Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/103/02. The contractual start date was in April 2014. The draft report began editorial review in November 2019 and was accepted for publication in August 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Griffin et al. This work was produced by Griffin et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Griffin et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Further reading on this trial is available in the trial protocol by Griffin et al. ,1 trial feasibility reports by Griffin et al. 2,3 and Wall,4 trial non-operative intervention report by Wall et al. 5 and trial results article by Griffin et al. 6

Background

Until recently, there was little understanding of the causes of hip pain in young adults. A proportion of young adults with hip pain have established osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis, avascular necrosis, fractures or childhood hip disease, but the majority have no specific diagnosis. Over the last decade, there has been increasing recognition of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) syndrome, which seems to account for a large proportion of the previously undiagnosed cases of hip pain in young adults. 7,8 Subtle deformities in the shape of the hip (ball and socket joint) combine to cause impingement between the femoral head (ball) or neck and the anterior rim of the acetabulum (socket), most often in flexion and internal rotation. 7,9 Excess contact force leads to damage to the acetabular labrum (fibrocartilage rim of the socket) and the adjacent acetabular cartilage surface. 7 FAI seems to be associated with progressive articular degeneration of the acetabulum and may account for a significant proportion of so-called idiopathic osteoarthritis, although this remains unproven. 9 The shape abnormalities of the hip joint are typically divided into the following three categories:9

-

cam-type impingement (in which the femoral head is oval rather than round, or there is prominent bone on the femoral neck)

-

pincer-type impingement (in which the rim of the acetabulum is too prominent in one or more areas of its circumference)

-

mixed-type hip impingement (which is a combination of cam and pincer types).

Surgery can be performed to improve bone shapes to prevent impingement between the femoral neck and rim of the acetabulum. In the case of cam-type FAI syndrome, this usually involves the removal of bone at the femoral head–neck junction. In the case of pincer-type FAI syndrome, it may involve the removal of bone at the rim of the acetabulum. At the same time as bony shape improvement, any soft tissue damage to the cartilage or labrum as a result of the FAI syndrome is debrided, repaired or reconstructed. Surgery can be undertaken using either keyhole (arthroscopic) surgery or more traditional open surgery to access the hip joint and correct the hip shape abnormalities associated with FAI syndrome.

Surgery for FAI syndrome has evolved more quickly than our understanding of the epidemiology or natural history of the condition, and is becoming an established treatment. 10–12 The risks of complications from open surgery are greater than those for arthroscopic surgery, and current evidence suggests that the outcomes of arthroscopic treatment for the symptoms of FAI syndrome are comparable to open surgery. 13,14 Consequently, hip arthroscopy for FAI syndrome is a rapidly growing new cost pressure for health providers. 15 However, a Cochrane review highlighted the absence of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing FAI surgery with conservative care, such as physiotherapist-led exercise. 16

Multicentre RCTs are acknowledged to be the best design for evaluating the effectiveness of health-care interventions, as they provide robust evidence. 17,18 However, there are often major challenges in performing RCTs of surgical technologies19 and there were concerns that a RCT of hip arthroscopy in FAI syndrome might not be feasible.

Summary of a feasibility and pilot trial

A feasibility and pilot study commissioned by the Health Technology Assessment programme (reference 10/41/02) was completed. 2,3 It comprised (1) a pre-pilot phase, including patient and clinician surveys and interviews, and a systematic review of non-operative care; (2) a workload survey of hip arthroscopy for FAI; (3) development of best conventional care and arthroscopic surgery protocols; (4) a pilot RCT to measure recruitment rate; and (5) an integrated programme of qualitative research to understand and optimise recruitment. 2,3

The feasibility study followed the commissioning brief and specifically addressed the following parameters to inform the design of the proposed full-scale RCT.

Define eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria were initially designed in collaboration with the Multicenter Arthroscopy of the Hip Outcomes Research Network (MAHORN), which is an academic group of highly experienced hip arthroscopists within the International Society for Hip Arthroscopy (Moffat, UK) (URL: www.isha.net). These criteria were then discussed with a further sample of 14 UK specialist hip surgeons with experience of treating patients with FAI syndrome. In individual interviews, a variety of clinical scenarios were presented and the surgeons were asked to describe decision-making for treatment. Minor modifications were made to the eligibility criteria. These criteria were then tested during the recruitment of real patients during the pilot RCT and were found to be easy to apply, with little disagreement among clinicians.

Define a protocol for hip arthroscopy for FAI syndrome

A draft protocol for arthroscopic treatment of FAI was developed in a consensus conference with MAHORN members. This draft was circulated among the sample of 14 UK hip surgeons for feedback. After editing, it was recirculated and approved by all. The protocol was then tested in 21 participants randomised to surgery in the pilot trial. We also developed a method to measure fidelity by intraoperative photographs and postoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which was assessed by a panel of independent international experts. We showed that this approach was acceptable to surgeons and demonstrated complete adherence to protocol in six of seven operations at the first panel conference.

Define a protocol for best conservative care (comparator)

We performed a systematic review of non-operative care for FAI. 20 This revealed little evidence of a standard for best conservative care, even though many NHS commissioners describe the failure of conservative care as a prerequisite for surgery. 21 There was some evidence that physiotherapy-led non-operative care is most frequently used. 20 This is complemented by established theory and evidence supporting treatment effects for physiotherapy in other painful musculoskeletal conditions, including osteoarthritis and back pain. 22,23

We used a combination of consensus methods (e.g. Delphi and nominal group techniques) among physiotherapists to agree a protocol for ‘best conservative care’. 5 We advertised to relevant networks of the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP) (London, UK) through their interactive communication system (interactiveCSP) and in the Frontline magazine24 (a twice-monthly magazine posted to 52,000 CSP members in the UK). These advertisements invited physiotherapists to help develop a consensus for a best conservative care treatment protocol for FAI syndrome. Electronic invitations were also sent to physiotherapists in the USA and Australia who were known to us through previous collaborative work on FAI syndrome. To encourage a process of ‘snowball sampling’ within the international community, these therapists were encouraged to invite colleagues with experience and interest in managing FAI syndrome to join in the consensus process.

We developed a physiotherapy-led four-component protocol to be delivered over 12 weeks, with a minimum of six one-to-one treatment sessions. 5 The protocol included (1) a detailed patient assessment; (2) education and advice about FAI syndrome; (3) help with pain relief, including hip joint steroid injections if required; and (4) an exercise programme that has the key features of individualisation, supervision and progression. We used a patient focus group to choose the most acceptable name for this protocol of best conservative care. The group made it clear that we should express that this was a coherent and valid alternative to surgery and different from the physiotherapy likely to have been received already, and recommended the name personalised hip therapy (PHT).

In the development of PHT, we struck a balance between the need for a meaningful comparator for hip arthroscopy, the need to ensure that PHT is different from previous physiotherapy that FAI syndrome patients’ may have experienced and the need for PHT to be deliverable in the NHS outside a trial. UK physiotherapists and patients felt that PHT was ‘best’ in that not all patients currently receive such a comprehensive package, but ‘conventional’ in that all its elements are widely used and the package is deliverable within usual constraints in the NHS. We tested the protocol and a logbook approach to assessing fidelity in 21 participants randomised to PHT in the pilot trial. The protocol was acceptable to patients and physiotherapists, and we demonstrated complete adherence in seven of the first eight participants.

Define willingness of centres and patients to be recruited to a randomised controlled trial

We performed a survey of all orthopaedic surgery departments in NHS hospital trusts in the UK. Clinical directors of those departments reported that 120 consultant surgeons were treating FAI syndrome. We contacted all 120 surgeons who reported having performed 2399 operations for FAI in 2011/12. A total of 1908 operations were performed by hip arthroscopy and 491 operations were open surgery. 3 Thirty-four hospital trusts had a workload of 20 or more hip arthroscopies for FAI syndrome in 1 year. We interviewed 18 of the highest-volume surgeons to explore their views about a trial comparing hip arthroscopy with best conservative care in patients with FAI syndrome. One surgeon felt that he could not participate in a trial because he was certain that surgery worked, five surgeons had a bias towards surgery but recognised the need for a trial and were prepared to randomise patients, and 12 surgeons expressed equipoise and were keen to take part in a trial.

We purposively sampled 18 patients who had been treated for FAI syndrome. Fourteen of these patients had received arthroscopic surgery and five had received physical therapy and steroid injections (one patient had both). These patients had a semistructured interview with a qualitative researcher who had not been involved in their care to explore their experiences of diagnosis and treatment, and their views on the proposed trial. The majority of the patients were young and physically active. Symptoms of FAI syndrome had affected their work, recreation and day-to-day activities, and many reported a great sense of relief when a diagnosis was made. Patients said that both surgical and conservative care would be acceptable. The majority of patients saw surgery as the solution for a condition that they perceived as mainly caused by abnormal bone shapes. On the other hand, non-operative care was perceived as attractive if it might be successful and could avoid the risks of surgery. Some patients commented that they had not been offered a non-operative option and saw this as a positive addition to available treatments. Patients were enthusiastic about research in this field, and about being involved, but had reservations about some of the language involved, for instance ‘trial’, ‘random’ and ‘50 : 50 chance’ implied a lack of personalised care. All of these patients said that they would have been prepared to take part in a RCT as long as the treatment options and uncertainty around them had been fully explained, the treatment they received had been personalised for them and they were assured that their care would be continued whatever happened in the research.

Our findings in these in-depth interviews were broadly consistent with Palmer et al. ’s25 questionnaire survey of 30 surgeons who performed FAI surgery and 31 patients with a diagnosis of FAI syndrome. In Palmer et al. ’s25 study, 71% of surgeons and 90% of patients felt that a trial of this question was appropriate.

We concluded that surgeons in most centres in the UK that perform hip arthroscopy for FAI syndrome, and their patients, would be willing to be included in a RCT.

Understand and optimise recruitment

An important objective of the pilot trial was to explore likely issues in recruitment and to develop optimum procedures for the full trial.

We interviewed all principal investigators (PIs) and research associates (RAs) during the pilot trial to ensure that the study was being described and recruitment procedures were being followed in accordance with the study protocol, and to identify when they were not. We developed training packages to correct common problems. We identified structural features associated with successful recruitment, such as running targeted clinics, having a dedicated RA in attendance and ensuring that referred patients arrived with expectations of receiving treatment for FAI syndrome, rather than being told they had been referred for surgery. This learning was shared across all sites.

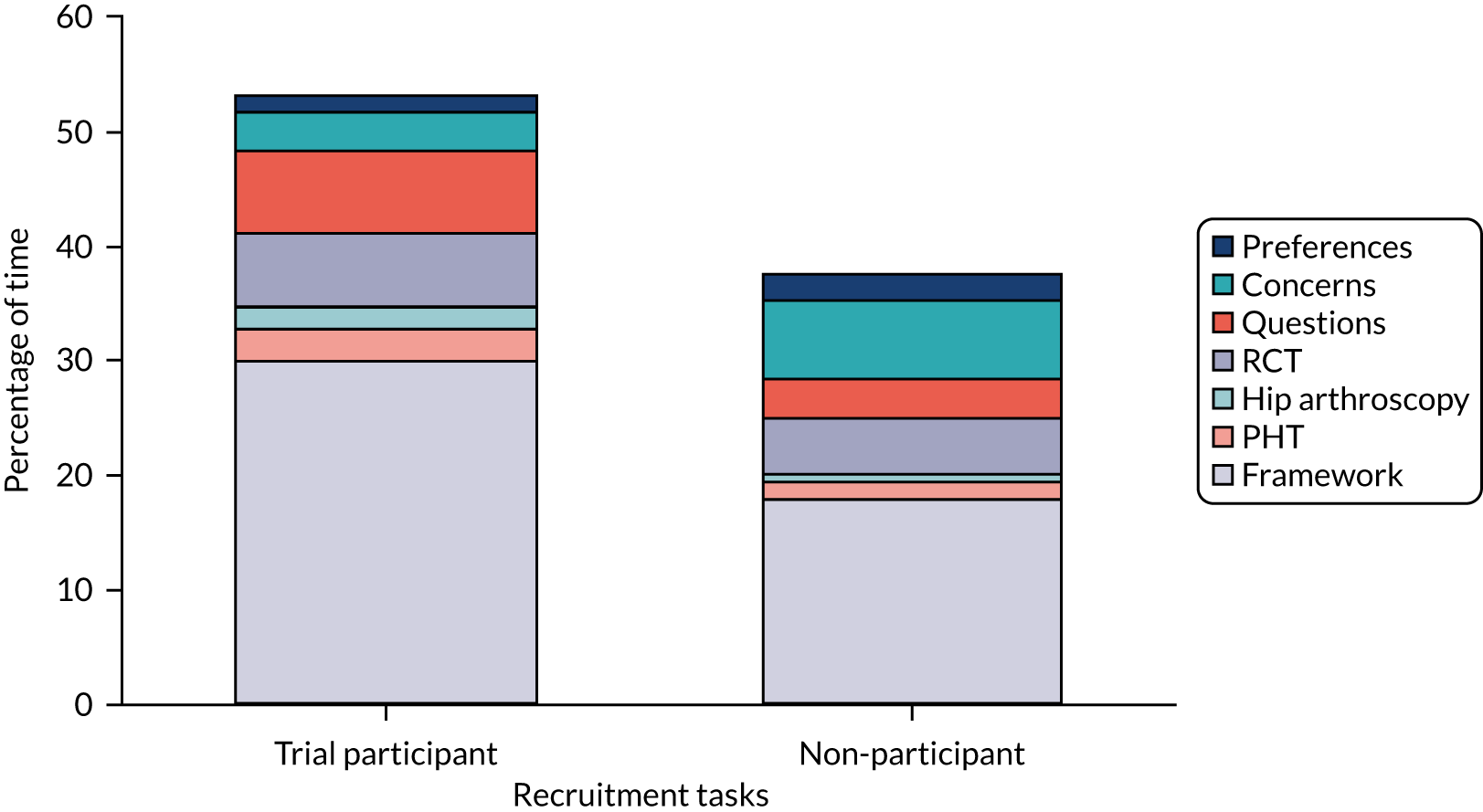

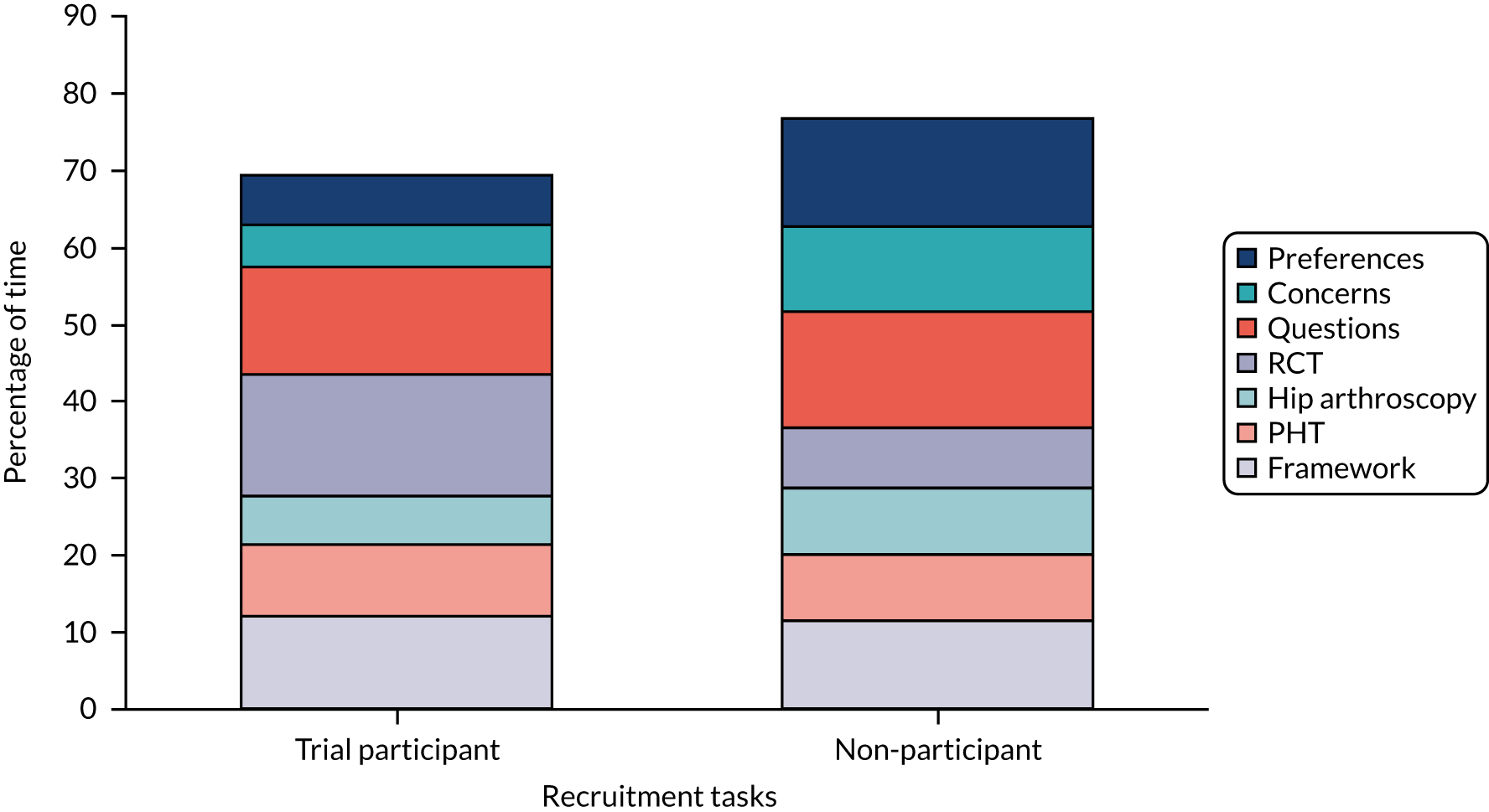

We recorded and analysed 87 diagnostic and recruitment consultations with 60 new patients during the pilot trial. We identified where improvements could be made in presenting trial information and in engaging patients to consider participation, guided by our previous work. 26,27 The analysis was targeted at the recruitment levels at specific sites, with individual confidential feedback for recruiters on good practice and areas for improvement, and with anonymised findings being fed back to all sites.

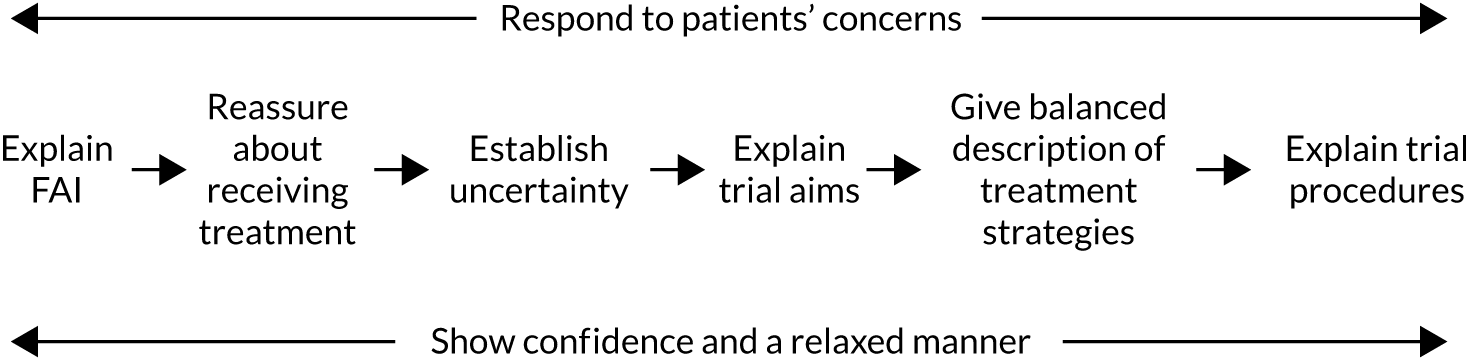

Common difficulties with recruitment that were identified included poorly balanced presentations of treatment options (where surgery was presented at greater length and more favourably than PHT), graphic descriptions of surgery that may have put patients off that option or discouraged participation, presenting trial information in an order that was confusing for patients and surgeons going beyond their protocol brief to explain the trial, rather than referring patients to the trial recruiter for this information. Analysis of the consultations led to the development of a six-step model for the presentation of trial information to optimise recruitment. 3,28

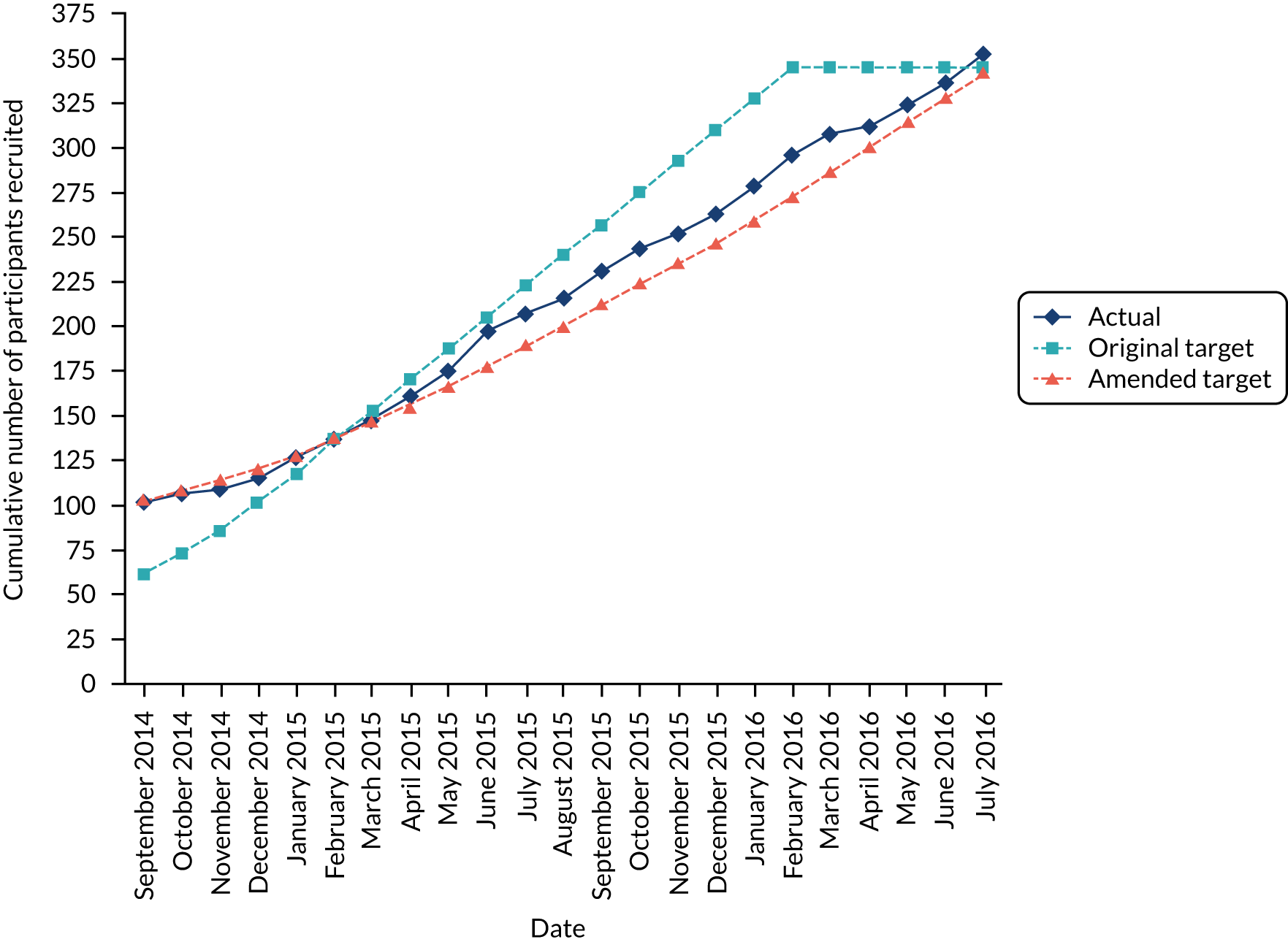

Estimate recruitment rate

Ten clinical centres participated in the pilot trial and nine opened to recruitment within 6 months. At one site, local research and development (R&D) approval was delayed until just before the end of the pilot and so no one was recruited.

