Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 03/37/06. The contractual start date was in January 2005. The draft report began editorial review in February 2007 and was accepted for publication in March 2008. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA Programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

None

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2008. This work was produced by Woodman et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2008 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Definition and burden of physical abuse

Physical abuse was defined in 2006 in the UK government’s Green Paper Working together to safeguard children as follows: ‘Physical abuse may involve hitting, shaking, throwing, poisoning, burning or scalding, drowning, suffocating, or otherwise causing physical harm to a child. Physical harm may also be caused when a parent or carer fabricates the symptoms of, or deliberately induces, illness in a child’ (Section 1.30). 2 In addition, local authorities have a duty under the 1989 Children Act to take any action to safeguard or promote a child’s welfare when they ‘have reasonable cause to suspect that a child who lives, or is found, in their area is suffering, or is likely to suffer, significant harm’. 5 This requirement recognises that physical abuse may occur as a result of physical violence, whether or not the child is injured.

The recent United Nationsworld report on violence against children published in 2006 left no room for doubt about the scale and impact of the global burden of violence against children. 5,6 Across the world, an estimated 80–98% of children suffered physical punishment in their homes, with one-third or more experiencing severe physical punishment resulting from the use of implements. The report emphasised that only a small proportion of the widespread violence is detected and reported to children’s services because of the hidden nature of abuse, fears of the child and family members, and stigma or mistrust of social services and others in authority. 6 These factors make the true incidence and characteristics of physical abuse difficult to measure.

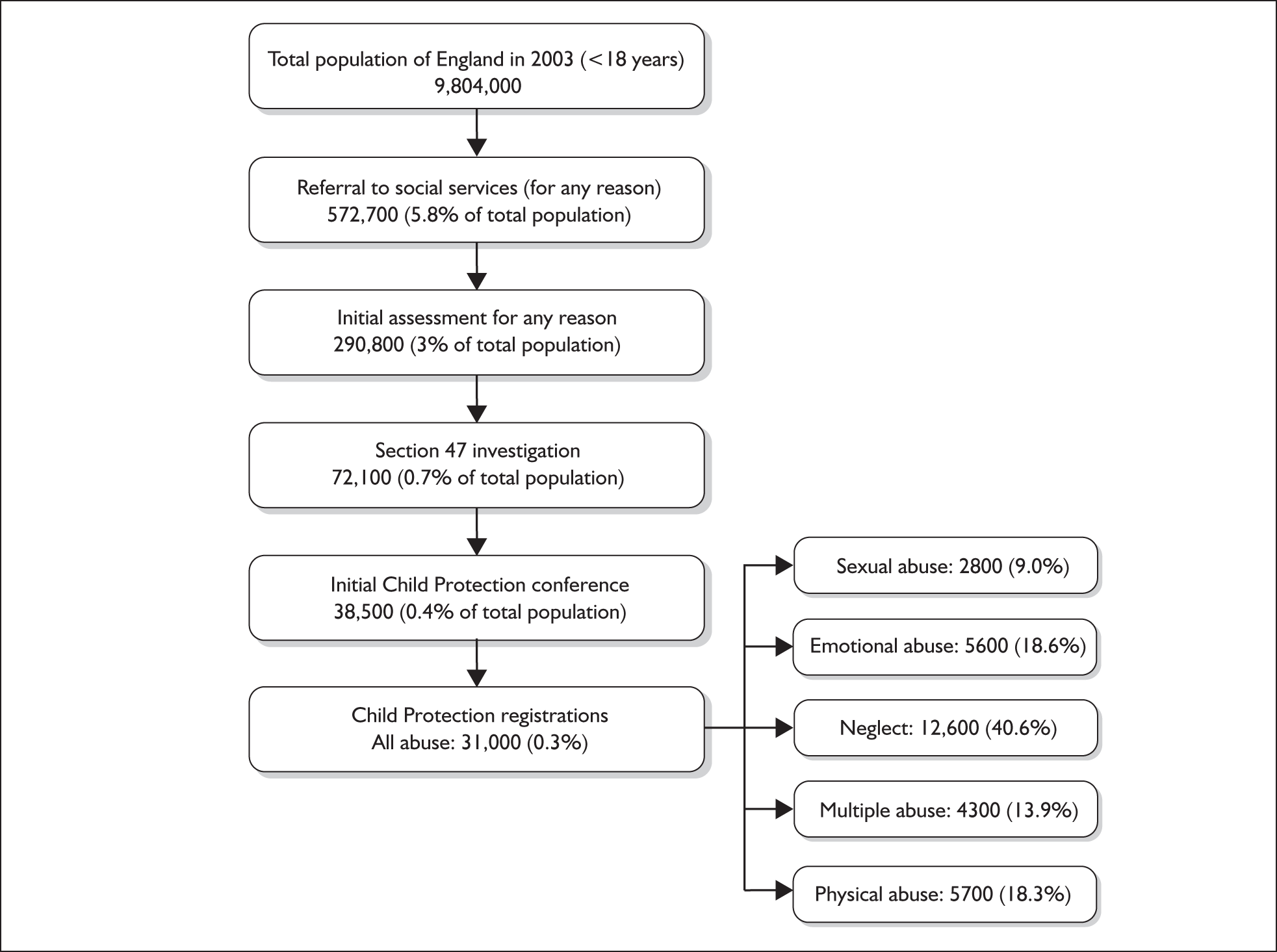

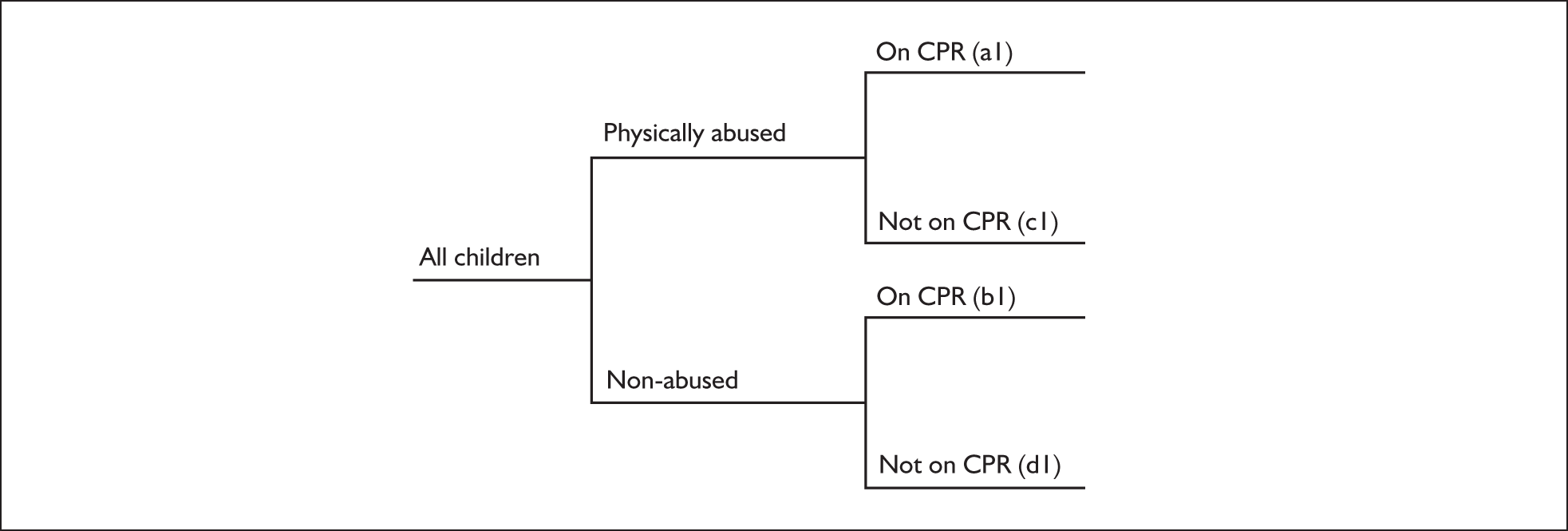

Even when physical abuse is suspected and reported it can be difficult to quantify because of problems with thresholds for confirmation and lack of routinely collected data. Currently in the UK, the child protection register (CPR) offers the only routine data on the incidence of physical abuse. As Figure 1 shows, registration is the final stage of child protection proceedings in the UK and represents a very high threshold for defining physical abuse. In 2003, only 0.1% of the child population under 16 years was newly registered on the CPR under the category of physical or multiple abuse (Figure 1). This figure substantially underestimates the incidence of physical abuse in the UK.

The impact of violence against children is often long term, resulting in increased susceptibility to adverse social, emotional, cognitive and health outcomes, and huge economic costs to society. 7 Social services costs alone are considerable. The annual survey of local authorities’ social services child and family teams estimated that in 2005 44% of their budget, or £30.5 million per week, was spent on child abuse and neglect, equivalent to £1.6 billion per year. 8

Policy in the UK

The tragic death of Victoria Climbié in 2000 highlighted the ineffective and muddled detection of abuse by agencies in the UK. In his inquiry into Victoria’s death, Lord Laming identified an ‘institutional malaise’ in children’s services and specified that the major failings were inefficient detection of abuse, failure to act appropriately when there were concerns, poor record keeping and poor communication within and between agencies. 10

In response to Lord Laming’s recommendations10 the government published a Green Paper, Every child matters. This committed the government to strengthening coordination of services and interagency communication by establishing local safeguarding boards, mandating a duty of cooperation between agencies, and integrating children’s services at a local level through the establishment of children’s trusts and Contact Point (previously known as the Information Sharing Index), an index of all children that documents their needs and contacts with agencies. 11 The Children Act 2004 (Sections 11 and 12)12 provided the legislative basis for these changes. Contact Point and the Common Assessment Framework (CAF) will be fully implemented in all areas of England by mid 2009; they have cost £224 million to implement with an anticipated £41 million running costs each year. 13

The Children Act 2004 mandated training in the recognition of and response to child abuse and neglect for all staff in contact with children. Professional bodies responded by publishing guidelines and competences for their members, which are designed to protect both children and the professional. 3,14–17 All accident and emergency (A&E) staff are expected to receive training in child protection, which ranges from hourly training sessions to a compulsory 3 days a year, depending on their level of contact with children and child protection responsibilities. 3,12,18 The process of screening, assessment and referral of children with suspected physical abuse in A&E is summarised in Table 1.

| Child attends A&E | Clerk notes demographic details and generates a medical record (sometimes electronic). This may include information on previous A&E attendances |

| Clinical screening assessment | A triage nurse and/or A&E senior house officer (SHO) take a history and examine the child. In children’s A&E departments, staff may be paediatric trained |

| Paediatric assessment | If abuse is suspected the child is referred for assessment by a paediatrician (usually on-call registrar or above). The paediatrician may be on site in children’s A&E. If the paediatric team suspect abuse the child will usually be admitted for further assessment. This may include the designated paediatrician and the hospital social worker. The child may be discharged if the paediatric consultant and social work team judge that the child is at no further risk of harm. If abuse is considered likely the paediatrician will contact the child’s local social services department. In some cases referral is preceded by discussion with social services about the appropriateness of referral |

| After discharge | A record of A&E attendance is sent to the GP for all children. In some departments this record is also sent to the health visitor or school nurse. In most departments, records of all children attending A&E are scrutinised the next day by a community liaison nurse (CLN) for social or child protection issues that may have been missed by A&E staff. Children with concerns are discussed at a weekly or monthly meeting involving the CLN and paediatric, A&E and social work staff at the hospital |

The recognition of the need for better training has focused attention on the signs and symptoms that staff should be trained to look for. The Royal College of Paediatricians and Child Health (RCPCH) recently produced guidelines on the detection and management of child abuse and neglect and highlighted the poor quality of the evidence underpinning many of the recommendations and the need for more research. 14 Signs and symptoms suggestive of physical abuse cited by the report included injury in infants, vague, unwitnessed, inconsistent or discrepant history, unexplained injuries, delayed presentation, injuries not consistent with a child’s development, repeated attendance for injury, and multiple bruises in certain areas such as the face, head and neck. In some cases the evidence underpinning these markers of abuse is based on case series of abused children or on comparisons between definitely abused children and healthy children seen in routine child health clinics. 19,20

Despite the uncertain evidence on the performance of these features for predicting physical abuse, they are being increasingly used in checklists, aide-memoires and protocols in A&E departments to improve detection by front-line A&E staff. 14,20–23 To date, no systematic evaluation has determined which factors are most predictive of physical abuse and which might overwhelm the paediatric team with false-positive referrals of non-abused children. The aim of this study was to address this gap in the evidence by evaluating the performance of screening tests for physical abuse in A&E.

Chapter 2 Aims, objectives and overview of methods

We aimed to determine the clinical effectiveness of screening tests for physical abuse in children attending A&E departments in the UK. The four specific objectives were to determine:

-

the burden of physical abuse among children in the community

-

the incidence of attendance at A&E with injury and the characteristics of attendees

-

the accuracy of screening tests for physical abuse in A&E

-

optimal screening strategies based on a clinical effectiveness model.

Overview of systematic review methods

We carried out a series of systematic reviews to address objectives (1), (2) and (3). Because of the paucity of valid and relevant evidence we adopted an ‘exploratory’ approach to each review question. We used broad inclusion criteria to select studies for review because we could not anticipate all of the important elements of the study methods that could affect validity and applicability. This approach allowed us to examine the relationship between study quality and results and helped to define limits within which the true estimate might lie. We selected studies to inform the parameters for the clinical effectiveness model using epidemiological principles. By making explicit the rationale for the estimates used in the clinical effectiveness model, readers can use the data to test alternative interpretations.

