Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA Programme on behalf of NICE as project number 06/13/01. The protocol was agreed in July 2006. The assessment report began editorial review in June 2007 and was accepted for publication in March 2008. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

None

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2008. This monograph may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2008 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of health problem

Atrial fibrillation (AF) and typical atrial flutter are common and debilitating abnormalities of the heart rhythm (arrhythmias). They are related but distinct conditions.

AF is characterised by irregular and rapid beating of the atria (the upper chambers of the heart). It may cause symptoms including palpitations, dizziness, chest pain and, in severe cases, loss of consciousness, but patients may also have AF without experiencing any symptoms.

An international consensus group has produced a definition and classification of AF and related arrhythmias2 that has also been used in recent international guidelines for the management of AF3 and in the UK guidelines produced by the National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions on behalf of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). 4 This classification recognises four different patterns of AF (Table 1).

| Terminology | Clinical features | Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| Initial event (first detected episode) | Symptomatic | May or may not recur |

| Asymptomatic (first detected) | ||

| Onset unknown (first detected) | ||

| Paroxysmal | Spontaneous termination within 7 days (usually within 48 hours) | Recurrent |

| Persistent | Not self-terminating | Recurrent |

| Lasting over 7 days or requiring cardioversion | ||

| Permanent (‘accepted’) | Not terminated | Established |

| Terminated but relapsed | ||

| No cardioversion attempt |

AF may be progressive: for example, paroxysmal AF may deteriorate with an increase in the frequency of episodes or may change to persistent or permanent AF, whereas persistent AF may progress to permanent AF. Reversion of permanent AF to normal sinus rhythm is also possible in some cases, particularly when an underlying disease responsible for AF is treated successfully. 4 The term ‘lone AF’ is sometimes used to refer to AF that occurs in the absence of clinical or echocardiographic evidence of cardiopulmonary disease, including hypertension.

Atrial flutter is also an arrhythmia of the atria, which usually occurs paroxysmally, lasting from a few seconds to several hours. 5 Symptoms are most prevalent when the flutter is paroxysmal and the ventricular rate in response to the flutter is rapid. 5 The most common symptoms are palpitations, dyspnoea, chest discomfort, dizziness and weakness. 5 Syncope is not a common symptom unless significant cardiac disease is also present. 5 Patients who have both atrial flutter and AF are usually more symptomatic. 5

Aetiology, pathology and prognosis

The normal beating rhythm of the heart involves propagation of electrical activity from the sinoatrial node of the heart to stimulate contraction of the heart muscle (myocardium). Regular and ordered stimulation of the myocardium produces efficient contraction of the heart, which in turn maintains the pumping of blood around the body.

In AF, the normal rhythmic pattern of electrical impulses in the heart is replaced by a more random pattern produced by larger areas of atrial tissue. This can be detected on an electrocardiogram (ECG) by the absence of characteristic ‘P waves’ and their replacement by unorganised electrical activity. The propagation of irregular electrical activity in AF is complex and may involve more than one mechanism. The substrate for AF is diffuse and it may involve the whole atrium. Initial interventional approaches, for example the Maze operation (see Current service provision), attempted to address this. An important milestone was the observation of Haissaguerre and colleagues6 that focal triggers within the pulmonary veins (PVs) served to initiate AF and were potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

In contrast to AF, atrial flutter is caused by a single wave of electrical activation that follows a consistent path around the atria as the result of an intra-atrial macroreentry. The circuit involved in typical atrial flutter passes through an area of the right atrium called the cavotricuspid isthmus (CTI) between the tricuspid valve and the inferior vena cava and this observation underlies the development of catheter ablation strategies for the treatment of atrial flutter. 7 On the ECG, atrial flutter is characterised by a ‘sawtooth’ pattern of electrical activity known as ‘flutter waves’. Atrial flutter is subdivided into typical (also known as type I and common atrial flutter) and atypical (type II) forms, which can be distinguished by differences in the flutter waves. Atypical flutter is not included in this report. Typical atrial flutter is divided into counterclockwise (the more common) and clockwise forms.

The irregular beating of the heart in AF and atrial flutter affects blood flow and increases the risk of formation of blood clots in the atria, which may subsequently be dislodged and travel to other parts of the body, disrupting the blood flow there (embolism). An embolism in the brain results in a stroke. Embolism to the lungs (pulmonary embolism) can also be life-threatening, although this is rarely seen in patients with AF. Population studies suggest that the risk of stroke is five times higher in people with AF compared with the general population,8 and mortality risk is also increased. 9 Similarly, studies have reported an increased mortality with atrial flutter, although lower than that with AF or a combination of AF and flutter. 10,11

Epidemiology and risk factors

AF is the common outcome of a wide range of pathological processes and a wide range of factors predispose to its development (Table 2). Increasing age, male sex, diabetes, hypertension and heart valve disease were associated with increased risk of developing AF in the Framingham (USA) epidemiological study. 12 AF is often associated with various other types of heart disease (e.g. ischaemic heart disease, rheumatic heart disease, hypertension and sick sinus syndrome). AF may also result from non-cardiac causes (e.g. infections such as pneumonia, and various chest and lung diseases). Surgery, particularly cardiothoracic surgery, may also lead to the development of AF. When AF results from an acute underlying condition, treatment of the underlying condition may resolve AF. Lifestyle factors associated with an increased risk of AF include excessive alcohol and caffeine consumption and stress.

| Cardiac causes | Non-cardiac causes |

|---|---|

| Common | Acute infections, especially pneumonia |

| Ischaemic heart disease | Electrolyte depletion |

| Rheumatic heart disease | Lung cancer |

| Hypertension | Other thoracic pathology (e.g. pleural effusion) |

| Sick sinus syndrome | Pulmonary embolism |

| Pre-excitation syndromes (e.g. Wolff–Parkinson–White) | Thyrotoxicosis |

| Less common | |

| Cardiomyopathy or heart muscle disease | |

| Pericardial disease | |

| Atrial septal defect | |

| Atrial myxoma |

Atrial flutter is associated with old age and male gender. 5 Medical conditions that are associated with atrial flutter include valvular heart disease, previous stroke, myocardial infarction, congenital heart disease and surgical repair of congenital heart disease, pericardial disease and thyrotoxicosis, cardiac tumours, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, cardiothoracic surgery, major non-cardiac surgery, chronic pulmonary disease, pulmonary embolism and acute alcohol intoxication. 5

Incidence/prevalence

AF is the most common arrhythmia. Prevalence increases with age (from about 0.5% in people aged 50–59 years to 9% in those aged 80–89 years) and is higher in men than in women. Prevalence of AF in the Renfrew–Paisley study in Scotland (a cohort aged 45–64 years, therefore typical of the population undergoing catheter ablation of AF) was 6.5 cases per 1000 examinations, with increased risk being associated with age and male gender (around 14 cases per 1000 males and 8 cases per 1000 females at 60–64 years of age). 13 The incidence of new cases of AF was 54 per 100,000 person-years. 13

Most data on prevalence and incidence of AF come from predominantly white populations and data on other ethnic groups are limited. A study in Birmingham found a prevalence of AF of 0.6% among Indo-Asian people aged over 50 years compared with an overall prevalence of 2.4%. 4 Overall prevalence is rising because of an aging general population and increased longevity resulting from improved medical care among patients with chronic cardiac conditions that predispose to AF. 14 This poses a major health-care challenge for the future.

The incidence of atrial flutter in the USA is reported to be 88 per 100,000 person-years. 15,16 The incidence increases with age: 5 per 100,000 at age less than 50 years increasing to 587 per 100,000 at age 80 years or more. 16 The incidence of atrial flutter is two to five times higher in men than in women.

Impact of health problem

Symptomatic AF and atrial flutter or their combination can have a marked negative effect on a patient’s quality of life (QoL). Symptoms impact on QoL particularly by reducing exercise tolerance and in some cases cognitive function,4 which may reduce the patient’s ability to work and take part in other everyday activities. Episodes of AF may require emergency treatment to improve symptoms such as breathlessness and chest pain. Treatment of AF also impacts on the patient through increased rates of consultation in primary and secondary care, hospitalisations and the adverse effects associated with AADs and other treatments. Many patients with AF and atrial flutter receive anticoagulation with warfarin, which requires regular monitoring to prevent over- and underdosing.

AF and atrial flutter are linked to other conditions such as stroke and heart failure. The presence of AF worsens the prognosis following a stroke, with increased disability, longer hospital stays and a reduced chance of being discharged home. 4

The fact that AF and atrial flutter are common and increasing in prevalence means that the cost to health-care systems of managing these conditions is high. A 2004 study17 (using 1995 data extrapolated to 2000) estimated the direct cost of AF to the UK NHS in 2000 as £459 million, equivalent to 0.97% of total NHS expenditure. AF and atrial flutter have an impact on all sectors of the NHS, from emergency care to primary and secondary care to specialist tertiary referral.

Current service provision

Management of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter

There are two broad strategies for the management of AF and atrial flutter. Rhythm control strategies attempt to control the arrhythmia by restoring and maintaining a normal heart rhythm (sinus rhythm) whereas rate control strategies involve control of heart rate without attempting to remove the underlying arrhythmia. Both strategies are normally combined with anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs such as aspirin to reduce the risk of stroke.

In recent UK guidelines it is recommended that patients with paroxysmal AF should be treated first with a rhythm control strategy, whereas a rate control strategy should be used first for patients with permanent AF. For those with persistent AF the choice between rhythm and rate control depends on a number of factors including age, severity of symptoms and presence of complicating factors, as well as patient preference. 4

Short-term treatment options for typical atrial flutter are similar to those for AF and include pharmacological rate and rhythm control, electric shock treatment to restore normal heart rhythm, and pacing (using a pacemaker to interrupt the flutter rhythm). 5 Standard options for longer-term management are continuing drug treatment and catheter ablation.

AADs may be used for both rate control and rhythm control. An imperfect but commonly used classification of AADs (Vaughan Williams classification) divides them into four classes (I–IV; class I has three subclasses, Ia–Ic) according to their effect on the different phases of electrical conduction in the myocardium. 18 Some AADs fall outside this classification (see Table 3).

| Class | Action | Drugs |

|---|---|---|

| I | Sodium channel blockade | |

| Ia | Prolong repolarisation | Quinidine, procainamide, disopyramide |

| Ib | Shorten repolarisation | Lidocaine, mexiletine, tocainide, phenytoin |

| Ic | Little effect on repolarisation | Encainide, flecainide, propafenone |

| II | Beta-adrenergic blockade | Propranolol, esmolol, acebutolol, l-sotalol |

| III | Prolong repolarisation (potassium channel blockade; other) | Amiodarone, bretylium, d,l-sotalol, ibutilide |

| IV | Calcium channel blockade | Verapamil, diltiazem, bepridil |

| Miscellaneous | Miscellaneous actions | Adenosine, digitalis, magnesium |

Rhythm control

The general term for restoration of AF or atrial flutter to normal sinus rhythm is ‘cardioversion’. Cardioversion may be carried out using drugs (pharmacological cardioversion) or by administering an electric shock to the heart (electrical cardioversion). Clinical trials suggest that electrical and pharmacological cardioversion are equally effective for restoration of sinus rhythm in patients with AF. 19 In UK clinical practice, electrical cardioversion is generally preferred to pharmacological cardioversion for relatively prolonged AF (over 48 hours) whereas pharmacological cardioversion may be preferred for AF of more recent onset. 4 Electrical cardioversion is associated with relatively high rates of reversion to AF and AADs are often given before and after the procedure.

A range of AADs in classes Ia, Ic and III are commonly used for pharmacological cardioversion and subsequently to maintain sinus rhythm in patients with AF or atrial flutter. Beta-blockers (class II) are also commonly used to maintain sinus rhythm following cardioversion. Such therapy has to be lifelong and, furthermore, is at best palliative as nearly all patients will continue to experience some degree of AF or flutter. In addition, AADs are associated with significant adverse events. 20 Some AADs can precipitate arrhythmia in patients with underlying heart disease. Therefore, careful monitoring of AAD therapy is required. Amiodarone in particular is associated with a range of adverse effects including pulmonary fibrosis, liver dysfunction, corneal deposits, thyroid problems, photosensitivity, peripheral neuropathy and central nervous system effects. Although there is evidence that amiodarone is more effective than some other AADs for maintenance of sinus rhythm,4 the risk of adverse effects means that in clinical practice amiodarone is generally reserved for use when other agents [e.g. beta-blockers, class Ic AADs and sotalol (class III)] have failed. This is the treatment sequence recommended in the UK national guidelines for patients with persistent or paroxysmal AF treated with a rhythm control strategy. 4

Pharmacological rhythm control in atrial flutter also commonly involves AADs from classes Ia, Ic and III. However, long-term efficacy of AADs in atrial flutter is less well established than in AF, partly because patients with AF and flutter have been grouped together in many clinical trials. 5 The risks of AAD treatment in patients with AF also apply to those with flutter.

Another option for rhythm control for some patients with paroxysmal AF is ‘pill-in-the-pocket’ therapy. This approach may be used with patients who have infrequent symptoms but the number of patients managed in this way in the UK is thought to be small.

Rate control

Rate control for the management of AF is most appropriate for patients with permanent AF and some patients with persistent AF. Drugs used for rate control include beta-blockers and rate-limiting calcium antagonists. Atrioventricular (AV) node ablation and pacing is a rate control procedure that involves ablation of the AV node to eliminate conduction of electrical signals from the atria to the ventricles, combined with implantation of a permanent pacemaker to control heart rate. Studies suggest that AV node ablation and pacing provides effective control of heart rate and improves symptoms in selected patients with AF. 3 A meta-analysis of studies published between 1989 and 1998 concluded that the procedure improved cardiac symptoms and QoL and reduced health-care resource use in patients with symptomatic AF resistant to medical treatment. 21 However, patients treated with this approach still need anticoagulation because the underlying arrhythmia and risk of stroke remains, and they are dependent on a pacemaker for life.

Surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter

Initial attempts to cure AF by selective creation of lesions within the atria used a surgical approach. The Maze procedure was pioneered by J. L. Cox and involved interrupting all of the circuits that could be involved in AF using a ‘cut and sew’ method. High rates of maintenance of sinus rhythm were reported following the Maze procedure but the procedure was technically difficult and was associated with relatively high mortality [30-day mortality of 0–7.2% in large case series (mean 2.1%)] and morbidity (including sinus node dysfunction, bleeding and stroke). 22 Modified versions of the Maze procedure were developed that involved creating a more limited set of lesions, and selected areas of tissue were ablated as an alternative to the ‘cut and sew’ approach. Cryoablation and radio frequency ablation can be performed using hand-held probes or clamp devices. Other energy sources for surgical ablation include laser, microwave and ultrasound. The vast majority of surgical procedures for ablation of AF are performed in conjunction with other heart surgery, particularly mitral valve surgery. 22 Surgical ablation may also be an option for a minority of cases of atrial flutter but is less important for this arrhythmia than for AF.

Current service cost

A recent report17 estimated that about 1% of all NHS expenditure is the result of AF. In total, 50% of this expenditure was associated with hospital admissions and 20% with the costs of drug treatment. Implementation of the 2006 NICE guidance on management of AF is expected to result in increased expenditure, primarily through increased use of ECG to confirm diagnosis and increased use of anticoagulants. These increased costs are anticipated to be offset by savings resulting from strokes and deaths avoided by improved treatment. 4 Costs directly associated with atrial flutter are likely to be lower than those for AF because the condition is much less common, but the close relationship between the two arrhythmias makes it difficult to separate them in terms of their cost to the health-care system.

Relevant national guidelines

Management of AF and related arrhythmias is covered in Chapter 8 of the National service framework for coronary heart disease. 23 There are NICE guidelines for the management of AF in primary and secondary care;4 most of the recommendations are stated to apply to atrial flutter as well as AF. NICE has also issued an interventional procedure overview specifically of RFCA for AF. 24 This is based on a rapid evidence review and expert opinion and is not intended as a definitive assessment of the procedure. The guidelines on management of AF recommend that patients with the following characteristics may benefit from referral for catheter ablation (PV isolation): patients with AF resistant to pharmacological treatment; younger rather than older patients (not defined); and those with ‘lone AF’.

Description of technology under assessment

Catheter ablation is a relatively new, invasive technique for the treatment of cardiac arrhythmias. Curative percutaneous catheter ablation developed from the surgical ablation techniques briefly described above. The most well-established approach involves the percutaneous insertion of catheters, which are guided by fluoroscopy to the heart. Ablation for atrial flutter and fibrillation is now well understood with defined targets for ablation of the arrhythmia substrate. There are well-defined end points for atrial flutter ablation that predict high (80–90%) success rates. 7 The end points for ablation of AF are less well defined, but success rates of 50–70% were reported by most centres in an early survey. 25

Catheter ablation for atrial flutter is a highly standardised technique. Atrial flutter is most commonly caused by a specific reentrant circuit in the right atrium, and the approach to ablating this typical form of atrial flutter is well established, with ablation of a line between the tricuspid valve and the inferior vena cava [cavotricuspid isthmus (CTI) ablation]. 26

Catheter ablation in AF has developed in recent years such that it now primarily involves ablation of atrial tissue around the PVs. 27 The procedure has changed over time because of changes in technology and increased knowledge of aetiology. Variations can relate to the type of catheter (standard or irrigated), type of ablation energy (e.g. radio frequency, cryoablation, microwave, laser, ultrasound), type of mapping technique used to locate and guide the catheters within the heart (e.g. intracardiac electrogram, intracardiac echocardiography, electroanatomical mapping), and the ablation approach itself (e.g. linear, focal, PV isolation). The two main types of approach are three-dimensional (3D)-guided compartmentalisation techniques and electrical disconnection of the PVs, sometimes referred to as circumferential and segmental ablation respectively.

Circumferential ablation uses a 3D guidance system to visualise the anatomical structure and ablation lines. This approach involves the creation of a continuous ablation line in the left atrium (LA) that surrounds and completely encloses the PVs. The end point of this type of procedure is completion of the planned ablation lines. Segmental ablation is an electrophysiological approach in which energy is applied near the PV–LA junction to destroy the electrical connections between the PV and LA. The end point of the procedure is achieved when all PV potentials are abolished or potentials are dissociated from the rest of the LA. Techniques that combine elements of both approaches, or that combine PV ablation with additional ablation lines in the LA, are increasingly used.

