Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/154/04. The contractual start date was in April 2016. The draft report began editorial review in September 2019 and was accepted for publication in March 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2022. This work was produced by Gumley et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health and Care Research, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2022 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Schizophrenia is a long-term and serious mental illness for which a wide variety of risk and protective factors have been evidenced. 1 It is a form of psychosis characterised by positive and negative symptoms. Positive symptoms relate to distortions of thinking, including fixed beliefs, delusions and paranoia, as well as auditory and visual hallucinations. Negative symptoms include deficits in cognitive functioning, low mood and blunted emotions. Schizophrenia has a lifetime prevalence rate of 4.0 (1.6–12.1) per 1000 people2 and is estimated to affect 21 million people worldwide. Onset of symptoms typically occurs in early adulthood, with the majority of people continuing to experience persisting or fluctuating symptoms. 2 Schizophrenia contributes 13.4 (9.9–16.7) million years of life lived with disability to burden of disease3 and is one of the top 15 leading global causes of disability. 4

People with a schizophrenia diagnosis die 14.5 (11.2–17.8) years earlier than those in the general population, with a mean age at death for men of 59.9 (55.5–64.3) years and 67.6 (63.1–72.1) years for women,5 meaning it is a major public health concern. In a recent longitudinal study,6 11.7% of 171 participants were deceased at follow-up 20 years after a first episode of psychosis, more than double the expected mortality. Worryingly, this differential mortality gap has widened over recent decades. 7 Although it is impossible to quantify the significant emotional distress and life disruption associated with schizophrenia and psychosis for people directly affected and for those closest to them, it is estimated that the overall costs to society are somewhere in the region of £11B in the UK8 and AU$4.9B annually in Australia. 9

Relapse in psychosis

Estimates suggest that around 80% of people with a schizophrenia diagnosis experience a relapse after 5 years. 10,11 A 2012 systematic review12 found pooled prevalence rates of relapse in positive symptoms following a first episode of 28% (range 12–47%) at 1-year follow-up, 43% (range 35–54%) at 18 months and 54% (range 40–63%) at 3 years, with similar relapse rates identified in more recent longitudinal studies. 13,14 The second Australian national survey of psychosis15 found that > 60% of respondents had experienced multiple episodes of psychosis symptoms interspersed with periods of full or partial remission, with 35% having experienced one or more hospital admissions in the previous year. Relapse and associated hospital admissions can be deeply distressing and traumatic experiences for people affected,16 and fear of future relapse can be disabling for service users17 and family members alike. 18

Direct treatment costs for people who experience a relapse are three times higher than they are for people who do not, with the majority of additional costs associated with unplanned hospital admissions. 19 Health-care costs for people characterised as unstable (defined as having had one or more admissions in the previous 2 years) have been found to be four times higher than for people who are stable, again with the vast majority of additional costs associated with hospital admissions. 20 Almost half (46%) of health sector costs for psychosis are generated by inpatient care in Australia, accounting for 96% of the total (AU$609M). 9 The greatest impact on these patterns of service use is relapsing psychosis. 15 Inpatient admissions are associated with suicidal ideation, younger age, poorer functioning and increased symptomology. 21

Relapse in psychosis is associated with a lifetime risk of functional and clinical deterioration,14 meaning that there is an urgency to identify and respond to valid predictors to inform personalised treatment responses. 22,23 A broad range of potential predictors of relapse have been investigated, with a small number consistently identified across the literature. 12,22 Non-adherence to treatment, including medication, increases the risk of relapse12,14 by potentially up to five times. 11 Medication non-adherence is, in turn, predicted by poorer insight of illness, previous involuntary treatment, poorer premorbid functioning, forensic service history and substance misuse, previous suicide attempts, embarrassment, wider issues with service engagement and poor working alliance. 24–28 Other predictors of relapse include substance misuse,12 cannabis use,13 younger age at onset of psychosis,14 poorer premorbid functioning, increased family criticism12 and fear of relapse itself. 17 Reduced social functioning, isolation11,12,29 and negative interpersonal style, possibly linked to poorer use of social support,30 may also predict relapse, with a potential dose–response effect noted between repeated relapses and poorer social functioning. 31

Evidence for the prevention of relapse

Recent review evidence suggests that it is possible to intervene to reduce the likelihood of psychosis relapses, with absolute risk reductions of between 13.6% and 37.0%. 32 At the same time, it has been argued that it is not possible to make specific recommendations about the predictors that should be included in a prognostic model, owing to a lack of high-quality evidence. 23 At present, oral antipsychotic medication in combination with psychological interventions is the recommended treatment for prevention of relapse in first-episode and recurrent psychosis. 33

Reviews and meta-analyses suggest that although antipsychotics are consistently more effective than placebo34 they tend to be of intermediate efficacy for relapse prevention, with limited differences noted between individual drugs. 35 Discontinuation of antipsychotics is common and, although discontinuation rates vary between drugs,36 one trial found that almost three-quarters of participants had an unplanned end to their antipsychotic treatment before the end of the 18-month study period. 37 The odds ratios of discontinuation compared with those for placebo have been found to range from 0.43 for the best-performing drug to 0.80 for the worst. 34 Discontinuation often relates to the intolerability of adverse effects of antipsychotics and, although the type and frequency of adverse effects vary considerably between medications, they can include weight gain, extrapyramidal side effects, sedation and prolactin increase. 34

Meta-analyses of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) for psychosis have found small to moderate effect sizes in favour of CBT for psychosis for a variety of outcomes, including improvement in mental state,38 reduction in positive39,40 and negative symptoms,40 reduced hospital admissions41,42 and improved mood and functioning. 40 Some have urged caution in the interpretation of positive effects given an apparent inverse relationship between effect size and methodological rigour, particularly in relation to masking,40,43 and effects in favour of CBT for psychosis may also be less clear when trials use other psychological therapies as the comparator. 44 Reviews of family interventions, which take different forms but tend to be underpinned by cognitive–behavioural principles,45 have shown reductions in relapse and hospital admissions38,46 as well as improvements in treatment compliance. 46 However, the availability of both CBT for psychosis and family therapies is limited by poor implementation in adult mental health services. 8,47

In summary, the strongest evidence among treatment approaches for relapse prevention is to be found for antipsychotic medication, but its benefits are limited by high levels of discontinuation and it is often associated with prevalent and burdensome side effects. Evidence in support of psychological therapies for relapse prevention is limited, with questions over methodological rigour. Access to psychological therapies is also limited by poor implementation in services. This means that there is a pressing need to investigate alternative methods of relapse prevention.

Early warning signs monitoring and interventions

A further well-established approach for relapse prevention in research and practice is early warning signs (EWS) monitoring, established by Birchwood, Herz and colleagues. 48,49 EWS monitoring is based on the assumption that it is possible to intervene to reduce the likelihood of a relapse of psychosis through its timely prediction. This is generally achieved by comparing ongoing assessments of EWS indicators against an individual’s ‘baseline’ score. 50 Relapse in psychosis is now understood to be the end point of a process of change associated with early signs including changes in affect and incipient psychotic experiences. 50 EWS may be identifiable for as long as 5–8 weeks prior to a relapse,51 creating significant opportunity for early intervention. However, review evidence suggests considerable variation in the proportion of relapses correctly predicted by EWS (sensitivity 10–80%, median 60%) and non-relapses correctly predicted (specificity 38–100%, median 81%), with more frequent monitoring and the inclusion of both affective and psychosis symptoms found to improve prediction. 52

Eisner et al. 52 identified 17 papers involving early signs interventions in their 2013 review. Early signs interventions involve responding to EWS changes with a plan designed to prevent or minimise relapse. Just one of these studies used a purely psychological approach, with two or three sessions of relapse prevention focused CBT administered in response to an assessed increase in EWS from baseline. 53 People in the CBT arm had significantly fewer relapses than people in a treatment-as-usual arm, but the findings may have been influenced by the lack of masked assessment of relapse. Four studies included interventions in response to EWS increases that Eisner et al. described as multicomponent relapse prevention techniques. These included stress management and problem-solving methods, increased practitioner contact and antipsychotic medication increases,54–57 as well as three interventions that involved a relative or friend. 54,55,57 In two out of the three studies that assessed relapse, those in the intervention arm had significantly improved outcomes compared with those receiving treatment as usual,54,55 and the other study was potentially underpowered to show an effect on relapse. 57

The remaining studies in the Eisner et al. 52 review related to interventions in response to EWS that involved changes in medication alone. In one study, targeted medication or placebo was given in addition to maintenance medication on the emergence of EWS. However, no differences were observed between the arms in relation to time to symptom exacerbation at 2-year follow-up. 58 The remaining 11 studies temporarily used targeted medication on the emergence of EWS but in the absence of other ‘maintenance’ antipsychotic medication. 59–70 Although there were variations in the method of treatment and in comparators, in all but one65 of the seven studies of targeted medication approaches where relapse was assessed the outcomes were better for people in receipt of a moderate dose of maintenance medication than for people receiving targeted medication alone. 61,62,64,67–69 Two studies59,60 measured hospital admission alone, finding no significant differences in admission rates between people in receipt of maintenance medication regimes and those in receipt of targeted medication regimes.

Across all of the included studies, comparison was complicated by the heterogeneity of EWS assessment and the definition of relapse alongside a number of methodological weaknesses, including potential sampling bias and underpowered studies. Despite this, a number of conclusions were drawn about EWS-informed interventions. Targeted medication in response to EWS was found to be less effective than maintenance for relapse prevention, and replication with blinded assessment of relapse was recommended for the lone psychological intervention53 before firm conclusions could be drawn about its seeming potential. Multicomponent responses to EWS were described as showing promise for relapse prevention, but methodological weaknesses were highlighted, suggesting the need for further research.

Additional evidence of the potential for EWS interventions was provided in a 2013 Cochrane review71 that compared the effectiveness of EWS interventions with that of treatment as usual on time to relapse, hospitalisation, functioning and symptoms. The review found that significantly fewer people relapsed with EWS interventions than with usual care [23% vs. 43%; risk ratio 0.53, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.36 to 0.79; 15 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), n = 1502] and significantly fewer people were readmitted to hospital (19% vs. 39%; risk ratio 0.48, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.66; 15 RCTs, n = 1457). There was, however, no effect on reducing time to relapse. However, the review found low overall quality of evidence, which limited generalisability to usual care, making it impossible to recommend the use of EWS interventions in routine practice until higher-quality evidence becomes available.

Service user barriers to relapse detection and prevention

Uncertainty about the prognostic validity of EWS52 brings with it a risk of unnecessary interventions from services, which may, in turn, heighten the fear of relapse in people with experiences of psychosis and their carers. 17 Feelings of fear, helplessness and depression are commonly experienced prior to full relapse. 72 Fear of illness or relapse is also associated with poorer insight,25 emotional dysfunction,73 suicide risk,74 more traumatic experiences of psychosis, and fear of psychosis symptoms and hospital. 16 It is also a barrier to coping and relapse prevention for family members. 18 Our 2015 RCT17 of relapse detection showed that fear of recurrence contributed independently to the prediction of relapse (sensitivity 72%, 95% CI 52% to 86%) compared with EWS (sensitivity 79%, 95% CI 62% to 89%) and should, therefore, be included in EWS monitoring. Fear of recurrence was also associated with increased depression and feelings of entrapment, self-blame and shame and was a significant predictor of time to relapse. This suggests that fear of recurrence may be a risk factor for relapse and for increased distress arising from psychosis experiences and that it may play some role in accelerating the process of relapse. All in all, this suggests that fear of recurrence is a key barrier to, and potential target for, interventions to predict and prevent relapse.

Concurrently, people affected by psychosis are more likely than those in the general population to adopt avoidant coping styles,75,76 which may be an attempt to prevent relapse and minimise the effects of public stigma. 73 Avoidant coping in psychosis has been associated with higher neuroticism and lower extraversion,77 reduced insight,78 negative early childhood experiences, insecure identity,79 cognitive deficits80 and a generally greater insecurity in relationships and reluctance to seek help in a crisis. 81,82 In the context of active psychosis symptoms, avoidance may represent a safety behaviour based on the perceived threat of other people. 83 Review evidence suggests that greater difficulties in forming relationships among people affected by psychosis is associated with poorer service engagement and poorer relationships with practitioners, as well as longer and more frequent inpatient admissions. 81 Reluctance to seek help may be an understandable response to fear generated through previous negative, and potentially traumatic, experiences of inpatient admission. 16 In totality, this suggests that identifying and responding to EWS may be constrained by a variety of factors. These include avoidant coping styles and an associated reluctance to seek help or disclose EWS, poor-quality relationships between people in receipt of services and those providing them, and a wider fear of relapse.