Of the 144 potentially eligible patients with hip problems identified at the pre-clinic screening of referral letters, 60 met the inclusion criteria after assessment and were approached for randomisation. The most frequent reasons for exclusion were a diagnosis other than FAI (53/84) and a judgement that the patient would not benefit from arthroscopic surgery (21/84). Forty-two patients (70% of those eligible) consented to take part in the pilot RCT. Among those who declined (n = 18), the most common reasons were a preference for surgery (n = 11) and a preference not to have surgery (n = 3). The mean duration and recruitment rate across all sites was 4.5 months and one patient per centre per month, respectively. The lead site recruited for the longest period (9.3 months) and recruited the largest number of patients (2.1 patients per month).

Selection of appropriate outcome measures

A variety of outcome measures have been used to study patients with FAI syndrome. Some, such as the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC®) and the Harris Hip Score, were intended for older patients with symptoms of severe arthritis and are most suitable to measure the effect of hip replacement surgery. 29,30 These measures tend to exhibit ceiling effects and are not sensitive to change after treatment in patients with FAI syndrome. 30,31

The Non-Arthritic Hip Score is a self-administered instrument to measure hip-related pain and function in younger patients without arthritis. The score is valid compared with other measures of hip performance, is internally consistent and is reproducible. 32 However, it is not patient derived, raising concern that it may not measure what is most important to patients.

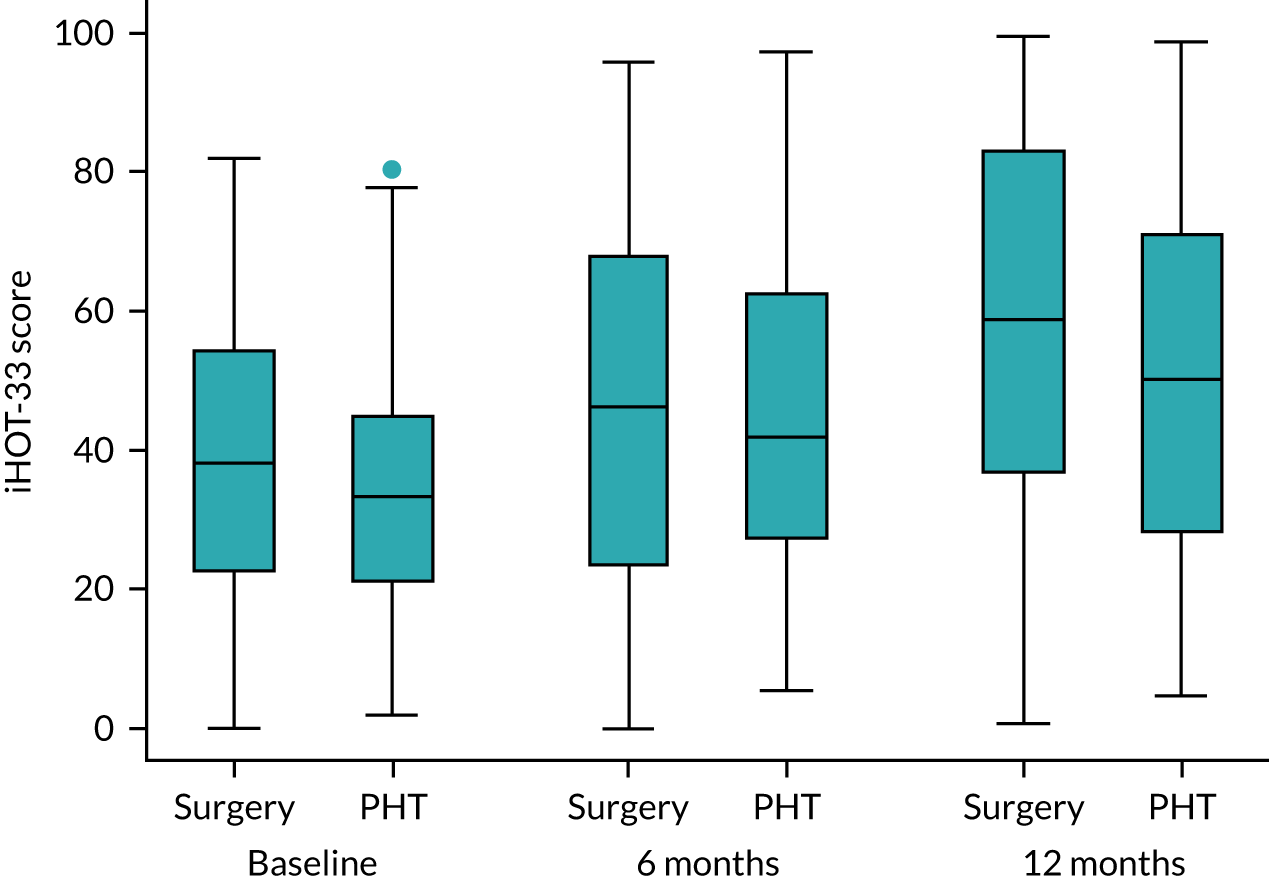

The International Hip Outcome Tool-33 (iHOT-33) is a patient-derived hip-specific patient-reported instrument that measures health-related quality of life in young, active patients with hip disorders. It was developed by a large international collaboration of patients and clinicians led by MAHORN over 5 years. It comprises 33 items, each measured on a visual analogue scale (VAS), to assess functional limitations, sports activities, and job-related and emotional concerns. Importantly, these items were generated and refined by patients, reflecting their most important concerns. The instrument generates a single score in the range of 0 to 100. People with no hip complaints usually score ≥ 95. A diverse international population of younger adults with a variety of hip pathologies had a mean score of 66, with a standard deviation (SD) of 19.3 (Damian R Griffin, University of Warwick, 2021, personal communication).

The iHOT-33 has been validated for use in patients with FAI syndrome and is sensitive to change after treatment. The minimum clinically important difference (MCID) has been determined using an anchor and distribution-based approach in a group of 27 young active patients who were independent of the development population. Clinical change was determined using a global rating scale that asked patients whether their hip condition had improved, had deteriorated or had not changed since the previous assessment, using a single VAS. The MCID was 6.1 points. 33,34

The iHOT-33 and EQ-5D-5L have been adopted as the principal outcome measures by the UK Non-Arthroplasty Hip Registry. This registry is led by the British Hip Society (London, UK) and its use in all patients having arthroscopic FAI surgery is required by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 15

In our pilot study, we tested the Non-Arthritic Hip Score and iHOT-33 as potential primary outcome measures, and found both to be easy to use and acceptable to patients. The extensive patient involvement in item generation, the availability of an independently determined MCID and the use of iHOT-33 as the principal outcome measure for the UK Non-Arthroplasty Hip Registry led us to choose iHOT-33 as the most appropriate primary outcome measure for a full trial.

Develop and test trial procedures

Protocols, eligibility criteria, patient information material and case report forms (CRFs) were designed for the pilot RCT and were available for the full trial. We interviewed 18 patients who had been treated for FAI syndrome to develop patient information sheets. These patient information sheets were scrutinised by a panel of expert patients with FAI syndrome who helped to improve the content and presentation so that they addressed patients’ key concerns and information needs, and provided explanations with appropriate language and detail. Twenty-eight clinicians, including surgeons, physicians and physiotherapists, also contributed to developing these procedures and documents.

Research Ethics Committee and national R&D approvals were granted for the pilot trial promptly and without any significant concerns. The majority of the recruitment sites were then able to complete local approval within 1 month of our site initiation visits. Typical causes for a delay to approval were identified within the first few sites, allowing these to be addressed in subsequent sites at a much earlier stage. This may help considerably to ensure that further sites in a full trial can obtain local R&D approval more quickly.

Conclusion of the feasibility study and pilot trial

We showed that a robust RCT of hip arthroscopy compared with best conservative care for patients with FAI syndrome was feasible, that patients and clinicians were willing to participate, that we were able to obtain ethics and R&D approval at multiple sites, and that the trial procedures we developed worked well. The pilot trial recruited successfully (70% recruitment rate) to the protocol that will be used for the full trial and these patients were, therefore, included in the full trial analysis.

Relevance of project

Young adults with hip pain are now often aware of the diagnosis of FAI syndrome. There are many descriptions in scientific literature, popular press and on the internet, but there is an overwhelming focus on the benefits of surgery, with little regard to other treatments. 7,20 With limited evidence of effectiveness and a significant increase in the cost of arthroscopic surgery (with an NHS tariff for hip arthroscopy of £5200), a number of NHS care commissioners have begun to limit the funding for this procedure. In some areas, hip arthroscopy is not commissioned at all and in others, only patients who have failed to respond to non-operative treatments are allowed access to arthroscopic surgery. 21 Provision of non-operative alternatives to surgery for FAI syndrome is inconsistent, and the evidence and guidance for this conservative care is weak. 20 PHT is a credible physiotherapy-led ‘best conventional care’ protocol for FAI syndrome, developed for the pilot trial through clinical consensus informed by existing literature. 5 This trial will establish the best treatment for patients with FAI syndrome, taking into account clinical effectiveness, costs and risks. This will allow clinicians within the NHS to offer treatment for FAI syndrome that is in patients’ best interests. Establishing the comparative cost-effectiveness of arthroscopy and PHT will help NHS commissioners to make funding decisions based on robust evidence and to avoid the current situation of unjustified variation in provision.

Null hypothesis

Our null hypothesis was that there is no difference in the iHOT-33 questionnaire score 12 months following randomisation between adults diagnosed with FAI syndrome treated with arthroscopic hip surgery and adults diagnosed with FAI syndrome treated with best conservative care.

Objectives

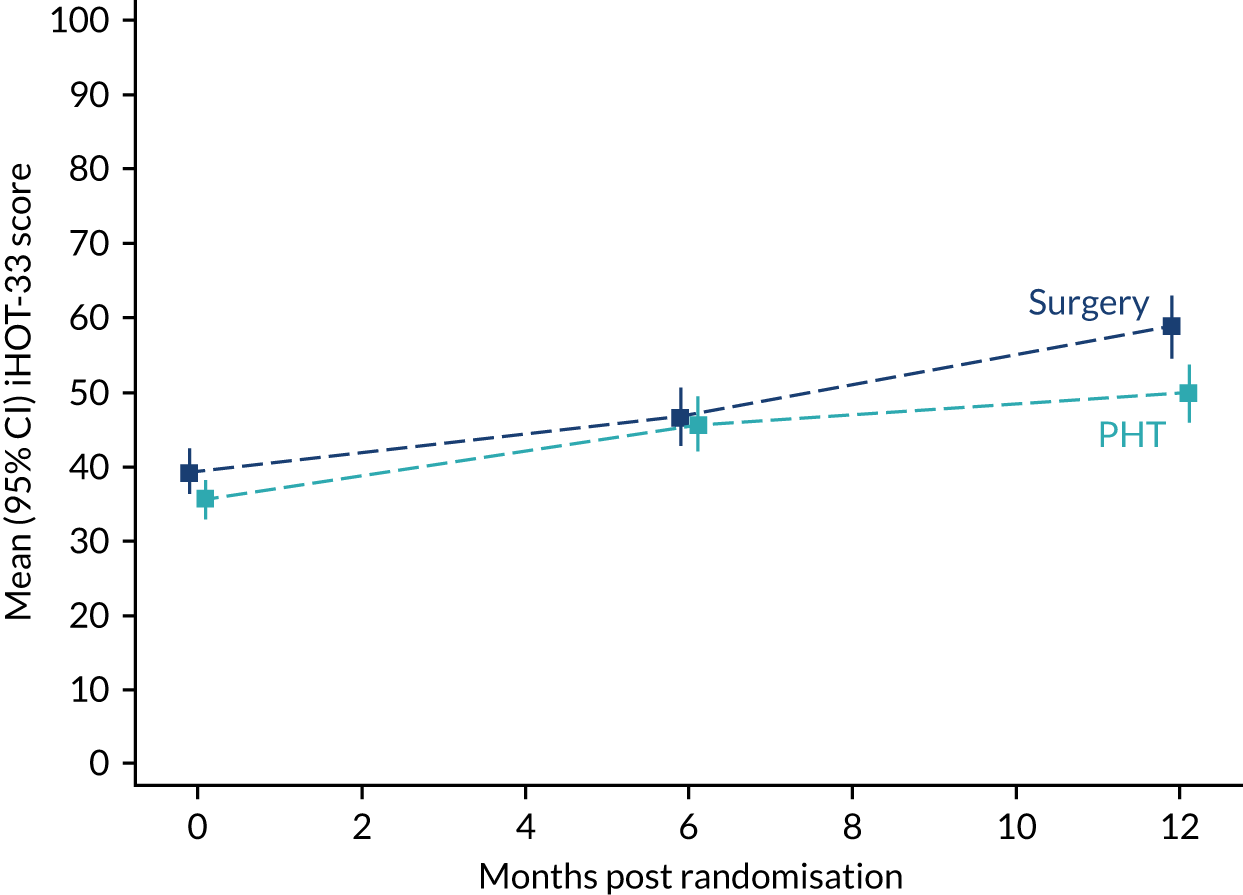

The primary objective was to measure the clinical effectiveness of hip arthroscopy compared with best conservative care for patients with FAI syndrome, assessed by patient-reported hip-specific quality of life after 1 year.

The secondary objectives were to:

-

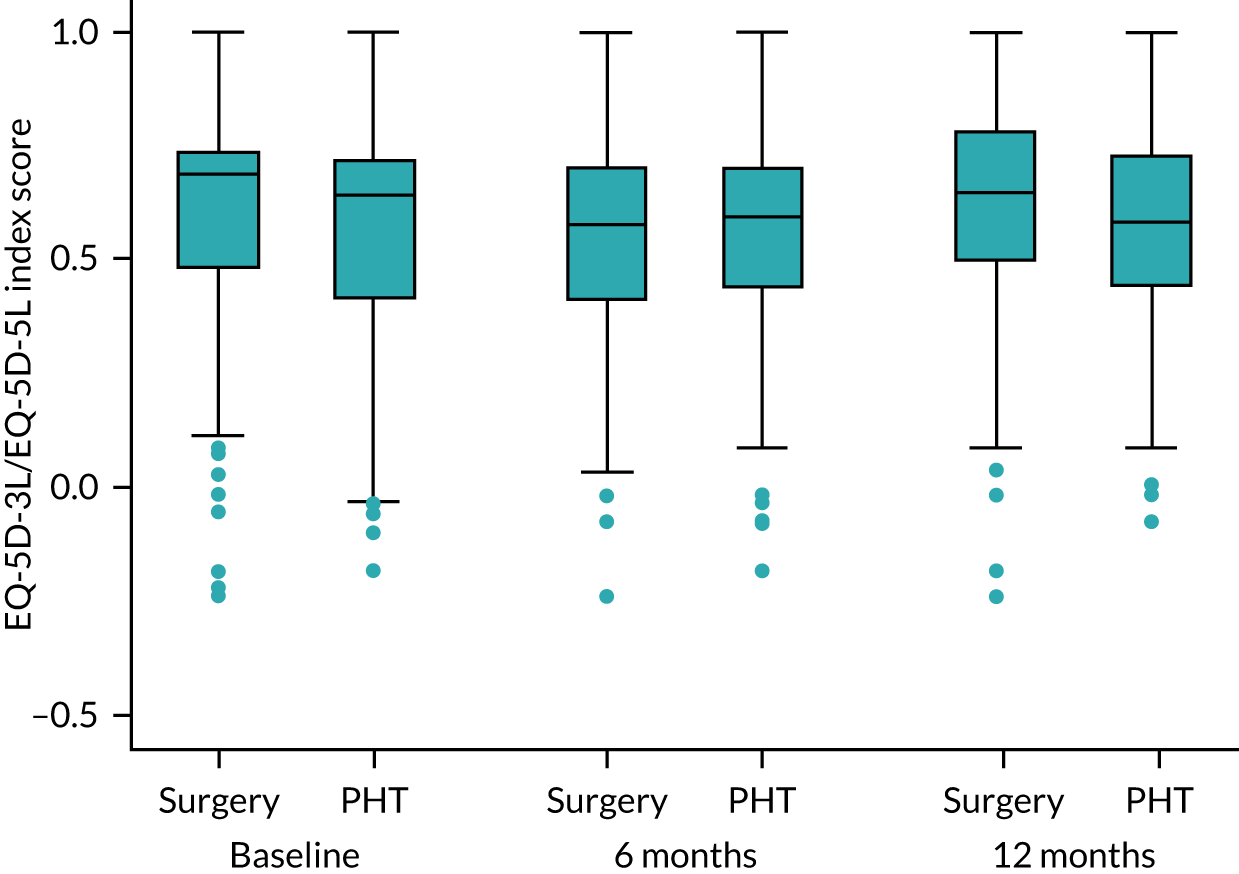

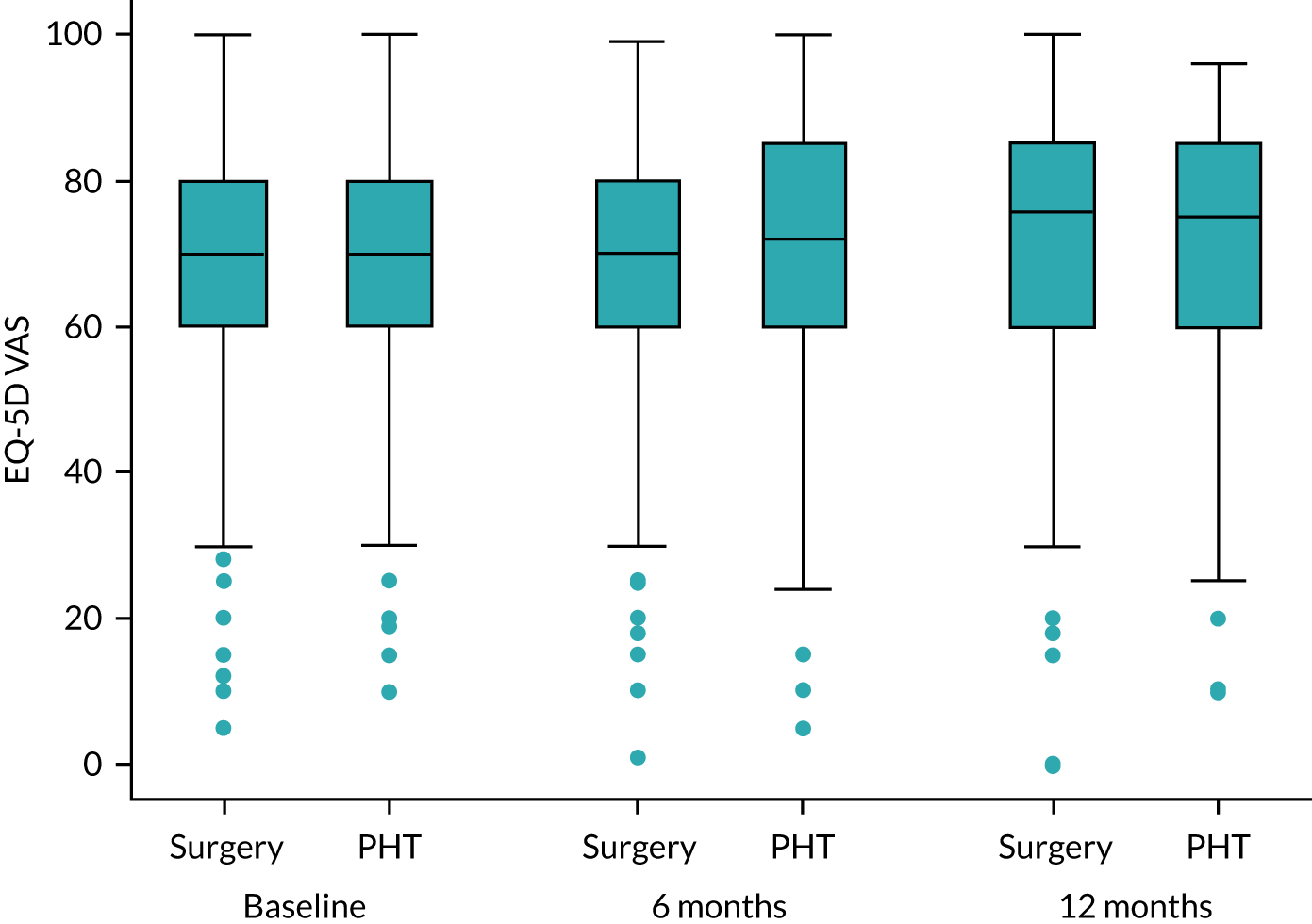

compare differences in general health status and in health-related quality of life after 12 months between treatment groups

-

compare, in a longitudinal analysis, the pattern of clinical change over 36 months

-

compare patient satisfaction with treatment and outcome after 1 year

-

compare the number and severity of adverse events (AEs) after treatment

-

compare the need for further procedures up to 3 years after initial treatment

-

compare the cost-effectiveness of hip arthroscopy for FAI with best conservative care, within the trial and for a patient’s lifetime

-

develop and report processes to optimise recruitment in a RCT or surgery compared with non-operative care

-

measure the fidelity of delivery of interventions.

Chapter 2 Methods

This trial was conducted in accordance with the Medical Research Council’s Good Clinical Practice principles and guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki,35 Warwick Clinical Trials Unit (WCTU) (Coventry, UK) standard operating procedures (SOPs), relevant UK legislation and the trial protocol. Ethics approval was granted on 1 May 2014 (reference 14/WM/0124) by the Edgbaston Research Ethics Committee (current approved protocol version 4.0, 18 August 2017). The trial was registered as ISRCTN64081839. This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme (feasibility and pilot trial grant number 10/41/02, full trial grant number 13/103/02).

