Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 16/152/01. The contractual start date was in November 2019. The draft report began editorial review in February 2023 and was accepted for publication in August 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this manuscript.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Brown et al. This work was produced by Brown et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Brown et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

In critically ill children, healthcare-associated infections (HCAIs) are a major cause of morbidity and mortality, with an incidence of 7–14%. 1–5 HCAIs can develop either as a direct result of healthcare interventions such as medical or surgical treatment or from being in contact with a healthcare setting. HCAIs can be caused by opportunistic microorganisms, residing in the oral cavity and gastrointestinal tract directly or haematogenously spreading to other organ systems. 1,2 Critical illness affects immune competence, and in those requiring prolonged organ support, this, along with the presence of invasive devices such as urinary catheters, vascular lines and endotracheal tubes, places them at risk of secondary infection. Evidence from adult intensive care studies suggests that using selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD) alongside standard infection control measures may reduce mortality and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), although results are mixed in terms of clinical benefit. 1,6 There are no data to suggest a significant increase in antimicrobial resistance following use of SDD; in fact, a recent multicentre clinical trial found a significant reduction in positive blood cultures and cultures of antibiotic-resistant organisms and no significant increase in new Clostridiodes difficile infections in patients who received SDD. Overall antibiotic use was not increased in patients receiving SDD. 7 A meta-analysis of 32 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) including 24,389 participants suggests that use of SDD compared with standard care or placebo was associated with reduced hospital mortality. 8

Despite these data, SDD has not been routinely adopted due to concerns that it may promote antimicrobial resistance. 9,10 Recent ecological studies conducted in adult intensive care have found that SDD was associated with a reduction in antimicrobial utilisation. 11–15

SDD has not been compared directly with modern infection control protocols in the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) population, with only single-centre and small observational studies reporting its implementation as part of infection control regimens. 16

A clinical trial comparing SDD with standard infection control methods to establish safety and clinical utility is needed in the PICU setting, but the paucity of available data in children suggested a need to establish whether a large, multicentre cluster RCT (cRCT) is feasible, and if so, what components of trial design, safety monitoring and clinical outcomes are of importance to patients and clinical staff caring for critically ill children.

Infection Control in Paediatric Intensive Care (PICnIC) is a feasibility study commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme, which aims to determine whether it is possible to conduct a cRCT of SDD in critically ill children who are likely to be ventilated for > 48 hours, and to explore and test the acceptability of key components of the study to healthcare professionals and families of patients.

Aim

The main aim of the PICnIC Feasibility Study was to determine whether it was feasible to conduct a multicentre trial in critically ill children comparing SDD with standard infection control procedures by undertaking a pilot cRCT with integrated mixed-methods study exploring the views of patients, their families and clinical staff both within the study PICUs and more broadly across the NHS England PICU setting.

Objectives

The Infection Control in Paediatric Intensive Care pilot randomised controlled trial

-

To test the ability to randomise PICUs to either control or intervention.

-

To test the willingness and ability of healthcare professionals to screen and recruit eligible children.

-

To estimate the recruitment rate of eligible children.

-

To test adherence to the SDD protocol.

-

To test the procedures for assessing and collecting selected clinical and ecological outcomes and for adverse event (AE) reporting.

-

To assess the generalisability of the study results to all PICUs using the Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network (PICANet).

The Infection Control in Paediatric Intensive Care mixed-methods study

Perspectives of PICU healthcare professionals:

-

To assess the acceptability of implementation of the SDD intervention, recruitment and consent procedures.

-

To assess the acceptability of collecting data to assess the selected clinical and ecological data.

-

To assess the acceptability of the SDD intervention and confirm interest in participation in a definitive trial in the wider PICU community.

Perspectives of parents/guardians of recruited patients:

-

To review and explore the acceptability of a definitive trial that includes the SDD intervention.

-

To test the acceptability of the recruitment and consent procedures for the definitive trial, including all proposed information materials.

-

To review and explore selection of important, relevant, patient-centred primary and secondary outcomes for a definitive trial.

Research governance

An ethics application was made to the West Midlands – Black Country Research Ethics Committee (20/WM/0061) and received a favourable opinion on 3 November 2020, with approval granted by the Health Research Authority (HRA) on 20 November 2020. The PICnIC pilot RCT was registered on the ClinicalTrials.gov database. Registration was confirmed on 30 October 2020 (reference number: ISRCTN40310490). The protocol is available at https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/12/3/e061838 (accessed 26 January 2023).

Local confirmation of capacity and capability was obtained from each of the six PICU sites participating in the PICnIC pilot RCT. The statement of activities and agreements for non-commercial research in the health service were signed by each participating hospital trust, the Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) and the sponsor (The Masters and Scholars of the University of Cambridge and Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust).

Clinical data collection on patients enrolled into the PICnIC pilot RCT was embedded in the PICANet, which has approval to collect patient-identifiable and personal data without consent. The release of non-identifiable patient data was requested through a customised data collection request to the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership for access to unidentifiable routine PICANet data and to collect the additional data required to assess the wider UK feasibility of a definitive PICnIC study. Approval was received for this purpose on 16 August 2022.

Study management

The PICnIC Study was sponsored jointly by the University of Cambridge and Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. The PICnIC pilot cRCT was led by chief investigator NP and coinvestigator PRM. It was coordinated by the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC) CTU (UK Clinical Research Collaboration ID number: 42). The PICnIC mixed-methods study was led by coinvestigator KW. An experienced research associate (MP) was employed to organise, conduct and analyse data from this study. A Study Management Group (SMG) was convened, comprising the chief investigator (NP) and coinvestigators (JP, BHC, RF, TG, RS, LNT, IS, KW, DAH, PRM, KR), and was responsible for overseeing management of the entire study. The SMG met regularly throughout the duration of the study to monitor the conduct and progress. One coinvestigator (IS) has experience of a critical illness and PICU admission, providing valuable input into the design and conduct of the PICnIC Study.

The study co-ordinators (AB, GM, LD) were responsible for day-to-day management of the PICnIC feasibility study, with support from the ICNARC CTU and the SMG.

Network support

To maintain the profile of the PICnIC study, including the mixed-methods work, updates were provided at national meetings, such as the biannual Paediatric Critical Care Society Study Group meetings.

Patient and public involvement

Caregivers of children admitted to PICU and a former patient were involved in prioritising the outcomes and designing the study protocol. Their input continued with patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives on the study oversight panel and development of the topic guide for the qualitative study. A patient representative (a former PICU patient) is a coinvestigator and is an author of this manuscript. IS undertook a review of the study protocol, participant documentation and giving patient perspectives to shape the approach to study recruitment. IS also reviewed documents for parent interviews and made suggestions that were integrated into the final version of the documents, such as follow-up questions on what did or did not influence parents’ decisions to participate in the pilot. IS continued to remain involved over the course of the study, reviewing progress and findings at the Trial Management Group (TMG) meetings.

Chapter 2 Methods for the Infection Control in Paediatric Intensive Care pilot cluster-randomised controlled trial

Aim and objectives

-

To test the ability to randomise PICUs to either control or intervention.

-

To test the willingness and ability of healthcare professionals to screen and recruit eligible children.

-

To estimate the recruitment rate of eligible children.

-

To test adherence to the SDD protocol.

-

To test the procedures for assessing and collecting selected clinical and ecological outcomes and for AE reporting.

-

To assess the generalisability of the study results to all PICUs using the PICANet.

Methods

Study design

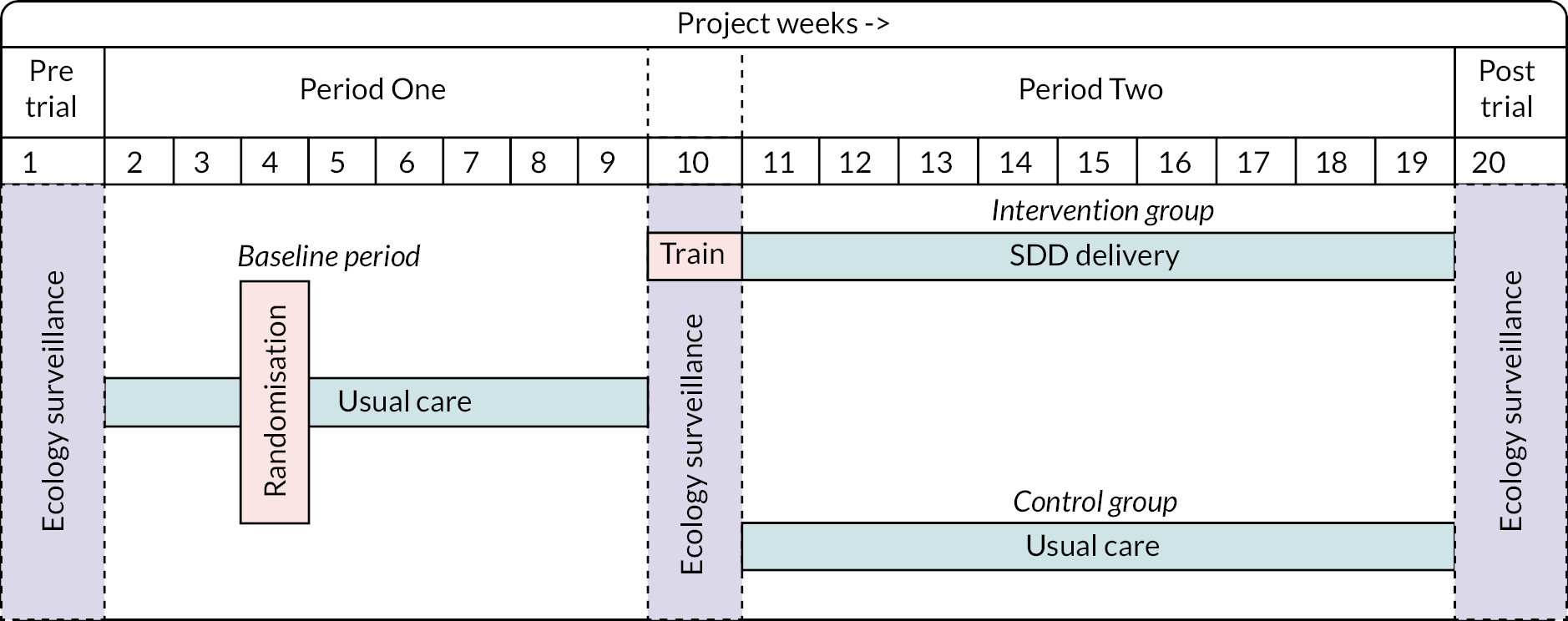

The PICnIC pilot cRCT was an external pilot, parallel-group cRCT, with recruitment for a period of 18 weeks. There were three ecology periods to monitor unit ecology before (week 1), during (week 10) and after (week 20) the two study periods.