Service barriers to relapse detection and prevention

One potentially important means of improving the implementation of EWS approaches without necessarily increasing fear of relapse is using interventions to increase shared decision-making for relapse prevention and risk management. Joint crisis plans (JCPs), which allow for the expression of service user preferences in the event of a future relapse, are one such example in the UK. The CRIMSON study84 compared the effectiveness of JCPs with that of treatment as usual for people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia but found no significant impact on the reduction of compulsory treatment, raising questions about the wider application of JCPs. An associated process evaluation85 examined how stakeholders perceived JCPs and shared decision-making as well as the barriers to implementation. The main barriers identified related to practitioners and included a general ambivalence towards JCPs and the perception that shared decision-making was already happening, as well as concerns about service users’ expressed wishes for JCPs. These barriers led to poor clinician engagement, which in turn undermined service users’ contributions to the process. It was also noted that, in times of crisis, JCPs were largely ignored, with practitioners reverting to standard practice. As a result of feeling unable to influence practitioner views through JCPs, people using services felt that there was a lack of respect for their views and that they were not able to influence shared decisions. Clinicians themselves experienced their ongoing clinical interactions as ritualised, particularly in relation to risk, while wider evidence highlights the need to be conscious that EWS monitoring for relapse prevention is also contingent on the person receiving services initiating help-seeking from a position of vulnerability and perceived threat (linked, for example, to previous experiences of coercive treatment). 86

People affected by psychosis may have had difficult or traumatic experiences of relapse,16 and there can be many barriers to help-seeking,87 which reduce the possibility of early intervention at times of crisis. This may in turn increase reliance on coercive practices, potentially building on already negative expectations in a vicious cycle. This means that there is some urgency to develop and evaluate an intervention that can facilitate safe and honest disclosure of possible EWS while also encouraging collaborative and non-coercive responses from mental health practitioners.

Conceptual framework for improving relapse detection and prevention

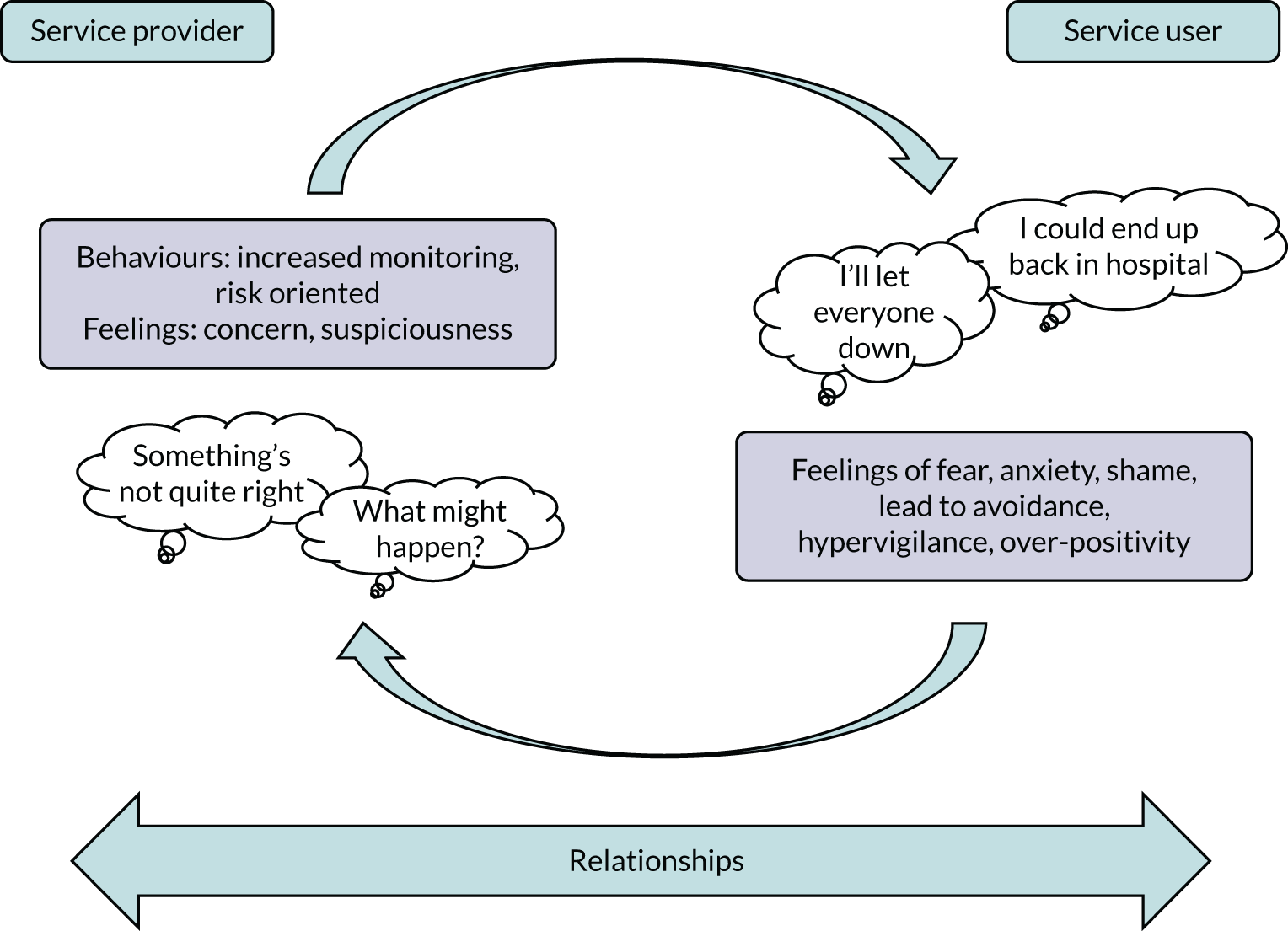

Our conceptual framework for improving relapse detection and prevention aims to understand the awareness of and response to EWS in the context of relationships. Figure 1 illustrates a cognitive–interpersonal model of EWS in which fear of recurrence drives negative emotions including fear, anxiety and shame. This distress may be regulated by coping strategies including avoidance and hypervigilance. Such responses may in turn influence practitioner responses at times of increased risk of relapse, for example interpreting avoidance (of appointments, telephone calls, etc.) as evidence of the need to focus more on risk management. For someone using services, such shifts in practice may in turn simply reaffirm existing negative expectations in a cyclical manner. Therefore, interventions that can enhance positive emotional awareness, choice and autonomy (through self-management promotion) and improved communication (through increased understanding) could provide a means to disrupt and change these negative interpersonal cycles. Given that the modal time window to intervene in the context of EWS is 2 weeks,52 interventions that can enhance access to data to inform help-seeking and shared decision-making could contribute to relapse detection and prevention. Digital technology may offer such an opportunity for this kind of timely intervention.

FIGURE 1.

Cognitive–interpersonal framework for EWS.

Digital technology for early warning signs monitoring and intervention

Mobile health technology, also known as mHealth, has the potential to make a variety of mental health interventions more widely available through a combination of computing power, portability and widespread ownership of mobile devices. There has been a rapid increase in internet-connected smartphone ownership with an estimated 3 billion smartphone users globally in 2019. 88 There are indications that a ‘digital divide’, restricting access to mobile technologies for people affected by psychosis in comparison with the general population, has diminished in recent years,89 with estimated rates of ownership ranging from 66.4% (95% CI 54.1% to 77.6%) to 81.4% in more recent studies. 90

The potential of mHealth to transform remote measurement of changes in health and well-being across health conditions has been recognised,91 and in mental health this includes the identification of its potential to improve EWS monitoring and relapse prevention. 92,93 Emerging evidence suggests that people with experiences of psychosis are generally comfortable with the application of digital mobile technologies to support self-management and enhance service engagement. 90,94 Many studies of mHealth for psychosis also show high levels of acceptability,95 although problems with inconsistent assessment and reporting of usability and acceptability in mHealth for psychosis studies need to be addressed. 96

Mobile technologies, in particular smartphones, provide an opportunity to overcome some of the known barriers to EWS implementation potentially through both ‘active’ and ‘passive’ data collection. Active data collection invites people to respond to intermittent EWS self-report assessments on their mobile device. 97 Passive monitoring relates to the assessment of relevant data routinely gathered on a mobile device, for example in relation to phone usage or location. 98 Both approaches may also be combined. 99

The mobile collection of data on repeated occasions in real-world circumstances represents a form of ecological momentary assessment (EMA). EMA, which is being applied increasingly in psychosis research,100 brings with it the potential to reduce the type of recall bias often associated with retrospectively gathered data. 101 Such routine monitoring can generate rich data about people’s experiences, which have the potential to support shared decision-making and to reduce the ambiguity within which practitioners may be required to reach clinical decisions, particularly at times of crisis. Bell et al. 100 reviewed nine EMA interventions for people with experiences of psychosis (n = 459),97,102–109 finding some evidence for improved clinical outcomes as well as reasonable feasibility and acceptability. Similarly, positive results have been reported in terms of feasibility, acceptability and adherence for a further 10 mHealth for psychosis studies that feature the prospective assessment of symptom course. Of particular relevance are studies of the Information Technology Aided Relapse Prevention Programme in Schizophrenia (ITAREPS)97,108,109 and ExPRESS110 early signs interventions.

The ITAREPS system, which was tested in Czech and Slovak mental health services, used text-based EWS data collection to notify clinicians when scores breached a specified threshold. Treating clinicians were expected to increase medication by 20% within 24 hours of an alert. Initial non-controlled mirror design testing suggested a 60% decrease in hospital admissions during ITAREPS participation over a mean of 283.3 days (± 111.9) when compared with the same time period before entering the programme. 108,109 However, a more rigorous follow-up double-blind randomised trial found no statistically significant differences in hospitalisation rates between people in an ITAREPS group and people in a control group. 97 However, there were significant problems with clinicians’ adherence to the treatment protocol, and a post hoc analysis suggested a ninefold reduction in the risk of hospitalisation for the subset of people among whom there was found to be high clinician adherence. A later study of the ITAREPS system, which removed the mHealth component, found that adherence to the protocol improved when mental health nurses were employed to triage EWS assessments. 111 More recently, Eisner et al. 110 tested the feasibility of combining conventional EWS monitoring with basic symptoms112 monitoring in an app (smartphone application), with scores above a specified threshold prompting a phone-based assessment of relapse. Participants completed 65% of app assessments over 6 months. App ratings also showed high concurrent validity with researcher assessments and there was preliminary evidence of the predictive validity of app ratings.

Although the overall results of mHealth for psychosis studies are promising, it should be noted that the vast majority of research in the field relates to small pilot or feasibility studies. Questions have been raised over the quality of reporting generally96 and the assessment and reporting of safety outcomes113 and also how end-user experience and engagement are measured114 and encouraged. 115 There is, however, emerging evidence to suggest that engagement with mHealth for psychosis interventions can be enhanced by providing social support, including peer support, as part of the interventions. 116,117

Peer support working

The creation of formalised peer support roles in mental health systems, where peer workers are employed and trained to work with people in receipt of services, in part based on a shared lived experience of mental distress, is considered to be an important component of recovery-oriented mental health systems. 118,119 Peer workers are theoretically well placed to reduce the power imbalances inherent in mental health services, drawing on their own experiences to build relationships with people using services that are reciprocal and founded on mutuality. 120 Although limitations in the conduct and reporting of research on peer support121 should be acknowledged, there is increasing evidence that peer supported interventions are at least as effective as non-peer-delivered equivalents122 and that peer workers are particularly well placed to deliver on recovery-related outcomes, including hope and empowerment. 119,121 Recent trial evidence also suggested that a peer-supported self-management intervention with people in receipt of crisis services was effective in reducing hospital re-admissions. 123 Fortuna et al. 124 have proposed a theoretical model of the role of peer support specific to digital health behaviour interventions. Central to this model are reciprocal accountability processes shared between peer supporters and people using digital interventions, which the authors argue build engagement through various mechanisms, including the promotion of autonomy, goal-setting, a strong peer-to-end-user working alliance and therapeutic bonding.