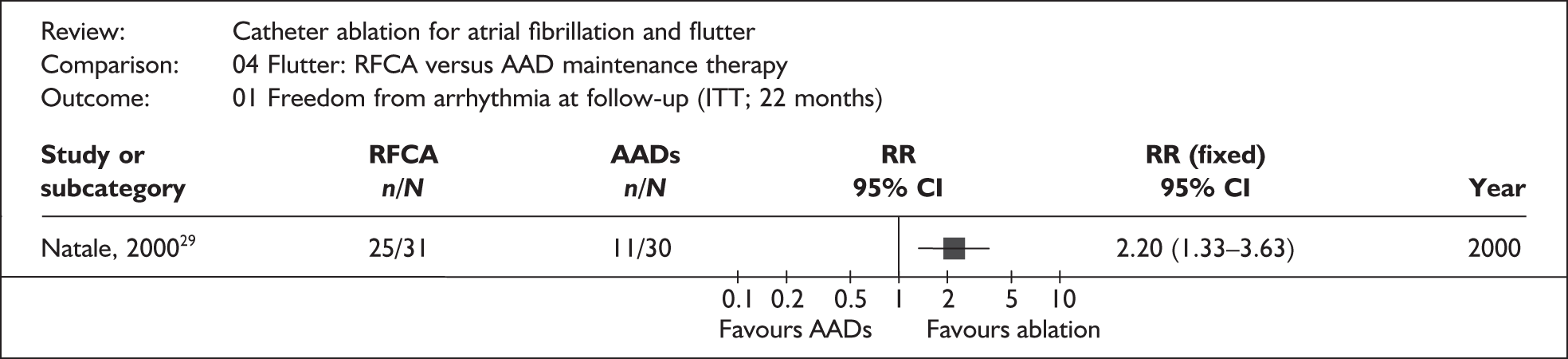

The Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment (CCOHTA) commissioned a systematic review28 (published in 2002) that covered RFCA for all types of arrhythmia. For atrial flutter, this review found one small RCT29 reporting reduced symptoms, a lower rate of complications and rehospitalisation, and improved QoL compared with drug therapy with almost 2 years’ mean follow-up. Case series30–44 suggested acute procedural success rates of 83–100% in patients with atrial flutter alone, but also suggested that up to 15% of patients may experience a recurrence. In relation to AF, the review summarised some of the earliest case series reporting PV isolation. 6,45–49 It concluded that the observed short-term clinical success rates of 62–88% in these series were ‘encouraging’ but that PV isolation for AF must, at that time, be considered an experimental procedure.

More recently, the NICE Interventional Procedures Programme published an overview of RFCA for AF to support guidance issued in April 2006. 24 This guidance concluded that current evidence ‘appears adequate to support the use of this procedure in appropriately selected patients’, defined as ‘symptomatic patients with atrial fibrillation refractory to anti-arrhythmic drug therapy or where medical therapy is contraindicated because of co-morbidity or intolerance’. We are not aware of any recent systematic reviews or guidelines of catheter ablation for typical atrial flutter.

An international survey on catheter ablation for AF was published by Cappato and colleagues in 2005. 25 The survey questionnaire was sent to 777 electrophysiology centres, of which 181 (23.3%) responded. The participating centres were considered by the authors to be representative of contemporary good clinical practice in interventional electrophysiology. Of the 181 centres that responded, 100 had ongoing programmes for catheter ablation of AF and they provided data on 11,762 procedures performed on 9370 patients between 1995 and 2002. The median number of procedures per centre was 37.5 (range 1–600). Complete data for assessment of efficacy of catheter ablation were provided for 8745 patients who were followed up for a median of 12 months (range 1–98 months).

Table 4 summarises the details and key findings of the study. Of the patients for whom full data were available, 52% became free of symptoms without AADs and a further 23.9% became free of symptoms on a previously ineffective AAD regimen. In total, 24.3% of patients required two ablation procedures and 3.1% required three procedures. The success rate free of AADs was 52.7% for 65 centres that treated patients with paroxysmal AF only, 48.5% for 17 centres that treated patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF, and 57.3% for eight centres that treated patients with all forms of AF.

| Study details | Main efficacy findings | Main safety findings |

|---|---|---|

|

Worldwide survey (181 centres) Procedures performed 1995–2002 9370 patients (11,762 procedures) Efficacy data for 8745 patients (68.3% male, age range 16–86 years) Inclusion criteria: paroxysmal AF 100% of centres; drug refractory 93%; persistent AF 53%; permanent AF 20% Exclusion criteria: lower limit of left ventricular ejection fraction between 30% and 35% (65% of centres); previous heart surgery (64%); upper limit of left atrial size between 50 and 60 mm of maximal transverse diameter (46%) |

Freedom from AF without AADs: 4550/8745 (52%, range among centres 14.5–76.5%) Freedom from AF with previously ineffective AADs: 2094/8745 (23.9%, range among centres 8.8–50.3%) Resolution of symptoms with or without AADs: 6644/8745 (76%, range among centres 22.3–91%) |

All major complications: 524/8745 (6%) Periprocedural death: 4/8745 (0.05%) Cardiac tamponade: 107/8745 (1.2%) Stroke: 20/8745 (0.2%) Transient ischaemic attack: 47/8745 (0.5%) PV stenosis: 117/8745 (1.3%) Sepsis, abscess or endocarditis: 1/8745 (0.01%) Pneumothorax: 2/8745 (0.02%) Haemothorax: 14/8745 (0.02%) Permanent diaphragmatic paralysis: 10/8745 (0.1%) Femoral pseudoaneurysm: 47/8745 (0.5%) Arteriovenous fistulae: 37/8745 (0.4%) Valve damage: 1/8745 (0.01%) Aortic dissection: 3/8745 (0.03%) New-onset atypical atrial flutter: 340/8745 (3.9%) |

Techniques used for catheter ablation of AF captured by the Cappato survey varied between centres and over time within centres. PV disconnection was the most prevalent technique overall and in the most recent years covered by the survey (2000–2002). Of 4918 patients for whom the energy source used for catheter ablation was known, 89% received radio frequency current ablation, 5% cryotherapy, 2% ultrasound, 2% laser ablation and 2% ablation using other energy sources. The most common techniques for mapping and ablation were CARTO™ (BioSense Webster; 1846 patients in 43% of centres), Lasso (BioSense Webster; 3385 patients, 77% of centres), EnSite® (Endocardial Solutions; 141 patients, 12% of centres) and basket-shaped electrode catheters (317 patients, 21% of centres).

Success rates tended to increase with volume of procedures performed, overall success increasing from 59.9% in centres performing 1–30 procedures to 91% in those performing 231–300 and 87.9% in those performing more than 300 procedures in total. Success rates remained relatively constant across follow-up times ranging from less than 3 months to more than 24 months (Table 5).

| Range of follow-up duration (months) | Number of centres | Overall success rate |

|---|---|---|

| 0–3 | 4 | 122/179 (68.2%) |

| 4–6 | 16 | 615/906 (67.8%) |

| 7–9 | 14 | 939/1271 (73.9%) |

| 10–12 | 15 | 1383/1537 (89.9%) |

| 13–18 | 17 | 2035/2607 (78.1%) |

| 19–24 | 8 | 326/467 (69.8%) |

| > 24 | 6 | 1125/1619 (69.5%) |

Major complications, including periprocedural death, cardiac tamponade, stroke, transient ischaemic attack and PV stenosis, occurred in 6% of patients. New-onset atypical atrial flutter was reported in 3.9% of patients; this phenomenon was significantly more frequent in centres using 3D-guided compartmentalisation techniques than in those that performed ablation of the triggering substrate or PV electrical disconnection.

The Cappato survey provides valuable information about success and complication rates of RFCA for AF in a worldwide sample of centres. It provides evidence of the range of techniques employed and the volume of procedures at different centres and their relationship to success rates. Potentially, the data relate to everyday clinical practice rather than to the sometimes highly selected populations included in clinical trials. On the other hand, the survey has a number of limitations:

-

Given the low response rate of around 23%, the centres that responded to the survey are unlikely to be a representative sample.

-

The survey reports procedures performed between 1995 and 2002; in view of the rapid developments in RFCA for AF, these results may not be representative of current practice.

-

The survey provides uncontrolled data and gives no indication of the effectiveness of RFCA relative to other treatment strategies.

-

The authors do not report any longer-term follow-up data on important clinical outcomes such as mortality and stroke.

Chapter 2 Definition of decision problem

Decision problem

RFCA is generally indicated for the treatment of those patients with AF or atrial flutter for whom AAD therapy has proven ineffective, intolerable or unsafe. When successful, RFCA can eliminate the need for AADs or prevent patients having to progress to more powerful but more toxic agents such as amiodarone. However, the procedure also carries a risk of complications and morbidity, in particular an increased risk of stroke. It is unclear how well these risks are offset by the level of benefit achieved.

When successful, RFCA restores and maintains normal sinus rhythm (NSR). Thus, it should be considered as a rhythm control strategy and compared with rhythm control strategies, i.e. AADs for cardioversion and maintenance of NSR.

Within the patient populations being evaluated there are important subgroups of patients for whom the differential effects of catheter ablation need to be investigated. AF and atrial flutter must be considered separately. With AF there is a distinction between patients with the paroxysmal form of AF (in which AF comes and goes by itself) and patients with persistent (in which AF can only be stopped by cardioversion) or permanent (either AF cannot be stopped or the clinician has elected not to attempt to do so) AF. The distinction is drawn because of the higher success rates of ablation for treating paroxysmal AF. 22 There is no similar distinction within atrial flutter.

Outcome measures to evaluate effectiveness and safety vary between studies and can include acute procedural success (e.g. re-established sinus rhythm), long-term maintenance of sinus rhythm, relief from symptoms, need for repeat ablation procedures, complications (e.g. cardiac tamponade), adverse events (e.g. sudden death, stroke), morbidity, mortality and QoL.

Possible modifiers of the effect of RFCA include the precise technology used for mapping and ablation, the experience of the team performing the procedure and follow-up care after the procedure.

RFCA is currently provided by the NHS at specialist tertiary referral centres. The technical aspects of the procedure are developing rapidly and its use is expanding worldwide. 25 RFCA is strongly advocated by many clinicians and recently there has been discussion of its use as a first-line treatment as an alternative to AAD therapy in selected patients. In view of the potential promise and uncertainties surrounding RFCA for AF and atrial flutter, an up-to-date review of the evidence for its clinical effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness is clearly justified.

Overall aims and objectives of the assessment

The aim of this project is to determine the safety, clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of RFCA for the curative treatment of (1) AF and (2) typical atrial flutter. It aims to examine the available evidence regarding the clinical and cost-effectiveness of catheter ablation compared with relevant comparator treatments.

For the clinical review, comparative clinical studies have been supplemented with observational studies, as these constitute much of the evidence base for RFCA. A specific aim is to focus on evidence from the setting of the NHS and to consider evidence from other sources in relation to its generalisability to NHS practice. Gaps in the evidence are highlighted and recommendations presented for further research.