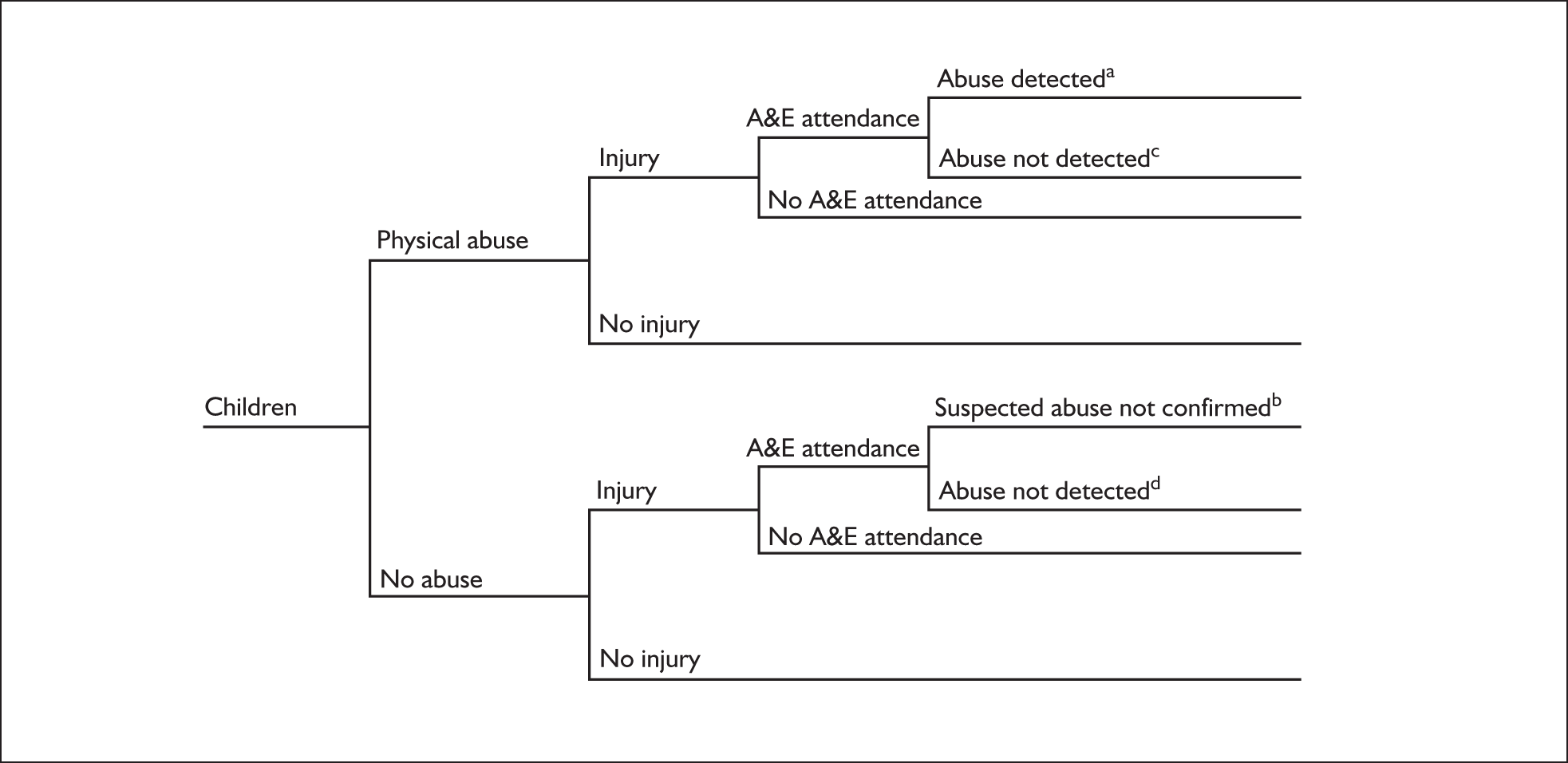

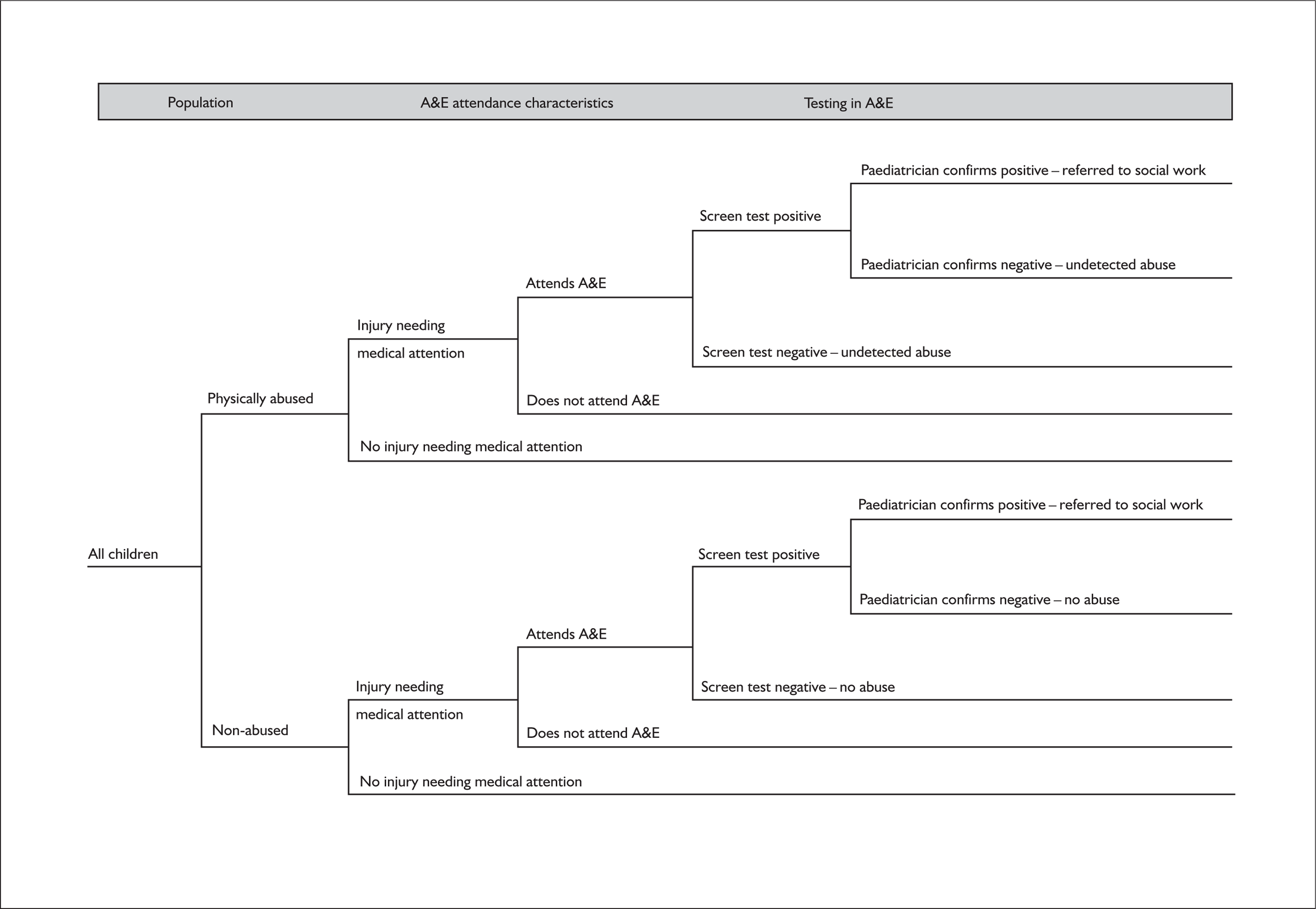

Clinical effectiveness model

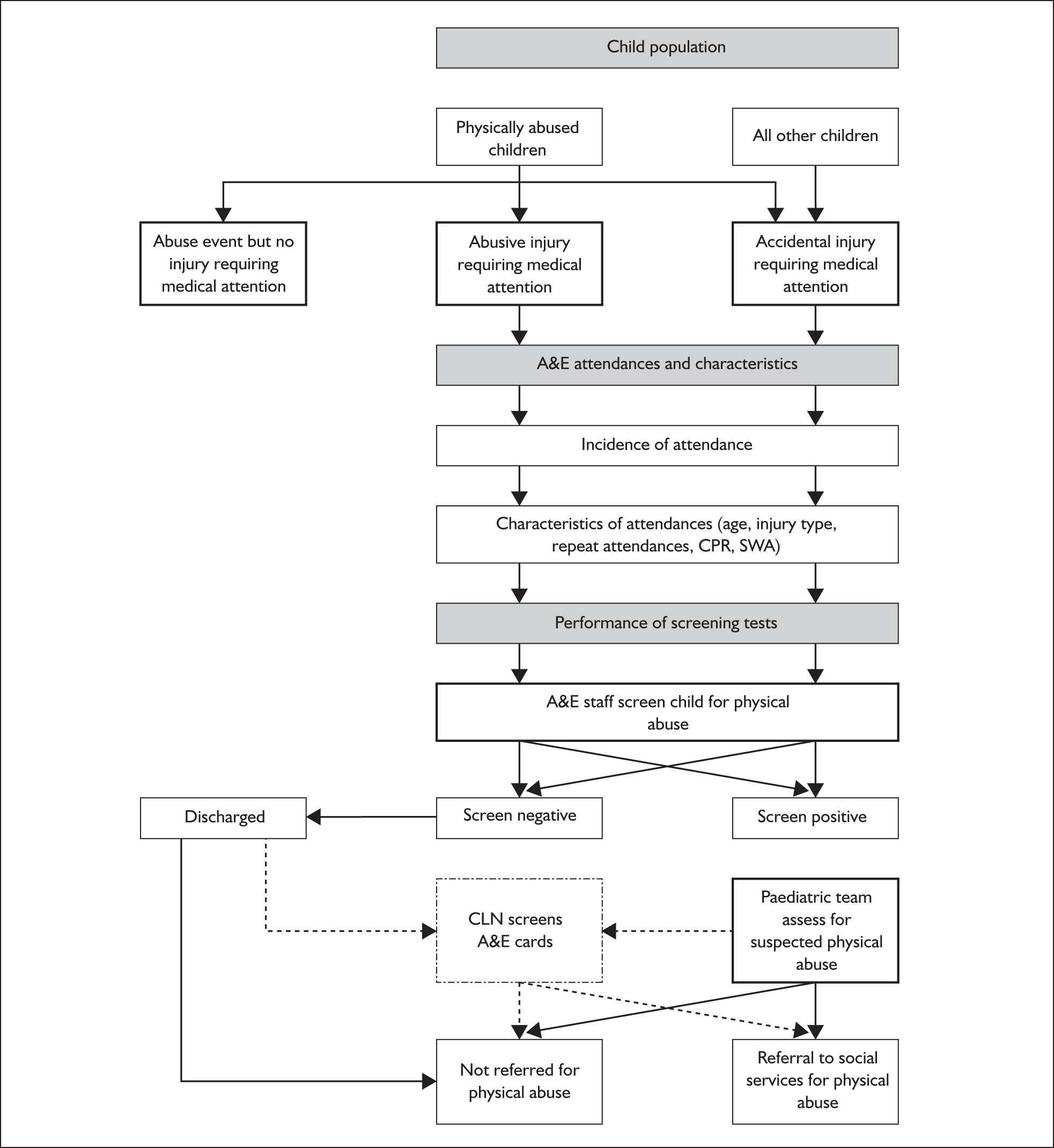

We developed a simple clinical effectiveness model based on a scoping review of the literature and discussions with health and social services providers (Figure 2). The model was based on a hypothetical population of children (< 16 years) in the UK and provides a simplified representation of the occurrence of physical abuse, the risk of resulting injury requiring medical attention, attendance at A&E of physically abused and non-abused injured children, detection by screening in A&E, and referral or not to social services. Injury was defined as head injury, fractures, burns, bruises or ‘other’ and excluded poisoning, foreign bodies and fabricated illness. More details on the classification of injuries are given in Table 10. Physical abuse was defined as at least one act of severe violence (kick, bite, scald/burn, ‘beat up’, hit with object, shake a young child, or threaten to use a weapon) from a parent or carer towards a child. 5

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram showing the steps included in the model. CLN, community liaison nurse; CPR, child protection register; SWA, social work active.

Parameters defining the probability of outcomes at each step of this pathway were obtained from the systematic reviews (Chapter 4) and entered into the model using Microsoft Excel®. The model then multiplied the parameters to generate the probabilities of the outcomes used to measure the clinical effectiveness of screening: the proportion of abused children detected in A&E and referred to social services, and the proportion of non-abused children unnecessarily referred to social services for suspected abuse. We assumed that all referrals from doctors in A&E to social services would result in an ‘initial assessment’ as required under Section 47 of the 1989 Children Act. 5

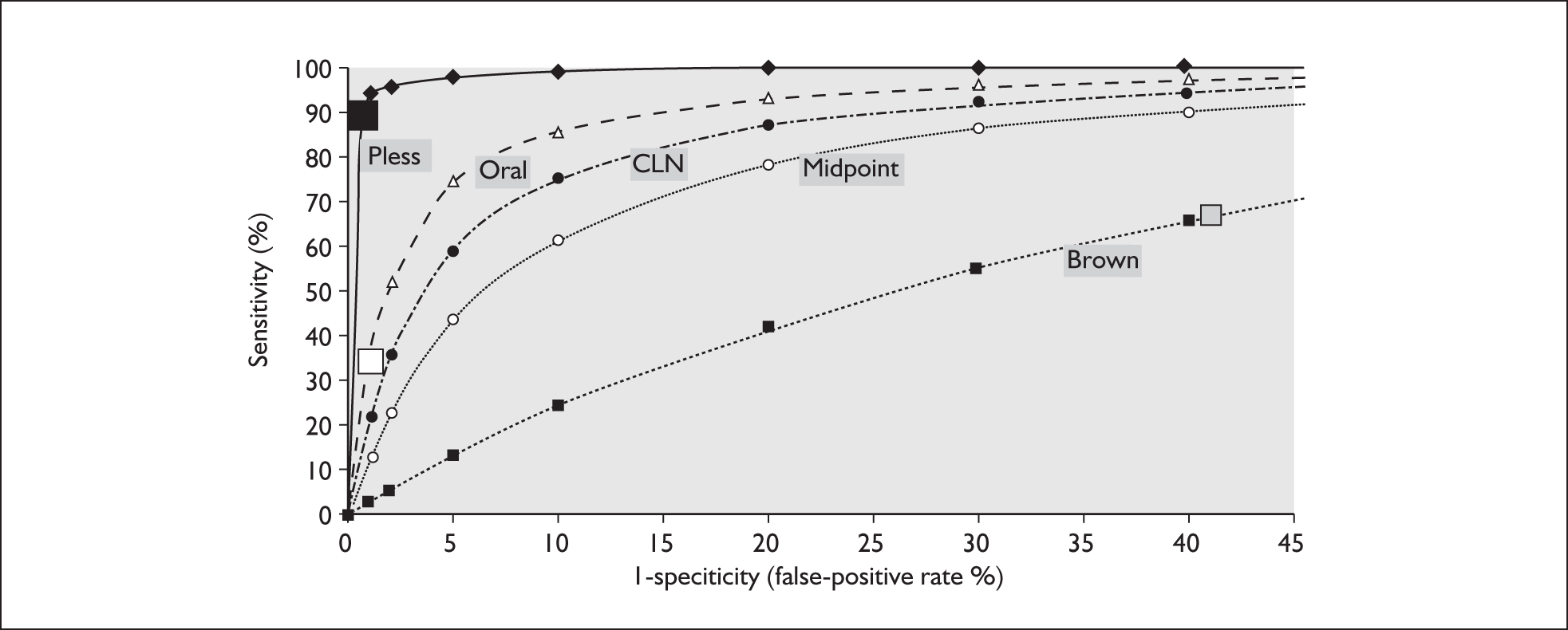

Screening tests

We defined screening tests as any criterion or ‘test’ that would be universally applied to all injured children to detect those with suspected physical abuse. We accepted any characteristic or form of assessment provided that it was universally applied. We selected screening strategies based on existing A&E protocols or tests used in UK A&E departments, as revealed in a review of the published literature and interviews with staff in five A&E departments. 14,20–23 We added one further protocol, whether the child is social work active (systematic review 8, Table 12). Although not yet in use, this information will be recorded on Contact Point in all local authorities in England by 2009. 13,24

The types of screening strategies examined are listed in Table 2. The base-case strategy, standard care, comprised the history and examination of an injured child conducted by A&E staff. We sought evidence on two other clinical screening tests: the use of a checklist to enhance the initial clinical screening assessment and the use of a community liaison nurse to scrutinise all child attendance records for children with possible abuse missed by A&E staff. We then evaluated the effectiveness of adding screening protocols, based on characteristics of the child, to the clinical assessment screen.

| Type of strategy | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical screening tests | ||

| 1 | Standard care | Base-case strategy. Screening involves the standard history and examination by A&E staff |

| 2 | Checklist for abuse | Used by the clinician who first examines the child. Usually a five-point checklist, e.g. explanation consistent with the injury, consistencies in explanations, delay in presentation, interaction between carer and child appropriate |

| 3 | Community liaison nurse (CLN) | The CLN scrutinises A&E attendance records for at-risk children who were not referred by A&E staff |

| Screening protocols | ||

| 4 | Age group | e.g. All infants referred for paediatric assessment |

| 5 | Injury type | e.g. Referral to paediatrician if head injury or fracture in infants |

| 6 | Repeat attendance | Repeat attendances at A&E for injury in the last year |

| 7 | Social work active (ISA) | The child is recorded on Contact Point as social work active.24 This means that the child is currently (or has been in the last 12 months) allocated to a social worker or duty social work team27 |

| 8 | Child protection register (CPR) | The child is currently on the CPR for any reason |

The study had three main limitations. First, it was restricted to physical abuse, the remit given by the funders, even though this is frequently linked to other forms of abuse. Second, we included only injured children, who account for about one-third of all A&E attendees. 25,26 Third, we did not consider the important policy question of whether screening reduces the adverse consequences of physical abuse over the child’s lifetime and improves their quality of life. This would require information on the benefits and harms of detection, failure to detect abuse and false-positive referrals, and the benefits and harms of interventions offered by social services and other agencies. These questions were beyond the scope of our study.

