteristics.

| Characteristic | Hughes repair (N = 401) | Standard mass closure (N = 401) | Total (N = 802) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 69.0 (10.7) | 68.1 (12.7) | 68.5 (11.7) |

| Age (years) (categories), n (%) | |||

| < 40 | 3 (0.8) | 12 (3.0) | 15 (1.9) |

| 40–50 | 10 (2.5) | 25 (6.2) | 35 (4.4) |

| 50–60 | 63 (15.7) | 58 (14.5) | 121 (15.1) |

| 60–70 | 127 (31.7) | 96 (23.9) | 223 (27.8) |

| 70–80 | 129 (32.2) | 132 (32.9) | 261 (32.5) |

| > 80 | 69 (17.2) | 78 (19.5) | 147 (18.3) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 262 (65.3) | 247 (61.6) | 509 (63.5) |

| Female | 139 (34.7) | 154 (38.4) | 293 (36.5) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 385 (96.0) | 386 (96.3) | 771 (96.1) |

| Black | 7 (1.8) | 5 (1.3) | 12 (1.5) |

| Asian | 6 (1.5) | 7 (1.8) | 13 (1.6) |

| Other | 3 (0.8) | 3 (0.8) | 6 (0.8) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 28.0 (5.3) | 27.7 (5.6) | 27.8 (5.4) |

| Missing | 4 (1.0) | 5 (1.3) | 9 (1.1) |

| BMI (kg/m2) (categories), n (%) | |||

| < 18.5 (low or underweight) | 10 (2.5) | 7 (1.8) | 17 (2.1) |

| ≥ 18.5 to < 25 (healthy) | 106 (26.4) | 122 (30.4) | 228 (28.4) |

| ≥ 25 to < 30 (overweight) | 157 (39.2) | 157 (39.2) | 314 (39.2) |

| ≥ 30 to < 40 (obese) | 114 (28.4) | 97 (24.2) | 211 (26.3) |

| ≥ 40 (severely obese) | 14 (3.5) | 18 (4.50) | 32 (4.0) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 65 (16.2) | 68 (17.0) | 133 (16.6) |

| No | 336 (83.8) | 333 (83.0) | 669 (83.4) |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 43 (10.7) | 34 (8.5) | 77 (9.6) |

| No | 358 (89.3) | 367 (91.5) | 725 (90.4) |

| Neoadjuvant radiotherapy, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 38 (9.5) | 32 (8.0) | 70 (8.7) |

| No | 363 (90.5) | 369 (92.0) | 732 (91.3) |

| COPD, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 50 (12.5) | 62 (15.5) | 112 (14) |

| No | 351 (87.5) | 339 (84.5) | 690 (86.0) |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 4 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) | 6 (0.8) |

| No | 397 (99.0) | 399 (99.5) | 796 (99.3) |

| Smoking, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 31 (7.7) | 37 (9.2) | 68 (8.5) |

| No | 228 (56.9) | 218 (54.4) | 446 (55.6) |

| Ex-smoker | 142 (35.4) | 144 (35.9) | 286 (35.7) |

| Missing | 0 | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) |

| High alcohol use, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 25 (6.2) | 25 (6.2) | 50 (6.2) |

| No | 376 (93.8) | 375 (93.5) | 751 (93.6) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) |

| ASA class, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 52 (13.0) | 51 (12.7) | 103 (12.8) |

| 2 | 223 (55.6) | 233 (58.1) | 456 (56.9) |

| 3 | 121 (30.2) | 110 (27.4) | 231 (28.8) |

| 4 | 5 (1.3) | 5 (1.3) | 10 (1.3) |

| Missing | 0 | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) |

| QoL measures | |||

| PCS score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 43.6 (5.5) | 43.7 (5.5) | 43.7 (5.5) |

| Missing | 78 (19.4) | 82 (20.4) | 160 (20.0) |

| MCS score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 52.5 (11.9) | 52.9 (12.1) | 52.7 (12.0) |

| Missing | 81 (20.2) | 78 (19.4) | 159 (19.8) |

| FACT-C | |||

| Mean (SD) | 70.5 (9.9) | 71.7 (10.0) | 71.1 (10.0) |

| Missing | 88 (22.0) | 90 (22.4) | 178 (22.2) |

| Abdominal surgery history, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 167 (41.7) | 169 (42.1) | 336 (41.9) |

| No | 234 (58.4) | 232 (57.9) | 466 (58.1) |

| Current hernia status | |||

| Incisional hernias, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 9 (2.2) | 3 (0.8) | 12 (1.5) |

| No | 392 (97.8) | 396 (98.8) | 788 (98.3) |

| Missing | 0 | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) |

| Non-incisional hernias, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 35 (8.7) | 28 (7.0) | 63 (7.9) |

| No | 366 (91.3) | 371 (92.5) | 737 (91.9) |

| Missing | 0 | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) |

| Characteristic | Hughes repair (N = 401) | Standard mass closure (N = 401) | Total (N = 802) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade of surgeon performing abdominal wall closure, n (%) | |||

| Surgical trainee (ST5 or below) | 31 (7.7) | 47 (11.7) | 78 (9.7) |

| Surgical trainee (ST6–8) | 105 (26.2) | 161 (40.2) | 266 (33.2) |

| Consultant | 262 (65.3) | 187 (46.6) | 449 (56.0) |

| Missing | 3 (0.8) | 6 (1.5) | 9 (1.1) |

| ASA class, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 52 (13.0) | 51 (12.7) | 103 (12.8) |