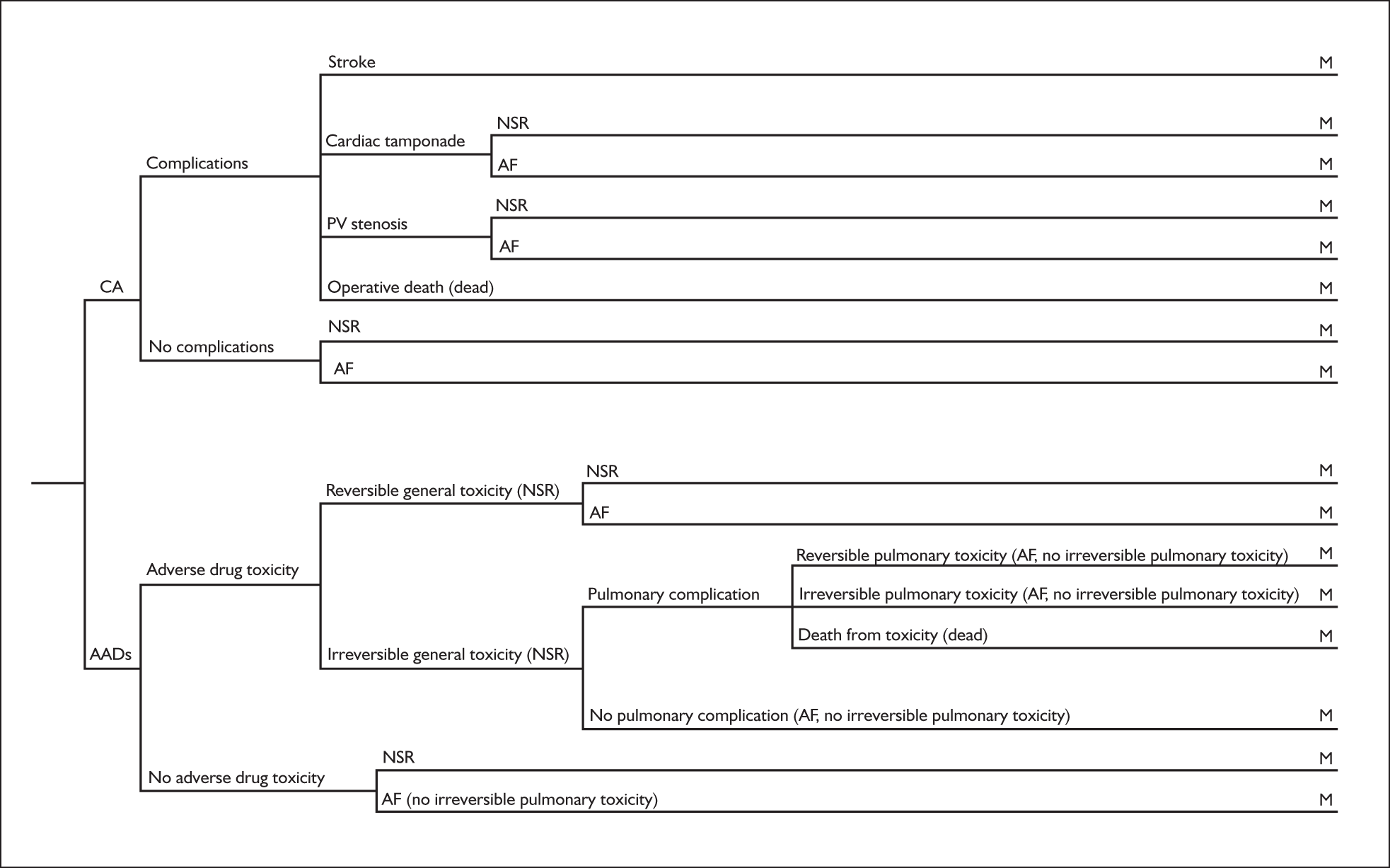

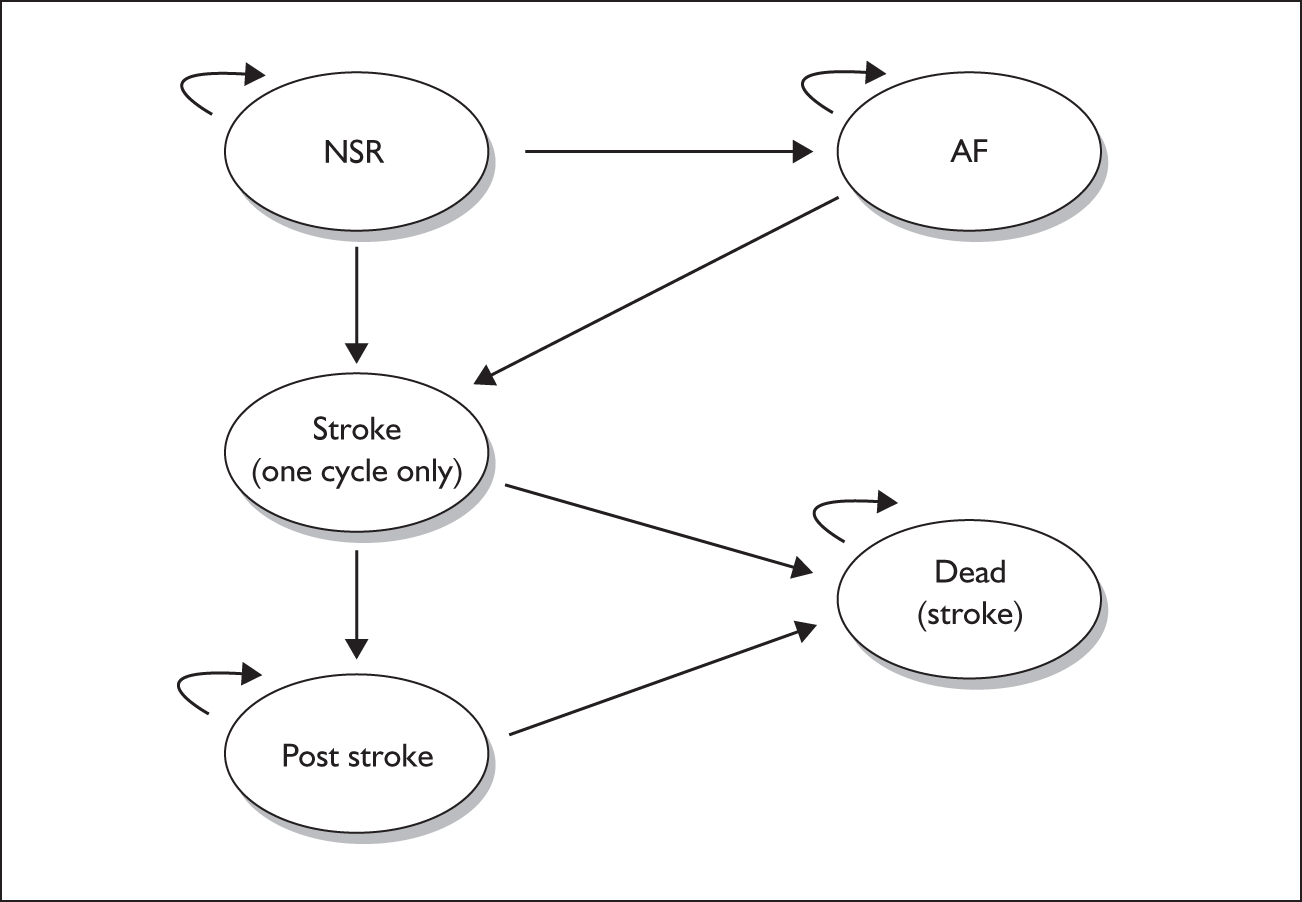

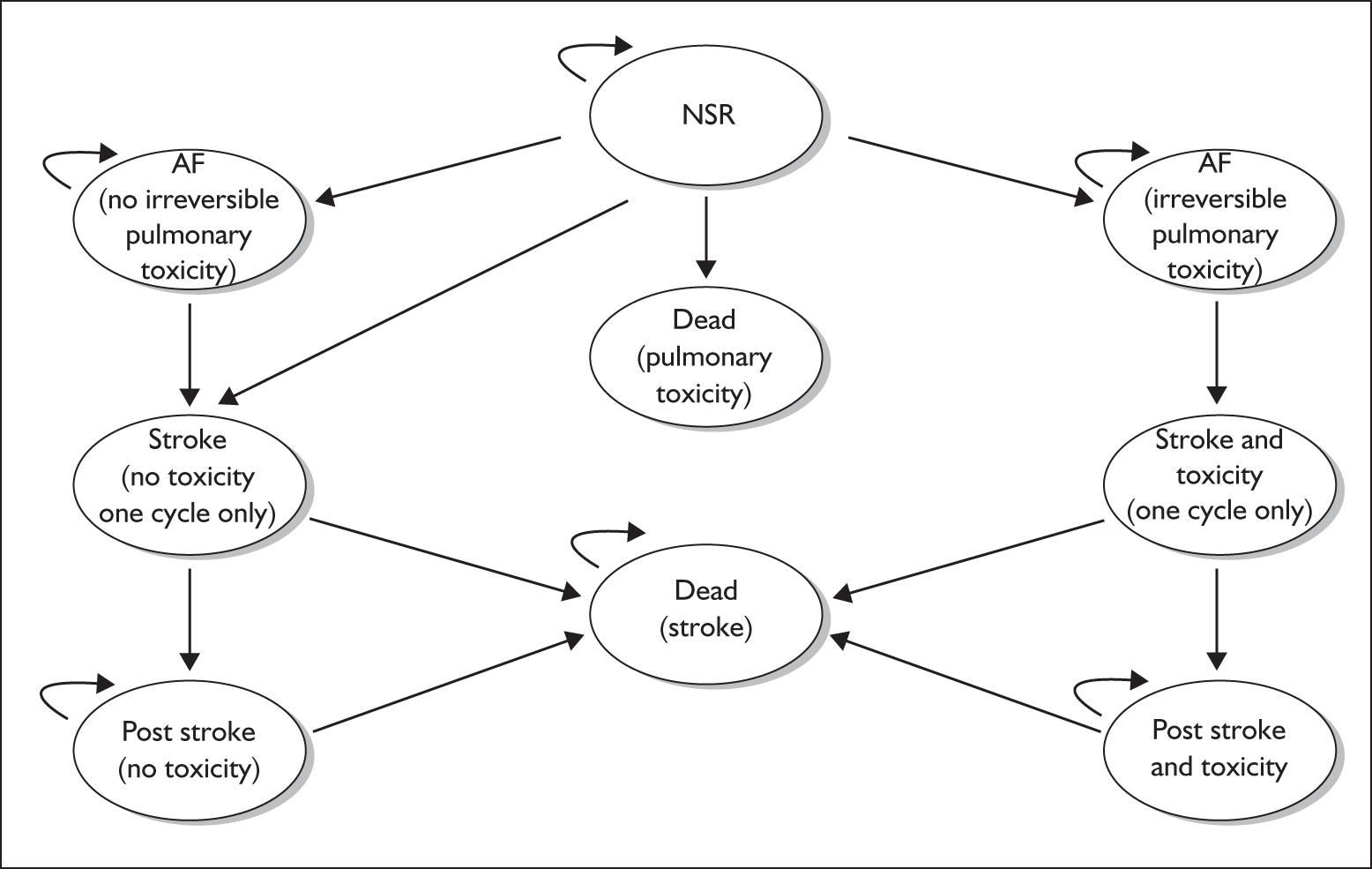

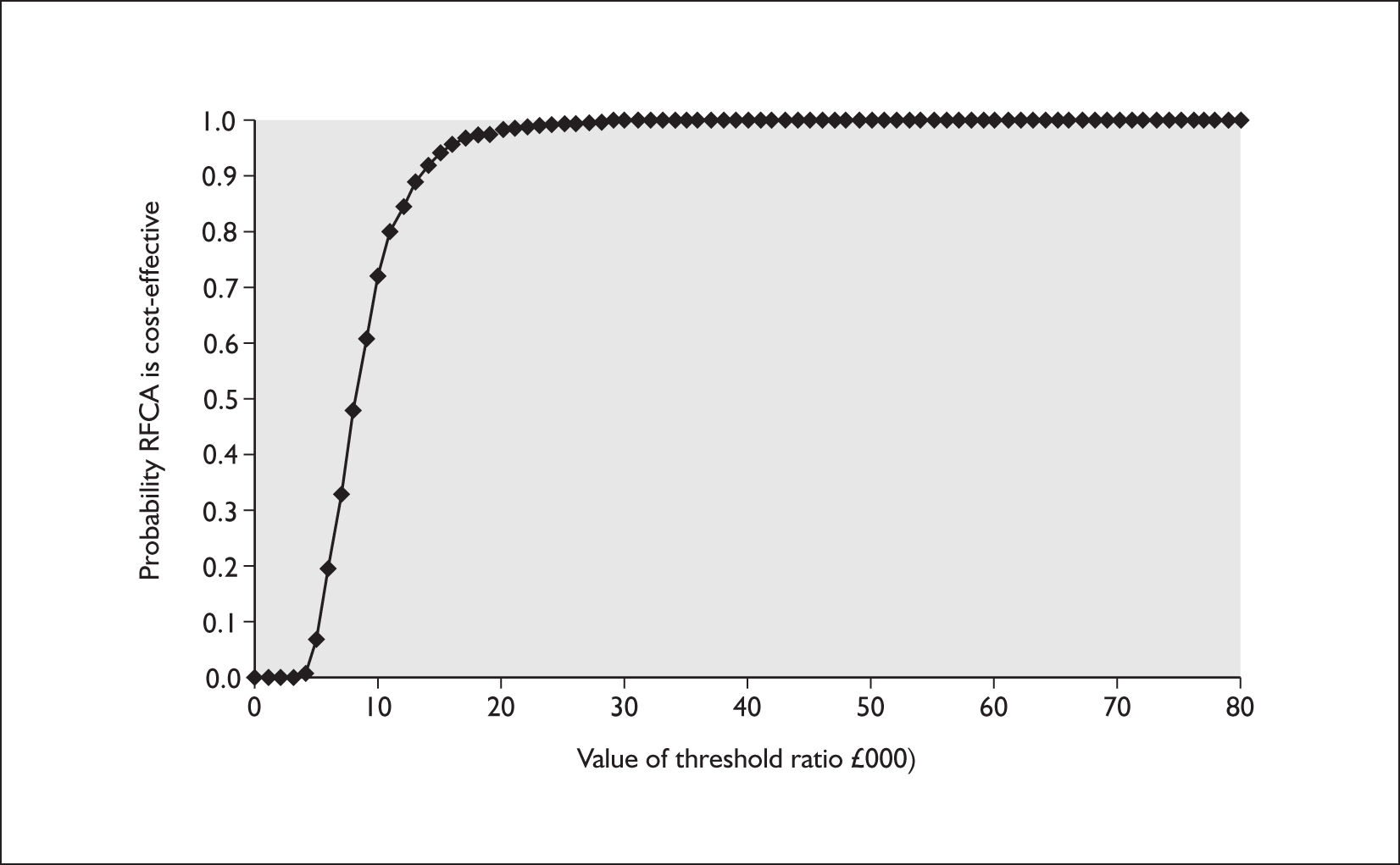

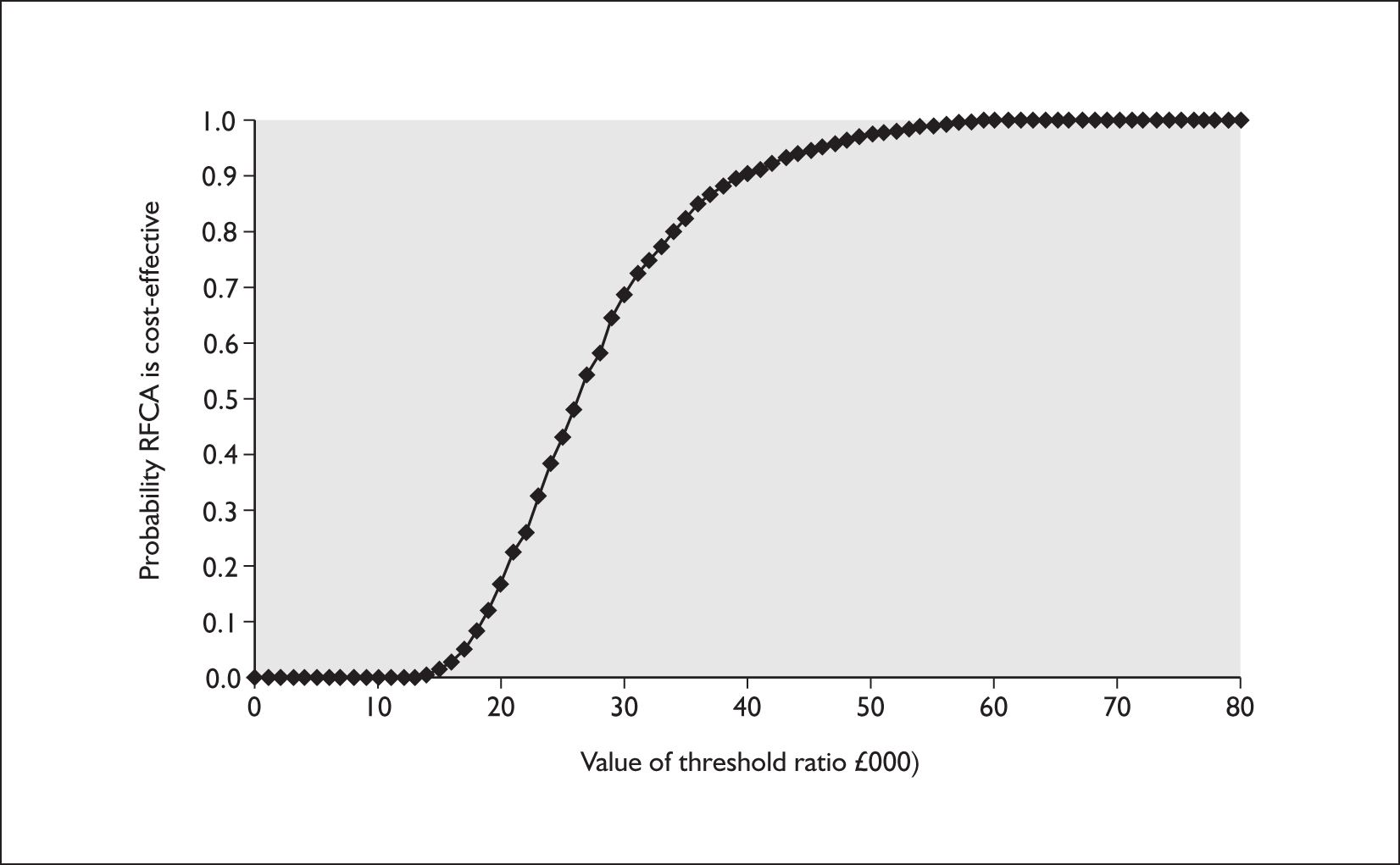

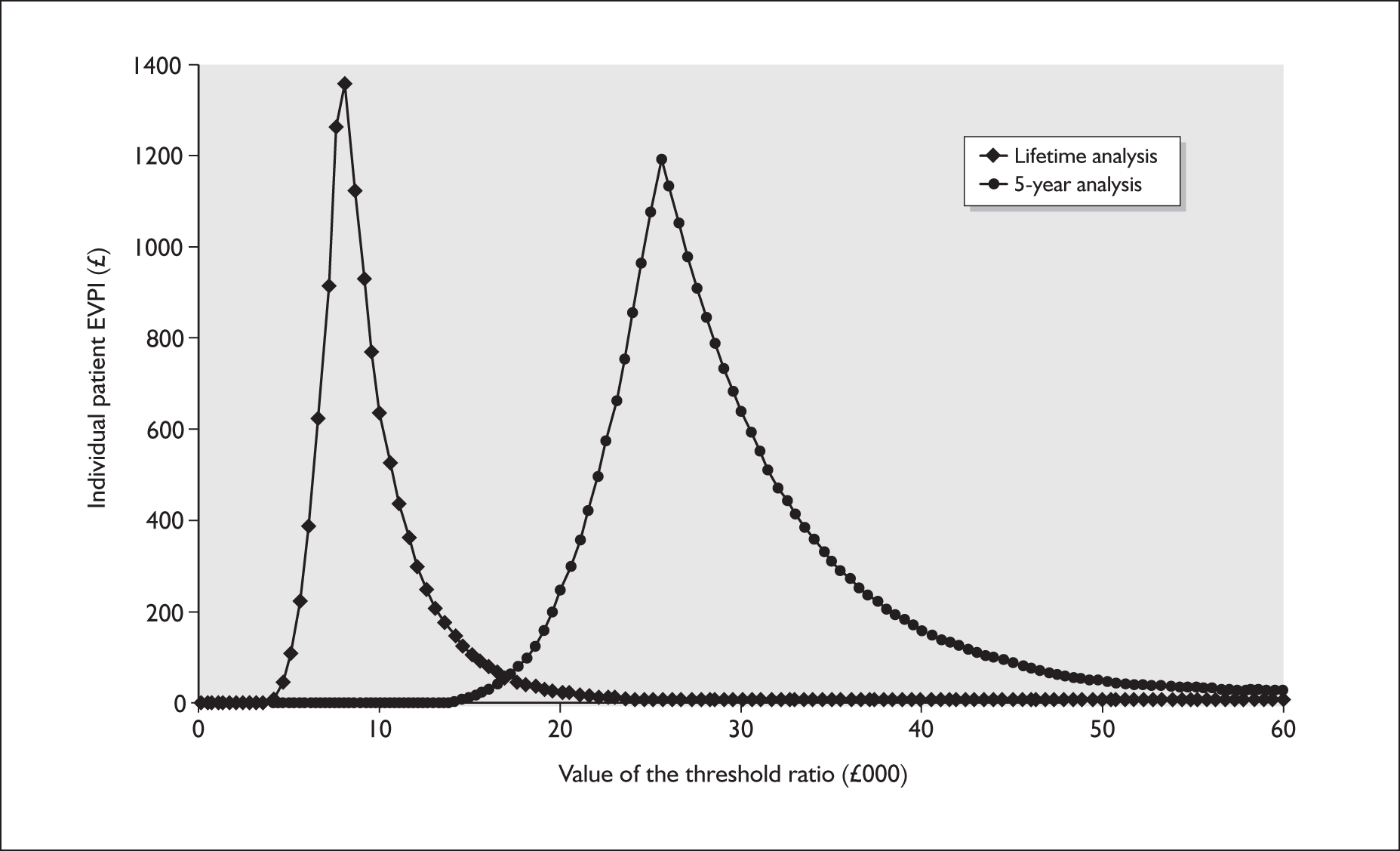

The specific objectives of the cost-effectiveness analysis are to: (1) structure an appropriate decision model to characterise patients’ care and subsequent prognosis and the impacts of alternative therapies; (2) populate this model using the most appropriate data identified systematically from published literature and routine sources; (3) relate intermediate outcomes to final health outcomes, expressed in terms of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs); (4) estimate the mean cost-effectiveness of catheter ablation; and (5) characterise the uncertainty in the data used to populate the model and to present the uncertainty in these results to decision-makers. To inform future research priorities in the NHS, the model will be used to undertake analyses of the expected value of information. The model focuses on the treatment of AF but consideration is given to extending the analysis to the treatment of typical atrial flutter.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing clinical effectiveness

Search strategy

Literature searches were conducted in 25 bibliographic databases and internet sources. They were originally conducted in July 2006, with subsequent update searches for controlled trials conducted in April 2007. Our review aimed to build on the findings of the previous CCOHTA systematic review,28 but with a focus on research evidence of higher quality or of relevance to current practice. Therefore, any controlled trials from the earlier review were obtained for screening and the search strategies used in the CCOHTA review were rerun from the year 2000 onwards. No language restrictions were applied to any of the search strategies; however, terms referring to issues beyond the scope of the current review (e.g. ventricular tachycardia) were excluded. A variety of keywords and search strategies were used (details of the search strategies for all of the databases are presented in Appendix 1). The bibliographies of all relevant reviews and guidelines and all included studies were checked for further potentially relevant studies. Citation searching was also undertaken for selected papers. The following databases were searched:

Guidelines databases

-

BMJ Clinical Evidence. URL: www.clinicalevidence.com/ceweb/index.jsp

-

Cardiovascular Diseases Specialist Library. URL: www.library.nhs.uk/cardiovascular

-

Health Evidence Bulletin Wales. URL: http://hebw.cf.ac.uk

-

HSTAT. URL: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=hstat

-

National Guidelines Clearing House. URL: www.guideline.gov

-

NICE. URL: www.nice.org.uk

-

NLH Guidelines Finder. URL: www.library.nhs.uk/guidelinesFinder

-

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). URL: www.sign.ac.uk

-

TRIP. URL: www.tripdatabase.com/index.html

Databases of systematic reviews

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (Cochrane Library). URL: www.library.nhs.uk/)

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) [Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) Internal Database]

Health-/medical-related databases

-

BIOSIS (DIALOG). URL: http://library.dialog.com/

-

CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) (Cochrane Library). URL: www.library.nhs.uk

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (OvidWeb). URL: http://gateway.ovid.com/athens

-

EMBASE (OvidWeb). URL: http://gateway.ovid.com/athens

-

Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA) (CRD Internal Database)

-

MEDLINE (OvidWeb). URL: http://gateway.ovid.com/athens

-

MEDLINE In-Process and other non-indexed citations (OvidWeb). URL: http://gateway.ovid.com/athens

-

Science Citation Index (SCI) (Web of Knowledge). URL: http://wos.mimas.ac.uk/

Databases of conference proceedings

-

ISI Proceedings: Science and Technology (Web of Knowledge). URL: http://wos.mimas.ac.uk/

-

Zetoc Conferences (MIMAS). URL: http://zetoc.mimas.ac.uk/

Databases for ongoing and recently completed research

-

ClinicalTrials.gov. URL: www.clinicaltrials.gov

-

ESRC SocietyToday Database. URL: www.esrc.ac.uk/ESRCInfoCentre/index.aspx

-

MetaRegister of Controlled Trials. URL: www.controlled-trials.com

-

National Research Register (NRR). URL: www.update-software.com/national

-

Research Findings Electronic Register (ReFeR). URL: www.info.doh.gov.uk/doh/refr_web.nsf/Home?OpenForm

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included in the review if they met the following inclusion criteria:

Population

Adults with symptomatic AF or adults with typical atrial flutter. For AF, patients had to be refractory to at least one AAD. Studies with a mixed group of patients with both AF and atrial flutter, without reporting separate outcomes for each arrhythmia, were excluded.

Interventions

Percutaneous RFCA for the curative treatment of AF or typical atrial flutter. Non-RF techniques were excluded. Similarly, evaluations of ablation techniques no longer in use or considered obsolete (i.e. pre-1998)6 were excluded, as were studies evaluating surgical ablation (i.e. variations on the Maze procedure) and AV node ablation and pacing.

Comparators

When controlled studies were identified, AAD treatment (e.g. flecainide, sotalol, amiodarone) and/or cardioversion were considered relevant comparators. Controlled studies comparing catheter ablation with no therapy, when standard therapy in the form of AADs was given to all patients in both treatment arms, were also eligible for inclusion. Studies were excluded if the comparator was not intended to achieve rhythm control.