Chapter 3 Searches and study selection

Methods

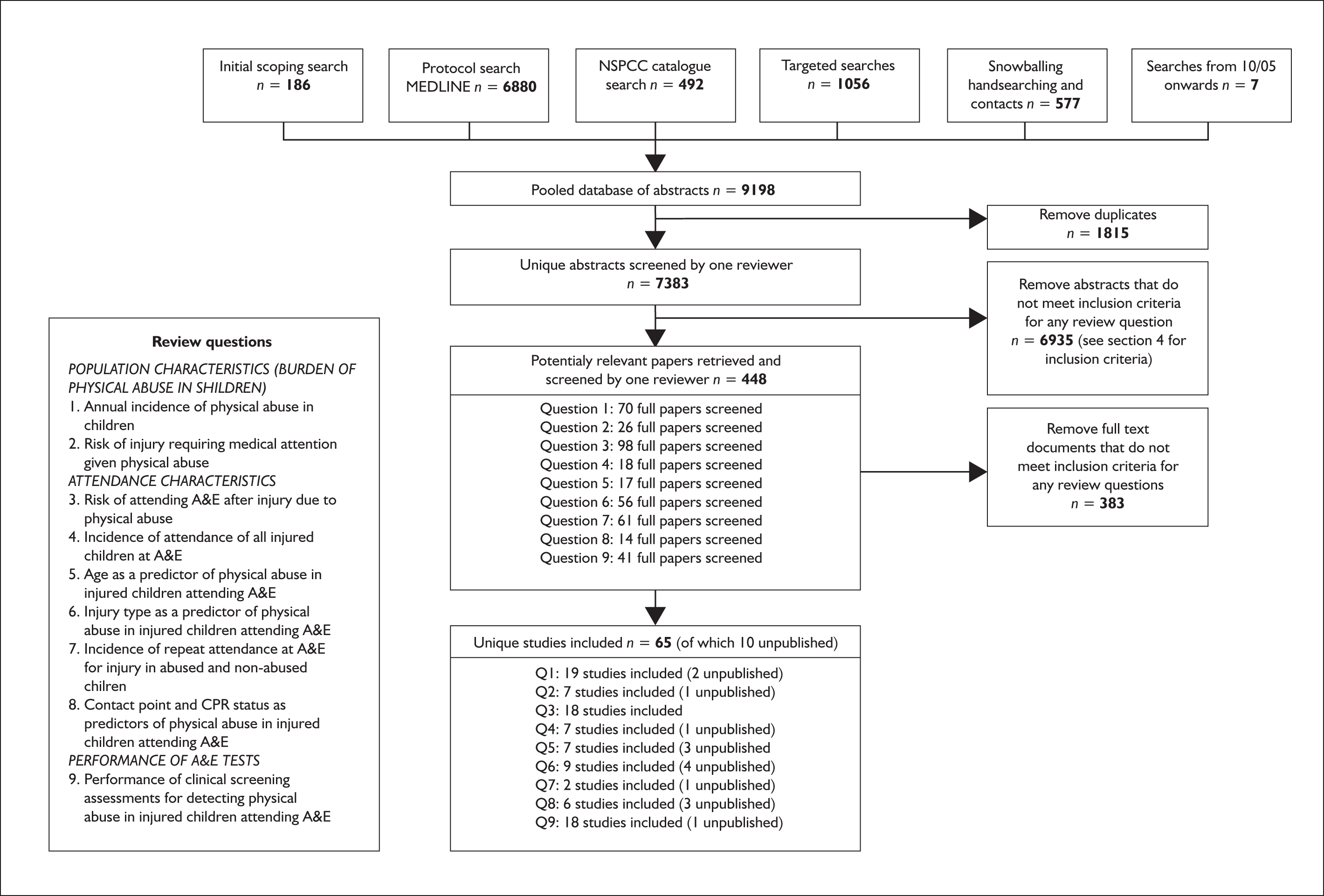

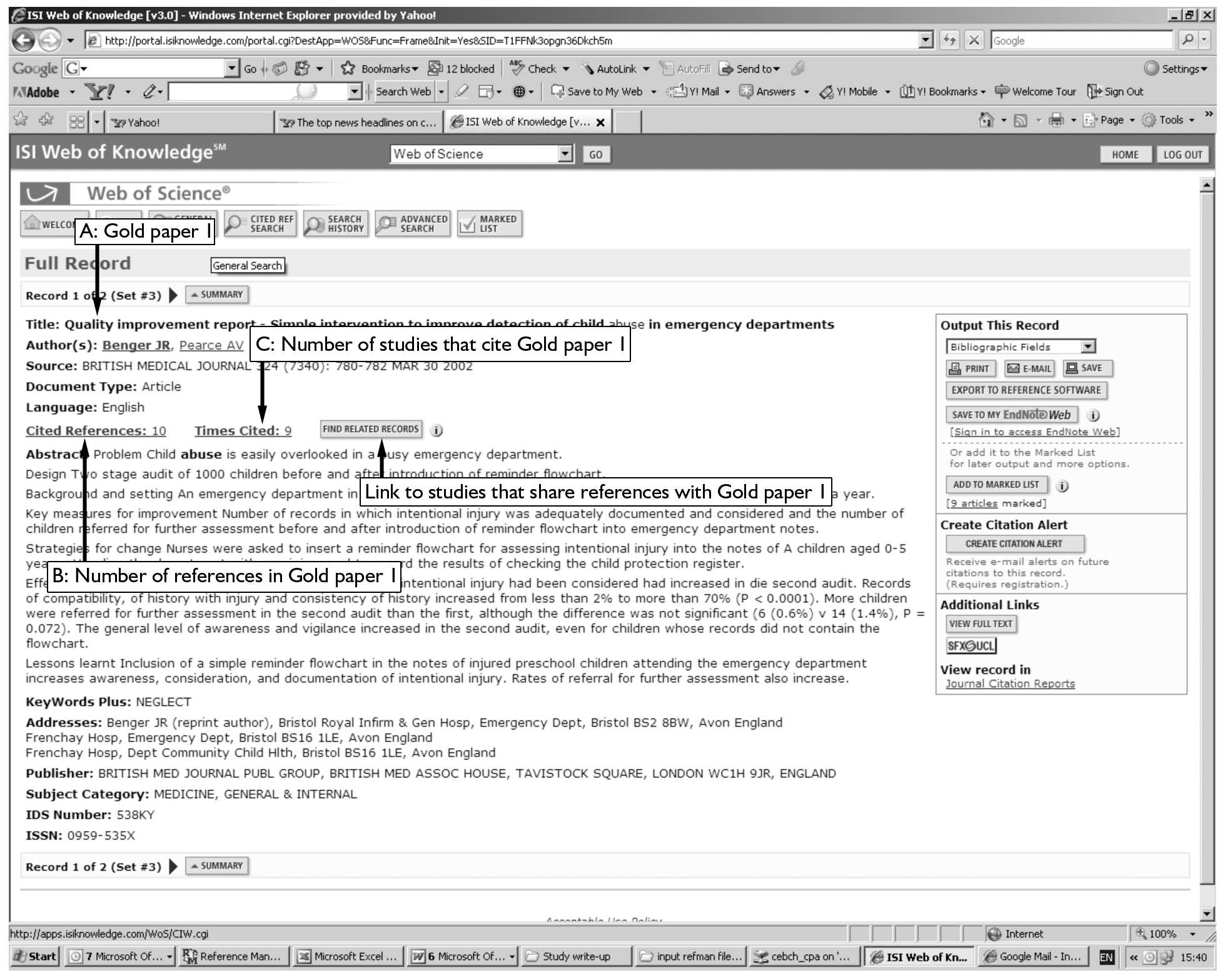

We developed a database of abstracts based on the six methods shown in Figure 3. Searches were limited to studies published after 1974 when major changes in the way that child abuse was managed were instituted in the UK (see Inclusion criteria). Start dates for each method are given below. Further details of the search methods are reported in Appendix 1.

-

Method 1: The initial scoping search was carried out in August 2004 and was based on Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and text word terms for child, abuse, maltreatment, violence and punishment. The search yielded 186 references.

-

Method 2: We developed a more detailed search strategy that was used on MEDLINE in October 2005. This search yielded 6880 references.

-

Methods 3: The third source was the publications catalogue of the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC), which was searched in September 2005. We included any references that appeared to be relevant to physical abuse. This search yielded 492 references.

-

Method 4: As the type of evidence sought was complex and heterogeneous and could relate to clinical, management or policy issues in health or social care, we complemented the protocol-driven search (method 2) by carrying out four types of ‘targeted search’ in January 2006 (Appendix 1, Table 25). 28

-

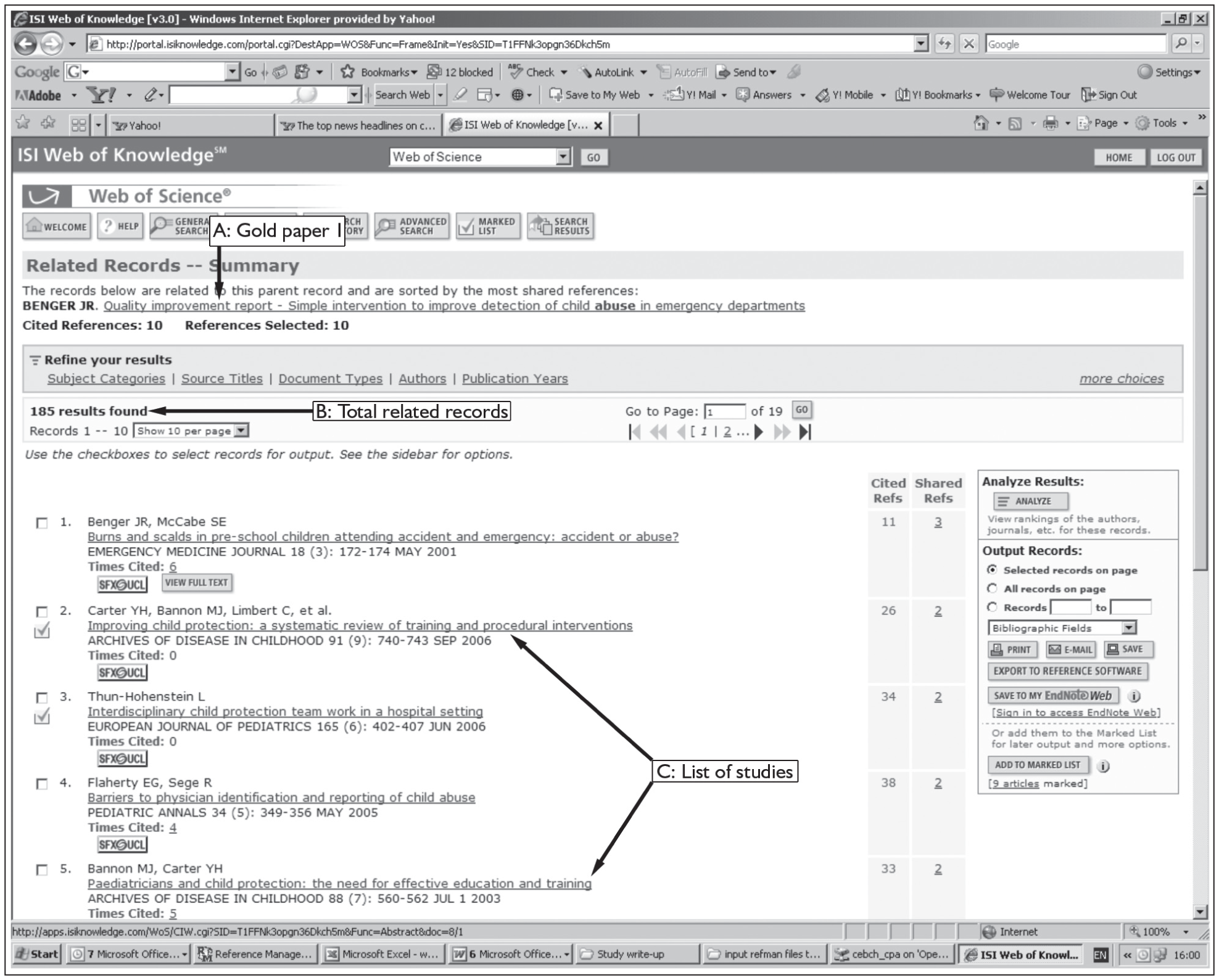

First, we listed the most valuable studies found from the scoping search (‘gold standard’ papers, n = 16). Using the Web of Science we found all subsequently published papers that cited each source paper.

-

Second, using the ‘related articles’ search on the Web of Science we found papers (previously or subsequently published) that shared references with each source paper.

-

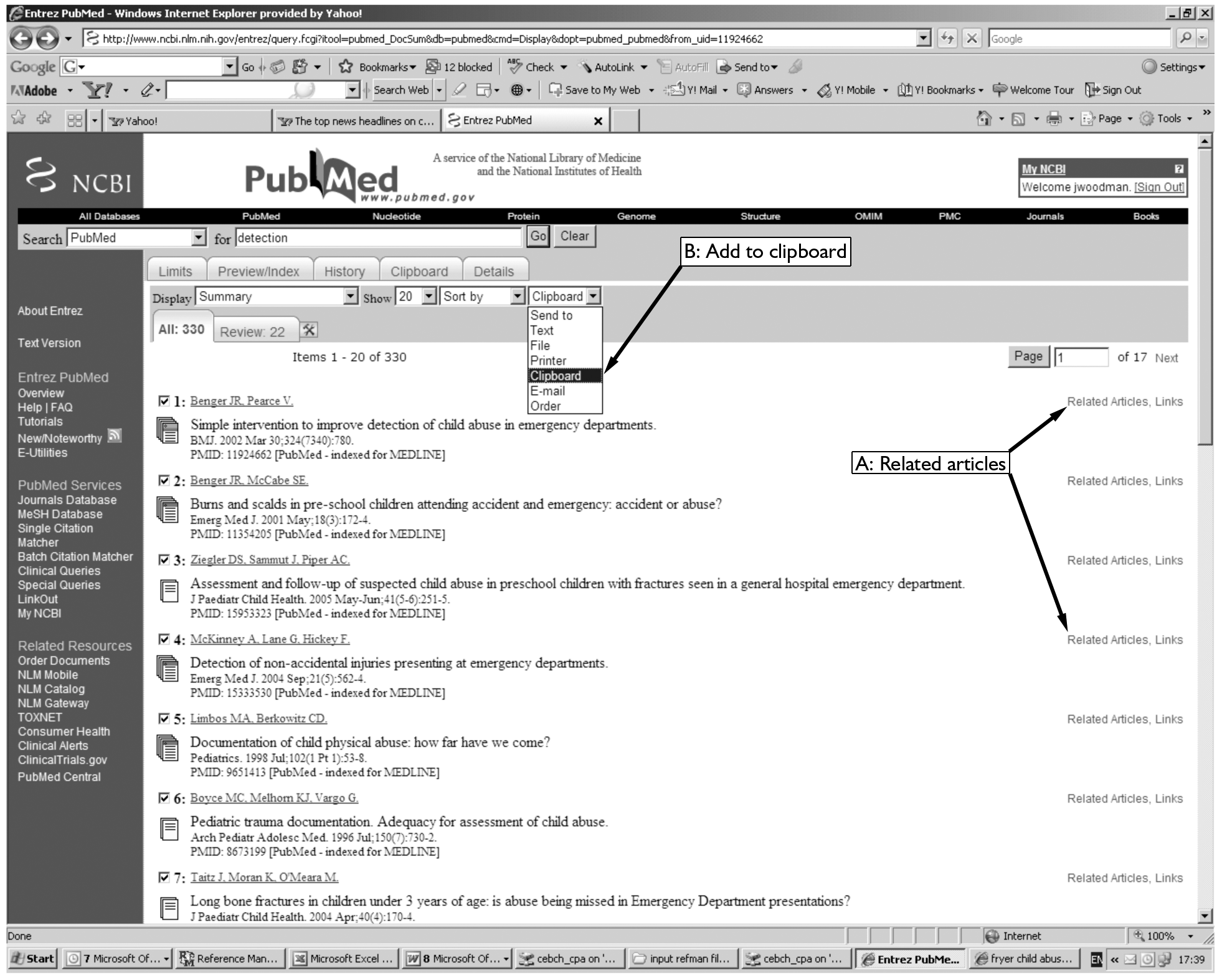

Third, we identified papers with the same subject terms, headings or MeSH terms as each of our source papers by using the ‘related articles’ algorithm on PubMed. We imported the 20 most relevant papers and those other papers identified by our search terms.