| 2 | 223 (55.6) | 233 (58.1) | 456 (56.9) |

| 3 | 121 (30.2) | 110 (27.4) | 231 (28.8) |

| 4 | 5 (1.3) | 5 (1.3) | 10 (1.3) |

| Missing | 0 | 2 (0.5) | (0.3) |

| Operation performed, n (%) | |||

| Abdominoperineal resection | 19 (4.7) | 13 (3.2) | 32 (4.0) |

| Anterior resection | 130 (32.4) | 122 (30.4) | 252 (31.4) |

| Hartmann’s procedure | 22 (5.5) | 26 (6.5) | 48 (6.0) |

| Left hemicolectomy | 19 (4.7) | 18 (4.5) | 37 (4.6) |

| Right hemicolectomy | 131 (32.7) | 147 (36.7) | 278 (34.7) |

| Extended right hemicolectomy | 24 (6.0) | 34 (8.5) | 58 (7.2) |

| Panproctocolectomy | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.3) | 4 (0.5) |

| Subtotal colectomy | 9 (2.2) | 11 (2.7) | 20 (2.5) |

| Sigmoid colectomy | 17 (4.2) | 10 (2.5) | 27 (3.4) |

| Other | 27 (6.7) | 19 (4.7) | 46 (5.7) |

| Stoma formed, n (%) | |||

| No stoma | 259 (64.6) | 277 (69.1) | 536 (66.8) |

| End ileostomy | 8 (2.0) | 8 (2.0) | 16 (2.0) |

| Loop ileostomy | 71 (17.7) | 64 (16.0) | 135 (16.8) |

| End colostomy | 49 (12.2) | 49 (12.2) | 98 (12.2) |

| Loop colostomy | 3 (0.8) | 3 (0.8) | 6 (0.8) |

| Other | 11 (2.7) | 0 | 11 (1.4) |

| Mode of operation, n (%) | |||

| Open | 171 (42.6) | 151 (37.7) | 322 (40.2) |

| Laparoscopic | 125 (31.2) | 127 (31.7) | 252 (31.4) |

| Laparoscopic assisted | 35 (8.7) | 64 (16.0) | 99 (12.3) |

| Laparoscopic converted to open (midline incision) | 70 (17.5) | 59 (14.7) | 129 (16.1) |

| Colorectal cancer resected, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 399 (99.5) | 400 (99.8) | 799 (99.6) |

| No | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.4) |

| Intraoperative blood transfusion | |||

| Yes, n (%) (mean number of units transfused) | 21 (5.2) (2.0) | 14 (3.5) (1.6) | 35 (4.4) |

| No, n (%) | 380 (94.8) | 387 (96.5) | 767 (95.6) |

| Intraoperative complications, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 20 (5.0) | 10 (2.5) | 30 (3.8) |

| No | 381 (95.0) | 390 (97.3) | 771 (96.1) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) |

| Wound closed as per randomisation, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 388 (96.8) | 399 (99.5) | 787 (98.1) |

| No | 13 (3.2) | 2 (0.5) | 15 (1.9) |

| Anti-adhesive agent used intraoperatively, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 7 (1.8) | 6 (1.5) | 13 (1.6) |

| No | 391 (97.5) | 390 (97.3) | 781 (97.4) |

| Missing | 3 (0.8) | 5 (1.3) | 8 (1.0) |

| Final length of midline incision (cm) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 15.5 (8.4) | 14.7 (8.2) | 15.1 (8.3) |

| Missing | 9 (2.2) | 20 (5.0) | 29 (3.6) |

| Skin closure method, n (%) | |||

| Surgical clips | 162 (40.4) | 144 (35.9) | 306 (38.2) |

| Subcuticular absorbable suture(s) | 238 (59.4) | 250 (62.3) | 488 (60.9) |

| Interrupted sutures | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.4) |

| Other | 0 | 4 (1.0) | 4 (0.5) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) |

| Total time taken for the procedure (minutes) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 202.9 (90.9) | 183.4 (75.1) | 193.2 (83.9) |

| Missing | 4 (1.0) | 8 (2.0) | 12 (1.5) |

| Time taken for the fascial closure (minutes) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 22.0 (9.7) | 13.2 (6.7) | 17.6 (9.5) |

| Missing | 8 (2.0) | 19 (4.7) | 27 (3.4) |

| Postoperative length of stay (days) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 10.6 (11.5) | 9.8 (12.4) | 10.2 (11.9) |

| Missing | 9 (2.2) | 7 (1.7) | 16 (2.0) |

| Level of postoperative care, n (%) | |||

| ITU | 19 (4.7) | 9 (2.2) | 28 (3.5) |

| HDU | 96 (23.9) | 100 (24.9) | 196 (24.4) |

| Ward/PACU | 286 (71.3) | 292 (72.8) | 578 (72.1) |

| POSSUM score | |||

| Physiological score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 17.5 (4.2) | 17.5 (4.3) | 17.5 (4.3) |

| Missing | 8 (2.0) | 11 (2.7) | 19 (2.4) |

| Operative severity score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 13.0 (3.9) | 12.5 (3.3) | 12.7 (3.6) |

