Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/35/64. The contractual start date was in April 2014. The draft report began editorial review in November 2021 and was accepted for publication in October 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Charteris et al. This work was produced by Charteris et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Charteris et al.

Introduction

Background

Trauma is an important cause of visual impairment and blindness worldwide and a leading cause of blindness in young adult males. 1 Globally, it has been estimated that 1.6 million people are blind as a result of ocular trauma, with 2.3 million suffering bilateral low vision. 2 Ocular trauma is the most common cause of unilateral blindness in the world today, with up to 19 million with unilateral blindness or low vision. 2 It is estimated that almost one million people in the United States live with trauma-related visual impairment. 3 Ocular trauma has extensive socioeconomic costs; patients with open globe injuries lose a mean of 70 days of work. 4 In the United States, work-related eye injuries cost over $300 million per year (www.preventblindness.org), which equates to an annual cost to the UK economy (for which no comparable data exist) of £37.5 million.

In the UK, it is estimated that 5000 patients per year sustain eye injuries serious enough to require hospital admission and, of these, 250 will be permanently blinded in the injured eye. 5 Recent European studies document incidences of 2.4 and 3.2 per 100,000 per year6,7 for open globe injuries, which suggests an annual incidence for the UK of between 1500 and 2000.

Ocular injuries that result in visual loss invariably affect the posterior segment of the eye, and prevention of visual loss involves posterior segment (vitreoretinal) surgery. It is clear from recent published data that although vitreoretinal surgical techniques have improved, outcomes remain unsatisfactory, and that development of the intraocular scarring response proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) is the leading cause. 8–11

Proliferative vitreoretinopathy

Eyes sustaining penetrating or open globe trauma (OGT) are a group at high risk of severe visual impairment. Retinal detachment (RD) is common in these eyes and multiple surgical interventions are often necessary. PVR is the most common cause of recurrent RD and visual loss in eyes with OGT. It is documented to occur in 10–45% of all OGT,8–11 its incidence varying with the nature of the penetrating injury. 8

Proliferative vitreoretinopathy is a process of fibrocellular scar tissue formation, which complicates 5–12% of cases of primary RD, 16–41% of giant retinal tears and 10–45% of cases of posterior segment trauma. 12 PVR represents a difficult vitreoretinal surgical challenge and although final retinal attachment may now be achieved in many cases, multiple surgeries are often needed and visual results are frequently very poor. 12,13 Binocular vision outcomes are notably unsatisfactory in PVR. 14 PVR management is costly in patient time and healthcare resources. 13

Preclinical data

Clinical observation and laboratory investigations undertaken on eyes with PVR and surgical specimens have identified potential targets for pharmacological adjuncts to its surgical management. 14 The cellular components of PVR peri-retinal membranes (retinal pigment epithelium, glial, inflammatory and fibroblastic cells) proliferate and may also be contractile and are thus targets for antiproliferative agents. There is a notable inflammatory component to the PVR process, with marked blood–retinal barrier breakdown and a greater tendency to intraocular fibrin formation. 15 Macrophages and T lymphocytes have been identified in PVR membranes14 and, although relatively small in number, they may play an important role in membrane development and contraction through growth factor production. Thus, both cellular proliferation and the intraocular inflammatory response are realistic targets for adjunctive treatments in PVR.

Steroid treatment has the potential to influence both the inflammatory and proliferative components of the pathological process of PVR. Previous experimental work has suggested that triamcinolone acetonide (TA) can reduce the severity of PVR. 16 It has also been demonstrated that periocular corticosteroids can reduce the severity of experimental PVR. 17 Laboratory work has indicated that TA appears to have no significant retinal toxicity,18 although in vitro it downregulates the proliferation of retinal cells.

Clinical data

Intravitreal TA has been used extensively clinically to treat macular oedema, intraocular inflammation and subretinal neovascularisation without demonstrable retinal toxicity but with a raised incidence of elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) and cataract. Previous small-scale clinical studies of PVR have suggested that systemic prednisolone,19 infused dexamethasone20 and intravitreal TA21–23 can reduce the severity of PVR, although none of these studies was of sufficient power to provide a definitive answer.

Rationale and risks/benefits

The Adjunctive Steroid Combination in Ocular Trauma (ASCOT) project was a phase 3, multicentre, randomised clinical trial to test the hypothesis that adjunctive steroid (TA) given locally at the time of surgery can improve the outcome of vitreoretinal surgery for OGT (both visually and anatomically). Open globe ocular trauma complicated by intraocular scarring (PVR) is a relatively rare, blinding, but potentially treatable, condition for which surgery is often unsatisfactory and visual results frequently poor. To date, no pharmacological adjuncts to surgery have been proven to be effective. Analysis of the costs and economic effectiveness of the trial intervention were also undertaken.

Assessment and management of risk

For the purposes of this study, TA was used outside the terms of its licence.

Risk–benefit analysis

We classified this trial as type A (no higher than the risk of standard medical care in the ADAMON project classification) based on the following analysis.

Triamcinolone acetonide has been used off-label in clinical ophthalmic practice for many years. Ophthalmologists have experience of its periocular administration for over 50 years, with administration via the intraocular route being adopted for over 30 years. It has been used to treat a variety of posterior segment ocular inflammatory pathology. 24–27 Its use as an intraocular surgical adjunctive tool for visualisation of the posterior hyaloid during pars plana vitrectomy has been well established. 28 Additionally, intraocular TA has been found to reduce postoperative inflammation following vitrectomy surgery. 29 It has been investigated specifically to determine its effect on vitreoretinal scarring (PVR), with varying success. 21–23

Triamcinolone acetonide has an extremely well documented safety profile with the most common significant adverse effect recorded as elevated IOP. 30 Data from the pilot study31 performed at the principal site found a similar incidence of elevated IOP 35% (n = 7) in patients who received intravenous TA compared with 25% (n = 5) in those patients who received standard care.

An audit of study sites revealed that over half (54%) of sites have used intraocular TA in vitrectomy surgery following OGT, with 25% of sites using it routinely in this patient population. The investigators concluded that there is extensive clinical experience with the product and had no reason to suspect a different safety profile in the trial population.

Objectives

The aim of ASCOT trial was to investigate the clinical effectiveness of adjunctive steroid medication in eyes undergoing surgery for OGT.

The objectives were:

-

Primary: To determine whether adjunctive intraocular and periocular steroid (TA) improves visual acuity (VA) at six months compared with standard treatment in eyes undergoing vitreoretinal surgery for OGT.

-

Secondary: To determine whether adjunctive intraocular and periocular steroid (TA) influences the development of scarring (PVR), RD, IOP abnormalities and other complications in eyes undergoing surgery for OGT, and in addition to assess the effects of treatment on quality of life measured using the EuroQol Five Dimensions (EQ-5D) and Visual Function Questionnaire-25 (VFQ-25) tools.

Methods

Trial design

The ASCOT study was a multicentre, prospective, individually randomised, patient and outcome assessor masked controlled trial that tested the superiority of the intervention at six months. The trial design was formulated in consultation with the accredited clinical trials unit at King’s College London, two trial statisticians, a methodologist at the Research Design Service and in partnership with patients who have suffered severe ocular trauma. 32 A total of 28 vitreoretinal surgery centres throughout the UK agreed to take part. Some 300 adult patients with OGT were scheduled to be randomised one to one to receive adjunctive intraocular and periocular steroid (TA) versus standard care (surgery without adjunctive treatment). Operating surgeons were masked until the end of surgery (when the adjunct is given). Patients and primary outcome observers were masked throughout.

The primary outcome was the proportion of participants with a clinically meaningful improvement in corrected VA in the study eye, defined as having a change in 10 letters or more in Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) score (measured using validated ETDRS vision charts at a starting distance of 4 m) between baseline and at six months. The sample size was based on detecting a 19% increase (55–74%) in the proportion of participants who have a meaningful minimum improvement in VA the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were the change in ETDRS score at six months after surgery, the development of scarring (PVR), RD, IOP abnormalities and other complications in the study eye between initial surgery and six months after initial surgery. Quality of life assessments were undertaken using the EQ-5D and VFQ-25 tools. Using these data, cost effectiveness and cost-consequence analyses to investigate the impact of injury and recovery were carried out. Data collection was undertaken at baseline (prior to initial study surgery), three months after initial surgery and six months after initial surgery.

Timetable

The project was projected to run for 48 months, with time allocated as follows: months 0–5 project set-up, 6–40 patient recruitment (6–11 stage 1 internal pilot, 12–18 stage 2 internal pilot, 19–40 phase III), 41–45 final follow-up, 46–48 write up and results dissemination.

Owing to slow patient recruitment, a 33-month extension to the recruitment phase was granted.

Selection of patients

Patients with an open globe injury undergoing vitrectomy either as a primary or secondary procedure were investigated. OGT was classified as one of the following: a full thickness eyewall injury in the form of a rupture caused by a blunt object, laceration caused by a sharp object or an intraocular foreign body (IOFB). Patients were recruited at vitreoretinal outpatient or emergency clinics at 28 participating vitreoretinal surgical centres throughout the UK. The worse injured eye in patients with bilateral eye injuries was selected as the study eye for randomisation and the better eye received standard treatment. As binocular trauma is a rare occurrence, the study was not stratified by binocularity.

Inclusion criteria

-

Adult subjects (aged 18 years or over at the time of enrolment).

-

Full thickness, open globe ocular trauma undergoing vitrectomy.

-

Ability to give written informed consent.

-

Willingness to accept randomization and attend follow-up for six months.

Exclusion criteria

-

Children (<18 years of age at time of enrolment).

-

Pre-existing uncontrolled uveitis.

-

Definitive diagnosis of previous steroid induced glaucoma – these patients were considered to be at risk of steroid related pressure rise and will be excluded (this did not include patients in whom a query of previous steroid-induced raised IOP has been postulated).

-

Pregnant or breastfeeding women. Women of childbearing potential were advised to use an effective method of contraception (hormonal or barrier method of birth control; true abstinence) from the time consent was signed until six weeks after their completion of the trial. Women of childbearing potential had to have a negative urinary pregnancy test within seven days prior to being registered for trial treatment (patients were considered not of childbearing potential if they were permanently sterile; i.e. they had undergone a hysterectomy, bilateral tubal occlusion or bilateral salpingectomy) or they were postmenopausal.

-

Allergy or previous known adverse reaction to TA.

-

Inability to attend regular follow-up.

-

Inability to give written informed consent.

-

Current or planned systemic corticosteroid use of a dose above physiological levels (e.g. >10 mg prednisolone).

Recruitment

The study was a multicentre trial involving 28 UK sites. Ethically approved trial specific adverts were distributed to all sites for display. Recruitment was monitored closely at regular intervals.

Study procedures and schedule of assessments

Informed consent procedure

Informed consent was taken by a suitably qualified and experienced individual who has been delegated this duty by the chief or principal investigator on the delegation log. Rarely, eligible patients presented for emergency surgery out of hours or on occasions where the site principal investigator or delegated individual was not on site. In this situation, informed consent was taken by individuals who are Good Clinical Practice aware and familiar with key aspects of the study.

Informed consent was obtained before any trial-specific procedures were completed; that is those that are outside routine clinical care. Clinical findings documented during an ocular assessment performed as part of routine clinical care populated the baseline case report form (CRF) provided that the assessment was performed within 14 days of the study intervention.

It was the responsibility of the principal investigator or a person delegated by the investigator to obtain written informed consent from each subject prior to participation in the trial, following adequate explanation of the aims, methods, anticipated benefits and potential hazards of the study. The date when the patient information sheet was given to the patient was recorded.

On occasions where emergency surgery was planned within 24 hours of patient identification, the investigator or designee ensured that the patient was happy that they had been given adequate time to consider their decision.

The investigator or designee explained that patients were under no obligation to enter the trial and that they could withdraw at any time during the trial without having to give a reason. A copy of the signed informed consent form was given to the participant. The original signed form was retained at the study site and a copy placed in the medical notes.

Randomisation procedures

Randomisation was conducted via a telephone service to the eSMS Global service, who accessed the Kings Clinical Trials Unit randomisation service, intraoperatively. All randomised patients were first registered on the study electronic CRF (eCRF) system.

Appropriate study site staff were delegated by the site principal investigator to access the eCRF system and submit patient details to acquire a study personal identification number (PIN), and enter patient baseline and outcome data.

Participants with ocular trauma were randomised one to one at the level of the individual using randomised permuted blocks of varying sizes with stratification by trial site. Randomisation and subsequent treatment allocation were performed intraoperatively once the operating surgeon had confirmed that the retinal status was satisfactory.

Randomisation followed the sequence below:

-

The patient was consented for study participation.

-

Preoperative eligibility criteria were satisfied (including a negative urinary pregnancy test where relevant) and baseline assessments were performed, including ETDRS vision.

-

The patient was registered on InferMed MACRO eCRF to receive a PIN.