-

In the fourth step we applied search terms across databases [including Department of Health database (DH-Data), British Nursing Index and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL)] that were not covered by our main protocol-driven search. These four search techniques yielded 1216 references (deduplicated, n = 1056).

-

-

Method 5: The third search method was snowballing. This involved judgement and was based on scanning reference lists, hand searching journals, searching the internet and chasing up professional contacts for unpublished data. This method is especially useful for identifying high-quality studies in obscure locations. 28 This search yielded 577 references.

-

Method 6: Finally, we carried out a search of three key journals (Pediatrics, Child Abuse and Neglect and Child Abuse Review) in October 2006 to identify any relevant studies published since the original protocol search was carried out in October 2005. Inclusion of studies in the database relied on the researcher’s judgement. This search yielded an additional seven studies.

FIGURE 3.

Flow diagram summarising methods used for identification of studies to include in the nine reviews.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria are reported separately for each review question in Chapter 4. Two inclusion criteria applied to all review questions. First, studies had to be published after 1974, as this was the year of the inquiry into the death of Maria Colwell, who died from injuries inflicted by her stepfather in 1973. The report made recommendations for child protection procedures that have formed the basis for child protection in the UK over the last 30 years. These recommendations included the establishment of area child protection committees (now replaced by local safeguarding boards),10 the establishment of a child protection register and the system of multidisciplinary case conferences. The Maria Colwell report identified inadequacies in the handling of the case by services and emphasised the need for professional accountability and multidisciplinary communication. 29 Second, we excluded studies relating to developing countries because recognition of child abuse and services for dealing with abuse are likely to differ from the UK setting.

All abstracts were scanned by a single reviewer (JW) who determined whether they were potentially relevant to one or more of the review questions. The full article was retrieved for all potentially eligible studies and separately appraised for each review question by one reviewer (JW). A second reviewer then appraised all included studies and any borderline decisions (RG).

Chapter 4 Systematic reviews

Methods, results and model parameters

In this chapter we report the methods and findings of a series of systematic reviews that informed parameter estimates at each step of the assessment pathway (see Figure 2). For each review question we report the inclusion criteria, the quality of the included studies and the results of the review. The derivation of the relevant parameters for the clinical effectiveness model is reported in Chapter 5. All forest plots are based on fixed-effects meta-analyses and show proportions and 95% confidence intervals.

The systematic reviews can be considered in three parts, representing the burden of abuse, the incidence and characteristics of attendees at A&E, and the performance of clinical screening tests.

Burden of abuse

Two reviews were conducted to determine the incidence of severe parental violence and the consequent risks of injury requiring medical attention. We classified severe violence from a parent or carer (defined as punching, kicking, biting, hitting with a hard object, inflicting a scald or burn, shaking a young child, or threatening with a weapon) as physical abuse. Over 80% of physical abuse is perpetrated by a parent, parental figure or non-professional carer and this figure remains constant across all age groups under 16 years. 30 Consequently, our definition captures the large majority of physical abuse cases. The definition also includes children at risk of injury as well as those actually injured and is therefore consistent with the minimum threshold for mandatory investigation as laid out in Section 47 of the 1989 UK Children Act5 and definitions of physical abuse used in recent reports by the World Health Organization and the United Nations. 6,31 In this study we assume that severe parental violence is equivalent to physical abuse.

Systematic review 1: Incidence of physical abuse

Review methods

The review aimed to determine the age-specific incidence of physical abuse. We included studies that reported any measure of physical abuse or severe physical punishment or discipline perpetrated by parents or carers which could be used to derive the annual incidence of physical abuse.

To aid comparison between studies we classified the results into two categories:

-

severe violence (assumed to be equivalent to physical abuse): kick, bite, scald/burn, ‘beat up’, hit with object, shake a young child, (threaten to) use a weapon

-

physical abuse (severity of abuse unknown) reported by agencies involved in child protection.

We grouped all included studies according to the reporting source: parents, self-report and agency. To assist analysis of the variation between the included studies we report additional results for minor violence [slap, spank, slap, push, grab, shove (no injury/lasting marks)] and for violence over the child’s lifetime. Table 27 in Appendix 2 shows excluded studies that reported physical abuse over the child’s lifetime but not in the past year.

Review results

A total of 19 studies were identified (Table 3). Five were based on parental reports, three on self-reports and 11 on agency reports (including two unpublished studies). Methods and results for the two unpublished studies30,32 are reported in Appendix 4. All studies underestimated the incidence of physical abuse as they reported the prevalence of children with one or more episodes of severe violence in the previous 12 months. Further reasons for underestimation of abuse from these studies are poor response to surveys, under-reporting by parents and misclassification of abuse as accidents in agency figures. One further UK study was excluded as it was based on violence perpetrated by mothers of 8-month-old babies. 33

| First author, country, year of publication | Methods | Risk of violence (% of total child population) |

|---|---|---|

| Parent reports | ||

| Ghate, UK, 200234 |

A total of 1249 parents with a child < 13 years, randomly selected from the 1991 UK census, had face-to-face interviews about discipline in the past 12 months (59.3% responded). Violence was measured by the Misbehaviour Response Scale. We classified punching, kicking and hitting with a hard object as consistent with physical abuse, and smacking, slapping on the arms or legs, grabbing and pushing as minor violence Minor violence in the past year [overall 868/1222 (71.0%)]: 0–1 years: 8%; 1–2 years: 61%; 2–4 years: 82.7%; 5–7 years: 64.7%; 8–10 years: 54.7%; 11–13 years: 37%; total < 13 years: 705/1222 (57.7%) The age-specific incidence as entered into our model gives a weighted average of 8.8% |

Physical abuse in the past year: 0–1 years: 7/203 (3.45%); 2–4 years: 34/292 (11.6%); 5–7 years: 25/261 (9.6%); 8–10 years: 30/261 (11.5%); 11–13 years: 15/205 (7.3%); total < 13 years: 111/1222 (9.1%) Physical abuse during childhood < 13 years: 134/1222 (11.0%) |

| Bardi, Italy, 200135 |

A total of 2388 families with school-age children < 13 years in Tuscany completed an anonymous questionnaire sent out through schools in 1998 (50% responded). Violence was measured using the Conflict Tactics scale (CT scale). 48,49 We classified punching, kicking and hitting with a hard object as physical abuse, and smacking, slapping on the arms or legs, grabbing or pushing as minor abuse Minor abuse over 12 months: 1877/2388 (78.6%) |

Physical abuse in the past year: 198/2388 (8.3%) |

| Theodore, USA, 200536 | A total of 1435 mothers (≥ 18 years) with an index child under 18 years in Carolina, USA, identified by random sampling, were interviewed anonymously by telephone in 2002 about discipline (52% responded). We classified punching, kicking, hitting with a hard object or shaking a child under 2 years as physical abuse. Only violence inflicted by the mother was recorded | Physical abuse in the past year: < 5 years: 10/365 (2.8%); 5–8 years: 17/321 (5.3%); 9–12 years: 18/298 (5.9%); 13–17 years: 17/448 (3.9%); total < 18 years: 62/1435 (4.3%) |

| Wolfner, USA, 199337 |

A total of 3232 parents (18–85 years) with a child < 18 years were identified by random sampling and interviewed by telephone in 1985 (84% responded). Measurement of violence was based on the CT scale. We classified violence intended to cause injury as physical abuse, including kicking, biting, hitting with an object and threatening with or using a knife or gun Minor physical abuse in past year: overall < 18 years: 2001/3232 (61.9%); < 2 years: 323/567 (57%); 3–6 years: 659/740 (88.8%); 7–12 years: 553/771 (71.7%); 13–17 years: 406/1149 (35.3%) |

Physical abuse in past year: < 2 years: 45/567 (7.9%); 3–6 years: 106/740 (14.3%); 7–12 years: 96/771 (12.5%); 13–17 years: 102/1149 (8.9%); total < 18 years: 356/3232 (11.0%) |

| Gelles, USA and Sweden, 198638 |

USA: 1146 two-parent families with children between 3 and 17 years; Sweden: nationally representative sample of 1105 single and two-parent families with children between 3 and 17 years in 1980 Parents were interviewed face to face at home about family violence (CT scale). Physical abuse: kicking, biting, hitting with an object, threatening with or using a knife or gun |

Physical abuse in the last year: USA: 162/1146 (14.2%); Sweden: 51/1105 (4.6%) |

| Self-reports | ||

| Sebre, Baltic/Eastern Europe, 200441 | A total of 1145 children (10–14 years) in Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia and Moldova were randomly selected to complete a questionnaire about ‘thought, feelings and relationships’ in 1998–2000. Violence was measured using the CT scale. Frequent minor violence such as slapping or being hit with an object, kicked, punched or burned/scalded was considered equivalent to physical abuse | Physical abuse in past year: 244/1145 (21.3%) |

| Sariola, Finland, 199242 |

Classes including 7435 students aged 14–15 years were randomly sampled and given questionnaires distributed by the school nurse (96% responded). Violence was measured using the CT scale. Hitting with a fist/object, kicking, biting and threatening/using a knife/weapon were classified as physical abuse; slapping, hitting and grabbing were classified as minor physical abuse Minor physical abuse: in the last year: 1344/7264 (18.5%); during childhood: 5223/7264 (71.9%) |

Physical abuse in past year: 334/7264 (4.6%); physical abuse during childhood < 15 years: 559/7264 (7.7%) |

| Nelson, USA, 199543 | A total of 1957 school students aged 14–18 years in 25 schools, randomly selected across Atlanta state, completed an adolescent survey questionnaire in 1993 including three questions about ‘physical abuse’ by parents (82% responded of whom 75% answered questions on physical abuse). We classified hitting with an object and punching and kicking as physical abuse | Physical abuse in past year: 319/1957 (16.3%); physical abuse during childhood < 18 years: 550/1957 (28.1%) |

| Agency reports | ||

| Social services data for Hammersmith and Fulham, 2005 (unpublished audit; see Appendix 4)32 |

Audit of initial assessments by social services for suspected physical abuse in children (< 18 years) in one referral centre during 3 months in 2005 (153 initial assessments, missing data for a further 28). Reports ranged from slapping to obvious injury The incidence of initial assessment for physical abuse was estimated as 13.6% times the incidence of initial assessments for any reason in England (290,800/9,804,000 = 0.29%)9 |

Initial assessment for physical abuse over 12 months: 17/153 (11.1%) |

| Metropolitan Police, UK (London), 2005 (unpublished)30 | All children < 16 years reported to London Metropolitan Police child protection unit in 12 months (2005) for ‘violence against the person’ by any perpetrator. We classified ‘acts of violence’ as physical abuse. We assumed that children comprised 19.5% of the total population of 7.2 million (based on census projections for London 2002). Some children may have been reported more than once | Physical abuse (reported to police) in the last year: 0–2 years: 317/184320 (0.20%); 2–4 years: 547/276480 (0.20%); 5–9 years: 1300/471600 (0.28%); 10–15 years: 2271/4716000 (0.48%); total < 16 years: 4435/1404000 (0.32%) |

| Child protection register (CPR), England, 20049 | Registrations on the CPR for physical abuse or ‘multiple abuse’ from 2003 to 2004. Denominator population taken from England Office for National Statistics 2003 figures.50 We derived the age distribution of new registrations by assuming it was equitable with the age distribution of children on the register on 31 March 2004 | CPR (new cases): < 1 year:1283/575000 (0.22%); 1–4 years: 2981/2273000 (0.013%); 5–9 years: 2794/3150000 (0.09%); 10–15 years: 2941/3780000 (0.08%); total < 16 years: 10000/9778000 (0.10%) |

| Creighton, UK, 200445 | Systematic review of sexual and physical abuse from substantiated reports to official agencies in 2003–4. Denominator estimates taken from national websites51 | CPR (12 months): USA: 145550/60646000 (0.24%); Australia: 7560/3978800 (0.19%) |

| Sibert, UK, 200252 | Consultant paediatricians and senior clinical medical officers in Wales returned cards about children < 14 years diagnosed with an injury (grievous bodily harm) following physical abuse in Wales 1996–8. Reports for babies < 1 year were supplemented by cases on the CPR. We have adjusted the data (reduced by 50%) to report cases over 12 months | Severe injury reported by senior medical staff over 12 months: < 1 year: 26/35200 (0.074%); 1–4 years: 13/141200 (0.0092%); 5–13 years: 2/424500 (0.00047%); total < 14 years: 41/600900 (0.007%) |

| Creighton, UK, 198553 | Children placed on CPR for physical abuse in 1981 in parts of England and Wales. Denominator population calculated from rates. All children were registered for physical abuse | CPR (over 12 months): < 16 years: 6532/10,910,300 (0.06%) |

| Lindell, Sweden, 200154 | Physical abuse in children (< 15 years) by a parent or carer reported to the police in one district in 1986 and 1996 and substantiated by/registered with official agencies. Denominator based on police district | Substantiated physical abuse in the past year (to police): 145/27724 (0.05%) |

| Christensen, Denmark, 199939 | Health visitors returned questionnaires reporting visible signs of parental violence in children. The study covered 80% of infants in Denmark in 1991 (83% response rate). Health visitors visit children 5–6 times in their first year | Visible injury reported by health visitor over 12 months: < 1 year: 502/50151 (1%); 1–2 years: 361/18042 (1%); 2–3 years: 136/6798 (2%); 3–4 years: 73/3634 (2%); total < 4 years: 1072/78625 (1.4%) |

| US Department of Health and Human Services, USA, 2006 (NIS-3)44 | New cases of suspected physical abuse identified by 5800 professionals involved in child protection in 42 counties in 1993 (Table 3–1 in NIS-3 report). Children were classified as physically abused according to the harm standard (requires demonstrable harm) or the endangerment standard (includes children at risk of injury). Overall there are an estimated additional 1,261,800 children defined as abused under the endangerment standard. Denominators calculated from the rate (difference caused by rounding) | New cases of physical abuse (harm) reported in all US children within 12 months: 381,700/66,964,912 (0.57%); physical abuse (endangerment): 614,100/67,483,516 (0.91%) |

| Trocmé, Canada, 200346 | Children (< 16 years) on the Canadian CPR for physical abuse in 1998 | On CPR for physical abuse (point prevalence): 15,300/5,583,942 (0.25%) |

| Gessner, Alaska, 200455 | Deaths or hospital admissions due to physical abuse in infants (< 1 year) born between 1994 and 2000 (n = 70,842) in four states, using linked databases. A total of 72 of the 325 reports of physical abuse led to hospitalisation (n = 58), death (n = 4) or both (n = 10) | Physical abuse (reported to social services) over 12 months: < 1 year: 325/70,842 (0.46%) |