| Missing | 7 (1.8) | 11 (2.7) | 18 (2.2) |

| Overall POSSUM score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 8.3 (7.9) | 7.8 (7.8) | 8.0 (7.8) |

| Missing | 10 (2.5) | 17 (4.2) | 27 (3.4) |

Primary outcome

Incidence of incisional hernia

The incidence of IH detected by clinical examination alone, by study arm, is shown in Table 5. Although the primary outcome was incidence of IH at year 1, the results for year 2 are presented alongside for comparison. Hughes repair was associated with a lower IH rate on clinical examination at 1 year [14.8% (n = 50) in the Hughes repair arm vs. 17.1% (n = 57) in the standard mass closure arm]; however, this difference did not reach statistical significance [odds ratio (OR) 0.84, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.27; p = 0.40]. The incidence of IH was also lower in the Hughes repair arm in year 2, but, again, the difference was not statistically significant (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.25; p = 0.43). Of the 107 patients who experienced IH in year 1, 20 (18.7%), underwent hernia repair in year 2 (nine in the Hughes repair arm and 11 in the standard mass closure arm).

| IH | Hughes repair arm, n (%) | Standard mass closure arm, n (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | ||||

| Sample size | 339 | 333 | ||

| Yes | 50 (14.8) | 57 (17.1) | 0.84 (0.55 to 1.27) | 0.402 |

| No | 289 (85.3) | 276 (82.9) | ||

| Over 2 years | ||||

| Sample size | 272 | 264 | ||

| Yes | 78 (28.7) | 84 (31.8) | 0.86 (0.59 to 1.25) | 0.429 |

| No | 194 (71.3) | 180 (68.2) | ||

Identification of risk factors for incisional hernia

Logistic regression analysis (Table 6), adjusted for baseline characteristics, suggests that increased age, male sex, increased BMI, higher POSSUM score, preoperative radiotherapy and lower physical activity (i.e. SF-12 PCS) are indicators of an increased odds of IH. The odds of IH were significantly increased with increasing age at year 1 and over year 2. The OR for age at year 1 was 1.03, indicating a 3% increased odds of an IH with a 1-year increase in age. Similar outcomes can be observed at year 2 (see Table 6).

| Parameter | Year 1 | Year 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Arms: Hughes repair | 0.73 (0.48 to 1.12) | 0.165 | 0.79 (0.54 to 1.17) | 0.235 |

| Age | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.05) | 0.009 | 1.02 (1.00 to 1.04) | 0.023 |

| Sex: male | 1.72 (1.07 to 2.77) | 0.027 | 1.48 (0.98 to 2.27) | 0.070 |

| BMI | 1.05 (1.01 to 1.10) | 0.053 | 1.07 (1.02 to 1.10) | 0.002 |

| Radiotherapy use | 3.80 (1.37 to 9.45) | 0.010 | 3.30 (1.20 to 9.02) | 0.020 |

| POSSUM score | 0.99 (0.85 to 1.03) | 0.692 | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.08) | 0.034 |

| SF-12: PCS (baseline) | 0.96 (0.92 to 1.00) | 0.054 | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.01) | 0.096 |

| Emergency admission | 2.46 (1.07 to 5.68) | 0.034 | 2.16 (0.90 to 5.19) | 0.084 |

Male sex was found to be associated with significantly increased odds of IH at year 1 (p = 0.0266) but not at year 2 (p = 0.077). At year 1, male patients were 72% more likely than female patients to have IH.

At year 1, BMI was not significantly associated with increased odds of IH (p = 0.05); however, it strongly affected the outcome of IH at year 2 (p = 0.00202).

Radiotherapy at baseline was a strong indicator of the odds of IH at year 1 and over year 2. The odds of having IH for someone having baseline radiotherapy were 3.88 (p = 0.01) times higher at year 1 and 3.33 (p = 0.02) times higher at year 2. The results relating to radiotherapy should be considered cautiously because of the wider CIs with the estimates (see Table 6).

The SF-12 PCS score remained in the final model of the stepwise regression at both year 1 and year 2 but with a non-significant outcome. The POSSUM score did not remain in the final step of the logistic regression model step for year 1; however, in the year 2 model, baseline POSSUM score seems to significantly affect the outcome of IH over 2 years. With a 1% increase in risk of death or POSSUM score at baseline, there was a 33% increase in odds of IH over 2 years.

Admission type also seems to have a statistically significant effect on the risk of having IH at year 1. The odds of having an IH at year 1 was 2.46 (p = 0.034) higher for patients admitted via emergency route. However, the effect of admission type on having an IH at year 2 is not statistically significant.

There were 662 observations in the final stepwise logistic regression model at year 1 and 529 observations in the final model at year 2.