Conclusion

In summary, mHealth interventions, and smartphone interventions specifically, offer a significant opportunity to deliver EMA-based monitoring of changes in well-being that are ecologically valid and contextually sensitive. They also offer potential solutions to some of the implementation barriers that have hindered the routine application of EWS approaches. Although there is a need for more rigorous and consistent research, preliminary studies have shown encouraging levels of user acceptability and engagement, including those specific to EWS interventions, facilitating timely assessment and intervention to promote self-management and relapse prevention. However, there are important implementation challenges to ensure that these technologies can enhance relationships and shared decision-making, particularly during times of increased stress and crisis. Blending peer support with digital EWS interventions has the potential to improve engagement and user experience, contributing to the need to develop interventions that enhance positive emotional awareness, choice and autonomy.

Chapter 2 Methods

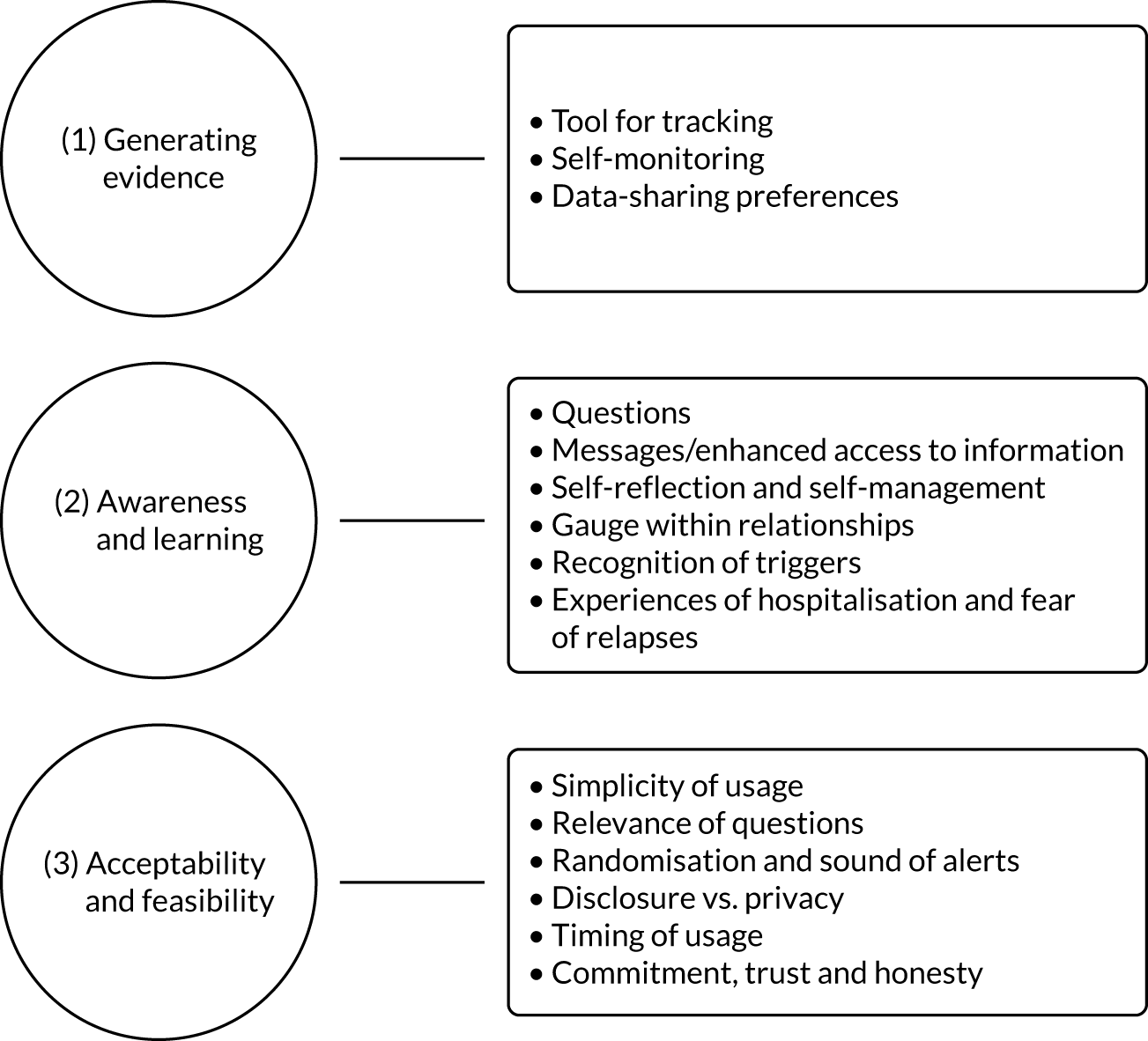

EMPOWER phase 1

Objective

The objective of phase 1 was to conduct task group interviews to (1) evaluate the acceptability and usability of mobile symptom reporting using smartphones among service users, carers and mental health staff; (2) identify incentives and barriers to use by service users and carers and to implementation by mental health staff; and (3) identify pathways to relapse identification and prevention. These interviews informed modifications to the EMPOWER mobile app, which was then subjected to a 5-week beta-testing phase.

The aims of the work packages (WPs) that constituted phase 1 are as follows.

-

WP 1: (1) evaluate the acceptability and usability of mobile symptom recording using smartphones among service users and their carers; and (2) identify incentives and barriers to use.

Deliverables: software and protocol updates in response to feedback from service users and carers.

-

WP 2: (1) evaluate the acceptability and usability of mobile symptom recording using smartphones among professional mental health care staff; (2) identify incentives and barriers to implementation by mental health staff; and (3) identify relapse prevention pathways and whole-team responses.

Deliverables: (1) carry out software and team protocol updates in response to feedback from professional care staff; (2) develop care pathways and identify operational barriers and enablers; and (3) identify the training needs of teams participating in the phase 2 pilot cluster randomised controlled trial.

-

WP 3: finalise the EMPOWER app for its implementation in phase 2.

Deliverables: (1) carry out software and protocol updates in response to feedback from service users, carers and staff; (2) agree on final modifications to the EMPOWER app to enhance its usability; (3) and finalise measurement methods for the assessment of self-reported acceptability and usability.

Settings

Parallel arms of data collection for phase 1 took place in NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde, UK, and NorthWestern Adult Community Mental Health Services in Melbourne, Australia.

Methods

Work package 1: task groups with service users and carers

A task group is a type of focus group designed to generate qualitative data and the principles for action, which are grounded in the experience of group members. Task groups were used to elicit views about experiences of relapse, incentives and barriers to help-seeking and optimal responses to relapse or the threat of relapse. Task groups explored:

-

the utility of early signs monitoring

-

views about using self-management messages and which self-management messages would have greatest salience

-

the design parameters of the system that could best sustain their involvement

-

views about help-seeking and activating a relapse prevention pathway

-

the best way to involve carer stakeholders

-

the best way to contact mental health staff

-

how they would like to use their data from EMPOWER.

A copy of the task group guide can be found in Report Supplementary Material 1. These data informed the final design and beta testing of the EMPOWER app to optimise the usability, salience, applicability and overall coherence of the intervention. We also recognised that some participants would be unable to attend task groups (e.g. owing to time constraints or difficulties engaging in groups). Therefore, to maximise engagement and diversity of views, we offered participants who were unable to attend task groups the opportunity to participate in individual interviews.

Work package 2: task groups with professional mental health care staff

The aim of the task groups with mental health care staff was to clarify the existing support pathways and procedures, systems and policies in teams participating in usual care, and to clearly differentiate these from our experimental intervention. We focused on the following topic areas:

-

strengths and limitations of these existing pathways

-

relevant policies and procedures that guide treatment as usual

-

feasibility and risks of and incentives to incorporating mobile phone technology into the monitoring and detection of risk of relapse

-

best methods to deal with false positives

-

opportunities to optimise pathways to relapse prevention.

A copy of the task group guide can be found in Report Supplementary Material 1. We recognised that some staff members may have been unable attend task groups, for example because of the time required. Therefore, to maximise engagement and diversity of views, we offered participants who were unable to attend task groups the opportunity to participate in individual interviews.

Work package 3: software beta testing

Beta testing was conducted with service users over a 5-week period. We utilised beta testing as a form of software user experience (UX) testing and investigation conducted to provide stakeholders with information about the quality of the tested software product. 125 Following the software beta testing, we conducted in-depth interviews exploring service user participants’ experiences of using the app and their perspectives on its acceptability and utility.

Study population

Recruitment procedure

Work package 1

Potential service user participants were approached to participate via community mental health services (CMHS). We invited mental health care staff to identify potentially eligible participants and we also placed posters in local CMHS advertising the research. Potential participants were provided with a participant information sheet and a consent form. They were advised that participation was entirely voluntary and that refusal to participate would not affect the care provided by their local CMHS. Following the provision of written and informed consent, service user participants were invited to nominate a carer to participate. When insufficient carers were recruited via service users, task group participation was opened to any carer associated with, and made known through carer organisations at, each participating site. Following an amendment to the protocol (SA01–AM02: see Table 1) in Glasgow, we also engaged with the Mental Health Network (Greater Glasgow & Clyde) and ACUMEN to support the recruitment of potentially eligible participants. Both of these organisations work directly with NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde to promote the wider involvement of service users and carers in shaping mental health services and facilitate collaboration through support and networking. In addition, we engaged with Support in Mind Scotland, which has strong engagement with carers of people diagnosed with schizophrenia. These organisations expressed a strong interest to engage with EMPOWER to highlight the study among members of their constituencies.

Work package 2

Professional mental health care staff were identified through service managers and through presentations at staff meetings. Staff members were invited to take part in a task group and provided with a participant information sheet and a consent form. They were advised that participation was entirely voluntary and that refusal to participate would not affect their employment.

Work package 3

In the first instance, service users who took part in WP 1 were invited to take part in the software beta testing. In addition, we recruited eligible participants from our local service user networks.

Eligibility criteria

Service users

Service users were eligible for participation in WP 1 if:

-

they were adults (≥ 16 years of age)

-

they were in contact with a local community-based service

-

they had either:

-

been admitted to a psychiatric inpatient service at least once in the previous 2 years for a relapse of psychosis or

-

received crisis intervention (e.g. via a crisis intervention service; re-engaged with a CMHS) in the previous 2 years for a relapse of psychosis

-

-

they had a diagnosis of a relevant DSM-5 schizophrenia-related disorder (i.e. schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or substance-/medication-induced psychotic disorder)

-

their current presentation did not include severe acute symptoms

-

they were able to provide informed consent as judged by their care co-ordinator/case manager or, if in doubt, the responsible consultant

-

they were able to manage the language requirement of participation.

Service users were eligible for participation in WP 3 if:

-

they were adults (≥ 16 years of age)

-

they were in contact with a local community-based service

-

they had a diagnosis of a relevant DSM-5 schizophrenia-related disorder (i.e. schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or substance-/medication-induced psychotic disorder)

-

their current presentation did not include severe acute symptoms

-

they were able to provide informed consent as judged by their care co-ordinator/case manager or, if in doubt, the responsible consultant

-

they were able to manage the language requirement of participation.

Carers

Carers were family members who were in regular (i.e. at least weekly) contact with an individual using services who had a diagnosis of a relevant DSM-5 schizophrenia-related disorder (i.e. schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or substance-/medication-induced psychotic disorder). The frequency of contact was the only eligibility criterion for carer participation. Carers nominated by eligible service users who provided informed consent were also approached for inclusion in the study.

Professional mental health care staff

Professional mental health care staff were eligible for participation if they had been working for the service for longer than 2 months, to ensure that they had an orientation to and were familiar with the local service system.

Sample size

The numbers projected for WPs 1 and 2 (i.e. 30 service users, 30 carers and 20–30 professional mental health care staff) and WP 3 (i.e. 10 service users) were to provide sufficient data to create the framework of analysis. No formal sample size calculation (e.g. power analysis) was considered appropriate for these WPs, as their aim was not to evaluate treatment effects.