Data collection was streamlined by integrating patient-level data collection with existing unit data entry into the national PICANet database. By nesting the study within the national clinical audit of paediatric critical care units in the UK, we ensured a cost-effective, time-efficient design with respect to data collection and trial management within the participating PICUs.

Period One consisted of usual care at all sites (from weeks 1 to 8) as per each unit’s own local practice. This was the baseline period. During this period, the six sites were randomised to either continue their routine infection control practice (usual care sites, n = 3) or incorporate SDD into their local infection control regime for eligible children (intervention sites, n = 3) in Period Two.

In Period Two, after a week of training and transition (week 11), sites were split into usual care and intervention sites from weeks 12 to 19 as per randomisation. The intervention period continued for 8 weeks, during which time intervention sites delivered the SDD intervention using research without prior consent (RWPC), while control sites continued to deliver usual care.

The study flow is demonstrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Trial schema pilot cRCT.

Handling of missing data

The proportion of variables included in the analyses that were missing were reported. No measures were taken to replace missing values.

Study management

The study co-ordinator at the ICNARC CTU was responsible for the day-to-day management of the pilot RCT with support from the SMG.

Patient and public involvement

Engagement with patients was vital to the successful conduct of the PICnIC pilot RCT and included the mixed-methods approaches (see Chapter 4), along with involvement of patient stakeholders in the development and oversight of the PICnIC RCT. A parent of a child who was admitted to a PICU with severe infection provided input to the PICnIC pilot RCT design. A former patient on a PICU (IS) is a coinvestigator and provided patient input for development of the pilot RCT, including reviewing the study literature given to patients and their families [e.g. participant information sheets (PISs)]. In addition to this, patients and members of the public were engaged through the PICnIC qualitative study, which has provided invaluable insight that has been incorporated into the recommendations arising from the overall study.

Design and development of the protocol

The PICnIC pilot RCT protocol was designed to inform key parameters and to test the design and possible conduct of the proposed definitive PICnIC RCT.

Amendments to the Infection Control in Paediatric Intensive Care pilot randomised controlled trial protocol

Following receipt of approval from the HRA on 20 November, 12 non-substantial amendments were approved and categorised.

National Health Service support costs

The NHS support costs were agreed prior to the submission of the research grant to include screening to identify eligible patients and obtaining informed consent from parents. These included costs for microbiology swab tests and the administration of SDD at sites allocated to intervention in Period Two of the study.

Setting

The setting for the pilot cRCT was six NHS PICUs in England. For the pilot RCT, each site was obliged to:

-

meet the responsibilities stated in the PICnIC pilot RCT clinical trial site agreement

-

identify and sign up a local principal investigator (PI)

-

identify a responsible research nurse

-

agree to incorporate SDD in infection control if randomised to intervention in Period Two

-

agree to adhere to the study protocol

-

agree, where possible, to recruit all eligible patients and to maintain a screening log.

Site selection

Six sites that had previously expressed an interest in participating in the PICnIC cRCT were selected. Potential sites were asked to complete a site feasibility questionnaire to confirm eligibility by the ICNARC CTU. None of the sites had experience of delivery of SDD in clinical care. Two sites expressed interest as reserve sites but did not need to participate. The reasons for selection included a good research track record, a display of a high level of enthusiasm and ensuring a good diversity of sites.

Site initiation

Site teams from all six participating sites attended a site initiation meeting prior to the commencement of patient screening. These were held online to minimise the risk of infection transmission during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the first meeting, the chief investigator presented the background and rationale for the PICnIC pilot RCT. The meetings included discussion of the protocol, screening and recruitment of patients, data collection and microbiology screening procedures.

Following randomisation, a second site initiation visit was undertaken for the three sites randomised to SDD, where the local PIs and pharmacists attended and were given information on the protocol for prescribing and administering the SDD oral solution and paste. The operational challenges of conducting the PICnIC pilot RCT at sites were discussed, including strategies for communicating the study to all PICU staff. The PI and trial manager maintained close contact with these sites to address any questions that arose as the clinical teams integrated SDD into their infection control procedures.

Investigator site file

An investigator site file was provided to all participating sites. This contained all essential documents for the conduct of the PICnIC pilot RCT and included the approved protocol; all relevant approvals (e.g. local confirmation of capacity and capability); a signed copy of the clinical trial site agreement; the delegation of trial duties log; and copies of the approved PISs, parent/legal representative consent forms and all standard operating procedures (e.g. for screening participants, delivery of the intervention, obtaining informed consent and entering data onto the secure, dedicated eCRF). The site PI was responsible for maintaining the investigator site file.

Randomisation procedure

During week 4, the six participating PICUs were randomised by the trial statistician using computer-based randomisation to either usual care or intervention. Sites were informed of the randomisation outcome on week 8.

Screening log

To enable full and transparent reporting, brief details of all patients who met the inclusion criteria were recorded in the screening log. If the patient was deemed ineligible because they met one or more of the exclusion criteria, this was recorded in the screening log. The reasons for eligible patients not being recruited were recorded under the following categories: limited research capacity, missed patients, clinical decision, nearly or reached recruitment target, anal atresia and no rectum.

Consent

Informed consent for routine microbiology and administration of SDD in sites randomised to intervention was not required, as these were undertaken as part of the routine PICU infection control procedures. Where the study protocol required additional swab samples, these were collected following consent. Staff members who had received training on the background, rationale and purpose of PICnIC and on the principles of good clinical practice were authorised by the PI to take informed consent from parents/legal representatives.

The method used for the PICnIC pilot RCT was RWPC. In line with guidance,17 once notified of the recruitment of a participant to the trial, a delegated member of the site research team approached the parents/legal representatives as soon as practical and appropriate following confirmation of eligibility (usually within 24–48 hours) to discuss consent for ongoing participation. Information about the PICnIC pilot RCT was provided to the parents/legal representatives, which included the purpose of the trial, the reasons why informed consent prior to randomisation could not be sought from parents/legal representatives, what participation in the trial meant (i.e. permission for the use of data already collected and/or for their child to continue to take part in the trial procedures when applicable), participant confidentiality, future availability of the results of the trial and funding of the study. It also provided information on completing a questionnaire and/or taking part in a telephone interview as part of the mixed-methods study. This information was provided in the PIS, along with the name and contact details of the local PI and research nurse(s), which was given to the parents/legal representatives to read before making their decision for their child’s data to be used, or not, and for their child to continue to take part, or not, in the trial. Once the staff member taking informed consent was satisfied that the parents/legal representatives had read and understood the PIS and that all their questions about the trial had been answered, the parents/legal representatives were invited to sign the consent form.

Intervention

The intervention selected was the addition of SDD to the standard infection control strategy of the participating PICU. The intervention consisted of three topical antimicrobial agents – colistin, tobramycin and nystatin – prepared according to international standards for Good Manufacturing Procedures and manufactured in a Therapeutic Goods Administration-approved facility (Verita Pharma®, Sydney, under licence from the George Institute for Global Health, Sydney; see Appendix 1). The SDD preparations were manufactured specifically for the Selective Decontamination of the Digestive Tract in the Intensive Care Unit (SuDDICU) RCT conducted in Australia and Canada between 2017 and 2023. 7 The SDD preparations were prepared as a topical oral paste and gastric suspension that underwent extensive temperature and stability testing. The SDD preparations were imported under temperature-controlled conditions to the UK for this pilot trial. The products were assigned a shelf life of 12 months, being stored at 4 °C. After reconstitution by the bedside nurse, the enteric suspension was stable at room temperature for up to 1 week. SDD paste and suspension were administered every 6 hours to all eligible patients as follows:

-

topical application of a pea-sized (0.5 g) SDD paste containing 2% polymyxin E (colistin), 2% tobramycin and 2% nystatin to the buccal mucosa and oropharynx

-

enteric administration via feeding tube of SDD liquid suspension on an age-based dosing schedule (Table 1) containing polymyxin E (colistin), tobramycin and nystatin.

| 0–4 years | 5–12 years | ≥ 13 years | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymyxin E (Colistin) | 25 mg | 50 mg | 100 mg |

| Tobramycin | 20 mg | 40 mg | 80 mg |

| Nystatin | 0.5 × 106 IU | 1 × 106 IU | 2 × 106 IU |

| Volume | 2.5 ml | 5 ml | 10 ml |

Selective decontamination of the digestive tract treatment was protocolised to be started within 6 hours of the patient being identified as eligible and continued for a maximum of 30 days (defined as the treatment period). Treatment continued until the patient was extubated or no longer mechanically ventilated (in tracheostomised patients). The intervention was restarted if patients were subsequently re-intubated (either during this PICU admission or re-admission to PICU from another inpatient area) during the treatment period. All other usual care was provided at the discretion of the treating clinical team.

In all sites during all trial periods, nasopharyngeal and faecal/rectal swab samples were taken from all patients at admission as part of routine care and then where consent was obtained these were repeated twice weekly. The nasopharyngeal swab was plated for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) detection. Faecal/rectal swabs were plated for:

-

extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) and AmpC producing organisms

-

carbapenemase producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE)

-

vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE)

-

Candida auris.

During the ecology surveillance weeks, where consent was obtained for additional study specific samples, patients had an additional sample taken at least every 48 hours during the course of the week if they remained an inpatient. Samples were not taken after the end of the ecology screening week, regardless of when the patient had been admitted. During Periods One and Two, where consent was obtained for additional study specific samples, these were taken at least twice weekly. Patients who did not consent for additional study samples had samples taken only if clinically indicated as part of routine care, according to local practice. At all time points, microbiology data were obtained from samples taken for clinical reasons, including blood, nasopharyngeal, stool/rectal swabs, urine, sputum/secretions from the endotracheal tube and wound swabs.

Participants

Pilot cluster-randomised controlled trial eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

> 37 weeks corrected gestational age to < 16 years.

-

Receiving mechanical ventilation.

-

Expected to remain on mechanical ventilation for ≥ 48 hours (from the time of screening).

Exclusion criteria

-

Known allergy, sensitivity or interaction to polymyxin E (colistin), tobramycin or nystatin.

-

Known to be pregnant.

-

Death perceived as imminent.

Ecology period eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

All patients admitted to the PICU, regardless of ventilation status, during any of the three ecological surveillance periods.

There were no exclusion criteria for the ecology periods.

Data collection

Baseline patient characteristics

Baseline data were collected at critical care admission via data linkage with PICANet, and directly via trial case report forms (CRFs). The following baseline demographic and clinical data were summarised overall and by allocated treatment group and study period:

-

age (years) – median [interquartile range (IQR)]

-

age group (< 1 year, 1 year, 2 – 4 years, 5 – 9 years, 10 – 16 years) – number and %

-

sex (male, female) – number and %

-

weight (kg) – median (IQR)

-

ethnic group

-

Paediatric Index of Mortality (PIM) 3 score18 – median (IQR)

-

main reason for PICU admission.