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life

All of the QoL measures (i.e. SF-12 PCS, SF-12 MCS and FACT-C scores) were well balanced between the arms at baseline. No significant difference in score was observed between the arms for either SF-12 or FACT-C at any time point (Tables 7 and 8).

| QoL measure | Hughes repair arm | Standard mass closure arm | Total | Mean difference (I – C) (95% CI) | p-value (t-test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-12: PCS | |||||

| Baseline | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 43.6 (5.5) | 43.7 (5.5) | 43.7 (5.5) | –0.09 (–0.93 to 0.76) | 0.8 |

| Missing, n (%) | 82 (20.5) | 78 (19.5) | 160 (20.0) | ||

| 30 days | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 41.5 (5.7) | 40.8 (5.8) | 41.2 (5.7) | 0.73 (–0.19 to 1.64) | 0.1 |

| Missing, n (%) | 108 (26.9) | 108 (26.9) | 216 (26.9) | ||

| 6 months | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 42.8 (5.0) | 42.9 (4.8) | 42.8 (4.9) | –0.08 (–0.88 to 0.72) | 0.8 |

| Missing, n (%) | 101 (25.2) | 121 (30.2) | 222 (27.7) | ||

| 1 year | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 43.1 (4.4) | 43.7 (4.5) | 43.4 (4.4) | –0.56 (–1.30 to 0.18) | 0.1 |

| Missing, n (%) | 112 (27.9) | 134 (33.4) | 246 (30.7) | ||

| 2 years | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 43.0 (4.3) | 43.2 (4.4) | 43.1 (4.3) | –0.13 (–0.95 to 0.68) | 0.75 |

| Missing, n (%) | 178 (44.4) | 187 (46.6) | 365 (45.5) | ||

| SF-12: MCS | |||||

| Baseline | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 52.5 (11.9) | 52.9 (12.1) | 52.7 (12.0) | –0.41 (–2.2 to 1.50) | 0.7 |

| Missing, n (%) | 81 (20.2) | 78 (19.4) | 159 (19.8) | ||

| 30 days | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 46.5 (13.2) | 48.2 (12.8) | 47.30 (13.0) | –1.77 (–3.87 to 0.33) | 0.1 |

| Missing, n (%) | 107 (26.7) | 106 (26.4) | 213 (26.6) | ||

| 6 months | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 51.50 (13.3) | 51.7 (12.3) | 51.6 (12.8) | –0.15 (–2.23 to 1.94) | 0.9 |

| Missing, n (%) | 101 (25.2) | 121 (30.2) | 222 (27.7) | ||

| 1 year | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 53.9 (12.1) | 53.7 (11.7) | 53.8 (11.9) | 0.21 (–1.77 to 2.18) | 0.8 |

| Missing, n (%) | 112 (27.9) | 133 (33.2) | 245 (30.5) | ||

| 2 years | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 54.0 (12.0) | 54.0 (12.8) | 54 (12.4) | 0.08 (–2.25 to 2.42) | 0.95 |

| Missing, n (%) | 178 (44.4) | 187 (46.6) | 365 (45.5) | ||

| Time point | Hughes repair arm | Standard mass closure arm | Total | Mean difference (I – C) (95% CI) | p-value (t-test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 70.6 (9.9) | 71.7 (10.0) | 71.08 (10.0) | –1.21 (–2.78 to 0.35) | 0.13 |

| Missing, n (%) | 88 (21.9) | 90 (22.4) | 178 (22.2) | ||

| 30 days | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 66.8 (8.9) | 65.9 (8.8) | 66.3 (8.9) | 0.86 (–0.59 to 2.32) | 0.25 |

| Missing, n (%) | 116 (28.9) | 116 (28.9) | 232 (28.9) | ||

| 6 months | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 66.3 (9.9) | 66.6 (9.3) | 66.5 (9.7) | –0.33 (–1.92 to 1.25) | 0.68 |

| Missing, n (%) | 107 (26.7) | 125 (31.2) | 232 (28.9) | ||

| 1 year | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 67.6 (8.7) | 67.3 (9.7) | 67.4 (9.2) | 0.34 (–1.21 to 1.89) | 0.66 |

| Missing, n (%) | 124 (30.9) | 133 (33.2) | 257 (32.0) | ||

| 2 years | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 67.0 (8.9) | 68.2 (8.9) | 67.6 (8.9) | –1.14 (–2.83 to 0.54) | 0.18 |

| Missing, n (%) | 171 (42.6) | 195 (48.6) | 366 (45.6) | ||

Tables 9 and 10 outline the QoL scores in patients with and patients without IH (regardless of their allocated arm). Patients with an IH at year 1 had significantly lower mean PCS scores than patients without an IH (p = 0.03) at baseline. However, this difference was not observed at other time points. No statistically significant differences were observed in mean SF-12 MCS (see Table 7) or FACT-C (see Table 8) scores when comparing patients with and patients without an IH at any time point.

| QoL measure | Patients with IH (N = 107) | Patients without IH (N = 565) | Total (N = 672) | Mean difference (IH – no IH) (95% CI); p-value (t-test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-12: PCS | ||||

| Baseline | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 42.6 (5.6) | 44.0 (5.4) | 43.8 (5.4) | –1.40 (–2.70 to –0.11); 0.03 |

| Missing, n (%) | 27 (25.2) | 96 (17.0) | 123 (18.3) | |

| 30 days | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 41.2 (5.9) | 41.1 (5.6) | 41.1 (5.7) | 0.13 (–1.18 to 1.44); 0.8 |

| Missing, n (%) | 21 (19.6) | 117 (20.7) | 138 (20.5) | |

| 6 months | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 42.4 (4.9) | 43.0 (4.9) | 42.9 (4.9) | –0.59 (–1.73 to 0.54); 0.3 |

| Missing, n (%) | 23 (21.5) | 111 (19.7) | 134 (19.9) | |

| 1 year | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 43.8 (4.6) | 43.3 (4.4) | 43.4 (4.4) | 0.51 (–0.50 to 1.52); 0.3 |