Trial design

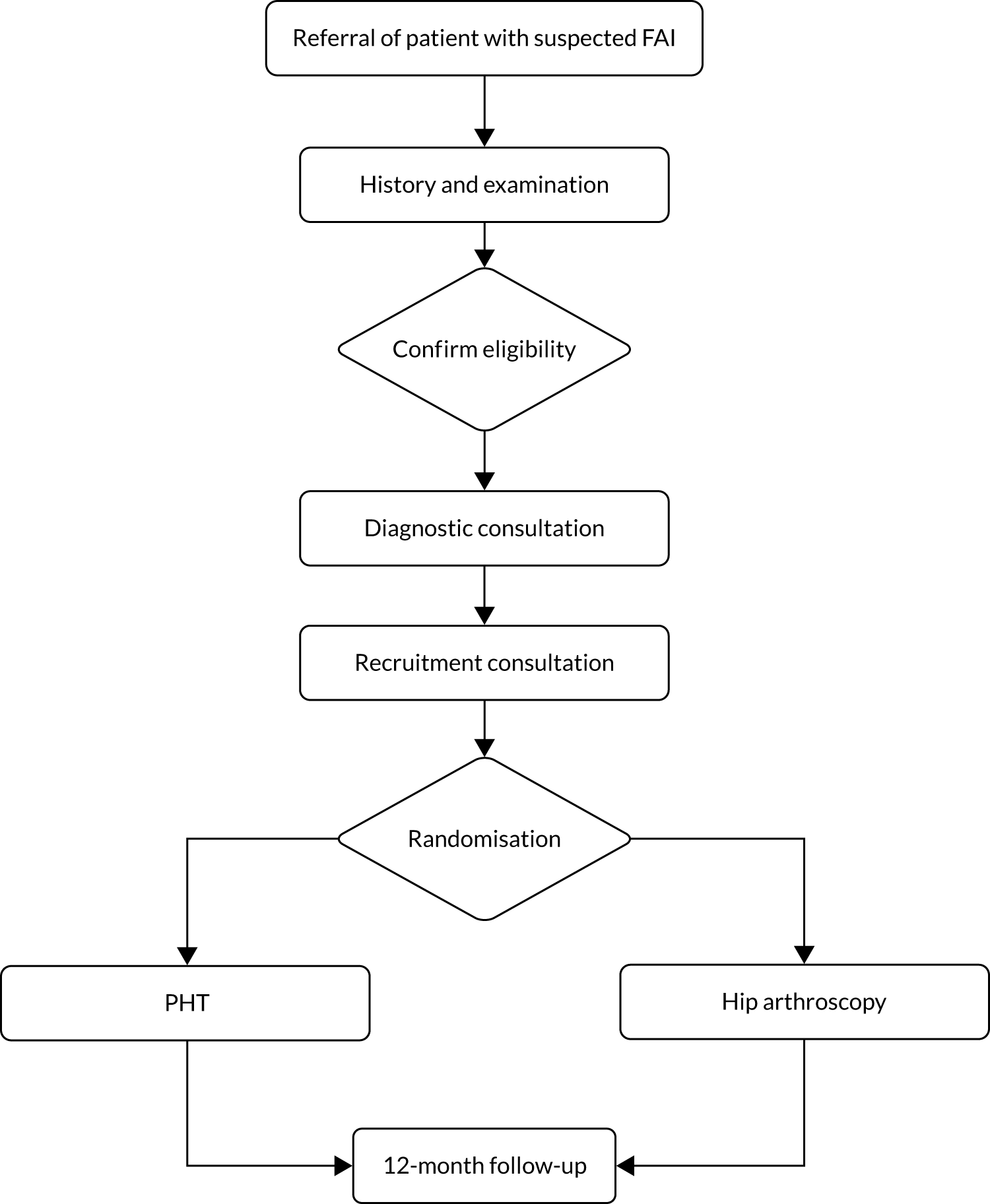

We conducted a multicentre, pragmatic, assessor-blinded parallel-arm 1 : 1 RCT of hip arthroscopy compared with conservative care for FAI syndrome, assessing patient pain, function, general health, quality of life, satisfaction and cost-effectiveness. There was an integrated qualitative recruitment intervention (QRI) that included interviews with recruiters and patients, and observations of recruitment appointments, to ensure that patients had the opportunity to fully consider participation in the trial. 28

We hypothesised that arthroscopic surgery is superior to conservative care at 12 months for self-reported hip pain and function for patients with FAI syndrome. The trial was conducted on consenting patients treated in the NHS. Hospitals participating in the FASHIoN trial had an organised hip arthroscopy service that treated at least 20 patients with arthroscopic surgery for FAI syndrome per year.

Participants

We recruited a cohort of typical patients with FAI syndrome deemed suitable for arthroscopic surgery. This cohort included patients who may have already received a course of physiotherapy.

Inclusion criteria

-

Age ≥ 16 years (with no upper age limit).

-

Symptoms of hip pain (including clicking, catching or giving way).

-

Radiographic evidence of pincer- and/or cam-type FAI morphology on plain radiographs and cross-sectional imaging, defined as:

-

The treating surgeon believes the patient would benefit from arthroscopic FAI surgery.

-

The patient is able to give written informed consent and to participate fully in the interventions and follow-up procedures.

Exclusion criteria

-

Evidence of pre-existing osteoarthritis, defined as Tönnis grade > 138 or a > 2-mm loss of superior joint space width on an anteroposterior pelvic radiograph. 39

-

Previous significant hip pathology, such as Perthes’ disease, slipped upper femoral epiphysis or avascular necrosis.

-

Previous hip injury, such as acetabular fracture, hip dislocation or femoral neck fracture.

-

Previous shape-changing surgery (open or arthroscopic) in the hip being considered for treatment.

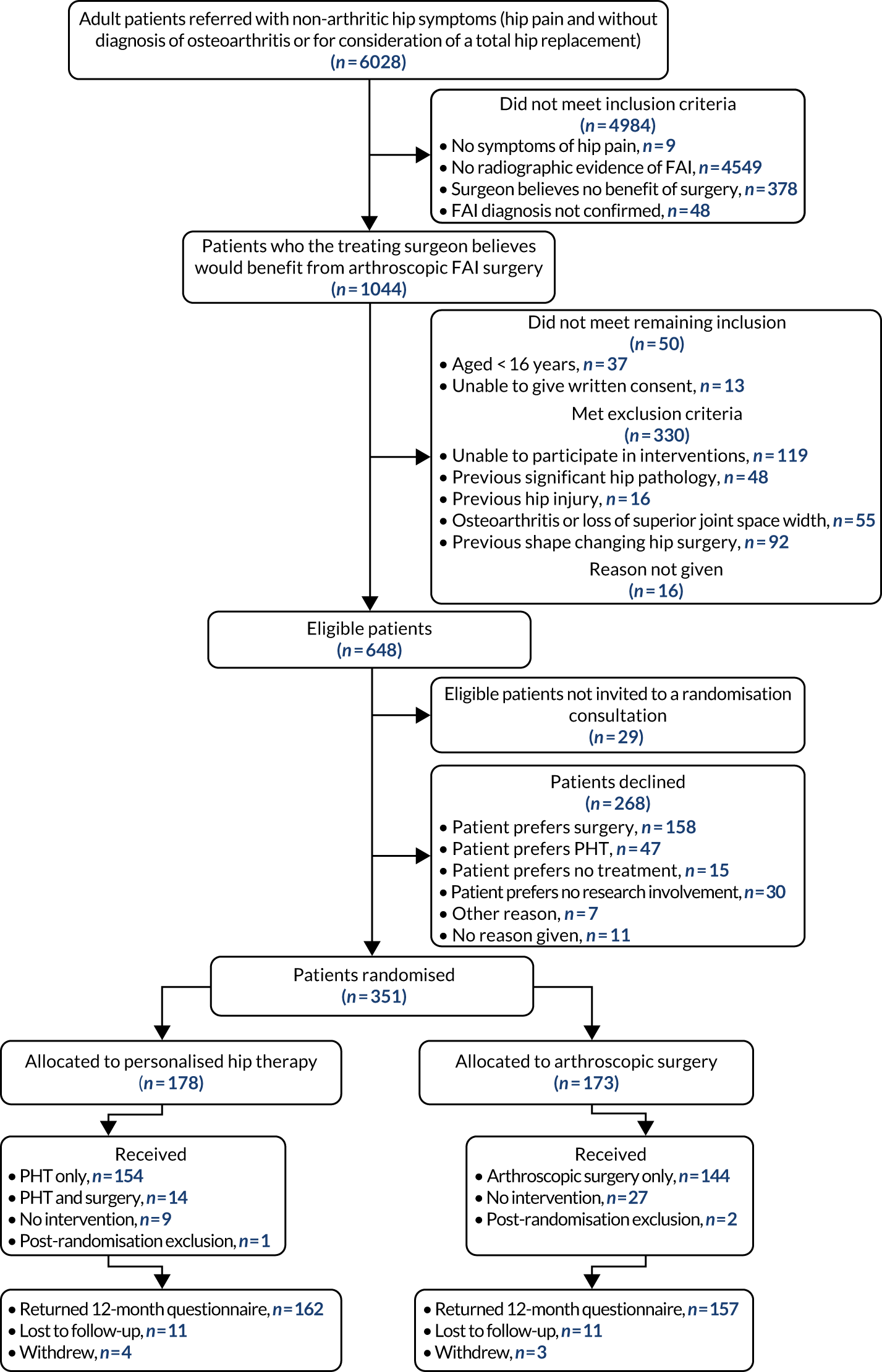

Screening and recruitment

Participants were recruited from among the patients presenting to young adult hip clinics in each of the centres. Patients who complained of hip pain and who did not already have a diagnosis of hip osteoarthritis were identified as potential participants by screening referral letters to collaborating surgeons. Research nurses/associates kept accurate screening logs to identify whether or not these potential participants met the eligibility criteria. Prior to their appointment, these patients were approached to seek consent for recording of their clinic consultations.

Surgeons assessed patients as usual, taking a history, examining the patient and performing appropriate imaging investigations. Patients in whom a diagnosis of FAI syndrome was made and who met the eligibility criteria received a description of the condition from their surgeon and an explanation that there were two possible treatments: (1) an operation or (2) a package of PHT. Patients were given patient information about FAI syndrome and the trial. Patients were then invited to a trial information consultation to discuss what action they would like to take.

Patients attended a trial information consultation with a trained clinical researcher. Information was again provided about FAI, FAI’s possible treatments and the trial. Patients were given an opportunity to ask questions. Patients were then invited to give their consent to become participants in the trial. Patients who wanted to take more time to consider were given an opportunity to do so. Patients who agreed to take part completed baseline questionnaires at this consultation.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained by a researcher delegated and trained by the research team. In general, patients had at least 1 month from initial consultation to the day of surgery or start of PHT so that there was sufficient time for patients to consider taking part in the trial.

Qualitative research intervention

To optimise recruitment and informed consent, trained qualitative researchers listened to recordings of the surgeons’ and RA/nurses’ trial information consultations to identify communication patterns that facilitated or hindered patient recruitment. 28 In-depth interviews with the recruiters were undertaken to identify clear obstacles and hidden challenges to recruitment, including the influence of patient preferences and equipoise. 40 Research teams were interviewed to identify clinician equipoise, patient pathways from eligibility to consent and staff training needs at each participating site. 28 Findings were fed back to the chief investigator and Trial Management Group (TMG) so that practice could be reviewed and any necessary changes (including additional training) implemented. The number of eligible patients and the percentages of these patients who were approached and consented to randomisation were monitored at each site.

This research was linked to the Quintet programme of research within the Medical Research Council ConDuCT-II (Collaboration and innovation in Difficult and Complex randomised controlled Trials II) Trial Methodology Hub (Bristol, UK).

Randomisation

Participants were randomised, in a 1 : 1 ratio, to arthroscopic surgery or PHT using a computer-generated sequence. Allocation was made by the research nurse/associate via a centralised telephone randomisation service provided remotely by WCTU. Allocation concealment was ensured, as the randomisation programme did not release the randomisation code until the patient had been recruited into the trial. Research nurses/associates who recruited participants ensured that they were referred for the allocated intervention.

Sequence generation

To improve the baseline balance between intervention group samples, a minimisation (adaptive stratified sampling) algorithm was implemented using study site and impingement type (i.e. cam, pincer or mixed) as factors.

Blinding

The patients could not be blind to their treatment. The treating surgeons were not blind to the treatment, but took no part in outcome assessment for the trial. The functional outcome data were collected and entered onto the trial central database via postal questionnaire by a research assistant who was blind to the treatment allocation. The statistical analysis was also performed blind.

Post randomisation withdrawals

Participants could withdraw from the trial treatment and/or the whole trial at any time without prejudice. If a participant decided to change from the treatment to which they were allocated, they were followed up and data collected as per the protocol until the end of the trial. However, every effort was made to minimise crossovers from both intervention arms. It was made clear to study participants and clinicians that it was important for the integrity of the trial that everyone followed their allocated treatment. For those participants who decided to move to the other intervention arm, the numbers, direction and reasons for moving were recorded and reported in line with CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidance. The QRI investigated how and why participants made their decision. The QRI team provided training for physiotherapists and surgeons so that they were equipped to answer patients’ questions about the trial during treatment. During the pilot trial, we found that this reduced the risk of participants losing confidence in the trial and breaching protocol.

Interventions

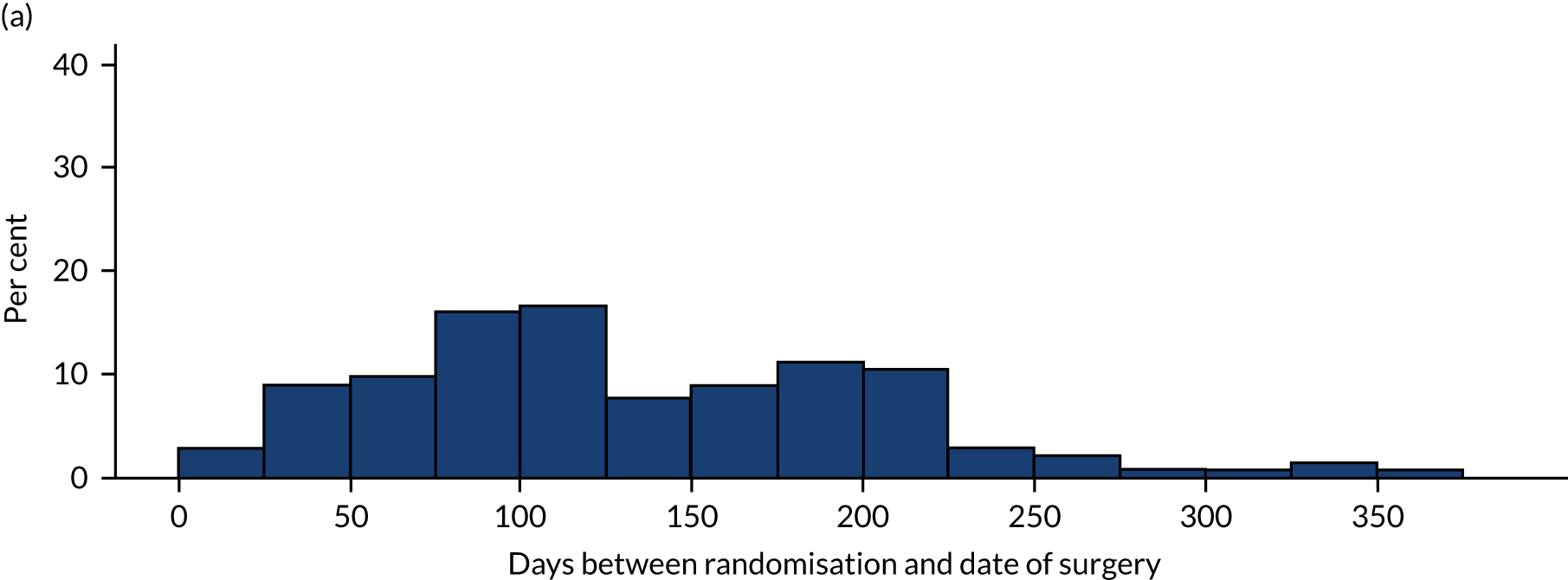

The two interventions commenced as soon as possible after randomisation. We recorded the dates of randomisation and the start of allocated treatment. As this was a pragmatic trial, participants were not prohibited from undergoing any additional/concomitant care.

Arthroscopic surgery

An operative protocol was established during and implemented in the pilot trial. The agreed protocol was typical of the surgical techniques used by the majority of surgeons around the world, and representative of those used in the UK. The surgeons delivering the intervention were all NHS consultants.

Preoperative protocol

Patients underwent routine preoperative care, which included an assessment of their general health and suitability for a general anaesthetic.

Perioperative protocol

Arthroscopic hip surgery was performed under general anaesthesia with the patient in a lateral or supine position. Arthroscopic portals were established in the central and peripheral compartment under radiographic guidance and in accordance with the surgeon’s usual practice. Shape abnormalities and consequent labral and cartilage pathology was treated. Bony resections at the acetabular rim and the head–neck junction were assessed by intraoperative image intensifier radiograph and/or satisfactory impingement free range of movement of the hip.

Postoperative protocol

Patients were allowed home when they could walk safely with crutches (usually within 24 hours). On discharge, all patients were referred to outpatient physiotherapy services for a course of rehabilitation, as per usual care for that surgeon. We did not specify a protocol for this postoperative physiotherapy, but recorded it using a treatment log. Postoperative physiotherapists were distinct from those providing PHT to avoid contamination between groups. Patients also had a postoperative MRI, which included a proton density volume acquisition sequence (for MRI protocol see Appendix 1).

Fidelity assessment

To ensure the fidelity of the surgery and to identify participants for a secondary analysis, a panel of international experts reviewed operation notes, intraoperative images and postoperative MRI scan to assess whether or not adequate surgery was undertaken (see Appendix 2). This panel included Mark Philippon (USA; then chairperson of the Research Committee of the International Society for Hip Arthroscopy), Martin Beck (Switzerland; one of the investigators credited with developing the early understanding of FAI), John O’Donnell (Australia; past president of the International Society of Hip Arthroscopy) and Professor Charles Hutchinson (UK; an expert in musculoskeletal radiology). The fidelity assessment process was tested in the pilot trial. The panel rated each surgical case as satisfactory, borderline satisfactory and unsatisfactory (see Appendix 1).

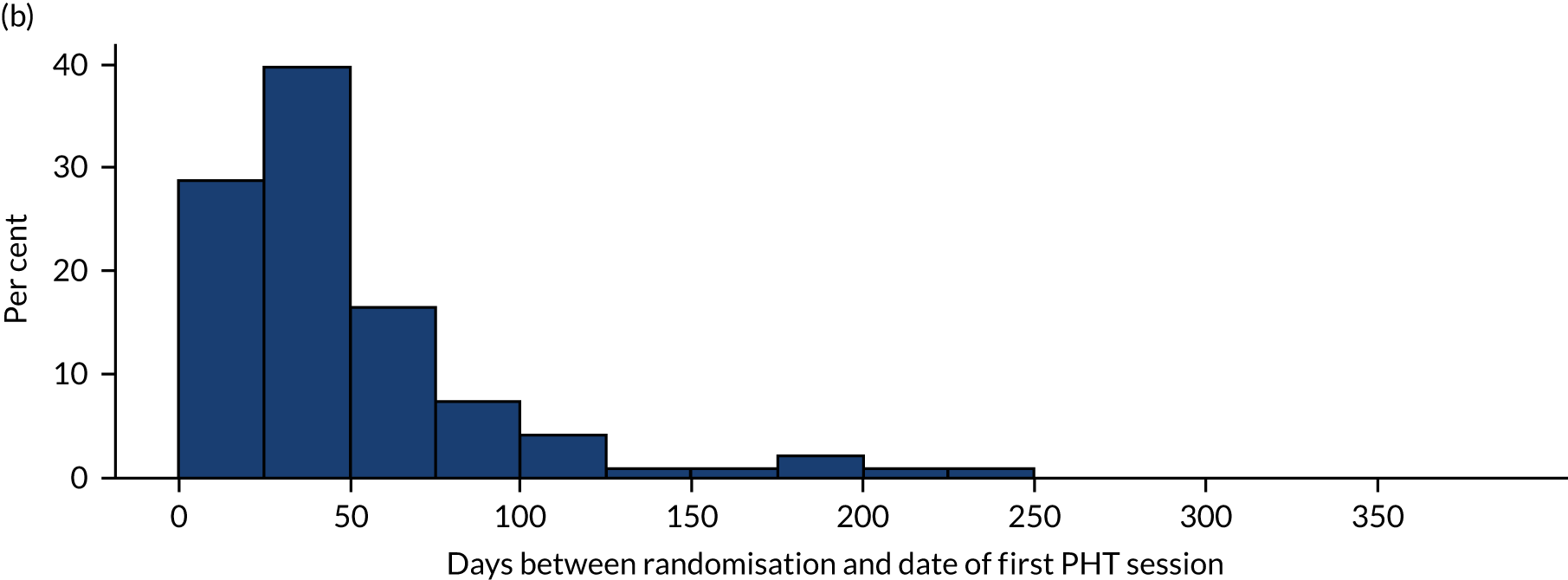

Personalised hip therapy

Personalised hip therapy was a package of physiotherapy-led best conservative care for FAI syndrome. 5 It was developed during the feasibility study and ‘road-tested’ during the pilot trial. 3 Although the name for this intervention was new, the care being offered represented a consensus of what physiotherapists, physicians and surgeons in the NHS provided and regard as ‘best conventional care’. PHT was delivered by at least one qualified physiotherapist at each site. To prevent contamination of the treatment groups, the physiotherapists who delivered PHT were distinct from those who delivered postoperative physiotherapy.

Training physiotherapists

Personalised hip therapy physiotherapists were trained in a FASHIoN PHT workshop and supported by the physiotherapy lead and research facilitator (NF and JS).

We developed and tested the 1-day workshop during our pilot trial. Following the initial PHT workshops during the feasibility study, the remaining workshops were delivered through the recruitment period from November 2014 to March 2016. The workshops included lectures, presentations, discussion of real cases and working through PHT progressions. A PHT manual and exercise sheets (for patients) were provided to all the PHT physiotherapists (see Appendix 1). Ongoing training and support was provided by the physiotherapy research facilitator and this included an initial site visit and monitoring visits. The purpose of the initial visit was to ensure that the treating physiotherapist fully understood the detail of PHT. The first visit was scheduled to occur after the first patients were randomised to PHT and before they had started treatment. Monitoring visits provided opportunities for further training and to conduct a source verification audit (see Fidelity assessment). Although PHT offered a framework to deliver best conservative care, the treatment was not a fully standardised regime. Physiotherapists were trained and encouraged to tailor their treatment to each patient, focusing on deficiencies identified in their assessment and based on the patients’ progression.

Pre treatment

Participants received a PHT information pack (see Appendix 1) that described what to expect during the course of their treatment. The first core component of PHT was an assessment of pain, function and range of hip motion.

Treatment

Personalised hip therapy had three further core components: (1) an exercise programme that had the key features of individualisation, progression and supervision; (2) education; and (3) help with pain relief (which may have included one X-ray or ultrasound-guided intra-articular steroid injection if pain prevented performance of the exercise programme). The intervention was delivered over a minimum of 12 weeks, with a minimum of six patient contacts. Some of the patient contacts were permissible using either telephone/e-mail for whom geographical distance prevented all contacts being carried out face to face. The number and frequency of the treatment sessions was at the discretion of the physiotherapist and was informed by the patients’ deficiencies and progression.