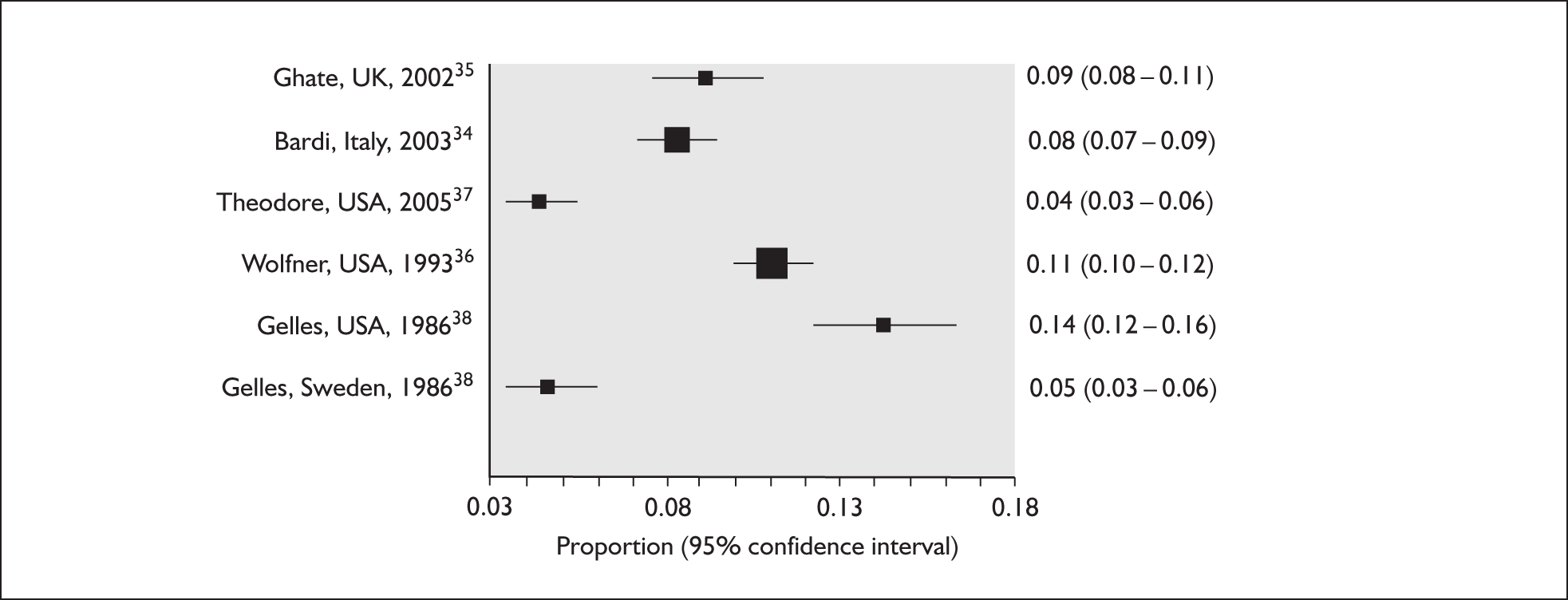

Parent-reported physical abuse

Figure 4 shows the proportion of parents who reported one or more episodes of physical abuse in the previous 12 months. Data were collected by telephone or face-to-face interviews except for one study35 based on anonymous questionnaires (see Table 3).

FIGURE 4.

Prevalence of parent-reported physical abuse in the past year.

The prevalence of 9.1% reported by Ghate et al. 34 in the UK study (age-adjusted figure for UK is 8.8%) was consistent with studies in the US (11%36) and Italy (8.3%34) but higher than a US study (4.3%36) in which only maternal violence was recorded. The relatively low rate of severe physical abuse in Sweden (4.6%38) may reflect long-standing legislation prohibiting physical punishment in the home. All but two studies37,39 had relatively low response rates (50–60%).

The annual prevalence of physical abuse reported in the UK study was similar to the rate reported for the child’s lifetime by May-Chahal and Cawson40 (7%), although different methods were used (see Appendix 2, Table 27). In studies using the same methods, the lifetime prevalence of abuse was close to but higher than the annual prevalence (Appendix 2, Table 27).

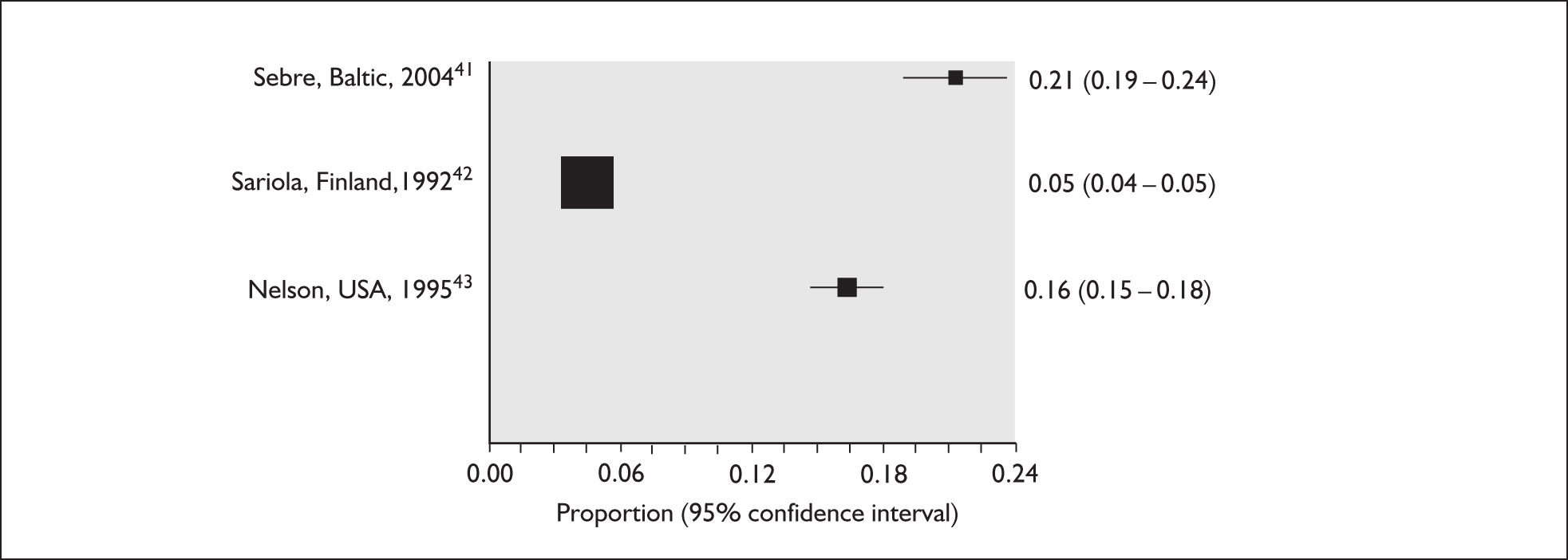

Self-reported physical abuse in the past year

Figure 5 shows results for three studies of self-reported physical abuse. All were based on questionnaires completed by adolescents. The annual incidence ranged from 4.6% to 21.3% and was highest in Eastern Europe41 and lowest in Finland. 42 One US study43 reported slightly higher rates of severe physical abuse (16.3%) than the parent-reported incidence for adolescents in the US national study37 (11%). This may reflect differences in the study populations, methods and definitions, as well as variation according to reporting source (see Table 3).

FIGURE 5.

Prevalence of self-reported physical abuse in the last year.

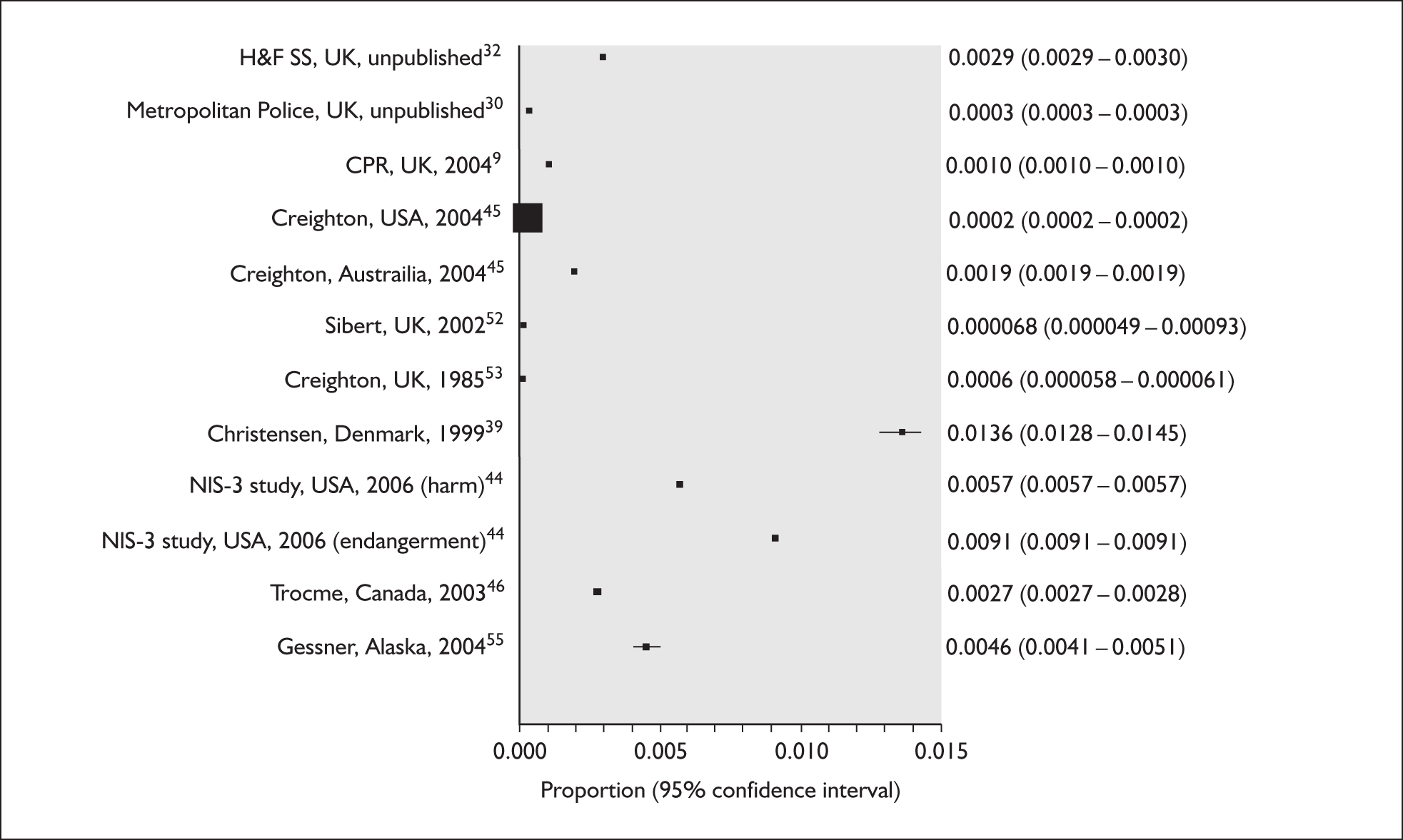

Agency-reported physical abuse in the past year

Figure 6 shows the prevalence of parent or carer physical abuse reported by agencies. Results varied enormously depending on the agency, their criteria for notification and the event reported (child affected by one or more episodes, as with the CPR figures,9 or individual episodes, as in the Metropolitan Police audit30).

FIGURE 6.

Incidence of agency-reported physical abuse in the past year.

In the UK, agencies reported substantially fewer children than the 8.8% subjected to physical abuse each year based on parent reports. The Metropolitan Police found 0.38 reports per 100 child-years in 2005. 30 This is roughly equivalent to 1 in 23 physically abused children, assuming both studies were drawn from the same population and that no children were reported to the police twice in 1 year [i.e. 1/(0.38/8.8)]. A similar rate was found for social services in an unpublished audit of one London borough. During 3 months in 2005, 11.1% (17/153) of ‘initial assessments’ for children under 18 years were for physical abuse. Extrapolating to the national rate of initial assessments (2.9%9), approximately 0.39% of children would undergo an initial assessment each year for physical abuse (see Table 3). The proportion of reports that were common to social services and police records is not known and we found no UK figures on the incidence of physical abuse suspected by professionals, referred to social services or investigated.

The fact that agencies detect far less abuse than is reported by parents or victims has been well established by North American studies. The large US National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS-3),44 which surveyed 5600 professionals involved in detecting child abuse in 42 counties, found that professionals reported one or more episodes of physical abuse in 0.58% of children each year, but estimated that only 28% of all types of abuse identified by professionals were investigated by child protection services. A similar discrepancy between identification and reporting is suggested by the high rate (1.4%) of visible evidence of physical abuse reported by health visitors in Denmark. 39 One explanation for these disparities is that some abused children may be followed up by social services for other reasons. An audit of consecutive initial assessments by social services in one London borough found 16 children undergoing initial assessment for suspected physical abuse, but a further 11 with currently documented parental violence were referred for other reasons and only 3 out of the 11 were investigated for other types of abuse (unpublished audit;32 Table 3 and Appendix 4).

Further decrement occurs in the frequency of investigation of physical abuse if agency reports are based on substantiated rather than suspected abuse. In the UK, the proportion of children placed on the CPR for physical abuse is less than 1 in 100 of those abused and less than one in three of the children who undergo initial assessment (per year: 0.08% of all children are on the CPR, 0.33% have initial assessment, 8.8% are physically abused). Similarly, Figure 6 shows that studies reporting suspected physical abuse found approximately twice as many cases as those reporting substantiated abuse in the US45 (0.24% versus 0.4%) and Canada46 (0.27% versus 0.5%). The US NIS-3 study found that 60% of all types of abuse investigated were unsubstantiated. 44,47 This is partly due to insufficient evidence or concern about further serious harm to warrant substantiation in abused children. In addition, children with accidental injuries may be falsely labelled as abused. There are few data on the proportion of false positives but expert opinion elicited for this study suggests that they account for only 10–20% of children undergoing initial assessment for physical abuse. An audit of social service referrals in the London Borough of Camden suggested that, among consecutive children referred for initial assessment for physical abuse to social services, only 3/26 index children (excluding siblings) were false positives (RE Gilbert, unpublished audit, Camden Social Services; Table 3 and Appendix 4).

The average figures reported in Table 3 hide substantial variation in overall rates of social services investigations according to locality8 and differences in age distributions according to agency. According to parent and self-report studies, the incidence of severe physical abuse is as high, or higher, in school-age children as in preschool children. Notification to the police follows a similar pattern. 30 However, the rate of child protection registration for physical abuse decreases markedly in school-age children. 9

In summary, these results provide strong evidence that parental physical abuse is poorly reported by agencies. As self-reported abuse is limited by the age of children who can be surveyed, parent reports provide the most reliable evidence of parent-inflicted physical abuse. The rates from such studies for severe parental violence in the past year are moderately consistent. 34–36 In the UK, approximately 1 in 11 children (8.8%) were subjected to violence each year of a severity consistent with physical abuse (Table 3).

Systematic review 2: Risk of injury requiring medical attention due to physical abuse

Review methods

The aim of the review was to determine the risk of injury requiring medical attention in children subjected to physical abuse. We included studies of physically abused children that reported the risk of injury after an episode of abuse. Although less representative of all abused children in the community, we restricted studies to agency reports of children presenting to services as the assessment of injury was likely to be objective. We excluded studies based on parent reports or self-reports as assessments of injury and the need for medical attention are less likely to be objective and parents may be reluctant to admit to injury. We defined injuries requiring medical attention as severe cuts or lacerations, fractures, severe burns, head injuries and internal injuries, or according to the author’s classification of injuries needing medical attention. As the data were limited we included high- or low-risk groups of children reported to services.