Outcome definitions

The outcomes of this study were selected to measure the respective objectives as previously stated and were focused on assessing the feasibility of a larger-scale definitive study. Specifically, these were as follows:

-

The ability to randomise PICUs to either control or intervention was assessed by the successful random assignment of three PICUs to the intervention without delay to subsequent phases of the trial.

-

The willingness and ability of healthcare professionals to screen and recruit eligible children were assessed by the proportion of eligible children recorded on study screening logs successfully recruited to the pilot cRCT as a percentage of total eligible admissions, and the reported reasons for non-recruitment.

-

The potential recruitment rate for a future definitive cRCT trial of SDD-enhanced infection control in eligible children was estimated by combining the proportion of eligible children recruited to the pilot cRCT with the size of the potentially eligible population (estimated from nesting the screening log data from participating PICUs with the national UK PICU data from PICANet).

-

Adherence to the SDD protocol was assessed using the proportion of eligible children allocated to the intervention receiving (1) both elements and (2) each individual element of the SDD intervention, the number of days on which these elements were received relative to days eligible for the SDD intervention and the reported reasons for non-adherence.

-

Procedures for assessing and collecting selected clinical and ecological outcomes and for AE reporting were assessed using the proportion of children with complete data for these outcomes (as listed later) including, for ecological outcomes, the proportion consenting to additional study specific sample collection.

-

Generalisability of the study results to all UK PICUs was assessed by comparing baseline characteristics (as listed earlier) and potential outcome measures (as listed later) for children recruited to the pilot cRCT with data from all potentially eligible children (receiving invasive mechanical ventilation for at least three calendar days) within participating PICUs and within all UK PICUs (from PICANet).

With the aim of understanding potential patient-centred primary and secondary outcome measures for the definitive cRCT, the following potential outcome measures were reported by arm and trial period (during the ecology surveillance weeks, only HCAIs and positive microbiology results were recorded):

-

HCAI (confirmed/presumed) – as defined by a local microbiology and clinical team as infections acquired during the PICU stay (presented as number and % of enrolled patients)

-

any positive microbiology swab or sample – result, n/N (% of enrolled patients)

-

duration of invasive ventilation (days) – mean [standard deviation (SD)] and median (IQR)

-

days alive and free of ventilation to day 28 – median (IQR)

-

length of hospital stay days from confirming eligibility to hospital discharge – mean (SD) and median (IQR)

-

length of stay in PICU: hours from confirming eligibility to PICU discharge – mean (SD) and median (IQR)

-

PICU survival: status (alive or dead) before PICU discharge – number and %

-

hospital mortality: status (alive or dead) before hospital discharge – number and %.

-

mortality within 30 days post enrolment (alive or dead): from the patients’ survival status as of 30 days post enrolment on the CRF – number and %.

Safety monitoring and adverse events

Adverse event reporting followed the HRA guidelines on safety reporting in non-clinical trial investigational medicinal product studies.

The ICNARC CTU monitored data for documented AEs that are not considered to be related to the trial treatment. In the event that any trial procedure appeared to be resulting in AEs, the TMG was contacted for their opinion.

Data management

Participant data were entered onto a secure web-based data entry system. The site PI oversaw and was responsible for data collection, quality and recording. Collection of data could be delegated by the site PI to qualified members of the research team recorded on the Delegation Log. All data were collected and processed in line with General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Data entered onto the secure trial database underwent validation checks for completeness, accuracy and consistency of data. Queries on incomplete, inaccurate or inconsistent data were sent to the research team at participating sites for resolution. During the conduct of the trial, all electronic participant data were encrypted, and all trial documents stored securely at the site or the ICNARC CTU, as appropriate. On completion of the trial, all participant data (electronic and paper) and other trial documents were archived securely and will be retained for 10 years at the site, the sponsor or at the ICNARC CTU, as appropriate.

Sample size

The PICnIC pilot study was set up to test the feasibility of the protocol to recruit eligible patients. Therefore, there was no primary outcome to be compared between the two groups and, hence, a power calculation to determine sample size was not appropriate. Instead, the sample size has been determined to be adequate to estimate critical parameters to be tested to a necessary degree of precision. Based on available data from PICANet, it was anticipated that the participating sites would see approximately 4.5 eligible children per week; therefore, the anticipated recruitment rate was three children per PICU per week providing a total of approximately 324 children in 18 weeks, of which 90 would receive the intervention. Assuming an intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.05 (average ICC for binary process measures in implementation studies, reported by the Health Services Research Unit at the University of Aberdeen),19 this sample size would enable rate parameters (recruitment, adherence, follow-up) with an observed value of 80% or greater to be estimated with a precision of ± 10% or less.

Statistical methods

The analyses were conducted using Stata/MP™ version 16.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). All recruited patients were included with the trial population, excluding only those who withheld or withdrew consent to data collection. Children were analysed according to the group they were randomised to (based on site and date of recruitment), irrespective of whether the treatment allocated was received.

Screening and eligibility

The numbers of participants screened and deemed eligible are reported overall and by site.

Recruitment

The numbers of participants enrolled, consented (for study-specific procedures and use of their clinical data) are reported by site and treatment summarised as a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram. 20 The numbers of patients enrolled are reported per site and period of the study. When reported, the reasons for exclusion and non-consent are also summarised. Recruitment to the pilot cRCT was summarised graphically and presented as a rate of patients per week, overall and by site and study period.

Baseline demographic and clinical data were summarised for the trial population overall and by treatment group and study period. In addition, using PICANet data, patients’ characteristics are reported for potentially eligible children within participating PICUs, and within all UK PICUs, by study period. There was no statistical testing for any of the summary measures while comparing the baseline variables.

Adherence and protocol deviations

The number of screened patients, and the number and percentage of patients found to have been ineligible, together with the reasons for ineligibility (inclusion criteria not met or exclusion criteria met), were reported by treatment group and study period.

The number and percentage of patients with at least one protocol deviation in the SDD intervention group was reported, and the total number of such deviations. A deviation was defined as any of the following:

-

SDD treatment starts > 6 hours after being identified as eligible

-

SDD treatment starts within 6 hours of being identified as eligible but continues for more than 30 days (treatment period) or finishes before the patient is extubated/no longer mechanically ventilated

-

dose of one or both SDD treatments were not given, and patient was mechanically ventilated

-

dose was wrongly administered (four per day, every 6 hours while intubated).

Analysis principles

Data completeness of clinical and ecological outcomes and for AE reporting are summarised using counts and percentages, by intervention group and treatment period.

Potential outcome measures were summarised using counts and percentages (for binary outcomes), median and IQR (for all continuous outcomes), and means and SDs (for length of stay and duration of treatment), and they were reported by intervention group and study period.

To account for cluster randomisation, multilevel logistic or generalised linear regressions were used to estimate potential treatment effects. The effect estimate was calculated as the interaction between treatment group and time period and reported either as an odds ratio with 95% confidence interval (CI; for binary outcomes) or as difference in means with 95% CIs (for continuous outcomes). These calculations were done only to inform planning of a definitive trial and should not be used to draw any conclusions regarding differences in outcomes between treatment groups.

To determine the most appropriate primary outcome for a definitive trial, for all potential outcome measures the number of patients with complete data in each treatment group are reported. For measures requiring data linkage with routine data sources (PICANet), the proportion of successfully linked records are reported.

Confidence intervals and p-values

As this was a pilot cRCT and not powered to detect differences in outcomes, analyses were treated as exploratory and were mainly descriptive. p-values were not calculated or quoted. Effect estimates were reported with a 95% CI.

Missing data

To assess the follow-up procedures, the number (%) of participants with complete follow-up data for each of the potential outcome measures for the definitive RCT, overall and by treatment group, is reported. All analyses were undertaken in the trial population. There was no imputation of missing data.

Harms

The number and percentage of participants experiencing each prespecified AE (plus any other AEs as reported) while in PICU were collected for each treatment group. Numbers of serious AEs (SAEs), severity and reported relatedness SDD administration in the intervention sites during Period Two are also reported.

Chapter 3 Results of the Infection Control in Paediatric Intensive Care pilot cluster-randomised controlled trial