Post treatment

Typically, PHT was delivered over a minimum of 12 weeks. However, in situations in which the patient needed additional review, support or guidance, further sessions with the physiotherapists were permitted up to a maximum of 10 sessions over 6 months.

Fidelity assessment

To assess the accuracy of the PHT CRFs a source verification audit was undertaken to compare the physiotherapists’ hospital notes and the PHT CRF. Source verification was undertaken at each site and with 10% of cases sampled. The CRFs were graded as either a satisfactory or unsatisfactory reflection of the hospital notes. The source verification was undertaken by the physiotherapy research facilitator (JS). The findings of the source verification audit were fed back to the fidelity assessment panel.

The PHT CRFs were assessed to determine the fidelity of each intervention and to identify participants for a secondary analysis. This assessment was completed by the panel that developed the protocol for PHT, including Nadine Foster (Senior Academic Research Physiotherapist), Ivor Hughes and David Robinson (UK; Extended Scope Musculoskeletal Physiotherapists) and Peter DH Wall (Academic Orthopaedic Surgeon).

Treatment was rated as satisfactory, borderline or unsatisfactory. The panel assessed whether or not a sufficient number of treatments had occurred (at least six sessions in 12 weeks, but fewer than 10 sessions in 6 months), whether or not the treatment included all four core components of PHT and whether or not the exercise programme was individualised, supervised and progressive.

Treatment crossover

Crossover of participants between interventions can be problematic in trials of this nature. To minimise this, care was taken prior to enrolment in the trial to ensure that potential participants:

-

were willing to receive either intervention

-

understood that both treatments were thought to provide benefit

-

were willing to remain with their allocation for 12 months

-

understood that both interventions may take 6 months to improve symptoms. 39,41

In instances where patients were not satisfied with how their treatment was progressing prior to reaching the primary outcome, they were able to have a further consultation with their treating surgeon where they were treated in their best interests.

Outcomes

Baseline data were collected from participants once consent was obtained and prior to randomisation. Follow-up questionnaires were administered centrally by a data clerk via post. If participants failed to respond, they were contacted via telephone, e-mail or via their next of kin, where necessary.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was hip pain, function and hip-related quality of life measured using the iHOT-33 at 12 months following randomisation. The iHOT-33 is a validated hip-specific patient-reported outcome tool that measures health-related quality of life in young, active patients with hip disorders. 31 The iHOT-33 consists of the following domains: symptoms and functional limitations, sports and recreational activities, job-related concerns and social, emotional and lifestyle concerns.

We chose it following our feasibility and pilot study, as it is more sensitive to change than other hip outcome tools, it does not show evidence of floor or ceiling effects in patients undergoing hip arthroscopy and patients were involved extensively in item generation and, therefore, we can be confident that it measures what is most important to patients. The iHOT-33 has an independently determined MCID. The iHOT-33 is also used as the principal outcome measure for the UK Non-Arthroplasty Hip Registry, which is mandated for arthroscopic FAI surgery by NICE. 15,31

Secondary outcome measures

Health-related quality of life: EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version

The EQ-5D-5L is a validated measure of health-related quality of life, consisting of a five-dimension health status classification system and a separate VAS. EQ-5D-5L is applicable to a wide range of health conditions and treatments, and provides a simple descriptive profile and a single index value for health status. 42 Responses were converted into health utility scores using established algorithms. 43

General health: Short Form questionnaire-12 items

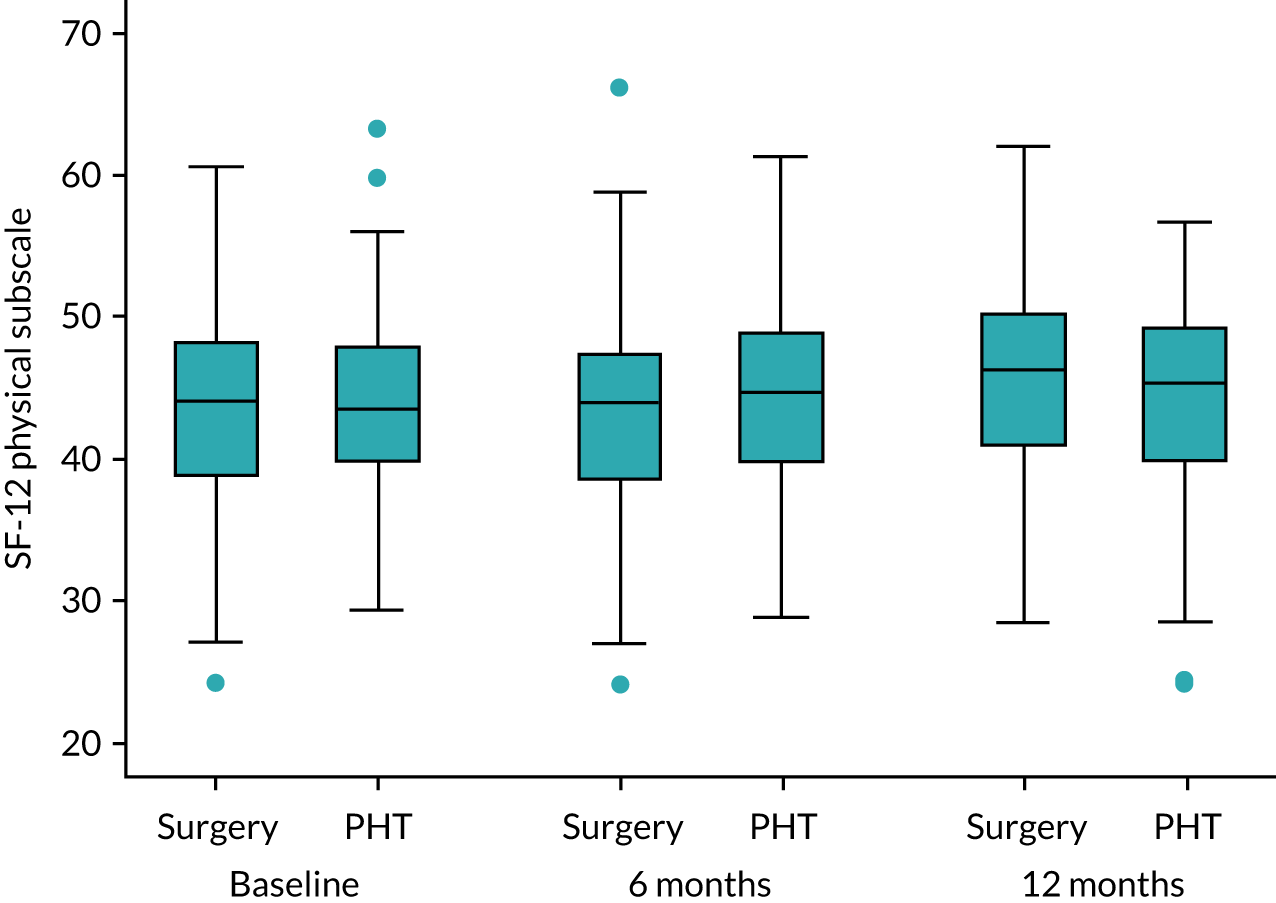

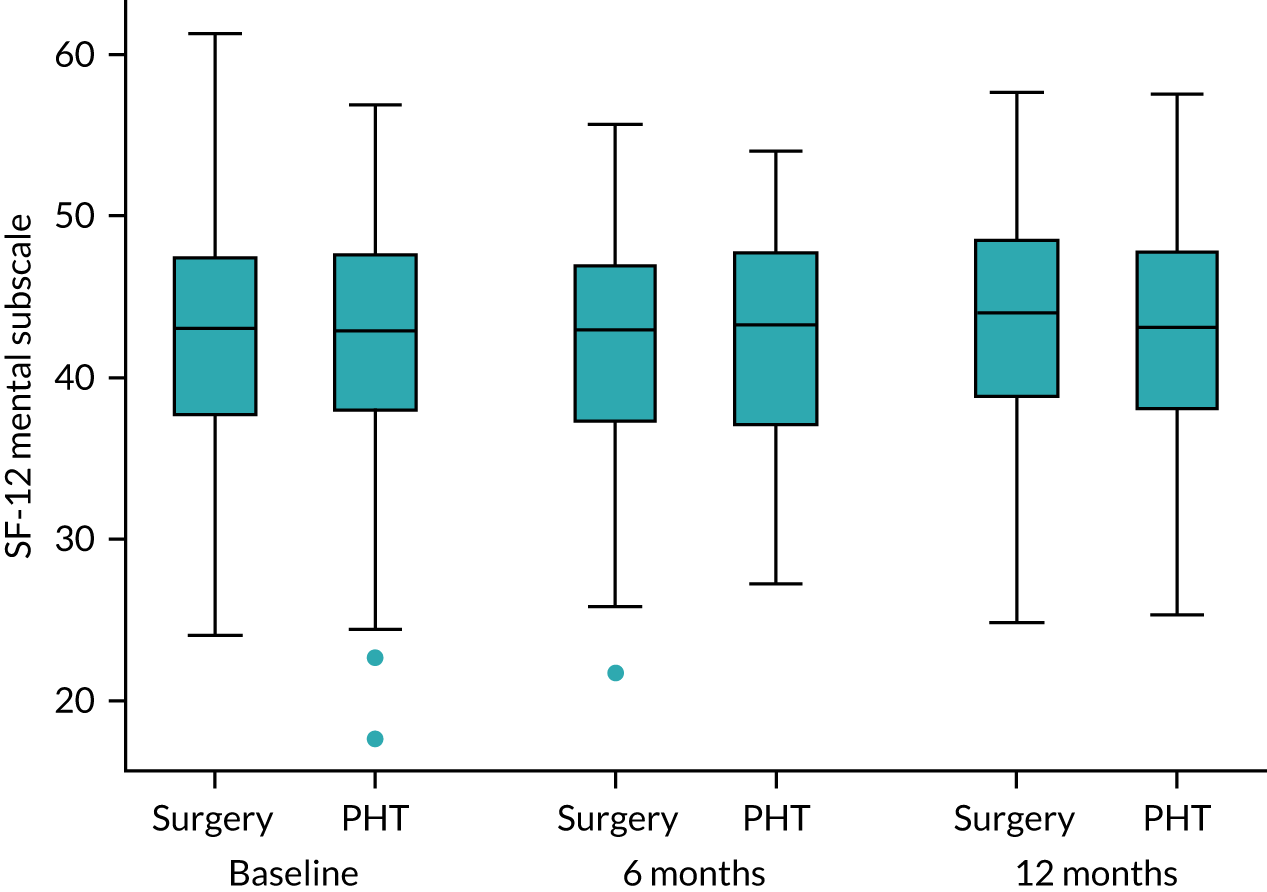

The Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12) is a validated and widely-used health-related quality-of-life measure that is used for hip conditions and treatments. 44 SF-12 is able to produce the physical and mental component scales originally developed from the Short Form questionnaire-36 items with considerable accuracy, but with far less respondent burden. 45 Responses were converted into health utility scores using established algorithms. 46

Patient satisfaction

Patient satisfaction was measured using questions that our team (NF) had used in previous trials with musculoskeletal pain patients. 47 We measured two distinct dimensions of satisfaction in all participants during follow-up: (1) ‘overall, how satisfied are you with the treatment you received?’ and (2) ‘overall, how satisfied are you with the results of your treatment?’ Responses were on a five-point Likert scale.

Qualitative assessment of outcome

We conducted in-depth one-to-one interviews with a purposively selected sample of 25–30 participants in each of the trial groups. These samples included older and younger, male and female, more and less active, and more and less satisfied participants recruited at different trial sites. The qualitative interviews supplement the quantitative outcomes. Interviews explored experiences of the trial processes, the treatments and the consequences of treatment to participants’ lives, health and well-being.

Adverse events

We recorded the number and type of AEs up to 12 months. Any AEs were reported on the appropriate CRF and returned to WCTU. Any serious adverse events (SAEs) were faxed to WCTU, within 24 hours of the local investigator becoming aware, where the chief investigator determined causality and expectedness. SAEs deemed unexpected and related to the trial were reported to the Research Ethics Committee within 15 days.

Resource utilisation

Information on health-care resource use was collected by incorporating questions within the patient follow-up questionnaires. We confirmed the feasibility and acceptability of this approach in our pilot trial. In addition, patient self-reported information on service use has been shown to be accurate in terms of the intensity of use of different services. 48

Need for further procedures

We recorded any further treatments performed in both groups, such as hip arthroscopy, open hip preservation surgery, hip replacement or additional ‘out-of-trial’ physiotherapy. We ascertained the need for further procedures by questionnaire at 2 and 3 years. In addition, we also propose a 5- and 10-year no-cost ascertainment of hip replacement by linkage to the UK National Joint Registry and Hospital Episode Statistic databases.

Follow-up

The follow-up schedule is outlined in Table 1. The primary outcome was collected 12 months following randomisation.

| Time point | Data collection |

|---|---|

| Baseline | Demographics, physical activity (UCLA Activity Scale),49 iHOT-33, SF-12, EQ-5D-5L, preoperative imaging and economics questionnaire |

| Intervention | Operation notes and photographs or PHT log, complications records 6 weeks post start of intervention and postoperative MRI (surgery intervention only) |

| 6 months | iHOT-33, SF-12, EQ-5D-5L, resource utilisation and AEs |

| 12 months (primary outcome) | iHOT-33, SF-12, EQ-5D-5L, patient satisfaction, resource utilisation and AEs |

| 2 years | iHOT-33, EQ-5D-5L and further procedures questionnaire |

| 3 years | iHOT-33, EQ-5D-5L and further procedures questionnaire |

| 5 and 10 years | Linkage to the National Joint Registry and Hospital Episode Statistics to identify need for hip replacement |

Adverse event management

Adverse events are defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a clinical trial patient that do not necessarily have a causal relationship with the treatment. All AEs were listed on the appropriate CRF and returned to the FASHIoN trial central office.

Serious adverse events are defined as any untoward and unexpected medical occurrences that:

-

result in death

-

are life-threatening

-

require hospitalisation or prolongation of existing inpatients’ hospitalisation

-

result in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

are a congenital anomaly or birth defect

-

are important medical conditions that, although not included in the above, may require medical or surgical intervention to prevent any of the outcomes listed above.

All SAEs were entered onto the reporting form and faxed to WCTU within 24 hours of the investigator becoming aware of them. Once received, causality and expectedness was confirmed by the chief investigator. The Research Ethics Committee were notified, within 15 days, of SAEs that were deemed to be unexpected and related to the trial. All such events were reported to the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) at their next meeting.

Serious adverse events that were expected as part of both interventions are listed in Risks and Benefits below. All participants who experienced SAEs were followed up as per protocol until the end of the study period.

Risks and benefits

Both interventions were thought to provide benefit in patients with FAI syndrome. The short-term risks of the study related to the two interventions. These risks are described below and informed the expected SAEs.

Arthroscopic surgery

Hip arthroscopy requires a general anaesthetic. The risk of complications from hip arthroscopy is about 1–2% and these include the following:

-

Infection, which is thought to occur in less than 1 in 1000 patients.

-

Bleeding, possibly causing bruising or a local haematoma.

-

Traction-related complications. (To perform hip arthroscopy, traction is required to separate the hip joint surfaces. Sometimes after the procedure, the pressure from the traction can cause some numbness in the leg, but the numbness usually resolves within a few hours or days.)

-

Osteonecrosis. (During surgery, the blood supply to the hip joint could be damaged; however, there are no reported cases of osteonecrosis following arthroscopic FAI surgery.)

-

Femoral neck fractures. (This is also a very rare complication and would require a further procedure to fix the fracture.)

Personalised hip therapy

There are some small risks with pain medications and joint injection. However, the main risk is muscle soreness and transient increases in pain from the exercises that were undertaken.

Statistical analysis

The primary analysis was the difference, at 12 months, in hip-related quality of life (using the iHOT-33) between the two treatment groups, blinded, on an intention-to-treat basis and presented as the mean difference between the trial groups with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The iHOT-33 data were assumed to be normally distributed after appropriate variance-stabilising transformation.

The minimisation randomisation procedure should have ensured treatment group balance across recruiting sites. We had no reason to expect that clustering effects would be important for this study, but the possibility of such effects was explored as part of the analysis. We planned to account for clustering by generalising a conventional linear (fixed-effects) regression approach to a mixed-effects modelling approach where patients are naturally grouped by recruiting sites (random effects) and, if amenable to analysis, also by physiotherapist and surgeon. This model formally incorporated terms that allowed for possible heterogeneity in responses for patients due to the recruiting centre, in addition to the fixed effects of the treatment groups and patient characteristics that may prove to be important moderators of treatment effect, such as age, sex and FAI type. The analysis was conducted using specialist mixed-effects modelling functions available in the software packages Stata® release 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). All tests were two sided and were considered to provide evidence for a statistically significant difference if p-values were < 0.05 (i.e. a 5% significance level).

Secondary analyses was performed using the above strategy for other approximately normally distributed outcome measures, including iHOT-33 at 6 months, SF-12 (and computed subscales) and EQ-5D-5L. Differences in dichotomous outcome variables, such as AEs, complications related to the trial interventions and the need for further procedures, were compared between groups using chi-squared tests (or Fisher’s exact test) and mixed-effects logistic regression analysis, adjusting for the stratifying variables, with differences between trial intervention groups quantified as odds ratios (and 95% CIs). The temporal patterns of AEs were presented graphically and, where appropriate, a time-to-event analysis (Kaplan–Meier survival analysis) to assess the overall risk and risk within individual classes of AEs. Ordinal scores for patient satisfaction were compared between intervention groups using proportional odds logistic regression analysis, assuming that the estimated intervention effect between any pair of categories is equivalent.

Our inferences were drawn from the intention-to-treat analysis. We performed two exploratory secondary analyses. One exploratory analysis compared patients who received surgery with those who received conservative care. A second exploratory analysis compared patients randomised to surgery and PHT and who received treatment deemed to be of a high fidelity by the respective review panels. We performed a subgroup analysis by FAI type because it was possible that treatment effect is moderated by type. We anticipated that adequate steps were taken to prevent crossovers from being a major issue in this study. Therefore, we expected the main intention-to-treat analysis to provide definitive results. An independent DMC monitored crossovers and adherence to treatment and advised on appropriate modifications to the statistical analysis plan as the full progressed.

The feasibility and pilot studies2,3 were designed explicitly to assess feasibility and measure recruitment rates, and not to estimate treatment effectiveness. Data from the pilot were pooled with data from the full trial, and analysed together.

Sample size

The development work for iHOT-33 reported a mean iHOT-33 score of 66 (SD 19.3) in a heterogeneous population with a variety of hip pathologies. The baseline iHOT-33 data from our pilot trial suggests that the target population of patients being considered for hip arthroscopy for FAI in the UK have lower scores with less variability than the heterogeneous population, with a mean score of 33 (SD 16).

During our feasibility study, we estimated the likely effect size of hip arthroscopy compared with best conventional care for FAI to be 0.5. The MCID for iHOT-33 in this population is 6.1 points. Our sample size calculation is, therefore, based on a SD of 16 and a MCID of 6.1 (i.e. a standardised effect difference between groups at 12 months of 0.38).

Table 2 shows the expected sample size for scenarios with 80% and 90% power to detect an effect of this size, at a 5% significance level, assuming an approximately normal distribution of the iHOT-33 score. Table 2 also shows sample sizes for small to moderate (0.32) and moderate (0.47) effect differences, which are broadly consistent with other pragmatic RCTs measuring clinical effectiveness.

| SD | Power | Standardised effect difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 80% | 90% | ||

| 13.3 | 144 | 192 | 0.47 |

| 16.0 | 218 | 292 | 0.38 |

| 19.3 | 316 | 422 | 0.32 |

A systematic review of observational studies50 reported effect sizes of hip arthroscopy for FAI of between 0.67 and 2.95 up to 5 years after surgery, but these are likely to be overestimates of the real effect we might measure in this trial. These observational studies were uncontrolled studies, and we anticipate that our best conventional care protocol will provide some benefit.

We have, therefore, adopted a conservative approach, seeking to demonstrate an effect difference between groups equal to the MCID. We proposed to recruit sufficient patients to be able to analyse 292 patients at the 12-month follow-up. Allowing for 15% loss to follow-up, we aimed to recruit a sample of 344 participants (i.e. 172 participants in each group). This would provide 90% power to detect a difference of 6.1 iHOT-33 points, if that is the true difference.

Analysis plan

A full statistical analysis plan was developed and approved by the trial statistician(s) and the chief investigator. This plan was also reviewed by the DMC once finalised, in line with the SOPs at WCTU.

Software

All routine interim data reports and final statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 14. A bespoke secure database was created by the programing team at WCTU to enter, store and maintain all trial data and monitor them for accuracy and integrity. A secure Open Database Connectivity data link was used to obtain data when necessary, and data export was restricted to only those members of the trial team who required access for analysis purposes.

Data validation

A FASHIoN data monitoring plan was developed at the outset of the study. The plan covered all aspects of data collection, including data entry, receipt, storage, checking, security and transfer.

Monitoring of data collection was also conducted by the independent DMC, which received regular reports on data quality and completeness as part of its ongoing support to the study. Prior to the final analysis, data were checked for outliers and missing data. Outcome data were validated using defined score ranges for each measure. Any queries were reported to the trial co-ordinator who liaised with the relevant recruiting centre, if appropriate. All subsequent changes to the data were recorded in accordance with the relevant SOP and the FASHIoN data management plan.

Missing data

Data were not available because of withdrawal of patients, lack of completion of individual data items and loss to follow-up. Reasons for missing data were ascertained and reported as far as possible. Any patterns of missing data were carefully considered, including, in particular, whether or not data could be treated as missing completely at random. No formal statistical testing was planned to assess missing data, but model assumptions were checked and patterns explored. If judged appropriate, missing data in the primary outcome (iHOT-33) were imputed using an imputation procedure in Stata (from the mi set of commands). Any imputed data were on an individual item level, as opposed to an overall score level. Reasons for ineligibility, non-compliance, withdrawal or other protocol violations and deviations are stated, and any patterns summarised, in Chapter 4.

Interim analyses

There were no pre-planned interim data analysis for the FASHIoN study, and the study sample size and design were powered only for the final analysis.

Exploratory analysis

A post hoc unplanned exploratory analysis was undertaken to investigate the effect of the timing of treatment on the primary outcome, an issue that was not identified prior to study design and conception. The most appropriate approach was to include an additional binary covariate in the model, which indicated whether treatment was early (< 12 weeks) or late (> 12 weeks) and assess whether or not the inclusion of this covariate improved the model fit and had an impact on the size and interpretation of the treatment effect.

Economic evaluation

Overview

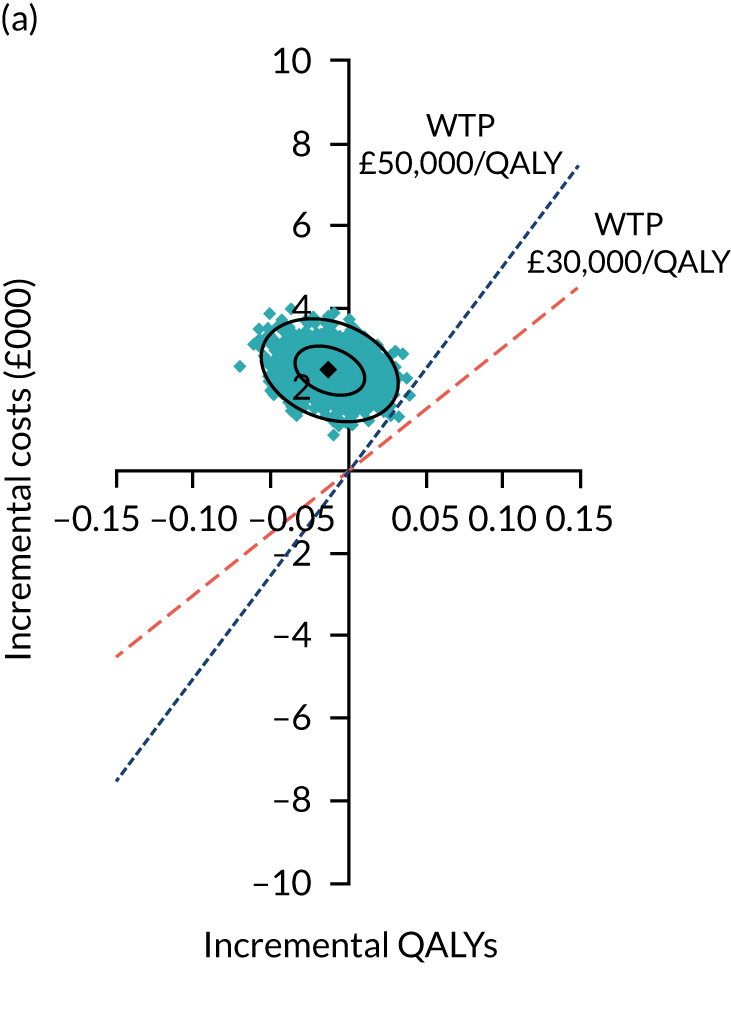

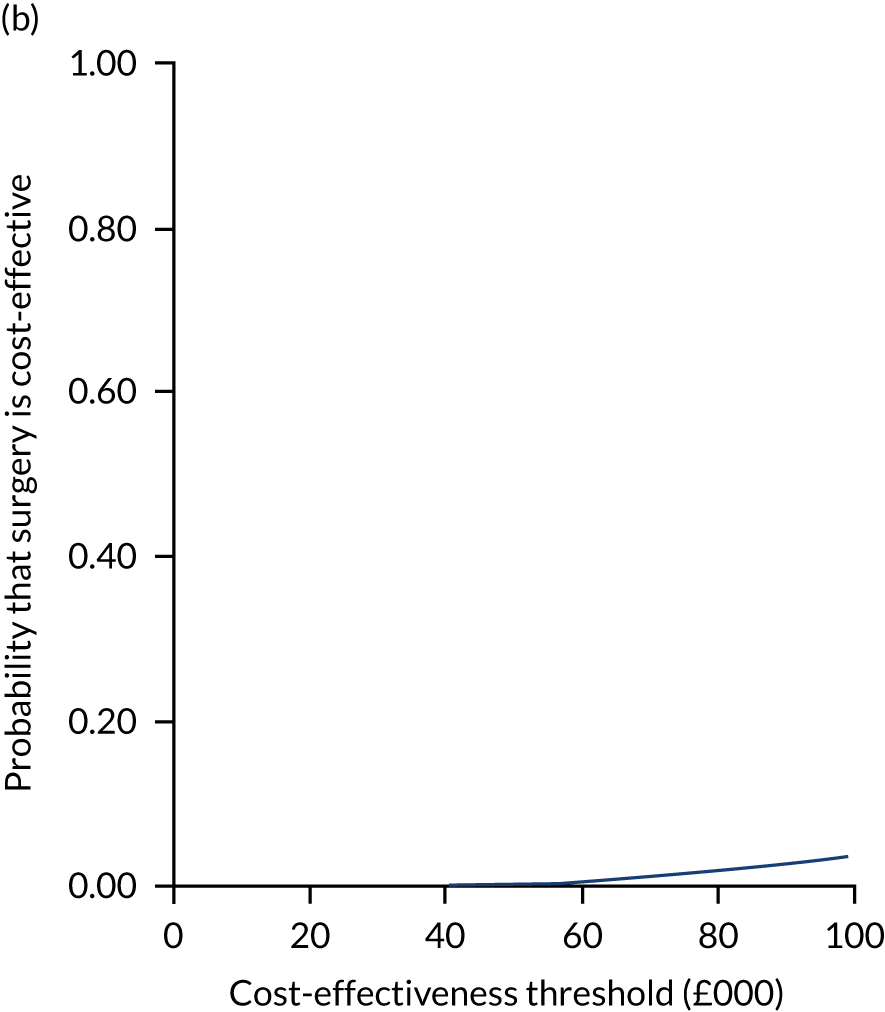

A prospective within-trial cost–utility analysis was conducted to estimate the cost-effectiveness of arthroscopic surgery compared with PHT as treatment options for FAI syndrome. Costs were expressed in GBP (2016 price year) and health outcomes in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). The base-case analysis was based on the intention-to-treat population and conducted from the perspective of UK NHS and Personal Social Services. The time horizon covered the period from randomisation to end of follow-up at 12 months post randomisation. Costs and outcomes were not discounted because of the short 1-year time horizon adopted for this within-trial evaluation. Sensitivity and subgroup analyses were conducted to investigate the likely impact of alternative data inputs and assumptions on cost-effectiveness, and identify subgroups most likely to benefit from treatment. Findings are reported in accordance with the CHEERS (Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards) guidelines. 51

Measurement of resource use and costs

Data were collected on (1) resource use and costs associated with delivery of the interventions, (2) health and social care service use during the 12 months of follow-up and (3) broader societal resource use and costs (e.g. private medical costs and lost productivity costs, such as lost income over the 12 months of follow-up).

Cost of personalised hip therapy

Personalised hip therapy was delivered to trial participants primarily by experienced physiotherapists (grade 7 and above) within NHS hospital outpatient clinics. The number and duration of PHT sessions attended were recorded for all patients who received this intervention. The unit cost of a band 7 hospital physiotherapist (including qualifications and overheads) was obtained from the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 201652 and was £55 per hour. Unit costs were multiplied by duration of physiotherapy contact (in minutes) and summed across sessions attended to give total treatment costs per patient. Indirect costs associated with delivery of the intervention, such as use of the treatment room facility, administrative support and overheads, are taken into account in PSSRU unit cost calculations and, therefore, separate costs for these were not included in our estimate of PHT costs.

Cost of surgery

A micro-costing exercise was undertaken to estimate resource use and costs associated with delivery of arthroscopic surgery for FAI. Resource use data were collected for a subsample of trial participants who had received the surgery using a specially designed costing questionnaire that captured the following items:

-

duration of surgery

-

post-surgical inpatient length of stay

-

number, specialty and grade of clinical staff involved in the surgical procedure

-

quantity and type of disposable arthroscopic equipment and/or implants used.

Surgery time was defined from start of anaesthesia to time patient left the operating room on completion of surgery. Inpatient length of stay was counted as 1 day if the patient was admitted and discharged on the same day, 2 days if the patient was discharged the next day and so on, which is in line with NHS reference costing methodology. 53 Anaesthetic drugs and associated consumables, such as syringes and needles, were collected separately during a sample of operations and assumed to be the same for all patients who had the surgery.

Total cost of surgery was calculated for each patient by summing across the following five categories: (1) staff time, (2) theatre use in hours, (3) disposal surgical equipment, (4) anaesthetic drugs and disposables and (5) post-surgery inpatient bed-days. Operating room/theatre running costs were estimated based on data published by Information Services Division (Edinburgh, UK). 54 The Scottish data reported total number of theatre hours used and total allocated costs across NHS hospitals in Scotland for the 2015–16 financial year. Allocated costs are defined to include expenditure on non-clinical staff, property and equipment maintenance, domestics and cleaning, utilities, fittings and capital expenditure, and excluded clinical staff costs. 55 The hourly running cost of an operating room/theatre was obtained by dividing the total allocated costs per year by the total theatre time (in hours) per year.

Unit costs of clinical staff time were obtained from the PSSRU Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 201652 compendium. As stated above, these unit costs already factor in direct cost of staff salaries and employer oncosts and training costs, as well revenue and capital overheads, administrative support, office space and work-related travel. The cost of disposal surgical equipment and implants were primarily obtained from the 2016 online edition of the NHS supply chain catalogue. 56 When cost data were not available from the NHS catalogue, procurement department unit costs from the University Hospital Coventry and Warwickshire (Coventry, UK) were applied (Felix Achana, University of Warwick, 2012, personal communication). Cost of anaesthetic drugs were obtained from the prescription costs analysis database. 53

Resource use during follow-up

Health and social care service use were collected from trial participants for the 3-month period prior to randomisation (to establish baseline data) and the 1-year period post randomisation. Resource use data were collected at three assessment points (i.e. baseline and 6 and 12 months post randomisation) and included:

-

details of hospital inpatient and day case admissions

-

details of outpatient and accident and emergency attendances

-

primary/community care encounters

-

use of personal social care services (e.g. Meals on Wheels, laundry services and social care contacts)

-

prescribed and over-the-counter medication use

-

supplied or self-purchased walking aids, such as crutches and walking sticks, and adaptations to home or work environments

-

any other additional costs incurred by patients and their families as a result of their hip pain, including private medical costs and out-of-pocket expenditures (e.g. travel costs by patients and family members), child care costs and lost income.

Resource inputs were valued by attaching unit costs derived from national compendia to resource inputs.

Hospital-based services included inpatient admissions, day care, outpatient and accident and emergency attendances, and diagnostic tests and scans. Unit costs for these services were obtained primarily from the 2015/16 NHS reference costs main schedules. 57 Per diem costs were calculated for each inpatient admission as a weighted average of Healthcare Resource Group (HRG) codes of related procedures and/or clinical conditions. For example, the average cost per day for inpatient stay in an orthopaedic ward with procedures carried out on the hip/leg was calculated as a sum total of the weighted average of lower limb orthopaedics (trauma) HRG codes divided by average length of stay across elective and non-elective inpatient services.

Primary and community health and social care services included face-to-face or telephone contacts and/or home visits by a general practice doctor, practice nurse, community physiotherapy or other community health or social care professionals. Consultation costs were derived from the PSSRU Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 201652 compendium.

The cost of private physiotherapy and other private medical costs were obtained from online sources and referenced appropriately in the unit cost tables.

The cost of prescribed medication was obtained primarily from the prescription cost analysis database53 and electronic searches of the British National Formulary (BNF) 2016 edition. 58 Typical dosage and duration of treatment reported in the BNF for each medication were used in calculating quantity of individual preparations if the daily dose and/or duration of the course of medication were not reported. The quantity of over-the-counter medicines were rounded to the nearest pack and unit costs obtained from online sources.

The cost of walking aids and adaptations were either provided by the patients themselves (if self-purchased) or taken from the NHS supply chain catalogue56 if supplied by a health provider during the trial follow-up period. It was assumed that walking aids, such as crutches, sticks, grab rails, dressing aids and specially adapted shoes, were supplied as part of treatment if the cost of purchase were not provided by trial participants.

Patient-level costs were generated for each resource variable by multiplying the quantity reported by the respective unit cost weighted by duration of contact, when appropriate. Summary statistics were generated for resource use variables by treatment allocation and assessment point. Between-treatment group differences in resource use and costs at each assessment point were compared using the two-sample t-test. Statistical significance was assessed at the 5% significance level. Standard errors (SEs) are reported for treatment group means and bootstrap 95% CIs for the between-group differences in mean resource use and cost estimates.

Measurement of outcomes

The health-related quality of life of trial participants was assessed at baseline and at 6 and 12 months post randomisation using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) in the feasibility study, the EQ-5D-5L in the main trial and the SF-12 in both feasibility and main trial samples. 59–61 Responses to each health dimension were categorised as optimal or suboptimal with respect to function, with optimal level of function indicating no impairment (e.g. ‘no problem’ on the EQ-5D-3L dimensions) and suboptimal indicating any functional impairment. Between-group differences in optimal and suboptimal level of function for each health dimension were compared for each outcome measure using chi-squared tests.

The responses to each health-related quality-of-life instrument were converted into health-related quality-of-life weights (also referred to as utility weights) using established algorithms for each instrument. Utility values were generated using the UK value set for the EQ-5D-3L, the interim crosswalk value set for mapping from the EQ-5D-5L to the EQ-5D-3L, the newly published EQ-5D-5L tariffs for the EQ-5D-5L and the Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions (SF-6D) tariff based on SF-12 responses. 46,62–64

Quality-adjusted life-years were generated for each patient using the area under the baseline-adjusted utility curve, assuming linear interpolation between the three utility measurements. QALYs were generated for patients in the feasibility sample using utilities derived from EQ-5D-3L and SF-6D tariffs and for those in the main study sample using the EQ-5D-5L crosswalk tariff, the new UK EQ-5D-5L tariff and the SF-6D tarrif. 46,62–64 Health utility values and QALYs accrued over the 12-month follow-up were summarised by treatment group and assessment point and presented as means and associated SEs. Between-group differences were compared using the two-sample t-test, similar to the summary analyses of resource inputs and costs.

Cost-effectiveness analysis methods

Missing data

Multiple imputation by chain equations implemented through the MICE package in R was used to handle missing costs and health utility data at each assessment point. Multiple imputation avoids problems associated complete-case analyses, is consistent with good practice and requires data to be missing at random only. 65 Appropriateness of this missing-at-random assumption was assessed by comparing the characteristics of patients with and without missing costs and health-related quality-of-life data at each follow-up time point. Imputations were generated separately by treatment group, as recommended by Faria et al.,66 using the predictive mean matching method, which has the advantage of preserving non-linear relationships and correlations between variables within the data. Twenty imputed data sets were generated and the analyses were fitted to each imputed data set. The results from the 20 data sets were then combined using Rubin’s rules. The imputation, analysis and pooling of results steps were performed simultaneously within the MICE package. The imputed data were used to inform the base case and all subgroup and sensitivity analyses, with the exception of one sensitivity analysis, which was conducted using only complete data.

Base-case cost-effectiveness analysis

The base case took the form of an intention-to-treat analysis conducted from a UK health and social service perspective. Health outcomes were expressed in QALYs using utilities generated from the EQ-5D-3L (for feasibility study participants) and the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L crosswalk tariff (for the main trial participants). Total costs accrued over 12 months of follow-up were calculated for each patient by summing the delivery costs of the intervention(s) received (irrespective of treatment allocation) and a sum total of follow-up costs reported at the 6- and 12-month assessment points relevant to the perspective of interest. For example, if a patient allocated to the surgery arm of the trial had PHT rather than surgery, then the treatment costs assigned would be the costs associated with delivery of the PHT intervention.

The cost of PHT was calculated by multiplying the unit cost of physiotherapy with the duration of contact (in minutes) and summed across all sessions attended. The cost of surgery was obtained from the micro-costing exercise carried out to estimate resource use and costs associated with the delivery of hip arthroscopy. Patients who had surgery were assigned treatment costs simulated from a normal distribution, with mean and variance estimates obtained from the surgery costing exercise. To avoid double counting treatment costs, self-reports of outpatient physiotherapy attendance (for treatment of lower limb problems) during follow-up were excluded from the total cost calculations for those in the PHT group (as these would have been included in the estimation of PHT costs). Similarly, self-reports of orthopaedic inpatient admissions (for the category ‘your hip/leg’) by those who had the surgery were excluded if one admission episode was reported during follow-up. When more than one orthopaedic inpatient stay was reported during follow-up, then the first admission episode was excluded in the total cost calculations and the remainder countered as repeat admissions.

Broader societal costs were also calculated (and used in sensitivity analyses) by adding to the health and social care costs, private medical costs and relevant indirect costs, such as lost income and purchase of specialised equipment.

