Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA Programme as project number 05/09/07. The contractual start date was in January 2006. The draft report began editorial review in May 2007 and was accepted for publication in June 2008. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA Programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

If funding bodies commission research in line with our recommendations, some of the report’s authors may apply.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2009 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO. This monograph may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NCCHTA, Alpha House, Enterprise Road, Southampton Science Park, Chilworth, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2009 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Aims of the review

This review has two aims:

-

to identify, appraise and synthesise research across a range of study designs that are relevant to selected UK National Screening Committee (NSC) criteria for a screening programme in relation to domestic (partner) violence

-

to make a judgment on whether current evidence is sufficient for fulfilment of selected NSC criteria for the implementation of screening for domestic (partner) violence in health-care settings.

Previous systematic reviews of partner violence studies

Screening

Our previous systematic review,1,2 based on an evaluation of quantitative studies that addressed the NSC criteria, concluded that these criteria were not fulfilled and that implementation of a screening programme was not justified. Contemporaneous reviews by North American colleagues have come to similar conclusions. 3 The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care used a broad analytic framework but only critically appraised intervention studies; its conclusion, that no recommendation could be made for or against screening, was based largely on those studies. 4 The US Preventive Task Force included and critically appraised assessment as well as intervention studies and concluded that there was insufficient evidence for a screening programme. 5 The main findings from these reviews are detailed in Appendix 1. The most recent systematic reviews evaluating the effectiveness of screening included studies published up until December 2002. No previous reviews have included qualitative studies to address any of the review questions.

The effectiveness of screening may vary between different health-care settings because of variation in prevalence of partner violence in different groups of patients, across the life course, and because of differences in acceptability within different health-care settings and between groups of health-care practitioners. Previous reviews of screening have not addressed this potential heterogeneity. Therefore it is possible that criteria for screening may be fulfilled in some settings with specific groups of patients but not in others. Our previous review evaluating the effectiveness of screening1 included three studies from primary care – community health centres, an internal medicine practice, and HMO (health management organisation) primary care clinics – two studies from antenatal settings and four from accident and emergency (A&E) departments.

Interventions after screening

A key element in the justification for a screening programme is an effective intervention or interventions following a positive screening test. In addition to reviews specifically designed to inform policy about screening, since 1998 there have been six systematic reviews of partner violence intervention studies relevant to health-care settings: Chalk and King,6 Abel,7 Hender,8 Cohn and colleagues,9 Klevens and Sadowski,10 and Ramsay and colleagues. 2 The most recent review of intervention studies, commissioned by the Department of Health’s policy research programme,11 included studies cited on the source bibliographic databases before October 2004.

This is a growing research field, and new studies may change the overall negative conclusion about the appropriateness of screening based on previous reviews.

Use of the term ‘partner violence’

A variety of terms are in current use to denote domestic violence perpetrated against an intimate partner, such as ‘partner violence’, ‘intimate partner violence’ (IPV), ‘spouse abuse’, ‘partner abuse’ and ‘battering’. There is still no international, or even national, consensus about the most appropriate term to use for this form of domestic violence. However, many experts in the field believe that ‘domestic violence’ is a misleading term because ‘domestic’ implies that the violence always happens within the home. Similarly, many see ‘IPV’ as inappropriate, as there is nothing ‘intimate’ about an abusive relationship. In this review we use the term ‘partner violence’ as this better reflects the nature of the problem. However, although this is our preferred term, when citing other sources we have retained their terminology where appropriate. We define partner violence against women as physical, sexual or emotional abuse with coercive control of a woman by a man or woman partner who is, or was, in an intimate relationship with the woman. In the US research literature ‘battered women’ is a common term; in this review we have consistently replaced this term with ‘survivors of partner violence’.

What about male survivors of partner violence?

Our overall review question is restricted to screening for partner violence perpetrated against women. Partner violence against men in heterosexual or same sex relationships is a social problem with potential long-term health consequences for male survivors,12 but is not the focus of this review. Although some population studies suggest that the lifetime prevalence of physical assaults against a partner is comparable between genders, even those studies report that violence against women is more frequent and more severe, and that women are three times more likely than men to sustain serious injury and five times more likely to fear for their lives. 13

Definitions of screening and routine enquiry

Screening, as defined by the NSC, is a public health service in which members of a defined population, who do not necessarily perceive they are at risk of, or are already affected by a disease or its complications, are asked a question or offered a test, to identify those individuals who are more likely to be helped than harmed by further tests or treatment to reduce the risk of a disease or its complications. 14

Routine enquiry, as it pertains to partner violence, refers to ‘asking all people within certain parameters about the experience of domestic violence, regardless of whether or not there are signs of abuse, or whether domestic violence is suspected.’15

The use of the term ‘screening’ as defined by the NSC refers to the application of a standardised question or test according to a procedure that does not vary from place to place, and that is how we use the term in this report. We acknowledge that many understand the term in a more general sense than this definition. To avoid confusion it is preferable to use the term routine enquiry where procedures are not necessarily standardised, but where question(s) are asked routinely, for example at every visit within time-specific or other parameters. Although there is not always a clear distinction between routine enquiry and screening, there is a flexibility of application in the former that is absent in the latter; a policy of routine enquiry does not necessarily have to fulfil the criteria for a screening programme. 16 Our review focuses on the criteria for screening, but in our final chapter we discuss the limitations of the screening model in relation to partner violence.

Extending the scope of previous reviews

We extended the scope of previous reviews in three ways. First, earlier reviews did not include a full assessment of the test characteristics of screening tools. We therefore aimed to evaluate the predictive properties of screening tools that could be used in clinical practice. Second, previous reviews have generated a vigorous correspondence,17 including an oft-repeated criticism that restriction to quantitative studies omits important evidence about the acceptability and value of screening or routine enquiry about partner violence in health-care settings. We therefore have included qualitative evidence in this review when it helped to answer a specific review question. Third, no previous review has addressed the economic costs related to the provision of services for abused women. We therefore searched for studies that evaluated the cost or cost-effectiveness of interventions for partner violence relevant to health-care settings and have also reported the economic modelling of a primary care partner violence intervention.

Chapter 2 Objectives and the review questions

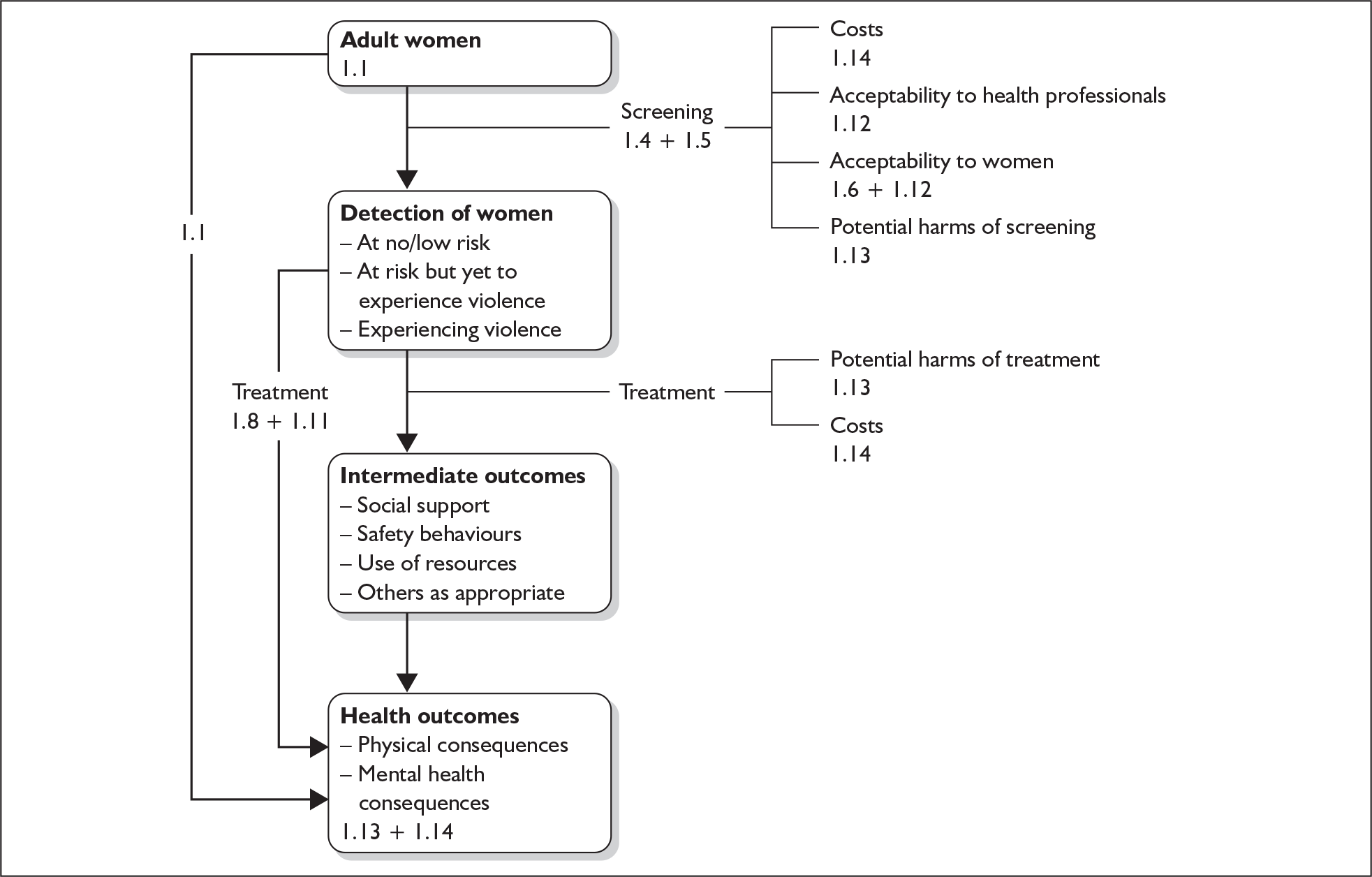

There are seven review questions. We have linked each of these to key NSC criteria for a screening programme. The figure in Appendix 2 places the criteria we are reviewing in an analytic framework for research on partner violence and health, and is adapted from a framework used by the Canadian Preventive Task Force. 18

Question I: What is the prevalence of partner violence against women and its health consequences?