| Missing, n (%) | 19 (17.8) | 108 (19.1) | 127 (18.90) | |

| SF-12: MCS | ||||

| Baseline | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 53.7 (11.4) | 53.2 (11.6) | 53.3 (11.6) | 0.48 (–2.30 to 3.23); 0.7 |

| Missing, n (%) | 27 (25.2) | 95 (16.8) | 122 (18.1) | |

| 30 days | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 47.3 (12.2) | 47.7 (12.9) | 47.6 (12.8) | –0.46 (3.42 to 2.50); 0.8 |

| Missing, n (%) | 21 (19.6) | 114 (20.2) | 135 (20.1) | |

| 6 months | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 52.1 (12.7) | 52.2 (12.4) | 52.2 (12.4) | –0.11 (–3.01 to 2.78); 0.9 |

| Missing, n (%) | 23 (21.5) | 111 (19.6) | 134 (19.9) | |

| 1 year | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 52.8 (12.1) | 53.9 (11.8) | 53.7 (11.9) | –1.01 (–3.73 to 1.70); 0.5 |

| Missing, n (%) | 19 (17.8) | 107 (18.9) | 126 (18.8) | |

| Time point | Patients with IH (N = 107) | Patients without IH (N = 565) | Total (N = 672) | Mean difference (I – C), 95% CI; p-value (t-test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 70.9 (8.5) | 71.6 (9.7) | 71.5 (9.5) | –0.74 (–30.2 to 1.55); 0.5 |

| Missing, n (%) | 29 (27.1) | 110 (19.5) | 139 (20.7) | |

| 30 days | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 66.7 (7.7) | 66.2 (9.1) | 66.3 (8.9) | 0.42 (–1.65 to 2.50); 0.7 |

| Missing, n (%) | 22 (20.6) | 132 (23.4) | 154 (22.9) | |

| 6 months | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 65.9 (9.8) | 66.7 (9.6) | 66.6 (9.6) | –0.85 (–3.13 to 1.42); 0.5 |

| Missing, n (%) | 25 (23.4) | 119 (21.1) | 144 (21.4) | |

| 1 year | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 67.5 (7.8) | 67.4 (9.5) | 67.4 (9.2) | 0.08 (–2.10 to 2.25); 0.9 |