Screening and recruitment

Sites

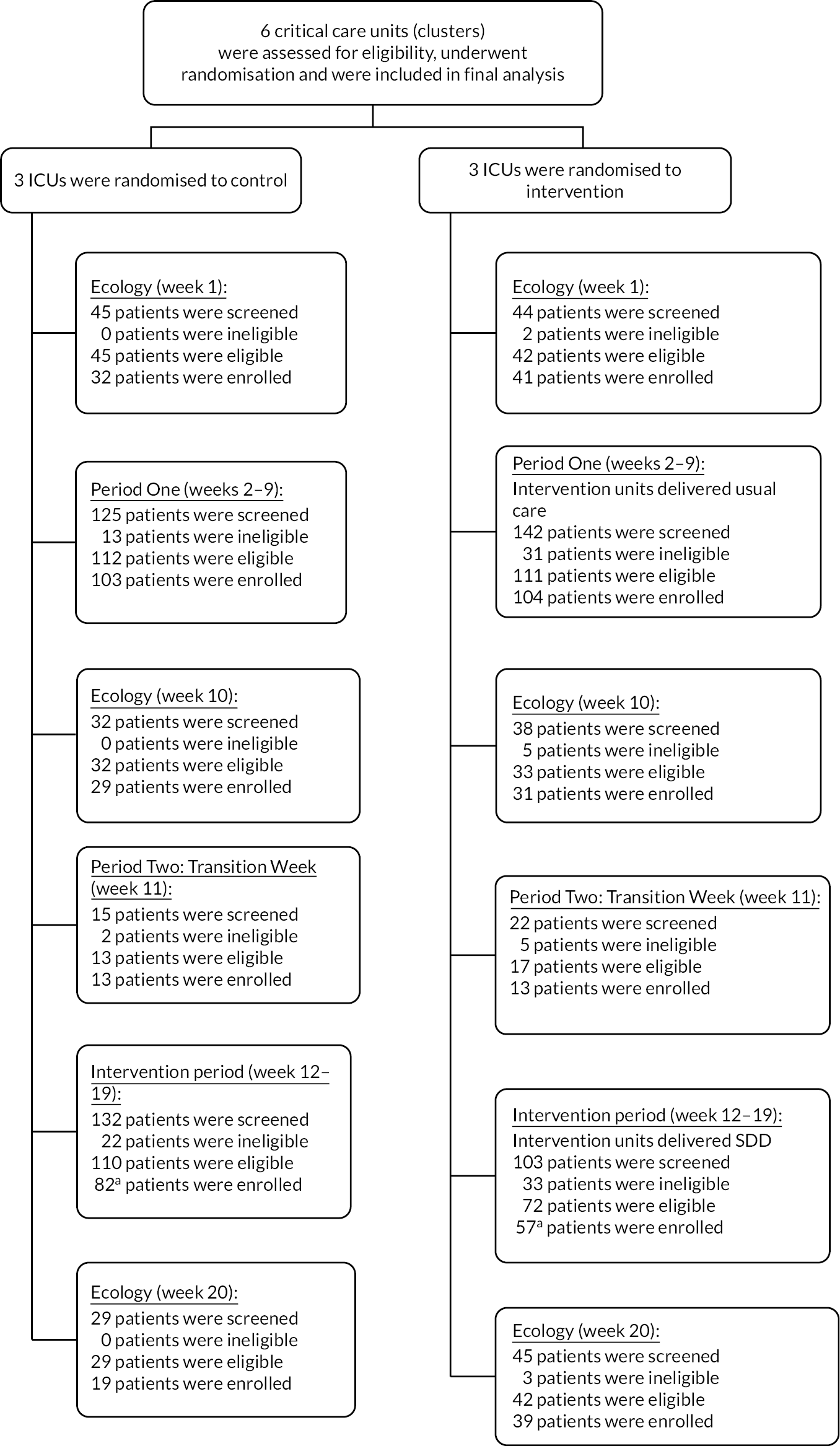

The six participating PICU sites obtained local NHS permissions/approvals and opened to recruitment in parallel on 19 September 2021. Site initiation visits were carried out at all participating sites prior to start of patient screening and recruitment. Sites were randomised in week 6 of recruitment (during the baseline period) on 25 October 2021. The flow of sites (clusters) through the cRCT is presented in Figure 2, according to the CONSORT extension for cluster trials. 21

FIGURE 2.

CONSORT flow of sites (clusters) and patients. a, Duplicate record.

As planned, six sites participated in the PICnIC pilot cRCT. Intervention site initiation visits were carried at all intervention group sites ahead of the delivery of the SDD during the first week of the transition period. The transition period was delayed by 1 week due to delays in delivery of the SDD to sites. One intervention site had a further delay of a week due to local pharmacy sign-off issues and was only able to start the intervention from week 12.

One site from the intervention group of sites closed to recruitment on 30 January 2022, earlier than the planned completion date due to reaching their recruitment target of 30 children and cited the need to direct research capacity to other ongoing studies. The remaining five sites remained open to screening and recruitment until the end of recruitment on 13 February 2022.

Participants

Screening and recruitment

In total, 539 children were screened across the six sites during Periods One and Two combined, of which 434 (80.5%) were eligible. The rates of eligibility were higher across periods in the control sites, compared to the intervention sites. Of the 434 eligible children, 351 (80.9%) children were recruited (207 in Period One; 161 in Period Two). This was higher than the pre-trial expected patient recruitment of 306 children across the course of both Period One and Period Two (Table 2).

| Study period | Week 1 | Weeks 2–9 (Period One) |

Week 10 | Weeks 11–19 (Period Two) |

Week 20 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sites | All | Intervention | Control | All | Intervention | Control | All |

| Screened, n | 89 | 142 | 125 | 70 | 125 | 147 | 74 |

| Eligible, n (% of screened) |

87 (97.8) | 111 (78.2) | 112 (89.6) | 65 (92.9) | 87 (69.6) | 123 (83.7) | 71 (95.9) |

| Recruited, n (% of eligible) |

73 (83.9) | 104 (93.7) | 103 (92.0) | 60 (92.3) | 67 (77.0) | 94 (76.4) | 58 (81.7) |

| Consented, n (% of recruited) |

22 (30.1) | 32 (30.8) | 46 (44.7) | 14 (23.3) | 38 (56.7) | 46 (48.9) | 19 (32.8) |

| Refused consent, n (% of recruited) | 7 (9.6) | 40 (38.5) | 17 (16.5) | 12 (20.0) | 16 (23.9) | 16 (17.0) | 17 (29.3) |

| Unable to approach for consent, n (% of recruited) | 44 (60.3) | 32 (30.8) | 40 (38.8) | 33 (55.0) | 11 (16.4) | 30 (31.9) | 22 (37.9) |

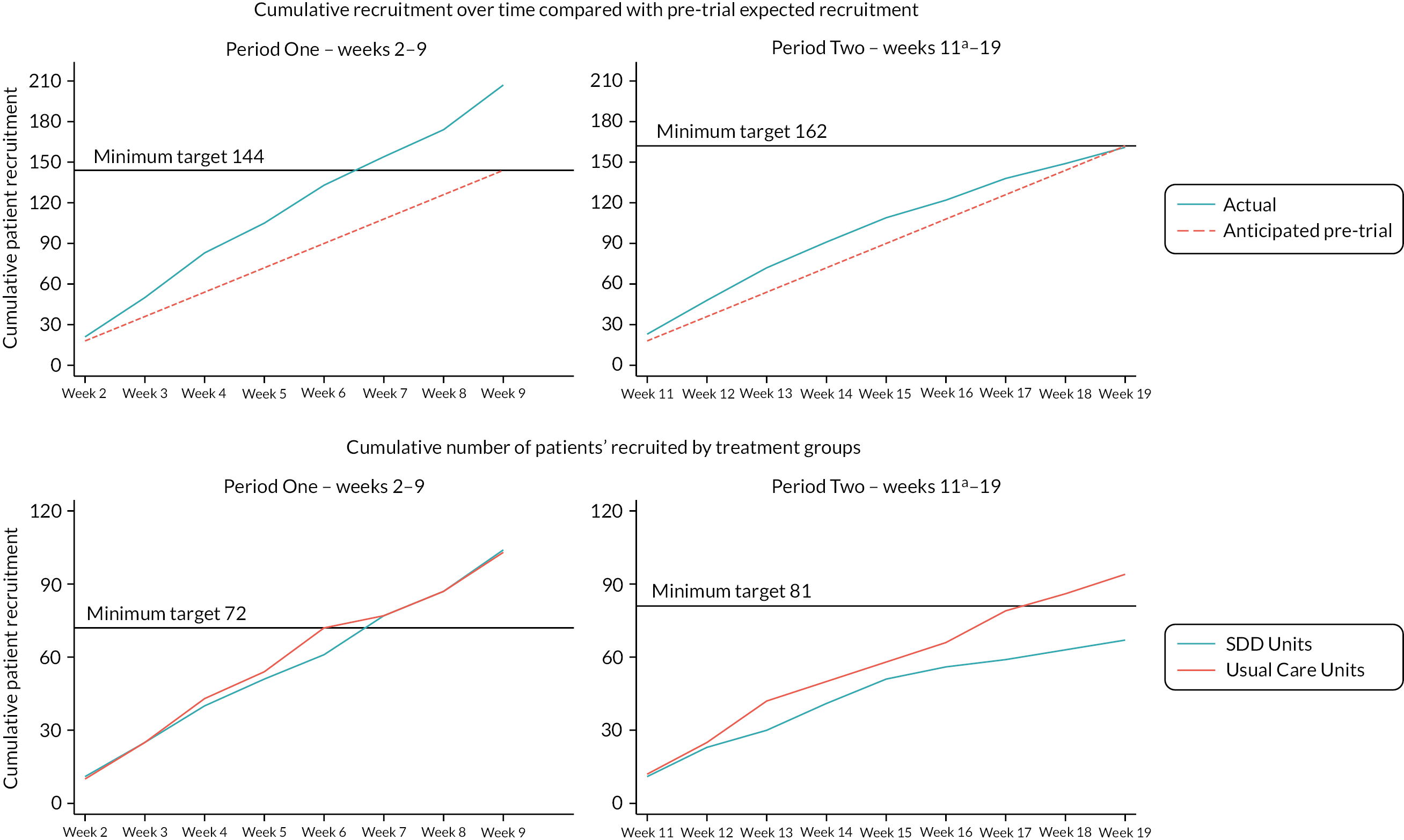

Overall recruitment was similar between intervention and control sites during Period One. During Period Two, a reduction in recruitment was observed across both groups, but due to the early cessation of recruitment at week 17 of the largest recruiting intervention site (Birmingham Children’s Hospital), this was more marked in the intervention sites (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Cumulative number of patients recruited over time and by treatment group. a, Week 11 was treated as a transition period.

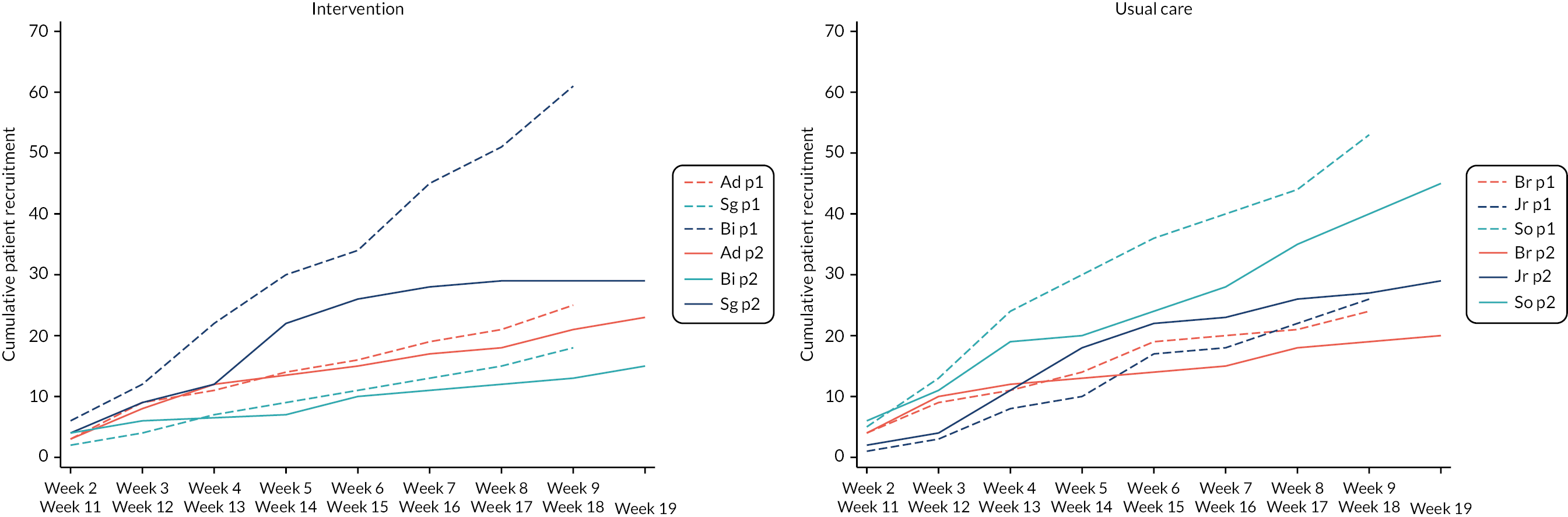

Recruitment varied across sites (Table 3, Figure 4). In Period One, with the exception of St George’s Hospital, the recruitment rate (patients per week) of each site met or exceeded the pre-trial estimates of three children per week. Within Period Two, there was a slight drop in recruitment across all sites, due to a seasonal reduction in eligible patients.

| Site | Period One | Period Two | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screened | Recruited | Screened | Recruited | |||||

| Total | Meana | Total n (%)b |

Meana | Total | Meana | Total n (%)b |

Meana | |

| Addenbrooke’s Hospital | 29 | 3.6 | 25 (100.0) | 3.1 | 37 | 4.1 | 23 (100.0) | 2.6 |

| Birmingham Children’s Hospital | 70 | 8.8 | 61 (93.8) | 7.6 | 57 | 6.3 | 29 (59.2) | 3.2 |

| St George’s Hospital, London | 43 | 5.4 | 18 (90.0) | 2.3 | 31 | 3.4 | 15 (88.2) | 1.7 |

| Total intervention | 142 | 17.8 | 104 (94.5) | 13.0 | 125 | 13.9 | 67 (75.3) | 7.4 |

| Bristol Royal Hospital for Children | 42 | 5.3 | 24 (77.4) | 3.0 | 55 | 6.1 | 20 (44.4) | 2.2 |

| John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford | 28 | 3.5 | 26 (96.3) | 3.3 | 38 | 4.2 | 29 (93.5) | 3.2 |

| Southampton Children’s Hospital | 55 | 6.9 | 53 (96.4) | 6.6 | 54 | 6.0 | 45 (97.8) | 5.0 |

| Total control | 125 | 15.6 | 103 (91.2) | 12.9 | 147 | 16.3 | 94 (77.0) | 10.4 |

FIGURE 4.

Cumulative number of patients recruited by sites (solid lines indicate Period Two). Hospitals: Br, Bristol Royal Hospital for Children; Jr, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford; So, Southampton Children’s Hospital; Ad, Addenbrooke’s Hospital; Bi, Birmingham Children’s Hospital; Sg, St George’s Hospital, London. Period: p1, Period One (weeks 2–9); p2, Period Two (weeks 11–19).

Consent

Consent for the collection of additional samples for study-specific ecology monitoring was obtained in 162 patients (44% of those recruited), with differences seen between intervention and control sites. Intervention sites showed a higher rate of refused consent, but this difference was reduced during Period Two (see Table 2). This was therefore not deemed to be related to the delivery of the intervention. In over 30% of the recruited patients (43 in the intervention group and 70 in the control group), the research teams stated that they were unable to approach the parents for consent, of which in 25 cases (22%) staff reported it was not appropriate to approach them.

Patient characteristics

Patients were well balanced across treatment groups and time periods (Table 4). The mean age of patients was similar in Period One (33.3 months in the usual care sites and 31.5 months in the intervention sites), and in Period Two (28.0 months in the usual care sites and 25.0 months in the intervention sites), with most of the recruited children being < 1 year old. Over 62% of the patients were male, although this proportion was slightly lower in the intervention group during Period One. The recruited children were predominantly white in ethnicity, with a slightly higher proportion of Asian ethnicity at intervention group sites. The PIM3 score was similar across treatment groups in both time periods but slightly lower during the intervention Period Two (than during the usual care Period One), with a median predicted risk of 2%. The most common primary diagnostic group of the recruited children was respiratory (43%), followed by cardiac (23%), with a slightly higher proportion of both diagnosis in the intervention group during Period One (49% and 27%, respectively) and a higher proportion with infection as primary diagnostic group in the intervention group during Period One (16%), and in the usual care group during Period Two (20%).

| Variables | Recruited patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention sites | Control sites | |||

| Period One | Period Two | Period One | Period Two | |

| N = 104 | N = 56 | N = 103 | N = 82 | |

| Age at admission (months) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 7 (48) | 5 (18) | 7 (43) | 5 (25) |

| Mean (SD) | 31.5 (46.5) | 25.0 (45.3) | 33.3 (52.5) | 28.0 (49.0) |

| Age category at admission | ||||

| < 1 year | 55/101 (54.5%) | 34/55 (61.8%) | 55/100 (55.0%) | 53/79 (67.1%) |

| 1 years | 13/101 (12.9%) | 9/55 (16.4%) | 15/100 (15.0%) | 5/79 (6.3%) |

| 2–4 years | 8/101 (7.9%) | 3/55 (5.5%) | 9/100 (9.0%) | 7/79 (8.9%) |

| 5–9 years | 15/101 (14.9%) | 5/55 (9.1%) | 9/100 (9.0%) | 6/79 (7.6%) |

| 10–16 years | 10/101 (9.9%) | 4/55 (7.3%) | 12/100 (12.0%) | 8/79 (10.1%) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 58/101 (57.4%) | 38/55 (69.1%) | 64/100 (64.0%) | 49/79 (62.0%) |

| Female | 43/101 (42.6%) | 17/55 (30.9%) | 36/100 (36.0%) | 30/79 (38.0%) |

| Ethnic category | ||||

| Asian | 12/101 (11.9%) | 8/55 (14.5%) | 5/100 (5.0%) | 4/79 (5.1%) |

| Black | 9/101 (8.9%) | 1/55 (1.8%) | 2/100 (2.0%) | 3/79 (3.8%) |

| Chinese | 0/101 (0.0%) | 1/55 (1.8%) | 0/100 (0.0%) | 0/79 (0.0%) |

| Mixed | 6/101 (5.9%) | 1/55 (1.8%) | 3/100 (3.0%) | 6/79 (7.6%) |

| White | 55/101 (54.5%) | 36/55 (65.5%) | 63/100 (63.0%) | 41/79 (51.9%) |

| Other | 8/101 (7.9%) | 3/55 (5.5%) | 2/100 (2.0%) | 0/79 (0.0%) |

| Unknown | 11/101 (10.9%) | 5/55 (9.1%) | 25/100 (25.0%) | 25/79 (31.6%) |

| PIM3 predicted risk of PICU mortality (%) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 4 (7) | 3 (5) | 2 (4) | 2 (5) |

| Mean (SD) | 5.8 (7.5) | 6.3 (12.6) | 4.2 (7.8) | 5.7 (11.9) |

| Primary diagnosis group | ||||

| Neurological | 5/101 (5.0%) | 3/55 (5.5%) | 7/100 (7.0%) | 4/79 (5.1%) |

| Cardiac | 22/101 (21.8%) | 15/55 (27.3%) | 25/100 (25.0%) | 16/79 (20.3%) |

| Respiratory | 42/101 (41.6%) | 27/55 (49.1%) | 43/100 (43.0%) | 33/79 (41.8%) |

| Oncology | 1/101 (1.0%) | 2/55 (3.6%) | 1/100 (1.0%) | 0/79 (0.0%) |

| Infection | 16/101 (15.8%) | 2/55 (3.6%) | 9/100 (9.0%) | 16/79 (20.3%) |

| Musculoskeletal | 0/101 (0.0%) | 0/55 (0.0%) | 0/100 (0.0%) | 1/79 (1.3%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 2/101 (2.0%) | 0/55 (0.0%) | 3/100 (3.0%) | 0/79 (0.0%) |

| Other | 5/101 (5.0%) | 2/55 (3.6%) | 6/100 (6.0%) | 7/79 (8.9%) |

| Blood and lymph | 2/101 (2.0%) | 1/55 (1.8%) | 1/100 (1.0%) | 1/79 (1.3%) |

| Trauma | 2/101 (2.0%) | 0/55 (0.0%) | 1/100 (1.0%) | 1/79 (1.3%) |

| Endocrine/metabolic | 2/101 (2.0%) | 1/55 (1.8%) | 3/100 (3.0%) | 0/79 (0.0%) |

| Multisystem | 0/101 (0.0%) | 0/55 (0.0%) | 0/100 (0.0%) | 0/79 (0.0%) |

| Body wall and cavities | 2/101 (2.0%) | 0/55 (0.0%) | 1/100 (1.0%) | 0/79 (0.0%) |

| Unknown | 0/101 (0.0%) | 2/55 (3.6%) | 0/100 (0.0%) | 0/79 (0.0%) |

Adherence to sampling

The vast majority of patients (91–99% across both periods) had samples taken at admission to the PICU. Consent for repeat samples was low (44%).

When consent was obtained for the additional sampling, adherence to the sampling regimen was good, with samples collected for more than 90% of eligible patients at each time point as shown in Table 5. Repeat samples were not taken (missed) for consented patients on a total of 11 occasions.

| Ecology surveillance (week 1) | Period One | Ecology surveillance (week 10) | Period Two | Ecology surveillance (week 20) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admission sample | |||||

| Enrolled, n | 73 | 207 | 60 | 138 | 58 |

| Sample taken, n (%) | 71 (97.3) | 204 (98.6) | 55 (91.7) | 137 (99.3) | 53 (91.4) |

| Sample not taken, n (%) | 2 (2.7) | 3 (1.4) | 5 (8.3) | 1 (0.7) | 5 (8.6) |

| Sample taken on day of admission, n (%) | n/aa | 184 (88.9) | n/aa | 123 (89.1) | n/aa |

| First repeat sample | |||||

| Consented and still in PICU, n | 8 | 56 | 9 | 43 | 5 |

| Research sample taken, n (%) | 7 (87.5) | 54 (96.4) | 6 (66.7) | 42 (97.7) | 5 (100.0) |

| Research sample not taken, n (%) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (3.6) | 3 (33.3) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Did not consent and still in PICU,a n | 50 | 22 | |||

| Did not consent and routine sample taken, n | 11 | 9 | |||

| Second repeat sample | |||||

| Consented and still in PICU, n | 42 | 26 | |||

| Research sample taken, n (%) | 40 (95.2) | 26 (100.0) | |||

| Research sample not taken, n (%) | 2 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Did not consent and still in PICU,a n | 30 | 15 | |||

| Did not consent and routine sample taken, n | 10 | 7 | |||

| Third repeat sample | |||||

| Consented and still in PICU, n | 20 | 15 | |||

| Research sample taken, n (%) | 19 (95.0) | 14 (93.3) | |||

| Research sample not taken, n (%) | 1 (5.0) | 1 (6.7) | |||

| Did not consent and still in PICU,a n | 19 | 8 | |||

| Did not consent and routine sample taken, n | 1 | 2 | |||

Adherence to selective decontamination of the digestive tract intervention

After excluding week 11 (transition week), a total of 56 children were recruited in the intervention sites, and 55 of them (98%) received SDD treatment (Table 6). Around 68% of eligible children received SDD within the first 6 hours as per protocol. The median (IQR) number of doses administered per patient was 14 (9–32) for the SDD oral paste and 14 (9–32) for the gastric suspension. Of the expected doses, 9.2% of the oral paste and 9.1% of the gastric suspension were not administered. The main reasons were being nil by mouth (29.5% and 31.1%, respectively) and dose missed (26.2% and 24.6%, respectively).

| SDD treatment method | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Any | Oral paste | Gastric suspension | |

| Patients | |||

| Enrolled, n | 56 | ||

| Received SDD, n (%) | 55 (98.2) | ||

| Received SDD within 6 hours of enrolment, n (%) | 38 (67.9) | ||

| Doses | |||

| Total expected,a n | 1330 | 1330 | |

| Total administered, n (%) | 1208 (90.8) | 1209 (90.9) | |

| Total not administered, n (%) | 122 (9.2) | 121 (9.1) | |

| Median (IQR) per patient | 14.0 (9.0–32.0) | 14.0 (9.0–32.0) | |

| Reasons for doses not given | |||

| Not applicable, n (%) | 13 (10.7) | 4 (3.3) | |

| Nil by mouth, n (%) | 36 (29.5) | 38 (31.1) | |

| Unable to administer via prescribed route, n (%) | 4 (3.3) | 5 (4.1) | |

| Dose missed, n (%) | 32 (26.2) | 30 (24.6) | |

| Omitted on clinician’s instruction, n (%) | 6 (4.9) | 6 (4.9) | |

| SDD not available, n (%) | 10 (8.2) | 13 (10.7) | |

| Prescription issues, n (%) | 9 (7.4) | 14 (11.5) | |

| Parent decision, n (%) | 11 (9.0) | 10 (8.2) | |

Potential outcome measures

Completeness of the ecology outcome measures was excellent in intervention sites and very good in the usual care sites (Table 7). Table 8 summarises the outcome data by ecology week.

| Outcome measure | Intervention sites | Control sites | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Week 10 | Week 20 | Week 1 | Week 10 | Week 20 | |

| Patients enrolled, n | 41 | 31 | 39 | 32 | 29 | 19 |

| Data completed, n (%) | 40 (97.6) | 31 (100.0) | 39 (100.0) | 30 (93.8) | 27 (93.1) | 19 (100.0) |

| Any microbiology positive result, n (%) | 40 (97.6) | 31 (100.0) | 39 (100.0) | 30 (93.8) | 27 (93.1) | 19 (100.0) |

| Site of positive sample, n (%) | 17/17 (100.0) | 10/10 (100.0) | 17/17 (100.0) | 8/8 (100.0) | 4/4 (100.0) | 6/6 (100.0) |

| Organism, n (%) | 17/17 (100.0) | 10/10 (100.0) | 17/17 (100.0) | 8/8 (100.0) | 4/4 (100.0) | 6/6 (100.0) |

| Outcome measure | Intervention sites | Control sites | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Week 10 | Week 20 | Week 1 | Week 10 | Week 20 | |

| Patients enrolled, n | 41 | 31 | 39 | 32 | 29 | 19 |

| Patients with positive microbiology result, n (%) | 17/40 (42.5) | 10/31 (32.3) | 17/39 (43.6) | 8/30 (26.7.0) | 4/27 (14.8) | 6/19 (31.6) |

| Total microbiology positive results, n | 22 | 12 | 32 | 13 | 7 | 9 |

| Site of positive sample | ||||||

| Nasopharyngeal, n (%) | 13 (59.1) | 4 (33.3) | 13 (40.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Stool/rectal, n (%) | 2 (9.1) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (6.3) | 5 (38.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (22.2) |

| Urine, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| ETT secretions, n (%) | 5 (22.7) | 6 (50.0) | 12 (37.5) | 8 (61.5) | 6 (85.7) | 5 (55.6) |

| Wound, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (8.3) | 3 (9.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Blood, n (%) | 2 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (22.2) |

| Organism(s) of positive samplea | ||||||

| Gram-negative bacteria, n (%) | 8 (36.4) | 2 (16.7) | 14 (43.8) | 6 (46.2) | 4 (57.1) | 6 (66.7) |

| Gram-positive bacteria, n (%) | 8 (36.4) | 3 (25.0) | 7 (21.9) | 6 (46.2) | 3 (42.9) | 3 (33.3) |

| Virology, n (%) | 9 (40.9) | 12 (100.0) | 17 (53.1) | 4 (30.8) | 3 (42.9) | 1 (11.1) |

| Fungal, n (%) | 2 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.3) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Overall, patient-centred potential outcomes measures had an excellent completion rate (Table 9), which was similar between groups with a range between 96.3% and 100%.

| Outcome measure | Intervention sites | Control sites | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period One (n = 104) | Period Twoa (n = 56) | Period One (n = 103) | Period Twoa (n = 82) | |

| Patients enrolled, n | 104 | 56 | 103 | 82 |

| HCAI, n (%) | 104 (100.0) | 56 (100.0) | 102 (99.0) | 82 (100.0) |

| Any positive microbiology result, n (%) | 104 (100.0) | 56 (100.0) | 103 (100.0) | 82 (100.0) |

| Duration of invasive ventilation (days), n (%) | 104 (100.0) | 56 (100.0) | 102 (99.0) | 82 (100.0) |

| Days alive and free of ventilation to day 28, n (%) | 101 (97.1) | 55 (98.2) | 100 (97.0) | 79 (96.3) |

| Length of PICU stay (days), n (%) | 104 (100.0) | 56 (100.0) | 102 (99.0) | 82 (100.0) |

| Length of hospital stay (days), n (%) | 104 (100.0) | 54 (96.4) | 98 (95.1) | 82 (100.0) |

| PICU mortality, n (%) | 104 (100.0) | 56 (100.0) | 102 (99.0) | 82 (100.0) |

| Hospital mortality, n (%) | 104 (100.0) | 54 (96.4) | 100 (97.1) | 82 (100.0) |

| 30-day mortality, n (%) | 103 (99.0) | 56 (100.0) | 101 (98.1) | 82 (100.0) |

Characteristics of the patient-centred potential outcomes among all patients receiving standard care (all children in control PICUs and children in intervention PICUs in Period One) are reported in Table 10.

| Outcome measure | Patient receiving standard care,a n (%) [N] | ICC (CI) |

|---|---|---|

| HCAI | 34 (11.8) [288] | 0.316 (0.060 to 0.771) |

| Any positive microbiology result | 172 (59.7) [288] | 0.374 (0.129 to 0.707) |

| Duration of invasive ventilation, days | 7.6 (7.9) [289] | 0.012 (0.001 to 0.177) |

| Days alive and free of ventilation to day 28 | 19.5 (8.1) [280] | 0.018 (0.001 to 0.188) |

| Length of PICU stay, days | 10.1 (10.6) [288] | 0.014 (0.001 to 0.164) |

| Length of hospital stay, days | 23.3 (26.9) [284] | 0.006 (0.000 to 0.296) |

| PICU mortality | 21 (7.3) [288] | 0.099 (0.007 to 0.629) |

| Hospital mortality | 27 (9.4) [286] | 0.068 (0.002 to 0.684) |

| 30-day mortality | 22 (7.7) [286] | 0.041 (0.000 to 0.803) |

Although the study has not been powered to compare outcomes between groups, a summary of the potential outcome effects is shown in Table 11 to allow consideration of plausible ranges of treatment effects for a definitive trial. As anticipated for a pilot study, the CIs do not rule out either substantial benefit or harm on any of the potential outcomes.

| Outcome measure | Intervention sites | Control sites | Effect estimate (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period One | Period Two | Period One | Period Two | ||

| HCAI, n/N (%) | 6/104 (5.8) | 4/56 (7.1) | 16/102 (15.7) | 12/82 (14.6) | 1.31a (0.27 to 6.38) |

| Any positive microbiology result, n/N (%) | 62/104 (59.6) | 30/56 (53.6) | 61/102 (59.8) | 49/82 (59.8) | 0.92a (0.34 to 2.46) |

| Duration of invasive ventilation (days), [N] | [104] | [56] | [102] | [82] | |

| Mean (SD) | 8.7 (10.8) | 8.5 (13.2) | 7.7 (6.3) | 6.0 (4.3) | 1.51 (−2.37 to 5.38) |

| Median (IQR) | 5 (3–8) | 5 (4–10) | 5 (3–9) | 4 (3–7) | |

| Days alive and free of ventilation to day 28b | [101] | [55] | [100] | [79] | |

| Mean (SD) | 19.0 (8.8) | 19.9 (7.3) | 18.8 (8.3) | 21.0 (6.6) | −1.57 (−5.05 to 1.91) |

| Median (IQR) | 23 (17–25) | 23 (18–25) | 23 (15–25) | 24 (20–25) | |

| Length of PICU stay (days), [N] | [104] | [56] | [102] | [82] | |

| Mean (SD) | 11.5 (13.6) | 11.5 (16.8) | 10.1 (9.3) | 8.3 (7.2) | 1.95 (−3.18 to 7.08) |

| Median (IQR) | 7 (4–13) | 6 (4–13) | 6 (5–13) | 6 (4–10) | |

| Length of hospital stay (days), [N] | [104] | [54] | [98] | [82] | |

| Mean (SD) | 26.4 (29.0) | 25.9 (25.2) | 21.7 (28.4) | 21.4 (21.5) | −0.11 (−11.76 to 11.55) |

| Median (IQR) | 16 (8–31) | 15 (8–39) | 12 (8–25) | 13 (8–26) | |

| PICU mortality, n/N (%) | 7/104 (6.7) | 3/56 (5.4) | 10/102 (9.8) | 4/82 (4.9) | 1.75a (0.27 to 11.17) |

| Hospital mortality, n/N (%) | 8/104 (7.7) | 3/54 (5.6) | 13/100 (13.0) | 6/82 (7.3) | 1.41a (0.25 to 7.85) |

| 30-day mortality, n/N (%) | 6/103 (5.8) | 3/56 (5.4) | 11/101 (10.9) | 5/82 (6.1) | 1.76a (0.29 to 10.72) |

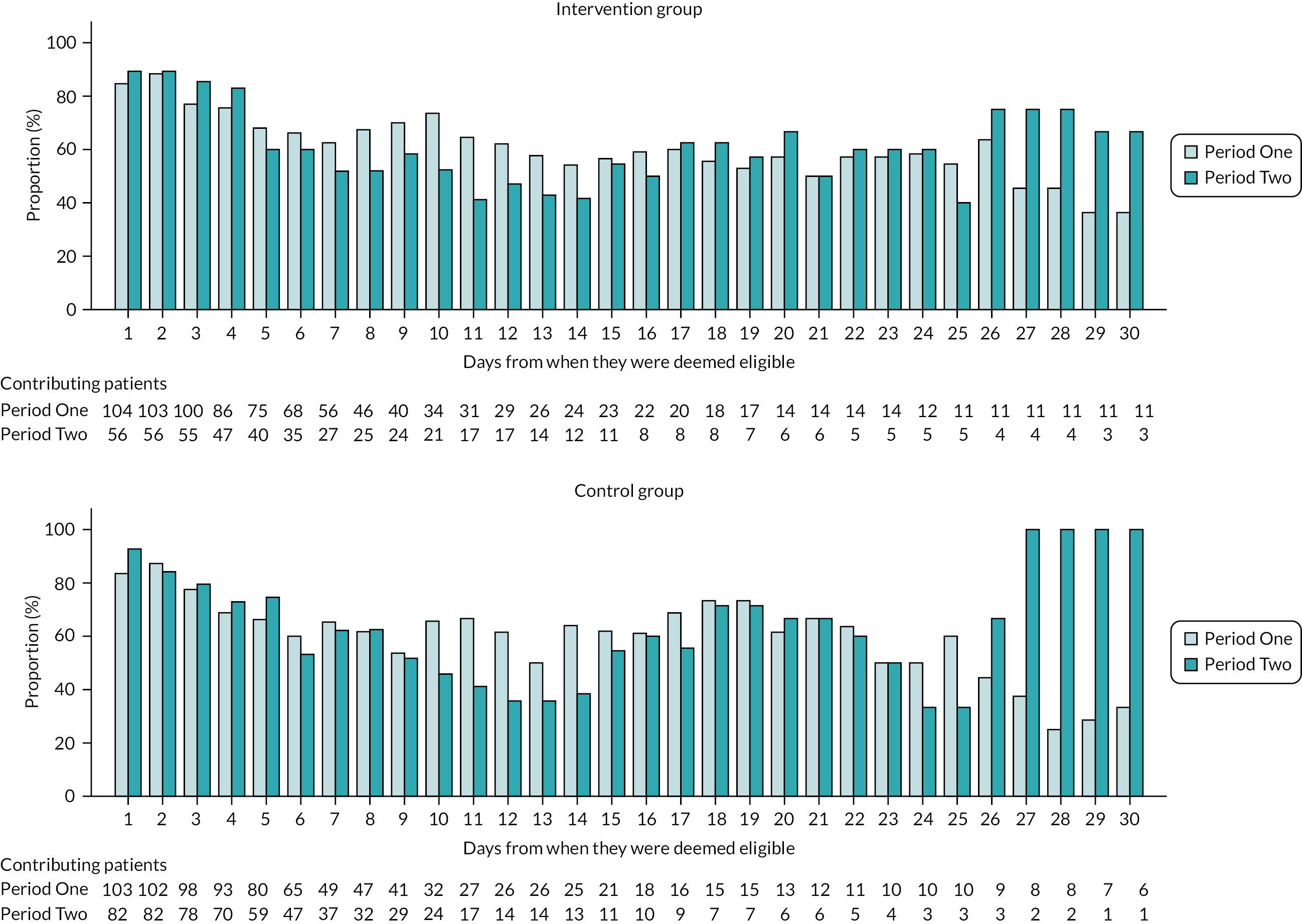

The proportions of children who received any antimicrobial therapy were similar across groups (Figure 5), with a reduction during the second week following eligibility.

FIGURE 5.

Proportion of children who received any antimicrobial therapy during PICU stay.

Adverse events

Among the 67 patients, there was only one AE reported during Period Two in the intervention sites, which was not assessed as serious. No SAEs were reported (Table 12).

| Intervention sites | Control sites | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 67 | 94 |

| Total number of AEs | 1 | 0 |

| Number (%) of patients experiencing one or more AEs | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Specified AEs, n (%) | ||

| NG tube blockage | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Choking on paste | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Allergic reaction to SDD | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Total number of SAEs | 0 | 0 |

| Number (%) of patients experiencing one or more SAEs | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Generalisability to the wider paediatric intensive care unit population

Characteristics of participating sites

The characteristics of the six PICUs that participated in the PICnIC pilot cRCT compared with all PICUs in PICANet (n = 29) are presented in Table 13. Overall, the sites participating in the study were a representative mix of small and large PICUs with a broad case mix of cardiac and general admissions drawn from across the NHS England geographical region.

| Participating sites | UK PICUs | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of PICU | |||

| General | 3 (50%) | 18 (62%) | |

| General and cardiac | 3 (50%) | 7 (24%) | |

| Cardiac | 0 (0%) | 4 (14%) | |

| PICU beds (intensive care and high dependency) | |||

| < 8 | 0 (0%) | 5 (17%) | |

| 8–11 | 1 (17%) | 1 (3%) | |

| 12–15 | 2 (33%) | 8 (28%) | |

| ≥ 16 | 3 (50%) | 15 (52%) | |

| Annual PICU admissions | |||

| < 550 | 2 (33%) | 18 (62%) | |

| 550–749 | 3 (50%) | 6 (21%) | |

| 750–999 | 0 (0%) | 3 (10%) | |

| ≥ 1000 | 1 (17%) | 2 (7%) | |

Characteristics of participating patients

Table 14 shows patient characteristics, for recruited patients by treatment group and study period, and for all potentially eligible patients in study PICUs, and in all UK PICUs over the period the study was recruiting.

| Variables | Overall | Potentially eligible patients | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 345 | Study PICUs (n = 6) | All UK PICUs (n = 29) | |

| N = 464 | N = 1730 | ||

| Age at admission (months) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (32) | 7.0 (42.5) | 5.0 (32.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 30.1 (48.7) | 31.4 (48.7) | 30.2 (49.5) |

| Age category at admission, n/N (%) | |||

| < 1 year | 197/335 (58.8%) | 269/464 (58%) | 1062/1730 (61%) |

| 1 years | 42/335 (12.5%) | 47/464 (10%) | 168/1730 (10%) |

| 2–4 years | 27/335 (8.1%) | 54/464 (12%) | 184/1730 (11%) |

| 5–9 years | 35/335 (10.4%) | 50/464 (11%) | 138/1730 (8%) |

| 10–16 years | 34/335 (10.1%) | 44/464 (9%) | 178/1730 (10%) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 209/335 (62.4%) | 280/464 (60%) | 976/1730 (56%) |

| Female | 126/335 (37.6%) | 184/464 (40%) | 754/1730 (44%) |

| Ethnic category, n/N (%) | |||

| Asian | 29/335 (8.7%) | 40/464 (9%) | 202/1730 (12%) |

| Black | 15/335 (4.5%) | 27/464 (6%) | 98/1730 (6%) |

| Chinese | 1/335 (0.3%) | 1/464 (0%) | 11/1730 (1%) |

| Mixed | 16/335 (4.8%) | 24/464 (5%) | 68/1730 (4%) |

| White | 195/335 (58.2%) | 262/464 (56%) | 1028/1730 (59%) |

| Other | 13/335 (3.9%) | 23/464 (5%) | 67/1730 (4%) |

| Unknown | 66/335 (19.7%) | 87/464 (19%) | 256/1730 (15%) |

| PIM3 predicted risk of PICU mortality (%) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 3 (5) | 3.2 (5.3) | 2.2 (4.9) |

| Mean (SD) | 5.4 (9.7) | 6.0 (10.5) | 5.2 (9.0) |

| Primary diagnosis group, n/N (%) | |||

| Neurological | 19/335 (5.7%) | 41/464 (9%) | 138/1730 (8%) |

| Cardiac | 78/335 (23.3%) | 109/464 (23%) | 440/1730 (25%) |

| Respiratory | 145/335 (43.3%) | 178/464 (38%) | 738/1730 (43%) |

| Oncology | 4/335 (1.2%) | 8/464 (2%) | 29/1730 (2%) |

| Infection | 43/335 (12.8%) | 48/464 (10%) | 120/1730 (7%) |

| Musculoskeletal | 1/335 (0.3%) | 3/464 (1%) | 20/1730 (1%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 5/335 (1.5%) | 21/464 (5%) | 68/1730 (4%) |

| Other | 20/335 (6.0%) | 29/464 (6%) | 72/1730 (4%) |

| Blood and lymph | 5/335 (1.5%) | 6/464 (1%) | 12/1730 (1%) |

| Trauma | 4/335 (1.2%) | 4/464 (1%) | 21/1730 (1%) |

| Endocrine/metabolic | 6/335 (1.8%) | 9/464 (2%) | 43/1730 (2%) |

| Multisystem | 0/335 (0.0%) | 0/464 (0%) | 3/1730 (0%) |

| Body wall and cavities | 3/335 (0.9%) | 3/464 (1%) | 21/1730 (1%) |

| Unknown | 2/335 (0.6%) | 5/464 (1%) | 5/1730 (0%) |

| Died in PICU during admission event, n/N (%) | |||

| No | 311/335 (92.8%) | 422/464 (91%) | 1605/1730 (93%) |

| Yes | 24/335 (7.2%) | 42/464 (9%) | 125/1730 (7%) |

| Length of stay (days) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 7 (8) | 8.4 (9.8) | 8.0 (9.7) |

| Mean (SD) | 12.0 (18.4) | 14.4 (20.3) | 14.7 (20.9) |

| Days free from invasive ventilation | |||

| Median (IQR)a | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 1 (4) |

To assess generalisability of the study results, baseline characteristics and outcomes for children recruited to the pilot cRCT are displayed alongside with data from PICANet for all potentially eligible children (receiving invasive mechanical ventilation for at least three calendar days) within participating PICUs and within all UK PICUs. Children who were recruited to the PICnIC study were representative of similar potentially eligible patients in the study PICUs and all UK PICUs, but they were more likely to be male and with a primary diagnosis of infection when compared with those in all UK PICUs.

Statistical approach to a definitive clinical trial of selective decontamination of the digestive tract in the paediatric intensive care unit setting

The potential recruitment rate for a future definitive cRCT was 2.98 children/site/week and was estimated by combining a potentially eligible population of 1730 children (estimated from nesting the screening log data from participating PICUs with the national UK PICU data from PICANet) and the overall proportion of eligible children recruited of 85%. It was extremely similar to the pre-trial estimated rate value of 3.0. The number of eligible children identified from screening logs in the six recruiting PICUs (434) was very similar to the estimate of potentially eligible children from PICANet for these PICUs (464).

Assuming a parallel-arm cluster-randomised design with a baseline period, and with only 29 PICUs in the UK, Table 15 shows the number of clusters per arm and overall sample size required to detect alternative treatment effects with 90% power and a significance level of 0.05. The number of children per cluster is set at 190 (based on 1 year of recruitment, including the baseline period), using the ICC observed and mean/proportion among all patients receiving usual care during the pilot cRCT. After considering different scenarios, none of the binary outcomes are feasible with the number of clusters in the UK, except maybe positive microbiology. However, we should note that it is not very patient-centred and corresponds to an unlikely large reduction. Continuous outcomes are feasible for small to moderate treatment effects. We are assuming a simple approach of difference in means here for illustration and a final definitive sample size calculation would require more in-depth work on analysis approach. Further modifications to study design may also be considered; for example, the use of a cluster-crossover design. The cluster sample size application (https://clusterrcts.shinyapps.io/rshinyapp/) was used for sample size calculations.

| Study outcome (% or mean) | Relative risk/effect sizes SD | Absolute difference | Clusters per arm (sample size per arm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCAI | 11.8% | 0.8 | 2.4% | 434 (82,460) |

| 11.8% | 0.6 | 4.4% | 120 (22,800) | |

| Any positive microbiology result | 59.7% | 0.8 | 11.9% | 53 (10,070) |

| 59.7% | 0.6 | 23.9% | 13 (2470) | |

| Duration of invasive ventilation, days | 7.6 | 0.2 SD | 1.6 | 12 (2280) |

| 7.6 | 0.3 SD | 2.4 | 5 (950) | |

| Days alive and free of mechanical ventilation at 28 days | 19.5 | 0.2 SD | 1.6 | 12 (2280) |

| 19.5 | 0.3 SD | 2.4 | 5 (950) | |

| Length of PICU stay, days | 10.1 | 0.2 SD | 2.0 | 12 (2280) |

| 10.1 | 0.3 SD | 3.2 | 5 (950) | |

| Length of hospital stay, days | 23.3 | 0.2 SD | 5.4 | 8 (1520) |

| 23.3 | 0.3 SD | 8.1 | 4 (760) | |

| PICU mortality | 7.3% | 0.8 | 1.5% | 290 (55,100) |

| 7.3% | 0.6 | 2.9% | 70 (13,300) | |

| Hospital mortality | 9.4% | 0.8 | 1.9% | 179 (34,010) |

| 9.4% | 0.6 | 3.8% | 40 (7600) | |

| 30-day mortality | 7.7% | 0.8 | 1.54 | 182 (34,580) |

| 7.7% | 0.6 | 3.1% | 38 (7220) |

Chapter 4 Infection Control in Paediatric Intensive Care mixed-methods study to assess trial design and processes

Research exploring family and practitioner perspectives can help identify whether a clinical trial is acceptable and feasible. Importantly, such insight, from qualitative or mixed-methods work, can help ensure that trials are designed in a way that is patient- and family-centred. Trials in paediatric intensive care can be challenging to conduct with the need to carefully consider recruitment and consent processes so they do not cause burden or delay clinical care.

Methods

Study design

The PICnIC pilot cRCT included an embedded mixed-methods study. This involved a questionnaire and interviews with parents/legal representatives of children involved in the pilot cRCT, as well as focus groups, interviews and an online survey with PICU practitioners.

Aims and objectives

To assess with input from PICU healthcare professionals:

-

the acceptability of implementation of the SDD intervention, recruitment and consent procedures

-

the acceptability of collecting data to assess the selected clinical and ecological data

-

the acceptability of the SDD intervention and confirm interest in participation in a definitive trial in the wider PICU community.

To review, explore and test with input from parents/guardians of recruited patients:

-

the acceptability of a definitive trial that includes the SDD intervention

-

the acceptability of the recruitment and consent procedures for the definitive trial, including all proposed information materials

-

the selection of important, relevant, patient-centred primary and secondary outcomes for a definitive trial.

Design and development of the protocol

The design and development of the protocol, including sample estimation, recruitment strategy and interview topic guide (see Appendix 2 and 3), were informed by previous feasibility studies22,23 and reviewed by a PPI member. A list of outcomes to explore with parents during interviews (see Appendix 4) was developed from a review of relevant literature22,23 (and through a discussion with the larger team involved in the PICnIC pilot study) and reviewed by a PPI member.

Participants

Based on previous studies,22,23 we anticipated recruiting 15–25 parents/legal representatives to an interview to reach the point of information power, and a balance of parents of children in each trial arm was reached. Information power24 is the point at which data address the study aims, including sample specificity, participants’ experience relevant to the study aims and sample diversity.

Based on previous studies and the cRCT sample size, we aimed to receive approximately 100 parent questionnaires if both parents were present at the time of recruitment. For practitioners, we aimed to include approximately 8 to 10 practitioners in each of the two focus groups and up to 10 interviews (for those who could not attend a focus group), as well as an online survey using snowball sampling to involve wider PICU staff not involved in the pilot cRCT.

Parents/legal representatives were recruited via the same process and information materials used in the pilot cRCT. During the recruitment discussion, practitioners invited parents to complete the questionnaire and/or provide contact details if they wished to take part in an interview. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, parents were offered interviews online [via Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA)] or via telephone. Parents were asked to complete the questionnaire before they left the PICU and return it in the envelope provided, which was addressed to the University of Liverpool team.

Pilot cRCT practitioners were recruited to focus groups and the online survey via an e-mail invitation and Twitter [now X (X Corp., San Francisco, CA, USA); www.twitter.com] advertising. To boost survey recruitment, MP attended the Paediatric Critical Care Society Study Group (PCCS-SG) meeting in May 2022 and presented a study recruitment update with link to the online survey and QR code.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria:

-

parents/legal representatives of children involved in the pilot cRCT, including those who withdraw from data collection.

Exclusion criteria:

-

parents/legal representatives who do not speak English.

We use the term parents to include legal representatives from this point forward for brevity.

Screening and conduct of interviews and focus groups interviews

Expressions of interest to participate in an interview were responded to in sequential order. Once eligibility was confirmed, an interview date and time were scheduled.

The draft pilot RCT PIS and list of potential outcomes were e-mailed to parents to read prior to the interview. Screening and interview conduct stopped when data saturation and sample variation (recruitment of parents via multiple recruitment routes) were achieved.

Informed consent

The University of Liverpool researcher (MP) contacted parents/legal representatives to arrange an interview within 1 month of consent (or withdrawn consent) for the pilot cRCT. Parents were offered either a telephone or online video conference interview via Zoom. Informed consent for participation, for audio recording and to receive a copy of the mixed-methods study findings was sought verbally before the interview commenced. This involved the researcher (MP) reading each aspect of the consent form to parents. Each box was initialled by the researcher on the consent form when verbal consent was provided by the parent. Informed consent discussions were audio-recorded for auditing purposes.

Conduct of the interviews

All parent interviews were conducted by MP using the parent/legal representative interview topic guide (see Appendix 2 and 3). Respondent validation was used so that previously unanticipated topics will be added to the topic guide and discussed with participants as interviewing and analyses progress. An example was additional questions to explore parental understanding about whether or not their child would have received the intervention if the pilot cRCT was not being conducted. A distress protocol was available but did not need to be used. After the interview, participants were sent a copy of the consent form and a thank you letter, including a £30 Amazon (Amazon.com, Inc., Bellevue, WA, USA) voucher to thank them for their time.

Focus groups

Focus groups took place towards the end of the pilot cRCT recruitment period. All were conducted online, facilitated by MP and KW and included a voting system using Poll Everywhere (Poll Everywhere, San Francisco, CA, USA) to gain quantitative data on key questions (e.g. ‘Overall how would you rate the PICnIC site training?’ and ‘How acceptable is the proposed PICnIC trial to conduct?’). The practitioner focus group topic guide (see Appendix 3) was developed using relevant literature and early findings from parent/legal representative questionnaires and interviews. Additional focus groups were arranged to accommodate practitioners’ availability so that all were able to attend and no individual interviews were needed.

Informed consent

Informed consent for participation, for audio recording and to receive a copy of the mixed-methods study findings was sought verbally before the focus group commenced. This involved a member of the University of Liverpool team reading each aspect of the consent form to individual practitioners in Zoom breakout rooms. Each box was initialled by the researcher on the consent form when verbal consent was provided. Informed consent discussions were audio-recorded for auditing purposes.

Conduct of the focus groups

Focus groups began with introductions and were semistructured, informed by the topic guide. Unanticipated topics were added as data collection and analysis progressed. Voting took place via Poll Everywhere throughout each focus group on topics as they were discussed. Once the focus group was complete, participants were thanked for their time.

Transcription

Digital audio-recordings were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription company (UK Transcription) in accordance with the Data Protection Act 1998. Twenty-three transcripts were anonymised and checked for accuracy. All identifiable information, such as names (e.g. of patients, family members or the hospital their child was admitted to), were removed.

Data analysis

Qualitative data analysis of the interviews and focus groups was interpretive and iterative (Table 16). Utilising a thematic analysis approach, the aim was to provide an accurate representation of parental views on trial design and acceptability. Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (or themes) within data. Analysis was informed by the work of Braun and Clarke and their guide to thematic analysis (see Table 16). 25 The NVivo 10 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to assist the coding of data. Survey and voting data from focus groups were analysed using SPSS version 27 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA) for descriptive statistics. Qualitative and quantitative data were analysed separately and then synthesised through constant comparative analysis. 26 MP (female, a social scientist) led the analysis with assistance from KW (female, a social scientist).

| Phase | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Familiarising with data | Mariana Popa (MP) read and re-read transcripts, noting down initial ideas |

| 2. Generating initial codes | Initially, a data-coding framework was developed using a priori codes identified from the study’s objectives and the interview topic guide. During the familiarisation stage, MP identified additional data-driven codes and concepts not previously captured in the initial coding frame |

| 3. Developing the coding frame | Kerry Woolfall (KW) coded 20% of the transcripts using the initial coding frame and made notes on any new themes identified and how the framework could be refined |

| 4. Defining and naming themes | Following review and reconciliation by MP and KW, a revised coding frame was subsequently developed and ordered into themes (nodes) within the NVivo database |

| 5. Completing coding of transcripts | KW and MP met regularly on Zoom to discuss developing themes, sample variance and potential data saturation by looking at the data and referring back to the study aims. When saturation was achieved, data collection stopped. MP completed coding of all transcripts in preparation for write-up |

| 6. Producing the report | KW and MP developed the manuscript using themes to relate back to the study aims, ensuring that key findings and recommendations were relevant to the PICnIC cRCT design and site staff training (i.e. catalytic validity27). Final discussion and development of selected themes took place during the write-up phase |

Results

Participants: paediatric intensive care unit staff

A total of 44 PICU staff completed the survey representing 11 UK PICU. Of these, 36 (81%) were involved in the PICnIC pilot and were from other PICUs representing six units. Six focus groups with 25 staff were conducted, which was an additional four than originally planned to ensure staff from all PICnIC pilot sites had an opportunity to participate. Within focus groups 24/25 (96%) used the voting system, because one of the practitioners arrived late and had difficulties accessing the platform. MP led facilitation of all focus groups; KW co-facilitated the first focus group to help inform the initial development of the topic guide.

Paediatric intensive care unit staff characteristics