There is no longer any debate about the public-health impact of partner violence, although prevalence rates and the magnitude of health sequelae vary depending on population and study design. But even the lower estimates for prevalence, morbidity and mortality make partner violence a potentially appropriate condition for screening and intervention. To answer this question we systematically searched for reviews from 1990 onwards on the health impact of partner violence, and summarised these along with prevalence data from individual studies from the UK published from 1995 onwards.

Question II: Are screening tools valid and reliable?

We reviewed the predictive properties and validity of current partner violence screening questions where they are evaluated against a standard criterion, such as the Conflict Tactics Scale. 19,20 We also summarised more general information about the screening tools, such as the number of items asked and the length of time required to administer the tool.

Specific questions:

-

Can screening efficiently and accurately identify women at risk of or experiencing partner violence?

-

Does accurate identification differ as a function of the number of items asked or the setting in which the tool is administered?

The distribution of test values in women experiencing partner violence was extracted and analysed.

Question III: Is screening for partner violence acceptable to women?

We reviewed acceptability of screening for partner violence by searching for quantitative surveys and qualitative studies eliciting the views of women. Findings from the different study designs were triangulated.

Specific review questions:

-

Is screening generally acceptable to women?

-

Do women’s views about screening differ as a function of previous exposure to screening?

-

Do women’s views about screening differ as a function of abuse status?

-

Are there any other factors associated with acceptability/non-acceptability?

-

age and ethnicity

-

health-care setting

-

mode of screening.

-

-

What harms do women report associated with screening for partner violence (qualitative studies only)?

Question IV: Are interventions effective once partner violence is disclosed in a health-care setting?

We reviewed quantitative studies of interventions that are relevant to women identified through screening procedures. This included studies of interventions initiated as a direct result of screening by health professionals, or interventions conducted outside of screening that nevertheless show what could be achieved if a woman’s abuse status was ascertained. We endeavoured to identify any evidence for a differential effect of early treatment on outcomes. We extended our previous systematic review,11 which included studies cited on the source bibliographic databases before October 2004.

Specific review questions:

-

Is there an improvement in abused women’s experience of abuse, perceived social support, quality of life and psychological outcome measures as a result of interventions accessed or potentially accessible as a result of screening (quantitative studies only)?

-

Is there an improvement for abused women’s children in terms of quality of life, behaviour and educational attainment following their mothers’ participation in programmes accessed or potentially accessed as a result of screening (quantitative studies only)?

-

What are the positive outcomes that abused women want for themselves and their children from programmes that include screening or other health-care-based interventions (qualitative studies only)?

We considered direct and indirect harms of whole screening programmes, where reported, by reviewing evidence from the intervention studies and qualitative studies.

Question V: Can mortality or morbidity be reduced following screening?

We searched for evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and reviewed these if available. We also included other controlled studies of interventions that implemented screening programmes or included partner violence screening as an aim in educational interventions for health-care professionals.

Specific review questions:

-

What are the changes in identification, information giving and referrals (made and attended) from screening and other system-based interventions in health-care and community/voluntary sector settings?

-

Is there evidence from RCTs and other controlled studies that there is a cessation or reduction in abuse following abused women’s participation in programmes including screening (quantitative studies only)?

-

Are there any measured harms from screening interventions (quantitative studies only)?

Question VI: Is a partner violence screening programme acceptable to health professionals and the public?

We reviewed quantitative and qualitative studies of acceptability to health professionals.

The issue of whether the test is acceptable to the public is addressed in question III, albeit only from the perspective of women. We did not address the issue of whether the programme is acceptable to male members of the general public.

Specific review questions:

-

Is screening for partner violence generally acceptable to health professionals?

-

Do health professionals’ views about screening differ as a function of previous experience of screening?

-

Do health professionals’ views about screening differ as a function of their role (e.g. physician, nurse, psychiatrist) or the setting in which they work (e.g. family practice, A&E, antenatal, dental practice)?

-

Are there any other factors associated with acceptability/non-acceptability?

-

age and ethnicity

-

training on partner violence.

-

Question VII: Is screening for partner violence cost-effective?

-

We reviewed studies evaluating the cost-effectiveness of screening. We complemented this with a cost-effectiveness model based on a pilot study of a primary care-based intervention that aimed to improve the identification of women patients experiencing partner violence.

NSC criteria not addressed by this review

We did not address this criterion because of its problematic application to the issue of partner violence: partner violence is not a condition in the disease model sense, and screening is not limited to detection of early stages of abuse.

In terms of partner violence, primary prevention interventions are largely in educational and media settings and we did not review these. This criterion is not relevant to a decision to implement a screening programme in health-care settings.

Review of evidence for criteria 8, 9 and 12 were part of our original proposal. Below we explain why we did not include them in the final review.

Further ‘diagnostic investigation’ is not relevant to the care of women who are identified in partner violence screening programmes.

Although some primary studies in our review discussed choices available to women disclosing abuse, there are no ‘evidenced-based policies’ for these treatment choices and, in the context of our resources for the reviews, we judged this criterion of secondary importance compared with those we did review.

The following criteria need to based on audit and policy research. They only need to be considered once the evidence-based criteria are met:

NSC criterion 12: Clinical management of the condition and patient outcomes should be optimised by all health-care providers prior to participation in a screening programme.

NSC criterion 17: There should be a plan for managing and monitoring the screening programme and an agreed set of quality assurance standards.

NSC criterion 18: Adequate staffing and facilities for testing, diagnosis, treatment and programme management should be available prior to the commencement of the screening programme.

NSC criterion 19: All other options for managing the condition should have been considered (e.g. improving treatment, providing other services), to ensure that no more cost effective intervention could be introduced or current interventions increased within the resources available.

NSC criterion 20: Evidence-based information, explaining the consequences of testing, investigation and treatment, should be made available to potential participants to assist them in making an informed choice.

NSC criterion 21: Public pressure for widening the eligibility criteria for reducing the screening interval, and for increasing the sensitivity of the testing process, should be anticipated. Decisions about these parameters should be scientifically justifiable to the public.

Chapter 3 Review methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The generic criteria that applied to all seven questions are listed in Tables 1 and 2.

| Inclusion criteria | Review questionsb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QI | QII | QIII | QIV | QV | QVI | QVII | |

| Participants | |||||||

| Women aged over 15 years | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ |

| Women that report a lifetime experience of partner violence | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ |

| Settings | |||||||

| Health-care settings – no restrictions on geographical/national setting | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Primary studies conducted in services outside health-care systems to which referral can be made from a health-care setting | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ |

| Study designs | |||||||

| Randomised controlled studies, non-randomised parallel group studies, interrupted time series studies, before-and-after studiesa | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| Cohort studies | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ | × |

| Case–control studies | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | × |

| Cross-sectional studies | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | × |

| Clusters of case studies | × | × | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | × |

| Prevalence studies | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | × | × | × |

| Qualitative designs | × | × | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | × |

| Questionnaire surveys | × | × | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | × |

| Studies where verbal interaction (researcher–participant) aids results’ formulation | × | × | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | × |

| Studies where abused women’s views discussed separately | × | × | ✓ | × | × | × | × |

| Studies evaluating a screening tool against a standard criterion | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | × |

| Economic evaluations of screening interventions | × | × | ✓ | × | × | × | ✓ |

| Aims of studies included | |||||||

| Interventions aimed at reducing abuse or improving the health of the women | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | × |

| Interventions aimed at training staff | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Interventions aimed at providing more organisation/system resources | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Studies determining effectiveness of screening interventions | × | × | × | ✓ | × | × | × |

| Studies determining prevalence of partner violence | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Studies determining validity and reliability of screening | × | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × |

| Studies determining cost-effectiveness of screening | × | × | × | × | × | × | ✓ |

| Studies determining acceptability of screening to women | × | × | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| Studies determining harms associated with screening | × | × | × | × | ✓ | × | × |

| Studies determining acceptability of screening to health professionals and public | × | × | × | × | × | ✓ | × |

| Included outcomes | |||||||

| Incidence of abuse (physical, sexual, psychological, emotional, financial) | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ |

| Physicalc and psychosociald health | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ |

| Proxy measurese | × | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ |

| Measures of validity and reliability of screening tools | × | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × |

| Degree of acceptability of screening amongst women | × | × | ✓ | × | × | × | × |

| Degree of acceptability of screening to health professionals | × | × | × | × | × | ✓ | × |

| Cost of providing screening | × | × | × | × | × | × | ✓ |

| Changes in identification, information giving and referrals from screening | × | × | × | × | ✓ | × | × |

| Included reporting formats | |||||||

| Studies published in peer-reviewed journals and in books by academic publishers | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Funder-published research reports | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Studies reported in European languagesf | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Reviews, from 1990, on the health impact of partner violence | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Studies, from 1995, reporting prevalence data for partner violence from the UK | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Exclusion criteria | Review questionsa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QI | QII | QIII | QIV | QV | QVI | QVII | |

| Participants | |||||||

| Female survivors of partner violence aged under 15 years | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | × |

| Female survivors of other (non-partner) abuse (e.g. stranger rape, adult survivors of child abuse, elder abuse) | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | × |

| Male survivors of partner abuse of any age | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Children of abused women, abused children, and the perpetrators of abuse | ✓ | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ |

| Participants with no previous history of partner violence | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | × |

| Settings | |||||||

| Studies conducted in non-health-care settings that are not considered relevant to health-care policy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Study designs | |||||||

| Single case studies | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Study aims excluded | |||||||

| Interventions targeted at perpetrators of partner violence | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Studies reporting joint treatments, such as couple and family therapy (even if the therapy was administered separately to women) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Interventions aimed at helping the survivors of child or elder abuse | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Intervention studies initiated to help the survivors of abuse committed by other family members (such as in-laws) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Interventions targeted directly at helping children of women being abused by intimate partners | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Interventions aimed at abused men | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Studies determining the acceptability of screening that have not distinguished the perspectives of male and female members of the public | × | × | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | × |

| Community and societal interventions conducted with the aim of increasing public awareness of the problem of partner abuse | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | × | ✓ |

| Criminal justice interventions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Excluded outcomes | |||||||

| Studies that do not report outcomes relating to abuse | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Studies that do not report outcomes relating to at least one of: physical and psychosocial health, socioeconomic indicators and other proxy measures | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ |

| Primary studies that only measure change in knowledge or attitudes of professionals about partner abuse | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | ✓ |

| Studies that only measure identification of abused women or documentation or safety assessments | ✓ | × | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | ✓ |

| Excluded reporting formats | |||||||

| Self-published research reports | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| PhD theses, masters’ and undergraduate dissertations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Papers published in non-European languages | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Conference abstracts | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Reviews, before 1990, on the health impact of partner violence | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × | × |

| Prevalence data for partner violence from the UK reported before 1995 | ✓ | × | × | × | × | × | × |

Further question-specific criteria are listed below. All criteria were applied independently by two reviewers and disagreements were adjudicated by a third reviewer.

-

Primary studies of prevalence restricted to UK populations from 1995 onwards.

-

Review of health consequences restricted to systematic reviews from 1990 onwards.

-

Included study designs had to be validation studies, i.e. they evaluated a screening tool against a standard criterion/comparator.

-

The comparator had to have high sensitivity and specificity.

-

The comparator could have any number of items, but the index screening tool had to comprise 12 items or fewer. The rationale behind this postprotocol decision was the requirement for screening tools to be used in a clinical, not research setting. Long screening tools would be unsuitable due to the time needed to complete them, and we chose 12 items as an arbitrary cut-off. This reduced the number of screening tools reviewed but improved the clinical applicability of our findings.

-

Studies were excluded if non-standardised clinical interviews were used as the comparator.

-

Studies only reporting women’s perceived barriers to disclosure but not their views about the acceptability of screening were excluded.

-

Intervention studies on co-morbid populations were included if all the participants had experienced partner violence or if the outcome data for those who had experienced partner violence were reported separately.

-

Studies of interventions with children were included if the mothers were also involved; either the mothers received their own interventions or they played a role in interventions targeted at their children.

-

Studies that measured mortality, morbidity or quality of life outcomes for women were included.

-

Studies of screening intervention studies that measured proxy measures that were potentially associated with decreased morbidity and mortality were included, particularly documentation of abuse or referral to expert partner violence services.

-

Studies where documentation was limited to recording the disclosure of abuse, without recording more detailed information (about, e.g., context, safety and, perhaps, the perpetrator), were excluded.

-

Studies reporting changes in identification rates with no other outcomes were excluded.

-

Studies that only reported one proxy outcome were excluded, unless this was referral to expert partner violence services.

-

In addition to survey studies, intervention studies reporting attitude change were included and the before and after data reported separately.

-

We did not include studies addressing the issue of whether screening is acceptable to male members of the public.

-

Papers that only reported on the perceived barriers to screening were excluded.

-

Studies were excluded if they only measured screening behaviour without reporting attitudes towards screening for partner violence.

-

Studies had to include an analysis of costs of a health-care-based partner violence intervention or screening programme.

Identification of primary studies

We systematically searched for relevant studies using strategies that combined content terms and study designs (search strings available from authors). Searches were made of the international literature for published peer-reviewed studies. The following sources were used to identify studies.

Electronic databases

-

Cochrane Collaboration Central Register (CENTRAL/CCTR)

-

Biomedical sciences databases:

-

MEDLINE

-

EMBASE

-

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature)

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews for Effectiveness (DARE)

-

National Research Register (NRR)

-

Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC)

-

MIDIRS (Midwives Informatin and Resource Service)

-

British Nursing Index (BNID)

-

NHS Economic Evaluation.

-

-

Social sciences databases:

-

Social Science Citation Index (SSCI)

-

International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS)

-

PsycINFO

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA).

-

Searches of these databases included all studies referenced from their respective start dates to 31 December 2006. In addition to original research papers, we also searched for any relevant review articles.

In the case of Question I, we only searched for review articles in six of the electronic databases: Medline, Embase, Cinahl, DARE, British Nursing Index and Social Science Citation Index. We also used backward and forward citation tracking to identify other studies and we scrutinised papers in the reference lists of included studies.

Other sources

-

Personal communication with the first or corresponding authors of all included articles.

-

Consultation with members of partner violence organisations/research networks in the UK, Western Europe, North America and Australasia.

We did not hand search any journals.

Selection of studies

Two reviewers independently selected studies for inclusion in the review. Where possible, disagreement between the two reviewers was resolved by discussion. If agreement could not be reached then a third reviewer adjudicated. Agreement rates across all databases ranged from 70% to 98%, the average inter-rater agreement being 88%. If additional information was needed to resolve a disagreement, then this was sought either from the first or corresponding author of the study in question.

Data extraction and methodological appraisal by reviewers

Data from included studies were extracted by one reviewer and entered onto electronic collection forms. All of the extractions were independently checked by a second reviewer. Again, where possible, any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion. If this was not possible, then a third reviewer adjudicated and all such decisions were documented. Where necessary, the first authors of studies or the correspondence authors were contacted to assist in resolving the disagreement. One reviewer appraised study quality and strength of design in relation to the review questions.

Analysis of primary data extracted

The data extraction forms were used to compile summary tables of the data and quality classification. These formed the basis for our narrative synthesis of the primary studies. We grouped the findings of the primary studies and analysed differences between studies in relation to setting (country, type of health-care facility), populations (ethnicity, socioeconomic status, method of identification/disclosure) and, in the case of intervention studies, the nature of the intervention. We performed narrative sensitivity analysis for each question, testing whether the overall findings persisted when the poor-quality studies were excluded. When effect sizes were not reported, we calculated Cohen’s d if the mean changes and standard deviations were reported in the papers or were available from the authors. For the quantitative studies, after consideration of the heterogeneity of interventions and outcomes and the overall purpose of this review – assessing the extent to which criteria for a screening programme were fulfilled – we chose not to pool the data from different studies.

Application of the appraisal criteria to our reviews

We appraised our reviews of intervention studies (Questions 4 and 8) using the Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses of Randomised Controlled Trials (QUORUM) criteria. 21 We appraised our review of prevalence studies using the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) criteria. 22

Synthesis of the qualitative data

There is no standard method for combining qualitative studies. We therefore used a type of qualitative meta-analysis. 23 We drew on Schutz’s framework of constructs24 and on the metaethnographic method articulated by Britten and colleagues,25,26 although we prefer the term ‘meta-analysis’ as the studies analysed were not ethnographies. The analysis started with two parallel strands: (1) identification and examination of first- and second-order constructs in the primary studies, and (2) methodological appraisal. These strands were brought together in the formulation of third-order constructs expressing the conclusions of the meta-analysis.

First-order constructs were based on results in the primary studies relevant to the review question. Second-order constructs were the interpretations or conclusions of the primary investigators that related to the review question. These constructs were identified and grouped from data on the extraction forms, referring back to the original papers when necessary. For identification of second-order constructs, where the investigators only presented recommendations, we interpreted these as the authors’ conclusions. We intended to examine three different types of relationship between the constructs extracted from the studies:

-

constructs that were similar across a number of studies (reciprocal constructs) and, through a process of repeated reading and discussion, would yield third-order constructs that would express our synthesis of findings that were directly supported across different studies

-

constructs that seemed in contradiction between studies; we planned to explain these contradictions by examining factors in the studies and, where there was a plausible explanation, to articulate these as third-order constructs

-

unfounded second-order constructs; i.e. conclusions by primary study authors that did not seem to be supported by first-order constructs.

This method allows generalisations to be made that are not possible from individual qualitative studies.

Further details of the analysis by review question are given below.

We summarised the prevalence data reported in primary studies and the evidence for health consequences in systematic reviews. We plotted incidence and prevalence with 95% confidence intervals and tested the effect on variation of type of population (clinical versus community) and types of violence with logistic regression models. For health consequences, when we cited primary studies this was for illustrative purposes only.

In our narrative analysis of the results of these studies we evaluated the effectiveness and accuracy of the screening tools in terms of: test sensitivity and specificity, test positive and negative predictive values, positive and negative likelihood ratios, and the diagnostic odds ratio. Where feasible, we had also planned to pool results from primary studies of the same screening tool that were graded good or fair and that had comparable effect measures (e.g. sensitivity/specificity, predictive values, risk estimates). 27 However, no meta-analyses of the screening tool evaluations were possible because of the heterogeneity of the index tools used in the primary studies. Some of the primary studies did not fully report diagnostic accuracy, but did report the numbers of true positives, false positives, true negatives and false negatives for both the index and comparator tools. In those cases we calculated the diagnostic accuracy of the index tool. If the raw data were not available, we requested it from the authors. Reliability was judged by Cronbach’s alpha, coefficient alpha or Cohen’s kappa.

In addition to summarising the data in terms of the acceptability of screening to women, we also examined if attitudes varied as a function of women-related variables (such as age, ethnicity, abuse status, educational status), demographic features (such as the country where the study was conducted, the setting in which the women were recruited) and features relating to the screening process (such as the questions asked and who asked them). In a synthesis of the interview- and focus group-based qualitative and questionnaire-based quantitative studies, we explored whether and how these factors are associated with women’s positive attitudes towards partner violence screening. We did not perform a meta-regression of the surveys because of the heterogeneity of the clinical settings, of the demographic data collected from the informants, and the measures of acceptability.

We calculated effect sizes where means and standard deviations were reported or were obtainable from the authors of studies. Meta-analyses of the studies were planned, but the data could not be pooled because of the heterogeneity of settings, demographics of the women participants, study designs (including the duration of follow-up) and the outcomes measured. It was not possible to construct funnel plots to investigate potential publication bias.

Where data were reported, we calculated confidence intervals for differences in identification and referrals between intervention and control groups. Pooling of data to calculate an overall effect size was not feasible because of the weak study designs: there was only one RCT.

These data were summarised in terms of the acceptability of screening to health professionals (women’s views are given above and we did not seek to include studies examining the views of male members of the public). We also analysed if attitudes varied as a function of individual health professional-related variables (such as age, ethnicity, previous training on partner violence, personal experience of caring for abused patients), demographic features (such as the country where the study was conducted, the occupation of the health professional) and features relating to the screening process (such as the questions asked, who should ask the questions, where the screening should occur, barriers to screening). By examining these factors we explored whether and how these factors interact to increase or decrease health professionals’ positive attitudes towards screening women for partner violence.

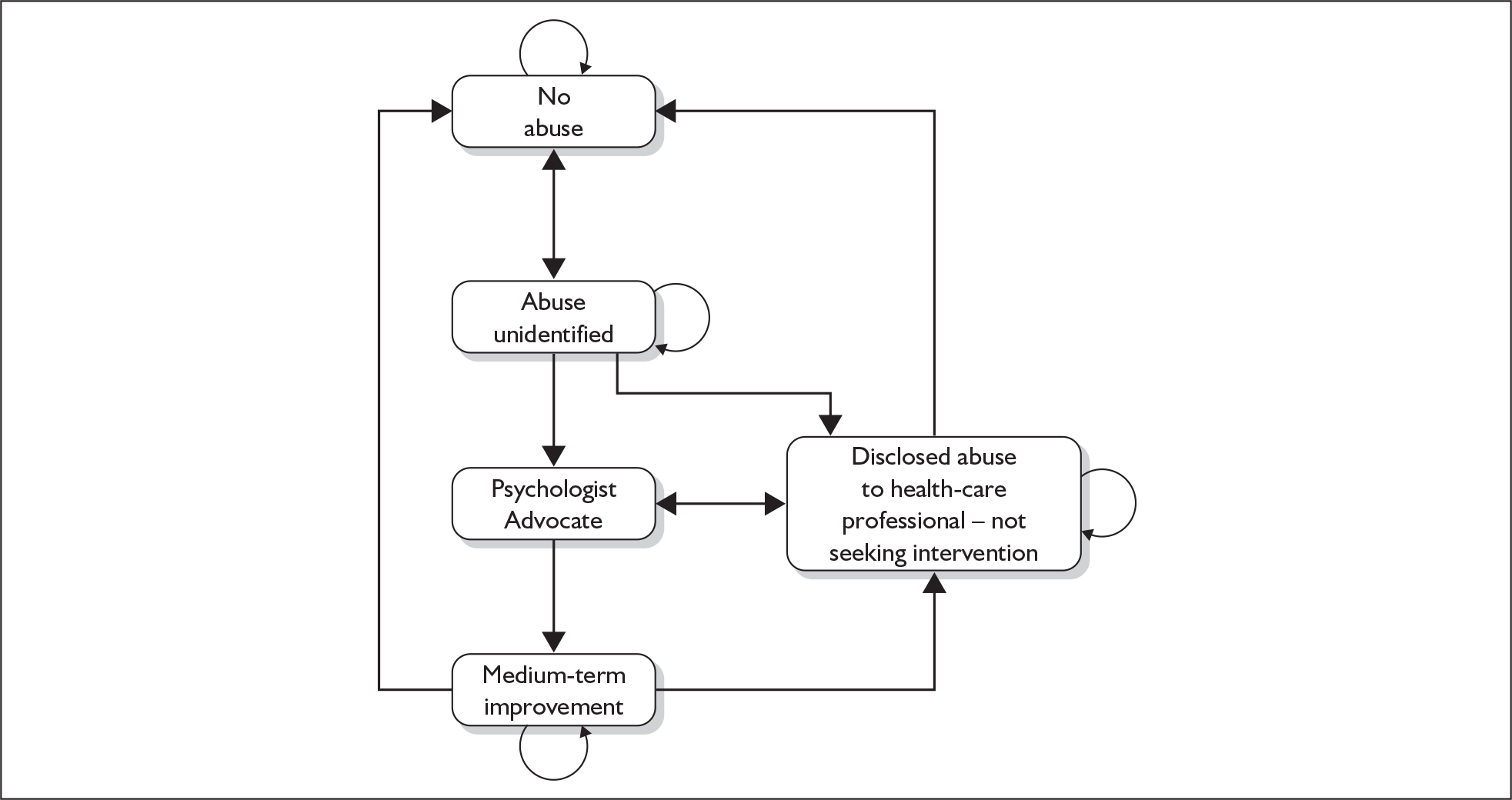

In anticipation of a paucity of cost-effectiveness (or any economic) studies of screening for partner violence in health-care settings, we modelled the impact of an intervention in general practice to increase identification and referral of women experiencing partner violence. We used real cost data from a pilot study (PreDoVe, Prevention of Domestic Violence) we completed in three east London practices. 28 This model allowed us to link intermediate outcomes such as referrals and levels of abuse, to medium- and longer-term outcomes and costs such as abuse measures, quality of life, employment, housing and civil justice. We combined our data with secondary sources to estimate the impact on outcomes and costs that could not be measured within the pilot study. The model estimated the cost-effectiveness of the intervention and gave special attention to the following aspects:

-

Micro-level data collection – PreDoVE collected detailed resource use by women data, and we have combined these with unit cost data available from the NHS and relevant studies. 29

-

Confidence intervals around the estimates – we estimated the distribution of costs and outcomes of partner violence. This allowed us to investigate the probability that the intervention is cost-effective and to establish a confidence interval around the cost-effectiveness estimate.

-

Sensitivity analyses – we varied all costs and outcomes by 25% in univariate analyses.

-

The time lag between cause and effect – the study captured the extent to which women access services over time, including periods of time when the women choose to delay seeking additional help.

Appraisal of methodological quality

The quality of the primary studies was assessed using appraisal tools in accord with the different review questions and the nature of the data collected.

The papers reporting the prevalence studies were appraised using the current version of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist. 30 In assessing the studies for inclusion, the following methodological issues were considered: selection, confounding and measurement bias. In this review, for each item in the checklist a score of zero or one was assigned. The maximum total score was 22. Although this tool focuses on reporting rather than the quality of the primary studies per se, it does discriminate between studies of better or worse quality. We appraised the methodological quality of reviews with the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) systematic review appraisal tool31. The scores for individual items informed a judgment about whether the review was high, medium or low quality. This judgment was made independently by two reviewers who did not disagree.

The papers reporting the validation of screening tools were appraised using the 14-item Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS). 32 The tool allows studies to be rated for bias (eight items), variability (one item) and reporting (five items); these include patient spectrum, selection criteria, reference standard, disease progress, partial verification, differential verification, incorporation, test execution, blind analysis, interpretation, indeterminate results and study withdrawals (see Appendix 3.1). The QUADAS does not have a scoring system and the outputs are narrative results relating to the various sources of bias rather than a single score. This is an advantage in assessing diagnostic accuracy studies, as total scores tend to ignore the importance of individual items and do not take account of the direction of bias under different contexts. We used the QUADAS to assess both within-study bias (the level of methodological quality of each primary study) and between-study bias (the proportion of studies that have not accounted for a particular bias) to give an overall picture of the quality of the validation studies in this field.

Question III: Is screening for partner violence acceptable to women? Quantitative studies that examined women’s attitudes towards screening for partner violence were appraised using the STROBE30 checklist (see Question I above). In addition to scoring the individual primary studies, we ranked all the studies and carried out a sensitivity analysis by comparing results for those studies in the top quartile with the results for all the studies.

We appraised the methodological quality of qualitative studies for this question with the CASP qualitative appraisal tool. 31 The tool has 10 questions that address three broad issues: rigour (has a thorough and appropriate approach been applied to key research methods in the study?); credibility (are the findings well presented and meaningful?); and relevance (how useful are the findings?). In this review, for each item in the checklist a score of zero or one was assigned and a maximum score of 41 was possible. As for the quantitative studies, the resulting scores of the primary studies were ranked and those in the upper quartile were used for a sensitivity analysis. We have shown in a previous study that ranking of CASP scores for qualitative studies is a relatively robust method for ranking them by quality. 33

The United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF)34 quality appraisal framework was used to assess the primary intervention studies included in the review. This tool rates the internal validity of a study (in terms of good, fair or poor) and its external validity, as well as the quality of execution of the study and its study design. The overall strength of evidence for each type of intervention could then be determined on the basis of the following criteria: the suitability of study design (greatest, moderate and least); the quality of execution of the study (based on the internal validity of the primary studies); the number of studies that fulfilled minimum suitability and quality criteria; and the size and consistency of reported effects. The combination of these factors determined the final score for evidence of effectiveness for each category of interventions (strong, sufficient or insufficient). For studies that used an RCT design, we also applied the Jadad score35 to obtain a further assessment of quality. Trials with lower Jadad scores are associated with overestimates of treatment effect. For further details of the USPSTF and Jadad quality appraisal methods, see Appendices 3.2 and 3.3.

These studies were also appraised using the USPSTF quality appraisal framework34 and the Jadad score. 35

In accordance with our assessment of the methodological quality of studies included under Question III, we once again used the STROBE checklist30 to appraise the quality of the quantitative studies and the CASP tool31 to appraise the qualitative studies we included. Sensitivity analyses of those studies that ranked in the upper quartiles for methodological quality were also performed.

We did not find any studies that fulfilled our inclusion criteria.

Application of review evidence to National Screening Committee criteria

Once the review was completed, its findings were summarised in relation to NSC criteria. The research group systematically considered each of these criteria against the review evidence using informal consensus to judge the extent to which the criteria were fulfilled. As noted in our proposal, the timescale of the review did not allow engagement with an external reference group. We did present our initial findings to a meeting of the National Domestic Violence and Health Research Forum. These findings and the design of the reviews were discussed by the Forum. There were no specific suggestions for further searching or analysis; comments on the questionable applicability of the NSC criteria to domestic violence screening informs our discussion of this issue in Chapter 11. We approached Health Ending Violence and Abuse Now (HEVAN), the domestic violence practitioners’ forum (Loraine Bacchus was secretary of the group), but no meeting was possible within the timescale of the review.

Chapter 4 What is the prevalence of partner violence against women and its impact on health? (Question I)

Prevalence of partner violence against women in the UK

One of the prerequisites for an effective screening programme in clinical settings, and the first NSC criterion, is that the condition is an important health problem. Two dimensions of importance are prevalence and health impact. In this section we review prevalence studies in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Methodological challenges

Measuring the prevalence of partner violence is problematic; studies employ different definitions, use different questions, and examine different populations and time frames. Additionally, there are various methods of administering questions, for example self-completed or researcher-completed, which may affect responses. 36

The most common definition of partner violence used in UK prevalence studies only includes physical violence. More recent studies have broadened the definition to include emotional, sexual, psychological and financial abuse, as well as stalking. Others, although making reference to emotional and sexual violence in the definition of partner violence, only report the prevalence of physical violence. Even with this restricted focus, there are disparities: some researchers include threats of physical violence, others include only severe physical violence. The number and content of questions used to measure prevalence vary between studies. An additional obstacle to comparing studies is the modification of instruments without detailing how, or if, the instrument in its adapted format has been validated. Prevalence rates are reported over differing time frames. Reporting lifetime prevalence rates may suffer from the problem of recall bias. However, reporting 1-year prevalence (abuse in the past year) may under-represent the problem as women may not yet have had sufficient time to acknowledge or identify their experiences as partner violence. These disparities go some way to accounting for the varying prevalence rates.

Prevalence studies are likely to under-represent the extent of the problem, as violence may not be disclosed to the researcher. Furthermore, it is likely that some women experiencing partner violence are beyond the reach of epidemiological studies as their abusive partners may not allow them to speak to a researcher alone, or may not even allow them to leave the house.

Results

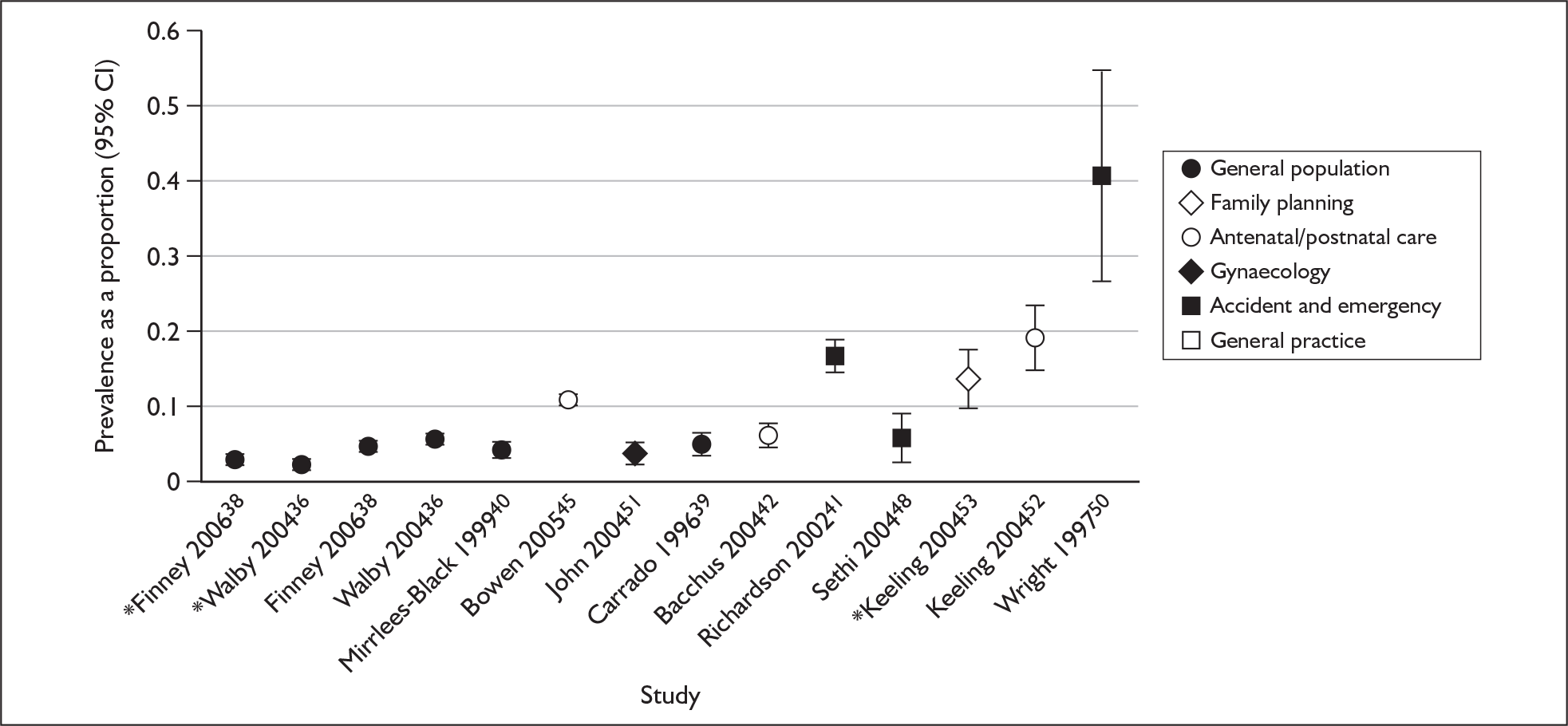

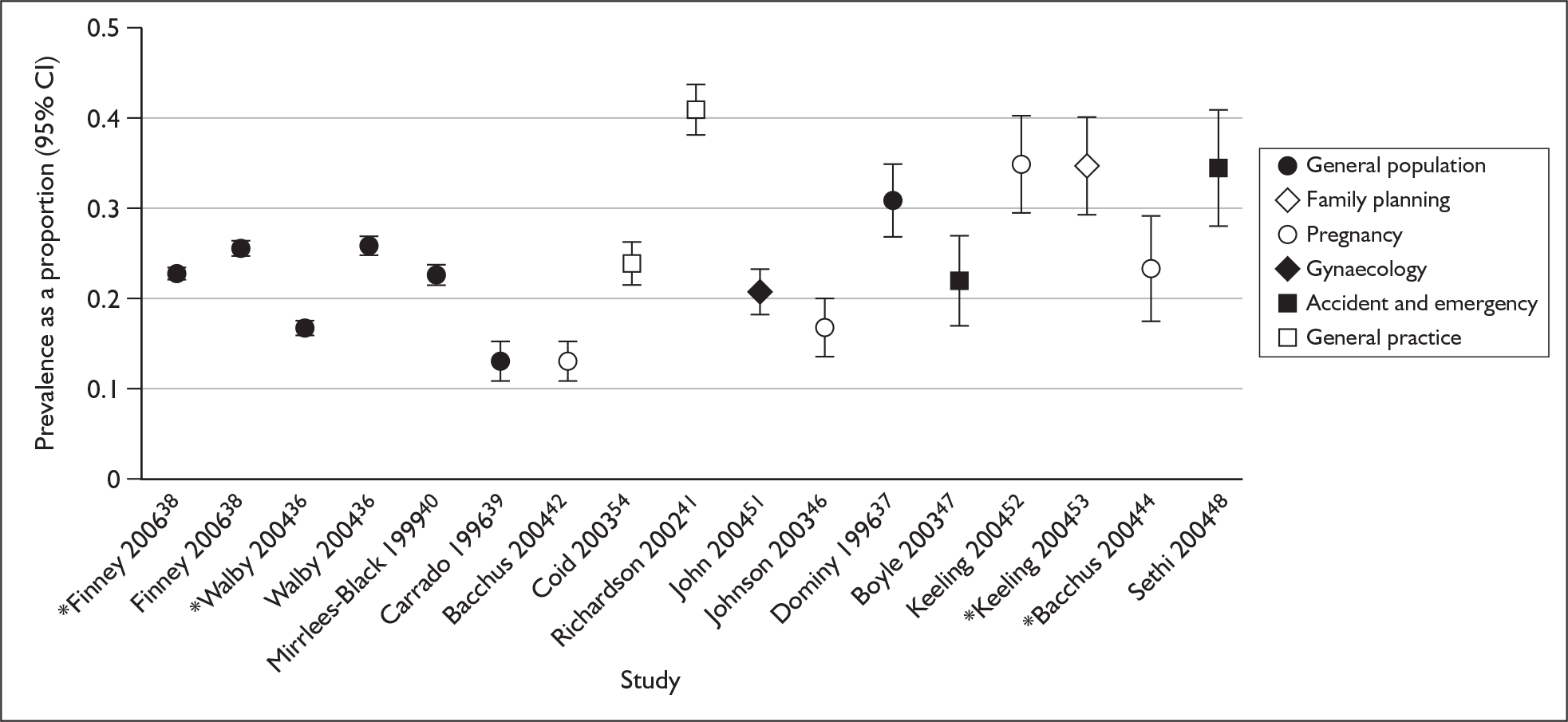

Sixteen studies (reported in 18 papers) met our inclusion criteria. Lifetime prevalence ranged from 13% to 31% in the five community-based samples (general population) and from 13% to 41% in the 11 studies of women recruited in health service settings (clinical populations). One-year prevalence ranged from 4.2% to 6% in the general population studies and from 4% to 19.5% in the clinical population studies. For details of study design, study results and quality appraisal, see Appendix 4.1.

General population

A study by Dominy and Radford37 reported a 31% lifetime prevalence of physical, emotional, sexual and psychological abuse in women living in Surrey. A random sample of 484 women in shopping malls and markets was administered a questionnaire. The sample was intended to be representative of the population of married women or those with long-term partners. However, the venues and timing of the sampling meant that women in full-time employment or education were likely to be under-represented. Women isolated by their partner or having their movements closely monitored by a partner were also likely to be under-represented. For these reasons, both the prevalence cited for partner isolation and the overall prevalence of partner violence may be an underestimate.

Walby and Allen36 measured the prevalence of physical and sexual violence in England and Wales. The study recruited a sample of 22,463 people, weighted to ensure that it was nationally representative. A lifetime prevalence of 25.9% and 1-year prevalence of 6%* were found for female respondents reporting physical, emotional and financial abuse, threats or force. Lifetime prevalence of sexual assault was estimated at 16.6% and 2.1%. These figures may be an underestimate as only people living in private households were included in the sampling frame, so women staying in refuges or with relatives were not included. The study found that younger women and those who were separated were at greater risk of violence.

An updated version of the above study38 used a computerised self-completion method to estimate the prevalence of physical, emotional and financial abuse, threats or force amongst a nationally representative sample of 24,498 men and women. Prevalence figures were adjusted to make them comparable with figures from the above study. The adjusted lifetime prevalence was 25.4% and the 1-year prevalence was 4.7%. The lifetime prevalence of sexual assault was 22.7% and the 1-year prevalence was 2.7%.

A study by Carrado39 used sampling quotas to ensure the sample of 971 women asked about partner violence was representative of the general population with regards to age, socioeconomic group, relationship status and geographical region. The questions relating to violence were administered as a self-completion questionnaire, part of a regular commercial bimonthly survey. The questions were derived from the Conflict Tactics Scale. 19 The study found a 13% lifetime prevalence of physical assault and 1-year prevalence of 5%. It also reported a higher prevalence in women who are young and single.

Mirrlees-Black and Byron40 used a representative sample of 6098 women to estimate the prevalence of partner violence (defined as physical assault) in 16–59-year-olds in England and Wales. They found a lifetime prevalence of 22.7% and 1-year prevalence of 4.2%. They also found that prevalence decreased with age.

Clinical populations

General practice

A study by Richardson et al. 41 measured the prevalence of partner violence in 1207 women attending a general practice, finding a 41% lifetime prevalence and a 17% 1-year prevalence of physical abuse by a partner. Prevalence was higher among women who were divorced or separated, and amongst women aged 16–24 years, and lower in women born outside the UK.

Antenatal/postnatal care

We found five papers (four studies) that estimated the prevalence of partner violence in women attending antenatal or postnatal clinics in the UK.

Bacchus and colleagues42 measured the lifetime prevalence and 1-year prevalence of physical, sexual and emotional abuse in a cohort of 892 women attending maternity services in south London; they asked about partner violence at booking, at 34 weeks of gestation and postpartum. The study reported a lifetime prevalence of 13% and prevalence (during the pregnancy) of 6.4%.

A second study conducted by Bacchus and colleagues43,44 measured a 23.5% lifetime prevalence of partner violence (physical, sexual and psychological) from a sample of 200 women receiving antenatal or postnatal care at a south London hospital.

In a study based on a cohort of 7591 women from 18 weeks’ gestation to 33 months postpartum, Bowen and colleagues45 found that the prevalence (during pregnancy and a 33-month postpartum period) of partner violence steadily increased through the second half of pregnancy and after delivery. At 18 weeks’ gestation, 5.1% of the women experienced some form of abuse (physical, sexual or emotional) and this increased to 11% at 33 months after the birth. However, this study had substantial limitations, including a high attrition rate (45%), which may result in an underestimated prevalence, because those experiencing partner violence were more likely to be lost to follow-up. Moreover, the questionnaires were posted to women, which may have discouraged some respondents from reporting abuse if they were still living with the abuser. A further complication of this study is that the women who completed the study differed from those lost to follow-up: they were more likely to have attended higher education, have fewer children, be married, be at least 25 years old when their first child was born, and be homeowners.

A questionnaire survey by Johnson and colleagues46 of 500 consecutive women in an antenatal booking clinic in a hospital in the north of England found a 17% lifetime prevalence of physical, sexual and emotional abuse in pregnant women. Abuse was most prevalent in women aged between 26 and 30 years.

Thus lifetime prevalence of partner abuse in women receiving antenatal or postnatal care in the UK ranges from 13% to 24%. One-year prevalence was estimated at 6.4% or 11% depending on the type of study and the stage of pregnancy at which women are asked about abuse.

Accident and emergency departments

We found three primary studies that measured the prevalence of partner violence in women attending accident and emergency departments in the UK.

In a study by Boyle and Todd,47 using randomly allocated time blocks, complete data were collected from 256 patients attending the emergency department of a Cambridge hospital. The study reported a 22.1% lifetime prevalence of physical, sexual and emotional abuse.

Sethi and colleagues48,49 purposefully sampled 22 nursing shifts, representative of day, night and weekend shifts. A questionnaire was administered to 198 women attending an inner city accident and emergency department. The study found a 34.8% lifetime prevalence of physical abuse. Prevalence was highest in women aged 30–39 and not in paid employment. A 6.1% 1-year prevalence of physical abuse in the past year was also reported. Neither this nor the Cambridge study reported which specific instrument was used to measure the rate of violence, so the difference in prevalence between the two studies might also be due to the use of different instruments in addition to population differences.

Wright and Kariya50 sought to ask consecutive assault victims attending a Scottish accident and emergency department over a 2-month period about partner violence. The paper reported that 41% of the 46 women asked had experienced partner violence in the past 2 months and that 63% of the women who were survivors of partner violence had experienced previous incidents. The paper did not define types of assault and probably only measured physical assault.

Among women attending accident and emergency departments in the UK, the prevalence of partner violence has been estimated between 22% and 35% depending on the definition adopted.

Gynaecology clinics

We found one study that examined the prevalence of partner violence in women attending gynaecology clinics in the UK. The study, by John and colleagues,51 reported a 21% lifetime prevalence of physical violence and a 1-year prevalence of 4%, with most abuse being perpetrated by ex-husbands or ex-boyfriends (32% and 29% respectively). Prevalence was highest in women aged 31–40 years.

Pregnancy counselling

A study by Keeling52 of women attending pregnancy counselling when seeking a termination reported a 35.1% lifetime prevalence for physical and emotional abuse, with 19.5% of the women having experienced abuse in the past year.

Family planning

A study by Keeling and Birch53 of women attending family planning clinics reported a 34.9% lifetime prevalence of physical, sexual, emotional and financial abuse, with a 1-year prevalence of 14%. Higher prevalence rates were observed in women aged 35–39 years and 45–49 years.

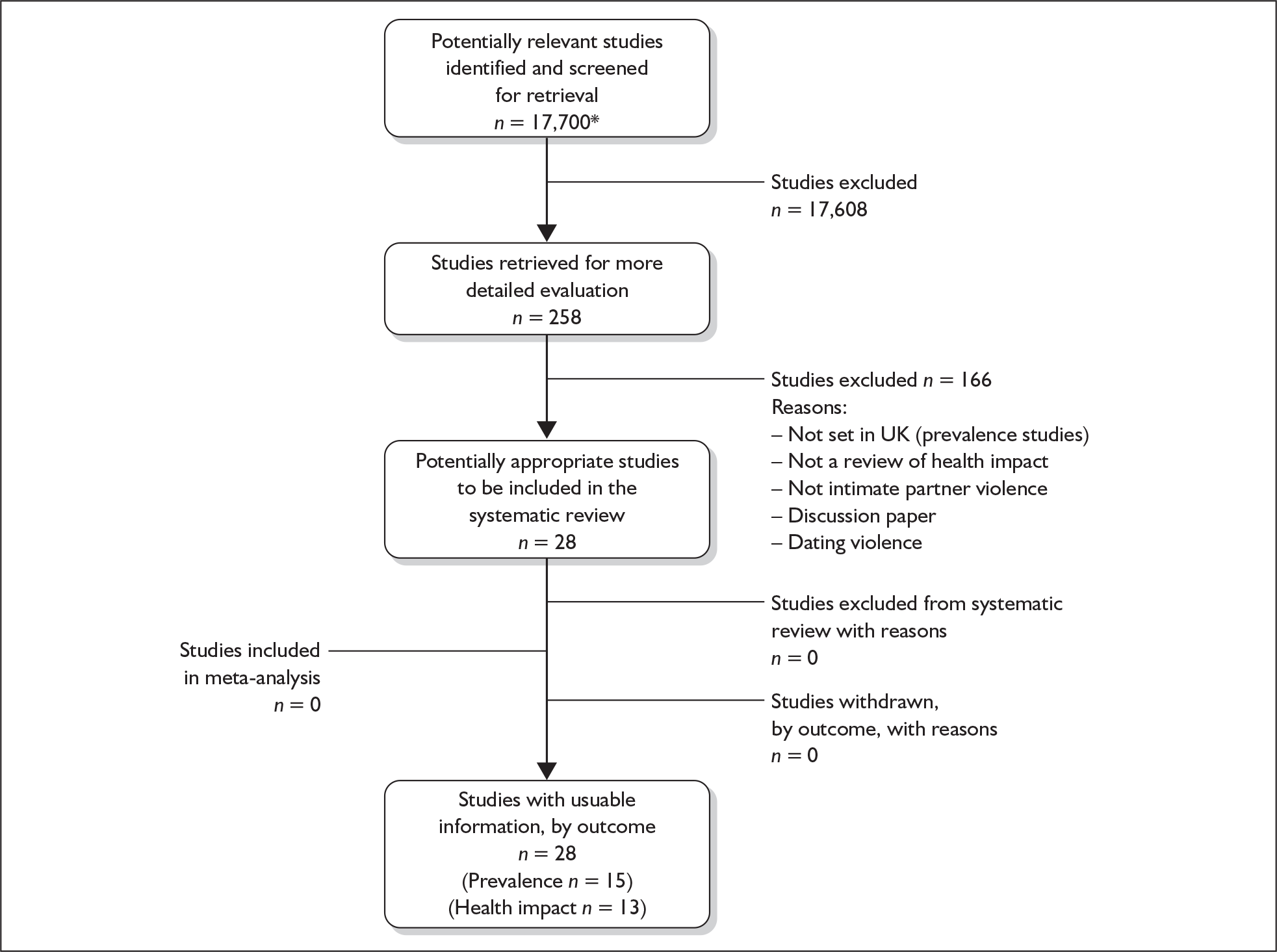

Figures 1 and 2 display the 1-year and lifetime prevalences (with 95% confidence intervals) of partner violence reported in the primary studies, in order of standard error. Table 3 lists the studies and the definitions of intimate partner violence (IPV) used.

FIGURE 2.

Plot of lifetime prevalence of partner violence with 95% confidence intervals. *See Table 3 for definitions of IPV used in these studies.

| Study | Definition of IPV | Study | Definition of IPV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacchus et al., 200442 | Physical, sexual, emotional | Johnson et al., 200346 | Physical, sexual, emotional |

| *Bacchus et al., 200444 | Physical, sexual, psychological | Keeling, 200452 | Physical, emotional |

| Bowen et al., 200545 | Physical, sexual, emotional | *Keeling and Birch, 200453 | Physical, sexual, emotional, financial |

| Boyle and Todd, 200347 | Physical, sexual, emotional | Mirrlees-Black and Byron, 199940 | Physical |

| Carrado, 199639 | Physical | Richardson et al., 200241 | Physical |

| Coid et al., 200354 | Sexual | Sethi et al., 200448 | Physical |

| Dominy and Radford, 199637 | Physical, emotional, sexual and psychological | Walby and Allen, 200436 | Physical, emotional, financial and threats |

| *Finney, 200638 | Physical, emotional, financial and threats | *Walby and Allen, 200436 | Sexual |

| *Finney, 200638 | Sexual | Wright and Kariya, 199750 | Physical |

| John et al., 200451 | Physical |

Table 4 shows the results of a logistic regression model testing whether the definition of IPV used in the studies or type of population (community versus clinical) is associated with variation in prevalence. We found that community populations have significantly lower prevalence, but there was no consistent relationship between the number of different types of IPV measured and the reported prevalence.

| Comparison | Incidence rate ratio | 95% Lower confidence limit | 95% Upper confidence limit | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime prevalence | ||||

| Setting: community vs clinical | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.82 | < 0.001 |

| Count of 2 vs 1 | 1.22 | 1.18 | 1.25 | < 0.001 |

| Types of 3 vs 1 | 0.74 | 0.66 | 0.82 | < 0.001 |

| Violence 4 vs 1 | 1.27 | 1.04 | 1.56 | 0.02 |

| One-year prevalence | ||||

| Setting: community vs clinical | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.27 | < 0.001 |

| Count of 2 vs 1 | 1.83 | 1.70 | 1.96 | < 0.001 |

| Types of 3 vs 1 | 0.93 | 0.83 | 1.05 | 0.24 |

| Violence 4 vs 1 | 1.19 | 0.86 | 1.65 | 0.30 |

Discussion

Estimates of prevalence based on community samples can underestimate the extent of partner violence,56 and estimates of prevalence in clinical samples will overestimate population prevalence, as survivors of partner violence are more likely to need health care than the general public (see below). Both types of studies are useful, however. Community samples will give a better estimate of population prevalence, and clinical samples are essential for understanding the impact of partner violence on health services. Several studies excluded non-English speakers, which may affect the generalisability of results, particularly in UK urban areas.

Those general population studies that scored most highly on the STROBE36,39 assessment tool (see Appendix 4.1) had estimates of prevalence that differed from the lower quality studies; however, there was similar variation in prevalence rates between high-quality studies, so this variation cannot be accounted for by study quality (see Appendix 4.2). It was difficult to compare the clinical population studies due to the heterogeneity of settings, age of the women and the definition of partner violence, but again study quality does not seem to predict prevalence. Within the clinical population studies, the prevalence seems to be highest in women attending accident and emergency departments. The lowest prevalence appears to be in antenatal populations; however, this may be due to women in these samples being younger than in other clinical populations.

Health impact

Results

We found 13 reviews reporting the health consequences of partner violence. Publication dates ranged from 1995 to 2006. Three reported mental health outcomes,57–59 five reported reproductive health effects 60–64 and five reported effects on children. 65–69 For details of review study design and quality appraisal see Appendix 4.3.

Mental health

A meta-analysis by Stith and colleagues70 synthesised results from primary studies published between 1980 and 2000 that measured the association of partner violence with depression and with alcohol abuse. Six studies, with a total of 899 participants, reported the association with depression. The pooled effect size was moderately large (r = 0.28, p < 0.001). The authors state that it is reasonable to assume that depression is a consequence of partner violence, although they did not substantiate this as a separate analysis of longitudinal studies. Eleven studies, with a total of 7084 participants, reported the association between alcohol abuse and partner violence, which was relatively small (r = 0.13, p < 0.001), with some evidence for a bidirectional effect.

Golding57 conducted a meta-analysis and reviewed results from published English language studies on physical abuse and threats of physical force as risk factors for mental health problems in women. Studies were excluded if no specific prevalence rates were given or if the study was limited to women experiencing abuse during pregnancy. Authors looked at the strength of association, consistency, temporality and biological gradient. Significant associations were found between partner violence and all outcome measures: depression, suicidality, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), alcohol abuse or dependence, and drug abuse or dependence. When prevalence rates of mental health problems among survivors of partner violence were compared with those reported in general populations, the association with abuse was strong. A second indicator of strength of association was the odds ratio calculated from the subset of studies of survivors of partner violence in which comparison groups were used. The weighted mean odds ratio ranged from 3.6 to 3.8 in studies of depression, suicidality and PTSD, and was 5.6 in studies of alcohol and drug abuse or dependence. Although absolute prevalence rates varied across studies, the magnitude of association between partner violence and mental health problems was more consistent. The size of this association was statistically homogeneous in studies of PTSD, alcohol abuse and drug abuse. In studies of depression and suicidality, the variability among odds ratios was accounted for by sampling frames. The studies indicate that depression tends to lessen following the cessation of violence, and depression and PTSD seem to respond to the presence or absence of violence. Severity or duration of violence was associated with the prevalence or severity of both depression and PTSD, suggesting that dose–response relationships appear to exist for these disorders. Overall this review provides compelling evidence that adverse mental health outcomes can be a consequence of physical abuse or the threat of physical violence.

Jones and colleagues58 reviewed 43 studies of survivors of partner violence published between 1991 and 2001, to estimate the association of partner violence and PTSD. A consistent finding across varied samples (from clinical settings, refuges, hospitals and community agencies) was that a substantial proportion of survivors (31–84%) exhibit PTSD symptoms. The review also found that the partner violence refuge population is at a higher risk for PTSD than survivors who are not in refuge. The extent, severity and type of abuse were found to be associated with the intensity of PTSD.

Reproductive health

In a review of 14 published case–control and cohort studies, Murphy and colleagues64 determined whether there is evidence for an association between physical, sexual or emotional abuse during pregnancy and low birthweight. Studies had to have English language abstracts, focus on women abused during pregnancy or pregnant women with a past abusive relationship, and fulfil quality criteria. Only 8 out of 14 studies fulfilled all the inclusion criteria and were entered into a meta-analysis; this gave a pooled odds ratio of 1.4 (95% confidence interval 1.1–1.8) for a low birthweight baby in women who reported physical, sexual or emotional abuse during pregnancy, compared with non-abused women. Removing the two case–control studies from the analysis reduced the odds ratio to 1.3 (95% confidence interval 1.0–1.8). This meta-analysis provides tentative evidence of an association between partner violence during pregnancy and low birthweight babies.

Boy and Salihu62 reviewed 30 peer-reviewed studies on the impact of partner violence (physical, sexual and emotional) on pregnancy and birth outcomes. To be included in their review, studies must have been peer reviewed and research based, included a study population of at least five women, pertained to partner violence, included pregnant participants and included data on the outcomes searched. One study, which focused on partner violence and trauma during pregnancy, found that 88% of the pregnant women who had been physically injured had been attacked by their husband or boyfriend. In this population eight fetal deaths occurred, with one fetal death being the result of an assault, yielding a violence-related fetal mortality rate of 16.0 per 1000. Of the six studies focusing on maternal mortality, one case–control death review found that a woman abused during pregnancy was three times more likely to be killed by a partner as a woman who is not abused (odds ratio 3.08, 95% confidence interval 1.9–5.1). The remaining five studies on maternal mortality were based on death reviews and reported that more than half the deaths were the result of murder; the involvement of a husband or boyfriend was documented in multiple instances. Three death reviews focused on intentional trauma deaths; all noted that the majority of homicides were the result of partner violence. Twenty-three studies looked at partner violence and pregnancy outcomes. Three cohort studies found no significant differences between abused women and non-abused women, 7 studies reported mixed results, and the remaining 13 found significant differences between the outcomes of abused women and non-abused pregnant women. The three cohort studies that found no association between physical violence and negative outcomes did, however, note differences between abused and non-abused pregnant women: abused women were more likely to have uterine contractions and increased peripartum complications (p < 0.05)71 and were also significantly more likely to report substance use during the pregnancy (p < 0.001). 72 Out of the seven studies reporting mixed results, two addressed fetal death and found that mothers abused during pregnancy were 3.7 times more likely to have a fetal death (95% confidence interval 1.36–9.94); they also suffered higher rates of miscarriage (p < 0.05). None of the seven studies indicated a relationship with low birthweight or preterm delivery; however, two studies found the smallest babies were born to abused women. Six of the seven studies reported a variety of negative behaviours and complications in abused women. Abused women were found to have more kidney infections (odds ratio 2.7, 95% confidence interval 1.3–5.5) and were 1.5 times more likely to deliver by Caesarean section. Three studies reported significantly higher rates of substance abuse during pregnancy in abused compared with non-abused women. Ten of the 13 studies with significant differences found a significantly higher proportion of low birthweight babies in women abused during pregnancy. In the studies reporting a relationship between low birthweight and partner violence, the percentage of abused women delivering a low birthweight infant ranged from 9% to 22%. Preterm delivery was also reported as a negative outcome due to violence. Four studies reported an increased risk of preterm delivery among abused women compared with non-abused women. One study found a statistically significant difference only in a private hospital. The relative risk for delivering a preterm infant if the pregnant woman was abused ranged from 1.6 (95% confidence interval 1.14–2.28) to 2.7 (95% confidence interval 1.7–4.4). Victims of violence were more likely to have negative health behaviours during pregnancy: 10 studies reported greater use of alcohol and other substances when compared with non-abused women; and two studies also noted that abused women were at increased risk of low weight gain during pregnancy.

A review of nursing studies (including qualitative designs) published after 1995 on the relationship between partner violence and women’s reproductive health was conducted by Campbell and colleagues. 61 Two studies examined the effects of forced sex on women’s health. One study found that sexually assaulted women had significantly more gynaecological problems than those who were not sexually assaulted (p = 0.026). That study also found that women reporting more forced sex experiences reported significantly greater levels of depression (p = 0.018) and a less positive physical self-image than those not sexually assaulted. The second study found that women who were sexually and physically abused had more symptoms than those who were only sexually abused. One study investigated the association between abuse and risk of sexually transmitted infections, and found the rate among the abused, assaulted and raped groups (29%, 31% and 31.3% respectively) was significantly higher than in non-abused women (14.9%, p = 0.0001). One study examined records from 389 sexual assault victims, 71% of whom knew the perpetrator; it found that more than three-quarters (78.3%) of those resuming sexual activities reported sexual difficulties and 17.1% reported gynaecological pain, but almost all of them had normal general physical (98%) and gynaecological (95%) examinations.

A literature review by Jasinski60 reviewed findings on the relationship between partner violence and pregnancy, including the health consequences for the mother and child. Two studies were found that suggested partner violence was associated with late booking into antenatal care. Five studies found an association between partner violence and low birthweight, whereas two did not. The author raised the possibility that the finding of no relationship may be due to confounding variables, such as low socioeconomic status and gestation. Sample size differences and the lack of a standard cut-off for what constitutes low birthweight may also account for the conflicting findings. Evidence regarding the relationship between partner violence and premature labour was also found to be contradictory, with four studies finding an association and three finding none.

Nasir and Hyder63 reviewed findings from three English language studies on the impact of partner violence on adverse pregnancy outcomes in developing countries. A study in Nicaragua demonstrated that women with low birthweight babies were more likely to have experienced abuse during pregnancy (odds ratio 2.07 for threats, 3.27 for slaps, 5.04 for blows), and a multivariate analysis showed partner violence to be a strong risk factor. A study in India reported that women who had suffered beatings were significantly more likely to have experienced miscarriage or infant death (p < 0.05). Another study failed to demonstrate any significant difference in pregnancy outcomes between abused and non-abused women in China; however, it is not stated which outcomes were measured.

Impact on children’s health

In total, we identified five reviews reporting the impact that witnessing partner violence had on the health of child witnesses. Publication dates range from 1995 to 2006.

Buehler and colleagues65 conducted a meta-analysis of 68 studies (including dissertations), published in English, to explore whether interparental conflict is associated with internalising and externalising problems in children aged 5–18 years. The average effect size of the association between interparental conflict and youth problem behaviour was 0.32 (weak to moderate effect). Variability in these effects was explained by the characteristics of participants and methodological variables. The review provides some evidence that conflict between parents is one of several important familial correlates of internalising and externalising youth problem behaviours; however, the authors state this conclusion must be tempered given that 66% of the effects in this meta-analysis were non-significant.

A review by Bair-Merritt and colleagues,66 measuring the relationship between exposure to partner violence and postnatal physical health using contemporaneous control groups, contained 22 studies. Eight studies addressed general health and use of health services. Although children exposed to partner violence are at risk of under-immunisation, the evidence is inconclusive regarding overall health status and use of health services. Evidence was insufficient to draw a conclusion about whether abused women are less likely to breastfeed than non-abused women, as only one study was found which addressed this issue. Evidence was also insufficient to draw a conclusion about whether infants born to abused mothers were more likely to have poor weight gain than infants born to non-abused mothers, as only two studies addressed this issue. Based on seven studies, there was an association between witnessing partner violence and adolescent and adult risk-taking behaviours (including smoking, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, sexually transmitted infections, teenage pregnancy and unintended adult pregnancy).