| Missing, n (%) | 24 (22.4) | 113 (20.0) | 137 (20.4) | |

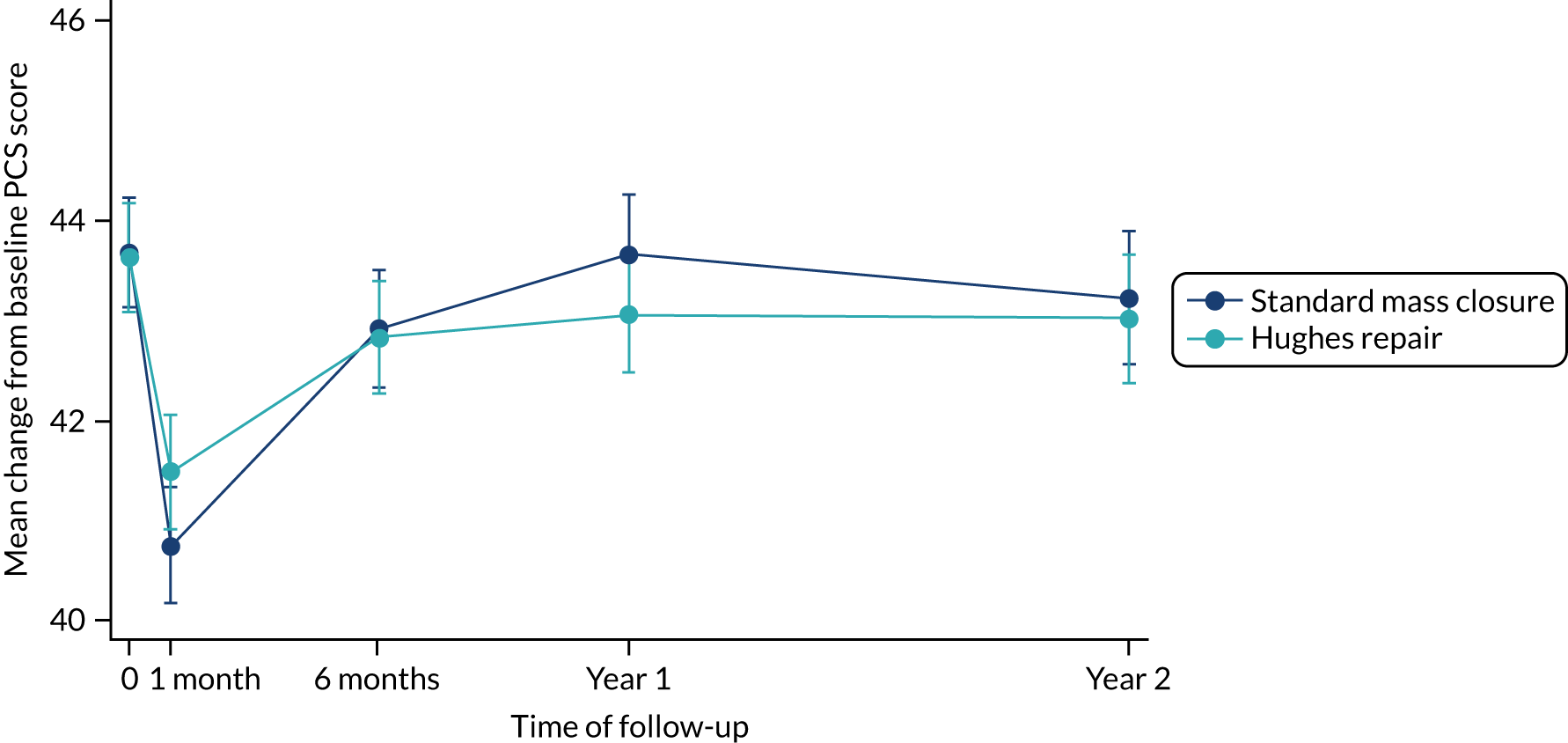

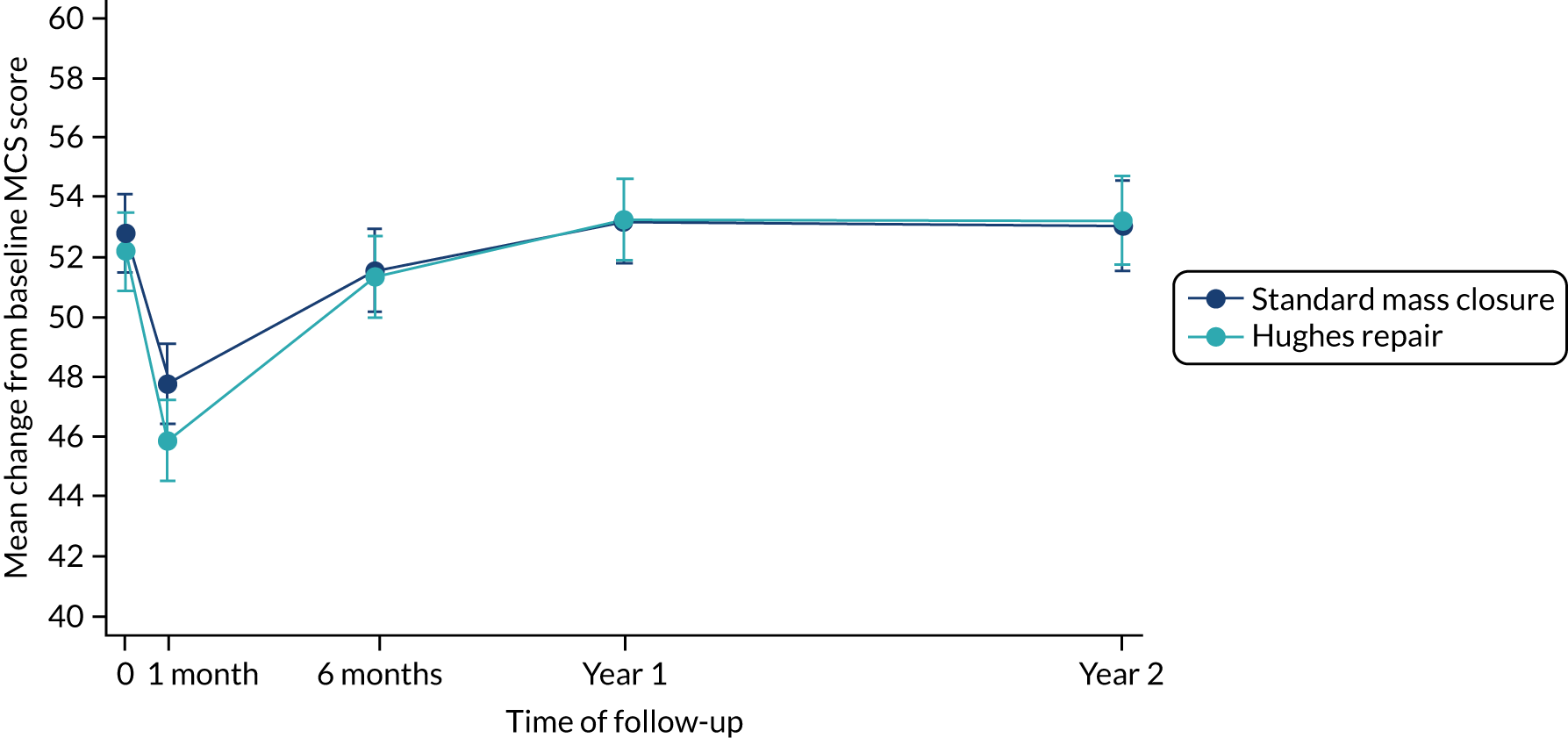

The results of the mixed-model repeated-measures analysis of the PCS scores showed no statistically significant differences in the between-group difference mean scores at any time point (Table 11 and Figure 6). Similar results were observed from the mixed-model repeated-measures analysis of the MCS scores (Table 12 and Figure 7). Following an initial sharp decline in MCS score in the month immediately following their index operation in both arms, patients reported improvement over time, with similar scores in both arms from 6 months onwards. In terms of FACT-C scores, the between-arm differences of the mean change from baseline to first month and to year 1 are statistically significant. Despite that the actual difference in the FACT-C score is not clinically relevant, the score in the standard mass closure arm seems to decrease steeply when compared with the Hughes repair arm at these two time points. The detailed mixed-model repeated analysis for the FACT-C score can be found in Appendix 5, Table 41 and Figure 13.