Analytic methods

Task groups (WPs 1 and 2) and follow-up interviews (WP 3) were digitally recorded, transcribed and anonymised before being entered into NVivo version 12 (a computer-assisted qualitative software package; QSR International, Warrington, UK) to organise the data and enable progression to analysis. Analysis drew on framework analysis, which is a qualitative approach specialising in pragmatic, generalisable qualitative methods designed for real-world implementation. 126,127 This approach has been developed specifically for applied or policy-relevant qualitative research in which the objectives of the investigation are typically set in advance and shaped by the information requirements of the funding body. The time scales of applied research tend to be short and there is often a need to link the analysis with quantitative findings.

Participant safety and withdrawal

Risk identification

Risks associated with work packages 1 and 2

The potential risks of harm or discomfort to service users, carers and professional mental health care staff who participated in the task groups (i.e. WPs 1 and 2) included:

-

risks to personal privacy associated with the dissemination of personal information by other participants

-

distress from inappropriate, abusive or offensive interaction(s) with other participants

-

increased paranoia resulting from participation, especially in the event of deterioration of the mental well-being of service user participants

-

potential distress from talking about experiences of relapse.

The likelihood of these risks eventuating was considered low based on the past experiences of the investigators.

Risks associated with work package 3

The potential risks of harm or discomfort to service users who participated in the software beta testing (i.e. WP 3) included:

-

risk to personal privacy associated with the unlawful dissemination of personal information by hackers

-

risks to the clinical safety of service user participants (i.e. true- and false-positive detections of relapse).

The likelihood that personal privacy would be breached by the unlawful dissemination of personal information by hackers was considered low given the past experiences of the investigators. Specifically, this related to experiences developing and implementing the ClinTouch system that was the platform for EMPOWER.

The likelihood that clinical safety would be comprimised (i.e. service user participants’ well-being deteriorating and the system flagging a true-positive detection of relapse, or the system flagging a false-positive detection of relapse) was also considered low given the short duration of the software beta testing.

Risk management

The potential risks of harm or discomfort to service users, carers and professional mental health care staff who participated in the task groups (i.e. WPs 1 and 2) as outlined above were negated, minimised or managed through the following processes:

-

All task groups were co-facilitated by two individuals. Key facilitator responsibilities included advising participants of rules of engagement with the group (e.g. confidentiality, respectful communication), and upholding the same.

-

Facilitators also monitored participants’ degree of distress and took action accordingly. Participants who displayed or reported distress were offered a debriefing session.

The potential risks to system and personal privacy and clinical safety associated with WP 3 were negated/minimised/managed via a rigorous safety protocol developed by the research team and experts from the information systems discipline. The safety protocol comprised two levels of security: system and privacy protection and clinical safety.

Clinical safety

A range of measures were also in place to ensure participants’ clinical safety. Changes in EWS were observable by the researchers, and responses were manual rather than automated. Information related to clinical safety (i.e. EWS, idiosyncratic signs, etc.) was screened three times per week on the clinician interface, and specific attention was paid to the deterioration of EWS. Any detected increase meant that the study research assistant advised the clinical team of any significant change to the participant’s mental health.

In the case that a participant contacted the study research assistant, or another member of the research team, communicating distress, the study research assistant or member of the research team provided immediate support, and then contacted the participant’s treating team.

If a participant stopped using the system (i.e. they missed more than two scheduled prompts), the following protocol was adopted: (1) after two missed prompts, a SMS would be sent reminding the service user to use the app, and (2) after subsequent instances/missed prompts, the research team would follow up with a supportive telephone call encouraging participation. Information was to be passed on to the service user’s treating team if the service user stopped responding to the prompts to monitor their EWS, and if they missed the follow-up interview with the study research assistant.

Risk monitoring

Risks were monitored by the study research assistant. As part of their role as interviewer and group facilitator of the various work packages, the study research assistant monitored participants’ degree of distress and took action accordingly. All interviewees were invited to discuss any feelings of distress associated with participating in the interview, and task group participants were also invited to speak privately with the study research assistant and/or co-facilitator at the conclusion of the task group if they felt distressed. The study research assistant monitored the risks associated with the software beta testing; information about clinical safety was screened three times per week.

Risk reporting

The study research assistant reported all instances of distress that came to their attention and any potential clinical deterioration in participants’ mental health to the chief investigator and to the participant’s treating team. The study research assistant also recorded all instances in a database, and the chief investigator reported any serious adverse events that were related and unexpected according to the International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines on reporting Serious Adverse Events (Section II B) to the sponsor and the Research Ethics Committee.

Handling of withdrawals

Procedures

Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time. As a part of the informed consent procedure, participants were instructed to let a member of the research team know of their withdrawal ahead of time. Participants who chose to withdraw were offered debriefing as a matter of course. The treating team overseeing the care of service user participants was also advised of any withdrawals. Information collected from participants up to the point of withdrawal was stored in the databank.

Data security and management

The confidentiality of all study data was ensured using the security mechanisms outlined below.

The EMPOWER app

A range of measures were in place to ensure the security of the EMPOWER app and the data generated by its users. The app was hosted on the University of Manchester web server, which had standard measures in place to prevent unauthorised access. All data transmitted to and from EMPOWER servers were encrypted over https with strong ciphers as detailed in Approved Cryptographic Algorithms: Good Practice Guideline. 128 Cipher suites were implemented in compliance with section 6 (‘Preferred uses of cryptographic algorithms in security protocols’) of the Good Practice Guidelines. 128 In cases where participant data were downloaded from the EMPOWER site, these data were securely encrypted with a pass phrase of appropriate length and complexity. Data transfers were secured using standard web security protocols. Uploading study data to a central server in real time enabled them to be captured and so this protected against data loss, such as if a phone was lost or stolen. This removed the need for personal data to be stored on the device. The purpose of the server in this case was secure data storage. We also incorporated ISO 25010,129 which provides for safety-in-use and measures satisfaction with security. These security measures correspond closely to the NHS standards.

A number of technical measures were also employed to protect personally identifiable data. Any data stored on the phone by the participant were encrypted. We also recommended that service users set a passcode to access their smartphone. All service users recruited to the study gave their informed consent, and this included acknowledging risks to the security of their data.

Other study data

Each study participant was assigned a unique trial identification number at the start of the assessment process. This number was written on all clinical assessment forms/datasheets and databases used to record data on study participants. A securely stored and encrypted electronic copy of a record sheet linking patient identity, contact details and trial identification numbers for all participants was kept at each site.

The local study research assistant entered the data on to an electronic database, and all of these data were checked for errors before being transferred to the appropriate statistical package. All data were kept secure at all times and maintained in accordance with General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)130 requirements.

Audio recordings of the task groups and participant interviews were also stored securely on a server at the University of Glasgow and were destroyed following transcription and analysis of the data. Digital recordings from Melbourne were sent by secure transfer and stored on secure servers at the University of Glasgow.

Protocol amendments

Protocol amendments are described in Table 1.

| Amendment number | Date | Protocol number | Main change summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| SA01 | 3 August 2016 | 1.2 |

|

| SA02 | 2 November 2016 | 1.3 |

|

| SA03 | 15 December 2016 | 1.4 |

|

Protocol breaches

The Post-Study System Usability Questionnaire was omitted from WP 3 follow-up interviews.

EMPOWER phase 2

Objectives

Our phase 2 protocol is published elsewhere. 131 The overall purpose of this study was to establish the feasibility of conducting a definitive cluster randomised controlled trial (cRCT) comparing EMPOWER with treatment as usual (TAU). We sought to establish the parameters of the feasibility, acceptability, usability, safety and outcome signals of an intervention as an adjunct to usual care that would be deliverable in the NHS and Australian CMHS settings. The EMPOWER intervention aimed to:

-

enhance the recognition of EWS among people using services and their carers

-

provide a stepped-care pathway that was either self-activated or in liaison with a carer and/or a community health-care professional, which then

-

triggered a relapse prevention strategy that could be stepped up to a whole-team response to reduce the likelihood of a psychotic relapse.

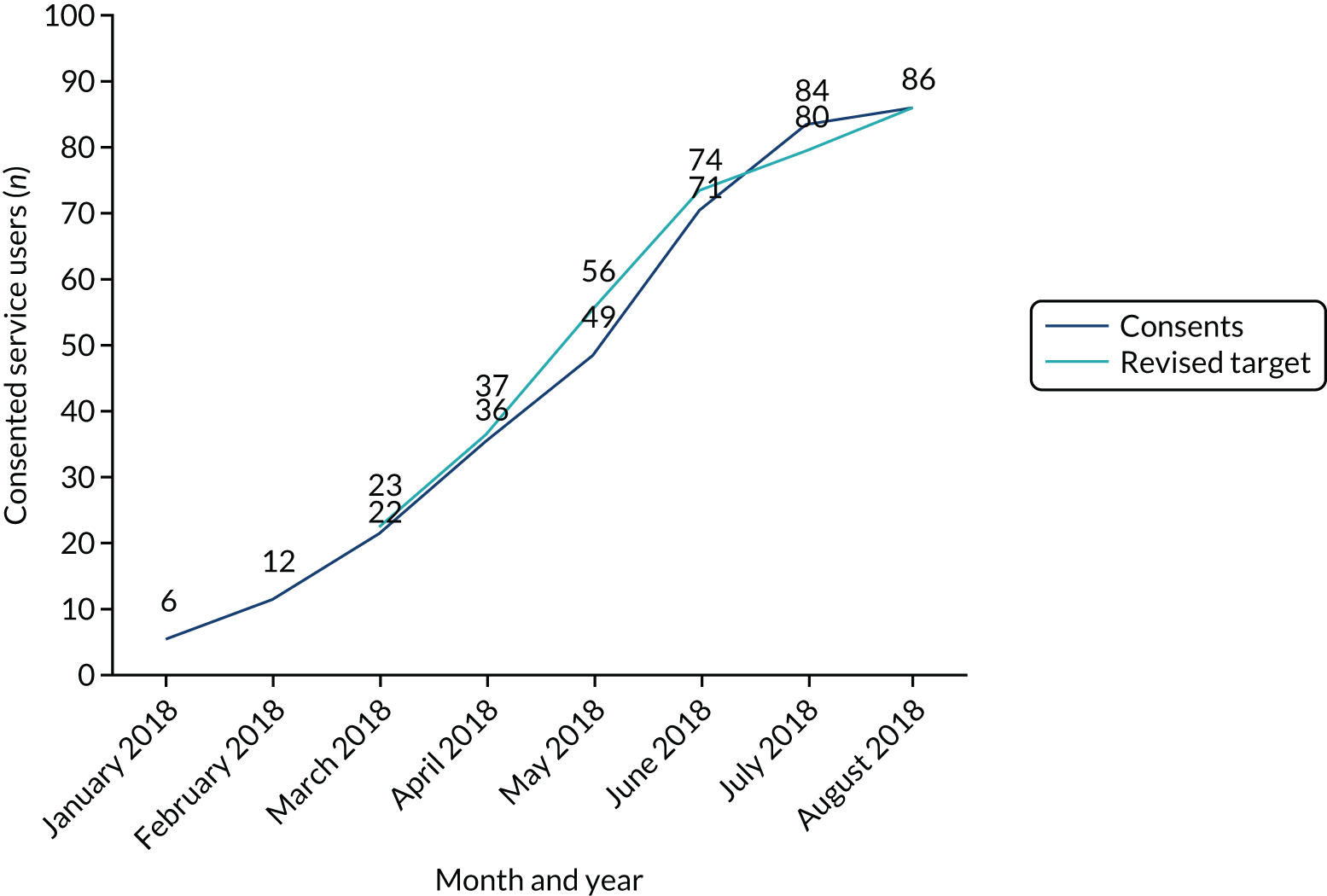

Specifically, we aimed to:

-

determine the rates of eligibility, consent and recruitment of potentially eligible participants (people using services, carers and care co-ordinators) to the study

-

assess the performance and safety of the EMPOWER class 1 medical device (CI/2017/0039)

-

assess the feasibility, acceptability and usability of the intervention, including feedback on suggested enhancements from people receiving the intervention, peer support workers and clinicians

-

assess primary and secondary outcomes to determine the preliminary signals of efficacy of the EMPOWER intervention as a basis for assessing the feasibility of collecting follow-up measures, determining primary and secondary outcomes, and determining probable sample size requirements for a future main trial

-

undertake a qualitative analysis of relapses to refine the intervention in the main trial

-

establish the study parameters and data-gathering frameworks required for a co-ordinated health economic evaluation of a full trial across the UK and Australia

-

enhance and tailor our mobile phone software app to deliver EWS monitoring, self-management interventions and access to a relapse prevention pathway that was embedded in whole-team protocols and action.