Review results

Seven studies met the inclusion criteria (Table 4 and Figure 7). All involved physically abused children referred to child protection services.

| First author, country, year of publication | Methods | Risk of injury |

|---|---|---|

| Suspected physical abuse | ||

| Metropolitan Police, UK (London), 2005 (unpublished data, Wareing 2006)30 |

Duty officer classified severity of injury in 5188 children (< 16 years) reported to the Metropolitan Police child protection unit in 2005 for physical abuse by parents. Injuries coded by police as moderate or serious were classified as requiring medical attention Any injury (minor or worse): < 2 years: 46.0%; 2–4 years: 39.3%; 5–9 years: 48.7%; 10–15 years: 64.7%; overall < 16 years: 55.5% |

Injury requiring medical attention: < 2 years: 88/317 (27.8%); 2–4 years: 79/574 (14.4%); 5–9 years: 172/1300 (13.2%); 10–15 years: 341/2271 (15.01%); total < 16 years: 680/4435(15.3%) |

| English, USA, 200060 | Children (< 18 years) with suspected physical abuse reported to social services and considered not to require further investigation. All (n = 862) were referred to a voluntary community-based support organisation. Injury ascertained by staff using a standard severity rating | Injury (> minor): 4/862 (0.46%) |

| Substantiated physical abuse | ||

| Gibbons, UK, 199556 | A total of 170 children (< 6 years) placed on NSPCC register for physical abuse in 1981. Injuries requiring medical attention (fractures, head injury, internal injury, severe burns or toxic ingestion) were documented from case conference reports | Injury requiring medical attention: 27/170 (16%) |

| Creighton, UK, 198553 | A total of 4329 children (< 18 years) placed on NSPCC register for physical abuse between 1977 and 1982. Injuries requiring medical attention (fractures, head injury, internal injury, severe burns or toxic ingestion) were documented from case conference reports | Injury requiring medical attention: 519/4329 (12%) |

| Lindell, Sweden, 200154 | A total of 145 children (< 15 years) with substantiated physical abuse reported to police (1986 and 1996). Fractures, burns and head or mouth injury were classified as requiring medical attention. Any injury reported in 75/145 (51.7%) | Injury requiring medical attention: 7/145 (4.8%) |

| Trocmé, Canada, 200357 | Nationally representative sample of 7672 children (< 16 years) reported to Canadian social services for suspected child abuse or neglect in 1998. A total of 3780 had substantiated abuse, of whom 1010 had physical abuse. Injury was reported by age group for 3780 children, classified as minor or requiring medical attention. Any injury reported in 379/1010 (37.5%) with physical abuse | Injury requiring medical attention: physical abuse: 70/1010 (6.9%); any abuse: < 1 year: 34/230 (14.8%); 1–3 years: 33/604 (5.5%); 4–7 years: 29/991 (2.9%); 8–11 years: 23/916 (2.5%); 12–15 years: 32/1012 (3.2%); < 16 years: 151/3753 (4%) |

| Zuravin, USA, 199461 | A total of 789 out of 2944 children reported to Child Protection Services in Baltimore City in 1984 for physical abuse were analysed. Injury classified as requiring medical attention included same or worse than sprain, mild concussion, broken teeth, cuts requiring sutures, second-degree burns, fractures or more than two ‘mild’ injuries on any body part. Any injury, including mild, reported in 497/789(63.0%) | Injury requiring medical attention: 146/789 (18.5%) |

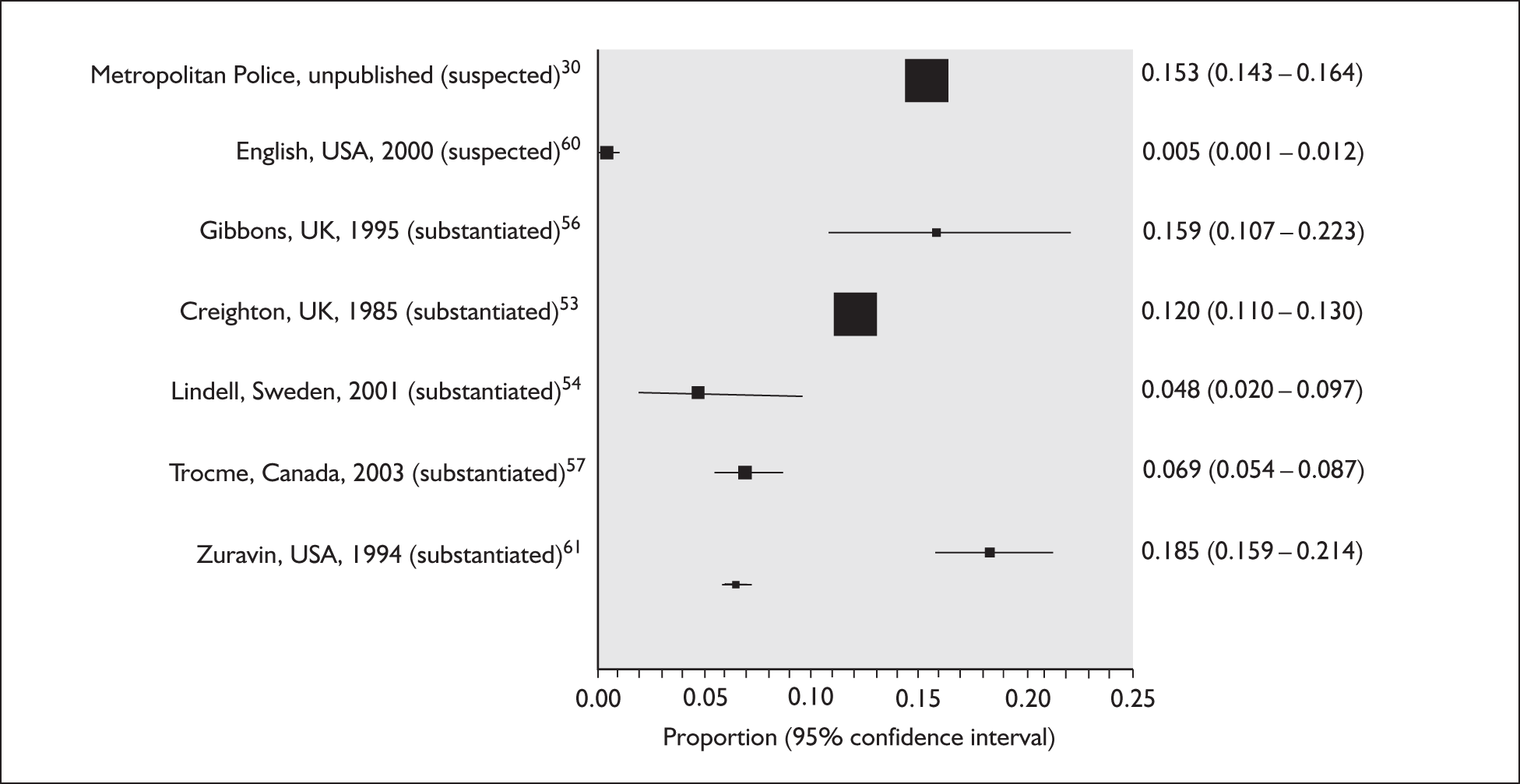

FIGURE 7.

Risk of injury requiring medical attention given a single physical abuse event.

Of the included studies, all three UK studies reported high rates of injury compared with recent studies elsewhere. The high rate in the Metropolitan Police study (15.3%) (2006, unpublished data30) may reflect increased police involvement when there is a visible injury, better recording of marks by police than by other agencies or, in the absence of guidelines, overestimation of the need for medical attention. The other two UK studies were based on children registered in the early 1980s (injury prevalence 12%53 and 16%56) and may reflect more severe abuse 25 years ago than currently or a higher threshold of severity before cases were registered.

The risk of injury was moderately consistent in the two most recent studies in Canada57 (6.9%) and Sweden54 (4.8%). Excluded studies based on self-reported injury occurring over a period ranging from 12 months to the whole of childhood reported high rates of injury requiring medical attention (from 14%58 to 26%59). In contrast, the study by Ghate et al. 34 found a very low rate of reported visible injury suggesting parental reluctance to disclose inflicted injury. Only four parents (out of 1249) responded to the question ‘Have you ever inflicted any injury on your child that required medical attention?’ All four parents said ‘No’.

Attendance at A&E

In this section we report a series of systematic reviews to determine the incidence of attendance at A&E and how the characteristics of the child vary according to whether or not the injury was due to physical abuse.

Systematic review 3: Risk of attending A&E after injury due to physical abuse

Direct measurement of the risk of a physically abused child attending A&E is difficult as some abused children may never be detected. Instead, we estimated this parameter indirectly (see Chapter 5) by addressing the following four questions, which can be mapped onto the tree in Figure 8:

-

What is the prevalence of A&E attendance in physically abused children who are injured [(a + c)/all abused and injured in Figure 8]?

-

What is the prevalence of confirmed physical abuse in all injured children attending A&E [a/(a + b + c + d) in Figure 8]?

-

What is the prevalence of confirmed and suspected physical abuse in injured children attending A&E [(a + b)/(a + b + c + d) in Figure 8]?

-

What is the prevalence of confirmed abuse in injured children with suspected physical abuse attending A&E [a/(a + b) in Figure 8]?

FIGURE 8.

Diagram showing how review questions (b)–(d) indirectly inform the probability of A&E attendance in injured, physically abused children [question (a)].

Review 3(a): Risk of A&E attendance in physically abused and injured children

Review methods

We included any study that reported presentation for medical services in children with confirmed physical abuse.

Review results

We found one study in which 4695 undergraduate students were interviewed and asked to recall any episodes of physical abuse by their parents (defined as injury due to parental violence) and whether they received medical attention (Table 5). A total of 592/4695 (12.6%) respondents reported one or more episodes of physical abuse, of which 146 involved fractures or head injury and were likely to have required medical attention. A total of 94 (0.16%) students reported having received medical attention for an abusive injury. If all A&E attendances were related to severe injuries (this is unclear in the report), 64% (94/146) of those with severe injury attended.

| First author, country, year of publication | Methods | Results |

|---|---|---|

| (a) Risk of A&E attendance in physically abused and injured children, (a + c)/all abused and injured | ||

| Berger, USA, 198889 | A representative sample of psychology undergraduates (n = 4695) completed a questionnaire including questions on parental violence during childhood, specific injuries resulting from violence and whether they ever received medical attention. A total of 592/4695 (12.6%) reported any injury due to parental violence in childhood, of which 55% were bruises, 18.1% cuts, 4.7% dental injuries, 7.6% burns, 6.7% broken bones and 10.5% head injury. We classified burns, broken bones and head injuries as likely to require medical attention (n = 146). A total of 94 attended A&E but it is not known for which type of injury | Risk of injury receiving medical attention: all injuries: 94/592 (15.9%); severe injuries: 94/146 (64.4%) |

| (b) Prevalence of confirmed physical abuse in all injured children attending A&E, a/(a + b + c + d) | ||

| Macgregor, UK (Scotland), 200362 | Records of 434 children < 1 year who presented to A&E with injury in 2000 were reviewed. Abuse was measured by referral to social services for suspected abuse | Confirmed abuse: 6/434 (1.3%) |

| Moore, UK (Liverpool), 199266 | A total of 110 children < 16 years presenting to children’s A&E in 1988 and claiming assault were interviewed by researchers. Abuse was based on disclosure by the child or caretaker (n = 15). We assumed that 27% (3767) of the 13,951 A&E attendances were for injury25,26,65 | Disclosed abuse: 15/3767 (0.40%) |

| Chang, USA, 200564 | Discharge records of 58,558 children (< 15 years) attending or admitted to hospital for injury in 1997 or 1998 were analysed for child abuse E-codes. We assumed that children with abuse recorded on the discharge database would have been referred to social services. ‘All centres’ includes non-trauma centre hospitals (n = 31,681) and data collected from a level 1 paediatric trauma centre during the development phase of the study (n = 11,919) | Abuse recorded on discharge: paediatric trauma centres: 65/551 (1.24%); trauma centres also serving adults: 158/21,326 (0.7%); total (all centres): 447/58,558 (0.76%) |

| Pless, Canada, 198765 | A total of 2211 children (< 6 years) attending children’s A&E with injury or poisoning in 1976. Specially trained nurses screened children using a checklist, full undressed examination, and discussion with physician (n = 1563). Abuse confirmed by hospital child protection team (resulting in referral to social services) | Confirmed abuse: 14/2211 (0.6%) |

| (c) Prevalence of suspected physical abuse in injured children attending A&E, (a + b)/(a + b + c + d) | ||

| Suspected abuse defined by referral to the paediatric team | ||

| Benger, UK (Bristol), 200221 | A total of 1000 injured children < 5 years consecutively attending a children’s A&E department. Referral to senior medical staff for suspected abuse recorded retrospectively from records | Referral to paediatrician: 6/1000 (0.6%) |

| Pless, Canada, 198765 | Children < 6 years attending A&E for injury/poisoning during 18 weeks in 1976 [see review 3(b)]. Referrals for suspected abuse to hospital child protection team | Suspect and confirmed: 36/2211 (1.6%) |

| Suspected abuse defined by a risk score | ||

| Palazzi, Italy, 200578 | A total of 10,175 children (< 15 years) presenting to 19 children’s A&E departments on random census days in 2000. Staff used a six-point suspicion index for all children. A score of equal to or more than 4 positive points indicated suspected abuse (n = 204). Of 204, 18% (36/204) were for suspected physical/sexual abuse | High score for physical/sexual abuse: 36/10175 (0.4%) |

| Johnson, USA, 198679 | A total of 333 children < 5 years presenting with injury to A&E (1981–2). Abuse (any) based on retrospective classification of inadequately explained/unexplained injury (45 children with incomplete records excluded) | Suspected abuse: 3/288 (1.0%) |