| Variable | Mean baseline PCS score (SD) | Mean change in PCS score from baseline (95% CI);a p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month 1 | Month 6 | Year 1 | Year 2 | ||

| Standard mass closure | 43.7 (5.5) | –2.9 (–3.65 to –2.21); 0.00 | –0.8 (–1.51 to –0.04); 0.04 | 0.0 (–0.76 to 0.73); 0.9 | 0.5 (–1.31 to 0.29); 0.2 |

| Hughes repair | 43.6 (5.5) | –2.2 (–2.91 to –1.46); 0.00 | –0.8 (–1.53 to –0.10); 0.03 | –0.6 (–1.35 to 0.10); 0.09 | –0.6 (–1.40 to 0.17); 0.13 |

| Between-arm difference in means | 0.8 (–0.27 to 1.77); 0.15 | –0.0 (–1.07 to 0.99); 0.94 | –0.6 (–1.64 to 0.43); 0.25 | –0.1 (–1.22 to 1.01); 0.86 | |

FIGURE 6.

Mean PCS scores over time by arm.

| Variable | Mean baseline MCS score (SD) | Mean change in MCS score from baseline (95% CI);a p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month 1 | Month 6 | Year 1 | Year 2 | ||

| Standard mass closure | 52.9 (12.1) | –5.2 (–6.58 to –3.87); 0.00 | –1.5 (–2.97 to –0.19); 0.03 | 0.0 (–1.4 to 1.4); 0.99 | 0.0 (–1.5 to 1.51); 0.99 |

| Hughes repair | 52.5 (11.9) | –6.2 (–7.57 to –4.86); 0.00 | –0.9 (–2.25 to 0.45); 0.2 | 0.8 (–0.54 to 2.2); 0.24 | 0.9 (–0.56 to 2.4); 0.22 |

| Between-arm difference in means | –1.0 (–2.91 to 0.93); 0.31 | 0.7 (–1.25 to 2.62); 0.49 | 0.8 (–1.13 to 2.78); 0.41 | 0.9 (–1.19 to 3.02); 0.40 | |

FIGURE 7.

Mean MCS scores over time by arm.

Wound dehiscence (burst abdomen)

There were three occurrences of full thickness wound dehiscence at 30 days post surgery – one in the Hughes repair arm and two in the standard mass closure arm – giving an overall rate of 0.79% for the whole study. The cumulative incidence of wound dehiscence at 30 days post surgery was 0.25% for Hughes repair and 0.50% for standard mass closure.

Prevalence of incisional hernia at 1 year

Twelve patients (Hughes repair arm, n = 9; standard mass closure arm, n = 3) had IH at baseline (see Table 22). By the 1-year follow-up, IH had been repaired in nine patients (Hughes repair arm, n = 6; standard mass closure arm, n = 3); in the remaining three patients (all of whom were in the Hughes repair arm), the IH had not been repaired at year 1 or this information was missing.