Trial design

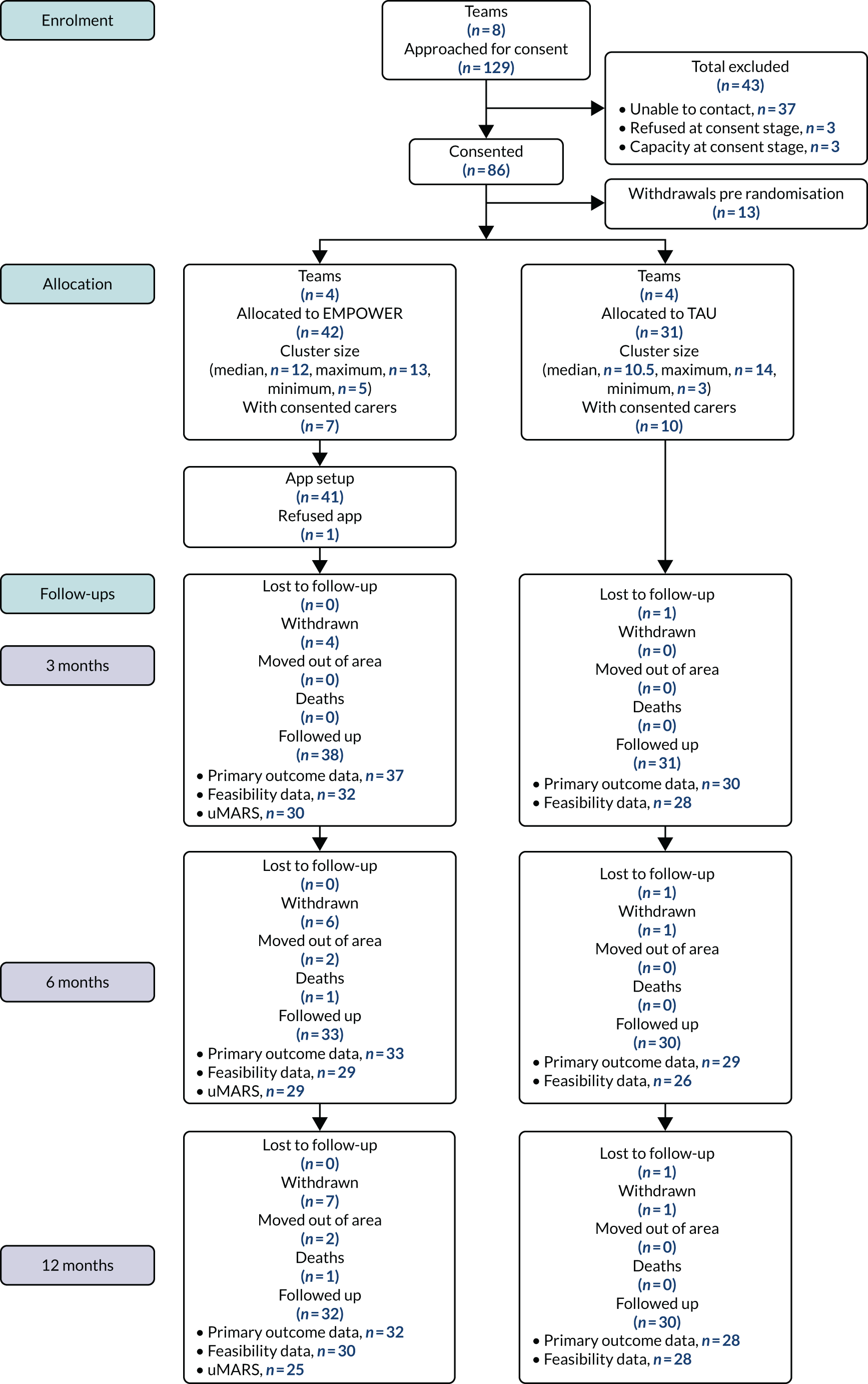

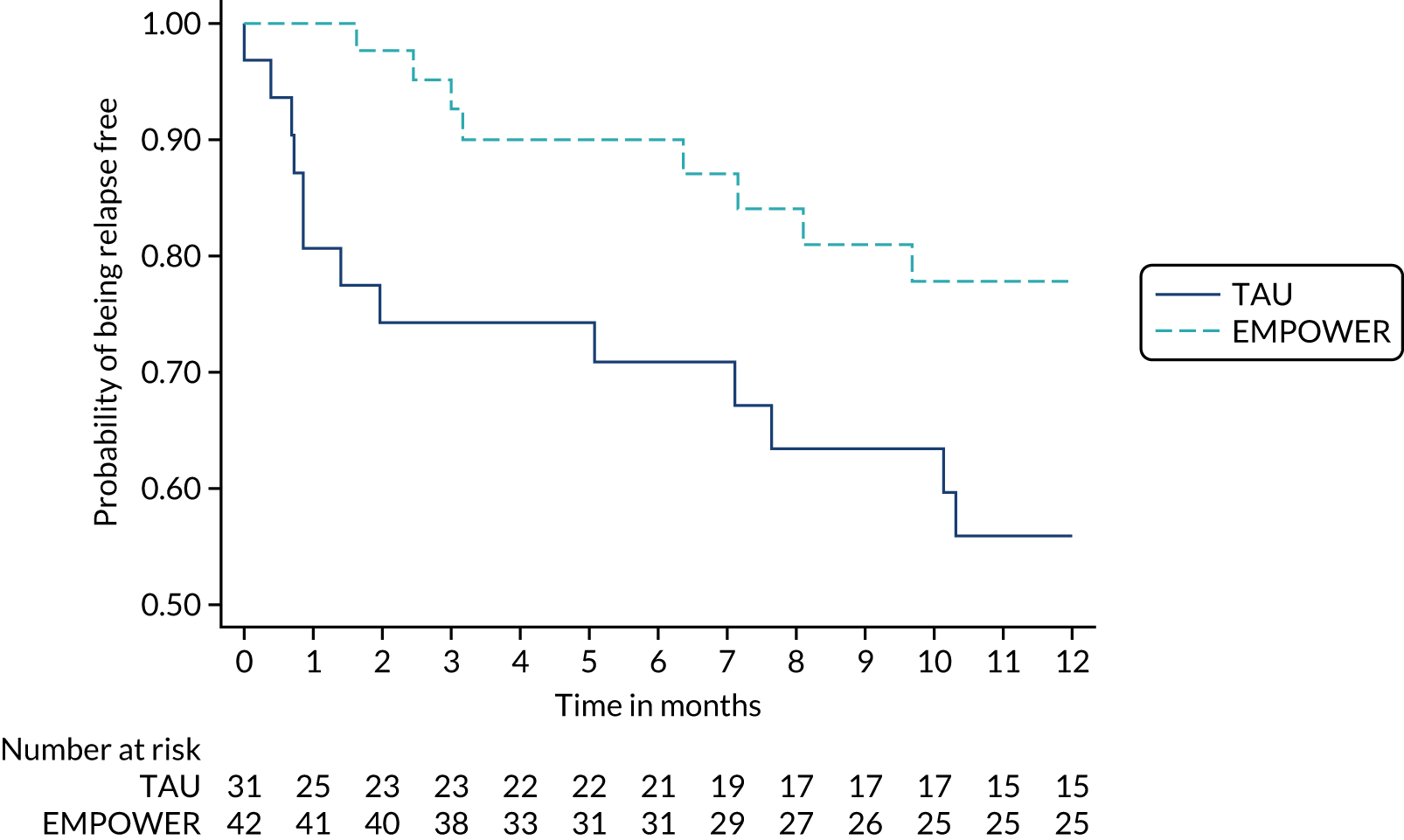

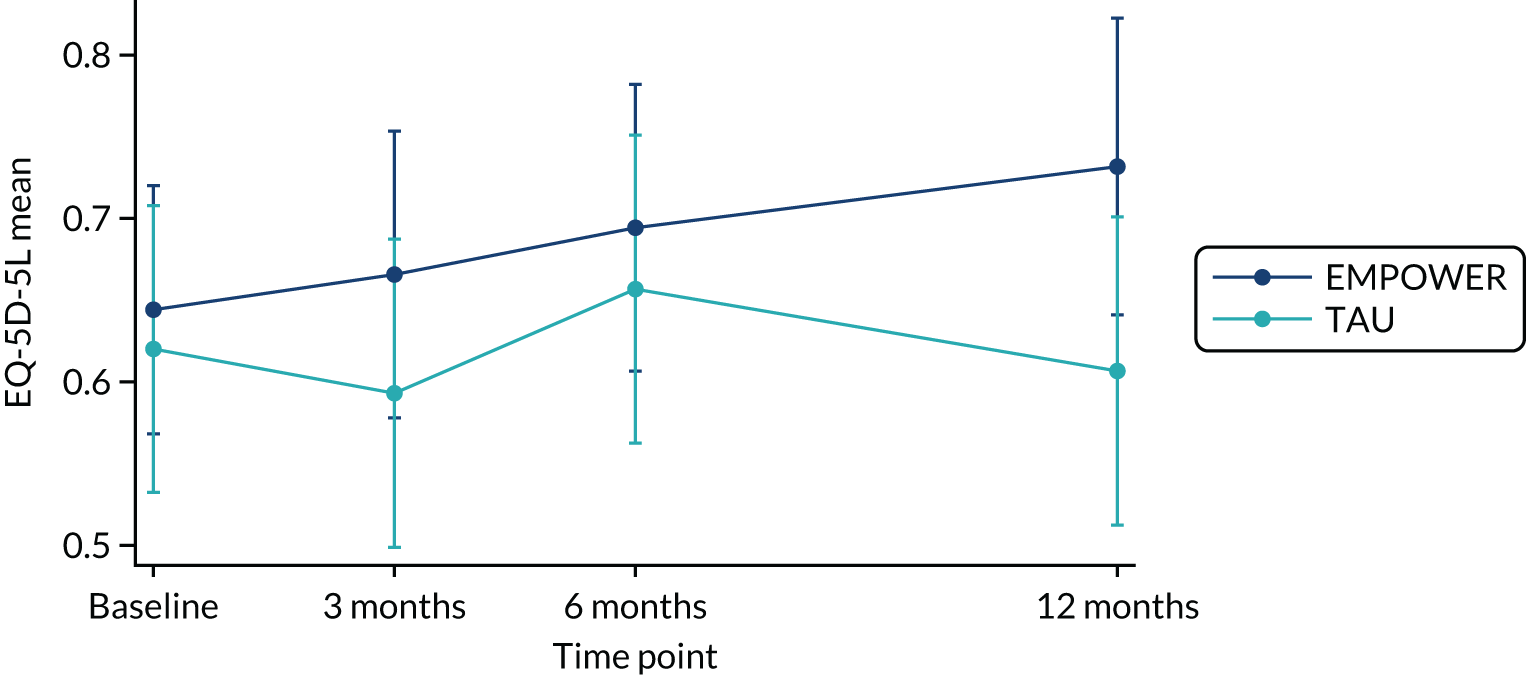

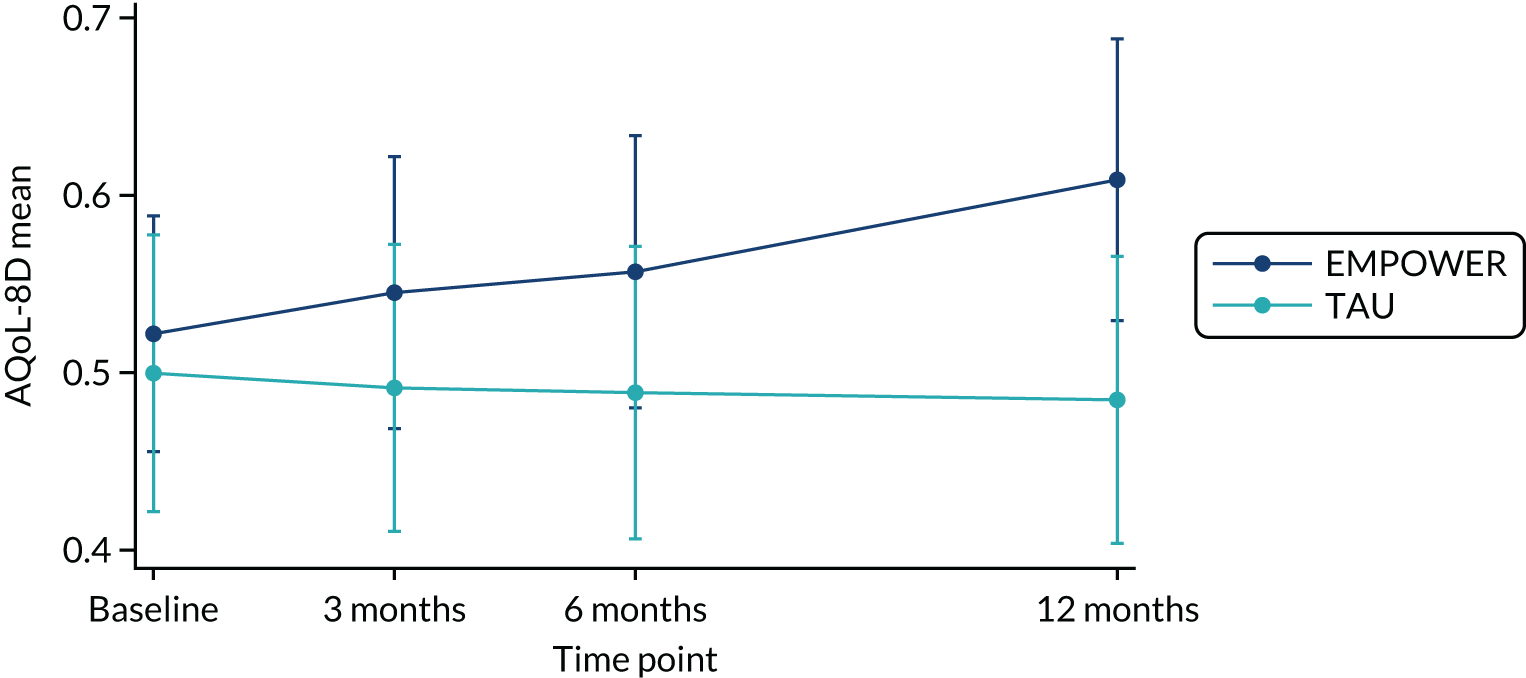

We evaluated EMPOWER using a multicentre, two-arm, parallel-group cRCT involving eight purposively selected CMHS (two in Melbourne, Australia, and six in Glasgow, UK) with 12-month follow-up. The CMHS were the unit of randomisation (the cluster), with the intervention delivered by the teams to people using services and with the outcomes assessed within these clusters. The study was planned and implemented in concordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) cluster trial extension132 and the extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. 133 We chose a cluster design as the EMPOWER intervention aimed to enable a team-based response to people in receipt of services whose real-time EWS monitoring activates a relapse prevention pathway.

Ethics and governance

The study received approvals from the West of Scotland Research Ethics Service (GN16MH271 reference 16/WS/0225) and Melbourne Health Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/15/MH/344). The study sponsors were NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde in the UK and the Australian Catholic University in Australia. The trial also received approvals from the NHS Health Research Authority and a notice of no objection for a trial of a medical device (CI/2017/0039) from the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), and was prospectively registered (ISRCTN99559262). The trial methods of enrolment, interventions and assessments are summarised in Table 2.

| Assessment | Enrolment: baseline | Allocation: 0 months | Post allocation | Close-out: 12 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months | 6 months | ||||

| Enrolment | |||||

| Eligibility screen | ✗a | —b | — | — | — |

| Informed consent | ✗ | — | — | — | — |

| Allocation | — | ✗ | — | — | — |

| Intervention | |||||

| EMPOWER | — | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Service user assessments | |||||

| Feasibility | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Acceptability and usability | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Remission status | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Relapse | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| PANSS | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Personal and Social Performance Scale | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| CDSS | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Timeline Followback | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| HADS | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| PBIQ-R | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Service Attachment Questionnaire | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Medication Adherence Rating Scale | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| EuroQol-5 Dimensions | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Assessment of quality of life | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Resource Use Questionnaire | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| General Self-Efficacy Scale | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Psychosis Attachment Measure | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Perceived Criticism and Warmth Measure | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Carer assessments | |||||

| Feasibility | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Carer Quality of Life-7 Dimensions | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Resource use questionnaire | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Perceived Criticism and Warmth Measure | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Involvement Evaluation Questionnaire | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Care co-ordinator | |||||

| Feasibility | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Service Engagement Scale | ✗ | — | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

A trial Study Steering Committee (SSC) and a Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) were constituted in accordance with National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) guidance. The DMEC reported to the SSC and the SSC reported to NIHR. Protocol amendments were reviewed by the DMEC and SSC before being submitted to the relevant Research Ethics Committee (see Table 4). The study was conducted in accordance with the recommendations for physicians involved in research on human participants adopted by the 18th World Medical Assembly, Helsinki 1964,134 and later revisions.

Preliminary work: patient and public involvement

Phase 1, as described above, was included to ensure extensive consultation with key stakeholders, namely mental health care staff, people with lived experience and carers, in a series of task groups across Glasgow and Melbourne. Stakeholder consultation directly shaped the development of the EMPOWER intervention. The Scottish Recovery Network also played a key role in shaping further consultation with people with lived experience to further refine intervention development and planning.

Eligibility criteria

Participation was sought from CMHS in NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde in the UK and NorthWestern Mental Health services in Melbourne, Australia. All participants (mental health care staff, service users and carers) were approached for their informed and written consent prior to assessment and randomisation. Research assistants were responsible for recruitment and taking informed consent. Written informed consent was obtained from all trial participants.

Community mental health services

We engaged CMHS that were likely to have five or more care co-ordinators willing to participate for a period of 12 months and had potential care co-ordinators with eligible service users on their caseload who were likely to consider participating.

Service users

Service users from participating CMHS were eligible for inclusion if they:

-

were adults (aged ≥ 16 years)

-

were in contact with a local CMHS

-

had either:

-

been admitted to a psychiatric inpatient service at least once in the previous 2 years for a relapse of psychosis or

-

received crisis intervention (e.g. via a crisis intervention service; re-engaged with a CMHS) in the previous 2 years for a relapse of psychosis.

-

-

had received a diagnosis of a schizophrenia-related disorder, specifically:

-

295.40 schizophreniform disorder [International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), F20.81]

-

295.70 schizoaffective disorder (ICD-10 F25)

-