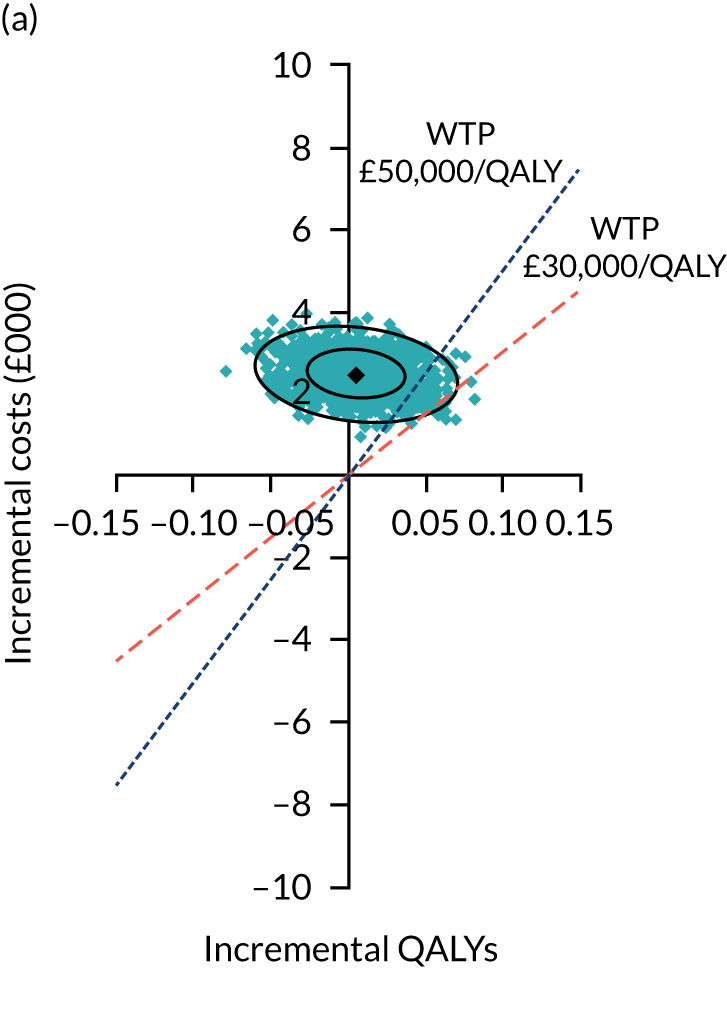

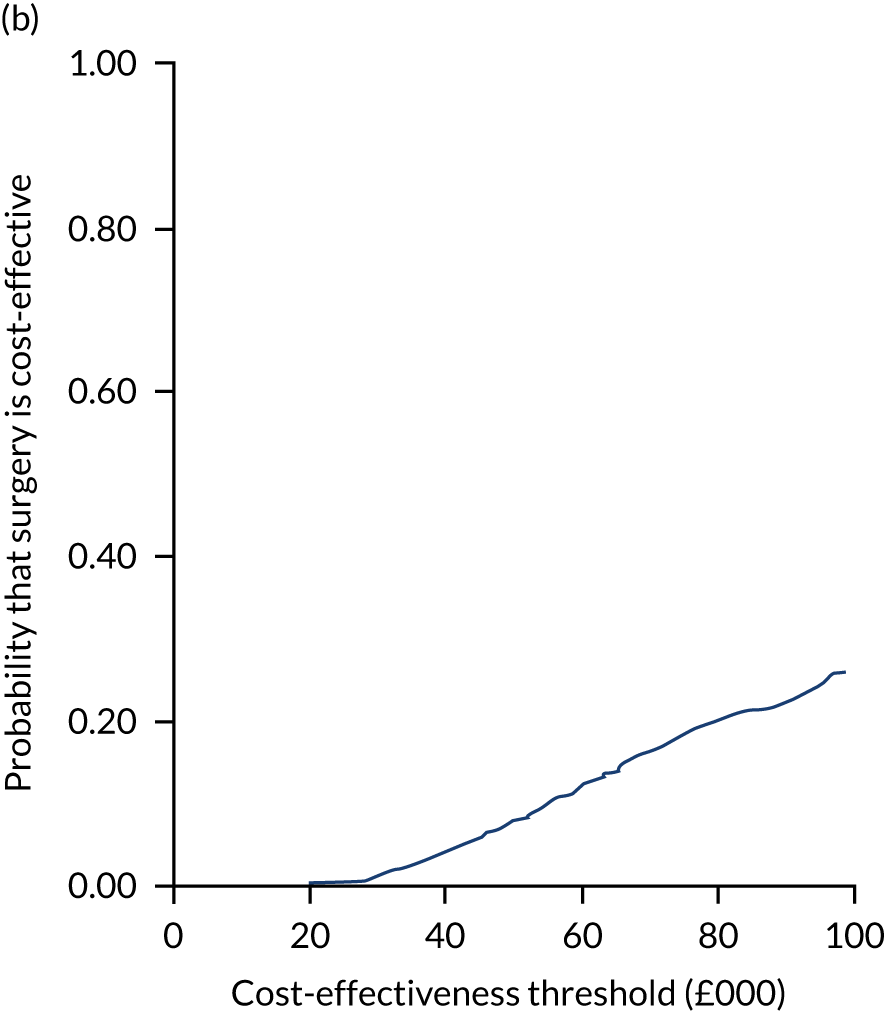

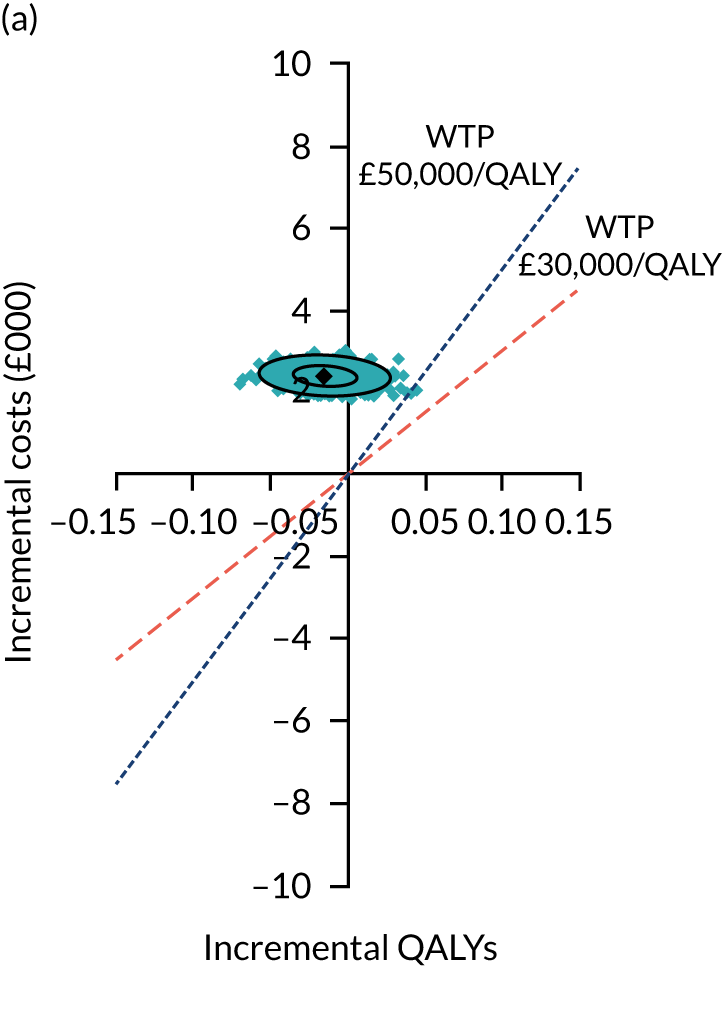

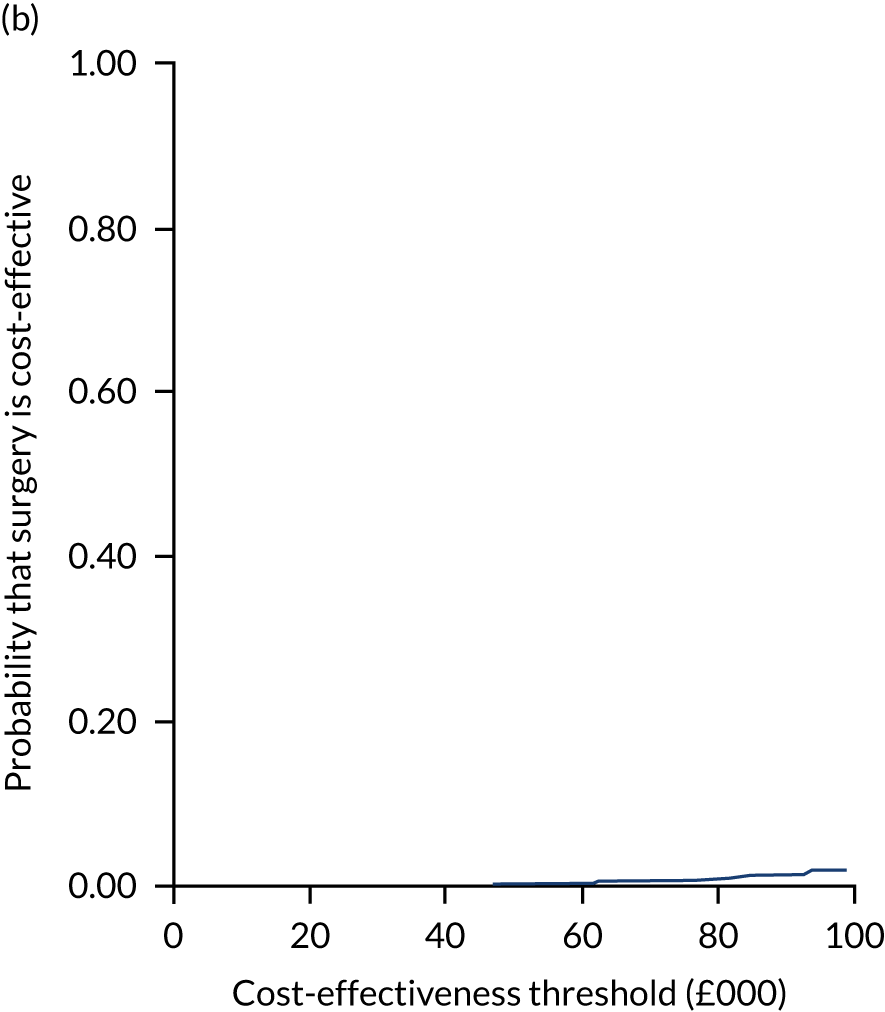

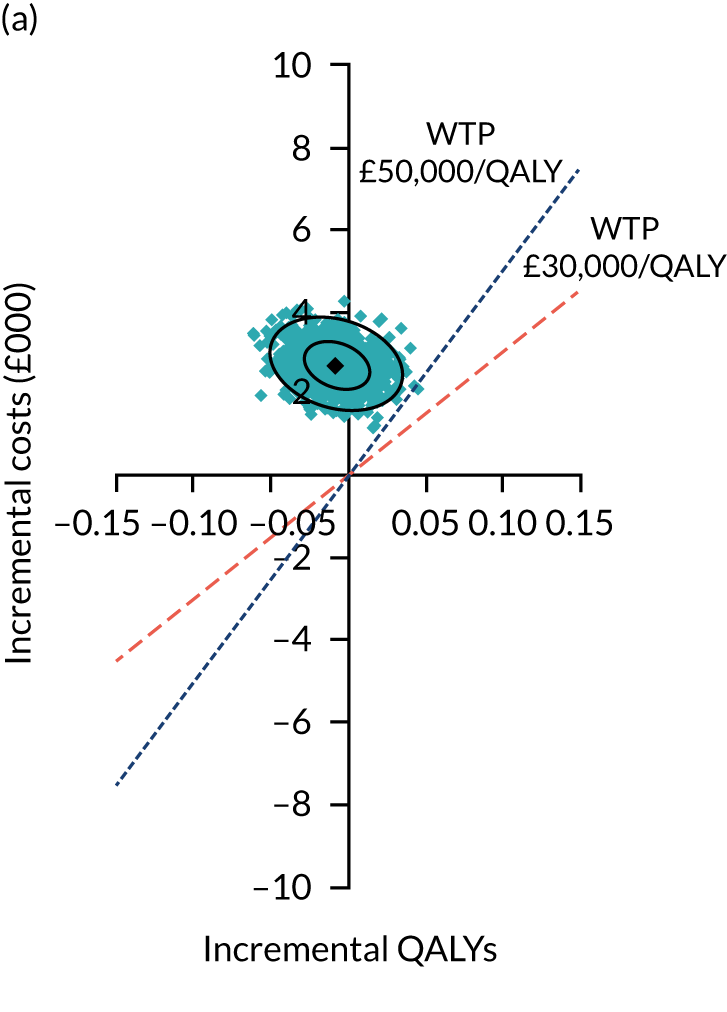

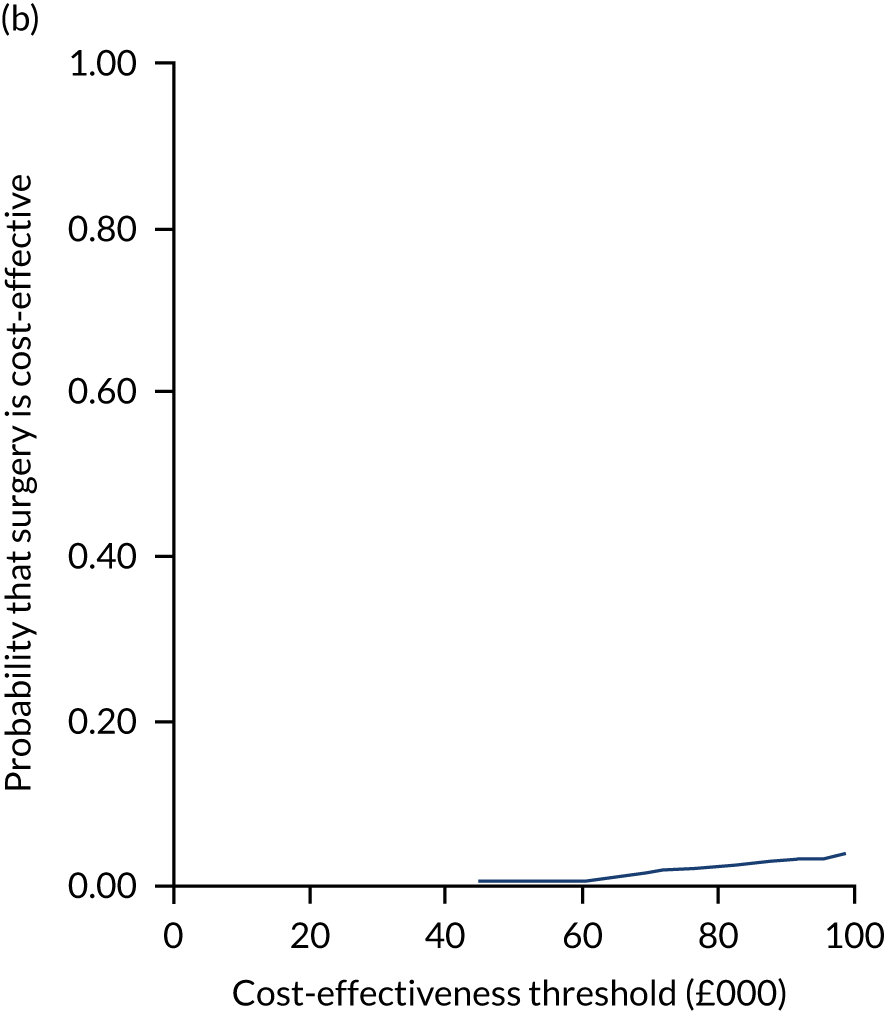

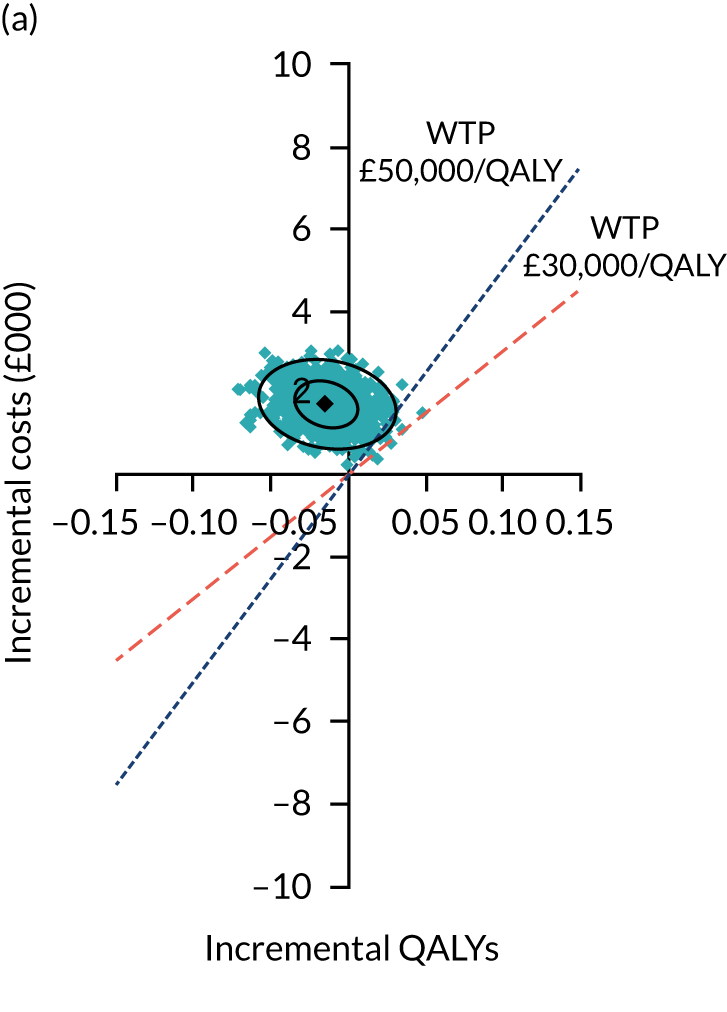

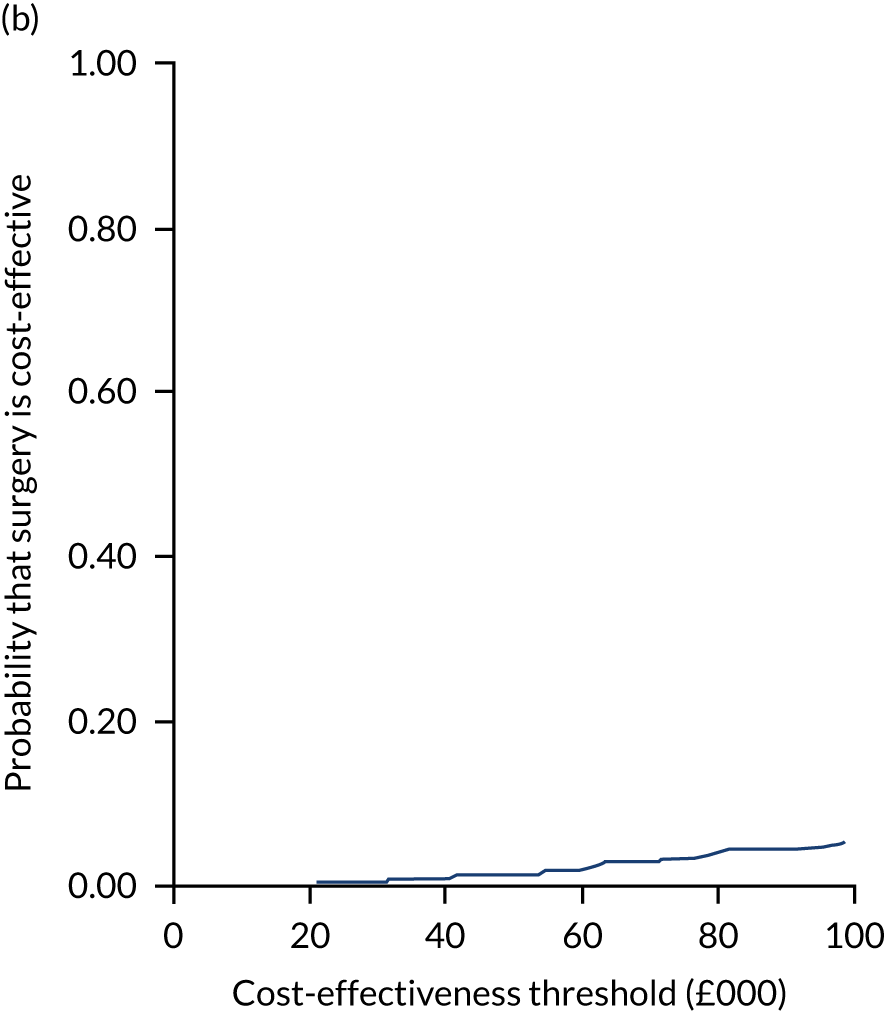

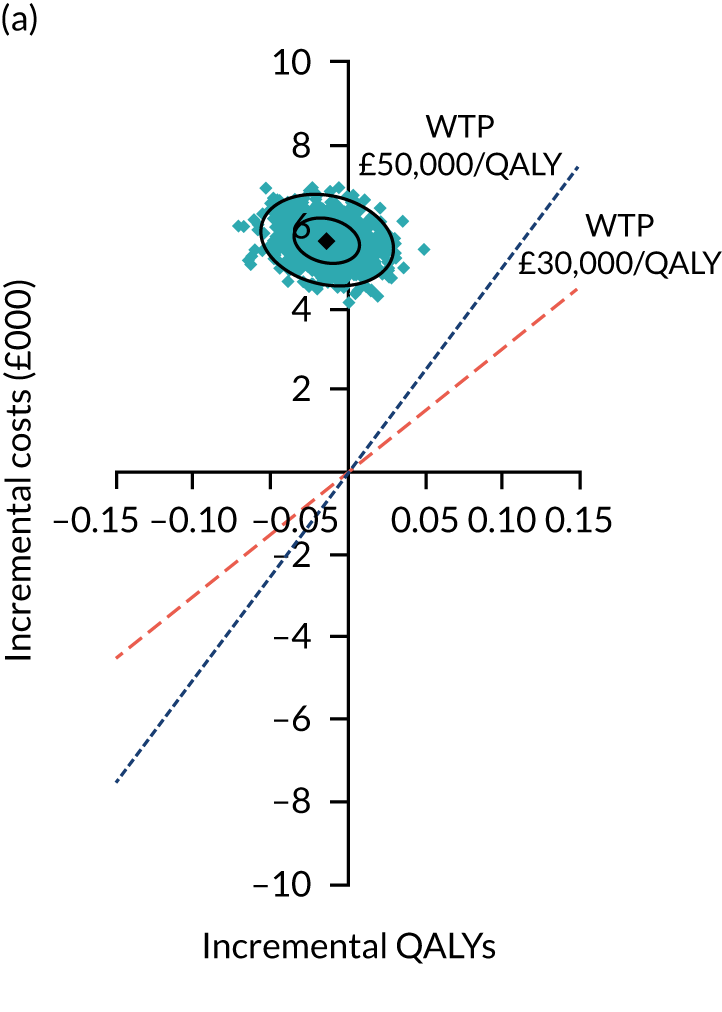

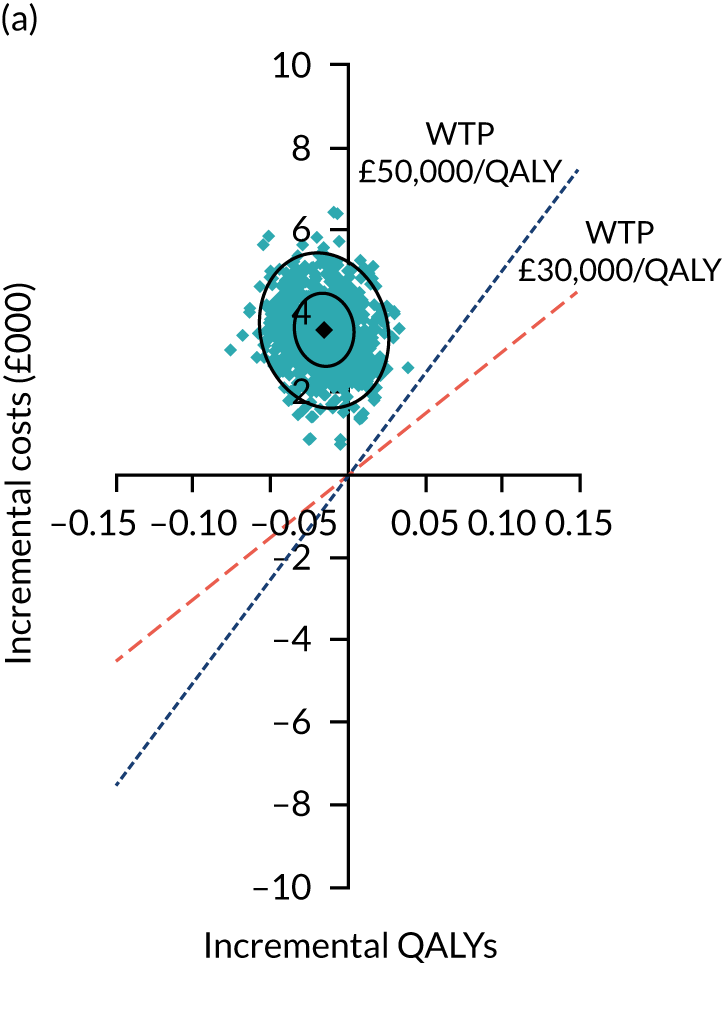

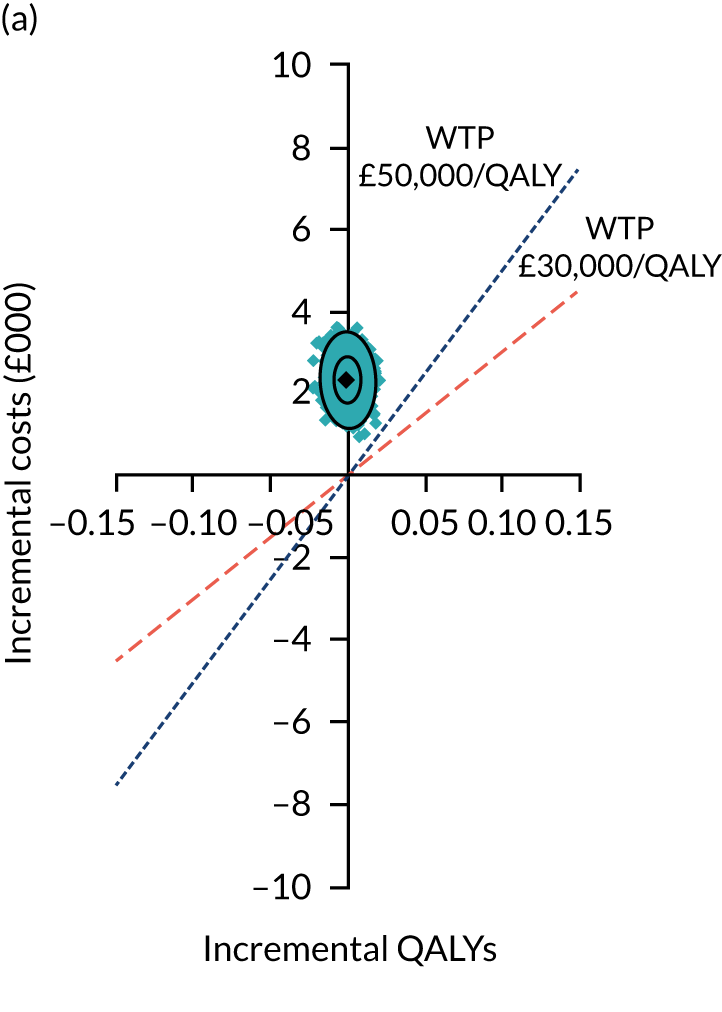

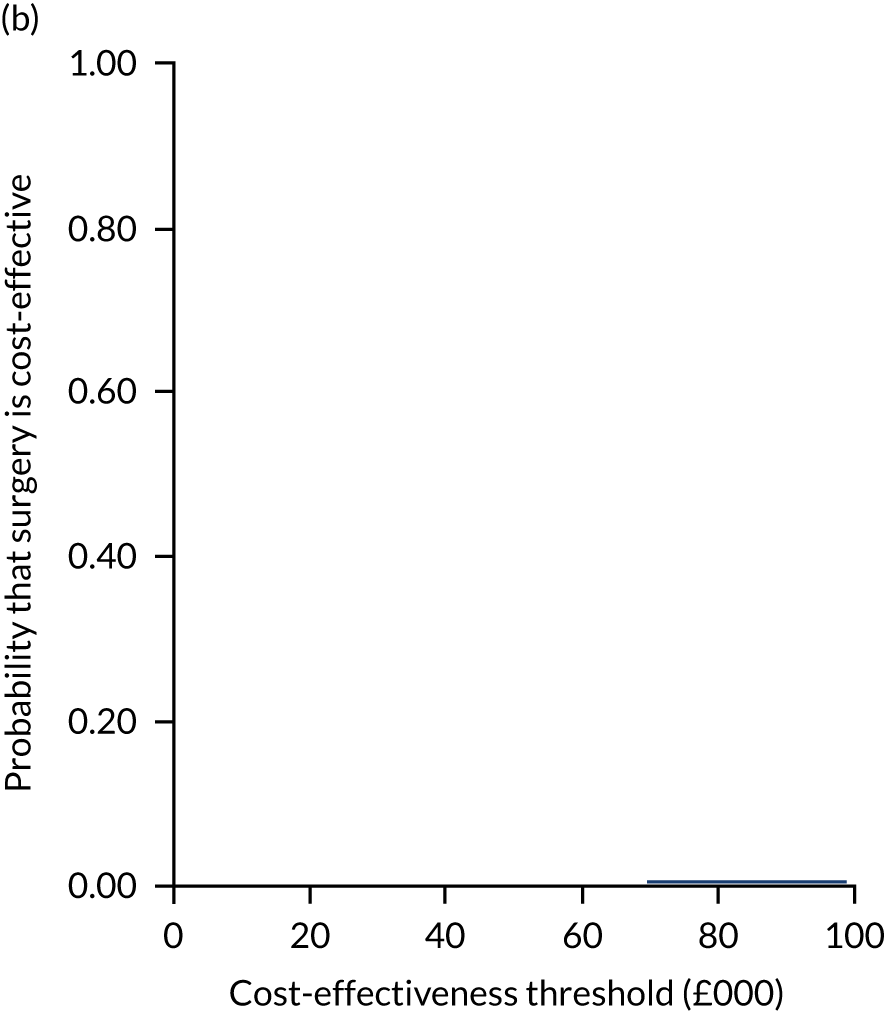

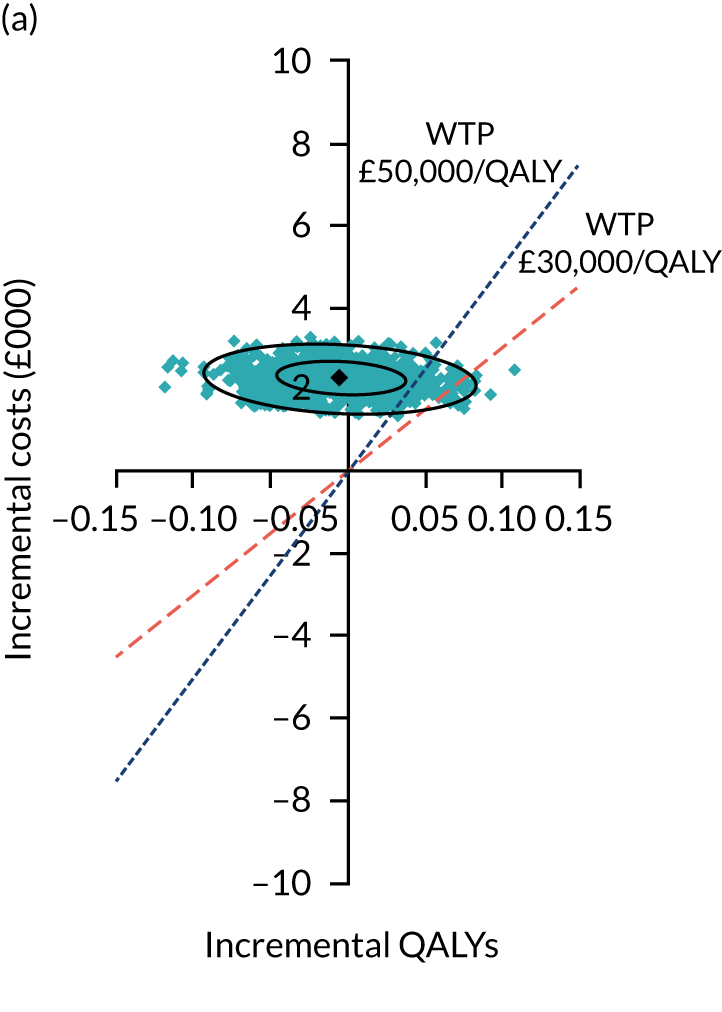

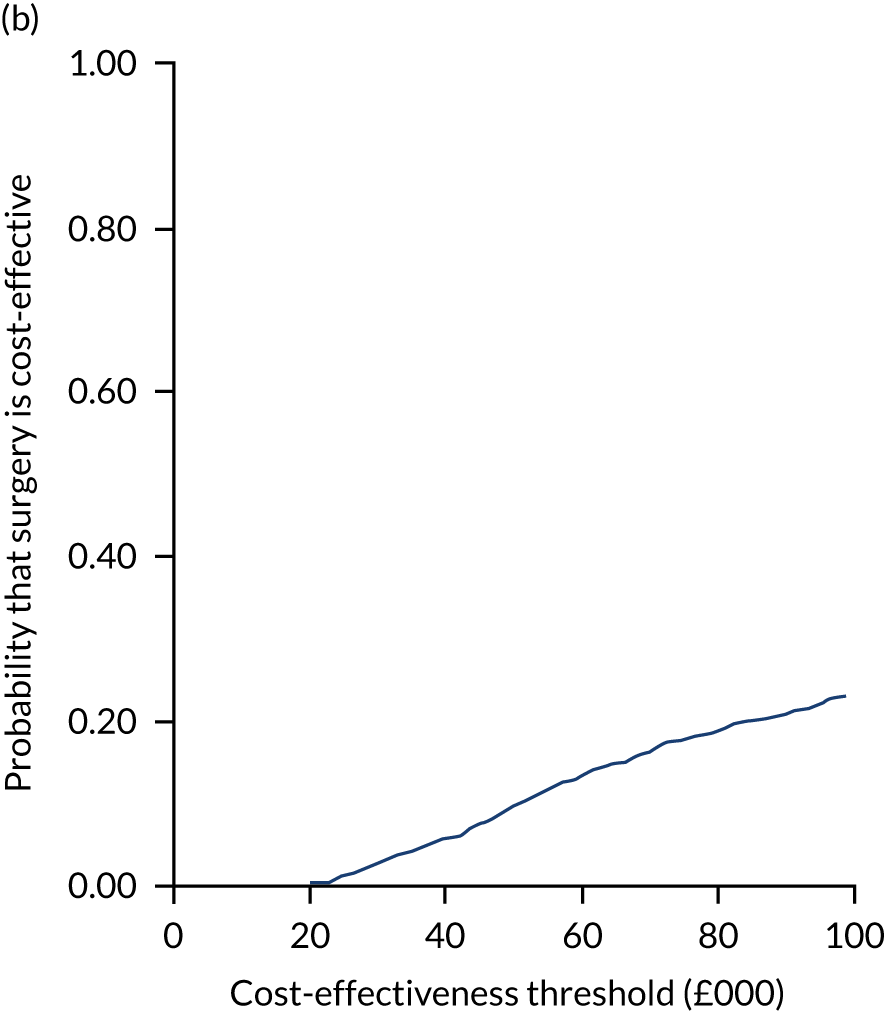

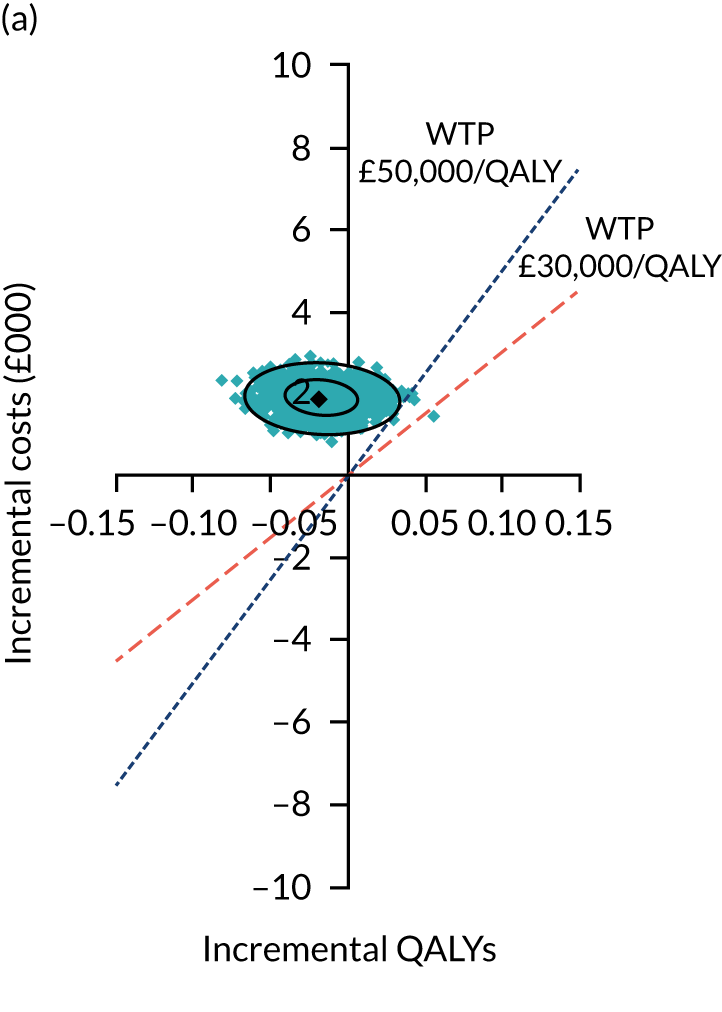

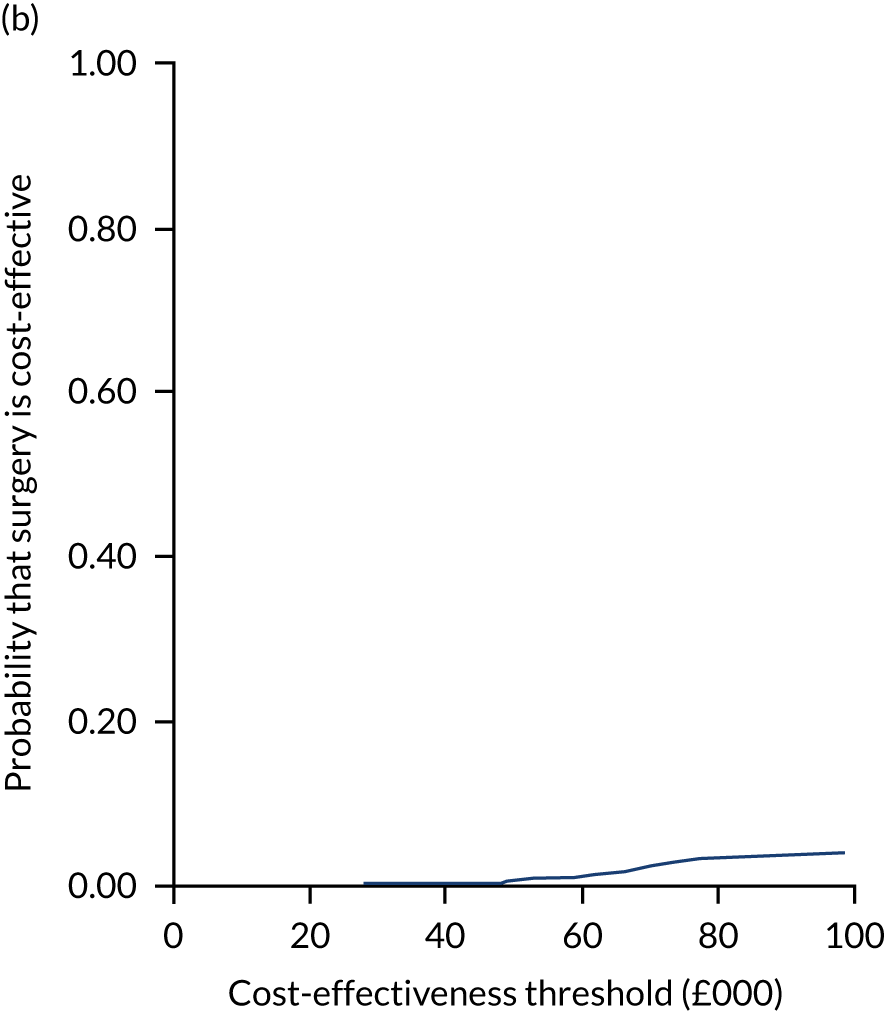

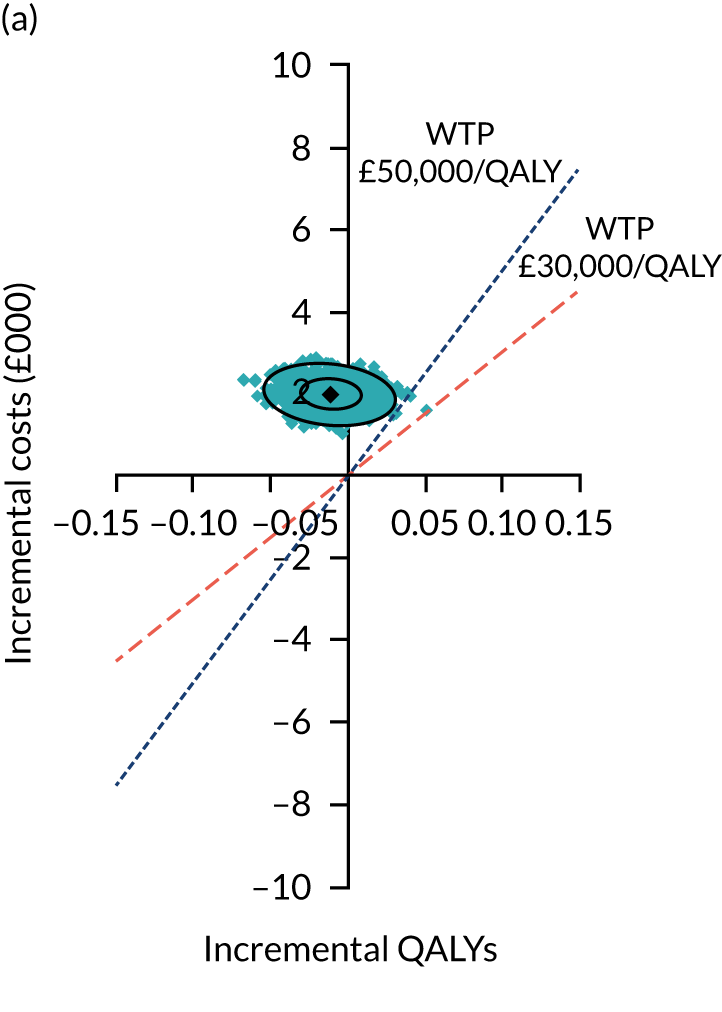

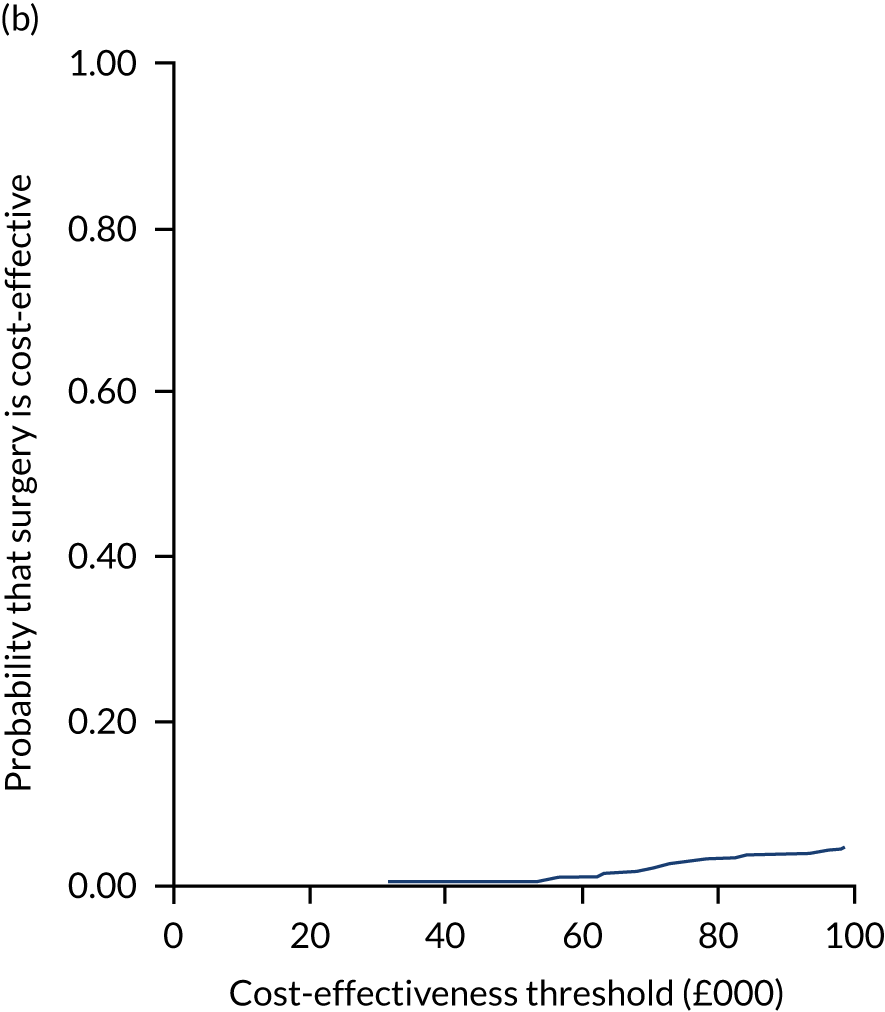

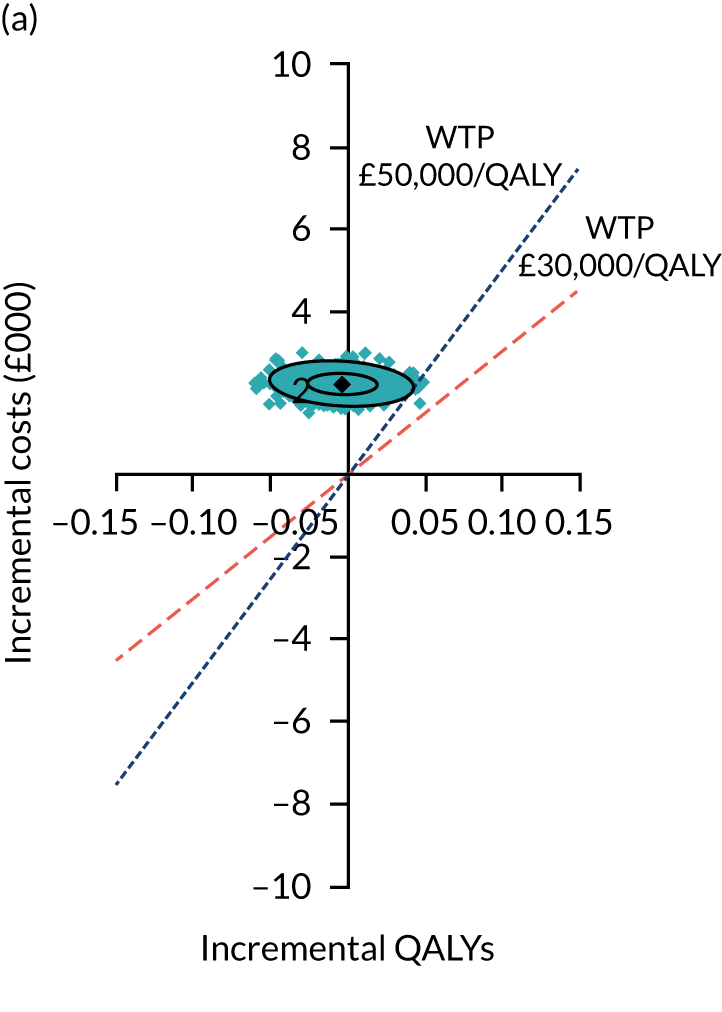

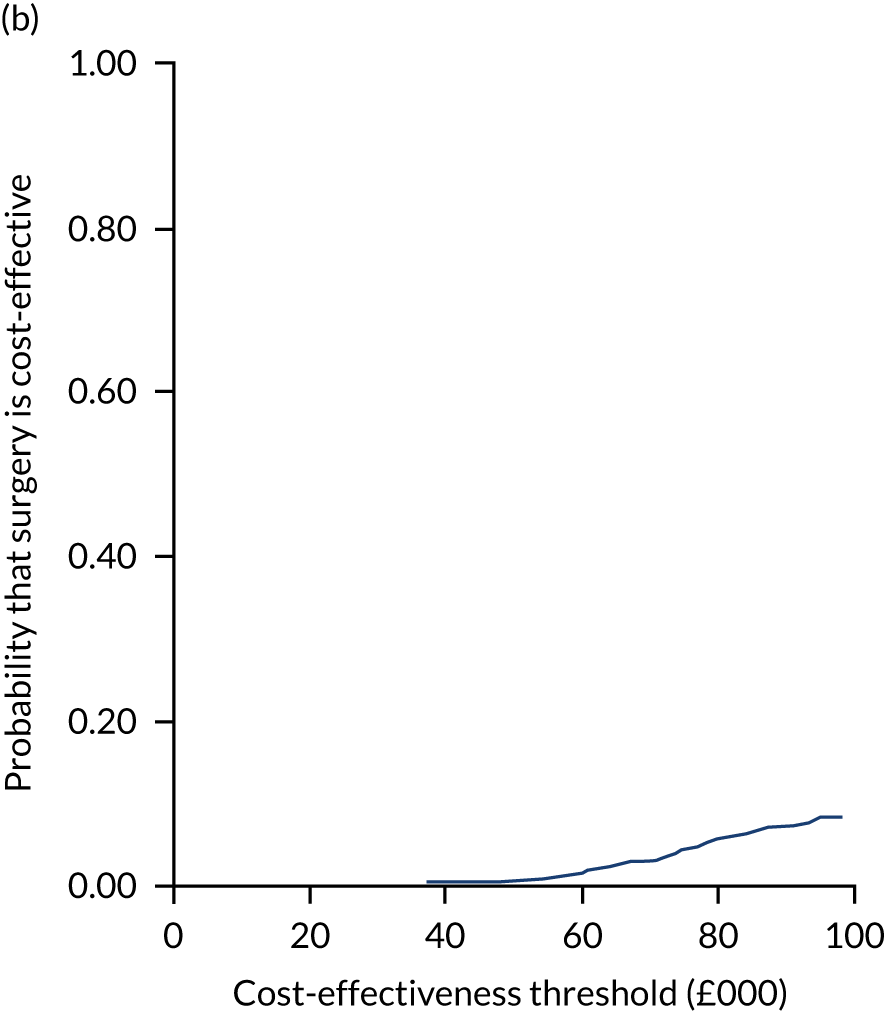

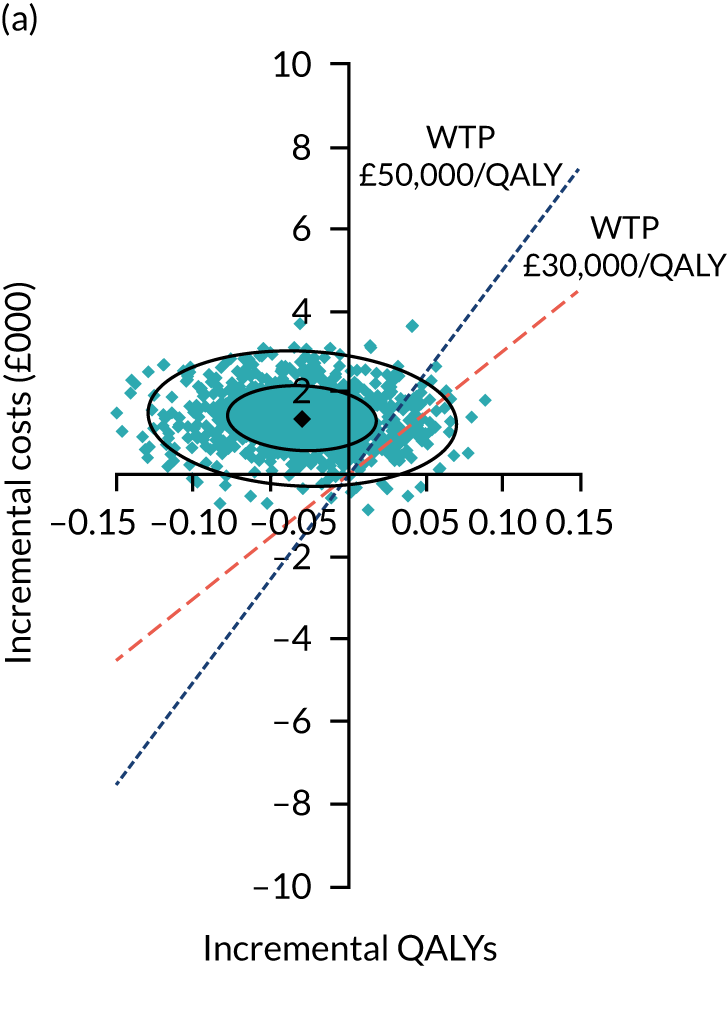

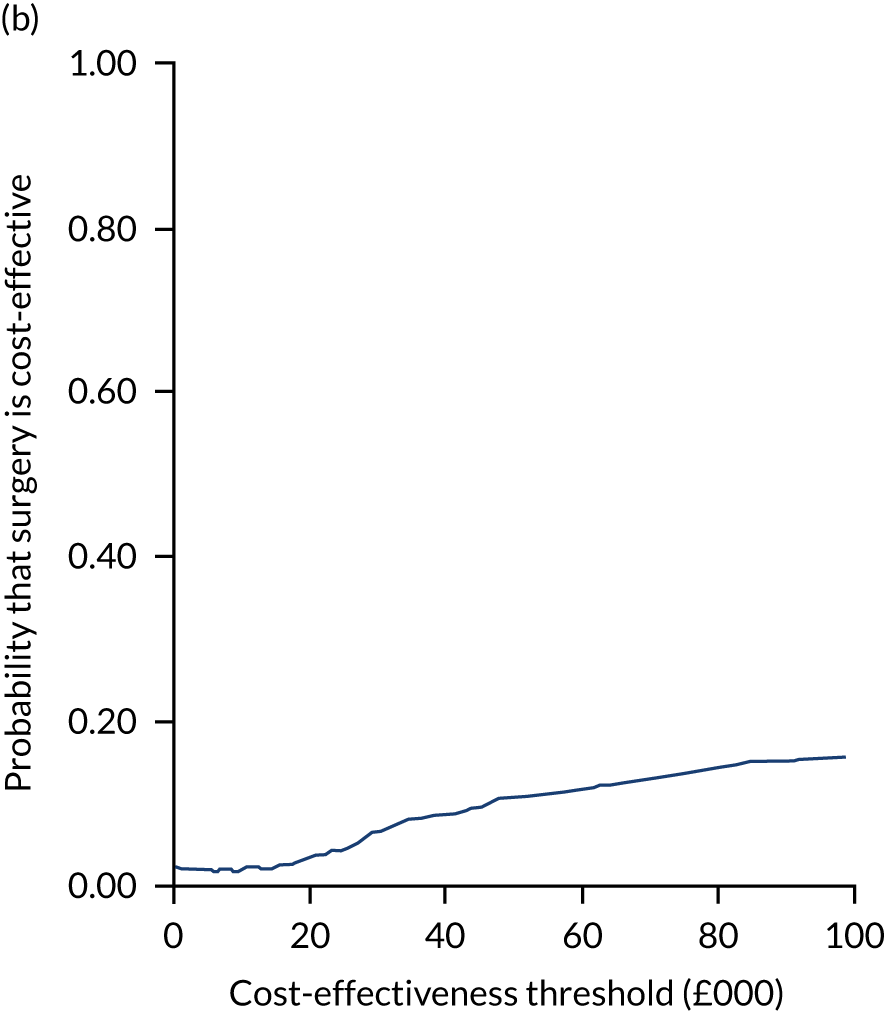

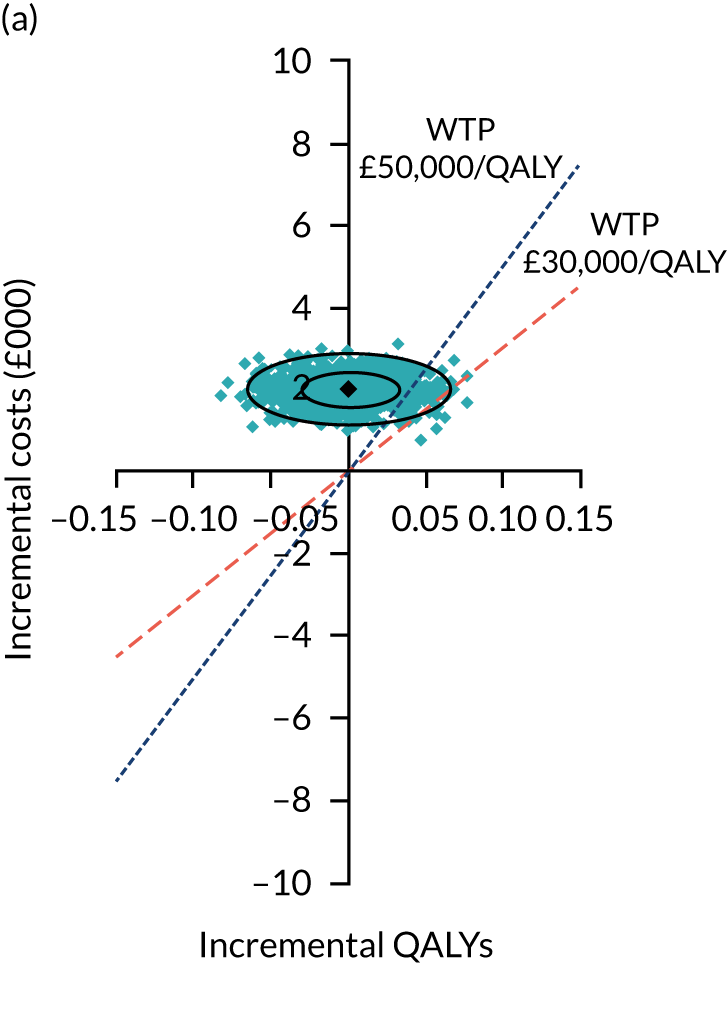

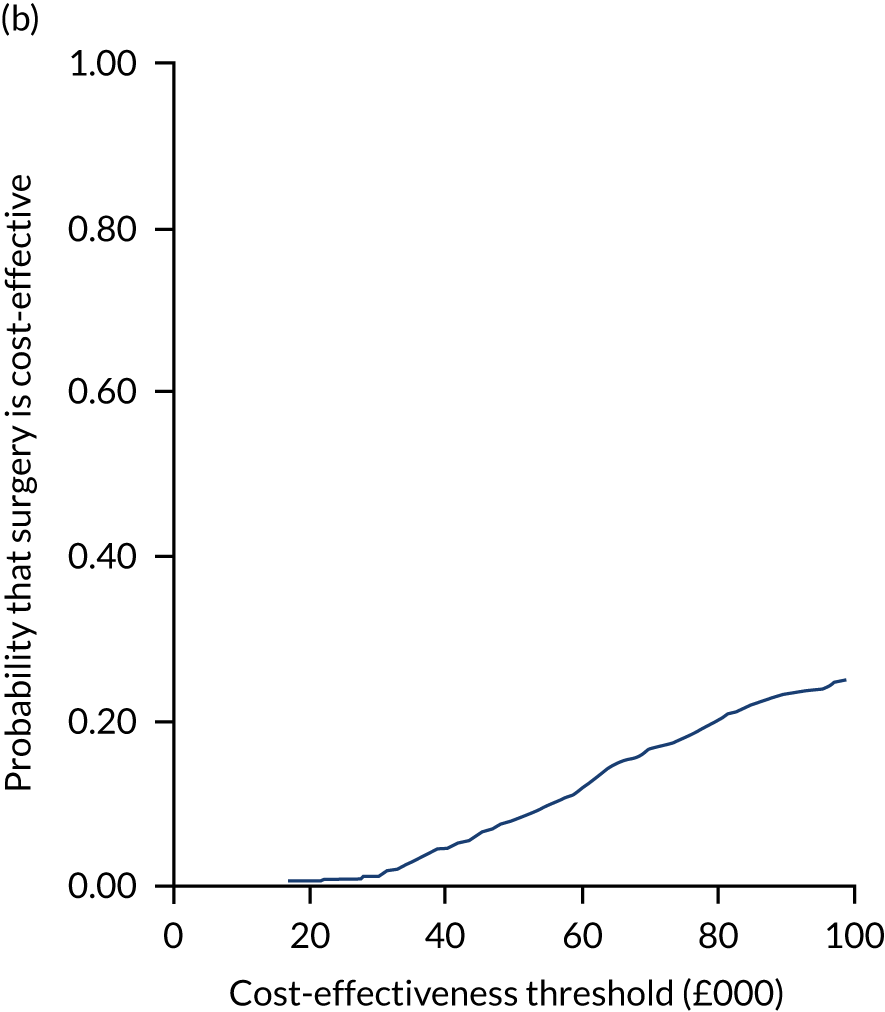

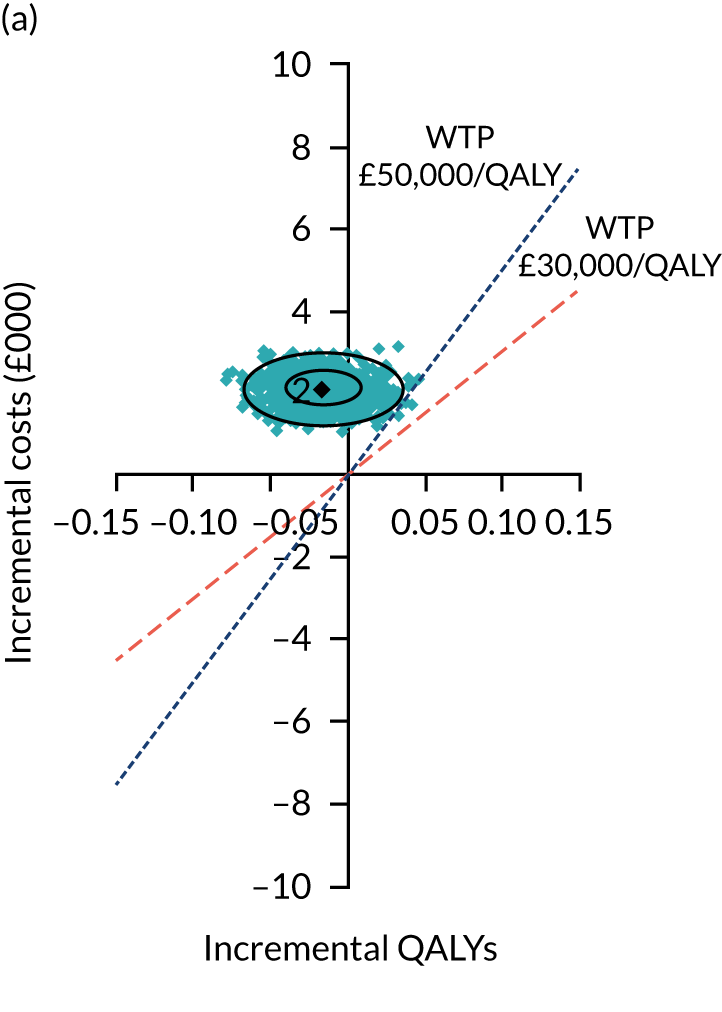

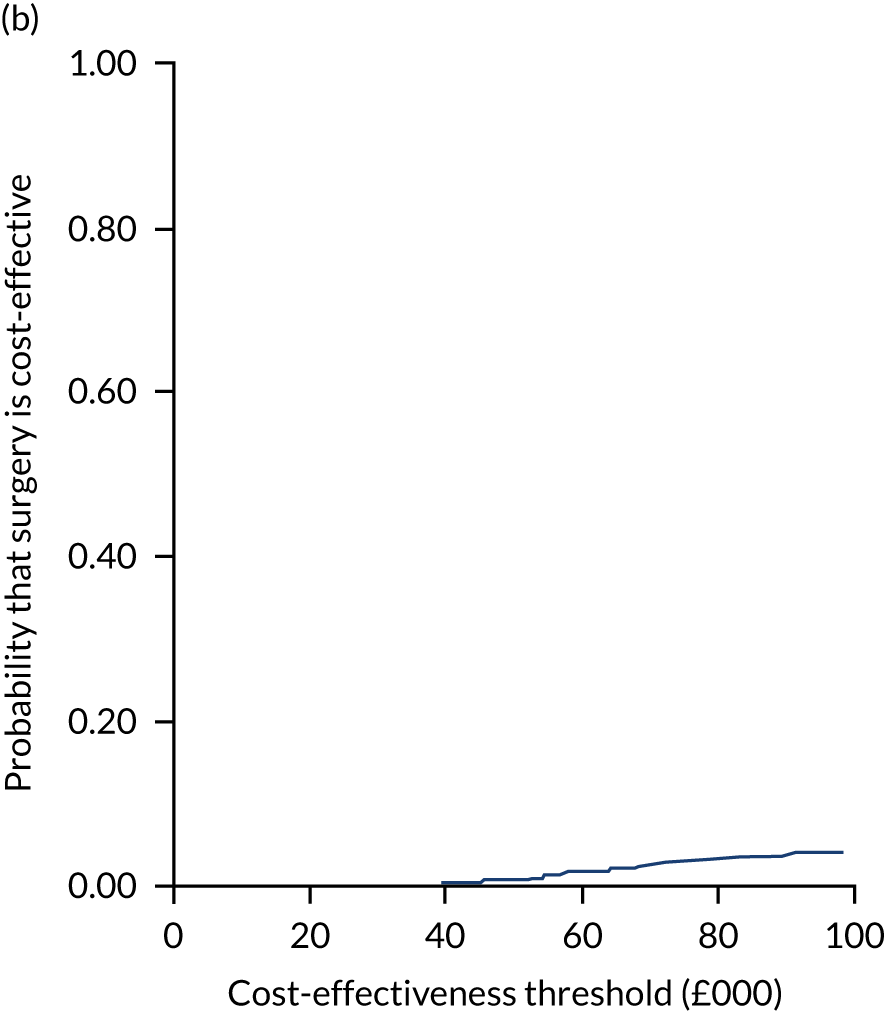

Two seemingly unrelated normal error regressions were fitted to the data using the systems fit implementation in R. These regressions were used to simultaneously estimate incremental costs and benefits of surgery compared with PHT while accounting for correlation between the two. The regressions controlled for treatment allocation, age, sex, recruitment site, type of impingement, baseline costs (regression equation for costs only) and baseline health-related quality of life (regression equation for outcomes). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated by dividing the between-group difference in adjusted mean total costs by the difference in adjusted mean QALYs. The cost-effectiveness of hip arthroscopy was determined by comparing the ICER value with cost-effectiveness thresholds of £20,000 and £30,000 per QALY gained, in accordance with NICE recommendations,67 and to the recent empirical £13,000 per QALY estimate suggested by Claxton et al. 68 The incremental net (monetary) benefit of the surgery compared with PHT was calculated for a range of cost-effectiveness thresholds. Net benefit values reflect the opportunity cost of (or the benefits forgone from) adopting a new treatment when resources could be put to use elsewhere. A positive net benefit would suggest that, on average, the new treatment provides net gain compared with the alternative, and can be considered cost-effective at the given cost-effectiveness threshold.

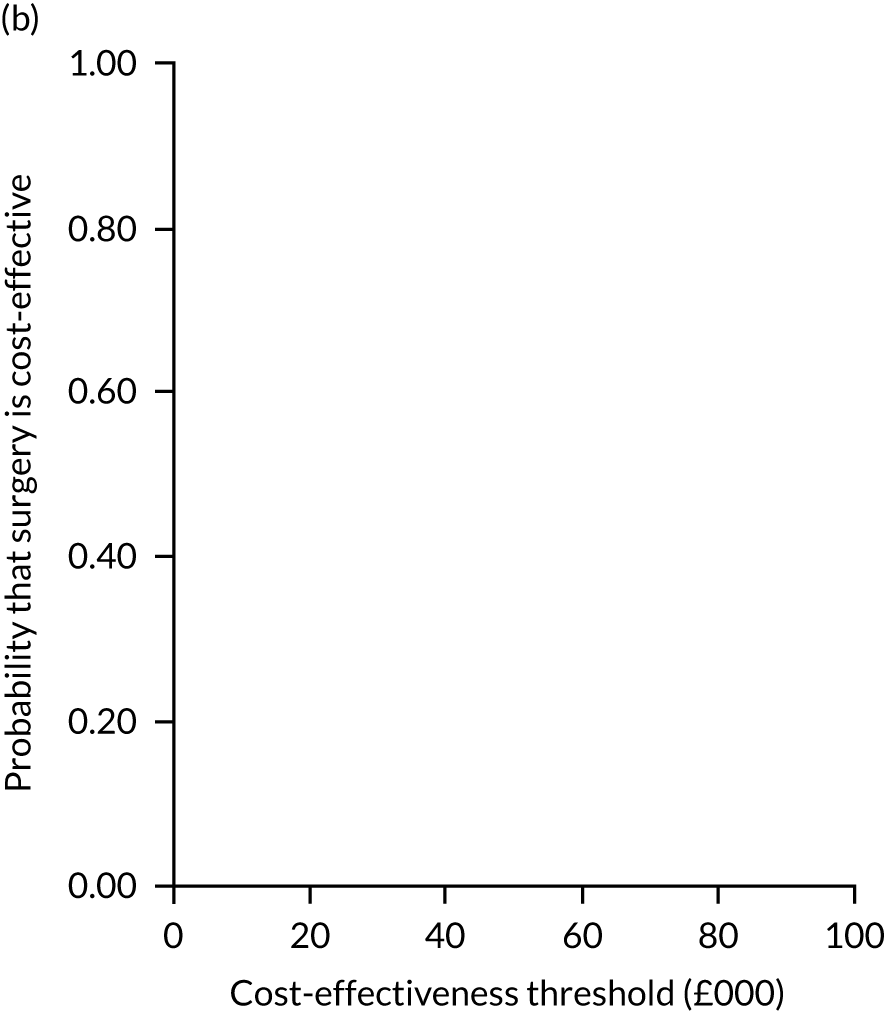

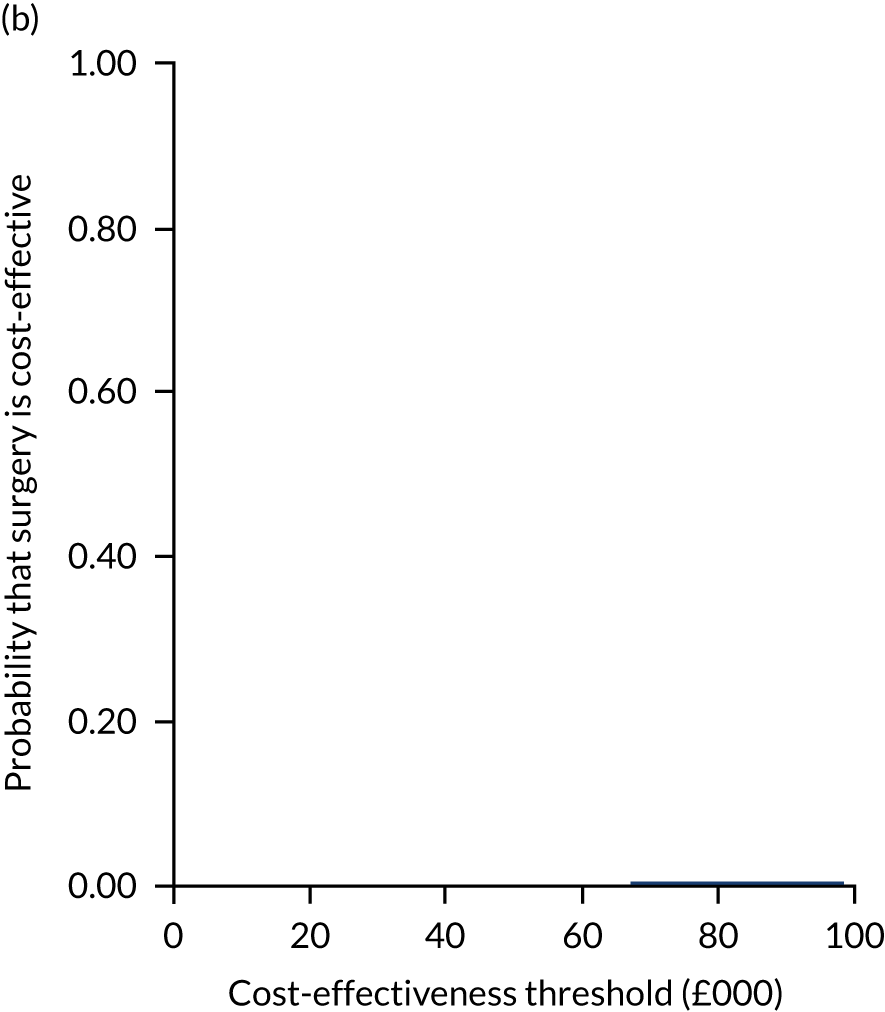

Uncertainty around the mean cost-effectiveness estimates was characterised through a Monte Carlo method. 69 This involved simulating 1000 replicates of the ICER from a joint distribution of the incremental costs and QALYs and plotting the simulated ICERs on the cost-effectiveness plane. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves were also plotted to give graphical displays of the probability that surgery is cost-effective across a wide range of cost-effectiveness thresholds.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to investigate aspects of study design and data collection for which alternative methods existed, but where there was uncertainty regarding which method or approach was best. For example, the cost of surgery was estimated based on data from a subsample of patients who had the surgery in the study. Surgery costs could also be obtained through the HRG case-mix method. Other sensitivity analyses included broadening the perspective of the analysis to capture wider societal costs and their impact on relative cost-effectiveness of the interventions. A list of all sensitivity analyses carried out are presented in Table 3.

| Sensitivity analysis | Description of changes to base case considered in sensitivity analysis |

|---|---|

| 1 | Unadjusted analysis |

| 2 | Complete-case analysis |

| 3 | Per protocol sample 1: restricted analysis to patients who received allocated treatment |

| 4 | Per protocol sample 2: restricted analysis to patients whose surgery or PHT was deemed to be of good quality, as assessed by clinical panel |

| 5 | Altering the cost of surgery from £3042 (estimate from the micro-costing) to £2680 based on HRG code HT15Z (Minor Hip Procedures for Trauma, elective long stay) |

| 6 | Altering the cost of surgery from £3042 (estimate from the micro-costing) to £5811 based on HRG code HT12A (Very Major Hip Procedures for Trauma with CC Score 12+, elective long stay) |

| 7 | Adopting a societal perspective that includes both direct health and social care costs and broader societal costs |

| 8 | Use QALYs generated using the SF-6D utility algorithm |

Subgroup analyses

Heterogeneity in cost-effectiveness estimates was explored through the following subgroup analyses:

-

recruitment period (feasibility vs. main trial samples)

-

type of impingement (cam vs. mixed/pincer)

-

sex (female vs. male).

Longer-term modelling

Given the known limitations of within-trial economic evaluations, the study protocol had allowed for long-term economic modelling to be conducted if the within-trial economic evaluation suggested surgery to be clinically effective and likely to be a cost-effective treatment for FAI. 70 The model would have estimated the long-term (i.e. lifetime) costs and consequences of surgery and assessed whether or not any short-term benefits are sustained over the medium to long term.

Research Ethics Committee approval

The trial obtained approval from the Nation Research Ethics Committee West Midlands – Edgbaston (14/WM/0124) on 1 May 2014 and has been registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number ISRCTN64081839.

Trial Management Group