Outcomes

Studies were included if they reported any of the following outcomes: acute (in hospital) and long-term procedural success (i.e. freedom from recurrence of arrhythmia), incidence of symptoms, need for repeat ablation procedures, assessment of QoL, or complications (e.g. cardiac tamponade, stroke).

Study designs

The following study designs were included: RCTs comparing RFCA against a comparator and including at least 20 patients; non-randomised controlled studies (CCTs) with at least 100 patients comparing RFCA against a comparator; and case series reporting at least 100 consecutive cases. RCTs and CCTs comparing different variations in RFCA technique or equipment were treated as uncontrolled studies of catheter ablation and included if they reported at least 100 consecutive patients. This was a practical decision reflecting the fact that: (1) RFCA techniques are evolving rapidly and (2) our primary objective was to assess the effectiveness of RFCA relative to alternative approaches for the management of AF. When the same centre reported multiple case series, each of the series was included in the review and, when possible, those with potential overlaps in patient populations were identified before analysis.

Animal models, preclinical and biological studies, reviews, editorials, opinions and non-English language papers were excluded.

Data extraction strategy

Titles and abstracts were independently screened for relevance by two reviewers and all potentially relevant papers were ordered. Full papers were independently screened by two reviewers and the decision to include studies or not made according to the inclusion criteria detailed above. Disagreements were resolved by consensus, consulting a third reviewer if necessary.

Data were extracted on participants (including age, gender distribution, proportion of drug-refractory patients, proportion with concomitant structural heart disease, etc.), interventions (e.g. technique used, mapping system, type of catheter tip), comparators (e.g. type of AAD, dosage), outcomes (e.g. freedom from arrhythmia, complications/adverse events, QoL, mortality) and study design/quality. Data were extracted into a predefined Microsoft Access database. All data extraction was performed by one reviewer and checked by a second.

Quality assessment strategy

An 18-item checklist was used to assess the quality of the included studies (see Appendix 2). All 18 items were applicable to controlled studies and a subgroup of eight of these items was applicable to case series. The items specific to controlled studies related to issues such as randomisation, concealment of allocation, baseline comparability of groups and blinding. Items common to both the case series and controlled studies addressed issues such as appropriateness of patient selection criteria, reporting of variability and loss to follow-up. These criteria were derived from CRD’s guidance on undertaking reviews of effectiveness51 and previously published reviews incorporating case series data. 52,53 Depending upon which specific quality criteria were met and the subsequent potential for bias, controlled studies could receive an overall quality rating of ‘poor’, ‘satisfactory’, ‘good’ or ‘excellent’ and case series could be rated as ‘poor’, ‘satisfactory’ or ‘good’. Each included study was quality assessed by one reviewer and the quality assessment was checked by a second reviewer. Disagreements were resolved by consensus, consulting a third reviewer if necessary.

Role of clinical advisors

Clinical experts (DT, CP) collaborated closely throughout the review of clinical effectiveness, helping to refine the review question, identify all of the relevant evidence and interpret results.

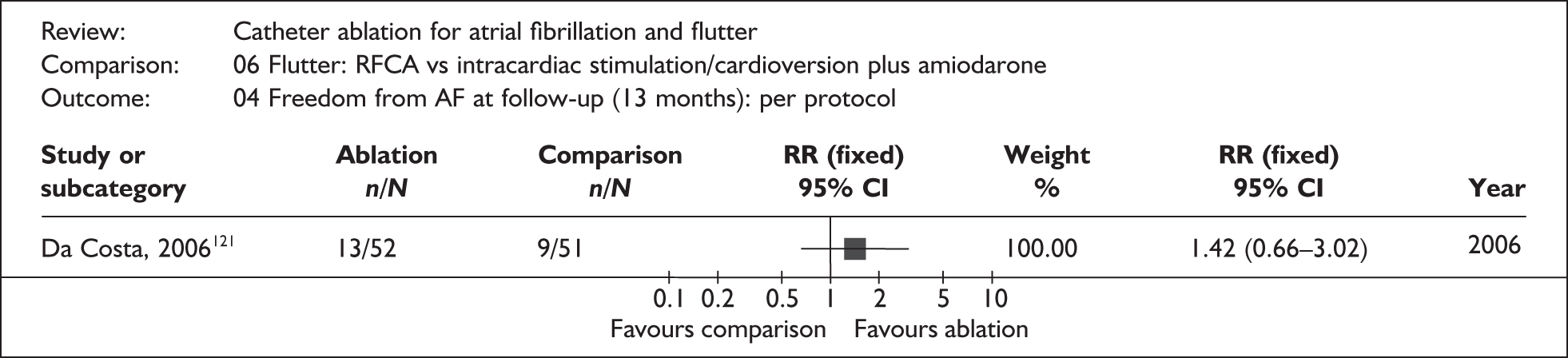

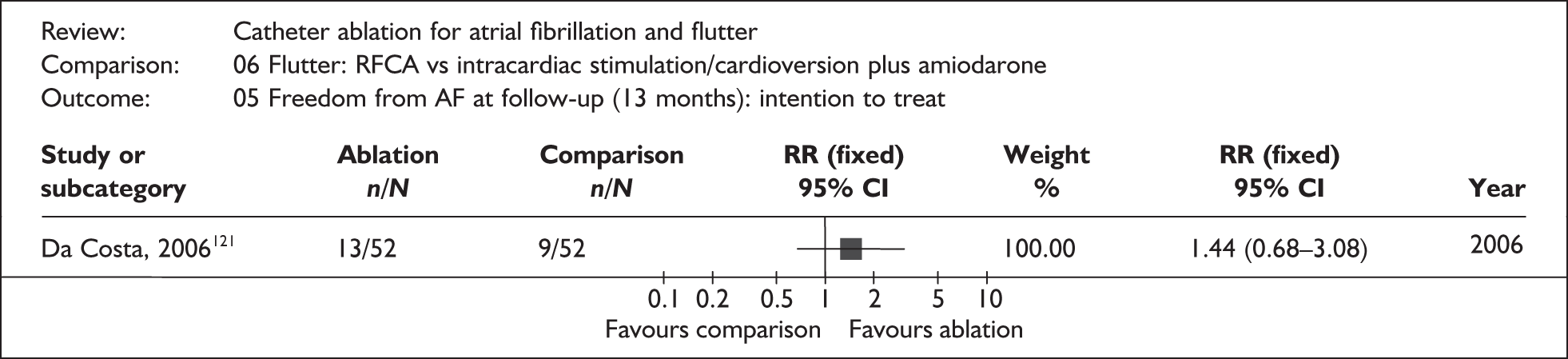

Data analysis

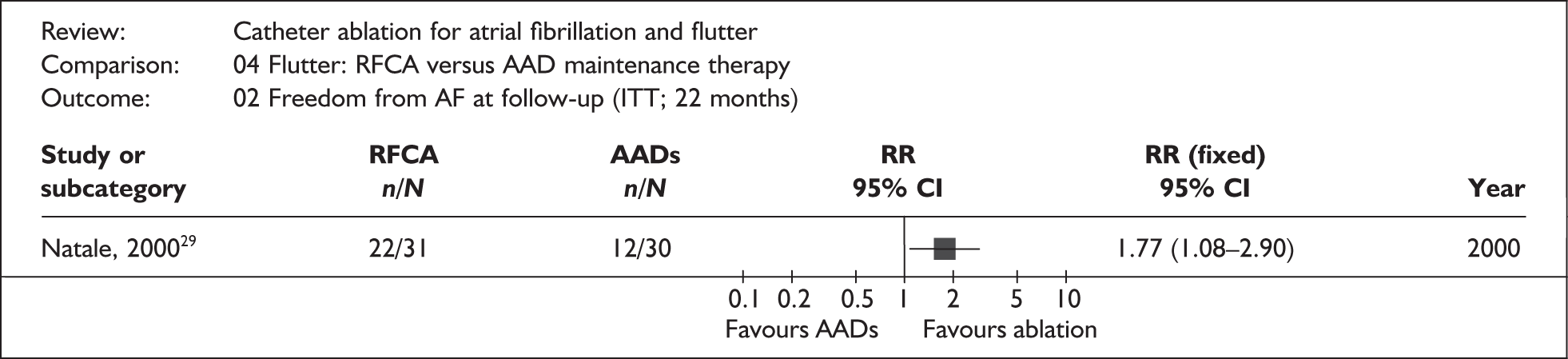

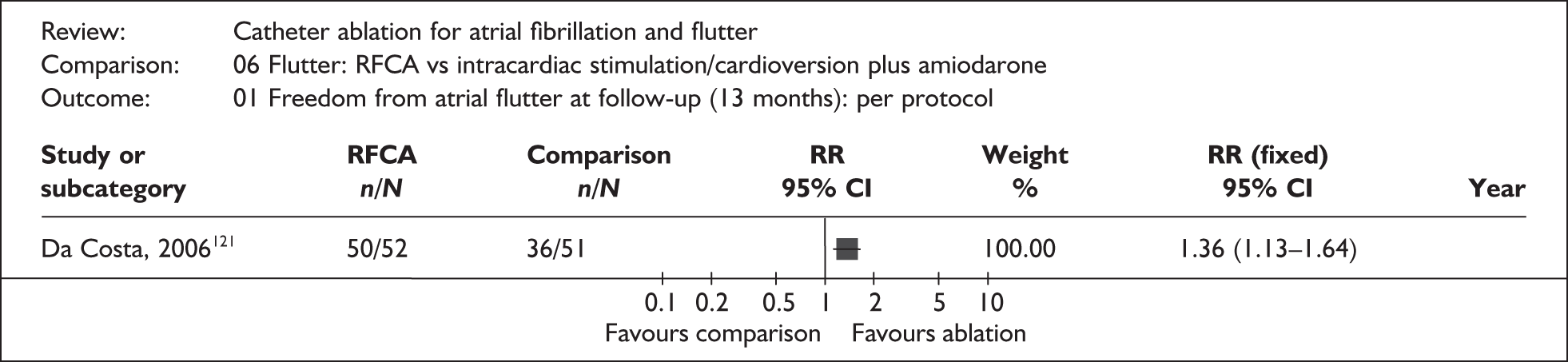

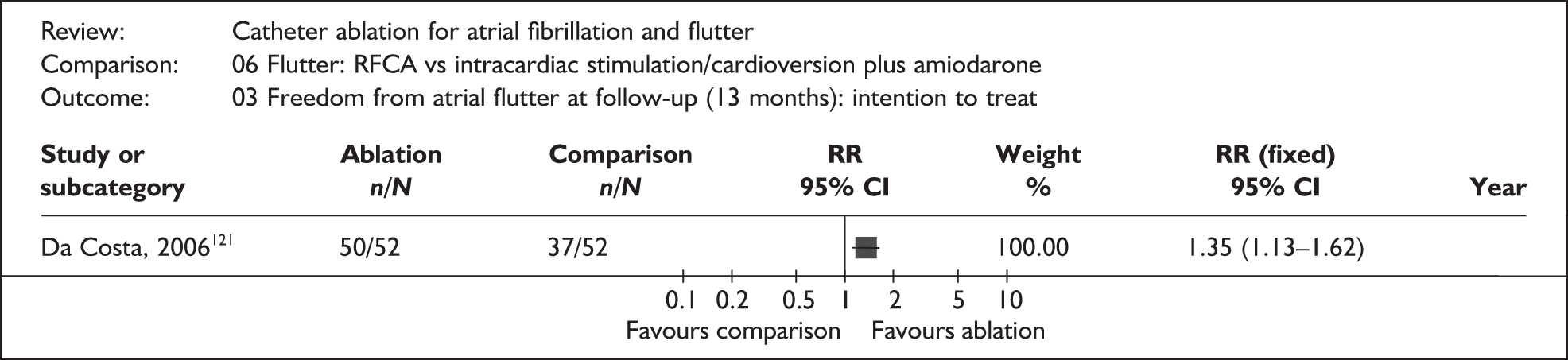

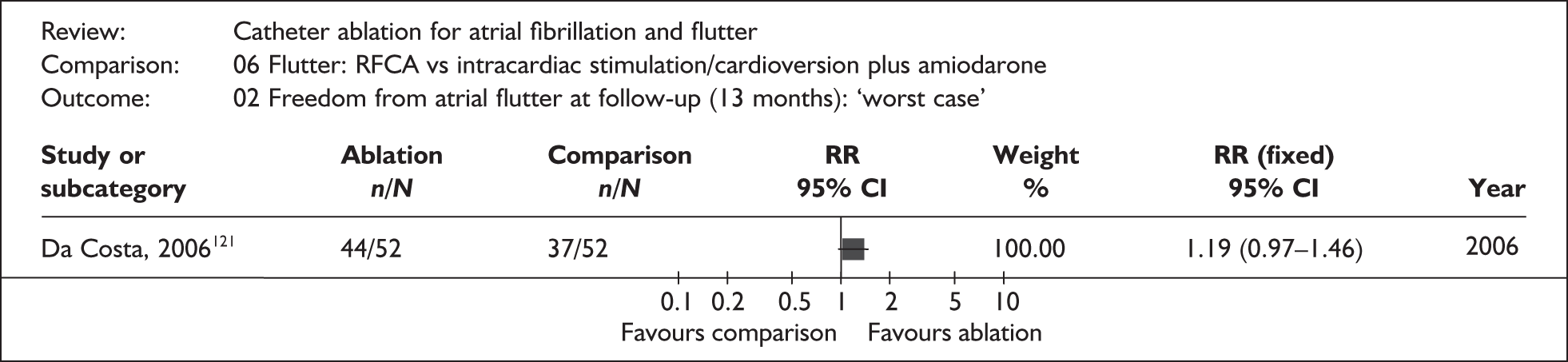

As the aim of the review was to evaluate RFCA as a curative procedure in the management of AF and typical atrial flutter, the primary outcome was the proportion of patients free of arrhythmia at 12 months’ follow-up. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has defined this as the preferred outcome for trials of catheter ablation. 54 Secondary outcomes were the occurrence of complications or adverse events and QoL. In addition, freedom from arrhythmia at other time points was also summarised. The results of RCTs reporting this outcome were displayed as risk ratios (RR) and related 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in forest plots and, when considered sufficiently homogenous, these were pooled in a meta-analysis using a fixed-effects model. Inconsistency was investigated using the standard chi-squared test for statistical heterogeneity and expressed as the I2 statistic. Where studies failed to report freedom from arrhythmia at 12 months, mean follow-up data were shown but not included in any pooled analyses.

To assess the impact of withdrawals and crossovers on trial results, the data were presented in three forms: per protocol (i.e. patients who remained on the protocol to which they were randomised and were available at follow-up); ‘worst case’ (in which withdrawals from the ablation group were assumed to have arrhythmia and those from the comparison group were assumed to be free of arrhythmia); and intention to treat (in which patients were analysed according to the group to which they were originally randomised, regardless of withdrawals or crossovers). FDA clinical study design guidance suggests that crossover from comparator to RFCA arm be treated as treatment failure in the comparator arm. 54 Therefore, we have placed greater emphasis on the estimates based on the per protocol results.

Some studies reported time-to-event data, such as hazard ratios (HR) or arrhythmia-free Kaplan–Meier survival curves. Where possible, HRs were either extracted from the paper or indirectly estimated using the methods described by Parmar et al. 55

From the case series, rates of freedom from arrhythmia at 12 months and at mean follow-up were presented and discussed in a narrative synthesis. Where reported, we calculated a weighted average for this outcome at 12 months using a random-effects model.

Data on complications were extracted from the case series and controlled studies and were tabulated and discussed in a narrative synthesis.

Results of review of clinical effectiveness – atrial fibrillation

Quantity and quality of research available

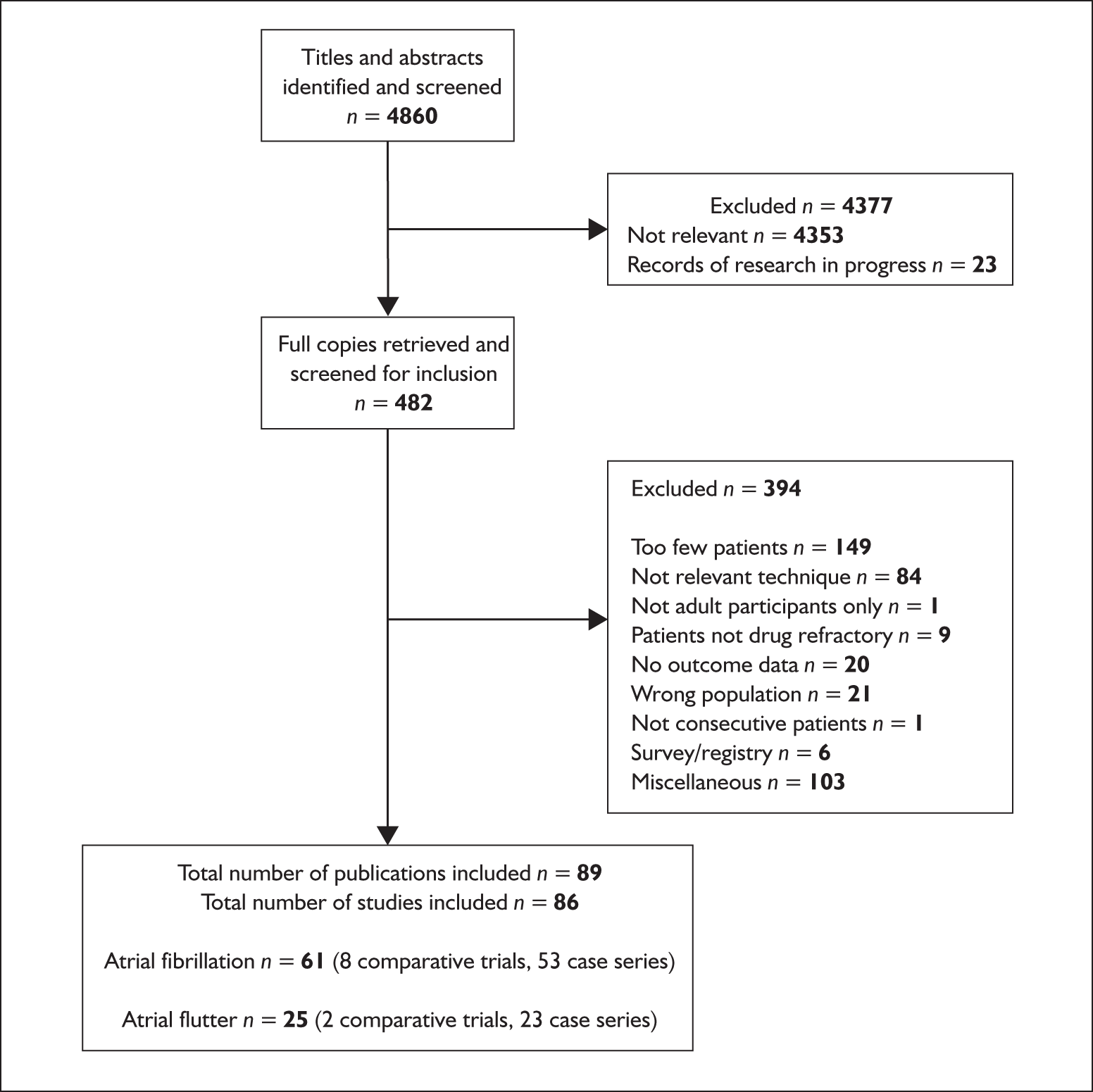

A total of 4860 studies were retrieved from the searches (see Figure 1). Of these, 483 were ordered and 86 studies (89 publications) met the inclusion criteria for the review. In total, 61 of these related to RFCA for AF (eight controlled studies and 53 case series).

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of studies through the review process.

Of the eight controlled studies evaluating the effectiveness of RFCA for AF, one was rated ‘good’,56 four were rated ‘satisfactory’57–60 and three were rated ‘poor’. 61–63 Two studies were non-randomised, one of which reported clear differences between groups at baseline. 61 The third ‘poor’ study was rated as such because of the very limited information available in the published abstract. 63 The study rated as ‘good’ was the only randomised study to blind outcome assessors to group allocation56 (see Table 6). One randomised60 and one large non-randomised61 controlled study included patients who had not been proven to be drug refractory. However, it was decided that these studies could provide important evidence on the relative effects of RFCA and so they were included in the review, but any potential impact of their patient populations on outcomes was emphasised where relevant.

| Study | Study design | Criteria met | Overall quality rating |

|---|---|---|---|

| Krittayaphong et al., 200357 | RCT | 1, 4, 11–16, 18 | Satisfactory |

| Pappone et al., 200361 | CCT | 4, 7, 9, 11, 13–18 | Poor |

| Wazni et al., 200560 | RCT | 1, 2, 4, 9, 11–16, 18 | Satisfactory |

| Oral et al., 200656 | RCT | 1, 2, 4, 7, 9–18 | Good |

| Pappone et al., 2006 (APAF)58 | RCT | 1, 4, 9–11, 13–18 | Satisfactory |

| Stabile et al., 200659 | RCT | 1, 2, 4, 10–18 | Satisfactory |

| Lakkireddy et al., 200662 | CCT | 4, 9, 11 | Poor |

| Jais et al., 200663 | RCT | 1, 9, 11, 12, 16, 17 | Poor |

Of 53 case series in AF, only two were rated as ‘good’64,65 and three as ‘satisfactory’66–68 (Table 7). The UK case series by Bourke and colleagues66 was one of those rated ‘satisfactory’. The remaining 48 series were rated as ‘poor’, most commonly because details of follow-up were lacking.

| Study | Criteria met | Overall quality rating |

|---|---|---|

| Berkowitsch et al., 200571 | 11, 13, 16, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Bertaglia et al., 200573 | 11, 12, 13, 15, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Beukema et al., 200575 | 12, 13, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Bhargava et al., 200477 | 12, 13, 15, 18 | Poor |

| Bourke et al., 200566 | 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 | Satisfactory |

| Cha et al., 200580 | 13, 18 | Poor |

| Chen et al., 200482 | 11, 12, 13, 15, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Daoud et al., 200667 | 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 | Satisfactory |

| Deisenhofer et al., 200484 | 11, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Della Bella et al., 200568 | 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 | Satisfactory |

| Dong et al., 200587 | 11, 13, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Ernst et al., 200389 | 12, 13, 18 | Poor |

| Essebag et al., 200591 | 12, 13, 15, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Fassini et al., 200593 | 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Herweg et al., 200595 | 11, 12, 13, 15, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Hindricks et al., 200597 | 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Hsieh et al., 200399 | 15 | Poor |

| Hsu et al., 2004101 | 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18 | Poor |

| Jais et al., 2004103 | 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Karch et al., 2005105 | 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18 | Poor |

| Kilicaslan et al., 2005106 | 11, 12, 13, 15, 18 | Poor |

| Kilicaslan et al., 2006108 | 11, 12, 13, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Kobza et al., 2004110 | 11, 12, 16, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Kottkamp et al., 2004112 | 11, 12, 13, 16, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Kumagai et al., 2005114 | 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Lee et al., 2004116 | 13, 15, 18 | Poor |

| Liu et al., 2005118 | 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Ma et al., 200672 | 11, 12, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Macle et al., 200274 | 11, 12, 13, 15, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Marchlinski et al., 200376 | 12, 17 | Poor |

| Marrouche et al., 200278 | 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18 | Poor |

| Nademanee et al., 200279 | 15 | Poor |

| Nademanee et al., 200481 | 12, 13, 18 | Poor |

| Nilsson et al., 200664 | 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 | Good |

| Oral et al., 200483 | 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Oral et al., 200485 | 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Pappone et al., 200186 | 11, 12, 14, 15, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Pappone et al., 200188 | 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Pappone et al., 200490 | 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Purerfellner et al., 200692 | 13, 18 | Poor |

| Ren et al., 200494 | 12, 13, 18 | Poor |

| Saad et al., 200396 | 12, 13, 15, 18 | Poor |

| Saad et al., 200398 | 12, 13, 15, 18 | Poor |

| Shah et al., 2001100 | 11, 12, 13, 15, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Shah et al., 2003102 | 11, 12, 15, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Trevisi et al., 2003104 | 12, 13, 18 | Poor |

| Verma et al., 200565 | 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 | Good |

| Wazni et al., 2005107 | 12, 13, 15, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Weerasooriya et al., 2003109 | 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Weerasooriya et al., 2003111 | 11, 12, 15, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Yamada et al., 2006113 | 12, 13, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Yamane et al., 2002115 | 11, 12, 13, 15, 17, 18 | Poor |

| Yu et al., 2001117 | 11 | Poor |

Ongoing research

The search of research registers for ongoing studies produced 23 records. Following contact with investigators, there were four studies which appeared relevant to the review that were in progress or completed but with no results available at the time of the review (Appendix 6).

In addition, the CABANA (Catheter Ablation versus Antiarrhythmic Drug Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation) trial69,70 began its pilot phase in late 2006. This large RCT (planned to follow 3000 patients for an estimated 5 years) is designed to determine whether there is a mortality benefit from catheter ablation compared with pharmacological rate and rhythm control strategies and will also evaluate effects on QoL, costs and resource use. Unfortunately, it will be some time before any results are available from this study.

Assessment of effectiveness from controlled trials

Trial characteristics

Six RCTs56–60,63 and two non-randomised studies61,62 compared the effects of RFCA against an alternative treatment strategy for AF (see Appendix 3.1). Patient characteristics are summarised in Table 8 with a brief summary of each study given below.

| Study | Country | Quality rating | Number randomised (treated): RFCA | Number randomised (treated): control | Mean age (years) (SD): RFCA | Mean age (years) (SD): control | Male (%) | Mean (SD) duration of symptoms: RFCA | Mean (SD) duration of symptoms: control | Previous AAD, mean (SD): RFCA | Previous AAD, mean (SD): control | Paroxysmal/chronic (%): RFCA | Paroxysmal/chronic (%): control | Heart disease (%): RFCA/control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jais et al., 200663 | France, Canada, USA | Poor | 53 (53) | 59 (59) | 51 (11) (overall) | 51 (11) (overall) | 83 | NR | NR | At least 1 | At least 1 | 100/0 | 100/0 | NR |

| Krittayaphong et al., 200357 | Thailand | Satisfactory | 15 (14) | 15 (15) | 55.3 (10.5) | 48.6 (15.4) | 63 | 62.9 (58.3) months | 48.2 (63.7) months | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.9 (0.7) | 73/27 | 67/33 | 13/13 |

| Lakkireddy et al., 200662 | USA | Poor | 138 (138) | 139 (139) | 70.6 (5.2) | 70.2 (5.5) | 67 | 2.5 (2.1) years | 6.5 (3.3) years | 3 (1) | 2.4 (0.8) | NR | NR | NR |

| 133 (133) | 70.3 (5.5) | 6.5 (3.6) years | 1.6 (1.4) | |||||||||||

| Oral et al., 200656 | Italy, USA | Good | 77 (77) | 69 (69) | 55 (9) | 58 (8) | 88 | 5 (4) years | 4 (4) years | 2 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.2) | 0/100 | 0/100 | 8/9 |

| Pappone et al., 200361 | Italy | Poor | 589 (589) | 582 (582) | 65 (9) | 65 (10) | 59 | 5.5 (2.8) years | 3.6 (1.9) years | 3.1 (2.1) | 2.3 (1.5) | 69/31 | 71/29 | 37/34 |

| Pappone et al., 2006 (APAF)58 | Italy | Satisfactory | 99 (99) | 99 (99) | 55 (10) | 57 (10) | 67 | 6 (4) years | 6 (6) years | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 100/0 | 100/0 | 7/4 |

| Stabile et al., 200659 | Italy | Satisfactory | 68 (68) | 69 (69) | 62.2 (9) | 62.3 (10.7) | 59 | 5.1 (3.9) years | 7.1 (5.9) years | NR | NR | 61.8/38.2 | 72.5/27.5 | 63/62 |

| Wazni et al., 200560 | USA, Italy, Germany | Satisfactory | 33 (33) | 37 (37) | 53 (8) | 54 (8) | – | 5 (2) months | 5 (2.5) months | 0 | 0 | 97/3 | 95/5 | 25/28 |

Results by trial

Krittayaphong et al., 200357

RCT (rated ‘satisfactory’) of RFCA versus amiodarone in patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF (70% paroxysmal, mean duration 4.6 years). All patients were refractory to at least one AAD but had never received amiodarone.

A total of 15 patients randomised to RFCA underwent circumferential PV ablation, with an additional line connecting the circular line to the mitral annulus. In addition, CTI ablation was performed, plus a horizontal line at the level of the mid right atrium. RFCA could not be performed in one patient because of failure of trans-septal puncture. Electrical cardioversion was performed in two patients still in AF following ablation, and all patients received amiodarone for 3 months post procedure.

A total of 15 patients were randomised to long-term amiodarone treatment. Cardioversion was performed in patients with persistent AF. When serious side effects occurred, amiodarone was discontinued in favour of class Ia or Ic agents.

At 12 months post randomisation, 11/15 patients in the RFCA group were free of AF compared with 6/15 patients in the amiodarone group.

Frequency of symptoms decreased from 42.8 (SD 22.6) attacks per month at baseline to 0.9 (2.8) attacks per month at 12 months in the RFCA group. There was a non-significant decrease over the same period in the amiodarone group. Differences between groups were not statistically significant.

SF-36 (Short Form 36) general health and physical functioning scores improved significantly at 12 months compared with baseline in the RFCA group but not in the amiodarone group. Between-group differences for general health score favoured ablation.

One stroke and one groin haematoma were associated with the ablation procedure. In the amiodarone group, seven patients experienced at least one adverse effect attributed to amiodarone: six had gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects (mainly nausea), two each had corneal microdeposit, hypothyroidism and abnormal liver function test, and one had hyperthyroidism and sinus node dysfunction. Three patients in the RFCA group had amiodarone-attributed adverse effects during the 3-month amiodarone treatment period: two had GI adverse effects and one had sinus node dysfunction.

Pappone et al., 200361

Large non-randomised controlled study (rated ‘poor’) comparing RFCA with long-term AAD treatment in patients with symptomatic AF (70% paroxysmal, mean duration 4.6 years).

A total of 589 consecutive patients underwent circumferential PV ablation. In total, 19.5% of patients were given previously ineffective AADs if they had in-hospital AF episodes or required cardioversion. AADs were discontinued 3 months after ablation in the absence of recurrences.

A control group of 582 patients received AAD therapy (33% amiodarone, 17% propafenone, 15% flecainide, 13% sotalol, 9% quinidine, 6% disopyramide and 7% combined AAD therapy).

At 12 months, an estimated 84% of patients in the RFCA group and 61% of patients in the AAD group were free of AF. At 2 years these values were 79% and 47%, respectively, and at 3 years they were 78% and 37% respectively. There were a total of 120 AF recurrences in the ablation group and 340 in the AAD group.

After a median follow-up of 29.6 months there were more deaths overall in the AAD group (83 versus 38). The difference remained apparent for deaths due to cardiovascular causes (59 versus 18).

Four patients in the RFCA group (0.7%) required pericardiocentesis for cardiac tamponade. A total of 46 ablated patients (8%) and 98 AAD-treated patients (19%) were managed for a total of 54 and 117 adverse events respectively. Sinus rhythm was associated with significantly lower mortality rates [HR 0.24 (95% CI 0.16–0.37)] and adverse event rates [HR 0.22 (95% CI 0.15–0.31)].

SF-36 physical and mental composite scores from a subgroup of patients improved significantly from baseline to 1 year in ablated patients (n = 109) but not in medically treated patients (n = 102).

Wazni et al., 200560

RCT (rated ‘satisfactory’) comparing RFCA with long-term AAD treatment as first-line therapy in patients with symptomatic AF (96% paroxysmal, mean duration 5 months).

A total of 33 patients were randomised to receive segmental PV ablation. AADs were not given as part of the treatment protocol, but beta-blocker therapy was continued in 43% of patients. There were no repeat ablation procedures within the first year of follow-up. One patient was lost to follow-up.

A total of 37 patients were randomised to receive the maximum tolerable dose of AAD chosen by the treating physician (typically flecainide, propafenone or sotalol). Amiodarone was given only when two other drugs had previously failed. Two patients were lost to follow-up.

At 12 months, 87.5% of patients in the RFCA group were in sinus rhythm after a single procedure. For the same time period in the AAD group, 37% of patients were in sinus rhythm at follow-up. Sensitivity analyses accounting for patients lost to follow-up did not substantially change these results. There were no crossovers during the 12-month follow-up.

There was a significantly greater improvement in the ablation group than in the AAD group at 6 months on five of the eight subscales of the SF-36 questionnaire (general health, physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, social functioning).

Two patients in the RFCA group developed mild to moderate PV stenosis. Three patients in the AAD group developed bradycardia. There were significantly more patients hospitalised in the AAD treatment group than in the RFCA group (54% versus 9%; p < 0.001).

Oral et al., 200656

RCT (rated ‘good’) comparing the effect of 3 months’ treatment with amiodarone and cardioversion with or without the addition of RFCA on long-term maintenance of sinus rhythm in patients with persistent AF (mean duration approximately 4.5 years).

A total of 77 patients were randomised to receive circumferential PV ablation followed by 3 months of amiodarone treatment, plus cardioversion if AF recurred within those 3 months. In total, 25 of these patients underwent a repeat ablation (20 for AF, five for flutter).

A total of 69 patients were randomised to receive amiodarone treatment for 3 months, plus cardioversion if AF recurred. In total, 53 of these patients (77%) ultimately elected to cross over into the RFCA group because of recurrent AF.

According to intention to treat analysis at 12 months, 74% of patients in the RFCA group were in sinus rhythm without AAD therapy, compared with 58% in the amiodarone group (p = 0.05). If the need for any treatment (ablation or drugs) after 3 months was considered a treatment failure, 74% of patients in the RFCA group were in sinus rhythm without AAD therapy, compared with 4% of those in the amiodarone group.

Patients in sinus rhythm had greater improvements in symptom severity score than those with recurrent AF or atrial flutter (p = 0.002).

In the RFCA group, five patients required further ablation for atypical atrial flutter. No other complications related to ablation or drug therapy were reported.

Pappone et al., 2006 (APAF)58

RCT (rated ‘satisfactory’) comparing RFCA with long-term AAD treatment in patients with drug-refractory paroxysmal AF (mean duration 6 years).

A total of 99 patients were randomised to receive circumferential PV ablation. Patients received AADs for 6 weeks post procedure, after which drug treatment was stopped. Nine of these patients underwent a repeat ablation (six for recurrent AF, of which five were successful, and three for atrial tachycardia, all successful). Five patients went on to have AAD therapy to maintain sinus rhythm.

A total of 99 patients were randomised to receive AADs (amiodarone, flecainide or sotalol, either singly or in combination) at the maximum tolerable doses. In total, 42 of these patients (42%) elected to cross over into the RFCA group after two failed AADs over 3 months. Of the 42 crossovers to RFCA, 36 were successful in terms of subsequent freedom from arrhythmia.

At 12 months, 86% of patients in the RFCA group were in sinus rhythm after a single procedure and without the need for AAD therapy. Including repeat ablations and patients on adjunctive AADs, 93% of patients in the RFCA group were in sinus rhythm at 12 months. For the same time period in the AAD group, 24% of patients were in sinus rhythm after the first tested AAD and 35% were in sinus rhythm after combination therapy.

No serious complications occurred in the RFCA group, although three patients developed post-ablation atrial tachycardia requiring further ablation. Significant adverse events leading to permanent drug withdrawal occurred in 23 patients. There were significantly more hospital admissions in the AAD treatment group than in the RFCA group (167 versus 24; p < 0.001).

Stabile et al., 200659

RCT (rated ‘satisfactory’) comparing long-term AAD treatment with or without RFCA in patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF for which AAD therapy had already failed (66% paroxysmal, mean duration 6.1 years).

A total of 68 patients were randomised to receive an AAD chosen by the physician (preferentially amiodarone, or class Ic if amiodarone could not be tolerated) and also undergo circumferential PV ablation, with an additional line connecting the left inferior PV to the mitral annulus. In addition, CTI ablation was performed when considered appropriate. There were no repeat ablations. Two patients were lost to follow-up.

A total of 69 patients were randomised to receive an AAD chosen by the physician without ablation. The AAD was only changed if the patient experienced a recurrence of arrhythmia. In total, 36 patients (52%) with AF relapses eventually crossed over to receive ablation while continuing the previously ineffective AAD regime. Two patients were lost to follow-up.

According to the authors’ analysis, at 12 months 56% of patients in the AAD plus ablation group were in sinus rhythm after a single procedure. For the same time period in the AAD therapy alone group, 9% of patients remained in sinus rhythm during follow-up.

Three major complications were related to the ablation procedure: one stroke (patient died 9 months later of a brain haemorrhage), one transient phrenic paralysis, and one pericardial effusion requiring pericardiocentesis. In the control group there was one transient ischaemic attack and two deaths (one sudden death, one cancer). There was no significant difference in the median number of hospitalisations needed between groups (one versus two; p = 0.34).

Jais et al., 200663

An unpublished RCT (rated ‘poor’, mainly because of the limited reporting of trial details) comparing RFCA with long-term AAD treatment in patients with drug-refractory paroxysmal AF.

A total of 53 patients were randomised to receive segmental PV ablation. A mean of 1.8 PV ablation procedures were conducted. In addition, 64% of patients were reported to have had CTI ablation, 30% had mitral isthmus ablation and 17% had ablation of the roof line.

A total of 59 patients were randomised to receive AADs (including beta-blockers and classes I, III and IV AADs, alone or in combination; amiodarone was used in 22 patients). In total, 37 patients (63%) elected to cross over into the RFCA group.

The primary end point was absence of AF for 3 minutes or more (either symptomatic or documented). At the 12-month follow-up, 75% of patients in the RFCA group and 6% of patients in the AAD group were AF free. RFCA was also favoured in terms of duration of recurrent AF episodes [8 minutes (SD 55) versus 150 minutes (SD 350)].

One tamponade and one PV stenosis (> 50%) occurred in the RFCA group. There was one case of amiodarone-induced hyperthyroidism.

Lakkireddy et al., 200662

An unpublished, non-randomised study (rated ‘poor’) comparing RFCA in older patients with AF (aged 60–80 years) with AV node ablation or direct current cardioversion (DCC) in age-matched control subjects.

The authors of this study concluded that PV ablation had significant mortality and morbidity benefits against the other therapeutic strategies; however, because of the inadequate and inconsistent data currently available for this study, it will not be discussed further here. For the sake of completeness, the available details are presented in Appendix 3.1.

Results by outcome

Freedom from arrhythmia at 12 months

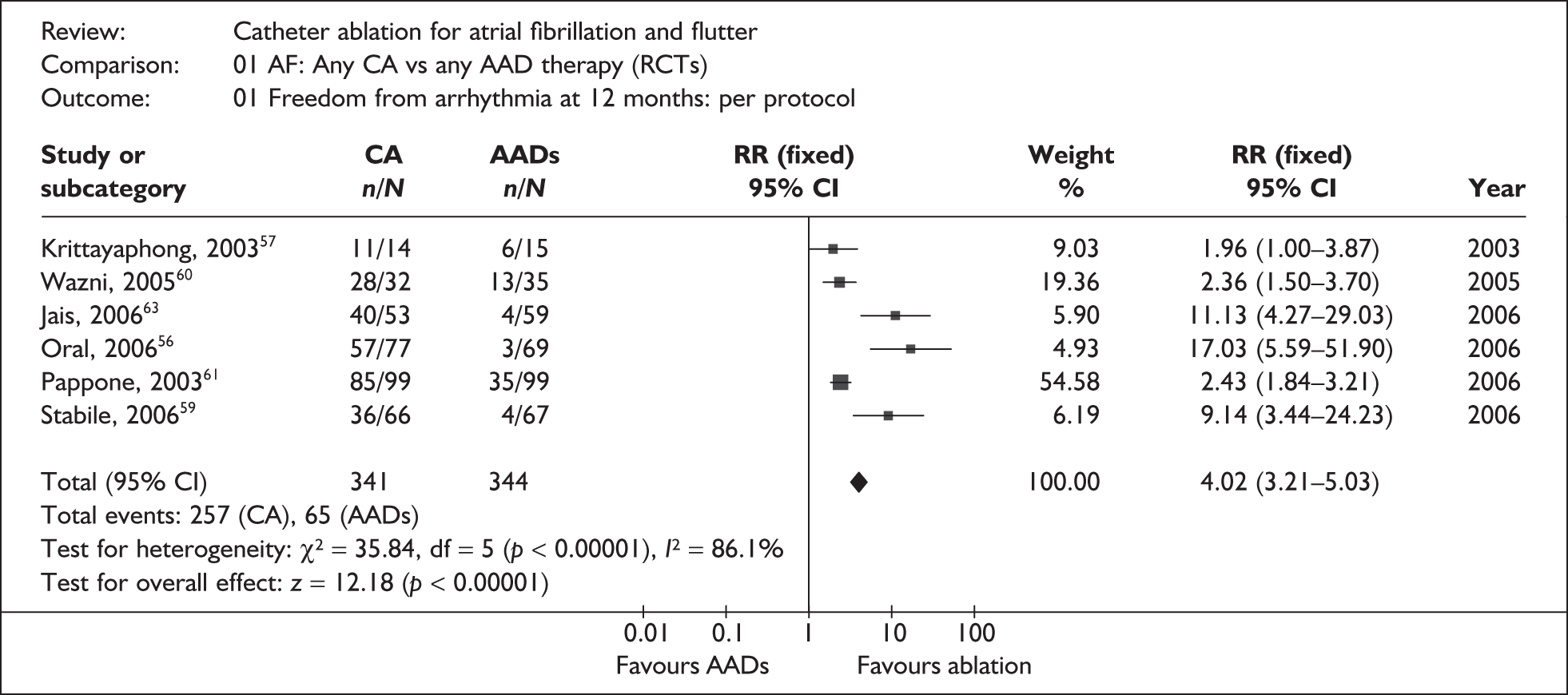

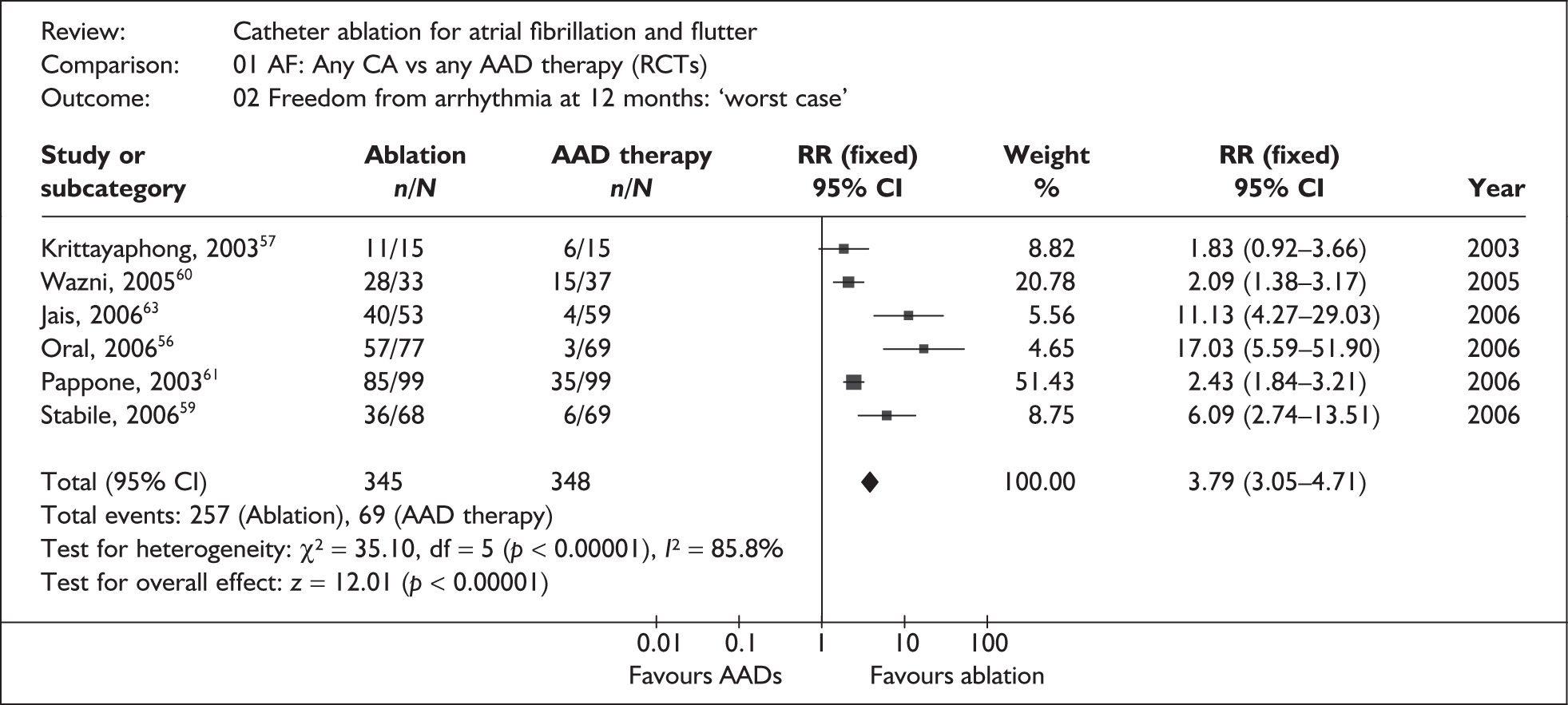

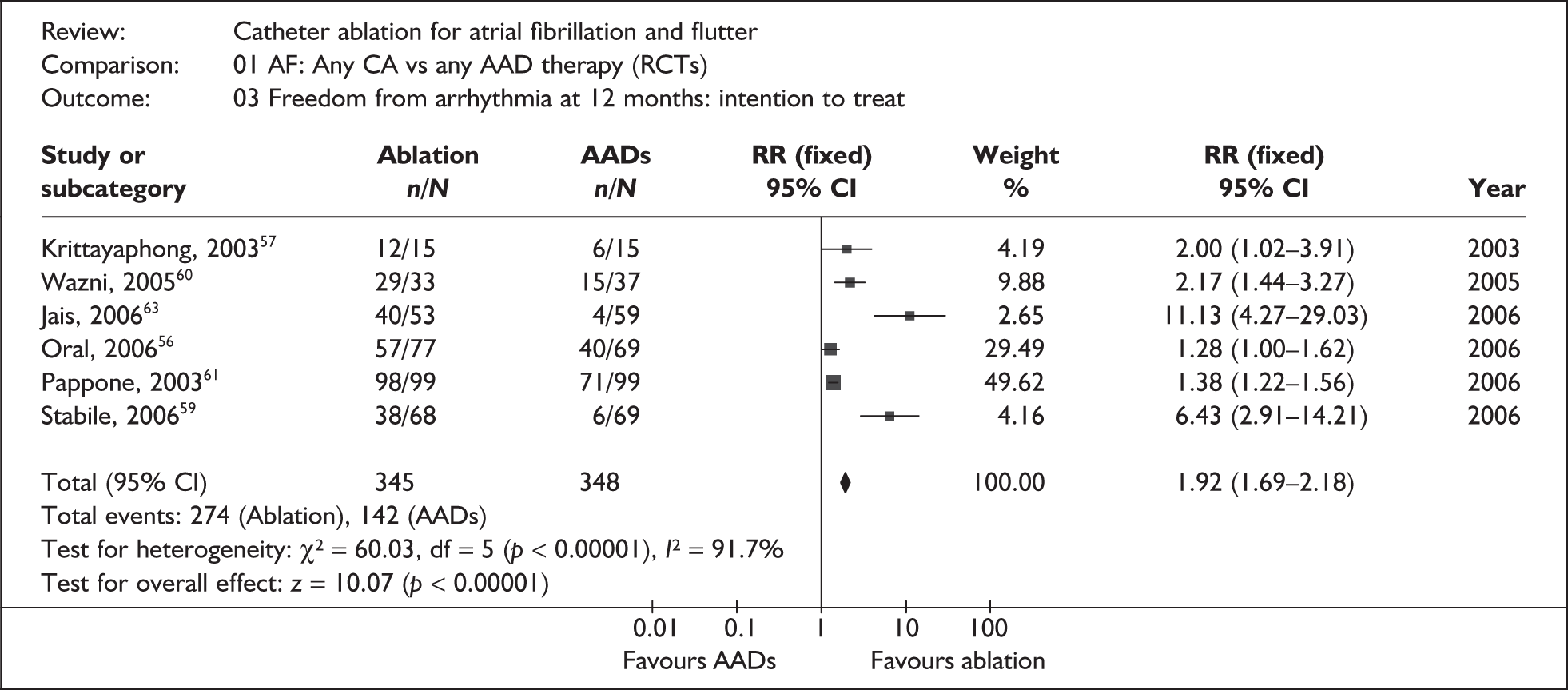

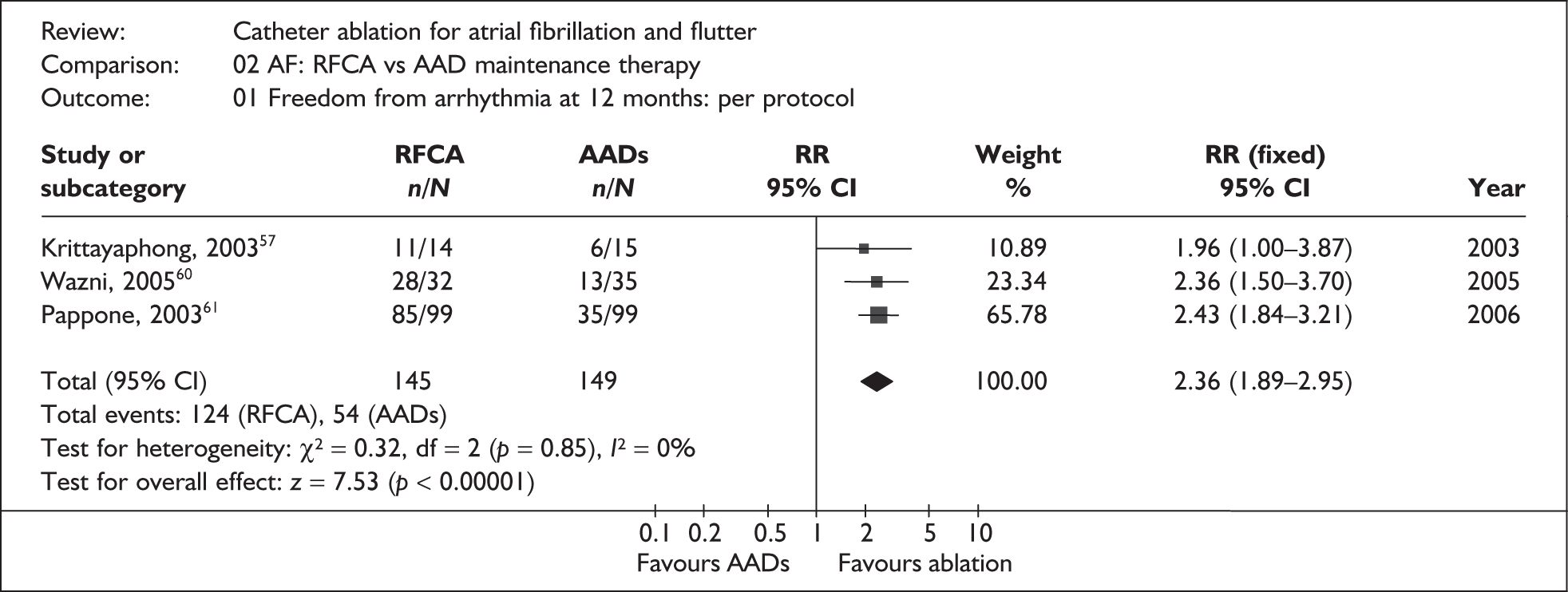

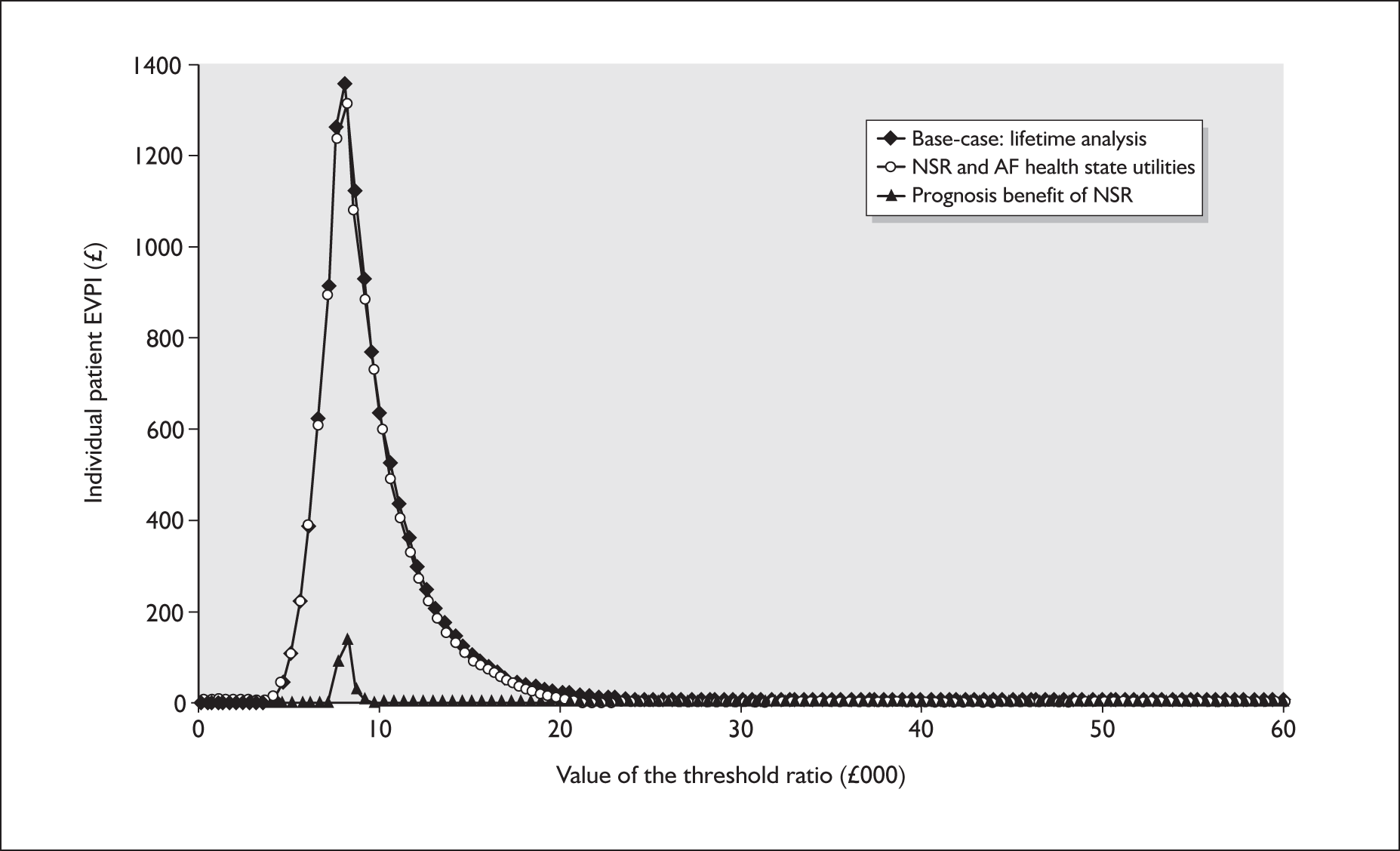

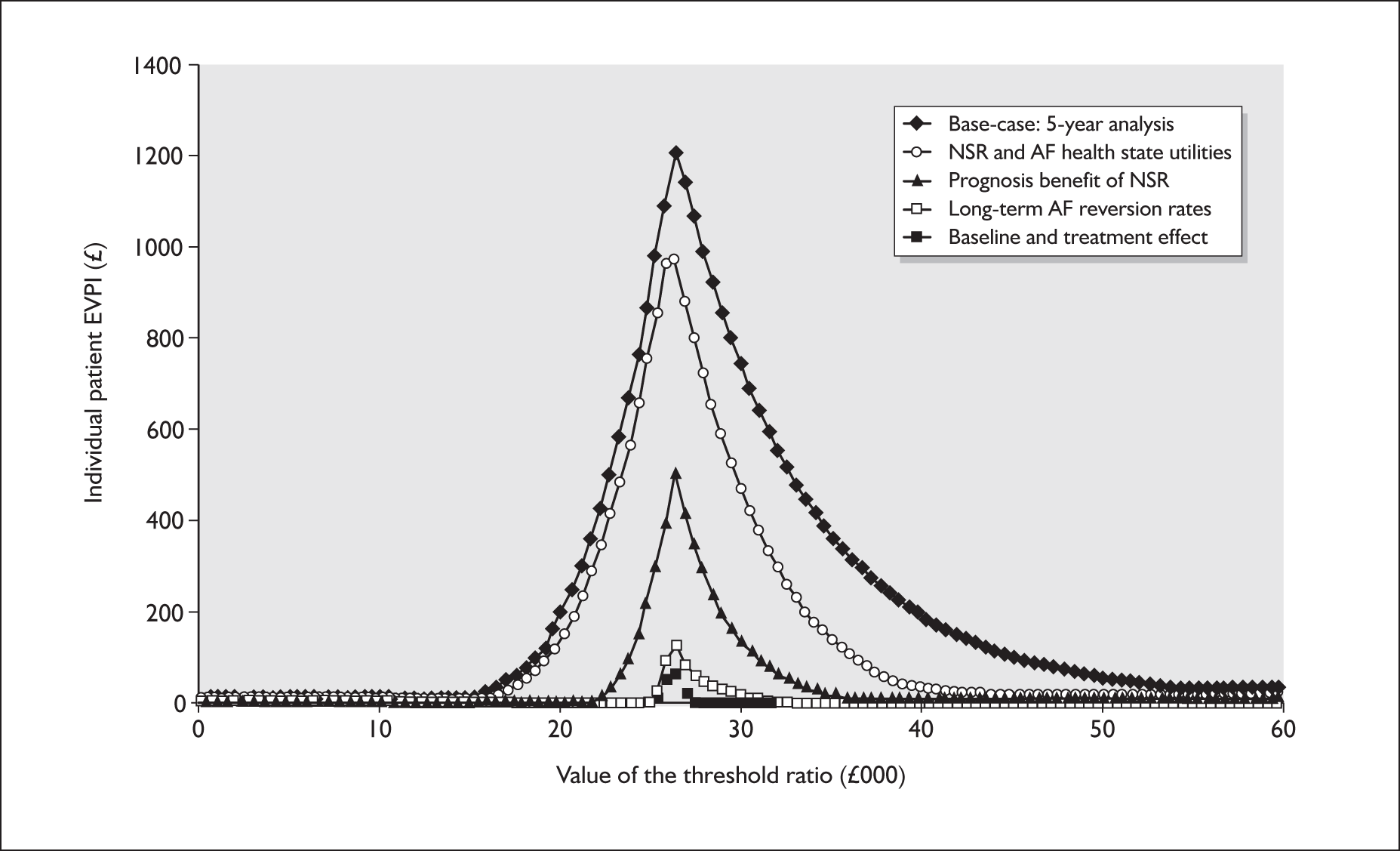

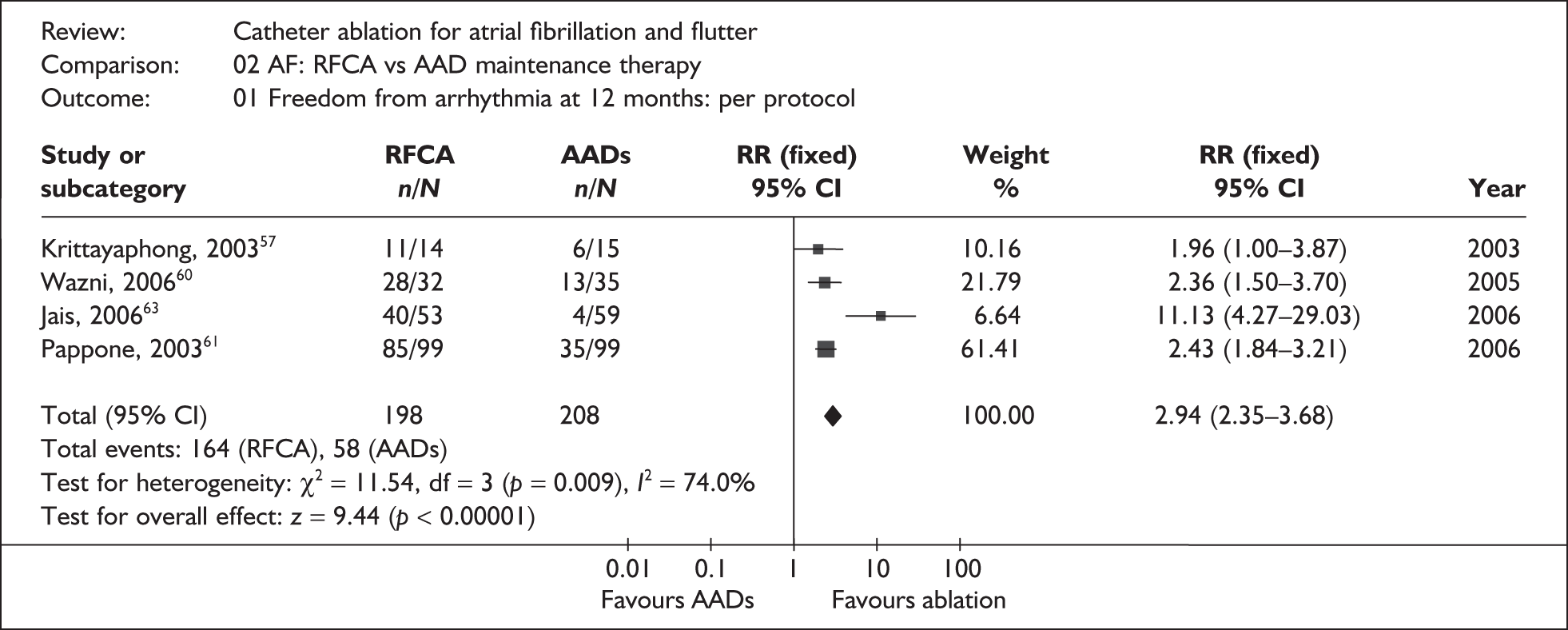

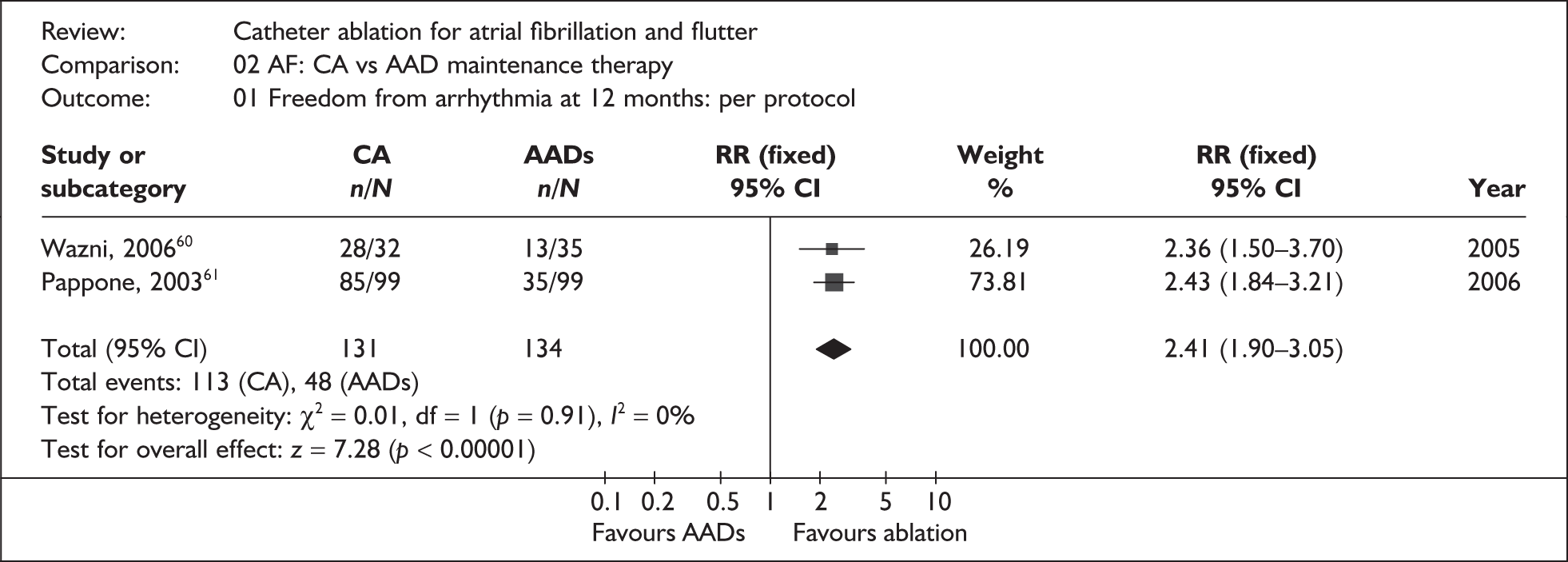

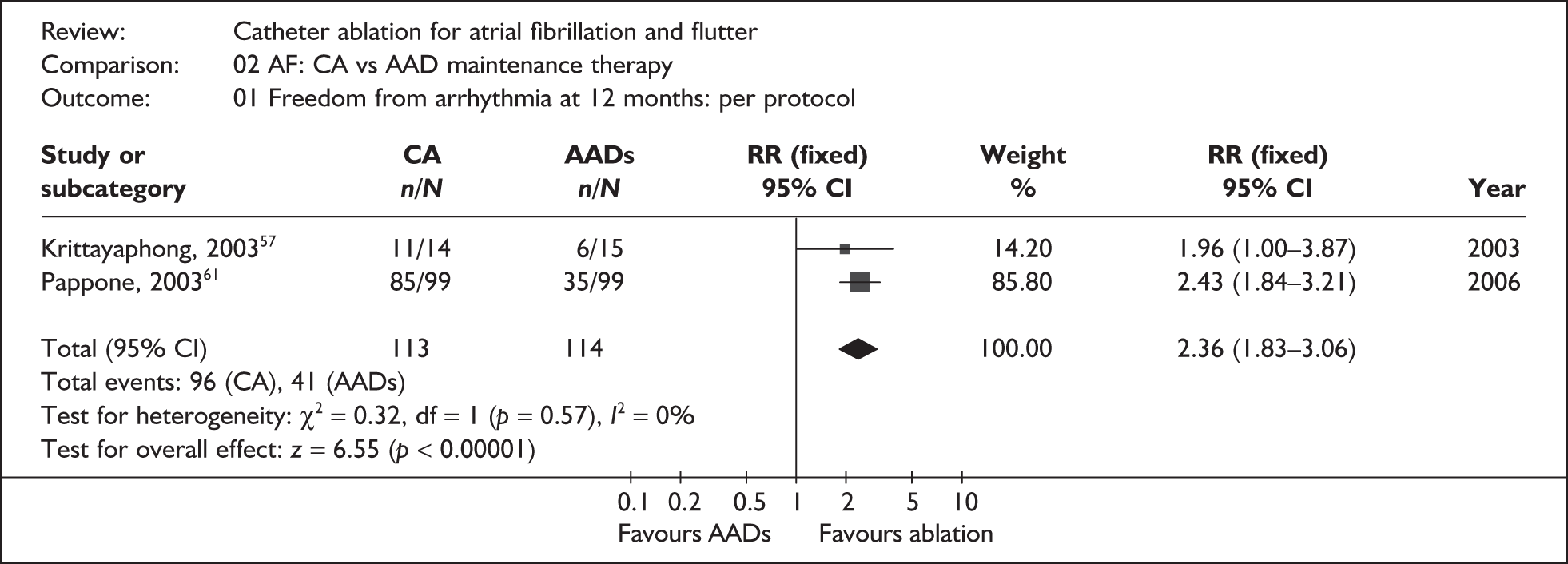

Figure 2 shows the RR and associated 95% confidence intervals for freedom from arrhythmia at 12 months for the six RCTs reporting sufficient data to calculate this outcome.

FIGURE 2.

Freedom from arrhythmia at 12 months: all atrial fibrillation randomised controlled trials.

The forest plots show that all of the included controlled studies favour ablation over AAD-based management, but the extremely high degree of statistical heterogeneity observed between the studies (I2 85.8–91.7%) indicates clearly that a pooled value for the group of studies as a whole is not considered appropriate. The heterogeneity can be partly explained by variation in patient populations and interventions: one study (Oral et al. 56) was limited to patients with persistent AF; one (Stabile et al. 59) evaluated combined RFCA/AAD treatment versus AADs alone (see Figure 2). The remaining randomised evidence included four RCTs57,58,60,63 comparing ablation with long-term AAD treatment (predominantly amiodarone, sotalol and class Ic agents, when reported) for the maintenance of sinus rhythm. However, when these four trials were pooled, highly significant statistical heterogeneity (I2 74%) remained (Appendix 4). One RCT63 intensively followed up arrhythmia in a way that differs from typical clinical practice and from follow-up protocols in other trials making the same comparison. This trial reported an unusually high rate of failures associated with AAD use, resulting in a very different relative effect from other RCTs. Removal of this study from the pooled comparison removed all statistical heterogeneity (I2 0%; see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Freedom from arrhythmia at 12 months: RFCA vs long-term AAD therapy in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation.

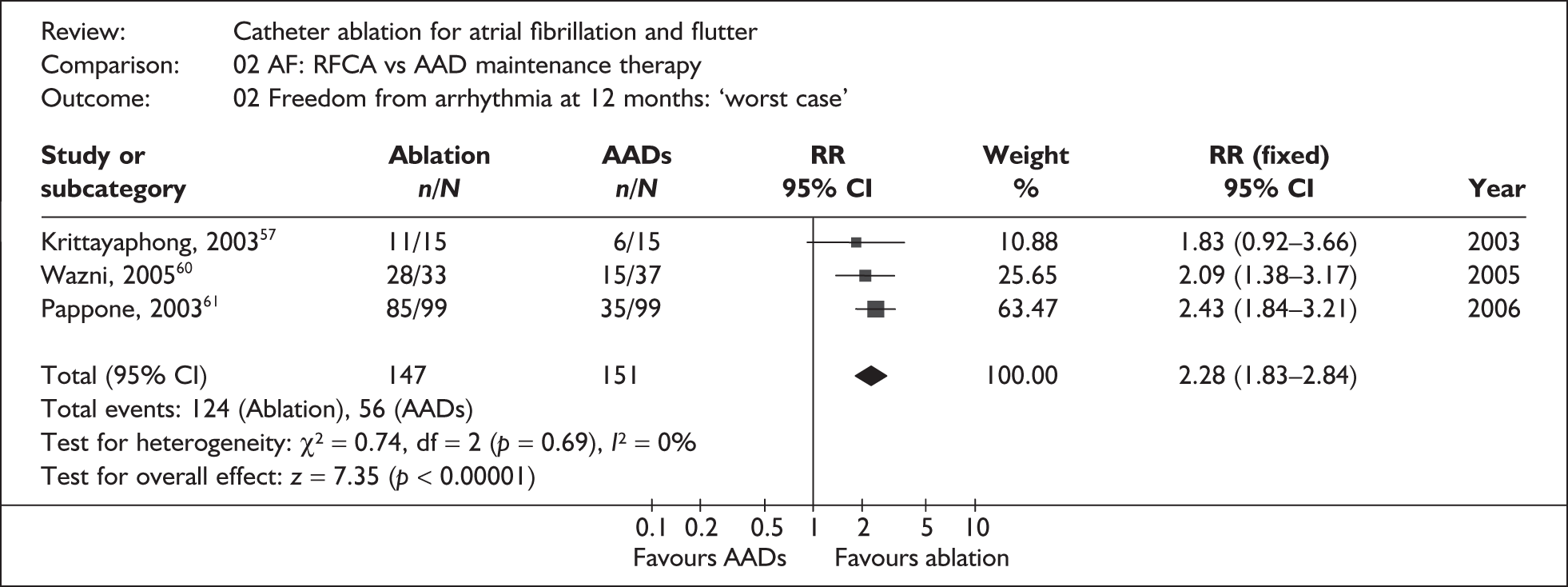

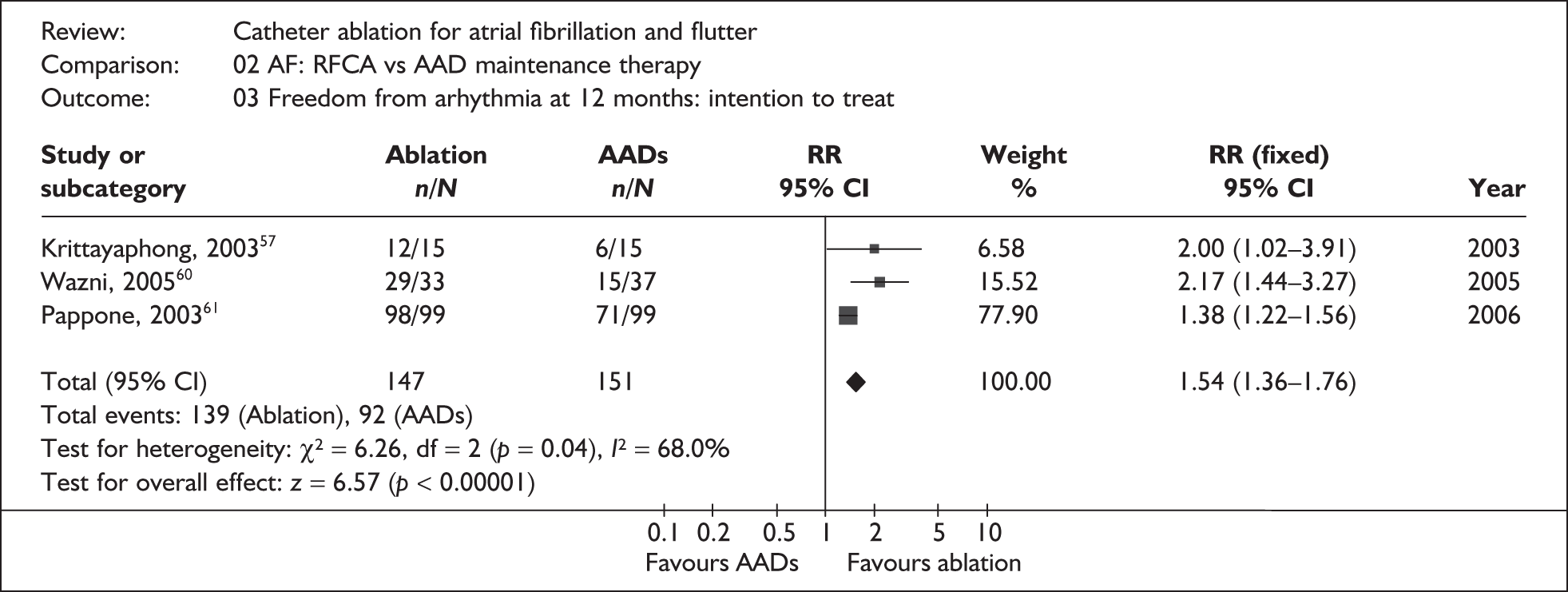

Within the three remaining RCTs comparing ablation with long-term AAD treatment that could be pooled in a meta-analysis,57,58,60 97% of the patients (Figure 3) were diagnosed with paroxysmal AF (ten patients in the Krittayaphong et al. 57 study had chronic AF) and the majority of patients (75%, 87%, 93%, respectively) were free of structural heart disease in the three trials. Only nine repeat ablation procedures were reported (all in the APAF study). The pooled per protocol results showed that significantly more patients undergoing RFCA were free of arrhythmia (without AADs) at 12 months’ follow-up than those receiving AAD maintenance therapy alone [RR 2.36 (95% CI 1.89–2.95)]. There were only four patients lost to follow-up across the three studies; assuming that data from these patients would be unfavourable to ablation had little influence on the pooled estimate [RR 2.28 (95% CI 1.83–2.84)]. The pooled intention to treat analysis ignoring crossovers indicated a smaller but statistically significant effect in favour of ablation [RR 1.54 (95% CI 1.36–1.76)]. As the study of Wazni et al. 60 was limited to patients undergoing first-line therapy, the mean duration of AF was considerably shorter in this trial (5 months) than in the other two trials (4.6 years and 6 years). However, sensitivity analyses involving the removal of the Krittayaphong and Wazni studies had little influence on the overall estimate of effect (see Appendix 4).