295.90 schizophrenia (ICD-10 F20.9)

-

297.10 delusional disorder (ICD-10 F22).

-

-

were able to provide informed consent as judged by the care co-ordinator or, if in doubt, the responsible consultant.

Carers

Carers of people receiving support from participating CMHS were eligible for inclusion if they:

-

had been nominated by eligible participants

-

were in regular contact (weekly) with the person receiving services

-

provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Individuals were ineligible for participation if they did not meet the inclusion criteria outlined above. In addition, participants were excluded if they had experienced a recent relapse, operationally defined as having been discharged from the care of a crisis team or psychiatric inpatient service within the previous 4 weeks.

Interventions

In describing the EMPOWER intervention we utilise the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist. 135

EMPOWER intervention

Rationale

The rationale for the EMPOWER intervention was informed by the cognitive–interpersonal model outlined in Chapter 1 and was designed to enable participants to monitor changes in their well-being on a daily basis. In EMPOWER, we referred to changes in well-being as ‘ebb and flow’ as a means of moving away from risk-orientated monitoring that can sensitise individuals to increased fear of relapse. The terminology also attempted to convey a normalising framework for understanding changes in emotions and psychotic experiences in daily life. Clinical triage of changes in well-being that were suggestive of EWS was enabled through an EMPOWER algorithm that triggered a check-in prompt (ChIP). This enabled the prompt identification of any EWS and triggered a relapse prevention pathway if warranted.

The EMPOWER app was developed in part through consultation with people using services, their carers and mental health care professionals. Service user participants had access to the EMPOWER app for up to 12 months of the intervention period. EMPOWER was developed as a flexible tool for users to:

-

monitor daily the ‘ebb and flow’ of changes in well-being

-

incorporate personalised EWS items

-

receive automated EMPOWER (self-management) messages directly

-

review their own data and keep a diary of their experiences via a smartphone user interface.

Materials

Daily monitoring of well-being was initiated by pseudo-random mobile phone notifications to complete the EMPOWER questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 2). Notification reminders were sent after 5 minutes (when there had been no response), after which app users were allowed a 5-hour time window within which they could respond to questions. The questionnaire contains 22 items reflecting 13 domains (e.g. mood, anxiety, coping, psychotic experiences, self-esteem, connectedness to others, fear of relapse and personalised EWS). Items included both positive (e.g. ‘I’ve been feeling close to others’) and negative (e.g. ‘I’ve been worrying about relapse’) content. Each item was completed using a simple screen swipe, which enabled quick and efficient completion by users. Each item was automatically scored on a scale of 1–7. Where particular items scored > 3, users were invited to complete supplementary questions to enable a more fine-grained assessment of that domain. This provided up to a maximum of 56 questionnaire items.

Peer support working in EMPOWER

The EMPOWER intervention was blended with peer support. Peer support workers are people who bring lived experience of mental health problems and recovery to their work in mental health services, with practices underpinned by a set of values and principles. 120,136 The role is increasingly well established in mental health policy and practice in many countries, including the UK and Australia. 137 Peer support is also being increasingly integrated with digital mental health interventions. 124 Two peer support workers were employed in Glasgow and one was employed in Melbourne, all on a part-time basis, to work with people in the intervention arm of the study. Their work was underpinned by a values framework developed by the Scottish Recovery Network,138 with supervision available at both sites and also across sites.

Peer support worker roles initially focused on introducing participants to the ethos and principles of the EMPOWER stepped-care approach and setting up and personalising the app on provided or personal handsets. Following this set-up and familiarisation period, peer support workers maintained regular contact with app users, at least weekly in the baseline period and approximately fortnightly following the baseline. Contact was maintained primarily through telephone calls, although text messaging and in-person meetings also took place, with the type and amount of contact determined by personal preference and need. Peer support worker roles included:

-

Supporting engagement with the intervention. This included checking in with people to assess whether or not there were any blocks to their successful use of the app and to advise on how usage might be adapted to individual needs, for example encouraging people to take breaks from self-monitoring as required.

-

Offering technical advice and support in relation to participants’ use of the phone. This included supporting people in becoming familiar with mobile phone functions and ensuring that they had mobile phone data connectivity and adequate credit for data.

-

Encouraging the general exploration of well-being and of how data generated through the app reflected life experience and aided self-management.

-

Reviewing and supporting participants’ use of different app functions. This included supporting participants to access and make use of chart and diary functions. In particular, peer support workers encouraged participants to review charts and sought to prompt curiosity about chart data and the implications of these for self-management and well-being.

-

Aiding the interpretation of messages generated by the app. This included giving app users additional information on message content, as required, for example providing further information on how to access support to develop an advance statement.

-

Sharing personal experiences of app use. Peer support workers had personal experience of using the EMPOWER app and were able to reflect with research participants on their own experiences and, if required, offer practical advice and share aspects of their experience that they felt might support participants.

-

Monitoring and reporting performance and safety issues. This included making routine enquiries in relation to any possible adverse events and the extent to which these were associated with the intervention.