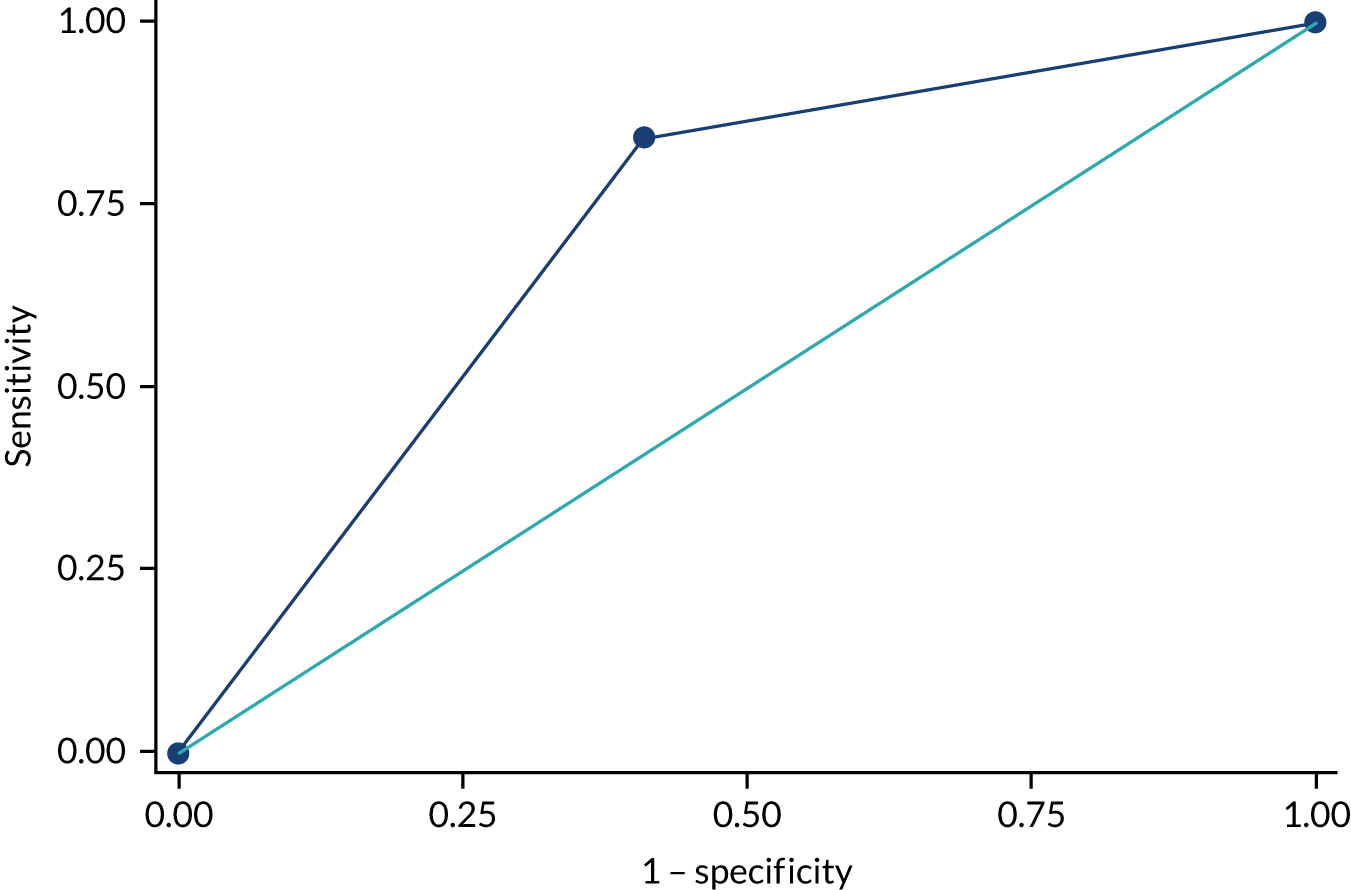

Sensitivity and specificity of computed tomography scanning compared with clinical examination for identification of incisional hernia at 1 year

The rate that IH was diagnosed by clinical examination or by CT scan at 1 year is reported in Table 13. Clinical examination was considered the reference test, and the results from this were considered the ‘true’ results. In total, 630 patients had both a 1-year clinical examination result and a CT scan available for analysis and are included in the analysis for sensitivity and specificity.

| Hughes repair arm, n | Standard mass closure arm, n | Total study (both arms), n | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IH on CE only | 7 | 9 | 16 |

| IH on CT only | 114 | 103 | 217 |

| IH on both CE and CT | 37 | 47 | 84 |

| Total IH | 158 | 159 | 317 |

| Negative for IH on both | 156 | 157 | 313 |

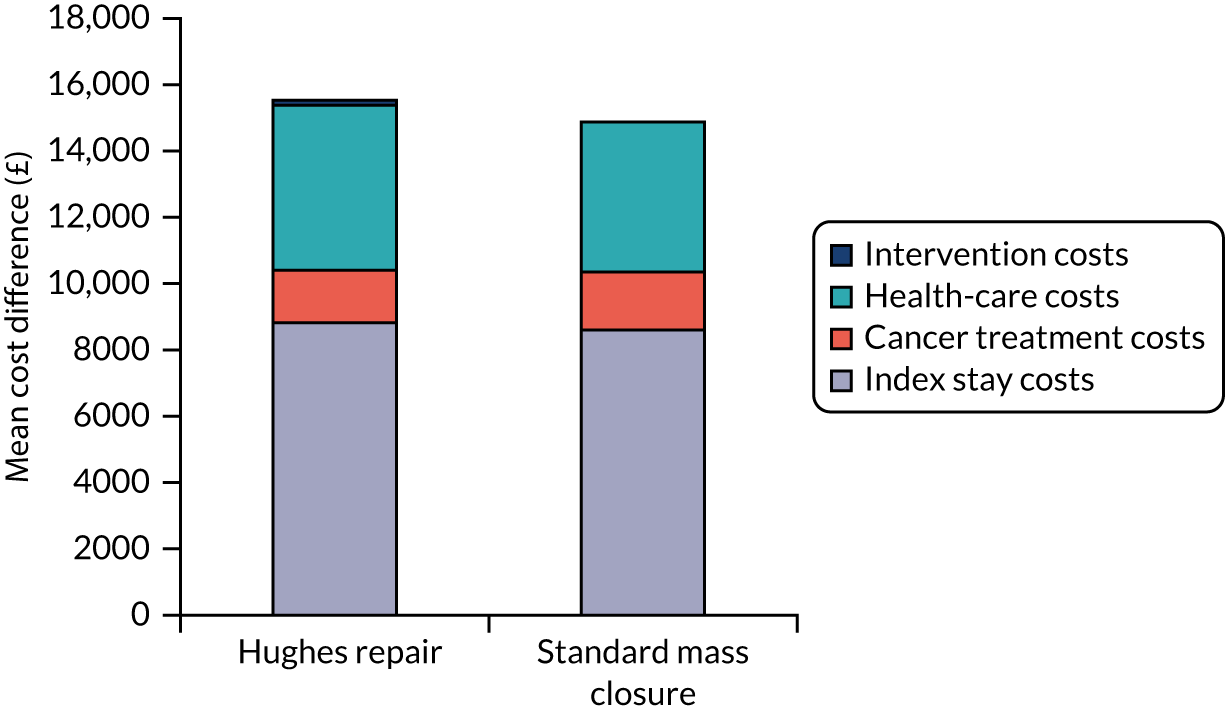

| Total | 314 | 316 | 630 |