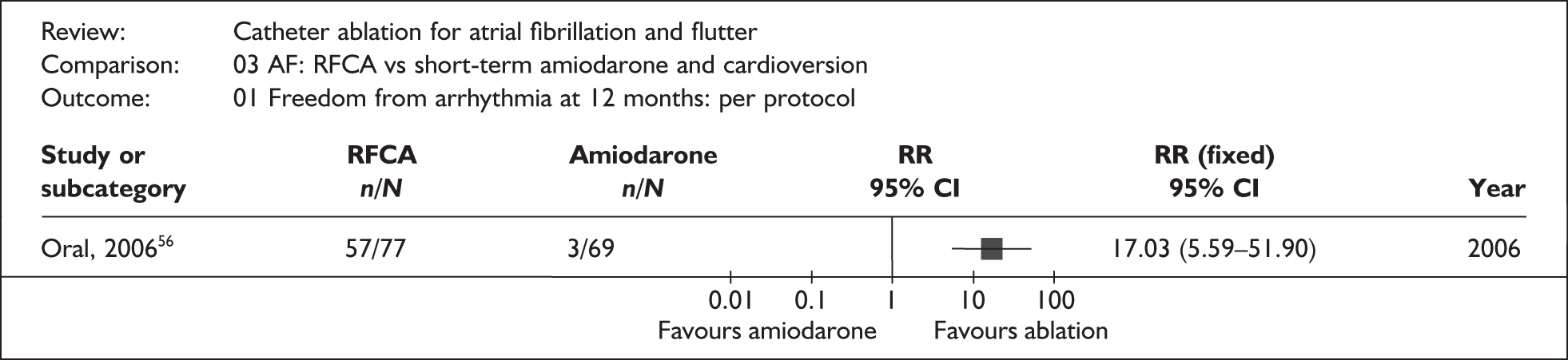

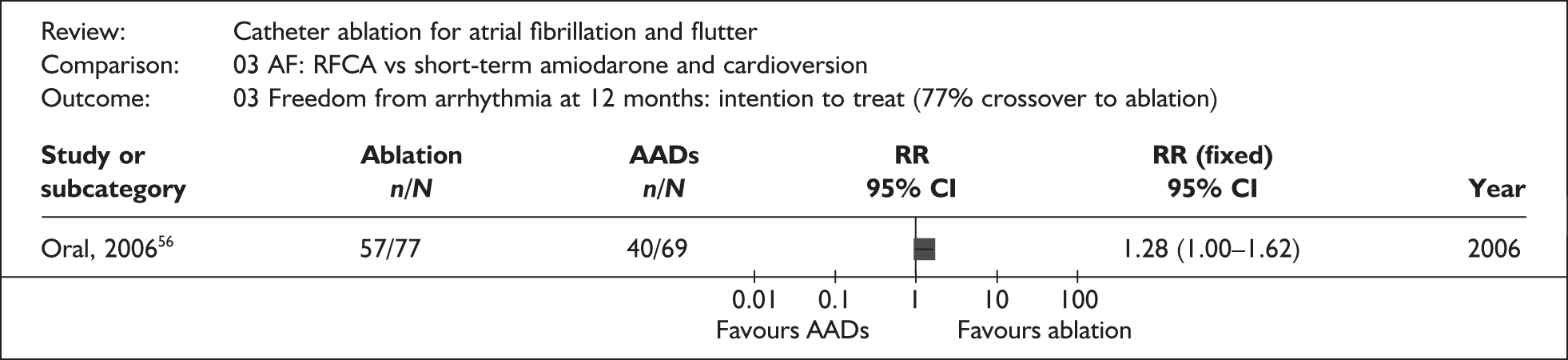

One RCT by Oral et al. 56 compared the effect of adding ablation to a short-term (3 month) amiodarone/cardioversion treatment strategy on subsequently achieving sinus rhythm without the need for AADs in patients with persistent AF. The majority of patients in the amiodarone/cardioversion treatment arm (77%) crossed over into the ablation arm before the 12-month follow-up. Forest plots showing the effect on sinus rhythm without AADs at 12 months are given in Appendix 4. Disregarding the very large crossover and analysing the data by original treatment allocation gives a relatively small effect, of borderline statistical significance, in favour of ablation [RR 1.28 (95% CI 1.00–1.62)]. If the need for additional treatment for recurrent AF after the initial 3 months was considered a failure of short-term therapy, the effect was much larger and significantly favoured the group that had received ablation [RR 17.03 (95% CI: 5.59–51.90)].

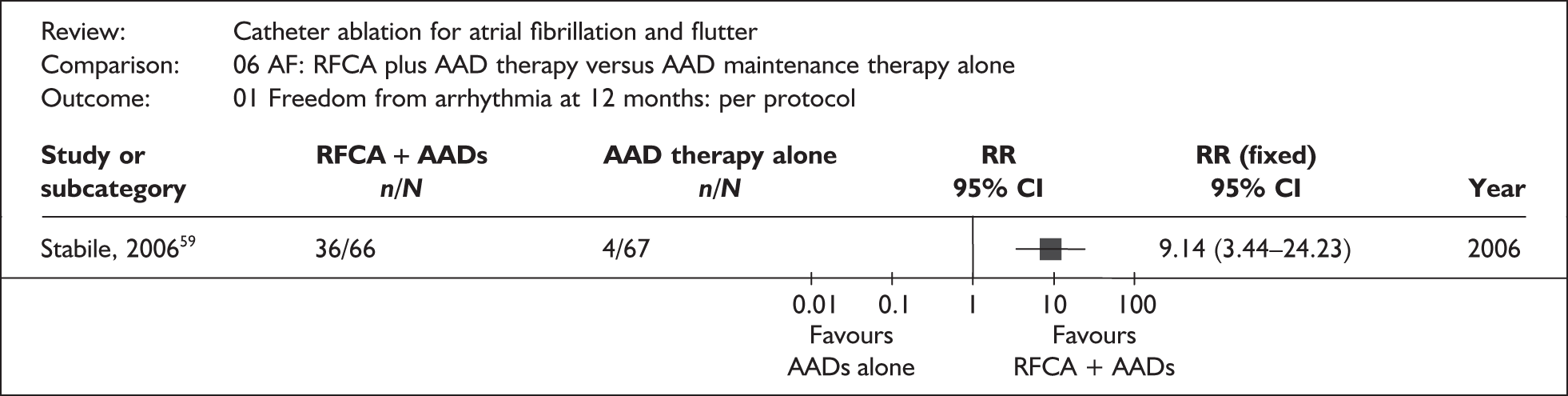

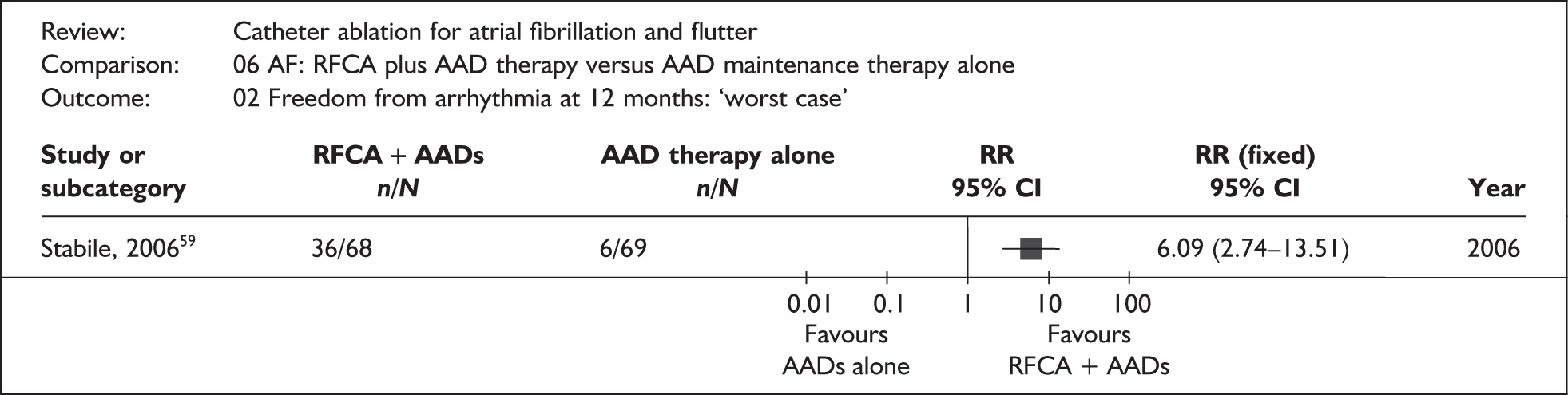

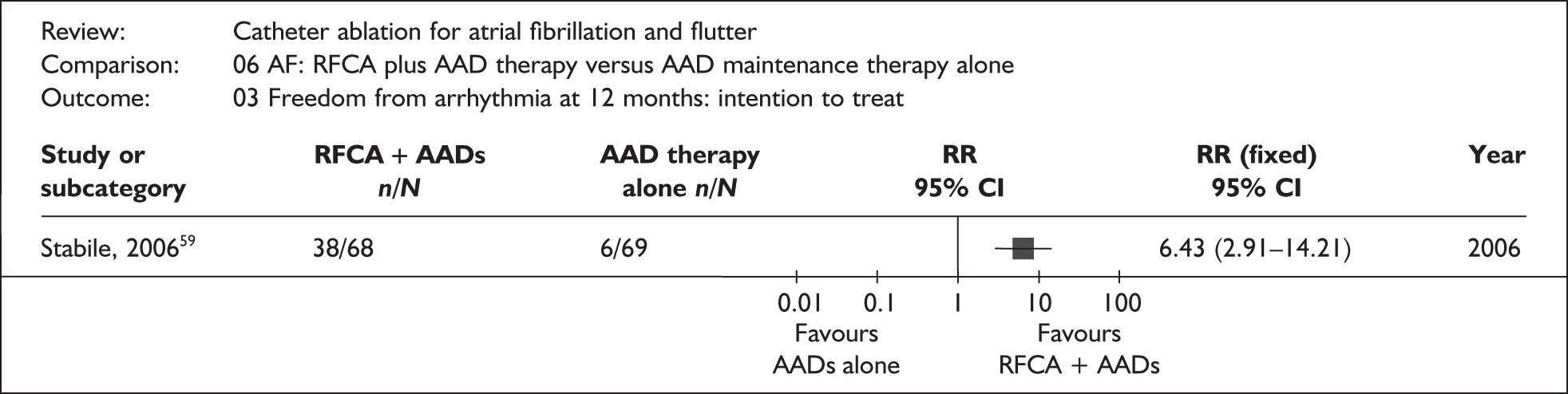

Stabile et al. 59 evaluated the effect of adding ablation to a long-term AAD maintenance strategy in patients for whom previous AAD therapy had already failed. As in the Oral et al. trial, a high proportion of patients (52%) crossed over from the AADs alone group to receive ablation after recurrence of AF. For freedom from arrhythmia at 12 months, the intention to treat analysis reported by the study authors showed a large, statistically significant effect in favour of ablation [RR 6.43 (95% CI 2.91–14.21)]. Assuming that data from patients lost to follow-up would have been unfavourable to ablation gave a slightly smaller pooled estimate [RR 6.09 (95% CI 2.74–13.51)], and per protocol analysis increased the pooled estimate [RR 9.14 (95% CI 3.44–24.23); see Appendix 4). It is not entirely clear why the relative effect for this comparison (RFCA plus AADs versus AADs alone) should be noticeably larger than that typically seen in the RCTs comparing RFCA against AADs alone, although the very low success rate seen in the AADs alone arm of Stabile et al. may be attributable to the intensive follow-up (patients had daily ECG recordings for 3 months) undertaken in this study.

The preliminary findings of a trial by Jais et al. were reported in a conference abstract. 63 This study appeared to have intensive follow-up of arrhythmia, similar to the trial by Stabile et al. , and similarly reported a large, statistically significant effect in favour of RFCA over ongoing AAD therapy [RR 11.13 (95% CI 4.27–29.03)].

For reference, Table 9 shows these results for the meta-analysis and trials that could not be pooled when calculated as odds ratios and related confidence intervals. However, our discussion of the findings will be limited to the RR estimates as relative probabilities are more easily interpreted than relative odds.

| Relative risk (95% confidence interval) | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|

| Any RFCA vs AAD maintenance therapy (three pooled studies) | ||

| Per protocol | 2.36 (1.89–2.95) | 10.35 (5.85–18.32) |

| ‘Worst case’ | 2.28 (1.83–2.84) | 9.11 (5.23–15.86) |

| Intention to treat | 1.54 (1.36–1.76) | 14.63 (6.13–34.95) |

| RFCA vs short-term amiodarone and cardioversion (one study) | ||

| Per protocol | 17.03 (5.59–51.90) | 62.7 (17.71–221.97) |

| Intention to treat | 1.28 (1.00–1.62) | 2.07 (1.03–4.15) |

| RFCA plus AAD therapy versus AAD maintenance therapy alone (one study) | ||

| Per protocol | 9.14 (3.44–24.23) | 18.9 (6.16–57.97) |

| ‘Worst case’ | 6.09 (2.74–13.51) | 11.81 (4.51–30.95) |

| Intention to treat | 6.43 (2.91–14.21) | 13.30 (5.07–34.89) |

Freedom from arrhythmia at other follow-up points

Of the studies reporting adequate freedom from arrhythmia data at other follow-up points, five were randomised and one was non-randomised. By far the largest of the studies was the non-randomised comparison of ablation against AAD therapy conducted by Pappone et al. 61 A lack of randomisation means that the two treatment arms are more likely to be unbalanced at baseline in terms of key participant characteristics. This appears to be true in the case of this particular study; at baseline the ablation group had longer duration of AF, a greater number of failed AADs and more frequent hospitalisation than the medical treatment group. However, survival analysis (mean follow-up of 900 days) indicated a significantly lower overall rate of AF recurrence in the ablation group [HR 0.30 (95% CI 0.24–0.37; p < 0.001)]. The difference in the estimated proportion of patients free from AF between the groups increased over time: 0.23 (95% CI 0.18–0.28) at 1 year, 0.32 (95% CI 0.28–0.38) at 2 years, and 0.41 (95% CI 0.33–0.49) at 3 years.

None of the randomised studies explicitly reported the number of patients free from arrhythmia before 12 months’ follow-up. When Kaplan–Meier analyses of AF recurrence were presented, these broadly indicated a steady rate of recurrences over time associated with AAD treatment, whereas recurrences associated with RFCA treatment tended to occur in the first 2–3 months post procedure before stabilising.

Complications, adverse events and mortality

Table 10 summarises the complications, adverse events and deaths reported in the controlled AF studies. A total of 1860 patients (932 ablation, 928 control) were included in these seven studies. Adverse events and complications were rarely reported; where data on major events/complications were not reported, we assumed that such an event/complication did not occur during the study. Some events were specific to ablation (tamponade, PV stenosis, groin haematoma) whereas others were specific to AADs (corneal microdeposit, thyroid dysfunction, pro-arrhythmia, sexual impairment).

| Study | Stroke/CVA | Tamponade/pericardial effusion | Mild/moderate PV stenosis | Death | Thyroid dysfunction | Liver dysfunction | Sinus node dysfunction | Atypical atrial flutter | Groin haematoma | Pro-arrhythmia | Sexual impairment | GI adverse events | Bradycardia | Tachycardia | ‘Bleeding’ | Transient phrenic paralysis | Transient ischaemic attack | Congestive heart failure | Myocardial infarction | Peripheral embolism | Corneal micro-deposit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Krittayaphong et al., 200357 | RFCA | 1/14 (7%) | – | – | – | – | – | 1/15 (7%) | – | 1/14 (7%) | – | – | 2/15 (13%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Amio | – | – | – | – | 4/15 (27%) | 2/15 (13%) | 1/14 (7%) | – | – | – | – | 6/15 (40%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2/15 (13%) | |

| Pappone et al., 200361 | RFCA | 6/589 (1%) | 4/589 (0.7%) | – | 38/589 (6.5%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 8/589 (1.4%) | 32/589 (5.4%) | 7/589 (1.2%) | 1/589 (0.2%) | – |

| AAD (LT) | 22/582 (3.8%) | – | – | 83/582 (14%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 27/582 (4.6%) | 57/582 (9.8%) | 8/582 (1.4%) | 3/582 (0.5%) | – | |

| Wazni et al., 200560 | RFCA | – | – | 2/33 (6%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2/33 (6%) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| AAD (LT) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3/37 (8%) | – | 1/37 (3%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Pappone et al., 2006 (APAF)58 | RFCA | – | 1/99 (1%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3/99 (3%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| AAD (LT) | – | – | – | – | 7/99 (7%) | – | – | – | – | 3/99 (3%) | 11/99 (11%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Oral et al., 200656 | RFCA + ST amio + CVN | – | – | – | 1/77 (1.3%) | – | – | – | 5/77 (7%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| ST amio + CVN | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Stabile et al., 200659 | RFCA + AAD (LT) | 1/68 (2%) | 1/68 (2%) | – | 1/68 (2%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1/68 (2%) | – | – | – | – | – |

| AAD (LT) | – | – | – | 2/69 (1%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1/69 (1%) | – | – | – | – | |