Procedures

A peer support worker met with participants on an individual basis to introduce the rationale for using the app, to collaboratively set up the app on their participant’s mobile phone or a study phone, and to support the individual’s familiarisation with the handset and app functions. Participants were invited to choose up to three personalised EWS items to be included in the EMPOWER questionnaire and further personalisation of delusion-specific items could also be made. Where possible, an individual’s care co-ordinator and nominated carer were invited to contribute to this meeting. Participants were asked to undertake daily monitoring for an initial 4-week baseline period to help establish their personal baseline of the ‘ebb and flow’ of their well-being. During this period, additional support was provided by peer support workers through weekly telephone follow-up. This provided an opportunity to encourage use of the app, solve any technical problems and identify any adverse effects. At the end of the 4 weeks, a further meeting was arranged with the peer support worker or mental health nurse to review monitoring, encourage engagement with EMPOWER messages, agree participants’ preferences for actions in response to changes in well-being that were suggestive of EWS and encourage participants to continue utilising local CMHS for clinical care. All participants were offered ongoing fortnightly peer support worker support to encourage them to use the app, to support their reflection on changes in well-being and their broader context including, for example, stressful life events, and to encourage them to use self-management strategies prompted by EMPOWER messages.

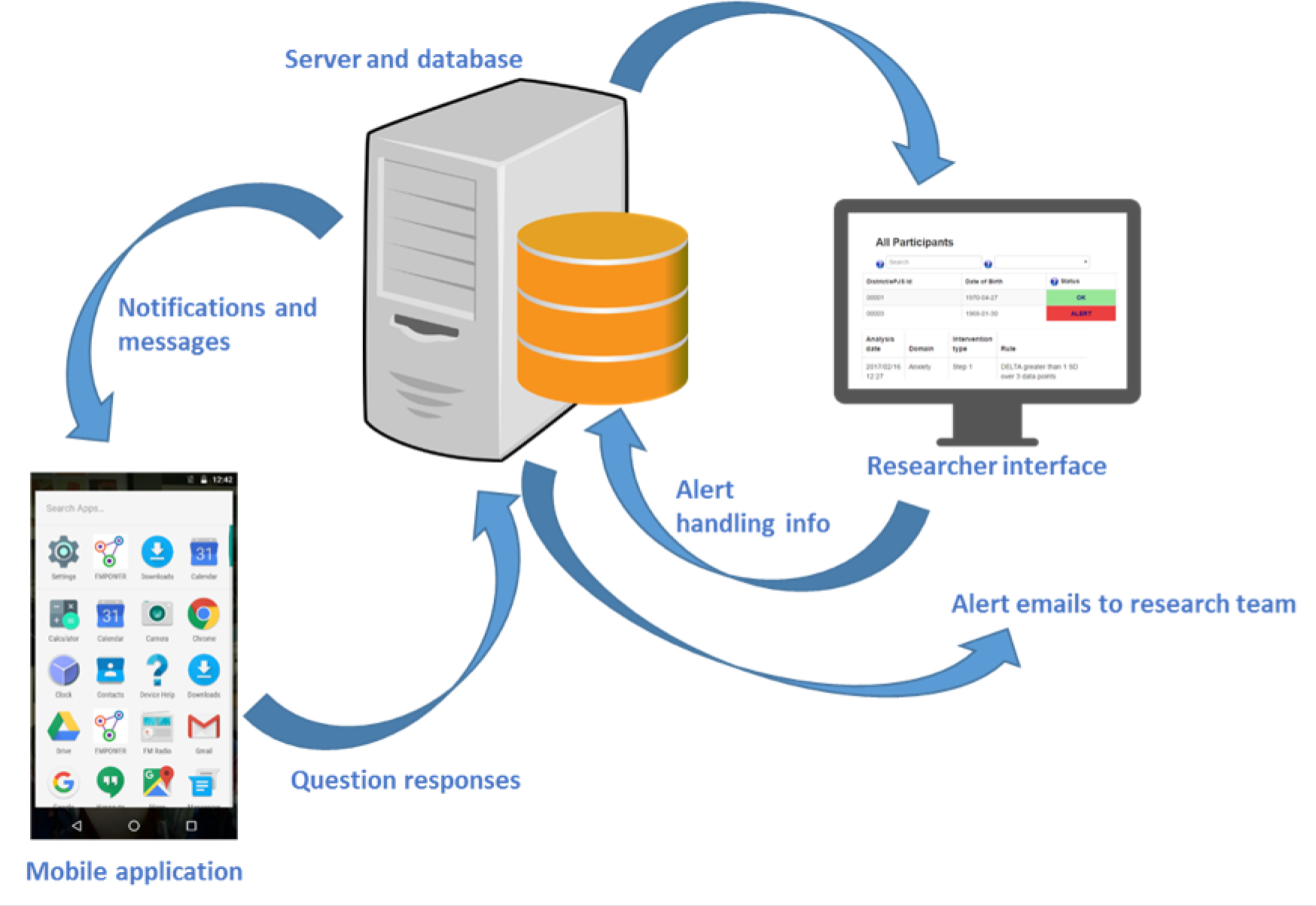

Digital procedures

The analysis and handling of questionnaire data was governed by the EMPOWER algorithm. The EMPOWER algorithm is a class 1 medical device (CI/2017/0039) that forms one part of a broader system that was designed to identify and respond to changes in well-being that were suggestive of EWS. Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of the system’s high-level components and data flow.

FIGURE 2.

The EMPOWER system. Google and the Google logo are registered trademarks of Google LLC, used with permission.

Participants used a mobile phone app that prompted them to answer a daily questionnaire about the potential EWS of psychosis. The data were then submitted to the EMPOWER server and analysed by the ChIP algorithm. The algorithm, which is summarised in Figure 3, compared a participant’s latest data entry against their personal baseline. If changes exceeded predefined thresholds, a ChIP was generated for the participant. The consequences of the ChIP were that the research team, which included a registered mental health nurse (in the UK), clinical psychologists (in the UK and Australia) and a general psychologist (in Australia only), were e-mailed about the participant and that participant’s status was set to ‘alert’ and was highly visible on a secure web-based researcher interface. In addition to viewing and handling ChIPs, researchers could view longitudinal graphs of their participants’ well-being and possible EWS, filtered by question or by domain (group of questions). ChIPs were initially screened by a member of the research team, followed by (1), in Australia, sharing a summary of relevant ChIP data with the clinical team, and (2), in the UK, a member of the research team checking in with the participant. Based on the outcome of this triage assessment the researcher could share an update with the participant’s care co-ordinator, who could, if indicated, escalate increased support to the participant from their local CMHS to reduce risk of relapse. We aimed to respond to ChIPs in some way within 24 hours or the next working day.

FIGURE 3.

EMPOWER algorithm responding.

The alert algorithm also ran a separate process scanning for EWS changes against the baseline. Based on these changes, the logic selected a message from the most appropriate of several content-based message pools (i.e. one message pool contained helpful messages about ‘mood’, another had messages about ‘anxiety and coping’, etc.). This message was delivered back to, and displayed on, the participant’s EMPOWER app. Messages were intended to help people have a greater sense of control over their mental health and well-being and to support self-management. We set up a specific patient and public involvement group to assist us in the co-design of the message function in the app. The group advised on the curation, content and delivery of messages. This group met on four occasions and had public representation from four people with direct lived experience of psychosis.

Training and support to community mental health service staff

After CMHS had been randomised to EMPOWER, we aimed to provide training to those mental health care staff in teams based on our model of relapse prevention, which emphasised:

-

therapeutic alliance

-

barriers to help-seeking

-

familiarisation with the app

-

developing an individualised formulation of risk of relapse

-

developing a collaborative relapse prevention plan.

Following this, we aimed to meet with care co-ordinators on a fortnightly basis to provide support in the implementation of EMPOWER. These meetings aimed to clarify and encourage formulation of any changes and participant responses within the model, and support clinicians to consider EMPOWER-consistent intervention options.

Background intellectual property

The background intellectual property and functionality was the pre-existing ClinTouch app developed in 2010 and funded by two grants from the UK Medical Research Council. The aims of the app were to help people with serious mental illnesses to manage their own symptoms and to prevent relapse. Software development and beta testing used an experience-driven design process in which service users with psychosis were involved in the design and development of the app, its functionality and its standard operating procedures. Health professionals were included in system design where it related to routine practice, and in the design of new, digitally enabled workflows. Randomised feasibility trials showed this method of active symptom monitoring to be safe, feasible and acceptable. 139–141 This personalised smartphone application triggers the collection of symptom self-ratings several times daily and wirelessly uploads these in real time to a secure central server. A semi-random beep (two to four times daily) alerts the user to complete a set of 12–14 branching items about current symptom severity using a touchscreen slider. A graphical summary of how symptoms fluctuate over time is assembled and displayed on the handset. A validation study compared face-to-face ratings on the gold-standard Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) with four-times-daily ClinTouch assessments over 1 week. This confirmed the validity of the self-reported items, with core psychotic symptom and mood items showing moderate to strong (r > 0.6) correlations between the two methods. 139 Non-core, behaviourally assessed items, such as negative symptoms, showed weaker correlations.

Based on this proof of concept, the standalone smartphone system was integrated via an application programming interface into NHS trust ICT (information and communication technology) platforms to allow the streaming of summary information into electronic health records, and to enable health professionals to track current symptoms on desktops at the team base and receive alerts when symptoms exceeded a pre-agreed personalised threshold. An open, randomised trial of ClinTouch active symptom monitoring compared with management as usual was conducted in NHS mental health trusts in Manchester and South London. 142 Recruitment to the trial took place between February 2014 and May 2015. The aims were to assess (1) the acceptability and safety of continuous monitoring over 3 months, (2) the impact of active self-monitoring on positive psychotic symptoms assessed at 6 and 12 weeks, (3) the feasibility of detecting EWS of relapse communicated to health-care staff via an application programming interface allowing data to be streamed into the electronic health record and (4) the impact of active self-monitoring on positive psychotic symptoms assessed at 6 and 12 weeks. Eligible participants with a DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition) diagnosis of schizophrenia and related disorders and a history of relapse within the previous 2 years were enrolled from an early intervention team and a community mental health team.

The findings were that, of 181 eligible patients, 81 (45%) consented and were randomised to either active symptom monitoring or management as usual. Of those in the active symptom monitoring group, 90% continued to use the system at 12-week follow-up. In this group, adherence, defined as responding to > 33% of alerts, was 84%. At 12 weeks, active symptom monitoring compared with usual management was associated with no difference on the empowerment scale. The pre-planned intention-to-treat analysis of the primary outcome (i.e. positive symptom score on the PANSS scale) showed a significant reduction in the active symptom monitoring group over 12 weeks in the early intervention centre. Alerts for personalised EWS of relapse were able to be built into the workflows of the two NHS trusts, and 100% of health professional staff used the system in a new digital workflow. Qualitative analyses supported the acceptability of the system to participants and staff.

Treatment-as-usual control

Treatment as usual (TAU) was chosen as a control condition in both the Glasgow and Melbourne centres as this provided a fair comparison with routine clinical practice. In Glasgow and Melbourne, secondary care is delivered by adult CMHS, which largely involves regular (fortnightly or monthly) follow-up with a care co-ordinator and regular review by a psychiatrist.

Outcomes

All outcome measures were administered at baseline and subsequently at 3, 6 and 12 months by research assistants who were trained in the use of all of the instruments and scales and had achieved a satisfactory level of inter-rater reliability (see Appendix 7). Research assistants had, as a minimum, a strong honours degree in psychology or a related discipline. Regular inter-rater reliability assessments were conducted during the trial. Research assistants entered anonymised participant data from paper records onto an electronic case record form hosted by the University of Aberdeen, with the exception of relapse data, which were entered by the trial manager. In Glasgow, data were collected in participants’ homes or in health service facilities. In Melbourne, all data were collected on health service premises. Data quality and error checking were conducted at each time point, namely baseline and 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation.

Primary outcomes

Feasibility: service users

For all participants, outcome assessment included:

-

proportion of eligible and willing service users who then consented and the proportion continuing for 3, 6 and 12 months to the end of the study

-

frequency of service user seeking help in relation to EWS

-

frequency of family member/carer seeking help in response to EWS

-

frequency of clinical care changes in response to EWS at 3, 6 and 12 months.

Feasibility: mental health care staff

We assessed:

-

self-reported frequency of discussing EWS with care co-ordinator

-

frequency of person seeking help in relation to EWS

-

frequency of care co-ordinator seeking help in response to EWS

-

frequency of clinical care changes in response to EWS at 3, 6 and 12 months (e.g. appointment brought forward, medication changed).