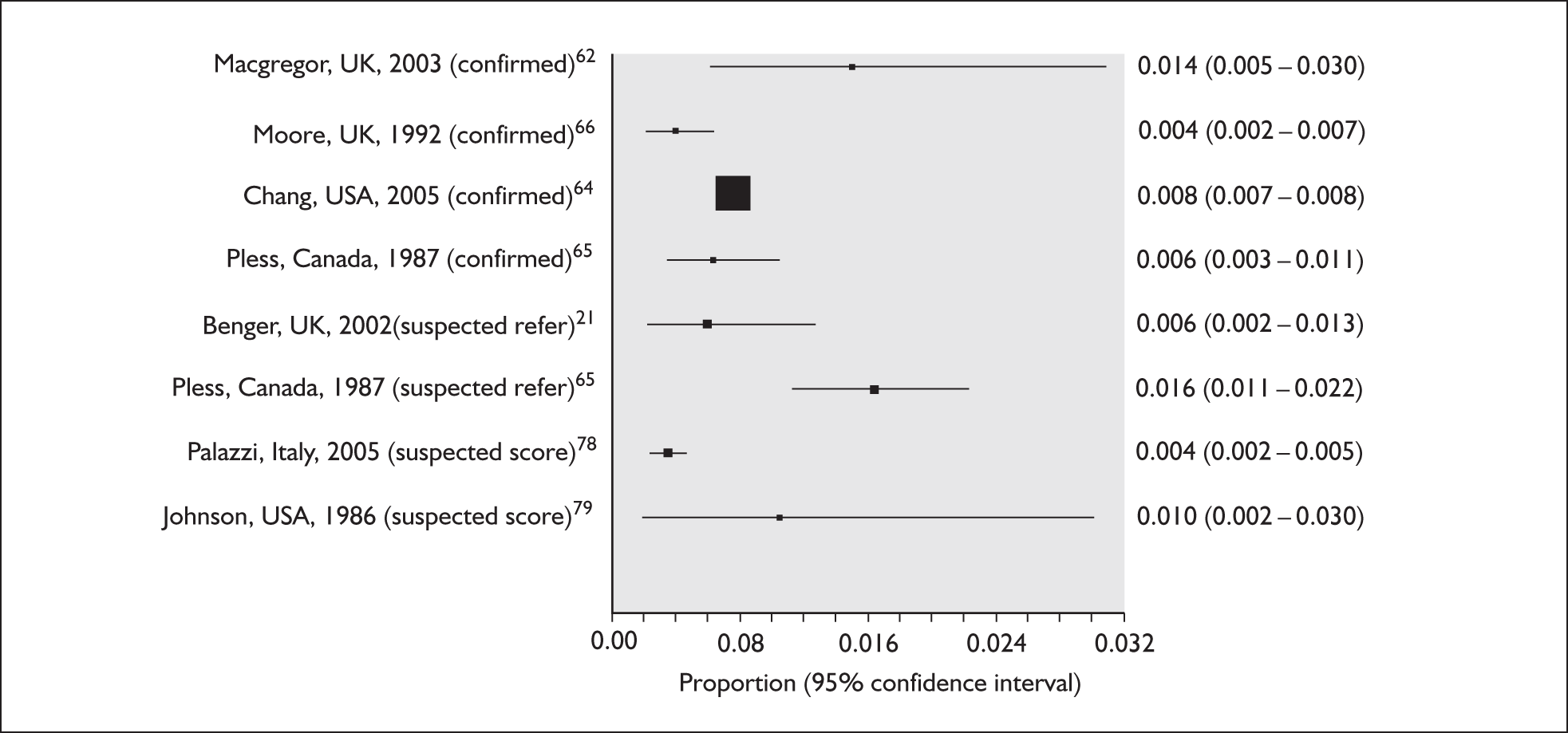

Review 3(b): Prevalence of confirmed physical abuse in all injured children attending A&E

Review methods

We included studies that reported confirmation of physical abuse in children attending A&E with any type of injury. We excluded studies that confined abuse detection to specific type of injuries (e.g. burns or fractures) as these are not representative of all attendances at A&E. We judged referral to social services to be an adequate marker of confirmation of physical abuse.

Review results

Four studies62–66 were included (Table 5; Figure 9, confirmed studies). The prevalence of confirmed physical abuse among injured children ranged from 0.37% to 1.38% (Figure 10). There were two UK studies. One,62 limited to injured infants attending A&E (1.3% had confirmed physical abuse), overestimates the risk for all children as infants are at higher risk of abuse. The other UK study by Moore and Robson66 likely underestimates the risk of abuse as detection of abuse required disclosure of parental assault. In a large US study by Chang et al. ,64 based on attendances for injury and discharge diagnoses at 1196 hospitals, the overall prevalence of confirmed abuse was 0.76%; however, the prevalence was higher in paediatric trauma centres, presumably because staff were more alert to the possibility of abuse. A similar prevalence of abuse (0.64%) was reported in a study by Pless et al. 65 from Canada in 1976, which was restricted to children under 6 years of age.

FIGURE 9.

Prevalence of confirmed and confirmed plus suspected physical abuse in all injured children attending A&E: systematic reviews 3(b) and 3(c). Note: confirmed abuse = a/(a + b + c + d), review 3(b); confirmed and suspected abuse = (a + b)/(a + b +c + d), review 3(c).

FIGURE 10.

Prevalence of confirmed abuse in injured children referred for suspected physical abuse [a/(a + b) in Figure 8]: systematic review 3(d).

These figures contrast with results from studies of high-risk patients or studies with low thresholds for measuring abuse that were excluded from this review. For example, in studies looking at fractures in children between birth and 3 years of age, the prevalence of abuse in injured children ranged from 23% to as high as 83% for children under 2 years with rib fractures. 67–70 The prevalence of abuse in young children with head injury was also high, ranging from 14% to 70% depending on the age of the child, the type and severity of head injury and the measurement of physical abuse. 71–76

Systematic review 3(c): Prevalence of confirmed and suspected physical abuse in injured children attending A&E

Review methods

We included studies that reported any measure of suspected abuse in children attending A&E for injury. Studies restricted to specific injuries were excluded. We included studies that did not differentiate between injury due to physical abuse or neglect, provided that they included physical abuse.

Review results

We found four studies, of which one (Pless et al. 65) was included in review 3(b) of confirmed physical abuse (see Table 5, Figure 9). These are analysed below according to the criteria for defining suspected abuse. 21,65,77–79

Two studies measured suspected abuse by referral to a paediatrician or the child abuse team within the hospital. 21,65 Benger and Pearce21 found that 0.6% of injured children under 5 years attending a UK children’s A&E department were referred to a paediatrician. Similar results were found in a Canadian children’s A&E department: between 0.6% and 1.4% of injured children under 6 years were referred to the hospital child protection team for any abuse, and about half of these were for physical abuse (i.e. 0.3–0.8% from 1976 to 1984; the figure for 1976 of 0.64% is used in Figure 9). 65

Two studies78,79 used a risk score to identify children with suspected abuse, although a suspicious score did not necessarily result in referral. Palazzi et al. 78 conducted a multicentre study in 19 A&E departments in Italy and found that 0.35% of 10,175 injured children had a high score (≥ 4 points) for physical abuse.

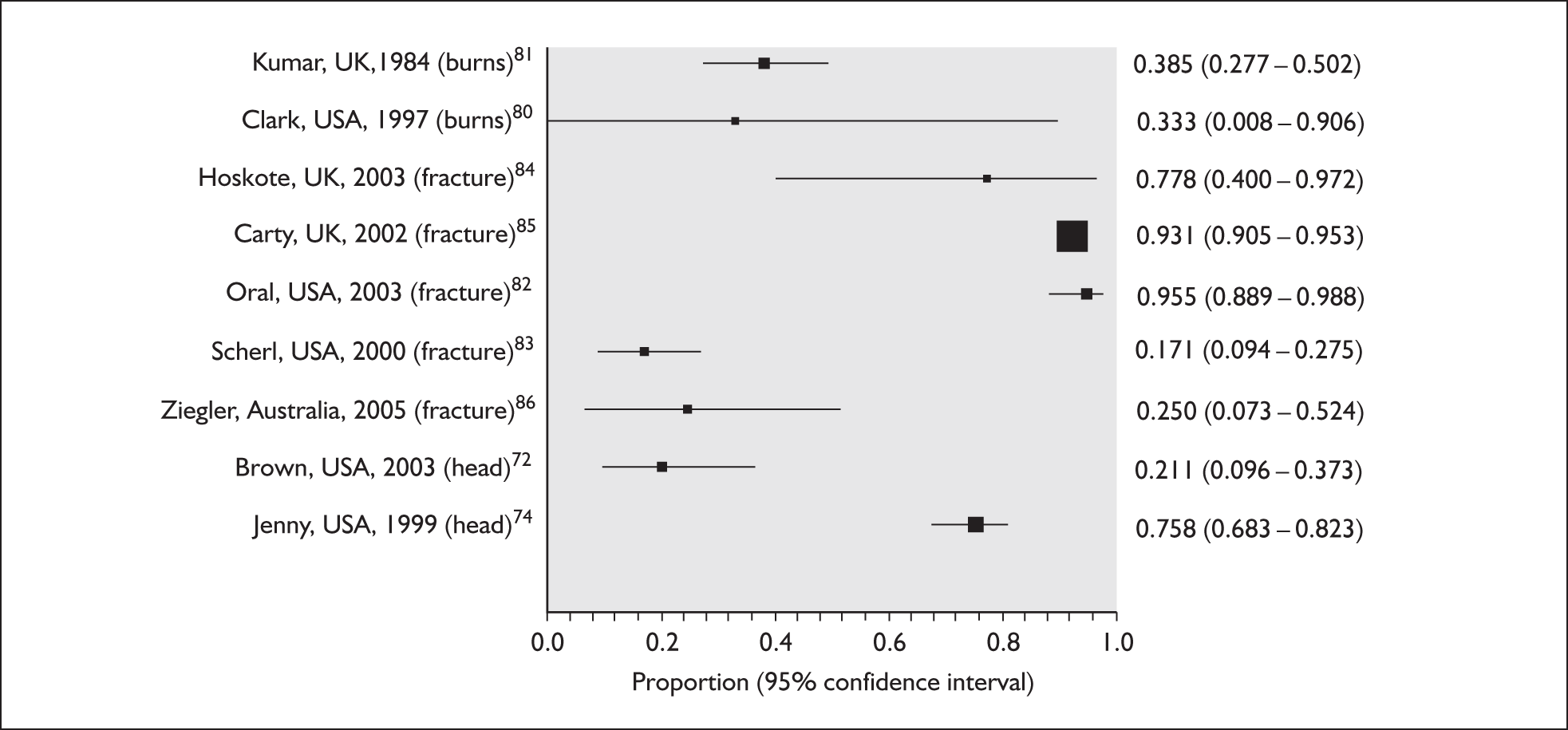

Systematic review 3(d): Prevalence of confirmed abuse in injured children referred for suspected physical abuse from A&E

Information on the probability of confirmed abuse in injured children referred from A&E can be used to validate estimates used in the clinical effectiveness model for the prevalence of confirmed abuse in injured children attending A&E [a/(a + b + c + d)]. This information, known as the positive predictive value or post-test probability, may be drawn from studies that follow up referrals for suspected abuse or from the paediatrician’s experience. Consequently, we addressed this question using published studies and estimates from experts.

Review methods

We included any study that reported any measure of confirmation of physical abuse (separately from other types of abuse) in children with any type of injury who were referred for suspected physical abuse. We assumed that ‘inflicted’ injury or ‘non-accidental’ injury referred to physical abuse, and ‘abuse’ (with no further definition) referred to all types of abuse and neglect. As few studies reported referrals from A&E we accepted any hospital setting. We sought expert opinion from three paediatricians who assess referrals from A&E.

Review results

We found nine studies (Table 6). 72,74,80–86 Post-test probability varied between 20% and 95% depending on the type and severity of injury, the threshold for referral, the criteria for confirmation of abuse and the accuracy of clinicians who decided which children to refer. All of the included studies were based on specific injury groups that would be classified post hoc, after investigation, and which are therefore likely to be based on highly selected populations, at higher risk of abuse than the average injured child attending A&E. 65,70,87 The included studies suggest some consistency in the risk of abuse for burns80,81 but not for other types of injury.

| First author, country, year of publication | Age | Admitted (Y/N) | Injury, setting, time | Test for abuse | Confirmation of abuse | Confirmed physical abuse (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burns | ||||||

| Kumar, UK, 198481 | < 9 years | Y | Burns unit, 1977–81 | Referral to SS | SS confirm | 30/78 (38.5%) |

| Clark, USA, 199780 | < 16 years | N | Burns, A&E, 1990–1 | Referral to SS (standard care) | SS confirm | 1/3 (33.3%) |

| < 18 years | N | Burns, A&E, 1992–3 | Referral to SS (checklist) | SS confirm | 7/26 (26.9%) | |

| Fractures | ||||||

| Hoskote, UK, 200384 | < 1 year | N | Fracture, A&E, 1993–4 | Referral to SS | Children registered on CPR | 7/9 (77.8%) |

| Carty, UK, 200285 | < 16 years | N | Fracture, radiology department, 1984–96 | Referral to SS | Admitted/court confirm | 435/467 (83.2%) |

| Oral, USA, 200382 | < 3 years | N | Fracture, children’s emergency department, 1995–8 | Referral to SS | Researchers confirm | 85/89 (95.5%) |

| Scherl, USA, 200083 | < 6 years | Y | Diaphyseal femur fracture, children’s hospital, 1986–96 | Referral to SS | SS confirm | 13/76 (17.1%) |

| Ziegler, Australia, 200586 | < 3 years | N | Fracture, emergency department (tertiary), 2001–2 | Referral to SS | SS confirm | 4/16 (25%) |

| Head injury | ||||||

| Brown, USA, 200372 | < 4 years | Y | Head injury, 1993–9 | Referral to SS/police | Hospital, SS, police confirm | 8/38 (21.0%) |

| Jenny, USA,199974 | < 3 years | Y | Head injury, children’s hospital, 1993–6 | Referral to hospital CAP team | CAP team confirm | 119/173 (68.8%) |

Three consultant paediatricians gave their opinion on the risk of confirmed physical abuse in injured children referred by A&E staff to the paediatric team, usually a paediatric registrar, for assessment. The estimates were 5–10%, higher than 2–10%, and 50–60%. Such variation reflects recall bias, variation in feedback about the outcome of referrals and knowledge about referrals to the paediatric team as a whole, as well as real differences in the skills of A&E staff, the threshold for referral and the populations studied. 35,57,64,88,89

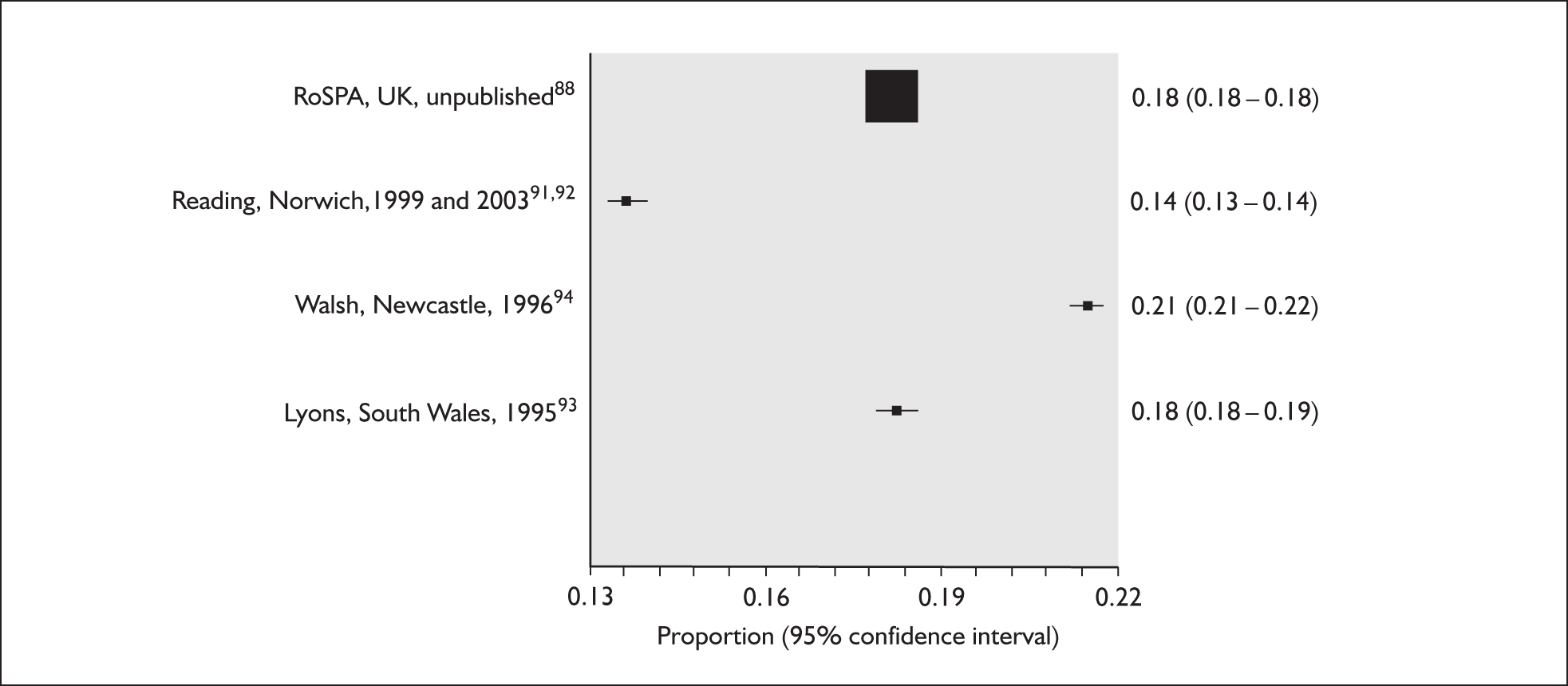

Systematic review 4: Incidence of attendance of all injured children at A&E

Review methods

To determine the annual incidence of attendance of injured children at A&E according to age group we included any UK study that reported the number of attendances for all injuries at A&E in any age group and the denominator population. We excluded studies from outside the UK as patterns of primary care and emergency care provision differ across countries. We accepted attendances for accidents as equivalent to attendances for injury but excluded reports of all attendances as the proportion due to injury varies by age group and may be affected by relative ease of access to primary care and A&E. 25,26

Review results

We found seven studies (Table 7 and Figure 11). 62,88,90–94 Two studies from Norwich91,92 were combined as they used the same geographic population and methods but studied different age groups. All six studies were based on children attending A&E after 1989 and all but one were based on routine hospital coding of the principal reason for attendance. The largest and most nationally representative study was based on unpublished data provided by the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) for A&E departments across the UK in 2000–2. 88 The RoSPA used interviews with patients in A&E departments to categorise reasons for attendance. The Norwich study estimated the denominator population based on person-years of residence using child health records. 91,92 All other studies estimated the denominator population from point prevalence census data. 62,88,90,93,94

| First author, place, year of publication | Methods | Number of injury attendances/denominator (rate per 100 child-years) |

|---|---|---|

| Brownscome, Bath, 200490 | Resident children (< 5 years) attending A&E for accidents, including those found to have no injury (n = 165), identified by A&E audit (1997–2000) | < 5 years: 2300/4245 (13.1 per 100 child-years) |

| MacGregor, Aberdeen, 200362 | Infants (< 1 year) attending A&E for injury were identified by case note review (2000). Population estimated. These data are not represented in Figure 11 as they are only for children under 1 year | < 1 year: 434/6000 (7.2 per 100 child-years) |

| Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA), UK, 2002 (unpublished)88 | Patients interviewed at 16 representative A&E departments (2000–2). Numerator assumed to be approximately 5% of all UK attendances. We calculated denominator based on mid-population estimates for 2002. Accident attendances with foreign bodies or ‘no injury’ were excluded (5% of total accidents). The age-specific incidence entered into our model gives a weighted average of 19.0 per 100 child-years | < 1 year: 3322/32,244 (10.3 per 100 child-years); 1–4 years: 26,791/134,293 (20.0 per 100 child-years); 5–9 years: 26,637/185,390 (16.9 per 100 child-years); 10–15 years 46,423/216,673 (21.4 per 100 child-years); total < 16 years: 103,173/568,600 (18.1 per 100 child-years) |

| Reading, Norwich, 199992 and Haynes, Norwich, 200391 | Resident children identified from A&E records and injury classified by researchers (0–4 years in 1994; 5–14 years in 1999). Poisoning or foreign bodies were excluded. Denominator recorded as person-time of residence from child health records | 0–4 years: 2012.02/18,693 (10.76 per 100 child-years); 5–10 years: 1829/12,868.2 (14.2 per 100 child-years); 11–14 years: 1636/8575.8 (19.1 per 100 child-years); total < 15 years: 5477/40,140 (13.6 per 100 child-years) |

| Walsh, Newcastle, 199694 | Random sample of resident children attending two A&E departments for accidental injury (< 16 years), identified from A&E records and classified by researchers (1990). Denominator based on census | < 5 years: (22.5 per 100 child-years); 5–9 years: (19.0 per 100 child-years); 10–15 years: (27.5 per 100 child-years); total < 16 years: 11,682/54,400 (21.5 per 100 child-years) |

| Lyons, South Wales, 199593 | Resident children (< 15 years) attending three A&E departments for injury (1993). Denominator based on census | < 15 years: 10117/55,588 (18.2 per 100 child-years) |

FIGURE 11.

Incidence of attendance of all injured children at A&E (per 100 child-years).

In the four studies that reported results for all ages, the incidence of attendance ranged from 13.6 per 100 child-years in Norwich to 21.5 per 100 child-years in Newcastle. 91,92,94 The RoSPA reported an incidence for the UK of 18.1 per 100 child-years. 88 The low rate of injury attendances in Norwich,79,80 Bath90 and Aberdeen62 may reflect better access to or a preference for primary care services in these areas. 88

Characteristics of children attending A&E for injury

In this section we review the evidence on the performance of a range of child characteristics or markers that have been used in screening protocols to determine which children should be referred directly to the paediatricians for assessment of suspected child abuse. Characteristics that have been used to date include young age (e.g. infants or children under 2 years), fractures or head injury in young children,22 children currently on the CPR,22,95 and repeated attendance for injury (Ian Maconochie, St Mary’s Hospital, London, February 2006, and Ben Lloyd and Jane Mattison, Royal Free Hospital, London, January 2006, personal communication). 1,20,96,97

Several potentially important characteristics were not evaluated because of a lack of UK data. These include presentation during night-time hours,98,99 parental mental illness and drug abuse, and domestic violence, all of which are factors evaluated by the community liaison nurse (Ben Lloyd, January 2006, personal communication).

As the prevalence of physical abuse in injured children attending A&E is very low (about 1%), only characteristics that are very strongly associated with abuse will have any appreciable impact on the probability of abuse. Consequently, although the quality of the research literature relating to this question was generally poor, strong associations should nevertheless be apparent.

Systematic review 5: Age as a predictor of physical abuse in injured children attending A&E

We aimed to determine the performance of the child’s age as a predictor of physical abuse. The results were used to derive a likelihood ratio (LR), a measure of diagnostic test performance, that estimates how many times as likely is a test result (e.g. age under 1 year) in abused compared with non-abused children. 100 LRs are preferable to sensitivity and specificity as they capture test performance for a specific marker (e.g. infancy) when multiple markers are possible (e.g. four different age groups).

The LR was calculated as:

The LR can be used to calculate the post-test probability of abuse in a specific age group using Bayes’ theorem (pre-test odds × LR = post-test odds). 100

Because of a paucity of evidence we evaluated two types of study. Those that:

-

directly compared abused and non-abused injured children

-

reported the age distribution of injuries in abused children or all children but which could be assumed to be drawn from a similar population (indirect comparison).

Systematic review 5(a): Studies that directly compared abused and non-abused injured children

Review methods

We included any study that reported age groups for children attending A&E for injury categorised into physically abused and non-abused using any measure.

Review results

Three studies were found (Table 8). Only one study,101 conducted in Hawaii, was based on all injured children attending A&E. Two other studies75,98 were based on a subset of children admitted with severe injuries.

| First author, place, year of publication | Methods | Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Studies comparing abused and non-abused children | Age | Abused | Non-abused | LR | Probability a | |

| Yamamoto, Hawaii, 1991101 | Children (< 16 years) seen in A&E with injury (not burns) in 1987–8. Suspicion of physical abuse by clinicians was recorded in a prospective survey | < 1 year | 11 (6.6%) | 171 (4.3%) | 1.54 | 6.0% |

| 1–5 years | 48 (28.9%) | 1953 (24.1%) | 1.12 | 2.5% | ||

| 6–10 years | 34 (20.5%) | 1047 (26.3%) | 0.78 | 3.2% | ||

| 11–15 years | 73 (44.0%) | 806 (20.7%) | 2.13 | 8.8% | ||

| < 16 years | 166 | 3977 | 4.0% | |||

| TARNlet, UK (unpublished)75 | Very severely injured children (< 16 years) admitted to 20 hospitals (30–50% of all trusts in England and Wales) between 1996 and 2004. Injury coding and classification of abuse was based on examination of records for the whole admission. We estimated that TARNlet comprises approximately 0.2–0.35% of all injury attendances in the UK in children | < 1 year | 231 (57.0%) | 754 (4.38%) | 13.0 | 23.5% |

| 1–4 years | 161 (39.8%) | 3286 (18.8%) | 2.1 | 4.7% | ||

| 5–9 years | 9 (2.2%) | 4486 (26.0%) | 0.09 | 0.2% | ||

| 10–15 years | 1 (0.2%) | 8712 (50.6% | 0.004 | 0.01% | ||

| < 16 years | 405 | 17,229 | 2.3% | |||

| Chang, USA, 200498 | Children (< 16 years) attending a level 1 paediatric trauma centre (1990–2002). Data retrospectively extracted from trauma registry. Abuse was defined by routine diagnostic codes | < 1 year | 97 (56.7%) | 873 (7.4%) | 7.7 | 11.1% |

| 1–5 years | 55 (32.2%) | 3111 (26.6%) | 1.2 | 1.7% | ||

| 5–15 years | 19 (11.1%) | 7867 (66.4%) | 0.2 | 0.2% | ||

| < 16 years | 171 | 11,851 | 1.4% | |||

| (b) Indirect comparison of age distributions in abused and non-abused injured children attending A&E | ||||||

| Abused children | ||||||

| Shrivastava, Coventry, 1988 (PhD thesis)102 | Injured children (≤ 16 years) admitted from A&E because of suspected abuse (1983–7, n = 126; abuse confirmed in 108), identified by retrospective review of admission charts | < 1 year: 29/126 (23%); 1–2 years: 19/126 (15.1%); 3 years: 15/126 (11.9%); 4–5 years:13/126 (10.3%); 6–7 years: 14/126 (11.1%); 8–10 years: 5/126 (4.0%); 11–15 years: 15/126 (11.9%); 16 years: 16/126 (12.7%) | ||||

| Roberton, Nottingham, 1982103 | Injured children (< 12 years) admitted from A&E with disclosed (n = 35) or suspected abuse (n = 49) in 1981. Retrospective record review | < 3 years: 37/84 (44.0%); 4–11 years: 47/84 (56.0%) | ||||

| Non-abused children | ||||||

| University College London Hospital, UK, 2003–5 (unpublished)25 | Children (< 16 years) attending general A&E for injury (2003–5). Routine records of primary reason for attendance | < 1 year: 235/5165 (4.6%); 1–4 years: 1599/5165 (31.0%); 5–10 years: 1660/5165 (32.1%); 11–15 years: 1671/5165 (32.4%) | ||||

| Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA), UK, 2002 (unpublished)88 | Children (< 16 years) attending 16 representative A&Es. Reasons for attendance based on interviews with patients. See www.hassandlass.org.uk/query/reports/2000_2002.pdf | < 1 year: 73431/2,427,303 (3.0%); 1–4 years: 610,510/2,427,303 (25.2%); 5–9 years: 632,568/2,427,303 (26.1%); 10–15 years 1,110,793/2,427,303 (45.7%) | ||||

The results show marked differences depending on the severity of injury. In the Hawaiian study, which reported a clinical suspicion of physical abuse in 4% of injured children, the LRs for age groups were all close to 1.0 and the post-test probability did not vary much between age groups. 101 In the two studies based on severe injury, infancy was predictive of abuse.

In the UK TARNlet study,75 which was restricted to the most severely injured 0.34% of all A&E attendances for injury, age was predictive of abuse for children under 1 year (risk of abuse increased) and over 5 years (risk of abuse decreased). In total, 2.3% of all children in the TARNlet study were recorded as injured because of physical abuse, but this rose to 23.5% for infants (Table 8). 75 Similar trends were reported by Chang et al. 98

In summary, we found no direct evidence that age is predictive of physical abuse in all injured children attending A&E, but admission with severe injury in infancy was moderately predictive of abuse.

Systematic review 5(b): Indirect comparison of age distributions in abused and non-abused injured children attending A&E

Review methods

We included any study that reported the age distribution of physically abused and injured children, or all injured children, attending A&E. We compared the age distributions in abused and non-abused children by assuming that they were drawn from the same population. Consequently, we included only UK studies.

Review results

We found two studies102,103 based on physically abused children (Table 8) and used two datasets25,88 based on routine A&E attendances to determine the age distribution for all injured children attending A&E.

Both UK studies were conducted in the 1980s. Both found that the youngest children accounted for the highest proportion of abuse cases per year of age. 102,103 As abuse was recorded only in injured children who were admitted from A&E, this may over-represent younger children as older children may not always be admitted. The age distributions in the two UK datasets (RoSPA and a central London trust) were remarkably consistent, showing a static rate of injury attendance in children over 1 year of age and a much lower rate for infants. 25,88

In summary, injured children under 1 year attending A&E appear to be more likely to have been abused than older children. 88,102

Systematic review 6: Type of injury as a predictor of physical abuse in children attending A&E

We determined the performance of five broad categories of injury for predicting physical abuse: head injury, fracture, bruises, burns and other. Because of the paucity of published evidence we conducted two reviews:

-

direct comparisons within study of the type of injury in abused and non-abused injured children

-

an indirect comparison of studies reporting type of injury in abused or all children.

Systematic review 6(a): Studies reporting a direct comparison of type of injury in abused and non-abused children

Review methods

We included studies that reported the type of injury in abused and non-abused injured children attending A&E. Studies based on children admitted to hospital were excluded.

Review results

We found no published studies that met our inclusion criteria. We included one unpublished UK national audit based on injured children admitted from A&E who met predefined severity criteria (TARNlet,75 described in Table 8). Table 9 shows that the LRs for injury type within each age group are all close to 1.0 (range 0.2–3.6) and the probability of physical abuse given each type of injury is similar to the probability for the age group overall (last column). Values for older school-age children were based on small numbers of abused children and were therefore very uncertain. These results indicate that, after taking age into account, type of injury is not a good predictor of physical abuse in this severely injured population.

| Age | Data | Head injury | Fractures | Bruises | Burns | Other injury | Total diagnoses (abused/all) | Total children (abused/all) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 1 year | Diagnoses (abused/all) | 172/460 | 79/454 | 85/208 | 6/92 | 0/10 | 324/1224 | 231/985 |

| LRa (95% CI) | 1.5 (1.3–1.8) | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | 1.8 (1.4–2.3) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 0.0b | |||

| Probability of abuse | 37.4% | 17.4% | 40.9% | 6.5% | 0%b | 27.9% | 23.5% | |

| 1–4 years | Diagnoses (abused/all) | 93/994 | 72/2032 | 56/482 | 17/475 | 1/89 | 239/4072 | 161/3447 |

| LR (95% CI) | 1.7 (1.4–2.0) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | 2.1 (1.6–2.7) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.2 (0.03–1.3) | |||

| Probability of abuse | 9.4% | 3.5% | 11.6% | 3.6% | 1.1% | 5.9% | 4.6% | |

| 5–9 years | Diagnoses (abused/all) | 3/1325 | 4/3103 | 3/629 | 1/145 | 1/198 | 12/5400 | 9/4495 |

| LR (95% CI) | 1.0 (0.4–2.7) | 0.6 (0.3–1.3) | 2.2 (0.8–5.7) | 3.1 (0.5–20.5) | 2.3 (0.3–15.0) | |||

| Probability of abuse | 0.23% | 0.1% | 0.5% | 0.7% | 0.5% | 0.2% | 0.2% | |

| 10–15 years | Diagnoses (abused/all) | 1/2413 | 0/6432 | 0/1200 | 0/151 | 0/386 | 1/10582 | 1/8713 |

| LR (95% CI) | 4.4 (4.2–4.5) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0b | |||

| Probability of abuse | 0.04% | 0%b | 0%b | 0%b | 0%b | 0%b | 0.01% | |