-

A staff member in theatre was identified who was responsible for making a telephone call to obtain treatment allocation, who has previously confirmed that they were familiar with eSMS telephone number and had patient identifiers, Kings College Clinical Trials Unit (KCTU) eCRF system (InferMed MACRO) PIN, stratification information and other details that were communicated to the eSMS service.

-

Theatre staff member located two vials of the study investigational medicinal product (TA 40 mg/ml) to ensure availability for use depending on treatment allocation and to provide details to eSMS at randomisation; theatre stock was used so there was no delay for dispensing by a clinical trials pharmacist post randomisation.

Intraoperative randomisation

-

The operating surgeon confirmed retina satisfactory (i.e. final confirmation of eligibility).

-

The surgeon completed the surgical procedure and confirmed that they were ready to randomise.

-

A theatre staff member telephoned eSMS global and communicated the patient information.

-

Treatment allocation was revealed and communicated to the operating surgeon such that patient was unaware and remained masked (i.e. if under local anaesthesia).

-

The surgeon administered the investigational medicinal product according to protocol, depending on treatment allocation.

If a participant was eligible for the study out of hours (overnight or at weekends) when their condition required urgent treatment and a member of the research team is unavailable, the site principal investigator or operating surgeon followed the above procedure for randomisation.

Masking

Masking

Participants and primary outcome assessors were masked to treatment allocation. The outcome assessors were technicians, nursing staff or healthcare assistants who were familiar with measuring VA using the ETDRS chart and followed a standard operating procedure. The operating surgeon was masked until the end of the study operation at the point of randomisation.

Emergency unmasking

Emergency unmasking enabled the study code to be broken for valid medical or safety reasons where it was necessary for the investigator or treating healthcare professional to know which treatment the patient was receiving before the participant could be treated.

Assessments

Baseline assessments

Baseline assessments were performed within 14 days prior to the study vitrectomy. Data collected as part of routine clinical care were used to populate the baseline CRF prior to informed consent but the patient was be registered on the eCRF and no data were entered on to the eCRF system until the patient had signed a consent form.

The following baseline assessments were recorded: demographics (including sex, date of birth, ethnicity), laterality (left or right eye being the study eye), date of ocular injury, date of primary repair, best corrected ETDRS VA in both eyes, injury classification, location of wound, IOFB status, presence of relative afferent pupillary defect, anterior segment status, IOP, lens status, vitreous cavity haemorrhage, retinal attachment status, and the presence and grade of PVR. Data were collected through a combination of medical history, applanation tonometry, slit-lamp biomicroscopy or indirect ophthalmoscopy and intraoperative findings. Quality of life data were collected using the ED-5Q and VFQ-25 tools and a Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI) questionnaire.

Subsequent assessments

Participants follow-up mirrored the schedule of standard NHS care. Data entry time points were: (1) baseline, (2) study vitrectomy, (3) month 3, and (4) month 6. At months 3 and 6, the following data were collected: ETDRS VA, biomicroscopic ocular examination, IOP, health questionnaires (VFQ-25, EQ-5D, CSRI), full eCRF documentation as for baseline. Additional surgical procedures and adverse event eCRFs were recorded until six months post vitrectomy.

Investigational treatment

The following medications were administered to participants allocated to the treatment arm of the study:

-

4 mg/0.1 ml TA administered into the vitreous cavity by the operating surgeon at end of procedure.

-

40 mg/1 ml of TA administered into the sub-Tenon’s space at the end of the procedure.

Usual care/control arm

Patients underwent standard vitreoretinal surgery and postoperative care appropriate to their ocular trauma without the addition of adjunctive medication.

Adverse events

Adverse events were recorded with clinical symptoms and accompanied with a simple, brief description of the event, including dates as appropriate. Adverse events were reported on the eCRF. Serious adverse events were reported in an expedited manner to the sponsor for each participant for their duration in the trial.

Data management and quality assurance

Confidentiality

All data were handled in accordance with the UK Data Protection Act 1998. The eCRFs did not bear the subject’s name or other personal identifiable data. The subject’s initials, date of birth and PIN was used for identification. Source data worksheets were completed for each participant but were not removed from the recruiting study sites. Signed consent forms were filed in the investigator site file. Study data were initially recorded on a source data worksheet and then transcribed to InferMed MACRO.

Data handling and analysis

InferMed MACRO eCRF version 4 was used to record the study data. Staff were allocated data entry or monitor roles to access the system by KCTU. At the end of the trial, after queries were resolved and all data fields completed, the database was locked for analysis. All study documents are to be retained for a period of five years following conclusion of the study. Data query reports were generated monthly by the data management team at KCTU and passed to the trial manager to be actioned. The trial manager raised data queries with sites via the eCRF during or between site monitoring visits.

Outcomes

Primary objective

The primary objective was to test the hypothesis that adjunctive TA, given at the time of surgery, can improve the outcome of vitreoretinal surgery for open globe ocular trauma.

The primary outcome is the proportion of participants with a clinically meaningful improvement in VA in the study eye, defined as having a 10-letters or more difference between the ETDRS score measured at six months after initial surgery and at baseline.

The principal secondary outcome is the change in ETDRS at six months from baseline, measured on a continuous scale.

Secondary objectives

To determine whether adjunctive TA, given at the time of surgery, influences the following secondary outcomes:

-

RD with PVR at any timepoint within six months of the study vitrectomy

-

stable complete retinal reattachment (without internal tamponade present) at six months post study vitrectomy

-

stable macular retinal reattachment (without internal tamponade present) at six months post study vitrectomy

-

tractional RD at any timepoint within six months of the study vitrectomy

-

the number of operations to achieve stable retinal reattachment (either complete or macula) at six months after the study vitrectomy

-

hypotony (<6 mmHg) at any timepoint within six months of the study vitrectomy

-

raised IOP (>25 mmHg) any timepoint within six months of the study vitrectomy

-

macular pucker by three and six months and/or require macular pucker surgery at any timepoint within six months of the study vitrectomy

-

quality of life measured using the VFQ-25

-

other complications in eyes undergoing surgery for OGT.

In addition, the effects of adjunctive TA on quality of life based on (1) Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI), and (2) the EQ-5D questionnaire were also be assessed.

Health economics objectives

The aim of the economic analysis of the ASCOT trial was to establish the incremental cost-effectiveness of adjunctive intraocular and periocular steroid (TA) treatment compared with standard treatment (no adjunctive treatment) in vitreoretinal surgery for OGT in terms of improved VA.

From an NHS perspective, to explore the incremental cost-effectiveness of adjunctive intraocular and periocular steroid (TA) treatment compared with standard treatment (no adjunctive treatment) in vitreoretinal surgery for OGT in terms of improved VA.

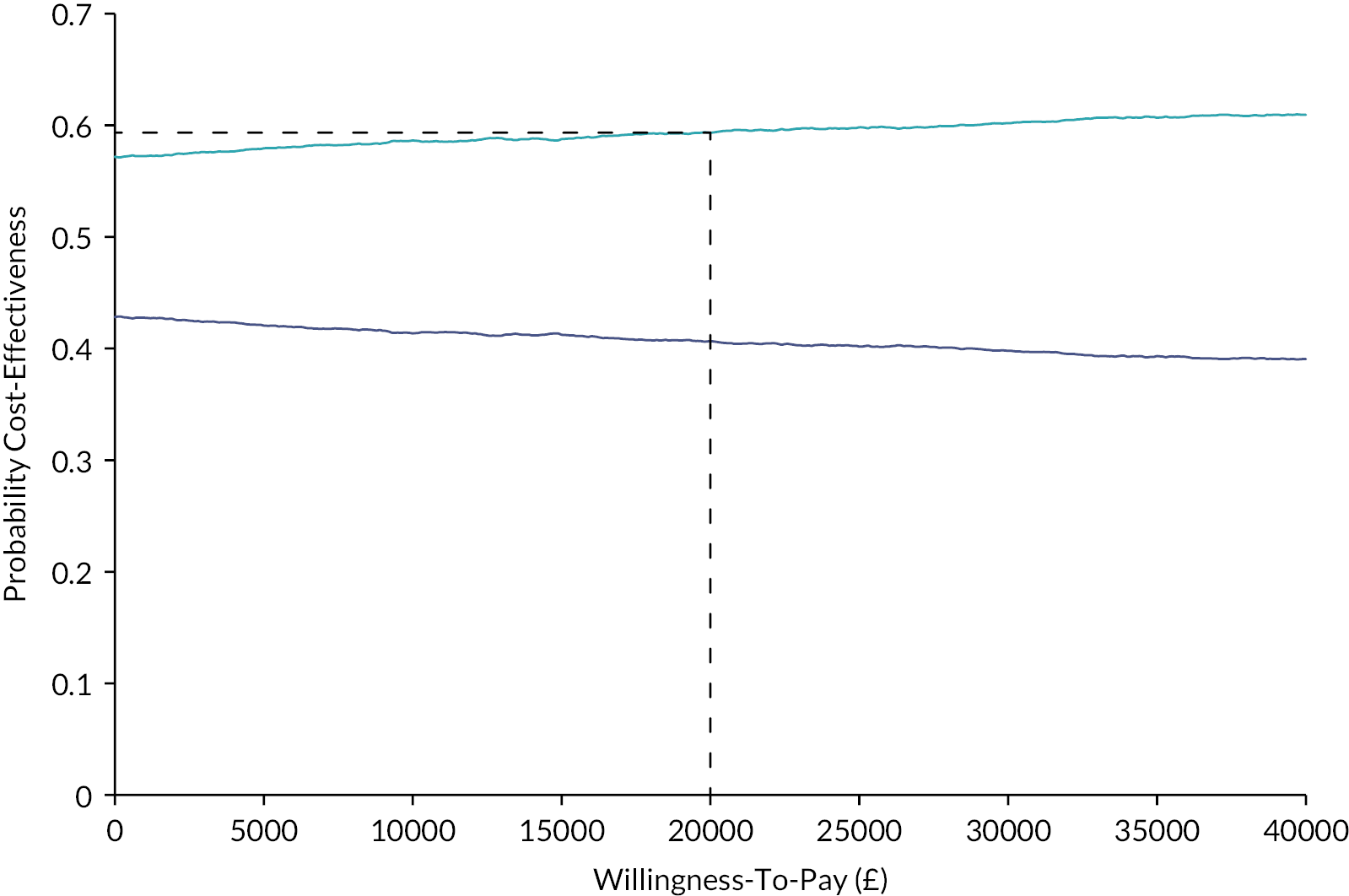

To explore the cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) of adjunctive intraocular and periocular steroid (TA) treatment compared with standard treatment (no adjunctive treatment) in vitreoretinal surgery for OGT to determine whether this falls below the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) threshold of £20,000–30,000 per QALY.

Sample size calculation

Published and pilot data indicate that VA, defined as ETDRS letter score at six months is skewed in this population and that the shape of the distribution of compared with VA differs between treatment arms. In a pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT), we observed small difference in mean VA between treatment arms but a sizable difference in proportion of patients (80% vs. 55%) with a meaningful improvement in VA (a change of ETDRS letter score of at least 10, which is widely accepted to be clinically meaningful in research studies of eye disease). 13,15,19–22 We defined the primary outcome as the proportion of patients with a meaningful improvement in VA. With 140 participants per group and a statistical significance of 5%, there is at least 90% power to detect a 19% increase (55–74% corresponding to an OR of 2.33) in participants who have a meaningful minimum improvement in VA of at least 10 letters. We therefore allowed for a 7% dropout rate and the target sample size for ASCOT was 300 participants (150 per arm).

Following slower than anticipated recruitment, the recruitment period was extended to 75 months. Over the full recruitment period, 280 eligible patients were recruited and are included within this analysis. Based on the original sample size parameters outlined above, it was established that the trial would still be adequately powered with a sample size of 280. A sample size of 280, assuming loss to follow-up of 7%; that is, 260 completers at 6 months provided 89.7% power to detect a 19% increase (55–74%) in meaningful improvement in VA (≥10 letters).

Statistical methods

General statistical principles

Analysis was conducted subgroup blind (i.e. as group A vs. group B) in accordance with the prespecified ASCOT statistical analysis plan. The main analysis was based on the intention-to-treat principle (i.e. all eligible participants were analysed in the group to which they were randomised regardless of subsequent treatment received). All regression analyses included centre. This was because adjustment for stratification factors in the randomisation process maintains the correct type I error rates. Additionally, for continuous outcomes, the outcome measured at baseline was included in regression analysis. Estimates are presented with 95% CIs and p-values. All statistical analysis was performed using Stata/IC version 15.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and throughout a two-sided p <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Descriptive analysis

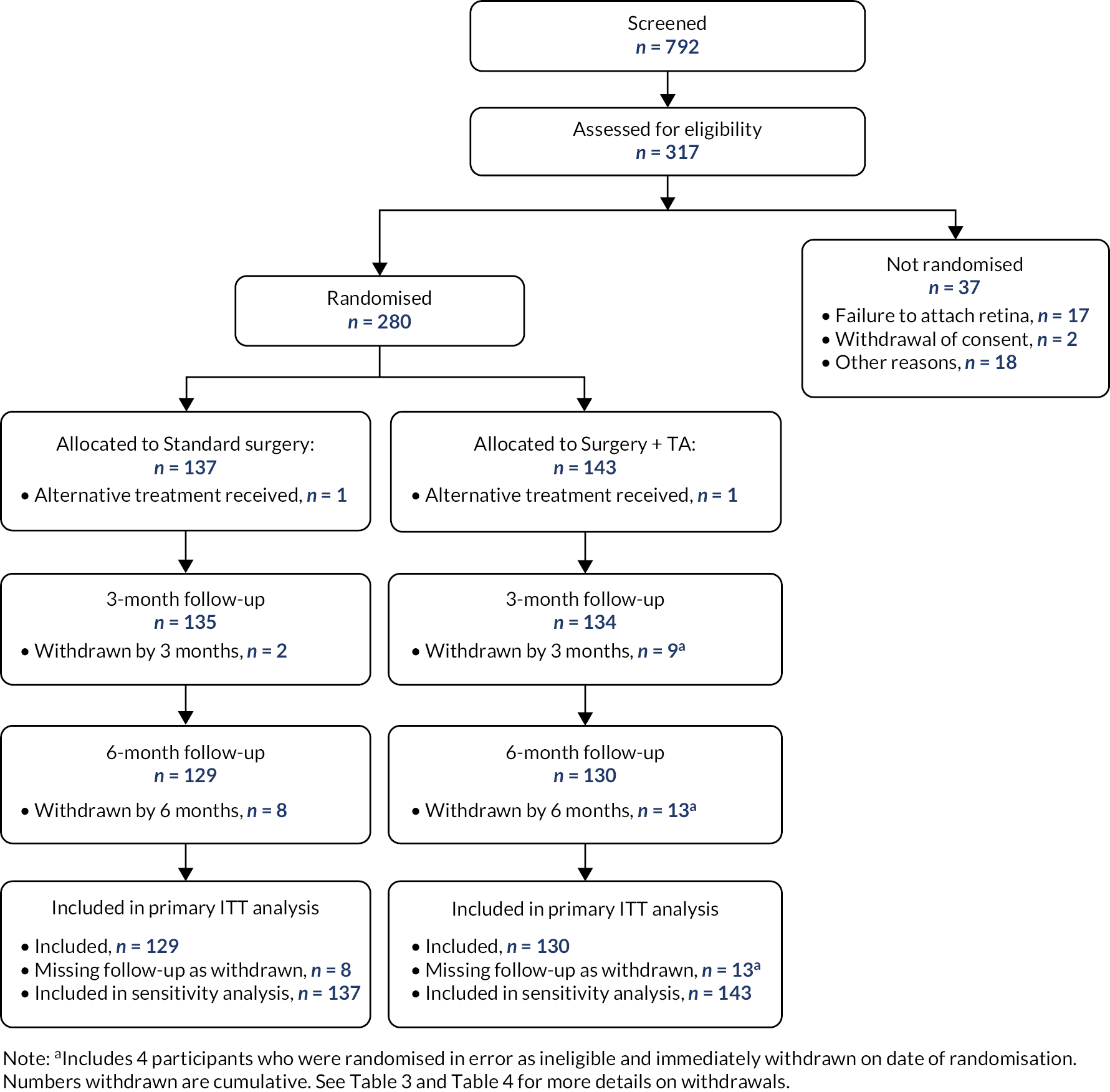

A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flowchart33 was constructed to summarise the flow of participants through the study. Baseline characteristics were summarised by randomised group to examine balance between the randomised groups at baseline. Continuous variables were reported as mean (standard deviation, SD) and median (interquartile range, IQR). Categorical variables were presented using frequencies and proportions (as a percentage). These summaries were based on observations only and the number of missing observations was reported.

The number withdrawing from the trial, including those lost to follow-up, was reported by treatment arm and time point of withdrawal, together with reasons for withdrawal. The proportions of participants missing ETDRS values (primary outcome) were summarised in each arm and at each time point the measurement was planned.

Descriptive statistics were presented for all outcome measures by treatment arm. For each primary and secondary outcome that is recorded at multiple time points, a single table summarises the outcome by visit and treatment arm. Only participants with a completely recorded outcome were used to calculate the summary measures.

Analysis of the primary outcome

The primary analysis model consisted of a mixed logistic model with change in VA (<10 change in six-month ETDRS score, ≥10 change in six-month ETDRS score) as the outcome and treatment arm and baseline value of the ETDRS as covariates. Centre was included as a random intercept as it was anticipated that there would be many sites with a small number of participants. The estimated treatment effect was reported as a subject-specific odds ratio (OR) (conditional on centre and baseline ETDRS) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and corresponding p-value.

The population-averaged probability of clinically meaningful improvement in VA was also presented by treatment group and the unadjusted difference in proportion of participants with an improvement in VA score of 10 or greater between treatment arms, with a two-sided 95% CI.

All missing response values were assumed to be missing-at-random (MAR; i.e. the probability that the response is missing does not depend on the value of the response after controlling for the observed variables of treatment and baseline vision). Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the impact of alternative missing data assumptions (see below) Results of the primary outcome analysis were verified by an independent statistician.

Planned sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome were performed. These included:

Analysis to assess the impact of missing outcome data:

-

Use of imputation to explore the optimistic (meaningful change in treatment arm – no change in surgery-only arm) or pessimistic (no change in treatment arm – meaningful change in surgery-only arm) scenario for participants with missing outcome data. The primary analysis model was retained for use in the sensitivity analysis, following imputation.

-

A mean score approach was employed to explore a range of more plausible missing-not-at-random (MNAR) scenarios. Within this analysis, the primary outcome was analysed under increasing departures from the primary MAR assumption, by assuming a gradual increase in the odds of the outcome (meaningful change in ETDRS) for those with missing data, from 0 (representing MAR) to 1 for (1) participants in the surgery arm only, (2) participants in the treatment arm only, and (3) for participants in both arms.

Analysis to assess the impact of out of window outcome data:

-

The visit window for the three- and six-month follow-up is ± 4 weeks. In line with the prespecified statistical analysis plan, data collected outside these recommended periods were included in the primary analysis. A sensitivity analysis was conducted where data collected outside the visit windows were excluded. The analysis model was the same as for the primary analysis.

-

An additional sensitivity analysis where data collected outside the visit windows were included, also using the primary analysis model, but where patients with data outside the visit windows were weighted by one-half was performed. Patients with data within the allowed visit window had a weight of one. This sensitivity analysis downweighted the data of those with data out of the visit windows such that the data of patients collected outside the allowed windows were considered half as trustworthy.

Analysis of secondary outcomes

Linear (Gaussian) mixed regression models were used for the analysis of the principle secondary outcome (change in ETDRS) and other continuous secondary outcomes (VFQ-25). Binary secondary outcomes were analysed using mixed logistic regression models. For count outcomes, a mixed-effect negative binomial model was fitted, which allowed for overdispersion. Similar to the primary analysis model, the models for secondary outcomes included centre as a random intercept and a fixed effect for treatment group. For continuous secondary outcomes, models additionally included a fixed effect for the baseline value of the outcome.

The continuous change in the six-month ETDRS (principle secondary outcome) was also analysed using a Bayesian linear mixed regression model analysis, fitted using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods. Similar to the main frequentist analysis for this principle secondary outcome, the model included fixed effects for baseline ETDRS, treatment group and a random intercept for centre. Uninformative priors were used for each model parameter, specifically for each fixed regression parameter Normal (0, 100) and igamma (0.01, 0.01) for the variance parameters. A burn in of 2500 and 10,000 MCMC iterations were used. Convergence of model parameters was assessed visually using diagnostic plots. From the model, we present the estimated average treatment effect for the six-month change in ETDRS with an accompanying 95% credible interval, together with posterior probabilities for the change in ETDRS being greater than 0–50, by treatment group and for the treatment group difference.

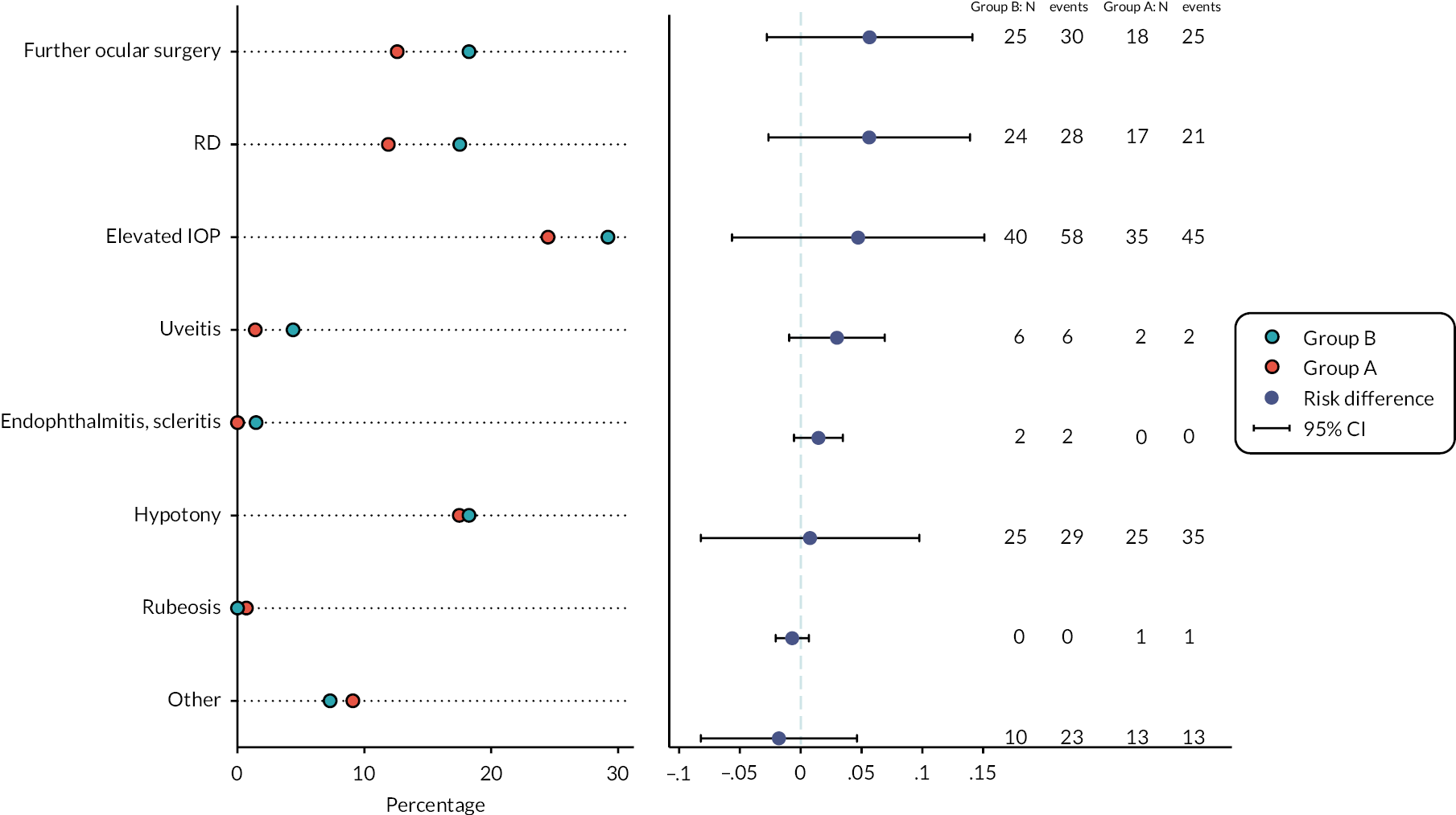

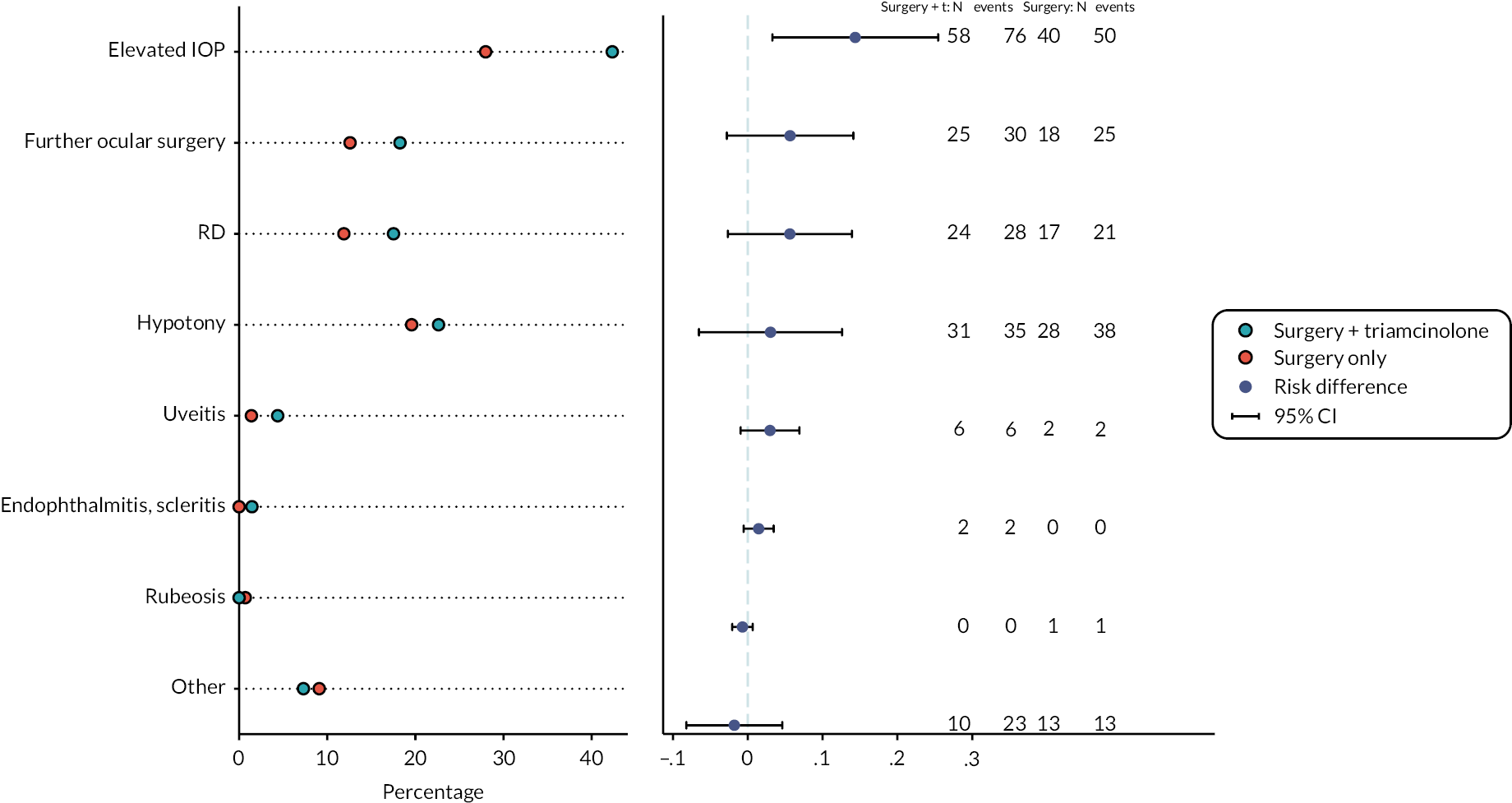

Adverse events were collected by means of spontaneous reports from participants, clinical observation and clinical examinations and blood tests. Data on safety outcomes are summarised for all randomised participants who underwent surgery. Adverse events were summarised by type: adverse events, adverse reactions (a subset of the adverse events), unexpected adverse reactions (a subset of the adverse reactions), serious adverse events, serious adverse reactions (a subset of the serious adverse events) and unexpected serious adverse reactions (a subset of the serious adverse reactions) and by treatment arm. Adverse events were tabulated by treatment group for both the number of events and the number of participants with the type of event. Adverse events were also summarised by event term and intensity (subjectively assessed by local clinical investigators as mild/moderate/severe). To identify the events with the strongest evidence for between-arm differences, adverse events were summarised visually in a dot plot, which display the proportions of individuals experiencing each type of event by treatment arm and the relative risk difference with 95% CI.

Subgroup analysis

Preplanned subgroup analysis investigated whether the treatment effect on the primary outcome differed by:

-

RD: attached

-

RD: tractional

-

RD: rhegmatogenous

-

fovea involvement: yes

-

fovea involvement: no

-

fovea involvement: splitting

-

presence of PVR: yes

-

presence of PVR: no

-

presence of retinal incarceration: yes

-

presence of retinal incarceration: no

-

lens status at baseline: clear (phakic)

-

lens status at baseline: cataract (phakic)

-

lens status at baseline: anterior chamber intraocular lens implant (ACIOL) and posterior chamber intraocular lens implant (pseudophakic)

-

lens status at baseline: aphakic.

Each subgroup analysis was performed by adding the relevant treatment-by-subgroup interaction term to the same analysis model as for the primary outcome; p-values for each interaction term were presented. No adjustment for multiple tests was made and the results were hypothesis generating only. The consistency of estimates was depicted visually by means of a forest plot.

Health economics analyses

The ASCOT study took an NHS perspective in terms of the identification, measurement and valuation of costs and outcomes.

Health economics outcomes

Quality-adjusted life-years

Quality-adjusted life-years are a generic measure of disease burden which incorporates both the quantity and quality of life lived. QALYs are used as a measure of health utility calculated by ‘weighting’ each period of follow-up time by the value corresponding to the HRQoL during that period.

Health-related quality of life

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was assessed using the EQ-5D and VFQ-25 questionnaires. 34–36 The EQ-5D is a generic preference-based HRQoL measure. It consists of two parts: a five-item questionnaire comprising five items covering mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain, anxiety and depression, each with three levels of severity (no problems, some problems, a lot of problems) and a visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS). The EQ-5D questionnaire is scored between –0.59 and 1, with 1 meaning full HRQoL. The EQ-VAS is a thermometer scored between 0 (worst possible health) and 100 (best possible health), with respondents asked to mark their current HRQoL level.

Resource use

In the ASCOT trial, all resource use, and hence costs, were measured from an NHS perspective. Resource use and cost information were collected on secondary care and prescribing. Secondary care and prescribing information were collected from hospital held patient records by researchers at each ASCOT trial centre. The CSRI as part of the CRF was informed by the DIRUM (Database of Instruments for Resource Use Measurement), including examples of CSRIs used in previous studies at Bangor University. Data collected from all centres were investigated for equivalence at baseline for both groups in terms of resource use and cost for any statistically significant differences between groups. No discount was applied to either cost or effect as the analysis was conducted for the time horizon of six months.

Unit costs

Unit costs for community services were sourced from the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) unit costs of health and social care and were reported in Great British pounds (£) and inflated to cost year 2018/19 where necessary using the PSSRU guide for inflation of hospital resources. 37 Drug costs were obtained from the Prescription Cost Analysis. 38 Costs relating to ophthalmology surgeries and procedures were obtained from NHS national reference costs. 39

Source of steroid costs as main intervention

The additional cost accrued for the intervention and the components that make up the intervention cost are shown in the results section. The costs are composed of costs from PSSRU and consultation with experts in the field where these costs are not clearly referenced in the NHS reference costs. 39

Costs of ophthalmic surgical procedures following initial trauma repair

The cost of the surgical procedure is a standard cost across the NHS; thus, both groups (intervention and control) incurred this cost. To avoid double counting, the health economics analysis assumes this as a zero cost for every patient. Other costs incurred post surgery were captured by CSRI, including hospital-based costs, community-based costs and medication use (see Results).

Handling missing data

The primary analysis included all patients with baseline and six-month ETDRS follow-up. As the intervention was a one-off treatment at the time of randomisation and the two follow-up appointments followed usual clinical care, we anticipated a low percentage of missing primary outcome data. It was therefore anticipated that missing data would be MAR. The primary analysis method employed the hot-deck method of estimation and was thus efficient for handing missing outcome data. 40

A sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome was undertaken to assess the impact of participants with missing VA scores at the six-month follow-up. The number, pattern and timing of missing data were examined by treatment arm, together with the reasons for withdrawal or reason for missing data. Potential bias due to missing data was investigated initially by comparing the baseline characteristics (using descriptive comparisons). A missing indicator variable (yes/no) was generated for data at six months and the relationship between study variables and missingness was examined using the K–nearest neighbours cluster analysis.

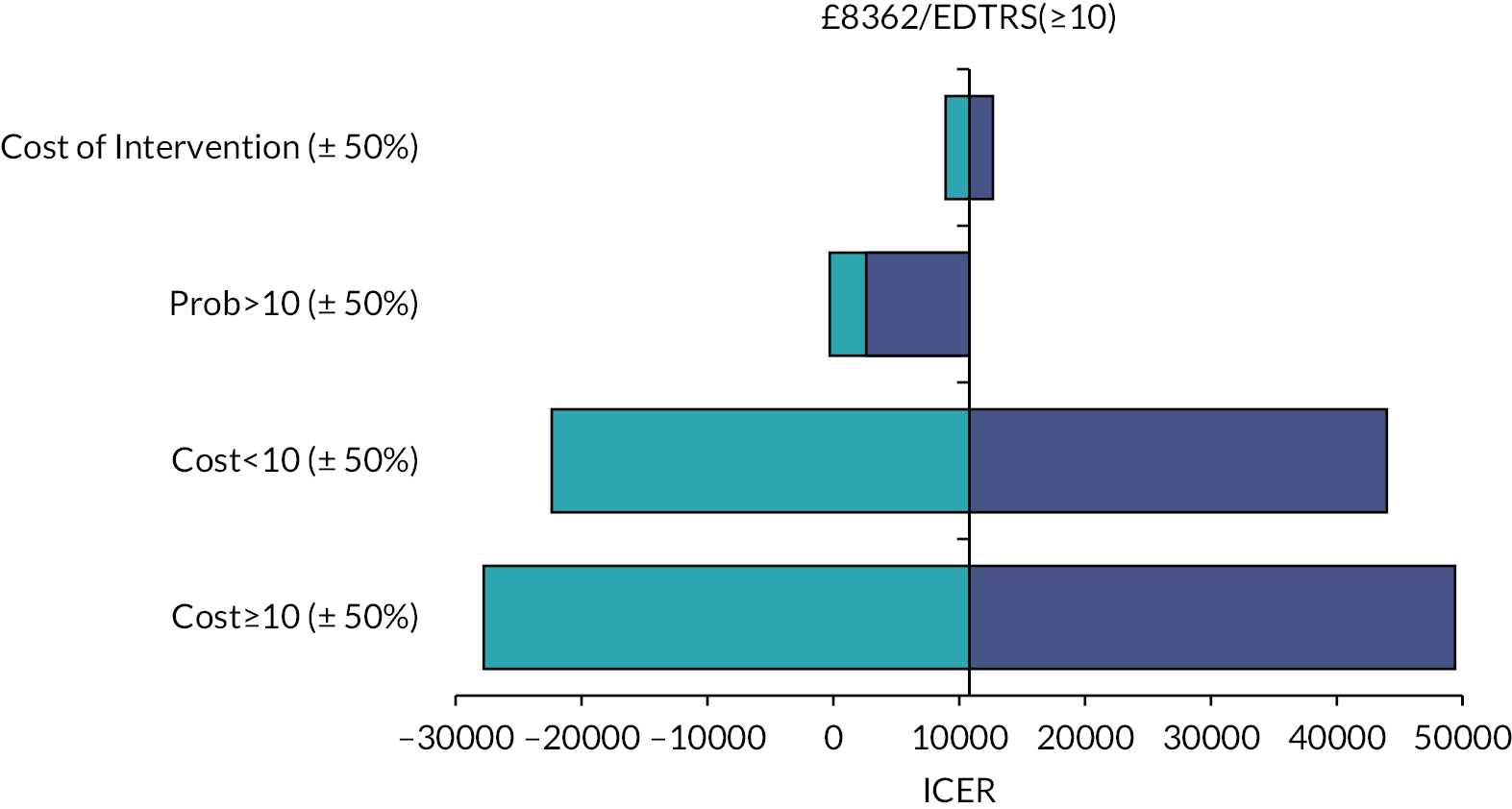

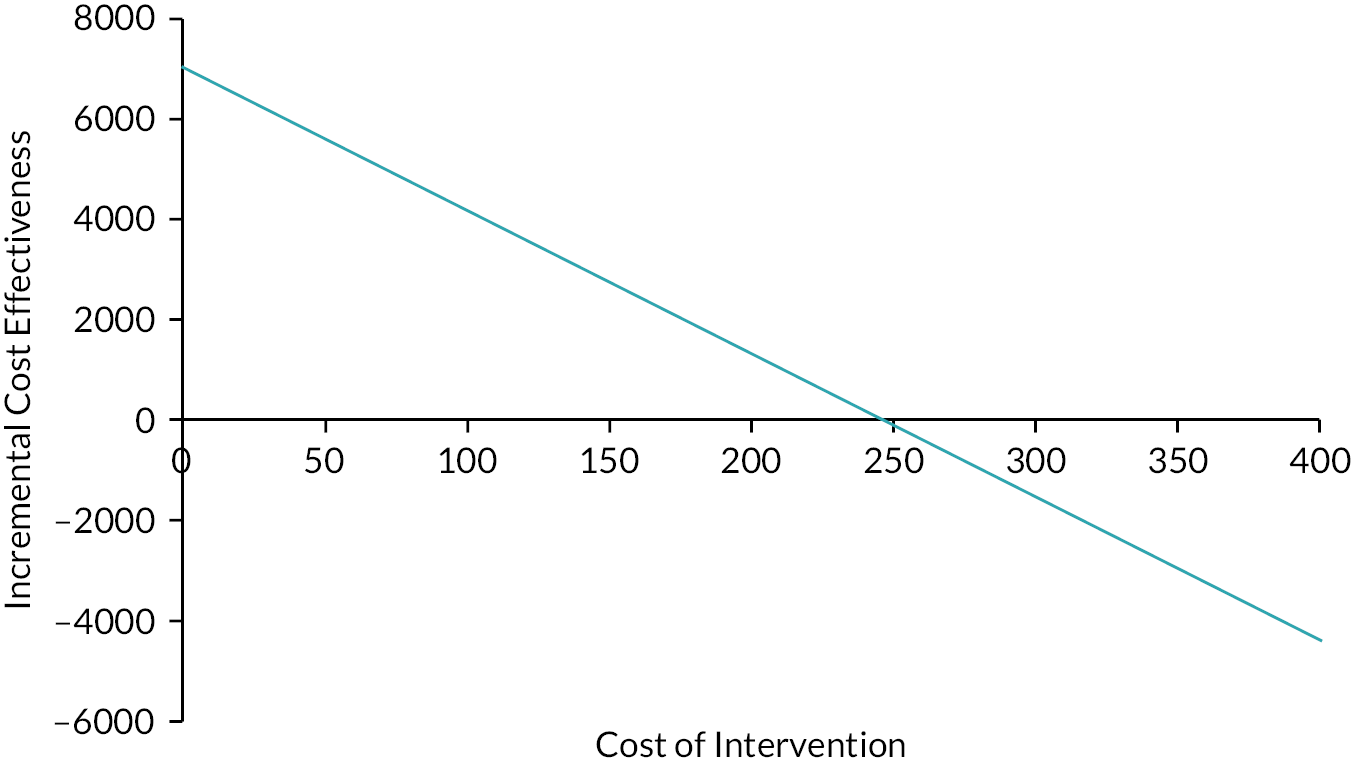

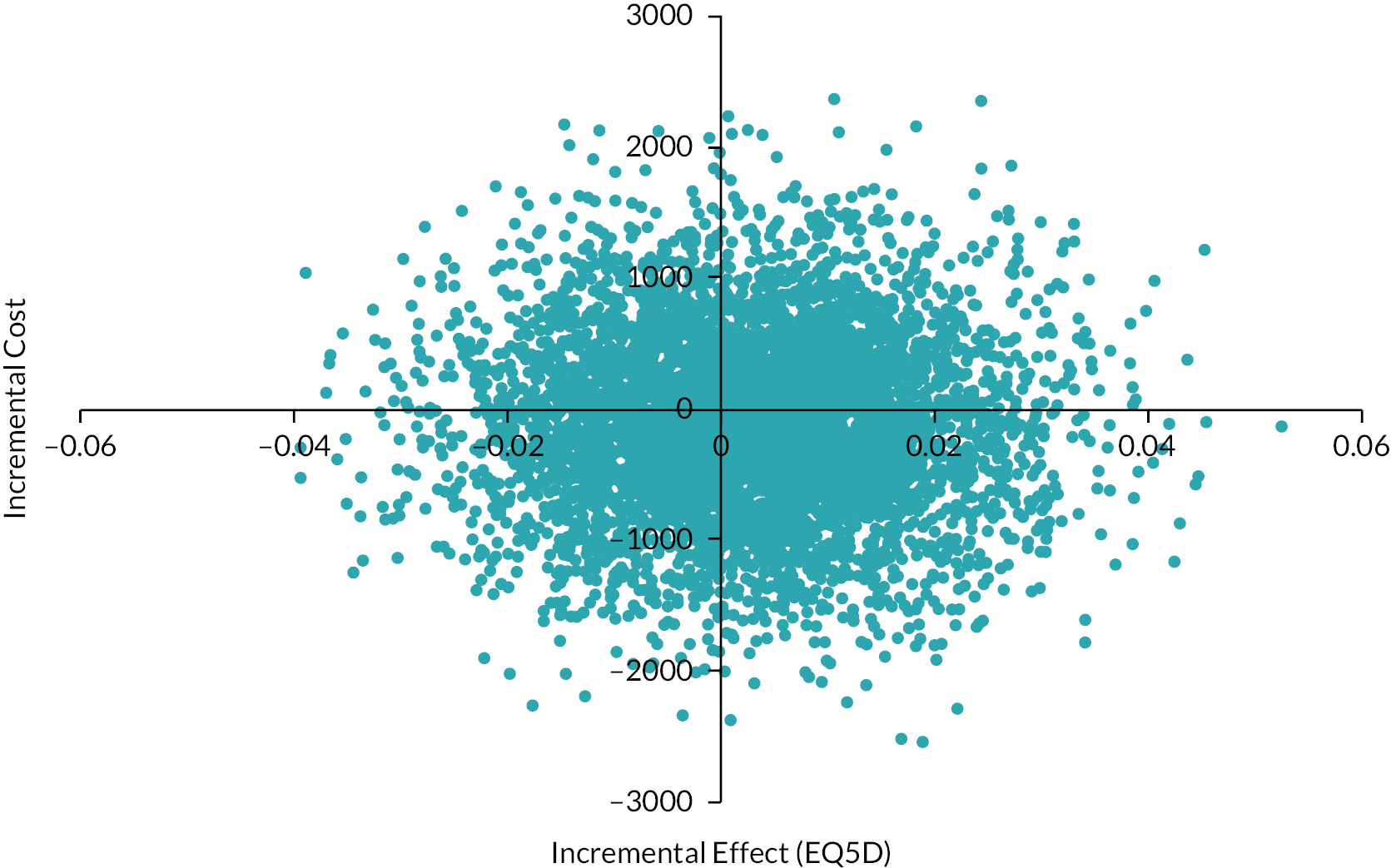

Sensitivity analysis

We undertook both deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analysis to test uncertainty of findings. Sensitivity analysis is used in economic evaluations to test how sensitive the findings are to basic assumptions used in the economic evaluation model. For instance, the cost of an intervention is to some extent based on assumptions about unit costs and staff time; likewise, effects are subject to uncertainty between individuals. By varying these assumptions, the stability of findings can be tested and uncertainty can be accounted for. The sensitivity analysis offered optimistic and pessimistic scenarios for patients in both treatment arms which are represented using the tornado plot. A sensitivity analysis considered the impact of a variation from the intervention cost for patients with ETDRS of 10 or above. Deterministic sensitivity analysis can be either univariate or multivariate, whereby single or multiple parameters may be individually adjusted (within a given range of uncertainty) to test findings of the model. For example, we varied the potential cost of adjunctive steroids, which may be incrementally increased or decreased (within given confidence limits) to examine the impact on cost-effectiveness or costs per QALY outcomes. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis assigns a distribution of point estimates to each parameter and randomly selects a single value for each model calculation. By running a number of replications (e.g. 5000) an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) plane can be generated to illustrate the potential variation in cost-effectiveness based on altering basic assumptions about effectiveness and costs.

We used bootstrapping to produce cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) and ICER planes to examine uncertainty. Furthermore, we used deterministic sensitivity analysis, in the form of best-worst scaling, to test the impact of basic economic model assumptions. 41

Disease-specific health-related quality of life outcome measure

The VFQ-25 questionnaire measures vision related quality of life (appendix questions were not included in this study). Guidelines to scoring the VFQ-25 are provided by the National Eye Institute (NEI)36 and it is a two-step process; first, original numeric values are recoded following the scoring rules outlined in NEI 2000. The VFQ-25 measures vision-related quality of life. Items are converted into a score between 0–100, where 100 represents full capability then the subscales are averaged to produce the composite score.

Health economics analyses

We analysed the incremental cost-effectiveness of the trial intervention (intraocular and periocular steroid) in eyes undergoing vitreoretinal surgery for ocular trauma compared with surgery alone in terms of changes in VA. To enable this analysis, from an NHS perspective, we:

-

fully costed the vitreoretinal surgery and follow up

-

recorded study participant primary and secondary care health service use and social care use over the six-month follow-up period (using a research nurse interviewer administered CSRI, costed using national unit costs) and making use of routine hospital data on surgical and postoperative care as part of the CRF

-

conducted a primary cost effectiveness analysis (using the trial primary outcome measure of VA, ≥10-letter improvement in ETDRS score, as our measure of effectiveness)

-

conducted a secondary cost utility analysis to explore the cost per QALY of adjunctive steroid intraocular and periocular steroid (TA) as compared with usual treatment relative to the £20,000–30,000 NICE payer threshold. NICE currently uses this threshold to determine whether the health benefits provided from a new drug or healthcare intervention is greater than the health likely to be lost as services are displaced to accommodate for the new intervention

-

through bootstrapping, generated CEACs to communicate to policy makers the probability that the intervention is cost-effective.

Patient and public contribution to study development

The trial was initially conceived with a primary outcome of anatomical success (retinal attachment without PVR). This was the approach used in previous clinical trial undertaken by the same investigators. 31,42–44 The investigator team undertook a series of meetings with patients who had suffered RD, ocular trauma and PVR, as well as patient groups affected by ocular trauma (Blind Veterans UK). There was a clear preference among patients and patient groups for a visual measure as the primary outcome. The primary outcome and the calculation of sample size for the study was therefore based on a measure of visual outcome (VA).

Results

Data description

Recruitment and participant flow

Between December 2014 and March 2020, a total of 792 patients were screened; 317 were assessed for eligibility and 280 eligible participants across 27 sites in England and Scotland were randomly allocated to standard surgery (137 participants) or surgery plus adjunctive TA (143 participants, Table 1). One site failed to recruit. Figure 1 is the CONSORT flowchart for the trial, which summarises the flow of participants through the trial. One participant in each arm received the alternative treatment. The three-month follow-up was obtained for 269 participants (standard surgery n = 135 and surgery plus adjunctive TA n = 134) and for 259 at the six-month follow-up (standard surgery n = 129 and surgery plus adjunctive TA n = 130).

| Study centre | Standard surgery, N (%) | Surgery + TA, N (%) | Total, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total randomised | 137 (49) | 143 (51) | 280 |

| Birmingham | 5 (4) | 4 (3) | 9 (3) |

| Bristol | 8 (6) | 7 (5) | 15 (5) |

| Cambridge | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Canterbury William Harvey Hospital | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Derby | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | 5 (2) |

| Edinburgh | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Frimley Park | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Glasgow | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | 5 (2) |

| Hull | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 4 (1) |

| King’s College London | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | 5 (2) |

| Liverpool | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Maidstone | 7 (5) | 8 (6) | 15 (5) |

| Manchester | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Moorfields | 56 (41) | 57 (40) | 113 (40) |

| Newcastle | 6 (4) | 6 (4) | 12 (4) |

| Oxford | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (0) |

| Plymouth | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Portsmouth | 4 (3) | 5 (3) | 9 (3) |

| Sheffield | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (0) |

| South Tees | 7 (5) | 7 (5) | 14 (5) |

| Southend | 3 (2) | 2 (1) | 5 (2) |

| St Thomas’ London | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | 5 (2) |

| Stoke Mandeville Stoke Mandeville Hospital | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Sunderland | 5 (4) | 6 (4) | 11 (4) |

| Western Eye London | 12 (9) | 11 (8) | 23 (8) |

| Whipps Cross London | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Wolverhampton | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 8 (3) |

Baseline characteristics

Table 2 summarises baseline characteristics by randomised arm. The median age of the participants was 43 years (IQR 30–55), 88% were male and 83% of white ethnicity. Most participants (75%) had a score of zero on the ETDRS chart indicating very low vision of counting fingers or worse at baseline. The baseline characteristics were generally well matched between the treatment arms, including demographic and ocular history. However, by chance, the surgery plus TA arm had slightly more severe pathology on presentation including a higher number of previous primary repair (77% vs. 69% standard surgery), more zone 3 (posterior) injuries (31% vs. 21% standard surgery), a higher rate of vitreous haemorrhage (69% vs. 63% standard surgery), retinal incarceration (27% vs. 18%), pre-existing RD (tractional and rhegmatogenous 54% vs. 48% standard surgery) and pre-existing PVR (27% vs. 21% standard surgery).

| Baseline characteristic | N standard/N TA | Standard surgery(N = 137) n (%) | Surgery + TA (N = 143) n (%) | Total (N = 280) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 137/143 | 123 (90) | 123 (86) | 246 (88) |

| Ethnicity: | 137/143 | |||

| White | 113 (82) | 120 (84) | 233 (83) | |

| Black | 11 (8) | 9 (6) | 20 (7) | |

| Asian | 7 (5) | 11 (8) | 18 (6) | |

| Other | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 6 (2) | |

| Mixed | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | |

| Current smoker | 133/140 | 55 (41) | 51 (36) | 106 (39) |

| Eye injured: | ||||

| Right | 137/143 | 67 (49) | 70 (49) | 137 (49) |

| Left | 66 (48) | 72 (50) | 138 (49) | |

| Both | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 5 (2) | |

| Glaucoma | 136/143 | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Previous eye surgery | 137/143 | 67 (49) | 82 (57) | 149 (53) |

| Macular disease | 136/143 | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (0) |

| How the eye was injured: | ||||

| Workplace incident | 137/143 | 40 (29) | 48 (34) | 88 (31) |

| Road traffic accident | 5 (4) | 6 (4) | 11 (4) | |

| Interpersonal violence | 33 (24) | 33 (23) | 66 (24) | |

| Sports injury | 5 (4) | 5 (3) | 10 (4) | |

| Other injury | 16 (12) | 21 (15) | 37 (13) | |

| Other domestic | 11 (8) | 10 (7) | 21 (8) | |

| Domestic gardening | 5 (4) | 3 (2) | 8 (3) | |

| Domestic DIY | 10 (7) | 3 (2) | 13 (5) | |

| Iatrogenic | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | 3 (1) | |

| Fall | 12 (9) | 11 (8) | 23 (8) | |

| Previous primary repair | 137/142 | 95 (69) | 110 (77) | 205 (73) |

| Severity of trauma: | 137/145 | |||

| Rupture | 53 (39) | 60 (42) | 113 (40) | |

| Penetrating | 51 (37) | 52 (36) | 103 (37) | |

| Perforating | 4 (3) | 7 (5) | 11 (4) | |

| IOFB | 29 (21) | 24 (17) | 53 (19) | |

| Severity of trauma: | 135/142 | |||

| Zone 1: cornea | 51 (38) | 44 (31) | 95 (34) | |

| Zone 2: scleral anterior to muscle insertion | 56 (41) | 54 (38) | 110 (40) | |

| Zone 3: scleral posterior to muscle insertion | 28 (21) | 44 (31) | 72 (26) | |

| RAPD present | 66/72 | 17 (26) | 26 (36) | 43 (31) |

| Visual axis corneal scar | 137/143 | 32 (23) | 40 (28) | 72 (26) |

| Uveitis | 137/143 | 26 (19) | 26 (18) | 52 (19) |

| Hyphaemia: | ||||

| No | 137/143 | 96 (70) | 90 (63) | 186 (66) |

| <50% | 24 (18) | 26 (18) | 50 (18) | |

| >50% | 17 (12) | 27 (19) | 44 (16) | |

| Iris | 135/141 | |||

| Normal | 52 (39) | 59 (42) | 111 (40) | |

| Incomplete | 63 (47) | 72 (51) | 135 (49) | |

| Incarcerated | 20 (15) | 10 (7) | 30 (11) | |

| Lens | 136/141 | |||

| Clear | 37 (27) | 33 (24) | 70 (25) | |

| Cataract | 46 (34) | 50 (36) | 96 (35) | |

| Apiol | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| PCIOL | 12 (9) | 8 (6) | 20 (7) | |

| Aphakic | 41 (30) | 48 (34) | 89 (32) | |

| Vitreous haemorrhage | 135/141 | 85 (63) | 97 (69) | 182 (66) |

| Endophthalmitis | 136/143 | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | 5 (2) |

| RD: | 137/143 | |||

| Attached | 71 (52) | 66 (46) | 137 (49) | |

| Tractional | 17 (12) | 21 (15) | 38 (14) | |

| Rhegmatogenous | 49 (36) | 56 (39) | 105 (38) | |

| Fovea off (macular involvement in RD)? | 66/77 | |||

| No | 25 (38) | 32 (42) | 57 (40) | |

| Yes | 41 (62) | 44 (57) | 85 (59) | |

| Splitting | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| Retinal incarceration | 137/143 | 25 (18) | 38 (27) | 63 (23) |

| PVR | 137/142 | 29 (21) | 38 (27) | 67 (24) |

| Age in years (median, IQR) | 137/143 | 43.0 (29.2–53.1) | 45.6 (32.2–57.1) | 43.5 (30.9–55.8) |

| ETDRS in study eye: | 137/143 | |||

| Median, IQR | 0 (0–11) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1) | |

| Minimum, maximum | (0, 99) | (0, 100) | (0, 100) | |

| Zero/very low | 98 (72) | 111 (78) | 209 (75) | |

| Where zero/very low, vision: | 98/111 | |||

| Counting finger | 10 (10) | 9 (8) | 19 (9) | |

| Hand movement | 60 (61) | 54 (49) | 114 (55) | |

| Perception light | 26 (27) | 45 (41) | 71 (34) | |

| No perception light | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 5 (2) | |

| Where ETDRS > 0: | 39/32 | |||

| Median, IQR | 64 (45–83) | 48 (21–66) | 58 (24–80) | |

| Minimum, maximum | (1, 99) | (1, 100) | (1, 100) | |

| IOP in study eye | 123/131 | |||

| Median, IQR | 11 (8–17) | 10 (8–15) | 11 (8–15) | |

| Minimum, maximum | (0, 43) | (0, 33) | (0, 43) | |

| Low <6 | 92 (75) | 103 (79) | 195 (77) | |

| Normal ≥6, ≤22 | 21 (17) | 18 (14) | 39 (15) | |

| High >22 | 10 (8) | 10 (8) | 20 (8) | |

Withdrawals and missing data

There were a total of 21 withdrawals from the trial (7.5% of participants), which included 8 from the standard surgery arm and 13 from the surgery plus adjunctive TA arm (Table 3). Reasons for withdrawal are summarised in Table 4. The primary endpoint (six-month change in ETDRS) was missing for 21/280 (7.5%) participants, which was in line with the 7% factored into the sample size calculation (Table 5). This meant that a total of 259 participants provided six-month ETDRS (primary outcome) data. Table 6 summarises selected baseline characteristics by completeness of the primary outcome.

| Point of withdrawal | Treatment arm | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard surgery, n (%) | Surgery + TA, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |

| Date of randomisation | 0 (0) | 4 (31)a | 4 (19) |

| By month 3 visit | 2 (25) | 5 (38) | 7 (33) |

| By month 6 visit | 6 (75) | 4 (31) | 10 (48) |

| Total | 8 | 13 | 21 |

| Reason for withdrawal | Treatment arm | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard surgery, n (%) | Surgery + TA, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |

| Lost to follow-up | 7 (88) | 7 (54) | 14 (67) |

| No longer wishes to take part | 1 (12) | 2 (15) | 3 (14) |

| Participant ineligible – randomised in errora | 0 (0) | 4 (31) | 4 (19) |

| Total, n | 8 | 13 | 21 |

| Missing | Standard surgery (N = 137), n (%) | Surgery + TA (N = 143) n, (%) | Total (N = 280), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 3 month visit | 5 (4) | 17 (12) | 22 (8) |

| 6 month visit | 8 (6) | 13 (9) | 21 (8) |

| Measurement closest to 6 month post-surgerya | 8 (6) | 13 (9) | 21 (8) |

| Change to 6 month post-surgery | 8 (6) | 13 (9) | 21 (8) |

| Baseline characteristic | Primary outcome at 6 months observed | Primary outcome at 6 months missing | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | Female | 33 (13) | 1 (5) | 34 | 12 |

| Male | 226 (87) | 20 (95) | 246 | 88 | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | White | 218 (84) | 15 (71) | 233 | 83 |

| Black | 18 (7) | 2 (10) | 20 | 7 | |

| Asian | 15 (6) | 3 (14) | 18 | 6 | |

| Other | 5 (2) | 1 (5) | 6 | 2 | |

| Mixed | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 | 1 | |

| Current smoker | No | 157 (62) | 10 (48) | 167 | 61 |

| Yes | 95 (38) | 11 (52) | 106 | 39 | |

| Age (years) | Median, IQR | 44.1 (31.1–56.3) | 40.1 (29.4–48.5) | 43.5 (30.9–55.8) | |

| ETDRS in study eye (total score) | Median, IQR | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–9.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | |

| Min, Max | (0.0, 100.0) | (0.0, 90.0) | (0.0, 100.0) | ||

| Zero/very low ETDRS in study eye, n (%) | Zero/very low | 194 (75) | 15 (71) | 209 (75) | |

| >0 | 65 (25) | 6 (29) | 71 (25) | ||

| ETDRS in study eye (total score) where >0, n (%) | Median, IQR | 58.0 (27.0–80.0) | 55.5 (11.0–87.0) | 58.0 (24.0–80.0) | |

| Minimum, maximum | (1.0, 100.0) | (9.0, 90.0) | (1.0, 100.0) | ||

| IOP in study eye, n (%) | Median, IQR | 11.0 (8.0–16.0) | 12.5 (7.0–14.0) | 11.0 (8.0–15.0) | |

| Min, Max | (0.0, 37.0) | (2.0, 43.0) | (0.0, 43.0) | ||

| IOP in study eye, n (%) | Low <6 | 35 (15) | 4 (20) | 39 (15) | |

| Normal ≤6, <22 | 180 (77) | 15 (75) | 195 (77) | ||

| Low <6 | 19 (8) | 1 (5) | 20 (8) | ||

Primary outcome: meaningful improvement (≥10) in the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study at six months

Descriptive statistics for primary outcome

Table 7 summarises the ETDRS by time point and treatment arm, with unadjusted mean treatment group differences. In both treatment groups, the mean ETDRS improved at six months. The unadjusted mean treatment arm difference in the six-month change in ETDRS was 0.6 (95% CI –6.8 to 7.9), where the point estimate was marginally in favour of surgery plus TA.

| Time | Treatment arm | Total N | Unadjusted mean differencea (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard surgery | Surgery + TA | |||||||

| N | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | N | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | |||

| Baseline | 137 | 16.6 (30.5) | 0 (0–11) | 143 | 10.4 (23.6) | 0 (0–0) | 280 | N/A |

| 3-month visit | 132 | 33.6 (31.7) | 29 (0–62) | 126 | 28.3 (29.4) | 20 (0–55) | 258 | –5.3 (–12.8 to 2.2) |

| 6-month visit | 129 | 35.2 (34.4) | 29 (0–71) | 130 | 29.9 (29.1) | 28.5(0–56) | 259 | –5.3 (–13.1 to 2.5) |

| Measurement closest to 6 months post surgery | 129 | 35.3 (34.6) | 29 (0–71) | 130 | 29.8 (29.3) | 23.5 (0–57) | 259 | –5.5 (–13.3 to 2.3) |

| Change to 6 months post surgery | 129 | 18.9 (29.2) | 5.0 (0–41) | 130 | 19.4 (30.8) | 5 (0–43) | 259 | 0.6 (–6.8 to 7.9) |

| ( N ) | (%) | ( N ) | (%) | Unadjusted difference in proportionsa (%) (95% CI) | ||||

| Meaningful improvement | 129 | 56 | 43 | 130 | 61 | 47 | 259 | 3.5 (–8.6 to 15.6) |

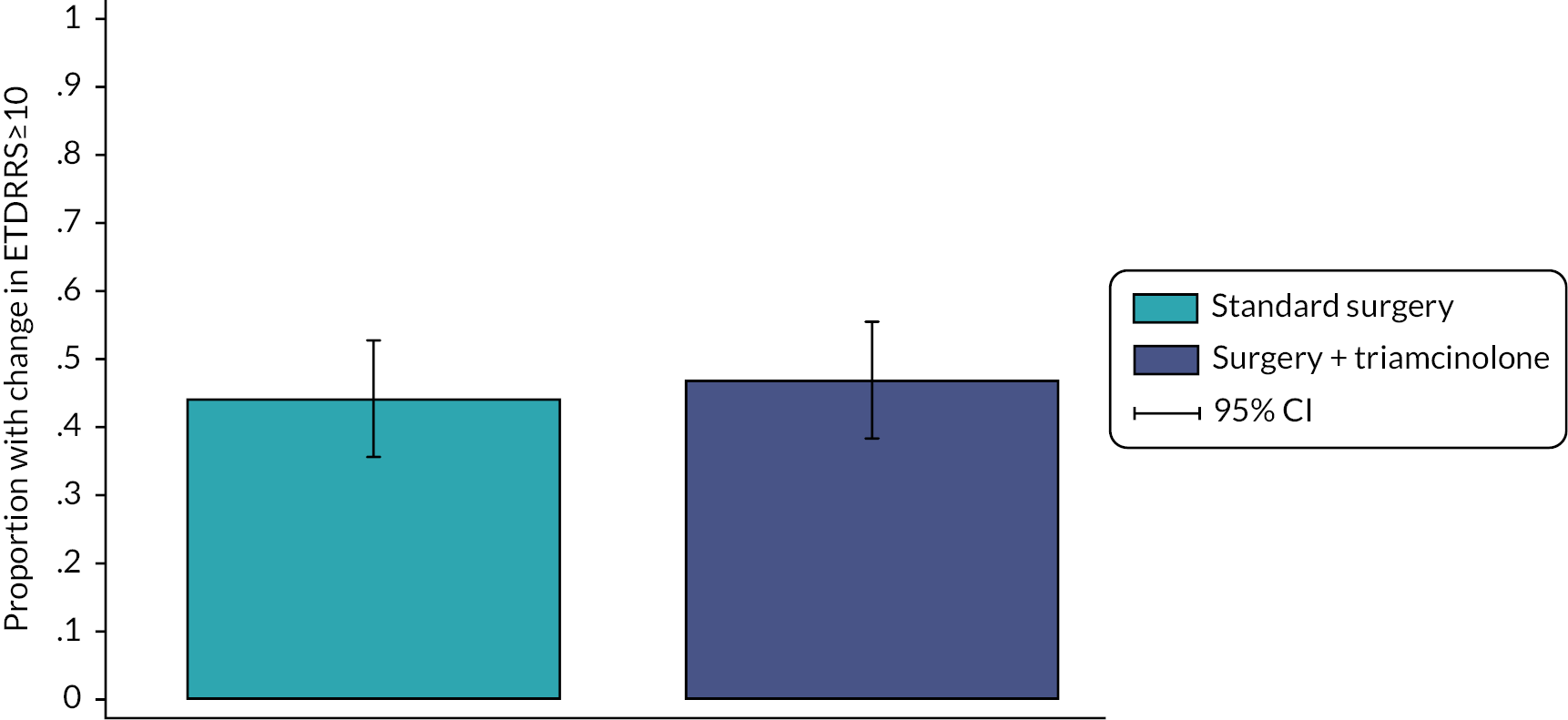

Primary outcome analysis

A total of 259 participants (standard surgery, n = 129; surgery plus adjunctive TA, n = 130) who had a six-month follow-up were included in the inferential analysis of the primary outcome. A total of 56 (43.4%) participants in the standard surgery arm experienced a clinically meaningful improvement in VA (6 month change in ETDRS ≥ 10) compared with 61 (46.9%) in the surgery plus adjunctive TA arm (unadjusted difference in proportion 3.5%, 95% CI –8.6% to 15.6%; Figure 2). The adjusted OR for a clinically meaningful change in VA for surgery plus adjunctive TA relative to standard surgery was 1.03 (95% CI 0.61 to 1.75, p = 0.908), indicating no difference between the treatment arms. The population averaged marginal probability of clinically meaningful improvement in VA was 41.8% in the standard surgery arm compared with 44.2% in the surgery plus adjunctive TA arm.

FIGURE 2.

Clinically meaningful improvement (≥10) in ETDRS at six months.

Missing data sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was conducted to explore the impact of the missing data on the primary ETRDS outcome. Table 5 summarises the missing data by treatment arm. Sensitivity analysis initially explored the robustness of the primary analysis results to two extreme MNAR assumptions (Table 8):

| Analysis | Treatment arm ORa (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Primary analysis ( N = 259) | ||

| MAR | 1.03 (0.61 to 1.75) | 0.908 |

| MNAR sensitivity analysis (N = 280) | ||

| Scenario 1 | 0.74 (0.45 to 1.23) | 0.245 |

| Scenario 2 | 1.46 (0.89 to 2.40) | 0.135 |

-

Participants in the standard surgery arm have meaningful change; participants in surgery plus adjunctive TA arm do not.

-

Participants in the standard surgery group do not have meaningful change; participants in surgery plus adjunctive TA arm do have meaningful change.

In comparison with the primary treatment effect (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.75), in scenario 1, the point estimate was more in favour of standard surgery (0.74, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.23) and in scenario 2, the point estimate was more in favour of surgery plus adjunctive TA (1.46, 95% CI 0.89 to 2.40). However, in both sensitivity analyses, inferences remained consistent with the primary analysis and did not identify a significant between treatment group difference.

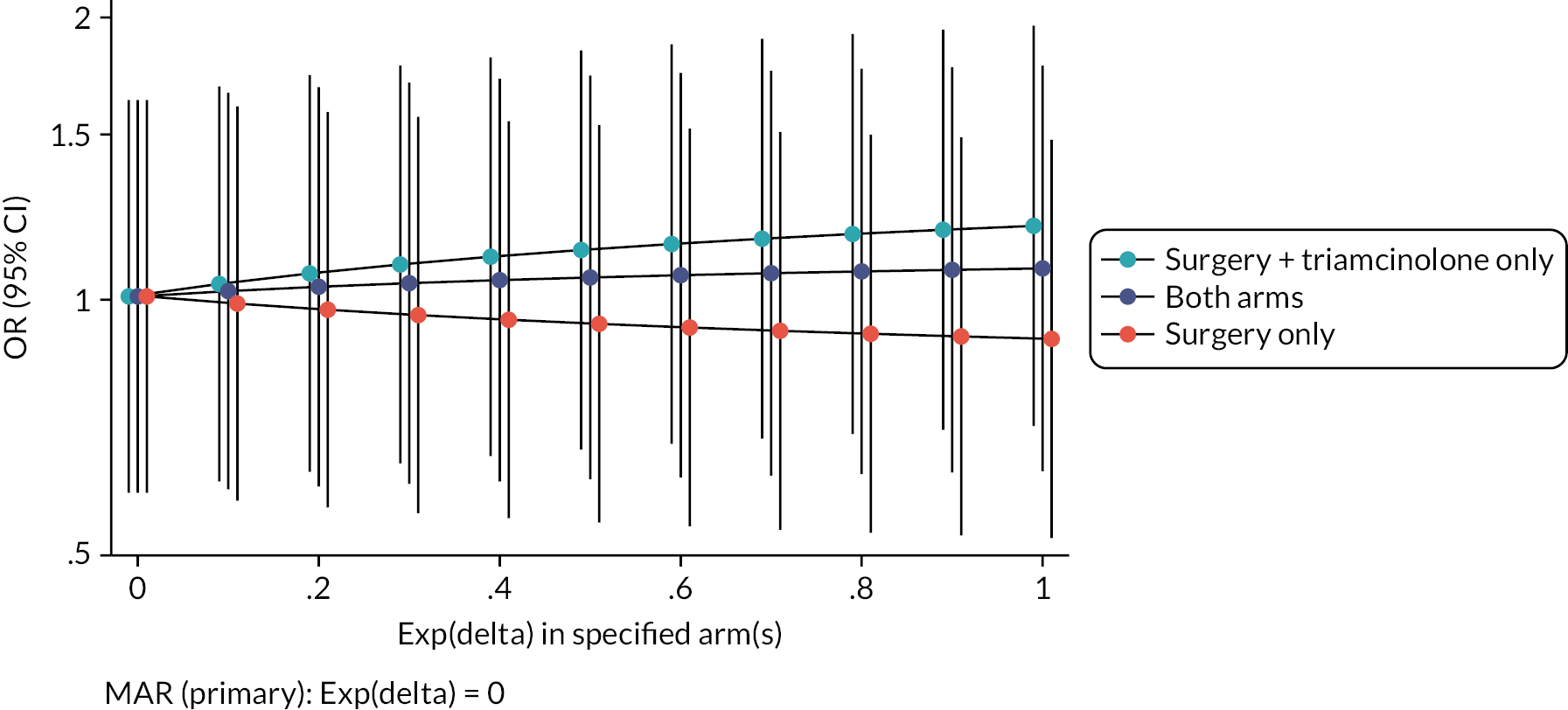

Further MNAR scenarios were explored using a range of plausible assumptions of the odds of clinically meaningful improvement among those with missing data being 0 to 1 times the odds of clinically meaningful improvement amongst the observed (Figure 3). In all additional MNAR analyses, the treatment effect (OR) remained close to 1 and the 95% CIs continued to contain OR = 1, indicating that in all evaluated scenarios there was no evidence of a significant treatment effect, consistent with the primary inference.

FIGURE 3.

Sensitivity analysis exploring the impact of data MNAR. (OR >1 indicates higher event rate in the adjunct arm).

Out of visit window sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis excluded data collected outside the visit window (6 months ± 4 weeks). An additional sensitivity analysis where data collected outside the four-week window was included, but where patients with data outside the four-week window were weighted by one-half was also be performed; Participants with data within the allowed visit window had a weight of one. In both sensitivity analyses, results were consistent with the primary analysis (Table 9).

| Analysis | Treatment arma OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Primary analysis: | ||

| Including out-of-window data (N = 259) | 1.03 (0.61 to 1.75) | 0.908 |

| Sensitivity analysis: | ||

| Excluding out-of-window data (N = 176) | 1.07 (0.56 to 2.07) | 0.833 |

| Weighting out-of-window data (N = 259) | 1.06 (0.60 to 1.88) | 0.847 |

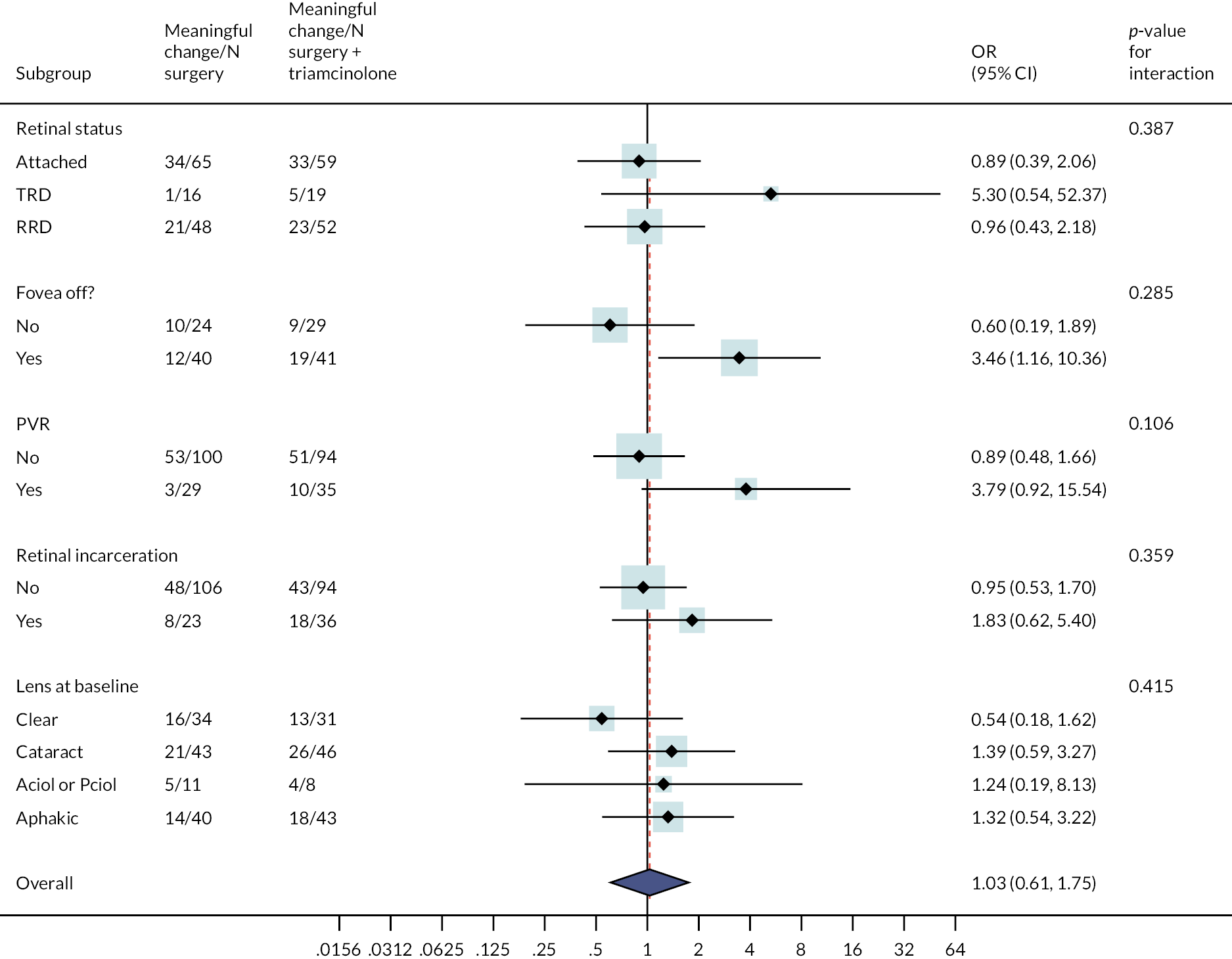

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis was performed for the primary outcome to explore the uniformity of the treatment effect found overall.

The p-values provide a test for whether there is any evidence to suggest that there is a difference in the overall treatment effect by the subgroups of interest. Subgroup effects should be interpreted with caution and viewed as exploratory, as the trial was not powered to detect subgroup effects; This is reflected by the large widths of the CIs for each subgroup effect depicted in Figure 4. For this reason, emphasis should be placed on the consistency of the treatment effect across the subgroups and not the individual effect within each subgroup. While there is some variation in the point estimates for individual subgroups, for all explored subgroup effects, the 95% CI overlap and the tests for interaction are not significant (p = 0.106 or larger).

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot showing the effect on meaningful change in ETDRS at six months of adding TA within subgroups. (a) Subgroup effects are not estimable for fovea involvement – splitting as only one participant observed in surgery plus TA arm to have splitting (no meaningful change). OR represents the baseline ETDRS adjusted odds of meaningful change for surgery plus TA relative to standard surgery for the associated subgroup. OR >1 means a higher event rate in the adjunct arm.

Principal secondary outcome

A total of 259 participants (standard surgery n = 129; surgery plus TA n = 130) were included in the analysis of the change in ETDRS at six months as a continuous outcome. The baseline adjusted mean difference in the month 6 change in ETDRS for surgery plus TA compared with standard surgery was –2.65 (95% CI –9.22 to 3.92, p = 0.430), with the point estimate in favour of standard surgery.

Bayesian analysis

In secondary Bayesian analysis using non-informative priors, the baseline adjusted mean difference in the month 6 change in ETDRS for surgery plus adjunctive TA compared with standard surgery was –1.01 (95% CI –7.13 to 5.75), with the point estimate in favour of standard surgery. The estimated probabilities of the six-month change in ETDRS and treatment group differences being greater than or equal to 0 to 50 letters are shown in Table 10. The probability of the six-month change in ETDRS being greater for surgery plus adjunctive TA relative to standard surgery was 0.372; this is a fairly low probability. The probability of the treatment group difference in six-month change in ETDRS being greater or equal than 10 points was very small, at 0.0001.

| Threshold change ETDRS | Posterior probability | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard surgerya | Surgery + TAb | Treatment group differencec | |

| ≥0 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.372 |

| ≥10 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.0001 |

| ≥20 | 0.830 | 0.741 | 0.000 |

| 30 | 0.018 | 0.007 | 0.000 |

| 40 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 50 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

There was high autocorrelation in the Bayesian MCMC sample, resulting in low precision for some model estimates. It was identified that the random centre effect was contributing to the high autocorrelation. Therefore, post hoc, the analysis model was simplified and a single-level linear regression model including fixed effects for baseline ETDRS and treatment group was also fitted with uninformative priors. In the simplified model, the adjusted mean difference in the month 6 change in ETDRS for surgery plus adjunctive TA compared with standard surgery was –0.19 (95% CI –6.34 to 5.94), with the point estimate in favour of standard surgery. Comparable to the results of the more complex Bayesian model, there was a low probability (0.495) of the six-month change in ETDRS being greater for surgery plus adjunctive TA compared with standard surgery and the probability of the treatment group difference in six-month change in ETDRS being greater or equal to 10 points higher for surgery plus adjunctive TA compared with standard surgery was very small, at 0.0001 (Table 11).

| Threshold change ETDRS | Posterior probability | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard surgerya | Surgery + TAb | Treatment group differencec | |

| ≥0 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.495 |

| ≥10 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.0001 |

| ≥20 | 0.952 | 0.940 | 0.000 |

| ≥30 | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| ≥40 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| ≥50 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Secondary outcomes

Retinal detachment with PVR at any time point within six months of the study vitrectomy

A total of 35/124 participants in the standard surgery arm experienced RD with PVR compared with 42/124 in the surgery plus adjunctive TA arm (28.2% vs. 33.9%). The OR for RD with PVR for surgery plus adjunctive TA, relative to standard surgery was 1.31 (95% CI 0.76 to 2.27, p = 0.327), with the point estimate in favour of standard surgery (Table 12).

| Treatment arm | Unadjusted difference in proportionsa (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard surgery (N = 124) | Surgery + TA (N = 124) | ||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| RD with PVR | 35 | 28.2 | 42 | 33.9 | 5.6 (–5.9 to 17.1) |

Stable complete retinal reattachment (without internal tamponade present) at six months post study vitrectomy

A total of 79/123 participants in the standard surgery arm experienced stable complete retinal reattachment (without internal tamponade present) at six months post study vitrectomy compared with 65/126 in the surgery plus adjunctive TA arm (64.2% vs. 51.6%). The OR for stable complete retinal reattachment for surgery plus adjunctive TA, relative to standard surgery, was 0.59 (95% CI 0.36 to 0.99, p = 0.044), in favour of standard surgery (Table 13).

| Treatment group | Unadjusted difference in proportionsa (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard surgery (N = 123) | Surgery + TA (N = 126) | ||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Stable complete retinal reattachment | 79 | 64.2 | 65 | 51.6 | –12.6 (–24.8 to –0.5) |

Stable macular retinal reattachment (without internal tamponade present) at six months post study vitrectomy

A total of 82/123 participants in the standard surgery arm experienced stable macular retinal reattachment (without internal tamponade present) at six months post study vitrectomy compared with 68/126 in the surgery plus adjunctive TA arm (66.7% vs. 54.0%). The OR for stable macular retinal reattachment for surgery plus adjunctive TA, relative to standard surgery was 0.59 (95% CI 0.35 to 0.98, p = 0.041), in favour of standard surgery (Table 14).

| Treatment group | Unadjusted difference in proportionsa (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard surgery (N = 123) | Surgery + TA (N = 126) | ||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Stable macular retinal reattachment | 82 | 66.7 | 68 | 54.0 | –12.7 (–24.7 to –0.7) |

Tractional retinal detachment within six months post study vitrectomy

A total of 30/123 participants in the standard surgery arm developed tractional RD within six months of the study vitrectomy compared with 35/124 in the surgery plus adjunctive TA arm (24.4% vs. 28.2%). The OR for tractional RD for surgery plus adjunctive TA relative to standard surgery was 1.22 (95% CI 0.69 to 2.15, p = 0.494), with the point estimate in favour of standard surgery (Table 15).

| Treatment group | Unadjusted difference in proportionsa (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard surgery (N = 123) | Surgery + TA (N = 124) | ||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Tractional RD within 6 months | 30 | 24.4 | 35 | 28.2 | 4.5 (–6.7 to 15.6) |

The number of additional operations to achieve stable retinal reattachment (either complete or macula) at six months after the study vitrectomy

The median number of additional operations to achieve stable retinal reattachment at six months after the study vitrectomy in the standard surgery arm was 0 (IQR 0–0), with minimum 0 and maximum 6 (N = 109). In the surgery plus adjunctive TA arm, the median number of operations was 0 (IQR = 0–1), with minimum 0 and maximum 4 (N = 114; Table 16). The incidence rate of operations over six months in the standard surgery arm was 0.37 (95% CI 0.27 to 0.50) and 0.42 (95% CI 0.32 to 0.56) in the surgery plus adjunctive TA arm. The unadjusted incident rate ratio for the number of operations by month 6 for the surgery plus adjunctive TA arm compared with the standard surgery arm was 1.15 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.75, p = 0.521). The adjusted incident rate ratio for the surgery plus adjunctive TA arm compared with the standard surgery arm was 1.15 (95% CI 0.68 to 1.94, p = 0.608) with the point estimate in favour of standard surgery.

| Number of operations | Standard surgery (N = 109) | Surgery + TA (N = 114) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| 0 | 86 | 79 | 76 | 67 |

| 1 | 16 | 15 | 30 | 26 |

| 2 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 6 |

| 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

Hypotony at any time point within six months of the study vitrectomy

A total of 26/124 participants in the standard surgery arm had hypotony within six months of the study vitrectomy compared with 25/123 in the surgery plus adjunctive TA arm (21.0% vs. 20.3%; Table 17). The adjusted OR of hypotony for surgery plus adjunctive TA relative to standard surgery was 0.96 (95% CI 0.52 to 1.78, p = 0.901), with the point estimate in favour of surgery plus TA.

| Treatment arm | Unadjusted difference in proportionsa (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard surgery (N = 124) | Surgery + TA (N = 123) | ||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Hypotony | 26 | 21.0 | 25 | 20.3 | –0.6 (–10.7 to 9.5) |

Post hoc sensitivity analysis

In accordance with the ASCOT statistical analysis plan, the above analysis of hypotony included data recorded on the secondary outcome forms at three and six months. Additional adverse events of hypotony (<6 mmHg) were recorded for eight participants (two standard surgery and six surgery plus adjunctive TA) on the adverse event form that were not captured on the three- or six-month secondary outcome form. This group of eight participants included one participant who later withdrew from the surgery plus adjunctive TA arm.

A post hoc analysis combined the data on hypotony across the two data sources. A total of 28/124 participants in the standard surgery arm had hypotony within six months of the study vitrectomy compared with 31/125 in the surgery plus adjunctive TA arm (22.6% vs. 24.8%) as recorded on the secondary outcome forms at three or six months or on the adverse event form (Table 18). The OR of hypotony for surgery plus adjunctive TA relative to standard surgery was 1.13 (95% CI 0.63 to 2.03, p = 0.680), which was comparable with the main analysis of hypotony with the point estimate in favour of surgery plus TA.

| Treatment arm | Unadjusted difference in proportionsa (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard surgery (N = 124) | Surgery + TA (N = 125) | ||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Hypotony | 28 | 22.6 | 31 | 24.8 | 2.2 (–8.3 to 12.8) |

Raised intraocular pressure at any time point within six months of the study vitrectomy

A total of 35/126 participants in the standard surgery arm experienced raised IOP within six months of the study vitrectomy compared with 56/124 in the surgery plus adjunctive TA arm (27.8% vs. 45.2%) as recorded on the secondary outcome forms at three or six months. The OR of raised IOP for surgery plus adjunctive TA relative to standard surgery was 2.14 (95% CI 1.26 to 3.62, p = 0.005) in favour of standard surgery (Table 19).

| Treatment arm | Unadjusted difference in proportionsa (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard surgery (N = 126) | Surgery + TA (N = 124) | ||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Raised IOP | 35 | 27.8 | 56 | 45.2 | 17.4 (5.6 to 29.1) |

Post hoc sensitivity analysis

In accordance with the ASCOT statistical analysis plan, the analysis of raised IOP included data recorded on the secondary outcome forms at three and six months. Additional adverse events of raised IOP (>25 mmHg) were recorded for seven participants (five standard surgery and two surgery plus adjunctive TA) on the adverse event form that were not captured on the three- or six-month secondary outcome form. This group of seven participants included two participants who withdrew from the trial sometime after the recording of IOP (one from each arm).

A post hoc analysis combined the data on IOP across the two data sources. A total of 40/127 participants in the standard surgery arm experienced raised IOP within six months of the study vitrectomy compared with 58/125 in the surgery plus adjunctive TA arm (31.5% vs. 46.4%) as recorded on the secondary outcome forms at three or six months or on the adverse event form. The OR of raised IOP for surgery plus adjunctive TA relative to standard surgery was 1.88 (95% CI 1.13 to 3.15, p = 0.016), which was comparable with the main analysis of raised IOP in favour of standard surgery (Table 20).

| Treatment arm | Unadjusted difference in proportionsa (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard surgery (N = 127) | Surgery + TA (N = 125) | ||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Raised IOP | 40 | 31.5 | 58 | 46.4 | 14.9 (3.0 to 26.8) |

Development of macular pucker by three and six months or macular pucker surgery at any time point within six months of study vitrectomy

A total of 25/122 participants in the standard surgery arm developed macular pucker within six months of the study vitrectomy or underwent macular pucker surgery compared with 37/124 in the surgery plus adjunctive TA arm (20.5% vs. 29.8%). The OR for surgery plus adjunctive TA relative to standard surgery was 1.65 (95% CI 0.92 to 2.96, p = 0.093) with the point estimate in favour of standard surgery (Table 21).

| Treatment group | Unadjusted difference in proportionsa (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard surgery (N = 122) | Surgery + TA (N = 124) | ||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Macular pucker | 25 | 20.5 | 37 | 29.8 | 9.3 (–1.4 to 20.1) |

Visual Function Questionnaire-25

A total of 213 participants (standard surgery n = 105; surgery plus adjunctive TA n = 108) had baseline and six-month VFQ-25 available and were included in the analysis of the VFQ-25. The adjusted mean difference in the month 6 VFQ-25 for surgery plus adjunctive TA relative to standard surgery was 0.78 (95% CI –3.53 to 5.10, p = 0.723), with the point estimate in favour of surgery plus TA (Table 22).

| Time | Treatment arm | Total N | Unadjusted mean differencea (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard surgery | Surgery + TA | |||||||

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | |||

| Baseline | 137 | 66.5 | 19.4 | 143 | 64.3 | 21.4 | 280 | – |

| Month 3 | 109 | 71.8 | 18.4 | 109 | 70.1 | 17.7 | 218 | –1.6 (–6.5 to 3.2) |

| Month 6 | 108 | 71.9 | 20.9 | 113 | 72.0 | 20.1 | 221 | 0.1 (–5.3 to 5.5) |

Safety event reporting