Feasibility: carers

We assessed:

-

self-reported frequency of discussing EWS with family member/carer

-

frequency of person seeking help in relation to EWS

-

frequency of family member/carer seeking help in response to EWS

-

frequency of clinical care changes in response to EWS at 3, 6 and 12 months (e.g. appointment brought forward, medication changed).

Acceptability and usability

For those randomised to EMPOWER, we assessed:

-

the length of time participants were willing to use the app

-

the number who completed > 33% EWS data sets

-

self-reported frequency of app use

-

frequency of sharing data with the key worker

-

frequency of sharing data with family member/carer

-

frequency of accessing charts at 3, 6 and 12 months

-

self-reported acceptability and usability using an adapted version of the Mobile App Rating Scale user version (uMARS;143 see Appendix 1).

Safety: adverse events

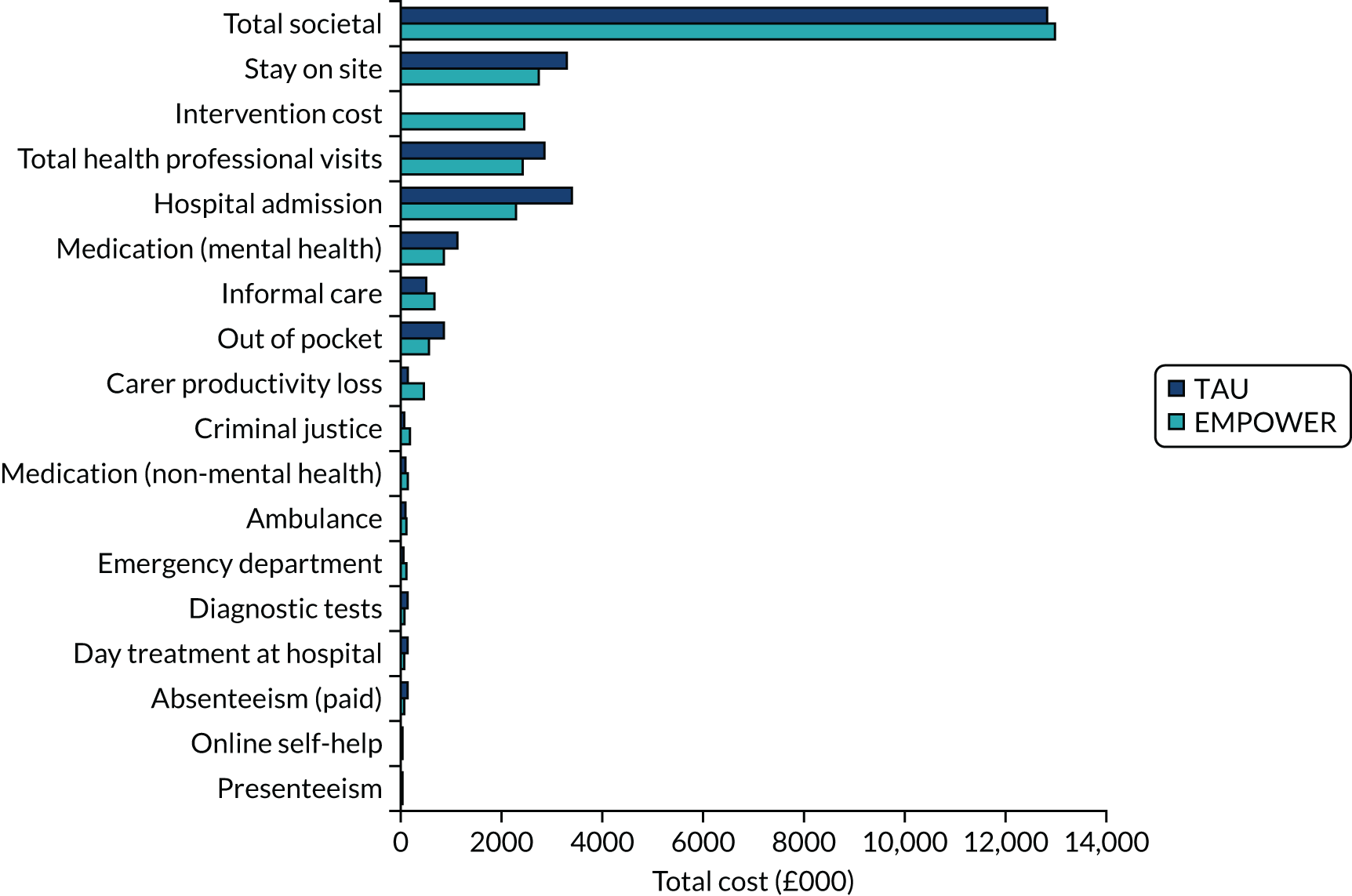

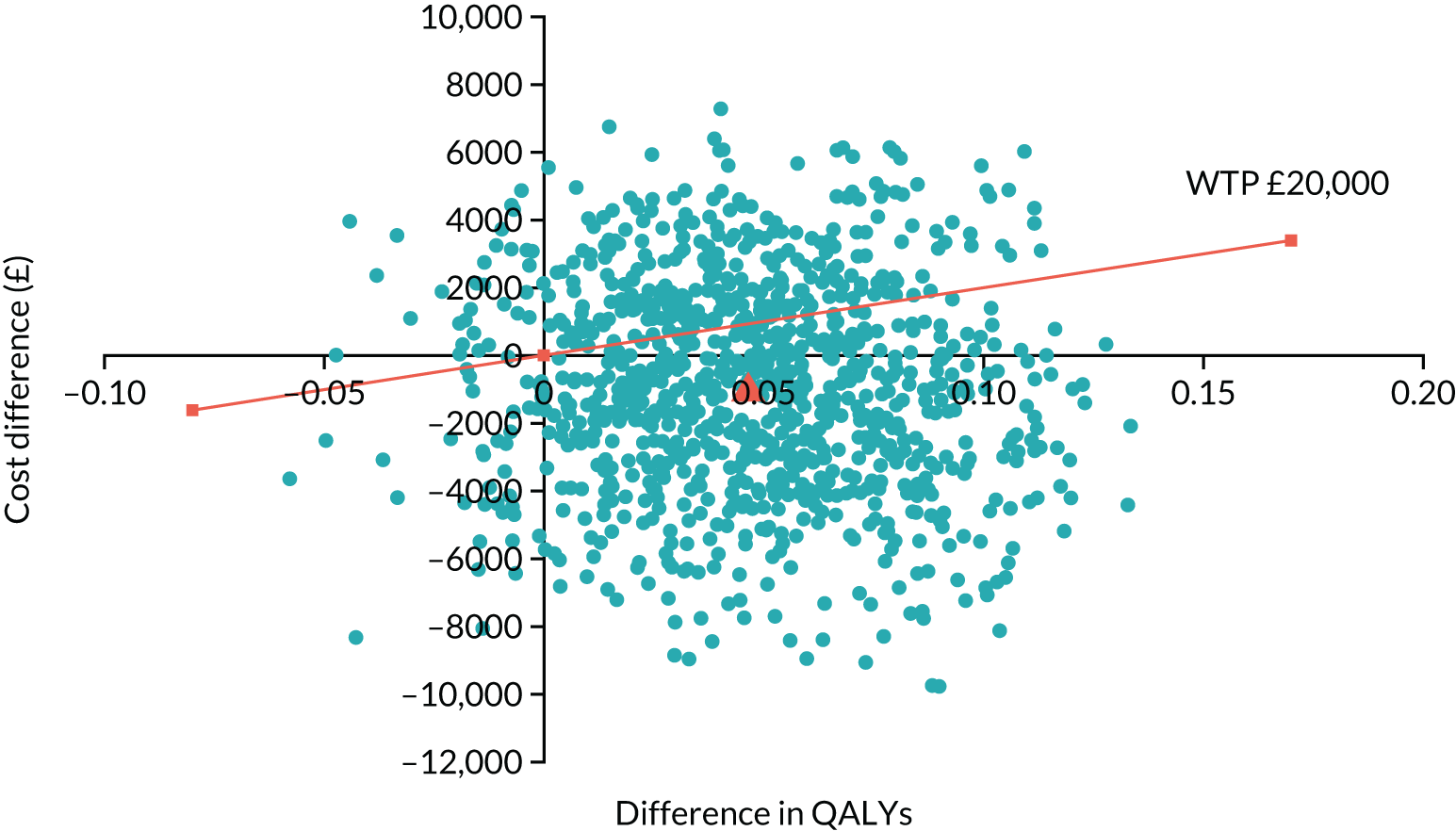

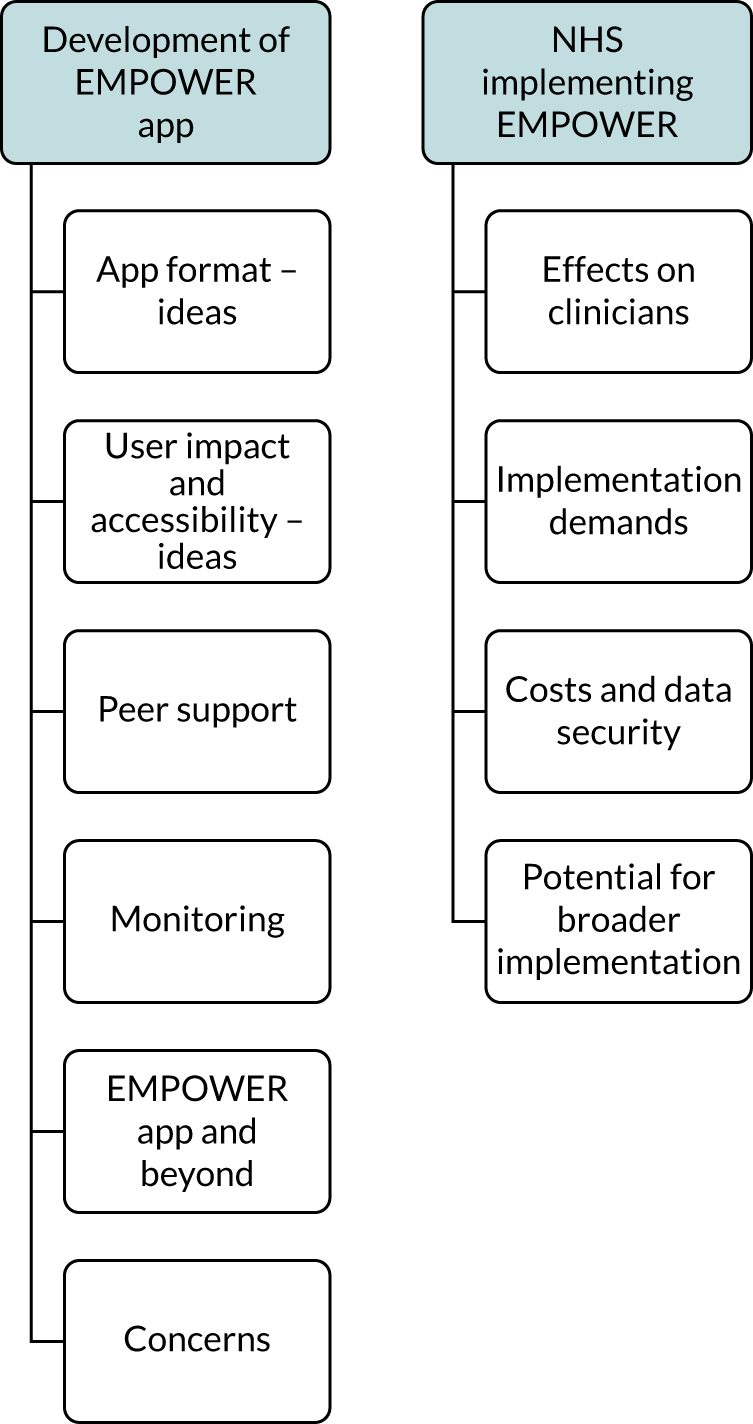

Details of recording and reporting of all adverse events complied with the Medical Devices Regulations 2002 (MEDDEV 2.1/6),144 ISO/FDIS 14155:2011145 and Standards for Good Clinical Practice. 146 An adverse event was defined as serious if it: